テロリズム

political terror, terrorism

United Airlines Flight 175 hits the South Tower of the World Trade Center during the September 11 attacks of 2001 in New York City, an act of terrorism planned by Osama bin Laden and executed by al-Qaeda

☆テ ロリズム(terrorism)とは、政治を遂行するために恐怖を手段として利用すること。テロリズムはしばしば恐怖政治(=恐怖の運用形 態)と呼ばれることがあるが、その語義に従えば恐怖主義(terror + -ism)、すなわち恐怖を手段とす る一時的、恒久的統治手段あるいは思想のことをいう。テロリズムを手段として利用する者をテロリストと呼ぶ。

通

常の用法では、恐怖は、広義の暴力や権力とアナロジーされることがあるので、このような文脈で捉えれば、現実の政治はおしなべてテロリズム的

性格を内包する。しかし、そのようなことに無自覚になれば、恐怖を使うことが、政治の本来の目標を凌駕し、暴力や権力行使そのものが自己目的化するような

逸脱ケースを、テロリズムと呼ぶことになる。しかし、これは上のように、恐怖の運用形態に他ならず、「恐怖を手段とす

る一時的、恒久的統治手段あるいは思想のこと」ことが忘れがちになる。いずれにせよ、テロリズムを常套的な手段として使うことのない人たちは、テロリズム

の運用形態よりも、その運用概念において恐怖する。そのテロリズムの圏外では、人々はテロリズムを恐怖するだけでなく、嫌悪することが一般である。そし

て、我々はテロリズムを非難する立場——テロリズムは全体主義と同様に合理的精神で管理することが困難な代物である——から、テロリズムやテロリストと、

敵対する政治党派やグループを価値判断し、かつスティグマ化して使うことに慣れている。そのため、テロリズムやテロリストは、負のレッテルとして世間に流

布することになる。

| Terrorism,

in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to

achieve political or ideological aims.[1] The term is used in this

regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or

in the context of war against non-combatants.[2] There are various

different definitions of terrorism, with no universal agreement about

it.[3][4][5] Different definitions of terrorism emphasize its

randomness, its aim to instill fear, and its broader impact beyond its

immediate victims.[1] Modern terrorism, evolving from earlier iterations, employs various tactics to pursue political goals, often leveraging fear as a strategic tool to influence decision makers. By targeting densely populated public areas such as transportation hubs, airports, shopping centers, tourist attractions, and nightlife venues, terrorists aim to instill widespread insecurity, prompting policy changes through psychological manipulation and undermining confidence in security measures.[6] The terms "terrorist" and "terrorism" originated during the French Revolution of the late 18th century,[7] but became widely used internationally and gained worldwide attention in the 1970s during the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the Basque conflict and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. The increased use of suicide attacks from the 1980s onwards was typified by the September 11 attacks in the United States in 2001. The Global Terrorism Database, maintained by the University of Maryland, College Park, has recorded more than 61,000 incidents of non-state terrorism, resulting in at least 140,000 deaths between 2000 and 2014.[8] Various organizations and countries have used terrorism to achieve their objectives. These include left-wing and right-wing political organizations, nationalist groups, religious groups, revolutionaries, and ruling governments.[9] In recent decades, hybrid terrorist organizations have emerged, incorporating both military and political arms.[1] State terrorism, with its institutionalized instrumentation of terror tactics through massacres, genocides, forced disappearances, carpet bombings and torture, is a deadlier form of terrorism than non-state terrorism.[10][11][12][13] |

テ

ロリズム(terrorism)とは、最も広義には、政治的または思想的な目的を達成するために非戦闘員に対して暴力を使うことを指します。[1]

この用語は、主に平時または戦争において非戦闘者に対して意図的に行われる暴力を指す。 [2]

テロリズムにはさまざまな定義があり、普遍的な合意は存在しない。[3][4][5]

テロリズムの定義は、その無差別性、恐怖の植え付けという目的、直接の犠牲者以外の広範な影響力など、さまざまな側面を強調したものがある。[1] 以前の形態から進化した現代のテロリズムは、政治的目的を達成するためにさまざまな戦術を採用し、意思決定者に影響を与えるための戦略的手段として恐怖を 利用することが多い。テロリストは、交通機関、空港、ショッピングセンター、観光名所、ナイトライフ施設など、人口密集した公共の場所を標的とし、心理操 作によって政策の変更を促し、治安対策に対する信頼を損なうことで、広範な不安を植え付けることを目指している。[6] 「テロリスト」と「テロリズム」という用語は、18世紀後半のフランス革命で生まれた[7]が、1970年代に北アイルランド紛争、バスク紛争、イスラエ ル・パレスチナ紛争を通じて国際的に広く使用され、世界的な注目を集めるようになった。1980年代以降、自爆攻撃の増加は、2001年のアメリカ合衆国 での9月11日同時多発テロ事件で典型化されました。メリーランド大学カレッジパーク校が維持する「グローバル・テロリズム・データベース」は、2000 年から2014年までの間に、非国家主体によるテロリズム事件61,000件以上を記録し、少なくとも140,000人の死亡者を出しています。[8] さまざまな組織や国が、その目的を達成するためにテロリズムを利用してきた。その中には、左翼および右翼の政治組織、ナショナリスト集団、宗教団体、革命 家、与党政府などが含まれる。[9] ここ数十年間、軍事部門と政治部門の両方を組み込んだハイブリッド型のテロ組織が出現している。[1] 国家テロリズムは、虐殺、ジェノサイド、強制失踪、絨毯爆撃、拷問などのテロ戦術を制度化して実施する形態であり、非国家テロリズムよりも致命的な形態の テロリズムです。[10][11][12][13] |

| Etymology and definition Etymology See also: Reign of Terror  Seal of the Jacobin Club The term "terrorism" itself was originally used to describe the actions of the Jacobin Club during the "Reign of Terror" in the French Revolution. "Terror is nothing other than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible", said Jacobin leader Maximilien Robespierre.[14] In 1795, Edmund Burke denounced the Jacobins for letting "thousands of those hell-hounds called Terrorists ... loose on the people" of France.[15] John Calvin's rule over Geneva in the 16th century has also been described as a reign of terror.[16][17][18] The terms "terrorism" and "terrorist" gained renewed currency in the 1970s as a result of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO),[19] the Irish Republican Army (IRA),[20] the Basque separatist group, ETA,[21] and the operations of groups such as the Red Army Faction.[22] Leila Khaled was described as a terrorist in a 1970 issue of Life magazine.[23] A number of books on terrorism were published in the 1970s.[24] The topic came further to the fore after the 1983 Beirut barracks bombings[25] and again after the 2001 September 11 attacks[25][26][27] and the 2002 Bali bombings.[25] |

語源と定義 語源 関連項目:恐怖政治  ジャコバンクラブの印章 「テロリズム」という用語自体は、もともとフランス革命の「恐怖政治」におけるジャコバンクラブの行動を表すために使用された。「恐怖とは、迅速、厳格、 そして柔軟性のない正義に他ならない」と、ジャコバンクラブの指導者、マキシミリアン・ロベスピエールは述べた。[14] 1795年、エドマンド・バークは、ジャコバン派が「テロリストと呼ばれる何千人もの地獄の犬たちを...フランスの人民に放った」と非難した。[15] 16世紀のジョン・カルヴァンのジュネーブ支配も、恐怖政治と表現されている。[16][17][18] 「テロリズム」および「テロリスト」という用語は、1970年代、パレスチナ解放機構(PLO)、[19] アイルランド共和国軍(IRA)、[20] バスクの分離独立組織 ETA、[21] および赤軍派などのグループの活動により、再び広く使用されるようになった。[22] レイラ・ハレドは、1970年の『ライフ』誌でテロリストと形容された。[23] 1970年代には、テロリズムに関する多くの書籍が出版された。[24] このテーマは、1983年のベイルート兵舎爆破事件[25]、2001年の9月11日同時多発テロ[25][26][27]、2002年のバリ島爆破事件 [25] を経て、さらに注目されるようになった。 |

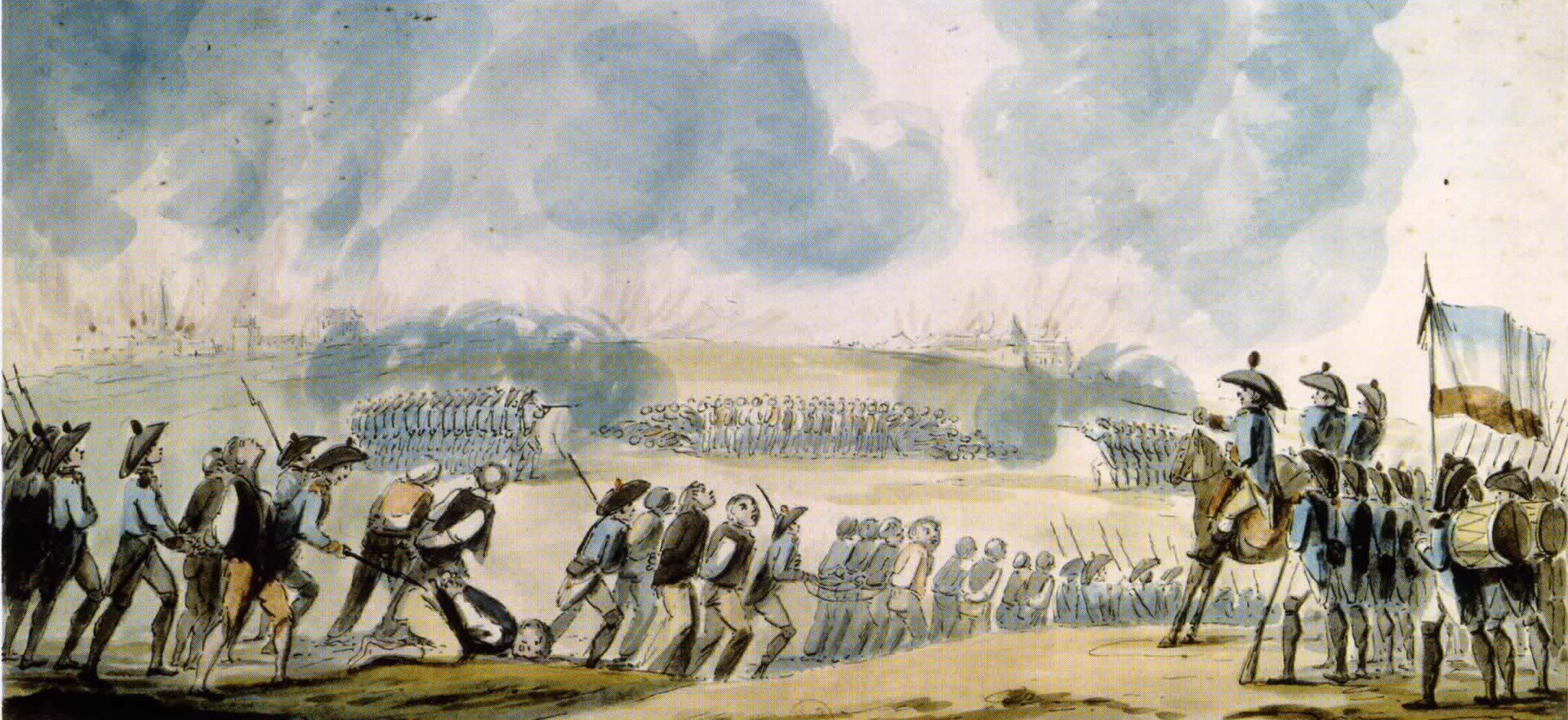

| Definition Main article: Definition of terrorism  Mass killings in the Vendée during the Reign of Terror in France, 1793 No definition of terrorism has gained universal agreement.[28][29] Challenges emerge due to the politically and emotionally charged nature of the term, the double standards used in applying it,[30] and disagreement over the nature of terrorist acts and limits of the right to self-determination.[31][32] Harvard law professor Richard Baxter, a leading expert on the law of war, was a skeptic: "We have cause to regret that a legal concept of 'terrorism' was ever inflicted upon us. The term is imprecise; it is ambiguous; and above all, it serves no operative legal purpose."[33][32] Different legal systems and government agencies employ diverse definitions of terrorism, with governments showing hesitation in establishing a universally accepted, legally binding definition. Title 18 of the United States Code §2231, part of Chapter 113B, defines terrorism as acts that are intended to (1) intimidate or coerce civilians, (2) influence government policy by coercion, or (3) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping.[34] The international community has been slow to formulate a universally agreed, legally binding definition of this crime, and has been unable to conclude a Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism that incorporates a single, all-encompassing, legally binding, criminal law definition of terrorism.[35] These difficulties arise from the fact that the term "terrorism" is politically and emotionally charged.[36][37] The international community has instead adopted a series of sectoral conventions, which do not have terrorism as a single cohesive criminal offense of terrorism. Rather sectoral conventions criminalizes various types of criminal activities involved in the commission of terrorism (for example homicide). [38] Counterterrorism analyst Bruce Hoffman has noted that it is not only individual agencies within the same governmental apparatus that cannot agree on a single definition of terrorism; experts and other long-established scholars in the field are equally incapable of reaching a consensus.[39] In 1992, terrorism studies scholar Alex P. Schmid proposed a simple definition to the United Nations Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (CCPCJ) as "peacetime equivalents of war crimes", but it was not accepted.[40][41] In 2006, it was estimated that there were over 109 different definitions of terrorism.[42] |

定義 主な記事:テロリズムの定義  1793年のフランス恐怖政治時代、ヴァンデ地方で起こった大量殺戮 テロリズムの定義について、普遍的な合意は得られていない[28][29]。この用語は政治的、感情的な要素が強いこと、その適用に二重基準が用いられる こと[30]、テロ行為の性質や自決権の限界について意見が分かれていることから、課題が生じている。[31][32] ハーバード大学法学教授で戦争法分野の権威であるリチャード・バクスターは懐疑的だった:「『テロリズム』という法的概念が私たちに強要されたことを後悔 すべきだ。この用語は不正確で曖昧であり、何より法的実効性がない。」[33][32] 異なる法制度や政府機関は、テロリズムについてさまざまな定義を採用しており、各国政府は、普遍的に受け入れられ、法的拘束力のある定義の確立に躊躇して いる。米国法典第18編第2231条(第113B章の一部)は、テロリズムを、(1) 民間人を威嚇または強制する目的、(2) 強制により政府の政策に影響を与える目的、または(3) 大規模破壊、暗殺、または誘拐により政府の行動に影響を与える目的でなされる行為と定義している。[34] 国際社会は、この犯罪に関する普遍的に合意された法的拘束力のある定義を策定する点で遅れており、テロリズムを単一で包括的な法的拘束力のある刑事法上の 犯罪として定義する「国際テロリズムに関する包括的条約」を締結できていない。[35] これらの困難は、テロリズムという用語が政治的・感情的に敏感な問題であることから生じている。[36][37] 国際社会は代わりに、テロリズムを単一の統合された犯罪として規定しない一連の分野別条約を採用してきた。むしろ、分野別条約は、テロリズムの遂行に関連 するさまざまな犯罪行為(例えば殺人)を犯罪化している。[38] テロ対策アナリストのブルース・ホフマン氏は、同じ政府機関内の個々の機関だけがテロリズムの単一の定義について合意できないのではなく、この分野の専門 家や長年の学者たちも同様に合意に達することができないと指摘している。[39] 1992 年、テロリズム研究者のアレックス・P・シュミットは、国連犯罪防止刑事司法委員会(CCPCJ)に対して、「平時の戦争犯罪に相当する行為」という単純 な定義を提案したが、これは採用されなかった。[40][41] 2006 年には、テロリズムの定義は 109 種類以上あると推定されていた。[42] |

| History Main article: History of terrorism Pre-modern terrorism Early published studies like Paul Wilkinson considered terrorism a product of 19th-century revolutionary politics. Technological developments like the pistol and dynamite made possible the relentless onslaught of successful attacks and assassinations that shook the 19th-century.[43][44] For the most part, scholars considered terrorism a modern phenomenon until David C. Rapoport published his seminal article Fear and Trembling: Terrorism in Three Religious Traditions in 1984.[43] Rapoport proposed three case studies to demonstrate "ancient lineage" of religious terrorism, which he called "sacred terror": the "Thugs", the Assassins and the Jewish Sicarii Zealots. Rapoport argued religious terrorism has been ongoing since ancient times and that "there are signs that it is reviving in new and unusual forms". He is the first to propose that religious doctrines were more important than political rationales for some terrorist groups.[45][46] Rapoport's work has since become the basis of the model of "New Terrorism" proposed by Bruce Hoffman and developed by other scholars. "New Terrorism" has had an unparalleled impact on policymaking. Critics have pointed out that the model is politically charged and over-simplified. The underlying historical assertions have received less critical attention.[47] According to The Oxford Handbook on the History of Terrorism:[43] Since the publication of Rapoport's article, it has become seemingly pre-requisite for standard works on terrorism to cite the three case studies and to reproduce uncritically its findings. In lieu of empirical research, authors tend to crudely paraphrase Rapoport and the assumed relevance of "Thuggee" to the study of modern terrorism is taken for granted. Yet the significance of the article is not simply a matter of citations―it has also provided the foundation for what has become known as the "New Terrorism" paradigm. While Rapoport did not suggest which late 20th century groups might exemplify the implied recurrence of "holy terror", Bruce Hoffman, recognized today as one of the world's leading terrorism experts, did not hesitate to do so. A decade after Rapoport's article. Hoffman picked up the mantle and taking the three case studies as inspiration, he formulated a model of contemporary "holy terror" or, as he defined it, "terrorism motivated by a religious imperative". Completely distinct from "secular terrorists", Hoffman argued that "religious terrorists" carry out indiscriminate acts of violence as a divine duty with no consideration for political efficacy―their aim is transcendental and "holy terror" constitutes an end in itself. Hoffman's concept has since been taken up and developed by a number of other writers, including Walter Laquer, Steven Simon and Daniel Benjamen, and rebranded as the "New Terrorism". |

歴史 主な記事:テロリズムの歴史 前近代的なテロリズム ポール・ウィルキンソンなどの初期の研究では、テロリズムは 19 世紀の革命政治の産物であると見なされていました。ピストルやダイナマイトなどの技術の発展により、19 世紀を揺るがすような、執拗な攻撃や暗殺が成功裏に繰り返されるようになったのです。[43][44] 1984年にデビッド・C・ラポポートが、画期的な論文「恐怖と震え:3つの宗教的伝統におけるテロリズム」を発表するまで、学者たちはテロリズムを主に 現代的な現象と捉えていた。[43] ラポポートは、宗教的テロリズムの「古代の系譜」を実証するために、3つの事例研究を提案した。彼はこれを「神聖な恐怖」と呼んだ。その3つは、「トゥグ ス」、「暗殺教団」、そしてユダヤ人のシカリイ・ゼアルトである。ラポポートは、宗教的テロリズムは古代から継続しており、「新たな形態で再興する兆候が ある」と主張した。彼は、一部のテロ組織において宗教的教義が政治的理由よりも重要だったと初めて指摘した。[45][46] ラポポートの著作は、ブルース・ホフマンが提唱し、他の学者によって発展させた「新テロリズム」モデルの基盤となった。「新テロリズム」は政策立案に前例 のない影響を与えた。批判者は、このモデルが政治的に偏向しており、過度に単純化されていると指摘している。その歴史的主張は、批判的な検討を十分に受け ていない。[47] 『オックスフォード・ハンドブック テロリズムの歴史』によると:[43] ラポポートの論文が発表されて以来、テロリズムに関する標準的な著作では、3つの事例研究を引用し、その発見を批判的に検討せずに再現することが、ほぼ必 須条件となっている。実証的研究に代わって、著者はラポポートの主張を粗雑に要約する傾向があり、「トゥギー」が現代テロリズムの研究に持つ関連性は当然 のこととして受け止められている。しかし、この記事の意義は単に引用数にあるわけではない。それは「新テロリズム」パラダイムと呼ばれるものの基盤を提供 した点にもある。ラポポートは、20世紀後半のどのグループが「聖なるテロ」の反復を体現するかを示唆しなかったが、現在世界有数のテロリズム専門家とし て知られるブルース・ホフマンは、躊躇なくそう指摘した。ラポポートの論文から10年後、ホフマンはバトンを継承し、3つのケーススタディをヒントに、現 代の「聖なるテロ」または彼が定義した「宗教的義務に基づくテロリズム」のモデルを提唱した。ホフマンは、「世俗的テロリスト」とは完全に異なる「宗教的 テロリスト」は、政治的有効性を考慮せず、神の命令として無差別な暴力行為を実行すると主張した。彼らの目的は超越的で、「聖なる恐怖」自体が目的であ る。ホフマンの概念はその後、ウォルター・ラカー、スティーブン・シモン、ダニエル・ベンジャメンなど多くの研究者によって取り上げられ発展し、 「ニュー・テロリズム」として再定義された。 |

| Birth of modern terrorism (1850-1890s) Arguably, the first organization to use modern terrorist techniques was the Irish Republican Brotherhood,[48] founded in 1858 as a revolutionary Irish nationalist group[49] that carried out attacks in England.[50] The group initiated the Fenian dynamite campaign in 1881, one of the first modern terror campaigns.[51] Instead of earlier forms of terrorism based on political assassination, this campaign used timed explosives with the express aim of sowing fear in the very heart of metropolitan Britain, in order to achieve political gains.[52]  Representation of the aftermath of the Saint Germain bombing in L'Illustration (19 March 1892),[53] an attack that ushered in the Ère des attentats Another early terrorist-type group was Narodnaya Volya, founded in Russia in 1878 as a revolutionary anarchist group inspired by Sergei Nechayev and "propaganda by the deed" theorist Carlo Pisacane.[54][55] The group developed ideas—such as targeted killing of the 'leaders of oppression', which were to become the hallmark of subsequent violence by small non-state groups, and they were convinced that the developing technologies of the age—such as the invention of dynamite, which they were the first anarchist group to make widespread use of[56]—enabled them to strike directly and with discrimination.[57] In the Western world, and more specifically in France, the repression faced by anarchists from the state led, in the early 1890s, to France's entry into the Ère des attentats (1892-1894). This period, characterized by a surge in terrorist acts following Ravachol's bombings, saw several shifts that pushed terrorism toward modern terrorism.[58][59] As with the Fenian campaign, terrorism shifted from being person-based to location-based, starting with the first attack of that period, the Saint-Germain bombing.[58] However, other major evolutions emerged during this period: the apparition of lone wolves[60] and the birth of mass or indiscriminate terrorism.[59] Indeed, in the second half of the Ère des attentats, three incidents laid the foundation for mass terrorism within a few months of each other. These were the Liceu bombing, the 13 November 1893 stabbing, and the Café Terminus attack.[59] In each of these attacks, the perpetrators targeted not a specific individual but a collective enemy.[59] Émile Henry, in particular, responsible for the Café Terminus bombing, explicitly claimed the birth of this new form of terrorism, stating that he wanted to 'strike at random'.[59] |

現代テロリズムの誕生(1850年代~1890年代) 現代的なテロ手法を初めて採用した組織は、1858年にアイルランドの革命的なナショナリスト集団として設立され、イギリスで攻撃を行ったアイルランド共 和国兄弟団[48] であるといえるでしょう。[50] この組織は、1881年に、最初の近代的なテロキャンペーンの一つであるフェニアン・ダイナマイト事件を起こした。このキャンペーンは、政治的な暗殺に基 づく以前のテロとは異なり、政治的な利益を得るために、英国の首都の心臓部に恐怖を植え付けることを明確な目的として、時限爆弾を使用した。  1892年3月19日の『L'Illustration』に掲載された、サン・ジェルマン爆弾事件後の様子[53]。この事件は、Ère des attentats(テロの時代)の幕開けとなった。 もう一つの初期のテロリスト集団は、1878年にセルゲイ・ネチャエフと「行動による宣伝」の理論家カルロ・ピサカーネに触発されてロシアで設立された革 命的なアナキスト集団、ナロドナヤ・ヴォリヤだった。[54][55] このグループは、「抑圧の指導者」を標的とした殺害など、その後の小規模な非国家組織による暴力の特徴となる考え方を発展させ、ダイナマイトの発明など、 当時発展していた技術(このグループは、アナキストとして初めてダイナマイトを広く利用した[56])を利用すれば、差別的に直接攻撃を行うことができる と確信していた。[57] 西洋世界、より具体的にはフランスでは、国家によるアナキストに対する弾圧により、1890年代初頭、フランスは「テロの時代」(1892年~1894 年)に入った。この期間は、ラヴァショールの爆弾事件をきっかけとしたテロ行為の急増が特徴で、テロリズムを現代のテロリズムへと押しやるいくつかの変化 が見られた[58]。[59] フェニアン運動と同様、テロリズムは、この時代の最初の攻撃であるサン・ジェルマン爆弾事件をきっかけに、人物を対象とするものから場所を対象とするもの へと変化した。[58] しかし、この期間には、他の大きな変化も起こった。それは、一匹狼の出現[60] と、大量または無差別テロリズムの誕生だ[59]。実際、テロの時代(Ère des attentats)の後半には、数ヶ月間に 3 件の事件が発生し、大量テロリズムの基盤が築かれた。それは、リセウ爆弾事件、1893 年 11 月 13 日の刺殺事件、カフェ・テルミナス襲撃事件だ。[59] これらの攻撃はいずれも、特定の個人ではなく、集団としての敵を標的としていた[59]。特に、カフェ・テルミニュの爆弾事件の実行犯であるエミール・ア ンリは、「無差別に攻撃する」と明言し、この新しい形のテロリズムの誕生を公言した[59]。 |

| Modern terrorism (1900-present) In 1920 Leon Trotsky wrote Terrorism and Communism to justify the Red Terror and defend the moral superiority of revolutionary terrorism.[61] The assassination of the Empress of Austria Elisabeth in 1898 resulted in the International Conference of Rome for the Social Defense Against Anarchists, the first international conference against terrorism.[62] According to Bruce Hoffman of the RAND Corporation, in 1980, 2 out of 64 terrorist groups were categorized as having religious motivation while in 1995, almost half (26 out of 56) were religiously motivated with the majority having Islam as their guiding force.[63][64] |

現代テロリズム(1900年~現在) 1920年、レオン・トロツキーは『テロリズムと共産主義』を執筆し、赤のテロを正当化し、革命テロリズムの道徳的優位性を擁護した[61]。 1898年のオーストリア皇后エリザベスの暗殺事件を受けて、テロリズムに対抗する最初の国際会議である「ローマ国際会議」が開催された。[62] ランド研究所のブルース・ホフマンによると、1980年には64のテロリスト集団のうち2つだけが宗教的動機を持つと分類されたが、1995年にはほぼ半数(56のうち26)が宗教的動機を持ち、その大半はイスラム教を指針としていた。[63][64] |

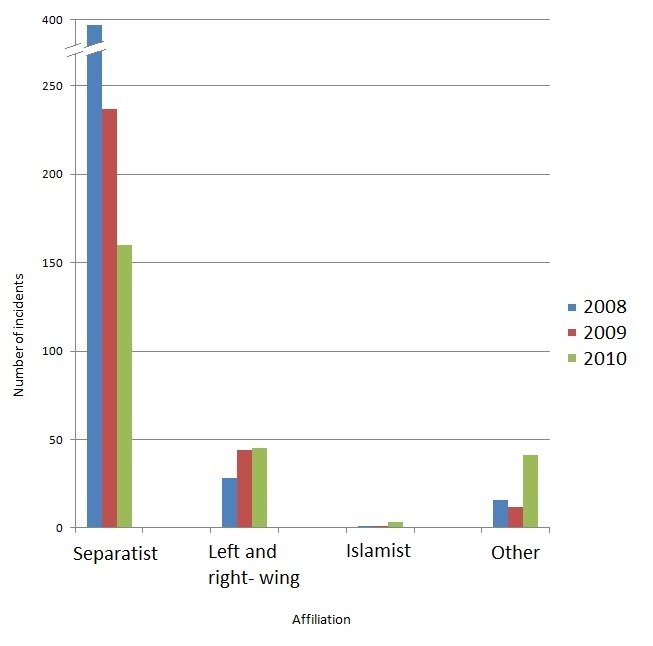

| Types of terrorism This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Depending on the country, the political system, and the time in history, the types of terrorism are varying.  Number of failed, foiled or successful terrorist attacks by year and type within the European Union. Source: Europol.[65][66][67]  A view of damage to the U.S. Embassy in the aftermath of the 1983 Beirut bombing caused by Islamic Jihad Organization and Hezbollah In early 1975, the Law Enforcement Assistant Administration in the United States formed the National Advisory Committee on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals. One of the five volumes that the committee wrote was titled Disorders and Terrorism, produced by the Task Force on Disorders and Terrorism under the direction of H. H. A. Cooper, Director of the Task Force staff. The Task Force defines terrorism as "a tactic or technique by means of which a violent act or the threat thereof is used for the prime purpose of creating overwhelming fear for coercive purposes". It classified disorders and terrorism into seven categories:[68] Civil disorder – A form of collective violence interfering with the peace, security, and normal functioning of the community. Political terrorism – Violent criminal behaviour designed primarily to generate fear in the community, or substantial segment of it, for political purposes. Non-Political terrorism – Terrorism that is not aimed at political purposes, but which exhibits "conscious design to create and maintain a high degree of fear for coercive purposes, but the end is individual or collective gain rather than the achievement of a political objective". Anonymous terrorism – In the two decades prior to 2016–19, "fewer than half" of all terrorist attacks were either "claimed by their perpetrators or convincingly attributed by governments to specific terrorist groups". A number of theories have been advanced as to why this has happened.[69] Quasi-terrorism – The activities incidental to the commission of crimes of violence that are similar in form and method to genuine terrorism, but which nevertheless lack its essential ingredient. It is not the main purpose of the quasi-terrorists to induce terror in the immediate victim as in the case of genuine terrorism, but the quasi-terrorist uses the modalities and techniques of the genuine terrorist and produces similar consequences and reaction.[70] For example, the fleeing felon who takes hostages is a quasi-terrorist, whose methods are similar to those of the genuine terrorist but whose purposes are quite different. Limited political terrorism – Genuine political terrorism is characterized by a revolutionary approach; limited political terrorism refers to "acts of terrorism which are committed for ideological or political motives but which are not part of a concerted campaign to capture control of the state". Official or state terrorism – "referring to nations whose rule is based upon fear and oppression that reach similar to terrorism or such proportions". It may be referred to as Structural Terrorism defined broadly as terrorist acts carried out by governments in pursuit of political objectives, often as part of their foreign policy. Other sources have defined the typology of terrorism in different ways, for example, broadly classifying it into domestic terrorism and international terrorism, or using categories such as vigilante terrorism or insurgent terrorism.[71] Some ways the typology of terrorism may be defined are:[72][73] Political terrorism Sub-state terrorism Social revolutionary terrorism Nationalist-separatist terrorism Religious extremist terrorism Religious fundamentalist Terrorism New religions terrorism Right-wing terrorism Left-wing terrorism Communist terrorism State-sponsored terrorism State terrorism Criminal terrorism Pathological terrorism |

テロリズムの種類 このセクションには、検証のための追加の引用が必要です。信頼できる情報源をこのセクションに追加して、この記事の改善にご協力ください。出典が明記され ていない情報は、削除される場合があります。(2017年3月) (このメッセージの削除方法についてはこちらをご覧ください) テロリズムの種類は、国、政治体制、歴史的時代によって異なります。  欧州連合(EU)における、失敗、未遂、成功したテロ攻撃の件数と種類(年別)。出典:Europol。[65][66][67]  1983年にイスラム聖戦機構とヒズボラによって引き起こされたベイルート爆破事件後の、米国大使館の被害の様子 1975 年初頭、米国の法執行支援局は、刑事司法の基準と目標に関する全国諮問委員会を設立した。同委員会が作成した 5 冊の報告書のうちの 1 冊は、「Disorders and Terrorism(混乱とテロリズム)」と題され、タスクフォースのスタッフディレクターである H. H. A. クーパーの指揮の下、混乱とテロリズムに関するタスクフォースによって作成された。 タスクフォースは、テロリズムを「強制的な目的のために圧倒的な恐怖を引き起こすことを主な目的として、暴力行為またはその脅威を用いる戦術または手法」と定義している。また、混乱とテロリズムを 7 つのカテゴリーに分類している[68]。 市民暴動 – コミュニティの平和、安全、および正常な機能を妨害する集団的暴力の一形態。 政治的テロリズム – 主に政治的目的のために、コミュニティまたはその大部分に恐怖を与えることを目的とした暴力的な犯罪行為。 非政治的テロリズム – 政治的目的を目的としないテロリズムであるが、「強制的な目的のために高度の恐怖を生み出し、維持する意図が意識的に存在し、その最終的な目的は政治的目的の達成ではなく、個人または集団の利益である」もの。 匿名テロリズム – 2016年から2019年までの20年間、すべてのテロ攻撃の「半分未満」が、実行者によって主張されたか、政府によって特定のテロ組織に明確に帰属されたものだった。この現象の理由について、いくつかの理論が提唱されている。[69] 準テロリズム – 暴力犯罪の遂行に付随する活動で、形態や方法が本物のテロリズムに類似しているが、その本質的な要素を欠くもの。準テロリストの主な目的は、本物のテロリ ズムの場合のように直近の被害者に恐怖を誘発することではなく、本物のテロリストの手法や技術を用い、同様の結果や反応を引き起こすことだ。[70] 例えば、人質を取って逃走する重罪犯は、その手法は本物のテロリストと類似しているが、その目的はまったく異なるため、準テロリストである。 限定的な政治テロリズム – 本物の政治テロリズムは革命的なアプローチを特徴としているが、限定的な政治テロリズムとは、「イデオロギー的または政治的な動機に基づいて行われるが、国家の支配権を奪うための組織的な運動の一部ではないテロ行為」を指す。 公式または国家テロリズム – 「テロリズムと類似した、あるいはテロリズムと同等の恐怖と抑圧に基づく支配を行う国民」を指す。これは、政治的目的、多くの場合は外交政策の一環とし て、政府によって行われるテロ行為と広く定義される構造的テロリズムと呼ばれることもある。 他の情報源では、テロリズムの類型をさまざまな方法で定義しており、例えば、国内テロリズムと国際テロリズムに大別したり、自警テロリズムや反乱テロリズ ムなどのカテゴリーを使用したりしている。[71]テロリズムの類型を定義するいくつかの方法としては、次のようなものがある。[72][73] 政治テロリズム 準国家テロリズム 社会革命テロリズム ナショナリスト・分離主義テロリズム 宗教的過激派テロリズム 宗教的原理主義テロリズム 新宗教テロリズム 右翼テロリズム 左翼テロリズム 共産主義テロリズム 国家支援テロリズム 国家テロリズム 犯罪テロリズム 病的なテロリズム |

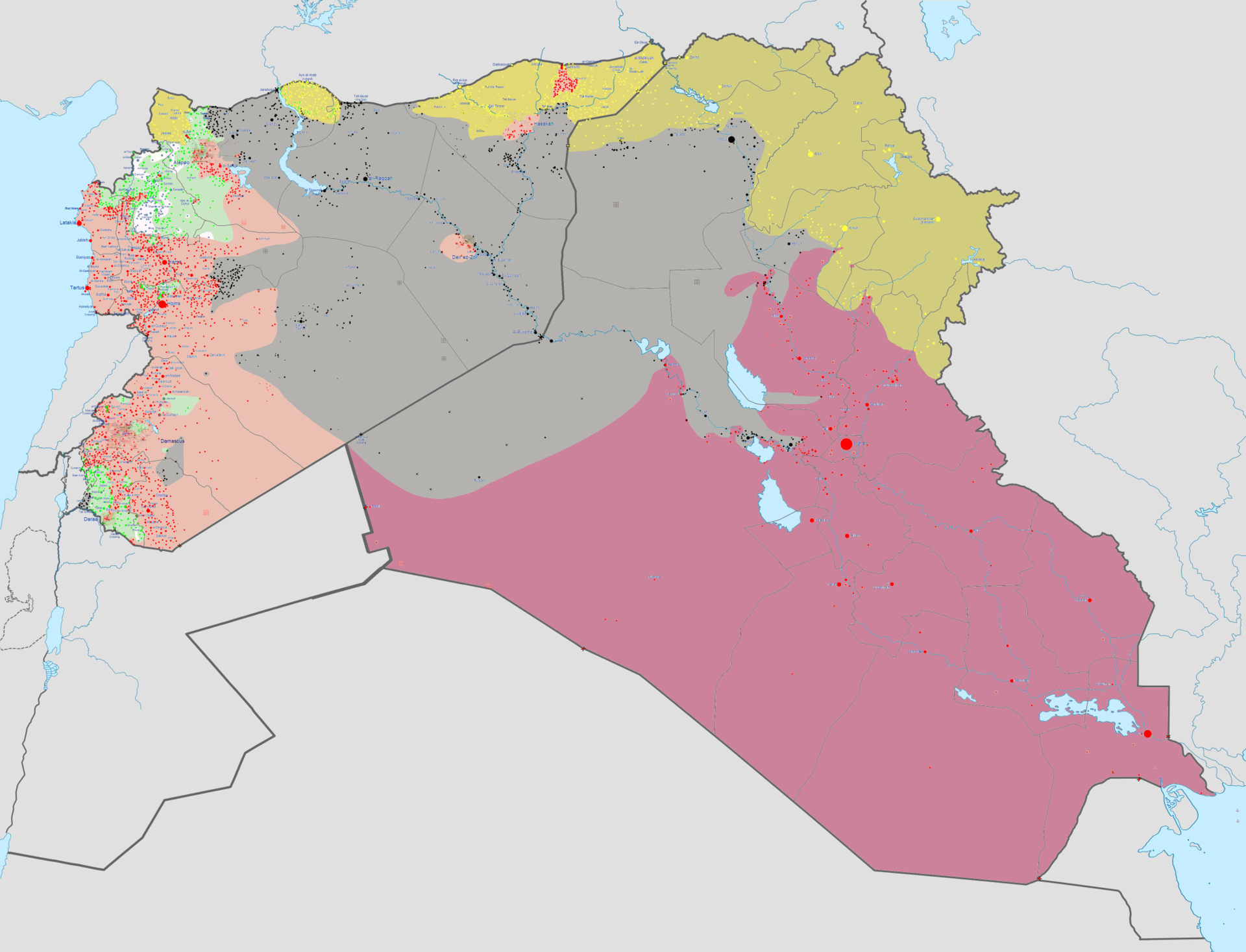

| Religious terrorism Main articles: Religious terrorism, List of Islamist terrorist attacks, and List of terrorist incidents linked to the Islamic State According to the Global Terrorism Index by the University of Maryland, College Park, religious extremism has overtaken national separatism and become the main driver of terrorist attacks around the world. Since 9/11 there has been a five-fold increase in deaths from terrorist attacks. The majority of incidents over the past several years can be tied to groups with a religious agenda. Before 2000, it was nationalist separatist terrorist organizations such as the IRA and Chechen rebels who were behind the most attacks. The number of incidents from nationalist separatist groups has remained relatively stable in the years since while religious extremism has grown. The prevalence of Islamist groups in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria and Syria is the main driver behind these trends.[74]  The Islamic State (IS) is a transnational Sunni Islamist insurgent and terrorist group. IS territory, in grey, at the time of its greatest territorial extent in May 2015. Map legend Hamas, the main Islamist movement in the Palestinian territories, was formed by Palestinian imam Ahmed Yassin in 1987. Some scholars, including constitutional law professor Alexander Tsesis, have voiced concerns over the Hamas Charter's apparent advocacy of genocidal aspirations.[75][76][77] In the periods of 1994–1996 and 2001–2007, Hamas orchestrated a series of suicide bombings, primarily directed at civilian targets in Israel, killing over 1,000 Israeli civilians.[78] Five of the terrorist groups that have been most active since 2001 are Hamas, Boko Haram, al-Qaeda, the Taliban and ISIL. These groups have been most active in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria and Syria. Eighty percent of all deaths from terrorism occurred in these five countries.[74] In 2015 four Islamic extremist groups were responsible for 74% of all deaths from Islamic terrorism: ISIS, Boko Haram, the Taliban, and al-Qaeda, according to the Global Terrorism Index 2016.[79] Since approximately 2000, these incidents have occurred on a global scale, affecting not only Muslim-majority states in Africa and Asia, but also states with non-Muslim majority such as United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Spain, Belgium, Sweden, Russia, Australia, Canada, Sri Lanka, Israel, China, India and Philippines. Such attacks have targeted both Muslims and non-Muslims, however the majority affect Muslims themselves.[80]  Islamabad Marriott Hotel bombing. Approximately 35,000 Pakistanis died from terrorist attacks between 2001 and 2011.[81] Terrorism in Pakistan has become a great problem. From the summer of 2007 until late 2009, more than 1,500 people were killed in suicide and other attacks on civilians[82] for reasons attributed to a number of causes—sectarian violence between Sunni and Shia Muslims; easy availability of guns and explosives; the existence of a "Kalashnikov culture"; an influx of ideologically driven Muslims based in or near Pakistan, who originated from various nations around the world and the subsequent war against the pro-Soviet Afghans in the 1980s which blew back into Pakistan; the presence of Islamist insurgent groups and forces such as the Taliban and Lashkar-e-Taiba. On July 2, 2013, in Lahore, 50 Muslim scholars of the Sunni Ittehad Council (SIC) issued a collective fatwa against suicide bombings, the killing of innocent people, bomb attacks, and targeted killings declaring them as Haraam or forbidden.[83] In 2015, the Southern Poverty Law Center released a report on domestic terrorism in the United States. The report (titled The Age of the Wolf) analyzed 62 incidents and found that, between 2009 and 2015, "more people have been killed in America by non-Islamic domestic terrorists than jihadists."[84] The "virulent racist and antisemitic" ideology of the ultra-right wing Christian Identity movement is usually accompanied by anti-government sentiments.[85] Adherents of Christian Identity are not connected with specific Christian denominations,[86] and they believe that whites of European descent can be traced back to the "Lost Tribes of Israel". Adherents have committed hate crimes, bombings and other acts of terrorism, including the Centennial Olympic Park bombing.[87][88] Its influence ranges from the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazi groups to the anti-government militia and sovereign citizen movements.[85] |

宗教的テロリズム 主な記事:宗教的テロリズム、イスラム教徒によるテロ攻撃の一覧、およびイスラム国に関連するテロ事件の一覧 メリーランド大学カレッジパーク校の「グローバル・テロリズム・インデックス」によると、宗教的過激主義は、国家分離主義を凌ぎ、世界中でテロ攻撃の主な 要因となっている。9.11 以降、テロ攻撃による死者数は 5 倍に増加している。過去数年間の事件の大半は、宗教的目標を持つグループと関連している。2000 年以前は、IRA やチェチェン反政府勢力などのナショナリスト分離主義テロ組織が、ほとんどの攻撃の背後にいた。それ以降、ナショナリスト分離主義グループによる事件の数 は比較的安定しているが、宗教的過激主義は拡大している。イラク、アフガニスタン、パキスタン、ナイジェリア、シリアにおけるイスラム教徒グループの台頭 は、こうした傾向の主な要因となっている。[74]  イスラム国(IS)は、国境を越えたスンニ派イスラム教徒の反乱軍およびテロリスト集団だ。2015年5月に領土が最大に拡大した当時の IS の領土(灰色部分)。 地図の凡例 パレスチナ自治区の主要なイスラム主義運動であるハマスは、1987年にパレスチナのイマーム、アフマド・ヤシンによって結成された。憲法学教授のアレク サンダー・ツェシス氏をはじめとする一部の学者は、ハマス憲章が明らかに大量虐殺の願望を擁護していることに懸念を表明している[75][76] [77]。1994年から1996年、および2001年から2007年にかけて、ハマスは、主にイスラエルの民間人を標的とした一連の自爆テロを組織し、 1,000人以上のイスラエル人民間人を殺害した。[78] 2001 年以降、最も活発な活動を行っているテロリスト集団は、ハマス、ボコ・ハラム、アルカイダ、タリバン、ISIL の 5 つだ。これらの集団は、イラク、アフガニスタン、パキスタン、ナイジェリア、シリアで最も活発に活動している。テロによる死亡者の80%は、これらの5カ 国で発生している。[74] 2016年のグローバル・テロリズム・インデックスによると、2015年にイスラム過激派によるテロで死亡した人の74%は、ISIS、ボコ・ハラム、タ リバン、アルカイダの4つのイスラム過激派組織によるものだった。[79] 2000年頃から、これらの事件は世界規模で発生し、アフリカやアジアのイスラム教徒が多数派を占める国々だけでなく、アメリカ合衆国、イギリス、フラン ス、ドイツ、スペイン、ベルギー、スウェーデン、ロシア、オーストラリア、カナダ、スリランカ、イスラエル、中国、インド、フィリピンなど、イスラム教徒 が多数派でない国々にも影響を及ぼしている。これらの攻撃はイスラム教徒と非イスラム教徒の両方を標的としているが、大多数はイスラム教徒自身に影響を及 ぼしている。[80]  イスラマバード・マリオットホテル爆破事件。2001年から2011年の間に、約35,000人のパキスタン人がテロ攻撃により死亡した。[81] パキスタンにおけるテロリズムは大きな問題となっている。2007 年夏から 2009 年後半にかけて、スンニ派とシーア派のイスラム教徒間の宗派間暴力、銃や爆発物の入手容易さ、「カラシニコフ文化」の存在、パキスタン国内またはその周辺 に拠点を置く、世界各国のさまざまな国々から流入したイデオロギーに駆られたイスラム教徒による、親ソ連のアフガニスタン人に対するその後の戦争など、さ まざまな原因により、1,500 人以上が自爆テロやその他の民間人に対する攻撃で死亡した[82]。「カラシニコフ文化」の存在、パキスタン国内および周辺地域に流入した、世界各国のさ まざまな民族出身のイデオロギーに駆られたイスラム教徒、1980年代にパキスタンにも波及した、親ソ連のアフガニスタン人に対する戦争、タリバンやラ シュカレ・タイバなどのイスラム過激派組織や勢力の存在など、さまざまな要因が挙げられる。2013年7月2日、ラホールで、スンニ派イスラム教徒の学者 50人が、自爆テロ、無実の人々の殺害、爆弾攻撃、標的を絞った殺害をハラーム(禁じられた行為)と宣言する集団ファトワを発表した。[83] 2015年、サザン・ポヴァティ・ロー・センターは、米国における国内テロに関する報告書を発表した。この報告書(『The Age of the Wolf』)は62件の事件を分析し、2009年から2015年の間に「米国では、ジハード主義者よりも非イスラム教徒の国内テロリストによってより多く の人が殺害されている」と結論付けた。[84] 極右のキリスト教アイデンティティ運動の「激しい人種差別的・反ユダヤ主義的」思想は、通常、反政府感情を伴う。[85] キリスト教アイデンティティの信奉者は特定のキリスト教派と関連していない。[86] 彼らは、ヨーロッパ系白人は「失われたイスラエルの12部族」に遡れると信じている。信奉者は、憎悪犯罪、爆破事件、その他のテロ行為を犯しており、その 中にはセンテニアル・オリンピック・パーク爆破事件も含まれる。[87][88] その影響は、クー・クラックス・クランやネオナチグループから、反政府民兵組織や主権市民運動まで及んでいる。[85] |

| Causes and motivations Terrorist acts frequently have a political purpose based on self-determination claims, ethnonationalist frustrations, single issue causes (like abortion or the environment), or other ideological or religious causes that terrorists claim are a moral justification for their violent acts.[89] Choice of terrorism as a tactic Individuals and groups choose terrorism as a tactic because it can: Act as a form of asymmetric warfare in order to directly force a government to agree to demands Intimidate a group of people into capitulating to the demands in order to avoid future injury Get attention and thus political support for a cause Directly inspire more people to the cause (such as revolutionary acts) – propaganda of the deed Indirectly inspire more people to the cause by provoking a hostile response or over-reaction from enemies to the cause[90] Attacks on "collaborators" are used to intimidate people from cooperating with the state in order to undermine state control. This strategy was used in Ireland, in Kenya, in Algeria and in Cyprus during their independence struggles.[91] Stated motives for the September 11 attacks included inspiring more fighters to join the cause of repelling the United States from Muslim countries with a successful high-profile attack. The attacks prompted some criticism from domestic and international observers regarding perceived injustices in U.S. foreign policy that provoked the attacks, but the larger practical effect was that the United States government declared a War on Terror that resulted in substantial military engagements in several Muslim-majority countries. Various commentators have inferred that al-Qaeda expected a military response and welcomed it as a provocation that would result in more Muslims fighting the United States. Some commentators believe that the resulting anger and suspicion directed toward innocent Muslims living in Western countries and the indignities inflicted upon them by security forces and the general public also contributes to radicalization of new recruits.[90] Despite criticism that the Iraqi government had no involvement with the September 11 attacks, Bush declared the 2003 invasion of Iraq to be part of the War on Terror. The resulting backlash and instability enabled the rise of Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and the temporary creation of an Islamic caliphate holding territory in Iraq and Syria, until ISIL lost its territory through military defeats. Attacks used to draw international attention to struggles that are otherwise unreported have included the Palestinian airplane hijackings in 1970 and the 1975 Dutch train hostage crisis. Causes motivating terrorism Specific political or social causes have included: Independence or separatist movements Irredentist movements Adoption of a particular political philosophy, such as socialism (left-wing terrorism), anarchism, or fascism (possibly through a coup or as an ideology of an independence or separatist movement) Environmental protection (eco-terrorism) Supremacism of a particular group Preventing a rival group from sharing or occupying a particular territory (such as by discouraging immigration or encouraging flight) Subjugation of a particular population (such as lynching of African Americans) Spread or dominance of a particular religion – religious terrorism Ending perceived government oppression Responding to a violent act (for example, tit-for-tat attacks in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, in The Troubles in Northern Ireland, or Timothy McVeigh's revenge for the Waco siege and Ruby Ridge incident) Causes for right-wing terrorism have included white nationalism, ethnonationalism, fascism, anti-socialism, the anti-abortion movement, and tax resistance. Sometimes terrorists on the same side fight for different reasons. For example, in the Chechen–Russian conflict secular Chechens using terrorist tactics fighting for national independence are allied with radical Islamist terrorists who have arrived from other countries.[92] Personal and social factors Main article: Radicalization Various personal and social factors may influence the personal choice of whether to join a terrorist group or attempt an act of terror, including: Identity, including affiliation with a particular culture, ethnicity, or religion Previous exposure to violence Financial reward (for example, the Palestinian Authority Martyrs Fund) Mental illness Social isolation Perception that the cause responds to a profound injustice or indignity A report conducted by Paul Gill, John Horgan and Paige Deckert [dubious – discuss] found that for "lone wolf" terrorists:[93] 43% were motivated by religious beliefs 32% had pre-existing mental health disorders, while many more are found to have mental health problems upon arrest At least 37% lived alone at the time of their event planning or execution, a further 26% lived with others, and no data were available for the remaining cases 40% were unemployed at the time of their arrest or terrorist event 19% subjectively experienced being disrespected by others 14% percent experienced being the victim of verbal or physical assault Ariel Merari, a psychologist who has studied the psychological profiles of suicide terrorists since 1983 through media reports that contained biographical details, interviews with the suicides' families, and interviews with jailed would-be suicide attackers, concluded that they were unlikely to be psychologically abnormal.[94] In comparison to economic theories of criminal behaviour, Scott Atran found that suicide terrorists exhibit none of the socially dysfunctional attributes—such as fatherless, friendless, jobless situations—or suicidal symptoms. By which he means, they do not kill themselves simply out of hopelessness or a sense of 'having nothing to lose'.[95] Abrahm suggests that terrorist organizations do not select terrorism for its political effectiveness.[96] Individual terrorists tend to be motivated more by a desire for social solidarity with other members of their organization than by political platforms or strategic objectives, which are often murky and undefined.[96] Michael Mousseau shows possible relationships between the type of economy within a country and ideology associated with terrorism.[example needed][97] Many terrorists have a history of domestic violence.[98] |

原因と動機 テロ行為は、多くの場合、自己決定の主張、民族主義的な不満、単一の課題(中絶や環境問題など)、あるいはテロリストが暴力行為の道徳的正当化理由とするその他のイデオロギー的または宗教的な原因に基づく政治的目的を持っている。[89] テロリズムを戦術として選択する理由 個人や集団がテロリズムを戦術として選択するのは、それが以下のことを可能にするためである。 政府に要求を直接受け入れるよう強制するための非対称戦争の一形態として機能する 将来の被害を回避するために、ある集団を威嚇して要求に屈服させる 注目を集め、その目的のための政治的支援を得る より多くの人々をその目的(革命行為など)に直接駆り立てる – 行動による宣伝 その目的に敵対する者たちに敵対的な反応や過剰反応を引き起こして、間接的により多くの人々をその目的に駆り立てる [90] 「協力者」に対する攻撃は、国家の支配を弱体化させるために、人々が国家と協力することを威嚇するために用いられる。この戦略は、アイルランド、ケニア、アルジェリア、キプロスの独立闘争で用いられた。[91] 9月11日の攻撃の表明された動機には、注目度の高い攻撃を成功させて、より多くの戦闘員をイスラム諸国から米国を駆逐する大義に駆り立てることなどが含 まれていた。この攻撃は、攻撃のきっかけとなった米国の外交政策の不正義について、国内外のオブザーバーから批判を呼びましたが、より大きな実際的な影響 は、米国政府が「対テロ戦争」を宣言し、イスラム教徒が多数を占めるいくつかの国々で大規模な軍事作戦が展開されたことです。さまざまなコメンテーター は、アルカイダは軍事的な対応を予想しており、より多くのイスラム教徒が米国と戦うきっかけとなる挑発としてこれを歓迎したと推測しています。一部の評論 家は、西欧諸国に住む無辜のイスラム教徒に対する怒りと不信感、および治安部隊や一般市民によって加えられた屈辱が、新規 recruits の過激化に寄与していると指摘している。[90] イラク政府が9月11日攻撃に関与しなかったとの批判にもかかわらず、ブッシュは2003年のイラク侵攻をテロとの戦争の一部と宣言した。その結果生じた 反発と不安定さは、イラクとレバントのイスラム国の台頭と、イラクとシリアに領土を持つイスラム教カリフ制国家の一時的な成立を可能にした。 報道されない闘争に国際的な注目を集めるために使用された攻撃には、1970年のパレスチナ人による航空機ハイジャック事件や1975年のオランダ列車人質事件がある。 テロリズムの動機 具体的な政治的または社会的要因としては、次のようなものが挙げられる。 独立または分離独立運動 領土回復運動 社会主義(左翼テロリズム)、アナキズム、ファシズムなどの特定の政治哲学の採用(クーデターや独立・分離独立運動のイデオロギーとして) 環境保護(エコテロリズム 特定の集団の優越主義 ライバル集団が特定の領土を共有または占領することを阻止すること(移民の阻止や逃亡の奨励など) 特定の集団の征服(アフリカ系アメリカ人のリンチなど) 特定の宗教の拡散または支配 – 宗教テロリズム 政府による抑圧の終結 暴力行為への対応(例えば、イスラエル・パレスチナ紛争、北アイルランド紛争における報復攻撃、ティモシー・マクベイのウェコ包囲事件およびルビー・リッジ事件に対する復讐など) 右翼テロリズムの原因としては、白人ナショナリズム、民族ナショナリズム、ファシズム、反社会主義、中絶反対運動、税抵抗などが挙げられる。 同じ陣営のテロリストが、異なる理由で戦う場合もある。例えば、チェチェン・ロシア紛争では、国家の独立のためにテロ戦術を用いる世俗的なチェチェン人が、他国からやってきた過激なイスラム教徒のテロリストと提携している。 個人的および社会的要因 主な記事:過激化 テロリスト集団に参加するか、テロ行為を行うかの個人的な選択には、以下のようなさまざまな個人的および社会的要因が影響する。 特定の文化、民族、宗教への帰属を含むアイデンティティ 暴力への過去の暴露 金銭的な報酬(例えば、パレスチナ自治政府の殉教者基金) 精神疾患 社会的孤立 その大義が深刻な不正や侮辱に対応しているとの認識 ポール・ギル、ジョン・ホーガン、ペイジ・デッカートが実施した報告書 [信頼性疑問 – 議論の余地あり] は、「孤独なオオカミ」テロリストについて、次のような結果を発表している[93]。 43% は宗教的信念によって動機付けられていた 32% は以前から精神疾患を患っており、さらに多くの者が逮捕時に精神疾患の問題があることが判明した 少なくとも 37% は、計画または実行時に一人暮らしであり、さらに 26% は他人と同居しており、残りのケースについてはデータがない 40% は、逮捕またはテロ行為の実行時に失業中だった 19% は、他者から軽蔑されていると主観的に感じていた 14%が言葉や身体的な暴力を受けた経験があった 1983年から、自殺テロリストの心理的プロフィールを、伝記的詳細を含むメディア報道、自殺者の家族へのインタビュー、投獄された自殺テロ未遂者へのイ ンタビューを通じて研究してきた心理学者アリエル・メラリは、彼らは心理的に異常である可能性は低いと結論付けた。[94] 犯罪行動に関する経済理論と比較すると、スコット・アトランは、自殺テロリストは、父親のいない、友人のいない、職のないといった社会的に機能不全の状態 や、自殺の兆候をまったく示していないことを発見した。つまり、彼らは、絶望や「失うものがない」という感覚から単に自殺するわけではないということだ。 [95] アブラハムは、テロ組織は、その政治的有効性からテロリズムを選択しているわけではないと示唆している。[96] 個々のテロリストは、多くの場合曖昧で定義が定まっていない政治的な政策や戦略的目標よりも、組織内の他のメンバーとの社会的連帯への欲求によって動機付 けられている傾向がある。[96] マイケル・ムソーは、国の経済の種類とテロリズムに関連するイデオロギーとの間に可能な関係があることを示している。[例が必要][97] 多くのテロリストは、家庭内暴力の過去を持っている。[98] |

| Democracy and domestic terrorism Terrorism is most common in nations with intermediate political freedom, and it is least common in the most democratic nations.[99][100][101][102] Some examples of terrorism in non-democratic nations include ETA in Spain under Francisco Franco (although the group's activities increased sharply after Franco's death),[103] the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in pre-war Poland,[104] the Shining Path in Peru under Alberto Fujimori,[105] the Kurdistan Workers Party when Turkey was ruled by military leaders, and the ANC in South Africa.[106] According to Boaz Ganor, "Modern terrorism sees the liberal democratic state, in all its variations, as the perfect launching pad and a target for its attacks. Moreover, some terrorist organizations—particularly Islamist-jihadist organizations—have chosen to cynically exploit democratic values and institutions to gain power and status, promote their interests, and achieve internal and international legitimacy".[1] Jihadist militants have shown an ambivalent view towards democracy, as they both exploit it for their ends and oppose it in their ideology. Various quotes from jihadist leaders note their disdain for democracy and their efforts to undermine it in favor of Islamic rule.[1] Democracies, such as Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, Israel, Indonesia, India, Spain, Germany, Italy and the Philippines, have all experienced domestic terrorism. While a democratic nation espousing civil liberties may claim a sense of higher moral ground than other regimes, an act of terrorism within such a state may cause a dilemma: whether to maintain its civil liberties and thus risk being perceived as ineffective in dealing with the problem; or alternatively to restrict its civil liberties and thus risk delegitimizing its claim of supporting civil liberties.[107] For this reason, homegrown terrorism has started to be seen as a greater threat, as stated by former CIA Director Michael Hayden.[108] This dilemma, some social theorists would conclude, may very well play into the initial plans of the acting terrorist(s); namely, to delegitimize the state and cause a systematic shift towards anarchy via the accumulation of negative sentiments towards the state system.[109] |

民主主義と国内テロリズム テロリズムは、政治的自由度が中程度の国々で最も多く発生し、最も民主的な国々では最も発生率が低い。[99][100][101][102] 非民主的な国におけるテロリズムの例としては、フランシスコ・フランコ政権下のスペインの ETA(ただし、このグループの活動はフランコ死後に急激に活発化した)、[103] 戦前のポーランドのウクライナ民族主義者組織、[104] アルベルト・フジモリ政権下のペルーの輝ける道、トルコが軍事政権下にあった頃のクルド労働者党、南アフリカの ANC などが挙げられる。[106] ボアズ・ガノールによると、「現代のテロリズムは、あらゆる形態の自由民主主義国家を、その攻撃の絶好の足掛かりおよび標的とみなしている。さらに、一部 のテロ組織、特にイスラム過激派組織は、権力と地位を獲得し、自らの利益を促進し、国内および国際的な正当性を獲得するために、民主主義の価値観や制度を 皮肉にも悪用することを選択している」。[1] ジハード主義の武装勢力は、民主主義に対して矛盾した態度を示している。彼らは民主主義を自らの目的のために利用しつつ、イデオロギー上では反対してい る。ジハード主義の指導者の発言には、民主主義への軽蔑と、イスラム支配を優先して民主主義を弱体化させる努力が繰り返し指摘されている。[1] 日本、イギリス、アメリカ合衆国、イスラエル、インドネシア、インド、スペイン、ドイツ、イタリア、フィリピンなどの民主主義国家は、いずれも国内テロリ ズムを経験している。 市民的自由を擁護する民主主義国家は、他の政権よりも高い道徳的立場にあると主張することができるが、そのような国家内でテロ行為が発生した場合、市民的 自由を維持し、問題に対処できないとみなされるリスクを冒すか、あるいは市民的自由を制限し、市民的自由を支持するという主張の正当性を失うリスクを冒す か、というジレンマに陥る。[107] このため、元CIA長官マイケル・ヘイデンが指摘するように、国内テロはより大きな脅威と見なされるようになってきた。[108] このジレンマは、一部の社会理論家が指摘するように、テロリストの初期計画に利用される可能性が高い。すなわち、国家の正当性を失わせ、国家システムに対 する否定的な感情の蓄積を通じて、無政府状態への体系的な移行を引き起こすことだ。[109] |

Perpetrators Al-Qaeda in Maghreb members pose with weapons. The perpetrators of acts of terrorism can be individuals, groups, or states. According to some definitions, clandestine or semi-clandestine state actors may carry out terrorist acts outside the framework of a state of war. The most common image of terrorism is that it is carried out by small and secretive cells, highly motivated to serve a particular cause and many of the most deadly operations in recent times, such as the September 11 attacks, the London underground bombing, 2008 Mumbai attacks and the 2002 Bali bombings were planned and carried out by a close clique, composed of close friends, family members and other strong social networks. These groups benefited from the free flow of information and efficient telecommunications to succeed where others had failed.[110] Over the years, much research has been conducted to distill a terrorist profile to explain these individuals' actions through their psychology and socio-economic circumstances.[111] Some specialists highlight the lack of evidence supporting the idea that terrorists are typically psychologically disturbed. The careful planning and detailed execution seen in many terrorist acts are not characteristics generally associated with mentally unstable individuals.[112] Others, like Roderick Hindery, have sought to discern profiles in the propaganda tactics used by terrorists. Some security organizations designate these groups as violent non-state actors.[citation needed] A 2007 study by economist Alan B. Krueger found that terrorists were less likely to come from an impoverished background (28 percent versus 33 percent) and more likely to have at least a high-school education (47 percent versus 38 percent). Another analysis found only 16 percent of terrorists came from impoverished families, versus 30 percent of male Palestinians, and over 60 percent had gone beyond high school, versus 15 percent of the populace.[42][113] To avoid detection, a terrorist will look, dress, and behave normally until executing the assigned mission. Some claim that attempts to profile terrorists based on personality, physical, or sociological traits are not useful.[114] The physical and behavioral description of the terrorist could describe almost any normal person.[115] The majority of terrorist attacks are carried out by military age men, aged 16 to 40.[115] |

実行者 マグレブのアラビア語圏のアルカイダメンバーが武器を持ってポーズをとる。 テロ行為の実行者は、個人、集団、または国家である可能性がある。一部の定義によると、秘密または半秘密の国家主体は、戦争状態の枠組み外でテロ行為を行 う可能性がある。テロリズムの最も一般的なイメージは、特定の目的のために強い動機を持つ、小規模で秘密主義の細胞によって実行されるものだが、9月11 日の同時多発テロ、ロンドン地下鉄爆破事件、2008年のムンバイ同時多発テロ、2002年のバリ島爆弾テロなど、最近の最も致命的なテロの多くは、親し い友人や家族、その他の強力な社会的ネットワークで構成される親密な集団によって計画、実行された。これらのグループは、情報の自由な流通と効率的な通信 手段を活用し、他者が失敗したところで成功を収めた。[110] 長年にわたり、これらの個人の行動をその心理や社会経済的状況から説明するためのテロリストのプロファイルを抽出するための多くの研究が行われてきた。 [111] 一部の専門家は、テロリストは一般的に精神的に不安定であるという考えを裏付ける証拠は不十分であると指摘している。多くのテロ行為に見られる慎重な計画 と詳細な実行は、精神的に不安定な個人に一般的に見られる特徴ではない。[112] ロデリック・ヒンダリーのような他の研究者は、テロリストが使用するプロパガンダ戦術からプロファイルを抽出しようとしている。一部の安全保障機関は、こ れらのグループを「暴力的な非国家主体」と指定している。[出典が必要] 経済学者アラン・B・クルーガーの2007年の研究では、テロリストは貧困層出身である割合が低く(28%対33%)、高校卒業以上の学歴を有する割合が 高かった(47%対38%)ことが示された。別の分析では、テロリストの16%が貧困家庭出身であるのに対し、パレスチナ人男性では30%、高校卒業以上 の学歴を持つ者は60%を超え、一般人口の15%を上回った。[42][113] 発見されないように、テロリストは任務を遂行するまで、外見、服装、行動は通常通りである。性格、身体的特徴、社会学的特徴に基づいてテロリストのプロ ファイルを作成することは無意味だと主張する者もいる[114]。テロリストの身体的特徴や行動の特徴は、ほとんどすべての正常な人間にも当てはまるから だ[115]。テロ攻撃の大部分は、16歳から40歳までの徴兵年齢の男性によって行われている[115]。 |

Non-state groups Picture of the front of an addressed envelope to Senator Daschle. There is speculation that the 2001 anthrax attacks were the work of a lone wolf. Main articles: List of designated terrorist groups, Lone wolf (terrorism), and Violent non-state actor Groups not part of the state apparatus of in opposition to the state are most commonly referred to as a "terrorist" in the media. According to the Global Terrorism Database, the most active terrorist group in the period 1970 to 2010 was Shining Path (with 4,517 attacks), followed by Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN), Irish Republican Army (IRA), Basque Fatherland and Freedom (ETA), Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), Taliban, Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, New People's Army, National Liberation Army of Colombia (ELN), and Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).[116] Israel has had problems with religious terrorism even before independence in 1948. During British mandate over Palestine, the secular Irgun were among the Zionist groups labelled as terrorist organisations by the British authorities and United Nations,[117] for violent terror attacks against Britons and Arabs.[118][119] Another extremist group, the Lehi, openly declared its members as "terrorists".[120][121] Historian William Cleveland stated many Jews justified any action, even terrorism, taken in the cause of the creation of a Jewish state.[122] In 1995, Yigal Amir assassinated Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. For Amir, killing Rabin was an exemplary act that symbolized the fight against an illegitimate government that was prepared to cede Jewish Holy Land to the Palestinians.[123] Members of Kach, a Jewish ultranationalist party, employed terrorist tactics in pursuit of what they viewed as religious imperatives. Israel and a few other countries have designated the party as a terrorist group.[124] |

非国家組織 ダシュル上院議員宛ての手紙の封筒の表面の写真。 2001年の炭疽菌攻撃は、単独犯によるものとの推測がある。 主な記事:指定テロ組織の一覧、単独犯(テロリズム)、暴力的な非国家主体 国家機構の一部ではない、あるいは国家に反対する組織は、メディアでは「テロリスト」と表現されることが多い。 グローバル・テロリズム・データベースによると、1970 年から 2010 年にかけて最も活発だったテロリスト集団は、輝ける道(4,517 件の攻撃)で、その後にファラブンド・マルティ民族解放戦線(FMLN)、アイルランド共和国軍(IRA)、バスク祖国と自由(ETA)、 コロンビア革命軍(FARC)、タリバン、タミル・イーラム解放の虎、新人民軍、コロンビア民族解放軍(ELN)、クルド労働者党(PKK)が続いた。 [116] イスラエルは、1948年の独立前から宗教的テロリズムの問題に悩まされてきた。パレスチナが英国の委任統治下にあった頃、世俗的なイールグンは、英国当 局および国連によってテロ組織と指定されたシオニスト集団のひとつだった[117]。これは、英国人およびアラブ人に対する暴力的なテロ攻撃によるもの だった[118][119]。別の過激派集団であるレヒは、そのメンバーを「テロリスト」と公然と宣言していた。[120][121] 歴史家のウィリアム・クリーブランドは、多くのユダヤ人が、ユダヤ人国家の創設のためなら、テロを含むいかなる行動も正当化すると主張したと述べていま す。[122] 1995年、イガル・アミールがイスラエルの首相イツハク・ラビンを暗殺しました。アミールにとって、ラビンを殺害することは、パレスチナ人にユダヤ人の 聖地を譲渡する用意のある不正な政府との闘いを象徴する模範的な行為だった。[123] ユダヤ人極右政党カハのメンバーは、宗教的義務と見なす目的のためにテロリズムの手法を採用した。イスラエルを含むいくつかの国は、この政党をテロ組織に 指定している。[124] |

| Funding Main article: Terrorist financing State sponsors have constituted a major form of funding; for example, Palestine Liberation Organization, Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine and other groups sometimes considered to be terrorist organizations, were funded by the Soviet Union.[125][126] Iran has provided funds, training, and weapons to organizations such as Lebanese Shi’ite group Hezbollah, the Yemenite Houthi movement, and Palestinian factions such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad.[127][128][129] Iranian funding for Hamas is estimated to reach several hundred million dollars annually.[130][131] These groups and others have played significant roles in Iran's foreign policy and served as proxies in conflicts.[127] The Stern Gang received funding from Italian Fascist officers in Beirut to undermine the British authorities in Palestine.[132] "Revolutionary tax" is another major form of funding, and essentially a euphemism for "protection money".[125] Revolutionary taxes "play a secondary role as one other means of intimidating the target population".[125] Other major sources of funding include kidnapping for ransoms, smuggling (including wildlife smuggling),[133] fraud, and robbery.[125] The Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant has reportedly received funding "via private donations from the Gulf states".[134] Irish Republican militants, primarily the Provisional Irish Republican Army and the Irish National Liberation Army, and Loyalist paramilitaries, primarily the Ulster Volunteer Force and Ulster Defence Association, received far more financing from criminal and legitimate activities within the British Isles than overseas donations, including Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi and NORAID (see Paramilitary finances in the Troubles for more information).[135][136][137][138] The Financial Action Task Force is an inter-governmental body whose mandate, since October 2001, has included combating terrorist financing.[139] |

資金 主な記事:テロ資金 国家の支援は、資金源の主要な形態となっている。例えば、パレスチナ解放機構、パレスチナ民主解放戦線、およびテロ組織とみなされることがあるその他の団 体は、ソビエト連邦から資金提供を受けていた。[125][126] イランは、レバノンのシーア派組織ヒズボラ、イエメンのフーシ派運動、パレスチナのハマスやイスラム聖戦組織などの組織に資金、訓練、武器を提供してき た。[127][128][129] イランのハマスへの資金提供は、年間数億ドルに上ると推定されている。[130][131] これらの組織を含む諸勢力は、イランの外交政策において重要な役割を果たし、紛争における代理戦争の役割を果たしてきた。[127] スターン・ギャングは、ベイルートのイタリア・ファシスト将校から資金提供を受け、パレスチナにおけるイギリス当局を弱体化させる目的で活動した。 [132] 「革命税」は別の主要な資金調達手段であり、本質的には「保護料」の婉曲表現である。[125] 革命税は「標的となる住民を威嚇するもう一つの手段として二次的な役割を果たしている」。[125] その他の主要な資金源には、身代金目的の人質誘拐、密輸(野生生物の密輸を含む)、[133] 詐欺、強盗などが挙げられる。[125] イラクとレバントのイスラム国(ISIL)は、「湾岸諸国からの私的寄付」を通じて資金提供を受けているとの報告がある。[134] アイルランド共和軍、主に暫定アイルランド共和国軍とアイルランド民族解放軍、およびロイヤリストの民兵組織、主にアルスター義勇軍とアルスター防衛協会 は、リビアの独裁者ムアンマル・カダフィや NORAID を含む海外からの寄付よりも、イギリス諸島内の犯罪活動や合法的な活動からはるかに多くの資金提供を受けていた(詳細については、北アイルランド紛争にお ける民兵組織の資金調達を参照)。[135][136][137][138] 金融活動作業部会(FATF)は、2001年10月以来、テロ資金対策を含む任務を担う政府間機関だ。[139] |

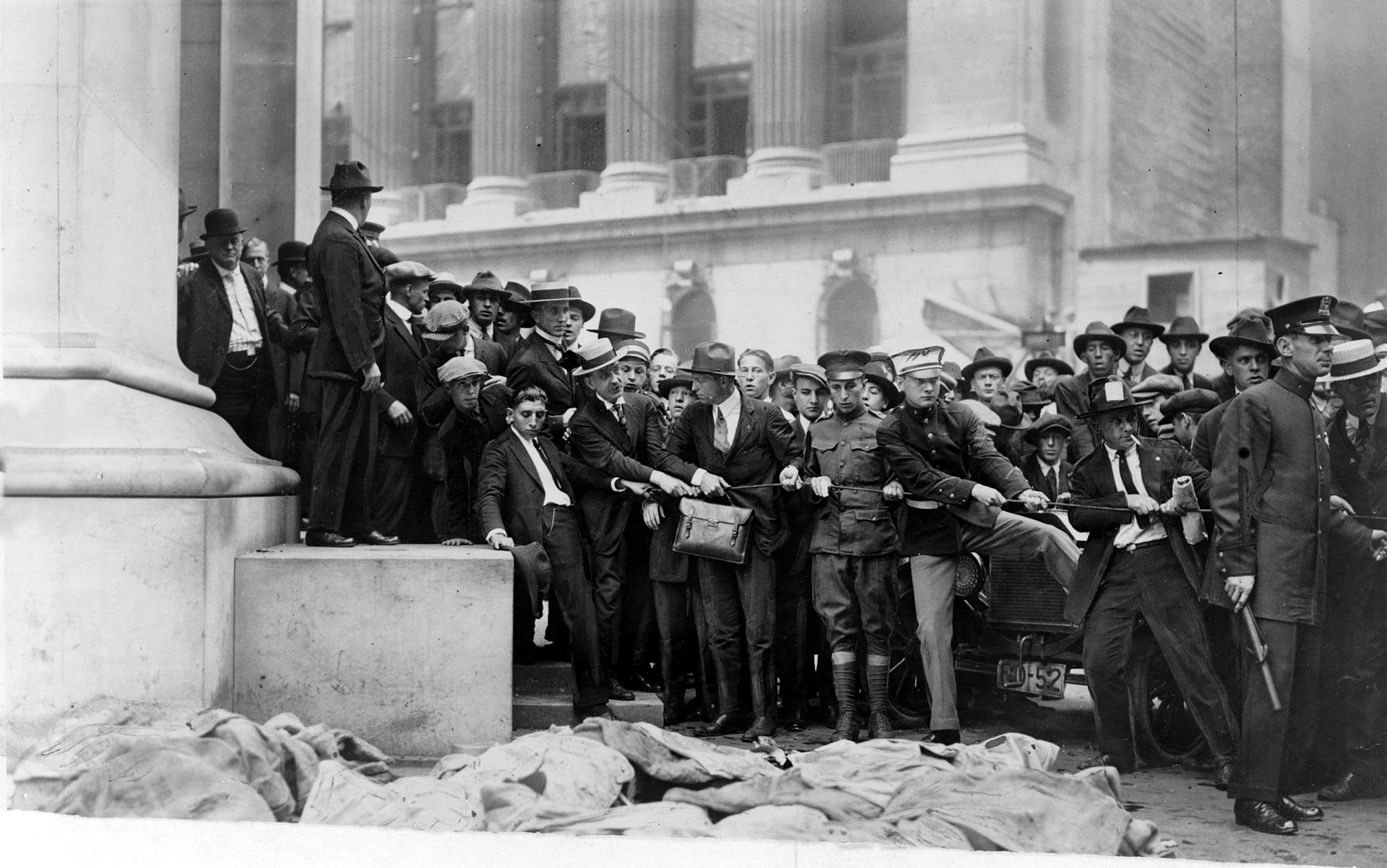

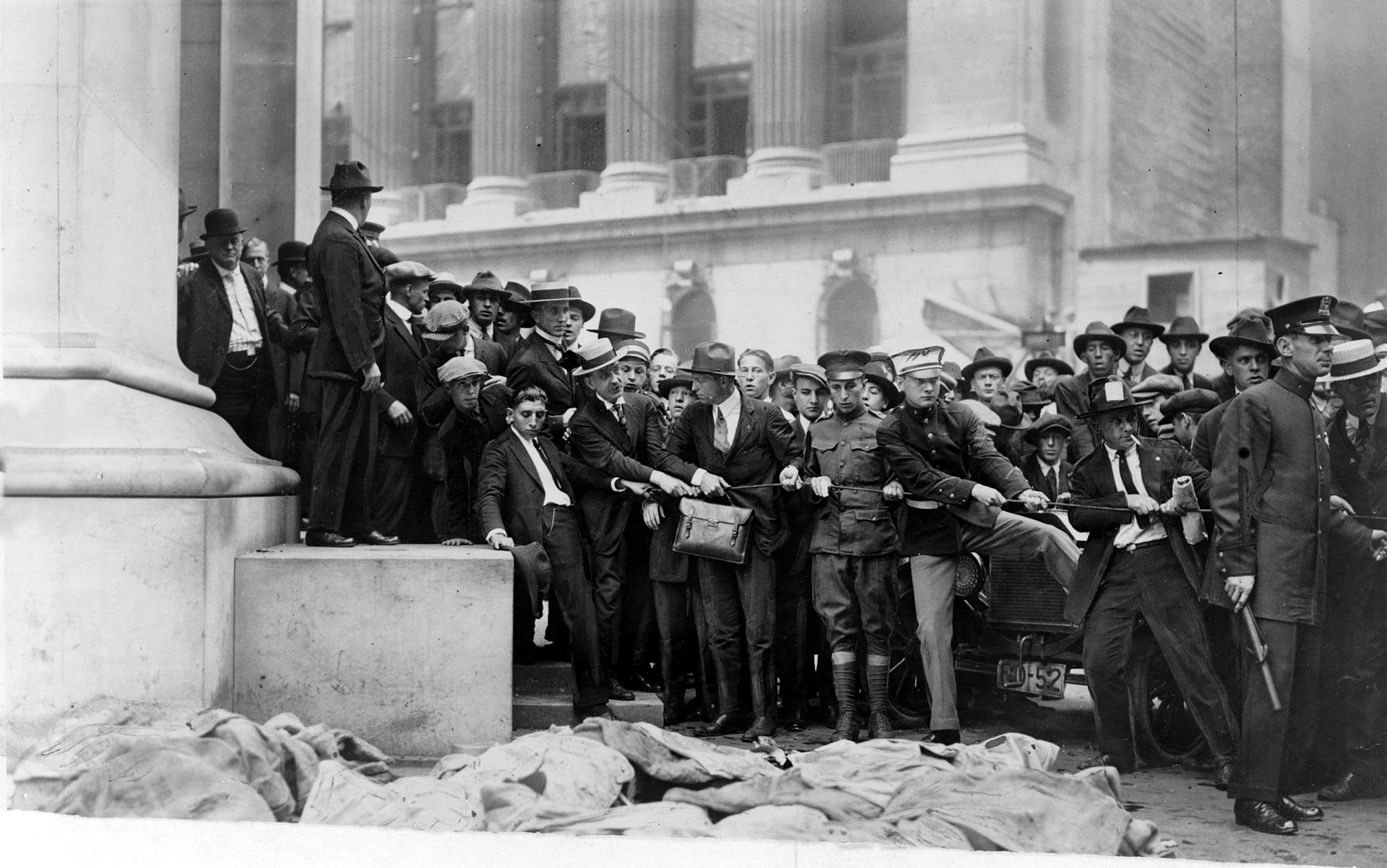

| Tactics Main article: Tactics of terrorism  The Wall Street bombing at noon on September 16, 1920, killed thirty-eight people and injured several hundred. The perpetrators were never caught.[140] Terrorist attacks are often targeted to maximize fear and publicity, most frequently using explosives.[141] Terrorist groups usually methodically plan attacks in advance, and may train participants, plant undercover agents, and raise money from supporters or through organized crime. Communications occur through modern telecommunications, or through old-fashioned methods such as couriers. There is concern about terrorist attacks employing weapons of mass destruction. Some academics have argued that while it is often assumed terrorism is intended to spread fear, this is not necessarily true, with fear instead being a by-product of the terrorist's actions, while their intentions may be to avenge fallen comrades or destroy their perceived enemies.[142] Terrorism is a form of asymmetric warfare and is more common when direct conventional warfare will not be effective because opposing forces vary greatly in power.[143] Yuval Harari argues that the peacefulness of modern states makes them paradoxically more vulnerable to terrorism than pre-modern states. Harari argues that because modern states have committed themselves to reducing political violence to almost zero, terrorists can, by creating political violence, threaten the very foundations of the legitimacy of the modern state. This is in contrast to pre-modern states, where violence was a routine and recognised aspect of politics at all levels, making political violence unremarkable. Terrorism thus shocks the population of a modern state far more than a pre-modern one and consequently the state is forced to overreact in an excessive, costly and spectacular manner, which is often what the terrorists desire.[144] The type of people terrorists will target is dependent upon the ideology of the terrorists. A terrorist's ideology will create a class of "legitimate targets" who are deemed as its enemies and who are permitted to be targeted. This ideology will also allow the terrorists to place the blame on the victim, who is viewed as being responsible for the violence in the first place.[145][146] Attack types Stabbing attacks, a historical tactic, have reemerged as a prevalent form of terrorism in the 21st century, notably during the 2010s and 2020s.[147] This resurgence originated with the GIA in the 1990s and later expanded among Palestinian terrorists and Islamic State militants.[148] The trend gained momentum with a wave of "lone wolf" terrorist stabbing attacks by Palestinians targeting Israelis beginning in 2015.[149] Subsequently, this pattern extended to Europe during the surge of Islamic terrorism in the 2010s, witnessing "at least" 10 stabbing attacks allegedly motivated by Islamic extremism by the spring of 2017, with France experiencing a notable concentration of such incidents.[150][151] Media spectacle Terrorists may attempt to use the media to spread their message or manipulate their target audience. Shamil Basayev used this tactic during the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis and again in the Moscow theater hostage crisis.[152] Terrorists may also target national symbols for attention.[153] Walter Lacquer wrote that "terrorism was always, to a large extent, about public relations and propaganda ('Propaganda by Deed' had been the slogan in the nineteenth century)".[154] The El Al Flight 426 hijacking is considered a turning point for modern terrorism studies. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) realized they could combine the tactics of targeting national symbols and civilians (in this case as hostages) to generate a mass media spectacle. Zehdi Labib Terzi made a public statement about this in 1976: "The first several hijackings aroused the consciousness of the world and awakened the media and world opinion much more ― and more effectively ― than 20 years of pleading at the United Nations".[155] |

戦術 主な記事:テロリズムの戦術  1920年9月16日正午、ウォール街で爆弾テロが発生し、38人が死亡、数百人が負傷した。犯人は結局捕まえられなかった。[140] テロ攻撃は、恐怖と宣伝効果を最大限に高めることを目的として、爆発物を使用することが多い。テロリスト集団は通常、事前に綿密な計画を立て、参加者を訓 練し、潜入工作員を送り込み、支持者や組織犯罪から資金を調達する。通信は、現代の通信手段や、宅配便などの昔ながらの方法で行われる。大量破壊兵器を使 用したテロ攻撃が懸念されている。一部の学者は、テロリズムは恐怖を広めることを目的としているとよく考えられているが、必ずしもそうとは限らない、と主 張している。恐怖はテロリストの行動の副産物であり、彼らの真の目的は、戦死した仲間を復讐したり、敵とみなす者を破壊したりすることであるかもしれな い、と。[142] テロリズムは非対称戦争の一形態であり、直接的な伝統的な戦争が効果的でない場合、特に敵対勢力の力が大きく異なる場合に一般的です。[143] ユバル・ハラリは、現代国家の平和性が、逆に前近代国家よりもテロリズムに対して脆弱にしているとの主張を展開しています。ハラリは、現代国家が政治的暴 力のほぼ完全な排除を誓約しているため、テロリストは政治的暴力を引き起こすことで、現代国家の正当性の基盤そのものを脅かすことができると指摘していま す。これは、暴力がいかなるレベルにおいても政治の日常的かつ認められた側面であった前近代国家とは対照的だ。そのため、テロリズムは現代国家の住民を前 近代国家の住民よりもはるかに衝撃を与え、国家は過剰で高コストかつ派手な対応を余儀なくされる。これがまさにテロリストが望む結果であることが多い。 [144] テロリストが標的とする人々のタイプは、テロリストのイデオロギーによって異なります。テロリストのイデオロギーは、その敵とみなされ、標的とすることが 許される「正当な標的」の層を作り出します。このイデオロギーにより、テロリストは、そもそも暴力の責任があるとする被害者に責任を転嫁することも可能に なります。[145][146] 攻撃の種類 刺殺攻撃は、歴史的な戦術であり、21 世紀、特に 2010 年代と 2020 年代に、テロリズムの一般的な形態として再登場した。[147] この復活は、1990 年代の GIA から始まり、その後、パレスチナのテロリストやイスラム国の過激派にも拡大した。[148] この傾向は、2015年からパレスチナ人がイスラエル人を標的とした「単独犯」の刺傷テロ攻撃が相次いだことで勢いを増した。[149] その後、このパターンは2010年代のイスラムテロの急増に伴いヨーロッパにも拡大し、2017年春までに「少なくとも」10件のイスラム過激主義を動機 としたとされる刺傷攻撃が発生し、フランスではこのような事件が集中的に発生した。[150][151] メディアの注目 テロリストは、メディアを利用して自分のメッセージを広めたり、標的となる視聴者を操作したりしようとする場合がある。シャミル・バサエフは、ブジェドノ フスク病院人質事件、そしてモスクワ劇場人質事件でもこの戦術を用いた。[152] テロリストは、注目を集めるために国の象徴を標的とする場合もある。[153] ウォルター・ラッカーは、「テロリズムは、その大部分が、広報と宣伝(19 世紀のスローガンは『行動による宣伝』だった)であった」と書いている。[154] エルアル航空426便ハイジャック事件は、現代テロリズム研究における転換点とみなされている。パレスチナ解放人民戦線(PFLP)は、国の象徴と民間人 (この場合は人質)を標的とする戦術を組み合わせることで、マスメディアの注目を引くことができると気づいた。ゼディ・ラビブ・テルジは 1976 年に、このことについて次のように公に述べている。「最初の数件のハイジャックは、20 年間にわたる国連での嘆願よりも、はるかに多く、そしてより効果的に、世界の意識を喚起し、メディアや世界世論を覚醒させた」。 |

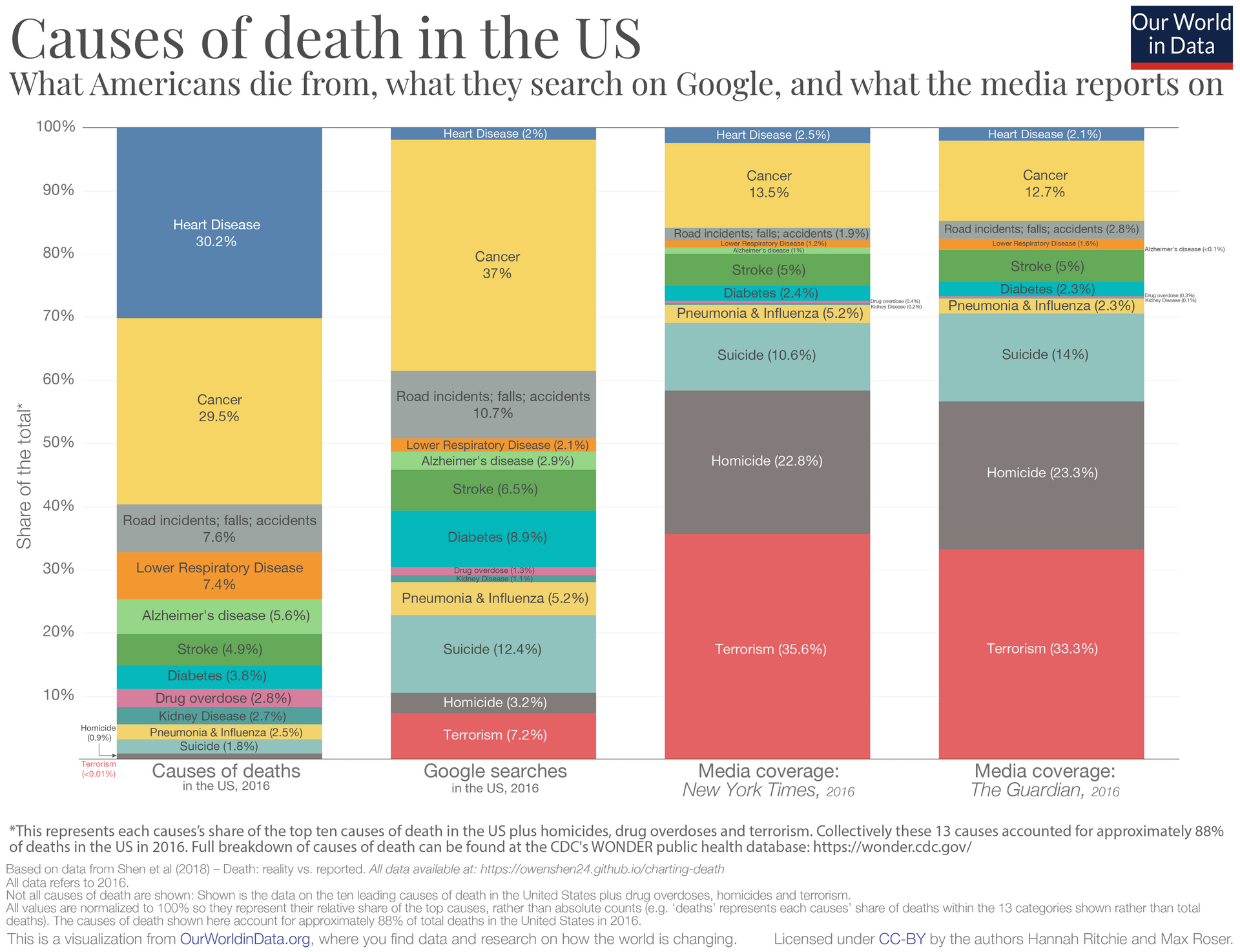

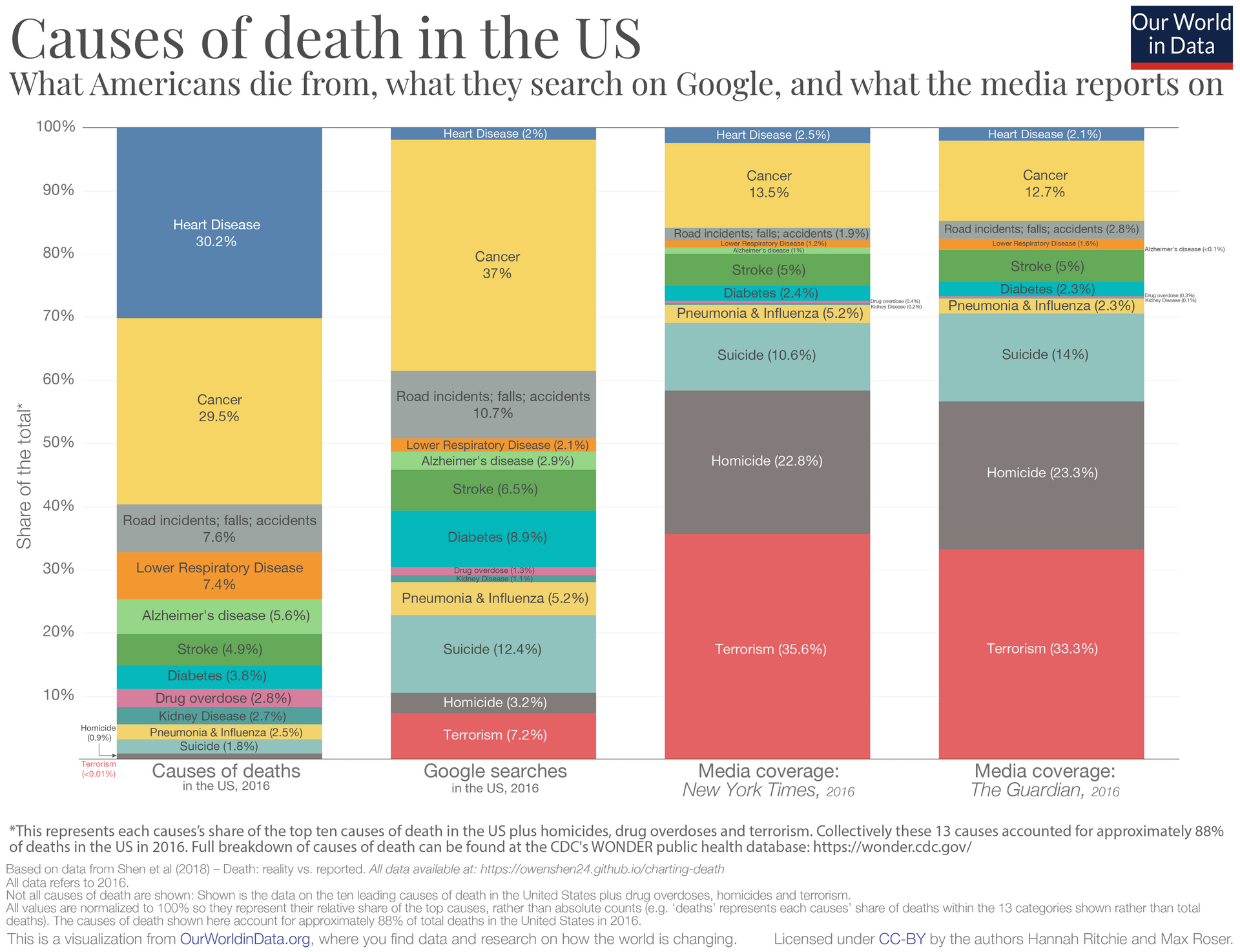

Mass media Causes of death in the US vs media coverage. The percentage of media attention for terrorism (about 33-35%) is much greater than the percentage of deaths caused by terrorism (less than 0.01%).  La Terroriste, a 1910 poster depicting a female member of the Combat Organization of the Polish Socialist Party throwing a bomb at a Russian official's car Mass media exposure may be a primary goal of those carrying out terrorism, to expose issues that would otherwise be ignored by the media. Some consider this to be manipulation and exploitation of the media.[156] The Internet has created a new way for groups to spread their messages.[157] This has created a cycle of measures and counter measures by groups in support of and in opposition to terrorist movements. The United Nations has created its own online counterterrorism resource.[158] The mass media will, on occasion, censor organizations involved in terrorism (through self-restraint or regulation) to discourage further terrorism. This may encourage organizations to perform more extreme acts of terrorism to be shown in the mass media. Conversely James F. Pastor explains the significant relationship between terrorism and the media, and the underlying benefit each receives from the other:[159] There is always a point at which the terrorist ceases to manipulate the media gestalt. A point at which the violence may well escalate, but beyond which the terrorist has become symptomatic of the media gestalt itself. Terrorism as we ordinarily understand it is innately media-related. — Novelist William Gibson, 2004[160] Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher famously spoke of the close connection between terrorism and the media, calling publicity 'the oxygen of terrorism'.[161] Terrorism and tourism The connection between terrorism and tourism has been widely studied since the 1997 Luxor massacre, during which 62 people, including 58 foreign nationals, were killed by Islamist group al-Jama'a al-Islamiyya in an archaeological site in Egypt.[162][163] In the 1970s, the targets of terrorists were politicians and chiefs of police while now, international tourists and visitors are selected as the main targets of attacks.[citation needed] The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, were the symbolic center, which marked a new epoch in the use of civil transport against the main power of the planet.[164] From this event onwards, the spaces of leisure that characterized the pride of West were conceived as dangerous and frightful.[165][166] |

マスメディア 米国における死因とメディアの報道。テロリズムに関するメディアの注目度(約 33~35%)は、テロリズムによる死亡者数(0.01% 未満)よりもはるかに高い。  『ラ・テロリスト』は、ポーランド社会主義党の戦闘組織に所属する女性が、ロシアの政府高官の車に爆弾を投げる様子を描いた1910年のポスター。 マスメディアへの露出は、メディアが通常無視する問題を世間に知らしめるという、テロ実行者の主な目的の一つであると考えられる。これをメディアの操作や利用だと考える人もいる。[156] インターネットは、集団がメッセージを広める新しい手段を生み出した。[157] これにより、テロ運動を支持するグループと反対するグループによる対策と対抗措置のサイクルが生まれている。国連は、独自のオンラインテロ対策情報源を開設している。[158] マスメディアは、さらなるテロを阻止するため、テロに関与する組織を(自主規制や規制によって)検閲する場合がある。これにより、組織はマスメディアで報 道されるようなより過激なテロ行為を行うよう促される可能性がある。一方、ジェームズ・F・パスターは、テロリズムとメディアの重要な関係、および両者が 相互に得る根本的な利益について次のように説明している。[159] テロリストがメディアのゲシュタルトを操ることをやめる時点は必ずある。その時点では、暴力はエスカレートするかもしれないが、テロリストはメディアのゲシュタルトそのものの症状となっている。私たちが通常理解しているテロリズムは、本質的にメディアと関連している。 —小説家ウィリアム・ギブソン、2004年[160] 元英国首相マーガレット・サッチャーは、テロリズムとメディアの密接な関係について、宣伝は「テロリズムの酸素」だと述べたことで有名だ。[161] テロリズムと観光 テロリズムと観光の関係は、1997年にエジプトの遺跡で、58人の外国人をはじめとする62人がイスラム過激派組織「アル・ジャマー・アル・イスラミ ヤ」によって殺害されたルクソール虐殺事件以来、広く研究されている。[162][163] 1970年代には、テロリストの標的は政治家や警察長官だったが、現在では国際的な観光客や訪問者が攻撃の主な標的として選択されている。[出典必要] 2001年9月11日のワールドトレードセンターとペンタゴンへの攻撃は、地球の主要な権力に対して民間交通機関が使用される新たな時代を画する象徴的な 中心となった。[164] この事件以降、西側の誇りであったレジャーの空間は、危険で恐ろしいものと捉えられるようになった。[165][166] |

Counterterrorism strategies Sign notifying shoppers of increased surveillance due to a perceived increased risk of terrorism Responses to terrorism are broad in scope. They can include re-alignments of the political spectrum and reassessments of fundamental values. Specific types of responses include: Targeted laws, criminal procedures, deportations, and enhanced police powers Target hardening, such as locking doors or adding traffic barriers Preemptive or reactive military action Increased intelligence and surveillance activities Preemptive humanitarian activities More permissive interrogation and detention policies Terrorism research Terrorism research, also called terrorism studies, or terrorism and counter-terrorism research, is an academic field which seeks to understand the causes of terrorism, how to prevent it, as well as its impact in the broadest sense. Terrorism research can be carried out in both military and civilian contexts, for example by research centres such as the British Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence, the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies, and the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT). There are several academic journals devoted to the field, including Perspectives on Terrorism.[167][168] International agreements One of the agreements that promote the international legal counterterrorist framework is the Code of Conduct Towards Achieving a World Free of Terrorism that was adopted at the 73rd session of the United Nations General Assembly in 2018. The Code of Conduct was initiated by Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev. Its main goal is to implement a wide range of international commitments to counterterrorism and establish a broad global coalition towards achieving a world free of terrorism by 2045. The Code was signed by more than 70 countries.[169] |

テロ対策戦略 テロの危険性が高まっていることを買い物客に知らせる看板 テロへの対応は幅広い。政治の構図の再編や、基本的な価値観の再評価も含まれる。 具体的な対応としては、次のようなものがある。 対象を絞った法律、刑事手続き、国外追放、警察権限の強化 ドアの施錠や交通障害物の設置などの施設強化 予防的または反応的な軍事行動 情報収集と監視活動の強化 予防的人道活動 取り調べと拘禁に関するより寛容な政策 テロリズム研究 テロリズム研究(terrorism studies)は、テロリズムの原因、その防止方法、および広義での影響を理解することを目的とする学術分野だ。テロリズム研究は、軍事的および民間的 な文脈の両方で実施される。例えば、イギリステロリズムと政治暴力研究センター、ノルウェー暴力とトラウマストレス研究センター、国際テロ対策センター (ICCT)などの研究機関がこれを行う。この分野に特化した学術誌には、『Perspectives on Terrorism』[167] などがある。[168] 国際協定 国際的なテロ対策の法的枠組みを推進する協定のひとつに、2018年の国連総会第73回会合で採択された「テロのない世界を実現するための行動規範」があ る。この行動規範は、カザフスタン大統領のヌルスルタン・ナザルバエフによって提唱された。その主な目的は、テロ対策に関する幅広い国際的な約束を実施 し、2045年までにテロのない世界を実現するための広範なグローバルな連携を構築することだ。この行動規範には、70カ国以上が署名している。 [169] |

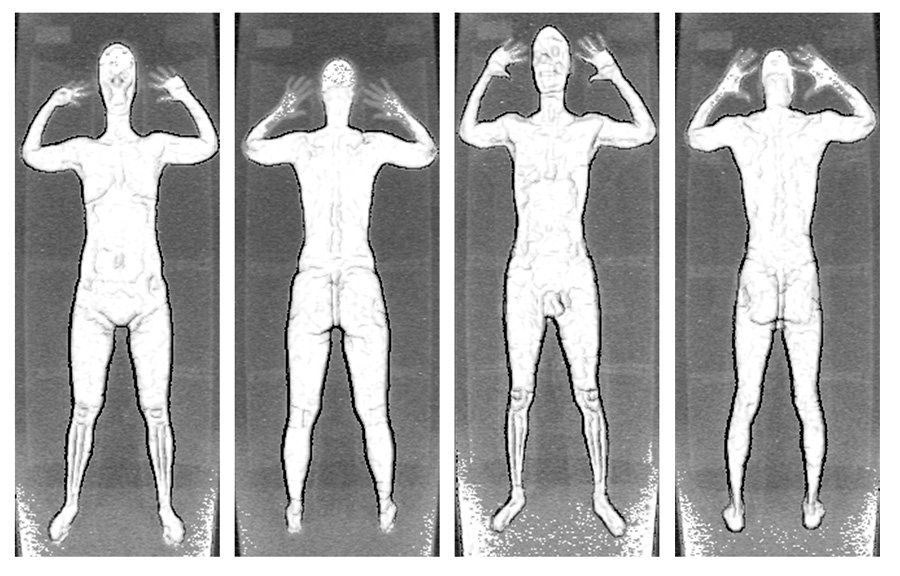

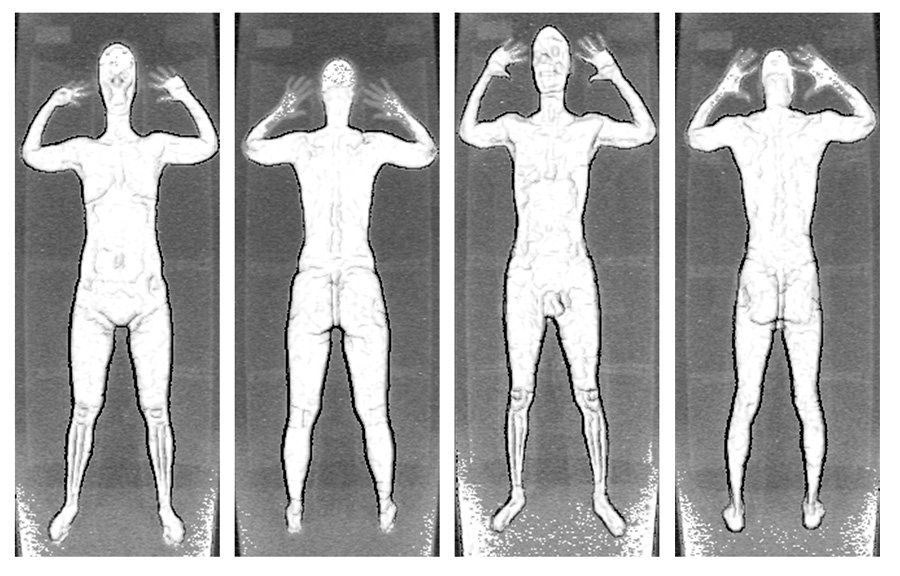

| Response in the United States See also: War on terror  X-ray backscatter technology (AIT) machine used by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) to screen passengers. According to the TSA, this is what the remote TSA agent would see on their screen. According to a report by Dana Priest and William M. Arkin in The Washington Post, "Some 1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in about 10,000 locations across the United States."[170] America's thinking on how to defeat radical Islamists is split along two very different schools of thought. Republicans, typically follow what is known as the Bush Doctrine, advocate the military model of taking the fight to the enemy and seeking to democratize the Middle East. Democrats, by contrast, generally propose the law enforcement model of better cooperation with nations and more security at home.[171] In the introduction of the U.S. Army / Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual, Sarah Sewall states the need for "U.S. forces to make securing the civilian, rather than destroying the enemy, their top priority. The civilian population is the center of gravity—the deciding factor in the struggle.... Civilian deaths create an extended family of enemies—new insurgent recruits or informants—and erode support of the host nation." Sewall sums up the book's key points on how to win this battle: "Sometimes, the more you protect your force, the less secure you may be.... Sometimes, the more force is used, the less effective it is.... The more successful the counterinsurgency is, the less force can be used and the more risk must be accepted.... Sometimes, doing nothing is the best reaction."[172] This strategy, often termed "courageous restraint", has certainly led to some success on the Middle East battlefield. However, it does not address the fact that terrorists are mostly homegrown.[171] |

米国での対応 関連項目:テロとの戦い  運輸保安局(TSA)が乗客の検査に使用するX線バックスキャッター技術(AIT)搭載の機械。TSAによると、これは遠隔地のTSA職員が画面に表示される映像だ。 ダナ・プリエストとウィリアム・M・アーキンが『ワシントン・ポスト』で発表した報告書によると、「米国全土の約10,000カ所で、1,271の政府機関と1,931の民間企業が、テロ対策、国土安全保障、諜報に関連するプログラムに従事している」[170]。 過激なイスラム教徒を打ち負かす方法について、アメリカの考え方は 2 つのまったく異なる学派に分かれている。共和党は、一般的にブッシュドクトリンとして知られる、敵と戦って中東の民主化を目指す軍事モデルを支持してい る。一方、民主党は、各国との協力強化と国内治安の強化という法執行モデルを一般的に提案している[171]。米陸軍・海兵隊の対反乱作戦フィールドマ ニュアルの序文で、サラ・セウォール氏は、「米軍は、敵を破壊することよりも、民間人の安全確保を最優先課題とすべきだ。民間人は、この闘争の重心であ り、勝敗を左右する要因だ。民間人の死は、敵の拡大家族、すなわち新たな反乱軍や情報提供者を生み出し、受入国の支持を侵食する」と述べている。 Sewall は、この戦いに勝つための要点を次のようにまとめている。「時には、自軍を保護すればするほど、安全は損なわれることがある。時には、武力行使が強ければ 強いほど、その効果は薄れる。反乱鎮圧が成功すればするほど、使用できる力は減り、リスクを受け入れる必要が増える……。時には、何もしないことが最善の 対応だ。」[172] この戦略は「勇気ある自制」と呼ばれ、中東の戦場では一定の成功を収めてきた。しかし、テロリストが主に国内出身者であるという事実には対応していない。 [171] |

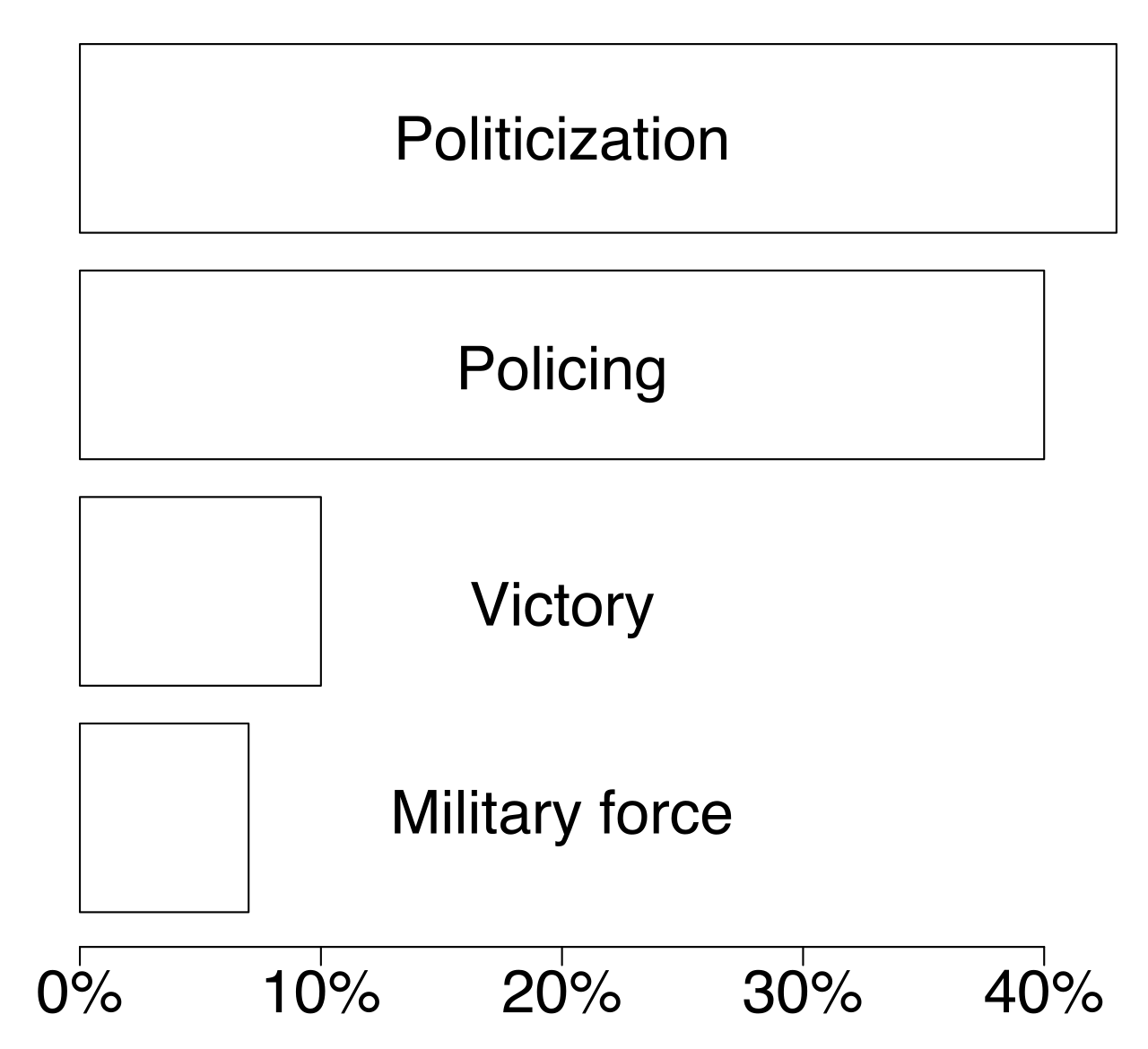

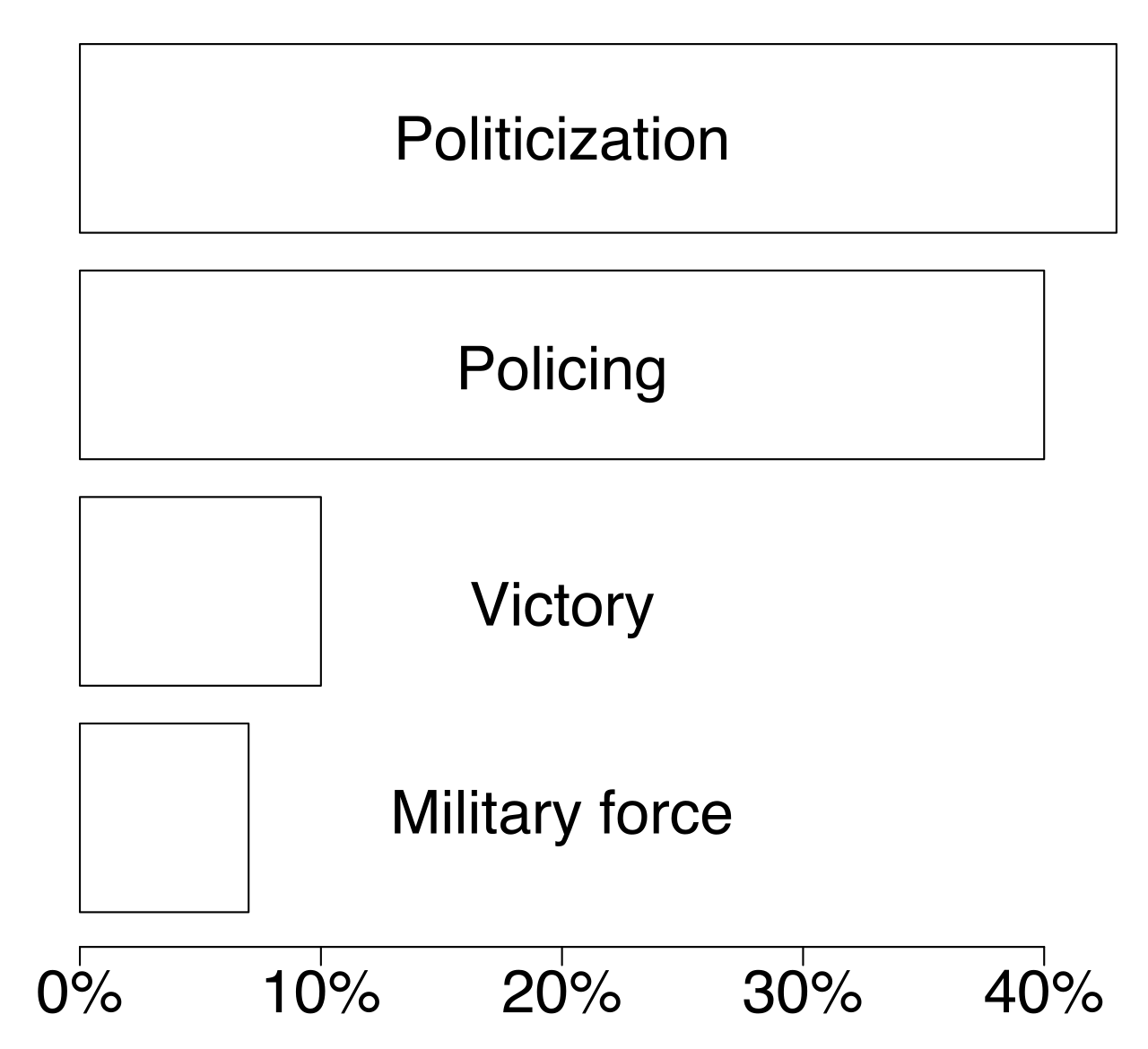

Ending terrorist groups How terrorist groups end (n = 268): The most common ending for a terrorist group is to convert to nonviolence via negotiations (43%), with most of the rest terminated by routine policing (40%). Groups that were ended by military force constituted only 7%.[173] Jones and Libicki (2008) created a list of all the terrorist groups they could find that were active between 1968 and 2006. They found 648. Of those, 136 splintered and 244 were still active in 2006.[174] Of the ones that ended, 43% converted to nonviolent political actions, like the Irish Republican Army in Northern Ireland; 40% were defeated by law enforcement; 7% (20 groups) were defeated by military force; and 10% succeeded. 42 groups became large enough to be labeled an insurgency; 38 of those had ended by 2006. Of those, 47% converted to nonviolent political actors. Only 5% were ended by law enforcement, and 21% were defeated by military force. 26% won.[175] Jones and Libicki concluded that military force may be necessary to deal with large insurgencies but are only occasionally decisive, because the military is too often seen as a bigger threat to civilians than the terrorists. To avoid that, the rules of engagement must be conscious of collateral damage and work to minimize it. When militant groups face violent competition from other groups, they often shift from high-profile attacks on civilians to more restrained tactics, a strategy of terrorist restraint that arises due to resource constraints and fear of civilian backlash.[176] Another researcher, Audrey Cronin, lists six primary ways that terrorist groups end:[177] Capture or killing of a group's leader (Decapitation) Entry of the group into a legitimate political process (Negotiation) Achievement of group aims (Success) Group implosion or loss of public support (Failure) Defeat and elimination through brute force (Repression) Transition from terrorism into other forms of violence (Reorientation) |

テロリスト集団の終結 テロリスト集団の終結(n = 268):テロリスト集団の最も一般的な終結は、交渉による非暴力への転換(43%)であり、残りの大部分は通常の警察活動によって終結している(40%)。軍事力によって終結した集団はわずか 7%だった。[173] ジョーンズとリビッキ(2008)は、1968年から2006年の間に活動していたすべてのテロリスト集団のリストを作成した。その結果、648の集団が 確認された。そのうち、136は分裂し、244は2006年にもなお活動していた。[174] 終結したグループの 43% は、北アイルランドのアイリッシュ・レパブリカン・アーミーのように非暴力的な政治活動へと転換した。40% は法執行機関によって敗北した。7%(20 グループ)は軍事力によって敗北した。10% は成功した。 42 グループは、反乱軍とみなされるほど規模が大きくなったが、そのうち 38 グループは 2006 年までに終結した。そのうち、47%が非暴力的な政治主体に転向した。法執行機関によって終結したのは5%のみで、21%が軍事力によって敗北した。 26%が勝利した。[175] ジョーンズとリビッキーは、大規模な反乱に対処するためには軍事力が不可欠である可能性があると結論付けたが、軍事力はしばしば市民に対する脅威としてテ ロリストよりも大きく見なされるため、決定的な役割を果たすのはまれだと指摘した。それを回避するためには、交戦規則は付随的損害を認識し、それを最小限 に抑えるよう努めなければならない。過激派グループが他のグループとの暴力的な競争に直面すると、多くの場合、民間人に対する注目度の高い攻撃から、より 抑制的な戦術へと移行する。これは、資源の制約と民間人の反発を恐れて生じるテロリストの抑制戦略である[176]。 別の研究者であるオードリー・クロニンは、テロリストグループが終結する6つの主な方法を挙げている。[177] グループのリーダーの捕獲または殺害(首謀者の排除) グループが合法的な政治プロセスに参加(交渉) グループの目標の達成(成功) グループの崩壊または民衆の支持の喪失(失敗) 武力による敗北および排除(抑圧) テロリズムから他の形態の暴力への移行(方向転換) |

| State and state sponsored-terrorism State terrorism Main article: State terrorism Civilization is based on a clearly defined and widely accepted yet often unarticulated hierarchy. Violence done by those higher on the hierarchy to those lower is nearly always invisible, that is, unnoticed. When it is noticed, it is fully rationalized. Violence done by those lower on the hierarchy to those higher is unthinkable, and when it does occur it is regarded with shock, horror, and the fetishization of the victims. — Derrick Jensen[178]  Infant crying in Shanghai's South Station after the Japanese bombing, August 28, 1937 As with "terrorism" the concept of "state terrorism" is controversial.[179] The Chairman of the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Committee has stated that the committee was conscious of 12 international conventions on the subject, and none of them referred to state terrorism, which was not an international legal concept. If states abused their power, they should be judged against international conventions dealing with war crimes, international human rights law, and international humanitarian law.[180] Former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan has said that it is "time to set aside debates on so-called 'state terrorism'. The use of force by states is already thoroughly regulated under international law".[181] He made clear that, "regardless of the differences between governments on the question of the definition of terrorism, what is clear and what we can all agree on is that any deliberate attack on innocent civilians [or non-combatants], regardless of one's cause, is unacceptable and fits into the definition of terrorism."[182]  USS Arizona (BB-39) burning during the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941 State terrorism has been used to refer to terrorist acts committed by governmental agents or forces. This involves the use of state resources employed by a state's foreign policies, such as using its military to directly perform acts of terrorism. Professor of Political Science Michael Stohl cites the examples that include the German bombing of London, the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the Allied firebombing of Dresden, and the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. He argues that "the use of terror tactics is common in international relations and the state has been and remains a more likely employer of terrorism within the international system than insurgents." He cites the first strike option as an example of the "terror of coercive diplomacy" as a form of this, which holds the world hostage with the implied threat of using nuclear weapons in "crisis management" and he argues that the institutionalized form of terrorism has occurred as a result of changes that took place following World War II. In this analysis, state terrorism exhibited as a form of foreign policy was shaped by the presence and use of weapons of mass destruction, and the legitimizing of such violent behavior led to an increasingly accepted form of this behavior by the state.[183][184][185] Charles Stewart Parnell described William Ewart Gladstone's Irish Coercion Act as terrorism in his "no-Rent manifesto" in 1881, during the Irish Land War.[186] The concept is used to describe political repressions by governments against their own civilian populations with the purpose of inciting fear. For example, taking and executing civilian hostages or extrajudicial elimination campaigns are commonly considered "terror" or terrorism, for example during the Red Terror or the Great Terror.[187] Such actions are often described as democide or genocide, which have been argued to be equivalent to state terrorism.[188] Empirical studies on this have found that democracies have little democide.[189][190] Western democracies, including the United States, have supported state terrorism[191] and mass killings,[192][193] with some examples being the Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66 and Operation Condor.[194][195][196] |

国家および国家が支援するテロリズム 国家テロリズム 主な記事:国家テロリズム 文明は、明確に定義され、広く受け入れられているが、しばしば明確に表現されていない階層構造に基づいています。階層の上位者が下位者に対して行う暴力 は、ほとんどの場合、目に見えない、つまり気づかれることのないものです。それが気づかれた場合、それは完全に合理化されます。階層の下位にある者が上位 にある者に対して行う暴力は考えられないことであり、それが発生した場合、衝撃と恐怖、そして犠牲者のフェティシズムが生まれます。 — デリック・ジェンセン[178]  1937年8月28日、日本の爆撃後の上海南駅で泣く乳児 「テロリズム」と同様、「国家テロリズム」という概念も議論の的となっている[179]。国連テロ対策委員会委員長は、同委員会は、この問題に関する 12 の国際条約を認識しているが、そのいずれもが、国際法上の概念ではない「国家テロリズム」について言及していないと述べた。国家が権力を乱用した場合、戦 争犯罪、国際人権法、国際人道法に関する国際条約に基づいて判断されるべきだ。[180] 元国連事務総長のコフィ・アナン氏は、「いわゆる『国家テロリズム』に関する議論は脇に置いておくべき時が来た。国家による武力の行使は、国際法によって すでに徹底的に規制されている」と述べた[181]。同氏は、「テロリズムの定義に関する各国政府の意見の相違はあれ、明確であり、私たち全員が合意でき ることは、その目的が何であれ、無実の民間人(または非戦闘員)に対する意図的な攻撃は容認できず、テロリズムの定義に該当する」と明言した[182]。  1941年12月7日、真珠湾攻撃で炎上する米海軍戦艦アリゾナ(BB-39)。 国家テロリズムとは、政府機関や政府軍によるテロ行為を指す。これには、軍事力によるテロ行為の直接実行など、国家の外交政策のために国家の資源が活用さ れる場合が含まれる。政治学教授のマイケル・ストールは、例として、ドイツのロンドン爆撃、日本の真珠湾攻撃、連合軍のドレスデン大空襲、第二次世界大戦 中のアメリカによる広島と長崎への原子爆弾投下を挙げる。彼は、「テロ戦術の使用は国際関係において一般的であり、国家は国際システム内において、反乱勢 力よりもテロリズムの雇用主としてより可能性が高い」と主張する。彼は、この形態の例として「強制的外交のテロ」として「先制攻撃オプション」を挙げ、核 兵器の使用を暗に脅かすことで「危機管理」において世界を人質に取る行為を指摘し、第二次世界大戦後の変化の結果、テロリズムの制度化された形態が生じた と主張している。この分析では、国家テロリズムが外交政策の一形態として現れたのは、大量破壊兵器の存在と使用によって形作られ、そのような暴力行為の正 当化が、国家によるこの行為の受け入れをますます広めた結果だとされている。[183][184][185] チャールズ・スチュアート・パーネルは、1881年のアイルランド土地戦争中に発表した「無地代宣言」の中で、ウィリアム・エワート・グラッドストーンの アイルランド強制法をテロリズムと表現した。[186] この概念は、恐怖を煽る目的で、政府が自国の民間人に対して行う政治的抑圧を表すために用いられる。例えば、民間人の人質取りや法外的な排除キャンペーン は、赤のテロや大恐怖政治などの場合、一般的に「テロ」またはテロリズムとみなされる。このような行為は、しばしば「デモサイド」または「ジェノサイド」 と表現され、国家テロリズムと同等であると主張されている。この点に関する実証研究では、民主主義国家ではデモサイドはほとんど発生していないことが明ら かになっている。[189][190] 西欧民主主義国家、特にアメリカ合衆国は、国家テロリズム[191]や大量殺戮[192][193]を支援してきた。例としては、1965年から1966 年のインドネシアの大量殺戮やオペレーション・コンドルが挙げられる。[194][195][196] |

| State-sponsored terrorism Main article: State-sponsored terrorism  Luis Posada and CORU are widely considered responsible for the 1976 bombing of a Cuban airliner that killed 73 people.[197] A state can sponsor terrorism by funding or harboring a terrorist group. Opinions as to which acts of violence by states consist of state-sponsored terrorism vary widely. When states provide funding for groups considered by some to be terrorist, they rarely acknowledge them as such.[198][citation needed] Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine starting in February 2022, the European Parliament adopted a resolution in November 2022 recognizing Russia as a state sponsor of terrorism and a state that ″uses means of terrorism″.[199] In addition, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Slovakia have designated Russia as a state sponsor of terrorism due to its actions in Ukraine.[200][201][202][203] |

国家支援テロリズム 主な記事:国家支援テロリズム  ルイス・ポサダとCORUは、1976年に73人が死亡したキューバの旅客機爆破事件の責任者と広く見なされている。[197] 国家は、テロリスト集団に資金を提供したり、保護したりすることで、テロリズムを支援することができる。国家によるどの暴力行為が国家支援テロリズムに該 当するかは、意見が大きく分かれている。国家が、一部の人々がテロリストとみなすグループに資金を提供する場合、その事実を認めることはほとんどない。 [198][要出典] 2022年2月に始まったロシアのウクライナ侵攻を受けて、欧州議会は2022年11月、ロシアをテロ支援国家および「テロ手段を用いる国家」と認定する 決議を採択した。[199] さらに、リトアニア、ラトビア、エストニア、スロバキアは、ウクライナでの行動を理由に、ロシアをテロ支援国家に指定している。[200][201] [202][203] |