Structural violence, violencia estructural

近代国家における暴力装置概念(意味の四角形)

構造的暴力

Structural violence, violencia estructural

近代国家における暴力装置概念(意味の四角形)

解説:池田光穂

暴力行使において行為者が特定しにくいも のを構造的暴力(structural violence)とよぶ。行為者が特定しにくい暴力行使の特徴は、力の行使と力の観念の間に複雑な関係があり、行使と観念の間に明確な区別がつきにくい ために、ヨハン・ガルトゥング(Johan Galtung, 1969)は人為的暴力や直接的暴力[→彼は後に行為者暴力とまとめる]との対概念として、この概念を提唱している[ガルトゥング 2003:117]。

ちなみ、トーマス・ホッブスによると、戦争は単に武力衝突が行われている状態の

ことではなく、継続する時間と、それを継続させようとする志向性があることが、その定義に含まれるという。したがって、戦争とは、ホッブスに従うと、極めて「構造的なもの」である。

通常暴力の行為者は、特定の個人や政治集 団、警察や軍隊などの国家暴力[執行]装置、あるいは国家そのものや社会制度(司法や裁判)などがある が、それらの主体が特的できうる暴力の行使は、それぞれ、政治暴力、国家暴力、軍事的暴力、司法的暴力(一般の法学者や政治学者はこの概念を容認しないか も知れないが)など、暴力主体や暴力の目的という形容詞を暴力に冠することで、暴力の行為者や意図を指し示すことができる。

それに対して構造的暴力は、どの特定の行 為者のどのような意図が、その暴力行使であるか、特定しにくいのが特徴である。つまり、構造的暴力は、 被害者に「非直接的に」はたらくというのだ。ただし、このようなガルトゥングの二分法は曖昧でほとんど「権力」の概念と区別がつかない点で問題がある。

構造的暴力は、国家や権力集団が、合法性 を装い持続的におこなわれる、人権・道徳・排外的な暴力の行使である。それゆえ、構造的暴力は、国家、 民族、人種、権利、正義、性別、宗教的ドグマの名の下に行使され、平和的や人道的であると正当化されることがある。

ガルトゥングは構造的暴力の形態を次の3 つに分類する[ガルトゥング 2003:118]

1)抑圧——政治的なるもの

2)搾取——経済的なるもの

3)疎外——文化的なるもの

平和維持のための軍隊の派兵や、途上国に おける当事者たちの同意なしの不妊手術や投薬は、典型的な構造的暴力である[と私は考える]が、このよ うに構造的暴力を捉えると、構造的暴力がはたして通常の暴力的行使と同じものであるがどうかという点については、いまだ議論の余地があり、また、誰がそれ を構造的暴力と認定するかという点で、極めて論争的な概念である。

ガルトゥングの構造的暴力の概念が、権力 概念と区別をつかないとか、あらゆるタイプの間接的暴力に適用可能であるということは、彼の理論が、い かに理性 的合理的モデルに依存しており、そのモデルの限界についてガルトゥングは自覚が足らず、これらの概念を鍛えようとも、その背景には奇妙な神学的弁論(=暴 力を理性により理解し、統御する)が見え隠れしている。

この点で考えると、ガルトゥングをより深 く理解するためには、その対極的な参照点として、大衆を動員するための神話的暴力あるいは象徴的暴力の 必要性を説いたジョルジュ・ソレルの暴力論について[も]考えることが重要になるかも知れない[→リ ンク]。

近代国家における暴力装置概念(意味の四角形)

「現代の国家観における暴力装置概念をグレマス[1992]の「意味の四角形」に配列してみたのが図2である。暴力(S1)の相反項は

もちろん非暴力(S2)である。国家は社会契約にもとづき個々の人民が武装し暴力(S1)を行使する権利を国家権力を介して回収する。権力(‾S2)は暴

力装置を維持するために不可欠なものにほかならないが、それは国家が人民の合意にもとづき行使されるべきものである。暴力装置が不要になる状態(=警察や

軍隊のない社会)とは、権力が極小化された状況すなわち平和(‾S1)に他ならない。このような理想的状況においては、国内の秩序維持に暴力装置(=警

察)を行使することは不要になり、ただ国民を守るためのもの(=軍隊)だけが必要となる」(出典:池田光穂「政治的暴力と人類学を考える——グアテマラの

現在——」『社会人類学年報』,第28巻,Pp.27-54,2002年)

ここから、力の発露としての暴力がなくて も、それが「低強度」でおこなわれていることは、構造的暴力の前駆的状態(precursor)であ り、そのような状態を構造的不正義(structural injustice)と命名してもよいだろう(Young 2006)

| Structural

violence is a form of violence wherein some social structure or

social institution may harm people by preventing them from meeting

their basic needs or rights. The term was coined by Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung, who introduced it in his 1969 article "Violence, Peace, and Peace Research".[1] Some examples of structural violence as proposed by Galtung include institutionalized racism, sexism, and classism, among others.[2][3] Structural violence and direct violence are said to be highly interdependent, including family violence, gender violence, hate crimes, racial violence, police violence, state violence, terrorism, and war.[4] It is very closely linked to social injustice insofar as it affects people differently in various social structures.[5] |

構造的暴力とは、ある社会構造や社会制度が、基本的なニーズや権利を満

たすことを妨げることによって、人々に害を与える暴力の一形態である。 この用語はノルウェーの社会学者ヨハン・ガルトゥングによって作られたもので、彼は1969年の論文「暴力、平和、そして平和研究」の中でこの用語を紹介 した[1]。ガルトゥングが提唱した構造的暴力の例としては、制度化された人種主義、性主義、階級主義などが挙げられる。 [2][3]構造的暴力と直接的暴力は、家族暴力、ジェンダー暴力、ヘイトクライム、人種暴力、警察暴力、国家暴力、テロリズム、戦争など、非常に相互依 存的であると言われている[4]。様々な社会構造の中で人々に異なる影響を与えるという点で、社会的不公正と非常に密接に関連している[5]。 |

| Definitions Galtung According to Johan Galtung, rather than conveying a physical image, structural violence is an "avoidable impairment of fundamental human needs."[6] Galtung contrasts structural violence with "classical violence:" violence that is "direct," characterized by rudimentary, impermanent "bodily destruction" committed by some actor. Galtung places this as the first category of violence. In this sense, the purest form of structural violence can be understood as violence that endures with no particular beginning, and that lacks an 'actor' to have committed it.[7]: 5, 11 Following this, by excluding the requirement of an identifiable actor from the classical definition of violence, Galtung lists poverty (i.e., the "deprival of basic human needs") as the second category of violence and "structurally conditioned poverty" as the first category of structural violence.[7]: 11 Asking why violence necessarily needs to be done to the human body for it to be considered violence—"why not also include violence done to the human mind, psyche or how one wants to express it"—Galtung proceeds to repression (i.e., the "deprival of human rights") as the third category of violence, and "structurally conditioned repression" (or, "repressive intolerance") as the second type of structural violence.[7]: 11 Lastly, Galtung notes that repression need not be violence associated with repressive regimes or declared on particular documents to be human-rights infractions, as "there are other types of damage done to the human mind not included in that particular tradition." From this sense, he categorizes alienation (i.e., "deprival of higher needs") as the fourth type of violence, leading to the third kind of structural violence, "structurally conditioned alienation"—or, "repressive tolerance," in that it is repressive but also compatible with repression, a lower level of structural violence.[7]: 11 Since structural violence is avoidable, he argues, structural violence is a high cause of premature death and unnecessary disability.[5] Some examples of structural violence as proposed by Galtung include institutionalized adultism, ageism, classism, elitism, ethnocentrism, nationalism, racism, sexism, and speciesism.[2][3] Structural violence and direct violence are said to be highly interdependent, including family violence, gender violence, hate crimes, racial violence, police violence, state violence, terrorism, and war.[4] |

定義 ガルトゥング ヨハン・ガルトゥングによれば、構造的暴力とは物理的なイメージを伝えるというよりもむしろ、「人間の基本的な欲求の回避可能な障害」である[6]。 ガルトゥングは構造的暴力を「古典的暴力」と対比している。それは「直接的」な暴力であり、何らかの行為者によって行われる初歩的で無常な「身体的破壊」 によって特徴づけられる。ガルトゥングはこれを暴力の最初のカテゴリーと位置づけている。この意味で、構造的暴力の最も純粋な形態は、特定の始まりもなく 永続し、それを犯した「行為者」を欠く暴力として理解することができる[7]: 5, 11 これに倣い、古典的な暴力の定義から特定可能な行為者の要件を除外することで、ガルトゥングは貧困(すなわち「人間の基本的欲求の剥奪」)を暴力の第2カ テゴリーとして、「構造的に条件づけられた貧困」を構造的暴力の第1カテゴリーとして挙げている[7]: 11 ガルトゥングは、暴力が暴力とみなされるためには、なぜ必ずしも人間の身体に加えられる必要があるのか、「なぜ人間の心や精神、あるいはそれをどう表現し たいかに加えられる暴力も含まれないのか」と問いかけながら、暴力の第三のカテゴリーとして抑圧(すなわち「人権の剥奪」)を、構造的暴力の第二のカテゴ リーとして「構造的に条件づけられた抑圧」(あるいは「抑圧的不寛容」)を挙げている[7]: 11 最後にガルトゥングは、抑圧が人権侵害であるためには、抑圧的な体制に関連した暴力である必要はなく、特定の文書で宣言された暴力である必要もないことを 指摘する。このような意味から、彼は疎外(すなわち「高次の欲求の剥奪」)を第4のタイプの暴力として分類し、第3の種類の構造的暴力である「構造的に条 件づけられた疎外」、すなわち抑圧的でありながら抑圧とも両立しうるという意味で「抑圧的寛容」、構造的暴力のより低いレベルへと導いている[7]: 11 構造的暴力は回避可能であるため、構造的暴力は早死や不必要な障害の高い原因であると彼は主張する[5]。 ガルトゥングが提唱する構造的暴力の例としては、制度化された成年主義、年齢主義、階級主義、エリート主義、民族中心主義、ナショナリズム、人種主義、性 差別主義、種差別主義などがある[2][3]。 家族暴力、ジェンダー暴力、ヘイトクライム、人種主義暴力、警察暴力、国家暴力、テロリズム、戦争など、構造的暴力と直接的暴力は相互依存性が高いと言わ れている[4]。 |

| Others In his book Violence: Reflections on a National Epidemic, James Gilligan defines structural violence as "the increased rates of death and disability suffered by those who occupy the bottom rungs of society, as contrasted with the relatively lower death rates experienced by those who are above them." Gilligan largely describes these "excess deaths" as "non-natural" and attributes them to the stress, shame, discrimination, and denigration that results from lower status. He draws on Richard Sennett and Jonathan Cobb (i.e., The Hidden Injuries of Class, 1973), who examine the "contest for dignity" in a context of dramatic inequality.[8] In her interdisciplinary textbook on violence, Bandy X. Lee wrote "Structural violence refers to the avoidable limitations that society places on groups of people that constrain them from meeting their basic needs and achieving the quality of life that would otherwise be possible. These limitations, which can be political, economic, religious, cultural, or legal in nature, usually originate in institutions that exercise power over particular subjects."[9] She goes on to say that "[it] is therefore an illustration of a power system wherein social structures or institutions cause harm to people in a way that results in maldevelopment and other deprivations."[9] Rather than the term being called social injustice or oppression, there is an advocacy for it to be called violence because this phenomenon comes from, and can be corrected by, human decisions, rather than just natural causes.[9] |

その他 ジェームス・ギリガンは、その著書『暴力』の中で、構造的暴力を次のように定義している: ジェームス・ギリガンは、その著書『暴力:ナショナリズム』の中で、構造的暴力を「社会の底辺を占める人々が被る死亡率や障害率の増加であり、それ以上の 人々が経験する死亡率の相対的な低さとは対照的である」と定義している。ギリガンは、これらの「過剰な死」を「非自然的なもの」とし、地位の低さがもたら すストレス、羞恥心、差別、誹謗中傷が原因であるとしている。彼はリチャード・セネットとジョナサン・コブ(すなわち、『The Hidden Injuries of Class』、1973年)を参考にし、劇的な不平等の文脈における「尊厳の争い」を検証している[8]。 暴力に関する学際的な教科書の中で、バンディ・X・リーは「構造的暴力とは、社会が人々の集団に課す回避可能な制限のことであり、それがなければ可能で あったであろう基本的なニーズを満たし、生活の質を達成することを制約する」と書いている。これらの制限は、政治的、経済的、宗教的、文化的、あるいは法 的なものである可能性があり、通常、特定の主体に対して権力を行使する制度に由来する。 この用語が社会的不公正や抑圧と呼ばれるのではなく、暴力と呼ばれるように提唱されているのは、この現象が単なる自然的な原因ではなく、人間の意思決定か ら生じ、それによって是正されうるからである[9]。 |

| Forms Cultural violence See also: Cultural conflict and Cultural genocide Cultural violence refers to aspects of a culture that can be used to justify or legitimize direct or structural violence, and may be exemplified by religion & ideology, language & art, and empirical science & formal science.[10] Cultural violence makes both direct and structural violence look or feel 'right', or at least not wrong, according to Galtung.[10]: 291 The study of cultural violence highlights the ways the act of direct violence and the fact of structural violence are legitimized and thus made acceptable in society. Galtung explains that one mechanism of cultural violence is to change the "moral color" of an act from "red/wrong" to "green/right," or at least to "yellow/acceptable."[10]: 292 Institutional violence Institutional violence is a form of structural violence in which organizations employ attitudes, beliefs, practices, and policies to marginalize or exploit vulnerable groups.[11] Rossiter and Rinaldi (2018) argue that particular organizational traits serve as the structural elements allowing for the reconstruction of one's sense of inhumane behavior (e.g., moral justification), its deleterious effects (e.g., minimizing), the responsibility for its impact (e.g., denial), and the subject harmed (e.g., dehumanization), which influences moral abdication and thus create an ethos of violence.[12] The authors mention that, as one example of such traits, the social or physical distance of organizations themselves from the wider society can be a key mechanism.[12] |

フォーム 文化的暴力 以下も参照のこと: 文化的紛争、文化的ジェノサイド 文化的暴力とは、直接的暴力または構造的暴力を正当化または正当化するために使用されうる文化の側面を指し、宗教とイデオロギー、言語と芸術、経験科学と 形式科学によって例示されることがある[10]。 ガルトゥングによれば、文化的暴力は直接的暴力と構造的暴力の両方を「正しい」、あるいは少なくとも間違っていないように見せたり感じさせたりする。ガル トゥングは、文化的暴力のメカニズムの一つは、ある行為の「道徳的色彩」を「赤/間違っている」から「緑/正しい」、あるいは少なくとも「黄色/容認でき る」に変えることだと説明している[10]: 292。 制度的暴力 制度的暴力は構造的暴力の一形態であり、組織が態度、信念、慣行、政策を用いて、社会的弱者を疎外したり搾取したりするものである[11]。 ロシターとリナルディ(2018)は、特定の組織的特性が、非人道的行動に対する自分の感覚(例えば、 道徳的正当化)、その有害な影響(例:最小化)、その影響に対する責任(例:否定)、被害を受ける主体(例:非人間化)を再構築することを可能にする構造 的要素として機能し、道徳的放棄に影響を与え、その結果暴力のエートスを生み出すと述べている[12]。 著者らは、そのような特質の一例として、組織自体がより広い社会から社会的または物理的に離れていることが重要なメカニズムになりうると言及している [12]。 |

| Cause and effects In The Sources of Social Power (1986),[13] Michael Mann makes the argument that within state formation, "increased organizational power is a trade-off, whereby the individual obtains more security and food in exchange for his or her freedom."[14] Siniša Malešević elaborates on Mann's argument: "Mann's point needs extending to cover all social organizations, not just the state. The early chiefdoms were not states, obviously; still, they were established on a similar basis—an inversely proportional relationship between security and resources, on the one hand, and liberty, on the other."[14] This means that, although those who live in organized, centralized social systems are not likely subject to hunger or to die in an animal attack, they are likely to engage in organized violence, which could include war. These structures make for opportunities and advances that humans could not create for themselves, including the development of agriculture, technology, philosophy, science, and art; however, these structures take tolls elsewhere, making them both productive and detrimental. In early human history, hunter-gatherer groups used organizational power to acquire more resources and produce more food; yet, at the same time, this power was also used to dominate, kill, and enslave other groups in order to expand territory and supplies.[14] Although structural violence is said to be invisible, it has a number of influences that shape it. These include identifiable institutions, relationships, social phenomenon, and ideologies, including discriminatory laws, gender inequality, and racism. Moreover, this does not solely exist for those of lower classes, though the effects are much heavier on them, including higher rates of disease and death, unemployment, homelessness, lack of education, powerlessness, and shared fate of miseries. The whole social order is affected by social power; other, higher-class groups, however have much more indirect effects on them, with the acts generally being less violent.[citation needed] Due to social and economic structures in place today—specifically divisions into rich and poor, powerful and weak, and superior and inferior—the excess premature death rate is between 10 and 20 million per year, which is over ten times the death rates from suicide, homicide, and warfare combined.[9] The work of Yale-based German philosopher, Thomas Pogge, is one major resource on the connection between structural violence and poverty, especially his book World Poverty and Human Rights (2002). |

原因と結果 マイケル・マンは『社会権力の源泉』(1986年)の中で[13]、国家形成の中では「組織権力の増大はトレードオフであり、それによって個人は自由と引 き換えに、より多くの安全と食料を手に入れる」[14]と主張している。 シニシャ・マレシェヴィッチはマンの議論を詳しく説明している: 「マンの指摘は、国家だけでなく、すべての社会組織をカバーするために拡張する必要がある。マンの指摘は、国家だけでなく、すべての社会組織を対象として 拡張する必要がある」[14]。つまり、組織化され、中央集権化された社会システムに住む人々は、飢餓にさらされたり、動物に襲われて死んだりする可能性 はないものの、戦争を含む組織的暴力に関与する可能性があるということである。このような構造は、農業、テクノロジー、哲学、科学、芸術の発展など、人類 が自分たちでは創造できなかった機会や進歩をもたらす。初期の人類史において、狩猟採集民の集団は、より多くの資源を獲得し、より多くの食料を生産するた めに組織の力を利用した。しかし同時に、この力は、領土と物資を拡大するために、他の集団を支配し、殺し、奴隷化するためにも利用された[14]。 構造的暴力は目に見えないと言われているが、それを形成する多くの影響がある。これには、差別的な法律、ジェンダー不平等、人種主義を含む、特定可能な制 度、人間関係、社会現象、イデオロギーが含まれる。さらに、これは下層階級の人々だけに存在するわけではなく、病気や死亡率の高さ、失業、ホームレス、教 育の欠如、無力感、不幸の運命共同体など、その影響ははるかに重い。社会秩序全体が社会的権力の影響を受けている。しかし、他の上流階級の集団は、一般的 に暴力的な行為が少なく、より間接的な影響を受けている[要出典]。 今日行われている社会的・経済的構造-特に富める者と貧しい者、権力者と弱者、優れた者と劣った者という区分-により、超過早死率は年間1,000万人か ら2,000万人の間であり、これは自殺、殺人、戦争を合わせた死亡率の10倍以上である[9]。 イェール大学を拠点とするドイツの哲学者、トーマス・ポッゲの研究は、構造的暴力と貧困の関連性、特に彼の著書『世界の貧困と人権』(2002年)に関す る主要な資料のひとつである。 |

| Access to health care Structural violence affects the availability of health care insofar as paying attention to broad social forces (racism, gender inequality, classism, etc.) can determine who falls ill and who will be given access to care. It is therefore considered more likely for structural violence to occur in areas where biosocial methods are neglected in a country's health care system. Since situations of structural violence are viewed primarily as biological consequences, it neglects problems stimulated by people's environment, such as negative social behaviours or the prominence of inequality, therefore ineffectively addressing the issue.[5] Medical anthropologist Paul Farmer argues that the major flaw in the dominant model of medical care in the US is that medical services are sold as a commodity, remaining only available to those who can afford them. As medical professionals are not trained to understand the social forces behind disease, nor are they trained to deal with or alter them, they consequently have to ignore the social determinants that alter access to care. As a result, medical interventions are significantly less effective in low-income areas. Similarly, many areas and even countries cannot afford to stop the harmful cycle of structural violence.[5] The lack of training has, for example, had a significant impact on diagnosis and treatment of AIDS in the United States. A 1994 study by Moore et al.[15] found that black Americans had a significantly lesser chance of receiving treatment than white Americans.[5] Findings from another study suggest that the increased rate of workplace injury among undocumented Latino immigrants in the United States can also be understood as an example of structural violence.[16] If biosocial understandings are forsaken when considering communicable diseases such as HIV, for example, prevention methods and treatment practices become inadequate and unsustainable for populations. Farmer therefore also states that structural forces account for most if not all epidemic diseases.[5] Structural violence also exists in the area of mental health, where systems ignore the lived experiences of patients when making decisions about services and funding without consulting with the ill, including those who are illiterate, cannot access computers, do not speak the dominant language, are homeless, are too unwell to fill out long formal surveys, or are in locked psychiatric and forensic wards. Structural violence is also apparent when consumers in developed countries die from preventable diseases 15–25 years earlier than those without a lived experience of mental health. |

保健医療へのアクセス 構造的暴力は、広範な社会的力(人種主義、ジェンダー不平等、階級主義など)に注意を払うことで、誰が病気になり、誰が医療を受けられるかを決定できる限 りにおいて、保健医療の利用可能性に影響を与える。したがって、その国の保健医療制度において生物社会的手法が軽視されている地域では、構造的暴力が起こ りやすいと考えられる。構造的暴力の状況は、主に生物学的な結果として捉えられているため、否定的な社会的行動や不平等の顕著さなど、人々の環境によって 刺激される問題がないがしろにされ、そのため問題への対処が効果的でない。 医療人類学者のポール・ファーマーは、アメリカにおける医療の支配的なモデルの大きな欠陥は、医療サービスが商品として売られ、それを買う余裕のある人に しか利用できないままであることだと論じている。医療従事者は、病気の背後にある社会的な力を理解する訓練を受けておらず、また、そうした力に対処した り、変化させたりする訓練も受けていないため、結果的に、医療へのアクセスを変化させる社会的決定要因を無視せざるを得ないのである。その結果、低所得地 域では医療介入の効果が著しく低くなる。同様に、多くの地域や国でさえ、構造的暴力の有害な連鎖を止める余裕がない。 例えば、トレーニングの欠如は、米国におけるエイズの診断と治療に大きな影響を及ぼしてきた。Mooreらによる1994年の研究 [15] では、黒人のアメリカ人は白人のアメリカ人に比べて治療を受ける機会が著しく少ないことがわかった。 例えば、HIVのような伝染病を考える際に、生物社会的な理解が見過ごされると、予防法や治療法が不十分となり、集団にとって持続不可能なものとなる。し たがってファーマーは、すべての伝染病とは言わないまでも、ほとんどの伝染病の原因は構造的な力にあると述べている。 構造的暴力は精神保健の分野にも存在し、制度がサービスや資金について決定する際に、読み書きのできない人、コンピューターにアクセスできない人、支配的 な言語を話せない人、ホームレスの人、具合が悪すぎて長い正式な調査に記入できない人、施錠された精神科病棟や法医学病棟にいる人など、病者と相談するこ となく患者の生活体験を無視している。構造的暴力は、先進国の消費者が予防可能な病気で死亡するのが、精神保健の生活経験のない人よりも15~25年早い ことからも明らかである。 |

| Solutions Farmer ultimately claims that "structural interventions" are one possible solution to such violence.[5] However, for structural interventions to be successful, medical professionals need to be capable of executing such tasks; as stated above, though, many of professionals are not trained to do so.[5] Medical professionals still continue to operate with a focus on individual lifestyle factors rather than general socio-economic, cultural, and environmental conditions. This paradigm is considered by Farmer to obscure the structural impediments to changes because it tends to avoid the root causes that should be focused on instead.[5] Moreover, medical professionals can rightly note that structural interventions are not their job, and as result, continue to operate under conventional clinical intervention. Therefore, the onus falls more on political and other experts to implement such structural changes. One response is to incorporate medical professionals and to acknowledge that such active structural interventions are necessary to address real public health issues.[5] Countries such as Haiti and Rwanda, however, have implemented (with positive outcomes) structural interventions, including prohibiting the commodification of the citizen needs (such as health care); ensuring equitable access to effective therapies; and developing social safety nets. Such initiatives increase the social and economic rights of citizens, thus decreasing structural violence.[5] The successful examples of structural interventions in these countries have shown to be fundamental. Although the interventions have enormous influence on economical and political aspects of international bodies, more interventions are needed to improve access.[5] Although health disparities resulting from social inequalities are possible to reduce, as long as health care is exchanged as a commodity, those without the power to purchase it will have less access to it. Biosocial research should therefore be the main focus, while sociology can better explain the origin and spread of infectious diseases, such as HIV or AIDS. For instance, research shows that the risk of HIV is highly affected by one's behavior and habits. As such, despite some structural interventions being able to decrease premature morbidity and mortality, the social and historical determinants of the structural violence cannot be omitted.[5] |

解決策 ファーマーは最終的に、「構造的介入」がこのような暴力に対するひとつの可能な解決策であると主張している[5]。しかし、構造的介入を成功させるために は、医療専門家がそのようなタスクを実行できる必要があるが、前述のように、多くの医療専門家はそのような訓練を受けていない[5]。このパラダイムは、 代わりに焦点を当てるべき根本的な原因を避ける傾向があるため、変化に対する構造的な障害をあいまいにしているとファーマーは考えている[5]。 さらに、医療専門家は、構造的な介入は自分たちの仕事ではないことを正しく認識することができ、その結果、従来の臨床的介入の下で活動を続けている。した がって、そのような構造的な変化を実行に移す責任は、政治家やその他の専門家の方にある。ひとつの対応策は、医療専門家を取り込み、このような積極的な構 造的介入が真の保健問題に取り組むために必要であることを認めることである[5]。 しかし、ハイチやルワンダのような国々は、市民のニーズ(保健など)の商品化の禁止、効果的な治療法への公平なアクセスの確保、社会的セーフティネットの 整備などの構造的介入を(肯定的な結果とともに)実施してきた。このようなイニシアチブは、市民の社会的・経済的権利を向上させ、構造的暴力を減少させる [5]。 これらの国々における構造的介入の成功例は、基本的なものであることを示している。 介入は国際機関の経済的・政治的側面に多大な影響を及ぼしているが、アクセスを改善するためにはさらなる介入が必要である[5]。 社会的不平等に起因する保健格差は縮小することが可能であるが、保健医療が商品として交換される限り、それを購入する力のない人々は、保健医療へのアクセ スが少なくなる。したがって、生物社会学的な研究が主な焦点となるべきであり、社会学はHIVやAIDSのような感染症の起源と蔓延をよりよく説明するこ とができる。例えば、HIVに感染するリスクは、その人の行動や習慣に大きく影響されることが研究で明らかになっている。そのため、構造的介入によって早 発性の罹患率や死亡率を減少させることができるにもかかわらず、構造的暴力の社会的・歴史的決定要因を省くことはできない[5]。 |

| International scope See also: Structural violence in Haiti Petra Kelly wrote in her first book, Fighting for Hope (1984): A third of the 2 Billion people in the developing countries are starving or suffering from malnutrition. Twenty-five percent of their children die before their fifth birthday […] Less than 10 per cent of the 15 million children who died this year had been vaccinated against the six most common and dangerous children's diseases. Vaccination costs £3 per child. But not doing so costs us five million lives a year. These are classic examples of structural violence. The violence in structural violence is attributed to the specific organizations of society that injure or harm individuals or masses of individuals. In explaining his point of view on how structural violence affects the health of subaltern or marginalized people, medical anthropologist Paul Farmer writes:[17][5] Their sickness is a result of structural violence: neither culture nor pure individual will is at fault; rather, historically given (and often economically driven) processes and forces conspire to constrain individual agency. Structural violence is visited upon all those whose social status denies them access to the fruits of scientific and social progress. This perspective has been continually discussed by Farmer, as well as by Philippe Bourgois and Nancy Scheper-Hughes. Farmer ultimately claims that "structural interventions" are one possible solution to such violence; structural violence is the result of policy and social structures, and change can only be a product of altering the processes that encourage structural violence in the first place.[5] Theorists argue that structural violence is embedded in the current world system; this form of violence, which is centered on apparently inequitable social arrangements, is not inevitable. Ending the global problem of structural violence will require actions that may seem unfeasible in the short term. To some,[who?] this indicates that it may be easier to devote resources to minimizing the harmful impacts of structural violence. Others, such as futurist Wendell Bell, see a need for long-term vision to guide projects for social justice. Many structural violences, such as racism and sexism, have become such a common occurrence in society that they appear almost invisible. Despite this fact, sexism and racism have been the focus of intense cultural and political resistance for many decades. Significant reform has been accomplished, though the project remains incomplete.[citation needed] Farmer notes that there are three reasons why structural violence is hard to see: Suffering is exoticized—that is, when something/someone is distant or far away, individuals tend to not be affected by it. When suffering lacks proximity, it's easy to exoticise. The weight of suffering is also impossible to comprehend. There is simply no way that many individuals are able to comprehend what suffering is like. Lastly, the dynamics and distribution of suffering are still poorly understood.[17] Anthropologist Seth Holmes studied suffering through the lens of structural violence in his 2013 ethnography Fresh Fruit Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States. He analyzed the naturalization of physical and mental suffering, violence continuum, and structural vulnerability experienced by Mexican migrants in the U.S. in their everyday lives.[18] Holmes used examples like governmental influences of structural violence—such as how American subsidization of corn industries force Mexican farmers out of business, thereby forcing them to make the very dangerous trip across the border, where the U.S. Border Patrol hinder these migrants' chances of finding work in America, and the impact this all has on the migrants’ bodies.[18] |

国際的な範囲 こちらも参照のこと: ハイチの構造的暴力 ペトラ・ケリーは最初の著書『Fighting for Hope』(1984年)の中でこう書いている: 発展途上国の20億人のうち3分の1が飢餓や栄養失調に苦しんでいる。今年亡くなった1,500万人の子どもたちのうち、最も一般的で危険な6つの子ども の病気の予防接種を受けていたのは10%にも満たない。ワクチン接種には子ども一人につき3ポンドかかる。しかし、そうしないことで年間500万人の命が 犠牲になっている。これらは構造的暴力の典型的な例である。 構造的暴力における暴力は、個人や個人の集団を傷つけ、傷つける社会の特定の組織に起因する。医療人類学者ポール・ファーマーは、構造的暴力がサバルタン や周縁化された人々の保健にどのような影響を与えるかについて、自身の見解を説明する中で、次のように書いている[17][5]。 彼らの病気は構造的暴力の結果である。文化や純粋な個人の意志が悪いのではなく、むしろ歴史的に与えられた(そしてしばしば経済的に動かされた)プロセス や力が、個人の主体性を制約するために共謀しているのである。構造的暴力は、社会的地位によって科学的・社会的進歩の果実へのアクセスを否定されるすべて の人々に襲いかかる。 この視点は、ファーマーだけでなく、フィリップ・ブルゴワやナンシー・シェパー=ヒューズも継続的に論じてきた。構造的暴力は政策と社会構造の結果であ り、変化はそもそも構造的暴力を助長するプロセスを変えることによってのみ生まれるものである。 理論家は、構造的暴力は現在の世界システムに埋め込まれていると主張する。明らかに不平等な社会的取り決めを中心とするこのような形態の暴力は、必然的な ものではない。構造的暴力という世界的な問題に終止符を打つには、短期的には実現不可能と思われるような行動が必要になる。このことは、構造的暴力の有害 な影響を最小化することに資源を割く方が容易であることを示す人もいる。また、未来学者のウェンデル・ベルのように、社会正義のためのプロジェクトを導く 長期的なビジョンが必要だと考える人もいる。人種主義や性差別のような構造的暴力の多くは、社会でよく見られるようになり、ほとんど見えなくなっている。 この事実にもかかわらず、人種主義や性差別は何十年もの間、激しい文化的・政治的抵抗の焦点となってきた。重要な改革は成し遂げられたが、プロジェクトは まだ不完全なままである[要出典]。 ファーマーは、構造的暴力が見えにくいのには3つの理由があると指摘する: つまり、何か/誰かが遠くにいたり、遠くにいたりすると、個人はその影響を受けない傾向がある。苦しみに近接性がない場合、異国化しやすい。 苦しみの重さを理解することも不可能だ。多くの個人は、苦しみがどのようなものかを理解することはできない。 最後に、苦しみの力学と分布はまだ十分に理解されていない[17]。 人類学者のセス・ホームズは、2013年に出版した民族誌『Fresh Fruit Broken Bodies』において、構造的暴力というレンズを通して苦しみを研究している: アメリカの移民農民たち)において、構造的暴力というレンズを通して苦しみを研究している。ホームズは、構造的暴力の政府による影響のような例-例えば、 アメリカのトウモロコシ産業への補助金がメキシコ人農家を廃業に追い込み、それによって彼らが国境を越えて非常に危険な旅をすることを余儀なくされるよう な例、アメリカ国境警備隊が移民たちがアメリカで仕事を見つけるチャンスを妨げるような例、そしてこのすべてが移民たちの身体に与える影響など-を用いて 分析した[18]。 |

| Criticism The concept of structural violence has come under criticism for being "increasingly outdated and poorly theorized".[19] |

批判 構造的暴力という概念は、「ますます時代遅れになり、理論化されていない」という批判にさらされている[19]。 |

| Accumulation by dispossession Communal violence Conflict theories Cycle of violence Economic violence Extermination through labour Institutional abuse Political violence Slow violence Social murder Structural violence Suicide among LGBTQIA+ people Symbolic violence |

収奪による蓄積 共同体の暴力 紛争理論 暴力のサイクル 経済的暴力 労働による絶滅 制度的虐待 政治的暴力 緩慢な暴力 社会的殺人 構造的暴力 LGBTQIA+の自殺 象徴的暴力 |

| Galtung, Johan. 1969. "Violence,

Peace, and Peace Research." Journal of Peace Research 6(3):167–91. Gilman, Robert. 1983. "Structural violence: Can we find genuine peace in a world with inequitable distribution of wealth among nations?" In Context 4(Autumn 1983):8–8. Henderson, Sophie. 2019. "State-Sanctioned Structural Violence: Women Migrant Domestic Workers in the Philippines and Sri Lanka." Violence Against Women 26(12-13):1598–615. doi:10.1177/1077801219880969. Ho, Kathleen. 2007. "Structural Violence as a Human Rights Violation." Essex Human Rights Review 4(2). ISSN 1756-1957. |

ガルトゥング、ヨハン 1969.

「暴力、平和、そして平和研究」. Journal of Peace Research 6(3):167-91. Gilman, Robert. 1983. 「構造的暴力: 国家間の富の分配が不公平な世界で、真の平和を見出すことができるのか?" In Context 4(Autumn 1983):1983:10. In Context 4(Autumn 1983):8-8. Henderson, Sophie. 2019. 「State-Sanctioned Structural Violence: フィリピンとスリランカにおける女性移住家事労働者」. Violence Against Women 26(12-13):1598-615. doi:10.1177/1077801219880969. Ho, Kathleen. 2007. 「Structural Violence as a Human Rights Violation.」. Essex Human Rights Review 4(2). ISSN 1756-1957. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Structural_violence |

リンク

文献

◆ 練習問題

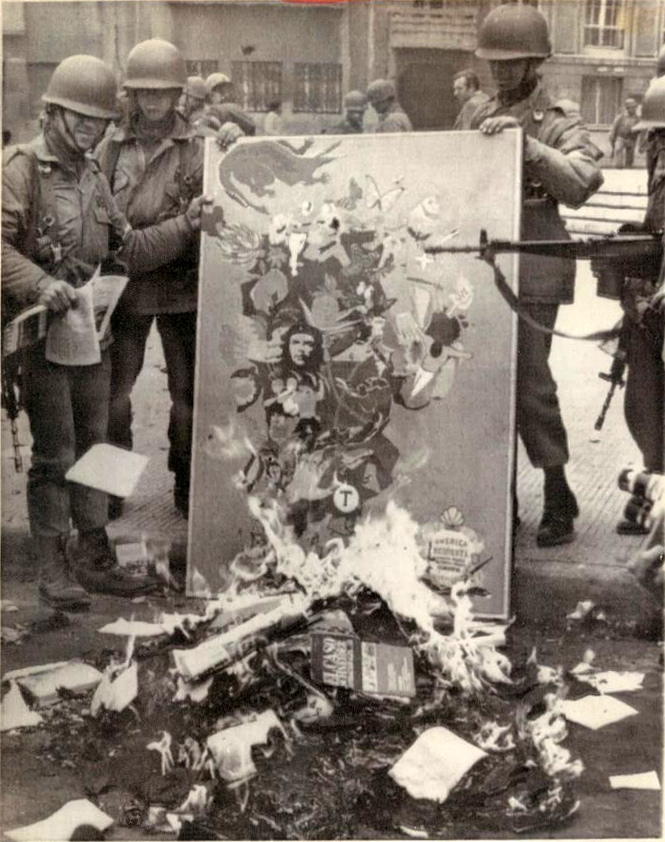

リア充の焚書や芸術の破壊の写真をみていると、まさにデジタル書籍における焚書や検閲というものは、どのようにして成立するのだろう かのか?と 考えてみたくなる。そして、1817年にドイチェ・ブルンシャフト愛国学生団体の大学における焚書があったことは、1933年5月10日のドイツにおける 焚書に十分立派な先駆形態であることがわかる。しかしながら、前者の事件にはプロシア政府は、その愛国的行為の拡大を阻止しようとし、後者のナチは、積極 的に人民を動員して、反ナチ思想とレッテルづける書籍を焚書破壊する。

左はナチスによる焚書のための図書の搬出。右はピノチェトの軍隊による共産主義・社会主義思想の弾圧

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆