ヴードゥー(オペラ作品)

Voodoo (opera)

☆『ヴードゥー』は、ハリー・ローレンス・フリーマンが音楽と台本を手が けた全3幕のオペラである。ハーレム・ルネッサンスの産物で、1928年5月20日にラジオ放送でピアノ伴奏付きで初演された。1928年9月10日、 ニューヨークのパーム・ガーデン(52番街劇場の仮の名称)でオーケストラ付きの初演が行われた[1]。

| Voodoo

is an opera in three acts with music and libretto by Harry Lawrence

Freeman. A product of the Harlem Renaissance, it was first performed

with piano accompaniment as a radio broadcast on May 20, 1928. The

first staged performance with orchestra took place on September 10,

1928, at the Palm Garden (a temporary name for the 52nd Street Theatre)

in New York City.[1] |

『ヴードゥー』は、ハリー・ローレンス・フリーマンが音楽と台本を手が

けた全3幕のオペラである。ハーレム・ルネッサンスの産物で、1928年5月20日にラジオ放送でピアノ伴奏付きで初演された。1928年9月10日、

ニューヨークのパーム・ガーデン(52番街劇場の仮の名称)でオーケストラ付きの初演が行われた[1]。 |

| History Freeman was a talented African-American musician, becoming assistant church organist at age 10. A seminal moment in his life was seeing Richard Wagner's opera Tannhäuser. In 1891, at age 18, he completed his first opera. He continued to compose numerous operas during much of his life.[2] In several articles concerning Voodoo, the New York Amsterdam News varied its reportage of the time Freeman had spent composing the opera. Initially, the paper said "Although Professor Freeman has been prepared for years for the opportunity to present the negro in opera he has had to bide his time."[3] After the opera had closed, the paper said that Freeman had been working on the opera for two years.[4] The paper corrected itself later when it reported that he had completed the opera in 1914.[5] (The finding aid for Freeman's papers at Columbia University indicates a vocal score dated 1912.)[2] |

歴史 フリーマンはアフリカ系アメリカ人の音楽家として才能を発揮し、10歳で教会のオルガン奏者のアシスタントになった。リヒャルト・ワーグナーのオペラ『タ ンホイザー』を観劇したことが、彼の人生にとって決定的な出来事となった。1891年、18歳で最初のオペラを完成させた。その後も、生涯を通じて数多く のオペラを作曲した[2]。 『ヴードゥー』に関するいくつかの記事の中で、ニューヨーク・アムステルダム・ニュースは、フリーマンがオペラの作曲に費やした時間に関する報道を変化さ せた。当初、同紙は「フリーマン教授はニグロをオペラに登場させる機会を何年も前から準備していたにもかかわらず、彼は時間を待たなければならなかった」 [3]と述べていたが、オペラが閉幕した後、同紙はフリーマンが2年間オペラに取り組んでいたと報じた[4]。 同紙は後に、彼が1914年にオペラを完成させたと報じた際に訂正している[5](コロンビア大学のフリーマンの書類のファインディング・エイドには、 1912年の日付のヴォーカル・スコアが記載されている)[2]。 |

| Synopsis Voodoo is set in Louisiana during the Reconstruction Era. Cleota, a house servant, is in love with Mando, a plantation overseer on the plantation where they live. The voodoo queen, Lolo, is jealous and, seeing Cleota as a rival, tries to put her out of the way. A voodoo ceremony takes place during which Lolo and her associate, Fojo, distribute amulets and charms to participants, then retreat to a glen to invoke the snake-god. Cleota is about to be put to death but is rescued by Mando and Chloe (Lolo's mother). Another attempt by Lolo to subdue Cleota results in the queen being shot.[6][7] The New York Herald Tribune reported that the opera was to illustrate "typical Negro life in the days of slavery, while the music includes spirituals, chants, arias, tangoes and other dances, among these a ritualistic voodoo ceremony."[8] |

あらすじ 『ヴードゥー』は再建時代のルイジアナを舞台にしている。屋敷の僕のクレオタは、二人が暮らす農園の監督マンドーに恋している。ヴードゥーの女王ロロは嫉 妬し、クレオタをライバル視して彼女を排除しようとする。ヴードゥーの儀式が行われ、ロロとその仲間のフォジョが参加者にお守りやお札を配り、蛇神を呼び 出すために渓谷に隠れる。クレオタは死刑にされそうになるが、マンドとクロエ(ロロの母)に助けられる。ロロがクレオタを制圧しようとした結果、女王は撃 たれてしまう[6][7]。 ニューヨーク・ヘラルド・トリビューン紙は、このオペラが「奴隷制時代の典型的なニグロの生活を描いており、音楽にはスピリチュアル、聖歌、アリア、タンゴ、その他のダンス、中でも儀式的なヴードゥー教の儀式が含まれている」と報じている[8]。 |

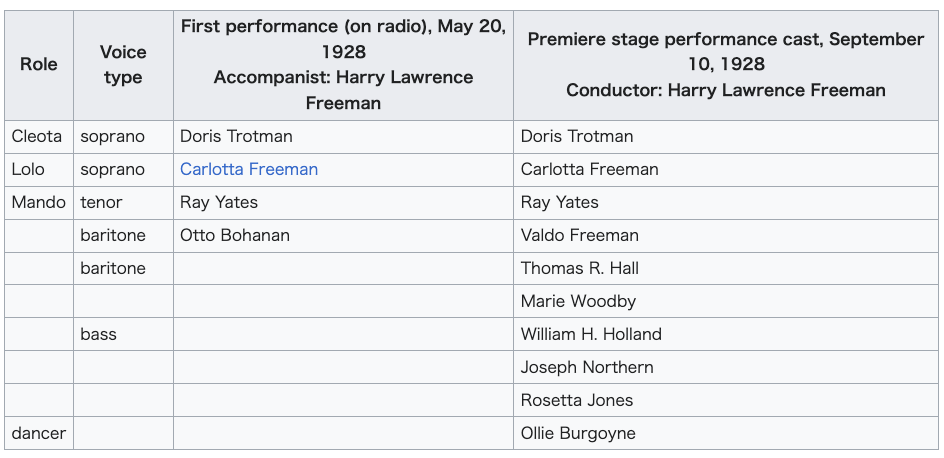

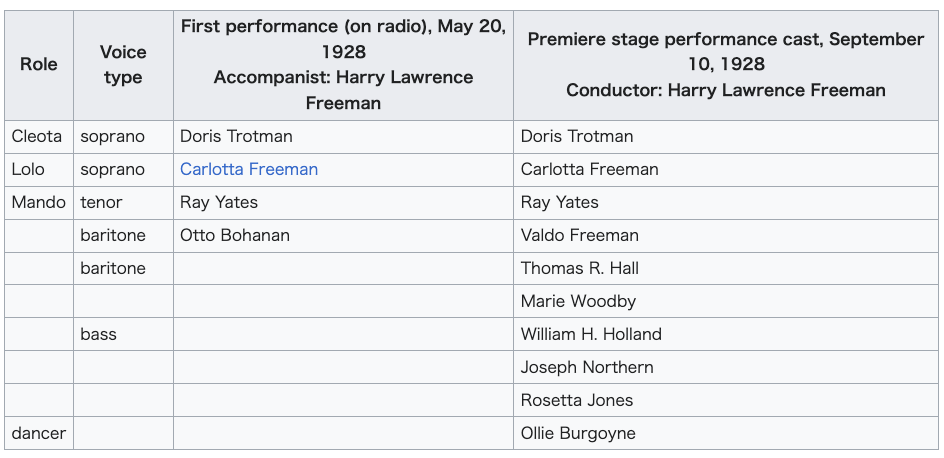

| Productions The opera was first presented as a radio broadcast with piano accompaniment (played by Freeman) on May 20, 1928, over station WGBS.[9] The cast included Doris Trotman, soprano; Carlotta Freeman, soprano; Ray Yates, tenor; Otto Bohanan, baritone.[10] A month later, Valdo Freeman, the composer's son and a baritone, sang excerpts from Voodoo as well as another of his father's operas, Plantation, during a radio recital also broadcast on WGBS on June 25, 1928.[11] Notices prior to the production's staged premiere mentioned a "company of over fifty people."[12][13] Advertisements also indicated the company was to include fifty people,[3] although this figure was reduced to thirty in later notices.[6][8][14] The "Negro jazz grand opera" (as it was called by the New York Amsterdam News[3]) had its first staged performance at the "Palm Garden" (apparently a temporary name for the 52nd Street Theatre) on September 10, 1928. Freeman conducted an orchestra of twenty-one musicians.[6] The review in the New York Herald Tribune said the presentation was "offered" by his son Valdo Freeman.[6] One review referred to the producing company as the "Negro Opera Company Inc."[15] Costumes were supplied by Chrisdie & Carlotta, and F. Berner supplied the wigs.[16] The executive staff included Robert Eichenberg, Leon Williams, Esther Thompson, Octavia Smith, Philip Williams, William Thompson, Grace Abrams, and Walter Mattis.[17] Voodoo was scheduled to run for a week with a matinée on Saturday.[6] Apparently it had to close early for lack of funding.[4] The score was never published. The manuscript resides in the Rare Book & Manuscript Library of Columbia University.[18] The first production of Voodoo since 1928 took place June 26–27, 2015 at Miller Theatre by the Harlem Opera Theatre, Morningside Opera, and the Harlem Chamber Players. It was conducted by Gregory Hopkins.[19] |

上演作品 このオペラは、1928年5月20日にWGBS局でピアノ伴奏(フリーマンが演奏)付きのラジオ放送として初めて上演された[9]。出演者は、ドリス・ト ロットマン(ソプラノ)、カルロッタ・フリーマン(ソプラノ)、レイ・イェーツ(テノール)、オットー・ボハナン(バリトン)であった[10]。 その1ヶ月後、作曲者の息子でバリトン歌手のヴァルド・フリーマンは、1928年6月25日にWGBSで放送されたラジオ・リサイタルで、ヴードゥーからの抜粋と父のもうひとつのオペラ『プランテーション』を歌った[11]。 舞台初演前の告知では「50人以上のカンパニー」[12][13]と言及されており、広告でもカンパニーには50人が含まれることが示されていた[3]が、後の告知ではこの数字は30人に減らされていた[6][8][14]。 ニグロ・ジャズ・グランド・オペラ」(『ニューヨーク・アムステルダム・ニュース』紙[3]はそう呼んでいた)は、1928年9月10日に「パーム・ガー デン」(52丁目劇場の仮の名称らしい)で初舞台を踏んだ。フリーマンは21人の音楽家からなるオーケストラを指揮した[6]。 ニューヨーク・ヘラルド・トリビューン紙の批評では、この上演は息子のヴァルド・フリーマンによって「提供された」と書かれていた[6]。ある批評では、 プロデュース・カンパニーを「ニグロ・オペラ・カンパニー・インク」と呼んでいた[15]。 衣装はクリスディ&カルロッタが提供し、F・バーナーがかつらを提供した[16]。エグゼクティブ・スタッフにはロバート・アイヘンバーグ、レオン・ウィ リアムズ、エスター・トンプソン、オクタヴィア・スミス、フィリップ・ウィリアムズ、ウィリアム・トンプソン、グレース・エイブラムス、ウォルター・マ ティスがいた[17]。 ヴードゥーは1週間上演され、土曜日にマチネがある予定だった[6]が、資金不足のため早々に閉幕せざるを得なかったようだ[4]。 楽譜は出版されなかった。原稿はコロンビア大学の貴重書・手稿図書館に所蔵されている[18]。 1928年以来初となるヴードゥーの上演が、ハーレム・オペラ・シアター、モーニングサイド・オペラ、ハーレム・チェンバー・プレイヤーズによって2015年6月26日から27日にかけてミラー・シアターで行われた。指揮はグレゴリー・ホプキンスだった[19]。 |

Cast  The alternate cast for the staged presentation included Rosetta Jones, Cordelia Paterson, Luther Lamont, Blanche Smith, John H. Eckles, Leo C. Evans, and Harold Bryant. Named participants also included the dancer Ollie Burgoyne, who had recently performed at the Folies Bergère in Paris.[8] |

キャスト ロゼッタ・ジョーンズ、コーデリア・パターソン、ルーサー・ラモント、ブランチ・スミス、ジョン・H・エクルズ、レオ・C・エヴァンス、ハロルド・ブライ アントらが出演した。また、最近パリのフォリー・ベルジェールで公演を行ったダンサーのオリー・バーゴインも名を連ねていた[8]。 |

| Response Calling it (incorrectly) the first opera composed, produced, and sung by African Americans,[1] the New York Herald Tribune's detailed review heralded the production, calling it "another step toward establishing a distinct negro culture in this country."[6] The review went on to note production limitations brought about due to lack of sufficient funding. The composer's style came in for harder criticism, with the reviewer calling his music "not original" since it was too dependent on external influences such as spirituals and Tin Pan Alley songs. But the same reviewer said the opening dance of the second act was most effective, and called the third act the most original, showing off the composer's "inspired creative powers" with "effectively barbaric moments the music accompanying the voodoo ceremony" and "various elements making a conglomerate rather than a homogeneous, well-fused score." Nevertheless, the combination of nineteenth-century Italian-French style arias with Freeman's modernistic trends created an odd juxtaposition. In general, the reviewer found the plot complex but believable, while the libretto was generally good but at times "a trifle lavish." Of the singers, the review noted Doris Trotman's "rich soprano" while Carlotta Freeman was good but with "weak high notes." While calling Valdo Freeman and Thomas R. Hall "the best voices of the evening," the review opined that "the performance was earnest rather than polished."[6] Writing in the Hartford Courant, Pierre Key reported that the production was "feeble" and "amateurish." But his estimation of the score was more positive: "A degree of rhythmic invention and facility for instrumental color are excellences this composer has."[20] The New York Times also felt that the "production [was] amateur in spirit." The unnamed reviewer noted, "The composer utilizes themes from spirituals, Southern melodies, and jazz rhythms which, combined with traditional Italian operatic forms, produce a curiously naive mélange of varied styles."[7] Writing for the Chicago Tribune, Alfred Frankenstein found the book formless (which he admitted was true of many operas) with most of the action taking place in the opera's final act, making the first two acts seem inconsequential. He criticized the use of language among the characters, the leads singing in proper English while subsidiary characters sang in "Negro dialect." He particularly condemned archaic-sounding language, such as the line "Ah, could I to thy for [my] life but restore." Frankenstein then continued his review by describing the stresses carried by African-Americans who must navigate a combination of racial inferiority and racial pride. He contended that these opposing forces can be heard in Voodoo as one hears the influences of Edward MacDowell, Richard Wagner, and Harry Burleigh as well as spirituals, although Freeman's musical expression was hampered by the poor libretto. Frankenstein concludes on a condescending note recommending that Freeman read the music history of various nationalities as a means of raising African-Americans' position within musical art.[15] The African-American press had more understanding words to say about the opera. The New York Amsterdam News highlighted how Freeman had to pay for the production with his own funding and questioned why the African-American community wasn't more supportive.[4] A letter from a reader also questioned why more African-Americans did not attend the opera.[21] Echoing the uneven musical style in other reviews, the Baltimore Afro-American noted that "the opera is not perfect." Its dependence on familiar styles resulted in the "impression of lacking a genuine authenticity and that it depends too much on outside influences to be completely Negro."[22] The appearance of Voodoo inspired other African-American operas to surface. Just a month after the opera's premiere, Billboard announced a presentation of Deep Harlem, "another negro opera," to be produced by actor/director Earl Dancer.[23] |

反響 ニューヨーク・ヘラルド・トリビューン紙の詳細な批評は、このオペラをアフリカ系アメリカ人が作曲し、制作し、歌った最初のオペラと呼び[1]、「この国 に独特の黒人文化を確立するための新たな一歩」[6]と称し、上演を歓迎した。作曲家の作風については、スピリチュアルやティン・パン・アレーの歌など、 外部からの影響に頼りすぎていて「オリジナルではない」と酷評した。しかし、同じ批評家は、第2幕の冒頭のダンスが最も効果的だったと述べ、第3幕が最も 独創的で、「ヴードゥーの儀式に伴う音楽が効果的に野蛮な瞬間」や「様々な要素が均質でうまく融合した楽譜というよりむしろ凝集体を作っている」など、作 曲家の「霊感に満ちた創造力」が発揮されていると評価した。とはいえ、19世紀のイタリア・フランス風アリアとフリーマンのモダニズム的傾向の組み合わせ は、奇妙な並置を生み出した。 リブレットは概して良かったが、時に 「少々贅沢 」だった。歌手については、ドリス・トロットマンの 「豊かなソプラノ 」に注目し、カルロッタ・フリーマンは良かったが 「高音が弱い 」と評している。ヴァルド・フリーマンとトーマス・R・ホールを「この晩最高の声」と称しながら、批評は「演奏は洗練されているというより、むしろ真剣 だった」と評している[6]。 ハートフォード・クーラント紙に寄稿したピエール・キーは、プロダクションは「弱々しく」「アマチュア的」であったと報告している。しかし、彼の楽譜に対 する評価はより肯定的であった。「ある程度のリズムの発明と楽器の色彩のための設備は、この作曲家の優れた点である」[20]。無名の批評家は、「この作 曲家は、スピリチュアル、南部のメロディー、ジャズのリズムのテーマを利用しており、伝統的なイタリア・オペラの形式と組み合わされることで、様々なスタ イルの不思議なほど素朴なメランジを生み出している」と指摘している[7]。 シカゴ・トリビューン紙に寄稿したアルフレッド・フランケンシュタインは、このオペラには形がなく(これは多くのオペラに当てはまることだが)、ほとんど のアクションがオペラの最終幕で行われるため、最初の2幕は取るに足らないものに思える。彼は登場人物の言葉の使い方を批判し、主役はきちんとした英語で 歌うのに、脇役は 「ニグロ方言 」で歌っている。彼は特に、「Ah, could I to thy for [my] life but restore. 」というセリフのような、古風に聞こえる言葉を非難した。そしてフランケンシュタインは、人種的劣等感と人種的プライドを併せ持つアフリカ系アメリカ人が 抱えるストレスについて述べ、批評を続けた。彼は、エドワード・マクダウェル、リチャード・ワグナー、ハリー・バーレイの影響やスピリチュアルな音楽が ヴードゥーに聴こえるが、フリーマンの音楽表現はリブレットの稚拙さによって妨げられていると主張した。フランケンシュタインは、音楽芸術におけるアフリ カ系アメリカ人の地位を高める手段として、フリーマンに様々な国民の音楽史を読むことを勧める慇懃無礼な言葉で締めくくっている[15]。 アフリカ系アメリカ人のプレスは、このオペラについてもっと理解ある言葉を述べていた。ニューヨーク・アムステルダム・ニュース』紙は、フリーマンが自己 資金で制作費を支払わなければならなかったことを強調し、アフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティがなぜもっと支持されなかったのかと疑問を呈した[4]。読者 からの手紙も、なぜもっと多くのアフリカ系アメリカ人がオペラに参加しなかったのかと疑問を呈した[21]。 ボルチモアのアフロ・アメリカン紙は、他の批評にある不均一な音楽スタイルと同じように、「このオペラは完璧ではない 」と指摘した。馴染みのあるスタイルに依存した結果、「本物の信憑性に欠け、完全にニグロであるためには外部の影響に依存しすぎているという印象を与え た」[22]。 ヴードゥーの登場は、他のアフリカ系アメリカ人のオペラに刺激を与えた。このオペラの初演からちょうど1ヶ月後、ビルボードは俳優/演出家のアール・ダンサーがプロデュースする「もうひとつのニグロ・オペラ」である『ディープ・ハーレム』の上演を発表した[23]。 |

| H. Lawrence Freeman papers 1870-1982 1890-1954 at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Columbia University. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voodoo_(opera) | |

Harry Lawrence Freeman (October 9, 1869 – March 24, 1954) was an American neoromantic opera composer,[1] conductor, impresario and teacher. He was the first African-American to write an opera (Epthalia, 1891) that was successfully produced. Freeman founded the Freeman School of Music and the Freeman School of Grand Opera, as well as several short-lived opera companies which gave first performances of his own compositions.[2] During his life, he was known as "the black Wagner."[3] |

ハリー・ローレンス・フリーマン(Harry Lawrence Freeman、1869年10月9日 - 1954年3月24日)は、アメリカのネオロマンティック・オペラの作曲家、指揮者、興行主、教師である[1]。彼はアフリカ系アメリカ人として初めてオ ペラを作曲し(『エプタリア』1891年)、上演に成功した。フリーマンはフリーマン音楽学校とフリーマン・スクール・オブ・グランド・オペラを設立した ほか、いくつかの短命のオペラ・カンパニーを設立し、自作オペラの初演を行った[2]。 生前は「黒いワーグナー」として知られていた[3]。 |

| Biography Harry Lawrence Freeman was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1869, to parents Lemuel Freeman and Agnes Silms-Freeman. Freeman learned to play the piano and was an assistant church organist by the age of 10.[3] At the age of 18, he was inspired to begin composing his own music after attending a performance of Richard Wagner's opera Tannhäuser. Early career: Freeman Opera Company By the age of 22, Freeman had founded the Freeman Opera Company in Denver, Colorado.[4] His first opera, Epthelia, was performed at the Deutsches Theater in Denver in 1891.[4] His second opera, The Martyr, premiered at the same theater on August 16, 1893. It was also produced by the Freeman Opera Company, and concerned an Egyptian nobleman put to death for accepting the religion of Jehovah. The Freeman Opera Company went on to produce The Martyr in Chicago in October 1893 and in Cleveland in 1894.[5] This was the first opera in the United States to be produced by an all-Black production company.[6] The Martyr is also listed by John Warthen Struble as "produced in Denver, first known opera by an African-American composer."[7] Although this is clearly incorrect given the staging of Epthelia two years earlier, Freeman was certainly a pioneering classical composer in the African-American community. In 1894, Freeman returned to live in Cleveland, and began formal training in music theory under Johann Heinrich Beck, conductor of the Cleveland Symphony (a different organization from the Cleveland Orchestra, which was founded in 1918). In 1898, Freeman married Charlotte Loise Thomas, a woman from Charleston, South Carolina who sang soprano.[8] Two years later, Charlotte (who was also known as Carlotta) gave birth to Freeman's son Valdo, and the same year, the Cleveland Orchestra gave readings of excerpts from Freeman's operas.[4] For the next decade, the new family lived in Cleveland, Chicago, and Xenia, Ohio, where Freeman was director of the music program at Wilberforce University in 1902 and 1903.[4] |

略歴 ハリー・ローレンス・フリーマンは1869年、オハイオ州クリーブランドでレミュエル・フリーマンとアグネス・シルムス=フリーマンの両親のもとに生まれた。18歳のとき、リヒャルト・ワーグナーのオペラ『タンホイザー』の公演を鑑賞したことをきっかけに、作曲を始める。 初期のキャリア フリーマン・オペラ・カンパニー 彼の最初のオペラ『エプテリア』は、1891年にデンバーのドイツ劇場で上演された[4]。このオペラもフリーマン・オペラ・カンパニーによって上演さ れ、エホバの宗教を受け入れたために死刑に処されたエジプトの貴族が主人公であった。フリーマン・オペラ・カンパニーはその後、1893年10月にシカゴ で、1894年にはクリーヴランドで『殉教者』を上演した[5]。これは、黒人だけのプロダクション・カンパニーによって上演されたアメリカ初のオペラで あった[6]。また、ジョン・ワーテン・ストラブルは『殉教者』を「デンバーで上演された、アフリカ系アメリカ人作曲家による最初のオペラ」としている [7]。 1894年、フリーマンはクリーヴランドに戻り、クリーヴランド交響楽団(1918年に設立されたクリーヴランド管弦楽団とは異なる組織)の指揮者ヨハ ン・ハインリヒ・ベックのもとで音楽理論の正式な訓練を始めた。1898年、フリーマンはサウスカロライナ州チャールストン出身の女性ソプラノ歌手シャー ロット・ロワーズ・トーマスと結婚した[8]。2年後、シャーロット(カルロッタとも呼ばれた)はフリーマンの息子ヴァルドを出産し、同年、クリーヴラン ド管弦楽団はフリーマンのオペラの抜粋を朗読した。 [フリーマンは1902年と1903年にウィルバーフォース大学で音楽プログラムのディレクターを務めた[4]。 |

| Harlem: Negro Grand Opera Company Around 1908, the Freeman family moved to the Harlem neighborhood of New York City. In 1912, ragtime composer Scott Joplin, who was then living in New York, asked Freeman's help in revising his three-act opera, "Treemonisha," production of which had stalled the previous year. The extent of Freeman's help is unknown. In 1920, he opened the Salem School of Music on 133rd Street in Harlem, later renamed Freeman School of Music.[4] Also in 1920, he founded the Negro Grand Opera Company, which produced several productions of his own works.[4] Freeman's wife Carlotta and his son Valdo, a baritone, sang principal roles in many of the Negro Grand Opera Company's productions.[9] In addition to grand opera, Freeman wrote stage music and served as musical director for vaudeville and musical theater companies in the early 1900s. These included Ernest Hogan's Musical Comedy Company, of which Carlotta Freeman was the prima donna; the Cole-Johnson African-American musical theater company, and the John Larkins Musical Comedy Company.[8] He was musical director and wrote additional music for the Hogan's Musical Comedy Company production Rufus Rastus, which premiered on January 29, 1906 at the American Theatre.[10] He wrote the music for the musical comedy Captain Rufus, which premiered August 12, 1907 at the Harlem Music Hall. He was guest conductor and composer/music director of the pageant O Sing a New Song at the Chicago World's Fair in 1934. Voodoo (1928) is perhaps Freeman's best known work. It deals with the cult of that name in Louisiana. Although Freeman finished composing the opera in 1914, it was not premiered until fourteen years later.[9] On September 10, 1928, at Palm Garden at 310 West 52nd Street in New York's Broadway district, with an all-black cast. A May 20, 1928 concert performance of Voodoo was broadcast live on New York radio station WGBS, which Elise Kirk identifies as one of the earliest operas composed by an American to be broadcast on radio.[2] It was the first opera by an African-American to be presented on Broadway.[11] Its score combines themes from spirituals, Southern melodies, jazz, and traditional Italian opera.[9] Freeman received the prestigious Harmon Foundation Award in 1930 for achievement in music.[4] At New York's Steinway Hall in 1930, Freeman accompanied at the piano a performance of excerpts from The Martyr, The Prophecy, The Octoroon, Plantation, Vendetta and Voodoo.[4] |

ハーレム:ニグロ・グランド・オペラ・カンパニー 1908年頃、フリーマン一家はニューヨークのハーレム地区に移り住んだ。1912年、当時ニューヨークに住んでいたラグタイムの作曲家スコット・ジョプ リンが、前年に上演が頓挫していた3幕のオペラ『トレモニシャ』の改訂をフリーマンに依頼した。フリーマンがどの程度協力したかは不明である。1920 年、彼はハーレムの133丁目にセーラム音楽学校を開校し、後にフリーマン音楽学校と改名した[4]。また、1920年にはニグロ・グランド・オペラ・カ ンパニーを設立し、いくつかの自作品を上演した[4]。フリーマンの妻カルロッタと息子のヴァルド(バリトン)は、ニグロ・グランド・オペラ・カンパニー の多くの作品で主役を歌った[9]。 グランドオペラに加え、フリーマンは舞台音楽を書き、1900年代初頭にはボードヴィルやミュージカル劇団の音楽監督も務めた。その中には、カルロッタ・ フリーマンがプリマドンナを務めたアーネスト・ホーガンのミュージカル・コメディ・カンパニー、コール・ジョンソン・アフリカン・アメリカン・ミュージカ ル・シアター・カンパニー、ジョン・ラーキンス・ミュージカル・コメディ・カンパニーなどが含まれる[8]。1906年1月29日にアメリカン・シアター で初演されたホーガンのミュージカル・コメディ・カンパニーの作品『ルーファス・ラスタス』の音楽監督と追加音楽を担当した[10]。1934年のシカゴ 万国博覧会のページェント『O Sing a New Song』では客演指揮者と作曲家/音楽監督を務めた。 ヴードゥー』(1928年)はフリーマンの最も有名な作品であろう。ルイジアナ州のカルト宗教を扱った作品である。フリーマンがこのオペラを作曲し終えた のは1914年だが、初演されたのはそれから14年後のことだった[9]。1928年9月10日、ニューヨークのブロードウェイ地区、310 West 52nd StreetにあるPalm Gardenで、黒人キャストのみで上演された。1928年5月20日のヴードゥーのコンサートは、ニューヨークのラジオ局WGBSで生放送され、エリ ス・カークは、アメリカ人が作曲したオペラの中で最も早くラジオ放送された作品のひとつであると認定している[2]。 ブロードウェイで上演されたアフリカ系アメリカ人による最初のオペラである[11]。 フリーマンは、1930年に音楽界での功績に対して名誉あるハーモン財団賞を受賞した[4]。 1930年にニューヨークのスタインウェイ・ホールで、フリーマンは『殉教者』、『予言』、『八分儀』、『プランテーション』、『ヴェンデッタ』、『ヴードゥー』からの抜粋をピアノで伴奏した[4]。 |

| Death and obscurity Freeman died of a heart ailment at his home at 214 West 127th Street, New York City on March 24, 1954. His wife Carlotta died only three months later.[4] The last couple of decades of his life were marked with frustration as he struggled to get any performances of his work. Almost all of his music was unpublished at the time of his death, and no recordings of his work have ever been released commercially. Twenty-one of his operas, as well as many of his other works, survive in Freeman's own manuscripts, and are kept in a collection of his papers at Columbia University.[4] |

死と無名時代 フリーマンは1954年3月24日、ニューヨークの西127丁目214番地の自宅で心臓の病気で亡くなった。妻のカルロッタはそのわずか3ヵ月後に亡く なった[4]。人生の最後の数十年間は、彼の作品が演奏される機会がなく、フラストレーションのたまる日々だった。死の間際、ほとんどすべての作品が未発 表であり、商業的にリリースされた録音もない。彼のオペラ21曲とその他の作品の多くは、フリーマン自身の手稿として残っており、コロンビア大学の彼の遺 品コレクションに保管されている[4]。 |

| List of works Freeman composed at least twenty-three operas,[2] Many, including a massive tetralogy Zululand which filled over 2,000 pages of score, were never performed.[3] In addition to composing the music, Freeman wrote his own librettos for almost all of his operas.[2] Freeman's works for stage include: Epthalia, opera (1891, Deutsches Theater, Denver) The Martyr, opera in two acts, libretto by the composer (August 16, 1893, Freeman Grand Opera Company, Deutsches Theater, Denver) Nada, opera in three acts, libretto by the composer (1898; unperformed) Zuluki (revision of Nada) (scenes performed by the Cleveland Symphony in 1900) An African Kraal, opera in one act, libretto by the composer (1903; student production at Wilberforce University) The Octoroon, opera in four acts with prologue, libretto by the composer (1904; unperformed) Valdo, opera in one act with intermezzo, libretto by the composer (May 1906, Freeman Grand Opera Company, Weisgerber's Hall, Cleveland) Captain Rufus, musical comedy (August 12, 1907, Harlem Music Hall, New York City) The Tryst, opera in one act, libretto by the composer (May 1911; Freeman Operatic Duo, Crescent Theater, N.Y. Wampum: Carlotta Freeman; Lone Star: Hugo Williams) The Prophecy, opera in one act, libretto by the composer (1911; unperformed) The Plantation, opera in three (or four) acts, libretto by the composer (1915; performed at Carnegie Hall 1930) Athalia, opera in three acts with prologue, libretto by the composer (1916; unperformed) Vendetta, opera in three acts, libretto by the composer (November 12, 1923, Negro Grand Opera Company, Inc., Lafayette Theater, Harlem) American Romance, jazz opera (1927) Voodoo, opera in three acts, libretto by the composer (composed c. 1914; premiered by the Negro Grand Opera Company on New York radio station WGBS on May 20, 1928, and on September 10, 1928 at the Palm Garden on Broadway) Leah Kleschna. Libretto by the composer, after the play of C. M. S. McLellan (1931; unperformed) Allah, opera, based on H. Rider Haggard's novels (1947) The Zulu King, opera, based on H. Rider Haggard's novels (1934) The Slave, symphonic poem (1932) Uzziah (1931) Zululand, a four-opera cycle based on H. Rider Haggard's novel Nada, the Lily (1941-1944). The titles of the individual operas are Chaka, The Ghost-Wolves, The Stone-Witch, and Umslopogaas and Nada. All were unperformed.[3] Freeman published quite a few popular songs, including arrangements of spirituals, and wrote some music for the concert hall, including: The Loves of Pompeii, a song cycle My Son, a cantata The Slave, a symphonic poem Salome, a ballet with chorus[4] Coleville Coon Cadets, a marching song |

作品リスト フリーマンは少なくとも23のオペラを作曲した[2]が、その多くは上演されることがなかった[3]。 フリーマンの舞台作品は以下の通りである: オペラ『エプタリア』(1891年、デンバーのドイツ劇場) オペラ『殉教者』(全2幕、リブレット:作曲者)(1893年8月16日、フリーマン・グランド・オペラ・カンパニー、デンバー、ドイツ劇場 オペラ『灘』全3幕、作曲者台本(1898年、未演出) ズルキ(灘の改訂版)(1900年にクリーヴランド交響楽団によって上演された場面) アン・アフリカン・クラール》(作曲者による台本、1幕のオペラ)(1903年、ウィルバーフォース大学の学生作品 オペラ『オクトゥルーン』(全4幕、プロローグ付き、作曲者台本)(1904年、未演出 間奏曲付き1幕オペラ「ヴァルド」作曲者台本(1906年5月、フリーマン・グランド・オペラ・カンパニー、ワイズガーバー・ホール、クリーブランド) ミュージカル・コメディ『キャプテン・ルーファス』(1907年8月12日、ニューヨーク、ハーレム・ミュージック・ホール) トライスト」1幕オペラ、作曲者台本(1911年5月、フリーマン・オペラ・デュオ、クレセント・シアター、N.Y.、Wampum: カーロッタ・フリーマン;ローンスター ヒューゴ・ウィリアムズ) オペラ「予言」全1幕、作曲者台本(1911年、未演奏) オペラ『プランテーション』全3幕(または全4幕)、作曲者台本(1915年、1930年カーネギーホールで上演) オペラ『アタリア』全3幕、プロローグ付き、作曲者台本(1916年、未演出) ヴェンデッタ》全3幕、作曲者台本(1923年11月12日、ニグロ・グランド・オペラ・カンパニー、ラファイエット劇場、ハーレム) アメリカン・ロマンス、ジャズ・オペラ(1927年) ヴードゥー、全3幕のオペラ、作曲者台本(1914年頃作曲、1928年5月20日にニューヨークのラジオ局WGBSでニグロ・グランド・オペラ・カンパニーにより初演、1928年9月10日にブロードウェイのパーム・ガーデンで上演された) レア・クレシュナ C.M.S.マクレーランの戯曲に基づく作曲家によるリブレット(1931年、未演出) オペラ『アラー』(H・ライダー・ハガードの小説に基づく)(1947年 ズールー王」(オペラ、H・ライダー・ハガードの小説に基づく)(1934年 交響詩「奴隷」(1932年) ウジヤ(1931年) ズルランド(Zululand):H.ライダー・ハガードの小説『百合の子ナダ(Nada, the Lily)』に基づく4つのオペラ・サイクル(1941-1944)。個々のオペラのタイトルは、『チャカ』、『幽霊狼』、『石の呪術師』、『ウムスロポ ガースとナダ』である。いずれも未演出であった[3]。 フリーマンは、スピリチュアルの編曲を含め、かなりの数のポピュラーソングを出版し、コンサートホールのための音楽もいくつか書いた: 歌曲集『ポンペイの恋』(The Loves of Pompeii 歌曲集『ポンペイの恋』(The Loves of Pompeii 交響詩『奴隷 合唱付きバレエ《サロメ》[4]。 コルヴィル・クーン・カデッツ(行進曲 |

| Influence Although many of his works were successful during his lifetime, they are not played today. He achieved many firsts for a black American in the field of classical and popular music. While Elise Kirk cites several operas composed by African-Americans earlier in the nineteenth century, it appears that none of these ever were staged in their entirety before Freeman's Epithalia in 1891.[3] Freeman founded and played important roles in the direction of several African-American opera companies and other arts organizations, including the Pekin Stock Company in Chicago, which was one of the first "legitimate" theaters in the United States to be owned and run by African-Americans.[4][8] Freeman was a close friend of famous Ragtime musician Scott Joplin[12] and was acquainted with many African-American musicians and artists associated with the Harlem Renaissance.[4] |

影響力 彼の作品の多くは存命中に成功を収めたが、今日では演奏されることはない。彼は、クラシック音楽とポピュラー音楽の分野で、黒人アメリカ人として初めての ことを数多く成し遂げた。エリス・カークは、19世紀以前にアフリカ系アメリカ人によって作曲されたオペラをいくつか挙げているが、フリーマンが1891 年に《エピタリア》を上演するまで、これらのオペラが全曲上演されたことはなかったようである[3]。 [フリーマンは、シカゴのペキン・ストック・カンパニーを含むいくつかのアフリカ系アメリカ人のオペラ・カンパニーやその他の芸術団体を設立し、その指導 において重要な役割を果たした。フリーマンは、有名なラグタイム・ミュージシャンであるスコット・ジョプリン[12]の親友であり、ハーレム・ルネッサン スに関連する多くのアフリカ系アメリカ人のミュージシャンやアーティストと知り合いであった[4]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Lawrence_Freeman |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

cc

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆