ハイチのヴードゥー

Haitian Vodou

A sequined drapo flag, depicting the vèvè symbol of the lwa Loko Atison; these symbols play an important role in Vodou ritual

☆ ハイチのヴードゥー[a](/ˈvo(Ⱘ)は、16世紀から19世紀にかけてハイチで発展したアフリカ系ディアスポラ宗教である。西アフリカと中央アフリ カのいくつかの伝統宗教とローマ・カトリックとのシンクレティズムの過程で生まれた。この宗教を支配する中央権力者は存在せず、ヴードゥーイスト、ヴードゥー イサン、セルヴィトゥールとして知られる修行者たちの間にも多くの多様性が存在する。

★ヴードゥーは超越的な創造主であるボンディエの存在を教え、その下にルワ(ロア)として知られる精霊が存在する。一般的に、ロアは西アフリカや中央アフリカ の伝統的な神々の名前や属性に由来し、ローマ・カトリックの聖人と同一視されている。ロアはナンチョン(「国民」)と呼ばれる異なる集団に分かれ、特にラ ダ族とペツォ族は様々な神話や物語に登場する。この神学は一神教的とも多神教的とも呼ばれている。イニシエーション的な伝統であるヴードゥー教徒は、ウン ガン(司祭)やマンボ(巫女)が運営するウンフォ(寺院)でロアを崇拝するのが一般的である。また、ヴードゥーは家族内やビザンゴのような秘密結社でも行わ れている。中心的な儀式は、ルワがメンバーのひとりに憑依し、彼らとの交信を促すために、修行者たちが太鼓を叩き、歌い、踊るというものだ。ロアや死者の 霊への捧げものには、果物、酒、生け贄の動物などがある。ルワからのメッセージを読み解くために、いくつかの占術が用いられる。癒しの儀式や、薬草やお守 りの準備も重要な役割を果たす。

| Haitian Vodou[a]

(/ˈvoʊduː/) is an African diasporic religion that developed in Haiti

between the 16th and 19th centuries. It arose through a process of

syncretism between several traditional religions of West and Central

Africa and Roman Catholicism. There is no central authority in control

of the religion and much diversity exists among practitioners, who are

known as Vodouists, Vodouisants, or Serviteurs. Vodou teaches the existence of a transcendent creator divinity, Bondye, under whom are spirits known as lwa. Typically deriving their names and attributes from traditional West and Central African deities, they are equated with Roman Catholic saints. The lwa divide into different groups, the nanchon ("nations"), most notably the Rada and the Petwo, about whom various myths and stories are told. This theology has been labelled both monotheistic and polytheistic. An initiatory tradition, Vodouists commonly venerate the lwa at an ounfò (temple), run by an oungan (priest) or manbo (priestess). Alternatively, Vodou is also practised within family groups or in secret societies like the Bizango. A central ritual involves practitioners drumming, singing, and dancing to encourage a lwa to possess one of their members and thus communicate with them. Offerings to the lwa, and to spirits of the dead, include fruit, liquor, and sacrificed animals. Several forms of divination are utilized to decipher messages from the lwa. Healing rituals and the preparation of herbal remedies and talismans also play a prominent role. Vodou developed among Afro-Haitian communities amid the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries. Its structure arose from the blending of the traditional religions of those enslaved West and Central Africans brought to the island of Hispaniola, among them Kongo, Fon, and Yoruba. There, it absorbed influences from the culture of the French colonialists who controlled the colony of Saint-Domingue, most notably Roman Catholicism but also Freemasonry. Many Vodouists were involved in the Haitian Revolution of 1791 to 1801 which overthrew the French colonial government, abolished slavery, and transformed Saint-Domingue into the republic of Haiti. The Roman Catholic Church left for several decades following the Revolution, allowing Vodou to become Haiti's dominant religion. In the 20th century, growing emigration spread Vodou abroad. The late 20th century saw growing links between Vodou and related traditions in West Africa and the Americas, such as Cuban Santería and Brazilian Candomblé, while some practitioners influenced by the Négritude movement have sought to remove Roman Catholic influences. Most Haitians practice both Vodou and Roman Catholicism, seeing no contradiction in pursuing the two different systems simultaneously. Smaller Vodouist communities exist elsewhere, especially among Haitian diasporas in Cuba and the United States. Both in Haiti and abroad Vodou has spread beyond its Afro-Haitian origins and is practiced by individuals of various ethnicities. Having faced much criticism through its history, Vodou has been described as one of the world's most misunderstood religions. |

ハ

イチのヴードゥー[a](/ˈvo(Ⱘ)は、16世紀から19世紀にかけてハイチで発展したアフリカ系ディアスポラ宗教である。西アフリカと中央アフリカ

のいくつかの伝統宗教とローマ・カトリックとのシンクレティズムの過程で生まれた。この宗教を支配する中央権力者は存在せず、ヴードゥーイスト、ヴードゥーイ

サン、セルヴィトゥールとして知られる修行者たちの間にも多くの多様性が存在する。 ヴードゥーは超越的な創造主であるボンディエの存在を教え、その下にルワ(ロア)として知られる精霊が存在する。一般的に、ロアは西アフリカや中央アフリカ の伝統的な神々の名前や属性に由来し、ローマ・カトリックの聖人と同一視されている。ルワはナンチョン(「国民」)と呼ばれる異なる集団に分かれ、特にラ ダ族とペツォ族は様々な神話や物語に登場する。この神学は一神教的とも多神教的とも呼ばれている。イニシエーション的な伝統であるヴードゥー教徒は、ウン ガン(司祭)やマンボ(巫女)が運営するウンフォ(寺院)でルワを崇拝するのが一般的である。また、ヴードゥーは家族内やビザンゴのような秘密結社でも行わ れている。中心的な儀式は、ロアがメンバーのひとりに憑依し、彼らとの交信を促すために、修行者たちが太鼓を叩き、歌い、踊るというものだ。ルワや死者の 霊への捧げものには、果物、酒、生け贄の動物などがある。ルワからのメッセージを読み解くために、いくつかの占術が用いられる。癒しの儀式や、薬草やお守 りの準備も重要な役割を果たす。 ヴードゥーは、16世紀から19世紀にかけての大西洋奴隷貿易の中で、アフロ・ヘイティアンのコミュニティの間で発展した。その構造は、奴隷としてイスパ ニョーラ島に連れてこられた西アフリカや中央アフリカの人々の伝統的な宗教(コンゴ、フォン、ヨルバなど)の融合から生まれた。そこでは、サン=ドマング 植民地を支配していたフランスの植民地主義者の文化からの影響を吸収した。多くのヴードゥーイストが1791年から1801年にかけてのハイチ革命に参加 し、フランス植民地政府を打倒し、奴隷制を廃止し、サン=ドマングをハイチ共和国に変えた。革命後数十年間はローマ・カトリック教会が去ったため、ヴー ドゥーがハイチの支配的な宗教となった。20世紀には移民が増加し、ヴードゥーは海外にも広まった。20世紀後半には、キューバのサンテリアやブラジルの カ ンドンブレなど、西アフリカやアメリカ大陸の関連する伝統とヴードゥーの結びつきが強まったが、ネグリチュード運動の影響を受けた一部の修行者たちは、 ロー マ・カトリックの影響を取り除こうとしている。 ほとんどのハイチ人はヴードゥーとローマ・カトリックの両方を実践しており、2つの異なるシステムを同時に追求することに矛盾はないと考えている。小規模 なヴードゥー派のコミュニティは、特にキューバとアメリカのハイチ人ディアスポラの間に存在する。ハイチでも海外でも、ヴードゥーはそのアフロ・ハイチの起源 を越えて広がり、さまざまな民族によって実践されている。その歴史を通じて多くの批判に直面してきたヴードゥーは、世界で最も誤解されている宗教のひとつと 言われている。 |

A sequined drapo flag, depicting the vèvè symbol of the lwa Loko Atison; these symbols play an important role in Vodou ritual |

スパンコールで飾られたドラポの旗。ロア・ロコ・アティソンのヴェヴェ・シンボルが描かれている。 |

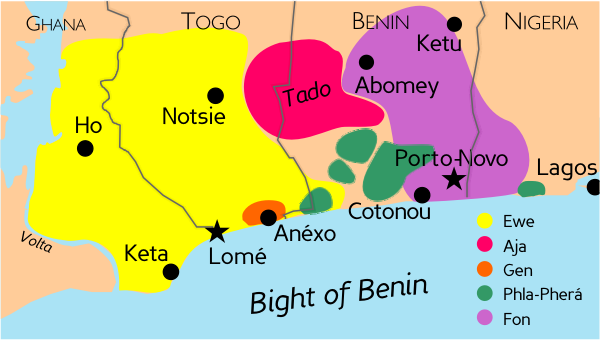

Definitions and terminology Vodou paraphernalia for sale at the Marché de Fer (Iron Market) in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Vodou is a religion.[6] More specifically, scholars have characterised it as an Afro-Haitian religion,[7] and as Haiti's "national religion".[8] Its main structure derives from the African traditional religions of West and Central Africa which were brought to Haiti by enslaved Africans between the 16th and 19th centuries.[9] Of these, the greatest influences came from the Fon and Bakongo peoples.[10] On the island, these African religions mixed with the iconography of European-derived traditions such as Roman Catholicism and Freemasonry,[11] taking the form of Vodou around the mid-18th century.[12] In combining varied influences, Vodou has often been described as syncretic,[13] or a "symbiosis",[14] a religion exhibiting diverse cultural influences.[15] As formed in Haiti, Vodou represented "a new religion",[16] "a creolized New World system",[17] one that differs in many ways from African traditional religions.[18] The scholar Leslie Desmangles therefore called it an "African-derived tradition",[19] Ina J. Fandrich termed it a "neo-African religion",[20] and Markel Thylefors called it an "Afro-Latin American religion".[21] Several other African diasporic religions found in the Americas formed in a similar way, and owing to their shared origins in West African traditional religion, Vodou has been characterized as a "sister religion" of Cuban Santería and Brazilian Candomblé.[22] Vodou has no central institutional authority,[23] no single leader,[24] and no developed body of doctrine.[25] It thus has no orthodoxy,[26] no central liturgy,[27] and no formal creed.[28] Developing over the course of several centuries,[29] it has changed over time.[30] It displays variation at both the regional and local level[31]—including variation between Haiti and the Haitian diaspora[32]—as well as among different congregations.[33] It is practiced domestically, by families on their land, but also by congregations meeting communally,[34] with the latter termed "temple Vodou".[35] In Haitian culture, religions are not generally deemed totally autonomous. Many Haitians thus practice both Vodou and Roman Catholicism,[36] with Vodouists usually regarding themselves as Roman Catholics.[37] In Haiti, Vodouists have also practiced Protestantism,[38] Mormonism,[39] or Freemasonry;[40] in Cuba they have involved themselves in Santería,[41] and in the United States with modern Paganism.[42] Vodou has also absorbed elements from other contexts; in Cuba, some Vodouists have adopted elements from Spiritism.[43] Influenced by the Négritude movement, other Vodouists have sought to remove Roman Catholic and other European influences from their practice of Vodou.[44] |

定義と用語 ハイチのポルトープランスにあるマルシェ・ド・フェル(鉄の市場)で売られているヴードゥーの道具。 ヴードゥーは宗教のひとつであり[6]、具体的にはアフロ・ハイティアの宗教であり[7]、ハイチの「ナショナリズム」である[8]。その主な構造は、16 世紀から19世紀にかけて奴隷となったアフリカ人によってハイチにもたらされた西アフリカと中央アフリカのアフリカ伝統宗教に由来する[9]。 [10]この島では、これらのアフリカの宗教が、ローマ・カトリックやフリーメーソンなどのヨーロッパ由来の伝統の図像と混ざり合い[11]、18世紀半 ば頃にヴードゥーという形になった[12]。様々な影響を組み合わせることで、ヴードゥーはしばしばシンクレティック[13]、あるいは「共生」 [14]、多様な文化的影響を示す宗教と表現されてきた[15]。 ハイチで形成されたヴードゥーは「新しい宗教」[16]、「クレオール化された新世界のシステム」[17]であり、アフリカの伝統的な宗教とは多くの点で異 なっている[18]。そのため学者のレスリー・デスマングレスは「アフリカ由来の伝統」と呼び[19]、イナ・J・ファンドリッチは「ネオ・アフリカの宗 教」と呼び[20]、マーケル・ティーレフォースは「アフロ・ラテンアメリカの宗教」と呼んだ。 [21]アメリカ大陸で発見された他のいくつかのアフリカ系ディアスポラ宗教も同様の方法で形成され、西アフリカの伝統宗教に起源を持つという共通点か ら、ヴードゥーはキューバのサンテリアやブラジルのカンドンブレの「姉妹宗教」と特徴づけられている[22]。 ヴードゥーは中央の組織的権威を持たず[23]、一人の指導者もおらず[24]、発展した教義体系もない[25]。そのため正統性も[26]、中心的な典礼 も[27]、正式な信条もない[28]。数世紀にわたって発展し[29]、時代とともに変化してきた。 [30]ハイチとハイチのディアスポラ[32]の間の差異を含め、地域レベルでも地方レベルでも[31]、また異なる信徒間でも差異が見られる[33]。 ハイチの文化では、宗教は一般的に完全に自律したものとはみなされない。ハイチでは、ヴードゥー信者はプロテスタント[38]、モルモン教[39]、フリー メーソン[40]、キューバではサンテリア[41]、アメリカでは現代的な異教徒とも関わっている。 [42]ヴードゥーはまた他の文脈からの要素を吸収しており、キューバではスピリチュアリズムの要素を取り入れたヴードゥーもいる[43]。 |

| Terminology In English, Vodou's practitioners are termed Vodouists;[45] in French and Haitian Creole, they are called Vodouisants[46] or Vodouyizan.[47] Another term for adherents is sèvitè (serviteurs, "devotees"),[48] reflecting their self-description as people who sèvi lwa ("serve the lwa"), the supernatural beings that play a central role in Vodou.[49]  An oungan (Vodou priest) with another practitioner at a ceremony in Haiti in 2011 Many words used in the religion derive from the Fon language of West Africa;[50] this includes the word Vodou itself.[51] First recorded in the 1658 Doctrina Christiana,[52] the Fon word Vôdoun was used in the West African kingdom of Dahomey to signify a spirit or deity.[53] In Haitian Creole, Vodou came to designate a specific style of dance and drumming,[54] before outsiders to the religion adopted it as a generic term for much Afro-Haitian religion.[55] The word Vodou now encompasses "a variety of Haiti's African-derived religious traditions and practices",[56] incorporating "a bundle of practices that practitioners themselves do not aggregate".[57] Vodou is thus a term primarily used by scholars and outsiders to the religion;[57] many practitioners describe their belief system with the term Ginen, which especially denotes a moral philosophy and ethical code regarding how to live and to serve the spirits.[32] Vodou is the common spelling for the religion among scholars, in official Haitian Creole orthography, and by the United States Library of Congress.[58] Some scholars prefer the spellings Vodoun, Voudoun, or Vodun,[59] while in French the spellings vaudou[60] or vaudoux also appear.[61] The spelling Voodoo, once common, is now generally avoided by practitioners and scholars when referring to the Haitian religion.[62] This is both to avoid confusion with Louisiana Voodoo, a related but distinct tradition,[63] and to distinguish it from the negative connotations that the term Voodoo has in Western popular culture.[64] |

用語 英語ではヴードゥーの実践者はヴードゥーイストと呼ばれ[45]、フランス語とハイチ・クレオール語ではヴードゥーイザン[46]またはヴードゥーイザンと呼ばれ る[47]。ヴードゥーで中心的な役割を果たす超自然的存在であるロアに仕える人々という自称を反映し、信者の別の呼称はセヴィテ(serviteurs、 「信者」)[48]である。  2011年にハイチで行われた儀式で、ウンガン(ヴードゥーの司祭)と他の修行者たち。 この宗教で使用される多くの言葉は西アフリカのフォン語に由来しており[50]、これにはヴードゥーという言葉自体も含まれている[51]。 1658年の『Doctrina Christiana』に初めて記録された[52]フォン語のヴードゥーンは、西アフリカのダホメー王国で精霊や神を意味する言葉として使用されていた [53]。 ハイチのクレオール語では、ヴードゥーは特定のスタイルのダンスや太鼓を指すようになり[54]、その後、この宗教の部外者がアフロ・ヘイトの宗教の総称と して採用した。 [55]ヴードゥーという言葉は現在では「ハイチのアフリカに由来する様々な宗教的伝統と実践」[56]を包含しており、「実践者自身が集約していない実践 の束」[57]を取り入れている。したがってヴードゥーは主に学者やこの宗教の部外者によって使用される用語であり、[57]多くの実践者は自分たちの信仰 体系をジネンという言葉で表現しており、これは特にどのように生き、どのように精霊に仕えるかに関する道徳哲学と倫理規範を示している[32]。 Vodouは学者の間やハイチ・クレオール語の正書法、アメリカ合衆国議会図書館によるこの宗教の一般的な綴りである[58]。Vodoun、 Voudoun、またはVodunという綴りを好む学者もおり[59]、フランス語ではvaudou[60]またはvaudouxという綴りも登場する。 [61]かつては一般的であったVoodooという綴りは、現在ではハイチの宗教に言及する際、修行者や学者によって一般的に避けられている[62]。 これは、関連はあるが別個の伝統であるルイジアナ・ブードゥーとの混同を避けるため[63]と、西洋の大衆文化においてブードゥーという用語が持つ否定的 な意味合いと区別するためである[64]。 |

| Beliefs Bondye and the lwa  A selection of ritual items used in Vodou practice on display in the Canadian Museum of Civilization. Vodou is monotheistic,[65] teaching the existence of a single supreme God.[66] This entity is called Bondye or Bonié,[67] a name deriving from the French term Bon Dieu ("Good God").[68] Another term for it is the Gran Mèt,[69] borrowed from Freemasonry.[40] For Vodouists, Bondye is the ultimate source of power,[70] the creator of the universe,[71] and the maintainer of cosmic order.[72] Haitians frequently use the phrase si Bondye vle ("if Bondye wishes"), suggesting a belief that all things occur in accordance with this divinity's will.[73] Vodouists regard Bondye as being transcendent and remote;[74] as the God is uninvolved in human affairs,[75] they see little point in approaching it directly.[76] While Vodouists often equate Bondye with the Christian God,[77] Vodou does not incorporate belief in a powerful antagonist that opposes the supreme being akin to the Christian notion of Satan.[78] Vodou has also been characterized as polytheistic.[76] It teaches the existence of beings called the lwa,[79] a term varyingly translated into English as "spirits", "gods", or "geniuses".[80] These lwa are also known as the mystères, anges, saints, and les invisibles,[48] and are sometimes equated with the angels of Christian cosmology.[77] Vodou teaches that there are over a thousand lwa.[81] Serving as Bondye's intermediaries,[82] they communicate with humans through their dreams or by directly possessing them.[83] Vodouists believe the lwa are capable of offering people help, protection, and counsel in return for ritual service.[84] Each lwa has its own personality,[48] and is associated with specific colors,[85] days of the week,[86] and objects.[48] Particular lwa are also associated with specific human family lineages.[87] These spirits are not seen as moral exemplars for practitioners to imitate.[88] The lwa can be either loyal or capricious in their dealings with their devotees;[48] they are easily offended, for instance if offered food they dislike.[89] When angered, the lwa are believed to remove their protection from their devotees, or to inflict misfortune, illness, or madness on an individual.[90] Although there are exceptions, most lwa derive their names from the Fon and Yoruba languages and originated as deities venerated in West or Central Africa.[91] New lwa are nevertheless added to the pantheon, with both talismans and certain humans thought capable of becoming lwa,[92] in the latter case through their strength of personality or power.[93] Vodouists often refer to the lwa living in the sea or in rivers,[86] or alternatively in Ginen,[87] a term encompassing a generalized understanding of Africa as the ancestral land of the Haitian people.[94] |

信念 ボンデイとルワ  カナダ文明博物館に展示されている、ヴードゥーの儀式に使用される儀式用品の数々。 ヴードゥーは一神教であり[65]、唯一の至高の神の存在を教えている[66]。この存在はボンディエ(Bondye)またはボニエ(Bonié)と呼ばれ [67]、フランス語のボン・デュー(Bon Dieu)(「善き神」)に由来する名前である[68]。別の呼び方としてグラン・メート(Gran Mèt)があり[69]、フリーメイソンから借用した[40]。 [72]ハイチ人はシ・ボンディエ・ヴレ(「ボンディエが望むなら」)というフレーズを頻繁に使用し、この神性の意志に従ってすべての物事が起こるという 信念を示唆している[73]。ヴードゥーイストはボンディエを超越的で遠隔の存在とみなしており[74]、この神は人間の問題には関与していないため [75]、ボンディエに直接近づくことはほとんど意味がないと考えている。 [76]ヴードゥーイストはしばしばボンディエをキリスト教の神と同一視するが[77]、ヴードゥーにはキリスト教のサタンの概念に似た、至高の存在に対抗す る強力な敵対者に対する信仰は組み込まれていない[78]。 ヴードゥーはまた多神教的であるとも特徴づけられている[76]。ロアと呼ばれる存在[79]の存在を教えており、この用語は英語では「精霊」、「神々」、 「天才」と様々に訳されている[80]。これらのルワはミステール、アンジェ、聖人、不可視の存在[48]としても知られており、キリスト教の宇宙論の天 使と同一視されることもある。 [77]ヴードゥーの教えでは、ルワは1000体以上存在し[81]、ボンディエの仲介役として、[82]夢を通して、あるいは直接憑依することによって人 間と交信する[83]。 [84]それぞれのルワは独自の個性を持ち[48]、特定の色、[85]曜日、[86]物と関連している[48]。 [88]ルワは帰依者との関係において忠実であったり、気まぐれであったりする[48]。例えば、嫌いな食べ物を出された場合など、ルワは簡単に怒る [89]。怒らせると、ロアは帰依者から守護を取り除いたり、個人に不幸や病気、狂気を与えたりすると信じられている[90]。 例外もあるが、ほとんどのロアはフォン語やヨルバ語に由来し、西アフリカや中央アフリカで崇拝されていた神々に由来する[91]。それにもかかわらず、新 しいルワがパンテオンに追加されることがあり、タリスマンと特定の人間の両方がルワになることができると考えられている[92]。 [93]ヴードゥーイストはしばしば海や川に住むルワに言及し[86]、あるいはジネン[87]に言及する。 |

The nanchon A painting of the lwa Danbala, a serpent, by Haitian artist Hector Hyppolite. Hyppolite was himself an oungan[95] The lwa divide into nanchon or "nations".[96] This classificatory system derives from the way in which enslaved Africans were divided into "nations" upon their arrival in Haiti, usually based on their African port of departure rather than their ethno-cultural identity.[48] The term fanmi (family) is sometimes used synonymously with nanchon or alternatively as a sub-division of the latter category.[97] It is often claimed that there are 17 nanchon,[98] of which the Rada and the Petwo are the largest and most dominant.[99] The Rada lwa are seen as being 'cool'; the Petwo lwa as 'hot'.[100] This means that the Rada are dous or doux, or sweet-tempered, while the Petwo are lwa cho, indicating that they can be forceful or violent and are associated with fire.[101] Whereas the Rada are generally righteous, their Petwo counterparts are more morally ambiguous and associated with issues like money.[102] The Rada owe more to Dahomeyan and Yoruba influences;[103] their name probably comes from Arada, a city in the Dahomey kingdom of West Africa.[104] The Petwo derive largely from Kongo religion,[105] although also exhibit Dahomeyan and creolised influences.[106] Some lwa exist andezo or en deux eaux, meaning that they are "in two waters" and are served in both Rada and Petwo rituals.[107] Vodou teaches that there are over a thousand lwa,[81] although certain ones are especially widely venerated.[108] In Rada ceremonies, the first lwa saluted is Papa Legba, also known as Legba.[109] Depicted as a feeble old man wearing rags and using a crutch,[110] Papa Legba is the protector of gates and fences and thus of the home, as well as of roads, paths, and crossroads.[111] In Petwo rites, the first lwa invoked is usually Mèt Kalfou.[112] The second lwa usually greeted are the Marasa or sacred twins.[113] In Vodou, every nanchon has its own Marasa,[114] reflecting a belief that twins have special powers.[115] Another important lwa is Agwe, also known as Agwe-taroyo, who is associated with aquatic life and is the protector of ships and fishermen.[116] Agwe is believed to rule the sea with his consort, La Sirène.[117] She is a mermaid, and is sometimes described as Èzili of the Waters because she is believed to bring good luck and wealth from the sea.[118] Also given the name Èzili is Èzili Freda or Erzuli Freda, the lwa of love and luxury who personifies feminine beauty and grace,[119] and Ezili Dantor, who takes the form of a peasant woman.[120] |

ナンチョン ハイチの画家ヘクトル・ヒポライトが描いたロア・ダンバラ(蛇)の絵。ハイポライト自身もウンガンであった[95]。 ルワ族はナンチョンまたは「国民」に分かれる[96]。この分類システムは、奴隷にされたアフリカ人がハイチに到着したときに、民族的・文化的アイデン ティティではなく、通常はアフリカの出港地に基づいて「国民」に分けられたことに由来する[48]。 [ファンミ(家族)という用語はナンチョンと同義語として、あるいは後者のカテゴリーの下位区分として使用されることもある[97]。17のナンチョンが 存在するとしばしば主張されるが[98]、その中でもラダとペトウォが最大かつ最も支配的である[99]。 ラダ族のルワは「クール」であり、ペト族のロアは「ホット」であると考えられている[100]。これはラダ族がドゥス(dous)またはドゥー (doux)、つまり甘口であるのに対し、ペト族はロア・チョー(lwa cho)であることを意味し、強引であったり暴力的であったりすることを示し、火と関連している[101]。ラダ族が一般的に正義であるのに対し、ペト族 はより道徳的に曖昧であり、金銭のような問題と関連している。 [102]ラダはダホメイアとヨルバの影響をより強く受けており[103]、その名前はおそらく西アフリカのダホメイア王国の都市アラダに由来する [104]。ペトウォはダホメイアとクレオール化の影響も見られるが、主にコンゴの宗教に由来する[105]。 ヴードゥーは千以上のロアが存在すると教えているが[81]、特定のロアは特に広く崇拝されている[108]。ラダの儀式では、最初に敬礼されるルワはパ パ・レグバであり、レグバとしても知られている[109]。ボロを着て松葉杖をついた弱々しい老人として描かれる[110]パパ・レグバは、門や柵、ひい ては家の守護者であり、道路、小道、交差点の守護者でもある。 [111]ペツォの儀式では、最初に呼び出されるルワは通常メト・カルフーである[112]。通常2番目に挨拶されるルワはマラサまたは聖なる双子である [113]。 [115]もう一人の重要なルワはアグウェであり、アグウェ・タロヨとしても知られている。アグウェは水生生物と関連しており、船と漁師の守護者である [116]。 [117]彼女は人魚であり、海から幸運と富をもたらすと信じられているため、「水のエジリ」と表現されることもある[118]。また、エジリという名を 与えられたエジリ・フレダまたはエジリ・フレダは、女性の美と優雅さを擬人化した愛と贅沢のルワであり[119]、エジリ・ダントールは農民の女性の姿を している[120]。 |

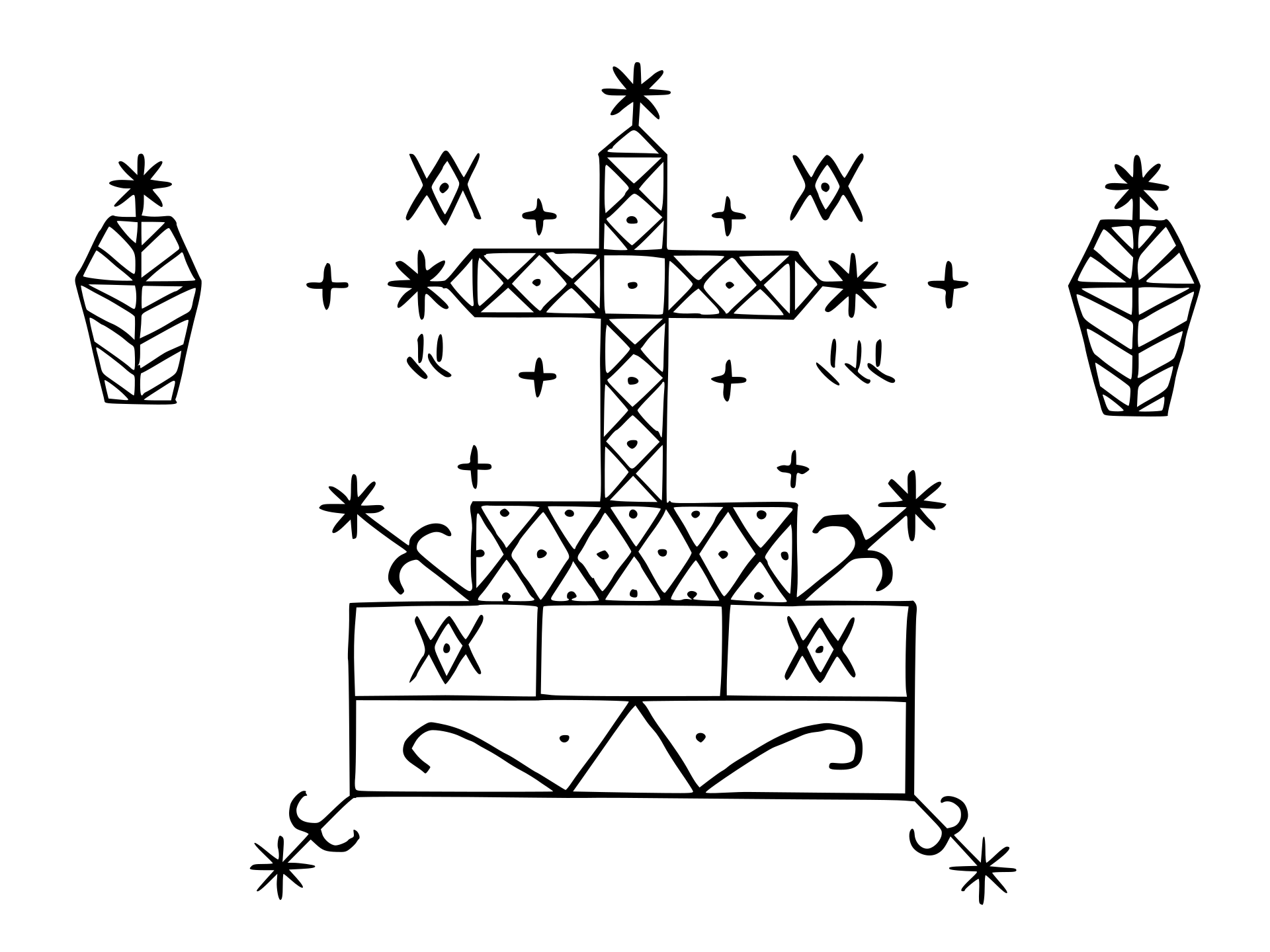

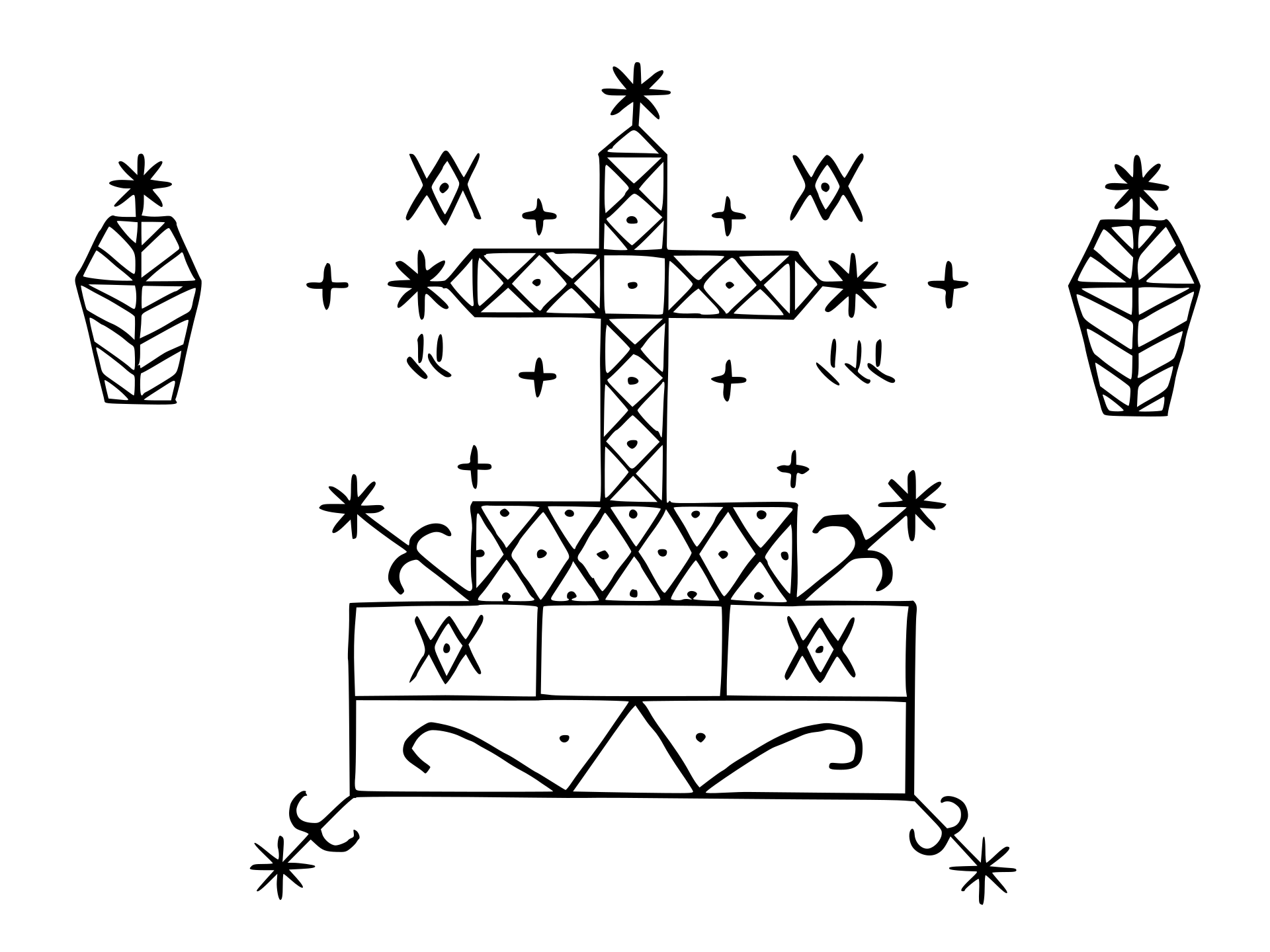

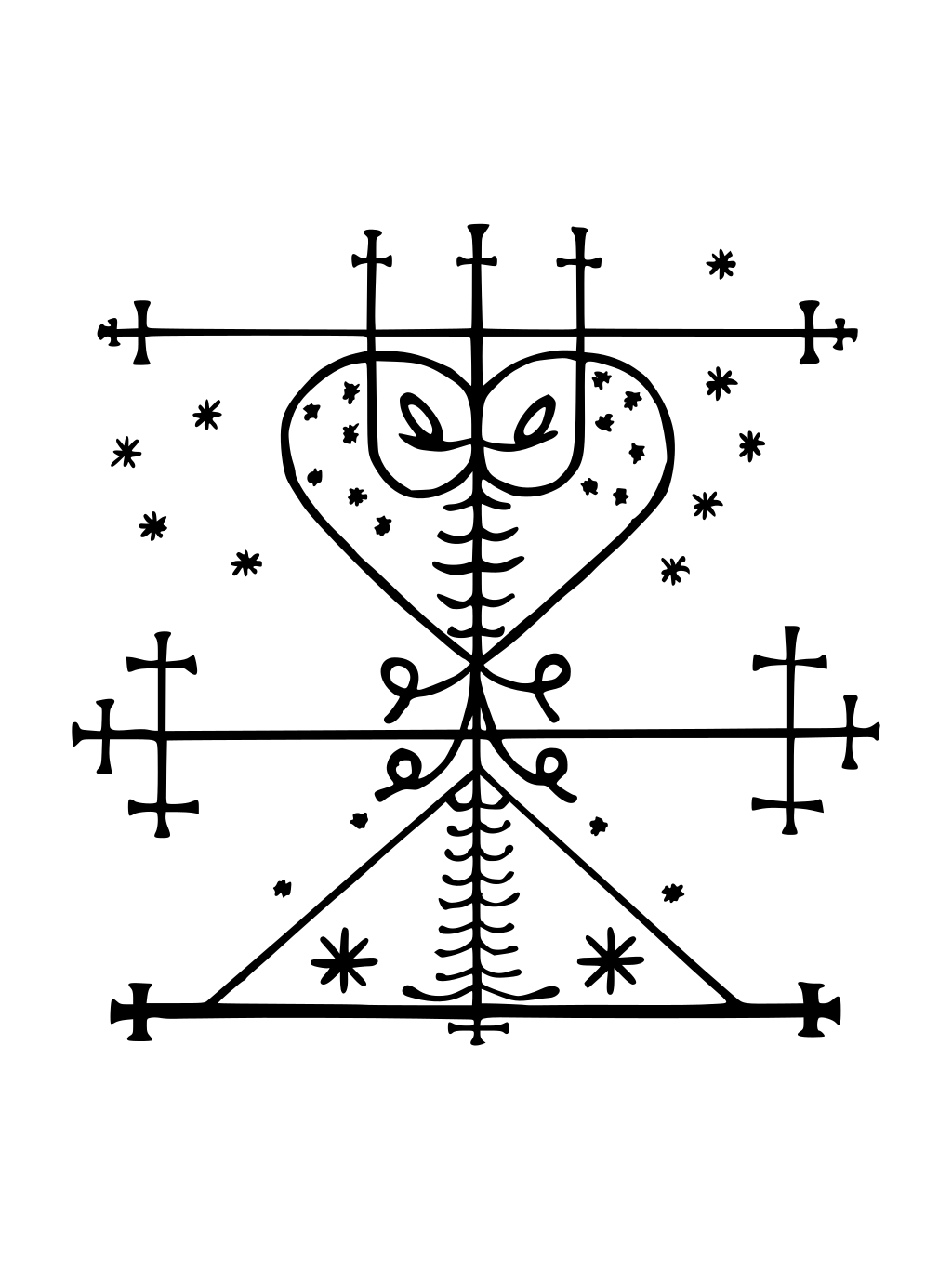

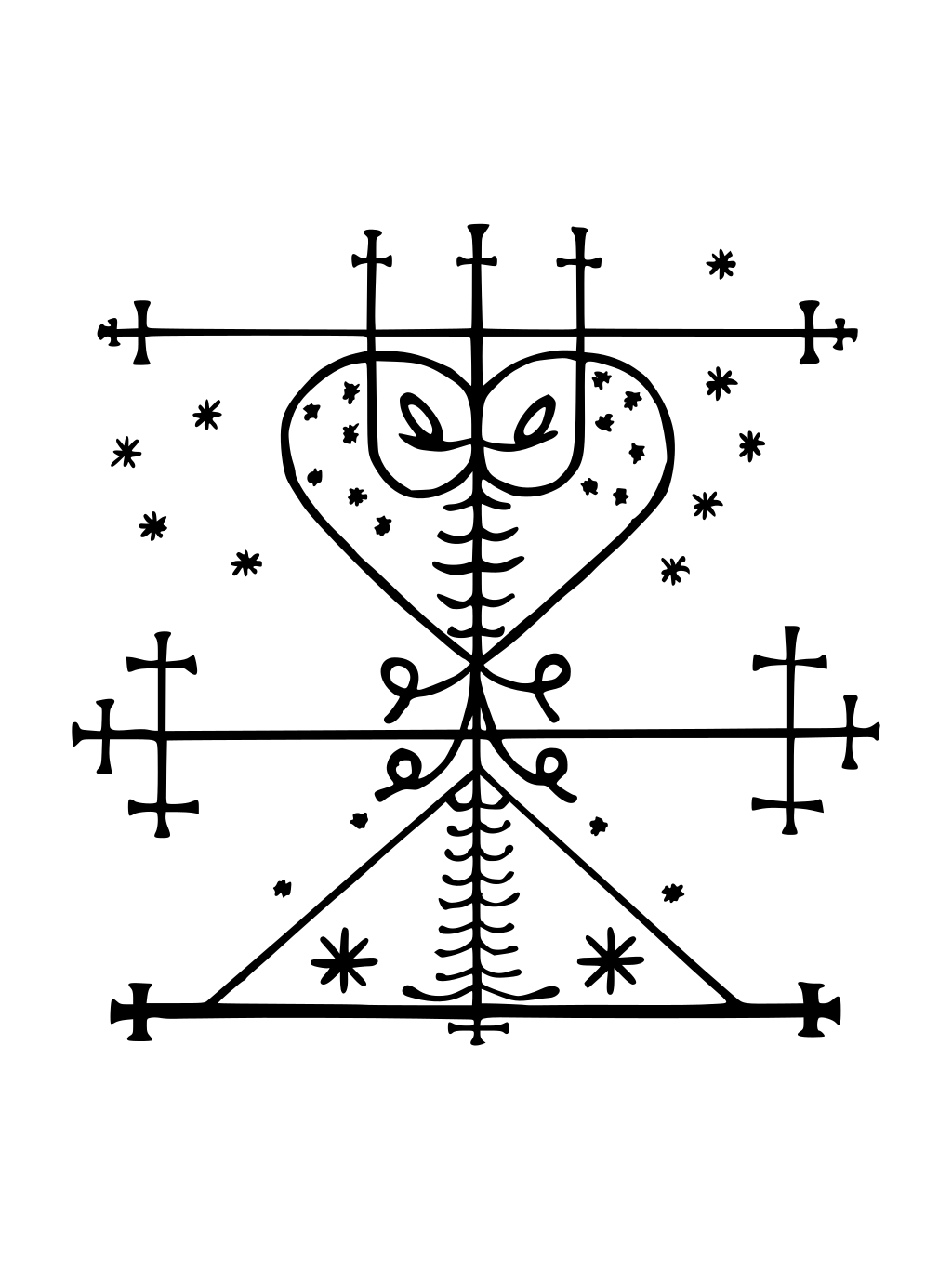

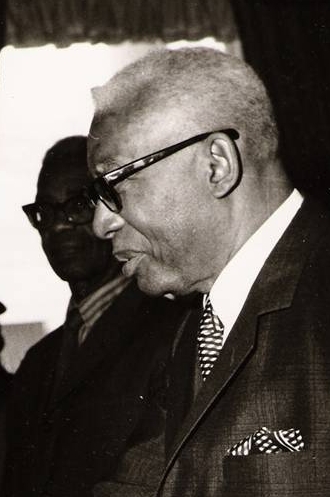

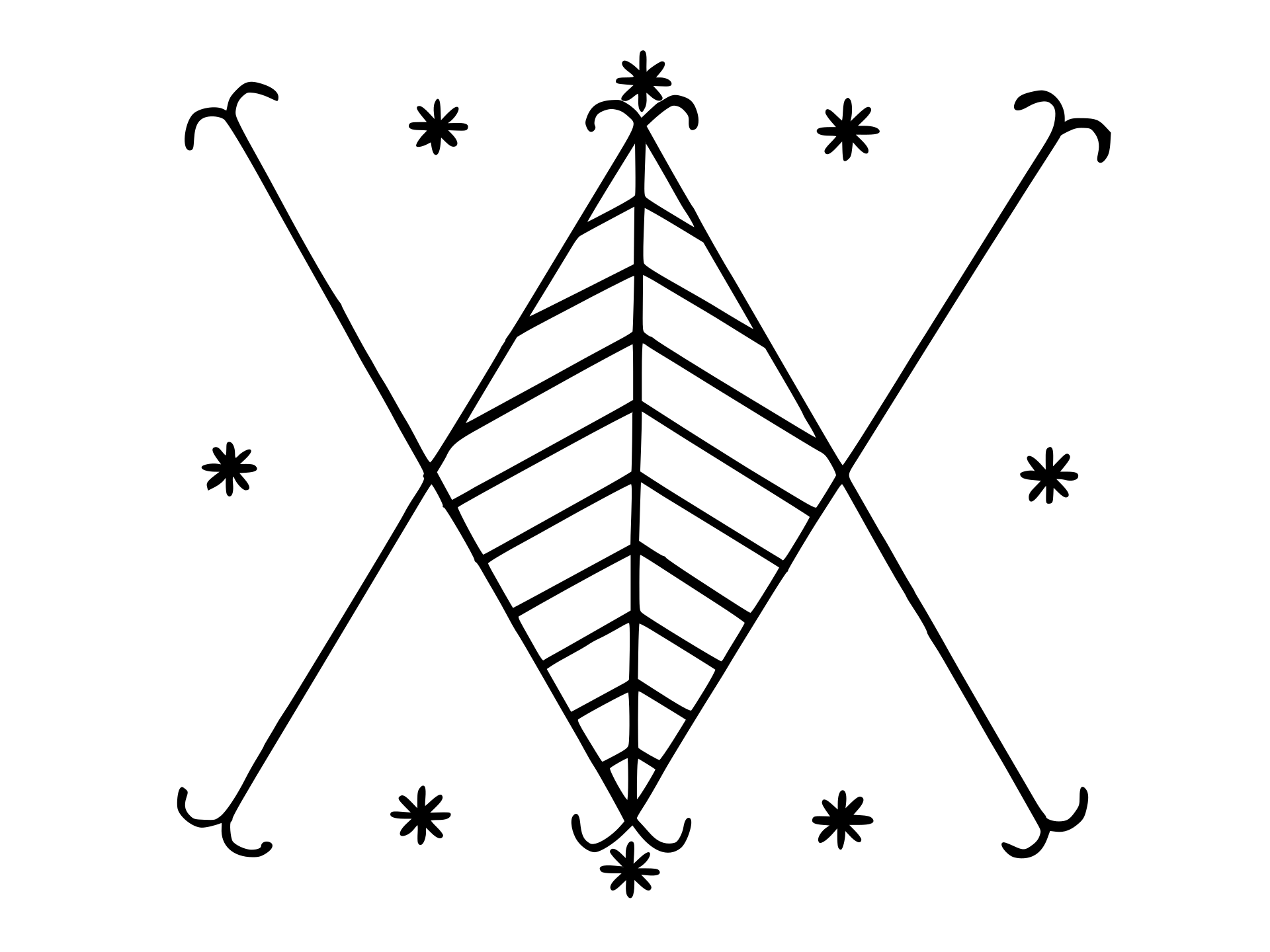

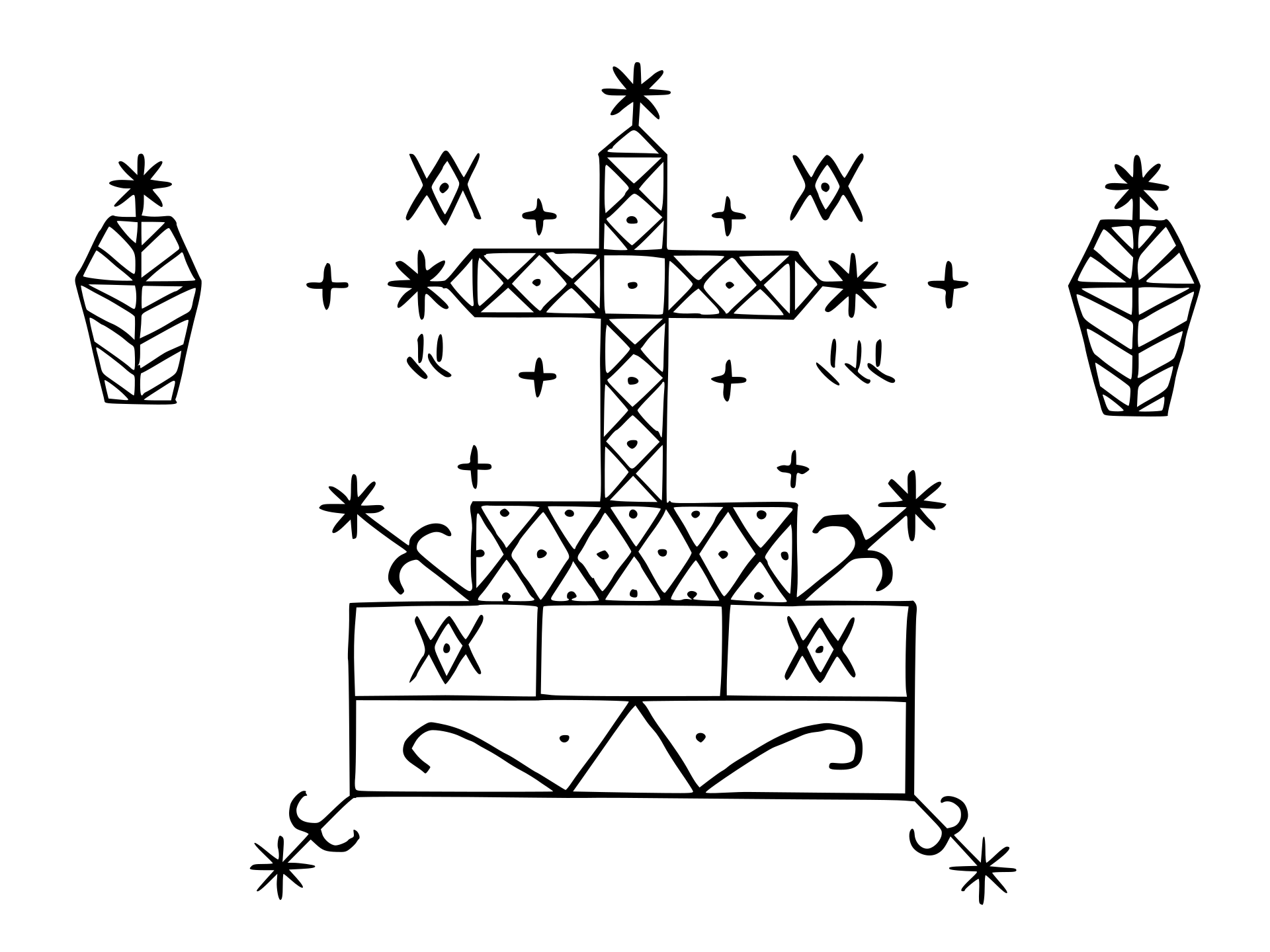

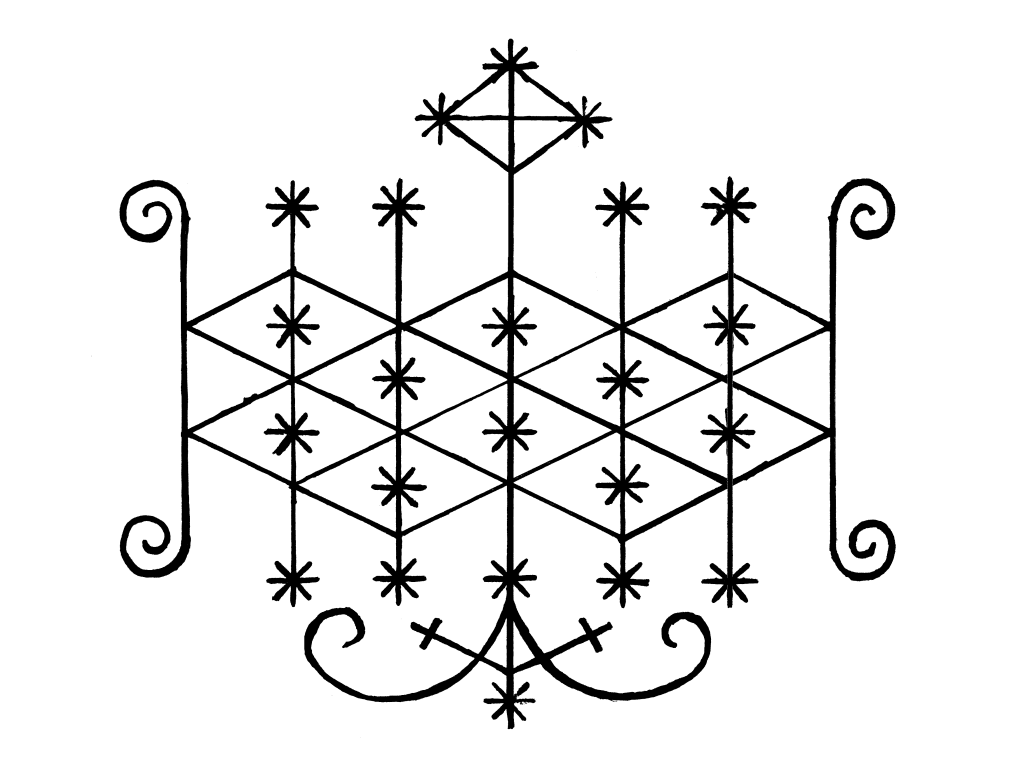

A vèvè pattern designed to invoke Baron Samedi, the chief of the Gede lwa Azaka is the lwa of crops and agriculture,[121] usually addressed as "Papa" or "Cousin".[122] His consort is the female lwa Kouzinn.[123] Loco is the lwa of vegetation, and because he is seen to give healing properties to various plant species is considered the lwa of healing too.[124] Ogou is a warrior lwa,[125] associated with weapons.[126] Sogbo is a lwa associated with lightning,[127] while his companion, Bade, is associated with the wind.[128] Danbala is a serpent lwa and is associated with water, being believed to frequent rivers, springs, and marshes;[129] he is one of the most popular deities in the pantheon.[130] Danbala and his consort Ayida-Weddo are often depicted as a pair of intertwining snakes.[129] The Simbi are understood as the guardians of fountains and marshes.[131] Usually seen as a fanmi rather than a nanchon,[132] the Gede are associated with the realm of the dead.[133] The head of the family is Baron Samedi ("Baron Saturday");[134] he is associated with the phallus, the skull, and the graveyard cross,[135] the latter used to mark out his presence in a Haitian cemetery.[136] His consort is Gran Brigit,[137] who has authority over cemeteries and is mother to many of the other Gede.[138] The Gede regularly satirise the ruling authorities,[139] and are welcomed to rituals as they are thought to bring merriment.[133] The Gede's symbol is an erect penis,[140] while the banda dance associated with them involves sexual-style thrusting,[141] and those possessed by these lwa typically make sexual innuendos.[142] The lwa and the saints Most lwa are associated with specific Roman Catholic saints.[143] These links are reliant on "analogies between their respective functions";[144] Azaka, the lwa of agriculture, is for instance associated with Saint Isidore the farmer.[145] Similarly, because he is understood as the "key" to the spirit world, Papa Legba is typically associated with Saint Peter, who is traditionally depicted holding keys in Roman Catholic imagery.[146] The lwa of love and luxury, Èzili Freda, is associated with Mater Dolorosa.[147] Danbala the serpent is often equated with Saint Patrick, who is traditionally depicted with snakes, or with Moses, whose staff turned into serpents.[148] The Marasa, or sacred twins, are typically equated with the twin saints Cosmos and Damian.[149] Scholars like Desmangles have argued that Vodouists originally adopted the Roman Catholic saints to conceal lwa worship when the latter was illegal during the colonial period.[150] Observing Vodou in the latter part of the 20th century, Donald J. Cosentino argued that by that point, the use of Roman Catholic saints reflected the genuine devotional expression of many Vodouists.[151] The scholar Marc A. Christophe concurred, stating that most modern Vodouists genuinely see the saints and lwa as one, reflecting Vodou's "all-inclusive and harmonizing characteristics".[152] Many Vodouists possess chromolithographic prints of the saints,[151] while images of these Christian figures can also be found on temple walls,[153] and on the drapo flags used in Vodou ritual.[154] Vodouists also often adopt and reinterpret biblical stories and theorise about the nature of Jesus of Nazareth.[155] |

グデ・ルワの長であるサメディ男爵を呼び出すためにデザインされたヴェーヴェのパターン。 アザカは農作物と農業のロアであり[121]、通常は「パパ」または「いとこ」と呼ばれる[122]。 [128]ダンバラは蛇のルワであり、水と関連しており、川、泉、沼地に頻繁に現れると信じられている[129]。 通常、ナンチョンよりもむしろファンミとして見られ[132]、ゲデは死者の領域と関連している[133]。 一族の長はサムディ男爵(「土曜日男爵」)であり[134]、彼はファルス、頭蓋骨、墓地の十字架と関連しており[135]、後者はハイチの墓地における 彼の存在を示すために使用される[136]。 彼の妃はグラン・ブリジットであり[137]、墓地に関する権威を持ち、他の多くのゲデの母親である。 [138]グデは支配的な権威を定期的に風刺しており[139]、陽気さをもたらすと考えられているため儀式に歓迎されている[133]。 ルワ(lwa :ロアとも読む)と聖人 ほとんどのルワは特定のローマ・カトリックの聖人と関連している[143]。これらの関連は「それぞれの機能の間の類似性」に依存している[144]。例 えば、農業のロアであるアザカは農夫の聖イジドールと関連している[145]。同様に、彼は霊界への「鍵」として理解されているため、パパ・レグバは一般 的にローマ・カトリックのイメージの中で伝統的に鍵を持って描かれている聖ペトロと関連している。 [146]愛と贅沢のルワであるエジリ・フレダは、マーテル・ドローローサと関連している[147]。蛇のダンバラは、伝統的に蛇と一緒に描かれている聖 パトリックや、杖が蛇に変わったモーゼと同一視されることが多い[148]。 デスマングレスのような学者は、ヴードゥー教徒はもともと植民地時代にロア崇拝が違法であったときに、ルワ崇拝を隠すためにローマ・カトリックの聖人を採 用したと主張している[150]。20世紀後半のヴードゥーを観察したドナルド・J・コセンティーノは、その時点ではローマ・カトリックの聖人の使用は多 くのヴードゥー教徒の真の献身的な表現を反映していると主張した[151]。クリストフ(Marc A. Christophe)も同意見で、現代のヴードゥーイストの多くは聖人とルワを純粋に一体として見ており、ヴードゥーの「すべてを包括し調和させる特徴」を 反映していると述べている[152]。 [152]多くのヴードゥー教徒は聖人のクロモリ版画を所有しており[151]、これらのキリスト教の人物の画像は寺院の壁や[153]、ヴードゥーの儀 式で使用されるドラポの旗にも見られる[154]。ヴードゥー教徒はまた、しばしば聖書の物語を採用し、再解釈し、ナザレのイエスの性質について理論化し ている[155]。 |

Soul and afterlife A Haitian drapo banner depicting a Roman Catholic saint Vodou holds that Bondye created humanity in its image, fashioning humans from water and clay.[156] It teaches the existence of a soul, usually called the nanm,[157] or sometimes the espri,[158] which is divided in two parts.[159] One of these is the ti bonnanj ("little good angel"), understood as the conscience that allows an individual to engage in self-reflection and self-criticism. The other part is the gwo bonnanj ("big good angel") and this constitutes the psyche, source of memory, intelligence, and personhood.[160] Both parts are believed to reside within an individual's head,[161] although the gwo bonnanj is thought capable of leaving the head and travelling while a person sleeps.[162] Vodouists believe that every individual is connected to a specific lwa, regarded as their mèt tèt (master of the head).[163] They believe that this lwa informs the individual's personality.[164] Vodou holds that the identity of a person's tutelary lwa can be identified through divination or by consulting lwa when they possess other humans.[165] Some of the religion's priests and priestesses are deemed to have "the gift of eyes", capable of seeing the identity of a person's tutelary lwa.[166] Vodou holds that Bondye has preordained the time of everyone's death,[167] but does not teach the existence of an afterlife realm akin to the Christian ideas of heaven and hell.[168] Instead, a common belief is that at bodily death, the gwo bonnanj join the Ginen, or ancestral spirits, while the ti bonnanj proceeds to face judgement before Bondye.[169] This idea of judgement is more common in urban areas, having been influenced by Roman Catholicism, while in the Haitian mountains it is more common for Vodouists to believe that the ti bonnanj dissolves into the navel of the earth nine days after death.[170] The land of the Ginen is often identified as being located beneath the sea, under the earth, or above the sky.[171] Some Vodouists believe that the gwo bonnanj stays in the land of the Ginen for a year and a day before being absorbed into the Gede family.[172] However, Vodouists usually distinguish the spirits of the dead from the Gede proper, for the latter are lwa.[173] Vodou also teaches that the dead continue to participate in human affairs,[174] with these spirits often complaining that they suffer from hunger, cold, and damp,[175] and thus requiring sacrifices from the living.[76] |

魂と死後の世界 ローマ・カトリックの聖人を描いたハイチのドラポの旗 ヴードゥーは、ボンデイが人間をその姿に似せて創造し、水と粘土から人間を作り出したと信じている[156]。通常ナンム[157]、あるいはエスプリ [158]と呼ばれる魂の存在を教え、その魂は2つの部分に分かれている[159]。もう一つの部分はグー・ボンナンジュ(「大きな善良な天使」)で、こ れは精神、記憶、知性、人格の源である[160]。両部分は個人の頭の中に存在すると信じられているが[161]、グー・ボンナンジュは人が眠っている間 に頭を離れて移動することができると考えられている[162]。 ヴードゥー教徒は、すべての個人は特定のロアとつながっており、そのルワはメット・テット(頭の主人)とみなされていると信じている[163]。 ヴードゥーは、ボンデイがすべての人の死の時をあらかじめ定めていると信じているが[167]、キリスト教の天国と地獄の考え方に似た死後の世界の存在は教 えていない[168]。その代わりに、一般的な信仰は、肉体が死ぬと、グー・ボンナンジュはジネン(祖先の霊)のもとに行き、ティ・ボンナンジュはボンデ イの前で裁きを受けるというものである。 [169]この審判の考えは、ローマ・カトリックの影響を受けた都市部では一般的であるが、ハイチの山岳地帯では、死後9日目にティ・ボンナンジが地球の へそに溶け込むと信じるヴードゥーイストが一般的である。 170]ジネンの地はしばしば海の下、地中、あるいは空の上にあるとされる[171]。一部のヴードゥーイストは、グオ・ボンナンジュは1年と1日の間ジネ ンの地に留まり、その後ゲデ家に吸収されると信じている[172]。 [172]しかし、ヴードゥーイストは通常、死者の霊をゲデ本家と区別しており、後者はルワであるからである[173]。ヴードゥーはまた、死者は人間の問題 に参加し続けていると教えており[174]、これらの霊はしばしば飢え、寒さ、湿気に苦しんでいると訴え[175]、生者からの犠牲を要求する[76]。 |

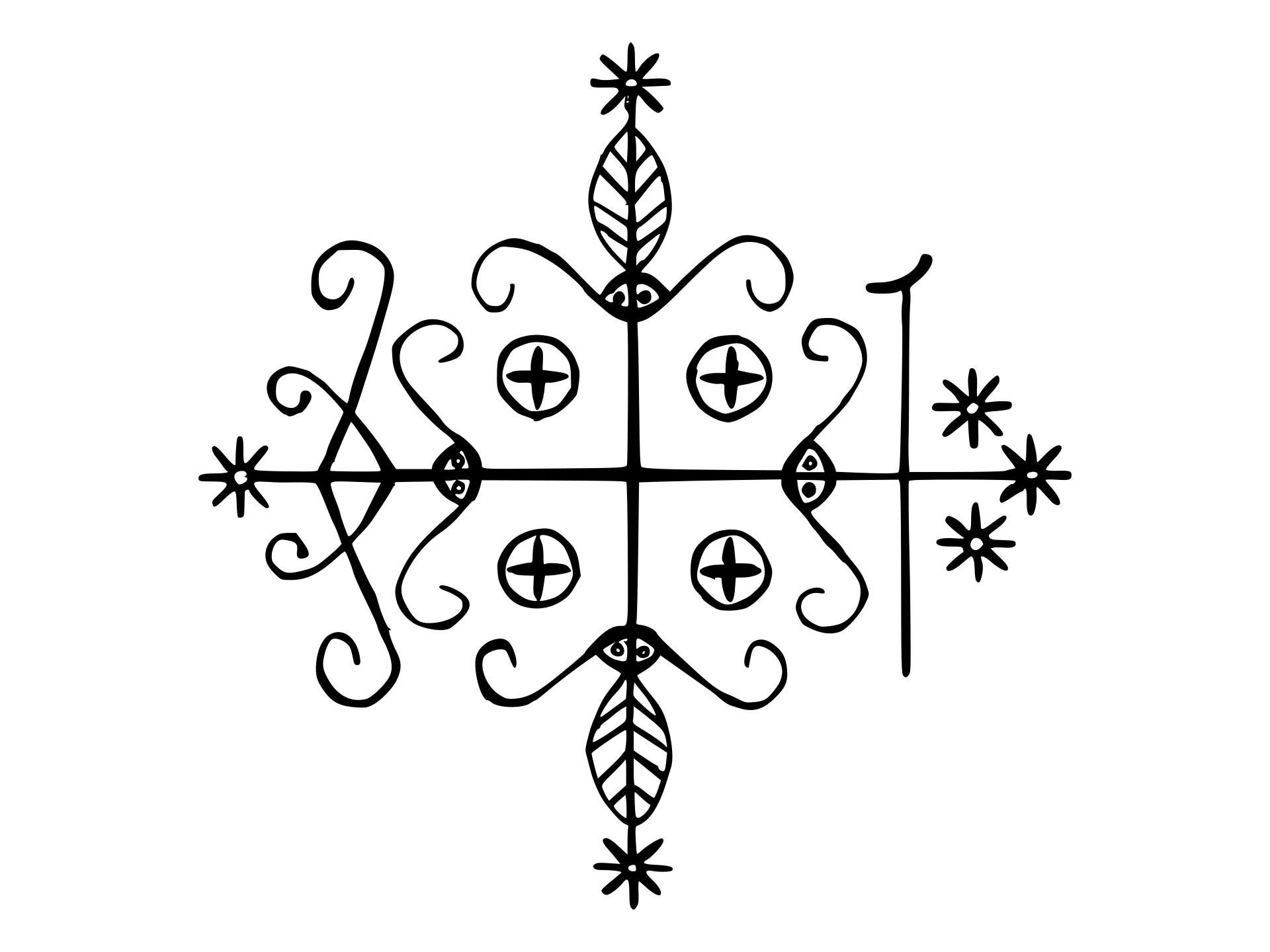

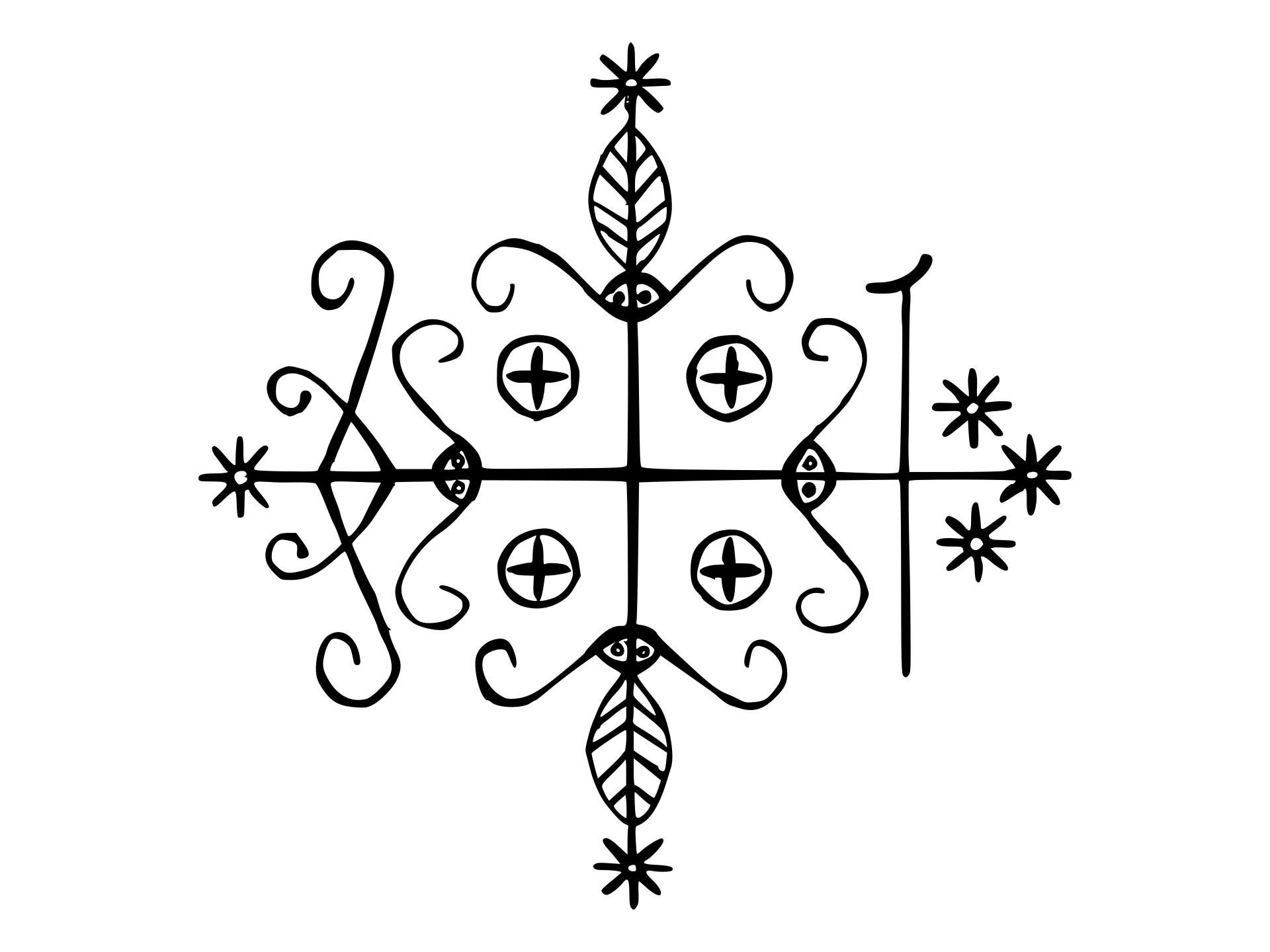

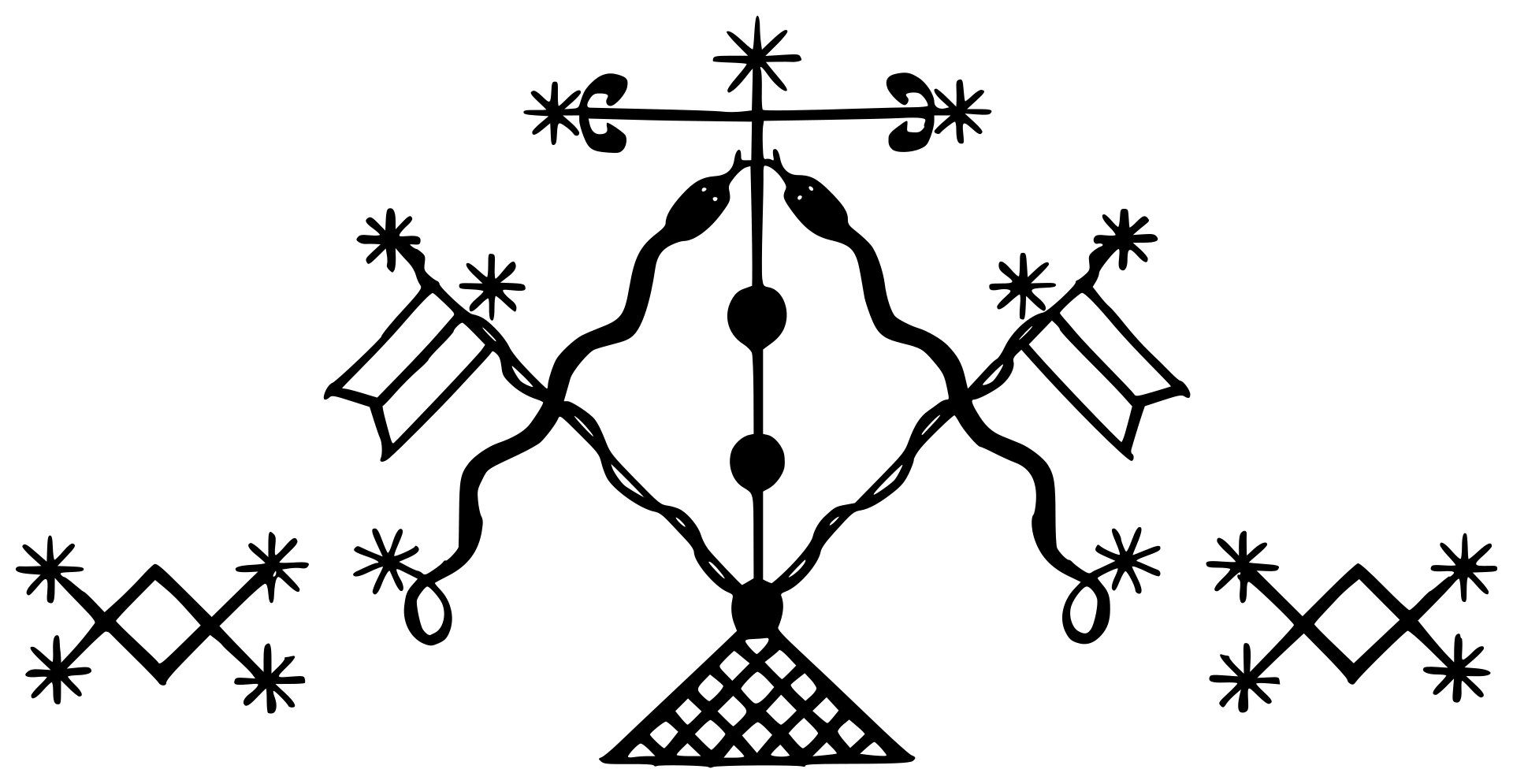

| Morality, ethics, and gender roles See also: Haitian Vodou and sexual orientation Vodou ethical standards correspond to its sense of cosmological order,[72] with a belief in the interdependence of things playing a role in Vodou approaches to ethical issues.[176] Serving the lwa is central to Vodou and its moral codes reflect the reciprocal relationship that practitioners have with these spirits;[177] for Vodouists, virtue is maintained by ensuring a responsible relationship with the lwa.[88] Vodou also promotes a belief in destiny, although individuals are still deemed to have freedom of choice.[178] This view of destiny has been interpreted as encouraging a fatalistic outlook,[179] something that the religion's critics, especially from Christian backgrounds, have argued has discouraged Vodouists from improving their society.[180] This has been extended into an argument that Vodou is responsible for Haiti's poverty,[181] a view that in turn has been accused of being rooted in European colonial prejudices towards Africans.[182]  A vèvè pattern designed to invoke Papa Legba, one of the main lwa spirits worshipped in Haitian Vodou Although Vodou permeates every aspect of its adherent's lives,[183] it offers no prescriptive code of ethics.[184] Rather than being rule-based, Vodou morality is deemed contextual to the situation,[185] with no clear binary division between good and evil.[186] Vodou reflects people's everyday concerns, focusing on techniques for mitigating illness and misfortune;[187] doing what one needs to in order to survive is considered a high ethic.[188] Among Vodouists, a moral person is regarded as someone who lives in tune with their character and that of their tutelary lwa.[185] In general, acts that reinforce Bondye's power are deemed good; those that undermine it are seen as bad.[72] Maji, meaning the use of supernatural powers for self-serving and malevolent ends, are usually thought bad.[189] The term is quite flexible; it is usually used to denigrate other Vodouists, although some practitioners have used it as a self-descriptor in reference to Petwo rites.[190] The extended family is of importance in Haitian society,[191] with Vodou reinforcing family ties,[192] and emphasising respect for the elderly.[193] Although there are accounts of male Vodou priests mistreating their female followers,[194] in the religion women can also lay claim to moral authority as social and spiritual leaders.[195] Vodou is also considered sympathetic to gay people,[196] with many gay and bisexual individuals holding status as Vodou priests and priestesses,[197] and some groups having largely gay congregations.[198] Some Vodouists state that the lwa determine a person's sexual orientation.[199] The lwa Èzili Dantò is sometimes regarded as a lesbian,[200] and is also seen as the patron of masisi (gay men).[201] |

道徳、倫理、性別役割分担 も参照のこと: ハイチ・ヴードゥーと性的指向 ヴードゥーの倫理基準はその宇宙論的秩序の感覚に対応しており[72]、物事の相互依存の信念が倫理的問題に対するヴードゥーのアプローチの役割を果たしてい る[176]。ルワに仕えることはヴードゥーの中心であり、その道徳規範は修行者がこれらの精霊と持つ相互関係を反映している[177]。 [178]この運命観は運命論的な見通しを助長していると解釈されており[179]、この宗教の批評家、特にキリスト教的背景を持つ者たちは、ヴードゥー信 者が自分たちの社会を改善する意欲をなくしていると主張している[180]。このことは、ヴードゥーがハイチの貧困の原因であるという議論にまで拡大されて おり[181]、この見解はアフリカ人に対するヨーロッパの植民地的偏見に根ざしていると非難されている[182]。  ハイチのヴードゥーで崇拝されている主なルワの精霊の一人であるパパ・レグバを呼び出すためにデザインされたヴェヴェのパターン ヴードゥーは信者の生活のあらゆる側面に浸透しているが[183]、倫理の規範は提供していない[184]。規則に基づくというよりは、ヴードゥーの道徳は状 況に応じたものとみなされ[185]、善と悪の明確な二元的区分はない[186]。ヴードゥーは人々の日常的な関心事を反映しており、病気や不幸を軽減する ための技術に焦点を当てている[187]。 [188]ヴードゥーイストの間では、道徳的な人とは自分の性格とその指導者であるルワの性格に調和した生き方をする人とみなされている[185]。一般的 に、ボンディエの力を強化する行為は善とみなされ、それを損なう行為は悪とみなされる。 [189]この用語は非常に柔軟であり、通常は他のヴードゥーイストを誹謗中傷するために用いられるが、ペツォの儀式を指して自称として用いる修行者もいる [190]。 ハイチ社会では大家族が重要であり[191]、ヴードゥーは家族の絆を強化し[192]、高齢者への敬意を強調している[193]。ヴードゥーの男性司祭が女 性の信者を虐待したという証言があるが[194]、この宗教では女性も社会的・精神的指導者として道徳的権威を主張することができる。 [195]ヴードゥーは同性愛者にも同情的であると考えられており[196]、多くの同性愛者や両性愛者がヴードゥーの司祭や巫女の地位に就いている [197]。 |

| Practices The anthropologist Alfred Métraux described Vodou as "a practical and utilitarian religion".[86] Its practices largely revolve around interactions with the lwa,[202] and incorporate song, drumming, dance, prayer, possession, and animal sacrifice.[203] Practitioners gather together for sèvices (services) in which they commune with the lwa.[204] Ceremonies for a particular lwa often coincide with the feast day of the Roman Catholic saint which that lwa is associated with.[205] The mastery of ritual forms is considered imperative in Vodou.[206] The purpose of ritual is to echofe ("heat things up"), thus bringing about change, whether that be to remove barriers or to facilitate healing.[207] Secrecy is important in Vodou.[208] It is an initiatory tradition,[209] operating through a system of graded induction or initiation.[102] When an individual agrees to serve a lwa, it is deemed a lifelong commitment.[210] Vodou has a strong oral culture, and its teachings are primarily disseminated through oral transmission,[211] although many practitioners began to use texts after they appeared in the mid-20th century.[212] The terminology used in Vodou ritual is called langaj.[213] Unlike in Santería and Candomblé, which employ Yoruba as a liturgical language not understood by most practitioners, in Vodou the liturgies are predominantly in Haitian Creole, the everyday language of most Vodouists.[214] Oungan and Manbo  Ceremonial suit worn in Haitian Vodou rites, on display in the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, Germany Male priests are referred to as an oungan, alternatively spelled houngan or hungan,[215] or a prèt Vodou ("Vodou priest").[216] Priestesses are termed manbo, alternatively spelled mambo.[217] Oungan numerically dominate in rural Haiti, while there is a more equitable balance of priests and priestesses in urban areas.[218] The oungan and manbo are tasked with organising liturgies, preparing initiations, offering consultations with clients using divination, and preparing remedies for the sick.[219] There is no priestly hierarchy, with oungan and manbo being largely self-sufficient.[219] In many cases, the role is hereditary.[220] Historical evidence suggests that the role of the oungan and manbo intensified over the course of the 20th century.[221] As a result, "temple Vodou" is now more common in rural areas of Haiti than it was in historical periods.[222] Vodou teaches that the lwa call an individual to become an oungan or manbo,[223] and if the latter refuses then misfortune may befall them.[224] A prospective oungan or manbo must normally rise through the other roles in a Vodou congregation before undergoing an apprenticeship with a pre-existing oungan or manbo lasting several months or years.[225] After this apprenticeship, they undergo an initiation ceremony, the details of which are kept secret from non-initiates.[226] Other oungan and manbo do not undergo any apprenticeship, but claim that they have gained their training directly from the lwa.[227] Their authenticity is often challenged, and they are referred to as hungan-macoutte, a term bearing some disparaging connotations.[225] Becoming an oungan or manbo is expensive, often requiring the purchase of ritual paraphernalia and land on which to build a temple.[228] To finance this, many save up for a long time.[228] Vodouists believe that the oungan's role is modelled on the lwa Loco;[229] in Vodou mythology, he was the first oungan and his consort Ayizan the first manbo.[230] The oungan and manbo are expected to display the power of second sight,[231] something regarded as a gift from Bondye that can be revealed to the individual through visions or dreams.[232] Many priests and priestesses are often attributed fantastical powers in stories told about them,[233] and may bolster their status with claims to have received revelations from the lwa, sometimes via visits to the lwa's own abode.[234] There is often bitter competition between different oungan and manbo.[235] Their main income derives from healing the sick, supplemented with payments received for overseeing initiations and selling talismans and amulets.[236] In many cases, oungan and manbo become wealthier than their clients.[237] Oungan and manbo are generally powerful and well-respected members of Haitian society.[238] Being an oungan or manbo provides an individual with both social status and material profit,[239] although the fame and reputation of individual priests and priestesses can vary widely.[240] Respected Vodou priests and priestesses are often literate in a society where semi-literacy and illiteracy are common.[241] They can recite from printed texts and write letters for illiterate members of their community.[241] Owing to their prominence in a community, the oungan and manbo can effectively become political leaders,[232] or otherwise exert an influence on local politics.[239] |

実践 人類学者のアルフレッド・メトローはヴードゥーを「実践的で実用的な宗教」と表現した[86]。その実践は主にロアとの交流を中心に展開され[202]、 歌、太鼓、踊り、祈り、憑依、動物の生け贄などが組み込まれている[203]。 [204]特定のルワのための儀式は、しばしばそのロアが関連しているローマ・カトリックの聖人の祝祭日と重なる[205]。ヴードゥーでは儀式の形式を習 得することが必須と考えられている[206]。儀式の目的はエコーフェー(「物事を熱くする」こと)であり、それによって障壁を取り除いたり、癒しを促進 したりといった変化をもたらすことである[207]。 ヴードゥーでは秘密主義は重要である[208]。ヴードゥーはイニシエーション的な伝統であり[209]、段階的な誘導やイニシエーションのシステムによって 運営されている[102]。 個人がルワに仕えることに同意した場合、それは生涯のコミットメントとみなされる[210]。ヴードゥーは強い口承文化を持っており、その教えは主に口承に よって広められている[211]が、20世紀半ばにテキストが登場してから多くの実践者がテキストを使用するようになった。 [212]ヴードゥーの儀式で使用される専門用語はランガジと呼ばれる[213]。ほとんどの修行者が理解できないヨルバ語を典礼言語として使用するサンテ リアやカンドンブレとは異なり、ヴードゥーでは典礼は主にハイチ・クレオール語、つまりヴードゥー信者の多くが日常的に使用する言語で行われる[214]。 ウンガンとマンボ  ドイツのベルリン民族学博物館に展示されている、ハイチのヴードゥー儀式で着用される儀礼服。 男性司祭はウンガン(別称ホウガン、フンガン)[215]、またはプレ・ヴードゥー(「ヴードゥー司祭」)と呼ばれる[216]。 [217]ハイチの農村部ではウンガンが圧倒的に多いが、都市部では神官と巫女のバランスがより均等である[218]。ウンガンとマンボは典礼を組織し、 イニシエーションを準備し、占いを用いて顧客の相談に乗り、病気の治療薬を準備する任務を負っている。 [多くの場合、その役割は世襲制である[220]。 歴史的な証拠によれば、ウンガンとマンボの役割は20世紀の間に強化された[221]。 その結果、「寺院ヴードゥー」は歴史的な時代よりもハイチの農村部で一般的になっている[222]。 ヴードゥーの教えでは、ロアはウンガンやマンボウになるように個人を呼び、[223]もしウンガンやマンボウがそれを拒否した場合には不幸が降りかかるとさ れている[224]。ウンガンやマンボウになろうとする者は通常、ヴードゥーの集会における他の役割を経てから、数ヶ月から数年に渡って既存のウンガンやマ ンボウの下で見習いをしなければならない[225]。 [226]他のウンガンやマンボは徒弟修行を経ず、ルワから直接修行を積んだと主張する[227]。彼らの信憑性にはしばしば疑問が呈され、彼らは渾沌と 呼ばれ、蔑視的な意味合いを持つ用語である[225]。 ウンガンの役割はロア・ロコをモデルにしているとヴードゥーイストは信じている。[229]ヴードゥー神話では、彼は最初のウンガンであり、彼の妃であるアイ ザンは最初のマンボウである[230]。 [232]多くの司祭や巫女は、彼らについて語られる物語の中でしばしば幻想的な力を持つとされ[233]、ロアから啓示を受けたと主張することでその地 位を高め、時にはルワ自身の住処を訪れることもある[234]。 異なるウンガンやマンボの間にはしばしば激しい競争がある[235]。彼らの主な収入は病気の治療から得ており、イニシエーションを監督したり、お守りや 魔除けを売ったりすることで受け取る報酬で補われている[236]。多くの場合、ウンガンやマンボはクライアントよりも裕福になる。 [237]ウンガンやマンボは一般的にハイチ社会の有力者であり、尊敬を集めている[238]。ウンガンやマンボであることは個人に社会的地位と物質的利 益の両方を与えるが[239]、個々の司祭や巫女の名声や評判は大きく異なることがある。 [240]尊敬されるヴードゥーの司祭や巫女は、半識字や非識字が一般的な社会では識字者であることが多い[241]。 彼らは印刷されたテキストを暗唱したり、コミュニティの非識字者のために手紙を書いたりすることができる[241]。 コミュニティにおける彼らの卓越性により、ウンガンやマンボは効果的に政治的指導者になることができ[232]、そうでなければ地元の政治に影響を及ぼす ことができる[239]。 |

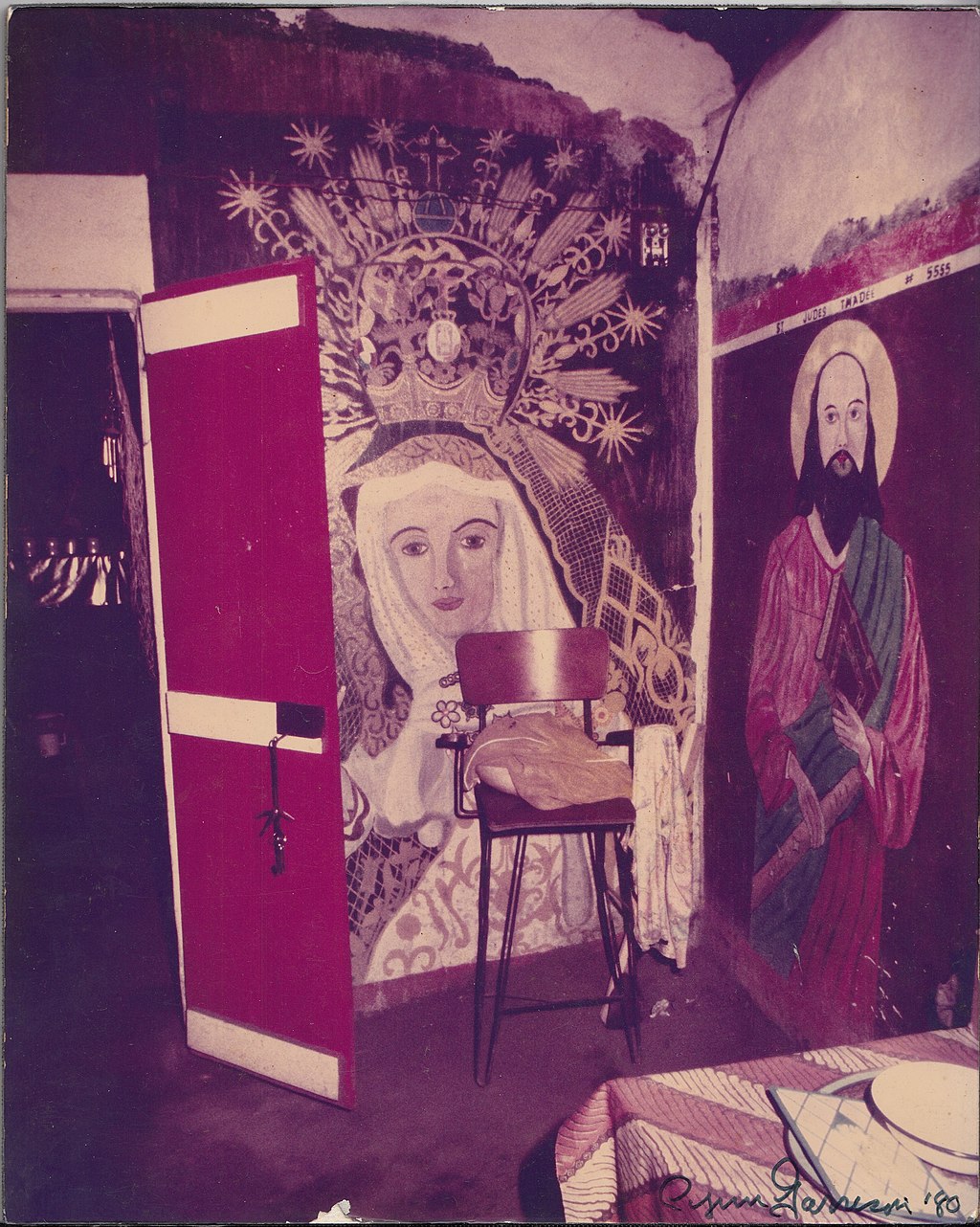

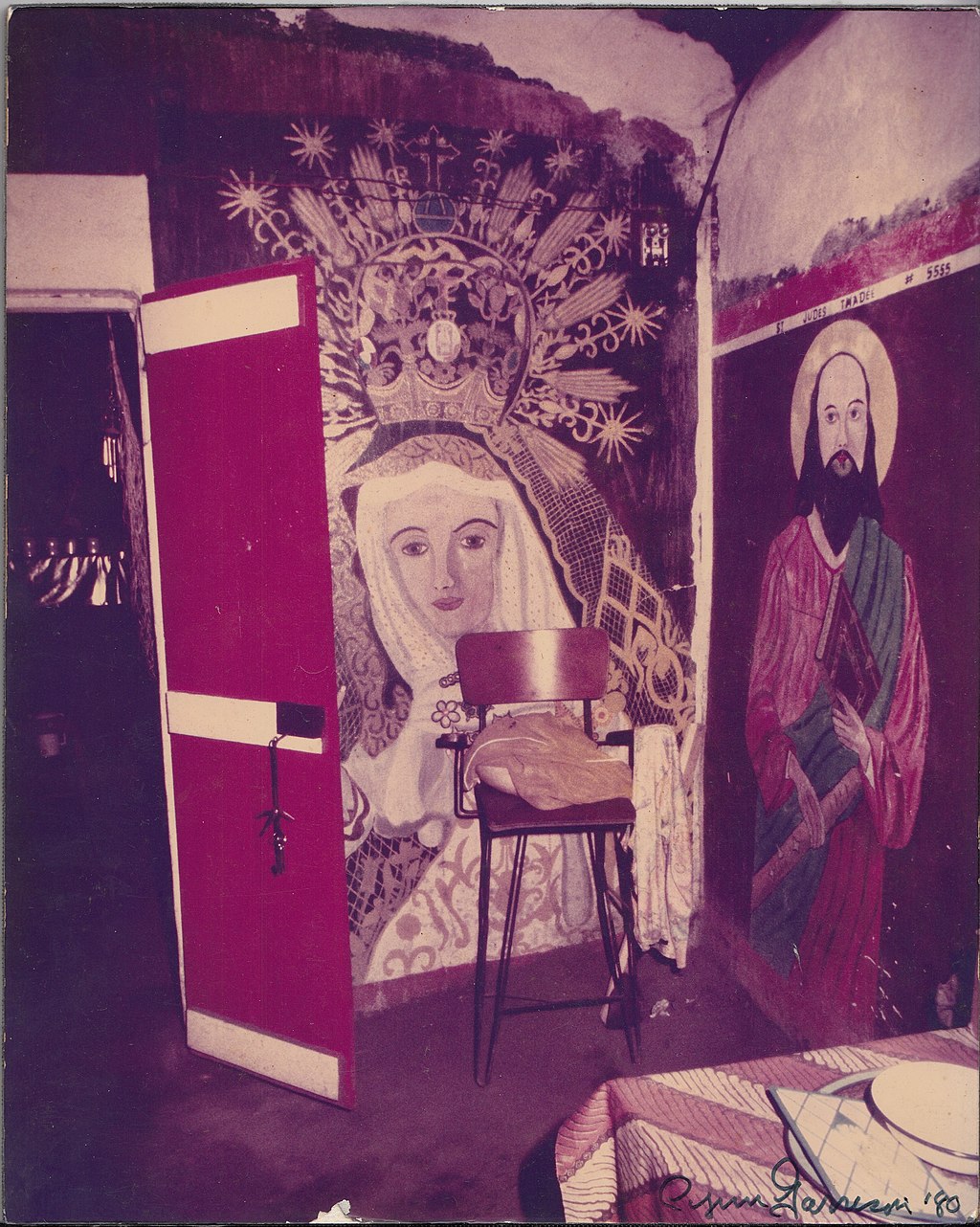

| The ounfò A Vodou temple is called an ounfò,[242] varyingly spelled hounfò,[243] hounfort,[244] or humfo.[34] An alternative term is gangan, although the connotations of this term vary regionally in Haiti.[245] Most communal Vodou activities centre around this ounfò,[230] forming what is called "temple Vodou".[35] The size and shape of ounfòs vary, from basic shacks to more lavish structures, the latter being more common in Port-au-Prince.[230] Their designs are dependent on the resources and tastes of the oungan or manbo running them.[246] Each ounfò is autonomous,[247] and often has its own unique customs.[248]  A Vodou peristil in Croix des Mission, Haiti, photographed in 1980 The main ceremonial room in the ounfò is the peristil,[249] understood as a microcosmic representation of the cosmos.[250] In the peristil, brightly painted posts hold up the roof;[251] the central post is the poto mitan,[252] which is used as a pivot during ritual dances and the pillar through which the lwa enter the room during ceremonies.[251] It is around this central post that offerings, including both vèvè patterns and animal sacrifices, are made.[202] However, in the Haitian diaspora many Vodouists perform their rites in basements, where no poto mitan are available.[253] The peristil typically has an earthen floor, allowing libations to the lwa to drain directly into the soil;[254] where this is not possible, libations are poured into an enamel basin.[255] Some peristil include seating around the walls.[256] Adjacent rooms in the ounfò include the caye-mystéres, also known as the bagi, badji, or sobadji.[257] This is where stonework altars, known as pè, stand against the wall or are arranged in tiers.[257] Also present may be a sink dedicated to the lwa Danbala-Wedo.[258] The caye-mystéres is also used to store clothing that will be worn by those possessed by the lwa during rituals.[259] If space is available, the ounfò may also have a room set aside for the patron lwa of that temple.[260] Many ounfòs have a room known as the djévo in which the initiate is confined during their initiatory ceremony.[259] Every ounfò usually has a room or corner of a room devoted to Erzuli Freda.[261] Some ounfò will also have additional rooms in which the oungan or manbo lives.[260] The area around the ounfò often contains objects dedicated to particular lwa, such as a pool of water for Danbala, a black cross for Baron Samedi, and a pince (iron bar) embedded in a brazier for Criminel.[262] Sacred trees, known as arbres-reposoirs, sometimes mark the ounfò's external boundary.[263] Hanging from these trees can be found macounte straw sacks, strips of material, and animal skulls.[263] Various animals, particularly birds but also some mammal species such as goats, are sometimes kept within the perimeter of the ounfò for use as sacrifices.[263] |

ウンフォ ヴードゥー寺院はウンフォと呼ばれ[242]、hounfò、[243]hounfort、[244]humfoなど様々な綴りがある[34]。 [35]ウンフォの大きさや形は、基本的な掘っ立て小屋からより豪華な建造物まで様々であり、後者はポルトープランスでより一般的である[230]。その 設計は、ウンガンやマンボが運営する資源や好みに左右される[246]。  1980年に撮影されたハイチのクロワ・デ・ミッションのヴードゥー・ペリスティル ウンフォの主要な儀式の部屋はペリスティルであり[249]、宇宙の小宇宙的な表現として理解されている[250]。ペリスティルでは、明るく塗られた柱 が屋根を支えている[251]。中央の柱はポト・ミタン[252]で、儀式の踊りの際にピボットとして使用され、儀式の際にはルワが部屋に入る柱となる [251]。この中央の柱の周囲で、ヴェヴェの文様と動物の犠牲を含む供物が捧げられる。 [202]しかし、ハイチのディアスポラでは、多くのヴードゥーイストがポト・ミタンが利用できない地下室で儀式を行っている[253]。ペリスティルは一 般的に土間になっており、ロアへの捧げ物が直接土に流されるようになっている[254]。 ウンフォに隣接する部屋には、バギ、バジ、ソバジとも呼ばれるカイエ・ミステレスがある[257]。ここには、ペー(pè)と呼ばれる石造りの祭壇が壁際 に立てられたり、段になって配置されたりする[257]。 [259]スペースに余裕がある場合、ウンフォにはその寺院の守護ルワのための部屋が用意されていることもある[260]。 多くのウンフォには、入門者が入門儀式の際に閉じ込められるジェヴォと呼ばれる部屋がある[259]。 ウンフォの周辺には、ダンバラのための水溜り、サメディ男爵のための黒い十字架、クリミネルのための火鉢に埋め込まれたピンス(鉄の棒)など、特定のロア に捧げられたものが置かれていることが多い[262]。 [263]これらの木には、藁の袋、短冊、動物の頭蓋骨などが吊るされている[263]。 |

The congregation A Vodou ceremony taking place in an ounfò in Jacmel, Haiti Forming a spiritual community of practitioners,[202] the ounfò's congregation are known as the pititt-caye (children of the house).[264] They worship under the authority of an oungan or manbo,[34] below whom is ranked the ounsi, individuals who make a lifetime commitment to serving the lwa.[265] Members of either sex can join the ounsi, although most are female.[266] The ounsi's duties include cleaning the peristil, sacrificing animals, and taking part in the dances at which they must be prepared to be possessed by a lwa.[267] The oungan and manbo conduct initiatory ceremonies whereby people become ounsi,[232] oversee their training,[230] and act as their counsellor, healer, and protector.[268] In turn, the ounsi are expected to be obedient to their oungan or manbo.[267] One of the ounsi becomes the hungenikon or reine-chanterelle, the mistress of the choir. They are responsible for overseeing the liturgical singing and shaking the chacha rattle which dictates the rhythm during ceremonies.[269] They are aided by the hungenikon-la-place, commandant general de la place, or quartermaster, who is charged with overseeing offerings and keeping order during the rites.[230] Another figure is le confiance (the confidant), the ounsi who oversees the ounfò's administrative functions.[270] Congregants often form a sosyete soutyen (société soutien, support society), through which subscriptions are paid to help maintain the ounfò and organize the major religious feasts.[271] Another ritual figure sometimes present is the prèt savann ("bush priest"), a man with a knowledge of Latin who is capable of administering Catholic baptisms, weddings, and the last rites, and who is willing to perform these at Vodou ceremonies.[272] In rural areas especially, a congregation may consist of an extended family.[219] Here, the priest will often be the patriarch of that family.[273] Families, particularly in rural areas, often believe that through their zansèt (ancestors) they are tied to a premye mèt bitasyon (original founder); their descent from this figure is seen as giving them their inheritance both of the land and of familial spirits.[32] In other examples, particularly in urban areas, an ounfò can act as an initiatory family.[274] A priest becomes the papa ("father") while the priestess becomes the manman ("mother") to the initiate;[275] the initiate becomes their initiator's pitit (spiritual child).[212] Those who share an initiator refer to themselves as "brother" and "sister."[225] Individuals may join a particular ounfò because it exists in their locality or because their family are already members. Alternatively, it may be that the ounfò places particular focus on a lwa whom they are devoted to, or that they are impressed by the oungan or manbo who runs the ounfò in question, perhaps having been treated by them.[267] |

集会 ハイチのジャクメルにあるウンフォで行われるヴードゥーの儀式 修行者の精神的共同体を形成するウンフォの信徒[202]はピティット・カイ(家の子供たち)として知られている[264]。彼らはウンガンまたはマンボ [34]の権威の下で礼拝を行い、その下にウンシが位置づけられる。 [266]ウンシの任務には、ペリスティルの掃除、動物の生け贄、ルワに憑依されるために準備しなければならない踊りに参加することなどが含まれる [267]。ウンガンとマンボは、人々がウンシになるための入門儀式を行い[232]、彼らの訓練を監督し[230]、彼らのカウンセラー、ヒーラー、プ ロテクターとしての役割を果たす[268]。 ウンシの一人は、聖歌隊の女主人であるハンゲニコンまたはライン・シャンテレルとなる。彼らは典礼の歌唱を監督し、儀式中にリズムを指示するチャチャ・ガ ラガラを振る責任を負う[269]。彼らは、供え物の監督と儀式中の秩序維持を任務とするHungenikon-la-place、Commandant General de la Place、またはQuartermasterに補佐される[230]。 [270]信徒はしばしばsosyete soutyen(société soutien、支援協会)を形成し、そこを通じてウンフォの維持と主要な宗教的祝祭の組織化を支援するために加入金を支払っている[271]。もう一人 の儀礼的な人物はprèt savann(「潅木の司祭」)であり、カトリックの洗礼式、結婚式、最後の儀式を執り行うことができるラテン語の知識を持つ男性であり、ヴードゥーの儀式 において進んでこれらを執り行う[272]。 特に農村部では、信徒は大家族で構成されることがある[219]。この場合、司祭はその家族の家長であることが多い[273]。家族、特に農村部では、ザ ンセート(先祖)を通して、プレミエ・メート・ビタシオン(最初の創始者)と結びついていると信じていることが多く、この人物からの子孫は、土地と家族の 霊魂の両方の相続権を与えると考えられている。 [他の例では、特に都市部において、ウンフォはイニシエーション・ファミリーとして機能することがある[274]。司祭はイニシエイトにとってパパ (「父」)となり、巫女はマンマン(「母」)となる[275]。あるいは、そのウンフォが特に重視しているルワに献身的であったり、そのウンフォを運営す るウンガンやマンボに感銘を受けたり、彼らに治療を受けたことがあったりすることもある[267]。 |

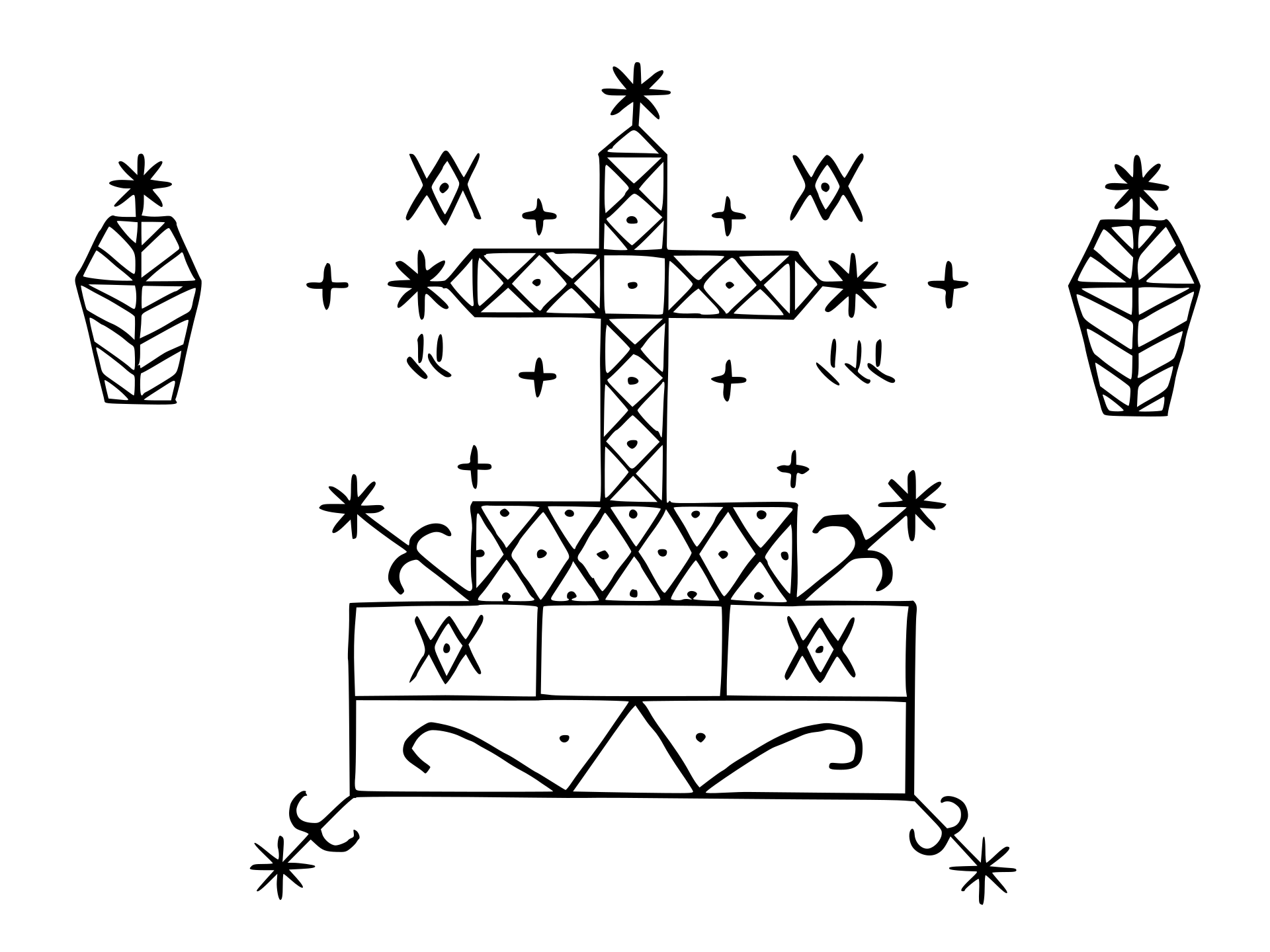

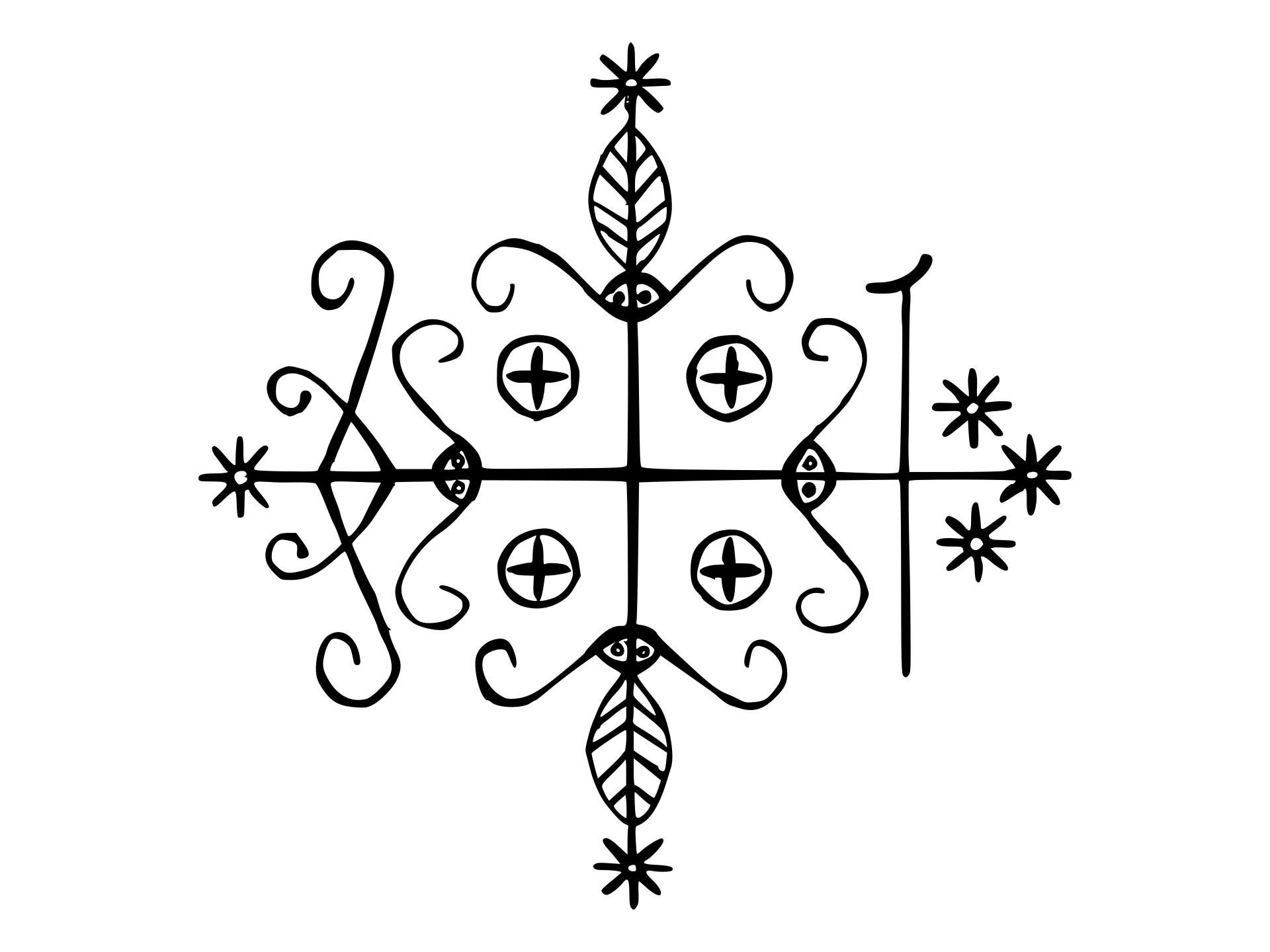

Initiation A vèvè pattern designed to invoke Gran Brigit, one of the lwa spirits worshipped in Haitian Vodou Vodou is hierarchical and includes a series of initiations.[276] There are typically four levels of initiation,[277] the fourth of which makes someone an oungan or manbo.[278] There is much variation in what these initiation ceremonies entail,[114] and the details are kept secret.[279] Each initiatory stage is associated with a state of mind called a konesan (conaissance or knowledge).[280] Successive initiations are required to move through the various konesans,[232] and it is in these konesans that priestly power is believed to reside.[281] The first initiation rite is the kanzo;[282] this term also describes the initiate themselves.[283] Initiation is generally expensive,[284] complex,[278] and requires significant preparation.[114] Prospective initiates are for instance required to memorise many songs and learn the characteristics of various lwa.[114] Vodouists believe the lwa may encourage an individual towards initiation, bringing misfortune upon them if they refuse.[285] Initiation will often be preceded by bathing in special preparations.[286] The first part of the initiation rite is known as the kouche or huño, and is marked by salutations and offerings to the lwa.[287] It begins with the chire ayizan, a ceremony in which palm leaves are frayed and then worn by the initiate.[114] Sometimes the bat ge or batter guerre ("beating war") is performed instead, designed to beat away the old.[114] During the rite, the initiate comes to be regarded as the child of a particular lwa, their mèt tèt.[114] This is followed by a period of seclusion within the djèvo known as the kouche.[114] A deliberately uncomfortable experience,[161] it involves the initiate sleeping on a mat on the floor, often with a stone for a pillow.[288] They wear a white tunic,[289] and a specific salt-free diet is followed.[290] It includes a lav tèt ("head washing") to prepare the initiate for having the lwa enter and reside in their head.[291] Voudoists believe that one of the two parts of the human soul, the gwo bonnanj, is removed from the initiate's head, thus making space for the lwa to enter and reside there.[161] The initiation ceremony requires the preparation of pot tèts (head pots), usually white porcelain cups with a lid in which a range of items are placed, including hair, food, herbs, and oils. These are regarded as a home for the spirits.[292] After the period of seclusion in the djèvo, the new initiate is brought out and presented to the congregation; they are now referred to as ounsi lave tèt.[114] When the new initiate is presented to the rest of the community, they carry their pot tèt on their head, before placing it on the altar.[161] The final stage of the process involves the initiate being given an ason rattle.[293] The initiation process is seen to have ended when the new initiate is first possessed by a lwa.[161] Initiation is seen as creating a bond between a devotee and their tutelary lwa,[294] and the former will often take on a new name that alludes to the name of this lwa.[295] Finally, after the kouche, the new initiate may be expected to visit a Catholic church.[296] |

イニシエーション ハイチのヴードゥーで崇拝されているルワの精霊の一人であるグラン・ブリギットを呼び出すためにデザインされたヴェーヴェのパターン。 ヴードゥーは階層的であり、一連のイニシエーションを含む[276]。一般的にイニシエーションには4つの段階があり[277]、4つ目の段階でウンガンま たはマンボとなる[278]。 [279]それぞれのイニシエーションの段階はコネサン(洞察または知識)と呼ばれる心の状態と関連している[280]。様々なコネサンを通過するために は連続したイニシエーションが必要とされ[232]、司祭の力が宿ると信じられているのはこれらのコネサンである[281]。 最初のイニシエーションの儀式はカンゾーであり[282]、この用語はイニシエート自身をも表す[283]。イニシエーションは一般的に高価であり [284]、複雑であり[278]、かなりの準備が必要である[114]。イニシエーション希望者は例えば多くの歌を暗記し、様々なロアの特徴を学ぶこと が求められる[114]。ヴードゥーイストはルワがイニシエーションに向けて個人を励まし、拒否すれば不幸をもたらすと信じている[285]。 イニシエーションの儀式の最初の部分はクーシェまたはフーニョとして知られ、ルワへの敬礼と供物によって示される[287]。 [114]。儀式の間、入門者は特定のルワの子供、彼らのメット・テット(mèt tèt)とみなされるようになる[114]。 これは意図的に不快な体験であり[161]、イニシエートは床にマットを敷き、しばしば石を枕にして寝る[288]。 [290]この儀式には、ルワがイニシエートの頭部に入り、そこに宿るための準備をするための「頭を洗う」儀式(lav tèt)が含まれる[291]。ヴードゥー教徒は、人間の魂の2つの部分のうちの1つであるグオ・ボナンジ(gwo bonnanj)がイニシエートの頭部から取り除かれることで、ルワがそこに入り、そこに宿るための空間ができると信じている[161]。 イニシエーションの儀式では、ポット・テット(頭壺)を用意する必要がある。これは通常、蓋つきの白い磁器のカップで、その中に髪の毛、食べ物、ハーブ、 オイルなど、さまざまなものが入れられる。これらは精霊の住処とみなされる[292]。djèvoに閉じこもる期間が終わると、新しい入信者は外に出さ れ、信徒に披露される。 [293]入信のプロセスは、新しい入信者が最初にルワに憑依されたときに終了したとみなされる[161]。入信は帰依者とその師であるルワとの間に絆を 生み出すとみなされ[294]、前者はしばしばこのルワの名前を暗示する新しい名前を名乗る[295]。最後に、クーチェの後、新しい入信者はカトリック 教会を訪れることが期待される[296]。 |

Shrines and altars An altar in Boston, Massachusetts established during the November festival of the Gede The creation of sacred works is important in Vodou.[206] Votive objects used in Haiti are typically made from industrial materials, including iron, plastic, sequins, china, tinsel, and plaster.[30] An altar, or pè, will often contain images (typically lithographs) of Roman Catholic saints.[297] Since developing in the mid-19th century, chromolithography has also had an impact on Vodou imagery, facilitating the widespread availability of images of the Roman Catholic saints who are equated with the lwa.[298] Various Vodouists have made use of varied available materials in constructing their shrines. Cosentino encountered a shrine in Port-au-Prince where Baron Samedi was represented by a plastic statue of Santa Claus wearing a black sombrero,[299] and in another by a statue of Star Wars-character Darth Vader.[300] In Port-au-Prince, it is common for Vodouists to include human skulls on their altar for the Gede.[216] In ounfòs where both Rada and Petwo deities are worshipped, their altars are kept separate.[301] Various spaces other than the temple are used for Vodou ritual.[302] Cemeteries are seen as places where spirits reside, making them suitable for certain rituals,[302] especially to approach the spirits of the dead.[303] In rural Haiti, cemeteries are often family owned and play a key role in family rituals.[304] Crossroads are also ritual locations, selected as they are believed to be points of access to the spirit world.[302] Other spaces used for Vodou rituals include Christian churches, rivers, the sea, fields, and markets.[302] |

神社と祭壇 マサチューセッツ州ボストンにある祭壇は、11月のゲデの祭りの際に設置された。 聖なる作品の創作はヴードゥーにおいて重要である[206]。ハイチで使用される奉納物は、一般的に鉄、プラスチック、スパンコール、陶器、ティンセル、 石膏などの工業材料で作られている[30]。 [297]19世紀半ばに発展して以来、彩色石版画もヴードゥーのイメージに影響を与え、ロアと同一視されるローマ・カトリックの聖人のイメージを広く利用 できるようになった[298]。コセンティーノはポルトープランスで、サムディ男爵が黒いソンブレロをかぶったサンタクロースのプラスチック像で表現され ている[299]神社に遭遇し、また別の神社ではスター・ウォーズのキャラクターであるダース・ベイダーの像で表現されている[300]。 ポルトープランスでは、ヴードゥーイストがゲデの祭壇に人間の頭蓋骨を置くことは一般的である[216]。 ヴードゥーの儀式には寺院以外の様々な空間が使用される[302]。墓地は霊が住む場所と考えられており、特定の儀式に適している[302]。 [304]十字路も儀式の場所であり、霊界に通じる地点であると信じられていることから選ばれている[302]。ヴードゥーの儀式に用いられるその他の空間 としては、キリスト教会、川、海、畑、市場などがある[302]。 |

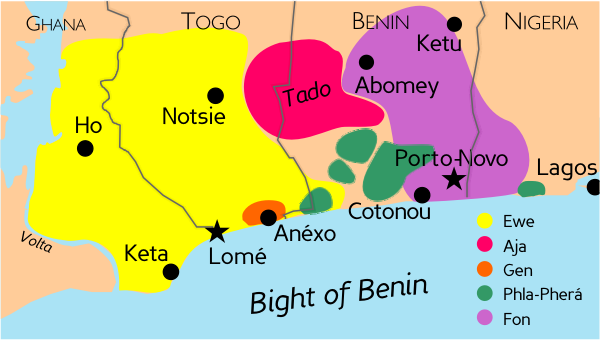

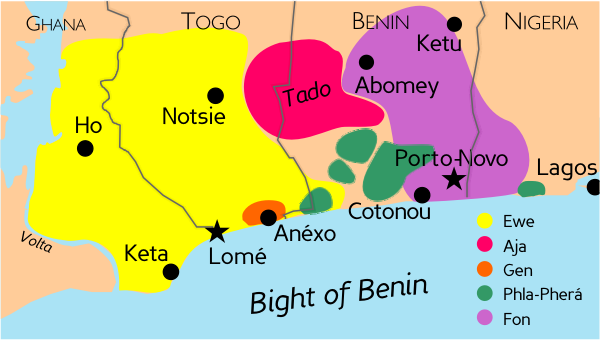

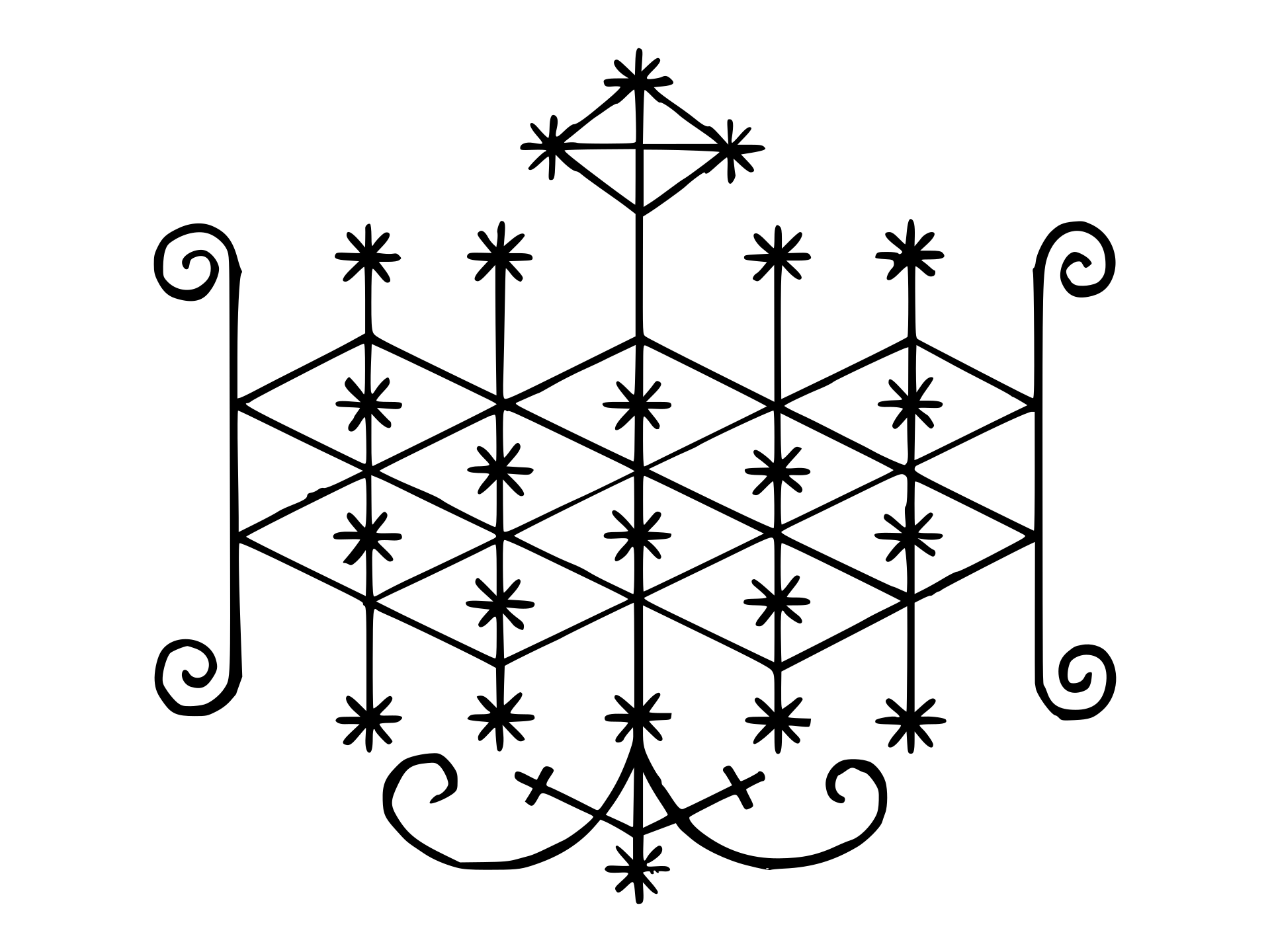

An ason, the ritual rattle emblematic of the Vodou priesthood Certain trees are regarded as having spirits resident in them and are used as natural altars.[241] Different species of tree are associated with different lwa; Oyu, for example, is linked with mango trees, and Danbala with bougainvillea.[86] Selected trees in Haiti have had metal items affixed to them, serving as shrines to Ogou, who is associated with both iron and the roads.[305] Spaces for ritual also appear in the homes of many Vodouists.[306] These may vary from complex altars to more simple variants including only images of saints alongside candles and a rosary.[35] Many practitioners will also have an altar devoted to their ancestors in their home, to which they direct offerings.[307] Drawings known as vèvè are sketched onto the floor of the peristil using cornmeal, ash, coffee grounds, or powdered eggshells;[308] these are central to Vodou ritual.[250] Usually arranged symmetrically around the poto-mitan,[309] these designs sometimes incorporate letters;[241] their purpose is to summon lwa.[309] Inside the peristil, practitioners also unfurl ceremonial flags known as drapo (flags) at the start of a ceremony.[310] Often made of silk or velvet and decorated with shiny objects such as sequins,[311] the drapo often feature either the vèvè of specific lwa they are dedicated to or depictions of the associated Roman Catholic saint.[154] These drapo are understood as points of entry through which the lwa can enter the peristil.[312] A batèms (baptism) is a ritual used to make an object a vessel for the lwa.[313] Objects consecrated for ritual use are believed to contain a spiritual essence or power called nanm.[314] The ason is a sacred rattle used in summoning the lwa,[315] especially for Rada rites.[316] It consists of an empty, dried gourd covered in beads and snake vertebra.[317] Prior to being used in ritual it requires consecration.[318] It is a symbol of the priesthood;[318] assuming the duties of a manbo or oungan is referred to as "taking the ason."[319] For Petwo rites a different rattle, the tcha-tcha, is favored.[316] Another type of sacred object are the "thunder stones", often prehistoric axe-heads, which are associated with specific lwa and kept in oil to preserve their power.[320] |

アソン、ヴードゥー神職を象徴する儀式用のガラガラ 例えば、オユはマンゴーの木と、ダンバラはブーゲンビリアと関連している[86]。ハイチでは、選ばれた木に金属が取り付けられており、鉄と道路に関連す るオゴウの祠となっている[305]。 [305]多くのヴードゥーイストの家にも儀式のための空間がある[306]。これらは複雑な祭壇から、ろうそくやロザリオと一緒に聖人の像だけを置いたシ ンプルなものまで様々である[35]。 ヴェヴェ(vèvè)として知られる絵は、コーンミール、灰、コーヒーかす、または粉末状の卵の殻を用いてペリスティルの床に描かれる[308]。これら はヴードゥーの儀式の中心的なものである[250]。通常、ポト・ミタンを中心に左右対称に配置され[309]、これらのデザインは時に文字を取り入れる [241]。 [310]しばしば絹やビロードで作られ、スパンコールなどの光沢のあるもので装飾された[311]ドラポには、奉納される特定のルワのヴェーヴェか、関 連するローマ・カトリックの聖人の絵が描かれていることが多い[154]。これらのドラポは、ルワがペリスティルに入るための入口として理解されている [312]。 バテムス(洗礼)は、物体をルワの器とするために用いられる儀式である[313]。儀式に用いるために聖別された物体は、ナンムと呼ばれる霊的なエッセン スや力を含んでいると信じられている[314]。 [318]それは神職の象徴であり、[318]マンボやウンガンの職務を引き受けることは「アソンを取る」と呼ばれる[319]。ペツォの儀式では、別の ガラガラであるチャチャが好まれる[316]。 |

Offerings and animal sacrifice A drapo flag, which are used to invoke the lwa at Vodou ceremonies Feeding the lwa is of great importance,[321] with offering rites often termed manje lwa ("feeding the lwa").[322] Offering food and drink to the lwa is Vodou's most common ritual, conducted both communally and in the home.[321] The choice of food and drink offered varies depending on the lwa in question, with different lwa believed to favor certain foodstuffs and beverages.[323] Danbala for instance requires white foods, especially eggs,[324] while Legba's offerings, whether meat, tubers, or vegetables, need to be grilled on a fire.[321] The lwa of the Ogu and Nago nations prefer raw rum or clairin,[321] while the lwa Ayizan avoids alcohol.[325] Certain foods are also offered in the belief that they are intrinsically virtuous, such as grilled maize, peanuts, and cassava.[177] A manje sèk (dry meal) is an offering of grains, fruit, and vegetables that often precedes a simple ceremony; it takes its name from the absence of blood.[326] Animal sacrifices are often favored at annual feasts that an oungan or manbo organizes for their congregation.[177] Species used for sacrifice include chickens, goats, and bulls, with pigs often favored for Petwo lwa.[327] The animal may be washed, dressed in the color of the specific lwa, and marked with food or water.[328] Often, the animal's throat will be cut and the blood collected in a calabash.[329] Chickens are often killed by the pulling off of their heads; their limbs may be broken beforehand.[330] In the case of Agwé, a lwa of the sea, a white sheep may be sailed out to Trois Ilets and thrown overboard as a sacrifice.[331] Once killed, the animal may be butchered and organs removed, sometimes cooked, and placed on the altar or vèvè.[332] Here, it sometimes sites within a kwi, a calabash shell bowl.[333] Vodouists believe that the lwa consume the essence of the food.[177] Food is typically offered when it is cool, and is left for a while before humans may eat it.[333] Offerings not consumed by the celebrants are often buried or left at a crossroads.[334] Libations might be poured into the ground.[177] |

供え物と生け贄 ヴードゥーの儀式でロアを呼び出すために使われるドラポの旗 ルワを養うことは非常に重要であり[321]、供え物の儀式はしばしばマンジェ・ロア(「ロアを養う」)と呼ばれる[322]。ロアに食べ物や飲み物を捧 げることはヴードゥーの最も一般的な儀式であり、共同体でも家庭でも行われる[321]。 [例えばダンバラは白い食べ物、特に卵を必要とし[324]、レグバの供え物は肉、塊茎、野菜のいずれであっても火で焼く必要がある[321]。オグとナ ゴの国民のルワは生のラムやクレアリンを好むが[321]、ロア・アイザンはアルコールを避ける[325]。特定の食べ物は、焼いたトウモロコシ、ピー ナッツ、キャッサバなど、本質的に徳の高いものであると信じられて供えられる[177]。 マンジェ・セック(乾燥した食事)は、穀物、果物、野菜の供え物であり、しばしば簡単な儀式に先立つ。 [327]動物は洗われ、特定のルワの色で服を着せられ、食べ物や水で印をつけられる[328]。多くの場合、動物の喉が切られ、血が瓢箪に集められる[329]。 殺された動物は屠殺され、内臓が取り除かれ、調理されて祭壇やヴェヴェに置かれることもある[332]。 [177]食べ物は一般的に冷めた状態で供えられ、人間が食べる前にしばらく放置される[333]。 祝福者によって消費されなかった供物はしばしば埋められたり、十字路に残されたりする[334]。 |

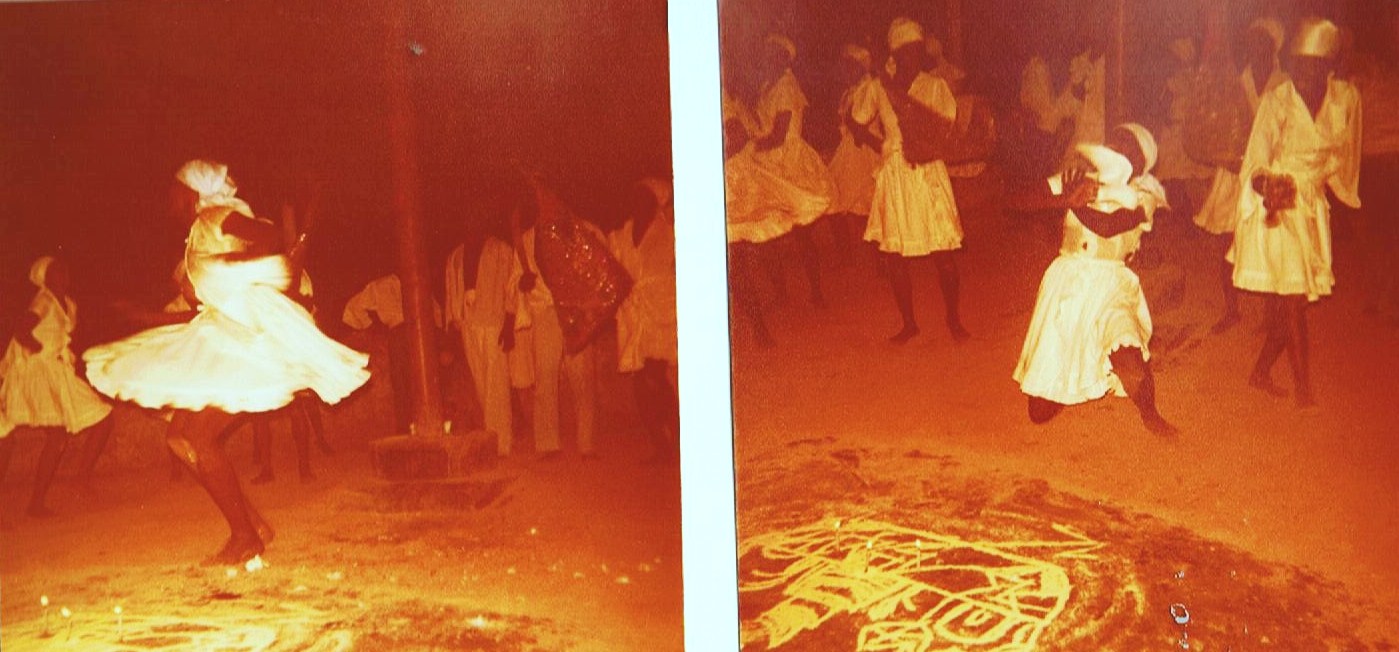

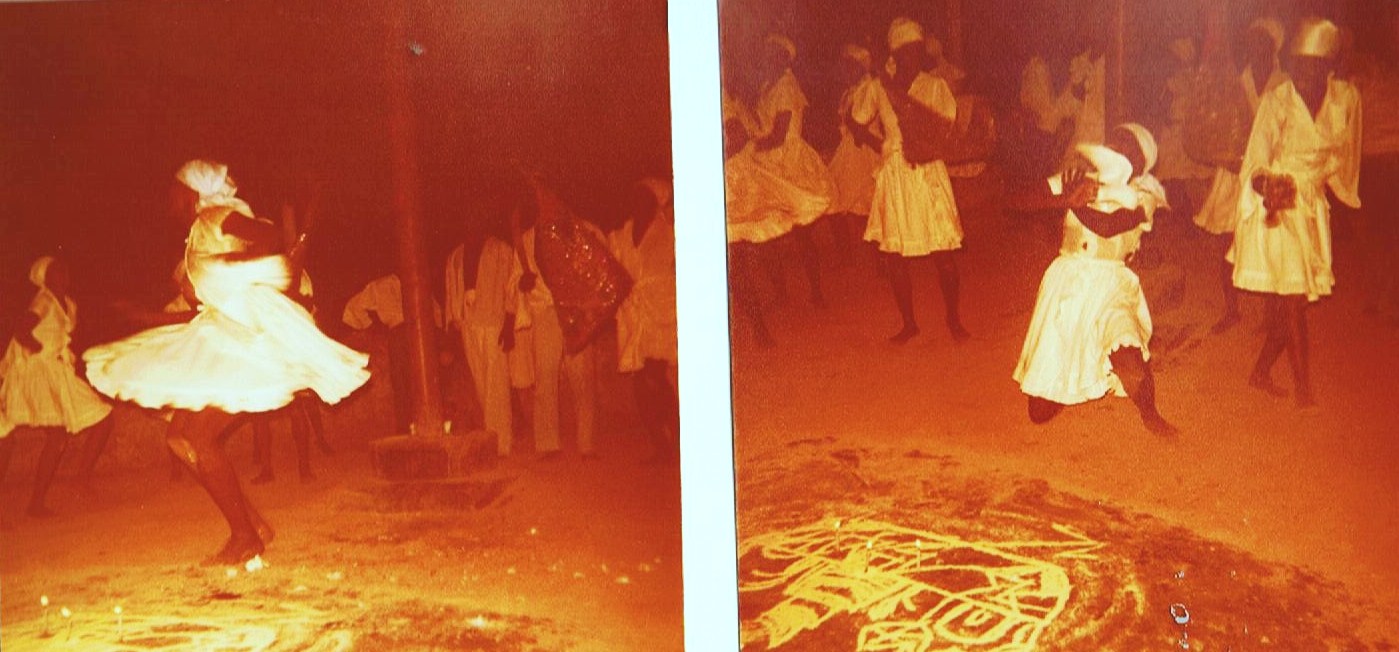

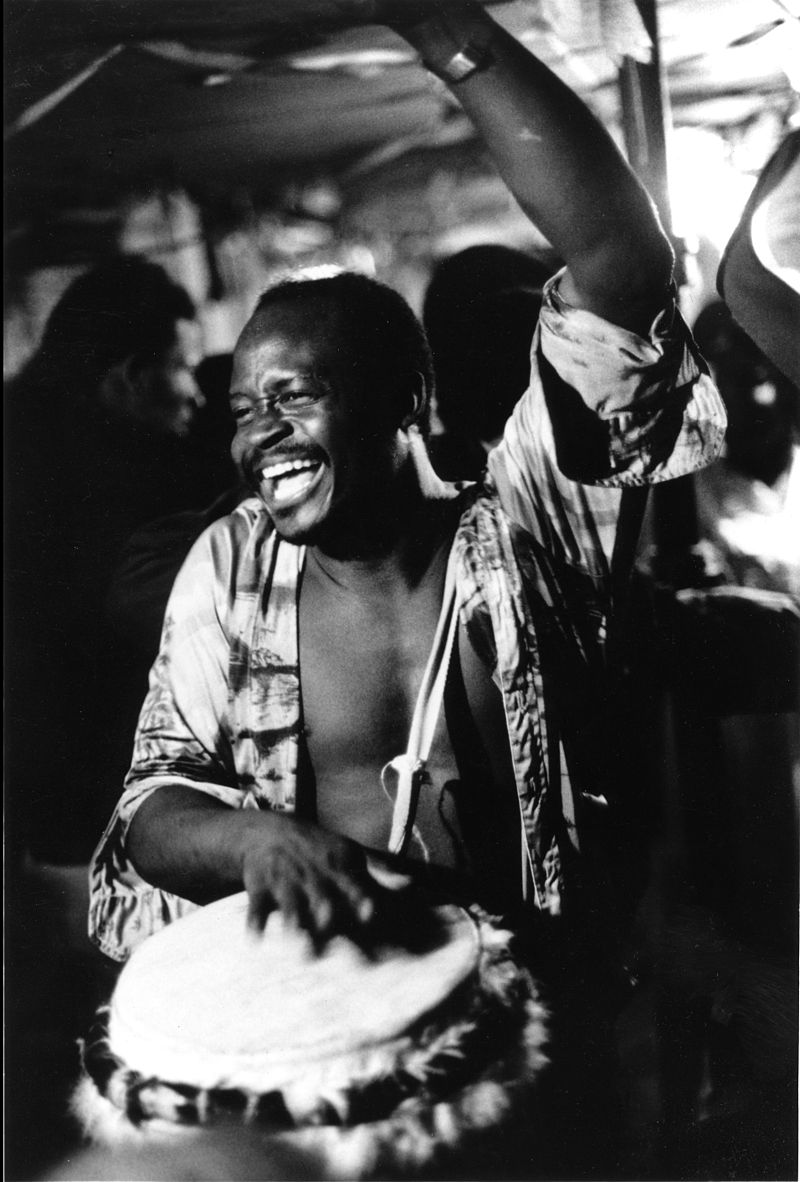

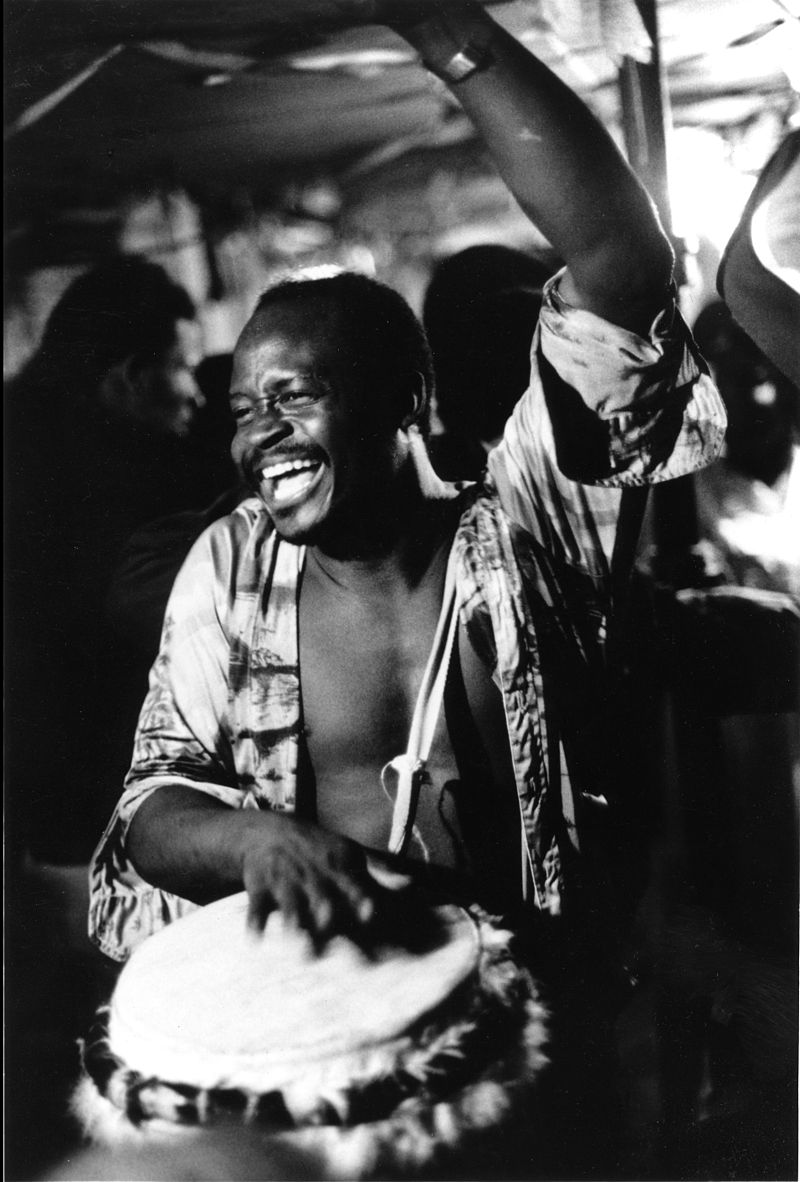

The Dans Multiple styles of drum are employed in Vodou ritual; this example is used in rites invoking Rada lwa Vodou's nocturnal gatherings are often referred to as the dans ("dance"), reflecting the prominent role that dancing has in such ceremonies.[253] Their purpose is to invite a lwa to enter the ritual space and possess one of the worshippers, through whom they can communicate with the congregation.[335] The success of this procedure is predicated on mastering the different ritual actions and on getting the aesthetic right to please the lwa.[335] The proceedings can last for the entirety of the night.[253] On arriving, the congregation typically disperse along the perimeter of the peristil.[253] The ritual often begins with Roman Catholic prayers and hymns;[336] these may be led by the prèt savann, although not all ounfò have anyone in this role.[337] This is followed by the shaking of the ason rattle to summon the lwa.[338] Two Haitian Creole songs, the Priyè Deyò ("Outside Prayers"), may then be sung, lasting from 45 minutes to an hour.[339] The main lwa are then saluted, individually, in a specific order.[339] Legba always comes first, as he is believed to open the way for the others.[339] Each lwa may be offered either three or seven songs, which are specific to them.[340] The rites employed to call down the lwa vary depending on the nanchon in question.[341] During large-scale ceremonies, the lwa are invited to appear through the drawing of vèvè on the ground using cornmeal.[222] Also used to call down the spirits is a process of drumming, singing, prayers, and dances.[222] Libations and offerings of food are made to the lwa, which includes animal sacrifices.[222] The order and protocol for welcoming the lwa is referred to as regleman.[342]  Dancing at Vodou ceremony in Port-au-Prince in 1976 A symbol of the religion,[343] the drum is perhaps the most sacred item in Vodou.[344] Vodouists believe that ritual drums contain an etheric force, the nanm,[345] and a spirit called ountò.[346] Specific ceremonies accompany the construction of a drum so that it is considered suitable for ritual use.[347] In the bay manje tanbou ("feeding of the drum") ritual, offerings are given to the drum itself.[345] Reflecting its status, when Vodouists enter the peristil they customarily bow before the drums.[348] Different types of drum are used, sometimes reserved for rituals devoted to specific lwa; Petwo rites for instance involve two types of drum, whereas Rada rituals require three.[349] Ritual drummers are called tanbouryes,[350] and becoming one requires a lengthy apprenticeship.[351] The drumming style, choice of rhythm, and composition of the orchestra differs depending on which nation of lwa are being invoked.[352] The drum rhythms typically generate a kase ("break"), which the master drummer will initiate to oppose the main rhythm being played by the rest of the drummers. This is seen as having a destabilizing effect on the dancers and helping to facilitate their possession.[353] Drumming is typically accompanied by singing,[348] usually in Haitian Creole,[354] although sometimes in Fon or Yoruba.[355] These songs are often structured around a call and response, with a soloist singing a line and the chorus responding with either the same line or an abbreviated version.[356] The soloist is the oundjenikon, who maintains the rhythm with a rattle.[357] Lyrically simple and repetitive, these songs are invocations to summon a lwa.[348] Dancing also plays a major role in ritual,[358] utilising the rhythm of the drummers.[356] The dances are simple, lacking complex choreography, and usually involve the dancers moving counterclockwise around the poto mitan.[359] Specific dance movements can indicate the lwa or their nanchon being summoned;[360] dances for Agwe for instance imitate swimming motions.[361] Vodouists believe that the lwa renew themselves through the vitality of the dancers.[362] |

太鼓 ヴードゥーの儀式では複数のスタイルの太鼓が使われるが、この例はラダ・ルワを呼び出す儀式で使われる。 ヴードゥーの夜間集会はしばしばダン(「ダンス」)と呼ばれるが、これはこのような儀式においてダンスが重要な役割を担っていることを反映している [253]。その目的は、ルワを儀式空間に招き入れ、参拝者の一人に憑依させ、その者を通して信徒とコミュニケーションをとることである[335]。この 手順を成功させるには、さまざまな儀式の動作をマスターし、ロアを喜ばせる美的感覚を身につけることが前提となる[335]。 儀式はしばしばローマ・カトリックの祈りと賛美歌で始まる[336]が、すべてのウンフォにこの役割を担う者がいるわけではないが、プレ・サヴァンが先導 することもある[337]。 [338]その後、ハイチ・クレオール語の歌であるPriyè Deyò(「外部の祈り」)が2曲歌われ、45分から1時間続くこともある[339]。その後、主要なルワが特定の順序で個別に敬礼する[339]。 レグバは他のロアのために道を開くと信じられているため、常に最初に来る[339]。 ルワを呼び出すために用いられる儀式は、問題となっているナンチョンによって異なる[341]。大規模な儀式の際には、トウモロコシ粉を用いて地面にヴェ ヴェ(vèvè)を描くことによってロアが現れるように招かれる[222]。また、精霊を呼び出すために、太鼓、歌、祈り、踊りが行われる[222]。  1976年にポルトープランスで行われたヴードゥーの儀式でのダンス 宗教の象徴である[343]ドラムはおそらくヴードゥーで最も神聖なアイテムである[344]。ヴードゥー教徒は儀式用のドラムにはエーテルの力であるナンム [345]とウントと呼ばれる精霊が宿っていると信じている[346]。 [347]ベイ・マンジェ・タンブー(「太鼓の給餌」)の儀式では、太鼓そのものに供物が捧げられる[345]。その地位を反映して、ヴードゥーイストがペ リスティルに入る際には太鼓の前で一礼するのが通例である。 [348]異なる種類の太鼓が使用され、特定のロアに捧げる儀式にのみ使用されることもある。例えばペトーの儀式では2種類の太鼓が使用されるが、ラダの 儀式では3種類の太鼓が使用される[349]。 [351]太鼓のスタイル、リズムの選択、オーケストラの構成は、どのルワの国民が呼び出されるかによって異なる[352]。太鼓のリズムは一般的にカセ (「ブレイク」)を発生させる。これは踊り手に対して不安定化させる効果があり、彼らの憑依を促進するのに役立つと考えられている[353]。 これらの歌はコール・アンド・レスポンスを中心に構成されることが多く、ソリストが一行を歌い、コーラスが同じ一行または省略されたバージョンで応答する [356]。 [348]踊りも儀礼において主要な役割を果たし[358]、太鼓奏者のリズムを利用する[356]。踊りは単純で複雑な振り付けはなく、通常はポト・ミ タンの周りを反時計回りに移動する[359]。特定の踊りの動きは、ロアやそのナンチョンが召喚されていることを示すことがある[360]。 |

Spirit possession Drummer Frisner Augustin in a Vodou ceremony in Brooklyn, New York City during the early 1980s. Spirit possession is important,[363] being central to many Vodou rituals.[88] The person being possessed is called the chwal (horse);[364] the act of possession is termed "mounting a horse".[365] Vodou teaches that both male and female lwa can possess either men or women.[366] Although children are often present at these ceremonies,[367] they are rarely possessed as it is considered too dangerous.[368] Some individuals attending the dance will put a certain item, often wax, in their hair or headgear to prevent possession.[369] While the specific drums and songs used are designed to encourage a specific lwa to possess someone, sometimes an unexpected lwa appears and takes possession instead.[370] The possession trance is termed the kriz lwa.[351] Vodouists believe that the lwa enters the head of the chwal and displaces their gwo bon anj,[371] making the chwal tremble and convulse.[372] As their consciousness has been removed from their head during the possession, Vodouists believe that the chwal will have no memory of the incident.[373] The length of the possession varies, often lasting a few hours but sometimes several days.[374] Sometimes a succession of lwa possess the same individual, one after the other.[375] Possession may end with the chwal collapsing in a semi-conscious state,[376] being left physically exhausted.[362] Once the lwa possesses an individual, the congregation greet it with a burst of song and dance.[362] The chwal will typically bow before the officiating priest or priestess and prostrate before the poto mitan.[377] The chwal is often escorted into an adjacent room where they are dressed in clothing associated with the possessing lwa. Alternatively, the clothes are brought out and they are dressed in the peristil itself.[378] These costumes and props help the chwal take on the appearance of the lwa;[356] many ounfò have a large wooden phallus used by those possessed by Gede lwa, for instance.[379] Once the chwal has been dressed, congregants kiss the floor before them.[366] The chwal adopts the behavior of the possessing lwa;[380] their performance can be very theatrical.[370] Those believing themselves possessed by the serpent Danbala, for instance, often slither on the floor, dart out their tongue, and climb the posts of the peristil.[129] Those possessed by Zaka, lwa of agriculture, will dress as a peasant in a straw hat with a clay pipe and will often speak in a rustic accent.[381] The chwal will often join in with the dances,[362] eat or drink.[356] Sometimes the lwa, through the chwal, will engage in financial transactions with members of the congregation, for instance by selling them food that has been given as an offering or lending them money.[382] Possession facilitates direct communication between Vodouists and the lwa;[362] through the chwal, the lwa communicates with their devotees, offering counsel, chastisement, blessings, warnings about the future, and healing.[383] Lwa possession has a healing function, with the possessed individual expected to reveal possible cures to the ailments of those assembled.[362] Clothing that the chwal touches is regarded as bringing luck.[384] The lwa may also offer advice to the individual they are possessing; because the latter is not believed to retain any memory of the events, it is expected that other members of the congregation will pass along the lwa's message.[384] In some instances, practitioners have reported being possessed at other times of ordinary life, such as when someone is in the middle of the market,[385] or when they are asleep.[386] |

霊の憑依 1980年代初頭にニューヨークのブルックリンで行われたヴードゥーの儀式でのドラマー、フリスナー・オーガスティン。 精霊の憑依は重要であり[363]、多くのヴードゥーの儀式の中心となっている[88]。憑依される者はシュワル(馬)と呼ばれ[364]、憑依の行為は 「馬に乗る」と呼ばれる[365]。 [368]ダンスに参加する個人の中には、憑依を防ぐために髪や頭髪に特定のアイテム(多くの場合ワックス)をつける者もいる[369]。使用される特定 の太鼓や歌は、特定のルワが誰かに憑依するように促すためのものだが、時には予期せぬルワが現れて代わりに憑依することもある[370]。 憑依のトランス状態はクリズ・ロアと呼ばれる[351]。ヴードゥーイストは、ロアがシュワルの頭の中に入り込み、グー・ボン・アンジュを変位させ [371]、シュワルを震え上がらせ、痙攣させると信じている[372]。憑依の間、意識が頭から取り除かれているため、ヴードゥーイストはシュワルが事件 の記憶を持たなくなると信じている。 [373]憑依の長さは様々で、数時間続くことも多いが、数日間続くこともある[374]。時には、同じ個人に次々とロアが憑依することもある [375]。憑依は、肉体的に疲れ果てたシュワルが半意識の状態で倒れることで終わることもある[376]。 ルワが個人に憑依すると、信徒は歌と踊りの嵐でそれを迎える[362]。シュワルは通常、司祭または巫女の前で一礼し、ポト・ミタンの前にひれ伏す [377]。あるいは、衣服が持ち出され、ペリスティルそのものに着せられる[378]。これらの衣装や小道具は、チュワルがロアの姿になるのを助ける。 [356]例えば、多くのウンフォには、ゲデ・ルワに憑依された者が使用する大きな木製のファルスがある[379]。チュワルの着衣が終わると、信徒は彼 らの前の床に接吻する[366]。 チュワルは憑依しているロアの振る舞いを採用し、[380]その演技は非常に演劇的であることがある[370]。例えば、大蛇ダンバラに憑依されていると 信じている者は、しばしば床の上でそそり立ち、舌を出し、ペリスティルの柱に登る[129]。農業のルワであるザカに憑依されている者は、麦わら帽子をか ぶり、土管を持った農民の格好をし、しばしば素朴なアクセントで話す。 [381]チュワルはしばしば踊りに参加し[362]、食べたり飲んだりする[356]。時にはルワルはチュワルを介して、例えば供え物として与えられた 食物を売ったり、金を貸したりすることによって、信徒のメンバーと金銭的な取引を行う[382]。 憑依はヴードゥーイストとルワとの間の直接的なコミュニケーションを促進する[362]。ルワはチュワルを介して信者とコミュニケーションをとり、助言、懲 らしめ、祝福、未来についての警告、癒しを提供する[383]。ルワの憑依には癒しの機能があり、憑依された者は集まった人々の病気に対する可能な治療法 を明らかにすることが期待される[362]。チュワルが触れる衣服は幸運をもたらすとみなされる。 [384]また、ルワは憑依している個人に助言を与えることもある。ルワは出来事の記憶を保持していないと信じられているため、集会の他のメンバーがルワ のメッセージを伝えることが期待されている[384]。 場合によっては、誰かが市場の真ん中にいる時[385]や眠っている時[386]など、普通の生活の他の時に憑依されることが報告されている。 |

| Divination A common form of divination employed by oungan and manbo is to invoke a lwa into a pitcher, where it will then be asked questions.[387] Other forms of divination used by Vodouists include the casting of shells,[387] cartomancy,[388] studying leaves, coffee grounds or cinders in a glass, or looking into a candle flame.[389] A form of divination associated especially with Petwo lwa is the use of a gembo shell, sometimes with a mirror attached to one side and affixed at both ends to string. The string is twirled and the directions of the shell used to interpret the responses of the lwa.[387 |

占い ウンガンやマンボウが用いる一般的な占いの形式は、ロアを水差しの中に呼び出し、そこでルワに質問することである[387]。ヴードゥーイストが用いる他の 占いの形式には、貝殻の鋳造、[387]カルトマンシー、[388]グラスの中の葉、コーヒーのかす、燃えかすを調べること、またはロウソクの炎を覗き込 むことなどがある[389]。特にペト・ルワに関連する占いの形式は、ゲンボの貝殻を用いることであり、その片面に鏡が付いていることもあり、両端が紐に 付けられている。紐をくるくる回して、貝殻の方向からルワの反応を解釈する[387]。 |

Healing A pakèt kongo on display in the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen in the Netherlands Healing plays an important role in Vodou.[390] A client will approach a manbo or oungan complaining of illness or misfortune and the latter will use divination to determine the cause and select a remedy.[391] Manbo and oungan typically have a wide knowledge of plants and their medicinal uses.[190] When collecting plants they are expected to show them respect, for instance by leaving coins in payment for removing leaves.[392] To heal, Vodou specialists often prescribe baths, consisting of water infused with various ingredients,[393] or produce powders for a specific purpose, such as to attract good luck or aid seduction.[394] Alternatively, they may create a material object infused with spirits or medicines, a wanga,[395] although these can also be devoted to harmful purposes.[396] Manbo and oungan often provide talismans,[397] called a pwen (point),[398] travay (work),[399] travay maji (magic work),[400] pakèt or pakèt kongo.[401] The latter term highlights the potential influence of the Bakongo minkisi on these Haitian ritual creations.[402] In Haiti, oungan or manbo may advise their clients to seek assistance from medical professionals, while the latter may also send their patients to see an oungan or manbo.[237] Although in the late 20th century there were concerns that the Haitian reliance on oungan and manbo was contributing to the spread of HIV/AIDS,[403] by the early 21st century, various NGOs and other groups were working on bringing Vodou officiants into the broader campaign against the virus.[404] In Haiti, there are also doktè fèy ("herb doctors"; "leaf doctors") who offer herbal remedies for ailments but deal in fewer problems than oungan and manbo.[405] |

癒し オランダのNationaal Museum van Wereldculturenに展示されているパケット・コンゴ ヒーリングはヴードゥーにおいて重要な役割を果たす[390]。依頼人は病気や災難を訴えるマンボウやウンガンに近づき、ウンガンは占いを使って原因を突 き止め、治療法を選ぶ[391]。マンボウやウンガンは一般的に植物とその薬用について幅広い知識を持っている[190]。 治癒のために、ヴードゥーの専門家はしばしば様々な成分を煎じた水からなる入浴を処方したり[393]、幸運を引き寄せたり誘惑を助けるといった特定の目的 のために粉を作ったりする[394]。 [396]マンボやウンガンはしばしば、プウェン(点)、[398]トラヴァイ(仕事)、[399]トラヴァイ・マジ(魔法の仕事)、[400]パケット またはパケット・コンゴと呼ばれるお守り[397]を提供する[401]。後者の用語は、ハイチのこれらの儀礼的創造物に対するバコンゴ族のミンキシの潜 在的な影響を強調している[402]。 ハイチでは、ウンガンやマンボは医療専門家に援助を求めるよう顧客に助言することがあり、一方、医療専門家もウンガンやマンボの診察を受けるよう患者を派 遣することがある。 [237]20世紀後半には、ハイチにおけるウンガンやマンボウへの依存がHIV/AIDSの蔓延を助長しているという懸念があったが[403]、21世 紀初頭には、様々なNGOやその他のグループが、ヴードゥーの司祭をウイルスに対するより広範なキャンペーンに参加させることに取り組んでいた[404]。 ハイチには、病気に対する薬草療法を提供するが、ウンガンやマンボウよりも扱う問題が少ないドクテ・フェイ(「薬草医」、「葉医」)も存在する [405]。 |

| Harming practices Vodou teaches that supernatural factors cause or exacerbate many problems.[406] It holds that humans can cause supernatural harm to others, either unintentionally or deliberately,[407] in the latter case exerting power over a person through possession of hair or nail clippings belonging to them.[408] Vodouists also often believe that supernatural harm can be caused by other entities. The lougawou is a human, usually female, who transforms into an animal and drains blood from sleeping victims,[409] while members of the Bizango secret society are feared for their reputed ability to transform into dogs, in which form they walk the streets at night.[410] An individual who turns to the lwa to harm others is a choché,[186] or a bòkò,[411] although this latter term can also refer to an oungan generally.[186] They are described as someone who sert des deux mains ("serves with both hands"),[412] or is travaillant des deux mains ("working with both hands").[223] As the good lwa have rejected them as unworthy, bòko are believed to work with lwa achte ("bought lwa"),[413] spirits that will work for anyone who pays them,[414] and often members of the Petwo nanchon.[415] According to Haitian popular belief, bòkò engage in anvwamò ("expeditions"), setting the dead against an individual to cause the latter's sudden illness and death,[416] and utilise baka, malevolent spirits sometimes in animal form.[417] In Haiti, there is much suspicion and censure toward those suspected of being bòkò.[223] The curses of the bòkò are believed to be countered by the oungan and manbo, who can revert the curse through an exorcism that incorporates invocations of protective lwa, massages, and baths.[418] In Haiti, some oungan and manbo have been accused of working with a bòkò, arranging for the latter to curse individuals so that they can financially profit from removing these curses.[223] |

加害行為 ヴードゥーは、超自然的な要因が多くの問題を引き起こしたり悪化させたりすることを教えている[406]。 ヴードゥーは、人間が他者に超自然的な危害を加えることができると信じており、意図的でないにせよ意図的であるにせよ[407]、後者の場合は、その人の髪 の毛や爪の切り抜きを持っていることによって、その人に力を及ぼすことができると信じている[408]。ルガウは通常女性の人間であり、動物に変身して 眠っている犠牲者から血を抜き取る[409]。一方、秘密結社ビザンゴのメンバーは、犬に変身することができるという評判の能力で恐れられており、その姿 で夜の街を歩く[410]。 他者に危害を加えるためにルワに変身する者はチョーチェ[186]またはボコ(bòkò)[411]であるが、後者の用語は一般的にウンガンを指すことも ある[186]。 [ボコはルワ・アクテ(「買われたルワ」)[413]と共に働くと信じられており、金を払えば誰のためにも働く精霊であり[414]、ペトー・ナンチョン のメンバーであることが多い。 [415] ハイチの俗信によれば、ボコはアンヴワモ(「遠征」)に従事し、死者を個人に仕向けて後者の急病や死を引き起こす[416]。 [ハイチでは、一部のウンガンやマンボがボコと共謀し、ボコが個人を呪うように仕向け、その呪いを取り除くことで金銭的な利益を得るように仕向けたとして 非難されている[223]。 |

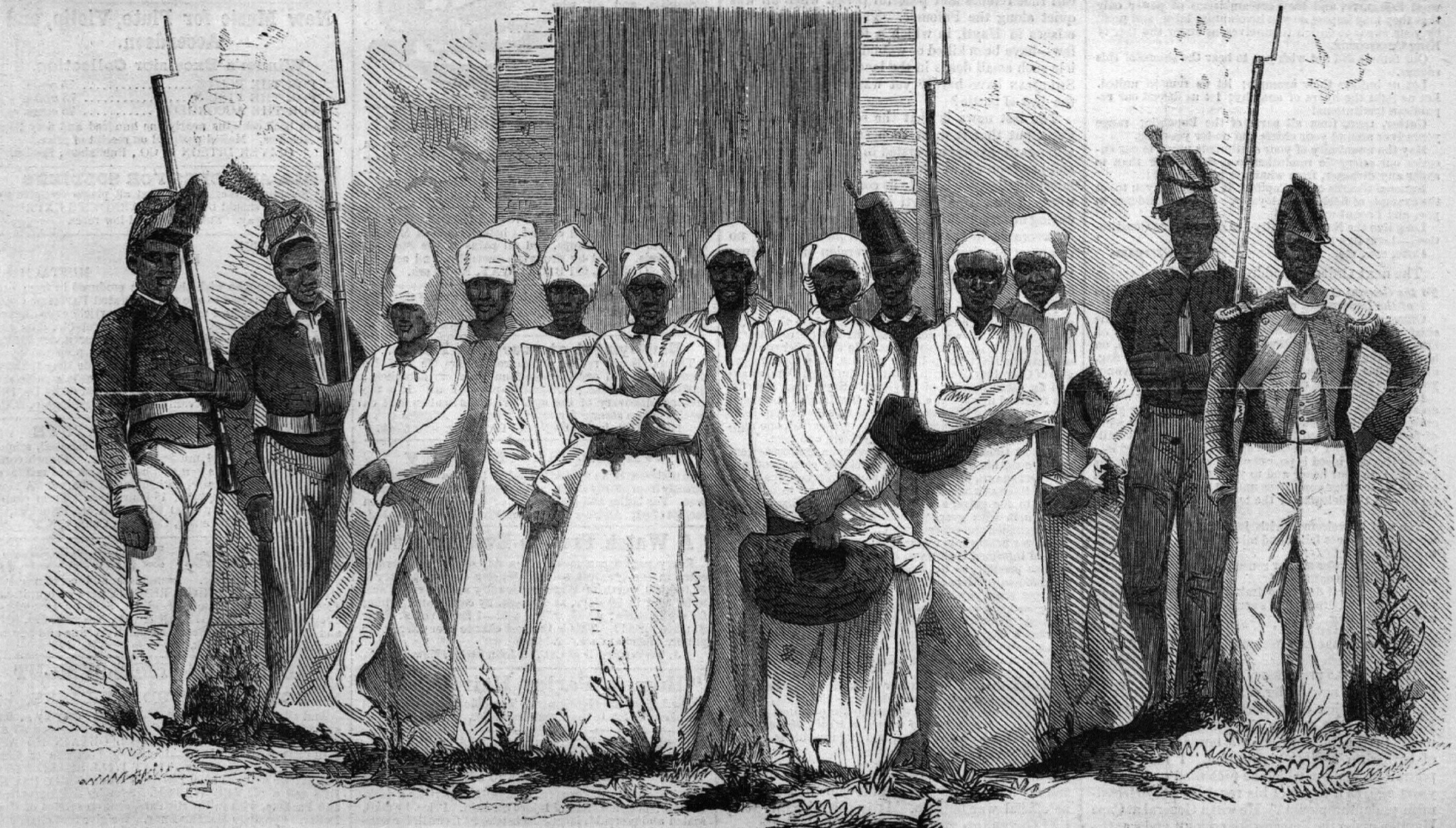

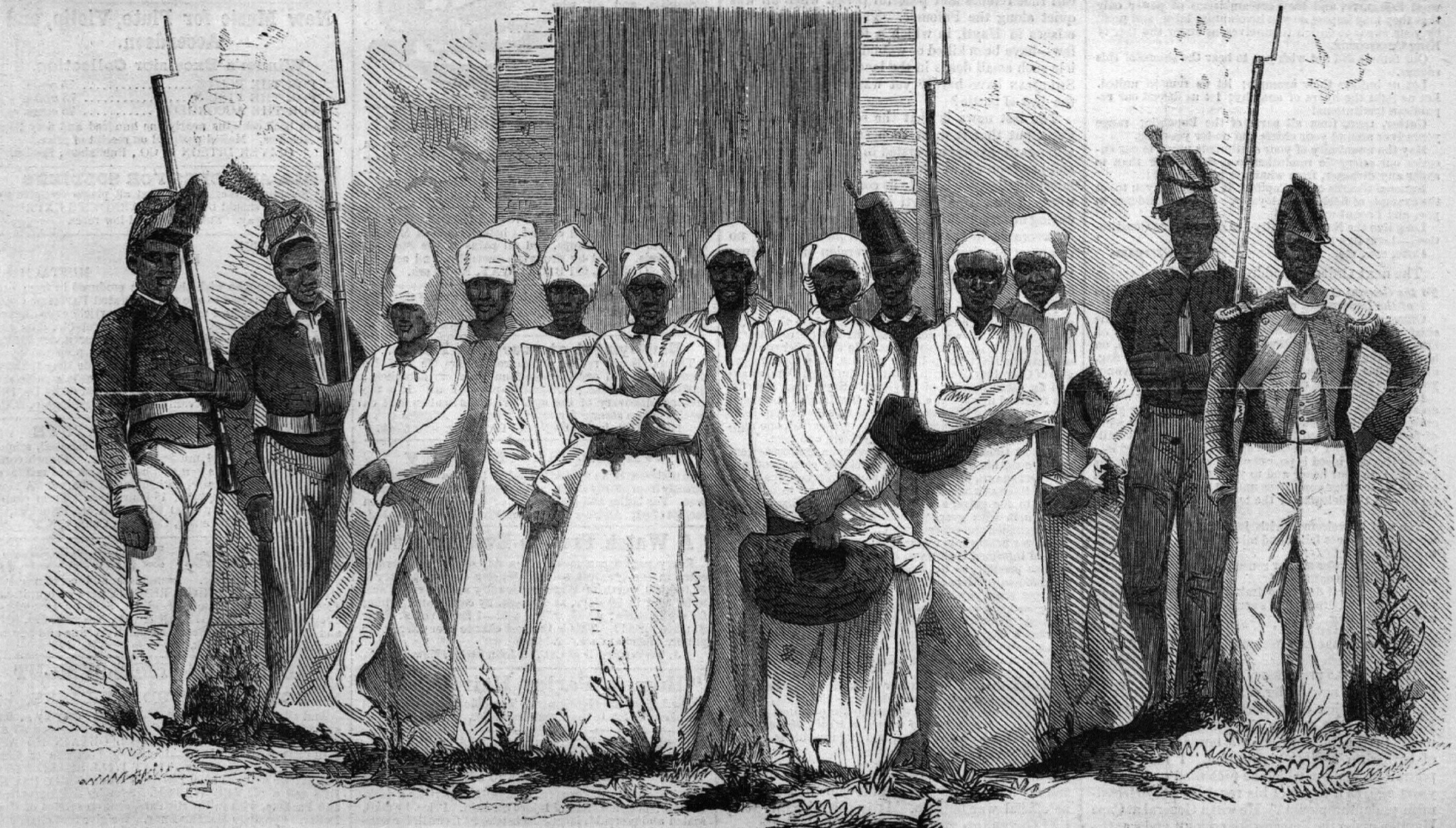

Funerals, the dead, and zonbis A cross in a Haitian cemetery, photographed in 2012. The crucifix is central to the iconography of the Gede; the Baron La Croix is a public crucifix associated with Baron Samedi, chief of the Gede.[419] Vodou features complex funerary customs.[420] Following an individual's death, the desounen ritual frees the gwo bonnanj from their body and disconnects them from their tutelary lwa.[421] The corpse is then bathed in a herbal infusion by an individual termed the benyè, who gives the dead person messages to take with them.[422] A wake, the veye, follows.[423] The body is then buried in the cemetery,[424] often according to Roman Catholic custom.[425] In northern Haiti, an additional rite takes place at the ounfò on the day of the funeral, the kase kanari (breaking of the clay pot). In this, a jar is washed in substances including kleren, placed within a trench dug into the peristil floor, and smashed. The trench is then refilled.[426] The night after the funeral, the novena takes place at the home of the deceased, involving Roman Catholic prayers;[427] a mass for them is held a year after death,[428] sometimes performed by a prèt savann.[429] Vodouists fear the dead's ability to harm the living;[430] it is believed that the deceased may for instance punish their living relatives if the latter fail to appropriately mourn them.[431] Many Vodouists believe that a practitioner's spirit dwells in the land of Ginen, located at the bottom of a lake or river, for a year and a day.[432] A year and a day after death, the wete mò nan dlo ("extracting the dead from the waters of the abyss") ritual may take place, in which the deceased's gwo bonnanj is reclaimed from the realm of the dead and placed into a clay jar or bottle called the govi. Now ensconced in the world of the living, the gwo bonnanj of this ancestor is deemed capable of assisting its descendants and guiding them with its wisdom.[433] Practitioners sometimes believe that failing to conduct this ritual can result in misfortune, illness, and death for the family of the deceased.[434] Offerings then given to this spirit of the dead are termed manje mò.[435] The notion of a spirit being encased in a vessel and then used for workings likely derives from Bakongo influences,[436] and has similarities with the Bakongo-derived Palo religion from Cuba.[437]. |

葬儀、死者、そしてゾンビ ハイチの墓地にある十字架(2012年撮影)。十字架はゲデの図像学の中心であり、バロン・ラ・クロワはゲデの首長であるサメディ男爵に関連する公的な十字架である[419]。 ヴードゥーは複雑な葬儀の習慣を特徴としている[420]。個人の死後、デスーネンの儀式はグオ・ボンナンジュを肉体から解放し、彼らの指導者であるルワか ら切り離す。 [421]その後、死体はベニエと呼ばれる人物によって薬草の煎じ汁を浴びせられ、ベニエは死者が持っていくようにメッセージを与える[422]。 ハイチ北部では、葬儀の日にウンフォでカセ・カナリ(土鍋を割る)という儀式が行われる。これは、クレレンを含む物質で壺を洗い、ペリスティルの床に掘ら れた溝に入れ、叩き割る。426]葬儀の翌日の夜、故人の家でローマ・カトリックの祈りを伴うノヴェナが行われる[427]。 多くのヴードゥーイストは、修行者の霊魂は1年と1日の間、湖や川の底にあるジネンの地に宿ると信じている[432]。死後1年と1日後に、死者のグー・ボ ナンジを死者の領域から取り戻し、ゴビと呼ばれる粘土製の壺や瓶に入れる儀式(wete mò nan dlo「深淵の水から死者を取り出す」)が行われることがある。この儀式を怠ると、故人の家族に災難、病気、死がもたらされると信じられている [433]。 [434]その後、この死者の霊に捧げられる供物はマンジェ・モと呼ばれる[435]。霊を容器に封じ込め、細工に用いるという概念は、おそらくバコンゴ の影響に由来し[436]、キューバのバコンゴ由来のパロ宗教と類似している[437]。 |