ハイチの歴史 (II): 1802-1946

History of Haiti, 1802-1946

ジャ ン=ジャック・デサリネス

ハイチの歴史(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Haiti)から、ここでは、ハイチの歴史 (II): 1802-1946 を描写する。

++++++++++++++++++++++

☆ハイチの歴史 (II): 1802-1946 (このページ)

++++++++++++++++++++++

ナポレオン敗北(1802-1804)

独立初期 (1804-1843)

黒人共和国(1804年)

第一ハイチ帝国 (1804-1806)

統一への闘い(1806年-1820年)

ボワイエによるイスパニョーラ支配(1820年-1843年)

政治闘争 (1843-1915)

アメリカ合衆国の占領(1915年-1934年)

選挙とクーデター(1934-1957年)

レスコ大統領時代(1941年-1946年)

1946年の革命

++

| Napoleon defeated

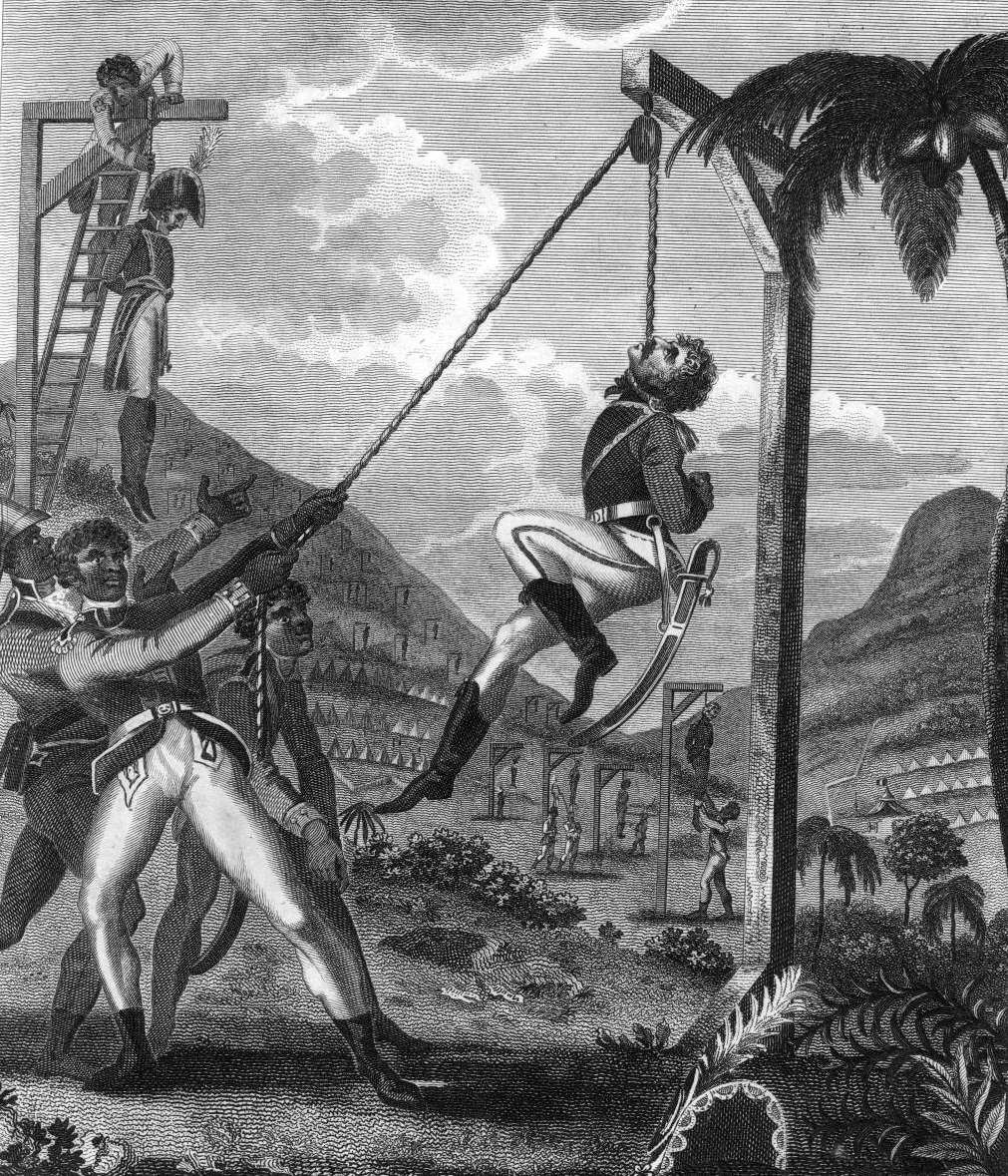

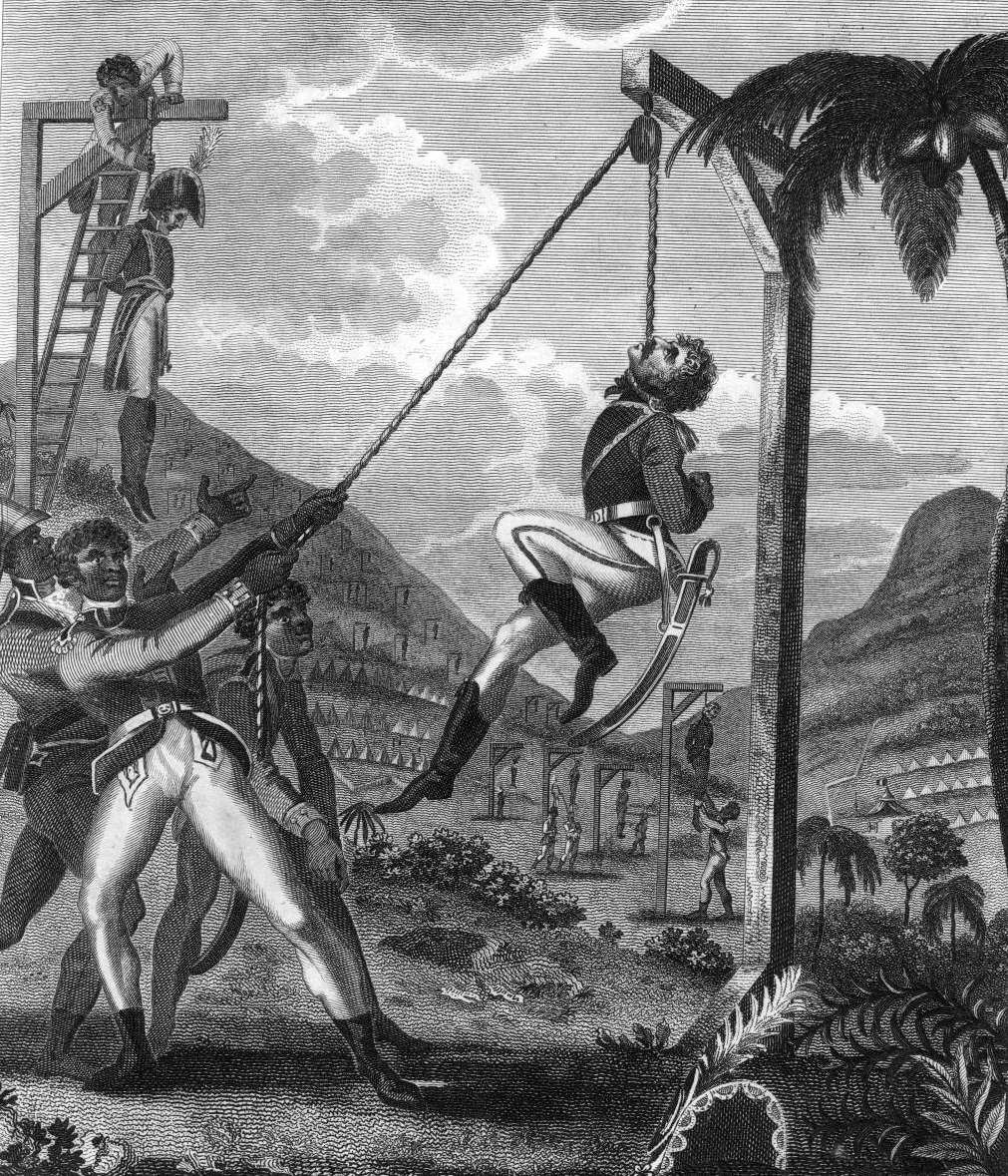

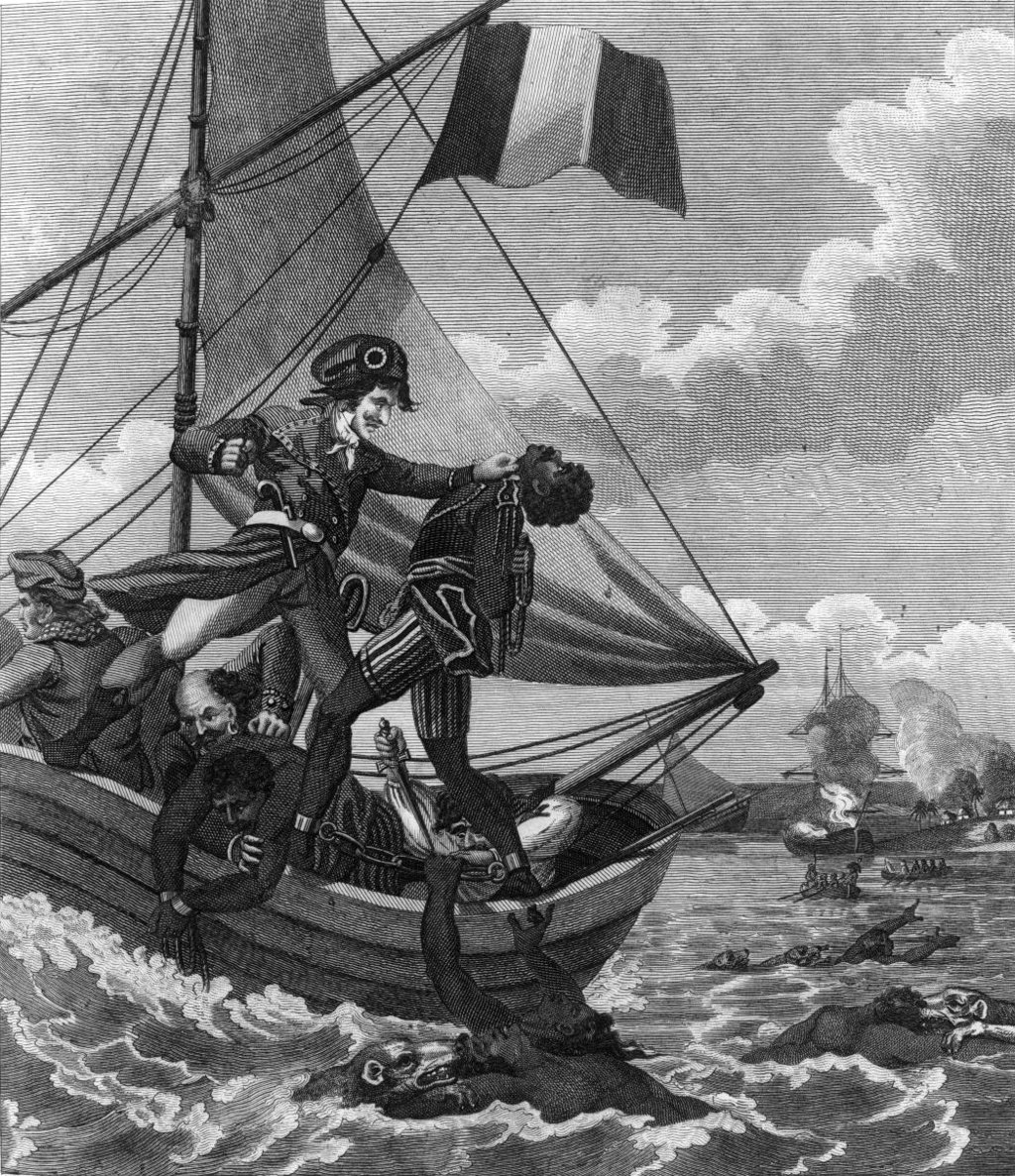

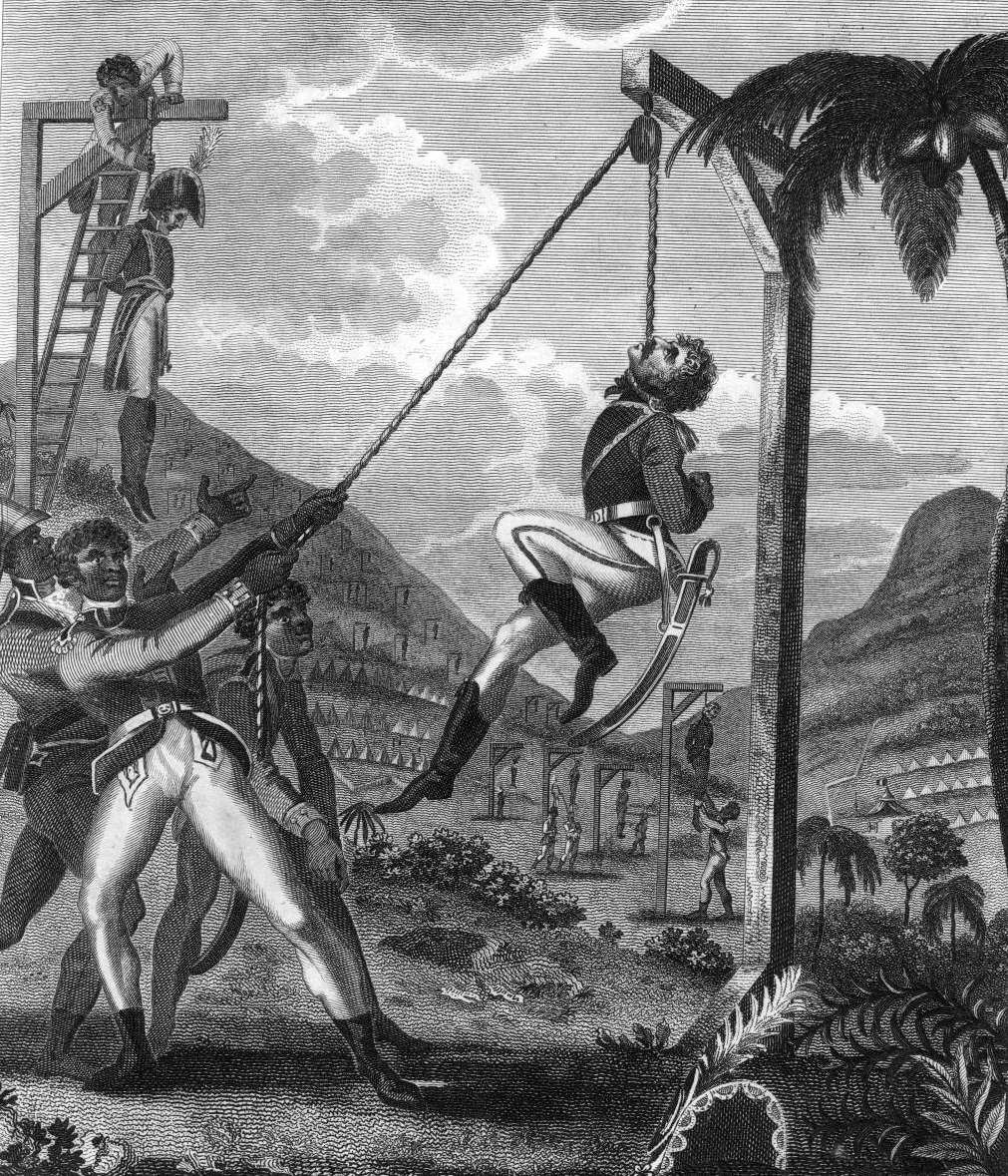

(1802–1804) Main article: Saint-Domingue expedition  The French army led by Le Clerc lands in Cap Français (1802)  Leclerc's veterans storm Ravine-a-Couleuvre (Snake Gully) in 1802.  Battle for Santo Domingo, by January Suchodolski (1845)  "The Mode of exterminating the Black Army, as practiced by the French", by Marcus Rainsford, 1805  "Revenge taken by the Black Army for the Cruelties practiced on them by the French", by Marcus Rainsford, 1805 Toussaint, however, asserted so much independence that in 1802, Napoleon sent a massive invasion force, under his brother-in-law Charles Leclerc, to increase French control. For a time, Leclerc met with some success; he also brought the eastern part of the island of Hispaniola under the direct control of France in accordance with the terms of the 1795 Treaties of Bâle with Spain. With a large expedition that eventually included 40,000 European troops, and receiving help from white colonists and mulatto forces commanded by Alexandre Pétion, a former lieutenant of Rigaud, the French won several victories after severe fighting. Two of Toussaint's chief lieutenants, Dessalines and Christophe, recognizing their untenable situation, held separate parleys with the invaders and agreed to transfer their allegiance. At this point, Leclerc invited Toussaint to negotiate a settlement. It was a deception; Toussaint was seized and deported to France, where he died in April 1803 of pneumonia, while imprisoned at Fort de Joux in the Jura Mountains. On 20 May 1802, Napoleon signed a law to maintain slavery where it had not yet disappeared, namely Martinique, Tobago, and Saint Lucia. A confidential copy of this decree was sent to Leclerc, who was authorized by Napoleon to restore slavery in Saint-Domingue when the time was opportune. At the same time, further edicts stripped the gens de couleur of their newly won civil rights. None of these decrees were published or executed in Saint-Domingue, but, by midsummer, word began to reach the colony of the French intention to restore slavery. The betrayal of Toussaint and news of French actions in Martinique undermined the collaboration of leaders such as Dessalines, Christophe, and Pétion. Convinced that the same fate lay in store for Saint-Domingue, these commanders and others once again battled Leclerc. As the French were intent on reconquest and re-enslavement of the colony's black population, the war became a bloody struggle of atrocity and attrition. The rainy season brought yellow fever and malaria, which took a heavy toll on the invaders. By November, when Leclerc died of yellow fever, 24,000 French soldiers were dead and 8,000 were hospitalized, the majority from disease.[36] Afterward, Leclerc was replaced by Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau. Rochambeau wrote to Napoleon that, to reclaim Saint-Domingue, France must "declare the negroes slaves, and destroy at least 30,000 negroes and negresses."[37] In his desperation, he turned to increasingly wanton acts of brutality; the French burned alive, hanged, drowned, and tortured black prisoners, reviving such practices as burying blacks in piles of insects and boiling them in cauldrons of molasses. One night, at Port-Républican, he held a ball to which he invited the most prominent mulatto ladies and, at midnight, announced the death of their husbands. However, each act of brutality was repaid by the Haitian rebels. After one battle, Rochambeau buried 500 prisoners alive; Dessalines responded by hanging 500 French prisoners.[38] Rochambeau's brutal tactics helped unite black and mulatto soldiers against the French. As the tide of the war turned toward the former slaves, Napoleon abandoned his dreams of restoring France's New World empire. In 1803, war resumed between France and Britain, and with the Royal Navy firmly in control of the seas, reinforcements and supplies for Rochambeau never arrived in sufficient numbers. To concentrate on the war in Europe, Napoleon signed the Louisiana Purchase in April, selling France's North American possessions to the United States. The Haitian army, now led by Dessalines, devastated Rochambeau and the French army at the Battle of Vertières on 18 November 1803. On 1 January 1804 Dessalines then declared independence,[39] reclaiming the indigenous Taíno name of Haiti ("Land of Mountains") for the new sovereign state. Most of the remaining French colonists fled ahead of the defeated French army, many migrating to Louisiana or Cuba. Unlike Toussaint, Dessalines showed little equanimity with regard to the whites. In a final act of retribution, the remaining French were slaughtered by Haitian military forces in a white genocide. Some 2,000 Frenchmen were massacred at Cap-Français, 900 in Port-au-Prince, and 400 at Jérémie. He issued a proclamation declaring, "we have repaid these cannibals, war for war, crime for crime, outrage for outrage."[40] One exception to Dessalines' proclamation was a group of Poles from the Polish Legions that had joined the French military under Napoleon.[41] A majority of Polish soldiers refused to fight against the Haitian forces. At the time, there was a familiar situation going on back in their homeland, as these Polish soldiers were fighting for their liberty from the invading Russians, Prussians and Austrians that began in 1772. As hopeful as the Haitians, many Poles were seeking union amongst themselves to win back their homeland. As a result, many Polish soldiers admired their enemy and decided to turn on the French army and join the Haitian former slaves, and participated in the Haitian revolution of 1804, supporting the principles of liberty for all the people. Władysław Franciszek Jabłonowski, who was half Black, was one of the Polish generals at the time. Polish soldiers had a remarkable input in helping the Haitians in their retaliation against the French oppressor. They were spared the fate of other Europeans. For their loyalty and support for overthrowing the French, some Poles acquired Haitian citizenship after Haiti gained its independence, and many of them settled there, never to return to Poland. It is estimated that around 500 of the 5,280 Poles chose this option. Of the remainder, 700 returned to France to eventually return to Poland, and some, after capitulating, agreed to serve in the British Army.[41] 160 Poles were later given permission to leave Haiti and some were sent to France at Haitian expense. To this day, many Polish Haitians still live in Haiti and are of multiracial descent; some have blonde hair, light eyes, and other European features. Today, descendants of those Poles who stayed are living in Cazale, Fond-des-Blancs, La Vallée-de-Jacmel, La Baleine, Port-Salut and Saint-Jean-du-Sud.[41] Following Haitian independence, the new independent state struggled economically, as European countries and the United States refused to extend diplomatic recognition to Haiti. In 1825, the French returned with a fleet of fourteen warships and demanded an indemnity of 150 million francs in exchange for diplomatic recognition; Haitian President Jean-Pierre Boyer agreed to the French demands under duress. In order to finance the debt, the Haitian government was forced to take numerous high-interest loans from foreign creditors, and the debt to France was not fully paid until 1947.[42][43][44] |

ナポレオン敗北(1802-1804) 主な記事 サン・ドマング遠征  キャップ・フランセに上陸したルクレール率いるフランス軍(1802年)  ルクレール率いる退役軍人がラヴィーヌ・ア・クルーヴル(蛇の渓谷)を襲撃する(1802年  サント・ドミンゴの戦い、1月スチョドルスキー作(1845年)  マーカス・レインズフォード著「フランス軍が実践した黒人軍退治の方法」1805年  「フランス人による残虐行為に対して黒人軍がとった復讐」マーカス・レインズフォード著1805年 1802年、ナポレオンは義弟シャルル・ルクレール率いる大規模な侵攻軍を送り込み、フランスの支配を強めた。ルクレールは1795年のスペインとのバー ル条約に基づき、イスパニョーラ島東部をフランスの直接統治下に置いた。最終的には4万人のヨーロッパ軍を含む大遠征を行い、リゴーの元中尉であったアレ クサンドル・ペシオンが指揮する白人入植者と混血部隊の支援を受け、フランス軍は激しい戦闘の末にいくつかの勝利を収めた。トゥーサンの2人の副官、デッ サリーヌとクリストフは、自分たちの不利な状況を認識し、侵略者と個別に交渉し、忠誠を移すことに同意した。この時点で、ルクレールはトゥーサンに和解交 渉を持ちかけた。トゥーサンは捕らえられてフランスに追放され、ジュラ山脈のジュウ砦に幽閉されていた1803年4月に肺炎で死亡した。 1802年5月20日、ナポレオンはマルティニーク、トバゴ、セントルシアというまだ奴隷制度が消滅していない地域で奴隷制度を維持する法律に署名した。 この勅令の機密コピーはルクレールに送られ、ルクレールはナポレオンから、時期が来たらサン=ドマングに奴隷制を復活させる権限を与えられた。同時に、さ らなる勅令が、新たに獲得した市民権を、青年の人々から剥奪した。これらの勅令はいずれもサン=ドマングでは公布も執行もされなかったが、真夏になると、 フランスが奴隷制を復活させる意図であることが植民地に伝わり始めた。トゥーサンの裏切りやマルティニークでのフランスの行動の知らせは、デサリンヌ、ク リストフ、ペシオンといった指導者たちの協力体制を蝕んだ。サン=ドマングにも同じ運命が待ち受けていると確信したこれらの指揮官らは、再びルクレールと 戦った。フランス軍は植民地の黒人のレコンキスタ(再征服)と再奴隷化を意図していたため、戦争は残虐行為と消耗による血みどろの戦いとなった。雨季には 黄熱病とマラリアが流行し、侵略者たちは大打撃を受けた。ルクレールが黄熱病で死亡した11月までに、24,000人のフランス兵が死亡し、8,000人 が入院したが、その大半は病気によるものであった[36]。 その後、ルクレールの後任としてロシャンボー総督ドナティアン=マリー=ジョゼフ・ド・ヴィムールが任命された。ロシャンボーはナポレオンに、サン・ドマ ングを取り戻すためには、フランスは「黒人を奴隷と宣言し、少なくとも3万人の黒人と黒人を滅ぼさなければならない」と書き送った[37]。ある夜、彼は ポルト・レピュブリカンで舞踏会を開き、最も著名な混血の女性たちを招待し、真夜中に彼女たちの夫の死を宣言した。しかし、その残忍な行為のひとつひとつ がハイチの反乱軍に返り討ちにされた。ある戦いの後、ロシャンボーは500人の捕虜を生き埋めにし、デサリネスはそれに応えて500人のフランス人捕虜を 絞首刑にした[38]。ロシャンボーの残忍な戦術は、黒人と混血の兵士をフランス軍に対して団結させるのに役立った。 戦争の流れが元奴隷たちに傾くと、ナポレオンはフランスの新世界帝国復活の夢を捨てた。1803年、フランスとイギリスの間で戦争が再開され、イギリス海 軍が制海権を握っていたため、ロシャンボーへの援軍や物資が十分な数届くことはなかった。ヨーロッパでの戦争に集中するため、ナポレオンは4月にルイジア ナ購入に調印し、フランスの北米領土をアメリカに売却した。デッサリーヌ率いるハイチ軍は、1803年11月18日のヴェルティエールの戦いでロシャン ボーとフランス軍を壊滅させた。 1804年1月1日、デサリーヌは独立を宣言し[39]、ハイチという先住民のタイノ語(「山の国」)を新たな主権国家として復活させた。残されたフラン ス人入植者のほとんどは、敗走するフランス軍に先んじて逃亡し、その多くはルイジアナやキューバに移住した。トゥーサンとは異なり、デッサリーヌは白人に 対して冷静さを欠いた。最後の報復として、残ったフランス人はハイチ軍によって虐殺された。約2000人のフランス人がキャップ・フランセで、900人が ポルトープランスで、400人がジェレミーで虐殺された。デサリーヌは「戦争には戦争を、犯罪には犯罪を、暴挙には暴挙を、我々はこの人食い人種に報復し た」と宣言した[40]。 デサリーヌの布告に対する一つの例外は、ナポレオン政権下でフランス軍に参加していたポーランド軍団のポーランド人グループであった[41]。 ポーランド兵の大多数はハイチ軍との戦闘を拒否した。当時、彼らの祖国では、1772年に始まったロシア、プロイセン、オーストリアの侵攻から自分たちの 自由を守るためにポーランド兵たちが戦っているという、見慣れた状況が進行していた。ハイチ人と同じように、多くのポーランド人が祖国を取り戻すため、自 分たちの間で団結を模索していた。その結果、多くのポーランド兵が敵に憧れ、フランス軍に反旗を翻してハイチの元奴隷に加わることを決意し、1804年の ハイチ革命に参加し、全人民の自由の原則を支持した。黒人とのハーフであったヴワディスワフ・フランシシェク・ヤブウォノフスキは、当時のポーランド軍将 兵の一人であった。ポーランドの兵士たちは、フランスの圧制者に対する報復においてハイチ人を助けるという目覚ましい働きをした。彼らは他のヨーロッパ人 の運命を免れた。フランス打倒への忠誠と支援のため、ハイチが独立した後、何人かのポーランド人はハイチの市民権を取得し、彼らの多くはそこに定住し、 ポーランドに戻ることはなかった。5,280人のポーランド人のうち、約500人がこの選択肢を選んだと推定されている。残りのうち700人はフランスに 戻り、最終的にポーランドに戻ることになり、何人かは降伏後、イギリス軍への従軍に同意した[41]。後に160人のポーランド人にハイチからの出国許可 が与えられ、何人かはハイチの費用でフランスに送られた。今日に至るまで、多くのポーランド系ハイチ人がハイチに住んでおり、多民族系であり、金髪、明る い目、その他のヨーロッパ系の特徴を持つ者もいる。今日、滞在したポーランド人の子孫は、カザール、フォン=デ=ブラン、ラ・ヴァレ=ド=ジャクメル、 ラ・バレーヌ、ポルト=サルト、サン=ジャン=デュ=スードに住んでいる[41]。 ハイチの独立後、ヨーロッパ諸国とアメリカがハイチへの外交的承認を拒否したため、新しい独立国家は経済的に苦戦した。1825年、フランスは14隻の軍 艦を率いて帰還し、外交的承認と引き換えに1億5,000万フランの賠償を要求した。ハイチ大統領ジャン=ピエール・ボワイエは、強要されてフランスの要 求に同意した。債務を調達するためにハイチ政府は外国の債権者から高利の融資を何度も受けることを余儀なくされ、フランスへの債務は1947年まで完済さ れなかった[42][43][44]。 |

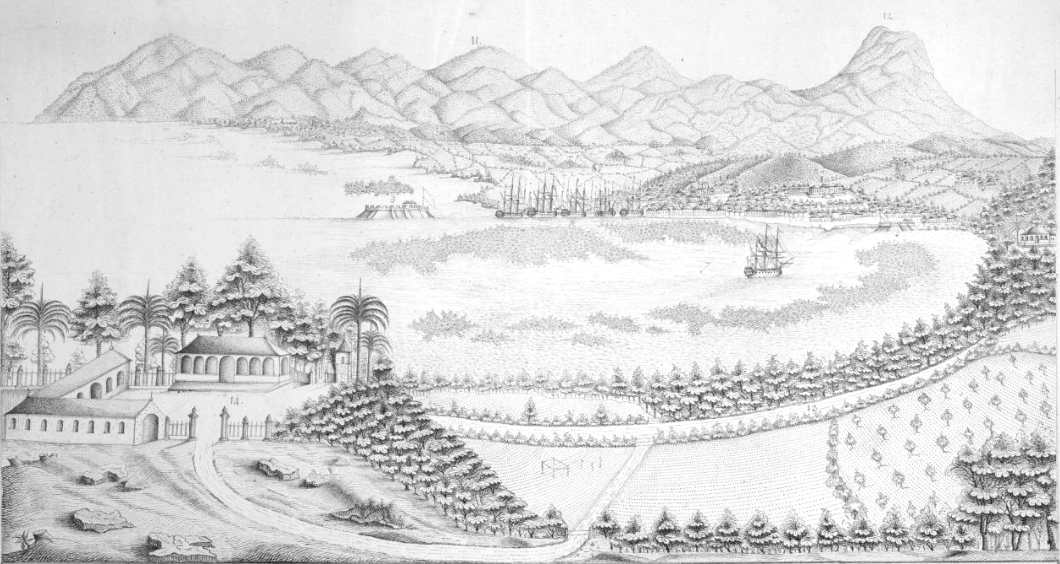

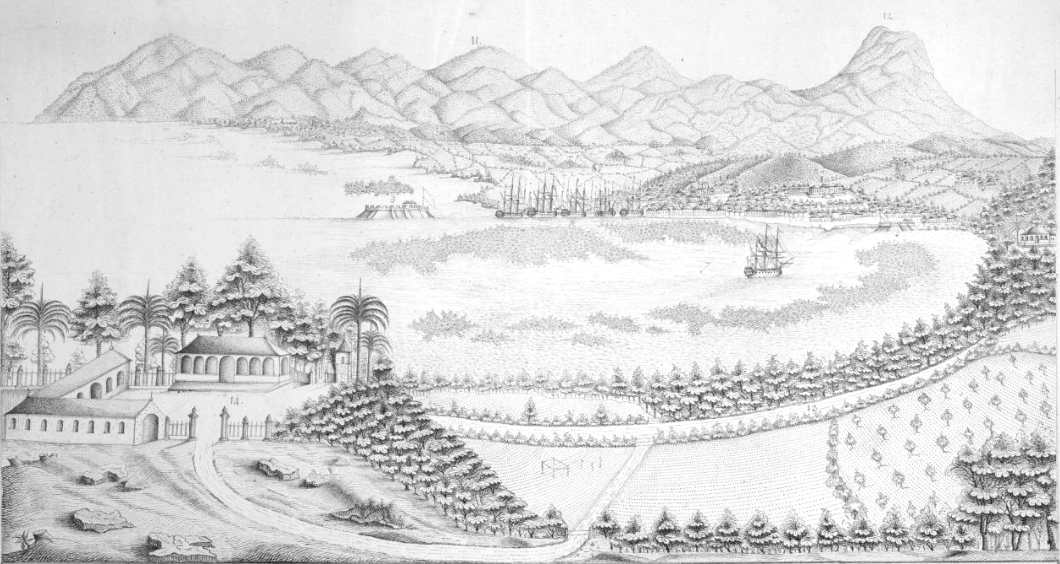

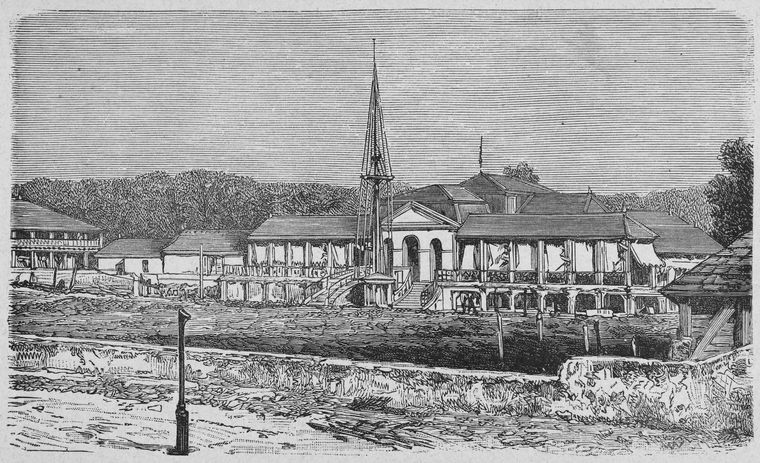

| Independence: The early years

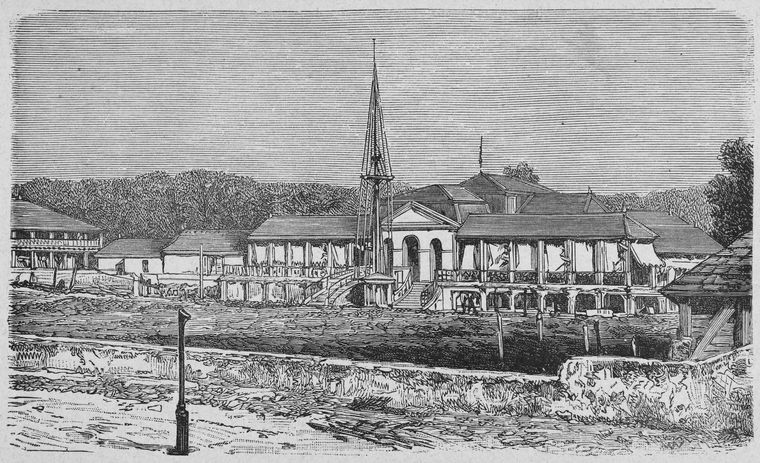

(1804–1843) Main article: Independence of Haiti  Port-au-Prince and surroundings at the start of the 19th century  Jean-Jacques Dessalines Black Republic (1804) Haiti became the second independent state in the Western Hemisphere after the United States.[45] Haiti actively assisted the independence movements of many Latin American countries – and secured a promise from the great liberator, Simón Bolívar, that he would free slaves after winning independence from Spain. The country inhabitated mostly by former slaves remained excluded from the hemisphere's first regional meeting of independent states, held in Panama in 1826, largely due to the atrocities of the 1804 Haitian Genocide which targeted European men, women and children who resided in Haiti, including those who were favorable to the revolution.[46] Despite the efforts of anti-slavery senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the United States did not recognize the independence of Haiti until 1862. The Southern slave states held a majority in Congress and, afraid of encouraging slave revolts, blocked this; Haiti was quickly recognized (along with other progressive measures, such as ending slavery in the District of Columbia), after these legislators left Washington in 1861, their states having declared their secession. Upon assuming power, General Dessalines authorized the Constitution of 1804. This constitution, in terms of social freedoms, called for: Freedom of religion. (Under Toussaint, Catholicism had been declared the official state religion.) All citizens of Haiti, regardless of skin color, to be known as "Black" (this was an attempt to eliminate the multi-tiered racial hierarchy that had developed in Haiti, with full or near full-blooded Europeans at the top, various levels of light to brown skin in the middle, and dark skinned "Kongo" from Africa at the bottom). White men were forbidden from possessing property or land on Haitian soil. Should the French return to reimpose slavery, Article 5 of the constitution declared: "At the first shot of the warning gun, the towns shall be destroyed and the nation will rise in arms."[47] |

独立 初期 (1804-1843) 主な記事 ハイチの独立  19世紀初頭のポルトープランスとその周辺  ジャン=ジャック・デサリネス 黒人共和国(1804年) ハイチは、西半球ではアメリカに次いで2番目の独立国となった[45]。ハイチは、ラテンアメリカ諸国の独立運動を積極的に支援し、偉大な解放者シモン・ ボリーバルから、スペインからの独立後に奴隷を解放するという約束を取り付けた。元奴隷が大半を占めるこの国は、1826年にパナマで開催された半球初の 地域独立国家会議から除外されたままであった。その主な理由は、1804年にハイチのジェノサイドが、革命に好意的だった人々を含む、ハイチ在住のヨー ロッパ人男性、女性、子供を標的にした残虐行為であったからである[46]。マサチューセッツ州の反奴隷制上院議員チャールズ・サムナーの努力にもかかわ らず、アメリカは1862年までハイチの独立を承認しなかった。南部の奴隷州が議会で多数を占めていたため、奴隷の反乱を助長することを恐れてこれを阻止 したのである。1861年にこれらの議員がワシントンを去り、各州が分離独立を宣言した後、ハイチは(コロンビア特別区の奴隷制廃止などの他の進歩的な措 置とともに)すぐに承認された。 デサリーヌ将軍は、政権に就くと1804年憲法を公布した。この憲法は、社会的自由の観点から、次のことを求めていた: 宗教の自由。(トゥーサンの時代には、カトリックが公式の国教とされていた)。 肌の色に関係なく、すべてのハイチ国民を「黒人」と呼ぶ(これは、完全な、あるいはそれに近いヨーロッパ人を頂点とし、中間に様々なレベルの明るい肌から 褐色の肌、そして最下層にアフリカから来た浅黒い肌の「コンゴ人」という、ハイチで発達した多層的な人種階層を排除しようとする試みであった)。 白人はハイチの土地で財産や土地を所有することを禁じられた。フランスが奴隷制を復活させるために戻ってきた場合、憲法第5条はこう宣言した: 「最初の威嚇射撃で町は破壊され、国民は武装して立ち上がる」[47]。 |

| First Haitian Empire (1804–1806) Main article: First Empire of Haiti On 1 January 1804, Dessalines proclaimed Haiti an independent sovereign state.[48] Mid-February, Dessalines told some cities (Léogâne, Jacmel, Les Cayes) to prepare for mass massacres.[49] On 22 February 1804, he signed a decree ordering that all whites in all cities should be put to death.[50] The weapons used should be silent weapons such as knives and bayonets rather than gunfire, so that the killing could be done more quietly, and avoid warning intended victims by the sound of gunfire and thereby giving them the opportunity to escape.[51] On 22 September 1804, Dessalines proclaimed himself Emperor Jacques I. Yet two of his own advisers, Henri Christophe and Alexandre Pétion, helped bring about his assassination in 1806. The conspirators ambushed him north of Port-au-Prince at Pont Larnage (now known as Pont-Rouge) on 17 October 1806 en route to battle rebels to his regime. The state created under Dessalines was the opposite of what the Haitian lower class wanted. While both the elite leaders, such as Dessalines, and the Haitian population agreed the state should be built on the ideals of freedom and democracy,[52][53] these ideals in practice looked very different for the two groups. The main reason for this difference in viewpoints of nationalisms come from the fact that one group lived as slaves, and the other did not.[when?][54] For one, the economic and agricultural practices of Dessalines, and leaders after him, were based on the need to create a strong economic state, that was capable of maintaining a strong military.[55] For the elite leaders of Haiti, maintaining a strong military to ward off either the French or other colonial powers and ensure independence would secure a free state. The leaders of Haiti saw independence from other powers as their notion of freedom. However, the Haitian peasantry tied their notion of freedom to the land. Because of the mountainous terrain, Haitian slaves were able to cultivate their own small tracts of land. Thus, freedom for them was the ability to cultivate their own land within a subsistence economy. Unfortunately, because of the leaders' desires, a system of coerced plantation agriculture emerged.[56] Furthermore, while all Haitians desired a black republic,[53] the cultural practices of African Americans were a point of contention. Many within the Haitian population wanted to maintain their African heritage, which they saw as a logical part of the black republic they wanted. However, the elites typically tried to prove the sophistication of Haitians through literature. Some authors wrote that the barbarism of Africa must be expelled, while maintaining African roots.[57] Furthermore, other authors tried to prove the civility of the elite Haitians by arguing that Blacks were capable of establishing and running a government by changing and augmenting the history of the revolution to favor the mulatto and black elites, rather than the bands of slaves.[58] Furthermore, to maintain freedom and independence, the elites failed to provide the civil society that the Haitian mass desired. The Haitian peasants desired not only land freedom but also civil rights, such as voting and political participation, as well as access to education.[54] The state failed to provide those basic rights. The state was essentially run by the military, which meant that it was very difficult for the Haitian population to participate in any democratic process. Most importantly, the state failed to provide the access to education that a state of former slaves needed.[59] It was nearly impossible for the former slaves to participate effectively because they lacked the basic literacy that had been intentionally denied to them under French colonial rule. Through their differing views on Haitian nationalism and freedom, the elites created a state that greatly favored them, instead of the Haitian peasantry. |

第一ハイチ帝国 (1804-1806) 主な記事 ハイチ第一帝国 1804年1月1日、デッサリーヌはハイチの独立を宣言した[48]。2月中旬、デッサリーヌはいくつかの都市(レオガン、ジャクメル、レ・ケイス)に対 し、大量虐殺の準備をするよう指示した[49]。1804年2月22日、デッサリーヌはすべての都市のすべての白人を死刑にするよう命じる法令に署名し た。 [50]使用される武器は銃声ではなく、ナイフや銃剣のような沈黙の武器であるべきであり、殺戮がより静かに行われ、銃声によって意図した犠牲者を警告 し、それによって彼らに逃げる機会を与えることを避けるためであった[51]。 1804年9月22日、デッサリーヌは自らを皇帝ジャック1世と宣言したが、1806年、アンリ・クリストフとアレクサンドル・ペシオンの2人の助言者が デッサリーヌの暗殺に協力した。陰謀家たちは1806年10月17日、ポルトープランスの北、ポン・ラルナージュ(現在のポン・ルージュ)で彼を待ち伏せ し、政権への反乱軍と戦わせた。 デサリーヌの下で誕生した国家は、ハイチの下層階級が望んでいたものとは正反対のものだった。デサリーヌのようなエリート指導者もハイチ国民も、国家が自 由と民主主義の理想に基づいて建設されるべきであるという点では同意していたが[52][53]、実際にはこれらの理想は2つのグループにとって非常に異 なるものであった。このようなナショナリズムの視点の差の主な理由は、一方の集団が奴隷として生活し、他方の集団は奴隷として生活していなかったことに由 来する[when?][54]。1つには、デサリネスや彼以降の指導者たちの経済的・農業的実践は、強力な軍隊を維持することができる強力な経済国家を創 設する必要性に基づいていた[55]。ハイチのエリート指導者たちにとっては、フランスや他の植民地勢力を追い払い、独立を確保するために強力な軍隊を維 持することが自由な国家を確保することになった。ハイチの指導者たちは、他の列強からの独立を自分たちの考える自由とみなしていた。 しかし、ハイチの農民たちは、自由という概念を土地に結びつけていた。山がちな地形のため、ハイチの奴隷たちは自分たちの小さな土地を耕すことができた。 したがって、彼らにとっての自由とは、自給自足経済の中で自分の土地を耕す能力だった。残念なことに、指導者たちの欲望のために、強制的なプランテーショ ン農業のシステムが出現した[56]。さらに、ハイチ人全員が黒人共和国を望んでいた一方で[53]、アフリカ系アメリカ人の文化的慣習が争点となった。 ハイチ国民の多くはアフリカの伝統を維持することを望み、それは彼らが望む黒人共和国の論理的な一部であると考えた。しかし、エリートたちは通常、文学を 通じてハイチ人の洗練性を証明しようとした。アフリカのルーツを維持しつつ、アフリカの野蛮さを追放しなければならないと書いた作家もいた[57]。 さらに他の著者は、奴隷の一団よりもむしろ混血や黒人のエリートに有利になるように革命の歴史を変更し補強することによって、黒人は政府を樹立し運営する 能力があると主張することによって、ハイチのエリートたちの礼節を証明しようとした[58]。さらに、自由と独立を維持するために、エリートたちはハイチ の大衆が望む市民社会を提供することができなかった。ハイチの農民は土地の自由だけでなく、選挙権や政治参加、教育へのアクセスといった市民権も望んでい た[54]。 国家は基本的に軍によって運営されていたため、ハイチの人々が民主的なプロセスに参加することは非常に困難だった。最も重要なことは、国家が元奴隷の国家 が必要としていた教育へのアクセスを提供できなかったことである。フランスの植民地支配下で意図的に否定されていた基本的な識字能力を欠いていたため、元 奴隷が効果的に参加することはほぼ不可能だった[59]。ハイチのナショナリズムと自由に対する異なる見解を通じて、エリートたちはハイチの農民の代わり に自分たちを大いに優遇する国家を作り上げた。 |

The struggle for unity

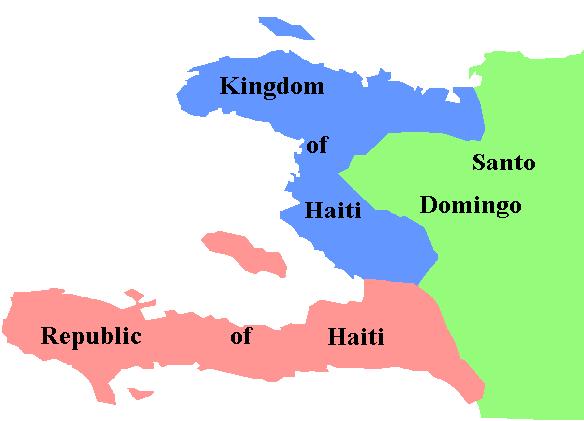

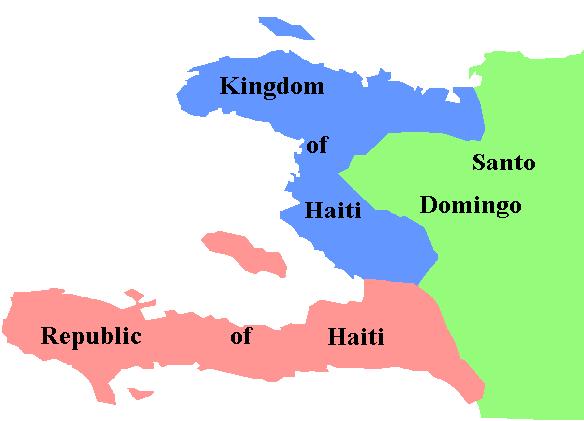

(1806–1820) The battle of Santo Domingo (1806) painted by Nicholas Pocock in 1808 After the Dessalines coup d'état, the two main conspirators divided the country in two rival regimes. Christophe created the authoritarian State of Haiti in the north, and the gens de couleur Pétion established the Republic of Haiti in the south. Christophe attempted to maintain a strict system of labor and agricultural production akin to the former plantations. Although, strictly speaking, he did not establish slavery, he imposed a semi-feudal system, fumage, in which every able man was required to work in plantations (similar to Spanish latifundios) to produce goods for the fledgling country. His method, though undoubtedly oppressive, produced the greater revenues of the two governments. In contrast, Pétion broke up the former colonial estates and parceled out the land into small holdings. In Pétion's south, the gens de couleur minority led the government and feared losing popular support, and thus, they reduced class tensions by land redistribution. Because of the weak international position and its labor policies (most peasants lived through a subsistence economy), Pétion's government was perpetually on the brink of bankruptcy. Yet, for most of its time, it produced one of the most liberal and tolerant Haitian governments ever. In 1815, at a key period of Bolívar's fight for Venezuelan independence, Pétion gave the Venezuelan leader asylum and provided him soldiers and substantial material support. Pétion also had the fewest internal military skirmishes, despite his continuous conflicts with Christophe's northern kingdom. In 1816, however, after finding the burden of the Senate intolerable,[further explanation needed] he suspended the legislature and turned his post into President for Life. Not long after, he died of yellow fever, and his assistant Jean-Pierre Boyer replaced him.  The Kingdom of Haiti in the North and the Republic of Haiti in the South In this period, the eastern part of the island rose against the new powers, following general Juan Sánchez Ramírez's claims of independence from France, which broke the Treaties of Bâle attacking Spain[further explanation needed] and prohibited commerce with Haiti. In the Palo Hincado battle (7 November 1808), all the remaining French forces were defeated by Spanish-creole insurrectionists. On 9 July 1809, the Spanish colony Santo Domingo was born. The government put itself under the control of Spain, earning it the nickname of "España Boba" (meaning "The Idiot Spain"). In 1811, Henri Christophe proclaimed himself King Henri I of the Kingdom of Haiti in the North and commissioned several extraordinary buildings. He even created a nobility class in the fashion of European monarchies. Yet in 1820, weakened by illness and with decreasing support for his authoritarian regime, he killed himself with a silver bullet rather than face a coup d'état. Immediately after, Pétion's successor, Boyer, reunited Haiti through diplomatic tactics and ruled as president until his overthrow in 1843. |

統一への闘い(1806年-1820年) 1808年にニコラス・ポコックが描いたサント・ドミンゴの戦い(1806年) デサリンヌのクーデター後、2人の主謀者は国を2つの対立する政権に分割した。クリストフは北部に権威主義的なハイチ国家を、ペシオンは南部にハイチ共和 国を樹立した。クリストフは、かつてのプランテーションのような厳格な労働・農業生産システムを維持しようとした。厳密には奴隷制度は設けなかったが、半 封建的な制度であるフマージュを課し、能力のある者はすべてプランテーション(スペインのラティフンディオに類似)で働き、新興国のために商品を生産する ことを義務づけた。彼の方法は、間違いなく抑圧的ではあったが、2つの政府の中でより大きな収入をもたらした。 対照的に、ペシオンは旧植民地領地を分割し、土地を小区画化した。ペティオンの南部では、少数派であるジェン・ド・クルールが政府を率いており、民衆の支 持を失うことを恐れていたため、土地の再分配によって階級間の緊張を緩和した。国際的な立場が弱く、労働政策(大半の農民は自給自足経済で生活していた) により、ペシオン政権は常に破綻の危機に瀕していた。しかし、そのほとんどの期間、ハイチ史上最も自由で寛容な政府を生み出した。1815年、ボリーバル がベネズエラ独立のために戦っていた重要な時期に、ペシオンはベネズエラの指導者を亡命させ、兵士と実質的な物質的支援を与えた。ペティオンはまた、クリ ストフの北方王国と絶えず対立していたにもかかわらず、軍事的小競り合いも最も少なかった。しかし1816年、元老院の負担に耐えられなくなったペティオ ンは[さらに説明が必要]、元老院を一時停止し、終身大統領となった。ほどなくして彼は黄熱病で死去し、助手のジャン=ピエール・ボワイエが後任となっ た。  北部のハイチ王国と南部のハイチ共和国 この時期、フアン・サンチェス・ラミレス将軍がフランスからの独立を主張し、スペインを攻撃したバール条約[さらに説明が必要]を破棄してハイチとの通商 を禁止したため、島の東部は新勢力に反旗を翻した。パロ・ヒンカドの戦い(1808年11月7日)では、残存していたフランス軍すべてがスペイン系クレ オール人の反乱軍に敗北した。1809年7月9日、スペインの植民地サント・ドミンゴが誕生した。政府は自らをスペインの支配下に置き、「エスパーニャ・ ボバ」(「バカなスペイン」の意)というニックネームを得た。 1811年、アンリ・クリストフは北のハイチ王国の国王アンリ1世を宣言し、いくつかの素晴らしい建物を建設した。ヨーロッパの君主制にならって貴族階級 まで創設した。しかし1820年、病気で衰弱し、権威主義的な政権への支持も減っていた彼は、クーデターに直面することなく銀の弾丸で自殺した。その直 後、ペシオンの後継者ボワイエが外交戦術によってハイチを統一し、1843年に倒されるまで大統領として統治した。 |

| Boyer's domination of Hispaniola

(1820–1843) Main article: Republic of Haiti (1820–1849)  Jean-Pierre Boyer Almost two years after Boyer had consolidated power in the west, Haiti invaded Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic) and declared the island free from European powers. Boyer, however, responding to a party on the east that preferred Haiti over Colombia, occupied the ex-Spanish colony in January 1822, encountering no military resistance. In this way he accomplished the unity of the island, which was only carried out for a short period of time by Toussaint Louverture in 1801. Boyer's occupation of the Spanish side also responded to internal struggles among Christophe's generals, to which Boyer gave extensive powers and lands in the east. This occupation, however, pitted the Spanish white elite against the iron fisted Haitian administration, and stimulated the emigration of many white wealthy families. The entire island remained under Haitian rule until 1844, when in the east a nationalist group called La Trinitaria led a revolt that partitioned the island into Haiti on the west and Dominican Republic on the east, based on what would appear to be a riverine territorial 'divide' from the pre-contact period. From 1824 to 1826, while the island was under one government, Boyer promoted the largest single free-Black immigration from the United States in which more than 6,000 immigrants settled in different parts of the island.[60] Today remnants of these immigrants live throughout the island, but the larger number reside in Samaná, a peninsula on the Dominican side of the island. From the government's perspective, the intention of the immigration was to help establish commercial and diplomatic relationships with the US, and to increase the number of skilled and agricultural workers in Haiti.[61]  The ruins of the Sans-Souci Palace, severely damaged in the 1842 earthquake and never rebuilt In exchange for diplomatic recognition from France, Boyer was forced to pay a huge indemnity for the loss of French property during the revolution. To pay for this, he had to float loans in France, putting Haiti into a state of debt. Boyer attempted to enforce production through the Code Rural, enacted in 1826, but peasant freeholders, mostly former revolutionary soldiers, had no intention of returning to the forced labor they fought to escape. By 1840, Haiti had ceased to export sugar entirely, although large amounts continued to be grown for local consumption as taffia-a raw rum. However, Haiti continued to export coffee, which required little cultivation and grew semi-wild. The 1842 Cap-Haïtien earthquake destroyed the city, and the Sans-Souci Palace, killing 10,000 people. This was the third major earthquake to hit Western Hispaniola following the 1751 and 1770 Port-au-Prince earthquakes, and the last until the devastating earthquake of 2010. |

ボワイエによるイスパニョーラ支配(1820年-1843年) 主な記事 ハイチ共和国(1820年-1849年)  ジャン=ピエール・ボワイエ ハイチ共和国(1820年-1849年): ボワイエが西方で権力を固めてから約2年後、ハイチはサント・ドミンゴ(現在のドミニカ共和国)に侵攻し、ヨーロッパ列強からの解放を宣言した。しかし、 ボワイエは、コロンビアよりもハイチを優先する東側の一派に呼応し、1822年1月に旧スペイン植民地を占領したが、軍事的抵抗はなかった。こうしてボワ イエは、1801年にトゥーサン・ルーヴェルチュールが短期間実行したに過ぎなかった島の統一を成し遂げた。ボワイエによるスペイン側の占領は、クリスト フの将軍たちの内部抗争にも呼応し、ボワイエは東部の広大な権限と土地を与えた。しかしこの占領は、スペインの白人エリート層と鉄拳制裁を加えるハイチ政 権を対立させ、多くの白人富裕層の移住を促した。島全体は1844年までハイチの統治下にあったが、東部でラ・トリニタリアと呼ばれる民族主義者グループ が反乱を起こし、島を西のハイチと東のドミニカ共和国に分割した。 1824年から1826年にかけて、島が1つの政府の下にあった間に、ボワイエはアメリカからの単一で最大規模の自由黒人移民を推進し、6,000人以上 の移民が島の各地に定住した[60]。今日、これらの移民の残党は島全体に居住しているが、より多くの移民が島のドミニカ共和国側の半島であるサマナに居 住している。政府から見た移民の意図主義は、アメリカとの商業・外交関係の確立を助け、ハイチにおける熟練労働者や農業労働者の数を増やすことであった [61]。  1842年の地震で甚大な被害を受け、再建されなかったサンスーシ宮殿跡 フランスからの外交的承認と引き換えに、ボワイエは革命で失ったフランスの財産に対して巨額の賠償金を支払うことを余儀なくされた。その支払いのためにフ ランスで借金をし、ハイチは借金地獄に陥った。ボワイエは、1826年に制定された農村法典によって生産を強制しようとしたが、農民の自由所有者は、その ほとんどが元革命兵士であり、逃れるために戦った強制労働に戻る意図はなかった。1840年までにハイチは砂糖の輸出を完全に停止したが、タフィア(ラム 酒の原料)として大量に栽培され、地産地消を続けた。しかし、ハイチはコーヒーの輸出を続け、コーヒーはほとんど耕作を必要とせず、半野生化していた。 1842年のカプ・ハイティエン地震により、ハイチは都市とサンスーシ宮殿を破壊し、1万人が死亡した。これは1751年と1770年のポルトープランス 地震に続く、イスパニョーラ西部を襲った3度目の大地震であり、2010年の壊滅的な地震まで続いた。 |

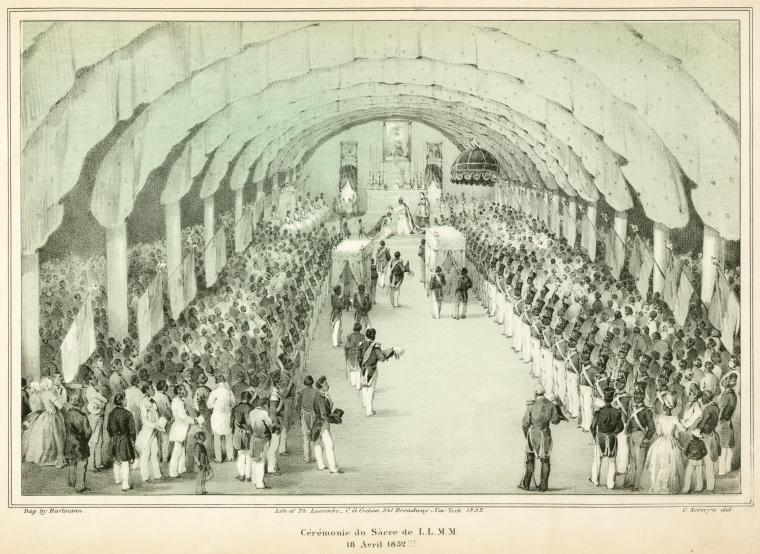

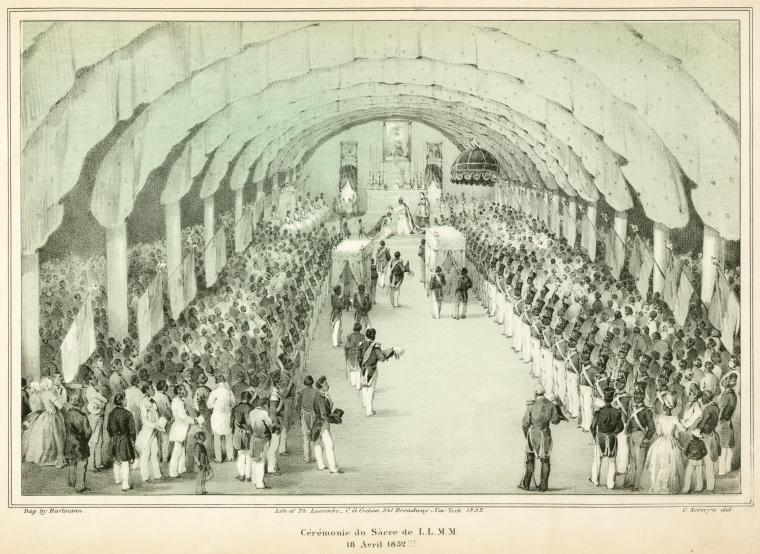

Political struggles (1843–1915) The coronation of Faustin I of Haiti in 1849  The National Palace burned down during the revolt against Salnave in 1868  Staff of the German legation and the Hamburg-Amerika Line agency at Port-au-Prince, Haiti in 1900. The agency was involved in the staffing and management of the legation. German nationals were comparatively numerous in Haiti and heavily involved in the Haitian economy until World War I.  Bishop's House in Cap-Haitien, 1907 In 1843, a revolt, led by Charles Rivière-Hérard, overthrew Boyer and established a brief parliamentary rule under the Constitution of 1843. Revolts soon broke out and the country descended into near chaos, with a series of transient presidents until March 1847, when General Faustin Soulouque, a former slave who had fought in the rebellion of 1791, became president. During this period, Haiti unsuccessfully waged war against the Dominican Republic. In 1849, taking advantage of his popularity, President Faustin Soulouque proclaimed himself Emperor Faustin I. His iron rule succeeded in uniting Haiti for a time, but it came to an abrupt end in 1859 when he was deposed by General Fabre Geffrard, styled the Duke of Tabara. Geffrard's military government held office until 1867, and he encouraged a successful policy of national reconciliation. In 1860, he reached an agreement with the Vatican, reintroducing official Roman Catholic institutions, including schools, to the country. In 1867 an attempt was made to establish a constitutional government, but successive presidents Sylvain Salnave and Nissage Saget were overthrown in 1869 and 1874 respectively. A more workable constitution was introduced under Michel Domingue in 1874, leading to a long period of democratic peace and development for Haiti. The debt to France was finally repaid in 1879, and the government of President Pierre Théoma Boisrond-Canal peacefully transferred power to Lysius Salomon, one of Haiti's abler leaders. Monetary reform, with the creation in 1880-1881 of the National Bank of Haiti, and a cultural renaissance ensued with a flowering of Haitian art. The last two decades of the 19th century were also marked by the development of a Haitian intellectual culture. Major works of history were published in 1847 and 1865. Haitian intellectuals, led by Louis-Joseph Janvier and Anténor Firmin, engaged in a war of letters against a tide of racism and Social Darwinism that emerged during this period. The Constitution of 1867 saw peaceful and progressive transitions in government that did much to improve the economy and stability of the Haitian nation and the condition of its people. Constitutional government restored the faith of the Haitian people in legal institutions. The development of industrial sugar and rum industries near Port-au-Prince made Haiti, for a while, a model for economic growth in Latin American countries. This period of relative stability and prosperity ended in 1911, when revolution broke out and the country slid once again into disorder and debt. From 1911 to 1915, there were six different presidents, each of whom was killed or forced into exile.[62] The revolutionary armies were formed by cacos, peasant brigands from the mountains of the north, along the porous Dominican border, who were enlisted by rival political factions with promises of money to be paid after a successful revolution and an opportunity to plunder. The United States was particularly apprehensive about the role of the German community in Haiti (approximately 200 in 1910), who wielded a disproportionate amount of economic power. Germans controlled about 80% of the country's international commerce; they also owned and operated utilities in Cap Haïtien and Port-au-Prince, the main wharf and a tramway in the capital, and a railroad serving the Plaine de Cul-du-Sac. The German community proved more willing to integrate into Haitian society than any other group of white foreigners, including the French. A number married into the nation's most prominent mulatto families, bypassing the constitutional prohibition against foreign land-ownership. They also served as the principal financiers of the nation's innumerable revolutions, floating innumerable loans – at high interest rates – to competing political factions. In an effort to limit German influence, in 1910–1911, the US State Department backed a consortium of American investors, assembled by the National City Bank of New York, in securing the currency issuance concession through the National Bank of the Republic of Haiti, which replaced the prior National Bank of Haiti as the nation's only commercial bank and custodian of the government treasury. In February 1915, Vilbrun Guillaume Sam established a dictatorship, but in July, facing a new revolt, he massacred 167 political prisoners, all of whom were from elite families, and was lynched by a mob in Port-au-Prince.  |

政治闘争 (1843-1915) 1849年、ハイチ王ファウスティン1世の戴冠式  1868年、サルナベの反乱で焼失した国民宮殿  1900年、ハイチのポルトープランスにあるドイツ公使館とハンブルク・アメリカライン代理店のスタッフ。代理店は公使館の人員配置と管理に携わってい た。ドイツ国民はハイチで比較的多く、第一次世界大戦までハイチ経済に深く関わっていた。  1907年、キャップハイティエンの司教館 1843年、シャルル・リヴィエール=エラール率いる反乱軍がボワイエを打倒し、1843年憲法の下、短期間の議会統治を確立した。やがて反乱が勃発し、 ハイチはほぼ混乱状態に陥った。1847年3月、1791年の反乱で戦った元奴隷のファウスティン・スールーク将軍が大統領に就任するまで、一過性の大統 領が続いた。この間、ハイチはドミニカ共和国との戦争に失敗した。 1849年、ファウスティン・スールーク大統領はその人気に乗じて皇帝ファウスティン1世を宣言した。彼の鉄の支配は一時期ハイチを統一することに成功し たが、1859年、タバラ公爵と呼ばれたファーブル・ゲフラール将軍によって退位させられ、突然終わりを告げた。 ゲフラールの軍政は1867年まで続き、彼は国民和解政策を推進し成功を収めた。1860年、彼はバチカンと協定を結び、学校を含むローマ・カトリックの 公的機関を再び国内に導入した。1867年には立憲政府の樹立が試みられたが、歴代の大統領シルヴァン・サルナーヴとニサージュ・サジェはそれぞれ 1869年と1874年に倒された。1874年、ミシェル・ドミンゲの下でより実行可能な憲法が導入され、ハイチは民主的な平和と発展の長い時代を迎える ことになった。1879年にはフランスへの債務がようやく返済され、ピエール・テオマ・ボワロン=カナル大統領の政府は、ハイチの優れた指導者の一人であ るリシウス・サロモンに平和的に政権を移譲した。1880年から1881年にかけてハイチ国民銀行が設立され、金融改革が行われ、ハイチ芸術の開花ととも に文化的ルネッサンスが起こった。 19世紀最後の20年間は、ハイチの知的文化の発展も顕著であった。1847年と1865年には、歴史に関する主要な著作が出版された。ルイ=ジョゼフ・ ジャンヴィエとアンテノール・フィルマンに率いられたハイチの知識人たちは、この時期に台頭した人種主義や社会ダーウィニズムの潮流に対抗して、書簡戦争 を繰り広げた。 1867年に制定された憲法は、平和的で進歩的な政権交代をもたらし、ハイチ国民の経済と安定、そして国民の状態を改善するために大いに貢献した。立憲政 治は、法的制度に対するハイチ国民の信頼を回復した。ポルトープランス近郊で砂糖とラム酒の工業が発展し、ハイチはしばらくの間、ラテンアメリカ諸国の経 済成長のモデルとなった。1911年に革命が勃発し、ハイチは再び混乱と負債に陥った。 1911年から1915年にかけて、6人の異なる大統領が誕生したが、いずれも殺害されるか亡命させられた[62]。革命軍は、北部の山間部、多孔質のド ミニカ国境沿いの農民の山賊であるカコスによって編成され、彼らは革命成功後に支払われる金と略奪の機会を約束され、対立する政治派閥によって入隊させら れた。 アメリカは特に、不釣り合いな経済力を持つハイチのドイツ人社会(1910年当時約200人)の役割を懸念していた。ドイツ人はハイチの国際商業の約 80%を支配し、キャップ・ハイチとポルトープランスの公共事業、首都の主要埠頭と路面電車、カルデュサック平野を走る鉄道も所有・運営していた。 ドイツ人社会は、フランス人を含む他のどの白人外国人グループよりもハイチ社会に積極的に溶け込もうとした。外国人の土地所有を禁止する憲法を回避して、 国民の有力なマルチーズの家系に嫁いだ者も少なくなかった。彼らはまた、ナショナリズムの主要な資金調達者としても機能し、競合する政治派閥に高利で無数 の融資を行った。 ドイツの影響力を制限するため、1910年から1911年にかけて、アメリカ国務省は、ニューヨーク・ナショナル・シティ銀行が集めたアメリカ人投資家コ ンソーシアムを支援し、ハイチ共和国国立銀行を通じて通貨発行権を確保した。 1915年2月、ヴィルブラン・ギョーム・サムは独裁体制を確立したが、7月、新たな反乱に直面し、エリート一族出身の政治犯167人を虐殺し、ポルトー プランスで暴徒にリンチされた。  |

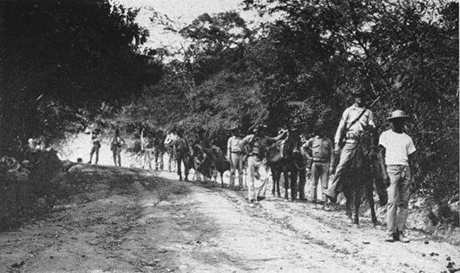

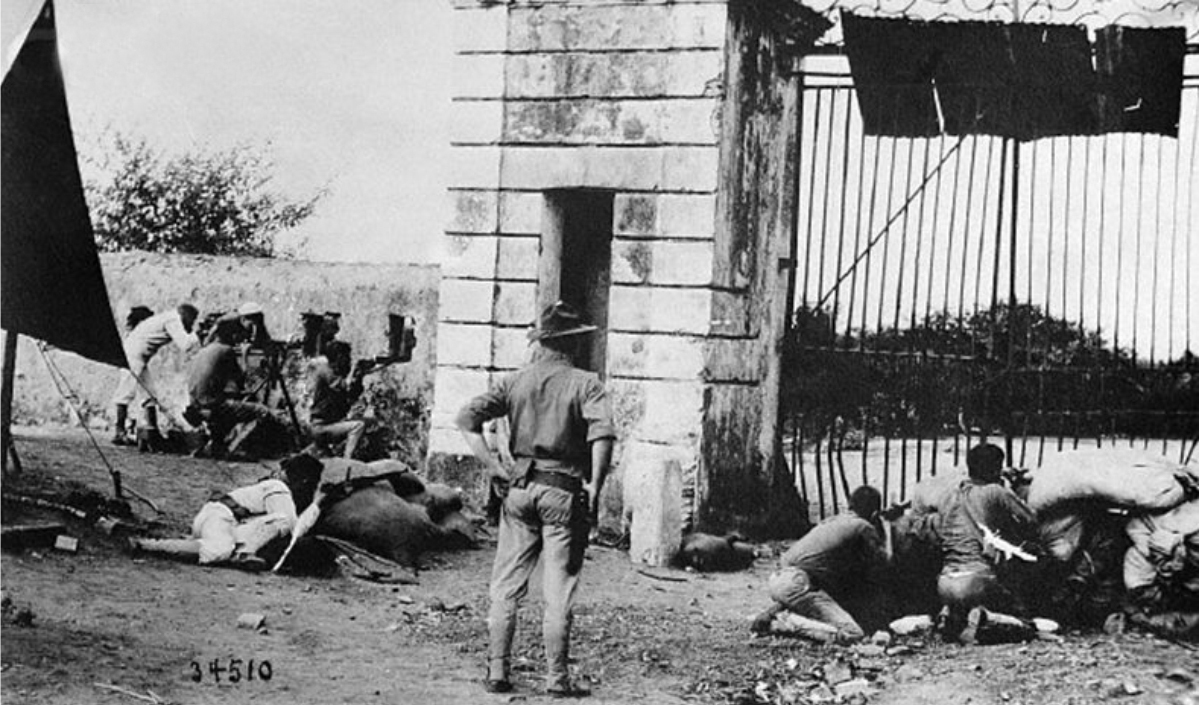

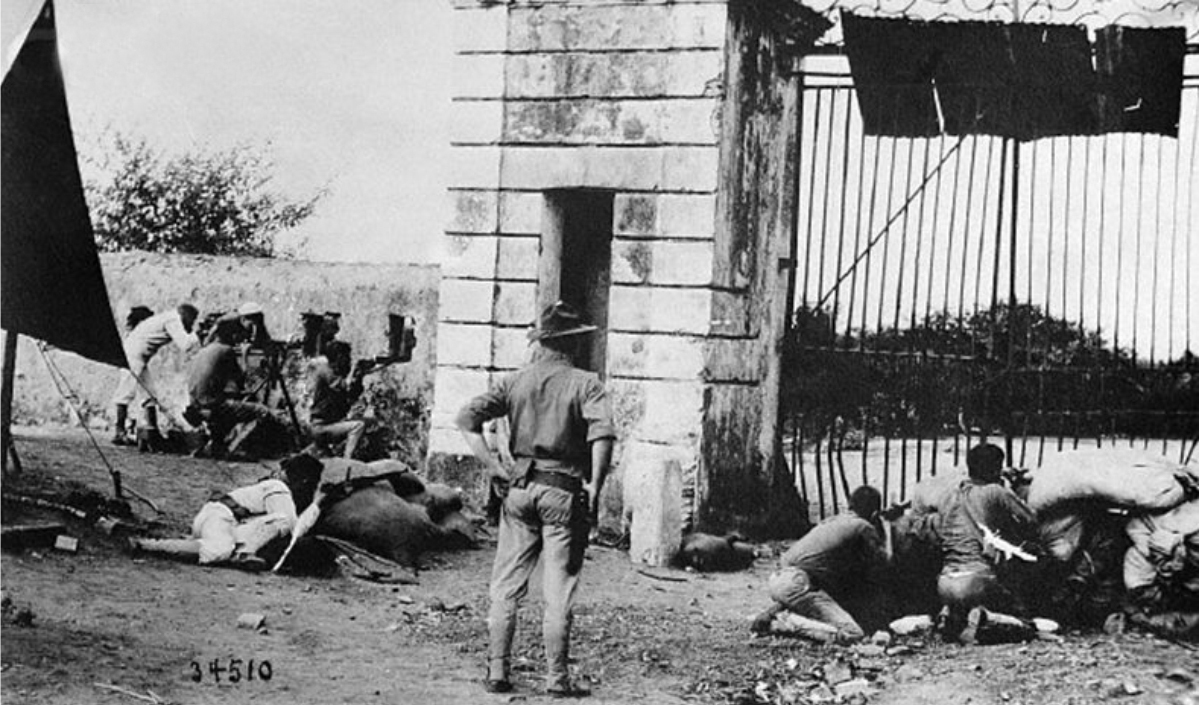

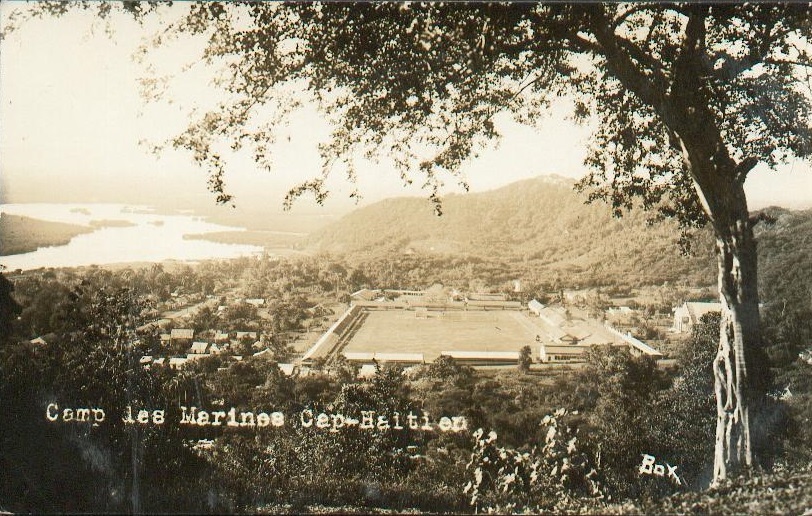

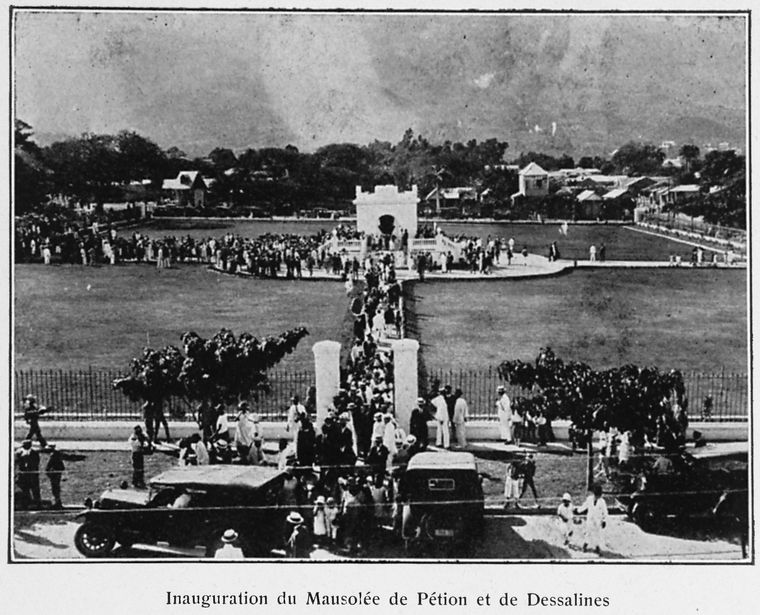

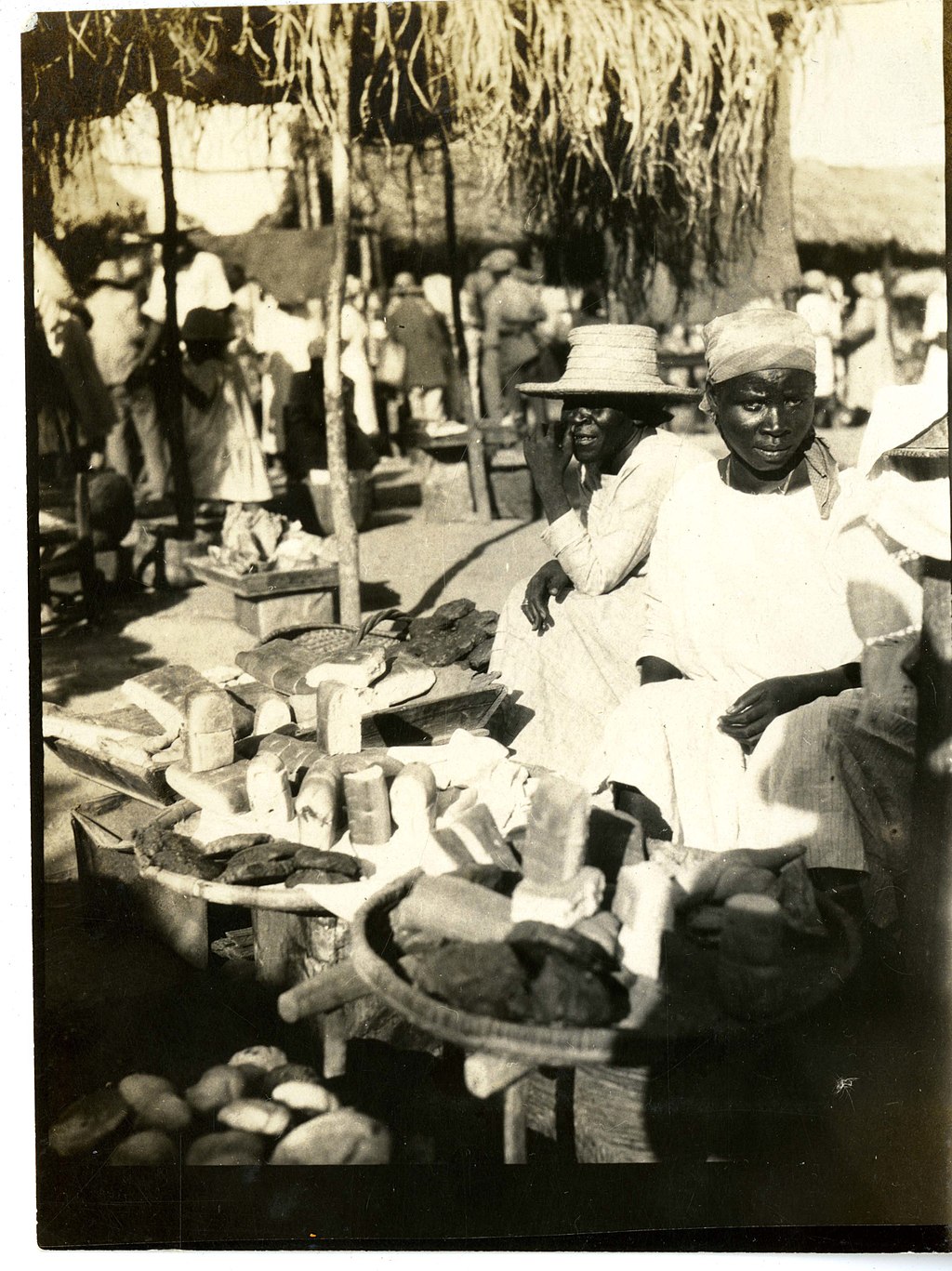

| United States occupation

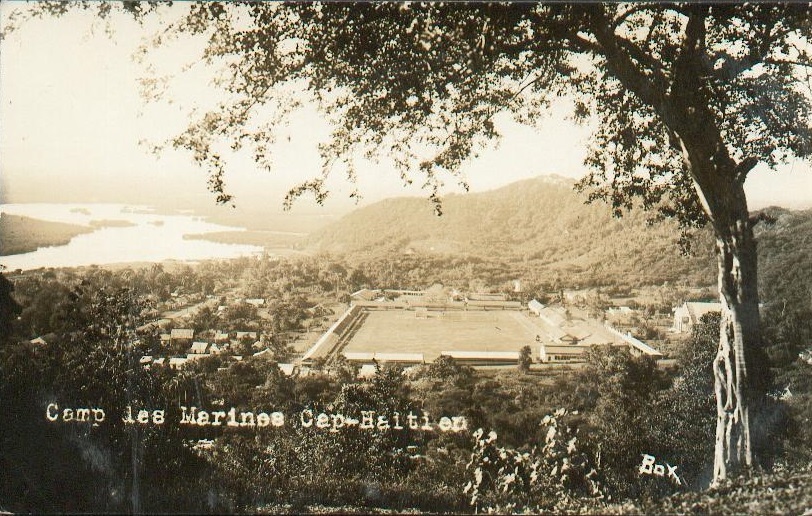

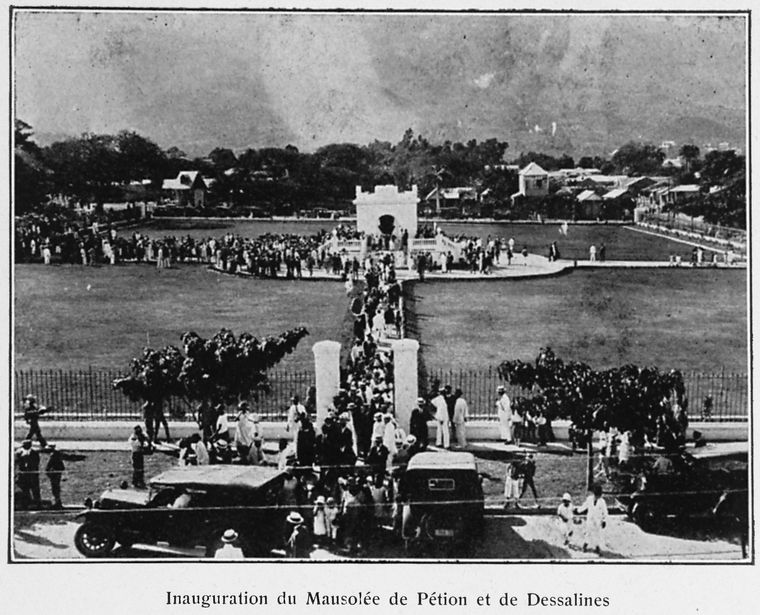

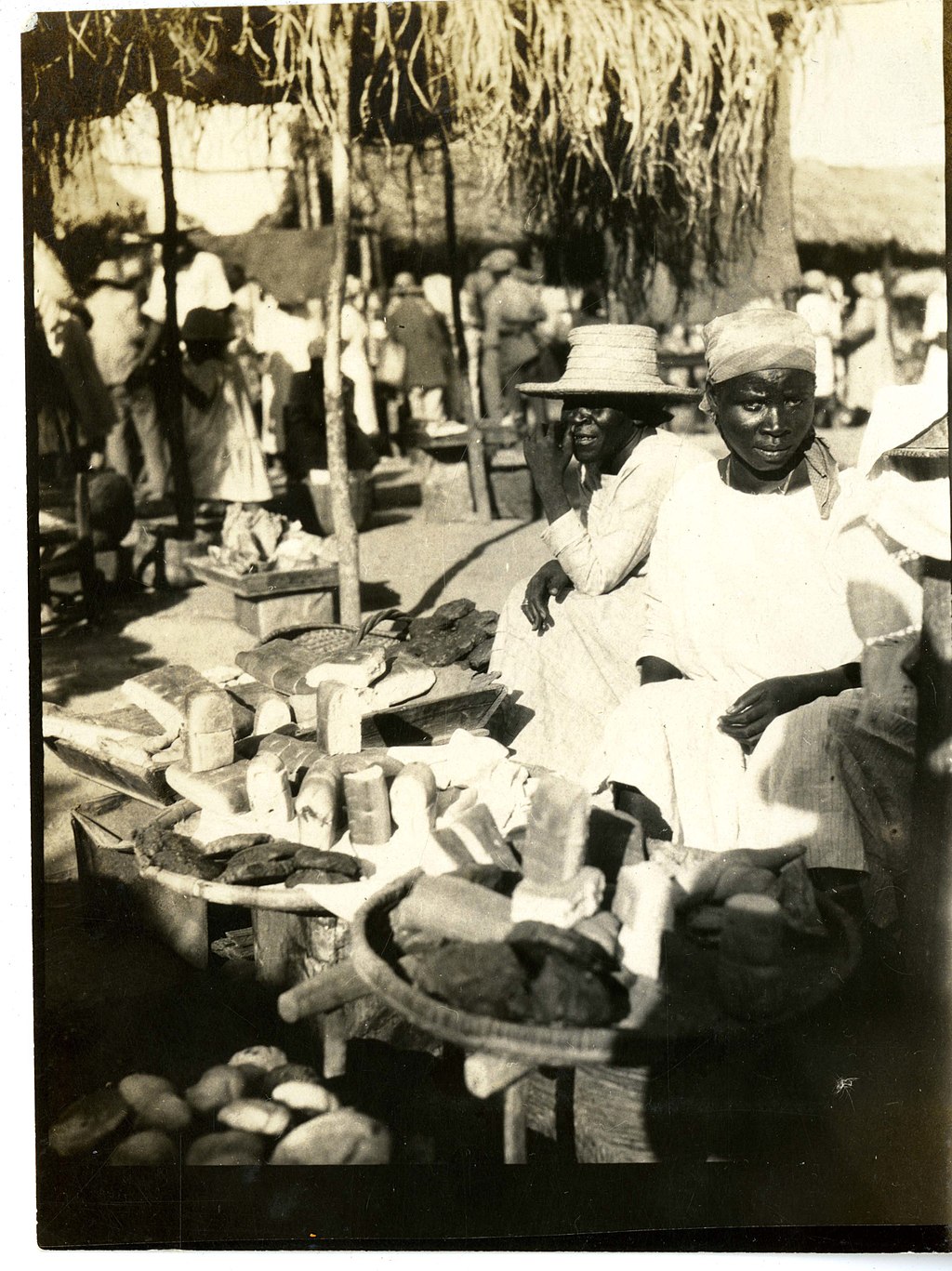

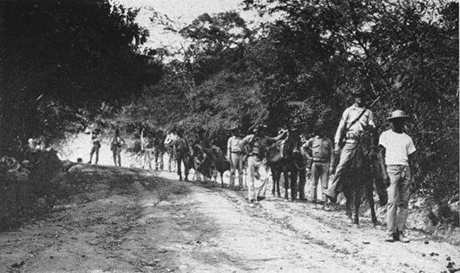

(1915–1934) Main article: United States occupation of Haiti  United States Marines and a Haitian guide patrolling the jungle in 1915 during the Battle of Fort Dipitie  American Marines in 1915 defending the entrance gate in Cap-Haïten  Marine's base at Cap-Haïtien  Opening of the mausoleum of Pétion and Dessalines in 1926  Bread market in St. Michel, 1928–1929 In 1915 the United States, responding to complaints to President Woodrow Wilson from American banks to which Haiti was deeply in debt, occupied the country. The occupation of Haiti lasted until 1934. The US occupation was resented by Haitians as a loss of sovereignty and there were revolts against US forces. Reforms were carried out despite this. Under the supervision of the United States Marines, the Haitian National Assembly elected Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave president. He signed a treaty that made Haiti a de jure US protectorate, with American officials assuming control over the Financial Advisory, Customs Receivership, the Constabulary, the Public Works Service, and the Public Health Service for a period of ten years. The principal instrument of American authority was the newly created Gendarmerie d'Haïti, commanded by American officers. In 1917, at the demand of US officials, the National Assembly was dissolved, and officials were designated to write a new constitution, which was largely dictated by officials in the US State Department and US Navy Department. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Under-Secretary for the Navy in the Wilson administration, claimed to have personally written the new constitution. This document abolished the prohibition on foreign ownership of land – the most essential component of Haitian law. When the newly elected National Assembly refused to pass this document and drafted one of its own preserving this prohibition, it was forcibly dissolved by Gendarmerie commandant Smedley Butler. This constitution was approved by a plebiscite in 1919, in which less than 5% of the population voted. The US State Department authorized this plebiscite presuming that "the people casting ballots would be 97% illiterate, ignorant in most cases of what they were voting for."[63] The Marines and Gendarmerie initiated an extensive road-building program to enhance their military effectiveness and open the country to US investment. Lacking any source of adequate funds, they revived an 1864 Haitian law, discovered by Butler, requiring peasants to perform labor on local roads in lieu of paying a road tax. This system, known as the corvée, originated in the unpaid labor that French peasants provided to their feudal lords. In 1915, Haiti had 3 miles (4.8 km) of road usable by automobile, outside the towns. By 1918, more than 470 miles (760 km) of road had been built or repaired through the corvée system, including a road linking Port-au-Prince to Cap-Haïtien.[64] However, Haitians forced to work in the corvée labor-gangs, frequently dragged from their homes and harassed by armed guards, received few immediate benefits and saw this system of forced labor as a return to slavery at the hands of white men. In 1919, a new caco uprising began, led by Charlemagne Péralte, vowing to 'drive the invaders into the sea and free Haiti.'[65] The Cacos attacked Port-au-Prince in October but were driven back with heavy casualties. Afterwards, a Creole-speaking American Gendarmerie officer and two US marines infiltrated Péralte's camp, killing him and photographing his corpse in an attempt to demoralize the rebels. Leadership of the rebellion passed to Benoît Batraville, a Caco chieftain from Artibonite, who also launched an assault on the capital. His death in 1920 marked the end of hostilities. During Senate hearings in 1921, the commandant of the Marine Corps reported that, in the twenty months of active resistance, 2,250 Haitians had been killed. However, in a report to the Secretary of the Navy he reported the death toll as being 3,250.[66] Haitian historians have estimated the true number was much higher; one suggested, "the total number of battle victims and casualties of repression and consequences of the war might have reached, by the end of the pacification period, four or five times that – somewhere in the neighborhood of 15,000 persons."[67] In 1922, Dartiguenave was replaced by Louis Borno, who ruled without a legislature until 1930. That same year, General John H. Russell, Jr., was appointed High Commissioner. The Borno-Russel dictatorship oversaw the expansion of the economy, building over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of road, establishing an automatic telephone exchange, modernizing the nation's port facilities, and establishing a public health service. Sisal was introduced to Haiti, and sugar and cotton became significant exports.[68] However, efforts to develop commercial agriculture had limited success, in part because much of Haiti's labor force was employed at seasonal work in the more established sugar industries of Cuba and the Dominican Republic. An estimated 30,000–40,000 Haitian laborers, known as braceros, went annually to the Oriente Province of Cuba between 1913 and 1931.[69] Most Haitians continued to resent the loss of sovereignty. At the forefront of opposition among the educated elite was L'Union Patriotique, which established ties with opponents of the occupation in the US itself, in particular the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[citation needed] The Great Depression decimated[citation needed] the prices of Haiti's exports and destroyed the tenuous gains of the previous decade. In December 1929, Marines in Les Cayes killed ten Haitians during a march to protest local economic conditions. This led Herbert Hoover to appoint two commissions, including one headed by a former US governor of the Philippines William Cameron Forbes, which criticized the exclusion of Haitians from positions of authority in the government and constabulary, now known as the Garde d'Haïti. In 1930, Sténio Vincent, a long-time critic of the occupation, was elected president, and the US began to withdraw its forces. The withdrawal was completed under US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR), in 1934, under his "Good Neighbor policy". The US retained control of Haiti's external finances until 1947.[70] All three rulers during the occupation came from the country's mulatto minority. At the same time, many in the growing black professional classes departed from the traditional veneration of Haiti's French cultural heritage and emphasized the nation's African roots, most notably ethnologist Jean Price-Mars and the journal Les Griots, edited by Dr. François Duvalier.[71] The transition government was left with a better infrastructure, public health, education, and agricultural development as well as a democratic system. The country had fully democratic elections in 1930, won by Sténio Vincent. The Garde was a new kind of military institution in Haiti. It was a force manned overwhelmingly by blacks, with a United States-trained black commander, Colonel Démosthènes Pétrus Calixte. Most of the Garde's officers, however, were mulattoes. The Garde was a national organization;[72] it departed from the regionalism that had characterized most of Haiti's previous armies. In theory, its charge was apolitical—to maintain internal order, while supporting a popularly elected government. The Garde initially adhered to this role.[72] |

アメリカ合衆国の占領(1915年-1934年)→「米国海兵隊占拠時代のハイチ」 主な記事 ハイチ占領  1915年、ディピティ要塞の戦いでジャングルをパトロールするアメリカ海兵隊とハイチ人ガイド  1915年、キャップハイテンの入り口ゲートを守るアメリカ海兵隊員  キャップハイティエンでの海兵隊基地  1926年、ペシオンとデッサリーヌの霊廟がオープンする。  サン・ミッシェルのパン市場、1928-1929年 1915年、ハイチが多額の負債を抱えていたアメリカの銀行からウッドロー・ウィルソン大統領に苦情が寄せられ、アメリカはハイチを占領した。ハイチ占領 は1934年まで続いた。アメリカの占領は、主権の喪失としてハイチ人の反感を買い、アメリカ軍に対する反乱が起こった。それでも改革は行われた。 アメリカ海兵隊の監督の下、ハイチ国民議会はフィリップ・スドレ・ダルティグナベを大統領に選出した。彼は、ハイチを実質的にアメリカの保護国とする条約 に調印し、アメリカの役人が10年間、財務顧問、税関管財人、憲兵隊、公共事業サービス、保健サービスを管理することになった。アメリカの権限の主要な手 段は、アメリカ人将校が指揮する新設の国家憲兵隊であった。1917年、アメリカ政府高官の要求により国民議会は解散させられ、新憲法の制定を命じられた が、この憲法はアメリカ国務省とアメリカ海軍省の高官の指示によるものであった。ウィルソン政権の海軍次官だったフランクリン・D・ルーズベルトは、新憲 法を自ら書いたと主張した。この文書は、外国人による土地所有の禁止--ハイチ法の最も重要な構成要素--を廃止した。新しく選出された国民議会がこの文 書の通過を拒否し、この禁止を維持する独自の文書を起草したため、国家憲兵隊司令官スメドリー・バトラーによって強制的に解散させられた。この憲法は 1919年の国民投票によって承認されたが、投票率は人口の5%にも満たなかった。アメリカ国務省は、「投票する人々は97%が読み書きができず、ほとん どの場合、自分たちが何に投票しているのか知らない」[63]と推定して、この国民投票を許可した。 海兵隊と国家憲兵隊は、軍事的効果を高め、米国の投資に国を開放するため、大規模な道路建設計画を開始した。十分な資金源がなかったため、彼らはバトラー によって発見された1864年のハイチの法律を復活させ、道路税を支払う代わりに農民に地方道路での労働を義務付けた。コルヴェとして知られるこの制度 は、フランスの農民が封建領主に提供していた無報酬労働に端を発している。1915年、ハイチには町以外で自動車が通れる道路が3マイル(4.8km)し かなかった。1918年までに、ポルトープランスとキャプハイティエン間を結ぶ道路を含め、470マイル(760km)以上の道路がコルヴェ制度によって 建設または修理された[64]。しかし、コルヴェの労役場で働かされることを余儀なくされたハイチ人は、しばしば家から引きずり出され、武装した警備員に よって嫌がらせを受けたが、すぐに得られる利益はほとんどなく、この強制労働制度を白人の手による奴隷制度への回帰と見なした。 1919年、「侵略者を海に追いやり、ハイチを解放する」と誓ったシャルルマーニュ・ペラルテに率いられた新たなカコの蜂起が始まった[65]。カコは 10月にポルトープランスを攻撃したが、多くの犠牲者を出して追い返された。その後、クレオール語を話すアメリカ国家憲兵隊将校と2人のアメリカ海兵隊員 がペラルテのキャンプに潜入し、反乱軍の士気を下げるために彼を殺害し、その死体を写真に撮った。反乱の主導権はアルティボニテ出身のカコ族族長ブノワ・ バトラヴィルに移り、彼は首都への攻撃も開始した。1920年のバトラヴィルの死により、敵対行為は終結した。1921年の上院公聴会で、海兵隊司令官 は、20ヶ月の活発な抵抗活動で2,250人のハイチ人が殺されたと報告した。しかし、海軍長官への報告では、死者数は3,250人であったと報告してい る[66]。ハイチの歴史家は、本当の数はもっと多かったと推定している。ある歴史家は、「戦闘による犠牲者、弾圧による犠牲者、戦争の結果の犠牲者の総 数は、平和化期間の終わりまでに、その4、5倍、つまり15,000人近辺に達していたかもしれない」と示唆している[67]。 1922年、ダルティゲナブの後任としてルイ・ボルノが就任し、1930年まで立法府なしで統治した。同年、ジョン・H・ラッセル・ジュニア将軍が高等弁 務官に任命された。ボルノ=ラッセル独裁政権は経済の拡大を監督し、1,600kmを超える道路の建設、自動電話交換機の設置、国民の港湾施設の近代化、 保健サービスの確立などを行った。サイザル麻がハイチに導入され、砂糖と綿花が重要な輸出品となった[68]。しかし、商業的農業を発展させる努力は、ハ イチの労働力の多くが、キューバやドミニカ共和国のより確立された砂糖産業で季節労働に従事していたこともあり、限られた成功に終わった。1913年から 1931年にかけて、ブラセロとして知られるハイチ人労働者3万人から4万人が毎年キューバのオリエンテ州に出稼ぎに行ったと推定されている[69]。ほ とんどのハイチ人は、主権の喪失に憤り続けた。教育を受けたエリートの間で反対運動の先頭に立ったのは愛国者同盟で、アメリカ国内の占領反対派、特に有色 人種地位向上国民協会(NAACP)との関係を築いた[要出典]。 世界大恐慌はハイチの輸出価格を壊滅させ[要出典]、それまでの10年間のわずかな利益を破壊した。1929年12月、レ・カイーズの海兵隊が地元の経済 状況に抗議するデモ行進中に10人のハイチ人を殺害した。その結果、ハーバート・フーバーは、元米国フィリピン総督ウィリアム・キャメロン・フォーブスを 委員長とする2つの委員会を任命し、ハイチ人が政府や警察(現在はガルド・ハイティとして知られる)の権威ある地位から排除されていることを批判した。 1930年、長年占領を批判してきたステニオ・ヴィンセントが大統領に選出され、アメリカは軍の撤退を開始した。撤退は1934年、フランクリン・D・ ルーズベルト(FDR)大統領の「善隣政策」の下で完了した。アメリカは1947年までハイチの対外財政を掌握していた[70]。占領下の3人の統治者は いずれも少数民族である混血出身者であった。同時に、成長しつつあった黒人専門家階級の多くは、ハイチのフランス文化遺産に対する伝統的な崇拝から離れ、 国民がアフリカにルーツを持つことを強調した。 移行政府は、より良いインフラストラクチャー、保健、教育、農業開発と民主的なシステムを残した。1930年には完全に民主的な選挙が行われ、ステニオ・ ヴァンサンが勝利した。ガルドはハイチにおける新しいタイプの軍事組織であった。圧倒的に黒人が多く、米国で訓練を受けた黒人司令官デモステーヌ・ペトル ス・カリクテ大佐がいた。しかし、ガルドの将校のほとんどは混血であった。ガルドは国民組織であり[72]、それまでのハイチの軍隊のほとんどを特徴づけ ていたナショナリズムとは一線を画していた。理論的には、ガルドの任務は非政治的であり、民選政府を支持しつつ国内秩序を維持することであった。ガルドは 当初、この役割を堅持していた[72]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Haiti | |

Elections and coups (1934–1957) Sténio Vincent Vincent's presidency (1934–1941) President Vincent took advantage of the comparative national stability, which was being maintained by a professionalized military, to gain absolute power. A plebiscite permitted the transfer of all authority in economic matters from the legislature to the executive, but Vincent was not content with this expansion of his power. In 1935 he forced through the legislature a new constitution, which was also approved by plebiscite. The constitution praised Vincent, and it granted the executive sweeping powers to dissolve the legislature at will, to reorganize the judiciary, to appoint ten of twenty-one senators (and to recommend the remaining eleven to the lower house), and to rule by decree when the legislature was not in session. Although Vincent implemented some improvements in infrastructure and services, he brutally repressed his opposition, censored the press, and governed largely to benefit himself and a clique of merchants and corrupt military officers.[72] Under Calixte the majority of Garde personnel had adhered to the doctrine of political nonintervention that their Marine Corps trainers had stressed. Over time, however, Vincent and Dominican dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina sought to buy adherents among the ranks. Trujillo, determined to expand his influence over all of Hispaniola, in October 1937 ordered the indiscriminate butchery by the Dominican army of an estimated 14,000 to 40,000 Haitians on the Dominican side of the Massacre River.[73] Some observers claim that Trujillo supported an abortive coup attempt by young Garde officers in December 1937. Vincent dismissed Calixte as commander and sent him abroad, where he eventually accepted a commission in the Dominican military as a reward for his efforts while on Trujillo's payroll. The attempted coup led Vincent to purge the officer corps of all members suspected of disloyalty, marking the end of the apolitical military.[72] |

選挙とクーデター(1934-1957年) ステニオ・ヴァンサン ヴィンセント(ヴァンサン)大統領時代(1934年-1941年) ヴィンセント(ヴァンサン)大統領は、専門化された軍によって維持されていた比較的ナショナリズムの安定を利用して、絶対的な権力を手に入れた。国民投票により、経済に 関するすべての権限が立法府から行政府に移譲されたが、ヴィンセントは権力の拡大に満足しなかった。1935年、彼は立法府に新憲法を強行採決し、これも 国民投票で承認された。この憲法はヴィンセント(ヴァンサン)を賞賛するもので、立法府を自由に解散させ、司法を再編成し、21人の上院議員のうち10人を任命し(残り の11人を下院に推薦する)、立法府が開かれていないときは政令で統治するという大権を行政府に与えた。ヴィンセント(ヴァンサン)はインフラストラクチャーやサービス の改善を実施したものの、反対派を残酷に弾圧し、報道を検閲し、自分自身と商人や腐敗した軍人の徒党の利益のために政治を行った[72]。 カリクスのもとでは、ガルド隊員の大半は、海兵隊の訓練生が強調していた政治不介入の教義を守っていた。しかし時が経つにつれ、ヴィンセントとドミニカの 独裁者ラファエル・レオニダス・トルヒーヨ・モリーナは、隊員の中から信奉者を買おうとした。トルヒーヨはイスパニョーラ全土への影響力拡大を決意し、 1937年10月、ドミニカ軍によるマサクレ川のドミニカ側での推定14,000人から40,000人のハイチ人の無差別虐殺を命じた[73]。1937 年12月、トルヒーヨは若いガルド将校によるクーデター未遂を支援したと主張する者もいる。ヴィンセントはカリクシュテを司令官から解任し、海外に派遣し たが、最終的に彼はトルヒーヨに雇われていた間の努力の報いとしてドミニカ軍での任務を受け入れた。このクーデター未遂事件をきっかけに、ヴィンセントは 不忠誠の疑いのある将校団を粛清し、無政治的な軍隊は終焉を迎えた[72]。 |

Lescot's presidency (1941–1946) Élie Lescot In 1941 Vincent showed every intention of standing for a third term as president, but after almost a decade of disengagement, the United States made it known that it would oppose such an extension. Vincent accommodated the Roosevelt administration and handed power over to Elie Lescot.[72] Lescot was of mixed race and had served in numerous government posts. He was competent and forceful, and many considered him a sterling candidate for the presidency, despite his elitist background. Like the majority of previous Haitian presidents, however, he failed to live up to his potential. His tenure paralleled that of Vincent in many ways. Lescot declared himself commander in chief of the military, and power resided in a clique that ruled with the tacit support of the Garde. He repressed his opponents, censored the press, and compelled the legislature to grant him extensive powers. He handled all budget matters without legislative sanction and filled legislative vacancies without calling elections. Lescot commonly said that Haiti's declared state-of-war against the Axis powers during World War II justified his repressive actions. Haiti, however, played no role in the war except for supplying the United States with raw materials and serving as a base for a United States Coast Guard detachment.[72] Aside from his authoritarian tendencies, Lescot had another flaw: his relationship with Rafael Trujillo. While serving as Haitian ambassador to the Dominican Republic, Lescot fell under the sway of Trujillo's influence and wealth. In fact, it was Trujillo's money that reportedly bought most of the legislative votes that brought Lescot to power. Their clandestine association persisted until 1943, when the two leaders parted ways for unknown reasons. Trujillo later made public all his correspondence with the Haitian leader. The move undermined Lescot's already dubious popular support.[72] In January 1946, events came to a head when Lescot jailed the Marxist editors of a journal called La Ruche (The Beehive). This action precipitated student strikes and protests by government workers, teachers, and shopkeepers in the capital and provincial cities. In addition, Lescot's mulatto-dominated rule had alienated the predominantly black Garde. His position became untenable, and he resigned on 11 January. Radio announcements declared that the Garde had assumed power, which it would administer through a three-member junta.[72] |

レスコ大統領時代(1941年-1946年) エリー・レスコ 1941年、ヴァンサンは3期目の大統領選挙に立候補する意図主義を示したが、10年近くにわたる不干渉の後、アメリカは大統領任期延長に反対することを 明らかにした。ヴァンサンはルーズベルト政権に便宜を図り、エリー・レスコに政権を譲った[72]。 レスコは混血で、数多くの政府のポストに就いていた。彼は有能で力持ちであり、エリート主義的な経歴にもかかわらず、多くの人々は彼を大統領候補とし て高く評価した。しかし、歴代のハイチ大統領の大半がそうであったように、彼はその潜在能力を発揮することができなかった。彼の在任期間は、多くの点で ヴィンセント(ヴァンサン)と類似していた。レスコは自らを軍の最高司令官と宣言し、権力はガルドの暗黙の支持のもとに支配する徒党に握られた。彼は反対派を弾圧し、報 道を検閲し、立法府に広範な権限を与えるよう強要した。彼は立法府の承認なしにすべての予算問題を処理し、選挙を招集することなく立法府の空席を埋めた。 レスコは、ハイチが第二次世界大戦中に枢軸国に対して宣戦布告していたことが、彼の抑圧的な行動を正当化する理由であるとよく言っていた。しかし、ハイチ は、アメリカに原材料を供給し、アメリカ沿岸警備隊の基地として機能した以外、戦争において何の役割も果たさなかった[72]。 レスコットには、その権威主義的傾向のほかに、ラファエル・トルヒーヨとの関係というもうひとつの欠点があった。ドミニカ共和国のハイチ大使を務めていた とき、レスコットはトルヒーヨの影響力と富の支配下に置かれた。実際、レスコットに権力をもたらした立法府の票の大半を買ったのは、トルヒーヨの金だった と言われている。2人の秘密の関係は1943年まで続いたが、2人の指導者は理由もわからず決別した。トルヒーヨは後にハイチ人指導者との書簡をすべて公 開した。この動きは、すでに怪しかったレスコットの民衆の支持を弱めた[72]。 1946年1月、大統領エリー・レスコットがラ・リューシュ(蜂の巣)という雑誌のマルクス主義者編集者を投獄したことで事態は収束に向かった。この行動 は、首都や地方 都市における学生ストライキや公務員、教師、商店主による抗議行動を引き起こした。さらに、レスコの混血支配は、黒人の多いガルドを疎外した。レスコの立 場は危うくなり、1月11日に辞任した。ラジオのアナウンスでは、ガルドが権力を掌握し、3人の議員からなる純政権によって統治すると宣言された [72]。 |

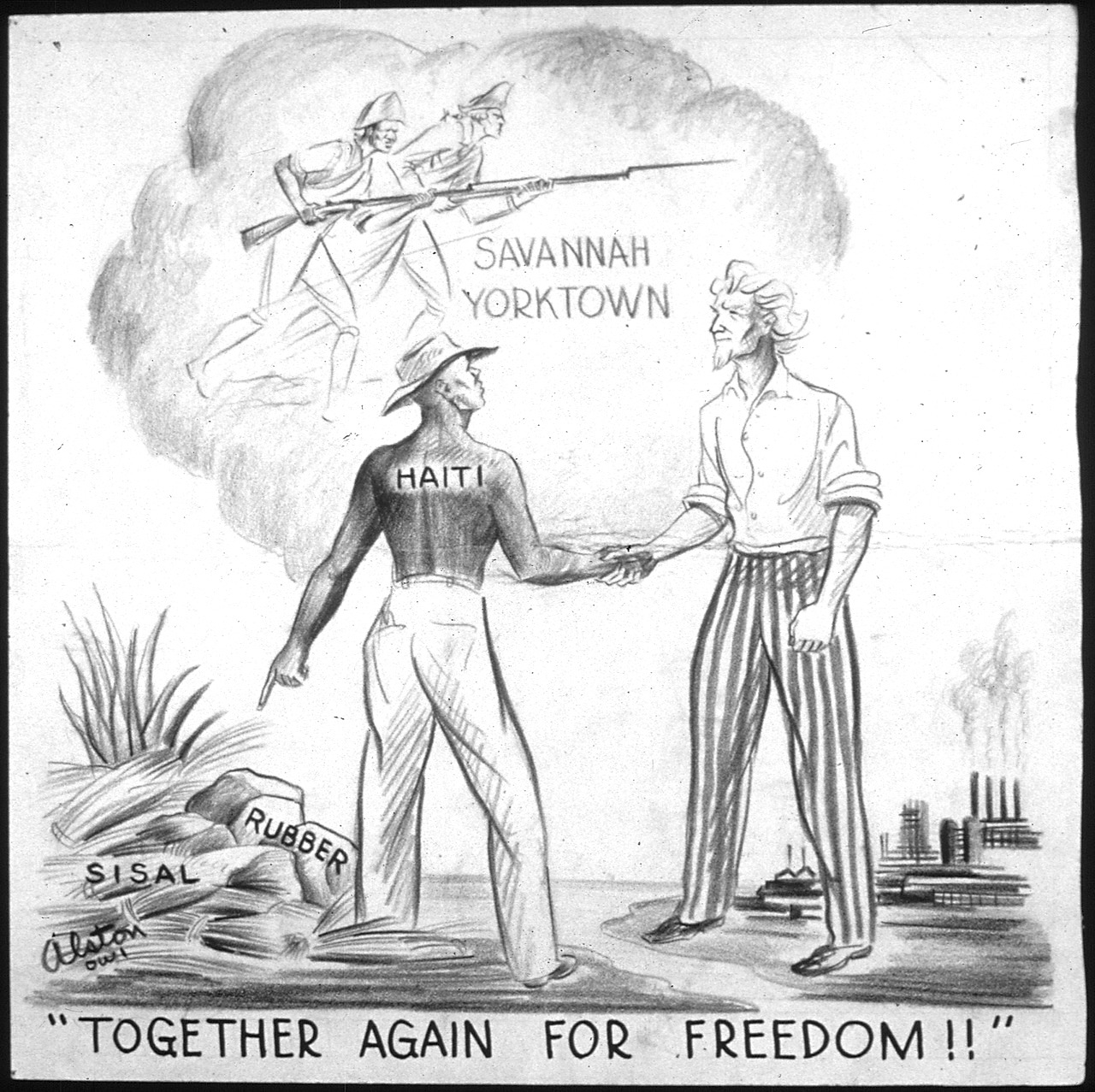

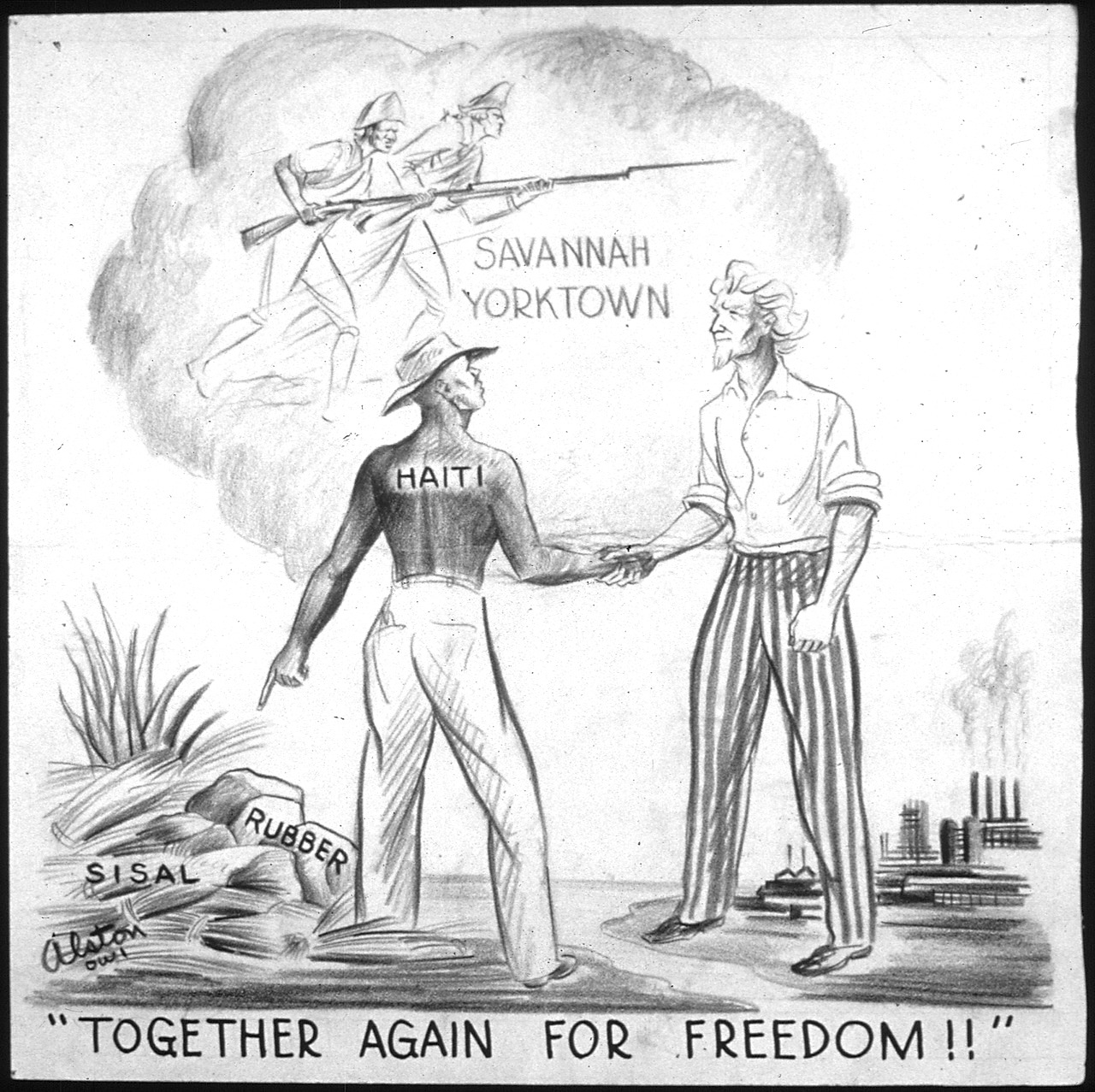

Revolution of 1946 "Together again for freedom", 1943 U.S. leaflet The Revolution of 1946 was a novel development in Haiti's history, as the Garde assumed power as an institution, not as the instrument of a particular commander. The members of the junta, known as the Military Executive Committee (Comité Exécutif Militaire), were Garde commander Colonel Franck Lavaud, Major Antoine Levelt, and Major Paul E. Magloire, commander of the Presidential Guard. All three understood Haiti's traditional way of exercising power, but they lacked a thorough understanding of what would be required to make the transition to an elected civilian government. Upon taking power, the junta pledged to hold free elections. The junta also explored other options, but public clamor, which included public demonstrations in support of potential candidates, eventually forced the officers to make good on their promise.[72] Haiti elected its National Assembly in May 1946. The Assembly set 16 August 1946, as the date on which it would select a president. The leading candidates for the office—all of whom were black—were Dumarsais Estimé, a former school teacher, assembly member, and cabinet minister under Vincent; Félix d'Orléans Juste Constant, leader of the Haitian Communist Party (Parti Communiste d'Haïti—PCH); and former Garde commander Démosthènes Pétrus Calixte, who stood as the candidate of a progressive coalition that included the Worker Peasant Movement (Mouvement Ouvrier Paysan—MOP). MOP chose to endorse Calixte, instead of a candidate from its own ranks, because the party's leader, Daniel Fignolé, was only thirty-three years old—too young to stand for the nation's highest office. Estimé, politically the most moderate of the three, drew support from the black population in the north, as well as from the emerging black middle class. The leaders of the military, who would not countenance the election of Juste Constant and who reacted warily to the populist Fignolé, also considered Estimé the safest candidate. After two rounds of polling, legislators gave Estimé the presidency.[72] |

1946年の革命 「自由のために再び共に」、1943年の米国のビラ 1946年の革命はハイチの歴史において斬新な展開であった。ガルドが特定の司令官の道具としてではなく、組織として権力を握ったからである。軍事執行委 員会(Comité Exécutif Militaire)として知られる軍閥のメンバーは、ガルド司令官のフランク・ラヴォー大佐、アントワーヌ・レベルト少佐、大統領警護隊司令官のポー ル・E・マグロワール少佐だった。3人ともハイチの伝統的な権力行使の方法を理解していたが、選挙で選ばれた文民政府への移行に何が必要かを十分に理解し ていなかった。政権を奪取したとき、民政党は自由選挙の実施を約束した。盟約者団は他の選択肢も検討したが、候補者候補を支持する市民デモを含む市民の喧 騒によって、結局、盟約者団は約束を果たすことを余儀なくされた[72]。 ハイチは1946年5月に国民議会を選出した。国民議会は1946年8月16日を大統領選出の日と定めた。大統領選の有力候補は、元学校教師で下院議員、 ヴァンサン政権下で閣僚を務めたドゥマルサイ・エスティメ、ハイチ共産党(Parti Communiste d'Haïti-PCH)党首のフェリックス・ドルレアン・ジュスト・コンスタン、労働者農民運動(Mouvement Ouvrier Paysan-MOP)を含む進歩的連合の候補として立候補した元ガルド司令官のデモステーヌ・ペトルス・キャリクスの3人で、いずれも黒人だった。 MOPは、党首ダニエル・フィニョレがまだ33歳で、ナショナリズムの最高権力者になるには若すぎたため、党内の候補者ではなくカリクスを推薦した。エス ティメは政治的には3人の中で最も穏健で、北部の黒人住民や新興の黒人中産階級から支持を集めた。ジュスト・コンスタンの当選を容認せず、ポピュリストの フィニョレを警戒していた軍の指導者たちも、エスティメが最も安全な候補者だと考えていた。2回の投票の後、議員たちはエスティメに大統領職を与えた [72]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Haiti |

リ ンク

ゾ ンビリンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆