The Eichmann trial

was the 1961 trial in Israel of major Holocaust perpetrator Adolf

Eichmann who was captured in Argentina by Israeli agents and brought to

Israel to stand trial.[1] The capturing of Eichmann was criticized by

the United Nations, calling it a "violation of the sovereignty of a

Member State". His trial, which opened on 11 April 1961, was televised

and broadcast internationally, intended to educate about the crimes

committed against Jews by Nazi Germany, which had been secondary to the

Nuremberg trials which addressed other war crimes of the Nazi

regime.[2] Prosecutor and Attorney General Gideon Hausner also tried to

challenge the portrayal of Jewish functionaries that had emerged in the

earlier trials, showing them at worst as victims forced to carry out

Nazi decrees while minimizing the "gray zone" of morally questionable

behavior.[3] Hausner later wrote that available archival documents

"would have sufficed to get Eichmann sentenced ten times over";

nevertheless, he summoned more than 100 witnesses, most of whom had

never met the defendant, for didactic purposes.[4] Defense attorney

Robert Servatius refused the offers of twelve survivors who agreed to

testify for the defense, exposing what they considered immoral behavior

by other Jews.[5] Political philosopher Hannah Arendt reported on the

trial in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of

Evil. The book had enormous impact in popular culture, but its ideas

have become increasingly controversial.

Eichmann was charged with fifteen counts of violating the Nazis and

Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law.[6] His trial began on 11 April

1961 and was presided over by three judges: Moshe Landau, Benjamin

Halevy, and Yitzhak Raveh.[7] Convicted on all fifteen counts, Eichmann

was sentenced to death. He appealed to the Supreme Court, which

confirmed the convictions and the sentence. President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi

rejected Eichmann's request to commute the sentence. In Israel's only

judicial execution to date, Eichmann was hanged on 1 June 1962 at Ramla

Prison.[8]

|

アイヒマン裁判は、1961年にイスラエルで行われたホロコーストの大

犯罪者アドルフ・アイヒマンの裁判である。アイヒマンの拘束は国連から「加盟国の主権侵害」と批判された。1961年4月11日に開廷したアイヒマンの裁

判はテレビ中継され、国際的に放送された。ナチス・ドイツによるユダヤ人に対する犯罪を啓蒙することを意図したもので、ナチス政権の他の戦争犯罪を取り上

げたニュルンベルク裁判とは二の次であった[2]。検事兼司法長官のギデオン・ハウスナーもまた、先の裁判で浮かび上がってきたユダヤ人官僚の描写に異議

を唱えようとし、彼らを最悪の場合、ナチスの命令を遂行することを余儀なくされた犠牲者として示す一方で、道徳的に問題のある行動という「グレーゾーン」

を最小限に抑えようとした。

[3]ハウズナーは後に、入手可能な公文書は「アイヒマンに10倍以上の判決を下すのに十分だっただろう」と書いている。それにもかかわらず、彼は教訓的

な目的のために、ほとんどが被告と面識のない100人以上の証人を召喚した[4]。弁護人のロバート・セルヴァティウスは、弁護側のために証言することに

同意した12人の生存者の申し出を拒否し、彼らが他のユダヤ人による不道徳な行動とみなしたことを暴露した[5]。政治哲学者のハンナ・アーレントは、著

書『エルサレムのアイヒマン』の中で裁判について報告している: A Report on the Banality of

Evil(悪の凡庸性に関する報告)』という本で裁判の様子を報告している。この本は大衆文化に多大な影響を与えたが、その考え方は次第に物議を醸すよう

になった。

アイヒマンは15件のナチスおよびナチス協力者(処罰)法違反の罪で起訴された[6]。

裁判は1961年4月11日に始まり、3人の裁判官が裁判長を務めた:

15件の訴因すべてで有罪となり、アイヒマンは死刑を宣告された[7]。彼は最高裁に上告し、最高裁は有罪と判決を確定した。イツハク・ベンズヴィ大統領

はアイヒマンの減刑要求を拒否した。1962年6月1日、イスラエルで唯一の死刑執行が行われ、アイヒマンはラムラ刑務所で絞首刑に処された[8]。

|

Background

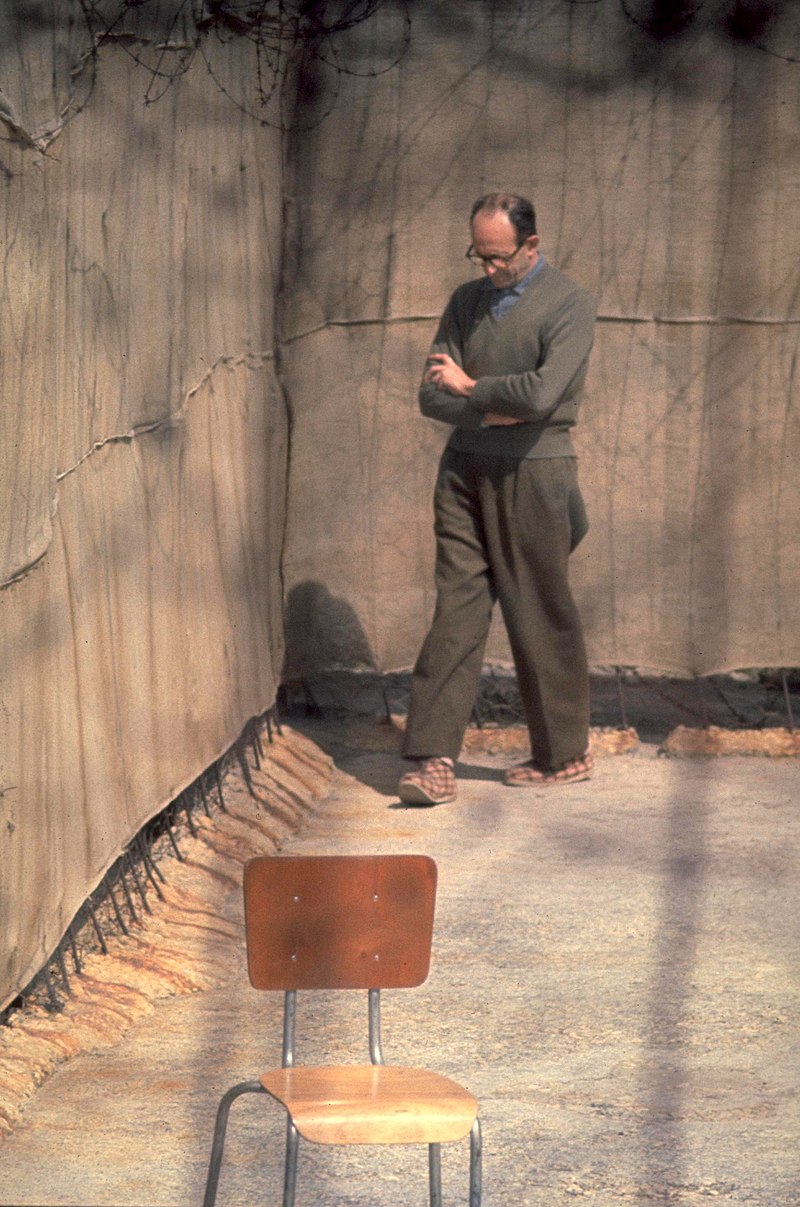

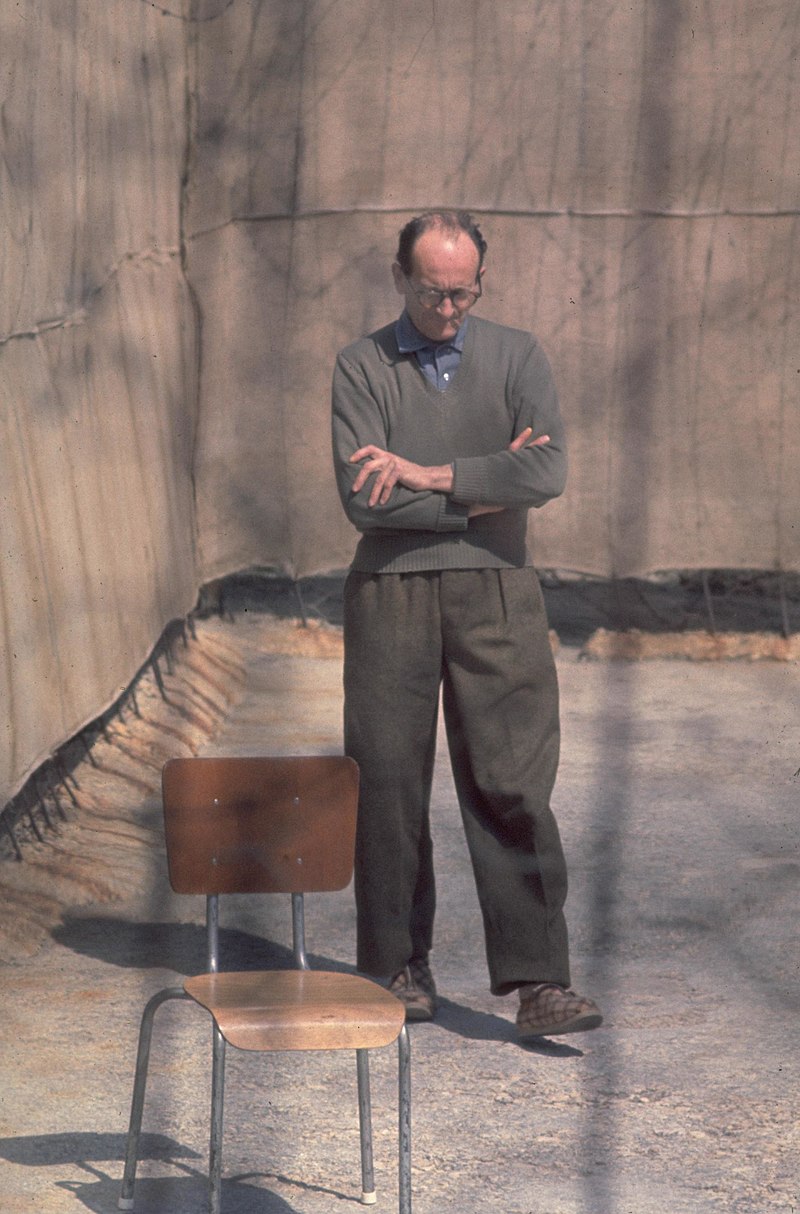

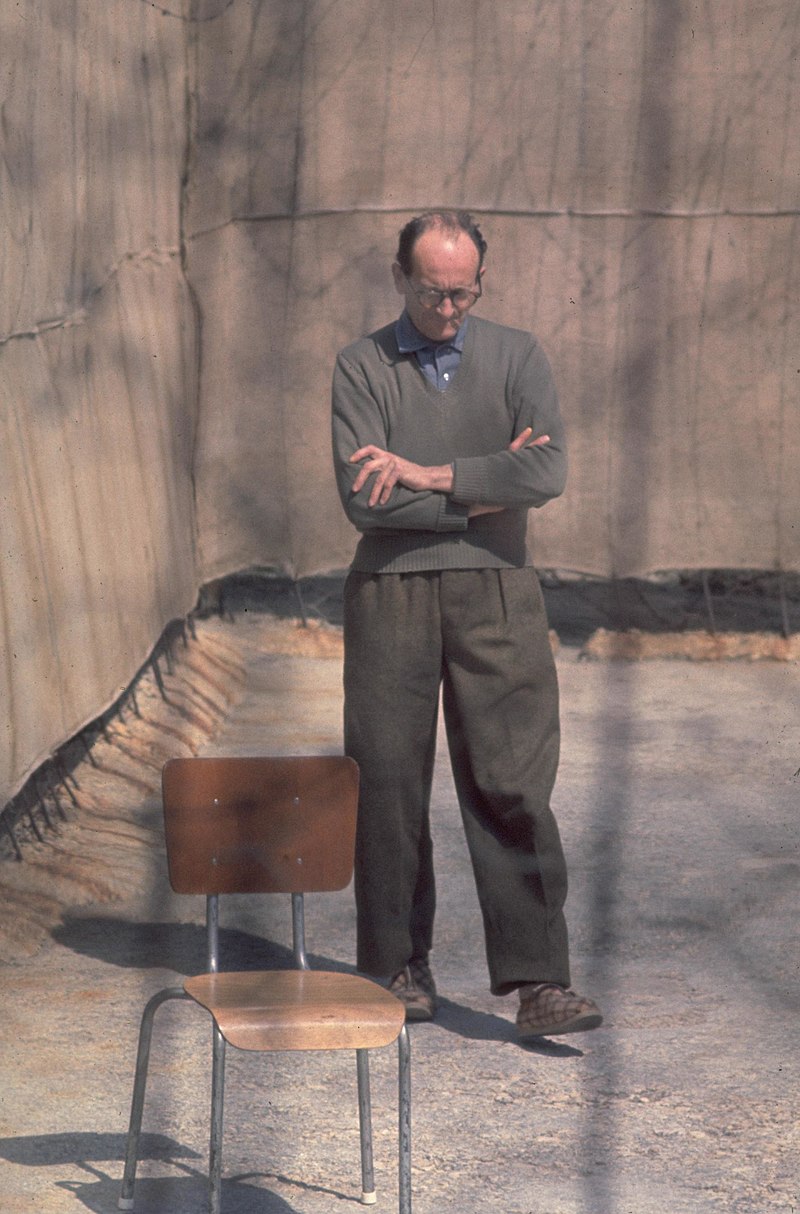

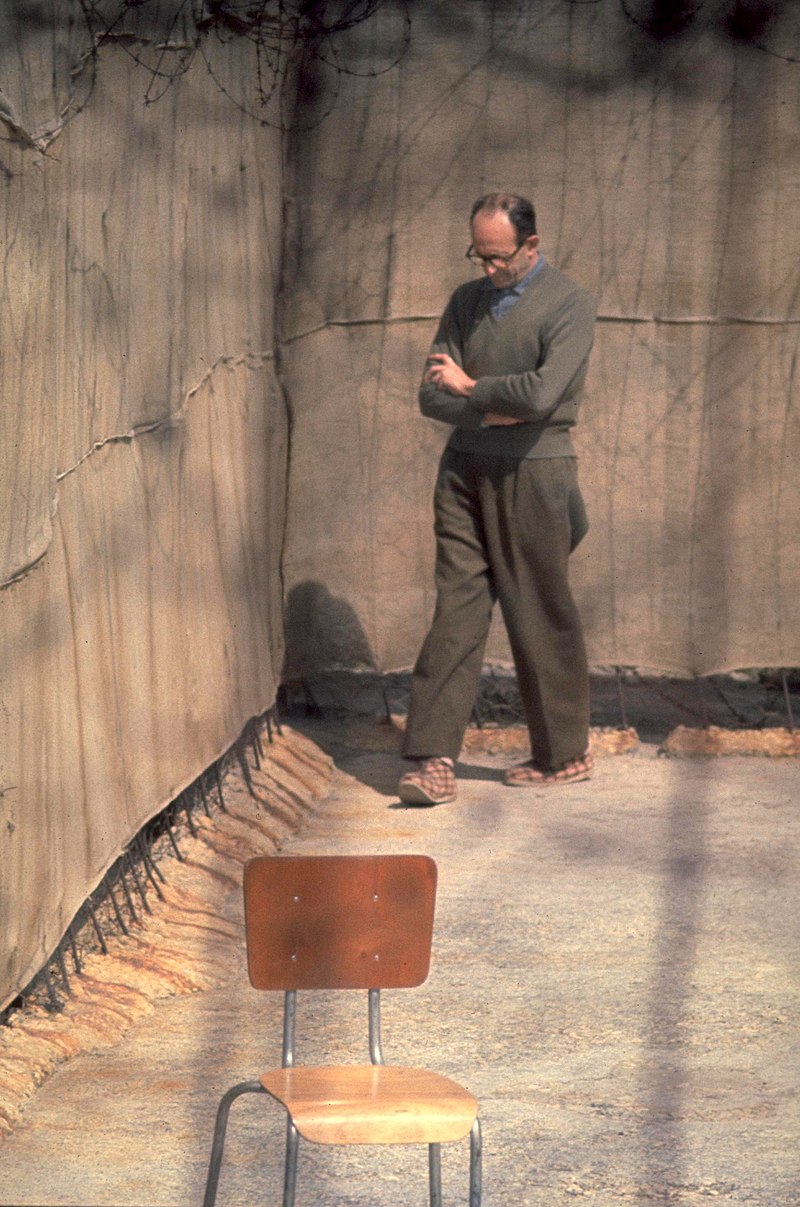

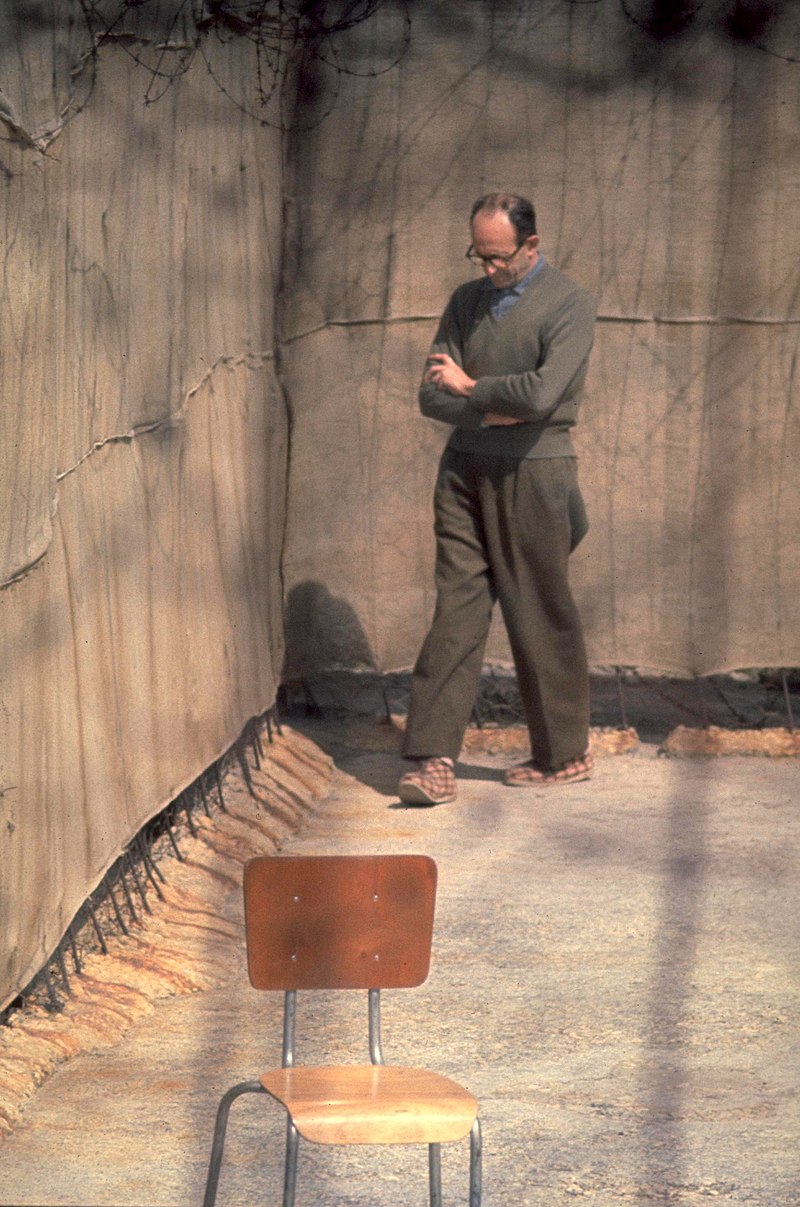

Eichmann in the yard at Ramla Prison in 1961

From 1933 to 1945, the Jews in Europe faced systematic persecution and

genocide at the hands of the Nazis in Germany and their collaborators

in the Holocaust.[9] From 1941 to 1945, this persecution increased as

part of the Final Solution, a plan to murder all of the Jews in Europe,

which resulted in the death of some six million Jews.[10]

Eichmann played a major part in the execution of the Holocaust. He fled

to Argentina at the end of the Second World War, but was abducted by

Israeli Mossad agents in 1960, and transported to Jerusalem to stand

trial.[11] Eichmann was held at a fortified police station in Yagur in

northern Israel for nine months prior to his trial.[12]

Trial

The trial of Eichmann was held from 11 April to 15 August 1961 at Beit

Ha'am, a community theatre temporarily reworked to serve as a courtroom

capable of accommodating 750 observers.[13]

|

背景

1961年、ラムラ刑務所の庭でのアイヒマン

1933年から1945年まで、ヨーロッパのユダヤ人は、ドイツのナチスとその協力者によるホロコーストの組織的迫害と大量虐殺に直面した[9]。

1941年から1945年まで、この迫害は、ヨーロッパのユダヤ人すべてを殺害する計画である最終的解決策の一環として強化され、約600万人のユダヤ人

が死亡した[10]。

アイヒマンはホロコーストの実行に大きな役割を果たした。彼は第二次世界大戦末期にアルゼンチンに逃亡したが、1960年にイスラエルのモサド工作員に

よって拉致され、裁判を受けるためにエルサレムに移送された[11]。アイヒマンは裁判を受けるまでの9ヵ月間、イスラエル北部のヤグルにある要塞化され

た警察署に拘束された[12]。

裁判

アイヒマンの裁判は1961年4月11日から8月15日まで、750人の傍聴人を収容できる法廷として一時的に改築されたコミュニティ劇場であるベイト・

ハームで行われた[13]。

|

Trial

The trial of Eichmann was held from 11 April to 15 August 1961 at Beit

Ha'am, a community theatre temporarily reworked to serve as a courtroom

capable of accommodating 750 observers.[13]

Charges

Counts 1–4 were for crimes against the Jewish people:[6]

Killing Jews, via the systematic deportation of millions of Jews to the

extermination camps beginning in August 1941[14]

Placing Jews in living conditions calculated to bring about their

physical destruction, by imprisoning them in concentration and

extermination camps[14]

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to Jews[14]

Preventing births against Jews, with an order for forced abortions in

Theresienstadt Ghetto[14]

Counts 5–7 were for crimes against humanity against Jews:[6]

Forced emigration of Jews from March 1938 to October 1941, deportation

of Jews in October 1939 during the Nisko Plan, and his role in the

Final Solution[15]

Persecuting Jews on national, religious, or political grounds[15]

The systematic plunder of the property of millions of Jews. Theft of

property was not enumerated in the law as a crime against humanity (it

was counted as a war crime), but the prosecution argued that it fit the

criteria of "any other inhuman act committed against any civilian

population" as stipulated in the law. Since Eichmann founded the

Central Office for Jewish Emigration, which confiscated the property of

deported Jews, and the court determined that the purpose of such

confiscation was in part to instill terror and facilitate the

deportation and murder of Jews, it found him guilty on this count.[16]

Count 8 was for war crimes, based on Eichmann's role in the systematic

persecution and murder of Jews during World War II.[17]

Counts 9–12 related to crimes against humanity against non-Jews:[6]

Mass deportations of Polish civilians[18]

Mass deportations of Slovene civilians[18]

Participation in the Romani genocide by the systematic forced

deportation of Romani people. Although the court did not find evidence

that Eichmann knew that the Romani victims were sent to extermination

camps, it nevertheless found him guilty on that count.[19]

Participation in the Lidice massacre; he was found guilty for

deportation of part of the population of Lidice, but not the massacre

itself.[19]

Counts 13–15 charged Eichmann with membership in enemy organizations,

respectively the Schutzstaffeln der NSDAP (SS), Sicherheitsdienst des

Reichführers SS (SD), and Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo). He was found

guilty on all three counts because he was not only proven to be a

member of these organizations but committed crimes as part of his role,

namely those discussed above.[17]

|

裁判

アイヒマンの裁判は1961年4月11日から8月15日まで、750人の傍聴人を収容できる法廷として一時的に改築されたコミュニティ劇場であるベイト・

ハームで開かれた[13]。

罪状

訴因1~4はユダヤ人に対する犯罪であった[6]。

1941年8月に始まった数百万人のユダヤ人の絶滅収容所への組織的な強制送還によるユダヤ人の殺害[14]。

ユダヤ人を強制収容所や絶滅収容所に収監することによって、身体的破壊をもたらすように計算された生活環境に置くこと[14]。

ユダヤ人に身体的または精神的に深刻な危害を加えること[14]。

テレジエンシュタット・ゲットーでの強制堕胎命令[14]をもって、ユダヤ人に対する出産を阻止した[14]。

5-7項はユダヤ人に対する人道に対する罪であった[6]。

1938年3月から1941年10月までのユダヤ人の強制移住、1939年10月のニスコ計画におけるユダヤ人の強制送還、最終解決における役割

[15]。

国家的、宗教的、政治的な理由でユダヤ人を迫害した[15]。

数百万人のユダヤ人の財産を組織的に略奪した。財産の略奪は人道に対する罪として法律には列挙されていなかったが(戦争犯罪としてカウントされていた)、

検察側はそれが法律に規定されている「あらゆる民間人に対して行われたその他の非人道的行為」の基準に合致すると主張した。アイヒマンはユダヤ人移住中央

事務所を設立し、強制送還されたユダヤ人の財産を没収しており、裁判所は、そのような没収の目的は、恐怖を植え付け、ユダヤ人の強制送還と殺害を容易にす

ることであったと判断したので、この訴因で有罪とした[16]。

第8郡は、第二次世界大戦中のユダヤ人の組織的迫害と殺害におけるアイヒマンの役割に基づく戦争犯罪に関するものであった[17]。

訴因9~12は、非ユダヤ人に対する人道に対する罪に関するものであった[6]。

ポーランド民間人の大量国外追放[18]。

スロベニア民間人の集団強制送還[18]。

ロマーニ人の組織的強制送還によるロマーニ人大量虐殺への参加。裁判所は、アイヒマンがロマニ人の犠牲者が絶滅収容所に送られることを知っていたという証

拠を発見しなかったが、それにもかかわらず、この訴因で有罪とした[19]。

リディツェの虐殺への参加;彼はリディツェの住民の一部を強制送還したことで有罪とされたが、虐殺そのものではなかった[19]。

第13-15項は、アイヒマンを、それぞれNSDAP親衛隊(SS)、ライヒフューラー親衛隊(SD)、ゲシュタポ(Gestapo)という敵対組織の一

員であった罪で起訴した。彼はこれらの組織のメンバーであったことが証明されただけでなく、その役割の一部として犯罪、すなわち上述の犯罪を犯したため、

3つの訴因すべてについて有罪とされた[17]。

|

Citations

Bazyler & Scheppach 2012, p. 438.

Bazyler & Scheppach 2012, p. 439.

Porat 2019, p. 173.

Porat 2019, p. 174.

Porat 2019, p. 180.

Bazyler & Scheppach 2012, p. 443.

Cesarani 2005, p. 255.

Bazyler & Scheppach 2012, p. 449.

Rogers, Alisdair; Castree, Noel; Kitchin, Rob (2013).

"Holocaust". A Dictionary of Human Geography. Oxford, England: Oxford

University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-175806-5.

Dear, I. C. B.; Foot, M. R. D. (2014). "Final Solution". The

Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford, England: Oxford University

Press. ISBN 978-0-19-172760-3.

Dear, I. C. B.; Foot, M. R. D. (2014). "Eichmann, Adolf". The

Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford, England: Oxford University

Press. ISBN 978-0-19-172760-3.

Cesarani 2005, pp. 237–240.

Cane, Peter; Conaghan, Joanne (2009). "Eichmann, Adolf". The New

Oxford Companion to Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN

978-0-19-172726-9.

Bazyler & Scheppach 2012, pp. 443–444.

Bazyler & Scheppach 2012, pp. 444–445.

Bazyler & Scheppach 2012, pp. 445–446.

Bazyler & Scheppach 2012, p. 447.

Bazyler & Scheppach 2012, p. 446.

Bazyler & Scheppach 2012, pp. 446–447.

|

Bibliography

Bazyler, Michael; Scheppach, Julia (2012). "The Strange and Curious

History of the Law Used to Prosecute Adolf Eichmann". Loyola of Los

Angeles International and Comparative Law Review. 34 (3): 417–461. ISSN

0277-5417.

Cesarani, David (2005). Eichmann: His Life and Crimes. London, England:

Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-944844-0. OCLC 224240952.

Porat, Dan (2019). Bitter Reckoning: Israel Tries Holocaust Survivors

as Nazi Collaborators. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-24313-2.

|

Further reading

Arendt, Hannah (2006). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality

of Evil. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-303988-4.

Lipstadt, Deborah E. (2011). The Eichmann Trial. New York: Schocken

Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-4260-7.

Segev, Tom (1993). The Seventh Million: The Israelis and the Holocaust.

New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-8563-7.

Wittmann, Rebecca, ed. (2021). Eichmann Trial Reconsidered. University

of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-0849-4.

Yablonka, Hanna (2004). The State of Israel vs. Adolf Eichmann. New

York: Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-4187-7.

|

|

|

|

Corpse-like obedience (German:

Kadavergehorsam, also translated as corpse obedience, cadaver

obedience, cadaver-like obedience, zombie-like obedience, slavish

obedience, unquestioning obedience, absolute obedience or blind

obedience) refers to an obedience in which the obeying person submits

unreservedly and passively to another's will, like a mindless, animated

cadaver.

Jesuit origin

The term originated with the Jesuit work by Ignatius of Loyola from

1553, the Letter on Obedience.[1] It has also been dated to 1558.[2]

That text said, in Latin: "Et sibi quisque persuadeat, quod qui sub

Obedientia vivunt, se ferri ac regi a divina Providentia per Superiores

suos sinere debent perinde, ac si cadaver essent" which can be

translated as "We should be aware that each of those who live in

obedience must allow himself to be led and guided by Divine Providence

through the Superior, as if he were a dead body".[6] The concept,

described in the Jesuit context as "fabled and misunderstood",[7] has

since been criticised by detractors of the Jesuit order as blind

obedience.[12] Jesuit supporters, in turn, refer to it as the "perfect

obedience".[1][10]

Modern use

The term is often associated with Germany (where it is known as

Kadavergehorsam), where it refers to "both obedience and loyalty until

death"[13] or simply "absolute obedience"[14] or "blind obedience".[15]

It has been associated with the discussion of German military and

administration of the Prussian[16][17][18] and Nazi eras and their

passive adherence to carrying out orders, including those later judged

to be war crimes (see also Prussian virtues, German militarism,

Befehlsnotstand, Führerprinzip, and superior orders).[24] The Law for

the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service of 1933 has been

credited with enforcing this idea in the Nazi German civil

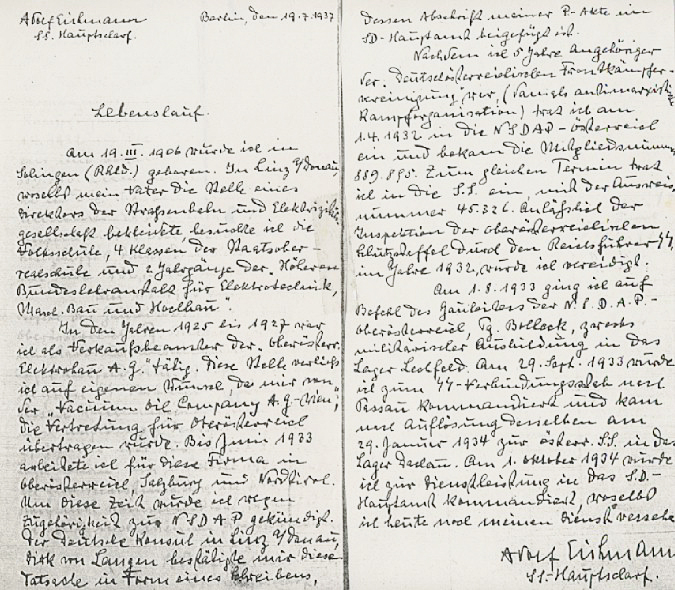

administration.[23] Adolf Eichmann, one of the major organisers of the

Holocaust, invoked this concept in his defence during his post-war

trial.[22][25][26]

The term has also been used in the context of other totalitarian

regimes, such as communist states and parties.[33] The concept has been

described as promoted by works such as The Communist Manifesto or Mein

Kampf.[27]

The concept has also been mentioned in the context of extreme

interpretation of military discipline.[5][34]

Some scholars have translated the term as zombie-like

obedience.[29][32][35] A similar variation occurs in Nigerian afrobeat

artist Fela Kuti's song "Zombie" (from the album of the same name), in

which Kuti calls Nigerian soldiers zombies as a critique of the

country's military government.[36][37]

|

死体のように服従する(ドイツ語:Kadavergehorsam、死

体服従、死体服従、死体様服従、ゾンビ様服従、奴隷的服従、疑わない服従、絶対服従、盲目的服従とも訳される)とは、服従する者が、無心で生気に満ちた死

体のように、他者の意志に無遠慮かつ受動的に服従する服従を指す。

イエズス会の起源

この用語は、1553年にロヨラのイグナチオによって書かれたイエズス会の著作『服従に関する書簡』に由来する[1]。 [2]

その文章はラテン語で、「Et sibi quisque persuadeat, quod qui sub Obedientia vivunt,

se ferri ac regi a divina Providentia per Superiores suos sinere debent

perinde, ac si cadaver essent

」とあり、これは「従順に生きる者は、あたかも死体であるかのように、上長を通して神の摂理に導かれ、導かれることを各自が許さなければならないことを自

覚すべきである」と訳すことができる。 [6] この概念はイエズス会の文脈では「寓話的で誤解されている」[7]

と評され、それ以来、イエズス会の支持者たちによって盲目的な従順として批判されている[12]

が、イエズス会の支持者たちはそれを「完全な従順」と呼んでいる[1][10]。

現代の使用

この用語はしばしばドイツ(カダヴェルゲホルサムとして知られる)と関連しており、そこでは「死ぬまで服従と忠誠の両方」[13]、あるいは単に「絶対服

従」[14]、あるいは「盲目的服従」を指す。 [15]

プロイセン時代[16][17][18]やナチス時代のドイツ軍や行政の議論や、後に戦争犯罪と判断されるものも含めて命令を遂行することへの消極的な服

従と関連付けられている(プロイセンの美徳、ドイツ軍国主義、ベフェールスノットスタンド、総統プリンツィップ、上級命令も参照)。

[ホロコーストの主要な組織者の一人であったアドルフ・アイヒマンは、戦後の裁判において、弁明においてこの概念を唱えた[22][25][26]。

この用語は、共産主義国家や政党など、他の全体主義体制の文脈でも使用されている[33]。

この概念は、『共産党宣言』や『我が闘争』などの著作によって促進されたと説明されている[27]。

また、この概念は軍事規律の極端な解釈という文脈でも言及されている[5][34]。

この用語をゾンビのような服従と訳した学者もいる[29][32][35]。

ナイジェリアのアフロビート・アーティストであるフェラ・クティの曲「ゾンビ」(同名のアルバムに収録)にも同様のバリエーションがあり、クティはナイ

ジェリアの軍政に対する批判としてナイジェリアの兵士をゾンビと呼んでいる[36][37]。

|

![]()