My friend, a

Zombie, Antonin Artaud, 1896-1948

アントナン・アルトー

My friend, a

Zombie, Antonin Artaud, 1896-1948

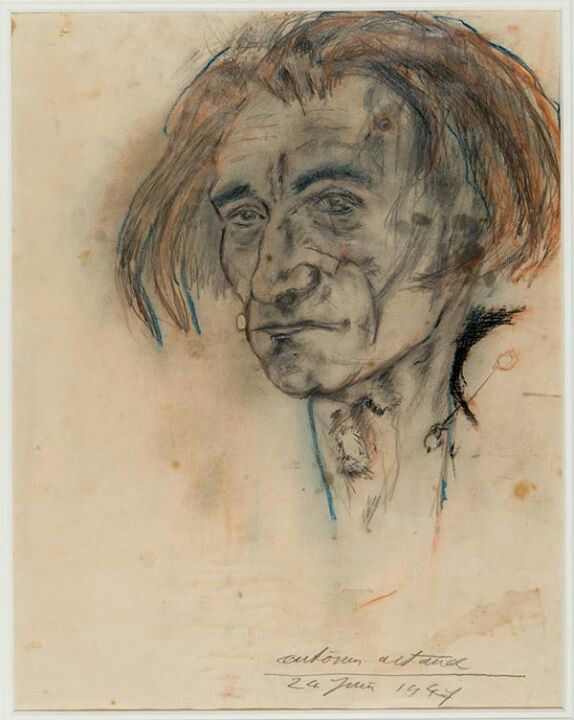

アントナン・アルトー(Antonin Artaud, 1896-1948)En 1926, Antonin Artaud incarne au cinéma le Juif errant.// Self-portrait of Artaud from 1947;解説:池田光穂

アントナン・アルトー(Antonin Artaud、1896年9月4日 - 1948年3月4日)は、フランスの俳優・詩人・小説家・演劇家。スミルナ(現在のイズミール)出身のギリシャ人の両親の元、マルセイユで生まれる [1]。 幼少に罹患した髄膜炎の後遺症の痛みに耐えるために一生阿片などの麻薬を服用し続けた。1920年ごろから俳優活動をはじめ、また詩も始める。1924 年、シュールレアリスム運動に加わるも、ブルトンと衝突。1928年、除名された[2]。『NRF』誌のリヴィエールとの交信は有名。アルフレッド・ジャ リ劇場を創設し、身体演劇である「残酷劇」を提唱。現代演劇に絶大な影響を与える。1920年代後半には映画に関わる仕事が続く。アベル・ガンス監督の超 大作映画『ナポレオン』(1926年)出演(ジャン=ポール・マラー役)に続いて、 サイレント映画の最高峰と評されるカール・ドライヤー監督の『裁かるゝジャンヌ』(1927年)に出演(修道士ジャン・マシュー役)。また同じ時期にジェ ルメーヌ・デュラック監督『貝殻と僧侶』(1927年)の脚本を書いているが、実質は映画の現場にも参加させて貰えず、脚本も監督に書き変えられている。 1936年、アイルランドの地に聖パトリックの杖を還すという目論見のもと、アイルランドを目指すが、道中に警察官に拘束され、統合失調症と診断され精神 病院に収監され、フランスに強制送還される。ジャック・ラカンやガストン・フェルディエールの診察を受けて、サンタンヌ病院、ル・アーヴル病院、イヴェー ル病院、ロデーズの病院を盥回しにされ、51回もの電気ショック療法を受け、9年間収容されることになった。1946年5月、ロベール・デスノスら友人ら の助力で退院する。退院した直後は母親の顔さえ分からないほど錯乱していた。後に、その当時の体験を告発し た。『ヴァン・ゴッホー社会による自殺者』でサント=ブーヴ賞受賞。その思想はドゥルーズ&ガタリやデリダに影響を与えた。その演劇論はピーター・ブルッ クらに受け継がれる。1948年3月4日、パリ郊外イブリーの療養所にて死去。満51歳没。ベッドに腰掛けたまま亡くなっていた[3](→「〈病む=苦悩する〉ことの人類学」)。

| Antoine Marie

Joseph Paul Artaud,

better known as Antonin Artaud (pronounced [ɑ̃tɔnɛ̃ aʁto]; 4 September

1896 – 4 March 1948), was a French writer, poet, dramatist, visual

artist, essayist, actor and theatre director.[1][2] He is widely

recognized as a major figure of the European avant-garde. In

particular, he had a profound influence on twentieth-century theatre

through his conceptualization of the Theatre of Cruelty.[3][4][5] Known

for his raw, surreal and transgressive work, his texts explored themes

from the cosmologies of ancient cultures, philosophy, the occult,

mysticism and indigenous Mexican and Balinese practices.[6][7][8][9] |

アントワーヌ・アルトー(Antoine Marie Joseph

Paul Artaud、発音: [ɑñ]、1896年9月4日 -

1948年3月4日)は、フランスの作家、詩人、劇作家、映像作家、エッセイスト、俳優、劇場監督である[1][2]。特に、残酷劇場の概念化を通じて

20世紀の演劇に大きな影響を与えた[3][4][5]。生々しい、超現実的で侵犯的な作品で知られる彼のテキストは、古代文化の宇宙論、哲学、オカル

ト、神秘主義、メキシコやバリ島の先住民の慣習からテーマを探求した[6][7][8][9]。 |

| Early life Antonin Artaud was born in Marseille, to Euphrasie Nalpas and Antoine-Roi Artaud.[2] His parents were first cousins—his grandmothers were sisters from Smyrna (modern day İzmir, Turkey). His paternal grandmother, Catherine Chilé, was raised in Marseille, where she married Marius Artaud, a Frenchman. His maternal grandmother, Mariette Chilé, grew up in Smyrna, where she married Louis Nalpas, a local ship chandler.[10] He was, throughout his life, greatly affected by his Greek ancestry.[2] Euphrasie gave birth to nine children, but four were stillborn and two others died in childhood.[2] Artaud was diagnosed with meningitis at age five, a disease which had no cure at the time.[11] Biographer David Shafer points out, "given the frequency of such misdiagnoses, coupled with the absence of a treatment (and consequent near-minimal survival rate) and the symptoms he had, it's unlikely that Artaud actually contracted it."[2] From 1907 to 1914, Artaud attended the Collége Sacré-Coeur. Here he began reading works by Arthur Rimbaud, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Edgar Allan Poe and founded a private literary magazine in collaboration with his friends. At the end of college he started to noticeably withdraw from social life and "destroyed most of his written work and gave away his books."[5]:3 Distressed, his parents arranged for him to see a psychiatrist.[2]:25 Over the next five years Artaud was admitted to a series of sanatoria.[12]:163 There was a pause in his treatment in 1916, when Artaud was conscripted into the French Army.[2]:26 He was discharged due to "an unspecified health reason" (Artaud later claimed it was "due to sleepwalking", while his mother ascribed it to his "nervous condition").[5]:4 In May 1919, the director of the sanatorium prescribed laudanum for Artaud, precipitating a lifelong addiction to that and other opiates.[12]:162 In March 1921, Artaud moved to Paris where he was put under the psychiatric care of Dr Édouard Toulouse who took him in as a boarder.[2]:29 |

幼少期 アントナン・アルトーはマルセイユでエウフレイシー・ナルパスとアントワーヌ・ロワ・アルトーの間に生まれた[2]。両親はいとこ同士で、祖母はスミルナ (現在のトルコ、イズミル)出身の姉妹であった。父方の祖母カトリーヌ・シレはマルセイユで育ち、フランス人のマリウス・アルトーと結婚した。母方の祖母 マリエット・シレはスミルナで育ち、地元の船具商ルイ・ナルパスと結婚した[10]。 アルトーは5歳の時に髄膜炎と診断されたが、この病気は当時治療法がなかった[11]。伝記作家のデヴィッド・シェイファーは、「このような誤診の頻度 と、治療法がないこと(その結果、生存率が極小に近い)、彼の症状から、アルトーが実際に感染したとは考えにくい」と指摘している[2]。 1907年から1914年まで、アルトーはサクレ・クール校に通いました。ここでアルチュール・ランボー、ステファン・マラルメ、エドガー・アラン・ポー の作品を読み始め、友人たちと共同で私設文芸誌を創刊した。大学卒業後、アルトーは社会生活から著しく遠ざかり、「書いたもののほとんどを破棄し、本を手 放した」[5]:3 悩んだ両親は、彼を精神科医に診せた[2]:25 1916年、アルトーはフランス軍に徴兵され、治療は一時中断された[2]:26 彼は「特定できない健康上の理由」によって除隊した(アルトーは後に「夢遊病のため」と主張し、彼の母は「神経症」によるものとした)。 [1919年5月、療養所の院長はアルトーにローダナムを処方し、そのローダナムと他のアヘンへの生涯の依存を促した[12]:162 1921年3月、アルトーはパリに移り、エドアール・トゥールーズ博士の精神医療の下に置かれ、彼は寮生として彼を迎え入れた[2]:29。 |

| Theatrical apprenticeships In Paris, Artaud worked with a number of celebrated French "teacher-directors". This included Jacques Copeau, André Antoine, Georges and Ludmilla Pitoëff, Charles Dullin, Firmin Gémier and Lugné Poe.[4] Lugné Poe, who gave Artaud his first work in a professional theatre, later described Artaud as "a painter lost in the midst of actors".[13]: 350 His core theatrical training was as part of Dullin's troupe, Théâtre de l'Atelier, which he joined in 1921.[13]:345 Artaud remained a member for eighteen months.[13]:345 As a member of Dullin's troupe, Artaud trained for 10 to 12 hours a day.[14]: 119 Originally Artaud was a strong proponent of Dullin's teaching, stating: "Hearing Dullin teach I feel that I'm rediscovering ancient secrets and a whole forgotten mystique of production."[13]:351 In particular, they shared a strong interest in east Asian theater, specifically performance traditions from Bali and Japan.[5]:10 Dullin, however, did not think Western theater should be adopting the language and style of east Asian theatre. Instead he promoted a theatre of transposition;[15] for Dullin, "To want to impose on our Western theater rules of a theatre of a long tradition which has its own symbolic language would be a great mistake."[13]: 351 Artaud came to disagree with many of Dullin's teachings.[13]:352 Their final disagreement was over his performance of the Emperor Charlemagne in Alexandre Arnoux's Huon de Bordeaux and he left the troupe in 1923.[1]:22 He joined the Pitoëff's troupe in 1923, remaining with them through the next year when he put more focus on his work in the cinema.[5]:15-16 |

演劇の見習い アルトーはパリで、フランスの著名な「教師演出家」たちと仕事をした。ジャック・コポー、アンドレ・アントワーヌ、ジョルジュ&リュドミラ・ピトエフ、 シャルル・デュラン、フィルミン・ジェミエ、ルグネ・ポーなどである[4]。ルグネ・ポーはアルトーにプロの劇場での最初の仕事を与え、後にアルトーを 「俳優たちの中に紛れ込んだ画家」と表現した[13]: 350 彼の演劇的訓練の中心は、1921年に加入したデュリンの劇団「アトリエの劇場」の一員としてのものであった[13]:345 アルトーは18ヶ月間メンバーにとどまった[13]:345。 デュリンの劇団員として、アルトーは1日に10時間から12時間の訓練を受けた[14]: 119 もともとアルトーはデュリンの教えを強く支持し、次のように述べている: 「デュリンの教えを聞くと、私は古代の秘密や、忘れられていた制作の神秘性を再発見しているような気がする」[13]:351 特に、二人は東アジア演劇、特にバリや日本のパフォーマンスの伝統に強い関心を共有していた [5]:10 しかしデュリンは、西洋演劇が東アジア演劇の言語やスタイルを取り入れるべきだとは考えていなかった。その代わりに彼は転置の演劇を推進した[15]。 デュリンにとって、「独自の象徴的言語を持つ長い伝統のある演劇のルールを我々の西洋演劇に押し付けようとするのは、大きな間違いである」[13]: 351 アルトーはデュランの教えの多くに反対するようになった[13]:352 二人の最後の不和は、アレクサンドル・アルヌーの『ボルドーのユーオン』で皇帝シャルルマーニュを演じたことであり、彼は1923年に劇団を去った[1] :22 彼は1923年にピトエフの劇団に参加、翌年まで所属したが映画での仕事に一層注力した[5] :15-16 。 |

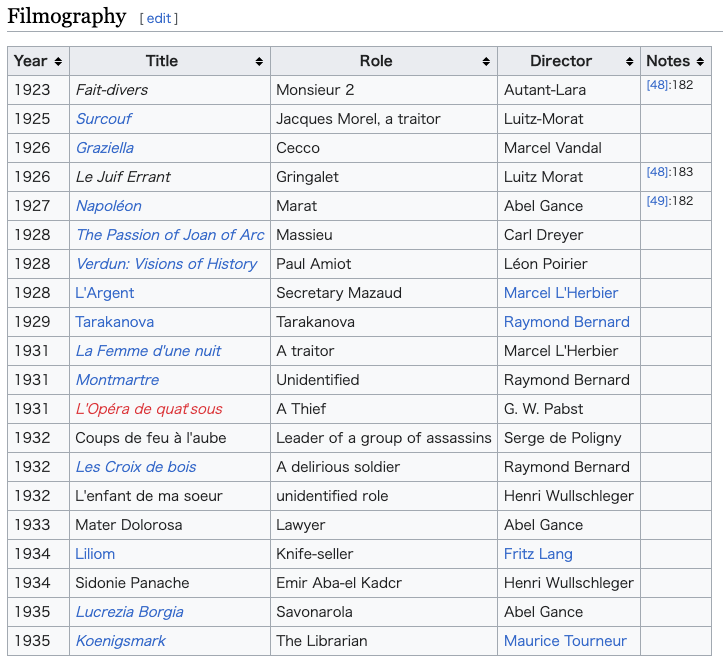

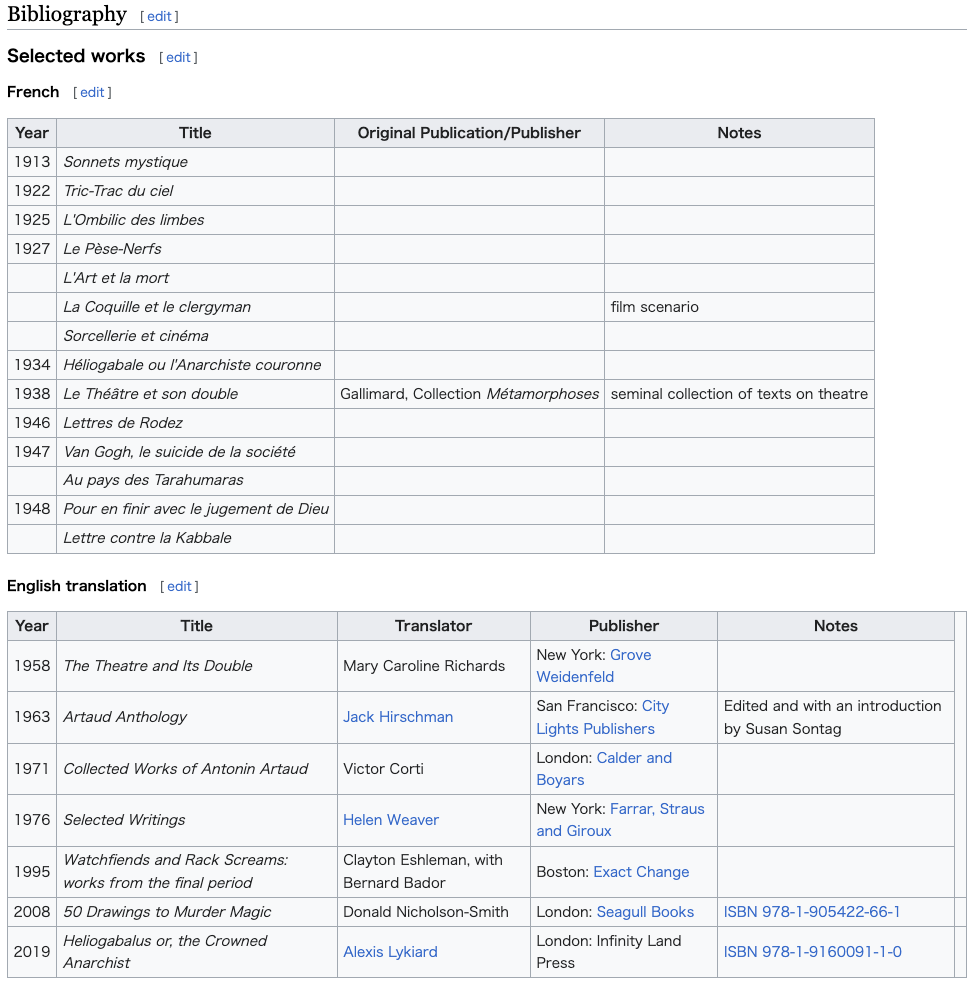

| Literary career In 1923, Artaud mailed some of his poems to the journal La Nouvelle Revue Française (NRF); they were rejected, but the author of the poems intrigued the NRF's editor, Jacques Rivière, who requested a meeting. After meeting via post they continued their relationship. The compilation of these letters into an epistolary work, Correspondance avec Jacques Rivière, was Artaud's first major publication.[5]:45 Artaud continued to publish some of his most important work in the NRF, including the "First Manifesto for a Theatre of Cruelty" (1932) and "Theatre and the plague" (1933).[1]:105 He drew from these publications when putting together The Theatre and Its Double.[1]:105  Antonin Artaud en 1926. Work in the cinema Artaud also had an active career in the cinema working as a critic, actor, and writer.[16] Artaud's performance as Jean-Paul Marat in Abel Gance's Napoléon (1927) used exaggerated movements to convey the fire of Marat's personality.[citation needed] He also played the monk Massieu in Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928).[5]:17 He wrote a number of film scenarios, ten of which have survived.[5]:23 Only one of Artaud's scenarios was produced, The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928). Directed by Germaine Dulac, many critics and scholars consider it to be the first surrealist film.[17][18] Association with surrealists Artaud was briefly associated with the surrealists, before being expelled by André Breton in 1927.[5]:21 This was in part due to the Surrealists increasing affiliation with the Communist Party in France.[19]:274 As Ros Murray notes, "Artaud was not into politics at all, writing things like: 'I shit on Marxism.'" Additionally, "Breton was becoming very anti-theatre because he saw theatre as being bourgeois and anti-revolutionary."[20] In "The Manifesto for an Abortive Theatre" (1926/27), written for the Theatre Alfred Jarry, Artaud makes a direct attack on the surrealists, whom he calls "bog-paper revolutionaries" that would "make us believe that to produce theatre today is a counter-revolutionary endeavour".[6]:24 He declares they are "bowing down to Communism",[6]:25 which is "a lazy man's revolution",[6]:24 and calls for a more "essential metamorphosis" of society.[6]:25 Théâtre Alfred Jarry (1926–1929) (For more details, including a full list of productions, see Théâtre Alfred Jarry) In 1926, Artaud, Robert Aron and the expelled surrealist Roger Vitrac founded the Théâtre Alfred Jarry (TAJ).[21] They staged four productions between June 1927 and January 1929. The Theatre was extremely short-lived, but was attended by an enormous range of European artists, including Arthur Adamov, André Gide, and Paul Valéry.[21]:249 At the Paris Colonial Exposition (1931) In 1931, Artaud saw Balinese dance performed at the Paris Colonial Exposition. Although Artaud misunderstood much of what he saw, it influenced many of his ideas for theatre.[5]:26 Adrian Curtin has noted the significance of the Balinese use of music and sound, stating that Artaud was struck by "the 'hypnotic' rhythms of the gamelan ensemble, its range of percussive effects, the variety of timbres that the musicians produced, and – most importantly, perhaps – the way in which the dancers' movements interacted dynamically with the musical elements instead of simply functioning as a type of background accompaniment."[22]: 253 The Cenci (1935) In 1935, Artaud staged an original adaptation of Percy Bysshe Shelley's The Cenci at the Théâtre des Folies-Wagram in Paris.[22]:250 The drama was Artaud's only chance to stage a Theatre of Cruelty production, and he emphasised its cruelty and violence, in particular "its themes of incest, revenge and familial murder".[5]:21 In the play's stage directions, Artaud describes the opening scene as "suggestive of extreme atmospheric turbulence, with wind-blown drapes, waves of suddenly amplified sound, and crowds of figures engaged in "furious orgy", accompanied by "a chorus of church bells", as well as the presence of numerous large mannequins.[14]: 120 Scholar Adrian Curtin has argued for the importance of the "sonic aspects of the production, which did not merely support the action but motivated it obliquely".[22]:251 While Shelley's version of The Cenci conveyed the motivations and anguish of the Cenci's daughter Beatrice with her father through monologues, Artaud was much more concerned with conveying the menacing nature of the Cenci's presence and the reverberations of their incest relationship though physical discordance, as if an invisible "force-field" surrounded them.[14]: 123 Jane Goodall writes of The Cenci, The predominance of action over reflection accelerates the development of events...the monologues...are cut in favor of sudden, jarring transitions...so that a spasmodic effect is created. Extreme fluctuations in pace, pitch, and tone heighten sensory awareness intensify ... the here and now of performance.[14]:119 The Cenci was a commercial failure, although it employed innovative sound effects—including the first theatrical use of the electronic instrument the Ondes Martenot—and had a set designed by Balthus.[citation needed] |

文筆家としてのキャリア 1923年、アルトーは自分の詩を雑誌『ヌーヴェル・ルヴュー・フランセーズ』(NRF)に送ったが却下され、その詩の作者がNRFの編集者ジャック・リ ヴィエールに興味を持ち、面会を申し込んだ。郵便で会った後、二人の関係は続いた。これらの手紙をエピソード形式の作品『Correspondance avec Jacques Rivière』にまとめたものが、アルトーの最初の主要出版物となった[5]:45 アルトーはNRFで、『残酷演劇のための第一宣言』(1932)や『演劇とペスト』(1933)などの重要作を発表し続けている[1] :105 彼は『演劇とその倍』をまとめる際にこれらの出版物を参考にしている[1] :105  Antonin Artaud en 1926. 映画館で働く アベル・ガンス監督の『ナポレオン』(1927年)でジャン=ポール・マラットを演じたアルトーは、マラットの人格の炎を伝えるために誇張された動きを 使っていた[quote]。 [また、カール・テオドール・ドレイヤーの『ジャンヌ・ダルクの受難』(1928年)では修道士マシューを演じた[5]:17 彼は多くの映画シナリオを書き、そのうち10本は現存する[5]:23 アルトーのシナリオのうち1本だけが製作された『貝と聖職』(1928年)だった。) 監督はジェルメーヌ・デュラックで、多くの批評家や学者はこの作品を最初のシュルレアリスム映画とみなしている[17][18]。 シュールレアリストとの交流 アルトーは一時的にシュルレアリスムに属していたが、1927年にアンドレ・ブルトンによって追放された[5]:21 これは、シュルレアリスムがフランスの共産党との連携を強めていたことが一因だった[19]:274 Ros Murrayによれば、「アルトーは政治にはまったく関心がなく、次のように書いている: マルクス主義なんてクソくらえだ」と書いている。さらに、「ブルトンは演劇をブルジョワ的で反革命的だと考えていたので、非常に反演劇的になっていた」 [20]。アルトーは、演劇のアルフレッド・ジャリーのために書いた『中止された演劇のための宣言』(1926/27)の中で、「今日演劇を作ることは反 革命的努力だと我々に思わせる」、彼が言う「紙屑革命家」のようなシュルレアリストたちを直接攻撃することを行った。 [6]:24 彼は、彼らが「共産主義に屈服」していると宣言し[6]:25、それは「怠け者の革命」であり[6]:24、社会のより「本質的な変容」を求めている [6]:25。 テアトル・アルフレッド・ジャリー(1926年~1929年) (作品リストなど詳細は、テアトル・アルフレッド・ジャリーをご覧ください) 1926年、アルトー、ロベール・アロン、そして追放されたシュールレアリストのロジェ・ヴィトラックはテアトル・アルフレッド・ジャリー(TAJ)を設 立した[21]。彼らは1927年6月から1929年1月にかけて4作品を上演している。劇場は極めて短命に終わったが、アルチュール・アダモフ、アンド レ・ジド、ポール・ヴァレリーなど、非常に幅広いヨーロッパの芸術家が参加した[21]:249。 パリ万国博覧会にて(1931年) 1931年、アルトーはパリ植民地博覧会で上演されたバリ舞踊を見た。アルトーは見たものの多くを誤解していたが、演劇に関する彼のアイデアの多くに影響 を与えた。 [5]:26エイドリアン・カーティンは、バリの音楽と音の使い方の重要性を指摘し、アルトーが「ガムラン・アンサンブルの『催眠』リズム、パーカッシブ な効果の範囲、音楽家が生み出すさまざまな音色、そして、おそらく最も重要だが、ダンサーの動きが、単に背景伴奏として機能するのではなく音楽要素と動的 に作用する方法」に感銘を受けたとしている[22]: 253. ザ・センシ(1935年) 1935年、アルトーはパリのフォリー・ワグラム劇場でパーシー・ビッシェ・シェリーの『チェンチ』を独自に脚色して上演した[22]:250 この作品はアルトーにとって残酷劇場の作品を上演する唯一の機会で、彼はその残酷さと暴力、特に「近親相姦、復讐、家族間の殺人をテーマ」にして強調し た。 [5]:21アルトーは劇中の舞台指示で、冒頭の場面を「極端な大気の乱流を暗示し、風になびく緞帳、突然増幅する音の波、「激しい乱交」に従事する人物 の群れ、「教会の鐘の合唱」、さらに多数の大きなマネキンの存在」と説明している[14]: 120 学者エイドリアン・カーティンは、「演出の音響的側面は、単に行動を支援するだけでなく、斜め上の動機づけをした」ことの重要性を主張している。 [22]:251 シェリー版の『チェンチ』が、チェンチの娘ベアトリーチェの父に対する動機と苦悩をモノローグで伝えたのに対し、アルトーは、チェンチの存在の脅威と近親 相姦関係の残響を、あたかも見えない「力場」が彼らを包んでいるかのように、物理的不協和を伴って伝えることに大いに関心があった[14]: 123 ジェーン・グドールは、「ザ・センシ」についてこう書いている、 考察よりも行動が優先されることで、出来事の展開が加速される...モノローグは...突然、耳障りなトランジションに切り替えられており、痙攣的な効果 が生み出されている....ペース、ピッチ、トーンの極端な変動は、感覚的な意識を高め、パフォーマンスの「今、ここ」を強化する[14]:119 Cenci』は、革新的な音響効果(電子楽器Ondes Martenotの劇場初使用を含む)を採用し、バルテュスがデザインしたセットもあったが、商業的には失敗した[citation needed]。 |

| Travels and institutionalization Journey to Mexico In 1935 Artaud decided to go to Mexico, where he was convinced there was "a sort of deep movement in favour of a return to civilisation before Cortez".[23]:11 The Mexican Legation in Paris gave him a travel grant, and he left for Mexico in January 1936, "where he would arrive one month later".[5]:29-30 In 1936 he met his first Mexican-Parisian friend, the painter Federico Cantú, when Cantú gave lectures on the decadence of Western civilization.[citation needed] Artaud also studied and lived with the Tarahumaran people and participated in peyote rites, his writings about which were later released in a volume called Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumara,[23]:14 published in English under the title The Peyote Dance (1976). The content of this work closely resembles the poems of his later days, concerned primarily with the supernatural.[citation needed][original research?] Artaud also recorded his horrific withdrawal from heroin upon entering the land of the Tarahumaras. Having deserted his last supply of the drug at a mountainside, he literally had to be hoisted onto his horse and soon resembled, in his words, "a giant, inflamed gum".[citation needed] Artaud returned to opiates later in life. |

旅行と制度化 メキシコへの旅 1935年、アルトーはメキシコに行くことを決意し、そこで「コルテス以前の文明への回帰を支持するある種の深い動き」があると確信した[23]:11 パリのメキシコ公使館は彼に旅行助成金を与え、彼は1936年1月にメキシコに向けて出発、「1ヶ月後に到着する」。 [5]:29-30 1936年、カントゥーが西洋文明の退廃に関する講義を行った際に、彼は最初のメキシコ・パリの友人である画家のフェデリコ・カントゥーと出会った [citation needed] アルトーはタラフマランの人々と共に研究・生活し、ペヨーテ儀式に参加した。これに関する彼の文章は後に『Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumara』という一冊の本にまとめられ[23]:14 英語ではThe Peyote Dance(1976)のタイトルで発表された。この作品の内容は、主に超自然的なものを扱った晩年の詩と酷似している[citation needed][独自調査?] アルトーはまた、タラフマラの土地に入ったときに、ヘロインから恐ろしいほど離脱したことを記録した。山腹で最後の薬を捨てた彼は、文字通り馬に吊り上げ られなければならず、やがて彼の言葉を借りれば「巨大で炎症を起こした歯茎」のような状態になった[citation needed] アルトーは後年、アヘンに復帰した。 |

| Ireland and repatriation to

France In 1937, Artaud returned to France, where his friend René Thomas gave him a walking-stick of knotted wood that Artaud believed contained magical powers and was the 'most sacred relic of the Irish church, the Bachall Ísu, or "Staff of Jesus".[5]:32 Artaud traveled to Ireland, landing at Cobh and travelling to Galway, possibly in an effort to return the staff.[5]:33 Speaking very little English and no Gaelic whatsoever, he was unable to make himself understood.[5]:33 He would not have been admitted at Cobh, according to Irish government documents, except that he carried a letter of introduction from the Paris embassy.[citation needed] Most of his trip was spent in a hotel room he was unable to pay for.[citation needed] He was forcibly removed from the grounds of Milltown House, a Jesuit community, when he refused to leave.[citation needed] Before deportation he was briefly confined in the notorious Mountjoy Prison.[2]:152 According to Irish Government papers he was deported as "a destitute and undesirable alien".[24] On his return trip by ship, Artaud believed he was being attacked by two crew members, and he retaliated; he was put in a straitjacket and he was involuntarily retained by the police upon his return to France.[5]:34 His return from Ireland brought about the beginning of the final phase of Artaud's life, which was spent in different asylums. It was at this time that his best known work The Theatre and Its Double (1938) was published.[5]:34 This book contained the two manifestos of the Theatre of Cruelty. There, "he proposed a theatre that was in effect a return to magic and ritual and he sought to create a new theatrical language of totem and gesture – a language of space devoid of dialogue that would appeal to all the senses."[25]: 6 "Words say little to the mind," Artaud wrote, "compared to space thundering with images and crammed with sounds." He proposed "a theatre in which violent physical images crush and hypnotize the sensibility of the spectator seized by the theatre as by a whirlwind of higher forces." He considered formal theatres with their proscenium arches and playwrights with their scripts "a hindrance to the magic of genuine ritual".[25]:6 |

アイルランドとフランスへの送還 1937年、アルトーはフランスに戻り、友人のルネ・トマから節のある木のステッキをもらったが、アルトーは魔法の力を秘めた「アイルランド教会の最も神 聖な遺物、Bachall Ísu(イエスの杖)」と信じていた[5]:32 アルトーはアイルランドへ行き、コブに上陸してゴールウェイまで旅をしたが、おそらくその杖を返そうとしたのだった。 [5]:33 英語はほとんど話せず、ゲール語も全く話せなかったため、自分を理解させることができなかった[5]:33 アイルランド政府の文書によれば、パリ大使館からの紹介状を携帯していた以外は、コブで入国できなかっただろう。 [彼はイエズス会の共同体であるミルタウン・ハウスの敷地から出ることを拒否したため、強制的に追い出された[citation needed] 強制送還の前に、彼は悪名高いマウントジョイ刑務所に短期間収容された。 [2]:152アイルランド政府の書類によると、彼は「貧困で望ましくない外国人」として強制送還された[24] 船で帰国する際、アルトーは2人の乗組員から攻撃されていると考え、報復した。 アイルランドからの帰国は、さまざまな精神病院で過ごしたアルトーの人生の最終局面の始まりをもたらした。最もよく知られている作品『劇場とその二重人 格』(1938年)が出版されたのはこの時期である[5]:34 この本には、「残酷劇場」の2つのマニフェストが書かれていた。そこでは、「彼は事実上、魔法と儀式への回帰である演劇を提案し、トーテムとジェスチャー の新しい演劇言語、つまりすべての感覚に訴えかけるような対話のない空間の言語を創造しようとした」[25]: 6 「言葉は心にとってほとんど意味を持たない」とアルトーは書き、「イメージで轟々と音を詰め込んだ空間に比べて」、「言葉は、心にとってほとんど意味を持 たない。彼は「暴力的な物理的イメージが、より高い力の渦に巻き込まれるように劇場に捕らえられた観客の感性を押し潰し、催眠術をかけるような劇場」を提 案しました。彼はプロセニアムアーチを持つ形式的な劇場と台本を持つ劇作家を「本物の儀式の魔法を妨げるもの」と考えた[25]:6。 |

| In Rodez In 1943, when France was occupied by the Germans and Italians, Robert Desnos arranged to have Artaud transferred to the psychiatric hospital in Rodez, well inside Vichy territory, where he was put under the charge of Dr. Gaston Ferdière.[26] At Rodez Artaud underwent therapy including electroshock treatments and art therapy.[27]:194 The doctor believed that Artaud's habits of crafting magic spells, creating astrology charts, and drawing disturbing images were symptoms of mental illness.[28] Artaud, at his peak began lashing out at others.[citation needed] Artaud denounced the electroshock treatments and consistently pleaded to have them suspended, while also ascribing to them "the benefit of having returned him to his name and to his self mastery".[27]:196 Scholar Alexandra Lukes points out that "the 'recovery' of his name" might have been "a gesture to appease his doctors" conception of what constitutes health".[27]:196 It was during this time that Artaud began writing and drawing again, after a long dormant period.[29] In 1946, Ferdière released Artaud to his friends, who placed him in the psychiatric clinic at Ivry-sur-Seine.[30] |

ロデーズにて 1943年、フランスがドイツとイタリアに占領されると、ロベール・デスノスはアルトーをヴィシー領内のロデーズの精神病院に移送するよう手配し、ガスト ン・フェルディエール医師が担当することになった。 [26] ロデーズでは電気ショック療法や芸術療法を受けた[27]:194 医師は、アルトーが魔法の呪文を作り、占星術のチャートを作り、不穏なイメージを描く習慣は精神疾患の症状だと考えた[28]。 アルトーは最盛期には他人に怒りをぶつけるようになった。 [引用者注:アルトーは電気ショック療法を非難し、一貫してその中止を嘆願したが、同時に「自分の名前と自己の支配を取り戻したという利益」を与えていた [27]:196 学者のアレクサンドラ・ルケスは、「自分の名前の『回復』」は、「健康とは何かについての医師の概念をなだめるための身振り」だったのかもしれないと指摘 している。 [27]:196この時期、アルトーは長い休眠期を経て、再び執筆や絵を描き始めた[29]。 1946年、フェルディエールはアルトーを友人たちに解放し、彼らは彼をイヴリー・シュル・セーヌの精神科クリニックに収容した[30]。 |

| Final years At Ivry-sur-Seine Artaud's friends encouraged him to write and interest in his work was rekindled. He visited a Vincent van Gogh exhibition at the Orangerie in Paris and wrote the study Van Gogh le suicidé de la société ["Van Gogh, The Man Suicided by Society"]; in 1947, the French magazine K published it.[31]:8 In 1949, the essay was the first of Artaud's to be translated in a United States based publication, the influential literary magazine Tiger's Eye.[31]:8  Self-portrait of Artaud from 1947 Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de Dieu He recorded Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de Dieu (To Have Done With the Judgment of God) on 22–29 November 1947. The work remained true to his vision for the theatre of cruelty, using "screams, rants and vocal shudders" to forward his vision.[31]:1 Wladimir Porché, the Director of French Radio, shelved the work the day before its scheduled airing on 2 February 1948.[1]:62 This was partly for its scatological, anti-American, and anti-religious references and pronouncements, but also because of its general randomness, with a cacophony of xylophonic sounds mixed with various percussion elements.[citation needed] While remaining true to his Theatre of Cruelty and reducing powerful emotions and expressions into audible sounds, Artaud had utilized various, somewhat alarming cries, screams, grunts, onomatopoeia, and glossolalia.[citation needed] As a result, Fernand Pouey, the director of dramatic and literary broadcasts for French radio, assembled a panel to consider the broadcast of Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de dieu.[1]:62 Among approximately 50 artists, writers, musicians, and journalists present for a private listening on 5 February 1948 were Jean Cocteau, Paul Éluard, Raymond Queneau, Jean-Louis Barrault, René Clair, Jean Paulhan, Maurice Nadeau, Georges Auric, Claude Mauriac, and René Char.[32] Porché refused to broadcast it even though the panel were almost unanimously in favor of Artaud's work being broadcast.[1]:62 Pouey left his job and the show was not heard again until 23 February 1948, at a private performance at Théâtre Washington.[citation needed] The work's first public broadcast did not take place until 8 July 1964 when the Los Angeles-based public radio station KPFK played an illegal copy provided by the artist Jean-Jacques Lebel.[31]:1 The first French radio broadcast of Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de dieu occurred 20 years after its original production.[33] Death In January 1948, Artaud was diagnosed with colorectal cancer.[34] He died shortly afterwards, on 4 March 1948 in a psychiatric clinic in Ivry-sur-Seine, a commune in the southeastern suburbs of Paris.[35] He was found by the gardener of the estate seated alone at the foot of his bed holding a shoe, and it was suspected that he died from a lethal dose of the drug chloral hydrate, although it is unknown whether he was aware of its lethality.[35][16] |

晩年 イヴリー・シュル・セーヌでアルトーは友人たちから執筆を勧められ、彼の作品への関心が再燃する。1947年、フランスの雑誌『K』に掲載された [31]:8。1949年、このエッセイはアルトーの作品として初めて、アメリカを拠点とする有力な文芸誌『タイガーズ・アイ』に翻訳される[31]: 8。  Self-portrait of Artaud from 1947 Dieu Jugementで締めくくるために。 彼は1947年11月22日から29日にかけて『Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de Dieu(神の裁きをやり遂げるために)』を録音した。この作品は、彼の残酷劇場の構想に忠実であり、「悲鳴、暴言、声の震え」を使って彼の構想を前進さ せた[31]:1 フランス放送局のディレクター、ウラディミール・ポルシェは、1948年2月2日の放送予定の前日にこの作品を棚上げにしてしまった。 [1]:62これは、そのスカトロ的、反米的、反宗教的な言及や宣言のためでもあったが、木琴の音の不協和音と様々な打楽器の要素を混ぜた、一般的なラン ダム性のためでもあった[citation needed] 残酷の劇場に忠実に、力強い感情や表現を聞こえる音に還元しながら、アルトーは様々でやや警戒すべき叫び、叫び、うめき、擬音語、そしてグソラリアを利用 していた[citation needs] 。 その結果、フランスのラジオ局で演劇・文学放送のディレクターを務めていたフェルナン・プエは、『Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de dieu』の放送を検討する委員会を結成した。 [1948年2月5日の非公開試聴会に出席した約50人の芸術家、作家、音楽家、ジャーナリストの中には、ジャン・コクトー、ポール・エリュアール、レイ モン・ケノー、ジャン=ルイ・バロー、ルネ・クレア、ジャン・ポーラン、モーリス・ナドー、ジョルジュ・オーリック、クロード・モーリアック、ルネ・ シャールがいた[32]。ポシェは委員会がほぼ満場一致でアルトーの作品を放送することを支持していても、これを放送しないことにしている。 [1]:62ポーイは仕事を辞め、この作品は1948年2月23日にテアトル・ワシントンで行われた個人公演まで再び聴かれることはなかった [citation needed] この作品の最初の公開放送は、1964年7月8日にロサンゼルスにある公共ラジオ局KPFKが芸術家ジャン=ジャック・ルベルが提供した違法コピーを放送 したときだった [31]:1 最初のフランスのラジオ放送『死ぬまで続く旅』は最初の作品から20年経っていた [33]. 死 1948年1月、アルトーは大腸癌と診断された[34]。その直後、1948年3月4日にパリ南東郊外のコミューン、イヴリー・シュル・セーヌの精神科医 院で亡くなった[35]。ベッドの足元に一人座り靴を持っていたところを屋敷の庭師が見つけた。致死性を認識していたかは不明だがクロラル水和物の服用が 死亡原因と推測された[35][16]。 |

| Legacy and influence Artaud has had a profound influence on theatre, avant-garde art, literature, psychiatry and other disciplines.[4][12][17][26][31] Theatre and Performance Artaud's has exerted a strong influence on the development of experimental theatre and performance art. His ideas helped inspire a movement away from the dominant role of language and rationalism in performance practice.[citation needed] Many of his works were not produced for the public until after his death. For instance, Spurt of Blood (1925) was not produced until 1964, when Peter Brook and Charles Marowitz staged it as part of their "Theatre of Cruelty" season at the Royal Shakespeare Company.[5]: 73 Artists such Karen Finley, Spalding Gray, Liz LeCompte, Richard Foreman, Charles Marowitz, Sam Shepard, Joseph Chaikin, Charles Bukowski, Allen Ginsberg, and more all named Artaud as one of their influences.[25]: 6–25 His influence can be seen in: Barrault's adaptation of Kafka's The Trial (1947).[36] The Theatre of the Absurd, particularly the works of Jean Genet and Samuel Beckett.[37] Peter Brook's production of Marat/Sade in 1964, which was performed in New York and Paris, as well as London.[citation needed] The Living Theatre.[citation needed] In the winter of 1968, Williams College offered a dedicated intersession class in Artaudian theatre, resulting in a week-long "Festival of Cruelty," under the direction of Keith Fowler. The Festival included productions of The Jet of Blood, All Writing is Pig Shit, and several original ritualized performances, one based on the Texas Tower killings and another created as an ensemble catharsis called The Resurrection of Pig Man.[38] In Canada, playwright Gary Botting created a series of Artaudian "happenings" from The Aeolian Stringer to Zen Rock Festival, and produced a dozen plays with an Artaudian theme, including Prometheus Re-Bound.[39] Charles Marowitz's play Artaud at Rodez is about the relationship between Artaud and Dr. Ferdière during Artaud's confinement at the psychiatric hospital in Rodez; the play was first performed in 1976 at the Teatro a Trastavere in Rome.[40] The writer and actor Tim Dalgleish wrote and produced the play The Life and Theatre of Antonin Artaud (1999) for the English physical theatre company Bare Bones. The play told Artaud's story from his early years of aspiration when he wished to be part of the establishment, through to his final years as a suffering, iconoclastic outsider.[citation needed] Philosophy Artaud also had a significant influence on philosophers.[31]:22 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, borrowed Artaud's phrase "the body without organs" to describe their conception of the virtual dimension of the body and, ultimately, the basic substratum of reality in their Capitalism and Schizophrenia.[41] Philosopher Jacques Derrida provided one of the key philosophical treatments of Artaud's work through his concept of "parole soufflée".[42] Feminist scholar Julia Kristeva also drew on Artaud for her theorisation of "subject in process".[31]:22-3 Literature Poet Allen Ginsberg claimed Artaud's work, specifically "To Have Done with the Judgement of God", had a tremendous influence on his most famous poem "Howl".[43] The Latin American dramatic novel Yo-Yo Boing! by Giannina Braschi includes a debate between artists and poets concerning the merits of Artaud's "multiple talents" in comparison to the singular talents of other French writers.[44] Music The band Bauhaus included a song about the playwright, called "Antonin Artaud", on their album Burning from the Inside.[45] Influential Argentine hard rock band Pescado Rabioso recorded an album titled Artaud. Their leader Luis Alberto Spinetta wrote the lyrics partly basing them on Artaud's writings.[46] Venezuelan rock band Zapato 3 included a song named "Antonin Artaud" on their album "Ecos punzantes del ayer" (1999) [1] Composer John Zorn has written many works inspired by and dedicated to Artaud, including seven CDs: "Astronome", "Moonchild: Songs Without Words", "Six Litanies for Heliogabalus", "The Crucible", "Ipsissimus", "Templars: In Sacred Blood" and "The Last Judgment", a monodrama for voice and orchestra inspired by Artaud's late drawings "La Machine de l'être" (2000), "Le Momo" (1999) for violin and piano, and "Suppots et Suppliciations" (2012) for full orchestra. Film Filmmaker E. Elias Merhige, during an interview by writer Scott Nicolay, cited Artaud as a key influence for the experimental film Begotten.[47] |

レガシーと影響力 アルトーは、演劇、前衛芸術、文学、精神医学などの分野に多大な影響を与えた[4][12][17][26][31] 。 シアター&パフォーマンス アルトーの作品は、実験演劇やパフォーマンス・アートの発展に強い影響を与えた。彼の思想は、パフォーマンスの実践において言語と合理主義の支配的な役割 から離れる動きを促すのに役立った[citation needed] 彼の作品の多くは、彼の死後まで一般向けに制作されることはなかった。例えば、『血の噴出』(1925年)は、1964年にピーター・ブルックとチャール ズ・マロウィッツがロイヤル・シェイクスピア・カンパニーの「残酷劇場」シーズンの一環として上演するまで制作されなかった[5]: 73 Karen Finley, Spalding Gray, Liz LeCompte, Richard Foreman, Charles Marowitz, Sam Shepard, Joseph Chaikin, Charles Bukowski, Allen Ginsbergなどの芸術家たちが影響を受けた一人としてアルトーの名前を挙げた [25]: 6-25. 彼の影響は、以下にも見られる: バローによるカフカの『裁判』の映画化(1947年)[36]。 不条理演劇、特にジャン・ジュネとサミュエル・ベケットの作品[37]。 1964年にピーター・ブルックが演出した『Marat/Sade』は、ロンドンだけでなくニューヨークやパリでも上演された[citation needed]。 リビングシアター」です[要出典]。 1968年の冬、ウィリアムズ・カレッジはアルトー演劇のインターセッション・クラスを開講し、キース・ファウラーの指揮のもと、1週間にわたる「残酷の 祭典」を開催しました。フェスティバルでは、『血のジェット』、『All Writing is Pig Shit』のほか、テキサスタワー殺人事件に基づくもの、『The Resurrection of Pig Man』というアンサンブルのカタルシスとして作られたオリジナルの儀式的パフォーマンスも上演された[38]。 カナダでは、劇作家のゲイリー・ボッティングが『エオリアン・ストリンガー』から『ゼン・ロック・フェスティバル』までの一連のアルトー的「出来事」を作 り、『プロメテウス・リ・バウンド』などアルトーをテーマにした12本の劇を制作した[39]。 シャルル・マロウィッツの戯曲『Artaud at Rodez』は、アルトーがロデーズの精神病院に収容されていた時のアルトーとフェルディエール医師の関係を描いたもので、1976年にローマのテアト ロ・ア・トラスタヴェレで初演されています[40]。 作家で俳優のティム・ダルグリーシュは、イギリスのフィジカル・シアター・カンパニー「ベアボーンズ」のために、「アントナン・アルトーの人生と演劇」 (1999年)を書き、制作した。この舞台は、体制に属したいと願った初期の頃から、苦悩し、象徴的なアウトサイダーとなった晩年までのアルトーの物語で ある[citation needed] 。 フィロソフィー ジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリは、『資本主義と分裂症』において、身体の仮想的な次元、ひいては現実の基本的な基層についての彼らの概念を説明 するのに、アルトーの「器官のない身体」という言葉を借用した[31]:22。 [41]哲学者のジャック・デリダは、「パロール・スフレ」という概念を通じて、アルトーの作品を重要な哲学的に扱った[42]。フェミニスト学者のジュ リア・クリステヴァも、「過程における主体」の理論化においてアルトーを利用している[31]:22-3。 文芸 詩人のアレン・ギンズバーグは、アルトーの作品、特に「神の裁きを受けよ」が彼の最も有名な詩「ハウル」に多大な影響を与えたと主張している[43]。 ジャンニナ・ブラスキによるラテンアメリカ演劇小説「ヨーヨー・ボーイング!」には、アルトーの「複数の才能」と他のフランス作家の特異な才能を比較し て、アーティストと詩人の間で議論する場面がある[44]。 音楽 バウハウスは、アルバム『Burning from the Inside』に劇作家を歌った「Antonin Artaud」を収録している[45] 影響力のあるアルゼンチンのハードロックバンド、ペスカド・ラビオソは、『Artaud』というタイトルのアルバムを録音した。彼らのリーダーであるルイ ス・アルベルト・スピネッタは、アルトーの著作に一部基づいて歌詞を書いた[46]。 ベネズエラのロックバンド、サパト3はアルバム『Ecos punzantes del ayer』(1999年)に「Antonin Artaud」という名前の曲を収録している[1]。 作曲家ジョン・ゾーンは、アルトーに触発され、アルトーに捧げた作品を数多く書いており、7枚のCDがあります: 「アストロノーム」「ムーンチャイルド ヘリオガバルスのための6つのリタニー」、「るつぼ」、「イプシムス」、「テンプル騎士団: また、アルトーの晩年の素描「La Machine de l'être」(2000年)に触発された声楽とオーケストラのためのモノドラマ「The Last Judgment」、ヴァイオリンとピアノのための「Le Momo」(1999年)、フルオーケストラによる「Supots et Suppliciations」(2012年)もある。 フィルム 映画監督のE・エリアス・メルヒゲは、作家のスコット・ニコレイのインタビューの中で、実験映画『Begotten』の重要な影響としてアルトーを挙げた [47]。 |

|

|

|

|

| Critical and biographic works In English Books Barber, Stephen. Antonin Artaud: Blows and Bombs (Faber and Faber: London, 1993) ISBN 0-571-17252-0 Bradnock, Lucy. No More Masterpieces: Modern Art After Artaud (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021). Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. R. Hurley, H. Seem, and M. Lane. (New York: Viking Penguin, 1977). Esslin, Martin. Antonin Artaud. London: John Calder, 1976. Greene, Naomi. Antonin Artaud: Poet Without Words. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971). Goodall, Jane. Artaud and the Gnostic Drama. Oxford: Clarendon Press; Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-19-815186-1 Jamieson, Lee. Antonin Artaud: From Theory to Practice (Greenwich Exchange: London, 2007) ISBN 978-1-871551-98-3. Jannarone, Kimberly. Artaud and His Doubles (Ann Arbor, MI, University of Michigan Press, 2010). Knapp, Bettina. Antonin Artaud: Man of Vision. (Athens, OH: Swallow Press, 1980). Morris, Blake. Antonin Artaud (London: Routledge, 2022). Plunka, Gene A. (ed). Antonin Artaud and the Modern Theater. (Cranbury: Associated University Presses. 1994). Rose, Mark. The Actor and His Double: Mime and Movement for the Theatre of Cruelty. (Actor Training Research Institute, 1986). Shafer, David. Antonin Artaud. (London: Reaktion Books, 2016) Articles and chapters Bataille, George. "Surrealism Day to Day". In The Absence of Myth: Writings on Surrealism. Trans. Michael Richardson. London: Verso, 1994. 34–47. Bersani, Leo. "Artaud, Defecation, and Birth". In A Future for Astyanax: Character and Desire in Literature. Boston: Little, Brown, 1976. Blanchot, Maurice. "Cruel Poetic Reason (the rapacious need for flight)". In The Infinite Conversation. Trans. Susan Hanson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993. 293–297. Deleuze, Gilles. "Thirteenth Series of the Schizophrenic and the Little Girl". In The Logic of Sense. Trans. Mark Lester with Charles Stivale. Ed. Constantin V. Boundas. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990. 82–93. Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. "28 November 1947: How Do You Make Yourself a Body Without Organs?". In A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987. 149–166. Derrida, Jacques. "The Theatre of Cruelty" and "La Parole Souffle". In Writing and Difference. Trans. Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978. ISBN 0-226-14329-5 Ferdière, Gaston. "I Looked after Antonin Artaud". In Artaud at Rodez. Marowitz, Charles (1977). pp. 103–112. London: Marion Boyars. ISBN 0-7145-2632-0. Innes, Christopher. "Antonin Artaud and the Theatre of Cruelty". In Avant-Garde Theatre 1892–1992 (London: Routledge, 1993). Jannarone, Kimberly. "The Theater Before Its Double: Artaud Directs in the Alfred Jarry Theater", Theatre Survey 46.2 (November 2005), 247–273. Koch, Stephen. "On Artaud." Tri-Quarterly, no. 6 (Spring 1966): 29–37. Pireddu, Nicoletta. "The mark and the mask: psychosis in Artaud's alphabet of cruelty," Arachnē: An International Journal of Language and Literature 3 (1), 1996: 43–65. Rainer, Friedrich. "The Deconstructed Self in Artaud and Brecht: Negation of Subject and Antitotalitarianism", Forum for Modern Language Studies, 26:3 (July 1990): 282–297. Shattuck, Roger. "Artaud Possessed". In The Innocent Eye. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1984. 169–186. Sontag, Susan. "Approaching Artaud". In Under the Sign of Saturn. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980. 13–72. [Also printed as Introduction to Antonin Artaud: Selected Writings, ed. Sontag.] Ward, Nigel "Fifty-one Shocks of Artaud", New Theatre Quarterly Vol. XV, Part 2 (NTQ58 May 1999): 123–128 In French Blanchot, Maurice. "Artaud" La Nouvelle Revue Française 4 (November 1956, no. 47): 873–881. Brau, Jean-Louis. Antonin Artaud. Paris: La Table Ronde, 1971. Héliogabale ou l'Anarchiste couronné, 1969 Florence de Mèredieu, Antonin Artaud, Portraits et Gris-gris, Paris: Blusson, 1984, new edition with additions, 2008. ISBN 978-2907784221 Florence de Mèredieu, Antonin Artaud, Voyages, Paris: Blusson, 1992. ISBN 978-2907784054 Florence de Mèredieu, Antonin Artaud, de l'ange, Paris: Blusson, 1992. ISBN 978-2907784061 Florence de Mèredieu, Sur l'électrochoc, le cas Antonin Artaud, Paris: Blusson, 1996. ISBN 978-2907784115 Florence de Mèredieu, C'était Antonin Artaud, biography, Fayard, 2006. ISBN 978-2213625256 Florence de Mèredieu, La Chine d'Antonin Artaud / Le Japon d'Antonin Artaud, Paris: Blusson, 2006. ISBN 978-2907784177 Florence de Mèredieu, L'Affaire Artaud, journal ethnographique, Paris: Fayard, 2009. ISBN 978-2213637600 Florence de Mèredieu, Antonin Artaud dans la guerre, de Verdun à Hitler. L'hygiène mentale, Paris: Blusson, 2013.ISBN 978-2907784269 Florence de Mèredieu, Vincent van Gogh, Antonin Artaud. Ciné-roman. Ciné-peinture, Paris: Blusson, 2014.ISBN 978-2907784283 Florence de Mèredieu, BACON, ARTAUD, VINCI. Une blessure magnifique, Paris: Blusson, 2019. ISBN 978-2-907784-29-0 Virmaux, Alain. Antonin Artaud et le théâtre. Paris: Seghers, 1970. Virmaux, Alain and Odette. Artaud: un bilan critique. Paris: Belfond, 1979. Virmaux, Alain and Odette. Antonin Artaud: qui êtes-vous? Lyon: La Manufacture, 1986. In German Seegers, U. Alchemie des Sehens. Hermetische Kunst im 20. Jahrhundert. Antonin Artaud, Yves Klein, Sigmar Polke (Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2003). |

批評および伝記的作品 英語 書籍 バーバー、スティーブン著『アントナン・アルトー:打撃と爆弾』(ファベル・アンド・ファベル:ロンドン、1993年)ISBN 0-571-17252-0 ブラッドノック、ルーシー著『もう傑作は要らない:アルトー以降の現代美術』(ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版、2021年)。 ドゥルーズ、ジル、フェリックス・ガタリ著。『アンチ・オイディプス:資本主義と分裂症』。R.ハーレイ、H.シーム、M.レーン訳。(ニューヨーク: ヴァイキング・ペンギン、1977年)。 エスリン、マーティン著。『アントナン・アルトー』。ロンドン:ジョン・カルダー、1976年。 グリーン、ナオミ。アントナン・アルトー:言葉なき詩人。(ニューヨーク:サイモン&シュスター、1971年)。 グドール、ジェーン。アルトーとグノーシス劇。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局、1994年。ISBN 0-19-815186-1 ジェイムソン、リー。アントナン・アルトー:理論から実践へ(グリニッジ・エクスチェンジ:ロンドン、2007年)ISBN 978-1-871551-98-3。 ジャナローネ、キンバリー。アルトーとその分身(ミシガン州アナーバー、ミシガン大学出版、2010年)。 クナップ、ベティナ著『アントナン・アルトー:ヴィジョンの人』(オハイオ州アセンズ:スワロー・プレス、1980年)。 モリス、ブレイク著『アントナン・アルトー』(ロンドン:ルートレッジ、2022年)。 プランカ、ジーン・A. 編著『アントナン・アルトーと現代演劇』(クランベリー:アソシエイテッド・ユニバーシティ・プレス、1994年)。 ローズ、マーク著『俳優とその分身:残酷劇のためのマイムと動き』(俳優トレーニング研究所、1986年)。 シェーファー、デイヴィッド著『アントナン・アルトー』(ロンドン:リアクション・ブックス、2016年) 記事および章 バタイユ、ジョルジュ。「日常のシュールレアリスム」。『神話の不在:シュールレアリスムに関する著作』所収。マイケル・リチャードソン訳。ロンドン: ヴァーソ、1994年。34-47ページ。 ベルサニ、レオ。「アルトー、排便、そして誕生」。『アステュアナクスの未来:文学における性格と欲望』所収。ボストン:リトル・ブラウン、1976年。 ブランショ、モーリス。「残酷な詩的理性(貪欲な逃走の必要性)」。『無限の対話』所収。スーザン・ハンソン訳。ミネアポリス:ミネソタ大学出版、 1993年。293-297ページ。 ドゥルーズ、ジル。「精神分裂病患者と少女の第13シリーズ」。『感覚の論理』所収。マーク・レスターとチャールズ・スティヴァーレ共訳。コンスタンタ ン・V・バウンダス編。ニューヨーク:コロンビア大学出版、1990年。82-93ページ。 ドゥルーズ、ジル、フェリックス・ガタリ。「1947年11月28日:どのようにして器官なき身体を創り出すか?」『千のプラトー:資本主義と分裂症』ブ ライアン・マスミ訳。ミネアポリス:ミネソタ大学出版、1987年。149-166ページ。 デリダ、ジャック。「残酷の劇場」および「息吹の言葉」。『書記と差異』。訳:アラン・バス。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版、1978年。ISBN 0-226-14329-5 Ferdière, Gaston. 「アントナン・アルトーの世話をした」。『ロデーズのアートー』所収。Marowitz, Charles (1977). pp. 103–112. London: Marion Boyars. ISBN 0-7145-2632-0. イネス、クリストファー。「アントナン・アルトーと残酷劇」『アヴァンギャルド演劇 1892-1992』(ロンドン:ルートレッジ、1993年)所収。 ジャナローネ、キンバリー。「その分身の前に立つ演劇:アルトーがアルフレッド・ジャリ劇場で演出する」『シアター・サーベイ 46.2』(2005年11月)、247-273ページ。 Koch, Stephen. 「アルトーについて」『Tri-Quarterly』第6号(1966年春):29-37ページ。 Pireddu, Nicoletta. 「刻印と仮面:アルトーの残酷のアルファベットにおける精神病」『Arachnē:言語と文学の国際ジャーナル』第3号(1996年):43-65ペー ジ。 ライナー、フリードリヒ。「アルトーとブレヒトにおける脱構築された自己:主体の否定と反全体主義」、フォーラム・フォー・モダン・ランゲージ・スタ ディーズ、26:3(1990年7月):282-297。 シャタック、ロジャー。「取り憑かれたアルトー」。『無垢な眼差し』所収。ニューヨーク:ファラ・ストラス・ジルー、1984年。169-186ページ。 ソンタグ、スーザン。「アルトーに近づく」。『土星の記号のもとに』所収。ニューヨーク:ファラ・ストラス・アンド・ジルー、1980年。13-72。 [アントナン・アルトー:選集、ソントン編の序文としても印刷されている。 ウォード、ナイジェル「アルトーの51の衝撃」、ニュー・シアター・クォータリー第15巻第2部(NTQ58、1999年5月):123-128 フランス語 ブランショ、モーリス。「アルトー」『ラ・ヌーベル・レヴュー・フランセーズ』4(1956年11月、第47号):873-881。 ブラウ、ジャン=ルイ。『アントナン・アルトー』パリ:ラ・ターブル・ロン、1971年。 『太陽王または冠を被ったアナーキスト』、1969年 フローレンス・ド・メレディュー著『アントナン・アルトー、肖像と蝋人形』、パリ:ブリュソン社、1984年、2008年に追加を加えて新版。ISBN 978-2907784221 フローレンス・ド・メレディュー著『アントナン・アルトー、旅』、パリ:ブリュッソン、1992年。ISBN 978-2907784054 フローレンス・ド・メレディュー著『アントナン・アルトー、天使』、パリ:ブリュッソン、1992年。ISBN 978-2907784061 フローレンス・ド・メレディュー著『電気ショックについて、アントナン・アルトーの場合』、パリ:ブリュソン、1996年。ISBN 978-2907784115 フローレンス・ド・メレディュー著『それはアントナン・アルトーだった』、伝記、フェアラール、2006年。ISBN 978-2213625256 フローレンス・ド・メレディュー著『アントナン・アルトーの中国/アントナン・アルトーの日本』パリ:ブリュソン、2006年。ISBN 978-2907784177 フローレンス・ド・メレディュー著『アルトー事件、民族誌的日記』パリ:フェイヤール、2009年。ISBN 978-2213637600 フローレンス・ド・メレディュー著『アントナン・アルトー、戦争の中で、ヴェルダンからヒトラーまで。精神衛生学』パリ:Blusson、2013年。 ISBN 978-2907784269 フローレンス・ド・メレディュー著『フィンセント・ファン・ゴッホ、アントナン・アルトー。シネロマン。シネ・ペインティング、パリ:ブリュソン、 2014年。ISBN 978-2907784283 フローレンス・ド・メレディュー、ベーコン、アルトー、ヴィンチ。素晴らしい傷跡、パリ:ブリュソン、2019年。ISBN 978-2-907784-29-0 ヴィルモー、アラン。アントナン・アルトーと演劇。パリ:セガール、1970年。 ヴィルモー、アラン、オデット。アルトー:批評的総括。パリ:ベルフォン、1979年。 ヴィルモー、アラン、オデット。アントナン・アルトー:あなたは何者か?リヨン:ラ・マニュファクチュール、1986年。 ドイツ語訳 Seegers, U. Alchemie des Sehens. Hermetische Kunst im 20. Jahrhundert. Antonin Artaud, Yves Klein, Sigmar Polke (Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2003). |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonin_Artaud |

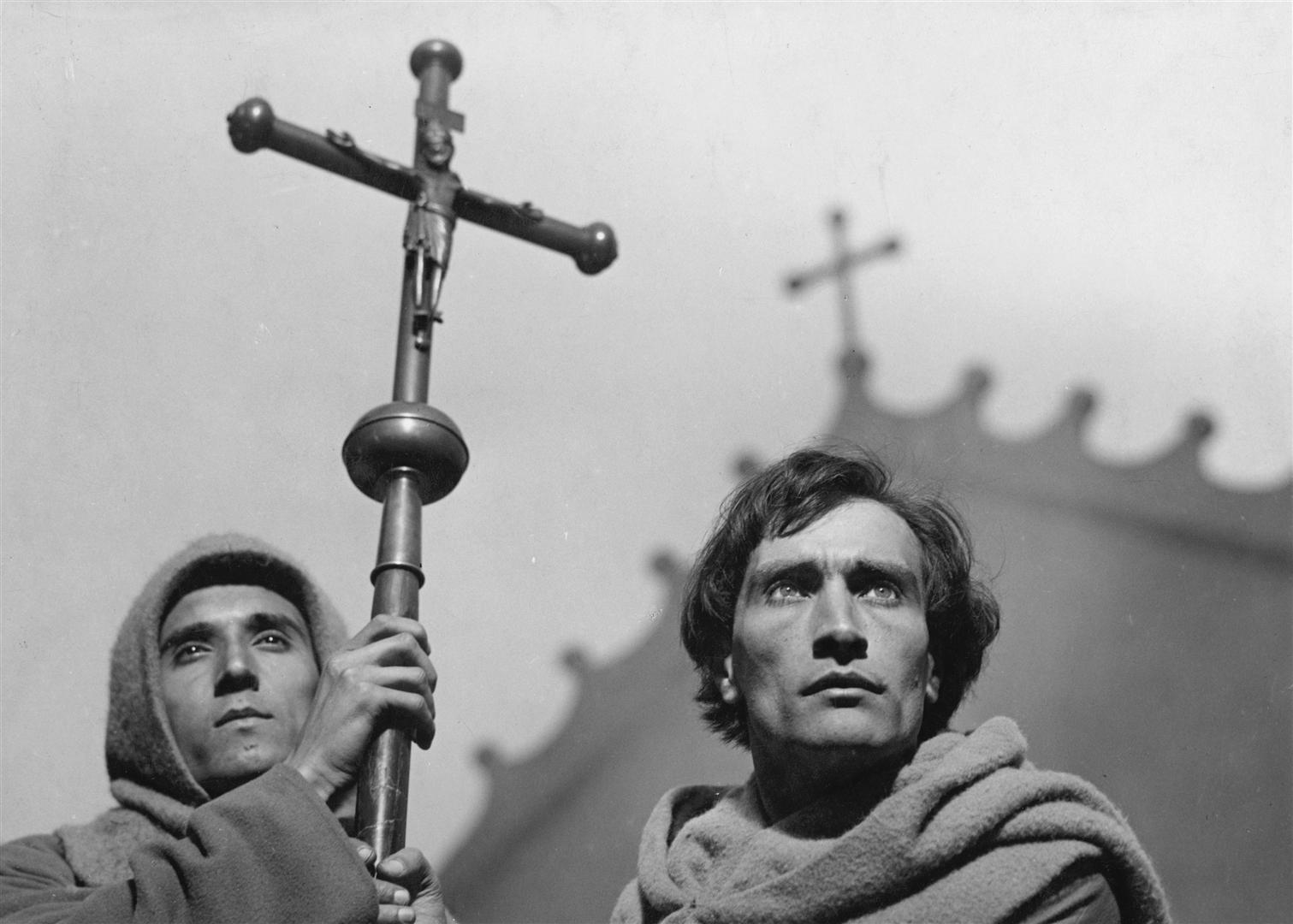

Artaud (right) in La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc

(1928)

リンク

文献

そ

の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099