Anthroplogy

of Suffering & Sickness

〈病む=苦悩する〉ことの人類学

Anthroplogy

of Suffering & Sickness

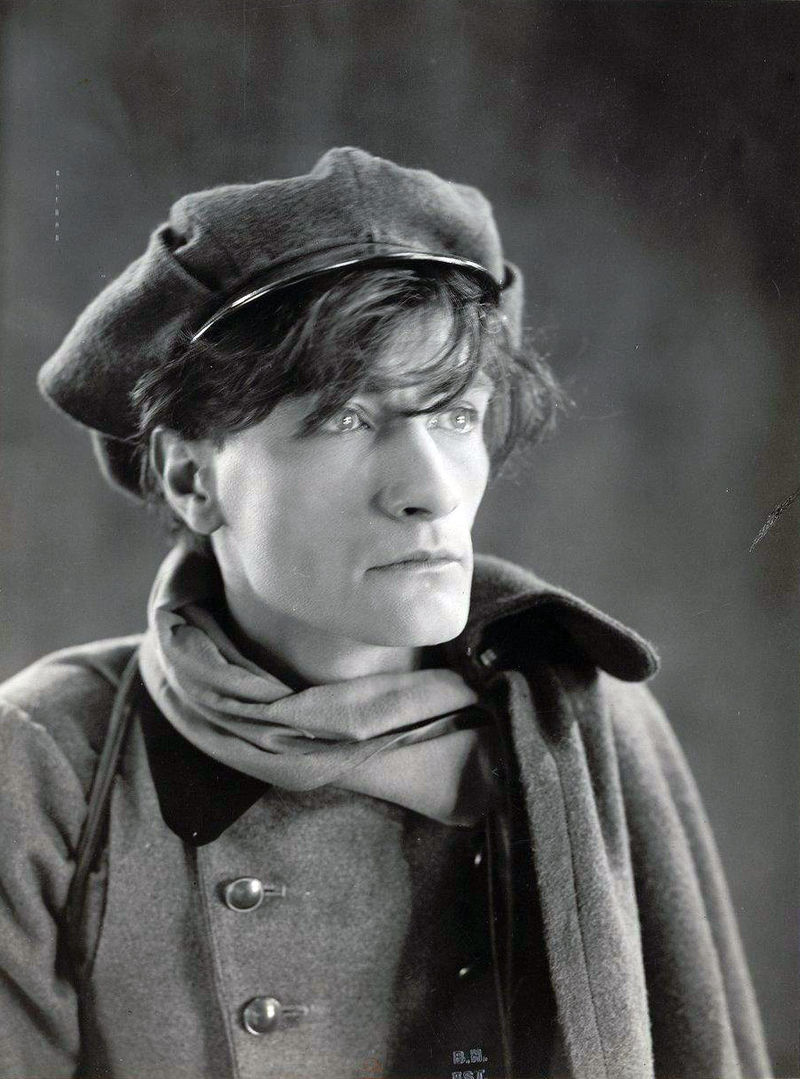

〈病む=苦悩する〉ことの人類学のインスピレーションを与えてくれる「アントナン・アルトー(Antonin Artaud, 1896-1948)」;解説:池田光穂

〈病む〉(Suffering & Sickness)ことの人類学は、医療人類学の 別名である。医 療人類学とは、医学と人類学を架橋(ブリッジ)する学問のことです。医学と人類学が 相互に架橋(ブリッジ)することで、医療は人類 学的に変わり、また人類学は医療の影響をうけて、また違った姿に変わっていく。これこそが私が医療人類学にもとめている理想的な姿です(→「我々の常識を解体する文化人類学的想像力」「〈病む〉ことの文化人類学」)。

| Suffering, or pain

in a broad sense,[1] may be an experience of unpleasantness or

aversion, possibly associated with the perception of harm or threat of

harm in an individual.[2] Suffering is the basic element that makes up

the negative valence of affective phenomena. The opposite of suffering

is pleasure or happiness. Suffering is often categorized as physical[3] or mental.[4] It may come in all degrees of intensity, from mild to intolerable. Factors of duration and frequency of occurrence usually compound that of intensity. Attitudes toward suffering may vary widely, in the sufferer or other people, according to how much it is regarded as avoidable or unavoidable, useful or useless, deserved or undeserved. Suffering occurs in the lives of sentient beings in numerous manners, often dramatically. As a result, many fields of human activity are concerned with some aspects of suffering. These aspects may include the nature of suffering, its processes, its origin and causes, its meaning and significance, its related personal, social, and cultural behaviors,[5] its remedies, management, and uses. |

苦悩、または広義の苦痛[1]とは、不快感や嫌悪感を経験することであ

り、個人における危害や危害の脅威の知覚に関連する可能性がある[2]。苦悩は感情現象の否定的価を構成する基本要素である。苦悩の反対は快楽または幸福

である。 苦悩はしばしば身体的なもの[3]と精神的なもの[4]に分類される。通常、持続期間と発生頻度の要因が、その強度をさらに高めている。苦悩に対する態度 は、苦悩が回避可能か不可避か、有用か無益か、当然か不相応かによって、苦悩者にも人民にも大きく異なることがある。 苦悩は生きとし生けるものの人生において、さまざまな形で、しばしば劇的に生じる。その結果、人間の活動の多くの分野が苦悩のある側面に関係している。こ れらの側面には、苦悩の性質、そのプロセス、その起源と原因、その意味と意義、それに関連する人格的、社会的、文化的行動[5]、その救済策、管理、利用 などが含まれる。 |

Tragic mask on the façade of the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm, Sweden |

スウェーデン、ストックホルムの王立劇場のファサードにある悲劇的な仮面 |

| Terminology The word suffering is sometimes used in the narrow sense of physical pain, but more often it refers to psychological pain, or more often yet it refers to pain in the broad sense, i.e. to any unpleasant feeling, emotion or sensation. The word pain usually refers to physical pain, but it is also a common synonym of suffering. The words pain and suffering are often used both together in different ways. For instance, they may be used as interchangeable synonyms. Or they may be used in 'contradistinction' to one another, as in "pain is physical, suffering is mental", or "pain is inevitable, suffering is optional". Or they may be used to define each other, as in "pain is physical suffering", or "suffering is severe physical or mental pain". Qualifiers, such as physical, mental, emotional, and psychological, are often used to refer to certain types of pain or suffering. In particular, mental pain (or suffering) may be used in relationship with physical pain (or suffering) for distinguishing between two wide categories of pain or suffering. A first caveat concerning such a distinction is that it uses physical pain in a sense that normally includes not only the 'typical sensory experience of physical pain' but also other unpleasant bodily experiences including air hunger, hunger, vestibular suffering, nausea, sleep deprivation, and itching. A second caveat is that the terms physical or mental should not be taken too literally: physical pain or suffering, as a matter of fact, happens through conscious minds and involves emotional aspects, while mental pain or suffering happens through physical brains and, being an emotion, involves important physiological aspects. The word unpleasantness, which some people use as a synonym of suffering or pain in the broad sense, may refer to the basic affective dimension of pain (its suffering aspect), usually in contrast with the sensory dimension, as for instance in this sentence: "Pain-unpleasantness is often, though not always, closely linked to both the intensity and unique qualities of the painful sensation."[6] Other current words that have a definition with some similarity to suffering include distress, unhappiness, misery, affliction, woe, ill, discomfort, displeasure, disagreeableness. |

用語解説 苦悩という言葉は、肉体的な苦痛という狭い意味で使われることもあるが、心理的な苦痛を指すことが多く、さらに広義の苦痛、つまりあらゆる不快な感情や感 覚を指すこともある。痛みという言葉は通常、肉体的な痛みを指すが、苦悩の対義語としてもよく使われる。痛みと苦悩という言葉は、しばしば異なる意味で併 用される。例えば、互換性のある同義語として使われることもある。あるいは、「痛みは肉体的なもので、苦悩は精神的なものである」とか、「苦悩は必然的な もので、苦悩は任意的なものである」というように、互いに「矛盾」して使われることもある。あるいは、「苦悩とは肉体的な苦痛である」、「苦悩とは肉体的 または精神的な激しい苦痛である」のように、互いを定義するために使われることもある。 肉体的、精神的、感情的、心理的といった修飾語は、特定のタイプの痛みや苦悩を指すのによく使われる。特に、精神的苦痛(または苦悩)は、身体的苦痛(ま たは苦悩)との関係で、苦痛や苦悩の2つの広いカテゴリーを区別するために使われることがある。このような区別に関する第一の注意点は、通常、「身体的苦 痛の典型的な感覚的経験」だけでなく、空気飢餓、空腹感、前庭の苦しみ、吐き気、睡眠不足、かゆみなど、その他の不快な身体的経験も含む意味で身体的苦痛 を使用していることである。第二の注意点は、肉体的、精神的という言葉をあまり文字通りに捉えるべきではないということである。肉体的な苦悩は、実のとこ ろ、意識を通して起こり、感情的な側面を伴うが、精神的な苦悩は肉体的な脳を通して起こり、感情であるため、重要な生理学的側面を伴う。 不快という言葉は、広義の苦悩や苦痛の同義語として使う人民もいるが、例えばこの文章のように、通常は感覚的な次元と対照的に、苦痛の基本的な感情的次元 (苦痛の側面)を指すことがある: 「苦痛-不快感は、常にではないが、しばしば、痛覚の強さと独特の性質の両方と密接に結びついている」[6]。苦悩と何らかの類似性を持つ定義を持つ他の 現在の言葉には、苦痛、不幸、悲惨、苦悩、災い、病気、不快、不快感、不愉快などがある。 |

| Philosophy Ancient Greek philosophy Many of the Hellenistic philosophies addressed suffering. In Cynicism suffering is alleviated by achieving mental clarity or lucidity (ἁτυφια: atyphia), developing self-sufficiency (αὐτάρκεια: autarky), equanimity, arete, love of humanity, parrhesia, and indifference to the vicissitudes of life (adiaphora). For Pyrrhonism, suffering comes from dogmas (i.e. beliefs regarding non-evident matters), most particularly beliefs that certain things are either good or bad by nature. Suffering can be removed by developing epoche (suspension of judgment) regarding beliefs, which leads to ataraxia (mental tranquility). Epicurus (contrary to common misperceptions of his doctrine) advocated that we should first seek to avoid suffering (aponia) and that the greatest pleasure lies in ataraxia, free from the worrisome pursuit or the unwelcome consequences of ephemeral pleasures. Epicureanism's version of Hedonism, as an ethical theory, claims that good and bad consist ultimately in pleasure and pain. For Stoicism, the greatest good lies in reason and virtue, but the soul best reaches it through a kind of indifference (apatheia) to pleasure and pain: as a consequence, this doctrine has become identified with stern self-control in regard to suffering. |

哲学 古代ギリシャ哲学 ヘレニズム哲学の多くは苦悩に取り組んでいた。 シニシズムでは、精神的な明晰さ(ἁτυφια: atyphia)、自給自足(αὐτάρκεια: autarky)、平静、アレテー、人間愛、パーレシア、人生の波乱に対する無関心(adiaphora)を達成することによって苦悩が軽減される。 ピュロニズムでは、苦悩はドグマ(=自明でない事柄に関する信念)、特に特定の物事が生まれつき善か悪かのどちらかであるという信念から生じる。苦悩は、 信念に関するエポチェ(判断の停止)を発達させることによって取り除くことができ、それはアタラクシア(精神的静謐)につながる。 エピクロスは(彼の教義に対する一般的な誤解に反して)、まず苦悩(アポニア)を避けようと努めるべきであり、儚い快楽の心配な追求や好ましくない結果か ら解放されたアタラクシアにこそ、最大の快楽があると提唱した。エピクロス主義のヘドニズム版は、倫理理論として、善と悪は究極的には快楽と苦痛にあると 主張する。 ストイシズムでは、最大の善は理性と徳にあるが、魂は快楽と苦悩に対する一種の無関心(アパテイア)を通じてそれに到達するのが最善である。結果として、この教義は苦悩に対する厳しい自制心と同一視されるようになった。 |

| Modern philosophy Jeremy Bentham developed hedonistic utilitarianism, a popular doctrine in ethics, politics, and economics. Bentham argued that the right act or policy was that which would cause "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". He suggested a procedure called hedonic or felicific calculus, for determining how much pleasure and pain would result from any action. John Stuart Mill improved and promoted the doctrine of hedonistic utilitarianism. Karl Popper, in The Open Society and Its Enemies, proposed a negative utilitarianism, which prioritizes the reduction of suffering over the enhancement of happiness when speaking of utility: "I believe that there is, from the ethical point of view, no symmetry between suffering and happiness, or between pain and pleasure. ... human suffering makes a direct moral appeal for help, while there is no similar call to increase the happiness of a man who is doing well anyway." David Pearce, for his part, advocates a utilitarianism that aims straightforwardly at the abolition of suffering through the use of biotechnology (see more details below in section Biology, neurology, psychology). Another aspect worthy of mention here is that many utilitarians since Bentham hold that the moral status of a being comes from its ability to feel pleasure and pain: therefore, moral agents should consider not only the interests of human beings but also those of (other) animals. Richard Ryder came to the same conclusion in his concepts of 'speciesism' and 'painism'. Peter Singer's writings, especially the book Animal Liberation, represent the leading edge of this kind of utilitarianism for animals as well as for people. Another doctrine related to the relief of suffering is humanitarianism (see also humanitarian principles, humanitarian aid, and humane society). "Where humanitarian efforts seek a positive addition to the happiness of sentient beings, it is to make the unhappy happy rather than the happy happier. ... [Humanitarianism] is an ingredient in many social attitudes; in the modern world it has so penetrated into diverse movements ... that it can hardly be said to exist in itself."[7] Pessimists hold this world to be mainly bad, or even the worst possible, plagued with, among other things, unbearable and unstoppable suffering. Some identify suffering as the nature of the world and conclude that it would be better if life did not exist at all. Arthur Schopenhauer recommends us to take refuge in things like art, philosophy, loss of the will to live, and tolerance toward 'fellow-sufferers'. Friedrich Nietzsche, first influenced by Schopenhauer, developed afterward quite another attitude, arguing that the suffering of life is productive, exalting the will to power, despising weak compassion or pity, and recommending us to embrace willfully the 'eternal return' of the greatest sufferings. [citation needed][8] Some philosophers have questioned whether suffering has a genuine positive counterpart. A phenomenological argument presented by Magnus Vinding claims that while positive experiences such as joy or excitement are real, they do not serve as opposites to suffering in either phenomenological or axiological terms.[9]: 38 Philosophy of pain is a philosophical speciality that focuses on physical pain and is, through that, relevant to suffering in general. |

近代哲学 ジェレミー・ベンサムは、倫理学、政治学、経済学において一般的な教義である快楽主義的功利主義を発展させた。ベンサムは、正しい行為や政策とは「最大多 数の最大幸福」をもたらすものであると主張した。彼は、どのような行為からどれだけの快楽と苦痛が生じるかを決定するために、ヘドニック計算 (hedonic calculus)またはフェリシフィック計算(felicific calculus)と呼ばれる手順を提案した。ジョン・スチュアート・ミルは快楽主義的功利主義の教義を改良し、促進した。カール・ポパーは『開かれた社 会とその敵』の中で、効用を語る際に幸福の増進よりも苦悩の軽減を優先する消極的功利主義を提唱した: 「私は、倫理的観点からは、苦悩と幸福、あるいは苦痛と快楽の間には対称性はないと考える。...人間の苦悩は直接的に道徳的に助けを求めるが、とにかく うまくいっている人間の幸福を増やそうという同じような呼びかけはない」 デイヴィッド・ピアース(David Pearce)は、バイオテクノロジーの利用によって苦悩をなくすことをストレートに目指す功利主義を提唱している(詳細は後述の「生物学、神経学、心理 学」の項を参照)。ベンサム以来、多くの功利主義者が、ある存在の道徳的地位は快楽と苦痛を感じる能力から生まれると主張している。リチャード・ライダー は「種差別」と「苦痛差別」という概念において、同じ結論に達した。ピーター・シンガーの著作、特に『動物の解放』は、この種の功利主義の最先端を行くも のである。 苦悩の救済に関連するもうひとつの教義が人道主義である(人道主義、人道援助、人道的社会も参照)。「人道主義的な取り組みが衆生の幸福にプラスになるこ とを求める場合、それは幸福な人を幸福にするのではなく、不幸な人を幸福にすることである。... [人道主義は)多くの社会的態度の成分であり、現代世界においては、それ自体が存在するとは言い難いほど、多様な運動に浸透している......」 [7]。 悲観主義者は、この世は主に悪いもの、あるいは最悪のものであり、とりわけ耐えがたく止められない苦悩に悩まされていると考える。苦悩を世界の本質と見な し、生命など存在しない方がましだと結論づける者もいる。アーサー・ショーペンハウアーは、芸術や哲学、生きる意欲の喪失、「苦悩する仲間」に対する寛容 さといったものに逃げ込むことを勧めている。 フリードリヒ・ニーチェはショーペンハウアーの影響を最初に受け、その後全く別の態度を展開し、人生の苦悩は生産的であると主張し、権力への意志を高揚さ せ、弱い同情や哀れみを軽蔑し、最大の苦悩の「永遠の回帰」を意志的に受け入れることを勧めた。[要出典][8]である。 哲学者の中には、苦悩が真に肯定的な対局を持つかどうか疑問視する者もいる。マグヌス・ヴィンディングによって提示された現象学的な議論では、喜びや興奮 といった肯定的な経験は実在するが、それらは現象学的にも公理論的にも苦悩と対をなすものではないと主張している[9]: 38 苦悩の哲学は、身体的苦痛に焦点を当てた哲学的専門分野であり、それを通じて苦悩全般に関連する。 |

| Religion Suffering plays an important role in a number of religions, regarding matters such as the following: consolation or relief; moral conduct (do no harm, help the afflicted, show compassion); spiritual advancement through life hardships or through self-imposed trials (mortification of the flesh, penance, asceticism); ultimate destiny (salvation, damnation, hell). Theodicy deals with the problem of evil, which is the difficulty of reconciling the existence of an omnipotent and benevolent god with the existence of evil. "Several attempts were made to preserve together both monotheism and God’s attributes from types of dualism (e. g. Gnosticism, Paulicianism, Catharism) and the idea of God’s reduced number of attributes, due to the tension between the existence of evil and the divine omnipotence and omnibenevolence."[10] A quintessential form of evil, for many people, is extreme suffering, especially in innocent children, or in creatures destined to an eternity of torments (see problem of hell). The 'Four Noble Truths' of Buddhism are about dukkha, a term often translated as suffering. They state the nature of suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the way leading to its cessation, the Noble Eightfold Path. Buddhism considers liberation from dukkha and the practice of compassion (karuna) as basic for leading a holy life and attaining nirvana. Hinduism holds that suffering follows naturally from personal negative behaviors in one's current life or in a past life (see karma in Hinduism).[11] One must accept suffering as a just consequence and as an opportunity for spiritual progress. Thus the soul or true self, which is eternally free of any suffering, may come to manifest itself in the person, who then achieves liberation (moksha). Abstinence from causing pain or harm to other beings, called ahimsa, is a central tenet of Hinduism, and even more so of another Indian religion, Jainism (see ahimsa in Jainism). In Judaism, suffering is often seen as a punishment for sins and a test of a person's faith, like the Book of Job illustrates. For Christianity, redemptive suffering is the belief that human suffering, when accepted and offered up in union with the "passion" (flogging and crucifixion) of Jesus,[12] can remit the just punishment for sins, and allow oneself to grow in the love of The Trinity, other people, and oneself.[13] In Islam, the faithful must endure suffering with hope and faith, not resist or ask why, accept it as Allah's will and submit to it as a test of faith. Allah never asks more than can be endured. One must also work to alleviate the suffering of others, as well as one's own. Suffering is also seen as a blessing. Through that gift, the sufferer remembers Allah and connects with him. Suffering expunges the sins of human beings and cleanses their soul for the immense reward of the afterlife, and the avoidance of hell.[14] According to the Bahá'í Faith, all suffering is a brief and temporary manifestation of physical life, whose source is the material aspects of physical existence, and often attachment to them, whereas only joy exists in the spiritual worlds.[15] |

宗教 多くの宗教において、苦悩は次のような事柄に関して重要な役割を果たしている:慰めや救済、道徳的行為(害を加えない、苦しんでいる人を助ける、慈悲を示 す)、人生の苦難や自らに課した試練を通じた精神的進歩(肉を断つ、苦行、無欲主義)、究極の運命(救済、天罰、地獄)。神義論は悪の問題を扱うが、それ は全能で慈悲深い神の存在と悪の存在を調和させることの難しさである。「グノーシス主義、パウロ主義、カタリ派などの二元論や、神の属性の数を減らすとい う考え方から、一神教と神の属性の両方を維持しようとする試みがいくつかなされたが、それは悪の存在と神の全能・全能の間の緊張のためであった」 [10]。 仏教の「四諦」はドゥッカ(苦悩と訳されることが多い)について述べている。苦悩の本質、その原因、苦悩の止滅、苦悩の止滅に至る道である八正道を述べて いる。仏教は、ドゥッカからの解脱と慈悲(カルナ)の実践を、聖なる生活を送り涅槃に到達するための基本であると考えている。 ヒンドゥー教では、苦悩は現世または過去世における人格的な否定的行動から自然に生じると考える(ヒンドゥー教におけるカルマを参照)[11]。こうし て、苦悩から永遠に自由である魂または真の自己が人格の中に現れ、その人格は解脱(モクシャ)を達成する。他の存在に苦痛や危害を与えないことは、アヒン サーと呼ばれ、ヒンドゥー教の中心的な信条であり、さらにインドのもうひとつの宗教であるジャイナ教でもそうである(ジャイナ教におけるアヒンサーを参 照)。 ユダヤ教では、苦悩はしばしば罪に対する罰として、またヨブ記に描かれているように人格の信仰心を試す試練として捉えられている。 キリスト教では、贖罪的苦悩とは、人間の苦悩がイエスの「受難」(鞭打ちと十字架刑)と一体となって受け入れられ、捧げられるとき[12]、罪に対する正 当な罰を免除し、三位一体、他の人民、そして自分自身への愛において成長することを可能にするという信念である[13]。 イスラームでは、信仰者は希望と信仰心を持って苦悩に耐えなければならず、抵抗したり理由を尋ねたりせず、それをアッラーの意志として受け入れ、信仰の試 練として服従しなければならない。アッラーは耐えられる以上のことを決して要求されない。また、自分の苦悩だけでなく、他人の苦悩を和らげるよう努めなけ ればならない。苦悩もまた祝福とみなされる。その贈り物を通して、苦悩する者はアッラーを思い出し、アッラーとつながる。苦悩は人間の罪を消滅させ、来世 の莫大な報酬と地獄の回避のために魂を浄化する[14]。 バハーイー教によれば、すべての苦悩は肉体生活の短期的かつ一時的な現れであり、その源は肉体的存在の物質的側面であり、しばしばそれらへの執着である。 |

Arts and literature Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by Pieter Bruegel the Elder Artistic and literary works often engage with suffering, sometimes at great cost to their creators or performers. Be it in the tragic, comic or other genres, art and literature offer means to alleviate (and perhaps also exacerbate) suffering, as argued for instance in Harold Schweizer's Suffering and the remedy of art.[16] This Bruegel painting is among those that inspired W. H. Auden's poem Musée des Beaux Arts: About suffering they were never wrong, The Old Masters; how well, they understood Its human position; how it takes place While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along; (...) In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely from the disaster; (...)[17] |

芸術と文学 イカロスの墜落のある風景 ピーテル・ブリューゲル作 芸術作品や文学作品はしばしば苦悩と関わり、時には作者やパフォーマーに多大な犠牲を強いることもある。例えば、ハロルド・シュヴァイザーの『苦悩と芸術 の救済』[16]で論じられているように、悲劇であれ、喜劇であれ、その他のジャンルであれ、芸術や文学は苦悩を緩和する(そしておそらくは悪化させる) 手段を提供する。 このブリューゲルの絵は、W・H・オーデンの詩『Musée des Beaux Arts』にインスピレーションを与えた作品のひとつである: 苦悩について、彼らは決して間違っていなかった、 オールド・マスターたちは、いかによく理解していたことか。 その人間の立場を、どれほどよく理解していたことか。 誰かが食事をしていたり、窓を開けていたり、ただぼんやりと歩いていたりする間に; (...) 例えば、ブリューゲルの『イカロス』では、いかにすべてが災難から遠ざかっているか。 (・・・)[17]。 |

| Social sciences Social suffering, according to Arthur Kleinman and others, describes "collective and individual human suffering associated with life conditions shaped by powerful social forces".[18] Such suffering is an increasing concern in medical anthropology, ethnography, mass media analysis, and Holocaust studies, says Iain Wilkinson,[19] who is developing a sociology of suffering.[20] The Encyclopedia of World Problems and Human Potential is a work by the Union of International Associations. Its main databases are about world problems (56,564 profiles), global strategies and solutions (32,547 profiles), human values (3,257 profiles), and human development (4,817 profiles). It states that "the most fundamental entry common to the core parts is that of pain (or suffering)" and "common to the core parts is the learning dimension of new understanding or insight in response to suffering".[21] Ralph Siu, an American author, urged in 1988 the "creation of a new and vigorous academic discipline, called panetics, to be devoted to the study of the infliction of suffering",[22] The International Society for Panetics was founded in 1991 to study and develop ways to reduce the infliction of human suffering by individuals acting through professions, corporations, governments, and other social groups.[23] In economics, the following notions relate not only to the matters suggested by their positive appellations, but to the matter of suffering as well: Well-being or Quality of life, Welfare economics, Happiness economics, Gross National Happiness, genuine progress indicator. In law, "Pain and suffering" is a legal term that refers to the mental distress or physical pain endured by a plaintiff as a result of injury for which the plaintiff seeks redress. Assessments of pain and suffering are required to be made for attributing legal awards. In the Western world these are typically made by juries in a discretionary fashion and are regarded as subjective, variable, and difficult to predict, for instance in the US,[24] UK,[25] Australia and New Zealand.[26] See also, in US law, Negligent infliction of emotional distress and Intentional infliction of emotional distress. In management and organization studies, drawing on the work of Eric Cassell, suffering has been defined as the distress a person experiences when they perceive a threat to any aspect of their continued existence, whether physical, psychological, or social.[27] Other researchers have noted that suffering results from an inability to control actions that usually define one's view of one's self and that the characteristics of suffering include the loss of autonomy, or the loss of valued relationships or sense of self. Suffering is therefore determined not by the threat itself but, rather, by its meaning to the individual and the threat to their personhood.[27] |

社会科学 アーサー・クラインマンらによれば、社会的苦悩とは「強力な社会的力によって形成された生活状況に関連する、集団的・個人的な人間の苦悩」のことである [18]。このような苦悩は、医療人類学、民族誌、マスメディア分析、ホロコースト研究において関心が高まっており、苦悩の社会学を展開しているイアン・ ウィルキンソン[19]は言う[20]。 The Encyclopedia of World Problems and Human Potentialは、国際協会連合による著作である。その主なデータベースは、世界の問題(56,564のプロフィール)、世界戦略と解決策 (32,547のプロフィール)、人間の価値(3,257のプロフィール)、人間開発(4,817のプロフィール)についてである。核となる部分に共通す る最も基本的な項目は苦悩である」とし、「核となる部分に共通するのは、苦悩に対する新たな理解や洞察という学習の側面である」と述べている[21]。 アメリカの作家であるラルフ・シウは1988年に「苦悩の付与の研究に専念するパネティクスと呼ばれる新しく活力ある学問分野の創設」を促し[22]、国 際パネティクス学会は1991年に設立され、職業、企業、政府、その他の社会集団を通じて行動する個人による人間の苦悩の付与を減少させる方法を研究し開 発することを目的としている[23]。 経済学において、以下の概念は、その肯定的な呼称によって示唆される事柄だけでなく、苦悩の問題にも関連している: 幸福または生活の質、福祉経済学、幸福経済学、国民総幸福量、真の進歩指標。 法律上、「苦悩」とは、原告が救済を求める傷害の結果として原告が耐えた精神的苦痛や肉体的苦痛を指す法律用語である。苦悩の評価は、法的裁定を下すため に必要である。欧米諸国では、これらは通常、陪審員によって裁量的に行われ、主観的で変動しやすく、予測が困難であるとみなされており、例えば、米国、 [24]英国、[25]オーストラリア、ニュージーランドでは、主観的で変動しやすく、予測が困難であるとみなされている[26]。 他の研究者は、苦悩は通常、自己の自己観を規定する行動を制御できないことから生じ、苦悩の特徴には自律性の喪失、または価値ある人間関係や自己意識の喪 失が含まれると指摘している[27]。したがって苦悩は、脅威それ自体によって決まるのではなく、むしろ個人にとっての意味と、その人らしさに対する脅威 によって決まるのである[27]。 |

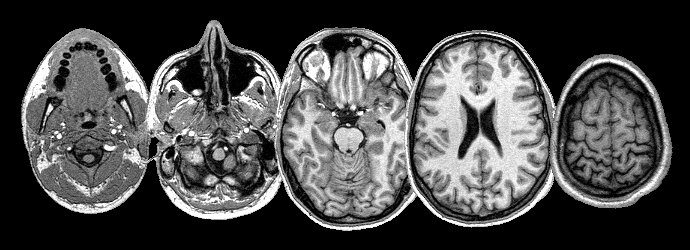

| Biology, neurology, psychology Suffering and pleasure are respectively the negative and positive affects, or hedonic tones, or valences that psychologists often identify as basic in our emotional lives.[28] The evolutionary role of physical and mental suffering, through natural selection, is primordial: it warns of threats, motivates coping (fight or flight, escapism), and reinforces negatively certain behaviors (see punishment, aversives). Despite its initial disrupting nature, suffering contributes to the organization of meaning in an individual's world and psyche. In turn, meaning determines how individuals or societies experience and deal with suffering.  Neuroimaging sheds light on the seat of suffering Many brain structures and physiological processes are involved in suffering (particularly the anterior insula and cingulate cortex, both implicated in nociceptive and empathic pain).[29] Various hypotheses try to account for the experience of suffering. One of these, the pain overlap theory[30] takes note, thanks to neuroimaging studies, that the cingulate cortex fires up when the brain feels suffering from experimentally induced social distress, as well as physical pain. The theory proposes therefore that physical pain and social pain (i.e. two radically differing kinds of suffering) share a common phenomenological and neurological basis. According to David Pearce's online manifesto "The Hedonistic Imperative",[31] suffering is the avoidable result of Darwinian evolution. Pearce promotes replacing the biology of suffering with a robot-like response to noxious stimuli[32] or with information-sensitive gradients of bliss,[33] through genetic engineering and other technical scientific advances. Different theories of psychology view suffering differently. Sigmund Freud viewed suffering as something humans are hardwired to avoid, while they are always in the pursuit of pleasure,[34] also known as the hedonic theory of motivation or the pleasure principle. This dogma also ties in with certain concepts of Behaviorism, most notably Operant Conditioning theory. In operant conditioning, a negative stimulus is removed thereby increasing a desired behavior, alternatively an aversive stimulus can be introduced as a punishing factor. In both methods, unfavorable circumstances are used in order to motivate an individual or an animal towards a certain goal.[35] However, other theories of psychology present contradicting ideas such as the idea that humans sometimes seek out suffering.[36] Many existentialists believe suffering is necessary in order to find meaning in our lives.[37] Existential Positive Psychology is a theory dedicated to exploring the relationship between suffering and happiness and the belief that true authentic happiness can only come from experiencing pain and hardships.[38] Hedonistic psychology,[39] affective science, and affective neuroscience are some of the emerging scientific fields that could in the coming years focus their attention on the phenomenon of suffering. |

生物学、神経学、心理学 苦悩と快楽はそれぞれ、心理学者がしばしば私たちの感情生活における基本的なものとして特定する否定的・肯定的な影響、すなわち快楽的色調、あるいは価値 観である[28]。自然淘汰による肉体的・精神的苦悩の進化的役割は原初的なものであり、脅威を警告し、対処(闘争か逃走か、逃避か)を動機付け、特定の 行動を否定的に強化する(罰、回避を参照)。苦悩はその最初の破壊的な性質にもかかわらず、個人の世界と精神における意味の構成に貢献する。ひいては、意 味は個人や社会が苦悩をどのように経験し、対処するかを決定する。  ニューロイメージングが苦悩の根源に光を当てる 苦悩には多くの脳構造と生理学的プロセスが関与している(特に前部島皮質と帯状皮質は、いずれも侵害受容性疼痛と共感性疼痛に関与している)[29]。そ のうちの1つである疼痛重複理論[30]は、神経画像研究のおかげで、実験的に誘発された社会的苦悩による苦悩を脳が感じたときに、身体的苦痛と同様に帯 状皮質が発火することに注目している。したがってこの理論では、身体的苦痛と社会的苦痛(つまり根本的に異なる2種類の苦悩)は、現象学的・神経学的基盤 を共有していると提唱している。 デイヴィッド・ピアースのオンラインマニフェスト『The Hedonistic Imperative』[31]によれば、苦悩はダーウィン進化の回避可能な結果である。ピアースは、遺伝子工学やその他の技術的な科学的進歩を通じて、 苦悩の生物学を、有害な刺激に対するロボットのような反応[32]、あるいは情報に敏感な至福の勾配[33]に置き換えることを推進している。 心理学の異なる理論は苦悩を異なるものとして捉えている。ジークムント・フロイトは苦悩を、人間は常に快楽を追い求める一方で、避けるように仕向けられた ものであると捉えており[34]、動機づけの快楽説や快楽原則としても知られている。このドグマは行動主義のある種の概念、とりわけオペラント条件づけ理 論とも結びついている。オペラント条件づけでは、否定的な刺激を除去することによって望ましい行動を増加させるが、その代わりに嫌悪的な刺激を罰因子とし て導入することもできる。しかし、心理学の他の理論では、人間は時に苦悩を求めるという考えなど、矛盾する考え方が示されている[35]。 ヘドニスティック心理学、[39]感情科学、感情神経科学は、今後数年のうちに苦悩という現象に注目する可能性のある新たな科学分野の一部である。 |

| Health care Disease and injury may contribute to suffering in humans and animals. For example, suffering may be a feature of mental or physical illness[40] such as borderline personality disorder[41][42] and occasionally in advanced cancer.[43] Health care addresses this suffering in many ways, in subfields such as medicine, clinical psychology, psychotherapy, alternative medicine, hygiene, public health, and through various health care providers. Health care approaches to suffering, however, remain problematic. Physician and author Eric Cassell, widely cited on the subject of attending to the suffering person as a primary goal of medicine, has defined suffering as "the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person".[44] Cassell writes: "The obligation of physicians to relieve human suffering stretches back to antiquity. Despite this fact, little attention is explicitly given to the problem of suffering in medical education, research or practice." Mirroring the traditional body and mind dichotomy that underlies its teaching and practice, medicine strongly distinguishes pain from suffering, and most attention goes to the treatment of pain. Nevertheless, physical pain itself still lacks adequate attention from the medical community, according to numerous reports.[45] Besides, some medical fields like palliative care, pain management (or pain medicine), oncology, or psychiatry, do somewhat address suffering 'as such'. In palliative care, for instance, pioneer Cicely Saunders created the concept of 'total pain' ('total suffering' say now the textbooks),[46] which encompasses the whole set of physical and mental distress, discomfort, symptoms, problems, or needs that a patient may experience hurtfully. Mental illness Gary Greenberg, in The Book of Woe, writes that mental illness might best be viewed as medicalization or labeling/naming suffering (i.e. that all mental illnesses might not necessarily be of dysfunction or biological-etiology, but might be social or cultural/societal).[47] |

保健医療 疾病や傷害は、人間や動物における苦悩の一因となりうる。例えば、苦悩は境界性パーソナリティ障害[41][42]のような精神疾患や身体疾患[40]の特徴であり、時には進行がんの場合もある[43]。 しかし、苦悩に対する保健医療のアプローチは、依然として問題を抱えている。医師であり作家であるエリック・カッセルは、医学の第一の目標として苦悩する 人に寄り添うというテーマで広く引用されているが、苦悩を「人格の無傷さを脅かす出来事に関連した深刻な苦悩の状態」と定義している。この事実にもかかわ らず、医学教育、研究、実践において、苦悩の問題に明確な関心が払われることはほとんどない。その教育や実践の根底にある伝統的な身体と心の二分法を反映 して、医学は苦悩と痛みを強く区別し、ほとんどの関心は痛みの治療に向けられる。それにもかかわらず、多くの報告によれば、身体的苦痛そのものは、医学界 から十分な関心を集めていない。その上、緩和ケア、疼痛管理(または疼痛医学)、腫瘍学、精神医学のような一部の医学分野では、「そのような」苦悩をいく らか取り上げている。例えば緩和ケアでは、パイオニアであるCicely Saundersが「トータルペイン」(現在では教科書に「トータルペインティング」と記載されている)という概念を創り出した[46]。 精神疾患 ゲーリー・グリーンバーグは『災いの書』の中で、精神疾患は医療化、あるいは苦悩にレッテルを貼ること/名前をつけること(すなわち、すべての精神疾患は 必ずしも機能障害や生物学的病因によるものではなく、社会的あるいは文化的/社会的なものであるかもしれない)として捉えるのが最善かもしれないと書いて いる[47]。 |

| Relief and prevention in society Since suffering is such a universal motivating experience, people, when asked, can relate their activities to its relief and prevention. Farmers, for instance, may claim that they prevent famine, artists may say that they take our minds off our worries, and teachers may hold that they hand down tools for coping with life hazards. In certain aspects of collective life, however, suffering is more readily an explicit concern by itself. Such aspects may include public health, human rights, humanitarian aid, disaster relief, philanthropy, economic aid, social services, insurance, and animal welfare. To these can be added the aspects of security and safety, which relate to precautionary measures taken by individuals or families, to interventions by the military, the police, the firefighters, and to notions or fields like social security, environmental security, and human security. The nongovernmental research organization Center on Long-Term Risk, formerly known as the Foundational Research Institute, focuses on reducing risks of astronomical suffering (s-risks) from emerging technologies.[48] Another organization also focused on research, the Center on Reducing Suffering, has a similar focus, with a stress on clarifying what priorities there should be at a practical level to attain the goal of reducing intense suffering in the future.[49] |

社会における救済と予防 苦悩は普遍的な原動力となる経験であるため、人民は自分の活動を苦悩の救済や予防に関連づけることができる。例えば、農家は飢饉を防いでいると主張し、芸 術家は心配事を取り除いてくれると言い、教師は人生の危険に対処するための道具を伝えていると主張するかもしれない。しかし、集団生活のある側面において は、苦悩はそれ自体が明確な関心事となりやすい。公衆衛生、人権、人道支援、災害救援、慈善活動、経済支援、社会サービス、保険、動物愛護などである。こ れらに、個人や家族による予防措置、軍隊や警察、消防士による介入、社会保障、環境保障、人間の安全保障といった概念や分野に関係する、安全保障や安心と いう側面を加えることができる。 非政府研究組織である長期リスク研究センター(旧基礎研究所)は、新興技術による天文学的な苦悩のリスク(Sリスク)の軽減に焦点を当てている[48]。 同じく研究に焦点を当てた組織である苦悩軽減センターも同様の焦点を持ち、将来的に激しい苦悩を軽減するという目標を達成するために、実務レベルでどのよ うな優先事項があるべきかを明らかにすることに重点を置いている[49]。 |

| Uses Philosopher Leonard Katz wrote: "But Nature, as we now know, regards ultimately only fitness and not our happiness ... and does not scruple to use hate, fear, punishment and even war alongside affection in ordering social groups and selecting among them, just as she uses pain as well as pleasure to get us to feed, water and protect our bodies and also in forging our social bonds."[50] People make use of suffering for specific social or personal purposes in many areas of human life, as can be seen in the following instances: In arts, literature, or entertainment, people may use suffering for creation, for performance, or for enjoyment. Entertainment particularly makes use of suffering in blood sports and violence in the media, including violent video games depiction of suffering.[51] A more or less great amount of suffering is involved in body art. The most common forms of body art include tattooing, body piercing, scarification, human branding. Another form of body art is a sub-category of performance art, in which for instance the body is mutilated or pushed to its physical limits. In business and various organizations, suffering may be used for constraining humans or animals into required behaviors. In a criminal context, people may use suffering for coercion, revenge, or pleasure. In interpersonal relationships, especially in places like families, schools, or workplaces, suffering is used for various motives, particularly under the form of abuse and punishment. In another fashion related to interpersonal relationships, the sick, or victims, or malingerers, may use suffering more or less voluntarily to get primary, secondary, or tertiary gain. In law, suffering is used for punishment (see penal law); victims may refer to what legal texts call "pain and suffering" to get compensation; lawyers may use a victim's suffering as an argument against the accused; an accused's or defendant's suffering may be an argument in their favor; authorities at times use light or heavy torture in order to get information or a confession. In the news media, suffering is often the raw material.[52] In personal conduct, people may use suffering for themselves, in a positive way.[53] Personal suffering may lead, if bitterness, depression, or spitefulness is avoided, to character-building, spiritual growth, or moral achievement;[54] realizing the extent or gravity of suffering in the world may motivate one to relieve it and may give an inspiring direction to one's life. Alternatively, people may make self-detrimental use of suffering. Some may be caught in compulsive reenactment of painful feelings in order to protect them from seeing that those feelings have their origin in unmentionable past experiences; some may addictively indulge in disagreeable emotions like fear, anger, or jealousy, in order to enjoy pleasant feelings of arousal or release that often accompany these emotions; some may engage in acts of self-harm aimed at relieving otherwise unbearable states of mind. In politics, there is purposeful infliction of suffering in war, torture, and terrorism; people may use nonphysical suffering against competitors in nonviolent power struggles; people who argue for a policy may put forward the need to relieve, prevent or avenge suffering; individuals or groups may use past suffering as a political lever in their favor. In religion, suffering is used especially to grow spiritually, to expiate, to inspire compassion and help, to frighten, to punish. In rites of passage (see also hazing, ragging), rituals that make use of suffering are frequent. In science, humans and animals are subjected on purpose to aversive experiences for the study of suffering or other phenomena. In sex, especially in a context of sadism and masochism or BDSM, individuals may use a certain amount of physical or mental suffering (e.g. pain, humiliation). In sports, suffering may be used to outperform competitors or oneself; see sports injury, and no pain, no gain; see also blood sport and violence in sport as instances of pain-based entertainment. |

用途 哲学者のレナード・カッツは次のように書いている。「しかし、今われわれが知っているように、自然は究極的には、われわれの幸福ではなく、適性だけを考え ている......そして、われわれに食物を与え、水を与え、身体を守らせるために、また、われわれの社会的な絆を築くために、苦痛を快楽と同様に用いる のと同じように、社会的な集団を秩序づけ、その中で選別するために、愛情とともに憎しみ、恐怖、罰、さらには戦争を用いることをためらわない」[50]。 以下の例に見られるように、人民は人間生活の多くの分野において、特定の社会的あるいは個人的な目的のために苦悩を利用している: 芸術、文学、娯楽において、人民は苦悩を創作のため、パフォーマンスのため、あるいは楽しむために利用することがある。エンターテインメントでは、特に血 のスポーツや、暴力的なビデオゲームによる苦悩の描写を含むメディアにおける暴力において苦悩が利用されている[51]。ボディアートには多かれ少なかれ 多くの苦悩が含まれている。ボディアートの最も一般的な形態は、タトゥー、ボディピアス、傷跡、人間の焼き印などである。ボディーアートのもう一つの形態 は、パフォーマービティのサブカテゴリーであり、例えば、身体を切断したり、肉体的限界まで追い込んだりするものである。 ビジネスやさまざまな組織では、人間や動物を必要な行動に拘束するために苦悩が使われることがある。 犯罪の文脈では、人民は苦悩を強制、復讐、快楽のために用いることがある。 対人関係、特に家族、学校、職場などでは、苦悩はさまざまな動機、特に虐待や罰という形で用いられる。対人関係に関連する別の態様では、病人や被害者、あ るいは悪意者は、第一次、第二次、あるいは第三次的な利益を得るために、多かれ少なかれ自発的に苦悩を利用することがある。 法律では、苦悩は刑罰のために用いられる(刑法を参照)。被害者は賠償金を得るために、法文で「苦悩」と呼ばれるものを参照することがある。弁護士は被告人に対する反論として被害者の苦悩を用いることがある。 ニュースメディアでは、苦悩がしばしば素材となる[52]。 個人的な行動において、人民は苦悩を肯定的な方法で自分自身のために利用することがある[53]。個人的な苦悩は、恨み、憂鬱、辛さが避けられるならば、 人格形成、精神的成長、道徳的達成につながるかもしれない[54]。あるいは、人民が苦悩を自己否定的に利用することもある。ある人は、つらい感情の強迫 的な再現にとらわれるかもしれない。それは、その感情が言いようのない過去の体験に由来していることを見ないようにするためである。ある人は、恐怖、怒 り、嫉妬などの不快な感情に耽るかもしれない。それは、これらの感情にしばしば伴う快い覚醒感や解放感を味わうためである。ある人は、そうでなければ耐え 難い心の状態を和らげることを目的とした自傷行為に及ぶかもしれない。 政治においては、戦争、拷問、テロリズムにおいて、意図的に苦悩を与えることがある。人民は、非暴力的な権力闘争において、競争相手に対して物理的でない苦悩を用いることがある。 宗教においては、苦悩は特に、精神的に成長するため、罪滅ぼしのため、慈悲や助けを鼓舞するため、恐怖を与えるため、罰するために用いられる。 通過儀礼(ヘージング、ボロ負けも参照)では、苦悩を利用した儀式が頻繁に行われる。 科学では、苦悩やその他の現象を研究するために、人間や動物が意図的に嫌悪的な体験をさせられる。 セックス、特にサディズムやマゾヒズム、BDSMの文脈では、個人はある程度の肉体的・精神的苦悩(痛みや屈辱など)を利用することがある。 スポーツでは、苦悩は競争相手や自分自身を凌駕するために使われることがある。スポーツ傷害、ノーペイン・ノーゲインを参照。また、苦痛に基づく娯楽の例として、ブラッドスポーツやスポーツにおける暴力も参照のこと。 |

| Topics related to suffering Physical pain-related topics Pain · Pain (philosophy) · Psychogenic pain · Chronic pain · Dehydration · Hunger Starvation · Terminal dehydration · Pain in animals (Amphibians, Cephalopods, Crustaceans, Fish, Invertebrates) Ethics-related topics Evil · Problem of evil · Hell · Good and evil: welfarist theories · Negative consequentialism · Suffering-focused ethics Compassion-related topics Compassion · Compassion fatigue · Pity · Mercy · Sympathy · Empathy Cruelty-related topics Cruelty · Schadenfreude · Sadistic personality disorder · Abuse · Physical abuse · Psychological or emotional abuse · Self-harm · Cruelty to animals Death-related topics Euthanasia · Animal euthanasia · Suicide Other related topics Eradication of suffering · Dukkha · Weltschmerz · Negative affectivity · Psychological pain · Amor fati · Victimology · Penology · Pleasure · Pain and pleasure · Happiness · Hedonic treadmill · Suffering risks · Wild animal suffering |

苦悩に関するトピック 身体的苦痛関連のトピック 苦痛 - 苦痛(哲学) - 心因性苦痛 - 慢性疼痛 - 脱水 - 飢餓 - 末期脱水 - 動物の苦痛(両生類、頭足類、甲殻類、魚類、無脊椎動物) 倫理関連トピック 悪 - 悪の問題 - 地獄 - 善と悪:ウェルファリスト理論 - 消極的帰結主義 - 苦悩に焦点を当てた倫理学 慈悲 - 慈悲疲れ - 憐れみ - 慈悲 - 同情 - 共感 残酷さ関連トピック 残酷さ - シャーデンフロイデ - サディスティック人格障害 - 虐待 - 身体的虐待 - 心理的または感情的虐待 - 自傷行為 - 動物への虐待 死に関連する話題 安楽死 - 動物安楽死 - 自殺 その他の関連トピック 苦悩の根絶 - ドゥッカ - ヴェルトシュメルツ - ネガティブ感情 - 心理的苦痛 - Amor fati - 被害者学 - 刑罰学 - 快楽 - 苦痛と快楽 - 幸福 - ヘドニック・トレッドミル - 苦悩のリスク - 野生動物の苦悩 |

| Selected bibliography Joseph A. Amato. Victims and Values: A History and a Theory of Suffering. New York: Praeger, 1990. ISBN 0-275-93690-2 James Davies. The Importance of Suffering: the value and meaning of emotional discontent. London: Routledge ISBN 0-415-66780-1 Casell, E. J. (1991). The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine (pertama ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. Cynthia Halpern. Suffering, Politics, Power: a Genealogy in Modern Political Theory. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002. ISBN 0-7914-5103-8 Jamie Mayerfeld. Suffering and Moral Responsibility. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-515495-9 Thomas Metzinger. Suffering.In Kurt Almqvist & Anders Haag (2017)[eds.], The Return of Consciousness. Stockholm: Axel and Margaret Ax:son Johnson Foundation. ISBN 978-91-89672-90-1 David B. Morris. The Culture of Pain. Berkeley: University of California, 2002. ISBN 0-520-08276-1 Elaine Scarry. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-19-504996-9 Spelman, E. V. (1995). Fruits of sorrow framing our attention to suffering. Boston, Mass., USA: Beacon Press. Ronald Anderson. World Suffering and Quality of Life, Social Indicators Research Series, Volume 56, 2015. ISBN 978-94-017-9669-9; Also: Human Suffering and Quality of Life, SpringerBriefs in Well-Being and Quality of Life Research, 2014. ISBN 978-94-007-7668-5 |

参考文献 ジョセフ・A・アマート 犠牲者と価値観: 苦悩の歴史と理論。ニューヨーク: Praeger, 1990. ISBN 0-275-93690-2 ジェームズ・デイヴィス 苦悩の重要性:感情的不満の価値と意味。ロンドン: Routledge ISBN 0-415-66780-1 Casell, E. J. (1991). The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine (pertama ed.). ニューヨーク: Oxford University Press. Cynthia Halpern. 苦悩、政治、権力:現代政治理論における系譜。オルバニー: ニューヨーク州立大学出版局, 2002. ISBN 0-7914-5103-8 ジェイミー・メイヤーフェルド 苦悩と道徳的責任. ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局, 2005. ISBN 0-19-515495-9 トーマス・メッツィンガー Suffering.In Kurt Almqvist & Anders Haag (2017)[eds.], The Return of Consciousness. Stockholm: Axel and Margaret Ax:son Johnson Foundation. ISBN 978-91-89672-90-1 デイヴィッド・B・モリス 痛みの文化. バークレー: カリフォルニア大学、2002年 ISBN 0-520-08276-1 エレイン・スキャリー 痛みのなかの身体:世界の生成と消滅. ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局, 1987. ISBN 0-19-504996-9 Spelman, E. V. (1995). Fruits of sorrow framing our attention to suffering. 米国マサチューセッツ州ボストン: Beacon Press. ロナルド・アンダーソン World Suffering and Quality of Life, Social Indicators Research Series, Volume 56, 2015. ISBN 978-94-017-9669-9;また: Human Suffering and Quality of Life, SpringerBriefs in Well-Being and Quality of Life Research, 2014. ISBN 978-94-007-7668-5 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suffering |

ディビス、W. 1988 『蛇と虹』田中昌太郎訳、草思社.The serpent and the rainbow.

ハ イチ(地名)のゾンビ伝説についてご存じかな? ハイチがどこにあるか知らなくても、死体 を意のままに操る悪魔的存在ないしは哀れな死体(ゾンビ)については、ホラー映画によく出てくる話題だ。この本は、ゾンビ伝説のあるハイチにわたった民族 植物学者が、ゾンビ伝説が生物学的に根拠のもつことを「実証」しようとその謎解きをするフィールドワークの記録である。もちろん、ゾンビ伝説はヴードゥ教 のシンボルとコスモロジー(宇宙観)と深く関わり——虹と蛇は重要な宗教的隠喩である——、また機能論的には、ゾンビにされる恐怖は、それが社会的制裁の 概念に結びついていることを明らかにする。ゾンビを特定の毒物(テトロドトキシン)の薬理作用に単純に関連づけることに、評者(池田光穂)は疑問を憶える が、ゾンビは荒唐無稽なファンタジーではなく、きちんと社会のメンバーが抱く恐怖や懲罰の概念に根ざしているということを解明してゆくプロセスは、フィー ルドワークの醍醐味を、読者の共感として再現してくれる。宗教現象の人類学の入門にぴったりの本だ(ディビスの「科学的証明」には疑問がおこり、彼のテト ロドトキシン説は、現在は誰も信用していない。研究倫理上の問題もある。それでもなお、当時ハイチで研究することの困難さを考えて再読すると、この本は(カルロス・カスタネダの「ドンファンの教え」問題とは別の意味での)スキャンダルにまみれているが、それなりに 興味深い本なのだ。)。この本を読んでから、ハイチと西洋のポストコロニアルな歴史的見直しの書物である、スーザン・バック=モース『ヘーゲルとハイチ』を読んでみよう。ぜったいに面白いはずだ!!!

「死んだ者が墓から甦る。これがハイチの有名なゾンビだ。ゾンビにするには薬が必要だが、 ハー ヴァード大学の人類学者・民族植物学者である著者は、その正体をついに解明する。だが、薬だけでは人をゾンビにできない。ヴードゥー教の秘術が関わってい るからだ。著者はその世界に踏み込んでいく。ゾンビにすることは正統な社会的制裁であり、その背景には蛇と虹を創造主とするヴードゥーの神話と世界観があ ることが、やがて明らかにされる。▲第1部 毒(ジャガー;「死のフロンティア」;カラバル説;白い闇と生ける死者;歴史の教訓;すべては毒にして毒にあ らず) 第2部 ハーヴァードでの幕間(黒板の二つの欄;ヴードゥーの死) 第3部 秘密結社(夏、巡礼たちは歩む;蛇と虹;わが馬に告げよ;ライオンの顎門で踊りつつ;密のように甘く、胆汁のように苦く)」

第1部 毒

第2部 ハーヴァードでの幕間

第3部 秘密結社

ブロック、M. 1998 『王の奇跡』井上泰男、渡邊昌美訳、刀水書房.

専門の歴史書で、約80年ほど前に書かれた本なので、初心者には少し難解かもしれません。し かし、14世紀から15世紀にかけての西ヨーロッパの王様が、瘰癧(るいれき)という結核性の結節を按手(あんしゅ=手かざしをして軽くタッチすること) によって治療していたというエピソードを軸に、王様の聖性や王様がおかれた社会制度などとの関連を論じることにより、王様の権威(=王権)という、現代人 がいっけん理解することのできない権力概念が、どのようにして人々に理解されたを解明した書物です。治療というものが、治療者の権力性と深く関わるという 点を考えさせる書物です。

ルイス、I.M. 1985 『エクスタシーの人類学』平沼孝之訳、法政大学出版局

シャーマニズムや精霊憑依の宗教の社会人類学的分析の古典です。この書物の特徴は、事例が豊 富に取り上げられていること、そして(フランスのデュルケーム的素養を基礎にした)イギリスの社会人類学的分析が縦横無尽に行われていること。つまり、ト ランスや憑依を伴う宗教現象が、社会構造と成員あいだに広げられるダイナミックな関係——より具体的には、社会の周縁部において虐げられた弱者(女性や病 者)の社会への再統合のプロセス——として見事に分析されています。日本でのシャーマニズム研究は、エリアーデらが先鞭をつけたエクスタシー/憑依の類型 論、つまりシャーマニズムという宗教現象をタイプとして分類し、その分布のパターンを考察するなどの形態論への関心がつよく、社会人類学的な分析が欠ける 嫌いがありました。その意味でも、ルイスが先鞭をつけた社会人類学的視座を活かす実証研究が出てくることが期待されます。

レヴィ=ストロース、C. 1972 『構造人類学』荒川幾男ほか訳、東京:みすず書房.(特に 「呪術師とその呪術」と「象徴的効果」の2論文)

レヴィ=ストロースは構造主義人類学の創始者と言われ、文化現象を普遍的モデルの中に還元し て論じる傾向の強い研究者です。しかしながら「呪術師とその呪術」は、呪術が使われる社会的文脈と呪術の社会的機能の役割、そして、呪術的な説明のやり 方、失敗の取り繕い方、そして、呪術になる過程における知識と技術の探求の過程などが紹介され、普段のレヴィ=ストロースのような難解ではない、リラック スした説明が試みられています。他方「象徴的効果」はスウェーデンの民族誌学者がパナマのカリブ海沿岸に住むクナの産婆が難産の時に唱える呪文の分析で す。呪文の分析の古典としてはマリノフスキーのトロブリアンドの呪文の分析や、トロブリアンドとザンデの呪文の比較の中にそれぞれの社会構造を見いだそう としたエヴァンズ=プリチャードの論文などが有名ですが、この論文もそれに劣らず有名です。そして、その3つの論文とも日本語で読めるのが大変嬉しいです ね。

■ 時系列に応じた病気の経験・診断・治療の多様性の縮減と、それらに応じた研究領域分野(→「〈病む〉ことと〈治 る〉ことの社会的決定」)

□クレジット:無難に「〈病む〉ことの人類学:ブックリスト」としたが、僕の本当の気持ちは「みんなで病もうぜ、こわくない!!」にしたい気分だ

リンク

文献

〈さらにこの分野を深める文献〉これらの文献についてのレビューは本ページの冒頭にあります。

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099