Contrapuntal Reading

Estadio Azteca bajo de construción en 1964 y El torre de Tokio en 1958

対位法的読解

Contrapuntal Reading

Estadio Azteca bajo de construción en 1964 y El torre de Tokio en 1958

解説:池田光穂

エドワード・ウィリアム・サイードに よる、批判的読解の方法のひとつである。(→サイードのオリエンタリズム)

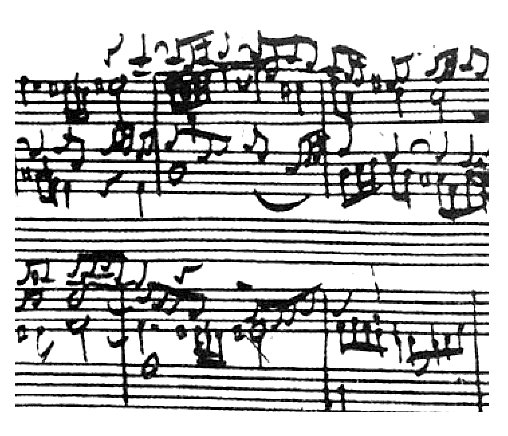

対位法(Counterpoint)とは、ポリフォニー(多声音楽)の技法で、同時に複数の旋律が存在し、個々の旋律(音の繋 がり)が独立性を失うことなく共存する(複音楽的な組合せという)ことである。

和声対位法の大成者のヨハン・セバスチャン・バッハの『フーガの技法』『二声と三声のインベ ンション』『平均率クラヴィア曲集』などを聞いてみれば一聴瞭然になるように、右手と左手の旋律がそれぞれ独立して旋律を奏でながら、同時に掛け合いをす るという——すばらしい漫才のように(私はボケとツッコミという古典的ペアを超脱して2人が駄洒落を掛け合いまくる絶頂期のWヤングを思い出します)—— 様子が手に取るようにわかります。

サイードはクラシックピアノ名手で、バッハの鍵盤音楽の革新的な演奏者であったグレン・グー ルドのよき理解者であるので、サイードが対位法という時に、バッハを念頭においていることは想像に難くありません。

【文献】サイード,エドワード・W.『音楽のエラボレーション』大橋洋一訳、東京:みすず書 房、1995年

| In music theory, counterpoint

is the relationship of two or more simultaneous musical lines (also

called voices) that are harmonically interdependent yet independent in

rhythm and melodic contour.[1] The term originates from the Latin

punctus contra punctum meaning "point against point", i.e. "note

against note". John Rahn describes counterpoint as follows: It is hard to write a beautiful song. It is harder to write several individually beautiful songs that, when sung simultaneously, sound as a more beautiful polyphonic whole. The internal structures that create each of the voices separately must contribute to the emergent structure of the polyphony, which in turn must reinforce and comment on the structures of the individual voices. The way that is accomplished in detail is ... 'counterpoint'.[2] Counterpoint has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradition, strongly developing during the Renaissance and in much of the common practice period, especially in the Baroque period. In Western pedagogy, counterpoint is taught through a system of species (see below). There are several different forms of counterpoint, including imitative counterpoint and free counterpoint. Imitative counterpoint involves the repetition of a main melodic idea across different vocal parts, with or without variation. Compositions written in free counterpoint often incorporate non-traditional harmonies and chords, chromaticism and dissonance. | 音楽理論において対位法とは、リズムや旋律の輪郭において独立していなが

ら、和声的に相互に依存している2つ以上の同時進行する楽線(声部とも呼ばれる)の関係のことである[1]。この用語は、ラテン語で「点と点」、すなわち

「音符と音符」を意味するpunctus contra punctumに由来する。ジョン・ラーンは対位法を次のように説明している: 美しい曲を書くのは難しい。美しい歌を書くのは難しいが、個別に美しい歌をいくつか書いて、それを同時に歌うと、より美しいポリフォニックな全体として聞 こえるようにするのはもっと難しい。それぞれの声部を個別に創り出す内部構造は、ポリフォニーの創発的な構造に貢献しなければならず、そのポリフォニーは 個々の声部の構造を補強し、コメントしなければならない。それが具体的に達成される方法が......「対位法」である[2]。 対位法はヨーロッパ古典派の伝統の中で最も一般的に確認されており、ルネサンス期と一般的な実践期の多く、特にバロック期に強く発展した。西洋の教育学では、対位法は種のシステム(下記参照)を通して教えられる。 対位法には、模倣対位法や自由対位法など、いくつかの異なる形式がある。模倣的対位法は、異なる声部間で、変奏の有無にかかわらず、主旋律的なアイディア を反復するものである。自由対位法で書かれた作品には、伝統的でない和声や和音、半音階的な表現、不協和音がよく使われる。 |

| General principles The term "counterpoint" has been used to designate a voice or even an entire composition.[3] Counterpoint focuses on melodic interaction—only secondarily on the harmonies produced by that interaction. Work initiated by Guerino Mazzola (born 1947) has given counterpoint theory a mathematical foundation. In particular, Mazzola's model gives a structural (and not psychological) foundation of forbidden parallels of fifths and the dissonant fourth. Octavio Agustin has extended the model to microtonal contexts.[4][5] Another theorist who has tried to incorporate mathematical principles in his study of counterpoint is Sergei Taneyev (1856-1915). Inspired by Spinoza,[6] Taneyev developed a theory which covers and generalizes a wide range of advanced contrapuntal phenomena, including what is known to the english-speaking theorists as invertible counterpoint (although he describes them mainly using his own, custom-built terminology), by means of linking them to simple algebraic procedures.[7] In counterpoint, the functional independence of voices is the prime concern. The violation of this principle leads to special effects, which are avoided in counterpoint. In organ registers, certain interval combinations and chords are activated by a single key so that playing a melody results in parallel voice leading. These voices, losing independence, are fused into one and the parallel chords are perceived as single tones with a new timbre. This effect is also used in orchestral arrangements; for instance, in Ravel's Bolero #5 the parallel parts of flutes, horn and celesta resemble the sound of an electric organ. In counterpoint, parallel voices are prohibited because they violate the heterogeneity of musical texture when independent voices occasionally disappear turning into a new timbre quality and vice versa.[8][9] |

一般原則 「対位法」という用語は、声部、あるいは作曲全体を指すのに使われてきた[3]。対位法は旋律の相互作用に焦点を当てるが、その相互作用によって生み出される和声については二の次である。 ゲリーノ・マッツォーラ(Guerino Mazzola、1947年生まれ)によって始められた研究は、対位法理論に数学的基礎を与えた。特に、マッツォーラのモデルは、第5音と不協和第4音の 禁じられた平行移動の構造的(心理的ではなく)基礎を与えている。オクタヴィオ・アグスティンは、このモデルを微分音的な文脈にまで拡張した[4] [5]。対位法の研究に数学的原理を取り入れようとしたもう一人の理論家は、セルゲイ・タネーエフ(1856-1915)である。スピノザに触発されたタ ネーエフ[6]は、英語圏の理論家たちに可逆対位法として知られているものを含む高度な対位法現象を、簡単な代数的手続きと結びつけることによって、幅広 くカバーし一般化する理論を開発した(ただし、彼は主に彼独自の特注の用語を用いてそれらを記述している)[7]。 対位法においては、声部の機能的独立性が最大の関心事である。この原則に反すると、対位法では避けられる特殊な効果が生じる。オルガンの音域では、特定の 音程の組み合わせや和音が1つの鍵盤によって活性化されるため、旋律を演奏すると並行して声部が導かれることになる。これらの声部は独立性を失って1つに 融合し、平行和音は新しい音色を持つ1つの音として知覚される。例えば、ラヴェルの『ボレロ』第5番では、フルート、ホルン、チェレスタの並行パートがエ レクトーンの音色に似ている。対位法においては、独立した声部が時折消えて新しい音色へと変化したり、その逆が起こることで音楽のテクスチュアの異質性が 損なわれるため、並行声部は禁止されている[8][9]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counterpoint |

★対位法的読解(読み)とは?

音楽の対位法にヒントを得て、サイードは対位法的読解(読み)を提唱する。これは、同時代的状況 の中で地理的にまったく離れたところで、まったく関係のないように思われた出来事によるテキストの生産をつき合わせることで、その相互に共通にみられる、 ないしは、独立した出来事(旋律)が絡み合う対位法的なハーモニーの生成——専門的には和声的対位法 harmonischer Kontrapunk ——を発見しようとすることである。

サイードのテキストでは以下のように表現されている。

「わたしが「対位法的読解」と読んだものは、実践的見地からいうと、テクストを読むときに、 そのテクストの作者が、たとえば、植民地の砂糖プランテーションを、イギリスでの生活様式を維持するプロセスにとって重要であると示しているとき、そこに どのような問題がからんでくるかを理解しながら読むことである」(サイード『文化と帝国主義1』p.137/原著、1993:66)。

サイードの対位法的読解は文学批判のみならず、歴史における因果的連鎖にこだわり暗黙利に「歴史 の原因」を追求する実証主義的歴史観から自由になれる可能性をもっている。また、世界の中心と周辺での出来事を統一的に理解しようとする世界システム論な どとの議論とも関連性をもっている。

社会事象を狭量な因果関係のみで把握してきた社会の理解や、客観的中立の分析態度に対して、(文 学批判における)対位法的読解や(社会科学領域における)世界システム論が登場することも、ある意味で対位法的に捉えることができるかもしれない。

■引用

「わたしが「対位法的読解」と呼んだものは、実践的見地からいうと、テクストを読むときに、

その

テクストの作者が、たとえば、植民地の砂糖プランテーションを、イギリスでの生活様式を維持するプロセスにとって重要であると示しているとき、そこにどの

ような問題がからんでくるかを理解しながら読むことである。またさらに、あらゆる文学テクストにいえることだが、文学テクストは、その形式上のはじまりと

終わりによって永遠に閉じられ拘束されることはない。『デイヴィッド・コパーフィールド』におけるオーストラリアに対する言及、あるいは『ジェイン・エ

ア』におけるインドに対する言及は、それらが言及可能であるがゆえになされるのである。つまり大がかりな植民地収奪について、小説家がことのついでに言及

することを可能にしているのは、イギリスという国家権力そのものである(それは小説家のたんなる気まぐれではないのだ)。しかし次のさらなる教訓も、これ

におとらず真実をついているかもしれない。つまり海外植民地は、やがて、直接支配からも間接支配からも解放されるのだが、このプロセスは、イギリス(ある

いはフランスやポルトガルやドイツなど)がまだそこにいるあいだからすでにはじまっていたのである。たとえ、このプロセスが、原住民のナショナリズムを抑

圧するいとなみのひとつとからまりあっていても、その点については、おざなりな注目のされかたしかされてこなかったとしても。要は、対位法的読解は、両方

のプロセス、つまり帝国主義のプロセスと、帝国主義への抵抗のプロセスの両方を考慮すべきであるということだ。テクストを読むときに、視野をひろげ、テク

ストから強制的に排除されているものをふくむようにすればいいのである。たとえばカミュの『異邦人』から排除されているのは、フランスの植民地主義の歴史

全体であり、アルジェリア人国家の破壊であり、その後の独立アルジェリアの台頭(カミュはこれに反対した)である」(サイード

1998:137-138)。

●フーガという課題

「フーガ(伊: fuga、遁走曲または追走曲)は、対位法を主体とした楽曲形式の1つ。"fuga"(逃走)という語が示すように、各声部が「追走」する模倣(英語版) の技法を特徴とする[1]。基本的に単一の主題にもとづいて展開するが、複数の主題をもつフーガもある(#多重フーガ)[2]。声部間の厳格な模倣が最後 まで続くカノン[1]とは区別される。その形式は、提示部(主調)→ 嬉遊部→提示部(主調以外)→ 嬉遊部 …→ 追迫部(主調)。この提示部ないし追迫部と嬉遊部の関係だけを見ると、リトルネロ形式と非常に似ている。フーガでは各提示部において、……各声部が同じ旋 律を定められた変形を伴って順次奏するのが特徴であるが、普通、回ごとに各パートが違う順序で導入される」フーガ)。

Mendelssohn

- Prelude and Fugue in D minor, Op. 37 のフーガIIIの部分(05:20)より

★『文化と帝国主義』とは、どんな本なのか?

| Culture and Imperialism

is a 1993 collection of thematically related essays by

Palestinian-American academic Edward Said, tracing the connection

between imperialism and culture throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th

centuries. The essays expand the arguments of Orientalism to describe

general patterns of relation, between the modern metropolitan Western

world and their overseas colonial territories.[1] |

1993年に出版された『文化と帝国主義』は、パレスチナ系アメリカ人の学者エドワード・サイードが、18世紀、19世紀、20世紀を通して帝国主義と文化の関係をテーマ別に論じたエッセイ集である。このエッセイは、オリエンタリズムの議論を拡大し、近代的なメトロポリタンである西欧世界とその海外植民地との関係の一般的なパターンを記述している[1]。 |

| Subject In the work, Said explored the impact British novelists such as Jane Austen, Joseph Conrad, E.M. Forster, and Rudyard Kipling had on the establishment and maintenance of the British Empire,[2] and how colonization, anti-imperialism, and decolonization influenced Western literature during the 19th and 20th centuries.[3] In the beginning of the work, Said claims that the Daniel Defoe novel Robinson Crusoe, published in 1719, set the precedent for such ideas in Western literature; the novel being about a European man who travels to the Americas and establishes a fiefdom in a distant, non-European island.[4] As the connection between culture and empire, literature has "the power to narrate, or to block other narratives from forming and emerging", which might contradict the colonization of a people.[5] Hence he analyzes cultural objects to understand how imperialism functions: "For the enterprise of empire depends upon the idea of having an empire . . . and all kinds of preparations are made for it within a culture; then, in turn, imperialism acquires a kind of coherence, a set of experiences, and a presence of ruler and ruled alike within the culture."[6] Imperialism is "the practice, the theory, and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory."[7] His definition of "culture" is more complex, but he strongly suggests that we ought not to forget imperialism when discussing it. Of his overall motive, Said states: "The novels and other books I consider here I analyze because first of all I find them estimable and admirable works of art and learning, in which I and many other readers take pleasure and from which we derive profit. Second, the challenge is to connect them not only with that pleasure and profit but also with the imperial process of which they were manifestly and unconcealedly a part; rather than condemning or ignoring their participation in what was an unquestioned reality in their societies, I suggest that what we learn about this hitherto ignored aspect actually and truly enhances our reading and understanding of them."[8] The title is thought to be a reference to two older works, Culture and Anarchy (1867–68) by Matthew Arnold and Culture and Society (1958) by Raymond Williams.[9] Said argues that, although the "age of empire" largely ended after the Second World War, when most colonies gained independence, imperialism continues to exert considerable cultural influence in the present. To be aware of this fact, it is necessary, according to Said, to look at how colonialists and imperialists employed "culture" to control distant land and peoples. |

主題 サイードはこの作品の中で、ジェーン・オースティン、ジョセフ・コンラッド、E.M.フォースター、ラドヤード・キップリングといったイギリスの小説家た ちが大英帝国の成立と維持に与えた影響[2]、そして植民地化、反帝国主義、脱植民地化が19世紀から20世紀にかけて西洋文学にどのような影響を与えた かを探求した。 [作品の冒頭でサイードは、1719年に出版されたダニエル・デフォーの小説『ロビンソン・クルーソー』が、西洋文学におけるそのような思想の先例を作っ たと主張している。この小説は、アメリカ大陸に渡り、遠く離れた非ヨーロッパの島に領地を築くヨーロッパ人を描いたものである[4]。 文化と帝国をつなぐものとして、文学には「物語る力、あるいは他の物語が形成され出現するのを阻止する力」があり、それはある民族の植民地化と矛盾するか もしれない: 「帝国という事業は、帝国を持つという考えに依存している。帝国の事業は、帝国を持つという構想に依存し、文化の内部でそのためにあらゆる準備がなされ る。そして、帝国主義は、文化の内部で、一種の一貫性、一連の経験、支配者と被支配者の存在を獲得する」[6]。 帝国主義とは「遠く離れた領土を支配する大都市中心の実践であり、理論であり、態度である」[7]。彼の「文化」の定義はより複雑だが、彼は帝国主義を論じる際に帝国主義を忘れてはならないと強く示唆している。彼の全体的な動機について、サイードはこう述べている: 「ここで取り上げる小説やその他の書物を分析するのは、まず第一に、私や他の多くの読者が喜びを感じ、そこから利益を得るような、芸術や学問の作品として 高く評価でき、称賛に値すると思うからである。第二に、その喜びと利益だけでなく、彼らが明白に、そして隠しようもなくその一部であった帝国のプロセスと も結びつけることが課題である。彼らの社会で疑いようのない現実であったことへの彼らの参加を非難したり無視したりするのではなく、これまで無視されてき たこの側面について学ぶことが、実際に、そして真に、彼らの読解と理解を深めることになると私は提案する」[8]。 このタイトルは、マシュー・アーノルドの『文化とアナーキー』(1867-68年)とレイモンド・ウィリアムズの『文化と社会』(1958年)という2つの古い著作を参照したものと考えられている[9]。 サイードは、「帝国の時代」はほとんどの植民地が独立した第二次世界大戦後にほぼ終わったものの、帝国主義は現在も文化的にかなりの影響を及ぼし続けてい ると主張している。この事実を認識するためには、サイードによれば、植民地主義者や帝国主義者が遠く離れた土地や民族を支配するために「文化」をどのよう に利用してきたかを見る必要がある。 |

| Synopsis Said argues that cultural productions such as literature, music, and art are shaped by the political and economic context in which they are produced. He argues that imperialism has played a significant role in shaping Western culture, and that many works of art and literature can be seen as reflections or products of imperialism. He also explores the ways in which imperialism has been represented in cultural productions, such as novels and films, and argues that these representations have often been used to justify and perpetuate imperialism. He highlights the importance of examining cultural productions in their historical and political context, and argues that doing so can reveal the complex ways in which culture and power are intertwined. The book covers a range of topics, from the impact of colonialism on the works of Joseph Conrad and Jane Austen, to the ways in which Western films have depicted the East. |

あらすじ サイードは、文学、音楽、芸術などの文化作品は、それらが生み出される政治的・経済的背景によって形作られると主張する。サイードは、帝国主義が西洋文化 の形成に重要な役割を果たしてきたとし、多くの芸術作品や文学作品は帝国主義の反映あるいは産物として見ることができると論じている。 また、帝国主義が小説や映画などの文化作品においてどのように表象されてきたかを探り、こうした表象がしばしば帝国主義を正当化し、永続させるために用い られてきたと論じる。彼は、文化作品を歴史的・政治的文脈の中で検証することの重要性を強調し、そうすることで文化と権力が複雑に絡み合っていることを明 らかにできると主張する。本書は、植民地主義がジョセフ・コンラッドやジェーン・オースティンの作品に与えた影響から、西洋映画が東洋を描く方法まで、さ まざまなトピックを取り上げている。 |

| Chapter 1. Overlapping Territories, Intertwined Histories Said says that West has positioned itself as a self-evidently superior, independently developed culture that naturally should share its civilization with inferior others via colonization, which is almost always a product of imperialism. Non-European cultures are therefore assigned a secondary status, which is paradoxically necessary for the supposed primacy of Western culture. Said argues for reading the literary canon with an awareness of these intertwined histories, that support the expansion of Western supremacy. |

第1章 重なり合う領土、絡み合う歴史 サイードによれば、西洋は自明な優越性を持ち、独自に発展した文化であり、植民地化を通じて劣った他国と文明を共有するのは当然である。それゆえ、非ヨー ロッパ文化は二次的な地位を与えられているが、それは逆説的に西洋文化の優位性のために必要なことなのである。サイードは、西洋至上主義の拡大を支える、 こうした絡み合った歴史を意識しながら文学の正典を読むことを主張している。 |

| Chapter 2. Consolidated Vision Said surveys several canonical works to argue that they support imperialism by the way they ignore or amplify certain narratives including works of Rudyard Kipling, Jane Austen, Giuseppe Verdi and Albert Camus. |

第2章 連結ビジョン 統合されたヴィジョン サイードは、ラドヤード・キップリング、ジェーン・オースティン、ジュゼッペ・ヴェルディ、アルベール・カミュなど、いくつかの正統的な作品を調査し、それらが特定の物語を無視したり増幅したりすることによって帝国主義を支持していると主張している。 |

| Chapter 3. Resistance and Opposition Resistance to imperialism is often times ignored in the Western narrative, but nevertheless, real. The voice of the colonized is not heard in the colony until independence is achieved. Said critiques the formation of a monolithic nationalism to replace a former colonial polity, instead drawing attention to the diversity and complexity of the individuals in the territory. He posits that peoples have multiple overlapping identities and shared heritage as compared to the divisiveness required by the imperial project. |

第3章. 抵抗と反対 帝国主義に対する抵抗は、西欧の物語ではしばしば無視されるが、それにもかかわらず現実のものである。独立が達成されるまで、植民地では被植民者の声は聞 こえない。サイードは、かつての植民地政治に代わる一枚岩のナショナリズムを形成することを批判し、その代わりに領土内の個人の多様性と複雑性に注目す る。彼は、帝国的プロジェクトが要求する分裂性と比較して、民族には複数の重なり合うアイデンティティと共有する遺産があると仮定する。 |

| Chapter 4. Freedom from Domination in the Future The United States has replaced Europe as the self-appointed guardian of a purported superior Western civilization, and the narratives of European civilizing mission continue to this day with its center in North America. Said laments this development and believes that imperialism will not cease until we understand that no culture can claim to be superior to others, claim international authority, or direct the destinies of inferior others. Said believes that diversity is valuable and complex and cannot be reduced to simple identity symbiology. Said indicts public intellectuals in their silence towards the continuing narrative of Western exceptionalism and superiority. He exhorts them to transcend their national interests and see common interests and values across the rest of the world. |

第4章. 未来における支配からの自由 アメリカはヨーロッパに代わって、優れた西洋文明の守護者を自任し、ヨーロッパ文明宣教の物語は北米を中心に今日まで続いている。サイードはこの発展を嘆 き、いかなる文化も他より優れていると主張したり、国際的権威を主張したり、劣った他者の運命を方向づけることはできないと理解するまで、帝国主義はなく ならないと考えている。サイードは、多様性は価値ある複雑なものであり、単純なアイデンティティの共生に還元することはできないと信じている。サイード は、西洋の例外主義と優越性の物語が続いていることに沈黙している知識人を非難する。彼は、国民的利益を超越し、世界全体に共通する利益や価値を見出すよ う促している。 |

| Reception Edward Said was considered "one of the most important literary critics and philosophers of the late 20th century".[10] Culture and Imperialism was hailed as long-awaited and seen as a direct successor to his main work, Orientalism. While The New York Times review notes the book's heavy resemblance to a collection of lectures, it concludes that "Yet that telegraphic style does not finally mar either the usefulness of 'Culture and Imperialism' or its importance."[9] The book is seen as a "classic study",[11] and has influenced many later authors, books and articles.[12][13] Philosopher and social anthropologist Ernest Gellner criticized Said for "exploiting Western guilt about imperialism."[14] |

受容 エドワード・サイードは「20世紀後半における最も重要な文芸批評家・哲学者の一人」と見なされていた[10]。『文化と帝国主義』は待望の書であり、彼 の主著『オリエンタリズム』の直接的な後継書と見なされていた。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の書評は、本書が講義集に酷似していることを指摘する一方で、 「しかし、その電信的な文体は、『文化と帝国主義』の有用性やその重要性を最終的に損なうものではない」と結論づけている[9]。本書は「古典的な研究」 と見なされており[11]、後の多くの作家、書籍、論文に影響を与えている[12][13]。 哲学者であり社会人類学者であるアーネスト・ゲルナーはサイードを「帝国主義に対する西洋の罪悪感を悪用している」と批判している[14]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_and_Imperialism |

★キューバの対位法とトランスカルチュレーションの概念(→「ミンツ『甘さと権力』」)

| Cuban Counterpoints and the concept of Transculturation Fernando Ortiz most known and read book was Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar originally published in 1940 in Spanish and translated to English in 1995.[17] In his book he draws comparisons between sugar and tabaco the most relevant products form Cuba that have entered the daily life of cubans.[4] In this work, he proposes the concept of transculturation as a phenomenon that is more appropriate than acculturation to describe how cultures converge and merge, without removing some of the original aspects of the original cultures.[4] The concept provided a more appropriate way to explain the merging of cultures in Cuba, from Spanish colonialism to Indigenous communities and Afro-Cubans, resulting in a new culture that incorporates elements from each.[4] In the introduction of the book the renowned Polish anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski (1884-1942) wrote the introduction supporting Ortiz's concept [18] His correspondence with Bronisław Malinowski shows they had numerous debates around the concept of transculturation and how it was being received within American anthropology.[19] This led to disputes between Oritz and Melville Herskovits the American anthropologist that coined the term acculturation.[19] The concept of transculturation that Ortiz developed resonates with the principles of British functionalism, which Malinowski himself helped pioneer.[2] Malinowski was not only a personal friend but also an admirer of Ortiz's work.[20] The letters published between Malinowski and Ortiz as part of a 2002 edition of Cuban Counterpoints, by Enrico Mario Santí, show that Malinowski commented the structure of the book, proposed ideas and concepts that influenced the book.[20] |

キューバの対位法とトランスカルチュレーションの概念 フェルナンド・オルティス(Fernando Ortiz Fernández)の最もよく知られ、読まれている著書は、1940年にスペイン語で出版され、1995年に英語に翻訳された『キューバの対位法: タバコと砂糖』である。[17] 著書の中で、彼はキューバの最も重要な産物である砂糖とタバコを比較し、それらがキューバ人の日常生活に入り込んでいることを示している。[4] こ の著作において、彼は、文化が融合し、融合する過程を説明する際に、元の文化のいくつかの原初的な側面を排除することなく、同化よりも適切な概念として 「トランスカルチュレーション」を提唱している。[4] この概念は、スペインの植民地時代から先住民コミュニティやアフリカ系キューバ人まで、キューバにおける文化の融合を説明するより適切な方法を提供し、各 文化の要素を取り入れた新しい文化の形成を説明した。[4] 書籍の序文で、著名なポーランドの人類学者ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキー(1884-1942)は、オルティスの概念を支持する序文を執筆した。[18] オルティスとマリノフスキーの書簡交換からは、両者が「トランスクルチュレーション」の概念と、それがアメリカ人類学界でどのように受け止められているか について、数多くの議論を交わしていたことがわかる。[19] これは、オルティスと「同化」という用語を考案したアメリカ人類学者のメルビル・ハーコビッツとの論争につながった。[19] オルティスが発展させた「トランスカルチュレーション」の概念は、マリノフスキー自身が先駆的に提唱したイギリス機能主義の原則と共鳴している。[2] マリノフスキーはオルティスの人格的な友人であっただけでなく、その業績を賞賛していた。[20] 2002年にエンリコ・マリオ・サンティが出版した『キューバの対位法』の中で、マリノフスキーとオルティスが交わした手紙が紹介されているが、それによ る と、マリノフスキは本の構成についてコメントし、本に影響を与えたアイデアやコンセプトを提案していた。[20] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fernando_Ortiz_Fern%C3%A1ndez |

■リンク

■文献

The final page of Contrapunctus XIV, The Art of Fugue

Contrapuntal imagesEstadio Azteca bajo de construción en 1964 y El torre de Tokio en 1958

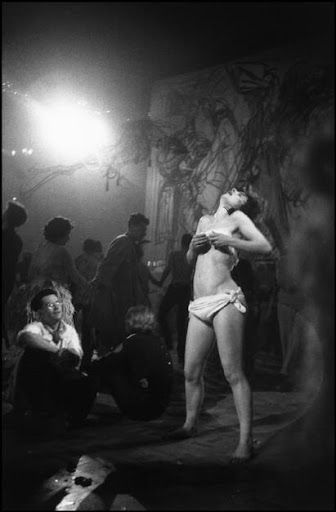

London 1958/1959 y Solora, Guatemala, 1940s

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆