Counterpoint

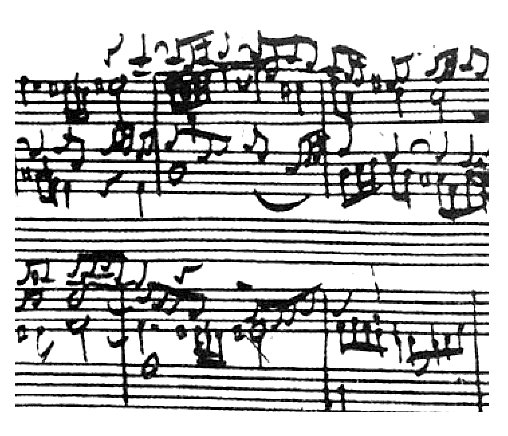

J.S. Bach's "The Art of Fugue"

対位法

Counterpoint

J.S. Bach's "The Art of Fugue"

解説:池田光穂

| In music theory, counterpoint is

the relationship of two or more simultaneous musical lines (also called

voices) that are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm

and melodic contour.[1] The term originates from the Latin punctus

contra punctum meaning "point against point", i.e. "note against note".

John Rahn describes counterpoint as follows: It is hard to write a beautiful song. It is harder to write several individually beautiful songs that, when sung simultaneously, sound as a more beautiful polyphonic whole. The internal structures that create each of the voices separately must contribute to the emergent structure of the polyphony, which in turn must reinforce and comment on the structures of the individual voices. The way that is accomplished in detail is ... 'counterpoint'.[2] Counterpoint has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradition, strongly developing during the Renaissance and in much of the common practice period, especially in the Baroque period. In Western pedagogy, counterpoint is taught through a system of species (see below). There are several different forms of counterpoint, including imitative counterpoint and free counterpoint. Imitative counterpoint involves the repetition of a main melodic idea across different vocal parts, with or without variation. Compositions written in free counterpoint often incorporate non-traditional harmonies and chords, chromaticism and dissonance. |

音楽理論において対位法とは、リズムや旋律の輪郭において独立していな

がら、和声的に相互に依存している2つ以上の同時進行する楽線(声部とも呼ばれる)の関係のことである[1]。この用語は、ラテン語で「点と点」、すなわ

ち「音符と音符」を意味するpunctus contra punctumに由来する。ジョン・ラーンは対位法を次のように説明している: 美しい曲を書くのは難しい。美しい歌を書くのは難しいが、個別に美しい歌をいくつか書いて、それを同時に歌うと、より美しいポリフォニックな全体として聞 こえるようにするのはもっと難しい。それぞれの声部を個別に創り出す内部構造は、ポリフォニーの創発的な構造に貢献しなければならず、そのポリフォニーは 個々の声部の構造を補強し、コメントしなければならない。それが具体的に達成される方法が......「対位法」である[2]。 対位法はヨーロッパ古典派の伝統の中で最も一般的に確認されており、ルネサンス期と一般的な実践期の多く、特にバロック期に強く発展した。西洋の教育学で は、対位法は種のシステム(下記参照)を通して教えられる。 対位法には、模倣対位法や自由対位法など、いくつかの異なる形式がある。模倣的対位法は、異なる声部間で、変奏の有無にかかわらず、主旋律的なアイディア を反復するものである。自由対位法で書かれた作品には、伝統的でない和声や和音、半音階的な表現、不協和音がよく使われる。 |

| General principles The term "counterpoint" has been used to designate a voice or even an entire composition.[3] Counterpoint focuses on melodic interaction—only secondarily on the harmonies produced by that interaction. Work initiated by Guerino Mazzola (born 1947) has given counterpoint theory a mathematical foundation. In particular, Mazzola's model gives a structural (and not psychological) foundation of forbidden parallels of fifths and the dissonant fourth. Octavio Agustin has extended the model to microtonal contexts.[4][5] Another theorist who has tried to incorporate mathematical principles in his study of counterpoint is Sergei Taneyev (1856-1915). Inspired by Spinoza,[6] Taneyev developed a theory which covers and generalizes a wide range of advanced contrapuntal phenomena, including what is known to the english-speaking theorists as invertible counterpoint (although he describes them mainly using his own, custom-built terminology), by means of linking them to simple algebraic procedures.[7] In counterpoint, the functional independence of voices is the prime concern. The violation of this principle leads to special effects, which are avoided in counterpoint. In organ registers, certain interval combinations and chords are activated by a single key so that playing a melody results in parallel voice leading. These voices, losing independence, are fused into one and the parallel chords are perceived as single tones with a new timbre. This effect is also used in orchestral arrangements; for instance, in Ravel's Bolero #5 the parallel parts of flutes, horn and celesta resemble the sound of an electric organ. In counterpoint, parallel voices are prohibited because they violate the heterogeneity of musical texture when independent voices occasionally disappear turning into a new timbre quality and vice versa.[8][9] |

一般原則 「対位法」という用語は、声部、あるいは作曲全体を指すのに使われてきた[3]。対位法は旋律の相互作用に焦点を当てるが、その相互作用によって生み出さ れる和声については二の次である。 ゲリーノ・マッツォーラ(Guerino Mazzola、1947年生まれ)によって始められた研究は、対位法理論に数学的基礎を与えた。特に、マッツォーラのモデルは、第5音と不協和第4音の 禁じられた平行移動の構造的(心理的ではなく)基礎を与えている。オクタヴィオ・アグスティンは、このモデルを微分音的な文脈にまで拡張した[4] [5]。対位法の研究に数学的原理を取り入れようとしたもう一人の理論家は、セルゲイ・タネーエフ(1856-1915)である。スピノザに触発されたタ ネーエフ[6]は、英語圏の理論家たちに可逆対位法として知られているものを含む高度な対位法現象を、簡単な代数的手続きと結びつけることによって、幅広 くカバーし一般化する理論を開発した(ただし、彼は主に彼独自の特注の用語を用いてそれらを記述している)[7]。 対位法においては、声部の機能的独立性が最大の関心事である。この原則に反すると、対位法では避けられる特殊な効果が生じる。オルガンの音域では、特定の 音程の組み合わせや和音が1つの鍵盤によって活性化されるため、旋律を演奏すると並行して声部が導かれることになる。これらの声部は独立性を失って1つに 融合し、平行和音は新しい音色を持つ1つの音として知覚される。例えば、ラヴェルの『ボレロ』第5番では、フルート、ホルン、チェレスタの並行パートがエ レクトーンの音色に似ている。対位法においては、独立した声部が時折消えて新しい音色へと変化したり、その逆が起こることで音楽のテクスチュアの異質性が 損なわれるため、並行声部は禁止されている[8][9]。 |

| Development Some examples of related compositional techniques include: the round (familiar in folk traditions), the canon, and perhaps the most complex contrapuntal convention: the fugue. All of these are examples of imitative counterpoint. |

発展(展開) 関連する作曲技法の例としては、ラウンド(民謡でおなじみ)、カノン、そしておそらく最も複雑な対位法的慣習であるフーガがある。これらはすべて模倣的対位法の例である。 |

| Examples from the repertoire There are many examples of song melodies that are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. For example, "Frère Jacques" and "Three Blind Mice" combine euphoniously when sung together. A number of popular songs that share the same chord progression can also be sung together as counterpoint. A well-known pair of examples is "My Way" combined with "Life on Mars".[10] Johann Sebastian Bach is revered as one of the greatest masters of counterpoint. For example the harmony implied in the opening subject of the Fugue in G-sharp minor from Book II of the Well-Tempered Clavier is heard anew in a subtle way when a second voice is added. "The counterpoint in bars 5-8... sheds an unexpected light on the tonality of the Subject."[11]: (以下省略) |

レパートリーからの例 和声的に相互に依存しながらも、リズムと旋律的輪郭が独立している歌曲の旋律には、多くの例がある。例えば、「Frère Jacques 」と 「Three Blind Mice 」は、一緒に歌うとユーフォニックに組み合わされる。同じコード進行を共有するポピュラーソングの多くは、対位法的に一緒に歌うこともできる。よく知られ ている例としては、「マイ・ウェイ」と「ライフ・オン・マーズ」の組み合わせがある[10]。 ヨハン・セバスティアン・バッハは対位法の最も偉大な巨匠の一人として尊敬されている。例えば、『平均律クラヴィーア曲集』第2巻の嬰ト短調のフーガの冒 頭主題に暗示されている和声は、第2声部が加わると微妙な形で新たに聴こえる。「第5~8小節の対位法は...主題の調性に思いがけない光を当てる」 [11]: |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counterpoint |

|

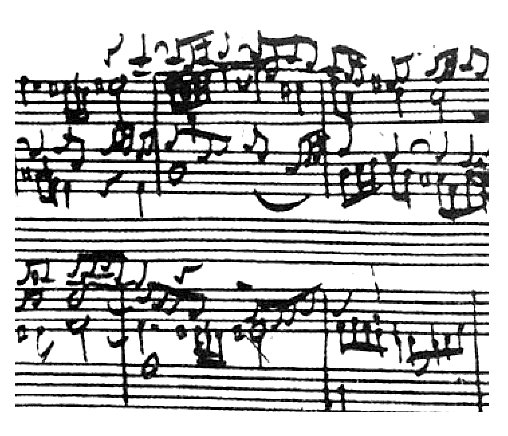

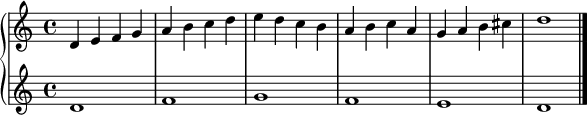

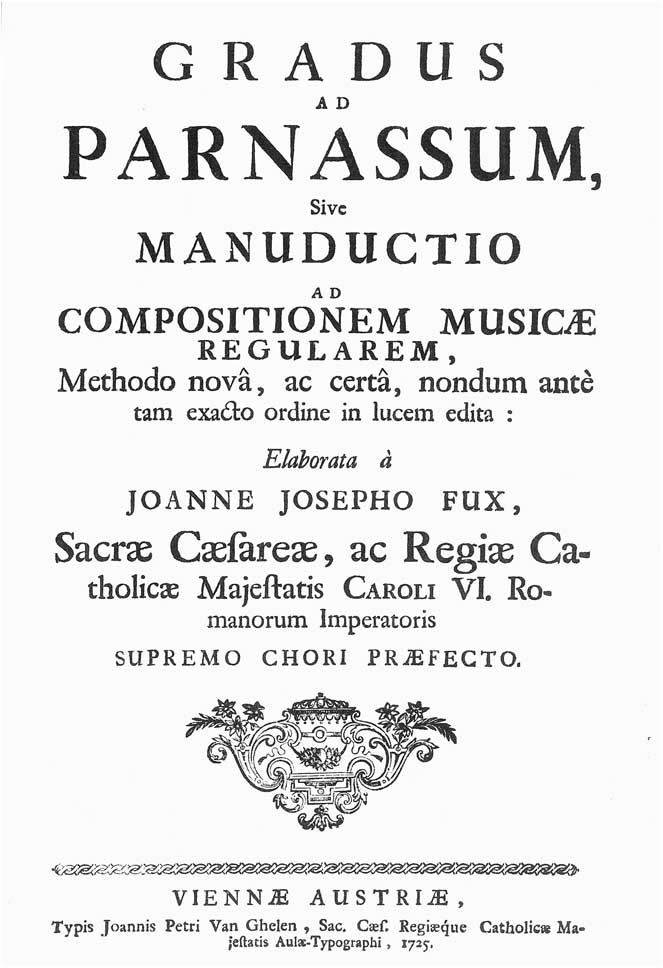

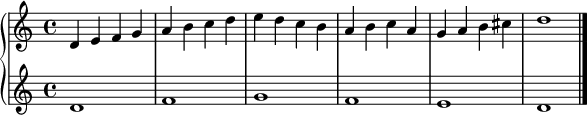

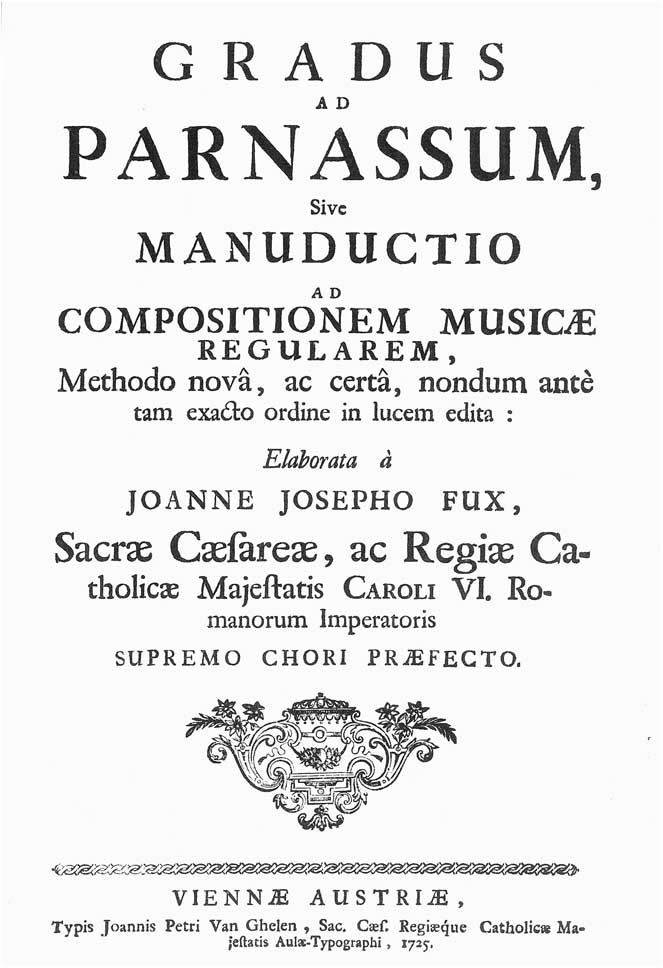

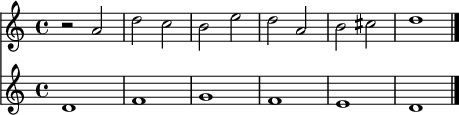

Species counterpoint Example of "third species" counterpoint Species counterpoint was developed as a pedagogical tool in which students progress through several "species" of increasing complexity, with a very simple part that remains constant known as the cantus firmus (Latin for "fixed melody"). Species counterpoint generally offers less freedom to the composer than other types of counterpoint and therefore is called a "strict" counterpoint. The student gradually attains the ability to write free counterpoint (that is, less rigorously constrained counterpoint, usually without a cantus firmus) according to the given rules at the time.[17] The idea is at least as old as 1532, when Giovanni Maria Lanfranco described a similar concept in his Scintille di musica (Brescia, 1533). The 16th-century Venetian theorist Zarlino elaborated on the idea in his influential Le institutioni harmoniche, and it was first presented in a codified form in 1619 by Lodovico Zacconi in his Prattica di musica. Zacconi, unlike later theorists, included a few extra contrapuntal techniques, such as invertible counterpoint.  Gradus ad Parnassum (1725) by Johann Joseph Fux defines the modern system of teaching counterpoint In 1725 Johann Joseph Fux published Gradus ad Parnassum (Steps to Parnassus), in which he described five species: Note against note; Two notes against one; Four notes against one; Notes offset against each other (as suspensions); All the first four species together, as "florid" counterpoint. A succession of later theorists quite closely imitated Fux's seminal work, often with some small and idiosyncratic modifications in the rules. Many of Fux's rules concerning the purely linear construction of melodies have their origin in solfeggio. Concerning the common practice era, alterations to the melodic rules were introduced to enable the function of certain harmonic forms. The combination of these melodies produced the basic harmonic structure, the figured bass.[citation needed] |

種の対位法 第3の種」対位法の例 種対位法は、カントゥス・フォルムス(ラテン語で「固定された旋律」の意)と呼ばれる非常に単純なパートを一定に保ちながら、生徒が複雑さを増していくい くつかの「種」を経て進んでいく教育的ツールとして開発された。種対位法は一般的に、他のタイプの対位法よりも作曲家の自由度が低いため、「厳格な」対位 法と呼ばれる。この考え方は、少なくとも1532年、ジョヴァンニ・マリア・ランフランコが『Scintille di musica』(Brescia, 1533)の中で同様の概念を述べている。16世紀のヴェネツィアの理論家ザルリーノは、彼の影響力のあるLe institutioni harmonicheの中でこの考えを詳しく述べ、1619年にロドヴィコ・ザッコーニが彼のPrattica di musicaの中で初めて成文化された形で提示した。ザッコーニは、後の理論家たちとは異なり、倒置対位法など、いくつかの対位法的技法を加えている。  ヨハン・ヨーゼフ・フックスによるGradus ad Parnassum (1725)は、対位法を教える近代的なシステムを定義している。 1725年、ヨハン・ヨーゼフ・フックス(Johann Joseph Fux)は『パルナッソスへの歩み(Gradus ad Parnassum)』を出版した: 音符に対する音符; 1音に対して2音 1音に対して4音 音符が互いにオフセットしている(サスペンションのように); 最初の4種をすべて合わせた「華麗な」対位法である。 後世の理論家たちは、Fuxの先駆的な研究をかなり忠実に模倣したが、その際、しばしば規則に若干の特異な修正を加えた。旋律の純粋に直線的な構成に関す るフックスの規則の多くは、ソルフェジオに起源を持つ。一般的な練習曲の時代に関しては、特定の和声形式を機能させるために旋律規則に変更が加えられた。 これらの旋律の組み合わせは、基本的な和声構造であるフィギュアド・バスを生み出した[要出典]。 |

| Considerations for all species The following rules apply to melodic writing in each species, for each part: The final note must be approached by step. If the final is approached from below, then the leading tone must be raised in a minor key (Dorian, Hypodorian, Aeolian, Hypoaeolian), but not in Phrygian or Hypophrygian mode. Thus, in the Dorian mode on D, a C♯ is necessary at the cadence.[18] Permitted melodic intervals are the perfect unison, fourth, fifth, and octave, as well as the major and minor second, major and minor third, and ascending minor sixth. The ascending minor sixth must be immediately followed by motion downwards. If writing two skips in the same direction—something that must be only rarely done—the second must be smaller than the first, and the interval between the first and the third note may not be dissonant. The three notes should be from the same triad; if this is impossible, they should not outline more than one octave. In general, do not write more than two skips in the same direction. If writing a skip in one direction, it is best to proceed after the skip with step-wise motion in the other direction. The interval of a tritone in three notes should be avoided (for example, an ascending melodic motion F–A–B♮)[19] as is the interval of a seventh in three notes. There must be a climax or high point in the line countering the cantus firmus. This usually occurs somewhere in the middle of exercise and must occur on a strong beat. An outlining of a seventh is avoided within a single line moving in the same direction. And, in all species, the following rules govern the combination of the parts: The counterpoint must begin and end on a perfect consonance. Contrary motion should dominate. Perfect consonances must be approached by oblique or contrary motion. Imperfect consonances may be approached by any type of motion. The interval of a tenth should not be exceeded between two adjacent parts unless by necessity. Build from the bass, upward. |

すべての種についての考察 各パートの旋律作曲には、以下のルールが適用される: 最終音は一歩ずつ近づいていかなければならない。最終音に下からアプローチする場合、短調(ドリアン、ヒポドリアン、エオリアン、ヒポエオリアン)では導 音を上げなければならないが、フリジアンモードやヒポフリジアンモードでは上げない。したがって、Dのドリアン・モードでは、カデンツでC♯が必要となる [18]。 許容される旋律的音程は、完全ユニゾン、第4、第5、オクターブ、および長短第2、長短第3、上行短第6である。上行短6度は、その直後に下降しなければならない。 同じ方向に2つの音飛びを書く場合は、めったにやってはいけないことだが、2つ目の音飛びは1つ目の音飛びより小さく、1つ目の音と3つ目の音の間隔は不 協和であってはならない。3つの音は同じトライアドのものでなければならない。それが不可能な場合は、1オクターブ以上のアウトラインをとってはならな い。一般的に、同じ方向に2つ以上の音飛びを書かないこと。 一方向に音飛びを書く場合は、音飛びの後にもう一方向に段階的に進むのがよい。 3つの音における3音の音程は避けるべきである(例えば、上行する旋律運動F-A-B♮)[19] 3つの音における7音の音程も同様である。 カントゥス・ファルマスに対抗するラインには、クライマックスまたは高いポイントがなければならない。これは通常、練習の中盤のどこかで起こり、強拍で起こらなければならない。 セブンスのアウトラインは、同じ方向に動く1つのラインの中では避ける。 そして、すべての種において、以下の規則が各パートの組み合わせに適用される: 対位法は完全な子音で始まり、完全な子音で終わらなければならない。 対位法は完全な子音で始まり、完全な子音で終わること。 完全な子音には、斜めの動きか反対の動きで近づかなければならない。 不完了体子音にはどのような動きでアプローチしてもよい。 必要な場合を除き、隣り合う2つのパート間で10分の1の音程を超えてはならない。 低音から上に向かって音を作る。 |

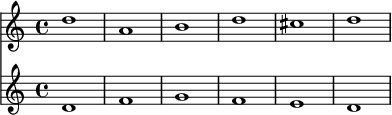

| First species In first species counterpoint, each note in every added part (parts being also referred to as lines or voices) sounds against one note in the cantus firmus. Notes in all parts are sounded simultaneously, and move against each other simultaneously. Since all notes in First species counterpoint are whole notes, rhythmic independence is not available.[20] In the present context, a "step" is a melodic interval of a half or whole step. A "skip" is an interval of a third or fourth. (See Steps and skips.) An interval of a fifth or larger is referred to as a "leap". A few further rules given by Fux, by study of the Palestrina style, and usually given in the works of later counterpoint pedagogues,[21] are as follows.  Short example of "first species" counterpoint Begin and end on either the unison, octave, or fifth, unless the added part is underneath, in which case begin and end only on unison or octave. Use no unisons except at the beginning or end. Avoid parallel fifths or octaves between any two parts; and avoid "hidden" parallel fifths or octaves: that is, movement by similar motion to a perfect fifth or octave, unless one part (sometimes restricted to the higher of the parts) moves by step. Avoid moving in parallel fourths. (In practice Palestrina and others frequently allowed themselves such progressions, especially if they do not involve the lowest of the parts.) Do not use an interval more than three times in a row. Attempt to use up to three parallel thirds or sixths in a row. Attempt to keep any two adjacent parts within a tenth of each other, unless an exceptionally pleasing line can be written by moving outside that range. Avoid having any two parts move in the same direction by skip. Attempt to have as much contrary motion as possible. Avoid dissonant intervals between any two parts: major or minor second, major or minor seventh, any augmented or diminished interval, and perfect fourth (in many contexts). In the adjacent example in two parts, the cantus firmus is the lower part. (The same cantus firmus is used for later examples also. Each is in the Dorian mode.) |

第1音種 第1音種の対位法では、付加されたすべてのパート(パートはラインまたは声部とも呼ばれる)の各音符は、カントゥス・ファルムの1つの音符に対して鳴る。 すべてのパートの音符は同時に発音され、互いに同時に動く。第1種の対位法ではすべての音符が全音符であるため、リズムの独立性はない[20]。 現在の文脈では、「ステップ」とは半音または全音の旋律的音程のことである。スキップ」は3分の1または4分の1の音程である。(ステップとスキップを参照。) 5分の1以上の音程は「跳躍」と呼ばれる。 パレストリーナ様式を研究したフックスによって与えられ、後の対位法の教育学者の著作[21]では通常与えられている、さらにいくつかの規則は以下の通りである。  第1種」対位法の短い例 ユニゾン、オクターブ、5thのいずれかで開始し、終了する。ただし、追加されたパートが下にある場合は、ユニゾンかオクターブのみで開始し、終了する。 最初か最後以外はユニゾンを使わない。 2つのパート間の平行5度やオクターブは避ける。また、「隠れた 」平行5度やオクターブも避ける。 平行4度の動きは避ける。(実際には、パレストリーナや他の人たちは、特にパート譜の最も低い部分を伴わない場合には、そのような進行を頻繁に認めていた)。 1つの音程を3回以上続けて使わない。 平行する3分の1または6分の1を3つまで連続して使うようにする。 隣接する2つのパートは、その範囲外を移動することで特別に美しい線が書ける場合を除き、互いに10分の1以内に収まるようにする。 スキップによって2つのパートが同じ方向に動くことは避ける。 できるだけ反対の動きをするようにする。 2つのパート間の不協和音程を避ける:長2度、短2度、長7度、短7度、すべての補数または減数音程、完全4度(多くの文脈で)。 隣接する2つのパートの例では、カントゥス・ファルムは下のパートである。(後の例でも同じカントゥス・ファルマスが使われている)。それぞれドリアン・モードである)。 |

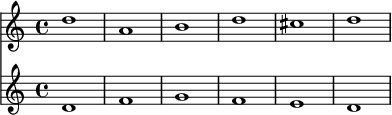

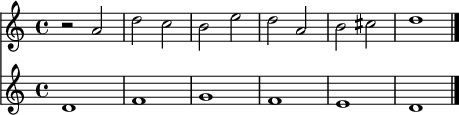

| Second species In second species counterpoint, two notes in each of the added parts work against each longer note in the given part.  Short example of "second species" counterpoint Additional considerations in second species counterpoint are as follows, and are in addition to the considerations for first species: It is permissible to begin on an upbeat, leaving a half-rest in the added voice. The accented beat must have only consonance (perfect or imperfect). The unaccented beat may have dissonance, but only as a passing tone, i.e. it must be approached and left by step in the same direction. Avoid the interval of the unison except at the beginning or end of the example, except that it may occur on the unaccented portion of the bar. Use caution with successive accented perfect fifths or octaves. They must not be used as part of a sequential pattern. The example shown is weak due to similar motion in the second measure in both voices. A good rule to follow: if one voice skips or jumps try to use step-wise motion in the other voice or at the very least contrary motion. |

第2音種 第2種の対位法では、追加された各パートの2つの音符が、与えられたパートの長い音符それぞれに対して働く。  第2種対位法の短い例 第2音種の対位法における追加的な考慮事項は以下の通りであり、第1音種に関する考慮事項に加えている: 付加音に半休符を残して、アップビートで始めることは許される。 アクセントのある拍は、子音(完全または不完全)だけでなければならない。アクセントのない拍は不協和音を持つことができるが、それは通過音としてのみである。 ユニゾンの音程は、小節のアクセントのない部分で発生することがあるが、例の最初か最後以外は避ける。 連続するアクセント付きの完全5分音符やオクターブには注意する。これらは連続したパターンの一部として使用してはならない。この例は、2小節目の両声部 の動きが似ているため、弱くなっている。片方の声部がスキップしたりジャンプしたりする場合は、もう片方の声部でステップ状の動きを使うか、少なくとも逆 の動きを使うようにする。 |

| (以下省略)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counterpoint |

|

| Contrapuntal derivations Since the Renaissance period in European music, much contrapuntal music has been written in imitative counterpoint. In imitative counterpoint, two or more voices enter at different times, and (especially when entering) each voice repeats some version of the same melodic element. The fantasia, the ricercar, and later, the canon and fugue (the contrapuntal form par excellence) all feature imitative counterpoint, which also frequently appears in choral works such as motets and madrigals. Imitative counterpoint spawned a number of devices, including: Melodic inversion The inverse of a given fragment of melody is the fragment turned upside down—so if the original fragment has a rising major third (see interval), the inverted fragment has a falling major (or perhaps minor) third, etc. (Compare, in twelve-tone technique, the inversion of the tone row, which is the so-called prime series turned upside down.) (Note: in invertible counterpoint, including double and triple counterpoint, the term inversion is used in a different sense altogether. At least one pair of parts is switched, so that the one that was higher becomes lower. See Inversion in counterpoint; it is not a kind of imitation, but a rearrangement of the parts.) Retrograde Whereby an imitative voice sounds the melody backwards in relation to the leading voice. Retrograde inversion Where the imitative voice sounds the melody backwards and upside-down at once. Augmentation When in one of the parts in imitative counterpoint the note values are extended in duration compared to the rate at which they were sounded when introduced. Diminution When in one of the parts in imitative counterpoint the note values are reduced in duration compared to the rate at which they were sounded when introduced. |

対位法の派生 ルネサンス期のヨーロッパ音楽以来、対位法音楽の多くは模倣対位法で書かれてきた。模倣的対位法では、2つ以上の声部が異なるタイミングで入り、(特に入 るときに)それぞれの声部が同じ旋律要素のいくつかのバージョンを繰り返す。ファンタジア、リチェルカーレ、後のカノンとフーガ(卓越した対位法形式)は すべて模倣的対位法を特徴とし、モテットやマドリガルなどの合唱作品にも頻繁に登場する。イミタティーヴォ的対位法は、以下のような多くの装置を生み出し た: 旋律的転回 旋律のある断片の逆は、その断片を逆さまにしたものである。つまり、元の断片が長3度(音程を参照)の上昇を持つ場合、反転した断片は長3度(あるいは短 3度)の下降を持つなどである(12音技法では、いわゆる素列を逆さまにした音列の反転を比較する)。(注:二重対位法や三重対位法を含む転回対位法で は、転回という用語はまったく異なる意味で使われる。少なくとも1組のパートが入れ替わり、高い方が低くなる。対位法における転回を参照のこと。これは一 種の模倣ではなく、パートの並べ替えである) 逆行 模倣声部が、主声部に対して旋律を逆に発音すること。 逆行性転回 模倣声部が旋律を一度に逆さまに発音する。 オーグメンテーション イミタティーヴォ的対位法において、音価の長さが、導入時に発音された速度よりも延長される。 減弱 イミタティーヴォ的対位法のパートの1つにおいて、音価の長さが、導入時に発音された速度に比べて短くなる。 |

| Free counterpoint Broadly speaking, due to the development of harmony, from the Baroque period on, most contrapuntal compositions were written in the style of free counterpoint. This means that the general focus of the composer had shifted away from how the intervals of added melodies related to a cantus firmus, and more toward how they related to each other.[citation needed][22] Nonetheless, according to Kent Kennan: "....actual teaching in that fashion (free counterpoint) did not become widespread until the late nineteenth century."[23] Young composers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, such as Mozart, Beethoven, and Schumann, were still educated in the style of "strict" counterpoint, but in practice, they would look for ways to expand on the traditional concepts of the subject.[citation needed] Main features of free counterpoint: All forbidden chords, such as second-inversion, seventh, ninth etc., can be used freely as long as they resolve to a consonant triad Chromaticism is allowed The restrictions about rhythmic-placement of dissonance are removed. It is possible to use passing tones on the accented beat Appoggiatura is available: dissonance tones can be approached by leaps. |

自由対位法 大雑把に言えば、和声の発展により、バロック時代以降、ほとんどの対位法的な楽曲は自由対位法のスタイルで書かれるようになった。つまり、作曲家の一般的 な焦点は、付加された旋律の音程がカントゥス・ファルマスとどのように関係しているかということから離れ、それらが互いにどのように関係しているかという ことに移っていったのである[要出典][22]。 それにもかかわらず、ケント・ケナンによれば、「......そのような方法(自由対位法)で実際に教えられるようになったのは、19世紀後半になってか らである」[23]。モーツァルト、ベートーヴェン、シューマンといった18世紀から19世紀にかけての若い作曲家たちは、依然として「厳格な」対位法の スタイルで教育を受けていたが、実際には、この主題の伝統的な概念を拡張する方法を模索していた[要出典]。 自由対位法の主な特徴 第2転回和音、第7転回和音、第9転回和音などの禁じられた和音は、子音三和音に解決する限り、すべて自由に使うことができる。 クロマティシズムが許される 不協和音のリズム配置に関する制限がなくなる。アクセントのある拍に通過音を使うことができる。 アポジャトゥーラが使用できる:不協和音に跳躍でアプローチできる。 |

| Linear counterpoint [example needed] Linear counterpoint is "a purely horizontal technique in which the integrity of the individual melodic lines is not sacrificed to harmonic considerations. "Its distinctive feature is rather the concept of melody, which served as the starting-point for the adherents of the 'new objectivity' when they set up linear counterpoint as an anti-type to the Romantic harmony."[3] The voice parts move freely, irrespective of the effects their combined motions may create."[24] In other words, either "the domination of the horizontal (linear) aspects over the vertical"[25] is featured or the "harmonic control of lines is rejected."[26] Associated with neoclassicism,[25] the technique was first used in Igor Stravinsky's Octet (1923),[24] inspired by J. S. Bach and Giovanni Palestrina. However, according to Knud Jeppesen: "Bach's and Palestrina's points of departure are antipodal. Palestrina starts out from lines and arrives at chords; Bach's music grows out of an ideally harmonic background, against which the voices develop with a bold independence that is often breath-taking."[24] According to Cunningham, linear harmony is "a frequent approach in the 20th century...[in which lines] are combined with almost careless abandon in the hopes that new 'chords' and 'progressions'...will result." It is possible with "any kind of line, diatonic or duodecuple".[26] |

線形対位法 要例 線型対位法は、「個々の旋律線の完全性が和声的配慮のために犠牲にされることのない、純粋に水平的な技法」である。「その特徴はむしろ旋律という概念であ り、「新しい客観性」の信奉者たちがロマン派和声に対するアンチ・タイプとして線形対位法を設定した際に、その出発点となった。 この技法は新古典主義と関連しており[25]、J・S・バッハとジョヴァンニ・パレストリーナに触発されたイーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキーの八重奏曲 (1923年)で初めて用いられた[24]。しかし、クヌード・イェッペセンによれば 「バッハとパレストリーナの出発点は対蹠的である。バッハの音楽は、理想的な和声的背景から成長し、それに対して声部がしばしば息をのむような大胆な独立 性をもって展開する」[24]。 カニンガムによれば、線的和声は「20世紀において頻繁に見られるアプローチで、新しい 「和音 」や 「進行 」が生まれることを期待して、ほとんど無頓着に線が組み合わされる。それは「ダイアトニックでもデュオデカップルでも、あらゆる種類の線」で可能である [26]。 |

| Dissonant counterpoint [example needed] Dissonant counterpoint was originally theorized by Charles Seeger as "at first purely a school-room discipline," consisting of species counterpoint but with all the traditional rules reversed. First species counterpoint must be all dissonances, establishing "dissonance, rather than consonance, as the rule," and consonances are "resolved" through a skip, not step. He wrote that "the effect of this discipline" was "one of purification". Other aspects of composition, such as rhythm, could be "dissonated" by applying the same principle.[27] Seeger was not the first to employ dissonant counterpoint, but was the first to theorize and promote it. Other composers who have used dissonant counterpoint, if not in the exact manner prescribed by Charles Seeger, include Johanna Beyer, John Cage, Ruth Crawford-Seeger, Vivian Fine, Carl Ruggles, Henry Cowell, Carlos Chávez, John J. Becker, Henry Brant, Lou Harrison, Wallingford Riegger, and Frank Wigglesworth.[28] |

不協和音対位法 要例 不協和対位法はもともとチャールズ・シーガーによって理論化されたもので、「最初は純粋に学校の授業で習うもの」であり、種対位法から構成されているが、 伝統的なルールはすべて逆になっている。まず、種対位法はすべて不協和音でなければならず、「規則として、子音よりもむしろ不協和音」を確立し、子音はス テップではなくスキップによって「解決」される。彼は「この規律の効果」は「浄化のひとつ」であると書いている。リズムなど作曲の他の側面も、同じ原理を 適用することで「不協和音」にすることができた[27]。 シーガーは不協和対位法を採用した最初の作曲家ではないが、それを理論化し広めた最初の作曲家である。チャールズ・シーガーが規定した正確な方法ではない にせよ、不協和対位法を用いた他の作曲家には、ヨハンナ・ベイヤー、ジョン・ケージ、ルース・クロフォード=シーガー、ヴィヴィアン・ファイン、カール・ ラグルズ、ヘンリー・カウエル、カルロス・チャベス、ジョン・J・ベッカー、ヘンリー・ブラント、ルー・ハリソン、ウォリングフォード・リーガー、フラン ク・ウィグルスワースなどがいる[28]。 |

| Counter-melody Hauptstimme Polyphony Polyrhythm Voice leading |

対旋律 ハウプトスティンメ ポリフォニー ポリリズム ヴォイス・リード |

| Sources Sachs, Klaus-Jürgen; Dahlhaus, Carl (2001). "Counterpoint". In Stanley Sadie; John Tyrrell (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (second ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. Salzer, Felix; Schachter, Carl (1989). Counterpoint in Composition: The Study of Voice Leading. New York: Stanley Persky, City University of New York. ISBN 023107039X. Further reading Kurth, Ernst (1991). "Foundations of Linear Counterpoint". In Ernst Kurth: Selected Writings, selected and translated by Lee Allen Rothfarb, foreword by Ian Bent, p. 37–95. Cambridge Studies in Music Theory and Analysis 2. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Paperback reprint 2006. ISBN 0-521-35522-2 (cloth); ISBN 0-521-02824-8 (pbk) Agustín-Aquino, Octavio Alberto; Junod, Julien; Mazzola, Guerino (2015). Computational Counterpoint Worlds: Mathematical Theory, Software, and Experiments. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-11236-7. ISBN 978-3-319-11235-0. S2CID 7203604. Prout, Ebenezer (1890). Counterpoint: Strict and Free. London: Augener & Co. Spalding, Walter Raymond (1904). Tonal Counterpoint: Studies in Part-writing. Boston, New York: A. P. Schmidt. Mann, Alfred (1965). The Study of Counterpoint: from Johann Joseph Fux's "Gradus ad Parnassum". W.W. Norton. |

情報源 Sachs, Klaus-Jürgen; Dahlhaus, Carl (2001). 「対位法」. In Stanley Sadie; John Tyrrell (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (second ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. Salzer, Felix; Schachter, Carl (1989). 作曲における対位法: The Study of Voice Leading. ニューヨーク: Stanley Persky, City University of New York. ISBN 023107039x. さらに読む Kurth, Ernst (1991). 「直線的対位法の基礎」. In Ernst Kurth: Selected Writings, selected and translated by Lee Allen Rothfarb, foreword by Ian Bent, p. 37-95. Cambridge Studies in Music Theory and Analysis 2. ケンブリッジとニューヨーク: Cambridge University Press. Paperback reprint 2006. ISBN 0-521-35522-2 (cloth); ISBN 0-521-02824-8 (pbk) Agustín-Aquino, Octavio Alberto; Junod, Julien; Mazzola, Guerino (2015). Computational Counterpoint Worlds: Mathematical Theory, Software, and Experiments. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-11236-7. ISBN 978-3-319-11235-0. S2CID 7203604. Prout, Ebenezer (1890). 対位法: Strict and Free. London: Augener & Co. Spalding, Walter Raymond (1904). Tonal Counterpoint: Studies in Part-writing. ボストン、ニューヨーク: A. P. Schmidt. Mann, Alfred (1965). The Study of Counterpoint: from Johann Joseph Fux's 「Gradus ad Parnassum」. W.W. Norton. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counterpoint |

●フーガという課題

「フーガ(伊: fuga、遁走曲または追走曲)は、対位法を主体とした楽曲形式の1つ。"fuga"(逃走)という語が示すように、各声部が「追走」する模倣(英語版) の技法を特徴とする[1]。基本的に単一の主題にもとづいて展開するが、複数の主題をもつフーガもある(#多重フーガ)[2]。声部間の厳格な模倣が最後 まで続くカノン[1]とは区別される。その形式は、提示部(主調)→ 嬉遊部→提示部(主調以外)→ 嬉遊部 …→ 追迫部(主調)。この提示部ないし追迫部と嬉遊部の関係だけを見ると、リトルネロ形式と非常に似ている。フーガでは各提示部において、……各声部が同じ旋 律を定められた変形を伴って順次奏するのが特徴であるが、普通、回ごとに各パートが違う順序で導入される」フーガ)。

Mendelssohn

- Prelude and Fugue in D minor, Op. 37 のフーガIIIの部分(05:20)より

■リンク

■文献

The final page of Contrapunctus XIV, The Art of Fugue

Contrapuntal imagesEstadio Azteca bajo de construción en 1964 y El torre de Tokio en 1958

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆