インターテクスチュアリティ

Intertextuality, 間テクスト性

☆ インターテクスチュアリティあるいは間テクスト性(Intertextuality) とは、引用、引用、引用文、盗用、翻訳、パスティーシュ、パロディなどの意図的な構成戦略によって、あるいはテキストの読者や読者が知覚する類 似作品や関連作品間の相互関連によって、他のテキストによってテキストの意味が形成 されることである。これらの参照は時に 意図的になされ、読者の参照元に関する予備知識や理解に依存するが、間テクスト性の効果は必ずしも意図的なものではなく、時には不注意な場合もある。しば しば想像的な領域(フィクション、詩、演劇、さらにはパフォーマンス・アートやデジタル・メディアのような非文章的なテキスト)で活動する作家が採用する 戦略と関連付けられてきたが、現在では間テクスト性はあらゆるテキストに内在するものとして理解されることがある(→ハイパーテキスト)。

★ 間テクスト性(Intertextualité) の概念は、1960年代後半に(フランスの)テル・ケル・グループの中で生まれた。ジュリア・クリステヴァは、間テ クスト性を「テクストの相互作用」と定義 し、「特定のテクスト構造の異なるシーケンス(またはコード)を、他のテクストから 引用されたシーケンス(コード)の変換として考える」ことを可能にして いる。こうして文学的テクストは、作者が使用するコードとして理解される過去のさまざまなテクストの変換と組み合わせとして構成される。こうして彼女 は、中世の小説『ジェハン・ド・サントレ』が、スコラ学のテクスト、宮廷詩のテクスト、町の口承文学、カーニバルの言説の相互作用として定義できることを 示す。 間テクスト性という概念は、1970年代と1980年代に復活した。1974年、ロラン・バルトは『百科全書(Encyclopædia Universalis)』の「テクスト(の理論)」という論文で、この概念を公式に提唱した。ロラン・バルトは「すべてのテキストはインターテキストであり、他のテ キストがさまざまなレベルで、多かれ少なかれ認識可能な形でその中に存在する。すでにモンテーニュはこう言っている「われわれがすることはすべて交じり合 うことであ る」[随想録](Essais, III, xiii)と述べている。。

| Intertextuality

is

the shaping of a text's meaning by another text, either through

deliberate compositional strategies such as quotation, allusion,

calque, plagiarism, translation, pastiche or parody,[1][2][3][4][5] or

by interconnections between similar or related works perceived by an

audience or reader of the text.[6] These references are sometimes made

deliberately and depend on a reader's prior knowledge and understanding

of the referent, but the effect of intertextuality is not always

intentional and is sometimes inadvertent. Often associated with

strategies employed by writers working in imaginative registers

(fiction, poetry, and drama and even non-written texts like performance

art and digital media),[7][8] intertextuality may now be understood as

intrinsic to any text.[9] Intertextuality has been differentiated into referential and typological categories. Referential intertextuality refers to the use of fragments in texts and the typological intertextuality refers to the use of pattern and structure in typical texts.[10] A distinction can also be made between iterability and presupposition. Iterability makes reference to the "repeatability" of certain text that is composed of "traces", pieces of other texts that help constitute its meaning. Presupposition makes a reference to assumptions a text makes about its readers and its context.[11] As philosopher William Irwin wrote, the term "has come to have almost as many meanings as users, from those faithful to Julia Kristeva's original vision to those who simply use it as a stylish way of talking about allusion and influence".[12] |

間テクスト性とは、引用、引用、引用文、盗用、翻訳、パスティーシュ、

パロディなどの意図的な構成戦略によって、あるいはテキストの読者や読者が知覚する類似作品や関連作品間の相互関連によって、他のテキストによってテキス

トの意味が形成されることである[1][2][3][4][5]。これらの参照は時に意図的になされ、読者の参照元に関する予備知識や理解に依存するが、

間テクスト性の効果は必ずしも意図的なものではなく、時には不注意な場合もある。しばしば想像的な領域(フィクション、詩、演劇、さらにはパフォーマン

ス・アートやデジタル・メディアのような非文章的なテキスト)で活動する作家が採用する戦略と関連付けられてきたが[7][8]、現在では間テクスト性は

あらゆるテキストに内在するものとして理解されることがある[9]。 間テクスト性は参照的なカテゴリーと類型的なカテゴリーに区別されている。参照的な相互テクスト性はテキストにおける断片の使用を指し、類型論的な相互テ クスト性は典型的なテキストにおけるパターンと構造の使用を指す[10]。反復可能性とは、「痕跡」、つまり意味を構成するのに役立つ他のテキストの断片 から構成されるあるテキストの「反復可能性」を指す。哲学者のウィリアム・アーウィンが書いているように、この用語は「ジュリア・クリステヴァのオリジナ ルなビジョンに忠実な人から、単に引用や影響について語るスタイリッシュな方法として使う人まで、使用者とほぼ同じ数の意味を持つようになった」 [12]。 |

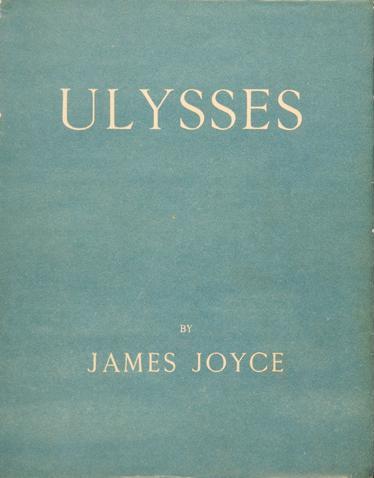

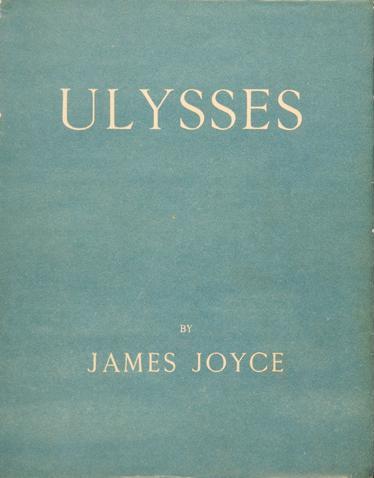

History James Joyce's 1922 novel Ulysses bears an intertextual relationship to Homer's Odyssey. Julia Kristeva was the first to coin the term "intertextuality" (intertextualité)[13] in an attempt to synthesize Ferdinand de Saussure's semiotics—his study of how signs derive their meaning within the structure of a text—with Bakhtin's dialogism—his theory which suggests a continual dialogue with other works of literature and other authors—and his examination of the multiple meanings, or "heteroglossia", in each text (especially novels) and in each word.[12] For Kristeva,[14] "the notion of intertextuality replaces the notion of intersubjectivity" when we realize that meaning is not transferred directly from writer to reader but instead is mediated through, or filtered by, "codes" imparted to the writer and reader by other texts. For example, when we read James Joyce's Ulysses we decode it as a modernist literary experiment, or as a response to the epic tradition, or as part of some other conversation, or as part of all of these conversations at once. This intertextual view of literature, as shown by Roland Barthes, supports the concept that the meaning of a text does not reside in the text, but is produced by the reader in relation not only to the text in question, but also the complex network of texts invoked in the reading process. While the theoretical concept of intertextuality is associated with post-modernism, the device itself is not new. New Testament passages quote from the Old Testament and Old Testament books such as Deuteronomy or the prophets refer to the events described in Exodus (for discussions on using 'intertextuality' to describe the use of the Old Testament in the New Testament, see Porter 1997; Oropeza 2013; Oropeza & Moyise, 2016). Whereas a redaction critic would use such intertextuality to argue for a particular order and process of the authorship of the books in question, literary criticism takes a synchronic view that deals with the texts in their final form, as an interconnected body of literature. This interconnected body extends to later poems and paintings that refer to Biblical narratives, just as other texts build networks around Greek and Roman Classical history and mythology. Bullfinch's 1855 work The Age Of Fable served as an introduction to such an intertextual network;[citation needed] according to its author, it was intended "for the reader of English literature, of either sex, who wishes to comprehend the allusions so frequently made by public speakers, lecturers, essayists, and poets...". Sometimes intertextuality is taken as plagiarism as in the case of Spanish writer Lucía Etxebarria whose poem collection Estación de infierno (2001) was found to contain metaphors and verses from Antonio Colinas. Etxebarria claimed that she admired him and applied intertextuality.[citation needed] Post-structuralism More recent post-structuralist theory, such as that formulated in Daniela Caselli's Beckett's Dantes: Intertextuality in the Fiction and Criticism (MUP 2005), re-examines "intertextuality" as a production within texts, rather than as a series of relationships between different texts. Some postmodern theorists[15] like to talk about the relationship between "intertextuality" and "hypertextuality" (not to be confused with hypertext, another semiotic term coined by Gérard Genette); intertextuality makes each text a "living hell of hell on earth"[16] and part of a larger mosaic of texts, just as each hypertext can be a web of links and part of the whole World-Wide Web. The World-Wide Web has been theorized as a unique realm of reciprocal intertextuality, in which no particular text can claim centrality, yet the Web text eventually produces an image of a community—the group of people who write and read the text using specific discursive strategies.[17] One can also make distinctions between the notions of "intertext", "hypertext" and "supertext".[citation needed] Take for example the Dictionary of the Khazars by Milorad Pavić. As an intertext, it employs quotations from the scriptures of the Abrahamic religions. As a hypertext, it consists of links to different articles within itself and also every individual trajectory of reading it. As a supertext, it combines male and female versions of itself, as well as three mini-dictionaries in each of the versions. |

歴史 ジェイムズ・ジョイスが1922年に発表した小説『ユリシーズ』は、ホメロスの『オデュッセイ ア』と間テクスト的な関係にある。 ジュリア・クリステヴァは、フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールの記号論(記号がテクストの構造の中でどのように意味を導き出すかという研究)と、バフチンの 対話論(他の文学作品や他の作家との継続的な対話を示唆する理論)、そして各テキスト(特に小説)や各単語に含まれる複数の意味、すなわち「ヘテログロシ ア」の考察を統合する試みとして、「間テクスト性」(intertextuality)という言葉を最初に作った[13]。 [クリステヴァにとって[12]、「間テクスト性という概念は、間主観性という概念に取って代わるもの」であり、それは、意味が作家から読者へと直接伝達 されるのではなく、他のテクストによって作家と読者に付与された「コード」を媒介する、あるいはそれによってフィルタリングされることを理解するときであ る。例えば、ジェイムズ・ジョイスの『ユリシーズ』を読むとき、私たちはそれをモダニズム文学の実験として、あるいは叙事詩の伝統への応答として、あるい は他の会話の一部として、あるいはこれらすべての会話の一部として解読する。ロラン・バルトが示したこのような文脈間的な文学観は、テクストの意味はテクストの中にあるのではなく、問題のテクストだけでなく、読書の過程で呼び 起こされるテクストの複雑なネットワークとの関係において、読者によって生み出されるという概念を支持するものである。 インターテクスチュアリティの理論的概念はポストモダニズムと関連しているが、その装置自体は新しいものではない。新約聖書の箇所は旧約聖書から引用さ れ、申命記や預言書などの旧約聖書の書物は出エジプト記に記述された出来事に言及している(新約聖書における旧約聖書の使用を説明するために「間テクスト 性」を使用することに関する議論については、Porter 1997; Oropeza 2013; Oropeza & Moyise, 2016を参照)。再編集批評家がこのような間テクスト性を用いて、問題となっている書物の著者の特定の順序とプロセスを主張するのに対し、文芸批評は、 相互接続された文学体として、最終的な形のテキストを扱う共時的な視点をとる。この相互接続体は、ギリシア・ローマ古典史や神話を中心にネットワークを構 築する他のテキストと同様に、聖書の物語を参照する後の詩や絵画にも及ぶ。ブルフィンチの1855年の作品『The Age Of Fable』は、そのような相互テクスト的ネットワークの入門書として機能した。[要出典]その著者によれば、この作品は「男女を問わず、英文学の読者 で、公の演説者、講演者、エッセイスト、詩人によって頻繁になされる引用を理解したいと望む人のためのもの」であった。 詩集『Estación de infierno』(2001年)にアントニオ・コリナスの比喩や詩が含まれていることが判明したスペイン人作家ルシア・エトセバリアのように、間テクス ト性が盗作と受け取られることもある。エトセバリアは、彼を尊敬し、間テクスト性を適用したと主張している[要出典]。 ポスト構造主義 ダニエラ・カゼッリ(Daniela Caselli)の『Beckett's Dantes: Intertextuality in the Fiction and Criticism (MUP 2005)では、「間テクスト性」を異なるテクスト間の一連の関係としてではなく、テクスト内の生成として再検討している。ポストモダンの理論家の中には [15]、「間テクスト性」と「ハイパーテキスト性」(ジェラール・ジュネットが作ったもう一つの記号論用語であるハイパーテキストと混同しないように) の関係について語りたがる者もいる。間テクスト性はそれぞれのテクストを「この世の地獄の生き地獄」[16]にし、より大きなテクストのモザイクの一部に する。ワールド・ワイド・ウェブは、相互テクスト性のユニークな領域として理論化されており、そこでは特定のテキストが中心性を主張することはできない が、ウェブ・テキストは最終的にコミュニティ(特定の言説戦略を用いてテキストを書き、読む人々の集団)のイメージを生み出す[17]。 また、「インターテキスト」、「ハイパーテキスト」、「スーパーテキスト」という概念を区別することもできる[要出典]。例えば、ミロラド・パヴィッチに よる『ハザール人の辞典』を見てみよう。インターテキストとしては、アブラハム宗教の聖典からの引用が用いられている。ハイパーテキストとしては、それ自 体の中にあるさまざまな記事へのリンクと、それを読む個々の軌跡で構成されている。スーパーテキストとして、男性版と女性版が組み合わされ、それぞれに3 つのミニ辞書がある。 |

| Some examples of intertextuality

in literature include: Perhaps the earliest example of a non-anonymous author alluding to another is when Euripides, in his Electra (410s BC), spoofs (in lines 524-38) the recognition scene from Aeschylus's The Libation Bearers.[18] East of Eden (1952) by John Steinbeck: A retelling of the account of Genesis, set in the Salinas Valley of Northern California. Ulysses (1922) by James Joyce: A retelling of Homer's Odyssey, set in Dublin. Absalom, Absalom! (1936) by William Faulkner: A retelling of the Absalom story from Samuel, set in antebellum Mississippi. Earthly Powers (1980) by Anthony Burgess: A retelling of Anatole France's Le Miracle du grand saint Nicolas during the 20th century. The Dead Fathers Club (2006) by Matt Haig: A retelling of Shakespeare's Hamlet, set in modern England. A Thousand Acres (1991) by Jane Smiley: A retelling of Shakespeare's King Lear, set in rural Iowa. Perelandra (1943) by C. S. Lewis: Another retelling of the account of Genesis, also leaning on Milton's Paradise Lost, but set on the planet Venus. Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) by Jean Rhys: A metatextual intervention on Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre, the story of the "mad woman in the attic" told from her perspective. The Legend of Bagger Vance (1996) by Steven Pressfield: A retelling of the Bhagavad Gita, set in 1931 during an epic golf game. Bridget Jones's Diary (1996) by Helen Fielding: A modern "chick lit" romantic comedy replaying and referencing Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. Tortilla Flat (1935) by John Steinbeck: A retelling of the Arthurian legends, set in Monterey, California, during the interwar period. Mourning Becomes Electra (1931) by Eugene O'Neill: A retelling of Aeschylus' The Oresteia, set in post-American Civil War New England. The Gospel of Matthew narrates the early years of the life of Jesus while following a pattern from the Hebrew Bible's Book of Exodus.[19] Frankissstein (2019) by Jeanette Winterson: A retelling of Mary Shelley's 1818 classic Frankenstein, examining updated issues of the monstrous, i.e. sex-bots and cryonics. |

文学における相互テクスト性の例としては、以下のようなものがある: エウリピデスが『エレクトラ』(紀元前410年代)の中で、(524行目から38行目にかけて)アイスキュロスの『酒を運ぶ者たち』の認識シーンをもじっ たのが、おそらく匿名でない作家が他の作家を引用した最も古い例であろう[18]。 ジョン・スタインベックによる『エデンの東』(1952年):北カリフォルニアのサリナス渓谷を舞台にした創世記の再話。 『ユリシーズ』(1922年)ジェイムズ・ジョイス作: ダブリンを舞台にしたホメロスの『オデュッセイア』の再話。 アブサロム、アブサロム (1936年)ウィリアム・フォークナー作: 前世のミシシッピを舞台に、『サミュエル』のアブサロムの物語を再話。 アンソニー・バージェス作『Earthly Powers』(1980年): アナトール・フランスの『大サン・ニコラの奇蹟』を20世紀に再映画化。 マット・ヘイグ著『The Dead Fathers Club』(2006年):シェイクスピアの『ハムレット』を現代イングランドを舞台に再映画化。 ジェーン・スマイリー著『A Thousand Acres』(1991年): アイオワ州の田舎町を舞台にした、シェイクスピアの『リア王』の再話。 C・S・ルイス著『Perelandra』(1943年): 創世記の再話で、ミルトンの『失楽園』にも傾倒しているが、舞台は金星。 『広いサルガッソー海』(1966年)ジーン・リース著: シャーロット・ブロンテの『ジェーン・エア』へのメタテキスト的介入で、「屋根裏部屋の狂女」の物語が彼女の視点から語られる。 『バガー・ヴァンスの伝説』(1996年)スティーブン・プレスフィールド著: バガヴァッド・ギーターの再話で、1931年の壮絶なゴルフゲームが舞台。 『ブリジット・ジョーンズの日記』(1996年)ヘレン・フィールディング著: ジェーン・オースティンの『高慢と偏見』を再演・参照した、現代の「ひよっこ」ロマンチック・コメディ。 ジョン・スタインベック著『Tortilla Flat』(1935年):戦間期のカリフォルニア州モントレーを舞台にしたアーサー王伝説の再話。 ユージン・オニール作『喪服はエレクトラに』(1931年): 南北戦争後のニューイングランドを舞台にした、アイスキュロスの『オレステイア』の再話。 マタイによる福音書は、ヘブライ語聖書の出エジプト記のパターンを踏襲 しながら、イエスの生涯の初期を叙述している[19]。 『フランキスシュタイン』(2019年)ジャネット・ウィンターソン著: メアリー・シェリーの1818年の名作『フランケンシュタイン』の再話で、怪物的なもの、すなわちセックスボットや人体冷凍保存の最新の問題を検証してい る。 |

| Related concepts Linguist Norman Fairclough states that "intertextuality is a matter of recontextualization".[20] According to Per Linell, recontextualization can be defined as the "dynamic transfer-and-transformation of something from one discourse/text-in-context ... to another".[21] Recontextualization can be relatively explicit—for example, when one text directly quotes another—or relatively implicit—as when the "same" generic meaning is rearticulated across different texts.[22]: 132–133 A number of scholars have observed that recontextualization can have important ideological and political consequences. For instance, Adam Hodges has studied how White House officials recontextualized and altered a military general's comments for political purposes, highlighting favorable aspects of the general's utterances while downplaying the damaging aspects.[23] Rhetorical scholar Jeanne Fahnestock has found that when popular magazines recontextualize scientific research they enhance the uniqueness of the scientific findings and confer greater certainty on the reported facts.[24] Similarly, John Oddo stated that American reporters covering Colin Powell's 2003 U.N. speech transformed Powell's discourse as they recontextualized it, bestowing Powell's allegations with greater certainty and warrantability and even adding new evidence to support Powell's claims.[22] Oddo has also argued that recontextualization has a future-oriented counterpoint, which he dubs "precontextualization".[25] According to Oddo, precontextualization is a form of anticipatory intertextuality wherein "a text introduces and predicts elements of a symbolic event that is yet to unfold".[22]: 78 For example, Oddo contends, American journalists anticipated and previewed Colin Powell's U.N. address, drawing his future discourse into the normative present. Allusion While intertextuality is a complex and multileveled literary term, it is often confused with the more casual term 'allusion'. Allusion is a passing or casual reference; an incidental mention of something, either directly or by implication.[26] This means it is most closely linked to both obligatory and accidental intertextuality, as the 'allusion' made relies on the listener or viewer knowing about the original source. It is also seen as accidental, however, as the allusion is normally a phrase so frequently or casually used that the true significance is not fully appreciated. Allusion is most often used in conversation, dialogue or metaphor. For example, "I was surprised his nose was not growing like Pinocchio's." This makes a reference to The Adventures of Pinocchio, written by Carlo Collodi when the little wooden puppet lies.[27] If this was obligatory intertextuality in a text, multiple references to this (or other novels of the same theme) would be used throughout the hypertext. |

関連概念 言語学者のノーマン・フェアクローは「間テクスト性とは再文脈化の問題である」と述べている[20]。ペール・リネルによれば、再文脈化とは「ある言説/ テクスト-イン-コンテクストから...別の言説/テクストへの、動的な移転と変容」[21]と定義することができる: 132-133 多くの学者が、再文脈化が重要なイデオロギー的・政治的帰結をもたらしうることを指摘している。例えば、アダム・ホッジスは、ホワイトハウスの高官が政治 的目的のために、将軍の発言をどのように再文脈化し、改変したかを研究しており、将軍の発言の好ましい面を強調する一方で、不利な面を軽視している [23]。レトリック学者のジャンヌ・ファーネストックは、大衆誌が科学研究を再文脈化するとき、科学的知見の独自性を高め、報告された事実により高い確 実性を与えることを発見している[24]。 [24] 同様に、ジョン・オッドは、2003年のコリン・パウエルの国連演説を取材したアメリカの記者たちが、パウエルの言説を再文脈化することによって、パウエ ルの主張により高い確実性と正当性を与え、さらにはパウエルの主張を裏付ける新たな証拠を加えることによって、パウエルの言説を変容させたと述べている [22]。 オッドはまた、再文脈化には未来志向の対極があり、それを「前文脈化」と呼ぶと主張している[25]。オッドによれば、前文脈化とは、「テキストが、まだ 展開されていない象徴的な出来事の要素を紹介し、予言する」[22]: 78 例えば、アメリカのジャーナリストはコリン・パウエルの国連演説を予期し、予言することで、彼の未来の言説を規範的な現在に引き込んだとオッドは主張して いる。 引用 間テクスト性は複雑で多層的な文学用語であるが、よりカジュアルな用語である「アリュージョン」と混同されがちである。アリュージョンとは、通りすがり の、あるいはさりげない言及のことであり、直接的に、あるいは暗示的に、何かに偶発的に言及することである[26]。つまり、「アリュージョン」がなされ るのは、聞き手や視聴者が元の出典について知っていることに依存しているため、義務的な、あるいは偶発的な文脈間性と最も密接に関連している。しかし、ア リュージョンは通常、頻繁に、あるいは何気なく使われるフレーズであるため、真の意味が十分に理解されることはなく、偶発的なものとも見なされる。引用 は、会話や対話、比喩で使われることが多い。例えば、"彼の鼻がピノキオのように伸びていないことに驚いた"。これは、小さな木の人形が嘘をつくときにカ ルロ・コッローディが書いた『ピノキオの冒険』に言及している[27]。これがテキストにおける義務的な相互テクスト性であれば、ハイパーテキスト全体を 通して、これ(または同じテーマの他の小説)への複数の言及が使われることになるだろう。 |

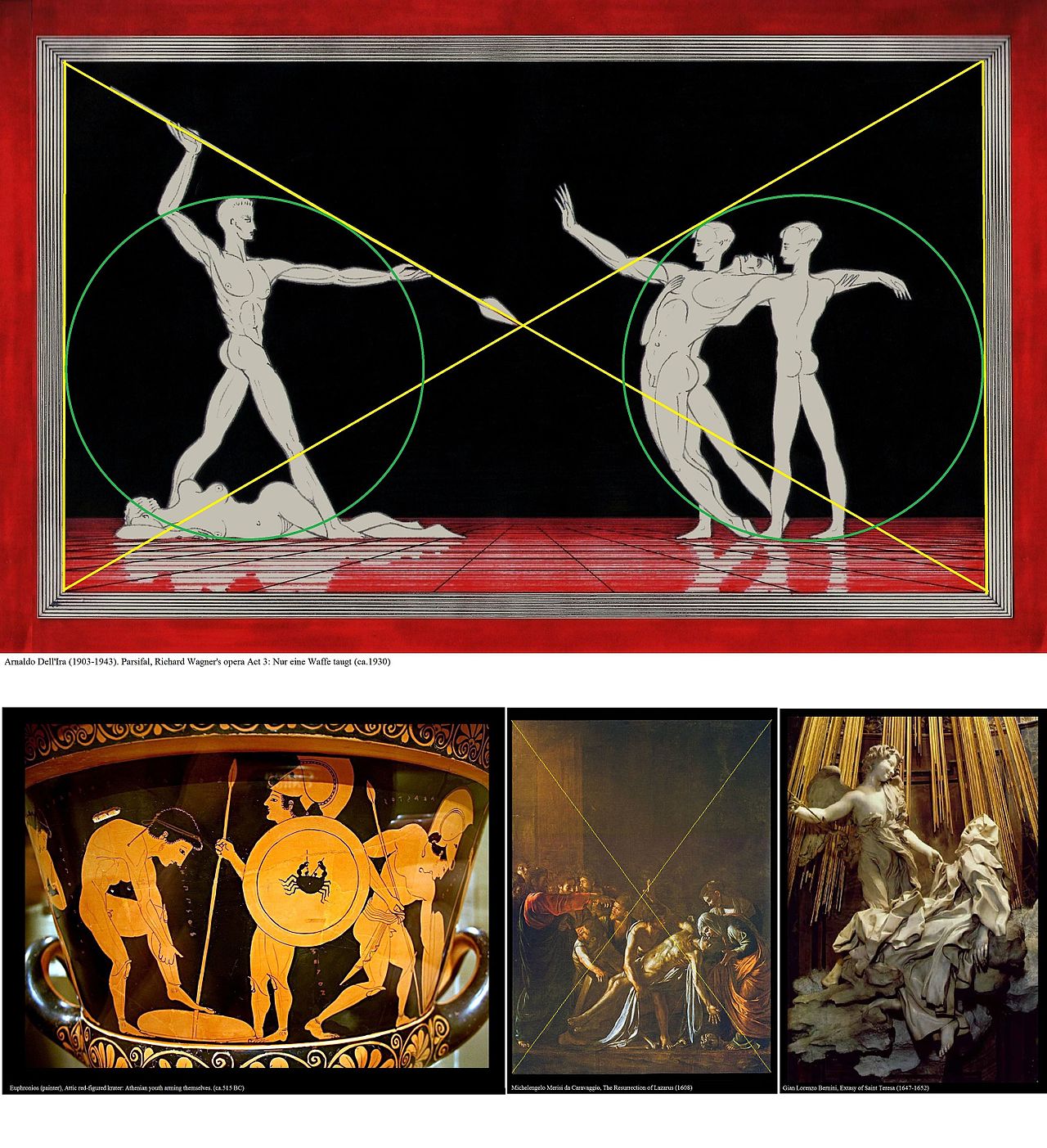

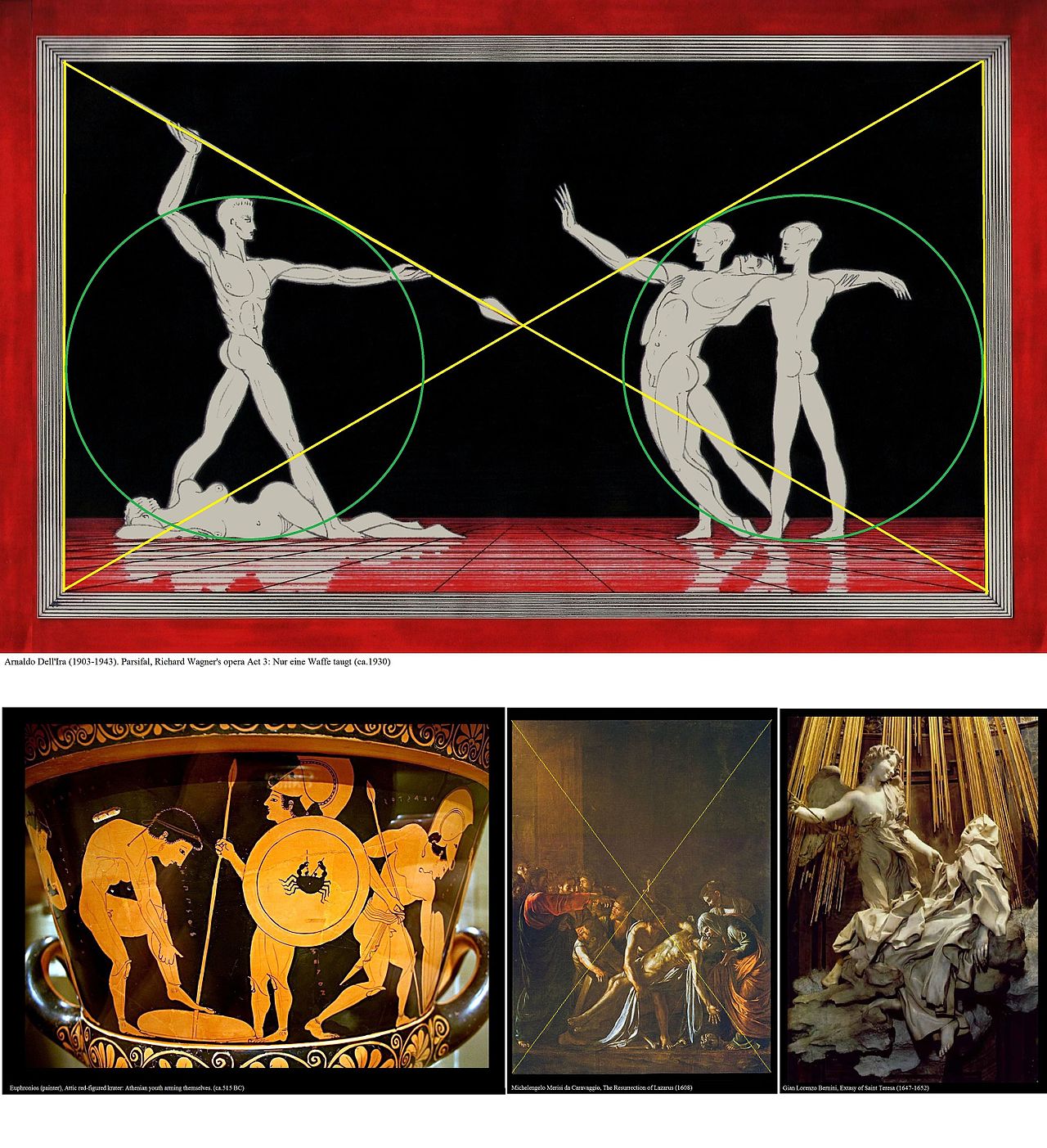

Plagiarism Intertextuality in art: "Nur eine Waffe taugt" (Richard Wagner, Parsifal, act III), by Arnaldo dell'Ira, ca. 1930 Sociologist Perry Share describes intertextuality as "an area of considerable ethical complexity".[28] Intertextuality does not necessarily involve citations or referencing punctuation (such as quotation marks) and can be mistaken for plagiarism.[29]: 86 While the two concepts are related, the intentions behind using another's work is critical in distinguishing the two. When making use of intertextuality, usually a small excerpt of a hypotext assists in the understanding of the new hypertext's original themes, characters, or contexts.[29][page needed] Aspects of existing texts are reused, often resulting in new meaning when placed in a different context.[30] Intertextuality hinges on the creation of new ideas, while plagiarism attempts to pass off existing work as one's own. Students learning to write often rely on imitation or emulation and have not yet learned how to reformulate sources and cite them according to expected standards, and thus engage in forms of "patchwriting," which may be inappropriately penalized as intentional plagiarism.[31] Because the interests of writing studies differ from the interests of literary theory, the concept has been elaborated differently with an emphasis on writers using intertextuality to position their statement in relation to other statements and prior knowledge.[32] Students often find it difficult to learn how to combine referencing and relying on others' words with marking their novel perspective and contribution.[33] |

剽窃 芸術における相互テクスト性 Nur eine Waffe taugt」(リヒャルト・ワーグナー『パ ルジファル』第3幕)、アルナルド・デッラ作、1930年頃 社会学者のペリー・シェアは、間テクスト性を「倫理的にかなり複雑な領域」と表現する。間テクスト性は、必ずしも引用や参照句読点(引用符など)を伴わ ず、剽窃と間違われることもある。 この2つの概念は関連しているが、他者の作品を利用する意図は、この2つを区別する上で非常に重要である。間テクスト性を利用する場合、通常はハイパーテ キストの小さな抜粋が、新しいハイパーテキストのオリジナルのテーマ、登場人物、文脈の理解を助ける。既存のテキストの側面が再利用され、異なる文脈に置 かれたときに新たな意味をもたらすことが多い。インターテクスチュアリティは新しいアイデアの創造にかかっているが、剽窃は既存の作品を自分のものとして 流用しようとするものである。 文章を書くことを学んでいる学生は、模倣や模倣に頼ることが多く、出典を再定義し、期待される基準に従って引用する方法をまだ学んでいない。 ライティング研究の関心事は文学理論の関心事とは異なるため、この概念は、他の記述や予備知識との関連において自分の記述を位置づけるために、書き手が間 テクスト性を用いることに重点を置いて、異なる形で精緻化されてきた。 学生はしばしば、他者の言葉を参照し、依拠することと、自分の斬新な視点や貢献を示すことを組み合わせる方法を学ぶのは難しいと感じる。 |

| Non-literary uses In addition, the concept of intertextuality has been used analytically outside the sphere of literature and art. For example, Devitt (1991) examined how the various genres of letters composed by tax accountants refer to the tax codes in genre-specific ways.[34] In another example, Christensen (2016)[35] introduces the concept of intertextuality to the analysis of work practice at a hospital. The study shows that the ensemble of documents used and produced at a hospital department can be said to form a corpus of written texts. On the basis of the corpus, or subsections thereof, the actors in cooperative work create intertext between relevant (complementary) texts in a particular situation, for a particular purpose. The intertext of a particular situation can be constituted by several kinds of intertextuality, including the complementary type, the intratextual type and the mediated type. In this manner the concept of intertext has had an impact beyond literature and art studies. In scientific and other scholarly writing intertextuality is core to the collaborative nature of knowledge building and thus citation practices are important to the social organization of fields, the codification of knowledge, and the reward system for professional contribution.[36] Scientists can be skillfully intentional in the use of references to prior work in order to position the contribution of their work.[37][38] Modern practices of scientific citation, however, have only developed since the late eighteenth century[39] and vary across fields, in part influenced by disciplines’ epistemologies.[40] |

文学以外の用途 さらに、間テクスト性の概念は文学や芸術の領域以外でも分析的に用いられてきた。例えば、Devitt(1991)は、税理士が作成する様々なジャンルの 手紙が、どのようにジャンル特有の方法で税法に言及しているかを調べた[34]。この研究は、ある病院の部署で使用され、作成された文書の集合体が、書か れたテキストのコーパスを形成していると言えることを示している。このコーパス、あるいはその一部分に基づいて、協同作業の行為者は、特定の状況、特定の 目的のために、関連する(補完的な)テキスト間のインターテキストを作成する。特定の状況のインターテキストは、補完型、テキスト内型、媒介型など、いく つかの種類のインターテキストによって構成される。このように、インターテキストの概念は、文学や芸術研究の枠を超えて影響を及ぼしている。 科学やその他の学術的な文章において、相互テクスト性は知識構築の共同的性質の中核をなすものであり、したがって引用の慣行は、分野の社会的組織、知識の 体系化、専門的貢献に対する報酬制度にとって重要である。しかし、科学的引用の近代的な慣行は、18世紀後半から発展してきたものであり、学問分野の認識 論の影響もあって、分野によって異なっている。 |

| Citationality Détournement Honkadori Interdiscursivity Julia Kristeva Literary theory Meta Post-structuralism Semiotics The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things Transmedia storytelling Transtextuality Type scene Umberto Eco |

引用 デトゥルヌマン 本歌取り 相互散逸性 ジュリア・クリステヴァ 文学理論 メタ ポスト構造主義 記号論 時のかたち モノの歴史についての考察 トランスメディア・ストーリーテリング トランステクシュアリティ タイプシーン ウンベルト・エーコ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intertextuality |

|

| L'intertextualité

est le caractère et l'étude de l'intertexte, qui est l'ensemble des

textes mis en relation, par le biais par exemple de la citation, de

l'allusion, du plagiat, de la référence et du lien hypertexte, dans un

texte donné. Origines La notion d'intertextualité est apparue à la fin des années 1960 au sein du groupe Tel Quel. Julia Kristeva définit l'intertextualité comme une « interaction textuelle » qui permet de considérer « les différentes séquences (ou codes) d'une structure textuelle précise comme autant de transforms de séquences (codes) prises à d'autres textes1. » Le texte littéraire se constituerait donc comme la transformation et la combinaison de différents textes antérieurs compris comme des codes utilisés par l'auteur. Elle montre ainsi que le roman médiéval Jehan de Saintré peut se définir comme l'interaction entre le texte de la scolastique, celui de la poésie courtoise, la littérature orale de la ville et le discours du carnaval. Cette définition de l'intertextualité emprunte beaucoup au dialogisme tel que l'a défini Mikhaïl Bakhtine2. Il considère en effet que le roman est un espace polyphonique dans lequel viennent se confronter divers composants linguistiques, stylistiques et culturels. La notion d'intertextualité emprunte donc à Bakhtine l'idée suivant laquelle la littérarité naîtrait de la transformation de différents éléments culturels et linguistiques en un texte particulier. Développements ultérieurs La notion d'intertextualité sera fortement reprise dans les décennies 1970 et 1980. En 1974, Roland Barthes l'officialise dans l'article « Texte (théorie du) » de l'Encyclopædia Universalis. Il souligne ainsi que « tout texte est un intertexte ; d'autres textes sont présents en lui à des niveaux variables, sous des formes plus ou moins reconnaissables : les textes de la culture antérieure et ceux de la culture environnante ; tout texte est un tissu nouveau de citations révolues. » Déjà Montaigne : « Nous ne faisons que nous entregloser. » (Essais, III, xiii) Par la suite la notion a pu être élargie et affaiblie au point de revenir à la critique des sources telle qu'elle était pratiquée auparavant3. L'évolution de la notion est marquée ensuite par les travaux de Michaël Riffaterre qui recherche la « trace intertextuelle » à l'échelle de la phrase, du fragment ou du texte bref. L'intertextualité est pour lui fondamentalement liée à un mécanisme de lecture propre au texte littéraire. Le lecteur identifie le texte comme littéraire parce qu'il perçoit « les rapports entre une œuvre et d'autres qui l'ont précédée ou suivie ». Gérard Genette apporte en 1982 avec Palimpsestes un élément majeur à la construction de la notion d'intertextualité. Il l'intègre en effet à une théorie plus générale de la transtextualité, qui analyse tous les rapports qu'un texte entretient avec d'autres textes4. Au sein de cette théorie le terme d'« intertextualité » est réservé aux cas de « présence effective d'un texte dans l'autre ». À cet égard il distingue la citation, référence littérale et explicite ; le plagiat, référence littérale mais non explicite puisqu'elle n'est pas déclarée ; et enfin l'allusion, référence non littérale et non explicite qui exige la compétence du lecteur pour être identifiée5. Ce concept assez récent mais qui a pris une place très importante dans le champ littéraire est donc en cours d'élaboration théorique depuis les années 1970. Pierre-Marc de Biasi considère que « loin d'être parvenu à son état d'achèvement, [l'intertextualité] entre vraisemblablement aujourd'hui dans une nouvelle étape de redéfinition6. » Problèmes notionnels Intertextualité et littérarité Deux conceptions s'affrontent concernant le rapport entre intertextualité et littérature7. Pour certains auteurs, l'intertextualité est intrinsèquement liée au processus littéraire. Elle permettrait même de définir la littérarité d'un texte, dans la mesure où le lecteur reconnaîtrait un texte littéraire à ce qu'il identifie ses intertextes. D'autres, au contraire, considèrent que cette notion peut et doit être élargie à l'ensemble des textes. L'intertextualité n'est alors qu'un cas particulier de l'« interdiscursivité », pensé comme carrefour de discours, ou du dialogisme, tel que l'a théorisé Mikhaïl Bakhtine. Dimension relationnelle et dimension transformationnelle Une certaine simplification de la notion a parfois amené à identifier intertextualité et recherche de références à un texte antérieur. L'intertextualité ne serait donc pas autre chose qu'une forme de critique des sources. Or l'intertextualité a été pensée dès l'origine8 comme un processus de production du texte passant par la transformation de textes antérieurs. En ce sens l'intertextualité n'est pas simplement la présence de la référence à un autre texte mais un véritable mode de production et d'existence du texte qui ne pourrait se comprendre qu'en ce qu'il transforme des textes antérieurs. Dans le même ordre d'idées, le rapport entre les textes n'est plus pensé du texte source vers le texte étudié mais du texte étudié vers ses textes sources9. En effet, en utilisant un texte antérieur, un auteur modifie le statut de ce texte et la lecture qu'on peut en avoir. Il s'agit donc bien d'un processus complexe qui dépasse largement la pratique de la citation ou de la référence. L'intertextualité, prétexte du plagiat ? Plusieurs auteurs soupçonnés de plagiat, dont Jacques Attali, Joseph Macé-Scaron et Patrick Poivre d'Arvor, se sont défendus de tout plagiat en invoquant l'intertextualité de leurs ouvrages10. Il paraît nécessaire d'étendre le concept à un architexte généralisé, comprenant les liaisons hypertextuelles au sens de l'internet contemporain, les échos rythmiques [archive], etc. (Vegliante [archive]). Dès lors, sur internet ou sur des corpus numériques de grande dimension, le repérage automatique de l'intertexte devient un enjeu méthodologique pour la linguistique et la littérature computationnelles. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intertextualit%C3%A9 |

間テクスト性とは、引用、引用、剽窃、参照、ハイパーテキストリンクな

どによって、あるテキストの中で互いにリンクされたテキストの集合である。 起源 間テクスト性の概念は、1960年代後半にテル・ケル・グループの中で生まれた。ジュリア・クリステヴァは、間テクスト性を「テクストの相互作用」と定義 し、「特定のテクスト構造の異なるシーケンス(またはコード)を、他のテクストから引用されたシーケンス(コード)の変換として考える」ことを可能にして いる1。こうして文学的テクストは、作者が使用するコードとして理解される過去のさまざまなテクストの変換と組み合わせとして構成される。こうして彼女 は、中世の小説『ジェハン・ド・サントレ』が、スコラ学のテクスト、宮廷詩のテクスト、町の口承文学、カーニバルの言説の相互作用として定義できることを 示す。 この相互テクスト性の定義は、ミハイル・バフチンの対話主義の定義から大 いに借用したものである2。彼は小説を、さまざまな言語的、文体的、文化的要素が接触するポリフォニックな空間と見なしている。このように間テクスト性と いう概念は、異なる文化的・言語的要素が特定のテクストに変換されることによって文学性が生まれるという考えをバフチンから借りている。 その後の展開 間テクスト性という概念は、1970年代と1980年代に復活した。1974年、ロラン・バルトは『百科全書(Encyclopædia Universalis)』の「テクスト(の理論)」という論文で、この概念を公式に提唱した。彼は「すべてのテキストはインターテキストであり、他のテ キストがさまざまなレベルで、多かれ少なかれ認識可能な形でその中に存在する。すでにモンテーニュは、「われわれがすることはすべて交じり合うことであ る」(『エッセ』III、xiii)と述べている。(Essais, III, xiii)。 その後、この概念は広がり、弱まり、以前行われていたような原典批評に戻るまでになった3。この概念の進化は、ミハエル・リファテールの研究によって顕著 になった。彼は、文、断片、短いテキストのレベルで「文脈間の痕跡」を探す。リファテールにとって、間テクスト性は文学的テクストに特有の読解のメカニズ ムと根本的に結びついている。読者は「ある作品と、それに先行する、あるいは後続する他の作品との関係」を認識することで、そのテクストが文学的であると 認識するのである。 1982年、ジェラール・ジュネットは『パリンプセステス』(Palimpsestes)で、間テクスト性という概念の構築に大きく貢献した。彼はこれ を、テクストが他のテクストと持つあらゆる関係を分析する、より一般的なトランテクスト性(transtextuality)の理論に組み入れた4。この 理論の中では、「インターテクスチュアリティ」という用語は、「あるテキストが他のテキストに効果的に存在する」場合にのみ使われる。この点で、「引用」 は文字通りの明示的な参照であり、「盗用」は文字通りの参照であるが宣言されていないため非明示的な参照であり、最後に「引用」は非文字通りの非明示的な 参照であり、読者の識別能力を必要とする5。 文学の分野で非常に重要な役割を担うようになったこの概念は、1970年代から理論的に発展してきた。ピエール=マルク・ドゥ・ビアシは、「完成の域に達 するどころか、[間テクスト性は]おそらく今、再定義の新たな段階に入りつつある」と考えている6。 概念上の問題 間テクスト性と文学性 間テクスト性と文学の関係について、対立する二つの概念がある7。 ある作家にとっては、間テクスト性は文学的プロセスと本質的に結びついている。読者がそのテクストの間テクストを識別することによって文学的テクストを認 識する以上、それはテクストの文学性を定義することさえ可能にする。 一方、この概念をすべてのテクストに拡張することが可能であり、また拡張すべきであると考える者もいる。その場合、間テクスト性は、ミハイル・バフチンが 理論化したように、言説の交差点、あるいは対話主義として考えられる「インターディスカーシビティ(interdiscursivity)」の特殊なケー スに過ぎない。 関係性と変容の次元 この概念を単純化するあまり、「間テクスト性」を以前のテクストへの言及を探すことと同一視してしまうことがある。したがって、間テクスト性は原典批評の 一形態に過ぎないことになる。 しかし、間テクスト性は当初から8、以前のテクストの変容を伴うテクスト生成のプロセスとして考えられてきた。この意味で、間テクスト性とは、単に別のテ クストへの言及が存在することではなく、それが以前のテクストを変容させる限りにおいてのみ理解されうる、テクストの現実的な生産様式であり存在なのであ る。同じように、テクスト間の関係は、もはや原典から研究対象のテクストへではなく、研究対象のテクストからその原典へと考えられる9。事実上、著者は以 前のテクストを用いることで、そのテクストの位置づけを変え、われわれがそのテクストに対して持ちうる読み方を変えるのである。それゆえ、引用や言及の域 をはるかに超えた複雑なプロセスなのである。 間テクスト性は盗作の口実か? ジャック・アタリ、ジョゼフ・マセ=スカロン、パトリック・ポワブル・ダルヴォールなど、盗作を疑われた何人かの作家は、作品の間テクスト性を引き合いに 出すことで、盗作から身を守ってきた10。この概念を、現代のインターネットにおけるハイパーテキストのリンクや、リズミック・エコー[archive] などを含む、一般化されたアーキテキストに拡張する必要があるようだ(Vegliante [archive])。これ以降、インターネット上や大規模なデジタルコーパス上では、インターテキストの自動識別が、計算言語学と文学の方法論的課題と なる。 |

| Tel Quel

est une revue de littérature française d'avant-garde, fondée en 1960 à

Paris aux Éditions du Seuil par plusieurs jeunes auteurs réunis autour

de Jean-Edern Hallier et Philippe Sollers. La revue avait pour objectif

de refléter la réévaluation par l'avant-garde des classiques de

l'histoire de la littérature. En dépit de son orientation littéraire,

les positions de la revue sont très caractéristiques des mouvements

d'idées des années 1960 et 1970, notamment le maoïsme affiché de

certains de ses membres. Histoire L'idée de fonder la revue Tel Quel est née, selon Philippe Sollers1 lui-même, lors d'un cocktail organisé en septembre 1958 par les Éditions du Seuil au bar de l'Hôtel Pont Royal. L'auteur d'Une curieuse solitude sympathise avec Jean-Edern Hallier et avec son ami Pierre-André Boutang, et, en fin de soirée, le trio décide de se lancer dans une entreprise littéraire commune. Dès la fin de l'année 1958, de nombreuses réunions préparatoires se tiennent, en particulier dans la propriété des parents d'Hallier, à Amblincourt, où se retrouvent entre autres Alain Robbe-Grillet, Jean-Loup Dabadie, Jacques Coudol ; l'ambition est de fonder une revue aussi prestigieuse que La Nouvelle Revue française, et de se rapprocher des courants littéraires émergents, les nouvelles voix, publiées notamment par les éditions de Minuit. Ils manifestent aussi un grand intérêt pour la littérature britannique d'avant guerre et la philosophie. Le 24 janvier 1960, le contrat est signé entre Paul Flamand, responsable du Seuil, et Jean-Edern Hallier, nommé directeur-gérant. Le nom de cette revue est emprunté à un aphorisme de Nietzsche : « Je veux le monde et le veux TEL QUEL, et le veux encore… le veux éternellement, et je crie insatiablement : bis ! et non seulement pour moi seul, mais pour toute la pièce et pour tout le spectacle ; et non pour tout le spectacle seul, mais au fond pour moi, parce que le spectacle m'est nécessaire parce que je lui suis nécessaire et parce que je le rends nécessaire. » Cette citation est placée en tête du numéro un puis, pendant les dix années suivantes, chaque numéro débute par une citation contenant l'expression « tel quel »2. Le comité de rédaction initial, fondé en janvier 1960, comprend Philippe Sollers, Jean-Edern Hallier, Jean-René Huguenin, Jacques Coudol, Renaud Matignon, et Fernand du Boisrouvray (1934-1996)3. Entre quelques évictions et départs, entrèrent par la suite au comité d'abord Jean Thibaudeau, puis Jean Ricardou, Michel Deguy, Marcelin Pleynet, Denis Roche, Jean-Louis Baudry, Jean-Pierre Faye, Jacqueline Risset, Julia Kristeva (en septembre 1971), le germaniste Michel Maxence et l'urbaniste Gislhaine Meffre4. Au bout de quelque temps, la presse parle du « groupe Tel Quel » pour qualifier les membres fondateurs encore actifs de cette revue5. Hallier sera exclu en février 1963, Coudol partira au mois de mars suivant. En novembre 1967, Faye quitte la revue pour s'en aller fonder Change. Le premier numéro est daté printemps 1960 et comporte 100 pages. Il propose en son sommaire Francis Ponge, Claude Simon, Jean Cayrol, Jean Lagrolet, Boisrouvray, Sollers, Virginia Woolf, Coudol, Huguenin, Hallier, Thibaudeau, Matignon, ainsi que des réponses à la question « Pensez-vous avoir un don d'écrivain ? ». Ponge est considéré comme le père tutélaire de la revue, ainsi que Cayrol, mais dans une moindre mesure. Les Éditions du Seuil lancent en 1963, trois ans après la création de la revue, la « Collection “Tel Quel” », collection d'essais à couverture ornée d'une bordure havane, dont la direction est confiée à Philippe Sollers uniquement. En vingt ans d'existence, 73 ouvrages de 32 auteurs différents y sont publiés6. La revue se politise à partir de 1966, en publiant des critiques virulentes contre l'intervention américaine au Viet Nam. Parmi les contributeurs, qui livrent des travaux généralement inédits, on note au cours de ces années les noms de Roland Barthes, Georges Bataille, James Joyce, Nathalie Sarraute, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault (qui encense la revue en 1963)7, Bernard-Henri Lévy, Maurice Roche, Tzvetan Todorov, Francis Ponge, Umberto Eco, Gérard Genette, Pierre Boulez, Jean-Luc Godard, Philippe Muray, Stephen Jourdain, Pierre Guyotat. La publication s'est interrompue en 1982 après 94 livraisons. Les Éditions du Seuil ayant refusé de céder le titre, la revue qui a déménagé aux Éditions Denoël doit changer de nom pour reparaître sous le titre L'Infini en hiver 1983 (et aux Éditions Gallimard à partir de 1987). Orientations politiques Tel Quel se veut au début une revue apolitique. Les inclusions et exclusions du comité de direction se font à l'unanimité. Les deux premières évictions n'ont rien de politique : Jean-René Huguenin est congédié fin mai 1960 car personne au sein du comité n'aime son premier roman, qui doit paraître au Seuil en août, La Côte sauvage : sur ce point, Jean-Edern Hallier et Renaud Matignon se sont toutefois montrés par trop réservés8. Matignon est exclu temporairement quelques semaines après (il l'est définitivement début 1963) ; quant à Hallier, il quitte la revue de son propre chef, en février 1963, pour aller travailler avec Dominique de Roux. L'événement politique de l'époque qui rassemble le groupe est bien entendu la guerre d'indépendance algérienne, certains de ces jeunes gens y effectuant (Candol, Boisrouvray) ou devant y effectuer leur service militaire (Sollers). La revue glisse ensuite vers le structuralisme, sous l'influence de Roland Barthes, puis vers le freudisme et enfin vers le maoïsme9. Dès avant mai 1968, la revue s'engage résolument à gauche et manifeste contre l'impérialisme américain, pour une plus grande liberté d'expression en France, etc. Caractéristique de cette période de maophilie « exacerbée »9 est la violente hostilité que provoque, dans les années 1970, au sein des milieux maoïstes de la revue, la publication des essais de Simon Leys sur la Chine communiste ; ou inversement l'accueil réservé au livre de Maria-Antonietta Macciocchi, De la Chine, qui a pour conséquence la rupture de la revue avec le Parti communiste français, qui survient en 1972. En 1974, une délégation de Tel Quel, composée de Philippe Sollers, Julia Kristeva, Marcelin Pleynet, François Wahl et Roland Barthes, se rend même en voyage officiel en Chine10. À leur retour, ils publient un numéro spécial consacré à la Révolution culturelle dont ils décrivent la « réussite ». Les deux numéros de la revue consacrées à la Chine maoïste connaissent des records de ventes (entre 20 000 et 25 000 exemplaires)11. Les années 1976-1982 sont politiquement plus floues. Elles sont marquées en leur milieu par la mort accidentelle de Roland Barthes, survenue en mars 1980. Réception Dominique de Roux écrit, dans Immédiatement, à propos de la revue : « Tel Quel : grimoire solennel, réticule des tournures mallarméennes, borgésiennes ; plagiat de Pound, emprunt aux uns, aux autres, jdanovisme pompeux, impossibilité d’écrire, ramassis de pédants encrassés, de cuistres, de valets de collège, querelles de lutrins. Ils tiennent le devant de la scène avec la complaisance d’une critique universitaire qui craint de ne pas être à la mode. Tel Quel brandit Artaud et Bataille, Lénine et Mao, comme ces soldats russes les réveille-matin et les montres. »12 https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tel_Quel_(revue) |

1960

年、パリのエディシオン・デュ・スイユで、ジャン=エデルン・ハリエとフィリップ・ソラーズを中心とする数人の若手作家によって創刊された前衛フランス文

学雑誌。この雑誌の目的は、文学史上の古典に対するアヴァンギャルドの再評価を反映させることであった。その文学的指向にもかかわらず、雑誌の立場は

1960年代と1970年代の思想運動、特にメンバーの何人かの公然たる毛沢東主義に非常に特徴的である。 歴史 フィリップ・ソラーズ1 自身によれば、雑誌『テル・ケル』の創刊のアイデアは、1958年9月にオテル・ポン・ロワイヤルのバーで開かれたエディシオン・デュ・スイユ主催のカク テル・パーティーで生まれた。Une curieuse solitude』の著者は、ジャン=エデルン・ハリエとその友人ピエール=アンドレ・ブータンと親交を深め、その晩の終わりに、3人は共同で文学事業に 乗り出すことを決めた。1958年末から何度も準備会議が開かれ、特にアンブランコールのハリエの両親の家では、アラン・ロブ=グリエ、ジャン=ルー・ダ バディ、ジャック・クードルらが集まっていた。 彼らの野望は、『ラ・ヌーヴェル・ルヴュ・フランセーズ』のような権威ある批評誌を創刊し、特にエディシオン・ド・ミニュイが出版する新しい文学の潮流、 新しい声に近づくことだった。彼らはまた、戦前のイギリス文学や哲学にも大きな関心を寄せていた。 1960年1月24日、ル・スイユ社のポール・フラマン社長とジャン=エデルン・ハリエ社長の間で契約が交わされた。 雑誌名はニーチェの格言から拝借した: 「私は世界を欲し、それをありのままに欲し、またそれを欲する......私は永遠にそれを欲し、飽くことなく叫ぶ:ビス! 私だけのためではなく、芝居全体のため、ショー全体のためであり、ショー全体のためではなく、基本的には私のためである。 この引用文は創刊号の頭に置かれ、以後10年間、毎号の冒頭には「ありのままに」というフレーズを含む引用文が掲載された2。 1960年1月に設立された最初の編集委員会は、フィリップ・ソレール、ジャン=エデルン・ハリエ、ジャン=ルネ・ユグナン、ジャック・クードル、ル ノー・マティニョン、フェルナン・デュ・ボワルヴレ(1934-1996)3から構成されていた。多くの立ち退きと離脱の間に、ジャン・ティボードーが委 員会に加わり、ジャン・リカルドゥ、ミシェル・デギー、マルセラン・プレイネ、ドゥニ・ロッシュ、ジャン=ルイ・ボードリー、ジャン=ピエール・フェイ、 ジャクリーヌ・リセ、ジュリア・クリステヴァ(1971年9月)、ゲルマニストのミシェル・マクサンス、都市計画家のジスレーヌ・メフレが続いた4。しば らくの後、マスコミは「テル・ケル・グループ」と称し、まだ活動していた雑誌の創刊メンバーを表現するようになった5。ハリエは1963年2月に追放さ れ、クードルは翌年3月に去った。1967年11月、フェイは『チェンジ』を創刊するために同誌を去った。 創刊号は1960年春号で100ページ。フランシス・ポンジュ、クロード・シモン、ジャン・カイロール、ジャン・ラグレ、ボワルーヴレイ、ソラーズ、 ヴァージニア・ウルフ、クードル、ユグナン、ハリエ、ティボドー、マティニョンの記事や、「あなたには書く才能があると思いますか?ポンジュは、カイロー ルと同様、この雑誌の師父とみなされている。 雑誌創刊から3年後の1963年、エディシオン・デュ・スイユは、フィリップ・ソレールのみが編集を担当し、表紙に褐色の縁取りを施したエッセイ集 『Collection Tel Quel』を創刊した。創刊から20年の間に、32人の作家による73の作品が出版された6。 1966年以降、この雑誌は政治色を強め、アメリカのヴェトナム介入に対する激しい批判を掲載した。 寄稿者の中には、ロラン・バルト、ジョルジュ・バタイユ、ジェイムズ・ジョイス、ナタリー・サローテ、ジャック・デリダ、ミシェル・フーコー(1963年 に同誌を称賛)7、ベルナール=アンリ・レヴィ、モーリス・ロッシュ、ツヴェタン・トドロフ、フランシス・ポンジュ、ウンベルト・エコ、ジェラール・ジュ ネット、ピエール・ブーレーズ、ジャン=リュック・ゴダール、フィリップ・ミュレイ、スティーヴン・ジュルダン、ピエール・ギョタなど、一般には未発表の 作家が名を連ねた。 1982年、94号をもって休刊。エディシオン・デュ・スイユが同誌の販売を拒否したため、エディシオン・ドゥノエルに移った同誌は、1983年冬に誌名 を変更し、『L'Infini』というタイトルで再登場することになった(1987年からはエディシオン・ガリマール)。 政治的志向 Tel Quel』は当初、非政治的な雑誌を目指していた。運営委員会への参加と脱退は全会一致だった。1960年5月末にジャン=ルネ・ユグナンが解任されたの は、彼の処女作『La Côte sauvage(野生の海岸)』が8月にSeuilから出版される予定であったが、委員会の誰も気に入らなかったからである。マティニョンは数週間後に一 時的に追放され(1963年の初めには永久追放)、ハリエはドミニク・ド・ルーと仕事をするために1963年2月に自らの意思で雑誌を去った。この時期の 政治的な出来事でグループをまとめたのは、もちろんアルジェリア独立戦争で、若者の何人かは兵役についていた(カンドール、ボワルーヴレイ)か、そうしな ければならなかった(ソレール)。 雑誌はその後、ロラン・バルトの影響を受けて構造主義、フロイト主義、そして毛沢東主義へとシフトしていく9。1968年5月以前から、この雑誌は左派に 傾倒し、アメリカ帝国主義に抗議し、フランスにおける表現の自由の拡大を求めていた。 この 「増悪した 」マオフィリア9の時期を特徴づけるのは、1970年代、シモン・レイスの共産主義中国に関するエッセイの出版によって、同誌の毛沢東主義サークル内で引 き起こされた激しい敵意であり、また逆に、マリア=アントニエッタ・マチョッキの著書『De la Chine』への歓迎であった。1974年には、フィリップ・ソラーズ、ジュリア・クリステヴァ、マルセラン・プレイネ、フランソワ・ヴァール、ロラン・ バルトからなるテル・ケル代表団が中国への公式旅行を行った10。帰国後、彼らは文化大革命特集号を発行し、「成功」と評した。毛沢東主義の中国を取り上 げたこの雑誌の2号は、記録的な売れ行きを見せた(20,000部から25,000部)11。 1976年から1982年にかけては、政治的にはあまり明確ではなかった。1980年3月にロラン・バルトが不慮の死を遂げたからである。 受容 Immédiatement』の中で、ドミニク・ド・ルーはこの雑誌について次のように書いている:「Tel Quel:厳粛な魔道書、マラルメ的、ボルヘス的な言い回しのレティキュール、パウンドの盗作、あらゆる人からの借用、尊大なjdanovism、書くこ との不可能性、詰まった女衒、曲者、スクールボーイ、講師同士のいさかいの寄せ集め。それらは、流行遅れになることを恐れるアカデミックな批評家たちの自 己満足で主役を演じている。テル・クエルは、アルトーやバタイユ、レーニンや毛沢東を、目覚まし時計や腕時計を持ったロシア兵のように振り回す。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆