La

phénoménologie de la perception, per Maurice Jean Jacques

Merleau-Ponty, 1945

知覚の現象学

La

phénoménologie de la perception, per Maurice Jean Jacques

Merleau-Ponty, 1945

上空飛行的思考(pensée du survol)を回避するメルロ=ポンティ(Maurice Merleau-Ponty, 1908-1961)。その手がかりとしての身体。

『知 覚の現象学』(フランス語:Phénoménologie de la perception)は、フランスの哲学者モーリス・メルロ=ポンティが1945年に発表した知覚に関する著作で、著者は「知覚の優位性」というテーゼ を説いた。この著作により、メルロ=ポンティは傑出した身体哲学者として確立され、フランス実存主義の主要な声明とみなされている。

1)知覚を、生きている 自己の身体とそれが知覚する世界との間の継続的な対話であると理解する。知覚者は受動的にも能動的にも、他者と協調して知覚した世界を表現しようと 努力する(→スピノザ的な身体観の類似?)。

2)デカ ルトの「コギト」に代わるものとして身体主体(le corps propre)の概念を展開している[出典を探す必要あり] 。この区別は、メルロ=ポンティが世界の本質を実在的に知覚する上でとりわけ重要である。

3)意識、世界、そして知覚するものとし ての人間の身体は複雑に絡み 合っており、相互に「関与」している。

4)現象的なものは、自然科学の不変の対 象ではなく、私たちの身体とその感覚運動機能の相関関係である。

5)受肉した主体と しての身体は、出会った感覚的な質を取り込み、「交感」(メルロ=ポンティの言葉)しながら、世界の構成に関する前意識的、予見的理解を用いて、常に存在 する世界の枠内で意図的に物事を精緻化する。しかし、その精緻化は「無尽蔵」である。

6)物とは、私 たちの身体が「握る=把握する」(prise)ものであり、把握すること自体は、世 界の物に対する私たちの接続性の関数である。

7)世界と自己の感覚は、現在進行中の 「なり ゆき」——対話のメタファーを使う——において出現する現象である。

★『知覚の現象学』(1945年)は、現 象学の創始者の一人である哲学者モーリス・メルロ=ポンティの代表作とされている。エドムント・フッサールの研究の精神を受け継ぎ、メルロ=ポンティのプ ロジェクトは知覚という現象の構造を明らかにすることに着手した。伝統的に、知覚とは、感覚によってもたらされる情報に基づいて、主体が自分の環境に存在 する対象や性質を認識する心の活動と定義されている1。モーリス・メルロ=ポンティは、1942年の著作『行動の構造』の中で、知覚という考え方が、真実 を曖昧にする多くの偏見に汚染されていることを示そうとした。パスカル・デュポン2 によれば、この2つの著作で著者は、彼が「世界との素朴な接触」と呼ぶ、実際には知覚の可能性に先立つ最初の接触について考えようとしている。知覚が存在 についての真理や物事それ自体についての真理を私たちに明らかにできると信じることは、非公式な一連の偏見に依存することである。 現象学は、客観的で記述的でありたいという理由で内観に反対し、具体的な主体の視点を維持し、自己の外にある超越的な「私」3へと蒸発したくないという理 由で超越論的哲学に反対する。同じように、著者は、何も知らないものを探すことはできないから失敗する「経験主義」も、逆に、探しているものを無視する必 要もあるから「知識主義」も否定する(p.52)。知覚の現象学は、「学習の過程における意識」(p.36)N 1に関わるものであり、本書の本文では、そのさまざまな側面が詳細に検討されている。

★フランス語版ウィキペディア解説

| La Phénoménologie de la Perception

(1945) est considérée comme l'œuvre majeure du philosophe Maurice

Merleau-Ponty, l'un des fondateurs de la phénoménologie. Dans l'esprit

des recherches d'Edmund Husserl, le projet de Merleau-Ponty entreprend

de révéler la structure du phénomène de la perception.

Traditionnellement la perception est définie comme l'activité de

l'esprit par laquelle un sujet prend conscience d'objets et de

propriétés présents dans son environnement sur le fondement

d'informations délivrées par les sens1. Maurice Merleau-Ponty s'est

attaché à montrer depuis une précédente œuvre qui date de 1942 La

Structure du comportement que l'idée de perception est entachée d'un

certain nombre de préjugés qui masquent la vérité. Dans ces deux œuvres

l'auteur chercherait à penser selon Pascal Dupond2 ce qu'il appelle un

premier « contact naïf avec le monde » qui de fait précéderait toute

possibilité de perception. Croire que la perception peut nous dévoiler

la vérité sur l'existence et la vérité des choses en soi, c'est prendre

appui sur un ensemble informulé de préjugés. La phénoménologie s’oppose à la fois à l’introspection, car elle veut être objective et descriptive, et à la philosophie transcendantale, car elle veut garder le point de vue d'un sujet concret, et ne pas s’évaporer, dans un « Je3 » transcendantal extérieur au moi. De la même manière, l'auteur récuse à la fois l'« empirisme » qui échoue car nous ne pouvons chercher quelque chose dont nous ne connaîtrions rien et l'« intellectualisme » parce qu'à l'inverse nous avons besoin aussi d'ignorer ce que nous cherchons (p. 52). La Phénoménologie de la perception, qui s'intéresse à la « conscience en train d'apprendre » (p. 36)N 1, est étudiée en détail, sous ses différents aspects, dans le corps du livre. |

『知覚の現象学』(1945年)は、現象学の創始者の一人である哲学者

モーリス・メルロ=ポンティの代表作とされている。エドムント・フッサールの研究の精神を受け継ぎ、メルロ=ポンティのプロジェクトは知覚という現象の構

造を明らかにすることに着手した。伝統的に、知覚とは、感覚によってもたらされる情報に基づいて、主体が自分の環境に存在する対象や性質を認識する心の活

動と定義されている1。モーリス・メルロ=ポンティは、1942年の著作『行動の構造』の中で、知覚という考え方が、真実を曖昧にする多くの偏見に汚染さ

れていることを示そうとした。パスカル・デュポン2

によれば、この2つの著作で著者は、彼が「世界との素朴な接触」と呼ぶ、実際には知覚の可能性に先立つ最初の接触について考えようとしている。知覚が存在

についての真理や物事それ自体についての真理を私たちに明らかにできると信じることは、非公式な一連の偏見に依存することである。 現象学は、客観的で記述的でありたいという理由で内観に反対し、具体的な主体の視点を維持し、自己の外にある超越的な「私」3へと蒸発したくないという理 由で超越論的哲学に反対する。同じように、著者は、何も知らないものを探すことはできないから失敗する「経験主義」も、逆に、探しているものを無視する必 要もあるから「知識主義」も否定する(p.52)。知覚の現象学は、「学習の過程における意識」(p.36)N 1に関わるものであり、本書の本文では、そのさまざまな側面が詳細に検討されている。 |

| Avant-propos Article connexe : Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Dans un avant-propos Merleau-Ponty fait un large panorama des avancées et des impasses de la phénoménologie. Renonçant à la définir il explique « qu'il s'agit de décrire, et non pas d'expliquer ni d'analyser ». Alexandre Hubeny4, croit pouvoir, dans sa thèse, la définir à partir de cet avant-propos, comme « volonté de saisir le sens du monde de l'histoire à l'état naissant, alors même qu'elle se heurte à l'impossibilité de postuler en histoire, un sens sous la figure d'une signification close et univoque »N 2 De même, Claudia Serban dans la revue Les Études Philosophiques5 extrait de cet avant-propos cette phrase : « le plus grand enseignement de la réduction est l’impossibilité d’une réduction complète (p14)– invitant à une exploration phénoménologique, non plus de la réduction mais de l’irréductible ». Pascal Dupond6 écrit dans une note « l'avant-propos montre pourquoi l'intellectualisme manque le phénomène de la perception ; jugeant de ce qui est par ce qui doit être, il réduit le phénomène du monde aux conditions de possibilité de l'expérience et le cogito à une « conscience constituante universelle ». Or il s'agit de reprendre le geste de la phénoménologie qui étudie l'apparition de l'être à la conscience au lieu d'en supposer la possibilité donnée d'avance et de revenir à la perception ». |

序文 関連記事:モーリス・メルロ=ポンティ。 序文でメルロ=ポンティは、現象学の進歩と行き詰まりを大まかに概観している。メルロ=ポンティは現象学を定義することを拒否し、「現象学は説明や分析で はなく、記述する問題である」と説明している。アレクサンドル・フベニー4はその論文の中で、この序文に基づいて現象学を定義することができると考えてい る。それは、「歴史において、閉鎖的で一義的な意味づけという形で意味を規定することの不可能性に直面しながらも、その萌芽的な状態で歴史世界の意味を把 握しようとする願望」である2。 同様に、『Les Études Philosophiques』誌のクラウディア・セルバン5 は、序文から次の一文を抜き出している。「還元の最大の教訓は、完全な還元の不可能性である(p14)。 まえがきは、なぜ知識主義が知覚の現象を見逃すのかを示している。あるべきものによってあるものを判断することで、世界の現象を経験の可能性の条件へと還 元し、コギトを『普遍的な構成意識』へと還元している。しかし、その可能性があらかじめ与えられていると仮定する代わりに、意識への存在の出現を研究する 現象学の身振りを再び取りあげ、知覚に立ち戻ることが問題なのである」。 |

Mouvement d'ensemble Maurice Merleau-Ponty Après l'avant propos, suit une introduction intitulée, « les préjugés classiques et le retour aux phénomènes », qui est consacrée à un aperçu des obstacles que la conception courante oppose à l'analyse phénoménologique de la perception. Le principal obstacle se situe au niveau du concept d'objet qui domine l'attitude naturelle, ainsi que la scienceN 3. L'expérience montre ainsi qu'il n'existe pas de sensation pure, « l'événement élémentaire est déjà revêtu d'un sens (pp 32) » que la perception opère toujours sur des « ensembles significatifs (p 34) »N 4,N 5. Le deuxième grand obstacle concerne la nature du monde perçu par la conscience. Celui-ci, n'est pas comme nous le fait croire l'empirisme « une somme de stimuli et de qualités [...], il y a un monde naturel qui fait fond et qui ne se confond pas avec celui de l'objet scientifique [...], le fond continue sous la figure [...] caché par la philosophie empiriste il enveloppe la présence de l'objet » (p. 48). Ce monde naturel, que le phénoménologue étudie sous le nom de « champ phénoménal » est masqué par « le monde objectif qui n'est premier, ni selon le temps, ni selon son sens (pp 50) » mais que privilégie l'analyse. L'essai se développe en trois grandes parties Une première partie, titrée simplement « le Corps » consacrée à l'analyse du corps percevant. « Le corps comme puissance motrice et projet du monde donne sens à son entourage, fait du monde un domaine familier, dessine et déploie son Umwelt, il est « puissance d’un certain monde »7. L’analytique du corps percevant développée dans la première partie de la Phénoménologie s’ancre dans un examen de la notion, issue des sciences neurologiques, de «schéma corporel ». La deuxième partie, intitulée le Monde perçu, développe le rapport vivant du « corps » avec ce monde à travers l'acte du sentir, son insertion naturelle dans l'espace au milieu des choses et des autres humains dans le monde familier tel qu'il est originairement perçu. L'essai se termine par une troisième partie consacrée aux conséquences de cette nouvelle approche sur les questions éternelles du cogito, de la temporalité et de la liberté. |

全体的な動き モーリス・メルロ=ポンティ 序文に続いて「古典的偏見と現象への回帰」と題された序論があり、現在の観念が知覚の現象学的分析を妨げている障害の概観に費やされている。主な障害は、 科学N 3と同様に、自然的態度を支配する対象の概念にある。経験は、純粋な感覚など存在しないこと、「初歩的な出来事はすでに意味を帯びている(32ページ)」 こと、そして知覚はつねに「重要な全体(34ページ)」に作用することを示しているN 4,N 5。 第二の大きな障害は、意識によって知覚される世界の性質に関するものである。これは経験主義が私たちに信じさせようとするように、「刺激と性質の総体 [...]ではなく、背景を形成し、科学的対象のそれと同じではない自然界[...]が存在し、背景は図形の下に続いている[...]経験主義哲学によっ て隠され、それは対象の存在を包んでいる」(p.48)。現象学者が「現象場」という名で研究しているこの自然界は、「時間によっても意味によっても一義 的ではない客観的世界(50頁)」によって覆い隠されているが、分析によって特権化されている。このエッセイは大きく3つの部分に分かれている。 第一部は、単に「身体」と題され、知覚する身体の分析に費やされている。「世界の運動力・投影としての身体は、周囲に意味を与え、世界を親しみやすい領域 とし、そのウムヴェルトを引き寄せ、展開する。現象学の第一部で展開された知覚する身体の分析は、神経科学から派生した「身体スキーマ」という概念の検討 によって支えられている。知覚された世界」と題された第二部では、感じるという行為を通して、「身体」とこの世界との生きた関係、つまり、本来知覚される 身近な世界において、事物や他の人間の中に自然に挿入される関係を展開する。このエッセイは、コギト、時間性、自由という永遠の問いに対するこの新しいア プローチの帰結に捧げられた第3部で締めくくられている。 |

| Le Corps La perception a pour objet de dévoiler des objets, c'est-à-dire, au sens large, des corps. « Voir c'est entrer dans un univers d'êtres qui se montrent et ils ne se montreraient pas s'ils ne pouvaient pas être cachés les uns derrière les autres ou derrière moi » (p. 96). C'est une attitude constante et universelle, tous les corps y compris celui qui est à la base de notre expérience, le nôtre, nous les traitons en objets (p. 99). L'auteur se propose de démonter le processus de cette pensée « objectivante ». Or « le « corps propre » se dérobe dans la science même, au traitement qu'on veut lui imposer » (p. 100). « En proposant une phénoménologie du corps propre, en dévoilant son rôle, Merleau-Ponty défend l’idée que le corps n’est pas un simple objet, mais qu’il se donne comme une réalité ambiguë puisqu’il se manifeste à la fois comme corps sensible et sentant, objet et sujet »8. « Dans la Phénoménologie de la perception, il s’appuie sur les analyses de la psychanalyse et de la psychologie moderne et sur les travaux des neurologues pour mettre en œuvre une phénoménologie du corps propre, en étudiant la question de la motricité, de la sexualité, de la parole »9.La connaissance que nous avons de notre corps n'est pas celle d'une représentation, ni d'un « je pense », mais celle d'un Je engagé dans le monde10 Nous résumerons les trois angles majeurs de cette recherche. |

身体 知覚の目的は、対象を明らかにすることである。「見るということは、自分自身を見せる存在の宇宙に入るということであり、もし彼らが互いに、あるいは私の 背後に隠れることができなければ、彼らは自分自身を見せることはないだろう」(p.96)。これは不変かつ普遍的な態度である。私たちはすべての身体を、 私たちの経験の基盤である自分自身を含めて、物体として扱っているのだ(99頁)。著者は、この「客体化」思考のプロセスを解体することに着手する。メル ロ=ポンティは、身体は単純な物体ではなく、鋭敏で感じやすい身体であり、物体であると同時に主体でもある8。「知覚の現象学』では、精神分析学や現代心 理学の分析、神経学者たちの研究を援用し、運動性、セクシュアリティ、音声の問題を研究することで、身体そのものの現象学を展開している9」。 |

| Le corps dans la physiologie mécaniste À partir de la pathologie dite du « membre fantôme », dans laquelle le malade a des sensations qui semblent provenir d'un membre (amputé) qui n'existe plus, l'auteur critique les explications empiriques physiologiques. Ce n'est que dans la perspective phénoménologique de notre rapport au monde que l'on peut comprendre le phénomène. « Ce qui en nous refuse la mutilation et la déficience, c'est un Je engagé dans un certain monde physique et interhumain, qui continue de se tendre vers son monde en dépit des déficiences ou des amputations [...] Avoir un bras fantôme c'est rester ouvert à toutes les actions dont le bras seul était capable [..] Le corps est le véhicule de l'« être-au-monde », et avoir un corps c'est pour un vivant se joindre à un milieu défini, se confondre avec certains projets et s'y engager continuellement » écrit l'auteur (p. 111). Eran Dorfman11 écrit « ce qu'on trouve derrière le phénomène de suppléance c'est le mouvement de l'être au monde [...] force est de constater qu'il ne s'agit pas du corps « normal » mais du corps en état de manque : du corps mutilé ». Merleau-Ponty assimile le mouvement de l'« être-au-monde » comme le mouvement de ce qui est « pré-objectif », le réflexe comme la perception n'en seraient que des modalités. « C'est parce qu'il est une vue pré-objective que l'« être-au-monde » pourra réaliser la jonction du psychique et du physiologique »11. Pour Merleau-Ponty, si nous voulons expliciter ce phénomène dans le cadre objectif de la science « nous tombons dans des difficultés insurmontables car nous nous trouvons devant le dilemme de considérer l'organisme soit comme un assemblage de relations mécaniques soit comme configuration de significations intelligibles. Or il ne se laisse réduire ni à l'un ni à l'autre [...] La seule manière de résoudre ce dilemme, c'est de renoncer à toute attitude distante et objectivante » écrit Frédéric Moinat12. Le phénomène du membre fantôme n'est pas le simple effet d'une causalité objective et pas davantage une cogitatio, pas l'effet d'un stimuli nerveux et pas non plus un « souvenir ». À l'instar des réflexes, ces phénomènes de persistance témoignent de l'importance de la situation vitale qui donne un sens aux stimuli partiels qui les fait compter, valoir ou exister pour l'organisme. « Je ne puis comprendre la fonction du corps vivant qu'en l'accomplissant moi-même et dans la mesure où je suis un corps qui se lève vers le monde »12. De plus, nous existons au milieu de stimuli constants et de situations typiques. Il y aurait « autour de notre existence personnelle comme une sorte de marge d'existence « impersonnelle », qui va pour ainsi dire de soi et à laquelle je me remets du soin de me maintenir en vie ». L'organisme vit d'une existence anonyme et générale, au-dessous de notre vie personnelle, le rôle d'un complexe inné (p. 113). Merleau-Ponty pense avoir démontré que le corps dans sa masse comme dans sa motricité a des relations avec son milieu qui relèvent moins de la causalité que de l'intentionnalité. Le « comportement » échappe à la fois au réductionnisme mécaniste (fondé sur une physiologie des réflexes) et au volontarisme de la conscience. « L’organisme ne répond pas indifféremment à son environnement, aux stimulations de son milieu : il répond à un environnement qu’il a déjà en quelque sorte façonné, parce qu’il est déjà qualitativement différencié pour lui [...]. Même lorsqu’il n’est pas un organisme « conscient » à proprement parler, par son initiative l’organisme, par les mouvements de son corps, donne toujours déjà une certaine forme, une certaine configuration à son environnement » écrit Florence Caeymaex13. |

機械論的生理学における身体 患者が、もはや存在しない(切断された)手足から来るような感覚を経験する「幻肢」として知られる病理学に基づき、著者は経験的な生理学的説明を批判す る。この現象は、私たちと世界との関係という現象学的観点からしか理解できない。「私たちの中で切断や欠損を拒むのは、ある種の身体的世界や人間間世界に 関わっている私であり、欠損や切断にもかかわらず、その世界に向かって手を伸ばし続ける私である[......]幻の腕を持つということは、腕だけが可能 であったすべての行為に対して開かれたままでいることである[......]身体は、それが可能であったすべての行為のための乗り物である。 身体は 「世界に存在すること 」の手段であり、生きている人間にとって身体を持つことは、定められた環境に参加することであり、特定のプロジェクトと融合することであり、それに継続的 にコミットすることである」と著者は書いている(p.111)。エラン・ドーフマン11 は、「サプレアンス現象の背後に見出されるのは、世界における存在の運動である[......]。私たちが語っているのは、『正常な』身体ではなく、欠落 状態にある身体、すなわち切断された身体についてであることは明らかである」と書いている。メルロ=ポンティは、「世界における存在」の運動を、「前観測 的」なものの運動と同化させている。「反射や知覚は、この運動の様式にすぎない。「世界における存在」が心的なものと生理的なものとの接合を達成すること ができるのは、それが前客観的な見方であるからである」11。 メルロ=ポンティにとって、この現象を科学の客観的な枠組みの中で説明しようとすれば、「乗り越えがたい困難に突き当たる。このジレンマを解決する唯一の 方法は、距離を置いて客観視する態度を捨てることである」とフレデリック・モワナ12は書いている。幻肢現象は、客観的な因果関係の単純な効果でも、コギ タチオでも、神経刺激の効果でも、「記憶」でもない。反射と同じように、これらの持続現象は、部分的な刺激に意味を与え、それらを生体にカウントさせ、価 値を持たせ、存在させる生命的状況の重要性を証言している。「生きている身体の機能は、私自身がそれを行うことによってのみ、また私が世界に向かって立ち 上がる身体である限りにおいてのみ、理解することができる」12。 さらに言えば、私たちは絶え間ない刺激と典型的な状況の中に存在している。私たちの個人的存在の周りには、いわば言うまでもない『非個人的な』存在の余白 のようなものがあり、私はそこに自分を生かすという仕事を委ねている」。有機体は、私たちの個人的な生の下に、生得的な複合体の役割を担う、匿名的で一般 的な存在を生きている(p.113)。 メルロ=ポンティは、身体はその質量と運動性において、環境との因果関係よりもむしろ意図性との関係を持っていることを証明したと考えている。「行動」 は、(反射の生理学に基づく)機械論的還元主義からも、意識の意志主義からも逃れられる。「生物はその環境、その環境の刺激に無関心に反応するのではな い。すでに何らかの形で形成された環境に反応するのである。厳密な意味での 「意識的 」な生物でない場合でも、生物はそのイニシアチブを発揮し、身体の動きを通して、常にその環境に一定の形、一定の構成を与えている」とフローレンス・カイ マエクスは書いている13。 |

| Le corps dans la psychologie classique Pour l'homme, le corps n'est pas un objet comme les autres car c'est avec lui qu'il observe, qu'il manie les objets. Déjà la psychologie classique n'assimilait pas le corps à un objet note Merleau-Ponty, pour autant elle n'en tirait aucune conséquence philosophique (p. 123). Elle attribuait à ce corps des caractères particuliers qui le rendaient incompatibles avec le statut d'objet, ainsi faisait-elle le constat que « notre corps se distingue de la table ou de la lampe parce qu'il est constamment perçu tandis que je peux me détourner d'elles » (p. 119). Si dans le savoir, l'on opposait le psychisme de l'être vivant au réel, on le traitait comme une seconde réalité, qui comme tout objet de science devait être soumis à des lois. On postulait que les difficultés qui découlaient de cette double perspective se résoudraient plus tard avec l'achèvement du système des sciences (p. 124). Merleau-Ponty apprend de deux théories psychologiques modernes, la Gestalttheorie, en français, « théorie de la forme », et de la théorie behavioriste ou comportementale que « le psychisme humain doit être compris par-delà l’alternative du sujet et de l’objet »14. Merleau-Ponty voit le corps comme « une habitude primordiale, qui conditionne toutes les autres et par laquelle elles se comprennent »N 6,N 7. |

古典心理学における身体 人間にとって、身体は他のどのような対象でもない。なぜなら、対象を観察し、扱うのは身体だからである。メルロ=ポンティは、古典派心理学は身体を物体と 同一視していなかったが、そこから哲学的な結論を導き出すことはなかったと指摘する(p.123)。そして、「私たちの身体はテーブルやランプと区別され るのは、それが常に知覚されるからであり、一方、私はそれらから目をそらすことができるからである」(p.119)と述べている。知識の領域において、生 者の精神が現実と対立しているとすれば、それは第二の現実として扱われ、科学の対象と同様に、法則に従わなければならなかった。この二重の視点から生じる 困難は、後に科学体系が完成することで解決されると仮定された(p.124)。メルロ=ポンティは、ゲシュタルト理論と行動主義理論という二つの近代心理 学理論から、「人間の精神は、主体と客体という代替を越えて理解されなければならない」ことを学んだ14。 メルロ=ポンティは身体を「他のすべてのものを条件づけ、それらを通して理解される、根源的な習慣」N 6,N 7とみなしている。 |

| La spatialité du corps propre et la motricité Ce chapitre est construit autour de la notion de «schéma corporel ». Né au sein de la neuropsychologie dans laquelle il signifiait la constance d'un certain nombre d'associations d'images acquises depuis l'enfance le « schéma corporel » devient chez Merleau-Ponty « une forme, c'est-à-dire un phénomène dans lequel le tout est considéré comme antérieur aux parties » (p. 129). Pascal Dupond15 écrit « la forme n'est pas une chose, une réalité physique, un être de nature étalé dans l'espace, un « être en soi » ; il appartient à son sens d'être d'exister pour une conscience, l'organisme est un ensemble significatif pour une conscience qui le connaît ». En tant qu'elle ne se révèle qu'au sein d'une intentionnalité, d'un projet, la spatialité du « corps propre » est toujours « située » (correspond à une situation) et « orientée » ne correspond pas à l'espace objectif qui lui est par définition homogène16. « Il ne faut pas dire que notre corps est dans l'espace, ni d'ailleurs qu'il est dans le temps. Il habite l'espace et le temps » (p. 174). L'expérience motrice ne passe pas par l'intermédiaire d'une représentation, comme manière d'accéder au monde elle est directe. Le corps connaît son entourage comme des points d'application de sa propre puissance (la direction qu'il doit prendre, les objets qu'il peut attraper). « Le sujet placé en face de ses ciseaux, de son aiguille et de ses tâches familières n'a pas besoin de chercher ses mains ou ses doigts, parce qu'ils ne sont pas des objets à trouver dans l'espace objectif [...] mais des « puissances » déjà mobilisées par la perception des ciseaux ou de l'aiguille [...] ce n'est jamais notre corps objectif que nous mouvons, mais notre « corps phénoménal » » (p. 136). « Le sujet possède son corps non seulement comme système de positions actuelles mais comme système ouvert d'une infinité de positions équivalentes dans d'autres orientations » (p. 176). Cet acquis ou cette réserve de possibilités est une autre manière de désigner le «schéma corporel » c'est-à-dire, « cet invariant immédiatement donné par lequel les différentes tâches motrices sont instantanément transposables » (p. 176). Dans ses mouvements, le sujet ne se contente pas de subir l'espace et le temps il les assume activement et leur confère une signification anthropologique. Ainsi quel sens pourrait avoir les mots « sur », « dessous » ou « à côté » pour un sujet qui ne serait pas situé par son corps en face du monde. Il implique la distinction d'un haut et d'un bas, du proche et du lointain, c'est-à-dire un espace orienté (p. 131). L'espace objectif, l'espace intelligible n'est pas dégagé de l'espace phénoménal orienté, au point que l'espace homogène ne peut exprimer le sens de l'espace orienté que parce qu'il l'a reçu de lui (p. 131). « C’est le corps qui donne sens à son entourage, nous ouvre accès à un milieu pratique et y fait naître des significations nouvelles, tout à la fois motrices et perceptives »17. Merleau-Ponty (p. 184) écrit « l'expérience révèle sous l'espace objectif, dans lequel le corps finalement prend place, une spatialité primordiale dont la première n'est que l'enveloppe et qui se confond avec l'être même du corps (d'où la notion de corps propre ou phénoménal). Être corps, c'est être noué à un certain monde [...] notre corps n'est pas d'abord dans l'espace : il est à l'espace ». |

身体の空間的性質と運動能力 この章は、「身体スキーマ」という概念を中心に構成されている。メルロ=ポンティの「身体スキーマ」は、神経心理学で生まれたもので、幼少期から獲得され たイメージの一定数の連想を意味し、「形、つまり全体が部分に先立つと考えられる現象」(p.129)となる。パスカル・デュポン15は、「形は物ではな く、物理的現実でもなく、空間に広がる自然の存在でもなく、『それ自体における存在』である。それが意図性、プロジェクトの中でしか姿を現さない限り、 「適切な身体」の空間性はつねに「位置づけられ」(状況に対応し)、「方向づけられ」ており、定義上均質である客観的空間には対応しない16。 「私たちの身体が空間の中にある、あるいは時間の中にあるとは言うべきではない。身体は空間と時間に存在する」(p.174)。運動体験は表象の仲介を通 さず、世界にアクセスする方法として、直接的である。身体は周囲の環境を、自らの力の適用点(進むべき方向、捕らえることのできる対象)として知ってい る。ハサミや針や身近な仕事の前に置かれた主体は、自分の手や指を探す必要はない。なぜなら、それらは客観的空間に見出される対象ではなく[...]、ハ サミや針の知覚によってすでに動員された「力」だからである[...]。「主体は自分の身体を、実際の位置のシステムとしてだけでなく、他の方向における 無限の等価な位置の開かれたシステムとして所有している」(176頁)。この可能性の獲得や予備は、「身体スキーマ」、すなわち「さまざまな運動課題が即 座に移し替え可能な、即座に与えられた不変性」(p.176)を指定する別の方法である。 彼の運動において、主体は単に空間と時間を受けるだけでなく、積極的にそれらを引き受け、人類学的な意味を与えるのである。では、世界の前に身体によって 位置していない主体にとって、「上」「下」「横」という言葉はどのような意味を持つのだろうか。それは、上と下、近いところと遠いところの区別、言い換え れば、方向づけられた空間を意味する(p.131)。客観的な空間、了解可能な空間は、志向的な現象的空間から自由なわけではなく、同質的な空間が志向的 空間の意味を表現できるのは、それが志向的空間から意味を受けているからにほかならない(p.131)。「周囲の環境に意味を与え、実践的な環境にアクセ スさせ、運動的・知覚的な新しい意味を生み出すのは身体である」17。 メルロ=ポンティ(p. 184)は、「経験は、身体が最終的にその位置を占める客観的空間の下に、前者が包絡体にすぎず、身体の存在そのものと融合する根源的な空間性を明らかに する(それゆえ、固有身体あるいは現象的身体という概念)」と書いている。身体であるということは、ある世界と結びついているということである [......]私たちの身体は、まず空間の中にあるのではない。 |

| Le corps comme expression et parole Selon l'articulation de l'auteur lui-même (p. 533). L'empirisme et l'intellectualisme dans la théorie de l'aphasie, apparaissent également insuffisants. Le langage a un sens, mais il ne présuppose pas la pensée mais l'accomplit. « Le sens du mot, n'est pas contenu dans le mot comme son. Mais c'est la définition du corps humain de s'approprier dans une série indéfine d'actes discontinus des noyaux significatifs qui dépassent et transfigurent ses pouvoirs naturels » (p. 235). Pascal Dupond18 écrit ; « La perception est l’opération d’une « puissance ouverte et indéfinie de signifier » (pp 236) qui se dessine dans la nature, mais devient, dans la vie humaine, un vecteur de liberté ». C'est l'occasion pour Pascal Dupond18 de souligner l'ambiguïté de la conception du corps, à la fois esprit et objectivité, dont Merleau-Ponty fera usage dans son concept de « corps phénoménal ». « Le « corps phénoménal » est l’existence même dans son déploiement multiforme sur une échelle qui s’étend du corps le plus vivant, c’est-à-dire le corps comme transcendance et invention de sens jusqu’au corps « extra partes », c’est-à-dire le corps qui n’opère pas sa propre synthèse, qui est corps pour autrui et non corps pour soi [...]. Le corps humain vit toujours selon différents régimes de corporéité (ou différents régimes de tension de durée) : il est toujours « un assemblage de parties réelles juxtaposées dans l’espace », un corps habituel, un corps qui se rassemble et se transfigure dans le geste et l’expression, enfin le corps d’une personne engagée dans une histoire ; et toute altération d’un régime d’existence ou de corporéité s’exprime ou se traduit dans les autres registres de l’existence ». |

表現と発話としての身体 著者自身がこう言っている(p.533)。失語症の理論における経験主義や知識主義もまた不十分であるように思われる。言語には意味があるが、それは思考 を前提とするものではなく、思考を達成するものである。「言葉の意味は音としての言葉には含まれていない。しかしそれは、不定形の不連続な行為の連続の中 で、人間の肉体が本来持っている力を凌駕し、変容させる重要な核を、適切なものにするための定義なのである」(p.235)。パスカル・デュポン18は、 「知覚とは、自然界では明白だが、人間の生活においては自由のベクトルとなる、「開かれた不定形の意味づけの力」(pp.236)の作用である」と書いて いる。パスカル・デュポン18はこの機会に、メルロ=ポンティが「現象的身体」という概念で用いている、精神であり客観性でもある身体という概念の両義性 を強調している。 「現象的身体」とは、最も生きている身体、すなわち超越と意味の発明としての身体から、「余分な」身体、すなわちそれ自身の統合を作動させない身体、他者 のための身体であってそれ自身のための身体ではない身体[......]にまで拡張するスケールにおける、その多形的展開における存在そのものである。人 間の身体は、つねに身体性の異なる体制(あるいは持続の緊張の異なる体制)に従って生きている。それはつねに「空間に並置された現実の部分の集合体」であ り、習慣的な身体であり、身振りや表現において集まり変容する身体であり、最終的には歴史に携わる人間の身体である。存在や身体性の体制のいかなる変化 も、存在の他のレジスターにおいて表現され、翻訳される」。 |

| Le Monde perçu À partir de l'exemple d'un cube, Merleau-Ponty cherche à comprendre le processus par lequel l'on saisit immédiatement son unité et son essence alors que l'on ne voit jamais les six faces égales même s'il est en verre(p. 245). Alors même que je puis penser en faire par imagination le tour cela ne me donne pas l'unité sans la médiation de l'expérience corporelle. Pour la philosophie classique, ce serait en pensant mon propre corps comme mobile que je puis déchiffrer et construire le cube vrai. L'auteur remarque que si, dans ce mouvement, l'on peut assembler la notion du nombre six, la notion de « côté », la notion d'égalité et lier le tout, ce tout n'inclut pas l'idée d'« enfermement » qui est celle par laquelle nous éprouvons physiquement ce qu'est un cube. Le cube est un « contenant », dont l'objet est d'« enfermer » en l'occurrence un morceau d'espace, enfermement qui ne peut avoir de sens que pour l'« être-au-monde » qui lui peut l'être entre les quatre murs de sa chambre (p. 246). |

知覚される世界 メルロ=ポンティは立方体を例にとり、たとえそれがガラス製であっても、6つの等しい面を見ることはないにもかかわらず、私たちがその統一性と本質を即座 に把握するプロセスを理解しようとする(p.245)。想像力によってそれを一周しようと考えることはできても、身体的経験の媒介なしに統一性を与えるこ とはできない。古典哲学にとって、自分の身体を移動可能なものとして考えることによってこそ、真の立方体を解読し、構築することができるのだ。著者は、こ の動きの中で、6という数の概念、「側面」の概念、平等の概念をまとめ、全体を束ねることはできるが、この全体には、立方体が何であるかを物理的に経験す る方法である「囲い」の概念が含まれていないと指摘する。立方体は「容器」であり、その対象は「囲む」ことであり、この場合は空間の一部であり、その囲み は「世界に存在するもの」にとってのみ意味を持ち、それはその部屋の四方の壁の中に囲むことができる(p.246)。 |

| Le sentir « Sentir et non sensation, le verbe exprime une opération par laquelle sont tenus conjointement les deux polarités qu'elle unit : le sentant et le sensible, le sujet et l'objet » écrit Pascal Dupond19. Appuyé sur des études de psychologie inductive[réf. nécessaire] Merleau-Ponty tente de comprendre le rapport vivant qui s'établit entre le sujet percevant et la chose perçue. Pour lui la sensation n'est ni une qualité, ni la conscience d'une qualité. |

感じる 感覚 「ではなく 」感じる 「という動詞は、」感じる 「と 」感じるもの「、」主体 「と 」客体 "という2つの極性を結びつける操作を表している」とパスカル・デュポンは書いている19。帰納的心理学の研究に基づき、メルロ=ポンティは知覚する主体 と知覚されるものとの間に成立する生きた関係を理解しようとした。メルロ=ポンティにとって感覚とは、質でも質の認識でもない。 |

| La sensation Maurice Merleau-Ponty analyse la notion de sensation pour en dégager le caractère complexe, malgré l'évidence que nous procure « l'attitude naturelle » (celle dans laquelle nous pensons pouvoir définir précisément ce que sont les mots « sentir », « voir », etc.). « Il récuse la notion de « sensation pure » qui ne correspond à aucune expérience vécue (les sensations sont relatives) et s'accorde avec la Gestalttheorie (la psychologie de la forme) pour définir le phénomène perceptif comme « une figure sur un fond » : aucune donnée sensible n'est isolée, elle se donne toujours dans un champ (il n'y a pas de « pure impression ») »20. Il réfute ensuite le « préjugé du monde objectif » : il n'y a pas de « réalité objective », la perception s'ancre dans une subjectivité qui, de fait, produit de l'indéterminé et de la confusion (lesquels ne résultent pas d'un « manque d'attention »). Merleau-Ponty en arrive à la conclusion que la psychologie n'est pas parvenue à définir la sensation ; mais la physiologie n'en a pas davantage été capable, puisque le problème du « monde objectif » se pose à nouveau et qu'il entre en contradiction avec l'expérience (exemple avec l'illusion de Müller-Lyer) : pour comprendre ce que signifie « sentir », il faut donc revenir à l'expérience interne pré-objective. « La perception ne réalise jamais la coïncidence entre le sujet sentant et la qualité (par exemple le rouge) perçue. L'auteur met en évidence l'intentionnalité de la conscience : la conscience est conscience perceptive de. Il réfute ensuite la thèse empiriste d' « association des idées » (en vogue depuis Locke) : si cette dernière ramène l'expérience passée, il y a aporie puisque la première expérience ne comportait pas de connexion avec d'autres expériences. Au contraire, la sensation prend corps au sein d'un « horizon » de sens » et c'est à partir de la signification du perçu qu'il peut y avoir des associations avec des expériences analogues (et non le contraire). Une impression ne peut pas « en réveiller d'autres » : la perception n'est pas faite de données sensibles complétées par une « projection des souvenirs » ; en effet, faire appel aux souvenirs présuppose précisément que les données sensibles se soient mises en forme et aient acquis un sens, alors que c'est ce sens que la « projection des souvenirs » était censé restituer »21. |

感覚 モーリス・メルロ=ポンティは、「自然的態度」(「感じること」「見ること」などの言葉の意味を正確に定義できると考える態度)が自明であるにもかかわら ず、感覚という概念を分析し、その複雑な性質を浮き彫りにした。「そして、知覚現象を「背景にある図形」と定義することで、ゲシュタルト理論(形の心理 学)に同意している。さらに彼は、「客観的世界の偏見」に反論する。「客観的現実」は存在せず、知覚は主観性に根ざしたものであり、それは事実、不確定性 と混乱を生み出す(それは「注意の欠如」の結果ではない)。メルロ=ポンティは、心理学は感覚を定義することに成功していないという結論に達するが、生理 学もまた、「客観的世界」の問題が再び生じ、経験と矛盾する(たとえば、ミュラー=ライヤーの錯覚)。 知覚は、感じる主体と知覚される質(例えば赤)との一致を決して達成しない」。著者は意識の意図性を強調する。意識とは知覚的認識である。そして、(ロッ ク以来流行している)経験主義的な「観念の連合」というテーゼに反論する。後者が過去の経験を呼び起こすのであれば、最初の経験は他の経験とは何のつなが りもなかったのだから、アポリアとなる。それとは逆に、感覚は意味の「地平」の中で形づくられ、知覚されたものの意味から、類似の経験との関連が生まれる のである(その逆はない)。知覚は「記憶の投影」によって完成された感覚的データから構成されているのではない。実際、記憶に訴えるということは、まさに 感覚的データが形象化され、意味を獲得していることを前提としているのであり、「記憶の投影」が回復させるはずだったのはこの意味なのである21。 |

| La motricité des qualités sensibles La neuropathologie montre que « certaines sensations visuelles ou sonores ont une valeur motrice ou une signification vitale supérieure qui leur est propre »22 La couleur verte posséderait une valeur reposante. « Alors que l'on a d'une manière générale d'un côté avec le rouge et le jaune l'expérience d'un arrachement, d'un mouvement qui s'éloigne du centre, on a d'un autre côté avec le bleu et le vert l'expérience du repos et de la concentration » (p. 255). Ces phénomènes ne sont pas saisissables objectivement, il n'y a pas, par exemple, de relation de causalité qui puisse être établi entre le stimulus de la qualité et la réponse du sujet percevant. En ce sens très particulier, il n'y a de signification motrice que si le stimulus atteint en moi, « un certain montage général par lequel je suis adapté au monde, si elles m'invitent à une nouvelle manière de l'évaluer » écrit Merleau-Ponty. |

敏感な性質の運動性 神経病理学は、「ある種の視覚的感覚や聴覚的感覚は、それ自体に運動的価値や高次の生命的意味がある」ことを示している22。「一方では、赤や黄色は、一 般に、引き裂かれるような、中心から遠ざかるような動きを経験するが、他方では、青や緑は、休息や集中を経験する」(p.255)。 これらの現象は客観的に把握することはできない。例えば、質の刺激と知覚する主体の反応との間には因果関係は成立しない。この極めて特殊な意味において、 刺激が私の中に到達しない限り、運動的な意味は存在しないのである。「もし刺激によって私が世界に適応し、世界を評価する新たな方法へと誘われるのであれ ば、それはある種の一般的な集合体である」とメルロ=ポンティは書いている。 |

| La fonction symbolique Constamment, allant de l'un à l'autre, l'homme navigue entre deux ordres, l'ordre animal, correspondant aux nécessités vitales, et l'ordre humain qui est le lieu de la fonction symbolique qui expose l'ensemble des symboles composant l'univers de la culture ou des œuvres de l'homme (mythes, religions, littératures, œuvres d'art23). « La fonction symbolique est d'abord une manière de percevoir, elle est fondamentalement l'acte d'un esprit incarné »24. Dans la Phénoménologie de la perception, Merleau-Ponty définit l'existence comme un « va-et-vient » entre vie biologique et la vie de relations de la conscience25. Alors que nos vues ne sont que des perspectives, Merleau-Ponty tente d'expliquer la perception de l'objet (qu'une table soit une table, toujours la même, que je touche et que je vois) dans son « aséité » (p. 276 sq). Il écarte le recours à la synthèse intellectuelle qui ne possède pas le secret de l'objet « pour confier cette synthèse au corps phénoménal [...] en tant qu'il projette autour de lui un certain milieu, que ses parties se connaissent dynamiquement l'une l'autre et que ses récepteurs se disposent de manière à rendre possible la perception de l'objet »(p. 269?). Rudolf Bernet26 écrit « le corps perçoit, mais il déploie aussi à l'avance le champ dans lequel une perception peut se produire (reprenant les paroles de Merleau-Ponty), [...] mon corps est ce noyau significatif qui se comporte comme une fonction générale [...], quand le corps perçoit une chose, il en appréhende le sens; et ce sens de la chose est tributaire d'une symbolique qui est celle précisément, de l'organisation interne du corps, ainsi que de ces mouvements et de son pouvoir de prise sur le monde ». Pour Stefan Kristensen27, « le schéma corporel est l’étalon de mesure des choses perçues, « invariant immédiatement donné par lequel les différentes tâches motrices sont instantanément transposables » ». Plus explicite encore Merleau-Ponty écrit « notre corps est cet étrange objet qui utilise ses propres parties comme symbolique générale du monde et par lequel en conséquence nous pouvons fréquenter ce monde, le comprendre et lui trouver une signification » (p. 274). « Comme « puissance » d’un certain nombre d’actions familières, le corps a ou comprend son monde sans avoir à passer par des représentations, il sait d’avance — sans avoir à penser ce que faire et comment le faire —, il connaît — sans le viser — son entourage comme champ à portée de ses actions »17,N 8. « Le sujet de la sensation n'est, ni un penseur qui note une qualité ni un milieu inerte qui serait affecté ou modifié par elle, il est une puissance qui « co-naît » à un certain milieu d'existence ou se synchronise avec lui »(p. 245). |

象徴機能 生命的必需品に対応する動物的秩序と、文化や人間の作品(神話、宗教、文学、芸術作品23 )の世界を構成するすべての象徴を設定する象徴機能の拠点である人間的秩序である。「象徴機能とは、何よりもまず知覚の方法であり、基本的には身体化され た精神の行為である」24。メルロ=ポンティは『知覚の現象学』の中で、存在を生物学的生命と意識関係の生命との間の「往来」として定義している25。 メルロ=ポンティは、われわれの見方が単なる視点にすぎないのに対して、対象の知覚(テーブルがテーブルであること、常に同じであること、私が触ったり見 たりすること)を、その「aséité」(p. 276 ff)の観点から説明しようと試みている。彼は、対象の秘密を持たない知的総合に頼ることを排除し、「この総合を現象的身体に委ねる[......]の は、それがそれ自身の周囲に一定の環境を投影し、その部分が動的に互いを知り、その受容体が対象の知覚を可能にするように配置されている限りにおいてであ る」(p.269?) ルドルフ・ベルネ26 は次のように書いている。「身体は知覚するが、知覚が起こりうる場を(メルロ=ポンティの言葉を借りれば)あらかじめ広げておくのであり、[...]私の 身体は、一般的な機能のように振る舞うこの重要な核である[...]、身体が何かを知覚するとき、その意味を理解する。ステファン・クリステンセン27に とって、「身体スキーマは知覚されるものを測定するための基準であり、異なる運動課題が即座に移し替えられる『即座に与えられる不変性』である」。 さらに明確に、メルロ=ポンティはこう書いている。「私たちの身体は、それ自身の部分を世界の一般的な象徴として用いる奇妙な物体であり、それによって私 たちはこの世界を頻繁に訪れ、理解し、そこに意味を見出すことができる」(p.274)。「身体は、一定の数の慣れ親しんだ行為の「力」として、表象を介 することなくその世界を持ち、あるいは理解し、何をすべきか、どのようにすべきかを考えることなく、あらかじめ知っている。 「感覚の主体は、ある特質に注目する思考者でもなければ、それによって影響を受けたり修正されたりする不活性な環境でもない。 |

| L'espace Depuis Kant, note Merleau-Ponty, l'espace n'est plus le milieu dans lequel se disposent les choses, mais le moyen par lequel la position des choses devient possible (p. 290). La Phénoménologie de la perception, ne consacre, contrairement à la tradition, qu’un chapitre relativement court au temps contre deux chapitres bien plus longs à l’espace remarque Miklós Vető28. « La phénoménologie merleaupontienne reconnaît et décrit la pluralité des expériences du spatial qu’elle fait remonter jusqu’à un espace subjectif général, celui de la perception, radicalement différent de l’espace un et abstrait de la géométrie [...] L’espace de la perception est à l’origine des diverses variantes d’espaces subjectifs (espaces du primitif, de l’enfant, du malade, du peintre) et le prétendu espace en soi, objectif, celui de la géométrie est subsumé, lui aussi, sous l’espace primordial de la perception. »29. Merleau-Ponty regroupe ces seconds espaces, qu'il multiplie en faisant preuve d'une grande imagination, sous la notion commune d' « espace anthropologique ». À noter que l'espace est pré-constitué avant toute perception. En effet pour l'auteur, contrairement à la tradition, « l'orientation dans l'espace n'est pas un caractère contingent de l'objet mais le moyen par lequel je le reconnais et j'ai conscience de lui comme d'un objet [...]. Renverser un objet c'est lui ôter toute signification »(p. 301). Il n'y a pas d'être qui ne soit situé et orienté, comme il n'y a pas de perception possible qui ne s'appuie sur une expérience antérieure d'orientation de l'espace. La première expérience est celle de notre corps dont toutes les autres vont utiliser les résultats acquis (p. 302). citation- Il y a donc un autre sujet au-dessous de moi, pour qui un monde existe avant que je sois là et qui y marquait ma place. Le corps, le sujet corporel, est à l’origine de la spatialité, il est le principe de la perception, sachant que le corps dont il est question n'est pas le corps matériel mais le « corps propre » ou phénoménal. Contrairement aux corps-objets qui se trouvent dans l’espace, et qui sont séparés les uns des autres par des distances, visibles à partir d’une perspective, le corps propre, n'est pas dans l'espace à une certaine distance des autres corps-objets mais constitue un centre d’où partent distances et direction. Bien que privé de toute visibilité notre corps propre est toujours là pour nous. |

空間 メルロ=ポンティは、カント以来、空間はもはや物事が配置される環境ではなく、物事の位置づけを可能にする手段であると指摘している(290頁)。 伝統に反して、『知覚の現象学』では、空間に関する2つの長い章に比べ、時間については比較的短い1章しか割かれていない、とミクローシュ・ヴェトゥー 28は指摘する。「メルローポン的現象学は、空間の複数の経験を認識し、それを、幾何学の統一的で抽象的な空間とは根本的に異なる、知覚という一般的な主 観的空間にまで遡って記述する[...]。 知覚の空間は、主観的空間のさまざまな変種(原始人の空間、子供の空間、病人の空間、画家の空間)の起源であり、いわゆる客観的空間そのものである幾何学 の空間もまた、知覚の根源的空間の下に包含される29。メルロ=ポンティは、想像力を駆使して増殖させたこれらの第二の空間を、「人間学的空間」という共 通の概念の下にグループ化している。 注意すべきは、空間は知覚が起こる前にあらかじめ構成されているということである。著者にとっては、伝統に反して、「空間における方向は、対象物の偶発的 な特徴ではなく、私がそれを認識し、対象物として認識するための手段である[...]。物体を逆さまにすることは、すべての意味を奪うことである」 (301頁)。空間的な方向づけの先行体験に基づかない知覚がありえないように、位置と方向づけのない存在は存在しない。それゆえ、私の下にはもう一人の 主体が存在し、その主体にとっては、私がそこに存在する以前に世界が存在し、その中に私の居場所を示すのである。 身体的主体である身体は空間性の起源であり、それは知覚の原理である。空間内の身体オブジェクトが、遠近法から見える距離によって互いに隔てられているの とは異なり、適切な身体は、他の身体オブジェクトから一定の距離を置いて空間内にあるのではなく、距離と方向がそこから発せられる中心を構成している。視 界を奪われてはいるが、私たちの身体は常にそこにある。 |

| La chose et le monde naturel « Dans le chapitre la chose et le monde naturel, Merleau-Ponty montre que « l’éclairage et la constance de la chose éclairée qui en est le corrélatif », la constance des formes et des dimensions, la permanence de la chose à travers ses différentes manifestations, dépendent directement de notre situation corporelle et plus particulièrement de l’acte pré-logique par lequel le corps s’installe dans le monde », écrit Lucia Angelino30. Pour Merleau-Ponty « Toute perception tactile, en même temps qu'elle s'ouvre sur une propriété objective, comporte une composante corporelle, et par exemple la localisation tactile d'un objet le met en place par rapport aux points cardinaux du « schéma corporel » » (p. 370). Rudolf Bernet31 relève « avec la notion de schéma corporel, ce n'est pas seulement l'unité du corps qui est décrite d'une manière neuve, c'est aussi, à travers elle l'unité des sens et l'unité de l'objet ». C'est pourquoi la chose ne peut jamais être séparée de la personne qui la perçoit (p. 376). Toutefois Merleau-Pont remarque « nous n'avons pas épuisé le sens de la chose en la définissant comme le corrélatif du corps et de la vie » (p. 378). En effet même si l'on ne peut concevoir la chose perçue sans quelqu'un qui la perçoive, il reste que la chose se présente à celui-là même qui la perçoit comme chose « en soi ». Le corps et le monde ne sont plus cote à cote, le corps assure « une fonction organique de connexion et de liaison, qui n’est pas le jugement, mais quelque chose d'immatériel qui permet l’unification des diverses données sensorielles, la synergie entre les différents organes du corps et la traduction du tactile dans le visuel [...] dès lors, Merleau-Ponty affronte le problème de l'articulation entre la structure du corps et la signification et la configuration du monde »32. |

事物と自然界 「メルロ=ポンティは、事物と自然界の章において、「照明と、その相関関係である照明された事物の不変性」、形態と寸法の不変性、さまざまな現れを通して の事物の永続性は、私たちの身体的状況、とりわけ身体が世界に定着する前論理的行為に直接依存していることを示している」とルシア・アンジェリーノは書い ている30。メルロ=ポンティにとって、「すべての触覚は、それが客観的な性質に開かれていると同時に、身体的な要素を含んでいる。 たとえば、対象の触覚的な定位は、それを『身体的スキーマ』の枢要点との関係において位置づける」(370頁)。 ルドルフ・ベルネ31は、「身体的スキーマという概念によって、新しい方法で記述されるのは身体の統一性だけでなく、それを通じて感覚の統一性と対象の統 一性でもある」と指摘する。だからこそ、事物はそれを知覚する人間から決して切り離すことができないのである(p.376)。しかし、メルロ=ポンは、 「われわれはそれを身体と生命の相関関係として定義することによって、事物の意味を使い果たしたわけではない」(p.378)と指摘する。たしかに、誰か が知覚することなしに知覚されるものを考えることができないとしても、知覚する人そのものに、「それ自体」の事物として事物が提示されるという事実は変わ らない。身体と世界はもはや隣り合わせにあるのではなく、身体は「接続と連絡の有機的な機能」を果たしている。それは判断ではなく、さまざまな感覚データ の統一、身体のさまざまな器官間の相乗効果、触覚の視覚への変換を可能にする非物質的な何かである[......それ以降、メルロ=ポンティは、身体の構 造と世界の意味づけと構成との間の連結の問題に直面する」32。 |

| Autrui et le monde humain Merleau-Ponty fait le constat « qu'il n'y a pas de place pour autrui et pour une pluralité de consciences dans la pensée objective » (p. 407). Il est impossible si je constitue le monde de penser une autre conscience qui à l'égal de moi-même me constituerait et pour laquelle je ne serais donc pas constituant. À ce problème l'introduction de la notion de « corps propre » apporterait un commencement de solution (p. 406. Or comme le note Denis Courville33) « faire l'expérience du sens de l’« alter ego » est paradoxale au sens où, par l’intermédiaire de son corps physique, autrui est appréhendé « en chair et en os » devant moi; et cela sans que son expérience et son vécu intentionnel ne me soient disponibles ». Ce dont nous avons l'expérience c'est celle du corps physique d'autrui qui ne se résume pas à celle d'objet mais qui témoigne d'une « immédiateté intentionnelle » par laquelle nous serait « donné » ce corps à la fois comme chair et conscience. Pour Husserl c'est par analogie et empathie que les « ego » partagent le même monde. Mais tant qu’il reste un analogue de moi-même, l’autre n’est qu’une modification de mon moi et si je veux le penser comme un véritable Je, je devrais me penser comme un simple objet pour lui, ce qui m'est impossible (p. 410). Merleau-Ponty pense qu'il n'y a de possibilité de rendre compte de l'évidence de l'existence d'autrui (comme Je et conscience autonome) que lorsque nous nous attachons aux comportements dans le monde qui nous est commun plutôt qu'à nos êtres rationnels (p. 410). « L’objectivité se constitue, non pas en vertu d’un accord entre des esprits purs, mais comme intercorporéité » écrit Denis Courville34. On peut parler de « comportement » spontané puisque la réflexion nous découvre, sous-jacent, le corps-sujet, pré-personnel (phénoménal), donné à lui-même, dont les « fonctions sensorielles, visuelles, tactiles, auditives communiquent déjà avec les autres, pris comme sujets » (p. 411) N 9. Outre le monde naturel l'existence s'éprouve dans un monde social « dont je peux me détourner mais non pas cesser d'être situé par rapport à lui car il est plus profond que toute perception expresse ou tout jugement » (p. 420). |

他者と人間世界 メルロ=ポンティは、「客観的思考には他者や複数の意識の居場所はない」(p.407)と述べている。もし私が世界を構成しているのであれば、私と同じよ うに私を構成し、したがって私が構成者ではない別の意識を考えることは不可能である。しかし、ドゥニ・クールヴィル33 が指摘するように、「『分身』の意味を経験することは、その肉体を媒介として、他者が私の前に『肉体をもって』理解されるという意味で逆説的である。私た ちが経験するのは、他者の身体であり、それは単に物体のそれではなく、身体が肉体と意識の両方として私たちに「与えられる」という「意図的即時性」の証人 となるのである。フッサールにとって、「自我」が同じ世界を共有するのは、類推と共感によってである。しかし、彼が私自身のアナローグであり続ける限り、 他者は私の自己の修正でしかなく、もし私が彼を真の私として考えたいのであれば、私は彼にとっての私自身を単なる対象として考えなければならないだろう が、それは不可能である(p.410)。 メルロ=ポンティは、私たちの理性的存在ではなく、私たちが共有する世界における振る舞いに注目するときにのみ、(私や自律的意識としての)他者の存在の 証拠を説明することが可能になると考えている(p. 410)。 客観性は、純粋な精神の間の合意によってではなく、身体間性によって構成される」とドゥニ・クールヴィルは書いている34。私たちが自然発生的な「行動」 について語ることができるのは、内省によって、「感覚、視覚、触覚、聴覚の機能が、すでに主体として捉えられた他者とコミュニケーションしている」 (p.411)、それ自体に与えられた、前人格的な(現象的な)身体主体が、根底にあることが明らかになるからである9。自然界に加えて、存在は社会的世 界でも経験される。「そこから目をそらすことはできても、それとの関係の中に位置することをやめることはできない。 |

| L'être-pour-soi et l'être-au-monde « Le corps anime le monde et forme avec lui un « ensemble ». L’être corporel se joint à un milieu défini, se confond avec certains projets et s’y engage continuellement.[...]. Le corps « co-existe » et se lie à travers l’espace et le temps avec les autres corps et les choses au sein du même monde »35. « Merleau-Ponty et Gabriel Marcel fondent leur pensées sur les liens vitaux qui se tissent entre moi et autrui, l’âme et le corps, le corps et le monde, l’homme et l’Être en vue de dépasser toute dualité. Pour Merleau-Ponty, ces liens se tissent dans la «Chair du monde », qu’il s’agisse de mes rapports avec les choses ou de mes liens avec les autres »9. |

自己のための存在と世界の中の存在 身体は世界を活気づけ、世界とともに 「全体 」を形成する。身体的存在は、定義された環境に加わり、あるプロジェクトと融合し、継続的にそれらに関与する[......]。身体は 「共存 」し、空間と時間を通じて、同じ世界内の他の身体や事物と結びついている」35。「メルロ=ポンティとガブリエル=マルセルは、あらゆる二元性の克服を視 野に入れながら、自己と他者、魂と身体、身体と世界、人間と存在との間に築かれる重要な結びつきに基づいて思考を進めている。メルロ=ポンティにとって、 こうした結びつきは、私と物との関係であれ、私と他者との関係であれ、「世界の肉」の中に織り込まれている9。 |

| Les thèmes principaux de l'œuvre Étienne Bimbenet résume ainsi, à son sens, la problématique de ce livre : « notre expérience sensorielle est-elle ou non informée par des capacités conceptuelles ? Percevoir est-ce déjà penser ? »36. Sur cette question Merleau-Ponty, dont il dit qu'il a fait de la perception le centre de sa pensée aurait produit « des arguments nouveaux, ou étonnants, ou décisifs »36. Pour Merleau-Ponty, il s'agit de revenir au monde vécu dans lequel la perception n'est pas une opération intellectuelle culminant dans une connaissance scientifique en gestation, comme la décrit la « philosophie criticiste »37. « La perception n'est pas l'œuvre d'un esprit connaissant surplombant son expérience et transformant les processus physiologiques en significations rationnelles ; elle est le fait d'un corps essentiellement agissant, et polarisant tout ce qui lui arrive depuis ses dimensions propres et non objectivables (le haut, le bas, la droite la gauche, le proche le lointain, etc.) »37. Pascal Dupond38 écrit « A la jointure de la nature et de l’esprit se trouve la « perception ». Elle est leur indivision, mais elle est aussi, avec le virage du temps naturel en temps historique, un premier échappement à la nature. La perception serait donc la nature qui s’échappe à elle-même, qui invente un régime du sens qui conduit la nature au-delà de la nature. La perception est l’opération d’une « puissance ouverte et indéfinie de signifier », qui se dessine dans la nature, mais devient, dans la vie humaine, un vecteur de liberté [..]. Une existence qui s’apparaît à elle-même comme surgissant d’une nature dans laquelle elle reste aussi engagée et qui se comprend donc comme étant à la fois « naturante » (esprit) et « naturée » (nature ou corps) ». Le monde de Merleau-Ponty n'est pas d'emblée unique et objectif, il est d'abord celui du sujet perceptif qui a sa propre façon de remplir l'espace autour de lui. Étienne Bimbenet parle « d'une logique perspective et égocentrique ». « L'orientation d'une figure, sa symétrie, la droite la gauche, le haut le bas requièrent un moi corporel, vivant situé quelque part pour être vus ; il suffit d'être ce moi vivant pour les voir, nul besoin de concepts pour ce cela »39. Nous possédons comme les animaux une sensibilité perceptive à des traits de notre environnement, mais ce qui fait notre spécificité, c'est que « nous les réorganisons constamment dans des ensembles nouveaux pendant que les comportements vitaux disparaissent comme tels »40. Étienne Bimbenet note la convergence de cette analyse comportementale avec celle du philosophe anglo-saxon John McDowell. Ainsi de la fonction symbolique qui nous permet d'objectiver le milieu et de varier nos points de vue sur lui conférant un sens neuf à des conduites vitales. La perception se démultiplie en une multiplicité de perspectives autorisant de viser une chose comme cette chose qu'elle est, « sous telle perspective immédiatement donnée, mais également projeté comme l'invariant d'une multiplicité d'aspects »40. |

作品の主要テーマ エティエンヌ・ビンブネは、本書の問題意識を次のように要約している。「私たちの感覚的経験は、概念的能力によってもたらされているのか、そうではないの か?知覚することはすでに思考しているのか?この問いについて、メルロ=ポンティは、知覚を思考の中心に据えていたとし、「新しい、あるいは驚くべき、あ るいは決定的な」議論を展開しただろう36。 メルロ=ポンティにとって、この問いは、知覚が「批評家 哲学」37 の言うような、科学的な知識を作り上げるための知的作業ではない、生かされて いる世界に立ち戻るための問題なのである。「知覚とは、経験を覆い隠し、生理的なプロセスを合理的な意味に変換する、物知りな心の仕事ではなく、本質的に 作用する身体の仕事であり、自分に起こるすべてのことを、自分自身の非対象的な次元(上下左右、近く、遠くなど)から分極化することである」37。 パスカル・デュポン38 は次のように書いている。「自然と精神の接点に『知覚』がある。それは両者の分断であるが、自然時間が歴史時間に転化することで、自然からの最初の逃避で もある。したがって知覚とは、自然が自分自身から逃れることであり、自然を超える意味の体制を発明することである。知覚とは「開かれた不定形の意味づけの 力」の作用であり、それは自然の中で形をとるが、人間の生活においては自由のベクトルとなる[......]。存在とは、自分自身が関与し続ける自然から 生じているように見えるものであり、それゆえ「naturante」(精神)であると同時に「naturée」(自然または身体)であると理解される。 メルロ=ポンティの世界は、即座に唯一無二の客観的なものではなく、何よりもまず、知覚する主体の世界である。エティエンヌ・ビンブネは「遠近法と自己中 心的論理」について語る。「図形の向き、左右の対称性、上下の対称性は、見るために、どこかに位置する身体的な、生きている自己を必要とする。 動物同様、私たちは環境の特徴に対する知覚的な感受性を持っているが、私たちをユニークな存在にしているのは、「重要な行動がそのようなものとして消えて しまう一方で、私たちは絶えずそれらを新しい全体へと再編成している」という点である40。エティエンヌ・ビンブネは、この行動分析がアングロサクソンの 哲学者ジョン・マクダウェルの分析に収斂していることを指摘している。象徴的機能によって、私たちは環境を客観化し、それに対する視点を変化させることが できる。知覚は多元的な視点に拡張され、あるものを「与えられた直接的な視点からだけでなく、多元的な側面の不変性として投影されたもの」として見ること ができるようになる40。 |

| Postérité et critiques Un certain rapprochement a pu être fait entre Merleau-Ponty et Emmanuel Levinas, tous deux, par exemple, reprochent à Husserl le caractère idéaliste et solipsiste de sa phénoménologie. Dans les deux cas le sujet perd de son rôle au profit du monde. Pour Merleau-Ponty la « « chair » vient établir la cohésion de notre situation dans le monde » et pour Emmanuel Levinas « le monde devient une nourriture permettant de combler une souffrance et un manque potentiellement mortel »41. De son côté, Étienne Bimbenet, s'attache à montrer, sans rien cacher de leurs différences, la parenté entre Merleau-Ponty et la pensée de Michel Foucault. Ce dont chacun se préoccupe essentiellement, à une vingtaine d'années d'existence, c'est, à travers la notion de « chiasme » « de la tâche d'élargir notre raison, pour la rendre capable de comprendre ce qui en nous et dans les autres précède et excède la raison »42. « Ce livre de 1945 qui se propose d’examiner à partir de la phénoménologie de la « perception » la "contribution que celle-ci apporte à notre idée du « vrai » méconnaît les difficultés de l’entreprise [...] Le philosophe reste ce spectateur du monde, le sujet a-cosmique, qui croit pouvoir survoler son objet et oublier son corps de chair et de paroles. Le présupposé de ce travail reste celui de toute philosophie de la conscience. Celle-ci est la source absolue » observe Franck Lelièvre43. On remarquera que ce livre est critiqué par Merleau-Ponty lui-même dans des notes de travail constituant son dernier ouvrage le Visible et l'invisible44, il y écrit explicitement « Les problèmes posés dans la Phénoménologie de la perception sont insolubles parce que j'y pars de la distinction conscience, objet ». La pensée de Merleau-Ponty a aussi été largement promue par Francisco Varela, biologiste théoricien d'origine chilienne qui, très critique vis-à-vis des sciences cognitives dites "computo-symboliques" de la fin du xxe siècle, a œuvré à une approche "incarnée" (embodied) de la cognition, au travers notamment de la notion d'énaction. |

後世(アフターライフ)と批判 メルロ=ポンティとエマニュエル・レヴィナスの間には、ある種の類似性がある。たとえば両者とも、フッサールの現象学が観念論的で独我論的であることを批 判している。どちらの場合も、主体は世界のためにその役割を失っている。メルロ=ポンティにとって、「肉」は世界におけるわれわれの状況の結束を確立する ものであり、エマニュエル・レヴィナスにとって、「世界は苦しみと潜在的に死すべき欠乏を補う糧となる」41。 エティエンヌ・ビンブネは、メルロ=ポンティとミシェル・フーコーの思想の親近性を、両者の違いを隠すことなく示そうとしている。その20年間、それぞれ が「キアスム」という概念を通して、「われわれの理性を拡大し、われわれと他者の中にある理性に先行し、理性を超えるものを理解できるようにすること」に 本質的な関心を寄せていた42。 「哲学者は依然として世界の見物人であり、自分の対象を俯瞰し、肉体と言葉を忘れることができると信じている無宇宙的主体である。この作品の前提は、すべ ての哲学の意識の前提であり続けている。意識は絶対的な源泉である」とフランク・ルリエーヴルは言う43。メルロ=ポンティ自身、最後の著作『見えるもの と見えないもの』(Le Visible et l'invisible)44を構成する作業ノートの中で、この本を批判している。 メルロ=ポンティの考え方は、チリ出身の理論的生物学者フランシスコ・ヴァレラ(Francisco Varela)にも広く支持されている。彼は、20世紀後半のいわゆる「計算記号的」認知科学に強く批判的であり、特に「行為(enaction)」とい う概念を通じて、認知に対する「身体化された」アプローチを目指している。 |

| Bibliographie Michel Blay, Dictionnaire des concepts philosophiques, Paris, Larousse, 2013, 880 p. (ISBN 978-2-03-585007-2). Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception, Paris, Gallimard, coll. « Tel », 2005, 537 p. (ISBN 2-07-029337-8). Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Le visible et l'invisible, Gallimard, coll. « Tel », 1988, 360 p. (ISBN 2-07-028625-8). Edmund Husserl (trad. de l'allemand par Paul Ricœur), Idées directrices pour une phénoménologie, Paris, Gallimard, coll. « Tel », 1985, 567 p. (ISBN 2-07-070347-9). Edmund Husserl (trad. Mlle Gabrielle Peiffer, Emmanuel Levinas), Méditations cartésiennes : Introduction à la phénoménologie, J.VRIN, coll. « Bibliothèque des textes philosophiques », 1986, 136 p. (ISBN 2-7116-0388-1). Eugen Fink (trad. Didier Franck), De la phénoménologie : Avec un avant-propos d'Edmund Husserl, Les Éditions de Minuit, coll. « Arguments », 1974, 242 p. (ISBN 2-7073-0039-X). Renaud Barbaras, Introduction à la philosophie de Husserl, Chatou, Les Éditions de la transparence, coll. « Philosophie », 2008, 158 p. (ISBN 978-2-35051-041-5). Jean-François Lyotard, La phénoménologie, Paris, PUF, coll. « Quadrige », 2011, 133 p. (ISBN 978-2-13-058815-3). Emmanuel Levinas, En découvrant l’existence avec Husserl et Heidegger, J. Vrin, coll. « Bibliothèque d'histoire de la philosophie », 1988, 236 p. (ISBN 2-7116-0488-8). Emmanuel Housset, Husserl et l’énigme du monde, Seuil, coll. « Points », 2000, 263 p. (ISBN 978-2-02-033812-7). Étienne Bimbenet, Après Merleau-Ponty : étude sur la fécondité d'une pensée, Paris, J.Vrin, coll. « Problèmes et Controverses », 2011, 252 p. (ISBN 978-2-7116-2355-6, lire en ligne [archive]). Rudolf Bernet, « Le sujet dans la nature. Réflexions sur la phénoménologie de la perception chez Merleau-Ponty », dans Marc Richir,Étienne Tassin (directeurs), Merleau-Ponty, phénoménologie et expériences, Jérôme Millon, 1992 (ISBN 978-2905614681), p. 56-77. |

参考文献 ミシェル・ブレ、『哲学概念事典』、パリ、ラルース、2013年、880ページ(ISBN 978-2-03-585007-2)。 モーリス・メルロ=ポンティ、『知覚の現象学』、パリ、ガリマール、「Tel」叢書、2005年、537ページ (ISBN 2-07-029337-8)。 モーリス・メルロ=ポンティ、『見えるものと見えざるもの』、ガリマール、1988年、360ページ(ISBN 2-07-028625-8)。 エドムント・フッサール(ポール・リクールによるドイツ語からの翻訳)、『現象学のための指導理念』、パリ、ガリマール、1985年、567ページ(ISBN 2-07-070347-9)。 エドムント・フッサール(ガブリエル・ペイファー嬢訳、エマニュエル・レヴィナス)、『カードスにおける省察:現象学入門』、J.VRIN、コレクション「哲学文献集」、1986年、136ページ(ISBN 2-7116-0388-1)。 オイゲン・フィンク(訳:ディディエ・フランク)、『現象学について:序文付』エドムンド・フッサール著、Les Éditions de Minuit、「Arguments」シリーズ、1974年、242ページ(ISBN 2-7073-0039-X)。 ルノー・バルバラ著『フッサール哲学入門』シャトゥー、レ・エディシオン・ド・ラ・トランスペランス、「哲学」コレクション、2008年、158ページ(ISBN 978-2-35051-041-5)。 ジャン=フランソワ・リオタール、『現象学』、パリ、PUF、「Quadrige」叢書、2011年、133ページ(ISBN 978-2-13-058815-3)。 エマニュエル・レヴィナス、『フッサールとハイデガーによる存在の発見』、J. Vrin、「Bibliothèque d'histoire de la philosophie」シリーズ、1988年、236ページ(ISBN 2-7116-0488-8)。 エマニュエル・ウッセ『フッサールと世界の謎』、Seuil、「Points」コレクション、2000年、263ページ(ISBN 978-2-02-033812-7)。 エティエンヌ・ビンベネ、『メルロー=ポンティ以後:ある思想の豊饒性に関する研究』、パリ、J.Vrin、「Problèmes et Controverses」叢書、2011年、252ページ(ISBN 978-2-7116-2355-6、オンラインで閲覧可能[アーカイブ])。 ルドルフ・ベルネ、「自然における主体。メルロ=ポンティにおける知覚現象学についての考察」、マルク・リシエール、エティエンヌ・タッサン(編)、『メ ルロ=ポンティ、現象学と経験』、ジェローム・ミロン、1992年(ISBN 978-2905614681)、56-77ページ。 |

| https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ph%C3%A9nom%C3%A9nologie_de_la_perception |

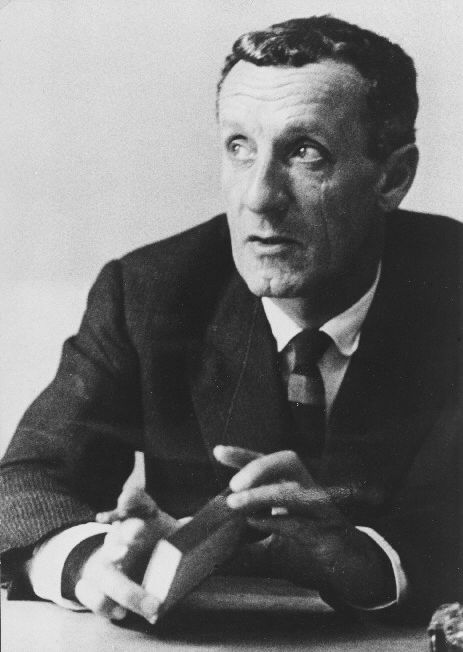

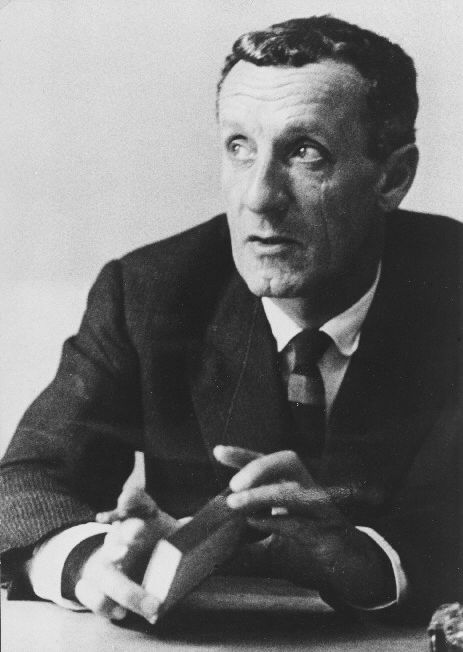

| Maurice

Jean Jacques

Merleau-Ponty[16] (French: [mɔʁis mɛʁlo pɔ̃ti, moʁ-]; 14

March 1908 – 3

May 1961) was a French phenomenological philosopher, strongly

influenced by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. The constitution of

meaning in human experience was his main interest and he wrote on

perception, art, politics, religion, biology, psychology,

psychoanalysis, language, nature, and history. He was the lead editor

of Les Temps modernes, the leftist magazine he established with

Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir in 1945. |

モーリス・ジャン・ジャック・メルロ=ポンティ[16](フランス語:

[mɔʁis mɛ moʁ -

1961年5月3日)はフランスの現象学の哲学者で、エドマンド・フッサールやマルティン・ハイデガーから強い影響を受けた。人間の経験における意味の構

成に主な関心を寄せ、知覚、芸術、政治、宗教、生物学、心理学、精神分析、言語、自然、歴史について執筆した。1945年にジャン=ポール・サルトル、シ

モーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールとともに創刊した左翼雑誌『レ・タン・モダン』の主幹編集長を務めた。 |

| At the core of Merleau-Ponty's

philosophy is a sustained argument for the foundational role that

perception plays in the human experience of the world. Merleau-Ponty

understands perception to be an

ongoing dialogue

between one's lived body and the world which it perceives, in which

perceivers passively and actively strive to express the perceived world

in concert with others. He was the only major phenomenologist of the

first half of the twentieth century to engage extensively with the

sciences. It is through this engagement that his writings became

influential in the project of naturalizing phenomenology, in which

phenomenologists use the results of psychology and cognitive science. |

メルロ=ポンティの哲学の核心は、知覚が人間の世界経験において果たす

基礎的な役割に対する持続的な議論である。メルロ=ポンティは、知覚を、生きている

自己の身体とそれが知覚する世界との間の継続的な対話であると理解し、そこでは知覚者は受動的にも能動的にも、他者と協調して知覚した世界を表現しようと

努力するのである。彼は、20世紀前半の主要な現象学者の中で唯一、科学と幅広く関わりを持った。現象学者が心理学や認知科学の成果を利用

する自然化現象学のプロジェクトにおいて、彼の著作が影響力を持ったのは、この関わりを通してである。 |

| Merleau-Ponty emphasized the

body as the primary site of knowing the world, a corrective to the long

philosophical tradition of placing consciousness as the source of

knowledge, and maintained that the perceiving body and its perceived

world could not be disentangled from each other. The articulation of

the primacy of embodiment (corporéité) led him away from phenomenology

towards what he was to call “indirect ontology” or the ontology of “the

flesh of the world” (la chair du monde), seen in his final and

incomplete work, The Visible and Invisible, and his last published

essay, “Eye and Mind”. |

メルロ=ポンティは、意識を知識の源泉とする長い哲学的伝統に対する修

正として、世界を知る第一の場として身体を強調し、知覚する身体とその知覚される世界とは、互いに切り離すことはできないと主張した。具現化の優位性を明

確にすることで、彼は現象学から「間接的存在論」あるいは「世界の肉体」(la chair du

monde)の存在論と呼ぶべきものへと向かい、それは彼の最後の不完全な著作『見えるものと見えないもの』や最後に出版されたエッセイ『眼と心』に見ら

れるものである。 |

| Merleau-Ponty engaged with

Marxism throughout his career. His 1947 book, Humanism and Terror, has

been widely misunderstood[17] as a defence of the Soviet farce trials.

In fact, this text avoids the definitive endorsement of a view on the

Soviet Union, but instead engages with the Marxist theory of history as

a critique of liberalism, in order to reveal an unresolved antinomy in

modern politics, between humanism and terror: if human values can only

be achieved through violent force, and if liberal ideas hide illiberal

realities, how is just political action to be decided?[18]

Merleau-Ponty maintained an engaged though critical relationship to the

Marxist left until the end of his life, particularly during his time as

the political editor of the journal Les Temps modernes. |

メルロ=ポンティはそのキャリアを通じてマルクス主義に関与していた。

彼の1947年の著書『ヒューマニズムとテロル』は、ソ連の茶番裁判を擁護するものであると広く誤解されている[17]。実際、このテキストはソ連に関す

る見解の決定的な支持を避ける代わりに、自

由主義への批判としてマルクス主義の歴史理論に関わり、近代政治におけるヒューマニズムと恐怖の間の未解決のアンチノミー、すなわち人間の価値が暴力に

よってのみ達成できるならば、そして自由主義の考えが非自由主義の現実を隠しているなら、公正な政治的行動はどのように決められるのだろうか、

ということを明らかにするために書かれたものである[18]。 メルロ=ポンティは、特に雑誌『Les Temps

Modernes』の政治編集者であった時期、マルクス主義左派と批判的ではあったが、その関係を最後まで維持した[18]。 |

| Maurice

Merleau-Ponty was born in 1908 in Rochefort-sur-Mer,

Charente-Inférieure (now Charente-Maritime), France. His father died in

1913 when Merleau-Ponty was five years old.[19] After secondary

schooling at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris, Merleau-Ponty became a

student at the École Normale Supérieure, where he studied alongside

Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Simone Weil, Jean Hyppolite, and

Jean Wahl. As Beauvoir recounts in her autobiography, she developed a

close friendship with Merleau-Ponty and became smitten with him, but

ultimately found him too well-adjusted to bourgeois life and values for

her taste. He attended Edmund Husserl's "Paris Lectures" in February

1929.[20] In 1929, Merleau-Ponty received his DES degree (diplôme

d'études supérieures [fr], roughly equivalent to a M.A. thesis) from

the University of Paris, on the basis of the (now-lost) thesis La

Notion de multiple intelligible chez Plotin ("Plotinus's Notion of the

Intelligible Many"), directed by Émile Bréhier.[21] He passed the

agrégation in philosophy in 1930. Merleau-Ponty was raised as a Roman Catholic. He was friends with the Christian existentialist author and philosopher Gabriel Marcel and wrote articles for the Christian leftist journal Esprit, but he left the Catholic Church in 1937 because he felt his socialist politics were not compatible with the social and political doctrine of the Catholic Church.[22] An article published in the French newspaper Le Monde in October 2014 makes the case of recent discoveries about Merleau-Ponty's likely authorship of the novel Nord. Récit de l'arctique (Grasset, 1928). Convergent sources from close friends (Beauvoir, Elisabeth "Zaza" Lacoin) seem to leave little doubt that Jacques Heller was a pseudonym of the 20-year-old Merleau-Ponty.[23] Merleau-Ponty taught first at the Lycée de Beauvais (1931–33) and then got a fellowship to do research from the Caisse nationale de la recherche scientifique [fr]. From 1934 to 1935 he taught at the Lycée de Chartres. He then in 1935 became a tutor at the École Normale Supérieure, where he tutored a young Michel Foucault and Trần Đức Thảo and was awarded his doctorate on the basis of two important books: La structure du comportement (1942) and Phénoménologie de la Perception (1945). During this time, he attended Alexandre Kojeve's influential seminars on Hegel and Aron Gurwitsch's lectures on Gestalt psychology. |

1908

年、フランスのシャラント=アンフェリユール県(現シャラント=マリティム県)のロシュフォール=シュル=メールに生まれる。パリのリセ・ルイ・ル・グラ

ンで中等教育を受けた後、高等師範学校の学生となり、ジャン=ポール・サルトル、シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワール、シモーヌ・ヴァイル、ジャン・ヒポリッ

ト、ジャン・ヴァールらと共に学んだ[19]。ボーヴォワールが自伝で語っているように、彼女はメルロ=ポンティと親しい友人関係を築き、彼に夢中になっ

たが、結局、ブルジョワの生活と価値観に適応しすぎていて、自分の趣味には合わないと感じた。1929年2月、エドムンド・フッサールの「パリ講演会」に

参加[20] 、パリ大学でDES(diplôme d'études supérieures [fr]

、ほぼ修士号と同等)の学位を取得。1929年、エミール・ブレヒエの指導による論文「プロティヌスの知性的多数概念」(La Notion de

multiple intelligible chez Plotin)に基づいて、パリ大学からDESの学位を取得した[21]。 メルロ=ポンティはローマ・カトリック教徒として育てられた。キリスト教実存主義の作家・哲学者であるガブリエル・マルセルと親交があり、キリスト教左派 の雑誌『エスプリ』に記事を書いていたが、社会主義的な政治がカトリック教会の社会・政治教義と相容れないと感じ、1937年にカトリック教会を脱退した [22]。 2014年10月にフランスの新聞『ル・モンド』に掲載された記事では、メルロ=ポンティが小説『ノルド』の作者である可能性が高いことが近年発見された ことを事例として挙げている。Récit de l'arctique (Grasset, 1928)のことである。親しい友人たち(ボーヴォワール、エリザベート・"ザザ"・ラコワン)からの収斂した情報源は、ジャック・ヘラーが20歳のメル ロ=ポンティの偽名であることをほとんど疑わないようである[23]。 メルロ=ポンティはまずボーヴェのリセで教え(1931-33)、その後、国立科学研究費補助金[fr]から研究のためのフェローシップを受ける。 1934年から1935年にかけては、シャルトルのリセで教鞭をとった。その後、1935年にエコール・ノルマル・シュペリウールの講師となり、若き日の ミシェル・フーコーやトタン・ドゥック・タオを指導し、2冊の重要な著書をもとに博士号を授与された。La structure du comportement (1942) とPhénoménologie de la Perception (1945) の2冊の重要な著書に基づいて博士号を授与された。この間、アレクサンドル・コジェーヴのヘーゲルに関する影響力のあるセミナーや、アロン・グルヴィッチ のゲシュタルト心理学に関する講義を受講した。 |

| In

the spring of 1939, he was the first foreign visitor to the newly

established Husserl Archives, where he consulted Husserl's unpublished

manuscripts and met Eugen Fink and Father Hermann Van Breda. In the

summer of 1939, as France declared war on Nazi Germany, he served on

the frontlines in the French Army, where he was wounded in battle in

June 1940. Upon returning to Paris in the fall of 1940, he married

Suzanne Jolibois, a Lacanian psychoanalyst, and founded an underground

resistance group with Jean-Paul Sartre called "Under the Boot". He

participated in an armed demonstration against the Nazi forces during

the liberation of Paris.[24] After teaching at the University of Lyon

from 1945 to 1948, Merleau-Ponty lectured on child psychology and

education at the Sorbonne from 1949 to 1952.[25] He was awarded the

Chair of Philosophy at the Collège de France from 1952 until his death

in 1961, making him the youngest person to have been elected to a chair. Besides his teaching, Merleau-Ponty was also political editor for the leftist journal Les Temps modernes from its founding in October 1945 until December 1952. In his youth, he had read Karl Marx's writings[26] and Sartre even claimed that Merleau-Ponty converted him to Marxism.[27] While he was not a member of the French Communist Party and did not identify as a Communist, he laid out an argument justifying the Soviet farce trials and political violence for progressive ends in general in the work Humanism and Terror in 1947. However, about three years later, he renounced his earlier support for political violence, rejected Marxism, and advocated a liberal left position in Adventures of the Dialectic (1955).[28] His friendship with Sartre and work with Les Temps modernes ended because of that, since Sartre still had a more favourable attitude towards Soviet communism. Merleau-Ponty was subsequently active in the French non-communist left and in particular in the Union of the Democratic Forces. Merleau-Ponty died suddenly of a stroke in 1961 at age 53, apparently while preparing for a class on René Descartes, leaving an unfinished manuscript which was posthumously published in 1964, along with a selection of Merleau-Ponty's working notes, by Claude Lefort as The Visible and the Invisible. He is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris with his mother Louise, his wife Suzanne and their daughter Marianne. |

1939年春、

新設されたフッサール資料館に外国人として初めて訪れ、フッサールの未発表原稿を閲覧し、オイゲン・フィンクやヘルマン・ヴァン・ブレダ神父に会った。

1939年夏、フランスがナチス・ドイツに宣戦布告すると、フランス軍の最前線に従軍し、1940年6月に戦場で負傷する。1940年秋にパリに戻ると、

ラカン派の精神分析医シュザンヌ・ジョリボワと結婚し、ジャン=ポール・サルトルとともに地下抵抗組織「ブーツの下」を設立する。1945年から1948

年までリヨン大学で教鞭をとった後、1949年から1952年までソルボンヌ大学で児童心理と教育について講義した[25]。1952年から1961年に

亡くなるまでコレージュ・ド・フランスの哲学講座を受け、史上最年少で講座に選出された。 また、1945年10月の創刊から1952年12月まで、左翼系雑誌『レ・タン・モダン』の政治編集長を務めた。若い頃、カール・マルクスの著作を読んで おり[26]、サルトルはメルロ=ポンティが自分をマルクス主義に改宗させたとさえ主張している[27]。 フランス共産党員ではなく、共産主義者であることも認めなかったが、1947年に著作『人倫と恐怖』でソ連の茶番裁判や進歩的目的のための政治暴力一般を 正当とする論点を打ち立てている。しかし、約3年後、『弁証法の冒険』(1955年)において、それまでの政治的暴力への支持を放棄し、マルクス主義を否 定し、自由主義左派の立場を主張する[28]... サルトルがソ連共産主義に対してより好意的態度をとっていたので、そのためにサルトルとの友情とレスタンプ・モデルンの仕事は終了した。その後、メルロ= ポンティはフランスの非共産主義左派、特に民主勢力連合で活動することになる。 1961年、ルネ・デカルトの講義の準備中に脳卒中で53歳の若さで急死したが、未完の原稿を残し、1964年にクロード・ルフォールが『可視と不可視』 として、メルロ=ポンティの作業メモの一部を添えて出版した。母ルイーズ、妻シュザンヌ、娘マリアンヌとともにパリのペール・ラシェーズ墓地に埋葬されて いる。 |

| Consciousness In his Phenomenology of Perception (first published in French in 1945), Merleau-Ponty develops the concept of the body-subject (le corps propre) as an alternative to the Cartesian "cogito".[citation needed] This distinction is especially important in that Merleau-Ponty perceives the essences of the world existentially. Consciousness, the world, and the human body as a perceiving thing are intricately intertwined and mutually "engaged". The phenomenal thing is not the unchanging object of the natural sciences, but a correlate of our body and its sensory-motor functions. Taking up and "communing with" (Merleau-Ponty's phrase) the sensible qualities it encounters, the body as incarnated subjectivity intentionally elaborates things within an ever-present world frame, through use of its pre-conscious, pre-predicative understanding of the world's makeup. The elaboration, however, is "inexhaustible" (the hallmark of any perception according to Merleau-Ponty). Things are that upon which our body has a "grip" (prise), while the grip itself is a function of our connaturality with the world's things. The world and the sense of self are emergent phenomena in an ongoing "becoming". The essential partiality of our view of things, their being given only in a certain perspective and at a certain moment in time does not diminish their reality, but on the contrary establishes it, as there is no other way for things to be copresent with us and with other things than through such "Abschattungen" (sketches, faint outlines, adumbrations). The thing transcends our view, but is manifest precisely by presenting itself to a range of possible views. The object of perception is immanently tied to its background—to the nexus of meaningful relations among objects within the world. Because the object is inextricably within the world of meaningful relations, each object reflects the other (much in the style of Leibniz's monads). Through involvement in the world – being-in-the-world – the perceiver tacitly experiences all the perspectives upon that object coming from all the surrounding things of its environment, as well as the potential perspectives that that object has upon the beings around it. Each object is a "mirror of all others". Our perception of the object through all perspectives is not that of a propositional, or clearly delineated, perception; rather, it is an ambiguous perception founded upon the body's primordial involvement and understanding of the world and of the meanings that constitute the landscape's perceptual Gestalt. Only after we have been integrated within the environment so as to perceive objects as such can we turn our attention toward particular objects within the landscape so as to define them more clearly. This attention, however, does not operate by clarifying what is already seen, but by constructing a new Gestalt oriented toward a particular object. Because our bodily involvement with things is always provisional and indeterminate, we encounter meaningful things in a unified though ever open-ended world. |

意識(コンシャスネス) メルロ=ポンティは『知覚の現象学』(1945年にフランス語で発表)の中で、デカ ルトの「コギト」に代わるものとして身体主体(le corps propre)の概念を展開している[citation needed] この区別は、メルロ=ポンティが世界の本質を実在的に知覚する上でとりわけ重要である。意識、世界、そして知覚するものとしての人間の身体は複雑に絡み 合っており、相互に「関与」している。現象的なものは、自然科学の不変の対象ではなく、私たちの身体とその感覚運動機能の相関関係である。受肉した主体と しての身体は、出会った感覚的な質を取り込み、「交感」(メルロ=ポンティの言葉)しながら、世界の構成に関する前意識的、予見的理解を用いて、常に存在 する世界の枠内で意図的に物事を精緻化する。しかし、その精緻化は「無尽蔵」である(メルロ=ポンティによれば、あらゆる知覚の特徴である)。物とは、私 たちの身体が「握る」(prise)ものであり、握ること自体は、世界の物に対する私たちの接続性の関数である。世界と自己の感覚は、現在進行中の「なり ゆき」において出現する現象である。 私たちのものの見方が本質的に偏向していること、ある視点とある瞬間にしか与えられないことは、ものの実在性を弱めるものではなく、逆にそれを確立するも のである。なぜなら、ものが私たちと他のものと共在するためには、このような「Abschattungen」(スケッチ、かすかな輪郭、装飾)を通して以 外に方法はないからである。事物は我々の視界を超越しているが、可能な視界の範囲に自らを提示することによって、まさに顕在化しているのである。知覚の対 象は、その背景である、世界の中の対象間の意味ある関係の結びつきに内在的に結びつけられている。対象は意味ある関係の世界と表裏一体であるため、それぞ れの対象は他を反映する(ライプニッツのモナドによく似たスタイル)。世界に関与すること、すなわち「世界に存在すること」を通して、知覚者は、その環境 の周囲のすべてのものから来るその対象へのすべての視点と、その対象が周囲の存在に持つ潜在的な視点を暗黙のうちに経験する。 それぞれの対象は、「他のすべての鏡」なのである。むしろそれは、世界と風景の知覚のゲシュタルトを構成する意味に対する身体の原初的な関与と理解に基づ く曖昧な知覚なのである。私たちは環境の中に統合され、物体をそのように認識できるようになって初めて、風景の中の特定の物体に注意を向け、それらをより 明確に定義することができるようになる。しかし、この注意は、すでに見えているものを明確にするのではなく、特定の対象に向かって新しいゲシュタルトを構 築することによって行われる。私たちの身体的な関わりは常に暫定的で不確定なものであるため、私たちは統一された、しかし常に開放的な世界の中で意味のあ るものに出会うのである。 |

| The primacy of perception From the time of writing Structure of Behavior and Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty wanted to show, in opposition to the idea that drove the tradition beginning with John Locke, that perception was not the causal product of atomic sensations. This atomist-causal conception was being perpetuated in certain psychological currents of the time, particularly in behaviourism. According to Merleau-Ponty, perception has an active dimension, in that it is a primordial openness to the lifeworld (the "Lebenswelt"). This primordial openness is at the heart of his thesis of the primacy of perception. The slogan of Husserl's phenomenology is "all consciousness is consciousness of something", which implies a distinction between "acts of thought" (the noesis) and "intentional objects of thought" (the noema). Thus, the correlation between noesis and noema becomes the first step in the constitution of analyses of consciousness. However, in studying the posthumous manuscripts of Husserl, who remained one of his major influences, Merleau-Ponty remarked that, in their evolution, Husserl's work brings to light phenomena which are not assimilable to noesis–noema correlation. This is particularly the case when one attends to the phenomena of the body (which is at once body-subject and body-object), subjective time (the consciousness of time is neither an act of consciousness nor an object of thought) and the other (the first considerations of the other in Husserl led to solipsism). The distinction between "acts of thought" (noesis) and "intentional objects of thought" (noema) does not seem, therefore, to constitute an irreducible ground. It appears rather at a higher level of analysis. Thus, Merleau-Ponty does not postulate that "all consciousness is consciousness of something", which supposes at the outset a noetic-noematic ground. Instead, he develops the thesis according to which "all consciousness is perceptual consciousness". In doing so, he establishes a significant turn in the development of phenomenology, indicating that its conceptualisations should be re-examined in the light of the primacy of perception, in weighing up the philosophical consequences of this thesis. |

知覚の優位性 メルロ=ポンティは『行動の構造』と『知覚の現象学』を執筆しているときから、ジョン・ロックに始まる伝統を牽引してきた考えと対立して、知覚は原子的感 覚の因果的産物ではないことを示したいと考えていた。この原子論的因果概念は、当時のある種の心理学的潮流、特に行動主義において永続して いた。メルロ= ポンティによれば、知覚は、生命界(「Lebenswelt」)に対する根源的な開放性という能動的な次元を持っている。 この原初的な開放性が、知覚の原初性という彼のテーゼの核心である。フッサールの現象学のスローガンは「すべての意識は何かの意識である」であり、これは 「思考の行為」(ノエシス)と「思考の意図的対象」(ノエマ)の 区別を意味する。したがって、ノエシスとノエマの相関関係は、意識分析の構成の第一歩とな る。しかし、メルロ=ポンティは、大きな影響を受け続けたフッサールの遺稿を研究する中で、フッサールの研究は、その進化の過程で、ノエシス-ノエマ相関 とは同化できない現象を浮かび上がらせていると指摘する。特に、身体(身体-主体であると同時に身体-客体である)、主観的時間(時間の意識は意識行為で も思考対象でもない)、他者(フッサールにおける他者の最初の考察は独在論につながった)の現象に注目するとき、このことが言える。 したがって、「思考行為」(ノエシス)と「思考の意図的対象」(ノエマ)の区別は、還元不可能な根拠を構成しているようには思われない。それはむしろ、よ り高次の分析レベルに現れるものである。したがって、メルロ=ポンティは、「すべての意識は何かの意識である」という、ノエシス-ノエマ的な根拠を最初か ら前提とするような仮定はしていない。その代わりに、「すべての意識は知覚的な意識である」というテーゼを展開する。そして、このテーゼの哲学的帰結を検 討する際に、知覚の優位性に照らして、現象学の概念化を再検討する必要があることを示唆している。 |

| Corporeity Taking the study of perception as his point of departure, Merleau-Ponty was led to recognize that one's own body (le corps propre) is not only a thing, a potential object of study for science, but is also a permanent condition of experience, a constituent of the perceptual openness to the world. He therefore underlines the fact that there is an inherence of consciousness and of the body of which the analysis of perception should take account. The primacy of perception signifies a primacy of experience, so to speak, insofar as perception becomes an active and constitutive dimension. Merleau-Ponty demonstrates a corporeity of consciousness as much as an intentionality of the body, and so stands in contrast with the dualist ontology of mind and body in Descartes, a philosopher to whom Merleau-Ponty continually returned, despite the important differences that separate them. In the Phenomenology of Perception Merleau-Ponty wrote: “Insofar as I have hands, feet, a body, I sustain around me intentions which are not dependent on my decisions and which affect my surroundings in a way that I do not choose” (1962, p. 440). |

コーポラリティ(身体性) メルロ=ポンティは、知覚の研究を出発点として、自分自身の身体(le corps propre)が単にモノであり、科学の研究対象となりうるだけでなく、経験の永続的条件、世界に対する知覚的開放の構成要素であることを認識するように なる。したがって、知覚の分析が考慮すべきは、意識と身体の不可分性であることを強調している。知覚の優位性は、知覚が能動的かつ構成的な次元となる限 り、いわば経験の優位性を意味する。 メルロ=ポンティは、意識の身体性を身体の意図性と同様に示しており、デカルトにおける心と身体の二元論的存在論と対照的である。メルロ=ポンティは『知 覚の現象学』の中で、「私に手と足と身体がある限り、私は私の決断に依存しない意図を私の周りに維持し、私が選択しない方法で私の周囲に影響を与える」 (1962、440頁)と書いている。 |

| Spatiality The question concerning corporeity connects also with Merleau-Ponty's reflections on space (l'espace) and the primacy of the dimension of depth (la profondeur) as implied in the notion of being in the world (être au monde; to echo Heidegger's In-der-Welt-sein) and of one's own body (le corps propre).[29] Reflections on spatiality in phenomenology are also central to the advanced philosophical deliberations in architectural theory.[30] |

空間性 身体性に関する問題は、メルロ=ポンティの空間(l'espace)に関する考察や、世界における存在(être au monde;ハイデガーのIn-der-Welt-sein)と自分自身の身体(le corps propre)の概念に暗示される深さの次元の優先性とも結びついている[29] 。現象学における空間性に関する考察は、建築理論における高度な哲学的検討の中心でもある[30]。 |

| Language The highlighting of the fact that corporeity intrinsically has a dimension of expressivity which proves to be fundamental to the constitution of the ego is one of the conclusions of The Structure of Behavior that is constantly reiterated in Merleau-Ponty's later works. Following this theme of expressivity, he goes on to examine how an incarnate subject is in a position to undertake actions that transcend the organic level of the body, such as in intellectual operations and the products of one's cultural life. He carefully considers language, then, as the core of culture, by examining in particular the connections between the unfolding of thought and sense—enriching his perspective not only by an analysis of the acquisition of language and the expressivity of the body, but also by taking into account pathologies of language, painting, cinema, literature, poetry, and music. This work deals mainly with language, beginning with the reflection on artistic expression in The Structure of Behavior—which contains a passage on El Greco (p. 203ff) that prefigures the remarks that he develops in "Cézanne's Doubt" (1945) and follows the discussion in Phenomenology of Perception. The work, undertaken while serving as the Chair of Child Psychology and Pedagogy at the University of the Sorbonne, is not a departure from his philosophical and phenomenological works, but rather an important continuation in the development of his thought. As the course outlines of his Sorbonne lectures indicate, during this period he continues a dialogue between phenomenology and the diverse work carried out in psychology, all in order to return to the study of the acquisition of language in children, as well as to broadly take advantage of the contribution of Ferdinand de Saussure to linguistics, and to work on the notion of structure through a discussion of work in psychology, linguistics and social anthropology. |

言語 身体性が本質的に表現性の次元を持ち、それが自我の構成にとって基本的であることを強調したことは、『行動の構造』の結論の一つであり、その後のメルロ= ポンティの著作で常に繰り返される。この表現力のテーマに続いて、彼は、受肉した主体が、知的活動や文化的生活の産物など、身体の有機的なレベルを超えた 行為を行う立場にあることを検証していく。 そして、言語の獲得と身体の表現力の分析だけでなく、言語、絵画、映画、文学、詩、音楽などの病理を考慮しながら、特に思考の展開と感覚の関連性を検討 し、文化の核である言語を注意深く考察していくのである。 この著作は、主に言語を扱い、『行動の構造』の芸術表現に関する考察から始まる。この中にあるエル・グレコに関する一節(203ff)は、『セザンヌの疑 惑』(1945)で展開する発言の前触れであり、『知覚の現象学』の議論に続くものである。ソルボンヌ大学で児童心理学・教育学の講座を担当しながら取り 組んだこの作品は、彼の哲学的・現象学的著作からの逸脱ではなく、むしろ彼の思想展開における重要な継続である。 ソルボンヌ大学での講義の概要が示すように、この時期、彼は現象学と心理学における多様な研究との対話を続け、子どもの言語習得の研究に立ち戻るととも に、フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールの言語学への貢献を広く活用し、心理学、言語学、社会人類学の研究の議論を通じて構造という概念に取り組んでいるので ある。 |