affordance

アフォーダンスとは思わずボタンを押したりクリックすることである:左は動画ではないが押してしまい、右は独裁者のオフィスからの核戦争がはじまる

脅威のジョークである

アフォーダンス

affordance

アフォーダンスとは思わずボタンを押したりクリックすることである:左は動画ではないが押してしまい、右は独裁者のオフィスからの核戦争がはじまる

脅威のジョークである

解説:池田光穂

アフォーダンスとは、与えられた環境の中 で適合的に遂行することができる主体の行動ならびにその特性のことをさす。

たとえばボタン型のスイッチは、適切な質 感と運動量をもつことで、スイッチとしてのアフォーダンスを誘発する。認知心理学(生態心理学)者であ るジェームズ・ジェローム・ギブソン(James Jerome Gibson, 1904-1979)は、環境のなかで生きる生き物が環境のなかで動き回る時に、適合的な主体の行動の引き起こす局所的な環境要因をもちうると考えて、〜 できる、〜する余地がある、〜を提供するという動詞アフォード(afford)の名詞化を考案し、そのような適合的な「主体の行動ならびにその特性」をア フォーダンス(affordance)と呼んだ。

アフォーダンスは、それに適合的な行動を 誘発させる点で、動物行動学におけるある種のリリーサー(誘発要因)に近いが、ギブソンの概念はより機 能的であり、またアフォーダンスの獲得は環境のなかでの生物学的特性と学習のアンサンブルとして理解されている。

生物種にとってアフォーダンスが異なる例 としては、高地の険しい崖と草原を移動するゲラダヒヒにとっては崖は捕食者から身を守る重要な環境とし てアフォードされるが、平地に適合した人間[高所で仕事する鳶職を除けば]は崖は危険な環境を示すアフォーダンスを提供する。もちろん、ゲラダヒヒも鳶職 も不幸にも崖や高所から転落する例外もあるが、アフォーダンス特性はそのような事件によっては変化しない。

ギブソンのアフォーダンスの概念の重要性 は、生物は環境の中で柔軟に適合的行動をとっているという主知主義的な行動概念に反省をもたらしたこと にある。すなわち、環境は生物にとって均質な空間ではなく、さまざまな異質な要素が絡まりあったものであるがゆえに、環境自体が生物の固有な行動を引き出 し、適合的な共生[生物と生物ではなく環境と生物の共生である]状態をつくるということである。ギブソンが自らを生態心理学者(ecological psychologist)と理解することが彼の理論からも明確にわかる。

文献

Affordance induced character is not only physical but signal one, you can see that small tires did afford in the white marker on the taxiway.

航空機の移動陸橋(Jet

bridge)——ボーディング・ブリッジって、和製英語だということに、ようやく気づく。それを使いたいときは、passenger

boarding bridge (PBB)というらしい——のタイアに誘導するプロセスはフィードバックループを形成する。

If there is no cue of affordance in surface of material, we should sign some maker in surface for inducing it's affordance.

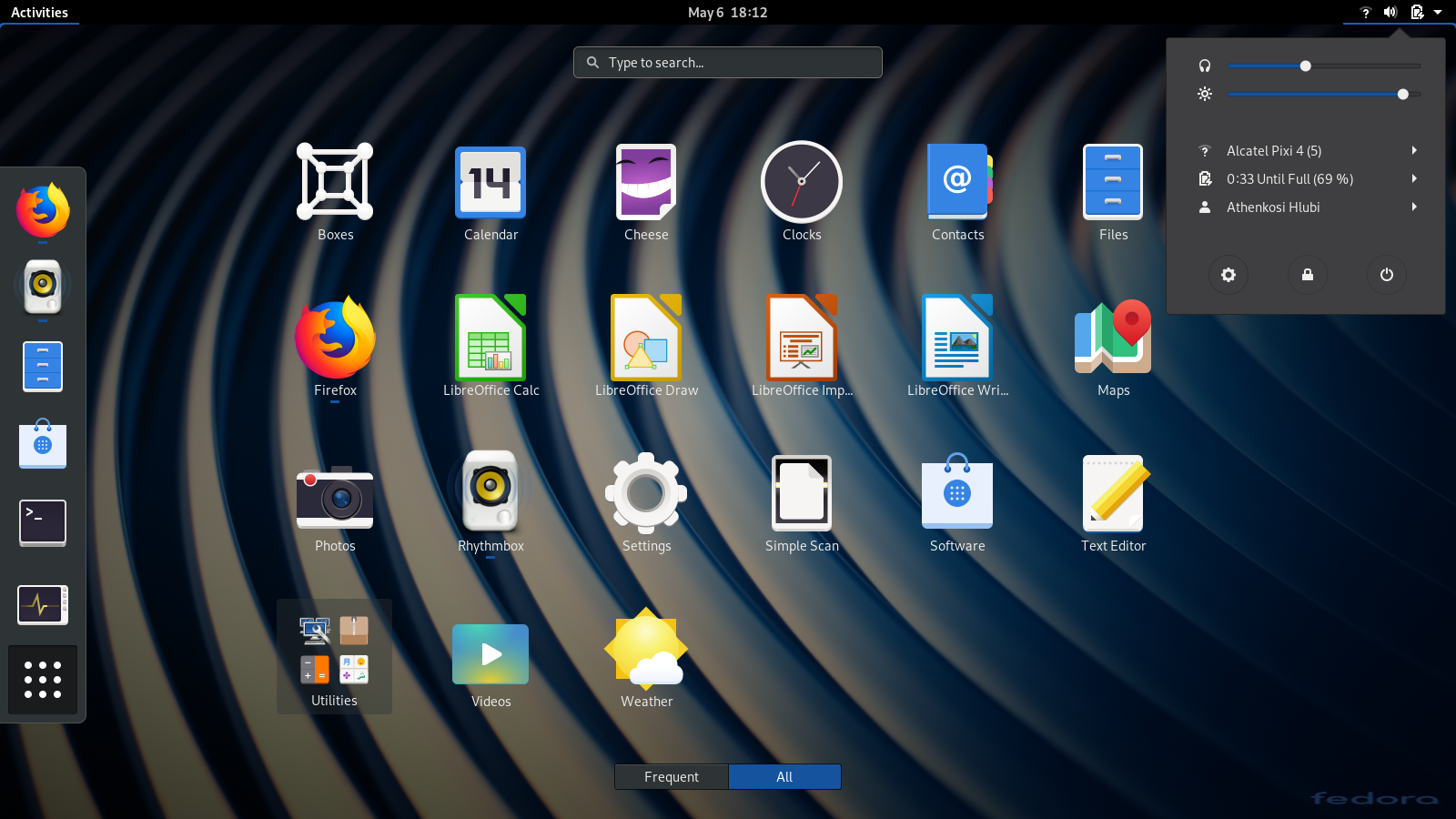

●下記の画像にみなさんはポインタをもっ てくると、中央のブルーの三角の部分をクリックしているはずだ、それも「アフォーダンス」がなせる技で ある。

アフォーダンスに対する反対語が「排除のためのコミュニ ケーションデザイン」である。老人が自分の小学校時代にあった木製の椅子に座ろうとしたくなるのは「アフォーダンス」のなせる技である。

●アフォーダンス・ジョークの窓口

|

|

| 子供たちに《絶対に!押すな》示すと多くの子どもたちが[その誘惑に負けて]実際に押すそうです |

Kim Jong-un's black cat |

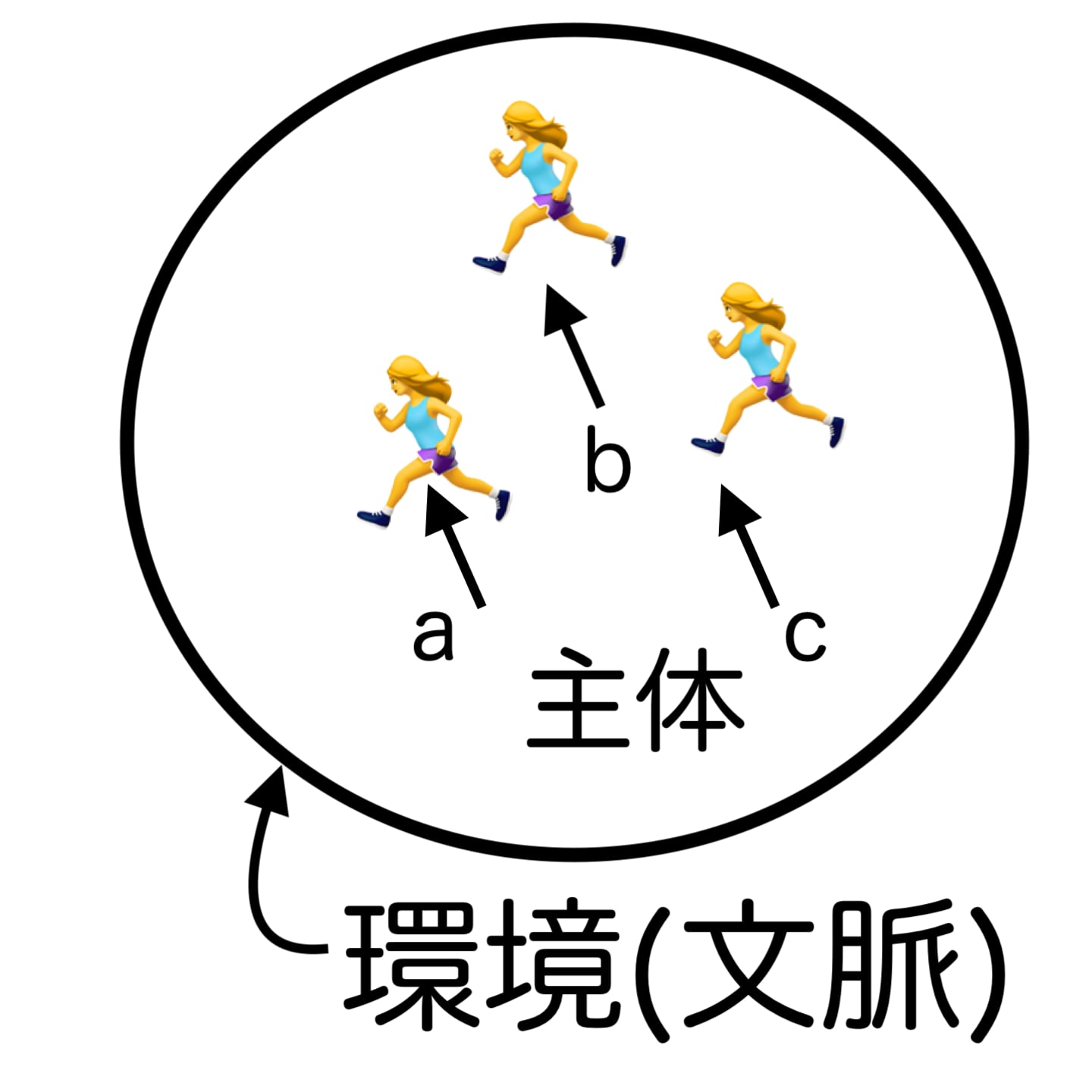

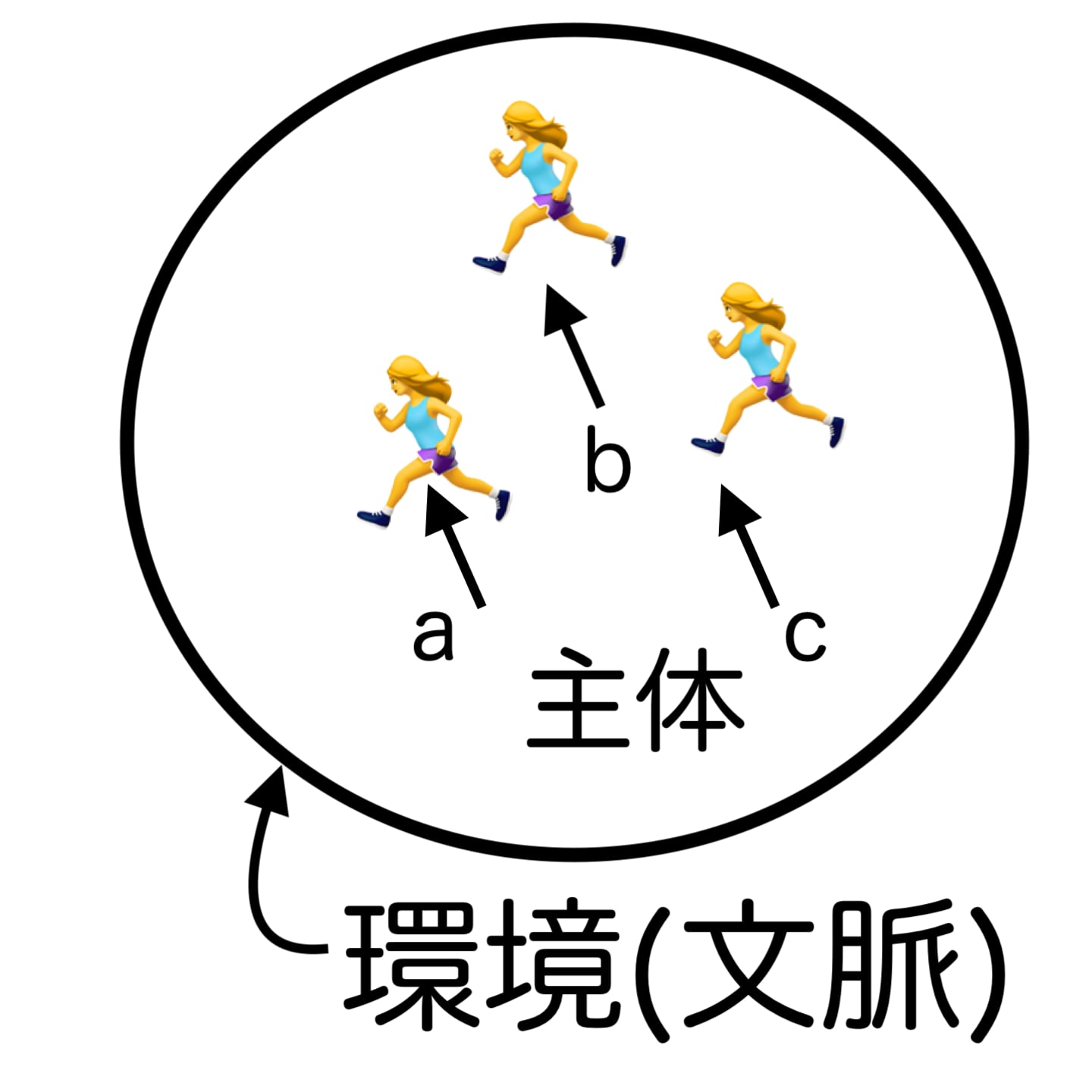

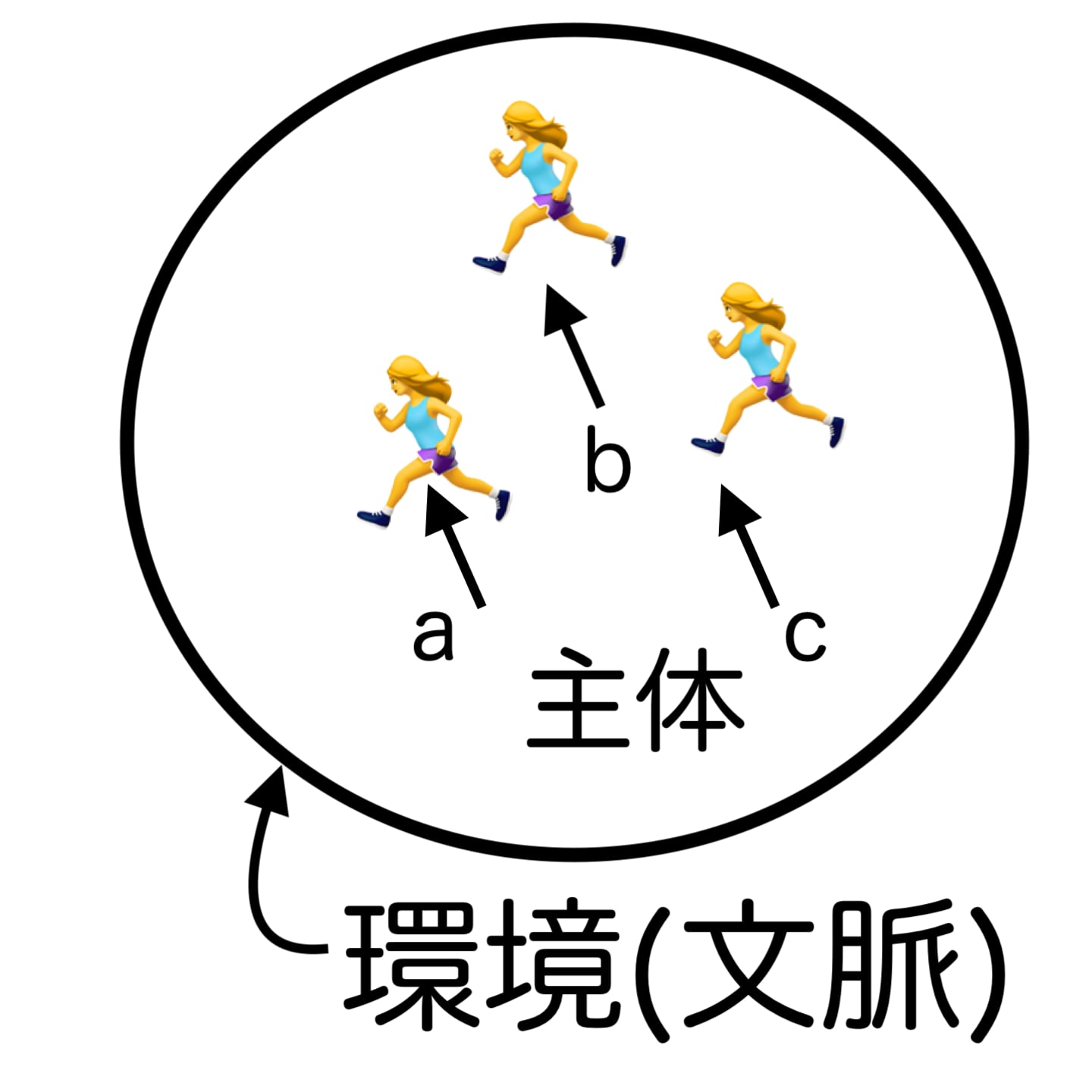

★ 《環境と主体は調和しなければならない》

「環 境と主体が一致する」のではなく、「環境と主体が調和する」のです。このことを図式を もって説明してみましょう。たとえば、環境は丸のなかですが、100m競走では競技者はグラウンドの中でないと競技できません。他方、マラソンランナー は、その環境が、競技場の外の一般公道まで拡張します。短距離競走の選手は競技場という環境と調和しますが、マラソンランナーの環境は公道をふくめた走路 まで拡張します(ただしマラソンもランナーが走路からはずれると、競技者は失格になります)

☆Affordance in Wikipedia

The design of tea

cups and a teapot suggest their respective functions

| In psychology, affordance

is what the environment offers the individual. In design, affordance

has a narrower meaning, it refers to possible actions that an actor can

readily perceive. American psychologist James J. Gibson coined the term in his 1966 book, The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems,[1] and it occurs in many of his earlier essays.[2] His best-known definition is from his 1979 book, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill. ... It implies the complementarity of the animal and the environment.[3] The word is used in a variety of fields: perceptual psychology; cognitive psychology; environmental psychology; criminology; industrial design; human–computer interaction (HCI); interaction design; user-centered design; communication studies; instructional design; science, technology, and society (STS); sports science; and artificial intelligence.  A door knob shaped to reflect how it is used, an example of perceptible affordance |

心理学では、アフォーダンスとは環境が個人に提供するものである。デザ

インにおけるアフォーダンスはより狭い意味を持っており、行為者が容易に知覚できる可能性のある行動を指す。 アメリカの心理学者ジェームス・J・ギブソンは、1966年に出版した著書『知覚システムとして考察される感覚』[1]の中でこの用語を作り出し、彼の初 期のエッセイの多くにも登場する[2]。彼の最もよく知られた定義は、1979年に出版した著書『視覚知覚への生態学的アプローチ』にある: 環境のアフォーダンスとは、環境が動物に提供するものであり、善かれ悪しかれ提供 するものである。それは動物と環境の相補性を意味する[3]。 この言葉は知覚心理学、認知心理学、環境心理学、犯罪学、工業デザイン、ヒューマンコンピュータインタラクション(HCI)、インタラクションデザイン、 ユーザー中心デザイン、コミュニケーション学、教育デザイン、科学・技術・社会(STS)、スポーツ科学、人工知能など様々な分野で使われている。  知覚可能なアフォーダンスの一例である、使い方を反映した形状のドアノブ。 |

| Original development Gibson developed the concept of affordance over many years, culminating in his final book, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception[4] in 1979. He defined an affordance as what the environment provides or furnishes the animal. Notably, Gibson compares an affordance with an ecological niche emphasizing the way niches characterize how an animal lives in its environment. The key to understanding affordance is that it is relational and characterizes the suitability of the environment to the observer, and so, depends on their current intentions and their capabilities. For instance, a set of steps which rises 1 metre (3 ft) high does not afford climbing to the crawling infant, yet might provide rest to a tired adult or the opportunity to move to another floor for an adult who wished to reach an alternative destination. This notion of intention/needs is critical to an understanding of affordance, as it explains how the same aspect of the environment can provide different affordances to different people, and even to the same individual at another point in time. As Gibson puts it, “Needs control the perception of affordances (selective attention) and also initiate acts.”[5] Affordances were further studied by Eleanor J. Gibson, wife of James J. Gibson, who created her theory of perceptual learning around this concept. Her book, An Ecological Approach to Perceptual Learning and Development, explores affordances further. Gibson's is the prevalent definition in cognitive psychology. According to Gibson, humans tend to alter and modify their environment so as to change its affordances to better suit them. In his view, humans change the environment to make it easier to live in (even if making it harder for other animals to live in it): to keep warm, to see at night, to rear children, and to move around. This tendency to change the environment is natural to humans, and Gibson argues that it is a mistake to treat the social world apart from the material world or the tools apart from the natural environment. He points out that manufacturing was originally done by hand as a kind of manipulation. Gibson argues that learning to perceive an affordance is an essential part of socialization. The theory of affordances introduces a "value-rich ecological object".[4] Affordances cannot be described within the value-neutral language of physics, but rather introduces notions of benefits and injuries to someone. An affordance captures this beneficial/injurious aspect of objects and relates them to the animal for whom they are well/ill-suited. During childhood development, a child learns to perceive not only the affordances for the self, but also how those same objects furnish similar affordances to another. A child can be introduced to the conventional meaning of an object by manipulating which objects command attention and demonstrating how to use the object through performing its central function.[6] By learning how to use an artifact, a child “enters into the shared practices of society” as when they learn to use a toilet or brush their teeth.[6] And so, by learning the affordances, or conventional meaning of an artifact, children learn the artifact's social world and further, become a member of that world. Anderson, Yamagishi and Karavia (2002) found that merely looking at an object primes the human brain to perform the action the object affords.[7]  Affordance is one of several design principles used when designing graphical user interfaces. |

独自の発展[編集] ギブソンは長年にわたってアフォーダンスの概念を発展させ、1979年に最後の著書『The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception』[4]を出版した。ギブソンはアフォーダンスを「環境が動物に与えるもの」と定義した。注目すべきは、ギブソンがアフォーダンスを 生態学的ニッチと比較し、ニッチがその環境における動物の生き方を特徴づけることを強調している点である。 アフォーダンスを理解する鍵は、アフォーダンスが関係的なものであり、観察者にとっての環境の適合性を特徴づけるものであるということである。例えば、高 さ1メートルの階段は、ハイハイしている幼児にとっては登ることはできないが、疲れている大人にとっては休息になり、別の目的地に行きたい大人にとっては 別の階に移動する機会になるかもしれない。この意図/ニーズという概念は、アフォーダンスを理解する上で非常に重要である。なぜなら、環境の同じ側面が、 異なる人々、さらには別の時点で同じ個人にさえ、異なるアフォーダンスを提供しうることを説明できるからである。ギブソンが言うように、「ニーズはア フォーダンスの知覚(選択的注意)を制御し、また行為を開始する」[5]。 アフォーダンスは、ジェームズ・J・ギブソンの妻であるエレノア・J・ギブソンによってさらに研究され、彼女はこの概念を中心に知覚学習の理論を構築し た。彼女の著書『An Ecological Approach to Perceptual Learning and Development(知覚学習と発達への生態学的アプローチ)』では、アフォーダンスについてさらに掘り下げている。 ギブソンの定義が認知心理学では一般的である。ギブソンによれば、人間は環境を変化させ、そのアフォーダンスをより自分に合うように変更する傾向がある。 ギブソンの考えでは、人間は(たとえ他の動物が住みにくくなったとしても)、暖をとるため、夜目が利くようにするため、子供を育てるため、移動するためな ど、住みやすいように環境を変える。環境を変えようとするこの傾向は人間にとって自然なことであり、ギブソンは、社会的世界を物質的世界から、あるいは道 具を自然環境から切り離して扱うのは間違いだと主張する。彼は、ものづくりはもともと一種の操作として手作業で行われていたと指摘する。ギブソンは、ア フォーダンスを知覚することを学ぶことは、社会化の本質的な部分であると主張する。 アフォーダンスの理論は「価値豊かな生態学的対象」[4]を導入している。アフォーダンスは物理学の価値中立的な言語では記述できず、むしろ誰かに対する 利益と損害の概念を導入している。アフォーダンスは物体のこの有益/有害な側面を捉え、それが適している/適していない動物と関連付ける。幼少期の発達の 中で、子どもは自分にとってのアフォーダンスだけでなく、同じモノが別の誰かにとってどのようなアフォーダンスをもたらすかについても学んでいく。子ども は、どの物体が注意を引くかを操作し、その物体の中心的な機能を実行することによって、その物体の使い方を示すことによって、その物体の従来の意味を知る ことができる[6]。人工物の使い方を学ぶことによって、子どもは、トイレの使い方や歯磨きの仕方を学ぶときのように、「社会の共有された慣習の中に入っ ていく」[6]。そして、人工物のアフォーダンス(従来の意味)を学ぶことによって、子どもは人工物の社会的世界を学び、さらにその世界の一員となる。 アンダーソン、山岸、カラヴィア(2002年)は、単に物体を見るだけで、人間の脳はその物体がもたらす行為を行うようになることを発見した[7]。  アフォーダンスとは、グラフィカル・ユーザー・インターフェースをデザインする際に用いられるいくつかのデザイン原則のひとつである。 |

| As perceived action possibilities In 1988, Donald Norman appropriated the term affordances in the context of Human–Computer Interaction to refer to just those action possibilities that are readily perceivable by an actor. This new definition of "action possibilities" has now become synonymous with Gibson's work, although Gibson himself never made any reference to action possibilities in any of his writing.[8] Through Norman's book The Design of Everyday Things,[9] this interpretation was popularized within the fields of HCI, interaction design, and user-centered design. It makes the concept dependent not only on the physical capabilities of an actor, but also on their goals, beliefs, and past experiences. If an actor steps into a room containing an armchair and a softball, Gibson's original definition of affordances allows that the actor may throw the chair and sit on the ball, because this is objectively possible. Norman's definition of (perceived) affordances captures the likelihood that the actor will sit on the armchair and throw the softball. Effectively, Norman's affordances "suggest" how an object may be interacted with. For example, the size, shape, and weight of a softball make it perfect for throwing by humans, and it matches their past experience with similar objects, as does the shape and perceptible function of an armchair for sitting. The focus on perceived affordances is much more pertinent to practical design problems [why?], which may explain its widespread adoption. Norman later explained that this restriction of the term's meaning had been unintended, and in his 2013 update of The Design of Everyday Things, he added the concept "signifiers". In the digital age, designers were learning how to indicate what actions were possible on a smartphone's touchscreen, which didn't have the physical properties that Norman intended to describe when he used the word "affordances". Designers needed a word to describe what they were doing, so they chose affordance. What alternative did they have? I decided to provide a better answer: signifiers. Affordances determine what actions are possible. Signifiers communicate where the action should take place. We need both.[10] However, the definition from his original book has been widely adopted in HCI and interaction design, and both meanings are now commonly used in these fields. Following Norman's adaptation of the concept, affordance has seen a further shift in meaning where it is used as an uncountable noun, referring to the easy discoverability of an object or system's action possibilities, as in "this button has good affordance".[11] This in turn has given rise to use of the verb afford – from which Gibson's original term was derived – that is not consistent with its dictionary definition (to provide or make available): designers and those in the field of HCI often use afford as meaning "to suggest" or "to invite".[12] The different interpretations of affordances, although closely related, can be a source of confusion in writing and conversation if the intended meaning is not made explicit and if the word is not used consistently. Even authoritative textbooks can be inconsistent in their use of the term.[11][12] When affordances are used to describe information and communications technology (ICT) an analogy is created with everyday objects with their attendant features and functions.[13] Yet, ICT's features and functions derive from the product classifications of its developers and designers. This approach emphasizes an artifact’s convention to be wholly located in how it was designed to be used. In contrast, affordance theory draws attention to the fit of the technology to the activity of the user and so lends itself to studying how ICTs may be appropriated by users or even misused.[13] One meta-analysis reviewed the evidence from a number of surveys about the extent to which the Internet is transforming or enhancing community. The studies showed that the internet is used for connectivity locally as well as globally, although the nature of its use varies in different countries. It found that internet use is adding on to other forms of communication, rather than replacing them.[14] |

知覚された行動の可能性として[編集]。 1988年、ドナルド・ノーマンは ヒューマン・コンピュータ・インタラクションの文脈で、行為者が容易に知覚可能な行動の可能性だけを指すためにアフォーダンスという用語を流用した。ノー マンの著書『The Design of Everyday Things』[9]を通して、この解釈はHCI、インタラクションデザイン、ユーザー中心設計の分野で広まった。この解釈は、概念を行為者の身体的能力 だけでなく、目標、信念、過去の経験にも依存させる。ある行為者が肘掛け椅子とソフトボールのある部屋に足を踏み入れたとすると、ギブソンのアフォーダン スのオリジナルな定義では、行為者は椅子を投げてボールの上に座ることができる。ノーマンの(知覚された)アフォーダンスの定義は、行為者が肘掛け椅子に 座り、ソフトボールを投げる可能性を捉えている。事実上、ノーマンのアフォーダンスは物体がどのように相互作用する可能性があるかを「示唆」している。例 えば、ソフトボールの大きさ、形、重さは人間が投げるのに最適なものであり、過去に同じようなものを使った経験と一致する。知覚されるアフォーダンスに焦 点を当てることは、実用的なデザイン問題により適切であり[なぜか? ノーマンは後に、この用語の意味の制限は意図的ではなかったと説明し、2013年の『The Design of Everyday Things』のアップデートで、「シニフィアン」という概念を追加した。デジタルの時代、デザイナーはスマートフォンのタッチスクリーンでどのような操 作が可能かを示す方法を学んでいたが、タッチスクリーンはノーマンが「アフォーダンス」という言葉を使ったときに説明しようとした物理的特性を持っていな かった。 デザイナーたちは、自分たちがやっていることを表現する言葉が必要だったので、アフォーダンスを選んだのだ。では、どんな代替案があったのだろうか?私は 「シニフィアン」という、より良い答えを提示することにした。アフォーダンスは、どのような行動が可能かを決定する。シニフィエは、そのアクションがどこ で行われるべきかを伝える。私たちにはその両方が必要なのだ。 しかし、彼の原著の定義はHCIとインタラクション・デザインの分野で広く採用され、今では両方の意味がこれらの分野で一般的に使われている。 Normanがこの概念を適応させた後、アフォーダンスは、「このボタンは良いアフォーダンスを持っている」というように、オブジェクトやシステムのアク ションの可能性を容易に発見できることを意味する不可算名詞として使われるようになり、さらに意味の変化が見られるようになった[11]。 アフォーダンスの異なる解釈は、密接に関連しているものの、意図された意味が明示されず、単語が一貫して使用されない場合、文章や会話における混乱の原因 となりうる。権威ある教科書でさえ、この用語の使い方に一貫性がないことがある[11][12]。 情報通信技術(ICT)を説明するためにアフォーダンスが使用されるとき、それに付随する特徴や機能を持つ日用品とのアナロジーが生み出される[13] が、ICTの特徴や機能はその開発者や設計者の製品分類に由来する。このアプローチは、人工物の慣習が、それがどのように使用されるように設計されたかに 完全に位置づけられることを強調する。これとは対照的に、アフォーダ ンス理論は、利用者の活動に対する技術の適合性に注目するため、 ICTが利用者によってどのように流用されるか、あるいは誤用され るかを研究するのに適している。その結果、インターネットは、国によって利用の性質は異なるものの、地域的・世界的なつながりのために利用されていること がわかった。インターネットの利用は、他のコミュニケーション形態に取って代わるというよりは、むしろそれに付加していることがわかった[14]。 |

| Mechanisms and conditions

framework of affordances Jenny L. Davis introduced the mechanisms and conditions framework of affordances in a 2016 article[15] and 2020 book.[16][17] The mechanisms and conditions framework shifts the orienting question from what technologies afford to how technologies afford, for whom and under what circumstances? This framework deals with the problem of binary application and presumed universal subjects in affordance analyses. The mechanisms of affordance indicate that technologies can variously request, demand, encourage, discourage, refuse, and allow social action, conditioned on users' perception, dexterity, and cultural and institutional legitimacy in relation to the technological object. This framework adds specificity to affordances, focuses attention on relationality, and centralizes the role of values, politics, and power in affordance theory. The mechanisms and conditions framework is a tool of both socio-technical analysis and socially aware design. |

アフォーダンスのメカニズムと条件の枠組み[編集]。 ジェニー・L・デイヴィスは2016年の論文[15]と2020年の著書[16][17]において、アフォーダンスのメカニズムと条件の枠組みを紹介して いる。この枠組みは、アフォーダンス分析における二元的な適用と推定される普遍的な主体の問題に対処するものである。アフォーダンスのメカニズムは、技術 対象との関係におけるユーザーの認識、器用さ、 文化的・制度的正当性を条件として、技術がさまざまに社会的行為を要求し、要求し、奨励し、落胆させ、拒否し、許容しうることを示している。 この枠組みは、アフォーダンスに特異性を加え、関係性に注目し、アフォーダンス理論における価値、政治、権力の役割を中心に据える。機構と条件の枠組み は、社会技術分析と社会認識デザインの両方のツールである。 |

| Three categories William Gaver[18] divided affordances into three categories: perceptible, hidden, and false. A false affordance is an apparent affordance that does not have any real function, meaning that the actor perceives possibilities for action that are nonexistent.[19] A good example of a false affordance is a placebo button.[20] Affordance is said to be hidden when there are possibilities for action, but these are not perceived by the actor. For example, it is not apparent from looking at a shoe that it could be used to open a wine bottle, but such a feat is possible by placing the bottle into the shoe and tapping it repeatedly against a wall until the cork starts to be pushed out.[21] Affordance is said to be perceptible when there is information available such that the actor perceives and can then act upon the existing affordance. This means that, when affordances are perceptible, they offer a direct link between perception and action, and, when affordances are hidden or false, they can lead to mistakes and misunderstandings. |

3つのカテゴリー[編集] ウィリアム・ゲイバー(William Gaver)[18]は、アフォーダンスを「知覚可能なアフォーダンス」、「隠されたアフォーダンス」、「偽のアフォーダンス」の3つに分類した。 偽のアフォーダンスは実際の機能を持たない見かけ上のアフォーダ ンスであり、行為者が存在しない行動の可能性を知覚することを意 味する[19]。偽のアフォーダンスの好例はプラセボ・ボタンである[20]。 アフォーダンスが隠されていると言われるのは、行動の可能性はあるが、それが行為者によって知覚されない場合である。例えば、靴を見ただけでは、それがワ インボトルを開 けるのに使えることはわからないが、靴の中にボトルを入れ、コルク が押し出され始めるまで何度も壁に叩きつけることで、そのような芸当 が可能になる[21]。 アフォーダンスは、行為者が既存のアフォーダンスを知覚し、それに基づいて行動できるような利用可能な情報があるときに知覚可能であると言われる。 つまり、アフォーダンスが知覚可能であれば、知覚と行動を直接的に結びつけることができ、アフォーダンスが隠されていたり誤っていたりすれば、間違いや誤 解を招くことになる。 |

| Affordance in robotics Problems in robotics[22] indicate that affordance is not only a theoretical concept from psychology. In object grasping and manipulation, robots need to learn the affordance of objects in the environment, i.e., to learn from visual perception and experience (a) whether objects can be manipulated, (b) to learn how to grasp an object, and (c) to learn how to manipulate objects to reach a particular goal. As an example, the hammer can be grasped, in principle, with many hand poses and approach strategies, but there is a limited set of effective contact points and their associated optimal grip for performing the goal. |

ロボット工学におけるアフォーダンス[編集] ロボット工学の問題[22]は、アフォーダンスが心理学の理論的概念だけではないことを示している。物体の把持や操作において、ロボットは環境中の物体の アフォーダンスを学習する必要がある。すなわち、(a)物体が操作可能かどうか、(b)物体を把持する方法を学習する、(c)特定のゴールに到達するため に物体を操作する方法を学習する、ということを視覚認識や経験から学習する必要がある。例として、ハンマーは原理的には多くの手のポーズとアプローチ戦略 で把持できるが、ゴールを実行するための効果的な接触点とそれに関連する最適なグリップのセットは限られている。 |

| Fire safety In the context of fire safety, affordances are the perceived and actual properties of objects and spaces that suggest how they can be used during an emergency. For instance, well-designed signage, clear pathways, and accessible exits afford quick evacuation. By understanding and applying affordance principles, designers can create environments that intuitively guide occupants towards safety, reduce evacuation time, and minimize the risk of injury during a fire. Incorporating affordance-based design in building layouts, emergency equipment placement, and evacuation procedures ensures that users can effectively interact with their surroundings under stressful conditions, ultimately improving overall fire safety. This theory has been applied to select best design for several evacuation systems using data from physical experiments and virtual reality experiments.[23][24][25] |

火災安全性[編集] 火災安全の文脈では、アフォーダンスとは、緊急時にどのように使用できるかを示唆する、物体や空間の知覚的および実際の特性のことである。例えば、よく設 計された標識、明確な通路、利用しやすい出口は、迅速な避難を可能にする。アフォーダンスの原則を理解し適用することで、設計者は居住者を直感的に安全な 方向へ導き、避難時間を短縮し、火災時の負傷リスクを最小限に抑える環境を作り出すことができる。アフォーダンスに基づいた設計を建物のレイアウト、非常 用設備の配置、避難手順に取り入れることで、ストレスの多い状況下でも利用者が周囲の環境と効果的に相互作用できるようになり、最終的に全体的な火災安全 性が向上する。この理論は、物理的実験や仮想現実実験から得られたデータを用いて、いくつかの避難システムの最適な設計を選択するために適用されている [23][24][25]。 |

| Affordances in language education Based on Gibson’s conceptualization of affordances as both the good and bad that the environment offers animals, affordances in language learning are both the opportunities and challenges that learners perceive of their environment when learning a language. Affordances, which are both learning opportunities or inhibitions, arise from the semiotic budget of the learning environment, which allows language to evolve. Positive affordances, or learning opportunities, are only effective in developing learner's language when they perceive and actively interact with their surroundings. Negative affordances, on the other hand, are crucial in exposing the learners’ weaknesses for teachers, and the learners themselves, to address their moment-to-moment needs in their learning process.[26] |

言語教育におけるアフォーダンス[編集] ギブソンの「アフォーダンスとは、環境が動物に与える良いものと悪いものの両方である」という概念に基づけば、言語学習におけるアフォーダンスとは、言語 を学習する際に学習者が環境から感じる機会と課題の両方である。アフォーダンスは学習の機会であると同時に抑制でもあり、学習環境の記号論的予算から生 じ、それによって言語が進化する。肯定的なアフォーダンス(学習機会)は、学習者が周囲の環境を認識し、積極的に相互作用するときにのみ、学習者の言語を 発達させるのに効果的である。一方、否定的なアフォーダンスは、教師や学習者自身が学習プロセスにおける瞬間瞬間のニーズに対処するために、学習者の弱点 を明らかにする上で極めて重要である[26]。 |

| Action-specific perception Ambient optic array Default effect Form follows function Usability |

行動特異的知覚 周囲の視標配列 デフォルト効果 形は機能に従う ユーザビリティ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affordance |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099