アンチ・オイディプス

Anti-Oedipus

『アンチ・オイディプス』(英語: Anti-Oedipus、反エディプス)は、1972年に哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズと精神分析家フェリックス・ガタリによって発表された著作であり、また 『資本主義と分裂症』のシリーズの第1巻である。この著作は、人類学から派生して研 究されていた構造主義を踏まえつつ、精神科医のジークムント・フロイトにより主張されていた学説に対して批判を加える哲学的な研究であっ た。ドゥルーズとガタリは、1968年にフランスで五月革命が発生した後に出会い、この著作をはじめとして『千のプラトー』、『カフカ』、『哲学とはなに か』を共著で発表している。それまで、ドゥルーズは西欧で前提とされてきた形而上学 を批判し、ガタリは従来の精神医学の革新を主張していた。 この著作では、人間の精神、経済活動、社会、歴史などさまざまな主題を扱っており、全体としては4部から構成されている。

『アンチ・オイディプス』(英語: Anti-Oedipus、反エディプス)は、1972年に哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズと精神分析家フェリックス・ガタリによって発表された著作であり、また 『資本主義と分裂症』のシリーズの第1巻である。この著作は、人類学から派生して研 究されていた構造主義を踏まえつつ、精神科医のジークムント・フロイトにより主張されていた学説に対して批判を加える哲学的な研究であっ た。ドゥルーズとガタリは、1968年にフランスで五月革命が発生した後に出会い、この著作をはじめとして『千のプラトー』、『カフカ』、『哲学とはなに か』を共著で発表している。それまで、ドゥルーズは西欧で前提とされてきた形而上学 を批判し、ガタリは従来の精神医学の革新を主張していた。 この著作では、人間の精神、経済活動、社会、歴史などさまざまな主題を扱っており、全体としては4部から構成されている。/この研究では、題名でも示され ている通り、フロイトが主張したエディプスコンプレックスの学説に対する反論として読むことができる。ここで議論の中心となっているのは、人間の無意識の 欲望の概念である。フロイトは、人間が児童から大人へ移行すると きや、社会が未開状態から文明状態へと移行するとき、欲望がどれほど抑圧されるのかを判断の基準においていた。つまり、欲望を抑制するほどに人間は大人で あり、社会は文明状態であると判断していた。 したがって、人間の欲望あるいは無意識とは、「欲望する諸機械」で、エディプスコン プレックスという欲望の抑圧を家族という社会的単位に留める装置が働く中でしか是認されないと考えられてきた。このような欲望の概念は、近 代においてルネ・デカルトやトマス・ホッブズが人間に備わっている「情念のある主」の実体を指す考え方に根ざしたものであった。ドゥルーズとガタリは、こ の説に対して、無意識の欲望の概念を再検討し、欲望とはそれ自体で成立している実体 ではなく、ある関係の中で存在するものであると考えた。そして、欲望 をさまざまな事物を生産する機械として定義している。この見解によれば、エディプスコンプレックスは、フロイトの弟子ラカンが言うように人 間が原初的に備えているものではなく、社会的な発明によるものである。

「フランスの精神分析家 J.ラカンが記述した,人間の子供の6ヵ月から

18ヵ月までの形成時期を指す言葉。鏡像段階は,主体の構造という観点に立つとき,発達の基本となる重要な時期である。子供は鏡の中に自分と同じ姿をした

像を見つけて,これに同一化しながら,自我の最初の輪郭を形づくる。これは将来の自我像のひな型になる。この時期の特徴を詳しく記述することによって,個

人の精神発達のみならず,個人間の攻撃的な関係についても知識が増し,また精神の想像的な働きが個人の発達において果たす役割について解明が進んだ」ブリ

タニカ国際大百科事典)

| 『アンチ・オイディ

プス』(英語:

Anti-Oedipus、反エディプス)は、1972年に哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズと精神分析家フェリックス・ガタリによって発表された著作であり、また

『資本主義と分裂症』のシリーズの第1巻である。この著作は、人類学から派生して研

究されていた構造主義を踏まえつつ、精神科医のジークムント・フロイトにより主張されていた学説に対して批判を加える哲学的な研究であっ

た。ドゥルーズとガタリは、1968年にフランスで五月革命が発生した後に出会い、この著作をはじめとして『千のプラトー』、『カフカ』、『哲学とはなに

か』を共著で発表している。それまで、ドゥルーズは西欧で前提とされてきた形而上学

を批判し、ガタリは従来の精神医学の革新を主張していた。

この著作では、人間の精神、経済活動、社会、歴史などさまざまな主題を扱っており、全体としては4部から構成されている。/この研究では、題名でも示され

ている通り、フロイトが主張したエディプスコンプレックスの学説に対する反論として読むことができる。ここで議論の中心となっているのは、人間の無意識の欲望の概念である。フロイトは、人間が児童から大人へ移行すると

きや、社会が未開状態から文明状態へと移行するとき、欲望がどれほど抑圧されるのかを判断の基準においていた。つまり、欲望を抑制するほどに人間は大人であり、社会は文明状態であると判断していた。

したがって、人間の欲望あるいは無意識とは、「欲望する諸機械」で、エディプスコン

プレックスという欲望の抑圧を家族という社会的単位に留める装置が働く中でしか是認されないと考えられてきた。このような欲望の概念は、近

代においてルネ・デカルトやトマス・ホッブズが人間に備わっている「情念のある主」の実体を指す考え方に根ざしたものであった。ドゥルーズとガタリは、こ

の説に対して、無意識の欲望の概念を再検討し、欲望とはそれ自体で成立している実体

ではなく、ある関係の中で存在するものであると考えた。そして、欲望

をさまざまな事物を生産する機械として定義している。この見解によれば、エディプスコンプレックスは、フロイトの弟子ラカンが言うように人

間が原初的に備えているものではなく、社会的な発明によるものであ

る。 |

Fascism in detail - "It could

even be said that Deleuze and Guattari care so little for

power that they have tried to neutralize the effects of power linked to

their own discourse. Hence the games and snares scattered throughout

the book, rendering its translation a feat of real prowess. But these

are

not the familiar traps of rhetoric; the latter work to sway the reader

without his being aware of the manipulation, and ultimately win him

over against his will. The traps of Anti-Oedipus are those of humor: so

many invitations to let oneself be put out, to take one's leave of the

text

and slam the door shut. The book of ten leads one to believe it is all

fun

and games, when something essential is taking place, something of

extreme seriousness: the tracking down of all varieties of fascism,

from

the enormous ones that surround and crush us to the petty ones that

constitute the tyrannical bitterness of our everyday lives." Michael

Foucault 1972[1977], Preface of "Anti-Oedipus." "It would be a mistake to read Anti-Oedipus as the new theoretical reference (you know, that much-heralded theory that finally encompasses everything, that finally totalizes and reassures, the one we are told we "need so badly" in our age of dispersion and specialization where "hope" is lacking). One must not look for a "philosophy" amid the extraordinary profusion of new notions and surprise concepts: AntiOedipus is not a flashy Hegel. I think that Anti-Oedipus can best be read as an "art," in the sense that is conveyed by the term "erotic art," for example. Informed by the seemingly abstract notions of multiplicities, flows, arrangements, and connections, the analysis of the relationship of desire to reality and to the capitalist "machine" yields answers to concrete questions. Questions that are less concerned with why this or that than with how to proceed. How does one introduce desire into thought, into discourse, into action? How can and must desire deploy its forces within the political domain and grow more intense in the process of overturning the established order? Ars erotica, ars theoretica, ars politica." |

| ウィキペディア「https://bit.ly/3t3QpN3」日本

語 |

|

| 第1章 欲望機械 第1節 欲望的生産 第2節 器官なき身体 第3節 主体と享受 第4節 唯物論的精神医学 第5節 欲望機械 第6節 全体と諸部分 第2章 精神分析と家族主義 すなわち神聖家族 第1節 オイディプス帝国主義 第2節 フロイトの三つのテクスト 第3節 生産の接続的総合 第4節 登録の離接的総合 第5節 消費の連接的総合 第6節 三つの総合の要約 第7節 抑制と抑圧 第8節 神経症と精神病 第9節 プロセス 第3章 未開人、野蛮人、文明人 第1節 登記する社会体 第2節 原始大地機械 第3節 オイディプス問題 第4節 精神分析と人類学 第5節 大地的表象 第6節 野蛮な専制君主機械 第7節 野蛮な、あるいは帝国の表象 第8節 <原国家> 第9節 文明資本主義機械 第10節 資本主義の表象 第11節 最後はオイディプス 第4章 分裂分析への序章 第1節 社会野 第2節 分子的無意識 第3節 精神分析と資本主義 第4節 分裂分析の肯定的な第一の課題 第5節 第二の肯定的課題 補遺 欲望機械のための総括とプログラム https://bit.ly/3t3QpN3 |

|

| Anti-Oedipus:

Capitalism and Schizophrenia (French: Capitalisme et schizophrénie.

L'anti-Œdipe) is a 1972 book by French authors Gilles Deleuze and Félix

Guattari, the former a philosopher and the latter a psychoanalyst. It

is the first volume of their collaborative work Capitalism and

Schizophrenia, the second being A Thousand Plateaus (1980). In the book, Deleuze and Guattari developed the concepts and theories in schizoanalysis, a loose critical practice initiated from the standpoint of schizophrenia and psychosis as well as from the social progress that capitalism has spurred. They refer to psychoanalysis, economics, the creative arts, literature, anthropology and history in engagement with these concepts.[1] Contrary to contemporary French uses of the ideas of Sigmund Freud, they outlined a "materialist psychiatry" modeled on the unconscious regarded as an aggregate of productive processes of desire, incorporating their concept of desiring-production which interrelates desiring-machines and bodies without organs, and repurpose Karl Marx's historical materialism to detail their different organizations of social production, "recording surfaces", coding, territorialization and the act of "inscription". Friedrich Nietzsche's ideas of the will to power and eternal recurrence also have roles in how Deleuze and Guattari describe schizophrenia; the book extends from much of Deleuze's prior thinking in Difference and Repetition and The Logic of Sense that utilized Nietzsche's ideas to explore a radical conception of becoming. Deleuze and Guattari also draw on and criticize the philosophies and theories of: Spinoza, Kant, Charles Fourier, Charles Sanders Peirce, Carl Jung, Melanie Klein, Karl Jaspers, Lewis Mumford, Karl August Wittfogel, Wilhelm Reich, Georges Bataille, Louis Hjelmslev, Jacques Lacan, Gregory Bateson, Pierre Klossowski, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jacques Monod, Louis Althusser, Victor Turner, Jean Oury, Jean-François Lyotard, Michel Foucault, Frantz Fanon, R. D. Laing, David Cooper, and Pierre Clastres.[2] They additionally draw on authors and artists whose works demonstrate their concept of schizophrenia as "the universe of productive and reproductive desiring-machines",[3] such as Antonin Artaud, Samuel Beckett, Georg Büchner, Samuel Butler, D. H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, Marcel Proust, Arthur Rimbaud, Daniel Paul Schreber, Adolf Wölfli, Vaslav Nijinsky, Gérard de Nerval and J. M. W. Turner.[2] Thus, given the richness and diversity of the source material it draws upon and the grand task it sets out to accomplish, Anti-Oedipus can, as Michel Foucault suggests in the preface to the text, "best be read as an 'art,'" and it would be a "mistake to read [it] as the new theoretical reference" in philosophy.[4] Anti-Oedipus became a sensation upon publication and was widely celebrated, creating shifts in contemporary philosophy. It is seen as a key text in the "micropolitics of desire", alongside Lyotard's Libidinal Economy. It has been credited with devastating Lacanianism due to its unorthodox criticism of the movement. |

反エディプス: フランス語:Capitalisme

et schizophrénie.

L'anti-Œdipe)は、フランスの作家ジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリ(前者は哲学者、後者は精神分析家)による1972年の著作。二人

の共著『資本主義と分裂症』の第一巻であり、第二巻は『千のプラトー』(1980年)である。 この本の中でドゥルーズとガタリは、精神分裂病や精神病の立場から、また資本主義がもたらした社会的進歩の立場から始まった緩やかな批評実践である精神分 析の概念と理論を展開した。彼らは精神分析、経済学、創造的芸術、文学、人類学、歴史学に言及し、これらの概念に取り組んでいる。 [ジークムント・フロイトの思想を現代フランス人が利用するのとは対照的に、彼らは欲望の生産過程の集合体とみなされる無意識をモデルとした「唯物論的精 神医学」を概説し、欲望機械と器官のない身体を相互に関連付ける欲望生産の概念を取り入れ、カール・マルクスの史的唯物論を再利用して、社会的生産、「記 録面」、コード化、領土化、「銘記」行為のさまざまな組織を詳述している。フリードリヒ・ニーチェの「力への意志」と「永遠回帰」の考え方は、ドゥルーズ とガタリが精神分裂病をどのように描写するかにも関わっている。本書は、『差異と反復』や『感覚の論理』におけるドゥルーズの先行思索の多くを発展させた もので、ニーチェの考えを利用して、ラディカルな「なりゆき」の概念を探求している。 ドゥルーズとガタリはまた、以下の哲学や理論を引用し、批判している: スピノザ、カント、シャルル・フーリエ、チャールズ・サンダース・パイス、カール・ユング、メラニー・クライン、カール・ヤスパース、ルイス・マンフォー ド、カール・アウグスト・ヴィトフォーゲル、ヴィルヘルム・ライヒ、ジョルジュ・バタイユ、ルイ・ヘルムスレフ、ジャック・ラカン、グレゴリー・ベイトソ ン、ピエール・クロソウスキー、クロード・レヴィ=ストロース、ジャック・モノー、ルイ・アルチュセール、ヴィクトール・ターナー、ジャン・オリー、ジャ ン=フランソワ・リオタール、ミシェル・フーコー、フランツ・ファノン、R. D.レイング、デイヴィッド・クーパー、ピエール・クラストル[2]。 彼らはさらに、アントナン・アルトー、サミュエル・ベケット、ゲオルク・ビュヒナー、サミュエル・バトラー、D・H・ローレンス、ヘンリー・ミラー、マル セル・プルースト、アルチュール・ランボー、ダニエル・ポール・シュレーバー、アドルフ・ヴェルフリ、ヴァスラフ・ニジンスキー、ジェラール・ド・ネル ヴァル、J・M・W・ターナーなど、「生産的で再生産的な欲望機械の宇宙」[3]としての精神分裂病の概念を実証する作家や芸術家の作品を利用している [2]。 このように、『アンチ・オイディプス』は、その典拠となる資料の豊かさと多様性、そして成し遂げようとする壮大な課題を考えれば、ミシェル・フーコーが序 文で示唆しているように、「『芸術』として読むのが最善」であり、哲学における「新たな理論的参照として読むのは間違い」であろう[4]。 アンチ・オイディプス』は出版と同時にセンセーションを巻き起こし、広く称賛され、現代哲学に変化をもたらした。リオタールの『リビディナル・エコノ ミー』と並んで、「欲望のミクロ政治学」の重要なテキストとみなされている。ラカニアニズムに対する異端的な批判により、ラカニアニズムに壊滅的な打撃を 与えたとされている。 |

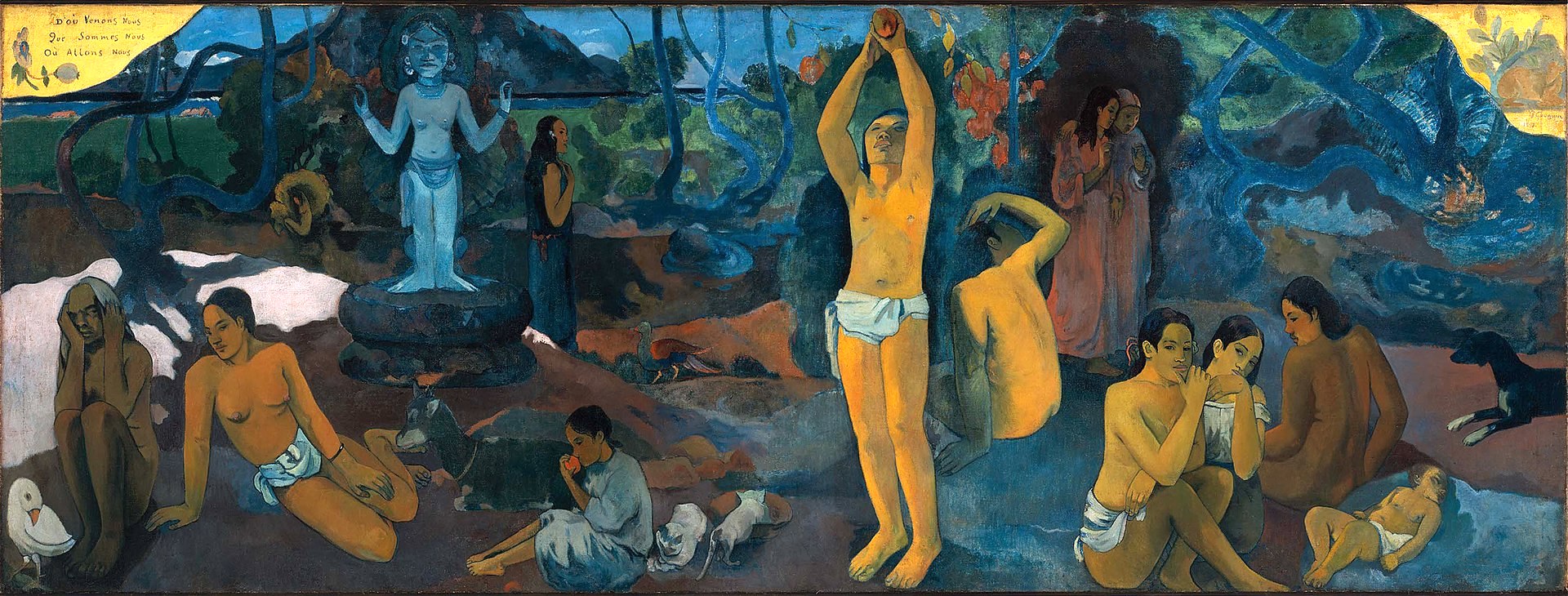

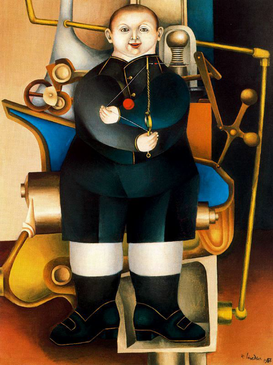

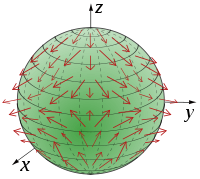

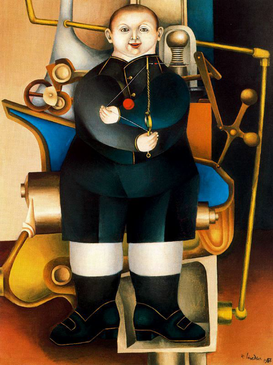

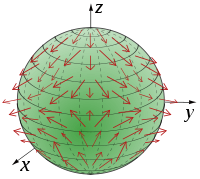

| Summary Schizoanalysis  Deleuze and Guattari argue that Richard Lindner's painting Boy with Machine (1954) demonstrates the schizoanalytic thesis of the primacy of desire's social investments over its familial ones: "the turgid little boy has already plugged a desiring-machine into a social machine, short-circuiting the parents."[5] Main article: Schizoanalysis Deleuze and Guattari's "schizoanalysis" is a social and political analysis that responds to what they see as the reactionary tendencies of psychoanalysis.[6] It proposes a functional evaluation of the direct investments of desire—whether revolutionary or reactionary—in a field that is social, biological, historical, and geographical.[7] Deleuze and Guattari develop four theses of schizoanalysis: Every unconscious libidinal investment is social and bears upon a socio-historical field. Unconscious libidinal investments of group or desire are distinct from preconscious investments of class or interest. Non-familial libidinal investments of the social field are primary in relation to familial investments. Social libidinal investments are distinguished according to two poles: a paranoiac, reactionary, fascisizing pole and a schizoid revolutionary pole.[8] In contrast to the psychoanalytic conception, schizoanalysis assumes that the libido does not need to be de-sexualised, sublimated, or to go by way of metamorphoses in order to invest economic or political factors. "The truth is," Deleuze and Guattari explain, "sexuality is everywhere: the way a bureaucrat fondles his records, a judge administers justice, a businessman causes money to circulate; the way the bourgeoisie fucks the proletariat; and so on. [...] Flags, nations, armies, banks get a lot of people aroused."[9] In the terms of classical Marxism, desire is part of the economic, infrastructural "base" of society, they argue, not an ideological, subjective "superstructure."[10] Unconscious libidinal investments of desire coexist without necessarily coinciding with preconscious investments made according to the needs or ideological interests of the subject (individual or collective) who desires.[11] A form of social production and reproduction, along with its economic and financial mechanisms, its political formations, and so on, can be desired as such, in whole or in part, independently of the interests of the desiring-subject. It was not by means of a metaphor, even a paternal metaphor, that Hitler was able to sexually arouse the fascists. It is not by means of a metaphor that a banking or stock-market transaction, a claim, a coupon, a credit, is able to arouse people who are not necessarily bankers. And what about the effects of money that grows, money that produces more money? There are socioeconomic "complexes" that are also veritable complexes of the unconscious, and that communicate a voluptuous wave from the top to the bottom of their hierarchy (the military–industrial complex). And ideology, Oedipus, and the phallus have nothing to do with this, because they depend on it rather than being its impetus.[12] Schizoanalysis seeks to show how "in the subject who desires, desire can be made to desire its own repression—whence the role of the death instinct in the circuit connecting desire to the social sphere."[13] Desire produces "even the most repressive and the most deadly forms of social reproduction."[14] Desiring machines and social production Main article: Desiring-production The traditional understanding of desire assumes an exclusive distinction between "production" and "acquisition."[15] This line of thought—which has dominated Western philosophy throughout its history and stretches from Plato to Freud and Lacan—understands desire through the concept of acquisition, insofar as desire seeks to acquire something that it lacks. This dominant conception, Deleuze and Guattari argue, is a form of philosophical idealism.[15] Alternative conceptions, which treat desire as a positive, productive force, have received far less attention; the ideas of the small number of philosophers who have developed them, however, are of crucial importance to Deleuze and Guattari's project: principally Nietzsche's will to power and Spinoza's conatus.[16] Deleuze and Guattari argue that desire is a positive process of production that produces reality.[17] On the basis of three "passive syntheses" (partly modelled on Kant's syntheses of apperception from his Critique of Pure Reason), desire engineers "partial objects, flows, and bodies" in the service of the autopoiesis of the unconscious.[18] In this model, desire does not "lack" its object; instead, desire "is a machine, and the object of desire is another machine connected to it."[17] On this basis, Deleuze and Guattari develop their notion of desiring-production.[19] Since desire produces reality, social production, with its forces and relations, is "purely and simply desiring-production itself under determinate conditions."[14] Like their contemporary, R. D. Laing, and like Reich before them, Deleuze and Guattari make a connection between psychological repression and social oppression. By means of their concept of desiring-production, however, their manner of doing so is radically different. They describe a universe composed of desiring-machines, all of which are connected to one another: "There are no desiring-machines that exist outside the social machines that they form on a large scale; and no social machines without the desiring machines that inhabit them on a small scale."[20] When they insist that a social field may be invested by desire directly, they oppose Freud's concept of sublimation, which posits an inherent dualism between desiring-machines and social production: "The truth is that sexuality is everywhere: the way a bureaucrat fondles his records, a judge administers justice, a businessman causes money to circulate; the way the bourgeoisie fucks the proletariat; and so on."[21] This dualism, they argue, limited and trapped the revolutionary potential of the theories of Laing and Reich. Deleuze and Guattari develop a critique of Freud and Lacan's psychoanalysis, anti-psychiatry, and Freudo-Marxism (with its insistence on a necessary mediation between the two realms of desire and the social). Deleuze and Guattari's concept of sexuality is not limited to the interaction of male and female gender roles, but instead posits a multiplicity of flows that a "hundred thousand" desiring-machines create within their connected universe; Deleuze and Guattari contrast this "non-human, molecular sexuality" to "molar" binary sexuality: "making love is not just becoming as one, or even two, but becoming as a hundred thousand," they write, adding that "we always make love with worlds."[22] Reframing the Oedipal complex The "anti-" part of their critique of the Freudian Oedipal complex begins with that original model's articulation of society[clarification needed] based on the family triangle of father, mother and child.[page needed] Criticizing psychoanalysis "familialism", they want to show that the oedipal model of the family is a kind of organization that must colonize its members, repress their desires, and give them complexes if it is to function as an organizing principle of society.[page needed] Instead of conceiving the "family" as a sphere contained by a larger "social" sphere, and giving a logical preeminence to the family triangle, Deleuze and Guattari argue that the family should be opened onto the social, as in Bergson's conception of the Open, and that underneath the pseudo-opposition between family (composed of personal subjects) and social, lies the relationship between pre-individual desire and social production. Furthermore, they argue that schizophrenia is an extreme mental state co-existent with the capitalist system itself[23] and capitalism keeps enforcing neurosis as a way of maintaining normality. However, they oppose a non-clinical concept of "schizophrenia" as deterritorialization to the clinical end-result "schizophrenic" (i.e. they do not intend to romanticize "mental disorders"; instead, they show, like Foucault, that "psychiatric disorders" are always second to something else). Body without organs  Deleuze and Guattari describe the BwO as an egg: "it is crisscrossed with axes and thresholds, with latitudes and longitudes and geodesic lines, traversed by gradients marking the transitions and the becomings, the destinations of the subject developing along these particular vectors."[24] Main article: Body without organs Deleuze and Guattari develop their concept of the "body without organs" (often rendered as BwO) from Antonin Artaud's text "To Have Done With the Judgment of God". Since desire can take on as many forms as there are persons to implement it, it must seek new channels and different combinations to realize itself, forming a body without organs for every instance. Desire is not limited to the affections of a subject, nor the material state of the subject. Bodies without organs cannot be forced or willed into existence, however, and they are essentially the product of a zero-intensity condition that Deleuze and Guattari link to catatonic schizophrenia that also becomes "the model of death". Criticism of psychoanalysts Deleuze and Guattari address the case of Gérard Mendel, Bela Grunberger and Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel, who were prominent members of the most respected psychoanalytic association (the International Psychoanalytical Association). They argue that this case demonstrates that psychoanalysis enthusiastically embraces a police state:[25] As to those who refuse to be oedipalized in one form or another, at one end or the other in the treatment, the psychoanalyst is there to call the asylum or the police for help. The police on our side!—never did psychoanalysis better display its taste for supporting the movement of social repression, and for participating in it with enthusiasm. [...] notice of the dominant tone in the most respected associations: consider Dr. Mendel and the Drs Stéphane, the state of fury that is theirs, and their literally police-like appeal at the thought that someone might try to escape the Oedipal dragnet. Oedipus is one of those things that becomes all the more dangerous the less people believe in it; then the cops are there to replace the high priests. Bela Grunberger and Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel were two psychoanalysts from the Paris section of the International Psychoanalytical Association. In November 1968 they disguised themselves under the pseudonym André Stéphane and published L'univers Contestationnaire, in which they argued that the left-wing rioters of May 68 were totalitarian stalinists, and proceeded to psychoanalyze them as having a sordid infantilism caught up in an Oedipal revolt against the Father.[26][27] Jacques Lacan regarded Grunberger and Chasseguet-Smirgel's book with great disdain; while they were still disguised under the pseudonym, Lacan remarked that he was certain that neither author belonged to his school, as none would abase themselves to such low drivel.[28] The IPa analysts responded with an accusation against the Lacan school of "intellectual terrorism."[26] Gérard Mendel published La révolte contre le père (1968) and Pour décoloniser l'enfant (1971). Fascism, the family, and the desire for oppression Desiring self-repression Deleuze and Guattari address a fundamental problem of political philosophy: the contradictory phenomenon whereby an individual or a group comes to desire their own oppression.[29] This contradiction had been mentioned briefly by the 17th-century philosopher Spinoza: "Why do men fight for their servitude as stubbornly as though it were their salvation?"[30] That is, how is it possible that people cry for "More taxes! Less bread!"? Wilhelm Reich discussed the phenomenon in his 1933 book The Mass Psychology of Fascism:[31][32] The astonishing thing is not that some people steal or that others occasionally go out on strike, but rather that all those who are starving do not steal as a regular practice, and all those who are exploited are not continually out on strike: after centuries of exploitation, why do people still tolerate being humiliated and enslaved, to such a point, indeed, that they actually want humiliation and slavery not only for others but for themselves?" To address this question, Deleuze and Guattari examine the relationships between social organisation, power, and desire, particularly in relation to the Freudian "Oedipus complex" and its familial mechanisms of subjectivation ("daddy-mommy-me"). They argue that the nuclear family is the most powerful agent of psychological repression, under which the desires of the child and the adolescent are repressed and perverted.[33][34] Such psychological repression forms docile individuals that are easy targets for social repression.[35] By using this powerful mechanism, the dominant class, "making cuts (coupures) and segregations pass over into a social field", can ultimately control individuals or groups, ensuring general submission. This explains the contradictory phenomenon in which people "act manifestly counter to their class interests—when they rally to the interests and ideals of a class that their own objective situation should lead them to combat".[36] Deleuze and Guattari's critique of these mechanisms seeks to promote a revolutionary liberation of desire: If desire is repressed, it is because every position of desire, no matter how small, is capable of calling into question the established order of a society: not that desire is asocial, on the contrary. But it is explosive; there is no desiring-machine capable of being assembled without demolishing entire social sectors. Despite what some revolutionaries think about this, desire is revolutionary in its essence—desire, not left-wing holidays!—and no society can tolerate a position of real desire without its structures of exploitation, servitude, and hierarchy being compromised.[37] The family under capitalism as an agent of repression The family is the agent to which capitalist production delegates the psychological repression of the desires of the child.[38] Psychological repression is distinguished from social oppression insofar as it works unconsciously.[39] Through it, Deleuze and Guattari argue, parents transmit their angst and irrational fears to their child and bind the child's sexual desires to feelings of shame and guilt. Psychological repression is strongly linked with social oppression, which levers on it. It is thanks to psychological repression that individuals are transformed into docile servants of social repression who come to desire self-repression and who accept a miserable life as employees for capitalism.[40] A capitalist society needs a powerful tool to counteract the explosive force of desire, which has the potential to threaten its structures of exploitation, servitude, and hierarchy; the nuclear family is precisely the powerful tool able to counteract those forces.[41] The action of the family not only performs a psychological repression of desire, but it disfigures it, giving rise to a consequent neurotic desire, the perversion of incestuous drives and desiring self-repression.[41] The Oedipus complex arises from this double operation: "It is in one and the same movement that the repressive social production is replaced by the repressing family, and that the latter offers a displaced image of desiring-production that represents the repressed as incestuous familial drives."[39] Capitalism and the political economy of desire Territorialization, deterritorialization, and reterritorialization Although (like most Deleuzo-Guattarian terms) deterritorialization has a purposeful variance in meaning throughout their oeuvre, it can be roughly described as a move away from a rigidly imposed hierarchical, arborescent context, which seeks to package things (concepts, objects, etc.) into discrete categorised units with singular coded meanings or identities, towards a rhizomatic zone of multiplicity and fluctuant identity, where meanings and operations flow freely between said things, resulting in a dynamic, constantly changing set of interconnected entities with fuzzy individual boundaries. Importantly, the concept implies a continuum, not a simple binary – every actual assemblage (a flexible term alluding to the heterogeneous composition of any complex system, individual, social, geological) is marked by simultaneous movements of territorialization (maintenance) and of deterritorialization (dissipation). Various means of deterritorializing are alluded to by the authors in their chapter "How to Make Yourself A Body Without Organs" in A Thousand Plateaus, including psychoactives such as peyote. Experientially, the effects of such substances can include a loosening (relative deterritorialization) of the worldview of the user (i.e. his/her beliefs, models, etc.), subsequently leading to an antiredeterritorialization (remapping of beliefs, models, etc.) that is not necessarily identical to the prior territory. Deterritorialization is closely related to Deleuzo-Guattarian concepts such as line of flight, destratification and the body without organs/BwO (a term borrowed from Artaud), and is sometimes defined in such a way as to be partly interchangeable with these terms (most specifically in the second part of Capitalism and Schizophrenia, A Thousand Plateaus). Deleuze and Guattari posit that dramatic reterritorialization often follows relative deterritorialization, while absolute deterritorialization is just that... absolute deterritorialization without any reterritorialization. Terminology borrowed from science  A vector field on a sphere During the course of their argument, Deleuze and Guattari borrow a number of concepts from different scientific fields. To describe the process of desire, they draw on fluid dynamics, the branch of physics that studies how a fluid flows through space. They describe society in terms of forces acting in a vector field. They also relate processes of their "body without organs" to the embryology of an egg, from which they borrow the concept of an inductor.[42] |

概要 分裂分析  ドゥルーズとガタリは、リチャード・リンドナーの絵画『機械を持つ少年』(1954年)は、欲望が家族的なものよりも社会的なものに優先的に投資されると いう精神分裂病のテーゼを示していると主張する: 「この退屈な少年は、すでに欲望機械を社会的機械に接続し、両親を短絡させている」[5]。 主な記事 分裂分析 ドゥルーズとガタリの「シゾアナリシス」は、彼らが精神分析の反動的傾向とみなすものに対応する社会的・政治的分析である: あらゆる無意識的なリビドー投資は社会的であり、社会歴史的な場に影響を及ぼす。 集団や欲望の無意識的なリビドナル投資は、階級や利害の事前意識的な投資とは区別される。 社会的場の非家族的リビドナル投資は、家族的投資との関係において第一義的である。 社会的なリビドナル投資はパラノイアック、反動的、ファシズム的な極とシゾイド的な革命的な極という2つの極によって区別される[8]。 精神分析の概念とは対照的に、精神分裂病はリビドーが経済的、政治的要素に投資するために、脱性的になったり、昇華されたり、変成する必要はないと仮定し ている。「真実は、」ドゥルーズとガタリは説明する。「セクシュアリティはどこにでもある。官僚が自分の記録をもてあそび、裁判官が正義を執行し、ビジネ スマンが貨幣を流通させる方法、ブルジョワジーがプロレタリアートを犯す方法などなど。[国旗、国家、軍隊、銀行は多くの人々を興奮させる」[9]。古典 的マルクス主義の用語で言えば、欲望は社会の経済的、インフラ的な「基盤」の一部であり、イデオロギー的、主観的な「上部構造」ではないと彼らは主張する [10]。 欲望の無意識的なリビドー的投資は、欲望する主体(個人または集団)のニーズやイデオロギー的利益に従って行われる事前意識的投資と必ずしも一致すること なく共存している[11]。 社会的生産と再生の形態は、その経済的・財政的メカニズムや政治的形成などとともに、欲望する主体の利益とは無関係に、全体的あるいは部分的に、そのよう なものとして欲望されうる。ヒトラーがファシストたちを性的に興奮させることができたのは、たとえ父性的な隠喩であっても、隠喩によってではない。銀行や 株式市場の取引、債権、クーポン、信用が、必ずしも銀行家ではない人々を興奮させることができるのは、比喩によるものではない。そして、成長する貨幣、よ り多くの貨幣を生み出す貨幣の効果についてはどうだろうか。社会経済的な 「コンプレックス 」は、無意識のコンプレックスでもあり、ヒエラルキーの頂点から底辺まで官能的な波を伝える(軍産コンプレックス)。そして、イデオロギー、オイディプ ス、そしてファルスは、このこととは何の関係もない。 分裂分析は「欲望する主体において、欲望がいかにしてそれ自身の抑圧を欲望させられるか-それゆえ、欲望と社会圏をつなぐ回路における死の本能の役割」 [13]を示そうとするものであり、欲望は「社会的再生産の最も抑圧的で最も致命的な形態さえも」生み出す[14]。 欲望機械と社会的生産 主な記事 欲望-生産 欲望に関する伝統的な理解は、「生産」と「獲得」の間の排他的な区別を前提としている[15]。この思想の流れは、その歴史を通じて西洋哲学を支配し、プ ラトンからフロイト、ラカンにまで及んでおり、欲望が欠けている何かを獲得しようとする限りにおいて、獲得の概念を通じて欲望を理解している。この支配的 な概念は哲学的観念論の一形態であるとドゥルーズとガタリは主張している[15]。欲望を肯定的で生産的な力として扱う代替的な概念はあまり注目されてこ なかったが、それらを発展させた少数の哲学者の考えはドゥルーズとガタリのプロジェクトにとって極めて重要である。 [このモデルでは、欲望はその対象を「欠く」のではなく、欲望は「機械であり、欲望の対象はそれに接続された別の機械である」。 「欲望は現実を生み出すので、その力と関係を伴う社会的生産は、「決定された条件のもとでの純粋かつ単純な欲望-生産そのもの」である[14]。 同時代のR.D.レインや彼ら以前のライヒのように、ドゥルーズとガタリは心理的抑圧と社会的抑圧を結びつけている。しかし、欲望生産という概念によっ て、その方法は根本的に異なっている。彼らは、欲望機械で構成された宇宙を描写している: 「大規模に形成される社会的機械の外に存在する欲求機械はなく、小規模に生息する欲求機械のない社会的機械はない」[20]。社会的場が欲求によって直接 的に投資されるかもしれないと主張するとき、彼らは欲求機械と社会的生産の間に固有の二元論を仮定するフロイトの昇華の概念に反対する: 「この二元論は、レイングとライヒの理論の革命的可能性を制限し、閉じ込めたと彼らは主張する。ドゥルーズとガタリは、フロイトとラカンの精神分析、反精 神医学、フロイト=マルクス主義(欲望と社会という2つの領域の間に必要な媒介を主張)への批判を展開する。ドゥルーズとガタリのセクシュアリティの概念 は、男性と女性のジェンダー的役割の相互作用に限定されるものではなく、「十万台」の欲望機械がその接続された宇宙の中で生み出す多様な流れを想定してい る。ドゥルーズとガタリは、この「非人間的で分子的なセクシュアリティ」を「臼歯状」の二元的セクシュアリティと対比させている: ドゥルーズとガタリは、この「非人間的な分子的セクシュアリティ」を「モル」的な二元的セクシュアリティと対比させている。 エディプス・コンプレックスのリフレーミング フロイトのエディプス・コンプレックスに対する彼らの批判の「反」部分は、父、母、子という家族の三角形に基づく社会[要明示]のオリジナル・モデルの明 確化から始まる[要ページ]。精神分析の「家族主義」を批判する彼らは、エディプス・モデルの家族が社会の組織原理として機能するためには、メンバーを植 民地化し、彼らの欲望を抑圧し、彼らにコンプレックスを与えなければならない一種の組織であることを示したいのである。 [ドゥルーズとガタリは、「家族」をより大きな「社会」圏に含まれる圏として考え、家族の三角形に論理的な優位性を与えるのではなく、ベルクソンの「開か れたもの」概念のように、家族は社会的なものの上に開かれるべきであり、(個人的主体からなる)家族と社会との間の擬似的な対立の根底には、個人以前の欲 望と社会的生産との関係があると主張する。 さらに彼らは、精神分裂病は資本主義システムそのものと共存する極端な精神状態であり[23]、資本主義は正常性を維持する方法として神経症を強制し続け ていると主張する。しかし、彼らは臨床的な最終結果である「精神分裂病患者」に対する非臨床的な概念としての「精神分裂病」に反対している(つまり、彼ら は「精神障害」をロマン主義的に捉えるつもりはなく、その代わりに、フーコーのように、「精神障害」は常に他の何かに次ぐものであることを示している)。 器官なき身体  ドゥルーズとガタリはBwOを卵のように表現している: 「それは軸と閾値、緯度と経度、測地線によって十字に交差しており、移行となること、これらの特定のベクトルに沿って展開する主体の行き先を示す勾配に よって横断されている」[24]。 主な記事 器官のない身体 ドゥルーズとガタリは、アントナン・アルトーのテクスト『神の裁きと決別する』から「器官なき身体」(しばしばBwOと表記される)の概念を発展させた。 欲望は、それを実現する人の数だけ形をとることができるため、欲望を実現するためには、新たな経路やさまざまな組み合わせを模索し、その都度、器官のない 身体を形成しなければならない。欲望は、対象の愛情や対象の物質的状態に限定されるものではない。ドゥルーズとガタリが緊張病型精神分裂病と結びつけ、 「死のモデル」ともなっている。 精神分析家への批判 ドゥルーズとガタリは、最も尊敬される精神分析協会(国際精神分析協会)の著名なメンバーであったジェラール・メンデル、ベラ・グランベルガー、ジャニー ヌ・シャスゲ=スミルゲルのケースを取り上げる。彼らは、この事件は精神分析が警察国家を熱狂的に受け入れていることを示していると主張している [25]。 何らかのかたちでエディプス化されることを拒否する人たちについては、治療の端か端かで、精神分析医は精神病院か警察に助けを求めるためにそこにいる。警 察は我々の味方だ!-社会的抑圧の動きを支援し、それに熱狂的に参加することに、精神分析がこれほどその趣味を発揮したことはない。[メンデル博士とステ ファン博士、彼らの怒り、そしてエディプスの網の目から逃れようとする者がいるかもしれないと考えたときの、文字通り警察のような訴え。オイディプスは、 人々がそれを信じなくなればなるほど危険になるもののひとつである。 ベラ・グランベルジェとジャニーヌ・シャスゲ=スミルゲルは、国際精神分析協会パリ支部の2人の精神分析家だった。1968年11月、彼らはAndré Stéphaneというペンネームで変装し、『L'univers Contestationnaire』を出版した。その中で彼らは、5月68日の左翼暴徒は全体主義的なスターリニストであると主張し、彼らを父に対する エディプスの反乱に巻き込まれた劣悪な幼児性を持っていると精神分析を進めた。 [26][27]ジャック・ラカンはグランベルジェとシャスゲ=スミルゲルの著書を非常に軽蔑して見ていた。彼らがまだペンネームの下に身を隠していたと き、ラカンは、このような低俗な戯言のために身を卑下するような著者はいないことから、どちらの著者も自分の学派に属していないと確信していると発言し た。 [28] IPaの分析家たちは、ラカン派を「知的テロリズム」と非難し、これに反論した[26] ジェラール・メンデルは、La révolte contre le père(1968年)とPour décoloniser l'enfant(1971年)を出版した。 ファシズム、家族、抑圧への欲望 自己抑圧への欲望 ドゥルーズとガタリは政治哲学の根本的な問題、すなわち個人や集団が自らの抑圧を望むようになるという矛盾した現象に取り組んでいる[29]。 この矛盾は17世紀の哲学者スピノザによって少し言及されている!パンを減らせ!」。ヴィルヘルム・ライヒは1933年の著書『ファシズムの大衆心理学』 の中で、この現象について次のように論じている[31][32]。 驚くべきことは、一部の人々が盗んだり、他の人々が時折ストライキに出たりすることではなく、むしろ飢えているすべての人々が常習的に盗んだりせず、搾取 されているすべての人々が継続的にストライキに出たりしないことである:何世紀にもわたって搾取されてきたのに、なぜ人々はいまだに屈辱を受け、奴隷にさ れることを容認しているのだろうか。 この問いに取り組むため、ドゥルーズとガタリは、社会組織、権力、欲望の関係を、特にフロイトの「エディプス・コンプレックス」とその家族的な主体化のメ カニズム(「パパ・ママ・私」)との関連において検証する。彼らは、核家族は心理的抑圧の最も強力なエージェントであり、そのもとで子どもや思春期の欲望 は抑圧され、変質させられると論じている[33][34]。このような心理的抑圧は、社会的抑圧の対象となりやすい従順な個人を形成する[35]。この強 力なメカニズムを利用することで、支配階級は「切断(coupures)と分離を社会的フィールドに通過させる」ことで、最終的に個人や集団を支配し、一 般的な服従を確保することができる。このことは、人々が「自分たちの階級的利益に反して明白に行動する-自分たち自身の客観的状況が闘うように導くはずの 階級の利益と理想に結集するとき」[36]という矛盾した現象を説明する: 欲望が抑圧されているとすれば、それは欲望のあらゆる立場が、どんなに小さなものであっても、社会の既成秩序に疑問を投げかけることができるからである。 欲望は非社会的なものではなく、それどころか爆発的なものなのである。社会全体を破壊することなく組み立てられる欲望機械など存在しないのだ。一部の革命 家がこのことについてどう考えているかにかかわらず、欲望はその本質において革命的である-欲望であって、左翼的な休日ではない!-そしていかなる社会 も、搾取、隷属、ヒエラルキーの構造が損なわれることなく、真の欲望の立場を容認することはできない[37]。 抑圧の主体としての資本主義下の家族 家族は、資本主義的生産が子どもの欲望の心理的抑圧を委ねる主体である。心理的抑圧は、それが無意識に働く限りにおいて、社会的抑圧とは区別される [39]。ドゥルーズとガタリは、それを通して、親は自分の怒りや不合理な恐怖を子どもに伝え、子どもの性的欲望を羞恥心や罪悪感に縛り付けると主張す る。心理的抑圧は社会的抑圧と強く結びついている。心理的抑圧のおかげで、個人は社会的抑圧の従順な下僕へと変容し、自己抑圧を望むようになり、資本主義 のための従業員として悲惨な人生を受け入れるようになるのである[40]。資本主義社会は、その搾取、隷属、ヒエラルキーの構造を脅かす可能性を持つ欲望 の爆発的な力に対抗する強力な道具を必要としている。核家族はまさに、こうした力に対抗することのできる強力な道具である[41]。 家族の作用は欲望を心理的に抑圧するだけでなく、欲望を形骸化させ、結果として神経症的な欲望、近親相姦的な衝動の倒錯、自己抑圧を欲望する欲望を生み出 す。エディプス・コンプレックスはこの二重の作用から生じる[41]: 「抑圧的な社会的生産が抑圧的な家族によって置き換えられ、後者が近親相姦的な家族的衝動として抑圧されたものを表象する欲望的生産のずれたイメージを提 供することは、同じ運動の中にある」[39]。 資本主義と欲望の政治経済学 領土化、非領土化、再領土化 ほとんどのドゥルーズ=ガタリアン用語と同様に)非領土化には、彼らの作品全体を通じて意図的な意味のばらつきがあるが、大まかに言えば、物事(概念、物 体など)を個別のカテゴリー化された単位にパッケージ化しようとする、厳格に押しつけられた階層的で樹枝状的な文脈からの脱却である。 そこでは、意味と操作が物事の間を自由に流れ、個々の境界があいまいな、相互に結びついたダイナミックで絶えず変化する実体の集合が生まれる。重要なの は、この概念が単純な二項対立ではなく、連続性を意味していることだ。実際のあらゆるアッサンブラージュ(個人、社会、地質など、あらゆる複雑なシステム の異質な構成を暗示する柔軟な用語)は、領土化(維持)と非領土化(消滅)の同時進行によって特徴づけられる。著者は『千のプラトー』の「臓器のない身体 を作る方法」の章で、ペヨーテのような精神薬も含め、非領土化のさまざまな手段に言及している。経験的に、このような物質の効果には、使用者の世界観(す なわち、その人の信念やモデルなど)を緩める(相対的な非領土化)ことが含まれ、その後、必ずしも以前の領域と同一ではない反領土化(信念やモデルなどの 再マッピング)をもたらすことがある。 脱領土化は、ドゥルーズ=ガタリの概念である「飛翔線」、「脱領土化」、「器官なき身体/BwO」(アルトーから借用した用語)と密接に関連しており、こ れらの用語と部分的に互換性を持つように定義されることもある(特に『資本論と分裂症』の第二部『千のプラトー』)。ドゥルーズとガタリは、劇的な再領土 化はしばしば相対的な非領土化の後に起こり、絶対的な非領土化はまさにそれである......再領土化を伴わない絶対的な非領土化であるとしている。 科学から借用した用語  球面上のベクトル場 議論の過程で、ドゥルーズとガタリはさまざまな科学分野から多くの概念を借りている。欲望のプロセスを記述するために、彼らは流体力学(流体が空間をどの ように流れるかを研究する物理学の一分野)を利用している。彼らはベクトル場に作用する力という観点から社会を描写する。彼らはまた、「臓器のない身体」 のプロセスを卵子の発生学に関連づけ、そこからインダクターの概念を借りている[42]。 |

| Reception and influence The philosopher Michel Foucault wrote that Anti-Oedipus can best be read as an "art", in the sense that is conveyed by the term "erotic art." Foucault considered the book's three "adversaries" as the "bureaucrats of the revolution", the "poor technicians of desire" (psychoanalysts and semiologists), and "the major enemy", fascism. Foucault used the term "fascism" to refer "not only historical fascism, the fascism of Hitler and Mussolini...but also the fascism in us all, in our heads and in our everyday behavior, the fascism that causes us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominates and exploits us." Foucault added that Anti-Oedipus is "a book of ethics, the first book of ethics to be written in France in quite a long time", and suggested that this explains its popular success. Foucault proposed that the book could be called Introduction to the Non-Fascist Life. Foucault argued that putting the principles espoused in Anti-Oedipus into practice involves freeing political action from "unitary and totalizing paranoia" and withdrawing allegiance "from the old categories of the Negative (law, limit, castration, lack, lacuna), which western thought has so long held sacred as a form of power and an access to reality."[43] The psychiatrist David Cooper described Anti-Oedipus as "a magnificent vision of madness as a revolutionary force", crediting its authors with using "the psychoanalytic language and the discourse of Saussure (and his successors)" to pit "linguistics against itself in what is already proving to be an historic act of depassment."[44] The critic Frederick Crews wrote that when Deleuze and Guattari "indicted Lacanian psychoanalysis as a capitalist disorder" and "pilloried analysts as the most sinister priest-manipulators of a psychotic society", their "demonstration was widely regarded as unanswerable" and "devastated the already shrinking Lacanian camp in Paris."[45] The philosopher Douglas Kellner described Anti-Oedipus as its era's publishing sensation, and, along with Jean-François Lyotard's Libidinal Economy (1974), a key text in "the micropolitics of desire."[46] The psychoanalyst Joel Kovel wrote that Deleuze and Guattari provided a definitive challenge to the mystique of the family, but that they did so in the spirit of nihilism, commenting, "Immersion in their world of 'schizoculture' and desiring machines is enough to make a person yearn for the secure madness of the nuclear family."[47] Anthony Elliott described Anti-Oedipus as a "celebrated" work that "scandalized French psychoanalysis and generated heated dispute among intellectuals" and "offered a timely critique of psychoanalysis and Lacanianism at the time of its publication in France". However, he added that most commentators would now agree that "schizoanalysis" is fatally flawed, and that there are several major objections that can be made against Anti-Oedipus. In his view, even if "subjectivity may be usefully decentred and deconstructed", it is wrong to assume that "desire is naturally rebellious and subversive." He believed that Deleuze and Guattari see the individual as "no more than various organs, intensities and flows, rather than a complex, contradictory identity" and make false emancipatory claims for schizophrenia. He also argued that Deleuze and Guattari's work produces difficulties for the interpretation of contemporary culture, because of their "rejection of institutionality as such", which obscures the difference between liberal democracy and fascism and leaves Deleuze and Guattari with "little more than a romantic, idealized fantasy of the 'schizoid hero'". He wrote that Anti-Oedipus follows a similar theoretical direction to Lyotard's Libidinal Economy, though he sees several significant differences between Deleuze and Guattari on the one hand and Lyotard on the other.[48] Some of Guattari's diary entries, correspondence with Deleuze, and notes on the development of the book were published posthumously as The Anti-Oedipus Papers (2004).[49] The philosopher Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen and the psychologist Sonu Shamdasani wrote that rather than having their confidence shaken by the "provocations and magnificent rhetorical violence" of Anti-Oedipus, the psychoanalytic profession felt that the debates raised by the book legitimated their discipline.[50] Joshua Ramey wrote that while the passage into Deleuze and Guattari's "body without organs" is "fraught with danger and even pain ... the point of Anti-Oedipus is not to make glamorous that violence or that suffering. Rather, the point is to show that there is a viable level of Dinoysian [sic] experience."[51] The philosopher Alan D. Schrift wrote in The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2015) that Anti-Oedipus was "read as a major articulation of the philosophy of desire and a profound critique of psychoanalysis."[52] |

受容と影響 哲学者ミシェル・フーコーは、『アンチ・オイディプス』は、「エロティック・アート 」という言葉が伝える意味で、「アート 」として読むのが最もふさわしいと書いた。フーコーは、この本の3人の「敵」を「革命の官僚」、「欲望の貧弱な技術者」(精神分析家と意味論者)、そして 「大敵」であるファシズムと考えた。フーコーは 「ファシズム 」という言葉を使って、「歴史的ファシズム、ヒトラーやムッソリーニのファシズムだけでなく......私たち全員の中にあるファシズム、私たちの頭の中 にあるファシズム、私たちの日常の行動の中にあるファシズム、私たちに権力を愛させ、私たちを支配し搾取するものそのものを欲望させるファシズム」を指し ている。フーコーは、『アンチ・オイディプス』は「倫理の書であり、フランスで書かれた久しぶりの倫理の書である」と付け加え、この本が人気を博した理由 をこう示唆した。フーコーは、この本を『非ファシズム的生活入門』と呼ぶこともできると提案した。フーコーは、『アンチ・オイディプス』で主張されている 原則を実践することは、「一元的で全体化するパラノイア」から政治的行動を解放し、「西洋思想が権力の形態として、また現実へのアクセスとして長い間神聖 視してきた否定的なものの古いカテゴリー(法則、制限、去勢、欠如、欠落)から」忠誠を撤回することを含むと主張した[43]。 精神科医のデイヴィッド・クーパーは、『アンチ・オイディプス』を「革命的な力としての狂気の壮大なヴィジョン」と評し、その著者たちが「精神分析的な言 語とソシュール(とその後継者たち)の言説」を用いて、「すでに歴史的な脱落行為であることが証明されつつある言語学を自分自身と戦わせた」と評価してい る。 批評家フレデリック・クルーズは、ドゥルーズとガタリが「ラカンの精神分析を資本主義的障害として告発」し、「分析者を精神病社会の最も邪悪な司祭操作者 として嘲笑」したとき、彼らの「実証は広く答えのないものとみなされ」、「すでに縮小していたパリのラカン陣営を荒廃させた」と書いている。 哲学者のダグラス・ケルナーは、『アンチ・オイディプス』を同時代の出版界のセンセーションであり、ジャン=フランソワ・リオタールの『リビディナル・エ コノミー』(1974年)とともに、「欲望のミクロ政治学」の重要なテキストであると評した。 精神分析学者のジョエル・コヴェルは、ドゥルーズとガタリは家族の神秘性への決定的な挑戦を提供したが、彼らはニヒリズムの精神でそれを行ったと書いてお り、「彼らの『分裂文化』と欲望機械の世界に浸ることは、核家族の安全な狂気への憧れを抱かせるのに十分である」とコメントしている[47]。 アンソニー・エリオットは『アンチ・オイディプス』を「フランスの精神分析をスキャンダラスにし、知識人の間で激しい論争を巻き起こした」「有名な」作品 であり、「フランスで出版された当時、精神分析とラカニアニズムに対するタイムリーな批判を提供した」と評している。しかし、現在ではほとんどの論者が 「分裂分析」には致命的な欠陥があり、『アンチ・オイディプス』にはいくつかの大きな反論があることに同意するだろう、と彼は付け加えた。彼の見解では、 たとえ「主観性が有益にまとも化され、脱構築される」としても、「欲望が自然に反抗的で破壊的である」と仮定するのは間違っている。彼は、ドゥルーズとガ タリは個人を「複雑で矛盾したアイデンティティではなく、さまざまな器官、強度、流れにすぎない」と見ており、精神分裂病に対して誤った解放的な主張をし ていると考えた。また、ドゥルーズとガタリの作品は現代文化の解釈に困難をもたらすが、それは彼らの「制度としての制度性の拒絶」が、自由民主主義とファ シズムの違いをあいまいにし、ドゥルーズとガタリに「『シゾイドの英雄』というロマンチックで理想化されたファンタジーに過ぎないもの」を残しているから だと論じた。彼は『アンチ・オイディプス』がリオタールの『リビディナル・エコノミー』と同様の理論的方向性を辿っていると書いているが、一方でドゥルー ズとガタリ、他方でリオタールの間にはいくつかの重大な違いがあると見ている[48]。 哲学者のミッケル・ボルク=ヤコブセンと心理学者のソヌ・シャムダサニは、『アンチ・オイディプス』の「挑発と壮大な修辞的暴力」によって自信を揺るがさ れるどころか、精神分析の専門家たちはこの本によって提起された議論が自分たちの学問領域を正当化していると感じていると書いている。 [50] ジョシュア・レイミーは、ドゥルーズとガタリの「器官なき身体」への通路は「危険と苦痛に満ちているが......『アンチ・オイディプス』のポイント は、その暴力や苦痛を美化することではない。むしろ重要なのは、ディノイス的な(中略)体験の実行可能なレベルが存在することを示すことである」 [51]。哲学者のアラン・D・シュリフトは『ケンブリッジ哲学辞典』(2015年)で、『アンチ・オイディプス』は「欲望の哲学の主要な明確化として、 また精神分析の深遠な批判として読まれている」と書いている[52]。 |

| Accelerationism Antipsychiatry Feminism and the Oedipus complex Id, ego, and super-ego La Borde clinic Plane of immanence Psychoanalytic conceptions of language Psychological repression Schizoanalysis |

加速主義 反精神医学 フェミニズムとエディプス・コンプレックス イド、自我、超自我 ラ・ボルド・クリニック 内在の平面 精神分析的言語概念 心理的抑圧 分裂分析 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-Oedipus |

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆