デサナ・プロジェクト2099 :

Proyecto Desana, una interpretación de la obra de "Reichel-Dolmatoff, Reichel. 1968. Desana: Simbolismo de los indios Tukano del Vaupes. Bogota"

R・ ドルマ トフ、1973『デサナ:アマゾンの性と宗教のシンボリズム』寺田和夫・友枝啓泰訳、岩波書店(Reichel-Dolmatoff, Reichel. 1968. Desana: Simbolismo de los indios Tukano del Vaupes. Bogota: Universidad de los Andes.)。

【章立て】

第1部 デサナ族:部族と環境

第2部 創造の神話

第3部 宗教的シンボリズム

第1章 創造主と創造

第2章 神々と悪魔

第3章 シンボルと観念連合

第4章 人間と超自然

第5章 社会と超自然

第6章 人間と社会

第7章 人間と自然

第8章 結論

付録 神話

【ドルマトフの文化の概念と生態学的な関 係】

「民族学者が人類の未来への遺産として救わねばならないのは、 まさしく哲学体系、ないしはその文化固有の内部情報の特質である」(p.viii)

「デサナ族の哲学=宗教的思惟は、生存のために必要な生物学的 均衡の保存という問題と密接に関係している……人間の生活の表出のあり方と思考形態」(p.xix)

「デサナ文化の現状についてのこれまでの簡単な記述は、そのか なりの部分バウペスーパプリ地域の部族全体に一般化しうる。……だがここのところで表面的な類似はおわり、もう少し深く文化の中に入っていくと、重要な相 違が浮かびあがってくる。その違いというのは特に宗教システムにあわられるが、経済上の多様性がその基本になっている」(p.19)

・「男はいわば蛋白質という栄養の範疇の生産者であり、女は炭 水化物という相補的な食物を生産する。毎日の料理によってこれらの食物は変化して人間が関与している新しいエネルギーをうみ、こうしてより広汎な生産の循 環の連続性が保証される」(p.306)。

【民族集団】(p.3)

I. トゥカノ語族

西トゥカノ(カケタ川地域)

東トゥカノ

デサナ:狩猟民(デサナ名「ウィラ」=風、「ウィラ=ポ ナ」風の子供たち、p.10)

トゥカノ:漁撈民

ピラ=タプヤ:漁撈民

ワナノ:漁撈民

カラパナ:園耕民

トュユカ:園耕民

ミリティ=タプヤ:園耕民

ユリティ=タプヤ:園耕民

クベオ(社会・宗教構造が詳しく調べられている p.9)

バラサナ

シリアノ:漁撈民(p.20)

II. アラワック語族

クリバッコ:園耕民

タリアナ:園耕民

III. マク族:森林を移動する採集民。言語類縁関係が定まっていない(ca.1968)デサナ名(ウィラ =ポヤ[だめな風=デサナ]:p.4; p.22)。「人々」(マフサ)のカテゴリーに入らず、近隣部 族から奴隷ーーデサナ、トゥカノ、タリアナが「マク族をもっている」つまり彼等の奉仕を利用する権利をもつと考えているーーのように扱われる(p.22)。「マクたちは普通に はダフスウと自称しているが、従属的地位に不満を示さないし、その地位も彼等なりに経済的利点がある。デサナにとっては重要な仲介者であり、主人である部 族間の人的接触面での仕事を引受けるだけでなく、彼等の魂までが、のちに見るように、パイェのある種の取引において抵当として使われる」(p.23)。

【トーテム】

・すべての氏族がハチドリをトーテムとみているため、自分たち を「ミミ・ポナ」つまり「ハチドリの子供たち」と呼ぶ(pp.10-11)

・「現状でデサナ族は30余の外婚制父系氏族に分れ、各々は神 話上の祖先に由来するとされるが、その中で鱒(ポレカ)の氏族が首位にあることを皆が認めている」(p.11) (→芸術様式への反映 p.311)

・「結婚は厳格に外婚と夫方居住制をとり、すべての氏族は「兄 弟」で、他の部族すなわち他の胞族の女性と結婚すべきだと考えられている」(p.17)

【生態学=宗教=人口を支える生業形態】

・生態学的安定(p.16)=デ サナはエコロジカルな民族? (自然認識に関する伝承=神話や、それにもとづくコスモロジーが人口が安定するように「森林の動物を守る精巧な機構」(p.16)だという。)

・「狩猟民、漁撈民、園耕民といった立場は、当然のことなが ら、人とその環境の間の各々に異なった関係を作っている。狩猟民や漁撈民は、農耕の仕事や植物に関した全てを世俗的に扱う傾向をもち、他面に狩猟や漁撈を 精緻な儀礼にしたてあげている。狩猟民にとってはもろもろの精霊は水の性格を帯び、漁撈民にとってはむしろ森林の性格を帯びている。こうして生態学的適応 の本質、シンボリズムの全体、社会的存続に不可欠な生物均衡の問題、これら全ての面での相違が存しているのである」(p.21)

・狩猟に対する高い位置:「動物が少ないというこの状況を、デ サナははっきりと知っているが、狩猟は彼等にとって特に好ましい基本的な男性活動であり、この活動をめぐって彼等の文化の他の局面のすべてが展開してい る」(p.15)

【パイェの存在】(pp.17-18)

・「社会集団と超自然的存在の仲介者」(p.17)

・「狩猟者と超自然的な動物の「所有者」との仲介者」(p.17)

・「その中心機能は本質的には経済的な性格のものである」(p.17)

・「パイェは動物の主にむかって、動物の若干を譲ってくれるよ うに働きかける任務があり、また狩猟者たちにさまざまな規律を守るように教えてくれたり準備しなければならない」(pp.17-18)

【性的抑圧】

・アウトラインは p.23 に記されている。

・太陽(父なる太陽:パグ・アベ)とその娘の近親相姦:太陽の 兄弟としての月と、太陽の娘への恋慕(p.27)

・近親相姦が月経のはじまり。

・太陽は創造神でもある。エムコーリ=マフスとディロア=マフ スを創造し、空と川を見守るようにさせた。

・創造者とは、太陽、太陽の娘、鱒の娘(p.44)

・ディロア=マフスと、ヴィホ=マフスの創造(p.32)

・太陽の娘の性の営みへの過剰な期待感(ガムーリ)(p.33)

・魚の所有者ウァイ=マフスとその妻たちウァイ=ノメ、娘の ウァイ=マンゴの姿が鱒だった(p.35)

・最初のデサナと鱒の性行為を覗いたさまざまな生物たちが、性 器の形や色に似せて変形して現在の形の由来になる(pp.35-36)

・鱒の出産をみていた動物もまた変形をおこし、現在のかたちや 行動の起源になる(p.36)

・デサナは鱒あるいは川魚と結婚する(→父系出自をたどる妻の 提供者となる外婚集団と彼等が漁撈民であることの関係)(pp.35-)

・邪悪な存在の増加(p.40)

・太陽の娘のアベ・マンゴが人間のさまざまな文化をもたらす(p.41)

・「精神的、心理的な面で、デサナは我々の文化の中でいう意味 では、けして円満で均衡のとれた適応性に富む人と呼べるような個人ではない。正常に性衝動を充足させるということと、文化がその分野に課す禁止条項との間 に均衡をみいだすという問題から生ずる重大なかっとうに、まずもって人間状況が左右されている。……デサナの文化世界においては人間と動物は真の共生を営 み、ただ一つの増殖と多産の循環と理解されている相互依存の状態で生きている。生きて生殖していくためには、人間は動物を必要とし、動物は提供する食糧を 通して人間に必要な生活エネルギーを伝達し、その活力はまさしく動物の側からの人間の増殖であると解されている。だが、その反対に人間も動物たちが増え続 けていくように、彼等を増殖しなければならない。この相互増殖はさまざまなやり方で実行される。後章で扱われるように種々の儀礼的活動を通じて人間は自然 を孕ませる。だがそれは自分たちの性の領分において大きな犠牲を払ってのことである。狩猟者にとっての基本的な規則は性の抑制であり、この規則は深い苦悩 の状態に追いやらずにはおかない強度の抑圧を要求してくる」(p.81)。

【循環としてのボガ】p.59〜65の 説明は重要で、かつ人間の 感覚の起源を説明する。

【人間と死後の転生としての動物】

・「死ねばアフピコン=ディアーに戻るが、ときにこの楽園に入 れない者が森にある山の子宮に入り、そこで動物の姿になって存在し続ける。変形はこうして継続し、個人は一つの状態から他の状態へと移るが、この世界での 道徳行為いかんで究極の行き先はきめられている。満ち足りたアフピコン=ディアーに戻れるか、あるいは動物の身におとし、非難されるべき生前の行為に責め られて、動物たちと命運を分かちあう破目になるかはそれによってきまる」(p.76)。

・「デサナ文化の道徳規範を守り通した徳の高い人の魂は、アフ ピコン=ディアーにいき、そこでハチドリ(蜂鳥)に姿を変える」(p.79)。

・アフピコン=ディアーにおけるハチドリのシンボリズム解釈(pp.238-241)

【コメント】

・VdCの議論はデ サナの民族誌において可能か?:この場合のVdCの 議論とは具体的には何をさすのか?

・もしGerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff(1912-1994) が生きていて、VdCの 議論に参 与すると、彼(R-D)はどんなコメントするだろうか?

・宗教的シンボリズム:生態学的適応生活の表出のあり方と思考 形態(p.xix)

・狩猟形態に対する絶対的優位の付与:1.外婚集団の位置づ け、2.狩猟と漁労の生態学的関係、3.神話上の関係。

【パイェのふるまい】pp.151-165

・禁欲と人倫の修業(pp.151-)

・「デサナ語ではパイェはイェエといわれ、この語はジャガーも 意味し、実際はパイェはこの動物に姿を変えることができるとも言われている。しかしながら、この語はイェエーリ(性交する)あるいはイェエール(陰茎)か らきており、したがってパイェはその力(イェエ・トゥラーリ)をもって直接に生命=宇宙の生殖過程に介入する男根的手段となる」(p.156)。

・パイェによる動物の獲物と人間の命の交換取引について(p.158)

【神官としてのクム】pp.165-169

・クムの遺骨に関する儀礼的カニバリズム(p.169)

【通過儀礼】pp.170-185

【仲介者の重要な役割】

・中立的仲介者の存在(p.21):マク族との、感情的 性的関係

・また第3部「宗教的シンボリズム」第2章 「神々と悪魔」には、「神格的仲介者」(pp.89-94)に関する記述 がある。

・供儀としてのマク族(p.159)

・VdCの功罪: (功)民族誌資料の読み直し、存在論への関心喚起(罪)

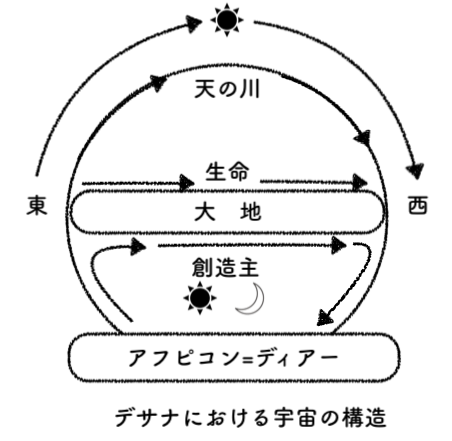

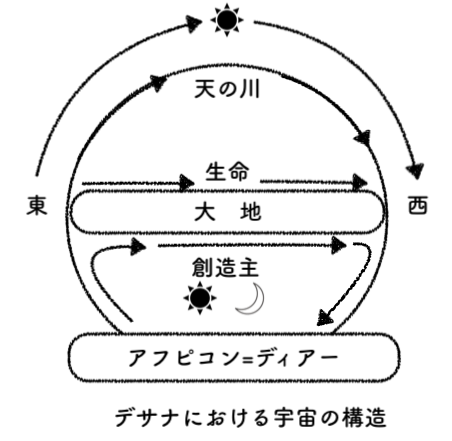

・アフピコン=ディアーの概念図(p.50):アフピコン=ディ アーは地下の楽園(p.28):東側はすべての川の水が注ぐ湖があり、西側は暗黒の世界(p.28):「アフピコン=ディ アー=母の子宮=マロカ=墓=アフピコン=ディアー」(p.309)

・人 間世界 もまた様々な親族関係の網の眼のように規定されている:multiple ontology

【女性・他民族・自然観】

・人間と動物の関係だけではなく、人間の間には、他者(女性や 異民族)が介在しており、複雑な単一の存在論的意味をもつ(159ページにおけるマクの老女の言挙げ(=供儀としてのマク族の自己認識):環境・コスモロ ジーをどう考えるのか)

・「だが彼等自身が設けている主要な区分は、伝統的な経済基盤 にかかわっており、彼等は狩猟民、漁撈民、園耕民の諸部族の間をはっきり分けている。……園耕民に一段と低い地位を、狩猟民に一段と高い地位を与えてい る」(pp.19-20)。つまり、デサナの狩猟民としての自民族中心主義的見解。また近隣の漁撈 民からは女性 を得て、園耕民からはほとんどもらわない、つまり婚姻は「例外」とみされている(p.20)。

・狩猟は男性的活動、漁撈は女性的活動で、漁撈民そのものが女 性的性格を有するとみなす(p.20)。

・「狩猟民、漁撈民、園耕民といった立場は、当然のことなが ら、人とその環境の間の各々に異なった関係を作っている。狩猟民や漁撈民は、農耕の仕事や植物に関した全てを世俗的に扱う傾向をもち、他面に狩猟や漁撈を 精緻な儀礼にしたてあげている。狩猟民にとってはもろもろの精霊は水の性格を帯び、漁撈民にとってはむしろ森林の性格を帯びている。こうして生態学的適応 の本質、シンボリズムの全体、社会的存続に不可欠な生物均衡の問題、これら全ての面での相違が存しているのである」(p.21)

・マク族は、その意味で特異的であるが、また同時に重要であ る:「マクたちは普通にはダフスウと自称しているが、従属的地位に不満を示さないし、その地位も彼等なりに経済的利点がある。デサナにとっては重要な仲介 者であり、主人である部族間の人的接触面での仕事を引受けるだけでなく、彼等の魂までが、のちに見るように、パイェのある種の取引において抵当として使わ れる」(p.23)。「デサナは強く否定してはいるが、彼等とマクの間には非常に親密な感情的、性 的関係 が存していて、それは単にマクの果たす子守りの役割のせいだけではないものがある。デサナにとってマクは単に下僕ではなくて、女性的要素、性の対象でもあ り、その上に相反した観念や感情が投影されている」(p.23)。

・供儀としてのマク族(p.159)

【動物の主】(Pp.94-102)

・シャーマンの階梯を上昇してゆくことと、彼らの認識的プロセ スが変わる:これは、彼らのコスモロジーが変わるということなのか?----単一の存在論を前提と すると、変化するのは認識論ではないのか?(Pp.168--)

・認識が変わるということは、子供の身体構成も変化するという ことである(VdC)(p.173)

・敵から視点(From enemy's point of view)

・デサナに対するDavid Maybury-Lewis (1929-2007)のNew York Times での書評で「全宇宙系に関する強引な 整然さ」に対する疑義を提出(p.363)。つまり、あまりにもよくでき過ぎたコスモロジーではな いかということ。

【動物と人間の交換交渉行為】

・パイェによる動物の獲物と人間の命の交換取引について(p.158)

・人間の多産行為は「森の動物の嫉妬をまねく」(p.178)

・ただ単に動物と人間が対等なエージェントとしてあるのではな く、精霊を媒介あるいは援軍とする第三者関係である可能性もある。「女の妊娠、特に受胎と出産は、動物の主であるウァイ=マフスの激しい嫉妬を誘う。いつ も女に興味を寄せているウァイ=マフスは、今や妊娠の男に対して激しい嫉妬を懐き、自分に備わっていると信じていた性の特権を侵害した男への復讐を遂げよ うとする。そこでウァイ=マフスは自分の動物、特に蜘蛛、さそり、蛇を使うが、単にこの「噛みつく動物」で男を追いかけるだけでなく、「貪り食う動物」つ まりジャガーとか大きな水棲の蛇も使うのである……」(p.180)

・「動物たちは大勢の人間の増殖を自分たちの分を減らすエネル ギーの浪費とか「盗みのように」考える。人間と動物はただ一つの生殖の潜在力にあずかっており、両者にはしかるべき分配と均衡があるべきだと考えられてい る。……こうした観念の根底には、動物相に関した自然環境には利用できる潜在力に限界があって、無制限な人口増加は必ず生物界の重大な均衡破壊をもたらす という意識が存在している。そこでこの均衡は制度化された2つのメカニズムによって維持されていることになる。一つには狩猟者の性的抑制で、彼は禁欲して はじめて狩猟の成功をおさめることができる。そして2つには避妊薬を用いた出産の調整である。第一のメカニズムは二重作用をしていて、一方で狩猟者に性的 な関係を避けさせ、他方こうして彼の分を蓄積しておいて、その分動物たちに生殖の潜在力にあずからせる」(p.178)。

・動物の分類(Pp.251-262):(1) 創造主である太陽が直接造った生物、(2)川や湖の魚、(3)ハチや小動物など「ひとりでに生まれた動物」という3つのカテゴリー

・動物の特徴(Pp.262-275)

・狩人と獲物(Pp.275-291):エネル ギー行為としての人間の性行動の抑制が、人間と動物の互酬性(p.276)のなかに反映される(→ 【狩猟は求愛と性行為である】も参照)。

・だからと言って、人間と動物は単純な対称関係ではない。イン フォーマントであるアントニオ・グスマンの弁「動物たちモラルはない。ただ生殖するやり方があるだけである。特別な規範というのもない。生殖し、生活し、 死んでゆく。だがいつもウァイ=マフスに従っている。ウァイ=マフスが何を食べ、どこを歩き、どんな風に生殖するかを彼等に命令する。これは第二の世界み たいなものである。ウァイ=マフスは人間行為に対する償いである。彼の嫉妬は、父なる太陽がうちたてた掟をきちんとしたものにする役にたっている。掟が守 られるように動物たちを利用する」と(p.288)。

・もちろん互酬関係があったからといって2つの集団(人間と動 物)が同じ存在論的範疇そのものである必要はない:「デサナ族によれば、生の目的、人間のすべての行動と態度の目的は、社会の生物的・文化的な継続性にあ る。この目的は、人間が生物領界、つまり彼ら自身の社会内部および動物との間で確立している諸関係の、厳密な互酬組織によってのみ達成される」(p.306)。

【狩猟は求愛と性行為である】

・「狩猟は実のところ求愛と性行為にほかならず、厳格な規範に のっとって慎重に対処すべき事態なのである」ーーレイチェル=ドルマトフ『デサナ』(1973:277[1968])

・「動物に恋をする」という動詞(ウァイ=ムラ・ガメタラー リ)において「表された観念は、自ら近づいて来て殺されるままになるように、動物を性的に誘いこむことであり、これ自体が性的な支配行為である」(p.277)

・よい狩人になるための訓練(pp.278-279)

・タブーと規範による武器庫としての狩人(pp.284-285)

・エロティック関係の解消(p.293)

【食物としての獲物】pp.292-301

・調理過程(p.295-)

・一年の食物サイクル(p.302)

【魚類と人間の関係】

・魚類は、動物と人間の対称的な関係性のなかに存在論的にある よりも、デサナの起源における鱒の娘とのデサナの性交渉の起源のなかにある(それは外婚集団との婚姻を隠喩する)(Pp.232-233)

・氏族の間の関係は、対等ではなく、偏向している。「最初の夫 婦から直接生まれたこの9人の子供が氏族のはじまりとなった。そしてこれらの氏族集団が形成するきまった順序が伝統的にあって、各人はより上位の氏族に対 して「奉仕を義務づけられ」ている」(pp.237-238)。

・漁撈(pp.288-291)

【病気と治療】pp.215-231

【余滴】2010年12月21日

OK:T、OK、KDの

論考

では、主体ないしは動物主体というキーワードが浮かび上がります。それらの

論文では、人間に対して、動物が主体的に考え、ふるまうことが、何らかの意味を持つと考えられます。テワーダでは、ウナギが、人間が唱える呪文に応じて、

主体(?)となり(あるいは、客体?)、プナンでは、苛まれた動物(の魂)が、(主体的に)雷神のところに駆け上がって告げ口をし、隠岐島では、猫が(主

体的に)人間を化かします。それらとの比較でいえば、河南蒙旗では、動物種ではなく、動物個体が、もっぱら、人間によって聖化されるわけで、別段、主体と

してふるまうわけではありません。神経生理学研究室では、どうでしょうか。ことによると、アニマルライツを視野に入れれば、動物の主体性というテーマが浮

かび上がるかもしれません。

IK:この発想は単に、主客を入れ替えて

いるだけにすぎませんか?つまり民族誌記述を、動物

を主人公にする動物誌記述としてリライトすることに繋がらないでしょうか?

古典的な民族誌記述(たとえば『デサ

ナ』)においても、動物

や精霊が意思をもってエージェントとしてふるまうことが報告されているので「人間に対して、動物が主体的に考え、ふるまうことが、何らかの意味を持つ」と

いうことは民族誌学上では了解済みの内容なのではないでしょうか?

むしろ(近隣異民族を含む)他者として

の動物が、人間生活上

においてどのような〈媒介的機能〉を果たしているのか構造論的に——つまりラドクリフ=ブラウン的に——明らかにすることが先決ではないでしょうか?もち

ろん、このような構造と機能を関連付ける古典的方法は、人間と動物の関係性のカテゴリー分けをおこない、社会のタイプの分類欲望へと導き、蝶々集めに堕す

る危険性を承知で言っています。でもこのような修練——ニーダム流のいろいろな社会の民族誌を精査してそのなかに扱いたい個別文化現象に伏在する家族的類

似性をあぶり出す——こそが、動物を主人公にする動物誌記述としてリライトにならない数少ない脱出方法ではないかと、妄想しています。ニーダムと論争した

L=Sは、

この社会人類学的批判が体質的に理解できず、民族誌の中に〈神話的真実=構造〉を発

見するゲームに夢中になりすぎたのではないでしょうか。乱暴で拙い議論ですが、その一部の可能性でもご検討ください。

OK:これまでの発

表などを聞いた限りでは、わたしとしては、自然と社会というテーマ

をいきなり問題とするのではなく、動物と人間の関係に絞って、民族誌を厚くし、さらにその先に、自然と社会をめぐる理論的な課題の検討を行っていく(仄め

かすくらい?)のがいいのではないかと思っています。

IK:というわけで、俺達のニーダム流の テーマは「人間と動物」の関係性の表象(隠喩・換 喩・提喩など)をめぐる、民族誌を厚くすることで、その図と地の関係性をずらして、何が人間の文化と社会をつくりあげているのかを明らかにすることに繋が るので、この部分のOK提言(2)は大いに首肯します。

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

★ライヘル=ドルマトフ教授とはこんな人

です【以下の記事】(→ナチ関連の情報はこちら「ジェラルド・ライ

ヘル・ドルマトフ」)

| Gerardo

Reichel-Dolmatoff (6 March 1912 – 17 May 1994[1]) was an Austrian

anthropologist and archaeologist. He is known for his fieldwork among

many different Amerindian cultures such as in the Amazonian tropical

rainforests (e.g. Desana Tucano), and also among dozens of other

indigenous groups in Colombia in the Caribbean Coast (such as the Kogi

of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta), as well as others living in the

Pacific Coast, Llanos Orientales, and in the Andean and inter-Andean

regions (Muisca) as well as in other areas of Colombia, and he also did

research on campesino societies. For nearly six decades he advanced

ethnographic and anthropological studies, as well as archeological

research, and as a scholar was a prolific writer and public figure

renowned as a staunch defender of indigenous peoples. Reichel-Dolmatoff

has worked with other archaeologists and anthropologists such as

Marianne Cardale de Schrimpff, Ana María Groot, Gonzalo Correal Urrego

and others. He died 17 May 1994 in Colombia.[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerardo_Reichel-Dolmatoff |

ジェラルド・ライヘル・ドルマトフ(Gerardo

Reichel-Dolmatoff、1912年3月6日 -

1994年5月17日[1])はオーストリアの人類学者、考古学者。アマゾンの熱帯雨林(例:デサナ・トゥカーノ)など、さまざまなアメリカインディアン

の文化をフィールドワークしたことで知られる。デサナ・トゥカーノなど)、またカリブ海沿岸のコギ族(サンタ・マルタ山脈のコギ族など)、太平洋岸、オリ

エンタル山脈、アンデス地域、アンデス間地域(ムイスカ)など、コロンビアの他の地域に住む数十の先住民グループとのフィールドワークで知られ、カンペ

シーノ社会の研究も行った。60年近くにわたり、民族誌学、人類学、考古学の研究を進め、学者として多作であり、先住民の擁護者として有名な公人であっ

た。ライチェル=ドルマトフは、マリアンヌ・カルデール・デ・シュリンプフ、アナ・マリア・グルート、ゴンサロ・コレアル・ウレゴなど、他の考古学者や人

類学者と共同研究を行った。1994年5月17日、コロンビアで死去[1]。 |

| Personal life Reichel was born in 1912 in Salzburg, then part of Austria-Hungary, as son of the artist Carl Anton Reichel and Hilde Constance Dolmatoff. Oriented in the classics (Latin and Greek) he did most of his high school at the Benedictine school of Kremsmunster in Austria. He attended classes at the Faculté des Lettres of the Sorbonne and in the École du Louvre from late 1937 to 1938. Reichel emigrated to Colombia in 1939, where he became a Colombian citizen in 1942.[2] Reichel became member and was the Secretary to the Free France Movement (1942-1943) with the help of his colleague and friend the French ethnologist Paul Rivet who was the Delegate of the Resistance of France Libre and living in Colombia. General Charles De Gaulle later awarded Reichel-Dolmatoff with the medal of the Ordre national du Mérite.[2] Reichel-Dolmatoff spent the rest of his life in research in the fields of anthropology, archaeology, ethnoecology, ethnohistory, ethnoastronomy, material culture, art, and vernacular architecture, among others. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerardo_Reichel-Dolmatoff Años en Europa Su educación secundaria estuvo orientada hacia los estudios clásicos (latín y cultura griega), la cual adquirió en el colegio Benedictino de Kremsmünster en Austria (1923-1931) (hay quienes dicen que nunca concluyó sus estudios). Más tarde se gradúo en artes en la Academia de Bellas Artes de Múnich de Munich (1934-1936). Allí pudo ver el horror del desarrollo de una Alemania nazi y esto lo impulsó a emigrar a París (1937-1939), donde atendió la Facultad de Letras de La Sorbona y asistió a la Universidad de París, así como a la Escuela del Louvre. Allí aprendió directamente de Marcel Mauss y del sociólogo Georges Gurvitch. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerardo_Reichel-Dolmatoff Llegada a Colombia A finales de 1939, en vísperas de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, viajó a Colombia por consejo del politólogo André Siegfried (fr). Una vez en Colombia, trabajó en la sección de paleontología de la compañía Texas Petroleum (1941-1946) en Bogotá. Entra en contacto con el etnólogo francés Paul Rivet, refugiado por entonces en Colombia a causa de la guerra y quien era, además, el delegado de la Resistencia de la Francia Libre organizada por el general Charles De Gaulle, en la que fue nombrado Secretario General por Rivet. Hizo parte del grupo de europeos y colombianos protagonistas en la institucionalización de la investigación etnológica y arqueológica en Colombia, participando entre 1941 y 1946 en el Instituto Etnológico Nacional fundado por Paul Rivet y el colombiano Gregorio Hernández de Alba, además de Justus W. Schottelius y José de Recasens, quienes también migraron para escapar del nazismo, invitados por el entonces presidente colombiano Eduardo Santos. Obtuvo la nacionalidad colombiana en 1942 y al año siguiente contrajo matrimonio con la antropóloga Alicia Dussán Maldonado, quien fue una de las primeras mujeres profesionales en Colombia, y formó parte de la primera generación de estudiantes graduados del Instituto Etnológico Nacional. Esta pareja se convirtió en equipo de investigación por el resto de su vida. |

私生活 ライヘルは1912年、当時オーストリア・ハンガリー帝国の一部だったザルツブルクで、芸術家のカール・アントン・ライヘルとヒルデ・コンスタンス・ドル マトフの息子として生まれた。古典(ラテン語とギリシャ語)に傾倒し、高校時代の大半をオーストリアのクレムスムンスターのベネディクト会学校で過ごし た。1937年末から1938年まで、ソルボンヌ大学文学部とルーヴル美術館付属美術学校で講義を受けた。1939年にコロンビアに移住し、1942年に コロンビア国籍を取得した。[2] ライチェルは、同僚であり友人である、自由フランス抵抗運動の代表でコロンビア在住のフランス人民族学者ポール・リヴェの支援を受けて、自由フランス運動 のメンバーとなり、1942年から1943年まで書記を務めた。後にシャルル・ド・ゴール将軍から、ライチェル・ドルマトフに国家功労勲章が授与された。 [2] ライヒェル=ドルマトフは、その後の人生を、人類学、考古学、民族生態学、民族史学、民族天文学、物質文化、芸術、民家建築などの分野の研究に捧げた。 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerardo_Reichel-Dolmatoff ヨーロッパでの年月 彼の初等教育は古典学(ラテン語とギリシャ文化)に重点を置いたもので、オーストリアのクレムスミュンスターのベネディクト会学院(1923-1931) で受けた(一部では、彼はこの教育を修了しなかったとされている)。その後、ミュンヘンのミュンヘン美術アカデミー(1934-1936)で美術の学位を 取得した。そこでナチスドイツの台頭の恐怖を目の当たりにし、これが彼をパリへの移住(1937-1939)に駆り立てた。パリではソルボンヌ大学文学部 で学び、パリ大学やルーヴル美術館付属美術学校にも通った。そこでマルセル・モースや社会学者のジョルジュ・グルヴィッチから直接指導を受けた。 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerardo_Reichel-Dolmatoff コロンビアへの到着 1939年末、第二次世界大戦直前に、政治学者のアンドレ・シグフリード(fr)の勧めでコロンビアへ渡った。コロンビア到着後、ボゴタのテキサス・ペト ロリウム社で古生物学部門で働いた(1941-1946)。フランス人民族学者ポール・リヴェと接触した。リヴェは当時戦争のためコロンビアに避難してお り、シャルル・ド・ゴール将軍が組織した自由フランス抵抗運動の代表でもあり、リヴェによって秘書長に任命された。 彼は、コロンビアにおける民族学と考古学の研究の制度化に主導的な役割を果たしたヨーロッパ人とコロンビア人のグループの一員として、1941年から 1946年まで、ポール・リヴェとコロンビア人のグレゴリオ・エルナンデス・デ・アルバ、およびユストス・W. シュトッテリウスとホセ・デ・レカセンと共に、ナチスから逃れるために移住した。彼らは当時のコロンビア大統領エドゥアルド・サントスによって招かれた。 1942年にコロンビア国籍を取得し、翌年に人類学者のアリシア・ドゥサン・マルドナードと結婚した。彼女はコロンビアで最初の女性専門職者の一人であり、国立民族学研究所の最初の卒業生の一人だった。この夫婦は生涯にわたって研究チームとして活動した。 |

| Career Reichel-Dolmatoff developed a keen interest for conducting fieldwork which would take him and his studies throughout the country, the Caribbean area, La Guajira desert, the Chocó rainforests, the Llanos Orientales, to the mountains of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and the Amazon rainforests. Some of Reichel-Dolmatoff's archeological research was essential in creating the basic chronological framework for most of the Colombian area, and is still used today.[citation needed] In a trip to the upper Meta River in the Orinoco plains in 1940, he conducted research and later published the earliest studies done on the Guahibo Indians. In 1943 Gerardo wrote his first article on the Muisca settlement of Soacha. That same year, together with his wife anthropologist and archeologist Alicia Dussán, he conducted an analysis on pre-Columbian burial urns of the Magdalena River. Working in the Tolima region inhabited by Amerindians and the renowned indigenous leader Quintin Lame, they also published a study indicating the indigenous culture of the local populations and also indicated the blood type variations among the indigenous groups of the Pijao in the Department of Tolima as further proof of their Amerindian identity as these tribes were arguing over rights to their ancestral territories. Switching residency to the city of Santa Marta in 1946, the Reichel-Dolmatoffs created and headed the Instituto Etnologico del Magdalena in 1945[2] and created also a small museum about the anthropology and archeology of the Sierra Nevada region. Reichel-Dolmatoff wrote a two volume monography of the Kogi Indians in the 1940s which to this day is considered a classic reference. For the next five years, Gerardo and his colleague and wife conducted research throughout the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region, focusing particularly on the Tairona descendants, the Kogui, also known as the Kogi or Kaggaba, and also worked with the Arhuaco and Wiwa indigenous groups, as well as ethnography of a peasant community among the people of Aritama (Kankuamo). Reichel-Dolmatoff carried out a regional study of the area covering archeology, ethnohistory and anthropology, making it one of the first such regional studies made in Colombia. Reichel also did research in the Pacific coast and studied amongst others the Kuna of the Caiman Nuevo River, west of the Gulf of Urabá. Several years later, Reichel published ethnohistorical studies and anthropological research related to the Kogi, demonstrating their connections to ancestral Tairona chiefdoms. In the late 1950s, Reichel and his family moved to the coastal city of Cartagena. Reichel taught classes in medical anthropology at the university there and engaged in programs of public health with an anthropological perspective. Actively involved in archeological excavations in the Caribbean region around Cartagena, in 1954, the Reichel-Dolmatoffs located and also excavated, amongst others, the Barlovento site, which was the first early Formative shell-midden site found in Colombia. At Momil, they conducted the first study of societies engaged in a subsistence change from shifting cultivation (manioc) to corn agriculturalists. After returning to live in Bogotá in 1960 Reichel was the founder, professor, and first Chair the first Department of Anthropology in Colombia. Reichel did archeological excavations at the site of Puerto Hormiga where they discovered the earliest dated pottery in all of the New World (at that time), -dated over 5 thousand years old- which indicated that pottery had been first developed in the Caribbean coast of Colombia and then spread elsewhere to the rest of the Americas (and hence was not brought through diffusion from the Old World as had been formerly suggested by other archeologists) .(Reichel see biblio). Reichel also excavated in other sites including in San Agustin, Huila.[2] He published his analyses of the Puerto Hormiga site regarding early Formative cultures, and of the San Agustin site regarding chiefdoms. Reichel also produced one of the first overviews of Colombian archeology and proposed an interpretive framework of its millenarian pre-historic past.[3] In 1963, Reichel and his wife taught courses in anthropology at the Universidad de los Andes, and then in 1964 formally created the first Department of Anthropology in Colombia at the university in Bogotá. Reichel-Dolmatoff worked for 5 years at the Department and left together with his wife and several other professors due to changes in the Department. Reichel received a short visiting fellowship to Cambridge University in 1970 and became an adjunct professor at the Anthropology Department of the University of California in Los Angeles. During the 1960s and until the mid-1990s Reichel-Dolmatoff advanced research on Amerindian shamanism, indigenous modes of life, ethnoecology, and on cosmologies and worldviews, and he also did research on hallucinogens related to shamanism, entheogens, ethnoastronomy, ethnobotany, ethnozoology, and on the vernacular architecture of temples and of the Amazonian 'maloca' longhouses; additionally he did research on the shamanic symbolism of pre-Columbian goldwork, as well as other Amerindian artifacts and material culture, including basketry. Reichel-Dolmatoff was a member of the Colombian Academy of Sciences, and a Foreign Associate Member of the NAS National Academy of Sciences of the United States and he was also a member of the Academia Real Española de Ciencias. He was awarded the Thomas H. Huxley medal by the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland in 1975. Reichel-Dolmatoff was the single author of 40 books and of over 400 articles, all dedicated to the archeology and anthropology of Colombia and specifically highlighting the relevance of indigenous peoples of the past and present. In 1983, Reichel-Dolmatoff was one of the founding members of the Third World Academy of Sciences (TWAS), which was created and headed by dr. Abdus Salam (Nobel Prize in Physics) with renowned scientists of the Third World who sought to focus differently on the issues of science and technology for the interests of the developing countries themselves. International recognition While living in Colombia for over half a century, Reichel-Dolmatoff provided his professional services to the national and departmental governments, and as university professor, researcher and author to public and private universities. In 1945 he founded in Santa Marta the Instituto Ethnologico Nacional del Magdalena and in the early 1950s he became professor of Medical Anthropology at the University of Cartagena. He occupied, amongst other positions, those of researcher and lecturer of the Instituto Etnologico Nacional and the Colombian Institute of Anthropology and he was Chair and professor of the Department of Anthropology of the Universidad de los Andes. He was visiting professor of the National Museum of Ethnology in Japan. Reichel-Dolmatoff participated in academic congresses and seminars and wrote conference papers in universities and international or national academic events in South America, North America and Central America as well as in Europe, Japan. In the field of archaeology, Reichel-Dolmatoff helped define the early archeological evidence of the Formative stage in Colombia, based on sites excavated which provided the then most ancient site in all the Americas where pottery had originated over 6,000 years ago, and this research was tied also to new interpretations of the meaning and connections of the cultural evolution of Colombia with other regions of the Americas. Reichel-Dolmatoff researched origins of early chiefdoms and explained the millenarian evolution of Amerindian cultures and their links to contemporary indigenous groups. His excavations focused mainly on living spaces and garbage heaps, where the archaeologist avoided exploring or excavating monumental sculptures, monumental architecture and indigenous burial sites. In the field of anthropology, Reichel-Dolmatoff focused on investigating and celebrating Colombia's ethnic and cultural diversity and especially of indigenous peoples. The scope and extent of his work and dedication to understanding, acknowledging and disseminating the importance and value of Colombia's contemporary indigenous peoples was significant. At a conference in 1987, Reichel-Dolmatoff spoke the following words: "Today I must acknowledge that since the beginning of the 1940s, it has been for me a real privilege to live with, and also try to understand in depth, diverse indigenous groups. I noted among them particular mental structures and value systems that seemed to be beyond any of the typologies and categories held then by Anthropology. I did not find the ‘noble savage’ nor the so-called ‘primitive’. I did not find the so-called degenerate or brutish Indian nor even less the inferior beings as were generally described by the rulers, missionaries, historians, politicians and writers. What I did find was a world with a philosophy so coherent, with morals so high, with social and political organizations of great complexity, and with sound environmental management based on well-founded knowledge. In effect, I saw that the indigenous cultures offered unsuspected options that offered strategies of cultural development that simply we should not ignore because they contain valid solutions and are applicable to a variety of human problems. All of this more and more made my admiration grow for the dignity, the intelligence and the wisdom of these aborigines, who not least have developed wondrous dynamics and forms of resistance thanks to which so-called ‘civilization’ has not been able to exterminate them. I have tried to contribute to the recuperation of the dignity of the Indians, that dignity that since the arrival of the Spaniards has been denied to them; in effect, for five hundred years there has been an open tendency to malign and try to ignore the millenary experience of the population of a whole continent. But humankind is one; human intelligence is a gift so precious that it can not be despised in any part of the world, and this country is in arrears in recognizing the great intellectual capacity of the indigenous peoples and their great achievements due to their knowledge systems, which do not lose validity for the mere fact they do not adjust to the logic of Western thinking. I hope my conceptualizations and works have had a certain influence beyond anthropological circles. Maybe I am too optimistic, but I think that anthropologists of the older and new generations, according to their epochs and the changing roles of the Social Sciences, have contributed to revealing new dimensions of the Colombian people and of nationhood. I also have trust that our anthropological work constitutes an input to the indigenous communities themselves, and to their persistent effort to attain the respect, in the largest sense of the term, that is owed to them within Colombian society. I think that the country must highlight the indigenous legacy and guarantee fully the survival of the contemporary ethnic groups. I think that the county should be proud to be mestizo. I do not think that it is possible to advance towards the future without building upon the knowledge of the proper millenarian history, nor overlook what occurred to the indigenous peoples nor the black populations (Afrodescendants) during the Conquest and the Colonies, and also during the Republic and to this day. These are, in sum, some of the ideas that have guided me through almost half a century. They have given sense to my life."[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerardo_Reichel-Dolmatoff |

経歴 ライチェル=ドルマトフは、カリブ海地域、ラ・グアヒラ砂漠、チョコ熱帯雨林、ラノス・オリエンタレス、シエラネバダ・デ・サンタ・マルタの山々、アマゾ ンの熱帯雨林など、コロンビア全土をフィールドワークすることに強い関心を抱くようになった。 1940年にオリノコ平野のメタ川上流域を訪れ、グアヒボ・インディアンに関する最古の研究を行い、後に出版した。1943年、ジェラルドはソアチャのム イスカ集落に関する最初の論文を書いた。同年、妻である人類学者・考古学者のアリシア・デュサンとともに、マグダレナ川流域の先コロンビア時代の墳墓の分 析を行った。アメリカインディアンと有名な先住民指導者キンティン・ラメが住むトリマ地方で活動し、地元住民の先住民文化を示す研究を発表した。また、先 祖伝来の領土の権利をめぐってこれらの部族が争っていたため、アメリカインディアンであることのさらなる証明として、トリマ県ピジャオの先住民グループ間 の血液型の違いを示した。 1946年にサンタ・マルタに居を移したライチェル=ドルマトフ夫妻は、1945年にマグダレナ人類学研究所を設立し[2]、シエラネバダ地域の人類学と 考古学に関する小さな博物館も設立した。ライチェル=ドルマトフは1940年代にコギ・インディアンの単行本を2巻書き、今日に至るまで古典的な文献とみ なされている。その後5年間、ジェラルドと彼の同僚夫妻はシエラ・ネバダ・デ・サンタ・マルタ地域全域で調査を行い、特にタイロナ族の末裔であるコギ族 (コギ族またはカガバ族とも呼ばれる)に焦点を当て、アルワコ族やウィワ族の先住民族、またアリタマ(カンクアモ)の人々の農民コミュニティの民族誌にも 取り組んだ。ライチェル=ドルマトフは、考古学、民族史学、人類学を網羅したこの地域の地域研究を行ない、コロンビアで最初に行なわれたこのような地域研 究のひとつとなった。ライチェルは太平洋岸でも調査を行い、特にウラバ湾の西にあるカイマン・ヌエボ川のクナを研究した。数年後、ライチェルはコギ族に関 する民族歴史学的研究と人類学的研究を発表し、コギ族が先祖代々のタイロナ族の首長国とつながっていることを明らかにした。 1950年代後半、ライチェルは家族とともに海岸沿いの都市カルタヘナに移り住んだ。ライチェルは同地の大学で医療人類学の授業を担当し、人類学の視点を 取り入れた公衆衛生プログラムに携わった。カルタヘナ周辺のカリブ海地域の考古学的発掘調査にも積極的に参加し、1954年、ライチェル=ドルマトフ夫妻 は、コロンビアで初めて発見された初期形成期の貝塚遺跡であるバルロベント遺跡などを発掘した。モミル遺跡では、移動耕作(マニオック)からトウモロコシ 農耕への自給自足の変化に取り組んだ社会の最初の研究を行った。1960年にボゴタに戻ったライチェルは、コロンビア初の人類学部の創設者であり、教授で あり、初代学部長であった。ライチェルはプエルト・ホルミガ遺跡で考古学的発掘調査を行い、新世界(当時)最古の土器(5,000年以上前のもの)を発見 した。これは、土器がコロンビアのカリブ海沿岸で最初に開発され、その後アメリカ大陸の他の地域に広まったことを示している(したがって、以前他の考古学 者が示唆していたような旧世界からの拡散によってもたらされたものではない)。ライチェルは、ウイラのサン・アグスティン遺跡など他の遺跡でも発掘調査を 行い、プエルト・ホルミガ遺跡では初期形成期の文化について、サン・アグスティン遺跡では首長制について分析を発表した[2]。ライチェルはまた、コロン ビア考古学の最初の概説書のひとつを作成し、千年前の先史時代の解釈の枠組みを提案した[3]。 1963年、ライチェルと彼の妻はアンデス大学で人類学の講義を行い、1964年にはボゴタの大学にコロンビア初の人類学科を正式に創設した。ライチェル =ドルマトフはこの学科に5年間勤めたが、学科の変更に伴い、妻や他の教授数名とともに退職した。 ライチェルは1970年にケンブリッジ大学で短期客員研究員を務めた後、ロサンゼルスのカリフォルニア大学人類学部の非常勤教授となった。1960年代か ら1990年代半ばまで、ライチェル=ドルマトフはアメリカ先住民のシャーマニズム、先住民の生活様式、民族生態学、宇宙論と世界観に関する研究を進め、 シャーマニズムに関連する幻覚剤、エンテオゲン、民族天文学、民族植物学、民族動物学、寺院やアマゾンの「マロカ」ロングハウスの地方建築に関する研究も 行った; さらに、コロンブス以前の金細工のシャーマニズム的シンボリズムや、籠細工などのアメリカインディアンの工芸品や物質文化についても研究した。 コロンビア科学アカデミー会員、米国科学アカデミー外国準会員、スペイン科学アカデミー会員。1975年、グレートブリテンおよびアイルランド王立人類学 研究所からトーマス・H・ハクスリーメダルを授与された。ライチェル=ドルマトフは、コロンビアの考古学と人類学を専門とし、特に過去と現在の先住民族と の関連性を強調した40冊の著書と400本以上の論文を単独で執筆した。 1983年、ライチェル=ドルマトフは、アブダス・サラム博士(ノーベル物理学賞受賞)を会長とし、開発途上国自身の利益のために科学技術の問題に異なる 焦点を当てようとする第三世界の著名な科学者たちとともに創設された第三世界科学アカデミー(TWAS)の創設メンバーの一人である。 国際的認知 コロンビアに半世紀以上住んだライチェル・ドルマトフは、国や州政府に専門的サービスを提供し、公立および私立大学の教授、研究者、作家としても 活躍した。1945年にサンタ・マルタに「マグダレナ国立民族学研究所」を設立し、1950年代初頭にはカルタヘナ大学で医療人類学の教授に就任した。彼 は、国立民族学研究所とコロンビア人類学研究所の研究員兼講師を務めるほか、アンデス大学人類学部の部長兼教授を歴任した。また、日本の国立民族学博物館 の客員教授も務めた。ライチェル・ドルマトフは、南米、北米、中米、ヨーロッパ、日本の大学や国際・国内学術イベントで、学術会議やセミナーに参加し、会 議論文を発表した。考古学の分野では、コロンビアの形成期における初期の考古学的証拠の定義に尽力し、発掘された遺跡から、アメリカ大陸で最も古い陶器が 6,000年以上前に起源を持つ遺跡を特定した。この研究は、コロンビアの文化進化の意味とアメリカ大陸の他の地域とのつながりに関する新たな解釈とも結 びついていた。ライチェル・ドルマトフは、初期首長制の起源を研究し、アメリカ先住民文化の千年の進化と現代の先住民グループとの関連を説明した。彼の発 掘調査は、主に居住空間やゴミ捨て場に焦点を当て、記念碑的な彫刻、記念碑的な建築物、先住民の埋葬地の発掘は避けた。人類学の分野では、ライチェル・ド ルマトフは、コロンビアの民族および文化の多様性、特に先住民の多様性の調査と評価に焦点を当てた。彼の研究の範囲と広さ、そしてコロンビアの現代先住民 たちの重要性と価値を理解し、認識し、広めることへの献身は、非常に大きなものでした。 1987年の会議で、ライチェル=ドルマトフは次のように語った: 「今日、私は 1940 年代の初めから、さまざまな先住民グループと暮らし、彼らを深く理解しようと努めてきたことは、私にとって本当に光栄なことだったと認識している。その中 では、当時の人類学が抱いていた類型や分類では説明できないような、独特の精神構造や価値観を見出した。私は「高貴な野蛮人」も、いわゆる「原始人」も見 つけることはできなかった。支配者、宣教師、歴史家、政治家、作家たちが一般的に描写していたような、いわゆる「退化した」インディアンや「野蛮な」イン ディアン、ましてや「劣った存在」などとはまったく出会わなかった。私が実際に見たのは、非常に首尾一貫した哲学、高い道徳観、非常に複雑な社会・政治組 織、そして確かな知識に基づく健全な環境管理のある世界だった。実際、先住民の文化は、文化の発展戦略として無視すべきではない、有効な解決策を含む選択 肢を提供していることがわかった。これらの選択肢は、多様な人間の問題に応用可能だ。これらすべてが、私の先住民に対する尊敬の念をますます深めた。彼ら は、いわゆる「文明」が彼らを絶滅させることができなかった、驚くべき抵抗のダイナミズムと形態を発展させたからだ。 私は、スペイン人の到来以来、インディアンから奪われてきた尊厳の回復に貢献しようとしてきました。実際、500年にわたり、大陸全体の住民が千年にわ たって積み重ねてきた経験を中傷し、無視しようとする傾向が公然と存在してきました。しかし、人類は一つであり、人間の知性は、世界のどの地域でも軽視で きないほど貴重な贈り物だ。この国は、先住民の優れた知的能力と、西洋の思考の論理に合わないという理由だけでその有効性を失わない、彼らの知識体系によ る偉大な成果を、まだ十分に認識していない。 私の概念化や研究が、人類学界以外にも一定の影響を与えていることを願っている。おそらく私は楽観的すぎるかもしれないが、新旧の人類学者たちは、それぞ れの時代や社会科学の役割の変化に応じて、コロンビアの人々と国家の新たな側面を明らかにすることに貢献してきたと思う。また、私たちの人類学的研究が、 先住民コミュニティ自身への貢献となり、彼らがコロンビア社会において、最も広い意味での尊重を得るための持続的な努力を支えるものだと信じています。私 は、この国が先住民の遺産を強調し、現代の民族集団の生存を完全に保障すべきだと考えています。この国は、メスティソであることに誇りを持つべきだと考え ています。私は、千年にわたる自国の歴史の知識を基盤とせずに、征服と植民地時代、そして共和国時代から今日に至るまで、先住民や黒人(アフリカ系住民) が経験してきたことを無視して、未来に向かって前進することは不可能だと考えている。以上が、半世紀近く私を支えてきた考えの一部だ。これらの考えが、私 の人生に意味を与えてくれたのだ。[4] |

| Bibliography This list is a selection.[5] People of Aritama (ISBN 0-415-33045-9) Land of the Elder Brothers (ISBN 958-638-323-7) Recent Advances in the Archaeology of the Northern Andes (ISBN 0-917956-90-7) Rainforest Shamans: Essays on the Tukano Indians of the Northwest Amazon (ISBN 0-9527302-4-3) Yurupari: Studies of an Amazonian Foundation Myth (ISBN 0-945454-08-2) The Forest Within: The World-view of the Tukano Amazonian Indians (ISBN 0-9527302-0-0) Indians of Colombia: Experience and Cognition (ISBN 958-9138-68-3) The Shaman and the Jaguar: A Study of Narcotic Drugs Among the Indians of Colombia (ISBN 0-87722-038-7) Amazonian Cosmos: The Sexual and Religious Symbolism of the Tukano Indians (ISBN 0-226-70732-6) Colombia (Ancient Peoples and Places) Libros A lo largo de su vida, Reichel-Dolmatoff publicó 40 libros y más de 200 artículos. Entre sus principales escritos se encuentran: Los Kogi: Una tribu indígena de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta Vol 1 y 2. 1950 y 1951. (Bogotá: Iqueima, 1951; segunda edición Procultura, 1985) Investigaciones Arqueológicas en el departamento del Magdalena: Arqueología del río Ranchería, Arqueología del río Cesar, (Bogotá: Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 1951) Datos histórico-culturales sobre las tibus de la antigua provincia de Cartagena, (Imprenta del Banco de la República, 1951) Diario de Viaje de P. Joseph Palacios de la Vega entre los indios y negros de la provinci de Cartagena - 1787 (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 1955) The People of Aritama: The Cultural Personality of a Colombian Mestizo Village (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961), en coautoría con Alicia Dussan Maldonado; Colombia: Ancient Peoples and Places (Londres: Thames and Hudson, 1955) Desana: simbolismo de los indios tukanod del Vaupés (Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, 1968) Amazonian Cosmos: The Sexual and Religious Symbolism of the Tukano Indians (Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1970) San Agustín: Culture of Colombia, (Londres: Thames & Hudson, Nueva York, Praeger Publishers, 1972) The Shaman and the Jaguar: a Study of Narcotic Drugs among the Indians of Colombia (Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 1975) Contribuciones a la estratigrafía cerámica de San Agustín, Colombia (Bogotá, Imprenta Banco Popular, 1975) Beyond the Milky Way, the Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indias (Los Ángeles, University of California, 1978) Estudios Antropologicos (Bogotá, Colcultura, 1977) Manual de Historia de Colombia (Director Jaime Jaramillo Uribe), "Colombia Indígena Periodo Prehispánica (Bogotá: Procultura S. A. tmeditores, 1984 Tercera Edición) Monsú: Un sitio arqueológico de la etapa formativa temprana (Bogotá: Biblioteca Banco Popular, 1985) murió en el 1995 por una enfermedad llamada tifus murina.si Desana: Simbolismo de los indios Tukano del Vaupés (Bogotá: Procultura, 1986) ISBN 958-9043-16-X |

参考文献 このリストは抜粋です。[5] 有田の人々 (ISBN 0-415-33045-9) 兄たちの土地 (ISBN 958-638-323-7) 北アンデス考古学の最近の進展 (ISBN 0-917956-90-7) 熱帯雨林のシャーマン:北西アマゾンのトゥカノ族に関するエッセイ (ISBN 0-9527302-4-3) Yurupari:アマゾン創世神話の研究 (ISBN 0-945454-08-2) 森の中の世界:アマゾン先住民トゥカノ族の世界観 (ISBN 0-9527302-0-0) コロンビアのインディアン:経験と認識 (ISBN 958-9138-68-3) シャーマンとジャガー:コロンビアのインディアンにおける麻薬の研究 (ISBN 0-87722-038-7) アマゾンの宇宙:トゥカノ族の性的および宗教的象徴 (ISBN 0-226-70732-6) コロンビア(古代の人々と場所) 書籍 生涯を通じて、ライシェル・ドルマトフは 40 冊の著書と 200 以上の論文を発表しました。主な著作には、以下のものがあります。 『コギ族:サンタ・マルタ山脈の先住民』第 1 巻および第 2 巻。1950 年および 1951 年。(ボゴタ:イケイマ、1951年、第2版はプロカルチュラ、1985年) 「マグダレナ県における考古学調査:ランチェリア川遺跡、セサル川遺跡」 (ボゴタ:教育省、1951年) カルタヘナ旧州のティバスに関する歴史的・文化的なデータ(Imprenta del Banco de la República、1951年) P. Joseph Palacios de la Vega のカルタヘナ州インディオと黒人に関する旅行記 - 1787年(教育省、1955年) アリタマの人々:コロンビアのメスティーソの村の文化的個性(シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局、1961年)、アリシア・ドゥッサン・マルドナドとの共著。 コロンビア:古代の人々と場所(ロンドン:テムズ&ハドソン、1955年) デサナ:ヴァウペスのトゥカノ族の象徴(ボゴタ:アンデス大学、1968年 『アマゾン宇宙:トゥカノ族の性的・宗教的象徴』(シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局、1970年) 『サン・アグスティン:コロンビアの文化』(ロンドン:テムズ&ハドソン、ニューヨーク:プレージャー出版社、1972年) 『シャーマンとジャガー:コロンビアのインディオにおける麻薬の研究』(フィラデルフィア:テンプル大学出版局、1975年) コロンビア、サン・アグスティンの陶器層位学への貢献(ボゴタ、Imprenta Banco Popular、1975年 銀河の向こう、トゥカノ・インディアスの幻覚的イメージ(ロサンゼルス、カリフォルニア大学、1978年 人類学的研究(ボゴタ、Colcultura、1977年 コロンビアの歴史マニュアル(ディレクター:ハイメ・ハラミロ・ウリベ)、「先コロンブス時代の先住民コロンビア(ボゴタ:プロカルチュラ S. A. tmeditores、1984 年第 3 版) Monsú: Un sitio arqueológico de la etapa formativa temprana (ボゴタ: Biblioteca Banco Popular、1985) 1995年に、鼠疫という病気で亡くなった。 Desana: Simbolismo de los indios Tukano del Vaupés (ボゴタ: Procultura、1986) ISBN 958-9043-16-X |

| Investigaciones etnográficas y

arqueológicas El trabajo de Reichel-Dolmatoff se inició en 1940 con un viaje a la parte alta del río Meta en las llanuras del Orinoco; de este trabajo surgió una de las primeras publicaciones sobre la cultura material de los indígenas Guahibo. En 1941, él y Alicia Dussán iniciaron estudios de arqueología en la sabana de Bogotá, en los abrigos rocosos en Zipaquirá, Suesca así como en la Laguna de la Herrera y excavaron principalmente en las poblaciones de Sopó y Soacha, y también en el valle del río Magdalena en cercanías a la ciudad de Girardot. En 1943, publicó su estudio sobre el asentamiento Muisca de Soacha. En compañía de Alicia, adelanté un estudio comparativo de las urnas funerarias del valle del río Magdalena. Ese mismo año publicaron uno de los trabajos primarios sobre variación de tipos de sangre entre los grupos Pijao del departamento del Tolima. En 1944 hizo su primer viaje a la Serranía del Perijá y publicó una de las etnografías más completas sobre los Motilones (Yuko). Luego continuó su trabajo en el oeste de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, recolectando información sobre los últimos sobrevivientes de los indígenas Chimila en la zona de bosque tropical del río Ariguaní. En 1946 se instaló en la ciudad de Santa Marta donde fundó el Instituto Etnológico del Magdalena, el cual dirigió hasta 1950. Los años en Santa Marta permitieron avanzar con las investigaciones arqueológicas en el sitio de Pueblito, donde por primera vez se estableció principalmente una secuencia cultural para dicha área. Igual proceso llevó a cabo en los ríos Cesar y Ranchería. Durante los años 1946 a 1948, desarrolló su programa de investigaciones sobre los Kogi, el cual publica en su clásica monografía. De su continua visita a la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta obtiene valiosa información que ha clarificado nuestra visión sobre los ancestrales cacicazgos Tairona. Reichel-Dolmatoff y su esposa pasaron el año de 1947 con los indígenas del río Caimán Nuevo, al oeste del Golfo de Urabá. Entre 1951 y 1952, se establecieron en el pueblo mestizo de Aritama, Guajira. El resultado de 14 meses de trabajo de campo permitió la recolección de datos, para lo que sería una de las monografías clásicas de la antropología mundial sobre una sociedad campesina, "The People of Aritama". La importancia de esta obra fue reconocida con su publicación en 1961 por parte de la Universidad de Chicago. En 1952 realizó investigaciones entre los Tucano del Vaupés, realizando un vasto plan de registro magnetofónico de textos chamanísticos en varias lenguas indígenas, en especial entre los Desano, Piratapuyo y las tribus del Pira-Paraná. Los temas del manejo indígena del medio ambiente, el mundo alucinatorio y los esquemas cognoscitivos chamanísticos, lo ocuparon en los últimos años. Estos estudios, junto con el de la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, le permitieron hacer comparaciones en cosmología indígena, los cuales serían publicados años después en libros como "Amazonian Cosmos" (Universidad de Chicago Press, 1971), "The Shaman and the Jaguar" (Universidad de Temple, 1975), y "Beyond the Milky Way" (UCLA, 1978). Estos trabajos son un ejemplo de investigación en etnoarqueología. Durante este año regresa a la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, pero esta vez su trabajo etnográfico se concentra en los indígenas Ijka del sur. Después de este trabajo de campo, publica el mejor estudio etnohistórico que se ha hecho sobre el cambio cultural en la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, logrando demostrar la relación y transformación cultural que ha tenido la etnia Kogi desde los tiempos de sus ancestros Tairona. Entre 1953 y 1960, Reichel-Dolmatoff entró a ser miembro del recién creado Instituto Colombiano de Antropología. Esta asociación institucional facilitó que él y su familia se radicaran en la ciudad de Cartagena. Allí dictó clases en la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de Cartagena. En 1954 se da inicio a la excavación en Barlovento, que es uno de los sitios más importantes con respecto a la historia de la arqueología en Colombia, porque fue el primer conchero (montículo de residuos de moluscos, acumulados por actividades de consumo humano) que se encontró en el país, indicando la existencia de una forma de adaptación humana desconocida para esta área del norte de Suramérica. Desde Cartagena, junto con Alicia Dussán, lanzan el programa de Arqueología del Bajo Magdalena, que permite por primera vez establecer una secuencia cultural para las áreas de Plato, Zambrano y Tenerife. En 1955 el trabajo es ampliado al Golfo de Morrosquillo y a la cuenca del río Sinú. Como resultado de este proyecto, que duró de 1945 hasta comienzos de la década de los setenta, establecieron el primer esquema cronológico para la prehistoria del Caribe colombiano: Paleoindio, Arcaico, Formativo, desarrollos regionales y confederaciones o Estados incipientes. Dicha periodización fue seguida en posteriores investigaciones como las desarrolladas en la Sabana de Bogotá por Gonzalo Correal Urrego (en) y Thomas van der Hammen en la región del Magdalena Medio. Otra de las áreas de investigación en que también fue un pionero es el de los estudios de cambios en la subsistencia de poblaciones indígenas. Uno de los trabajos capitales en esa línea fue la excavación de Momil en el actual departamento de Córdoba. En 1957, los Reichel exploran las cabeceras del río Sinú, donde colectan información etnográfica de los indígenas Embera. Al año siguiente realizan el primer estudio arqueológico del Golfo de Urabá y la parte baja del valle del río Atrato y del estrecho del Darién. En 1959, continuaron la investigación arqueológica en la parte baja del Magdalena. En 1960, Reichel-Dolmatoff y Alicia comienzan a explorar arqueológicamente la costa Pacífica, desde el límite fronterizo con Panamá hasta Ecuador en un proyecto que dura tres años. La prospección es interrumpida en 1961 con el trabajo de campo en Puerto Hormiga, cerca a Cartagena. Allí descubren lo que sería la cerámica más antigua del continente americano. Es en ese mismo año que el profesor publica su artículo clásico en la arqueología de continente americano "The Agricultural Basis of the Sub-Andean Chiefdoms of Colombia". (Las Bases Agrícolas de los Cacicazgos SubAndinos de Colombia). En 1963 funda el primer Departamento de Antropología de Colombia en la Universidad de Los Andes. Desde allí logran terminar las excavaciones de Puerto Hormiga. Como Jefe del Departamento (1963-1969), produce la primera síntesis de arqueología colombiana en inglés, "Colombia: Ancient Peoples and Places", libro que se convirtió en un clásico internacional y obra de consulta obligatoria en la arqueología americana.1 En 1966 inicia su trabajo arqueológico en San Agustín (Huila) para comprobar su teoría de que no se trataba allí de una necrópolis, sino ante todo de una zona cultural densamente poblada de antiguas sociedades agrícolas. Publica otra obra de gran reconocimiento internacional, que nunca fue traducida al español (San Agustín: A Culture of Colombia, Praeger, 1972). En 1970, recibe una beca de la Universidad de Cambridge, que le permite terminar varios de sus manuscritos. En 1974, Reichel-Dolmatoff y Alicia reinician el proyecto del Formativo Temprano de la costa del Caribe. Esta vez excavan el sitio de Monsú, el cual permitió refinar el conocimiento sobre la transición de recolectores de moluscos y plantas hacia la agricultura. En ese año entra como profesor adscrito del Departamento de Antropología de la Universidad de California en Los Ángeles, donde continuó ocasionalmente con la docencia. |

民族誌的・考古学的研究 ライチェル=ドルマトフの研究は1940年、オリノコ平原のメタ川上流への旅行から始まった。この研究からグアヒボ・インディアンの物質文化に関する最初 の出版物のひとつが生まれた。1941年、アリシア・デュサンとともにボゴタのサバンナ、ジパキラ、スエスカ、ラグーナ・デ・ラ・エレーラの岩窟で考古学 調査を開始し、主にソポとソアチャの町で発掘調査を行った。1943年には、ソアチャのムイスカ集落に関する研究を発表した。アリシアとともにマグダレナ 川流域の葬祭用骨壷の比較研究を行った。同年、彼らはトリマ県のピジャオ族における血液型の変異に関する主要な研究のひとつを発表した。1944年にはペ リハ山脈を初めて訪れ、モティロネス(ユコ)族に関する最も完全な民族誌のひとつを出版した。その後、サンタ・マルタのシエラネバダ西部で仕事を続け、ア リグアニ川の熱帯雨林地帯でチミラ族最後の生き残りに関する情報を収集した。 1946年、サンタ・マルタ市に定住し、マグダレナ民族学研究所を設立、1950年まで所長を務めた。サンタ・マルタでの数年間で、プエブリト遺跡での考 古学的研究が進展し、初めてその地域の文化的順序が確立された。セサル川とランチェリア川でも同様の調査が行われた。1946年から1948年にかけて は、コギ族に関する研究プログラムを発展させ、古典的なモノグラフを出版した。シエラネバダ・デ・サンタ・マルタへの継続的な訪問から、彼は先祖代々のタ イロナ族首長国に関する我々の見解を明らかにする貴重な情報を得た。ライチェル=ドルマトフ夫妻は1947年、ウラバ湾の西にあるカイマン・ヌエボ川の先 住民とともに過ごした。 1951年から1952年にかけて、彼らはグアヒラ州アリタマのメスティーソ村に定住した。14ヵ月にわたるフィールドワークの結果、農民社会に関する世 界人類学の古典的なモノグラフのひとつとなる『アリタマの人々』のデータを収集することができた。この著作は1961年にシカゴ大学から出版され、その重 要性が認められた。 1952年にはバウペスのトゥカノ族を調査し、特にデサノ族、ピラタプヨ族、ピラ=パラナ族を対象に、さまざまな先住民言語でシャーマニズムのテキストを 記録する膨大な計画を実施した。近年は、先住民の環境管理、幻覚の世界、シャーマニズムの認識スキームといったテーマに取り組んでいる。これらの研究は、 シエラネバダ・デ・サンタ・マルタの研究とともに、先住民の宇宙論の比較を可能にし、数年後に "Amazonian Cosmos" (University of Chicago Press, 1971)、"The Shaman and the Jaguar" (Temple University, 1975)、"Beyond the Milky Way" (UCLA, 1978)などの著書で発表されることになる。これらの著作は民族考古学的研究の一例である。この年、彼はサンタ・マルタのシエラネバダに戻るが、今度は 南部のイジャカ・インディオに民族誌的研究を集中させる。このフィールドワークの後、彼はシエラネバダ・デ・サンタ・マルタの文化的変化に関する最高の民 族史的研究を発表し、タイロナ族の祖先の時代からのコギ族との関係と文化的変容を明らかにした。 1953年から1960年にかけて、ライチェル=ドルマトフは新設されたコロンビア人類学研究所のメンバーとなった。この機関団体のおかげで、彼と彼の家 族はカルタヘナ市に定住しやすくなった。そこで彼はカルタヘナ大学医学部で教鞭をとった。この遺跡はコロンビアで初めて発見された貝塚(人間の消費活動に よって蓄積された軟体動物の排泄物の塚)であり、南米北部のこの地域では未知の人類適応様式の存在を示しているからである。カルタヘナからアリシア・デュ サンとともにマグダレナ下流考古学プログラムを開始し、プラト、サンブラノ、テネリフェの地域の文化的順序を初めて確立した。1955年には、モロスキー ジョ湾とシヌ川流域にまで調査が拡大された。1945年から1970年代初頭まで続いたこのプロジェクトの結果、彼らはコロンビア・カリブ海の先史時代に ついて、古インディアン期、アルカイック期、形成期、地域的発展期、連合体または初期国家という最初の年代分類を確立した。この時代区分は、ゴンザロ・コ レアル・ウレゴ(Gonzalo Correal Urrego, en)やトーマス・ファン・デル・ハンメン(Thomas van der Hammen)がボゴタのサバナ地方で行ったマグダレナ・メディオ地域の調査など、その後の調査でも踏襲された。 彼が先駆者であったもうひとつの研究分野は、先住民の生計の変化に関する研究である。この分野での最も重要な研究のひとつが、現在のコルドバ県にあるモミ ルの発掘である。1957年、ライチェル夫妻はシヌ川の源流を探検し、そこでエンベラ先住民の民族誌的情報を収集した。翌年には、ウラバ湾、アトラト川流 域の下部、ダリエン海峡で最初の考古学調査を行った。1959年、彼らはマグダレナ川下流域の考古学調査を継続した。 1960年、ライチェル=ドルマトフとアリシアは、パナマとの国境からエクアドルまでの太平洋沿岸の考古学的調査を開始し、3年間にわたるプロジェクトを 行った。調査は1961年、カルタヘナ近郊のプエルト・ホルミガでのフィールドワークで中断された。そこで彼らはアメリカ大陸最古の土器を発見した。この 年、教授はアメリカ大陸の考古学に関する古典的論文『コロンビアのサブ・アンデスの首長国の農業基盤』を発表した。(The Agricultural Basis of the Sub-Andean Chiefdoms of Colombia)を発表した。 1963年、コロンビア初の人類学部をロス・アンデス大学に設立。そこからプエルト・ホルミガでの発掘調査を完成させた。学科長として (1963~1969年)、コロンビア考古学の最初の英文総合書である "Colombia: Ancient Peoples and Places "を著した。 1966年、彼はサン・アグスティン(ウイラ)で考古学調査を開始し、そこがネクロポリスではなく、何よりも古代農耕社会の人口密集文化圏であったという 自説を証明した。スペイン語には翻訳されなかったが、国際的に高く評価された著作を出版した(San Agustín: A Culture of Colombia, Praeger, 1972)。 1970年にはケンブリッジ大学から助成金を受け、いくつかの原稿を仕上げることができた。1974年、ライチェル=ドルマトフとアリシアは、カリブ海沿 岸の初期形成期のプロジェクトを再開した。今度はモンスー遺跡を発掘し、軟体動物と植物の採集から農耕への移行に関する知識を深めた。その年、彼はカリ フォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校の人類学部に加わり、時々教鞭をとるようになった。 |

| Obra Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff, en compañía de su esposa Alicia Dussán, escribieron más de 200 artículos para revistas científicas y 40 libros sobre investigaciones en arqueología, antropología, etnohistoria y etnoecologia de Colombia, e investigaciones etnográficas de pueblos indígenas de regiones de las costas Caribe y Pacífica, del Amazonas, los llanos, región Andina y otras regiones de Colombia, dedicando su obra y vida en Colombia a resaltar el valor e importancia de la diversidad cultural y étnica del país y en especial de las culturas indígenas. Crea las bases del conocimiento de los grupos indígenas que habitaban el territorio colombiano. Su interés no se limitó a su propia investigación sino a la creación de una conciencia internacional sobre la importancia de los recursos culturales de un país donde la diversidad étnica y el conocimiento de los indígenas era una gran riqueza a la espera de ser divulgada y apreciada. Para Reichel-Dolmatoff, este era un nuevo mundo de conocimiento, donde la humanidad podía aprender sobre formas alternas de conceptualizar sobre el medio ambiente, el cosmos, y la razón de existencia del ser al ponerlo a reflexionar críticamente sobre su propia cultura "occidental". El consideraba que esta reflexión se lograba a partir de conocer al "otro" mediante su estudio etnográfico y arqueológico, pero en forma holística, teniendo en cuenta el contexto medioambiental. Reichel-Dolmatoff y su esposa iniciaron una amplia labor de conocer directamente la situación de los grupos indígenas del país y de su pasado prehispánico. Este proyecto los llevó a los rincones más apartados del territorio colombiano. Su conocimiento abarcaba desde el Amazonas hasta el desierto de la Guajira y desde la selva tropical chocoana hasta las sabanas de los Llanos Orientales. Su constante viajar e investigación sistemática lo llevó a ser un pionero del conocimiento básico que tenemos de la arqueología y etnografía colombiana. Su investigación creó las bases para el conocimiento de la cronología de las ocupaciones humanas y los desarrollos culturales prehispánicos. Sus reconstrucciones de la historia cultural del país desde la perspectiva arqueológica se ampliaron para explicar los procesos que dieron origen a la agricultura, la vida sedentaria, e incluso de tecnologías como la orfebrería y la cerámica. Entre sus contribuciones teóricas se destaca por ser uno de los pioneros en tratar de entender los procesos de formación de cacicazgos o sociedades complejas. Toda su contribución arqueológica permitió poner en el mapa mundial de discusión la investigación hecha en Colombia, al grado de llegar a ser reconocido como uno de los países de Latinoamérica donde más logros se han alcanzado en dicho campo. En el campo de la arqueología, sus investigaciones lograron definir por primera vez en suelo colombiano la Etapa Formativa, lo que permitió correlacionar la arqueología del país con los desarrollos contemporáneos en los grandes centros prehistóricos de Mesoamérica y los Andes Centrales. Comenzando con excavaciones en la zona Tairona, el bajo río Ranchería, el río Cesar y el Bajo Magdalena, los Reichel-Dolmatoff trazaron la primera cronología local, que luego ampliaron al extender las excavaciones estratigráficas a las sabanas de Bolívar, el río Sinú, al golfo de Urabá y varios sitios costaneros. Durante más de medio siglo de residencia en Colombia, Reichel-Dolmatoff prestó sus servicios profesionales al gobierno nacional y como profesor universitario. En 1945 fundó en Santa Marta el Instituto Etnológico del Magdalena, y en 1964, fundador y primer director del Departamento de Antropología de la Universidad de los Andes en Bogotá, el primer Departamento de Antropología del país, estableciendo en Colombia la carrera académica. Ocupó, entre otros, los cargos de investigador y profesor del Instituto Etnológico Nacional y del Instituto Colombiano de Antropología; Visiting Scholar de la Universidad de Cambridge, y de la Universidad de Oxford; Visiting Professor del Museo Nacional de Etnología, Osaka, Japón; y durante veinte años fue profesor investigador del Departamento de Antropología de la Universidad de California en Los Ángeles. Dictó conferencias y seminarios en muchas universidades del Norte y Suramérica, Europa y Japón, y asistió a numerosos congresos y simposios internacionales. Fue profesor visitante y conferencista en otros países tanto de América Latina como otros piases del mundo, y miembro de Academias de Ciencia de Colombia y de otros países. La enorme contribución a la antropología y arqueología mundial hecha por Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff es reconocida al recibir en 1975 la medalla Thomas H. Huxley, del Royal Anthropological Institute de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda. Durante su vida, recibió numerosas distinciones por su contribución a la ciencia. Sin duda su enorme producción se encuentra publicada en inglés y está a la espera de ser conocida en Hispanoamérica. Esta inclinación por publicar en inglés se debía a la dificultad de que se le publicaran en español sus trabajos en el país y por otro lado al afán del profesor Reichel-Dolmatoff, de dar a conocer la etnografía y arqueología de Colombia en el exterior, poniéndola así en la arena de discusión académica internacional. «Mucho de su trabajo fue incomprendido por los intelectuales protagonistas de su tiempo, época donde el discurso de la retórica es lo que se valoraba o por sus estudiantes de finales de los años 60 y comienzos de los 70, influenciados por el marxismo, y sin una autocrítica válida de las modas académicas, quienes nunca ayudaron a llenar el vacío de conocimiento que existe sobre nosotros mismos como cultura multiétnica, como pueblo, como indígenas, o como campesinos. El profesor sabía bien que su trabajo solo sería apreciado en el futuro. El profesor Reichel-Dolmatoff y su esposa Alicia Dussán alcanzaron un nivel de calidad investigativa difícil de superar o igualar, que debe ser tomado como ejemplo donde prime el sacrificio por el país. Es increíble pensar que su producción académica es más conocida internacionalmente que dentro de Colombia, lo cual se explica por las prioridades y valores que se han establecido en el país en los últimos 20 años. Se puede afirmar que el Gran Jaguar fue un exilado intelectual, que a pesar de vivir en Colombia, la mayor parte de su vida, tenía mayores opciones de divulgación en el exterior. Muchas veces se aterraba de la mediocridad en que había caído la antropología y la arqueología del país, donde el discurso se politizó o se volvió de promoción individual. Esta crítica hizo que sus últimos años fueran amargos al encontrar muy pocos discípulos, colegas, o interlocutores válidos con quien discutir seriamente diversos temas antropológicos y arqueológicos. Esta situación lo empujó a salir del país con frecuencia, y así evitar perderse en el conformismo local.» Augusto Oyuela Caicedo |

仕事と作品 ゲラルド・ライチェル=ドルマトフは、妻のアリシア・ドゥッサンとともに、コロンビアの考古学、人類学、民族史学、民族生態学、カリブ海沿岸や太平洋沿 岸、アマゾン、平原、アンデス地域などの先住民の民族誌的研究に関する200以上の学術誌への寄稿と40冊以上の著書を執筆し、コロンビアの文化と民族の 多様性、特に先住民文化の価値と重要性を強調するために、コロンビアでの仕事と生涯を捧げた。彼はコロンビアの領土に住む先住民族に関する知識の基礎を築 いた。彼の関心は彼自身の研究にとどまらず、この国の文化的資源の重要性を国際的に認識させることにあった。ライチェル=ドルマトフにとって、これは新た な知の世界であり、人類は自らの「西洋」文化を批判的に振り返ることで、環境や宇宙、存在理由を概念化する別の方法を学ぶことができた。この反省は、民族 誌的・考古学的研究を通じて「他者」を知ることによって達成されるが、環境的背景を考慮した総合的な方法で達成されると彼は考えた。 ライチェル=ドルマトフ夫妻は、この国の先住民族の状況と、彼らの先スペイン時代の過去について直接知るために、広範な取り組みを始めた。このプロジェク トは、彼らをコロンビア領土の最も辺鄙な場所に連れて行った。彼らの知識は、アマゾンからグアヒラ砂漠、チョコアの熱帯雨林から東部平原のサバンナにまで 及んだ。彼の絶え間ない旅と体系的な研究は、コロンビア考古学と民俗学の基礎知識の先駆者となった。彼の研究は、人類の職業と先ヒスパニック文化発展の年 代に関する知識の基礎を築いた。彼の考古学的視点からのコロンビアの文化史の再構築は、農業、定住生活、さらには金細工や陶磁器などの技術を生み出した過 程を説明するまでに拡大した。彼の理論的貢献の中でも、首長国や複合社会の形成過程を理解しようとした先駆者の一人として際立っている。彼の考古学的貢献 により、コロンビアで行われた研究は世界地図に載るようになり、この分野で最も偉大な業績を残したラテンアメリカの国のひとつとして認識されるまでになっ た。 考古学の分野では、彼の研究によって、コロンビアの大地で初めて形成期が定義され、メソアメリカと中央アンデスの偉大な先史時代の中心地における現代の発 展とコロンビアの考古学を関連付けることが可能になった。タイロナ地域、ランチェリア川下流域、セサル川、マグダレナ川下流域での発掘を皮切りに、ライ チェル=ドルマトフ夫妻は、最初の地域年代を追跡し、その後、ボリーバルのサバンナ、シヌ川、ウラバ湾、いくつかの沿岸遺跡にまで地層学的発掘を拡大し た。 半世紀以上にわたってコロンビアに滞在したライチェル=ドルマトフは、国家政府に専門的なサービスを提供し、大学教授としても活躍した。1945年にはサ ンタマルタにマグダレナ民族学研究所を設立し、1964年にはボゴタのアンデス大学人類学部の創設者兼初代学部長となり、コロンビア初の人類学部としてコ ロンビアでの学問的キャリアを確立した。国立民族学研究所やコロンビア人類学研究所で研究員や教授、ケンブリッジ大学やオックスフォード大学で客員研究 員、国立民族学博物館(大阪)で客員教授などを歴任。北米、南米、ヨーロッパ、日本の多くの大学で講義やセミナーを行い、数多くの国際会議やシンポジウム に出席した。ラテンアメリカをはじめ世界各国で客員教授や講師を務め、コロンビアなどの科学アカデミーのメンバーでもある。 1975年、グレート・ブリテン・アイルランド王立人類学研究所からトーマス・H・ハックスレー・メダルを授与され、世界の人類学と考古学への多大な貢献 が認められた。生前、彼は科学への貢献に対して数々の栄誉を受けている。彼女の膨大な業績は間違いなく英語で出版され、ラテンアメリカで知られるのを待っ ている。英語での出版に傾倒したのは、国内でスペイン語の著作を出版することが困難であったためであり、他方では、コロンビアの民族学と考古学を海外に知 らしめ、国際的な学術的議論の場に置きたいというライチェル=ドルマトフ教授の願望によるものであった。 「マルクス主義の影響を受け、学問の流行に対する正当な自己批判を持たない60年代後半から70年代前半の学生たちは、多民族文化として、民族として、先 住民として、農民として存在する知識の空白を埋める手助けをすることはなかった。教授は、自分の仕事が評価されるのは未来のことだとよく知っていた。ライ チェル=ドルマトフ教授とその妻アリシア・デュサンは、追い越すことも匹敵することも困難なレベルの研究の質を達成し、国のための犠牲の模範として受け止 められるべきである。彼らの学問的業績がコロンビア国内よりも国際的に知られていることは信じられないことだが、それは過去20年間にコロンビアで確立さ れた優先順位と価値観によって説明することができる。グレート・ジャガーは、人生の大半をコロンビアで過ごしたにもかかわらず、海外に発信する選択肢をよ り多く持っていた知的亡命者だったと言える。彼はしばしば、コロンビアの人類学と考古学が凡庸に陥り、言説が政治化されたり、個人的な宣伝のひとつになっ ていることに恐怖を感じていた。人類学や考古学のさまざまなテーマについて真剣に議論できる弟子や同僚、有効な対話相手がほとんどいなかったからだ。この ような状況に追い込まれた彼は、その土地の順応主義に迷い込むことを避けるため、頻繁に国外に出るようになった」。 アウグスト・オユエラ・カイセド |

| Extracto de ponencia de

Reichel-Dolmatoff en la Universidad Nacional de Colombia "Hoy debo destacar que, desde comienzos de la década de los cuarenta, para mí fue un verdadero privilegio convivir y tratar de comprender en profundidad algunos grupos indígenas. Pude constatar entre ellos ciertas estructuras mentales y sistemas de valores, que parecían salirse por completo de las tipologías y categorías de la Antropología de entonces. No encontré al "buen salvaje" ni tampoco al así llamado "primitivo". No encontré aquel indio degenerado y embrutecido ni mucho menos aquel ser inferior por entonces descrito generalmente por gobernantes, misioneros, historiadores, políticos y literatos. Lo que si encontré fue un mundo de una filosofía tan coherente, de una moral tan elevada, una organización social y política de gran complejidad, un manejo acertado del medio ambiente con base en conocimientos bien fundados. En efecto, vi que las culturas indígenas ofrecían opciones insospechadas; que ofrecían estrategias de desarrollo cultural que simplemente no podemos ignorar, porque contienen soluciones válidas y aplicables a una variedad de problemas humanos. Todo aquello hizo crecer más y más mi admiración por la dignidad, la inteligencia y sabiduría de estos aborígenes, quienes no por último han desarrollado sorprendentes dinámicas y formas de resistencia, gracias a las cuales la llamada "civilización" no ha podido exterminarlos. Yo he tratado de contribuir a la recuperación de la dignidad del indio, esta dignidad que desde la llegada de los españoles se le ha negado; en efecto, durante quinientos años ha habido una abierta tendencia a difamar y a tratar de ignorar la experiencia milenaria de la población de todo un continente. Pero la humanidad es una sola; la inteligencia humana es un don tan precioso que no se le puede despreciar en ninguna parte del mundo y el país está en mora de reconocer la gran capacidad intelectual de los indígenas y sus grandes logros gracias a sus sistemas cognoscitivos, los cuales no pierden validez por el mero hecho de no ajustarse a la lógica del pensamiento occidental. Espero que mis conceptualizaciones y trabajos hayan tenido cierta influencia más allá del círculo antropológico. Tal vez soy demasiado optimista, pero me parece que los antropólogos de viejas y nuevas generaciones, según su época y el cambiante papel de la Ciencias Sociales, hemos contribuido a ir develando nuevas dimensiones del Hombre Colombiano y de la nacionalidad. También confío que nuestra labor antropológica constituye un aporte a las propias comunidades indígenas, en su persistente esfuerzo de lograr el respeto, en el más amplio sentido de la palabra, que les corresponde dentro de la sociedad colombiana. Yo creo que el país debe realzar la herencia indígena y garantizar plenamente la supervivencia de los actuales grupos étnicos. Creo que el país debe estar orgulloso de ser mestizo. No pienso que se pueda avanzar hacia el futuro sin afirmarse en el conocimiento de la propia historia milenaria, ni pasando por alto qué sucedió con el indio y con el negro no solo en la Conquista y la Colonia, sino también en la República y hasta el presente. Son estas, en fin, algunas de las ideas que me han guiado a través de casi medio siglo. Ellas han dado sentido a mi vida".2 |

コロンビア国立大学でのライチェル=ドルマトフのプレゼンテーションよ

り抜粋 「1940年代初頭から、特定の先住民グループと生活を共にし、深く理解しようと努めたことは、私にとって本当に光栄なことであった。私は彼らの中に、当 時の人類学の類型やカテゴリーから完全に外れたような、ある種の精神構造や価値体系を観察することができた。私は「良い野蛮人」やいわゆる「原始人」を見 つけることはできなかった。退廃的で残忍なインディアンも、ましてや当時の支配者、宣教師、歴史家、政治家、文人たちによって一般的に語られていたような 劣った存在も見つけられなかった。私が見つけたのは、これほど首尾一貫した哲学、これほど高い道徳観、これほど複雑な社会的・政治的組織、これほど根拠の ある知識に基づいた健全な環境管理を備えた世界だった。実際、私は先住民の文化が思いもよらない選択肢を提供していること、人類のさまざまな問題に対する 有効かつ応用可能な解決策を含んでいるため、私たちが無視することのできない文化的発展戦略を提供していることを知った。このようなことから私は、原住民 の尊厳、知性、知恵に対する感嘆の念をますます募らせた。原住民は少なくとも、いわゆる「文明」が彼らを絶滅させることができなかったおかげで、驚くべき 動力学と抵抗の形態を発達させてきたのである。 私は、スペイン人の到来以来否定されてきたインディオの尊厳の回復に貢献しようと努めてきた。実際、500年もの間、大陸全体の住民の千年にわたる経験を 中傷し、無視しようとする傾向が公然と存在してきた。しかし、人類はひとつであり、人間の知性は貴重な賜物であるため、世界のどこであろうと軽視すること はできない。そしてこの国は、先住民の偉大な知的能力と、西洋思想の論理に適合していないという理由だけで正当性を失うことのない彼らの認識システムのお かげで、彼らの偉大な業績を認識する過程にある。 私の概念構成と仕事が、人類学のサークルを超えて何らかの影響力を持つことを願っている。楽観的すぎるかもしれないが、新旧の世代の人類学者が、それぞれ の時代と社会科学の役割の変化に応じて、コロンビアの人間と民族の新たな側面を明らかにすることに貢献してきたように思う。また、私たちの人類学的研究 は、コロンビア社会における先住民の広義の尊重を実現するための粘り強い努力において、先住民コミュニティ自身への貢献にもなっていると確信している。私 は、国が先住民族の遺産を強化し、現在の民族グループの存続を完全に保証しなければならないと信じている。国はメスチソであることを誇りに思うべきだと思 う。また、征服時代や植民地時代だけでなく、共和制時代や現在に至るまで、インディオや黒人に起こったことを見過ごすことなく、未来に向かって前進するこ とは不可能だと思います。 要するに、これらは半世紀近くにわたって私を導いてきた思想の一部である。私の人生に意味を与えてくれた」2。 |

| Gerardo Reichel y su papel en la

pre-guerra y la Segunda Guerra Mundial Durante el 54º Congreso de Americanistas, celebrado en Viena en 2012, el profesor Augusto Oyuela de la Universidad de la Florida, presentó una ponencia en la que hizo públicos los resultados parciales de una investigación acerca de la vinculación del profesor Reichel-Dolmatoff a las Juventudes Hitlerianas y su vinculación a la SS entre sus 14 y 26 años de edad. Según documentos del Archivo Federal de Alemania, Reichel-Dolmatoff fue expulsado de la SS en 1936. Después de una estadía corta en Francia, en 1939 aconsejado por el Profesor André Siegfried, Reichel llega a Colombia y después de trabajar como dibujante y en la Francia Libre, conoce al francés Paul Rivet (1942-1943) quien era el fundador del Museo del Hombre de París y quien además era el delegado de la Resistencia de la Francia Libre. Este lo nombra su secretario (1942-1943). Charles De Gaulle posteriormente condecoró a Gerardo Reichel con la Orden Nacional del Mérito por su valiosa colaboración en la lucha antinazi.3 Las acusaciones y los análisis publicados por el profesor Oyuela (y la antropóloga alemana Manuela Fischer, y otros antropólogos que además participaron en esta disputa) causaron una airada polémica al interior de la comunidad Científica colombiana. Antropólogos de Colombia y otros países como el mexicano Claudio Lomnitz se manifestaron a favor de reflexionar sobre el nazismo en Latinoamérica y sobre las largamente conocidas relaciones de los científicos sociales con los movimientos fascistas o comunistas u otras posiciones políticas y que habría que investigar sus posteriores procesos de "conversión" al antifascismo o la democracia.4 En diciembre de 2012 Oyuela publicó un segundo trabajo ampliando el análisis 'biográfico' de Reichel-Dolmatoff inicialmente publicado el mismo año en Viena.5 1. Reichel-Dolmatoff, G. 1965. 'Colombia: Ancient Peoples and Places'. Thames and Hudson. London 2. Extracto de ponencia de Reichel-Dolmatoff en la Universidad Nacional de Colombia 3. Biografía de Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff 4. Claudio Lomnitz, El expediente Reichel-Dolmatoff. 5. Arqueología Biográfica: Las raíces Nazis de Erasmus Reichel, la vida en Austria (1912-1933). |

ジェラルド・ライヘルと戦前および第二次世界大戦における彼の役割 2012年にウィーンで開催された第54回アメリカニスト会議において、フロリダ大学のアウグスト・オユエラ教授が論文を発表し、ライヘル=ドルマトフ教 授のヒトラーユーゲントとの関わりと、14歳から26歳までのSSとの関わりについての調査結果の一部を公表した。ドイツ連邦公文書館の文書によると、ラ イヒェル=ドルマトフは1936年にSSから追放された。アンドレ・ジークフリート教授の勧めで1939年にフランスに短期滞在した後、ライヘルはコロン ビアに到着し、製図技師として、また自由フランスで働いた後、パリの人間博物館の創設者であり、自由フランス・レジスタンスの代表でもあったフランス人 ポール・リヴェット(1942-1943)と知り合った。リヴェは彼を秘書に任命した(1942-1943年)。シャルル・ド・ゴールはその後、反ナチス 闘争における彼の貴重な協力に対して、ジェラール・レイシェルに国家功労勲章を授与した3。 オユエラ教授(およびドイツの人類学者マヌエラ・フィッシャー、そしてこの論争に参加した他の人類学者たち)が発表した告発と分析は、コロンビアの科学界 に怒りの極論を引き起こした。メキシコ人のクラウディオ・ロムニッツのようなコロンビアや他国の人類学者は、ラテンアメリカにおけるナチズムや、社会科学 者とファシスト運動や共産主義運動、その他の政治的立場との古くから知られている関係について考察し、彼らのその後の反ファシズムや民主主義への「転向」 過程を調査すべきだと主張した4。2012年12月、オユエラは同年ウィーンで発表されたライチェル=ドルマトフの「伝記的」分析を拡大した2本目の論文 を発表した5。 |

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

リンク

文献

その他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099