「日本人」の遺伝的ならびに身体計測研究

Genetic and anthropometric studies on

Japanese people

☆ In population genetics, research has been done on the genetic origins of modern Japanese people.- Genetic and anthropometric studies on Japanese people.

| In population genetics, research has been done on the genetic origins of modern Japanese people.- Genetic and anthropometric studies on Japanese people. | 集団遺伝学では、現代日本人の遺伝的起源に関する研究が行われている(→「日本人起源論のなかにみられる人種主義」)。 |

| Overview From the point of view of genetic studies, Japanese people: mainly descended from the Yayoi people, the heterogeneous Jōmon population and the Kofun period influx.[1][2][3][4] can be categorized into three separate but related groups: Ainu, Ryukyuan and Mainland (Yamato). are closely related to clusters found in North-Eastern Asia[5][6][4] with the Ainu group being most similar to Ryukyuans[6][7] and the Yamato group being most similar to Koreans[8][9][10] among other East Asian people. |

概要 日本人は遺伝学的に見ると、弥生人、縄文人、古墳時代からの渡来人の子孫である: 主に弥生人、異質な縄文人、古墳時代の流入者の子孫である[1][2][3][4]。 の3つに分類される: アイヌ、琉球、本土(ヤマト)である。 アイヌ民族は琉球民族[6][7]に、ヤマト民族は朝鮮民族[8][9][10]に最も近い。 |

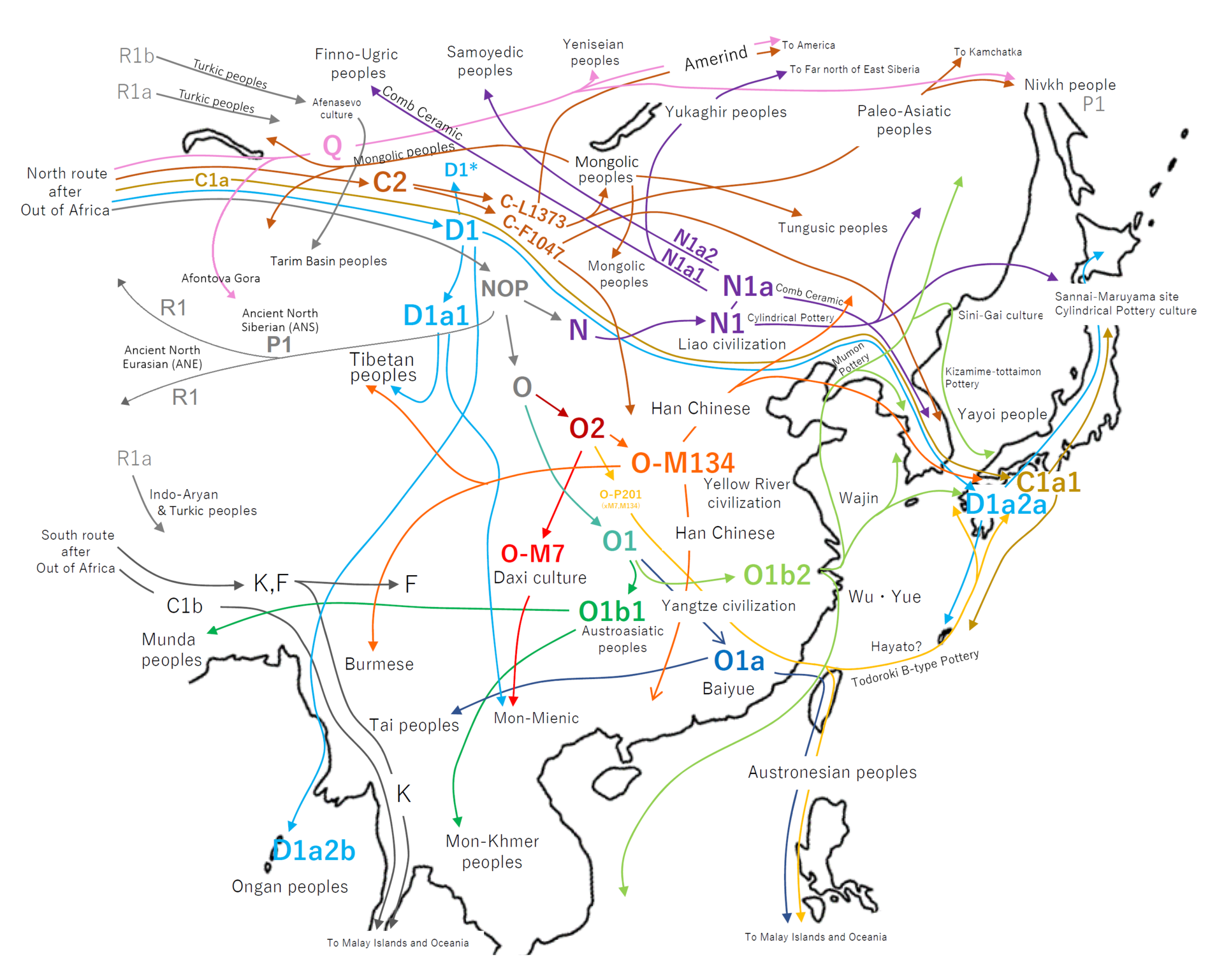

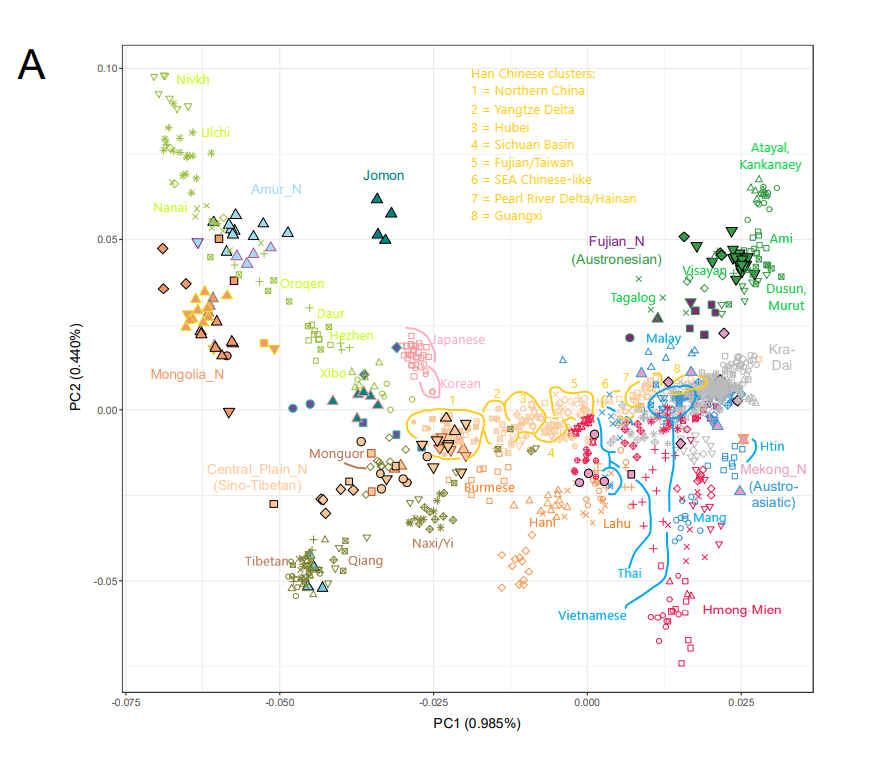

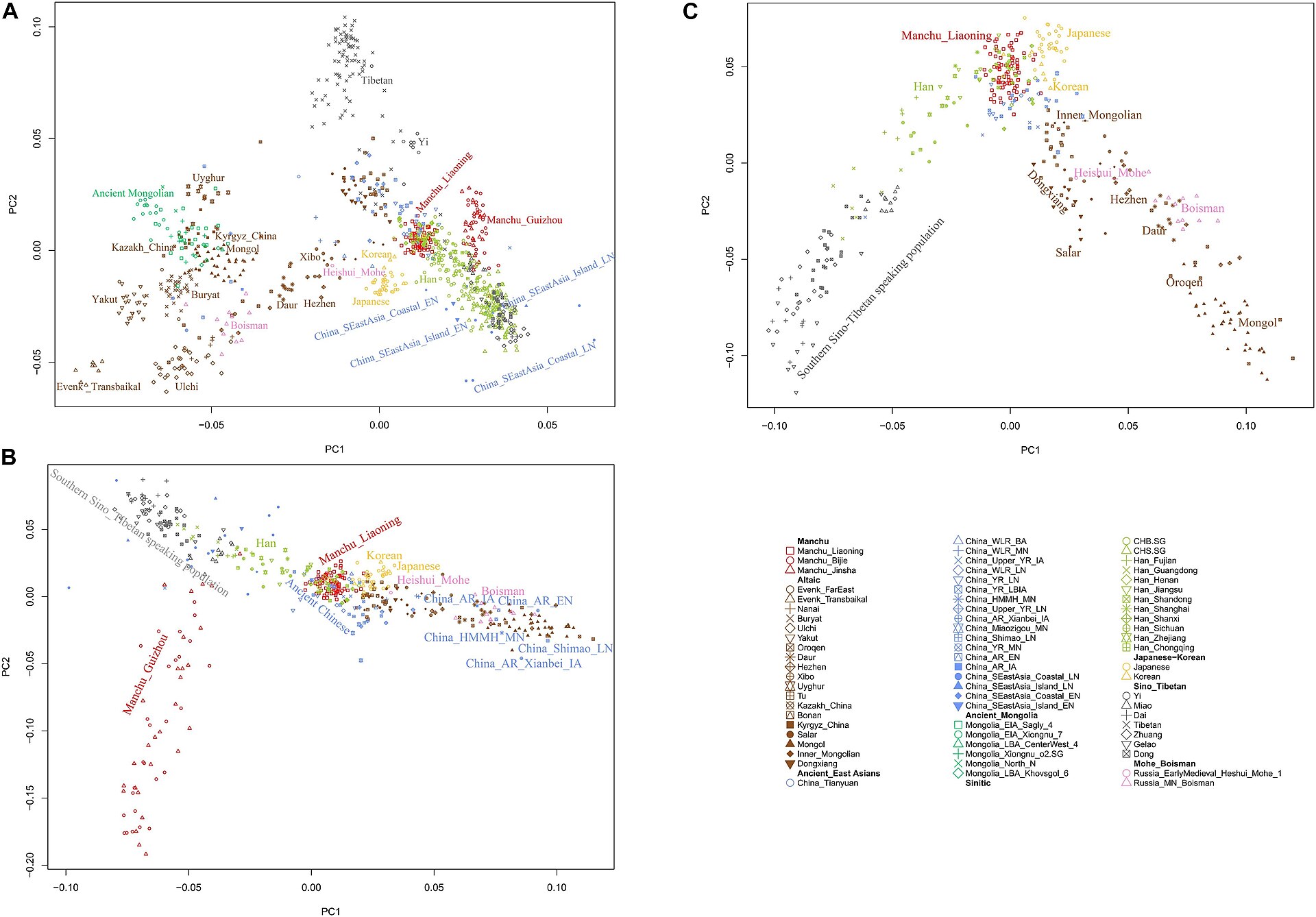

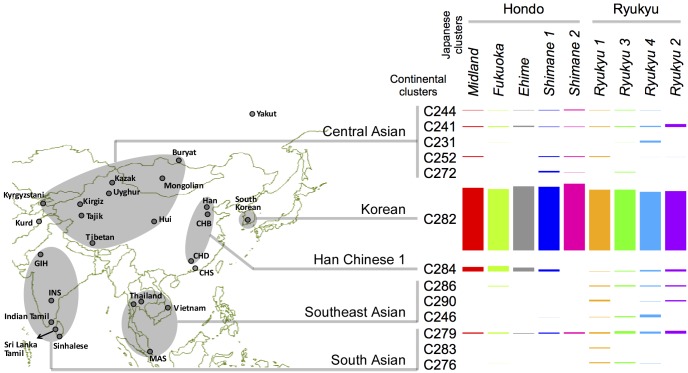

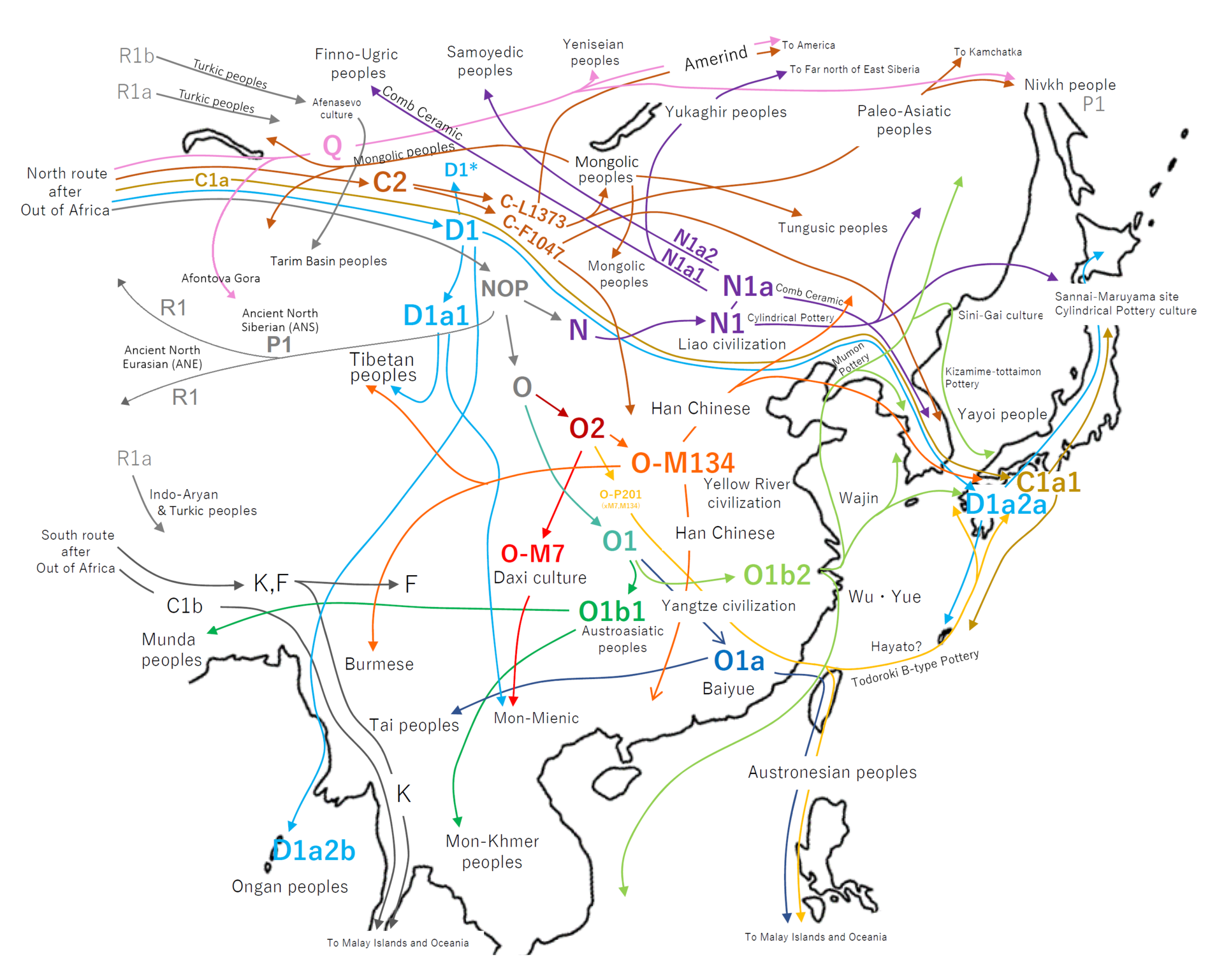

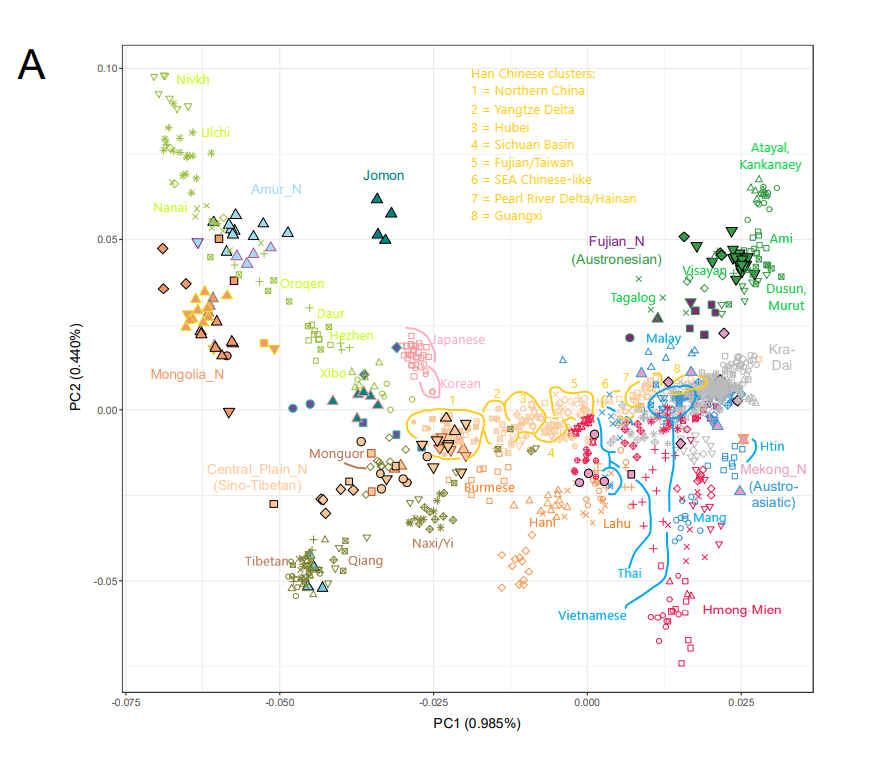

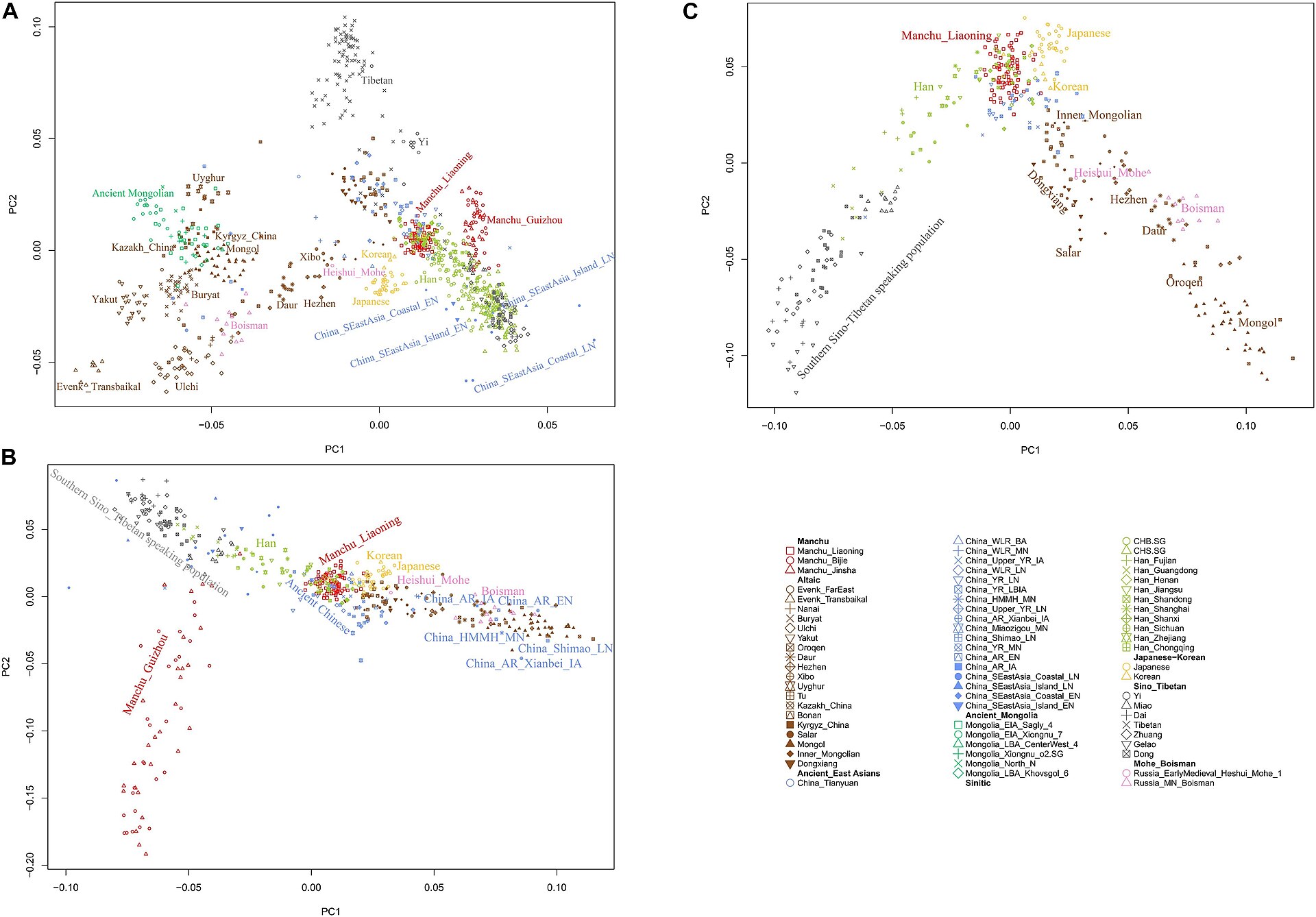

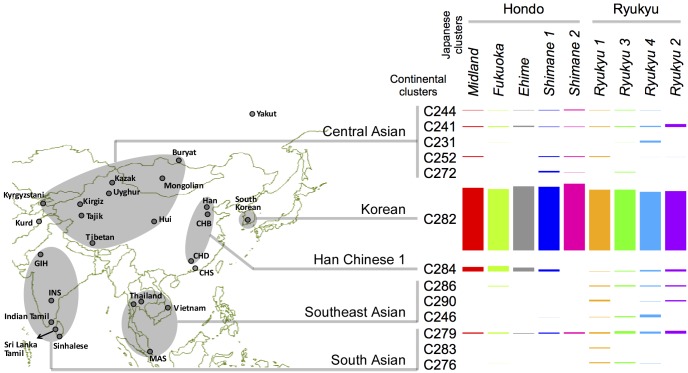

| Origins Main articles: Jōmon people, Yayoi people, and Genetic history of East Asians § Japanese people  Glacier cover in Japan at the height of the last glaciation about 20,000 years ago A common origin of Japanese has been proposed by a number of scholars since Arai Hakuseki first brought up the theory and Fujii Sadamoto, a pioneer of modern archaeology in Japan, also treated the issue in 1781.[11] But after the end of World War II, Kotondo Hasebe and Hisashi Suzuki claimed that the origin of Japanese people was not the newcomers in the Yayoi period (300 BCE – 300 CE) but the people in the Jōmon period.[12] However, Kazuro Hanihara announced a new racial admixture theory in 1984.[12] Hanihara also announced the theory "dual structure model" in English in 1991.[13] According to Hanihara, modern Japanese lineages began with Jōmon people, who moved into the Japanese archipelago during the Paleolithic. Hanihara believed that there was a second wave of immigrants, from northeast Asia to Japan from the Yayoi period. Following a population expansion in Neolithic times, these newcomers then found their way to the Japanese archipelago sometime during the Yayoi period. As a result, miscegenation was common in the island regions of Kyūshū, Shikoku, and Honshū, but did not prevail in the outlying islands of Okinawa and Hokkaidō, and the Ryukyuan and Ainu people continued to dominate there. Mark J. Hudson claimed that the main ethnic image of Japanese people was biologically and linguistically formed from 400 BCE to 1,200 CE.[12] Currently, the most well-regarded theory is that present-day Japanese are descendants of both the indigenous Jōmon people and the immigrant Yayoi people.  Main migration routes into Japan during the Jōmon and Yayoi period On the other hand, a study published in October 2009 by the National Museum of Nature and Science et al. concluded that the Minatogawa Man, who was found in Okinawa and was regarded as evidence that the Jōmon people were not a homogenous group and that these southern Jōmon came to Japan via a southern route and had a slender and more neo-Mongoloid face unlike the northern Jōmon.[14] Hiroto Takamiya of the Sapporo University suggested that the people of Kyushu immigrated to Okinawa between the 10th and 12th centuries CE.[15][16] A 2011 study by Sean Lee and Toshikazu Hasegawa[17] reported that a common origin of Japonic languages had originated around 2,182 years before present.[18] A study conducted in 2017 by Ulsan University in Korea presented evidence that the genetic origin of Koreans is closer to that of Southeast Asians (Vietnamese people).[19] This was additionally supported by Japanese research conducted in 1999 that supported the theory that the origin of the Yayoi people was in southern China near the Yangtze river.[20] The origins of the Jōmon and Yayoi people have often been a subject of dispute, and a recent Japanese publisher[21] has divided the potential routes of the people living on the Japanese archipelago as follows:  A population genomic PCA graph, showing the substructure of Eastern Asian populations, including analyzed Japanese Jōmon samples. Japanese people's cluster (square) is almost indistinguishable to the Korean people's cluster (circle), while the Jōmon samples are shifted towards the Siberian cluster in a more distinct position. (2019) Aboriginals that have been living in Japan for more than 10,000 years. (Without geographic distinction, which means, the group of people living in islands from Hokkaido to Okinawa may all be considered to be Aboriginals in this case.) Immigrants from the northern route (北方ルート in Japanese) including the people from the Korean Peninsula, mainland China and Sakhalin Island. Immigrants from the southern route (南方ルート in Japanese) including the people from the Pacific Islands, Southeast Asia, and in some context, India. However, a clear consensus has not been reached.[22][23][24][25][26] A study in 2017 estimates the Jōmon ancestry in people from Tokyo at approximately 12%.[27] In 2018, an independent research conducted by director Kenichi Shinoda and his team at National Museum of Nature and Science was broadcast on NHK Science ZERO and it was discovered that the modern day Japanese are genetically extremely close to the modern day Koreans.[28]  A recent PCA graph illustrating the genetic affinity of the Japanese people (classified under the Japanese-Korean cluster) with other East Asians (2022) A genome study (Takahashi et al. 2019) shows that modern Japanese (Yamato) do not have much Jōmon ancestry at all. Nuclear genome analysis of Jōmon samples and modern Japanese samples show strong differences.[29] Various studies estimate the proportion of Jōmon ancestry in Japanese people at around 9-13%, with the remainder derived from later migrations from Asia including the Yayoi people.[27][30][2] Recent studies have revealed that Jomon people are considerably genetically different from any other population, including modern-day Japanese. — Takahashi et al. 2019, (Adachi et al., 2011; Adachi and Nara, 2018)  Ancestry profile of Japanese genetic clusters illustrating their genetic similarities to five mainland Asian populations A study, published in the Cambridge University Press in 2020, suggests that the Jōmon people were rather heterogeneous, and that there was also a pre-Yayoi migration during the Jōmon period, which may be linked to the arrival of the Japonic languages, meaning that Japonic is one of the Jōmon languages. This migration is suggested to have happened before 6000BC, thus before the actual Yayoi migration.[31] The most popular theory is that the Yayoi people were the people who brought wet rice cultivation to Japan from the Korean peninsula and Jiangnan near the Yangtze River Delta in ancient China.[32][page needed] According to several Japanese historians, the Yayoi and their ancestors, the Wajin, originated in the today Yunnan province in southern China.[33] Suwa Haruo[34] considered Wa-zoku (Wajin) to be part of the Baiyue (百越).[35] Recent full genome analyses in 2020 by Boer et al. 2020 and Yang et al. 2020, reveals some further information regarding the origin of the Jōmon peoples. They were found to have largely formed from a Paleolithic Siberian population and an East Asian related population.[11][36] According to a March 2021 study on genetic distance measurements from a large scale genetic study titled 'Genomic insights into the formation of human populations in East Asia', the modern "Japanese populations can be modelled as deriving from Korean (91%) and Jōmon (9%)."[37] A September 2021 study published in the journal Science Advances found that the people of Japan bore genetic signatures from three ancient populations rather than just two as previously thought.[4] The study states that in addition to the previously discovered Jōmon and Yayoi strands, a new strand was hypothesized to have been introduced, most likely from the southern Korean peninsula, during the Yayoi-Kofun transition period that had strong cultural and political affinity with Korea and China.[38] The genomes of three Kofun individuals analyzed in the study document the arrival of people with "majority East Asian ancestry and their admixture with the Yayoi population" with the additional ancestry coming from migrants who were "already highly admixed" and "best represented by the Han, who have multiple ancestral components."[39] According to the study, the genetic profile of present-day Japanese population was established by the three major ancestral components in place by the Kofun period, with the East Asian ancestry component introduced during the Kofun period accounting for nearly 70% of the present day Japanese population admixture proportion, while Yayoi component accounting for 15-20% and the remainder by the Jōmon component.[4] The Nikkei published an article that showed the Kofun strand in modern-day Japanese was concentrated in specific regions such as Kinki, Hokuriku and Shikoku.[40] The aforementioned studies are further supported by recent studies in 2022 which concluded that the ancient Jōmon people were present outside of Japan,[41] but were later significantly diminished due to the influx of proto-Koreans originating from the West Liao River, arriving in both the Korean peninsula and Japanese archipelago.[42] |

起源 主な記事 縄文人、弥生人、東アジア人の遺伝史 § 日本人  約2万年前の最終氷河期の日本の氷河被覆 日本人の共通起源説は、新井白石が初めて提唱し、日本の近代考古学の先駆者である藤井貞元も1781年にこの問題を扱って以来、多くの学者によって提唱さ れてきた[11]が、第二次世界大戦後、長谷部言人と鈴木尚は、日本人の起源は弥生時代の渡来人ではなく、縄文時代の人々であると主張した[12]。 [しかし、埴原和郎は1984年に新たな人種混血説を発表し[12]、さらに埴原は1991年に英語で「dual structure model(二重構造モデル)」という説を発表した[13]。埴原は、弥生時代から北東アジアから日本への移民の第二波があったと考えた。新石器時代に人 口が拡大した後、弥生時代のある時期にこれらの新人が日本列島にたどり着いた。その結果、九州、四国、本州の島嶼部では混血が進んだが、沖縄や北海道の離 島では混血が進まず、琉球人やアイヌ人が支配を続けた。マーク・J・ハドソンは、日本人の主な民族像は生物学的・言語学的に紀元前400年から紀元後 1,200年にかけて形成されたと主張している[12]。現在、最も有力な説は、現在の日本人は先住民族である縄文人と渡来人である弥生人の両方の子孫で あるというものである。  縄文時代と弥生時代の日本への主な移動ルート 一方、2009年10月に国立科学博物館らによって発表された研究では、沖縄で発見された湊川人は、縄文人が均質な集団ではなかったことを示す証拠であ り、これらの南方系縄文人は南方ルートで日本に渡来し、北方系縄文人とは異なり、細身でより新モンゴロイド的な顔立ちであったと結論付けている[14]。 [14] 札幌大学の高宮寛人は、九州の人々が紀元10世紀から12世紀の間に沖縄に移住したことを示唆した[15][16]。 ショーン・リーと長谷川敏一による2011年の研究[17]は、ジャポニック言語の共通の起源は現在より2,182年ほど前に生まれたと報告している[18]。 韓国の蔚山大学が2017年に行った研究は、韓国人の遺伝的起源が東南アジア人(ベトナム人)のそれに近いという証拠を提示した[19]。 これはさらに、弥生人の起源が長江近くの中国南部であるという説を支持した1999年に行われた日本の研究によっても支持された[20]。 縄文人と弥生人の起源はしばしば論争の対象となっており、最近の日本の出版社[21]は、日本列島に住む人々の潜在的なルートを以下のように分けている:  集団ゲノムPCAグラフ。解析された日本の縄文人サンプルを含む東アジア集団の部分構造を示す。日本人のクラスター(四角)は朝鮮人のクラスター(丸)と ほとんど区別がつかないが、縄文人のサンプルはより明確な位置でシベリアのクラスターに向かってシフトしている。(2019) 日本に1万年以上住んでいる原住民。(地理的な区別なし。つまり、この場合、北海道から沖縄までの島々に住む人々のグループは、すべてアボリジニとみなすことができる) 朝鮮半島、中国大陸、サハリン島からの人々を含む北方ルートからの移民。 南方ルートからの移民(日本語では南方ルート)とは、太平洋諸島、東南アジア、ある文脈ではインドからの人々を含む。 しかし、明確なコンセンサスは得られていない[22][23][24][25][26]。 2017年の研究では、東京出身者の縄文人の祖先は約12%と推定されている[27]。 2018年、国立科学博物館の篠田建一館長と彼のチームが行った独自の研究がNHKサイエンスZEROで放送され、現代の日本人は現代の韓国人と遺伝的に極めて近いことが判明した[28]。  日本人(日韓クラスターに分類される)と他の東アジア人の遺伝的親和性を示す最近のPCAグラフ(2022年) ゲノム研究(Takahashi et al. 2019)は、現代の日本人(大和民族)には縄文人の祖先が全くと言っていいほどいないことを示している。縄文人のサンプルと現代日本人のサンプルの核ゲ ノム解析は強い違いを示している[29]。様々な研究は、日本人の縄文人の祖先の割合を約9-13%と推定しており、残りは弥生人を含むアジアからの後の 移住に由来する[27][30][2]。 近年の研究により、縄文人は現代の日本人を含む他のどの集団とも遺伝的にかなり異なることが明らかになっている。 - 高橋ら、2019、(足立ら、2011;足立・奈良、2018)  アジア本土の5つの集団との遺伝的類似性を示す日本人遺伝子クラスターの祖先プロファイル 2020年にケンブリッジ大学出版局で発表された研究では、縄文人はむしろ異質であり、縄文時代には弥生以前の移動もあったことが示唆されており、これは ジャポニック語の伝来と関連している可能性がある、つまりジャポニック語も縄文語の一つであることを意味している。この移動は紀元前6000年以前、つま り実際の弥生人の移動よりも前に起こったと示唆されている[31]。 最も有力な説は、弥生人は古代中国の長江デルタに近い朝鮮半島と江南から日本に湿稲作をもたらした人々であるというものである。 [32][要ページ]複数の日本の歴史家によれば、弥生人とその祖先である和人は現在の中国南部の雲南省に起源を持つとされている[33]。 Boerらによる2020年とYangらによる2020年の最近の全ゲノム解析によって、縄文人の起源に関するいくつかのさらなる情報が明らかになった。彼らは大部分が旧石器時代のシベリアの集団と東アジアに関連する集団から形成されたことが判明した[11][36]。 2021年3月に発表された「Genomic insights into the formation of human populations in East Asia」と題された大規模な遺伝子研究による遺伝的距離の測定に関する研究によれば、現代の「日本人の集団は朝鮮人(91%)と縄文人(9%)から派生 したとモデル化することができる」[37]。 2021年9月にScience Advances誌に発表された研究によると、日本人はこれまで考えられていたような2つの集団ではなく、3つの古代の集団の遺伝的特徴を有していること が判明した[4]。この研究によると、これまで発見されていた縄文人と弥生人に加えて、朝鮮半島南部から、朝鮮半島や中国と文化的・政治的に強い親和性を 持つ弥生・古墳遷移期に持ち込まれた可能性が高い、新たな集団の仮説が立てられている[38]。 [38] 研究で分析された古墳時代の3人のゲノムは、「東アジア人の祖先が大多数を占め、弥生人と混血した」人々が、「すでに混血が進んでいた」移民から追加的に 祖先を持ち、「複数の祖先成分を持つ漢族に最もよく代表される」人々が、古墳時代にやってきたことを記録している[39]。 この研究によれば、現在の日本人の遺伝的プロフィールは、古墳時代までに形成された3つの主要な祖先構成要素によって確立されており、古墳時代に導入され た東アジアの祖先構成要素が現在の日本人の混血比率の70%近くを占め、弥生構成要素が15~20%、残りを縄文構成要素が占めている[4]。 日本経済新聞は、現代の日本人の古墳層が近畿、北陸、四国などの特定の地域に集中していることを示す記事を発表した[40]。 前述の研究は、古代の縄文人は日本以外の地域にも存在したが[41]、後に西遼河を起源とする原始朝鮮人が流入し、朝鮮半島と日本列島の両方に到着したために著しく減少したと結論づけた2022年の最近の研究によってさらに裏付けられている[42]。 |

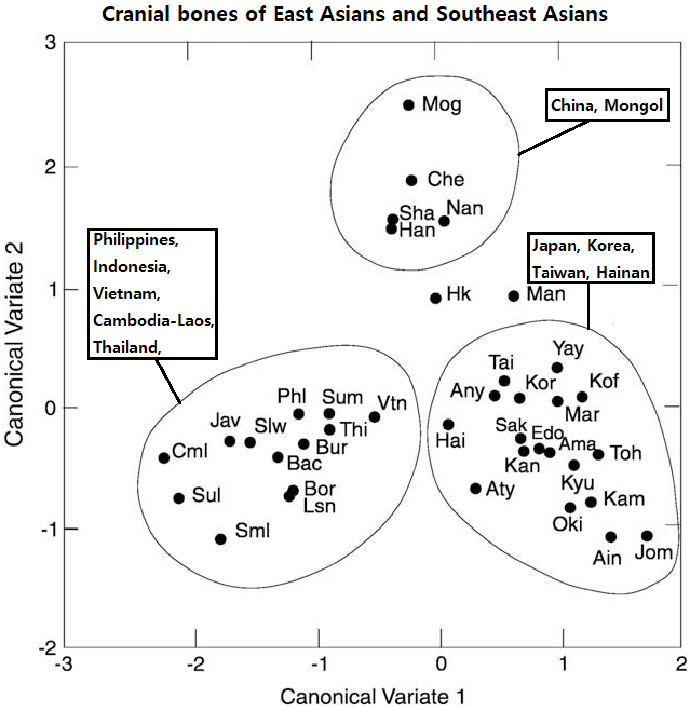

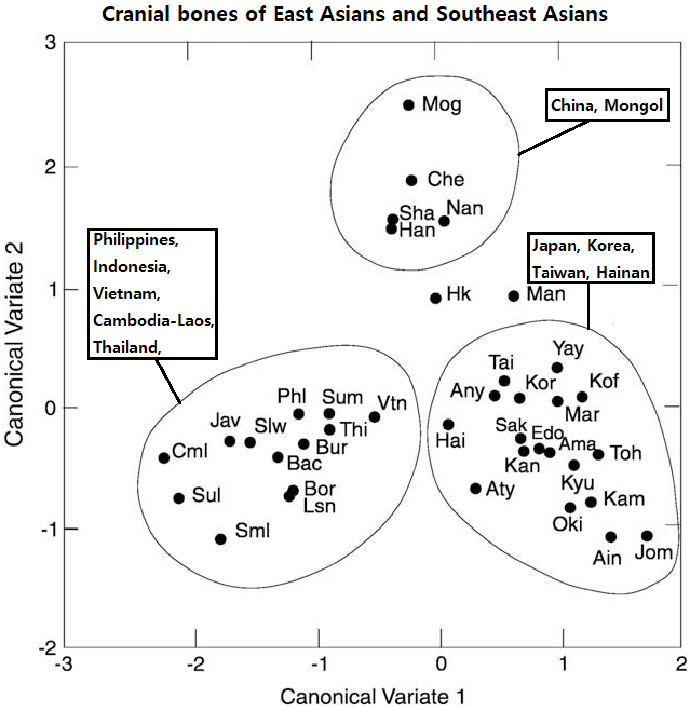

| Anthropometry Stephen Pheasant (1986), who taught anatomy, biomechanics and ergonomics at the Royal Free Hospital and the University College, London, said that Far Eastern people have proportionately shorter lower limbs than European and black African people. Pheasant said that the proportionately short lower limbs of Far Eastern people is a difference that is most characterized in Japanese people, less characterized in Korean and Chinese people, and least characterized in Vietnamese and Thai people.[43][44] Rajvir Yadav et al. (2000) stated the sitting height to stature ratios of different populations: South Indian (0.4922), female Indian (0.4974), Eastern Indian (0.4991), Southeastern African (0.5096), Central Indian (0.5173), US (0.5202), Western Indian (0.5243), German (0.5266) and Japanese (0.5452).[45] Hirofumi Matsumura et al. (2001) and Hideo Matsumoto et al. (2009) said that the Japanese and Vietnamese people are regarded to be a mix of Northeast Asians and Southeast Asians. However, the amount of northern genetics is higher in Japanese people compared to Vietnamese, who are closer to other Southeast Asians (Thai or Bamar people).[46][47] Neville Moray (2005) said that, for Korean and Japanese pilots, sitting height is more than 54% of their stature, with about 46% of their stature from leg length. Moray said that, for Americans and most Europeans, sitting height is about 52% of their stature, with about 48% of their stature from leg length. Moray indicated that modifications in basic cockpit geometry are required to accommodate Japanese and Vietnamese pilots. Moray said that the Japanese have longer torsos and a higher shoulder point than the Vietnamese, but the Japanese have about similar arm lengths to the Vietnamese, so the control stick would have to be moved 8 cm closer to the pilot for the Japanese and 7 cm closer to the pilot for the Vietnamese. Moray said that, due to having shorter legs than Americans, rudder pedals must be moved closer to the pilot by 10 cm for the Japanese and 12 cm for the Vietnamese.[48] Craniometry  According to Pietrusewsky, the group most similar to the Japanese cranial bones were the Koreans. Meanwhile, Chinese, Mongolians and Southeast Asians were distinguished from the Japanese.[49] (2010) Ashley Montagu (1989) said that the "Mongoloid skull generally, whether Chinese or Japanese, has been rather more neotenized than the Caucasoid or European..."[50] Ann Kumar (1998) said that Michael Pietrusewsky (1992) said that, in a craniometric study, the cranial bones of Southeast Asians (Borneo, Vietnam, Sulu, Java, and Sulawesi etc.) are closer to Japanese, in that order, than Mongolian and Chinese populations are close to Japanese. In the craniometric study, Michael Pietrusewsky (1992) said that, even though Japanese people cluster with Mongolians, Chinese and Southeast Asians in a larger Asian cluster, the cranial bones of Japanese people are more closely aligned with several mainland and island Southeast Asian samples than with Mongolians and Chinese. However, Pietrusewsky (1992) also said, more research is needed on the similarity of the cranial bones between Japanese and Southeast Asians.[51][52] In a craniometric study, Pietrusewsky (1994) found that the Japanese series, which was a series that spanned from the Yayoi period to modern times, formed a single branch with Korea.[53] Later, Pietrusewsky (1999) found, however, that Korean and Yayoi people were very highly separated in the East Asian cluster, indicating that the connection that Japanese have with Korea would not have derived from Yayoi people.[53] However, in a follow-up study, Pietrusewsky (2010) corrected that East Asians and Southeast Asians were markedly separated from each other. He found that Koreans had the most similar cranial bones to ancient and modern Japanese including the Yayoi people and Jōmon people, followed by Taiwan and Hainan.[49] He stated that a common origin of Northeast Asians could be traced and that they began entering the Japanese archipelago at the beginning of the Yayoi period.[49] Park Dae-kyoon et al. (2001) said that distance analysis based on thirty-nine non-metric cranial traits showed that Koreans are closer craniometrically to Kazakhs and Mongols than to the populations in China and Japan.[54] |

人体計測 ロンドンのロイヤル・フリー病院とユニバーシティ・カレッジで解剖学、バイオメカニクス、人間工学を教えていたスティーブン・キザント(1986年)は、 極東の人々はヨーロッパやアフリカの黒人に比べて下肢が比例して短いと述べている。キジは、極東の人々の比例して短い下肢は、日本人に最も特徴的で、韓国 人と中国人にはあまり特徴的ではなく、ベトナム人とタイ人には最も特徴的でない違いであると述べている[43][44]。 Rajvir Yadavら(2000)は、異なる集団の座高対身長比を述べている: 南インド人(0.4922)、女性インド人(0.4974)、東インド人(0.4991)、南東アフリカ人(0.5096)、中央インド人 (0.5173)、米国人(0.5202)、西インド人(0.5243)、ドイツ人(0.5266)および日本人(0.5452)[45]。 松村博文ら(2001)と松本秀夫ら(2009)は、日本人とベトナム人は北東アジア人と東南アジア人の混血とみなされると述べている。しかし、他の東南アジア人(タイ人やバマー人)に近いベトナム人に比べて、日本人は北方系の遺伝子の量が多い[46][47]。 ネヴィル・モレイ(2005年)は、韓国人と日本人のパイロットの場合、座高は身長の54%以上であり、脚の長さから身長の約46%を占めていると述べて いる。Morayによると、アメリカ人とほとんどのヨーロッパ人は、座高が身長の約52%で、脚の長さが身長の約48%である。モレイは、日本人とベトナ ム人のパイロットに対応するためには、基本的なコックピットの形状を変更する必要があると指摘した。モレイ氏によると、日本人はベトナム人よりも胴体が長 く、肩の位置が高いが、日本人の腕の長さはベトナム人とほぼ同じであるため、操縦桿を日本人は8cm、ベトナム人は7cmパイロットに近づける必要がある という。モレイによれば、アメリカ人よりも足が短いため、ラダーペダルを日本人は10cm、ベトナム人は12cmパイロットに近づけなければならない [48]。 クラニオメトリー  ピエトルーセフスキーによれば、日本人の頭蓋骨に最も似ているのは朝鮮人であった。一方、中国人、モンゴル人、東南アジア人は日本人とは区別された[49](2010年)。 アシュレイ・モンタグ(1989)は、「モンゴロイドの頭蓋骨は一般的に、中国人であれ日本人であれ、コーカソイドやヨーロッパ人よりもむしろネオテニー化している」と述べている[50]。 アン・クマール(1998)は、マイケル・ピエトルーセフスキー(1992)が頭蓋計測の研究で、東南アジア人(ボルネオ、ベトナム、スールー、ジャワ、 スラウェシなど)の頭蓋骨は、モンゴル人や中国人の集団が日本人に近いというよりも、この順に日本人に近いと述べていると述べている。マイケル・ピエト ルーセフスキー(1992)は、頭蓋計測の研究で、日本人はモンゴル人、中国人、東南アジア人と大きなアジアのクラスターに集まっているにもかかわらず、 日本人の頭蓋骨はモンゴル人や中国人よりも、いくつかの本土や島の東南アジアのサンプルとより密接に並んでいると述べている。しかしながら、 Pietrusewsky(1992)は、日本人と東南アジア人の間の頭蓋骨の類似性についてはより多くの研究が必要であるとも述べている[51] [52]。 ピエトルーセフスキー(1994年)は頭蓋計測の研究において、弥生時代から現代に至る日本人の系列が朝鮮半島と一つの枝を形成していることを発見した。 [しかしその後、ピエトルーセフスキー(1999)は、韓国人と弥生人は東アジアのクラスターの中で非常に高度に分離していることを発見し、日本人が韓国 と持っているつながりは弥生人から派生したものではないことを示した[53]。しかし、その後の研究でピエトルーセフスキー(2010)は、東アジア人と 東南アジア人は著しく分離していることを訂正した。彼は、韓国人が弥生人や縄文人を含む古代および現代の日本人と最も類似した頭蓋骨を持っており、台湾と 海南がそれに続くことを発見した[49]。彼は、東北アジア人の共通の起源をたどることができ、彼らは弥生時代の初めに日本列島に入り始めたと述べた [49]。 Park Dae-kyoonら(2001年)は、39の非計量的頭蓋形質に基づく距離分析によって、韓国人は中国や日本の集団よりもカザフ族やモンゴル族に頭蓋形状的に近いことが示されたと述べている[54]。 |

| Demographics of Japan Genetic studies on Japanese Americans History of Japan Japanese people |

日本の人口統計 日系アメリカ人の遺伝学的研究 日本の歴史 日本人 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genetic_and_anthropometric_studies_on_Japanese_people | |

| Boer, Elisabeth de; Yang, Melinda A.; Kawagoe, Aileen;

Barnes, Gina L. (2020). "Japan considered from the hypothesis of

farmer/language spread". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2: e13.

doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.7. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 10427481. PMID 37588377. Formally, the Farming/Language Dispersal hypothesis as applied to Japan relates to the introduction of agriculture and spread of the Japanese language (between ca. 500 BC–AD 800). We review current data from genetics, archaeology, and linguistics in relation to this hypothesis. However, evidence bases for these disciplines are drawn from different periods. Genetic data have primarily been sampled from present-day Japanese and prehistoric Jōmon peoples (14,000–300 BC), preceding the introduction of rice agriculture. The best archaeological evidence for agriculture comes from western Japan during the Yayoi period (ca. 900 BC–AD 250), but little is known about northeastern Japan, which is a focal point here. And despite considerable hypothesizing about prehistoric language, the spread of historic languages/ dialects through the islands is more accessible but difficult to relate to prehistory. Though the lack of Yayoi skeletal material available for DNA analysis greatly inhibits direct study of how the pre-agricultural Jōmon peoples interacted with rice agriculturalists, our review of Jōmon genetics sets the stage for further research into their relationships. Modern linguistic research plays an unexpected role in bringing Izumo (Shimane Prefecture) and the Japan Sea coast into consideration in the populating of northeastern Honshu by agriculturalists beyond the Kantō region. |

Boer, Elisabeth de; Yang, Melinda A.; Kawagoe, Aileen;

Barnes, Gina L. (2020). "Japan considered from the hypothesis of

farmer/language spread". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2: e13.

doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.7. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 10427481. PMID 37588377. 正式には、日本に適用される「農耕/言語拡散仮説」は、農耕の伝来と日本語の普及(紀元前500年頃~西暦800年頃)に関連している。この仮説に関連し て、遺伝学、考古学、言語学の最新のデータを検証する。しかし、これらの学問分野の根拠となる証拠は、異なる時代から得られたものである。遺伝学のデータ は主に、現代の日本人と、稲作が伝わる前の縄文時代の先史時代の人々(紀元前14,000年~紀元前300年)から採取されたものである。農業に関する最 良の考古学的証拠は、弥生時代(紀元前900年頃~紀元250年)の西日本から得られているが、ここで焦点となる東北日本についてはほとんど知られていな い。また、先史時代の言語については多くの仮説が立てられているが、歴史時代の言語や方言が島々を通じて広まったことについては、より入手しやすい情報が あるものの、先史時代との関連性を立証するのは難しい。弥生人の骨格資料がDNA分析に利用できないため、農耕以前の縄文人が稲作農耕民とどのように交流 していたかを直接研究することが非常に妨げられているが、縄文人の遺伝学に関する我々の研究は、両者の関係をさらに研究するための土台となる。現代の言語 学の研究は、関東地方以外の農耕民による本州北東部の入植について、出雲(島根県)と日本海沿岸を考慮に入れるという予期せぬ役割を果たしている。 |

| Wang, Chuan-Chao (2021). "Genomic insights into the formation

of human populations in East Asia". Nature. 591 (7850): 413–419.

Bibcode:2021Natur.591..413W. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03336-2. PMC

7993749. PMID 33618348. The deep population history of East Asia remains poorly understood owing to a lack of ancient DNA data and sparse sampling of present-day people1,2. Here we report genome-wide data from 166 East Asian individuals dating to between 6000 BC and AD 1000 and 46 present-day groups. Hunter-gatherers from Japan, the Amur River Basin, and people of Neolithic and Iron Age Taiwan and the Tibetan Plateau are linked by a deeply splitting lineage that probably reflects a coastal migration during the Late Pleistocene epoch. We also follow expansions during the subsequent Holocene epoch from four regions. First, hunter-gatherers from Mongolia and the Amur River Basin have ancestry shared by individuals who speak Mongolic and Tungusic languages, but do not carry ancestry characteristic of farmers from the West Liao River region (around 3000 BC), which contradicts theories that the expansion of these farmers spread the Mongolic and Tungusic proto-languages. Second, farmers from the Yellow River Basin (around 3000 BC) probably spread Sino-Tibetan languages, as their ancestry dispersed both to Tibet—where it forms approximately 84% of the gene pool in some groups—and to the Central Plain, where it has contributed around 59–84% to modern Han Chinese groups. Third, people from Taiwan from around 1300 BC to AD 800 derived approximately 75% of their ancestry from a lineage that is widespread in modern individuals who speak Austronesian, Tai–Kadai and Austroasiatic languages, and that we hypothesize derives from farmers of the Yangtze River Valley. Ancient people from Taiwan also derived about 25% of their ancestry from a northern lineage that is related to, but different from, farmers of the Yellow River Basin, which suggests an additional north-to-south expansion. Fourth, ancestry from Yamnaya Steppe pastoralists arrived in western Mongolia after around 3000 BC but was displaced by previously established lineages even while it persisted in western China, as would be expected if this ancestry was associated with the spread of proto-Tocharian Indo-European languages. Two later gene flows affected western Mongolia: migrants after around 2000 BC with Yamnaya and European farmer ancestry, and episodic influences of later groups with ancestry from Turan. |

Wang, Chuan-Chao (2021). "Genomic insights into the formation

of human populations in East Asia". Nature. 591 (7850): 413–419.

Bibcode:2021Natur.591..413W. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03336-2. PMC

7993749. PMID 33618348. 古代のDNAデータが不足しており、また現代人のサンプリングもまばらであるため、東アジアの人口の深い歴史は依然として十分に理解されていない1、2。 ここでは、紀元前6000年から西暦1000年の間にさかのぼる166人の東アジア人と、現代の46グループのゲノムワイドのデータを報告する。日本、アムール川流域、新石器時代および鉄器時代の台湾、チベット高原の狩猟採集民は、おそらく更新世後期の沿岸部への移住を反映した、大きく分岐した系統によってつながっている。 また、その後の完新世における4つの地域からの拡大についても追跡している。まず、モンゴルとアムール川流域の狩猟採集民は、モンゴル語族とツングース語 族の言語を話す人々と共通の祖先を持つが、西遼河流域(紀元前3000年頃)の農耕民の特徴を持つ祖先は持っていない。これは、農耕民の拡大がモンゴル語 族とツングース語族の祖語を広めたとする説と矛盾している。第二に、黄河流域(紀元前3000年頃)の農耕民は、おそらくシナ・チベット語族を広めたと考 えられる。彼らの祖先は、チベット(一部のグループでは遺伝子プールの約84%を占める)と中央平原(現代の漢民族グループの約59~84%に貢献してい る)の両方に広がった。第三に、紀元前1300年頃から西暦800年頃の台湾の人々は、その祖先の約75%を、オーストロネシア語族、タイ・カダイ語族、 オーストロアジア語族を話す現代の個人に広く分布している系統に由来しており、私たちは、その系統が揚子江流域の農耕民に由来すると仮説を立てている。台 湾の先住民も、祖先の約25%を黄河流域の農耕民と関連するが異なる北方の系統から受け継いでおり、南北両方向への拡散を示唆している。第四に、紀元前 3000年頃にモンゴル西部にやってきたヤムナヤ草原の遊牧民の家系は、中国西部に定着していたものの、以前から定着していた家系に取って代わられた。こ れは、この家系が原トカラ語インド・ヨーロッパ語族の拡散に関連していると予想される。紀元前2000年頃にヤムナヤ文化とヨーロッパ農耕民の系譜を持つ 人々による移住、そして、後にトゥーランの系譜を持つ集団による断続的な影響という、2つの後世の遺伝子流入が西モンゴルに影響を与えた。 |

| Cooke NP, Mattiangeli V, Cassidy LM, Okazaki K, Stokes CA,

Onbe S, et al. (September 2021). "Ancient genomics reveals tripartite

origins of Japanese populations". Science Advances. 7 (38): eabh2419.

Bibcode:2021SciA....7.2419C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abh2419. PMC 8448447.

PMID 34533991. Prehistoric Japan underwent rapid transformations in the past 3000 years, first from foraging to wet rice farming and then to state formation. A long-standing hypothesis posits that mainland Japanese populations derive dual ancestry from indigenous Jomon hunter-gatherer-fishers and succeeding Yayoi farmers. However, the genomic impact of agricultural migration and subsequent sociocultural changes remains unclear. We report 12 ancient Japanese genomes from pre- and postfarming periods. Our analysis finds that the Jomon maintained a small effective population size of ~1000 over several millennia, with a deep divergence from continental populations dated to 20,000 to 15,000 years ago, a period that saw the insularization of Japan through rising sea levels. Rice cultivation was introduced by people with Northeast Asian ancestry. Unexpectedly, we identify a later influx of East Asian ancestry during the imperial Kofun period. These three ancestral components continue to characterize present-day populations, supporting a tripartite model of Japanese genomic origins. |

先史時代の日本では、過去3000年の間に

急速な変化が起こり、まず狩猟から水稲農耕へ、そして国家形成へと移行した。長年にわたって提唱されてきた仮説によると、日本本土の人口は、先住民族であ

る縄文時代の狩猟採集民と、その後に続く弥生時代の農耕民という2つの祖先を持つとされている。しかし、農耕の移住とそれに続く社会文化の変化がゲノムに

与えた影響については、依然として不明な点が多い。私たちは、農耕の前後における12人の古代日本人のゲノムを報告する。分析の結果、(1)縄文人は数千年にわたって1000人程度の小さな実効集団サイズを維持しており、2万~1万5000年前の大陸の集団とは大きく異なっていることが分かった。この期間は、海面上昇により日本列島が孤立化した時期にあたる。稲作は、(3)北東アジアの祖先を持つ人々によってもたらされた。意外にも、(3)古墳時代には東アジア系の祖先が流入していたことが判明した。これら3つの祖先構成要素は、現代の人口の特徴を今も示しており、日本人のゲノムの起源に関する3つのモデルを裏付けている。 |

1.

Gakuhari, Takashi; Nakagome, Shigeki; Rasmussen, Simon; Allentoft,

Morten; Sato, Takehiro; Korneliussen, Thorfinn; Chuinneagáin, Blánaid;

Matsumae, Hiromi; Koganebuchi, Kae; Schmidt, Ryan; Mizushima, Souichiro

(March 15, 2019) [2019]. "Jomon genome sheds light on East Asian

population history" (PDF). bioRxiv. pp. 3–5.

2. Late Jomon male and female genome sequences from the

Funadomari site in Hokkaido, Japan - Hideaki Kanzawa-Kiriyama,

Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Nature and Science

2018/2019en

3. "'Jomon woman' helps solve Japan's genetic mystery". NHK World. Retrieved 2020-11-20.

4. Cooke NP, Mattiangeli V, Cassidy LM, Okazaki K, Stokes CA,

Onbe S, et al. (September 2021). "Ancient genomics reveals tripartite

origins of Japanese populations". Science Advances. 7 (38): eabh2419.

Bibcode:2021SciA....7.2419C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abh2419. PMC 8448447.

PMID 34533991.

5. Mitsuru Sakitani (2009). 『DNA・考古・言語の学際研究が示す新・日本列島史』 [New

History of the Japanese Islands Shown by Interdisciplinary Studies on

DNA, Archeology, and Language] (in Japanese). Bensei Publishing. ISBN

9784585053941.

6. Suzuki, Yuka (December 6, 2012). "Ryukyuan, Ainu People

Genetically Similar". Asian Scientist. Archived from the original on

June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

7. "'Jomon woman' helps solve Japan's genetic mystery". NHK World. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

8. 弥生人DNAで迫る日本人の起源」 [The origin of Japanese people approaching

with Yayoi DNA]. ja:サイエンスZERO (Television production) (in Japanese).

NHK. 2018-12-23.

9. Boer, Elisabeth de; Yang, Melinda A.; Kawagoe, Aileen; Barnes,

Gina L. (2020). "Japan considered from the hypothesis of

farmer/language spread". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2: e13.

doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.7. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 10427481. PMID 37588377.

10. Wang, Chuan-Chao (2021). "Genomic insights into the formation

of human populations in East Asia". Nature. 591 (7850): 413–419.

Bibcode:2021Natur.591..413W. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03336-2. PMC

7993749. PMID 33618348.

11. Miller, Roy A. The Japanese Language. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle. 1967, pp. 61-62

12. Nanta, Arnaud (2008). "Physical Anthropology and the

Reconstruction of Japanese Identity in Postcolonial Japan". Social

Science Japan Journal. 11 (1): 29–47. doi:10.1093/ssjj/jyn019.

13. Hanihara, K (1991). "Dual structure model for the population history of the Japanese". Japan Review. 2: 1–33.

14. Watanabe, Nobuyuki (October 1, 2009). 旧石器時代の「港川1号」、顔ほっそり

縄文人と差. The Asahi Shimbun (in Japanese). Archived from the original on

June 29, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

15. Nakamura, Shunsuke (April 16, 2010). 沖縄人のルーツを探る. The Asahi

Shimbun (in Japanese). p. 2. Archived from the original on June 29,

2011. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

16. Hideaki Kanzawa-Kiriyama, Kirill Kryukov, Timothy A Jinam,

Kazuyoshi Hosomichi, Aiko Saso: . In: . Band 62, Nr. 2, 1. September

2016

17. "メンバー". 13 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

18. Lee, Sean; Hasegawa, Toshikazu (2011). "Bayesian phylogenetic

analysis supports an agricultural origin of Japonic languages".

Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1725):

3662–3669. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0518. PMC 3203502. PMID 21543358.

19. "Researchers discover Korean genetic roots in 7,700-year-old

skull". Korea.net. Korean Culture and Information Service. Retrieved

2017-03-18.

20. "Yayoi linked to Yangtze area". Trussel.com. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

21. from the book, 2009, Japanese published by Heidansha. "日本人".

マイペディア. 平凡社. Original

sentence:旧石器時代または縄文時代以来、現在の北海道から琉球諸島までの地域に住んだ集団を祖先に持つ。シベリア、樺太、朝鮮半島などを経由す

る北方ルート、南西諸島などを経由する南方ルートなど複数の渡来経路が考えられる

22. Tajima, Atsushi; Pan, I.-Hung; Fucharoen, Goonnapa;

Fucharoen, Supan; Matsuo, Masafumi; Tokunaga, Katsushi; Juji, Takeo;

Hayami, Masanori; Omoto, Keiichi; Horai, Satoshi (1 January 2002).

"Three major lineages of Asian Y chromosomes: implications for the

peopling of east and southeast Asia". Human Genetics. 110 (1): 80–88.

doi:10.1007/s00439-001-0651-9. PMID 11810301. S2CID 30808716.

23. "Japanese Roots - news education science magazines technology

science …". Discover.com. 16 March 2006. Archived from the original on

16 March 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

24. Diamond, Jared (June 1998). "Japanese Roots". livjm.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2005-08-24.

25. "Lost Tribes of Israel - Where are the Ten Lost Tribes? (3)". Pbs.org. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

26. Hammer, Michael F; Karafet, Tatiana M; Park, Hwayong; Omoto,

Keiichi; Harihara, Shinji; Stoneking, Mark; Horai, Satoshi (2006).

"Dual origins of the Japanese: common ground for hunter-gatherer and

farmer Y chromosomes" (PDF). Journal of Human Genetics. 51 (1): 47–58.

doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0322-0. PMID 16328082. Archived (PDF) from the

original on 25 June 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

27. "「縄文人」は独自進化したアジアの特異集団だった! : 深読み". 読売新聞オンライン (in Japanese). 2017-12-15. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

28. 弥生人DNAで迫る日本人の起源」 [The origin of Japanese people approaching

with Yayoi DNA]. ja:サイエンスZERO (Television production) (in Japanese).

NHK. 2018-12-23.

29. Nara, Takashi; Adachi, Noboru; Yoneda, Minoru; Hagihara,

Yasuo; Saeki, Fumiko; Koibuchi, Ryoko; Takahashi, Ryohei (2019).

"Mitochondrial DNA analysis of the human skeletons excavated from the

Shomyoji shell midden site, Kanagawa, Japan". Anthropological Science.

127 (1): 65–72. doi:10.1537/ase.190307. ISSN 0918-7960.

30. "'Jomon woman' helps solve Japan's genetic mystery". NHK World. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Driem, George van (2020). "Munda languages

are father tongues, but Japanese and Korean are not". Evolutionary

Human Sciences. 2: e19. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.14. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC

10427457. PMID 37588351.

32. Mitsuru Sakitani (2009). 『DNA・考古・言語の学際研究が示す新・日本列島史』 [New

History of the Japanese Islands Shown by Interdisciplinary Studies on

DNA, Archeology, and Language] (in Japanese). Bensei Publishing. ISBN

9784585053941.

33. 鳥越憲三郎『原弥生人の渡来 』(角川書店,1982)、『倭族から日本人へ』(弘文堂

,1985)、『古代朝鮮と倭族』(中公新書,1992)、『倭族トラジャ』(若林弘子との共著、大修館書店,1995)、『弥生文化の源流考』(若林弘

子との共著、大修館書店,1998)、『古代中国と倭族』(中公新書, 2000)、『中国正史倭人・倭国伝全釈』(中央公論新社, 2004)

24. "SUWA Haruo (諏訪春雄)" (in Japanese). 2018-01-18.

35. 諏訪春雄編『倭族と古代日本』(雄山閣出版、1993)また諏訪春雄通信100

36. Boer, Elisabeth de; Yang, Melinda A.; Kawagoe, Aileen;

Barnes, Gina L. (2020). "Japan considered from the hypothesis of

farmer/language spread". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2: e13.

doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.7. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 10427481. PMID 37588377.

37. Wang, Chuan-Chao (2021). "Genomic insights into the formation

of human populations in East Asia". Nature. 591 (7850): 413–419.

Bibcode:2021Natur.591..413W. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03336-2. PMC

7993749. PMID 33618348.

38. Cooke 2021: "Several lines of archaeological evidence support

the introduction of new large settlements to Japan, most likely from

the southern Korean peninsula, during the Yayoi-Kofun transition.

Strong cultural and political affinity between Japan, Korea, and China

is also observable from several imports, including Chinese mirrors and

coins, Korean raw materials for iron production, and Chinese characters

inscribed on metal implements (e.g., swords)."「弥

生時代から古墳時代への移行期に、おそらくは朝鮮半島南部から日本に新しい大規模な集落がもたらされたことを裏付ける考古学的証拠がいくつかある。中国鏡

や中国銭、朝鮮半島から伝わった鉄生産の原材料、金属製の道具(刀剣など)に刻まれた漢字など、いくつかの輸入品からも、日本、朝鮮半島、中国間の強い文

化的・政治的親和性がうかがえる」

39. Cooke 2021:"Their genomes document the arrival of people with

majority East Asian ancestry to Japan and their admixture with the

Yayoi population. This additional ancestry is best represented in our

analysis by Han, who have multiple ancestral components. A recent study

has reported that people became morphologically homogeneous in the

continent from the Neolithic onward, which implies that migrants during

the Kofun period were already highly admixed."「彼

らのゲノムは、東アジアに起源を持つ人々が日本に到着し、弥生人と混血したことを証明している。この追加の祖先は、複数の祖先要素を持つ韓民族によって、

我々の分析で最もよく表されている。最近の研究では、新石器時代以降、大陸では人々が形態的に均質化したことが報告されており、これは古墳時代に渡来人が

すでに高度に混血していたことを示唆している」

40. Nikkei Science (23 June 2021). "渡来人、四国に多かった? ゲノムが明かす日本人ルーツ"

[Were there many migrants in Shikoku? Japanese roots revealed by genome

analysis]. nikkei.com (in Japanese). Retrieved 1 May 2022.

41. "1,700-year-old Korean genomes show genetic heterogeneity in

Three Kingdoms period Gaya". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

42. Wang, Rui; Wang, Chuan-Chao (2022-08-08). "Human genetics:

The dual origin of Three Kingdoms period Koreans". Current Biology. 32

(15): R844–R847. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.06.044. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID

35944486. S2CID 251410856.

43. Pheasant, Stephen. (2003). Bodyspace: Anthropometry,

ergonomics and the design of work (2nd. ed.). Taylor & Francis.

Page 159. Retrieved March 14, 2018, from Google Books.

44. Buckle, Peter (1996). "Obituary". Work & Stress. 10 (3): 282. doi:10.1080/02678379608256807.

45. Rajvir Yadav; et al. (2000). "An Anthropometry of Indian

Agricultural Workers". Agricultural Mechanization in Asia, Africa and

Latin America. 31 (3): 59.

46. Matsumura, Hirofumi; Cuong, Nguyen Lan; Thuy, Nguyen Kim;

Anezaki, Tomoko (2001). "Dental Morphology of the Early Hoabinian, the

Neolithic da but and the Metal Age Dong Son Civilized Peoples in

Vietnam". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie. 83 (1): 59–73.

doi:10.1127/zma/83/2001/59. JSTOR 25757578. PMID 11372468.

47. Mastsumoto, Hideo (2009). "The origin of the Japanese race

based on genetic markers of immunoglobulin G". Proceedings of the Japan

Academy, Series B. 85 (2): 69–82. Bibcode:2009PJAB...85...69M.

doi:10.2183/pjab.85.69. ISSN 0386-2208. PMC 3524296. PMID 19212099.

48. Moray, Neville. (2005). Ergonomics: The history and scope of

human factors. London and New York: Taylor & Francis. Pages 298

& 327. ISBN: 0-415-32258-8 Google Books link.

49. Pietrusewsky, Michael (January 2010). "A multivariate

analysis of measurements recorded in early and more modern crania from

East Asia and Southeast Asia". Quaternary International. 211 (1–2):

42–54. Bibcode:2010QuInt.211...42P. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2008.12.011.

ISSN 1040-6182.

50. Montagu, Ashley. (1989). Growing Young (2nd. ed.). Granby,

MA: Bergin & Garvey Publishers, inc. ISBN 0-89789-167-8 Retrieved

March 13, 2018, from Google Books.

51. Kumar, Ann. (1998). An Indonesian Component in the Yayoi?:

the Evidence of Biological Anthropology. Anthropological Science

106(3). Page 268. Retrieved February 22, 2018, from link to the PDF

document.

52. Pietrusewsky, Michael. (1992). Japan, Asia and the Pacific: A

multivariate craniometric investigation. In book: Japanese as a member

of the Asian and Pacific populations, Publisher: Kyoto: International

Research Center for Japanese Studies. International Symposium No. 4.,

Page 47. Retrieved February 22, 2018, from link to the article.

53. Kumar, Ann. (2009). Globalizing the Prehistory of Japan:

Language, Genes and Civilisation. London and New York: Routledge Taylor

& Francis Group. Page 79 & 88. Retrieved January 23, 2018, from

link.

54. Park, Dae Kyoon; Lee, U Young; Lee, Jun Hyun; Choi, Byoung

Young; Koh, Ki Seok; Kim, Hee Jin; Park, Sun Joo; Han, Seung Ho (2001).

"Non-metric Traits of Korean Skulls". Korean Journal of Physical

Anthropology. 14 (2): 117. doi:10.11637/kjpa.2001.14.2.117.

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆