Read this first

My Testament to Students Studying Critical Medical Anthropology

Mitzub'ixi Qu'q Ch'ij

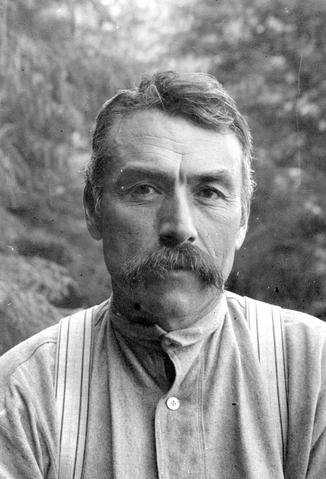

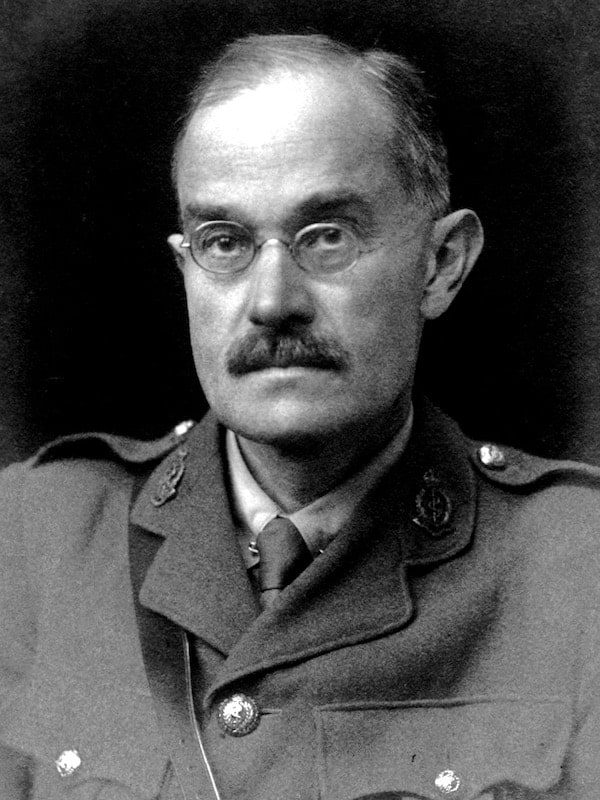

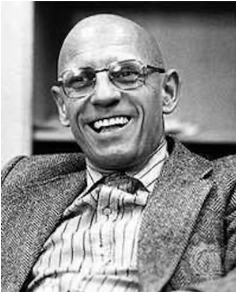

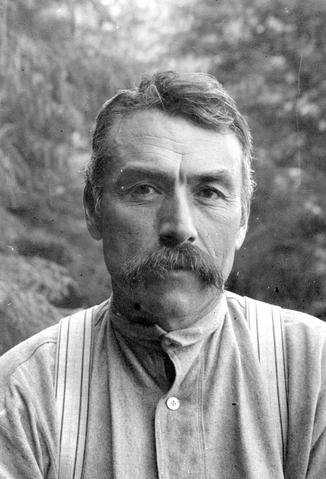

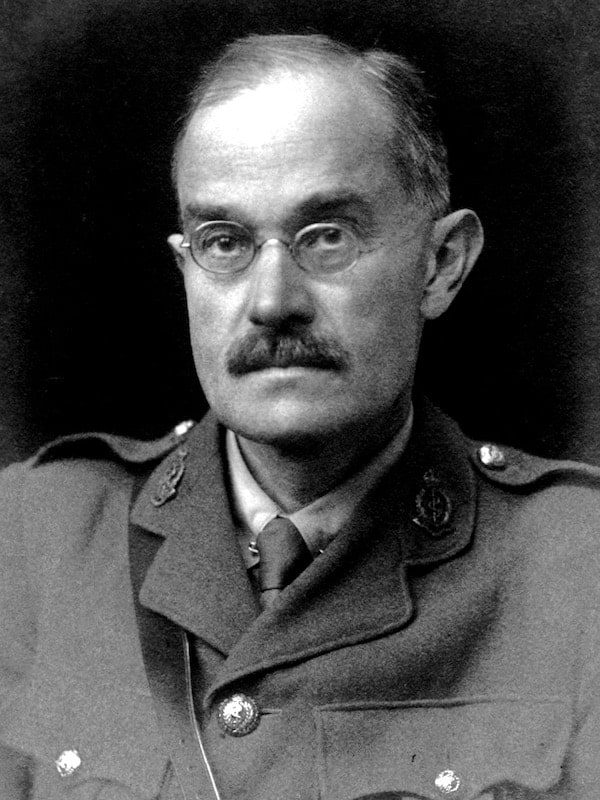

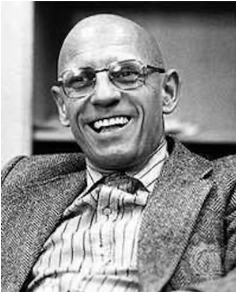

Pictures

present from left to right; Rudolf Virchow, George Hunt, WHR Rivers,

and Michel Foucaut.

My Testament to Students Studying Critical Medical Anthropology

Mitzubixi IKEDA

Osaka University, Toyonaka JAPAN

(My_Testament240629_mikeda.pdf)

Dear friends,

■At the time to say good-bye for my students in medical anthropology, I

will confess sincerely my testament mentioned bellow. This document can

be divided two parts; the former mentions my own experience in rural

Honduras in mid-1980s, and the latter mentions my respectable heroes

when I was graduate student of public health and social medicine.

■In the mid-1980s, I joined in the Japan Overseas Cooperation

Volunteers, JOCVs, in Honduras, Central America. My work was an

assistance for public health education in rural areas in western

mountainous part of Honduras. I have researched how people think and

act about “health” through specific practices. The local people who

received our public health program understand “health” simply as the

absence from disease. They do not give the word “salud” (in Spanish,

that means “health”) the positive meaning that westerner can mention

sometime as "positive health". I think the concept of “health” of the

latter was newly introduced from outside the community. There existed

two concepts of “health,” one is traditional thought of conditions of

body that mention "there is no disease." The another was "positive

health" in modern westerner sense that we would try to introduce from

outside the community.

■Nonetheless, we have tried to introduce new “positive health” into

communities, the people did not accept and maintain old one. We

confront epistemological barrier of the local people. The one of

Honduran Ministry of Health officials used to say they were “ignorant.”

He said that because of local people's ignorance, our public health

program would be failed. He thought that the villagers were ignorant in

public health knowledge. However, this officer has completely forgotten

that his own concept of positive health also had been once educated.

■On the other hands, villagers, of course, did not consider themselves

ignorant. Nor are they aware that they are “resisting” against official

public health program. The village people expressed that the new public

health program was simply too difficult to understand. Consequently,

they were ironically labeled as “resisters” by the officials.

■Of course, the programs had attractive points for the villagers. If

they could attend a free seminar of our programs, they were offered

basic drugs, a notebook, a meal, or some snacks as reword by

registering their names. Also, there was an advantage such as to making

friends by attending the workshops. Once the project has been started,

villagers were benefited from being able to borrow free-loan money for

the installation of latrines. Small but new latrine can be strong

symbol of introducing new concept of positive health. Those who

accepted the project recognize themselves as “progressive,” while those

who did not accept it were as "being still ignorant." But the ones who

did not accept were criticized “progressive men” as those who had “sold

their souls” to the outsiders, such as government people. Then the

public health program had introduced the seed of discord into village.

The officers never express people who did not accept the program

“ignorance” in front of them. Unfortunately, this kind of insult

concepts also had been introduced into village through the public

health program. At the same time, in a village where various social

dynamics were functioning, informed consent does not always proceed

rationally.

■In so far, all villagers will not accept a new public health program.

Program supervisors were evaluating by yield rates and performance into

communities. Officers there participated explicit competition by

according their yield rates and performance among their own different

community's programs. For whom was the public health program? Naturally

for the common people, but also for the working officers who were

ordered by their project provide supervisors.

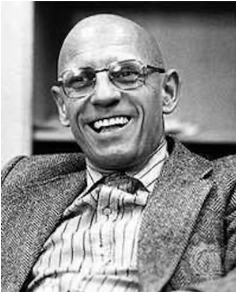

■Here, I would explain this case using the Foucauldian theory. For

instance, a person who had once studied these theories would interpret

it this way. Michel Foucault said that the power, especially political

power, does not only oppress the people but create them new subjects

that practice under social effects. In my case, to be a recipient of

public health program is to be a subject through acting on. However,

then the person who rejects the public health program coming into the

village must also “become another new subject.” These “resisters” who

oppose the program, and this is why the stereotypical adjectives,

“ignorant,” “conservative,” and “no progressive,” were attached by the

proponents of the program. When I participated in the health care

program in Honduras was in the world-wide Primary Health Care, the Alma

Ata Declaration in 1978. As above, I suppose that the Foucauldian

theory can be applied on the primary health care approach.

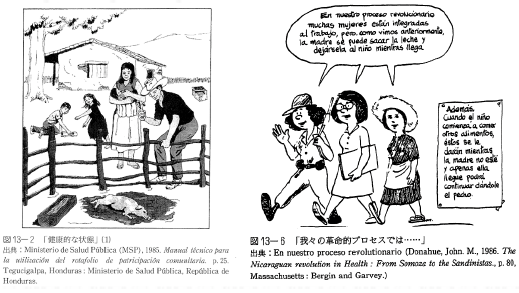

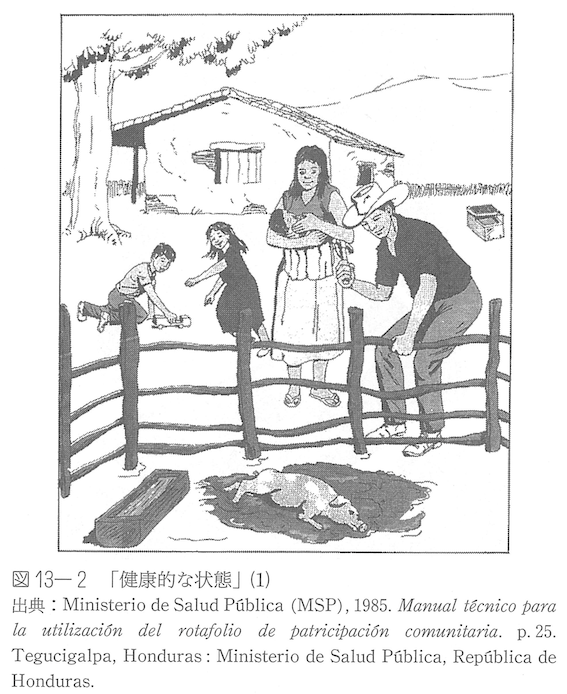

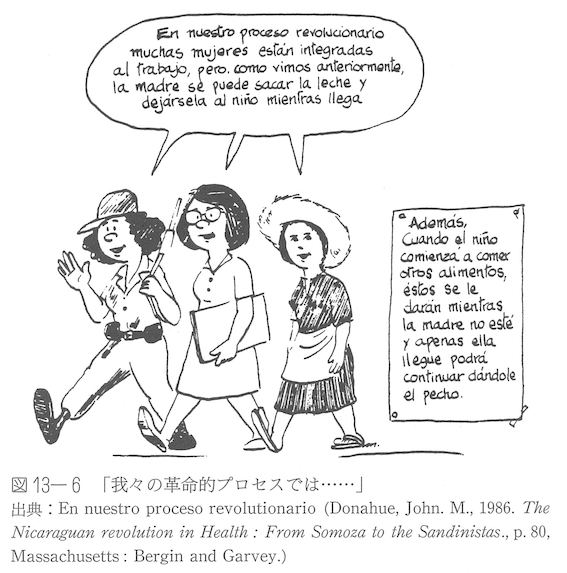

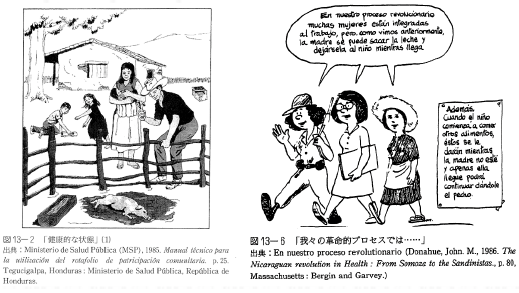

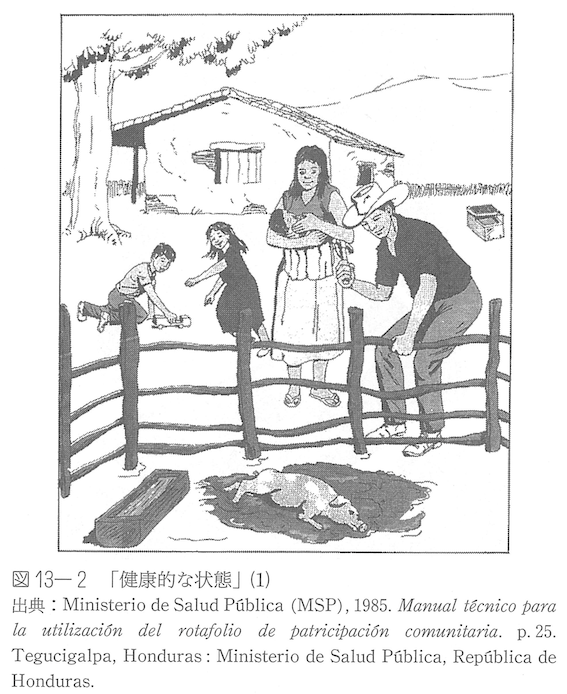

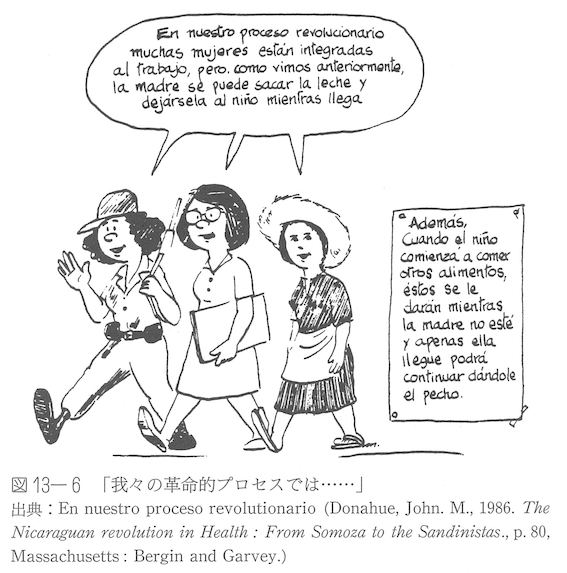

■Here there are two images of “good health” both Honduran in left and

of the Nicaraguan in right. These two images of good health were

different by depending on their governmental political ideology;

Honduras was an anti-communist country supported by former President

Ronald Regan of the United States, Nicaragua had Sandinista

Revolutionary Government which promoted the anti-capitalist good health

policy under the support by Cuba. The mid-1980s' figures demonstrate

the national differences between them.

■Two figures

demonstrate the national difference of "good health or healthy lives"

between Honduras and Nicaragua in the mid-1980s.

■Then, even if “community-based” and “community’s participation” based

on informed consent are central, the self-determination of “resistance”

to the introduction of external programs might also be respected. I was

not very aware of this during my stay in Honduras. After leaving the

country, I learned about the Rural Appraisal by Dr. Robert Chambers,

the principle of the action research by Sol Tax, which has a long

history in anthropology, and the subsequent Community-Based

Participatory Research (CBPR), in which the option of “rejection” from

the peoples' point of view, rather than “resistance” from the side of

power holder, I found that it should be respect for accepting the

option of “refusal” as equal as for “accordance and/ or acceptance.”

Just as I have learned the peoples' autonomous spirits in public health

programs.

■When medical anthropologists have the “will” to change the

conservative or traditional things in a village, this is always

considered problematic as it violates the dogma or doctrine of

“cultural relativism” that anthropology has long accepted as discipline

to its work. On the other hand, in applied anthropology, it is

commonplace to identify malfunctions within a community and, through

discussions with the residents, to confirm the “will” of the community

to promote projects. Today, when the former term “applied anthropology”

has faded and become public anthropology and/ or engaged anthropology,

egalitarian dialogue within the community's autonomy is very important.

The cold-hearted word of “cultural relativism” has now receded in

medical anthropology, and the emphasis is now on “cultural

egalitarianism,” “dialogue under equal conditions,” and

“community-based autonomy.”

■Over there, in the 1980s, a project of communities’ total conversion

for modern public health based on paternalism, is not different from

the “medical missionary work/medical mission” of the colonial era. When

I was writing the paper about the story mentioned above, later entitled

“Health Promotion and Health Ideology,” I guess I had not yet arrived

at this perception of medical anthropology as “medical missionary

work.” There, I was probably stuck in the doxa that it is the residents

who change their ideas and actions through health and medical treatment

projects, not the medical anthropologists themselves who change their

own ideas and attitudes.

■

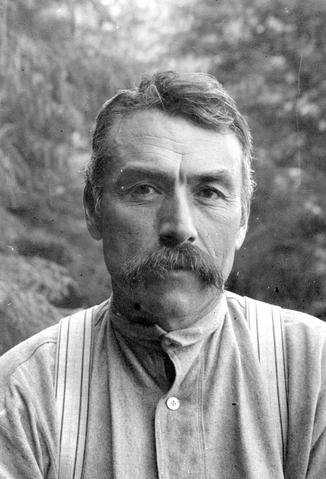

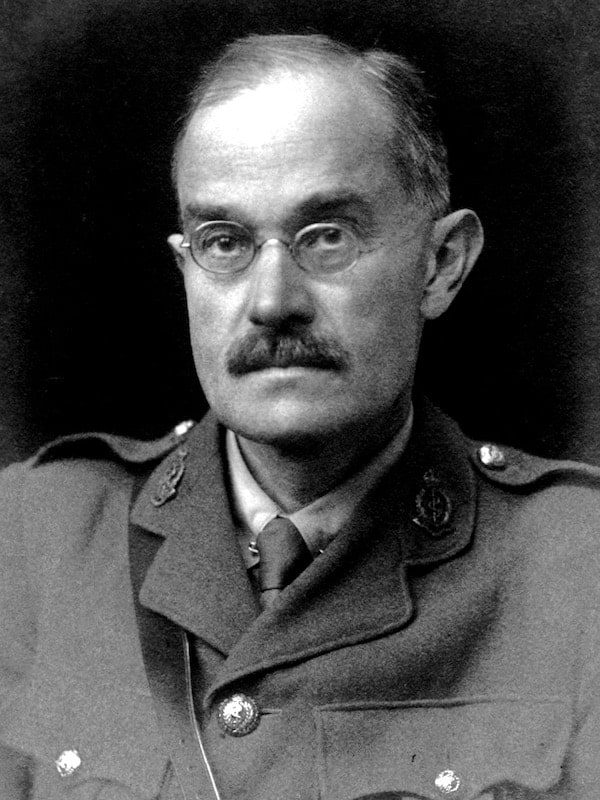

Pictures present from left to right; Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow

(1821-1902), George Hunt (1854-1933), W.H.R. Rivers (1864-1922), and

Michel Foucault (1926-1984)

■I began studying medical anthropology in 1981, and there were four

heroes for me at that time. In order of their birth dates, they are

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow (1821-1902), George Hunt (1854-1933),

William Halse Rivers Rivers (1864-1922), and Paul-Michel Foucault

(1926-1984). Foucault was born in the same year as my mentor, Yonezo

Nakagawa (1926-1997). Virchow and Rivers are well known as the founders

of medical anthropology in the Anglo-American world. Each of them is a

unique and brilliant individual who has influenced my books and

articles in various ways.

■Yonezo Nakagawa (1926-1997)

■Virchow brought us a practical challenge at the roots of medical

anthropology with his dictum, “medicine is a social science to the

bone.” W.H.R. Rivers was the psychiatrist who, along with Sigmund

Freud, described war neuroses or shell shock (a kind of combat

fatigue), considered to be a related syndrome of Post Traumatic Stress

Disorder, PTSD. He also established the genealogical method, a

significant advance in kinship research. On the other hand, he

participated in the Cambridge University Torres Strait Expedition,

organized by Alfred Cort Haddon, and argued that, apart from their

capacity for acuity, the “savages” had no physiological differences in

their repertoire of sensibilities, and that language and metaphor

provided diversity in illness expression and classification. In

particular, he suggested that the classification of sickness was as

systematic in “uncivilized societies” as to be comparable to the

Western taxonomy of diseases or nosology. Foucault not only developed

the concept of bio-power, but also considered the concept of governing,

the term, governmentality, how to govern people and society through

biomedicine and demography. Today, the concept of governmentality has

become an essential analytical tool for many researchers analyzing the

public health and medical ethics.

■Many of you may not know George Hunt. However, he is called as

"Quesalid," a sorcerer or shaman who appears pseudonymously in Franz

Boas' “Ethnography of the Kwakiutl,” today as the Kwakwaka'wakw. In the

chapter of “The Sorcerer and His Magic” in Lévi-Strauss' monumental

book, entitled as “Structural Anthropology,” published in 1963

translated from French to English. Among many anthropologists it is

known the name of Quesalid but never known his real name George Hunt. I

learned that Quesalid was George Hunt from James Clifford's book, “The

Predicament of Culture” (1988). Hunt's genealogical origins were both

Tlingit and British, not Kwakwaka'wakw, and he grew up in Kwakwaka'wakw

territory with his parents and through intermarriage and adoption

became himself a native anthropologist familiar with Kwakwaka'wakw

language and culture. Franz Boas became friends with Gorge Hunt to

exhibit the Kwakwaka'wakw at the World’s Columbian Exposition in

Chicago in 1893. Boas taught Hunt linguistic anthropology and phonetic

notation, especially Kwakwaka'wakw orthograph. Hunt is said to have

written more than 10,000 pages of ethnographic notes of Kwakwaka'wakw

including his autobiographical experience for Franz Boas.

■When I still read the chapter, “The Sorcerer and His Magic” by

Lévi-Strauss, through his storytelling, I am still impressed by the

auto-ethnography of George Hunt, that is the things about Quesalid. It

seems to me that native anthropologists can reach the inner recesses of

cultural understanding without going through the dogma of “cultural

relativism.” It also seems to me that the technique for reading across

cultures is not to immerse oneself in the culture of the others. The

technique for reading across cultures is always to be “conscious” of

the fact that one's own culture dissolves in the culture of the others

by forgetting what one has learned. In other words, as an

anthropologist himself, George Hunt could dissolve his role as a

sorcerer because he analyzed other healers in the culture in question

by practice of his cross-cultural reading as reflexive process. The

important thing is not that he took epistemological relativism but that

he did understand what is to be powerful healer among the Kwakwaka'wakw

through his devious and an-ethical performance among Indians.

■Japanese social medicine from the 1920s onward, as described in the

proceedings of this meeting, tried to live up to Virchow's dictum that

“medicine is a social science to the bone.” Medical doctors, like

applied medical anthropologists today, tried to practice their social

medicine by spending time in rural villages and urban squatters.

However, in Japan from the 1930s to 1945, they were grabbed by thought

control policy, recruited by military soldiers (and even some of them

defected to the Soviet Union and were purged by dictator Joseph

Stalin). And young idealist medical doctor survivors were disappointed

by Japan's defeat in the war. After Japan's defeat, the occupied

military had introduced United States' public health policy instead of

pre-war German Sozialmedizin.

■Now we confront with dilemma of whether to change our mind or reform

our society. We are requested to behave with reflective criticism. It

can fall into another pitfall of reproducing unreflective criticism,

criticism for criticism's sake, and falling into “mere condemnation.”

Criticism is an act like walking a tightrope. But it worths to try

again and again.

■My last words, my testament, are as follows: We must not only hope

that through criticism, the future of the subject will change in a

favorable and appropriate manner, but we must also have the courage to

change ourselves as critics.

■Yours Sincerely,

■Mitzub'ixi Qu'q Ch'ij

Your good friend.

tiocaima7n@gmail.com is valid until the end of my life....

■P.S.

I would be annoying you with citated from Samuel Beckett’s poem…I love it!!!

■First the body. No. First the place. No. First both. Now either. Now

the other. Sick of the either try the other. Sick of it back sick of

the either. So on. Somehow on. Till sick of both. Throw up and go.

Where neither. Till sick of there. Throw up and back. The body again.

Where none. The place again. Where none. Try again. Fail again. Better

again. Or better worse. Fail worse again. Still worse again. Till sick

for good. Throw up for good. Go for good. Where neither for good. Good

and all. – “Worstward Ho,” 1983

■I quart my fever phrases of the passage on Heraclitus’ “All things change” by Quincy Jones and Ray Brown,

■Everything must change

Nothing stays the same

Everyone will change

No one stays the same

The young become the old

And mysteries do unfold

‘Cause that’s the way of time

Nothing and no one goes unchanged

-- Everything must change

■your notes:

|

Two figures demonstrate the

national difference of "good health or healthy lives" between Honduras

and Nicaragua in the mid 1980s.

|

|

Two figures demonstrate the

national difference of "good health or healthy lives" between Honduras

and Nicaragua in mid 1980s. |

Link

Bibliography

other

information

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆

☆

☆