きかいひよう、opprtunity cost

Demand and supply of hospital beds and days during COVID-19

機会費用

きかいひよう、opprtunity cost

Demand and supply of hospital beds and days during COVID-19

解説:池田光穂

機会費用とは、使われなかった選択肢によって得られるであろう(最善)価 値のことをいう。

ある会合がキャンセルになっての私の得失について例をとって考えてみよう。

私は、研究室での原稿執筆(5時間かければ1回2万円原稿料の連載が1本分書けるとする)を、キャンセルして、往復3時間、会議時間2時間の会 議に出席しなければならないとする。往復の電車賃は1,500円である。

もし会議がキャンセルされたことを主宰者側の都合で現場で知らされたり、会議の内容が単純に時間の浪費レベルのものであれば、この5時間の損失 に関わる機会費用は、1,500円プラス20,000円で合計21,500円である。

機会費用は、冒頭の定義のように最善の価値のことをいう——つまり、会議をキャンセルして5時間以上の原稿をそれ以上の余計な労力をかけずに成 功する場合がある一方で、時間がかかったり、アイディアを補充するた めに、図書館へ寄ったり、ネットのサイトで必要な文献を注文する損出については考えな い。

逆に、会議を主催する側の人間も、私がそれだけの機会費用が(潜在的に)かかっているということを考慮してまで、会議に招致しているわけではな いと考える ので、主宰者が謝ればなんとかなるだろうと考える。

つまり、機会費用は、期待する側には未来の効用を最大化して見積もる一方

で、期待してない側には(ありえない潜在力の過大評価という点で)法外

なコストに映る。謝罪や補償にあたる機会費用の算出は双方の(主張の強さを考慮した)期待値の平均ということになる。

機会費用というのは、得られた幸福などにも(拡張して)計算や適用が可能である。したがって、この考え方は、使われなかった治療の選択肢によっ て得られるであろう最善の価値についての考え方が、当事者(患者とその家族)と治療者(医療者やシャーマンなど)で大きく齟齬をおこすことについて、説明 が可能である。

ADR(裁判外紛争解決)などの医事紛争解決などでは、対話や紛争解決のゲーム理論が用いられるが、その考え方にも機会費用の思想の考え方が大 きく蔭を落としてい るとみたほうがよい。

The opportunity cost, or alternative cost,

of making a particular choice is the value of the most valuable choice

out of those that were not taken. When an option is chosen from

alternatives, the opportunity cost is the "cost" incurred by not

enjoying the benefit associated with the best alternative choice. - opportunity cost.

Sunk cost (also known as

retrospective cost) is a cost that has already been incurred and cannot

be recovered.

| In microeconomic theory, the opportunity cost

of a choice is the value of the best alternative forgone where, given

limited resources, a choice needs to be made between several mutually

exclusive alternatives. Assuming the best choice is made, it is the

"cost" incurred by not enjoying the benefit that would have been had if

the second best available choice had been taken instead.[1] The New

Oxford American Dictionary defines it as "the loss of potential gain

from other alternatives when one alternative is chosen". As a

representation of the relationship between scarcity and choice,[2] the

objective of opportunity cost is to ensure efficient use of scarce

resources.[3] It incorporates all associated costs of a decision, both

explicit and implicit.[4] Thus, opportunity

costs are not restricted to monetary or financial costs: the real cost

of output forgone, lost time, pleasure, or any other benefit that

provides utility should also be considered an opportunity cost. |

ミクロ経済学において、選択の機会費用とは、限られた資源の中で複数の

互いに排他的な選択肢から一つを選ばねばならない状況において、放棄された最良の代替案の価値を指す。最良の選択がなされたと仮定した場合、次に良い選択

肢を選んだ場合に得られたであろう便益を享受できなかったことによる「コスト」である。[1]

『ニューオックスフォードアメリカン辞典』はこれを「ある選択肢を選んだ際に他の選択肢から得られる可能性があった利益の損失」と定義する。希少性と選択

の関係を表すものとして[2]、機会費用の目的は希少な資源の効率的な利用を確保することにある[3]。これは決定に伴う明示的・暗黙的な全ての関連費用

を包含する。[4] したがって機会費用は金銭的・財務的コストに限定されない。放棄された生産物、失われた時間、快楽、あるいは効用をもたらすその他の利益といった実質的なコストも機会費用と見なされるべきである。 |

| Types Explicit costs Explicit costs are the direct costs of an action (business operating costs or expenses), executed through either a cash transaction or a physical transfer of resources.[4] In other words, explicit opportunity costs are the out-of-pocket costs of a firm, that are easily identifiable.[5] This means explicit costs will always have a dollar value and involve a transfer of money, e.g. paying employees.[6] With this said, these particular costs can easily be identified under the expenses of a firm's income statement and balance sheet to represent all the cash outflows of a firm.[7][6] Examples include:[5][8] Land and infrastructure costs Operation and maintenance costs—wages, rent, overhead, materials Potential scenarios include:[7] If a person leaves work for an hour and spends $200 on office supplies, then the explicit costs for the individual equates to the total expenses for the office supplies of $200. If a company's printer malfunctions, then the explicit costs for the company equates to the total amount to be paid to the repair technician. Implicit costs Implicit costs (also referred to as implied, imputed or notional costs) are the opportunity costs of utilising resources owned by the firm that could be used for other purposes. These costs are often hidden to the naked eye and are not made known.[8] Unlike explicit costs, implicit opportunity costs correspond to intangibles. Hence, they cannot be clearly identified, defined or reported.[7] This means that they are costs that have already occurred within a project, without exchanging cash.[9] This could include a small business owner not taking any salary in the beginning of their tenure as a way for the business to be more profitable. As implicit costs are the result of assets, they are also not recorded for the use of accounting purposes because they do not represent any monetary losses or gains.[9] In terms of factors of production, implicit opportunity costs allow for depreciation of goods, materials and equipment that ensure the operations of a company.[10] Examples of implicit costs regarding production are mainly resources contributed by a business owner. These include:[5][10] Human labour Infrastructure Risk Time spent: also involves considering other valuable activities that could have been undertaken in order to maximize the return on time invested Some potential scenarios are:[7] If a person leaves work for an hour to spend $200 on office supplies, and has an hourly rate of $25, then the implicit costs for the individual equates to the $25 that they could have earned instead. If a company's printer malfunctions, the implicit cost equates to the total production time that could have been utilized if the machine did not break down. |

種類 明示的費用 明示的費用とは、現金取引または資源の物理的移転を通じて実行される行動の直接費用(事業運営コストまたは経費)である。[4] 言い換えれば、明示的機会費用とは、企業が負担する実費であり、容易に特定できるものである。[5] これは、明示的費用には常に金額的価値があり、金銭の移転を伴うことを意味する。例えば、従業員への給与支払いなどである。[6] したがって、これらの特定コストは企業の損益計算書や貸借対照表の費用項目で容易に特定でき、企業の全現金流出を表す。[7][6] 例としては以下がある:[5][8] 土地・インフラコスト 運営・維持コスト—賃金、賃料、間接費、資材費 想定されるシナリオ: [7] ある人格が1時間仕事を離れて事務用品に200ドルを費やした場合、その個人の明示的コストは事務用品の総費用200ドルに等しい。 会社のプリンターが故障した場合、その会社の明示的コストは修理技術者に支払う総額に等しい。 暗黙のコスト 暗黙のコスト(暗黙的・帰属的・名目コストとも呼ばれる)とは、企業が所有する資源を他の目的に転用できた場合の機会費用である。これらのコストは通常、 目に見えず、公表されない。[8] 明示的コストとは異なり、暗黙の機会費用は無形資産に対応する。したがって、明確に特定・定義・報告することはできない。[7] これは、現金交換を伴わずにプロジェクト内で既に発生した費用を意味する。[9] 例えば、事業主が創業初期に給与を受け取らないことで企業の収益性を高めるケースが該当する。暗黙的費用は資産の結果であるため、金銭的損益を表さないこ とから、会計目的でも記録されない。[9] 生産要素の観点では、暗黙の機会費用は企業の運営を支える物品・資材・設備の減価償却を可能にする。[10] 生産に関連する暗黙の費用の例は、主に事業主が投入する資源である。これには以下が含まれる:[5][10] 人的労力 インフラ リスク 費やした時間:投資した時間の収益を最大化するために実施できた他の価値ある活動も考慮する必要がある 具体的なシナリオ例は以下の通りである[7]: ある人格が1時間仕事を離れて事務用品に200ドルを費やし、時給が25ドルの場合、その個人的な暗黙的コストは代わりに稼げたはずの25ドルに等しい。 企業のプリンターが故障した場合、暗黙的コストは機械が故障していなければ活用できた総生産時間に等しい。 |

| Excluded from opportunity cost Sunk costs Main article: Sunk cost Sunk costs (also referred to as historical costs) are costs that have been incurred already and cannot be recovered. As sunk costs have already been incurred, they remain unchanged and should not influence present or future actions or decisions regarding benefits and costs.[11] Marginal cost See also: Marginal cost icon This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The concept of marginal cost in economics is the incremental cost of each new product produced for the entire product line. For example, building a single aircraft costs a lot of money, but when building a hundred, the cost of the 100th will be much lower. When building a new aircraft, the materials used may be more useful,[clarification needed] so make as many aircraft as possible from as few materials as possible to increase the margin of profit. Marginal cost is abbreviated MC or MPC. The increase in cost caused by an additional unit of production is called marginal cost. By definition, marginal cost (MC) is equal to the change in total cost (△TC) divided by the corresponding change in output (△Q): MC(Q) = △TC(Q)/△Q or, taking the limit as △Q goes to zero, MC(Q) = lim(△Q→0) △TC(Q)/△Q = dTC/dQ. In theory marginal costs represent the increase in total costs (which include both constant and variable costs) as output increases by 1 unit. Adjustment cost The phrase "adjustment costs" gained significance in macroeconomic studies, referring to the expenses a company bears when altering its production levels in response to fluctuations in demand and input costs. These costs may encompass those related to acquiring, setting up, and mastering new capital equipment, as well as costs tied to hiring, dismissing, and training employees to modify production. "Adjustment costs" describe shifts in the firm's product nature rather than merely changes in output volume. The notion of adjustment costs is expanded in this manner because, to reposition itself in the market relative to rivals, a company usually needs to alter crucial features of its goods or services to enhance competition based on differentiation or cost. In line with the conventional concept, the adjustment costs experienced during repositioning may involve expenses linked to the reassignment of capital and/or labor resources. However, they might also include costs from other areas, such as changes in organizational abilities, assets, and expertise.[12][verification needed] |

機会費用から除外されるもの 沈没費用(サンク・コスト) 主な記事: 沈没費用(サンク・コスト) 沈没費用(歴史的費用とも呼ばれる)は、既に発生しており回収できない費用である。沈没費用は既に発生しているため、変化せず、現在または将来の利益と費用に関する行動や決定に影響を与えるべきではない。[11] 限界費用 関連項目: 限界費用 icon この節は出典を一切示していない。信頼できる出典を追加して、この節を改善してほしい。出典のない記述は削除される可能性がある。(2023年6月)(このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 経済学における限界費用の概念とは、製品ライン全体において新たに生産される各製品に対する追加費用を指す。例えば、航空機1機の製造には多額の費用がか かるが、100機製造する場合、100機目の製造コストは大幅に低くなる。新たな航空機を製造する際、使用される材料はより有用である可能性があるため、 利益率を高めるには、可能な限り少ない材料で可能な限り多くの航空機を製造すべきである。限界費用はMCまたはMPCと略される。 生産単位の増加によって生じるコストの増加分を限界費用と呼ぶ。定義上、限界費用(MC)は総費用の変化量(△TC)を生産量の変化量(△Q)で割った値に等しい:MC(Q) = △TC(Q)/△Q あるいは、△Qがゼロに近づく極限をとると MC(Q) = lim(△Q→0) △TC(Q)/△Q = dTC/dQ。 理論上、限界費用は生産量が1単位増加する際に生じる総費用(固定費と変動費の両方を含む)の増加分を表す。 調整費用 「調整費用」という概念はマクロ経済学研究において重要性を増した。これは需要や投入コストの変動に応じて生産量を変更する際、企業が負担する費用を指 す。これらの費用には、新たな資本財の取得・設置・習得に関連する費用、ならびに生産調整に伴う従業員の雇用・解雇・訓練に関連する費用が含まれる。 「調整費用」は、単なる生産量の変動ではなく、企業の製品特性そのものの変化を意味する。この概念が拡張される背景には、企業が市場で競合他社に対する優 位性を確立するためには、差別化やコスト競争力を高めるために製品・サービスの重要な特性を変更する必要があるという現実がある。従来概念に沿えば、再配 置時に生じる調整コストには、資本や労働資源の再配分に関連する費用が含まれる。しかし、組織能力・資産・専門知識の変化など、他の領域からのコストも含 まれる可能性がある。[12][検証が必要] |

| Uses Economic profit versus accounting profit The main objective of accounting profits is to give an account of a company's fiscal performance, typically reported on quarterly and annually. As such, accounting principles focus on tangible and measurable factors associated with operating a business such as wages and rent, and thus, do not "infer anything about relative economic profitability".[13] Opportunity costs are not considered in accounting profits as they have no purpose in this regard. The purpose of calculating economic profits, and thus opportunity costs, is to aid in better business decision-making through the inclusion of opportunity costs. In this way, a business can evaluate whether its decision and the allocation of its resources is cost-effective or not and whether resources should be reallocated.[14] Simplified example of comparing economic profit vs accounting profit Economic profit does not indicate whether or not a business decision will make money. It signifies if it is prudent to undertake a specific decision against the opportunity of undertaking a different decision. As shown in the simplified example in the image, choosing to start a business would provide $10,000 in terms of accounting profits. However, the decision to start a business would provide −$30,000 in terms of economic profits, indicating that the decision to start a business may not be prudent as the opportunity costs outweigh the profit from starting a business. In this case, where the revenue is not enough to cover the opportunity costs, the chosen option may not be the best course of action.[15] When economic profit is zero, all the explicit and implicit costs (opportunity costs) are covered by the total revenue and there is no incentive for reallocation of the resources. This condition is known as normal profit. Several performance measures of economic profit have been derived to further improve business decision-making such as risk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC) and economic value added (EVA), which directly include a quantified opportunity cost to aid businesses in risk management and optimal allocation of resources.[16] Opportunity cost, as such, is an economic concept in economic theory which is used to maximise value through better decision-making. In accounting, collecting, processing, and reporting information on activities and events that occur within an organization is referred to as the accounting cycle. To encourage decision-makers to efficiently allocate the resources they have (or those who have trusted them), this information is being shared with them.[17] As a result, the role of accounting has evolved in tandem with the rise of economic activity and the increasing complexity of economic structure. Accounting is not only the gathering and calculation of data that impacts a choice, but it also delves deeply into the decision-making activities of businesses through the measurement and computation of such data. In accounting, it is common practice to refer to the opportunity cost of a decision (option) as a cost.[18] The discounted cash flow method has surpassed all others as the primary method of making investment decisions, and opportunity cost has surpassed all others as an essential metric of cash outflow in making investment decisions.[19] For various reasons, the opportunity cost is critical in this form of estimation. First and foremost, the discounted rate applied in DCF analysis is influenced by an opportunity cost, which impacts project selection and the choice of a discounting rate.[20] Using the firm's original assets in the investment means there is no need for the enterprise to utilize funds to purchase the assets, so there is no cash outflow. However, the cost of the assets must be included in the cash outflow at the current market price. Even though the asset does not result in a cash outflow, it can be sold or leased in the market to generate income and be employed in the project's cash flow. The money earned in the market represents the opportunity cost of the asset utilized in the business venture. As a result, opportunity costs must be incorporated into project planning to avoid erroneous project evaluations.[21] Only those costs directly relevant to the project will be considered in making the investment choice, and all other costs will be excluded from consideration. Modern accounting also incorporates the concept of opportunity cost into the determination of capital costs and capital structure of businesses, which must compute the cost of capital invested by the owner as a function of the ratio of human capital. In addition, opportunity costs are employed to determine to price for asset transfers between industries. |

用途 経済的利益と会計上の利益 会計上の利益の主な目的は、企業の財務実績を報告することである。通常、四半期ごとや年次で報告される。したがって、会計原則は賃金や家賃など、事業運営 に関連する有形かつ測定可能な要素に焦点を当てる。ゆえに「相対的な経済的収益性について何も示唆しない」のである[13]。機会費用は会計上の利益では 考慮されない。この点において意味を持たないからである。 経済的利益、ひいては機会費用を計算する目的は、機会費用を含めることでより良い経営判断を支援することにある。これにより企業は、自らの決定と資源配分が費用対効果的かどうか、また資源の再配分が必要かどうかを評価できる。[14] 経済的利益と会計利益の比較を簡略化した例 経済的利益は、経営判断が利益を生むかどうかを示さない。それは、異なる意思決定を行う機会に対して、特定の意思決定を行うことが賢明かどうかを示すもの である。図の簡略化された例が示すように、起業を選択することは会計上の利益として10,000ドルをもたらす。しかし、起業の意思決定は経済的利益とし て-30,000ドルをもたらす。これは、起業の機会費用が起業による利益を上回っているため、起業の意思決定は賢明ではない可能性があることを示してい る。この場合、収益が機会費用を賄えないため、選択された選択肢は最善策ではない可能性がある[15]。経済的利益がゼロの場合、明示的・暗黙的コスト (機会費用)の全てが総収益で賄われ、資源の再配分インセンティブは生じない。この状態は正常利益と呼ばれる。 経済的利益の測定指標として、リスク調整後資本利益率(RAROC)や経済的付加価値(EVA)などが開発されている。これらは定量化された機会費用を直 接含み、企業のリスク管理と資源の最適配分を助ける。[16] 機会費用は、より良い意思決定を通じて価値を最大化するために用いられる経済理論上の概念である。 会計において、組織内で発生する活動や事象に関する情報を収集・処理・報告するプロセスは会計サイクルと呼ばれる。意思決定者が自ら(あるいは信頼を寄せ た者)が保有する資源を効率的に配分するよう促すため、この情報が共有されるのである。[17] その結果、会計の役割は経済活動の拡大と経済構造の複雑化に歩調を合わせて進化してきた。会計は単に選択に影響するデータの収集・計算にとどまらず、そう したデータの測定・計算を通じて企業の意思決定活動に深く関与する。会計では、意思決定(選択肢)の機会費用をコストと呼ぶのが一般的である。[18] 割引キャッシュフロー法は投資判断の主要手法として他を圧倒し、機会費用は投資判断における資金流出の必須指標として他を凌駕している。[19] 様々な理由から、この形式の推定において機会費用は極めて重要である。 第一に、DCF分析で適用される割引率は機会費用の影響を受ける。これはプロジェクト選定と割引率の選択に影響する。[20] 投資に自社資産を使用する場合、企業は資産購入資金を調達する必要がなく、現金流出は生じない。しかし、資産のコストは時価で現金流出に含めなければなら ない。資産が現金流出をもたらさない場合でも、市場で売却またはリースして収入を生み出し、プロジェクトのキャッシュフローに充てることができる。市場で 得られる資金は、事業に活用された資産の機会費用を表す。したがって、誤ったプロジェクト評価を避けるため、機会費用はプロジェクト計画に組み込まなけれ ばならない。[21] 投資判断においては、プロジェクトに直接関連する費用のみが考慮され、その他の費用は全て除外される。現代会計では、機会費用の概念が企業の資本コストと 資本構成の決定にも組み込まれている。これは、所有者が投資した資本コストを人的資本比率の関数として計算する必要があるためである。さらに、機会費用は 産業間の資産移転価格を決定するためにも用いられる。 |

| Comparative advantage versus absolute advantage When a nation, organisation or individual can produce a product or service at a relatively lower opportunity cost compared to its competitors, it is said to have a comparative advantage. In other words, a country has comparative advantage if it gives up less of a resource to make the same number of products as the other country that has to give up more.[22] A simple example of comparative advantage Using the simple example in the image, to make 100 tonnes of tea, Country A has to give up the production of 20 tonnes of wool which means for every 1 tonne of tea produced, 0.2 tonnes of wool has to be forgone. Meanwhile, to make 30 tonnes of tea, Country B needs to sacrifice the production of 100 tonnes of wool, so for each tonne of tea, 3.3 tonnes of wool is forgone. In this case, Country A has a comparative advantage over Country B for the production of tea because it has a lower opportunity cost. On the other hand, to make 1 tonne of wool, Country A has to give up 5 tonnes of tea, while Country B would need to give up 0.3 tonnes of tea, so Country B has a comparative advantage over the production of wool. Absolute advantage on the other hand refers to how efficiently a party can use its resources to produce goods and services compared to others, regardless of its opportunity costs. For example, if Country A can produce 1 tonne of wool using less manpower compared to Country B, then it is more efficient and has an absolute advantage over wool production, even if it does not have a comparative advantage because it has a higher opportunity cost (5 tonnes of tea).[22] Absolute advantage refers to how efficiently resources are used whereas comparative advantage refers to how little is sacrificed in terms of opportunity cost. When a country produces what it has the comparative advantage of, even if it does not have an absolute advantage, and trades for those products it does not have a comparative advantage over, it maximises its output since the opportunity cost of its production is lower than its competitors. By focusing on specialising this way, it also maximises its level of consumption.[22] |

比較優位と絶対優位 ある国民、組織、個人が、競合相手と比べて相対的に低い機会費用で製品やサービスを生産できる場合、その主体は比較優位を持つと言われる。言い換えれば、 ある国が同じ量の製品を作るために、より多くの資源を放棄しなければならない他国よりも少ない資源を放棄すれば、その国は比較優位を持つことになる。 [22] 比較優位の簡単な例 図の単純な例で言えば、100トンの茶を生産するために、国Aは20トンの羊毛生産を放棄しなければならない。つまり、茶1トンを生産するごとに、0.2 トンの羊毛を犠牲にする必要がある。一方、国Bが30トンの茶を生産するには100トンの羊毛生産を犠牲にする必要がある。つまり茶1トンあたり3.3ト ンの羊毛を放棄することになる。この場合、国Aは機会費用が低いため、茶生産において国Bに対して比較優位を持つ。一方、羊毛1トンを生産するには、国A は5トンの茶を、国Bは0.3トンの茶を犠牲にしなければならない。したがって、羊毛生産においては国Bが比較優位にある。 絶対優位とは、機会費用に関係なく、他者と比べて資源をいかに効率的に活用して財やサービスを生産できるかを指す。例えば、国Aが国Bより少ない労働力で 1トンの羊毛を生産できるなら、機会費用(5トンの茶)が高いから比較優位はなくても、より効率的で羊毛生産において絶対優位を持つことになる。[22] 絶対優位とは資源の効率的な利用を指し、比較優位とは機会費用の犠牲を最小限に抑えることを指す。ある国が、たとえ絶対優位を持たない場合でも、自国が比 較優位を持つものを生産し、自国が比較優位を持たない製品と取引すれば、その生産の機会費用が競合相手より低いため、生産量を最大化できる。このように専 門化に焦点を当てることで、消費水準も最大化されるのである。[22] |

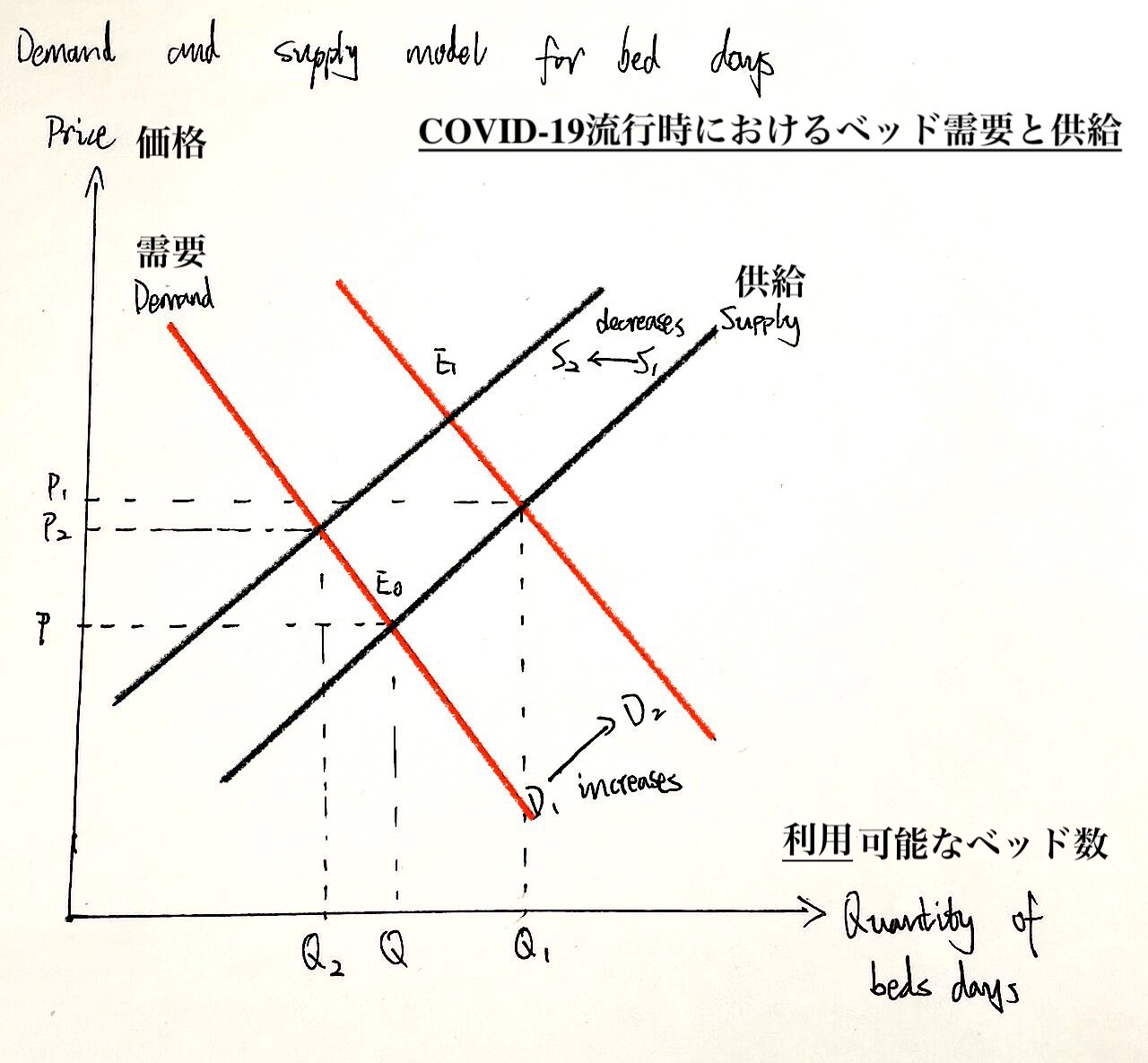

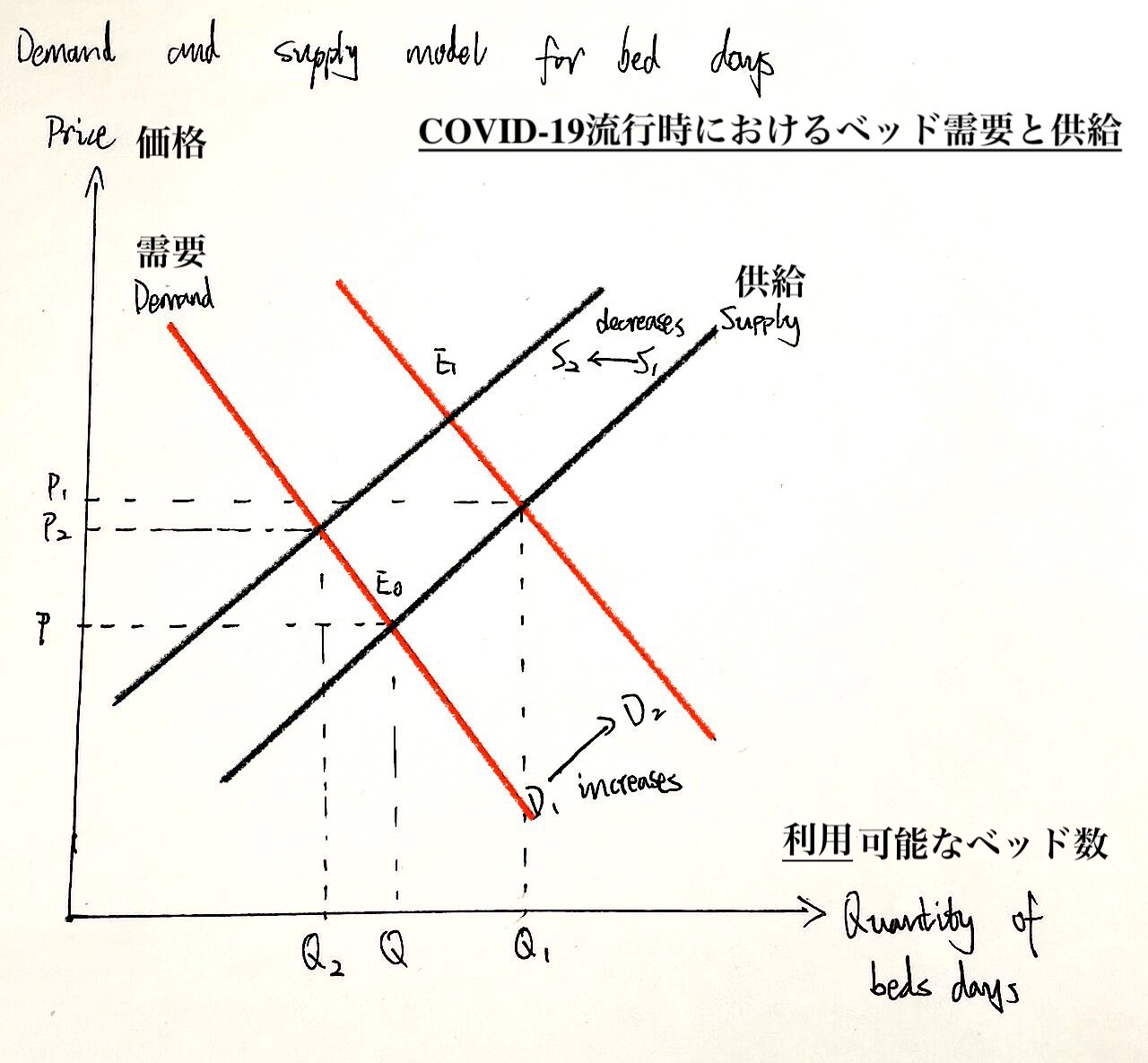

| Governmental level Similar to the way people make decisions, governments frequently have to take opportunity cost into account when passing legislation. The potential cost at the government level can be seen when considering, for instance, government spending on war. Assume that entering a war would cost the government $840 billion. They are thereby prevented from using $840 billion to fund, say, healthcare, education, or tax cuts, or to diminish by that sum any budget deficit. The explicit costs are the wages and materials needed to fund soldiers and required equipment, whilst an implicit cost would be the lost output as resources are directed from civilian to military tasks. Opportunity cost at a government level example Another example of opportunity cost at government level is the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Governmental responses to the COVID-19 epidemic have resulted in considerable economic and social consequences, both implicit and apparent. Explicit costs are the expenses that the government incurred directly as a result of the pandemic which included $4.5 billion dollars on medical bills, vaccine distribution of over $17 billion dollars, and economic stimulus plans that cost $189 billion dollars. These costs, which are often simpler to measure, resulted in greater public debt, decreased tax income, and increased expenditure by the government. The opportunity costs associated with the epidemic, including lost productivity, slower economic growth, and weakened social cohesiveness, are known as implicit costs. Even while these costs might be more challenging to estimate, they are nevertheless crucial to comprehending the entire scope of the pandemic's effects. For instance, the implementation of lockdowns and other limitations to stop the spread of the virus resulted in a $158 billion dollar loss due to decreased economic activity, job losses, and a rise in mental health issues.[23]  Demand and supply of hospital beds and days during COVID-19 The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic that broke out in recent years on economic operations is unavoidable, the economic risks are not symmetrical, and the impact of Covid-19 is distributed differently in the global economy. Some industries have benefited from the pandemic, while others have almost gone bankrupt. One of the sectors most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic is the public and private health system. Opportunity cost is the concept of ensuring efficient use of scarce resources,[24] a concept that is central to health economics. The massive increase in the need for intensive care has largely limited and exacerbated the department's ability to address routine health problems. The sector must consider opportunity costs in decisions related to the allocation of scarce resources, premised on improving the health of the population.[25] However, the opportunity cost of implementing policies to the sector has limited impact in the health sector. Patients with severe symptoms of COVID-19 require close monitoring in the ICU and in therapeutic ventilator support, which is key to treating the disease.[26] In this case, scarce resources include bed days, ventilation time, and therapeutic equipment. Temporary excess demand for hospital beds from patients exceeds the number of bed days provided by the health system. The increased demand for days in bed is due to the fact that infected hospitalized patients stay in bed longer, shifting the demand curve to the right (see curve D2 in Graph1.11).[clarification needed][24] The number of bed days provided by the health system may be temporarily reduced as there may be a shortage of beds due to the widespread spread of the virus. If this situation becomes unmanageable, supply decreases and the supply curve shifts to the left (curve S2 in Graph1.11).[clarification needed][24] A perfect competition model can be used to express the concept of opportunity cost in the health sector.[27] In perfect competition, market equilibrium is understood as the point where supply and demand are exactly the same (points P and Q in Graph1.11).[clarification needed][24] The balance is Pareto optimal equals marginal opportunity cost. Medical allocation may result in some people being better off and others worse off. At this point, it is assumed that the market has produced the maximum outcome associated with the Pareto partial order.[24] As a result, the opportunity cost increases when other patients cannot be admitted to the ICU due to a shortage of beds. |

政府レベル 人々が意思決定を行うのと同様に、政府も立法を行う際には機会費用を考慮せざるを得ない場合が多い。例えば戦争への政府支出を考えると、政府レベルでの潜 在的なコストが明らかになる。戦争に参戦すると政府に8400億ドルの費用がかかると仮定しよう。これにより政府は、例えば医療、教育、減税に8400億 ドルを充てることも、その額だけ財政赤字を削減することもできなくなる。顕在費用とは、兵士や装備に必要な賃金や資材の費用である。一方、潜在費用とは、 資源が民生から軍事任務に振り向けられることで生じる生産量の損失を指す。 政府レベルにおける機会費用の例 政府レベルにおける機会費用の別の例は、COVID-19パンデミックの影響である。COVID-19流行に対する政府の対応は、顕在的・潜在的を問わ ず、重大な経済的・社会的結果をもたらした。顕在費用とは、政府がパンデミックの結果として直接負担した費用であり、医療費45億ドル、ワクチン配布費 170億ドル超、経済刺激策1890億ドルなどが含まれる。こうした費用は測定が比較的容易であり、公的債務の増加、税収の減少、政府支出の増加をもたら した。一方、生産性の低下、経済成長の鈍化、社会的結束の弱体化など、パンデミックに伴う機会費用は暗黙のコストとして知られる。これらのコストは見積も りが難しいかもしれないが、パンデミックの影響の全容を理解する上で極めて重要だ。例えば、ウイルスの拡散を防ぐためのロックダウンやその他の制限措置の 実施は、経済活動の減少、雇用喪失、メンタル健康問題の増加により1580億ドルの損失をもたらした。[23]  COVID-19における病院ベッドと入院日数の需要と供給 近年発生したCOVID-19パンデミックが経済活動に与えた影響は避けられず、経済リスクは対称的ではない。COVID-19の影響は世界経済において 異なる形で分布している。パンデミックによって利益を得た産業がある一方で、ほぼ破綻寸前まで追い込まれた産業もある。COVID-19パンデミックで最 も大きな影響を受けた分野の一つが、公的・民間医療システムである。機会費用とは、希少な資源の効率的な利用を確保する概念であり[24]、医療経済学の 中核をなす概念だ。集中治療の需要が急増したことで、同部門が日常的な健康問題に対処する能力は大きく制限され、悪化している。この分野では、人口の健康 改善を前提に、希少な資源の配分に関する意思決定において機会費用を考慮しなければならない。[25] しかし、政策実施の機会費用が健康分野に与える影響は限定的だ。COVID-19の重症患者は集中治療室での厳重な監視と治療用人工呼吸器による支援を必 要とし、これが治療の鍵となる。[26] この場合、限られた資源には病床日数、人工呼吸器使用時間、治療用機器が含まれる。患者からの一時的な病床需要の過剰は、医療システムが提供する病床日数 を上回る。病床日数需要の増加は、感染入院患者の在院期間が長期化したことに起因し、需要曲線を右方にシフトさせる(図1.11の曲線D2参照)。[説明 が必要][24] ウイルスが広範に蔓延した場合、病床不足が生じる可能性があり、医療システムが提供する病床日数は一時的に減少するかもしれない。この状況が制御不能にな ると、供給は減少し、供給曲線は左方にシフトする(図1.11の曲線S2)。[説明が必要][24] 健康分野における機会費用の概念は、完全競争モデルを用いて表現できる。[27] 完全競争では、市場の均衡点は需要と供給が完全に一致する点(図1.11の点PとQ)と理解される。[説明が必要][24] この均衡点はパレート最適であり、限界機会費用と等しい。医療資源の配分により、ある人々はより良くなり、他の人々はより悪くなる可能性がある。この時点 で、市場はパレート部分順序に関連する最大の結果を生み出したと仮定される。[24] その結果、病床不足により他の患者が集中治療室に入院できない場合、機会費用は増加する。 |

| Austrian School Best alternative to a negotiated agreement Budget constraint Dead-end job Economies of scale Econometrics Fear of missing out Lost sales No such thing as a free lunch Parable of the broken window Production–possibility frontier Reduced cost Time management Time sink Trade-off Transaction cost You can't have your cake and eat it Perverse subsidies |

オーストリア学派 交渉合意に代わる最良の選択肢 予算制約 行き詰まった仕事 規模の経済 計量経済学 取り残される恐怖 失われた売上 タダ飯はない 割れた窓の寓話 生産可能性曲線 削減されたコスト 時間管理 時間の無駄遣い トレードオフ 取引コスト ケーキを持っていて、それを食べることもできない 逆効果な補助金 |

| References 1. "Opportunity Cost". Investopedia. Retrieved 18 September 2010. 2. Buchanan, James M. (1991). "Opportunity Cost". The World of Economics. The New Palgrave. pp. 520–525. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-21315-3_69. ISBN 978-0-333-55177-6 – via SpringerLink. 3. "Economics A-Z terms beginning with O". The Economist. Retrieved 1 November 2020. 4. Hutchison, Emma (2017). Principles of Microeconomics. University of Victoria. 5. "Explicit and implicit costs and accounting and economic profit". Khan Academy. 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2020. 6. "Explicit Costs - Overview, Types of Profit, Examples". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved 30 April 2021. 7. "Explicit Costs: Definition and Examples". Indeed. 5 February 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020. 8. Crompton, John L.; Howard, Dennis R. (2013). "Costs: The Rest of the Economic Impact Story" (PDF). Journal of Sport Management. 27 (5): 379–392. doi:10.1123/JSM.27.5.379. S2CID 13821685. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2019. 9. Kenton, Will. "How Implicit Costs Work". Investopedia. Retrieved 30 April 2021. 10. "Reading: Explicit and Implicit Costs". Lumen Learning. Retrieved 1 November 2020. 11. Devine, Kevin; O Clock, Priscilla (March 1995). "The effect on sunk costs and opportunity costs on a subjective capital allocation decision". The Mid-Atlantic Journal of Business. 31 (1): 25–38. 12. Argyres, Nicholas; Mahoney, Joseph T.; Nickerson, Jackson (25 January 2019). "Strategic responses to shocks: Comparative adjustment costs, transaction costs, and opportunity costs". Strategic Management Journal. 40 (3): 357–376. doi:10.1002/smj.2984. ISSN 0143-2095. S2CID 169892128. 13. Holian, Matthew; Reza, Ali (19 July 2010). "Firm and industry effects in accounting versus economic profit data". Applied Economics Letters. 18 (6): 527–529. doi:10.1080/13504851003761756. S2CID 154558882. 14. Goolsbee, Austan; Levitt, Steven; Syverson, Chad (2019). Microeconomics (3rd ed.). Macmillan Learning. pp. 8a – 8j. ISBN 9781319306793. 15. Layton, Allan; Robinson, Tim; Tucker, Irvin B. III (2015). Economics for Today (5th ed.). Cengage Australia. pp. 131–132, 479–486. ISBN 9780170276313. 16. Kimball, Ralph (1998). "Economic Profit and Performance Measurement in Banking". New England Economic Review. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston: 35–39. ISSN 0028-4726. Retrieved 13 March 2021. 17. Magee, Robert P. (1986). Advanced managerial accounting. Harper & Row. OCLC 1287886441. 18. Vera-Munoz, Sandra C. (1998). The effects of accounting knowledge and context on the omission of opportunity costs in resource allocation decisions. American Accounting Association. OCLC 926973835. 19. Biondi, Yuri; Canziani, Arnaldo; Kirat, Thierry (12 April 2007). "Accounting and the theory of the firm". The Firm as an Entity. Routledge. pp. 94–103. doi:10.4324/9780203931110-13. ISBN 9780429240607. Retrieved 2 May 2022. 20. Chung, Kee H. (1 May 1989). "Inventory Control and Trade Credit Revisited". Journal of the Operational Research Society. 40 (5): 495–498. doi:10.1057/jors.1989.77. ISSN 0160-5682. S2CID 16422604. 21. Herroelen, Willy S. (1995). Project network models with discounted cash flows: a guided tour through recent developments. Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Departement Toegepaste Economische Wetenschappen. OCLC 68978777. 22. Layton, Allan; Robinson, Tim; Tucker, Irvin B. III (2015). Economics for Today (5th ed.). Cengage Australia. pp. 131–132, 479–486. ISBN 9780170276313. 23. Pettinger, Tejvan (6 December 2019). "Opportunity Cost Definition". Economics Help. Retrieved 23 April 2023. 24. Olivera, Mario J. (29 December 2020). "Opportunity cost and COVID-19: A perspective from health economics". Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 34: 177. doi:10.47176/mjiri.34.177. ISSN 1016-1430. PMC 8004566. PMID 33816376. 25. Drummond, M. F. (2005). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852945-3. OCLC 300939640. 26. World Health Organization (20 May 2020). "Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected. Interim guidance". Pediatria I Medycyna Rodzinna. 16 (1): 9–26. doi:10.15557/pimr.2020.0003. ISSN 1734-1531. S2CID 219964509. 27. Lipsey, R. G.; Chrystal, K. A. (2007). Economics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928641-6. OCLC 475315028. |

参考文献 1. 「機会費用」. Investopedia. 2010年9月18日閲覧. 2. Buchanan, James M. (1991). 「機会費用」. 『経済学の世界』. The New Palgrave. pp. 520–525. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-21315-3_69. ISBN 978-0-333-55177-6 – via SpringerLink. 3. 「Oで始まる経済学用語集」。エコノミスト。2020年11月1日取得。 4. ハッチソン、エマ (2017). 『ミクロ経済学の原理』. ビクトリア大学. 5. 「明示的・暗黙的コストと会計・経済的利益」. カーンアカデミー. 2016年. 2020年11月1日取得. 6. 「明示的コスト - 概要、利益の種類、事例」. コーポレートファイナンス協会. 2021年4月30日取得. 7. 「明示的コスト:定義と例」。インディード。2020年2月5日。2020年11月1日取得。 8. クロンプトン、ジョン・L.;ハワード、デニス・R.(2013)。「コスト:経済的影響の残りの物語」(PDF)。スポーツ経営ジャーナル。27 (5): 379–392。doi:10.1123/JSM.27.5.379. S2CID 13821685. 2019年3月4日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブされた。 9. ケントン、ウィル。「暗黙的コストの仕組み」。インベスティーポディア。2021年4月30日閲覧。 10. 「読書:明示的コストと暗黙的コスト」. Lumen Learning. 2020年11月1日取得. 11. Devine, Kevin; O Clock, Priscilla (1995年3月). 「主観的な資本配分決定に対する沈没コストと機会費用の影響」. The Mid-Atlantic Journal of Business. 31 (1): 25–38. 12. Argyres, Nicholas; Mahoney, Joseph T.; Nickerson, Jackson (2019年1月25日). 「ショックへの戦略的対応:比較調整費用、取引費用、機会費用」. Strategic Management Journal. 40 (3): 357–376. doi:10.1002/smj.2984. ISSN 0143-2095. S2CID 169892128. 13. Holian, Matthew; Reza, Ali (2010年7月19日). 「会計利益データと経済利益データにおける企業効果と産業効果」. Applied Economics Letters. 18 (6): 527–529. doi:10.1080/13504851003761756. S2CID 154558882. 14. Goolsbee, Austan; Levitt, Steven; Syverson, Chad (2019). 『ミクロ経済学』(第3版). Macmillan Learning. pp. 8a – 8j. ISBN 9781319306793。 15. レイトン、アラン; ロビンソン、ティム; タッカー、アーヴィン・B・III (2015). 『今日の経済学 (第5版)』. キャンゲージ・オーストラリア. pp. 131–132, 479–486. ISBN 9780170276313. 16. キムボール、ラルフ(1998)。「銀行における経済的利益と業績測定」。『ニューイングランド経済レビュー』。ボストン連邦準備銀行:35–39頁。ISSN 0028-4726。2021年3月13日閲覧。 17. Magee, Robert P. (1986). 『上級管理会計』. Harper & Row. OCLC 1287886441. 18. Vera-Munoz, Sandra C. (1998). 「資源配分決定における機会費用の省略に対する会計知識と文脈の影響」. American Accounting Association. OCLC 926973835. 19. ビオンディ, ユリ; カンツィアーニ, アルナルド; キラット, ティエリー (2007年4月12日). 「会計と企業理論」. 『企業という実体』. ラウトレッジ. pp. 94–103. doi:10.4324/9780203931110-13. ISBN 9780429240607。2022年5月2日取得。 20. チョン、キー・H.(1989年5月1日)。「在庫管理と貿易信用の再考」。『オペレーションズ・リサーチ学会誌』。40巻5号:495–498頁。 doi:10.1057/jors.1989.77. ISSN 0160-5682. S2CID 16422604. 21. Herroelen, Willy S. (1995). 割引キャッシュフローを用いたプロジェクトネットワークモデル:近年の発展のガイドツアー. カトリック・ルーヴェン大学応用経済学部. OCLC 68978777. 22. Layton, Allan; Robinson, Tim; Tucker, Irvin B. III (2015). 今日の経済学(第5版)。Cengage Australia。pp. 131–132, 479–486。ISBN 9780170276313。 23. Pettinger, Tejvan (2019年12月6日)。「機会費用の定義」。Economics Help。2023年4月23日に閲覧。 24. オリベラ、マリオ・J.(2020年12月29日)。「機会費用とCOVID-19:健康経済学からの視点」。『イラン・イスラム共和国医学雑誌』。 34: 177。doi:10.47176/mjiri.34.177。ISSN 1016-1430。PMC 8004566。PMID 33816376. 25. Drummond, M. F. (2005). 『健康プログラムの経済評価手法』. オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-852945-3. OCLC 300939640. 26. 世界健康機関 (2020年5月20日). 「COVID-19が疑われる場合の重症急性呼吸器感染(SARI)の臨床管理。暫定ガイダンス」. Pediatria I Medycyna Rodzinna. 16 (1): 9–26. doi:10.15557/pimr.2020.0003. ISSN 1734-1531. S2CID 219964509. 27. リプシー, R. G.; クリスタル, K. A. (2007). 『経済学』. オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-928641-6. OCLC 475315028. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opportunity_cost |

Robert H. Frank, |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 2009-2019

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099