命題の形式について

Post

festum, or On the Form of Propositions

命題の形式について

Post

festum, or On the Form of Propositions

解説:池田光穂

哲学者は宴の後で(post festum)で やってくる ——カール・マルクス

「1840年代の若いへーゲル学徒たちをヘーゲル自 身から分つものは、歴史は〈創られる〉という確信であった。それは過去におけるように盲目にではなく、完全な意識においてである。——なぜなら、人は意識 していなくとも、つねに自分自身の歴史をある意味では〈創っている〉からである。マルクスは、この時期にこの問題でヘーゲルと縁を切った唯一の革命的人間 ではなかったが、彼(→ルカーチ、引用者)がなしとげたこの決裂は、世界史的な意味を 帯びている。なぜなら、それは、世界を変革するという目的をもつ理論を実践とかみ合せたからである。マルクスの思想は、彼の後継者たちによって稀薄にされ てしまい、1914年のヨーロッパ社会主義の進化論的見解のなかには殆ど認められないのであるが、この次元でのマルクスの思想を回復することによって、ル カーチは、1845年にすでに〈フォイエルバッハ・テーゼ〉とし て述べられている命題の論理に従っている」(リヒトハイム 1973:36)。

| If anyone opens

his mouth and promises to state what God is,

namely God is -- God, expectation is cheated, for what was

expected was a different determination; and if this statement is

absolute truth, such absolute verbiage is very lightly esteemed;

nothing will be held to be more boring and tedious than conversation

which merely reiterates the same thing, or than such

talk which yet is supposed to be truth.

Looking more closely at this tedious effect produced by such

truth, we see that the beginning, 'The plant is-,' sets out to say

something, to bring forward a further determination. But since

only the same thing is repeated, the opposite has happened,

nothing has emerged. Such identical talk therefore contradicts

itself. Identity, instead of being in its own self truth and absolute

truth, is consequently the very opposite; instead of being the

unmoved simple, it is the passage beyond itself into the dissolution

of itself. |

も

し誰かが口を開き、神とは何かを述べると約束したとしても、つまり神とは神であると述べたとしても、期待は裏切られる。なぜなら、期待されていたのは異な

る決定だったからだ。そして、もしこの発言が絶対的な真実であるならば、このような絶対的な言葉遣いは非常に軽んじられる。同じことを繰り返すだけの会話

や、真実であるはずの会話ほど退屈でつまらないものはない。このような真実がもたらす退屈な効果をより詳しく見てみると、冒頭の「その植物は~」は、何か

を伝えようとし、さらなる決定を導こうとしている。しかし、同じことが繰り返されているだけなので、反対の結果が生じ、何も出てこない。このような同一の

話は、それゆえ、それ自体と矛盾している。同一性は、それ自体の真理と絶対的な真理ではなく、その結果、まったく逆のものとなる。不動の単純さではなく、

それ自体を越えてそれ自体の解消へと至る道となる。 |

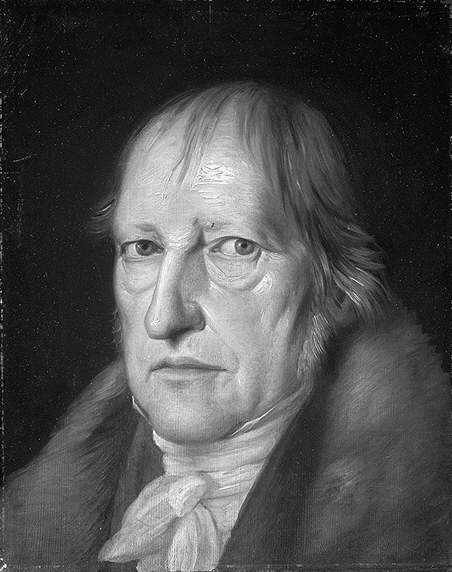

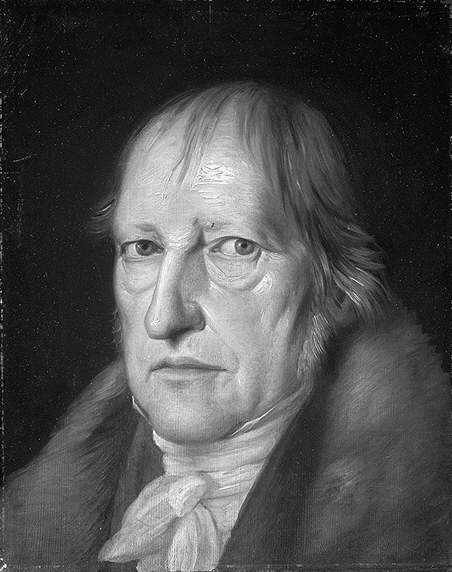

| Hegel had synthesized Vico's approach with the creed of the Enlightenment, but while he abandoned the belief in a cyclical motion, he retained the conviction that Spirit comes to self-consciousness in philosophy only after an epoch has reached its term : Minerva's owl flies out at dusk, as he put it in the preface to his Philosophy of Right; or, to cite Marx's rather less flattering characterization of Hegel's procedure, "The philosopher comes post festum." What distinguished the Young Hegelians of the 1840s from Hegel was the conviction that history could be made: not blindly, as in the past-for of course men had in a certain sense always "made" their own history, though they had not been aware of it-but with full consciousness. Marx was not the only radical of his time who broke with Hegel on this issue, but the rupture he effected assumed world-historical significance because it meshed with the theory and practice of a movement that aimed to transform the world. In recovering this dimension of Marx's thought, which had been diluted by his followers and was barely recognizable in the evolutionist outlook of European socialism in 1914, Lukacs followed the logic of an argument already set out in the 1845 Theses on Feuerbach. - Lichtheim 1970:22-23. | ヘー

ゲルはヴィーコの考え方を啓蒙主義の信条と統合したが、循環的な運動という考え方は放棄したものの、ある時代がその期間に達した後にのみ、精神は哲学にお

いて自己意識に到達するという信念は保持した。ヘーゲルは『法哲学』の序文で次のように述べている。「ミネルヴァの梟は黄昏時に飛び立つ」と。あるいは、

ヘーゲルの手法をあまり褒めていないマルクスの表現を引用すると、「

「哲学者は事後的にやって来る」と述べている。1840年代の若いヘーゲル派がヘーゲルと異なっていたのは、歴史は作ることができるという信念を持ってい

たことである。もちろん、人々はそれと気づいていなかったかもしれないが、ある意味では常に自分たちの歴史を「作ってきた」のである。しかし、それは盲目

的にではなく、完全に意識的に行われてきたのである。この問題についてヘーゲルと決別した急進派はマルクスだけではないが、彼が引き起こした決裂は、世界

を変革することを目的とした運動の理論と実践とが一致したため、世界史的な意義を持つこととなった。マルクスの思想のこの側面を回復するにあたり、

1914年のヨーロッパ社会主義の進化論的見解では、マルクスの思想は信奉者たちによって薄められ、ほとんど認識できないほどになっていたが、ルカーチは

1845年の『フォイエルバッハに関するテーゼ』ですでに提示されていた論理に従った。 - Lichtheim 1970:22-23. |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆