︎供犠

Sacrifice

︎供犠

Sacrifice

解説:池田光穂

☆供犠(Sacrifice, Opfer )一般についての復習

★宗教において供犠とは、生物を捧げたり、無生物を捧げたりすることである。想像力によっ

て、この力には祖先、精霊、神などが与えられる。

生け贄は通常、儀式や特別な祭りを伴うプロセスであり、「生け贄祭り」として宗教の初歩的な構成要素となることもある。儀式は人間の共存において重要な役

割を果たし、あらゆる集団に固有のものである。犠牲的儀礼は、人々がしばしば意識的かつ意図的に環境に影響を与えようとする社会的行為である[1]。

宗教学においては、供犠は「償いの供犠」「請願の供犠」「感謝の供犠」「浄化の供犠」「賛美の供犠」に分類することができる[2]。歴史的に最も古い供犠

には、「初穂」と「死者のための供犠」も含まれる[3]。

ほとんどの規則によれば、動物が供犠された場合、その肉と血は儀式化された食事で消費される。習慣によっては、生け贄の共同体全体が参加するか、生け贄の

指導者が彼らの前に立つ。これは司祭、シャーマン、またはその他のカルト宗教的行為の代理人である場合もあり、民衆とそれぞれの神との仲介役とみなされ

る。人身御供を好む宗教では、人身御供は質的にも最高の供え物とされる。

宗教的な犠牲行為の対象は、概念的あるいは意味的に、交換行為の対象とは区別されなければならない[4]

| Ein Opfer

ist in der Religion die Darbringung von materiellen Objekten belebter

oder unbelebter Art an eine dem opfernden Menschen vorgestellte

übergeordnete metaphysische Macht. Mit dieser Macht können je nach

Vorstellung Ahnen, Geister oder Gottheiten ausgestattet sein. Die Opferung ist ein Vorgang, der zumeist mit einem Ritual verbunden ist und mit einem besonderen Fest, das als „Opferfest“ elementarer Bestandteil einer Religion sein kann. Rituale spielen eine bedeutende Rolle im menschlichen Zusammenleben und sind anlageweise für jedes Kollektiv aufzufinden. Opferungsrituale stellen soziale Handlungen dar, mit denen Menschen oft bewusst und intentional auf ihre Umwelt einzuwirken suchen.[1] Religionswissenschaftlich lassen sich Opfer klassifizieren[2] in „Sühneopfer“, „Bittopfer“, „Dankopfer“, „Reinigungsopfer“ und „Lobopfer“. Zu den historisch ältesten Opfern gehört auch das „Erstlings-“ und „Totenopfer“.[3] Beim Opfern von Tieren wird deren Fleisch und Blut nach den meisten Regeln bei einem kultgebundenen Mahl verzehrt. Je nach Brauch nimmt daran die gesamte Opfergemeinschaft teil oder stellvertretend der ihr voranstehende Opferleiter. Dies kann ein Priester, Schamane oder anderer Agent kultisch-religiöser Handlungen sein, dem eine Mittlerrolle zwischen den Menschen und der jeweiligen Gottheit zugesprochen wird. In Religionen, die Menschenopfer befürworten, gelten diese als die qualitativ höchste Form einer Opfergabe. Das Objekt einer religiösen Opferhandlung ist begrifflich bzw. semantisch vom Objekt einer Tauschhandlung abzugrenzen.[4] |

宗教において供犠とは、生物を捧げたり、無生物を捧げたりすることであ

る。想像力によって、この力には祖先、精霊、神などが与えられる。 生け贄は通常、儀式や特別な祭りを伴うプロセスであり、「生け贄祭り」として宗教の初歩的な構成要素となることもある。儀式は人間の共存において重要な役 割を果たし、あらゆる集団に固有のものである。犠牲的儀礼は、人々がしばしば意識的かつ意図的に環境に影響を与えようとする社会的行為である[1]。 宗教学においては、供犠は「償いの供犠」「請願の供犠」「感謝の供犠」「浄化の供犠」「賛美の供犠」に分類することができる[2]。歴史的に最も古い供犠 には、「初穂」と「死者のための供犠」も含まれる[3]。 ほとんどの規則によれば、動物が供犠された場合、その肉と血は儀式化された食事で消費される。習慣によっては、生け贄の共同体全体が参加するか、生け贄の 指導者が彼らの前に立つ。これは司祭、シャーマン、またはその他のカルト宗教的行為の代理人である場合もあり、民衆とそれぞれの神との仲介役とみなされ る。人身御供を好む宗教では、人身御供は質的にも最高の供え物とされる。 宗教的な犠牲行為の対象は、概念的あるいは意味的に、交換行為の対象とは区別されなければならない[4]。 |

| Etymologie Das Nomen „Opfer“ ist eine Rückbildung aus dem Verb „opfern“. Dieses bereits im Althochdeutschen belegte Verb (opfarōn) wird auf das lateinische Verb operari („ausführen“, „verrichten“) oder zu lateinisch offerre („darbringen“, „schenken“) zurückgeführt, in der Bedeutung „der Gottheit dienen“, „Almosen geben“.[5] Einfluss auf die Bedeutung hat dem Etymologischen Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (Kluge/Seebold) zufolge auch das lateinische offerre („darbieten“) ausgeübt, das über das Altsächsische zu englisch offer („Angebot“) wurde.[6] Das Grimm’sche Wörterbuch hatte 1889 noch eine direkte Ableitung von offerre angenommen und sich dabei auf die Chronik des Johannes Aventinus gestützt.[7][8] Zusätzlich kann in der deutschen Sprache das Wort „Opfer“ in dreifacher Bedeutung genutzt werden. Es bezeichnet sowohl die Opferhandlung als auch das Objekt der Opferung sowie die Opfergabe. |

語源 「供犠(Opfer)」という名詞は、「生贄に捧げる」という動詞の後退形である。この動詞(opfarōn)は、古高ドイツ語ではすでに使われていた が、ラテン語の動詞 operari(「実行する」、「遂行する」)またはラテン語の offerre(「捧げる」、「与える」)まで遡る。[5]ドイツ語語源辞典(Kluge/Seebold)によると、ラテン語のofferre(「捧げ る」)は、古ザクセン語を経て英語のoffer(「提供する」)となり、この意味にも影響を与えている[6]。 1889年、グリム語辞典は、ヨハネス・アヴェンティヌスの年代記に基づいて、依然としてofferreの直接的な派生を仮定していた[7][8]。さら に、「犠牲」という言葉は、ドイツ語では3つの意味で使われる。生け贄」は、生け贄の行為と生け贄の対象、そして供え物を意味する。 |

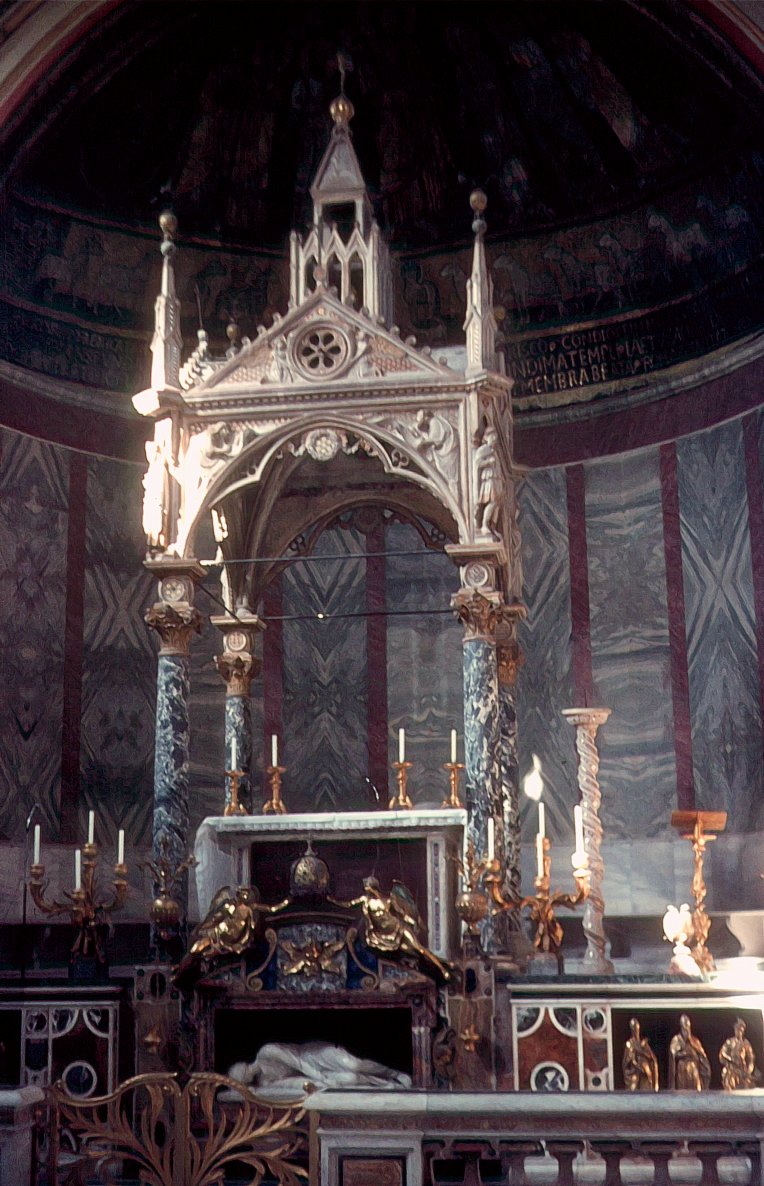

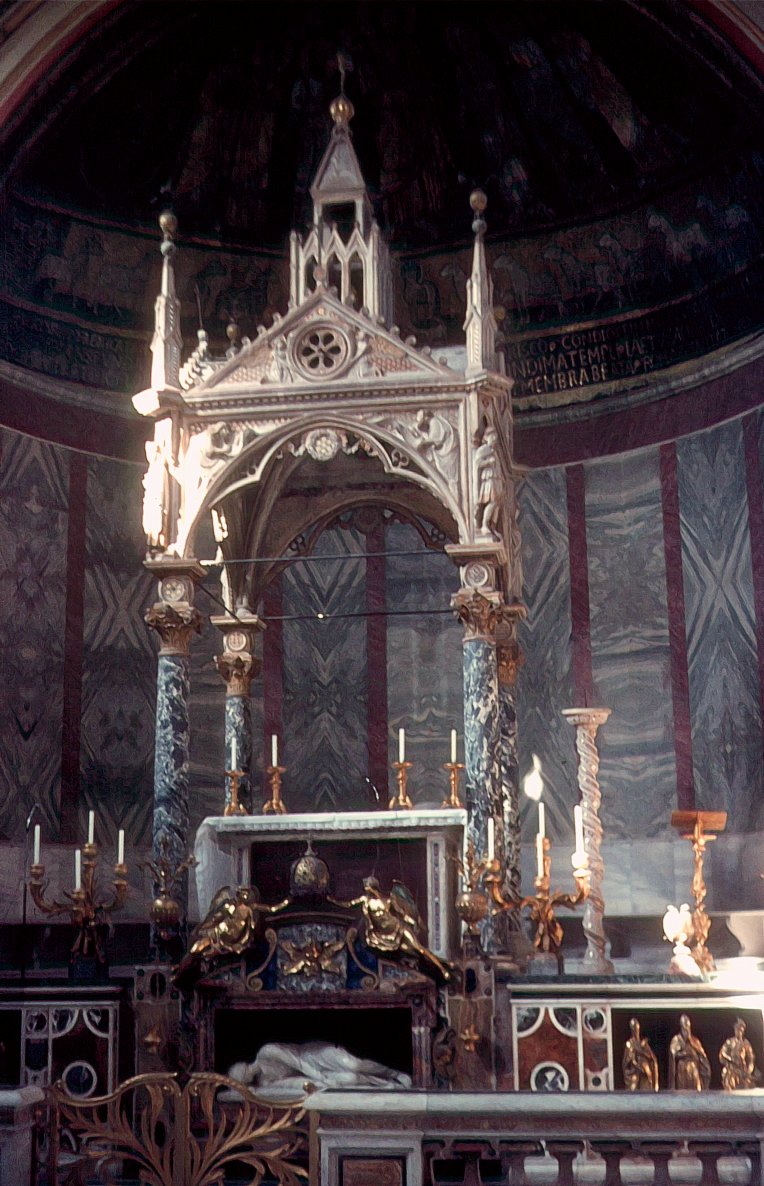

| Einführung und Grundlagen Grundlage von Religionen sind entsprechende (religiöse) Vorstellungsinhalte[9][10] die im jeweiligen Glauben an bestimmte transzendente (überirdische, übernatürliche, übersinnliche) Kräfte ihren Ausdruck finden. Vorstellungen, die Allmächtiges und Übernatürliches integrieren, schaffen und festigen in religiöse Ritualen, so Voland (2010),[11] menschliche Gemeinschaften, die über die Familie oder Sippe hinausgehen. Rituale sind menschliche Handlungen und Handlungskomplexe. Dabei kann zwischen dem Ritual im engeren Sinne und möglichen routinisierten Alltagshandlungen oder Ritualisierungen unterschieden werden.[12] Auch bei den Alltagshandlungen sind förmliche, repetitive, performative Handlungsmuster vorhanden, es fehlen aber bestimmte kulturelle Ordnungszeichen, die eine Überhöhung der Handlungen und Normativität ausmachten. Kulturelle Ordnungszeichen sind etwa (priesterliche) Herrschaftszeichen, Metaphern und Medien der Überlieferungen tradierter (religiöser) Vorstellungen auf deren überpersönliche Wertevorstellung im Ritual Bezug genommen wird. Rituale werden im Sinne des Symbolischen Interaktionismus primär als Handlungen gesehen, also als Formen des bewussten zielgerichteten (intentionalen) Einwirkens des Menschen auf seine Umwelt. Rituale und hierzu zählen auch die Opferrituale werden in einer förmlichen, stilisierten, teils stereotypen Performanz ausgeführt. Damit bestehen Opferrituale aus überwiegend wiederholten und nachahmbaren Handlungen.[13][14] Religiöse Rituale sind die Kommunikationsmittel in einer Strategie des Zusammenhalts. Dabei gilt, je aufwendiger die Opfer für das einzelne Gruppenmitglied, desto fester und sicherer die Gemeinschaft. Rituelle Performanz sei nicht selten rigide, redundant, zwanghaft und auf unnütze Verhaltensziele hin ausgerichtet, da hier die synchronisierende, emotionale Gleichschaltung im religiösen Ritus, welche mit einer Ich-Entgrenzung einhergeht, die Funktion einer Stärkung der Lebensgemeinschaft der Gruppe habe. Tabus, Zeremonien schützten dabei die Gruppe und ihre Außengrenzen. Nach Heinsohn (2012)[15] begründeten Überlebende globaler Naturkatastrophen die Opferkulte, so sieht er Menschenopfer und Tötungsrituale als prägendes Element der bronzezeitlichen Hochkulturen, einer Epoche vom Ende des 3. Jahrtausend v. Chr. und dem Ende des 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Das gälte nicht nur in Mesopotamien, Kleinasien, dem Mittelmeerraum, Nordafrika und Europa, sondern auch für Zentralasien, Indien und China. Nach Seiwert (1998)[16] lässt sich das Opfer in einem engeren und einem weiteren Sinne definieren: Opfer als ritueller Akt, i. e. S. wäre eine religiöse Handlung, die in der rituellen Entäußerung eines materiellen Objektes bestünde. Religiöse Handlung steht hier in einem Gegensatz zu profanen Handlungen; materielle Objekte können Lebewesen (Tier, Mensch, Pflanzen) und auch unbelebte Objekte (Nahrungsmittel, Gebrauchsgegenstände usw.) sein; Akt des Entäußerns bedeutet, dass das Objekt, das Opfer, zunächst in der Einflusssphäre oder Verfügungsgewalt des Akteurs, des Opferers ist, um dann aus dessen Verfügungsgewalt entlassen zu werden; dies kann ganz oder teilweise, endgültig oder zeitweise sein; ritueller Charakter des Entäußerns impliziert einen stilisierten Handlungsablauf, in welchem der Akt symbolische Bedeutung hat. Welche symbolische Bedeutung dieser einnimmt, kann nur aus dem Kontext des rituellen Gesamtkomplexes und den damit verbundenen Vorstellungen ermittelt werden. Opfer als ritueller Komplex, i. w. S. ist ein Komplex ritueller Handlungsabläufe, in dem mindestens ein Akt der rituellen Entäußerung eines materiellen Objektes vorkommt und darin eine mehr oder weniger zentrale Stellung bezieht. Bestimmte Religionen kannten die Opferung von Früchten, die wie das geschlachtete Tieropfer verbrannt oder ganz oder teilweise gegessen wurden, zuweilen auch in den Besitz der Priesterschaft übergingen. Beim „Trankopfer“ werden Getränke, insbesondere Wasser, Wein und Öl, in oder vor Gräbern oder Tempeln abgestellt oder am Kultplatz vergossen. Das Opfer wird manchmal geschwungen („Schwingopfer“) oder auch emporgehoben („Hebopfer“), um es vor Gott sichtbar zu machen. Darüber hinaus gibt es auch duftende Rauchopfer, bei denen wohlriechendes Räucherwerk wie Weihrauch und Myrrhe dargebracht wird. Blutige Opfer sind bereits von den Jägern und Sammlern der Altsteinzeit bekannt, wo die Tiere zu ebener Erde abgelegt oder mit Steinen beschwert im Wasser versenkt wurden. Aus den Funden solcher Opferstätten lässt sich schließen, dass es zu dieser Zeit eine personalisierte Vorstellung einer jenseitigen Welt gegeben haben muss. Tieropfer wurden später vor allem von Wanderfeldbau treibenden Kulturen übernommen. Zur Opferpraxis antiker Kulturen zählte auch das Menschenopfer, in geschichtlicher Zeit meist von Kriegsgefangenen an den Kriegs-, Stammes- oder Nationalgott, teilweise auch das Opfern erstgeborener Kinder. Geopfert wurde auch Edelmetalle, Hausrat, Waffen, Schmuck, Statuen, zum Beispiel durch Versenken in Flüssen, Seen, Sümpfen oder dem Meer oder durch Aufstellen bzw. Verbringen an Kultplätze (zum Beispiel auf heilige Haine oder Berge, in heilige Höhlen), in Tempel von Göttern oder an bzw. in Gräber von Ahnen. Nicht gemeint ist die Mitgabe von Teilen des Eigentums des Toten als Ausrüstung für das angenommene Leben nach dem Tod als sogenannte Grabbeigaben. Denn so behielt der Tote nach dem Verständnis der Angehörigen, was ihm persönlich im Tod gehört; er erhält kein Opfer von den Überlebenden, auch wenn es zusätzlich häufig zu Opferungen kam. Opfer an Ahnen werden nicht nur dargebracht, um sich diese gewogen zu machen, sondern auch um sie im Jenseits zu versorgen oder zu befragen (Mantik). Teilweise wurden auch Handlungen wie mühsame und weite Wallfahrten, die Errichtung eines Kultplatzes, zum Beispiel die Errichtung eines Opferaltars selbst, eines Tempels, einer Kapelle oder Kirche, die Errichtung eines Klosters, die Stiftung eines Kunstwerkes für einen solchen Platz, wie Bilder oder Statuen, als Opfer verstanden. Ein Mönch, ein Fürst oder König oder auch eine Gemeinde, ein Dorf oder eine Stadt zum Beispiel opfert einem Gott, indem eine Kirche errichtet wird, sei es durch körperliche Arbeit oder sei es durch Hingabe von Geld für diesen Zweck. Durch dieses Verhalten wurden Tempel oder Kirchen oft aufwändig errichtet, oft sehr reich ausgestattet mit prächtigen Kunstwerken und teuersten Materialien, wie Edelsteinen und Edelmetallen, und es wurden oft große Tempel- oder Kirchenschätze angehäuft. Selten werden auch das bloße Selbstzufügen von Qualen und Schmerzen, wie das Zurücklegen von langen Strecken auf den Knien oder Geißelungen als Opfer verstanden. |

序論と基礎 宗教は対応する(宗教的な)概念[9][10]に基づいており、それは特定の超越的な(超自然的な、超自然的な、超感覚的な)力に対するそれぞれの信仰に おいて表現される。Voland(2010)によれば[11]、全能と超自然を統合する観念は、家族や氏族を超えた宗教的儀礼において人間共同体を創造 し、統合する。儀式とは人間の行為であり、行為の複合体である。狭い意味での儀式と、可能な限りルーティン化された日常的行為や儀式化とは区別することが できる[12]。形式的で反復的、パフォーマティブな行為パターンも日常的行為には存在するが、行為や規範性の誇張を構成する、ある種の文化的秩序記号が 欠如している。秩序を表す文化的なしるしとは、たとえば権威を表す(司祭の)しるしであり、メタファーであり、儀式において超個人的な価値が言及される伝 統的な(宗教的な)思想を伝達するためのメディアである。象徴的相互作用論(symbolic interactionism)の意味では、儀礼は主として行為として、すなわち意識的、目的意識的(intentional)な人々の環境への影響の形 態として捉えられる。儀式は、生贄儀式を含めて、形式的、様式化された、時にはステレオタイプなパフォーマンスで行われる。したがって、犠牲儀礼は主に反 復され模倣可能な行為からなる[13][14]。 宗教儀礼は、結束戦略におけるコミュニケーションの手段である。個々の集団メンバーの犠牲が精巧であればあるほど、共同体はより強固で安全なものとなる。 儀式はしばしば厳格で、冗長で、強迫的で、無益な行動目標に向けられたものである。宗教的儀式における同調、感情の一致は、自我の境界の解消と密接に関連 し、集団の共同体を強化する機能を持つからである。タブーと儀式は集団とその外部の境界を守るものだった。 Heinsohn(2012)[15]によれば、世界的な自然災害の生存者が生贄カルトを創設し、人身供犠と殺戮儀礼が青銅器文明(紀元前3千年紀の終わ りから紀元前1千年紀の終わりまでの時代)の形成要素であった。 Seiwert(1998)[16]によれば、生け贄は狭義にも広義にも定義できる: 儀礼行為としての生け贄は、狭義には、物質的なものを儀式的に捨てることからなる宗教的行為である。 ここでの宗教的行為は、冒涜的行為と対照的である; 物質的対象とは、生物(動物、人間、植物)だけでなく、無生物(食物、食器など)も含まれる; 離脱の行為とは、被害者である対象が、最初は行為者である被害者の影響範囲や処分権の中にあり、その後、その処分権から解放されることを意味する; 離脱の儀式的性格は、その行為が象徴的意味を持つ、様式化された一連の行為を意味する。その象徴的意義は、全体的な儀式複合体とそれに関連する観念の文脈 からしか判断できない。 儀礼的複合体としての生贄とは、広義には、儀礼的行為列の複合体であり、その中で少なくとも一つの物質的対象物の儀礼的離脱行為が行われ、多かれ少なかれ 中心的な位置を占めている。 屠殺された動物の生贄と同様に、その全部または一部が焼かれたり食べられたりし、時には神職の所有物になることさえある。捧げ物」では、飲み物、特に水、 ワイン、油が、墓や神殿の中や前に置かれたり、礼拝の場で注がれたりした。供え物は、神に見えるように、揺らされたり(「スイング供え物」)、持ち上げら れたり(「ヒーブ供え物」)することもある。また、乳香や没薬などの香油を捧げる香煙供犠もある。 血の犠牲は、旧石器時代の狩猟採集民からすでに知られており、動物を地面に置いたり、石で重しをしたり、水に沈めたりしていた。このような生け贄場の発見 から、この『存在と時間』には異界に対する個人的な観念があったに違いないと結論づけられる。動物の生け贄はその後、焼畑耕作を行う文化圏で特に取り入れ られるようになった。古代文化における生け贄の習慣には、人間の生け贄も含まれており、歴史的な時代には、戦争捕虜を軍神、部族、国家に捧げることがほと んどであった。 貴金属、家財道具、武器、宝飾品、彫像なども、例えば川、湖、沼地、海に沈めたり、崇拝の場所(例えば神聖な木立や山、神聖な洞窟の中)、神々の神殿、先 祖の墓やその中に置いたりして、生け贄に捧げられた。故人の財産の一部を、いわゆる墓用品として、死後の世界を想定した道具として贈ることは意味しない。 というのも、親族の理解によれば、故人は死後も個人的に所有していたものであり、たとえしばしば追加の犠牲があったとしても、遺族から供物を受け取ること はなかったからである。 先祖への生贄は、先祖を好意的に処分するためだけでなく、死後の世界で先祖を供養するため、あるいは先祖を問いただすため(マンティック)にも行われた。 場合によっては、長く困難な巡礼、礼拝所の建設、たとえば犠牲祭壇そのものの建立、寺院、礼拝堂、教会、修道院の建設、そのような場所のための芸術作品、 たとえば絵や彫像の寄贈などの行為も、犠牲として理解された。僧侶、王子や王、あるいは共同体、村や町でさえも、たとえば教会を建てることによって、肉体 労働によって、あるいはそのために金銭を提供することによって、神に犠牲を捧げる。このような行動の結果、寺院や教会はしばしば精巧に建てられ、壮麗な芸 術作品や宝石や貴金属といった最も高価な材料で非常に豪華に調えられ、寺院や教会の財宝はしばしば巨額になった。 ひざまずいて長い距離を歩いたり、鞭打ちのような苦痛を与えたりすることも、生け贄とみなされることはほとんどない。 |

| Theorieansätze Die Geschichte der Theorien zum Begriff „Opfer“ lassen sich grob gliedern; das 19. Jahrhundert und frühe 20. Jahrhundert war geprägt durch evolutionistische Ansätze; die Frage nach den ursprünglichsten Formen des Opferns stand im Vordergrund, etwa zeitgleich wurde aber auch versucht, Typen von Opfern zu unterscheiden. An diesen theoretischen Überlegungen schlossen sich die Fragen nach der Struktur des Opferrituals und der damit ausgedrückten Symbolik an. Seiwert arbeitete fünf Aspekte der klassischen Opfertheorie heraus: das Opfer als Geschenk oder Gabe an eine Gottheit, hierdurch wird eine Beziehung der Abhängigkeit und wechselseitigen Verpflichtung zwischen Mensch und Gottheit konstruiert (Vertreter: Edward Burnett Tylor, Marcel Mauss) das Opfer als ritueller Vollzug der Gemeinschaft von Mensch und Gottheit; dokumentiere sich in der Kommensalität und dem Opfermahl (Vertreter: William Robertson Smith) das Opfer als rituelle Form der Kommunikation zwischen der Sphäre des sakralen und der Welt des profanen, wobei das Opfer als Medium des Kontaktes zwischen beiden dient (Vertreter: Henri Hubert und Marcel Mauss) das Opfer als rituelles Mittel um den Kreislauf der unpersönlichen Lebenskraft sicherzustellen (Vertreter: Gerardus van der Leeuw und Marcel Mauss) das Opfer als rituelle Anerkennung der Macht Gottes über das Leben und der Abhängigkeit des Menschen (Vertreter: Wilhelm Schmidt).[17] Für Tylor (1871)[18] und Frazer (1890)[19] stand das „Wort“, der Mythos als narrativer kosmologischer Gestalter der Welt, womit dem Ritual die Bedeutung der sinnlichen Ausführung und der dramatischen Darstellung des Erzählten im Kultus zufallen sollte. Stand hingegen die „Tat“, das Ritual am Anfang, so sollte der Mythos den Handlungsprozess mit exegetischer Erklärung und dogmatischer Auslegung verbinden, so Smith (1889)[20][21] Im Opfer versucht der Mensch Beziehungen zu außer- oder übermenschlichen Wesen aufzunehmen, um diese zu beeinflussen, sei es, um auf ein vermutetes Einwirken dieser Wesen in den menschlichen Bereich zu reagieren, oder um ein gewünschtes Einwirken hervorzurufen (Theurgie). Opferhandlungen finden sich bei fast allen Kulturen der Menschheit. Weitreichende Forschungen zur Theorie des Opfers wurden vom englischen Anthropologen Tylor in seinem Werk Primitive Culture von 1871 und von den französischen Soziologen durchgeführt. In ihren Essais sur la nature et la fonction du sacrifice (1898–1899) erarbeiteten sie unter anderem die vier Grundelemente des Opfers: der Opferer das Opfer der Adressat des Opfers und der Opferherr, für den und auf dessen Rechnung das Opfer vollzogen wird. René Girard (1972)[22] entwickelte in seinen Überlegungen zur mimetischen Theorie, die einen Zusammenhang zwischen Nachahmung und Gewalt herstellt, auch eine Theorie des Opfers. Die zentrale Annahme der mimetischen Theorie ist die Feststellung, dass menschliche Gesellschaften nur dann überleben können, wenn sie in der Lage sind, dem Ausbreiten der Gewalt innerhalb der Gruppe erfolgreich entgegenzuwirken. Ursache zwischenmenschlicher Konflikte ist das Nachahmungsverhalten von Menschen, die in engem Kontakt miteinander leben: Dieses Verhalten stiftet Rivalität, Neid und Eifersucht, ist ansteckend, wird von allen Mitgliedern der Gruppe mitgetragen und führt zu raschen Gewalteskalationen, in denen das ursprüngliche Objekt keine Rolle mehr spielt: sie werden lediglich durch das Imitieren des Anderen in Gang gehalten.[23] So ginge die Entwicklung des religiösen Denkens in den früheren archaischen Gesellschaften mit einer Abarbeitung von Normen einher, die das Ausbreiten der Gewalt innerhalb der Gruppe verhinderten oder steuerten. Für archaische Gesellschaften ist das Bewusstsein, dass Mimesis und Gewalt dasselbe Phänomen sind, von zentraler Bedeutung. Gewalt wird verhindert, indem man die mimetische Verdoppelung/Spiegelung zwischen Individuen derselben Gruppe verbietet. Verbote, die von archaischen Religionen aufgestellt werden, sind aus dieser Perspektive zu deuten und sind umso aufschlussreicher, je absurder sie uns erscheinen (etwa das Verbieten von Zwillingen, Spiegeln usw.). Girard postulierte die Existenz einer fundierenden Erfahrung, dass die Gewaltspirale durch die Opferung eines Sündenbocks, in einem Sündenbockmechanismus, auch direkt als „Opfermechanismus“ (französisch mécanisme victimaire[24]) bezeichnet, unterbrochen würde. Hat die mimetische Gewalt in einer Gruppe einen Punkt erreicht, in dem alle die Gewalt aller nachahmen und das Objekt, das die Rivalität ausgelöst hat, „vergessen“ ist, so stelle das Auftreten eines einmütig als schuldig empfundenen Individuums eine einheitsstiftende Polarisierung der Gewalt dar: Die Tötung oder Ausstoßung des „Schuldigen“ reinige die Gruppe von der Gewaltseuche, weil diese letzte – gemeinsam vollbrachte – Gewaltanwendung keinen mimetischen Vorgang (Rache) mit sich brächte. Da auch das Objekt, das die Krise ausgelöst hat, vergessen sei, ist die Reinigung durch diese Opferung vollständig. Insofern die Auswahl des Sündenbocks eine mutwillige oder auch zufällige ist, ist der Sündenbock austauschbar: Seine Bedeutung für die Gruppe bestünde in der durch ihn wiederhergestellten Einmütigkeit. Gleichzeitig ist aber der ermordete/ausgestoßene Sündenbock in seiner heilbringenden Abwesenheit einzigartig und unaustauschbar.[25][26] Dieses Geschehen ist mit seiner „wunderbaren“ Wirkung die Offenbarung des Heiligen, das das Überleben der Gruppe ermöglicht: Die dem Opfer nach seiner Tötung dargebrachte Verehrung kommt der Erfindung der Göttlichkeit gleich, und die Wiederholung des Sündenbockvorgangs ist die rituelle Vergegenwärtigung des Heiligen zusammen mit dessen Ausstoßung aus der menschlichen Gesellschaft. Besondere Beachtung verdient die Tatsache, dass die Wiederholbarkeit des Vorgangs und die Austauschbarkeit des Opfers – das, was einen Kult ermöglicht, – in der a-priori-Bösartigkeit des Sündenbocks, also in seiner Unschuld, gründen. Die Gesamtheit der Gebote und Regeln, die das Wiederholen dieses Vorgangs fördern und seinen Ausgang überwachen, machen den eigentlichen Bestand an Riten und positiven Verhaltensnormen jeder archaischen Gesellschaft aus. Nach Michaels (1998 und 1997)[27][28][29] können Ritualhandlungen durch fünf Kategorien von Alltagshandlungen unterschieden werden: Ursächliche Veränderungen, causa transitionis Förmlicher Beschluss, solemnis intentio Formale Handlungskriterien, actiones formaliter ritorum, Förmlichkeit (Repetivität), Öffentlichkeit, Unwiderrufbarkeit, Limininalität Modale Handlungskriterien, actiones modaliter ritorum, subjektive Wirkung, impressio, Vergemeinschaftung, societas, Transzendenz, religio Veränderungen von Identität, Rolle, Status, Kompetenz, novae clasificationes, transitio vitae. Zunächst steht jedes Ritual in Verbindung zu einer Veränderung; es wird im Rahmen einer Grenzüberschreitung ausgeführt. Dennoch ist nicht jeder Wechsel ein Ritual, da sich ritualisierte Veränderungen in der Regel durch den Übergang zwischen verschiedenen Dichotomien wie alt – neu, unrein – rein auszeichnen. Außerdem muss ein förmlicher Beschluss gegeben sein, der etwa durch einen Spruch, Eid oder Schwur gekennzeichnet wird. Rituale sind folglich niemals willkürlich und spontan, sondern werden immer bewusst und mit Absicht, also intentional ausgeführt. Die dritte Komponente von Ritualen ist die Erfüllung formaler Handlungskriterien. Damit sind Ritualhandlungen stereotyp, förmlich, repetitiv, öffentlich, unwiderrufbar und oft auch liminal. Weiterhin zeichnen sie sich auch durch modale Handlungskriterien aus: Rituale sind immer auf die Gemeinschaft bezogen, sie repräsentieren diese also. Außerdem bezieht ein Ritual sich auf etwas Transzendentales und hat auf jeden Teilnehmer eine ganz subjektive Wirkung. Das letzte Kriterium nach Michaels ist die „Veränderung von Identität, Rolle, Status und Kompetenz“, die durch Rituale notwendigerweise herbeigeführt wird. Falls eine der genannten Komponenten nicht gegeben ist, handelt es sich also nicht um ein Ritual. Für Carl Heinz Ratschow (1986)[30] ist Opfer zutiefst immer Selbstopfer. Es geht um die kultisch vollzogene Tötung des Menschen. Es vollzieht sich nach der Logik, nach der nur durch das Sterben das Leben wach bleibt. Es geht um den Weg, sich selbst los zu werden. |

理論的アプローチ 19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけては、進化論的なアプローチが特徴的であった。犠牲の最も原初的な形態に関する問題が最前線にあったが、ほぼ同時期に、犠 牲の種類を区別する試みも行われた。こうした理論的考察に続いて、犠牲の儀式の構造とそこに表現される象徴性についての疑問が提起された。ザイヴェルト は、古典的な犠牲理論の5つの側面を解明した: 神への贈り物や捧げものとしての犠牲、それによって人間と神との間に依存と相互義務の関係を構築する(代表者:エドワード・バーネット・タイラー、マルセ ル・モース)。 人間と神との交わりの儀式的成就としての犠牲;交わりと犠牲の食事に記録されている(代表者:ウィリアム・ロバートソン・スミス) 聖なる世界と俗なる世界との間の儀礼的なコミュニケーションとしての生け贄;生け贄が両者をつなぐ媒介となる(代表者:アンリ・ユベール、マルセル・モー ス) 非人間的な生命力の循環を確保する儀礼的手段としての生贄(代表者:ゲラルドゥス・ファン・デル・リュー、マルセル・モース) 生命に対する神の力と人間の依存を認識する儀式としての犠牲(代表者:ヴィルヘルム・シュミット)[17]。 タイラー(1871年)[18]とフレイザー(1890年)[19]にとっては、「言葉」である神話は世界の物語的な宇宙論的な形成者として立ち、それに よって儀式はカルトにおける官能的なパフォーマンスと物語の劇的な表象の意義を帯びることになる。一方、儀式という「行為」が始まりに立つのであれば、ス ミス(1889)によれば、神話は行為の過程と訓詁学的な説明や教義的な解釈とを結合させるはずである[20][21]。生贄において、人間は超人あるい は超人的な存在に影響を与えるために、超人的な存在との関係を築こうとする。犠牲行為は、人類のほとんどすべての文化に見られる。 犠牲の理論に関する広範な研究は、イギリスの人類学者タイラーが1871年に発表した『原始文化』やフランスの社会学者によって行われた。彼らは『犠牲の 本質と機能に関するエッセー』(1898-1899年)の中で、とりわけ犠牲の4つの基本的要素を提唱した: 犠牲者 犠牲者 犠牲を受ける者 生け贄は誰のために、誰の責任で行われるのか。 ルネ・ジラール(1972年)[22]もまた、模倣と暴力の関係を確立する模倣理論に関する考察において、犠牲の理論を展開している。模倣理論の中心的な 仮定は、人間社会は集団内での暴力の拡散にうまく対抗することができなければ存続できないというものである。対人紛争の原因は、互いに密接に接触して生活 する人々の模倣行動である: この行動は対抗心、ねたみ、嫉妬を生み、伝染し、集団の全メンバーによって共有され、暴力が急速にエスカレートすることにつながるが、その際、本来の対象 はもはや役割を果たさない。古代の社会にとって、擬態と暴力が同じ現象であるという認識は、中心的な重要性を持つ。暴力は、同じ集団に属する個人間の模倣 的複製/模倣を禁止することによって防止される。古代の宗教が課していた禁止事項は、この観点から解釈されるべきであり、私たちにとって不条理に見えれば 見えるほど、より明らかになる(双子や鏡の禁止など)。 ジラールは、「犠牲のメカニズム」(フランス語でmécanisme victimaire[24])とも直接的に呼ばれるスケープゴート・メカニズムにおいて、暴力のスパイラルはスケープゴートの犠牲によって中断されると いう根底にある経験の存在を仮定した。ひとたび集団における模倣的暴力が、誰もが他者の暴力を模倣し、対立の引き金となった対象が「忘れ去られる」ところ まで達すると、満場一致で有罪と認識される個人の出現は、暴力の統一的な分極化を意味する: 罪を犯した」個人を殺すか追放することで、集団から暴力の疫病が一掃される。なぜなら、この最終的な(共同で達成される)暴力の行使は、模倣の過程(復 讐)を伴わないからである。危機の引き金となった対象も忘れ去られるため、この犠牲による浄化は完了する。スケープゴートの選択が意志的なもの、あるいは 無作為なものである限り、スケープゴートは交換可能である。しかし同時に、殺された/追放されたスケープゴートは、その救いの不在において唯一無二であ り、かけがえのない存在である[25][26]。 この出来事は、その「奇跡的な」効果とともに、集団の存続を可能にする聖なるものの啓示である。殺害後に犠牲者に捧げられる崇敬は、神性の発明に等しく、 スケープゴートのプロセスの反復は、人間社会からの追放とともに、聖なるものの儀式的視覚化である。 このプロセスの反復可能性と生贄の交換可能性、つまりカルトを可能にするものは、先験的な身代わりの邪悪さ、つまりその潔白さに基づいているという事実 に、特に注意を払うべきである。 このプロセスの反復を促し、その結果を監視する戒律や規則の総体が、あらゆる古風な社会の儀式や積極的な行動規範の実際のストックを構成している。 マイケルズ(1998および1997)[27][28][29]によれば、儀礼行為は5つのカテゴリーによって日常的行為と区別することができる: 原因的変化、causa transitionis 形式的解決、solemnis intentio 行為の形式的基準、actiones formaliter ritorum、形式性(反復性)、公然性、取消不能性、限界性 行為の様相的基準、actiones modaliter ritorum、主観的効果、印象、共同体化、社会性、超越、religio アイデンティティの変化、役割、地位、能力、新しい分類、transitio vitae。 まず第一に、すべての儀式は変化と結びついている。しかし、すべての変化が儀式というわけではない。儀式的な変化は通常、古い-新しい、不純-純粋といっ た異なる二項対立の間の移行によって特徴づけられるからである。加えて、たとえば呪文や誓い、誓約によって特徴づけられるような正式な決定がなければなら ない。したがって、儀式は決して恣意的で自然発生的なものではなく、常に意識的かつ意図的に、すなわち意図的に行われるものである。儀礼の第三の要素は、 行為の形式的な基準を満たすことである。つまり、儀式行為は定型的で、形式的で、反復的で、公的で、取消不能で、しばしば限界的である。さらに、儀式は行 為に関する様式的基準によっても特徴づけられる: 儀式はつねに共同体に関係し、共同体を代表する。さらに、儀式は超越的なものを指し示し、参加者それぞれに非常に主観的な影響を与える。マイケルズによれ ば、最後の基準は、儀式によって必然的にもたらされる「アイデンティティ、役割、地位、能力の変化」である。これらの構成要素のいずれかが存在しなけれ ば、それは儀式ではない。 カール・ハインツ・ラッチョー(1986)[30]にとって、犠牲とは常に深い自己犠牲である。それは儀式化された人間の殺害のことである。それは、生命 は死ぬことによってのみ生き続けることができるという論理に従って行われる。それは、自分自身を処分する方法についてである。 |

| Vor- und frühgeschichtliche Opfer → Hauptartikel: Menschenopfer Die spärliche archäologische Fundlage der vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Zeit erlaubt keine näheren Aussagen über Glaubensinhalte in den unterschiedlichen Ethnien und den historischen Perioden und Epochen. In dieser Zeit sind immer wieder Deponierungen zu beobachten, die als Gaben für Gottheiten oder auch als deponierte Jenseitsausstattungen für Verstorbene zu verstehen sind. Als Opfer sieht man insbesondere solche Deponierungen an, die offenbar unwiderrufbar niedergelegt wurden. |

先史時代と原始時代の供犠 → 主な記事 人間の生け贄 先史時代や原始時代からの考古学的出土品が乏しいため、さまざまな民族や歴史的時代やエポックの信仰について、これ以上詳しく述べることはできない。この 『存在と時間』の間に、神への供え物として、あるいは死者のための死後の生活用具として理解されるような堆積物が何度も観察された。特に、明らかに不可逆 的に埋葬されたものは供犠とみなされる。 |

Opfer bei keltischen und

germanischen Stämmen Das Opfermoor bei Niederdorla mit stilisierter Göttergestalt Archäologische Funde wie auch philologische Zeugnisse ergeben das Bild einer polytheistischen Anschauung bei den keltischen Stämmen mit zahlreichen lokalen und regionalen, aber auch einigen überregional verbreiteten keltischen Gottheiten. Überliefert sind die Namen der Gottheiten festlandkeltischer Kulturen durch Inschriften und die Werke antiker griechischer und römischer Autoren. Die religiöse Praxis der Kelten umfasst insgesamt den heiligen Ort, die heilige Zeit, die kultischen und magischen Verrichtungen – Opfer, Gebet und Mantik (Weissagung) –, den Kopfkult, das Sterben und das Totengedenken, das Kultpersonal und die diesem Brauchtum zugrundeliegenden Vorstellungen.[31] Sie ist durch Berichte antiker Autoren und vor allem durch die große Zahl von archäologischen Funden etwas besser belegt als die keltische Götterwelt und die keltische Mythologie. Da jedoch aus Fundstücken und wesentlich später verfassten Texten Glaubensinhalte und dazugehörende Rituale nur unsicher bis gar nicht erschlossen werden können, ist die keltische Religion ebenfalls nur unvollständig rekonstruierbar.[32] Verschiedene keltische Götter verlangten verschiedene Opfer. Die Opfer für Esus wurden erhängt, die für Taranis verbrannt, und die für Teutates ertränkt. Kelten wie Germanen wählten mitunter ein Moor als Ort der Opferung. Beispiele dafür sind Moorleichen wie der Lindow-Mann in Großbritannien oder der Grauballe-Mann in Dänemark. Bei ersterem wird freiwillige Annahme der Opferung vermutet. In der irischen Mythologie gibt es Hinweise darauf, dass die Tötung eines Einzelnen auf mehrfache Weise diesen Regeln entsprechen konnte.  Grauballe-Mann aus Dänemark der wahrscheinlich in einem sakralen „Overkill“ starb. Das „Opfer“[33] wurde von den Germanen an Naturheiligtümern und personifizierten Gottheiten wie auch sogenannten Pfahlgötzen dargebracht. Es war elementarer Bestandteil im religiösen Kult der jeweiligen sozialen Gemeinschaft.[34] Der besondere Begriff für die Opferhandlung lautet germ. *blætan „opfern“ und ist eine Abform aus germ. *blæstra-, *blæstram „Opfer“. In altnordischer Variation lautet der Begriff blót (Varianten in der gotischen, der altenglischen, und althochdeutschen Sprache) mit der Bedeutung von „stärken“, „anschwellen“ – eine sprachliche Verbindung zum Begriff Blut und im übertragenen Sinn zu einem blutigen Opfer besteht nicht. Weitere semantische Begriffe für Opfer stehen mit unterschiedlichen Kult- und Opferpraktiken in Zusammenhang. Im wesentlichen Sinn war das Opfer von der Bestimmung her als Bitt- und Dankopfer gestaltet nach dem Prinzip do ut des – „ich gebe damit du (Gottheit) gibst“. Geopfert wurde individuell im privaten Kult, aber auch gemeinschaftlich organisiert, dann auch zu Festen unterjährigen Anlässen wie im Frühjahr, im Mittsommer oder zum Herbst und Mittwinter.  Tollund-Mann der eines gewaltsamen Todes starb und möglicherweise im Rahmen eines Opferrituals getötet wurde. Örtlichkeiten für die Opferhandlungen waren seit der vorhistorischen Zeit, der römischen Kaiserzeit neben Baumheiligtümern oder Hainen, besonders Landmarken im feuchten Gelände- und Bodenkontext von Mooren (Opfermoor), Seen, Quellen oder Fließgewässern. Namentlich archäologische Fundstätten in Deutschland und Dänemark geben einen umfangreichen Einblick in die Kult- und Opferpraxis.[35] Beim Opfer, das konkret einer Gottheit bestimmt war, wurde zum einen das Idol (wenn archäologisch lokal bestätigt) symbolisch „gespeist“, zum anderen hatte durch den Verzehr des Opfermahls – bestehend aus den zuvor geopferten und anschließend gegarten Tieren – die Opfergemeinschaft Anteil. Bezeichnenderweise ist die Bezeichnung des Opfertieres germ. *saudi-, *saudiz, *sauþi-, *sauþiz in neuhochdeutscher Wiedergabe: das Opfer in übertragener Form, und als Gattungsname des gemeinen Hausschafs, sowie in der Erweiterung und eigentlichen Wurzel „Gesottenes“. Eine weitere begriffliche Kategorie ist das Nomen germ. *tibra-, *tibram, *tifra-, *tifram für nhd. Opfertier, Opfer. Die Ableitung Geziefer, beziehungsweise Ungeziefer aus der althochdeutschen Zwischenstufe unterscheidet von der Grundbedeutung her Tiere in die fürs Opfer geeigneten oder ungeeigneten. Die heidnische Opfertätigkeit war daher ein Schwerpunkt der karolingischen Mission im Niederdeutschland des 8. bis 9. Jahrhunderts und spiegelt sich in kirchlichen Verbotsschriften wider (Indiculien).[36] Weitere signifikante Opfergaben sind Waffen und andere militärische Ausrüstung (vermutlich von besiegten Feinden), diese wurden bei den Orten ebenfalls dargebracht. Auffällig ist, dass geopferte Waffen zuvor unbrauchbar gemacht wurden. Teilweise sind diese Gegenstände von hohem materiellen wie ideellen Wert (Schwerter, aber auch Schmuck, Fibeln), wodurch der kultisch-rituelle Bezug ersichtlich ist (Brunnenopfer von Bad Pyrmont). Menschenopfer sind seit historischer Zeit schriftlich belegt, wie beispielsweise die Opferung eines Sklaven beim Nerthuskult, so beschrieben von Tacitus. Die archäologischen Fundauswertungen zeigen hingegen, dass Menschenopfer statistisch sehr selten praktiziert wurden. Für die in Norddeutschland und Dänemark gefundenen Moorleichen, die oft mit Menschenopfern in Verbindung gebracht werden gilt: lediglich ein kleiner Teil der etwa 500 Funde weisen sicher auf einen kultischen Hintergrund hin. Im Zusammenhang mit Menschenopfern ist eine bedingte kultische Anthropophagie nachgewiesen, die auch die animistischen Züge der germanischen Religion anzeigen.[37] Siehe auch: Nordgermanische Religion und Angelsächsische Religion |

ケルトとゲルマン民族の供犠 ニーダードルラ近郊の生け贄沼と様式化された神像 考古学的な発見や文献学的な証拠から、ケルト諸部族は多神教的な信仰を抱いていたことがわかる。ケルト文化圏の神々の名前は、碑文や古代ギリシャ・ローマ 時代の著者の作品を通して伝えられてきた。ケルト人の宗教的実践は、聖なる場所、聖なる時間、供犠、祈祷、マンティック(占い)といった崇拝的・呪術的実 践、頭部崇拝、死と死者の追悼、カルト要員、そしてこれらの習慣の根底にある思想を包含している[31]。 ケルトの神々の世界やケルト神話よりも、古代の著者の報告や、とりわけ考古学的な発掘品の多さによって、いくぶんよく記録されている。しかし、信仰や関連 する儀式の内容は、かなり後になって書かれた遺物や文書から不確かな、あるいはまったく推測することができないため、ケルトの宗教もまた不完全にしか再構 築することができない[32]。エスースへの供犠は絞首刑に、タラニスへの供犠は火葬に、テウタテスへの供犠は水葬にされた。ケルト人もゲルマン民族も、 生け贄の場所として沼地を選ぶことがあった。その例が、イギリスのリンドウマンやデンマークの灰色俵男などの沼地死体である。前者の場合、生贄を自発的に 受け入れたと考えられる。アイルランドの神話では、個人の殺害がいくつかの方法でこのルールを満たす可能性が示唆されている。  おそらく神聖な「殺し過ぎ=過剰殺戮」で死んだデンマークのグレイ・ベール人。 供犠」[33]はゲルマン民族によって自然の祠や擬人化された神々、いわゆる杭の偶像に捧げられた。それはそれぞれの社会共同体の宗教的カルトの初歩的な 構成要素であった[34]。 犠牲的行為を表す特別な用語はドイツ語である。*blætanは「供犠」であり、germの派生語である。*blæstra-、*blæstram「供 犠」の派生語である。古ノルド語のバリエーションでは、この用語はblót(ゴート語、古英語、古高ドイツ語のバリエーション)であり、「強化する」、 「膨張させる」という意味である。供犠を意味する他の用語は、さまざまなカルトや供犠の実践に関連している。基本的に、供犠はドゥ・トゥ・デス(do ut des)の原則に従った嘆願と感謝の供犠として意図されていた。供犠は、個人的な礼拝の中で個別に捧げられたが、集団的に組織されることもあり、春、真 夏、秋、真冬など、1年のうちの祭りの際にも行われた。  トッランド人は非業の死を遂げたが、おそらくは生贄儀式の一環として殺されたのだろう。 先史時代からローマ帝国時代にかけて、生け贄の儀式を行う場所は、樹木の聖域や木立、特に湿った地形や土壌の背景となる湿原(生け贄の湿原)、湖、泉、流 水などのランドマークであった。特にドイツとデンマークの考古学的遺跡は、カルトと生け贄の実践に関する包括的な洞察を提供している[35]。 特に神のための供犠の間、(現地で考古学的に確認された場合)偶像は象徴的に「養われ」、供犠の共同体もまた、以前に供犠され、その後調理された動物から なる供犠の食事の消費を共有した。重要なのは、犠牲動物の名前が細菌であることだ。新高ドイツ語訳では、*saudi-, *saudiz, *sauþi-, *sauþiz:比喩的な形での供犠、一般的な家畜である羊の総称としての供犠、また拡張語源および実際の語源である「ゲソッテネス (Gesottenes)」である。もう1つの概念的カテゴリーは、名詞の胚芽である。*tibra-、*tibram、*tifra-、*tifram は、犠牲動物、供犠の名詞である。古高ドイツ語の中間段階から派生したGeziefer(害獣)は、動物を基本的な意味から供犠に適したものと適さないも のに区別する。そのため、異教徒の生け贄活動は、8世紀から9世紀にかけてのカロリング朝のニーダー・ドイツにおける宣教の焦点であり、教会の禁止事項 (indiculia)に反映されている[36]。 その他の重要な捧げ物としては、武器やその他の軍事装備(おそらく敵を倒したもの)があり、これらもまた遺跡に捧げられていた。生け贄に捧げられた武器 が、以前は使用不可能なものであったことが印象的である。これらのものの中には、物質的・感傷的に価値の高いもの(剣だけでなく、宝飾品やフィブラ)もあ り、カルト的・儀礼的であることは明らかである(バート・ピルモントでは生贄が捧げられた)。人身御供は『存在と時間』の時代から記録されており、例えば タキトゥスが記述したネルトス教団における奴隷の生贄がそうである。しかし、考古学的な発見は、人身御供が統計的に非常にまれであったことを示している。 北ドイツやデンマークで発見された泥沼の死体は、しばしば人間の生け贄と関連づけられるが、次のことが当てはまる:500体ほどの発見物のうち、カルト的 背景を示すものはごくわずかである。人身供犠に関連して、条件付きでカルト的な人食いが証明されており、ゲルマン宗教のアニミズム的特質も示している [37]。 北ゲルマン宗教とアングロ・サクソン宗教も参照のこと。 |

| Altorientalische Opferriten und

Vorstellungswelt Die altorientalischen Vorstellungen interpretierten die Welt als einen permanenten Konflikt zwischen Ordnung, gedacht als ‚Kosmos‘ und Unordnung dem ‚Chaos‘. Alle lebensfördernde Kräfte und Mächte, Ordnung, Wahrheit, Herrschaft, Regeln, Normen zeigten sich für den altorientalischen Menschen im Wiederkehrenden, in zeitlichen Strukturen, wie Jahreslauf, Gesundheit, Geburt und Tod in erwartbarem Rahmen. Interruptionen des Regelmäßigen stellten den Einbruch des Chaos dar. Sie zeigten sich in Himmelserscheinungen, wie einer Sonnen- und Mondfinsternis, in Erdbeben, Dürren, Wetterkatastrophen, Seuchen und Krankheiten. Ordnung zeigte sich, wenn die chaotischen Erscheinungen im Abstand zum bestehenden blieben und nicht auf die geordneten Strukturen ausgriffen. Der höchste Garant für eine geordnete Welt sei Gott bzw. die Götter. Obgleich auch die Erscheinungen des Chaos ihre Götter hätten, wären diese Gottheiten in ihrer Existenz die Voraussetzung dafür, dass die (ordnenden) Gottheiten sich erst im Stande versetzt sähen eine Ordnung überhaupt zu etablieren. Eine göttliche Weltordnung ist vom Menschen erfahrbar und muss in ihren Konsequenzen von ihm umgesetzt werden. Hierzu sind Ritualspezialisten aufgerufen mit dem höchsten Gott bzw. Gottheiten in Kontakt zu treten, durch Rituale, Kulthandlungen, Gebeten und Opferungen zumeist in einem Haupttempel.[38] Der Zweck, den Menschen mit Opfern verfolgten, lässt sich im Gilgamesch-Epos nachvollziehen, das auf Keilschrifttäfelchen zu finden ist. Er ist erst als solches ab der zweiten Hälfte des 2. Jahrtausends v. Chr. belegt; der Titel „Derjenige, der die Tiefe sah“ (ša naqba īmuru). Eine vermutlich ältere Fassung des Epos war unter dem Titel „Derjenige, der alle anderen Könige übertraf“ (Šūtur eli šarrī) bereits seit altbabylonischer Zeit (1800 bis 1595 v. Chr., während der mittleren Bronzezeit) bekannt. |

古代近東の犠牲儀礼と想像力 古代オリエントの思想は、世界を「コスモス」として構想される秩序と、「カオス」である無秩序との間の永続的な対立として解釈した。生命を維持する力や 力、秩序、真理、支配、規則、規範はすべて、古代東洋人にとっては、一年の経過、健康、誕生、死といった時間的構造の中で、予期された枠組みの中で繰り返 されるものとして明白であった。規則性の中断は混沌の侵入を意味した。それらは、日食や月食、地震、干ばつ、気象災害、伝染病、病気などの天体現象に現れ た。秩序が現れるのは、カオス的な現象が既存の構造から距離を置き、秩序ある構造に影響を与えない場合である。秩序ある世界の最高の保証人は、神または神 々であった。カオスの現象にも神々が存在したが、これらの神々が存在することが、そもそも(組織化する)神々が秩序を確立できる前提条件だった。 神の世界秩序は人間によって経験され、その結果において人間によって実現されなければならない。この目的のために、儀礼の専門家は、儀式、儀礼行為、祈 り、生け贄を通じて、最高位の神や神々と接触するよう要請され、通常は本殿で行われる[38]。 人々が供犠によって追い求めた目的は、楔形文字に記された『ギルガメシュ叙事詩』に見ることができる。ギルガメシュ叙事詩は紀元前2千年紀の後半に書かれ たもので、タイトルは「深淵を見た者」(ša naqba īmuru)である。この叙事詩のおそらく古いバージョンは、古バビロニア時代(紀元前1800年から紀元前1595年、青銅器時代中期)からすでに「他 のすべての王を凌駕する者」(Šūtur eli šarrī)というタイトルで知られていた。 |

| Opfer im alten Mesopotamien Sumerer und Assyrer Die sumerische Religion kann als die erste verschriftliche Religion im Übergang der Kupferzeit zur frühen Bronzezeit in der Region Mesopotamien angesehen werden. Sie prägte die nachfolgenden Zeit- und Kulturepochen mit ihren im Umfeld liegenden Kulturen, so z. B. die Akkader, Assyrer und Babylonier. Der Mythos wird so erzählt, dass die Götter den Unterwelt-, gelegentlich auch als Pestgott bezeichneten Namtar beauftragten die Menschen zu vernichten. Dieser begann, sie mit der Pest zu töten. Ein Gott aber, der Mitleid mit den Menschen hatte, nämlich Enki, verriet dem Priester Atraḫasis ein Ritual, mit dem die Seuche einzudämmen sei. Die Menschen sollten nur noch den Pestgott Namtar verehren und allein ihm opfern, bis er, überschüttet mit Opfern, von seinem tödlichen Tun abließe. Dank der Opfer fühlte sich der Pestgott geschmeichelt und ließ von seinem Wüten ab, und die Menschen vermehren sich weiter. Nun beschlossen die Götter, dass der Regengott Adad es nicht mehr regnen lassen und die Korngöttin Nisaba kein Korn mehr wachsen lassen solle. Wieder verriet der Gott Enki dem Atrachasis das rituelle Gegenrezept: Nun verehrten und opferten die Menschen allein Adad und Nisaba, und zwar, bis Regen fiel und die Vegetation wieder auflebte (siehe auch das Atraḫasis-Epos). |

古代メソポタミアにおける供犠 シュメール人とアッシリア人 シュメールの宗教は、メソポタミア地域の銅器時代から初期青銅器時代への移行期における最初の文字による宗教とみなすことができる。この宗教は、アッカド 人、アッシリア人、バビロニア人などの周辺文化とともに、その後の『存在と時間』を特徴づけた。この神話は、神々が冥界の神ナムタル(疫病神とも呼ばれ る)に人々を滅ぼすよう命じたと伝えられている。彼は疫病で人々を殺し始めた。しかし、民を憐れんだ神エンキが、疫病を封じ込めるための儀式を祭司アトラ エバシスに教えた。人々は疫病の神ナムタルを崇拝し、供犠を捧げるだけでよかった。供犠のおかげで疫病神は気をよくして暴れるのをやめ、人々は増え続け た。次に神々は、雨の神アダドに雨を降らせることをやめさせ、穀物の女神ニサバに穀物が育つことをやめさせることにした。再びエンキ神がアトラカシスに対 して儀式の解毒剤を示した。雨が降り、植生が復活するまで、人々はアダドとニサバだけを崇拝し、供犠した(アトラカシス叙事詩も参照)。 |

| Babylonier Für den aus Enki, dem sumerischen Gott der Weisheit, hervorgegangenen babylonischen Gott Ea opferte eine besondere, kalu genannte Priesterschaft einen schwarzen Stier, mit dessen Haut im Opferritual die heilige Trommel lilissu bespannt wurde.[17] Das altmesopotamischen Ritualexpertentum hatte sowohl seine Techniken, als auch die handelnden Akteure weit differenziert und entwickelt, um so die Zeichen der angekündigten Warnungen und Botschaften zu deuten. Dabei kann zwischen Ritualexperten, die die göttliche Botschaften direkt erhielten, und solchen, die Zeichen anhand standardisierter Interpretationen auslegten, unterschieden werden. Zu den Akteuren der ersten Gruppe gehören Propheten (akkadisch raggimu, ragintu), Ekstatiker (akkadisch muḫḫû oder maḫḫû) und solche Mantiker, die etwa während eines Inkubationsrituals (Inkubation bzw. Enkoimesis) den Willen der Götter erträumten.[39] Eine weitere, zweite Gruppe von Akteuren bildeten die Schriftkundigen (akkadisch ṭupšarru „Schreiber“, ummânu „Weiser“), die Ritualexperten für die Opfer- oder Eingeweideschau (akkadisch bārû „Seher“, eigentlich „derjenige, der inspiziert“) sowie die Experten für magische Handlungen (akkadisch āšipu „Beschwörungskunst“).[40] |

バビロニア人 シュメールの知恵の神エンキから生まれたバビロニアの神イーアのために、カルーと呼ばれる特別な神職が黒い雄牛を捧げ、その皮は供犠の儀式で神聖な太鼓リ リスで覆われた[17]。 古代メソポタミアの儀礼の専門家は、告げられた警告やメッセージの兆候を解釈するために、その技法と関与する行為者の両方を区別し、発展させてきた。神の メッセージを直接受け取る儀礼の専門家と、標準化された解釈に基づいてしるしを解釈する専門家とを区別することができる。第一のグループには、予言者 (アッカド語のragimu、ragintu)、恍惚論者(アッカド語のmuḫ、maḫ)、孵化儀式(incubation、enkoimesis)の際 に神々の意志を夢想したマンティクなどが含まれる。[39]もう一つの、第二の行為者グループは、書記(アッカド語のṭupšarru「書記」、 ummânu「賢者」)、供犠や内臓検査の儀式の専門家(アッカド語のbārû「先見者」、実際には「検査する者」)、呪術行為の専門家(アッカド語の āšipu「呪術」)であった[40]。 |

| Opfer im Judentum → Hauptartikel: Tahara → Hauptartikel: Jerusalemer Tempel → Hauptartikel: Kohanim Bedeutung Der Begriff hebräisch קָרְבָּן qårbān[41] ist ein Aktionsnomen, das sich vom Wurzelkonsonant hebräisch קרב qrb, deutsch ‚sich nähern‘ ableitet.[42] Damit hatte die Opferung in der jüdischen Antike eine andere Konnotation, etwa im Vergleich zu den Opferungen des antiken Griechenlands oder des Römischen Imperiums oder auch im Umkreis der altorientalischen Religionen, denn das Opfer sollte eine Verbindung zu Gott herstellen, sich ihm annähern und war nicht als eine Gabe oder Geschenk an einen polytheistischen Gott gedacht.[43] Historische Entwicklungen Das Opferwesen im Judentum findet eine starke Zäsur nach der Zerstörung des Herodianischen Tempels 70 n. Chr. Die bereits vor dem Jüdischen Krieg festzustellenden Bestrebungen, das religiöse Leben neu zu organisieren, wurden unter dem Eindruck der neuen Bedingungen umgesetzt. Es kam zur Ausbildung des rabbinischen Judentums, denn als Folge der Tempelzerstörung endete der Tieropferkult, und das Amt des Hohepriesters (auf hebräisch כהן גדול kohen gadol, deutsch ‚großer Priester‘, siehe Kohen), war damit seine Grundlage entzogen worden. Biblischer Bezug Seit Abraham seinen Sohn nicht opfern musste, gilt auch im Judentum, dass JHWH keine Menschenopfer will.[44] Denn von Abraham berichtet das Alte Testament der Bibel, Gott habe zwar prinzipiell von ihm auch die Opferung des Sohnes Isaak verlangt (Menschenopfer sind aus Nachbarreligionen und dem Buch der Richter bekannt[45]), jedoch den Ersatz durch Opfertier angeordnet. Ausführung Im Judentum wurden zur Zeit des zweiten Tempels[46] die Tieropfer zentral im Tempel von Jerusalem vollzogen. Diese wurden durch Schlachtung dargebracht.[47] Der Hauptakteur im jüdischen Opferkult war der Hohepriester.[48] Er trug symbolische Gewänder und Insignien. Seine Hauptaufgabe war es, die täglichen Tieropfer darzubringen, auch durfte nur der Hohepriester einmal im Jahr am Jom Kippur das Allerheiligste betreten. Er besprengte die Bundeslade mit dem Blut von zwei Opfertieren, hierin begegnete Gott symbolisch seinem Volk Israel.[49] Im 3. Buch Mose, hebräisch וַיִּקְרָא Wajikra, deutsch ‚Gott sucht das Gespräch‘ (Lev 1,3 EU) wird über die Qualität der tierischen Opfermaterie berichtet: „Will er ein Brandopfer darbringen von Rindern, so opfere er ein männliches Tier, das ohne Fehler ist.“[50] Für die vegetabile Opfermaterie Lev 2,2O EU: „Und der Priester soll eine Handvoll nehmen von dem Mehl und Öl samt dem ganzen Weihrauch und es als Gedenkopfer in Rauch aufgehen lassen auf dem Altar als ein Feueropfer zum lieblichen Geruch für den Herrn.“ Dennoch präferierte JHWH nach 1 Mos 4,5 EU das Tieropfer, so gefiel JHWH Kains vegetabiles Opfer nicht. Im Ausdruck seiner Unzufriedenheit säte er durch seine Zurückweisung der Opfermaterie die erste Zwietracht unter den biblischen Menschen. Einmal im Jahr fand ein Entsündigungsopfer für das Heiligtum selbst und die Priesterschaft statt: der Versöhnungstag (siehe dazu Wajikra (3. Buch Mose) Kapitel 16). Ein Opferritual, wie durch die Schechita eines ausgewählten Tieres, war ein Ereignis, bei dem zwei Gruppen, allgemein der Zuschauer („Israeliten“) und die Akteure („Hohepriester“), miteinander in Interaktion traten. Dabei nahmen die Tempelbesucher in einer spezifischen Art und Weise an der Kulthandlung teil, indem ihre physische Präsenz, die Wahrnehmung, die Rezeption und spezifische Reaktion Einfluss auf das Erleben der Opferung hatten. So muss man vermuten, dass etwa die olfaktorische Wahrnehmung der verbrennenden Tierkadaver ebenso bedeutsam war wie das (schockierende) Arrangement des Tötens eines Tieres vor den Augen der Besucher.[51] |

ユダヤ教における供犠 → 主な記事 田原 → 主な記事 エルサレム神殿 → 主な記事 コハニム 意味 ヘブライ語קָרְבָּן qårbān[41]は、「近づく」を意味する子音ヘブライ語קרב qrbを語源とする動作名詞である。[なぜなら、供犠は神とのつながりを確立し、神に近づくためのものであり、多神教の神への贈り物や捧げ物として意図さ れたものではなかったからである[43]。 歴史的発展 ユダヤ教における生け贄制度は、紀元70年のヘロディア神殿の破壊後に大きな断絶を迎える。神殿の破壊によって動物犠牲の崇拝が終わり、大祭司(ヘブライ 語で]הן גדול kohen gadol、ドイツ語で「偉大な祭司」、「コーヘン」を参照)の職がその基盤を失ったため、ラビ派ユダヤ教が形成された。 聖書への言及 アブラハムは息子を供犠する必要がなかったため、ユダヤ教もまたYHWHは人間の供犠を望んでいないとしている[44]。聖書の旧約聖書では、神は原則と してアブラハムにも息子イサクの供犠を要求したが(人間の供犠は近隣の宗教や士師記[45]で知られている)、それを供犠に置き換えるよう命じたと報告さ れている。 処刑 ユダヤ教では、動物のいけにえは『第二神殿』の存在と時間』エルサレム神殿で集中的に執行された[46]。47] ユダヤ教の生贄崇拝の主役は大祭司であり[48]、彼は象徴的なローブと記章を身に着けていた。彼の主な仕事は毎日の動物の犠牲を捧げることであり、大祭 司だけが年に一度、ヨム・キプールの日に至聖所に入ることを許された。モーセの書』第3章(ヘブライ語 וֵיִ↪Mn_5רּקָא Wajikra、ドイツ語 『God seeks dialogue』 (Lev 1:3 EU))には、動物の供犠の質について次のように記されている:"牛の燔祭をささげようとするならば、傷のない雄の動物をささげなければならない。 「[50]植物性のものについては、レビ2:2O EU: 」祭司は、小麦粉と油の一握りをすべての香とともに取り、これを記念の供え物として、主に喜ばれる香りのために火による供え物として祭壇の上で焼かなけれ ばならない。". それにもかかわらず、創世記4:5 EUによれば、YHWHは動物の供犠を好まれたので、YHWHはカインの野菜の供犠を喜ばれなかった。不満を表明したカインは、いけにえを拒否すること で、聖書の民の間に最初の不和の種をまいた。 年に一度、聖所そのものと祭司職のために贖いのいけにえが捧げられた:贖罪の日(ワジクラ(創世記3章)16節参照)。 犠牲の儀式は、選ばれた動物のシキタなどを通じて行われ、一般的には観客(「イスラエル人」)と行為者(「大祭司」)という2つのグループが互いに影響し 合うイベントであった。神殿を訪れた人々は、その物理的な存在感、知覚、受容、具体的な反応が生贄の体験に影響を与えるという点で、特別な形で儀式行為に 参加した。例えば、燃えている動物の死骸の嗅覚は、参詣者の目の前で動物が殺されるという(衝撃的な)配置と同じくらい重要であったと想定されなければな らない[51]。 |

| Opferformen Die unterschiedlichen Opferformen zeigen, dass das Verständnis des Opfers in der Tora vielschichtig war, es findet sich das Motiv der Speisung der Gottheit ebenso (Ex 25,23–30 EU, Ps 50,8–13 EU) wie des Verzichts auf Wertvolles. Ein Opfer kann der Gottheit huldigen oder ihren Zorn stillen, es kann Dank oder Buße ausdrücken. Hinzu kommt bei Verspeisung des Opfertieres die Vorstellung einer heilvollen Mahlgemeinschaft zwischen Gott und den Opfernden.[52][53] Die Bedeutung des Räucherns bzw. der rituellen Rauchopfer bei den Juden zeigt sich bereits im hebräischen Wort (rûaḥ רוּחַ), das sich mit Geist, Wind, Atem bzw. Atem Gottes, aber auch mit Duft, Feuerluft oder Feuernebel übersetzen lässt. Duft und Rauch werden semantisch hier in einem engen Zusammenhang mit dem Göttlichen gesehen. Zudem wird der Rauch von verbranntem Räucherwerk als Zeichen der Anwesenheit Gottes gedeutet. Er garantiert dessen Präsenz in seinem Heiligtum und ist zugleich Schutzmittel des Hohenpriesters vor der Gegenwart Gottes im Offenbarungszelt (Lev 16,12f. EU), damit dieser nicht sterbe. In der jüdischen Opfertheologie wird mit dem Verbrennen von Räucherwerk der Kontakt zu Gott hergestellt. Der Rauch des aufsteigenden Opfers verbindet oben und unten miteinander. Auf diese Weise wird die Verbindung von Gott und Mensch zeichenhaft sichtbar gemacht. Eine Beschreibung der verschiedenen Opfer und ihrer Rituale und Gründe findet sich an verschiedenen Stellen in der Tora, vor allem aber in Wajikra (3. Mose 1–8 EU). In alttestamentlicher Zeit gab es fünf Opfergaben: Die Tora (fünf Bücher Moses) kennt fünf Opferarten, die sich durch ihre Rituale und ihre Anlässe unterschieden. Olah (עלה) [übersetzt mit: Aufstiegsopfer, Ganzopfer, Brandopfer, Holocaust] Mincha (מנחה) [übersetzt mit: Speiseopfer, Getreideopfer] Sebach Schlamim (זבח שלמים) [übersetzt mit: Heilsopfer, Mahlopfer, Friedensopfer] Chattat (חטאת) [übersetzt mit: Sündopfer, Verfehlungsopfer, Reinigungsopfer] Ascham (אשם) [übersetzt mit: Schuldopfer] Außerdem gab es die Möglichkeit zu freiwilligen Gaben an den Tempel aus Dank oder zur Erfüllung eines Gelübdes. |

いけにえの形式 供犠のさまざまな形は、律法における供犠の理解が重層的であったことを示している。神に食物を与えるというモチーフ(出エジプト25:23-30 EU、詩篇50:8-13 EU)が見られるだけでなく、価値あるものを放棄することもある。供犠は神に敬意を表したり、怒りを鎮めたり、感謝や悔恨を表したりする。さらに、犠牲の 動物が食べられるとき、神と犠牲者の間に神聖な交わりという考えがある[52][53]。 ユダヤ人における香や儀式の煙の供え物の意味は、ヘブライ語の(rûaḥ רו ּ ַ)ですでに明らかであり、それは精霊、風、息、神の息と訳すことができるが、香り、火の空気、火の霧とも訳すことができる。香りと煙は、ここでは意味的 に神と密接に結びついている。さらに、香を焚く煙は神の臨在のしるしと解釈される。それは、聖所における神の臨在を保証し、大祭司が死なないように、会見 の天幕における神の臨在から大祭司を守る手段でもある(レビ16:12f. EU)。ユダヤ教の犠牲の神学では、香を焚くことは神との接触を確立する。立ち上る供犠の煙は上と下をつなぐ。このようにして、神と人とのつながりが象徴 的に視覚化されるのである。さまざまな供犠とその儀式と理由についての記述は、トーラー(律法)のさまざまな箇所に見られるが、とりわけワジクラ(レビ記 1-8章EU)に詳しい。旧約聖書』の存在と時間には、5つの犠牲の捧げものがあった: 律法(モーセの5書)には、儀式や場面が異なる5種類のいけにえが認められている。 オラ(עלה)[昇天のいけにえ、全供え物、燔祭、ホロコーストと訳される]。 ミンチャ(מנחה)[穀物の供え物、穀物の犠牲と訳される] セバク・シュラミム(זבח שළמים)[訳:救いのいけにえ、食事のささげ物、平和のささげ物] チャタット(חטאת)【訳:罪の捧げ物、不義の捧げ物、清めの捧げ物 アシャム(אשם)[訳注:罪の供え物] また、感謝の気持ちや誓いを果たすために、寺院に自発的に供え物をすることも可能だった。 |

| Olah (עלה) („Brandopfer“) Die Olah (z. B. Ex 24,5) bestand aus der vollständigen Verbrennung (Brandopferaltar) eines Rindes, Schafes oder eines Widders, gelegentlich auch einer Taube (wenn jemand arm war). In Bemidbar (Num 28,3–8 elb) wird das Ganzopfer von zwei Schafen – eines am Morgen und eines am späten Nachmittag – als tägliches Opfer geboten. An Festtagen soll ein zusätzliches Schaf geopfert werden, der Zeitpunkt des Opfers ist nicht festgelegt. Hierbei wurde nie eine Ziege geopfert, weil diese für das Chattat-Opfer reserviert ist. Auch als sogenanntes Ganzopfer, kalîl (כָּלִיל) (Dtn 33,10 EU). Man verbrannte das ganze Tier ohne Haut und unreinen Teilen auf dem Altar für die Gottheit. Damit wird die Macht Gottes anerkannt, (Gen 8,20 EU). Opferbare Tiere waren Ziege, Schaf, Rind und Taube. In späterer Zeit werden Brandopfer als Tamid-Opfer (ein festgesetztes, ständiges Opfer) täglich morgens und abends vor dem Tempel dargebracht. Mincha (מנחה) („Speiseopfer“) Die Mincha ist die Darbringung eines Brotfladens aus Mehl, vermischt mit Öl und Weihrauch und Salz. Es dient vor allem zum Lebensunterhalt der Priester am Tempel. Die Juden in Israel partizipierten an einer im Alten Orient häufigen religiösen Vorstellung, dass die Gottheit mit Nahrung zu versorgen sei. Geopfert wurden (gesalzene) Brotfladen und Ölkuchen, die vom Priester in das Feuer gegeben werden, dazu als Trankopfer Wein und Wasser. Sebach Schlamim (זבח שלמים) („Friedensopfer“, auch „Ganzopfer“) Das Sebach Schlamim ist eine festliche Mahlzeit einer Personengruppe. Fett und Nieren des Tieres werden auf dem Altarherd verbrannt, der Rest zubereitet und von den Opfernden verzehrt. Es wird z. B. am Sinai in Ex 24,5 erwähnt. Chattat (חטאת) („Sündopfer“) Die Chattat dient zur Entsündigung nach einer versehentlichen Gebotsübertretung. Der Hohepriester nimmt eine Ziege, stemmt die Hände auf den Kopf der Ziege und überträgt die Sünde des Menschen auf die Ziege. Die Ziege wird geschlachtet und ihr Blut an den Altar und an den Vorhang im Tempel gesprengt. (Dieser Vorhang trennte das Allerheiligste mit der Bundeslade vom Heiligen, dem normalen Innenraum des Tempels.) Sünd- und Schuldopfer (Lev 4–5,26 EU) waren eher Riten zur Entsühnung als Opfer. Gott nahm dem Menschen die Sünde ab, indem diese auf das zu opfernde Tier übertragen wurde. Hiernach tötete man das Tier und versprengte sein Blut, die Überreste wurden außerhalb des Tempels verbrannt. Ascham (אשם) („Schuldopfer“) Das Ascham dient zur Entsündigung einer groben und vorsätzlichen Gebotsübertretung. Das Ritual ist ähnlich wie bei der Chattat. Hinzu kommt jedoch noch die Verpflichtung, dass der Opfernde den angerichteten Schaden ersetzen muss.[54] Rabbinisches Judentum Die Rabbinen diskutierten nach der Zerstörung des Tempels von Jerusalem im Jahr 70 n. Chr. darüber, welche Handlungen nun an die Stelle der Tieropfer treten könnten. Sie kamen zu drei Ergebnissen: das Gebet (damit ist die Amida[55] gemeint) Erfüllung der Mitzwot das Studium der Tora Untermauert von prophetischen Texten wie Hosea, Hos 14,3 EU oder Psalm, Ps 51,17–19 EU setzte sich schließlich rechtsgültig das Gebet als liturgische Opfer-Ersatzhandlung für die tägliche Olah durch. Im Judentum wurde das Gebet daher eine religiöse Pflicht, die wie das antike Opfer zu festgelegten Zeiten (morgens und nachmittags) mit einem festgelegten Bittenkanon erfüllt wird. Schon das Alte Testament kennt auch geistige Opfer, so etwa in Psalm 51,19: Das Opfer, das Gott gefällt, ist ein zerknirschter Geist, ein zerbrochenes und zerschlagenes Herz wirst du, Gott, nicht verschmähen. Die Propheten kritisierten zuweilen die scheinheilige Opferpraxis: „Ich habe Lust an der Liebe und nicht am Opfer“ (Hosea, Hos 6,6 EU), oder Jes 1,11-17 EU. Sie forderten im Namen Gottes statt der Tieropfer, die Gott nicht brauche, Barmherzigkeit gegenüber sozial Benachteiligten wie Witwen und Waisen.  Nachbildung des Goldenen Räucheraltars, Timna, Israel |

オラ(עלה)(「燔祭) オラは(出エジプト24:5など)、牛、羊、雄羊の完全な焼燔祭(燔祭の祭壇)であり、時には鳩も捧げられた(貧しい人の場合)。ベミドバル(民数記 28:3-8)では、毎日、朝と昼過ぎに2頭の羊の供犠が捧げられる。祝祭日にはさらに一頭の羊が供犠されるが、その時刻は特定されていない。ヤギはチャ タットの生贄に捧げられるため、供犠されることはない。また、いわゆる全部のいけにえとして、カリエル(כ לִיל)が捧げられた(申33:10 EU)。動物全体が、皮や汚れた部分なしに、神に捧げる祭壇の上で焼かれた。これは神の力を認めるものである(創世記8:20 EU)。生け贄に捧げられる動物は、山羊、羊、牛、鳩であった。後の『存在と時間』では、燔祭はタミド供犠(固定された永続的な供犠)として、毎朝夕、神 殿の前で捧げられた。 ミンチャ(מנחה)(「穀物の供え物) ミンチャとは、一斤の小麦粉に油、香、塩を混ぜたものを捧げることである。主に神殿の祭司を支えるために使われる。イスラエルのユダヤ人は、神に食物を捧 げるという古代近東によく見られた宗教的概念に参加していた。(塩漬け)パンと油餅が供犠され、祭司によって火に入れられ、飲み物としてワインと水が供え られた。 セバハ・シュラミム(זמיבם שלמיבם)(「平和の供え物」、「全供え物」とも言う) セバハ・シュラミム(Sebach Schlamim)は、祝いの食事である。動物の脂肪と腎臓は祭壇の囲炉裏で焼かれ、残りは生け贄が調理して食べる。例えば、出エジプト記24:5のシナ イで言及されている。 チャタット(חטאת)(「罪の捧げ物) チャタットは、不注意による戒律違反の贖罪に用いられる。大祭司はヤギを取り、ヤギの頭に手を置き、その人の罪をヤギに移す。ヤギは屠られ、その血が祭壇 と神殿の幕に振りかけられる。(この幕が、契約の箱のある至聖所と、神殿の通常の内部である聖所を隔てていた)。罪の供え物と罪の供え物(レビ4-5: 26 EU)は、供犠というよりむしろ贖罪の儀式であった。神は人間の罪を供犠される動物に移すことによって取り除かれた。その後、その動物は殺され、血がまか れ、残骸は神殿の外で焼かれた。 アシャム(אשם)(「罪の捧げ物) アシャムは、戒律に対する重大かつ故意の違反を償うためのものである。儀式はチャタットに似ている。ただし、供犠者は生じた損害を賠償しなければならない という義務もある[54]。 ラビ時代のユダヤ教 西暦70年にエルサレム神殿が破壊された後、ラビたちはどの行為が動物の犠牲の代わりになるかを議論した。彼らは3つの結論に達した: 祈り(これはアミダのことである[55])。 ミツボットの履行 律法の研究 ホセア書14:3(EU)や詩篇51:17-19(EU)のような預言的テキストに支えられ、祈りはついに、毎日のオラに代わる典礼的な供犠として法的に 確立された。そのためユダヤ教では、祈りは宗教的な義務となり、古代の生贄のように、『存在と時間』を決めて(朝と午後)、決められた願いの大要を唱える ようになった。 旧約聖書は霊的供犠も認めている。例えば詩篇51:19「神に喜ばれる供犠は、悔いる心である。 私は愛を喜びとし、供犠を喜ばない」(ホセア、ホセ6:6 EU)、あるいはイザ1:11-17 EU)。神が必要としない動物の犠牲の代わりに、彼らは神の名の下に、寡婦や孤児など社会的に恵まれない人々に対する憐れみを求めたのだ。  イスラエル、ティムナ、香の黄金祭壇のレプリカ |

| Zoroastrische Kulte und

Opferhandlungen Bildliche Darstellungen von Göttern sind dem Zoroastrismus fremd. Im Feuertempel, in denen ein ständig brennendes Feuer (als heilige Flamme) gehütet wird, tritt ein Symbol der Gottheit Atar, auch Atash, Azar oder Avestan symbolisch in Erscheinung, er wird auch als „brennendes und nicht brennendes Feuer“ oder „sichtbares und unsichtbares Feuer“ beschrieben.[56] Das Feuer wird als sichtbare Präsenz von Ahura Mazda und seiner Asha (Wahrheit, kosmische Ordnung) angesehen. Das bedeutendste Ritual im Zoroastrismus ist das Yasna (avestisch „Anbetung, Opfer“). Es wird als „innere“ Zeremonie, d. h. in ritueller Reinheit am Altar eines Feuertempels vollbracht. Die Funktion der Yasna-Zeremonie besteht grob erläutert darin, die geordneten geistigen und materiellen Schöpfungen von Ahura Mazda gegen den Angriff der zerstörerischen Kräfte von Angra Mainyu zu stärken. Das Wort „Yasna“ ist mit dem vedischen und dem späteren Sanskritwort „yajna“ verwandt, im Gegensatz zu Sanskrit yajna, das sich auf eine Klasse von Ritualen bezieht, ist in Zoroastrismus „Yasna“ eine besondere Liturgie. Der Höhepunkt des Yasna-Rituals ist der Ab-Zohr, die Stärkung des Wassers. Es gliedert sich in zwei Schritte: Erster Schritt: es werden Vorbereitungen getroffen, unter anderem eine Weihe des Bereichs, in dem das Ritual stattfindet, und die Zubereitung der ersten Parahaoma-Mischung. Zweiter Schritt: die eigentliche Yasna-Zeremonie, eine aus dem Gedächtnis erfolgende Rezitierung der Liturgie, begleitet durch mehrere rituelle Handlungen, unter anderem die Zubereitung einer zweiten Parahaoma-Mischung. Der Höhepunkt und eigentlicher Zweck der Zeremonie sind die Ape-Zaothra (mittelpersisch und neupersisch: ab-zohr, wörtlich „Gabe/Geschenk an das Wasser“), die Stärkung des Wassers, die durch eine Mischung der zwei Parahaoma-Zubereitungen symbolisch vollbracht wird. Die Texte der Yasnaliturgie sind in 72 Kapitel unterteilt, jedes Element der 72 Fäden des zoroastrischen Kusti – des heiligen Gürtels, der um die Taille getragen wird – repräsentiert eines der 72 Kapitel der Yasna.[57] Innerhalb der Priesterschaft gab es unterschiedliche Grade, so etwa den Magier, oder den Mobed, Ervad und Zaotar mit diesen Bezeichnungen wurden weitere Priesterfunktionen innerhalb der zoroastrischen Religion bestimmt.[58][59] |

ゾロアスター教のカルトと生贄 ゾロアスター教では、神々の絵による表現は異質なものである。神聖な炎として)常に燃え続ける火が保管されている火の神殿では、アタシュ、アザール、ア ヴェスターンとしても知られるアタル神の象徴が象徴的に現れる。それは「燃える火と燃えない火」あるいは「見える火と見えない火」とも表現される [56]。 ゾロアスター教で最も重要な儀式はヤスナ(アヴェスター語の「礼拝、供犠」)である。ヤスナは「内なる」儀式として、つまり火の神殿の祭壇で儀式的に清ら かに行われる。大まかに説明すると、ヤスナの儀式の機能は、アグラ・マインユの破壊的な力の攻撃に対して、アフラ・マズダの秩序ある霊的・物質的創造物を 強化することである。ヤスナ」という言葉は、ヴェーダ語や後のサンスクリット語の「ヤジュナ」に関連しているが、サンスクリット語の「ヤジュナ」が儀式の 一群を指すのとは異なり、ゾロアスター教の「ヤスナ」は特定の典礼である。ヤスナの儀式のクライマックスは、アブ・ゾール(水の強化)である。この儀式は 2つの段階に分かれている: 第一段階:儀式が行われる場所の聖別や最初のパラホーマの調合を含む準備が行われる。 第二段階:実際のヤスナの儀式。典礼を暗唱し、第二のパラホーマの調合を含むいくつかの儀式を伴う。この儀式のクライマックスと実際の目的は、アペ・ザオ トラ(中世ペルシア語および新ペルシア語: ab-zohr、文字通り「水への贈り物/プレゼント」)であり、2つのパラホーマの混合物によって象徴される水の強化である。 ヤスナの典礼のテキストは72章に分かれており、ゾロアスター教のクスティ(腰に巻く神聖なベルト)の72本の糸の各要素は、ヤスナの72章の1つを表し ている[57]。 司祭職の中には、魔術師、あるいはモベド、エルヴァド、ザオターといった異なる位階があり、ゾロアスター教における更なる司祭職が決定された[58] [59]。 |

| Opfer und -kultus im antiken

Griechenland, Rom und mediterranen Raum Griechische Götter und Kultus → Hauptartikel: Mysterienkult Die Namen einiger griechischer Götter waren bereits durch schriftliche Zeugnisse in Linearschrift B aus der Zeit um 1200 v. Chr. (siehe Späthelladikum) überliefert worden, aber die eigentliche griechische Götterwelt wurde erst durch die Dichter Homer und Hesiod literarisch ausgeformt. Die Erzählungen wurden aber nicht vor dem 8. Jahrhundert v. Chr. verschriftlicht.[60] Nach dem dunklen Zeitalter im 9. Jahrhundert v. Chr. wirkte die griechische Religion unheimlich, ihre Götter gefährlich, grausam und despotisch. In der griechischen Götterwelt gab es keinen wohlwollenden Schöpfergott oder eine göttliche Ordnung im Anbetracht der Zeiten, sondern erbarmungslosen Hass und Streit, so standen etwa schon die zwei Urkräfte Chaos und Gaia im Zwist.[61] Typisch für die griechische Götterwelt und damit bestimmend für das Verhältnis der Götter zur Welt des zwischenmenschlichen Handelns ist, dass Zeus und die übrigen polytheistischen Götter die Ordnungsstrukturen der Welt garantierten, diese aber ebenso wie die Menschen selbst nicht schufen. Die vorgestellte der Welt der antiken Griechen war nicht Ausdruck der göttlichen Schöpfungskraft und deren intendierten Gestaltung, sie war Wohnstätte der Götter und der Menschen. Götter und Menschen führten eine parallele Existenz in einem gemeinsamen Kosmos. Aber die Götter hatten gestalterisches Potential und waren den menschlichen Handlungsmöglichkeiten unendlich überlegen. Sie beherrschten die Kräfte in der Natur ebenso, wie sie mit ihrem Handeln tief in die Gesellschaft hineinwirken konnten. In dieser vorgestellten Asymmetrie und dem tiefen Gefühl der Abhängigkeit vom Wohlwollen der göttlichen Mächte. war es den Menschen ein Bedürfnis die Götter im Kult zu ehren. Die Zuwendung zu den Göttern war eine wichtige Voraussetzung für deren Wohlwollen.[62] Griechische Götter waren nicht für den Menschen verfügbar, es umgab sie ein Aspekt der Ferne. Sie zeigten ihre Anwesenheit durch Handlungen, Naturereignisse oder symbolische Zeichen, einzelnen Menschen konnte sie aber in Träumen oder psychischen Grenzzuständen erscheinen. Die Fähigkeit der Götter in das menschliche Handeln hineinzuwirken, ließ ihre Verehrung zur fundamentalen Basis der menschlichen Existenz werden. das zentrale Ritual der griechischen Religion war das Opfer, es war das Medium um eine Beziehung zu den sakralen Mächten herzustellen. Dabei gab es zyklisch auftretende, also jährlich wiederkehrende Opferhandlungen und solche zu besonderen Anlässen und in Not- und Krisensituationen durchgeführt wurden.  Darstellung: Hermes der eine Ziege zum Opfer führt. Malerei auf einem kampanischen rotfigurigen Vase, etwa 360 bis 350 v. Chr. Bremmer (1996)[63] sieht im Tieropfer den Kernpunkt im Ritual der antiken griechischen Religion. Eine Gottheit war eindringlich nur durch ein dargebrachtes, blutiges Opfer ehrbar. Hierbei war die Auswahl des richtigen Opfertieres von hoher Bedeutung. Es waren Haustiere wie Hausrinder und von ihnen wiederum die Stiere die, die geschätztesten Opfertiere darstellten. Aber auch andere Nutztiere, wie Schafe, Ziegen und Geflügel, fanden ihre Verwendung. Hingegen kamen Wildtiere als Opfertiere selten vor. Für einige Götter sah man offenbar bestimmte Tiere vor, so etwa für Hestia, Demeter und Dionysos denen traditionell Hausschweine geopfert wurden. Die als unrein geltende Göttin Eileithyia oder auch der als grausam bestimmte Kriegsgott Ares oder der Hekate wurden hingegen Hunde geopfert. Hingegen brachte man Aphrodite oder Asklepios Vögel als Opfertiere dar. Dem Priapos wurden ausnahmsweise auch Fische geopfert. Die Farbe des Fells der Opfertiere hatte bei ihrer Auswahl ebenfalls eine symbolische Bedeutung, so wurden den Göttern der Unterwelt überwiegend dunkle, bzw. schwarze Tiere und olympische Götter Tiere mit hellerem Fell geopfert. Verbindliche Regularien zur Auswahl bestanden nicht, allgemein musste das Tier den Anforderungen der Reinheit entsprechen, so galt etwa ein Fleck im Fell als unrein. Fast immer war das Tieropfer mit einem anschließenden Festmahl verbunden, bei dem das Fleisch von der Opfergemeinschaft zur Gänze verzehrt werden musste, da es das Temenos (griechisch τέμενος temenos für Heiligtum) nicht verlassen durfte. Wurden die geschlachteten Tiere zur Gänze verbrannt, so sprach man von Holokauston (altgriechisch ὁλόκαυστον holókauston, das wie das zugehörige Substantiv ὁλοκαύτωμα holokautoma von ὅλος holos, „ganz, vollständig“, und καῦσις kausis, „Brand, Verbrennung“, abgeleitet ist). Erstmals überliefert ist es bei dem griechischen Historiker Xenophon (ca. 426–355 v. Chr.) für ein Tieropfer.[64] Das Opfertier dient zur Reinigung des Einzelnen oder der auch ganzer Gemeinschaften. Als unrein galt, wer mit „Geburt“ oder „Tod“ in Berührung gekommen war oder wer selbst einen Menschen getötet hatte. Einem Kult oder dem Göttlichen durfte man sich nur gereinigt nähern. Einige Begriffe aus den Opferkulten fanden in veränderter Form den Zugang zur griechischen Alltagssprache. So der Begriff der „Tragödie“ wie er im Theater der griechischen Antike verwendet wurde. Er entstammte dem „Bocksgesang“ bzw. „Gesang um den Bockspreis“ (altgriechisch τραγῳδία tragōdía). Hierbei handelte es sich um einen dionysischen Kult bzw. Ritual, bei welchem ein „Komos“ (κῶμος kōmos) veranstaltet wurde, ein festlicher Umzug oder eine Prozession mit Gesang, bei welchem einige Protagonisten mit Maske und Bocksfell (τράγος tragos) verkleidet waren. Sie sollten den Gott selbst oder die ihn begleitenden Satyrn darstellen. So entwickelte sich die Form der Tragödie aus einem im Chor gesungenen Mythos, der Dichtung einer meist heldischen Vergangenheit. Die Chorpartien der erhaltenen Dramen sind Rudimente dieser Urform, der Dialog und die dargestellte Handlung spätere Entwicklungen, in historischer Sicht sekundär. Träger der Handlung im Drama war ursprünglich ein einziger Schauspieler, ein Sprecher, der mehrere Figuren repräsentieren konnte, indem er ihre Reden übernahm. Erst Aischylos führte einen zweiten Schauspieler ein. Das Chorlied entwickelte seine eigene Chorlyrik, es entstanden Spezialformen mit eigenen Bezeichnungen, Hymne, Paian, Dithyrambus, Epinikion, Epithalamium, und andere mehr. In den antiken und spätantiken synkretistischen Mysterienkulte wurden vielfältige Formen von Opferritualen praktiziert. |

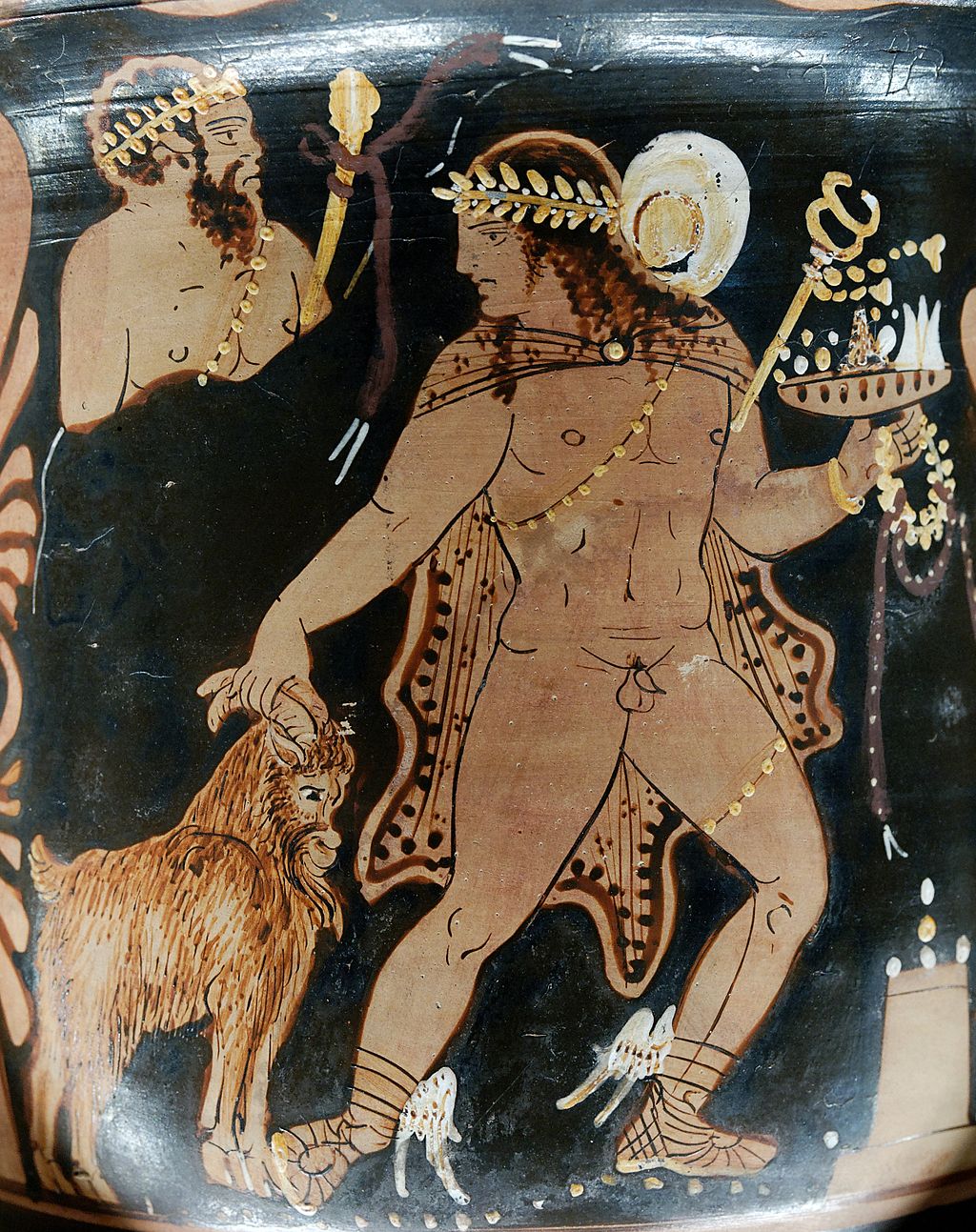

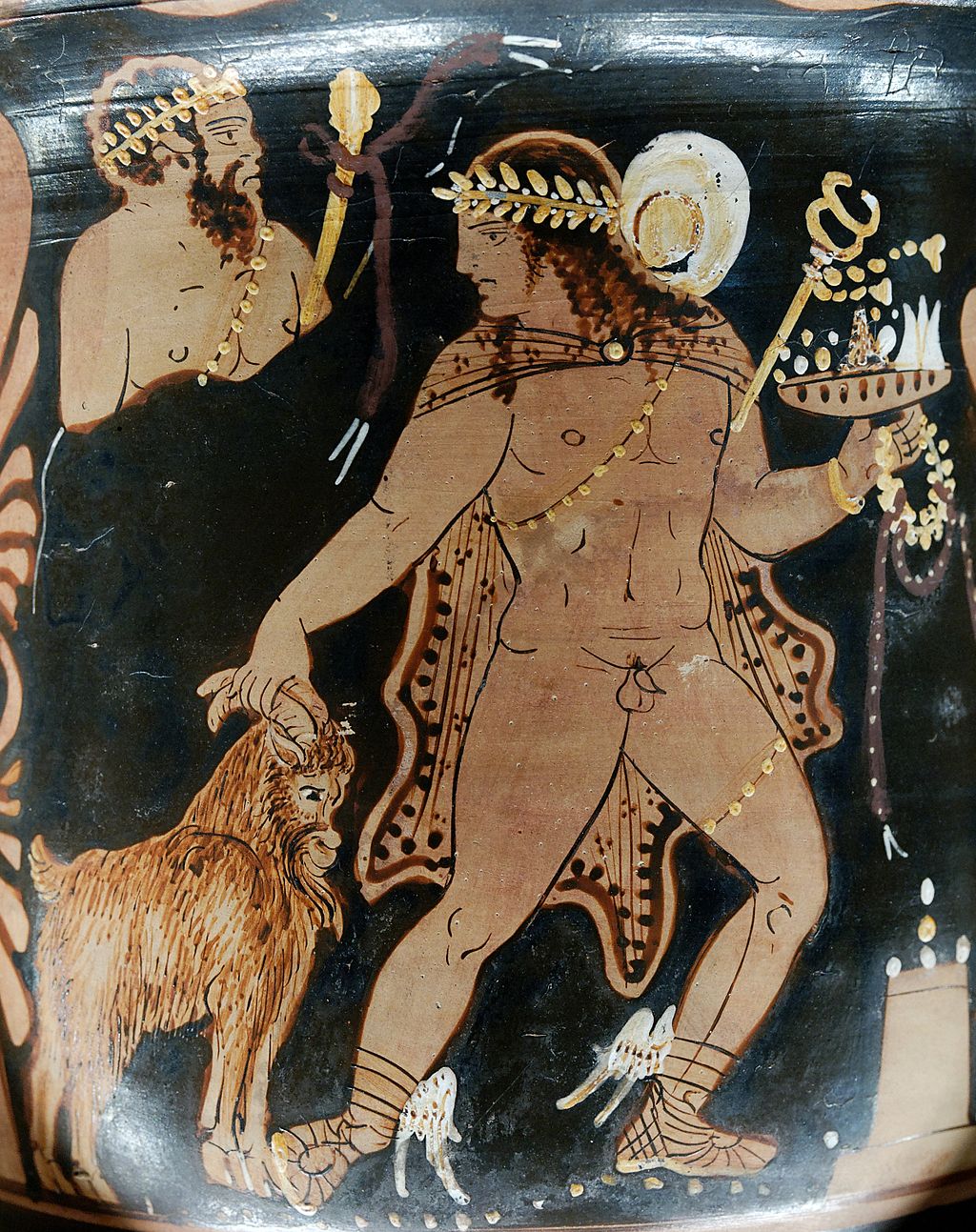

古代ギリシャ、ローマ、地中海地域における供犠と崇拝 ギリシアの神々とカルト → 主な記事 ミステリー・カルト ギリシア神話の神々の名前は、紀元前1200年頃からすでにリニアBの文字記録として伝えられていた(ヘラド後期を参照)が、ギリシア神話の神々の実際の 世界は、詩人ホメロスやヘシオドスによって初めて文学として形成された。しかし、物語は紀元前8世紀以前には書き留められなかった[60]。 紀元前9世紀の暗黒時代以降、ギリシアの宗教は不吉に見え、その神々は危険で残酷で専制的だった。ギリシアの神々の世界では、時代を鑑みた慈悲深い創造神 や神の秩序は存在せず、無慈悲な憎悪と対立が存在し、例えば2つの元素の力であるカオスとガイアはすでに対立していた[61]。 ギリシアの神々の世界の典型であり、したがって対人行動の世界と神々の関係にとって決定的なのは、ゼウスと他の多神教の神々が、人間自身と同じように、世 界の秩序構造を保証することはあっても、それを創造することはなかったということである。古代ギリシア人が想像した世界は、神の創造力とその意図されたデ ザインの表現ではなく、神々と人間の住処であった。神々と人間は、共有された宇宙の中で並列的な存在であった。しかし、神々には創造的な可能性があり、人 間の能力よりも無限に優れていた。神々は自然の力を支配し、その行動によって社会に大きな影響を与えることができた。この想像上の非対称性と、神々の慈悲 深さへの深い依存意識の中で、人々は神々を敬う必要性を感じていた。神々に立ち返ることは、神々の博愛のための重要な前提条件であった[62]。ギリシア の神々は人間にとって身近な存在ではなく、距離のある存在であった。神々は行動や自然現象、象徴的な徴候によってその存在を示したが、夢や精神的な境界状 態の中で個々の人間に現れることもあった。人間の行動に影響を与える神々の能力によって、神々への崇拝は人間存在の基本的な基盤となった。 ギリシアの宗教の中心的な儀式は供犠であり、供犠は聖なる力との関係を確立するための媒体であった。生け贄には、周期的に、つまり毎年繰り返される生け贄 行為と、特別な機会や緊急・危機的状況で行われる生け贄行為があった。  描写:ヤギを供犠に導くヘルメス。紀元前360年から350年頃、カンパニア赤像壺に描かれた絵。 Bremmer(1996)[63]は、動物の生け贄を古代ギリシアの宗教儀礼の中心的存在と見なしている。神は血塗られた供犠によってのみ尊ばれた。正 しいいけにえの動物を選ぶことは非常に重要であった。牛や雄牛のような家畜は、犠牲動物として最も重んじられた。しかし、ヒツジ、ヤギ、家禽など他の家畜 も使われた。一方、野生動物が犠牲動物として使われることはほとんどなかった。ヘスティア、デメテル、ディオニュソスのように、特定の動物を尊ぶ神々がい たことは明らかで、その神々には伝統的に家畜の豚が供犠された。対照的に、犬は不浄とされた女神エイレイシア、残酷とされた軍神アレス、あるいはヘカテー の供犠とされた。対照的に、鳥はアフロディーテやアスクレピオスに捧げられた。例外として、魚もプリアポスに供犠された。犠牲となる動物の毛皮の色にも象 徴的な意味があり、黒っぽい動物は冥界の神々に、明るい毛皮の動物はオリュンポスの神々に供犠された。一般的に、動物は純潔の条件を満たしていなければな らず、例えば毛皮にシミがあると不浄とみなされた。生け贄に捧げられた動物は、テメノス(ギリシャ語で聖域を意味するτέμενος temenos)から持ち出すことが許されなかったため、生け贄を捧げた共同体がその肉をすべて食べなければならなかった。 屠殺した動物を丸ごと焼いた場合は、ホロカウストンと呼ばれた(古代ギリシア語 ὁλόκαυστον holókauston、対応する名詞 ὁλοκαύτωμα holokautoma と同様、ὅλος holos「全体、完全な」、καῦσις kausis「火、焼く」に由来する)。ギリシャの歴史家クセノフォン(紀元前426~355年頃)によって、動物の生け贄として初めて記録された [64]。誕生」や「死」に接触した者、あるいは人を殺した者は汚れた者とみなされた。清浄でなければカルトや神に近づくことは許されなかった。 生け贄カルトに由来する用語のいくつかは、形を変えてギリシアの日常語に入り込んだ。たとえば、古代ギリシャの演劇で使われていた「悲劇」という言葉だ。 これは「山羊の歌」または「山羊の代価のための歌」(古代ギリシャ語 τραγῳδία tragōdía)に由来する。これはディオニュソス崇拝の儀式で、「コモス」(κῶμος kōmos)が組織され、仮面とバックスキン(τράγος tragos)に身を包んだ主人公たちが歌いながら祝祭のパレードや行列を行った。彼らは神自身、あるいは神に付き従うサテュロスを表していると考えられ ていた。 このように、悲劇の形式は、合唱で歌われる神話から発展したものであり、ほとんど英雄的な過去の詩であった。現存する戯曲の合唱部分は、この原型の初歩で あり、台詞とアクションは、歴史的に見れば二次的な、後の発展を描いたものである。戯曲のアクションはもともと一人の俳優によって担われていた。二人目の 俳優を導入したのはアイスキュロスだけである。合唱曲は独自の合唱叙情主義を発展させ、讃美歌、パイアン、ディティラム、エピニキオン、エピタラミウムな ど、独自の名称を持つ特殊な形式が出現した。 古代や後期のシンクレティックのミステリー・カルトでは、さまざまな形式の生贄儀式が行われていた。 |

| Römische Götter und Kultus → Hauptartikel: Römische Priester und Priesterschaften → Hauptartikel: Gewohnheits- und Sakralrechtswesen im antiken Rom → Hauptartikel: Religionen der Spätantike  Bronzetafel mit Ehreninschrift für einen römischen Mithraspriester, die neben dem Porträt der Gottheit ein Opfermesser und eine Schale (patera) für das Trankopfer zeigt Beard (2015)[65] beschrieb die antike und spätantike römische Religion, als ein System, das keine einheitliche Glaubenslehre aufwies, auf keine verschriftlichen, heiligen Texte zurückgriff. Die Römer hätten gewusst, dass es Götter gab, aber sie hätten nicht an sie geglaubt in einem verinnerlichten Sinn. Auch gäbe es nicht das individuelle Seelenheil. Vielmehr konzentrierten sie sich vorrangig um die Ausführung von Ritualen. Rituale bildeten in Rom einen festen Bestandteil des öffentlichen, sozialen Lebens. Zwar erfuhren die Rituale immer wieder neue Sinnzuweisungen, doch das überaus strenge Festhalten an den überlieferten Riten war, als typische Eigenheit orthopraxer Religionen, auch ein Charakteristikum der römischen Religion und resultierte in einer kaum übersehbaren Fülle von Geboten und Verboten für alle Gebiete des Kultes. Bereits geringste Abweichungen vom überkommenen heiligen Verfahren zwangen zu dessen Wiederholung, um nicht den göttlichen Zorn herauszufordern. Die „römische Religion“ war eine staatstragende Tugend, ein Fundament der res publica.[66] Die vergleichende Religionswissenschaft unterscheidet orthopraxe von orthodoxen Religionen. Orthopraxe Religionen („es richtig machen“), zu der die römische Religion als polytheistische Volks- und Stammesreligion gehört, basieren auf dem do-ut-des-Prinzip („Ich gebe, damit du gibst.“), das heißt, es gibt eine vertragsmäßige Übereinkunft zwischen Göttern und Menschen. Als Gegenleistung für deren kultische Verehrung gewähren die Götter den Menschen demnach Hilfe und Beistand und halten die natürliche und öffentliche Ordnung aufrecht. Wichtig ist nicht, was der Mensch bei der Praktizierung des Kultes glaubt, sondern dass der Kult richtig ausgeführt wird. Eine kultische Handlung kann z. B. in der Darbringung eines Opfers bestehen, daher spricht man auch von einer „Opferreligion“.[67] Dagegen steht, im Allgemeinen, bei einer orthodoxen Religion („richtig glauben“) der Glaube oder das Bekenntnis (Bekenntnisreligion) im Mittelpunkt. Die penibel einzuhaltenden Vorschriften für die Opferung von Tieren – eine der wichtigsten Kulthandlungen der römischen Religion – seien hier als Beispiel aufgeführt für die „Detailversessenheit“ eines Rituals. Die Opfertiere, meistens Haustiere wie Schafe, Schweine oder Rinder, wurden unterschieden nach Geschlecht, Alter, Hautfarbe, ob sie kastriert waren oder nicht, noch gesäugt wurden (lactentes) oder nicht (maiores). Grundsätzlich ist, dass die weiblichen Gottheiten weibliche und die männlichen Gottheiten männliche Opfertiere erhielten; dafür gab es explizite Regeln.[68] Als besonders geeignet galten zweijährige Tiere (damals genannt bidentes: „zweizahnig“). Für verschiedene Tiere waren verschiedene Holzarten für das Opferfeuer vorgeschrieben, man unterschied u. a. glücksbringende Bäume (arbores felices) und unheilvolle Bäume (arbores infelices). Das ausgesuchte Tier wurde festlich geschmückt und in einer feierlichen Prozession zum Altar geführt. Unter der Begleitung von Flötenmusik zog sich der Opferherr die Toga über den Kopf, dann sprach er exakt die bisweilen komplizierte Darbringungsformel nach. Dann bestrich er die Stirn des Tieres mit Salz und Schrot (mola salsa) und fuhr mit dem Messer vom Nacken bis zum Schwanz über den Rücken des Tieres, danach erst erfolgte die Tötung. Die Untersuchung der Eingeweide des Tieres (Hieroskopie und hier wiederum die Hepatomantie), die in ihrer Form wiederum bestimmten Regeln entsprechen mussten, entschied über die Frage, ob der Gott das Opfer akzeptiert hatte, also ob die Opferung gültig war oder wiederholt werden musste.[69] Im römischen Tieropferritual werden die Opferungen an einem Altar vor dem Tempel durchgeführt, der explizit Teil des als Eigentum der Gottheit ausgewiesenen Tempelgeländes war.[70] Neben den expliziten Regeln gab es auch implizite Regularien, die durch die regelmäßige Teilnahme an den Ritualen verinnerlicht wurden, einfach durch Nachahmung und Ausprobieren. Aus der späten römischen Republik sowie der frühen römischen Kaiserzeit sind vier wichtige Priesterkollegien bekannt: sechzehn Pontifices sechzehn Auguren die Quindecimviri sacris faciundis (Fünfzehnmänner) Epulonen (Festveranstalter). Während der römischen Königszeit galt der König auch als oberster Priester. Mit dem Beginn der römischen Republik wurden nunmehr die zeremoniellen und religiösen Verpflichtungen einem Oberpriester, pontifex maximus anvertraut. Sein administratives Zentrum war die Regia, auf de Forum Romanum. In der römischen Kaiserzeit wiederum hatte der amtierende Imperator dieses Amt inne. Der Pontifex war mehr ein Berater für religiöse Angelegenheiten und mehr für die Durchführung der religiösen Zeremonien und Rituale zuständig. Die Auguren waren wichtig, da sie an den Opferhandlungen und Ritualen direkt wirkten, so in den Auspizien (Ornithomantie) aus dem Flug verschiedener Vögel zu deuten, welche Bedingungen und Unternehmungen die Billigung der Götter besaßen.[71] Nach Veyne (2005)[72] stellte der antike Mensch sich die Götter als überwältigende, anbetungswürdige, den Menschen überlegene Wesen vor. Dabei waren die Götter weniger reale Wesen als vielmehr fiktionale Gestalten einer erzählerischen Phantasie entsprungen. Sie waren Inhalt eines einfachen Narrativs, im Sinne einer Literarischen Figur. Die Götter hatten, in der Vorstellungswelt der Glaubenden, alle ein bestimmtes Alter erreicht, woran sich ebenso wenig änderte, wie an der Anzahl ihrer Nachkommen. Die heidnische Religion und Kulte aber machten kein Angebot eines liebenden Gottes. Die pagane Frömmigkeit gründet auf die Opfer. Die Götter sind aus der paganenen Vorstellungswelt nicht sehr eng mit der Menschheit verbunden, so dass man sie beständig stören dürfte. Sie werden nicht über die eigene, individuelle seelische Befindlichkeit in Kenntnis gesetzt. Einzig darf der Glaubende sie an die Beziehung erinnern, die mit einem von ihnen durch wiederholt dargebrachte Opferungen entstanden ist. Pagane Religiosität sei nach Veyne ein Ensemble von Praktiken, es ginge nicht um dezidierte Überzeugungen und Vorstellungen, sondern darum seine Religion zu praktizieren. Die Götter, so in der Vorstellung der Glaubenden, achteten darauf, dass ihre Person, ihr Namen und Tempel, ihre Würde respektiert und bemerkt würden. Im Paganismus sei jede sich im Bewusstsein des Glaubenden abspielende Verbindung zwischen den Göttern und den Menschen fremd. |

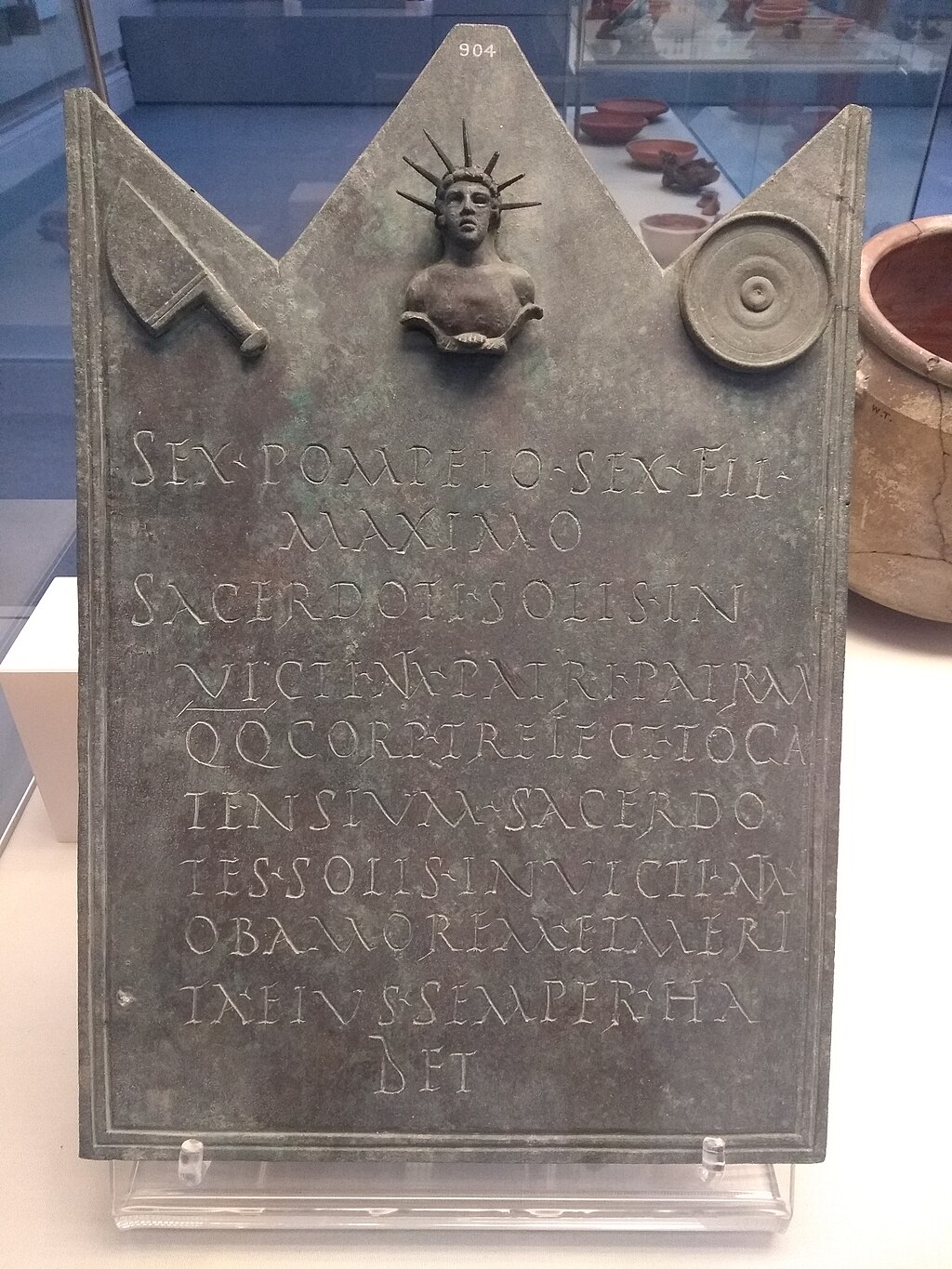

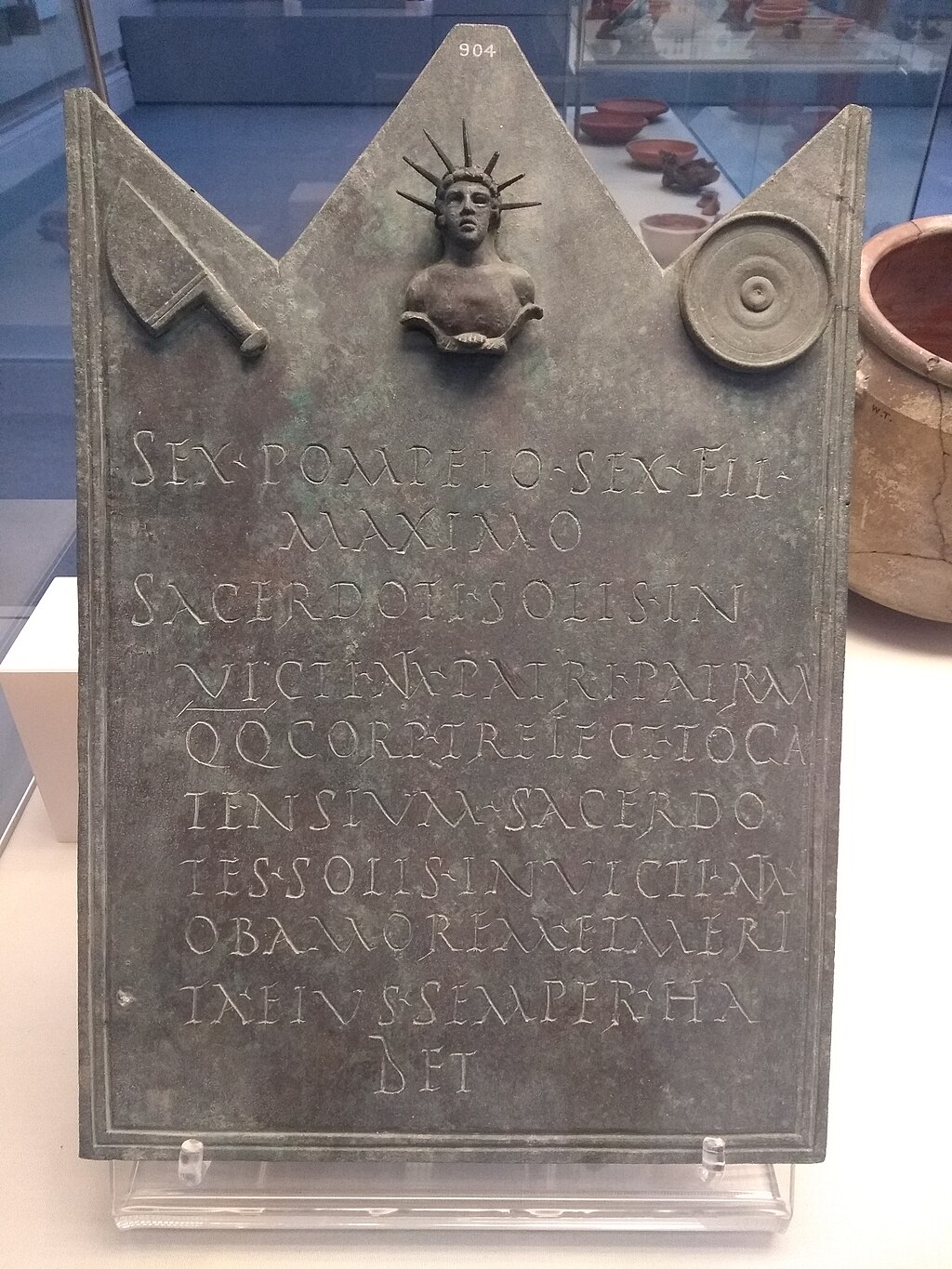

ローマの神々とカルト → 主な記事 ローマの神官と神職 → 主な記事 古代ローマの慣習法と聖法 → 主な記事 古代末期の宗教  ローマ時代のミトラ教の祭司の名誉を記したブロンズ製のプレート。神の肖像画の横に、犠牲用のナイフと献杯用のボウル(パテラ)が描かれている。 Beard(2015)[65]は、古代・後期ローマの宗教を、統一された信仰の教義を持たず、書かれた聖典もないシステムであったと述べている。ローマ 人は神々の存在を知っていただろうが、内面化された意味で神々を信じていたわけではないだろう。また、個人の救済というものもなかった。むしろ、儀式を行 うことに主眼を置いていた。儀式はローマにおける公的な社会生活に不可欠なものであった。儀式には繰り返し新しい意味が与えられたが、伝統的な儀式を極め て厳格に守ることは、オルソプラクス宗教の典型的な特徴として、ローマ宗教の特徴でもあり、礼拝のあらゆる分野での戒律や禁止事項がほとんど手に負えない ほど豊富になった。伝統的な神聖な手順から少しでも逸脱すると、神の怒りを買わないために、その繰り返しを余儀なくされた。ローマの宗教」は国家を支える 美徳であり、公共性(res publica)の基盤であった[66]。比較宗教学では、オーソプラックスな宗教とオーソドックスな宗教を区別している。ローマ宗教が多神教的な民俗宗 教・部族宗教として属する正教宗教(「正しく行う」宗教)は、ドゥ・トゥ・デス原理(「私が与えるからあなたも与える」)に基づいている。つまり、神々と 人間との間には契約関係があるのだ。神々は崇拝の見返りとして、人間を助け、援助し、自然や公共の秩序を維持する。重要なのは、人々がカルトを実践する際 に何を信じるかではなく、カルトが正しく遂行されることである。カルト的行為は、たとえば供犠からなることもあり、そのため「犠牲宗教」とも呼ばれる [67]。対照的に、正統的な宗教(「正しく信じる」宗教)は、一般的に信仰や告白に重点を置く(告白宗教)。 ローマ宗教の最も重要な儀式行為の一つである動物の生贄のための綿密に守られた規則は、儀式の「細部へのこだわり」の例としてここに挙げられている。犠牲 となる動物は、主に羊、豚、牛などの家畜であったが、性別、年齢、皮膚の色、去勢の有無、乳飲み子(lactentes)かそうでないか (maiores)によって区別された。原則として、女性の神々は女性の犠牲動物を、男性の神々は男性の犠牲動物を受け取ったが、これには明確な規則が あった[68]。犠牲の火には、動物によって異なる種類の木が使われ、幸運をもたらす木(arbores felices)と不運をもたらす木(arbores infelices)が区別された。選ばれた動物は華やかに飾られ、荘厳な行列で祭壇に導かれた。フルートの音楽に合わせ、生贄の主はトーガを頭からかぶ り、時には複雑な捧げ物の処方を正確に唱えた。そして、動物の額に塩とショット(モラサルサ)を塗り、動物の背中の首から尻尾にかけてナイフを走らせてか ら殺す。動物の内臓の検査(ヒエロスコピー、そしてここでもまたヘパトマンシー)は、一定の規則に従わなければならず、神が供犠を受け入れたかどうか、す なわち供犠が有効であるか、あるいは繰り返さなければならないかを決定した[69]。ローマの動物供犠の儀式では、供犠は神殿の前の祭壇で行われ、その祭 壇は神殿の敷地の一部として明確に神の所有物として指定されていた[70]。 明示的なルールに加えて、儀式に定期的に参加することによって、単純に模倣と試行錯誤によって内面化される暗黙のルールも存在した。ローマ共和国末期から ローマ帝国初期にかけて、4つの重要な司祭団が知られている: 16人の司祭 16人のオーガ クインデシムヴィリ・サクリス・ファシウンディス(15人) epulones(祭りの主催者)。 ローマ王家の時代には、王も最高の祭司とみなされていた。ローマ共和国が始まると、儀式と宗教的な職務は大祭司であるポンティフェクス・マキシムスに委ね られるようになった。彼の行政の中心は、フォロ・ロマーヌムにあるレジアであった。ローマ帝国時代には、この役職は在位中の皇帝が務めていた。ポンティ フェクスは宗教的な問題の相談役であり、宗教的な儀式や儀礼の執行に責任を負っていた。オーガーが重要だったのは、彼らが犠牲行為や儀式に直接関与してい たからであり、たとえば、さまざまな鳥の飛翔から、どのような条件や事業が神々の承認を得ているかを読み解く吉兆占い(オーニソマンシー)にも関与してい た。 ヴェイン(2005)[72]によれば、古代人は神々を崇拝に値する圧倒的な存在であり、人間よりも優れた存在であると想像していた。神々は実在の存在と いうよりも、物語上の空想に登場する架空の人物であった。神々は、文学上の人物という意味で、単純な物語の内容であった。信者たちの想像の中では、神々は みな一定の年齢に達しており、それは子孫の数と同じようにほとんど変化しなかった。しかし、異教の宗教とカルトは、愛にあふれた神の存在を提示しなかっ た。異教徒の信心は供犠に基づいていた。異教徒の想像力では、神々は人間とあまり密接に結びついていないため、常に邪魔される可能性がある。神々は個人の 精神状態については知らされない。信者は、繰り返される生贄の捧げものによって、神々の一柱との間に築かれた関係を神々に思い出させるだけである。ヴェイ ヌによれば、異教徒の宗教性とは実践の集合体であり、決められた信念や思想の問題ではなく、自分の宗教を実践することである。信者によれば、神々は彼らの 人格、名前、寺院、尊厳が尊重され、認められるようにした。異教では、信者の意識の中で起こる神々と人間との結びつきはすべて異質なものだった。 |

| Opferkult der Phönizier Die religiösen Vorstellungen und Praktiken der Phönizier sind mangels Datenlage nur unvollständig rekonstruierbar. Neben Inschriften und Personennamen ist die Phönizische Geschichte des Herennios Philon eine wichtige aber auch problematische Quelle. Die darin enthaltenen Mythen ähneln denen der Religion in Ugarit.[73] Dort herrscht der Schöpfer und Hauptgott El über ein Pantheon, zu dem Gottheiten wie Dagān, Anat und Aschera gehörten. Neben diesen allgemein in Syrien und Kanaan verbreiteten Vorstellungen zeichnet sich die Religion der phönizischen Stadtstaaten durch die Verehrung einer Triade aus, die an der Spitze des jeweiligen Pantheons stand.[74] Die genaue Komposition der Trias war zwar von Stadt zu Stadt verschieden, aber sie bestand immer aus einem Herrn, einer Herrin und einem jugendlichen Sohn. Trotz ihrer verschiedenen Namen unterschieden sich die phönizischen Götter in Funktion und Charakter kaum voneinander. Sie wurden als weniger individuell vorgestellt als etwa die Gottheiten der griechischen und römischen Mythologie.[74] Das zeigt sich etwa daran, dass die Gottheiten oft nur als Herr (Ba’al) und Herrin (Baalat) bezeichnet wurden. Auch die Punier mit ihrem Zentrum Karthago verehrten einen phönizischen Pantheon, es unterschied sich allerdings von dem der Mutterstadt Tyros.[75] So war nicht Melkart der höchste Gott, sondern vermutlich Baal schamim („Herr der Himmel“). Die wichtigste Göttin war Tanit, die Gefährtin des Baal-Hammon. Tanit war gleichzeitig Jungfrau und Mutter und zuständig für Fruchtbarkeit und den Schutz der Toten. Sie wurde in Karthago deutlich von Astarte unterschieden.[76] Weitere Gottheiten der, auch nur unvollständig rekonstruierbaren, punischen Religion waren etwa Baal Sapon, Eschmun und Sardus Pater. Aus den Ausgrabungen des Astarte-Tempels in Kition (Zypern) wo Tieropferungen ausgeführt wurden, fanden sich 1328 Zähne und Tierknochen vor, die durch den Archäozoologen Günter Nobis analysiert wurden. Sie datieren um 950 v. Chr., ca. 25 Prozent wurden tierartlich bestimmt.  Anteile der Körperteile des Schafes in Tempel 1 von Kition Die Knochen der geopferten Tiere wurden in Gruben auf dem Tempelgelände (bothroi) deponiert. Das häufigste Opfertier war das Schaf (viele Lämmer), gefolgt vom Rind. Vier vollständige Schafskelette im Vorhof von Tempel 1 werden von Nobis als Bauopfer gedeutet. In der Nähe des Altars lagen 15 Rinderschädel, meist von noch nicht völlig ausgewachsenen Stieren (unter zwei Jahren). Die Schädel wurden vielleicht auch im Kult verwendet, worauf Bearbeitungsspuren an den Schädeln hindeuten. Manche Schulterblätter sind gekerbt, vielleicht wurden sie bei Orakeln verwendet. Von Schaf und Rind liegen jedoch die verschiedenen Körperteile in durchaus unterschiedlichen Anteilen vor, sodass bezweifelt werden kann, dass immer ganze Tiere geopfert wurden bzw. im Tempelbereich verblieben. Die geopferten Esel entsprechen in der Größe den rezenten Hauseseln. Unter den zwölf Damhirschresten befinden sich auch Geweihfragmente, allerdings macht Nobis keine Angaben, ob es sich um schädelechte oder Abwurfstangen handelt – die Bedeutung des Damhirsches als Opfertier (Dionysos?) wird so also vielleicht überbewertet. Außer den Geweihen liegen nur Beinknochen vor. Die Vogelknochen wurden nicht tierartlich bestimmt, sodass sich die Frage nach Taubenopfern, in einem Astarte-Tempel nach den Schriftzeugnissen zu erwarten, nicht klären lässt. Aus einer Opfergrube von Tempel 4 im Heiligen Bezirk von Kition liegt auch ein einzelner Schweine-Humerus vor. |

フェニキア人の犠牲崇拝 フェニキア人の宗教的信仰と慣習は、資料不足のため不完全にしか復元できない。碑文や人名に加えて、ヘレニオス・フィロンの『フェニキア史』は重要な資料 だが、問題もある。その神話はウガリトの宗教に類似しており[73]、そこでは創造主であり主神であるエルが、ダガン、アナト、アシェラといった神々を含 むパンテオンを支配していた。 シリアやカナンでも広まっていたこれらの考え方に加えて、フェニキア都市国家の宗教は、それぞれのパンテオンの先頭に立つ三位一体の崇拝によって特徴づけ られていた[74]。三位一体の正確な構成は都市によって異なるが、それは常に領主、愛人、若い息子から成っていた。異なる名前にもかかわらず、フェニキ アの神々は機能と性格においてほとんど互いに異なっていなかった。神々がしばしば主(Ba'al)と女(Baalat)としか呼ばれなかったことからもわ かるように、彼らはギリシア神話やローマ神話の神々よりも個性的ではなかった[74]。 カルタゴを中心とするプニキア人もまたフェニキアのパンテオンを崇拝していたが、それは母都市ティレのそれとは異なっており[75]、最高神はメルカルト ではなく、おそらくバール・シャミム(「天界の主」)であった。最も重要な女神はバアル・ハモンの妃であるタニトであった。タニトは処女であると同時に母 でもあり、豊穣と死者の保護に責任を負っていた。カルタゴではアスタルテとは明確に区別されていた[76]。不完全にしか復元できないが、プニキア宗教の 他の神々には、バール・サポン、エシュムン、サルドゥス・パテルなどがいた。 動物の生贄が捧げられたキティオン(キプロス)のアスタルテ神殿の発掘から、1328年に歯と動物の骨が発見され、古生物学者ギュンター・ノービスによっ て分析された。それらは紀元前950年頃のもので、約25パーセントが動物の種類によって識別された。  キティオン神殿1における羊の体の部位の割合 生け贄に捧げられた動物の骨は、神殿の敷地内にある穴(bothroi)に納められていた。最も一般的な犠牲動物は羊(子羊が多い)で、次いで牛であっ た。第1神殿の前庭にある4体の羊の完全な骸骨は、ノビスによって建物の生け贄と解釈されている。祭壇の近くには15頭の牛の頭蓋骨が置かれていたが、そ のほとんどはまだ成長しきっていない(2歳未満)雄牛のものだった。頭骨に加工された跡があることから、これらの頭骨も祭祀に使われた可能性がある。いく つかの肩甲骨には切り込みがあり、おそらく神託に使われたのだろう。しかし、羊や牛の様々な体の部位は、全く異なる割合で存在するため、常に一頭丸ごと供 犠されたか、神殿のエリアに残されていたかは疑わしい。 犠牲になったロバの大きさは、最近の家畜のロバに相当する。ノビスは、これが抜け落ちた角なのか、それとも抜け落ちた角なのかについて明言していないが、 12頭の雌ジカの遺体の中には角の破片もある。角以外には脚の骨しかない。鳥の骨は種が特定されていないため、文献的証拠によればアスタルテ神殿で予想さ れる鳩の生贄に関する疑問は解明されていない。キティスの聖域にある第4神殿の犠牲穴からは、豚の上腕骨が1本出土している。 |