記号論

semiotics

☆ 記号論=記号学=セミオティクス(記号研究とも呼ばれる)は、意味生成の研究であり、記号過程(セミオーシス)および意味のあるコミュニケーションの研究である。 記号論の部分集合である記号学(semiology)と呼ばれるソシュール派の伝統と混同しな いこと。これには、記号と記号過程(セミオーシス; Semiosis)、指示、指定、類似、類 推、アレゴリー、メトニミー、隠喩、象徴、意味づけ、コミュニケーションの研究が含まれる。- Semiotics.

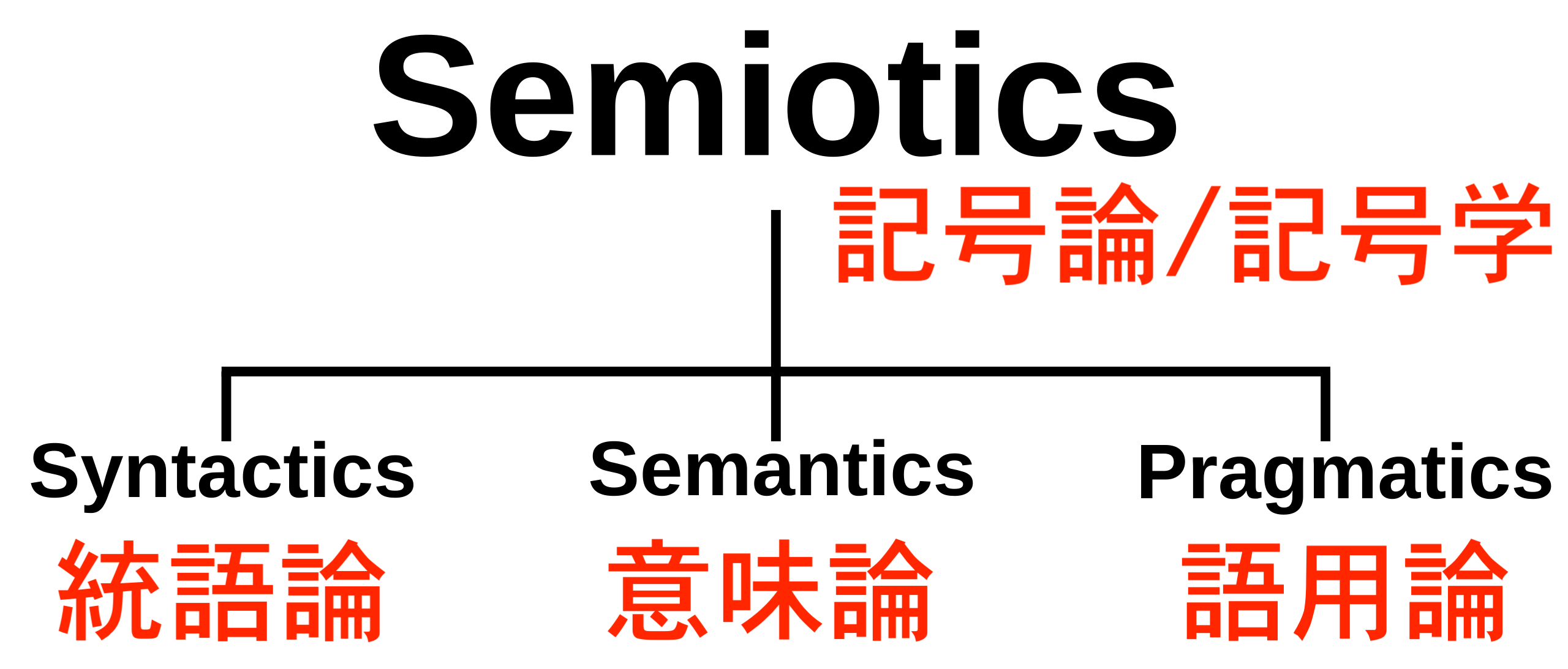

★ 記号学=記号論(Semiotics)

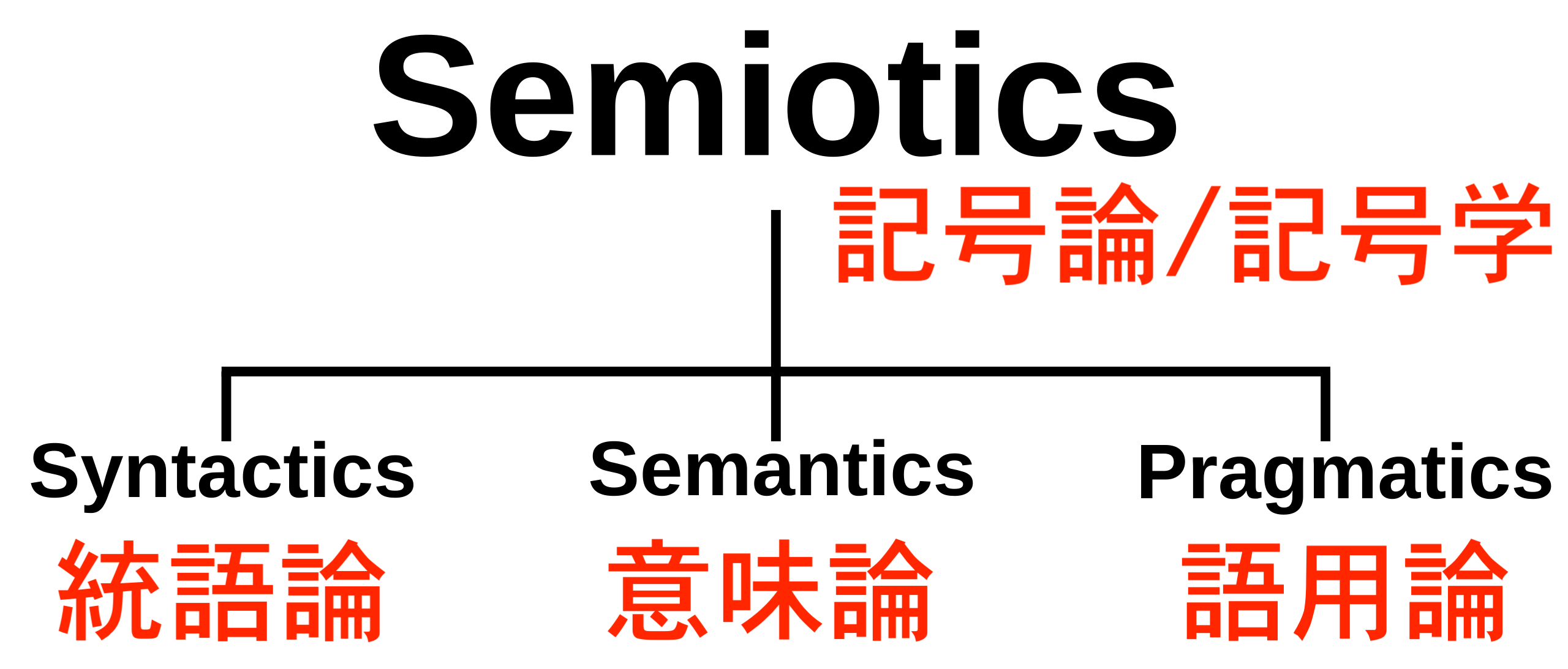

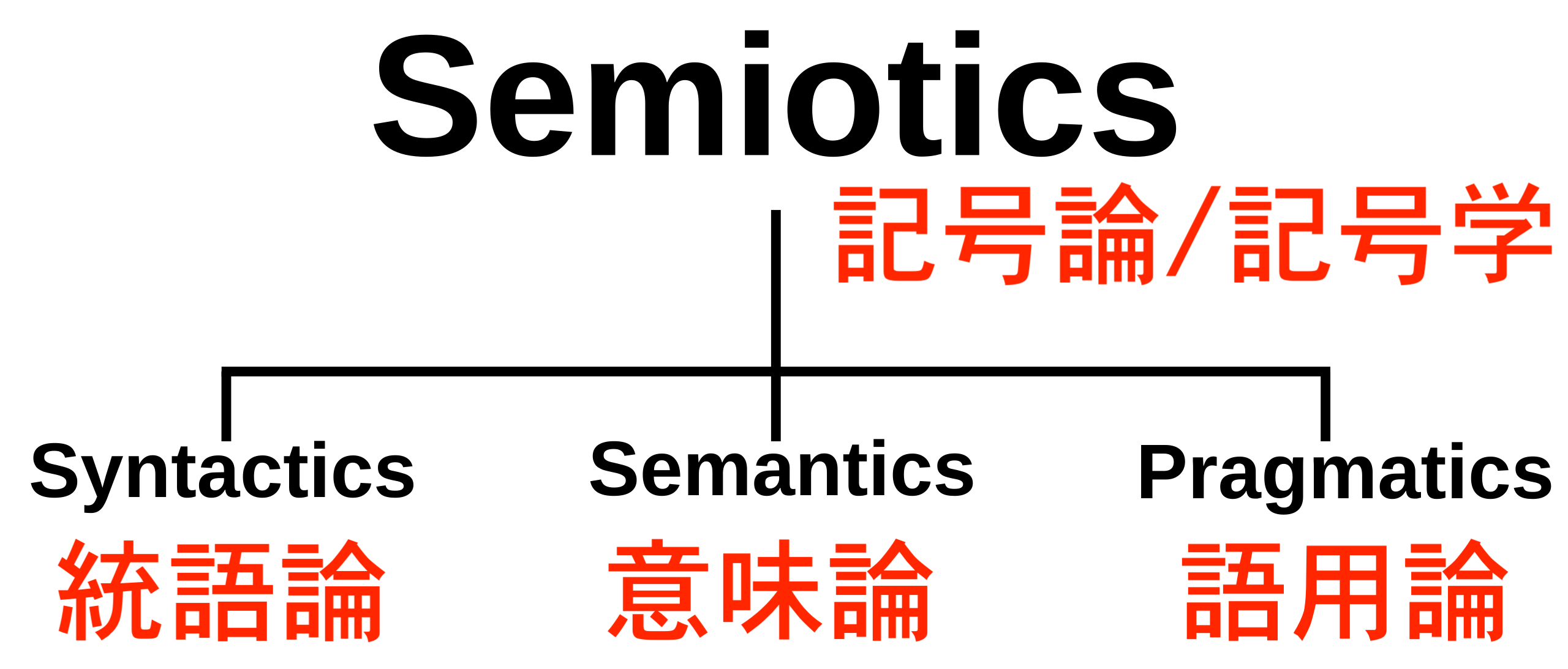

| Semiotics[a]

is the study of signs. It is an interdisciplinary field that examines

what signs are, how they form sign systems, and how individuals use

them to communicate meaning. Its main branches are syntactics, which

addresses formal relations between signs, semantics, which addresses

the relation between signs and their meanings, and pragmatics, which

addresses the relation between signs and their users. Semiotics is

related to linguistics but has a broader scope that includes

nonlinguistic signs, such as maps and clothing. |

記

号論[a]とは、記号の研究である。これは学際的な分野であり、記号とは何か、記号がどのように記号体系を形成するか、そして個人が意味を伝達するために

それらをどのように用いるかを考察する。その主要な分野は、記号間の形式的関係を扱う統語論、記号とその意味の関係を扱う意味論、そして記号とその使用者

の関係を扱う語用論である。記号論は言語学と関連しているが、地図や衣服などの非言語的記号も含むより広い範囲を扱う。 |

Signs

are entities that stand for something else, like the word cat, which

stands for a carnivorous mammal. They can take many forms, such as

sounds, images, written marks, and gestures. Iconic signs operate

through similarity. For them, the sign vehicle resembles the referent,

such as a portrait of a person. Indexical signs are based on a direct

physical link, such as smoke as a sign of fire. For symbolic signs, the

relation between sign vehicle and referent is conventional or

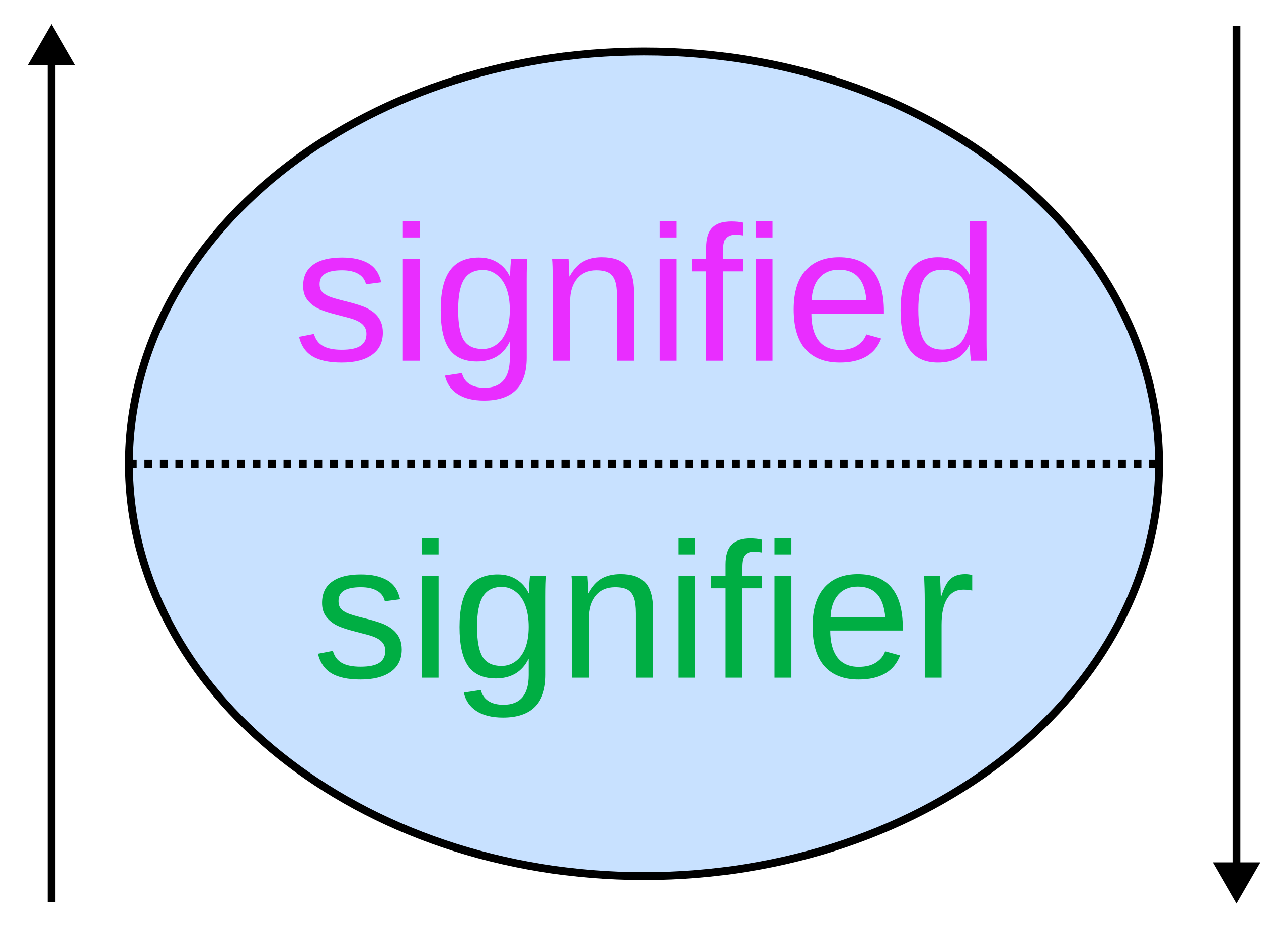

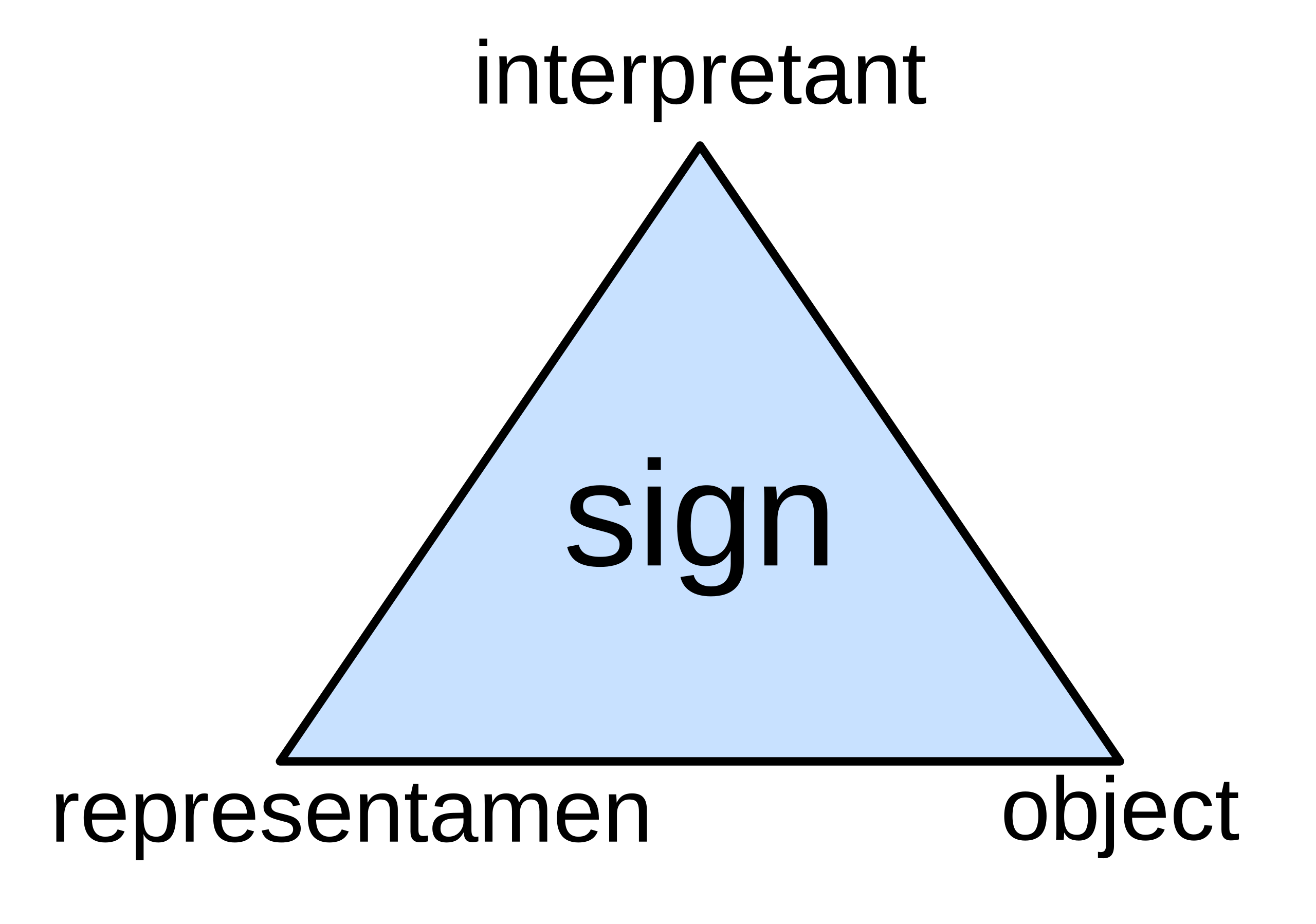

arbitrary, which applies to most linguistic signs. Models of signs

analyze the basic components of signs.   Ferdinand de Saussure's dyadic model identifies a perceptible image and a concept as the core elements, whereas Charles Sanders Peirce's triadic model distinguishes a sign vehicle, a referent, and an effect in the interpreter's mind. |

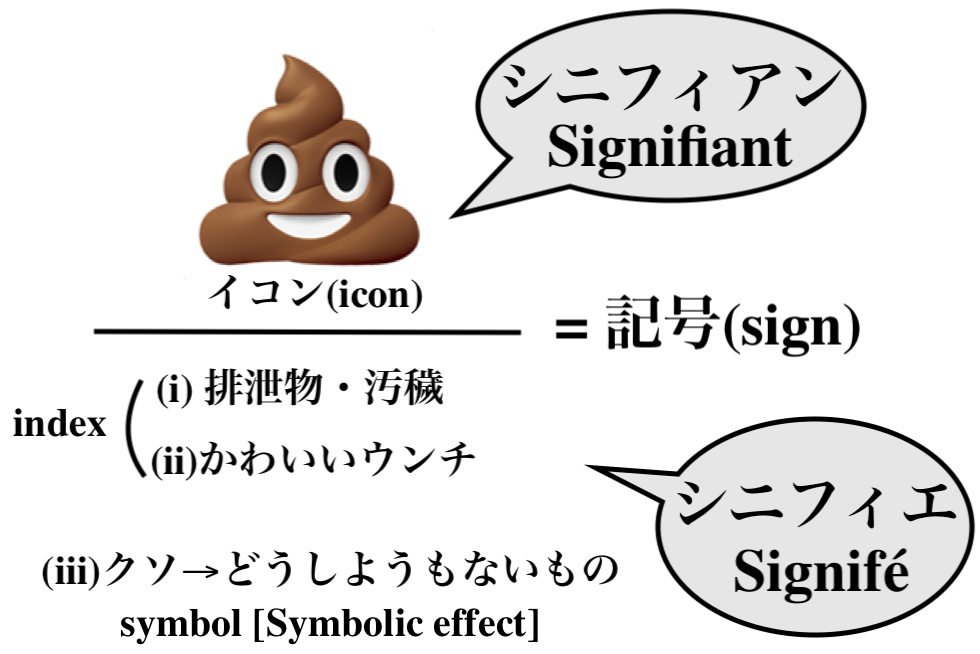

記

号とは、何か他のものを表す存在である。例えば「猫」という言葉は肉食哺乳類を表す。記号は音、画像、文字、身振りなど様々な形態をとる。図像的記号は類

似性によって機能する。この種の記号では、記号媒体が指称対象に似ている。人格の肖像画がその例だ。指示記号は直接的な物理的関連に基づく。煙が火の兆候

であるように。記号的記号においては、記号媒体と指称対象の関係は慣習的あるいは恣意的であり、これはほとんどの言語的記号に当てはまる。記号のモデルは

記号の基本構成要素を分析する。  フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールの二項モデルは知覚可能なイメージと概念を中核要素と特定する一方、チャールズ・サンダース・パースの三項モデルは記号媒 体、指称対象、解釈者の心における効果を区別する。 |

| Sign

systems are structured networks of interrelated signs, such as the

English language. Semioticians study how signs combine to form larger

expressions, called texts. They explore how the message of a text

depends on the meanings of the signs composing it and how contextual

factors and tropes influence this process. They also investigate the

codes employed to communicate meaning, including conventional codes,

such as the color code of traffic signals, and natural codes, such as

DNA encoding hereditary information. |

記 号体系とは、英語のような相互に関連する記号の構造化されたネットワークである。記号論者は、記号が組み合わさってより大きな表現、すなわちテクストを形 成する方法を研究する。彼らは、テクストのメッセージがそれを構成する記号の意味にどう依存するか、また文脈的要因や修辞法がこの過程にどう影響するかを 考察する。さらに、意味を伝達するために用いられるコード、例えば交通信号の色コードのような慣習的コードや、遺伝情報をコード化するDNAのような自然 コードについても調査する。 |

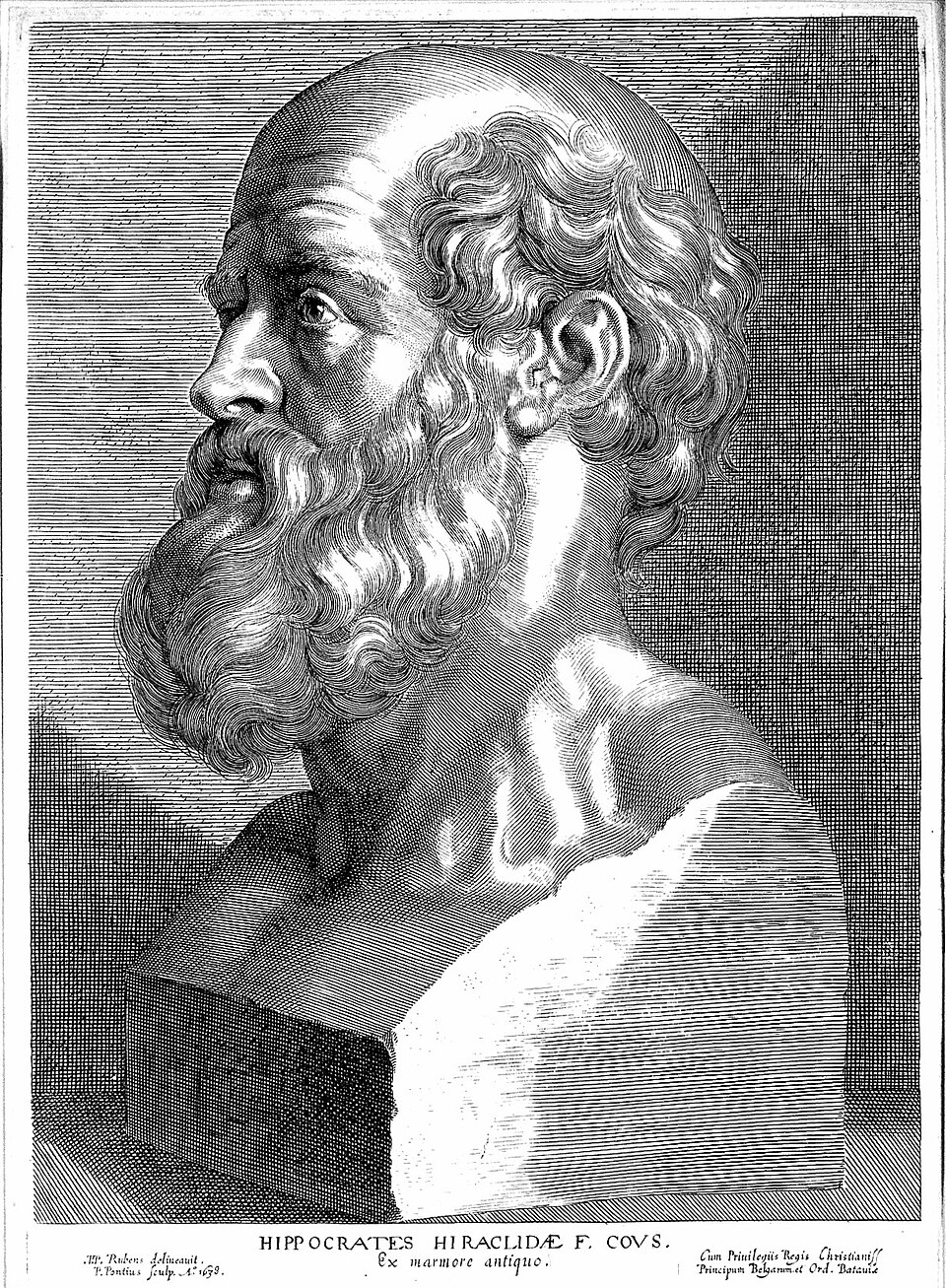

| Semiotics

has diverse applications because of the pervasive nature of signs. Many

semioticians study cultural products, such as literature, art, and

media, investigating both the elements used to express meaning and the

subtle ideological messages they convey. The psychological activities

associated with sign use are another research topic. Biosemiotics

extends the scope of inquiry beyond human communication, examining sign

processes within and between animals, plants, and other organisms.

Semioticians typically adjust their research approach to their specific

domain without a single methodology adopted by all subfields. Although

the roots of semiotic research lie in antiquity, it was not until the

late 19th and early 20th centuries that semiotics emerged as an

independent field of inquiry. |

記

号論は、記号の遍在性ゆえに多様な応用分野を持つ。多くの記号論研究者は、文学・芸術・メディアといった文化的産物を研究対象とし、意味を表現する要素

と、それらが伝える微妙なイデオロギー的メッセージの両方を調査する。記号使用に伴う心理的活動もまた研究テーマである。生物記号論は研究範囲を人間のコ

ミュニケーションを超えて拡大し、動物、植物、その他の生物内および生物間の記号プロセスを検証する。記号論研究者は通常、特定の領域に合わせて研究手法

を調整し、全てのサブ分野で共通の方法論を採用することはない。記号論研究の起源は古代に遡るものの、独立した研究分野として確立されたのは19世紀末か

ら20世紀初頭にかけてのことである。 |

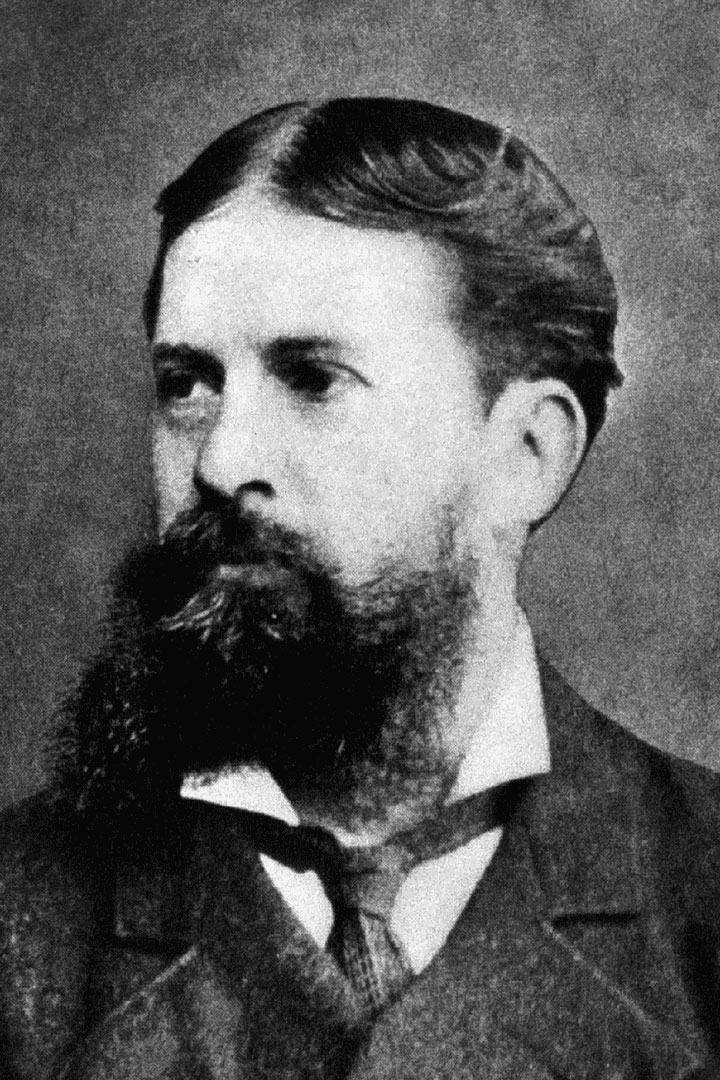

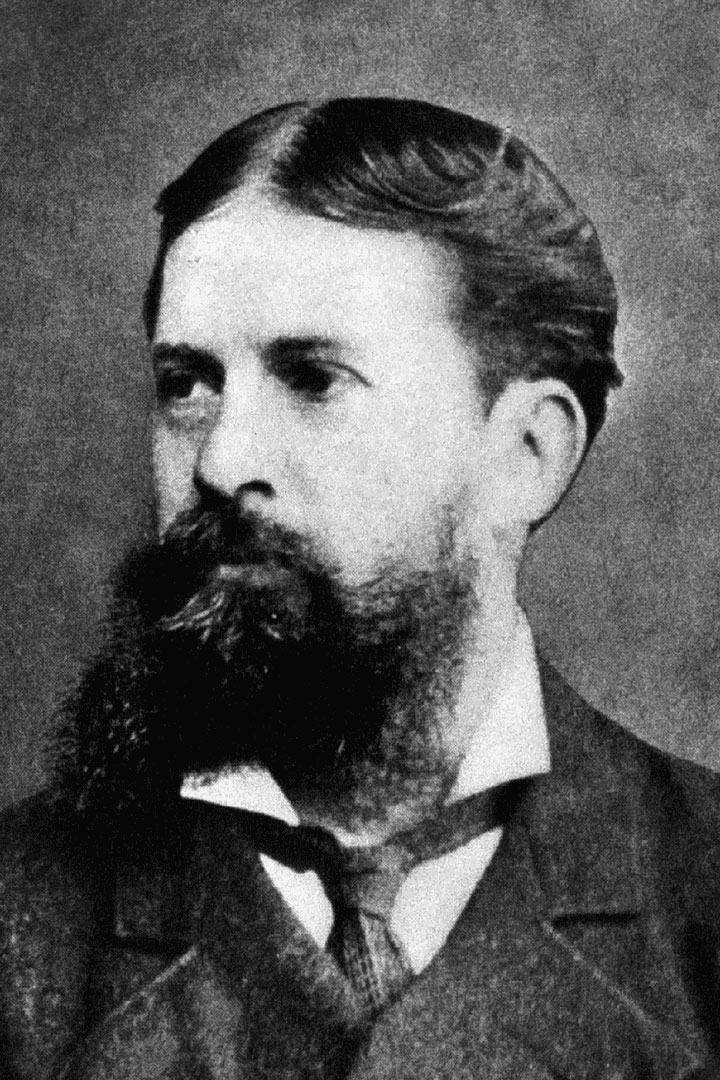

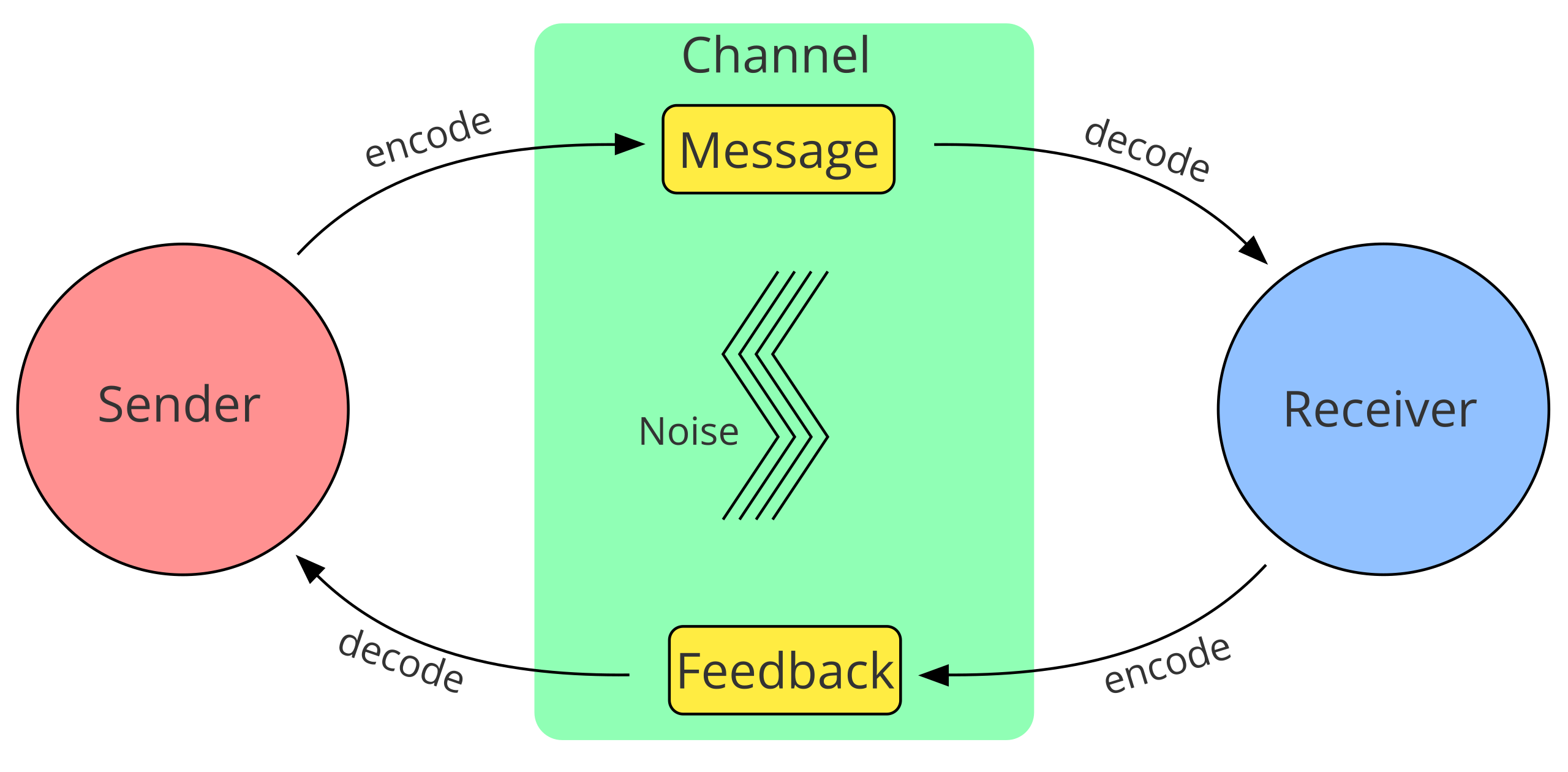

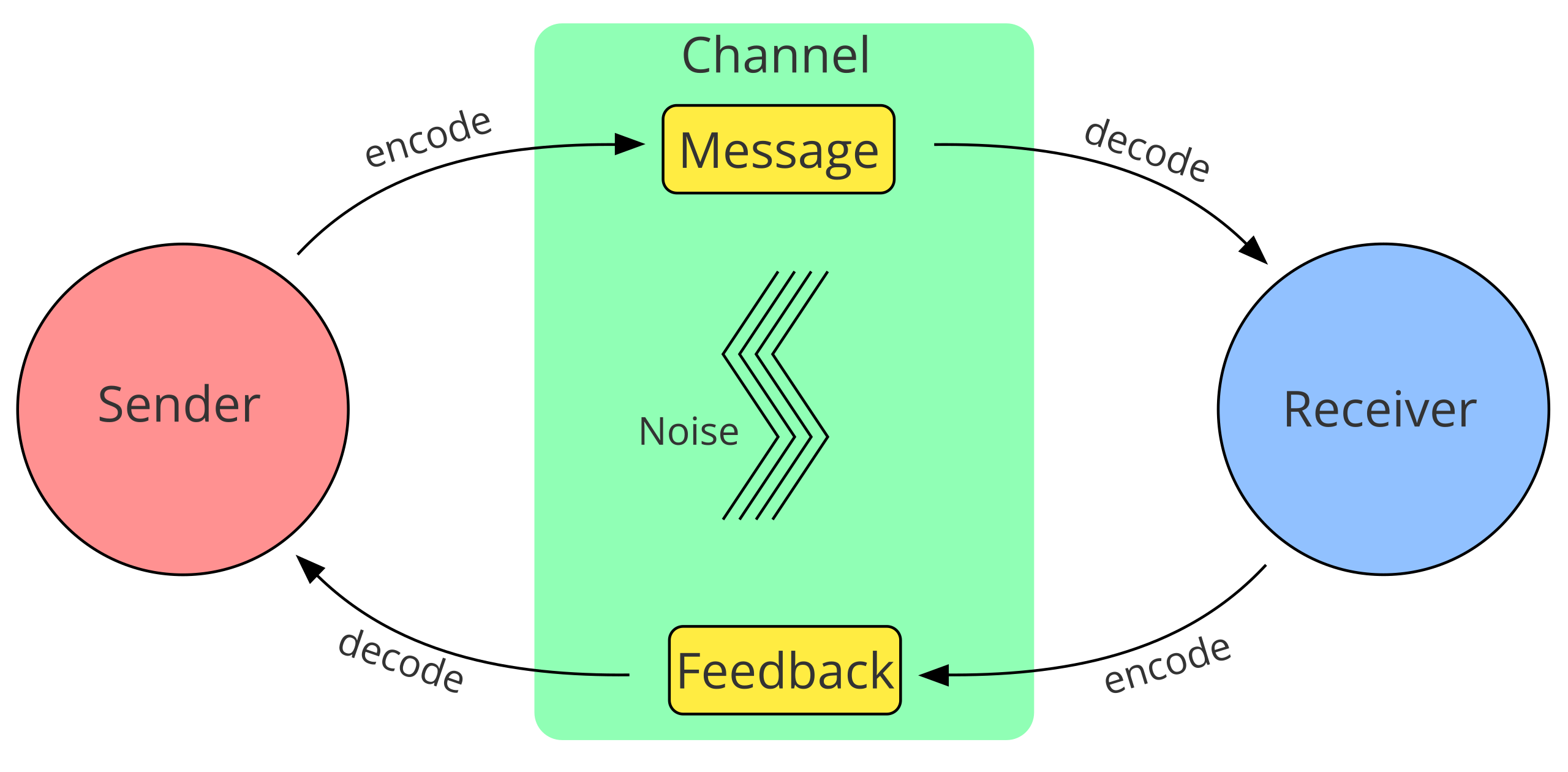

Definitions and related fields Black-and-white photo of a bearded man  Black-and-white photo of a man with a moustache Charles Sanders Peirce and Ferdinand de Saussure helped establish semiotics as a distinct field of inquiry.[2] Semiotics is the study of signs or of how meaning is created and communicated through them. Also called semiology,[b] it examines the nature of signs, their organization into signs systems, like language, and the ways individuals interpret and use them. Semiotics has wide-reaching applications because of the pervasive nature of signs, affecting how individuals experience phenomena, communicate ideas, and interact with the world.[4] These applications make it an interdisciplinary field, originating in philosophy and linguistics and closely related to disciplines like psychology, anthropology, aesthetics, sociology, and education sciences.[5] Because most sciences rely on sign processes in some form, semiotics is sometimes characterized as a meta-discipline that provides a general approach for the analysis of signs across domains.[6] It is controversial whether semiotics is itself a science since there are no universally accepted theoretical assumptions or methods on which semioticians agree.[7] Semiotics has also been characterized as a theory, a doctrine, a movement, or a discipline.[8] Apart from its interdisciplinary applications, pure semiotics is typically divided into three branches: semantics, syntactics, and pragmatics, studying how signs relate to objects, to each other, and to sign users, respectively.[9] Semiotic inquiry overlaps in various ways with linguistics and communication theory. It shares with linguistics the interest in the analysis of sign systems, examining the meanings of words, how they are combined to form sentences, and how they convey messages in concrete contexts. A key difference is that linguistics focuses on language, while semiotics also studies non-linguistic signs, such as images, gestures, traffic signs, and animal calls.[10] Communication theory studies how individuals encode, convey, and interpret both linguistic and non-linguistic messages. It typically focuses on technical aspects of how messages are transmitted, usually between distinct organisms. Semiotics, by contrast, concentrates on the meaning of messages and the creation of meaning, including the role of non-communicative signs.[11][c] For example, semioticians also study naturally occurring biological signs, like disease symptoms, and signs based on inanimate relations, such as smoke as a sign of fire.[13] The term semiotics derives from the Greek word σημειωτική (semeiotike), originally associated with the study of disease symptoms.[14] Proposing a new field of inquiry of signs, John Locke suggested the Greek term as its name.[15] The first use of the English term semiotics dates to the 1670s.[1] Semiotics became a distinct field of inquiry following the works of the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce and the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, the founders of the discipline.[2] |

定義と関連分野 ひげを生やした男の白黒写真  口ひげを生やした男の白黒写真 チャールズ・サンダース・パースとフェルディナン・ド・ソシュールは、記号論を独立した研究分野として確立するのに貢献した。[2] 記号論とは、記号、あるいは記号を通じて意味がどのように生成され伝達されるかを研究する学問である。記号学とも呼ばれ、記号の本質、言語のような記号体 系への組織化、そして個人がそれらを解釈し使用する方法を考察する。記号が遍在する性質ゆえに、記号論は広範な応用可能性を持ち、個人が現象を体験し、ア イデアを伝達し、世界と相互作用する方法に影響を与える。[4] こうした応用性から、記号論は学際的な分野となっている。哲学や言語学に起源を持ち、心理学、人類学、美学、社会学、教育学などの分野と密接に関連してい る。[5] ほとんどの科学が何らかの形で記号プロセスに依存しているため、記号論は領域横断的な記号分析の汎用的手法を提供するメタ学問と位置付けられることもあ る。[6] 記号論自体が科学であるか否かは議論の余地がある。なぜなら、記号論者が合意する普遍的に受け入れられた理論的前提や方法論が存在しないからである。 [7] 記号論は理論、学説、運動、あるいは学問分野とも特徴づけられる。[8] 学際的応用とは別に、純粋な記号論は通常、意味論、統語論、語用論の三分野に分けられる。それぞれ記号と対象物、記号同士、記号使用者の関係を研究する。 [9] 記号論の研究は、言語学やコミュニケーション理論と様々な形で重なる。言語学と同様に記号体系の分析に関心を持ち、言葉の意味、それらが組み合わさって文 を形成する方法、具体的な文脈でメッセージを伝達する方法を検討する。重要な違いは、言語学が言語に焦点を当てるのに対し、記号論は画像、ジェスチャー、 交通標識、動物の鳴き声などの非言語的記号も研究対象とする点だ。[10] コミュニケーション理論は、個人が言語的・非言語的メッセージを符号化し、伝達し、解釈する方法を研究する。通常、異なる生物間でのメッセージ伝達の技術 的側面に焦点を当てる。これに対し記号論は、メッセージの意味と意味の生成、非コミュニケーション的記号の役割を含む、メッセージの本質に集中する。 [11][c] 例えば記号論者は、病気の症状のような自然発生的な生物学的記号や、煙が火の兆候であるといった無生物的関係に基づく記号も研究する。[13] 記号論(semiotics)という用語は、ギリシャ語の「σημειωτική(semeiotike)」に由来し、元々は病気の症状の研究に関連して いた。[14] 記号の新たな研究分野を提唱したジョン・ロックは、その名称としてこのギリシャ語を提案した。[15] 英語の「semiotics」という用語が初めて使用されたのは1670年代である。[1] 記号論は、この学問分野の創始者である哲学者チャールズ・サンダース・パースと言語学者フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールの著作を経て、独立した研究領域と なった。[2] |

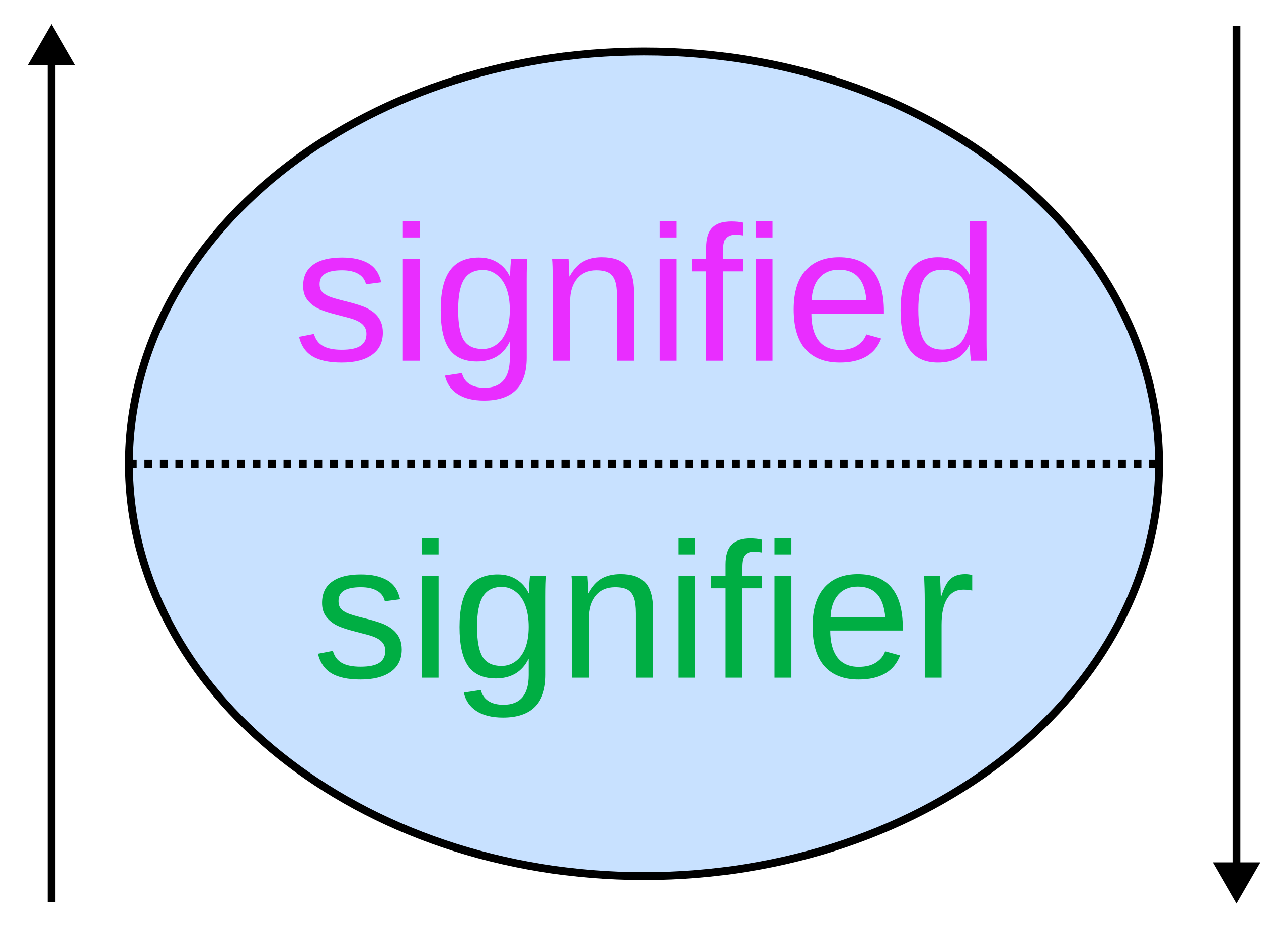

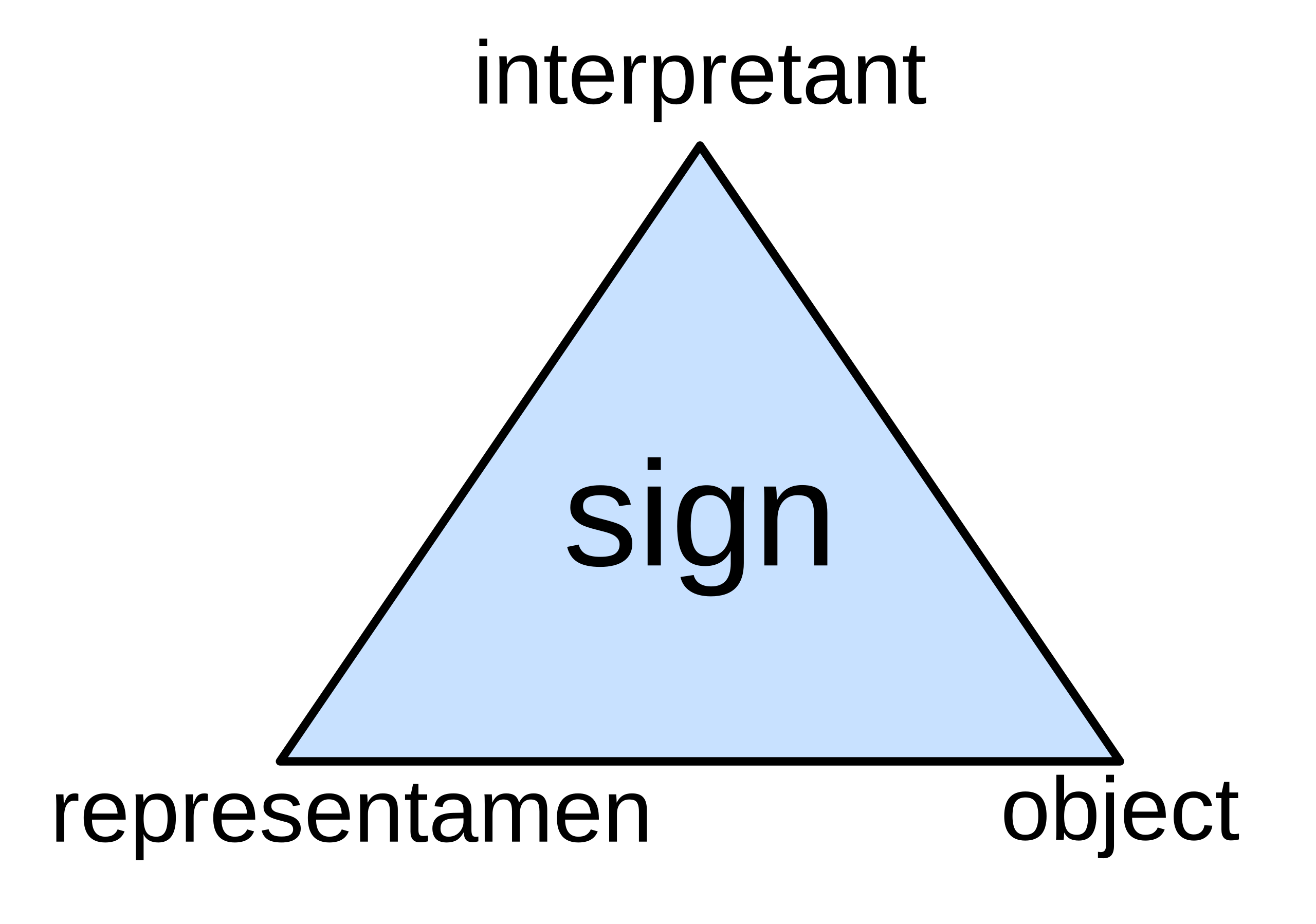

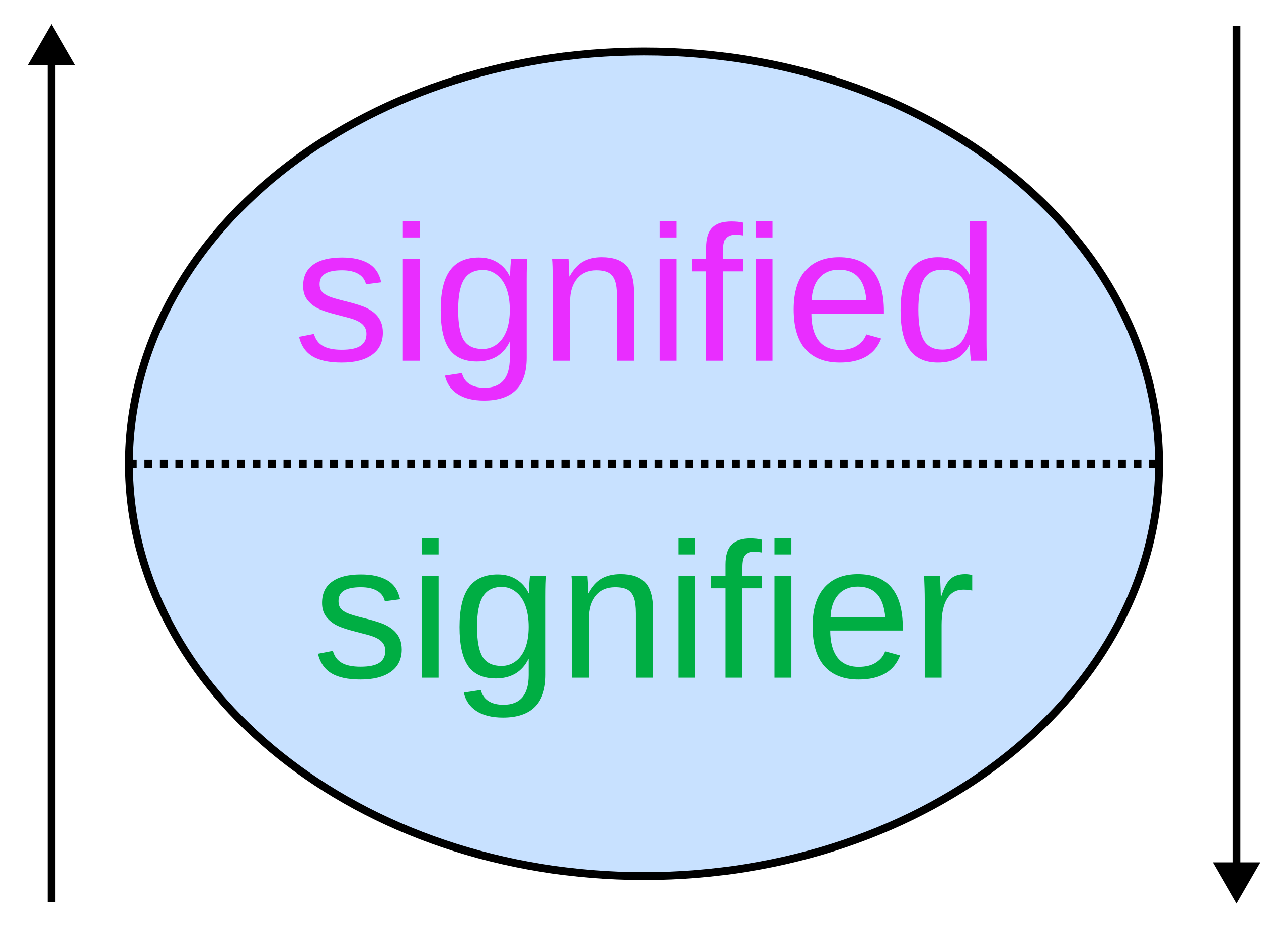

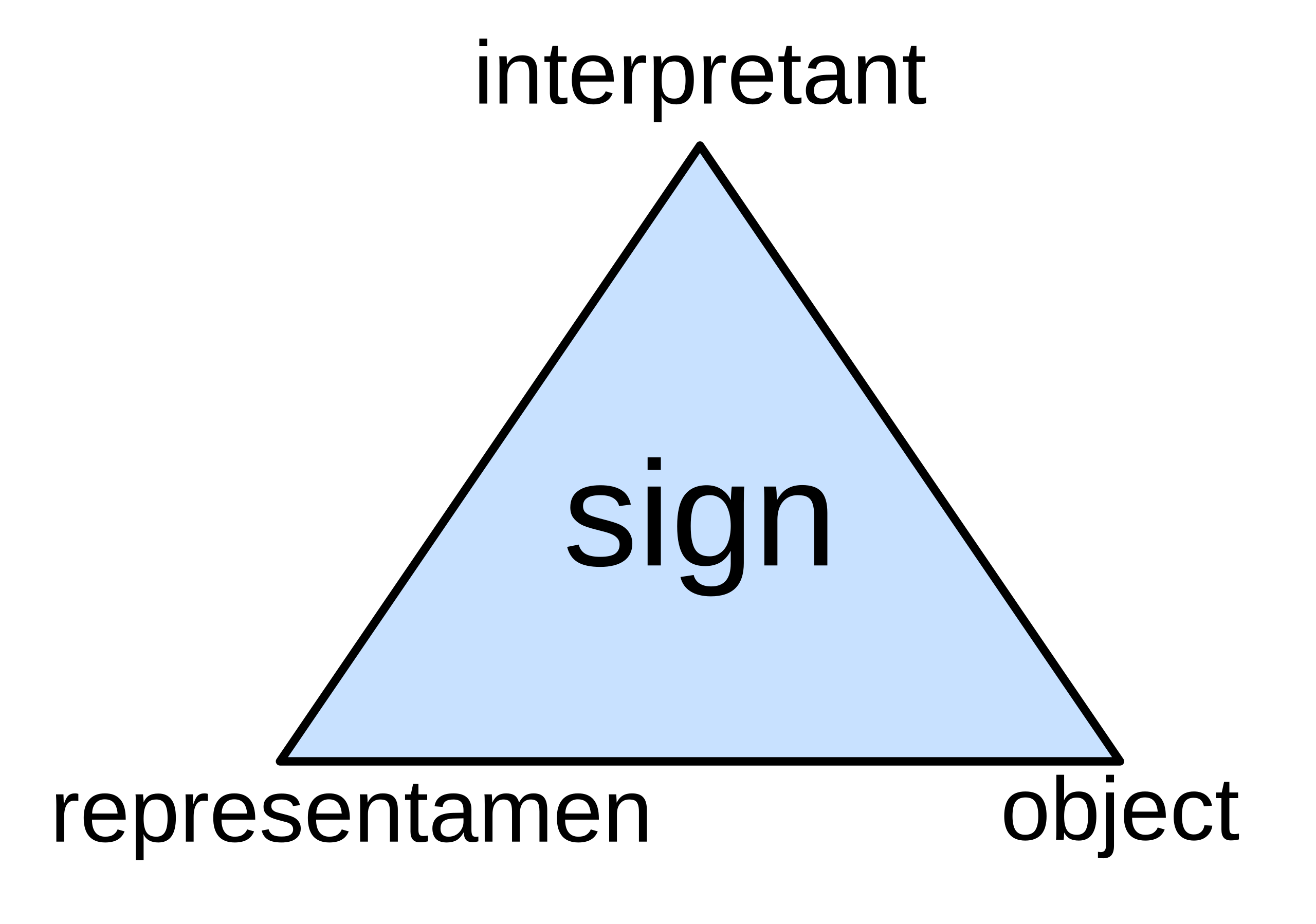

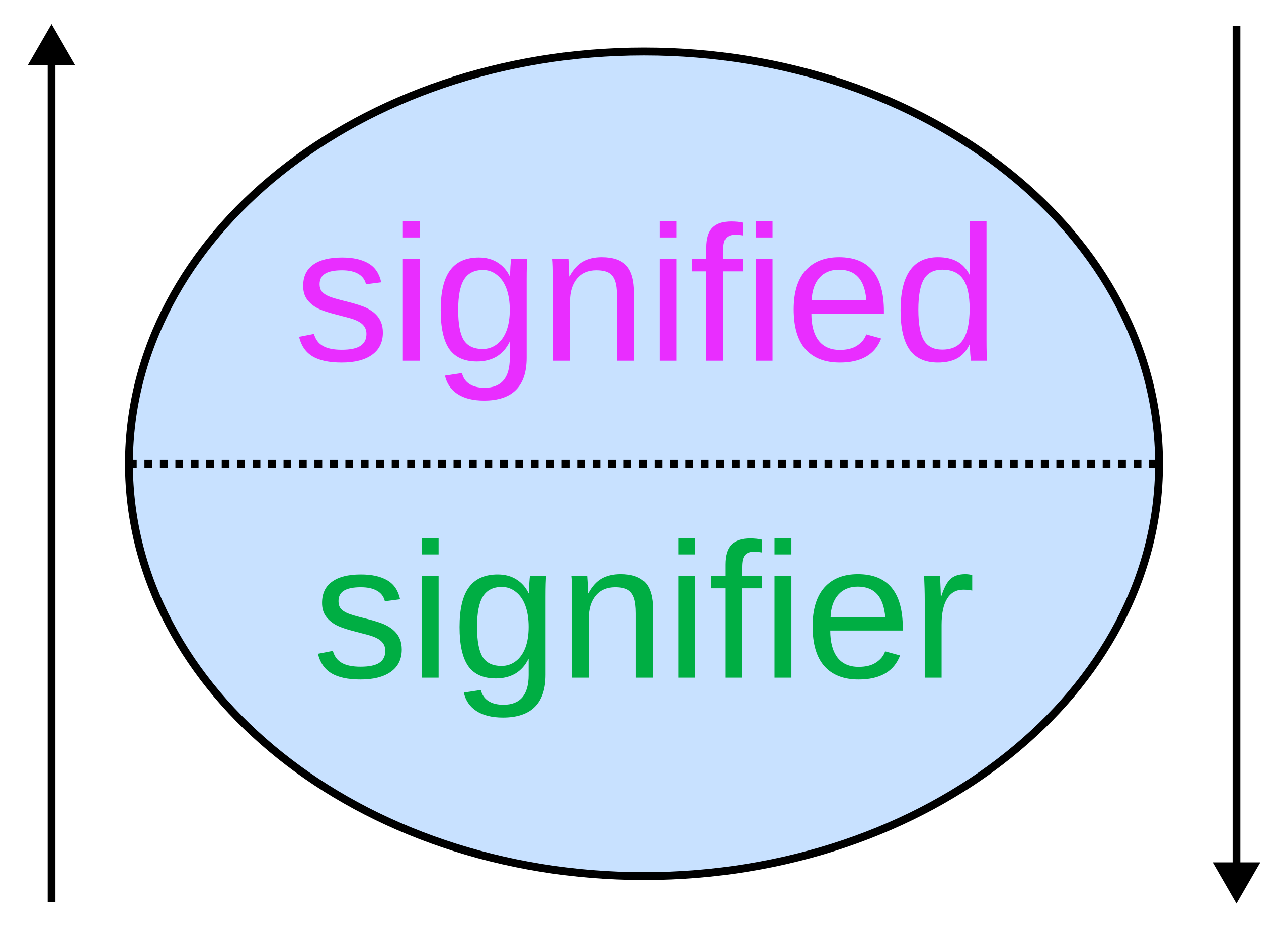

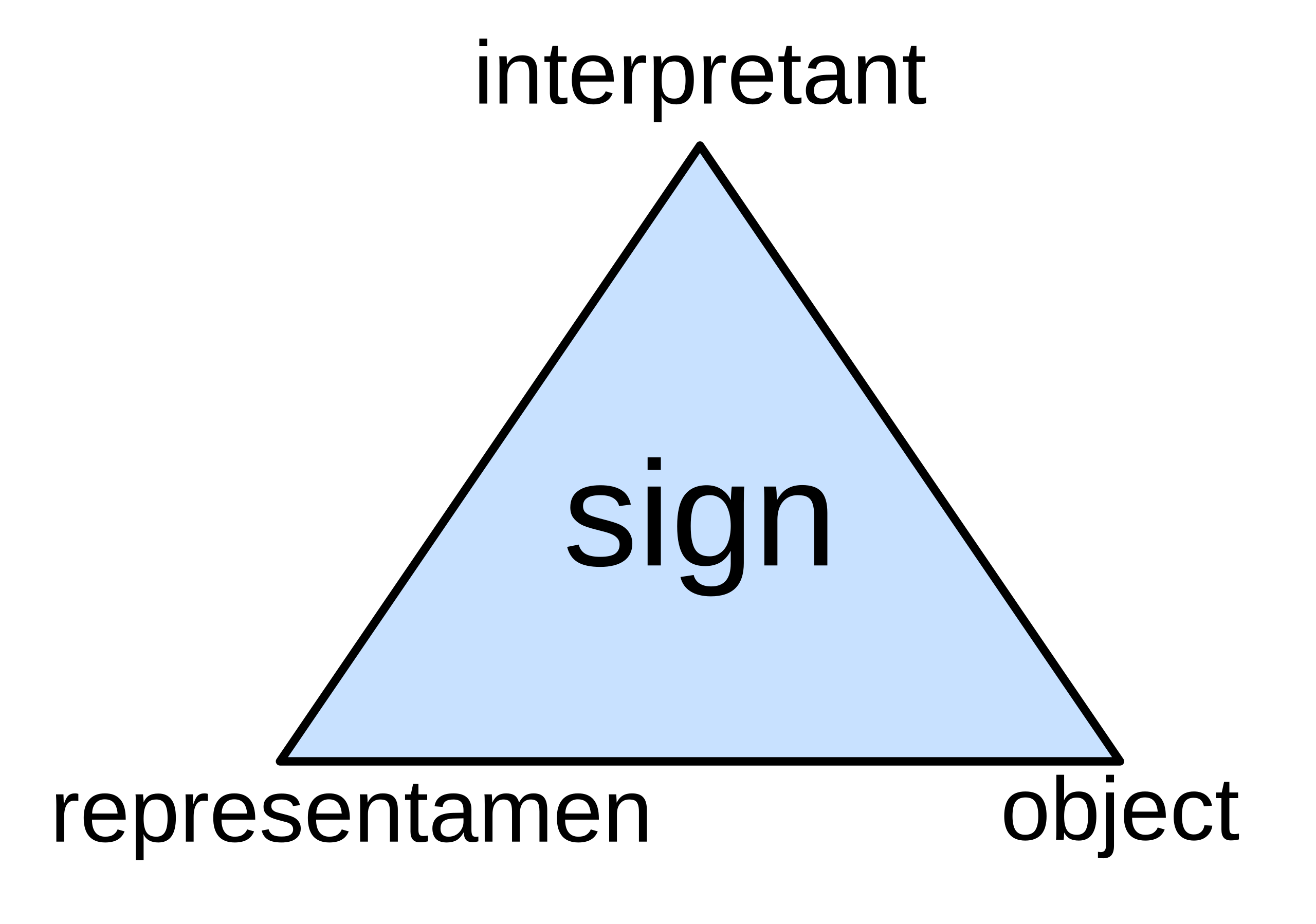

| Signs Main article: Sign (semiotics) A sign is an entity that stands for something else. For example, the word cat is a sign that stands for a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. Signs direct the attention of interpreters away from themselves and toward the entities they represent. They can take many forms, such as words, images, sounds, and odours. Similarly, they can refer to many types of entities, including physical objects, events, or places, psychological feelings, and abstract ideas. They help people recognize patterns, predict outcomes, make plans, communicate ideas, and understand the world.[16] Semioticians distinguish different elements of signs. The sign vehicle is the physical form of the sign, such as sound waves or printed letters on a page, whereas the referent is the object it stands for. The precise number and nature of these elements is disputed and different models of signs propose distinct analyses.[17] The referent of a sign can itself be a sign, leading to a chain of signification. For instance, the expression "red rose" is a sign for a particular type of flower, which can itself act as a sign of love.[18] Semiosis is the capacity or activity of comprehending and producing signs. Also characterized as the action of signs, it involves the interplay between sign vehicle and referent as organisms interpret meaning within a given context.[19] Different types of semiosis are distinguished by the type of organisms engaging in the sign activity, such as the contrast between anthroposemiosis involving humans, zoösemiosis involving other animals, and phytosemiosis involving plants.[20] Meaning, sense, and reference The meaning of a sign is what is generated in the process of semiosis. Meaning is typically analyzed into two aspects: sense and reference.[d] This distinction is also known by the terms connotation and denotation as well as intension and extension. The reference of a sign is the object for which it stands. For example, the reference of the term morning star is the planet Venus. The sense of a sign is the way it stands for the object or the mode in which the object is presented. For instance, the terms morning star and evening star have the same reference since they point to the same object. However, their meanings are not identical since they differ on the level of sense by presenting this object from distinct perspectives.[22] Various theories of meaning have been proposed to explain its nature and identify the conditions that determine the meanings of signs. Referential or extensional theories define meaning in terms of reference, for example, as the signified object or as a context-dependent function that points to objects.[23] Ideational or mentalist theories interpret the meaning of a sign in relation to the mental states of language users, for example, as the ideas it evokes.[24] Pragmatic theories describe meaning based on behavioral responses and use conditions.[25] Types and sign relations  Oil painting of a bearded man wearing a coat Icons represent through similarity, such as a portrait referring to Vincent van Gogh by resembling him.[26]  Photo of a footprint of a dog in the sand Indexical signs represent through a direct physical link, such as a footprint of a dog referring to the dog.[27]  Diagram with the word "apple", and an arrow, and an apple image Symbols are signs with an arbitrary relation between sign vehicle and referent, such as the link between the word "apple" and the fruit.[28] Semioticians distinguish various types of signs, often based on the sign relation or how the sign vehicle is connected to the referent.[29] A type is a general pattern or universal class, corresponding to shared features of individual signs. Types contrast with tokens, which are individual instances of a type. For example, the word banana encompasses six letter tokens (b, a, n, a, n, and a), which belong to three distinct types (b, a, and n).[30] A historically influential classification of sign types relies on the contrast between conventional and natural signs. Conventional signs depend on culturally established norms and intentionality to establish the link between sign vehicle and referent. For example, the meaning of the term tree is fixed by social conventions associated with the English language rather than a natural connection between the term and actual trees. Natural signs, by contrast, are based on a substantial link other than conventions. For instance, the footprint of a bear signifies the presence of a bear as a result of the bear's movement rather than a matter of convention. In modern semiotics, the distinction between natural and conventional signs has been replaced by the threefold classification into icons, indices, and symbols, initially proposed by Peirce.[29] Icons are signs that operate through similarity: sign vehicles resemble or imitate the referents to which they are linked. They include direct physical similarity, such as a life-like portrait depicting a person, but also encompass more abstract resemblance, such as metaphors and diagrams.[31] Icons are also used in animal communication. For instance, ants of the species Pogonomyrmex badius use a smell-based warning signal that resembles the type of danger with a correspondence between intensity and duration of signal and danger.[32] Indices are signs that operate through a direct physical link. Typically, the referent is the cause of the sign vehicle. For example, smoke indicates the presence of fire because it is a physical effect produced by the fire itself. Similarly, disease symptoms are signs of the disease causing them and a thermometer's gauge reading indicates the temperature responsible. Other material links besides a direct cause-effect relation are also possible such as a directional signpost physically pointing the path to a nearby campsite.[33] Symbols are signs that operate through convention-based associations. For them, the relation between sign vehicle and referent is arbitrary. It arises from social agreements, which an individual needs to learn in order to decode the meaning. Examples are the numeral "2", the colors on traffic lights, and national flags.[34] The categories of icon, index, and symbol are not exclusive, and the same sign may belong to more than one. For example, some road warning signs combine iconic elements, like an image of falling rocks to indicate rockslide, with symbolic elements, such as a red triangle to signal danger.[35] Various other categories are discussed in the academic literature. Thomas Sebeok expands the icon-index-symbol classification by adding three more categories: signals are signs that typically trigger behavioral responses in the receiver; symptoms are automatic, non-arbitrary signs; names are extensional signs that identify one specific individual.[36] Other categorizations of signs are based on the channel of transmission, the intentions of the communicators, vagueness, ambiguity, reliability, complexity, and type of referent.[37] Models Models of signs seek to identify the essential components of signs. Many models have been proposed and most introduce a unique terminology for the different components although they often share substantial conceptual overlap. A common classification distinguishes between dyadic and triadic models.[38]  Diagram of a circle with the words "signified" and "signifier" inside According to Saussure's dyadic model, signs are composed of a sensible image (signifier) and a concept (signified).[39] Dyadic models assert that signs have essentially two components, a sign vehicle and its meaning. An influential dyadic model was proposed by Saussure, who names the components signifier and signified. The signifier is a sensible image, whereas the signified is a concept or an idea associated with this form. For Saussure, the sign is a relation that connects signifier and signified, functioning as a bridge from a sensory form to a concept. He understands both signifier and signified as psychological elements that exist in the mind. As a result, the meaning of signs is limited to the realm of ideas and does not directly concern the external objects to which signs refer. Focusing on language as a general model of signs, Saussure argued that the relation between signifier and signified is arbitrary, meaning that any sensible image could in principle be paired with any concept. He held that individual signs need to be understood in the context of sign systems, which organize and regulate the arbitrary connections.[40] Various interpreters of Saussure's model, such as Louis Hjelmslev[e] and Roman Jakobson, rejected the purely psychological interpretation of signs. For them, signifiers are material forms that can be seen or heard, not mental images of material forms. Similarly, critics have objected to the idea that the relation between signs and signifiers are always arbitrary, pointing to iconic and indexical signs as counterexamples.[42][f]  Diagram of a triangle with the words "sign", "representamen", "interpretant", and "object" According to Peirce's triadic model, signs are composed of a sign vehicle (representamen), a referent (object), and an effect in the interpreter's mind (interpretant).[44] Triadic models assert that signs have three components. An influential triadic model proposed by Peirce argues that the third component is required to account for the individual that interprets signs, implying that there is no meaning without interpretation. According to Peirce, a sign is a relation between representamen, object, and interpretant. The representamen is a perceptible entity, the object is the referent for which the representamen stands, and the interpretant is the effect produced in the mind of the interpreter.[45] Peirce distinguishes various aspects of these components. The immediate object is the object as the sign presents it—a mental representation. The dynamic object, by contrast, is the actual entity as it really is, which anchors the meaning of the sign. The immediate interpretant is the sign's potential meaning, whereas the dynamic interpretant is the sign's actual effect or the understanding it produces. The final interpretant is the ideal meaning that would be reached after an exhaustive inquiry.[46] Peirce emphasizes that semiosis or meaning-making is a continuously evolving process. Analyzing Peirce's model, Umberto Eco talks of an "unlimited semiosis" in which the interpretation of one sign leads to more signs, resulting in an endless chain of signification.[47] Another triadic model, proposed by Charles Kay Ogden and I. A. Richards, distinguishes between symbol, thought, and referent. Known as the semiotic triangle, it asserts that the connection between symbol and referent is not direct but requires the mediation of thought to establish the link.[48] |

記号 主な記事: 記号 (記号論) 記号とは、何か他のものを表す存在である。例えば、「猫」という言葉は、小型の家畜化された肉食哺乳類を表す記号である。記号は、解釈者の注意を自身から 離れ、それが表す対象へと向かわせる。記号は言葉、画像、音、匂いなど、様々な形態をとることができる。同様に、物理的な物体、出来事、場所、心理的な感 情、抽象的な概念など、様々な種類の対象を指し示すこともできる。記号は、人々がパターンを認識し、結果を予測し、計画を立て、考えを伝え、世界を理解す るのに役立つ。[16] 記号論者は記号の異なる要素を区別する。記号媒体は、音波や紙面上の印刷文字など、記号の物理的な形態である。一方、表象対象は、それが表す対象そのもの である。これらの要素の正確な数や性質については議論があり、異なる記号モデルが独自の分析を提案している。[17] 記号の指称対象自体が記号となり、意味の連鎖を生むこともある。例えば「赤いバラ」という表現は特定の花を意味する記号であり、それ自体が愛の記号として 機能し得る。[18] 記号作用(セミオシス)とは、記号を理解し生成する能力または活動である。記号の作用とも特徴づけられ、生物が特定の文脈内で意味を解釈する際に、記号媒 体と指称対象の相互作用を伴う[19]。異なる記号作用の種類は、その活動に関わる生物の種類によって区別される。例えば、人間を伴う人類記号作用(アン トロポセミオシス)、他の動物を伴う動物記号作用(ズーセミオシス)、植物を伴う植物記号作用(フィトセミオシス)の対比が挙げられる。[20] 意味、感覚、参照 記号の意味とは、記号生成の過程で生み出されるものである。意味は通常、感覚と参照という二つの側面に分析される。[d] この区別は、内包と外延、あるいは内包と外延という用語でも知られる。記号の参照とは、それが指し示す対象である。例えば、「明けの明星」という用語の参 照は金星である。記号の意味とは、対象を表す方法、あるいは対象が提示される様式である。例えば「明けの明星」と「夕の明星」は同じ対象を指すため参照対 象は同一である。しかし、この対象を異なる視点から提示するという意味のレベルで差異があるため、両者の意味は同一ではない。[22] 意味の本質を説明し、記号の意味を決定する条件を特定するため、様々な意味論が提唱されてきた。参照理論あるいは外延理論は、意味を参照物、例えば表象さ れる対象や文脈依存的な対象指示機能として定義する[23]。観念論あるいは精神論的理論は、記号の意味を言語使用者の精神状態との関係で解釈する。例え ば、それが喚起する観念として[24]。語用論的理論は、行動的反応と使用条件に基づいて意味を記述する。[25] 記号の種類と関係  コートを着たひげ面の男性の油絵 アイコンは類似性によって表象する。例えば肖像画がフィンセント・ファン・ゴッホに似ていることで彼を指すように。[26]  砂浜に犬の足跡が写った写真 指標的記号は直接的な物理的連結によって表象する。例えば犬の足跡が犬を指すように。[27]  「りんご」という文字、矢印、りんごの画像が記された図 記号は、記号媒体と指称対象の間に恣意的な関係を持つ記号である。例えば「りんご」という単語と果実の関係がそれにあたる。[28] 記号論者は、記号関係や記号媒体が指称対象とどう結びつくかに基づき、様々な記号類型を区別する。[29] 類型とは、個々の記号に共通する特徴に対応する、一般的なパターンや普遍的な分類である。類型は、類型の個々の実例であるトークンと対比される。例えば、 単語「banana」は6つの文字トークン(b, a, n, a, n, a)を含むが、これらは3つの異なる類型(b, a, n)に属する。[30] 歴史的に影響力のある記号類型の分類は、慣習的記号と自然記号の対比に基づく。慣習的記号は、記号媒体と指称対象の関連性を確立するために、文化的に確立 された規範と意図主義に依存する。例えば「tree」という用語の意味は、英語に関連する社会的慣習によって固定されており、実際の樹木との自然な関連性 によるものではない。これに対し自然記号は、慣習以外の実質的な関連性に基づいている。例えば、熊の足跡は、慣習の問題ではなく、熊の移動の結果として熊 の存在を示す。現代記号論では、自然記号と慣習記号の区別は、パースが最初に提唱したアイコン、インデックス、シンボルの三分類に置き換えられている。 [29] アイコンは類似性を通じて機能する記号である:記号媒体は、それらが結びつけられる指称対象に似ているか、模倣する。これには人格を描いた写実的な肖像画 のような直接的な物理的類似性だけでなく、隠喩や図表のようなより抽象的な類似性も含まれる[31]。アイコンは動物のコミュニケーションでも用いられ る。例えば、Pogonomyrmex badiusという種の蟻は、危険の種類に似た匂いによる警告信号を使用し、信号の強度と持続時間が危険に対応している[32]。 指標は直接的な物理的リンクを通じて機能する記号である。典型的には、指し示す対象が記号媒体の原因となる。例えば煙は火の存在を示す。なぜなら煙は火そ のものが生み出す物理的効果だからだ。同様に、病気の症状はそれを引き起こす病気の兆候であり、体温計の目盛りは原因となる温度を示す。直接的な因果関係 以外の物質的リンクも可能である。例えば方向指示標識が物理的に近くのキャンプ場への道を指し示す場合などだ。[33] 記号は慣習に基づく関連性を通じて機能する記号である。記号媒体と指称対象の関係は恣意的だ。それは社会的合意から生じるものであり、個人が意味を解読す るにはこれを学ぶ必要がある。例としては数字の「2」、信号機の色、国民旗などが挙げられる。[34] アイコン、インデックス、シンボルの分類は排他的ではなく、同一の記号が複数に属し得る。例えば、落石を示す岩の絵といったアイコン的要素と、危険を示す 赤い三角形といったシンボリック的要素を組み合わせた道路警告標識がある。[35] 学術文献では他にも様々な分類が議論されている。トーマス・セベックは、アイコン・インデックス・シンボルの分類をさらに三つのカテゴリーで拡張してい る。シグナルは受信者に典型的な行動反応を引き起こす記号である。シンプトムは自動的で非恣意的な記号である。ネームは特定の個体を識別する外延的記号で ある。[36] 記号の他の分類法は、伝達経路、発信者の意図、曖昧さ、信頼性、複雑さ、参照対象の種類などに基づく。[37] モデル 記号のモデルは、記号の本質的な構成要素を特定しようとするものである。多くのモデルが提案されており、それらのほとんどは異なる構成要素に対して独自の 用語を導入しているが、概念的にはかなりの重複が見られることが多い。一般的な分類では、二項モデルと三項モデルが区別される。[38]  円図に「表象」と「表象物」の文字を内側に配置した図 ソシュールの二項モデルによれば、記号は知覚可能な形象(表象物)と概念(表象)から構成される。[39] 二項モデルは、記号が本質的に二つの要素、すなわち記号媒体とその意味を持つと主張する。影響力のある二項モデルはソシュールによって提案され、彼はその 要素を表象物と表象と呼んだ。表象(シニフィアン)は知覚可能な形象であり、表意(シニフィエ)はこれと結びついた概念や観念である。ソシュールにとって 記号とは、表象と表意を結びつける関係であり、感覚的形象から概念への架け橋として機能する。彼は表象と表意の両方を、精神内に存在する心理的要素として 理解する。その結果、記号の意味は観念の領域に限定され、記号が指し示す外部対象に直接関わるものではない。記号の一般モデルとして言語に焦点を当てたソ シュールは、表象と表意の関係は恣意的であると主張した。つまり、あらゆる感覚的イメージは原則としてあらゆる概念と結びつけられるというのだ。個々の記 号は、恣意的な結びつきを組織化し規制する記号体系の文脈で理解されるべきだと彼は考えた。[40] ソシュールのモデルを解釈したルイ・ヘルムスレフやロマン・ヤコブソンらは、記号の純粋心理学的解釈を拒否した。彼らにとって記号表象は物質形態の精神的 イメージではなく、視覚や聴覚で認識可能な物質的形態である。同様に、記号と記号表象の関係が常に恣意的であるという考えに対しても、批判が寄せられてお り、象徴的記号や指標的記号が反例として挙げられている。  「記号」「表象」「解釈」「対象」の三角図 パースの三項関係モデルによれば、記号は記号媒体(表象)、参照対象(対象)、解釈者の心における効果(解釈)から構成される。[44] 三項関係モデルは記号が三つの要素を持つと主張する。パースが提唱した影響力のある三項モデルは、記号を解釈する個人を説明するために第三の構成要素が必 要だと主張し、解釈なしに意味は存在しないことを示唆している。パースによれば、記号とは表象、対象、解釈項の関係である。表象は知覚可能な実体であり、 対象は表象が指し示す参照対象であり、解釈項は解釈者の心の中で生み出される効果である。[45] パースはこれらの構成要素の様々な側面を区別する。直接対象とは、記号が提示する対象、すなわち心的表象である。対照的に、動的対象とは、記号の意味を固 定する実在する実体そのものである。直接解釈対象とは記号の潜在的な意味であり、動的解釈対象とは記号の実際の効果、すなわちそれが生み出す理解である。 最終解釈項は徹底的な探究の末に到達する理想的な意味である。[46] パースは記号作用(意味形成)が継続的に進化する過程であることを強調する。ウンベルト・エーコはパースのモデルを分析し、一つの記号の解釈がさらなる記 号へと導く「無限の記号作用」を論じ、意味の連鎖が終わりなく続くことを指摘する。[47] チャールズ・ケイ・オグデンとI・A・リチャーズが提唱した別の三項モデルは、記号、思考、表象対象を区別する。記号論的三角形として知られるこのモデル は、記号と表象対象の結びつきが直接的ではなく、思考という媒介を通じて確立されると主張する。[48] |

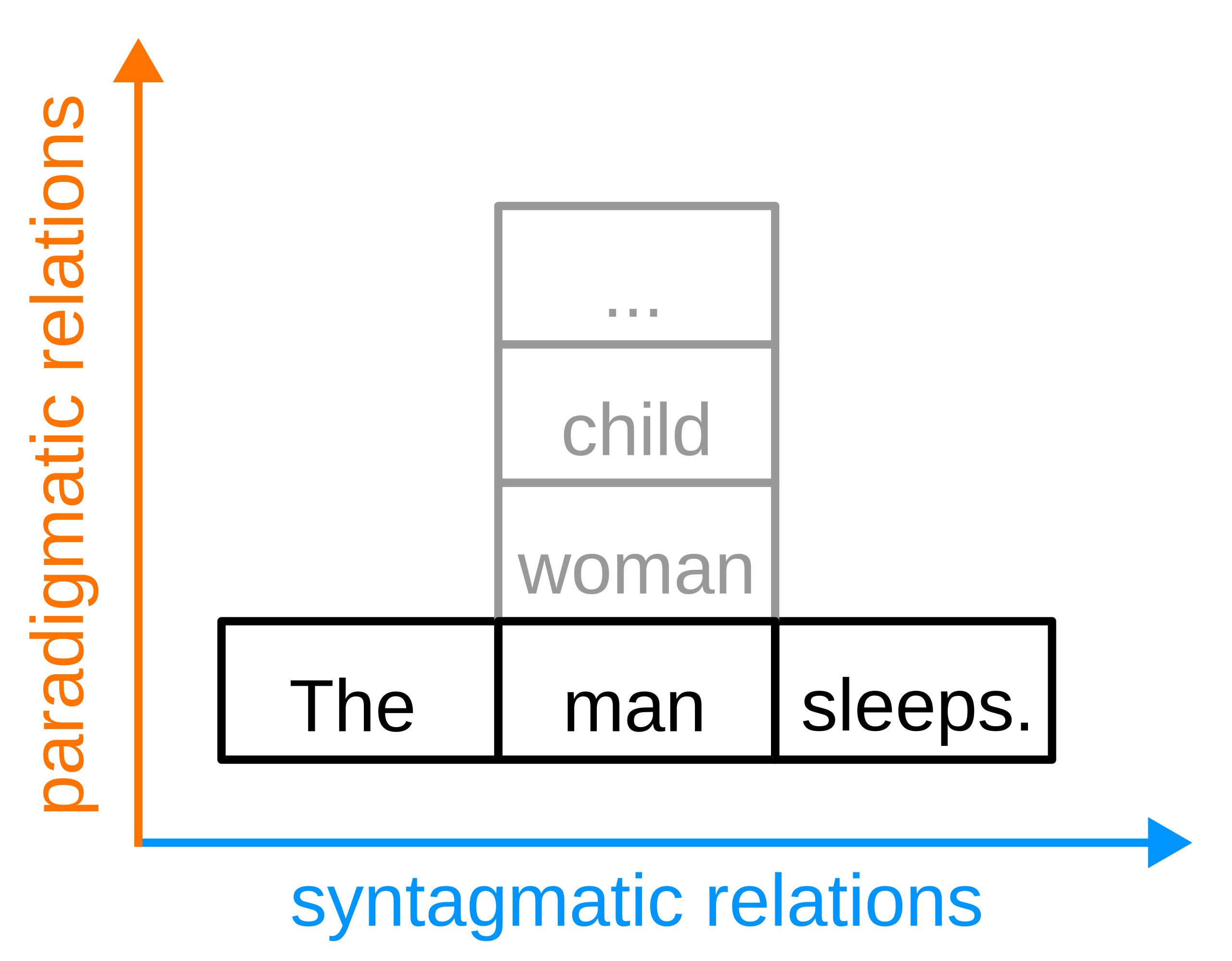

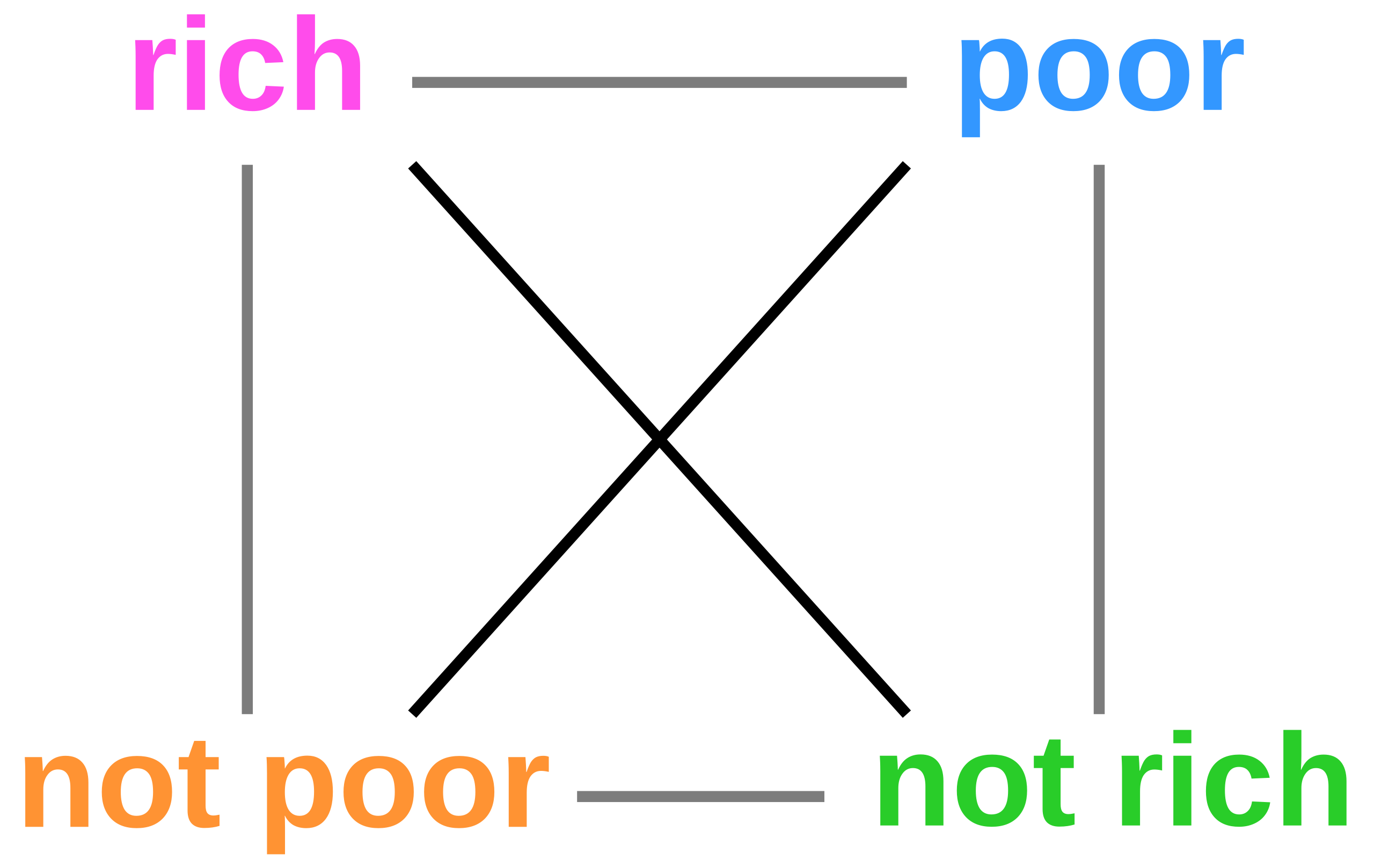

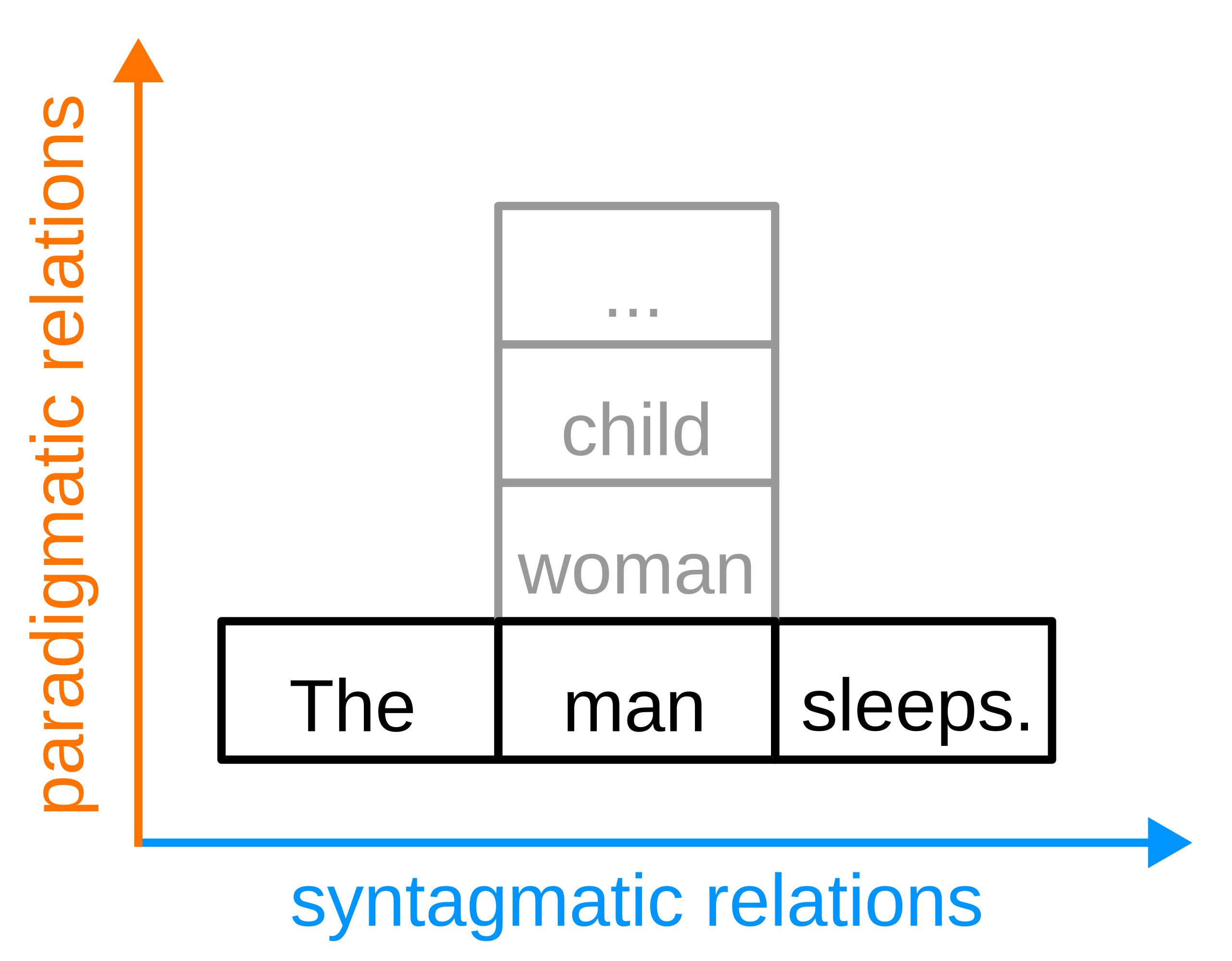

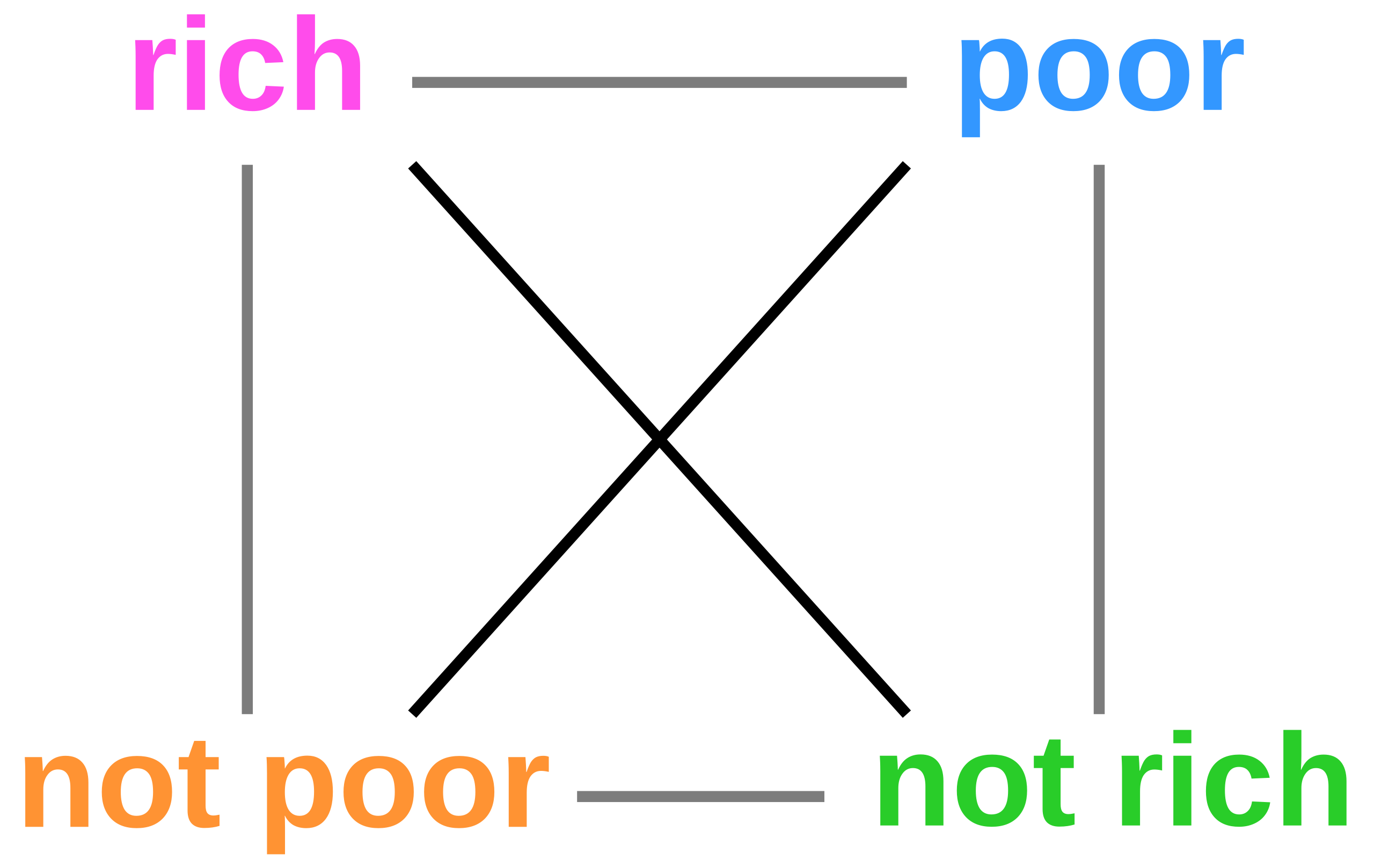

| Sign systems Main article: Sign system A sign system is a complex of relations governing how signs are formed, combined, and interpreted, such as a specific language. Signs usually occur in the context of a sign system, and some semiotic theories assert that isolated signs have little meaning apart from their systemic relations to other signs.[49] Sign elements and texts Sign systems often rely on basic constituents or sign elements to compose signs. For example, alphabetic writing systems use letters as sign elements to construct words, while Morse code uses dots and dashes. Letters are essential for differentiating word meanings, like the contrast between the words cat, rat, and hat based on their initial letter. The basic sign elements usually do not have a meaning of their own unless combined in systematic ways.[50] A text is a large sign composed of several smaller signs according to a specific code.[51] Unlike basic sign elements, the units composing a text are themselves meaningful. The meaning of a text, called its message, depends on its components. However, it is usually not a mere aggregate of their isolated meanings, but shaped by their interaction and organization. In addition to linguistic texts, such as a novel or a mathematical formula, there are also non-linguistic texts, such as a diagram, a poster, or a musical composition consisting of several movements.[52] The capacity to create and understand texts, known as textuality, is also present in some non-human animals. For example, honey bees perform a complex dance combining diverse features to communicate information about their environment to other bees.[53] The meaning of a text can depend on and refer to other texts—a feature called intertextuality.[54] Semioticians distinguish several aspects of texts. Paratext encompasses elements that frame or surround a text, such as titles, headings, acknowledgments, footnotes, and illustrations. Architext refers to the general categories to which a text belongs, such as its genre, style, medium, and authorship. A metatext is a text that comments on another text. A hypotext is a text that serves as the basis of another text, such as a novel that has a sequel or is parodied in another work. In such cases, the derivative text that refers to the earlier work is the hypertext.[55][g] Structural relations between signs  Diagram showing syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations for the sentence "The man sleeps." Diagram showing syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations for the sentence "The man sleeps."[57] The signs in a sign system are connected through several structural relations, like the contrast between syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations. Syntagmatic relations govern how individual signs or sign elements can be combined to form larger expressions. For example, sentences are linear arrangements of words, and syntagmatic relations govern which words can be combined to produce grammatically correct sentences. Similarly, a dinner menu is a sequence of courses with syntagmatic relations governing their arrangement, like beginning with a starter, followed by a main course and a dessert. Some sign systems use non-linear arrangements, such as traffic signs combining the shape of a sign with the symbol it shows.[58] Paradigmatic relations are links between signs that belong to the same structural category. They specify which elements can occupy a particular position and can substitute for each other without breaking the system's rules. For example, in the sentence "The man sleeps.", the word man stands in paradigmatic relations to words like woman, child, and person because substituting them also results in a correct sentence. For the dinner menu, the same holds for the different options for the dessert, such as cake, ice cream, and fruit salad. In the case of traffic signs, there are paradigmatic relations between the shape options, such as triangle and circle. The meaning of the chosen paradigmatic option is influenced by the absent options, which form a background of meaningful alternatives. In natural language, these alternatives are typically related to specific word classes. For instance, when a particular word position in a sentence calls for a verb then the paradigmatic options consist of verbs.[59]  Diagram of a square with contrasting terms in each corner The semiotic square is a tool to analyze the meanings of contrasting terms, such as rich/poor.[60] Another form of semiotic analysis examines sign pairs consisting of opposites where two signs denote contrasting features and exclude each other, like the pairs good/bad, hot/cold, and new/old. Some contrasts involve a continuous scale with intermediate levels, like fast/slow, whereas others are polar oppositions without degrees in between, such as alive/dead.[61] Early structuralist philosophy is associated with the idea that meaning arises primarily from binary oppositions.[62] The semiotic square, proposed by Algirdas Greimas, offers a more fine-grained differentiation. It relates a sign, such as rich, to three contrasting terms: its contradictory (not rich), its contrary (poor), and the contradictory of its contrary (not poor).[63] Another structural feature is asymmetric sign pairs where one item is unmarked and the other marked. The unmarked sign is the generic and neutral expression often taken for granted, whereas the marked sign is specialized and denotes additional features. The unmarked term is more commonly used and is typically privileged as the default or norm. Examples are the pairs dog/bitch, day/night, he/she, and right/left. This asymmetry is of particular interest to the semiotic study of culture as a guide to implicit background assumptions and power relations.[64] For example, patriarchal societies tend to use unmarked forms for masculine terms, while unmarked forms for feminine terms are more common in matriarchal societies.[65] Tropes Semioticians study associative mechanisms through which a sign acquires alternative meanings by interacting with other signs. This change in meaning can occur in cases where the literal meaning of a sign is inadequate or absurd, leading to a shift toward a figurative meaning. For example, the term snake literally refers to a limbless reptile but has a different meaning in the sentence "The professor is a snake."[66] The mechanisms through which this shift in meaning happens are called tropes. Discussions of tropes sometimes focus on four master tropes[h] as the basis of most others: metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, and irony.[68] A metaphor is an analogy in which attributes from one entity are carried over to another, such as associating the snake-like attributes of being sneaky and cold-blooded with a professor.[69] A metonymy is a way of referring to one object by naming another closely related thing, like speaking of a king as the crown.[70] Similarly, a synecdoche is a way of referring to one object by naming one of its parts, like speaking of one's car as my wheels.[71] The trope of irony works through dissimilarity, literally expressing the opposite of what is meant, such as remarking "Great job!" after a horrible failure.[72] Semiotic tropes are primarily discussed in relation to linguistic sign systems, where they are also known as figures of speech. However, their underlying mechanisms also affect non-linguistic sign systems.[73] For example, an advertisement for an airline may juxtapose the landing of a plane with the tranquil touchdown of a swan as a pictorial metaphor for grace and reliability.[74] Comics often rely on pictorial metonymies to express emotions, like a raised fist to stand for anger.[75] In photography, close-ups can function as synecdoches by presenting the whole through a part.[76] In film, one type of audiovisual irony presents a horrific visual scene accompanied by incongruously cheerful music.[77] Codes Main article: Code A code is a sign system used to communicate. It includes a set of signs, the meaning relations among them, and the rules for combining them to create and interpret messages.[78][i] Digital codes rely on clear and precise distinctions of how signs are formed and combined, as in written language. They contrast with analog codes, which use continuous variations to convey meaning, such as seamless gradations of color in painting.[80] Simple codes include only few basic elements and relations, as in the color code of traffic signals. Complex codes, like the English language, can encompass countless elements as well as syntactic and sociocultural norms involved in meaning-making. Conventional codes are human-made constructs, including aesthetic codes used in the creation of artworks, like music and painting. They contrast with natural codes,[j] like DNA, which functions as a biochemical information system encoding hereditary information through nucleotide sequences.[82] Semioticians analyze codes along several dimensions, such as the domain and context they operate in, the sensory channel they rely on, and the function they perform. Some codes focus on the precise expression of knowledge, such as mathematical formulas, while others govern cultural and behavioral norms, including conventions of politeness and ceremonial practices.[83] A code can have domain-specific subcodes that refine its scope of meaning or regulate usage in particular settings. Codes and subcodes are not static frameworks but can evolve as new conventions or technologies emerge.[84]  Diagram showing the most common components of models of communication Models of communication are representations of the main components of communication, often including the processes of encoding and decoding.[85]  Code also plays a central role in models of communication—conceptual representations of the main components of communication. Many include the idea that a sender conveys a message through a channel to a receiver, who interprets it and may respond with feedback. Encoding is the process of expressing meaning in the form of a message using the system of a specific code. Decoding is the reverse process of interpreting the message to understand its meaning. In some cases, different codes can be used to express the same message. Similarly, messages can sometimes be translated from one code into another, such as transcribing a written text into Morse code.[86] Discourse is the social use of language or other codes, taking place at a specific moment in a particular context. Discourse analysis examines how meaning arises in a discourse, considering the communicators and their respective roles, as well as the influences of context and institutional backgrounds.[87] Semioticians are also interested in how codes reflect and shape human perception of the world.[88] By influencing perception, codes can affect behavior by making individuals aware of possible courses of action.[89] The controversial Whorfian hypothesis suggests that language shapes thought by providing fundamental categories of understanding, with the potential consequence that speakers of different languages think differently.[90] |

記号体系 主な記事: 記号体系 記号体系とは、特定の言語のように、記号が形成され、組み合わされ、解釈される方法を規定する関係の複合体である。記号は通常、記号体系の文脈の中で現れ る。一部の記号論理論は、孤立した記号は他の記号との体系的な関係から切り離すとほとんど意味を持たないと主張する。[49] 記号要素とテキスト 記号体系はしばしば、記号を構成するための基本構成要素や記号要素に依存する。例えば、アルファベット表記体系は文字を記号要素として単語を構築し、モー ルス信号は点と線を用いる。文字は単語の意味を区別するために不可欠であり、例えば「cat」「rat」「hat」といった単語は頭文字の違いによって意 味が対比される。基本的な記号要素は、体系的な方法で組み合わされない限り、通常それ自体に意味を持たない。[50] テキストとは、特定のコードに従って複数の小さな記号で構成される大きな記号である。[51] 基本的な記号要素とは異なり、テキストを構成する単位自体が意味を持つ。テキストの意味(メッセージと呼ばれる)はその構成要素に依存する。しかし、それ は通常、それらの孤立した意味の単なる集合体ではなく、相互作用と組織化によって形作られる。小説や定式といった言語的テキストに加え、図表やポスター、 複数の楽章から成る楽曲といった非言語的テキストも存在する。[52] テキストを創造し理解する能力(テクスト性)は、一部の非人間動物にも見られる。例えばミツバチは、環境情報を他の蜂に伝えるため、多様な特徴を組み合わ せた複雑なダンスを実行する。[53] テキストの意味は他のテキストに依存し、参照することがある。この特徴を相互テクスト性と呼ぶ。[54]記号論者はテキストの複数の側面を区別する。パラ テクストはタイトル、見出し、謝辞、脚注、図版など、テキストを囲む要素を指す。アーキテクストはジャンル、様式、媒体、作者など、テキストが属する一般 的なカテゴリーを指す。メタテクストとは、別のテクストについて論評するテクストである。ハイポテクストとは、別のテクストの基盤となるテクストを指す。 例えば続編が書かれた小説や、別の作品でパロディ化された小説などである。こうした場合、先行作品を参照する派生テクストはハイパーテクストと呼ばれる。 [55][g] 記号間の構造的関係  「男は眠っている」という文の連鎖的・範疇的関係を示す図 「男は眠っている」という文の連鎖的・範疇的関係を示す図[57] 記号体系内の記号は、連鎖的関係と範疇的関係の対比など、いくつかの構造的関係を通じて結びついている。連鎖的関係は、個々の記号や記号要素が組み合わ さってより大きな表現を形成する方法を規定する。例えば、文は単語の直線的配列であり、連鎖関係は文法的に正しい文を生成するためにどの単語を組み合わせ られるかを規定する。同様に、夕食のメニューは料理の順序であり、前菜から始まり、メインディッシュ、デザートと続くといった連鎖関係がその配列を規定す る。一部の記号体系は非直線的配列を用いる。例えば、交通標識は標識の形状と表示される記号を組み合わせている。[58] パラダイム関係とは、同じ構造的カテゴリーに属する記号間の結びつきである。特定の位置を占めることのできる要素を規定し、システムの規則を破ることなく 互いに置き換え可能であることを示す。例えば文「男は眠る。」において、「男」という語は「女」「子供」「人格」といった語とパラダイム関係にある。これ らを置き換えても正しい文となるからである。夕食メニューでは、異なるデザートの選択肢(ケーキ、アイスクリーム、フルーツサラダなど)にも同様の関係が 成立する。交通標識の場合、形状の選択肢(三角形と円など)の間にパラダイム関係が存在する。選択されたパラダイム項目の意味は、意味のある代替案の背景 を形成する不在の選択肢によって影響を受ける。自然言語では、こうした代替案は通常特定の品詞に関連している。例えば文中の特定位置が動詞を要求する場 合、パラダイム的選択肢は動詞群で構成される。[59]  対比語を四隅に配置した正方形の図 記号学的な正方形は、富裕/貧困といった対比語の意味を分析するツールである。[60] 別の記号論的分析法では、対立する二項の記号対を調べる。例えば善/悪、熱/冷、新/旧のように、二つの記号が対照的な特徴を示し互いを排除する対であ る。速/遅のように連続的な尺度を持つ対立もあれば、生/死のように中間段階のない両極対立もある[61]。初期構造主義哲学は、意味が主に二項対立から 生じるという考えと結びついている。[62] アルギルダス・グレイマスが提唱した記号学的な四角形は、より細分化された区別を提供する。例えば「富裕」という記号を、三つの対照的な用語——その矛盾 項(非富裕)、その対立項(貧困)、そしてその対立項の矛盾項(非貧困)——と関連付ける。[63] もう一つの構造的特徴は、非標示項と標示項からなる非対称な記号対である。非標示項は一般的で中立的な表現であり、しばしば当然のものとして扱われる。一 方、標示項は特殊化され、追加的な特徴を示す。非標示項はより一般的に使用され、デフォルトや規範として特権的扱いを受けるのが通例である。例としては犬 /雌犬、昼/夜、彼/彼女、右/左といった対がある。この非対称性は、暗黙の背景前提や権力関係を解明する指針として、文化の記号論的研究において特に重 要である。[64] 例えば家父長制社会では男性用語に無標形を用いる傾向がある一方、母系社会では女性用語に無標形がより一般的である。[65] トロープ 記号論者は、記号が他の記号と相互作用することで代替的な意味を獲得する連想的メカニズムを研究する。この意味の変化は、記号の文字通りの意味が不十分ま たは不合理な場合に生じ、比喩的な意味への移行をもたらす。例えば「蛇」という用語は文字通り四肢のない爬虫類を指すが、「教授は蛇だ」という文では異な る意味を持つ。[66] この意味転換の仕組みを修辞技法と呼ぶ。修辞技法の議論では、他の技法の基盤となる四つの基本技法[h]が焦点となることがある:比喩、換喩、部分代表 法、逆説[68]。比喩とは、ある対象の属性を別の対象に移す類推であり、例えば教授に「蛇のような」狡猾さや冷血性を結びつける場合が該当する。 [69] 換喩とは、密接に関連する別のものを名指すことで対象を指す手法である。例えば王を「王冠」と呼ぶような場合だ。[70] 同様に、換喩とは対象の一部を名指すことで全体を指す手法である。例えば自分の車を「俺の車輪」と呼ぶような場合だ。[71] 皮肉の修辞技法は非類似性によって機能する。文字通り真逆の意味を表現するもので、例えばひどい失敗の後で「よくやった!」と述べるような場合だ。 [72] 記号論的修辞技法は主に言語的記号体系との関係で論じられ、ここでは修辞表現とも呼ばれる。しかしその根底にあるメカニズムは非言語的記号体系にも影響を 及ぼす。[73] 例えば航空会社の広告では、優雅さと信頼性を視覚的隠喩として、飛行機の着陸と白鳥の静かな水面への降り立ちを並置することがある。[74] 漫画は感情表現に視覚的換喩を多用する。怒りを拳を握る動作で表すのが典型だ。[75] 写真では、クローズアップが部分を通して全体を示す換喩として機能し得る。[76] 映画では、不釣り合いな陽気な音楽を伴った恐ろしい映像シーンを提示する、一種の視聴覚的アイロニーが存在する。[77] コード 詳細記事: コード コードとは、意思疎通に用いられる記号体系である。それは一連の記号、それらの間の意味関係、そしてメッセージを作成・解釈するための組み合わせ規則を含 む。[78][i] デジタルコードは、文字言語のように記号の形成と結合方法が明確かつ精密に区別される。これに対しアナログコードは、絵画における滑らかな色のグラデー ションのように、連続的な変化で意味を伝える。[80] 単純なコードは、信号機の色コードのように、ごく少数の基本要素と関係性のみを含む。複雑なコードは英語のように、無数の要素と意味形成に関わる統語的・ 社会文化的規範を包含し得る。慣習的コードは人間が構築したもので、音楽や絵画といった芸術作品の創作に用いられる美的コードも含まれる。これらはDNA のような自然コード[j]とは対照的である。DNAは生化学的情報システムとして機能し、ヌクレオチド配列を通じて遺伝情報を符号化する。[82] 記号論者は、コードを複数の次元で分析する。例えば、コードが作用する領域や文脈、依存する感覚チャネル、果たす機能などだ。数学式のように知識の精密な 表現に焦点を当てるコードもあれば、礼儀作法や儀礼慣行を含む文化的・行動的規範を規定するコードもある。[83] コードは、意味の範囲を精緻化したり特定の状況での使用を規制したりする、領域固有のサブコードを持つ場合がある。コードとサブコードは静的な枠組みでは なく、新たな慣習や技術が出現するにつれて進化し得る。[84]  コミュニケーションモデルの主要構成要素を示す図 コミュニケーションモデルとは、コミュニケーションの主要構成要素を表現したものであり、しばしば符号化と復号化のプロセスを含む。[85]  コードは、コミュニケーションの主要構成要素を概念的に表現したモデルにおいても中心的な役割を果たす。多くのモデルは、発信者がチャネルを通じて受信者 にメッセージを伝達し、受信者がそれを解釈してフィードバックで応答する概念を含む。符号化とは、特定のコード体系を用いて意味をメッセージの形で表現す る過程である。復号化は、メッセージを解釈してその意味を理解する逆の過程だ。場合によっては、異なるコードで同じメッセージを表現できることもある。同 様に、メッセージをあるコードから別のコードへ変換することもある。例えば、書かれたテキストをモールス信号に変換するといった場合だ。[86] 言説(ディスクール)とは、特定の文脈における特定の瞬間に生じる、言語やその他のコードの社会的使用を指す。言説分析は、コミュニケーションの主体とそ の役割、文脈や制度的背景の影響を考慮しつつ、言説において意味がどのように生じるかを検証する。[87] 記号論者はまた、コードが人間の世界認識をいかに反映し形成するかに関心を持つ。[88] 認識に影響を与えることで、コードは個人が可能な行動の選択肢を自覚させることにより、行動に影響を与えうる。[89] 論争の的となっているウォーフ仮説は、言語が理解の根本的なカテゴリーを提供することで思考を形成し、異なる言語を話す者では思考の仕方が異なる可能性が あると示唆している。[90] |

Core branches Diagram with lines between the words "semiotics", "syntactics", "semantics", and "pragmatics" Semiotics is typically divided into three branches: syntactics, semantics, and pragmatics.[91] General semiotics studies the nature of signs and their operation within sign systems in the widest sense, independent of the domains to which they belong. It contrasts with applied semiotics, which examines signs in particular domains or from discipline-specific perspectives.[92] An influential categorization, proposed by Morris, divides general semiotics into three branches: syntactics, semantics, and pragmatics.[91] Syntactics studies formal relations between signs. It investigates how signs combine to form compound signs and which rules govern this process. For example, the rules of grammar in natural languages specify how words may be arranged to form sentences and how different arrangements influence meaning. As a result of the syntactic rules of the English language, the expression "elephants are big" is grammatically correct, whereas "elephants big are" is not.[93] Syntactics is not limited to language and includes the study of non-linguistic compound signs, such as the arrangement of visual elements in geographic maps.[94] Semantics studies the relation between signs and what they stand for, examining how signs refer to concrete things and abstract ideas. It typically focuses on the general meaning of a sign rather than its meaning in a particular context. Semantics addresses the meaning of both basic and compound signs. In the linguistic domain, it includes lexical semantics, which explores word meaning, and phrasal semantics, which studies sentence meaning.[95] Other areas include animal semantics, which investigates, for example, how animal warning calls stand for predators.[96] Pragmatics studies the relation between signs and sign users. It examines how individuals produce and interpret signs in concrete contexts, applying syntactic insights into formal structures and semantic insights into general meaning to real-life situations. The pragmatic dimension of sign use in communication encompasses aspects such as social conventions and expectations, speaker intention, audience, and other contextual factors. For example, it depends on the concrete situation whether the expression "she found a mole" refers to the discovery of an animal, a skin mark, or a spy.[97] Various academic discussions address the relation between the three branches, such as their relative importance or hierarchy. Historically, syntactics and semantics have received more attention than pragmatics, particularly in the study of linguistic sign systems. One reason for this preferential treatment is the idea that sign usage is largely determined by what signs mean and how they can be combined. As a result, pragmatics has often been regarded as a secondary discipline, reserved for diverse problems that could not be adequately addressed from the perspectives of the other two disciplines. However, this marginal treatment of pragmatics is questioned in the contemporary discourse. Some proposals reverse the priority and see pragmatics as the primary discipline. One reason is the idea that syntactics and semantics are abstractions that cannot be scientifically studied on their own without examining actual sign use.[98] |

中核分野 「記号論」「統語論」「意味論」「語用論」の間に線を引いた図 記号論は通常、統語論、意味論、語用論の三分野に分けられる。[91] 一般記号論は、記号の本質と、それらが属する領域とは独立した、最も広い意味での記号体系内でのその作用を研究する。これは、特定の領域や学問分野固有の 視点から記号を考察する応用記号論とは対照的である。[92] モリスが提案した影響力のある分類では、一般記号論を三つの分野に分けられる:統語論、意味論、語用論である。[91] 統語論は記号間の形式的関係を研究する。記号が複合記号を形成する仕組みと、その過程を支配する規則を調査する。例えば自然言語の文法規則は、単語がどの ように並べられて文を形成するか、また異なる並び方が意味にどう影響するかを規定する。英語の統語規則の結果、「elephants are big」という表現は文法的に正しいが、「elephants big are」は正しくない。[93] 統語論は言語に限定されず、地理地図における視覚要素の配置など、非言語的複合記号の研究も含まれる。[94] 意味論は記号とそれが表象する対象の関係を研究し、記号が具体的物や抽象的概念をいかに指し示すかを検討する。通常、特定の文脈における意味ではなく、記 号の一般的な意味に焦点を当てる。意味論は基本記号と複合記号の両方の意味を扱う。言語学の領域では、語の意味を探る語彙意味論や、文の意味を研究する句 意味論を含む。[95] その他の分野には、例えば動物の警戒鳴きが捕食者をどう表象するかを調査する動物意味論がある。[96] 語用論は、記号と記号使用者の関係を研究する。これは個人が具体的な文脈で記号を生産・解釈する方法を検証し、形式構造への統語的洞察や一般的意味への意 味論的洞察を実生活に適用する。コミュニケーションにおける記号使用の語用論的側面は、社会的慣習や期待、話者の意図、聴衆、その他の文脈的要因などを包 含する。例えば「she found a mole」という表現が動物の発見、皮膚のほくろ、あるいはスパイを指すかは具体的な状況に依存する。[97] これら三分野の関係性、例えば相対的な重要性や階層性については様々な学術的議論がある。歴史的に、特に言語的記号体系の研究においては、統語論と意味論 が語用論よりも注目されてきた。この優先的な扱いの理由の一つは、記号の使用法は主に記号の意味や組み合わせ方によって決定されるという考え方にある。そ の結果、語用論はしばしば二次的な学問と見なされ、他の二分野の視点では十分に対処できない多様な問題に限定されてきた。しかし現代の言説では、この語用 論の周辺的扱いが疑問視されている。優先順位を逆転させ、語用論を主要な学問と位置付ける提案もある。その理由の一つは、統語論と意味論は実際の記号使用 を検証せずに単独で科学的に研究できない抽象概念だという考え方だ。[98] |

| Applications Biology Main article: Biosemiotics  Photo of a yellow bird Biosemiotics includes the study of animal communication, such as bird calls.[99] While traditional semiotics focuses on human communication and culture, biosemiotics integrates this perspective with biology. It studies how living beings produce and interpret signs through channels such as vision, sound, movement, and chemical cues like smell.[100] It does not restrict sign processes to conscious mental activities and explicitly includes nonintentional processes within its scope.[101] Biosemiotics has branches dedicated to different types of organisms, such as zoosemiotics (animals), phytosemiotics (plants), bacteriosemiotics (bacteria), mycosemiotics (fungi), and protistosemiotics (protists).[102] Anthroposemiotics, which addresses humans, is sometimes included in zoosemiotics or treated as a distinct branch.[103] The scope of biosemiotics covers semiotic activities on different levels of organization, ranging from cellular information processes to communication between distinct individuals. At the microlevel, there are sign activities within individual organisms. For example, genes encode information about hereditary traits, and diverse biological processes decode and activate this information. Similarly, hormones function as signaling molecules that control physiological functions by conveying information over long distances in the body. Biosemioticians also study how nerve cells communicate with each other and how neurotransmitters regulate this process.[104] This topic is more closely examined by neurosemiotics, which investigates neural processes involved in sign interpretation and meaning-making.[105] At the macrolevel, there are sign processes between distinct organisms. They happen primarily between individuals of the same species as forms of cooperation or coordination.[106] For example, birds use calls to attract mates, warn of predators, and maintain territorial boundaries.[99] Similar semiotic processes also happen in the plant kingdom, such as airborne chemicals released by maple trees as a warning signal of herbivore attacks.[107] In some cases, communication happens between members of distinct species.[108] For instance, flowers use symmetrical shapes and vivid colors as signs to guide insects to nectar.[109] Because of the pervasive nature of sign processes, biosemioticians typically argue that semiosis is not a rare phenomenon limited to specific biological niches but an intrinsic feature of life in general.[1 |

応用分野 生物学 詳細記事: 生物記号論  黄色い鳥の写真 生物記号論には、鳥の鳴き声などの動物のコミュニケーション研究が含まれる。[99] 伝統的な記号論が人間のコミュニケーションと文化に焦点を当てるのに対し、生物記号論はこの視点を生物学と統合する。生物が視覚、音、動き、匂いなどの化 学的合図といった経路を通じて、いかに記号を生成し解釈するかを研究する。[100] 記号プロセスを意識的な精神活動に限定せず、非意図的なプロセスも明示的に範囲に含める。[101] 生物記号学には、動物記号学(動物)、植物記号学(植物)、細菌記号学(細菌)、菌類記号学(菌類)、原生生物記号学(原生生物)など、異なる生物種に特 化した分野が存在する。[102] 人間を対象とする人類記号論は、動物記号論に含まれる場合もあれば、独立した分野として扱われる場合もある。[103] 生物記号論の対象範囲は、細胞レベルの情報処理から個体間のコミュニケーションに至るまで、異なる組織レベルにおける記号活動をカバーする。ミクロレベル では、個々の生物内部で記号活動が起きている。例えば、遺伝子は遺伝的形質に関する情報を符号化し、多様な生物学的プロセスがこの情報を復号・活性化させ る。同様に、ホルモンは体内を長距離移動して情報を伝達し、生理機能を制御するシグナル分子として機能する。生物記号論者は神経細胞間の通信方法や、神経 伝達物質がこのプロセスを調節する仕組みも研究する[104]。この主題は、記号解釈と意味形成に関わる神経プロセスを調査する神経記号論によってより詳 細に検討される。[105] マクロレベルでは、異なる生物間の記号プロセスが存在する。これらは主に同種個体間で、協力や調整の形態として発生する。[106] 例えば鳥類は、求愛行動、捕食者への警戒、縄張り維持のために鳴き声を用いる。[99] 植物界でも同様の記号プロセスが起きる。例えばカエデが放出する気中化学物質は、草食動物の攻撃に対する警告信号となる。[107] 場合によっては、異なる種の個体間でコミュニケーションが成立することもある。[108] 例えば花は、対称的な形状や鮮やかな色を記号として用い、昆虫を蜜へと誘導する。[109] 記号過程の遍在性ゆえに、生物記号論者は通常、記号作用が特定の生態的ニッチに限定された稀な現象ではなく、生命全般に内在する特性であると主張する。 [1 |

| Culture Several branches of applied semiotics study cultural phenomena, which encompass systems of beliefs, values, norms, and practices shared in society. The semiotics of culture analyzes sign systems used in cultural practices by examining the meanings and ideological assumptions they embody. It integrates findings from fields such as psychology, anthropology, archaeology, linguistics, and neuroscience. It addresses both the fundamental characteristics of culture in general and the distinctive features of specific cultural formations, such as myths, aesthetics, cuisine, clothing, rituals, and artifacts.[111] On a more general level, the semiotics of culture explores how culture differs from nature and which processes are responsible for the emergence of cultural formations.[112] Social semiotics, a related field, studies sign practices as social phenomena in cultural contexts.[113] It also investigates the social construction of reality. This includes semiotic practices that establish social meanings, categories, and norms shaping how people perceive the world and what they take for granted.[114] Related fields include semiotic anthropology, which analyzes how sign systems reproduce, transmit, and change culture,[115] and ethnosemiotics, which examines and compares semiotic phenomena in specific ethnic groups.[116] Semioticians have been particularly interested in cultural myths, which they understand as structures of meaning that codify ideologies. In this sense, myths are not only a specific genre of literature but encompass widely shared views about human nature or the world. For example, pervasive ideological myths in Western culture include the idea of progress, which frames history as a linear series of improvements, and individualism, which conceives individuals as autonomous and self-reliant agents. Myths help people make sense of experience and guide behavior through common frameworks that conceptualize phenomena. Semiotic analysis sees myths as secondary sign systems that use other signs as vehicles to convey their ideas, often in the form of metaphors. For instance, the image of a child represents a child on the literal level. However, it can at the same time embody a myth of childhood associated with innocence and purity, motivating social arrangements associated with protection and parenting. Semioticians analyze this secondary level of signification across diverse media, such as literature, film, and advertising.[117] In specific areas of culture, semiotics examines the codes and conventions they employ and the meanings they produce.[118] The semiotics of clothing studies clothing as a nonverbal sign system. Clothes are often implicitly interpreted as signs of the personality and social status of the wearer, covering features such as gender, age, and political beliefs. Different social occasions are associated with distinct dress codes, such as uniforms for sport, the military, and religious rituals.[119] Similarly, the semiotics of food analyzes food items as bearers of cultural meanings. It explores how culinary practices reflect social organization and belief systems, like cooking methods, table etiquette, taboos against eating certain items, the cultural roles of fasting and feasting, and food symbolism.[120] Research topics in popular internet culture include the codes and conventions of emojis and internet memes.[121] |

文化 応用記号論のいくつかの分野は、社会で共有される信念、価値観、規範、慣行の体系を含む文化的現象を研究する。文化の記号論は、文化的慣行で使用される記 号体系を、それらが体現する意味やイデオロギー的前提を検証することで分析する。心理学、人類学、考古学、言語学、神経科学などの分野からの知見を統合す る。それは文化全般の基本的特性と、神話、美学、食文化、服装、儀礼、工芸品といった特定の文化的形成物の特徴の両方に対処する。[111] より一般的なレベルでは、文化記号論は文化が自然とどう異なるか、そして文化的形成物の出現に責任を持つプロセスは何かを探求する。[112] 関連分野である社会記号論は、文化的文脈における社会的現象としての記号実践を研究する。[113] また現実の社会的構築も調査対象とする。これには、人々の世界認識や当然視する事柄を形作る社会的意味・カテゴリー・規範を確立する記号論的実践が含まれ る。[114] 関連分野には、記号体系が文化を再生産・伝達・変化させる過程を分析する記号論的人類学[115]、特定民族集団における記号論的現象を検証・比較する民 族記号論がある。[116] 記号論者は特に文化的神話に関心を寄せている。彼らは神話をイデオロギーを体系化する意味構造と理解する。この意味で神話は特定の文学ジャンルにとどまら ず、人間性や世界に関する広く共有された見解を包含する。例えば西洋文化に浸透するイデオロギー的神話には、歴史を直線的な進歩の連鎖と捉える「進歩」の 思想や、個人を自律的で自立した主体と考える「個人主義」がある。神話は現象を概念化する共通の枠組みを通じて、人々が経験を理解し行動を導く助けとな る。記号論的分析では、神話は他の記号を媒体として(しばしば隠喩の形で)自らの思想を伝達する二次的な記号体系と見なされる。例えば、子供のイメージは 文字通りの意味で子供を表す。しかし同時に、無垢や純粋さといった幼年期の神話を体現し、保護や子育てに関連する社会的仕組みを促すこともある。記号論者 は、文学、映画、広告など多様なメディアにおいて、この二次的な意味生成のレベルを分析する[117]。 文化の特定領域において、記号論はそこで用いられるコードや慣習、そしてそれらが生み出す意味を検証する[118]。衣服の記号論は、衣服を非言語的記号 体系として研究する。衣服はしばしば、ジェンダー・年齢・政治的信念といった特徴を覆い隠しつつ、着用者の人格や社会的地位を示す記号として暗黙的に解釈 される。スポーツ・軍隊・宗教儀礼用の制服など、異なる社会的場面にはそれぞれ固有の服装規定が存在する。同様に、食物記号論は食品を文化的意味の担い手 として分析する。調理法、食卓マナー、特定の食品摂取のタブー、断食と饗宴の文化的役割、食物の象徴性など、食習慣が社会組織や信念体系をいかに反映する かを探究する。インターネットポピュラー・カルチャーの研究対象には、絵文字やインターネットミームのコードと慣習が含まれる。 |

| Literature Text semiotics studies the meanings of linguistic texts. It typically focuses on larger fragments of discourse, leaving the analysis of smaller units, like phonemes, to linguistics.[122] Text semiotics plays a central role in literary criticism by exploring the codes, conventions, and tropes employed in literary texts. It situates these insights within broader cultural and semiotic frameworks.[123] Central schools of thought in text semiotics include structuralism and poststructuralism.[124] Structuralism assumes that structural relations within sign systems are the primary source of meaning and understanding. It examines how texts employ these patterns, such as binary oppositions between good and evil or nature and culture, often with the goal of identifying ideological biases.[125] Post-structuralism argues that sign systems are self-referential and cannot provide a stable representation of reality. The post-structuralist method of deconstruction aims to reveal contradictions and ambiguities within texts, for example, by showing how a text unintentionally undermines a binary opposition on which it relies.[126] A historically influential tradition in text semiotics is hermeneutics—the study of interpretation. Hermeneutics originates in the examination of mythological and religious texts. It was used by medieval Christian philosophers to decode the theological and moral doctrines of the Bible, for instance, by distinguishing literal from spiritual meanings and analyzing symbolic structures associated with allegories. Modern hermeneutics extends these practices to secular texts. The hermeneutic circle is a central concept in this field. It is the idea that understanding involves a circular movement in which preconceptions guide interpretation and interpretation shapes preconceptions. It is sometimes explained as an interplay where understanding the text as a whole depends on understanding its parts and vice versa.[127] It is debated whether there is a single correct interpretation of every text or whether incompatible interpretations can be valid at the same time.[128] Narratology is a branch of semiotics that studies narrative texts, such as tales and stories. It assumes that there is a universal narrative code of the different elements found in narratives, meaning that individual texts only express variations of the same underlying code. For example, according to Algirdas Julien Greimas's actantial model, these elements include a subject, such as the hero of the story, an entity that they desire, and an opponent or obstacle to their goal.[129] Other research directions in text semiotics are stylistics and rhetorics, which compare different styles and explore how texts persuade.[130] |

文学 テキスト記号論は言語的テキストの意味を研究する。通常、より大きな言説断片に焦点を当て、音素のような小さな単位の分析は言語学に委ねる。[122] テキスト記号論は、文学テキストで用いられるコード、慣習、修辞を探求することで、文学批評において中心的な役割を果たす。これらの洞察をより広範な文化 的・記号論的枠組みに位置づけるのである。[123] テクスト記号論の主要な学派には構造主義とポスト構造主義がある。[124] 構造主義は、記号体系内の構造的関係が意味と理解の主要な源泉だと仮定する。善と悪、自然と文化といった二項対立など、テクストがこれらのパターンをどう 用いるかを検証し、しばしばイデオロギー的偏向を特定することを目的とする。[125] ポスト構造主義は、記号体系が自己言及的であり現実の安定した表象を提供できないと主張する。ポスト構造主義の脱構築手法は、例えばテキストが依存する二 項対立を意図せず損なう過程を示すなどして、テキスト内の矛盾や曖昧性を明らかにすることを目指す。[126] テキスト記号論において歴史的に影響力のある伝統が解釈学である。解釈学は神話や宗教的テキストの分析に起源を持つ。中世キリスト教哲学者らは、例えば文 字通りの意味と霊的な意味を区別し、寓話に関連する象徴的構造を分析することで、聖書の神学的・道徳的教義を解読するためにこれを用いた。現代解釈学はこ うした実践を世俗的テキストへと拡張している。解釈学の循環はこの分野の中核概念である。理解には循環的な動きが伴うという考え方だ。先入観が解釈を導 き、解釈が先入観を形成する。テキスト全体を理解するにはその部分を理解する必要があり、その逆もまた然りという相互作用として説明されることもある。 [127] あらゆるテキストに唯一の正しい解釈が存在するのか、それとも互いに矛盾する解釈が同時に有効となり得るのかは議論の的となっている。[128] ナラトロジーは、物語やストーリーなどの叙述的テキストを研究する記号論の一分野である。ナラトロジーは、物語に見られる異なる要素には普遍的な叙述コー ドが存在すると仮定する。つまり、個々のテキストは同じ基盤となるコードのバリエーションを表現しているに過ぎないという考え方だ。例えばアルジダルス・ ジュリアン・グレマスの行為者モデルによれば、これらの要素には物語の主人公のような主体、彼らが求める対象、そして目標達成の妨げとなる敵対者や障害物 が含まれる。[129] テキスト記号論における他の研究方向としては、異なる文体を比較しテキストの説得方法を考察する文体論や修辞学がある。[130] |

| Arts and media Coca Cola advertisement of a woman holding a glass In the study of advertising, semioticians examine the use of linguistic and non-linguistic codes to target consumers.[131] Semiotics has diverse applications in the analysis of art and other media, ranging from film and music to advertising and video games.[132] The field of media semiotics studies how meaning is produced, interpreted, and shared in media, such as newspapers, radio, television, and the internet. Understood in the widest sense, it encompasses all channels of everyday communication, including shop signs and posters.[133] In the visual arts, semioticians examine how meaning is created through aspects such as color, shape, texture, composition, and perspective. For example, colors can express different moods, emotions, and atmospheres, such as warm and soft colors in contrast to cold and harsh ones. Colors can also have culture-specific symbolic meanings, such as pink signifying femininity.[134] Semioticians are further interested in the representational dimension of images, studying how they may act as icons that represent their motive through similarity. In photography, images may additionally function as indexical signs because of the causal connection between the depicted object and the photograph.[135] Musical semiotics studies music as a meaning-making process involving signifiers and signifieds.[136] There is substantial disagreement about the extent to which music is a semiotic activity. Some theoretical attempts treat sounds as individual signs and compositions as compound signs or messages, while others argue that sounds and compositions signify nothing beyond themselves.[137] Another research approach investigates the cultural significance of music, for example, how musical styles, like heavy metal, reggae, and classical music, are associated with different subcultures and lifestyles.[138] Film semiotics analyzes films as sign activities, exploring how visual and auditory codes interact. Some theorists compare films to language, arguing that individual shots act as words and that montages, which combine several shots, correspond to sentences. A key difference to many other forms of language is that film involves asymmetrical communication since there is usually no direct way for spectators to respond to messages.[139] The semiotics of architecture, another field, examines how buildings communicate meaning, including their practical functions, historical heritage, and social significance.[140] The semiotics of advertising studies how advertisements use and combine signs to influence consumers. Advertisements typically combine linguistic and non-linguistic codes. For instance, print ads typically use language for the brand name and verbal commentary, while visual elements convey non-verbal messages to the target audience. In many cases, the core message, related to the economic reality of selling a product, is not stated explicitly. Instead, an indirect message is used to make the product appealing.[131] Computer games integrate elements from many other media and combine them with an interactive dimension. They include diverse sign elements, for example, to explain how to interact with the virtual world, set goals, provide feedback, and establish a narrative.[141] |

芸術とメディア コカ・コーラの広告で女性がグラスを持っているもの 広告研究において、記号論者は消費者をターゲットとする言語的・非言語的コードの使用を分析する。[131] 記号論は、映画や音楽から広告やビデオゲームに至るまで、芸術やその他のメディアの分析において多様な応用を持つ。[132] メディア記号論の分野では、新聞、ラジオ、テレビ、インターネットなどのメディアにおいて、意味がどのように生成され、解釈され、共有されるかを研究す る。最も広い意味で理解すれば、店の看板やポスターを含む日常のあらゆるコミュニケーション手段を包含する。[133] 視覚芸術において、記号論者は色彩、形状、質感、構図、遠近法といった要素を通じて意味が如何に創出されるかを検証する。例えば色は、暖色と寒色のような 対比を通じて、異なる気分や感情、雰囲気を表現し得る。またピンクが女性性を示すように、文化固有の象徴的意味を持つこともある。[134] 記号論者はさらに、イメージの表象的側面に関心を持ち、類似性によって対象を象徴するアイコンとして機能する方法を研究する。写真においては、写された対 象と写真との因果関係により、画像は追加的に指標的記号として機能し得る[135]。 音楽記号論は、音楽を記号と意味対象を含む意味形成過程として研究する[136]。音楽がどの程度記号論的活動であるかについては、大きな意見の相違があ る。理論的な試みの中には、音を個々の記号とし、楽曲を複合記号またはメッセージとして扱うものがある一方、音や楽曲はそれ自体を超えて何も意味しないと する主張もある。[137] 別の研究アプローチでは、音楽の文化的意義、例えばヘビーメタル、レゲエ、クラシック音楽といった音楽スタイルが、異なるサブカルチャーやライフスタイル とどのように関連しているかを調査する。[138] 映画記号論は、映画を記号活動として分析し、視覚的コードと聴覚的コードがどのように相互作用するかを探求する。一部の理論家は映画を言語に例え、個々の ショットを単語に、複数のショットを組み合わせたモンタージュを文に相当すると論じる。他の言語形態との重要な差異は、映画が非対称的コミュニケーション を伴う点だ。観客がメッセージに直接応答する手段が通常存在しないためである[139]。建築記号学という別の分野では、建物が意味を伝達する方法を検証 する。実用的な機能、歴史的遺産、社会的意義などが含まれる[140]。 広告記号学は、広告が消費者を影響するために記号をどう使用し組み合わせるかを研究する。広告は通常、言語的コードと非言語的コードを組み合わせる。例え ば印刷広告では、ブランド名や解説文に言語を用いる一方、視覚的要素が対象層に非言語的メッセージを伝える。多くの場合、製品販売という経済的現実に関わ る核心的なメッセージは明示されない。代わりに間接的なメッセージを用いて製品を魅力的に見せようとする。[131] コンピュータゲームは、他の多くのメディアの要素を統合し、それらを相互作用的な次元と組み合わせる。仮想世界との関わり方を説明したり、目標を設定した り、フィードバックを提供したり、物語を構築したりするために、多様な記号要素を含む。[141] |

| Cognition Main article: Cognitive semiotics Cognitive semiotics is an interdisciplinary field that examines how mental processes contribute to meaning-making. It integrates insights of diverse disciplines, covering semiotics, cognitive science, linguistics, anthropology, psychology, and philosophy.[142] Cognitive semioticians study sign activity from complementary perspectives: the subjective first-person perspective, the intersubjective second-person perspective, and the objective third-person perspective. While acknowledging the validity of each perspective in its respective area, the field privileges first-person and second-person methods as offering more direct access to the mental dimension of meaning. For example, it relies on the phenomenological description to analyze how sign processes shape experience.[143] By examining how meaning operates in the mind, it contrasts with certain aspects of biosemiotics that address sign processes without mental activity, like in genetics.[144] Cognitive semioticians typically understand mind and cognition in terms of practical engagement with the world rather than theoretical attempts to model or depict it. They argue that meaning includes representation as one way of engaging with the world, but is not limited to it. Their primary focus is on non-representational forms of meaning, such as habits, values, and other ways how individuals attune to their environment. From this perspective, sign structures are understood as processes that shape habits and dispositions to act in different circumstances, emphasizing that meaning is a dynamic process rather than a static product.[145] The theory of finite semiotics explains semiosis as an effect of the finite nature of the human mind that occurs as an individual passes from one cognitive state to another.[146] |

認知 主な記事: 認知記号論 認知記号論は、精神的なプロセスが意味形成にどのように寄与するかを検討する学際的な分野である。記号論、認知科学、言語学、人類学、心理学、哲学など、 多様な学問分野の知見を統合している。[142] 認知記号論者は、補完的な視点から記号活動を研究する。すなわち、主観的な一人称視点、相互主観的な二人称視点、そして客観的な三人称視点である。各視点 がそれぞれの領域で有効であることを認めつつも、この分野では意味の精神的側面に直接的にアクセスできるとして、一人称および二人称の手法を重視する。例 えば、記号プロセスが経験を形成する方法を分析するために現象学的記述に依拠する。[143] 意味が心の中でどのように作用するかを検討することで、遺伝学のように精神的活動なしに記号プロセスを扱うバイオ記号論の特定の側面とは対照をなす。 [144] 認知記号論者は通常、心と認知を世界との実践的関与の観点から理解し、理論的なモデル化や描写の試みとは区別する。彼らは意味には世界と関わる一つの方法 としての表象が含まれるが、それに限定されないとする。彼らの主な焦点は、習慣や価値観、個人が環境に適応する他の方法など、非表象的な意味の形態にあ る。この観点から、記号構造は異なる状況下で行動する習慣や傾向を形成するプロセスとして理解され、意味が静的な産物ではなく動的なプロセスである点が強 調される。[145] 有限記号論の理論は、記号作用を人間の精神の有限性による効果として説明し、個人が一つの認知状態から別の状態へ移行する過程で生じるとする。[146] |

| Others In the field of non-verbal communication, semioticians investigate the exchange of information without linguistic sign systems.[147] For example, body language includes signifying practices like raising a thumb and other gestures, as well as facial expressions like laughing and frowning.[148] Other types of non-verbal communication encompass touching behavior, like shaking hands or kissing, and the use of personal space, such as the distance between speakers to express their degree of familiarity.[149] Paralanguage encompasses non-verbal elements of linguistic messages. For instance, pitch and loudness in a conversation can express emotion or emphasis without stating them explicitly.[150] Semiotics has various applications in psychoanalysis. Sigmund Freud proposed a theory of dream interpretation to understand and resolve psychological conflicts. He argued that dream elements act as symbols that stand for unconscious desires and fears. For example, dreams of losing a tooth can signify castration or fear of impotence.[151] Semiotics also plays a central role in the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan, who argued that the unconscious is structured like a language.[152] In the field of computing, semiotics has been used to describe programming languages and analyze human–computer interaction. There are also attempts to develop formal theories of semiotics, allowing computational processes to perform semiotic analyses.[153] Cybersemiotics, another approach, combines biosemiotics with cybernetics to provide a unified framework of semiotic processes across biological, social, and technological domains.[154] Edusemiotics is a research movement that conceptualizes semiotic activity as the foundation of educational theory. For instance, it understands teaching and learning as sign processes.[155] Semioethics is a critical approach that examines the ethical dimension of sign activities. It seeks to diagnose problems that arise in the context of global communication.[156] Medical semiotics studies how disease symptoms, such as pain, dizziness, and fever, indicate medical conditions.[157] Legal semiotics investigates sign activities in legal practice, including the interpretation of evidence, testimony, and legal texts.[158] |

その他 非言語コミュニケーションの分野では、記号論者が言語的記号体系を用いない情報交換を研究している。[147] 例えば、ボディランゲージには親指を立てるなどのジェスチャーや、笑い顔やしかめ面といった表情が含まれる。[148] その他の非言語コミュニケーションには、握手やキスといった接触行為、話者間の距離といった個人的なスペースの活用(親密さの度合いを表現するため)が含 まれる。[149] パラ言語は言語メッセージの非言語的要素を扱う。例えば会話における声の高さや大きさは、明示せずに感情や強調を表現し得る。[150] 記号論は精神分析学において様々な応用を持つ。ジークムント・フロイトは心理的葛藤を理解し解決するための夢解釈理論を提唱した。彼は夢の要素が無意識の 欲望や恐怖を表す象徴として機能すると主張した。例えば歯が抜ける夢は去勢や無力感への恐怖を意味しうる。[151] ジャック・ラカンの精神分析理論においても記号論は中心的な役割を果たし、彼は無意識が言語のように構造化されていると論じた。[152] 計算機科学の分野では、記号論はプログラミング言語の記述や人間と計算機の相互作用の分析に用いられてきた。また、計算プロセスが記号論的分析を実行でき るようにする形式的な記号論理論の開発も試みられている。[153] サイバー記号論という別のアプローチは、生物記号論とサイバネティクスを組み合わせ、生物学的・社会的・技術的領域にまたがる記号論的プロセスの統一的な 枠組みを提供する。[154] 教育記号論は、記号活動を教育理論の基盤として概念化する研究運動である。例えば、教育と学習を記号プロセスとして理解する。[155] 記号倫理学は、記号活動の倫理的側面を検証する批判的アプローチである。グローバルコミュニケーションの文脈で生じる問題の診断を目指す。[156] 医療記号論は、痛み、めまい、発熱などの疾病症状が医学的状態をいかに示すかを研究する。[157] 法的記号論は、証拠、証言、法的文書の解釈を含む、法的実践における記号活動を調査する。[158] |

| Methods Semioticians use diverse methods to analyze and compare signs and sign systems. Different domains of signs and perspectives of inquiry typically call for distinct techniques depending on the forms of representation and modes of meaning-making under study. As a result, there is no universally adopted methodology but only an interdisciplinary, loosely connected set of approaches.[159] Within a given domain, semioticians typically seek to determine what meaning is produced, why it emerges the way it does, and how it is encoded.[160] Structural analysis examines the structural framework of texts and sign systems, exploring the syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations underlying signification. The commutation test is an influential tool for structural analysis. It explores how the meanings of linguistic and non-linguistic texts are shaped by their components and what roles specific signs play in this process. It proceeds by changing certain elements of a text, either actually or as a thought experiment, and assesses whether or how this change affects the overall meaning. For example, in the analysis of an advertisement, a semiotician may probe whether the overall message changes if a woman is shown using the product instead of a man. If it does then gender is a signifying element. The way how the overall message changes provides insights into the semiotic role of the changed aspect. The commutation test can be applied to a wide range of elements or features, such as shape, size, color, camera angle, typeface, age, class, and ethnicity. Instead of replacing one element with another, other versions of the commutation test add or remove elements to explore, for instance, what draws attention by its absence or what is taken for granted.[161][k] In the study of cultural sign systems, semioticians often focus on hidden meanings and connotations, such as ideological messages and power dynamics that influence meaning-making without being immediately apparent to observers.[163] This dimension can be studied in diverse ways, such as comparing marked and unmarked terms to reveal how cultural norms privilege certain meanings and marginalize others.[64] Critical discourse analysis has a similar goal, seeking to understand how texts and social reality shape each other. It is particularly interested in how ideologies and power relations are reproduced in discourse, for example, by analyzing how political actors depict immigrants as threats to promote restrictive immigration policies.[164] Another approach to semiotics focuses on the historical dimension of sign systems and semiotic practices. It examines how they came into existence and evolved, studying how the relevant codes and media developed and how new conventions and genres emerged. The historical inquiry also considers the effects of technological developments, for instance, by tracing how the invention of the printing press and the internet have shaped the way people engage with written texts.[165] Although qualitative investigation is the dominant approach in semiotics, some researchers also use quantitative methods. For example, many forms of content analysis examine objective patterns found in an individual document or an entire discourse and employ statistical analysis to discover systematic patterns in sign usage. Applied to the news coverage of a violent incident, a content analyst may gather statistical information about how often the perpetrators are described as rebels rather than terrorists. Quantitative data on its own is usually not sufficient to explain complex semiotic processes, which is why content analysis is typically combined with other approaches.[166] In applied semiotics, researchers often tailor their approach to the specific area of signs under investigation.[167] For instance, biosemioticians may adapt concepts intended for linguistic analysis to biological codes like DNA. In some cases, this requires conceptual modifications, for example, when terms like interpretation are applied to sign processes without a conscious subject.[168] |

方法論 記号論者は、記号や記号体系を分析・比較するために多様な方法を用いる。記号の異なる領域や研究の視点は、研究対象となる表象の形態や意味形成の様式に応 じて、通常、異なる技法を必要とする。その結果、普遍的に採用された方法論は存在せず、学際的で緩やかに結びついた一連のアプローチのみが存在する。 [159] 特定の領域内では、記号論者は通常、どのような意味が生み出されるのか、なぜそのように現れるのか、そしてどのように符号化されるのかを明らかにしようと する。[160] 構造分析は、テキストや記号体系の構造的枠組みを検証し、意味生成の基盤となる連鎖的・範疇的関係を探求する。置換テストは構造分析における有力な手法で ある。言語的・非言語的テキストの意味が構成要素によって如何に形成されるか、またこの過程で特定の記号が如何なる役割を果たすかを検証する。これはテキ ストの特定要素を、実際に変更するか思考実験として変更し、その変更が全体の意味に影響を与えるか否か、あるいは如何に影響するかを評価する手順で進めら れる。例えば広告分析において、記号論者は男性ではなく女性が製品を使用する場面を提示した場合、全体メッセージが変化するか検証する。変化が生じるな ら、ジェンダーは意味形成要素である。全体メッセージの変化の様相から、変更された要素の記号論的役割が明らかになる。置換テストは形状、サイズ、色、カ メラアングル、書体、年齢、階級、民族性など多様な要素に適用可能だ。要素を置き換える代わりに、置換テストの別形態では要素を追加・削除し、例えば「不 在によって注目されるもの」や「当然視されているもの」を探求する。[161][k] 文化的記号体系の研究において、記号論者はしばしば隠された意味や含意、例えば観察者に即座には明らかではないが意味形成に影響を与えるイデオロギー的 メッセージや権力力学に焦点を当てる[163]. この次元は多様な方法で研究可能であり、例えば標示された用語と非標示された用語を比較することで、文化的規範が特定の意味を優遇し他の意味を周縁化する 仕組みを明らかにする[64]. 批判的言説分析も同様の目的を持ち、テキストと社会的現実が互いにどのように形成し合うかを理解しようとする. 特に、イデオロギーや権力関係が言説の中で如何に再生産されるかに関心が集まる。例えば、政治家が移民を脅威として描写することで制限的な移民政策を推進 する手法を分析する。[164] 記号論の別のアプローチは、記号体系と記号論的実践の歴史的側面に焦点を当てる。それらが如何に誕生し進化したかを検証し、関連するコードやメディアが如 何に発展し、新たな慣習やジャンルが如何に現れたかを研究する。歴史的探究では技術発展の影響も考慮される。例えば活版印刷やインターネットの発明が、人 々が書かれたテキストと関わる方法をどう形作ったかを追跡する。[165] 記号論では質的調査が主流だが、一部の研究者は量的手法も用いる。例えば多くの内容分析は、個々の文書や言説全体に見られる客観的パターンを調べ、統計分 析で記号使用の体系的パターンを発見する。暴力事件の報道分析に適用する場合、内容分析者は加害者がテロリストではなく反乱分子として描写される頻度に関 する統計情報を収集するかもしれない。複雑な記号論的プロセスを説明するには、定量データだけでは通常不十分であるため、内容分析は通常他の手法と組み合 わされる。[166] 応用記号論では、研究者は調査対象の記号領域に応じて手法を調整することが多い。[167] 例えば生物記号論者は、言語分析向けに考案された概念をDNAのような生物学的コードに適応させる。場合によっては概念的修正が必要となる。例えば「解 釈」といった用語を、意識的な主体を伴わない記号過程に適用する場合などが該当する。[168] |