ソーシャル・メディア依存症

Social Media Addiction

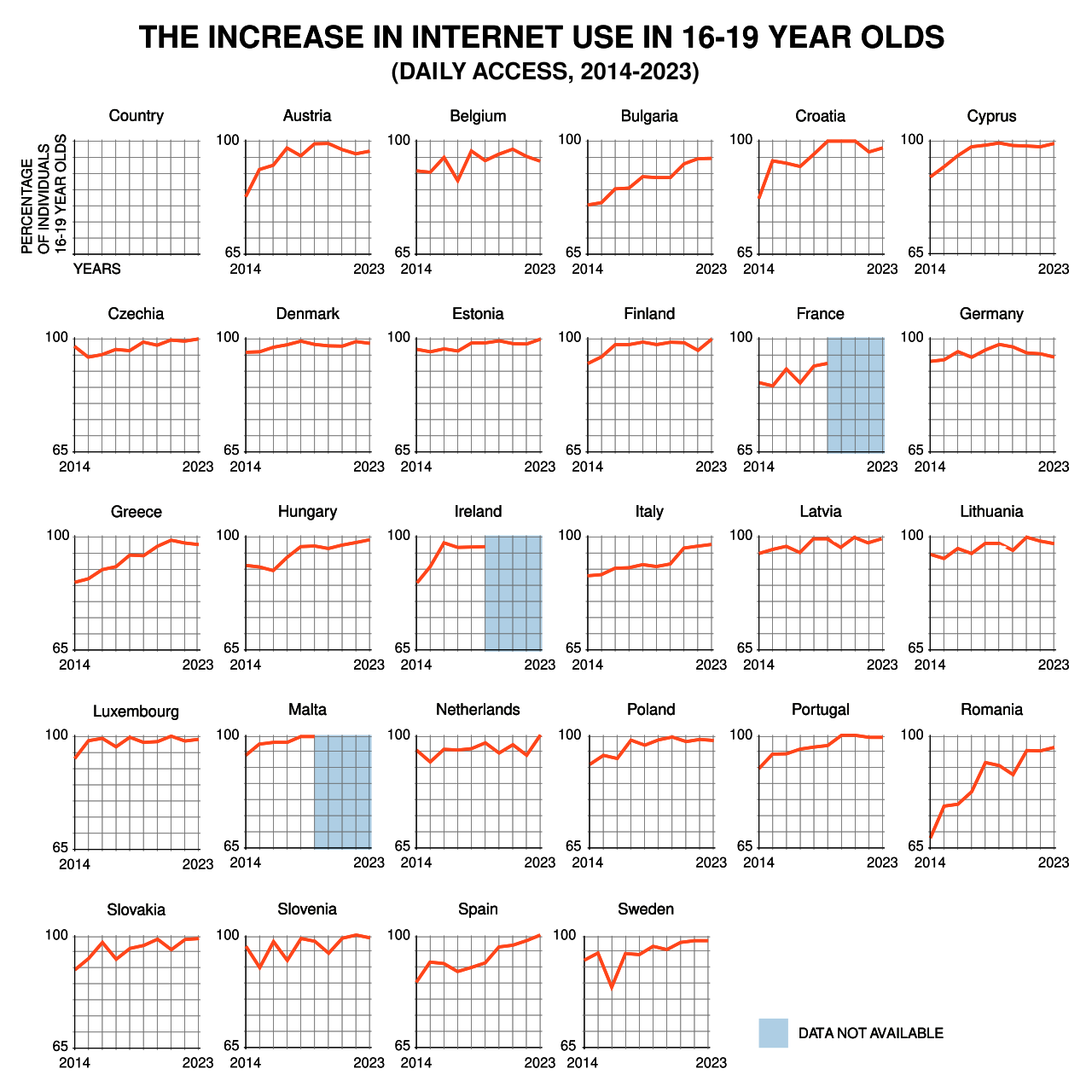

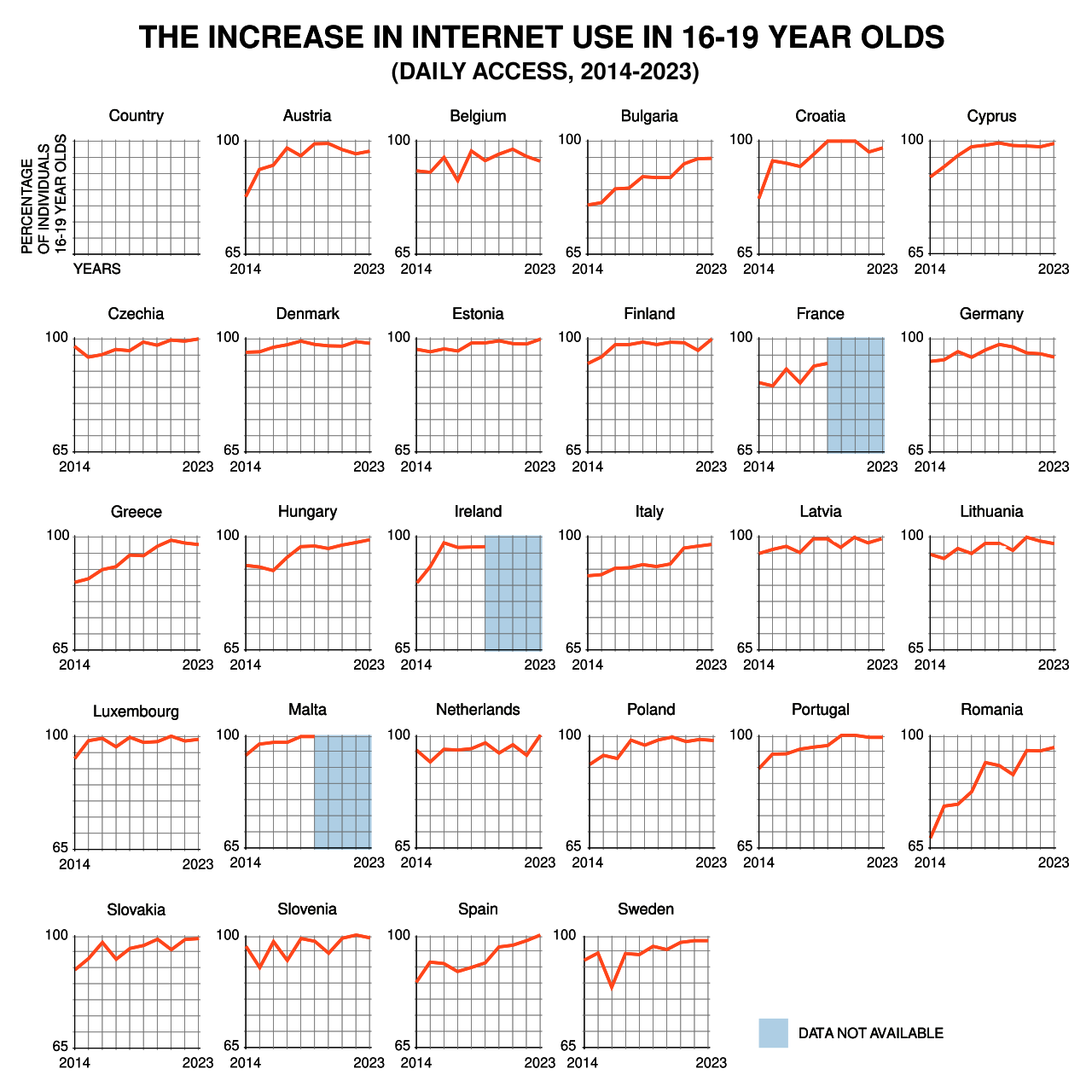

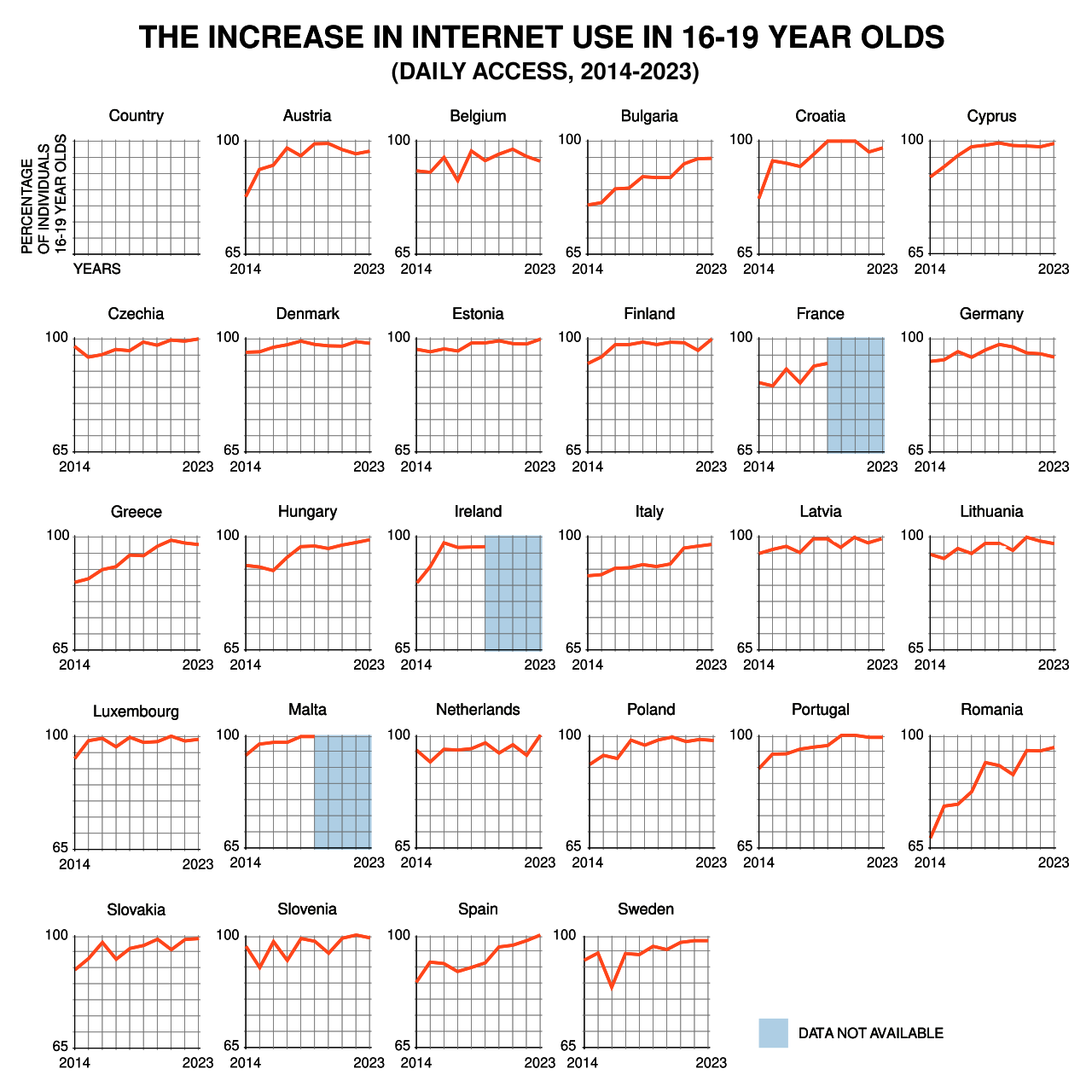

The increase in Internet access in 16-19 year olds living in EU countries

☆

インターネット依存症(IAD)は、コンピューター使用やインターネットアクセスに関する過度または制御不能な執着、衝動、行動によって特徴づけられ、機

能障害や苦痛をもたらす。[295]

若年層は特にインターネット依存症を発症するリスクが高い[296]。事例研究では、オンライン時間を増やすにつれて学業成績が低下する学生が指摘されて

いる[297]。スクロールやチャット、ゲームに没頭して夜更かしする結果、睡眠不足による健康被害を経験する者もいる[298]。[299]

過剰なインターネット使用は、米国精神医学会のDSM-5や世界保健機関のICD-11では障害として認定されていない[300]。ただし、ゲーム障害は

ICD-11に記載されている[301]。この診断を巡る論争には、この障害が独立した臨床的実体なのか、それとも潜在的な精神障害の現れなのかという点

が含まれる。定義は標準化されておらず合意も得られていないため、エビデンスに基づく推奨事項の策定は複雑化している。

| Addiction Main article: Problematic social media use See also: Digital media use and mental health These paragraphs are an excerpt from Internet addiction disorder.[edit] Internet addiction disorder (IAD) is characterized by excessive or poorly controlled preoccupations, urges, or behaviors regarding computer use and Internet access that lead to impairment or distress.[295] Young people are at particular risk of developing internet addiction disorder,[296] with case studies highlighting students whose academic performance declines as they spend more time online.[297] Some experience health consequences from loss of sleep[298] as they stay up to continue scrolling, chatting, and gaming.[299] Excessive Internet use is not recognized as a disorder by the American Psychiatric Association's DSM-5 or the World Health Organization's ICD-11.[300] However, gaming disorder appears in the ICD-11.[301] Controversy around the diagnosis includes whether the disorder is a separate clinical entity, or a manifestation of underlying psychiatric disorders. Definitions are not standardized or agreed upon, complicating the development of evidence-based recommendations. Many different theoretical models have been developed and employed for many years in order to better explain predisposing factors to this disorder. Models such as the cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet have been used to explain IAD for more than 20 years. Newer models, such as the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution model, have been developed more recently and are starting to be applied in more clinical studies.[302] In 2011 the term "Facebook addiction disorder" (FAD) emerged.[303] FAD is characterized by compulsive use of Facebook. A 2017 study investigated a correlation between excessive use and narcissism, reporting "FAD was significantly positively related to the personality trait narcissism and to negative mental health variables (depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms)".[304][305] In 2020, the documentary The Social Dilemma, reported concerns of mental health experts and former employees of social media companies over social media's pursuit of addictive use. For example, when a user has not visited Facebook for some time, the platform varies its notifications, attempting to lure them back. It also raises concerns about the correlation between social media use and child and teen suicidality.[306] Additionally in 2020, studies have shown that there has been an increase in the prevalence of IAD since the COVID-19 pandemic.[307] Studies highlighting the possible relationship between COVID-19 and IAD have looked at how forced isolation and its associated stress may have led to higher usage levels of the Internet.[307] Turning off social media notifications may help reduce social media use.[308] For some users, changes in web browsing can be helpful in compensating for self-regulatory problems. For instance, a study involving 157 online learners on massive open online courses examined the impact of such an intervention. The study reported that providing support in self-regulation was associated with a reduction in time spent online, particularly on entertainment.[309] Research suggests that social media platforms trigger a cycle of compulsive behavior, which reinforces addictive patterns and makes it harder for individuals to break the cycle.[310] Various lawsuits have been brought regarding social media addiction, such as the Multi-District Litigation alleging harms caused by social media addiction on young users.[311] |

依存症 主な記事: 問題のあるソーシャルメディア利用 関連項目: デジタルメディア利用とメンタル健康 これらの段落はインターネット依存症からの抜粋である。[編集] インターネット依存症(IAD)は、コンピューター使用やインターネットアクセスに関する過度または制御不能な執着、衝動、行動によって特徴づけられ、機 能障害や苦痛をもたらす。[295] 若年層は特にインターネット依存症を発症するリスクが高い[296]。事例研究では、オンライン時間を増やすにつれて学業成績が低下する学生が指摘されて いる[297]。スクロールやチャット、ゲームに没頭して夜更かしする結果、睡眠不足による健康被害を経験する者もいる[298]。[299] 過剰なインターネット使用は、米国精神医学会のDSM-5や世界保健機関のICD-11では障害として認定されていない[300]。ただし、ゲーム障害は ICD-11に記載されている[301]。この診断を巡る論争には、この障害が独立した臨床的実体なのか、それとも潜在的な精神障害の現れなのかという点 が含まれる。定義は標準化されておらず合意も得られていないため、エビデンスに基づく推奨事項の策定は複雑化している。 この障害の素因をよりよく説明するため、長年にわたり異なる理論モデルが開発・採用されてきた。病的なインターネット使用の認知行動モデルなどは、20年 以上も前からIADの説明に用いられてきた。近年では、PACE(Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution)相互作用モデル などの新しいモデルが開発され、より多くの臨床研究で適用され始めている。[302] 2011年には「フェイスブック依存症(FAD)」という用語が登場した[303]。FADはフェイスブックの強迫的使用を特徴とする。2017年の研究 では過剰使用とナルシシズムの相関を調査し、「FADは人格特性としてのナルシシズムおよび精神的健康の負の変数(抑うつ、不安、ストレス症状)と有意な 正の関連を示した」と報告している[304]。[305] 2020年公開のドキュメンタリー『ソーシャル・ジレンマ』は、ソーシャルメディア企業が中毒性のある利用を追求することに対する、精神保健専門家や元従 業員の懸念を報じた。例えば、ユーザーが一定期間Facebookを利用していない場合、プラットフォームは通知内容を変化させ、ユーザーを呼び戻そうと する。また、ソーシャルメディア利用と児童・青少年の自殺傾向との相関関係についても懸念が示されている。[306] さらに2020年には、COVID-19パンデミック以降、IAD(インターネット依存症)の有病率が上昇していることが研究で示された。[307] COVID-19とIADの関連性を指摘する研究では、強制的な隔離とそれに伴うストレスがインターネット利用量の増加につながった可能性を検証してい る。[307] ソーシャルメディアの通知をオフにすることは、利用削減に役立つ可能性がある。[308] 一部のユーザーにとって、ウェブ閲覧方法の変更は自己規制の問題を補うのに有効だ。例えば、大規模公開オンライン講座(MOOC)の受講者157名を対象 とした研究では、このような介入の影響を検証した。その結果、自己規制の支援を提供することで、特に娯楽目的のオンライン利用時間が減少することが報告さ れている。[309] 研究によれば、ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームは強迫的行動のサイクルを引き起こし、依存パターンを強化するため、個人がそのサイクルを断ち切るのが 困難になる。[310] ソーシャルメディア依存症に関する様々な訴訟が提起されている。例えば、若年ユーザーへのソーシャルメディア依存症による被害を主張する多地区訴訟 (MDL)などである。[311] |

| Debate over use by young people See also: Social media in education Whether to restrict the use of phones and social media among young people has been debated since smartphones became ubiquitous.[312] A study of Americans aged 12–15, reported that teenagers who used social media over three hours/day doubled their risk of negative mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety.[313] Platforms have not tuned their algorithms to prevent young people from viewing inappropriate content. A 2023 study of Australian youth reported that 57% had seen disturbingly violent content, while nearly half had regular exposure to sexual images.[314] Further, youth are prone to misuse social media for cyberbullying.[315] As result, phones have been banned from some schools, and some schools in the US have blocked social media websites.[316] Intense discussions are taking place regarding the imposition of certain restrictions on children's access to social media. It is argued that using social media at a young age brings with it many problems. For example, according to a survey conducted by Ofcom, the media regulator in the UK, 22% of children aged 8-17 lie about being over 18 on social media. According to a system implemented in Norway, more than half of nine-year-olds and the vast majority of 12-year-olds spend time on social media. A series of measures have begun to be taken across Europe to prevent the risks caused by such problems. The countries that have taken concrete steps in this regard are Norway and France. Since June 2023, France has started requiring social media platforms to verify the ages of their users and to obtain parental consent for those under the age of 15. In Norway, there is a minimum age requirement of 13 to access social media. The Online Safety Law in the UK has given social media platforms until mid-2025 to strengthen their age verification systems.[317] |

若者の利用をめぐる議論 関連項目:教育におけるソーシャルメディア 若者のスマートフォンやソーシャルメディア利用を制限すべきか否かは、スマートフォンの普及以来議論されてきた。[312] 12~15歳のアメリカ人を対象とした研究では、1日3時間以上ソーシャルメディアを利用する十代の若者は、うつ病や不安症を含む精神健康上の悪影響を受 けるリスクが2倍になることが報告されている。[313] プラットフォームは若年層が不適切なコンテンツを閲覧するのを防ぐようアルゴリズムを調整していない。2023年のオーストラリアの若年層調査では、 57%が衝撃的な暴力コンテンツを目撃し、ほぼ半数が性的画像に定期的に接触していると報告された[314]。さらに若年層はソーシャルメディアをネット いじめに悪用しやすい傾向がある[315]。 その結果、一部の学校では携帯電話が禁止され、米国ではソーシャルメディアサイトをブロックする学校も存在する。[316] 子どものソーシャルメディア利用に一定の制限を設けるべきか否かについて、激しい議論が交わされている。幼い年齢でのソーシャルメディア利用は多くの問題 を引き起こすと主張される。例えば、英国のメディア規制機関Ofcomが実施した調査によれば、8~17歳の子供の22%がソーシャルメディア上で18歳 以上と虚偽の申告をしている。ノルウェーで導入された制度によれば、9歳児の半数以上と12歳児の大多数がソーシャルメディアを利用している。こうした問 題によるリスクを防ぐため、欧州各国で一連の対策が始まっている。具体的な措置を講じた国はノルウェーとフランスだ。フランスでは2023年6月から、 ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームに対し、ユーザーの年齢確認と15歳未満の親権者同意の取得を義務付け始めた。ノルウェーではソーシャルメディア利用 の最低年齢を13歳と定めている。英国のオンライン安全法は、ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームに対し、2025年半ばまでに年齢確認システムを強化す るよう求めている。[317] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_media |

|

| Problematic social media use |

問題のあるソーシャル・メディア利用 |

| Excessive

use of social media can lead to problems including impaired functioning

and a reduction in overall wellbeing, for both users and those around

them. Such usage is associated with a risk of mental health problems,

sleep problems, academic struggles, and daytime fatigue.[5] Psychological or behavioural dependence on social media platforms can result in significant negative functions in peoples daily lives.[6] Women are at a great risk for experiencing problems related to social media use.[citation needed] The risk of problems is also related to the type of platform of social media or online community being used. People of different ages and genders may be affected in different ways by problematic social media use.[citation needed] |

ソーシャルメディアの過剰使用は、利用者本人と周囲の人々双方に、機能障害や全体的な幸福感の低下といった問題を引き起こす可能性がある。このような使用は、精神健康上の問題、睡眠障害、学業不振、日中の疲労感といったリスクと関連している。[5] ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームへの心理的・行動的依存は、人民の日々の生活に重大な悪影響をもたらす可能性がある。[6] 女性はソーシャルメディア利用に関連する問題を抱えるリスクが特に高い。[出典が必要] 問題発生のリスクは、利用するソーシャルメディアプラットフォームやオンラインコミュニティの種類にも関連している。年齢や性別が異なる人民は、問題のあ るソーシャルメディア利用によって異なる影響を受ける可能性がある。[出典が必要] |

| Signs and symptoms Signs of social media addiction or excessive use of social media include many behaviours similar to substance use disorders, including mood modification, salience, tolerance, stress withdrawal symptoms, psychological distress, anxiety and depression, conflict, and relapse, and low self esteem.[7][8][9][10][11] People with problematic social media habits are at risk of being addicted and may require more time on social media as time passes.[12] Frequent social media use may also be associated self-reported symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.[13] Social anxiety (or fear of missing out) is another potential symptom. Social anxiety is defined as having intense anxiety or fear of being judged, negatively evaluated, or rejected in a social or performance situation.[14][15][16] The fear of missing out can contribute to excessive usage due to frequent checking the media constantly throughout the day to check in and see what others are doing instead of doing other activities.[citation needed] Displacement, or replacing meaningful other activities with social media,[17] and loneliness[18][19] are common signs. |

兆候と症状 ソーシャルメディア依存症や過度な使用の兆候には、物質使用障害と類似した多くの行動が含まれる。具体的には、気分の変化、重要性の増大、耐性の形成、ス トレスによる離脱症状、心理的苦痛、不安や抑うつ、対人関係の衝突、再発、そして低い自尊心などである。[7][8][9][10][11] 問題のあるソーシャルメディア習慣を持つ人民は依存症のリスクがあり、時間の経過とともにソーシャルメディアに費やす時間を増やす必要があるかもしれな い。[12] ソーシャルメディアの頻繁な利用は、注意欠陥・多動性障害(ADHD)の自己申告症状とも関連している可能性がある。[13] 社会的不安(あるいはFOMO:見逃すことへの恐怖)もまた潜在的な症状である。社会的不安とは、社会的状況やパフォーマンス状況において、判断された り、否定的に評価されたり、拒絶されたりする強い不安や恐怖を抱くことを指す。[14][15][16] FOMOは、他の活動を行う代わりに一日中頻繁にメディアをチェックし、他人の行動を確認する過剰使用の一因となり得る。[出典が必要] 置換、つまり意味のある他の活動をソーシャルメディアで置き換えること[17]や孤独感[18][19]は、よくある兆候だ。 |

| Causes and mechanisms There are many theories for the mechanism or cause behind a person having problematic social media use.[20] The transition from normal to problematic social media use occurs when a person relies on it to relieve stress, loneliness, depression, or provide continuous rewards.[21] 1. Cognitive-behavioral model – People increase their use of social media when they are in unfamiliar environments or awkward situations; 2. Social skill model – People pull out their phones and use social media when they prefer virtual communication as opposed to face-to-face interactions because they lack self-presentation skills; 3. Socio-cognitive model – This person uses social media because they love the feeling of people liking and commenting on their photos and tagging them in pictures. They are attracted to the positive outcomes they receive on social media. There are parallels to the gambling industry inherent to the design of various social media sites, with "'ludic loops' or repeated cycles of uncertainty, anticipation and feedback" potentially contributing to problematic social media use.[22] Another factor directly facilitating the development of addiction to social media is the implicit attitude toward the IT artifact.[23] Social media use may also stimulate the reward pathway in the brain.[24] There is also a theory that social media addiction fulfills a basic evolutionary drives in the wake of mass urbanization worldwide. The basic psychological needs of "secure, predictable community life that evolved over millions of years" remain unchanged, leading some to find online communities to cope with the new individualized way of life in some modern societies.[25] The “Evolutionary Mismatch” hypothesis holds that modern digital platforms amplify social competition and comparison in ways our ancestors never faced, possibly triggering maladaptive patterns such as anxiety, depression, or compulsive use. Similarly, some scholars compare social media to “junk food”:[26][27] The approach taken to develop social media platforms may contribute to problematic social media use.[28] The ability to scroll and stream content endlessly and how app developers distort time by affecting the 'flow' of content when scrolling,[29] potentially resulting in the Zeigarnik effect (the human brain will continue to pursue an unfinished task until a satisfying closure.[28][30] Autoplay modes,[28] the personalized nature of the content results in emotional attachment (ie, the user values this above its actual value, which is referred to as the endowment effect[31][32][33]), and the exposure effect (repeated exposure to a distinct stimulus by the user can condition the user into an enhanced or improved attitude toward it).[34][28] The interactive nature of the platforms, including the ability to "like" content has also been linked. Even though social media can satisfy personal communication needs, those who use it at higher rates are shown to have higher levels of psychological distress.[35] |

原因とメカニズム 問題のあるソーシャルメディア利用のメカニズムや原因については多くの理論がある。[20] 通常の利用から問題のある利用への移行は、ストレスや孤独感、抑うつを和らげたり、継続的な報酬を得るために依存した時に起こる。[21] 1. 認知行動モデル – 人民は見知らぬ環境や気まずい状況にいる時、ソーシャルメディアの利用を増やす。 2. 社会的スキルモデル – 自己表現スキルが不足しているため、対面交流よりも仮想コミュニケーションを好む人民は、スマートフォンを取り出してソーシャルメディアを利用する。 3. 社会認知モデル – この人格は、自分の写真に「いいね」やコメントが付いたり、写真にタグ付けされたりする感覚を好むためソーシャルメディアを利用する。ソーシャルメディア上で得られる肯定的な結果に惹かれているのである。 各種ソーシャルメディアサイトの設計にはギャンブル産業との類似性が内在しており、「不確実性、期待、フィードバックの反復サイクル(ルーディック・ルー プ)」が問題のあるソーシャルメディア利用に寄与する可能性がある[22]。ソーシャルメディア依存症の発達を直接促進する別の要因は、IT製品に対する 暗黙の態度である[23]。ソーシャルメディア利用は脳内の報酬経路を刺激する可能性もある。[24] また、ソーシャルメディア依存症は、世界的な大規模都市化の流れの中で、基本的な進化的な欲求を満たすという理論もある。「何百万年もの間進化してきた、 安全で予測可能な共同体生活」という基本的な心理的ニーズは変わらず、現代社会における新たな個人主義的な生活様式に対処するため、オンラインコミュニ ティを求める人々も現れている。[25] 「進化的ミスマッチ」仮説によれば、現代のデジタルプラットフォームは、先祖が経験したことのない形で社会的競争や比較を増幅させ、不安や抑うつ、強迫的 使用といった不適応パターンを引き起こす可能性がある。同様に、一部の学者はソーシャルメディアを「ジャンクフード」に例える。[26] [27] ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームの開発手法自体が、問題のある利用を助長している可能性がある[28]。コンテンツを無限にスクロール・ストリーミン グできる機能や、アプリ開発者がスクロール時のコンテンツ「流れ」を操作して時間を歪める手法[29]は、ツァイガルニク効果(未完了の課題は満足のいく 完結を得るまで脳が追い続ける現象)を引き起こす恐れがある。[28][30] 自動再生モード[28]、コンテンツのパーソナライズ化による感情的愛着(ユーザーが実際の価値以上に評価する「所有効果」[31][32][33])、 露出効果(特定の刺激への反復接触が態度強化を促す現象)[34]などが挙げられる。[28] コンテンツへの「いいね」機能を含むプラットフォームの双方向性も関連性が指摘されている。 ソーシャルメディアは人格のコミュニケーション欲求を満たす一方で、利用頻度が高いユーザーほど心理的苦痛のレベルが高いことが示されている。[35] |

| Diagnosis While there is no official diagnostic term or measurement, problematic social media use is conceptualized as a non-substance-related disorder, resulting in preoccupation and compulsion to engage excessively in social media platforms despite negative consequences.[36] No diagnosis exists for problematic social media use in either the ICD-11 or DSM-5. Excessive use of an activity, like social media, does not directly equate with addiction.[25] There are other factors that could lead to someone's social media addiction including personality traits and pre-existing tendencies.[25] While the extent of social media use and addiction are positively correlated, it is erroneous to employ use (the degree to which one makes use of the site’s features, the effort exerted during use sessions, access frequency, etc.) as a proxy for addiction.[37] Indicators of a potential dependence on social media include:[38] 1. Mood swings: a person uses social media to regulate his or her mood, or as a means of escaping real world conflicts. 2. Relevance: social media starts to dominate a person's thoughts at the expense of other activities. 3. Salience: social media becomes the most important part of someone's life. 4. Tolerance: a person increases their time spent on social media to experience previously associated feelings they had while using social media. 5. Withdrawal: when a person can not access social media their sleeping or eating habits change or signs of depression or anxiety can become present. 6.Conflicts in real life: when social media is used excessively, it can affect real-life relationships with family and friends. 7. Relapse: the tendency for previously affected individuals to revert to previous patterns of excessive social media use. There have been several scales developed and validated that help to understand the issues regarding problematic social media use.[39][40][41][42] There is not one single scale that is being used by all researchers.[43] |

診断 公式な診断用語や測定基準は存在しないが、問題のあるソーシャルメディア利用は非物質関連障害として概念化されている。これは、悪影響があるにもかかわら ず、ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームに過度に没頭し、強迫的に関与する状態を指す。[36] ICD-11やDSM-5のいずれにも、問題のあるソーシャルメディア利用の診断は存在しない。ソーシャルメディアのような活動の過剰な利用は、直接的に 依存症と同義ではない。[25] ソーシャルメディア依存症に至る要因には、人格特性や既存の傾向性も含まれる。[25] 利用頻度と依存症の程度には正の相関があるが、利用状況(サイト機能の使用度合い、利用時の集中度、アクセス頻度など)を依存症の代用指標とすることは誤 りである。[37] ソーシャルメディア依存の可能性を示す指標には以下がある:[38] 1. 気分の変動:気分を調節するため、あるいは現実世界の葛藤から逃れる手段としてソーシャルメディアを利用する人格。 2. 重要性:他の活動を犠牲にして、ソーシャルメディアが思考の大部分を占めるようになる。 3. 顕著性:ソーシャルメディアが生活の中で最も重要な部分となる。 4. 耐性:人格が以前感じていた感覚を得るために、ソーシャルメディア使用時に使用時間を増やす傾向。 5. 離脱症状:人格がソーシャルメディアにアクセスできない場合、睡眠や食事習慣の変化、抑うつや不安の兆候が現れる。 6. 現実生活での葛藤:ソーシャルメディアの過剰使用が、家族や友人との現実の人間関係に影響を与える。 7. 再発:問題を抱えた個人が、以前の過剰なソーシャルメディア使用パターンに逆戻りする傾向。 問題のあるソーシャルメディア使用に関する課題を理解するのに役立つ、いくつかの尺度(尺度)が開発され、検証されている。[39][40][41][42] 全ての研究者が使用する単一の尺度(尺度)は存在しない。[43] |

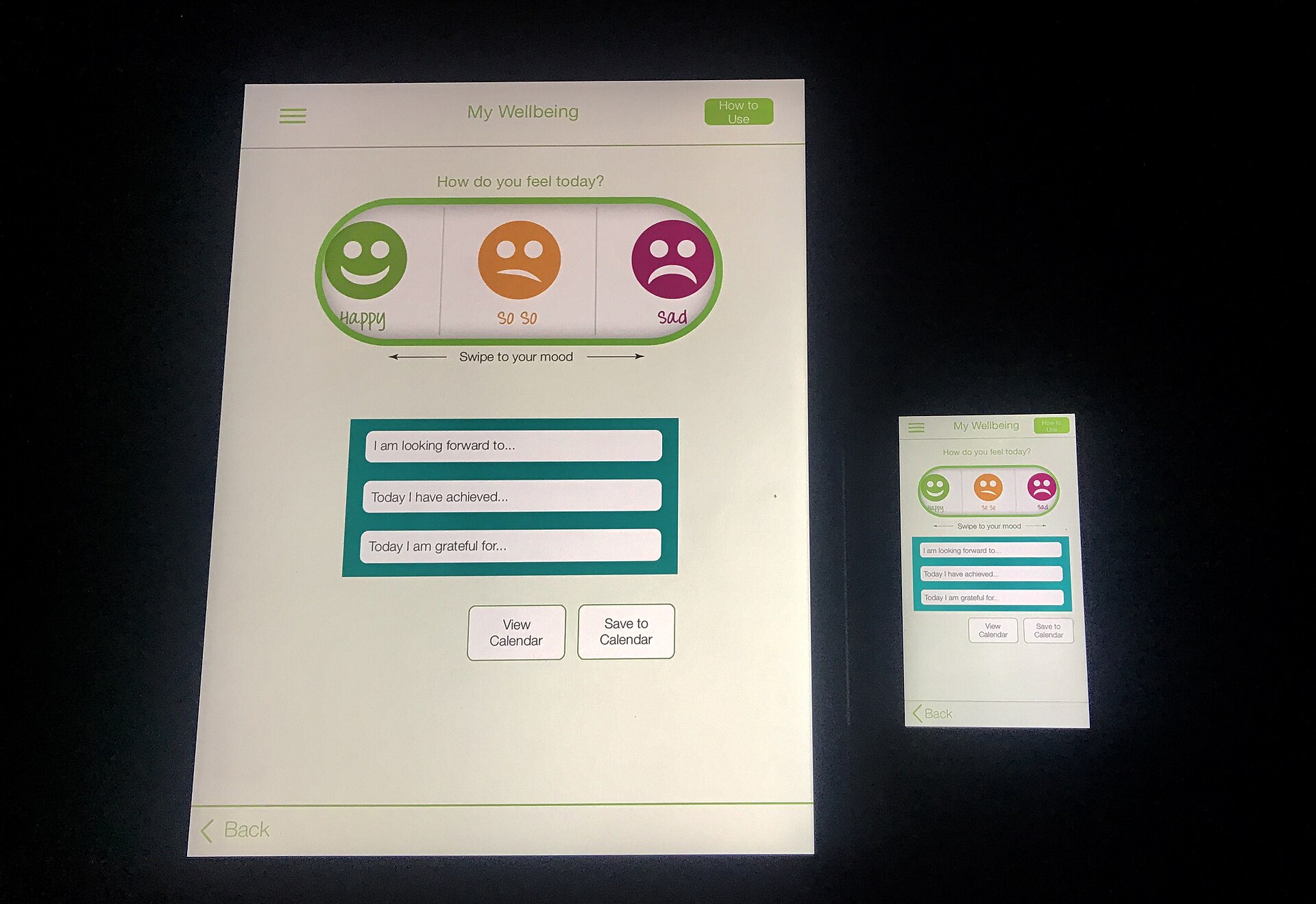

| Treatment Screen time recommendations for children and families have been developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics.[44][45] Possible therapeutic interventions published include: Self-help interventions, including application-specific timers; Cognitive behavioural therapy;[46] and Organisational and schooling support.[47] Medications have not been shown to be effective in randomized, controlled trials for the related conditions of Internet addiction disorder or gaming disorder.[47] |

治療 小児科学会が子供と家族向けのスクリーンタイム推奨時間を策定している。[44][45] 公表されている治療的介入法には以下が含まれる: アプリケーション専用タイマーを含む自助的介入法; 認知行動療法;[46]および 組織的・教育的支援。[47] インターネット依存症やゲーム障害といった関連疾患に対して、薬物療法が有効であることは無作為化比較試験で示されていない。[47] |

| Prevention Prevention approaches include screen time monitoring apps and other tech-based approaches to improve efficiency and decrease screen time and tools to help with addiction to online platform products.[48][49][50][51][52] Parents' methods for monitoring, regulating, and understanding their children's social media use are referred to as parental mediation.[53] Parental mediation strategies include active, restrictive, and co-using methods. Active mediation involves direct parent-child conversations that are intended to educate children on social media norms and safety, as well as the variety and purposes of online content. Restrictive mediation entails the implementation of rules, expectations, and limitations regarding children's social media use and interactions. Co-use is when parents jointly use social media alongside their children, and is most effective when parents are actively participating (like asking questions, making inquisitive/supportive comments) versus being passive about it.[54] Active mediation is the most common strategy used by parents, though the key to success for any mediation strategy is consistency/reliability.[53] When parents reinforce rules inconsistently, have no mediation strategy, or use highly restrictive strategies for monitoring their children's social media use, there is an observable increase in children's aggressive behaviours.[55][56] When parents openly express that they are supportive of their child's autonomy and provide clear, consistent rules for media use, problematic usage and aggression decreases.[55][57] Knowing that consistent, autonomy-supportive mediation has more positive outcomes than inconsistent, controlling mediation, parents can consciously foster more direct, involved, and genuine dialogue with their children. This can help prevent or reduce problematic social media use in children and teenagers.[55][56] |

予防 予防策には、画面時間の監視アプリやその他の技術ベースのアプローチが含まれる。これらは効率を向上させ画面時間を減らすためのものであり、オンラインプラットフォーム製品への依存症を助けるツールでもある。[48][49][50][51] 親が子供のソーシャルメディア利用を監視・規制・理解する方法を「親による仲介」と呼ぶ。[53] 親による仲介戦略には、積極的、制限的、共同利用の方法がある。積極的仲介は、ソーシャルメディアの規範や安全性、オンラインコンテンツの多様性と目的に ついて子供を教育することを目的とした、直接的な親子対話を伴う。制限的仲介は、子供のソーシャルメディア利用や交流に関するルール、期待、制限の実施を 伴う。共同利用は、親が子供と一緒にソーシャルメディアを利用することを指し、親が受動的ではなく(質問をしたり、探求的・支援的なコメントをしたりする など)積極的に参加する場合に最も効果的である。[54] 積極的仲介は親が最もよく用いる戦略だが、どの仲介戦略でも成功の鍵は一貫性と信頼性にある。[53] 親がルールを不規則に強化したり、仲介戦略を持たなかったり、子どものソーシャルメディア利用を監視するために過度に制限的な戦略を用いたりすると、子ど もの攻撃的行動が明らかに増加する。[55][56] 親が子どもの自律性を支持すると公に表明し、メディア利用について明確で一貫したルールを提供すると、問題のある利用や攻撃性は減少する。[55] [57] 一貫した自律性支持型仲介が、一貫性のない統制型仲介よりも良好な結果をもたらすことを理解すれば、親は意識的に子どもとの直接的で関与した本物の対話を 育める。これは子どもや青少年の問題のあるソーシャルメディア利用を予防・軽減するのに役立つ。[55][56] |

| Outcomes Adolescents and teens Increased social media use and exposure to social media platforms can lead to negative results and bullying over time.[58] While social media's main intention is to share information and communicate with friends and family, there is more evidence pertaining to negative factors rather than positive ones. Social media use has been linked to an increased risk of depression and self harm.[59] Those from the ages of 13-15 may struggle the most with these issues, but they can be seen in college students as well.[60] According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, data showed that approximately 15% of high school students were electronically bullied in the 12 months prior to the survey that students were asked to complete.[61] Bullying over social media has sparked suicide rates immensely within the last decade.[62] Older people Older generations are affected by social media in different areas to teens and young adults. Social media plays an integral role in the daily lives of middle aged adults, especially in regards to their career and communication. Studies have suggested that many individuals feel that smartphones are vital for their career planning and success, but a pressure to connect with family and friends via social media becomes an issue.[63] This is reinforced by further studies suggesting that middle aged people feel more isolated and lonely due to the use of social media, to the extent of diagnosis of anxiety and depression with excessive use. Similarly to teens and young adults, comparisons to others is often the reason for negative mental impacts amongst middle aged individuals. Surveys suggest that a pressure to perform and feelings of inferiority due to observing others lives through social media has caused depression and anxiety amongst middle class individuals specifically.[64] However, older generations do reap the benefits of the rise of social media. The feelings of loneliness and isolation have decreased in elderly individuals who use social media to connect to others, ultimately leading to a more fulfilling and physically healthy lifestyle, due to the ability to communicate and stay in touch with people they would have physically not been able to see.[63] Education Excessive use of social media may impact academic performance negatively. An increase usage on social media may take time away from spending away from time dedicated to academics.[citation needed] In school, many teachers report that their students are unfocused and unmotivated.[65] There may be a link between spending free time on social media and weaker critical thinking skills, impatience, and a lack in perseverance.[citation needed] There is also a risk of students struggling with attention and focusing because of how fast their phone can change from topic to topic.[65] Eating disorders People with problematic social media use have an increased risk for eating disorders (especially in females),[66] Through the extensive use of social media, adolescents are exposed to images of bodies that are unattainable, especially with the growing presence of photo-editing apps that allow you to alter the way that your body appears in a photo and social media can foster an environment for harmful online communities such as those that promote unhealthy habits.[67][68] Along with that is the normalization of cosmetic surgery which sets unrealistic beauty standards as well. This can, in turn, influence both the diet and exercise practices of adolescents as they try to fit the standard that their social media consumption has set for them.[67] |

結果 思春期と十代の若者 ソーシャルメディアの利用増加とプラットフォームへの露出は、時間の経過とともに悪影響やいじめに繋がる可能性がある。[58] ソーシャルメディアの主な目的は情報や友人・家族との交流を共有することだが、ポジティブな要素よりもネガティブな要素に関する証拠の方が多い。ソーシャ ルメディアの利用は、うつ病や自傷行為のリスク増加と関連している。[59] 13~15歳の年齢層がこれらの問題に最も苦しむ可能性があるが、大学生にも同様の傾向が見られる。[60] 米国疾病予防管理センター(CDC)の2019年青少年リスク行動監視システムによると、調査実施前の12ヶ月間に電子的いじめの被害を受けた高校生は約 15%に上った。[61] ソーシャルメディアを通じたいじめは、過去10年間で自殺率を著しく増加させた。[62] 高齢者 高齢世代がソーシャルメディアの影響を受ける領域は、10代や若年成人とは異なる。ソーシャルメディアは、特にキャリアやコミュニケーションの面で、中高 年層の日常生活に不可欠な役割を果たしている。多くの個人がキャリア形成と成功にスマートフォンが不可欠と感じている一方、ソーシャルメディアを介した家 族・友人との繋がりへのプレッシャーが問題となっていることが研究で示されている。[63] さらに、ソーシャルメディア利用により中年の孤立感や孤独感が増幅され、過剰使用が不安や抑うつ症の診断に繋がる可能性を示唆する研究もある。青少年と同 様に、他者との比較が中年の精神的悪影響の主な要因である。調査によれば、ソーシャルメディアを通じて他人の生活を観察することで生じるパフォーマンスへ のプレッシャーや劣等感が、特に中流階級の人々にうつ病や不安を引き起こしている。[64] しかし、高齢世代はソーシャルメディアの普及による恩恵を確かに受けている。ソーシャルメディアを利用して他者と繋がる高齢者は、孤独感や孤立感が減少 し、結果としてより充実した身体的に健康な生活を送っている。これは、物理的に会うことが難しかった人々とコミュニケーションを取り、繋がりを保つ能力に よるものである。[63] 教育 ソーシャルメディアの過剰利用は学業成績に悪影響を及ぼす可能性がある。ソーシャルメディアの利用時間が増えると、学業に充てる時間が奪われる。[出典必 要] 学校では、多くの教師が生徒の集中力や意欲の低下を報告している。[65] 自由時間をソーシャルメディアに費やすことと、批判的思考力の低下、忍耐力の欠如、焦燥感の増加には関連性がある可能性がある。[出典必要] また、スマートフォンの画面が瞬時に話題を切り替える性質上、生徒が注意力を維持し集中することに困難をきたすリスクもある。[65] 摂食障害 ソーシャルメディアの使用に問題がある人は、摂食障害(特に女性)のリスクが高まる。[66] ソーシャルメディアの多用により、青少年は現実には達成不可能な身体像に晒される。特に、写真編集アプリが普及し、写真に写る自分の身体の見た目を変えら れるようになったことで、ソーシャルメディアは不健康な習慣を助長する有害なオンラインコミュニティを育む環境を作り出しうる。[67][68] これに加え、美容整形の一般化も非現実的な美の基準を定着させている。その結果、若者はソーシャルメディアが設定した基準に合わせようと、食事や運動習慣 に影響を受ける可能性がある。[67] |

| Epidemiology Psychologists estimate that as many as 5 to 10% of Americans meet the criteria for social media addiction today.[69] A survey conducted by Pew Research Center from January 8 through February 7, 2019, found that 80% of Americans go online every day.[70] Among young adults, 48% of 18- to 29-year-olds reported going online 'almost constantly' and 46% of them reported going online 'multiple times per day.'[70] Young adults going online 'almost constantly' increased by 9% just since 2018. On July 30, 2019, U.S. Senator Josh Hawley introduced the Social Media Addiction Reduction Technology (SMART) Act which is intended to crack down on "practices that exploit human psychology or brain physiology to substantially impede freedom of choice". It specifically prohibits features including infinite scrolling and Auto-Play.[71][72] A study conducted by Junling Gao and associates in Wuhan, China, on mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak revealed that there was a high prevalence of mental health problems including generalized anxiety and depression.[73] This had a positive correlation to 'frequent social media exposure.'[73] Based on these findings, the Chinese government increased mental health resources during the COVID-19 pandemic, including online courses, online consultation and hotline resources.[73] |

疫学 心理学者の推定によれば、現在アメリカ人の5~10%がソーシャルメディア依存症の基準を満たしているという。[69] ピュー・リサーチ・センターが2019年1月8日から2月7日にかけて実施した調査では、アメリカ人の80%が毎日インターネットを利用していることが判 明した。[70] 若年層では、18~29歳の48%が「ほぼ常に」オンラインを利用し、46%が「1日に複数回」利用していると報告した。[70] 「ほぼ常に」オンラインを利用する若年層は、2018年以降だけで9%増加した。2019年7月30日、米国上院議員ジョシュ・ホーリーは「ソーシャルメ ディア依存症削減技術(SMART)法案」を提出した。これは「人間の心理や脳の生理機能を悪用し、選択の自由を著しく阻害する行為」を取り締まることを 目的としている。具体的には無限スクロールや自動再生などの機能を禁止する。[71][72] 中国武漢で高俊玲らが実施したCOVID-19流行期のメンタルヘルス調査では、全般性不安障害やうつ病を含む精神健康問題の高い有病率が明らかになっ た。[73]これは「頻繁なソーシャルメディア接触」と正の相関を示した。[73]この結果を受け、中国政府はパンデミック期間中にオンライン講座・相談 窓口・ホットライン資源を拡充した。[73] |

| Cultural and history From an anthropological lens, addiction to social media is a socially constructed concept that has been medicalized because this behavior does not align with behavior accepted by certain hegemonic social groups.[74] Molly Russell case Main article: Death of Molly Russell In November 2017, a fourteen-year-old British girl from Harrow, London, named Molly Russell, took her own life after viewing negative, graphic, and descriptive content primarily on social media platforms such as Instagram and Pinterest.[75] The coroner of this case, Andrew Walker also concluded that Molly's death was "an act of self harm suffering from depression and the negative effects of online content".[75] Molly's case has sparked a lot of attention not only across the UK but in the U.S. as well. It raises the question on whether or not policies and regulations will either be set into place or changed to protect the safety of children on the Internet. Child safety campaigners hope that creating regulations will help to shift the fundamentals that are associated with social media platforms such as Instagram and Pinterest.[76] Laws, policies, and regulations to minimize harm Molly Russell's case sparked discussion both in the UK and the U.S. on how to protect individuals from harmful online content. In the UK, the Online Safety Bill was officially introduced into Parliament in March 2022: the bill covers a range of possible dangerous content such as revenge porn, grooming, hate speech, or anything related to suicide.[77] Overall, the bill will not only protect children from online content but talk about how they can deal with this content that may be illegal. It also covers verification roles and advertising as this will all be covered on the social media platform's terms and conditions page. If the social media platforms fail to comply with these new regulations, they will face a $7500 fine for each offense. When it comes to the U.S., recommendations were offered such as finding an independent agency to implement a system of regulations similar to the Online Safety Bill in the U.K.[78] Another potential idea was finding a specific rule making agency where the authority is strictly and solely focused on a digital regulator who is available 24/7.[78] California already launched an act called the Age Appropriate Design Code Act in August 2022, which aims to protect children under the age of eighteen especially regarding privacy on the Internet.[79] The overall hope and goal of these new laws, policies, and regulations set into place is to 1) ensure that a case such as Molly's never happens again and 2) protects individuals from harmful online content that can lead to mental health problems such as suicide, depression, and self-harm. In 2022, a case was successfully litigated that implicated a social media platform in the suicide of a Canadian teenage girl named Amanda Todd who died by hanging. This was the first time that any social media platform was held liable for a user's actions.[citation needed] |

文化と歴史 人類学的な視点から見ると、ソーシャルメディアへの依存は社会的に構築された概念であり、特定の支配的な社会集団によって受け入れられる行動と一致しないため、医療化されてきた。[74] モリー・ラッセル事件 主な記事:モリー・ラッセルの死 2017年11月、ロンドン、ハロー出身の14歳の英国人少女、モリー・ラッセルは、主にInstagramやPinterestなどのソーシャルメディ アプラットフォーム上で、否定的で、生々しく、描写的なコンテンツを閲覧した後、自らの命を絶った。[75] この事件の検死官であるアンドルー・ウォーカーも、モリーの死は「うつ病とオンラインコンテンツの悪影響による苦悩による自傷行為」であると結論づけた。 [75] モリーの事件は、英国だけでなく米国でも大きな注目を集めた。インターネット上で子供たちの安全を守るために、政策や規制が導入されるか、あるいは変更さ れるかという問題が提起されている。児童の安全を守る活動家たちは、規制を設けることで、Instagram や Pinterest などのソーシャルメディアプラットフォームに関連する根本的な問題の変化につながることを望んでいる。[76] 害を最小限に抑えるための法律、政策、規制 モリー・ラッセルの事件は、有害なオンラインコンテンツから個人をどのように保護すべきかについて、英国と米国の両方で議論を巻き起こした。英国では 2022年3月、オンライン安全法案が議会に正式提出された。同法案はリベンジポルノ、グルーミング、ヘイトスピーチ、自殺関連情報など多様な危険コンテ ンツを網羅する[77]。全体として、本法案は児童をオンラインコンテンツから保護するだけでなく、違法な可能性のあるコンテンツへの対処法についても規 定する。また、ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームの利用規約ページに記載される検証機能や広告も対象となる。プラットフォームが新規制に違反した場合、 違反1件につき7500ドルの罰金が科される。米国では、英国のオンライン安全法案に類似した規制システムを実施する独立機関の設置などが提案された。 [78] 別の案として、権限が厳密かつ専らデジタル規制機関に集中し、24時間体制で対応可能な特定の規則制定機関を設置することも検討されている。[78] カリフォルニア州では既に2022年8月、「年齢に応じたデザイン規範法」と呼ばれる法案を施行しており、特にインターネット上のプライバシーに関して 18歳未満の児童を保護することを目的としている。[79] こうした新たな法律・政策・規制の全体的な目的は、1) モリーのような事例が二度と起きないこと、2) 自殺・うつ病・自傷行為といった精神健康問題を引き起こす有害なオンラインコンテンツから個人を保護することにある。 2022年には、カナダ人少女アマンダ・トッドが首吊り自殺した事件で、ソーシャルメディアプラットフォームが関与したとして訴訟が成立した。これはソーシャルメディアプラットフォームがユーザーの行為に対して責任を問われた初めての事例である。[出典が必要] |

| Research Empirical research indicates that addiction to social media is triggered by dispositional factors (such as personality, desires, and self-esteem), but specific socio-cultural and behavioural reinforcement factors remain to be investigated empirically.[80] Social media addiction may also have other neurobiological risk factors; understanding this addiction is still being actively studied and researched, but there is some evidence that suggests a possible link between problematic social media use and neurobiological aspects.[81] |

研究 実証研究によれば、ソーシャルメディア依存は気質的要因(人格、欲求、自尊心など)によって引き起こされるが、具体的な社会文化的要因や行動的強化要因については、まだ実証的に調査される必要がある。[80] ソーシャルメディア依存症には他の神経生物学的リスク要因も存在する可能性がある。この依存症の理解は現在も活発に研究が進められているが、問題のあるソーシャルメディア利用と神経生物学的側面との関連性を示唆する証拠がいくつか存在する。[81] |

| Algorithmic radicalization – Radicalization via social media algorithms Computer addiction – Excessive or compulsive use of computers Digital media use and mental health – Mental health effects of using digital media Dopamine fasting – Temporary abstinence from addictive technologies Evolutionary mismatch – Scientific concept Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal – 2010s social media data misuse Facebook Files – Document leak regarding harm done by social networks Instagram impact on people Social media bias Problematic smartphone use – Psychological dependence on smartphones Social media as a news source - How people use social media to consume news Social influence bias – Herd behaviours in online social media Social media restrictions on children in Australia The Social Dilemma – 2020 American docudrama film by Jeff Orlowski Vicarious trauma after viewing media Adolescence (TV series) – 2025 British crime drama TV series |

アルゴリズムによる過激化 – ソーシャルメディアのアルゴリズムを介した過激化 コンピューター依存症 – コンピューターの過剰または強迫的な使用 デジタルメディア利用とメンタル健康 – デジタルメディア利用がメンタル健康に及ぼす影響 ドーパミン断食 – 依存性技術の一時的な断ち 進化論的ミスマッチ – 科学的概念 フェイスブック・ケンブリッジアナリティカデータスキャンダル – 2010年代のソーシャルメディアデータ悪用 フェイスブックファイル – ソーシャルネットワークによる被害に関する文書流出 インスタグラムが人民に与える影響 ソーシャルメディアバイアス 問題のあるスマートフォン利用 – スマートフォンへの心理的依存 ソーシャルメディアをニュースソースとして - 人民がソーシャルメディアでニュースを消費する方法 社会的影響バイアス - オンラインソーシャルメディアにおける群畜行動 オーストラリアにおける子供へのソーシャルメディア制限 ソーシャル・ディレンマ - ジェフ・オルロウスキー監督による2020年アメリカ製ドキュメンタリードラマ映画 メディア視聴後の代理トラウマ 『アドルセンス』(TVシリーズ) - 2025年英国製犯罪ドラマTVシリーズ |

| National Institute of Mental

Health, (2099), Social Anxiety Disorder : More Than Just Shyness, U.S.,

retrieved from Social Anxiety Disorder: More Than Just Shyness -

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Al-Rahmi WM, Othman MS (2013). "The Impact of Social Media use on Academic Performance among university students: A Pilot Study". Journal of Information Systems Research and Innovation: 1–10. Mateus, Samuel (2012). "Social Networks Scopophilic dimension – social belonging through spectatorship". Observatorio (OBS*) Journal (Special Issue). doi:10.15847/obsOBS000605. hdl:10400.13/2918. |

国民精神衛生研究所(2099年)。「社交不安障害:単なる内気以上のもの」。米国。出典:社交不安障害:単なる内気以上のもの - 国民精神衛生研究所(NIMH) Al-Rahmi WM, Othman MS (2013). 「大学生におけるソーシャルメディア利用が学業成績に与える影響:パイロット研究」 情報システム研究・革新ジャーナル:1–10. Mateus, Samuel (2012). 「ソーシャルネットワークのスコポフィリック次元 – 観客性を通じた社会的帰属」. Observatorio (OBS*) ジャーナル(特別号). doi:10.15847/obsOBS000605. hdl:10400.13/2918. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Problematic_social_media_use |

|

★デジタル・メディアの利用と精神保健

【注意書き】こ

の記事はウィキペディアの品質基準に準拠するため、書き直す必要があるかもしれない。試験の一覧はWP:MEDMOSの引用基準を満たしておらず、出典が

明記されていない。出典は主に「関連する精神疾患」の節で、部分的にしか理解できない形で記述されている。協力してほしい。トークページに提案があるかも

しれない。(2024年7月)/本記事にはインライン引用が含まれているが、それらは適切にフォーマットされていない。それらを修正することで本記事を改

善してほしい。ハードコードされた脚注参照は引用リンクに置き換えるべきである。(2025年9月)

(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングについて)

| Digital media use and mental health |

デジタル・メディアの利用と精神保健 |

| Researchers from fields like

psychology, sociology, anthropology, and medicine have studied the

relationship between digital media use and mental health since the

mid-1990s, following the rise of the World Wide Web and text messaging.

Much research has focused on patterns of excessive use, often called

"digital addictions" or "digital dependencies," which can vary across

different cultures and societies. At the same time, some experts have

explored the positive effects of moderate digital media use, including

its potential to support mental health and offer innovative treatments.

For example, participation in online support communities has been found

to provide mental health benefits, although the overall impact of

digital media remains complex.[1] The difference between beneficial and pathological use of digital media has not been established. There are no widely accepted diagnostic criteria associated with digital media overuse, although some experts consider overuse a manifestation of underlying psychiatric disorders. The prevention and treatment of pathological digital media use are not standardized, although guidelines for safer media use for children and families have been developed. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, 2013) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) currently do not recognize problematic internet use or problematic social media use as official diagnoses. However, the ICD-11 does include gaming disorder—often referred to as video game addiction—while the DSM-5 does not. As of 2023, there remains ongoing debate about if and when these behaviors should be formally diagnosed. Additionally, the use of the term "addiction" to describe these conditions has been increasingly questioned. Digital media and screen time amongst modern social media apps such as Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat and Facebook have changed how children think, interact and develop in positive and negative ways, but researchers are unsure about the existence of hypothesized causal links between digital media use and mental health outcomes. Those links appear to depend on the individual and the platforms they use. |

心理学、社会学、人類学、医学などの分野の研究者は、1990年代半ば

のワールドワイドウェブとテキストメッセージの普及以降、デジタルメディアの使用とメンタルヘルスとの関係について研究してきた。多くの研究は、しばしば

「デジタル依存症」や「デジタル依存」と呼ばれる過剰使用のパターンに焦点を当ててきた。これは異なる文化や社会によって異なる場合がある。同時に、一部

の専門家は、適度なデジタルメディア利用のプラスの効果、すなわちメンタルヘルスを支え、革新的な治療法を提供する可能性を探求してきた。例えば、オンラ

イン支援コミュニティへの参加はメンタルヘルス上の利益をもたらすことが分かっている。ただし、デジタルメディアの全体的な影響は依然として複雑である。

[1] デジタルメディアの有益な利用と病的な利用の境界線は確立されていない。デジタルメディアの過剰利用に関連する広く受け入れられた診断基準は存在しない が、一部の専門家は過剰利用を潜在的な精神疾患の現れと見なしている。病的なデジタルメディア利用の予防と治療は標準化されていないが、子どもや家族向け の安全なメディア利用ガイドラインは開発されている。『精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル』第5版(DSM-5, 2013)および『国際疾病分類』(ICD-11)は現在、問題のあるインターネット使用やソーシャルメディア使用を正式な診断として認めていない。ただ しICD-11には「ゲーム障害」(しばしばビデオゲーム依存症と呼ばれる)が含まれる一方、DSM-5には含まれていない。2023年現在、これらの行 動を正式に診断すべきかどうか、またその時期については議論が続いている。さらに、これらの状態を「依存症」と呼ぶこと自体も疑問視される傾向が強まって いる。 Instagram、TikTok、Snapchat、Facebookといった現代のソーシャルメディアアプリにおけるデジタルメディアやスクリーンタ イムは、子供たちの思考、交流、発達を良い面も悪い面も変えてきた。しかし研究者たちは、デジタルメディア利用とメンタル健康結果の間に仮説的な因果関係 が存在するかどうか確信が持てない。それらの関連性は個人と利用するプラットフォームに依存しているようだ。 |

| History and terminology The relationship between digital technology and mental health has been studied from multiple perspectives.[1][2][3] Research has identified benefits of digital media use for childhood and adolescent development.[4][5] However, researchers, clinicians, and the public have also expressed concern over compulsive behaviors linked to digital media use, as increasing evidence shows correlations between excessive technology use and mental health issues.[2][3][4][5] Terminologies used to refer to compulsive digital-media-use behaviours are not standardized or universally recognised. They include "digital addiction", "digital dependence", "problematic use", or "overuse", often delineated by the digital media platform used or under study (such as problematic smartphone use or problematic internet use).[6] Unrestrained use of technological devices may affect developmental, social, mental and physical well-being and may result in symptoms akin to other psychological dependence syndromes, or behavioral addictions.[7][5] The focus on problematic technology use in research, particularly in relation to the behavioural addiction paradigm, is becoming more accepted, despite poor standardization and conflicting research.[8] Internet addiction has been proposed as a diagnosis since the 1998[9] and social media and its relation to addiction has been examined since 2009.[10] A 2018 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report stated there were benefits of structured and limited internet use in children and adolescents for developmental and educational purposes, but that excessive use can have a negative impact on mental well-being. The report also noted a 40% overall increase in internet use among school-age children between 2010 and 2015, with significant variations in usage rates and platform preferences across different OECD countries.[1] The American Psychological Association recommends that adolescents receive training or coaching on social media use to help them develop psychologically informed skills and competencies, promoting balanced, safe, and meaningful engagement online.[11] The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has not formally classified problematic digital media use as a diagnostic category but identified internet gaming disorder as a condition warranting further study in 2013.[1] Meanwhile, gaming disorder—commonly known as video game addiction—is recognized in the ICD-11.[2][3] The differing recommendations between the DSM and ICD partly reflect a lack of expert consensus, variations in the focus of each classification system, and challenges in applying animal models to behavioral addictions.[7] The utility of the term addiction in relation to the overuse of digital media has been questioned, in regard to its suitability to describe new, digitally mediated psychiatric categories, as opposed to overuse being a manifestation of other psychiatric disorders.[12][13] Usage of the term has also been criticised for drawing parallels with substance use behaviours. Careless use of the term may cause more problems—both downplaying the risks of harm in seriously affected people, as well as overstating risks of excessive, non-pathological use of digital media.[13] The evolution of terminology relating excessive digital media use to problematic use rather than addiction was encouraged by Panova and Carbonell, psychologists at Ramon Llull University, in a 2018 review.[14] Due to the lack of recognition and consensus on the concepts used, diagnoses and treatments are difficult to standardize or develop. Heightened levels of public anxiety around new media (including social media, smartphones and video games) adds confusion to the interpretation of population-based assessments, as well as posing management dilemmas.[12] Radesky and Christakis, the 2019 editors of JAMA Paediatrics, published a review that investigated "concerns about health and developmental/behavioral risks of excessive media use for child cognitive, language, literacy, and social-emotional development."[15] Due to the ready availability of multiple technologies to children worldwide, the problem is bi-directional, as taking away digital devices may have a detrimental effect, in areas such as learning, family relationship dynamics, and overall development.[16] |

歴史と用語 デジタル技術とメンタル健康の関係は、様々な観点から研究されてきた。[1][2][3] 研究により、デジタルメディアの利用が児童期および青年期の発達に有益であることが確認されている。[4][5] しかし、研究者、臨床医、一般市民は、デジタルメディア利用に関連する強迫的行動についても懸念を表明している。なぜなら、過度な技術利用とメンタル健康 問題との相関関係を示す証拠が増えているからだ。[2][3][4] [5] 強迫的なデジタルメディア利用行動を指す用語は標準化されておらず、普遍的に認知されているわけでもない。これには「デジタル依存症」「デジタル依存」 「問題のある利用」「過剰利用」などが含まれ、多くの場合、使用または研究対象のデジタルメディアプラットフォームによって区別される(例:問題のあるス マートフォン利用、問題のあるインターネット利用)。[6] 技術機器の無制限な使用は、発達的・社会的・精神的・身体的健康に影響を与え、他の心理的依存症候群や行動依存症に類似した症状を引き起こす可能性があ る。[7][5] 研究における問題のある技術使用への注目、特に行動依存症パラダイムとの関係性は、標準化が不十分で研究結果が矛盾しているにもかかわらず、より広く受け 入れられつつある。[8] インターネット依存症は1998年[9]から診断対象として提案され、ソーシャルメディアと依存症の関係は2009年[10]から検討されている。 2018年の経済協力開発機構(OECD)報告書は、発達・教育目的での構造化された限定的なインターネット利用には児童・青少年に利益がある一方、過剰 利用は精神的健康に悪影響を及ぼし得ると述べた。同報告書はまた、2010年から2015年にかけて学齢期児童のインターネット利用が全体で40%増加し たことを指摘し、OECD加盟国間で利用率やプラットフォーム選好に顕著な差異があることを示した[1]。アメリカ心理学会は、青少年が心理学的知見に基 づいたスキルと能力を育成し、オンライン上で均衡のとれた安全かつ有意義な関与を促進できるよう、ソーシャルメディア利用に関する指導やコーチングを受け ることを推奨している。[11] 精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル(DSM)は、問題のあるデジタルメディア利用を正式な診断カテゴリーとして分類していないが、2013年にインターネッ トゲーム障害をさらなる研究が必要な状態として特定した。一方、ゲーム障害(一般にビデオゲーム依存症として知られる)はICD-11で認められている。 [2][3] DSMとICDの推奨内容は異なるが、その理由は専門家間の合意不足、各分類体系の焦点の違い、行動依存症への動物モデル適用における課題などを部分的に 反映している。[7] デジタルメディアの過剰使用に関連して「依存症」という用語の有用性は疑問視されている。過剰使用が他の精神疾患の現れである場合と異なり、デジタルを介 した新たな精神医学的カテゴリーを記述するのに適しているかどうかが問題だ。[12][13] また、この用語の使用は物質使用行動との類似性を強調する点でも批判されている。この用語の不注意な使用は、深刻な影響を受ける人々における危害リスクを 過小評価すると同時に、病的ではない過剰なデジタルメディア使用のリスクを過大評価するという二重の問題を引き起こす可能性がある。[13] ラモン・リュイ大学(Ramon Llull University)の心理学者パノバ(Panova)とカルボネル(Carbonell)は、2018年のレビューにおいて、過剰なデジタルメディア 使用を「依存症」ではなく「問題のある使用」に関連付ける用語の進化を推奨した。[14] 使用される概念に対する認識と合意が欠如しているため、診断と治療の標準化や開発は困難である。ソーシャルメディア、スマートフォン、ビデオゲームを含む 新メディアに対する公衆の不安の高まりは、集団ベースの評価の解釈に混乱をもたらすだけでなく、管理上のジレンマも生じさせている。[12] 2019年に『JAMA小児科学』の編集を担当したラデスキーとクリスタキスは、「過剰なメディア利用が子どもの認知・言語・リテラシー・社会情緒的発達 に及ぼす健康リスク及び発達・行動リスクに関する懸念」を検証したレビューを発表した。[15] 世界中の子どもが複数の技術を容易に入手できる現状では、問題は双方向性を持つ。デジタル機器を取り上げることが、学習や家族関係、総合的な発達といった 領域に悪影響を及ぼす可能性があるからだ。[16] |

| Problematic use See also: Cyberpathology, Digital Revolution, Social aspects of television, and Television consumption Though associations have been observed between digital media use and mental health symptoms or diagnoses, causality has not been established; nuances and caveats published by researchers are often misunderstood by the general public, or misrepresented by the media.[13] Problematic social media use can also result in fear of missing out (FoMO) in which symptoms of anxiety and psychological stress exasperated with the fear of potentially missing content present online leaving the individual feeling unfulfilled or left out of the loop.[17][18][19][20] Worsening mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, have been linked to digital use—particularly among younger users who may be more vulnerable to social comparison.[1] Neuroscientific findings that support a structural change in the brain, similar to behavioural addictions; have not found a specific biological or neural processes that may lead to excessive digital media use.[13] When an individual has FoMo they will be more likely to constantly check their social media accounts using their personal devices to check social media or messages to ensure they are up to date with information that is occurring within the individual's social network. This constant need to check social media platforms for information induces feelings of anxiety driving individuals to get involved with problematic social media use.[21] |

問題のある利用 関連項目:サイバー病理学、デジタル革命、テレビの社会的側面、テレビ視聴 デジタルメディアの利用と精神健康症状や診断との関連性は観察されているが、因果関係は確立されていない。研究者が発表した微妙な差異や注意点は大衆に誤 解されがちであり、メディアによって誤って伝えられることもある。[13] 問題のあるソーシャルメディア利用は、FOMO(見逃す恐怖)を引き起こすこともある。これは、オンライン上のコンテンツを見逃すかもしれないという恐怖 によって不安や心理的ストレスの症状が悪化し、個人が満たされない感覚や取り残された感覚を抱く状態である。[17][18][19][20] 不安や抑うつといった精神健康問題の悪化は、デジタル利用と関連付けられている。特に社会的比較の影響を受けやすい若年層において顕著だ[1]。行動依存 症に類似した脳の構造的変化を示す神経科学的知見はあるものの、過剰なデジタルメディア利用につながる特定の生物学的・神経学的プロセスは特定されていな い。[13] FoMo(取り残される恐怖)を抱える個人は、自身のソーシャルネットワーク内で発生している情報に遅れを取らないよう、個人用デバイスでソーシャルメ ディアやメッセージを頻繁に確認する傾向が強くなる。この絶え間ない情報確認欲求は不安感を引き起こし、問題のあるソーシャルメディア利用へと駆り立てる のである。[21] |

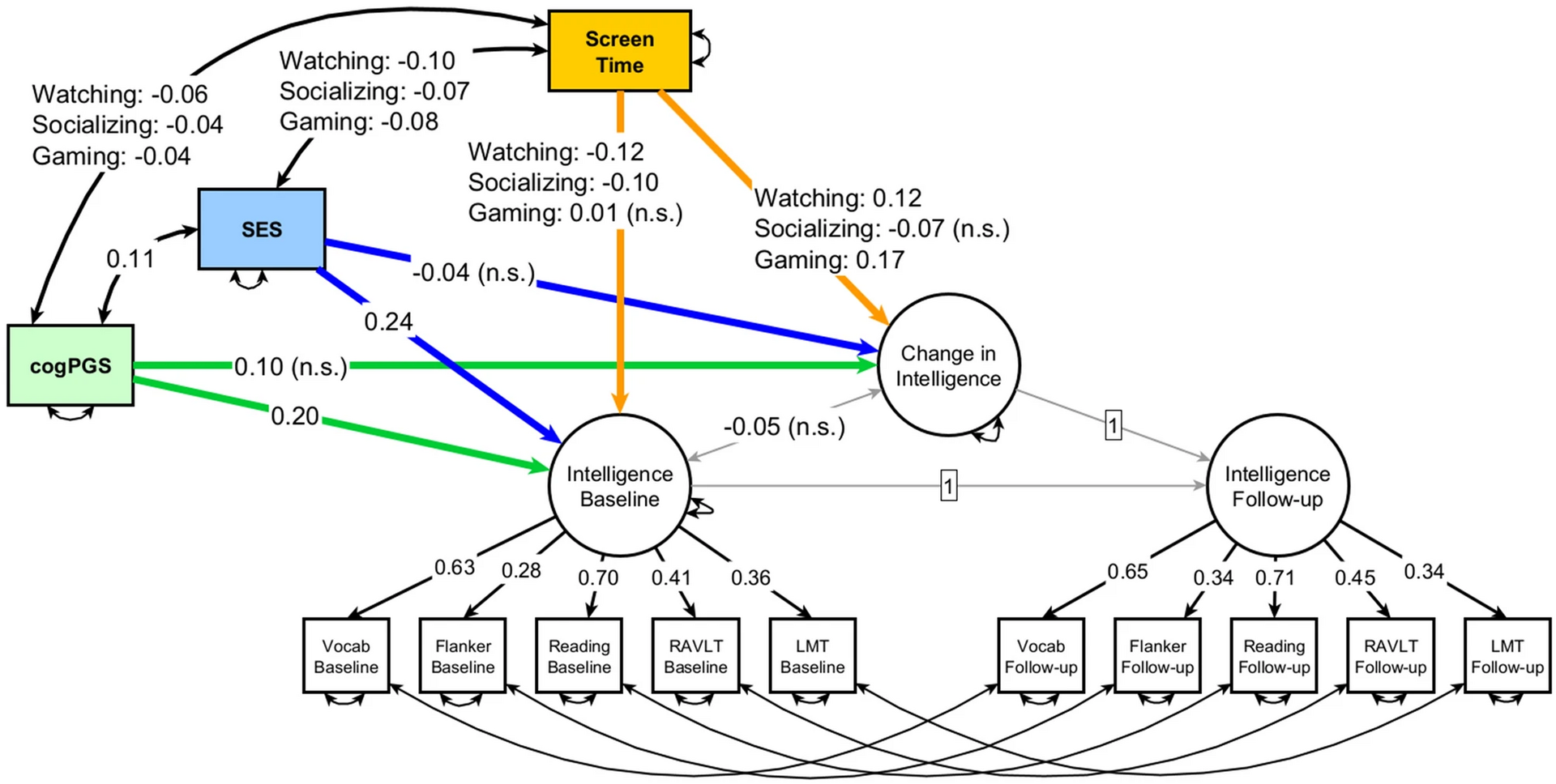

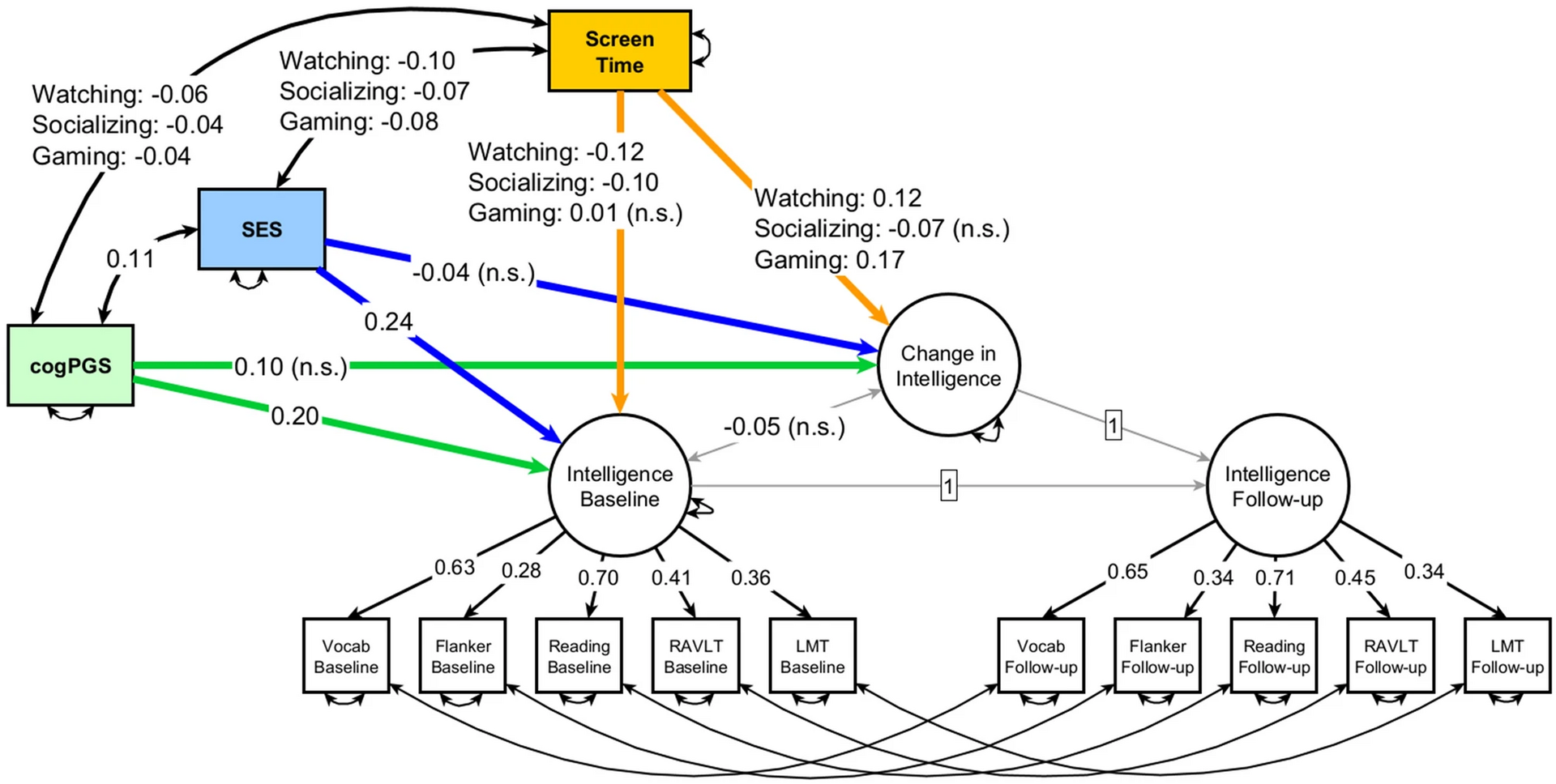

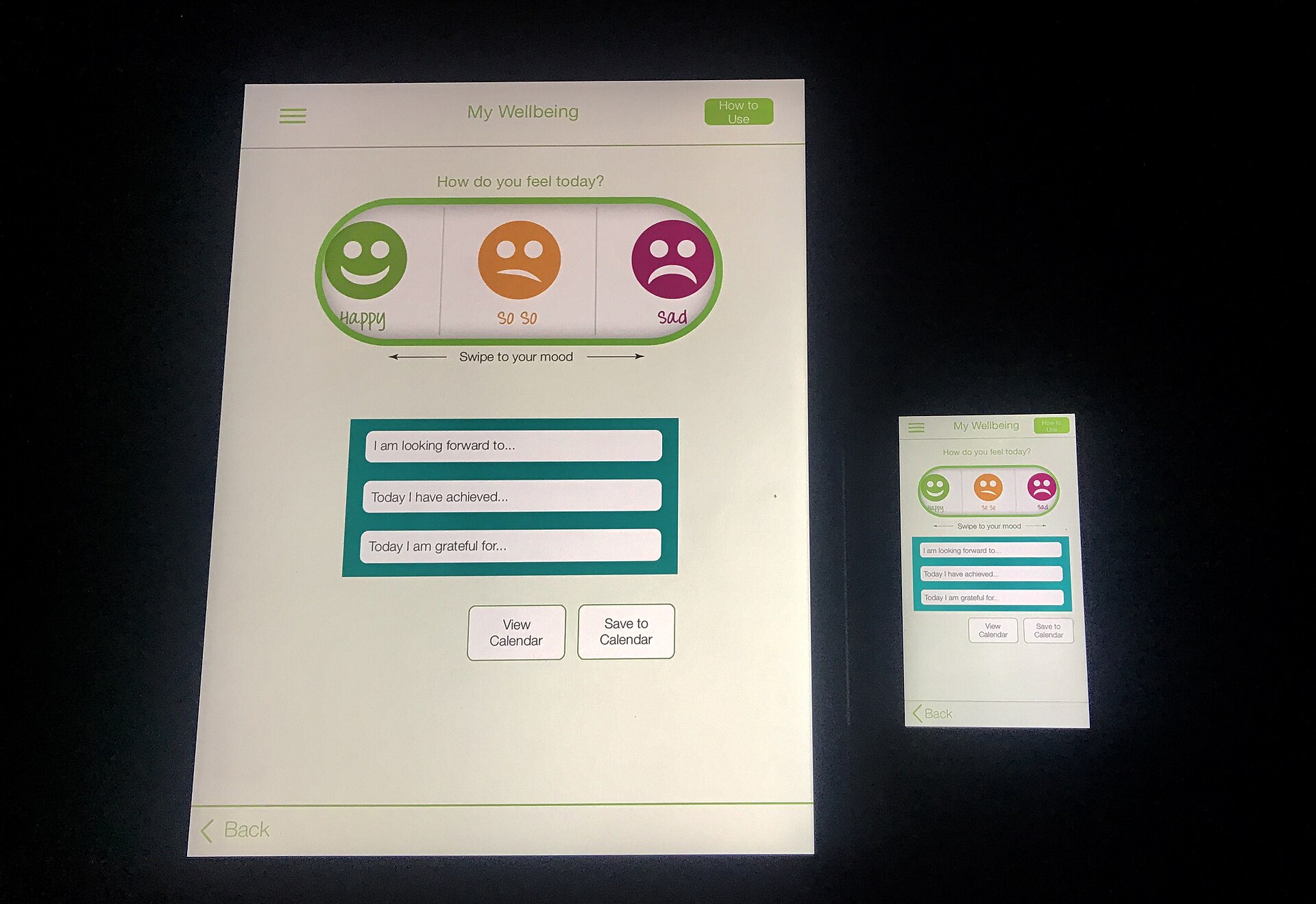

| Screen time and mental health See also: Criticism of Facebook § Psychological/sociological effects, and Social media and suicide Certain types of problematic internet use have been linked to psychiatric and behavioral issues such as depression, anxiety, hostility, aggression, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). However, studies have not established clear causal relationships—for instance, it remains unclear whether individuals with depression overuse the internet because of their condition, or if excessive internet use contributes to developing depression.[1] Research also suggests that social media’s effects can be both positive and negative, depending on individual circumstances.[2] While digital media overuse has been associated with depressive symptoms, it may also be used in some cases to improve mood.[3][4] A large prospective study found a positive correlation between ADHD symptoms and digital media use.[5] Although the ADHD symptom of hyperfocus may lead some individuals to spend excessive time on video games, social media, or online chatting, the link between hyperfocus and problematic social media use is relatively weak.[6]A 2018 review found associations between the self-reported mental health symptoms by users of the Chinese social media platform WeChat and excessive platform use. However, the motivations and usage patterns of WeChat users affected overall psychological health, rather than the amount of time spent using the platform.[5] The evidence, although of mainly low to moderate quality, shows a correlation between heavy screen time and a variety of physical and mental health problems.[4] However, moderate use of digital media has been linked to positive outcomes, including improved social integration, mental health, and overall well-being for young people.[4] In fact, certain digital platforms, when used in moderation, have even been associated with enhanced mental health.[22] In a 2022 review, it was discovered that when it comes to adolescents' well-being that perhaps there is too much focus on locating a negative correlation between digital technologies and adolescents' well-being, If a negative correlation between the two are located the impact would potentially be minimal to the point where it would have little to no impact on adolescent well-being or quality of life.[17]  Social media applications in which users can easily access social feeds, be notified of new content, and connect with others in real time |

スクリーンタイムとメンタル健康 関連項目:フェイスブックへの批判 § 心理的・社会学的影響、ソーシャルメディアと自殺 特定の種類の問題のあるインターネット利用は、うつ病、不安、敵意、攻撃性、注意欠陥・多動性障害(ADHD)などの精神医学的・行動的問題と関連してい る。しかし、研究では明確な因果関係は確立されていない。例えば、うつ病の個人がその状態のためにインターネットを過剰利用するのか、それとも過剰なイン ターネット利用がうつ病の発症に寄与するのかは不明である。[1] 研究はまた、ソーシャルメディアの影響は個人の状況によってプラスにもマイナスにもなり得ると示唆している。[2] デジタルメディアの過剰使用は抑うつ症状と関連しているが、場合によっては気分改善に利用されることもある。[3][4] 大規模な前向き研究では、ADHD症状とデジタルメディア使用の間に正の相関が認められた。[5] ADHD症状であるハイパーフォーカス(過集中)が、一部の人々にビデオゲーム、ソーシャルメディア、オンラインチャットへの過剰な時間を費やす原因とな る可能性があるが、ハイパーフォーカスと問題のあるソーシャルメディア使用の関連性は比較的弱い。[6]2018年のレビューでは、中国SNSプラット フォーム「WeChat」利用者の自己申告によるメンタルヘルス症状と過剰なプラットフォーム利用の関連性が確認された。ただし、WeChat利用者の動 機や使用パターンが心理的健康全体に影響を与えており、プラットフォーム利用時間そのものは影響要因ではなかった。[5] 証拠は主に低~中程度の質ではあるが、長時間の画面使用と様々な身体的・精神的健康問題との相関を示している。[4] しかし、デジタルメディアの適度な使用は、若年層の社会的統合性、精神的健康、全体的な幸福感の向上といった好ましい結果と関連している。[4] 実際、特定のデジタルプラットフォームは、適度に使用すれば精神的健康の向上とさえ関連している。[22] 2022年のレビューでは、青少年の幸福度に関して、デジタル技術と青少年の幸福度の間に否定的な相関関係を見出そうとする傾向が強すぎる可能性が指摘さ れた。仮に両者の間に否定的な相関関係が認められたとしても、その影響は青少年の幸福度や生活の質にほとんど、あるいは全く影響を与えないほど最小限であ る可能性が高い。[17]  ソーシャルメディアアプリケーションでは、ユーザーは簡単にソーシャルフィードにアクセスし、新しいコンテンツの通知を受け取り、リアルタイムで他者とつながることができる。 |

| Social media and mental health Excessive time spent on social media may be more harmful than digital screen time as a whole, especially for young people. Some research has found a "substantial" association between social media use and mental health issues, but most studies have found only a weak or inconsistent relationship.[23][24][25][26] Social media can have both positive and negative effects on mental health; whether the overall effect is harmful or helpful may depend on a variety of factors, including the quality and quantity of social media usage. In the case of those over 65, studies have found high levels of social media usage was associated with positive outcomes overall, such as flourishing, though it remains unclear if social media use is a causative factor.[27][28] Social media can be a valuable tool that, when used appropriately, brings positive benefits both online and offline. For adolescents, social media offers opportunities to build and maintain relationships, access information, connect with others in real time, and express themselves through creating and engaging with content.[1][2] However, improper use of social media can pose risks. Adolescents may be exposed to cyberbullying, sexual predators, inappropriate adult content, substance use, and unrealistic portrayals of people and lifestyles.[1][2] Digital technologies tend to focus more on hedonic well-being, in which users are exposed to content that evokes joy and laughter towards positive content, to anger and sadness towards negative content. In turn these negative impacts on adolescence or any users of social media will only experience temporary impacts on mental well-being, which will not have a permanent effect on the user's quality of life and life satisfaction.[17] When asked about the amount of time spent on social media teenagers reported that 55 percent have the right amount of time spent on social media. 35 percent of teenagers reported they spent too much time on social media, while 8 percent stated they spent too little time on social media.[17] Youth 95% of people between the ages of 13-17 have reported using some form of social media. Almost 2/3 of teenagers reported that they use social media daily. Social media in youth provides benefits and risks. Children who spend more than 3 hours per day using social media face a risk of problems including but not limited to depression, anxiety, and suicide risk.[29][30] |

ソーシャルメディアとメンタルヘルス ソーシャルメディアに費やす時間が過剰だと、デジタル画面を見る時間全体よりも有害な場合がある。特に若年層においてそうだ。一部の研究ではソーシャルメ ディア利用とメンタルヘルス問題の間に「顕著な」関連性が確認されているが、大半の研究では弱い関連性か一貫性のない関係しか見出せていない。[23] [24][25][26] ソーシャルメディアはメンタルヘルスに良い影響も悪い影響も与え得る。全体として有害か有益かは、利用の質や量を含む様々な要因に依存する。65歳以上で は、ソーシャルメディアの高頻度利用が「繁栄」といった全体的な好結果と関連すると研究で示されているが、利用が直接的な要因かは不明だ。[27] [28] ソーシャルメディアは、適切に使用すればオンライン上でもオフライン上でも有益な効果をもたらす貴重なツールとなり得る。青少年にとって、ソーシャルメ ディアは人間関係を構築・維持する機会、情報へのアクセス、リアルタイムでの他者との繋がり、コンテンツの作成や交流を通じた自己表現の場を提供する。 [1][2] しかし、ソーシャルメディアの不適切な使用はリスクをもたらす可能性がある。青少年は、ネットいじめ、性的加害者、不適切な成人向けコンテンツ、薬物使 用、非現実的な人々やライフスタイルの描写に晒される可能性がある。[1][2] デジタル技術は快楽的幸福感に重点を置く傾向があり、ユーザーはポジティブなコンテンツに対して喜びや笑いを、ネガティブなコンテンツに対して怒りや悲し みを引き起こすコンテンツに晒される。その結果、思春期やソーシャルメディア利用者に生じるこうした悪影響は、精神的な幸福感に一時的な影響を与えるだけ で、利用者の生活の質や人生の満足度に永続的な影響を与えることはない。[17] ソーシャルメディアの利用時間について尋ねたところ、10代の55%が「適切な時間」と回答した。35%は「時間をかけすぎている」と答え、8%は「時間が足りない」と述べた。[17] 若者 13~17歳の95%の人民が何らかのソーシャルメディアを利用していると報告している。ほぼ3分の2のティーンエイジャーが毎日ソーシャルメディアを利 用していると回答した。若年層におけるソーシャルメディアには利点とリスクがある。1日3時間以上ソーシャルメディアを利用する子供は、うつ病、不安、自 殺リスクなど(これらに限定されない)問題のリスクに直面する。[29][30] |

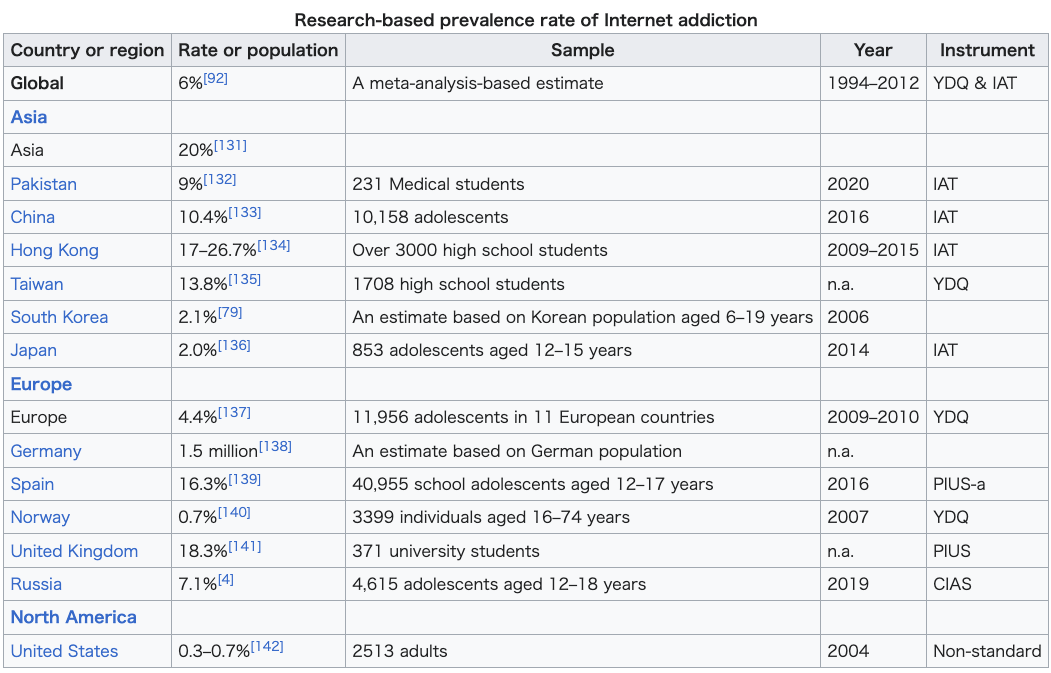

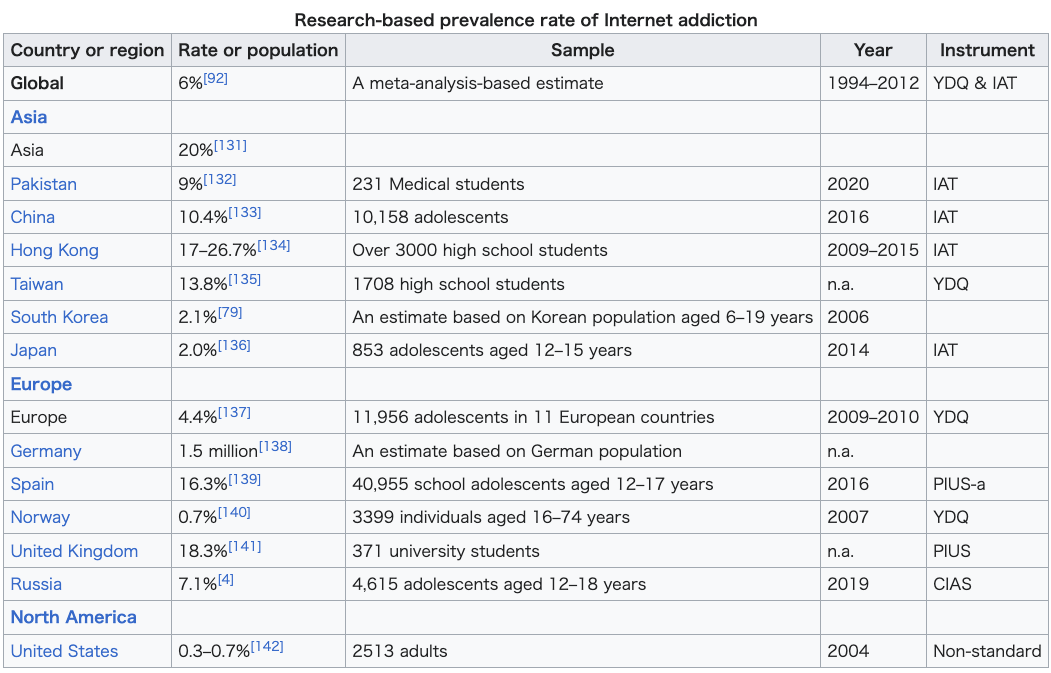

| Proposed diagnostic categories See also: Computer addiction, Internet addiction disorder, Internet sex addiction, Nomophobia, Problematic smartphone use, Problematic social media use, Television addiction, and Video game addiction Gaming disorder has been considered by the DSM-5 task force as warranting further study (as the subset internet gaming disorder), and was included in the ICD-11.[31] Concerns have been raised by Aarseth and colleagues over this inclusion, particularly in regard to stigmatization of heavy gamers.[32] Christakis has asserted that internet addiction may be "a 21st century epidemic".[33] In 2018, he commented that childhood Internet overuse may be a form of "uncontrolled experiment[s] on ... children".[34] International estimates of the prevalence of internet overuse have varied considerably, with marked variations by nation. A 2014 meta-analysis of 31 nations yielded an overall worldwide prevalence of six percent.[35] A different perspective in 2018 by Musetti and colleagues reappraised the internet in terms of its necessity and ubiquity in modern society, as a social environment, rather than a tool, thereby calling for the reformulation of the internet addiction model.[36] Some medical and behavioural scientists recommend adding a diagnosis of "social media addiction" (or similar) to the next Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders update.[37][38][5] A 2015 review concluded there was a probable link between basic psychological needs and social media addiction, stating, "Social network site users seek feedback, and they get it from hundreds of people—instantly. It could be argued that the platforms are designed to get users 'hooked'."[39] Internet sex addiction, also called cybersex addiction, is proposed as a sexual addiction involving virtual sexual activities online that can lead to significant negative effects on a person’s physical, mental, social, or financial well-being.[1][2] It is often regarded as a form of problematic internet use.[3] |

ソーシャルメディアとメンタルヘルス ソーシャルメディアに費やす時間が過剰だと、デジタル画面を見る時間全体よりも有害な場合がある。特に若年層ではそうだ。一部の研究ではソーシャルメディ ア利用とメンタルヘルス問題の間に「顕著な」関連性が確認されているが、大半の研究では弱い関連性か一貫性のない関係しか見出せていない。[23] [24][25][26] ソーシャルメディアはメンタルヘルスに良い影響も悪い影響も与え得る。全体として有害か有益かは、利用の質や量を含む様々な要因に依存する。65歳以上で は、ソーシャルメディアの高頻度利用が「繁栄」といった全体的な好結果と関連すると研究で示されているが、利用が直接的な要因かは不明だ。[27] [28] ソーシャルメディアは、適切に使用すればオンライン上でもオフライン上でも有益な効果をもたらす貴重なツールとなり得る。青少年にとって、ソーシャルメ ディアは人間関係を構築・維持する機会、情報へのアクセス、リアルタイムでの他者との繋がり、コンテンツの作成や交流を通じた自己表現の場を提供する。 [1][2] しかし、ソーシャルメディアの不適切な使用はリスクをもたらす可能性がある。青少年は、ネットいじめ、性的捕食者、不適切な成人向けコンテンツ、薬物使 用、非現実的な人々やライフスタイルの描写に晒される可能性がある。[1][2] デジタル技術は快楽的幸福感に重点を置く傾向があり、ユーザーはポジティブなコンテンツに対して喜びや笑いを、ネガティブなコンテンツに対して怒りや悲し みを引き起こすコンテンツに晒される。その結果、思春期やソーシャルメディア利用者に生じるこうした悪影響は、精神的な幸福感に一時的な影響を与えるだけ で、利用者の生活の質や人生の満足度に永続的な影響を与えることはない。[17] ソーシャルメディアの利用時間について尋ねたところ、10代の55%が「適切な時間」と回答した。35%は「時間をかけすぎている」と答え、8%は「時間が足りない」と述べた。[17] 若者 13~17歳の95%の人民が何らかのソーシャルメディアを利用していると報告している。ほぼ3分の2のティーンエイジャーが毎日ソーシャルメディアを利 用していると回答した。若年層におけるソーシャルメディアには利点とリスクが存在する。1日3時間以上ソーシャルメディアを利用する子供は、うつ病、不 安、自殺リスクを含む(ただしこれらに限定されない)問題のリスクに直面する。[29][30] |

| Related phenomena Online problem gambling Main article: Online gambling § Problem gambling A 2015 review found evidence of higher rates of mental health comorbidities, as well as higher amounts of substance use, among internet gamblers, compared to non-internet gamblers. Causation, however, has not been established. The review postulates that there may be differences in the cohorts between internet and land-based problem gamblers.[40] Cyberbullying Main article: Cyberbullying Cyberbullying, bullying or harassment using social media or other electronic means, has been shown to have effects on mental health. Victims may have lower self-esteem, increased suicidal ideation, decreased motivation for usual hobbies, and a variety of emotional responses, including being scared, frustrated, angry, anxious or depressed. These victims may also begin to distance themselves from friends and family members.[41][42][43] According to the EU Kids Online project, the incidence of cyberbullying across seven European countries in children aged 8–16 increased from 8% to 12% between 2010 and 2014. Similar increases were shown in the United States and Brazil.[44] Media multitasking Main article: Media multitasking Concurrent use of multiple digital media streams, commonly known as media multitasking, has been shown to be associated with depressive symptoms, social anxiety, impulsivity, sensation seeking, lower perceived social success and neuroticism.[45] A 2018 review found that while the literature is sparse and inconclusive, overall, heavy media multitaskers also have poorer performance in several cognitive domains.[46] One of the authors commented that the data does not "unambiguously show that media multitasking causes a change in attention and memory", therefore it is possible to argue that it is inefficient to multitask on digital media.[47] Distracted road use Main articles: Mobile phones and driving safety and Smartphones and pedestrian safety See also: Distracted driving, Human multitasking, and Texting while driving A 2023 systematic review of 47 samples across 45 studies investigating associations between problematic mobile phone use and road safety outcomes found that problematic mobile phone use was associated with greater risk of simultaneous mobile phone use and road use and risk of vehicle collisions and pedestrian collisions or falls.[48] Noise-induced hearing loss See also: Tinnitus and Occupational hearing loss This section is an excerpt from Noise-induced hearing loss § Video game sound levels.[edit] A 2024 systematic review of 14 studies investigating associations between sound-induced hearing loss and playing video games and esports found that a significant association between gaming and hearing loss or tinnitus and that the average measured sound levels during gameplay by subjects (which averaged 3 hours per week) exceeded or nearly exceeded permissible sound exposure levels.[49] Physical Affects Extended periods of screen use have been linked to poor posture, eye strain, and reduced physical activity, which may contribute to more serious health issues such as obesity, musculoskeletal pain, and even cardiovascular problems. Sedentary behavior, especially when combined with poor diet habits during screen time, increases the risk of long-term health complications. Also, blue light exposure from screens can disrupt sleep patterns, reducing sleep quality and affecting overall physical recovery.[50] |

関連現象 オンライン問題ギャンブル 詳細記事: オンラインギャンブル § 問題ギャンブル 2015年のレビューでは、インターネットギャンブラーは非インターネットギャンブラーと比較して、精神健康上の併存疾患の発生率が高く、薬物使用量も多 いという証拠が示された。ただし因果関係は確立されていない。このレビューは、インターネット問題ギャンブラーと実店舗型問題ギャンブラーの間には集団に 差異がある可能性を提唱している。[40] ネットいじめ 主な記事:ネットいじめ ソーシャルメディアやその他の電子的手段を用いたネットいじめ、いじめ、嫌がらせは、精神健康に影響を与えることが示されている。被害者は自尊心の低下、 自殺念慮の増加、通常の趣味への意欲減退、恐怖、欲求不満、怒り、不安、抑うつなど様々な感情的反応を示す可能性がある。また、友人や家族から距離を置き 始める場合もある。[41][42] [43] EU Kids Onlineプロジェクトによれば、欧州7カ国における8~16歳の児童・生徒のネットいじめの発生率は、2010年から2014年の間に8%から12%に増加した。米国とブラジルでも同様の増加が確認されている。[44] メディアマルチタスキング 詳細記事: メディアマルチタスキング 複数のデジタルメディアストリームを同時に使用すること(一般にメディアマルチタスキングと呼ばれる)は、抑うつ症状、社会不安、衝動性、刺激追求、低い 社会的成功感、神経症的傾向と関連していることが示されている。[45] 2018年のレビューでは、文献は乏しく決定的ではないものの、全体として、メディアマルチタスキングを頻繁に行う者は複数の認知領域でパフォーマンスが 低下していることが判明した。[46] 著者の一人は「メディアマルチタスキングが注意や記憶の変化を引き起こすことを明確に示しているわけではない」とコメントしており、デジタルメディアでの マルチタスキングは非効率的だと主張することも可能だ。[47] 注意散漫な道路利用 主な記事:携帯電話と運転安全、スマートフォンと歩行者安全 関連項目:注意散漫運転、人間のマルチタスク、運転中のテキストメッセージ送信 2023年の系統的レビュー(45研究47サンプル)は、問題のある携帯電話使用と道路安全結果の関連性を調査し、問題のある携帯電話使用が、携帯電話使 用と道路利用の同時発生リスク、車両衝突リスク、歩行者衝突または転倒リスクの増加と関連していることを発見した。[48] 騒音性難聴 関連項目:耳鳴り、職業性難聴 この節は騒音性難聴 § ビデオゲームの音量からの抜粋である。[編集] 2024年の系統的レビュー(14研究)は、騒音性難聴とビデオゲーム・eスポーツの関連性を調査した。その結果、ゲームプレイと難聴・耳鳴りの間に有意 な関連性が認められ、被験者のゲームプレイ中(週平均3時間)の平均測定音量は、許容騒音暴露レベルを超過またはほぼ超過していた。[49] 身体的影響 長時間の画面使用は、姿勢不良、眼精疲労、身体活動量の減少と関連しており、これらは肥満、筋骨格系の痛み、さらには心血管疾患といったより深刻な健康問 題の一因となり得る。特に画面使用中の不適切な食習慣と相まって、座りがちな行動は長期的な健康合併症のリスクを高める。また、画面からのブルーライト曝 露は睡眠パターンを乱し、睡眠の質を低下させ、身体全体の回復に影響を与える。[50] |

| Assessment and treatment Rigorous, evidence-based assessment of problematic digital media use is yet to be comprehensively established. This is due partially to a lack of consensus around the various constructs and lack of standardization of treatments.[51] The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has developed a Family Media Plan, intending to help parents assess and structure their family's use of electronic devices and media more safely. It recommends limiting entertainment screen time to two hours or less per day.[52][53] The Canadian Paediatric Society produced a similar guideline. Ferguson, a psychologist, has criticised these and other national guidelines for not being evidence-based.[54] Other experts, cited in a 2017 UNICEF Office of Research literature review, have recommended addressing potential underlying problems rather than arbitrarily enforcing screen time limits.[13] Different methodologies for assessing pathological internet use have been developed, mostly self-report questionnaires, but none have been universally recognised as a gold standard.[55] For gaming disorder, both the American Psychiatric Association[56] and the World Health Organization (through the ICD-11)[57] have released diagnostic criteria. There is limited evidence supporting the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy and family-based interventions for treating problematic digital media use. Randomized controlled trials have not demonstrated the efficacy of medications for this purpose.[1] A 2016 study involving 901 adolescents suggested that mindfulness techniques may help prevent and treat problematic internet use.[2] A 2019 UK parliamentary report emphasized the importance of parental engagement, awareness, and support in fostering "digital resilience" among young people and in managing online risks.[3] Treatment centers addressing digital dependence have grown in number, particularly in countries like China and South Korea, which have declared it a public health crisis and opened approximately 300 and 190 centers nationwide, respectively.[4] Several other countries have also established similar treatment facilities.[5][6] NGOs, support and advocacy groups provide resources to people overusing digital media, with or without codified diagnoses,[58][59] including the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.[60][61] A 2022 study outlines the mechanisms by which media-transmitted stressors affect mental well-being. Authors suggest a common denominator related to problems with the media's construction of reality is increased uncertainty, which leads to defensive responses and chronic stress in predisposed individuals.[62] |

評価と治療 問題のあるデジタルメディアの使用について、厳格で証拠に基づく評価は、まだ包括的に確立されていない。これは、さまざまな概念に関する合意が欠如してお り、治療法の標準化が進んでいないことが一因である。[51] 米国小児科学会 (AAP) は、親が家族の電子機器やメディアの使用をより安全に評価し、構造化するのを支援することを目的とした「家族メディア計画」を策定した。この計画では、娯 楽のためのスクリーンタイムを 1 日 2 時間以下に制限することを推奨している[52][53]。カナダ小児科学会も同様のガイドラインを作成している。心理学者であるファーガソンは、これらの ガイドラインやその他の国民のガイドラインが証拠に基づいていないことを批判している[54]。2017 年のユニセフ研究室の文献レビューで引用された他の専門家たちは、スクリーンタイムの制限を恣意的に実施するよりも、潜在的な根本的な問題に対処すること を推奨している[13]。 病的なインターネット使用を評価するための異なる方法論が開発されているが、そのほとんどは自己申告式アンケートであり、ゴールドスタンダードとして普遍 的に認められているものは存在しない。[55] ゲーム障害については、米国精神医学会[56] と世界保健機関(ICD-11 を通じて)[57] の両方が診断基準を発表している。 問題のあるデジタルメディアの使用を治療するための認知行動療法や家族ベースの介入の有効性を裏付ける証拠は限られている。この目的での薬物療法の有効性 は、無作為化比較試験で実証されていない。[1] 2016年の901人の青少年を対象とした研究では、マインドフルネス技術が問題のあるインターネット利用の予防と治療に役立つ可能性が示唆された。 [2] 2019年の英国議会報告書は、若者の「デジタルレジリエンス」育成とオンラインリスク管理において、親の関与・認識・支援の重要性を強調した。[3] デジタル依存症を扱う治療施設は増加しており、特に中国と韓国では公衆健康上の危機と宣言され、それぞれ全国に約300ヶ所と190ヶ所の施設を開設して いる。[4] 他のいくつかの国々でも同様の治療施設が設立されている。[5][6] NGOや支援団体、擁護団体は、診断の有無にかかわらずデジタルメディアを過剰利用する人々にリソースを提供している。[58][59] アメリカ小児青年精神医学会もその一例だ。[60][61] 2022年の研究は、メディアを介したストレス要因が精神的健康に及ぼす作用機序を明らかにしている。著者らは、メディアによる現実構築の問題に関連する 共通要因として「不確実性の増大」を指摘する。これは、素因を持つ個人において防御的反応と慢性ストレスを引き起こす。[62] |

| Associated psychiatric disorders ADHD Main article: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder Meta-analysis and systematic reviews of studies have shown a link between internet use, gaming disorders, social media use, and ADHD or symptoms of ADHD including impulsive traits; however, associations and causality are not clear.[63][64][65] There is some evidence of a bi-directional relationship in which people with ADHD may be more likely to engage with problematic internet or gaming use, and higher digital media use may worsen existing ADHD symptoms.[66][67][68] An important group to talk about regarding the relationship between ADHD and digital media is adolescents, a meta-analysis has shown that it is more common for adolescents to have problematic gaming if they also have ADHD, it also showed results indicating that ADHD may predict future problematic gaming aswell. [69] Anxiety Main articles: Generalized anxiety disorder and Social anxiety disorder There is evidence of weak to moderate associations between gaming disorder or smartphone use and social anxiety and depressive symptoms,[64][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79] and nomophobia.[80] However these are also not causal, the nature of the associations is not clear.[81][65][82][83] There is also some evidence of bi-directionality.[84] There are some conflicting results from systematic reviews.[85] There are also some links between the amount of personal information uploaded, and social media addictive behaviors all correlated with anxiety.[74] Autism Main article: Autism In August 2015, NeuroTribes identified autistic digital communities such as Autism Network International, Wrong Planet, and the Autism List mailing list at St. John's University (New York City).[86] Steve Silberman argued that these communities "provided a natural home" where autistic members "could interact at their own pace."[87] Jim Sinclair (activist) was a member of Autism List and participated in founding Autism Network International. A 2018 systematic review of 47 studies published from 2005 to 2016 concluded that associations between autism and screen time was inconclusive.[88] Another 2019 systematic review of 16 studies that found that autistic children and adolescents are exposed to more screen time than typically developing peers and that the exposure starts at a younger age.[89] A 2021 systematic review of 12 studies of video game addiction in autistic subjects found that children, adolescents, and autistic adults are at greater risk of video game addiction than non-autistic adults, and that the data from the studies suggested that internal and external factors (sex, attention and oppositional behavior problems, social aspects, access and time spent playing video games, parental rules, and game genre) were significant predictors of video game addiction in autistic subjects.[90] A 2022 systematic review of 21 studies investigating associations between autism, problematic internet use, and gaming disorder found that the majority of studies found positive associations between the disorders.[91] Another 2022 systematic review of 10 studies found that autistic subjects had more symptoms of problematic internet use than control group subjects, had higher screen time online and an earlier age of first-time use of the internet, and also greater symptoms of depression and ADHD.[92] A 2023 meta-analysis of 46 studies comprising 562,131 subjects that concluded that while screen time may be a developmental cause of autism in childhood, associations between autism and screen time were not statistically significant when accounting for publication bias.[93] |

関連する精神疾患 ADHD 詳細な記事: 注意欠陥・多動性障害 研究のメタ分析と系統的レビューは、インターネット利用、ゲーム障害、ソーシャルメディア利用とADHDまたは衝動性を含むADHD症状との関連性を示し ている。しかし、関連性と因果関係は明確ではない。[63][64] [65] 双方向の関係を示す証拠もある。つまり、ADHDを持つ人民は問題のあるインターネットやゲーム利用に陥りやすく、デジタルメディアの利用が増えると既存 のADHD症状が悪化する可能性がある。[66][67] [68] ADHDとデジタルメディアの関係で重要な対象は青少年である。メタ分析によれば、ADHDを併せ持つ青少年は問題のあるゲーム利用をしがちであり、 ADHDが将来の問題のあるゲーム利用を予測する可能性も示唆されている。[69] 不安 主な記事:全般性不安障害および社交不安障害 ゲーム障害やスマートフォン使用と、社交不安や抑うつ症状[64][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77] [78][79] 及びノモフォビアとの関連性が示されている。[80] ただしこれらは因果関係ではなく、関連性の性質は不明確である。[81][65][82][83] 双方向性の証拠も一部存在する。[84] 系統的レビューからは矛盾する結果も報告されている。[85] さらに、人格の投稿量とソーシャルメディア依存行動の間には関連性が認められ、いずれも不安と相関している。[74] 自閉症 主な記事: 自閉症 2015年8月、NeuroTribesはAutism Network International、Wrong Planet、セントジョンズ大学(ニューヨーク市)のAutism Listメーリングリストなどの自閉症デジタルコミュニティを特定した。[86] スティーブ・シルバーマンは、これらのコミュニティが「自閉症のメンバーが自分のペースで交流できる自然な居場所を提供している」と主張した。[87] ジム・シンクレア(活動家)はAutism Listのメンバーであり、Autism Network Internationalの設立に関わった。 2005年から2016年までに発表された47の研究を対象とした2018年の系統的レビューは、自閉症とスクリーンタイムの関連性は決定的ではないと結 論づけた。[88] 別の2019年の系統的レビュー(16研究)では、自閉症の児童・青年は通常発達する同年代よりも多くのスクリーンタイムに曝露されており、その曝露はよ り幼い年齢から始まっていることが判明した。自閉症対象者におけるビデオゲーム依存症に関する12研究の2021年系統的レビューでは、自閉症の小・青 年・成人は非自閉症成人より依存症リスクが高く、研究データは内因的・外的要因(性別、注意欠陥・反抗行動問題、社会的側面、ゲームへのアクセス・プレイ 時間、 親のルール、ゲームジャンル)が自閉症対象者のビデオゲーム依存症の重要な予測因子であることを示唆している。[90] 自閉症、問題のあるインターネット利用、ゲーム障害の関連性を調査した21件の研究を対象とした2022年の系統的レビューでは、大多数の研究がこれらの 障害間に正の関連性を認めた。[91] 別の2022年の10研究を対象とした系統的レビューでは、自閉症対象者は対照群対象者よりも問題のあるインターネット使用の症状が多く、オンライン画面 時間が長く、インターネット初回使用年齢が早く、またうつ病とADHDの症状もより大きいことが判明した。[92] 2023年のメタ分析(46研究・562,131名対象)は、画面使用時間が小児期自閉症の発達要因となり得る一方、出版バイアスを考慮すると自閉症と画 面使用時間の関連性は統計的に有意でないと結論付けた。[93] |

| Bipolar disorder Main article: Bipolar disorder There is some evidence of an association between problematic internet use as a risk factor for bipolar disorder.[94] Depression Main article: Major depressive disorder There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating an association between screen-based behaviours and depressive symptoms or clinical depression.[64][81][95][96][65][97][82][78] Studies across a wide range of populations including different ages, genders, [98] and cultures report small to moderate associations between these behaviors and depression symptoms, with problematic use more strongly associated with depression than general use.[74][71][72][75][99] While some studies suggest these associations may be bidirectional or influenced by factors like social support or content type, the overall direction of findings points to screen-based behaviours as a potential risk factor for a person to experience depressive symptoms.[84][100] The strength and nature of these associations has been reported to vary and may depend on usage and patterns, individual vulnerabilities, and geographic context. Causality remains unclear.[101][73][76][83][77][102][103][79] Sleep Main article: Insomnia Sleep quality and screen time or digital media use have been linked, including studies looking at media type, time of day, and age of person.[104][105][71][65][106][107][108][109][110][111] Various sleep challenges or outcomes have been studied including a reduction in sleep duration, increased sleep onset latency, modifications to rapid eye movement sleep and slow-wave sleep, increased sleepiness and self-perceived fatigue, and impaired post-sleep attention span and verbal memory.[112] Narcissism Main article: Narcissistic personality disorder There are some reports of positive correlations between grandiose narcissism and social networking site usage, [113][96] highlighting the potential for a correlation between time spent on social media, frequency of status updates, number of friends or followers, and frequency of posting self-portrait digital photographs.[114][115] Obsessive–compulsive disorder Main article: Obsessive–compulsive disorder There is some evidence suggesting a significant correlation between digital media overuse and obsessive–compulsive disorder symptoms.[64][116] |

双極性障害 詳細記事: 双極性障害 問題のあるインターネット利用が双極性障害の危険因子となる可能性を示す証拠が存在する。[94] うつ病 詳細記事: 大うつ病性障害 画面ベースの行動と抑うつ症状または臨床的うつ病との関連性を示す証拠が増加している。[64][81][95][96][65] [97][82][78] 異なる年齢層、性別、[98] 文化圏を含む広範な対象集団を対象とした研究では、これらの行動と抑うつ症状との間に小~中程度の関連性が報告されており、問題のある使用は一般的な使用 よりも抑うつとの関連性が強い。[74][71][72][75] [99] 一部の研究では、この関連性が双方向である可能性や、社会的支援やコンテンツの種類などの要因の影響を受ける可能性が示唆されているが、研究結果の全体的 な方向性は、画面ベースの行動が人格が抑うつ症状を経験する潜在的な危険因子となり得ることを示している。[84][100] これらの関連性の強さや性質は様々であり、使用状況やパターン、個人の脆弱性、地理的背景に依存する可能性がある。因果関係は依然として不明である。 [101][73][76][83][77][102][103][79] 睡眠 詳細記事: 不眠症 睡眠の質とスクリーン時間またはデジタルメディアの使用には関連性が認められており、メディアの種類、時間帯、年齢層を調べた研究も含まれる。[104] [105][71] [65][106][107][108][109][110][111] 睡眠時間の短縮、入眠潜時の増加、レム睡眠と徐波睡眠の変化、眠気や自覚的疲労の増大、睡眠後の注意力や言語記憶の障害など、様々な睡眠障害や結果が研究 されている。[112] ナルシシズム 詳細記事: 自己愛性人格障害 誇大ナルシシズムとソーシャルネットワーキングサイト利用の間に正の相関関係があるとする報告がある。[113][96] これは、ソーシャルメディアの利用時間、ステータス更新頻度、友人やフォロワーの数、自撮り写真の投稿頻度との相関関係の可能性を示唆している。 [114] [115] 強迫性障害 詳細記事: 強迫性障害 デジタルメディアの過剰使用と強迫性障害症状の間に有意な相関関係があることを示唆する証拠が存在する。[64][116] |

| Mental health benefits See also: Video game controversies § Positive effects of video games  Smartphones and other digital devices are ubiquitous in many societies. There is some evidence that people with mental illness can have a positive outcomes based on digital media use, such as the potential to develop social connections over social media and foster a sense of social inclusion in online communities.[117][3] Digital communities or social media may also have the potential for some people with mental illness to share personal stories in a perceived safer space, as well as gaining peer support for developing coping strategies.[117][3] There are some reports of people avoiding stigma and gaining further insight into their mental health condition, including the potential for dialogue with healthcare professionals, as benefits of using social media.[117][118][119] This comes with the usual digital media risk of the potential for unhealthy influences, misinformation, and delayed access to traditional mental health outlets.[117] Other benefits include the potential to gain connections to supportive online communities, including illness or disability specific communities, as well as the LGBTQIA community.[3] Young people with cancer have reported an improvement in their coping abilities due to their participation in an online community.[120] Furthermore, in children, there may be educational benefits of digital media use.[117] For example, screen-based programs may help increase both independent and collaborative learning. A variety of quality apps and software may decrease learning gaps and increase skill in certain educational subjects.[121][122] The benefits (and risks) may also be specific to cultures and geographic locations.[123] Young people may have different experiences online, depending on their socio-economic background, noting lower-income youths may spend up to three hours more per day using digital devices, compared to higher-income youths.[124] Lower-income youths, who are already vulnerable to mental illness, may be more passive in their online engagements, being more susceptible to negative feedback online, with difficulty self-regulating their digital media use.[124] It has been suggested that this may be a new form of digital divide between at-risk young people and other young people, pre-existing risks of mental illness becoming amplified among the already vulnerable population.[124] |

健康に関する利点 関連項目:ビデオゲームの論争 § ビデオゲームの好影響  スマートフォンやその他のデジタル機器は多くの社会で広く普及している。 精神疾患を持つ人民がデジタルメディアの利用によって良好な結果を得られる可能性があるという証拠がいくつか存在する。例えば、ソーシャルメディアを通じ て社会的つながりを築き、オンラインコミュニティにおける社会的包摂感を育む可能性が挙げられる。[117][3] デジタルコミュニティやソーシャルメディアは、精神疾患を持つ一部の人々が、より安全と感じられる空間で個人的な経験を共有したり、対処法を開発するため の仲間からの支援を得たりする可能性も秘めている。[117][3] ソーシャルメディア利用の利点として、スティグマを回避し、自身の精神状態への理解を深める人民の事例が報告されている。これには医療専門家との対話の可 能性も含まれる。[117][118][119] ただし、不健全な影響や誤情報の可能性、従来の精神保健サービスへのアクセス遅延といった、デジタルメディアに共通するリスクも伴う。[117] その他の利点として、支援的なオンラインコミュニティ(特定の疾患や障害を持つコミュニティ、LGBTQIAコミュニティなど)との繋がりを得られる可能 性がある。[3] がんを患う若者は、オンラインコミュニティへの参加によって対処能力が向上したと報告している。[120] さらに、子どもにおいては、デジタルメディア利用に教育的利点があるかもしれない。[117] 例えば、画面ベースのプログラムは、自律的な学習と協調的な学習の両方を促進する可能性がある。質の高い様々なアプリやソフトウェアは、学習格差を縮小 し、特定の教科における技能向上に寄与しうる。[121][122] こうした利点(およびリスク)は、文化や地理的場所によっても異なる可能性がある。[123] 若者のオンライン体験は、社会経済的背景によって異なる。低所得層の若者は、高所得層の若者と比較して、デジタル機器の使用時間が1日あたり最大3時間長 い傾向がある。[124] 精神疾患のリスクが元々高い低所得層の若者は、オンライン上での関与が受動的になりがちで、ネット上の否定的なフィードバックを受けやすく、デジタルメ ディア利用の自己制御が困難である。[124] これは、リスクのある若者と他の若者との間に生じる新たなデジタルデバイドであり、既に脆弱な集団において既存の精神疾患リスクが増幅される可能性が示唆 されている。[124] |