A

soundscape is the acoustic environment as perceived by humans, in

context. The term was originally coined by Michael Southworth,[1] and

popularised by R. Murray Schafer.[2] There is a varied history of the

use of soundscape depending on discipline, ranging from urban design to

wildlife ecology to computer science.[3] An important distinction is to

separate soundscape from the broader acoustic environment. The acoustic

environment is the combination of all the acoustic resources, natural

and artificial, within a given area as modified by the environment. The

International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standardized these

definitions in 2014. (ISO 12913-1:2014)

A soundscape is a sound or combination of sounds that forms or arises

from an immersive environment. The study of soundscape is the subject

of acoustic ecology or soundscape ecology. The idea of soundscape

refers to both the natural acoustic environment, consisting of natural

sounds, including animal vocalizations, the collective habitat

expression of which is now referred to as the biophony, and, for

instance, the sounds of weather and other natural elements, now

referred to as the geophony; and environmental sounds created by

humans, the anthropophony through a sub-set called controlled sound,

such as musical composition, sound design, and language, work, and

sounds of mechanical origin resulting from use of industrial

technology. Crucially, the term soundscape also includes the listener's

perception of sounds heard as an environment: "how that environment is

understood by those living within it" and therefore mediates their

relations. The disruption of these acoustic environments results in

noise pollution.[5]

The term "soundscape" can also refer to an audio recording or

performance of sounds that create the sensation of experiencing a

particular acoustic environment, or compositions created using the

found sounds of an acoustic environment, either exclusively or in

conjunction with musical performances.[6][7]

Pauline Oliveros, composer of post-World War II electronic art music,

defined the term "soundscape" as "All of the waveforms faithfully

transmitted to our audio cortex by the ear and its mechanisms".[8]

|

サウンドスケープ(soundscape)とは、人間が知覚する音響環

境のことである[1]。この用語はもともとMichael

Southworthに

よって作られ[1] 、R. Murray Schaferによって広められた[2]

。都市設計から野生生物生態学、コンピュータ科学まで、分野によってサウンドスケープの使用の歴史は様々である[3]

。重要な違いは、より広い音響環境からサウンドスケープの分離である。音響環境は、環境によって変化する、ある地域内の自然および人工のすべての音響資源

の組み合わせである。国際標準化機構(ISO)は、2014年にこれらの定義を標準化した。(ISO12913-1:2014)を参照してください。

サウンドスケープとは、没入型環境(immersive

environment)を形成する、またはそこから生じる音や音の組み合わせのことである。サウンドスケープの研究は、音響生態学またはサウンドスケー

プ生態学の主題である。サウンドスケープとは、動物の鳴き声などの自然音、その集合体である生息域の表現はバイオフォニー、気象などの自然音はジオフォ

ニーと呼ばれ、人間が作り出す環境音は、作曲、サウンドデザイン、言語、作業、工業技術の使用による機械音などのコントロールサウンドと呼ばれるサブセッ

トからなる自然音響環境と呼ばれるものの両方を指している。また、サウンドスケープという言葉には、聴衆が聴いた音を環境として認識することも含まれてい

る。「その環境は、その中で生活する人々によってどのように理解されるか」、つまり彼らの関係を媒介するものである。これらの音響環境が破壊されること

で、騒音公害が発生する[5]。

また、「サウンドスケープ」という用語は、特定の音響環境を体験する感覚を生み出す音の録音や演奏、あるいは音響環境の発見された音を用いて、専らあるい

は音楽演奏と組み合わせて作られた作曲を指すこともできる[6][7]。

第二次世界大戦後の電子芸術音楽の作曲家であるポーリン・オリベロスは、「サウンドスケープ」という言葉を「耳とそのメカニズムによって我々の音声皮質に

忠実に伝達される波形のすべて」と定義している[8]。

|

Historical context

The origin of the term soundscape is somewhat ambiguous. It is often

miscredited as having been coined by Canadian composer and naturalist,

R. Murray Schafer, who indeed led much of the groundbreaking work on

the subject from the 1960s and onwards. According to an interview with

Schafer published in 2013 [9] Schafer himself attributes the term to

city planner Michael Southworth. Southworth, a former student of Kevin

Lynch, led a project in Boston in the 1960s, and reported the findings

in a paper entitled "The Sonic Environment of Cities", in 1969,[1]

where the term is used. To complicate matters, however, a search in

Google NGram reveals that soundscape had been used in other

publications prior to this. More research is needed to establish the

historical background in detail.

Around the same time as Southworth's project in Boston, Schafer

initiated the World Soundscape Project together with colleagues like

Barry Truax and Hildegard Westerkamp. Schafer subsequently collected

the findings from the world soundscape project and fleshed out the

soundscape concept in more detail in his seminal work about the sound

environment, "Tuning of the World".[10] Schafer has also used the

concept in music education.[11]

|

歴史的背景

サウンドスケープという言葉の起源は、やや曖昧である。カナダの作曲家であり自然科学者でもあるR.マレー・シェーファーが作ったと誤解されることが多い

が、彼は実際に1960年代以降、このテーマに関する画期的な仕事の多くを主導した。2013年に出版されたシェーファーへのインタビュー[9]による

と、シェーファー自身はこの言葉を都市計画家のマイケル・サウスワースによるとしている。サウスワースはケヴィン・リンチの元教え子で、1960年代にボ

ストンでのプロジェクトを主導し、その成果を1969年に「都市の音波環境」という論文で報告し、そこでこの用語が使われている[1]。しかし、ややこし

いことに、Google

NGramで検索すると、これ以前にも他の出版物でサウンドスケープが使われていたことがわかる。歴史的背景を詳細に確定するためには、さらなる研究が必

要である。

ボストンでのSouthworthのプロジェクトと同時期に、SchaferはBarry TruaxやHildegard

Westerkampといった同僚と一緒にWorld Soundscape

Projectを開始しました。その後、シェーファーはワールド・サウンドスケープ・プロジェクトで得られた知見をまとめ、音環境に関する代表的な著作

「Tuning of the World」でサウンドスケープの概念をより詳細に説明した[10]。

またシェーファーはこの概念を音楽教育にも用いている[11]。

|

In music

In music, soundscape compositions are often a form of electronic music,

or electroacoustic music. Composers who use soundscapes include

real-time granular synthesis pioneer Barry Truax, Hildegard Westerkamp,

and Luc Ferrari, whose Presque rien, numéro 1 (1970) is an early

soundscape composition.[7][12] Soundscape composer Petri Kuljuntausta

has created soundscape compositions from the sounds of sky dome and

Aurora Borealis and deep sea underwater recordings, and a work entitled

"Charm of Sound" to be performed at the extreme environment of Saturn's

moon Titan. The work landed on the ground of Titan in 2005 after

traveling inside the spacecraft Huygens over seven years and four

billion kilometres through space.

Irv Teibel's Environments series (1969–79) consisted of 30-minute,

uninterrupted environmental soundscapes and synthesized or processed

versions of natural sound.[13]

Music soundscapes can also be generated by automated software methods,

such as the experimental TAPESTREA application, a framework for sound

design and soundscape composition, and others.[14][15]

The soundscape is often the subject of mimicry in timbre-centered music

such as Tuvan throat singing. The process of Timbral Listening is used

to interpret the timbre of the soundscape. This timbre is mimicked and

reproduced using the voice or rich harmonic producing instruments.[16]

|

音楽における

音楽において、サウンドスケープの作曲は、しばしば電子音楽、または電気音響音楽の一形態である。サウンドスケープを用いる作曲家には、リアルタイムグラ

ニュラーシンセシスのパイオニアであるバリー・トゥラックス、ヒルデガード・ウェスターカンプ、リュック・フェラーリなどがおり、『Presque

rien, numéro 1』(1970)は初期のサウンドスケープ作曲である。 [7][12]

サウンドスケープ作曲家のペトリ・クルユンタウスタはスカイドームやオーロラ、深海水中録音から音風景作曲し、「Charm of

Sound」という作品を土星衛星ティタンの極限環境で上演するために制作している。この作品は、宇宙船ホイヘンス号の中で7年40億キロの宇宙を旅した

後、2005年にタイタンの地上に降り立ちました。

アーヴ・タイベルの『エンバイロメンツ』シリーズ(1969-79)は、30分の途切れることのない環境音風景と自然音の合成または加工されたバージョン

で構成されていた[13]。

音楽のサウンドスケープは、サウンドデザインとサウンドスケープ作曲のためのフレームワークである実験的なアプリケーション「TAPESTREA」など、

自動化されたソフトウェア手法によって生成することもできる[14][15]。

トゥバンの喉歌のような音色を中心とした音楽では、サウンドスケープがしばしば模倣の対象となる。サウンドスケープの音色を解釈するためにティンブラル・

リスニングのプロセスが用いられる。この音色は声や豊かな倍音を生み出す楽器を用いて模倣され再現される[16]。

|

The environment

In Schafer's analysis, there are two distinct soundscapes, "hi-fi" and

"lo-fi", created by the environment. A hi-fi system possesses a

positive signal-to-noise ratio.[17] These settings make it possible for

discrete sounds to be heard clearly since there is no background noise

to obstruct even the smallest disturbance. A rural landscape offers

more hi-fi frequencies than a city because the natural landscape

creates an opportunity to hear incidences[spelling?] from nearby and

afar. In a lo-fi soundscape, signals are obscured by too many sounds,

and perspective is lost within the broad-band of noises.[17] In lo-fi

soundscapes everything is very close and compact. A person can only

listen to immediate encounters; in most cases even ordinary sounds have

to be exuberantly amplified in order to be heard.

All sounds are unique in nature. They occur at one time in one place

and cannot be replicated. In fact, it is physically impossible for

nature to reproduce any phoneme twice in exactly the same manner.[17]

According to Schafer there are three main elements of the soundscape:

Keynote sounds

This is a musical term that identifies the key of a piece, not always

audible ... the key might stray from the original, but it will return.

The keynote sounds may not always be heard consciously, but they

"outline the character of the people living there" (Schafer). They are

created by nature (geography and climate): wind, water, forests,

plains, birds, insects, animals. In many urban areas, traffic has

become the keynote sound.

Sound signals

These are foreground sounds, which are listened to consciously;

examples would be warning devices, bells, whistles, horns, sirens, etc.

Soundmark

This is derived from the term landmark. A soundmark is a sound which is

unique to an area. In his 1977 book, The Soundscape: Our Sonic

Environment and the Tuning of the World, Schafer wrote, "Once a

Soundmark has been identified, it deserves to be protected, for

soundmarks make the acoustic life of a community unique."[18]

The elements have been further defined as to essential sources:

Bernie Krause, naturalist and soundscape ecologist, redefined the

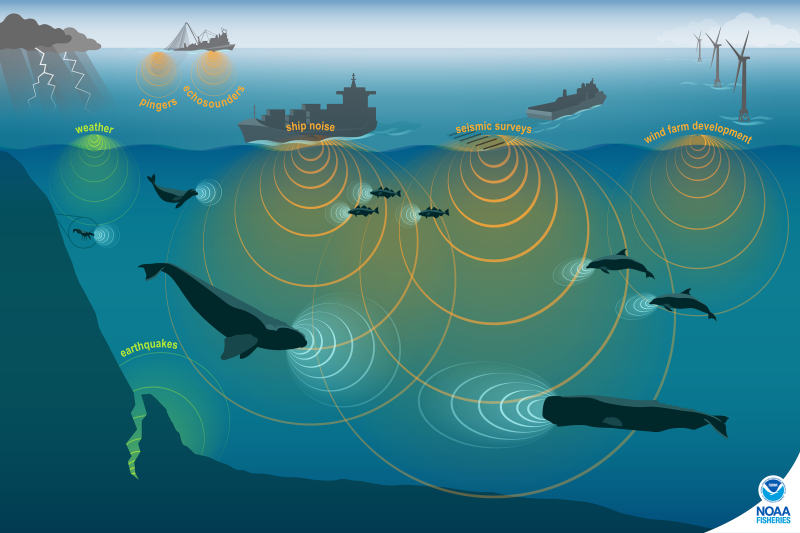

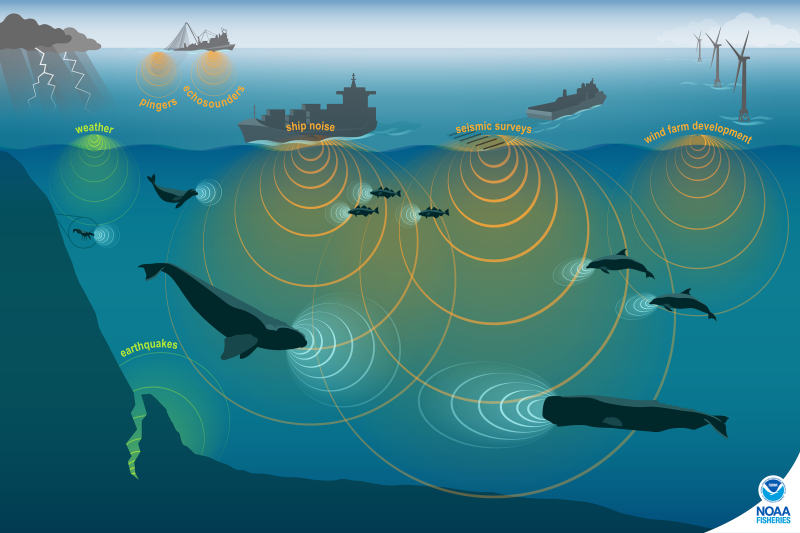

sources of sound in terms of their three main components: geophony,

biophony, and anthropophony.[19][20][21]

Geophony

Consisting of the prefix, geo (gr. earth), and phon (gr. sound), this

refers to the soundscape sources that are generated by non-biological

natural sources such as wind in the trees, water in a stream or waves

at the ocean, and earth movement, the first sounds heard on earth by

any sound-sentient organism.

Biophony

Consisting of the prefix, bio (gr. life) and the suffix for sound, this

term refers to all of the non-human, non-domestic biological soundscape

sources of sound.

Anthropophony

Consisting of the prefix, anthro (gr. human), this term refers to all

of the sound signatures generated by humans.

|

環境

シェーファーの分析によると、環境によるサウンドスケープには「ハイファイ」と「ローファイ」の2種類がある。ハイファイ・システムは正のS/N比を持っ

ており[17]、このような環境では、わずかな妨害も妨げる背景雑音がないため、個別の音をはっきりと聞き取ることが可能である。田園風景は都市よりも

Hi-Fiな周波数を提供する。なぜなら、自然の風景は近くと遠くからの事件[spelling]を聞く機会を作るからである。ローファイなサウンドス

ケープでは、信号が多すぎる音によって不明瞭になり、広帯域のノイズの中で遠近感が失われてしまう[17]。ほとんどの場合、普通の音でさえも、聴き取る

ために大きく増幅されなければならない。

すべての音は、自然界で唯一無二の存在である。その時、その場所で、その音を再現することはできない。実際、自然界ではどんな音素も全く同じように2度再

現することは物理的に不可能である[17]。

シェーファーによれば、サウンドスケープには3つの主要な要素がある。

基調音

これは楽曲の調を特定する音楽用語であり、常に聞こえるわけではない・・・調は原曲から外れるかもしれないが、戻ってくるだろう。基調となる音は、必ずし

も意識して聞こえるとは限らないが、「そこに住む人々の性格を概説する」(シェーファー)。風、水、森、平野、鳥、虫、動物など、自然(地理・気候)が作

り出すものである。多くの都市部では、交通音が基調音になっている。

サウンドシグナル

警告音、ベル、ホイッスル、ホーン、サイレンなど、意識的に聞くことができる前景音。

サウンドマーク

ランドマーク(Landmark)に由来する。サウンドマークとは、その地域特有の音のことである。1977年に出版された「The

Soundscape: シェーファーは1977年の著書「The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and

the Tuning of the

World」において、「サウンドマークが特定されたなら、それは保護されるべきものであり、サウンドマークはコミュニティの音響生活をユニークなものに

するからだ」と記している[18]。

さらに、その要素は本質的な出所として定義されている。

自然科学者であり、サウンドスケープの生態学者であるバーニー・クラウスは、ジオフォニー、バイオフォニー、アントロポニーという3つの主要な要素から音

の発生源を再定義している[19][20][21]。

ジオフォニー

ジオ(gr.earth)とフォン(gr.sound)という接頭語からなり、樹木の風、小川の水、海の波、地球の動きなど、生物以外の自然発生源によっ

て生じるサウンドスケープの音源を指し、音感を持つ生物が地球上で最初に聞く音とされている。

バイオフォニー

バイオという接頭語とサウンドという接尾語からなる言葉で、人間以外の生物学的なサウンドスケープの音源をすべて指す。

アンソロポニー

アンソロ(gr.human)という接頭辞で構成され、人間によって生成されるすべての音の特徴を指す。

|

In health care

Research has traditionally focused mostly on the negative effects of

sound on human beings, as in exposure to environmental noise. Noise has

been shown to correlate with health-related problems like stress,

reduced sleep and cardiovascular disease.[22] More recently however, it

has also been shown that some sounds, like sounds of nature and music,

can have positive effects on health.[23][24][25][26][27] While the

negative effects of sound has been widely acknowledged by organizations

like EU (END 2002/49) and WHO (Burden of noise disease), the positive

effects have as yet received less attention. The positive effects of

nature sounds can be acknowledged in everyday planning of urban and

rural environments, as well as in specific health treatment situations,

like nature-based sound therapy[25] and nature-based rehabilitation.[27]

Soundscapes from a computerized acoustic device with a camera may also

offer synthetic vision to the blind, utilizing human echolocation, as

is the goal of the seeing with sound project.[28]

|

健康管理において

従来は、環境騒音にさらされるなど、音が人間に与える負の影響について主に研究されてきました。しかし、最近では、自然音や音楽など、いくつかの音が健康

に良い影響を与えることが示されている[23][24][25][26][27]。音の悪影響は、EU (END 2002/49) や WHO

(Burden of noise disease)

などで広く認められているが、プラスの効果はまだそれほど注目されていない。自然音がもたらすポジティブな効果は,都市や農村の日常的な環境計画や,自然

音療法[25]や自然リハビリテーションのような特定の健康治療の場面で認めることができる[27].

カメラ付きのコンピュータ音響装置からのサウンドスケープは、音で見る

プロジェクトの目標であるように、人間のエコロケーションを利用して、視覚障害者に合成視覚を提供することもできるかもしれない[28]。

|

Soundscapes and noise pollution

Papers on noise pollution are increasingly taking a holistic,

soundscape approach to noise control. Whereas acoustics tends to rely

on lab measurements and individual acoustic characteristics of cars and

so on, soundscape takes a top-down approach. Drawing on John Cage's

ideas of the whole world as composition,[citation needed] soundscape

researchers investigate people's attitudes to soundscapes as a whole

rather than individual aspects – and look at how the entire environment

can be changed to be more pleasing to the ear. This body of knowledge

approaches the sonic environment subjectively as well, as in how some

sounds are tolerated while others disdained, with still others

preferred, as seen in Fong's 2016 research comparing the soundscapes of

Bangkok, Thailand and Los Angeles, California.[29] To respond to

unwanted sounds, however, a typical application of this is the use of

masking strategies, as in the use of water features to cover unwanted

white noise from traffic. It has been shown that masking can work in

some cases, but that the successful outcome is dependent on several

factors, like sound pressure levels, orientation of the sources, and

character of the water sound.[30][31]

Research has shown that variation is an important factor to consider,

as a varied soundscape give people the possibility to seek out their

favorite environment depending on preference, mood and other

factors.[30] One way to ensure variation is to work with "quiet areas"

in urban situations. It has been suggested that people's opportunity to

access quiet, natural places in urban areas can be enhanced by

improving the ecological quality of urban green spaces through targeted

planning and design and that in turn has psychological benefits.[32]

Soundscaping as a method to reducing noise pollution incorporates

natural elements rather than just man made elements.[33] Soundscapes

can be designed by urban planners and landscape architects. By

incorporating knowledge of soundscapes in their work, certain sounds

can be enhanced, while others can be reduced or controlled.[34] It has

been argued that there are three main ways in which soundscapes can be

designed: localization of functions, reduction of unwanted sounds and

introduction of wanted sounds,[30] each of which should be considered

to ensure a comprehensive approach to soundscape design.

|

サウンドスケープと騒音公害

騒音公害に関する論文では、騒音対策として全体的なサウンドスケープのアプローチをとることが多くなっています。音響学が実験室での測定や自動車などの個

々の音響特性に依存する傾向があるのに対し、サウンドスケープはトップダウンのアプローチをとっている。ジョン・ケージの「世界全体を構成する」という考

えをもとに、サウンドスケープの研究者は、個々の側面ではなく、全体としてのサウンドスケープに対する人々の態度を調査し、環境全体をどのように変えれ

ば、より耳に心地よく聞こえるようになるかを研究している。この一連の知識は、タイのバンコクとカリフォルニアのロサンゼルスのサウンドスケープを比較し

たFongの2016年の研究に見られるように、ある音が許容され、ある音が軽蔑され、さらにある音が好まれるように、主観的にも音環境にアプローチしま

す[29]。一方、不要な音に対応するには、交通からの不要なホワイトノイズに水場を使用するように、マスク戦略の使用は、その典型的な応用例です。マス

キングがうまくいく場合もあるが、成功するかどうかは、音圧レベル、音源の方向、水音の特徴など、いくつかの要因に依存することが示されている[30]

[31]。

研究によって、変化に富んだサウンドスケープは、人々に好みや気分などの要素に応じて好きな環境を求める可能性を与えるため、バリエーションは考慮すべき

重要な要素であることが示されている[30]。バリエーションを確保する方法の1つは、都市状況における「静かなエリア」で作業することです。都市部の静

かで自然な場所にアクセスする人々の機会は、的を射た計画とデザインによって都市の緑地の生態的な質を向上させることによって高めることができ、それがひ

いては心理的な利益をもたらすことが示唆されている[32]。

騒音公害を軽減する方法としてのサウンドスケープは、人工的な要素だけでなく、自然の要素を取り入れている[33]。サウンドスケープは、都市計画家や造

園家がデザインすることができる。サウンドスケープの知識を仕事に取り入れることで、ある音を強化することができ、他の音を低減または制御することができ

る[34]。サウンドスケープのデザインには、機能の局所化、不要な音の低減、欲しい音の導入という3つの主な方法があると主張されており、サウンドス

ケープのデザインに包括的にアプローチするには、それぞれの方法を検討する必要がある[30]。

|

In United States National Parks

The National Park Service Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division[35]

actively protects the soundscapes and acoustic environments in national

parks across the country. It is important[according to whom?] to

distinguish and define certain key terms as used by the National Park

Service. Acoustic resources are physical sound sources, including both

natural sounds (wind, water, wildlife, vegetation) and cultural and

historic sounds (battle reenactments, tribal ceremonies, quiet

reverence). The acoustic environment is the combination of all the

acoustic resources within a given area – natural sounds and

human-caused sounds – as modified by the environment. The acoustic

environment includes sound vibrations made by geological processes,

biological activity, and even sounds that are inaudible to most humans,

such as bat echolocation calls. Soundscape is the component of the

acoustic environment that can be perceived and comprehended by the

humans. The character and quality of the soundscape influence human

perceptions of an area, providing a sense of place that differentiates

it from other regions. Noise refers to sound which is unwanted, either

because of its effects on humans and wildlife, or its interference with

the perception or detection of other sounds. Cultural soundscapes

include opportunities for appropriate transmission of cultural and

historic sounds that are fundamental components of the purposes and

values for which the parks were established.

Sounds recorded in national parks[36]

Yellowstone National Park Sound Library[37]

|

アメリカ合衆国の国立公園における

国立公園局のNatural Sounds and Night Skies

Division[35]は、全米の国立公園におけるサウンドスケープと音響環境の保護を積極的に行っています。国立公園局で使用されている特定の重要な

用語を区別し、定義することは重要です(誰に言われた?音響資源とは、自然音(風、水、野生生物、植生)と文化・歴史音(戦闘の再現、部族の儀式、静かな

敬意)の両方を含む物理的な音源のことを指します。音響環境とは、ある地域内のすべての音響資源(自然音と人為的な音)の組み合わせであり、環境によって

変化するものである。音響環境には、地質学的プロセスや生物学的活動によって生じる音の振動、さらにはコウモリの反響音のようなほとんどの人間には聞こえ

ない音も含まれる。サウンドスケープは、人間が知覚し理解することができる音響環境の構成要素である。サウンドスケープの特徴と質は、その地域に対する人

間の知覚に影響を与え、他の地域と区別する場所としての感覚を提供する。騒音とは、人間や野生生物への影響、あるいは他の音の知覚や検知を妨げるという理

由で、好ましくない音のことである。文化的なサウンドスケープには、公園が設立された目的や価値の基本的な構成要素である文化的・歴史的な音を適切に伝え

る機会が含まれる。

国立公園で録音された音[36]。

イエローストーン国立公園サウンドライブラリー[37]。

|

Ambient music

Anthropophony

Biomusic

Biophony

Ecoacoustics

Environments (series)

Field recording

Geophony

Musique concrète

Noise map

Program music

Sharawadji effect

Sound art

Sound installation

Sound map

Sound sculpture

Soundscape ecology

Space music

Underwater acoustics

|

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soundscape

|

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator

|

Soundscapes

Soundscapes are made up of the anthrophony, geophony and biophony of a

particular environment. They are specific to location and change over

time.[11] Acoustic ecology aims to study the relationship between these

things, i.e. the relationship between humans, animals and nature,

within these soundscapes. Soundscapes are very dense and sensitive;

even something like a change in temperature can significantly affect

the quality of the sound that can thrive.[14]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acoustic_ecology

|

サウンドスケープ

サウンドスケープは、特定の環境のアンソロフォニー、ジオフォニー、バイオフォニーで構成されている[11]。音響生態学は、これらのサウンドスケープに

おける人間、動物、自然との関係を研究することを目的としている[11]。サウンドスケープは非常に高密度で敏感であり、気温の変化のようなものでさえ、

繁栄できる音の質に大きく影響を与えることができる[14]。

|