|

|

I would like

to talk about how the racial and ethnic category of

“indio, indígena” (indigenous people) can be understood as an identity

that is being transformed from a stigma of indigeneity and inferiority

(i.e., representation of the other) to an identity that is both

self-forming and requires recognition from the other (i.e.,

representation of self) in the process of reorganizing Guatemala's

nation-state after the Cold War. I would like to talk about my research

experience in the region over the past 20 years.

|

|

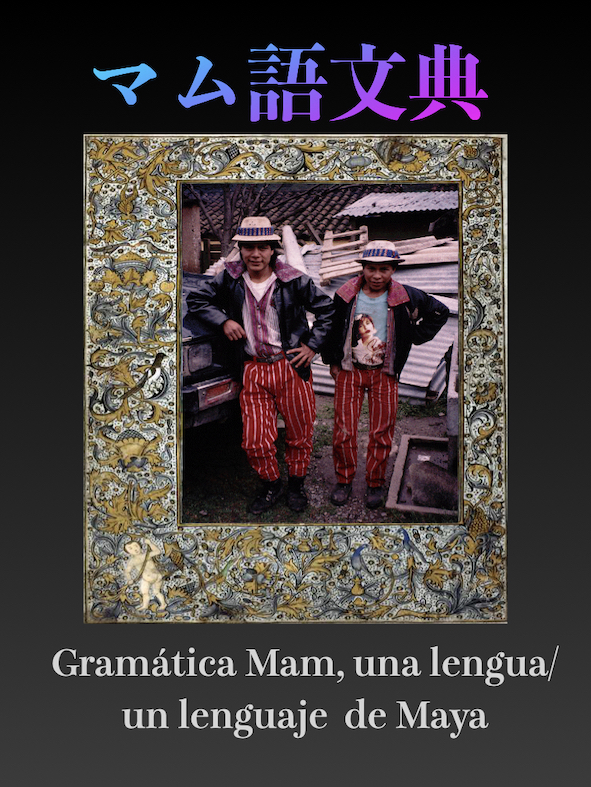

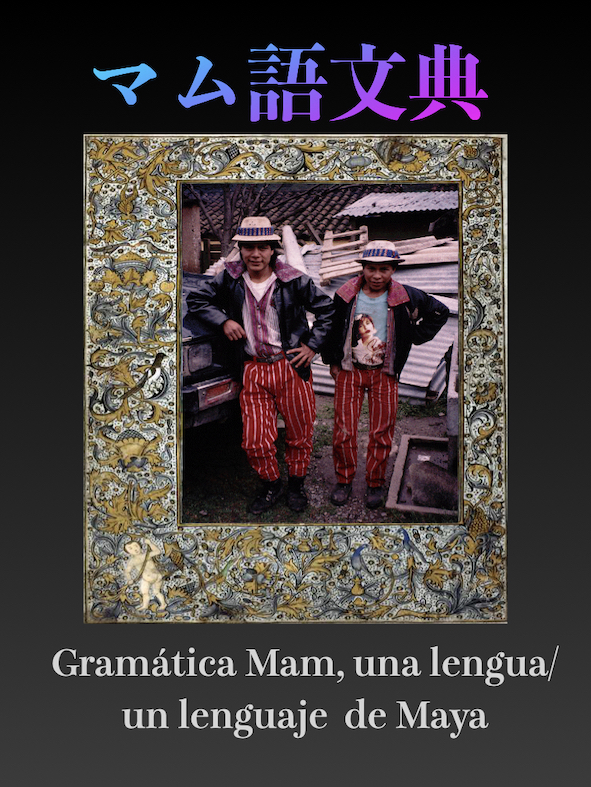

The

population under consideration is about the Mam, one of the Mayan

indigenous peoples of the western highlands of the Republic of

Guatemala. The Mam are the third most populous Mam-speaking linguistic

group in Guatemala--more than several hundred thousand, according to

several statistics and estimates--and are the only Maya “language

community” recognized by the government-affiliated Guatemalan It is one

of the recognized Maya “language communities” as well as a cultural

group, recognized by the Academy of Linguistics. This seems to be

related to the national institutionalization of the academy's

definition of the “culture” of the area, in that the Mam language is

used there in the compilation of a dictionary of new words for the

needs of socioeconomic change and a dictionary of place names that

incorporates etymological interpretation, both of which were prepared

by the academy.

In reality, of course, it is difficult to attribute the indigenous

identity of the region simply to the Mam culture, as these politically

desiccated “teaching materials” are not, in reality, sufficiently

universalized in society or effectively fed back into public education.

However, I would like to point out that the concept and name “Mam” or

“Maya Mam” (Mam as Maya people), which is set in the classical or

seemingly archaic anthropological and linguistic sense, may be

incorporated as one of the elements of their own indigenous identity,

depending on their own use in the future. I would like to point out

that the concept and name “Mam” or “Maya Mam” (Mam as Mayan) may become

an element of their own indigenous identity depending on their own use.

|

|

|

On the other

hand, within the framework of classical anthropology,

which has focused exclusively on the study of indigenous peoples of

Guatemala, the position of the municipio as a unit of regional research

and as a municipality as an administrative community does not seem to

be shaky at the moment. This is due to the theory of the American

anthropologist Sol Tax [Tax 1937], which has been examined in detail by

Hideki Nakata [2013] this year, and the “closed corporate community” as

taken for granted by his successor, Eric Wolf [Wolf 1957], and others.

The indigenous community, the municipio, as a “closed corporate

community,” which was taken for granted by its successor, Eric Wolf

[Wolf 1957], and others. I myself have taken the munisipio as the basic

unit of a natural and natural object of research and investigation up

to the present day [Ikeda 2012]. I have seen in the munisipio an

intrinsic primordial attachment that is characteristic of the nature of

their identity belonging. Of course, the indigenous group as a research

unit does not always correspond to the tribal boundaries that the

munisipio have, but rather to the boundaries of the etnies--Anthony D.

Smith's term --I believe that the mam or maya, which is the boundary of

the municipio, can have a greater reach under the influence of the

media and various social movements, as I will describe in this

presentation.

I first visited the Mam community in the west-central part of the

Cuchumatan Highlands in the province of Wewetenango in late 1987 or

early 1988, dating back about 26 years, starting with a stay of about

two months, adding another Mam community in the province of San Marcos

in the Sierra Madre Highlands located in the neighboring province to

the south, Five years had passed since the massacre in this town in the

Cuchumatan highlands during the reign of General Rios Montt, the

military council that overthrew President Benedicto Lucas Garcia in

March 1982 by political upheaval. Despite the fact that five years had

passed since the massacre in this town in the Cuchumatan highlands

during the reign of General Rios Montt, the military council that had

overthrown President Garcia in a political coup, the people had not

healed from the trauma of the military violence, and the residents were

very quiet and only gave essential responses to foreigners, and there

seemed to be no talk among foreigners or among fellow citizens about

the village's history. Incidentally, 1982, the year of the massacre,

was also the time when the Working Group on Indigenous Peoples (WGIP,

1982-2006) was established under the UN Commission on Human Rights,

following the submission of a report by the UN Economic and Social

Council (ECOSOC) on social discrimination against indigenous

populations (Study of the problem of (Study of the problem of

discrimination against indigenous populations, Economic and Social

Council Resolution 1982/34.)

|

|

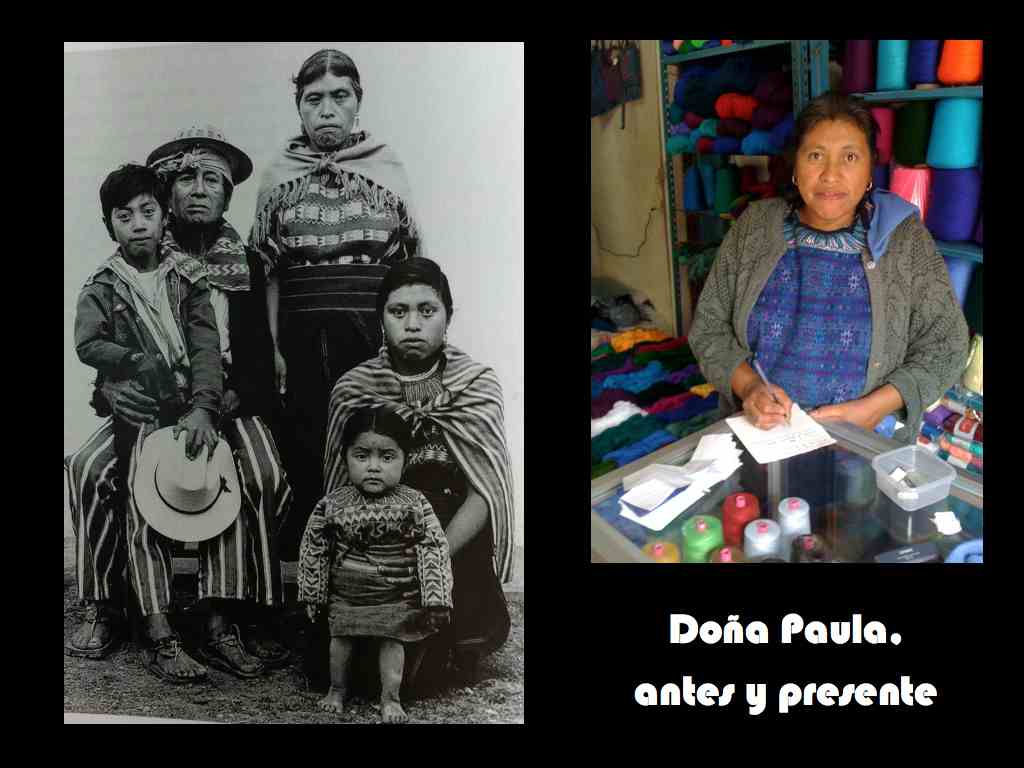

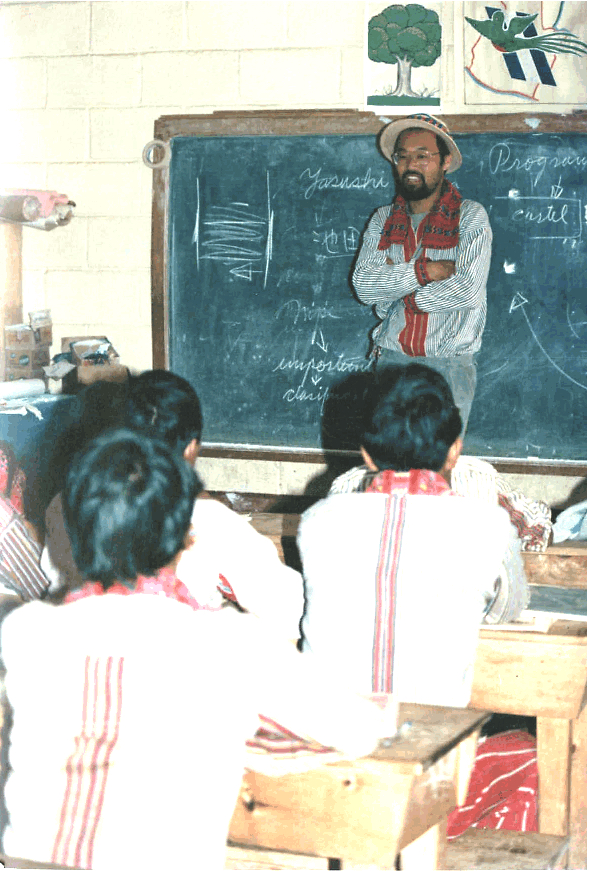

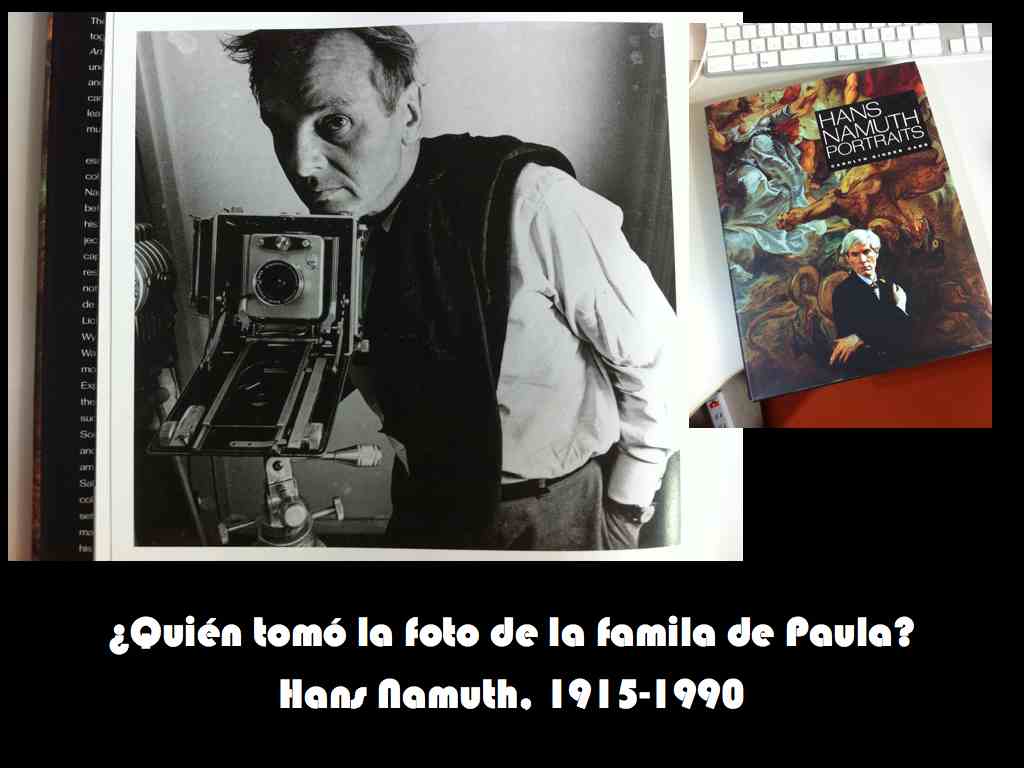

At this time

(1987-1988), I became very close friends with a family of

civil war victims whose wives and children were already grown. These

children were four male brothers and two female sisters, but we became

especially close friends with her son and his brother, who had just

married and were living in the home of their widowed mother at the

time. Soon after our acquaintance, we entered into a compadre

relationship with this young couple through the baptism of their

daughter. Compadre means to enter into a pseudo kinship, or

compadrinasgo, with them through becoming the religious and moral

teaching parents, padrino/madrina, of their daughter (or son),

aihadah/aihad, in baptism. My “daughter” as a teaching father is now 26

years old, and she is currently living in Oakland, California, after

meeting and marrying a young man from the same community in the United

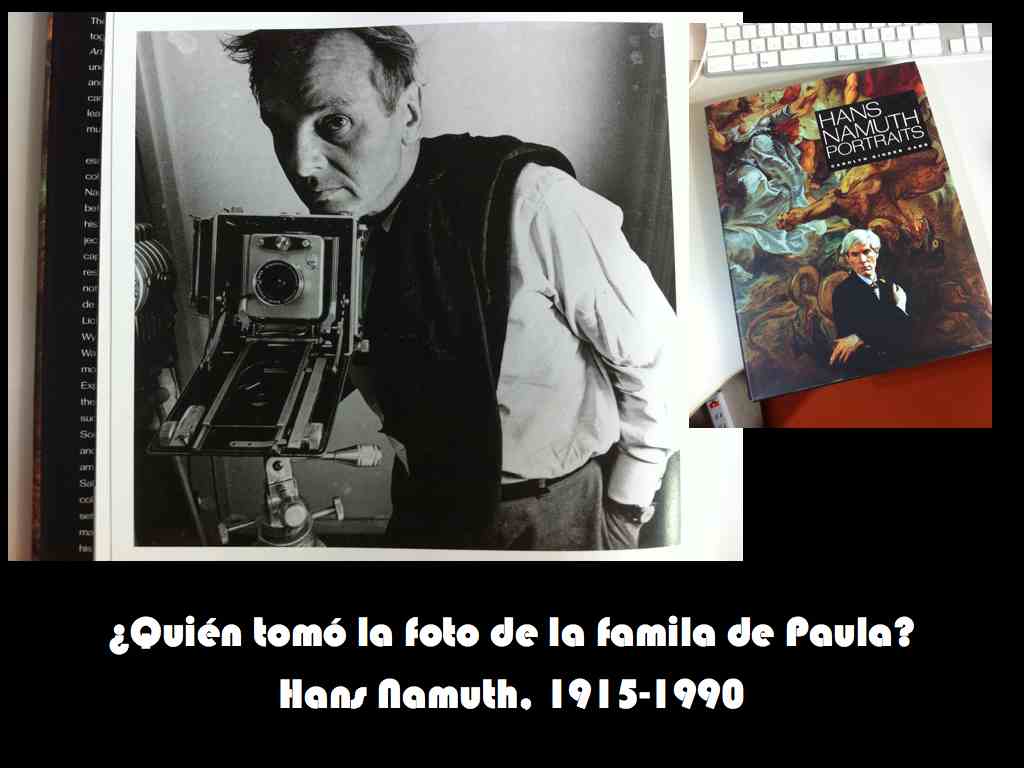

States, where she immigrated. My compadre grandfather Domingo, then a

20-year-old local elementary school teacher, was the subject of a book

by Maud Oakes (1903-1990), an ethnographer who did fieldwork in the

area from 1945-47, The two crosses of Todos Santos: survivals of Mayan

religious ritual. He was one of the servants (moso) and informants of

the “survivals of Mayan religious ritual” [1951]. Domingo's child, my

compadre's father, is shown as a small child in the photograph in the

same book. This photo was taken by Hans Namuth, a photographer famous

for his work during the Spanish Civil War (Civil War) who accompanied

Oakes. This child eventually grew up to become my friend's father and

was abducted in the middle of the night by members of the EGP (Ejercito

Guerrillero de los Pobres), a rebel guerrilla group that (according to

my friend's theory) had temporarily taken control of the town before

the military invasion and was found dead in the milpa (cornfield) the

next morning. The next morning, he was found dead in a milpa

(cornfield).

|

|

|

At the end

of my research period in 1988, I invite Compadre to travel

to San Cristobal de las Casas to cross the border and see the

indigenous people of Chiapas, who are also Mayan. As the bus

accelerates through the desolate Cuchumatán Plateau, he suddenly takes

off the traditional costume his wife had made for him and puts it in a

rickshaw, and then puts on a simple jumper that contrasts nicely with

his flamboyant traditional costume. He then changed into a simple

jumper, which was a sharp contrast to his flashy traditional costume.

He told me that all natives who go into town change their clothes

because they are mistaken for Indians once they enter the Mexican

border, and even in the city of Wewetenango, mixed-race Ladinos are

severely discriminated against - even those in the neighboring town of

San Juan don't change their clothes in town, so how do you know what

their culture is? They don't change their clothes, so their [culture?]

He also said that the San Juan people in the next town over do not

change their clothes even in town, so they still maintain a strong

(fuerte) traditional practice.

However, five years later, in the early 1990s, the town had changed

dramatically. The town was experiencing an unprecedented economic boom

through dollar money sent by parents and siblings who had immigrated to

North America using brokers called coyotes, and ethnic tourism, which

had returned again with the growing momentum of peace. It was then that

the opportunity arose for them to begin talking about their indigeneity

and self-representation of being a Mam to the foreigners they knew at

home and abroad.

|

|

Due to the

“costume change operation” by Compadre, I was the more

conspicuous target at the Mexican immigration checkpoint on the side of

the road across the border past Comitan in Chiapas, and I was able to

pass through without having to show identification because the man in

the seat next to me was assumed to be a local Mexican Ladino. He was a

local Mexican ladino, and we were able to pass through without having

to show ID - people with Guatemalan IDs are not allowed in the state of

Chiapas west of Comitán. After half a day we arrived at the town of San

Cris, just before the Lenten carnival in San Juan Chamula on the

Chiapas Plateau (Cuaresma), which we were to visit in a small

shared-ride bus (combi). He was surprised by the warning at the

entrance to the town that Indians had killed a foreign tourist who

pointed a camera at him, and when he saw the “real Indians” church,

which did not have a concrete floor like the church in his hometown,

but rather bare ground in the former ancient Mayan style, he said, “(In

my hometown) we abandoned traditional practices (costumbre ), so their

town was attacked and torched by the army and the inhabitants killed,”

he explained to me. Indios were a stigma of indigeneity and inferiority

in Guatemala, but I was surprised when he pointed out that for him,

Indios in Mexico were an expression of pride - a mixture of catholic

nuances of his Mexican brethren ( He was moved by the nuestro hermanos,

a mixture of catholic nuances. This was invierno (winter) 1988.

|

|

|

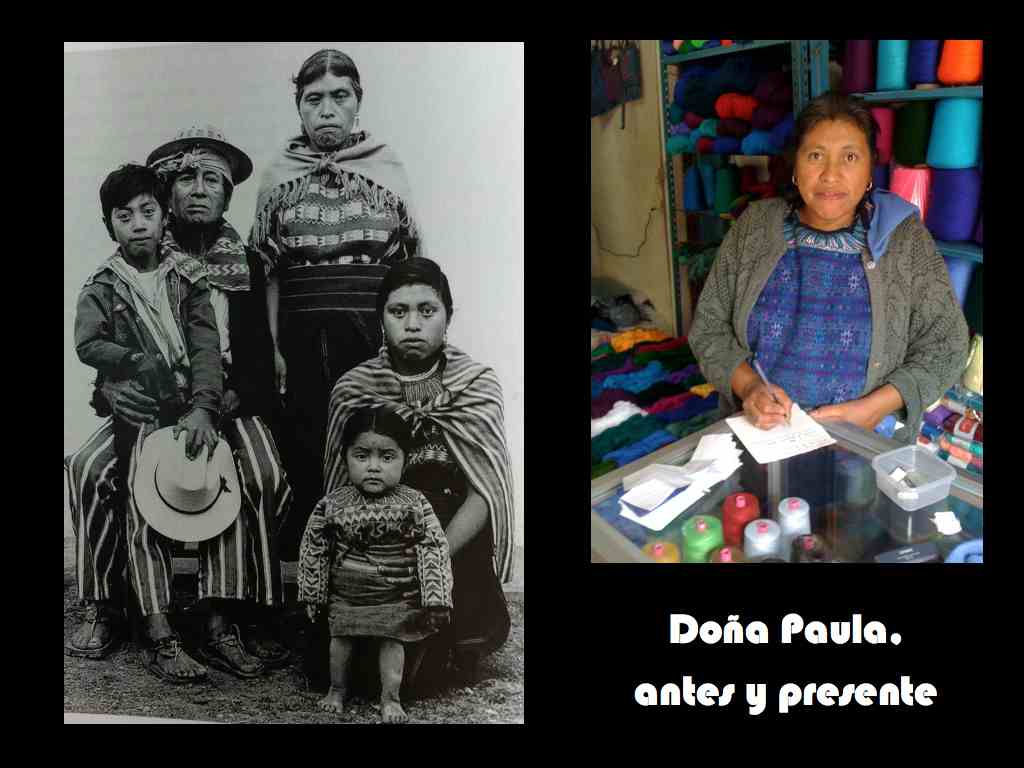

It can be

said that the dynamically changing economic situation has

shaken the traditional views of class, gender, and traditional culture

of indigenous peoples, creating a diversity of competing, cooperating,

and mutually influencing self-representations of indigenous peoples.

The following episode concerning Dominga (a pseudonym) is typical

[Ikeda 2005; Ikeda 2004].

Dominga is the most prominent woman in the city and is considered

powerful by the people. She was 39 years old at the time of the ......

survey. Dominga and her hairdresser husband have been running the hotel

that has become the most famous tourist attraction in town for the past

five years. Although she is illiterate, she is eloquent to both the

townspeople and foreign tourists ...... and has started to donate the

money she makes from running the hotel to various public activities in

the town. ...... She is a woman of ideas, and has changed the town's

inns, which until then had only rented out dimly lit rooms, by locating

them in places with good views, enlarging the windows and creating

balconies for foreigners, and creating a place where tourists could

only peek in from the side of the road with a blank stare. She also

made an effort to demonstrate and sell the traditional weaving of

Indigena women in the courtyard of her hotel, which until then tourists

had only been able to observe from the sidewalk. She believes it is

important to entertain tourists well, as she does, in order to improve

the status of women in the town and to retain young people who come to

the U.S. because of their poverty. ...... It is also acknowledged that

Dominga is in the middle of a series of social advancement initiatives

for women, such as the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Rigoberta Menchu,

which took place outside the town, and the movement for the advancement

of Indigenous women, which is actively promoted by NGOs. It is also an

acknowledgement of Dominga's economic success. The fact that it was an

Indigenous woman who achieved economic success became the talk of the

town. Hence, Dominga, who became the town's emerging female

entrepreneur, was subjected to a variety of slurs from her peers in the

neighborhood. These included accusations of aggressive touting,

souvenir sales that falsely claimed to be cooperative operations, and

the self-righteous canonization of the town's women's history in the

eyes of tourists, an activity that had never been practiced by the

town's population.

|

|

|

I introduced

Dominga in approximately this way during a session at the

Margaret Mead Memorial Symposium, “Social Uses of Anthropology in the

Modern World,” held at the National Museum of Ethnology in 2004.

Dominga is the woman who appears as a masked figure in Olivia Carrescia

(Dir.), “Todos Santos: The Surviviors”, First Run / Icaarus Films,

1989, on the town's post-civil war record, and at the time this

documentary film was shot I don't think she was running the hotel at

the time this documentary was shot. Dominga was the subject of

Carrescia's first documentary (Olivia Carrescia (Dir.), “Todos Santos

Cuchumatan: Report from a Guatemalan Village”, First Run / Icaarus

Films, 1989), filmed more than a year before the arrival of the army in

this town. ), and seven years later, in her 1989 film, as the narrator

of a village patrolled by the military and vigilantes during the 1982

massacre. -victims of the civil war- appear in the film as victims of

the civil war.

|

|

Five years

later, however, in the early 1990s, the face of the town had

changed dramatically. The town was experiencing an unprecedented

economic boom through dollar money sent by parents and siblings who had

immigrated to North America using brokers known as coyotes, and through

ethnic tourism, which had returned again as the momentum for peace

grew. It was then that the opportunity arose for them to begin talking

about their indigeneity and self-representation of being a Mam to the

foreigners they knew at home and abroad.

|

|

|

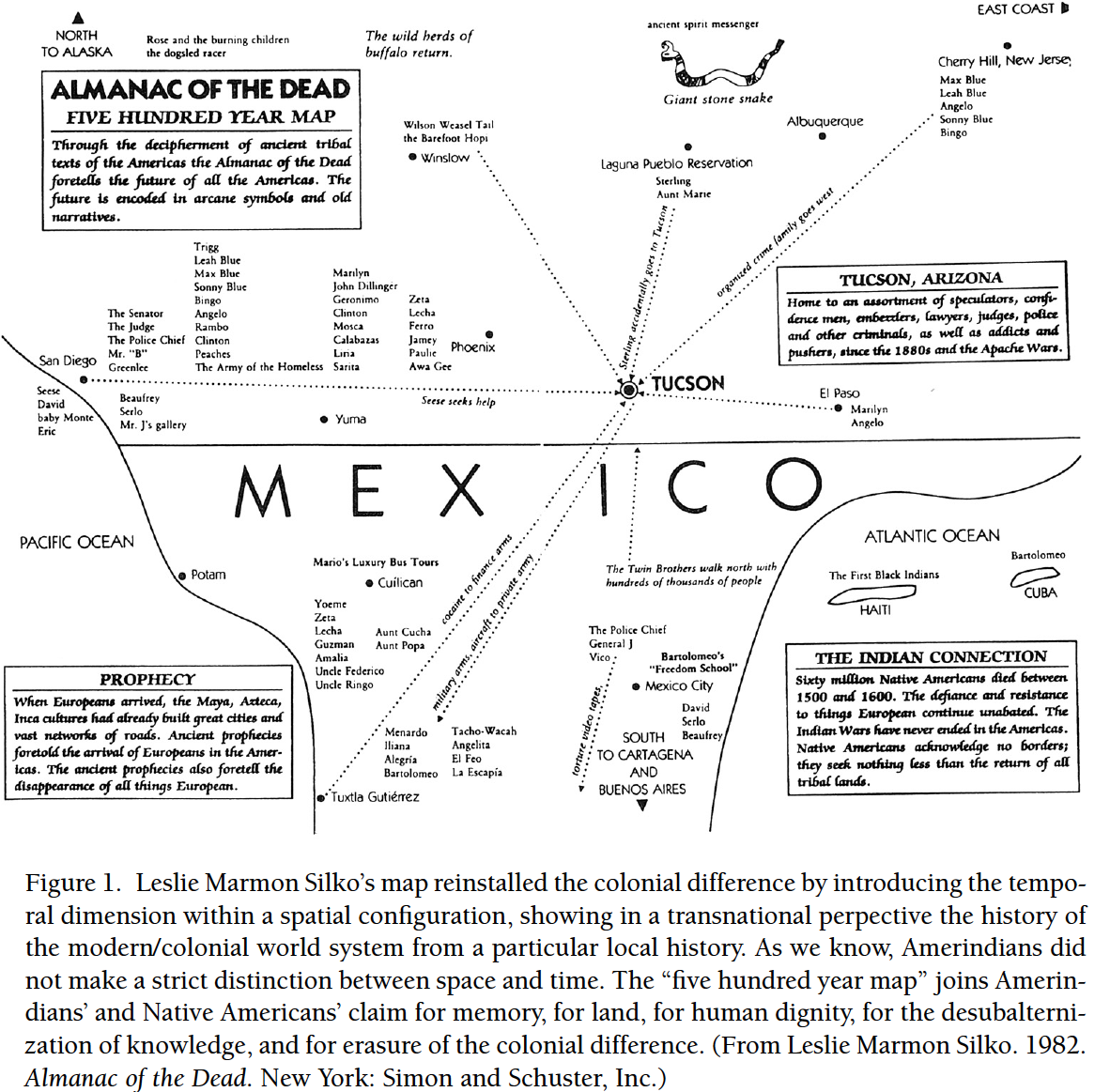

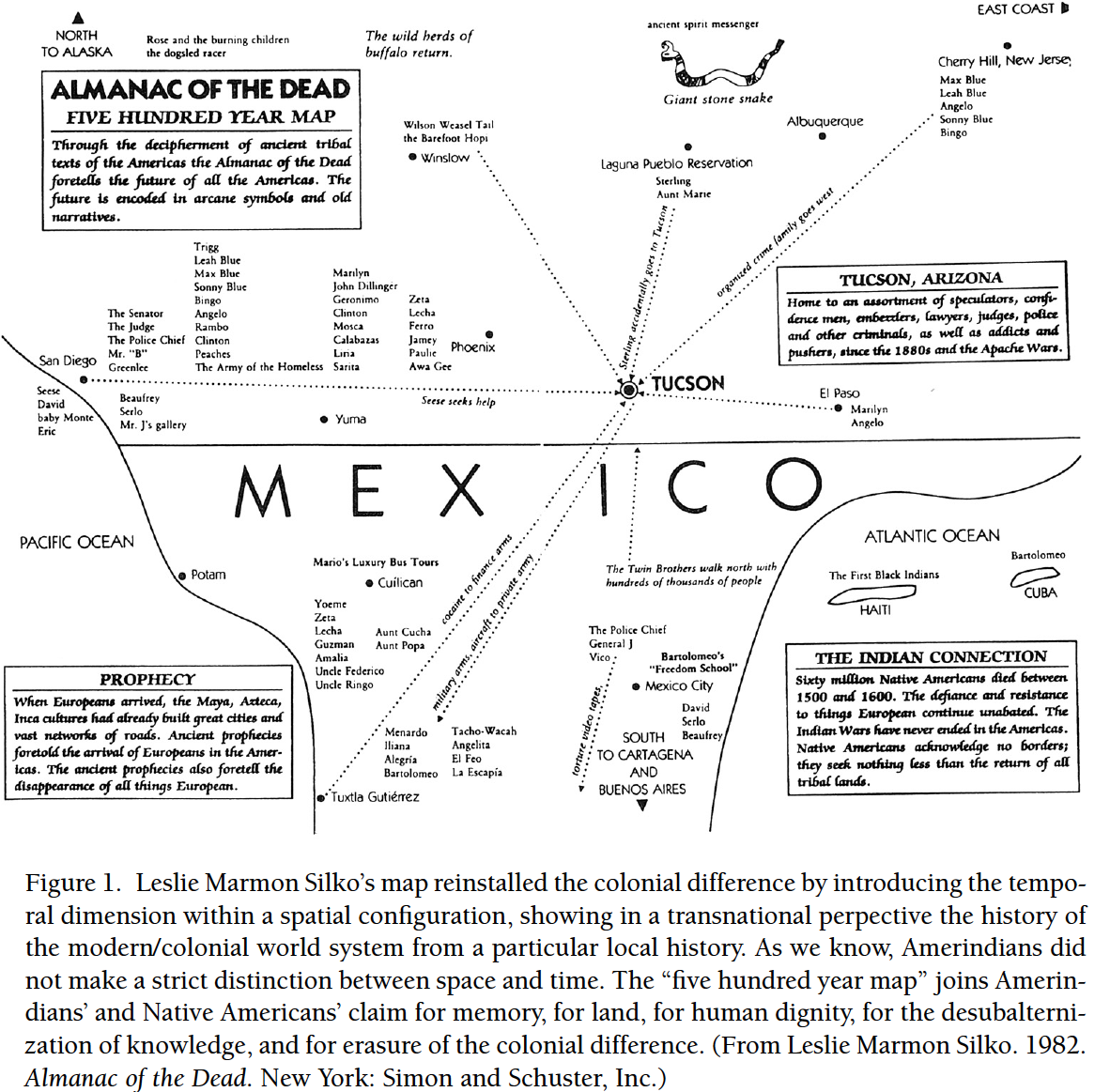

The year

1992, which coincidentally was the Quinquennial of the

Discovery and Encounter of the New World, saw the Nobel Peace Prize

awarded to Rigoberta Menchu, and the following year the UN Decade of

Indigenous Peoples (1994-2004) began. Indigenous teachers addressed in

their school lessons that the Five Hundred Years of Indigenous

Discovery was (using Eduardo Galeano's theory of place) Five Hundred

Years of Conquest and Exploitation. A training project was started to

teach Spanish to foreigners that my compadre was involved in. The

residents of the town contracted for that project felt that allowing

white (gringo) tourists to rent a room in their home and provide meals

for their lodgers would be greatly appreciated and would be an ample

addition to their household income. I also began to feel the

significance of behaving in various ways as an indigenous person to

these whites. They said they were more comfortable using the

politically correct (corrección política) Spanish term “indígena,” or

“indigenous,” as a self-identification than the term “indio,” which

they had used in the past. In my field notes from my research on ethnic

tourism at the time, there were several episodes in which innkeepers

and innkeepers indicated how eager whites were to make friends with the

“indigena.

|

|

|

Returning to

the terminology of collective identity, “Who are we?” we

can clearly see that this consciousness is formed in conflict with

situations that attempt to define them externally. It seems that the

events and things that define indigeneity are semantically rearranged

within a particular context. Of course, this can only be known through

a constant dialogue between the informant and the researcher. In

historical identity, the process of associative recall of historical

episodes, or “historical memory” as we interact with what we believe

the locals hold or should hold, as we often do in our oral history

elicitation, is essential. It is essential to have a process that is

like playing an association game. The memory of Mam as a “not so

distant” historical entity, an object of exploitation by the “masters”

or modern state of the non-indigenous criollos (colonial-born whites)

who inherited their black heritage from the Spanish conquistadores

(conquistadores), including forced labor laws (1934) and seasonal labor

on the plantations that continues to this day The memory of how they

were the “masters” of the Spanish conquistadores (conquistadores) is

recounted.

|

|

|

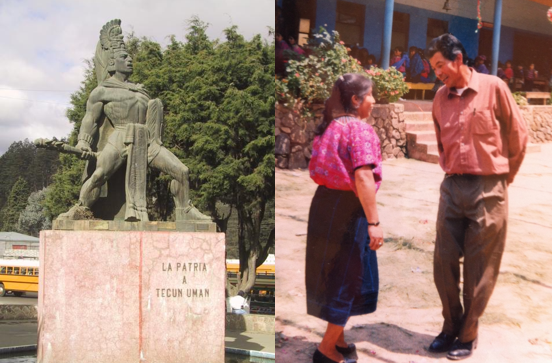

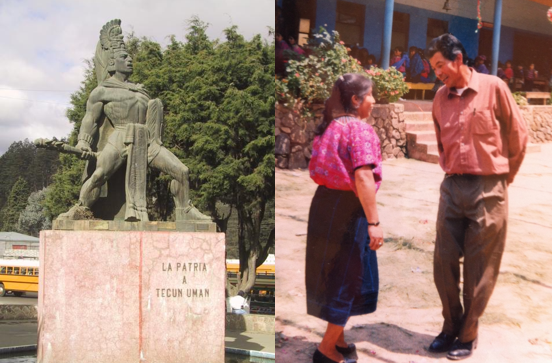

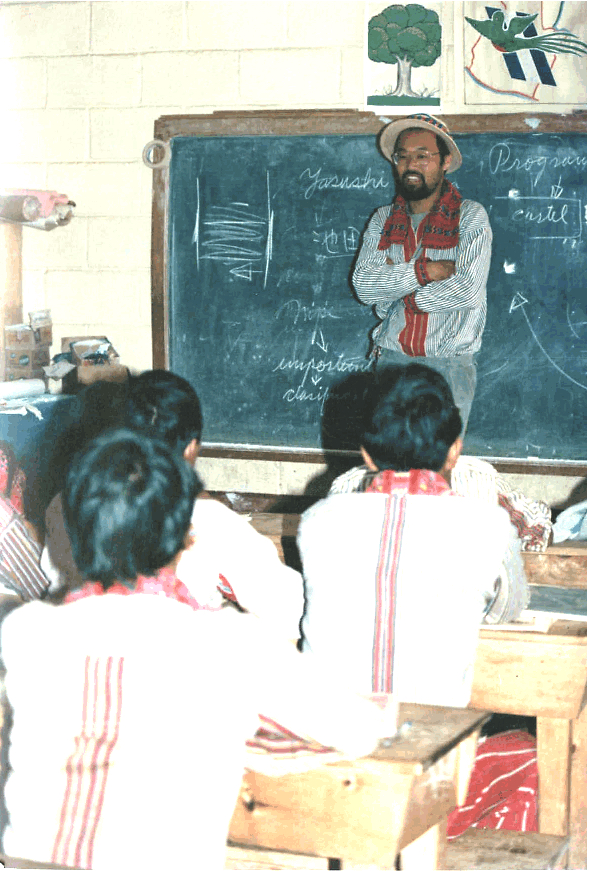

In school

education, Tekun Umam of the Quiché Maya, a symbol of the

indigenous rebels who resisted the Conquistadores by force and was

killed in February 1524, is a major presence, and he too is spoken of

as Guatemala's national hero rather than as a Mayan hero. On the other

hand, the history of the epidemic that decimated the indigenous

population, the tax collection by the church and encomienda, the

Inquisition, and the control of moonshine is rarely mentioned. However,

indigenous teachers are familiar with the history of these “own”

oppressions, and the history that is not told in textbooks is also told

in the school setting.

|

|

Since the

full-scale immigration to North America that began in the

1990s, I have often heard about the “excellence” of Guatemalan natives

as a superior labor force in the neoliberal economy, more diligent,

tough, and hardworking than other Latin Americans, especially Mexicans

(choros). This is one example of a change in the opposite direction

from the previous negative representation of indigenous peoples as

labor force subjects. At a traffic roundabout on the outskirts of

Quetzaltenango (Xela), Guatemala's second largest city, a standing

statue of a North American migrant worker is erected alongside the

current giant standing statue of Tecun Uman. My friends in San Marcos

proudly tell me that it was modeled after their fellow Indigena illegal

immigrants, as if it were the Tecun Uman for them today.

|

|

Women who

spun textiles for their own use became victims of the civil

war and later became handicraft producers or union members to rebuild

their lives, and even microfinance borrowers for post-civil war social

reconstruction. Their children would further plunge into the

proletariat in the maquilas or maquiladoras of Guatemala City and

Quetzaltenango, the major cities in the region, where sewing factories

were owned by Chinese and Korean capital. The ethos of work preached by

the indigenous parents who educate their children is that of hard work,

diligence, and recognition by “good patrons”-but as one might imagine

from the reality of the intense labor in the maquilas, the reality is

not as sweet as the parents might expect. The reality, however, is not

as sweet as parents might expect. I have witnessed the transformation

of the indigenous Guatemalan population from penny capitalists (Sol

Tax) to a proletariat that is in desperate need of ketzal and US

dollars.

|

|

In an article in an area

studies journal, I argued that the birth of a

new economic ethos among the booming bubble economy of the Kucumatan

Plateau was the result of a violent post-civil war cleanup of old

economic practices that made their rapid articulation into the global

economy surprisingly easy [Ikeda 2000]. Ikeda 2000]. However, this

claim apparently offended one of the reviewers. According to the

reviewer, my argument was the same as “explaining that Japan's postwar

economic growth required destruction by war,” and was criticized as

nothing more than “condoning the existence of a military that destroyed

villages for the sake of economic development in indigenous areas. I am

not going to defend in the slightest the evil deeds of the abominable

gods Mars and Pluto, the military that has no blood or tears for the

indigenous peoples. I wanted to point out that economic ethos is not

always rooted in cultural structures, but can change with changes in

political structures. I simply wanted to describe the social context in

which the townspeople themselves were surprised to find themselves so

focused on “making money,” as I describe in my paper. I could not seem

to bridge the gap between this reviewer, who continues to see

indigenous peoples as victims of Guatemala's political violence, and

me, who focuses on how those who were at the mercy of their “accidental

fate” have developed a new identity as economic actors “after the

violence.

|

|

A little more than ten

years have passed since then, and here we are

today. In the town of Cuchumatan Plateau, hotel owners who have been

visiting for a long time blame the murder of a Japanese tourist and a

Guatemalan bus driver in May 2000 as the reason for the sharp decline

in the number of foreign tourists. In reality, however, the decline in

tourism has been gradual, beginning in 2007, when the U.S. subprime

mortgage housing crisis surfaced, and continuing until the Guatemalan

economic crisis of 2009, which seems to have dealt the fatal blow. This

was followed by the frequent attacks and robberies (banditry) of

private cars and buses at night and in the early morning, which became

a regular occurrence around that time, and which made the region

dangerous and unattractive to tourists.

|

|

Under a former military

president (2012-15 term) who won amid social

unrest since the new millennium, with a drug problem and rising

criminal population, a clash between a group of peasant protesters and

police forces in the western highlands in October 2012 resulted in

casualties. Last week, in a panel discussion I organized at another

Japan Association for Latin American Studies conference, a political

scientist who discussed the relationship between indigenous peoples and

the state in a political action model made the eerie prediction that we

are in a “bad” cycle of violence and violent exchanges, without calmly

seeking rational solutions. Violent confrontations between indigenous

peoples and the state could escalate demands for sovereignty and

governance by the indigenous peoples themselves. Although the

government has taken a forceful stance in response, including the

deployment of the national army, I believe that the prediction will be

wrong and that from some equilibrium point, a different political

dimension will develop. This is because since 2002, with the

implementation of the decentralization law, community autonomy has been

gaining momentum, and the topic of entrenching democracy and good

government is becoming a frequently heard theme in rural areas. The

theme of local autonomy has also brought Western Enlightenment

inquiries into who we are, what we can do, and what we should do to the

cities of the western highlands of Guatemala, but they have changed in

various ways in response to individual circumstances, such as the

movement against mining development and the emergence of the circuit of

opinion called the local council (COCODE). The reason is that they have

undergone diverse changes in response to their individual circumstances

[Ikeda a 2012, Ikeda b 2012].

|

|

The term indigenous has the

fictional anecdote of historical meaning

assignment that it has been “discovered” by explorers and colonizers

who were not indigenous to begin with. Similar to the identification of

indigenous plants and animals, the term lacks the concept of

reaffirmation or changeability of content by the parties themselves.

Paradoxically, this is precisely why the concept of indigenous peoples

may have the potential for “resistance” to external pressures when it

comes to internalizing this kind of “unchanging” universality and

essentiality. The lack of a clear definition in the United Nations

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007), which consists

of a number of prohibitions based on the history of human rights

violations suffered by indigenous peoples, is another reason why the

concept of indigenous peoples is not clearly defined in the

Declaration. The fact that the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples (Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007) lacks a

clear definition and consists of a number of prohibitions based on the

history of human rights violations suffered by indigenous peoples to

date is also a reflection of the mentality of the urgent need to

protect specific human rights even if the definition of indigenous

concepts is shelved.

|

|

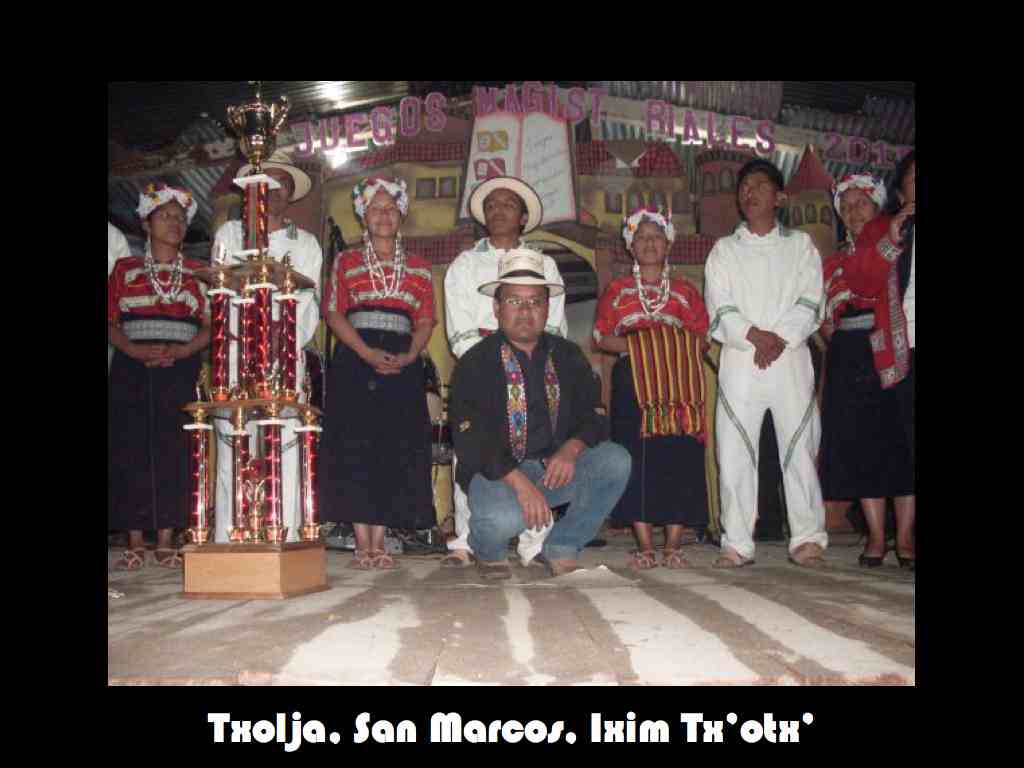

<<< Mitzub’ixi Quq

Chi’j tuj Paxil, Chinab’jul, Ixim Tx’otx’, diciembre

1987

In a situation dominated by globalization forces that

sweetly whisper

that win-win is possible if we are flexible, any anthropologist who

steadily and emotionally assimilates and approaches the lives of

indigenous peoples will be fascinated by this practical concept of

“resistance. However, having followed the Mamu community for a

relatively long time, it seems to me that this entity of resistance is

not a group that opposes everything in the dark. At times they seem

obstinate and conservative traditionalists, and at other times they

seem very flexible and flexible opportunists. In the national and

international context, and in relation to the nation to which they

belong, the indigenous Mamu people of today recognize, reinterpret,

revise, and own the dynamism of their history as it happens. What I

said at the beginning, that is, from the stigma of indigeneity and

inferiority (i.e., representation of the other) as Indians, they

gradually began to use their collective identity as a

self-representation or nomenclature as Indigena, a politically correct

term, and then to act as Mayans and Mamus, a historical background in

which they have come to act as Mayans and Mamus. This is the argument

of this presentation. This is the argument of this presentation, and it

is my current impression.

--Initium ut esset homo creatus est (The beginning is made as man is

created: Augustine)

|

☆

☆