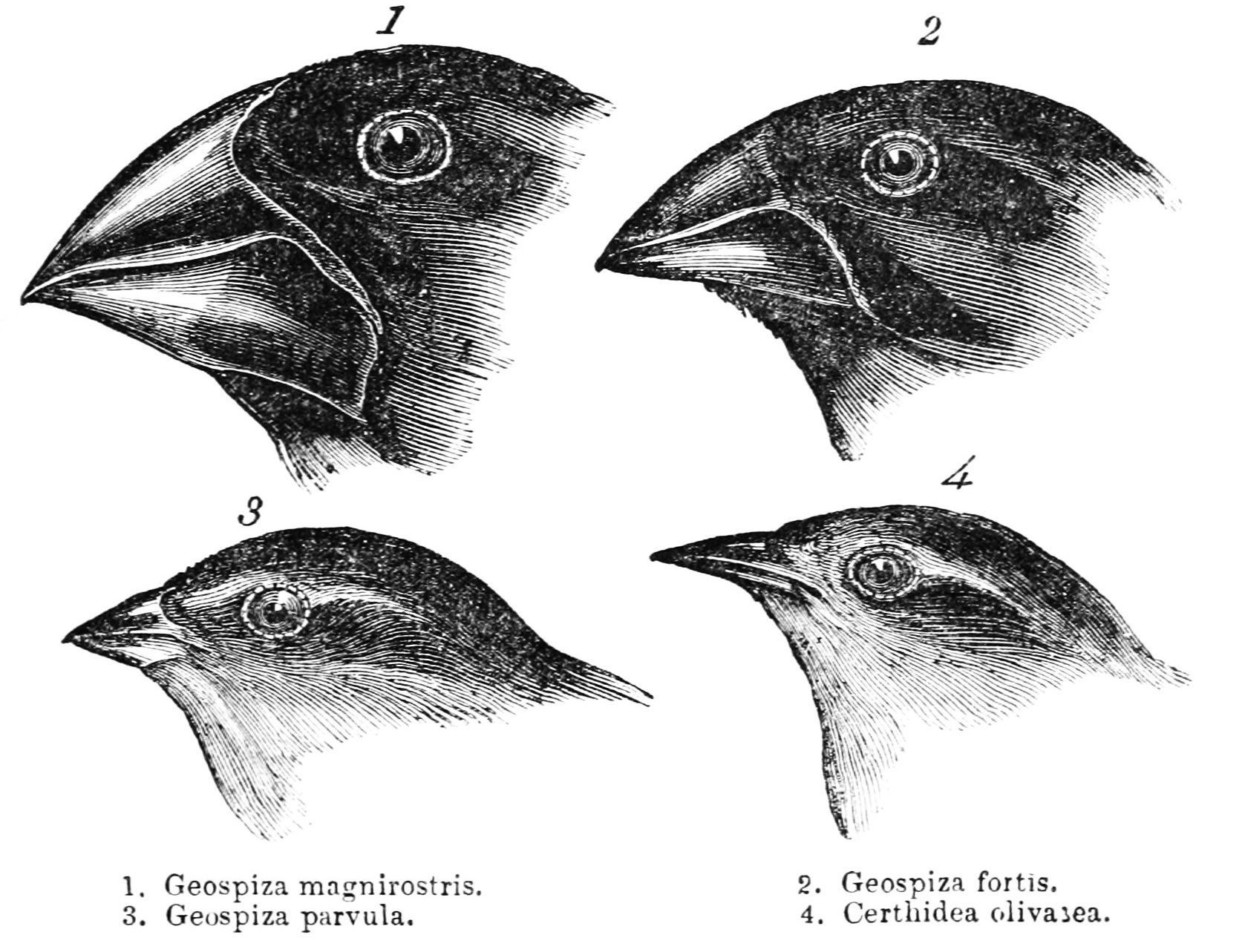

規範性の4タイプ

Four

types of the Normativity

★規範的(normative)とは一般的に、評価基準に関することを意味する。規範性(Normativity)とは、人間社会において、ある行動や結果を良いもの、望まし いも の、許容されるものとして指定し、他の行動や結果を悪いもの、望ましくないもの、許容されないものとして指定する現象のことである。この意 味での規範と は、行動や結果を評価したり判断したりするための基準を意味する。「規範的」とは、やや紛らわしいが、記述的な基準に関連するという意味で使われることも ある。この意味で、規範は評価的なものではなく、行動や結果を判断するための根拠となるものでもなく、単に行動や結果に関する事実や観察であり、判断を伴 わない。科学、法律、哲学の研究者の多くは、「規範的」という用語の使用を評価的な意味に限定し、行動や結果の記述を肯定的、記述的、予測的、経験的と呼 ぼうとしている。

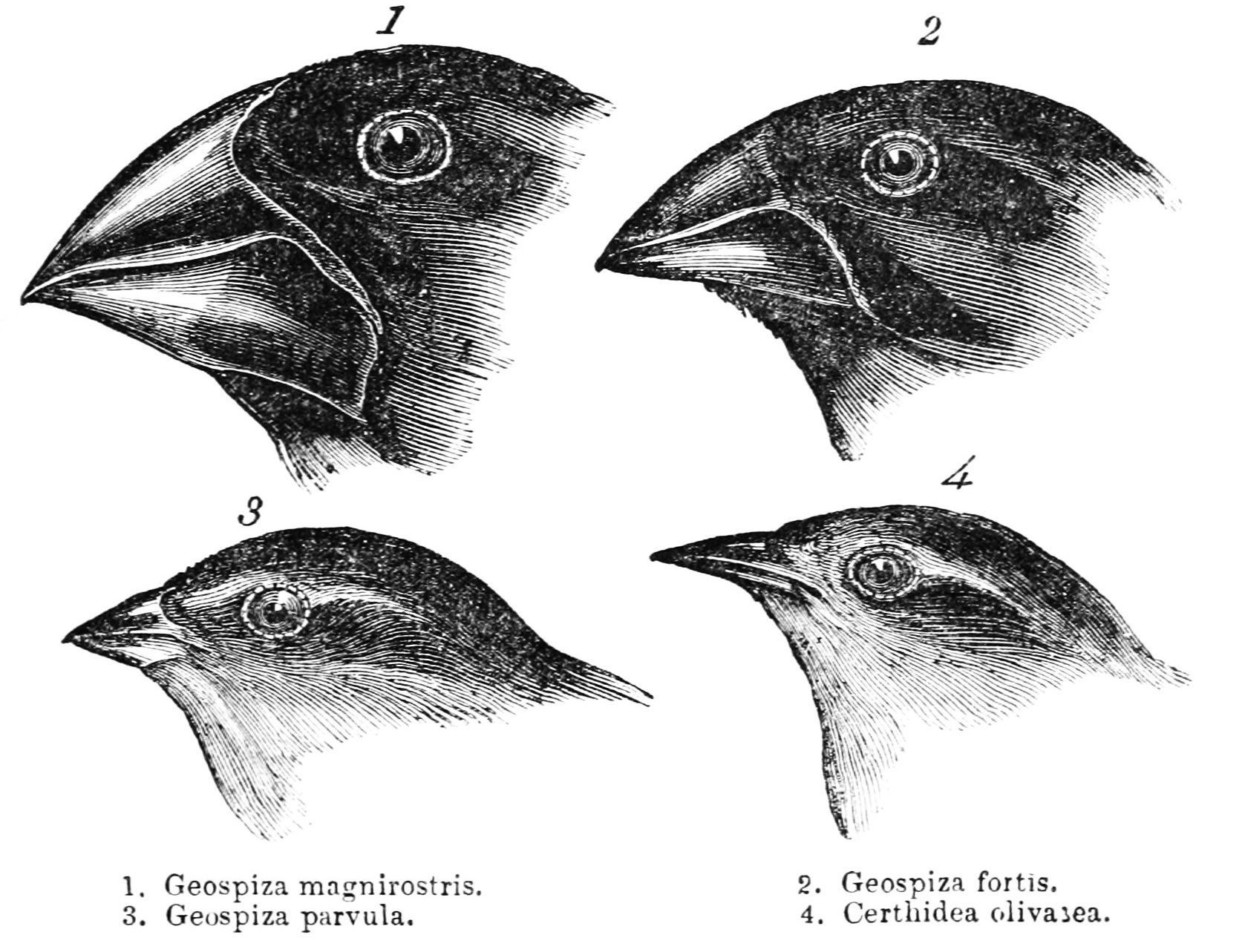

規範性の4タイプについて考える。すなわち、主意主義、実在論、反省的認証、ならびに自律で ある(コースガード 2005:21-23)。

| 主意主義 | voluntarianism |

・ホッブス ・プーフェンドルフ |

| 実在論 |

realism |

・サムエル・クラーク ・procedual moral realism ・substantial moral realism ・トーマス・ネーゲル |

| 反省的認証 |

reflective endosement |

・反省にもとづく認証 ・デイヴィッド・ヒューム(Human Nature の1巻の末尾のペシミズムと、第三巻の末尾の自信に満ちた記述の退避)(コースガード 2005:71) ・バーナード・ウィリアム ・ジョン・スチュアート・ミル |

| 自律 |

autonomy |

・道徳的義務 |

◎義務とアイデンティティの倫理学 : 規範性の源泉 / クリスティーン・コースガード著 ; G.A.コーエン [ほか論評] ; オノラ・オニール編 ; 寺田俊郎 [ほか] 訳、岩波書店 , 2005.

* 序論 卓越と義務—西洋形而上学のごく簡潔な歴史(紀元前三八七年から紀元一八八七年まで)

*第1講 規範性の問い

* 第2講 反省に基づく認証

* 第3講 反省の権威

* 第4講 価値の起源と義務の範囲

* 第5講 理性。人間性、道徳法則

* 第6講 道徳とアイデンティティ

* 第7講 普遍性と反省する自己

* 第8講 歴史、道徳反省のテスト

* 第9講 回答

★規範性(normativity)とはなにか?

| Normative

generally means relating to an evaluative standard. Normativity is the

phenomenon in human societies of designating some actions or outcomes

as good, desirable, or permissible, and others as bad, undesirable, or

impermissible. A norm in this sense means a standard for evaluating or

making judgments about behavior or outcomes. "Normative" is sometimes

also used, somewhat confusingly, to mean relating to a descriptive

standard: doing what is normally done or what most others are expected

to do in practice. In this sense a norm is not evaluative, a basis for

judging behavior or outcomes; it is simply a fact or observation about

behavior or outcomes, without judgment. Many researchers in science,

law, and philosophy try to restrict the use of the term "normative" to

the evaluative sense and refer to the description of behavior and

outcomes as positive, descriptive, predictive, or empirical.[1][2] Normative has specialised meanings in different academic disciplines such as philosophy, social sciences, and law. In most contexts, normative means 'relating to an evaluation or value judgment.' Normative propositions tend to evaluate some object or some course of action. Normative content differs from descriptive content.[3] Though philosophers disagree about how normativity should be understood; it has become increasingly common to understand normative claims as claims about reasons.[4] As Derek Parfit explains: We can have reasons to believe something, to do something, to have some desire or aim, and to have many other attitudes and emotions, such as fear, regret, and hope. Reasons are given by facts, such as the fact that someone's finger-prints are on some gun, or that calling an ambulance would save someone's life. It is hard to explain the concept of a reason, or what the phrase 'a reason' means. Facts give us reasons, we might say, when they count in favour of our having some attitude, or our acting in some way. But 'counts in favour of' means roughly 'gives a reason for'. The concept of a reason is best explained by example. One example is the thought that we always have a reason to want to avoid being in agony.[5] |

規範的とは一般的に、評価基準に関することを意味する。規範性

(Normativity)とは、人間社会において、ある行動や結果を良いもの、望ましいもの、許容されるものとして指定し、他の行動や結果を悪いもの、

望ましくないもの、許容されないものとして指定する現象のことである。この意味での規範とは、行動や結果を評価したり判断したりするための基準を意味す

る。「規範的」とは、やや紛らわしいが、記述的な基準に関連するという意味で使われることもある。この意味で、規範は評価的なものではなく、行動や結果を

判断するための根拠となるものでもなく、単に行動や結果に関する事実や観察であり、判断を伴わない。科学、法律、哲学の研究者の多くは、「規範的」という

用語の使用を評価的な意味に限定し、行動や結果の記述を肯定的、記述的、予測的、経験的と呼ぼうとしている[1][2]。 規範的とは、哲学、社会科学、法学など、さまざまな学問分野において特殊な意味を持つ。ほとんどの文脈では、規範的とは「評価や価値判断に関連する」とい う意味である。規範的な命題は、何らかの対象や行動方針を評価する傾向がある。規範的な内容は記述的な内容とは異なる[3]。 哲学者たちは規範性をどのように理解すべきかについて意見を異にしているが、規範的主張を理由についての主張として理解することが一般的になってきている [4]: 私たちは何かを信じる理由、何かをする理由、何らかの願望や目的を持つ理由、そして恐怖、後悔、希望といった多くの態度や感情を持つ理由を持つことができ る。例えば、ある銃に誰かの指紋がついているとか、救急車を呼べば誰かの命が助かるとか。理由という概念、あるいは「理由」という言葉の意味を説明するの は難しい。事実が私たちに理由を与えてくれるのは、私たちが何らかの態度を取ったり、何らかの行動を取ったりすることを支持してくれる場合だと言えるかも しれない。しかし、「賛成に値する」とは、おおよそ「理由を与える」という意味である。理由という概念は、例を挙げて説明するのが一番わかりやすい。一例 として、私たちは常に苦悩を避けたいと思う理由があると考えることができる[5]。 |

| Philosophy Main article: Ethics In philosophy, normative theory aims to make moral judgements on events, focusing on preserving something they deem as morally good, or preventing a change for the worse.[6] The theory has its origins in Greece.[7] Normative statements of such a type make claims about how institutions should or ought to be designed, how to value them, which things are good or bad, and which actions are right or wrong.[8] Claims are usually contrasted with positive (i.e. descriptive, explanatory, or constative) claims when describing types of theories, beliefs, or propositions. Positive statements are (purportedly) factual, empirical statements that attempt to describe reality.[citation needed] For example, "children should eat vegetables", and "those who would sacrifice liberty for security deserve neither" are philosophically normative claims. On the other hand, "vegetables contain a relatively high proportion of vitamins", and "a common consequence of sacrificing liberty for security is a loss of both" are positive claims. Whether a statement is philosophically normative is logically independent of whether it is verified, verifiable, or popularly held. There are several schools of thought regarding the status of philosophically normative statements and whether they can be rationally discussed or defended. Among these schools are the tradition of practical reason extending from Aristotle through Kant to Habermas, which asserts that they can, and the tradition of emotivism, which maintains that they are merely expressions of emotions and have no cognitive content. There is large debate in philosophy surrounding whether one can get a normative statement of such a type from an empirical one (i.e. whether one can get an 'ought' from an 'is', or a 'value' from a 'fact'). Aristotle is one scholar who believed that one could in fact get an ought from an is. He believed that the universe was teleological and that everything in it has a purpose. To explain why something is a certain way, Aristotle believed one could simply say that it is trying to be what it ought to be.[9] On the contrary, David Hume believed one cannot get an ought from an is because no matter how much one thinks something ought to be a certain way it will not change the way it is. Despite this, Hume used empirical experimental methods whilst looking at the philosophically normative. Similar to this was Kames, who also used the study of facts and the objective to discover a correct system of morals.[10] The assumption that 'is' can lead to 'ought' is an important component of the philosophy of Roy Bhaskar.[11] Philosophically normative statements and norms, as well as their meanings, are an integral part of human life. They are fundamental for prioritizing goals and organizing and planning. Thought, belief, emotion, and action are the basis of much ethical and political discourse; indeed, normativity of such a type is arguably the key feature distinguishing ethical and political discourse from other discourses (such as natural science).[citation needed] Much modern moral/ethical philosophy takes as its starting point the apparent variance between peoples and cultures regarding the ways they define what is considered to be appropriate/desirable/praiseworthy/valuable/good etc. (In other words, variance in how individuals, groups and societies define what is in accordance with their philosophically normative standards.) This has led philosophers such as A.J. Ayer and J.L. Mackie (for different reasons and in different ways) to cast doubt on the meaningfulness of normative statements of such a type. However, other philosophers, such as Christine Korsgaard, have argued for a source of philosophically normative value which is independent of individuals' subjective morality and which consequently attains (a lesser or greater degree of) objectivity.[12] |

哲学 主な記事 倫理学 哲学において規範的理論は、道徳的に善とみなされるものを維持すること、または悪い方向への変化を防ぐことに焦点を当て、出来事に対して道徳的判断を下す ことを目的としている[6]。 [このようなタイプの規範的言明は、制度がどのように設計されるべきか、または設計されるべきか、どのように評価すべきか、どのような物事が良いか悪い か、どのような行為が正しいか間違っているかについて主張する[8]。肯定的主張とは、現実を記述しようとする(と称する)事実的で経験的な主張である [要出典]。 例えば、「子どもは野菜を食べるべきだ」、「安全のために自由を犠牲にしようとする者は、そのどちらにも値しない」は、哲学的に規範的な主張である。一 方、「野菜は比較的高い割合でビタミンを含む」、「安全保障のために自由を犠牲にすることの一般的な帰結は、両方を失うことである」というのは肯定的な主 張である。ある声明が哲学的に規範的であるかどうかは、それが検証可能であるかどうか、一般に信じられているかどうかとは論理的に無関係である。 哲学的に規範的な主張の位置づけや、それが合理的に議論・擁護できるかどうかについては、いくつかの学派がある。アリストテレスからカント、ハーバーマス に至る実践理性の伝統は、規範的言明は理性的であると主張し、感情主義の伝統は、規範的言明は単なる感情の表現であり、認知的内容を持たないと主張する。 哲学の世界では、経験的なものからこのようなタイプの規範的言明を得ることができるかどうか(すなわち、「ある」から「べき」を得ることができるかどう か、「事実」から「価値」を得ることができるかどうか)をめぐって大きな議論がある。アリストテレスは、「あるもの」から「あるべきもの」を見出すことが できると考えた学者の一人である。彼は、宇宙は目的論的であり、宇宙に存在するすべてのものには目的があると信じていた。反対に、デイヴィッド・ヒューム は、あるものがあるべき姿であるべきだといくら考えても、その姿は変わらないので、あるものからあるべき姿は得られないと考えていた。にもかかわらず、 ヒュームは哲学的に規範的なものを見る一方で、経験的な実験方法を用いた。これと類似していたのがケイムズであり、彼もまた正しい道徳体系を発見するため に事実と目的の研究を用いていた[10]。 哲学的に規範となる声明や規範、そしてそれらの意味は、人間の生活に不可欠なものである。それらは目標に優先順位をつけ、組織化し、計画するための基本で ある。思考、信念、感情、行動は多くの倫理的・政治的言説の基礎であり、実際、このようなタイプの規範性は、倫理的・政治的言説を他の言説(自然科学な ど)と区別する重要な特徴であることは間違いない[要出典]。 現代の道徳/倫理哲学の多くは、何が適切/望ましい/賞賛に値する/価値ある/善であるなどと考えられているかを定義する方法に関する、民族や文化間の明 らかな差異を出発点としている(言い換えれば、個人、集団、社会が、哲学的に規範となる基準に従って何があるかを定義する方法における差異である)。この ため、A.J.エイヤーやJ.L.マッキーといった哲学者たちは、(それぞれ異なる理由や方法で)このようなタイプの規範的言明の意味性に疑問を投げかけ てきた。しかしながら、クリスティン・コルスガードのような他の哲学者は、哲学的に規範的な価値の源泉を主張しており、それは個人の主観的な道徳性から独 立しており、その結果(多少なりとも)客観性を獲得している[12]。 |

| Social sciences In the social sciences, the term "normative" has broadly the same meaning as its usage in philosophy, but may also relate, in a sociological context, to the role of cultural 'norms'; the shared values or institutions that structural functionalists regard as constitutive of the social structure and social cohesion. These values and units of socialization thus act to encourage or enforce social activity and outcomes that ought to (with respect to the norms implicit in those structures) occur, while discouraging or preventing social activity that ought not occur. That is, they promote social activity that is socially valued (see philosophy above). While there are always anomalies in social activity (typically described as "crime" or anti-social behaviour, see also normality (behavior)) the normative effects of popularly endorsed beliefs (such as "family values" or "common sense") push most social activity towards a generally homogeneous set. From such reasoning, however, functionalism shares an affinity with ideological conservatism. Normative economics deals with questions of what sort of economic policies should be pursued, in order to achieve desired (that is, valued) economic outcomes. |

社会科学 社会科学において「規範的」という用語は、哲学における用法とほぼ同じ意味を持つが、社会学的な文脈では、文化的な「規範」の役割、すなわち構造機能主義 者が社会構造や社会的結束を構成するものとみなす共有の価値観や制度に関係することもある。このような価値観や社会化の単位は、(その構造に内在する規範 に照らして)起こるべき社会活動や成果を奨励したり強制したりする一方で、起こるべきでない社会活動を抑制したり防止したりする。つまり、社会的に評価さ れる社会活動を促進するのである(上記の哲学を参照)。社会活動には常に異常が存在するが(典型的には「犯罪」や反社会的行動として表現される。しかし、 このような推論から、機能主義はイデオロギー的保守主義と親和性を共有している。 規範的経済学は、望ましい(つまり価値ある)経済的成果を達成するために、どのような経済政策を追求すべきかという問題を扱う。 |

| Politics See also: Political philosophy The use of normativity and normative theory in the study of politics has been questioned, particularly since the rise in popularity of logical positivism. It has been suggested by some that normative theory is not appropriate to be used in the study of politics, because of its value based nature, and a positive, value neutral approach should be taken instead, applying theory to what is, not to what ought to be.[13] Others have argued, however, that to abandon the use of normative theory in politics is misguided, if not pointless, as not only is normative theory more than a projection of a theorist's views and values, but also this theory provides important contributions to political debate.[14] Pietrzyk-Reeves discussed the idea that political science can never truly be value free, and so to not use normative theory is not entirely helpful. Furthermore, perhaps the normative dimension political study has is what separates it from many branches of social sciences.[13] |

政治 こちらも参照: 政治哲学 特に論理実証主義が台頭して以来、政治学研究において規範性や規範理論を用いることに疑問が投げかけられてきた。規範理論はその価値観に基づく性質から、 政治学研究に用いるのは適切ではなく、代わりに肯定的で価値中立的なアプローチを取るべきであり、あるべきものではなく、あるべきものに理論を適用すべき であるとする意見もある[13]。 [13]しかし、規範理論は理論家の見解や価値観の投影以上のものであるだけでなく、この理論は政治的議論に重要な貢献を提供するものでもあるため、政治 における規範理論の使用を放棄することは、無意味ではないにせよ、見当違いであると主張する者もいる[14]。さらに、おそらく政治学が持つ規範的な側面 こそが、社会科学の多くの分野と政治学を隔てるものである[13]。 |

| International relations In the academic discipline of International relations, Smith, Baylis & Owens in the Introduction to their 2008 [15] book make the case that the normative position or normative theory is to make the world a better place and that this theoretical worldview aims to do so by being aware of implicit assumptions and explicit assumptions that constitute a non-normative position, and align or position the normative towards the loci of other key socio-political theories such as political liberalism, Marxism, political constructivism, political realism, political idealism and political globalization. |

国際関係論 国際関係論という学問分野では、スミス、ベイリス、オーエンズの2008年の著書[15]の序論で、規範的立場や規範的理論は世界をより良い場所にするこ とであり、この理論的世界観は、非規範的立場を構成する暗黙の前提や明示的前提を意識することによってそうすることを目的とし、政治的自由主義、マルクス 主義、政治的構成主義、政治的現実主義、政治的理想主義、政治的グローバリゼーションといった他の主要な社会政治理論の位置づけに規範的立場を合わせる、 あるいは位置づけるものであるとしている。 |

| Law See also: Normative jurisprudence In law, as an academic discipline, the term "normative" is used to describe the way something ought to be done according to a value position. As such, normative arguments can be conflicting, insofar as different values can be inconsistent with one another. For example, from one normative value position the purpose of the criminal process may be to repress crime. From another value position, the purpose of the criminal justice system could be to protect individuals from the moral harm of wrongful conviction. |

法律 こちらもご覧ください: 規範的法学 学問分野である法学において、「規範的」という用語は、ある価値観に従って何かを行うべきであるということを表すのに使われる。そのため、異なる価値観が 互いに矛盾する可能性がある限り、規範的な主張は矛盾する可能性がある。例えば、ある規範的価値観の立場からすれば、刑事手続きの目的は犯罪を抑圧するこ とかもしれない。別の価値観の立場からすれば、刑事司法制度の目的は、冤罪による道義的被害から個人を守ることかもしれない。 |

| Standards documents The CEN-CENELEC Internal Regulations describe "normative" as applying to a document or element "that provides rules, guidelines or characteristics for activities or their results" which are mandatory.[16] Normative elements are defined in International Organization for Standardization Directives Part 2 as "elements that describe the scope of the document, and which set out provisions".[17] Provisions include "requirements", which are criteria that must be fulfilled and cannot be deviated from, and "recommendations" and "statements", which are not necessary to comply with. |

規格文書 CEN-CENELEC内部規則では,"規範的 "とは,"活動又はその結果に対する規則,指針又は特性を提供する "文書又は要素に適用され,強制的であると説明している[16]。 規範的要素は,国際標準化機構指令第 2 部において,「文書の範囲を記述し,規定を定める要素」と定義されている[17]。規定には,満たさなければならず逸脱できない基準である「要求事項」 と,遵守する必要のない「勧告」及び「声明」が含まれる。 |

| Conformity Decision theory Economics Hypothesis Is-ought problem Linguistic prescription Norm (philosophy) Normative economics Normative ethics Normative science Philosophy of law Political science Scientific method Value |

適合性 意思決定理論 経済学 仮説 イズ・オート問題 言語的処方 規範(哲学) 規範的経済学 規範倫理学 規範科学 法哲学 政治学 科学的方法 価値観 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Normativity |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099