プラトンと音楽

Music in Plato's The Republic

★プラトンと音楽(「︎古代ギリシアの音楽」より)

ある時、プラトンは新しい音楽について苦言を呈した:

われわれの音楽はかつて適切な形に分割されていた。われわれの音楽は、かつてその適切な形式に分けられた......そして、これらの確立された形式と他

の形式の旋律様式を交換することは許されなかった。知識と情報に基づいた判断が、不服従を罰したのだ。口笛も、音楽的でない群衆のノイズも、拍手のための

手拍子もなかった。少年たち、教師たち、そして群衆は、棒で脅すことによって秩序を保っていた。しかしその後、天賦の才能を持ちながら音楽の法則を知らな

い詩人たちによって、音楽とは無縁の無政府状態が生まれた。彼らは愚かさによって、音楽には正しい道も間違った道もなく、それが与える快楽によって良し悪

しが判断されるものだと自分たちを欺いた。自分たちの作品や理論によって、大衆は自分たちが適切な判断者だと思い込むようになった。こうして、かつては沈

黙していたわが国の劇場は声高になり、音楽の貴族主義は悪質な劇場主義へと道を譲った......その基準は音楽ではなく、乱雑な巧みさの評判と掟破りの

精神であった[28]。Plato, Laws 700-701a. cited in Wellesz, p. 395.

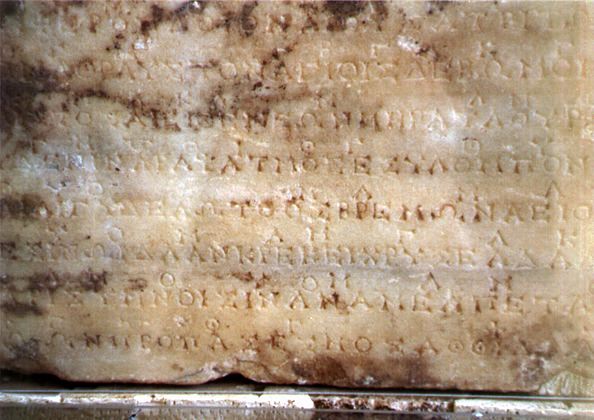

アポロンへの2つの賛歌のうちの2番を含むデルフィの原石の写真。楽譜は、ギリシャ文字の途切れることのない主要な線の上に、時折記号が並んでいる。

確立された形式」と「音楽の法則」についての彼の言及から、少なくともピタゴラスの倍音と協和音の体系の形式的な部分が、少なくともプロの音楽家が公の場

で演奏するようなギリシア音楽に定着していたこと、そしてプラトンは、そのような原則から「掟破りの精神」へと堕落していくことに苦言を呈していたことが

推測できる。

いい音」で演奏することは、プラトンの時代までにギリシア人が確立していたモードの倫理観に反するものだった。様々なモードの名前は、ギリシャの部族や民

族の名前に由来しており、その気質や感情は、それぞれのモードの独特な響きによって特徴付けられると言われていた。したがって、ドリアン・モードは「辛

辣」、フリギア・モードは「官能的」といった具合である。プラトンは『共和国』[29]の中で、ドリアン、フリギア、リディアンなど、さまざまなモードの

適切な使い方について語っている。現代の聴き手が、音楽におけるエトスという概念に共感するのは、哀愁には短調の音階が使われ、幸福な音楽から英雄的な音

楽まで、それ以外のほとんどすべての音楽には長調の音階が使われるという私たち自身の認識と比較する以外には難しい。

[29] Plato, Republic, cited in Strunk, pp. 4–12.

音

階の響きは、音の配置によって異なる。現代の西洋音階では、CからDといった全音や、Cから嬰Cといった半音は使われるが、4分音符(現代の鍵盤では

「割れ目」)はまったく使われない。ギリシア人は全音、半音、さらには4分音符(あるいはさらに小さな音程)の配置を駆使して、それぞれ独自のエスプリを

持つ音階のレパートリーを大量に開発していました。ギリシアの音階の概念(名前も含めて)は、後のローマ音楽、そしてヨーロッパ中世へと伝わり、例えば

「リディアン・チャーチ・モード」という呼称が見られるようになった。

ピエロ・ディ・コジモが16世紀に描いた「アンドロメダを助けるペルセウス」の細部。手に持っている楽器は時代錯誤のもので、撥弦楽器とファゴットを組み合わせた想像上のものと思われる。

プラトン、アリストクセノス[30]、後にボエティウス[31]などの著作を通じて私たちに伝

わってきた記述から、少なくともプラトン以前の古代ギリシア

人が聴いていた音楽は主に単旋律であった。和声とは、一度に多くの音が聴き手の解決への期待に貢献するような、発展した作曲のシステムという意味で、ヨー

ロッパの中世に発明されたものであり、古代文化には発展した和声のシステムはなかったというのが音楽学の通説である。

[30]Aristoxenus.

[31]Boethius.

プ ラトンの『共和国』には、ギリシアの音楽家が一度に複数の音を演奏することがあったと記されているが、これは高度な技術と考えられていたようだ。古代地 中海の音楽分野の研究[33]-楔形文字の解読-は、ギリシア人が文字を学ぶ何世紀も前に、異なる音程を同時に鳴らすこと、そして「音階」を理論的に認識 していたことを論じている。入手可能な証拠から言えることは、ギリシアの音楽家たちは明らかに複数の音を同時に鳴らすテクニックを採用していたが、ギリシ ア音楽の最も基本的で一般的なテクスチャーは単旋律であったということだ。

[33]Kilmer and Crocker.Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn, and Richard L. Crocker. (1976) Sounds from Silence: Recent Discoveries in Ancient Near Eastern Music. (CD BTNK 101 plus booklet) Berkeley: Bit Enki Records.

そのことは、プラトンの別の一節からも明らかなようだ:

...

竪琴は声楽と一緒に使われるべきである......奏者と生徒がユニゾンで音符と音符を作り出すこと、ヘテロフォニーと竪琴による刺繍......弦楽器

は詩人が作曲したメロディアとは異なる旋律線を投げかける......彼の音符がまばらであるところでは混雑した音符、彼の遅い音符には速い時

間......そして同様に、声楽に対するあらゆる種類のリズムの複雑さ......このどれも生徒に課すべきではない.....[34]。

[34]Plato, Laws 812d., cited in Henderson, p. 338.

☆ 音楽についてのプラトン(https://www.popularbeethoven.com/plato-on-music/ より)

ギ

リシア神話や伝説には、音楽の素晴らしさについて多くの物語が語られている。実際、古代ギリシャでは、音楽は基礎教育の一部であり、宗教的、市民的な集ま

りでさえあった。ギリシャの哲学者プラトンは、音楽を特別なものと考え、その著作『共和国』や『法学』の中で、この主題に幅広い関心を寄せている。この記

事では、プラトンが音楽とその人間への影響について何を語っているのかを発見しよう。

プラトンは、音楽が魂と肉体に与える影響についてどう考えていたのだろうか?

プラトンによれば、音楽は理性を迂回して自己の核心に入り込み、人格に大きな影響を与える: 「リズムとハーモニーは何よりも魂の奥底に入り込み、それを強く支配するからである」。

古代ギリシャ人はまた、空気とともに伝わる音楽は、魂への入り口である耳から体内に入ると信じていた。そして脳が音を処理し、やがて血液とともに全身に伝わる。こうして音楽の効果は各器官に届き、最終的に魂に到達する。

生化学の知識がなくても、古代ギリシャ人はこのテーマについて驚くほど正確な見解を持っていた。今日、私たちはすでに、ある種の音に脳が反応し、それに対応する生体反応が実際に身体に伝わることを知っている。

児童教育における音楽の機能とは何か?

プラトンはその著作『法学』の中でこう続けている: 「す

べての若い生き物は、生まれつき疲れやすく、手足も声も静かに保つことができない。しかし、他のどの動物も秩序感覚を発達させないのに対し、人類は唯一の

例外を形成している。運動における秩序はリズムと呼ばれ、調音における秩序は鋭音と重音の融合と呼ばれ、この2つの組み合わせはコーリック・アートと呼ば

れる」。

彼の推論によれば、最初のうちは子供たちは2種類の教育を受けるべきだ。ひとつは身体を発達させるための体操、もうひとつは魂(自己)を形成し、豊かに

し、強化するための音楽である。これらが一緒になれば、バランスの取れた人間になる。プラトンは、音楽は聴く人の感情を揺さぶり、正しい気分にさせること

ができる。

彼はその論理を、夜中に子供をあやす母親の例で強調している。適切なアプローチは、静寂や静けさではなく、揺れ動く動きやハミングのような音である。これはダンスや歌のようなもので、最終的に興奮や恐怖を内面化し、抑制する外的影響である。

音楽はどのように人格を形成するのか?

プ

ラトンは、音楽の力を感情を模倣する能力に見出している。プラトンは『共和国』の中で、音楽を聴く人が「沈着、勇気、自由、高邁、そしてそれらの同類やそ

の反対も含めて」といったあらゆる種類の感情を認識できることを書いている。誰かが音楽を聴くと、やがてその感情の動きに同調し、それに合わせていく。こ

のように、良い音楽は聴く人の心を動かすだけでなく、その人を良い(徳のある)秩序だった感情状態へと導く。悪い音楽は、インパクトが十分でなかったり強

すぎたりすることで、逆に人を弱さや悪に向かわせることがある。

人格にはさらに持続的な影響がある。もし子供が、良い音楽に従って、感情を適切な方法で解放することを学べば、良い気分も適切な尺度を持ち、極端になるこ

とはない。言い換えれば、良い音楽はその人の「気分の良いレベル」を調整することができる!この「良い」という感覚は、他の分野にも広がり、(例えば子供

の場合)良い悪いを知らなくても自然に(感覚として)身につくようになる。最後に、良い音楽が与える影響として、学習に対する心の準備が挙げられる。プラ

トンは、音楽は知りたいという欲求を喚起し、同時に知覚を研ぎ澄ますと主張する。

音楽の好みで本当の人格がわかる?

で

は、人間が音楽を楽しむという普遍的な現象はなぜ起こるのだろうか?プラトンによれば、すべての人間はリズムやメロディーを知覚し、楽しむ能力を持ってい

るが、この点では人間はみな同じではない。各人が特定のリズムやメロディーに惹かれるのだ。彼の解釈では、音楽の質はそれを楽しむ聴衆によって測られる。

彼はこう書いている。"最高の音楽とは、最高の人間、適切に教育された人間、とりわけ善良さと教育において最高の人間を喜ばせるものであると考えなければ

ならない"。

結論

音 楽に関するプラトンの見解をまとめると、良い音楽を聴くこと、特に幼少期には3つの利点があることがわかる。第一に、音楽は感情に影響を与え、善徳に向か わせる。第二に、音楽は測定された喜びを与え、魂が善良で美しいものに自然に惹かれるように形成する。第三に、知覚が研ぎ澄まされ、学習がより簡単に、よ り深くなる。

※出典は、https://www.popularbeethoven.com/plato-on-music/

| Next

as to the music. A song or ode has three parts,—the subject, the

harmony, and the rhythm; of which the two last are dependent upon the

first. As we banished strains of lamentation, so we may now banish the

mixed Lydian harmonies, which are the harmonies of lamentation; and as

our citizens are to be temperate, we may also banish convivial

harmonies, such as the Ionian and pure Lydian. Two remain—the Dorian

and Phrygian, the first for war, the second for peace; the one

expressive of courage, the other of obedience or instruction or

religious feeling. And as we reject varieties of harmony, we shall also

reject the many-stringed, variously-shaped instruments which give

utterance to them, and in particular the flute, which is more complex

than any of them. The lyre and the harp may be permitted in the town,

and the Pan’s-pipe in the fields. Thus we have made a purgation of

music, and will now make a purgation of metres. These should be like

the harmonies, simple and suitable to the occasion. There are four

notes of the tetrachord, and there are three ratios of metre, 3/2, 2/2,

2/1, which have all their characteristics, and the feet have different

characteristics as well as the rhythms. But about this you and I must

ask Damon, the great musician, who speaks, if I remember rightly, of a

martial measure as well as of dactylic, trochaic, and iambic rhythms,

which he arranges so as to equalize the syllables with one another,

assigning to each the proper quantity. We only venture to affirm the

general principle that the style is to conform to the subject and the

metre to the style; and that the simplicity and harmony of the soul

should be reflected in them all. This principle of simplicity has to be

learnt by every one in the days of his youth, and may be gathered

anywhere, from the creative and constructive arts, as well as from the

forms of plants and animals. Other artists as well as poets should be warned against meanness or unseemliness. Sculpture and painting equally with music must conform to the law of simplicity. He who violates it cannot be allowed to work in our city, and to corrupt the taste of our citizens. For our guardians must grow up, not amid images of deformity which will gradually poison and corrupt their souls, but in a land of health and beauty where they will drink in from every object sweet and harmonious influences. And of all these influences the greatest is the education given by music, which finds a way into the innermost soul and imparts to it the sense of beauty and of deformity. At first the effect is unconscious; but when reason arrives, then he who has been thus trained welcomes her as the friend whom he always knew. As in learning to read, first we acquire the elements or letters separately, and afterwards their combinations, and cannot recognize reflections of them until we know the letters themselves;—in like manner we must first attain the elements or essential forms of the virtues, and then trace their combinations in life and experience. There is a music of the soul which answers to the harmony of the world; and the fairest object of a musical soul is the fair mind in the fair body. Some defect in the latter may be excused, but not in the former. True love is the daughter of temperance, and temperance is utterly opposed to the madness of bodily pleasure. Enough has been said of music, which makes a fair ending with love. |

次

に音楽について。歌や頌歌には、主題(ハーモニー)、和声、リズムの3つの部分があり、最後の2つは最初の部分に依存している。私たちが哀歌の系統を追放

したように、今度は哀歌のハーモニーである混合リディアン・ハーモニーを追放してもよい。私たちの市民は節制を旨とするので、イオニアンや純粋リディアン

のような和やかなハーモニーも追放してもよい。一方は勇気を、もう一方は服従や指導、宗教的感情を表す。和声の多様性を否定するように、それを表現する多

弦で様々な形をした楽器、特にフルートも否定しなければならない。竪琴とハープは町では許され、パンズパイプは野原で許される。こうして我々は音楽の浄化

を行ったが、次は音律の浄化を行う。これらはハーモニーと同様、シンプルでその場にふさわしいものでなければならない。テトラコードには4つの音符があ

り、3/2、2/2、2/1という3つの音律比があり、これらにはすべて特徴があり、リズムと同様に足にもさまざまな特徴がある。私の記憶が正しければ、

彼は武骨な小節について、またダクティリック、トロケール、イアンビックのリズムについて語っているが、彼は音節を互いに等しくするように配置し、それぞ

れに適切な量を割り当てている。私たちはあえて、文体は主題に、音律は文体に適合し、魂の単純さと調和がそのすべてに反映されるべきであるという一般原則

を断言するだけである。この単純さの原則は、誰もが若い頃に学ばなければならないし、創造的・建設的な芸術や動植物の形から学ぶことができる。 詩人だけでなく他の芸術家も、卑屈さや見苦しさを戒めるべきである。彫刻や絵画も音楽と同様に、簡素の法則に従わなければならない。これに違反する者は、 私たちの都市で働くことを許されず、私たちの市民の趣味を堕落させることもできない。われわれの保護者たちは、次第に魂を蝕み堕落させるような奇形のイ メージの中で育つのではなく、あらゆるものから甘美で調和のとれた影響を飲み込むような、健康と美の土地で育たなければならないからである。音楽は魂の奥 底に入り込み、美と奇形の感覚を与える。最初のうちは、その影響は意識されない。しかし、理性が芽生えたとき、こうして訓練された者は、彼女をいつも知っ ている友人として迎え入れる。読書を学ぶとき、まず要素や文字を個別に習得し、その後にそれらの組み合わせを習得する。魂の音楽は世界の調和に応えるもの であり、音楽魂の最も美しい対象は、美しい肉体に宿る美しい心である。後者の多少の欠点は許されるかもしれないが、前者の欠点は許されない。真の愛は節制 の娘であり、節制は肉体的快楽の狂気と完全に対立する。音楽は、愛と公正な結末を結ぶものである。 |

| Glaucon

then asks Socrates whether the best physicians and the best judges will

not be those who have had severally the greatest experience of diseases

and of crimes. Socrates draws a distinction between the two

professions. The physician should have had experience of disease in his

own body, for he cures with his mind and not with his body. But the

judge controls mind by mind; and therefore his mind should not be

corrupted by crime. Where then is he to gain experience? How is he to

be wise and also innocent? When young a good man is apt to be deceived

by evil-doers, because he has no pattern of evil in himself; and

therefore the judge should be of a certain age; his youth should have

been innocent, and he should have acquired insight into evil not by the

practice of it, but by the observation of it in others. This is the

ideal of a judge; the criminal turned detective is wonderfully

suspicious, but when in company with good men who have experience, he

is at fault, for he foolishly imagines that every one is as bad as

himself. Vice may be known of virtue, but cannot know virtue. This is

the sort of medicine and this the sort of law which will prevail in our

State; they will be healing arts to better natures; but the evil body

will be left to die by the one, and the evil soul will be put to death

by the other. And the need of either will be greatly diminished by good

music which will give harmony to the soul, and good gymnastic which

will give health to the body. Not that this division of music and

gymnastic really corresponds to soul and body; for they are both

equally concerned with the soul, which is tamed by the one and aroused

and sustained by the other. The two together supply our guardians with

their twofold nature. The passionate disposition when it has too much

gymnastic is hardened and brutalized, the gentle or philosophic temper

which has too much music becomes enervated. While a man is allowing

music to pour like water through the funnel of his ears, the edge of

his soul gradually wears away, and the passionate or spirited element

is melted out of him. Too little spirit is easily exhausted; too much

quickly passes into nervous irritability. So, again, the athlete by

feeding and training has his courage doubled, but he soon grows stupid;

he is like a wild beast, ready to do everything by blows and nothing by

counsel or policy. There are two principles in man, reason and passion,

and to these, not to the soul and body, the two arts of music and

gymnastic correspond. He who mingles them in harmonious concord is the

true musician,—he shall be the presiding genius of our State. |

グ

ラウココンはソクラテスに、最良の医者や最良の裁判官は、病気や犯罪を最も多く経験した人ではないか、と問う。ソクラテスは二つの職業を区別する。医者は

自分の身体で病気を経験したはずである。しかし、裁判官は心によって心を支配する。したがって、彼の心は犯罪によって堕落してはならない。では、どこで経

験を積めばよいのか。どうすれば賢明になれるのか。それゆえ、裁判官はある年齢に達していなければならない。彼の青春時代は無垢であるべきであり、悪を実

践することによってではなく、他人の悪を観察することによって、悪に対する洞察力を身につけるべきである。これが裁判官の理想である。刑事になった犯罪者

は素晴らしく疑い深いが、経験を積んだ善人と一緒にいると、彼は過ちを犯す。悪は徳を知ることはできても、徳を知ることはできない。このような医学と法律

が、私たちの国家に広まるだろう。これらは、より良い性質を持つ人々への癒しの術となるだろう。そして、魂に調和を与える優れた音楽と、肉体に健康を与え

る優れた体操によって、どちらの必要性も大幅に減少するだろう。この音楽と体操の区分は、魂と肉体に本当に対応しているわけではない。というのも、両者は

等しく魂に関係しており、魂は一方によって飼いならされ、他方によって喚起され、維持されるからである。この二つは共に、私たちの守護者にその二重の性質

を与えている。情熱的な気質が体操をやりすぎると硬化し残忍になり、穏やかで哲学的な気質が音楽をやりすぎると萎縮する。音楽が耳の漏斗から水のように流

れ込むのを許している間に、その人の魂の縁は次第にすり減り、情熱的な、あるいは気骨のある要素はその人から溶け出してしまう。少なすぎる精神は疲れやす

く、多すぎるとすぐに神経過敏になる。野生の獣のように、打撃によってすべてをなしとげようとし、助言や政策によって何もなしとげようとしない。人間には

理性と情熱という2つの原理があり、音楽と体操という2つの芸術は、魂と肉体ではなく、これらに対応している。両者を調和させながら混ぜ合わせる者こそ真

の音楽家であり、彼こそわが国の国家を統率する天才となるであろう。 |

| 6.

Two paradoxes which strike the modern reader as in the highest degree

fanciful and ideal, and which suggest to him many reflections, are to

be found in the third book of the Republic: first, the great power of

music, so much beyond any influence which is experienced by us in

modern times, when the art or science has been far more developed, and

has found the secret of harmony, as well as of melody; secondly, the

indefinite and almost absolute control which the soul is supposed to

exercise over the body. In the first we suspect some degree of exaggeration, such as we may also observe among certain masters of the art, not unknown to us, at the present day. With this natural enthusiasm, which is felt by a few only, there seems to mingle in Plato a sort of Pythagorean reverence for numbers and numerical proportion to which Aristotle is a stranger. Intervals of sound and number are to him sacred things which have a law of their own, not dependent on the variations of sense. They rise above sense, and become a connecting link with the world of ideas. But it is evident that Plato is describing what to him appears to be also a fact. The power of a simple and characteristic melody on the impressible mind of the Greek is more than we can easily appreciate. The effect of national airs may bear some comparison with it. And, besides all this, there is a confusion between the harmony of musical notes and the harmony of soul and body, which is so potently inspired by them. |

6. 第一に、音楽の偉大な力は、芸術や科学がはるかに発達し、旋律だけでなく調和の秘密も発見された現代において、われわれが経験するどのような影響力をもはるかに超えていること、第二に、魂が肉体に及ぼすとされる明確でほとんど絶対的な支配力である。 第一の点については、ある程度の誇張が疑われるが、これは現在、私たちが知らないわけではないが、この芸術のある種の巨匠たちの間にも見られることであ る。プラトンには、アリストテレスにはなじみのない、ピュタゴラス的な数への畏敬の念と、数比例への畏敬の念が混じっているように思われる。音と数の間隔 は、彼にとって神聖なものであり、感覚の変化に左右されない独自の法則を持っている。それらは感覚を凌駕し、イデアの世界とつながるものとなる。しかし、 プラトンが事実と思われることを述べているのは明らかである。単純で特徴的な旋律がギリシア人の印象的な心に与える力は、私たちが容易に理解できる以上の ものである。国民的な音楽の効果も、それに匹敵するかもしれない。それに加えて、音符のハーモニーと、音符によって強力に鼓舞される魂と肉体のハーモニー との間には混乱がある。 |

| 7. Lesser matters of style may be remarked. (1) The affected ignorance of music, which is Plato’s way of expressing that he is passing lightly over the subject. (2) The tentative manner in which here, as in the second book, he proceeds with the construction of the State. (3) The description of the State sometimes as a reality, and then again as a work of imagination only; these are the arts by which he sustains the reader’s interest. (4) Connecting links, or the preparation for the entire expulsion of the poets in Book X. (5) The companion pictures of the lover of litigation and the valetudinarian, the satirical jest about the maxim of Phocylides, the manner in which the image of the gold and silver citizens is taken up into the subject, and the argument from the practice of Asclepius, should not escape notice. |

7. 文体については、もっと細かいことが指摘できる。 (1)音楽に対する無知ぶりは、プラトンがこの主題を軽く通り過ぎていることを表現している。 (2)第二の書と同様に、ここでも国家の建設に暫定的なやり方で進んでいること。 (3)国家をあるときは現実として、またあるときは想像の産物として描写する。 (4) 繋がり、あるいは第X巻で詩人たちを完全に追放するための準備。 (5)訴訟愛好家とバレチュディナリアン、フォシリデスの格言に対する風刺的な冗談、金銀市民のイメージを主題に取り上げるやり方、アスクレピオスの実践からの論証は、注目の的である。 |

| Still,

mathematics admit of other applications, as the Pythagoreans say, and

we agree. There is a sister science of harmonical motion, adapted to

the ear as astronomy is to the eye, and there may be other applications

also. Let us inquire of the Pythagoreans about them, not forgetting

that we have an aim higher than theirs, which is the relation of these

sciences to the idea of good. The error which pervades astronomy also

pervades harmonics. The musicians put their ears in the place of their

minds. ‘Yes,’ replied Glaucon, ‘I like to see them laying their ears

alongside of their neighbours’ faces—some saying, “That’s a new note,”

others declaring that the two notes are the same.’ Yes, I said; but you

mean the empirics who are always twisting and torturing the strings of

the lyre, and quarrelling about the tempers of the strings; I am

referring rather to the Pythagorean harmonists, who are almost equally

in error. For they investigate only the numbers of the consonances

which are heard, and ascend no higher,—of the true numerical harmony

which is unheard, and is only to be found in problems, they have not

even a conception. ‘That last,’ he said, ‘must be a marvellous thing.’

A thing, I replied, which is only useful if pursued with a view to the

good. All these sciences are the prelude of the strain, and are profitable if they are regarded in their natural relations to one another. ‘I dare say, Socrates,’ said Glaucon; ‘but such a study will be an endless business.’ What study do you mean—of the prelude, or what? For all these things are only the prelude, and you surely do not suppose that a mere mathematician is also a dialectician? ‘Certainly not. I have hardly ever known a mathematician who could reason.’ And yet, Glaucon, is not true reasoning that hymn of dialectic which is the music of the intellectual world, and which was by us compared to the effort of sight, when from beholding the shadows on the wall we arrived at last at the images which gave the shadows? Even so the dialectical faculty withdrawing from sense arrives by the pure intellect at the contemplation of the idea of good, and never rests but at the very end of the intellectual world. And the royal road out of the cave into the light, and the blinking of the eyes at the sun and turning to contemplate the shadows of reality, not the shadows of an image only—this progress and gradual acquisition of a new faculty of sight by the help of the mathematical sciences, is the elevation of the soul to the contemplation of the highest ideal of being. |

そ

れでも、ピタゴラス派が言うように、数学には他の応用も可能である。天文学が眼に適するように、耳にも適する調和運動という姉妹学があり、他の応用も可能

であろう。ピュタゴラス派に、それらについて尋ねてみよう。われわれには彼らよりも高い目標があることを忘れてはならない。天文学に蔓延している誤りは、

倍音学にも蔓延している。音楽家は耳を心の代わりにしている」。ある者は「これは新しい音だ」と言い、またある者は「二つの音は同じだ」と言う。そうだ、

と私は言った。しかし、あなたが言っているのは、竪琴の弦をいつもひねっていじくりまわして、弦の調子について言い争っている経験主義者たちのことだ。彼

らは、耳に聞こえる子音の数だけを調べて、それ以上のことは考えない。耳に聞こえない、問題の中にしかない真の数的ハーモニーについては、彼らは概念すら

持っていないのだ。その最後のものは、驚くべきものに違いない」と彼は言った。それは、善を目的として追求される場合にのみ有用なものだ」と私は答えた。 これらの学問はすべてひずみの前段階であり、互いに自然な関係で考えれば有益なものだ」。ソクラテス、あえて言おう」グラウコンが言った。どのような学問 のことですか?単なる数学者が弁証法家だとでもお思いですか」。もちろん違います。理屈のわかる数学者を私はほとんど知らない」。グラウコンよ、真の推論 とは、知的世界の音楽である弁証法賛歌のことではないのか。感覚から離れた弁証法的能力も、純粋な知性によって善の観念の観想に到達する。そして、洞窟か ら光に向かう王道、太陽に向かって目を瞬かせ、イメージの影だけでなく、現実の影を観想するために目を向けること、このような数学的科学の助けによる新た な視覚能力の進歩と漸進的な獲得は、魂が存在の最高の理想の観想へと昇華することなのである。 |

| The

second difficulty relates to Plato’s conception of harmonics. Three

classes of harmonists are distinguished by him:—first, the

Pythagoreans, whom he proposes to consult as in the previous discussion

on music he was to consult Damon—they are acknowledged to be masters in

the art, but are altogether deficient in the knowledge of its higher

import and relation to the good; secondly, the mere empirics, whom

Glaucon appears to confuse with them, and whom both he and Socrates

ludicrously describe as experimenting by mere auscultation on the

intervals of sounds. Both of these fall short in different degrees of

the Platonic idea of harmony, which must be studied in a purely

abstract way, first by the method of problems, and secondly as a part

of universal knowledge in relation to the idea of good. |

第

二の難点は、プラトンのハーモニックスの概念に関するものである。第一に、ピュタゴラス人であり、前回の音楽論でデイモンに相談したように、彼は彼らに相

談することを提案している。彼らは芸術の達人であることは認められているが、その高次の重要性と善との関係についての知識にはまったく欠けている。これら

はいずれも、プラトン的な調和という概念には程度の差こそあれ及ばないものであり、調和は純粋に抽象的な方法で、第一に問題の方法によって、第二に善の概

念に関連して普遍的な知識の一部として研究されなければならない。 |

| Plato

begins by speaking of a perfect or cyclical number (Tim.), i.e. a

number in which the sum of the divisors equals the whole; this is the

divine or perfect number in which all lesser cycles or revolutions are

complete. He also speaks of a human or imperfect number, having four

terms and three intervals of numbers which are related to one another

in certain proportions; these he converts into figures, and finds in

them when they have been raised to the third power certain elements of

number, which give two ‘harmonies,’ the one square, the other oblong;

but he does not say that the square number answers to the divine, or

the oblong number to the human cycle; nor is any intimation given that

the first or divine number represents the period of the world, the

second the period of the state, or of the human race as Zeller

supposes; nor is the divine number afterwards mentioned (Arist.). The

second is the number of generations or births, and presides over them

in the same mysterious manner in which the stars preside over them, or

in which, according to the Pythagoreans, opportunity, justice,

marriage, are represented by some number or figure. This is probably

the number 216. The explanation given in the text supposes the two harmonies to make up the number 8000. This explanation derives a certain plausibility from the circumstance that 8000 is the ancient number of the Spartan citizens (Herod.), and would be what Plato might have called ‘a number which nearly concerns the population of a city’; the mysterious disappearance of the Spartan population may possibly have suggested to him the first cause of his decline of States. The lesser or square ‘harmony,’ of 400, might be a symbol of the guardians,—the larger or oblong ‘harmony,’ of the people, and the numbers 3, 4, 5 might refer respectively to the three orders in the State or parts of the soul, the four virtues, the five forms of government. The harmony of the musical scale, which is elsewhere used as a symbol of the harmony of the state, is also indicated. For the numbers 3, 4, 5, which represent the sides of the Pythagorean triangle, also denote the intervals of the scale. The terms used in the statement of the problem may be explained as follows. A perfect number (Greek), as already stated, is one which is equal to the sum of its divisors. Thus 6, which is the first perfect or cyclical number, = 1 + 2 + 3. The words (Greek), ‘terms’ or ‘notes,’ and (Greek), ‘intervals,’ are applicable to music as well as to number and figure. (Greek) is the ‘base’ on which the whole calculation depends, or the ‘lowest term’ from which it can be worked out. The words (Greek) have been variously translated—‘squared and cubed’ (Donaldson), ‘equalling and equalled in power’ (Weber), ‘by involution and evolution,’ i.e. by raising the power and extracting the root (as in the translation). Numbers are called ‘like and unlike’ (Greek) when the factors or the sides of the planes and cubes which they represent are or are not in the same ratio: e.g. 8 and 27 = 2 cubed and 3 cubed; and conversely. ‘Waxing’ (Greek) numbers, called also ‘increasing’ (Greek), are those which are exceeded by the sum of their divisors: e.g. 12 and 18 are less than 16 and 21. ‘Waning’ (Greek) numbers, called also ‘decreasing’ (Greek) are those which succeed the sum of their divisors: e.g. 8 and 27 exceed 7 and 13. The words translated ‘commensurable and agreeable to one another’ (Greek) seem to be different ways of describing the same relation, with more or less precision. They are equivalent to ‘expressible in terms having the same relation to one another,’ like the series 8, 12, 18, 27, each of which numbers is in the relation of (1 and 1/2) to the preceding. The ‘base,’ or ‘fundamental number, which has 1/3 added to it’ (1 and 1/3) = 4/3 or a musical fourth. (Greek) is a ‘proportion’ of numbers as of musical notes, applied either to the parts or factors of a single number or to the relation of one number to another. The first harmony is a ‘square’ number (Greek); the second harmony is an ‘oblong’ number (Greek), i.e. a number representing a figure of which the opposite sides only are equal. (Greek) = ‘numbers squared from’ or ‘upon diameters’; (Greek) = ‘rational,’ i.e. omitting fractions, (Greek), ‘irrational,’ i.e. including fractions; e.g. 49 is a square of the rational diameter of a figure the side of which = 5: 50, of an irrational diameter of the same. For several of the explanations here given and for a good deal besides I am indebted to an excellent article on the Platonic Number by Dr. Donaldson (Proc. of the Philol. Society). |

プ

ラトンはまず、完全数あるいは循環数(Tim.)、すなわち除数の和が全体に等しい数について語る。彼はまた、人間的な数、つまり不完全な数についても述

べている。4つの項と3つの間隔を持つ数で、一定の比率で互いに関連している;

また、ツェラーが考えているように、第一の数は世界の周期を、第二の数は国家の周期を、あるいは人類の周期を表しているという示唆もない。 ).

第二の数は世代や誕生の数であり、星がそれらを司るのと同じ神秘的な方法でそれらを司り、ピタゴラス派によれば、機会、正義、結婚が何らかの数や図形で表

される。これはおそらく216という数字であろう。 本文にある説明では、2つのハーモニーが8000という数を構成していると仮定している。この説明は、8000が古代のスパルタ市民の数(ヘロデ)であ り、プラトンが「都市の人口にほぼ関係する数」と呼んだであろうという状況から、ある種の妥当性を導き出す。また、3、4、5という数字はそれぞれ、国家 における3つの秩序、あるいは魂の部分、4つの徳、政府の5つの形態を指しているのかもしれない。また、国家の調和の象徴として用いられる音階の調和も示 されている。ピタゴラスの三角形の辺を表す3、4、5という数字は、音階の音程も表している。 問題文に使われている用語は次のように説明できる。完全数(ギリシャ語)とは、すでに述べたように、その約数の和に等しい数である。したがって、最初の完 全数または循環数である6は、1+2+3である。ギリシャ語の)「項」や「音符」、(ギリシャ語の)「音程」という言葉は、数や図形だけでなく音楽にも当 てはまる。(ギリシア語)は、計算全体が依存する「ベース」、あるいは計算できる「最低項」である。ギリシャ語)は、「2乗と3乗」(ドナルドソン)、 「等倍と等倍」(ウェーバー)、「インボリューションとエボリューションによって」、すなわち(訳語のように)べき乗を上げ、根を取り出すことによって、 などさまざまに訳されてきた。数は、それらが表す平面や立方体の因数や辺が同じ比率であったりそうでなかったりするとき、「似ている、似ていない」(ギリ シャ語)と呼ばれる。下降」(ギリシア語)数は「増加」(ギリシア語)数とも呼ばれ、それらの除数の和を超える数である:例えば、12と18は16と21 より小さい。減少'(ギリシャ語)とも呼ばれる'衰える'(ギリシャ語)数は、それらの除数の合計を引き継ぐものである:例えば、8と27は7と13を超 える。ギリシア語で「互いに釣り合い、一致する」と訳される言葉は、同じ関係を多かれ少なかれ正確に表現する異なる方法のようである。これらは、8、 12、18、27という級数のように、「互いに同じ関係を持つ言葉で表現できる」ことと等価であり、それぞれの数は前の数に対して(1と1/2)の関係に ある。基本となる数」、つまり「1/3を加えた基本数」(1と1/3)=4/3、つまり音楽の4分の1である。(ギリシャ語)とは、音符のように数の「比 例」であり、一つの数の部分や因数、あるいはある数と他の数との関係に適用される。第1和声は「正方形」の数(ギリシア語)であり、第2和声は「長方形」 の数(ギリシア語)、すなわち対辺のみが等しい図形を表す数である。(ギリシア語)=「直径の2乗」または「直径の2乗」;(ギリシア語)=「有理」、す なわち分数を省略したもの、(ギリシア語)、「非有理」、すなわち分数を含むもの;例えば、49は、一辺が5である図形の有理直径の2乗であり、50は、 同じ直径の非有理直径の2乗である。ここに挙げた説明のいくつか、およびそれ以外の多くの説明については、ドナルドソン博士によるプラトン数に関する素晴 らしい論文(Proc.) |

| He

treats first of music or literature, which he divides into true and

false, and then goes on to gymnastics; of infancy in the Republic he

takes no notice, though in the Laws he gives sage counsels about the

nursing of children and the management of the mothers, and would have

an education which is even prior to birth. But in the Republic he

begins with the age at which the child is capable of receiving ideas,

and boldly asserts, in language which sounds paradoxical to modern

ears, that he must be taught the false before he can learn the true.

The modern and ancient philosophical world are not agreed about truth

and falsehood; the one identifies truth almost exclusively with fact,

the other with ideas. This is the difference between ourselves and

Plato, which is, however, partly a difference of words. For we too

should admit that a child must receive many lessons which he

imperfectly understands; he must be taught some things in a figure

only, some too which he can hardly be expected to believe when he grows

older; but we should limit the use of fiction by the necessity of the

case. Plato would draw the line differently; according to him the aim

of early education is not truth as a matter of fact, but truth as a

matter of principle; the child is to be taught first simple religious

truths, and then simple moral truths, and insensibly to learn the

lesson of good manners and good taste. He would make an entire

reformation of the old mythology; like Xenophanes and Heracleitus he is

sensible of the deep chasm which separates his own age from Homer and

Hesiod, whom he quotes and invests with an imaginary authority, but

only for his own purposes. The lusts and treacheries of the gods are to

be banished; the terrors of the world below are to be dispelled; the

misbehaviour of the Homeric heroes is not to be a model for youth. But

there is another strain heard in Homer which may teach our youth

endurance; and something may be learnt in medicine from the simple

practice of the Homeric age. The principles on which religion is to be

based are two only: first, that God is true; secondly, that he is good.

Modern and Christian writers have often fallen short of these; they can

hardly be said to have gone beyond them. |

『共

和国』では乳幼児期についてはまったく触れていないが、『諸法令』では子供の養育と母親の管理について賢明な助言を与えており、出生以前の教育についても

触れている。しかし『共和国』では、子供が思想を受け取ることができるようになる年齢から始め、現代の耳には逆説的に聞こえる言葉で、子供が真を学ぶ前に

偽を教えなければならないと大胆に主張している。現代の哲学界と古代の哲学界は、真理と虚偽について意見が一致していない。一方の哲学界は、真理をほとん

ど専ら事実と同一視し、他方の哲学界は観念と同一視している。これが我々とプラトンとの違いであり、言葉の違いでもある。私たちも、子供が不完全にしか理

解できない多くの教訓を受けなければならないこと、図式だけで教えられなければならないこと、大きくなっても信じられるとは到底思えないようなことも教え

られなければならないことを認めるべきである。プラトンに言わせれば、早期教育の目的は事実としての真理ではなく、原理としての真理である。クセノファネ

スやヘラクレイトスのように、彼は自分の時代とホメロスやヘシオドスとの間に深い溝があることに気づいている。神々の欲望や裏切りは追放されるべきであ

り、下界の恐怖は払拭されるべきであり、ホメロスの英雄たちの不品行は青少年の模範となるべきものではない。しかし、ホメロスには、私たちの若者に忍耐力

を教えてくれるかもしれない別の系統がある。宗教の基礎となる原則は、ただ二つである。第一に、神は真実であるということ、第二に、神は善であるというこ

とである。近代キリスト教の作家たちは、しばしばこれらの原則に欠けていた。 |

| The

second stage of education is gymnastic, which answers to the period of

muscular growth and development. The simplicity which is enforced in

music is extended to gymnastic; Plato is aware that the training of the

body may be inconsistent with the training of the mind, and that bodily

exercise may be easily overdone. Excessive training of the body is apt

to give men a headache or to render them sleepy at a lecture on

philosophy, and this they attribute not to the true cause, but to the

nature of the subject. Two points are noticeable in Plato’s treatment

of gymnastic:—First, that the time of training is entirely separated

from the time of literary education. He seems to have thought that two

things of an opposite and different nature could not be learnt at the

same time. Here we can hardly agree with him; and, if we may judge by

experience, the effect of spending three years between the ages of

fourteen and seventeen in mere bodily exercise would be far from

improving to the intellect. Secondly, he affirms that music and

gymnastic are not, as common opinion is apt to imagine, intended, the

one for the cultivation of the mind and the other of the body, but that

they are both equally designed for the improvement of the mind. The

body, in his view, is the servant of the mind; the subjection of the

lower to the higher is for the advantage of both. And doubtless the

mind may exercise a very great and paramount influence over the body,

if exerted not at particular moments and by fits and starts, but

continuously, in making preparation for the whole of life. Other Greek

writers saw the mischievous tendency of Spartan discipline (Arist. Pol;

Thuc.). But only Plato recognized the fundamental error on which the

practice was based. |

教

育の第二段階は体操で、筋肉の成長と発達の時期にあたる。プラトンは、肉体の鍛錬は精神の鍛錬と矛盾する可能性があり、肉体の鍛錬はやりすぎになりやすい

ことを認識している。プラトンは、肉体の鍛錬は精神の鍛錬と矛盾する可能性があること、肉体の鍛錬は容易にやり過ぎてしまう可能性があることを認識してい

る。肉体の鍛錬が過剰になると、人は頭痛を感じたり、哲学の講義で眠くなったりする。プラトンの体操の扱いには2つのポイントがある。第一に、体操の時間

は文学教育の時間から完全に切り離されている。プラトンは、正反対で性質の異なる2つのことを同時に学ぶことはできないと考えたようだ。経験則から判断す

れば、14歳から17歳までの3年間を単なる肉体運動に費やしても、知性の向上にはほど遠いだろう。第二に、彼は、音楽と体操は、一般的な意見が想像しが

ちなように、一方は精神を、他方は肉体を養うためのものではなく、どちらも精神を向上させるために等しく考案されたものであると断言している。彼の考えで

は、肉体は精神の下僕であり、低次のものを高次のものに従わせることは、両者の利益のためである。そして間違いなく、特定の瞬間に、あるいは発作的にでは

なく、継続的に、人生全体に対する準備をするために、心を働かせるならば、心は身体に対して非常に大きな、最も重要な影響力を行使することができる。他の

ギリシア人作家は、スパルタの規律が持つ禍々しい傾向を見抜いていた(Arist. Pol;

Thuc.)。しかし、プラトンだけは、この習慣の根底にある根本的な誤りを認識していた。 |

| https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1497/1497-h/1497-h.htm |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆