1967年オーストラリアの国民投票(アボリジニ)

1967 Australian

referendum (Aboriginals)

1967年オーストラリアの国民投票(アボリジニ)

1967 Australian

referendum (Aboriginals)

1967年5月27日、ホルト政権が呼びかけたオー ストラリアの国民投票の第2問は、オーストラリア先住民に関するものであった。有権者は、連邦政府に州のオーストラリア先住民のための特別法を制定する権 限を与えるかどうか[1]、憲法上の人口計算においてすべてのオーストラリア先住民を含めるかどうかを問われた[2][3][4][5]。 質問の中で「アボリジニ民族」という用語が使われた[a]. For the first part, increasing the number of Members in the House of Representatives, see 1967 Australian referendum (Parliament).

以下は、英語ウィキペディア"1967 Australian referendum (Aboriginals)" の引用ならびに翻訳である。

| general description |

The

second question of the 1967 Australian referendum of 27 May 1967,

called by the Holt Government, related to Indigenous Australians.

Voters were asked whether to give the Federal Government the power to

make special laws for Indigenous Australians in states,[1] and whether

in population counts for constitutional purposes to include all

Indigenous Australians.[2][3][4][5] The term "the Aboriginal Race" was

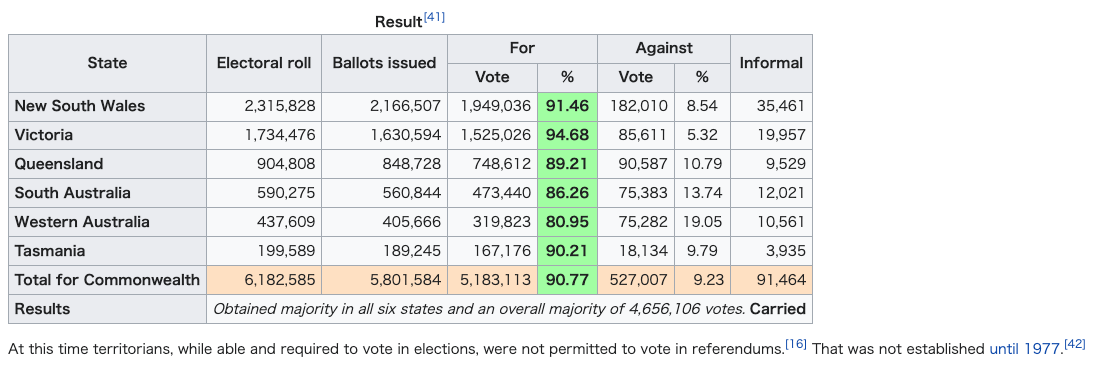

used in the question.[a] Technically the referendum question was a vote on the Constitution Alteration (Aboriginals) Bill 1967 that would amend section 51(xxvi) and repeal section 127.[7] The amendments to the Constitution were overwhelmingly endorsed, winning 90.77% of votes cast and having majority support in all six states.[8] The Bill became an Act of Parliament on 10 August 1967.[7] |

1967

年5月27日、ホルト政権が呼びかけたオーストラリアの国民投票の第2問は、オーストラリア先住民に関するものであった。有権者は、連邦政府に州のオース

トラリア先住民のための特別法を制定する権限を与えるかどうか[1]、憲法上の人口計算においてすべてのオーストラリア先住民を含めるかどうかを問われた

[2][3][4][5]。 質問の中で「アボリジニ民族」という用語が使われた[a]. 厳密には国民投票の質問は、第51条(xxvi)を改正し第127条を廃止する1967年憲法改正(アボリジニ)法案に対する投票であった[7]。 憲法改正は圧倒的な支持を受け、投票数の90.77%を獲得し、6州すべてで過半数の支持を得た[8]。 この法案は1967年8月10日に国会法となった[7]。 |

| Background |

In

1901, the Attorney-General Alfred Deakin provided a legal opinion on

the meaning of section 127 of the Constitution.[9] Section 127 excluded

"aboriginal natives" from being counted when reckoning the numbers of

the people of the Commonwealth or a state.[9] His legal advice was that

"half-castes" were not "aboriginal natives".[9] Prior to 1967, censuses asked a question about Aboriginal race to establish numbers of "half-castes" and "full-bloods".[10][b] "Full-bloods" were then subtracted from the official population figure in accordance with the legal advice from the Attorney-General.[10] Strong activism by individuals and both Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups greatly aided the success of the 1967 referendum in the years leading up to the vote. Calls for Aboriginal issues to be dealt with at the Federal level began as early as 1910.[12] Despite a failed attempt in the 1944 Referendum, minimal changes were instigated for Aboriginal rights until the 1960s, where the Bark Petition in 1963 and the ensuing Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd and Commonwealth of Australia (Gove Land Rights Case),[13][14] and Gurindji Strike highlighted the negative treatment of Indigenous workers in the Northern Territory.[15] From here, the overall plight of Aboriginal Australians became a fundamental political issue.[12] On 7 April 1965, the Menzies Cabinet decided that it would seek to repeal section 127 of the Constitution at the same time as it sought to amend the nexus provision, but made no firm plans or timetable for such action. In August 1965, Attorney-General Billy Snedden proposed to Cabinet that abolition of section 127 was inappropriate unless section 51(xxvi) was simultaneously amended to remove the words "other than the aboriginal race in any state". He was rebuffed, but gained agreement when he made a similar submission to the Holt Cabinet in 1966. In the meantime, his Liberal colleague Billy Wentworth had introduced a private member's bill proposing inter alia to amend section 51(xxvi).[16] In 1964, the Leader of the Opposition, Arthur Calwell, had proposed such a change and pledged that his party, the Australian Labor Party, would back any referendum to that effect.[17] In 1967 the Australian Parliament was unanimous in voting for the alteration Bill. The Australian Board of Missions, the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science, the Australian Aborigines League, the Australian Council of Churches, the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI), and spokespeople such as Ruby Hammond, Bill Onus and Faith Bandler are just some of the many groups and individuals who effectively utilised the media and their influential platforms to generate the momentum needed to achieve a landslide "Yes" vote.[18][12] |

1901

年、検事総長のアルフレッド・ディーキンは憲法の第127条の意味について法的見解を示した[9]。第127条は連邦または州の国民の数を計算する際に

「原住民」を数えることから除外した[9]。彼の法的助言は「ハーフカスト」は「原住民」ではないとのことである[9]。 1967年以前の国勢調査では、「ハーフカスト」と「フルブラッド」の数を確定するためにアボリジニの人種について質問していました[10][b]。その後、検事総長の法的助言に従って「フルブラッド」が公式の人口数から差し引かれていた[10]。 投票までの数年間、個人と先住民・非住民の両グループによる強力な活動が、1967年の国民投票の成功を大きく後押しした。1944年の住民投票では失敗 したものの、1960年代までアボリジニの権利に関する変化はほとんどなかった。 [15] ここから、オーストラリアのアボリジニの全体的な窮状が基本的な政治問題となった[12]。 1965年4月7日、メンジース内閣は、縁故規定の改正を求めると同時に憲法第127条の廃止を求めることを決定したが、そのための確たる計画やスケ ジュールは示さなかった。1965年8月、ビリー・スネデン司法長官は内閣に対し、第51条26項を同時に改正して「いずれかの州における原住民以外の人 種」という文言を削除しない限り、第127条の廃止は不適切であると提案しました。彼は拒否されたが、1966年にホルト内閣に同様の提案をしたところ、 同意を得た。一方、自由党の同僚であるビリー・ウェントワースは、特に第51条(xxvi)の改正を提案する私的議員法案を提出していた[16]。 1964年には、野党党首のアーサー・カルウェルがそのような変更を提案し、自党であるオーストラリア労働党がその趣旨の国民投票を支持すると公約していた[17]。 1967年、オーストラリア議会は全会一致で変更法案に賛成した。 オーストラリア宣教会、オーストラリア科学振興協会、オーストラリア・アボリジンズ・リーグ、オーストラリア教会協議会、アボリジニ・トレス海峡諸島民振 興連邦評議会(FCAATSI)、ルビー・ハモンド、ビル・オナス、フェイス・バンドラーなどのスポークスマンは、メディアと影響力のあるプラットフォー ムを有効に活用して、地滑り的に「賛成」投票を達成するのに必要な勢いを生み出すことになった多くの団体や個人の一例に過ぎない[18][12]。 |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

Voters were asked to approve, together, changes to two provisions in the Constitution section 51(xxvi) and section 127. Section 51 begins: The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to:[19] And the extraordinary clauses that follow (ordinarily referred to as "heads of power") list most of the legislative powers of the federal parliament. The amendment deleted the text in bold from subsection xxvi (known as the "race" or "races" power): The people of any race, other than the aboriginal race in any State, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws;[19] The amendment gave the Commonwealth parliament power to make "special laws" with respect to Aborigines living in a state; the parliament already had unfettered power in regard to territories under section 122 of the Constitution. The intent was that this new power for the Commonwealth would be used only beneficially, though the High Court decision in Kartinyeri v Commonwealth,[20] was that the 1967 amendment did not impose such a restriction and the power could be used to the detriment of an identified race.[21] The Hindmarsh Island bridge controversy,[16][20] and the Northern Territory Intervention are two circumstances where the post-1967 race power has arguably been used in this way.[22] Section 127 was wholly removed. Headed "Aborigines not to be counted in reckoning population", it had read: In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives shall not be counted.[23] The Constitution required the calculation of "the people" for several purposes in sections 24, 89, 93 and 105.[24][25] Section 89 related to the imposition of uniform customs duties and operated until 1901.[26][27] Section 93 related to uniform custom duties after being imposed by section 89 and operated until 1908.[26] Section 105 related to taking over state debts and was superseded by section 105A inserted in the Constitution in 1929 following the 1928 referendum.[27][28] Accordingly, in 1967 only section 24 in relation to the House of Representatives had any operational importance to section 127.[24] Section 24 "requires the membership of the House of Representatives to be distributed among the States in proportion to the respective numbers of their people".[27] The number of people in section 24 is calculated using the latest statistics of the Commonwealth which are derived from the census.[29][30] Section 51(xi) of the Constitution enabled the Parliament to make laws for "census and statistics" and it exercised that power to pass the Census and Statistics Act 1905.[31][29] |

有権者は、憲法第51条(xxvi)と第127条の2つの条項の変更について、共に承認するよう求められた。 第51条はこう始まる。 議会は、この憲法に従い、以下に関して、連邦の平和、秩序および善政のために法律を制定する権限を有する[19]。 そして、その後に続く特別条項(通常「権力の長」と呼ばれる)は、連邦議会の立法権のほとんどを列挙している。修正案は、第XVI節(「人種」または「民族」権として知られる)から太字の文章を削除した。 特別な法律を制定する必要があるとみなされる、あらゆる州の原住民以外のあらゆる人種の人々[19]。 連邦議会は、憲法第122条のもと、領土に関する自由な権力をすでに持っていたのである。しかし、Kartinyeri v Commonwealthの高等裁判所の判決[20]では、1967年の改正はそのような制限を課しておらず、特定人種の不利益のためにこの権力が使われ る可能性があるとされた[21]。 Hindmarsh Island bridge controversy, [16] [20] and the Northern Territory Interventionは、1967年の後の人種権力が間違いなくこの方法で使われた状況2例となる[22]。 127条は全面的に削除された。アボリジニは人口の計算に入れない」という見出しで、次のような内容であった。 連邦、または連邦の州やその他の地域の国民の数を計算する際に、原住民は数えられてはならない[23]。 憲法は第24条、89条、93条、105条においていくつかの目的のために「国民」の算出を要求した[24][25]。89条は一律関税の賦課に関するも ので、1901年まで運用された[26][27]。93条は89条で賦課された後の一律関税に関するもので1908年まで運用された。 [26] 第105条は国債の引継ぎに関するもので、1928年の国民投票を経て1929年に憲法に挿入された105A条によって置き換えられた[27][28]。 したがって、1967年には衆議院に関する第24条のみが第127条と運用上重要であった[24]。 第24条は「下院の議員をそれぞれの州の人口数に比例して州に分配することを要求する」[27]。第24条の人口数は、国勢調査から得られる連邦の最新の 統計を使って計算される[29][30]。 憲法51条(xi)により議会は「センサスおよび統計」についての法律を制定することができ、その権限を行使して1905年にセンサス・統計法を通過させ た[31][29]。 |

| What the referendum did not do |

Give voting rights It is frequently stated that the 1967 referendum gave Aboriginal people Australian citizenship and that it gave them the right to vote in federal elections; however this is not the case.[16][32][33] From 1944 Aboriginal people in Western Australia could apply to become citizens of the state,[34] which gave them various rights, including the right to vote. This citizenship was conditional on adopting "the manner and habits of civilised life"[35] and not associating with Aboriginal people other than their parents, siblings, children,[c] or grandchildren,[d] and could be taken away at any time.[35] This situation continued until 1971.[32][33] Most Indigenous Australians continued to be denied the right to vote in elections for the Australian Parliament even after 1949.[16] The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1949 gave Aboriginal people the right to vote in federal elections only if they were able to vote in their state elections (they were disqualified from voting altogether in Queensland, while in Western Australia and in the Northern Territory the right was conditional), or if they had served in the defence force.[36] The Commonwealth Electoral Act 1962 gave all Aboriginal people the option of enrolling to vote in federal elections.[37] It was not until the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 1983 that voting became compulsory for Aboriginal people, as it was for other Australians.[38][39] Aboriginal people (and all other people) living in the Northern Territory were not allowed to vote in the referendum, which remained the case for both the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory until the Constitutional amendment to section 128 after a referendum in 1977.[23] |

投票権の付与 1967年の国民投票によってアボリジニにオーストラリア市民権が与えられ、連邦選挙の投票権も与えられたとよく言われるが、これは事実ではない[16][32][33]。 1944年から西オーストラリア州のアボリジニは州の市民権を申請することができ[34]、投票権を含む様々な権利が与えられた。この市民権は、「文明的 生活の方法と習慣」[35]を採用し、親、兄弟、子、孫以外のアボリジニと付き合わないことが条件であり[d]、いつでも取り上げることができた。 この状況は1971年まで続いた[32][33] オーストラリア先住民のほとんどは、1949年以降もオーストラリア議会の選挙で投票権を拒否され続けていた。 [1949年の連邦選挙法では、アボリジニは州選挙で投票できる場合(クイーンズランド州では完全に投票権を失い、西オーストラリア州とノーザンテリト リーでは条件付きであった)、または国防軍に所属していた場合のみ連邦選挙で投票する権利を与えられた[36]。 1962年の連邦選挙法では、すべてのアボリジニに連邦選挙の投票権登録の選択肢が与えられました[37]。 1983年の連邦選挙改正法まで、他のオーストラリア人と同様にアボリジニに投票が義務付けられるようにはならなかった[38][39]。 ノーザン・テリトリーに住むアボリジニ(および他のすべての人々)は住民投票に参加することができず、1977年の住民投票の後に128条が憲法改正されるまで、ノーザン・テリトリーとオーストラリア首都特別地域はこのままであった[23]。 |

| Supersede a "Flora and Fauna Act" |

It

is also sometimes mistakenly stated that the 1967 referendum overturned

a "Flora and Fauna Act". This is believed to have come from the New

South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974, which controlled

Aboriginal heritage, land, and culture. The other states had equivalent

Acts, which were managed by various departments, including those

relating to agriculture and fishing.[33] |

ま

た、1967年の住民投票で「動植物法」が覆されたと誤解されていることがある。これは、アボリジニの遺産、土地、文化を管理するニューサウスウェールズ

州国立公園・野生生物法(1974年)に由来すると考えられている。他の州にも同等の法律があり、農業や漁業に関するものなど、様々な部門によって管理さ

れていた[33]。 |

| Question |

DO

YOU APPROVE the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution

entitled— 'An Act to alter the Constitution so as to omit certain words

relating to the People of the Aboriginal Race in any State and so that

Aboriginals are to be counted in reckoning the Population'?[40] |

あなたは、「いずれかの州のアボリジニ人種の人々に関する特定の言葉を省略し、アボリジニが人口を計算する際に数えられるように、憲法を変更するための法律」と題する、憲法の変更に関する提案に賛成しますか[40]。 |

|

結果 |

|

| Legacy |

Ninety

percent of voters voted yes, and the overwhelming support gave the

Federal Government a clear mandate to implement policies to benefit

Aboriginal people. A lot of misconceptions have arisen as to the

outcomes of the referendum, some as a result of it taking on a symbolic

meaning during a period of increasing Aboriginal self-confidence. It

was some five years before any real change occurred as a result of the

referendum,[16] but federal legislation has since been enacted covering

land rights,[43][44] discriminatory practices,[45] financial

assistance,[46][47] and preservation of cultural heritage.[48] The referendum result had two main outcomes: The first was to alter the legal boundaries within which the Federal Government could act. The Federal Parliament was given a constitutional head-of-power under which it could make special laws "for" Aboriginal people (for their benefit or, as has the High Court has made clear,[20] their detriment) in addition to other "races".[49] The Australian Constitution states that federal law prevails over state law, where they are inconsistent, so that the Federal Parliament could, if it so chose, enact legislation that would end discrimination against Aboriginal people by state governments.[50] However, during the first five years following the referendum the Federal Government did not use this new power.[16][51] The other key outcome of the referendum was to provide Aboriginal people with a symbol of their political and moral rights. The referendum occurred at a time when Aboriginal activism was accelerating, and it was used as a kind of "historical shorthand" for all the relevant political events of the time, such as the demands for land rights by the Gurindji people, the equal-pay case for pastoral workers, and the "Freedom Rides" to end segregation in New South Wales. This use as a symbol for a period of activism and change has contributed to the misconceptions about the effects of the constitutional changes themselves.[16] |

投

票者の90%が賛成票を投じ、圧倒的な支持を得て、連邦政府はアボリジニーの人々のためになる政策を実施することが明確に命じられた。この国民投票の結果

については、アボリジニーの自信の高まりの中で象徴的な意味を持つものとして、多くの誤解が生まれた。住民投票の結果、実際に変化が起こるまでには5年ほ

どかかったが[16]、その後、土地の権利、差別的慣習、財政支援、文化遺産の保護[46][47]などを対象とした連邦法が制定された[48]。 住民投票の結果には2つの主要な成果があった。 1つ目は、連邦政府が行動できる法的境界を変更することであった。連邦議会は、他の「人種」に加えて、アボリジニの「ために」(彼らの利益のため、あるい は高等法院が明らかにしたように[20]彼らの不利益のために)特別な法律を制定できる憲法上の首長権を持っていたのである[49]。 [49] オーストラリア憲法は、州法と連邦法が矛盾する場合には、連邦法が州法に優先すると定めており、連邦議会は、その選択により、州政府によるアボリジニに対 する差別をなくすための法律を制定することができた[50]。 しかし、国民投票後の最初の5年間、連邦政府はこの新しい権限を行使することはなかった[16][51]。 国民投票のもう一つの重要な成果は、アボリジニーの人々に彼らの政治的・道徳的権利の象徴を提供したことであった。国民投票は、アボリジニーの活動が加速 していた時期に行われ、グリンジ族による土地権利の要求、牧畜労働者の同一賃金訴訟、ニューサウスウェールズでの隔離を終わらせるための「フリーダムライ ド」など、当時のあらゆる関連政治事件の一種の「歴史の省略形」として使われるようになった。このように、活動や変化の時代の象徴として使われたことが、 改憲の効果そのものに対する誤解を生む一因となった[16]。 |

| Symbolic effect The 1967 referendum has acquired a symbolic meaning in relation to a period of rapid social change during the 1960s. As a result, it has been credited with initiating political and social change that was the result of other factors. The real legislative and political impact of the 1967 referendum has been to enable, and thereby compel, the federal government to take action in the area of Aboriginal Affairs. Federal governments with a broader national and international agenda have attempted to end the discriminatory practices of state governments such as Queensland and to introduce policies that encourage self-determination and financial security for Aboriginal people. However, the effectiveness of these policies has been tempered by an unwillingness of most federal governments to deal with the difficult issues involved in tackling recalcitrant state governments.[52] |

象徴的な効果 1967年の国民投票は、1960年代の急激な社会変化の時期との関連で象徴的な意味を持つようになった。その結果、他の要因の結果であった政治的・社会 的変化を開始させたと評価されてきた。1967年の国民投票がもたらした実際の立法的、政治的影響は、連邦政府がアボリジニ問題の分野で行動を起こすこと を可能にし、それによって強制されたことである。国内外に幅広い課題を持つ連邦政府は、クイーンズランド州などの州政府の差別的な慣習を終わらせ、アボリ ジニーの人々の自己決定と経済的保障を促す政策を導入しようとした。しかし、これらの政策の有効性は、ほとんどの連邦政府が、反抗的な州政府への取り組み に伴う困難な問題に対処しようとしないことによって、弱められてきた[52]。 |

|

| Land rights The benefits of the referendum began to flow to Aboriginal people in 1972. On 26 January 1972, Aboriginal peoples erected the Aboriginal Tent Embassy on the lawns of the Federal Parliament building in Canberra to express their frustration at the lack of progress on land rights and racial discrimination issues. This became a major confrontation that raised Aboriginal affairs high on the political agenda in the federal election later that year. One week after gaining office, the Whitlam Government (1972–1975) established a Royal Commission into land rights for Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory under Justice Woodward.[53] Its principal recommendations, delivered in May 1974, were: that Aboriginal people should have inalienable title to reserve lands; that regional land councils should be established; to establish a fund to purchase land with which Aboriginal people had a traditional connection, or that would provide economic or other benefits; prospecting and mineral exploration on Aboriginal land should only occur with their consent (or that of the Federal Government if the national interest required it); entry onto Aboriginal land should require a permit issued by the regional land council. The recommendations were framed in terms to enable application outside the Northern Territory. The Federal Government agreed to implement the principal recommendations and in 1975 the House of Representatives passed the Aboriginal Councils and Associations Bill and the Aboriginal Land (Northern Territory) Bill, but the Senate had not considered them by the time parliament was dissolved in 1975.[54] The following year, the Fraser government (1975–1983) amended the Aboriginal Land (Northern Territory) Bill by introducing the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Bill. The new bill made a number of significant changes such as limitation on the operations and boundaries of land councils; giving Northern Territory law effect on Aboriginal land, thereby enabling land rights to be eroded; removing the power of land councils to issue permits to non-Aboriginal people; and allowing public roads to be built on Aboriginal land without consent. This bill was passed as the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976.[55] It is significant however that this legislation was implemented at all, given the political allegiances of the Fraser Government, and shows the level of community support for social justice for Aboriginal people at the time.[56] |

土地の権利 住民投票の恩恵がアボリジニーの人々に流れ始めたのは1972年のことである。1972年1月26日、アボリジニーの人々はキャンベラの連邦議会ビルの芝 生にアボリジニーテント大使館を建て、土地の権利と人種差別の問題が進展しないことへの不満を表明した。これは、同年末の連邦選挙でアボリジニ問題を政治 課題の上位に上げる大きな対立軸となった。ウィットラム政権(1972-1975)は、大統領就任の1週間後にウッドワード判事の下でノーザンテリトリー のアボリジニの土地権利に関する王立委員会を設立した[53]。 [その主な勧告は1974年5月に発表され、アボリジニは保護区の土地に対して譲れない権利を持つべきである、地域土地評議会を設立すべきである、アボリ ジニが伝統的に関係のある土地や、経済やその他の利益をもたらす土地を購入するための基金を設立すべきである、アボリジニの土地での試掘や鉱物探査は彼ら の同意(または国益が必要な場合は連邦政府の同意)がなければ行われるべき、アボリジニの土地への立ち入りには地域土地評議会による許可が必要べきであ る、というものであった。この勧告は、ノーザンテリトリー以外の地域でも適用できるように構成されていた。連邦政府は主要な勧告を実施することに同意し、 1975年に下院はアボリジニ評議会と協会法案とアボリジニ土地(ノーザンテリトリー)法案を可決したが、1975年の議会解散までに上院での審議は行わ れなかった[54]。 翌年、フレーザー政権(1975-1983)は、アボリジナル土地(ノーザンテリトリー)法案を修正し、アボリジナル土地権利(ノーザンテリトリー)法案 を提出した。この新法案は、土地評議会の運営と境界を制限すること、アボリジニの土地に北部準州の法律を効力が及ぶようにし、それによって土地の権利が侵 食されるようにすること、土地評議会が非アボリジニの人々に許可を出す権限をなくすこと、アボリジニの土地に同意なしに公道を建設できるようにするなど、 多くの重要な変更を加えている。この法案は、アボリジニ土地権利法1976として可決された[55]。しかし、フレーザー政府の政治的忠誠心を考えると、 この法案が全く実施されなかったことは重要であり、当時のアボリジニの社会正義に対するコミュニティの支持のレベルを示している[56]。 |

|

| Use of "race power" in legislation The Whitlam Government used its constitutional powers to overrule racially discriminatory state legislation. On reserves in Queensland, Aboriginal people were forbidden to gamble, use foul language, undertake traditional cultural practices, indulge in adultery, or drink alcohol. They were also required to work without payment.[57] In the Aboriginal Courts in Queensland the same official acted as judge as well as the prosecuting counsel.[58] Defendants almost invariably pleaded "guilty" as pleas of "not guilty" were more than likely to lead to a longer sentence.[59] The Whitlam Government, using the "race power", enacted the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (Queensland Discriminatory Laws) Act 1975 to override the state laws and eliminate racial discrimination against Aboriginal people.[50] No federal government ever enforced this Act.[60] The race power was also used by the Whitlam Government to positively discriminate in favour of Aboriginal people. It established schemes whereby Aboriginal people could obtain housing, loans, emergency accommodation and tertiary education allowances.[47] It also increased funding for the Aboriginal Legal Service enabling twenty-five offices to be established throughout Australia.[61] The race power gained in the 1967 referendum has been used in several other pieces of significant Federal legislation. One of the pieces of legislation enacted to protect the Gordon River catchment used the race power but applied it to all people in Australia. The law prohibited anyone from damaging sites, relics and artefacts of Aboriginal settlement in the Gordon River catchment.[62] In the Tasmanian Dam Case,[63] the High Court held that even though this law applied to all people and not only to Aboriginal people, it still constituted a special law.[64] In the 1992 Mabo judgement, the High Court of Australia established the existence of Native Title in Australian Common Law.[65] Using the race power, the Keating Government enacted the Native Title Act 1993 and successfully defended a High Court challenge from the Queensland Government.[66] |

立法における「人種権」の利用 ウィットラム政権は、憲法上の権限を行使し、人種差別的な州法を覆した。クイーンズランド州の保留地では、アボリジニは賭博、汚い言葉の使用、伝統的な文 化的慣習、姦通、飲酒を禁じられていた。クイーンズランド州のアボリジニ法廷では、同じ職員が裁判官として、また検察側の弁護士として働いていました [58]。 [59] ウィットラム政権は、「人種権力」を利用して、州法を上書きし、アボリジニに対する人種差別を撤廃するために、1975年にアボリジニ・トレス海峡諸島民 (クイーンズランド州差別法)法を制定した[50] 連邦政府はこの法律を施行したことはない[60]。 人種権力は、ウィットラム政府によってアボリジニを積極的に差別するためにも利用された。それは、アボリジニーの人々が住宅、ローン、緊急宿泊施設、高等 教育手当を得ることができる制度を設立した[47]。 また、アボリジニー法務サービスに対する資金を増やし、オーストラリア中に25の事務所を設立することができるようにした[61]。 1967年の国民投票で獲得された民族の権限は、他のいくつかの重要な連邦法に利用された。ゴードン川の流域を保護するために制定された法律のひとつは、 民族の力を利用したものであったが、オーストラリアのすべての人々に適用されるものであった。この法律は、ゴードン川流域のアボリジニ入植の遺跡、遺物、 工芸品を損傷することを禁じていた[62]。タスマニアダム事件[63]において、高等法院は、この法律がアボリジニだけでなく全ての人々に適用されると しても、特別法を構成していると判断している[64]。 1992年のマボ判決において、オーストラリア高等法院はオーストラリアの慣習法における先住民の権利の存在を確立した[65]。 レースパワーを用いて、キーティング政権は1993年に先住民の権利法を制定し、クイーンズランド州政府からの高等法院の挑戦を見事に退けた[66]。 |

|

| Benefits of demographic count One last impact of the referendum has been the benefits of counting all Indigenous Australians flowing from the removal of counting "aboriginal natives" ("full-blood") in the official population statistics.[67] Without official statistics as to their number, age structure or distribution, it was not possible for government agencies to establish soundly-based policies for serving Indigenous Australians, especially in the area of health. The availability of demographic data following the 1971 census (and onwards) relating to Indigenous Australians enabled the determination and monitoring of key health indicators such as infant mortality rates and life expectancy. Indigenous Australians life expectancy, especially for males, was significantly lower than the average population. Infant mortality rates in the early 1970s were among the highest in the world. Substantial improvements had occurred by the early 1990s[68] but Indigenous Australians health indicators still lag behind those of the total population, especially for those living in remote areas. The Close the Gap campaign highlighted these deficits, and the federal government developed its Closing the Gap strategy to address these and other issues.[69] |

人口計算の利点 国民投票の最後の影響として、公式の人口統計において「原住民」(「完全血族」)のカウントがなくなったことにより、すべてのオーストラリア先住民をカウ ントするメリットが生まれた[67]。 彼らの数、年齢構成、分布に関する公式統計がなければ、政府機関は、特に健康分野において、オーストラリア先住民のために健全に基づいた政策を確立するこ とができなかったのである。1971年の国勢調査以降、オーストラリア先住民に関する人口統計データが入手可能になったことで、乳児死亡率や平均寿命な ど、主要な健康指標の決定と監視が可能になった。オーストラリア先住民の平均寿命、特に男性の平均寿命は、平均的な人口よりも著しく低いものであった。 1970年代初頭の乳幼児死亡率は、世界で最も高い水準にあった。1990年代初頭までにかなりの改善がみられたが[68]、オーストラリア先住民の健康 指標は、特に遠隔地に住む人々にとっては、依然として全人口のそれと比べて遅れをとっている。Close the Gapキャンペーンはこれらの赤字を強調し、連邦政府はこれらの問題やその他の問題に対処するためにClosing the Gap戦略を策定した[69]。 |

|

| Negative application of "race power" When John Howard's Coalition government came to power in 1996, it intervened in the Hindmarsh Island bridge controversy in South Australia with legislation that introduced an exception to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984,[70] to allow the bridge to proceed.[71] The Ngarrindjeri challenged the new legislation in the High Court on the basis that it was discriminatory to declare that the Heritage Protection Act applied to sites everywhere but Hindmarsh Island, and that such discrimination – essentially on the basis of race – had been disallowed since the Commonwealth was granted the power to make laws with respect to the "Aboriginal race" as a result of the 1967 Referendum. The High Court decided, by a majority, that the amended s.51(xxvi) of the Constitution still did not restrict the Commonwealth parliament to making laws solely for the benefit of any particular "race", but still empowered the parliament to make laws that were to the detriment of any race.[20][21][72] This decision effectively meant that those people who had believed that they were casting a vote against the discrimination of Indigenous people in 1967 had in fact allowed the Commonwealth to participate in the discrimination against Indigenous people which had been practised by the states.[16] |

"人種パワー "の否定的な適用 1996年にジョン・ハワードの連合政権が誕生すると、南オーストラリア州のヒンドマーシュ島の橋の論争に介入し、橋の建設を許可するために1984年の アボリジニ・トレス海峡諸島民文化遺産保護法 [70] に例外を導入する法案を提出することになった。 [71] ナリンジェリ族は、遺産保護法がヒンドマーシュ島以外のすべての場所に適用されると宣言するのは差別であり、1967年の国民投票の結果、連邦が「アボリ ジニ民族」に関する法律を制定する権限を与えられて以来、このような差別(基本的に人種に基づく)は認められないとして、高等裁判所でこの新法に異議を唱 えた。高等法院は、多数決で、改正された憲法51条(xxvi)を認めました。 (この決定は、1967年に先住民の差別に反対する票を投じていると信じていた人々が、実際には連邦が州によって行われてきた先住民に対する差別に参加す ることを認めていたことを事実上意味していた[20][21][72]。 |

|

| significant links |

Council for Aboriginal Rights History of Australia Politics of Australia Referendums in Australia Voting rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1967_Australian_referendum_%28Aboriginals%29 |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報