Indigenous peoples of the Americas, so called "Amerindian"

アメリカスにおける先住民

Indigenous peoples of the Americas, so called "Amerindian"

池田光穂

アメリインディアン(amerindian) と は、新大陸であるアメリカ(合州国のことではなく、南北両米大陸のこと)の先住民のことをさす。アメリカインディアン(america indian)の短縮形とも考えるが、多くの文脈では、北アメリカ先住民の——アメリカ合州国のテリトリー内の ——ことをさすために、このような呼び方が代替的に使われてきたようだ。OEDには、amerindian の同義の名詞あるいは形容詞として amerind と使われているとの指摘があり、同辞書によると20世紀の初頭からであるという。その用例は、

1900 Ann. Rep. Bur. Amer. Ethnol. 1897–98 i. p. xlviii, The tribal fraternities of the Amerinds. Ibid. ii. 835 The four worlds of widespread Amerindian mythology. 1901 Dellenbaugh N.-Americans Yest. 247 The communal principle of living had much to do almost everywhere with the size and character of the Amerind houses. 1902 Man II. 101 A group of Amerind tribes are known as Algonquians.

とある。しかしながら、現在の用法だと、南米の先住 民のことを意味することが多く。ウィキペディア(英語)の項目"Indigenous peoples of the Americas"には、アルゼンチン(スペイン語圏)では、アボリヘン(Aborígen)と呼ぶが、ガイアナ (英連邦加盟国)ではアメリインディアンと呼び、他の国でもそれに準ずる呼称をしていると記述し、その根拠を、世界的な規模の非営利・非政府系の先住民保 護団体であるサバイバル・インターナショナルの用語法のウェブページから引いている(http: //www.survivalinternational.org/info/terminology)。当該箇所のサバイバル・ナショナルの説明では、 なぜガイアナでこのような説明が定着したかというと、同じ英連邦加盟国であるインドの民つまり、インディアンとの区別をつけるために、この用語があるとい うことだ。同様な混同を避ける用法に「西インド諸島」というものがあることは御存知のとおり。ともに、コロンブス一行が新大陸の人たちと出会った時に、そ こをインドと間違えたという逸話から来ている。

先に触れた、ウィキペディアの両アメリカ大陸 (the Americas, las americas)の先住民の項目によると、アメリインディアンの推定人口は約480万人である。アメリインディアン全体の研究は、スミソニアン研究所な どの機関による長年の支援による、Handbook of American Indians North Mexico(1907-1910)、Handbook of North American Indians(1978- )、Handbook of Middle American Indian(1971-1976)、Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians(1981-1985)、Handbook of South American Indians(1940-1947)などが、ある。『南アメリカインディアン・ハンドブック』を編纂したジュリアン・スチュアード(Julian Steward, 1902-1972)によると、南北のアメリカの先住民は文化的にみて、北米と南米の巨大二大集団に分類されて、メソアメリカ より、つまり現在の、ホンジュラス東部より南からパナマにかけては「中間地帯」という両大陸の特徴をもつと説明されている。

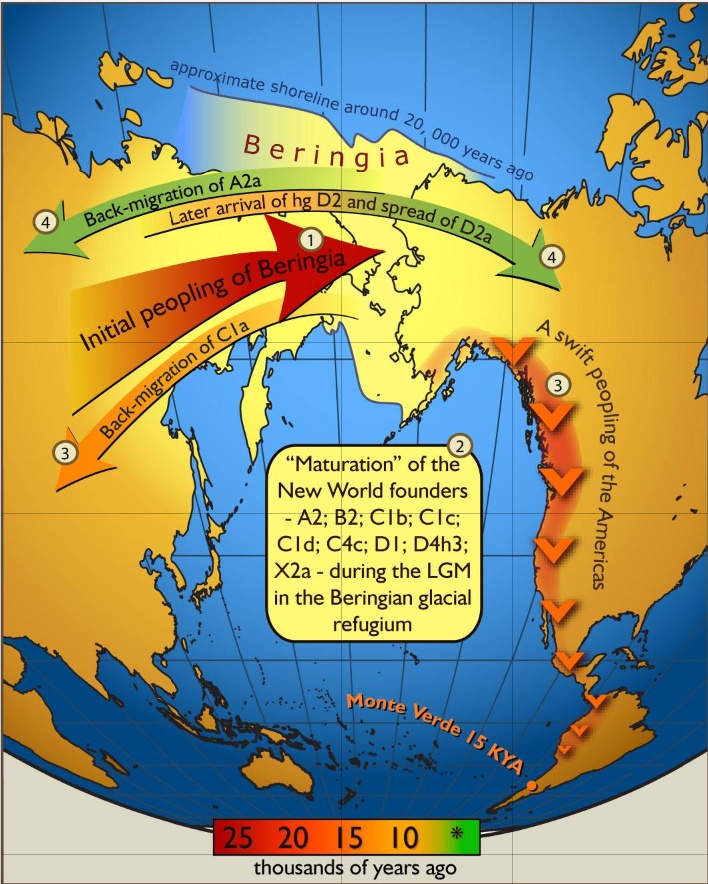

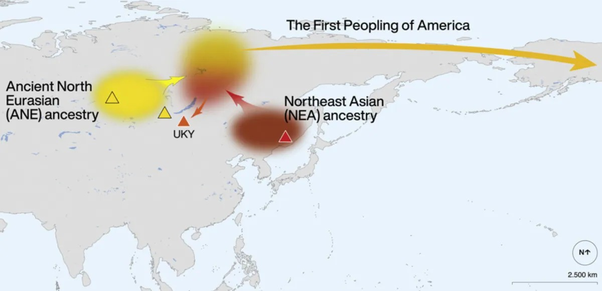

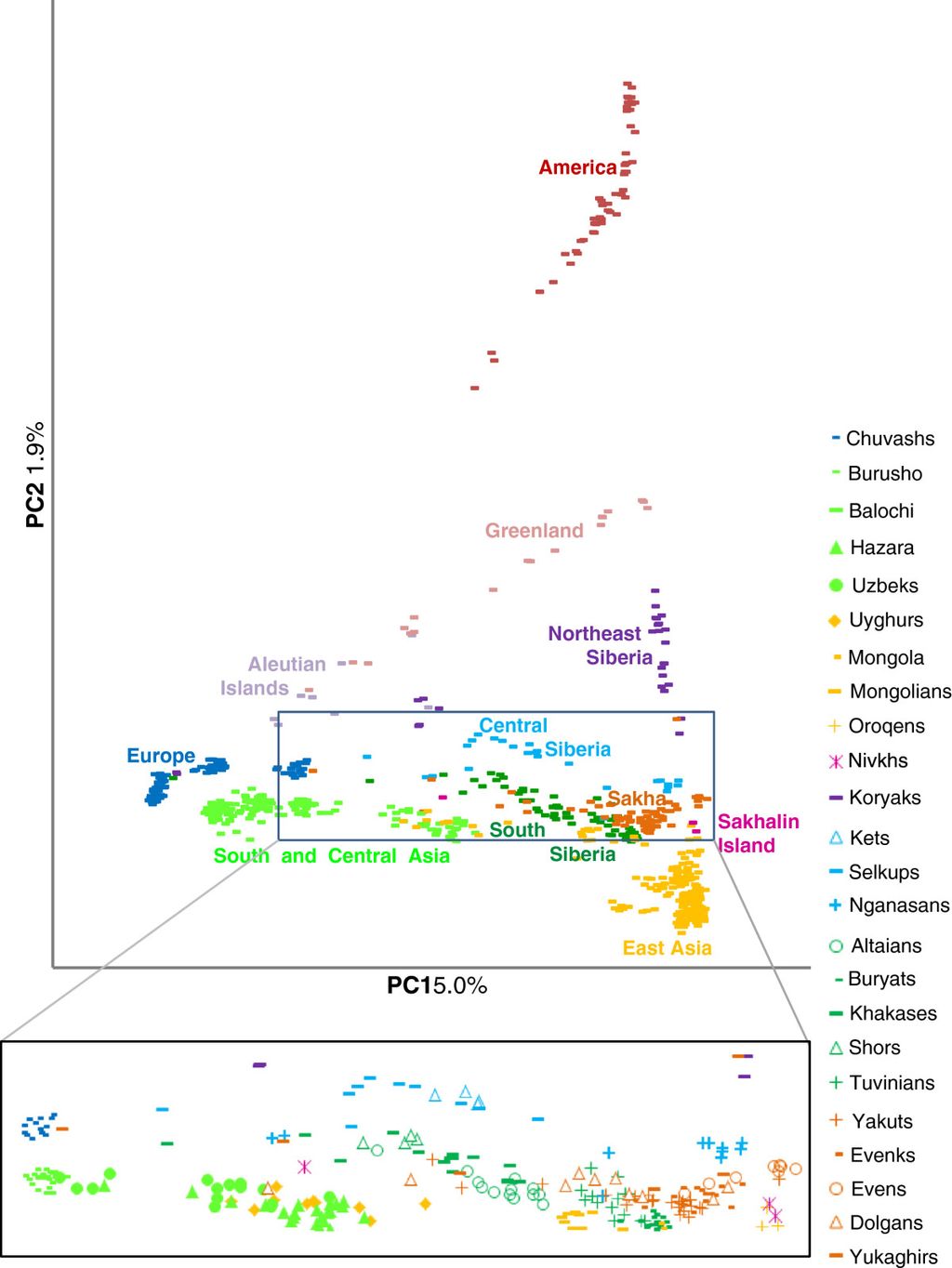

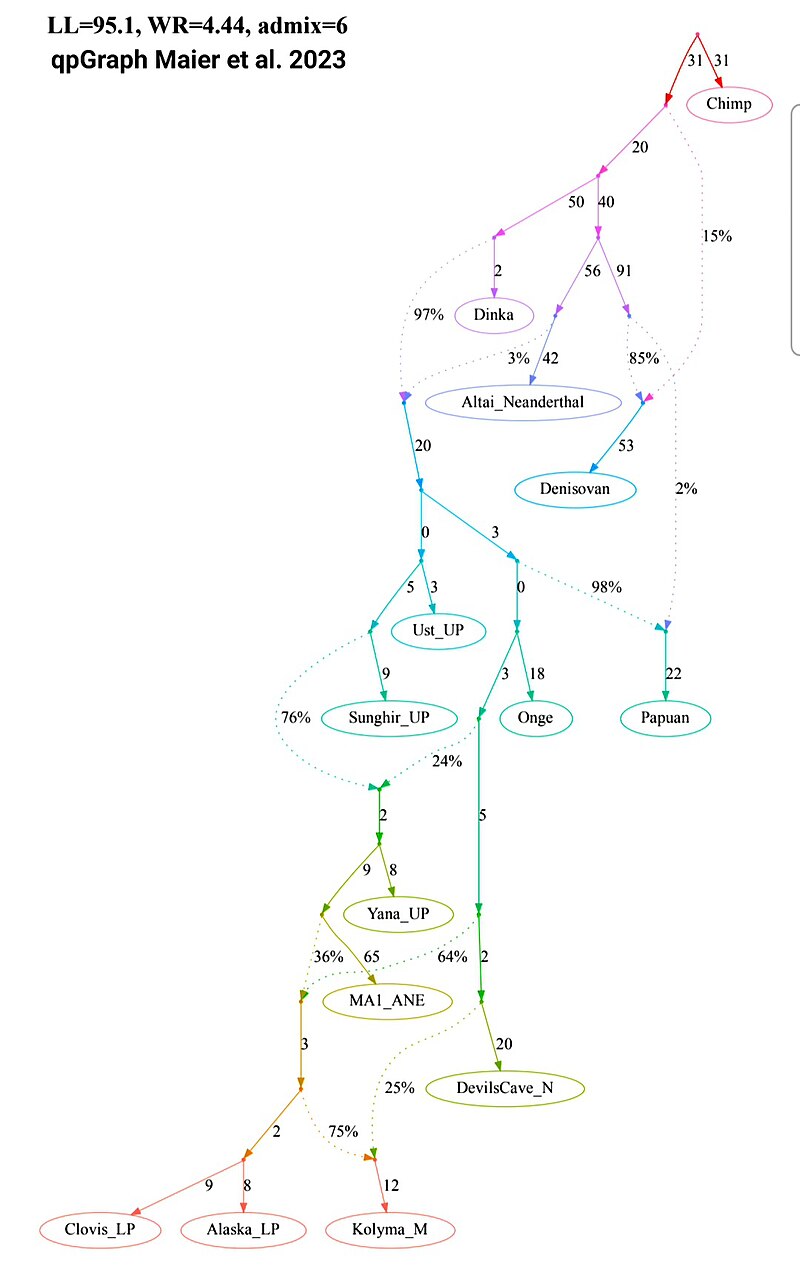

アメリインディアンの末裔は、2万年か2万5千万年 前に、北アメリカ大陸北西端のベーリング海峡が氷により徒歩可能な時期に、シベリアを経由してモンゴ ロイドが移住した末裔であることがわかっている。赤ちゃんにみられる蒙古班や、母から子に伝わるミトコンドリアの遺伝子から、現在の南北両大陸に住むラテ ン系の混血の人たちには、アメリインディアン起源のルーツが認められていて、彼/彼女らの「大いなる母」を共有していることは間違いないようだ。もちろ ん、日本や韓国あるいはモンゴルの人たちにとっては「大いなる伯母」さんにあたるわけだが……。だから、先住民やそうでない民の間の人種差別を正当化した り、国家という了見の狭い統治単位に括られている国民の間での優劣の話をジョークだと考えない連中が、いかにスケールの小さい奴であり、人類の歴史的伝統 を軽視することがこれでおわかりになったことであろう。

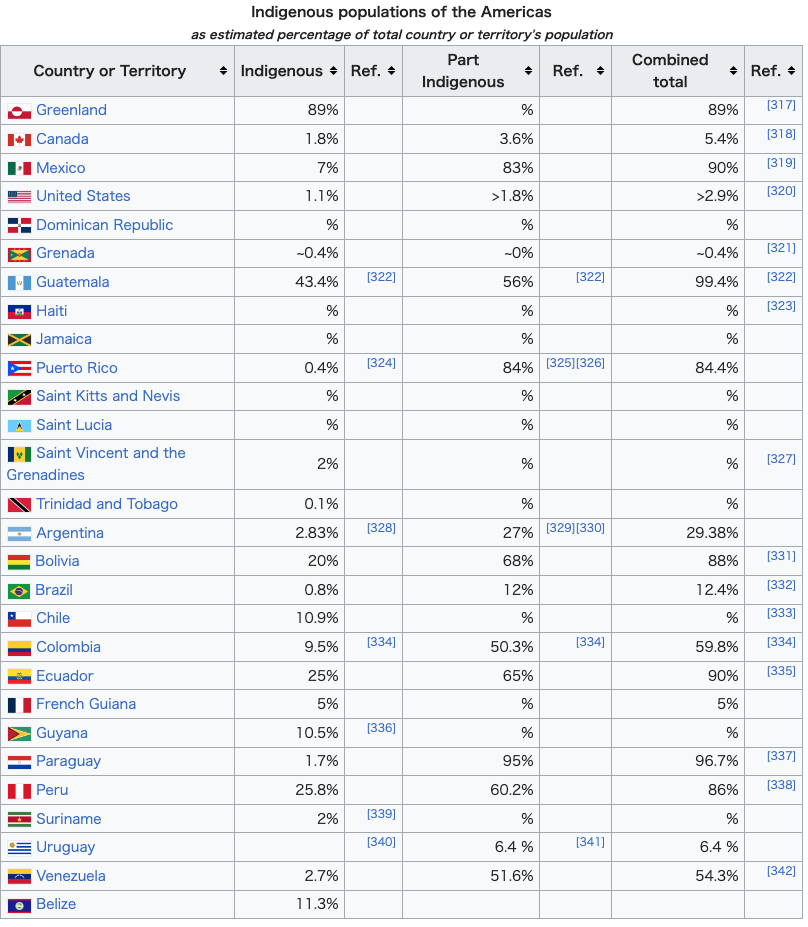

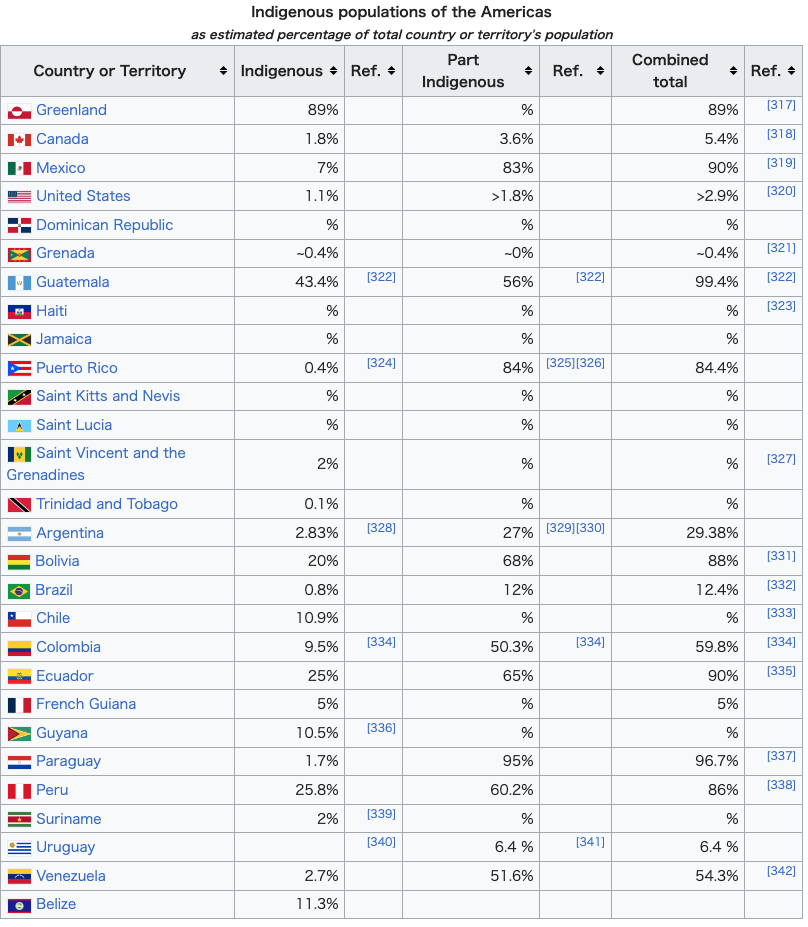

| The Indigenous

peoples of the Americas are the peoples who are native to the Americas

or the Western Hemisphere. Their ancestors are among the pre-Columbian

population of South or North America, including Central America and the

Caribbean. Indigenous peoples live throughout the Americas. While often

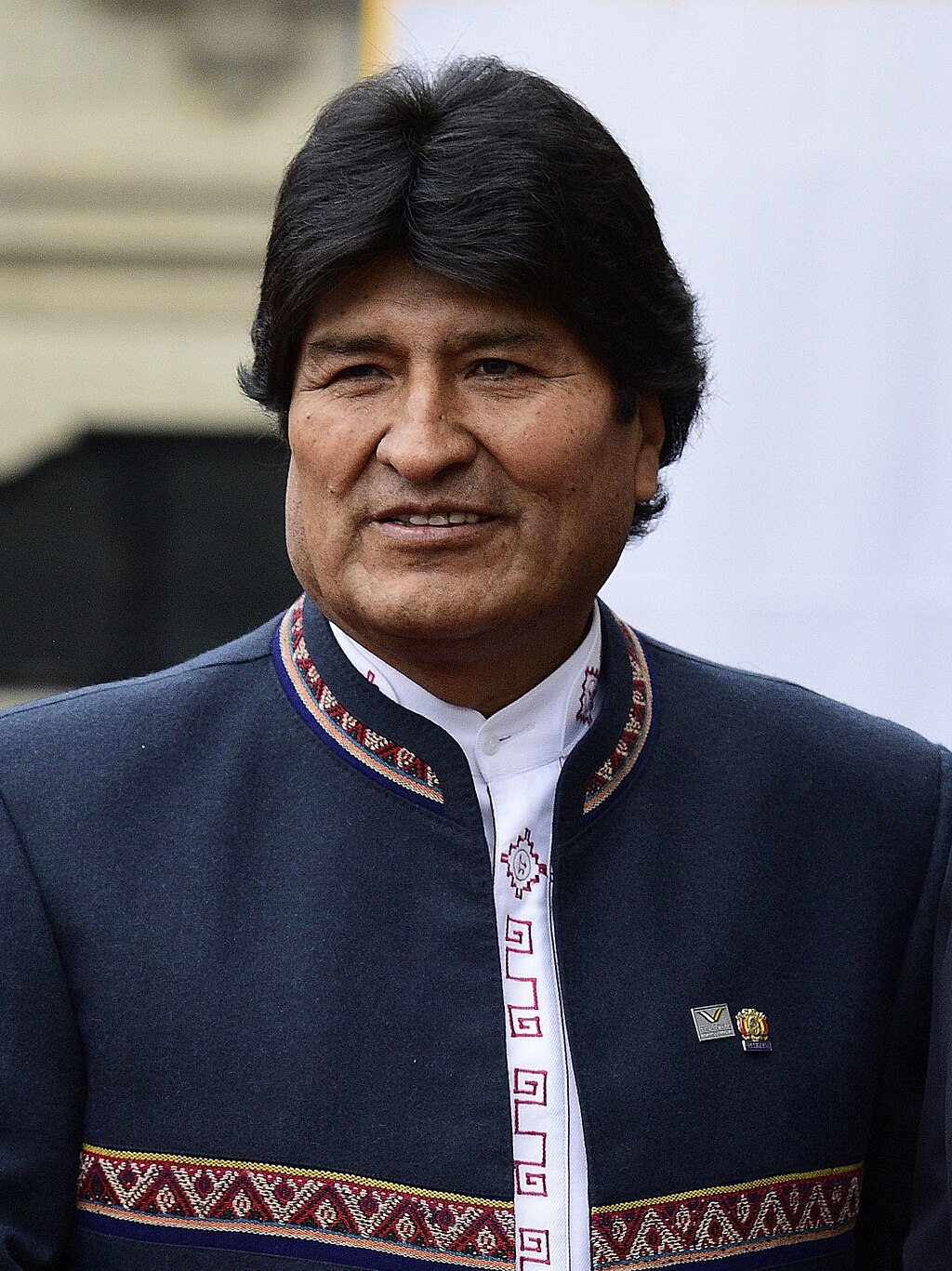

minorities in their countries, Indigenous peoples are the majority in

Greenland[36] and close to a majority in Bolivia[37] and Guatemala.[38] There are at least 1,000 different Indigenous languages of the Americas. Some languages, including Quechua, Arawak, Aymara, Guaraní, Nahuatl, and some Mayan languages, have millions of speakers and are recognized as official by governments in Bolivia, Peru, Paraguay, and Greenland. Indigenous peoples, whether residing in rural or urban areas, often maintain aspects of their cultural practices, including religion, social organization, and subsistence practices. Over time, these cultures have evolved, preserving traditional customs while adapting to modern needs. Some Indigenous groups remain relatively isolated from Western culture, with some still classified as uncontacted peoples. The Americas also host millions of individuals of mixed Indigenous, European, and sometimes African or Asian descent, historically referred to as mestizos in Spanish-speaking countries.[39][40] In many Latin American nations, people of partial Indigenous descent constitute a majority or significant portion of the population, particularly in Central America, Mexico, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Chile, and Paraguay.[41][42][43] Mestizos outnumber Indigenous peoples in most Spanish-speaking countries, according to estimates of ethnic cultural identification. However, since Indigenous communities in the Americas are defined by cultural identification and kinship rather than ancestry or race, mestizos are typically not counted among the Indigenous population unless they speak an Indigenous language or identify with a specific Indigenous culture.[44] Additionally, many individuals of wholly Indigenous descent who do not follow Indigenous traditions or speak an Indigenous language have been classified or self-identified as mestizo due to assimilation into the dominant Hispanic culture. In recent years, the self-identified Indigenous population in many countries has increased as individuals reclaim their heritage amid rising Indigenous-led movements for self-determination and social justice.[45] In past centuries, Indigenous peoples had diverse societal, governmental, and subsistence systems. Some Indigenous peoples were historically hunter-gatherers, while others practiced agriculture and aquaculture. Various Indigenous societies developed complex social structures, including precontact monumental architecture, organized cities, city-states, chiefdoms, states, monarchies, republics, confederacies, and empires.[46] These societies possessed varying levels of knowledge in fields such as engineering, architecture, mathematics, astronomy, writing, physics, medicine, agriculture, irrigation, geology, mining, metallurgy, art, sculpture, and goldsmithing. |

アメリカ大陸の先住民とは、アメリカ大陸または西半球に土着する人々を

指す。彼らの祖先は、中央アメリカやカリブ海地域を含む南北アメリカ大陸のコロンブス以前の住民に属する。先住民はアメリカ大陸全域に居住している。自国

では少数派であることが多いが、グリーンランドでは多数派[36]であり、ボリビア[37]やグアテマラではほぼ多数派に近い。[38] アメリカ大陸には少なくとも1,000の異なる先住民言語が存在する。ケチュア語、アラワク語、アイマラ語、グアラニー語、ナワトル語、および一部のマヤ 語を含むいくつかの言語は、数百万人の話者を有し、ボリビア、ペルー、パラグアイ、グリーンランドの政府によって公用語として認められている。 先住民は、農村部や都市部に居住しているかに関わらず、宗教、社会組織、生業など、自らの文化的慣行の側面を維持していることが多い。時を経て、これらの 文化は進化し、伝統的な慣習を守りつつ現代のニーズに適応してきた。一部の先住民集団は西洋文化から比較的孤立したままであり、未接触部族に分類される集 団も存在する。 アメリカ大陸にはまた、先住民とヨーロッパ人、時にアフリカやアジアの血を引く混血の人が何百万人も住んでいる。スペイン語圏では歴史的に「メスティー ソ」と呼ばれてきた人々だ[39][40]。多くのラテンアメリカ国民では、部分的に先住民の血を引く人々が人口の多数派あるいは相当な割合を占めてお り、特に中央アメリカ、メキシコ、ペルー、ボリビア、エクアドル、コロンビア、ベネズエラ、チリ、パラグアイで顕著である。[41][42][43] 民族の文化的帰属意識に基づく推計によれば、スペイン語圏諸国の大半ではメスティソが先住民を上回る。ただし、アメリカ大陸の先住民コミュニティは祖先や 人種ではなく文化的帰属意識と血縁関係によって定義されるため、メスティソは先住民言語を話したり特定の先住民文化に帰属意識を持たない限り、通常は先住 民人口に算入されない。[44] さらに、先住民の伝統に従わず先住民言語も話さない純粋な先住民血統の多くの人々が、支配的なヒスパニック文化への同化により、メスティソとして分類され たり自己認識したりしている。近年、先住民主導の自己決定と社会正義を求める運動の高まりの中で、自らの遺産を取り戻す動きが広がり、多くの国で自己認識 する先住民人口が増加している。[45] 過去数世紀にわたり、先住民は多様な社会・統治・生業システムを有していた。狩猟採集民であった先住民もいれば、農業や水産業を営む先住民もいた。様々な 先住民社会は、接触以前の記念碑的建造物、組織化された都市、都市国家、首長国、国家、君主制、共和制、連合体、帝国など、複雑な社会構造を発展させた。 [46] これらの社会は、工学、建築、数学、天文学、文字、物理学、医学、農業、灌漑、地質学、鉱業、冶金学、美術、彫刻、金細工などの分野で、様々なレベルの知 識を有していた。 |

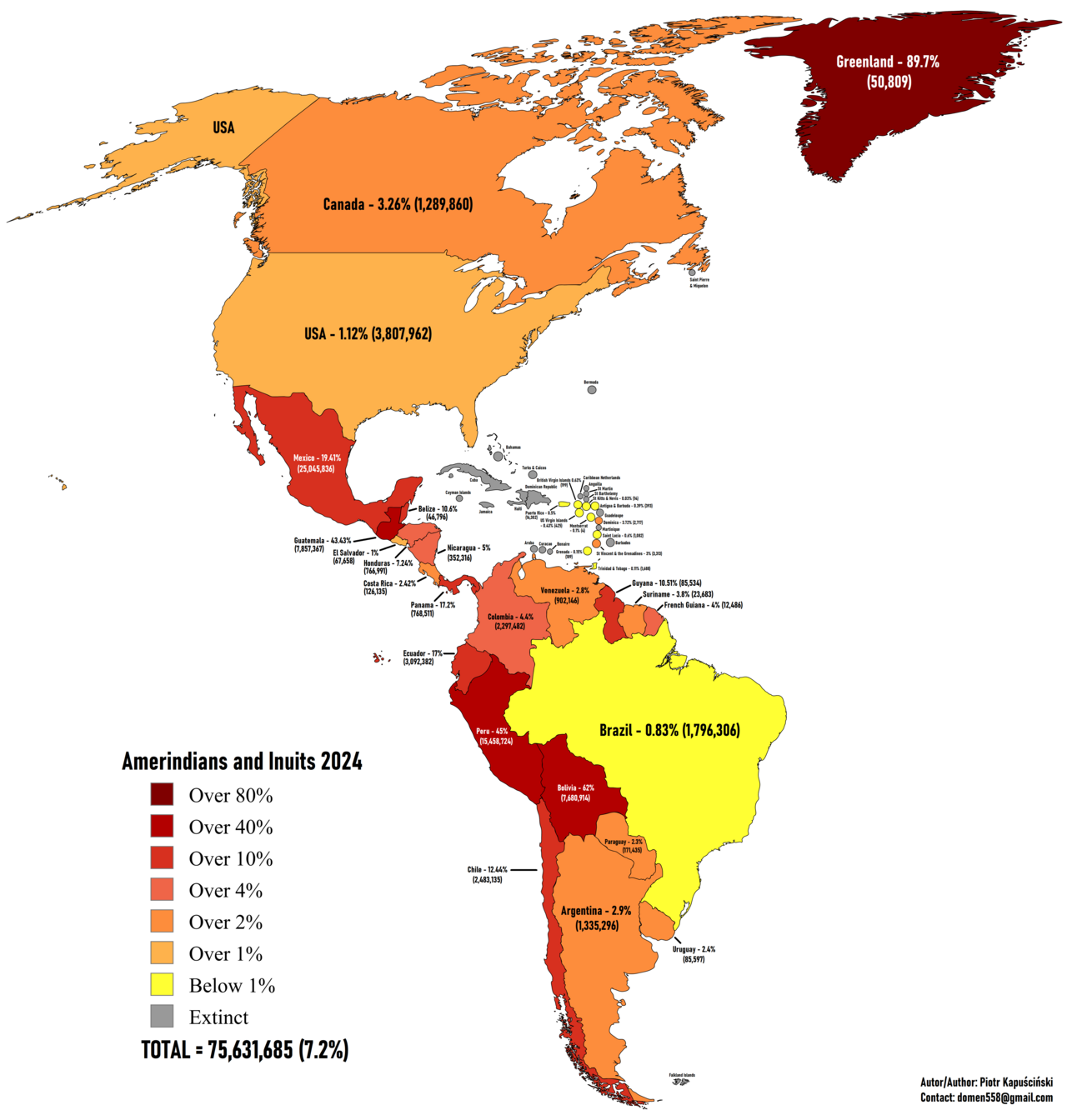

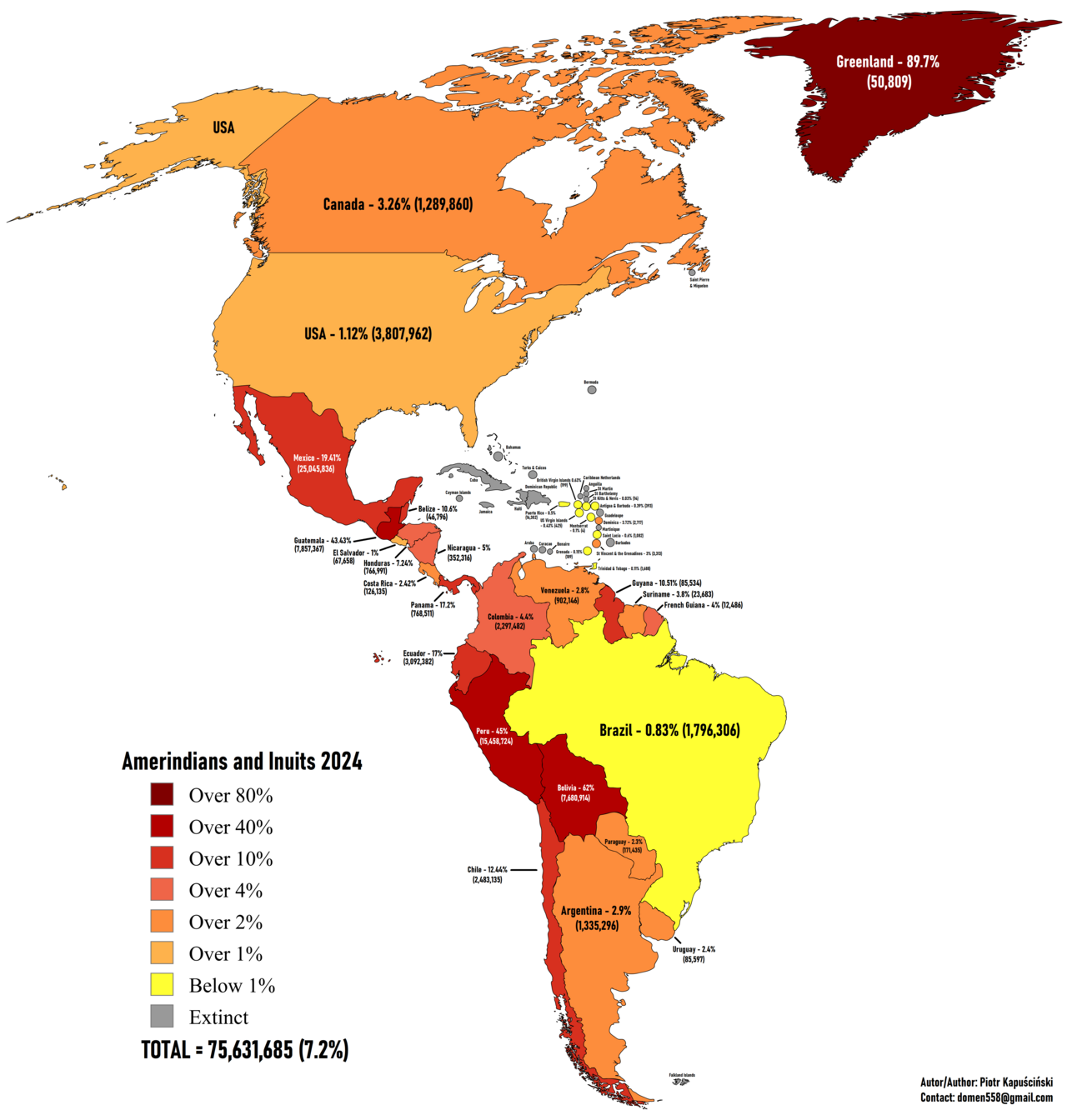

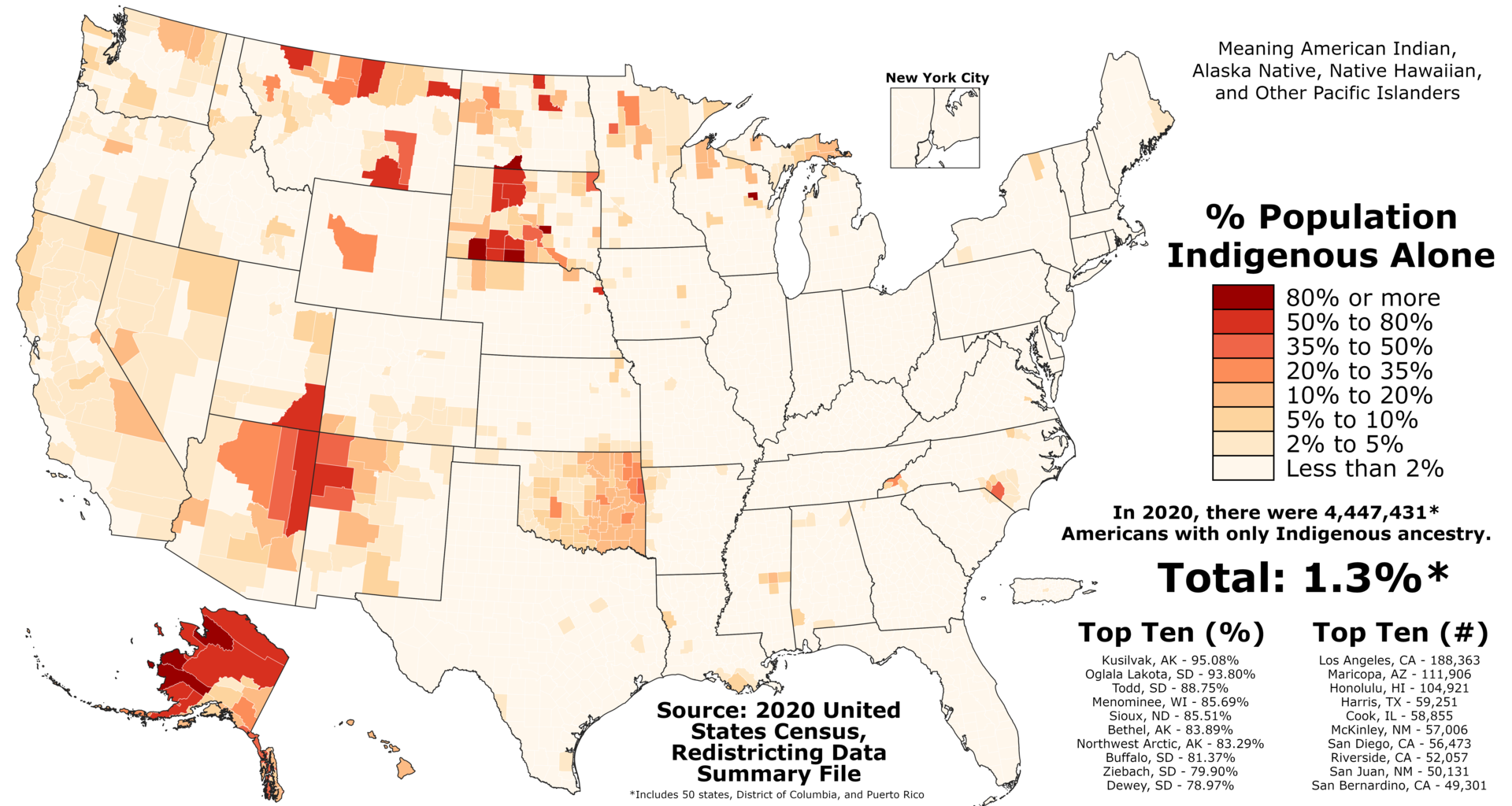

Terminology The West Indies (or Antilles) in relation to the continental Americas Further information: Native American name controversy  A Navajo boy in the desert in present-day Monument Valley in Arizona with the "Three Sisters" rock formation in the background in 2007  American Indian, Alaska Native, and Inuit populations of the Americas in 2024 Indigenous populations of the Americas in 2024 Application of the term "Indian" originated with Christopher Columbus, who, when searching for India, made landfall in the Americas but thought he had arrived in the East Indies.[47][48][49][50][51][52] The islands came to be known as the "West Indies" (or "Antilles"), a name that is still used to describe the islands. This led to the blanket term "Indies" and "Indians" (Spanish: indios; Portuguese: índios; French: indiens; Dutch: indianen) for the Indigenous inhabitants, which implied some kind of ethnic or cultural unity among the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. This unifying concept, codified in law, religion, and politics, was not originally accepted by the myriad groups of Indigenous peoples themselves but has since been embraced or tolerated by many over the last two centuries.[53] The term First Nations is used in Canada to identify that type of Indigenous people. The term "Indian" (or First Nations in Canada) generally does not include the culturally and linguistically distinct Indigenous peoples of the Arctic regions of the Americas, including the Aleuts, Inuit, or Yupik peoples. These peoples entered the continent as a second, more recent wave of migration several thousand years later and have much more recent genetic and cultural commonalities with the Indigenous peoples of Siberia. However, these groups are nonetheless considered among the "Indigenous peoples of the Americas".[54] The term Amerindian, a portmanteau of "American Indian", was coined in 1902 by the American Anthropological Association. It has been controversial ever since its creation. It was immediately rejected by some leading members of the Association, and, while adopted by many, it was never universally accepted.[55] While never popular in Indigenous communities themselves, it remains a preferred term among some anthropologists, notably in some parts of Canada and the English-speaking Caribbean.[56][57][58][59] "Indigenous peoples in Canada" is used as the collective name for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.[60][61] The term Aboriginal peoples as a collective noun (also describing First Nations, Inuit, and Métis) is a specific term of art used in some legal documents, including the Constitution Act, 1982.[62] Over time, as societal perceptions and government–indigenous relationships have shifted, many historical terms have changed definitions or been replaced as they have fallen out of favor.[63] The use of the term "Indian" is frowned upon because it represents the imposition and restriction of Indigenous peoples and cultures by the Canadian Government.[63] The terms "Native" and "Eskimo" are generally regarded as disrespectful (in Canada), and so are rarely used unless specifically required.[64] While "Indigenous peoples" is the preferred term, many individuals or communities may choose to describe their identity using a different term.[63][64] The Métis people of Canada can be contrasted, for instance, to the Indigenous-European mixed-race mestizos (or caboclos in Brazil) of Hispanic America whose large populations constitute outright majorities, pluralities, or at the least large minorities in most Latin American countries. They identify largely as an ethnic group distinct from Europeans and Indigenous, but consider themselves a subset of the European-derived Hispanic or Brazilian peoplehood in culture and ethnicity (cf. ladinos). Among Spanish-speaking countries, indígenas or pueblos indígenas ("Indigenous peoples") is a common term, though nativos or pueblos nativos ('native peoples') may also be heard; moreover, aborigen ('aborigine') is used in Argentina and pueblos originarios ('original peoples') is common in Chile. In Brazil, indígenas and povos originários ("Indigenous peoples") are common formal-sounding designations, while índio ('Indian') is still the more often heard term (the noun for the South-Asian nationality being indiano), but since the early 2010s has been considered offensive and pejorative.[citation needed] Aborígene and nativo are rarely used in Brazil in Indigenous-specific contexts (e.g., aborígene is usually understood as the ethnonym for Indigenous Australians). The Spanish and Portuguese equivalents to Indian, nevertheless, could be used to mean any hunter-gatherer or full-blooded Indigenous person, particularly to continents other than Europe or Africa—for example, indios filipinos.[citation needed] Indigenous peoples of the United States are commonly known as Native Americans, Indians, as well as Alaska Natives.[clarification needed] The term "Indian" is still used in some communities and remains in use in the official names of many institutions and businesses in Indian Country.[65] |

用語 西インド諸島(またはアンティル諸島)とアメリカ大陸との関係 詳細情報:ネイティブアメリカンの名称論争  2007年、アリゾナ州モニュメントバレーの砂漠で「三姉妹」岩層を背景に立つナバホ族の少年  2024年におけるアメリカ大陸のアメリカ先住民、アラスカ先住民、イヌイットの人口 2024年におけるアメリカ大陸の先住民人口 「インディアン」という用語の適用は、クリストファー・コロンブスに端を発する。彼はインドを探して航海し、アメリカ大陸に上陸したが、東インドに到着したと思い込んだのである。[47][48][49][50][51][52] 島々は「西インド諸島」(または「アンティル諸島」)と呼ばれるようになり、この名称は現在も島々を指すのに使われている。これが「インド諸島」および 「インディアン」(スペイン語: indios、ポルトガル語: índios、フランス語: indiens、オランダ語: indianen)という包括的な呼称につながり、アメリカ大陸の先住民に何らかの民族的・文化的統一性があることを暗示した。この統一概念は法律、宗 教、政治に規定されたが、元来は数多くの先住民集団自身によって受け入れられていなかった。しかし過去2世紀の間に、多くの集団がこれを容認または受容す るに至った[53]。カナダではこの種の先住民を指す言葉として「ファースト・ネーションズ」が用いられる。 「インディアン」(カナダではファースト・ネーションズ)という用語は、一般的に、アリューシャン、イヌイット、ユピックなど、アメリカ大陸の北極圏に居 住する文化的・言語的に異なる先住民は含まない。これらの民族は、数千年後に第二の、より新しい移住の波として大陸に到達し、シベリアの先住民とは遺伝 的・文化的により近縁である。しかしながら、これらの集団は依然として「アメリカ大陸の先住民」の一員と見なされている。[54] 「アメリカ先住民」を意味する造語「アメリディアン」は、1902年にアメリカ人類学会によって考案された。この用語は誕生以来、議論を呼んできた。協会 内の主要メンバーの一部から即座に拒否され、多くの者によって採用されたものの、普遍的な受容は得られなかった。[55] 先住民族コミュニティ自体では決して普及しなかったが、一部の人類学者、特にカナダの一部地域や英語圏カリブ海地域では、依然として好まれる用語として 残っている。[56][57][58] [59] 「カナダの先住民」は、ファースト・ネーションズ、イヌイット、メティスの総称として用いられる。[60][61] 集合名詞としての「アボリジナル・ピープルズ」(これもファースト・ネーションズ、イヌイット、メティスを指す)は、1982年憲法法を含む一部の法的文 書で使用される特定の専門用語である。[62] 時間の経過とともに、社会の認識や政府と先住民の関係が変化するにつれ、多くの歴史的用語は定義が変更されたり、廃れて置き換えられたりした。[63] 「インディアン」という用語の使用は、カナダ政府による先住民とその文化への強制と制限を表すため、好ましくないとされる. [63] 「ネイティブ」や「エスキモー」という用語は(カナダにおいて)一般的に不敬と見なされ、特に必要でない限りほとんど使用されない。[64] 「先住民」が推奨用語ではあるが、多くの個人やコミュニティは自らのアイデンティティを異なる用語で表現することを選択する場合がある。[63][64] 例えばカナダのメティス民族は、ヒスパニック系アメリカにおける先住民とヨーロッパ人の混血のメスティーソ(ブラジルではカボクロ)と対比できる。後者は ラテンアメリカ諸国の大半で圧倒的多数派、あるいは少なくとも大規模な少数派を形成している。彼らは主にヨーロッパ系や先住民とは異なる民族集団として自 己認識しているが、文化や民族性においてはヨーロッパ系に由来するヒスパニック系またはブラジル人集団の一派と見なしている(ラディーノ参照)。 スペイン語圏では、indígenas(先住民)やpueblos indígenas(先住民族)が一般的な呼称だが、nativos(先住民)やpueblos nativos(先住民族)も用いられる。さらにアルゼンチンではaborigen(先住民)、チリではpueblos originarios(原住民族)が広く使われている。ブラジルでは、インディジェーナスとポボス・オリジナリオス(「先住民」)が正式な呼称として一 般的だが、インディオ(「インディアン」)という呼称が依然として頻繁に聞かれる(南アジアの国民を表す名詞はインディアーノ)。ただし2010年代初頭 以降、この呼称は侮蔑的で差別的と見なされるようになった。[出典必要] ブラジルでは先住民固有の文脈でアボリジネやナティボが使用されることは稀である(例:アボリジネは通常オーストラリア先住民の民族名として理解され る)。しかしながら、スペイン語やポルトガル語におけるインディアンに相当する語は、狩猟採集民や純血の先住民全般を指す場合があり、特にヨーロッパやア フリカ以外の大陸において使用される。例えばフィリピンの先住民を指す「インディオス・フィリピノス」などである。[出典が必要] アメリカ合衆国の先住民は、一般にネイティブ・アメリカン、インディアン、またアラスカ先住民として知られている。[説明が必要] 「インディアン」という用語は、一部のコミュニティでは依然として使用されており、インディアン・カントリー内の多くの機関や企業の正式名称にも残ってい る。[65] |

| Name controversy Main article: Native American name controversy  Wayuu women in the Guajira Peninsula, which encompasses parts of Colombia and Venezuela  Quechua women in festive dress on Taquile Island on Lake Titicaca, west of Peru The various nations, tribes, and bands of Indigenous peoples of the Americas have differing preferences in terminology for themselves.[66][page needed] While there are regional and generational variations in which umbrella terms are preferred for Indigenous peoples as a whole, in general, most Indigenous peoples prefer to be identified by the name of their specific nation, tribe, or band.[66][67] Early settlers often adopted terms that some tribes used for each other, not realizing these were derogatory terms used by enemies. When discussing broader subsets of peoples, naming has often been based on shared language, region, or historical relationship.[68] Many English exonyms have been used to refer to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Some of these names were based on foreign language terms used by earlier explorers and colonists, while others resulted from the colonists' attempts to translate or transliterate endonyms from the native languages. Other terms arose during periods of conflict between the colonists and Indigenous peoples.[69] Since the late 20th century, Indigenous peoples in the Americas have been more vocal about how they want to be addressed, pushing to suppress the use of terms widely considered to be obsolete, inaccurate, or racist. During the latter half of the 20th century and the rise of the Indian rights movement, the United States federal government responded by proposing the use of the term "Native American", to recognize the primacy of Indigenous peoples' tenure in the nation.[70] As may be expected among people of over 400 different cultures in the US alone, not all of the people intended to be described by this term have agreed on its use or adopted it. No single group naming convention has been accepted by all Indigenous peoples in the Americas. Most prefer to be addressed as people of their tribe or nations when not speaking about Native Americans/American Indians as a whole.[71] Since the 1970s, the word "Indigenous", which is capitalized when referring to people, has gradually emerged as a favored umbrella term. The capitalization is to acknowledge that Indigenous peoples have cultures and societies that are equal to Europeans, Africans, and Asians.[67][72] This has recently been acknowledged in the AP Stylebook.[73] Some consider it improper to refer to Indigenous people as "Indigenous Americans" or to append any colonial nationality to the term because Indigenous cultures existed before European colonization. Indigenous groups have territorial claims that are different from modern national and international borders, and when labeled as part of a country, their traditional lands are not acknowledged. Some who have written guidelines consider it more appropriate to describe an Indigenous person as "living in" or "of" the Americas, rather than calling them "American"; or simply calling them "Indigenous" without any addition of a colonial state.[74][75] |

名称論争 詳細記事: ネイティブアメリカンの名称論争  コロンビアとベネズエラにまたがるグアヒラ半島のワユー族女性  ペルー西部のティティカカ湖、タキーレ島で祝祭衣装をまとったケチュア族女性 アメリカ大陸の先住民は、自民族を指す呼称について異なる好みを持つ。[66][出典ページ] 先住民全体を指す包括的呼称については地域や世代による差異があるものの、概して大多数の先住民は自らの特定の国民・部族・集団名で呼ばれることを好む。[66][67] 初期入植者たちは、敵対部族が互いを蔑称として用いていた呼称を、その意図に気づかずに採用することが多かった。より広範な集団を議論する際、名称は共通 言語・地域・歴史的関係に基づいて付けられることが多かった。[68] アメリカ大陸の先住民を指す英語の異称は数多く存在する。これらの名称の一部は、初期の探検家や入植者が用いた外国語に基づくものであり、他は入植者が先 住民の言語から固有名詞を翻訳・音訳しようとした結果である。その他の呼称は、入植者と先住民の対立期に生まれたものである。[69] 20世紀後半以降、アメリカ大陸の先住民は自らの呼称に関する意向をより強く表明し、時代遅れ・不正確・差別的と見なされる呼称の使用抑制を推進してき た。20世紀後半、インディアン権利運動の高まりを受けて、アメリカ合衆国連邦政府は「ネイティブ・アメリカン」という用語の使用を提案した。これは、先 住民がこの国民における最古の居住者であることを認めるためであった[70]。しかし、アメリカ国内だけでも400以上の異なる文化を持つ人々がいる中 で、この用語で指されるべきすべての人々がその使用に同意したり、採用したりしているわけではない。アメリカ大陸の先住民全体が合意した単一の呼称は存在 しない。大多数は、ネイティブ・アメリカン/アメリカン・インディアンという集団全体を指す場合を除き、自らの部族や国民の民として呼ばれることを好む。 [71] 1970年代以降、「先住民」という語(人を指す場合は大文字表記)が徐々に好まれる包括的呼称として定着してきた。大文字表記は、先住民の文化や社会が ヨーロッパ人、アフリカ人、アジア人と同等であることを認めるためである[67][72]。これは最近APスタイルブックでも認められた[73]。先住民 を「先住アメリカ人」と呼ぶことや、植民地時代の国籍を付加することは不適切だと考える者もいる。なぜなら先住文化はヨーロッパの植民地化以前に存在して いたからだ。先住民族集団の領土主張は、現代の国家境界や国際境界とは異なる。彼らが特定の国の一部として分類されると、伝統的な土地が認められない。ガ イドラインを策定した者の中には、先住民族を「アメリカ人」と呼ぶよりも「アメリカ大陸に居住する」あるいは「アメリカ大陸の」と表現する方が適切だと考 える者もいる。あるいは単に植民地国家の名称を付加せずに「先住民族」と呼ぶべきだとする意見もある。[74][75] |

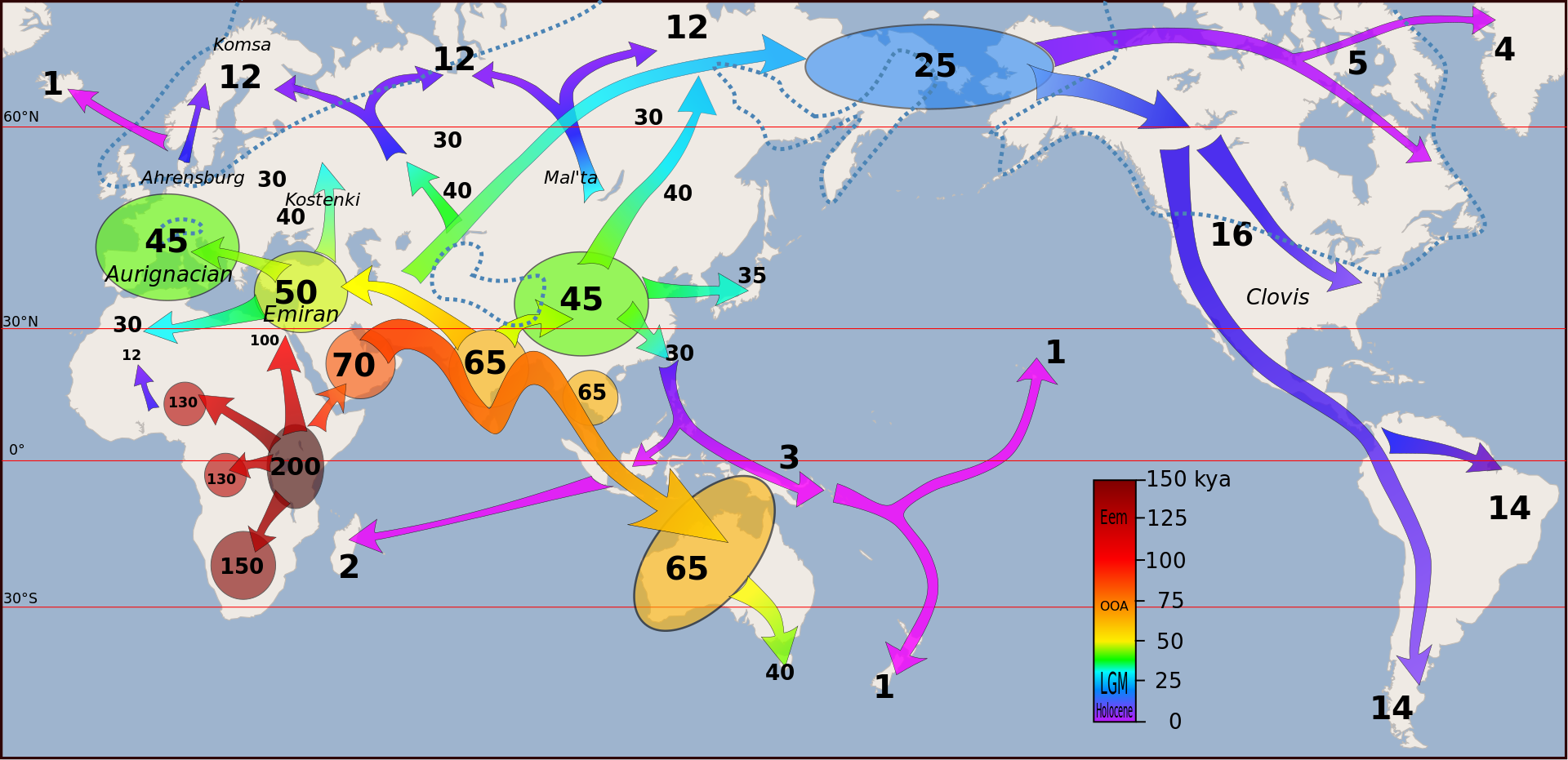

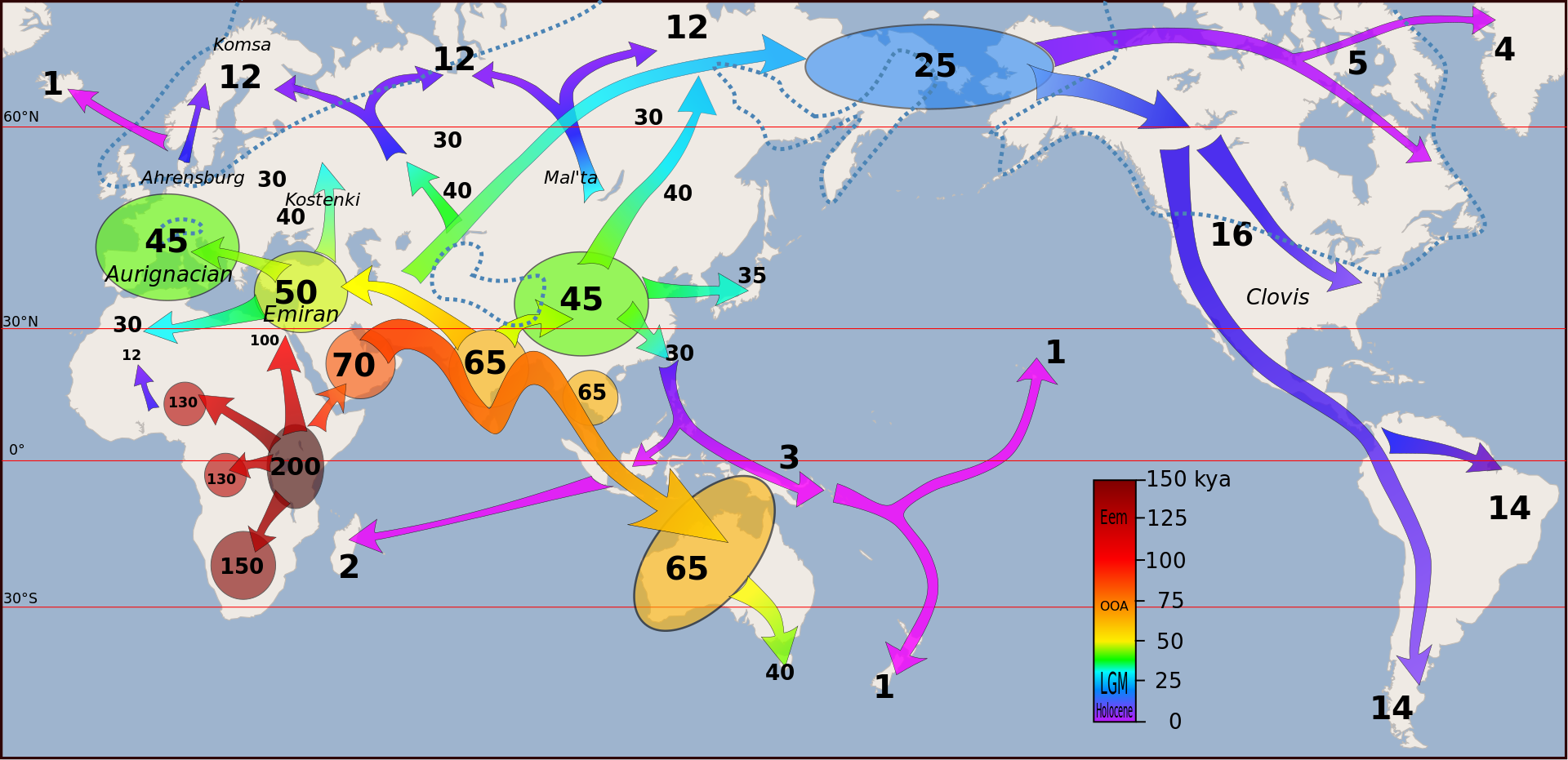

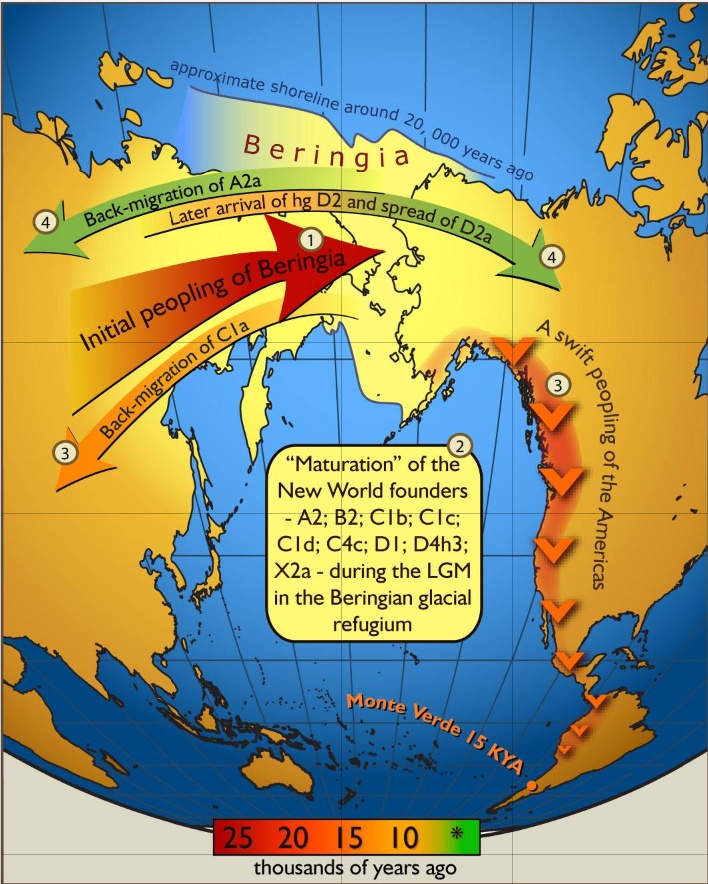

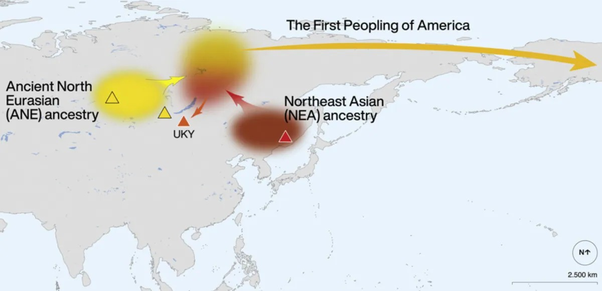

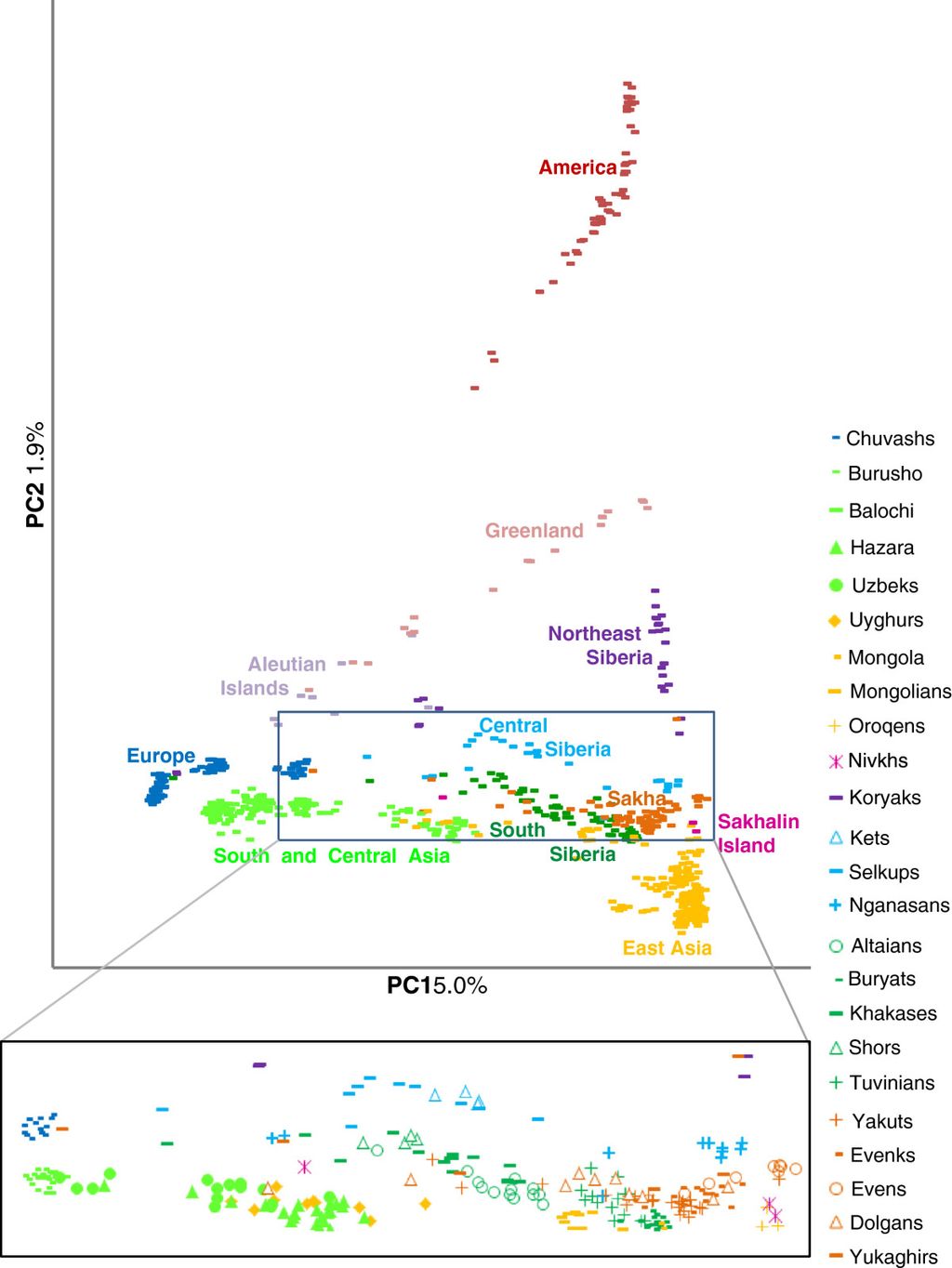

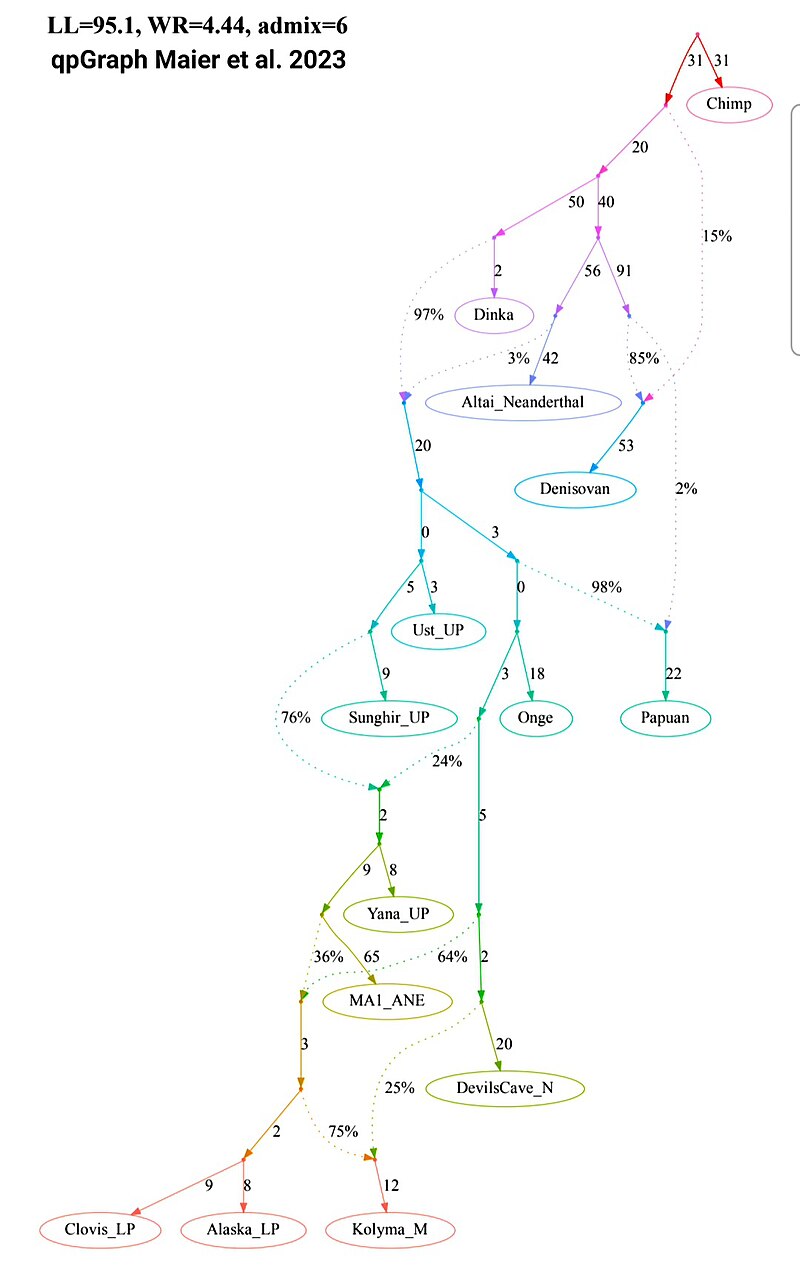

| History Peopling of the Americas This section is an excerpt from Peopling of the Americas.[edit]  Map of early human migrations based on the Out of Africa theory; figures are in thousands of years ago (kya).[76] It is believed that the peopling of the Americas began when Paleolithic hunter-gatherers (Paleo-Indians) entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering of sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum (26,000 to 19,000 years ago).[77] These populations expanded south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, either by sea or land, and spread rapidly southward, occupying both North and South America no later than 14,000 years ago, and possibly before 20,000 years ago.[78][79][80][81][82] The earliest populations in the Americas, before roughly 10,000 years ago, are known as Paleo-Indians. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by proposed linguistic factors, the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA.[83][84] While there is general agreement that the Americas were first settled from Asia, the pattern of migration and the place(s) of origin in Eurasia of the peoples who migrated to the Americas remain unclear.[79] The most generally accepted theory is that Ancient Beringians moved when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation,[85][86] following herds of now-extinct Pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[87] Another proposed route has them migrating down the Pacific coast to South America as far as Chile, either on foot or using boats.[88] Any archaeological evidence of coastal occupation during the last Ice Age would now have been covered by the sea level rise, up to a hundred metres since then.[89] The precise date for the peopling of the Americas is a long-standing open question. While advances in archaeology, Pleistocene geology, physical anthropology, and DNA analysis have progressively shed more light on the subject, significant questions remain unresolved.[90][91] The Clovis First theory refers to the hypothesis that the Clovis culture represents the earliest human presence in the Americas about 13,000 years ago.[92] Evidence of pre-Clovis cultures has accumulated and pushed back the possible date of the first peopling of the Americas.[93][94][95][96] Academics generally believe that humans reached North America south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet at some point between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago.[90][93][97][98][99][100] Some new controversial archaeological evidence suggests the possibility that human arrival in the Americas may have occurred prior to the Last Glacial Maximum more than 20,000 years ago.[93][101][102][103][104][105] The Swan Point Archaeological Site located in Alaska has yielded the oldest evidence of human habitation that is not disputed, with artifacts that have radiocarbon dates of 14,000 years, indicating the site was occupied around 12,000 BCE.[106][107][108] |

歴史 アメリカ大陸の定住 この節は『アメリカ大陸の定住』からの抜粋である。[編集]  アフリカ起源説に基づく初期人類移動の地図。数値は数千年前(kya)を示す。[76] アメリカ大陸への移住は、旧石器時代の狩猟採集民(パレオインディアン)が、最終氷期最大期(26,000~19,000年前)の海面低下によりシベリア 北東部とアラスカ西部に形成されたベーリンジア陸橋を経由し、北アジアのマンモス草原から北アメリカへ進入した時に始まったと考えられている。[77] これらの集団は、ローレンタイド氷床の南側へ、海路または陸路で拡大し、急速に南下して、遅くとも14,000年前、おそらくは20,000年前までに南 北アメリカ大陸を占拠した。[78][79][80][81] [82] 約1万年前以前のアメリカ大陸最古の集団は古インディアンとして知られる。アメリカ先住民は、言語学的要因、血液型の分布、DNAなどの分子データに反映 される遺伝的構成から、シベリアの集団との関連性が示唆されている。[83] [84] アメリカ大陸への最初の移住がアジアからであった点については概ね合意があるものの、移住のパターンやユーラシア大陸における移住者の起源地は依然として 不明である。[79] 最も広く受け入れられている説は、第四紀氷河期による海面の大幅な低下[85][86]を機に、古代ベーリング人がローレンタイド氷床とコルディリェラ氷 床の間に広がる無氷回廊を、現在は絶滅した更新世の群畜を追って移動したというものだ[87]。別の説では、太平洋沿岸を南下しチリまで到達したとする。 徒歩か船を使った移動である。[88] 最終氷期における沿岸居住の考古学的証拠は、その後最大100メートル上昇した海面によって現在では水没している。[89] アメリカ大陸への人民到達時期の正確な年代は、長年の未解決問題である。考古学、更新世地質学、自然人類学、DNA分析の進歩により次第に解明が進む一 方、重要な疑問点は未解決のままである。[90][91] クロヴィス・ファースト説とは、クロヴィス文化が約13,000年前のアメリカ大陸最古の人類存在を示すとする仮説を指す。[92] クロヴィス以前の文化の証拠が蓄積され、アメリカ大陸への最初の人類到達時期の可能性はさらに遡った。[93][94][95][96] 学者は一般的に、人類がローレンタイド氷床の南側にある北アメリカ大陸に到達したのは、1万5000年から2万年前の間のどこかの時点だと考えている。 [90][93] [97][98][99][100] 一部新たな論争を呼ぶ考古学的証拠は、人類のアメリカ大陸到達が最終氷期最盛期(2万年以上前)以前に起こった可能性を示唆している。[93][101] [102][103][104] [105] アラスカにあるスワンポイント遺跡からは、放射性炭素年代測定で14,000年前と判定された遺物が発見されており、紀元前12,000年頃に人が居住し ていたことを示す、議論の余地のない最古の人類居住の証拠となっている。[106][107][108] |

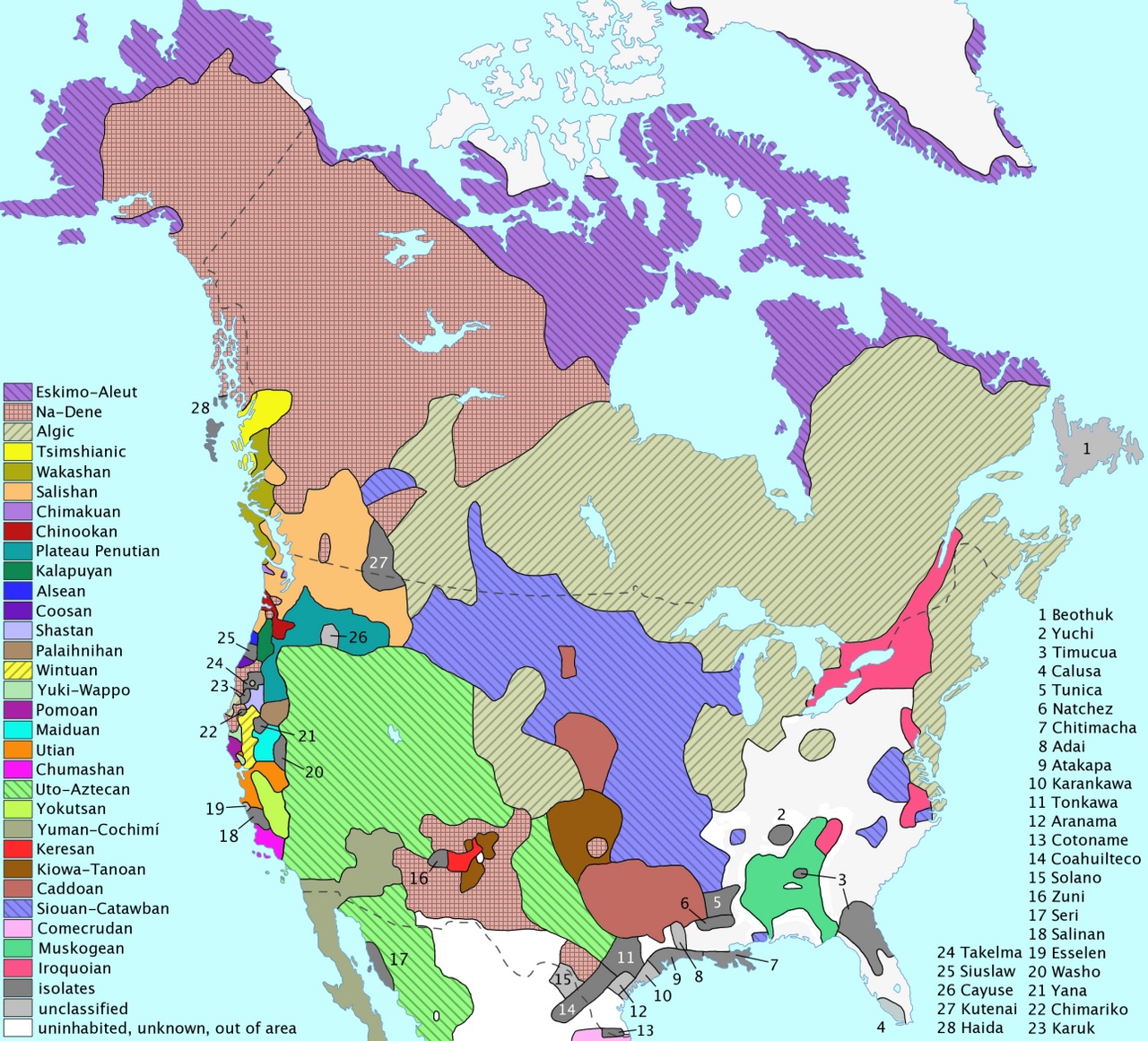

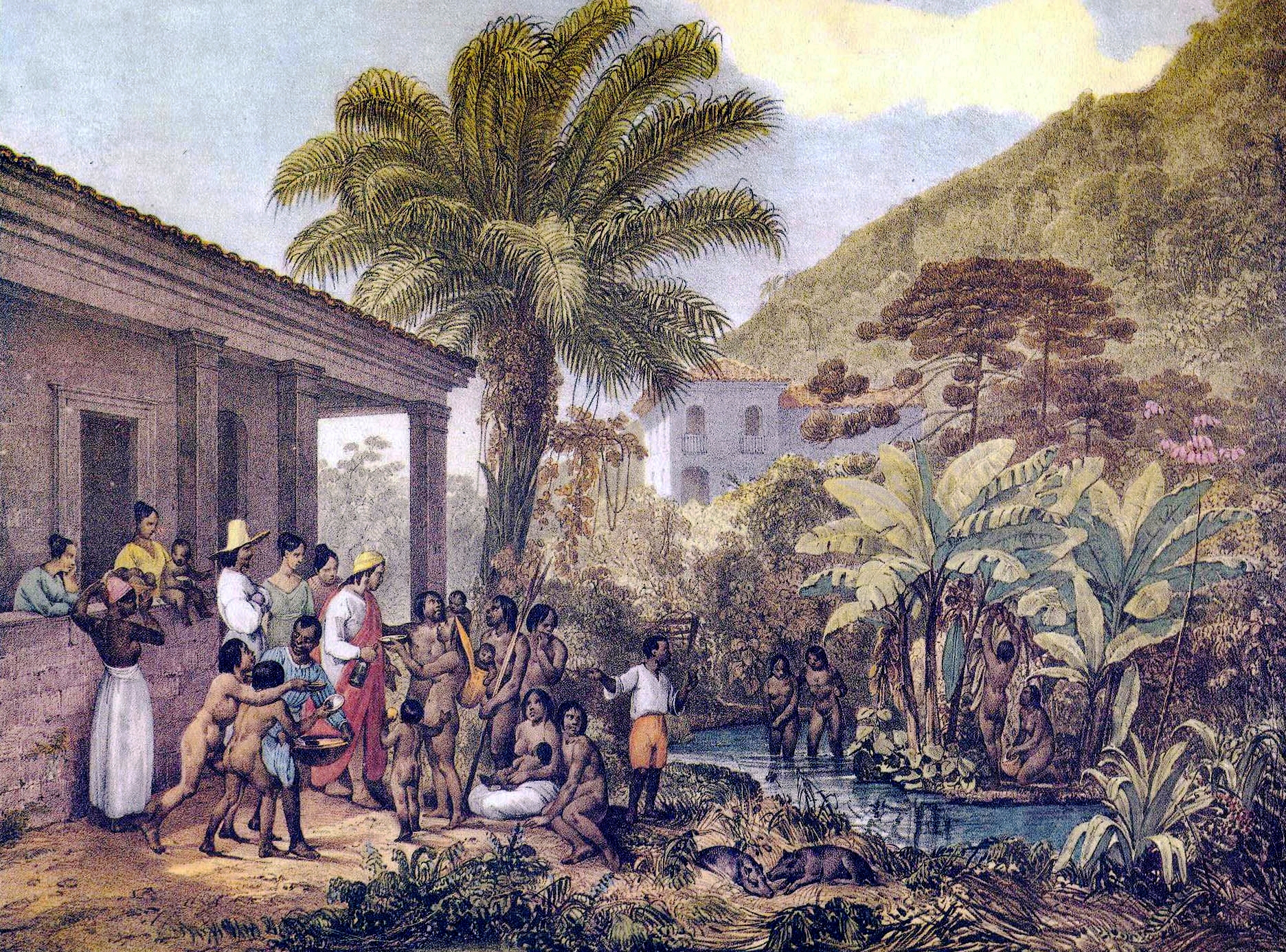

| Pre-Columbian era Main articles: Pre-Columbian era and Archaeology of the Americas  Language families of Indigenous peoples in North America shown across present-day Canada, Greenland, the United States, and northern Mexico  Moche portrait vessel from Peru, 100 BCE–500 CE  Ceramic portrait of a Maya noblewoman, Jaina Island, Mexico, 600–800 CE While technically referring to the era before Christopher Columbus' voyages of 1492 to 1504, in practice the term usually includes the history of Indigenous cultures until Europeans either conquered or significantly influenced them.[109] "Pre-Columbian" is used especially often in the context of discussing the pre-contact Mesoamerican Indigenous societies: Olmec; Toltec; Teotihuacano' Zapotec; Mixtec; Aztec and Maya civilizations; and the complex cultures of the Andes: Inca Empire, Moche culture, Muisca Confederation, and Cañari. The pre-Columbian era refers to all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European and African influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original arrival in the Upper Paleolithic to European colonization during the early modern period.[110] The Norte Chico civilization (in present-day Peru) is one of the defining six original civilizations of the world, arising independently around the same time as that of Egypt.[111][112] Many later pre-Columbian civilizations achieved great complexity, with hallmarks that included permanent or urban settlements, agriculture, engineering, astronomy, trade, civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies. Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first significant European and African arrivals (ca. late 15th–early 16th centuries), and are known only through oral history and through archaeological investigations. Others were contemporary with the contact and colonization period and were documented in historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Mayan, Olmec, Mixtec, Aztec, and Nahua peoples, had their written languages and records. However, the European colonists of the time worked to eliminate non-Christian beliefs and burned many pre-Columbian written records. Only a few documents remained hidden and survived, leaving contemporary historians with glimpses of ancient culture and knowledge. According to both Indigenous and European accounts and documents, American civilizations before and at the time of European encounter had achieved great complexity and many accomplishments.[113] For instance, the Aztecs built one of the largest cities in the world, Tenochtitlan (the historical site of what would become Mexico City), with an estimated population of 200,000 for the city proper and a population of close to five million for the extended empire.[114] By comparison, the largest European cities in the 16th century were Constantinople and Paris with 300,000 and 200,000 inhabitants respectively.[115] The population in London, Madrid, and Rome hardly exceeded 50,000 people. In 1523, right around the time of the Spanish conquest, the entire population in the country of England was just under three million people.[116] This fact speaks to the level of sophistication, agriculture, governmental procedure, and rule of law that existed in Tenochtitlan, needed to govern over such a large citizenry. Indigenous civilizations also displayed impressive accomplishments in astronomy and mathematics, including the most accurate calendar in the world.[citation needed] The domestication of maize or corn required thousands of years of selective breeding, and continued cultivation of multiple varieties was done with planning and selection, generally by women. Inuit, Yupik, Aleut, and Indigenous creation myths tell of a variety of origins of their respective peoples. Some were "always there" or were created by gods or animals, some migrated from a specified compass point, and others came from "across the ocean".[117] |

コロンブス以前の時代 主な記事:コロンブス以前の時代とアメリカ大陸の考古学  北米先住民の言語族。現在のカナダ、グリーンランド、アメリカ合衆国、メキシコ北部における分布を示す  ペルーのモチェ文化の肖像壺。紀元前100年~紀元500年  メキシコ・ハイナ島出土のマヤ貴族女性の陶器肖像。紀元600年~800年 技術的には1492年から1504年にかけてのクリストファー・コロンブスの航海以前の時代を指すが、実際にはこの用語は通常、ヨーロッパ人が先住民文化 を征服するか、あるいは重大な影響を与えるまでの歴史を含む。[109] 「コロンブス以前」という表現は、特に接触前のメソアメリカ先住民社会について論じる文脈で頻繁に用いられる:オルメカ、トルテカ、テオティワカノ、サポ テカ、ミシュテカ、 アステカ、マヤ文明。そしてアンデス地域の複雑な文化:インカ帝国、モチェ文化、ムイスカ連合、カニャリ。 コロンブス以前の時代とは、アメリカ大陸にヨーロッパやアフリカからの重大な影響が現れる前の、アメリカ大陸の歴史および先史時代の全期間を指す。旧石器 時代後期における最初の到達から、近世におけるヨーロッパの植民地化までの期間に及ぶ。[110] ノルテ・チコ文明(現在のペルー)は、エジプト文明とほぼ同時期に独立して興った、世界を定義する六大原始文明の一つである。[111][112] 後世のコロンブス以前の文明の多くは高度な複雑性を達成し、恒久的あるいは都市的な定住地、農業、工学、天文学、交易、公共建築や記念建造物、複雑な社会 階層といった特徴を備えていた。これらの文明の一部は、ヨーロッパ人およびアフリカ人による最初の重要な到達時(15世紀末~16世紀初頭頃)にはすでに 長く衰退しており、口承歴史や考古学的調査を通じてのみ知られている。他の文明は接触・植民地化期と同時期に存在し、当時の歴史記録に文書化されている。 マヤ、オルメカ、ミシュテカ、アステカ、ナワなどの少数の民族は、独自の文字言語と記録を残していた。しかし当時のヨーロッパ人入植者は非キリスト教的信 仰を消去法による排除に取り組み、多くの先コロンブス期の文書記録を焼却した。ごく一部の文書だけが隠され生き延び、現代の歴史家に古代文化と知識の断片 を残している。 先住民とヨーロッパ双方の記録によれば、ヨーロッパ人との接触前および接触期のアメリカ文明は高度な複雑性と多くの成果を達成していた[113]。例えば アステカは世界最大級の都市テノチティトラン(後のメキシコシティの史跡)を建設し、市街地人口は20万人、帝国全体では500万人近くに達した。 [114] 比較すると、16世紀のヨーロッパで最大規模の都市はコンスタンティノープルとパリで、それぞれ30万人と20万人の住民を擁していた。[115] ロンドン、マドリード、ローマの住民は5万人をわずかに超える程度だった。1523年、スペインによる征服が行われたまさにその頃、イングランド全土の人 民は300万人弱であった。[116] この事実は、テノチティトランに存在した高度な文明、農業技術、統治手続き、法の支配の水準を物語っている。これらは、これほど大規模な市民社会を統治す るために必要だったのだ。先住民文明は天文学や数学の分野でも驚異的な成果を示し、世界最高精度のカレンダーを確立した[出典必要]。トウモロコシの栽培 化には数千年にわたる選択的育種が必要であり、複数の品種の継続的栽培は計画と選別によって行われ、主に女性が担っていた。 イヌイット、ユピック、アレウト、および先住民の創造神話では、それぞれの民族の起源について様々な説が語られている。ある民族は「常にそこに存在してい た」か、神々や動物によって創造された。ある民族は特定の方角から移住してきた。また別の民族は「海の向こうから」来たという。[117] |

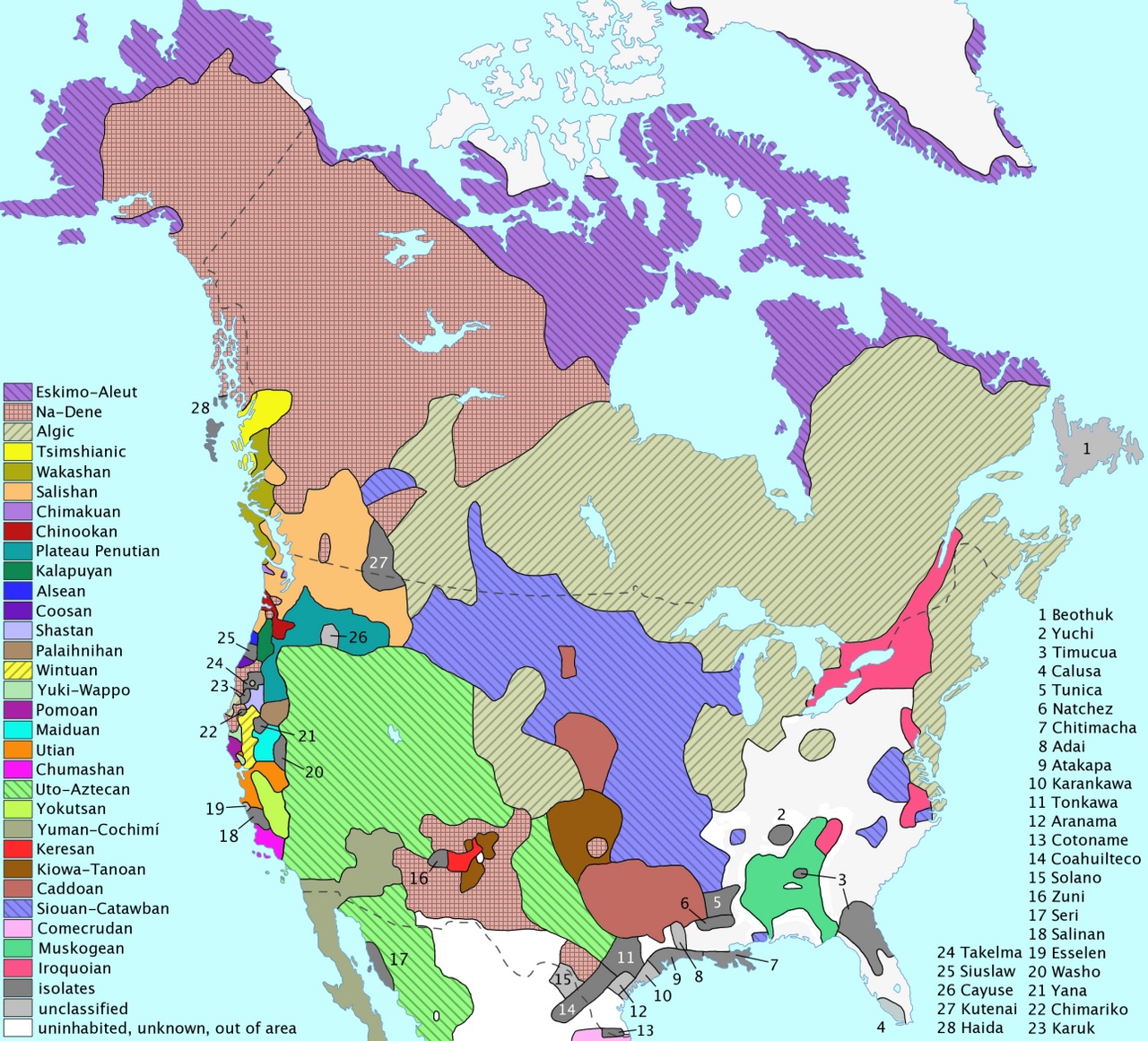

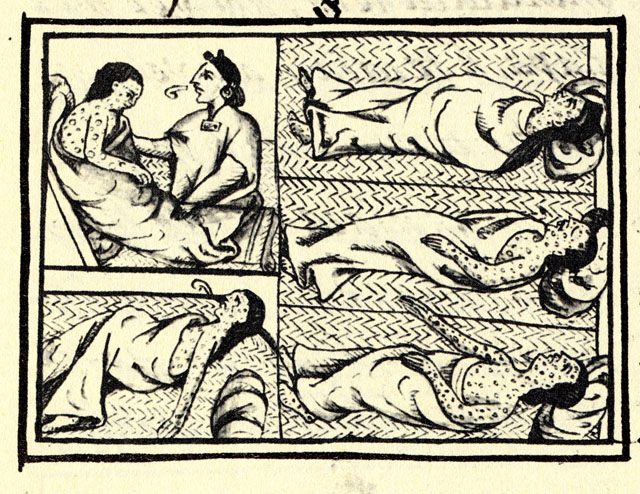

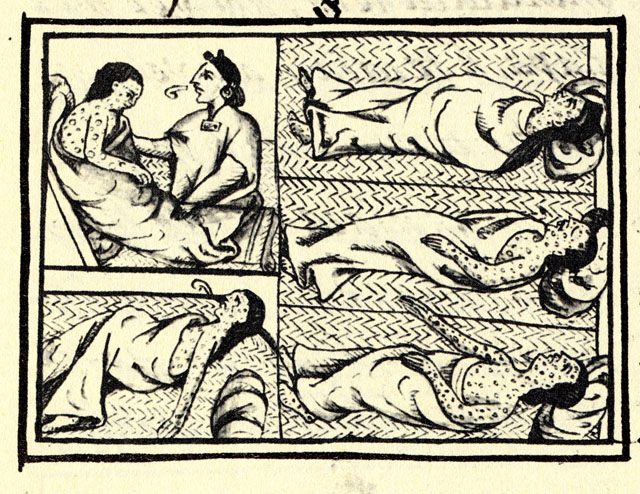

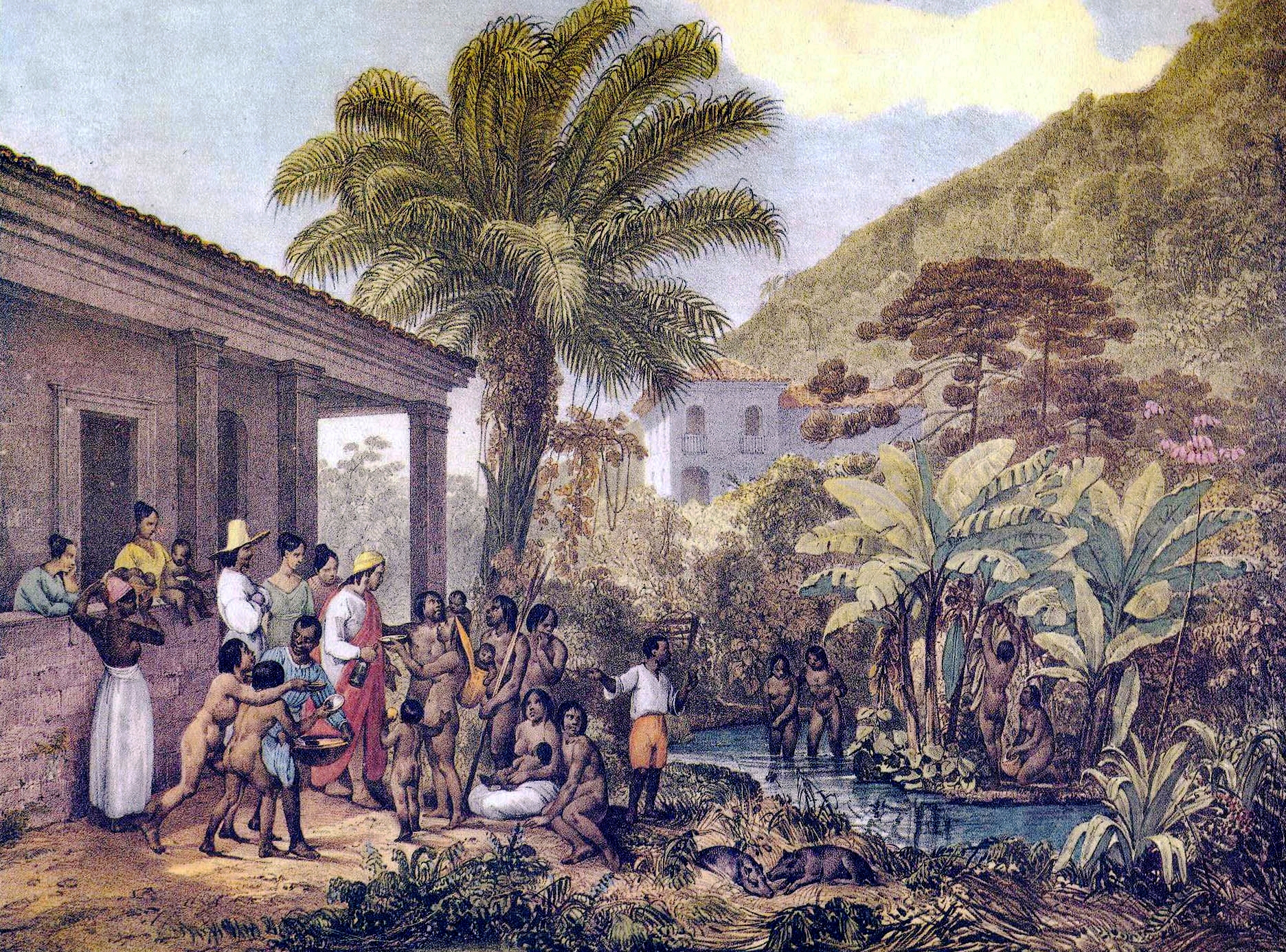

| European colonization Main article: European colonization of the Americas See also: Population history of Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Columbian exchange, and Society of the Spanish-Americans in the Spanish Colonial Americas  Areas of Indigenous peoples in North America at time of European colonization  Areas of Indigenous peoples in South and Central America at the time of European colonization (in Spanish)  An illustration in Florentine Codex, compiled between 1540 and 1585 CE, depicting the Nahua peoples suffering from smallpox during the conquest-era in central Mexico  Indigenous people at a farm plantation in Minas Gerais in present-day Brazil, c. 1824  Members of an uncontacted tribe encountered in Acre in Brazil in 2009 The European colonization of the Americas fundamentally changed the lives and cultures of the resident Indigenous peoples. Although the exact pre-colonization population count of the Americas is unknown, scholars estimate that Indigenous populations diminished by between 80% and 90% during the first centuries of European colonization. Most scholars estimate a pre-colonization population of around 50 million, with other scholars arguing for an estimate of 100 million. Estimates reach as high as 145 million.[118][119][120] William Denevan estimates of the pre-contact population range from 8 million to 112 million, falling to under 6 million by 1650.[121] Epidemics ravaged the Americas with diseases, such as smallpox, measles, and cholera, which the early colonists brought from Europe. The spread of infectious diseases was slow initially, as European populations were relatively small. This changed when the Europeans began the trafficking of massive numbers of enslaved Western and Central African people to the Americas, drastically increasing the population. These enslaved Africans carried many of the same diseases as Europeans, such as smallpox, along with many tropical diseases unknown to both the indigenous populations and Europeans. In 1520, an African who had been infected with smallpox had arrived in Yucatán. By 1558, the disease had spread throughout South America and had arrived at the Plata basin.[122] Colonist violence towards Indigenous peoples accelerated the loss of lives. European colonists perpetrated massacres on the Indigenous peoples and enslaved them.[123][124][125] According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1894), the North American Indian Wars of the 19th century had a known death toll of about 19,000 Europeans and 30,000 Native Americans, and an estimated total death toll of 45,000 Native Americans.[126] The first Indigenous group encountered by Columbus, the 250,000 Taínos of Hispaniola, represented the dominant culture in the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. Within thirty years about 70% of the Taínos had died.[127] They had no immunity to European diseases, so outbreaks of measles and smallpox ravaged their population.[128] One such outbreak occurred in a camp of enslaved Africans, where smallpox spread to the nearby Taíno population and reduced their numbers by 50%.[122] Increasing punishment of the Taínos for revolting against forced labor, despite measures put in place by the encomienda, which included religious education and protection from warring tribes,[129] eventually led to the last great Taíno rebellion (1511–1529). Following years of mistreatment, the Taínos began to adopt suicidal behaviors, with women aborting or killing their infants and men jumping from cliffs or ingesting untreated cassava, a violent poison.[127] Eventually, a Taíno Cacique named Enriquillo managed to hold out in the Baoruco Mountain Range for thirteen years, causing serious damage to the Spanish, Carib-held plantations and their Indian auxiliaries.[130][failed verification] Hearing of the seriousness of the revolt, Emperor Charles V (also King of Spain) sent Captain Francisco Barrionuevo to negotiate a peace treaty with the ever-increasing number of rebels. Two months later, after consultation with the Audencia of Santo Domingo, Enriquillo was offered any part of the island to live in peace. The Laws of Burgos, 1512–1513, were the first codified set of laws governing the behavior of Spanish settlers in America, particularly concerning Indigenous peoples. The laws forbade the maltreatment of them and endorsed their conversion to Catholicism.[131] The Spanish crown found it difficult to enforce these laws in distant colonies. Epidemic disease was the overwhelming cause of the population decline of the Indigenous peoples.[132][133] After initial contact with Europeans and Africans, Old World diseases caused the deaths of 90 to 95% of the native population of the New World in the following 150 years.[134] Smallpox killed from one-third to half of the native population of Hispaniola in 1518.[135][136] By killing the Incan ruler Huayna Capac, smallpox caused the Inca Civil War of 1529–1532. Smallpox was only the first epidemic. Typhus (probably) in 1546, influenza and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria in 1614, and measles in 1618—all ravaged the remains of Inca culture. Smallpox killed millions of native inhabitants of Mexico.[137][138] Unintentionally introduced at Veracruz with the arrival of Pánfilo de Narváez on 23 April 1520, smallpox ravaged Mexico in the 1520s,[139] possibly killing over 150,000 in Tenochtitlán (the heartland of the Aztec Empire) alone, and aiding in the victory of Hernán Cortés over the Aztec Empire at Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City) in 1521.[citation needed][122] There are many factors as to why Indigenous peoples suffered such immense losses from Afro-Eurasian diseases. Many Old World diseases, like cow pox, are acquired from domesticated animals that are not indigenous to the Americas. European populations had adapted to these diseases, and built up resistance, over many generations. Many of the Old World diseases that were brought over to the Americas were diseases, like yellow fever, that were relatively manageable if infected as a child, but were deadly if infected as an adult. Children could often survive the disease, resulting in immunity to the disease for the rest of their lives. But contact with the disease by adults without this childhood or inherited immunity often proved fatal.[122][140] Colonization of the Caribbean led to the destruction of the Arawaks of the Lesser Antilles. Their culture was destroyed by 1650. Only 500 had survived by the year 1550, though the bloodlines continued through to the modern populace. In Amazonia, Indigenous societies weathered centuries of colonization and genocide.[141] Contact with European diseases such as smallpox and measles killed between 50 and 67 percent of the Indigenous population of North America in the first hundred years after the arrival of Europeans.[142] Some 90 percent of the native population near Massachusetts Bay Colony died of smallpox in an epidemic in 1617–1619.[143] In 1633, in Fort Orange (New Netherland), the Native Americans there were exposed to smallpox because of contact with Europeans. As it had done elsewhere, the virus wiped out entire population groups of Native Americans.[144] It reached Lake Ontario in 1636, and the lands of the Iroquois by 1679.[145][146] During the 1770s smallpox killed at least 30% of the West Coast Native Americans.[147] The 1775–82 North American smallpox epidemic and the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic brought devastation and drastic population depletion among the Plains Indians.[148][149] In 1832 the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans (The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832).[150] The Indigenous peoples in Brazil declined from a pre-Columbian high of an estimated three million[151] to some 300,000 in 1997.[dubious – discuss][failed verification][152] The Spanish Empire and other Europeans re-introduced horses to the Americas. Some of these animals escaped and began to breed and increase their numbers in the wild.[153] The reintroduction of the horse, extinct in the Americas for over 7500 years, had a profound impact on Indigenous cultures in several regions, such as those of the Great Plains, the Northwest Plateau, the Great Basin, Aridoamerica, the Gran Chaco and the Southern Cone. By domesticating horses, some tribes had great success: horses enabled them to expand their territories, exchange more goods with neighboring tribes, and more easily capture game, such as bison. According to Erin McKenna and Scott L. Pratt, the Indigenous population of the Americas was 145 million in the late 15th and by the late 17th century, had been reduced to 15 million due to epidemics, wars, massacres, mass rapes, starvation, and enslavement.[120] |

ヨーロッパによる植民地化 主な記事: ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化 関連項目: アメリカ先住民の人口史、コロンブス交換、スペイン植民地時代のアメリカにおけるスペイン系アメリカ人社会  ヨーロッパによる植民地化当時の北米先住民の居住地域  ヨーロッパによる植民地化当時の南米・中央アメリカ先住民の居住地域(スペイン語)  1540年から1585年の間に編纂された『フィレンツェ写本』の挿絵。メキシコ中央部における征服時代に天然痘により苦悩するナワ族の人々を描いている  現在のブラジル、ミナスジェライス州の農場プランテーションにおける先住民。約1824年  2009年にブラジル・アクレ州で遭遇した未接触部族のメンバー ヨーロッパによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化は、先住民の生活と文化を根本的に変えた。植民地化前の人口は正確には不明だが、学者らはヨーロッパ植民地化の最 初の数世紀で先住民の人口が80%から90%減少したと推定している。大半の学者は植民地化前の人口を約5000万人と推定しているが、1億人とする見解 もある。推定値は1億4500万人に達することもある[118][119][120]。ウィリアム・デネヴァンの推定では、接触前の人口は800万人から 1億1200万人に及び、1650年までに600万人を下回ったとされる。[121] 天然痘、麻疹、コレラといった疫病がアメリカ大陸を襲った。これらは初期の入植者がヨーロッパから持ち込んだものだ。伝染病の拡散は当初、ヨーロッパの人 口が比較的少なかったため緩やかだった。しかしヨーロッパ人が西・中央アフリカから大量の奴隷をアメリカ大陸へ移送し始めると状況は一変し、人口が急増し た。これらの奴隷となったアフリカ人は、天然痘などヨーロッパ人と同様の疾病に加え、先住民にもヨーロッパ人にも未知の熱帯病を多数持ち込んでいた。 1520年、天然痘に感染したアフリカ人がユカタン半島に到着した。1558年までに、この病気は南アメリカ全域に広がり、プラタ川流域にも到達した [122]。先住民に対する入植者の暴力は、死者の増加を加速させた。ヨーロッパ人入植者は先住民に対して虐殺を行い、奴隷化した。[123][124] [125] 米国国勢調査局(1894年)によれば、19世紀の北米インディアン戦争における確認死者はヨーロッパ人約19,000人、先住民約30,000人で、先 住民の推定総死者数は45,000人に上る。[126] コロンブスが最初に遭遇した先住民集団、イスパニョーラ島の25万人のタイノ族は、大アンティル諸島とバハマ諸島における支配的な文化を代表していた。 30年以内にタイノ族の約70%が死亡した[127]。彼らはヨーロッパの伝染病に対する免疫を持たなかったため、麻疹や天然痘の流行が人口を壊滅させた [128]。そうした流行の一つは奴隷化されたアフリカ人のキャンプで発生し、天然痘が近隣のタイノ族に広がり、その人口を50%減少させた。[122] 強制労働への反乱に対するタイノ族への処罰強化は、宗教教育や他部族からの保護を含むエンコミエンダ制度の導入にもかかわらず[129]、最終的に最後の 大きなタイノ族反乱(1511年~1529年)を引き起こした。 長年の虐待を受けたタイノ族は自殺的行動を取り始めた。女性は流産や乳児殺害を行い、男性は崖から飛び降りたり、猛毒である未処理のキャッサバを摂取した [127]。最終的にエンリキーヨという名のタイノ族首長がバオルコ山脈で13年間抵抗を続け、スペイン人、カリブ族が支配するプランテーション、および 彼らのインディアン補助部隊に深刻な損害を与えた。[130][検証失敗] この反乱の深刻さを知った皇帝カルロス5世(スペイン国王も兼任)は、増え続ける反乱軍との和平交渉のためフランシスコ・バリオンエボ大尉を派遣した。2 か月後、サントドミンゴ高等裁判所との協議を経て、エンリキージョには島の任意の地域に平和に居住する権利が提示された。 1512年から1513年にかけて制定されたブルゴス法は、アメリカ大陸におけるスペイン人入植者の行動、特に先住民に関する初の成文化された法体系で あった。この法律は先住民への虐待を禁じ、カトリックへの改宗を推奨していた[131]。しかしスペイン王室は、遠隔地の植民地でこれらの法律を施行する ことが困難であった。 伝染病が先住民人口減少の圧倒的主因であった[132][133]。ヨーロッパ人・アフリカ人との接触後、旧世界の疾病により新世界先住民人口の 90~95%が、その後150年間で死亡した。[134] 1518年には天然痘がイスパニョーラ島の先住民人口の3分の1から半分を死に至らしめた。[135][136] インカ帝国の統治者ワイナ・カパックを死に至らしめた天然痘は、1529年から1532年にかけてのインカ内戦を引き起こした。天然痘は最初の疫病に過ぎ なかった。1546年には(おそらく)チフス、1558年にはインフルエンザと天然痘の同時流行、1589年には再び天然痘、1614年にはジフテリア、 1618年には麻疹が、インカ文化の残存部分を次々と荒廃させた。 天然痘はメキシコの先住民数百万を死に至らしめた[137][138]。1520年4月23日、パンフィロ・デ・ナルバエスの到着と共にベラクルスへ意図 せず持ち込まれた天然痘は、 天然痘は1520年代にメキシコを荒廃させ[139]、テノチティトラン(アステカ帝国の中心地)だけで15万人以上を死に至らしめ、1521年にエルナ ン・コルテスがテノチティトラン(現在のメキシコシティ)でアステカ帝国に勝利する一因となった[出典必要]。[122] 先住民がアフリカ・ユーラシア由来の疾病によってこれほど甚大な苦悩を蒙った背景には、多くの要因がある。牛痘のような旧世界の疾病の多くは、アメリカ大 陸に自生しない家畜から感染する。ヨーロッパの人々は、何世代にもわたってこれらの病気に適応し、抵抗力を培ってきた。アメリカ大陸に持ち込まれた旧世界 の病気の多くは、黄熱病のように、子供時代に感染すれば比較的対処可能だが、成人後に感染すると致命的となるものだった。子供はしばしばこの病気を生き延 び、生涯にわたる免疫を獲得した。しかし、この幼少期の免疫や獲得免疫を持たない成人が病気と接触すると、しばしば致命的となった。[122] [140] カリブ海の植民地化は小アンティル諸島のアラワク族の壊滅をもたらした。彼らの文化は1650年までに消滅した。1550年までに生き残ったのはわずか 500人だったが、その血筋は現代の人々に受け継がれている。アマゾニアでは、先住民社会が何世紀にもわたる植民地化とジェノサイドを耐え抜いた。 [141] ヨーロッパ人による天然痘や麻疹などの伝染病との接触は、ヨーロッパ人到着後100年間で北米先住民人口の50~67%を死に至らしめた。[142] マサチューセッツ湾植民地周辺の先住民人口の約90%は、1617年から1619年にかけての天然痘の流行で死亡した。[143] 1633年、フォート・オレンジ(ニューネーデルラント)では、先住民がヨーロッパ人との接触により天然痘に感染した。他の地域と同様に、このウイルスは 先住民集団全体を壊滅させた。[144] 1636年にはオンタリオ湖に、1679年までにイロコイ族の居住地に到達した。[145][146] 1770年代には、西海岸の先住民の少なくとも30%が天然痘で死亡した。[147] 1775年から1782年にかけての北米天然痘流行と、1837年のグレートプレーンズ天然痘流行は、平原部族のインディアンに壊滅的な打撃を与え、人口 を激減させた。[148][149] 1832年、アメリカ合衆国連邦政府は先住民向けの天然痘予防接種プログラムを設立した(1832年先住民予防接種法)。[150] ブラジルの先住民の人口は、コロンブス以前の推定300万人[151]から、1997年には約30万人に減少した。[疑わしい – 議論が必要][検証不能][152] スペイン帝国や他のヨーロッパ諸国が馬をアメリカ大陸に再導入した。これらの動物の一部は逃げ出し、野生で繁殖し数を増やした[153]。7500年以上 もアメリカ大陸で絶滅していた馬の再導入は、グレートプレーンズ、北西高原、グレートベイスン、乾燥アメリカ、グランチャコ、南錐体など、いくつかの地域 の先住民文化に深い影響を与えた。馬を家畜化した部族の中には大きな成功を収めた者もいた。馬は彼らの領土拡大を可能にし、近隣部族との物資交換を活発化 させ、バイソンなどの獲物をより容易に捕獲することを可能にした。 エリン・マッケナとスコット・L・プラットによれば、アメリカ大陸の先住民人口は15世紀末に1億4500万人だったが、17世紀末までに疫病、戦争、虐殺、集団強姦、飢餓、奴隷化によって1500万人にまで減少した。 |

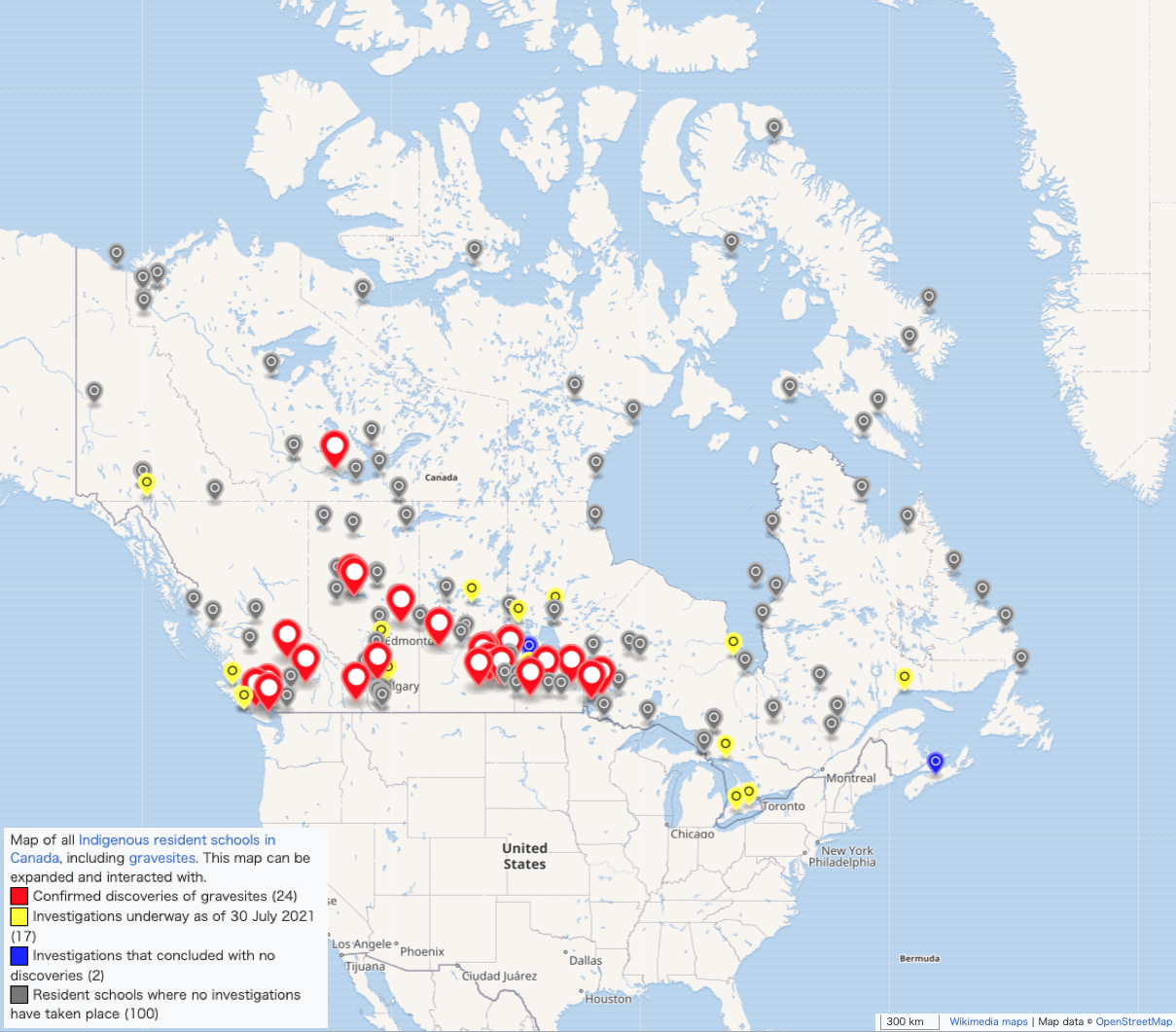

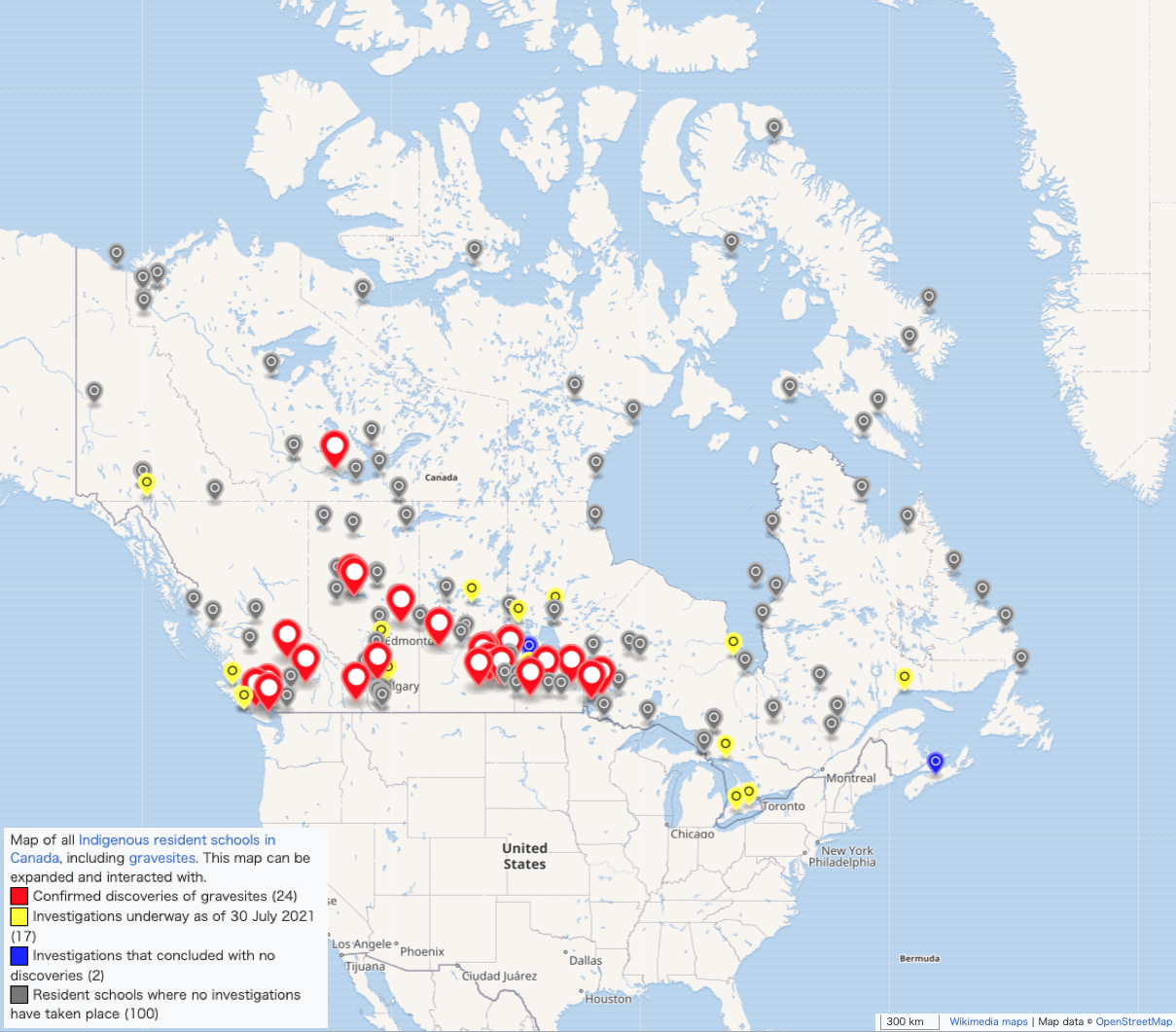

| Indigenous historical trauma See also: Historical trauma § Indigenous historical trauma  Map Wikimedia | © OpenStreetMap Map of all Indigenous resident schools in Canada, including gravesites. This map can be expanded and interacted with. Confirmed discoveries of gravesites (24) Investigations underway as of 30 July 2021 (17) Investigations that concluded with no discoveries (2) Resident schools where no investigations have taken place (100) Data Indigenous historical trauma (IHT) is the trauma that can accumulate across generations and develop as a result of the historical ramifications of colonization and is linked to mental and physical health hardships and population decline.[154] IHT affects many different people in a multitude of ways because the Indigenous community and their history are diverse. Many studies (such as Whitbeck et al., 2014;[155] Brockie, 2012; Anastasio et al., 2016;[156] Clark & Winterowd, 2012;[157] Tucker et al., 2016)[158] have evaluated the impact of IHT on health outcomes of Indigenous communities from the United States and Canada. IHT is a difficult term to standardize and measure because of the vast and variable diversity of Indigenous people and their communities. Therefore, it is an arduous task to assign an operational definition and systematically collect data when studying IHT. Many of the studies that incorporate IHT measure it in different ways, making it hard to compile data and review it holistically. This is an important point that provides context for the following studies that attempt to understand the relationship between IHT and potential adverse health impacts. Some of the methodologies to measure IHT include a "Historical Losses Scale" (HLS), "Historical Losses Associated Symptoms Scale" (HLASS), and residential school ancestry studies.[154]: 23 HLS uses a survey format that includes "12 kinds of historical losses", such as loss of language and loss of land and asks participants how often they think about those losses.[154]: 23 The HLASS includes 12 emotional reactions, and asks participants how they feel when they think about these losses.[154] Lastly, the residential school ancestry studies ask respondents if their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, or "elders from their community" went to a residential school to understand if family or community history in residential schools is associated with negative health outcomes.[154]: 25 In a comprehensive review of the research literature, Joseph Gone and colleagues[154] compiled and compared outcomes for studies using these IHT measures relative to the health outcomes of Indigenous peoples. The study defined negative health outcomes to include such concepts as anxiety, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, polysubstance abuse, PTSD, depression, binge eating, anger, and sexual abuse.[154] The connection between IHT and health conditions is complicated because of the difficult nature of measuring IHT, the unknown directionality of IHT and health outcomes, and because the term Indigenous people used in the various samples comprises a huge population of individuals with drastically different experiences and histories. That being said some studies such as Bombay, Matheson, and Anisman (2014),[159] Elias et al. (2012),[160] and Pearce et al. (2008)[161] found that Indigenous respondents with a connection to residential schools have more negative health outcomes (e.g., suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and depression) than those who did not have a connection to residential schools. Additionally, Indigenous respondents with higher HLS and HLASS scores had one or more negative health outcomes.[154] While there are many studies[156][162][157][163][158] that found an association between IHT and adverse health outcomes, scholars continue to suggest that it remains difficult to understand the impact of IHT. IHT needs to be systematically measured. Indigenous people also need to be understood in separate categories based on similar experiences, location, and background as opposed to being categorized as one monolithic group.[154] |

先住民の歴史的トラウマ 関連項目:歴史的トラウマ § 先住民の歴史的トラウマ  地図 ウィキメディア | © OpenStreetMap カナダ国内の全先住民寄宿学校(墓地を含む)の地図。この地図は拡大・操作が可能だ。 墓地の発見が確認された場所(24か所) 2021年7月30日現在調査中の場所(17か所) 調査の結果、発見されなかったもの(2件) 調査が行われていない寄宿学校(100件) データ 先住民の歴史的トラウマ(IHT)とは、植民地化の歴史的帰結の結果として蓄積され、発展する可能性のあるトラウマであり、精神的・身体的な健康や人口減 少と関連している[154]。先住民コミュニティとその歴史は多様であるため、IHTはマルチチュードの異なる人々に対して多様な形で影響を及ぼす。 多くの研究(例えばWhitbeck et al., 2014;[155] Brockie, 2012; アナスタシオら、2016年;[156] クラーク&ウィンタロウ、2012年;[157] タッカーら、2016年)[158]は、米国とカナダの先住民コミュニティにおける健康結果へのIHTの影響を評価している。先住民とそのコミュニティの 多様性が広範かつ変動的であるため、IHTは標準化や測定が困難な概念である。したがって、IHTを研究する際に運用上の定義を割り当て、体系的にデータ を収集することは困難な作業である。IHTを取り入れた研究の多くは異なる方法で測定しているため、データをまとめ、包括的に検討することが難しい。これ は、IHTと潜在的な健康への悪影響との関連性を理解しようとする以下の研究に文脈を提供する重要な点である。 IHTを測定する手法には、「歴史的喪失尺度(HLS)」、「歴史的喪失関連症状尺度(HLASS)」、寄宿学校祖先調査などがある[154]: 23。 HLSは「言語喪失」「土地喪失」など「12種類の歴史的喪失」を含む調査形式を採用し、参加者にそれらの喪失についてどの程度頻繁に考えるかを尋ねる。 [154]: 23 HLASSは12種類の感情的反応を含み、参加者にこれらの喪失について考えた際の感情を尋ねる。[154] 最後に、寄宿学校祖先調査は、回答者の両親、祖父母、曾祖父母、または「コミュニティの長老」が寄宿学校に通ったかどうかを尋ね、家族やコミュニティの寄 宿学校歴が健康上の悪影響と関連しているかを理解しようとするものである。[154]: 25 ジョセフ・ゴーンらは研究文献の包括的レビューにおいて[154]、先住民の健康結果に対するこれらのIHT測定値を用いた研究の成果をまとめ比較した。 本研究では、健康上の悪影響を不安、自殺念慮、自殺企図、多剤乱用、PTSD、うつ病、過食、怒り、性的虐待などの概念を含むものと定義した。[154] IHTと健康の関連性は複雑である。その理由は、IHTの測定が困難であること、IHTと健康結果の方向性が不明確であること、そして様々なサンプルで使 用される「先住民」という用語が、経験や歴史が大きく異なる膨大な個人群を包含していることにある。とはいえ、ボンベイ、マセソン、アニスマン (2014)[159]、エリアスら(2012)[160]、ピアースら(2008)[161]などの研究では、寄宿学校との関連性を持つ先住民回答者の 方が、より多くの健康上の悪影響(例:自殺念慮)を示すことが判明している。(2012)[160]、ピアースら(2008)[161]などの研究では、 寄宿学校との関連を持つ先住民回答者は、関連を持たない回答者と比べて、より多くの負の健康結果(自殺念慮、自殺企図、うつ病など)を示していることが判 明している。さらに、HLSおよびHLASSスコアが高い先住民回答者は、一つ以上の健康上の悪影響を有していた[154]。先住民のトラウマ(IHT) と健康上の悪影響との関連性を示す研究は多数存在する[156][162][157][163][158]が、学者は依然としてIHTの影響を理解するこ とは困難であると指摘し続けている。IHTは体系的に測定される必要がある。先住民はまた、単一の画一的な集団として分類されるのではなく、類似した経 験、居住地、背景に基づいて個別のカテゴリーで理解される必要がある。[154] |

| Agriculture See also: Agriculture in Mesoamerica, Incan agriculture, Eastern Agricultural Complex, Prehistoric agriculture on the Great Plains, and Prehistoric agriculture in the Southwestern United States  A bison hunt depicted in a painting by George Catlin (1844)  A representation of the domesticated plant species cultivated by Indigenous peoples have influenced the crops that were produced globally. Plants  The ancient Mesoamerican engraving of maize now on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico For thousands of years, Indigenous peoples domesticated, bred, and cultivated a large array of plant species. These species now constitute between 50% and 60% of all crops in cultivation worldwide.[164] In certain cases, the Indigenous peoples developed entirely new species and strains through artificial selection, as with the domestication and breeding of maize from wild teosinte grasses in the valleys of southern Mexico. Numerous such agricultural products retain their Native names in the English and Spanish lexicons. The South American highlands became a center of early agriculture. Genetic testing of the wide variety of cultivars and wild species suggests that the potato has a single origin in the area of southern Peru,[165] from a species in the Solanum brevicaule complex. Over 99% of all modern cultivated potatoes worldwide are descendants of a subspecies indigenous to south-central Chile,[166] Solanum tuberosum ssp. tuberosum, where it was cultivated as long as 10,000 years ago.[167][168] According to Linda Newson, "It is clear that in pre-Columbian times some groups struggled to survive and often suffered food shortages and famines, while others enjoyed a varied and substantial diet."[169] Persistent drought around AD 850 coincided with the collapse of the Classic Maya civilization, and the famine of One Rabbit (AD 1454) was a major catastrophe in Mexico.[170]  The common bean is native to Mexico and Central America and later began to be cultivated in South America. Indigenous peoples of North America began practicing farming approximately 4,000 years ago, late in the Archaic period of North American cultures. Technology had advanced to the point where pottery had started to become common and the small-scale felling of trees had become feasible. Concurrently, the Archaic Indigenous peoples began using fire in a controlled manner. They carried out the intentional burning of vegetation to mimic the effects of natural fires that tended to clear forest understories. It made travel easier and facilitated the growth of herbs and berry-producing plants, which were important both for food and for medicines.[171] In the Mississippi River valley, Europeans noted that Native Americans managed groves of nut and fruit trees not far from villages and towns and their gardens and agricultural fields. They would have used prescribed burning farther away, in forest and prairie areas.[172]  The tomato (jitomate, in central Mexico) was later cultivated by the pre-Hispanic civilizations of Mexico. Many crops first domesticated by Indigenous peoples are now produced and used globally, most notably maize (or "corn") arguably the most important crop in the world.[173] Other significant crops include cassava; chia; squash (pumpkins, zucchini, marrow, acorn squash, butternut squash); the pinto bean, Phaseolus beans including most common beans, tepary beans, and lima beans; tomatoes; potatoes; sweet potatoes; avocados; peanuts; cocoa beans (used to make chocolate); vanilla; strawberries; pineapples; peppers (species and varieties of Capsicum, including bell peppers, jalapeños, paprika, and chili peppers); sunflower seeds; rubber; brazilwood; chicle; tobacco; coca; blueberries, cranberries, and some species of cotton. Studies of contemporary Indigenous environmental management—including agro-forestry practices among Itza Maya in Guatemala and hunting and fishing among the Menominee of Wisconsin—suggest that longstanding "sacred values" may represent a summary of sustainable millennial traditions.[174] |

農業 関連項目:メソアメリカの農業、インカの農業、東部農業複合体、グレートプレーンズの先史時代農業、南西部アメリカ合衆国の先史時代農業  ジョージ・キャトリンの絵画に描かれたバイソン狩り(1844年)  先住民が栽培した家畜化された植物種の表現は、世界中で生産された作物に影響を与えた。(復元ジオラマ) 植物  メキシコ国立人類学博物館に展示されている古代メソアメリカのトウモロコシの彫刻 何千年もの間、先住民は多種多様な植物種を家畜化し、品種改良し、栽培してきた。これらの種は現在、世界中で栽培されている全作物の50%から60%を占 めている。[164] 特定の事例では、先住民が人工選択によって全く新しい種や品種を開発した。例えばメキシコ南部渓谷の野生トウモロコシ(テオシント)からトウモロコシが家 畜化・品種改良されたケースがそれだ。こうした農産物の多くは、英語やスペイン語の語彙において先住民由来の名称を今なお保持している。 南米高地は初期農業の中心地となった。多様な栽培品種と野生種の遺伝子検査から、ジャガイモはペルー南部地域に単一起源を持つことが示唆されている [165]。その起源はソラヌム・ブレヴィカウレ複合体の種である。現代世界で栽培されるジャガイモの99%以上は、チリ中南部に自生する亜種の子孫であ る。[166] ソラヌム・テュベロサム亜種テュベロサムである。この地域では1万年前から栽培されていた[167][168]。リンダ・ニューソンによれば、「コロンブ ス以前の時代、生存をかけた闘いを強いられ、食糧不足や飢饉という苦悩に直面する集団もあれば、多様で十分な食生活を享受する集団も存在したことは明らか である」[169]。 西暦850年頃の持続的な干ばつは古典期マヤ文明の崩壊と一致し、ウサギの飢饉(西暦1454年)はメキシコにおける大災害であった。[170]  インゲンマメはメキシコと中央アメリカ原産であり、後に南アメリカでも栽培が始まった。 北米先住民は、北米文化の古風期後期にあたる約4000年前に農耕を始めた。技術は陶器が普及し始め、小規模な伐採が可能になるほど進歩していた。同時 に、古風期の先住民は火を制御して使うようになった。彼らは意図的に植生を焼き払い、森林の下層を清掃する自然火災の効果を模倣したのである。これにより 移動が容易になり、薬草やベリー類を実らせる植物の生育が促進された。これらは食料としても薬としても重要であった。[171] ミシシッピ川流域では、ヨーロッパ人が先住民が村や町、菜園や農地の近くでナッツや果樹の林を管理していることに気づいた。彼らはより遠くの森林や草原地帯では計画焼却を行っていたはずだ。[172]  トマト(中央メキシコでは「jitomate」)は後に、ヒスパニック以前のメキシコ文明によって栽培された。 多くの作物は、最初に先住民によって栽培化されたが、現在では世界中で生産・利用されている。最も顕著なのはトウモロコシ(または「コーン」)であり、お そらく世界で最も重要な作物である。[173] その他の重要な作物には、キャッサバ、チア、カボチャ類(カボチャ、ズッキーニ、マーロウ、アコーンカボチャ、バターナットカボチャ)、ピント豆、インゲ ン豆(一般的な豆類、テパリ豆、リマ豆を含む)、トマト、ジャガイモ、サツマイモ、アボカド、落花生、カカオ豆(チョコレート製造用)、 バニラ、イチゴ、パイナップル、トウガラシ(パプリカ、ハラペーニョ、パプリカ、チリペッパーを含むカプシカム属の種と品種)、ヒマワリの種、ゴム、ブラ ジルの木、チクル、タバコ、コカ、ブルーベリー、クランベリー、そしていくつかの綿花種がある。 グアテマラのイツァ・マヤにおける農林業実践やウィスコンシン州メノミニー族の狩猟・漁労など、現代先住民の環境管理に関する研究は、長年にわたる「神聖な価値」が、持続可能な千年単位の伝統の集約を表している可能性を示唆している。[174] |

| Animals Numerous Native American dog breeds have been used by the people of the Americas, such as the Canadian Eskimo dog, the Carolina dog, and the Chihuahua. Some Indigenous peoples in the Great Plains used dogs for pulling travois, while others like the Tahltan bear dog were bred to hunt larger game. Some Andean cultures also bred the Chiribaya to herd llamas. The vast majority of indigenous dog breeds in the Americas went extinct, due to being replaced by dogs of European origin.[175] The Fuegian dog was a domesticated variation of the culpeo that was raised by several cultures in Tierra del Fuego, like the Selkʼnam and the Yahgan.[176] It was exterminated by Argentine and Chilean settlers, due to supposedly posing as a threat to livestock.[177] Several bird species, such as turkeys, Muscovy ducks, Puna ibis, and neotropic cormorants were domesticated by various peoples in Mesoamerica and South America to be used for poultry. In the Andean region, Indigenous peoples domesticated llamas and alpacas to produce fiber and meat. The llama was the only beast of burden in the Americas before European colonization. Guinea pigs were domesticated from wild cavies to be raised for meat consumption in the Andean region. Guinea pigs are now widely raised in Western society as household pets. In Oasisamerica, several cultures raised scarlet macaws imported from Mesoamerica for their feathers.[178][179] In the Maya civilization, stingless bees were domesticated to produce balché.[180] Cochineal were harvested by Mesoamerican and Andean civilizations for coloring fabrics via carminic acid.[181][182][183] |

動物 アメリカ大陸では、カナディアン・エスキモー・ドッグ、カロライナ・ドッグ、チワワなど、数多くの先住民犬種が利用されてきた。グレートプレーンズの先住 民の中には、トラヴォワ(荷曳き用そり)を引くために犬を使った者もいれば、タールタン・ベア・ドッグのように大型の獲物を狩るために飼育された犬種も あった。アンデス地方の文化では、ラマの群れを群畜するためにチリバヤを飼育した。アメリカ大陸の先住民犬種の大半は、ヨーロッパ原産の犬に取って代わら れたため絶滅した。[175] フエゴ島犬は、セルクナム族やヤガン族などフエゴ島諸文化で飼育されたクルペオの飼い犬種だった。[176] 家畜への脅威とされるため、アルゼンチンとチリの入植者によって絶滅させられた。[177] 七面鳥、マスコビ鴨、プーナイビス、新熱帯区鵜など、いくつかの鳥類は、家禽として利用するために、メソアメリカや南アメリカの様々な民族によって家畜化された。 アンデス地域では、先住民が繊維と肉を得るためにラマとアルパカを家畜化した。ラマは、ヨーロッパによる植民地化以前、アメリカ大陸で唯一の荷役動物であった。 モルモットはアンデス地域で肉食目的として野生カビィから家畜化された。現在では西洋社会で広く家庭用ペットとして飼育されている。 オアシスアメリカでは、いくつかの文化圏が羽根を得るためにメソアメリカから輸入されたスカーレットマコーを飼育していた[178][179]。 マヤ文明では、バルチェを生産するために刺さない蜂が家畜化された[180]。 コチニールは、カルミン酸による布地の染色を目的として、メソアメリカとアンデスの文明圏で採取されていた[181][182][183]。 |

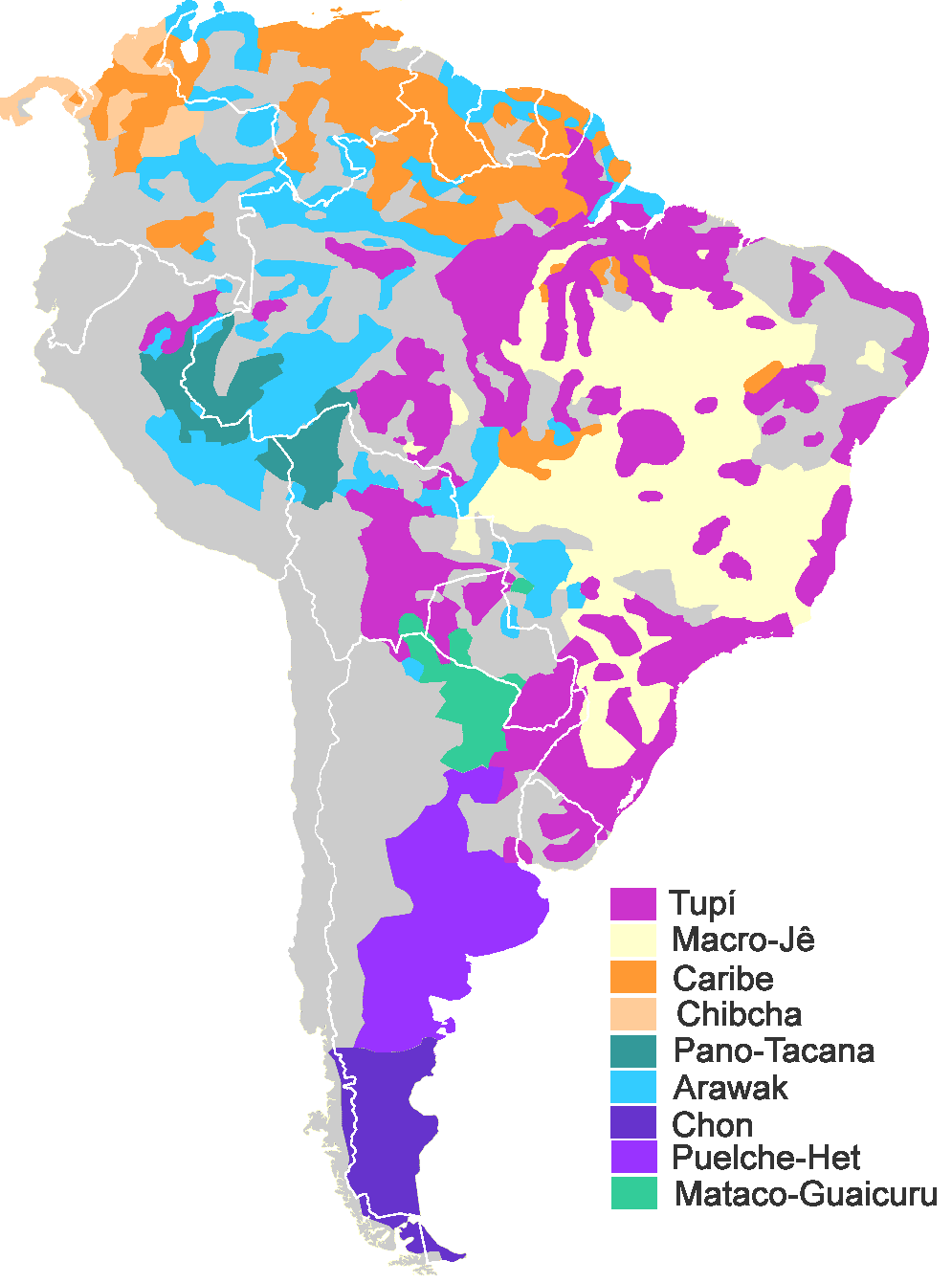

| Culture Further information: Classification of Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Mythologies of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Category:Archaeological cultures of North America, and Category:Archaeological cultures of South America Cultural practices in the Americas seem to have been shared mostly within geographical zones where distinct ethnic groups adopt shared cultural traits, similar technologies, and social organizations. An example of such a cultural area is Mesoamerica, where millennia of coexistence and shared development among the peoples of the region produced a fairly homogeneous culture with complex agricultural and social patterns. Another well-known example is the North American plains where until the 19th century several peoples shared the traits of nomadic hunter-gatherers based primarily on bison hunting. Languages Main article: Indigenous languages of the Americas  The major indigenous language families of much of present-day South America and Panama Indigenous languages in North America have been classified into 56 groups or stock tongues, in which the spoken languages of the various nations may be said to center. In connection with speech, reference may be made to gesture language which was highly developed in parts of this area. Of equal interest is the picture writing especially well developed among the Anishinaabe and Lenape nations.[184] |

文化 詳細情報: アメリカ先住民の分類、アメリカ先住民の神話体系、カテゴリ:北アメリカの考古学的文化、カテゴリ:南アメリカの考古学的文化 アメリカ大陸における文化的慣行は、主に地理的領域内で共有されていたようだ。そこでは、異なる民族集団が共通の文化的特徴、類似の技術、社会組織を採用 していた。そうした文化圏の一例がメソアメリカである。この地域では、数千年にわたる共存と共同発展が、複雑な農業・社会構造を備えた比較的均質な文化を 生み出した。もう一つの有名な例は北米平原で、19世紀まで複数の人民がバイソン狩りを主とする遊牧的狩猟採集民の特性を共有していた。 言語 詳細記事: アメリカ先住民言語  現在の南アメリカとパナマの大部分を占める主要な先住民言語族 北アメリカの先住民言語は56のグループまたは語族に分類されており、各国民の話し言葉はこれらを中心に発展したと言える。言語に関連して、この地域の一 部で高度に発達したジェスチャー言語に言及できる。同様に興味深いのは、特にアニシナベ族とレナペ族の間で高度に発達した絵文字である。[184] |

| Writing systems See also: Syllabics used by Indigenous peoples living in Canada, Cherokee syllabary, and Quipu  Maya glyphs in stucco now on display at Museo de sitio in Palenque, Mexico Beginning in the 1st millennium BCE, pre-Columbian cultures in Mesoamerica developed several Indigenous writing systems (independent of any influence from the writing systems that existed in other parts of the world). The Cascajal Block is perhaps the earliest-known example in the Americas of what may be an extensive written text. The Olmec hieroglyphs tablet has been indirectly dated (from ceramic shards found in the same context) to approximately 900 BCE which is around the same time that the Olmec occupation of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán began to weaken.[185] The Maya writing system was logosyllabic (a combination of phonetic syllabic symbols and logograms). It is the only pre-Columbian writing system known to have completely represented the spoken language of its community. It has more than a thousand different glyphs, but a few are variations on the same sign or have the same meaning, many appear only rarely or in particular localities, no more than about five hundred were in use in any given time, and, of those, it seems only about two hundred (including variations) represented a particular phoneme or syllable.[186][187][188] The Zapotec writing system, one of the earliest in the Americas,[189] was logographic and presumably syllabic.[189] There are remnants of Zapotec writing in inscriptions on some of the monumental architecture of the period, but so few inscriptions are extant that it is difficult to fully describe the writing system. The oldest example of the Zapotec script, dating from around 600 BCE, is on a monument that was discovered in San José Mogote.[190][full citation needed] Aztec codices (singular codex) are books that were written by pre-Columbian and colonial-era Aztecs. These codices are some of the best primary sources for descriptions of Aztec culture. The pre-Columbian codices are largely pictorial; they do not contain symbols that represent spoken or written language.[191] By contrast, colonial-era codices contain not only Aztec pictograms, but also writing that uses the Latin alphabet in several languages: Classical Nahuatl, Spanish, and occasionally Latin. Spanish mendicants in the sixteenth century taught Indigenous scribes in their communities to write their languages using Latin letters, and there are a large number of local-level documents in Nahuatl, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Yucatec Maya from the colonial era, many of which were part of lawsuits and other legal matters. Although Spaniards initially taught Indigenous scribes alphabetic writing, the tradition became self-perpetuating at the local level.[192] The Spanish crown gathered such documentation, and contemporary Spanish translations were made for legal cases. Scholars have translated and analyzed these documents in what is called the New Philology to write histories of Indigenous peoples from Indigenous viewpoints.[193] The Wiigwaasabak, birch bark scrolls on which the Ojibwa, an Anishinaabe) people, wrote complex geometrical patterns and shapes, can also be considered a form of writing, as can Mi'kmaq hieroglyphics. Aboriginal syllabic writing, or simply syllabics, is a family of abugidas used to write some Indigenous languages of the Algonquian, Inuit, and Athabaskan language families. |

文字体系 関連項目:カナダ先住民が使用する音節文字、チェロキー音節文字、キプ  メキシコ・パレンケの現地博物館で展示中の漆喰製マヤ文字 紀元前1千年紀から、メソアメリカの先コロンブス期文化は複数の独自文字体系を発展させた(世界の他の地域で存在した文字体系の影響とは無関係に)。カス カハール石碑は、おそらくアメリカ大陸で現存する最古の、大規模な文字記録の例である。オルメカ象形文字碑文は間接的に(同一遺跡から出土した陶片の年代 測定により)紀元前900年頃と推定される。これはオルメカ文明がサン・ロレンソ・テノチティトランでの支配力を弱め始めた時期とほぼ一致する。 マヤ文字体系はロゴシラビック(音節記号と表語文字の組み合わせ)であった。これは、その共同体の話し言葉を完全に表現した唯一の先コロンブス期文字体系 として知られている。千を超える異なる文字を持つが、同じ記号の変形や同義の文字も存在する。多くの文字は稀にしか現れないか特定地域限定であり、同時に 使用されていたのは約500文字に過ぎない。そのうち特定の音素や音節を表すのは(変形を含めて)約200文字程度と見られる。[186][187] [188] サポテック文字体系は、アメリカ大陸で最も古い文字体系の一つであり、表語文字であり、おそらく音節文字であったと考えられている。当時の記念碑的建造物 に刻まれた碑文にサポテック文字の痕跡が残っているが、現存する碑文が極めて少ないため、文字体系を完全に記述することは困難である。ザポテク文字の最古 の例は紀元前600年頃のもので、サン・ホセ・モゴテで発見された記念碑に刻まれている。[190][詳細な出典が必要] アステカ・コデックス(単数形はcodex)は、コロンブス以前および植民地時代のアステカ人によって書かれた書物である。これらのコデックスはアステカ 文化を記述する最良の一次資料の一部だ。コロンブス以前のコデックスは主に絵文字で構成されており、話し言葉や書き言葉を表す記号は含まれていない [191]。これに対し、植民地時代のコデックスにはアステカの絵文字だけでなく、ラテン文字を用いた複数の言語(古典ナワトル語、スペイン語、時にラテ ン語)の文字も記されている。 16世紀、スペインの修道僧たちは現地の書記官たちに、ラテン文字を用いて自国語を記す方法を教えた。その結果、植民地時代にはナワトル語、サポテカ語、 ミシュテカ語、ユカテコ・マヤ語で書かれた地方レベルの文書が大量に存在する。その多くは訴訟やその他の法的問題に関連するものだった。スペイン人が当初 はアルファベット表記を教えたものの、この伝統は地域レベルで自律的に継承された[192]。スペイン王室はこうした文書を収集し、法廷案件向けに当時の スペイン語訳を作成した。学者たちは「新文献学」と呼ばれる手法でこれらの文書を翻訳・分析し、先住民の視点から先住民の歴史を記述している[193]。 ウィグワサバック(Wiigwaasabak)は、アニシナベ(Anishinaabe)族の一派であるオジブワ(Ojibwa)人民が複雑な幾何学模様 や図形を記した樺の樹皮巻物であり、ミクマク(Mi'kmaq)族の象形文字と同様に、一種の文字体系と見なすことができる。 先住民音節文字、あるいは単に音節文字は、アルゴンキン語族、イヌイット語族、アサバスカ語族に属するいくつかの先住民言語を記述するために用いられるアブギダ文字の一群である。 |

| Music and art Main articles: Visual arts by Indigenous peoples of the Americas and Indigenous music  Indigenous peoples textile art in 1995 by Julia Pingushat, including Inuk, Arviat, Nunavut, Canada, wool, and embroidery floss  Chimu culture feather pectoral, feathers, reed, copper, silver, hide, cordage, c. 1350–1450  An Indigenous man playing a panpipe, antara, or siku Indigenous music can vary between cultures, however, there are significant commonalities. Traditional music often centers around drumming and singing. Rattles, clapper sticks, and rasps are also popular percussive instruments, both historically and in contemporary cultures. Flutes are made of river cane, cedar, and other woods. The Apache have a type of fiddle, and fiddles are also found many First Nations and Métis cultures. The music of the Indigenous peoples of Central Mexico and Central America, like that of the North American cultures, tends to be spiritual ceremonies. It traditionally includes a large variety of percussion and wind instruments such as drums, flutes, sea shells (used as trumpets), and "rain" tubes. No remnants of pre-Columbian stringed instruments were found until archaeologists discovered a jar in Guatemala, attributed to the Maya of the Late Classic Era (600–900 CE); this jar was decorated with imagery depicting a stringed musical instrument, which has since been reproduced. This instrument is one of the very few stringed instruments known in the Americas before the introduction of European musical instruments; when played, it produces a sound that mimics a jaguar's growl.[194] Visual arts by Indigenous peoples of the Americas comprise a major category in the world art collection. Contributions include pottery, paintings, jewelry, weavings, sculptures, basketry, carvings, and beadwork.[195] Because too many artists were posing as Native Americans and Alaska Natives[196] to profit from the cachet of Indigenous art in the United States, the U.S. passed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, requiring artists to prove that they were enrolled in a state or federally recognized tribe. To support the ongoing practice of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian arts and cultures in the United States,[197] the Ford Foundation, arts advocates, and American Indian tribes created an endowment seed fund and established a national Native Arts and Cultures Foundation in 2007.[198][199] After the entry of the Spaniards, the process of spiritual conquest was favored, among other things, by the liturgical musical service to which the natives, whose musical gifts came to surprise the missionaries, were integrated. The musical gifts of the natives were of such magnitude that they soon learned the rules of counterpoint and polyphony and even the virtuous handling of the instruments. This helped to ensure that it was not necessary to bring more musicians from Spain, which significantly annoyed the clergy.[200] The solution that was proposed was not to employ but a certain number of Indigenous people in the musical service, not to teach them counterpoint, not to allow them to play certain instruments (brass breaths, for example, in Oaxaca, Mexico) and, finally, not to import more instruments so that the Indigenous people would not have access to them. The latter was not an obstacle to the musical enjoyment of the natives, who experienced the making of instruments, particularly rubbed strings (violins and double basses) or plucked (third). It is there where we can find the origin of what is now called traditional music whose instruments have their tuning and a typical Western structure.[201] |

音楽と芸術 主な記事:アメリカ先住民の視覚芸術と先住民音楽  1995年ジュリア・ピンガシャット作、イヌク、アルヴィアット、ヌナブト準州、カナダ、羊毛、刺繍糸を用いた先住民のテキスタイルアート  チムー文化の羽根胸飾り、羽根、葦、銅、銀、皮革、縄、約1350–1450年  パンスフルート(アンタラ、シク)を演奏する先住民の男性 先住民の音楽は文化によって異なるが、重要な共通点もある。伝統音楽はしばしば打楽器と歌唱を中心とする。ガラガラ、クラッパースティック、ラスペも、歴 史的にも現代文化においても人気の打楽器だ。フルートは川竹、杉、その他の木材で作られる。アパッチ族にはバイオリンの一種があり、バイオリンは多くの先 住民族やメティス文化でも見られる。 メキシコ中部と中央アメリカの先住民の音楽は、北米の文化と同様に、霊的な儀式に用いられる傾向がある。伝統的には、太鼓、笛、貝殻(トランペットとして 使用)、雨音管など、多種多様な打楽器や管楽器が含まれる。コロンブス以前の弦楽器の痕跡は、考古学者がグアテマラで発見した壺が確認されるまで見つから なかった。この壺は後期古典期(西暦600~900年)のマヤ文化に属するとされ、弦楽器を描いた装飾が施されていた。この楽器は後に再現されている。こ の楽器は、ヨーロッパの楽器が導入される前にアメリカ大陸で知られていた数少ない弦楽器の一つだ。演奏すると、ジャガーの唸り声を模した音を発する。 [194] アメリカ先住民による視覚芸術は、世界の美術コレクションにおいて主要なカテゴリーを構成している。その貢献には、陶器、絵画、宝飾品、織物、彫刻、籠細 工、木彫り、ビーズ細工などが含まれる。[195] 米国では先住民芸術の威信を利用して利益を得ようとする、自称ネイティブアメリカンやアラスカ先住民の芸術家があまりにも多すぎたため[196]、 1990年に「インディアン芸術工芸法」が制定された。これにより芸術家は、州または連邦政府が認定する部族に登録されていることを証明することが義務付 けられた。アメリカインディアン、アラスカインディアン、ハワイインディアン の芸術と文化を米国で継続的に支援するため[197]、フォード財団、芸術支援団体、アメリカインディアン部族は2007年に基金の種銭を創設し、全国的 なネイティブ・アーツ・アンド・カルチャーズ財団を設立した[198][199]。 スペイン人の到来後、精神的征服のプロセスは、とりわけ典礼音楽奉仕によって促進された。この奉仕には、その音楽的才能が宣教師たちを驚かせた先住民たち が組み込まれたのである。先住民の音楽的才能は極めて高く、彼らはすぐに対位法やポリフォニーの規則、さらには楽器の高度な演奏技法さえも習得した。これ により、スペインから追加の音楽家を連れてくる必要がなくなり、聖職者たちを大いに苛立たせた。[200] 提案された解決策は、音楽奉仕に一定数の先住民を雇用すること、彼らに対位法を教えないこと、特定の楽器(例えばメキシコ・オアハカ州の金管楽器など)を 演奏させないこと、そして最後に、先住民がそれらにアクセスできないように、これ以上楽器を輸入しないことだった。後者の措置は、楽器製作、特に摩擦弦楽 器(ヴァイオリンやコントラバス)や撥弦楽器(第三弦楽器)の製作を体験する先住民の音楽的楽しみを妨げるものではなかった。現代で伝統音楽と呼ばれるも のの起源はここにあり、その楽器は独自の調律と典型的な西洋的構造を有しているのだ。[201] |

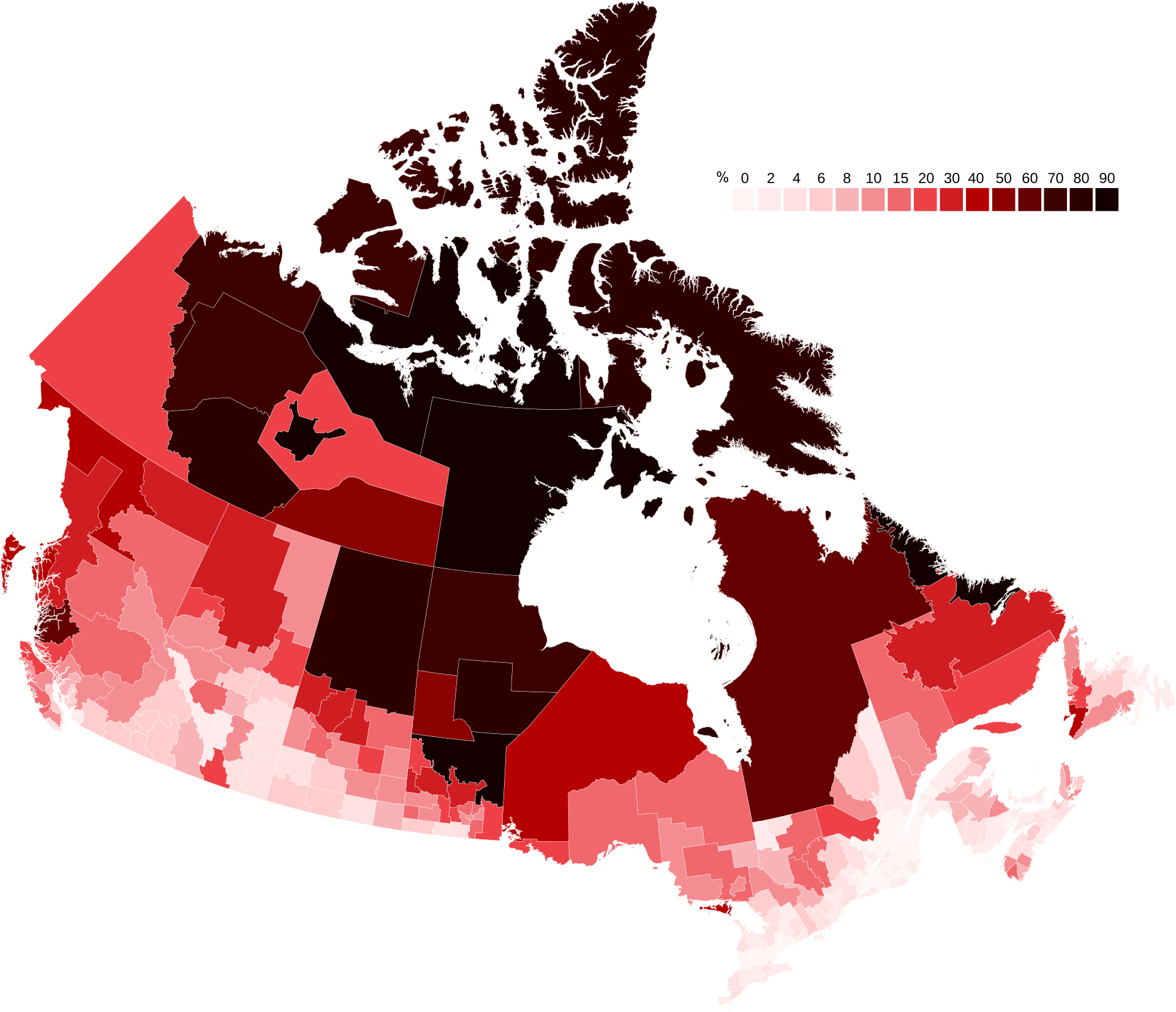

| History and status by continent and country North America Canada Main article: Indigenous peoples in Canada  A map of Canada showing the percent of self-reported Indigenous identity (First Nations, Inuit, Métis) by census division, according to the 2021 Canadian census[202] These paragraphs are an excerpt from Indigenous peoples in Canada.[edit] Indigenous peoples in Canada (also known as Aboriginals)[203] are the Indigenous peoples within the boundaries of Canada. They comprise the First Nations,[204] Inuit,[205] and Métis,[206] representing roughly 5.0% of the total Canadian population. There are over 600 recognized First Nations governments or bands with distinctive cultures, languages, art, and music.[207][208] Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves are some of the earliest known sites of human habitation in Canada.[209] The characteristics of Indigenous cultures in Canada prior to European colonization included permanent settlements,[210] agriculture,[211] civic and ceremonial architecture,[212] complex societal hierarchies, and trading networks.[213] Métis nations of mixed ancestry originated in the mid-17th century when First Nations and Inuit married Europeans, primarily French settlers.[214] First Nations and Métis peoples played a critical part in the development of European colonies in Canada, particularly for their role in assisting Europeans during the North American fur trade. Various Aboriginal laws, treaties, and legislation have been enacted between European immigrants and Indigenous groups across Canada. The impact of settler colonialism in Canada can be seen in its culture, history, politics, laws, and legislatures.[215] Historically, this included assimilationist policies affecting Indigenous languages, traditions, religion and the degradation of Indigenous communities that has contemporarily been described by some, including academics and politicians, as a cultural genocide, or genocide.[216] The modern Indigenous right to self-government provides for Indigenous self-government in Canada and the management of cultural, political, health and economic responsibilities within Indigenous communities. National Indigenous Peoples Day recognizes the vast cultures and contributions of Indigenous peoples to the history of Canada.[217] First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples of all backgrounds have become prominent figures in Canada and have helped shape the Canadian cultural identity.[218] |

大陸および国別の歴史と現状 北アメリカ カナダ 詳細記事: カナダの先住民  2021年カナダ国勢調査に基づく、国勢調査区分ごとの自己申告による先住民(ファースト・ネーションズ、イヌイット、メティス)の割合を示すカナダ地図[202] これらの段落は「カナダの先住民」からの抜粋である。[編集] カナダの先住民(アボリジナルとも呼ばれる)[203]は、カナダ国内に居住する先住民族である。ファースト・ネーションズ[204]、イヌイット [205]、メティス[206]で構成され、カナダ総人口の約5.0%を占める。600以上の公認ファースト・ネーションズ政府またはバンドが存在し、そ れぞれ独自の文化、言語、芸術、音楽を有する[207]。[208] オールド・クロウ・フラッツやブルーフィッシュ洞窟は、カナダにおける人類居住の最古の遺跡として知られている。[209] ヨーロッパ人による植民地化以前のカナダ先住民文化の特徴には、恒久的な集落、[210] 農業、[211] 公共建築や儀式用建築、[212] 複雑な社会階層、交易ネットワークなどが含まれていた。[213] 混血のメティス国民は、17世紀半ばに先住民やイヌイットが主にフランス人入植者であるヨーロッパ人と結婚したことで生まれた。[214] 先住民とメティス人民は、特に北米毛皮交易においてヨーロッパ人を支援した役割から、カナダにおけるヨーロッパ植民地の発展に重要な役割を果たした。 カナダ全土で、ヨーロッパ系移民と先住民族グループの間で様々な先住民法、条約、立法が制定されてきた。カナダにおける入植者植民地主義の影響は、その文 化、歴史、政治、法律、立法府に見られる。[215] 歴史的には、先住民の言語、伝統、宗教に影響を及ぼす同化政策や、先住民コミュニティの衰退が含まれ、現代では学者や政治家を含む一部の人々によって文化 的ジェノサイド、あるいはジェノサイドと表現されている。[216] 現代の先住民自治権は、カナダにおける先住民自治と、先住民コミュニティ内での文化的・政治的・健康・経済的責任の管理を規定している。全国先住民の日 は、先住民の多様な文化とカナダ史への貢献を認めるものである。[217]あらゆる背景を持つファースト・ネーションズ、イヌイット、メティスの人々は、 カナダで著名な存在となり、カナダの文化的アイデンティティ形成に貢献してきた。[218] |

| Greenland Main article: Greenlandic Inuit  Tunumiit Inuit couple from Kulusuk, Greenland The Greenlandic Inuit (Kalaallisut: kalaallit, Tunumiisut: tunumiit, Inuktun: inughuit) are the Indigenous and most populous ethnic group in Greenland.[219] This means that Denmark has one officially recognized Indigenous group. the Inuit – the Greenlandic Inuit of Greenland and the Greenlandic people in Denmark (Inuit residing in Denmark). Approximately 89 percent of Greenland's population of 57,695 is Greenlandic Inuit, or 51,349 people as of 2012.[36][220] Ethnographically, they consist of three major groups: the Kalaallit of west Greenland, who speak Kalaallisut the Tunumiit of Tunu (east Greenland), who speak Tunumiit oraasiat ("East Greenlandic") the Inughuit of north Greenland, who speak Inuktun ("Polar Inuit") |

グリーンランド 主な記事: グリーンランド・イヌイット  クルスク出身のトゥヌミット・イヌイットの夫婦 グリーンランド・イヌイット(カラアルリート語: カラアルリット、トゥヌミート語: トゥヌミート、イヌクトゥン語: イヌグイット)は、グリーンランドの先住民族であり、最も人口の多い民族集団である。[219] これはデンマークが公式に認める先住民が1つだけであることを意味する。イヌイットである――グリーンランドのグリーンランド・イヌイットと、デンマーク 在住のグリーンランド人(デンマーク居住イヌイット)だ。 2012年時点で、グリーンランドの人口57,695人の約89%がグリーンランド・イヌイットであり、51,349人に上る。[36][220] 民族誌的には、彼らは三つの主要なグループから成る: 西グリーンランドのカラリット(Kalaallit)。カラアリスート(Kalaallisut)を話す。 東グリーンランド(トゥヌ)のトゥヌミット(Tunumiit)。トゥヌミット・オラアシート(Tunumiit oraasiat、いわゆる「東グリーンランド語」)を話す。 北グリーンランドのイヌイット(Inughuit)。イヌクトゥン(Inuktun、いわゆる「極地イヌイット語」)を話す。 |

| Mexico Main article: Indigenous peoples of Mexico  Proportion of Native Mexicans in each municipalities in 2020.  A Huichol woman from Zacatecas, Mexico  A carnival with Tzeltal people in Tenejapa Municipality, Chiapas The territory of modern-day Mexico was home to numerous Indigenous civilizations before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores: The Olmecs, who flourished from between 1200 BCE to about 400 BCE in the coastal regions of the Gulf of Mexico; the Zapotecs and the Mixtecs, who held sway in the mountains of Oaxaca and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec; the Maya in the Yucatán (and into neighboring areas of contemporary Central America); the Purépecha in present-day Michoacán and surrounding areas, and the Aztecs/Mexica, who, from their central capital at Tenochtitlan, dominated much of the center and south of the country (and the non-Aztec inhabitants of those areas) when Hernán Cortés first landed at Veracruz. In contrast to what was the general rule in the rest of North America, the history of the colony of New Spain was one of racial intermingling (mestizaje). Mestizos, which in Mexico designate people who do not identify culturally with any Indigenous grouping, quickly came to account for a majority of the colony's population. Today, Mestizos in Mexico of mixed Indigenous and European ancestry (with a minor African contribution) are still a majority of the population. Genetic studies vary over whether Indigenous or European ancestry predominates in the Mexican Mestizo population.[221][222] In the 2020 INEGI census, 23.2 million people (19.4% of the Mexican population aged 3 years and older) self-identified as Indigenous.[2] Somewhat contradictorily, in the same 2020 census, 11.8 million people (9.3% of the Mexican population) were determined to be Indigenous by the Mexican government based on the language spoken in their households.[1] The Indigenous population is distributed throughout the territory of Mexico but is especially concentrated in the Sierra Madre del Sur, the Yucatán Peninsula, and the most remote and difficult-to-access areas, such as the Sierra Madre Oriental, the Sierra Madre Occidental, and neighboring areas.[223] The CDI identifies 62 Indigenous groups in Mexico, each with a unique language.[224][225] In the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca and the interior of the Yucatán Peninsula, a large amount of the population is of Indigenous descent with the largest ethnic group being Maya with a population of 900,000.[226] Large Indigenous minorities, including Aztecs or Nahua, Purépechas, Mazahua, Otomi, and Mixtecs are also present in the central regions of Mexico. In the Northern and Bajio regions of Mexico, Indigenous people are a small minority. The General Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Peoples grants all Indigenous languages spoken in Mexico, regardless of the number of speakers, the same validity as Spanish in all territories in which they are spoken, and Indigenous peoples are entitled to request some public services and documents in their native languages.[227] Along with Spanish, the law has granted them—more than 60 languages—the status of "national languages". The law includes all Indigenous languages of the Americas regardless of origin; that is, it includes the Indigenous languages of ethnic groups non-native to the territory. The National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples recognizes the language of the Kickapoo, who immigrated from the United States[228] and recognizes the languages of the Indigenous refugees from Guatemala.[229] The Mexican government has promoted and established bilingual primary and secondary education in some Indigenous rural communities. Nonetheless, of the Indigenous peoples in Mexico, 93% are either native speakers or bilingual second-language speakers of Spanish with only about 62.4% of them (or 5.4% of the country's population) speaking an Indigenous language and about a sixth do not speak Spanish (0.7% of the country's population).[230]  The Rarámuri marathon in Urique The Indigenous peoples in Mexico have the right of free determination under the second article of the constitution. According to this article, the Indigenous peoples are granted:[231] the right to decide the internal forms of social, economic, political, and cultural organization; the right to apply their normative systems of regulation as long as human rights and gender equality are respected; the right to preserve and enrich their languages and cultures; the right to elect representatives before the municipal council in which their territories are located; amongst other rights. |

メキシコ 主な記事: メキシコの先住民  2020年における各自治体ごとの先住民比率。  メキシコ・サカテカス州出身のウィチョル族の女性  チアパス州テネハパ自治体におけるツェルタル族のカーニバル 現代のメキシコ領土には、スペインの征服者が到来する以前から数多くの先住民文明が存在していた。メキシコ湾沿岸地域で紀元前1200年から紀元前400 年頃にかけて栄えたオルメカ文明、オアハカ山地とテワントペック地峡を支配したサポテカ族とミシュテカ族、 ユカタン半島(及び現代の中米に隣接する地域)のマヤ、現在のミチョアカン州及び周辺地域にいたプレペチャ、そしてテノチティトランを中心の都として、エ ルナン・コルテスがベラクルスに初めて上陸した当時、国内の中部及び南部の大部分(及びそれらの地域の非アステカ系住民)を支配していたアステカ/メシカ である。 北米の他の地域における一般的な傾向とは対照的に、ヌエバ・エスパーニャ植民地の歴史は人種的混交(メスティサヘ)の歴史であった。メスティソとは、メキ シコにおいて先住民集団のいずれにも文化的帰属意識を持たない人民を指す言葉であり、彼らは植民地人口の過半数を占めるまでに急速に増加した。今日でも、 メキシコでは先住民とヨーロッパ人の混血のメスティソ(アフリカ系の寄与は少ない)が人口の大多数を占めている。メキシコのメスティソ集団において、先住 民系とヨーロッパ系のどちらの祖先が優勢かについては、遺伝子研究によって結果が異なる。[221][222] 2020年のINEGI国勢調査では、2320万人(3歳以上のメキシコ人民の19.4%)が自らを先住民と認識した[2]。やや矛盾するが、同じ 2020年の国勢調査では、1180万人(メキシコ人民の9.3%)が、家庭で話される言語に基づいてメキシコ政府により先住民と認定された。[1] 先住民人口はメキシコ全土に分布しているが、特にシエラ・マドレ・デル・スル、ユカタン半島、そしてシエラ・マドレ・オリエンタル、シエラ・マドレ・オク シデンタル及びその周辺地域など、最も辺境でアクセス困難な地域に集中している。[223] CDIはメキシコ国内に62の先住民集団を特定しており、それぞれが固有の言語を有している。[224][225] チアパス州、オアハカ州、ユカタン半島内陸部では、人口の多くが先住民の血を引いており、最大民族グループは人口90万人のマヤ系である。[226] アステカ(ナワ)、プレペチャ、マサワ、オトミ、ミステクなど、大規模な先住民少数民族もメキシコ中部地域に存在する。メキシコ北部およびバヒオ地域で は、先住民は少数派である。 先住民言語権利基本法は、メキシコ国内で話される全ての先住民言語に対し、話者数に関わらず、その言語が話される全地域においてスペイン語と同等の効力を 認めている。また先住民は、公的サービスや文書を母語で要求する権利を有する[227]。同法はスペイン語に加え、60以上の言語に「国民言語」の地位を 付与している。この法律は、起源を問わずアメリカ大陸の全ての先住民言語を対象とする。つまり、その地域に元々住んでいなかった民族グループの先住民言語 も含まれる。先住民開発国家委員会は、アメリカ合衆国から移住したキカプー族の言語を認定している[228]。またグアテマラからの先住民難民の言語も認 定している[229]。メキシコ政府は、一部の先住民農村地域において二言語による初等・中等教育を推進し確立してきた。しかしながら、メキシコの先住民 のうち93%はスペイン語の母語話者もしくはバイリンガルの第二言語話者であり、先住民言語を話すのは約62.4%(国内人口の5.4%)に過ぎない。ま た約6分の1はスペイン語を話さない(国内人口の0.7%)。[230]  ウリケのララムリ族マラソン メキシコの先住民は、憲法第2条に基づき自由な決定権を有する。同条により先住民には以下の権利が認められる: [231] 社会的・経済的・政治的・文化的組織の内部形態を決定する権利 人権と男女平等が尊重される限り、自らの規範的規制システムを適用する権利 自らの言語と文化を保存し豊かにする権利 自らの領土が所在する市町村議会に代表者を選出する権利 その他の権利 |