アンティゴネー

Antigone

「政治的対立を法的訴えにつくりかえて、国家にフェ ミズムの主張を支持するような合法化を求めようとする現在のフェミニズムの試みのなかでは、アンティゴネーの反抗の遺産は失われているように思えた」—— ジュディス・バトラー『アンティゴネーの主張』竹村和子訳、p.14, 青土社, 2002年(→バトラーにとって のアンティゴネーはこちらです)(→アンティゴネーとヘーゲル)

「彼女は、ある無条件の「しなければならない(マスト)」——ポリュネイケスを埋葬しなけれ

ばならない——に突き動かされているのである。……しかし、この種の倫理は、カントが切り拓き、ラカンが再び議論

の俎上に載せた領域まで踏み込むことができない。彼らの倫理は、「世のため、人のため」などという心地

よいものではない。彼らの言う倫理的行為は、一般的な意味での「法」や「法からの逸脱」という次元には

存在しないアンティゴネは、暴君によって踏みにじられた人権をとり戻すために戦う社会運動家ではな

い。彼らにとっての倫理的行為は、〈真実=ザ・リアル〉の次元にあるのだ」——アレンカ・ジュパンチッチ『リアルの倫理 : カントとラカン』冨樫剛訳, pp.75-76、東京 : 河出書房新社 , 2003.2.

『アンティゴネ』 (アンティゴネー、古代ギリシア語: Ἀντιγόνη、ラテン語: Antigone)は「古代ギリシア三大悲劇詩人の一人であるソポクレスが紀元前442年ごろに書いたギリシア悲劇。オイディプスの娘でテーバイの王女で あるアンティゴネを題材とする。……先王オイディプスが自己の呪われた運命を知って盲目となり(『オイディプス王』)、放浪の末にこの世を去った(『コロ ノスのオイディプス』)後、アンティゴネとイスメネはテーバイへ戻った。しかしテーバイでもアンティゴネの兄たちが王位を巡って争いを始めて、アルゴス人 の援助を受けてテーバイに攻め寄せたポリュネイケスとテーバイの王位にあったエテオクレスが刺し違えて死に、クレオンがテーバイの統治者となった。/クレオンは国家に対する反逆者であるポリュネイケスの埋葬や一切の葬礼を禁止し、見張りを立て てポリュネイケスの遺骸を監視させる。アンティゴネはこの禁令を犯し、見張りに捕らえられてクレオンの前に引き立てられる。人間の自然に基づく法を主張するアンティゴネと国家の法の厳正さを主張するクレオンは互いに譲らず、イスメネやハイモンの取り 成しの甲斐もなくて、クレオンは実質の死刑宣告として、一日分の食料を持たせてアンティゴネを地下に幽閉することを決定する。/その後、クレオンはテイレシアースの占いと長老たちの進言を受けてアンティゴネへの処分を撤回し、ポ リュネイケスの遺体の埋葬を決める。しかし時既に遅く、アンティゴネは首を吊り、父(クレオン)を恨んだアンティゴネの夫ハイモンも剣に伏 して自殺した。、クレオンが自らの運命を嘆く場面で劇は終わる」 #Wiki.

ポイントを整理しよう;テーバイで、アンティゴネの 兄たちが王位を巡って争いを始めて、最終的に彼らの叔父にあたるクレオンが新しい統治者になる。クレオンは、謀反者のポ リュネイケス(アンティゴネの兄)らを埋葬を禁じる。しかし、アンティゴネは、その国禁を侵し、兄を埋葬することを主張する。アンティゴネは捕まり、クレ オンの前で、自然なキョウダイへの愛を実践する兄の埋葬の正当性を主張する。クレオンは法の厳密な実行こそが重要だと譲らない。クレオンは、アンティゴネ を幽閉することを決めるが、託宣により、アンティゴネへの処分を取り消すが、アンティゴネもその夫のハイモンも自死して、クレオンはその運命を呪いつつ劇 はおわる。

Antigone, by Frederic

Leighton

「アンティゴネーの 悲劇は、兄への弔意という肉親の情および人間を埋葬するという人倫的習俗と神への宗 教的義務と、国家による法の適用の対立から来るもので ある。哲学者ヘーゲルは『精神現象学』の人倫(Sittlichkeit)の章にて、アンティゴネーを人間意識の客観的段階のひとつである人倫の象徴とし て分析している」- #Wiki.

ヘーゲルによるアンティゴネーの議論は、『精神現象 学』の他に、『美学』詩、『法哲学』家族、においてみられるという。ヘーゲルの時代に、その盟友ヘルダーリンは、『アンティゴネ』の新訳を完成させる。

●クレオンの呪詛

「私が彼女(アンティゴネ)を生かしておけば、私は もはや男ではなく、彼女のほうが男だ」

クレオンの本音は、女性的なものが、侵食していき、

社会が危険なものになる。

●アンティゴネーに対するさまざまな解釈

・女(アンティゴネ)が、クレオンの原理(=私情を 交えず法に厳密にしたがうべし)に従わねば、女は死や暴力にさらされる。

・クレオンのアンティゴネに対する立場が、微妙にぶ れるので、人間の自然な情念を「否定」して、社会秩序は構築されることを示唆している。

・国法の原理は、私情のあり方を理解できないが、同 時に、自然や自然法に対して「つねに負債を担う」ことをこのシステムは示唆している。

・法の執行による正義の実現と、私情や慣習による服

喪がもつ倫理的情感とは、まったく別の原理である。

●まとめ

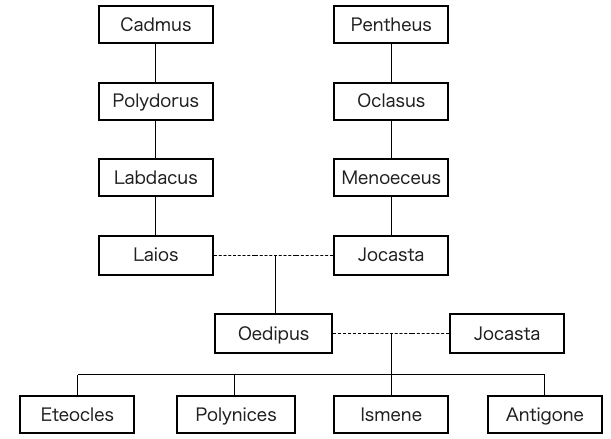

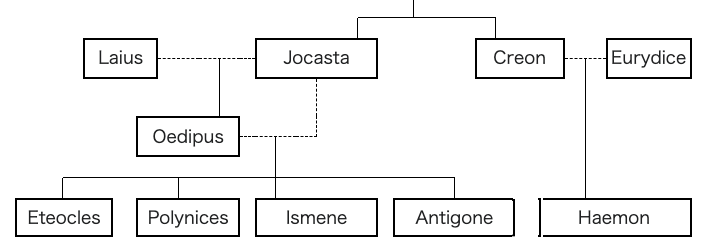

・エテオクレス、ポリュネイケス、アンティゴネは、 イオカステを母に、オイディプスを父にもつ兄弟たちである。

・イオカステの兄弟、すなわちアンティゴネたちの叔 父で、現在のテバイの王であるクレオンは、刺し違えた兄弟の兄のエテオクレスの死を賞賛するが、(叛逆の科を認定された)ポリュネイケスの埋葬は禁止し た。クレオンは「人間による命令」で埋葬を禁止する。

・アンティゴネは人間の「決められた正義」=慣行 の・普遍的で神的な理由(=ノモス)を尊重すべきだと主張した。

・クレオンは怒り、アンティゴネを岩窟に閉じ込めて 生き埋めにせよと命令がくだった時に、クレオンは自分で縊死する。

・スタシスとは、ポリスを内側から崩壊させる反乱の 原理である。ポレモスはポリスの栄光を高める外部戦争である。彼女の縊死は、ポリスからスタシスの毒を吸い出したとも言われる。

****

| Prior to the

beginning of the play, the brothers Eteocles and Polynices, leading

opposite sides in Thebes' civil war, died fighting each other for the

throne. Creon, the new ruler of Thebes and brother of the former Queen

Jocasta, has decided that Eteocles will be honored and Polynices will

be in public shame. The rebel brother's body will not be sanctified by

holy rites and will lie unburied on the battlefield, prey for carrion

animals,[a] the harshest punishment at the time. Antigone and Ismene

are the sisters of the dead Polynices and Eteocles. |

劇が始まる前、テーベの内戦で敵味方に分かれていたエテオクレースとポ

リュニケースの兄弟は、王位を巡って互いに戦い、命を落とした。テーベの新たな支配者であり、前女王ヨカスタの弟であるクレオンは、エテオクレースを称

え、ポリュニケースを公に辱めることを決めた。反逆者の死体は神聖な儀式によって清められることはなく、戦場に埋葬されることもなく、野獣の餌食となる。

これは当時最も厳しい処罰であった。アンティゴネーとイスメネーは、死んだポリュニケースとエテオクレースの姉妹である。 |

| In the opening of the play,

Antigone brings Ismene outside the palace gates late at night for a

secret meeting: Antigone wants to bury Polynices' body, in defiance of

Creon's edict. Ismene refuses to help her, not believing that it will

actually be possible to bury their brother, who is under guard, but she

is unable to stop Antigone from going to bury her brother herself. |

劇の冒頭で、アンティゴネーは深夜にイスメネを宮殿の外に連れ出し、秘

密の会合を開く。クレオンの命令に背いてポリュニケスの遺体を埋葬したいとアンティゴネーは言う。イスメネは、警備の目をくぐって本当に埋葬できるとは思

えないので、彼女を手伝うことを拒否するが、アンティゴネーが自分で弟の埋葬に行くのを止めることはできない。 |

| The Chorus, consisting of Theban

elders, enter and cast the background story of the Seven against Thebes

into a mythic and heroic context. |

テーベの長老たちで構成されるコーラスが現れ、七人対テーベの物語を神

話的かつ英雄的な文脈に置き換える。 |

| Creon enters, and seeks the

support of the Chorus in the days to come and in particular, wants them

to back his edict regarding the disposal of Polynices' body. The leader

of the Chorus pledges his support out of deference to Creon. A sentry

enters, fearfully reporting that the body has been given funeral rites

and a symbolic burial with a thin covering of earth, though no one saw

who actually committed the crime. Creon, furious, orders the sentry to

find the culprit or face death himself. The sentry leaves. |

クレオンが入場し、今後数日間のコーラスの支持を求め、特にポリュニケ

スの遺体の処理に関する勅令を支持してほしいと願う。

コーラスのリーダーは、クレオンへの敬意から支持を誓う。一人の見張り番が恐る恐る入ってきて、死体が葬儀の儀式を受け、土を薄く被せただけの象徴的な埋

葬をされたと報告するが、実際に犯行を行った人物は誰なのかは誰も見ていない。激怒したクレオンは、見張り番に犯人を見つけ出さなければ自らが死ぬことに

なるよう命じる。見張り番が出て行く。 |

| The Chorus sing of the ingenuity

of human beings; but add that they do not wish to live in the same city

as law-breakers. |

コーラスは人間の創意工夫を歌っているが、法律違反者と同じ都市に住み たいとは思わないと付け加える。 |

| The sentry returns, bringing

Antigone with him. The sentry explains that the watchmen uncovered

Polynices' body and then caught Antigone as she did the funeral

rituals. Creon questions her after sending the sentry away, and she

does not deny what she has done. She argues unflinchingly with Creon

about the immorality of the edict and the morality of her actions.

Creon becomes furious, and seeing Ismene upset, thinks she must have

known of Antigone's plan. He summons her. Ismene tries to confess

falsely to the crime, wishing to die alongside her sister, but Antigone

will not have it. Creon orders that the two women be imprisoned. |

番兵が戻り、アンティゴネーを連れてくる。番兵は、ポリュニケーの死体

が発見され、葬儀の儀式を行おうとしたアンティゴネーが捕らえられたと説明する。クレオンは番兵を帰すと、彼女を問い詰めるが、彼女は自分のしたことを否

定しない。彼女は、クレオンに、命令の非道徳性と自分の行動の道徳性について、毅然として反論する。クレオンは激怒し、動揺するイスメネを見て、彼女がア

ンティゴネーの計画を知っていたに違いないと考えた。彼は彼女を呼び寄せた。イスメネは姉とともに死ぬことを望み、罪を偽って告白しようとしたが、アン

ティゴネーはそれを許さなかった。クレオンは2人の女性を投獄するよう命じた。 |

| The Chorus sing of the troubles

of the house of Oedipus. |

コーラスはオイディプス家の災難を歌う。 |

| Haemon, Creon's son, enters to

pledge allegiance to his father, even though he is engaged to Antigone.

He initially seems willing to forsake Antigone, but when he gently

tries to persuade his father to spare Antigone, claiming that "under

cover of darkness the city mourns for the girl", the discussion

deteriorates, and the two men are soon bitterly insulting each other.

When Creon threatens to execute Antigone in front of his son, Haemon

leaves, vowing never to see Creon again. |

クレオンの息子であるヘモーンは、アンティゴネーと婚約中にもかかわら

ず、父への忠誠を誓うためにその場に入る。彼は当初、アンティゴネーを捨てるつもりであるかのように見えるが、父にアンティゴネーを助命するようにと「夜

の闇に覆われ、この街は彼女のために嘆いている」と優しく説得しようとしたとき、議論は悪化し、2人はすぐに互いを激しく侮辱し合う。クレオンが息子の前

でアンティゴネーを処刑すると脅すと、ヘーモンは二度とクレオンには会わないと誓ってその場を去る。 |

| The Chorus sing of the power of

love. |

コーラスは愛の力を歌う。 |

| Antigone is brought in under

guard on her way to execution. She sings a lament. The Chorus compares

her to the goddess Niobe, who was turned into a rock, and say it is a

wonderful thing to be compared to a goddess. Antigone accuses them of

mocking her. |

アンティゴネーは護衛付きで処刑場へと連行される。彼女は嘆きの歌を歌

う。コーラスは、岩に変えられた女神ニオベと彼女を比較し、女神と比較されるのは素晴らしいことだと言う。アンティゴネーは彼らを嘲笑していると非難す

る。 |

| Creon decides to spare Ismene

and to bury Antigone alive in a cave. By not killing her directly, he

hopes to pay minimal respects to the gods. She is brought out of the

house, and this time, she is sorrowful instead of defiant. She

expresses her regrets at not having married and dying for following the

laws of the gods. She is taken away to her living tomb. |

クレオンはイスメネーを助けることにし、アンティゴネーを生きたまま洞

窟に埋めることにした。彼女を直接殺さないことで、神々への最低限の敬意を表そうとしたのだ。彼女は家から連れ出され、今度は反抗的な態度ではなく、悲し

みに暮れていた。彼女は、神々の定めに従って結婚もせず死ぬことになったことを悔やんだ。そして、生きた墓へと連れて行かれた。 |

| The Chorus encourage Antigone by singing of the great women of myth who suffered. | コーラスは、苦難に耐えた神話上の偉大な女性たちを歌い、アンティゴ

ネーを勇気づける。 |

| Tiresias, the blind prophet,

enters. Tiresias warns Creon that Polynices should now be urgently

buried because the gods are displeased, refusing to accept any

sacrifices or prayers from Thebes. However, Creon accuses Tiresias of

being corrupt. Tiresias responds that Creon will lose "a son of [his]

own loins"[3] for the crimes of leaving Polynices unburied and putting

Antigone into the earth (he does not say that Antigone should not be

condemned to death, only that it is improper to keep a living body

underneath the earth). Tiresias also prophesies that all of Greece will

despise Creon and that the sacrificial offerings of Thebes will not be

accepted by the gods. The leader of the Chorus, terrified, asks Creon

to take Tiresias' advice to free Antigone and bury Polynices. Creon

assents, leaving with a retinue of men. |

盲目の預言者ティレシアスが入場する。ティレシアスはクレオンに、神々 が不快感を示しているため、ポリュニケスをすぐに埋葬すべきだと警告する。テーベからのいかなる犠牲や祈りも受け入れようとしないのだ。しかし、クレオン はティレシアスを堕落していると非難する。ティレシアスは、ポリュニケーを埋葬しないこととアンティゴネーを土葬した罪により、クレオンは「自分の骨肉の 息子」を失うことになるだろうと答えた。[3](アンティゴネーを死刑にすべきではないとは言わず、生きている人間の遺体を土葬するのは不適切であるとだ け述べた。また、ティレシアスは、ギリシャ全土がクレオンを軽蔑し、テーベの生贄は神々に受け入れられないだろうと予言する。コーラスのリーダーは恐れお ののき、アンティゴネーを解放しポリュニケーを埋葬するよう、ティレシアスの助言に従うようクレオンに懇願する。クレオンはこれに同意し、家来たちを引き 連れて立ち去る。 |

| The Chorus deliver an oral ode

to the god Dionysus. |

コーラスは、ディオニュソス神への口頭による頌歌を歌う。 |

| A messenger enters to tell the

leader of the Chorus that Haemon has killed himself. Eurydice, Creon's

wife and Haemon's mother, enters and asks the messenger to tell her

everything. The messenger reports that Creon saw to the burial of

Polynices. When Creon arrived at Antigone's cave, he found Haemon

lamenting over Antigone, who had hanged herself. Haemon unsuccessfully

attempted to stab Creon, then stabbed himself. Having listened to the

messenger's account, Eurydice silently disappears into the palace. |

使者(メッセンジャー)がコーラスのリーダーにヘーモンが自殺したこと

を伝えるために入ってくる。クレオンの妻でヘーモンの母であるエウリュディケが現れ、メッセンジャーにすべてを伝えるよう頼む。メッセンジャーは、クレオ

ンがポリュニケの埋葬を行ったことを報告する。クレオンがアンティゴネーの洞窟に到着すると、彼は自害したアンティゴネーを嘆き悲しむヘモンを見つけた。

ヘモンはクレオンを刺そうとしたが失敗し、その後、自らを刺した。使者から話を聞いたエウリュディケは、静かに宮殿へと姿を消した。 |

| Creon enters, carrying Haemon's

body. He understands that his own actions have caused these events and

blames himself. A second messenger arrives to tell Creon and the Chorus

that Eurydice has also killed herself. With her last breath, she cursed

her husband for the deaths of her sons, Haemon and Megareus. Creon

blames himself for everything that has happened, and, a broken man, he

asks his servants to help him inside. The order he valued so much has

been protected, and he is still the king, but he has acted against the

gods and lost his children and his wife as a result. After Creon

condemns himself, the leader of the Chorus closes by saying that

although the gods punish the proud, punishment brings wisdom. |

クレオンがヘーモンの遺体を抱えて入ってくる。彼は、自分の行動がこの

ような事態を引き起こしたことを理解し、自分を責める。2人目の使者があらわれ、エウリュディケも自殺したことをクレオンとコーラスに告げる。彼女は最後

の息で、息子たち、ヘーモンとメガレウスの死の責任を夫に問うた。クレオンは、起こったことすべてを自分の責任とし、打ちのめされたように、召使たちに中

へ入るのを手伝うように頼む。彼が非常に大切にしていた秩序は守られ、彼は依然として王であるが、彼は神々に逆らい、その結果、子供たちと妻を失った。ク

レオンが自らを非難した後、コーラスのリーダーは、神々は高慢な者を罰するが、罰は知恵をもたらす、と締めくくる。 |

| Characters - Antigone, compared with her beautiful and docile sister, is portrayed as a heroine who recognizes her familial duty. Her dialogues with Ismene reveal her to be as stubborn as her uncle.[4] In her, the ideal of the female character is boldly outlined.[5] She defies Creon's decree despite the consequences she may face, in order to honor her deceased brother. - Ismene serves as a foil for Antigone, presenting the contrast in their respective responses to the royal decree.[4] Considered the beautiful one, she is more lawful and obedient to authority. She hesitates to bury Polynices because she fears Creon. - Creon is the current King of Thebes, who views law as the guarantor of personal happiness. He can also be seen as a tragic hero, losing everything for upholding what he believes is right. Even when he is forced to amend his decree to please the gods, he first tends to the dead Polynices before releasing Antigone.[4] - Eurydice of Thebes is the Queen of Thebes and Creon's wife. She appears towards the end and only to hear confirmation of her son Haemon's death. In her grief, she dies by suicide, cursing Creon, whom she blames for her son's death. - Haemon is the son of Creon and Eurydice, betrothed to Antigone. Proved to be more reasonable than Creon, he attempts to reason with his father for the sake of Antigone. However, when Creon refuses to listen to him, Haemon leaves angrily and shouts he will never see him again. He dies by suicide after finding Antigone dead. - Koryphaios is the assistant to the King (Creon) and the leader of the Chorus. He is often interpreted as a close advisor to the King, and therefore a close family friend. This role is highlighted in the end when Creon chooses to listen to Koryphaios' advice. - Tiresias is the blind prophet whose prediction brings about the eventual proper burial of Polynices. Portrayed as wise and full of reason, Tiresias attempts to warn Creon of his foolishness and tells him the gods are angry. He manages to convince Creon, but is too late to save the impetuous Antigone. - The Chorus, a group of elderly Theban men, is at first deferential to the king.[5] Their purpose is to comment on the action in the play and add to the suspense and emotions, as well as connecting the story to myths. As the play progresses they counsel Creon to be more moderate. Their pleading persuades Creon to spare Ismene. They also advise Creon to take Tiresias's advice. |

登場人物 - アンティゴネーは、美しくおとなしい妹と比較され、家族の義務を認識するヒロインとして描かれている。イスメネとの対話では、彼女が叔父と同じくらい頑固 であることが明らかになっている。[4] 彼女には、大胆に描かれた理想的な女性像がある。[5] 彼女は、亡くなった兄を称えるために、直面するかもしれない結果を顧みず、クレオンの命令に逆らう。 イスメネーはアンティゴネーの対照的な存在であり、王の命令に対するそれぞれの反応の対照を示している。[4] 美しいとされるイスメネーは、より従順で権威に従順である。彼女はクレオンを恐れているため、ポリュニケーを埋葬することをためらう。 クレオンはテーベの現王であり、法を人格的な幸福の保証者と見なしている。また、正しいと信じるものを守るためにすべてを失う悲劇の英雄とも見ることがで きる。神々の機嫌を取るためにやむなく命令を変更したときでさえ、彼はまずポリュニケーの死体を丁重に扱い、それからアンティゴネーを解放した。 - テーベのエウリュディケはテーベの王妃であり、クレオンの妻である。彼女は終盤に登場し、息子のヘーモンの死を確認するためにのみ登場する。悲嘆に暮れた 彼女は自殺し、息子の死の責任をクレオンに押し付け、彼を罵りながら死んでいく。 - ヘーモンはクレオンとエウリュディケーの息子であり、アンティゴネーの婚約者である。クレオンよりも分別があり、アンティゴネーのために父親を説得しよう とする。しかし、クレオンが耳を貸そうとしないため、ヘーモンは怒ってその場を立ち去り、二度と父親に会わないと叫ぶ。ヘーモンはアンティゴネーの死体を 発見した後、自殺する。 コリファイスは王(クレオン)の補佐官であり、コーラスのリーダーである。彼はしばしば王の側近であり、したがって王の家族の親しい友人であると解釈され る。この役割は、最後にクレオンがコリファイオスの助言に耳を傾けることを選択したときに強調される。 - ティレシアスは、ポリュニケスの埋葬を最終的に適切に行うことを可能にした盲目の予言者である。賢明で思慮深い人物として描かれるティレシアスは、クレオ ンの愚かさを警告し、神々が怒っていると告げる。彼はクレオンを説得することに成功するが、衝動的なアンティゴネーを救うには遅すぎた。 - テーベの高齢の男性たちによる合唱団は、最初は王に恭順している。[5] 彼らの目的は、劇中の行動について論評し、サスペンスと感情を盛り上げ、物語を神話と結びつけることである。劇が進むにつれ、彼らはクレオンに穏健な態度 を取るよう助言する。彼らの懇願により、クレオンはイスメネを助けることにする。また、彼らはクレオンに、ティレシアスの助言に従うよう助言する。 |

★テーマ

| 市民的不服従 |

アンティゴネーにおける確立されたテーマは、個人が個人的な義務を遂行

する自由を社会が侵害することを拒否する権利である。[20]

アンティゴネーはイスメネに、クレオンの勅令について「彼は私を私自身から引き離す権利などない」と語っている。 [21]

このテーマに関連して、アンティゴネーが弟を埋葬したいという意志は、理性的な思考に基づくものなのか、それとも本能的なものなのかという疑問がある。こ

の議論にはゲーテも参加している。 国家の法律よりも上位の法に関するクレオンとアンティゴネーの対照的な見解は、市民的不服従に関する彼らの異なる結論を導いている。クレオンは、何が正し かろうが間違っていようが、何よりも法に従うことを要求する。彼は「権威への不服従ほど悪いものはない」と言う(アン。671)。アンティゴネーは、国家 の法は絶対的なものではなく、極端な場合、クレオンの法や権威よりも上位にある神々を崇めることなどにおいては、市民的不服従によって法を破ることができ るという考えで応える。 |

| 自然法と現代の法制度 |

ポリュネイケスを埋葬しないというクレオンの命令は、それ自体が市民で

あることの意味と、市民権の放棄とは何かについて大胆な主張をしている。各都市が自らの市民の埋葬に責任を持つという慣習は、ギリシア人によってしっかり

と守られていた。ヘロドトスは、大規模な戦いの後、各都市の住民が自分たちの死者を収集して埋葬する方法について論じている。[22]

したがって、『アンティゴネー』において、テーベの人々がアルゴイ人を埋葬しなかったのは当然であるが、クレオンがポリュネイケスの埋葬を禁止したことは

非常に印象的である。彼もテーベの市民である以上、テーベ人たちが彼を埋葬するのは当然のことだった。クレオンは、ポリュネイケスが自分たちから離反した

のだと民に告げ、彼を同胞として扱うことや、市民の慣習に従って彼を埋葬することを禁じたのだ。 ポリュネイケスを埋葬することをテーベの人々に禁じたクレオンは、本質的には彼を他の襲撃者たち、すなわち外国人のアルゴイ人と同等に扱っている。クレオ ンにとって、ポリュネイケスが都市を攻撃したという事実は、彼の市民権を事実上無効にし、彼を外国人にしてしまう。この布告で定義されているように、市民 権は忠誠心に基づいている。ポリュネイケスがクレオンの目には反逆罪に値する行為を犯した時点で、市民権は無効となる。アンティゴネーの見解と対立するこ の市民権の理解は、新たな対立軸を生み出す。アンティゴネーはポリュネイケスが国家を裏切ったことを否定するわけではないが、この裏切りによって彼が都市 とのつながりを失うことはないと単純に考えている。一方、クレオンは、市民権とは契約であり、絶対的でも不可侵でもなく、特定の状況下では失われる可能性 があると考えている。市民権は絶対的で否定できないという考えと、市民権は特定の行動に基づくという考えという、この2つの相反する見解は、それぞれ「生 まれながらの市民権」と「法律上の市民権」として知られている。[22] |

| 忠誠 |

ポリュネイケスを葬るというアンティゴネーの決意は、家族に名誉をもた

らし、神々のより高次の法を尊重したいという願いから生じている。彼女は「死者たち」を喜ばせるために行動しなければならないと繰り返し宣言している

(An.

77)。なぜなら、彼らはどんな支配者よりも重みがあり、すなわち神聖な法の重みがあるからだ。冒頭の場面で、彼女は妹のイスメネに感情的に訴えかける。

たとえ彼が国を裏切ったとしても、姉妹愛から彼を守らなければならないと。アンティゴネーは、最高権威、すなわち神聖な法そのものから由来する権利は譲渡

できないと信じている。 家族の名誉を理由にアンティゴネーの行動を否定する一方で、クレオンは家族を大切にしているように見える。クレオンはヘーモンに、市民としてだけでなく息 子としても従順であることを要求する。クレオンは「他のことはすべて、父の決定に従うべきである」と述べる(「アンティゴネ」640-641)。クレオン が王であることよりもヘーモンの父であることを強調していることは、特に、クレオンが他の箇所で国家への服従を何よりも優先することを提唱しているという 事実を踏まえると、奇妙に思えるかもしれない。この二つの価値観が対立した場合に彼がどう対処するのかは明確ではないが、劇中ではそれは問題にならない。 なぜなら、テーベの絶対的支配者であるクレオンは国家そのものであり、国家はクレオンそのものであるからだ。 彼がこの二つの価値観の対立を、他者であるアンティゴネーに当てはめた場合、どう感じるかは明らかである。国家への忠誠は家族への忠誠よりも優先されるべ きであり、彼はアンティゴネーに死刑を宣告する。 |

| 神々の描写 |

アンティゴネーやその他のテーベの劇においても、神々についての言及は

非常に少ない。最もよく言及されるのは冥王ハーデスであるが、これは死の化身として言及されることが多い。ゼウスは劇全体で13回名前が言及されるが、ア

ポロは予言の化身として言及されるだけである。この言及の少なさは、悲劇的な出来事が人間の過ちの結果として起こることを描いており、神の介入ではないこ

とを示している。神々は冥界の神として描かれており、冒頭近くに「神々と共に冥界に住まう正義」という表現がある。ソフォクレスは『アンティゴネー』の中

でオリンポスについて2度言及している。これは、オリンポスについて頻繁に言及している他のアテナイの悲劇詩人たちとは対照的である。 |

| 家族への愛 |

アンティゴネーの家族への愛は、彼女が弟ポリュネイケスを埋葬する場面

で示されている。ヘーモンは従姉妹であり婚約者であったアンティゴネーに深く愛されていたが、最愛のアンティゴネーが自らの手で首を吊ったことを知った

ヘーモンは悲嘆のあまり自殺した。 |

| 正義 |

アリストテレスの伝統に従い、アンティゴネーは正義の事例研究としても

見られている。キャサリン・ティティは、アンティゴネーの「神聖な」法を現代の強行規範である慣習国際法(強行規範)に例え、アンティゴネーのジレンマ

を、法を修正するために正義のcontra legemの適用を促す状況として論じている。[23] |

****

| Antigone

(/ænˈtɪɡəni/ ann-TIG-ə-nee; Ancient Greek: Ἀντιγόνη) is an Athenian

tragedy written by Sophocles in (or before) 441 BC and first performed

at the Festival of Dionysus of the same year. It is thought to be the

second oldest surviving play of Sophocles, preceded by Ajax, which was

written around the same period. The play is one of a triad of tragedies

known as the three Theban plays, following Oedipus Rex and Oedipus at

Colonus. Even though the events in Antigone occur last in the order of

events depicted in the plays, Sophocles wrote Antigone first.[1] The

story expands on the Theban legend that predates it, and it picks up

where Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes ends. The play is named after the

main protagonist Antigone. After Oedipus' self-exile, his sons Eteocles and Polynices engaged in a civil war for the Theban throne, which resulted in both brothers dying fighting each other. Oedipus' brother-in-law and new Theban ruler Creon ordered the public honoring of Eteocles and the public shaming of Thebes' traitor Polynices. The story follows the attempts of Antigone, the sister of Eteocles and Polynices, to bury Polynices, going against the decision of her uncle Creon and placing her relationship with her brother above human laws. |

ア

ンティゴネー(/ænˈtɪɡəni/ ann-TIG-ə-nee; 古代ギリシア語:

Ἀντιγόνη)は、ソフォクレスが紀元前441年(またはそれ以前)に書いたアテナイ悲劇であり、同年に行われたディオニュソス祭で初演された。これ

は、同時期に書かれた『アイアス』に次いで、現存するソフォクレスの戯曲としては2番目に古い作品と考えられている。この作品は、オイディプス王、オイ

ディプス・アテネーに次ぐ「テーベ三部作」と呼ばれる3つの悲劇のひとつである。アンティゴネーの事件は、劇中で描かれる出来事の順番では最後であるにも

かかわらず、ソフォクレスはアンティゴネーを最初に書いた。[1]

この物語は、それ以前から伝わるテーベ伝説をさらに発展させたもので、アイスキュロスの『テーベ攻め七人』の結末から始まる。この劇は、主人公のアンティ

ゴネーにちなんで名付けられている。 オイディプスが自らの亡命の後、彼の息子であるエテオクレースとポリュニケースはテーベ王位を巡って内戦を繰り広げ、その結果、兄弟は互いに戦って死ん だ。オイディプスの義理の兄弟であり、テーベの新たな統治者となったクレオンは、エテオクレースを称え、テーベの裏切り者であるポリュニケースを辱めるよ う命じた。この物語は、エテオクレースとポリュニケースの姉であるアンティゴネーが、叔父であるクレオン王の決定に背き、人間としての法よりも兄弟との関 係を優先してポリュニケースを埋葬しようとする試みを描いている。 |

| Characters - Antigone, compared with her beautiful and docile sister, is portrayed as a heroine who recognizes her familial duty. Her dialogues with Ismene reveal her to be as stubborn as her uncle.[4] In her, the ideal of the female character is boldly outlined.[5] She defies Creon's decree despite the consequences she may face, in order to honor her deceased brother. - Ismene serves as a foil for Antigone, presenting the contrast in their respective responses to the royal decree.[4] Considered the beautiful one, she is more lawful and obedient to authority. She hesitates to bury Polynices because she fears Creon. - Creon is the current King of Thebes, who views law as the guarantor of personal happiness. He can also be seen as a tragic hero, losing everything for upholding what he believes is right. Even when he is forced to amend his decree to please the gods, he first tends to the dead Polynices before releasing Antigone.[4] - Eurydice of Thebes is the Queen of Thebes and Creon's wife. She appears towards the end and only to hear confirmation of her son Haemon's death. In her grief, she dies by suicide, cursing Creon, whom she blames for her son's death. - Haemon is the son of Creon and Eurydice, betrothed to Antigone. Proved to be more reasonable than Creon, he attempts to reason with his father for the sake of Antigone. However, when Creon refuses to listen to him, Haemon leaves angrily and shouts he will never see him again. He dies by suicide after finding Antigone dead. - Koryphaios is the assistant to the King (Creon) and the leader of the Chorus. He is often interpreted as a close advisor to the King, and therefore a close family friend. This role is highlighted in the end when Creon chooses to listen to Koryphaios' advice. - Tiresias is the blind prophet whose prediction brings about the eventual proper burial of Polynices. Portrayed as wise and full of reason, Tiresias attempts to warn Creon of his foolishness and tells him the gods are angry. He manages to convince Creon, but is too late to save the impetuous Antigone. - The Chorus, a group of elderly Theban men, is at first deferential to the king.[5] Their purpose is to comment on the action in the play and add to the suspense and emotions, as well as connecting the story to myths. As the play progresses they counsel Creon to be more moderate. Their pleading persuades Creon to spare Ismene. They also advise Creon to take Tiresias's advice. |

登場人物(再掲) - アンティゴネーは、美しくおとなしい妹と比較され、家族の義務を認識するヒロインとして描かれている。イスメネとの対話では、彼女が叔父と同じくらい頑固 であることが明らかになっている。[4] 彼女には、大胆に描かれた理想的な女性像がある。[5] 彼女は、亡くなった兄を称えるために、直面するかもしれない結果を顧みず、クレオンの命令に逆らう。 イスメネーはアンティゴネーの対照的な存在であり、王の命令に対するそれぞれの反応の対照を示している。[4] 美しいとされるイスメネーは、より従順で権威に従順である。彼女はクレオンを恐れているため、ポリュニケーを埋葬することをためらう。 クレオンはテーベの現王であり、法を人格的な幸福の保証者と見なしている。また、正しいと信じるものを守るためにすべてを失う悲劇の英雄とも見ることがで きる。神々の機嫌を取るためにやむなく命令を変更したときでさえ、彼はまずポリュニケーの死体を丁重に扱い、それからアンティゴネーを解放した。 - テーベのエウリュディケはテーベの王妃であり、クレオンの妻である。彼女は終盤に登場し、息子のヘーモンの死を確認するためにのみ登場する。悲嘆に暮れた 彼女は自殺し、息子の死の責任をクレオンに押し付け、彼を罵りながら死んでいく。 - ヘーモンはクレオンとエウリュディケーの息子であり、アンティゴネーの婚約者である。クレオンよりも分別があり、アンティゴネーのために父親を説得しよう とする。しかし、クレオンが耳を貸そうとしないため、ヘーモンは怒ってその場を立ち去り、二度と父親に会わないと叫ぶ。ヘーモンはアンティゴネーの死体を 発見した後、自殺する。 コリファイスは王(クレオン)の補佐官であり、コーラスのリーダーである。彼はしばしば王の側近であり、したがって王の家族の親しい友人であると解釈され る。この役割は、最後にクレオンがコリファイオスの助言に耳を傾けることを選択したときに強調される。 - ティレシアスは、ポリュニケスの埋葬を最終的に適切に行うことを可能にした盲目の予言者である。賢明で思慮深い人物として描かれるティレシアスは、クレオ ンの愚かさを警告し、神々が怒っていると告げる。彼はクレオンを説得することに成功するが、衝動的なアンティゴネーを救うには遅すぎた。 - テーベの高齢の男性たちによる合唱団は、最初は王に恭順している。[5] 彼らの目的は、劇中の行動について論評し、サスペンスと感情を盛り上げ、物語を神話と結びつけることである。劇が進むにつれ、彼らはクレオンに穏健な態度 を取るよう助言する。彼らの懇願により、クレオンはイスメネを助けることにする。また、彼らはクレオンに、ティレシアスの助言に従うよう助言する。 |

| Historical context Antigone was written at a time of national fervor. In 441 BCE, shortly after the play was performed, Sophocles was appointed as one of the ten generals to lead a military expedition against Samos. It is striking that a prominent play in a time of such imperialism contains little political propaganda, no impassioned apostrophe, and—with the exception of the epiklerate (the right of the daughter to continue her dead father's lineage)[6] and arguments against anarchy—makes no contemporary allusion or passing reference to Athens.[7] Rather than become sidetracked with the issues of the time, Antigone remains focused on the characters and themes within the play. It does, however, expose the dangers of the absolute ruler, or tyrant, in the person of Creon, a king to whom few will speak freely and openly their true opinions, and who therefore makes the grievous error of condemning Antigone, an act that he pitifully regrets in the play's final lines. Athenians, proud of their democratic tradition, would have identified his error in the many lines of dialogue which emphasize that the people of Thebes believe he is wrong, but have no voice to tell him so. Athenians would identify the folly of tyranny. Notable features The Chorus in Antigone departs significantly from the chorus in Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes, the play of which Antigone is a continuation. The chorus in Seven Against Thebes is largely supportive of Antigone's decision to bury her brother. Here, the chorus is composed of old men who are largely unwilling to see civil disobedience in a positive light. The chorus also represents a typical difference in Sophocles' plays from those of both Aeschylus and Euripides. A chorus of Aeschylus' almost always continues or intensifies the moral nature of the play, while one of Euripides' frequently strays far from the main moral theme. The chorus in Antigone lies somewhere in between; it remains within the general moral in the immediate scene, but allows itself to be carried away from the occasion or the initial reason for speaking.[8] Significance and interpretation Once Creon has discovered that Antigone buried her brother against his orders, the ensuing discussion of her fate is devoid of arguments for mercy because of youth or sisterly love from the Chorus, Haemon or Antigone herself. Most of the arguments to save her center on a debate over which course adheres best to strict justice.[9][10] Both Antigone and Creon claim divine sanction for their actions; but Tiresias the prophet supports Antigone's claim that the gods demand Polynices' burial. It is not until the interview with Tiresias that Creon transgresses and is guilty of sin. He had no divine intimation that his edict would be displeasing to the Gods and against their will. He is here warned that it is, but he defends it and insults the prophet of the Gods. This is his sin, and it is this that leads to his punishment. The terrible calamities that overtake Creon are not the result of his exalting the law of the state over the unwritten and divine law that Antigone vindicates, but are his intemperance that led him to disregard the warnings of Tiresias until it was too late. This is emphasized by the Chorus in the lines that conclude the play.[11] The German poet Friedrich Hölderlin, whose translation had a strong impact on the philosopher Martin Heidegger, brings out a more subtle reading of the play: he focuses on Antigone's legal and political status within the palace, her privilege to be the heiress (according to the legal instrument of the epiklerate) and thus protected by Zeus. According to the legal practice of classical Athens, Creon is obliged to marry his closest relative (Haemon) to the late king's daughter in an inverted marriage rite, which would oblige Haemon to produce a son and heir for his dead father in law. Creon would be deprived of grandchildren and heirs to his lineage – a fact that provides a strong realistic motive for his hatred against Antigone. This modern perspective has remained submerged for a long time.[12] Heidegger, in his essay, The Ode on Man in Sophocles' Antigone, focuses on the chorus' sequence of strophe and antistrophe that begins on line 278. His interpretation is in three phases: first to consider the essential meaning of the verse, and then to move through the sequence with that understanding, and finally to discern what was nature of humankind that Sophocles was expressing in this poem. In the first two lines of the first strophe, in the translation Heidegger used, the chorus says that there are many strange things on earth, but there is nothing stranger than man. Beginnings are important to Heidegger, and he considered those two lines to describe the primary trait of the essence of humanity within which all other aspects must find their essence. Those two lines are so fundamental that the rest of the verse is spent catching up with them. The authentic Greek definition of humankind is the one who is strangest of all. Heidegger's interpretation of the text describes humankind in one word that captures the extremes — deinotaton. Man is deinon in the sense that he is the terrible, violent one, and also in the sense that he uses violence against the overpowering. Man is twice deinon. In a series of lectures in 1942, Hölderlin's Hymn, The Ister, Heidegger goes further in interpreting this play, and considers that Antigone takes on the destiny she has been given, but does not follow a path that is opposed to that of the humankind described in the choral ode. When Antigone opposes Creon, her suffering the uncanny is her supreme action.[13][14] The problem of the second burial An important issue still debated regarding Sophocles' Antigone is the problem of the second burial. When she poured dust over her brother's body, Antigone completed the burial rituals and thus fulfilled her duty to him. Having been properly buried, Polynices' soul could proceed to the underworld whether or not the dust was removed from his body. However, Antigone went back after his body was uncovered and performed the ritual again, an act that seems to be completely unmotivated by anything other than a plot necessity so that she could be caught in the act of disobedience, leaving no doubt of her guilt. More than one commentator has suggested that it was the gods, not Antigone, who performed the first burial, citing both the guard's description of the scene and the chorus's observation.[15] It's possible, however, that Antigone not only wants her brother to have burial rites, but that she wants his body to stay buried. The guard states that after they found that someone covered Polynices' body with dirt, the birds and animals left the body alone (lines 257–258). But when the guards removed the dirt, then the birds and animals returned, and Tiresias emphasizes that birds and dogs have defiled the city's altars and hearths with the rotting flesh from Polynices' body; as a result of which the gods will no longer accept the peoples' sacrifices and prayers (lines 1015–1020). It's possible, therefore, that after the guards remove the dirt protecting the body, Antigone buries him again to prevent the offense to the gods.[16] Even though Antigone has already performed the burial rite for Polynices, Creon, on the advice of Tiresias (lines 1023–1030), makes a complete and permanent burial for his body. Richard C. Jebb suggests that the only reason for Antigone's return to the burial site is that the first time she forgot the Choaí (libations), and "perhaps the rite was considered completed only if the Choaí were poured while the dust still covered the corpse."[17] Gilbert Norwood explains Antigone's performance of the second burial in terms of her stubbornness. His argument says that had Antigone not been so obsessed with the idea of keeping her brother covered, none of the deaths of the play would have happened. This argument states that if nothing had happened, nothing would have happened, and does not take much of a stand in explaining why Antigone returned for the second burial when the first would have fulfilled her religious obligation, regardless of how stubborn she was. This leaves that she acted only in passionate defiance of Creon and respect to her brother's earthly vessel.[18] Tycho von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff justifies the need for the second burial by comparing Sophocles' Antigone to a theoretical version where Antigone is apprehended during the first burial. In this situation, news of the illegal burial and Antigone's arrest would arrive at the same time and there would be no period of time in which Antigone's defiance and victory could be appreciated. J. L. Rose maintains that the problem of the second burial is solved by close examination of Antigone as a tragic character. Being a tragic character, she is completely obsessed by one idea, and for her this is giving her brother his due respect in death and demonstrating her love for him and for what is right. When she sees her brother's body uncovered, therefore, she is overcome by emotion and acts impulsively to cover him again, with no regards to the necessity of the action or its consequences for her safety.[18] Bonnie Honig uses the problem of the second burial as the basis for her claim that Ismene performs the first burial, and that her pseudo-confession before Creon is actually an honest admission of guilt.[19] |

歴史的背景 アンティゴネーは国民の熱狂に包まれた時代に書かれた。紀元前441年、この劇が上演された直後にソフォクレスはサモス島への遠征軍の10人の将軍の一人 に任命された。帝国主義の時代における著名な戯曲が、政治的なプロパガンダをほとんど含まず、熱烈なアポストロフィも含まれていないことは注目に値する。 また、娘が父の血統を継承する権利(epiklerate)[6]や無政府状態に対する議論を除いて、アテネを現代的に暗示したり、言及したりすることも 一切ない。 [7] アンティゴネーは、当時の問題に気を取られることなく、あくまでも劇中の登場人物とテーマに焦点を当てている。しかし、クレオンという絶対的支配者、つま り暴君の危険性を暴いている。クレオンは、真の意見を率直に口にする者がほとんどいない王であり、そのため、劇の最後のセリフで哀れにも後悔するが、アン ティゴネーを非難するという痛恨のミスを犯す。民主主義の伝統を誇るアテナイ人なら、テーベの人々は彼が間違っていると信じているが、それを伝える声がな いことを強調する多くの台詞から、彼の誤りに気づいただろう。アテナイ人は暴君の愚かさを見抜くだろう。 主な特徴 アンティゴネーの合唱は、その続きとして上演されるエウリピデスの『テーベ攻め』の合唱とは大きく異なる。『テーベの七人』の合唱は、主に、弟を埋葬する というアンティゴネーの決断を支持している。一方、この作品の合唱は、市民的不服従を肯定的に捉えることに消極的な老人たちで構成されている。また、この 合唱は、ソフォクレスの作品がエウリピデスやアイスキュロスの作品と異なる典型的な例でもある。エウリピデスの作品では、コーラスはしばしば道徳的なテー マから大きく逸脱するが、一方、エウリピデスの作品では、劇の道徳的な本質を継続または強化する。アンティゴネーのコーラスは、その中間的な位置づけであ り、その場面の一般的な道徳観の範囲内にとどまるが、その場や、発言の当初の理由から逸脱することもある。 意義と解釈 クレオンがアンティゴネーが自分の命令に背いて弟を埋葬したことを知ると、彼女の運命についてのその後の議論では、合唱団、ヘエモン、あるいはアンティゴ ネー自身による若さや姉妹愛を理由とした慈悲の主張は見られない。彼女を救うための議論のほとんどは、厳格な正義に最も適うのはどちらの道なのかという議 論に集中している。 アンティゴネーとクレオンは、どちらも自らの行動に神の加護があることを主張するが、預言者ティレシアスは、神々がポリュニケーの埋葬を要求しているとい うアンティゴネーの主張を支持する。クレオンが罪を犯し、有罪となるのは、ティレシアスとの面談の時である。彼は、自らの命令が神々の不興を買い、神々の 意志に反するものであるという神のお告げを受けなかった。彼はここでそれを警告されるが、それを擁護し、神々の預言者を侮辱する。これが彼の罪であり、そ れが彼の処罰につながる。クレオンに降りかかる恐ろしい災難は、彼がアンティゴネーが正当化する不文律の神聖な法よりも国家の法を優先した結果ではなく、 彼が節度を欠いたために、手遅れになるまでティレシアスの警告を無視してしまったことによるものである。これは劇の結末の合唱で強調されている。[11] ドイツの詩人フリードリヒ・ヘーデルリンは、その翻訳が哲学者マルティン・ハイデガーに強い影響を与えたが、劇のより繊細な解釈を提示している。彼は、宮 殿内のアンティゴネーの法的・政治的地位、すなわち(エピクレーテーの法律文書によると)相続人となる特権、そしてそれゆえにゼウスに守られているという 点に注目している。古典時代のギリシャの法律慣習に従えば、クレオンは近親者(ヘーモン)を亡き王の娘と逆縁の儀式で結婚させる義務があり、ヘーモンは義 理の父親の跡継ぎとなる息子を産む義務が生じる。クレオンは孫や自分の血統の跡継ぎを失うことになるが、この事実がアンティゴネーに対する彼の憎悪の現実 的な動機となっている。この近代的な視点は長い間、注目されてこなかった。[12] ハイデガーは、ソフォクレスの『アンティゴネー』における「人間の頌歌」という論文で、278行目から始まるコーラスのストロフェとアンティストロフェの 連続に焦点を当てている。彼の解釈は3つの段階に分かれている。まず、この詩の根本的な意味を考察し、次にその理解に基づいて一連の流れをたどり、最後に ソフォクレスがこの詩で表現しようとした人間の本質とは何かを見極める。ハイデガーが用いた訳では、第一連の最初の2行で、コーラスが「地上には奇妙なも のがたくさんあるが、人間ほど奇妙なものはない」と述べている。ハイデガーにとって始まりは重要であり、彼はこの2行が、人間性の本質的な特徴を描写して おり、その本質的な特徴のなかに、他のすべての側面がその本質を見出さなければならないと考えた。この2行はあまりにも根本的なものであるため、詩の残り の部分は、この2行に追いつくことに費やされている。ギリシャ語で「人間」を意味する言葉の本来の意味は、「最も奇妙な存在」である。ハイデガーのテキス トの解釈では、人間を極端な意味を持つ単語「deinotaton」で表現している。人間は「恐ろしい存在」であり、「暴力を振るう存在」であるという意 味で「deinon」である。人間は「deinon」である。1942年の一連の講義で、ヘーデルリンの『賛歌』『イスター』について、ハイデガーはさら に踏み込んでこの劇を解釈し、アンティゴネーは与えられた運命を受け入れるが、合唱頌歌で描かれた人類のそれとは対立する道を歩むわけではないと考える。 アンティゴネーがクレオンに抗議するとき、彼女の苦悩は並外れたものであり、それが彼女の最高の行動である。 2度目の埋葬の問題 ソフォクレスの『アンティゴネー』に関して今も議論されている重要な問題は、2度目の埋葬の問題である。彼女が弟の遺体に土をかぶせたとき、アンティゴ ネーは埋葬の儀式を完了し、弟に対する義務を果たした。ポリュニケスの遺体が適切に埋葬されたのであれば、遺体から土が取り除かれたかどうかに関わらず、 ポリュニケスの魂は冥界へと進むことができた。しかし、アンティゴネーは遺体が再び露出した後に戻ってきて、再び埋葬の儀式を行った。この行為は、プロッ ト上の必要性以外の動機は全くないように思われ、彼女が不従順の罪で捕まることで、彼女の罪に疑いの余地を残さない。複数のコメンテーターは、最初の埋葬 を行ったのは神々であり、アンティゴネーではないと指摘している。警備員の描写と合唱団の観察の両方を引用して、そのように述べている。[15] しかし、アンティゴネーは弟に埋葬の儀式を行いたいだけでなく、弟の遺体を埋めたままにしておきたいのかもしれない。衛兵は、ポリュニケスの遺体を土で 覆った者がいた後、鳥や動物がその遺体をそのままにしていたと述べている(257-258行)。しかし、衛兵たちが土を取り除いたところ、鳥や動物たちが 戻ってきた。そして、テレイシアスは、鳥や犬がポリュニケスの腐敗した肉で都市の祭壇や炉を汚したことを強調する。その結果、神々はもはや人々の犠牲や祈 りを認めないだろう(1015-1020行)。したがって、警備員が死体を覆っていた土を取り除いた後、アンティゴネーが再び死体を埋葬し、神々への冒涜 を防いだ可能性もある。[16] アンティゴネーがポリュニケスの埋葬儀式をすでに済ませていたにもかかわらず、クレオンはテレシアスの助言に従って(1023-1030行)、ポリュニケ スの死体を完全に永続的な埋葬を行った。 リチャード・C・ジェブは、アンティゴネーが埋葬地に戻った唯一の理由は、彼女が初めて「チョアイ(灌酒)」を忘れたからであり、「おそらく、死体にまだ 土がかかっている間にチョアイが注がれれば、儀式は完了したと見なされた」と示唆している[17]。 ギルバート・ノースウッドは、アンティゴネーが二度目の埋葬を行った理由を、彼女の頑固さから説明している。彼の主張によると、もしアンティゴネーが弟の 遺体を覆い隠すという考えにそれほど執着していなかったら、劇中の死は起こらなかったはずだという。この議論は、何も起こらなければ何も起こらなかったは ずであり、アンティゴネーが最初の埋葬で宗教上の義務を果たしたにもかかわらず、なぜ2度目の埋葬に戻ったのかを説明するには説得力に欠ける。このことか ら、彼女はクレオン王に反抗する情熱的な行動と、亡き弟への敬意から行動しただけであるという結論になる。[18] ティコ・フォン・ヴィラモヴィッツ・メレンドルフは、ソフォクレスの『アンティゴネー』を、アンティゴネーが最初の埋葬中に捕らえられるという理論上の バージョンと比較することで、2度目の埋葬の必要性を正当化している。この状況では、違法な埋葬とアンティゴネーの逮捕のニュースが同時に到着し、アン ティゴネーの反抗と勝利が評価される期間は存在しない。 J. L. ローズは、悲劇の登場人物としてのアンティゴネーを詳細に検討することで、2度目の埋葬の問題が解決されると主張している。悲劇の登場人物であるアンティ ゴネーは、ある考えに完全に囚われている。彼女にとってそれは、死後も弟に敬意を表し、弟と正しいことに対する愛を示すことである。従って、彼女は弟の遺 体が覆われていないのを目にしたとき、感情に駆られて衝動的に弟の遺体を再び覆い隠すという行動に出た。その行動の必要性や、その行動が彼女の安全に及ぼ す結果については一切考慮しなかったのである。[18] ボニー・ホニッグは、イスメネが最初の埋葬を行い、クレオン王に対する彼女の偽りの自白は、実際には罪の自白であるという主張の根拠として、2度目の埋葬 の問題を挙げている。[19] |

| Themes Civil disobedience A well established theme in Antigone is the right of the individual to reject society's infringement on one's freedom to perform a personal obligation.[20] Antigone comments to Ismene, regarding Creon's edict, that "He has no right to keep me from my own."[21] Related to this theme is the question of whether Antigone's will to bury her brother is based on rational thought or instinct, a debate whose contributors include Goethe.[20] The contrasting views of Creon and Antigone with regard to laws higher than those of state inform their different conclusions about civil disobedience. Creon demands obedience to the law above all else, right or wrong. He says that "there is nothing worse than disobedience to authority" (An. 671). Antigone responds with the idea that state law is not absolute, and that it can be broken in civil disobedience in extreme cases, such as honoring the gods, whose rule and authority outweigh Creon's. Natural law and contemporary legal institutions Creon's decree to leave Polynices unburied in itself makes a bold statement about what it means to be a citizen, and what constitutes abdication of citizenship. It was the firmly kept custom of the Greeks that each city was responsible for the burial of its citizens. Herodotus discussed how members of each city would collect their own dead after a large battle to bury them.[22] In Antigone, it is therefore natural that the people of Thebes did not bury the Argives, but very striking that Creon prohibited the burial of Polynices. Since he is a citizen of Thebes, it would have been natural for the Thebans to bury him. Creon is telling his people that Polynices has distanced himself from them, and that they are prohibited from treating him as a fellow-citizen and burying him as is the custom for citizens. In prohibiting the people of Thebes from burying Polynices, Creon is essentially placing him on the level of the other attackers—the foreign Argives. For Creon, the fact that Polynices has attacked the city effectively revokes his citizenship and makes him a foreigner. As defined by this decree, citizenship is based on loyalty. It is revoked when Polynices commits what in Creon's eyes amounts to treason. When pitted against Antigone's view, this understanding of citizenship creates a new axis of conflict. Antigone does not deny that Polynices has betrayed the state, she simply acts as if this betrayal does not rob him of the connection that he would have otherwise had with the city. Creon, on the other hand, believes that citizenship is a contract; it is not absolute or inalienable, and can be lost in certain circumstances. These two opposing views – that citizenship is absolute and undeniable and alternatively that citizenship is based on certain behavior – are known respectively as citizenship 'by nature' and citizenship 'by law.'[22] Fidelity Antigone's determination to bury Polynices arises from a desire to bring honor to her family, and to honor the higher law of the gods. She repeatedly declares that she must act to please "those that are dead" (An. 77), because they hold more weight than any ruler, that is the weight of divine law. In the opening scene, she makes an emotional appeal to her sister Ismene saying that they must protect their brother out of sisterly love, even if he did betray their state. Antigone believes that there are rights that are inalienable because they come from the highest authority, or authority itself, that is the divine law. While he rejects Antigone's actions based on family honor, Creon appears to value family himself. When talking to Haemon, Creon demands of him not only obedience as a citizen, but also as a son. Creon says "everything else shall be second to your father's decision" ("An." 640–641). His emphasis on being Haemon's father rather than his king may seem odd, especially in light of the fact that Creon elsewhere advocates obedience to the state above all else. It is not clear how he would personally handle these two values in conflict, but it is a moot point in the play, for, as absolute ruler of Thebes, Creon is the state, and the state is Creon. It is clear how he feels about these two values in conflict when encountered in another person, Antigone: loyalty to the state comes before family fealty, and he sentences her to death. Portrayal of the gods In Antigone as well as the other Theban Plays, there are very few references to the gods. Hades is the god who is most commonly referred to, but he is referred to more as a personification of Death. Zeus is referenced a total of 13 times by name in the entire play, and Apollo is referenced only as a personification of prophecy. This lack of mention portrays the tragic events that occur as the result of human error, and not divine intervention. The gods are portrayed as chthonic, as near the beginning there is a reference to "Justice who dwells with the gods beneath the earth." Sophocles references Olympus twice in Antigone. This contrasts with the other Athenian tragedians, who reference Olympus often. Love for family Antigone's love for family is shown when she buries her brother, Polynices. Haemon was deeply in love with his cousin and fiancée Antigone, and he killed himself in grief when he found out that his beloved Antigone had hanged herself. Equity Following in the Aristotelian tradition, Antigone is also seen as a case-study for equity. Catharine Titi has likened Antigone's 'divine' law to modern peremptory norms of customary international law (ius cogens) and she has discussed Antigone's dilemma as a situation that invites the application of equity contra legem in order to correct the law.[23] |

テーマ 市民的不服従 『アンティゴネー』のテーマとしてよく知られているのは、個人的な義務を果たす自由に対する社会の侵害を拒絶する個人の権利である[20]。 アンティゴネーはクレオンの勅令について、イスメーネに「彼は私を私自身のものから遠ざける権利はない」とコメントしている[21]。このテーマと関連し て、弟を葬るというアンティゴネーの意志が合理的な思考に基づいているのか、それとも本能に基づいているのかという問題があり、ゲーテもこの議論に参加し ている[20]。 クレオンとアンティゴネーの、国家より上位の法に関する対照的な見解は、市民的不服従に関する二人の異なる結論に影響を与えている。クレオンは、善悪を問 わず、何よりも法律への服従を要求する。彼は「権威に背くことほど悪いことはない」(An. 671)と言う。アンティゴネは、国家法は絶対的なものではなく、クレオンの支配と権威を凌駕する神々を敬うような極端な場合には、市民的不服従としてそ れを破ることができるという考えで反論する。 自然法と現代の法制度 ポリュニケスを埋葬しないままにしておくというクレオンの命令自体が、市民であることの意味と、市民権の放棄を構成するものについて大胆な声明を出してい る。ギリシアでは、各都市が市民の埋葬に責任を持つという習慣が固く守られていた。アンティゴネー』では、テーベの人々がアルギヴ人を埋葬しなかったのは 当然だが、クレオンがポリニスの埋葬を禁止したのは非常に印象的だった。彼はテーベの市民であるから、テーベの人々が彼を埋葬するのは当然であったはずで ある。クレオンは、ポリュニケスが自分たちと距離を置いていること、ポリュニケスを同胞として扱い、市民の慣習に従って埋葬することを禁じていることを民 衆に伝えているのである。 テーベの民がポリュニケスを埋葬することを禁止することで、クレオンはポリュニケスを他の襲撃者たち(外国のアルギヴ人)と同列に扱うことになる。クレオ ンにとって、ポリニスがテーベを攻撃したという事実は、ポリニスの市民権を事実上剥奪し、彼を外国人にしてしまう。この勅令で定義されているように、市民 権は忠誠心に基づいている。ポリニスがクレオンの目に反逆と映る行為を犯したとき、市民権は剥奪される。アンティゴネの考えと対立させると、市民権に対す るこの理解は新たな対立軸を生み出す。アンティゴネーはポリニスが国家を裏切ったことを否定しないが、この裏切りによってポリニスが持っていたはずの都市 とのつながりが奪われることはないかのように振る舞うだけである。一方クレオンは、市民権は契約であり、絶対的なものでも不可分のものでもなく、状況に よっては失うこともあり得ると考えている。市民権は絶対的で否定できないものであり、また、市民権は特定の行動に基づいているという、この二つの対立する 見解は、それぞれ「自然による」市民権、「法による」市民権として知られている[22]。 忠誠 ポリニスを葬るというアンティゴネの決意は、家族に名誉をもたらし、神々の崇高な掟に敬意を表したいという願望から生じている。彼女は繰り返し、「死んだ 者たち」(An. 77)を喜ばせるために行動しなければならないと宣言する。冒頭のシーンでは、妹のイスメネに、たとえ兄が国を裏切ったとしても、姉妹愛から兄を守らなけ ればならないと感情的に訴える。アンティゴネは、神の掟という最高の権威、つまり権威そのものに由来するものだからこそ、譲れない権利があると信じてい る。 家族の名誉に基づくアンティゴネーの行動を否定する一方で、クレオンは自分自身は家族を大切にしているように見える。クレオンはヘーモンに向かって、市民 としての服従だけでなく、息子としての服従も要求する。クレオンは「他のことはすべて、父上の決定に従わなければならない」(『あん』640-641)と 言う。クレオンは他の場面で、何よりも国家への服従を唱えている。テーベの絶対的支配者として、クレオンは国家であり、国家はクレオンなのだから。この2 つの価値観の対立についてクレオンがどう考えているかは、別の人物であるアンティゴネが遭遇したときに明らかになる。 神々の描写 『アンティゴネー』と他の『テーバン劇』では、神々についての言及はほとんどない。ハデスは最もよく言及される神だが、死の擬人化として言及されることが多 い。ゼウスは戯曲全体で合計13回しか名前が言及されず、アポロは予言の擬人化として言及されるだけである。この言及の少なさは、神の介入ではなく、人間 の過ちの結果として起こる悲劇的な出来事を描いている。神々は、冒頭近くで "地底の神々と共にある正義 "について言及されているように、神々のような存在として描かれている。ソフォクレスは『アンティゴネー』の中でオリンポスに二度言及している。これは、 オリンポスに頻繁に言及する他のアテナイの悲劇家たちとは対照的である。 家族への愛 アンティゴネーの家族への愛は、彼女が弟ポリニスを埋葬するときに示される。ヘーモンは従兄弟で婚約者のアンティゴネを深く愛していたが、最愛のアンティ ゴネが首を吊ったことを知り、悲しみのあまり自殺した。 衡平性 アリストテレスの伝統に従って、『アンティゴネー』も衡平性のケーススタディとされている。キャサリン・ティティは、アンティゴネーの「神的な」法を現代 の国際慣習法の厳格な規範(ius cogens)になぞらえ、アンティゴネーのジレンマを、法を正すために衡平法(equity contra legem)の適用を招く状況として論じている[23]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antigone_(Sophocles_play) |

|

| D'abord : deux colonnes.

Tronquées, par le haut et par le bas;

taillées aussi dans leur flanc : incises, tatouages, incrustations. Une

première lecture peùt faire comme si deux textes dressés, l'un contre

l'autre ou l'un sans_ l'autre, entre eux ne communiquaient pas. Et

d'une

certaine façon délibérée, cela reste vrai, quant au prétexte, à

l'objet, à

la langue, au i,tyle, au rythme, à la loi. Une dialectique d'un côté,

une

galactique de l'autre, hétérogènes et cependant indiscernables dans

leurs

effets, parfois jusqu'à l'hallucination. Entre les deux, le battant

d'un

autre texte, on dirait d'une autre « logique » : aux surnoms d'

obséquence,

de penêtre, de stricture, de serrure, d'anthérection, de mors,

etc. Pour qui tient à la signature, au corpus et au propre, déclarons que, mettant en· jeu, en pièces plutôt, mon nom, mon corps et mon seing, j'élabore d'un même coup, en toutes lettres, ceux du dénommé Hegel dans une çolonne, ceux du dénommé Genet dans l'autre. On verra pourquoi, chance et nécessité, ces deux-là. La chose, donc, s'élève, se détaille - et détache selon deux tours, et l'accélération incessante d'un tour-àtour. Dans leur double solitude, les colosses échangent une infinité de clins, par exemple d'oeil, se doublent à l'envi, se pénètr.ent, collent et décollent, passant l'un dans l'autre, entre l'un et dans l'autre. Chaque colonne figureici un colosse (colossos), nom donné au double du mort, au substitut de son érection. Plus qu'un, avant tout. L'écriture colossale déjoue tout autrement les calculs . du deuil. Elle surprend et dérésonne l'économie àe la mort dans tous ses ret(;!..ntisse. ments. Glas en décomposition, (son ou sa) double bande, bande contre bande, c'est d'abord l'analyse du niot glas dans les virtualités retorses et retranchées de son « sens » (portées, volées de toutes les cloches, la sépulture, la pompe funèbre, le legs; le testament, le contrat, la signature, te nom propre, le prénom, le surnom, la classification et la lutte des classes, le travail du deuil dans les rapports de production, le fétichisme, le travestissement, la toilette du mort, l'incorporation, l'introjection du cadavre, l'idéalisation, la sublimation, la relève, le rejet, le reste, etc.) et de son « signifiant » (vol et déportation de toutes les formes sonores et graphiques, musicales et rythmiques, chorégraphie de Glas dans ses lettres et fécondations polyglottiques. Mais cette opposition (Sé/Sa), comme toutes les oppositions du reste, la sexuelle en particulier, par chance régulière se compromet, chaque terme en deux divisé s'agglutinant à l'autre. Un effet de gl (colle, glu, crachat, sperme, chrême, onguent, etc.} forme le conglomérat sans identité de ce cérémonial. Il rejoue la mimesis et l'arbitraire de la signature dans un accouplement déchaîné (toc/seing/lait), ivre comme un sonneur à sa corde pendu. Que reste-t-il du savoir absolu ? de l'histoire, de la philosophie, de l'économie politique, de la psychanalyse, de la sémiotique, de la linguistique, de la poétique ? du travail, de la langue, de la sexualité, de la famille, de la religion, de l'Etat, etc. ? Que reste-t-il, à détailler, du reste ? Pourquoi ces questions en forme de colosses et de fleurs phalliques ? Pourquoi exulter. dans la thanatopraxie ? De quoi jouir à célébrer, moi, ici, maintenant, à telle heure, le baptême ou la circoncision, le mariage ou la mort, du père et de la mère, celui de Hegel, celle de Genet ? Reste à savoir .....:.c.e.. . qu'on n'a pu penser : le détaillé d'un coup. Collection « Digraphe », dirigée par Jean Ristat 1 vol. 25 X 25, 296 pages, 62 F ÉDITIONS GALILÉE 9, rue Linné, 75005 Paris J.D. |

ま

ず、2本の柱。上から下まで切り詰められ、側面には切り込み、入れ墨、象眼が刻まれている。一見したところ、2つのテキストが互いに背中合わせに、あるい

は背中合わせに置かれているように見えるかもしれない。そして、口実、主題、言語、文体、リズム、法則に関して、ある意図的な方法で、これは真実のままで

ある。一方では弁証法、他方では銀河、異質でありながらその効果は区別がつかず、時には幻覚を見るほどである。この2つの間には、オブセクエンス、ペネト

ル、ストリクチュール、セリュール、アンセレクション、モルスなどのニックネームを持つ、もうひとつのテキスト、もうひとつの「論理」の鼓動がある。 署名、コーパス、適切なものを重んじる人たちのために、私の名前、私の身体、私の印章を、遊びの中に、いや、ばらばらにすることによって、私は、一方の列 にはいわゆるヘーゲルのものを、もう一方の列にはいわゆるジュネのものを、一挙に、完全な文字で精巧に再現していることを宣言しよう。その理由は、偶然と 必然、このふたつを見ればわかるだろう。そしてものは立ち上がり、切り離される-そして切り離されるのは、二つの回転と、回転-回転の絶え間ない加速に 従ってである。二重の孤独の中で、コロッシは無限のウインクを交わし、何度も何度もお互いを倍増させ、お互いを貫通し、くっついたりくっつかなかったりし ながら、お互いを通り抜け、お互いの間を通り抜け、お互いの中に入っていく。それぞれの柱は巨像(コロッソス)であり、死者の二重像、勃起の身代わりにつ けられた名前である。何よりも1つではないのだ。 コロッサル・ライティングは、弔いの計算をまったく異なる方法で妨害する。それは、死の経済性を驚かせ、軽んじる。グラス・アン・デコンポジション、(息 子と彼女の)二重のバンド、バンド・コント・バンドは、何よりもまず、その「意味」のねじれ、後退したヴァーチャル性(五線譜、すべての鐘の飛行、埋葬、 葬儀用ポンプ、遺産、遺言、契約書、署名。遺書、契約書、署名、固有名詞、ファーストネーム、ニックネーム、分類と階級闘争、生産関係における喪の作業、 フェティシズム、女装、死者の身だしなみ、取り込み、死体の導入、理想化、昇華、救済、拒絶、その他)とその「シニフィアン」。 )とその「シニフィアン」(あらゆる音、図形、音楽、リズム形式の窃盗と国外追放、手紙におけるグラの振り付け、多言語の受精)。しかし、この対立 (Sé/Sa)は、他のすべての対立、特に性的対立と同様に、規則的な偶然性によって損なわれており、2つの用語はそれぞれ他方によって分割されている。 糊、接着剤、唾液、精子、クリスム、軟膏など}の効果が、この儀式のアイデンティティのない集合体を形成する。それは、怒涛のカップリング (toc/seing/lait)において、サインの模倣と恣意性を再現し、吊るされたロープの上で鈴を鳴らすように酔いしれている。 歴史、哲学、政治経済、精神分析、記号論、言語学、詩学、仕事、言語、セクシュアリティ、家族、宗教、国家などに関する絶対的な知識として、何が残ってい るのだろうか?その他に何があるのだろうか?なぜコロッシや男根の花の形をしたこれらの問いなのか?なぜタナトプラクシーに歓喜するのか?洗礼や割礼、結 婚や死、父と母、ヘーゲルのそれ、ジュネのそれを、私が、今ここで、こんな時間に、祝うことに何の楽しみがあるのか。それはまだわからない......。 J.D. https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

●ジュディス・バトラー『アンティゴネーの主張』竹村和子訳、 青土社, 2002年

1)アンティゴネーの主張 Antigone's

Claim

2)書かれない法、逸脱する伝達

Unwritten Laws, Aberrant Transmissions

3)乱行的服従 Promiscuous Obedience

●バトラーにとってのアンティゴネー Butler on Antigone

「……アンティゴネーとは誰なのか、……。彼女は人

間でないが、人間の言葉で語る。行動を禁じられていながらも行動し、彼女の行動は既存の規範の単純な同化ではない。しかも行動する権利をもたないものとし

て行動することによって、人間の前提条件である親族関係の語彙を混乱させ、このような前提条件が本当はどんなものであるべきかという問題を、私たちにそれ

となく提示している。……。彼女にけっして属することはない語彙に彼女が従事するかぎり、彼女は政治的規範を語る言葉のなかで、ある種の交差対句として機

能する」(バトラー 2002:158-159)。

★オイディプスの娘アンティゴネー

Antoni Brodowski (Antigone leads Oedipus in his exile, in Colonos, 1828)

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆