ヘーゲルとアンティゴネー

Antigone and G.W.F. Hegel

「政治的対立を法的訴えにつくりかえて、国家にフェ ミズムの主張を支持するような合法化を求めようとする現在のフェミニズムの試みのなかでは、アンティゴネーの反抗の遺産は失われているように思えた」—— ジュディス・バトラー『アンティゴネーの主張』竹村和子訳、p.14, 青土社, 2002年

「ヘーゲルにおけるアンティゴネー読解でラカンが気に入らないのは、ヘーゲルがアンティゴネーとクレオンに、対立する原理や諸力、親族〈対〉国家、個人〈対〉普遍を代表させようとしている点です」(バトラー2019:19)

「共同体意識が、自分と対立する掟と権力の存在をあらかじめ承知し、それを暴力的で不当な権

力、たまたま共同体を代表しているにすぎない権力と見なし、犯罪と知りつつ犯罪を犯すアンティゴネーのような場合には、共同体意識としていっそう完全な意

識であり、その責任も純粋である」——ヘーゲル『精神現象学』(長谷川訳 1998:318)

『アンティゴネ』 (アンティゴネー、古代ギリシア語: Ἀντιγόνη、ラテン語: Antigone)は「古代ギリシア三大悲劇詩人の一人であるソポクレスが紀元前442年ごろに書いたギリシア悲劇。オイディプスの娘でテーバイの王女で あるアンティゴネを題材とする。……先王オイディプスが自己の呪われた運命を知って盲目となり(『オイディプス王』)、放浪の末にこの世を去った(『コロ ノスのオイディプス』)後、アンティゴネとイスメネはテーバイへ戻った。しかしテーバイでもアンティゴネの兄たちが王位を巡って争いを始めて、アルゴス人 の援助を受けてテーバイに攻め寄せたポリュネイケスとテーバイの王位にあったエテオクレスが刺し違えて死に、クレオンがテーバイの統治者となった。/クレオンは国家に対する反逆者であるポリュネイケスの埋葬や一切の葬礼を禁止し、見張りを立て てポリュネイケスの遺骸を監視させる。アンティゴネはこの禁令を犯し、見張りに捕らえられてクレオンの前に引き立てられる。人間の自然に基づく法を主張するアンティゴネと国家の法の厳正さを主張するクレオンは互いに譲らず、イスメネやハイモンの取り 成しの甲斐もなくて、クレオンは実質の死刑宣告として、一日分の食料を持たせてアンティゴネを地下に幽閉することを決定する。/その後、クレオンはテイレシアースの占いと長老たちの進言を受けてアンティゴネへの処分を撤回し、ポ リュネイケスの遺体の埋葬を決める。しかし時既に遅く、アンティゴネは首を吊り、父(クレオン)を恨んだアンティゴネの夫ハイモンも剣に伏 して自殺した。、クレオンが自らの運命を嘆く場面で劇は終わる」 #Wiki.

| Kreon: Now tell me, not at length, but in brief space, Knew you the order not to do it? Antigone: Yes I knew it; what should hinder? It was plain. Kreon: And you made free to overstep my law? Antigone: Because it was not Zeus who ordered it, Nor Justice, dweller with the Nether Gods, Gave such a law to men; nor did I deem Your ordinance of so much binding force, As that a mortal man could overbear The unchangeable unwritten code of Heaven; This is not of today and yesterday, But lives forever, having origin Whence no man knows: whose sanctions I were loath In Heaven’s sight to provoke, fearing the will Of any man. I knew that I should die – How otherwise? Even although your voice Had never so prescribed. And that I die Before my hour is due, that I count gain. For one who lives in many ills, as I – How should he fail to gain by dying? Thus To me the pain is light, to meet this fate: But had I borne to leave the body of him My mother bare unburied, then, indeed, I might feel pain; but as it is, I cannot: And if my present actions seems to you Foolish – ‘tis like I am found guilty of folly At a fool’s mouth! (ll 446-470, Young translation) |

クレオン: さて、長々とではなく、簡潔に教えてくれ、 それをするなという命令を知っていたのか? アンティゴネー:はい: 知っていた。 知っていた。明白なことだ。 クレオン: 私の掟を自由に踏み越えたのか? アンティゴネー: それを命じたのはゼウスではないからだ、 ネザー神々の住まいである正義でもない、 そのような掟を人に与えたのでもない。 あなたの掟がそれほど拘束力があるとは思わなかった、 死すべき人間が、この不変の不文律に打ち勝つことができるほど 天の不変の不文律を、死すべき人間が覆すほどの拘束力があるとは思わなかった; これは今日や昨日のものではない、 永遠に生き続ける。 その制裁を,わたしは憎む。 天の御目には,人の意志を恐れて,挑発することを嫌う。 その制裁を私は天の目には恐れた。私は死ぬことを知っていた。 そうでなければどうする?たとえあなたの声が 私は死ぬのだ。そして私は死ぬ 私は得をしたと思っている。 わたしと同じように、多くの悪の中に生きている者が 死んで得をしないはずがない。このように 私にとっては、この運命を迎える苦痛は軽い: だが、もし私が、彼の遺体を、母が埋葬されないままにしておくのを忍んでいたなら 母が埋葬されずに彼の遺体を残していたなら、確かにそうであっただろう、 苦痛を感じるかもしれない: そして、もし私の今の行動が、あなたがたに愚かに見えるなら 愚かなことだ。 愚か者の口で!(446-470, ヤング訳) |

| https://creatureandcreator.ca/?p=1830/ |

ポイントを整理しよう;テーバイで、アンティゴネの 兄たちが王位を巡って争いを始めて、最終的に彼らの叔父にあたるクレオンが新しい統治者になる。クレオンは、謀反者のポ リュネイケス(アンティゴネの兄)らを埋葬を禁じる。しかし、アンティゴネは、その国禁を侵し、兄を埋葬することを主張する。アンティゴネは捕まり、クレ オンの前で、自然なキョウダイへの愛を実践する兄の埋葬の正当性を主張する。クレオンは法の厳密な実行こそが重要だと譲らない。クレオンは、アンティゴネ を幽閉することを決めるが、託宣により、アンティゴネへの処分を取り消すが、アンティゴネもその夫のハイモンも自死して、クレオンはその運命を呪いつつ劇 はおわる。

Antigone, by Frederic

Leighton

アンティゴネーの 悲劇は、兄への弔意という肉親の情および人間を埋葬するという人倫的習俗と神への宗 教的義務と、国家による法の適用の対立から来るもので ある。哲学者ヘーゲルは『精神現象学』の「BB 精神 VI 精神 A真の精神——共同体精神(つまり道徳)」の章にて、アンティゴネーを人間意識の客観的段階のひとつである道徳=人倫の象徴とし て分析している(長谷川訳「精神現象学」Pp.313-324.)。

| Phänomenologie des Geistes |

精神現象学 |

| VI Der Geist |

VI 精神 |

| A Der wahre Geist , die Sittlichkeit |

A 真の精神、道徳 |

| b Die sittliche Handlung, das menschliche und göttliche Wissen, die Schuld und das Schicksal |

b 道徳的行為、人間的および神的な知識、罪、そして運命 |

| Wie aber in diesem Reiche der

Gegensatz beschaffen ist, so ist das Selbstbewußtsein noch nicht in

seinem Rechte als einzelne Individualität aufgetreten; sie gilt in ihm

auf der einen Seite nur als allgemeiner Willen, auf der andern als Blut

der Familie; dieser Einzelne gilt nur als der unwirkliche Schatten. --

Es ist noch keine Tat begangen; die Tat aber ist das wirkliche Selbst.

-- Sie stört die ruhige Organisation und Bewegung der sittlichen Welt.

Was in dieser als Ordnung und Übereinstimmung ihrer beiden Wesen

erscheint, deren eins das andere bewährt und vervollständigt, wird

durch die Tat zu einem Übergange entgegengesetzter, worin jedes sich

vielmehr als die Nichtigkeit seiner selbst und des andern beweist, denn

als die Bewährung; -- es wird zu der negativen Bewegung oder der ewigen

Notwendigkeit des furchtbaren Schicksals, welche das göttliche wie das

menschliche Gesetz, sowie die beiden Selbstbewußtsein, in denen diese

Mächte ihr Dasein haben, in den Abgrund seiner Einfachheit verschlingt

-- und für uns in das absolute Für-sich-sein des rein einzelnen

Selbstbewußtseins übergeht. |

しかし、この領域における対立の性質上、自己意識はまだ個々の個性とし

てその権利を発揮していない。この領域では、自己意識は、一方では一般的な意志として、他方では家族の血としてのみ機能しており、この個人は、非現実的な

影にすぎない。まだ行為は実行されていない。しかし、行為こそが真の自己である。--

それは、道徳の世界の穏やかな組織と動きを乱す。この世界において、その二つの存在の秩序と調和として現れ、一方が他方を証明し、完成しているものは、行

為によって、反対のものへと移行し、そこでは、それぞれが、むしろ、自分自身と他方の無意味さを証明するものであり、証明ではない。--

それは、神聖な法則と人間の法則、そしてこれらの力が現存在(Dasein)を持つ2つの自己意識を、その単純さの深淵に飲み込む、恐ろしい運命の否定的

な動き、あるいは永遠の必然性となり、そして私たちにとっては、純粋に個別の自己意識の絶対的な「それ自体」へと移行する。 |

| 1. 個性と本質の矛盾 |

1. Contradiction of Individuality with its Essence |

| Der Grund, von dem diese

Bewegung aus- und auf dem sie vorgeht, ist das Reich der Sittlichkeit;

aber die Tätigkeit dieser Bewegung ist das Selbstbewußtsein. Als

sittliches Bewußtsein ist es die einfache reine Richtung auf die

sittliche Wesenheit, oder die Pflicht. Keine Willkür, und ebenso kein

Kampf, keine Unentschiedenheit ist in ihm, indem das Geben und das

Prüfen der Gesetze aufgegeben worden, sondern die sittliche Wesenheit

ist ihm das Unmittelbare, Unwankende, Widerspruchslose. Es gibt daher

nicht das schlechte Schauspiel, sich in einer Kollision von

Leidenschaft und Pflicht, noch das Komische, in einer Kollision von

Pflicht und Pflicht zu befinden -- einer Kollision, die dem Inhalte

nach dasselbe ist als die zwischen Leidenschaft und Pflicht; denn die

Leidenschaft ist ebenso fähig, als Pflicht vorgestellt zu werden, weil

die Pflicht, wie sich das Bewußtsein aus ihrer unmittelbaren

substantiellen Wesenheit in sich zurückzieht, zum Formell-Allgemeinen

wird, in das jeder Inhalt gleich gut paßt, wie sich oben ergab. Komisch

aber ist die Kollision der Pflichten, weil sie den Widerspruch, nämlich

eines entgegengesetzten Absoluten, also Absolutes und unmittelbar die

Nichtigkeit dieses sogenannten Absoluten oder Pflicht, ausdrückt. --

Das sittliche Bewußtsein aber weiß, was es zu tun hat; und ist

entschieden, es sei dem göttlichen oder dem menschlichen Gesetze

anzugehören. Diese Unmittelbarkeit seiner Entschiedenheit ist ein

An-sich-sein, und hat daher zugleich die Bedeutung eines natürlichen

Seins, wie wir gesehen; die Natur, nicht das Zufällige der Umstände

oder der Wahl, teilt das eine Geschlecht dem einen, das andere dem

andern Gesetze zu -- oder umgekehrt, die beiden sittlichen Mächte

selbst geben sich an den beiden Geschlechtern ihr individuelles Dasein

und Verwirklichung. |

この運動の出発点であり、その基盤となっているのは道徳の領域である

が、この運動の活動は自己意識だ。道徳的意識として、それは道徳の本質、すなわち義務への単純で純粋な指向なのである。そこには、恣意も、闘争も、優柔不

断さも存在しない。なぜなら、法律の制定と検証が放棄されているからだ。道徳の本質は、彼にとって直接的で、揺るぎない、矛盾のないものである。したがっ

て、情熱と義務の衝突という悪い光景も、義務と義務の衝突という滑稽な光景も存在しない。この衝突は、その内容としては情熱と義務の衝突と同じである。な

ぜなら、情熱は義務として表現することも可能だからだ。義務は、その直接的な実体的な本質から意識が後退すると、形式的な一般性となり、上述のように、あ

らゆる内容が等しく適合するからだ。しかし、義務の衝突は、矛盾、すなわち相反する絶対、つまり絶対と、このいわゆる絶対、あるいは義務の無意味さを直接

的に表現しているから、滑稽なんだ。しかし、道徳的意識は、自分がすべきことを知っていて、それが神の法則に属するか、人間の法則に属するかについて決定

している。この決意の直接性は、それ自体であるということであり、したがって、これまで見てきたように、自然の存在という意味も持つ。偶然の事情や選択で

はなく、自然が、ある性別には一方の法則を、別の性別にはもう一方の法則を割り当てている。あるいは逆に、2つの道徳的力自体が、2つの性別にそれぞれの

個別の現存在(Dasein)と実現を与えている。 |

| Hiedurch nun, daß einesteils die

Sittlichkeit wesentlich in dieser unmittelbaren Entschiedenheit

besteht, und darum für das Bewußtsein nur das eine Gesetz das Wesen

ist, andernteils, daß die sittlichen Mächte in dem Selbst des

Bewußtseins wirklich sind, erhalten sie die Bedeutung, sich

auszuschließen und sich entgegengesetzt zu sein; -- sie sind in dem

Selbstbewußtsein für sich, wie sie im Reiche der Sittlichkeit nur an

sich sind. Das sittliche Bewußtsein, weil es für eins derselben

entschieden ist, ist wesentlich Charakter; es ist für es nicht die

gleiche Wesenheit beider; der Gegensatz erscheint darum als eine

unglückliche Kollision der Pflicht nur mit der rechtlosen Wirklichkeit.

Das sittliche Bewußtsein ist als Selbstbewußtsein in diesem Gegensatze,

und als solches geht es zugleich darauf, dem Gesetze, dem es angehört,

diese entgegengesetzte Wirklichkeit durch Gewalt zu unterwerfen, oder

sie zu täuschen. Indem es das Recht nur auf seiner Seite, das Unrecht

aber auf der andern sieht, so erblickt von beiden dasjenige, welches

dem göttlichen Gesetze angehört, auf der andern Seite menschliche

zufällige Gewalttätigkeit; das aber dem menschlichen Gesetze zugeteilt

ist, auf der andern den Eigensinn und den Ungehorsam des innerlichen

Für-sich-seins; denn die Befehle der Regierung sind der allgemeine, am

Tage liegende öffentliche Sinn; der Willen des andern Gesetzes aber ist

der unterirdische, ins Innre verschlossne Sinn, der in seinem Dasein

als Willen der Einzelnheit erscheint, und im Widerspruche mit dem

ersten der Frevel ist. |

このように、一方では道徳は本質的にこの直接的な決定性に存在し、それ

ゆえ意識にとって唯一の法則がその本質である一方、他方では道徳的力は意識の自己の中に実在しているため、それらは互いに排除し合い、対立する意味を持

つ。--

それらは、道徳の領域ではそれ自体としてのみ存在するのに対し、自己意識の中ではそれ自体として存在する。道徳的意識は、そのうちの1つとして決定されて

いるため、本質的に性格である。それは、その両方と同じ本質ではない。したがって、その対立は、義務と無権利の現実との不幸な衝突として現れる。道徳的意

識は、この対立において自己意識として存在し、そのようにして、同時に、それが属する法則に対して、この対立する現実を暴力によって服従させるか、あるい

は欺くか、という行動に走ります。正義は自分の側にあり、不正は相手側にあると見ることで、神聖な法則に属するものを一方に見、他方では人間の偶発的な暴

力を見出す。一方、人間の法則に属するものとして、内面の自己存在の頑固さと不服従を見ます。なぜなら、政府の命令は、表面的で公的な一般的な意味である

のに対し、

しかし、もう一方の法則の意志は、地下に隠され、内面に閉じ込められた意味であり、その現存在(Dasein)において、個々の意志として現れ、最初の法

則と矛盾する不敬(=共同体に対する反抗)である。 |

| Es entsteht hiedurch am

Bewußtsein der Gegensatz des Gewußten und des Nichtgewußten, wie in der

Substanz, des Bewußten und Bewußtlosen; und das absolute Recht des

sittlichen Selbstbewußtseins kommt mit dem göttlichen Rechte des Wesens

in Streit. Für das Selbstbewußtsein als Bewußtsein hat die

gegenständliche Wirklichkeit als solche Wesen; nach seiner Substanz

aber ist es die Einheit seiner und dieses Entgegengesetzten; und das

sittliche Selbstbewußtsein ist das Bewußtsein der Substanz; der

Gegenstand als dem Selbstbewußtsein entgegengesetzt, hat darum gänzlich

die Bedeutung verloren, für sich Wesen zu haben. Wie die Sphären, worin

er nur ein Ding ist, längst verschwunden, so auch diese Sphären, worin

das Bewußtsein etwas aus sich befestiget und ein einzelnes Moment zum

Wesen macht.. |

これにより、意識において、知られているものと知られていないもの、つ

まり実体における意識と無意識との対立が生じ、道徳的自己意識の絶対的権利は、存在の神聖な権利と対立する。意識としての自己意識にとって、対象的な現実

はそれ自体として実体を有している。しかし、その実体としては、自己意識は、自己とこの対立物との統一である。そして、道徳的自己意識は、実体の意識であ

る。自己意識と対立する対象は、それゆえ、それ自体として実体を持つという意味を完全に失っている。彼がただ一つの物である領域は、とっくに消滅している

ように、意識がそれ自体から何かを固定し、単一の瞬間を本質とする領域も消滅している。 |

| Gegen solche Einseitigkeit hat

die Wirklichkeit eine eigene Kraft; sie steht mit der Wahrheit im Bunde

gegen das Bewußtsein, und stellt diesem erst dar, was die Wahrheit ist.

Das sittliche Bewußtsein aber hat aus der Schale der absoluten Substanz

die Vergessenheit aller Einseitigkeit des Für-sich-seins, seiner Zwecke

und eigentümlichen Begriffe getrunken, und darum in diesem stygischen

Wasser zugleich alle eigne Wesenheit und selbstständige Bedeutung der

gegenständlichen Wirklichkeit ertränkt. Sein absolutes Recht ist daher,

daß es, indem es nach dem sittlichen Gesetze handelt, in dieser

Verwirklichung nicht irgend etwas anderes finde, als nur die

Vollbringung dieses Gesetzes selbst, und die Tat nichts anders zeige,

als das sittliche Tun ist. -- |

そのような偏見に対して、現実は独自の力を持っている。それは真実と結

託して意識に対抗し、意識に真実とは何であるかを初めて示すのだ。しかし、道徳的意識は、絶対的な実体の殻から、自己存在の一方的な側面、その目的、そし

て固有の概念のすべてを忘却し、そのスティクス川の水の中で、対象的な現実の固有の本質と自立した意味を同時に溺死させてしまった。したがって、道徳的意

識の絶対的な権利とは、道徳的法則に従って行動する際に、その実現において、その法則自体の成就以外の何物も発見せず、行為が道徳的行為以外の何物も示さ

ないことである。-- |

| Das Sittliche, als das absolute

Wesen und die absolute Macht zugleich kann keine Verkehrung seines

Inhalts erleiden. Wäre es nur das absolute Wesen ohne die Macht, so

könnte es eine Verkehrung durch die Individualität erfahren; aber diese

als sittliches Bewußtsein hat mit dem Aufgeben des einseitigen

Für-sich-seins dem Verkehren entsagt; so wie die bloße Macht umgekehrt

vom Wesen verkehrt werden würde, wenn sie noch ein solches

Für-sich-sein wäre. Um dieser Einheit willen ist die Individualität

reine Form der Substanz, die der Inhalt ist, und das Tun ist das

Übergehen aus dem Gedanken in die Wirklichkeit, nur als die Bewegung

eines wesenlosen Gegensatzes, dessen Momente keinen besondern von

einander verschiedenen Inhalt und Wesenheit haben. Das absolute Recht

des sittlichen Bewußtseins ist daher, daß die Tat, die Gestalt seiner

Wirklichkeit, nichts anders sei, als es weiß |

道徳は、絶対的な存在であり、同時に絶対的な力でもあるため、その内容

に逆転は起こらない。もしそれが権力のない絶対的な存在だけなら、個性の影響を受けてその内容が逆転する可能性はある。しかし、道徳的意識としての個性

は、一方的な自己存在を放棄することで、その逆転を拒否している。逆に、単なる権力が、もしそれがまだそのような自己存在であったならば、存在によって逆

転されるだろう。この統一のために、個性は、内容である実体の純粋な形態であり、行為は、思考から現実への移行であり、その瞬間は、互いに異なる内容や実

体を持たない、実体のない対立の運動としてのみ存在する。したがって、道徳的意識の絶対的な権利は、その現実の形である行為が、それが知っているもの以外

の何物でもないことにある。 |

| Aber das sittliche Wesen hat

sich selbst in zwei Gesetze gespalten, und das Bewußtsein, als

unentzweites Verhalten zum Gesetze, ist nur einem zugeteilt. Wie dies

einfache Bewußtsein auf dem absoluten Rechte besteht, daß ihm als

sittlichem das Wesen erschienen sei, wie es an sich ist, so besteht

dieses Wesen auf dem Rechte seiner Realität, oder darauf, gedoppeltes

zu sein. Dies Recht des Wesens steht aber zugleich dem Selbstbewußtsein

nicht gegenüber, daß es irgendwoanders wäre, sondern es ist das eigne

Wesen des Selbstbewußtseins; es hat darin allein sein Dasein und seine

Macht, und sein Gegensatz ist die Tat des Letztern. Denn dieses, eben

indem es sich als Selbst ist und zur Tat schreitet, erhebt sich aus der

einfachen Unmittelbarkeit und setzt selbst die Entzweiung. Es gibt

durch die Tat die Bestimmtheit der Sittlichkeit auf, die einfache

Gewißheit der unmittelbaren Wahrheit zu sein, und setzt die Trennung

seiner selbst in sich als das Tätige und in die gegenüberstehende für

es negative Wirklichkeit. Es wird also durch die Tat zur Schuld. Denn

sie ist sein Tun, und das Tun sein eigenstes Wesen; und die Schuld

erhält auch die Bedeutung des Verbrechens: denn als einfaches

sittliches Bewußtsein hat es sich dem einen Gesetze zugewandt, dem

andern aber abgesagt, und verletzt dieses durch seine Tat. -- |

しかし、道徳的存在はそれ自体を二つの法則に分割し、法則に対する分割

されていない行動としての意識は、そのうちの1つだけに割り当てられている。この単純な意識が、道徳的存在としてその本質がそのまま現れているという絶対

的な権利に基づいて存在しているように、この本質は、その現実性、すなわち二重性という権利に基づいて存在している。しかし、この実体の権利は、自己意識

に対して、それがどこか別の場所にあるという対立関係にあるのではなく、自己意識の固有の実体であり、自己意識は、その中にのみその現存在

(Dasein)と力を持ち、その対立は、後者の行為である。なぜなら、後者は、まさに自己として存在し、行為へと進むことによって、単純な直接性から立

ち上がり、自ら二分するからだ。行為によって、道徳は、直接的な真実であるという単純な確実性を放棄し、行為としての自己と、それに対して否定的な現実と

の分裂を、自己の中に設定する。したがって、行為によってそれは罪となる。なぜなら、行為はそれ自身の行動であり、行動はそれ自身の最も本質的な性質であ

るから。そして、罪は犯罪の意味も持つ。なぜなら、単純な道徳的意識として、ある法則に従うことを選び、別の法則を拒否し、その行為によってその法則に違

反するからである。-- |

| Die Schuld ist nicht das

gleichgültige doppelsinnige Wesen, daß die Tat, wie sie wirklich am

Tage liegt, Tun ihres Selbsts sein könne oder auch nicht, als ob mit

dem Tun sich etwas Äußerliches und Zufälliges verknüpfen könnte, das

dem Tun nicht angehörte, von welcher Seite das Tun also unschuldig

wäre. Sondern das Tun ist selbst diese Entzweiung, sich für sich, und

diesem gegenüber eine fremde äußerliche Wirklichkeit zu setzen; daß

eine solche ist, gehört dem Tun selbst an und ist durch dasselbe.

Unschuldig ist daher nur das Nichttun wie das Sein eines Steines, nicht

einmal eines Kindes. -- |

罪は、その行為が実際にその日に起こったものとして、その行為自体がそ

れ自体であるかもしれないし、そうでないかもしれないという、無関心で曖昧な性質ではない。それは、その行為に、その行為に属さない、外的な、偶然的なも

のが結びついているかのように、その行為がどちらの側面から見て無罪であるかを決定するものではない。むしろ、行為そのものが、自分自身に対して、そして

それに対して、外部の現実を対立させるという分裂である。そのような現実が存在することは、行為そのものに属し、行為によって生じる。したがって、無罪な

のは、石の存在のように、あるいは子供でさえもない、行為をしないことだけだ。-- |

| Dem Inhalte nach aber hat die

sittliche Handlung das Moment des Verbrechens an ihr, weil sie die

natürliche Verteilung der beiden Gesetze an die beiden Geschlechter

nicht aufhebt, sondern vielmehr als unentzweite Richtung auf das Gesetz

innerhalb der natürlichen Unmittelbarkeit bleibt, und als Tun diese

Einseitigkeit zur Schuld macht, nur die eine der Seiten des Wesens zu

ergreifen, und gegen die andre sich negativ zu verhalten, d.h. sie zu

verletzen. Wohin in dem allgemeinen sittlichen Leben Schuld und

Verbrechen, Tun und Handeln fällt, wird nachher bestimmter ausgedrückt

werden; es erhellt unmittelbar soviel, daß es nicht dieser Einzelne

ist, der handelt und schuldig ist; denn er als dieses Selbst ist nur

der unwirkliche Schatten, oder er ist nur als allgemeines Selbst, und

die Individualität rein das formale Moment des Tuns überhaupt, und der

Inhalt die Gesetze und Sitten, und bestimmt für den Einzelnen, die

seines Standes; er ist die Substanz als Gattung, die durch ihre

Bestimmtheit zwar zur Art wird, aber die Art bleibt zugleich das

Allgemeine der Gattung. Das Selbstbewußtsein steigt innerhalb des

Volkes vom Allgemeinen nur bis zur Besonderheit, nicht bis zur

einzelnen Individualität herab, welche ein ausschließendes Selbst, eine

sich negative Wirklichkeit in seinem Tun setzt; sondern seinem Handeln

liegt das sichre Vertrauen zum Ganzen zugrunde, worin sich nichts

Fremdes, keine Furcht noch Feindschaft einmischt. |

しかし、その内容から言えば、道徳的行為には犯罪の要素がある。なぜな

ら、それは、2つの法律を2つの性別に自然に分配することを止揚するのではなく、むしろ、自然の直接性の中で法律に対する分割不可能な方向性として残って

おり、行為として、この一方的な側面だけを取り上げ、もう一方の側面に対して否定的な態度、すなわちそれを侵害する行為を行うという罪悪感をもたらすから

だ。一般的な道徳的生活において、罪と犯罪、行為と行動がどこに該当するかは、後でより明確に表現される。このことは、行為を行い、罪を犯すのはこの個人

ではないことはすぐに明らかだ。なぜなら、この個人は、この自己として、ただ非現実的な影にすぎず、あるいは、一般的な自己としてのみ存在し、個体性は、

行為そのものの形式的な要素にすぎず、その内容は、法則や道徳であり、個人にとっては、その地位に固有のものであるからだ。彼は、その決定性によって種と

なる物質であるが、同時に種は種の一般性であり続ける。国民の中で、自己意識は、一般性から特殊性までしか下降せず、その行為において排他的な自己、否定

的な現実を設定する個々の個性まで下降することはない。その行為の根底には、何ものにも邪魔されない、恐怖や敵意が混ざらない、全体に対する確固たる信頼

がある。 |

| 2. 倫理的行動の反対の特徴 |

2. Opposite Characteristics of Ethical Action |

| Die entwickelte Natur des

wirklichen Handelns erfährt nun das sittliche Selbstbewußtsein an

seiner Tat, ebensowohl wenn es dem göttlichen, als wenn es dem

menschlichen Gesetze sich ergab. Das ihm offenbare Gesetz ist im Wesen

mit dem entgegengesetzten verknüpft; das Wesen ist die Einheit beider;

die Tat aber hat nur das eine gegen das andere ausgeführt. Aber im

Wesen mit diesem verknüpft, ruft die Erfüllung des einen das andere

hervor, und, wozu die Tat es machte, als ein verletztes, und nun

feindliches, Rache forderndes Wesen. Dem Handeln liegt nur die eine

Seite des Entschlusses überhaupt an dem Tage; er ist aber an sich das

Negative, das ein ihm Anderes, ein ihm, der das Wissen ist, Fremdes

gegenüberstellt. Die Wirklichkeit hält daher die andere dem Wissen

fremde Seite in sich verborgen, und zeigt sich dem Bewußtsein nicht,

wie sie an und für sich ist -- dem Sohne nicht den Vater in seinem

Beleidiger, den er erschlägt; nicht die Mutter in der Königin, die er

zum Weibe nimmt. Dem sittlichen Selbstbewußtsein stellt auf diese Weise

eine lichtscheue Macht nach, welche erst, wenn die Tat geschehen,

hervorbricht und es bei ihr ergreift; denn die vollbrachte Tat ist der

aufgehobne Gegensatz des wissenden Selbst und der ihm

gegenüberstehenden Wirklichkeit. Das Handelnde kann das Verbrechen und

seine Schuld nicht verleugnen; -- die Tat ist dieses, das Unbewegte zu

bewegen und das nur erst in der Möglichkeit Verschlossene

hervorzubringen, und hiemit das Unbewußte dem Bewußten, das

Nichtseiende dem Sein zu verknüpfen. In dieser Wahrheit tritt also die

Tat an die Sonne; -- als ein solches, worin ein Bewußtes einem

Unbewußten, das Eigne einem Fremden verbunden ist, als das entzweite

Wesen, dessen andere Seite das Bewußtsein, und auch als die seinige

erfährt, aber als die von ihm verletzte und feindlich erregte Macht. |

現実の行動の展開した性質は、それが神の法則に従った場合でも、人間の

法則に従った場合でも、その行為において道徳的自己意識を経験する。彼に明らかにされた法則は、その本質において反対の法則と結びついている。その本質は

両者の統一であるが、行為は一方を他方に対して実行したにすぎない。しかし、その本質と結びついているため、一方の実現は他方を呼び起こし、行為がそれに

したこと、すなわち、傷つけられた、そして今や敵対的で復讐を求める存在として。行為には、その日その日に下された決定の一面しか存在しない。しかし、行

為はそれ自体、否定的なものであり、それとは別の、知識であるそれとは異質なものを対峙させる。したがって、現実は、知識にとって異質なもう一方の側面を

その中に隠しており、それ自体が本来ある姿で意識に現れない。息子には、彼が殺した父親の侮辱者としての側面は現れない。また、彼が妻とする女王の母親と

しての側面も現れない。このように、道徳的な自己意識には、光を嫌う力が追いかけてきて、行為が行われたときに初めて現れて、それを捕らえる。なぜなら、

実行された行為は、知的な自己と、その対極にある現実との矛盾が解消されたものだからだ。行為者は、犯罪とその罪を否定することはできない。行為とは、動

かないものを動かし、可能性の中にのみ閉じ込められていたものを引き出すことであり、それによって、無意識を意識と結びつけ、存在しないものを存在と結び

つけることだ。この真実において、行為は太陽の下に現れる。それは、意識が、無意識、つまり自己と他者との結びつき、つまり分裂した存在であり、そのもう

一方の側面は意識であり、また、その側面も、自分によって傷つけられ、敵対的に刺激された力として認識する。 |

| Es kann sein, daß das Recht,

welches sich im Hinterhalte hielt, nicht in seiner eigentümlichen

Gestalt für das handelnde Bewußtsein, sondern nur an sich, in der

innern Schuld des Entschlusses und des Handelns vorhanden ist. Aber das

sittliche Bewußtsein ist vollständiger, seine Schuld reiner, wenn es

das Gesetz und die Macht vorher kennt, der es gegenübertritt, sie für

Gewalt und Unrecht, für eine sittliche Zufälligkeit nimmt, und

wissentlich, wie Antigone, das Verbrechen begeht. Die vollbrachte Tat

verkehrt seine Ansicht; die Vollbringung spricht es selbst aus, daß was

sittlich ist, wirklich sein müsse; denn die Wirklichkeit des Zwecks ist

der Zweck des Handelns. Das Handeln spricht gerade die Einheit der

Wirklichkeit und der Substanz aus, es spricht aus, daß die Wirklichkeit

dem Wesen nicht zufällig ist, sondern mit ihm im Bunde keinem gegeben

wird, das nicht wahres Recht ist. Das sittliche Bewußtsein muß sein

Entgegengesetztes um dieser Wirklichkeit willen, und um seines Tuns

willen, als die seinige, es muß seine Schuld anerkennen; |

隠れていた権利は、行動する意識にとってその固有の形態では存在せず、

ただそれ自体として、決定と行動の内的な罪悪感の中に存在しているだけかもしれない。しかし、道徳的意識は、それに対峙する法律と権力をあらかじめ知って

おり、それらを暴力と不正、道徳的な偶然性であると認識し、アンティゴネのように故意に犯罪を犯す場合、より完全であり、その罪はより純粋である。実行さ

れた行為は、その見解を覆す。実行自体が、道徳的なものは現実でなければならないことを表明している。なぜなら、目的の実在性が、行動の目的であるから

だ。行動はまさに現実と実体の統一を表明し、現実は本質に偶然に与えられたものではなく、本質と結びついて、真の権利ではないものには与えられないことを

表明する。道徳的意識は、この現実のために、そして自らの行為のために、その反対を自らのものとして認め、その罪を認めなければならない。 |

| weil wir leiden, anerkennen wir, daß wir gefehlt. | 私たちは苦しむということは、自分が間違っていたことを認めることなのでしょう(アンティゴネーの言葉) |

| Dies Anerkennen drückt den

aufgehobenen Zwiespalt des sittlichen Zweckes und der Wirklichkeit, es

drückt die Rückkehr zur sittlichen Gesinnung aus, die weiß, daß nichts

gilt als das Rechte. Damit aber gibt das Handelnde seinen Charakter und

die Wirklichkeit seines Selbsts auf, und ist zugrunde gegangen. Sein

Sein ist dieses, seinem sittlichen Gesetze als seiner Substanz

anzugehören; in dem Anerkennen des Entgegengesetzten hat dies aber

aufgehört, ihm Substanz zu sein; und statt seiner Wirklichkeit hat es

die Unwirklichkeit, die Gesinnung, erreicht. -- |

この認識は、道徳的目的と現実との矛盾の解消を表しており、正しいこと

だけが価値あるものであることを認識した道徳的態度への回帰を表している。しかし、それにより、行為者はその性格と自己の現実性を放棄し、滅びてしまう。

その存在は、道徳的法則をその本質として属することにある。しかし、その反対を認めることで、それはその本質ではなくなり、その現実性の代わりに、非現実

性、すなわち態度に達した。-- |

| Die Substanz erscheint zwar an

der Individualität als das Pathos derselben, und die Individualität als

das, was sie belebt, und daher über ihr steht; aber sie ist ein Pathos,

das zugleich sein Charakter ist; die sittliche Individualität ist

unmittelbar und an sich eins mit diesem seinem Allgemeinen, sie hat

ihre Existenz nur in ihm, und vermag den Untergang, den diese sittliche

Macht durch die entgegengesetzte leidet, nicht zu überleben. |

その物質は、個性のパトスとして、そして個性を活気づけるもの、した

がって個性よりも上位にあるものとして現れるが、それは同時にその特徴でもあるパトスである。道徳的個性は、この普遍的なものと直接かつ本質的に一体であ

り、その中にのみ存在し、この道徳的力が反対の力によって被る滅亡を生き残ることはできない。 |

| Sie hat aber dabei die

Gewißheit, daß diejenige Individualität, deren Pathos diese

entgegengesetzte Macht ist, nicht mehr Übel erleidet, als sie zugefügt.

Die Bewegung der sittlichen Mächte gegeneinander und der sie in Leben

und Handlung setzenden Individualitäten hat nur darin ihr wahres Ende

erreicht, daß beide Seiten denselben Untergang erfahren. Denn keine der

Mächte hat etwas vor der andern voraus, um wesentlicheres Moment der

Substanz zu sein. Die gleiche Wesentlichkeit und das gleichgültige

Bestehen beider nebeneinander ist ihr selbstloses Sein; in der Tat sind

sie als Selbstwesen, aber ein verschiedenes, was der Einheit des

Selbsts widerspricht, und ihre Rechtlosigkeit und notwendigen Untergang

ausmacht. Der Charakter gehört ebenso teils nach seinem Pathos oder

Substanz nur der einen an, teils ist nach der Seite des Wissens der

eine wie der andere in ein Bewußtes und Unbewußtes entzweit; und indem

jeder selbst diesen Gegensatz hervorruft, und durch die Tat auch das

Nichtwissen sein Werk ist, setzt er sich in die Schuld, die ihn

verzehrt. Der Sieg der einen Macht und ihres Charakters und das

Unterliegen der andern Seite wäre also nur der Teil und das

unvollendete Werk, das unaufhaltsam zum Gleichgewichte beider

fortschreitet. Erst in der gleichen Unterwerfung beider Seiten ist das

absolute Recht vollbracht, und die sittliche Substanz als die negative

Macht, welche beide Seiten verschlingt, oder das allmächtige und

gerechte Schicksal aufgetreten. |

しかし、その一方で、その反対の力である個性が、与えた悪以上の悪を受

けることはないと確信している。道徳的な力同士の対立と、それを生命と行動に具現化する個性の動きは、双方が同じ破滅を経験することによってのみ、その真

の意味での終焉を迎える。なぜなら、どちらの力も、本質的な要素として他よりも優れているところはないからだ。両者が並存する同じ本質と無差別な存在が、

その無私の存在だ。実際、それらは自己存在であるが、自己の統一性に反する異なる存在であり、その無権利性と必然的な滅亡を構成している。性格も、その感

情や本質によっては一方にのみ属し、知識の面では、一方も他方も意識と無意識に二分されている。そして、それぞれがこの対立を引き起こし、その行為によっ

て無知も自分の仕業となることで、自分を滅ぼす罪を犯している。一方の力とその性格の勝利、そしてもう一方の側の敗北は、したがって、両者の均衡に向かっ

て止まることなく進む、部分的で不完全な成果にすぎない。両者が等しく服従して初めて、絶対的な正義が達成され、両者を飲み込む否定的な力、すなわち全能

で公正な運命としての道徳的本質が現れる。 |

| Werden beide Mächte nach ihrem

bestimmten Inhalte und dessen Individualisation genommen, so bietet

sich das Bild ihres gestalteten Widerstreits, nach seiner formellen

Seite, als der Widerstreit der Sittlichkeit und des Selbstbewußtseins

mit der bewußtlosen Natur und einer durch sie vorhandenen Zufälligkeit

-- diese hat ein Recht gegen jenes, weil es nur der wahre Geist, nur in

unmittelbarer Einheit mit seiner Substanz ist -- und seinem Inhalte

nach als der Zwiespalt des göttlichen und menschlichen Gesetzes dar. --

Der Jüngling tritt aus dem bewußtlosen Wesen, aus dem Familiengeiste,

und wird die Individualität des Gemeinwesens; daß er aber der Natur,

der er sich entriß, noch angehöre, erweist sich so, daß er in der

Zufälligkeit zweier Brüder heraustritt, welche mit gleichem Rechte sich

desselben bemächtigen; die Ungleichheit der frühern und spätern Geburt

hat für sie, die in das sittliche Wesen eintreten, als Unterschied der

Natur, keine Bedeutung. Aber die Regierung, als die einfache Seele oder

das Selbst des Volksgeistes, verträgt nicht eine Zweiheit der

Individualität; und der sittlichen Notwendigkeit dieser Einheit tritt

die Natur als der Zufall der Mehrheit gegenüber auf. Diese beiden

werden darum uneins, und ihr gleiches Recht an die Staatsgewalt

zertrümmert beide, die gleiches Unrecht haben. Menschlicherweise

angesehen, hat derjenige das Verbrechen begangen, welcher, nicht im

Besitze, das Gemeinwesen, an dessen Spitze der andere stand, angreift;

derjenige dagegen hat das Recht auf seiner Seite, welcher den andern

nur als Einzelnen, abgelöst von dem Gemeinwesen, zu fassen wußte und in

dieser Machtlosigkeit vertrieb; er hat nur das Individuum als solches,

nicht jenes, nicht das Wesen des menschlichen Rechts, angetastet. Das

von der leeren Einzelnheit angegriffene und verteidigte Gemeinwesen

erhält sich, und die Brüder finden beide ihren wechselseitigen

Untergang durcheinander; denn die Individualität, welche an ihr

Für-sich-sein die Gefahr des Ganzen knüpft, hat sich selbst vom

Gemeinwesen ausgestoßen, und löst sich in sich auf. Den einen aber, der

auf seiner Seite sich fand, wird es ehren; den andern hingegen, der

schon auf den Mauern seine Verwüstung aussprach, wird die Regierung,

die wiederhergestellte Einfachheit des Selbsts des Gemeinwesens, um die

letzte Ehre bestrafen; wer an dem höchsten Geiste des Bewußtseins, der

Gemeine, sich zu vergreifen kam, muß der Ehre seines ganzen vollendeten

Wesens, der Ehre des abgeschiedenen Geistes, beraubt werden. |

両者の力が、その特定のコンテンツとその個別性に基づいて捉えられる

と、その形式的な側面から、道徳と自己意識が、無意識の自然と、それによって生じる偶然性との対立という構図が浮かび上がる。--

これは、真の精神は、その本質と直接的に一体である場合にのみ存在するため、それに対して権利を有している --

内容的には、神法と人間法の対立として現れる。--

青年は、無意識の存在、家族精神から抜け出し、共同体の個性となる。しかし、彼が、自ら脱した自然にもまだ属していることは、同じ権利をもってそれを奪い

合う2人の兄弟の偶然性から抜け出すことで明らかになる。道徳的な存在となった彼らにとって、生まれの早さの違いは、自然の違いとして何の意味も持たな

い。しかし、単純な魂、あるいは国民精神の自己である政府は、個性の二元性を容認できない。そして、この統一の道徳的必然性に対して、自然は多数決の偶然

性として対峙する。このため、この二者は対立し、国家権力に対する同等の権利によって、同等の不正を犯した両者が打ち砕かれる。人間的に見れば、所有権を

持たない者が、他者がトップに立つ共同体を攻撃したのは犯罪だ。一方、他者を共同体から切り離した個人としてのみ認識し、その無力な状態を利用して追放し

た者は、権利を自分の側に持っている。彼は、人間としての本質ではなく、個人としてのみその者を攻撃しただけだからだ。空虚な個別性によって攻撃され、防

衛された共同体は存続し、兄弟たちは互いに滅び合う。なぜなら、その存在そのものに全体としての危険を結びつける個別性は、共同体から自らを排除し、その

内部で崩壊するからだ。一方、自分の立場を見出した者は、名誉を授けられる。しかし、城壁の上で破壊を叫んだ者は、共同体の自己の単純さが回復した政府に

よって、最後の名誉を罰される。最高意識、すなわち共同体そのものを冒涜した者は、その完成された存在の栄誉、すなわち分離した精神の栄誉を奪われる。 |

| Aber wenn so das Allgemeine die

reine Spitze seiner Pyramide leicht abstößt, und über das sich

empörende Prinzip der Einzelnheit, die Familie, zwar den Sieg

davonträgt, so hat es sich dadurch mit dem göttlichen Gesetze, der

seiner selbstbewußte Geist sich mit dem Bewußtlosen nur in Kampf

eingelassen; denn dieser ist die andre wesentliche und darum von jener

unzerstörte und nur beleidigte Macht. Er hat aber gegen das

gewalthabende, am Tage liegende Gesetz seine Hülfe zur wirklichen

Ausführung nur an dem blutlosen Schatten. Als das Gesetz der Schwäche

und der Dunkelheit unterliegt er daher zunächst dem Gesetze des Tages

und der Kraft, denn jene Gewalt gilt unten, nicht auf Erden. Allein das

Wirkliche, das dem Innerlichen seine Ehre und Macht genommen, hat damit

sein Wesen aufgezehrt. Der offenbare Geist hat die Wurzel seiner Kraft

in der Unterwelt; die ihrer selbst sichere und sich versichernde

Gewißheit des Volkes hat die Wahrheit ihres Alle in Eins bindenden

Eides nur in der bewußtlosen und stummen Substanz Aller, in den Wässern

der Vergessenheit. Hiedurch verwandelt sich die Vollbringung des

offenbaren Geistes in das Gegenteil, und er erfährt, daß sein höchstes

Recht das höchste Unrecht, sein Sieg vielmehr sein eigener Untergang

ist. Der Tote, dessen Recht gekränkt ist, weiß darum für seine Rache

Werkzeuge zu finden, welche von gleicher Wirklichkeit und Gewalt sind

mit der Macht, die ihn verletzt. Diese Mächte sind andere Gemeinwesen,

deren Altäre die Hunde oder Vögel mit der Leiche besudelten, welche

nicht durch die ihr gebührende Zurückgabe an das elementarische

Individuum in die bewußtlose Allgemeinheit erhoben, sondern über der

Erde im Reiche der Wirklichkeit geblieben, und als die Kraft des

göttlichen Gesetzes, nun eine selbstbewußte wirkliche Allgemeinheit

erhält. Sie machen sich feindlich auf, und zerstören das Gemeinwesen,

das seine Kraft, die Pietät der Familie, entehrt und zerbrochen hat. |

しかし、そうして一般性がそのピラミッドの純粋な頂点をわずかに押し下

げ、個性の反逆的な原理、すなわち家族に対して勝利を収めたとしても、それによって、その自己意識のある精神は、無意識と闘争にのみ巻き込まれただけであ

り、それは神聖な法則に反するものではない。なぜなら、無意識は、そのもう一つの本質的な力であり、それゆえ、前者に破壊されることはなく、ただ侮辱され

るだけだからだ。しかし、暴力的な、昼間の法則に対して、その実際の執行のための助けは、血なき影にしか見出せない。弱さと闇の法則は、したがって、まず

昼間の法則と力、すなわち、その暴力は地下で、地上では効力を有しない。しかし、内面にその名誉と力を奪った現実だけが、その本質を消耗してしまう。顕在

的な精神は、その力の根源を冥界に持ってる。民衆の、それ自体で確固とした、そして確信に満ちた確信は、すべてを一つに結ぶ誓いの真実を、意識のない、無

言のすべての物質、忘却の海の中にのみ持ってる。これにより、顕在的な精神の達成は正反対のものへと変化し、その精神は、自らの最高の権利が最高の不正で

あり、その勝利はむしろ自らの滅亡であることを知る。その権利を侵害された死者は、その復讐のために、自分を傷つけた力と同じ現実と暴力を持つ道具を見つ

けることを知っている。これらの力は、他の共同体であり、その祭壇は、死体を汚した犬や鳥たちによって汚されている。死体は、本来あるべき姿である、元素

の個体へと返されることなく、無意識の普遍性へと昇華されることなく、現実の領域である地上に残り、神の法の力として、今や、自己意識のある現実の普遍性

として存在している。それらは敵対し、その力を、家族の敬虔さを汚し、破壊した共同体を破壊する。 |

| In dieser Vorstellung hat die

Bewegung des menschlichen und göttlichen Gesetzes den Ausdruck ihrer

Notwendigkeit an Individuen, an denen das Allgemeine als ein Pathos und

die Tätigkeit der Bewegung als individuelles Tun erscheint, welches der

Notwendigkeit derselben den Schein der Zufälligkeit gibt. Aber die

Individualität und das Tun macht das Prinzip der Einzelnheit überhaupt

aus, das in seiner reinen Allgemeinheit das innere göttliche Gesetz

genannt wurde. Als Moment des offenbaren Gemeinwesens hat es nicht nur

jene unterirdische oder in seinem Dasein äußerliche Wirksamkeit,

sondern ein ebenso offenbares an dem wirklichen Volke wirkliches Dasein

und Bewegung. In dieser Form genommen, erhält das, was als einfache

Bewegung des individualisierten Pathos vorgestellt wurde, ein anderes

Aussehen, und das Verbrechen und die dadurch begründete Zerstörung des

Gemeinwesens die eigentliche Form ihres Daseins. -- |

この観念において、人間的および神聖な法則の動きは、その必然性を、一

般性がパトスとして、動きの活動が個々の行為として現れる個人に表現している。この個々の行為は、その必然性に偶然性の外観を与える。しかし、個性と行為

は、その純粋な一般性において、内なる神の法則と呼ばれた、個性の原理そのものを構成している。明白な共同体としての瞬間として、それは、その現存在の外

にある地下的な効力だけでなく、現実の民衆における現実の現存在と運動という、同様に明白な効力も持っている。この形で捉えると、個別化された情念の単純

な運動として考えられていたものは、別の姿となり、犯罪とそれによって生じた共同体の破壊は、その現存在の真の姿となる。-- |

| Das menschliche Gesetz also in

seinem allgemeinen Dasein, das Gemeinwesen, in seiner Betätigung

überhaupt die Männlichkeit, in seiner wirklichen Betätigung die

Regierung, ist, bewegt und erhält sich dadurch, daß es die Absonderung

der Penaten oder die selbstständige Vereinzelung in Familien, welchen

die Weiblichkeit vorsteht, in sich aufzehrt, und sie in der Kontinuität

seiner Flüssigkeit aufgelöst erhält. Die Familie ist aber zugleich

überhaupt sein Element, das einzelne Bewußtsein allgemeiner

betätigender Grund. Indem das Gemeinwesen sich nur durch die Störung

der Familienglückseligkeit und die Auflösung des Selbstbewußtseins in

das allgemeine sein Bestehen gibt, erzeugt es sich an dem, was es

unterdrückt und was ihm zugleich wesentlich ist, an der Weiblichkeit

überhaupt seinen innern Feind. Diese -- die ewige Ironie des

Gemeinwesens -- verändert durch die Intrige den allgemeinen Zweck der

Regierung in einen Privatzweck, verwandelt ihre allgemeine Tätigkeit in

ein Werk dieses bestimmten Individuums, und verkehrt das allgemeine

Eigentum des Staats zu einem Besitz und Putz der Familie. Sie macht

hiedurch die ernsthafte Weisheit des reifen Alters, das, der

Einzelnheit -- der Lust und dem Genusse, sowie der wirklichen Tätigkeit

-- abgestorben, nur das Allgemeine denkt und besorgt, zum Spotte für

den Mutwillen der unreifen Jugend, und zur Verachtung für ihren

Enthusiasmus; erhebt überhaupt die Kraft der Jugend zum Geltenden --

des Sohnes, an dem die Mutter ihren Herrn geboren, des Bruders, an dem

die Schwester den Mann als ihresgleichen hat, des Jünglings, durch den

die Tochter ihrer Unselbstständigkeit entnommen, den Genuß und die

Würde der Frauenschaft erlangt. -- |

つまり、人間の法律は、その一般的な現存在として、共同体として、その

活動として、男性性として、その実際の活動として、政府として、ペナテスの分離、すなわち、女性が主導する家族への自立的な分離を、その流動性の連続性の

中で解消し、維持することによって、動き、維持されている。しかし、家族は同時に、その要素であり、個々の意識が一般的に活動する根拠でもある。共同体

は、家族の幸福の混乱と、自己意識の一般的な存在への解消によってのみその存在を確立するため、抑圧し、同時にその本質である女性性、すなわちその内なる

敵を生み出している。この、共同体の永遠の皮肉は、陰謀によって、政府の一般的な目的を私的な目的へと変え、その一般的な活動を、この特定の個人の仕事へ

と変え、国家の一般的な所有物を、家族の所有物および装飾品へと変える。これにより、成熟した年齢の真剣な知恵、つまり、個々の人間性、つまり快楽と享

楽、そして現実の活動から死滅し、普遍的なものだけを考え、それを追求する知恵は、未熟な若者の気まぐれに対する嘲笑の対象となり、彼らの熱狂に対する軽

蔑の対象となる。そして、若者の力、すなわち、母親が主として産んだ息子、姉妹が同等の夫として迎える兄弟、娘が自立から解放され、女性の喜びと尊厳を得

る青年、を一般に有効なものとして高めている。 |

| 3. 倫理的存在の解消 |

3. Dissolution of the Ethical Being |

| Das Gemeinwesen kann sich aber

nur durch Unterdrückung dieses Geistes der Einzelnheit erhalten, und,

weil er wesentliches Moment ist, erzeugt es ihn zwar ebenso, und zwar

durch die unterdrückende Haltung gegen denselben als ein feindseliges

Prinzip. Dieses würde jedoch, da es vom allgemeinen Zwecke sich

trennend, nur böse und in sich nichtig ist, nichts vermögen, wenn nicht

das Gemeinwesen selbst die Kraft der Jugend, die Männlichkeit, welche

nicht reif noch innerhalb der Einzelnheit steht, als die Kraft des

Ganzen anerkannte. Denn es ist ein Volk, es ist selbst Individualität

und wesentlich nur so für sich, daß andere Individualitäten für es

sind, daß es sie von sich ausschließt und sich unabhängig von ihnen

weiß. Die negative Seite des Gemeinwesens, nach innen die Vereinzelung

der Individuen unterdrückend, nach außen aber selbsttätig, hat an der

Individualität seine Waffen. Der Krieg ist der Geist und die Form,

worin das wesentliche Moment der sittlichen Substanz, die absolute

Freiheit des sittlichen Selbstwesens von allem Dasein, in ihrer

Wirklichkeit und Bewährung vorhanden ist. Indem er einerseits den

einzelnen Systemen des Eigentums und der persönlichen Selbstständigkeit

wie auch der einzelnen Persönlichkeit selbst die Kraft des Negativen zu

fühlen gibt, erhebt andererseits in ihm eben dies negative Wesen sich

als das Erhaltende des Ganzen; der tapfre Jüngling, an welchem die

Weiblichkeit ihre Lust hat, das unterdrückte Prinzip des Verderbens

tritt an den Tag und ist das Geltende. Nun ist es die natürliche Kraft

und das, was als Zufall des Glücks erscheint, welche über das Dasein

des sittlichen Wesens und die geistige Notwendigkeit entscheiden; weil

auf Stärke und Glück das Dasein des sittlichen Wesens beruht, so ist

schon entschieden, daß es zugrunde gegangen. -- Wie vorhin nur Penaten

im Volksgeiste, so gehen die lebendigen Volksgeister durch ihre

Individualität itzt in einem allgemeinen Gemeinwesen zugrunde, dessen

einfache Allgemeinheit geistlos und tot, und dessen Lebendigkeit das

einzelne Individuum, als einzelnes ist. Die sittliche Gestalt des

Geistes ist verschwunden, und es tritt eine andere an ihre Stelle. |

しかし、共同体は、この個人主義の精神を抑圧することによってのみ存続

することができる。そして、この精神は本質的な要素であるため、共同体は、それを敵対的な原理として抑圧する姿勢を通じて、この精神を同様に生み出してい

る。しかし、これは、一般的な目的から分離しているため、悪であり、それ自体では無意味であり、共同体自体が、まだ成熟しておらず、個人の中に留まってい

る若さの力、男らしさを、全体としての力として認めなければ、何の効果も持たない。なぜなら、共同体とは、それ自体が個性であり、他の個性がそのために存

在し、それらを排除し、それらから独立していると認識している、そのようにしてのみ本質的に存在するものだからだ。共同体の否定的な側面は、内部では個人

の孤立を抑圧し、外部に対しては自発的に作用し、その武器は個性にある。戦争は、道徳的実体の本質的な要素、すなわち、あらゆる現存在から解放された道徳

的自己の存在の絶対的自由が、その現実性と実証において存在する精神と形態である。一方では、個々の財産制度や個人の自立、そして個々の人格そのものに否

定的な力を感じさせる一方で、他方では、まさにこの否定的な本質が、全体を維持する力として立ち上がる。女性たちが欲望の対象とする勇敢な青年は、抑圧さ

れた腐敗の原理を露わにし、支配的な存在となる。さて、道徳的存在の現存在と精神的な必然性を決定するのは、自然の力と、偶然の幸運のように見えるものな

のだ。道徳的存在の現存在は力と幸運に依存しているため、その滅亡はすでに決定している。--

以前、民衆の精神の中にペナテスだけが存在していたように、今や、民衆の生き生きとした精神は、その個性によって、単純で無精神で死んだ一般的な共同体の

中で滅びていく。その共同体の活気は、個々の個人、つまり個々にあるものにある。精神の道徳的な形は消滅し、別の形がそれに取って代わる。 |

| Dieser Untergang der sittlichen

Substanz und ihr Übergang in eine andere Gestalt ist also dadurch

bestimmt, daß das sittliche Bewußtsein auf das Gesetz wesentlich

unmittelbar gerichtet ist; in dieser Bestimmung der Unmittelbarkeit

liegt, daß in die Handlung der Sittlichkeit die Natur überhaupt

hereinkommt. Ihre Wirklichkeit offenbart nur den Widerspruch und den

Keim des Verderbens, den die schöne Einmütigkeit und das ruhige

Gleichgewicht des sittlichen Geistes eben an dieser Ruhe und Schönheit

selbst hat; denn die Unmittelbarkeit hat die widersprechende Bedeutung,

die bewußtlose Ruhe der Natur, und die selbstbewußte unruhige Ruhe des

Geistes zu sein. -- Um dieser Natürlichkeit willen ist überhaupt dieses

sittliche Volk eine durch die Natur bestimmte und daher beschränkte

Individualität, und findet also ihre Aufhebung an einer andern. Indem

aber diese Bestimmtheit, die im Dasein gesetzt, Beschränkung, aber

ebenso das Negative überhaupt und das Selbst der Individualität ist,

verschwindet, ist das Leben des Geistes und diese in Allen ihrer

selbstbewußte Substanz verloren. Sie tritt als eine formelle

Allgemeinheit an ihnen heraus, ist ihnen nicht mehr als lebendiger

Geist inwohnend, sondern die einfache Gediegenheit ihrer Individualität

ist in viele Punkte zersprungen. |

道徳的実体の崩壊と、それが別の形へと移行することは、道徳的意識が本

質的に法律に直接向けられていることによって決定される。この直接性の決定には、道徳的行為に自然がまったく介入するという事実がある。その現実性は、道

徳的精神の美しい一致と穏やかな均衡が、まさにその静けさと美しさそのものに持つ矛盾と腐敗の芽を明らかにするだけだ。なぜなら、直接性は、自然の無意識

の静けさと、精神の自己意識的な不安定な静けさという、相反する意味を持っているからだ。この自然性のために、この道徳的な民族は、自然によって決定さ

れ、したがって制限された個別性であり、したがって、他の個別性においてその止揚を見出す。しかし、現存在に置かれたこの決定性は、制限であると同時に、

否定そのものであり、個別性の自己でもあるため、それが消滅すると、精神の生命と、その自己意識的な実体はすべて失われる。それは、彼らの中に形式的な普

遍性として現れ、もはや彼らの中に生きた精神として内在するものではなく、彼らの個性の単純な純粋さは多くの点に分裂してしまう。 |

| https://www.waste.org/~roadrunner/Hegel/PhenSpirit/464_BIL.html |

ヘーゲルによるアンティゴネーの議論は、『精神現象 学』の他に、『美学』詩、『法哲学』家族、においてみられるという。ヘーゲルの時代に、その盟友ヘルダーリンは、『アンティゴネ』の新訳を完成させる。

●クレオンの呪詛

「私が彼女(アンティゴネ)を生かしておけば、私は もはや男ではなく、彼女のほうが男だ」

クレオンの本音は、女性的なものが、侵食していき、

社会が危険なものになる。

●アンティゴネーに対するさまざまな解釈

・女(アンティゴネ)が、クレオンの原理(=私情を 交えず法に厳密にしたがうべし)に従わねば、女は死や暴力にさらされる。

・クレオンのアンティゴネに対する立場が、微妙にぶ れるので、人間の自然な情念を「否定」して、社会秩序は構築されることを示唆している。

・国法の原理は、私情のあり方を理解できないが、同 時に、自然や自然法に対して「つねに負債を担う」ことをこのシステムは示唆している。

・法の執行による正義の実現と、私情や慣習による服

喪がもつ倫理的情感とは、まったく別の原理である。

●まとめ

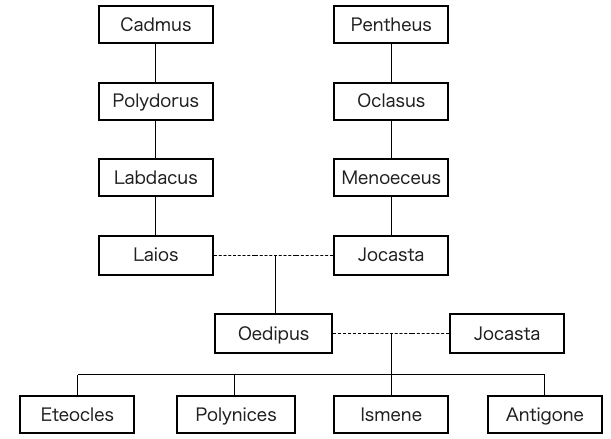

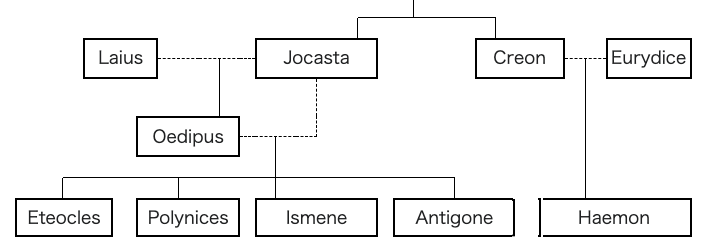

・エテオクレス、ポリュネイケス、アンティゴネは、 イオカステを母に、オイディプスを父にもつ兄弟たちである。

・イオカステの兄弟、すなわちアンティゴネたちの叔 父で、現在のテバイの王であるクレオンは、刺し違えた兄弟の兄のエテオクレスの死を賞賛するが、(叛逆の科を認定された)ポリュネイケスの埋葬は禁止し た。クレオンは「人間による命令」で埋葬を禁止する。

・アンティゴネは人間の「決められた正義」=慣行 の・普遍的で神的な理由(=ノモス)を尊重すべきだと主張した。

・クレオンは怒り、アンティゴネを岩窟に閉じ込めて 生き埋めにせよと命令がくだった時に、クレオンは自分で縊死する。

・スタシスとは、ポリスを内側から崩壊させる反乱の 原理である。ポレモスはポリスの栄光を高める外部戦争である。彼女の縊死は、ポリスからスタシスの毒を吸い出したとも言われる。

★アンティゴネー入門——演劇の構造

| Antigone

(/ænˈtɪɡəni/ ann-TIG-ə-nee; Ancient Greek: Ἀντιγόνη) is an Athenian

tragedy written by Sophocles in (or before) 441 BC and first performed

at the Festival of Dionysus of the same year. It is thought to be the

second oldest surviving play of Sophocles, preceded by Ajax, which was

written around the same period. The play is one of a triad of tragedies

known as the three Theban plays, following Oedipus Rex and Oedipus at

Colonus. Even though the events in Antigone occur last in the order of

events depicted in the plays, Sophocles wrote Antigone first.[1] The

story expands on the Theban legend that predates it, and it picks up

where Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes ends. The play is named after the

main protagonist Antigone. |

アンティゴネー』(/ænˈtəni/

ann-TIGA-ə-nee; Ancient Greek:

Ἀντιγόνη)は、紀元前441年(またはそれ以前)にソフォクレスによって書かれたアテナイの悲劇で、同年のディオニュソス祭で初演された。現存す

るソフォクレスの戯曲としては、同時期に書かれた『エイジャックス』に次いで2番目に古いものと考えられている。オイディプス王』と『コロノスのオイディ

プス』に続く、テーバン三部作と呼ばれる悲劇のひとつである。アンティゴネー』で描かれる出来事は、戯曲の中で描かれる出来事の順序としては最後に起こる

にもかかわらず、ソフォクレスは『アンティゴネー』を最初に書いた[1]。この物語は、それ以前のテーバンの伝説を発展させたもので、アイスキュロスの

『テーベに対する七人』が終わったところから始まる。戯曲名は主人公アンティゴネーにちなむ。 |

| After Oedipus' self-exile, his

sons Eteocles and Polynices engaged in a civil war for the Theban

throne, which resulted in both brothers dying fighting each other.

Oedipus' brother-in-law and new Theban ruler Creon ordered the public

honoring of Eteocles and the public shaming of Thebes' traitor

Polynices. The story follows the attempts of Antigone, the sister of

Eteocles and Polynices, to bury Polynices, going against the decision

of her uncle Creon and placing her relationship with her brother above

human laws. |

オイディプスが自害した後、息子のエテオクレスとポリュニケスはテーベ

王位をめぐって内戦を繰り広げ、その結果、兄弟は互いに争って死んでしまう。オイ

ディプスの義兄でテーベンの新支配者クレオンは、エテオクレスを讃え、テーベの裏切り者ポリニスを辱めるよう命じた。物語は、エテオクレスとポリュニクス

の妹であるアンティゴネが、叔父クレオンの決定に反し、兄との関係を人間の掟よりも優先してポリュニクスを葬ろうとする姿を描く。 |

| Prior to the beginning of the

play, the brothers Eteocles and Polynices, leading opposite sides in

Thebes' civil war, died fighting each other for the throne. Creon, the

new ruler of Thebes and brother of the former Queen Jocasta, has

decided that Eteocles will be honored and Polynices will be in public

shame. The rebel brother's body will not be sanctified by holy rites

and will lie unburied on the battlefield, prey for carrion animals,[a]

the harshest punishment at the time. Antigone and Ismene are the

sisters of the dead Polynices and Eteocles. |

戯曲が始まる前、テーベの内戦で敵味方を率いたエテオクレスとポリニス

の兄弟は、王位をめぐって互いに争って死んだ。テーベの新しい統治者であり、前王妃ジョカスタの弟であるクレオンは、エテオクレスは讃えられ、ポリュニケ

スは公の恥となることを決定した。反乱を起こした弟の遺体は聖なる儀式によって聖別されることなく、戦場に埋葬されないまま横たわり、当時最も過酷な罰で

あった[a]腐肉動物の餌食となる。アンティゴネとイスメネは死んだポリニスとエテオクレスの姉妹である。 |

| In the opening of the play,

Antigone brings Ismene outside the palace gates late at night for a

secret meeting: Antigone wants to bury Polynices' body, in defiance of

Creon's edict. Ismene refuses to help her, not believing that it will

actually be possible to bury their brother, who is under guard, but she

is unable to stop Antigone from going to bury her brother herself. |

戯曲の冒頭で、アンティゴネはイスメネを夜遅くに宮殿の門の外に連れ出

し、密会をする:

アンティゴネは、クレオンの勅令に背いてポリニスの遺体を埋葬しようとしていた。クレオンの勅令を無視してポリニスの遺体を埋葬しようとするアンティゴネ

を止めることはできなかった。 |

| The Chorus, consisting of Theban

elders, enter and cast the background story of the Seven against Thebes

into a mythic and heroic context. Creon enters, and seeks the support of the Chorus in the days to come and in particular, wants them to back his edict regarding the disposal of Polynices' body. The leader of the Chorus pledges his support out of deference to Creon. A sentry enters, fearfully reporting that the body has been given funeral rites and a symbolic burial with a thin covering of earth, though no one saw who actually committed the crime. Creon, furious, orders the sentry to find the culprit or face death himself. The sentry leaves. |

テーベの長老たちで構成される合唱団が登場し、テーベに対抗する七人という背景の物語を神話的で英雄的な文脈に落とし込む。 クレオンは合唱団の支持を求め、特にポリュニセスの遺体処理に関する勅令を支持するよう求める。合唱団のリーダーはクレオンに敬意を表し、支持を約束す る。歩哨が入ってきて、遺体は葬儀の儀式を受け、薄い土で覆われた象徴的な埋葬をされたが、実際に誰が罪を犯したのかは誰も見ていないと恐る恐る報告す る。クレオンは激怒し、衛兵に犯人を見つけなければ自分が死ぬと命じる。歩哨は立ち去る。 |

| The Chorus sing of the ingenuity of human beings; but add that they do not wish to live in the same city as law-breakers. The sentry returns, bringing Antigone with him. The sentry explains that the watchmen uncovered Polynices' body and then caught Antigone as she did the funeral rituals. Creon questions her after sending the sentry away, and she does not deny what she has done. She argues unflinchingly with Creon about the immorality of the edict and the morality of her actions. Creon becomes furious, and seeing Ismene upset, thinks she must have known of Antigone's plan. He summons her. Ismene tries to confess falsely to the crime, wishing to die alongside her sister, but Antigone will not have it. Creon orders that the two women be imprisoned. |

合唱団は人間の巧妙さを歌うが、法を犯す者と同じ街には住みたくないと付け加える。 見張りがアンティゴネを連れて戻ってくる。見張りがポリニスの遺体を発見し、葬儀を執り行うアンティゴネを捕らえたと説明する。クレオンは見張りを追い 払った後、アンティゴネを問い詰めるが、アンティゴネは自分のしたことを否定しない。彼女はクレオンに、勅令の不道徳さと自分の行為の道徳性について堂々 と反論する。クレオンは激怒し、動揺するイスメネを見て、彼女がアンティゴネの計画を知っていたに違いないと考える。彼女を呼び出す。イスメネは姉と一緒 に死にたいと罪を偽り告白しようとするが、アンティゴネはそれを許さなかった。クレオンは二人を投獄するよう命じる。 |

| The Chorus sing of the troubles of the house of Oedipus. Haemon, Creon's son, enters to pledge allegiance to his father, even though he is engaged to Antigone. He initially seems willing to forsake Antigone, but when he gently tries to persuade his father to spare Antigone, claiming that "under cover of darkness the city mourns for the girl", the discussion deteriorates, and the two men are soon bitterly insulting each other. When Creon threatens to execute Antigone in front of his son, Haemon leaves, vowing never to see Creon again. |

合唱団はオイディプス家の災難を歌う。 クレオンの息子ヘーモンが、アンティゴネと婚約しているにもかかわらず、父に忠誠を誓うために入ってくる。当初はアンティゴネを見捨てる気でいるようだっ たが、「闇に紛れて都は少女を悼む」と主張してアンティゴネを助けるよう父を優しく説得しようとすると、話し合いは悪化し、二人はすぐに激しく侮辱し合 う。クレオンが息子の前でアンティゴネを処刑すると脅すと、ヘーモンはクレオンに二度と会わないと誓って立ち去る。 |

| The Chorus sing of the power of love. Antigone is brought in under guard on her way to execution. She sings a lament. The Chorus compares her to the goddess Niobe, who was turned into a rock, and say it is a wonderful thing to be compared to a goddess. Antigone accuses them of mocking her. |

コーラスが愛の力を歌う。 アンティゴネーは処刑される途中、警護のもとに連行される。彼女は嘆きを歌う。合唱団は彼女を岩に変えられた女神ニオベにたとえ、女神にたとえられるのは素晴らしいことだと言う。アンティゴネーは自分を馬鹿にしていると非難する。 |

| Creon decides to spare Ismene

and to bury Antigone alive in a cave. By not killing her directly, he

hopes to pay minimal respects to the gods. She is brought out of the

house, and this time, she is sorrowful instead of defiant. She

expresses her regrets at not having married and dying for following the

laws of the gods. She is taken away to her living tomb. |

クレオンはイスメネを惜しみ、アンティゴネーを洞窟に生き埋めにするこ

とを決める。彼女を直接殺さないことで、神々に最低限の敬意を払おうと考えたのだ。家から連れ出されたアンティゴネは、今度は反抗的ではなく悲しげな表情

を浮かべる。彼女は、神々の掟に従ったために結婚せず死んでしまったことへの後悔を口にする。彼女は生きている墓に連れて行かれる。 |

| The Chorus encourage Antigone by singing of the great women of myth who suffered. Tiresias, the blind prophet, enters. Tiresias warns Creon that Polynices should now be urgently buried because the gods are displeased, refusing to accept any sacrifices or prayers from Thebes. However, Creon accuses Tiresias of being corrupt. Tiresias responds that Creon will lose "a son of [his] own loins"[3] for the crimes of leaving Polynices unburied and putting Antigone into the earth (he does not say that Antigone should not be condemned to death, only that it is improper to keep a living body underneath the earth). Tiresias also prophesies that all of Greece will despise Creon and that the sacrificial offerings of Thebes will not be accepted by the gods. The leader of the Chorus, terrified, asks Creon to take Tiresias' advice to free Antigone and bury Polynices. Creon assents, leaving with a retinue of men. |

合唱団は苦悩した神話の偉大な女性たちを歌い、アンティゴネーを励ます。 盲目の預言者ティレシアスが入ってくる。ティレシアスはクレオンに、ポリュネイケスを早急に葬るべきだと警告する。神々は不興を買い、テーベからの生贄や 祈りを拒んだからだ。しかしクレオンは、ティレシアスが堕落していると非難する。ティレシアスは、ポリュネイケスを埋葬せずに放置し、アンティゴネーを土 に埋めた罪で、クレオンは「自分の子」[3]を失うだろうと答える(彼はアンティゴネーを死刑にするべきではないと言っているのではなく、生きている遺体 を土の下に埋めておくのは不適切だと言っているだけである)。ティレジアスはまた、ギリシア全土がクレオンを軽蔑し、テーベの生贄は神々に受け入れられな いだろうと予言する。恐怖におののいた合唱団の団長は、アンティゴネーを解放しポリュケネイスを葬るよう、ティレシアスの忠告を聞くようクレオンに頼む。 クレオンはそれを承諾し、従者を連れてその場を去る。 |

| The Chorus deliver an oral ode to the god Dionysus. A messenger enters to tell the leader of the Chorus that Haemon has killed himself. Eurydice, Creon's wife and Haemon's mother, enters and asks the messenger to tell her everything. The messenger reports that Creon saw to the burial of Polynices. When Creon arrived at Antigone's cave, he found Haemon lamenting over Antigone, who had hanged herself. Haemon unsuccessfully attempted to stab Creon, then stabbed himself. Having listened to the messenger's account, Eurydice silently disappears into the palace. |

合唱団がディオニュソス神への頌歌を口上する。 合唱団の団長に、ヘーモンが自殺したことを伝える使者が入ってくる。クレオンの妻でハエモンの母であるエウリュディケが入ってきて、使者にすべてを話すよ うに頼む。使者は、クレオンがポリュネイケスの埋葬を見届けたことを報告する。クレオンがアンティゴネーの洞窟に着くと、首を吊ったアンティゴネーを嘆く ハエモンがいた。ヘーモンはクレオンを刺そうとしたが失敗し、自らも刺した。使者の話を聞いたエウリュディケは、静かに宮殿へと消えていく。 |

| Creon enters, carrying Haemon's

body. He understands that his own actions have caused these events and

blames himself. A second messenger arrives to tell Creon and the Chorus

that Eurydice has also killed herself. With her last breath, she cursed

her husband for the deaths of her sons, Haemon and Megareus. Creon

blames himself for everything that has happened, and, a broken man, he

asks his servants to help him inside. The order he valued so much has

been protected, and he is still the king, but he has acted against the

gods and lost his children and his wife as a result. After Creon

condemns himself, the leader of the Chorus closes by saying that

although the gods punish the proud, punishment brings wisdom. |

クレオンがヘーモンの遺体を抱えて入ってくる。彼は自分の行いがこのよ

うな事態を引き起こしたことを理解し、自分を責める。二人目の使者がクレオンと合唱団に、エウリディーチェも自殺したことを告げにやってくる。彼女は息を

引き取る際、息子であるハエモンとメガレウスの死について夫を呪った。クレオンは、起こったことのすべてを自分のせいだと責め、打ちひしがれた彼は、使用

人たちに自分の家の手伝いを頼む。彼が大切にしていた秩序は守られ、王であることに変わりはないが、神々に背く行為をした結果、子供たちと妻を失ったの

だ。クレオンが自責の念に駆られた後、合唱団のリーダーは、神々は高慢な者を罰するが、罰は知恵をもたらす、と締めくくる。 |

| Characters Antigone, compared with her beautiful and docile sister, is portrayed as a heroine who recognizes her familial duty. Her dialogues with Ismene reveal her to be as stubborn as her uncle.[4] In her, the ideal of the female character is boldly outlined.[5] She defies Creon's decree despite the consequences she may face, in order to honor her deceased brother. Ismene serves as a foil for Antigone, presenting the contrast in their respective responses to the royal decree.[4] Considered the beautiful one, she is more lawful and obedient to authority. She hesitates to bury Polynices because she fears Creon. Creon is the current King of Thebes, who views law as the guarantor of personal happiness. He can also be seen as a tragic hero, losing everything for upholding what he believes is right. Even when he is forced to amend his decree to please the gods, he first tends to the dead Polynices before releasing Antigone.[4] Eurydice of Thebes is the Queen of Thebes and Creon's wife. She appears towards the end and only to hear confirmation of her son Haemon's death. In her grief, she dies by suicide, cursing Creon, whom she blames for her son's death. Haemon is the son of Creon and Eurydice, betrothed to Antigone. Proved to be more reasonable than Creon, he attempts to reason with his father for the sake of Antigone. However, when Creon refuses to listen to him, Haemon leaves angrily and shouts he will never see him again. He dies by suicide after finding Antigone dead. Koryphaios is the assistant to the King (Creon) and the leader of the Chorus. He is often interpreted as a close advisor to the King, and therefore a close family friend. This role is highlighted in the end when Creon chooses to listen to Koryphaios' advice. Tiresias is the blind prophet whose prediction brings about the eventual proper burial of Polynices. Portrayed as wise and full of reason, Tiresias attempts to warn Creon of his foolishness and tells him the gods are angry. He manages to convince Creon, but is too late to save the impetuous Antigone. The Chorus, a group of elderly Theban men, is at first deferential to the king.[5] Their purpose is to comment on the action in the play and add to the suspense and emotions, as well as connecting the story to myths. As the play progresses they counsel Creon to be more moderate. Their pleading persuades Creon to spare Ismene. They also advise Creon to take Tiresias's advice. |

登場人物 アンティゴネーは、美しく従順な姉に比べ、家族の義務を自覚するヒロインとして描かれている。イスメネとの対話は、彼女が叔父のように頑固であることを明 らかにしている[4]。彼女の中には、女性の理想像が大胆に描かれている[5]。彼女は、亡くなった兄を敬うために、自分が直面するかもしれない結果にも かかわらず、クレオンの命令に逆らう。 イスメネはアンティゴネーの箔の役割を果たし、勅令に対するそれぞれの反応の対照を示す[4]。彼女がポリュネイケスを葬るのをためらうのは、クレオンを恐れているからである。 クレオンはテーベの現王であり、法を人格の幸福を保証するものと考えている。彼はまた、自分が正しいと信じることを守るためにすべてを失う、悲劇のヒー ローともいえる。神々を喜ばせるために命令を修正せざるを得なくなったときでさえ、彼はアンティゴネーを解放する前に、まず死んだポリュネイケスの看病を する[4]。 テーベのエウリュディケはテーベの女王であり、クレオンの妻である。テーベの王妃でクレオンの妻である。悲しみのあまり、息子の死を責めたクレオンを呪いながら自殺する。 ヘーモンはクレオンとエウリュディケの息子で、アンティゴネーと婚約していた。クレオンよりも理性的であることが証明され、アンティゴネーのために父親を 説得しようとする。しかしクレオンに拒絶されると、ヘーモンは怒って立ち去り、二度と会わないと叫ぶ。彼はアンティゴネーの死体を見つけて自殺する。 コリファイオスは王(クレオン)の補佐役であり、コーラスのリーダーでもある。彼はしばしば王の側近であり、従って家族の親友であると解釈される。この役割は、クレオンがコリファイオスの助言に耳を傾けることを選択するラストで強調される。 ティレシアスは盲目の予言者で、その予言によって最終的にポリュネイケスがきちんと埋葬されることになる。賢くて理性に満ちた人物として描かれるティレシ アスは、クレオンに自分の愚かさを警告し、神々が怒っていることを告げる。彼はなんとかクレオンを説得するが、気の早いアンティゴネーを救うには遅すぎ た。 テーバンの老人たちからなる合唱団は、最初は王に従順である[5]。彼らの目的は、劇中の行動にコメントし、サスペンスと感情を盛り上げ、物語を神話に結 びつけることである。劇が進むにつれて、彼らはクレオンにもっと節度を持つよう助言する。彼らの懇願により、クレオンはイスメネを助けるよう説得される。 彼らはまた、ティレシアスの忠告を聞くようクレオンに助言する。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antigone_(Sophocles_play) |

★アンティゴネーの解析、これまでの識者の講釈、原作の翻訳や翻案など

| Historical context Antigone was written at a time of national fervor. In 441 BCE, shortly after the play was performed, Sophocles was appointed as one of the ten generals to lead a military expedition against Samos. It is striking that a prominent play in a time of such imperialism contains little political propaganda, no impassioned apostrophe, and—with the exception of the epiklerate (the right of the daughter to continue her dead father's lineage)[6] and arguments against anarchy—makes no contemporary allusion or passing reference to Athens.[7] Rather than become sidetracked with the issues of the time, Antigone remains focused on the characters and themes within the play. It does, however, expose the dangers of the absolute ruler, or tyrant, in the person of Creon, a king to whom few will speak freely and openly their true opinions, and who therefore makes the grievous error of condemning Antigone, an act that he pitifully regrets in the play's final lines. Athenians, proud of their democratic tradition, would have identified his error in the many lines of dialogue which emphasize that the people of Thebes believe he is wrong, but have no voice to tell him so. Athenians would identify the folly of tyranny. |

歴史的背景 アンティゴネーは、国民が熱狂していた時代に書かれた。この戯曲が上演された直後の前441年、ソフォクレスはサモスに対する軍事遠征を指揮する10人の 将軍のひとりに任命された。このような帝国主義の時代の著名な戯曲が、政治的プロパガンダをほとんど含まず、熱烈なアポストロフィーもなく、エピクラーテ (死んだ父の血統を継ぐ娘の権利)[6]と無政府主義に反対する主張を除いては、アテネに関する現代的な言及や通り一遍の言及もないのは驚くべきことであ る[7]。しかし、絶対的な支配者、すなわち暴君の危険性を、クレオンという人格の中で暴いている。クレオンは、自分の本当の意見を自由かつ率直に語ろう としない王であり、それゆえにアンティゴネーを断罪するという重大な過ちを犯す。民主主義の伝統を誇るアテネ人なら、テーベの人々は彼が間違っていると信 じているが、それを彼に伝える声がないことを強調する台詞の数々から、彼の誤りを見抜いただろう。アテネ人なら、専制政治の愚かさを見抜くだろう。 |

| Notable features The Chorus in Antigone departs significantly from the chorus in Aeschylus' Seven Against Thebes, the play of which Antigone is a continuation. The chorus in Seven Against Thebes is largely supportive of Antigone's decision to bury her brother. Here, the chorus is composed of old men who are largely unwilling to see civil disobedience in a positive light. The chorus also represents a typical difference in Sophocles' plays from those of both Aeschylus and Euripides. A chorus of Aeschylus' almost always continues or intensifies the moral nature of the play, while one of Euripides' frequently strays far from the main moral theme. The chorus in Antigone lies somewhere in between; it remains within the general moral in the immediate scene, but allows itself to be carried away from the occasion or the initial reason for speaking.[8] |

注目すべき特徴 『アンティゴネー』の合唱は、『アンティゴネー』の続編であるアイスキュロスの『テーベに対する七人』の合唱とは大きく異なっている。アンティゴネー』の 合唱は、兄を埋葬するというアンティゴネーの決断を支持している。ここで合唱団は、市民的不服従を肯定的にとらえようとしない老人たちで構成されている。 合唱はまた、ソフォクレスの戯曲における、アイスキュロスやエウリピデスの戯曲との典型的な相違を表している。エスキロスの合唱は、ほとんど常に劇の道徳 的性格を継続させるか強めるが、エウリピデスの合唱は、しばしば主要な道徳的テーマから大きく逸脱する。アンティゴネー』の合唱はその中間に位置し、直前 の場面では一般的な道徳の範囲内にとどまるが、その場あるいは最初に話した理由からは外れてしまうのである[8]。 |

| Significance and interpretation Once Creon has discovered that Antigone buried her brother against his orders, the ensuing discussion of her fate is devoid of arguments for mercy because of youth or sisterly love from the Chorus, Haemon or Antigone herself. Most of the arguments to save her center on a debate over which course adheres best to strict justice.[9][10] |

意義と解釈 アンティゴネーが自分の命令に反して兄を埋葬したことをクレオンが発見した後、彼女の運命について続く議論には、コーラス、ヘーモン、アンティゴネー自身から、若さや姉妹愛ゆえの慈悲を求める議論は出てこない。彼女を救おうとする議論のほとんどは、厳格な正義に最も忠実なのはどの道かという議論が中心となっている[9][10]。 |

| Both

Antigone and Creon claim divine sanction for their actions; but

Tiresias the prophet supports Antigone's claim that the gods demand

Polynices' burial. It is not until the interview with Tiresias that

Creon transgresses and is guilty of sin. He had no divine intimation

that his edict would be displeasing to the Gods and against their will.

He is here warned that it is, but he defends it and insults the prophet

of the Gods. This is his sin, and it is this that leads to his

punishment. The terrible calamities that overtake Creon are not the

result of his exalting the law of the state over the unwritten and

divine law that Antigone vindicates, but are his intemperance that led

him to disregard the warnings of Tiresias until it was too late. This

is emphasized by the Chorus in the lines that conclude the play.[11] |

アンティゴネーもクレオンも、自分たちの行動に神の許しが

あると主張するが、預言者ティレシアスは、神がポリュネイケスの埋葬を要求しているというアンティゴネーの主張を支持する。クレオンが罪を犯すのは、ティ

レジアスとの面談のときである。彼は、自分の勅令が神々の不興を買い、神々の意思に反するものであるという神のお告げを受けていなかった。しかし、彼はそ

れを擁護し、神々の預言者を侮辱した。これが彼の罪であり、これが彼の罰につながるのである。クレオンを襲う恐ろしい災難は、アンティゴネーが擁護する不

文律や神の掟よりも国家の掟を尊んだ結果ではなく、手遅れになるまでティレシアスの警告を無視した彼の不摂生が招いたものである。このことは、劇を締めく

くる台詞でコーラスによって強調されている[11]。 |

| The

German poet Friedrich Hölderlin, whose translation had a strong impact

on the philosopher Martin Heidegger, brings out a more subtle reading

of the play: he focuses on Antigone's legal and political status within

the palace, her privilege to be the heiress (according to the legal

instrument of the epiklerate) and thus protected by Zeus. According to

the legal practice of classical Athens, Creon is obliged to marry his

closest relative (Haemon) to the late king's daughter in an inverted

marriage rite, which would oblige Haemon to produce a son and heir for

his dead father in law. Creon would be deprived of grandchildren and

heirs to his lineage – a fact that provides a strong realistic motive

for his hatred against Antigone. This modern perspective has remained

submerged for a long time.[12] |

ド

イツの詩人フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリンは、その翻訳が哲学者マルティン・ハイデガーに強い影響を与えたが、この戯曲をより微妙に読み解く。彼は、アンティ

ゴネーの王宮内での法的・政治的地位、(エピクラーテという法的手段による)相続人としての特権、したがってゼウスによって保護されていることに焦点を当

てる。古典アテネの法律慣習によれば、クレオンは最も近親の者(ヘーモン)と亡き王の娘との逆結婚の儀式を義務づけられ、ヘーモンは死んだ義父のために息

子と跡継ぎを生むことを義務づけられる。クレオンは孫や世継ぎを奪われることになる。この事実は、アンティゴネーに対する憎しみの強い現実的な動機とな

る。この現代的な視点は、長い間没却されたままであった[12]。 |

| Heidegger, in his essay, The Ode on Man in Sophocles' Antigone, focuses on the chorus' sequence of strophe and antistrophe that begins on line 278. His interpretation is in three phases: first to consider the essential meaning of the verse, and then to move through the sequence with that understanding, and finally to discern what was nature of humankind that Sophocles was expressing in this poem. In the first two lines of the first strophe, in the translation Heidegger used, the chorus says that there are many strange things on earth, but there is nothing stranger than man. Beginnings are important to Heidegger, and he considered those two lines to describe the primary trait of the essence of humanity within which all other aspects must find their essence. Those two lines are so fundamental that the rest of the verse is spent catching up with them. The authentic Greek definition of humankind is the one who is strangest of all. Heidegger's interpretation of the text describes humankind in one word that captures the extremes — deinotaton. Man is deinon in the sense that he is the terrible, violent one, and also in the sense that he uses violence against the overpowering. Man is twice deinon. In a series of lectures in 1942, Hölderlin's Hymn, The Ister, Heidegger goes further in interpreting this play, and considers that Antigone takes on the destiny she has been given, but does not follow a path that is opposed to that of the humankind described in the choral ode. When Antigone opposes Creon, her suffering the uncanny is her supreme action.[13][14] | ハ

イデガーは小論『ソフォクレスのアンティゴネーにおける人間頌歌』の中で、278行目から始まる合唱のストロープとアンチスロープの連続に注目している。

彼の解釈は三段階に分かれている。まず、この詩の本質的な意味を考察し、次にその理解に基づいて一連の流れを進め、最後にソフォクレスがこの詩で表現した

人間の本質とは何かを見極める。ハイデガーが用いた訳では、最初のストロープの最初の2行で、合唱は「地上には奇妙なものがたくさんあるが、人間ほど奇妙

なものはない」と言っている。ハイデガーにとって始まりは重要であり、彼はこの2行が人間の本質の主要な特徴を表していると考えた。この2行は非常に基本

的なものであるため、詩の残りの部分はこの2行に追いつくことに費やされている。本場ギリシアにおける人間の定義は、「最も奇妙な者」である。ハイデガー

の解釈では、その両極端を捉える一つの言葉、デイノタトンで人類を表現している。人間は、恐ろしい、暴力的な者であるという意味でデイノタトンであり、ま

た、圧倒的なものに対して暴力を行使するという意味でもデイノタトンである。人間は二度、デイノタトンなのである。ハイデガーは1942年の連続講義『ヘ

ルダーリンの讃歌』において、この戯曲の解釈をさらに進め、アンティゴネーは与えられた運命を引き受けるが、合唱の頌歌に描かれた人類の運命と対立する道

を歩むことはないと考察している。アンティゴネーがクレオンに対抗するとき、不気味な苦悩は彼女の至高の行動である[13][14]。 |

| The problem of the second burial An important issue still debated regarding Sophocles' Antigone is the problem of the second burial. When she poured dust over her brother's body, Antigone completed the burial rituals and thus fulfilled her duty to him. Having been properly buried, Polynices' soul could proceed to the underworld whether or not the dust was removed from his body. However, Antigone went back after his body was uncovered and performed the ritual again, an act that seems to be completely unmotivated by anything other than a plot necessity so that she could be caught in the act of disobedience, leaving no doubt of her guilt. More than one commentator has suggested that it was the gods, not Antigone, who performed the first burial, citing both the guard's description of the scene and the chorus's observation.[15] It's possible, however, that Antigone not only wants her brother to have burial rites, but that she wants his body to stay buried. The guard states that after they found that someone covered Polynices' body with dirt, the birds and animals left the body alone (lines 257–258). But when the guards removed the dirt, then the birds and animals returned, and Tiresias emphasizes that birds and dogs have defiled the city's altars and hearths with the rotting flesh from Polynices' body; as a result of which the gods will no longer accept the peoples' sacrifices and prayers (lines 1015–1020). It's possible, therefore, that after the guards remove the dirt protecting the body, Antigone buries him again to prevent the offense to the gods.[16] Even though Antigone has already performed the burial rite for Polynices, Creon, on the advice of Tiresias (lines 1023–1030), makes a complete and permanent burial for his body. |

二度目の埋葬の問題 ソフォクレスの『アンティゴネー』に関していまだに議論されている重要 な問題は、二度目の埋葬の問題である。兄の遺体に塵をかけたとき、アンティゴネーは埋葬の儀礼を完了し、兄に対する義務を果たした。適切に埋葬されたポ リュネイケスの魂は、遺体から塵が取り除かれようが取り除かれまいが、冥界へと進むことができた。しかしアンティゴネーは、彼の死体が暴かれた後に戻って 再び儀礼を行った。この行為は、彼女が自分の罪を疑うことなく、不従順の行為で捕らえられるという筋書きの必要性以外には、まったく動機がないように思わ れる。しかし、アンティゴネーは弟に埋葬の儀式を受けさせたいだけでなく、弟の遺体を埋葬したままにしておきたいのかもしれない。衛兵は、誰かがポリュネ イケスの遺体を土で覆ったのを発見した後、鳥や動物は遺体を放っておいたと述べている(257-258行)。ティレシアスは、鳥や犬がポリュネイセスの遺 体の腐った肉で街の祭壇や囲炉裏を汚し、その結果、神々はもはや人々の犠牲や祈りを受け入れないと強調する(1015-1020行)。アンティゴネーがポ リュネイケスの埋葬の儀式を済ませたにもかかわらず、クレオンはティレシアスの助言によって(1023-1030行)、ポリュネイケスの遺体を完全かつ永 続的に埋葬する。 |

| Richard C. Jebb suggests that

the only reason for Antigone's return to the burial site is that the

first time she forgot the Choaí (libations), and "perhaps the rite was

considered completed only if the Choaí were poured while the dust still

covered the corpse."[17] |

リチャード・C・ジェブは、アンティゴネーが埋葬地に戻ってきた唯一の理由は、一度目にチョアイ(献杯)を忘れたことであり、「おそらく、まだ埃が死体を覆っている間にチョアイを注いで初めて儀式が完了したと見なされたのだろう」と示唆している[17]。 |

| Gilbert Norwood explains

Antigone's performance of the second burial in terms of her

stubbornness. His argument says that had Antigone not been so obsessed

with the idea of keeping her brother covered, none of the deaths of the

play would have happened. This argument states that if nothing had

happened, nothing would have happened, and does not take much of a

stand in explaining why Antigone returned for the second burial when

the first would have fulfilled her religious obligation, regardless of

how stubborn she was. This leaves that she acted only in passionate

defiance of Creon and respect to her brother's earthly vessel.[18] |

ギルバート・ノーウッドは、アンティゴネーが2度目の埋葬を行ったこと

を、彼女の頑固さという観点から説明している。彼の主張によれば、アンティゴネーが兄を隠しておくという考えに固執していなければ、劇中の死は何も起こら

なかったというのだ。この主張は、何も起こらなかったら何も起こらなかったとするもので、アンティゴネーがどれほど頑固であったとしても、最初の埋葬で宗

教的義務は果たせたはずなのに、なぜ2度目の埋葬のために戻ってきたのかを説明する立場にはあまり立っていない。このことは、彼女がクレオンへの熱烈な反

抗と、兄の地上での器への敬意から行動したに過ぎないということを残している[18]。 |

| Tycho von

Wilamowitz-Moellendorff justifies the need for the second burial by

comparing Sophocles' Antigone to a theoretical version where Antigone

is apprehended during the first burial. In this situation, news of the

illegal burial and Antigone's arrest would arrive at the same time and

there would be no period of time in which Antigone's defiance and

victory could be appreciated. |

ティコ・フォン・ウィラモヴィッツ=メレンドルフは、ソフォクレスの

『アンティゴネー』を、アンティゴネーが最初の埋葬中に逮捕されるという理論的なバージョンと比較することで、二度目の埋葬の必要性を正当化している。こ

の状況では、不法埋葬とアンティゴネー逮捕の知らせが同時に届き、アンティゴネーの反抗と勝利が評価される期間はないだろう。 |

| J. L. Rose maintains that the

problem of the second burial is solved by close examination of Antigone

as a tragic character. Being a tragic character, she is completely

obsessed by one idea, and for her this is giving her brother his due

respect in death and demonstrating her love for him and for what is

right. When she sees her brother's body uncovered, therefore, she is

overcome by emotion and acts impulsively to cover him again, with no

regards to the necessity of the action or its consequences for her

safety.[18] |

J.

L.ローズは、二度目の埋葬の問題は、悲劇的人物としてのアンティゴネーを詳細に検討することによって解決されると主張している。悲劇的な性格である彼女

は、ある一つの考えに完全にとらわれており、それは彼女にとって、兄に死後相応の敬意を払い、兄への愛と正しいことを示すことである。それゆえ、兄の死体

が覆い隠されていないのを見たとき、彼女は感情に打ちひしがれ、その行為の必要性や自分の安全に対するその結果を顧みることなく、兄を再び覆い隠そうと衝

動的に行動する[18]。 |

| Bonnie Honig uses the problem of

the second burial as the basis for her claim that Ismene performs the

first burial, and that her pseudo-confession before Creon is actually

an honest admission of guilt.[19] |

ボニー・ホーニグは、2回目の埋葬の問題を根拠に、イスメネが1回目の埋葬を行い、クレオンの前での彼女の偽りの告白は、実は罪を素直に認めたものだと主張している[19]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antigone_(Sophocles_play) |

|

| Modern adaptations Drama Felix Mendelssohn composed a suite of incidental music for Ludwig Tieck's staging of the play in 1841. It includes an overture and seven choruses. Walter Hasenclever wrote an adaptation in 1917, inspired by the events of World War I. Jean Cocteau created an adaptation of Sophocles' Antigone at Théâtre de l'Atelier in Paris on December 22, 1922. French playwright Jean Anouilh's tragedy Antigone was inspired by both Sophocles' play and the myth itself. Anouilh's play premièred in Paris at the Théâtre de l'Atelier in February 1944, during the Nazi occupation of France. Right after World War II, Bertolt Brecht composed an adaptation, Antigone, which was based on a translation by Friedrich Hölderlin and was published under the title Antigonemodell 1948. The Haitian writer and playwright Félix Morisseau-Leroy translated and adapted Antigone into Haitian Creole under the title, Antigòn (1953). Antigòn is noteworthy in its attempts to insert the lived religious experience of many Haitians into the content of the play through the introduction of several Loa from the pantheon of Haitian Vodou as voiced entities throughout the performance. Antigone inspired the 1967 Spanish-language novel La tumba de Antígona (English title: Antigone's Tomb) by María Zambrano. Puerto Rican playwright Luis Rafael Sánchez's 1968 play La Pasión según Antígona Pérez sets Sophocles' play in a contemporary world where Creon is the dictator of a fictional Latin American nation, and Antígona and her 'brothers' are dissident freedom fighters. The Island, a 1973 apartheid-era play by the South African playwrights Athol Fugard, John Kani, and Winston Nthsona, features two cellmates who rehearse and ultimately perform Antigone for the other prisoners, drawing parallels between Antigone herself and black political prisoners held in Robben Island prison. In 1977, Antigone was translated into Papiamento for an Aruban production by director Burny Every together with Pedro Velásquez and Ramon Todd Dandaré. This translation retains the original iambic verse by Sophocles. Antigona Furiosa, written in the period of 1985-86 by Griselda Gambaro, is an Argentinian drama heavily influenced by Antigone by Sophocles, and comments on an era of government terrorism that later transformed into the Dirty War of Argentina. In 2004, theatre companies Crossing Jamaica Avenue and The Women's Project in New York City co-produced the Antigone Project written by Tanya Barfield, Karen Hartman, Chiori Miyagawa, Pulitzer Prize winner Lynn Nottage and Caridad Svich, a five-part response to Sophocles' text and to the US Patriot Act. The text was published by NoPassport Press as a single edition in 2009 with introductions by classics scholar Marianne McDonald and playwright Lisa Schlesinger. Bangladeshi director Tanvir Mokammel in his 2008 film Rabeya (The Sister) also draws inspiration from Antigone to parallel the story to the martyrs of the 1971 Bangladeshi Liberation War who were denied a proper burial.[26] In 2000, Peruvian theatre group Yuyachkani and poet José Watanabe adapted the play into a one-actor piece that remains as part of the group's repertoire.[27] An Iranian absurdist adaptation of Antigone was written and directed by Homayoun Ghanizadeh and staged at the City Theatre in Tehran in 2011.[28] In 2012, the Royal National Theatre adapted Antigone to modern times. Directed by Polly Findlay,[29] the production transformed the dead Polynices into a terrorist threat and Antigone into a "dangerous subversive."[30] Roy Williams's 2014 adaptation of Antigone for the Pilot Theatre relocates the setting to contemporary street culture.[31] Syrian playwright Mohammad Al-Attar adapted Antigone for a 2014 production at Beirut, performed by Syrian refugee women.[32] Antigone in Ferguson is an adaptation conceived in the wake of the shooting of Michael Brown by police in 2014, through a collaboration between Theater of War Productions and community members from Ferguson, Missouri. Translated and directed by Theater of War Productions Artistic Director Bryan Doerries and composed by Phil Woodmore.[33] Elena Carapetis' rewritten version, described as a response to the original, portrays a feminist theme. It was produced by the State Theatre Company of South Australia in Adelaide in June 2022, directed by Anthony Nicola.[34] Antigone in the Amazon (premiered March 2023), a performance that combines storytelling, music, and film to create a political performance, by Belgian theatre-maker Milo Rau.[35][36][37][38] Antigone - Marie Senf. 25.01.2025. Schauspiel Dortmund. Federative Republic of Germany. Marie Senf, a playwright from the Federal Republic of Germany, wrote the anti-totalitarian, anti-fascist and also acrobatic "Antigone". This "Antigone" was premiered at the Schauspiel Dortmund - Dortmund Drama Theatre on January 25th, 2025. This production contains an intertemporal dramatic allusion to Charlie Chaplin's "The Great Dictator" and Istvan Szabo's "Mephisto". And the political, cultural and historical spirit of Marie Senff's dramatic creation continues the Thespian civil tradition of Bertolt Brecht's "Antigone". |