フェミニスト理論

Feminist theory

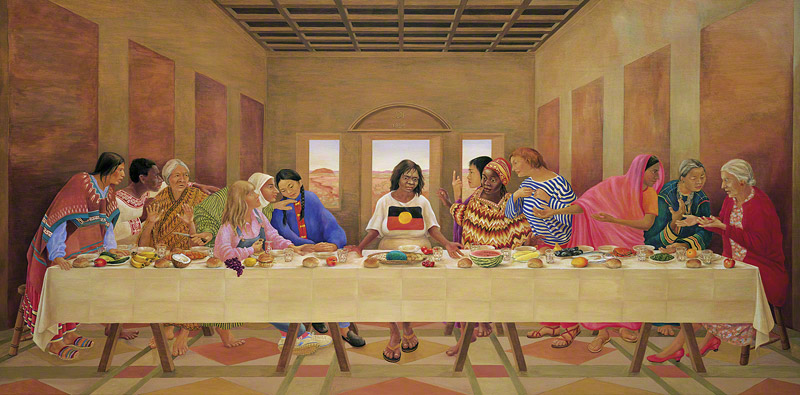

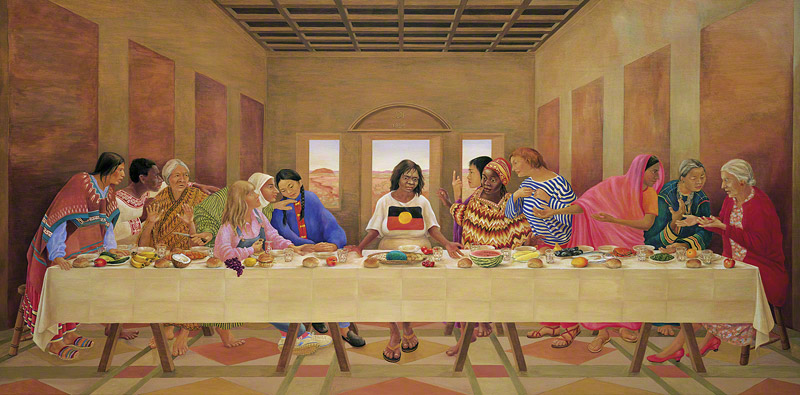

The First Supper 1988 acrylic on panel, 120

x 240 cm by Susan

Dorothea White

☆ フェミニズム理論とは、フェミニズムを理論的、フィクション的、哲学的言説に拡張し たものである。ジェンダー不平等の本質を理解することを目的としてい る。人類学や社会学、コミュニケーション、メディア研究、精神分析、政治理論、家庭経済学、文学、教育学、哲学など様々な分野で、女性と男性の社会 的役割、経験、関心、家事、フェミニズム政治を検証している。フェミニズム理論はしばしばジェンダー不平等の分析に焦点を当てている。フェミニズム理論に おいてしばしば探求されるテーマには、差別、対象化(特に性的 対象化)、抑圧、家父長制、ステレオタイプ、美術史や現代美術、美学などが含まれる。

★この項目の目次(今後変動します)

☆ フェミニスト理論の理論装置とディシプリン

| Bodies In western thought, the body has been historically associated solely with women, whereas men have been associated with the mind. Susan Bordo, a modern feminist philosopher, in her writings elaborates the dualistic nature of the mind/body connection by examining the early philosophies of Aristotle, Hegel, and Descartes, revealing how such distinguishing binaries such as spirit/matter and male activity/female passivity have worked to solidify gender characteristics and categorization. Bordo goes on to point out that while men have historically been associated with the intellect and the mind or spirit, women have long been associated with the body, the subordinated, negatively imbued term in the mind/body dichotomy.[37] The notion of the body (but not the mind) being associated with women has served as a justification to deem women as property, objects, and exchangeable commodities (among men). For example, women's bodies have been objectified throughout history through the changing ideologies of fashion, diet, exercise programs, cosmetic surgery, childbearing, etc. This contrasts to men's role as a moral agent, responsible for working or fighting in bloody wars. The race and class of a woman can determine whether her body will be treated as decoration and protected, which is associated with middle or upper-class women's bodies. On the other hand, the other body is recognized for its use in labor and exploitation which is generally associated with women's bodies in the working-class or with women of color. Second-wave feminist activism has argued for reproductive rights and choice. The women's health movement and lesbian feminism are also associated with this Bodies debate. |

身体 西洋思想において、身体は歴史的に女性のみと結びついてきたのに対し、男性は心と結びついてきた。現代のフェミニスト哲学者であるスーザン・ボルドは、そ の著作の中で、アリストテレス、ヘーゲル、 デカルトの初期の哲学を検証することで、精神と物質、男性の活動性と女性の受動性といった二項対立が、いかに ジェンダーの特徴や分類を強固にするために働いてきたかを明らかにし、精神と身体の結びつきの二元論的性質を詳しく説明している。ボルドはさらに、男性が 歴史的に知性や心や精神と結びつけられてきたのに対して、女性は長い間、心/体の二項対立の中で従属的で否定的な意味を帯びた言葉である身体と結びつけら れてきたと指摘する[37]。身体(心ではない)が女性と結びつけられてきたという概念は、女性を(男性の間で)所有物、物体、交換可能な商品とみなす正 当化の役割を果たしてきた。例えば、女性の身体は、ファッション、ダイエット、運動プログラム、美容整形、出産などのイデオロギーの変化を通じて、歴史を 通じて客観化されてきた。これは、男性が道徳的な代理人として、働いたり、血なまぐさい戦争で戦ったりする役割を担っているのとは対照的だ。女性の人種や 階級によって、その身体が装飾品として扱われ、保護されるかどうかが決まり、それは中流階級や上流階級の女性の身体に関連している。一方、もう一方の身体 は、労働や搾取に使われることで認識され、それは一般的に労働者階級の女性の身体や有色人種の女性の身体と結びつけられる。第二波フェミニズムの活動は、 リプロダクティブ・ライツと選択を主張してきた。女性の健康運動やレズビアン・フェミニズムもまた、この「身体」の議論と関連している。 |

| The standard and contemporary sex and gender system The standard sex determination and gender model consists of evidence based on the determined sex and gender of every individual and serve as norms for societal life. The model that the sex-determination of a person exists within a male/female dichotomy, giving importance to genitals and how they are formed via chromosomes and DNA-binding proteins (such as the sex-determining region Y genes), which are responsible for sending sex-determined initialization and completion signals to and from the biological sex-determination system in fetuses. Occasionally, variations occur during the sex-determining process, resulting in intersex conditions. The standard model defines gender as a social understanding/ideology that defines what behaviors, actions, and appearances are normal for males and females. Studies into biological sex-determining systems also have begun working towards connecting certain gender conducts such as behaviors, actions, and desires with sex-determinism.[38] |

標準的で現代的な性と性別のシステム 標準的な性決定・性別モデルは、すべての個人の決定された性と性別に基づく証拠から成り、社会生活の規範として機能する。人の性決定は男性/女性の二分法 の中に存在し、染色体やDNA結合タンパク質(性決定領域Y遺伝子など)を介して性器やその形成方法が重要視され、これらのタンパク質は胎児の生物学的性 決定システムとの間で性決定の初期化と完了のシグナルを送る役割を担っているというモデルである。時折、性決定過程で変異が起こり、インターセックスが生 じる。標準的なモデルでは、ジェンダーを、男性と女性にとってどのような行動、行為、外見が正常であるかを定義する社会的理解/イデオロギーとして定義し ている。生物学的な性決定システムに関する研究もまた、行動、行為、欲望などの特定のジェンダー行為を性決定主義と結びつける方向で取り組み始めている [38]。 |

| Socially-biasing children sex and gender system This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. Please help improve it by rewriting it in an encyclopedic style. (July 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) The socially biasing children's sex and gender model broadens the horizons of the sex and gender ideologies. It revises the ideology of sex to be a social construct that is not limited to either male or female. The Intersex Society of North America which explains that "nature doesn't decide where the category of 'male' ends and the category of 'intersex' begins, or where the category of 'intersex' ends and the category of 'female' begins. Humans decide. Humans (today, typically doctors) decide how small a penis has to be, or how unusual a combination of parts has to be before it counts as intersex".[39] Therefore, sex is not a biological/natural construct but a social one instead since, society and doctors decide on what it means to be male, female, or intersex in terms of sex chromosomes and genitals, in addition to their personal judgment on who or how one passes as specific sex. The ideology of gender remains a social construct but is not as strict and fixed. Instead, gender is easily malleable and is forever changing. One example of where the standard definition of gender alters with time happens to be depicted in Sally Shuttleworth's Female Circulation in which the "abasement of the woman, reducing her from an active participant in the labor market to the passive bodily existence to be controlled by male expertise is indicative of the ways in which the ideological deployment of gender roles operated to facilitate and sustain the changing structure of familial and market relations in Victorian England".[40] In other words, this quote shows what it meant growing up into the roles of a female (gender/roles) changed from being a homemaker to being a working woman and then back to being passive and inferior to males. In conclusion, the contemporary sex gender model is accurate because both sex and gender are rightly seen as social constructs inclusive of the wide spectrum of sexes and genders and in which nature and nurture are interconnected. |

社会的に偏見を持つ子どもの性と性別のシステム このセクションは、ウィキペディア編集者の個人的な感想を述べたり、トピックに関する独自の議論を提示したりする、個人的な考察、個人的なエッセイ、また は議論的なエッセイのように書かれています。百科事典風に書き直すことで改善にご協力ください。(2018年7月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除す る方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 社会的に偏った子どものセックスとジェンダーのモデルは、セックスとジェンダーのイデオロギーの視野を広げる。それは、性のイデオロギーを、男性か女性の どちらかに限定されない社会的構築物であると修正するものである。北米インターセックス協会は、「『男性』というカテゴリーがどこで終わり、『インター セックス』というカテゴリーがどこで始まるか、あるいは『インターセックス』というカテゴリーがどこで終わり、『女性』というカテゴリーがどこで始まるか は、自然が決めることではありません。人間が決めるのだ。人間(今日、典型的な医者)は、ペニスがどの程度小さければインターセックスとしてカウントされ るのか、あるいはパーツの組み合わせがどの程度珍しいものでなければインターセックスとしてカウントされないのかを決める」[39]。したがって、性とは 生物学的/自然的な構成要素ではなく、社会的な構成要素なのである。ジェンダーのイデオロギーは依然として社会的構築物であるが、それほど厳格で固定的な ものではない。その代わり、ジェンダーは容易に変更可能であり、永遠に変化し続ける。標準的なジェンダーの定義が時代とともに変化する一例として、サ リー・シャトルワースの『Female Circulation』(邦題『女性循環』)が描かれている。「女性を労働市場の積極的な参加者から、男性の専門知識によって管理されるべき受動的な身 体的存在に引き下げるという軽蔑は、ジェンダーの役割のイデオロギー的展開が、ヴィクトリア朝イギリスにおける家族関係と市場関係の構造の変化を促進し、 維持するために作用した方法を示している。 [40]言い換えれば、この引用は、女性としての役割(ジェンダー/役割)が主婦から働く女性へと変化し、そしてまた男性に対して受動的で劣等な存在へと 戻るという成長の意味を示している。結論として、現代のセックス・ジェンダー・モデルは正確である。なぜなら、セックスとジェンダーの両方が、多様なセッ クスとジェンダーを包含する社会的構築物であり、自然と育ちが相互に関連し合っていると考えるのが正しいからである。 |

| Epistemologies Questions about how knowledge is produced, generated, and distributed have been central to Western conceptions of feminist theory and discussions on feminist epistemology. One debate proposes such questions as "Are there 'women's ways of knowing' and 'women's knowledge'?" And "How does the knowledge women produce about themselves differ from that produced by patriarchy?"[41] Feminist theorists have also proposed the "feminist standpoint knowledge" which attempts to replace the "view from nowhere" with the model of knowing that expels the "view from women's lives".[41] A feminist approach to epistemology seeks to establish knowledge production from a woman's perspective. It theorizes that from personal experience comes knowledge which helps each individual look at things from a different insight. It is central to feminism that women are systematically subordinated, and bad faith exists when women surrender their agency to this subordination (for example, acceptance of religious beliefs that a man is the dominant party in a marriage by the will of God). Simone de Beauvoir labels such women "mutilated" and "immanent".[42][43][44][45] |

認識論 知識がどのように生み出され、生成され、分配されるかについての疑問は、西洋におけるフェミニズム理論の概念やフェミニズム認識論に関する議論の中心と なってきた。ある議論では、"女性の知る方法 "や "女性の知識 "は存在するのか?また、"女性が自分自身について生み出す知識は、家父長制によって生み出される知識とどのように異なるのか?"[41]。フェミニスト の理論家たちは、"どこからでもないところからの視点 "を、"女性の生活からの視点 "を追放した知ることのモデルに置き換えようとする "フェミニストの立場からの知識 "も提唱している[41]。認識論へのフェミニストのアプローチは、女性の視点からの知識生産を確立しようとするものである。個人的な経験から知識が生ま れ、それは各個人が異なる洞察から物事を見る助けとなると理論化している。 フェミニズムの中心は、女性が組織的に従属させられていることであり、この従属に女性が主体性を明け渡すときに悪意が存在する(たとえば、結婚生活では神 の意志によって男性が優位に立つという宗教的信念を受け入れること)。シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールは、そのような女性を「切断された」「内在的な」と表 現している[42][43][44][45]。 |

| Intersectionality Main article: Intersectionality Intersectionality is the examination of various ways in which people are oppressed, based on the relational web of dominating factors of race, sex, class, nation and sexual orientation. Intersectionality "describes the simultaneous, multiple, overlapping, and contradictory systems of power that shape our lives and political options". While this theory can be applied to all people, and more particularly all women, it is specifically mentioned and studied within the realms of black feminism. Patricia Hill Collins argues that black women in particular, have a unique perspective on the oppression of the world as unlike white women, they face both racial and gender oppression simultaneously, among other factors. This debate raises the issue of understanding the oppressive lives of women that are not only shaped by gender alone but by other elements such as racism, classism, ageism, heterosexism, ableism etc. |

交差性 主な記事 交差性 交差性とは、人種、性、階級、国家、性的指向といった支配的要因の関係網に基づいて、人々が抑圧される様々な方法を検討することである。インターセクショ ナリティは、「私たちの生活や政治的選択肢を形成している、同時的、多重的、重複的、矛盾的な権力システムを説明するもの」である。この理論はすべての 人、とりわけすべての女性に適用することができるが、黒人フェミニズムの領域では特に言及され、研究されている。パトリシア・ヒル・コリンズは、特に黒人 女性は白人女性とは異なり、とりわけ人種的抑圧とジェンダー的抑圧の両方に同時に直面しているため、世界の抑圧に対して独自の視点を持っていると主張して いる。この議論は、ジェンダーだけでなく、人種差別、階級差別、年齢差別、ヘテロセクシズム、能力差別など、他の要素によっても形成される女性の抑圧的な 生き方を理解するという問題を提起している。 |

| Language See also: Feminist language reform, Gender-neutral language, and Category:Feminist terminology In this debate, women writers have addressed the issues of masculinized writing through male gendered language that may not serve to accommodate the literary understanding of women's lives. Such masculinized language that feminist theorists address is the use of, for example, "God the Father", which is looked upon as a way of designating the sacred as solely men (or, in other words, biblical language glorifies men through all of the masculine pronouns like "he" and "him" and addressing God as a "He"). Feminist theorists attempt to reclaim and redefine women through a deeper thinking of language. For example, feminist theorists have used the term "womyn" instead of "women". Some feminist theorists have suggested using neutral terminology when naming jobs (for example, police officer versus policeman or mail carrier versus mailman). Some feminist theorists have reclaimed and redefined such words as "dyke" and "bitch". |

言語 こちらも参照: フェミニスト言語改革、ジェンダー・ニュートラル言語、Category:フェミニスト用語 この議論の中で、女性作家たちは、女性の生き方を文学的に理解するのに役立たないかもしれない男性ジェンダー化された言語を通して、男性化された文章の問 題を取り上げてきた。フェミニストの理論家たちが取り上げる男性化された言語とは、例えば「父なる神」の使用であり、これは聖なるものをもっぱら男性とし て指定する方法と見なされている(言い換えれば、聖書の言葉は「彼」や「彼」のような男性代名詞をすべて使い、神を「彼」と呼ぶことによって男性を美化し ている)。フェミニストの理論家たちは、言葉をより深く考えることによって、女性を取り戻し、再定義しようと試みている。例えば、フェミニスト理論家は 「女性」の代わりに「女性」という言葉を用いてきた。フェミニスト理論家のなかには、職業名をつけるときに中立的な用語を使うことを提案する者もいる(た とえば、警察官と警察官、郵便配達員と郵便配達員など)。一部のフェミニスト理論家は、「レズ」や「ビッチ」といった言葉を再生し、再定義している。 |

| Psychology Feminist psychology is a form of psychology centered on societal structures and gender. Feminist psychology critiques the fact that historically psychological research has been done from a male perspective with the view that males are the norm.[46] Feminist psychology is oriented on the values and principles of feminism. It incorporates gender and the ways women are affected by issues resulting from it. Ethel Dench Puffer Howes was one of the first women to enter the field of psychology. She was the executive secretary of the National College Equal Suffrage League in 1914. One major psychological theory, relational-cultural theory, is based on the work of Jean Baker Miller, whose book Toward a New Psychology of Women proposes that "growth-fostering relationships are a central human necessity and that disconnections are the source of psychological problems".[47] Inspired by Betty Friedan's Feminine Mystique, and other feminist classics from the 1960s, relational-cultural theory proposes that "isolation is one of the most damaging human experiences and is best treated by reconnecting with other people", and that a therapist should "foster an atmosphere of empathy and acceptance for the patient, even at the cost of the therapist's neutrality".[48] The theory is based on clinical observations and sought to prove that "there was nothing wrong with women, but rather with the way modern culture viewed them".[25] |

心理学 フェミニスト心理学は、社会構造とジェンダーを中心とした心理学の一形態である。フェミニスト心理学は、歴史的に心理学研究が男性が規範であるという見方 で男性の視点から行われてきたことを批判している[46]。それは、ジェンダーと、それに起因する問題によって女性が影響を受ける方法を取り入れている。 エセル・デンチ・パファー・ハウズは、心理学の分野に入った最初の女性の一人である。彼女は1914年に全国大学平等選挙権連盟の事務局長を務めた。 主な心理学理論のひとつである関係文化論は、ジーン・ベイカー・ミラーの研究に基づくもので、その著書『女性の新しい心理学に向けて』では、「成長を促す 人間関係は人間の中心的な必需品であり、断絶は心理的な問題の原因である」と提唱している[47]。 [47]ベティ・フリーダンの『女性の神秘』や1960年代の他のフェミニストの古典に触発された関係文化理論は、「孤立は最も有害な人間体験の一つであ り、他の人々とのつながりを取り戻すことによって最もよく治療される」とし、セラピストは「セラピストの中立性を犠牲にしても、患者への共感と受容の雰囲 気を醸成する」べきであると提唱している。 [48]この理論は臨床的観察に基づいており、「女性には何の問題もなく、むしろ近代文化が女性を見る方法に問題がある」ことを証明しようとした [25]。 |

| Psychoanalysis See also: Psychoanalysis and Feminism and the Oedipus complex Psychoanalytic feminism and feminist psychoanalysis are based on Freud and his psychoanalytic theories, but they also supply an important critique of it. It maintains that gender is not biological but is based on the psycho-sexual development of the individual, but also that sexual difference and gender are different notions. Psychoanalytical feminists believe that gender inequality comes from early childhood experiences, which lead men to believe themselves to be masculine, and women to believe themselves feminine. It is further maintained that gender leads to a social system that is dominated by males, which in turn influences the individual psycho-sexual development. As a solution it was suggested by some to avoid the gender-specific structuring of the society coeducation.[1][4] From the last 30 years of the 20th century, the contemporary French psychoanalytical theories concerning the feminine, that refer to sexual difference rather than to gender, with psychoanalysts like Julia Kristeva,[49][50] Maud Mannoni, Luce Irigaray,[51][52] and Bracha Ettinger that invented the concept matrixial space and matrixial Feminist ethics,[53][54][55][56][57] have largely influenced not only feminist theory but also the understanding of the subject in philosophy, art, aesthetics and ethics and the general field of psychoanalysis itself.[58][59] These French psychoanalysts are mainly post-Lacanian. Other feminist psychoanalysts and feminist theorists whose contributions have enriched the field through an engagement with psychoanalysis are Jessica Benjamin,[60] Jacqueline Rose,[61] Ranjana Khanna,[62] and Shoshana Felman.[63] |

精神分析 こちらも参照: 精神分析とフェミニズム、エディプス・コンプレックス 精神分析的フェミニズムとフェミニスト精神分析は、フロイトと彼の精神分析理論に基づいているが、それに対する重要な批判も提供している。ジェンダーは生 物学的なものではなく、個人の精神的・性的発達に基づくものであり、性的差異とジェンダーは異なる概念であると主張する。精神分析的フェミニストは、ジェ ンダーの不平等は幼児期の体験に由来し、男性は自分を男性的であると信じ、女性は自分を女性的であると信じるようになると考える。さらに、ジェンダーは男 性に支配された社会システムにつながり、それが個人の心理的・性的発達に影響を及ぼすと主張する。その解決策として、男女共学による社会の構造化を避ける ことが提案された。 1][4]20世紀の最後の30年間から、ジュリア・クリステヴァ、[49][50]モード・マンノーニ、ルーチェ・イリガライ[51][52]のような 精神分析家たちによって、ジェンダーよりもむしろ性的差異に言及する、女性性に関する現代フランスの精神分析理論が生まれた、 [51][52]やブラシャ・エッティンガーのような精神分析家たちによって、母系空間という概念と母系フェミニスト倫理が発明され[53][54] [55][56][57]、フェミニズム理論だけでなく、哲学、芸術、美学、倫理、そして精神分析という一般的な分野自体における主体の理解にも大きな影 響を与えてきた。 [58][59]これらのフランスの精神分析家は主にポスト・ラカニアンである。その他のフェミニスト精神分析家やフェミニスト理論家は、精神分析との関 わりを通してこの分野を豊かにしてきた貢献者として、ジェシカ・ベンジャミン、[60]ジャクリーン・ローズ、[61]ランジャナ・カンナ、[62]ショ シャナ・フェルマンが挙げられる[63]。 |

| Literary theory Main article: Feminist literary criticism See also: Gynocriticism Feminist literary criticism is literary criticism informed by feminist theories or politics. Its history has been varied, from classic works of female authors such as George Eliot, Virginia Woolf,[64] and Margaret Fuller to recent theoretical work in women's studies and gender studies by "third-wave" authors.[65] In the most general terms, feminist literary criticism before the 1970s was concerned with the politics of women's authorship and the representation of women's condition within literature.[65] Since the arrival of more complex conceptions of gender and subjectivity, feminist literary criticism has taken a variety of new routes. It has considered gender in the terms of Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis, as part of the deconstruction of existing power relations.[65] |

文学理論 主な記事 フェミニスト文学批評 以下も参照: 女性批評 フェミニスト文学批評とは、フェミニズムの理論や政治に影響を受けた文学批評のことである。その歴史は、ジョージ・エリオット、ヴァージニア・ウルフ [64]、マーガレット・フラーといった女性作家の古典的な作品から、「第三の波」の作家による女性学やジェンダー研究における最近の理論的な作品まで、 様々である[65]。 最も一般的な言い方をすれば、1970年代以前のフェミニスト文芸批評は、女性の作家性の政治性と文学における女性の状態の表現に関心を持っていた [65]。ジェンダーと主観性のより複雑な概念の到来以来、フェミニスト文芸批評は様々な新しい道を歩んできた。それは既存の権力関係の解体の一部とし て、フロイトやラカンの精神分析の観点からジェンダーを考察してきた[65]。 |

| Film theory Main article: Feminist film theory Many feminist film critics, such as Laura Mulvey, have pointed to the "male gaze" that predominates in classical Hollywood film making. Through the use of various film techniques, such as shot reverse shot, the viewers are led to align themselves with the point of view of a male protagonist. Notably, women function as objects of this gaze far more often than as proxies for the spectator.[66][67] Feminist film theory of the last twenty years is heavily influenced by the general transformation in the field of aesthetics, including the new options of articulating the gaze, offered by psychoanalytical French feminism, like Bracha Ettinger's feminine, maternal and matrixial gaze.[68][69] |

映画理論 主な記事 フェミニスト映画理論 ローラ・マルヴェイのような多くのフェミニスト映画批評家は、古典的なハリウッド映画製作において支配的な「男性の視線」を指摘してきた。リバースショッ トなど様々な映画技法を用いることで、観客は男性主人公の視点に同調するように誘導される。特筆すべきは、女性が観客の代理としてよりも、このまなざしの 対象として機能することの方がはるかに多いということである[66][67]。ここ20年のフェミニズム映画論は、ブラシャ・エッティンガーの女性的まな ざし、母性的まなざし、行列的まなざしのような、精神分析的フランス・フェミニズムが提供するまなざしを明確にする新たな選択肢を含む、美学の分野におけ る一般的な変容に大きな影響を受けている[68][69]。 |

| Art history Linda Nochlin[70] and Griselda Pollock[71][72][73] are prominent art historians writing on contemporary and modern artists and articulating Art history from a feminist perspective since the 1970s. Pollock works with French psychoanalysis, and in particular with Kristeva's and Ettinger's theories, to offer new insights into art history and contemporary art with special regard to questions of trauma and trans-generation memory in the works of women artists. Other prominent feminist art historians include: Norma Broude and Mary Garrard; Amelia Jones; Mieke Bal; Carol Duncan; Lynda Nead; Lisa Tickner; Tamar Garb; Hilary Robinson; Katy Deepwell. |

美術史 リンダ・ノクリン[70]とグリセルダ・ポロック[71][72][73]は、1970年代以降、現代と近代のアーティストについて執筆し、フェミニズム の視点から美術史を明確にしている著名な美術史家である。ポロックはフランスの精神分析、特にクリステヴァとエッティンガーの理論を用いて、女性アーティ ストの作品におけるトラウマと世代を超えた記憶に関する問題を中心に、美術史と現代美術に新たな洞察を提供している。その他の著名なフェミニスト美術史家 は以下の通り: ノーマ・ブルード、メアリー・ガラード、アメリア・ジョーンズ、ミケ・バル、キャロル・ダンカン、リンダ・ニード、リサ・ティックナー、タマール・ガー ブ、ヒラリー・ロビンソン、ケイティ・ディープウェル。 |

| History Main article: Feminist history Feminist history refers to the re-reading and re-interpretation of history from a feminist perspective. It is not the same as the history of feminism, which outlines the origins and evolution of the feminist movement. It also differs from women's history, which focuses on the role of women in historical events. The goal of feminist history is to explore and illuminate the female viewpoint of history through rediscovery of female writers, artists, philosophers, etc., in order to recover and demonstrate the significance of women's voices and choices in the past.[74][75][76][77][78] |

歴史 主な記事 フェミニスト史 フェミニスト史とは、フェミニストの視点から歴史を読み直し、再解釈することを指す。フェミニズム運動の起源と展開を概説するフェミニズム史とは異なる。 また、歴史的出来事における女性の役割に焦点を当てる女性史とも異なる。フェミニズム史の目的は、女性作家、芸術家、哲学者などの再発見を通じて、歴史に おける女性の視点を探求し、照らし出すことであり、過去における女性の声や選択の意義を回復し、実証することである[74][75][76][77] [78]。 |

| Philosophy Main article: Feminist philosophy The Feminist philosophy refers to a philosophy approached from a feminist perspective. Feminist philosophy involves attempts to use methods of philosophy to further the cause of the feminist movements, it also tries to criticize and/or reevaluate the ideas of traditional philosophy from within a feminist view. This critique stems from the dichotomy Western philosophy has conjectured with the mind and body phenomena.[82] There is no specific school for feminist philosophy like there has been in regard to other theories. This means that Feminist philosophers can be found in the analytic and continental traditions, and the different viewpoints taken on philosophical issues with those traditions. Feminist philosophers also have many different viewpoints taken on philosophical issues within those traditions. Feminist philosophers who are feminists can belong to many different varieties of feminism. The writings of Judith Butler, Rosi Braidotti, Donna Haraway, Bracha Ettinger and Avital Ronell are the most significant psychoanalytically informed influences on contemporary feminist philosophy. |

哲学 主な記事 フェミニズム哲学 フェミニスト哲学とは、フェミニストの視点からアプローチされた哲学を指す。フェミニスト哲学は、フェミニズム運動の大義を促進するために哲学の方法を使 用する試みを含み、それはまた、フェミニストのビューの中から伝統的な哲学のアイデアを批判および/または再評価しようとします。この批評は、西洋哲学が 心と身体の現象について推測してきた二項対立から生じている[82]。フェミニズム哲学には、他の理論に関してあったような特定の学派は存在しない。つま り、フェミニスト哲学者は分析哲学や大陸哲学の伝統の中に見出すことができ、それらの伝統の中で哲学的な問題に対して取られた様々な視点がある。また、 フェミニスト哲学者は、それらの伝統の中で、哲学的な問題に関して様々な視点を持っている。フェミニストである哲学者は、様々なフェミニズムに属すること ができる。ジュディス・バトラー、ロージ・ブライドッティ、ドナ・ハラウェイ、ブラチャ・エッティンガー、アヴィタル・ロネルの著作は、現代のフェミニス ト哲学に最も大きな影響を与えた精神分析学的知見に基づくものである。 |

| Sexology Main article: Feminist sexology Feminist sexology is an offshoot of traditional studies of sexology that focuses on the intersectionality of sex and gender in relation to the sexual lives of women. Feminist sexology shares many principles with the wider field of sexology; in particular, it does not try to prescribe a certain path or "normality" for women's sexuality, but only observe and note the different and varied ways in which women express their sexuality. Looking at sexuality from a feminist point of view creates connections between the different aspects of a person's sexual life. From feminists' perspectives, sexology, which is the study of human sexuality and sexual relationship, relates to the intersectionality of gender, race and sexuality. Men have dominant power and control over women in the relationship, and women are expected to hide their true feeling about sexual behaviors. Women of color face even more sexual violence in the society. Some countries in Africa and Asia even practice female genital cutting, controlling women's sexual desire and limiting their sexual behavior. Moreover, Bunch, the women's and human rights activist, states that society used to see lesbianism as a threat to male supremacy and to the political relationships between men and women.[83] Therefore, in the past, people viewed being a lesbian as a sin and made it death penalty. Even today, many people still discriminate homosexuals. Many lesbians hide their sexuality and face even more sexual oppression. |

性科学 主な記事 フェミニスト性科学 フェミニスト性科学は、伝統的な性科学研究の分派であり、女性の性生活に関するセックスとジェンダーの交差性に焦点を当てている。フェミニスト性科学は、 より広い分野の性科学と多くの原則を共有している。特に、女性のセクシュアリティについて一定の道筋や「正常性」を規定しようとせず、女性がセクシュアリ ティを表現するさまざまな方法を観察し、注意するだけである。フェミニストの視点からセクシュアリティを見ることで、人の性生活のさまざまな側面につなが りが生まれる。 フェミニストの視点から見ると、人間の性と性的関係の研究である性科学は、ジェンダー、人種、セクシュアリティの交差性に関連している。男性は女性との関 係において支配的な権力と支配力を持っており、女性は性行動に関する本音を隠すことが期待されている。有色人種の女性は、社会でより多くの性的暴力に直面 している。アフリカやアジアの一部の国では、女性の性欲をコントロールし、性行動を制限するために、女性器切除が行われている。さらに、女性・人権活動家 のバンチは、かつて社会はレズビアンを男性至上主義や男女の政治的関係を脅かすものとみなしていたと述べている。今日でも、多くの人々が同性愛者を差別し ている。多くのレズビアンは自分のセクシュアリティを隠し、さらに性的抑圧に直面している。 |

| Monosexual paradigm Main article: Monosexuality Monosexual Paradigm is a term coined by Blasingame, a self-identified African American, bisexual female. Blasingame used this term to address the lesbian and gay communities who turned a blind eye to the dichotomy that oppressed bisexuals from both heterosexual and homosexual communities. This oppression negatively affects the gay and lesbian communities more so than the heterosexual community due to its contradictory exclusiveness of bisexuals. Blasingame argued that in reality dichotomies are inaccurate to the representation of individuals because nothing is truly black or white, straight or gay. Her main argument is that biphobia is the central message of two roots; internalized heterosexism and racism. Internalized heterosexism is described in the monosexual paradigm in which the binary states that you are either straight or gay and nothing in between. Gays and lesbians accept this internalized heterosexism by morphing into the monosexial paradigm and favoring single attraction and opposing attraction for both sexes. Blasingame described this favoritism as an act of horizontal hostility, where oppressed groups fight amongst themselves. Racism is described in the monosexual paradigm as a dichotomy where individuals are either black or white, again nothing in between. The issue of racism comes into fruition in regards to the bisexuals coming out process, where risks of coming out vary on a basis of anticipated community reaction and also in regards to the norms among bisexual leadership, where class status and race factor predominately over sexual orientation.[84] |

単性愛パラダイム 主な記事 単性愛 モノセクシュアル・パラダイムとは、自称アフリカ系アメリカ人でバイセクシュアルの女性であるブラジンガムによる造語である。異性愛者や同性愛者のコミュ ニティからバイセクシュアルを抑圧する二項対立に目をつぶってきたレズビアンやゲイのコミュニティに対して、ブラジンガムはこの言葉を使った。この抑圧 は、バイセクシュアルを排他的に扱うという矛盾のために、異性愛者のコミュニティよりもゲイやレズビアンのコミュニティに悪影響を及ぼしている。白か黒 か、ストレートかゲイか、といった二項対立は、個人を表現する上で不正確である。彼女の主な主張は、バイフォビアは内面化されたヘテロセクシズムと人種差 別という2つの根の中心的メッセージであるというものだ。内面化されたヘテロセクシズムとは、自分がストレートかゲイのどちらかであり、その中間は存在し ないという二元論によるモノセクシュアル・パラダイムで説明される。ゲイやレズビアンはこの内面化されたヘテロセクシズムを、モノセクシャル・パラダイム に変容し、単一の魅力を支持し、両性の魅力に反対することで受け入れている。ブラジンガムはこの好意主義を、抑圧された集団同士が争う水平的敵対行為と表 現した。人種差別はモノセクシュアル・パラダイムでは、個人は黒人か白人かという二分法であり、その中間は存在しない。人種差別の問題は、バイセクシュア ルのカミングアウトのプロセスに関して結実する。そこでは、カミングアウトのリスクは、予想されるコミュニティの反応に基づいて変化し、また、バイセク シュアルの指導者たちの間の規範に関しても結実する。 |

| Politics Main article: Feminist political theory Feminist political theory is a recently emerging field in political science focusing on gender and feminist themes within the state, institutions and policies. It questions the "modern political theory, dominated by universalistic liberalist thought, which claims indifference to gender or other identity differences and has therefore taken its time to open up to such concerns".[85] Feminist perspectives entered international relations in the late 1980s, at about the same time as the end of the Cold War. This time was not a coincidence because the last forty years the conflict between US and USSR had been the dominant agenda of international politics. After the Cold War, there was continuing relative peace between the main powers. Soon, many new issues appeared on international relation's agenda. More attention was also paid to social movements. Indeed, in those times feminist approaches also used to depict the world politics. Feminists started to emphasize that while women have always been players in international system, their participation has frequently been associated with non-governmental settings such as social movements. However, they could also participate in inter-state decision making process as men did. Until more recently, the role of women in international politics has been confined to being the wives of diplomats, nannies who go abroad to find work and support their family, or sex workers trafficked across international boundaries. Women's contributions has not been seen in the areas where hard power plays significant role such as military. Nowadays, women are gaining momentum in the sphere of international relations in areas of government, diplomacy, academia, etc.. Despite barriers to more senior roles, women currently hold 11.1 percent of the seats in the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and 10.8 percent in the House. In the U.S. Department of State, women make up 29 percent of the chiefs of mission, and 29 percent of senior foreign positions at USAID.[86] In contrast, women are profoundly impacted by decisions the statepersons make.[87] |

政治 主な記事 フェミニスト政治理論 フェミニスト政治理論は、国家、制度、政策におけるジェンダーとフェミニストのテーマに焦点を当てた、政治学において最近台頭してきた分野である。ジェン ダーやその他のアイデンティティの差異に無関心であると主張する普遍主義的な自由主義思想に支配された現代の政治理論に疑問を投げかけ、そのような懸念に 対して時間をかけて開かれてきた」[85]。 フェミニストの視点が国際関係論に参入したのは1980年代後半であり、冷戦の終結とほぼ同時期であった。この40年間は米ソ対立が国際政治の主要な議題 であったからである。冷戦の後、主要国の間には相対的な平和が続いた。やがて、国際関係のアジェンダに多くの新しい問題が登場した。社会運動にも注目が集 まった。実際、当時はフェミニズムのアプローチも世界政治を描くのに使われていた。フェミニストたちは、女性は常に国際システムのプレーヤーであったが、 その参加はしばしば社会運動のような非政府的な場と結びついてきたことを強調し始めた。しかし、男性と同様に国家間の意思決定プロセスにも参加することが できた。つい最近まで、国際政治における女性の役割は、外交官の妻、仕事を見つけて家族を養うために外国に行く乳母、国際的な境界を越えて人身売買される セックスワーカーなどに限られていた。軍事などハードパワーが重要な役割を果たす分野では、女性の貢献は見られなかった。今日、女性は政府、外交、学界な ど国際関係の分野で勢いを増している。より上級の役職に就くには障壁があるにもかかわらず、現在、米国上院外交委員会では女性が11.1%、下院では 10.8%の議席を占めている。米国務省では、女性はミッションチーフの29%を占め、USAIDでは対外的な上級職の29%を占めている[86]。対照 的に、女性は国家主席が下す決定に大きな影響を受けている[87]。 |

| Economics Main articles: Feminist critique of economics and Feminist economics Feminist economics broadly refers to a developing branch of economics that applies feminist insights and critiques to economics. However, in recent decades, feminists like for example Katrine Marçal, author of Who cooked Adam Smith's dinner has also taken up a critique of economics.[88] Research in feminist economics is often interdisciplinary, critical, or heterodox. It encompasses debates about the relationship between feminism and economics on many levels: from applying mainstream economic methods to under-researched "women's" areas, to questioning how mainstream economics values the reproductive sector, to deeply philosophical critiques of economic epistemology and methodology.[89] One prominent issue that feminist economists investigate is how the gross domestic product (GDP) does not adequately measure unpaid labor predominantly performed by women, such as housework, childcare, and eldercare.[90][91] Feminist economists have also challenged and exposed the rhetorical approach of mainstream economics.[92] They have made critiques of many basic assumptions of mainstream economics, including the Homo economicus model.[93] In the Houseworker's Handbook Betsy Warrior presents a cogent argument that the reproduction and domestic labor of women form the foundation of economic survival; although, unremunerated and not included in the GDP.[94] According to Warrior: Economics, as it's presented today, lacks any basis in reality as it leaves out the very foundation of economic life. That foundation is built on women's labor; first her reproductive labor which produces every new laborer (and the first commodity, which is mother's milk and which nurtures every new "consumer/laborer"); secondly, women's labor composed of cleaning, cooking, negotiating social stability and nurturing, which prepares for market and maintains each laborer. This constitutes women's continuing industry enabling laborers to occupy every position in the work force. Without this fundamental labor and commodity there would be no economic activity. Warrior also notes that the unacknowledged income of men from illegal activities like arms, drugs and human trafficking, political graft, religious emoluments and various other undisclosed activities provide a rich revenue stream to men, which further invalidates GDP figures.[94] Even in underground economies where women predominate numerically, like trafficking in humans, prostitution and domestic servitude, only a tiny fraction of the pimp's revenue filters down to the women and children he deploys. Usually the amount spent on them is merely for the maintenance of their lives and, in the case of those prostituted, some money may be spent on clothing and such accouterments as will make them more salable to the pimp's clients. For instance, focusing on just the U.S., according to a government sponsored report by the Urban Institute in 2014, "A street prostitute in Dallas may make as little as $5 per sex act. But pimps can take in $33,000 a week in Atlanta, where the sex business brings in an estimated $290 million per year."[95] Proponents of this theory have been instrumental in creating alternative models, such as the capability approach and incorporating gender into the analysis of economic data to affect policy. Marilyn Power suggests that feminist economic methodology can be broken down into five categories.[96] |

経済 主な記事 フェミニスト経済学批判、フェミニスト経済学 フェミニスト経済学とは、広義には、フェミニストの洞察と批評を経済学に適用する経済学の発展途上の一分野を指す。しかし、ここ数十年、例えば『誰がアダ ム・スミスの夕食を作ったのか』の著者であるカトリーヌ・マルサルのようなフェミニストも経済学批判を取り上げている[88]。主流の経済学的手法を十分 に研究されていない「女性の」分野に適用することから、主流の経済学が生殖部門をどのように評価しているかを問うこと、経済認識論や方法論に対する深く哲 学的な批判まで、様々なレベルでフェミニズムと経済学の関係についての議論を包含している[89]。 フェミニスト経済学者が調査する顕著な問題のひとつは、国内総生産(GDP)が家事、育児、高齢者介護といった女性が主に行う無償労働をいかに適切に測定 していないかということである[90][91]。 [彼らはホモ・エコノミクス・モデルを含む主流派経済学の多くの基本的前提に対して批判を行っている: 今日提示されている経済学は、経済生活の根幹を置き去りにしているため、現実には何の根拠もない。その基盤は女性の労働の上に築かれている。第一に、すべ ての新しい労働者を生み出す女性の生殖労働(そして、すべての新しい「消費者/労働者」を育む母乳という最初の商品)、第二に、市場投入の準備をし、各労 働者を維持する、掃除、料理、社会的安定の交渉、養育からなる女性の労働である。これは、労働者が労働力のあらゆる地位を占めることを可能にする、女性の 継続的な産業を構成している。この基本的な労働と商品がなければ、経済活動は成り立たない。 ウォリアーはまた、武器、麻薬、人身売買のような違法活動、政治的接待、宗教的報酬、その他さまざまな非公開活動から得られる男性の知られざる収入が、男 性に豊かな収入源を提供し、GDPの数字をさらに無効にしていると指摘する[94]。人身売買、売春、家事奴隷のような、女性が多数を占める地下経済にお いてさえ、ポン引きの収入のごく一部しか、ポン引きが派遣する女性や子どもには行き渡らない。通常、彼女たちに費やされる金額は、単に彼女たちの生活を維 持するためのものであり、売春させられている人々の場合、ポン引きの顧客にとってより売り物になるような衣服や装飾品にいくらかのお金が費やされることも ある。例えば、2014年のアーバン・インスティテュートによる政府主催の報告書によれば、「ダラスの路上売春婦は、1回の性行為で5ドルしか稼げないか もしれない。しかし、アトランタではポン引きが週に3万3,000ドルを手にすることができ、セックスビジネスが年間2億9,000万ドルをもたらすと推 定されている」[95]。 この理論の支持者たちは、ケイパビリティ・アプローチのような代替モデルを生み出したり、政策に影響を与えるために経済データの分析にジェンダーを取り入 れたりすることに尽力してきた。マリリン・パワーは、フェミニストの経済学的方法論は5つのカテゴリーに分けることができると提案している[96]。 |

| Legal theory Main article: Feminist legal theory Feminist legal theory is based on the feminist view that law's treatment of women in relation to men has not been equal or fair. The goals of feminist legal theory, as defined by leading theorist Clare Dalton, consist of understanding and exploring the female experience, figuring out if law and institutions oppose females, and figuring out what changes can be committed to. This is to be accomplished through studying the connections between the law and gender as well as applying feminist analysis to concrete areas of law.[97][98][99] Feminist legal theory stems from the inadequacy of the current structure to account for discrimination women face, especially discrimination based on multiple, intersecting identities. Kimberlé Crenshaw's work is central to feminist legal theory, particularly her article Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics. DeGraffenreid v General Motors is an example of such a case. In this instance, the court ruled the plaintiffs, five Black women including Emma DeGraffenreid, who were employees of General Motors, were not eligible to file a complaint on the grounds they, as black women, were not "a special class to be protected from discrimination".[100] The ruling in DeGraffenreid against the plaintiff revealed the courts inability to understand intersectionality's role in discrimination.[100] Moore v Hughes Helicopters, Inc. is another ruling, which serves to reify the persistent discrediting of intersectionality as a factor in discrimination. In the case of Moore, the plaintiff brought forth statistical evidence revealing a disparity in promotions to upper-level and supervisory jobs between men and women and, to a lesser extent, between Black and white men.[100] Ultimately, the court denied the plaintiff the ability to represent all Blacks and all females.[100] The decision dwindled the pool of statistical information the plaintiff could pull from and limited the evidence only to that of Black women, which is a ruling in direct contradiction to DeGraffenreid.[100] Further, because the plaintiff originally claimed discrimination as a Black female rather than, more generally, as a female the court stated it had concerns whether the plaintiff could "adequately represent white female employees".[100] Payne v Travenol serves as yet another example of the courts inconsistency when dealing with issues revolving around intersections of race and sex. The plaintiffs in Payne, two Black females, filed suit against Travenol on behalf of both Black men and women on the grounds the pharmaceutical plant practiced racial discrimination.[100] The court ruled the plaintiffs could not adequately represent Black males; however, they did allow the admittance of statistical evidence, which was inclusive of all Black employees.[100] Despite the more favorable outcome after it was found there was extensive racial discrimination, the courts decided the benefits of the ruling – back pay and constructive seniority – would not be extended to Black males employed by the company.[100] Moore contends Black women cannot adequately represent white women on issues of sex discrimination, Payne suggests Black women cannot adequately represent Black men on issues of race discrimination, and DeGraffenreid argues Black women are not a special class to be protected. The rulings, when connected, display a deep-rooted problem in regards to addressing discrimination within the legal system. These cases, although they are outdated are used by feminists as evidence of their ideas and principles. |

法理論 主な記事 フェミニスト法理論 フェミニスト法理論は、男性に対する法の女性の扱いは平等でも公平でもないというフェミニストの見解に基づいている。代表的な理論家であるクレア・ダルト ンによって定義されたフェミニスト法理論の目標は、女性の経験を理解し探求すること、法や制度が女性に反対しているかどうかを見極めること、そしてどのよ うな変革にコミットできるかを見極めることである。これは、法とジェンダーのつながりを研究するとともに、法の具体的な領域にフェミニスト分析を適用する ことによって達成される[97][98][99]。 フェミニストの法理論は、女性が直面する差別、特に複数の交差するアイデンティティに基づく差別を説明するための現在の構造の不十分さに起因している。キ ンバーレ・クレンショーの研究はフェミニスト法理論の中心であり、特に彼女の論文「Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: 反差別ドクトリン、フェミニズム理論、反人種主義政治に対する黒人フェミニストの批評。デグラフェンレイド対ゼネラル・モーターズは、そのようなケースの 一例である。この事件で裁判所は、ゼネラル・モーターズの従業員であったエマ・デグラフェンレイドを含む5人の黒人女性である原告を、黒人女性である自分 たちは「差別から保護されるべき特別な階級」ではないという理由で、提訴する資格がないと裁定した。 [100] 原告に対するデグラフェンレイドの判決は、裁判所が差別における交差性の役割を理解していないことを明らかにした[100]。ムーア事件では、原告は統計 的証拠を提出し、上層職や監督職への昇進における男女間、そしてより少ない程度ではあるが、黒人男性と白人男性間の格差を明らかにした[100]。最終的 に、裁判所は原告に対し、すべての黒人とすべての女性を代表する能力を否定した[100]。この判決は、原告が引き出せる統計的情報のプールを減らし、証 拠を黒人女性のものだけに限定したものであり、これはデグラフェンレイドに真っ向から反する判決である。 [100]さらに、原告はもともと、より一般的な女性としてではなく黒人女性として差別を訴えていたため、裁判所は原告が「白人女性従業員を適切に代表す る」ことができるかどうか懸念していると述べた[100]。ペインの原告である黒人女性2名は、製薬工場が人種差別を行なっていたとして、黒人男女を代表 してトラベノール社を提訴した[100]。裁判所は、原告らが黒人男性を十分に代表することはできないと判断したが、黒人従業員全員を含む統計的証拠の提 出は認めた[100]。 [100]広範な人種差別があったことが判明し、より有利な結果となったにもかかわらず、裁判所は、この判決の恩恵であるバックペイと仮の年功序列は、同 社に雇用されている黒人男性には適用されないと決定した[100]。ムーアは、黒人女性は性差別の問題に関して白人女性を適切に代表することはできないと 主張し、ペインは、黒人女性は人種差別の問題に関して黒人男性を適切に代表することはできないと示唆し、デグラフェンレイドは、黒人女性は保護されるべき 特別な階級ではないと主張する。これらの判決をつなぎ合わせると、法制度における差別への対処に関して根深い問題があることがわかる。これらの判例は時代 遅れではあるが、フェミニストたちは自分たちの考えや主義主張の証拠として利用している。 |

| Communication theory Feminist communication theory has evolved over time and branches out in many directions. Early theories focused on the way that gender influenced communication and many argued that language was "man made". This view of communication promoted a "deficiency model" asserting that characteristics of speech associated with women were negative and that men "set the standard for competent interpersonal communication", which influences the type of language used by men and women. These early theories also suggested that ethnicity, cultural and economic backgrounds also needed to be addressed. They looked at how gender intersects with other identity constructs, such as class, race, and sexuality. Feminist theorists, especially those considered to be liberal feminists, began looking at issues of equality in education and employment. Other theorists addressed political oratory and public discourse. The recovery project brought to light many women orators who had been "erased or ignored as significant contributors". Feminist communication theorists also addressed how women were represented in the media and how the media "communicated ideology about women, gender, and feminism".[101][102] Feminist communication theory also encompasses access to the public sphere, whose voices are heard in that sphere, and the ways in which the field of communication studies has limited what is regarded as essential to public discourse. The recognition of a full history of women orators overlooked and disregarded by the field has effectively become an undertaking of recovery, as it establishes and honors the existence of women in history and lauds the communication by these historically significant contributors. This recovery effort, begun by Andrea Lunsford, Professor of English and Director of the Program in Writing and Rhetoric at Stanford University and followed by other feminist communication theorists also names women such as Aspasia, Diotima, and Christine de Pisan, who were likely influential in rhetorical and communication traditions in classical and medieval times, but who have been negated as serious contributors to the traditions.[102] Feminist communication theorists are also concerned with a recovery effort in attempting to explain the methods used by those with power to prohibit women like Maria W. Stewart, Sarah Moore Grimké, and Angelina Grimké, and more recently, Ella Baker and Anita Hill, from achieving a voice in political discourse and consequently being driven from the public sphere. Theorists in this vein are also interested in the unique and significant techniques of communication employed by these women and others like them to surmount some of the oppression they experienced.[102] Feminist theorist also evaluate communication expectations for students and women in the work place, in particular how the performance of feminine versus masculine styles of communicating are constructed. Judith Butler, who coined the term "gender performativity" further suggests that, "theories of communication must explain the ways individuals negotiate, resist, and transcend their identities in a highly gendered society". This focus also includes the ways women are constrained or "disciplined" in the discipline of communication in itself, in terms of biases in research styles and the "silencing" of feminist scholarship and theory.[102] Who is responsible for deciding what is considered important public discourse is also put into question by feminist theorists in communication scholarship. This lens of feminist communication theory is labeled as revalorist theory which honors the historical perspective of women in communication in an attempt to recover voices that have been historically neglected.[102] There have been many attempts to explain the lack of representative voices in the public sphere for women including, the notion that, "the public sphere is built on essentialist principles that prevent women from being seen as legitimate communicators in that sphere", and theories of subalternity", which, "under extreme conditions of oppression...prevent those in positions of power from even hearing their communicative attempts".[102] |

コミュニケーション理論 フェミニストのコミュニケーション理論は時代とともに進化し、さまざまな方向に枝分かれしている。初期の理論は、ジェンダーがコミュニケーションに与える 影響に焦点を当て、言語は「人間が作った」ものだと主張するものが多かった。このようなコミュニケーション観は「欠乏モデル」を推進し、女性に関連する話 し方の特徴は否定的であり、男性は「有能な対人コミュニケーションの基準を設定する」と主張し、それが男女が使用する言語のタイプに影響を与える。これら の初期の理論では、民族性、文化的背景、経済的背景にも対処する必要があることも示唆された。彼らはジェンダーが階級、人種、セクシュアリティといった他 のアイデンティティ構成要素とどのように交差しているかに注目した。フェミニストの理論家たち、特にリベラル・フェミニストとされる人たちは、教育や雇用 における平等の問題に目を向け始めた。他の理論家たちは、政治的な弁舌や公論を取り上げた。回復プロジェクトは、「重要な貢献者として抹殺されたり無視さ れたりしてきた」多くの女性弁士を明るみに出した。フェミニスト・コミュニケーションの理論家たちは、女性がメディアにおいてどのように表現されている か、またメディアが「女性、ジェンダー、フェミニズムに関するイデオロギーをどのように伝えているか」にも取り組んでいた[101][102]。 フェミニスト・コミュニケーション論はまた、公共圏へのアクセス、公共圏において誰の声が聞かれるのか、そしてコミュニケーション学の分野が公共的な言説 に不可欠であるとみなされているものを制限してきた方法をも包含している。この分野によって見落とされ、軽視されてきた女性弁論家の全歴史を認識すること は、歴史における女性の存在を確立し、称え、歴史的に重要な貢献者たちによるコミュニケーションを称賛することであり、事実上、回復の事業となっている。 スタンフォード大学の英語教授であり、ライティングとレトリックのプログラムのディレクターであるアンドレア・ランスフォードによって始められ、他のフェ ミニスト・コミュニケーション理論家たちによって追随されたこの回復の努力は、アスパシア、ディオティマ、クリスティーヌ・ド・ピサンといった、古典時代 や中世の修辞学やコミュニケーションの伝統に影響を与えたと思われるが、その伝統への重大な貢献者として否定されてきた女性たちの名前も挙げている [102]。 フェミニスト・コミュニケーション理論家はまた、マリア・W・スチュワート、サラ・ムーア・グリムケ、アンジェリーナ・グリムケ、そして最近ではエラ・ベ イカーやアニタ・ヒルのような女性たちが政治的言説において発言力を獲得することを禁じ、結果として公共圏から追いやられることを禁じた権力者たちによっ て用いられた方法を説明しようとする回復の努力にも関心を持っている。この系統の理論家はまた、彼女たちが経験した抑圧のいくつかを克服するために、彼女 たちや彼女たちのような他の人々が採用したユニークで重要なコミュニケーションの技法に関心を持っている[102]。 フェミニストの理論家はまた、学生や職場における女性に対するコミュニケーションへの期待、特に女性的なコミュニケーションのスタイルと男性的なコミュニ ケーションのスタイルがどのように構築されているかを評価している。ジェンダー・パフォーマティヴィティ」という言葉を作ったジュディス・バトラーはさら に、「コミュニケーションの理論は、個人が高度にジェンダー化された社会でアイデンティティを交渉し、抵抗し、超越する方法を説明しなければならない」と 提案している。この焦点はまた、研究スタイルにおける偏見や、フェミニストの学問や理論に対する「沈黙」という観点から、女性がコミュニケーションという 学問分野において制約を受けたり、「規律づけ」られたりする方法自体も含んでいる[102]。 何が重要な公共的言説とみなされるかを決定する責任が誰にあるのかも、コミュニケーション研究におけるフェミニストの理論家によって疑問視されている。 フェミニストコミュニケーション理論のこのレンズは、歴史的に無視されてきた声を回復する試みにおいて、コミュニケーションにおける女性の歴史的視点を尊 重する再評価論としてラベル付けされている[102]。 [102]公共圏における女性の代表的な声の欠如を説明するために、「公共圏は、その圏において女性が正当なコミュニケーターとみなされることを妨げる本 質主義的な原則の上に構築されている」という考え方や、「極端な抑圧状況のもとでは...権力の座にある人々が、彼女たちのコミュニケーションの試みを聞 くことさえも妨げてしまう」という「サバルタニティ」の理論など、多くの試みがなされてきた[102]。 |

| Public relations Feminist theory can be applied to the field of public relations. The feminist scholar Linda Hon examined the major obstacles that women in the field experienced. Some common barriers included male dominance and gender stereotypes. Hon shifted the feminist theory of PR from "women's assimilation into patriarchal systems " to "genuine commitment to social restructuring".[103] Similarly to the studies Hon conducted, Elizabeth Lance Toth studied Feminist Values in Public Relations.[104] Toth concluded that there is a clear link between feminist gender and feminist value. These values include honesty, sensitivity, perceptiveness, fairness, and commitment. |

パブリック・リレーションズ フェミニズム理論はパブリック・リレーションズの分野にも適用できる。フェミニスト学者のリンダ・ホンは、この分野の女性が経験した主な障害を調査した。 一般的な障害には、男性優位やジェンダーの固定観念などがあった。HonはPRのフェミニスト理論を「家父長的システムへの女性の同化」から「社会再構築 への真のコミットメント」へとシフトさせた[103]。Honが行った研究と同様に、Elizabeth Lance Tothはパブリック・リレーションズにおけるフェミニスト的価値観について研究した[104]。これらの価値観には、誠実さ、感受性、知覚力、公正さ、 コミットメントなどが含まれる。 |

| Design Technical writers[who?] have concluded that visual language can convey facts and ideas clearer than almost any other means of communication.[105] According to the feminist theory, "gender may be a factor in how human beings represent reality."[105] Men and women will construct different types of structures about the self, and, consequently, their thought processes may diverge in content and form. This division depends on the self-concept, which is an "important regulator of thoughts, feelings and actions" that "governs one's perception of reality".[106] With that being said, the self-concept has a significant effect on how men and women represent reality in different ways. Recently, "technical communicators'[who?] terms such as 'visual rhetoric,' 'visual language,' and 'document design' indicate a new awareness of the importance of visual design".[105] Deborah S. Bosley explores this new concept of the "feminist theory of design"[105] by conducting a study on a collection of undergraduate males and females who were asked to illustrate a visual, on paper, given to them in a text. Based on this study, she creates a "feminist theory of design" and connects it to technical communicators. In the results of the study, males used more angular illustrations, such as squares, rectangles and arrows, which are interpreted as a "direction" moving away from or a moving toward, thus suggesting more aggressive positions than rounded shapes, showing masculinity. Females, on the other hand, used more curved visuals, such as circles, rounded containers and bending pipes. Bosley takes into account that feminist theory offers insight into the relationship between females and circles or rounded objects. According to Bosley, studies of women and leadership indicate a preference for nonhierarchical work patterns (preferring a communication "web" rather than a communication "ladder"). Bosley explains that circles and other rounded shapes, which women chose to draw, are nonhierarchical and often used to represent inclusive, communal relationships, confirming her results that women's visual designs do have an effect on their means of communications.[undue weight? – discuss] Based on these conclusions, this "feminist theory of design" can go on to say that gender does play a role in how humans represent reality. |

デザイン テクニカルライター[who?]は、視覚的言語はほとんど他のどのコミュニケーション手段よりも明確に事実や考えを伝えることができると結論付けている [105]。フェミニスト理論によれば、「ジェンダーは人間が現実をどのように表現するかという要因であるかもしれない」[105]。 男性と女性は自己について異なるタイプの構造を構築し、その結果、彼らの思考プロセスは内容と形式において分かれるかもしれない。この区分は自己概念に依 存しており、自己概念は「思考、感情、行動の重要な調整装置」であり、「現実に対する自分の認識を支配する」ものである[106]。 とはいえ、自己概念は男女がどのように現実を異なる方法で表現するかに大きな影響を与える。 最近、「テクニカルコミュニケーターの[誰?]『視覚的修辞』、『視覚的言語』、『文書デザイン』といった用語は、視覚的デザインの重要性に対する新たな認識を示している」[105]。 デボラ・S・ボスレーは、テキストの中で与えられたビジュアルを紙の上で説明するよう求められた学部生の男女を集めて研究を行うことで、「デザインのフェ ミニズム理論」[105]というこの新しい概念を探求している。この研究に基づいて、彼女は「デザインのフェミニズム理論」を構築し、それをテクニカル・ コミュニケーターに結びつける。 その結果、男性は四角形や長方形、矢印などの角ばったイラストを多く使い、丸みを帯びた形よりも、遠ざかったり向かったりする「方向」と解釈され、より攻撃的な立場を示唆し、男性らしさを示した。 一方、女性は円や丸みを帯びた容器、曲がったパイプなど、曲線的なビジュアルを多用した。ボスレーは、フェミニズム理論が女性と円や丸みを帯びたオブジェ クトとの関係に洞察を与えることを考慮している。ボズレーによれば、女性とリーダーシップに関する研究では、非階層的な仕事のパターンを好む(コミュニ ケーションの「はしご」よりもコミュニケーションの「網」を好む)ことが示されている。ボスレーは、女性が描くことを選んだ円やその他の丸みを帯びた形は 非階層的であり、しばしば包括的で共同的な関係を表すために使われると説明し、女性の視覚的デザインがコミュニケーション手段に影響を与えるという彼女の 結果を裏付けている。 これらの結論に基づき、この「デザインのフェミニズム理論」は、人間が現実をどのように表現するかにおいて、ジェンダーが役割を果たしていると言うことができる。 |

| Black feminist criminology Black feminist criminology theory is a concept created by Hillary Potter in 2006 to act as a bridge that integrates Feminist theory with criminology. It is based on the integration of Black feminist theory and critical race feminist theory.[107] As Potter articulates this theory, Black feminist criminology describes experiences of Black women as victims of crimes. Other scholars, such as Patrina Duhaney and Geniece Crawford Mondé, have explored Black feminist criminology in relation to current and formerly incarcerated Black women.[108][109] For years, Black women were historically overlooked and disregarded in the study of crime and criminology; however, with a new focus on Black feminism that sparked in the 1980s, Black feminists began to contextualize their unique experiences and examine why the general status of Black women in the criminal justice system was lacking in female specific approaches.[110] Potter explains that because Black women usually have "limited access to adequate education and employment as consequences of racism, sexism, and classism", they are often disadvantaged. This disadvantage materializes into "poor responses by social service professionals and crime-processing agents to Black women's interpersonal victimization".[111] Most crime studies focused on White males/females and Black males. Any results or conclusions targeted to Black males were usually assumed to be the same situation for Black females. This was very problematic since Black males and Black females differ in what they experience. For instance, economic deprivation, status equality between the sexes, distinctive socialization patterns, racism, and sexism should all be taken into account between Black males and Black females. The two will experience all of these factors differently; therefore, it was crucial to resolve this dilemma. Black feminist criminology is proposed as the solution to this problem. It takes four factors into account: The social structural oppression of Black women (such as through the lens of Crenshaw's intersectionality). Nuances of Black communities and cultures. Black intimate and familial relations. The Black woman as an individual. These four factors, Potter argues, helps Black feminist criminology describe the differences between Black women's and Black men's experiences within the criminal justice system. Still, Potter urges caution, noting that, just because this theory aims to help understand and explain Black women's experiences with the criminal justice system, one cannot generalize so much that nuances in experiences are ignored. Potter writes that Black women's "individual circumstances must always be considered in conjunction with the shared experiences of these women."[107] |

黒人フェミニスト犯罪学 ブラック・フェミニスト犯罪学は、フェミニズム理論と犯罪学を統合する架け橋として、2006年にヒラリー・ポッターによって創始された概念である。それは黒人フェミニスト理論と批判的人種フェミニスト理論の統合に基づいている[107]。 ポッターがこの理論を明確にしているように、黒人フェミニスト犯罪学は、犯罪の被害者としての黒人女性の経験を記述している。Patrina DuhaneyやGeniece Crawford Mondéのような他の学者は、ブラック・フェミニスト犯罪学を現在及びかつて投獄された黒人女性との関連において探求している[108][109]。 何年もの間、黒人女性は犯罪や犯罪学の研究において歴史的に見過ごされ、軽視されてきた。しかし、1980年代に端を発した黒人フェミニズムへの新たな注 目によって、黒人フェミニストたちは彼女たちのユニークな経験を文脈化し、刑事司法制度における黒人女性の一般的な地位がなぜ女性特有のアプローチに欠け ているのかを検証し始めた[110]。 ポッターは、黒人女性は通常「人種差別、性差別、階級差別の結果として、適切な教育や雇用へのアクセスが制限されている」ため、しばしば不利な立場に置か れていると説明する。この不利な状況は、「黒人女性の対人被害に対する社会サービスの専門家や犯罪処理機関の不十分な対応」[111]として具体化する。 ほとんどの犯罪研究は、白人男性/女性と黒人男性に焦点を当てている。黒人男性を対象とした結果や結論は、通常、黒人女性も同じ状況であると仮定されてい た。黒人男性と黒人女性では経験することが異なるため、これは非常に問題であった。例えば、経済的な困窮、男女間の地位の平等、独特の社会化パターン、人 種差別、性差別などはすべて、黒人男性と黒人女性の間で考慮されなければならない。両者が経験するこれらの要因はすべて異なるため、このジレンマを解決す ることが極めて重要であった。 この問題の解決策として、黒人フェミニスト犯罪学が提唱されている。それは4つの要因を考慮に入れている: 黒人女性の社会構造的抑圧(クレンショーの交差性のレンズを通してなど)。 黒人コミュニティと文化のニュアンス 黒人の親密で家族的な関係。 個人としての黒人女性。 これら4つの要素は、ブラック・フェミニスト犯罪学が刑事司法制度における黒人女性と黒人男性の経験の違いを説明するのに役立つとポッターは主張する。そ れでもポターは、この理論が黒人女性の刑事司法制度における経験を理解し、説明するのを助けることを目的としているからといって、経験のニュアンスが無視 されるほど一般化することはできないと指摘し、注意を促している。ポターは、黒人女性の「個々の状況は常に、彼女たちが共有する経験とともに考慮されなけ ればならない」と書いている[107]。 |

| Feminist science and technology studies Main article: Feminist technoscience Feminist science and technology studies (STS) refers to the transdisciplinary field of research on the ways gender and other markers of identity intersect with technology, science, and culture. The practice emerged from feminist critique on the masculine-coded uses of technology in the fields of natural, medical, and technical sciences, and its entanglement in gender and identity.[112] A large part of feminist technoscience theory explains science and technologies to be linked and should be held accountable for the social and cultural developments resulting from both fields.[112] Some key issues feminist technoscience studies address include: The use of feminist analysis when applied to scientific ideas and practices Intersections between race, class, gender, science, and technology The implications of situated knowledges Politics of gender on how to understand agency, body, rationality, and the boundaries between nature and culture[112] |

フェミニスト科学技術研究 主な記事 フェミニスト科学技術研究 フェミニスト科学技術研究(STS)とは、ジェンダーやその他のアイデンティティの指標と技術、科学、文化との交わり方に関する学際的な研究分野のことで ある。この実践は、自然科学、医学、技術科学の分野における男性的にコード化された技術の使用、およびジェンダーとアイデンティティにおけるその絡み合い に関するフェミニスト批判から生まれた[112]。フェミニスト技術科学理論の大部分は、科学と技術が結びついており、両分野から生じる社会的・文化的発 展に対して責任を負うべきであると説明している[112]。 フェミニスト技術科学研究が取り組んでいる重要な問題には以下のようなものがある: 科学的な考え方や実践に適用される際のフェミニズム分析の使用 人種、階級、ジェンダー、科学、技術の相互作用 状況化された知識の意味 エージェンシー、身体、合理性、自然と文化の境界をどのように理解するかについてのジェンダーの政治学[112]。 |

| Ecological feminism or ecofeminism In the 1970s, the impacts of post-World War II technological development led many women to organise against issues from the toxic pollution of neighbourhoods to nuclear weapons testing on indigenous lands. This grassroots activism emerging across every continent was both intersectional and cross-cultural in its struggle to protect the conditions for reproduction of Life on Earth. Known as ecofeminism, the political relevance of this movement continues to expand. Classic statements in its literature include Carolyn Merchant, United States, The Death of Nature;[113] Maria Mies, Germany, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale;[114] Vandana Shiva, India, Staying Alive: Women Ecology and Development;[115] Ariel Salleh, Australia, Ecofeminism as Politics: nature, Marx, and the postmodern.[116] Ecofeminism involves a profound critique of Eurocentric epistemology, science, economics, and culture. It is increasingly prominent as a feminist response to the contemporary breakdown of the planetary ecosystem. |

エコロジカル・フェミニズムまたはエコフェミニズム 1970年代、第二次世界大戦後の技術開発の影響により、多くの女性が近隣の有毒物質汚染から先住民の土地での核兵器実験に至るまで、様々な問題に反対す る組織化を行った。あらゆる大陸で生まれたこの草の根運動は、地球上の生命の再生産条件を守ろうとする闘いにおいて、交差的かつ異文化的であった。エコ フェミニズムとして知られるこの運動の政治的関連性は、拡大し続けている。その文献における古典的な声明には、キャロリン・マーチャント(アメリカ)の 『自然の死』、[113] マリア・ミース(ドイツ)の『世界規模での家父長制と蓄積』、[114] ヴァンダナ・シヴァ(インド)の『Staying Alive』などがある: 114]ヴァンダナ・シヴァ(インド)『Staying Alive: Women Ecology and Development』[115]アリエル・サレー(オーストラリア)『Ecofeminism as Politics: Nature, Marx, and the Postmodern』[116]エコフェミニズムは、ヨーロッパ中心主義的な認識論、科学、経済、文化に対する深い批判を含んでいる。現代の惑星生態系 の崩壊に対するフェミニストの反応として、ますます顕著になっている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminist_theory |

★

フェミニスト理論一般

| Feminist theory

is the extension of feminism into theoretical, fictional, or

philosophical discourse. It aims to understand the nature of gender

inequality. It examines women's and men's social roles, experiences,

interests, chores, and feminist politics in a variety of fields, such

as anthropology and sociology, communication, media studies,

psychoanalysis,[1] political theory, home economics, literature,

education, and philosophy.[2] Feminist theory often focuses on analyzing gender inequality. Themes often explored in feminist theory include discrimination, objectification (especially sexual objectification), oppression, patriarchy,[3][4] stereotyping, art history[5] and contemporary art,[6][7] and aesthetics.[8][9] |

フェ

ミニズム理論とは、フェミニズムを理論的、フィクション的、哲学的言説に拡張したものである。ジェンダー不平等の本質を理解することを目的としている。人

類学や社会学、コミュニケーション、メディア研究、精神分析、[1]政治理論、家庭経済学、文学、教育学、哲学など様々な分野で、女性と男性の社会的役

割、経験、関心、家事、フェミニズム政治を検証している[2]。 フェミニズム理論はしばしばジェンダー不平等の分析に焦点を当てている。フェミニズム理論においてしばしば探求されるテーマには、差別、対象化(特に性的 対象化)、抑圧、家父長制、[3][4]ステレオタイプ、美術史[5]や現代美術、[6][7]、美学などが含まれる[8][9]。 |

| History Feminist theories first emerged as early as 1794 in publications such as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft, "The Changing Woman",[10] "Ain't I a Woman",[11] "Speech after Arrest for Illegal Voting",[12] and so on. "The Changing Woman" is a Navajo Myth that gave credit to a woman who, in the end, populated the world.[13] In 1851, Sojourner Truth addressed women's rights issues through her publication, "Ain't I a Woman". Sojourner Truth addressed the issue of women having limited rights due to men's flawed perception of women. Truth argued that if a woman of color can perform tasks that were supposedly limited to men, then any woman of any color could perform those same tasks. After her arrest for illegally voting, Susan B. Anthony gave a speech within court in which she addressed the issues of language within the constitution documented in her publication, "Speech after Arrest for Illegal voting" in 1872. Anthony questioned the authoritative principles of the constitution and its male-gendered language. She raised the question of why women are accountable to be punished under law but they cannot use the law for their own protection (women could not vote, own property, nor maintain custody of themselves in marriage). She also critiqued the constitution for its male-gendered language and questioned why women should have to abide by laws that do not specify women. Nancy Cott makes a distinction between modern feminism and its antecedents, particularly the struggle for suffrage. In the United States she places the turning point in the decades before and after women obtained the vote in 1920 (1910–1930). She argues that the prior woman movement was primarily about woman as a universal entity, whereas over this 20-year period it transformed itself into one primarily concerned with social differentiation, attentive to individuality and diversity. New issues dealt more with woman's condition as a social construct, gender identity, and relationships within and between genders. Politically, this represented a shift from an ideological alignment comfortable with the right, to one more radically associated with the left.[14] Susan Kingsley Kent says that Freudian patriarchy was responsible for the diminished profile of feminism in the inter-war years,[15] others such as Juliet Mitchell consider this to be overly simplistic since Freudian theory is not wholly incompatible with feminism.[16] Some feminist scholarship shifted away from the need to establish the origins of family, and towards analyzing the process of patriarchy.[17] In the immediate postwar period, Simone de Beauvoir stood in opposition to an image of "the woman in the home". De Beauvoir provided an existentialist dimension to feminism with the publication of Le Deuxième Sexe (The Second Sex) in 1949.[18] As the title implies, the starting point is the implicit inferiority of women, and the first question de Beauvoir asks is "what is a woman"?[19] A woman she realizes is always perceived of as the "other", "she is defined and differentiated with reference to man and not he with reference to her". In this book and her essay, "Woman: Myth & Reality", de Beauvoir anticipates Betty Friedan in seeking to demythologize the male concept of woman. "A myth invented by men to confine women to their oppressed state. For women, it is not a question of asserting themselves as women, but of becoming full-scale human beings." "One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman", or as Toril Moi puts it "a woman defines herself through the way she lives her embodied situation in the world, or in other words, through the way in which she makes something of what the world makes of her". Therefore, the woman must regain subject, to escape her defined role as "other", as a Cartesian point of departure.[20] In her examination of myth, she appears as one who does not accept any special privileges for women. Ironically, feminist philosophers have had to extract de Beauvoir herself from out of the shadow of Jean-Paul Sartre to fully appreciate her.[21] While more philosopher and novelist than activist, she did sign one of the Mouvement de Libération des Femmes manifestos. The resurgence of feminist activism in the late 1960s was accompanied by an emerging literature of concerns for the earth and spirituality, and environmentalism. This, in turn, created an atmosphere conducive to reigniting the study of and debate on matricentricity, as a rejection of determinism, such as Adrienne Rich[22] and Marilyn French[23] while for socialist feminists like Evelyn Reed,[24] patriarchy held the properties of capitalism. Feminist psychologists, such as Jean Baker Miller, sought to bring a feminist analysis to previous psychological theories, proving that "there was nothing wrong with women, but rather with the way modern culture viewed them".[25] Elaine Showalter describes the development of feminist theory as having a number of phases. The first she calls "feminist critique" – where the feminist reader examines the ideologies behind literary phenomena. The second Showalter calls "Gynocritics" – where the "woman is producer of textual meaning" including "the psychodynamics of female creativity; linguistics and the problem of a female language; the trajectory of the individual or collective female literary career and literary history". The last phase she calls "gender theory" – where the "ideological inscription and the literary effects of the sex/gender system" are explored".[26] This model has been criticized by Toril Moi who sees it as an essentialist and deterministic model for female subjectivity. She also criticized it for not taking account of the situation for women outside the west.[27] From the 1970s onwards, psychoanalytical ideas that have been arising in the field of French feminism have gained a decisive influence on feminist theory. Feminist psychoanalysis deconstructed the phallic hypotheses regarding the Unconscious. Julia Kristeva, Bracha Ettinger and Luce Irigaray developed specific notions concerning unconscious sexual difference, the feminine, and motherhood, with wide implications for film and literature analysis.[28] In the 1990s and the first decades of the 21st century, intersectionality played a major role in feminist theory, leading to the development of transfeminism and queer feminism and the consolidation of Black, anti-racist and postcolonial feminisms, among others.[29] The rise of the fourth wave in the 2010s led to new discussions on sexual violence, consent and body positivity, as well as a deepening of intersectional perspectives.[30][31][32] Simultaneously, feminist philosophy and anthropology saw a rise in new materialist, affect-oriented, posthumanist and ecofeminist perspectives.[33][34][35][36] |

歴史 フェミニズムの理論が最初に登場したのは1794年のことで、メアリー・ウルストンクラフトによる『A Vindication of the Rights of Woman』、『The Changing Woman』[10]、『Ain't I a Woman』[11]、『Speech after Arrest for Illegal Voting』[12]などの出版物がある。「1851年、ソジャーナー・トゥルースは "Ain't I a Woman "を出版し、女性の権利問題に取り組んだ。ソジャーナー・トゥルースは、男性の女性に対する欠陥認識のために女性の権利が制限されているという問題を取り 上げた。トゥルースは、もし有色人種の女性が、本来男性に限定されるはずの仕事をこなせるのであれば、どんな有色人種の女性でも同じ仕事をこなせるはずだ と主張した。スーザン・B・アンソニーは不法投票により逮捕された後、法廷内でスピーチを行い、1872年に出版された『Speech after Arrest for Illegal voting(不法投票による逮捕後のスピーチ)』に記されている憲法内の言葉の問題を取り上げた。アンソニーは、憲法の権威ある原則とその男性差別的な 表現に疑問を呈した。彼女は、なぜ女性には法の下で処罰される責任があるのに、自分たちを守るために法を利用できないのか(女性は選挙権も、財産も、結婚 して親権を維持することもできない)という疑問を提起した。彼女はまた、憲法が男性性差別的な表現をしていることを批判し、なぜ女性が女性を特定しない法 律に従わなければならないのかと疑問を呈した。 ナンシー・コットは、現代のフェミニズムとその前身、特に参政権闘争とを区別している。アメリカでは、1920年に女性が参政権を獲得する前後の数十年間 (1910年〜1930年)がターニングポイントとなる。それ以前の女性運動は、主として普遍的な存在としての女性に関するものであったのに対し、この 20年の間に、女性運動は、主として社会的分化に関係し、個性と多様性に配慮するものへと変化したと彼女は主張する。新たな問題は、社会的構築物としての 女性の状態、ジェンダー・アイデンティティ、ジェンダー内およびジェンダー間の関係をより多く扱うものであった。政治的には、これは右派になじむイデオロ ギー的な調整から、左派とより根本的に結びついたものへの転換を意味していた[14]。 スーザン・キングスレー・ケントは、フロイトの家父長制が戦間期におけるフェミニズムの知名度を低下させた原因であると述べているが[15]、ジュリエッ ト・ミッチェルのような他の者は、フロイトの理論はフェミニズムと完全に相容れないものではないため、これは単純化しすぎていると考えている。 [16]一部のフェミニズムの研究は、家族の起源を確立する必要性から離れ、家父長制のプロセスを分析する方向へとシフトしていった[17]。ド・ボー ヴォワールは1949年に『第二の性』を出版し、フェミニズムに実存主義的な側面を提供した[18]。タイトルが暗示するように、出発点は女性の暗黙の劣 等性であり、ド・ボーヴォワールが最初に問うのは「女性とは何か」である[19]。本書とエッセイ『女: 神話と現実 "において、ド・ボーヴォワールはベティ・フリーダンを先取りして、男性の女性概念を脱神話化しようとしている。「女性を抑圧された状態に閉じ込めるため に男性が作り出した神話。女性にとっては、女性として自己主張することではなく、一人前の人間になることが問題なのです」。「トリル・モワが言うように、 "女性は、世界における自分の身体化された状況の生き方を通して、言い換えれば、世界が彼女を作るものから何かを作る方法を通して、自分自身を定義する "。したがって、女性は、デカルト的出発点として、「他者」としての規定された役割から逃れるために、主体を取り戻さなければならない[20]。神話につ いての考察において、彼女は、女性の特別な特権を一切認めない者として登場する。皮肉なことに、フェミニストの哲学者たちは、ド・ボーヴォワールを十分に 評価するために、ジャン=ポール・サルトルの影からド・ボーヴォワール自身を引き出さなければならなかった[21]。活動家というよりは哲学者であり小説 家であったが、彼女は女性解放運動マニフェストのひとつに署名している。 1960年代後半におけるフェミニズム活動の復活は、地球や精神性、環境主義への懸念という新たな文学の台頭を伴っていた。このことは、アドリアン・リッ チ[22]やマリリン・フレンチ[23]のような決定論の拒絶としての母性中心性についての研究や議論を再燃させ、一方でエヴリン・リード[24]のよう な社会主義フェミニストにとっては家父長制が資本主義の特性を保持しているという雰囲気を作り出した。ジーン・ベイカー・ミラーなどのフェミニスト心理学 者は、それまでの心理学理論にフェミニスト的な分析を加え、「女性には何の問題もなく、むしろ近代文化の捉え方に問題があった」ことを証明しようとした [25]。 エレイン・ショウォルターは、フェミニズム理論の発展にはいくつかの段階があると述べている。最初の段階を彼女は「フェミニズム批評」と呼び、そこでは フェミニストの読者が文学現象の背後にあるイデオロギーを検証する。第二の段階は「女性批評」と呼ばれるもので、「女性がテクストの意味を生み出す」もの であり、「女性の創造性の心理力学、言語学と女性言語の問題、個人的あるいは集団的な女性の文学的キャリアの軌跡と文学史」などが含まれる。最後の段階を 彼女は「ジェンダー論」と呼び、そこでは「性/ジェンダー・システムのイデオロギー的刻印と文学的効果」が探求される。1970年代以降、フランスのフェ ミニズムの分野で生まれた精神分析の考え方は、フェミニズム理論に決定的な影響を与えた。フェミニスト精神分析は、無意識に関する男根仮説を解体した。 ジュリア・クリステヴァ、ブラシャ・エッティンガー、ルーチェ・イリガライは、無意識の性的差異、女性性、母性に関する特定の概念を発展させ、映画や文学 の分析に広く影響を与えた[28]。 1990年代と21世紀の最初の数十年間において、交差性はフェミニズム理論において主要な役割を果たし、トランスフェミニズムやクィア・フェミニズムの 発展や黒人フェミニズム、反人種主義フェミニズム、ポストコロニアル・フェミニズムなどの統合につながった。 [29]2010年代の第4の波の台頭は、性的暴力、同意、ボディポジティブに関する新たな議論や、交差性の視点の深化につながった[30][31] [32]。同時にフェミニズム哲学や人類学では、新しい唯物論、影響志向、ポストヒューマニズム、エコフェミニズムの視点が台頭した[33][34] [35][36]。 |

| Disciplines See also: Feminist movements and ideologies There are a number of distinct feminist disciplines, in which experts in other areas apply feminist techniques and principles to their own fields. Additionally, these are also debates which shape feminist theory and they can be applied interchangeably in the arguments of feminist theorists. |

ディシプリン(個々のものは上掲「フェミニスト理論の理論装置とディシプリン」に記載) こちらもご覧ください: フェミニズム運動とイデオロギー 他の分野の専門家が、フェミニズムの技術や原則を自分の分野に適用する、明確なフェミニズムの学問分野が数多く存在する。さらに、これらはフェミニズム理論を形成する議論でもあり、フェミニストの理論家の議論に互換的に適用されることもある。 |

| Anarcha-feminism Antifeminism Atheist feminism Chicana feminism Christian feminism Conflict theories Conservative feminism Cultural feminism Difference feminism Equality feminism Feminism and modern architecture Fat feminism Feminist anthropology Feminist sociology First-wave feminism Fourth-wave feminism French feminism Gender equality Global feminism Hermeneutics of feminism in Islam Hip-hop feminism Indigenous feminism Individualist feminism Islamic feminism Jewish feminism Lesbian feminism Lipstick feminism Liberal feminism Material feminism Marxist feminism Networked feminism Neofeminism New feminism Postcolonial feminism Postmodern feminism Post-structural feminism Pro-feminism Pro-life feminism Radical feminism Rape culture Separatist feminism Second-wave feminism Sex-positive feminism Sikh feminism Socialist feminism Standpoint feminism State feminism Structuralist feminism Third-wave feminism Transfeminism Transnational feminism |

アナーカ・フェミニズム 反フェミニズム 無神論的フェミニズム チカーナ・フェミニズム キリスト教フェミニズム 対立理論 保守フェミニズム 文化的フェミニズム 差異フェミニズム 平等フェミニズム フェミニズムと近代建築 ファット・フェミニズム フェミニスト人類学 フェミニスト社会学 第一波フェミニズム 第四波フェミニズム フランスのフェミニズム ジェンダー平等 グローバル・フェミニズム イスラームにおけるフェミニズムの解釈学 ヒップホップフェミニズム 先住民フェミニズム 個人主義フェミニズム イスラム・フェミニズム ユダヤ教フェミニズム レズビアン・フェミニズム リップスティック・フェミニズム リベラル・フェミニズム マテリアル・フェミニズム マルクス主義フェミニズム ネットワーク・フェミニズム ネオフェミニズム ニューフェミニズム ポストコロニアル・フェミニズム ポストモダンフェミニズム ポスト構造フェミニズム プロフェミニズム プロライフフェミニズム ラディカル・フェミニズム レイプ文化 分離主義フェミニズム 第二波フェミニズム セックス・ポジティブ・フェミニズム シーク・フェミニズム 社会主義フェミニズム 立場主義フェミニズム 国家フェミニズム 構造主義フェミニズム 第三波フェミニズム トランスフェミニズム トランスナショナル・フェミニズム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminist_theory |

|

| "Lexicon

of Debates". Feminist Theory: A Reader. 2nd Ed. Edited by Kolmar, Wendy

and Bartowski, Frances. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005. 42–60. |

「議論の語彙」。フェミニズム理論: A Reader. 第2版。Kolmar, Wendy and Bartowski, Frances編。New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005. 42-60. |

| Evolutionary Feminism Feminist theory website (Center for Digital Discourse and Culture, Virginia Tech) Feminist Theories and Anthropology by Heidi Armbruster The Radical Women Manifesto: Socialist Feminist Theory, Program and Organizational Structure (Seattle: Red Letter Press, 2001) Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women, Brown University Feminist Theory Archive, Brown University The Feminist eZine – An Archive of Historical Feminist Articles Women, Poverty, and Economics- Facts and Figures (archived 3 November 2013) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminist_theory |

進化論的フェミニズム フェミニズム理論のウェブサイト(バージニア工科大学デジタル言説文化センター) ハイディ・アームブルスター著『フェミニズム理論と人類学 ラディカル・ウーマン・マニフェスト 社会主義フェミニストの理論、プログラム、組織構造(シアトル:レッド・レター・プレス、2001年) ブラウン大学女性教育研究ペンブロークセンター ブラウン大学フェミニズム理論アーカイブ The Feminist eZine - 歴史的フェミニスト記事のアーカイブ 女性、貧困、経済-事実と数字 (2013年11月3日アーカイブ) |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆