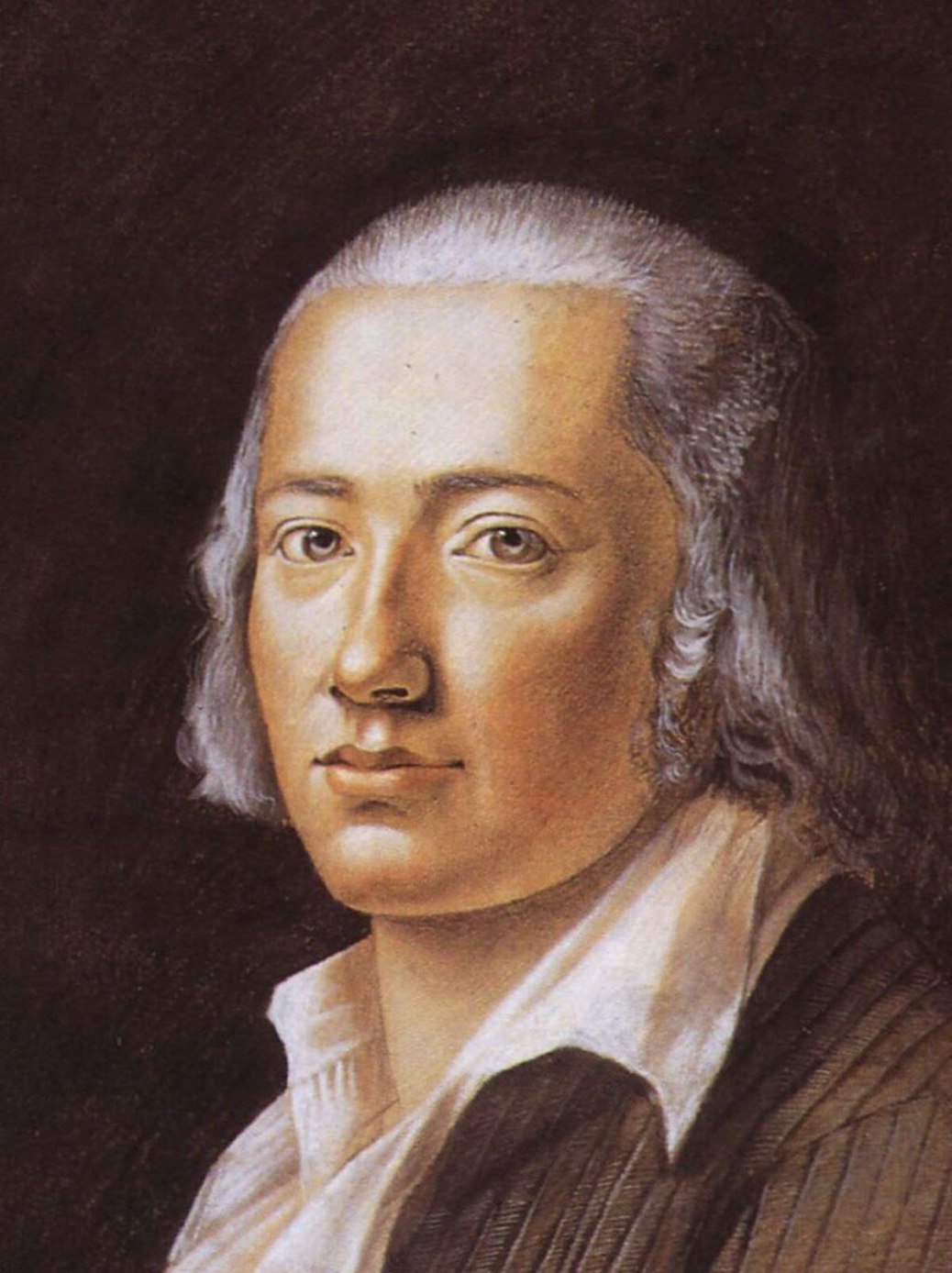

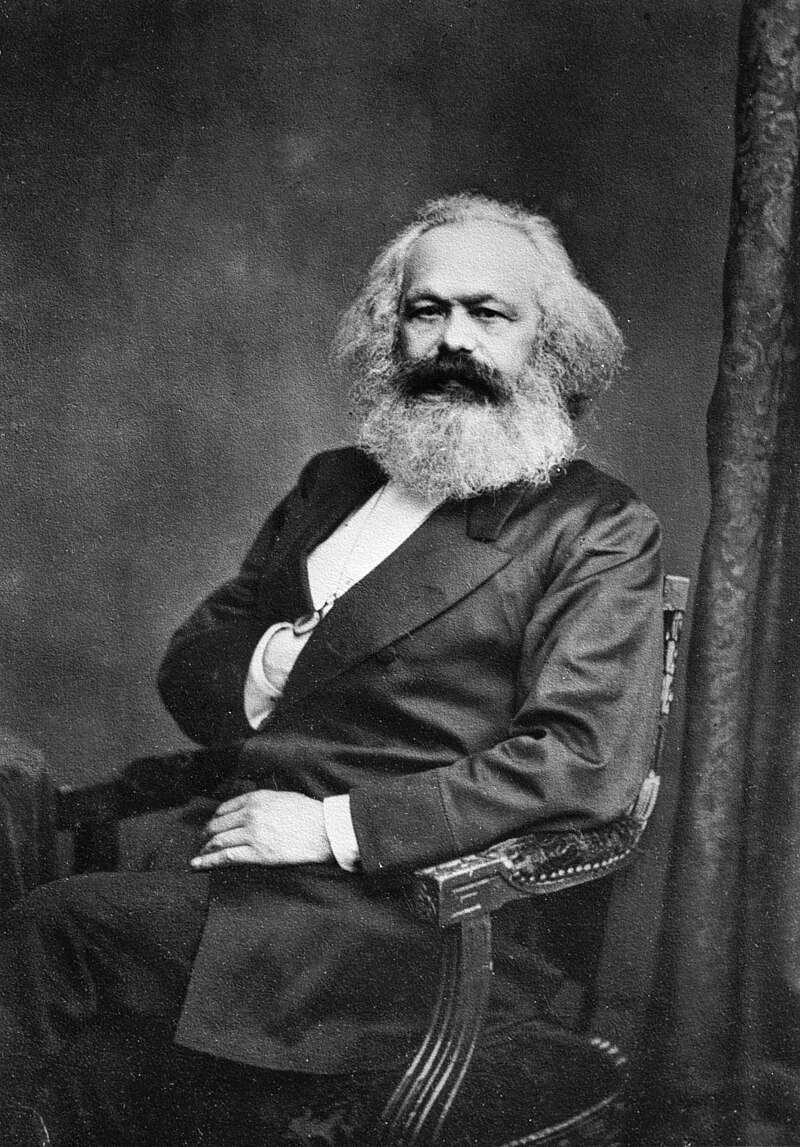

ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

1831

Schlesinger Philosoph Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel anagoria

☆

ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル[a](1770年8月27日 -

1831年11月14日)は、ドイツの哲学者であり、ドイツ観念論および19世紀の哲学に最も影響を与えた人物の一人である。彼の影響力は、認識論や存在

論における形而上学的な問題から、政治哲学、歴史哲学、芸術哲学、宗教哲学、哲学史に至るまで、現代の哲学のトピックのあらゆる分野に及んでいる。

☆1770 年に神聖ローマ帝国シュトゥットガルトで生まれたヘーゲルは、ヨーロッパのゲルマン地域における啓蒙思想とロマン主義の過渡期に生まれ、フランス 革命やナポレオン戦争を経験し、その影響を受けた。彼の名声は主に『精神現象学』、『(大)論理学』、歴史に関する目的論的考察、そして『哲学科学の百科 事典(エンチクロペディ)』 のテーマに関するベルリン大学での講義に基づいている(→「ヘーゲル年譜」)。

☆ ヘーゲルは、その著作全体を通じて、カント主義をはじめとする近代哲学の抱える問題のある二元論を論じ、修正しようと努めた。その際、古代哲学、特にアリ ストテレスの知見を活用することが多かった。ヘーゲルは、理性と自由は歴史的な達成であり、自然に与えられたものではないと、いたるところで主張してい る。ヘーゲルの弁証法的思索の手法は内在性の原則、すなわち主張を常にその内部基準に従って評価するという原則に基づいている。懐疑論を真剣に受け止め、 ヘーゲルは経験の試練を経ていない真理など存在し得ないとし、論理学におけるア・プリオリなカテゴリーでさえも、自然界や人類の歴史的功績において「検 証」されなければならないと主張した。

☆

デルフィの神託「汝自身を知れ」の命題に導かれ、ヘーゲルは《自由な自己決定》を人類の本質として提示する。これは1806年から1807年にかけて執筆

され

た『精神現象学』の結論であり、ヘーゲルは後の『百科

事典(エンチクロペディ)』において、論理、自然、精神の相互依存関係を体系的に説明することで、この結論をさらに裏付けたと

主張している。彼は、論理は物質と精神の二元論を同時に保存し克服する、つまり、自然と文化の領域を特徴づける連続性と異なる性質の両方を説明する、形而

上学的に必要かつ首尾一貫した「同一性と非同一性の同一性」であると主張している。

| Georg

Wilhelm

Friedrich Hegel[a] (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German

philosopher and one of the most influential figures of German idealism

and 19th-century philosophy. His influence extends across the entire

range of contemporary philosophical topics, from metaphysical issues in

epistemology and ontology, to political philosophy, the philosophy of

history, philosophy of art, philosophy of religion, and the history of

philosophy. Born in 1770 in Stuttgart, Holy Roman Empire, during the transitional period between the Enlightenment and the Romantic movement in the Germanic regions of Europe, Hegel lived through and was influenced by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars. His fame rests chiefly upon The Phenomenology of Spirit, The Science of Logic, his teleological account of history, and his lectures at the University of Berlin on topics from his Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences. Throughout his work, Hegel strove to address and correct the problematic dualisms of modern philosophy, Kantian and otherwise, typically by drawing upon the resources of ancient philosophy, particularly Aristotle. Hegel everywhere insists that reason and freedom are historical achievements, not natural givens. His dialectical-speculative procedure is grounded in the principle of immanence, that is, in assessing claims always according to their own internal criteria. Taking skepticism seriously, he contends that people cannot presume any truths that have not passed the test of experience; even the a priori categories of the Logic must attain their "verification" in the natural world and the historical accomplishments of humankind. Guided by the Delphic imperative to "know thyself", Hegel presents free self-determination as the essence of humankind – a conclusion from his 1806–07 Phenomenology that he claims is further verified by the systematic account of the interdependence of logic, nature, and spirit in his later Encyclopedia. He asserts that the Logic at once preserves and overcomes the dualisms of the material and the mental – that is, it accounts for both the continuity and difference marking the domains of nature and culture – as a metaphysically necessary and coherent "identity of identity and non-identity". |

ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル[a](1770年8

月27日 -

1831年11月14日)は、ドイツの哲学者であり、ドイツ観念論および19世紀の哲学に最も影響を与えた人物の一人である。彼の影響力は、認識論や存在

論における形而上学的な問題から、政治哲学、歴史哲学、芸術哲学、宗教哲学、哲学史に至るまで、現代の哲学のトピックのあらゆる分野に及んでいる。 1770年に神聖ローマ帝国シュトゥットガルトで生まれたヘーゲルは、ヨーロッパのゲルマン地域における啓蒙思想とロマン主義の過渡期に生まれ、フランス 革命やナポレオン戦争を経験し、その影響を受けた。彼の名声は主に『精神現象学』、『論理学』、歴史に関する目的論的考察、そして『哲学科学の百科事典』 のテーマに関するベルリン大学での講義に基づいている。 ヘーゲルは、その著作全体を通じて、カント主義をはじめとする近代哲学の抱える問題のある二元論を論じ、修正しようと努めた。その際、古代哲学、特にアリ ストテレスの知見を活用することが多かった。ヘーゲルは、理性と自由は歴史的な達成であり、自然に与えられたものではないと、いたるところで主張してい る。ヘーゲルの弁証法的思索の手法は内在性の原則、すなわち主張を常にその内部基準に従って評価するという原則に基づいている。懐疑論を真剣に受け止め、 ヘーゲルは経験の試練を経ていない真理など存在し得ないとし、論理学におけるア・プリオリなカテゴリーでさえも、自然界や人類の歴史的功績において「検 証」されなければならないと主張した。 デルフィの神託「汝自身を知れ」の命題に導かれ、ヘーゲルは自由な自己決定を人類の本質として提示する。これは1806年から1807年にかけて執筆され た『現象学』の結論であり、ヘーゲルは後の『百科全書』において、論理、自然、精神の相互依存関係を体系的に説明することで、この結論をさらに裏付けたと 主張している。彼は、論理は物質と精神の二元論を同時に保存し克服する、つまり、自然と文化の領域を特徴づける連続性と異なる性質の両方を説明する、形而 上学的に必要かつ首尾一貫した「同一性と非同一性の同一性」であると主張している。 |

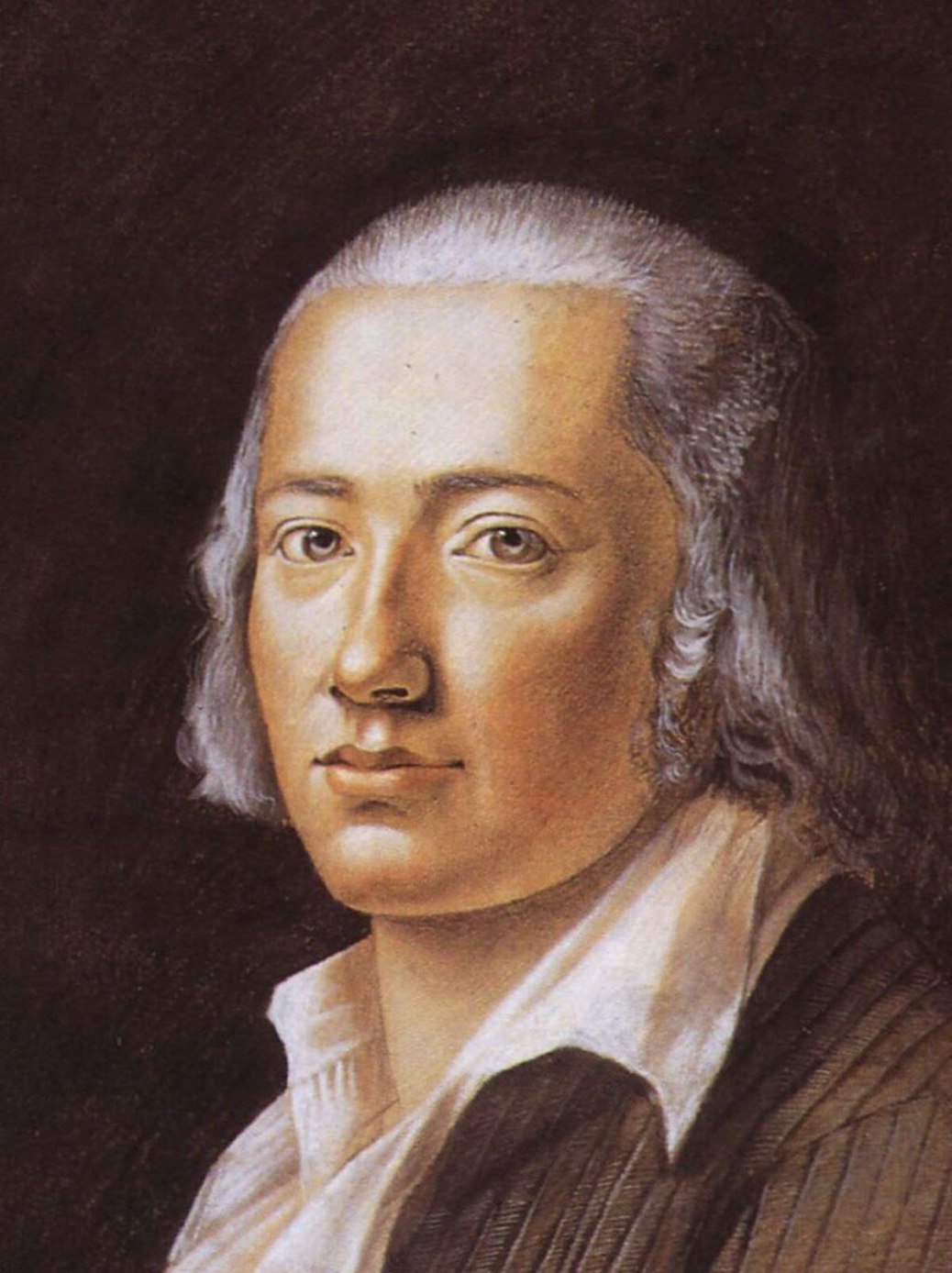

| Life Formative years Stuttgart, Tübingen, Berne, Frankfurt (1770–1800)  The birthplace of Hegel in Stuttgart, which now houses the Hegel Museum Hegel was born on 27 August 1770 in Stuttgart, capital of the Duchy of Württemberg in the Holy Roman Empire (now southwestern Germany). Christened Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, he was known as Wilhelm to his close family. His father, Georg Ludwig Hegel (1733–1799), was secretary to the revenue office at the court of Karl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg.[4][5] Hegel's mother, Maria Magdalena Louisa Hegel, née Fromm (1741–1783), was the daughter of a lawyer at the High Court of Justice at the Württemberg court Ludwig Albrecht Fromm (1696–1758). She died of bilious fever when Hegel was thirteen. Hegel and his father also caught the disease but narrowly survived.[6] Hegel had a sister, Chistiane Luise [de] (1773–1832); and a brother, Georg Ludwig (1776–1812), who perished as an officer during Napoleon's 1812 Russian campaign. At the age of three, Hegel went to the German School. When he entered the Latin School two years later, he already knew the first declension, having been taught it by his mother.[7]: 4 In 1776, he entered Stuttgart's Eberhard-Ludwigs-Gymnasium and during his adolescence read voraciously, copying lengthy extracts in his diary. Authors he read include the poet Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock and writers associated with the Enlightenment, such as Christian Garve and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. In 1844, Hegel's first biographer, Karl Rosenkranz described the young Hegel's education there by saying that it "belonged entirely to the Enlightenment with respect to principle, and entirely to classical antiquity with respect to curriculum."[8] His studies at the Gymnasium concluded with his graduation speech, "The abortive state of art and scholarship in Turkey."[9]  Hegel, Schelling, and Hölderlin are believed to have shared the room on the second floor above the entrance doorway while studying at this institute – (a Protestant seminary called "the Tübinger Stift"). At the age of eighteen, Hegel entered the Tübinger Stift, a Protestant seminary attached to the University of Tübingen, where he had as roommates the poet and philosopher Friedrich Hölderlin and the future philosopher Friedrich Schelling.[10][5][11] Sharing a dislike for what they regarded as the restrictive environment of the Seminary, the three became close friends and mutually influenced each other's ideas. (It is mostly likely that Hegel attended the Stift because it was state-funded, for he had "a profound distaste for the study of orthodox theology" and never wanted to become a minister.[12]) All three greatly admired Hellenic civilization, and Hegel additionally steeped himself in Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Lessing during this time.[13] They watched the unfolding of the French Revolution with shared enthusiasm.[5] Although the violence of the 1793 Reign of Terror dampened Hegel's hopes, he continued to identify with the moderate Girondin faction and never lost his commitment to the principles of 1789, which he expressed by drinking a toast to the storming of the Bastille every fourteenth of July.[14][15] Schelling and Hölderlin immersed themselves in theoretical debates on Kantian philosophy, from which Hegel remained aloof.[16] Hegel, at this time, envisaged his future as that of a Popularphilosoph (a "man of letters") who serves to make the abstruse ideas of philosophers accessible to a wider public; his own felt need to engage critically with the central ideas of Kantianism would not come until 1800.[17]  The poet Friedrich Hölderlin (1770–1843) was one of Hegel's closest friends and roommates at Tübinger Stift. Having received his theological certificate from the Tübingen Seminary, Hegel became Hofmeister (house tutor) to an aristocratic family in Berne (1793–1796).[18][5][11] During this period, he composed the text which has become known as the Life of Jesus and a book-length manuscript titled "The Positivity of the Christian Religion." His relations with his employers becoming strained, Hegel accepted an offer mediated by Hölderlin to take up a similar position with a wine merchant's family in Frankfurt in 1797. There, Hölderlin exerted an important influence on Hegel's thought.[19] In Berne, Hegel's writings had been sharply critical of orthodox Christianity, but in Frankfurt, under the influence of early Romanticism, he underwent a sort of reversal, exploring, in particular, the mystical experience of love as the true essence of religion.[20] Also in 1797, the unpublished and unsigned manuscript of "The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism" was written. It was written in Hegel's hand, but may have been authored by Hegel, Schelling, or Hölderlin.[21] While in Frankfurt, Hegel composed the essay "Fragments on Religion and Love."[22] In 1799, he wrote another essay titled "The Spirit of Christianity and Its Fate", unpublished during his lifetime.[5] |

人生 形成期 シュトゥットガルト、テュービンゲン、ベルン、フランクフルト(1770年~1800年  ヘーゲルの生誕地であるシュトゥットガルトには現在、ヘーゲル博物館がある ヘーゲルは1770年8月27日、神聖ローマ帝国(現在の南西ドイツ)のヴュルテンベルク公国の首都シュトゥットガルトで生まれた。洗礼名はゲオルク・ ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒで、親しい家族の間ではヴィルヘルムと呼ばれていた。父ゲオルク・ルートヴィヒ・ヘーゲル(1733年 - 1799年)は、ヴュルテンベルク公爵カール・オイゲンの宮廷の歳入事務所の秘書であった。[4][5] ヘーゲルの母マリア・マグダレーナ・ルイーザ・ヘーゲル(旧姓フロム、1741年 - 1783年)は、ヴュルテンベルク宮廷の高等裁判所の弁護士ルートヴィヒ・アルブレヒト・フロム(1696年 - 1758年)の娘であった。彼女はヘーゲルが13歳の時に黄疸熱で死去した。ヘーゲルと父親もこの病気にかかったが、辛うじて一命を取り留めた。ヘーゲル にはクリスティアーネ・ルイーゼ(1773年 - 1832年)という妹と、ゲオルク・ルートヴィヒ(1776年 - 1812年)という弟がいた。ゲオルクはナポレオンの1812年ロシア戦役で士官として戦死した。3歳でヘーゲルはドイツ学校に入学した。2年後にラテン 学校に入学したときには、すでに最初の語形変化を習得しており、それは母親から教わったものだった。[7]:4 1776年、彼はシュトゥットガルトのエバーハルト・ルートヴィヒ・ギムナジウムに入学し、思春期には熱心に読書し、日記に長文の抜粋を書き写していた。 彼が読んだ作家には、詩人のフリードリヒ・ゴットリープ・クロプシュトックや、啓蒙主義の作家であるクリスティアン・ガーベやゴットホルト・エフライム・ レッシングなどが含まれる。1844年、ヘーゲルの最初の伝記を書いたカール・ローゼンクランツは、若いヘーゲルの教育について「理念に関しては啓蒙主義 に、カリキュラムに関しては古典古代に完全に属する」と述べている。[8] ギムナジウムでの彼の研究は、卒業スピーチ「トルコにおける芸術と学問の未熟な状態」で締めくくられた。[9]  ヘーゲル、シェリング、そしてヘルダーリンは、この教育機関(「テュービンゲン・シュティフト」と呼ばれるプロテスタント神学校)で学んでいた当時、入り 口のドアの上にある2階の部屋を共有していたとされている。 18歳のとき、ヘーゲルはテュービンゲン大学付属のプロテスタント神学校であるテュービンゲン・シュティフトに入学し、詩人であり哲学者でもあったフリー ドリヒ・ヘルダーリンと、後の哲学者フリードリヒ・シェリングとルームメイトになった。[10][5][11] 彼らは神学校の制限的な環境を嫌っていたため、親しい友人となり、互いの考えに影響を与え合った。(ヘーゲルが神学校に通っていた可能性が高い。なぜな ら、それは国費で賄われており、彼は「正統派神学の研究に強い嫌悪感を抱いていた」ためであり、聖職者になることを望んでいなかったからである。 [12]) 3人ともギリシャ文明に深い感銘を受けており、ヘーゲルはさらにこの時期にジャン=ジャック・ルソーとレッシングに傾倒した。[13] 彼らはフランス革命の展開を興奮しながら見守った。[5] 1793年の恐怖政治の暴力はヘーゲルの希望を打ち砕いたが、彼は穏健派のジロンド派に共感し続け、1789年の原則への献身を決して失うことはなかっ た。毎年7月14日には、バスティーユ襲撃に乾杯していた。[14][15] シェリングとヘルダーリンはカント哲学に関する理論的な議論に没頭していたが、ヘーゲルは距離を置いていた。[16] この頃のヘーゲルは、哲学者の難解な思想をより広い大衆に理解できるようにする「人民哲学者(文士)」としての将来を思い描いていた。カント哲学の中心的 な考え方と批判的に取り組む必要性を感じたのは、1800年になってからだった。[17]  詩人フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリン(1770年-1843年)は、ヘーゲルの最も親しい友人であり、チュービンゲンのシュティフトでルームメイトでもあっ た。 テュービンゲン神学校で神学の資格を取得したヘーゲルは、ベルンで貴族の家庭教師(1793年から1796年)となった。[18][5][11] この期間に、後に『イエスの生涯』として知られるようになるテキストと、『キリスト教信仰の肯定性』と題された長編の原稿を執筆した。雇用主との関係が悪 化したため、ヘーゲルは1797年に、ヘルダーリンの仲介でフランクフルトのワイン商人の家庭で同様の職に就くことを受け入れた。そこで、ヘーゲルの思想 にヘルダーリンが重要な影響を与えた。[19] ベルンでは正統派キリスト教を痛烈に批判していたヘーゲルだが、初期ロマン主義の影響を受けたフランクフルトでは、ある種の転換期を迎え、特に宗教の真髄 としての愛の神秘体験を探求した。[20] また1797年には、未発表で署名のない「ドイツ観念論の最古の体系プログラム」の原稿が書かれた 理想主義」が書かれた。これはヘーゲルの手で書かれたものだが、ヘーゲル、シェリング、またはヘルダーリンのいずれかによって書かれた可能性もある。 [21] フランクフルト滞在中、ヘーゲルは「宗教と愛についての断片」という論文を書いた。[22] 1799年には「キリスト教の精神とその運命」という題の論文を書いたが、これは生前には出版されなかった。[5] |

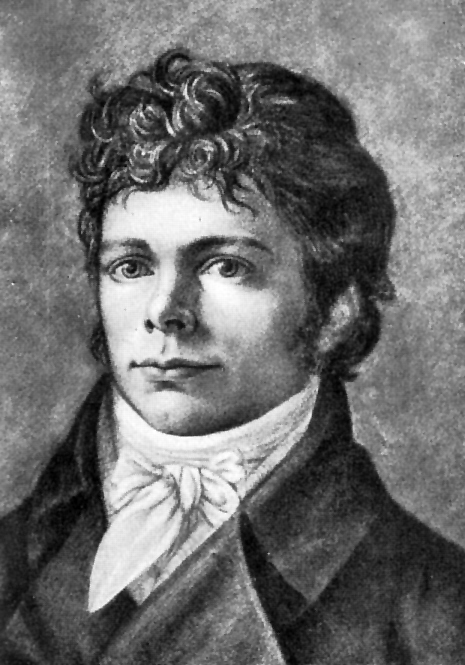

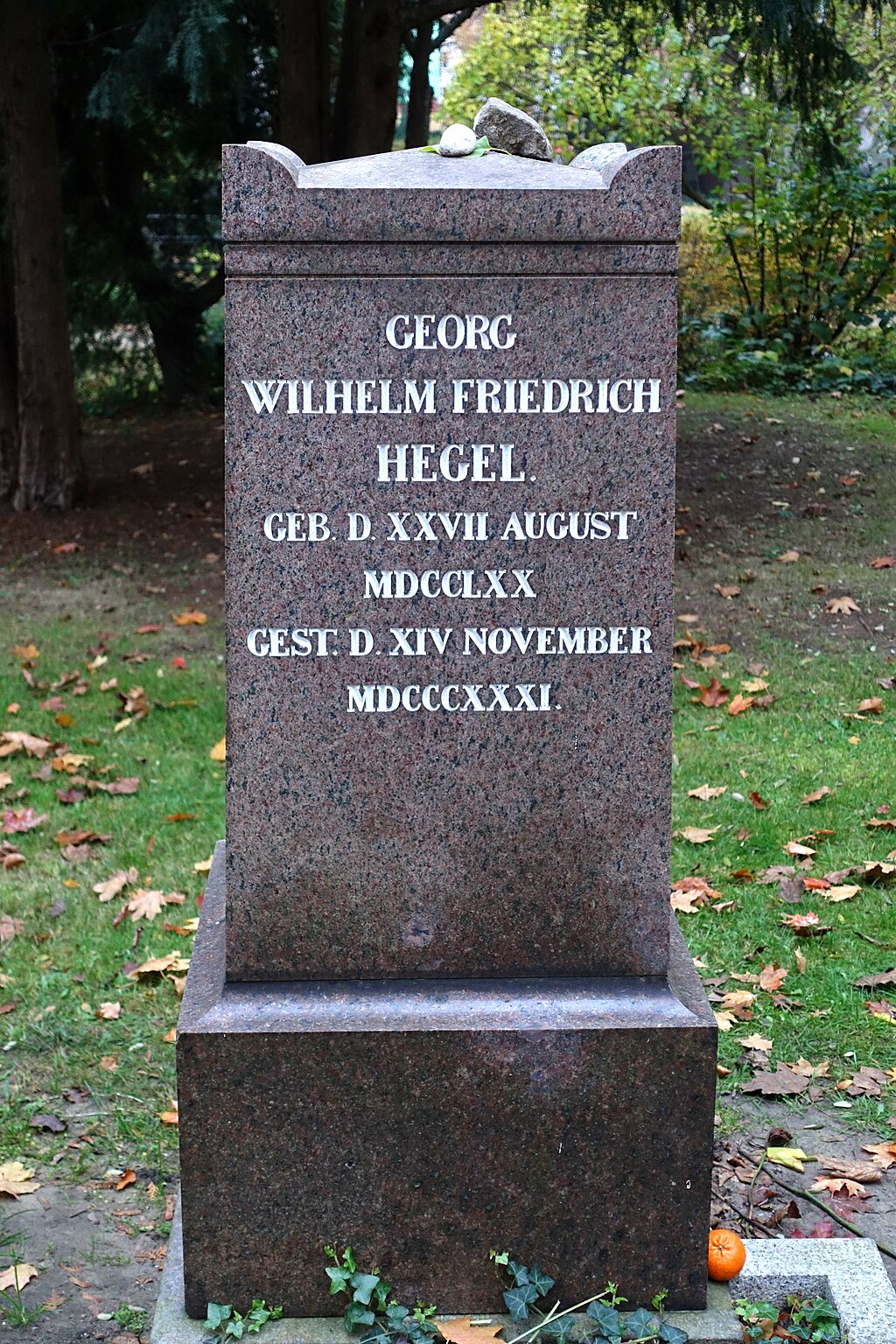

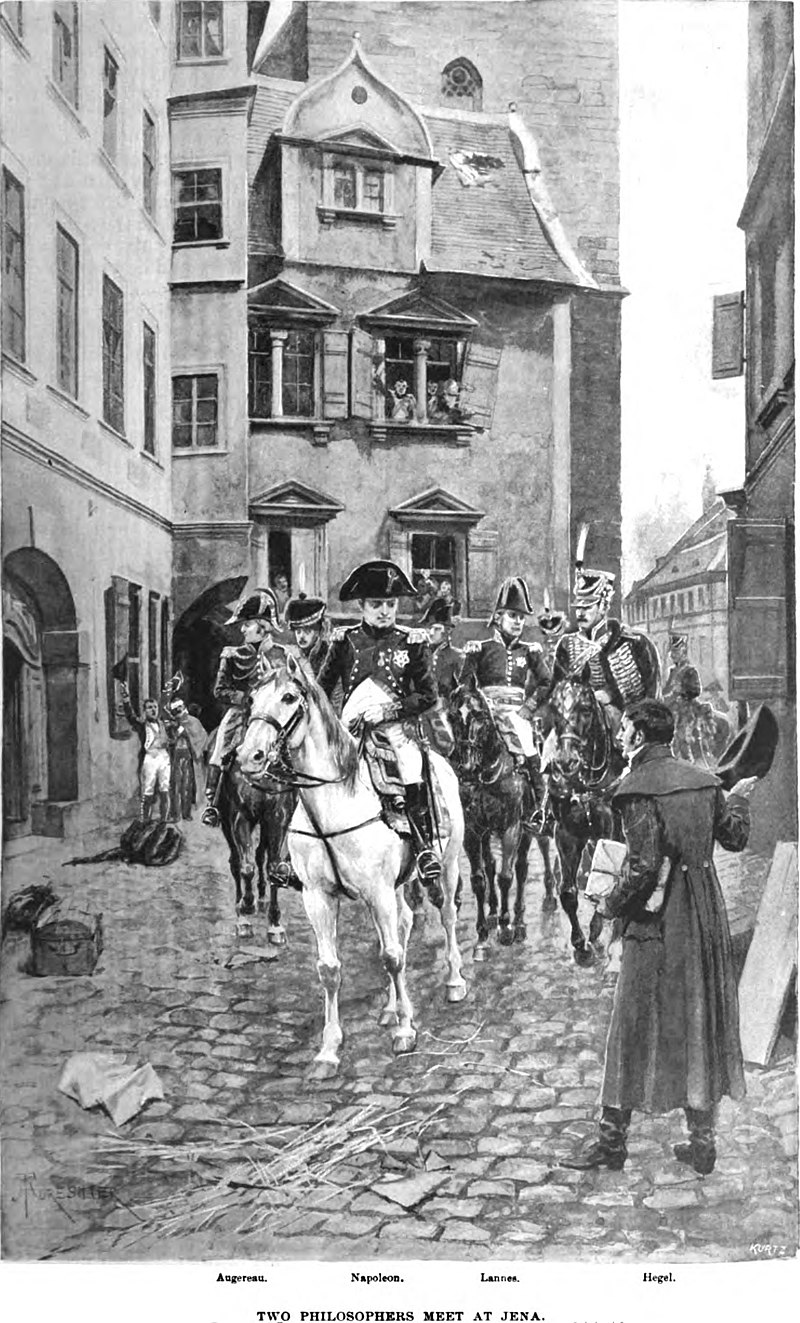

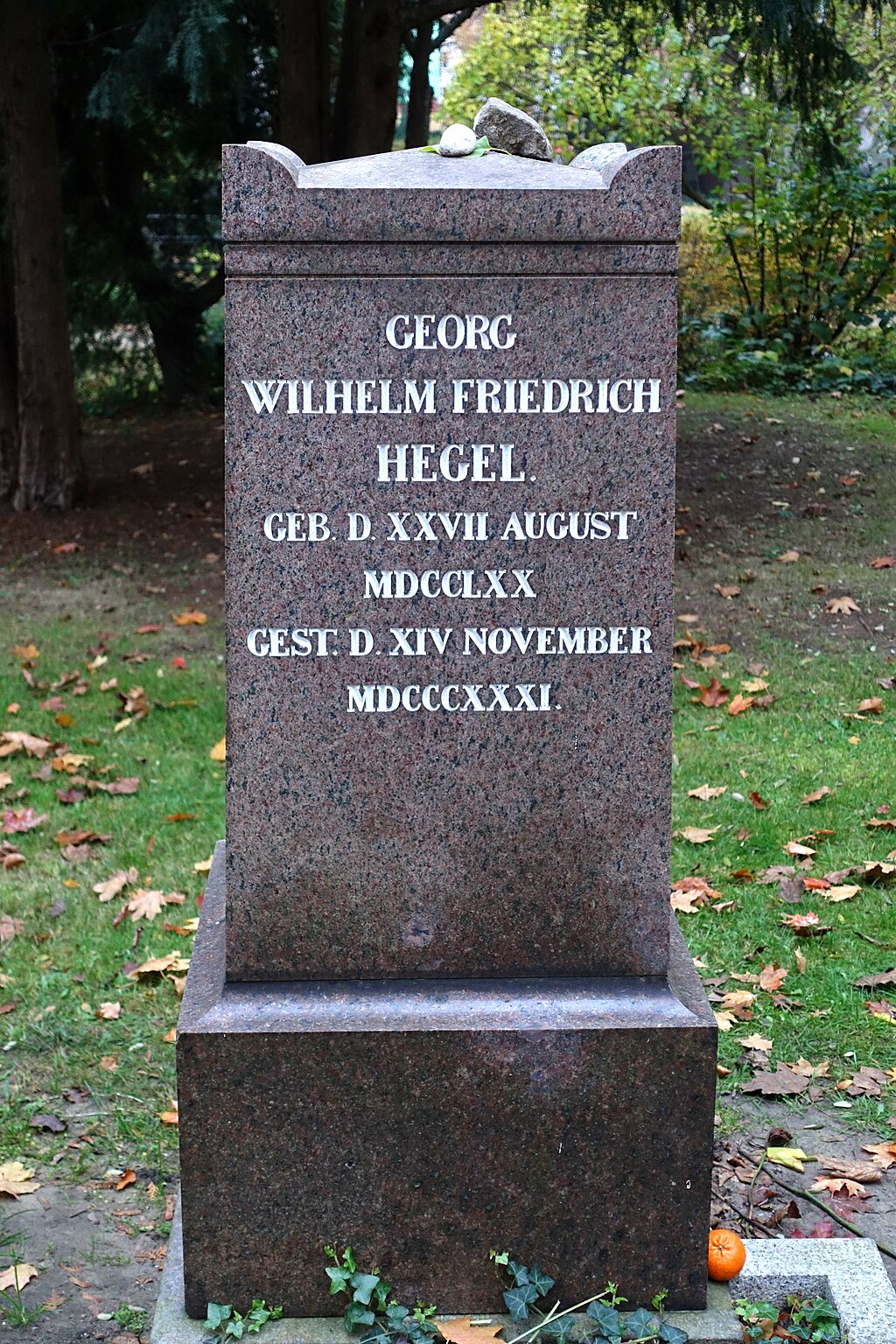

| Career years Jena, Bamberg, Nuremberg (1801–1816)  While at Jena, Hegel helped found a philosophical journal with his friend from Seminary, the young philosophical prodigy Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling. In 1801, Hegel came to Jena at the encouragement of Schelling, who held the position of Extraordinary Professor at the University of Jena.[5] Hegel secured a position at the University of Jena as a Privatdozent (unsalaried lecturer) after submitting the inaugural dissertation De Orbitis Planetarum, in which he briefly criticized mathematical arguments that assert that there must exist a planet between Mars and Jupiter.[23][b] Later in the year, Hegel's essay The Difference Between Fichte's and Schelling's System of Philosophy was completed.[25] He lectured on "Logic and Metaphysics" and gave lectures with Schelling on an "Introduction to the Idea and Limits of True Philosophy" and facilitated a "philosophical disputorium."[25][26] In 1802, Schelling and Hegel founded the journal Kritische Journal der Philosophie (Critical Journal of Philosophy) to which they contributed until the collaboration ended when Schelling left for Würzburg in 1803.[25][27] In 1805, the university promoted Hegel to the unsalaried position of extraordinary professor after he wrote a letter to the poet and minister of culture Johann Wolfgang von Goethe protesting the promotion of his philosophical adversary Jakob Friedrich Fries ahead of him.[28] Hegel attempted to enlist the help of the poet and translator Johann Heinrich Voß to obtain a post at the renascent University of Heidelberg, but he failed. To his chagrin, Fries was, in the same year, made ordinary professor (salaried).[29] The following February marked the birth of Hegel's illegitimate son, Georg Ludwig Friedrich Fischer (1807–1831), as the result of an affair with Hegel's landlady Christiana Burkhardt née Fischer.[30] With his finances drying up quickly, Hegel was under great pressure to deliver his book, the long-promised introduction to his philosophical system.[31] Hegel was putting the finishing touches to it, The Phenomenology of Spirit, as Napoleon engaged Prussian troops on 14 October 1806 in the Battle of Jena on a plateau outside the city.[11] On the day before the battle, Napoleon entered the city of Jena. Hegel recounted his impressions in a letter to his friend Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer:  "Hegel and Napoleon in Jena" (illustration from Harper's Magazine, 1895), an imaginary meeting that became proverbial due to Hegel's notable use of Weltseele ("world-soul") in reference to Napoleon ("the world-soul on horseback", die Weltseele zu Pferde) I saw the Emperor – this world-soul [Weltseele] – riding out of the city on reconnaissance. It is indeed a wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrated here at a single point, astride a horse, reaches out over the world and masters it.[32] Hegel biographer Terry Pinkard notes that Hegel's comment to Niethammer "is all the more striking since he had already composed the crucial section of the Phenomenology in which he remarked that the Revolution had now officially passed to another land (Germany) that would complete 'in thought' what the Revolution had only partially accomplished in practice."[33] Although Napoleon had spared the University of Jena from much of the destruction of the surrounding city, few students returned after the battle and enrollment suffered, making Hegel's financial prospects even worse.[34] Hegel traveled in the winter to Bamberg and stayed with Niethammer to oversee the proofs of the Phenomenology, which was being printed there.[34] Although Hegel tried to obtain another professorship, even writing Goethe in an attempt to help secure a permanent position replacing a professor of botany,[35] he was unable to find a permanent position. In 1807, he had to move to Bamberg since his savings and the payment from the Phenomenology were exhausted and he needed money to support his illegitimate son Ludwig.[36][34] There, he became the editor of the local newspaper, Bamberger Zeitung [de],[5] a position he obtained with the help of Niethammer. Ludwig Fischer and his mother stayed behind in Jena.[36]  Hegel's friend Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer (1766–1848) financially supported Hegel and used his political influence to help him obtain multiple positions. In Bamberg, as editor of the Bamberger Zeitung [de], which was a pro-French newspaper, Hegel extolled the virtues of Napoleon and often editorialized the Prussian accounts of the war.[37] Being the editor of a local newspaper, Hegel also became an important person in Bamberg social life, often visiting with the local official Johann Heinrich Liebeskind [de], and becoming involved in local gossip and pursued his passions for cards, fine eating, and the local Bamberg beer.[38] However, Hegel bore contempt for what he saw as "old Bavaria", frequently referring to it as "Barbaria" and dreaded that "hometowns" like Bamberg would lose their autonomy under new the Bavarian state.[39] After being investigated in September 1808 by the Bavarian state for potentially violating security measures by publishing French troop movements, Hegel wrote to Niethammer, now a high official in Munich, pleading for Niethammer's help in securing a teaching position.[40] With the help of Niethammer, Hegel was appointed headmaster of a gymnasium in Nuremberg in November 1808, a post he held until 1816. While in Nuremberg, Hegel adapted his recently published Phenomenology of Spirit for use in the classroom. Part of his remit was to teach a class called "Introduction to Knowledge of the Universal Coherence of the Sciences."[41] In 1811, Hegel married Marie Helena Susanna von Tucher (1791–1855), the eldest daughter of a Senator.[5] This period saw the publication of his second major work, the Science of Logic (Wissenschaft der Logik; 3 vols., 1812, 1813 and 1816), and the birth of two sons, Karl Friedrich Wilhelm (1813–1901) and Immanuel Thomas Christian (1814–1891).[42] Heidelberg, Berlin (1816–1831) Hegel's Inaugural Oration on Assuming the Rectorship at the University of Berlin; delivered in Latin, with English subtitles Having received offers of a post from the Universities of Erlangen, Berlin and Heidelberg, Hegel chose Heidelberg, where he moved in 1816. Soon after, his illegitimate son Ludwig Fischer (now ten years old) joined the Hegel household in April 1817, having spent time in an orphanage after the death of his mother Christiana Burkhardt.[43] In 1817, Hegel published The Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Outline as a summary of his philosophy for students attending his lectures at Heidelberg.[5][11] It is also while in Heidelberg that Hegel first lectured on the philosophy of art.[44] In 1818, Hegel accepted the renewed offer of the chair of philosophy at the University of Berlin, which had remained vacant since Johann Gottlieb Fichte's death in 1814. Here, Hegel published his Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1821). Hegel devoted himself primarily to delivering lectures; his lectures on the philosophy of fine art, the philosophy of religion, the philosophy of history, and the history of philosophy were published posthumously from students' notes. In spite of his notoriously terrible delivery, his fame spread and his lectures attracted students from all over Germany and beyond.[45] Meanwhile, Hegel and his pupils, such as Leopold von Henning, Friedrich Wilhelm Carové, were harassed and put under the surveillance of Prince Sayn-Wittgenstein, the interior minister of Prussia and his reactionary circles in the Prussian court.[46][47][48] In the remainder of his career, he made two trips to Weimar, where he met with Goethe for the last time, and to Brussels, the Northern Netherlands, Leipzig, Vienna, Prague, and Paris.[49]  Hegel's tombstone in Berlin During the last ten years of his life, Hegel did not publish another book but thoroughly revised the Encyclopedia (second edition, 1827; third, 1830). In his political philosophy, he criticized Karl Ludwig von Haller's reactionary work, which claimed that laws were not necessary. A number of other works on the philosophy of history, religion, aesthetics and the history of philosophy[50] were compiled from the lecture notes of his students and published posthumously.[51] Hegel was appointed University Rector of the university in October 1829, but his term ended in September 1830. Hegel was deeply disturbed by the riots for reform in Berlin in that year. In 1831 Frederick William III decorated him with the Order of the Red Eagle, 3rd Class for his service to the Prussian state.[52] In August 1831, a cholera epidemic reached Berlin and Hegel left the city, taking up lodgings in Kreuzberg. Now in a weak state of health, Hegel seldom went out. As the new semester began in October, Hegel returned to Berlin in the mistaken belief that the epidemic had largely subsided. By 14 November, Hegel was dead.[5] The physicians pronounced the cause of death as cholera, but it is likely he died from another gastrointestinal disease.[53] His last words are said to have been, "There was only one man who ever understood me, and even he didn't understand me."[54] He was buried on 16 November. In accordance with his wishes, Hegel was buried in the Dorotheenstadt cemetery next to Fichte and Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand Solger.[55] Hegel's illegitimate son, Ludwig Fischer, had died shortly before while serving with the Dutch army in Batavia and the news of his death never reached his father.[56] Early the following year, Hegel's sister Christiane committed suicide by drowning. Hegel's two remaining sons – Karl, who became a historian; and Immanuel [de], who followed a theological path – lived long and safeguarded their father's manuscripts and letters, and produced editions of his works.[57] |

キャリアの年 イエナ、バンベルク、ニュルンベルク(1801年~1816年)  イエナ在学中、ヘーゲルは神学校時代の友人で、若き哲学の天才フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・ヨゼフ・シェリングとともに哲学雑誌の創刊を手伝った。 1801年、ヘーゲルはイエナ大学の非常勤教授であったシェリングの勧めでイエナにやって来た。[5] ヘーゲルは、博士論文『惑星の軌道について』を提出し、イエナ大学の非常勤講師(無給講師)の地位を確保した。この論文では、火星と木星の間に惑星が存在 しなければならないとする数学的論拠を簡単に批判している。[23][b] 同年後半には、 ヘーゲルの論文『フィヒテとシェリングの哲学体系の相違』が完成した。[25] 彼は「論理学と形而上学」の講義を行い、シェリングとともに「真の哲学の理念と限界への序説」の講義を行い、「哲学論争の場」を促進した。[25] [26] 1802年、シェリングとヘーゲルは雑誌『批判的哲学ジャーナル』(Kritische Journal der Philosophie)を創刊し、 シェリングが1803年にヴュルツブルクへ去るまで、彼らはその雑誌に寄稿した。[25][27] 1805年、ヘーゲルが詩人であり文化大臣でもあったヨハン・ヴォルフガング・フォン・ゲーテに宛てて、哲学上の敵対者であるヤコブ・フリードリヒ・フ リースの昇進を抗議する手紙を書いた後、大学は彼を無給の臨時教授に昇進させた。[28] ヘーゲルは 詩人であり翻訳家でもあったヨハン・ハインリヒ・フォスに助けを求め、復活したハイデルベルク大学での職を得ようとしたが、失敗した。彼の悔しがるのも無 理はないが、フリースは同年、正教授(給与支給)に昇進した。[29] 翌年2月、ヘーゲルの家主クリスティアーナ・ブルクハルト(旧姓フィッシャー)との情事の結果、ヘーゲルの非嫡出子ゲオルク・ルートヴィヒ・フリードリ ヒ・フィッシャー(1807年 - 1831年)が誕生した。[30] 経済状態が急速に悪化する中、ヘーゲルは、長らく 約束されていた彼の哲学体系の入門書であった。[31] ヘーゲルは『精神現象学』の仕上げの作業を行っていた。1806年10月14日、ナポレオンがイエナの戦いでプロイセン軍と戦っていたとき、その戦いは市 外の高原で行われた。[11] 戦いの前日に、ナポレオンはイエナ市に入った。ヘーゲルは友人のフリードリヒ・イマヌエル・ニーダムラーに宛てた手紙の中で、そのときの印象を次のように 語っている。  「イエナのヘーゲルとナポレオン」(1895年の『ハーパーズ・マガジン』掲載のイラスト)は、ヘーゲルがナポレオンを指して「世界精神 (Weltseele)」という言葉を頻繁に使用したことで、その架空の出会いはことわざとなった。「馬上の世界精神(die Weltseele zu Pferde)」 私は皇帝を見た。この世界精神[Weltseele]が、偵察のために街から出て行くところだった。馬にまたがり、一点に集中しながら世界全体に目を向 け、それを支配するような人物を目にするのは、実に素晴らしい感覚だ。 ヘーゲルの伝記作家テリー・ピンカードは、ニーダムラーに対するヘーゲルのコメントは「とりわけ印象的である。なぜなら、彼は『精神現象学』の重要な部分 をす でに書き上げており、その中で、革命は今や公式に別の土地(ドイツ)に引き継がれ、革命が実践において部分的にしか達成できなかったことを『思考の中で』 完遂するだろうと述べていたからだ」と指摘している。[33] ナポレオンはイエナ大学を周辺の都市のほとんどの破壊から免れたが、戦いの後、戻ってきた学生はほとんどおらず、 ヘーゲルの経済状況はさらに悪化した。[34] ヘーゲルは冬の間、バンベルクを訪れ、ニーダマ―の家に滞在し、そこで印刷されていた『現象学』の校正作業を監督した。[34] ヘーゲルは別の教授職を得ようとし、植物学の教授の後任として常勤職を確保しようとゲーテに手紙を書くことさえしたが、[35] 常勤職を見つけることはできなかった。1807年には、蓄えと『現象学』からの支払いが底をつき、非嫡出子ルートヴィヒを養うためにも金銭が必要となった ため、バンベルクに移住せざるを得なかった。[36][34] そこで彼は、ニーダマーの助力により、地元紙『バンベルガー・ツァイトゥング』[de]の編集者となった。ルートヴィヒ・フィッシャーと彼の母親はイエナ に残った。[36]  ヘーゲルの友人フリードリヒ・イマヌエル・ニーダムラー(1766年 - 1848年)はヘーゲルを経済的に支援し、政治的な影響力を駆使してヘーゲルが複数の役職を得られるよう尽力した。 バンベルクでは、親仏派の新聞『バンベルガー・ツァイトゥング』の編集者として、ヘーゲルはナポレオンの美徳を称賛し、しばしばプロイセン側の戦争報道に 論説を寄稿した。[37] 地方紙の編集者として、ヘーゲルはバンベルクの社交界でも重要な人格となり、しばしば地元の役人ヨハン・ハインリヒ・リーベスキンドと会い、地元のゴシッ プに首を突っ込み、トランプや美食、 しかし、ヘーゲルは「旧バイエルン」と見なしたものに対して軽蔑を抱いており、それを「バルバリア」と呼ぶことが多く、バンベルクのような「故郷」が新し いバイエルン国家の下で自治を失うことを恐れていた。[39] 1808年9月に、フランス軍の動きを公表することで治安対策に違反した可能性があるとしてバイエルン政府に調査された後、ヘーゲルはミュンヘンで高官と なっていたニータマーに手紙を書き、 、教職を得るためにニーダムラーの助力を懇願する手紙を送った。[40] ニーダムラーの助力により、ヘーゲルは1808年11月にニュルンベルクのギムナジウムの校長に任命され、1816年までその職に就いた。ニュルンベルク に滞在中、ヘーゲルは最近出版された『精神現象学』を授業で使用できるように改訂した。彼の任務の一部には、「科学の普遍的整合性の知識入門」という授業 を教えることも含まれていた。[41] 1811年、ヘーゲルは上院議員の長女マリー・ヘレナ・スザンナ・フォン・トゥーチャー(1791年 - 1855年)と結婚した。[5] この時期には、彼の2番目の主要著作である『論理学の科学』(Wissenschaft der Logik、全3巻、1812年、18 1813年、1816年)が出版され、カール・フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム(1813年 - 1901年)とイマヌエル・トマス・クリスティアン(1814年 - 1891年)の2人の息子が誕生した。[42] ハイデルベルク、ベルリン(1816年~1831年) エアランゲン、ベルリン、ハイデルベルクの大学から教授職のオファーを受けたヘーゲルは、ハイデルベルクを選び、1816年に移り住んだ。間もなく、母親 クリスティアーナ・ブルクハルトの死後、孤児院で過ごしていた非嫡出子ルートヴィヒ・フィッシャー(当時10歳)が、1817年4月にヘーゲルの家庭に加 わった。[43] 1817年、ヘーゲルは、ハイデルベルクでの講義の受講生向けに、自身の哲学の要約として『哲学の科学の概要』を出版した。[5][11] また、ハイデルベルク在住中に、ヘーゲルは初めて 芸術哲学について講義したのもこの時期である。[44] 1818年、ヘーゲルは1814年にヨハン・ゴットリープ・フィヒテが死去して以来空席となっていたベルリン大学の哲学教授職のオファーを再び受け入れ た。ここでヘーゲルは『法の哲学要綱』(1821年)を出版した。ヘーゲルは主に講義に専念し、美術哲学、宗教哲学、歴史哲学、哲学史に関する講義は、学 生のノートをもとに死後に出版された。ヘーゲルの悪名高い下手な講義にもかかわらず、彼の名声は広まり、講義にはドイツ全土、そしてそれ以外の国からも学 生たちが集まった。[45] 一方、ヘーゲルと弟子たち、例えばレオポルト・フォン・ヘニングやフリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム・カロヴェなどは、プロイセンの内務大臣であり、プロイセン 宮廷の反動的勢力であったザイン=ヴィッテンシュタイン公から嫌がらせを受け、監視下に置かれた。[46][47][48] 残りのキャリアにおいて、彼は ワイマールに2度赴き、そこでゲーテと最後となる対面を果たした。また、ブリュッセル、北オランダ、ライプツィヒ、ウィーン、プラハ、パリにも足を運ん だ。  ベルリンにあるヘーゲルの墓碑 晩年の10年間、ヘーゲルは新たな著書を出版することはなかったが、『エンサイクロペディア』の改訂版(第2版、1827年、第3版、1830年)を出版 した。政治哲学においては、彼はカール・ルートヴィヒ・フォン・ハラーの反動的な著作を批判した。この著作は、法は必要ないとする主張を展開していた。歴 史哲学、宗教、美学、哲学史に関するその他の著作の多くは[50]、彼の学生たちの講義ノートを基にまとめられ、死後に出版された。 ヘーゲルは1829年10月に大学の学長に任命されたが、任期は1830年9月に終了した。ヘーゲルは、その年にベルリンで起こった改革を求める暴動に深 く心を乱された。1831年、プロイセン国家への貢献を称えられ、フリードリヒ・ウィルヘルム3世から赤鷲勲章3等級を授与された。[52] 1831年8月、コレラがベルリンに蔓延し、ヘーゲルはクロイツベルクに宿舎を構え、ベルリンを離れた。体調が優れないヘーゲルは、めったに外出しなく なった。10月に新学期が始まると、ヘーゲルは伝染病がほぼ沈静化したと誤解してベルリンに戻った。11月14日までにヘーゲルは死去した。[5] 医師団は死因をコレラと断定したが、おそらくは別の胃腸疾患によるものだったと考えられている。[53] 彼の最期の言葉は「私を理解してくれたのはただ一人の男だけだったが、その男さえも私を理解してくれなかった」だったと言われている。[54] 彼は11月16日に埋葬された。ヘーゲルの遺言に従って、彼はフィヒテとカール・ヴィルヘルム・フェルディナント・ゾルガーの隣にドロテーエンシュタット 墓地に埋葬された。 ヘーゲルの非嫡出子であるルートヴィヒ・フィッシャーは、バタビアのオランダ軍に所属していた際に間もなく死亡したが、その知らせは父親の元に届かなかっ た。翌年初頭、ヘーゲルの姉クリスティアーネは入水自殺した。ヘーゲルの残された2人の息子、すなわち歴史家となったカールと、神学の道に進んだイマヌエ ル(仏語名)は、父の原稿や手紙を大切に保管し、父の著作の版を出版した。[57] |

Influences Aristotle (384–322 BCE) and the ancient Greeks were a major influence. As H. S. Harris recounts, when Hegel entered the Tübingen seminary in 1788, "he was a typical product of the German Enlightenment – an enthusiastic reader of Rousseau and Lessing, acquainted with Kant (at least at second hand), but perhaps more deeply devoted to the classics than to any thing modern."[58] During this early period of his life "the Greeks – especially Plato – came first."[59] Although he later elevated Aristotle above Plato, Hegel never abandoned his love of ancient philosophy, the imprint of which is everywhere in his thought.[60]  The critical philosophy of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) was a major influence on Hegel. Hegel's concern with various forms of cultural unity (Judaic, Greek, medieval, and modern) during this early period would remain with him throughout his career.[61] In this way, he was also a typical product of early German romanticism.[62] "Unity of life" was the phrase used by Hegel and his generation to express their concept of the highest good. It encompasses unity "with oneself, with others, and with nature. The main threat to such unity consists in division (Entzweiung) or alienation (Entfremdung)."[63] In this respect, Hegel was particularly taken with the phenomenon of love as a kind of "unity-in-difference," this both in the ancient articulation provided by Plato and in the Christian religion's doctrine of agape, which Hegel at this time viewed as "already 'grounded on universal Reason.'"[64][65] This interest, as well as his theological training, would continue to mark his thought, even as it developed in a more theoretical or metaphysical direction.[c] According to Glenn Alexander Magee, Hegel's thought (in particular, the tripartite structure of his system) also owes much to the hermetic tradition, in particular, the work of Jakob Böhme.[67] The conviction that philosophy must take the form of a system Hegel owed, most particularly, to his Tübingen roommates, Schelling and Hölderlin.[68] Hegel also read widely and was much influenced by Adam Smith and other theorists of the political economy.[69] It was Kant's critical philosophy that provided what Hegel took as the definitive modern articulation of the divisions that must be overcome.[70] This led to his engagement with the philosophical programs of Fichte and Schelling, as well as his attention to Spinoza and the Pantheism controversy.[71][d] The influence of Johann Gottfried von Herder, however, would lead Hegel to a qualified rejection of the universality claimed by the Kantian program in favor of a more culturally, linguistically, and historically informed account of reason.[72] |

影響 アリストテレス(紀元前384年~322年)と古代ギリシアは大きな影響を与えた。 H. S. ハリスが述べているように、1788年にヘーゲルがテュービンゲン神学校に入学した際には、「彼はドイツ啓蒙主義の典型的な産物であり、ルソーとレッシン グの熱心な読者であり、カント(少なくとも間接的には)に精通していたが、おそらくは現代的なものよりも古典に深く傾倒していた」[58]。この時期の彼 の人生においては、「ギリシア人、特にプラトンが第一であった」[59]。アリストテレスをプラトンよりも上位に位置づけたが、ヘーゲルは古代哲学への愛 を捨てず、その影響は彼の思想の至る所に見られる。  イマニュエル・カント(1724年-1804年)の批判哲学はヘーゲルに大きな影響を与えた。 ヘーゲルがこの初期の時期にユダヤ教、ギリシャ、中世、近代といったさまざまな文化の統一について関心を抱いていたことは、その後の生涯を通じて彼の中に 残り続けた。[61] このように、ヘーゲルは初期ドイツロマン主義の典型的な産物でもあった。[62] 「生活の統一」とは、ヘーゲルとその同世代の人々が最高の善の概念を表現するために用いた言葉である。それは「自分自身、他人、そして自然との」統一を包 含する。このような統一に対する主な脅威は、分裂(Entzweiung)または疎外(Entfremdung)である。 この点において、ヘーゲルは「差異の中の統一」の一種である愛の現象に特に注目していた。これは、プラトンが提示した古代の概念と、キリスト教の「アガ ペー」の教義の両方に当てはまる。ヘーゲルは当時、この教義を「すでに『普遍的理性に基づく』もの」と捉えていた。[64][65] この関心は、彼の神学的な訓練と同様に、彼の思想に影響を与え続けた。それは、より理論的または形而上学的方向へと発展したとしても、である。 。 グレン・アレクサンダー・マギーによると、ヘーゲルの思想(特に、彼の体系の三分構造)は、ヘルメス主義の伝統、特にヤコブ・ベーメの業績にも多くを負っ ているという。[67] ヘーゲルが哲学は体系の形を取らなければならないと確信したのは、とりわけ、テュービンゲンのルームメイトであったシェリングとヘルダーリンのおかげであ る。[68] ヘーゲルは広く読書し、アダム・スミスやその他の政治経済理論家から大きな影響を受けた。 克服すべき諸相を明確に現代的に表現したものとしてヘーゲルが受け入れたのは、カントの批判哲学であった。[70] これがきっかけとなり、ヘーゲルはフィヒテやシェリングの哲学プログラムに関心を抱くようになり、スピノザや汎神論論争にも注目するようになった。 [71][d] しかし、ヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダーの影響により、ヘーゲルはカントのプログラムが主張する普遍性を条件付きで拒絶し、 より文化的に、言語的に、歴史的に根拠のある理性の説明を支持する |

| The Phenomenology of Spirit Main article: The Phenomenology of Spirit The Phenomenology of Spirit was published in 1807. This is the first time that, at the age of thirty-six, Hegel lays out "his own distinctive approach" and adopts an "outlook that is recognizably 'Hegelian' to the philosophical problems of post-Kantian philosophy".[73] Yet, the book was poorly understood even by Hegel's contemporaries and received mostly negative reviews.[74] To this day, the Phenomenology is infamous for, among other things, its conceptual and allusive density, idiosyncratic terminology, and confusing transitions.[75] Its most comprehensive commentary, scholar H. S. Harris's two-volume Hegel's Ladder (The Pilgrimage of Reason and The Odyssey of Spirit),[76] runs more than three times the length of the text itself.[77] The fourth chapter of the Phenomenology includes Hegel's first presentation of the lord-bondsman dialectic,[e] the section of the book that has been most influential in general culture.[80] What is at stake in the conflict Hegel presents is the practical (not theoretical) recognition or acknowledgement [Anerkennung, anerkennen] of the universality – i.e., personhood, humanity – of each of two opposed self-consciousnesses.[81][f] What the readers learn, but what the self-consciousnesses described do not yet realize, is that recognition can only be successful and actual as reciprocal or mutual.[84] This is the case for the simple reason that the recognition of someone you do not recognize as properly human cannot count as genuine recognition.[85] Hegel can also be seen here as criticizing the individualist worldview of people and society as a collection of atomized individuals, instead taking a holistic view of human self-consciousness as requiring the recognition of others, and people's view of themselves as being shaped by the views of others.[86]  Title page of the original 1807 edition Hegel describes The Phenomenology as both the "introduction" to his philosophical system and also as the "first part" of that system as the "science of the experience of consciousness."[87] Yet it has long been controversial in both respects; indeed, Hegel's own attitude changed throughout his life.[g] Nevertheless, however complicated the details, the basic strategy by which it attempts to make good on its introductory claim is not difficult to state. Beginning with only the most basic "certainties of consciousness itself," "the most immediate of which is the certainty that I am conscious of this object, here and now," Hegel aims to show that these "certainties of natural consciousness" have as their consequence the standpoint of speculative logic.[88][89] This does not, however, make the Phenomenology a Bildungsroman. It is not the consciousness under observation that learns from its experience. Only "we," the phenomenological observers, are in a position to profit from Hegel's logical reconstruction of the science of experience.[90] The ensuing dialectic is long and hard. It is described by Hegel himself as a "path of despair," in which self-consciousness finds itself to be, over and again, in error.[91] It is the self-concept of consciousness itself that is tested in the domain of experience, and where that concept is not adequate, self-consciousness "suffers this violence at its own hands, and brings to ruin its own restricted satisfaction."[92][93] For, as Hegel points out, one cannot learn how to swim without getting into the water.[94] By progressively testing its concept of knowledge in this way, by "making experience his standard of knowledge, Hegel is embarking upon nothing less than a transcendental deduction of metaphysics."[95][h] In the course of its dialectic, the Phenomenology purports to demonstrate that – because consciousness always includes self-consciousness – there are no 'given' objects of direct awareness not already mediated by thought. Further analysis of the structure of self-consciousness reveals that both the social and conceptual stability of the experiential world depend upon networks of reciprocal recognition. Failures of recognition, then, demand reflection upon the past as a way "to understand what is required of us at the present." For Hegel, this ultimately involves rethinking an interpretation of "religion as the collective reflection of the modern community on what ultimately counts for it." He contends, finally, that this "historically, socially construed philosophical account of that whole process" elucidates the genesis of a distinctly "modern" standpoint.[97] Another way of putting this is to say that the Phenomenology takes up Kant's philosophical project of investigating the capacities and limits of reason. Under the influence of Herder, however, Hegel proceeds historically, instead of altogether a priori. Yet, although proceeding historically, Hegel resists the relativistic consequences of Herder's own thought. In the words of one scholar, "It is Hegel's insight that reason itself has a history, that what counts as reason is the result of a development. This is something that Kant never imagines and that Herder only glimpses."[98] In praise of Hegel's accomplishment, Walter Kaufmann writes that the guiding conviction of the Phenomenology is that a philosopher should not "confine him or herself to views that have been held but penetrate these to the human reality they reflect." In other words, it is not enough to consider propositions, or even the content of consciousness; "it is worthwhile to ask in every instance what kind of spirit would entertain such propositions, hold such views, and have such a consciousness. Every outlook in other words, is to be studied not merely as an academic possibility but as an existential reality."[99] The Phenomenology of Spirit shows that the search for an externally objective criterion of truth is a fool's errand. The constraints on knowledge are necessarily internal to spirit itself. Yet, although theories and self-conceptions may always be reevaluated, renegotiated, and revised, this is not a merely imaginative exercise. Claims to knowledge must always prove their own adequacy in real historical experience.[100] Although Hegel seemed during his Berlin years to have abandoned The Phenomenology of Spirit, at the time of his unexpected death, he was in fact making plans to revise and republish it. As Hegel was no longer in need of money or credentials, H. S. Harris argues that "the only rational conclusion that can be drawn from his decision to republish the book… is that he still regarded the 'science of experience' as a valid project in itself" and one for which later system has no equivalent.[101] There is, however, no scholarly consensus about the Phenomenology with respect to either of the systematic roles asserted by Hegel at the time of its publication.[i][j] |

精神現象学 詳細は「精神現象学」を参照 『精神現象学』は1807年に出版された。これは、36歳のヘーゲルが「彼自身の独特なアプローチ」を提示し、「カント以降の哲学の問題に対して、明らか に『ヘーゲル的』な見解」を採用した最初のものである。[73] しかし、この本はヘーゲルの同時代人にも理解されず、ほとんど否定的な評価を受けた。[74] 今日に至るまで、『現象学』は、とりわけ、その概念的 含蓄に富む密度、独特な専門用語、混乱を招くような展開などである。[75] 最も包括的な注釈である学者H. S. ハリスによる2巻本『ヘゲルの梯子』(『理性の巡礼』および『精神のオデュッセイア』)は、[76] テキスト自体の3倍以上の長さがある。[77] 『現象学』の第4章には、ヘーゲルによる主従の弁証法の最初の提示が含まれている。[e] この本のこの部分は、一般文化に最も大きな影響を与えた。[80] ヘーゲルが提示する対立において問題となるのは、2つの対立する自己意識のそれぞれが持つ普遍性、すなわち人格性や人間性といったものを、理論的ではなく 実践的に認識または承認することである。[Anerkennung, anerkennen] 81][f] 読者は理解しているが、説明されている自己意識はまだ理解していないのは、認識は相互的または相互的でなければ成功せず、現実的にもなりえないということ である。[84] これは、人間として適切に認識していない誰かの認識は、真の認識とはみなされないという単純な理由による。[85] ヘーゲルは、個人主義的世界観を持つ人々や、個人がばらばらに集まった社会を批判しているとも見ることができる。その代わりに、 他者からの承認を必要とする人間の自己意識や、他者の見方によって形作られる人々の自己観について、全体論的な見方をしている。[86]  1807年初版のタイトルページ ヘーゲルは『現象学』を、自身の哲学体系への「序論」であると同時に、その体系の「意識の経験の科学」としての「第一部」でもあると述べている。[87] しかし、この両方の観点において、長きにわたって論争の的となってきた。実際、ヘーゲル自身の態度も生涯を通じて変化した。[g] しかし、その詳細がどんなに複雑であろうとも、その序文の主張を裏付けるための基本戦略を述べるのはそれほど難しいことではない。最も基本的な「意識その ものの確実性」から始めて、「その最も直接的なものは、私が今、この対象を意識しているという確実性である」とヘーゲルは述べ、これらの「自然な意識の確 実性」が帰結として観念論の立場を持つことを示そうとしている。 しかし、このことは『現象学』を教養小説にするものではない。観察下にある意識がその経験から学ぶわけではない。経験の科学をヘーゲルが論理的に再構築し たものから利益を得ることができるのは、「私たち」、すなわち現象学的な観察者だけである。 続く弁証法は長く困難である。それはヘーゲル自身によって「絶望の道」と表現されている。自己意識は、何度も何度も誤りを犯すことになる。[91] 経験の領域で試されるのは、意識そのものの自己概念であり、その概念が適切でない場合、自己意識は「自らにこの暴力を受け、自らに制限された満足を破滅さ せる」ことになる。[92][93] なぜなら、ヘーゲルが指摘するように、 水に入らなければ泳ぎ方を学ぶことはできない。[94] このようにして、ヘーゲルは知識の概念を段階的に検証し、「経験を知識の基準とする」ことで、形而上学の超越論的演繹に他ならないものに着手している。 [95][h] 弁証法の過程において、現象学は、意識にはつねに自己意識が含まれているため、思考によって媒介されていない直接的な意識の対象は存在しないことを証明し ようとしている。自己意識の構造をさらに分析すると、経験世界の社会的安定性と概念的安定性の両方が相互承認のネットワークに依存していることが明らかに なる。認識の失敗は、過去を振り返り、「現在、私たちに何が求められているのかを理解する」ことを求める。ヘーゲルにとって、これは最終的には「現代社会 が最終的に重要視するものに対する集団的な反映としての宗教」という解釈を再考することを意味する。そして、最終的に「その全過程の歴史的、社会的解釈に よる哲学的説明」が、明らかに「現代」の立場を生み出したことを明らかにする、と主張している。[97] これを別の言い方で表現すると、現象学はカントの哲学プロジェクト、すなわち理性の能力と限界を調査するプロジェクトを引き継いだということになる。しか し、ヘーゲルはヘルダーの影響を受けながらも、完全にア・プリオリにではなく、歴史的に進んでいく。 とはいえ、歴史的に進んでいくとはいえ、ヘーゲルはヘルダー自身の思想の相対主義的な帰結には抵抗する。 ある学者の言葉を借りれば、「理性そのものに歴史があること、理性と見なされるものは発展の結果であるというヘーゲルの洞察である。 これはカントが想像することのないものであり、ヘルダーが垣間見たに過ぎないものである」[98]。 ヘーゲルの功績を称賛するウォルター・カウフマンは、『現象学』の指針となる信念は、哲学者は「これまで信じられてきた見解に自らを閉じ込めるのではな く、それらを反映する人間の実在へと突き抜けるべきである」というものであると記している。言い換えれば、命題を考察するだけでは不十分であり、意識の内 容を考察するだけでも不十分である。「あらゆる場合において、どのような精神がそのような命題を思い付き、そのような見解を持ち、そのような意識を持つの かを問うことは価値がある。言い換えれば、あらゆる見解は、単に学問的な可能性としてではなく、実存的な現実として研究されるべきである。」[99] 『精神現象学』は、真理の客観的な基準を外部に求めることは無駄であることを示している。知識に対する制約は、必然的に精神そのものに内在する。しかし、 理論や自己概念は常に再評価、再交渉、修正される可能性があるとはいえ、これは単なる想像上の演習ではない。知識の主張は、常に現実の歴史的経験におい て、その妥当性を証明しなければならないのである。 ヘーゲルはベルリン時代には『精神現象学』を放棄したかのように見えたが、予期せぬ死を迎える直前には、実際にはその改訂と再出版の計画を立てていた。 ヘーゲルはもはや金銭や権威を必要としていなかったが、H. S. ハリスは「この本の再版という彼の決断から導き出される唯一の合理的な結論は、彼が依然として『経験の科学』をそれ自体として有効なプロジェクトとみなし ていたということである」と主張している。また、このプロジェクトは後の体系には見られないものであるとも主張している。[101] しかし、この『現象学』に関しては、出版時にヘーゲルが主張した体系上の役割のいずれについても、学術的なコンセンサスは得られていない 。[i][j] |

| Philosophical system See also: Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences Hegel's philosophical system is divided into three parts: the science of logic, the philosophy of nature, and the philosophy of spirit (the latter two of which together constitute the real philosophy). This structure is adopted from Proclus's Neoplatonic triad of "'remaining-procession-return' and from the Christian Trinity."[103][k] Although evident in draft writings dating back as early as 1805, the system was not completed in published form until the 1817 Encyclopedia (1st ed.).[105] Frederick C. Beiser argues that the position of the logic with respect to the real philosophy is best understood in terms of Hegel's appropriation of Aristotle's distinction between "the order of explanation" and "the order of being."[l] To Beiser, Hegel is neither a Platonist who believes in abstract logical entities, nor a nominalist according to whom the particular is first in the orders of explanation and being alike. Rather, Hegel is a holist. For Hegel, the universal is always first in the order of explanation even if what is naturally particular is first in the order of being. With respect to the system as a whole, that universal is supplied by the logic.[107] Michael J. Inwood states, "The logical idea is non-temporal and therefore does not exist at any time apart from its manifestations." To ask "when" it divides into nature and spirit is analogous to asking "when" 12 divides into 5 and 7. The question does not have an answer because it is predicated upon a fundamental misunderstanding of its terms.[108] The task of the logic (at this high systemic level) is to articulate what Hegel calls "the identity of identity and non-identity" of nature and spirit. Put another way, it aims to overcome subject-object dualism.[109] This is to say that, among other things, Hegel's philosophical project endeavors to provide the metaphysical basis for an account of spirit that is continuous with, yet distinct from, the "merely" natural world – without thereby reducing either term to the other.[110] Furthermore, the final sections of Hegel's Encyclopedia suggest that to give priority to any one of its three parts is to have an interpretation that is "one-sided," incomplete or otherwise inaccurate.[98][110][111] As Hegel famously declares, "The true is the whole."[112] |

哲学体系 参照:哲学科学事典 ヘーゲルの哲学体系は3つの部分に分けられる。すなわち、論理学の科学、自然哲学、精神哲学(後者2つを併せて真の哲学と呼ぶ)である。この構造はプロク ロスによる新プラトン主義の「『残存-進行-回帰』の三つ組」とキリスト教の「三位一体」から採用されたものである。[103][k] 1805年まで遡る草稿の文章にも明らかであるが、この体系は1817年の『百科全書』(第1版)まで出版された形では完成されなかった。[105] フレデリック・C・ベイザーは、現実の哲学に対する論理学の位置づけは、ヘーゲルがアリストテレスの「説明の秩序」と「存在の秩序」の区別を借用したとい う観点から理解するのが最も適切であると主張している。[l] ベイザーにとって、ヘーゲルは抽象的な論理実体を信奉するプラトン主義者でもなく、また、個別的なものが説明と存在の秩序において第一であるとするノミナ ル主義者でもない。むしろ、ヘーゲルは全体論者である。ヘーゲルにとって、存在の順序では自然に個別的なものが最初に来るとしても、説明の順序では常に普 遍的なものが最初に来る。システム全体に関して言えば、その普遍的なものは論理によって供給される。[107] マイケル・J・インウッドは、「論理的な考え方は非時間的であり、したがって、その顕現を除いては、いかなる時にも存在しない」と述べている。自然と精神 に「いつ」分かれるのかと問うことは、「いつ」12が5と7に分かれるのかと問うことに類似している。この問いには答えがない。なぜなら、それは用語の根 本的な誤解に基づいているからだ。[108] 論理学の課題(この高度な体系レベルにおける)は、ヘーゲルが「自然と精神の同一性と非同一性」と呼ぶものを明確にすることである。別の言い方をすれば、 主客二元論を克服することを目的としている。[109] つまり、ヘーゲルの哲学プロジェクトは、とりわけ、「単なる」自然界と連続性がありながらも、それとは異なる精神の説明のための形而上学的基礎を提供しよ うとしている。ただし、そのことによって、いずれかの概念を他方に還元するわけではない。[110] さらに、ヘーゲルの『エンサイクロペディア』の最終章では、その3つの部分のいずれかを優先することは、「一面的」で不完全、あるいは不正確な解釈である と示唆している。[98][110][111] ヘーゲルが有名なように宣言しているように、「真実とは全体である。」[112] |

| Science of Logic Main article: Science of Logic Hegel's concept of logic differs greatly from that of the ordinary English sense of the term. This can be seen, for instance, in such metaphysical definitions of logic as "the science of things grasped in [the] thoughts that used to be taken to express the essentialities of the things."[113] As Michael Wolff explains, Hegel's logic is a continuation of Kant's distinctive logical program.[114] Its occasional engagement with the familiar Aristotelian conception of logic is only incidental to Hegel's project. Twentieth-century developments by such logicians as Frege and Russell likewise remain logics of formal validity and so are likewise irrelevant to Hegel's project, which aspires to provide a metaphysical logic of truth.[115] There are two texts of Hegel's Logic. The first, The Science of Logic (1812, 1813, 1816; bk.I revised 1831), is sometimes also called the "Greater Logic." The second is the first volume of Hegel's Encyclopedia and is sometimes known as the "Lesser Logic." The Encyclopedia Logic is an abbreviated or condensed presentation of the same dialectic. Hegel composed it for use with students in the lecture hall, not as a substitute for its proper, book-length exposition.[116][m] Hegel presents logic as a presuppositionless science that investigates the most fundamental thought-determinations [Denkbestimmungen], or categories, and so constitutes the basis of philosophy.[118][119] In putting something into question, one already presupposes logic; in this regard, it is the only field of inquiry that must constantly reflect upon its own mode of functioning.[120] The Science of Logic is Hegel's attempt to meet this foundational demand.[n] As he puts it, "logic coincides with metaphysics."[113][121] In the words of scholar Glenn Alexander Magee, the logic provides "an account of pure categories or ideas which are timelessly true" and which make up "the formal structure of reality itself".[122] It is important to see, however, that Hegel's metaphysical program is not a return to the Leibnizian-Wolffian rationalism critiqued by Kant, which is a criticism Hegel accepts.[123] In particular, Hegel rejects any form of metaphysics as speculation about the transcendent. His procedure, an appropriation of Aristotle's concept of form, is fully immanent.[124] More generally, Hegel agrees wholeheartedly with Kant's rejection of all forms of dogmatism and also agrees that any future metaphysics must pass the test of criticism.[125] It is the assessment of scholar Stephen Houlgate that Hegel's method of immanent logical development and critique is historically unique.[126] Philosopher Béatrice Longuenesse holds that this project may be understood, on analogy to Kant, as "inseparably a metaphysical and a transcendental deduction of the categories of metaphysics."[127][o] This approach insists, and claims to demonstrate, that the insights of logic cannot be judged by standards external to thought itself, that is, that "thought... is not the mirror of nature." Yet, she argues, this does not imply that these standards are arbitrary or subjective.[127] Hegel's translator and scholar of German idealism George di Giovanni likewise interprets the Logic as (drawing upon, yet also in opposition to, Kant) immanently transcendental; its categories, according to Hegel, are built into life itself, and define what it is to be "an object in general."[129] Books one and two of the Logic are the doctrines of "Being" and "Essence." Together they comprise the Objective Logic, which is largely occupied with overcoming the assumptions of traditional metaphysics. Book three is the final part of the Logic. It discusses the doctrine of "the Concept," which is concerned with reintegrating those categories of objectivity into a thoroughly idealistic account of reality.[p] Simplifying greatly, Being describes its concepts just as they appear, Essence attempts to explain them with reference to other forces, and the Concept explains and unites them both in terms of an internal teleology.[131] The categories of Being "pass over" from one to the next as denoting thought-determinations only extrinsically connected to one another. The categories of Essence reciprocally "shine" into one another. Finally, in the Concept, thought has shown itself to be fully self-referential, and so its categories organically "develop" from one to the next.[132][133] It is clear then, that in Hegel's technical sense of the term, the concept (Begriff, sometimes also rendered "notion," capitalized by some translators but not others[q]) is not a psychological concept. When deployed with the definitive article ("the") and sometimes modified by the term "logical," Hegel is referring to the intelligible structure of reality as articulated in the Subjective Logic. (When used in the plural, however, Hegel's sense is much closer to the ordinary dictionary sense of the term.[135]) Hegel's inquiry into thought is concerned to systematize thought's own internal self-differentiation, that is, how pure concepts (logical categories) differ from one another in their various relations of implication and interdependence. For instance, in the opening dialectic of the Logic, Hegel claims to display that the thought of "being, pure being – without further determination" is indistinguishable from the concept of nothing, and that, in this "passing back and forth" of being and nothing, "each immediately vanishes in its opposite."[136] This movement is neither one concept nor the other, but the category of becoming. There is not a difference here to which one can "refer," only a dialectic that one can observe and describe.[137] The final category of the Logic is "the idea." As with "the concept", the sense of this term for Hegel is not psychological. Rather, following Kant in The Critique of Pure Reason, Hegel's usage harks back to the Greek eidos, Plato's concept of form that is fully existent and universal:[138] "Hegel's Idee (like Plato's idea) is the product of an attempt to fuse ontology, epistemology, evaluation, etc., into a single set of concepts."[139] The Logic accommodates within itself the necessity of the realm of natural-spiritual contingency, that which cannot be determined in advance: "To go further, it must abandon thinking altogether and let itself go, opening itself to that which is other than thought in pure receptivity."[140] Simply put, logic realizes itself only in the domain of nature and spirit, in which it attains its "verification."[r] Hence the conclusion of the Science of Logic with "the idea freely discharging [entläßt] itself" into "objectivity and external life" – and, so too, the systematic transition to the Realphilosophie.[142][143] |

論理学 詳細は「論理学」を参照 ヘーゲルの論理の概念は、通常の英語の用語の意味とは大きく異なる。例えば、「物事の本質を表現するものとして考えられていた思考によって把握された物事 の科学」[113] といった形而上学的な論理学の定義に見られる。マイケル・ウォルフが説明しているように、ヘーゲルの論理学はカントの独特な論理計画の延長線上にある。 [114] 時折見られる、馴染み深いアリストテレスの論理学の概念との関わりは、ヘーゲルのプロジェクトにとっては付随的なものに過ぎない。20世紀におけるフリー ゲやラッセルなどの論理学者による発展も同様に、形式的な妥当性の論理にとどまり、ヘーゲルのプロジェクトとは無関係である。ヘーゲルは、真理の形而上学 的論理を提供しようとしていたのである。[115] ヘーゲルの『論理学』には2つのテキストがある。最初の『論理学の科学』(1812年、1813年、1816年;第1巻改訂版1831年)は、時に「大論 理学」とも呼ばれる。2つ目は『ヘーゲル百科全書』の第1巻であり、時に「小論理学」とも呼ばれる。『エンサイクロペディア・ロジック』は、同じ弁証法の 要約または凝縮版である。ヘーゲルは、講義室で学生が使用することを目的としてこれを構成したが、本来の、書籍としての解説の代替物としてではない。 [116][m] ヘーゲルは、前提を必要としない科学として論理学を提示し、最も根本的な思考決定(Denkbestimmungen)すなわちカテゴリーを調査し、哲学 の基礎を構成する。[118][119] 何かを疑問視するということは、すでに論理学を前提としている。この点において、論理学は、その機能のあり方を絶えず自らに反映させなければならない唯一 の分野である。[120] 論理学は、ヘーゲルがこの基礎的な要求に応えようとした試みである。[ 彼が言うように、「論理学は形而上学と一致する」のである。[113][121] 学者グレン・アレクサンダー・マギーの言葉を借りれば、論理学は「時代を超えて真実である純粋なカテゴリーまたは観念の説明」を提供し、それらは「現実そ のものの形式的な構造」を構成する。[122] しかし、ヘーゲルの形而上学的プログラムは、カントが批判したライプニッツ・ヴォルフの合理主義への回帰ではないという点に注目することが重要である。 ヘーゲルは、この批判を受け入れている。[123] 特に、ヘーゲルは超越に関する思索としての形而上学を一切否定している。彼の手法は、アリストテレスの形相概念を借用したもので、完全に内在的である。 [124] より一般的に、ヘーゲルはカントのあらゆる形の独断論の拒絶に全面的に同意しており、また、いかなる未来の形而上学も批判の試練に合格しなければならない という点にも同意している。[125] 内在的な論理展開と批判というヘーゲルの手法が歴史的に唯一無二のものであるという評価は、学者スティーヴン・ホールゲートの見解である。[126] 哲学者のベアトリス・ロンゲネスは、このプロジェクトはカントになぞらえて「形而上学の範疇の不可分の形而上学的・超越論的演繹」として理解できるかもし れないと主張している。[127][o] このアプローチは、論理学の洞察は思考そのもの以外の基準では判断できない、つまり「思考は自然の鏡ではない」と主張し、それを実証しようとしている。し かし、彼女は、このことがこれらの基準が恣意的または主観的であることを意味するものではないと主張している。[127] ヘーゲルの翻訳者であり、ドイツ観念論の研究者であるジョージ・ディ・ジョヴァンニも同様に、『論理学』を内在的に超越論的であると解釈している(カント に依拠しながらも、カントに反対する立場でもある)。ヘーゲルによれば、その範疇は生命そのものに組み込まれており、「一般対象」であることの定義となっ ている。[129] 『論理学』の第1巻と第2巻は、「存在」と「本質」の教義である。この2巻は合わせて客観的論理学を構成し、伝統的な形而上学の前提を克服することに主眼 が置かれている。第3巻は『論理学』の最終部分である。それは「概念」の教義について論じており、客観性のそれらの範疇を徹底した観念論的な現実の説明に 再統合することに関係している。[p] 大幅に単純化すると、存在は概念をそれらが現れる通りに説明し、本質は他の力との関連でそれらを説明しようとし、概念は内部目的論の観点から両者を説明 し、統合する。[131] 存在の範疇は、思考決定を示すものとして、互いに外見上のみ関連しているものとして「移り変わる」 。本質のカテゴリーは相互に「輝き」を放ち合う。最後に、概念において、思考は完全に自己言及的であることを示し、そのカテゴリーは有機的に次から次へと 「展開」する。[132][133] したがって、ヘーゲルの専門的な意味において、概念(Begriff、時には「観念」とも訳され、大文字表記する訳者もいれば、そうでない訳者もいる [q])は心理的な概念ではないことは明らかである。冠詞(「the」)を付けて用いられ、時には「論理的」という修飾語を伴う場合、ヘーゲルは『主観的 論理学』で明確にされた現実の理解可能な構造を指している。(ただし、複数形で使用される場合、ヘーゲルの意味は、この用語の一般的な辞書的な意味により 近いものとなる。[135]) ヘーゲルの思想への探究は、思想の自己内部における自己分化を体系化することに関係している。つまり、純粋概念(論理カテゴリー)が、含意と相互依存のさ まざまな関係において、どのように互いに異なるのかということである。例えば、『論理学』の冒頭の弁証法において、ヘーゲルは「存在、純粋存在、それ以上 何らかの規定を伴わないもの」という思考は「無」という概念と区別できないことを示し、存在と無が「行ったり来たり」する中で、「それぞれがすぐにその反 対のものに消え去る」と主張している。[136] この動きは、ある概念でも別の概念でもなく、「存在」のカテゴリーである。ここでは「参照」できるような差異は存在せず、観察し記述できる弁証法のみが存 在する。[137] 論理学の最後のカテゴリーは「理念」である。「概念」と同様に、ヘーゲルにとってこの用語の意味は心理学的ではない。むしろ、カントの『純粋理性批判』に 従い、ヘーゲルの用法は、ギリシャ語のイーデイア(eidos)に遡る。イーデイアとは、プラトンが唱えた、完全に存在し、普遍的な形相の概念である。 「ヘーゲルのイデー(プラトンのイデアのように)は、存在論、認識論、評価などをひとつの概念体系に融合させようとする試みの産物である。」[139] 論理学は、自然と精神の偶然性の領域における必然性を、すなわち事前に決定できないものを、その中に包含している。「さらに進むには、思考を完全に放棄 し、思考以外のものに純粋な受容性をもって自らを開放しなければならない」[140] 簡単に言えば、論理学は自然と精神の領域においてのみ自己を実現し、そこで「検証」[r]を達成する。したがって、『論理学』の結論は、「客観性と外部の 生活」へと「自由に放たれる(entläßt)」「観念」であり、また、 実在哲学への体系的な移行である。[142][143] |

Philosophy of the real Hegel uses the Owl of Minerva as a metaphor for how philosophy can understand historical conditions only after they occur. In contrast to the first, logical part of Hegel's system, the second, real-philosophical part – the philosophy of nature and of spirit – is an ongoing project with respect to its historical content, which continues to change and develop.[144][145] For instance, although Hegel regards "the basic structure" of the philosophy of nature as complete, he was "aware that science is not 'finished' and will continue to make new discoveries".[146] Philosophy is, as Hegel puts it, "its own time comprehended in thoughts."[147] He expands upon this definition: A further word on the subject of issuing instructions on how the world ought to be: philosophy, at any rate, always comes too late to perform this function. As the thought of the world, it appears only at a time when actuality has gone through its formative process and attained its completed state [sich fertig gemacht]. This lesson of the concept is necessarily also apparent from history, namely that it is only when actuality [Wirklichkeit] has reached maturity that the ideal appears opposite the real and reconstructs this real world, which it has grasped in its substance, in the shape of an intellectual realm. When philosophy paints its gray in gray, a shape of life has grown old, and it cannot be rejuvenated, but only recognized, by the gray in gray of philosophy; the owl of Minerva begins its flight only with the onset of dusk.[148] This frequently has been read as an expression of the impotence of philosophy, political or otherwise, and a rationalization of the status quo.[149] Allegra de Laurentiis, however, points out that the German expression "sich fertig machen", translated as "getting ready" or "to get ready", does not only imply completion, but also preparedness. This additional meaning is important because it better reflects Hegel's Aristotelian concept of actuality. He characterizes actuality as being-at-work-staying-itself that can never be once-and-for-all completed or finished.[150] Hegel describes the relationship between the logical and the real-philosophical parts of his system in this way: "If philosophy does not stand above its time in content, it does so in form, because, as the thought and knowledge of that which is the substantial spirit of its time, it makes that spirit its object."[151] This is to say that what makes the philosophy of the real scientific in Hegel's technical sense is the systematically coherent logical form it uncovers in its natural-historical material – and so also displays in its presentation.[152] |

現実の哲学 ヘーゲルは、哲学が歴史的条件をそれが生じた後にのみ理解できることを示す比喩としてミネルヴァのふくろうを用いている。 ヘーゲルの体系の最初の論理的な部分とは対照的に、2番目の現実的な哲学の部分、すなわち自然と精神の哲学は、歴史的内容に関して進行中のプロジェクトで あり、変化と発展を続けている。[144][145] 例えば、ヘーゲルは自然哲学の「基本構造」を完成したものとみなしているが、一方で「科学は『完成』したものではなく、新たな発見が継続される」ことを認 識していた。[14 6] ヘーゲルが言うように、哲学とは「思考によって理解されたその時代の姿」である。[147] 彼はこの定義をさらに次のように展開する。 世界がどうあるべきかという指示を出すというテーマについて、さらに一言付け加えると、哲学は、いずれにせよ、この機能を果たすには常に遅すぎる。世界の 思考として、それは現実がその形成過程を経て完成した状態(sich fertig gemacht)に達した時にのみ現れる。この概念の教訓は、必然的に歴史からも明らかである。すなわち、現実(Wirklichkeit)が成熟に達し たときにのみ、理想が現実の向こう側に現れ、その本質を把握したこの現実世界を、知的な領域の形に再構築するということである。哲学が灰色を灰色で塗り分 けるとき、生命の形は老いてしまい、哲学の灰色の灰色によって若返らせることはできず、ただ認識することしかできない。ミネルヴァの梟は、黄昏の訪れとと もに初めて飛び立つのである。 これは、政治的あるいはその他の哲学の無力さの表現であり、現状の合理化であると解釈されることが多い。[149] しかし、アレグラ・デ・ローレンティスは、ドイツ語の「sich fertig machen」という表現は、「準備をする」あるいは「準備する」と訳されるが、完了だけでなく、準備も意味すると指摘している。この追加の意味は、ヘー ゲルのアリストテレス的な現実概念をよりよく反映しているため、重要である。ヘーゲルは、現実を「働き続けること自体」と特徴づけ、それは決して一度で完 全に完了したり、終わったりすることはないと述べている。[150] ヘーゲルは、彼の体系における論理と現実の哲学的な部分の関係を次のように説明している。「哲学がその時代の内容において時代を超越しないのであれば、そ れはその形式において時代を超越する。なぜなら、その時代の真髄である思想と知識として、その精神をその対象とするからだ。」[151] つまり、ヘーゲルの専門的な意味で哲学を真に科学的とするのは、自然史的な素材から体系的に首尾一貫した論理形式を明らかにし、その提示においても示して いることである。[152] |

| The Philosophy of Nature The philosophy of nature organizes the contingent material of the natural sciences systematically. As part of the philosophy of the real, in no way does it presume to "tell nature what it must be like."[153][154] Historically, various interpreters have questioned Hegel's understanding of the natural sciences of his time. However, this claim has been largely refuted by recent scholarship.[155][156] One of the very few ways in which the philosophy of nature might correct claims made by the natural sciences themselves is to combat reductive explanations; that is to discredit accounts employing categories not adequate to the complexity of the phenomena they purport to explain, as for instance, attempting to explain life in strictly chemical terms.[157] Although Hegel and other Naturphilosophen aim to revive a teleological understanding of nature, they argue that their strictly internal or immanent concept of teleology is "limited to the ends observable within nature itself." Hence, they claim, it does not violate the Kantian critique.[158] Even more strongly, Hegel and Schelling claim that Kant's restriction of teleology to regulative status effectively undermines his own critical project of explaining the possibility of knowledge. Their argument is that "only under the assumption that there is an organism is it possible to explain the actual interaction between the subjective and the objective, the ideal and the real." Hence the organism must be acknowledged to have constitutive status.[159] Introducing Hegel's philosophy of nature for a 21st-century audience, Dieter Wandschneider [de] observes that "contemporary philosophy of science" has lost sight of "the ontological issue at stake, namely, the question of an intrinsically lawful nature": "Consider, for example, the problem of what constitutes a law of nature. This problem is central to our understanding of nature. Yet philosophy of science has not provided a definitive response to it up to now. Nor can we expect to have such an answer from that quarter in future."[160] It is back to Hegel that Wandschneider would direct philosophers of science for guidance in the philosophy of nature.[161] Recent scholars have also argued that Hegel's approach to the philosophy of nature provides valuable resources for theorizing and confronting recent environmental challenges entirely unforeseen by Hegel. These philosophers point to such aspects of his philosophy as its distinctive metaphysical grounding and the continuity of its conception of the nature-spirit relationship.[162][163] |

自然哲学 自然哲学は、自然科学の偶発的な素材を体系的に整理する。現実の哲学の一部として、決して「自然がどうあるべきかを自然に伝える」ことを想定しているわけ ではない。[153][154] 歴史的に、さまざまな解釈者がヘーゲルの当時の自然科学に対する理解に疑問を呈してきた。しかし、この主張は最近の研究によってほぼ否定されている。 [155][156] 自然科学の哲学が自然科学自体の主張を修正できる数少ない方法のひとつは、還元主義的な説明と戦うことである。つまり、説明しようとする現象の複雑さに適 さないカテゴリーを使用する説明を否定することであり、例えば、生命を厳密に化学用語で説明しようとすることである。 ヘーゲルや他の自然哲学の専門家たちは、目的論的な自然観の復活を目指しているが、彼らは、厳密に内的または内在的な目的論の概念は「自然そのものの中で 観察可能な目的に限定される」と主張している。したがって、彼らの主張によれば、それはカントの批判を侵害することにはならない。さらに強く、ヘーゲルと シェリングは、カントが目的論を調整的な地位に制限したことは、知識の可能性を説明するカント自身の批判的なプロジェクトを事実上損なうことになると主張 している。彼らの主張は、「有機体という前提があって初めて、主観と客観、理想と現実の間の実際の相互作用を説明することが可能になる」というものであ る。したがって、有機体は構成的な地位を持つと認められなければならない。[159] ディーター・ヴァンシュナイダー(Dieter Wandschneider)は、21世紀の読者に向けてヘーゲルの自然哲学を紹介し、「現代科学哲学」は「本質的な法則性という問題、すなわち、本質的 に法則的な性質という問題」という「存在論的な問題」を見失っていると指摘している。「例えば、自然法則を構成するものは何かという問題を考えてみよう。 この問題は、自然に対する我々の理解の中心にある。しかし、科学哲学はこれまで、この問題に対する決定的な回答を提供してこなかった。また、今後、その方 面からそのような答えが得られることも期待できない。」[160] ヴァンシュナイダーが自然科学の哲学者たちに自然哲学の指針を求めたのは、ヘーゲルに立ち返ることだった。[161] 最近の学者たちも、ヘーゲルの自然哲学へのアプローチは、ヘーゲルがまったく予期しなかった最近の環境問題に理論的に対処するための貴重なリソースを提供 していると主張している。これらの哲学者たちは、ヘーゲルの哲学の特徴的な形而上学的根拠や、自然と精神の関係についての概念の連続性などを指摘してい る。[162][163] |

The Philosophy of Spirit Priestess of Delphi (1891) by John Collier. The Delphic imperative to "know thyself" governs Hegel's entire philosophy of spirit. The German Geist has a wide range of meanings.[164] In its most general Hegelian sense, however, "Geist denotes the human mind and its products, in contrast to nature and also the logical idea."[165] (Some older translations render it as "mind," rather than "spirit."[s]) As is especially evident in the Anthropology, Hegel's concept of spirit is an appropriation and transformation of the self-referential Aristotelian concept of energeia.[167] Spirit is not something above or otherwise external to nature. It is "the highest organization and development" of nature's powers.[168] According to Hegel, "the essence of spirit is freedom."[169] The Encyclopedia Philosophy of Spirit charts the progressively determinate stages of this freedom until spirit fulfills the Delphic imperative with which Hegel begins: "Know thyself."[170] As becomes clear, Hegel's concept of freedom is not (or not merely) the capacity for arbitrary choice, but has as its "core notion" that "something, especially a person, is free if and only if, it is independent and self-determining, not determined by or dependent upon something other than itself."[171] It is, in other words, (at least predominantly, dialectically) an account of what Isaiah Berlin would later term positive liberty.[172] |

精神哲学 (1891年)ジョン・コリアー作。「汝自身を知れ」というデルフィの命題は、ヘーゲルの精神哲学全体を支配している。 ドイツ語の「ガイスト」には幅広い意味がある。[164] しかし、ヘーゲル的な最も一般的な意味では、「ガイストは、自然や論理的な概念とは対照的に、人間の精神とその産物を意味する」[165](古い翻訳の中 には、「精神」ではなく「心」と訳しているものもある。[s] 特に『人類学』において明白であるように、ヘーゲルの精神の概念は、自己言及的なアリストテレスのエネルゲイアの概念を借用し、それを発展させたものであ る。[167] 精神は、自然の上にあるもの、あるいは自然の外にあるものではない。それは自然の力の「最高の組織化と発展」である。[168] ヘーゲルによれば、「精神の本質は自由である」[169]。『精神哲学事典』は、ヘーゲルが冒頭で述べている「汝自身を知れ」というデルフィの命題を精神 が達成するまで、この自由が段階的に決定されていく様子を明らかにしている。[170] 明らかになるように、ヘーゲルの自由の概念は、任意の選択の能力ではなく(あるいは、単なる能力ではない)、「何か、特に人格が自由であるためには、それ が独立しており、自己決定している場合に限られる。つまり、それ自体以外の何かに決定されたり、依存したりしていない場合に限られる」という「中核となる 概念」である。[171] 言い換えれば、少なくとも主として弁証法的に、アイザイア・バーリンが後に「積極的自由」と呼ぶものを説明するものである。[1 72] |

| Subjective spirit Standing at the transition from nature to spirit, the role of the Philosophy of Subjective Spirit is to analyze "the elements necessary for or presupposed by such relations [of objective spirit], namely, the structures characteristic of and necessary to the individual rational agent." It does this by elaborating "the fundamental nature of the biological/spiritual human individual along with the cognitive and the practical prerequisites of human social interaction."[173] This section, particularly its first part, contains various comments that were commonplace in Hegel's day and can now be recognized as openly racist, such as unfounded claims about the "naturally" lower intellectual and emotional development of Black people. In his perspective, these racial differences are related to climate: according to Hegel, it is not racial characteristics, but the climactic conditions in which a people lives that variously limit or enable its capacity for free self-determination. He believes that race is not destiny: any group could, in principle, improve and transform its condition by migrating to friendlier climes.[174][t] Hegel divides his philosophy of the subjective spirit into three parts: anthropology, phenomenology, and psychology. Anthropology "deals with 'soul', which is spirit still mired in nature: all that within us which precedes our self-conscious mind or intellect." In the section "Phenomenology", Hegel examines the relation between consciousness and its object and the emergence of intersubjective rationality. Psychology "deals with a great deal that would be categorized as epistemology (or 'theory of knowledge') today. Hegel discusses, among other things, the nature of attention, memory, imagination and judgement."[175] Throughout this section, but especially in the Anthropology, Hegel appropriates and develops Aristotle's hylomorphic approach to what is today theorized as the mind–body problem: "The solution to the mind–body problem [according to this theory] hinges upon recognizing that mind does not act upon the body as cause of effects but rather acts upon itself as an embodied living subjectivity. As such, mind develops itself, progressively attaining more and more of a self-determined character."[176][177] Its final section, Free Spirit, develops the concept of "free will," which is foundational for Hegel's philosophy of right.[178][179] |

主観的精神 自然から精神への移行点に立つ主観的精神哲学の役割は、「客観的精神の関係に必要な、あるいは前提となる要素、すなわち、個々の理性的行為者に特有で、か つ必要な構造」を分析することである。 これを「生物学的/精神的個人の本質的な性質と、人間の社会的交流に必要な認識的および実践的な前提条件」を詳しく説明することで行う。[173] このセクション、特にその最初の部分には、ヘーゲルの時代には一般的であったが、現在では公然と人種差別的であると認識されるようなさまざまな意見が含ま れている。例えば、黒人の知性や感情の発達が「自然に」劣っているという根拠のない主張などである。ヘーゲルによれば、人種的特性ではなく、その民族が暮 らす気候的条件が、その民族の自由な自己決定能力をさまざまに制限したり、可能にしたりするというのである。ヘーゲルは、人種は宿命ではないと考えてい る。どの集団も、より友好的な気候の地に移住することで、原則的にはその状態を改善し、変革することが可能である。[174][t] ヘーゲルは主観的精神の哲学を3つの部分に分けている。すなわち、人間学、現象学、心理学である。人間学は「魂」を扱う。魂とは、自然の中に埋もれたまま の精神であり、自己意識や知性よりも前の段階にある、私たちの中にあるものすべてである。「現象学」のセクションでは、ヘーゲルは意識とその対象との関 係、および相互主観的合理性の出現について考察している。心理学は「今日では認識論(または「知識論」)に分類される多くの事柄を扱っている。ヘーゲル は、とりわけ注意、記憶、想像力、判断の性質について論じている」[175]。 このセクション全体を通して、特に『人類学』において、ヘーゲルは今日「心身問題」として理論化されているものに対して、アリストテレスの形相的アプロー チを借用し、発展させた。「心身問題の解決策(この理論によると)は、心は身体に作用して効果を生み出すのではなく、むしろ身体に作用して、具現化された 生きている主体として自らに作用する、という認識にかかっている。このように、心は自らを成長させ、自己決定の特性を徐々に獲得していくのである。」 [176][177] 最終章「自由な精神」では、「自由意志」の概念が展開され、これはヘーゲルの正義哲学の基礎となるものである。[178][179] |

Objective spirit King Frederick William III of Prussia (1797–1840) stifled the political reforms for which Hegel had hoped and advocated.[180] In the broadest terms, Hegel's philosophy of objective spirit "is his social philosophy, his philosophy of how the human spirit objectifies itself in its social and historical activities and productions."[181] Or, put differently, it is an account of the institutionalization of freedom.[182] Besier declares this a rare instance of unanimity in Hegel scholarship: "all scholars agree there is no more important concept in Hegel's political theory than freedom." This is because it is the foundation of right, the essence of spirit, and the telos of history.[183] This part of Hegel's philosophy is presented first in his 1817 Encyclopedia (revised 1827 and 1830) and then at greater length in the 1821 Elements of the Philosophy of Right, or Natural Law and Political Science in Outline (like the Encyclopedia, intended as a textbook), upon which he also frequently lectured. Its final part, the philosophy of world history, was additionally elaborated in Hegel's lectures on the subject.[184][185] Hegel's Elements of the Philosophy of Right has been controversial from the date of its original publication.[186][187] It is not, however, a straightforward defense of the autocratic Prussian state, as some have alleged, but is rather a defense of "Prussia as it was to have become under [proposed] reform administrations."[188] The German Recht in Hegel's title does not have a direct English equivalent (though it does correspond to the Latin ius and the French droit). As a first approximation, Michael Inwood distinguishes three senses: a right, claim or title justice (as in, e.g., 'to administer justice'...but not justice as a virtue...) 'the law' as a principle, or 'the laws' collectively.[189] Beiser observes that Hegel's theory is "his attempt to rehabilitate the natural law tradition while taking into account the criticisms of the historical school." He adds that "without a sound interpretation of Hegel's theory of natural law, we have very little understanding of the very foundation of his social and political thought."[190][u] Consistent with Beiser's position, Adriaan T. Peperzak documents Hegel's arguments against social contract theory and stresses the metaphysical foundations of Hegel's philosophy of right.[194][v] Observing that "analyzing the structure of Hegel's argument in the Philosophy of Right shows that achieving political autonomy is fundamental to Hegel's analysis of the state and government," Kenneth R. Westphal provides this brief outline: "'Abstract Right,' treats principles governing property, its transfer, and wrongs against property." "'Morality,' treats the rights of moral subjects, responsibility for one's actions, and a priori theories of right." "'Ethical Life' (Sittlichkeit), analyzes the principles and institutions governing central aspects of rational social life, including the family, civil society, and the state as a whole, including the government."[196] Hegel describes the state of his time, a constitutional monarchy, as rationally embodying three cooperative and mutually inclusive elements. These elements are "democracy (rule of the many, who are involved in legislation), aristocracy (rule of the few, who apply, concretize, and execute the laws), and monarchy (rule of the one, who heads and encompasses all power)."[197][198] It is what Aristotle called a "mixed" form of government, which is designed to include what is best of each of the three classical forms.[199] The division of powers "prevents an single power from dominating others."[200] Hegel is particularly concerned to bind the monarch to the constitution, limiting his authority so that he can do little more than to declare of what his ministers have already decided that it is to be so.[201] The relation of Hegel's philosophy of right to modern liberalism is complex. He sees liberalism as a valuable and characteristic expression of the modern world. However, it carries the danger within itself to undermine its own values. This self-destructive tendency may be avoided by measuring "the subjective goals of individuals by a larger objective and collective good." Moral values, then, have only a "limited place in the total scheme of things."[202] Yet, although it is not without reason that Hegel is widely regarded as a major proponent of what Isaiah Berlin would later term positive liberty, he was just as "unwavering and unequivocal" in his defense of negative liberty.[203] If Hegel's ideal sovereign is much weaker than was typical in monarchies his time, so too is his democratic element much weaker than is typical in democracies of modern times. Although he insists upon the importance of public participation, Hegel severely limits suffrage and follows the English bicameral model, in which only members of the lower house, that of commoners and bourgeoisie, are elected officials. Nobles in the upper house, like the monarch, inherit their positions.[204] The final part of the Philosophy of Objective Spirit is entitled "World History." In this section, Hegel argues that "this immanent principle [the Stoic logos] produces with logical inevitability an expansion of the species' capacities for self determination ('freedom') and a deepening of its self understanding ('self-knowing')."[205] In Hegel's own words: "World history is progress in the consciousness of freedom – a progress that we must comprehend conceptually."[206] |

客観的精神 プロイセン王フリードリヒ・ウィルヘルム3世(1797年-1840年)は、ヘーゲルが期待し、提唱した政治改革を阻止した。[180] 最も広い意味で、ヘーゲルの客観的精神の哲学は「彼の社会哲学であり、人間の精神が社会的・歴史的活動や生産において自己を客観化する方法についての哲学 である」[181]。あるいは、異なる表現を用いるなら、それは自由の制度化についての説明である。[182] ベジエは、これはヘーゲル研究における珍しい一致した見解であると主張している。「ヘーゲルの政治理論において、自由よりも重要な概念はないという点で は、すべての学者が一致している」と述べている。これは、自由が権利の基礎であり、精神の本質であり、歴史の目的であるからである。[183] ヘーゲルの哲学のこの部分は、まず1817年の『百科全書』(1827年と1830年に改訂)で提示され、さらに1821年の『法の哲学の諸要素、あるい は自然法と概略の政治学』(『百科全書』と同様に教科書として意図された)でより詳細に説明されている。その最終部分である世界史哲学は、ヘーゲルの同 テーマに関する講義でさらに詳しく説明されている。[184][185] ヘーゲルの『法の哲学要論』は、初版刊行以来、物議を醸し続けている。[186][187] しかし、これは一部で主張されているような専制的なプロイセン国家の単純な擁護ではなく、「改革行政下で実現されるはずだったプロイセン」の擁護である。 [188] ヘーゲルの著書のタイトルにあるドイツ語の「ドイツ・レヒト」には、直接的な英語訳はない(ただし、ラテン語の「ユス」やフランス語の「ドロワ」に相当す る)。マイケル・インウッドは、その意味を大まかに3つに区別している。 権利、主張、または権原 正義(例えば「正義を執行する」のように…ただし、美徳としての正義ではない) 原則としての「法」、または集合的な「法」[189] Beiserは、ヘーゲルの理論は「歴史学派の批判を考慮に入れつつ、自然法の伝統を復権させようとする試み」であると指摘している。また、「ヘーゲルの 自然法理論の健全な解釈なしには、彼の社会思想および政治思想の基盤をほとんど理解できない」とも付け加えている。[190][u] ベイザーの立場と一致するものとして、アドリアーン・T・ペパーザックは、社会契約説に対するヘーゲルの論拠を記録し、ヘーゲルの正義哲学の形而上学的基 盤を強調している。[194][v] 「『法哲学』におけるヘーゲルの議論の構造を分析すると、政治的自律性を達成することが、ヘーゲルの国家と政府の分析にとって根本的なものであることがわ かる」と指摘した上で、ケネス・R・ウェストファルは次のような簡潔な概要を示している。 「『抽象的権利』では、財産、その移転、財産に対する侵害を支配する原則を扱う。」 「『道徳』では、道徳的主題の権利、自らの行動に対する責任、権利に関するア・プリオリな理論を扱う。」 「倫理的生活(Sittlichkeit)」は、家族、市民社会、政府を含む国家全体など、理性的な社会生活の中心的な側面を規定する原則と制度を分析す る。[196] ヘーゲルは、当時の国家形態である立憲君主制を、3つの協調的かつ相互に包含的な要素を合理的に体現しているものとして説明している。これらの要素とは、 「民主主義(立法に関与する多数者の統治)、貴族政治(法律を適用し、具体化し、執行する少数者の統治)、そして君主制(すべての権力を統括する唯一者の 統治)」である。[197][198] これはアリストテレスが「混合」形態と呼んだ政治形態であり、3つの古典的な形態のそれぞれから最良のものを組み入れることを目的としている。[199] 権力の分割は 「単一の権力が他を支配することを防ぐ」[200]。ヘーゲルは特に君主を憲法に縛り付けることに懸念を示し、君主の権限を制限することで、大臣がすでに 決定したことを「そのように決定する」と宣言すること以上のことはほとんどできないようにした。[201] ヘーゲルの正義哲学と近代リベラリズムの関係は複雑である。彼はリベラリズムを近代世界の価値ある特徴的な表現と見なしている。しかし、リベラリズムは自 らの価値を損なう危険性を内包している。この自己破壊的な傾向は、「個人の主観的な目標をより大きな客観的かつ集団的な善によって」測ることによって回避 できるかもしれない。道徳的価値は、物事の全体的な枠組みの中で「限られた位置」しか占めていないのである。[202] とはいえ、ヘーゲルが後にアイザイア・バーリンが「積極的自由」と呼ぶものを主唱した主要な人物と広く見なされているのには理由がある。しかし、彼は「揺 るぎない、明確な」否定的自由の擁護者でもあった。[203] ヘーゲルの理想的な君主は、彼が生きた時代の君主制の典型よりもはるかに弱体であるが、彼の民主主義の要素もまた、現代の民主主義の典型よりもはるかに弱 体である。ヘーゲルは市民の参加の重要性を主張しているが、選挙権を厳しく制限し、下院の議員のみが選挙で選ばれるという英国の二院制モデルを採用してい る。上院の貴族は君主と同様に、その地位を世襲する。 『目的精神の哲学』の最終章は「世界史」と題されている。この章でヘーゲルは、「この内在的原則(ストア派のロゴス)は、論理的に必然的に、自己決定能力 (「自由」)の拡大と自己理解の深化(「自己認識」)を生み出す」と論じている。[205] ヘーゲル自身の言葉で言えば、「世界史とは、自由の意識における進歩である。この進歩を我々は概念的に理解しなければならない」[206] |

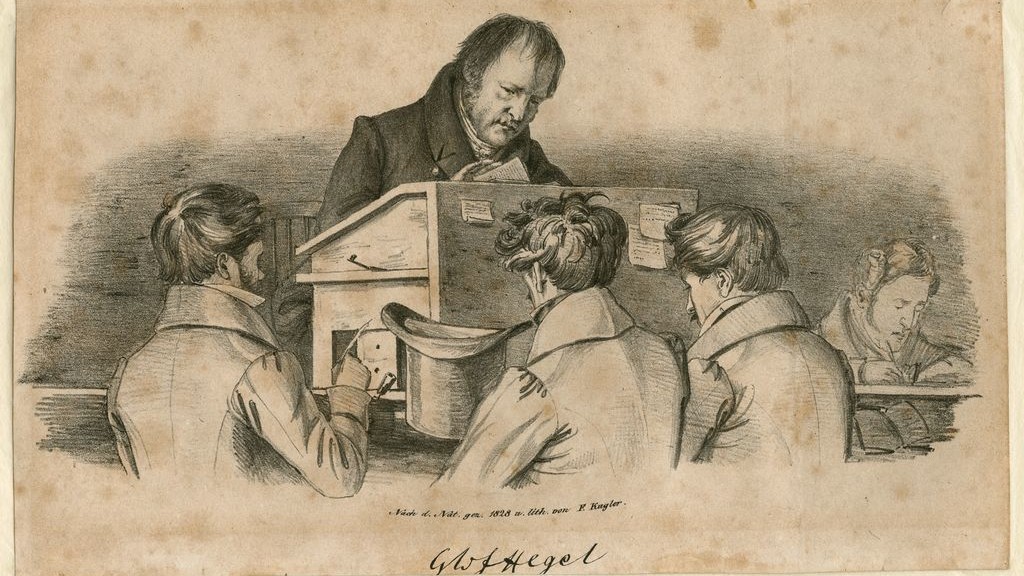

Absolute spirit Hegel with his Berlin students (1828 sketch by F. T. Kugler) Hegel's use of the term "absolute" is easily misunderstood. Inwood, however, clarifies: derived from the Latin absolutus, it means "not dependent on, conditional on, relative to or restricted by anything else; self-contained, perfect, complete."[207] For Hegel, this means that absolute knowing can only denote "an 'absolute relation' in which the ground of experience and the experiencing agent are one and the same: the object known is explicitly the subject who knows."[208] That is, the only "thing" (which is really an activity) that is truly absolute is that which is entirely self-conditioned, and according to Hegel, this only occurs when spirit takes itself up as its own object. The final section of his Philosophy of Spirit presents the three modes of such absolute knowing: art, religion, and philosophy.[w] It is with reference to different modalities of consciousness – intuition, representation, and comprehending thinking – that Hegel distinguishes the three modes of absolute knowing.[x] Frederick Beiser summarizes: "art, religion and philosophy all have the same object, the absolute or truth itself; but they consist in different forms of knowledge of it. Art presents the absolute in the form of immediate intuition (Anschauung); religion presents it in the form of representation (Vorstellung); and philosophy presents it in the form of concepts (Begriffe)."[210] Rüdiger Bubner additionally clarifies that the increase in conceptual transparency according to which these spheres are systematically ordered is not hierarchical in any evaluative sense.[211] Although Hegel's discussion of absolute spirit in the Encyclopedia is quite brief, he develops his account at length in lectures on the philosophy of fine art, the philosophy of religion, and the history of philosophy.[185] |

絶対的精神 ベルリンの学生たちと一緒にいるヘーゲル (1828年の F. T. クグラーによるスケッチ) ヘーゲルによる「絶対」という用語の使用は、誤解されやすい。しかし、インウッドは、この用語はラテン語の「absolutus」から派生したもので、 「他の何にも依存しない、条件付けられない、相対的ではない、制限されない、自己完結的、完全」という意味であると明快に説明している[207]。ヘーゲ ルにとって、これは、絶対的認識とは、「経験の根拠と経験主体が同一である『絶対的関係』」のみを指すことを意味する。つまり、認識される対象は、明らか に認識する主体そのものである。[208] つまり、真に絶対的な「もの」(実際には活動である)は、完全に自己条件付けられたものであり、ヘーゲルによると、これは精神が自身を自身の対象として取 り込む場合にのみ起こる。彼の『精神の哲学』の最終章では、このような絶対的認識の三つの形態が提示されている:芸術、宗教、哲学。[w] ヘーゲルは、直感、表象、理解的思考という異なる意識の様式を参照して、絶対的認識の 3 つの様式を区別している。[x] フレデリック・ベイザーは、次のように要約している。「芸術、宗教、哲学は、すべて同じ対象、つまり絶対者、あるいは真実そのものを対象としているが、そ れに対する知識の形態が異なる。芸術は、絶対を直接的な直観(Anschauung)の形で表現し、宗教は表象(Vorstellung)の形で表現し、 哲学は概念(Begriffe)の形で表現する。」[210] Rüdiger Bubner はさらに、これらの領域が体系的に整理される概念の透明性の高まりは、評価的な意味での階層的なものではないことを明確にしている。[211] ヘーゲルは『百科全書』では絶対精神についてごく簡単に論じているが、美術哲学、宗教哲学、哲学史に関する講義で、その説明を詳しく展開している。 [185] |

| Philosophy of art Main article: Lectures on Aesthetics  The ancient Athenian, according to Hegel, apprehends the meaning of Athena Parthenos directly as his own rational essence.[212] (The Varvakeion Athena, National Archaeological Museum of Athens) In the Phenomenology, and even in the 1817 edition of the Encyclopedia, Hegel discusses art only as it figures in what he terms the "Art-Religion" of the ancient Greeks. In 1818, however, Hegel begins lecturing on the philosophy of art as an explicitly autonomous domain.[211][213][y] Although H. G. Hotho titled his edition of the Lectures Vorlesungen über die Ästhetik [Lectures on Aesthetics], Hegel directly states that his topic is not "the spacious realm of the beautiful," but "art, or, rather, fine art."[214] He doubles down on this in the next paragraph by explicitly distinguishing his project from the broader philosophical projects pursued under the heading of "aesthetics" by Christian Wolff and Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten.[z] Some critics – most canonically, Benedetto Croce, in 1907[215] – have attributed to Hegel some form of the thesis that art is "dead." Hegel, however, never said any such thing, nor can such a view be plausibly attributed to him.[aa] Indeed, one commentator places that debate in perspective with the observation that Hegel's claim that "art no longer serves our highest aims" is "radical not for the suggestion that art now fails to do so but for the suggestion that it ever did."[216] Hegel's detailed and systematic treatment of the various arts over such a great span has even led Ernst Gombrich to present Hegel as "the father of art history." Indeed, until recently,[when?] Hegel's Lectures were largely ignored by philosophers and received most of their attention from literary critics and art historians.[217] The more narrowly conceptual project of the philosophy of art, however, is to articulate and defend "the autonomy of art, making possible an account of the special individuality distinguishing works of aesthetic worth."[218] According to Hegel, "'artistic beauty reveals absolute truth through perception.'[219] He holds that the best art conveys metaphysical knowledge by revealing, through sense perception, what is unconditionally true," that is, "what his metaphysical theory affirms to be unconditional or absolute."[220] So, while Hegel "ennobles art insofar as it conveys metaphysical knowledge," "he tempers his assessment in view of his belief that art's sensory media can never adequately convey what completely transcends the contingency of sensation."[221] This is why, according to Hegel, art can only be one of three mutually complementary modes of absolute spirit.[ab] |