フェミニズム

feminism

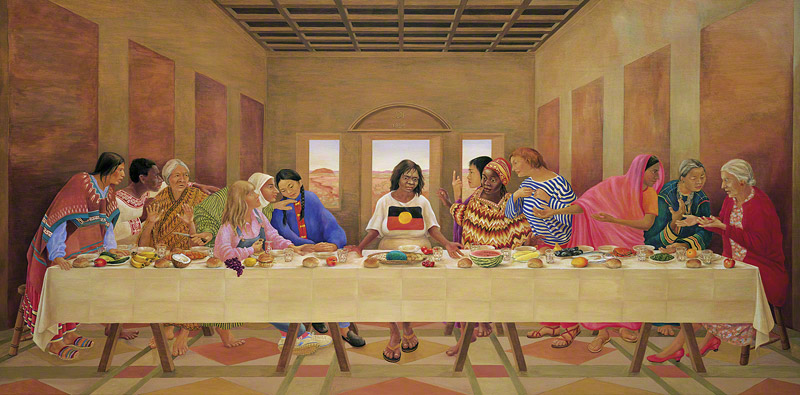

The First Supper 1988 acrylic on panel, 120 x 240 cm by Susan Dorothea White

フェミニズムは、性差別主義的な抑圧をなくすための闘いである—— bell hooks.

フェミニズムを理想化された学問のように考えてはいけません。自分自身のジェンダリズムを解

体する作戦指令書あるいは敵の状況が不案内な時の危機管理マニュアルのように理解しないとなりません——垂水源之猫(2021)

フェミニズムとは、いわゆる民主主義的な近代社会に おいて、法の理念や人権概念において、男女の平等が達成されていないという現状認識から出発し、女性に とっての、政治的、法的、権利的、経済的、アイデンティティ的、文化的、心理的などの視座を包含する社会運動と、そのイデオロギーからなり、基本的に、政 治運動の形態をもつものの総称である。女性にとっての「政治的、法的、権利的……心理的などの視座」が、民主主義的な近代社会において多様・多元的である ために、フェミニズムそのものも多様な姿をもつ。それぞれの運動の方向性や思想には、統一的方向性や最終目標(テロス)を定めることは難しいが、現況にお いて「男女の平等が達成されていないという現状認識から出発」し、そのための平等の是正は、普遍的に正しいという立場が崩れることはない(→「フェミニスト理論」)。

さて、かつて私はフェミニズムを次のように定義して いる:「フェミニズム(feminism)とは、 ジェンダーならびにセックスの区分において《女性》——フェミナ(fēmin-a)的 存在——に対する差別や抑圧を告発し、その人間的権利において自由と平等を求めるための理論と実践の総体のことをさす」(→「はじめてのフェミニズム」)

いずれにせよ「女性」という政治的分類概念・文化的 社会的概念・生物学概念が問題となる。政治的分類概念(ideological classifiction)としての女性は、既存の(ということは保守的な)文化的社会的分類概念(gendered classification)ならびに生物学的分類概念(sexual classification)にもとづいて、女性の社会的身分とその範囲を確定する。それゆえ、女性の概念は、最終的に生物学的な本質性にもとづいて 「男性」と対比的に配列される。

爾来、女性は、生物学的な性別のみで峻別されるもの だといういうふうに理解されてきた。それゆえ、両性具有あるいは「ふたなり」と呼ばれる生物学的な特質をもつ個体はアノマリー(性的異常)として、女性/ 男性というカテゴリーには属さないものとみなされてきた。さて、男性中心的な社会において、女性を男性に比肩できる法的社会的に同等な資格を持たないもの と当初規定してきた西洋近代社会は、女性の劣等性を生物学や医学に仮託してそれを正当化してきた。しかしながら、男女の法的平等性の達成が近代社会の成立 にとって喫緊の課題となり、法的権利(参政権、労働権、親権など)において平等化の思想が普及していくと、女性と男性の種別的差異に生得的なものは存在し ないことが明らかになり、それを支持する生物学・生物医学理論がヘゲモニーを握るようになる。そのような仮定で、男性と女性の生物学的な差異を担保しなが らも、社会的な性別はそれとは独立した区別であるという立場が登場してくる。それが社会文化的な男女の区別であるところのジェンダー概念の登場である。

それ以来、生物学的な性別(sex)と社会的文化的 性別(gender)という形で峻別されてきた。しかしながら、いつしかこの二分法は、生物学的にも文化社会的にも性別の分割は可能であるという無批判な イデオロギーを生んでしまった。また、ジュディス・バトラー[1990=1999]のように、ジェンダーとセックスの峻別は、本来は生物学的定義を社会文 化的概念で相対化しようとするために登場してきたのにかかわらず、最終的に生物学的女性は本質的であるというイデオロギーを温存させてきたことに貢献した という批判が登場する。しかしながら、このような二分法をあざ笑うかのような、異性装(ドラアグ)やゲイ/レスビアン、ホルモン化による性的志向の改変さ らには性転換などの「性別」のパロディの存在がある。これらの現象は、社会の隙間にある、道化や撹乱的存在であると同時に、ジェンダーもセックスも社会的 な構築物であり、すべては相対的決められ、それを男女というカテゴリーに分類しているにすぎないことを、皮肉という表現を通して批判的に体現しているので ある(→「ジェンダー・とらぶってる!!!」)。

フェミニズム運動の担い手であるフェミニストの多く が、そのような「性的マイノリティたち」に対して同情的・共感的・連帯的であるのは、ともに男性中心主義が押しつけてくる権力構造のなかでは、ともに政治 権力的マイノリティとして、中心的な権力構造から排除されてきたゆえの、類的集団意識=アイデンティティから生じるものだと考えられる。

★ウィキペディア英語(冒頭のフェミニズム)解説

| Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes.[a][2][3][4][5] Feminism holds the position that societies prioritize the male point of view and that women are treated unjustly in these societies.[6] Efforts to change this include fighting against gender stereotypes and improving educational, professional, and interpersonal opportunities and outcomes for women. | フェミニズムとは、両性の政治的、経済的、個人的、社会的平等を定義し、確立することを目的と する様々な社会政治運動やイデオロギーのことである[a] [2][3][4][5]。フェミニズムは、社会は男性の視点を優先し、女性はこれらの社会で不当に扱われているという立場をとっている[6]。これを変 えるための努力には、ジェンダー・ステレオタイプと闘い、女性の教育的、職業的、対人的な機会や成果を改善することが含まれる。 |

| Originating in late 18th-century Europe, feminist movements have campaigned and continue to campaign for women's rights, including the right to vote, run for public office, work, earn equal pay, own property, receive education, enter into contracts, have equal rights within marriage, and maternity leave. Feminists have also worked to ensure access to contraception, legal abortions, and social integration; and to protect women and girls from sexual assault, sexual harassment, and domestic violence.[7] Changes in female dress standards and acceptable physical activities for females have also been part of feminist movements.[8] | 18世紀後半のヨーロッパで始まったフェミニスト運動は、女性の権利

(投票権、公職への立候補権、就労権、同等の賃金、財産所有権、教育を受ける権利、契約を結ぶ権利、婚姻における平等な権利、産休など)を求め、現在も活

動を続けている。フェミニストたちはまた、避妊手段へのアクセス、合法的な中絶、社会的統合の確保に努めるとともに、女性と少女を性的暴力、性的ハラスメ

ント、家庭内暴力から保護する活動も行ってきた。[7]

女性のための服装基準や許容される身体活動の変化も、フェミニスト運動の一部を構成してきた。[8] |

| Many scholars consider feminist campaigns to be a main force behind major historical societal changes for women's rights, particularly in the West, where they are near-universally credited with achieving women's suffrage, gender-neutral language, reproductive rights for women (including access to contraceptives and abortion), and the right to enter into contracts and own property.[9] Although feminist advocacy is, and has been, mainly focused on women's rights, some argue for the inclusion of men's liberation within its aims, because they believe that men are also harmed by traditional gender roles.[10] Feminist theory, which emerged from feminist movements, aims to understand the nature of gender inequality by examining women's social roles and lived experiences. Feminist theorists have developed theories in a variety of disciplines in order to respond to issues concerning gender.[11][12] | 多くの学者は、フェミニスト運動が、特に欧米において、女性の権利に関

する歴史的な社会変革の主な原動力となったと評価している。欧米では、女性の参政権、ジェンダーニュートラルな言語、女性の生殖権(避妊や中絶へのアクセ

スを含む)、契約締結や財産の所有権などの権利の獲得は、ほぼすべてフェミニスト運動の成果であると広く認識されている。[9]

フェミニストの主張は、現在も過去も主に女性の権利に焦点を当てていますが、伝統的な性別役割が男性にも害を及ぼすと考えている一部の人々は、男性の解放

をその目的の中に含めるべきだと主張しています。[10]

フェミニスト理論は、フェミニスト運動から生まれたもので、女性の社会的役割と実際の経験を通じて、性別不平等

の本質を理解することを目的としています。フェミニスト理論家は、ジェンダーに関する問題に対応するため、多様な学問分野で理論を構築してきた。[11]

[12] |

| Numerous feminist movements and ideologies have developed over the years, representing different viewpoints and political aims. Traditionally, since the 19th century, first-wave liberal feminism, which sought political and legal equality through reforms within a liberal democratic framework, was contrasted with labour-based proletarian women's movements that over time developed into socialist and Marxist feminism based on class struggle theory.[13] Since the 1960s, both of these traditions are also contrasted with the radical feminism that arose from the radical wing of second-wave feminism and that calls for a radical reordering of society to eliminate patriarchy. Liberal, socialist, and radical feminism are sometimes referred to as the "Big Three" schools of feminist thought.[14] | 長年にわたり、さまざまな見解や政治的目的を持つ数多くのフェミニズム 運動やイデオロギーが発展してきた。19 世紀以来、伝統的に、自由民主主義の枠組みの中で改革を通じて政治的・法的平等を求めた第一波の自由主義フェミニズムは、階級闘争理論に基づく社会主義 フェミニズムやマルクス主義フェミニズムへと発展した労働者階級の女性運動と対比されてきた。[13] 1960年代以降、これらの2つの伝統は、第2波フェミニズムの過激派から生まれた、家父長制を排除するための社会の根本的な再構築を求める急進的フェミ ニズムとも対比されるようになった。自由主義、社会主義、急進的フェミニズムは、フェミニズム思想の「3大流派(ビッグ3)」と呼ばれることもある。[14] |

| Since the late 20th century, many newer forms of feminism have emerged. Some forms, such as white feminism and gender-critical feminism, have been criticized as taking into account only white, middle class, college-educated, heterosexual, or cisgender perspectives. These criticisms have led to the creation of ethnically specific or multicultural forms of feminism, such as black feminism and intersectional feminism.[15] Some have argued that feminism often promotes misandry and the elevation of women's interests above men's, and criticize radical feminist positions as harmful to both men and women.[16] | 20世紀後半以降、多くの新しい形態のフェミニズムが登場した。白人

フェミニズムやジェンダー批判的フェミニズムなど、一部の形態は、白人、中流階級、大学教育を受けた、異性愛者、またはシスジェンダーの視点のみを考慮し

ていると批判されてきた。これらの批判は、黒人フェミニズムや交差性フェミニズムなど、民族的に特定されたり多文化的な形態のフェミニズムの誕生につな

がった。[15]

一部の人々は、フェミニズムはしばしば男性嫌悪を促進し、女性の利益を男性の利益よりも優先させるとして、過激なフェミニストの立場を男性と女性の双方に

有害だと批判している。[16] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Feminism |

★フェミニズム理論とその課題を3つのウェーブで理解する(出典は「交差性・インターセクショナリティ」より)

1)第一波フェミニズム:1960年代以前:主に白 人男性と白人女性の間の政治的平等を得ることに関心があった。

2)第二波フェミニズム:1960年代から1980 年代;黒人フェミニスト、チカーナやその他のラティーナ・フェミニスト、先住民フェミニスト、アジア系アメリカ人 フェミニスト、など全世界的なフェミニズムが隆盛した。

3)第三波フェミニズム:1980年代後半以降:初 期のフェミニズム運動における人種、階級、性的指向、ジェンダー・アイデンティティへの関心の欠如に注目し、政治的・社会的格差に対処するチャンネルを提 供しようとしている。

4)第四波フェミニズム:[定説やコンセンサスにつ

いては不詳]あくまでも仮説ですが、1990年のジュディス・バトラーの『ジェンダー

トラブル』の出版以降の、ジェンダー・パフォーマティビティ(Gender performativity)

をインターセクショナリティの中で実践するフェミズムの現在形が確立されつつある現在かもしれません!!!(Z世代のフェミニズム)

★さまざまなフェミニズムを知るには「フェミニズム理論・フェミニスト理論」をご参照ください。

■ポスト・フェミニズム、あるいはアフター・フェミ ニズムについて

| The term postfeminism

(alternatively rendered as post-feminism) is used to describe reactions

against contradictions and absences in feminism, especially second-wave

feminism and third-wave feminism. The term postfeminism is sometimes

confused with "4th wave-feminism", and "women of color feminism" (e.g.

hooks, 1996; Spivak, 1999). |

ポストフェミニズム(またはポスト・フェミニズム)という用語は、フェ

ミニズム、特に第二波フェミニズムと第三波フェミニズムにおける矛盾や欠如に対する反応を表すために使用される。ポストフェミニズムという用語は、しばし

ば「第4波フェミニズム」や「有色人種女性フェミニズム」(例:フックス、1996年;スピヴァク、1999年)と混同されることがある。 |

| The ideology of postfeminism is often recognised by its contrast with a prevailing or preceding feminism. Postfeminism strives towards the next stage in gender-related societal progress, and as such is often conceived as in favor of a society that is no longer defined by gender binary and gender role. A postfeminist is a person who believes in, promotes, or embodies any of various ideologies springing from the feminism of the 1970s, whether supportive of or antagonistic towards classical feminism. | ポストフェミニズムの思想は、支配的または先行するフェミニズムとの対

比によって認識されることが多い。ポストフェミニズムは、ジェンダーに関する社会的進歩の次の段階を目指しており、そのため、性別二元論や性別役割によっ

て定義されない社会を支持するものとして捉えられることが多い。ポストフェミニストとは、1970年代のフェミニズムから派生したさまざまなイデオロギー

を信奉、推進、または体現する人格のことだ。 |

| Postfeminism can be considered a critical way of understanding the changed relations between feminism, popular culture and femininity. Postfeminism may also present a critique of second-wave feminism or third-wave feminism by questioning the second wave or third-wave's binary thinking and essentialism, their vision of sexuality, and the perception of relationships between femininity and feminism. | ポストフェミニズムは、フェミニズム、大衆文化、女性らしさの変化した

関係を理解する批判的な方法と捉えることができる。ポストフェミニズムは、第二波フェミニズムや第三波フェミニズムの二元論的思考や本質主義、セクシュア

リティに対する見解、女性らしさとフェミニズムの関係の認識に疑問を投げかけることで、第二波フェミニズムや第三波フェミニズムに対する批判を提示してい

るとも考えられる。 |

| Second-wave feminism is often critiqued for being too 'white', too 'straight', and too 'liberal', and resulting in the needs of women from marginalized groups and cultures being ignored. However, since intersectionality is a product of third-wave feminism, the references to such as postfeminist are open to challenge and may be more properly considered feminist. | 第二波フェミニズムは、「白人」的、「異性愛者」的、「リベラル」的す

ぎ、その結果、周縁化されたグループや文化の女性のニーズが無視されていると批判されることが多い。しかし、交差性

(intersectionality)は第三波フェミニズムの産物であるため、ポストフェミニズムなどの表現は議論の余地があり、より適切にフェミニズ

ムとみなすこともできる。 |

| Postfeminism, by Wiki |

リンク先(フェミニスト・ツール・ボック ス)

文献

その他の情報(ウィキペディア英語(冒頭のフェミニズム)解説の続きです!!)

| History of Feminism Main article: History of feminism For a chronological guide, see Timeline of feminism. Terminology See also: Protofeminism Mary Wollstonecraft is seen by many as a founder of feminism due to her 1792 book titled A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in which she argues that class and private property are the basis of discrimination against women, and that women as much as men needed equal rights.[17][18][19][20] Charles Fourier, a utopian socialist and French philosopher, is credited with having coined the word "féminisme" in 1837.[21] but no trace of the word have been found in his works.[22] The word "féminisme" ("feminism") first appeared in France in 1871 in a medicine thesis about men suffering from tuberculosis and having developed, according to the author Ferdinand-Valère Faneau de la Cour, feminine traits.[23] The word "féministe" ("feminist"), inspired by its medical use, was coined by Alexandre Dumas fils in a 1872 essay, referring to men who supported women rights. In both cases, the use of the word was very negative and reflected a criticism of a so called "confusion of the sexes" by women who refused to abide by the sexual division of society and challenged the inequalities between sexes.[23] The concepts appeared in the Netherlands in 1872,[24] Great Britain in the 1890s, and the United States in 1910.[25][26] The Oxford English Dictionary dates the first appearance in English in this meaning back to 1895.[27] Depending on the historical moment, culture and country, feminists around the world have had different causes and goals. Most western feminist historians contend that all movements working to obtain women's rights should be considered feminist movements, even when they did not (or do not) apply the term to themselves.[28][29][30][31][32][33] Other historians assert that the term should be limited to the modern feminist movement and its descendants. Those historians use the label "protofeminist" to describe earlier movements.[34] |

沿革 主な記事 フェミニズムの歴史 年表はフェミニズム年表を参照のこと。 用語 以下も参照のこと: プロトフェミニズム メアリ・ウルストンクラフトは1792年に出版した『A Vindication of the Rights of Woman』という本の中で、階級と私有財産が女性差別の基礎であり、男性と同様に女性にも平等な権利が必要であると主張していることから、多くの人が フェミニズムの創始者と考えている[17][18][19][20]。 [21]しかし、彼の著作にはこの言葉の痕跡は見つかっていない[22]。「féminisme」(「feminisme」)という言葉は、1871年に フランスで初めて登場し、結核を患う男性について書かれた医学論文の中で、著者のフェルディナン・ヴァレール・ファノー・ド・ラ・クールによれば、女性的 な特徴を持つようになったというものであった[23]。「féministe」(「feminist」)という言葉は、医学的な使われ方に触発され、 1872年にアレクサンドル・デュマがエッセイの中で、女性の権利を支持する男性について言及したものである。いずれの場合も、この言葉の使用は非常に否 定的であり、社会の性的分裂に従うことを拒否し、男女間の不平等に異議を唱える女性たちによる、いわゆる「男女の混同」に対する批判を反映していた [23]。 この概念は1872年にオランダで、[24]1890年代にイギリスで、1910年にアメリカで登場した[25][26]。オックスフォード英語辞典は、 この意味での英語での最初の登場を1895年にまでさかのぼらせている[27]。歴史的瞬間、文化、国によって、世界中のフェミニストは異なる大義や目標 を持っていた。ほとんどの西洋のフェミニストの歴史家は、女性の権利を獲得するために活動するすべての運動は、たとえその言葉を自分たちに当てはめなかっ た(または当てはめない)としても、フェミニスト運動とみなされるべきであると主張している[28][29][30][31][32][33]。他の歴史 家は、この言葉は現代のフェミニスト運動とその子孫に限定されるべきであると主張している。それらの歴史家は、それ以前の運動を表現するために「プロト フェミニスト」というラベルを使用している[34]。 |

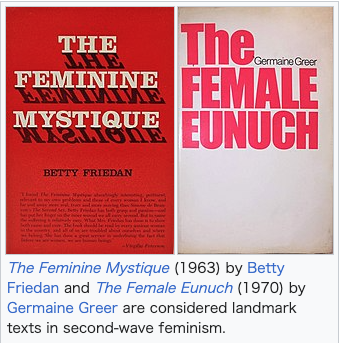

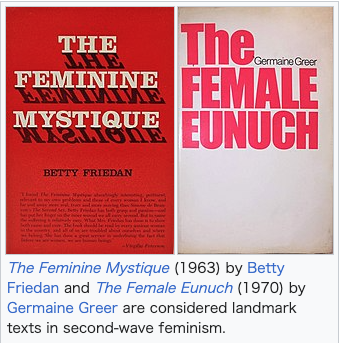

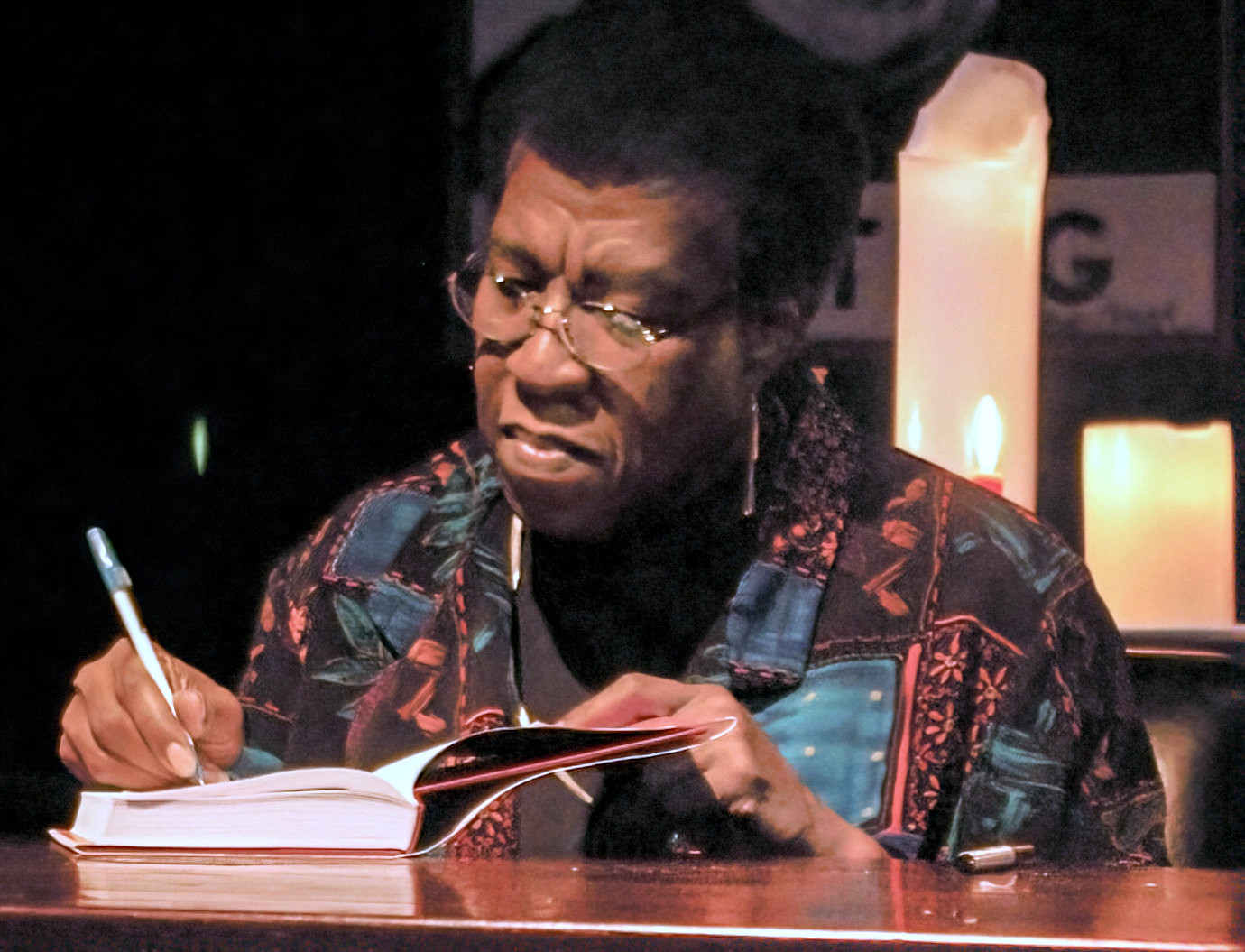

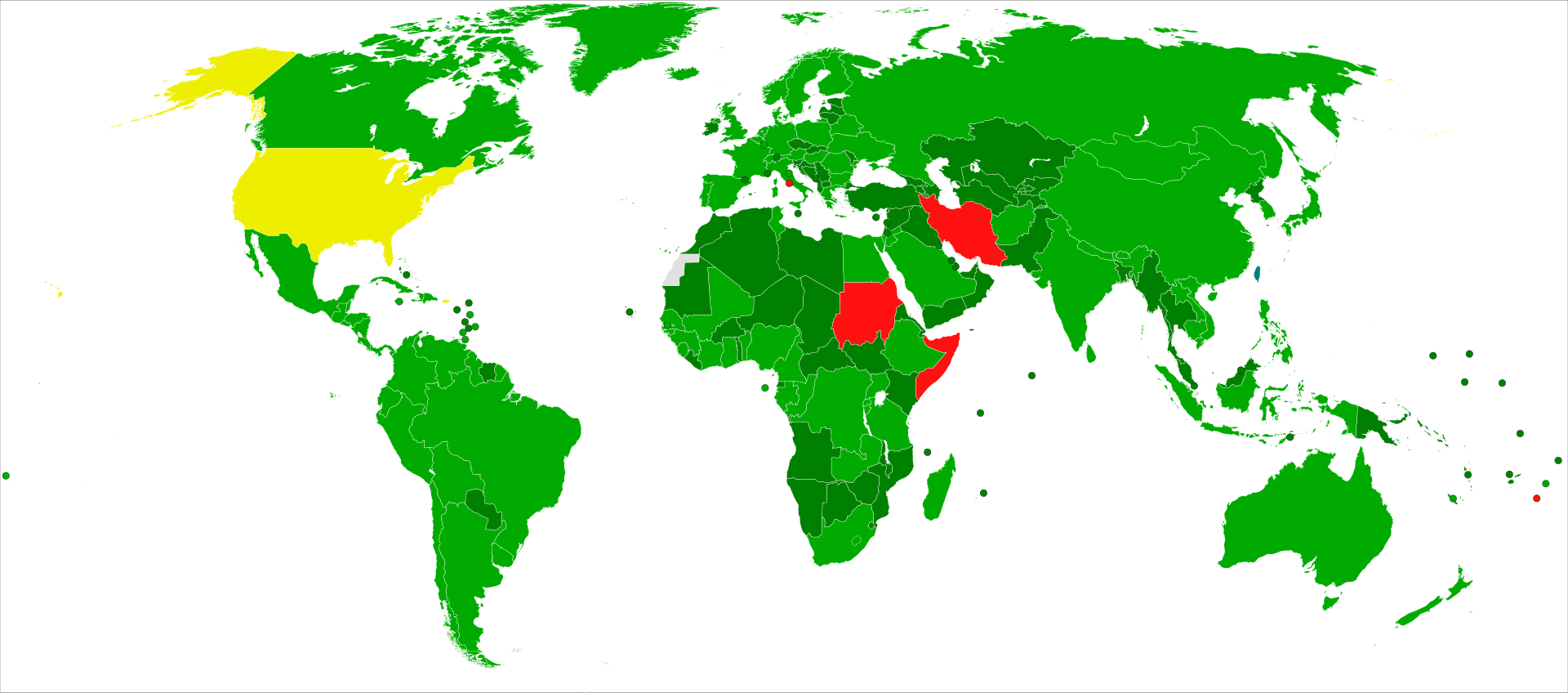

| Waves The history of the modern western feminist movement is divided into multiple "waves".[35][36][37] The first comprised women's suffrage movements of the 19th and early-20th centuries, promoting women's right to vote. The second wave, the women's liberation movement, began in the 1960s and campaigned for legal and social equality for women. In or around 1992, a third wave was identified, characterized by a focus on individuality and diversity.[38] Additionally, some have argued for the existence of a fourth wave,[39] starting around 2012, which has used social media to combat sexual harassment, violence against women and rape culture; it is best known for the Me Too movement.[40] 19th and early 20th centuries Main article: First-wave feminism First-wave feminism was a period of activity during the 19th and early-20th centuries. In the UK and US, it focused on the promotion of equal contract, marriage, parenting, and property rights for women. New legislation included the Custody of Infants Act 1839 in the UK, which introduced the tender years doctrine for child custody and gave women the right of custody of their children for the first time.[41][42][43] Other legislation, such as the Married Women's Property Act 1870 in the UK and extended in the 1882 Act,[44] became models for similar legislation in other British territories. Victoria passed legislation in 1884 and New South Wales in 1889; the remaining Australian colonies passed similar legislation between 1890 and 1897. With the turn of the 19th century, activism focused primarily on gaining political power, particularly the right of women's suffrage, though some feminists were active in campaigning for women's sexual, reproductive, and economic rights too.[45] Women's suffrage (the right to vote and stand for parliamentary office) began in Britain's Australasian colonies at the end of the 19th century, with the self-governing colony of New Zealand granting women the right to vote in 1893; South Australia followed suit with the Constitutional Amendment (Adult Suffrage) Act 1894 in 1894. This was followed by Australia granting female suffrage in 1902.[46][47] In Britain, the suffragettes and suffragists campaigned for the women's vote, and in 1918 the Representation of the People Act was passed granting the vote to women over the age of 30 who owned property. In 1928, this was extended to all women over 21.[48] Emmeline Pankhurst was the most notable activist in England. Time named her one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century, stating: "she shaped an idea of women for our time; she shook society into a new pattern from which there could be no going back."[49] In the US, notable leaders of this movement included Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony, who each campaigned for the abolition of slavery before championing women's right to vote. These women were influenced by the Quaker theology of spiritual equality, which asserts that men and women are equal under God.[50] In the US, first-wave feminism is considered to have ended with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (1919), granting women the right to vote in all states. The term first wave was coined retroactively when the term second-wave feminism came into use.[45][51][52][53][54] In Germany, feminists like Clara Zetkin was very interested in women's politics, including the fight for equal opportunities and women's suffrage, through socialism. She helped to develop the social-democratic women's movement in Germany. From 1891 to 1917, she edited the SPD women's newspaper Die Gleichheit (Equality). In 1907 she became the leader of the newly founded "Women's Office" at the SPD. She also contributed to International Women's Day (IWD).[55][56] During the late Qing period and reform movements such as the Hundred Days' Reform, Chinese feminists called for women's liberation from traditional roles and Neo-Confucian gender segregation.[57][58][59] Later, the Chinese Communist Party created projects aimed at integrating women into the workforce, and claimed that the revolution had successfully achieved women's liberation.[60] According to Nawar al-Hassan Golley, Arab feminism was closely connected with Arab nationalism. In 1899, Qasim Amin, considered the "father" of Arab feminism, wrote The Liberation of Women, which argued for legal and social reforms for women.[61] He drew links between women's position in Egyptian society and nationalism, leading to the development of Cairo University and the National Movement.[62] In 1923 Hoda Shaarawi founded the Egyptian Feminist Union, became its president and a symbol of the Arab women's rights movement.[62] The Iranian Constitutional Revolution in 1905 triggered the Iranian women's movement, which aimed to achieve women's equality in education, marriage, careers, and legal rights.[63] However, during the Iranian revolution of 1979, many of the rights that women had gained from the women's movement were systematically abolished, such as the Family Protection Law.[64] Mid-20th century By the mid-20th century, women still lacked significant rights. In France, women obtained the right to vote only with the Provisional Government of the French Republic of 21 April 1944. The Consultative Assembly of Algiers of 1944 proposed on 24 March 1944 to grant eligibility to women but following an amendment by Fernard Grenier, they were given full citizenship, including the right to vote. Grenier's proposition was adopted 51 to 16. In May 1947, following the November 1946 elections, the sociologist Robert Verdier minimized the "gender gap", stating in Le Populaire that women had not voted in a consistent way, dividing themselves, as men, according to social classes. During the baby boom period, feminism waned in importance. Wars (both World War I and World War II) had seen the provisional emancipation of some women, but post-war periods signalled the return to conservative roles.[65] In Switzerland, women gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971;[66] but in the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden women obtained the right to vote on local issues only in 1991, when the canton was forced to do so by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland.[67] In Liechtenstein, women were given the right to vote by the women's suffrage referendum of 1984. Three prior referendums held in 1968, 1971 and 1973 had failed to secure women's right to vote.[68]  Photograph of American women replacing men fighting in Europe, 1945 Feminists continued to campaign for the reform of family laws which gave husbands control over their wives. Although by the 20th century coverture had been abolished in the UK and US, in many continental European countries married women still had very few rights. For instance, in France, married women did not receive the right to work without their husband's permission until 1965.[69][70] Feminists have also worked to abolish the "marital exemption" in rape laws which precluded the prosecution of husbands for the rape of their wives.[71] Earlier efforts by first-wave feminists such as Voltairine de Cleyre, Victoria Woodhull and Elizabeth Clarke Wolstenholme Elmy to criminalize marital rape in the late 19th century had failed;[72][73] this was only achieved a century later in most Western countries, but is still not achieved in many other parts of the world.[74] French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir provided a Marxist solution and an existentialist view on many of the questions of feminism with the publication of Le Deuxième Sexe (The Second Sex) in 1949.[75] The book expressed feminists' sense of injustice. Second-wave feminism is a feminist movement beginning in the early 1960s[76] and continuing to the present; as such, it coexists with third-wave feminism. Second-wave feminism is largely concerned with issues of equality beyond suffrage, such as ending gender discrimination.[45]  The Feminine Mystique (1963) by Betty Friedan and The Female Eunuch (1970) by Germaine Greer are considered landmark texts in second-wave feminism. Second-wave feminists see women's cultural and political inequalities as inextricably linked and encourage women to understand aspects of their personal lives as deeply politicized and as reflecting sexist power structures. The feminist activist and author Carol Hanisch coined the slogan "The Personal is Political", which became synonymous with the second wave.[7][77] Second- and third-wave feminism in China has been characterized by a reexamination of women's roles during the communist revolution and other reform movements, and new discussions about whether women's equality has actually been fully achieved.[60] In 1956, President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt initiated "state feminism", which outlawed discrimination based on gender and granted women's suffrage, but also blocked political activism by feminist leaders.[78] During Sadat's presidency, his wife, Jehan Sadat, publicly advocated further women's rights, though Egyptian policy and society began to move away from women's equality with the new Islamist movement and growing conservatism.[79] However, some activists proposed a new feminist movement, Islamic feminism, which argues for women's equality within an Islamic framework.[80] In Latin America, revolutions brought changes in women's status in countries such as Nicaragua, where feminist ideology during the Sandinista Revolution aided women's quality of life but fell short of achieving a social and ideological change.[81] In 1963, Betty Friedan's book The Feminine Mystique helped voice the discontent that American women felt. The book is widely credited with sparking the beginning of second-wave feminism in the United States.[82] Within ten years, women made up over half the First World workforce.[83] In 1970, Australian writer Germaine Greer published The Female Eunuch, which became a worldwide bestseller, reportedly driving up divorce rates.[84][85] Greer posits that men hate women, that women do not know this and direct the hatred upon themselves, as well as arguing that women are devitalised and repressed in their role as housewives and mothers. Late 20th and early 21st centuries Third-wave feminism Main article: Third-wave feminism  Feminist, author and social activist bell hooks (1952–2021) Third-wave feminism is traced to the emergence of the riot grrrl feminist punk subculture in Olympia, Washington, in the early 1990s,[86][87] and to Anita Hill's televised testimony in 1991—to an all-male, all-white Senate Judiciary Committee—that Clarence Thomas, nominated for the Supreme Court of the United States, had sexually harassed her. The term third wave is credited to Rebecca Walker, who responded to Thomas's appointment to the Supreme Court with an article in Ms. magazine, "Becoming the Third Wave" (1992).[88][89] She wrote: So I write this as a plea to all women, especially women of my generation: Let Thomas' confirmation serve to remind you, as it did me, that the fight is far from over. Let this dismissal of a woman's experience move you to anger. Turn that outrage into political power. Do not vote for them unless they work for us. Do not have sex with them, do not break bread with them, do not nurture them if they don't prioritize our freedom to control our bodies and our lives. I am not a post-feminism feminist. I am the Third Wave.[88] Third-wave feminism also sought to challenge or avoid what it deemed the second wave's essentialist definitions of femininity, which, third-wave feminists argued, overemphasized the experiences of upper middle-class white women. Third-wave feminists often focused on "micro-politics" and challenged the second wave's paradigm as to what was, or was not, good for women, and tended to use a post-structuralist interpretation of gender and sexuality.[45][90][91][92] Feminist leaders rooted in the second wave, such as Gloria Anzaldúa, bell hooks, Chela Sandoval, Cherríe Moraga, Audre Lorde, Maxine Hong Kingston, and many other non-white feminists, sought to negotiate a space within feminist thought for consideration of race-related subjectivities.[91][93][94] Third-wave feminism also contained internal debates between difference feminists, who believe that there are important psychological differences between the sexes, and those who believe that there are no inherent psychological differences between the sexes and contend that gender roles are due to social conditioning.[95] Standpoint theory Standpoint theory is a feminist theoretical point of view stating that a person's social position influences their knowledge. This perspective argues that research and theory treat women and the feminist movement as insignificant and refuses to see traditional science as unbiased.[96] Since the 1980s, standpoint feminists have argued that the feminist movement should address global issues (such as rape, incest, and prostitution) and culturally specific issues (such as female genital mutilation in some parts of Africa and Arab societies, as well as glass ceiling practices that impede women's advancement in developed economies) in order to understand how gender inequality interacts with racism, homophobia, classism and colonization in a "matrix of domination".[97][98] Fourth-wave feminism Main article: Fourth-wave feminism  Protest against La Manada sexual abuse case sentence, Pamplona, 2018 Fourth-wave feminism is a proposed extension of third-wave feminism which corresponds to a resurgence in interest in feminism beginning around 2012 and associated with the use of social media.[99][100] According to feminist scholar Prudence Chamberlain, the focus of the fourth wave is justice for women and opposition to sexual harassment and violence against women. Its essence, she writes, is "incredulity that certain attitudes can still exist".[101] Fourth-wave feminism is "defined by technology", according to Kira Cochrane, and is characterized particularly by the use of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Tumblr, and blogs such as Feministing to challenge misogyny and further gender equality.[99][102][103]  2017 Women's March, Washington, D.C. Issues that fourth-wave feminists focus on include street and workplace harassment, campus sexual assault and rape culture. Scandals involving the harassment, abuse, and murder of women and girls have galvanized the movement. These have included the 2012 Delhi gang rape, 2012 Jimmy Savile allegations, the Bill Cosby allegations, 2014 Isla Vista killings, 2016 trial of Jian Ghomeshi, 2017 Harvey Weinstein allegations and subsequent Weinstein effect, and the 2017 Westminster sexual scandals.[104]  International Women's Strike, Paraná, Argentina, 2019 Examples of fourth-wave feminist campaigns include the Everyday Sexism Project, No More Page 3, Stop Bild Sexism, Mattress Performance, 10 Hours of Walking in NYC as a Woman, #YesAllWomen, Free the Nipple, One Billion Rising, the 2017 Women's March, the 2018 Women's March, and the #MeToo movement. In December 2017, Time magazine chose several prominent female activists involved in the #MeToo movement, dubbed "the silence breakers", as Person of the Year.[105][106] Decolonial feminism Decolonial feminism reformulates the coloniality of gender by critiquing the very formation of gender and its subsequent formations of patriarchy and the gender binary, not as universal constants across cultures, but as structures that have been instituted by and for the benefit of European colonialism. Marìa Lugones proposes that decolonial feminism speaks to how "the colonial imposition of gender cuts across questions of ecology, economics, government, relations with the spirit world, and knowledge, as well as across everyday practices that either habituate us to take care of the world or to destroy it." Decolonial feminists like Karla Jessen Williamson and Rauna Kuokkanen have examined colonialism as a force that has imposed gender hierarchies on Indigenous women that have disempowered and fractured Indigenous communities and ways of life. Postfeminism Main article: Postfeminism The term postfeminism is used to describe a range of viewpoints reacting to feminism since the 1980s. While not being "anti-feminist", postfeminists believe that women have achieved second wave goals while being critical of third- and fourth-wave feminist goals. The term was first used to describe a backlash against second-wave feminism, but it is now a label for a wide range of theories that take critical approaches to previous feminist discourses and includes challenges to the second wave's ideas.[107] Other postfeminists say that feminism is no longer relevant to today's society.[108][109] Amelia Jones has written that the postfeminist texts which emerged in the 1980s and 1990s portrayed second-wave feminism as a monolithic entity.[110] Dorothy Chunn describes a "blaming narrative" under the postfeminist moniker, where feminists are undermined for continuing to make demands for gender equality in a "post-feminist" society, where "gender equality has (already) been achieved". According to Chunn, "many feminists have voiced disquiet about the ways in which rights and equality discourses are now used against them".[111] |

波 近代西洋のフェミニズム運動の歴史は複数の「波」に分けられる[35][36][37]。 第一の波は19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけての女性参政権運動であり、女性の選挙権を推進した。第二の波である女性解放運動は1960年代に始まり、女性 の法的・社会的平等を求める運動を展開した。さらに、2012年頃から始まった第4の波[39]の存在を主張する人もいる。第4の波は、セクシャルハラス メント、女性に対する暴力、レイプ文化と闘うためにソーシャルメディアを利用したもので、Me Too運動で最もよく知られている[40]。 19世紀と20世紀初頭 主な記事 第一波フェミニズム 第一波フェミニズムは19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけての活動である。イギリスとアメリカでは、女性の平等な契約、結婚、子育て、財産権の促進に焦点を当 てた。1839年にイギリスで制定された乳幼児監護法(Custody of Infants Act)は、子どもの監護に関する年少者法(Tender Years Doctrine)を導入し、初めて女性に子どもの監護権を与えた[41][42][43]。1870年にイギリスで制定され、1882年に延長された既 婚女性財産法(Married Women's Property Act)[44]など、他のイギリス領でも同様の法律が制定されるモデルとなった。ビクトリア州では1884年に、ニュー・サウス・ウェールズ州では 1889年に法律が制定され、残りのオーストラリア植民地でも1890年から1897年にかけて同様の法律が制定された。19世紀に入ると、活動主義は主 に政治権力の獲得、特に女性の参政権の獲得に焦点を当てたが、一部のフェミニストは女性の性的、生殖的、経済的権利も求めるキャンペーンを積極的に行った [45]。 女性の参政権(選挙権と国会議員に立候補する権利)は19世紀末にイギリスのオーストラレーシア植民地で始まり、自治植民地であるニュージーランドは 1893年に女性に選挙権を付与し、南オーストラリアも1894年に憲法改正(成人参政権)法1894を制定してこれに続いた。これに続いて、オーストラ リアは1902年に女性の参政権を認めた[46][47]。 イギリスでは、サフラジェットや参政権論者たちが女性の参政権を求める運動を行い、1918年には、財産を所有する30歳以上の女性に参政権を認める「人 民代表法」が成立した。1928年、これは21歳以上のすべての女性に拡大された[48]。エメリン・パンクハーストはイギリスで最も注目された活動家で あった。タイム誌は彼女を「20世紀の最も重要な100人」のひとりに選び、こう述べている: 「彼女は社会を揺り動かし、そこから後戻りできないような新しいパターンに変えた」[49]。アメリカでは、この運動の著名な指導者として、ルクレティ ア・モット、エリザベス・キャディ・スタントン、スーザン・B・アンソニーが挙げられ、彼女たちはそれぞれ、女性の選挙権を擁護する前に、奴隷制廃止のた めの運動を行った。これらの女性たちは、男女は神のもとで平等であると主張するクエーカー教徒の精神的平等の神学に影響を受けていた[50]。アメリカで は、合衆国憲法修正第19条(1919年)が成立し、全州で女性に選挙権が与えられたことで、第一波のフェミニズムは終わったと考えられている。第一波と いう用語は、第二波フェミニズムという用語が使われるようになったときに遡及的に作られたものである[45][51][52][53][54]。 ドイツでは、クララ・ゼトキンのようなフェミニストが、社会主義を通じた機会均等や女性の参政権を求める闘いなど、女性の政治に大きな関心を寄せていた。 彼女はドイツにおける社会民主主義的な女性運動の発展に貢献した。1891年から1917年まで、SPDの女性新聞『平等』(Die Gleichheit)を編集した。1907年、SPDに新設された「女性事務所」のリーダーとなる。また、国際女性デー(IWD)にも貢献した[55] [56]。 清朝末期や百日回心のような改革運動において、中国のフェミニストたちは伝統的な役割や新儒教的な男女隔離からの女性の解放を求めた[57][58] [59]。 その後、中国共産党は女性を労働力に統合することを目的としたプロジェクトを立ち上げ、革命が女性の解放を成功させたと主張した[60]。 ナワール・アル=ハッサン・ゴリーによれば、アラブのフェミニズムはアラブのナショナリズムと密接に結びついていた。1899年、アラブ・フェミニズムの 「父」とされるカシーム・アミンは『女性の解放』を著し、女性のための法的・社会的改革を主張した[61]。彼はエジプト社会における女性の地位とナショ ナリズムの間に関連性を持たせ、カイロ大学や国民運動の発展につながった[62]。 1923年、ホーダ・シャーラウィはエジプト・フェミニスト同盟を設立し、その会長となり、アラブ女性の権利運動の象徴となった[62]。 1905年のイラン憲法革命はイラン女性運動を引き起こし、教育、結婚、キャリア、法的権利における女性の平等を達成することを目指した[63]。 しかし、1979年のイラン革命では、女性運動によって女性が得た権利の多くが、家族保護法などのように組織的に廃止された[64]。 20世紀半ば 20世紀半ばまで、女性は依然として重要な権利を欠いていた。 フランスでは、女性は1944年4月21日のフランス共和国臨時政府によって初めて選挙権を獲得した。1944年のアルジェ諮問議会は1944年3月24 日、女性に参政権を与えることを提案したが、フェルナール・グルニエの修正案により、参政権を含む完全な市民権が与えられた。グルニエの提案は51対16 で採択された。1946年11月の選挙後の1947年5月、社会学者ロベール・ヴェルディエは、『ル・ポピュレール』誌上で、女性は一貫した方法で投票し たわけではなく、男性と同様に社会階級によって区分して投票したと述べ、「男女格差」を最小限に抑えた。ベビーブームの時代、フェミニズムの重要性は低下 した。戦争(第一次世界大戦と第二次世界大戦)により、一部の女性は暫定的に解放されたが、戦後は保守的な役割への回帰を示した[65]。 スイスでは、1971年に連邦選挙で女性が投票権を得たが[66]、アッペンツェル・インナーローデン州では、1991年にスイス連邦最高裁判所によって 強制され、初めて地方選挙で女性が投票権を得た[67]。リヒテンシュタインでは、1984年の女性参政権の国民投票によって女性に投票権が与えられた。 それ以前の1968年、1971年、1973年に行われた3回の国民投票では、女性の選挙権を確保することはできなかった[68]。  男性に代わってヨーロッパで戦うアメリカ人女性の写真(1945年) フェミニストたちは、夫が妻を支配する家族法の改革を求める運動を続けた。20世紀までにイギリスとアメリカでは庇護制度が廃止されたが、ヨーロッパ大陸 の多くの国では、既婚女性の権利はまだほとんどなかった。例えばフランスでは、既婚女性は1965年まで夫の許可なく働く権利を得られなかった[69] [70]。フェミニストたちはまた、妻をレイプした夫を訴追することを妨げていたレイプ法における「婚姻の免除」の廃止にも取り組んできた[71]。 [71]ヴォルテリーヌ・ド・クレール、ヴィクトリア・ウッドハル、エリザベス・クラーク・ウォルステンホルム・エルミーといった第一波のフェミニストた ちによる、19世紀後半における夫婦間のレイプを犯罪化しようとする初期の努力は失敗に終わった[72][73]。 フランスの哲学者シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールは、1949年に『Le Deuxième Sexe(第二の性)』を出版し、フェミニズムの問題の多くにマルクス主義的な解決策と実存主義的な見解を提供した。第二波フェミニズムは1960年代初 頭に始まり[76]、現在に至るフェミニズム運動であり、第三波フェミニズムと共存している。第二波フェミニズムは、男女差別の解消など、参政権を超えた 平等の問題に大きく関わっている[45]。  ベティ・フリーダンによる『女性の神秘』(1963年)とジャーメイン・グリアによる『去勢された女性』 (1970年)は、第二波フェミニズムにおける画期的なテキストとみなされている。 第二波フェミニストたちは、女性の文化的不平等と政治的不平等を表裏一体のものとしてとらえ、女性が個人的な生活の側面を深く政治化されたものとして、ま た性差別的な権力構造を反映したものとして理解することを奨励している。フェミニスト活動家で作家のキャロル・ハニッシュは「個人は政治的である」という スローガンを作り、第二の波の代名詞となった[7][77]。 中国における第二波と第三波のフェミニズムは、共産主義革命やその他の改革運動における女性の役割の再検討や、女性の平等が実際に完全に達成されたかどう かについての新たな議論によって特徴づけられている[60]。 1956年、エジプトのガマル・アブデル・ナセル大統領は「国家フェミニズム」を開始し、性別による差別を非合法化し、女性の参政権を認めたが、フェミニ スト指導者による政治活動も封じた。 [78]サダトの大統領在任中、妻のジェハン・サダトは公然と女性の権利の拡大を提唱したが、エジプトの政策と社会は新たなイスラム主義運動と保守主義の 高まりとともに女性の平等から遠ざかり始めた[79]。しかし、一部の活動家はイスラムの枠組みの中での女性の平等を主張するイスラム・フェミニズムとい う新たなフェミニズム運動を提唱した[80]。 ラテンアメリカでは、革命はニカラグアのような国において女性の地位に変化をもたらしたが、サンディニスタ革命におけるフェミニズムのイデオロギーは女性 の生活の質を助けたが、社会的、イデオロギー的な変化を達成するには至らなかった[81]。 1963年、ベティ・フリーダンの著書『The Feminine Mystique』は、アメリカの女性たちが感じていた不満を代弁するのに役立った。この本は、アメリカにおける第二波フェミニズムの始まりに火をつけた と広く信じられている[82]。 1970年、オーストラリアの作家であるジャーメイン・グリアは、世界的なベストセラーとなった『女の宦官』を出版し、離婚率を上昇させたと報じられた [84][85]。 グリアは、男性は女性を憎んでいるが、女性はそれを知らず、憎しみを自分自身に向けていると仮定し、また、女性は主婦や母親としての役割において、活力を 奪われ、抑圧されていると主張した。 20世紀後半から21世紀初頭 第三波フェミニズム 主な記事 第三波フェミニズム  フェミニスト、作家、社会活動家ベル・フックス(1952年〜2021年) 第三の波フェミニズムは、1990年代初頭にワシントン州オリンピアでライオット・グラール・フェミニスト・パンクのサブカルチャーが出現したこと [86][87]、そして1991年にアニタ・ヒルが、男性ばかりで白人ばかりの上院司法委員会に対して、連邦最高裁判事に指名されたクラレンス・トーマ スがセクハラをしたという証言をテレビで行ったことに端を発する。サード・ウェーブという言葉は、レベッカ・ウォーカーに由来する。彼女は、トーマスの最 高裁判事就任に対して、『Ms』誌に「サード・ウェーブになる」(1992年)という記事を寄稿した[88][89]: だから私は、すべての女性、特に私と同世代の女性への嘆願としてこれを書く: 私がそうであったように、トーマスの承認は、戦いがまだ終わっていないことを思い起こさせるものである。一人の女性が経験したことを否定されたことに怒り を覚えよう。その怒りを政治的な力に変えよう。私たちのために働かない限り、彼らに投票してはならない。私たちの身体と人生をコントロールする自由を優先 してくれないなら、セックスもしなければ、一緒に食事もしない。私はポスト・フェミニズムのフェミニストではない。私は第三の波なのだ。 第三波のフェミニズムはまた、第二波のフェミニニティの本質主義的な定義に異議を唱えたり、それを回避しようとしたものであり、第三波のフェミニストたち は、上流中産階級の白人女性の経験を過度に強調していると主張していた。第三波のフェミニストたちはしばしば「ミクロ政治」に焦点を当て、何が女性にとっ て良いことなのか、あるいは良くないことなのかについて第二波のパラダイムに異議を唱え、ジェンダーとセクシュアリティについてポスト構造主義的な解釈を 用いる傾向があった。 [45][90][91][92]グロリア・アンザルドゥア、ベル・フックス、シェラ・サンドヴァル、シェリー・モラガ、オードレ・ロード、マキシン・ホ ン・キングストン、その他多くの非白人フェミニストなど、第二の波に根ざしたフェミニストの指導者たちは、人種に関連した主体性を考慮するための空間を フェミニズム思想の中で交渉しようとした。 [91][93][94]第三波のフェミニズムはまた、男女の間に重要な心理的差異があると信じる差異フェミニストと、男女の間に固有の心理的差異はない と信じ、ジェンダー的役割は社会的条件付けによるものであると主張する人々との間の内部的な議論も含んでいた[95]。 立場論(スタンドポイントセオリー) 立場理論とは、人の社会的立場がその人の知識に影響を及ぼすとするフェミニストの理論的視点である。この視点は、研究や理論が女性やフェミニズム運動を取 るに足らないものとして扱い、伝統的な科学を偏りのないものとして見ることを拒否していると主張している。 [1980年代以降、立場的フェミニストは、ジェンダー不平等が「支配のマトリックス」において人種主義、同性愛嫌悪、階級主義、植民地化とどのように相 互作用しているかを理解するために、フェミニズム運動がグローバルな問題(レイプ、近親相姦、売春など)や文化的に特異な問題(アフリカやアラブ社会の一 部における女性性器切除、先進経済圏における女性の進出を妨げるガラスの天井の慣習など)を扱うべきだと主張してきた[97][98]。 第4波フェミニズム 主な記事 第四波フェミニズム  ラ・マナダ性的虐待事件の判決に対する抗議行動(2018年、パンプローナ) 第4波フェミニズムは、第3波フェミニズムの延長線上に提唱されたもので、2012年頃から始まったフェミニズムへの関心の復活に対応し、ソーシャルメ ディアの利用に関連している[99][100]。フェミニスト学者のプルーデンス・チェンバレンによれば、第4波の焦点は女性の正義であり、女性に対する セクハラや暴力への反対である。その本質は、「ある種の態度がいまだに存在しうることが信じられない」ということだと彼女は書いている[101]。 キラ・コクランによれば、第4の波のフェミニズムは「テクノロジーによって定義される」ものであり、特にフェイスブック、ツイッター、インスタグラム、 ユーチューブ、タンブラー、そして女性差別に異議を唱え、ジェンダーの平等を促進するためのFeministingのようなブログの利用によって特徴づけ られる[99][102][103]。  2017年ウィメンズ・マーチ、ワシントンD.C. 第4波フェミニストが焦点を当てている問題には、路上や職場でのハラスメント、キャンパスでの性的暴行、レイプ文化などがある。女性や女児のハラスメン ト、虐待、殺人に関わるスキャンダルは、この運動に活気を与えてきた。これには、2012年のデリーの集団レイプ、2012年のジミー・サヴィル疑惑、ビ ル・コスビー疑惑、2014年のイスラビスタ殺人事件、2016年のジアン・ゴメシ裁判、2017年のハーヴェイ・ワインスタイン疑惑とその後のワインス タイン効果、2017年のウェストミンスターの性的スキャンダルなどが含まれる[104]。  2019年、アルゼンチン、パラナ州、国際女性ストライキ 第4波のフェミニスト・キャンペーンの例としては、Everyday Sexism Project、No More Page 3、Stop Bild Sexism、Mattress Performance、10 Hours of Walking in NYC as a Woman、#YesAllWomen、Free the Nipple、One Billion Rising、2017 Women's March、2018 Women's March、#MeToo運動などがある。2017年12月、『タイム』誌は「沈黙を破る者たち」と呼ばれる#MeToo運動に関わった著名な女性活動家 数名をパーソン・オブ・ザ・イヤーに選んだ[105][106]。 脱植民地主義フェミニズム 脱植民地主義フェミニズムは、ジェンダーの形成そのものと、それに続く家父長制や男女二元論の形成を、文化を超えた普遍的な不変のものとしてではなく、 ヨーロッパの植民地主義によって、またその利益のために制定された構造として批判することによって、ジェンダーの植民地性を再定義する。マリア・ルゴネス は、脱植民地主義的フェミニズムが、「ジェンダーの植民地的な押しつけが、生態学、経済学、政府、精神世界との関係、知識といった問題や、世界を大切にす るか破壊するかのどちらかを習慣化させる日常的な実践をいかに横断しているか」を語るものだと提唱している。カーラ・ジェッセン・ウィリアムソンやラウ ナ・クオッカネンのような脱植民地主義フェミニストたちは、先住民のコミュニティや生活様式を無力化し分断してきたジェンダー階層を先住民女性に押し付け てきた力としての植民地主義を検証してきた。 ポストフェミニズム 主な記事 ポストフェミニズム ポストフェミニズムという用語は、1980年代以降のフェミニズムに反発する様々な視点を表すのに使われる。反フェミニズム」ではないが、ポストフェミニ ストは、女性が第二波の目標を達成したと考える一方で、第三波や第四波のフェミニズムの目標には批判的である。この用語は最初、第二波フェミニズムに対す る反発を表すために使用されたが、現在では、以前のフェミニズム言説に対して批判的なアプローチをとり、第二波の思想に対する挑戦も含む幅広い理論に対す るラベルとなっている[107]。他のポストフェミニストは、フェミニズムはもはや現代社会とは関係ないと言っている。 [アメリア・ジョーンズは、1980年代から1990年代にかけて登場したポストフェミニストのテキストは、第二波フェミニズムを一枚岩の存在として描い ていたと書いている[110]。ドロシー・チャンは、ポストフェミニストの呼称のもとでの「非難する物語」について述べており、そこではフェミニストたち は、「ジェンダー平等が(すでに)達成された」「ポストフェミニズム」社会においてジェンダー平等の要求をし続けることで貶められている。チュンによれ ば、「多くのフェミニストは、権利と平等の言説が現在自分たちに不利に使われる方法について不穏な声を上げている」[111]。 |

| Feminist theory |

フェ

ミニスト理論 |

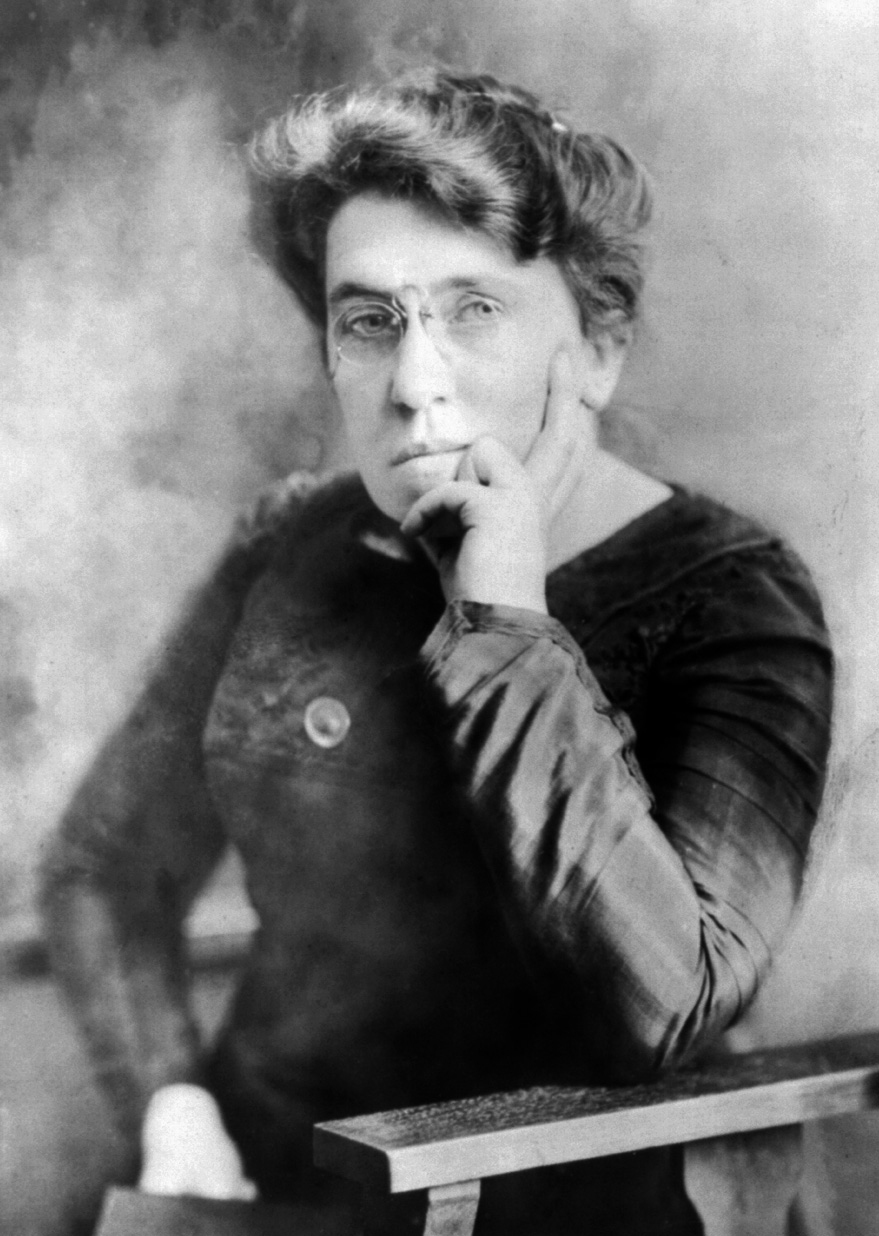

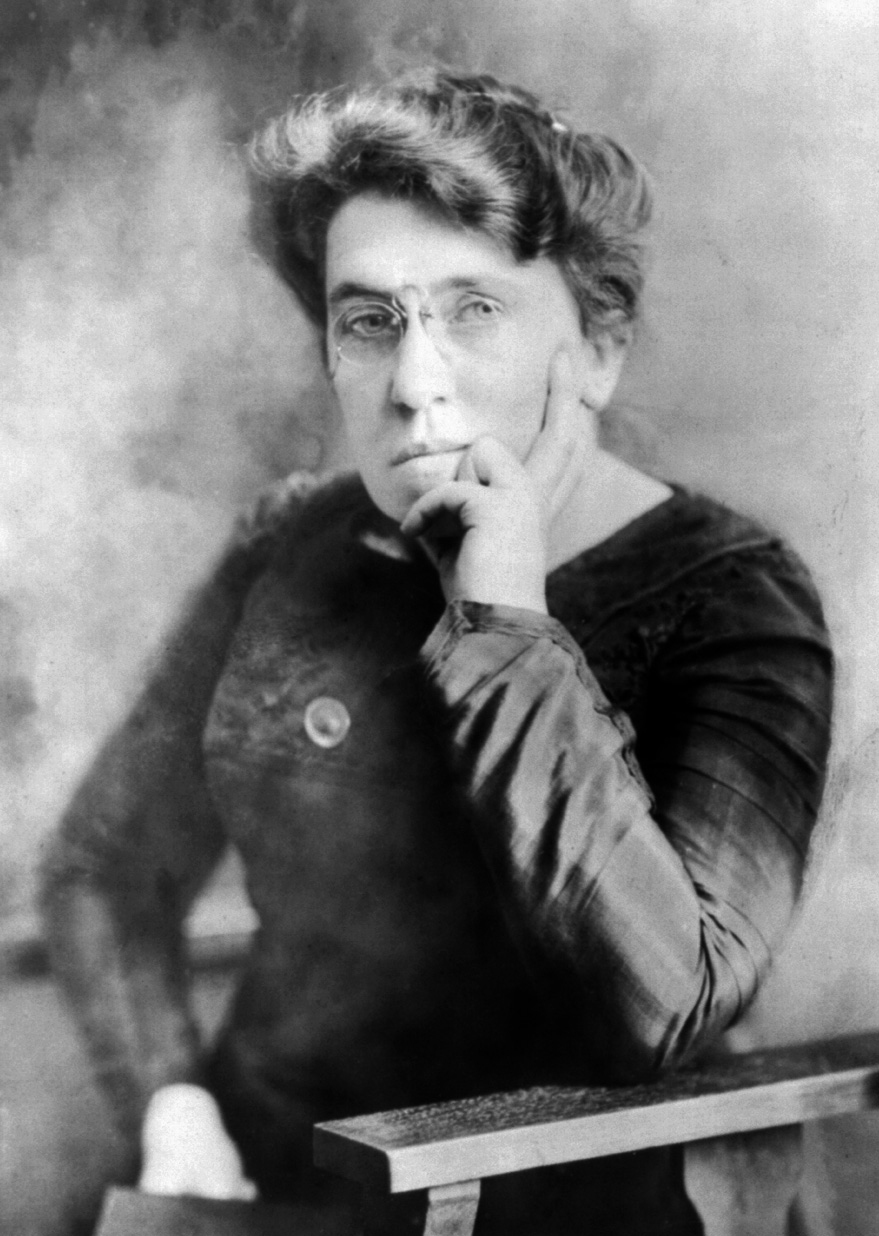

| Movements and ideologies Main article: Feminist movements and ideologies Many overlapping feminist movements and ideologies have developed over the years. Feminism is often divided into three main traditions called liberal, radical and socialist/Marxist feminism, sometimes known as the "Big Three" schools of feminist thought. Since the late 20th century, newer forms of feminisms have also emerged.[14] Some branches of feminism track the political leanings of the larger society to a greater or lesser degree, or focus on specific topics, such as the environment. Liberal feminism Main article: Liberal feminism  Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a major figure in 19th-century liberal feminism Liberal feminism, also known under other names such as reformist, mainstream, or historically as bourgeois feminism,[121][122] arose from 19th-century first-wave feminism, and was historically linked to 19th-century liberalism and progressivism, while 19th-century conservatives tended to oppose feminism as such. Liberal feminism seeks equality of men and women through political and legal reform within a liberal democratic framework, without radically altering the structure of society; liberal feminism "works within the structure of mainstream society to integrate women into that structure".[123] During the 19th and early 20th centuries liberal feminism focused especially on women's suffrage and access to education.[124] Former Norwegian supreme court justice and former president of the liberal Norwegian Association for Women's Rights, Karin Maria Bruzelius, has described liberal feminism as "a realistic, sober, practical feminism".[125] Susan Wendell argues that "liberal feminism is an historical tradition that grew out of liberalism, as can be seen very clearly in the work of such feminists as Mary Wollstonecraft and John Stuart Mill, but feminists who took principles from that tradition have developed analyses and goals that go far beyond those of 18th and 19th century liberal feminists, and many feminists who have goals and strategies identified as liberal feminist ... reject major components of liberalism" in a modern or party-political sense; she highlights "equality of opportunity" as a defining feature of liberal feminism.[126] Liberal feminism is a very broad term that encompasses many, often diverging modern branches and a variety of feminist and general political perspectives; some historically liberal branches are equality feminism, social feminism, equity feminism, difference feminism, individualist/libertarian feminism and some forms of state feminism, particularly the state feminism of the Nordic countries.[127] The broad field of liberal feminism is sometimes confused with the more recent and smaller branch known as libertarian feminism, which tends to diverge significantly from mainstream liberal feminism. For example, "libertarian feminism does not require social measures to reduce material inequality; in fact, it opposes such measures ... in contrast, liberal feminism may support such requirements and egalitarian versions of feminism insist on them."[128] Catherine Rottenberg notes that the raison d'être of classic liberal feminism was "to pose an immanent critique of liberalism, revealing the gendered exclusions within liberal democracy's proclamation of universal equality, particularly with respect to the law, institutional access, and the full incorporation of women into the public sphere." Rottenberg contrasts classic liberal feminism with modern neoliberal feminism which "seems perfectly in sync with the evolving neoliberal order."[129] According to Zhang and Rios, "liberal feminism tends to be adopted by 'mainstream' (i.e., middle-class) women who do not disagree with the current social structure." They found that liberal feminism with its focus on equality is viewed as the dominant and "default" form of feminism.[130] Some modern forms of feminism that historically grew out of the broader liberal tradition have more recently also been described as conservative in relative terms. This is particularly the case for libertarian feminism which conceives of people as self-owners and therefore as entitled to freedom from coercive interference.[131] Radical feminism The merged Venus symbol with raised fist is a common symbol of radical feminism, one of the movements within feminism Radical feminism arose from the radical wing of second-wave feminism and calls for a radical reordering of society to eliminate male supremacy. It considers the male-controlled capitalist hierarchy as the defining feature of women's oppression and the total uprooting and reconstruction of society as necessary.[7] Separatist feminism does not support heterosexual relationships. Lesbian feminism is thus closely related. Other feminists criticize separatist feminism as sexist.[10] Materialist ideologies  Emma Goldman a union activist, labour organizer and feminist anarchist Rosemary Hennessy and Chrys Ingraham say that materialist forms of feminism grew out of Western Marxist thought and have inspired a number of different (but overlapping) movements, all of which are involved in a critique of capitalism and are focused on ideology's relationship to women.[132] Marxist feminism argues that capitalism is the root cause of women's oppression, and that discrimination against women in domestic life and employment is an effect of capitalist ideologies.[133] Socialist feminism distinguishes itself from Marxist feminism by arguing that women's liberation can only be achieved by working to end both the economic and cultural sources of women's oppression.[134] Anarcha-feminists believe that class struggle and anarchy against the state[135] require struggling against patriarchy, which comes from involuntary hierarchy. Other modern feminisms Ecofeminism Ecofeminists see men's control of land as responsible for the oppression of women and destruction of the natural environment. Ecofeminism has been criticized for focusing too much on a mystical connection between women and nature.[136] Black and postcolonial ideologies Further information: Intersectional feminism Sara Ahmed argues that Black and postcolonial feminisms pose a challenge "to some of the organizing premises of Western feminist thought".[137] During much of its history, feminist movements and theoretical developments were led predominantly by middle-class white women from Western Europe and North America.[93][97][138] However, women of other races have proposed alternative feminisms.[97] This trend accelerated in the 1960s with the civil rights movement in the United States and the end of Western European colonialism in Africa, the Caribbean, parts of Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Since that time, women in developing nations and former colonies and who are of colour or various ethnicities or living in poverty have proposed additional feminisms.[138] Womanism[139][140] emerged after early feminist movements were largely white and middle-class.[93] Postcolonial feminists argue that colonial oppression and Western feminism marginalized postcolonial women but did not turn them passive or voiceless.[15] Third-world feminism and indigenous feminism are closely related to postcolonial feminism.[138] These ideas also correspond with ideas in African feminism, motherism,[141] Stiwanism,[142] negofeminism,[143] femalism, transnational feminism, and Africana womanism.[144] Social constructionist ideologies Main article: Social construction of gender In the late 20th century various feminists began to argue that gender roles are socially constructed,[145][146] and that it is impossible to generalize women's experiences across cultures and histories.[147] Post-structural feminism draws on the philosophies of post-structuralism and deconstruction in order to argue that the concept of gender is created socially and culturally through discourse.[148] Postmodern feminists also emphasize the social construction of gender and the discursive nature of reality;[145] however, as Pamela Abbott et al. write, a postmodern approach to feminism highlights "the existence of multiple truths (rather than simply men and women's standpoints)".[149] Transgender people Main article: Feminist views on transgender topics Third-wave feminists tend to view the struggle for trans rights as an integral part of intersectional feminism.[150] Fourth-wave feminists also tend to be trans-inclusive.[150] The American National Organization for Women (NOW) president Terry O'Neill said the struggle against transphobia is a feminist issue[151] and NOW has affirmed that "trans women are women, trans girls are girls."[152] Several studies have found that people who identify as feminists tend to be more accepting of trans people than those who do not.[153][154][155] An ideology variously known as trans-exclusionary radical feminism (or its acronym, TERF)[156] or gender-critical feminism is critical of concepts of gender identity and transgender rights, holding that biological sex characteristics are an immutable determination of gender or supersede the importance of gender identity,[157][158][159][160][161] that trans women are not women, and that trans men are not men.[162] These views have been described as transphobic by many other feminists.[163][164][165][166][167][168] Cultural movements Riot grrrls took an anti-corporate stance of self-sufficiency and self-reliance.[169] Riot grrrl's emphasis on universal female identity and separatism often appears more closely allied with second-wave feminism than with the third wave.[170] The movement encouraged and made "adolescent girls' standpoints central", allowing them to express themselves fully.[171] Lipstick feminism is a cultural feminist movement that attempts to respond to the backlash of second-wave radical feminism of the 1960s and 1970s by reclaiming symbols of "feminine" identity such as make-up, suggestive clothing and having a sexual allure as valid and empowering personal choices.[172][173] |

運動とイデオロギー 主な記事 フェミニストの運動とイデオロギー 多くのフェミニズム運動とイデオロギーが、長年にわたって重なり合って発展してきた。フェミニズムはしばしば、リベラル、ラディカル、社会主義/マルクス 主義フェミニズムと呼ばれる3つの主要な伝統に分けられ、フェミニズム思想の「ビッグスリー」学派として知られることもある。20世紀後半以降、より新し い形態のフェミニズムも出現している[14]。フェミニズムのいくつかの分派は、多かれ少なかれ、より大きな社会の政治的傾向を追跡したり、環境などの特 定のトピックに焦点を当てたりしている。 リベラル・フェミニズム 主な記事 リベラルフェミニズム  19世紀のリベラル・フェミニズムの主要人物、エリザベス・キャディ・スタントン リベラル・フェミニズムは、改革主義、主流主義、あるいは歴史的にはブルジョア・フェミニズムなどの別名でも知られ[121][122]、19世紀の第一 波フェミニズムから発生し、歴史的には19世紀の自由主義や進歩主義と結びついていた。リベラル・フェミニズムは、社会の構造を根本的に変えることなく、 自由民主主義の枠組みの中で政治的・法的な改革を通じて男女の平等を求めるものであり、リベラル・フェミニズムは「主流社会の構造の中で女性をその構造に 統合するために活動する」[123]。19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、リベラル・フェミニズムは特に女性の参政権と教育へのアクセスに焦点を当てた [124]。 元ノルウェー最高裁判事であり、リベラルなノルウェー女性の権利協会の元会長であるカリン・マリア・ブルゼリウスは、リベラル・フェミニズムを「現実的で 冷静で実践的なフェミニズム」と表現している[125]。 Susan Wendellは、「リベラルフェミニズムは、Mary WollstonecraftやJohn Stuart Millのようなフェミニストの活動にはっきりと見られるように、リベラリズムから発展した歴史的な伝統であるが、その伝統から原理を受け継いだフェミニ ストたちは、18世紀や19世紀のリベラルフェミニストのそれをはるかに超える分析や目標を発展させてきた、そしてリベラルフェミニストとして認識される 目標や戦略を持つ多くのフェミニストたちは...リベラリズムの主要な要素を拒否している」と主張している。 リベラル・フェミニズムは非常に広範な用語であり、多くの、しばしば分岐する現代の分派や様々なフェミニストや一般的な政治的視点を包含している。歴史的 にリベラルな分派としては、平等フェミニズム、社会的フェミニズム、平等フェミニズム、差異フェミニズム、個人主義者/リバタリアンフェミニズム、そして 国家フェミニズムのいくつかの形態、特に北欧諸国の国家フェミニズムが挙げられる[127]。リベラル・フェミニズムの広範な分野は、リベラル・フェミニ ズムの主流から大きく分岐する傾向にあるリバタリアンフェミニズムとして知られる、より最近の小規模な分派と混同されることがある。例えば、「リバタリア ンフェミニズムは、物質的不平等を軽減するための社会的措置を必要とせず、事実、そのような措置に反対している......対照的に、リベラルフェミニズ ムはそのような要件を支持することがあり、平等主義的なフェミニズムのバージョンはそれを主張している」[128]。 キャサリン・ロッテンバーグは、古典的リベラル・フェミニズムの存在意義は「リベラリズムに対する内在的な批判を提起し、リベラル・デモクラシーの普遍的 平等の宣言の中にあるジェンダー的排除を明らかにすることであり、特に法律、制度的アクセス、公共圏への女性の完全な取り込みに関してであった」と指摘し ている。ロッテンバーグは、古典的なリベラル・フェミニズムと、「進化するネオリベラル秩序と完全に同調しているように見える」現代のネオリベラル・フェ ミニズムとを対比させている[129]。チャンとリオスによれば、「リベラル・フェミニズムは、現在の社会構造に異を唱えない「主流派」(すなわち中流階 級)の女性たちによって採用される傾向がある」。彼女たちは、平等を重視するリベラル・フェミニズムがフェミニズムの支配的で「デフォルト」な形態とみな されていることを発見した[130]。 歴史的に広範なリベラルの伝統から発展したフェミニズムのいくつかの現代的な形態は、最近では相対的に保守的であると評されることもある。これは特にリバ タリアンフェミニズムの場合であり、人々を自己所有者と考え、それゆえに強制的な干渉からの自由を得る権利があるとする[131]。 急進的フェミニズム 合体した金星のシンボルと振り上げた拳は、フェミニズムの中の運動の一つであるラディカル・フェミニズムの共通のシンボルである。 ラディカル・フェミニズムは第二波フェミニズムの急進派から生まれたもので、男性至上主義を排除するために社会の急進的な再編成を要求している。男性に支 配された資本主義のヒエラルキーが女性抑圧の決定的な特徴であり、社会の全面的な根こそぎ再構築が必要であると考える[7]。分離主義フェミニズムは異性 間の関係を支持しない。したがって、レズビアン・フェミニズムは密接に関連している。他のフェミニストは分離主義フェミニズムを性差別主義として批判して いる[10]。 唯物論的イデオロギー  エマ・ゴールドマン......組合活動家、労働運動家、フェミニスト・アナキスト ローズマリー・ヘネシー(Rosemary Hennessy)とクリス・イングラハム(Chrys Ingraham)によれば、唯物論的なフェミニズムの形態は西洋のマルクス主義思想から発展したものであり、多くの異なる(しかし重複する)運動に影響 を与えた。 [133]社会主義フェミニズムは、女性の抑圧の経済的・文化的源泉の両方を終わらせるために働くことによってのみ女性の解放を達成することができると主 張することによって、マルクス主義フェミニズムとは一線を画している[134]。アナーカ・フェミニストは、階級闘争と国家に対する無政府状態[135] は、不本意なヒエラルキーから来る家父長制と闘うことを必要とすると信じている。 その他の現代フェミニズム エコフェミニズム エコフェミニストは、男性による土地の支配が女性への抑圧と自然環境の破壊の原因であると考える。エコフェミニズムは、女性と自然との神秘的なつながりに 焦点を当てすぎていると批判されている[136]。 黒人思想とポストコロニアル思想 さらなる情報 インターセクション・フェミニズム サラ・アーメッドは、黒人フェミニズムとポストコロニアル・フェミニズムが「西洋のフェミニズム思想の組織的前提のいくつかに対する」挑戦を提起している と論じている[137]。その歴史の多くの期間において、フェミニズム運動と理論的発展は、主に西ヨーロッパと北アメリカの中産階級の白人女性によって主 導されていた[93][97][138]。それ以来、発展途上国や旧植民地、有色人種や様々な民族、貧困にあえぐ女性たちがさらなるフェミニズムを提唱し てきた[138]。初期のフェミニズム運動が主に白人や中流階級であった後にウーマニズム[139][140]が出現した[93]。ポストコロニアル・ フェミニストたちは、植民地抑圧や西欧のフェミニズムはポストコロニアルの女性たちを疎外したが、彼女たちを受動的な存在や声なきものにしたわけではない と主張している。 [15]第三世界のフェミニズムや土着のフェミニズムはポストコロニアル・フェミニズムと密接な関係がある[138]。 これらの考え方はアフリカン・フェミニズム、マザーズ・フェミニズム、[141]スティワニズム、[142]ネゴフェミニズム、[143]フェマリズム、 トランスナショナル・フェミニズム、アフリカーナ・ウーマニズムの考え方とも対応している[144]。 社会構築主義イデオロギー 主な記事 ジェンダーの社会的構築 20世紀後半に様々なフェミニストがジェンダーの役割は社会的に構築されたものであり[145][146]、文化や歴史を超えて女性の経験を一般化するこ とは不可能であると主張し始めた[147]。ポスト構造フェミニズムは、ジェンダーの概念は言説を通じて社会的、文化的に創造されると主張するためにポス ト構造主義と脱構築の哲学を利用している。 [145]しかし、パメラ・アボットらが書いているように、フェミニズムに対するポストモダンのアプローチは「(単に男性と女性の立場ではなく)複数の真 実の存在」を強調している[149]。 トランスジェンダー 主な記事 トランスジェンダーに関するフェミニストの見解 第三波のフェミニストたちは、トランスジェンダーの権利のための闘いを、交差するフェミニズムの不可欠な部分とみなす傾向がある[150]。 第四波のフェミニストたちもトランスジェンダーを包括する傾向がある。 [150]アメリカの全米女性組織(NOW)の会長であるテリー・オニールはトランスフォビアとの闘いはフェミニストの問題であると述べており [151]、NOWは「トランスの女性は女性であり、トランスの女の子は女の子である」と断言している[152]。いくつかの研究では、フェミニストであ ると自認する人々はそうでない人々よりもトランスの人々を受け入れる傾向があることが判明している[153][154][155]。 トランス排他的ラディカル・フェミニズム(またはその略語であるTERF)[156]またはジェンダー批判的フェミニズムとして様々に知られているイデオ ロギーは、ジェンダー・アイデンティティとトランスジェンダーの権利の概念に批判的であり、生物学的性徴が性別の不変の決定であるか、ジェンダー・アイデ ンティティの重要性に取って代わるものであるとし、[157][158][159][160][161]トランス女性は女性ではなく、トランス男性は男性 ではないとする。 [162]これらの見解は他の多くのフェミニストによってトランスフォビックであると評されている[163][164][165][166][167] [168]。 文化運動 ライオット・グリルは自給自足と自立という反企業的なスタンスをとっていた[169]。ライオット・グリルの普遍的な女性のアイデンティティと分離主義へ の強調は、しばしば第三の波よりも第二の波のフェミニズムとより密接に連携しているように見える。 [171]リップスティック・フェミニズムは文化的フェミニズム運動であり、1960年代と1970年代の第二波の急進的フェミニズムの反動に対応しよう とするものであり、化粧、暗示的な服装、性的魅力を持つことなどの「女性的」アイデンティティの象徴を、有効で力を与える個人的な選択として取り戻すもの である[172][173]。 |

| Demographics According to 2014 Ipsos poll covering 15 developed countries, 53 percent of respondents identified as feminists, and 87 percent agreed that "women should be treated equally to men in all areas based on their competency, not their gender". However, only 55 percent of women agreed that they have "full equality with men and the freedom to reach their full dreams and aspirations".[174] Taken together, these studies reflect the importance differentiating between claiming a "feminist identity" and holding "feminist attitudes or beliefs".[175] According to a 2015 poll, 18 percent of Americans use the label of "feminist" to describe themselves, while 85 percent are feminists in practice as they reported they believe in "equality for women". The poll found that 52 percent did not identify as feminist, 26 percent were unsure, and 4 percent provided no response.[176] Sociological research shows that, in the US, increased educational attainment is associated with greater support for feminist issues. In addition, politically liberal people are more likely to support feminist ideals compared to those who are conservative.[177][178] According to a 2016 Survation poll for the Fawcett Society, 7 percent of Britons use the label of "feminist" to describe themselves, while 83 percent say they support equality of opportunity for women – this included higher support from men (86%) than women (81%).[179][180] |

人口統計 先進15カ国を対象とした2014年のイプソスの世論調査によると、回答者の53%がフェミニストであると認識し、87%が「女性は性別ではなく、能力に 基づいてあらゆる分野で男性と同等に扱われるべきだ」という意見に同意した。しかし、「男性と完全に平等であり、自分の夢や願望に完全に到達する自由があ る」ことに同意した女性は55パーセントに過ぎなかった[174]。これらの調査を総合すると、「フェミニストとしてのアイデンティティ」を主張すること と、「フェミニストとしての態度や信念」を持つことを区別することの重要性が反映されている[175]。 2015年の世論調査によれば、アメリカ人の18パーセントが自分自身を表現するために「フェミニスト」というラベルを使用しているが、85パーセントは 「女性の平等」を信じていると回答しており、実際にはフェミニストである。世論調査では、52パーセントがフェミニストであると認識しておらず、26パー セントがわからないと回答し、4パーセントが無回答であった[176]。 社会学的研究によれば、アメリカでは、学歴が高いほどフェミニズム問題への支持が高い。さらに、政治的にリベラルな人々は、保守的な人々に比べてフェミニ ストの理想を支持する傾向が強い[177][178]。 フォーセット・ソサエティのための2016年のSurvationの世論調査によれば、イギリス人の7%が自分自身を表現するために「フェミニスト」とい うラベルを使用している一方で、83%が女性の機会の平等を支持していると回答しており、これは女性(81%)よりも男性(86%)からの支持が高いこと を含んでいる[179][180]。 |

| Sexuality Main article: Feminist views on sexuality Feminist views on sexuality vary, and have differed by historical period and by cultural context. Feminist attitudes to female sexuality have taken a few different directions. Matters such as the sex industry, sexual representation in the media, and issues regarding consent to sex under conditions of male dominance have been particularly controversial among feminists. This debate has culminated in the late 1970s and the 1980s, in what came to be known as the feminist sex wars, which pitted anti-pornography feminism against sex-positive feminism, and parts of the feminist movement were deeply divided by these debates.[181][182][183][184][185] Feminists have taken a variety of positions on different aspects of the sexual revolution from the 1960s and 70s. Over the course of the 1970s, a large number of influential women accepted lesbian and bisexual women as part of feminism.[186] Sex industry Main articles: Sex industry, Feminist views on pornography, Feminist views on prostitution, Feminist sex wars, and Male prostitution § Feminist studies Opinions on the sex industry are diverse. Feminists who are critical of the sex industry generally see it as the exploitative result of patriarchal social structures which reinforce sexual and cultural attitudes complicit in rape and sexual harassment. Alternately, feminists who support at least part of the sex industry argue that it can be a medium of feminist expression and reflect a woman's right to control and define her own sexuality. Individualist feminists support the existence of a sex industry on the grounds that adult women have the right to consent to sexual acts as they choose and should have access to labor rights, to earn money how they choose.[187] In this view, banning the sex industry effectively strips women of their right to work and earn money on their own terms, treating them as children who cannot make decisions for themselves. In this view, women who consider the sex industry degrading do not have to partake in it. Women who do choose to work in the sex industry however should not be banned from doing so, given that they are doing so willingly. Libertarian Feminist Zine, Reclaim, has argued that sex work has helped more women (including students, freelancers, and women in poverty) achieve financial independence than all government grants combined. Feminist views of pornography range from condemnation of pornography as a form of violence against women, to an embracing of some forms of pornography as a medium of feminist expression and a legitimate career.[181][182][183][184][185] Similarly, feminists' views on prostitution vary, ranging from critical to supportive.[188] Affirming female sexual autonomy See also: My body, my choice For feminists, a woman's right to control her own sexuality is a key issue and one that is heavily contested between different branches of feminism. Radical feminists such as Catharine MacKinnon argue that women have very little control over their own bodies, with female sexuality being largely controlled and defined by men in patriarchal societies. Radical feminists argue that sexual violence committed by men is often rooted in ideologies of male sexual entitlement and that these systems grant women very few legitimate options to refuse sexual advances.[189][190] Some radical feminists have argued that women should not engage in heterosexual sex, and choose lesbianism as a lifestyle and political choice, a view that has fallen out of favor, as sexuality is seen as largely biologically influenced rather than a choice one can make for political reasons. Some radical feminists argue that all cultures are, in one way or another, dominated by ideologies that deny women's right to sexual expression, because men under a patriarchy define sex on their own terms. This entitlement can take different forms, depending on the culture. In some conservative and religious cultures marriage is regarded as an institution which requires a wife to be sexually available at all times, virtually without limit; thus, forcing or coercing sex on a wife is not considered a crime or even an abusive behaviour.[191][192] In 1968, radical feminist Anne Koedt argued in her essay The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm that women's biology and the clitoral orgasm had not been properly analyzed and popularized, because men "have orgasms essentially by friction with the vagina" and not the clitoral area.[193][194] Other branches of feminism such as individualist feminism consider themselves sex-positive, and see women's expression of their own sexuality as a right. In this view, what is or is not "degrading" is subjective, and each person has a right to decide for themselves what sexual acts they find degrading and if they want to participate in them or not. Individualist feminist, Wendy McElroy wrote in her book, XXX: A Woman's Right to Pornography, "let's examine [...] the idea that pornography is degrading to women. Degrading is a subjective term. Personally, I find detergent commercials in which women become orgasmic over soapsuds to be tremendously degrading to women. I find movies in which prostitutes are treated like ignorant drug addicts to be slander against women. Every woman has the right—the need!—to define degradation for herself." According to this view, part of sexual autonomy is the right to define one's boundaries, desires and limits around their sexuality rather than accept a narrative in which all women are victims of men during a sex act. |

セクシュアリティ 主な記事 フェミニストのセクシュアリティ観 フェミニストのセクシュアリティ観は様々で、時代や文化的背景によって異なっている。女性のセクシュアリティに対するフェミニストの態度は、いくつかの異 なる方向性を持っている。性産業、メディアにおける性的表現、男性優位の状況下でのセックスへの同意に関する問題などは、フェミニストの間で特に議論を呼 んできた。この議論は1970年代後半から1980年代にかけて、反ポルノ・フェミニズムとセックス・ポジティブ・フェミニズムを戦わせるフェミニスト・ セックス戦争として知られるようになったことで頂点に達し、フェミニズム運動の一部はこれらの議論によって深く分裂した[181][182][183] [184][185] フェミニストは1960年代から70年代にかけての性革命のさまざまな側面についてさまざまな立場をとってきた。1970年代にかけて、影響力のある多く の女性がレズビアンやバイセクシュアルの女性をフェミニズムの一部として受け入れた[186]。 セックス産業 主な記事 性産業、ポルノに対するフェミニストの見解、売春に対するフェミニストの見解、フェミニストのセックス戦争、男性売春§フェミニスト研究 性産業に対する意見は多様である。性産業に批判的なフェミニストは一般に、性産業は家父長制的な社会構造の搾取的な結果であり、レイプやセクハラに加担す る性的・文化的態度を強化するものだと考える。一方、性産業の少なくとも一部を支持するフェミニストたちは、性産業はフェミニズム表現の媒体であり、女性 が自らのセクシュアリティをコントロールし定義する権利を反映するものだと主張する。 個人主義的フェミニストは、成人女性には自分の選択で性行為に同意する権利があり、自分の選択でお金を稼ぐ労働権を利用できるはずだという理由で、性産業 の存在を支持する[187]。この見解では、性産業を禁止することは、女性が自分の条件で働きお金を稼ぐ権利を事実上剥奪し、自分で決定できない子供とし て扱うことになる。この考え方では、性産業が卑劣であると考える女性は、性産業に参加する必要はない。しかし、性産業で働くことを選んだ女性たちは、自ら 望んでそうしているのだから、それを禁止されるべきではない。リバタリアン系フェミニスト雑誌『Reclaim』は、セックスワークは、政府の助成金をす べて合わせたよりも多くの女性(学生、フリーター、貧困にあえぐ女性を含む)が経済的自立を達成するのに役立っていると主張している。 ポルノに対するフェミニストの見解は、女性に対する暴力の一形態としてポルノを非難するものから、フェミニストの表現の媒体や正当なキャリアとしていくつ かの形態のポルノを受け入れるものまで様々である[181][182][183][184][185]。同様に、売春に対するフェミニストの見解も様々 で、批判的なものから支持的なものまである[188]。 女性の性的自律性を肯定する 以下も参照のこと: 私の身体、私の選択 フェミニストにとって、女性が自らのセクシュアリティをコントロールする権利は重要な問題であり、フェミニズムのさまざまな分派の間で激しく争われている 問題である。キャサリン・マッキノン(Catharine MacKinnon)のような急進的なフェミニストは、女性は自分の身体をほとんどコントロールできず、女性のセクシュアリティは家父長制社会の男性に よって大きくコントロールされ、定義されていると主張する。急進的なフェミニストは、男性による性的暴力はしばしば男性の性的権利のイデオロギーに根ざし ており、こうしたシステムは女性に性的誘惑を拒否する正当な選択肢をほとんど与えないと主張する[189][190]。急進的なフェミニストの中には、女 性は異性間のセックスに従事せず、ライフスタイルや政治的な選択としてレズビアンを選ぶべきだと主張する者もいるが、セクシュアリティは政治的な理由で選 択できるものではなく、生物学的な影響が大きいと考えられているため、この見解は支持されなくなっている。 ラディカル・フェミニストの中には、家父長制のもとでは男性が自分たちの言葉でセックスを定義するため、すべての文化は何らかの形で、女性の性的表現の権 利を否定するイデオロギーに支配されていると主張する者もいる。この権利は、文化によってさまざまな形をとる。一部の保守的で宗教的な文化では、結婚は妻 が事実上無制限に、いつでも性的に利用可能であることを要求する制度とみなされている。したがって、妻にセックスを強制したり強要したりすることは犯罪と はみなされず、虐待行為とさえみなされない[191][192]。 1968年、急進的なフェミニストのアン・コエットは彼女のエッセイ『膣オーガズムの神話』の中で、女性の生物学とクリトリスのオーガズムが適切に分析さ れ、一般化されていないと主張した。 個人主義フェミニズムのようなフェミニズムの他の分派は、自らをセックス・ポジティブであると考え、女性が自らのセクシュアリティを表現することを権利で あるとみなす。この見解では、何が「下劣」であるか否かは主観的なものであり、各人にはどのような性行為を下劣と感じるか、またそれに参加したいか否かを 自ら決定する権利がある。個人主義のフェミニストであるウェンディ・マッケロイは、著書『XXX:ポルノに対する女性の権利』の中で、「ポルノが女性の品 位を落とすものであるという考え方を検証してみよう。劣化というのは主観的な言葉だ。個人的には、女性が石鹸の泡でオーガズムに達する洗剤のコマーシャル は、女性にとってとてつもなく品位を下げるものだと思う。売春婦が無知な麻薬中毒者のように扱われる映画は、女性に対する中傷だと思う。すべての女性に は、劣化を自ら定義する権利がある。 この考え方によれば、性の自律性の一部とは、すべての女性が性行為において男性の犠牲になるという物語を受け入れるのではなく、自分のセクシュアリティに まつわる境界線、欲望、限界を定義する権利である。 |

| Science Further information: Feminist epistemology Sandra Harding says that the "moral and political insights of the women's movement have inspired social scientists and biologists to raise critical questions about the ways traditional researchers have explained gender, sex and relations within and between the social and natural worlds."[195] Some feminists, such as Ruth Hubbard and Evelyn Fox Keller, criticize traditional scientific discourse as being historically biased towards a male perspective.[196] A part of the feminist research agenda is the examination of the ways in which power inequities are created or reinforced in scientific and academic institutions.[197] Physicist Lisa Randall, appointed to a task force at Harvard by then-president Lawrence Summers after his controversial discussion of why women may be underrepresented in science and engineering, said, "I just want to see a whole bunch more women enter the field so these issues don't have to come up anymore."[198] Lynn Hankinson Nelson writes that feminist empiricists find fundamental differences between the experiences of men and women. Thus, they seek to obtain knowledge through the examination of the experiences of women and to "uncover the consequences of omitting, misdescribing, or devaluing them" to account for a range of human experience.[199] Another part of the feminist research agenda is the uncovering of ways in which power inequities are created or reinforced in society and in scientific and academic institutions.[197] Furthermore, despite calls for greater attention to be paid to structures of gender inequity in the academic literature, structural analyses of gender bias rarely appear in highly cited psychological journals, especially in the commonly studied areas of psychology and personality.[200] One criticism of feminist epistemology is that it allows social and political values to influence its findings.[201] Susan Haack also points out that feminist epistemology reinforces traditional stereotypes about women's thinking (as intuitive and emotional, etc.); Meera Nanda further cautions that this may in fact trap women within "traditional gender roles and help justify patriarchy".[202] Biology and gender Further information: Gender essentialism and Sexual differentiation Modern feminism challenges the essentialist view of gender as biologically intrinsic.[203][204] For example, Anne Fausto-Sterling's book, Myths of Gender, explores the assumptions embodied in scientific research that support a biologically essentialist view of gender.[205] In Delusions of Gender, Cordelia Fine disputes scientific evidence that suggests that there is an innate biological difference between men's and women's minds, asserting instead that cultural and societal beliefs are the reason for differences between individuals that are commonly perceived as sex differences.[206] Feminist psychology Main article: Feminist psychology Feminism in psychology emerged as a critique of the dominant male outlook on psychological research where only male perspectives were studied with all male subjects. As women earned doctorates in psychology, women and their issues were introduced as legitimate topics of study. Feminist psychology emphasizes social context, lived experience, and qualitative analysis.[207] Projects such as Psychology's Feminist Voices have emerged to catalogue the influence of feminist psychologists on the discipline.[208] |

科学 さらに詳しい情報 フェミニスト認識論 サンドラ・ハーディングは、「女性運動の道徳的・政治的洞察は、社会科学者や生物学者に、従来の研究者が社会的世界と自然的世界の内と間のジェンダー、 性、関係を説明してきた方法について批判的な疑問を提起するよう促した」と述べている[195]。ルース・ハバードやイヴリン・フォックス・ケラーのよう な一部のフェミニストは、伝統的な科学的言説が歴史的に男性の視点に偏っていると批判している。 [196]フェミニストの研究課題の一つは、科学的・学術的機関において権力の不平等がどのように生み出され、あるいは強化されているかを検証することで ある[197]。 物理学者のリサ・ランドールは、ローレンス・サマーズ学長(当時)が、なぜ科学や工学において女性の割合が少ないのかについて議論を呼んだ後、ハーバード 大学のタスクフォースに任命され、「私はただ、このような問題がこれ以上出てこないように、もっとたくさんの女性がこの分野に参入するのを見たいのです」 と述べている[198]。 リン・ハンキンソン・ネルソンは、フェミニスト経験論者は男女の経験の間に根本的な違いを見出すと書いている。したがって、彼らは女性の経験を検証するこ とで知識を得ようとし、人間の経験の範囲を説明するために「女性の経験を省略したり、誤って記述したり、軽んじたりすることの結果を明らかにする」のであ る[199]。フェミニストの研究アジェンダのもう一つの部分は、社会や科学的・学術的機関において権力の不平等が生み出されたり強化されたりする方法を 明らかにすることである。 [197]さらに、学術文献においてジェンダー不公平の構造にもっと注意を払うことが求められているにもかかわらず、ジェンダー・バイアスの構造的分析 は、特に心理学とパーソナリティの一般的に研究されている分野において、引用の多い心理学雑誌にはほとんど掲載されていない[200]。 フェミニスト認識論に対する批判の一つは、社会的・政治的価値観がその発見に影響を与えることを許容していることである[201]。スーザン・ハックはま た、フェミニスト認識論が女性の思考に関する伝統的な固定観念(直感的で感情的であるなど)を強化することを指摘している。ミーラ・ナンダはさらに、これ が実際には女性を「伝統的なジェンダー役割の中に閉じ込め、家父長制の正当化を助ける」可能性があると警告している[202]。 生物学とジェンダー さらなる情報 ジェンダー本質主義と性的分化 例えば、アン・ファウスト=スターリングの著書『Myths of Gender(ジェンダーの神話)』は、生物学的に本質主義的なジェンダー観を支持する科学的研究に具現化された仮定を探求している。 [205] コーデリア・ファインは『Delusions of Gender』において、男女の心には生得的な生物学的差異があることを示唆する科学的証拠に異議を唱え、代わりに文化的・社会的信念が一般的に性差とし て認識される個人間の差異の理由であると主張している[206]。 フェミニスト心理学 主な記事 フェミニスト心理学 心理学におけるフェミニズムは、男性の視点のみがすべての男性を対象として研究されるという、心理学研究における支配的な男性観への批判として登場した。 女性が心理学の博士号を取得するにつれて、女性とその問題が正当な研究テーマとして紹介されるようになった。フェミニスト心理学は、社会的背景、生活体 験、質的分析を重視している。心理学のフェミニストの声』のようなプロジェクトは、フェミニスト心理学者の学問分野への影響を目録化するために出現した [208]。 |