ideology

イデオロギー

ideology

解説:池田光穂

イデオロギー(ideology)とは「ある特定の観念についての理論体 系」のことであり、それが明文化されていようがいまいが「観念に権威を与え、理解し、それに 基づいて何かの実践を引き出すことができるもの」とここでは定義することができます。したがって、イデオロギーはその渦中にいる人にとって は良い/悪い、 正しい/間違っているという価値の判断を(とりわけ深く考えなくても)もたらすことができます。イデオロギーの定義は、現在では主要な思想家の数だけある と言っても過言ではない(→「文化体系としてのイデオロギー」)。

| An ideology

is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of

persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about

belief in certain knowledge,[1][2] in which "practical elements are as

prominent as theoretical ones".[3] Formerly applied primarily to

economic, political, or religious theories and policies, in a tradition

going back to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, more recent use treats

the term as mainly condemnatory.[4] The term was coined by Antoine Destutt de Tracy, a French Enlightenment aristocrat and philosopher, who conceived it in 1796 as the "science of ideas" to develop a rational system of ideas to oppose the irrational impulses of the mob. In political science, the term is used in a descriptive sense to refer to political belief systems.[4] |

イデオロギーとは、個人や集団に帰属する一連の信念や価値観を指す。特

に、特定の知識への純粋な信仰以外の理由で保持されるものであり[1][2]、「理論的要素と同様に実践的要素が顕著である」[3]。かつては主に経済・

政治・宗教の理論や政策に適用され、カール・マルクスやフリードリヒ・エンゲルスに遡る伝統があったが、近年の用法では主に非難的な意味合いで用いられ

る。[4] この用語は、フランス啓蒙主義の貴族哲学者アントワーヌ・デストゥ・ド・トラシーによって造語された。彼は1796年、群衆の非合理的な衝動に対抗する合 理的な思想体系を構築するため、「観念の科学」としてこの概念を構想した。政治学においては、政治的信念体系を指す記述的意味で使用される。[4] |

| Etymology The term ideology originates from French idéologie, itself coined from combining Greek: idéā (ἰδέα, 'notion, pattern'; close to the Lockean sense of idea) and -logíā (-λογῐ́ᾱ, 'the study of'). An ideologue is someone who strongly believes in an ideology. The term carries negative connotations, often referring to someone who is blindly partisan, zealous, or fanatical in their beliefs. |

語源 イデオロギーという用語は、フランス語のidéologieに由来する。この語は、ギリシャ語のidéā(ἰδέα、「概念、様式」;ロック的な意味でのideaに近い)と-logíā(-λογῐ́ᾱ、「研究」を意味する)を組み合わせた造語である。 イデオロギーを強く信じる者をイデオロジストと呼ぶ。この用語には否定的な意味合いが伴い、往々にして盲目的な党派性や熱狂的・狂信的な信念を持つ者を指す。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ideology |

以下ではイデオロギーを理解するための「現代イデオロギー論者七人衆」をご紹介します。

1. ルイ・アルチュセール

アルチュセールに言わせると、イデオロギーとは「自分は外にあるにも 関わ らず、自分の外にはないもの」という自己矛盾したものであるということ です(上野 2014:226-227)。ルイ・アルチュセールのテーゼだと「イデオロ ギーには外がない、と同時にイデオロギーは外にしかない」「イデオロギーには歴史がな い」「イデオロギーは永遠である」ということになります。これは、イデオロギーがイデオロギーとして機能している時には、(あたかも)歴史性をもたず普遍 で 「永遠」なものとしてその行為者たちには錯認してしまうからです(→イデオロギー概念の自然化)。

2. アントニオ・グラムシ

アルチュセールは、マルクスがイデオロギーの概念を根本的に変えて、それ(=イデオロギー)を「ひとりの人間、あるいは社会的な一集団の精神を支配する諸観念や諸表象の体系」と説明しています(アルチュセール[下] 2010:208)。この「精神を支配する」 ことこそが、ヘゲモニーを掌握するというアントニオ・グラムシのテーゼになるので す。そしてアルチュセールのテーゼに従うと、イデオロギーの支配とは、 それが各個人個人に直接訴えます。すなわちイデオロギーは主体に訴えかける機能をもつのです(アルチュセール[下]2010:217)。

3. クリフォード・ギアーツ

クリフォード・ギアツ(ギアーツ)は、イデオロギーの機能としては「政治を意味あるもの とす るような権威あ る概念を与えることによって、すなわち政治を理解し得るような形で把握する手段としての説得力あるイメージを与えることによって、自律的な政治を可能にす ることである」(邦訳:第2分冊:42ページ)と述べています。(→出典「文化としてのイデオ ロギー論に関する対話」)

4. カール・マンハイム

カール・マンハイム(『イデオロギーとユートピア(Ideology and Utopia)』)によると、イデオロギーは、存在被拘束性(Seinsverbundenheit)という性格をもち、支配集団の現状維持 を承認する「虚偽意識」といってます。

5. ハンナ・アーレント

アーレントによると、イデオロギーは世界観と同義だけれど、人間に考えることを停止させる、思想的装置ないしは武器のように思えてきます。 次の 引 用を参照してください(→「イデオロギーとテラー」)。

「哲学的思想に必然的にそなわる不確実さを捨ててイ デオロギーとその世界観(Weltanschaung)による全体的説明を取ることの危険は、何らかの 大抵は月並な、しかも常に無批判な臆断にはまりこんでしまうということよりも、人間の思考能力に固有の自由を捨てて強制的論理を取るということである。人 間はこの強制的論理をもって、何らかの外力によって強制されるのとほとんど同じくらい乱暴に自分自身に強制を加えるのだ」[アーレント 1981:313]。

6. ヒューマン・ケアというイデオロ

ギーあるいはジェンダー・イデオロギー

端的に言って、ケアの現場において、手厚く看護や介護する人は〈女性の役割〉で医療や診断などの知的労働は〈男性の役割〉だと考える人がい た ら、それは古い考え方をもっているのではなく、〈ケアのジェンダー〉や〈労働のジェンダー〉というイデオロギーに呪縛されている人だとい うことができます(→「ケアの倫理」「ミソジニーのイデオロギー的機能」「ジェ ンダー・とらぶってる」)。

7. ジョークネタとしてのイデオロギー

(スラヴォイ・ジジェクの

場合)

「量子力学のヒーロ、ニールス・ボーア、コペンハーゲンの男である。彼が、週末の田舎の別荘かなにかに客と一緒にいった。そこで入り口の横 に、馬蹄がかけてある。馬蹄はなにかの魔除けであることを知っている来客は不思議に思った。ボーアは骨太の科学者で、迷信なんかこれっぽっちも信じない。 『ボーアさん、迷信など信じないあなたが、かけてあるこの馬蹄、いったい、あなたは信じるのでしょうか?』と客はたずねた。ボーアは真顔で言った。『あ あ、もちろん、そんなものなど信じていないよ。けど、これは、僕のような不信心者でも、効き 目があるって人が言うんだよね』(会場大爆笑)。みなさん、これこそが、イデオロギーなんですね!!!」スラヴォイ・ジジェクの講演での ジョーク(梗概)[→ジョークを通して学ぶイデオロギー入門]

8. 真理を探究する自然科学により人種主義を正当化する「科学的レイシズム」もイデオロギーの一種である。

科学はイデオロギーの一種だという主張もありますので、科学とイデオロギーは相互排除的ではないという考え方もあります。なぜなら「イデオロギー(ideology) とは「ある特定の観念についての理論体系」のことであり、それが明文化されていようがいまいが「観念に権威を与え、理解し、それに 基づいて何かの実践を引き出すことができるもの」」だからです。科学はその意味では「ある特定の観念(=普遍)についての理論体系」ですから科学もまたイ デオロギーと主張することも可能です(→詳しくは「科学的レイシズム」を参照)。

◎イデオロギーという用語の発明者につい

て

今日的用法とは若干異なるがイデオロギー という言葉の発明者はデスチュット・ド・トラシ(Antonie Louis Claude Destutt de Tracy, 1754-1836)である。

ド・トラシは「フランスの哲学者。パリに 生まれ、軍隊に入る。フランス革命直前の三部会に貴族代表として参加したが、革命時には逮捕された。の ち総裁政府下では主として教育行政の立案に参加。哲学的にはコンディヤックの感覚論の系譜を引く。感覚を基礎にして観念の形成、展開を研究し、これを観念 学(イデオロジーidéologie、フランス語)と名づけた。その際、コンディヤックとは異なり、意志、判断、想起も、感覚と同じく観念を構成する究極 的要素として認められている。そして、この狭義の観念学(人間の心理作用の分析)から、倫理、教育、政治の理論を導き出すことを企てた。主著には、この構 想を述べた『観念学の原理』5巻(1801~1815)」香川知晶)。

(以 下はウィキ英語版をまとめたものである):デスチュット・ド・トラシは、コンディヤックがロックの一方的な解釈に基づいてフランスに設立した官能主義学派 の最後の著名な代表者である。カバニスの唯物論的見解に全面的に賛同し、ド・トラシはコンディヤックの官能主義的原則を最も必要な結果まで押し進めた。カ バニスが人間の生理的側面に関心を寄せていたのに対し、ド・トラシの関心は、当時新たに決定された人間の「心理的」ではなく「思想的」な側面に向けられて いた。彼の基盤となるイデオロギーという概念は、「動物学(生物学)の一部」に分類されるべきものだと率直に述べている。ド・トラシが 意識生活を区分する4つの能力、すなわち知覚、記憶、判断、意志は、すべて感覚の一種である。知覚は神経の外端の現在の興奮によって引き起こされる感覚で あり、記憶は現在の興奮がないときに過去の経験の結果である神経の性質によって引き起こされる感覚であり、判断は感覚間の関係の認識であり、それ自体感覚 の一種である、もし我々が感覚を認識するならば、それらの間の関係も認識する必要がある。

彼の哲学が及ぼした影響から考えると、 ド・トラシは、能動的触覚と受動的触覚を区別し、最終的に筋肉感覚に関する心理学的理論の発展に寄与した という点で、最低限の評価に値すると思われる。外的存在の概念は純粋な感覚ではなく、一方では作用、他方では抵抗の経験に由来するという彼の説明は、この 観点からアレクサンダー・ベインや後の心理学者の業績と比較されるべきものである。

主な著作は、『イデオロジーの厳密な定 義』として発表された第1巻のÉléments d'idéologie (1817-1818) 5巻、Commentaire sur l'esprit des lois de Montesquieu (1806) および Essai sur le génie, et les ouvrages de Montesquieu (1808) で、先に完成したモノグラフでの論点を補完するものであった。Eléments d'idéologie』の第4巻は、『Traité de la volonté』と題した9部作のうちの第2部の序章と位置づけられるものであった。このため、デ・トラシは政治ではなく、意志とその決定条件を理解する 可能性という、より基本的な問題に取り組んでいることが明らかになった。

ド・トラシは、社会理論において演繹的手 法を厳格に用い、経済学を行為(プラクセオロジー)と交換(カタラクチック)の観点から捉えることを推 進した。ド・トラシの影響は大陸(特にスタンダール、オーギュスタン・ティエリ、オーギュスト・コント、シャルル・デュノワイエ)でもアメリカでも見ら れ、フランス自由主義派の政治経済学は、アーサー・レーサム・ペリーの業績や評判に見られるように、19世紀末まではイギリスの古典政治経済と互角に戦っ てきた。ド・トラシは、政治的著作において君主制を否定し、アメリカの共和制を支持した。この共和制と、哲学における理性、経済政策における自由放任主義 の提唱は、ナポレオンに気に入られず、彼はド・トラシの造語である「イデオロギー」を罵倒語に変えてしまった。カール・マルクスはこの流れを汲み、ド・ト ラシを「fischblütige Bourgeoisoisdoktrinär」(「魚の血を引くブルジョワの教条主義者」)と呼んだ。

一方、トーマス・ジェファーソンはデス チュット・ド・トラシの仕事を高く評価し、彼の原稿のうち2本をアメリカでの出版に用意した。1817年 の出版に際し、ジェファーソンはその序文で「政治経済学の健全な原則を普及させることによって、現在消費している寄生虫組織から公共産業を保護することが できるだろう」と書いている。ド・トラシのモンテスキュー批判と代議制民主主義の支持は、ジェファーソンの思想に影響を与えた。

★https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ideology の続き(イデオロギーの歴史から始まる)

| History The term "ideology" and the system of ideas associated with it were developed in 1796 by Antoine Destutt de Tracy (1754–1836), who crystallised his ideas while in prison (November 1793 to October 1794) pending trial during the Reign of Terror of c. 1793 to July 1794. While imprisoned he read the works of Locke and Étienne Bonnot de Condillac.[5] Hoping to form a secure foundation for the moral and political sciences, Tracy devised the term for a "science of ideas", basing such upon two things: (1) the sensations that people experience as they interact with the material world; and (2) the ideas that form in their minds due to those sensations. Tracy conceived of ideology as a liberal philosophy that would defend individual liberty, property, free markets, and constitutional limits on state power. He argues that, among these aspects, ideology is the most generic term because the 'science of ideas' also contains the study of their expression and deduction.[6] The coup d'état that overthrew Maximilien Robespierre in July 1794 allowed Tracy to pursue his work.[6][need quotation to verify] Tracy reacted to the terroristic phase of the revolution (during the Napoleonic regime of 1799 to 1815 as part of the Napoleonic Wars)[clarification needed] by trying to work out a rational system of ideas to oppose the irrational mob-impulses that had nearly destroyed him. A subsequent early source for the near-original meaning of ideology is Hippolyte Taine's work on the Ancien Régime, Origins of Contemporary France (French: Les Origines de la France Contemporaine) volume I (1875). He describes ideology as rather like teaching philosophy via the Socratic method, though without extending the vocabulary beyond what the general reader already possessed, and without the examples from observation that practical science would require. Taine identifies it not just with Tracy but also with his milieu, and includes Condillac as one of its precursors. Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) came to view ideology as a term of abuse, which he often hurled against his liberal foes in Tracy's Institut national.[citation needed] According to Karl Mannheim's historical reconstruction of the shifts in the meaning of ideology, the modern meaning of the word was born when Napoleon used it to describe his opponents as "the ideologues".[citation needed] Tracy's major book, The Elements of Ideology (French: Élémens d'idéologie, published 1804–1815), was soon translated into major European languages. In the century following Tracy's formulations, the term ideology moved back and forth between positive and negative connotations. When post-Napoleonic governments adopted a reactionary stance, the concept influenced the Italian, Spanish and Russian thinkers who had begun to describe themselves as liberals and who attempted to reignite revolutionary activity in the early 1820s, including the Carbonari societies in France and Italy and the Decembrists in Russia. Karl Marx (1818–1883) adopted Napoleon's negative sense of the term, using it in his writings, in which he once described Tracy as a fischblütige Bourgeoisdoktrinär (a "fish-blooded bourgeois doctrinaire").[7] The term has since dropped some of its pejorative sting (euphemism treadmill), and has become a neutral term in the analysis of differing political opinions and views of social groups.[8] While Marx situated the term within class struggle and domination,[9][10] others believed it was a necessary part of institutional functioning and social integration.[11] In parallel with post-Soviet Russian ideas about the mono-ideologies of (for example) monotheism, Walter Brueggemann (1933–2025) has examined "ideological extension" in historical religious/political contexts.[12] |

歴史 「イデオロギー」という用語とそれに伴う思想体系は、1796年にアントワーヌ・デストゥ・ド・トラシー(1754–1836)によって発展させた。彼は 恐怖政治期(1793年頃~1794年7月)に裁判待ちで投獄されていた期間(1793年11月~1794年10月)に自らの思想を結晶化した。投獄中、 彼はロックとエティエンヌ・ボノ・ド・コンディヤックの著作を読んだ[5]。 道徳科学と政治科学の確固たる基盤を築こうと、トラシーは「観念の科学」を指すこの用語を考案した。その根拠は二つ:(1) 物質世界と関わる中で人々が経験する感覚、(2) その感覚によって心に形成される観念である。トラシーはイデオロギーを、個人の自由、財産、自由市場、国家権力に対する憲法上の制限を擁護する自由主義哲 学として構想した。彼は、これらの側面の中でイデオロギーが最も一般的な用語であると主張する。なぜなら「観念の科学」には観念の表現と演繹の研究も含ま れるからである[6]。1794年7月にマクシミリアン・ロベスピエールを打倒したクーデターにより、トラシーは研究を続けることができた。[6][出典 引用が必要] トラシーは革命の恐怖政治期(1799年から1815年までのナポレオン政権下、ナポレオン戦争の一部として)[説明が必要] に対し、自らを破滅寸前に追い込んだ非合理的な群衆の衝動に対抗する合理的な思想体系を構築しようと試みた。 イデオロギーのほぼ原初的な意味を示す初期の出典として、ヒッポリテ・テーヌの旧体制論『現代フランスの起源』(仏語: Les Origines de la France Contemporaine)第1巻(1875年)が挙げられる。彼はイデオロギーを、ソクラテス式対話法による哲学教育に似ていると説明している。ただ し一般読者が既に持つ語彙を超えず、実践科学が要求する観察に基づく例示も伴わない形で。テーヌはイデオロギーをトラシーだけでなくその思想圏全体と同一 視し、コンディヤックをその先駆者の一人に含めている。 ナポレオン・ボナパルト(1769–1821)は、イデオロギーを罵倒語と見なすようになり、トラシーの国立研究所に属する自由主義的敵対者たちに対して 頻繁にこの言葉を浴びせた。[出典必要] カール・マンハイムによるイデオロギーの意味変遷の歴史的再構築によれば、この言葉の現代的意味は、ナポレオンが敵対者を「イデオロギー派」と称した際に 誕生したとされる。[出典必要] トラシーの主要著作『イデオロギーの要素』(仏語原題:Éléments d'idéologie、1804-1815年刊行)は、間もなく主要なヨーロッパ諸言語に翻訳された。 トラシーの提唱から続く世紀において、「イデオロギー」という用語は肯定的・否定的な意味合いを行き来した。ナポレオン後の政府が反動的姿勢を取る中、こ の概念は自らを自由主義者と称し始めたイタリア、スペイン、ロシアの思想家に影響を与えた。彼らは1820年代初頭に革命活動を再燃させようと試み、フラ ンスとイタリアのカルボナリ運動やロシアの十二月党人運動などがその例である。カール・マルクス(1818–1883)はナポレオンの否定的な用法を採用 し、著作でこの用語を用いた。彼はトラシーを「魚の血を引くブルジョワ教条主義者」と評したこともある。[7] その後この用語は蔑称的な意味合いを幾分失い(婉曲表現の回転木馬)、異なる政治的意見や社会集団の見解を分析する中立的な用語となった。[8] マルクスがこの用語を階級闘争と支配の文脈に位置づけた一方で[9][10]、他者たちはそれが制度機能と社会統合に不可欠な要素だと考えた。[11] 一神教などの単一イデオロギーに関するポストソビエトロシアの思想と並行して、ウォルター・ブリュッゲマン(1933–2025)は歴史的宗教/政治的文脈における「イデオロギー的拡張」を考察した。[12] |

| Definitions and analysis There are many different kinds of ideologies, including political, social, epistemological, and ethical. Recent analysis tends to posit that ideology is a 'coherent system of ideas' that rely on a few basic assumptions about reality that may or may not have any factual basis. Through this system, ideas become coherent, repeated patterns through the subjective ongoing choices that people make. These ideas serve as the seed around which further thought grows. The belief in an ideology can range from passive acceptance up to fervent advocacy. Definitions, such as by Manfred Steger and Paul James, emphasize both the issue of patterning and contingent claims to truth. They wrote: "Ideologies are patterned clusters of normatively imbued ideas and concepts, including particular representations of power relations. These conceptual maps help people navigate the complexity of their political universe and carry claims to social truth."[13] Studies of the concept of ideology itself (rather than specific ideologies) have been carried out under the name of systematic ideology in the works of George Walford and Harold Walsby, who attempt to explore the relationships between ideology and social systems.[example needed] David W. Minar describes six different ways the word ideology has been used:[14] 1. As a collection of certain ideas with certain kinds of content, usually normative; 2. As the form or internal logical structure that ideas have within a set; 3. By the role ideas play in human-social interaction; 4. By the role ideas play in the structure of an organization; 5. As meaning, whose purpose is persuasion; and 6. As the locus of social interaction. For Willard A. Mullins, an ideology should be contrasted with the related (but different) issues of utopia and historical myth. An ideology is composed of four basic characteristics:[15] 1. it must have power over cognition; 2. it must be capable of guiding one's evaluations; 3. it must provide guidance towards action; and 4. it must be logically coherent. Terry Eagleton outlines (more or less in no particular order) some definitions of ideology:[16] 1. The process of production of meanings, signs and values in social life 2. A body of ideas characteristic of a particular social group or class 3. Ideas that help legitimate a dominant political power 4. False ideas that help legitimate a dominant political power 5. Systematically distorted communication 6. Ideas that offer a position for a subject 7. Forms of thought motivated by social interests 8. Identity thinking 9. Socially necessary illusion 10. The conjuncture of discourse and power 11. The medium in which conscious social actors make sense of their world 12. Action-oriented sets of beliefs 13. The confusion of linguistic and phenomenal reality 14. Semiotic closure[16]: 197 15. The indispensable medium in which individuals live out their relations to a social structure 16.The process that converts social life to a natural reality German philosopher Christian Duncker called for a "critical reflection of the ideology concept".[17] In his work, he strove to bring the concept of ideology into the foreground, as well as the closely connected concerns of epistemology and history, defining ideology in terms of a system of presentations that explicitly or implicitly lay claim to absolute truth. |

定義と分析 イデオロギーには、政治的、社会的、認識論的、倫理的など、さまざまな種類がある。最近の分析では、イデオロギーは、事実に基づく場合とそうでない場合の ある、現実に関するいくつかの基本的な仮定に基づく「首尾一貫した思想体系」であると定義される傾向がある。この体系を通じて、人々の主観的な継続的な選 択によって、思想は首尾一貫した繰り返しのパターンとなる。これらの思想は、さらなる思考が育つ種としての役割を果たす。イデオロギーへの信念は、受動的 な受容から熱烈な支持まで様々である。マンフレッド・スティーガーやポール・ジェームズによる定義は、パターン化の問題と、真実に対する条件付きの主張の 両方を強調している。彼らは次のように書いている。「イデオロギーとは、規範的に浸透した考えや概念、特に権力関係の表現を含む、パターン化された集合体 である。こうした概念的な地図は、人民が政治的な宇宙の複雑さをナビゲートし、社会的真実に対する主張を運ぶのに役立つ」[13]。 イデオロギーそのものの概念(特定のイデオロギーではなく)に関する研究は、イデオロギーと社会システムの関係を探求しようとするジョージ・ウォルフォー ドとハロルド・ウォルズビーの著作の中で、体系的なイデオロギーという名称で実施されてきた。デイヴィッド・W・マイナーは、イデオロギーという言葉が6 つの異なる方法で使用されてきたことを説明している。 1. 通常、規範的な、特定の種類の内容を持つ特定の考えの集合として。 2. 集合体内で思想が持つ形式または内部論理構造として; 3. 人間社会における相互作用で思想が果たす役割として; 4. 組織構造において思想が果たす役割として; 5. 説得を目的とする意味として; 6. 社会的相互作用の場として。 ウィラード・A・マリンズによれば、イデオロギーはユートピアや歴史的神話といった関連する(だが異なる)問題と対比されるべきである。イデオロギーは四つの基本特性から成る:[15] 1. 認知に対する支配力を有すること 2. 個人の評価を導く能力を有すること 3. 行動への指針を提供すること 4. 論理的に一貫していること テリー・イーグルトンは(ほぼ順不同で)イデオロギーの定義を概説する:[16] 1. 社会生活における意味・記号・価値の生産過程 2. 特定の社会集団や階級に特徴的な思想体系 3. 支配的な政治権力を正当化する思想 4. 支配的な政治権力を正当化する虚偽の思想 5. 体系的に歪められたコミュニケーション 6. 主体に立場を提供する思想 7. 社会的利益に動機づけられた思考形態 8. アイデンティティ思考 9. 社会的に必要な幻想 10. 言説と権力の結合 11. 意識的な社会主体が自らの世界を解釈する媒体 12. 行動指向的な信念体系 13. 言語的現実と現象的現実の混同 14. 記号論的閉鎖[16]: 197 15. 個人が社会構造との関係を生きる上で不可欠な媒体 16. 社会生活を自然的現実へと変換する過程 ドイツの哲学者クリスティアン・ダンカーは「イデオロギー概念の批判的省察」を求めた[17]。彼の著作では、イデオロギー概念を前面に押し出すととも に、密接に関連する認識論と歴史学の課題を追求し、イデオロギーを絶対的真実を明示的または暗示的に主張する表象体系として定義した。 |

Marxist interpretation Karl Marx posits that a society's dominant ideology is integral to its superstructure. Marx's analysis sees ideology as a system of false consciousness that arises from economic relationships, reflecting and perpetuating the interests of the dominant class.[18] In the Marxist base and superstructure model of society, base denotes the relations of production and modes of production, and superstructure denotes the dominant ideology (i.e. religious, legal, political systems). The economic base of production determines the political superstructure of a society. Ruling class-interests determine the superstructure and the nature of the justifying ideology—actions feasible because the ruling class control the means of production. For example, in a feudal mode of production, religious ideology is the most prominent aspect of the superstructure, while in capitalist formations, ideologies such as liberalism and social democracy dominate. Hence the great importance of ideology justifies a society and politically confuses the alienated groups of society via false consciousness. Some explanations have been presented. Antonio Gramsci uses cultural hegemony to explain why the working-class have a false ideological conception of what their best interests are. Marx argued: "The class which has the means of material production at its disposal has control at the same time over the means of mental production."[19] The Marxist formulation of "ideology as an instrument of social reproduction" is conceptually important to the sociology of knowledge,[20] viz. Karl Mannheim, Daniel Bell, and Jürgen Habermas et al. Moreover, Mannheim has developed and progressed from the "total" but "special" Marxist conception of ideology to a "general" and "total" ideological conception acknowledging that all ideology (including Marxism) resulted from social life, an idea developed by the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Slavoj Žižek and the earlier Frankfurt School added to the "general theory" of ideology a psychoanalytic insight that ideologies do not include only conscious but also unconscious ideas. |

マルクス主義的解釈 カール・マルクスは、社会の支配的イデオロギーがその上部構造に不可欠であると主張する。 マルクスの分析では、イデオロギーは経済関係から生じる虚偽の意識体系であり、支配階級の利益を反映し永続させるものである。[18] マルクス主義の社会基盤と上部構造モデルにおいて、基盤は生産関係と生産様式を指し、上部構造は支配的イデオロギー(すなわち宗教的、法的、政治的システ ム)を指す。生産の経済的基盤が社会の政治的上部構造を決定する。支配階級の利益が上部構造と正当化イデオロギーの性質を決定する——支配階級が生産手段 を掌握しているため、こうした行動が可能となる。例えば封建的生産様式では宗教イデオロギーが上部構造の顕著な側面であり、資本主義体制では自由主義や社 会民主主義といったイデオロギーが支配的である。ゆえにイデオロギーは社会を正当化し、虚偽の意識を通じて疎外された社会集団を政治的に混乱させる上で極 めて重要だ。いくつかの説明がなされてきた。アントニオ・グラムシは文化的ヘゲモニーを用いて、労働者階級が自らの最善の利益について虚偽のイデオロギー 的認識を持つ理由を説明している。マルクスはこう論じた。「物質的生産手段を掌握する階級は、同時に精神的生産手段も支配する」[19]。 「イデオロギーは社会再生産の道具である」というマルクス主義の定式化は、知識社会学にとって概念的に重要である[20]。すなわちカール・マンハイム、 ダニエル・ベル、ユルゲン・ハーバーマスらがこれを取り上げた。さらにマンハイムは、マルクス主義の「全体的」だが「特殊な」イデオロギー概念を発展さ せ、全てのイデオロギー(マルクス主義を含む)が社会生活から生じるという社会学者ピエール・ブルデューの思想を採り入れ、「一般的」かつ「全体的」なイ デオロギー概念へと進展させた。スラヴォイ・ジジェクや初期のフランクフルト学派は、イデオロギーには意識的な思想だけでなく無意識的な思想も含まれると いう精神分析的洞察を、イデオロギーの「一般理論」に付加した。 |

| Ideology and the commodity (Debord) The French Marxist theorist Guy Debord, founding member of the Situationist International, argued that when the commodity becomes the "essential category" of society, i.e. when the process of commodification has been consummated to its fullest extent, the image of society propagated by the commodity (as it describes all of life as constituted by notions and objects deriving their value only as commodities tradeable in terms of exchange value), colonizes all of life and reduces society to a mere representation, The Society of the Spectacle.[21] |

イデオロギーと商品(ドボルド) フランス人マルクス主義理論家であり、シチュアシオニスト・インターナショナルの創設メンバーであるギー・ドゥボールは、商品が社会の「本質的カテゴ リー」となる時、すなわち商品化の過程が完全に達成された時、商品によって拡散される社会のイメージ(あらゆる生活が交換価値において取引可能な商品とし ての価値のみを得る概念や物体によって構成されていると描写するイメージ)は、 あらゆる生活を植民地化し、社会を単なる表象へと還元する。これが『スペクタクルの社会』である[21]。 |

| Unifying agents (Hoffer) The American philosopher Eric Hoffer identified several elements that unify followers of a particular ideology:[22] 1. Hatred: "Mass movements can rise and spread without a God, but never without belief in a devil."[22] The "ideal devil" is a foreigner.[22]: 93 2. Imitation: "The less satisfaction we derive from being ourselves, the greater is our desire to be like others…the more we mistrust our judgment and luck, the more are we ready to follow the example of others."[22]: 101–2 3. Persuasion: The proselytizing zeal of propagandists derives from "a passionate search for something not yet found more than a desire to bestow something we already have."[22]: 110 4. Coercion: Hoffer asserts that violence and fanaticism are interdependent. People forcibly converted to Islamic or communist beliefs become as fanatical as those who did the forcing. He says: "It takes fanatical faith to rationalize our cowardice."[22]: 107–8 5. Leadership: Without the leader, there is no movement. Often the leader must wait long in the wings until the time is ripe. He calls for sacrifices in the present, to justify his vision of a breathtaking future. The skills required include: audacity, brazenness, iron will, fanatical conviction; passionate hatred, cunning, a delight in symbols; ability to inspire blind faith in the masses; and a group of able lieutenants.[22]: 112–4 Charlatanism is indispensable, and the leader often imitates both friend and foe, "a single-minded fashioning after a model." He will not lead followers towards the "promised land", but only "away from their unwanted selves".[22]: 116–9 6. Action: Original thoughts are suppressed, and unity encouraged, if the masses are kept occupied through great projects, marches, exploration and industry.[22]: 120–1 7. Suspicion: "There is prying and spying, tense watching and a tense awareness of being watched." This pathological mistrust goes unchallenged and encourages conformity, not dissent.[22]: 124 |

統一要因(ホッファー) アメリカの哲学者エリック・ホッファーは、特定のイデオロギーの信奉者を統一する要素をいくつか特定した:[22] 1. 憎悪:「大衆運動は神なしで興り広がるが、悪魔への信仰なしでは決して興らない」[22]。「理想的な悪魔」とは外国人である。[22]: 93 2. 模倣:「 自分であることに満足が得られないほど、他人のようになりたいという欲求は強くなる…自らの判断や運を疑えば疑うほど、他人の模範に従う準備は整う。」[22]: 101–2 3. 説得:宣伝工作員の布教熱意は「既に持っているものを与えたいという欲求よりも、まだ見出されていない何かを熱心に探求する姿勢」に由来する。[22]: 110 4. 強制:ホッファーは暴力と狂信は相互依存関係にあると主張する。イスラム教や共産主義の信念に強制的に改宗させられた人民は、強制した者たちと同じくらい狂信的になる。彼は言う:「我々の臆病さを正当化するには狂信的な信仰が必要だ」[22]: 107–8 5. 指導者性:指導者なしに運動は成立しない。指導者は往々にして時機が熟すまで長い間、舞台裏で待機せねばならない。彼は息をのむような未来像を正当化する ため、現在における犠牲を要求する。必要な資質には以下が含まれる:大胆不敵さ、厚かましさ、鉄の意志、狂信的な確信;激しい憎悪、狡猾さ、象徴への嗜 好;大衆に盲目的な信仰を喚起する能力;そして有能な副官たちの集団。[22]: 112–4 ペテン師的技法は不可欠であり、指導者はしばしば味方と敵の両方を模倣する。「一つのモデルへのひたむきな追随」である。彼は追随者を「約束の地」へ導く のではなく、単に「望まぬ自己から遠ざける」だけだ。[22]: 116–9 6. 行動:大衆を壮大な計画、行進、探検、産業で忙しくさせれば、独自の思考は抑圧され、団結が促される。[22]: 120–1 7. 疑念:「詮索やスパイ行為、緊張した監視、そして監視されているという緊張した自覚がある」。この病的な不信感は疑問視されず、異議ではなく同調を促す。[22]:124 |

| Ronald Inglehart Ronald Inglehart of the University of Michigan is author of the World Values Survey, which, since 1980, has mapped social attitudes in 100 countries representing 90% of global population. Results indicate that where people live is likely to closely correlate with their ideological beliefs. In much of Africa, South Asia and the Middle East, people prefer traditional beliefs and are less tolerant of liberal values. Protestant Europe, at the other extreme, adheres more to secular beliefs and liberal values. Alone among high-income countries, the United States is exceptional in its adherence to traditional beliefs, in this case Christianity. |

ロナルド・イングルハート ミシガン大学のロナルド・イングルハートは、1980年以降、世界人口の90%を占める100カ国における社会的態度を調査してきた「世界価値観調査」の 著者である。調査結果によれば、人民の居住地は彼らのイデオロギー的信念と密接に関連している可能性が高い。アフリカ、南アジア、中東の大部分では、人民 は伝統的信念を好み、リベラルな価値観への寛容性が低い。対極にあるプロテスタント圏のヨーロッパでは、世俗的信念とリベラルな価値観への帰依が強い。高 所得国の中で唯一、アメリカ合衆国は伝統的信念、この場合はキリスト教への帰依において特異な存在である。 |

| Political ideologies See also: List of political ideologies In political science, a political ideology is a certain ethical set of ideals, principles, doctrines, myths, or symbols of a social movement, institution, class, or large group that explains how society should work, offering some political and cultural blueprint for a certain social order. Political ideologies are concerned with many different aspects of a society, including but not limited to: the economy, the government, the environment, education, health care, labor law, criminal law, the justice system, social security and welfare, public policy and administration, foreign policy, rights, freedoms and duties, citizenship, immigration, culture and national identity, military administration, and religion. Political ideologies have two dimensions: 1. Goals: how society should work; and 2. Methods: the most appropriate ways to achieve the ideal arrangement. A political ideology largely concerns itself with how to allocate power and to what ends power should be used. Some parties follow a certain ideology very closely, while others may take broad inspiration from a group of related ideologies without specifically embracing any one of them. Each political ideology contains certain ideas on what it considers the best form of government (e.g., democracy, demagogy, theocracy, caliphate etc.), scope of government (e.g. authoritarianism, libertarianism, federalism, etc.) and the best economic system (e.g. capitalism, socialism, etc.). Sometimes the same word is used to identify both an ideology and one of its main ideas. For instance, socialism may refer to an economic system, or it may refer to an ideology that supports that economic system. Post 1991, many commentators claim that we are living in a post-ideological age,[23] in which redemptive, all-encompassing ideologies have failed. This view is often associated with Francis Fukuyama's writings on the end of history.[24] Contrastly, Nienhueser (2011) sees research (in the field of human resource management) as ongoingly "generating ideology".[25] There are many proposed methods for the classification of political ideologies. Ideologies can identify themselves by their position on the political spectrum (e.g. left, center, or right). They may also be distinguished by single issues around which they may be built (e.g. civil libertarianism, support or opposition to European integration, legalization of marijuana). They may also be distinguished by political strategies (e.g. populism, personalism). The classification of political ideology is difficult, however, due to cultural relativity in definitions. For example, "what Americans now call conservatism much of the world calls liberalism or neoliberalism"; a conservatism in Finland would be labeled socialism in the United States.[26] Philosopher Michael Oakeshott defines single-issue ideologies as "the formalized abridgment of the supposed sub-stratum of the rational truth contained in the tradition". Moreover, Charles Blattberg offers an account that distinguishes political ideologies from political philosophies.[27] Slavoj Žižek argues how the very notion of post-ideology can enable the deepest, blindest form of ideology. A sort of false consciousness or false cynicism, engaged in for the purpose of lending one's point of view the respect of being objective, pretending neutral cynicism, without truly being so. Rather than help avoiding ideology, this lapse only deepens the commitment to an existing one. Zizek calls this "a post-modernist trap".[28] Peter Sloterdijk advanced the same idea already in 1988.[29] Studies have shown that political ideology is somewhat genetically heritable.[30][31][32][33][34][35][36] |

政治イデオロギー 関連項目: 政治イデオロギーの一覧 政治学において、政治イデオロギーとは、社会運動、制度、階級、あるいは大規模な集団が抱く倫理的な理想、原則、教義、神話、あるいは象徴の集合体であ る。それは社会がどのように機能すべきかを説明し、特定の社会秩序のための政治的・文化的青写真を提供する。政治イデオロギーは社会の様々な側面に関わ る。具体的には経済、政府、環境、教育、健康保険、労働法、刑法、司法制度、社会保障と福祉、公共政策と行政、外交政策、権利・自由・義務、市民権、移 民、文化と国民的アイデンティティ、軍事行政、宗教などが含まれるが、これらに限定されない。 政治イデオロギーには二つの側面がある: 1. 目標:社会がどうあるべきか 2. 方法:理想的な体制を達成するための最適な手段 政治イデオロギーは主に、権力をどう配分し、権力を何のために使うべきかに焦点を当てる。特定のイデオロギーを厳密に追う政党もあれば、関連するイデオロ ギー群から広く影響を受けつつ、特定のイデオロギーを明確に採用しない政党もある。各政治イデオロギーは、理想的な政府形態(例:民主主義、民衆煽動政 治、神権政治、カリフ制など)、政府の役割範囲(例:権威主義、自由主義、連邦主義など)、最適な経済システム(例:資本主義、社会主義など)に関する特 定の考えを含む。同じ言葉がイデオロギーそのものと、その主要な思想の両方を指す場合もある。例えば社会主義は経済システムを指すこともあれば、その経済 システムを支持するイデオロギーを指すこともある。1991年以降、多くの論者は我々がポストイデオロギー時代[23]に生きていると主張する。この時代 では、救済的で包括的なイデオロギーは失敗したとされる。この見解は、フランシス・フクヤマの「歴史の終わり」論と結びつけられることが多い[24]。対 照的に、ニーエンヒューザー(2011)は(人的資源管理分野における)研究が継続的に「イデオロギーを生み出している」と見る[25]。 政治イデオロギーの分類法は数多く提案されている。イデオロギーは政治スペクトル上の位置(左派、中道、右派など)によって自己を識別し得る。また、単一 の問題(市民的自由主義、欧州統合への支持・反対、マリファナ合法化など)を核として構築されることで区別され得る。さらに政治戦略(ポピュリズム、パー ソナリズムなど)によっても区別され得る。しかし、定義における文化的相対性ゆえに、政治イデオロギーの分類は困難である。例えば「現代アメリカ人が保守 主義と呼ぶものは、世界の多くの地域では自由主義あるいは新自由主義と呼ばれる」のである。フィンランドにおける保守主義は、アメリカでは社会主義と称さ れるだろう。[26] 哲学者マイケル・オークショットは単一課題イデオロギーを「伝統に内在する合理的真理の基盤とされるものの形式化された要約」と定義する。さらにチャールズ・ブラットバーグは政治イデオロギーと政治哲学を区別する見解を提示している[27]。 スラヴォイ・ジジェクは、ポストイデオロギーという概念そのものが、最も深く盲目的なイデオロギー形態を可能にすることを論じている。一種の偽りの意識、 あるいは偽りのシニシズムである。自らの見解に客観性という威厳を与え、中立的なシニシズムを装うために用いられるが、真に中立ではない。イデオロギー回 避の助けとなるどころか、この過ちは既存のイデオロギーへの帰依を深化させるだけだ。ジジェクはこれを「ポストモダニズムの罠」と呼ぶ[28]。ペー ター・スローターダイクは1988年に既に同様の考えを提示していた。[29] 研究によれば、政治的イデオロギーはある程度遺伝的に継承される。[30][31][32][33][34][35][36] |

| Ideology and state Main article: Ideocracy When a political ideology becomes a dominantly pervasive component within a government, one can speak of an ideocracy.[37] Different forms of government use ideology in various ways, not always restricted to politics and society. Certain ideas and schools of thought become favored, or rejected, over others, depending on their compatibility with or use for the reigning social order. In The Anatomy of Revolution, Crane Brinton said that new ideology spreads when there is discontent with an old regime.[38] The may be repeated during revolutions itself; extremists such as Vladimir Lenin and Robespierre may thus overcome more moderate revolutionaries.[39] This stage is soon followed by Thermidor, a reining back of revolutionary enthusiasm under pragmatists like Napoleon and Joseph Stalin, who bring "normalcy and equilibrium".[40] Brinton's sequence ("men of ideas>fanatics>practical men of action") is reiterated by J. William Fulbright,[41] while a similar form occurs in Eric Hoffer's The True Believer.[42] |

イデオロギーと国家 主な記事: イデオクラシー 政治的イデオロギーが政府内で支配的かつ浸透した要素となるとき、それはイデオクラシーと呼べる。[37] 異なる形態の政府はイデオロギーを多様な方法で利用し、必ずしも政治や社会に限定されない。特定の思想や学派は、支配的な社会秩序との適合性や有用性に応 じて、他の思想よりも優遇されたり拒絶されたりする。 『革命の解剖学』において、クレーン・ブリントンは、古い体制への不満がある時に新しいイデオロギーが広まると述べた[38]。これは革命の過程で繰り返 される可能性がある。ウラジーミル・レーニンやロベスピエールのような過激派が、より穏健な革命家たちを打ち負かすことがあるのだ[39]。この段階の直 後にはテルミドール期が訪れる。ナポレオンやヨシフ・スターリンのような現実主義者たちによって革命的熱狂が抑制され、「正常性と均衡」がもたらされるの である。[40] ブリントンの段階(「思想家>狂信者>実践的行動者」)はJ・ウィリアム・フルブライトによって再論され[41]、エリック・ホッファーの『真の信者』に も類似の形式が現れる[42]。 |

| Epistemological ideologies Even when the challenging of existing beliefs is encouraged, as in scientific theories, the dominant paradigm or mindset can prevent certain challenges, theories, or experiments from being advanced. A special case of science that has inspired ideology is ecology, which studies the relationships among living things on Earth. Perceptual psychologist James J. Gibson believed that human perception of ecological relationships was the basis of self-awareness and cognition itself.[43] Linguist George Lakoff has proposed a cognitive science of mathematics wherein even the most fundamental ideas of arithmetic would be seen as consequences or products of human perception—which is itself necessarily evolved within an ecology.[44] Deep ecology and the modern ecology movement (and, to a lesser degree, Green parties) appear to have adopted ecological sciences as a positive ideology.[45] Some notable economically based ideologies include neoliberalism, monetarism, mercantilism, mixed economy, social Darwinism, communism, laissez-faire economics, and free trade. There are also current theories of safe trade and fair trade that can be seen as ideologies. |

認識論的イデオロギー 科学理論のように既存の信念への挑戦が奨励される場合でさえ、支配的なパラダイムや思考様式が特定の挑戦や理論、実験の進展を阻むことがある。イデオロ ギーに影響を与えた科学の特殊な事例が生態学であり、これは地球上の生物間の関係を研究する学問である。知覚心理学者ジェームズ・J・ギブソンは、生態学 的関係に対する人間の知覚こそが自己認識や認知そのものの基盤だと考えた[43]。言語学者ジョージ・レイコフは、算術の最も基礎的な概念さえも人間の知 覚の結果や産物として捉える数学の認知科学を提唱している。この知覚自体が必然的に生態学の中で進化したものだ。[44] 深層エコロジーや現代のエコロジー運動(そして程度は低いもののグリーン党)は、生態学を積極的なイデオロギーとして採用しているように見える。[45] 経済を基盤とする著名なイデオロギーには、新自由主義、金融政策主義、重商主義、混合経済、社会ダーウィニズム、共産主義、自由放任主義、自由貿易などが ある。また、安全貿易や公正貿易といった現代の理論もイデオロギーと見なせる。 |

| Psychological explanations of ideology A large amount of research in psychology is concerned with the causes, consequences and content of ideology,[46][47][48] with humans being dubbed the "ideological animal" by Althusser.[49]: 269 Many theories have tried to explain the existence of ideology in human societies.[49]: 269 Jost, Ledgerwood, and Hardin (2008) propose that ideologies may function as prepackaged units of interpretation that spread because of basic human motives to understand the world, avoid existential threat, and maintain valued interpersonal relationships.[50] The authors conclude that such motives may lead disproportionately to the adoption of system-justifying worldviews.[51] Psychologists generally agree that personality traits, individual difference variables, needs, and ideological beliefs seem to have something in common.[51] Just-world theory posits that people want to believe in a fair world for a sense of control and security and generate ideologies in order to maintain this belief, for example by justifiying inequality or unfortunate events. A critique of just world theory as a sole explanation of ideology is that it does not explain the differences between ideologies.[49]: 270–271 Terror management theory posits that ideology is used as a defence mechanism against threats to their worldview which in turn protect and individuals sense of self-esteem and reduce their awareness of mortality. Evidence shows that priming individuals with an awareness of mortality does not cause individuals to respond in ways underpinned by any particular ideology, but rather the ideology that they are currently aware of.[49]: 271 System justification theory posits that people tend to defend existing society, even at times against their interest, which in turn causes people to create ideological explanations to justify the status quo. Jost, Fitzimmons and Kay argue that the motivation to protect a preexisting system is due to a desire for cognitive consistency (being able to think in similar ways over time), reducing uncertainty and reducing effort, illusion of control and fear of equality.[49]: 272 According to system justification theory,[50] ideologies reflect (unconscious) motivational processes, as opposed to the view that political convictions always reflect independent and unbiased thinking.[50] |

イデオロギーの心理学的説明 心理学における多くの研究は、イデオロギーの原因、結果、内容に関心を寄せている[46][47][48]。アルチュセールは人間を「イデオロギー的動 物」と呼んだ[49]: 269。多くの理論が、人間社会におけるイデオロギーの存在を説明しようとしてきた[49]: 269。 ヨスト、レジャーウッド、ハーディン(2008)は、イデオロギーは世界を理解し、実存的脅威を回避し、価値ある対人関係を維持したいという人間の基本的 動機によって拡散する、あらかじめパッケージ化された解釈単位として機能し得ると提案している。[50] 著者らは、こうした動機がシステム正当化的世界観の採用を不均衡に促進すると結論づけている。[51] 心理学者は概ね、性格特性・個人差変数・欲求・イデオロギー的信念には共通点があると認めている。[51] 公正世界理論は、人民が支配感と安全のために公正な世界を信じたいと望み、この信念を維持するためにイデオロギーを生成すると主張する。例えば不平等や不 幸な出来事を正当化することで。公正世界理論をイデオロギーの唯一の説明とする批判は、それがイデオロギー間の異なる点を説明しない点にある。[49]: 270–271 恐怖管理理論は、イデオロギーが世界観への脅威に対する防衛機構として用いられ、それによって個人の自尊心が保護され、死への意識が軽減されるとする。証 拠によれば、死への意識を喚起しても、特定のイデオロギーに基づく反応は生じず、むしろ個人が現在意識しているイデオロギーに基づく反応が生じる。 [49]:271 システム正当化理論は、人民が自らの利益に反する場合でも既存社会を擁護する傾向があり、その結果現状を正当化するイデオロギー的説明を構築すると主張す る。ヨスト、フィッツィモンズ、ケイは、既存システム保護の動機は認知的一貫性(時間を超えた思考の統一性)への欲求、不確実性の低減、努力の削減、支配 感の幻想、平等への恐怖によるものだと論じる。[49]: 272 システム正当化理論によれば[50]、イデオロギーは(無意識の)動機付けプロセスを反映するものであり、政治的信念が常に独立かつ偏りのない思考を反映 するという見解とは対照的である[50]。 |

| Ideology and the social sciences Semiotic theory According to semiotician Bob Hodge:[52] [Ideology] identifies a unitary object that incorporates complex sets of meanings with the social agents and processes that produced them. No other term captures this object as well as 'ideology'. Foucault's 'episteme' is too narrow and abstract, not social enough. His 'discourse', popular because it covers some of ideology's terrain with less baggage, is too confined to verbal systems. 'Worldview' is too metaphysical, 'propaganda' too loaded. Despite or because of its contradictions, 'ideology' still plays a key role in semiotics oriented to social, political life. Authors such as Michael Freeden have also recently incorporated a semantic analysis to the study of ideologies. Sociology Sociologists define ideology as "cultural beliefs that justify particular social arrangements, including patterns of inequality".[53] Dominant groups use these sets of cultural beliefs and practices to justify the systems of inequality that maintain their group's social power over non-dominant groups. Ideologies use a society's symbol system to organize social relations in a hierarchy, with some social identities being superior to other social identities, which are considered inferior. The dominant ideology in a society is passed along through the society's major social institutions, such as the media, the family, education, and religion.[54] As societies changed throughout history, so did the ideologies that justified systems of inequality.[53] Sociological examples of ideologies include racism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism, and ethnocentrism.[54] |

イデオロギーと社会科学 記号論的理論 記号論者ボブ・ホッジによれば:[52] [イデオロギー]とは、複雑な意味の集合を包含する単一の対象を、それを生み出した社会的主体やプロセスと共に特定するものである。この対象を「イデオロ ギー」ほど的確に捉える用語は他にない。フーコーの「エピステーム」は狭すぎて抽象的であり、社会的要素が不足している。彼の「言説」は、イデオロギーの 領域の一部をより少ない付随概念でカバーするため人気があるが、言語システムに限定されすぎている。「世界観」は形而上学的すぎ、「プロパガンダ」は偏見 が強すぎる。矛盾があるにもかかわらず、あるいはそのために、「イデオロギー」は依然として社会的・政治的生活を志向する記号論において重要な役割を果た している。 マイケル・フリーデンなどの著者も、近年イデオロギー研究に意味論的分析を取り入れている。 社会学 社会学者たちはイデオロギーを「特定の社会秩序、すなわち不平等構造を正当化する文化的信念体系」と定義する[53]。支配的集団はこうした文化的信念と 実践の集合体を用いて、非支配的集団に対する自らの社会的権力を維持する不平等システムを正当化する。イデオロギーは社会の記号体系を利用し、ある社会的 アイデンティティを他より優位と位置付け、他を劣位と見なす階層的な社会関係を形成する。社会の支配的イデオロギーは、メディア、家族、教育、宗教といっ た主要な社会制度を通じて継承される。[54] 歴史の中で社会が変化するにつれ、不平等システムを正当化するイデオロギーも変化してきた。[53] イデオロギーの社会学的例には、人種主義、性差別、異性愛主義、障害者差別、民族中心主義が含まれる。[54] |

| Quotations "We do not need…to believe in an ideology. All that is necessary is for each of us to develop our good human qualities. The need for a sense of universal responsibility affects every aspect of modern life." — Dalai Lama[55] "The function of ideology is to stabilize and perpetuate dominance through masking or illusion." — Sally Haslanger[56] "[A]n ideology differs from a simple opinion in that it claims to possess either the key to history, or the solution for all the 'riddles of the universe,' or the intimate knowledge of the hidden universal laws, which are supposed to rule nature and man." — Hannah Arendt[57] |

引用 「我々は…イデオロギーを信じる必要はない。必要なのは、一人ひとりが人間としての良き資質を育むことだ。普遍的な責任感の必要性は、現代生活のあらゆる側面に影響を及ぼしている。」 — ダライ・ラマ[55] 「イデオロギーの機能とは、覆い隠したり幻想を張ったりすることで支配を安定させ永続させることだ。」 — サリー・ハスランガー[56] 「イデオロギーが単なる意見と異なる点は、歴史の鍵、あるいは『宇宙の謎』すべてへの解決策、あるいは自然と人間を支配するとされる隠された普遍的法則への深い知識を、自ら有していると主張する点にある。」 — ハンナ・アーレント[57] |

| See also icon Politics portal icon Society portal -ism – English-language suffix Belief § Belief systems Capitalism – Economic system based on private ownership Dogma – Beliefs accepted by members of a group without question Feminism – Range of socio-political movements and ideologies Hegemony – Political, economic or military predominance of one state over other states Ideocracy – State governed by a particular ideology List of communist ideologies – Schools of thought on classless society List of ideologies named after people Noble lie – Untruth propagated to strengthen social harmony Politicisation – Political contestation of ideas, entities and facts Social criticism – Form of interpreting and sorting issues in contemporary society Socially constructed reality State collapse – Catastrophic government dissolution State ideology of the Soviet Union The Anatomy of Revolution – 1938 book by Crane Brinton The True Believer – Book by Eric Hoffer World Values Survey – Global research project Worldview – Fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society |

関連項目 アイコン 政治ポータル アイコン 社会ポータル -ism – 英語の接尾辞 信念 § 信念体系 資本主義 – 私有財産に基づく経済システム 教義 – 集団の成員が疑いなく受け入れる信念 フェミニズム – 様々な社会政治運動及びイデオロギー ヘゲモニー – ある国家が他の国家に対して持つ政治的、経済的、軍事的な優位性 イデオクラシー – 特定のイデオロギーによって統治される国家 共産主義イデオロギー一覧 – 階級なき社会に関する思想体系 人物に因んで名付けられたイデオロギー一覧 高貴な嘘 – 社会的調和を強化するために広められる虚偽 政治化 – 思想、実体、事実に対する政治的争い 社会批判 – 現代社会における問題を解釈し整理する形式 社会的に構築された現実 国家崩壊 – 政府の壊滅的解体 ソビエト連邦の国家イデオロギー 革命の解剖学 – クレーン・ブリントン著(1938年) 真の信者 – エリック・ホッファー著 世界価値観調査 – グローバル研究プロジェクト 世界観 – 個人または社会の根本的な認知的指向 |

| References 1. Honderich, Ted (1995). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-19-866132-0. 2. "ideology". Lexico. Archived from the original on 2020-02-11. 3. Cranston, Maurice. [1999] 2014. "Ideology Archived 2020-06-09 at the Wayback Machine" (revised). Encyclopædia Britannica. 4. van Dijk, T. A. (2006). "Politics, Ideology, and Discourse" (PDF). Discourse in Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2019-01-28. 5. Vincent, Andrew (2009). Modern Political Ideologies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4443-1105-1. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020. 6. Kennedy, Emmet (Jul–Sep 1979). ""Ideology" from Destutt De Tracy to Marx". Journal of the History of Ideas. 40 (3): 353–368. doi:10.2307/2709242. JSTOR 2709242. 7. de Tracy, Antoine Destutt. [1801] 1817. Les Éléments d'idéologie, (3rd ed.). p. 4, as cited in Mannheim, Karl. 1929. "The problem of 'false consciousness.'" In Ideologie und Utopie. 2nd footnote. 8. Eagleton, Terry (1991) Ideology: An Introduction, Verso, p. 2 9. Tucker, Robert C (1978). The Marx-Engels Reader, W. W. Norton & Company, p. 3. 10. Marx, MER, p. 154 11. Susan Silbey, "Ideology". Archived 2021-06-01 at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge Dictionary of Sociology. 12. Brueggemann, Walter (1 January 1998). "'Exodus' in the Plural (Amos 9:7)". In Brueggemann, Walter; Stroup, George W. (eds.). Many Voices, One God: Being Faithful in a Pluralistic World : in Honor of Shirley Guthrie. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 16, 28. ISBN 9780664257576. Retrieved 6 January 2025. [...] ideological extension of the 'onlyness' of Yahweh to include the 'onlyness' of Israel, which I shall term mono-ideology. [...] As Deuteronomy is a main force for mono-ideology in ancient Judaism, so it is possible to conclude that Calvinism has been a primary force for mono-ideology in modern Christian history because of its insistence upon God's sovereignty, which is very often allied with socioeconomic-political hegemony. 13. James, Paul, and Manfred Steger. 2010. Globalization and Culture, Vol. 4: Ideologies of Globalism Archived 2020-04-29 at the Wayback Machine. London: Sage. 14. Minar, David W (1961). "Ideology and Political Behavior". Midwest Journal of Political Science. 5 (4): 317–31. doi:10.2307/2108991. JSTOR 2108991. 15. Mullins, Willard A (1972). "On the Concept of Ideology in Political Science". American Political Science Review. 66 (2): 498–510. doi:10.2307/1957794. 16. Eagleton, Terry. 1991. Ideology: An Introduction Archived 2021-06-01 at the Wayback Machine. Verso. ISBN 0-86091-319-8. 17. "Christian Duncker" (in German). Ideologie Forschung. 2006. 18. Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1974). "I. Feuerbach: Opposition of the Materialist and Idealist Outlooks". The German Ideology. [Students Edition]. Lawrence & Wishart. pp. 64–68. ISBN 9780853152170. 19. Marx, Karl (1978a). "The German Ideology: Part I", The Marx-Engels Reader 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 20. In this discipline, there are lexical disputes over the meaning of the word "ideology" ("false consciousness" as advocated by Marx, or rather "false position" of a statement in itself is correct but irrelevant in the context in which it is produced, as in Max Weber's opinion): Buonomo, Giampiero (2005). "Eleggibilità più ampia senza i paletti del peculato d'uso? Un'occasione (perduta) per affrontare il tema delle leggi ad personam". Diritto&Giustizia Edizione Online. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24. 21. Guy Debord (1995). The Society of the Spectacle. Zone Books. 22. Hoffer, Eric. 1951. The True Believer. Harper Perennial. p. 91, et seq. 23. Bell, D. 2000. The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 393. 24. Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press. p. xi. 25. Nienhueser, Werner (October 2011). "Empirical Research on Human Resource Management as a Production of Ideology". Management Revue. 22 (4). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG: 367–393. doi:10.5771/0935-9915-2011-4-367. ISSN 0935-9915. JSTOR 41783697. S2CID 17746690. [...] current empirical research in HRM is generating ideology. 26. Ribuffo, Leo P. (January 2011). "Twenty Suggestions for Studying the Right Now that Studying the Right Is Trendy". Historically Speaking. 12 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1353/hsp.2011.0013. ISSN 1944-6438. S2CID 144367661. 27. Blattberg, Charles (2009). "Political Philosophies and Political Ideologies" (PDF). Public Affairs Quarterly. 15 (3): 193–217. doi:10.1515/9780773576636-002. ISBN 978-0-7735-7663-6. S2CID 142824378. SSRN 1755117. Archived from the original on 2021-06-01. 28. Žižek, Slavoj (2008). The Sublime Object of Ideology (2nd ed.). London: Verso. pp. xxxi, 25–27. ISBN 978-1-84467-300-1. 29. Sloterdijk, Peter (1988). Critique of Cynical Reason. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-1586-5. 30. Bouchard, Thomas J.; McGue, Matt (2003). "Genetic and environmental influences on human psychological differences". Journal of Neurobiology. 54 (1): 44–45. doi:10.1002/neu.10160. PMID 12486697. 31. Cloninger, et al. (1993). 32. Eaves, L. J.; Eysenck, H. J. (1974). "Genetics and the development of social attitudes". Nature. 249: 288–89. doi:10.1038/249288a0. 33. Alford, John, Carolyn Funk, and John R. Hibbing. 2005. "Are Political Orientations Genetically Transmitted? Archived 2017-08-09 at the Wayback Machine." American Political Science Review 99(2):153–167. 34. Hatemi, Peter K.; Medland, Sarah E.; Morley, Katherine I.; Heath, Andrew C.; Martin, Nicholas G. (2007). "The genetics of voting: An Australian twin study" (PDF). Behavior Genetics. 37 (3): 435–448. doi:10.1007/s10519-006-9138-8. 35. Hatemi, Peter K.; Hibbing, J.; Alford, J.; Martin, N.; Eaves, L. (2009). "Is there a 'party' in your genes?". Political Research Quarterly. 62 (3): 584–600. doi:10.1177/1065912908327606. SSRN 1276482. 36. Settle, Jaime E.; Dawes, Christopher T.; Fowler, James H. (2009). "The heritability of partisan attachment" (PDF). Political Research Quarterly. 62 (3): 601–13. doi:10.1177/1065912908327607. 37. Piekalkiewicz, Jaroslaw; Penn, Alfred Wayne (1995). Jaroslaw Piekalkiewicz, Alfred Wayne Penn. Politics of Ideocracy. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2297-7. Archived from the original on 2021-04-13. Retrieved 2020-08-27. 38. Brinton, Crane. 1938. "Chapter 2." The Anatomy of Revolution. 39. Brinton, Crane. 1938. "Chapter 6." The Anatomy of Revolution. 40. Brinton, Crane. 1938. "Chapter 8." The Anatomy of Revolution. 41. Fulbright, J. William. 1967. The Arrogance of Power. ch. 3–7. 42. Hoffer, Eric. 1951. The True Believer. ch. 15–17. 43. Gibson, James J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Taylor & Francis. 44. Lakoff, George (2000). Where Mathematics Comes From: How the Embodied Mind Brings Mathematics Into Being. Basic Books. 45. Madsen, Peter. "Deep Ecology". Britannica. Archived from the original on 2021-04-13. Retrieved 2021-04-10. 46. Jost, John T.; Federico, Christopher M.; Napier, Jaime L. (January 2009). "Political Ideology: Its Structure, Functions, and Elective Affinities". Annual Review of Psychology. 60 (1): 307–337. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163600. PMID 19035826. 47. Schlenker, Barry R.; Chambers, John R.; Le, Bonnie M. (April 2012). "Conservatives are happier than liberals, but why? Political ideology, personality, and life satisfaction". Journal of Research in Personality. 46 (2): 127–146. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2011.12.009. 48. Saucier, Gerard (2000). "Isms and the structure of social attitudes". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 78 (2): 366–385. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.366. PMID 10707341. 49. Greenberg, Jeff; Koole, Sander Leon; Pyszczynski, Thomas A. (2004). Handbook of experimental existential psychology. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-59385-040-1. 50. Jost, John T., Alison Ledgerwood, and Curtis D. Hardin. 2008. "Shared reality, system justification, and the relational basis of ideological beliefs." pp. 171–186 in Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2. 51. Lee S. Dimin (2011). Corporatocracy: A Revolution in Progress. p. 140. 52. Hodge, Bob. "Ideology Archived 2008-09-05 at the Wayback Machine." Semiotics Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 12 June 2020. 53. Macionis, John J. (2010). Sociology (13th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Education. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-205-74989-8. OCLC 468109511. 54. Witt, Jon (2017). SOC 2018 (5th ed.). [S.l.]: McGraw Hill. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-259-70272-3. OCLC 968304061. 55. Bunson, Matthew, ed. 1997. The Dalai Lama's Book of Wisdom. Ebury Press. p. 180. 56. Haslanger, Sally (2017). "I – Culture and Critique". Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume. 91: 149–73. doi:10.1093/arisup/akx001. hdl:1721.1/116882. 57. Arendt, Hannah. 1968. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Harcourt. p. 159. |

参考文献 1. ホンデリッチ、テッド(1995)。『オックスフォード哲学事典』。オックスフォード大学出版局。392ページ。ISBN 978-0-19-866132-0。 2. 「イデオロギー」。Lexico。2020年2月11日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。 3. Cranston, Maurice. [1999] 2014. 「イデオロギー 2020-06-09 ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ」 (改訂版). ブリタニカ国際大百科事典. 4. van Dijk, T. A. (2006). 「政治、イデオロギー、言説」 (PDF). Discourse in Society. 2011年7月8日にオリジナルからアーカイブ(PDF)。2019年1月28日に取得。 5. Vincent, Andrew (2009). Modern Political Ideologies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4443-1105-1. 2020年8月3日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2020年5月7日に取得。 6. ケネディ、エメット (1979年7月~9月)。「デストゥ・ド・トラシーからマルクスまでの『イデオロギー』」 『思想史ジャーナル』 40 (3): 353–368. doi:10.2307/2709242. JSTOR 2709242. 7. デ・トラシー、アントワーヌ・デストゥット。[1801] 1817. 『イデオロギーの要素』(第3版)。p. 4、カール・マンハイムによる引用。1929. 「『誤った意識』の問題」。『イデオロギーとユートピア』所収。第2脚注。 8. イーグルトン、テリー(1991)『イデオロギー入門』、ヴェルソ、p. 2 9. タッカー、ロバート・C(1978)。『マルクス・エンゲルス選集』、W. W. ノートン・アンド・カンパニー、p. 3。 10. マルクス、MER、p. 154 11. スーザン・シルベイ、「イデオロギー」。2021年6月1日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。ケンブリッジ社会学辞典。 12. ブルーグマン、ウォルター(1998年1月1日)。「『出エジプト記』の複数形(アモス書9:7)」。ブルーグマン、ウォルター;ストラウプ、ジョージ・ W(編)。『多様な声、唯一の神:多元的な世界における信仰の在り方:シャーリー・ガスリーへの敬意を込めて』。ケンタッキー州ルイビル:ウェストミンス ター・ジョン・ノックス出版社。pp. 16, 28. ISBN 9780664257576. 2025年1月6日取得。[...] ヤハウェの「唯一性」をイザヤの「唯一性」にまで拡張したイデオロギー的展開であり、これを単一イデオロギーと呼ぶ. [...] 申命記が古代ユダヤ教における単一イデオロギーの主要な原動力であるように、カルヴァン主義は、社会経済的・政治的ヘゲモニーと結びつくことが多い神の主 権を主張しているため、現代キリスト教史における単一イデオロギーの主要な原動力であったと結論づけることができる。 13. ジェームズ、ポール、マンフレッド・スティーガー。2010年。『グローバリゼーションと文化』第4巻:グローバリズムのイデオロギー 2020年4月29日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ。ロンドン:セージ。 14. ミナー、デビッド・W(1961年)。「イデオロギーと政治行動」。『中西部政治学ジャーナル』5 (4): 317–31。doi:10.2307/2108991. JSTOR 2108991. 15. マリンズ、ウィラード A (1972). 「政治学におけるイデオロギーの概念について」. American Political Science Review. 66 (2): 498–510. doi:10.2307/1957794. 16. イーグルトン、テリー。1991年。『イデオロギー:入門』 [2021-06-01 ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ]。ヴェルソ。ISBN 0-86091-319-8。 17. 「クリスティアン・ダンカー」(ドイツ語)。イデオロギー研究。2006年。 18. マルクス, カール; エンゲルス, フリードリヒ (1974). 「I. フェーエルバッハ: 唯物論的見解と観念論的見解の対立」. 『ドイツ・イデオロギー』. [学生版]. ローレンス・アンド・ウィシャート. pp. 64–68. ISBN 9780853152170. 19. マルクス、カール(1978a)。「ドイツ・イデオロギー:第一部」、『マルクス・エンゲルス選集』第2版。ニューヨーク:W.W.ノートン・アンド・カンパニー。 20. この分野では、「イデオロギー」という言葉の意味について語彙上の論争がある(マルクスが主張する「誤った意識」、あるいはマックス・ヴェーバーの見解の ように、その発言自体は正しいが、それが生み出された文脈では無関係である「誤った立場」)。Buonomo, Giampiero (2005). 「横領罪の制限のない、より広範な選挙権?個人向け法律の問題に取り組む(失われた)機会」『Diritto&Giustizia Edizione Online』2016年3月24日、オリジナルからアーカイブ。 21. ギー・ドゥボール(1995)。『スペクタクルの社会』Zone Books。 22. ホッファー、エリック。1951年。『真の信者』。ハーパー・ペレニアル。91頁以降。 23. ベル、D. 2000年。『イデオロギーの終焉:1950年代における政治思想の枯渇について(第2版)』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。393頁。 24. 福山、フランシス。1992. 『歴史の終わりと最後の人間』. ニューヨーク: フリープレス. p. xi. 25. ニーヌエザー, ヴェルナー (2011年10月). 「イデオロギーの産物としての人的資源管理に関する実証研究」. 『マネジメント・レヴュー』. 22 (4). ノモス出版株式会社: 367–393. doi:10.5771/0935-9915-2011-4-367. ISSN 0935-9915. JSTOR 41783697. S2CID 17746690. [...] 現在の人的資源管理における実証研究はイデオロギーを生み出している。 26. リブッフォ、レオ・P. (2011年1月). 「右派研究が流行している今、右派を研究するための20の提案」. 『歴史的に見て』. 12 (1): 2–6. doi:10.1353/hsp.2011.0013. ISSN 1944-6438. S2CID 144367661. 27. Blattberg, Charles (2009). 「政治哲学と政治イデオロギー」 (PDF). Public Affairs Quarterly. 15 (3): 193–217. doi:10.1515/9780773576636-002. ISBN 978-0-7735-7663-6。S2CID 142824378。SSRN 1755117。2021年6月1日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。 28. Žižek, Slavoj (2008). 『イデオロギーの崇高なる対象』(第2版)。ロンドン: Verso. pp. xxxi, 25–27. ISBN 978-1-84467-300-1. 29. スローターダイク, Peter (1988). 『シニカルな理性の批判』. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-1586-5. 30. ブシャール、トーマス・J.;マクグー、マット(2003)。「人間の心理的差異に対する遺伝的および環境的影響」。『神経生物学ジャーナル』。54(1): 44–45。doi:10.1002/neu.10160。PMID 12486697。 31. クロニンガー他(1993)。 32. イーブス、L. J.;アイゼンク、H. J. (1974). 「遺伝学と社会的態度の発達」. ネイチャー. 249: 288–89. doi:10.1038/249288a0. 33. アルフォード、ジョン、キャロリン・ファンク、ジョン・R・ヒビング. 2005. 「政治的志向は遺伝的に伝達されるのか?2017-08-09 ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ」 American Political Science Review 99(2):153–167. 34. Hatemi, Peter K.; Medland, Sarah E.; Morley, Katherine I.; Heath, Andrew C.; Martin, Nicholas G. (2007). 「投票の遺伝学:オーストラリアの双子研究」 (PDF). Behavior Genetics. 37 (3): 435–448. doi:10.1007/s10519-006-9138-8. 35. ハテミ、ピーター K.; ヒビング、J.; アルフォード、J.、マーティン、N.、イーブス、L. (2009). 「あなたの遺伝子には『政党』が刻まれているのか?」. 政治研究季刊. 62 (3): 584–600. doi:10.1177/1065912908327606. SSRN 1276482. 36. Settle, Jaime E.; Dawes, Christopher T.; Fowler, James H. (2009). 「党派的愛着の遺伝率」 (PDF). 政治研究季刊. 62 (3): 601–13. doi:10.1177/1065912908327607. 37. ピエカルキエヴィチ, ヤロスワフ; ペン, アルフレッド・ウェイン (1995). ヤロスワフ・ピエカルキエヴィチ, アルフレッド・ウェイン・ペン. 『イデオクラシーの政治学』. ニューヨーク州立大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-7914-2297-7. 2021年4月13日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2020年8月27日に閲覧. 38. ブリントン、クレイン。1938年。「第2章」。『革命の解剖学』。 39. ブリントン、クレイン。1938年。「第6章」。『革命の解剖学』。 40. ブリントン、クレイン。1938年。「第8章」。『革命の解剖学』。 41. フルブライト、J・ウィリアム。1967年。『権力の傲慢』。第3章~第7章。 42. ホッファー、エリック。1951年。『真の信者』。第15章~第17章。 43. ギブソン、ジェームズ・J。(1979年)。『視覚知覚への生態学的アプローチ』。テイラー&フランシス社。 44. レイコフ、ジョージ(2000)。『数学はどこから来るのか:身体化された心が数学をいかに生み出すか』。ベーシック・ブックス。 45. マドセン、ピーター。「ディープ・エコロジー」。ブリタニカ。2021年4月13日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2021年4月10日に取得。 46. ヨスト、ジョン・T.; フェデリコ, クリストファー・M.; ネイピア, ハイメ・L. (2009年1月). 「政治イデオロギー:その構造、機能、および選択的親和性」. 『心理学年次レビュー』. 60 (1): 307–337. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163600. PMID 19035826. 47. シュレンカー、バリー・R.;チェンバース、ジョン・R.;レ、ボニー・M. (2012年4月). 「保守派はリベラル派より幸福である、しかしなぜか?政治イデオロギー、人格、そして生活満足度」. Journal of Research in Personality. 46 (2): 127–146. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2011.12.009. 48. Saucier, Gerard (2000). 「イズムと社会的態度の構造」. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 78 (2): 366–385. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.366. PMID 10707341. 49. Greenberg, Jeff; Koole, Sander Leon; Pyszczynski, Thomas A. (2004). 『実験的実存心理学ハンドブック』. ニューヨーク: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-59385-040-1. 50. ヨスト, ジョン・T., アリソン・レジャーウッド, カーティス・D・ハーディン. 2008. 「共有現実、システム正当化、およびイデオロギー的信念の関係的基盤」. pp. 171–186 in 『社会心理学・人格心理学コンパス 2』. 51. リー・S・ディミン(2011)。『コーポラトクラシー:進行中の革命』。140頁。 52. ホッジ、ボブ。「イデオロギー Archived 2008-09-05 at the Wayback Machine」。『記号学百科事典オンライン』。2020年6月12日閲覧。 53. マシオニス、ジョン・J.(2010)。『社会学』(第13版)。アッパーサドルリバー、ニュージャージー州:ピアソン・エデュケーション。p. 257。ISBN 978-0-205-74989-8。OCLC 468109511。 54. ウィット、ジョン(2017)。『SOC 2018』(第5版)。[発行地不明]:McGraw Hill。65頁。ISBN 978-1-259-70272-3。OCLC 968304061。 55. バンソン、マシュー編(1997)。『ダライ・ラマの知恵の書』。エバリー・プレス。180頁。 56. ハスランガー、サリー(2017)。「I – 文化と批判」。『アリストテレス学会補遺』91: 149–73頁。doi:10.1093/arisup/akx001. hdl:1721.1/116882. 57. アレント, ハナ. 1968. 『全体主義の起源』. ハーコート. p. 159. |

| Bibliography Althusser, Louis. [1970] 1971. "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses." In Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. Monthly Review Press ISBN 1-58367-039-4. Belloni, Claudio. 2013. Per la critica dell’ideologia: Filosofia e storia in Marx. Milan: Mimesis. Debord, Guy. 1967 The Society of the Spectacle. Bureau of Public Secrets 2014 (Annotated Edition) Duncker, Christian 2006. Kritische Reflexionen Des Ideologiebegriffes. ISBN 1-903343-88-7. —, ed. 2008. "Ideologiekritik Aktuell." Ideologies Today 1. London. ISBN 978-1-84790-015-9. Eagleton, Terry. 1991. Ideology: An Introduction. Verso. ISBN 0-86091-319-8. Ellul, Jacques. [1965] 1973. Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes, translated by K. Kellen and J. Lerner. New York: Random House. Freeden, Michael. 1996. Ideologies and Political Theory: A Conceptual Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829414-6 Feuer, Lewis S. 2010. Ideology and Ideologists. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers. Gries, Peter Hays. 2014. The Politics of American Foreign Policy: How Ideology Divides Liberals and Conservatives over Foreign Affairs. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Haas, Mark L. 2005. The Ideological Origins of Great Power Politics, 1789–1989. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-7407-8. Hawkes, David. 2003. Ideology (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29012-0. James, Paul, and Manfred Steger. 2010. Globalization and Culture, Vol. 4: Ideologies of Globalism. London: Sage. Lukács, Georg. [1967] 1919–1923. History and Class Consciousness, translated by R. Livingstone. Merlin Press. Malesevic, Sinisa, and Iain Mackenzie, eds. Ideology after Poststructuralism. London: Pluto Press. Mannheim, Karl. 1936. Ideology and Utopia. Routledge. Marx, Karl. [1845–46] 1932. The German Ideology. Minogue, Kenneth. 1985. Alien Powers: The Pure Theory of Ideology. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-01860-6. Minar, David W (1961). "Ideology and Political Behavior". Midwest Journal of Political Science. 5 (4): 317–331. doi:10.2307/2108991. JSTOR 2108991. Mullins, Willard A (1972). "On the Concept of Ideology in Political Science". American Political Science Review. 66 (2): 498–510. doi:10.2307/1957794. Ostrowski, Marius S. 2022. Ideology. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 978-1509540730. Owen, John. 2011. The Clash of Ideas in World Politics: Transnational Networks, States, and Regime Change, 1510–2010. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-14239-4. Pinker, Steven. 2002. The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 0-670-03151-8. Sorce Keller, Marcello (2007). "Why is Music so Ideological, Why Do Totalitarian States Take It So Seriously: A Personal View from History, and the Social Sciences". Journal of Musicological Research. 26 (2–3): 91–122. Steger, Manfred B.; James, Paul (2013). "Levels of Subjective Globalization: Ideologies, Imaginaries, Ontologies". Perspectives on Global Development and Technology. 12 (1–2): 17–40. doi:10.1163/15691497-12341240. Verschueren, Jef. 2012. Ideology in Language Use: Pragmatic Guidelines for Empirical Research. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-69590-0 |

参考文献 アルチュセール、ルイ。[1970] 1971. 「イデオロギーとイデオロギー的国家装置」『レーニンと哲学、その他の論文』所収。Monthly Review Press ISBN 1-58367-039-4. ベローニ、クラウディオ。2013. 『イデオロギー批判のために:マルクスにおける哲学と歴史』. ミラノ:ミメーシス. ドボルド、ギー. 1967年 『スペクタクルの社会』. ビューロー・オブ・パブリック・シークレッツ 2014年 (注釈版) ダンカー、クリスティアン 2006年. 『イデオロギー概念の批判的考察』. ISBN 1-903343-88-7. —編. 2008. 「現代におけるイデオロギー批判」『現代のイデオロギー』第1号. ロンドン. ISBN 978-1-84790-015-9. イーグルトン, テリー. 1991. 『イデオロギー入門』ヴェルソ. ISBN 0-86091-319-8. エリュール、ジャック。[1965] 1973. 『プロパガンダ:人間の態度の形成』K. ケレン、J. ラーナー訳。ニューヨーク:ランダムハウス。 フリーデン、マイケル。1996. 『イデオロギーと政治理論:概念的アプローチ』。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-829414-6 フォイアー、ルイス・S. 2010. 『イデオロギーとイデオロギー家たち』. ニュージャージー州ピスカタウェイ: トランザクション出版社. グリーズ、ピーター・ヘイズ. 2014. 『アメリカ外交政策の政治学:外交問題におけるリベラルと保守のイデオロギー的分断』. スタンフォード: スタンフォード大学出版局. ハース、マーク・L. 2005. 大国の政治のイデオロギー的起源、1789-1989。コーネル大学出版局。ISBN 0-8014-7407-8。 ホークス、デイヴィッド。2003年。イデオロギー(第2版)。ラウトレッジ。ISBN 0-415-29012-0。 ジェームズ、ポール、マンフレッド・スティーガー。2010年。グローバル化と文化、第 4 巻:グローバリズムのイデオロギー。ロンドン:セージ。 ルカーチ、ゲオルグ。[1967] 1919–1923。歴史と階級意識、R. リヴィングストン訳。マーリン・プレス。 マレセヴィッチ、シニサ、およびイアン・マッケンジー、編。ポスト構造主義後のイデオロギー。ロンドン:プルート・プレス。 マンハイム、カール。1936年。イデオロギーとユートピア。ラウトレッジ。 マルクス、カール。[1845–46] 1932年。ドイツイデオロギー。 ミノーグ、ケネス。1985年。異質な力:イデオロギーの純粋理論。パルグレイブ・マクミラン。ISBN 0-312-01860-6。 ミナール、デイヴィッド・W(1961)。「イデオロギーと政治行動」。『中西部政治学ジャーナル』。5(4): 317–331。doi:10.2307/2108991。JSTOR 2108991。 マリンズ、ウィラード・A(1972)。「政治学におけるイデオロギー概念について」『アメリカ政治学レビュー』66巻2号: 498–510頁. doi:10.2307/1957794. オストロウスキー, マリウス・S. 2022. 『イデオロギー』ケンブリッジ: ポリティ. ISBN 978-1509540730. オーウェン、ジョン。2011年。『世界政治における思想の衝突:1510年から2010年までの越境ネットワーク、国家、体制変革』。プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 0-691-14239-4。 ピンカー、スティーブン。2002年。『白紙の状態:人間性の現代的否定』。ニューヨーク:ペンギン・グループ。ISBN 0-670-03151-8。 ソース ケラー、マルチェロ (2007)。「なぜ音楽はそれほどイデオロギー的であり、なぜ全体主義国家はそれをそれほど真剣に受け止めるのか:歴史と社会科学からの個人的見解」。音楽学研究ジャーナル。26 (2–3): 91–122。 スティーガー、マンフレッド B.、ジェームズ、ポール (2013). 「主観的グローバル化のレベル:イデオロギー、想像、存在論」. グローバル開発とテクノロジーに関する視点. 12 (1–2): 17–40. doi:10.1163/15691497-12341240. Verschueren, Jef. 2012. 『言語使用におけるイデオロギー:実証研究のための実用的なガイドライン』ケンブリッジ大学出版局 ISBN 978-1-107-69590-0 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ideology |

★イデオロギー批判(critique of ideology)

| The critique of

ideology

is a concept used in critical theory, literary studies, and cultural

studies. It focuses on analyzing the ideology found in cultural texts,

whether those texts be works of popular culture or high culture,

philosophy or TV advertisements. These ideologies can be expressed

implicitly or explicitly. The focus is on analyzing and demonstrating

the underlying ideological assumptions of the texts and then

criticizing the attitude of these works. An important part of ideology

critique has to do with “looking suspiciously at works of art and

debunking them as tools of oppression”.[1] |

イデオロギー批判とは、批判理論、文学研究、文化研究で用いられる概念

である。大衆文化やハイカルチャー、哲学、テレビ広告など、文化的なテキストに見られるイデオロギーの分析に焦点を当てている。これらのイデオロギーは、

暗黙的または明示的に表現される。テキストの根底にあるイデオロギー的前提を分析し、明示し、その上でこれらの作品の姿勢を批判することに重点が置かれて

いる。イデオロギー批判の重要な部分は、「芸術作品を疑いの目で見て、抑圧の道具として暴く」ことである。[1] |

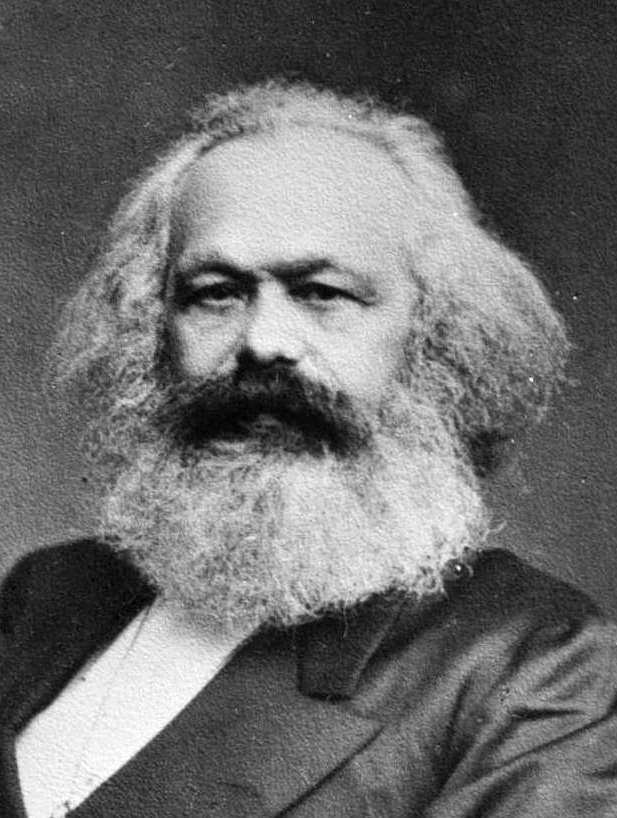

| Terminology The critique of ideology has a particular understanding of "ideology," distinct from political perspective or opinions. This specialized meaning comes from the term's root in the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. For the critique of ideology, ideology is a form of false consciousness. Ideology is a lie about the real state of affairs in the world. In Raymond Williams's words, it is about "ideology as illusion, false consciousness, unreality, upside-down reality".[2] German philosopher Markus Gabriel defines ideology as "any attempt to objectify the human mind [...] to eradicate the historical dimensions of it, to turn something which is historically contingent, produced by humans, into some kind of natural necessity."[3] In the work of Marx and Engels, ideology was the false belief that capitalist society was a product of human nature, when in reality it had been imposed, often violently, in particular circumstances, in particular places, at particular historical periods. The term "critique" is also employed in a special manner. Rather than a synonym for criticism, "critique" comes from Immanuel Kant's usage of the term, which meant an investigation into the structures under which we live, think, and act. A critic of ideology, in this sense, is not merely one who expresses disagreement or disapproval, but who is able to bring to light the belief's true conditions of possible existence. Because conditions are constantly changing, showing a belief's existence to be built on mere conditions implicitly shows that they are not eternal, natural, or organic, but are instead historical, contingent, and therefore changeable. Frankfurt School philosopher Max Horkheimer termed a theory critical if it aims "to liberate human beings from the circumstances that enslave them."[4]  The critique of ideology is rooted in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels's writings. The above is an 1875 portrait of Marx. |

用語 イデオロギー批判は、「イデオロギー」を政治的な視点や意見とは異なるものとして特別に理解している。この専門的な意味は、カール・マルクスとフリードリ ヒ・エンゲルスの著作における用語の語源に由来する。イデオロギー批判において、イデオロギーは偽りの意識の一形態である。イデオロギーは、世界の現実の 状態に関する嘘である。レイモンド・ウィリアムズの言葉を借りれば、それは「幻想としてのイデオロギー、偽りの意識、非現実、逆転した現実」である。 [2] ドイツの哲学者、マルクス・ガブリエルはイデオロギーを「人間の心を客観化しようとするあらゆる試み、すなわち、その歴史的次元を根絶し、歴史的に偶発的 で人間によって作り出されたものを、ある種の自然的な必然性へと変える試み」と定義している。[3] マルクスとエンゲルスの著作では、イデオロギーとは資本主義社会が人間の本性の産物であるという誤った信念であったが、実際には特定の状況下、特定の場 所、特定の歴史的時代において、しばしば暴力的に押し付けられたものであった。 「批判」という用語もまた特別な意味で用いられている。「批判」は、単に「批判」と同義語というよりも、イマニュエル・カントの用法に由来するもので、私 たちが生き、考え、行動する構造を調査することを意味する。この意味において、イデオロギーの批判者は、単に反対や不賛成を表明するだけでなく、信念の存 在しうる真の条件を明らかにすることができる人である。状況は常に変化しているため、信念の存在が単なる状況の上に成り立っていることを示すことは、その 信念が永遠でも自然でも有機的でもないことを暗に示し、歴史的で偶発的であり、したがって変化し得るものであることを示す。フランクフルト学派の哲学者 マックス・ホルクハイマーは、「人間を奴隷化する状況から人間を解放する」ことを目的とする理論を批判理論と呼んだ。[4]  イデオロギー批判の根源は、カール・マルクスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルスの著作にある。 上の写真は、1875年のマルクスの肖像画である。 |

| After Marx See also: Frankfurt School, Critical theory, and Marxism There is no universally agreed upon definition or model of ideology. The classical and orthodox Marxist definition of ideology is false belief, emergent from the oppressive society which educates its citizens to be obedient workers. The failures of the 1918 revolutions, the rise of Stalinism and fascism, and the explosion of another world war saw a new focus on the importance of ideology among Marxists. Rather than a mere lie of the political-economic establishment, ideology was recognized to be a force in its own right. Wilhelm Reich and later the Frankfurt School complemented Marx's theory of society with Freud's theory of the subject, departing from orthodox Marxism and the Leninist traditions, and setting the foundations of what later came to be called "critical theory." Reich saw the rise of fascism as an expression of a long-repressed sexuality. Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno wrote in his essay "The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception" how the mass entertainment blunts the possibilities for liberatory action by creating and satisfying false needs. Interested parties like to explain the culture industry in technological terms. Its millions of participants, they argue, demand reproduction processes which inevitably lead to the use of standard products to meet the same needs at countless locations. The technical antithesis between few production centers and widely dispersed reception necessitates organization and planning by those in control. The standardized forms, it is claimed, were originally derived from the needs of the consumers: that is why they are accepted with so little resistance. In reality, a cycle of manipulation and retroactive need is unifying the system ever more tightly.[5] Adorno identifies supply and demand reasoning as ideological. It is not merely a false belief: it is a false worldview or philosophy which enables the maintenance of the contingent, historical status quo while appearing to be objective and scientific. A major theme of the Frankfurt School is that those modes of thinking which, at first, are liberatory, may become ideological as time goes on.[5] |

マルクス以降 参照:フランクフルト学派、批判理論、マルクス主義 イデオロギーの定義やモデルについて、世界的に合意されたものは存在しない。古典的かつ正統派のマルクス主義におけるイデオロギーの定義は、抑圧的な社会 から生じる誤った信念であり、市民を従順な労働者として教育するものである。1918年の革命の失敗、スターリニズムとファシズムの台頭、そして新たな世 界大戦の勃発により、マルクス主義者たちの間でイデオロギーの重要性が改めて注目されるようになった。イデオロギーは、政治経済体制の単なる嘘ではなく、 それ自体が力を持つものとして認識されるようになった。ヴィルヘルム・ライヒやその後のフランクフルト学派は、正統派マルクス主義やレーニン主義の伝統か ら離れ、フロイトの自我理論をマルクスの社会理論に補完し、後に「批判理論」と呼ばれるようになるものの基礎を築いた。 ライヒは、ファシズムの台頭を長い間抑圧されてきた性的衝動の表れと捉えていた。フランクフルト学派の哲学者テオドール・アドルノは、エッセイ「文化産 業:大衆欺瞞としての啓蒙」の中で、偽りのニーズを生み出し、それを満たすことで、大衆娯楽が解放的行動の可能性を鈍らせる仕組みについて書いている。 文化産業を技術的な観点から説明しようとする人々もいる。彼らは、何百万人もの参加者が、同じニーズを無数の場所で満たすために、標準的な製品の使用を必 然的に導く再生プロセスを要求していると主張する。少数の生産拠点と広範囲に分散した受信者との間の技術的な対立は、管理者の組織化と計画を必要とする。 標準化された形態は、もともと消費者のニーズから派生したものであると主張されている。それが抵抗なく受け入れられる理由である。実際には、操作と事後的 なニーズのサイクルがシステムをますます強固に結びつけている。[5] アドルノは、需要と供給の論理をイデオロギー的であると指摘している。それは単なる誤った信念ではなく、客観的かつ科学的であるかのように見せかけなが ら、偶発的な歴史的現状を維持することを可能にする誤った世界観や哲学である。フランクフルト学派の主要なテーマは、当初は解放的であった思考様式が、時 が経つにつれてイデオロギー的になる可能性があるということである。[5] |

| Binary opposition Immanent critique Interpellation "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses" Louis Althusser The Sublime Object of Ideology Slavoj Žižek Culture industry Cultural hegemony Antonio Gramsci |

二項対立 内在的批判 呼びかけ 「イデオロギーとイデオロギー的国家装置」 ルイ・アルチュセール イデオロギーの崇高な対象 スラヴォイ・ジジェク 文化産業 文化的ヘゲモニー アントニオ・グラムシ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critique_of_ideology |

関連用語集&リンク集

余滴

【冗長語法というイデオロギーあるいはイデオロギーの逆説】

「つまらないイデオロギーを超える」という表現に出会う——「つまらなくないイデオロギーってあるの?」と自問する、それはイデオロギーなどではないと言 えばいいのに。ここでの僕たちが得る結論はただひとつ:「冗長語法はイデオロギー的表現のひとつである」。あるいは「〜を超える」というのは、敵を非難し エゴセントリックな主張する彼らの思考(=つまりイデオロギーの)扇動家の常套句なのだ。そして、こういう回りくどいということもイデオロギーの特徴なの である。

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099