霊長類学の文化政治バイアス

Socio-Cultural Bias of our

Primatological Sciences

霊長類学の文化政治バイアス

Socio-Cultural Bias of our

Primatological Sciences

★ダナ・ハラウェイ『猿と女とサイボーグ : 自然の再発明(Simians, cyborgs, and women : the reinvention of nature)』高橋さきの訳、青土社、2017年:「霊長類学、免疫学、生態学など、生物科学が情報科学と接合される—。高度資本主義と先端的科学知が 構築しつづける“無垢なる自然”を解読=解体し、フェミニズムの囲い込みを突破する闘争マニフェスト。」

第1部 生産・再生産システムとしての自然

1. 動物社会学とボディポリティックの自然経済:優位性の政治生理学

2. 過去こそが、論争の場である:霊長類の行動研究における人間の本性と、生産と再生産の理論

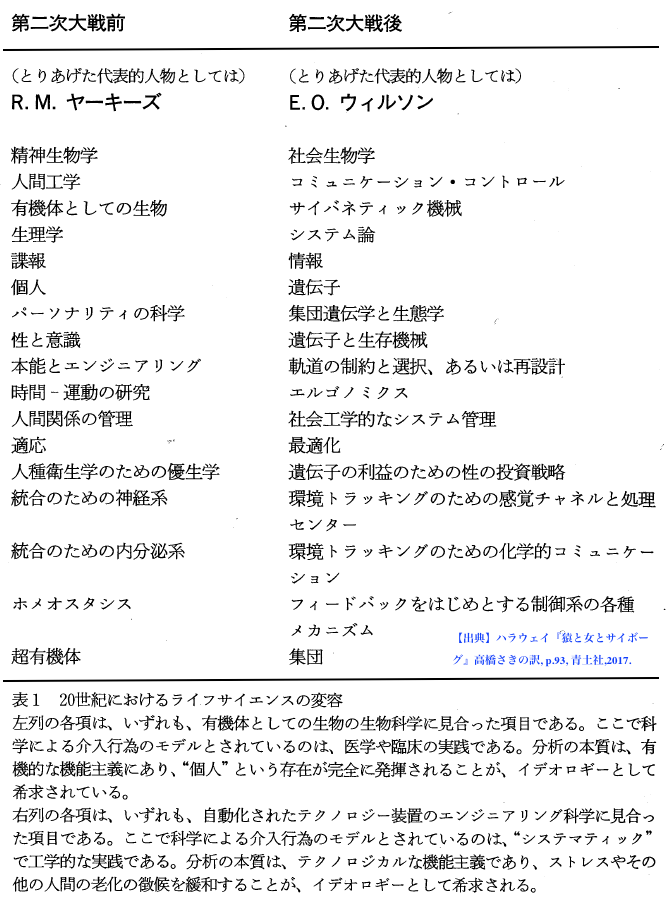

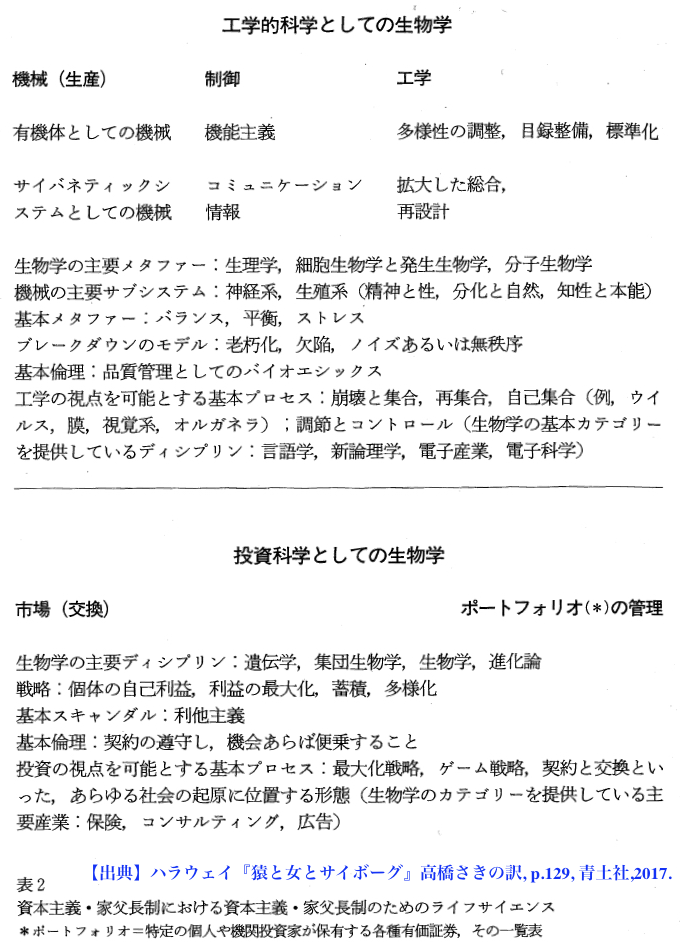

3. 生物学というエンタプライズ:人間工学から社会生物学に至る性、意識、利潤

第2部 論争をはらんだ読み:語りの本質と語りとしての自然

4. はじめにことばありき:生物学理論のはじまり

5. 霊長類の本質をめざした争い:フィールドに出た男性=狩猟者の娘たちの1960〜1980

6. ブチ・エメチェタを読む:女性学における「女性の経験」への挑戦)

第3部 場違いではあるものの領有されることもない他者たる人々にとっての、それぞれに異なるポリティクス

7. マルクス主義事典のための「ジェンダー」:あることばをめぐる性のポリティクス

8. サイボーグ宣言:二〇世紀後半の科学、技術、社会主義フェミニズム

9. 状況に置かれた知:フェミニズムにおける科学という問題と、部分的視角が有する特権

10. ポスト近代の身体/生体のバイオポリティクス:免疫系の言説における自己の構成)

| 第1部 生産・再生産システムとしての自然 |

|

| 1. 動物社会学とボディポリティックの自然経済:優位性の政治生理学 |

|

| 2. 過去こそが、論争の場である:霊長類の行動研究における人間の本性と、生産と再生産の理論 |

******* |

| 3. 生物学というエンタプライズ:人間工学から社会生物学に至る性、意識、利潤 |

*******  ************  |

| 第2部 論争をはらんだ読み:語りの本質と語りとしての自然 |

|

| 4. はじめにことばありき:生物学理論のはじまり |

|

| 5. 霊長類の本質をめざした争い:フィールドに出た男性=狩猟者の娘たちの1960〜1980 |

|

| 6. ブチ・エメチェタを読む:女性学における「女性の経験」への挑戦) |

|

| 第3部 場違いではあるものの領有されることもない他者たる人々にとっての、それぞれに異なるポリティクス |

|

| 7. マルクス主義事典のための「ジェンダー」:あることばをめぐる性のポリティクス |

|

| 8. サイボーグ宣言:二〇世紀後半の科学、技術、社会主義フェミニズム |

|

| 9. 状況に置かれた知:フェミニズムにおける科学という問題と、部分的視角が有する特権 |

|

| 10. ポスト近代の身体/生体のバイオポリティクス:免疫系の言説における自己の構成) |

|

| Donna J. Haraway

is an American Professor Emerita in the History of Consciousness

Department and Feminist Studies Department at the University of

California, Santa Cruz, and a prominent scholar in the field of science

and technology studies. She has also contributed to the intersection of

information technology and feminist theory, and is a leading scholar in

contemporary ecofeminism. Her work criticizes anthropocentrism,

emphasizes the self-organizing powers of nonhuman processes, and

explores dissonant relations between those processes and cultural

practices, rethinking sources of ethics.[2] Haraway has taught women's studies and the history of science at the University of Hawaii (1971-1974) and Johns Hopkins University (1974-1980).[3] She began working as a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1980 where she became the first tenured professor in feminist theory in the United States.[4] Haraway's works have contributed to the study of both human–machine and human–animal relations. Her works have sparked debate in primatology, philosophy, and developmental biology.[5] Haraway participated in a collaborative exchange with the feminist theorist Lynn Randolph from 1990 to 1996. Their engagement with specific ideas relating to feminism, technoscience, political consciousness, and other social issues, formed the images and narrative of Haraway's book Modest_Witness for which she received the Society for Social Studies of Science's (4S) Ludwik Fleck Prize in 1999.[6][7] She was also awarded the Section on Science, Knowledge and Technology's Robert K. Merton award in 1992 for her work Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science.[8] |

ドナ・J・ハラウェイは、カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校の意識史

部門およびフェミニスト研究部門の名誉教授で、科学技術研究の分野で著名なアメリカ人学者である。また、情報技術とフェミニズム理論の交差点に貢献し、現

代のエコフェミニズムの代表的な研究者でもある。人間中心主義を批判し、非人間的プロセスの自己組織化能力を強調し、それらのプロセスと文化的実践の間の

不協和な関係を探求し、倫理の源を再考している[2]。 ハワイ大学(1971-1974)、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学(1974-1980)で女性学と科学史を教え、1980年からカリフォルニア大学サンタク ルーズ校の教授となり、アメリカで最初のフェミニズム理論の終身教授となった[4]。1990年から1996年まで、フェミニスト理論家のリン・ランドル フとの共同研究に参加。フェミニズム、科学技術、政治意識、その他の社会問題に関連する具体的なアイデアへの取り組みが、ハラウェイの著書 『Modest_Witness』のイメージと物語を形成し、1999年に科学社会研究協会(4S)のルードヴィク・フレック賞を受賞した[6][7]。 また、1992年に科学、知識、技術に関するセクションから『Primate Visions』でRobert K. Merton賞を授与されている。現代科学の世界におけるジェンダー、人種、自然[8]。 |

| Biography Early life Donna Jeanne Haraway was born on September 6, 1944, in Denver, Colorado. Haraway's father, Frank O. Haraway, was a sportswriter for The Denver Post and her mother Dorothy Mcguire Haraway, who came from an Irish Catholic background, died from a heart attack when Haraway was 16 years old.[9] Although she is no longer religious, Catholicism had a strong influence on her as she was taught by nuns in her early life. The impression of the Eucharist influenced her linkage of the figurative and the material.[10] Haraway attended high school at St. Mary's Academy in Cherry Hills Village, Colorado.[11] Education Haraway majored in Zoology, with minors in philosophy and English at the Colorado College, on the full-tuition Boettcher Scholarship.[12] After college, Haraway moved to Paris and studied evolutionary philosophy and theology at the Fondation Teilhard de Chardin on a Fulbright scholarship.[13] She completed her Ph.D. in biology at Yale in 1972 writing a dissertation about the use of metaphor in shaping experiments in experimental biology titled The Search for Organizing Relations: An Organismic Paradigm in Twentieth-Century Developmental Biology,[14] later edited into a book and published under the title Crystals, Fabrics, and Fields: Metaphors of Organicism in Twentieth-Century Developmental Biology.[15] |

略歴 生い立ち 1944年9月6日、コロラド州デンバーに生まれる。父フランク・O・ハラウェイは『デンバー・ポスト』紙のスポーツライター、母ドロシー・マクガイア・ ハラウェイはアイルランド系カトリックの出身で、ハラウェイが16歳の時に心臓発作で亡くなっている[9]。聖体拝領の印象は、彼女の具象と物質の結びつ きに影響を与えた[10]。 教育 コロラド大学で動物学を専攻し、ベッチャー奨学金を得て哲学と英語を副専攻した[12]。 大学卒業後、パリに移り、フルブライト奨学金を得てテイヤール・ド・シャルダン財団で進化哲学と神学を学んだ[13] 1972年にイェール大学で博士号(生物)を取得、実験生物学における実験の形成におけるメタファーの使用について論文「The Search for Organizing Relations」を執筆。後に『Crystals, Fabrics, and Fields』というタイトルで書籍化されている。20世紀の発生生物学における有機主義のメタファー[15]。 |

| Later work Haraway was the recipient of several scholarships. Alluding to the Cold War and post-war American hegemony, she said of these, "...people like me became national resources in the national science efforts. So, there was money available for educating even Irish Catholic girls' brains."[16] In 1999, Haraway received the Society for Social Studies of Science's (4S) Ludwik Fleck Prize. In September 2000, Haraway was awarded the Society for Social Studies of Science's highest honor, the J. D. Bernal Award, for her "distinguished contributions" to the field.[17] Haraway's most famous essay was published in 1985: "A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the 1980s"[18] and was characterized as "an effort to build an ironic political myth faithful to feminism, socialism, and materialism". In Haraway's thesis, "Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective" (1988), she means to expose the myth of scientific objectivity. Haraway defined the term "situated knowledges" as a means of understanding that all knowledge comes from positional perspectives.[19] Our positionality inherently determines what it is possible to know about an object of interest.[19] Comprehending situated knowledge "allows us to become answerable for what we learn how to see".[20] Without this accountability, the implicit biases and societal stigmas of the researcher's community are twisted into ground truth from which to build assumptions and hypothesis.[19] Haraway's ideas in "Situated Knowledges" were heavily influenced by conversations with Nancy Hartsock and other feminist philosophers and activists.[21] Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science, published in 1989 (Routledge), focuses on primate research and primatology: "My hope has been that the always oblique and sometimes perverse focusing would facilitate revisions of fundamental, persistent western narratives about difference, especially racial and sexual difference; about reproduction, especially in terms of the multiplicities of generators and offspring; and about survival, especially about survival imagined in the boundary conditions of both the origins and ends of history, as told within western traditions of that complex genre".[22] Currently, Donna Haraway is an American Professor Emerita in the History of Consciousness Department and Feminist Studies Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, United States.[23] She lives North of San Francisco with her partner Rusten Hogness.[24] In an interview with Sarah Franklin in 2017, Haraway addresses her intent to incorporate collective thinking and all perspectives: "It isn't that systematic, but there is a little list. I notice if I have cited nothing but white people, if I have erased indigenous people, if I forget non-human beings, etc. I notice on purpose. I notice if I haven't paid the slightest bit of attention ... You know, I run through some old-fashioned, klutzy categories. Race, sex, class, region, sexuality, gender, species. I pay attention. I know how fraught all those categories are, but I think those categories still do important work. I have developed, kind of, an alert system, an internalized alert system."[25] |

その後の仕事 ハラウェイは、いくつかの奨学金を得ている。冷戦と戦後のアメリカの覇権主義を暗示するように、彼女はこれらについて、「...私のような人間は、国家的 な科学の取り組みにおいて国家的資源となった。つまり、アイルランドのカトリックの女の子の頭脳まで教育できるお金があった」[16] 1999年、ハラウェイは科学社会研究会(4S)のルドウィック・フレック賞を受賞。2000年9月には、科学社会研究学会への「卓越した貢献」に対し て、同学会の最高栄誉であるJ・D・バーナル賞を受賞している[17]。 ハラウェイの論文では、「Situated Knowledges: フェミニズムにおける科学問題と部分的視点の特権」(1988)において、彼女は科学的客観性の神話を暴露することを意味する。ハラウェイは、すべての知 識は位置的な視点から来るということを理解するための手段として「位置的知識」という言葉を定義した[19]。私たちの位置性は、関心のある対象について 知ることが可能であることを本質的に決定する[19]。 [この説明責任がなければ、研究者のコミュニティの暗黙の偏見や社会的なスティグマは、仮定や仮説を構築するための基本的な真実にねじ曲げられる [19]。 Primate Visions: 1989年に出版された『霊長類のヴィジョン:現代科学の世界におけるジェンダー、人種、自然』(ラウトレッジ社)は、霊長類研究および霊長類学に焦点を 当てたものである。「私の望みは、常に斜に構え、時に倒錯的な焦点を当てることで、違い、特に人種や性の違い、生殖、特に世代や子孫の多重性、生存、特に 歴史の起源と終焉の両方の境界条件において想像される生存について、西洋の複雑なジャンルの伝統の中で語られてきた基本的で根強い物語の修正を促すこと だった」[22]......。 [22] 現在、ドナ・ハラウェイはアメリカ合衆国のカリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校の意識史学部とフェミニスト研究部の名誉教授である[23] 彼女はパートナーのラステン・ホグネスとサンフランシスコの北に住んでいる[24] 。2017年のサラ・フランクリンとのインタビューで、ハラウェイが集団的思考とあらゆる視点を取り入れる意図について言及している。"それほど体系的な ものではないが、ちょっとしたリストがある。白人ばかりを引用していないか、先住民を消していないか、人間以外の存在を忘れていないか、などに気がつくの だ。意図的に気づく。ほんの少しも注意を払ってないことに気づく.私は、昔ながらの不器用なカテゴリーに目を通すんだ。人種、性別、階級、地域、セクシュ アリティ、ジェンダー、種。私は注意を払う。しかし、これらのカテゴリーが重要な働きをしていることは確かである。私は、ある種の、警戒システム、内面化 された警戒システムを開発した」[25]。 |

| Major themes "A Cyborg Manifesto" In 1985, Haraway published the essay "Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the 1980s" in Socialist Review. Although most of Haraway's earlier work was focused on emphasizing the masculine bias in scientific culture, she has also contributed greatly to the feminist narratives of the twentieth century. For Haraway, the Manifesto offered a response to the rising conservatism during the 1980s in the United States at a critical juncture at which feminists, to have any real-world significance, had to acknowledge their situatedness within what she terms the "informatics of domination."[26][27] Women were no longer on the outside along a hierarchy of privileged binaries but rather deeply imbued, exploited by and complicit within networked hegemony, and had to form their politics as such. Cyborg feminism In her updated essay "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century", in her book Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (1991), Haraway uses the cyborg metaphor to explain how fundamental contradictions in feminist theory and identity should be conjoined, rather than resolved, similar to the fusion of machine and organism in cyborgs.[26][28][29] The manifesto is also an important feminist critique of capitalism by revealing how men have exploited women's reproduction labor, providing a barrier for women to reach full equality in the labor market.[30] Primate Visions Haraway also writes about the history of science and biology. In Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science (1990), she focused on the metaphors and narratives that direct the science of primatology. She asserted that there is a tendency to masculinize the stories about "reproductive competition and sex between aggressive males and receptive females [that] facilitate some and preclude other types of conclusions".[31] She contended that female primatologists focus on different observations that require more communication and basic survival activities, offering very different perspectives of the origins of nature and culture than the currently accepted ones. Drawing on examples of Western narratives and ideologies of gender, race and class, Haraway questioned the most fundamental constructions of scientific human nature stories based on primates. In Primate Visions, she wrote: My hope has been that the always oblique and sometimes perverse focusing would facilitate revisions of fundamental, persistent western narratives about difference, especially racial and sexual difference; about reproduction, especially in terms of the multiplicities of generators and offspring; and about survival, especially about survival imagined in the boundary conditions of both the origins and ends of history, as told within western traditions of that complex genre.[32] Haraway's aim for science is "to reveal the limits and impossibility of its 'objectivity' and to consider some recent revisions offered by feminist primatologists".[33] Haraway presents an alternative perspective to the accepted ideologies that continue to shape the way scientific human nature stories are created.[34] Haraway urges feminists to be more involved in the world of technoscience and to be credited for that involvement. In a 1997 publication, she remarked: I want feminists to be enrolled more tightly in the meaning-making processes of technoscientific world-building. I also want feminist—activists, cultural producers, scientists, engineers, and scholars (all overlapping categories) — to be recognized for the articulations and enrollment we have been making all along within technoscience, in spite of the ignorance of most "mainstream" scholars in their characterization (or lack of characterizations) of feminism in relation to both technoscientific practice and technoscience studies.[35] Make Kin not Population: Reconceiving Generations Haraway created a panel called 'Make Kin not Babies' in 2015 with five other feminist thinkers named: Alondra Nelson, Kim TallBear, Chia-Ling Wu, Michelle Murphy, and Adele Clarke. The panel's emphasis is on moving human numbers down while paying attention to factors, such as the environment, race, and class. A key phrase of hers is "Making babies is different than giving babies a good childhood."[25] This led to the inspiration for the publication of Making Kin not Population: Reconceiving Generations, by Donna Haraway and Adele Clarke, two of the panelist members. The book addresses the growing concern of the increase in the human population and its consequences on our environment. The book consists of essays from the two authors, incorporating both environmental and reproductive justice along with addressing the functions of family and kinship relationships.[36] Speculative fabulation Speculative fabulation is a concept that is included in many of Haraway's works. It includes all of the wild facts that will not hold still, and it indicates a mode of creativity and the story of the Anthropocene. Haraway stresses how this does not mean it is not a fact. In Staying with the Trouble, she defines speculative fabulation as "a mode of attention, theory of history, and a practice of worlding," and she finds it an integral part of scholarly writing and everyday life.[37] In Haraway's work she addresses a feminist speculative fabulation and its focusing on making kin instead of babies to ensure the good childhood of all children while controlling the population.[25] Making Kin not Population: Reconceiving Generations highlights practices and proposals to implement this theory in society.[36] The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness The companion Species Manifesto is to be read as a “personal document”. This work was written to tell the story of cohabitation, coevolution and embodied cross-species sociality.[38] Haraway argues that humans ‘companion’ relationship with dogs can show us the importance of recognizing differences and ‘how to engage with significant otherness'.[39] The link between humans and animals like dogs can show people how to interact with other humans and nonhumans. Haraway believes that we should be using the term "companion species" instead of "companion animals" because of the relationships we can learn through them.[40] |

主なテーマ "サイボーグ宣言" 1985年、ハラウェイは『社会主義評論』誌に小論「サイボーグ宣言:1980年代の科学・技術・社会主義フェミニズム」を発表した。それ以前のハラウェ イの研究は、科学文化における男性的偏向を強調することに重点が置かれていたが、20世紀のフェミニストの物語にも大きく貢献している。ハラウェイにとっ て、マニフェストは1980年代のアメリカにおける保守主義の高まりに対応するものであり、フェミニストが現実的な意義を持つためには、彼女が「支配の情 報学」と呼ぶものの中に自分たちが位置していることを認めなければならない重要な岐路にあった[26][27]。女性はもはや特権的二元性の階層に沿って 外にいるのではなく、深く染み込み、利用され、ネットワーク上のヘゲモニーの中で共犯であり、そのように政治を形成しなければならなかったのである。 サイボーグ・フェミニズム サイボーグ・マニフェスト」(A Cyborg Manifesto: サイボーグ・フェミニズムは、その著書『サイミアン、サイボーグ、そして女たち』の中で、「サイボーグ宣言:20世紀後半における科学、技術、そして社会 主義フェミニズム」と題する最新のエッセイを発表している。26][28][29] このマニフェストは、男性がいかに女性の生殖労働を搾取し、労働市場における完全な平等に到達するための障壁を女性に提供してきたかを明らかにすることに よって、資本主義に対する重要なフェミニスト批判にもなっている[30]。 霊長類のヴィジョン ハラウェイは、科学や生物学の歴史についても執筆しています。Primate Visions: Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science (1990)』では、霊長類学の科学を方向づけるメタファーと物語に焦点をあてています。彼女は、「攻撃的なオスと受容的なメスの間の生殖競争とセックス (それはある種の結論を容易にし、他の種の結論を排除する)」に関する物語を男性化する傾向があると主張し、女性の霊長類学者はよりコミュニケーションと 基本的な生存活動を必要とする異なる観察に焦点を当て、自然と文化の起源について現在認められているものとは非常に異なる視点を提供すると主張している [31]。西洋の物語やジェンダー、人種、階級のイデオロギーの例を引きながら、ハラウェイは、霊長類に基づく科学的な人間性の物語の最も基本的な構成に 疑問を呈したのである。Primate Visions』の中で彼女はこう書いている。 私の希望は、常に斜に構え、時に倒錯的な焦点を当てることで、違い、特に人種や性の違い、生殖、特に世代や子孫の多重性、生存、特に歴史の起源と終焉の両 方の境界条件において想像される生存についての、その複雑なジャンルの西洋の伝統の中で語られてきた基本的で根強い西洋の物語の修正を促すことだった」 32[34]。 ハラウェイの科学に対する目的は「その『客観性』の限界と不可能性を明らかにし、フェミニストの霊長類学者によって提供されたいくつかの最近の修正を検討 すること」であり[33]、ハラウェイは科学の人間性の物語が作られる方法を形成し続けている受け入れられたイデオロギーに対して代替の視点を提示する。 34] ハナウェイはフェミニストに技術科学の世界にもっと関わるように、その関わりに対して信用を得るように促している。1997年の出版物において、彼女はこ う発言している。 私は、技術科学的な世界構築の意味づけの過程に、フェミニストがもっとしっかりと登録されることを望んでいます。また、私はフェミニストの活動家、文化的 生産者、科学者、技術者、学者(すべて重複するカテゴリー)が、技術科学の実践と技術科学研究の両方との関係においてフェミニズムを特徴付ける(あるいは 特徴付けない)ほとんどの「主流」学者の無知にもかかわらず、我々がずっと行ってきた表現と登録のために認められることを望む[35]。 人口ではなく、親族を作れ。世代を再認識する ハラウェイは2015年に他の5人のフェミニスト思想家と名付けた「Make Kin not Babies」というパネルを作成した。アロンドラ・ネルソン、キム・トールベア、チア・リン・ウー、ミシェル・マーフィー、そしてアデル・クラークで す。このパネルでは、環境や人種、階級といった要素に注意を払いながら、人間の数を減らしていくことに重点を置いています。彼女のキーワードは「赤ちゃん を作ることは、赤ちゃんに良い子供時代を与えることとは違う」[25]であり、これが『人口ではなく親族を作る』出版のきっかけとなった。パネリストの一 人であるドナ・ハラウェイとアデル・クラークによる『世代を捉えなおす』(Reconceiving Generations)である。この本は、人類の人口増加とそれが環境に及ぼす影響について、発展している問題を扱っている。この本は二人の著者による エッセイで構成されており、環境と生殖に関する正義の両方を取り入れ、家族と親族関係の機能についても言及している[36]。 投機的寓話 投機的な空想は、ハラウェイの作品の多くに含まれる概念である。それは静止することのない荒々しい事実のすべてを含み、創造性の様式と人新世の物語を示す ものである。ハラウェイは、これがいかに事実でないことを意味しないかを強調する。ハラウェイの作品において、彼女はフェミニストの思索的ファブレーショ ンと、人口をコントロールしながらすべての子どもたちの良い子供時代を保証するために、赤ちゃんの代わりに親族を作ることに焦点を当てたことを扱っている [37]。Reconceiving Generations』は、この理論を社会で実行するための実践と提案に焦点を当てている[36]。 コンパニオン・スピーシーズ宣言。犬、人、そして重要な他者性 伴侶種宣言』は「個人的な文書」として読まれるものである。この作品は同居、共進化、そして体現された異種社会性を語るために書かれた[38]。ハラウェ イは、人間と犬との「コンパニオン」の関係は、違いを認識することの重要性と「重要な他者性とどう関わるか」を示すことができると主張する[39]。人間 と犬などの動物とのつながりは、他の人間や非人間とどう関わっていけばいいのかを人々に示すことができるのである。ハラウェイは、コンパニオンアニマルを 通じて学ぶことができる関係性から、「コンパニオン種」ではなく「コンパニオン種」という言葉を使うべきだと考えている[40]。 |

| Critical responses to Haraway Haraway's work has been criticized for being "methodologically vague"[41] and using noticeably opaque language that is "sometimes concealing in an apparently deliberate way".[42] Several reviewers have argued that her understanding of the scientific method is questionable, and that her explorations of epistemology at times leave her texts virtually meaning-free.[42][43] A 1991 review of Haraway's Primate Visions, published in the International Journal of Primatology, provides examples of some of the most common critiques of her view of science,[43] and a 1990 review in the American Journal of Primatology, offers a similar criticism.[42] However, a review in the Journal of the History of Biology by Anne Fausto-Sterling, a sexologist, disagrees.[44] |

ハラウェイに対する批判的な反応 ハラウェイの作品は「方法論的に曖昧」[41]であり、「時には明らかに意図的な方法で隠している」顕著に不透明な言語を用いていると批判されている [42]。 何人かの評者は、彼女の科学方法に対する理解が疑問であり、認識論に関する彼女の探求が時として彼女のテキストを実質的に意味のないものにすると論じてい る[42][43]。 インターナショナル・ジャーナル・オブ・プリマトロジーに掲載されたハラウェイの『霊長類の幻影』の1991年のレビューでは、彼女の科学観に対する最も 一般的な批評のいくつかの例を示しており[43]、アメリカン・ジャーナル・オブ・プリマトロジーの1990年のレビューでも同様の批判がなされている。 しかし性科学者のアン・フォースト=スターリングによる「生物学の歴史」のレビューでは同意されていない[44]。 |

| Publications Crystals, Fabrics, and Fields: Metaphors of Organicism in Twentieth-Century Developmental Biology, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0-300-01864-6 Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science, Routledge: New York and London, 1989. ISBN 978-0-415-90294-6 Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, New York: Routledge, and London: Free Association Books, 1991 (includes "A Cyborg Manifesto"). ISBN 978-0-415-90387-5 Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan©Meets_OncoMouse™: Feminism and Technoscience, New York: Routledge, 1997 (winner of the Ludwik Fleck Prize). ISBN 0-415-91245-8 How Like a Leaf: A Conversation with Donna J. Haraway, Thyrza Nichols Goodeve, New York: Routledge, 1999. ISBN 978-0-415-92402-3 The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness, Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003. ISBN 0-9717575-8-5 When Species Meet, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. ISBN 0-8166-5045-4 The Haraway Reader, New York: Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0415966892. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Durham: Duke University Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0-8223-6224-1 Manifestly Haraway, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0816650484 Making Kin not Population: Reconceiving Generations, Donna J. Haraway and Adele Clarke, Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2018. |

|

| A Cyborg Manifesto Cyborg anthropology Ecofeminism Postgenderism Posthumanism Postmodernism Sandy Stone Techno-progressivism Feminist technoscience Judith Butler |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donna_Haraway |

|

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報