アウシュヴィッツ=ビルケナウ強制収容所

Das Konzentrationslager Auschwitz-Birkenau,

Auschwitz concentration camp, Konzentrationslager Auschwitz

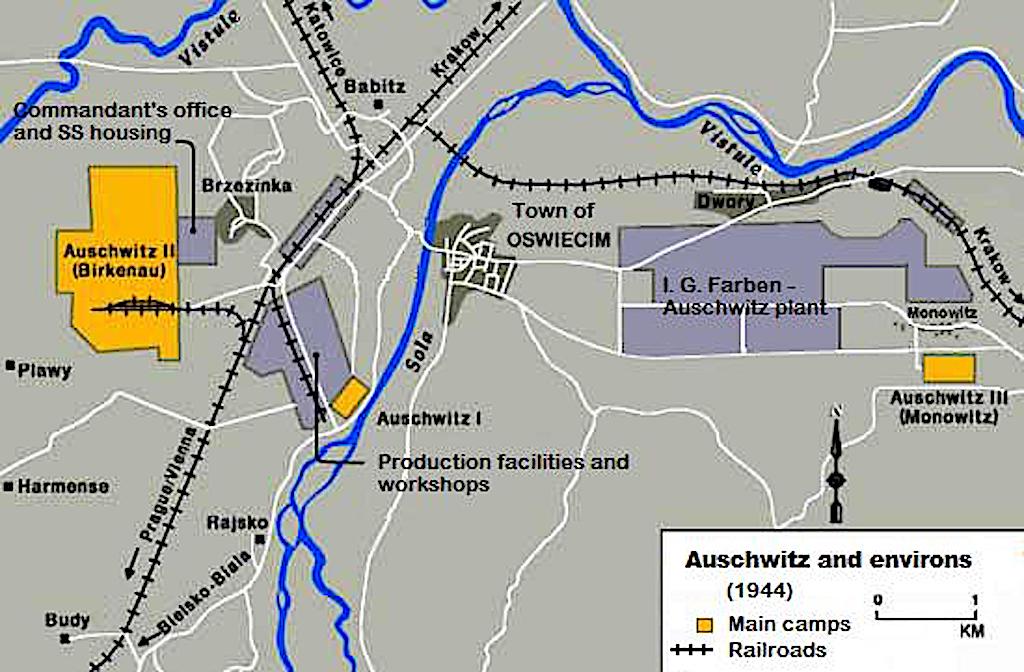

☆ アウシュヴィッツ強制収容所(Konzentrationslager Auschwitz, 発音: [kɔntsɛntʁaˈtsi̯o-ˌlaːɡɐaˈʔaʊʃvɪts] Ɉ; KL AuschwitzまたはKZ Auschwitzとも)は、第二次世界大戦とホロコーストの間にナチス・ドイツが占領下のポーランド(1939年にドイツに併合された部分)で運 営した40以上の強制収容所と絶滅収容所の複合体である。収容所は、オシヴィエチムのメイン収容所(シュタムラーゲル)であるアウシュヴィッツI、ガス室 を備えた強制絶滅収容所であるアウシュヴィッツII・ビルケナウ、化学複合企業IGファルベンの労働収容所であるアウシュヴィッツIII・モノヴィッツ、 および数十のサブ収容所から構成されていた。

| Auschwitz

concentration camp (German: Konzentrationslager Auschwitz, pronounced

[kɔntsɛntʁaˈtsi̯oːnsˌlaːɡɐ ˈʔaʊʃvɪts] ⓘ; also KL Auschwitz or KZ

Auschwitz) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination

camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed

into Germany in 1939)[3] during World War II and the Holocaust. It

consisted of Auschwitz I, the main camp (Stammlager) in Oświęcim;

Auschwitz II-Birkenau, a concentration and extermination camp with gas

chambers; Auschwitz III-Monowitz, a labour camp for the chemical

conglomerate IG Farben; and dozens of subcamps.[4] The camps became a

major site of the Nazis' Final Solution to the Jewish question. After Germany initiated World War II by invading Poland in September 1939, the Schutzstaffel (SS) converted Auschwitz I, an army barracks, into a prisoner-of-war camp.[5] The initial transport of political detainees to Auschwitz consisted almost solely of Poles (for whom the camp was initially established). For the first two years, the majority of inmates were Polish.[6] In May 1940, German criminals brought to the camp as functionaries established the camp's reputation for sadism. Prisoners were beaten, tortured, and executed for the most trivial of reasons. The first gassings—of Soviet and Polish prisoners—took place in block 11 of Auschwitz I around August 1941. Construction of Auschwitz II began the following month, and from 1942 until late 1944 freight trains delivered Jews from all over German-occupied Europe to its gas chambers. Of the 1.3 million people sent to Auschwitz, 1.1 million were murdered. The number of victims includes 960,000 Jews (865,000 of whom were gassed on arrival), 74,000 non-Jewish Poles, 21,000 Romani, 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war, and up to 15,000 others.[7] Those not gassed were murdered via starvation, exhaustion, disease, individual executions, or beatings. Others were killed during medical experiments. At least 802 prisoners tried to escape, 144 successfully, and on 7 October 1944, two Sonderkommando units, consisting of prisoners who operated the gas chambers, launched an unsuccessful uprising. 789 Schutzstaffel personnel (no more than 15 percent) ever stood trial after the Holocaust ended;[8] several were executed, including camp commandant Rudolf Höss. The Allies' failure to act on early reports of mass murder by bombing the camp or its railways remains controversial. As the Soviet Red Army approached Auschwitz in January 1945, toward the end of the war, the SS sent most of the camp's population west on a death march to camps inside Germany and Austria. Soviet troops entered the camp on 27 January 1945, a day commemorated since 2005 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day. In the decades after the war, survivors such as Primo Levi, Viktor Frankl, and Elie Wiesel wrote memoirs of their experiences, and the camp became a dominant symbol of the Holocaust. In 1947, Poland founded the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum on the site of Auschwitz I and II, and in 1979 it was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. |

アウシュヴィッツ強制収容所(ドイツ語:

アウシュヴィッツ強制収容所(ドイツ語: Konzentrationslager Auschwitz, 発音:

[kɔntsɛntʁaˈtsi̯o-ˌlaːɡɐaˈʔaʊʃvɪts] Ɉ; KL AuschwitzまたはKZ

Auschwitzとも)は、第二次世界大戦とホロコーストの間にナチス・ドイツが占領下のポーランド(1939年にドイツに併合された部分)[3]で運

営した40以上の強制収容所と絶滅収容所の複合体である。収容所は、オシヴィエチムのメイン収容所(シュタムラーゲル)であるアウシュヴィッツI、ガス室

を備えた強制絶滅収容所であるアウシュヴィッツII・ビルケナウ、化学複合企業IGファルベンの労働収容所であるアウシュヴィッツIII・モノヴィッツ、

および数十のサブ収容所から構成されていた[4]。 ドイツが1939年9月にポーランドに侵攻して第二次世界大戦を開始すると、親衛隊(SS)は、陸軍兵舎であったアウシュヴィッツIを捕虜収容所に改造し た[5]。アウシュヴィッツへの政治的抑留者の最初の移送は、ほとんどポーランド人(収容所が最初に設立されたのはこのポーランド人のためであった)だけ で構成されていた。最初の2年間、収容者の大半はポーランド人であった[6]。1940年5月、機能要員として収容所に連行されたドイツ人犯罪者が、収容 所のサディズムの評判を確立した。囚人たちは殴打され、拷問され、些細な理由で処刑された。1941年8月頃、アウシュヴィッツIのブロック11で、ソ連 人とポーランド人囚人の最初のガス処刑が行われた。 アウシュヴィッツIIの建設はその翌月に始まり、1942年から1944年後半まで、貨物列車がドイツ占領下のヨーロッパ中からユダヤ人をガス室に送り込 んだ。アウシュビッツに送られた130万人のうち、110万人が殺害された。犠牲者の数には、96万人のユダヤ人(うち86万5千人は到着時にガス処 刑)、7万4千人の非ユダヤ系ポーランド人、2万1千人のロマ人、1万5千人のソ連軍捕虜、その他最大1万5千人が含まれる[7]。ガス処刑されなかった 人々は、飢餓、疲労、病気、個別処刑、または殴打によって殺害された。医療実験中に殺された者もいた。 少なくとも802名の囚人が脱出を試み、144名が脱出に成功し、1944年10月7日には、ガス室を操作していた囚人からなる2つのゾンダーコマンド部 隊が蜂起したが、失敗に終わった。ホロコースト終結後、789名(15パーセント以下)のシュッツシュタッフェルが裁判にかけられたが[8]、収容所司令 官ルドルフ・ヘスを含む数名が処刑された。連合国が初期の大量殺戮の報告に対して、収容所やその鉄道を爆撃するという行動をとらなかったことについては、 いまだに議論の的となっている。 戦争末期の1945年1月、ソ連赤軍がアウシュヴィッツに接近すると、SSは収容所の住民のほとんどをドイツとオーストリア国内の収容所への死の行進に送 り出した。ソ連軍が収容所に入ったのは1945年1月27日で、この日は2005年から国際ホロコースト記念日として記念されている。戦後数十年の間に、 プリモ・レヴィ、ヴィクトール・フランクル、エリー・ヴィーゼルなどの生存者が体験手記を執筆し、収容所はホロコーストの象徴となった。1947年、ポー ランドはアウシュヴィッツ1世と2世の跡地にアウシュヴィッツ・ビルケナウ州立博物館を設立し、1979年にはユネスコの世界遺産に登録された。 |

Background Camps and ghettos in German-occupied Europe, 1944  Auschwitz I, II, and III The ideology of Nazism combined elements of "racial hygiene", eugenics, antisemitism, pan-Germanism, and territorial expansionism, Richard J. Evans writes.[9] Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party became obsessed by the "Jewish question".[10] Both during and immediately after the Nazi seizure of power in Germany in 1933, acts of violence against German Jews became ubiquitous,[11] and legislation was passed excluding them from certain professions, including the civil service and the law.[a] Harassment and economic pressure encouraged Jews to leave Germany; their businesses were denied access to markets, forbidden from advertising in newspapers, and deprived of government contracts.[13] On 15 September 1935, the Reichstag passed the Nuremberg Laws. One, the Reich Citizenship Law, defined as citizens those of "German or related blood who demonstrate by their behaviour that they are willing and suitable to serve the German People and Reich faithfully", and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor prohibited marriage and extramarital relations between those with "German or related blood" and Jews.[14] When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, triggering World War II, Hitler ordered that the Polish leadership and intelligentsia be destroyed.[15] The area around Auschwitz was annexed to the German Reich, as part of first Gau Silesia and from 1941 Gau Upper Silesia.[16] The camp at Auschwitz was established in April 1940, at first as a quarantine camp for Polish political prisoners. On 22 June 1941, in an attempt to obtain new territory, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union.[17] The first gassing at Auschwitz—of a group of Soviet prisoners of war—took place around August 1941.[18] By the end of that year, during what most historians regard as the first phase of the Holocaust, 500,000–800,000 Soviet Jews had been murdered in mass shootings by a combination of German Einsatzgruppen, ordinary German soldiers, and local collaborators.[19] At the Wannsee Conference in Berlin on 20 January 1942, Reinhard Heydrich outlined the Final Solution to the Jewish Question to senior Nazis,[20] and from early 1942 freight trains delivered Jews from all over occupied Europe to German extermination camps in Poland: Auschwitz, Bełżec, Chełmno, Majdanek, Sobibór, and Treblinka. Most prisoners were gassed on arrival.[21] |

背景 ドイツ占領下のヨーロッパの収容所とゲットー(1944年  アウシュヴィッツI、II、III ナチズムのイデオロギーは、「人種衛生」、優生学、反ユダヤ主義、汎ドイツ主義、領土拡張主義の要素を組み合わせたものであったと、リチャード・J・エ ヴァンスは書いている[9]。 アドルフ・ヒトラーと彼のナチ党は「ユダヤ人問題」に取りつかれるようになった[10]。 1933年にナチがドイツの政権を掌握した際もその直後も、ドイツのユダヤ人に対する暴力行為はいたるところで見られるようになり[11]、公務員や法律 を含む特定の職業からユダヤ人を排除する法律が制定された[a]。 嫌がらせと経済的な圧力はユダヤ人のドイツからの離脱を促し、彼らのビジネスは市場へのアクセスを拒否され、新聞への広告を禁じられ、政府との契約を奪わ れた[13]。1935年9月15日、帝国議会はニュルンベルク法を可決した。そのひとつである帝国市民権法は、「ドイツ人またはその近親者の血を引く者 で、ドイツ国民と帝国に忠実に奉仕する意思と適性があることを行動によって示す者」を市民と定義し、ドイツ人の血とドイツの名誉の保護に関する法律は、 「ドイツ人またはその近親者の血を引く者」とユダヤ人との婚姻および婚外関係を禁止した[14]。 1939年9月にドイツがポーランドに侵攻し、第二次世界大戦が勃発すると、ヒトラーはポーランドの指導層と知識層の破壊を命じた[15]。アウシュ ヴィッツ周辺地域はドイツ帝国に併合され、最初はシレジア州、1941年からは上シレジア州に編入された[16]。1941年6月22日、新たな領土を獲 得しようとするヒトラーはソ連に侵攻した[17]。 アウシュヴィッツでの最初のガス処刑(ソ連軍捕虜の一団)は1941年8月頃に行われた[18]。 その年の終わりまでに、ほとんどの歴史家がホロコーストの第一段階とみなしているように、ドイツのアインザッツグルッペン、一般のドイツ兵、地元の協力者 の組み合わせによって、50万人から80万人のソ連系ユダヤ人が大量射殺された。 [19] 1942年1月20日にベルリンで開かれたヴァンゼー会議で、ラインハルト・ハイドリヒはナチス幹部にユダヤ人問題の最終解決策の概要を説明し[20]、 1942年初頭から貨物列車が占領下のヨーロッパ各地からポーランドのドイツ人絶滅収容所にユダヤ人を送り込んだ: アウシュヴィッツ、ベウジェツ、チェルムノ、マジャダネク、ソビボル、トレブリンカである。ほとんどの囚人は到着と同時にガス処刑された[21]。 |

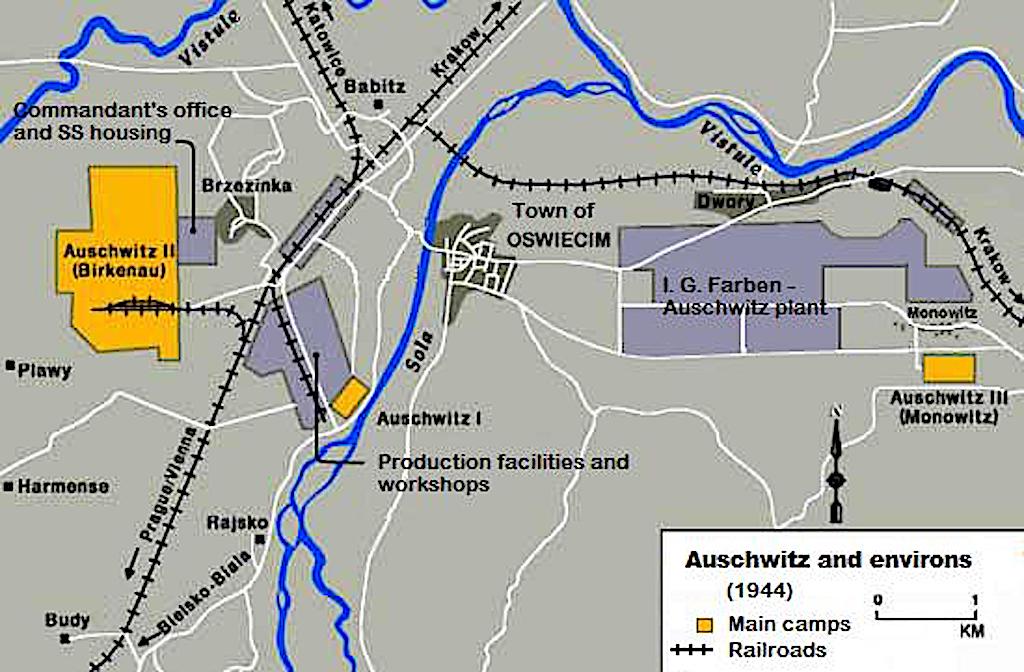

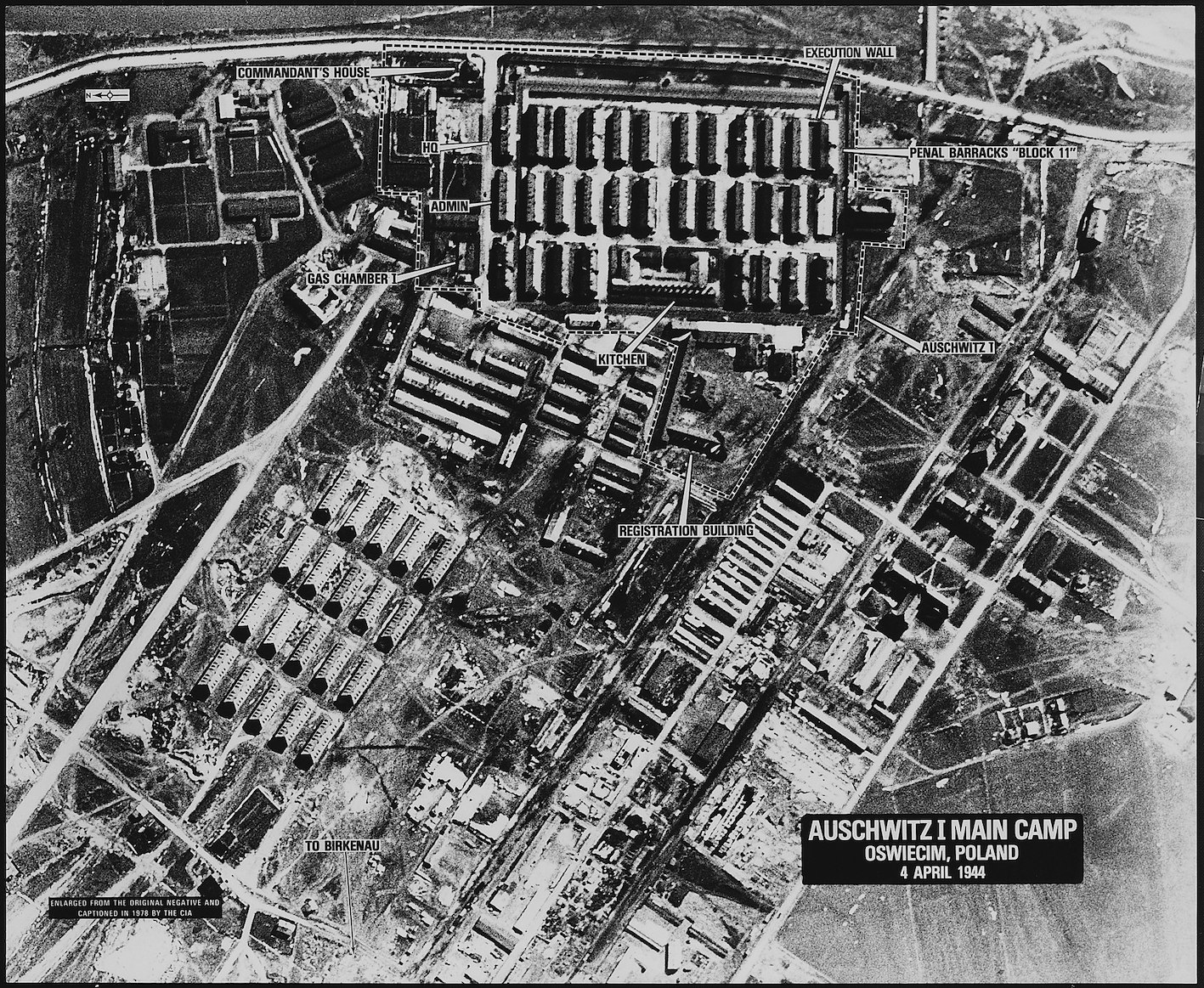

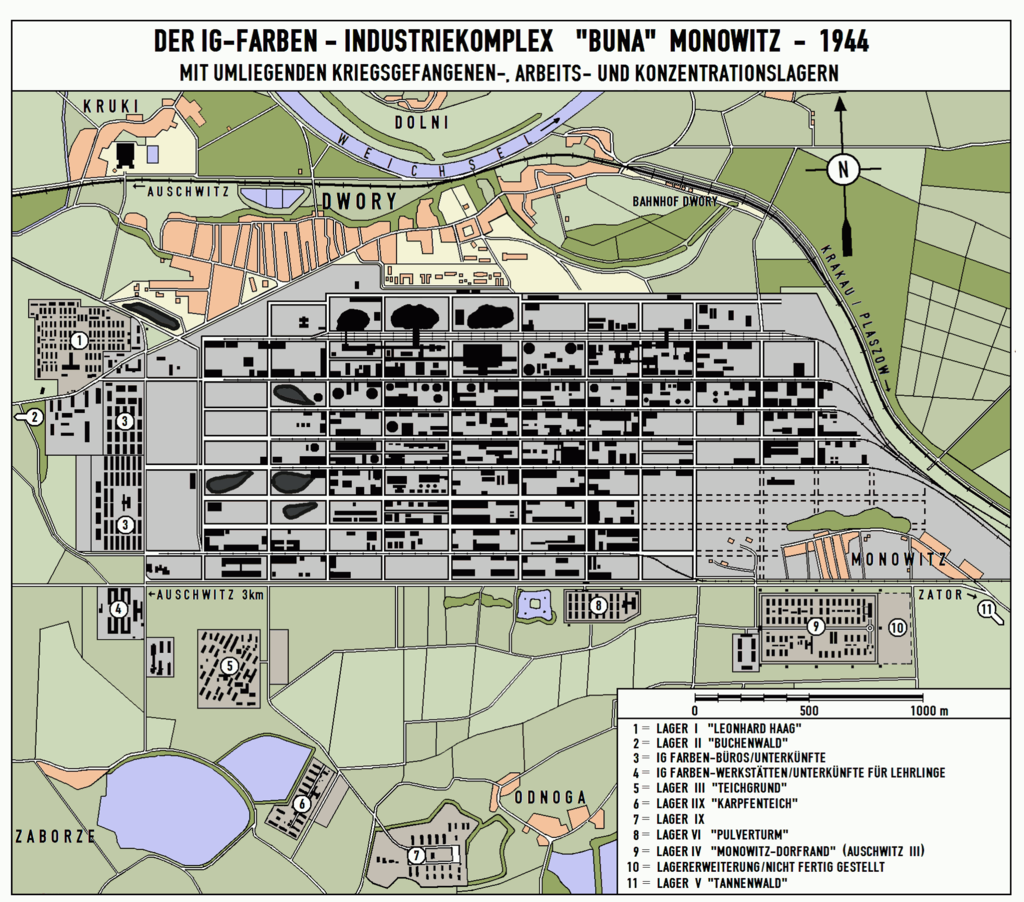

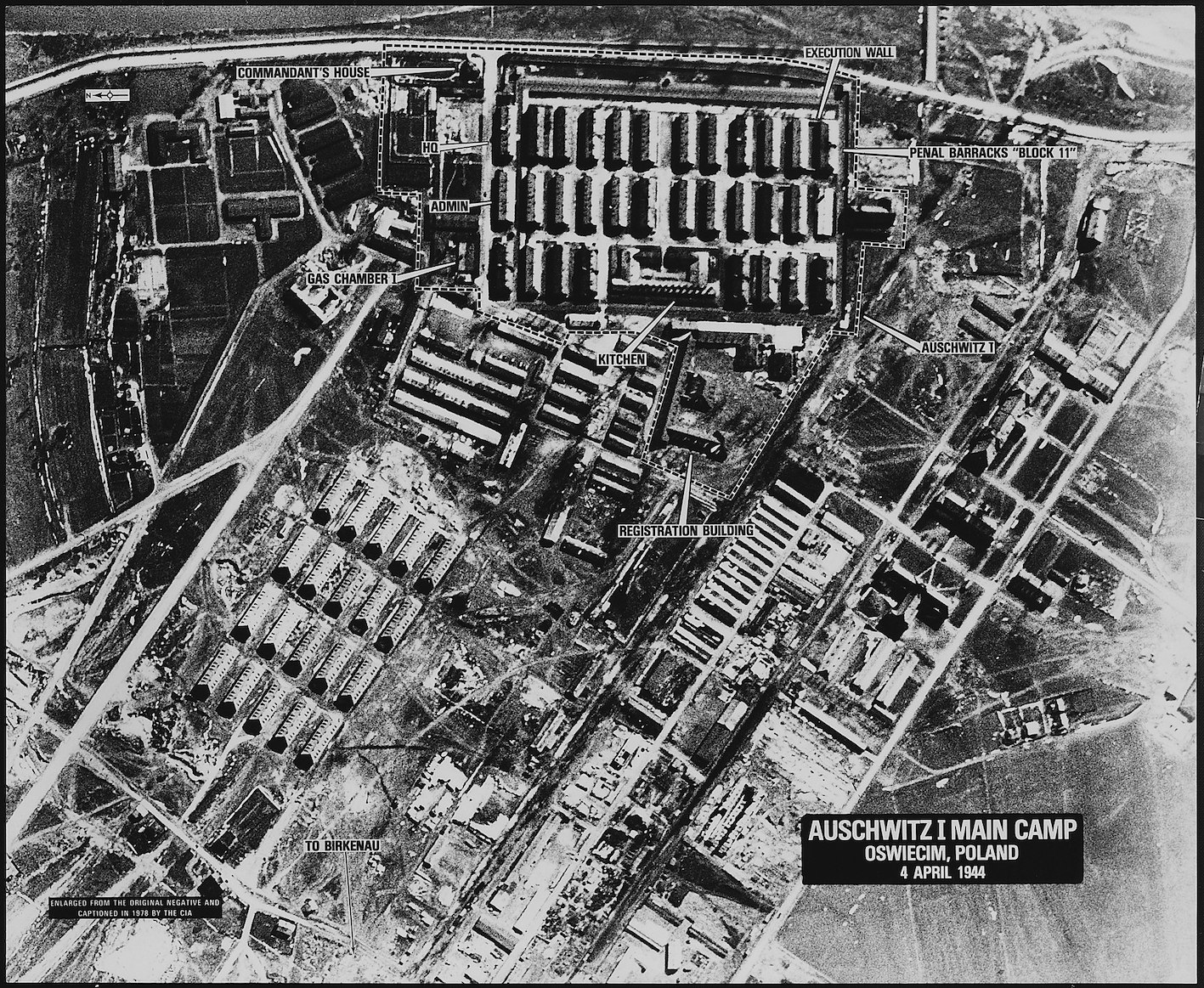

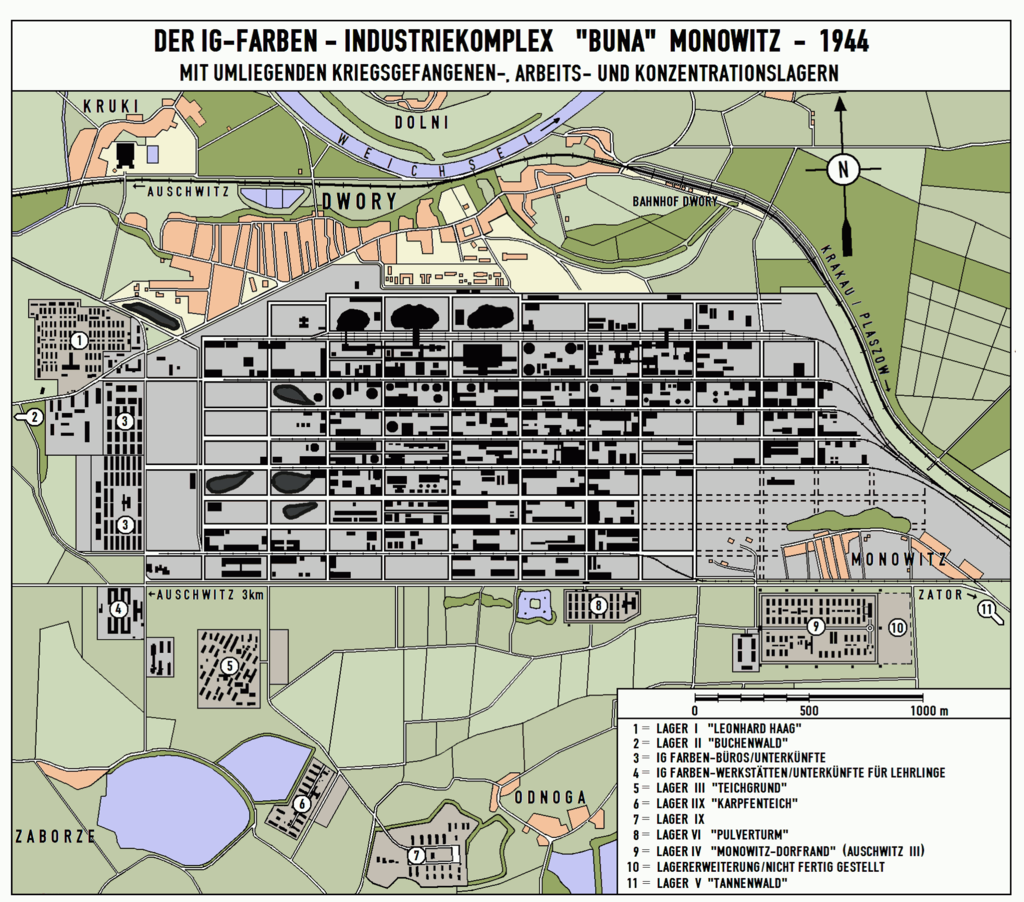

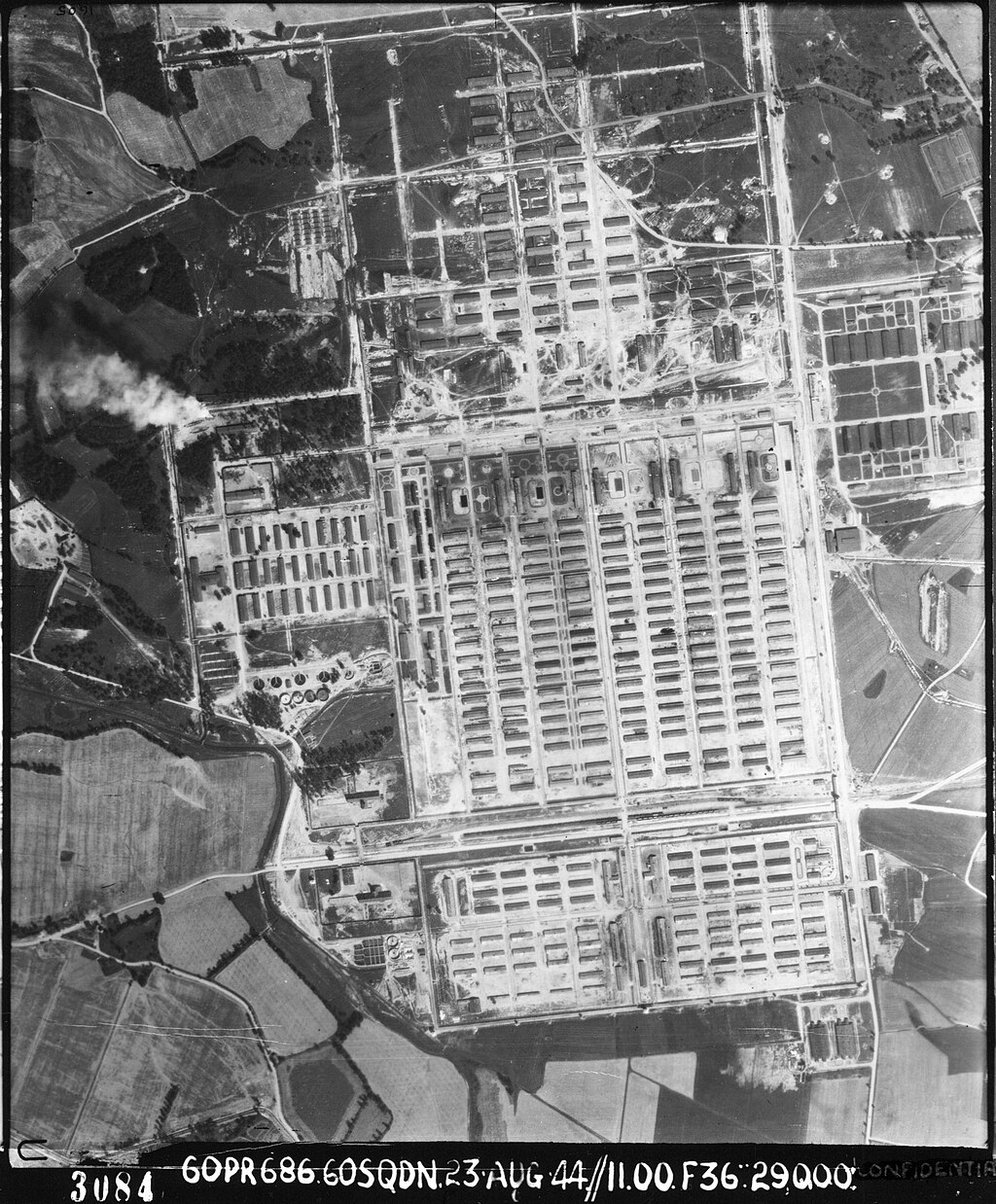

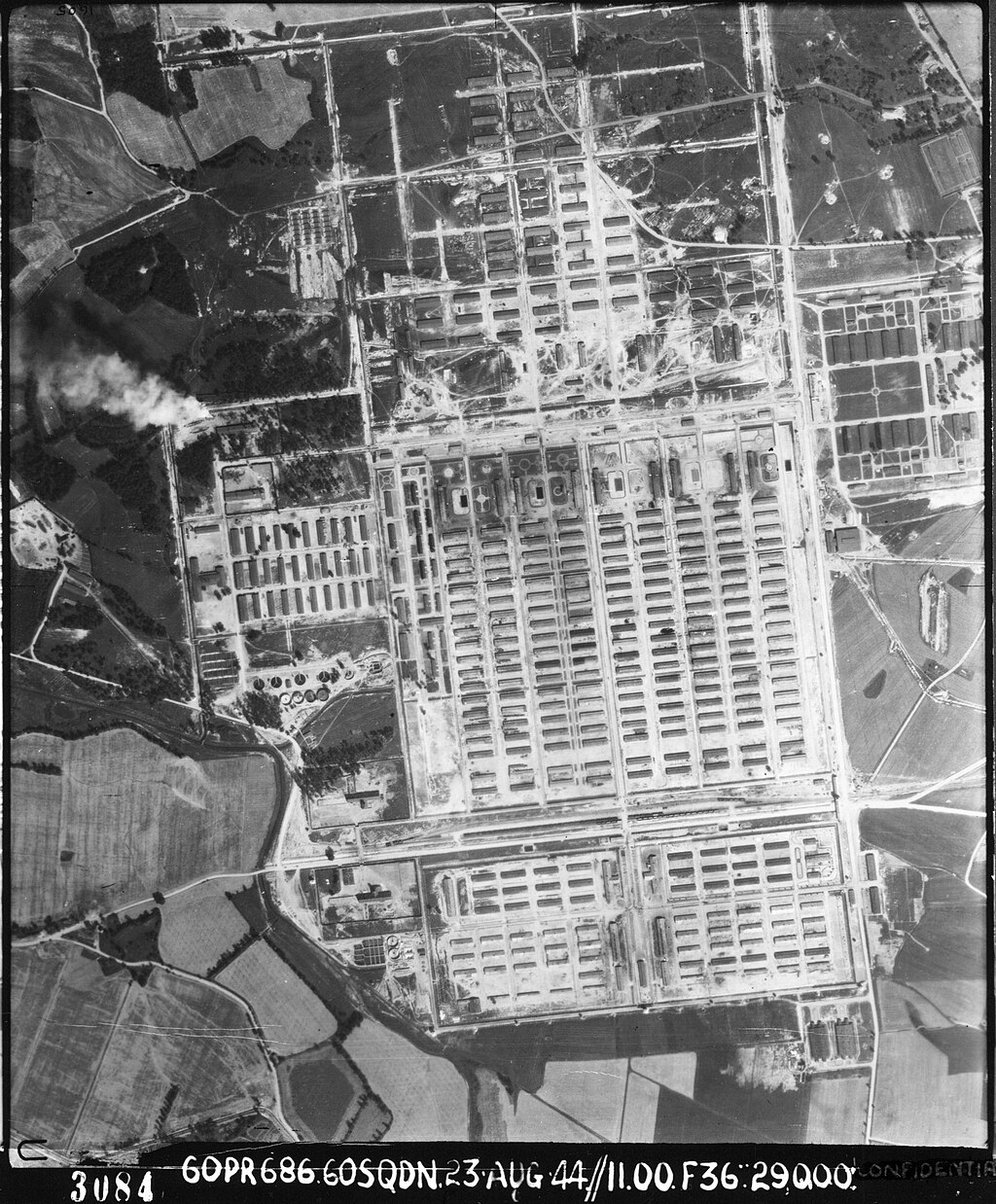

| Camps Auschwitz I Growth  Auschwitz I, 2013 (50.0275°N 19.2050°E)  Auschwitz I, 2009; the prisoner reception center of Auschwitz I became the visitor reception center of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.[22]  Former prisoner reception center; the building on the far left with the row of chimneys was the camp kitchen.  An aerial reconnaissance photograph of the Auschwitz concentration camp showing the Auschwitz I camp, 4 April 1944 A former World War I camp for transient workers and later a Polish army barracks, Auschwitz I was the main camp (Stammlager) and administrative headquarters of the camp complex. Fifty km southwest of Kraków, the site was first suggested in February 1940 as a quarantine camp for Polish prisoners by Arpad Wigand, the inspector of the Sicherheitspolizei (security police) and deputy of Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski, the Higher SS and Police Leader for Silesia. Richard Glücks, head of the Concentration Camps Inspectorate, sent Walter Eisfeld, former commandant of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, to inspect it.[23] Around 1,000 m long and 400 m wide,[24] Auschwitz consisted at the time of 22 brick buildings, eight of them two-story. A second story was added to the others in 1943 and eight new blocks were built.[25] Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, approved the site in April 1940 on the recommendation of SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Höss of the camps inspectorate. Höss oversaw the development of the camp and served as its first commandant. The first 30 prisoners arrived on 20 May 1940 from the Sachsenhausen camp. German "career criminals" (Berufsverbrecher), the men were known as "greens" (Grünen) after the green triangles on their prison clothing. Brought to the camp as functionaries, this group did much to establish the sadism of early camp life, which was directed particularly at Polish inmates, until the political prisoners took over their roles.[26] Bruno Brodniewicz, the first prisoner (who was given serial number 1), became Lagerälteste (camp elder). The others were given positions such as kapo and block supervisor.[27] First mass transport Further information: First mass transport to Auschwitz concentration camp The first mass transport—of 728 Polish male political prisoners, including Catholic priests and Jews—arrived on 14 June 1940 from Tarnów, Poland. They were given serial numbers 31 to 758.[b] In a letter on 12 July 1940, Höss told Glücks that the local population was "fanatically Polish, ready to undertake any sort of operation against the hated SS men".[29] By the end of 1940, the SS had confiscated land around the camp to create a 40-square-kilometer (15 sq mi) "zone of interest" (Interessengebiet) patrolled by the SS, Gestapo and local police.[30] By March 1941, 10,900 were imprisoned in the camp, most of them Poles.[24] An inmate's first encounter with Auschwitz, if they were registered and not sent straight to the gas chamber, was at the prisoner reception centre near the gate with the Arbeit macht frei sign, where they were tattooed, shaved, disinfected, and given a striped prison uniform. Built between 1942 and 1944, the center contained a bathhouse, laundry, and 19 gas chambers for delousing clothing. The prisoner reception center of Auschwitz I became the visitor reception center of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.[22] Crematorium I, first gassings Further information: § Gas chambers  Crematorium I, photographed in 2016, reconstructed after the war[31] Construction of crematorium I began at Auschwitz I at the end of June or beginning of July 1940.[32] Initially intended not for mass murder but for prisoners who had been executed or had otherwise died in the camp, the crematorium was in operation from August 1940 until July 1943, by which time the crematoria at Auschwitz II had taken over.[33] By May 1942 three ovens had been installed in crematorium I, which together could burn 340 bodies in 24 hours.[34] The first experimental gassing took place around August 1941, when Lagerführer Karl Fritzsch, at the instruction of Rudolf Höss, murdered a group of Soviet prisoners of war by throwing Zyklon B crystals into their basement cell in block 11 of Auschwitz I. A second group of 600 Soviet prisoners of war and around 250 sick Polish prisoners were gassed on 3–5 September.[35] The morgue was later converted to a gas chamber able to hold at least 700–800 people.[34][c] Zyklon B was dropped into the room through slits in the ceiling.[34] First mass transport of Jews Further information: Bytom Synagogue and Beuthen Jewish Community Historians have disagreed about the date the all-Jewish transports began arriving in Auschwitz. At the Wannsee Conference in Berlin on 20 January 1942, the Nazi leadership outlined, in euphemistic language, its plans for the Final Solution.[36] According to Franciszek Piper, the Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss offered inconsistent accounts after the war, suggesting the extermination began in December 1941, January 1942, or before the establishment of the women's camp in March 1942.[37] In Kommandant in Auschwitz, he wrote: "In the spring of 1942 the first transports of Jews, all earmarked for extermination, arrived from Upper Silesia."[38] On 15 February 1942, according to Danuta Czech, a transport of Jews from Beuthen, Upper Silesia (Bytom, Poland), arrived at Auschwitz I and was sent straight to the gas chamber.[d][40] In 1998 an eyewitness said the train contained "the women of Beuthen".[e] Saul Friedländer wrote that the Beuthen Jews were from the Organization Schmelt labor camps and had been deemed unfit for work.[42] According to Christopher Browning, transports of Jews unfit for work were sent to the gas chamber at Auschwitz from autumn 1941.[43] The evidence for this and the February 1942 transport was contested in 2015 by Nikolaus Wachsmann.[44] Around 20 March 1942, according to Danuta Czech, a transport of Polish Jews from Silesia and Zagłębie Dąbrowskie was taken straight from the station to the Auschwitz II gas chamber, which had just come into operation.[45] On 26 and 28 March, two transports of Slovakian Jews were registered as prisoners in the women's camp, where they were kept for slave labour; these were the first transports organized by Adolf Eichmann's department IV B4 (the Jewish office) in the Reich Security Head Office (RSHA).[f] On 30 March the first RHSA transport arrived from France.[46] "Selection", where new arrivals were chosen for work or the gas chamber, began in April 1942 and was conducted regularly from July. Piper writes that this reflected Germany's increasing need for labour. Those selected as unfit for work were gassed without being registered as prisoners.[47] There is also disagreement about how many were gassed in Auschwitz I. Perry Broad, an SS-Unterscharführer, wrote that "transport after transport vanished in the Auschwitz [I] crematorium."[48] In the view of Filip Müller, one of the Auschwitz I Sonderkommando, tens of thousands of Jews were murdered there from France, Holland, Slovakia, Upper Silesia, and Yugoslavia, and from the Theresienstadt, Ciechanow, and Grodno ghettos.[49] Against this, Jean-Claude Pressac estimated that up to 10,000 people had been murdered in Auschwitz I.[48] The last inmates gassed there, in December 1942, were around 400 members of the Auschwitz II Sonderkommando, who had been forced to dig up and burn the remains of that camp's mass graves, thought to hold over 100,000 corpses.[50] Auschwitz II–Birkenau "Birkenau" redirects here. For other uses, see Birkenau (disambiguation). Construction  Auschwitz II-Birkenau gate from inside the camp, 2007  Same scene, May/June 1944, with the gate in the background. "Selection" of Hungarian Jews for work or the gas chamber. From the Auschwitz Album, taken by the camp's Erkennungsdienst.  Gate with the camp remains in the background, 2009 After visiting Auschwitz I in March 1941, it appears that Himmler ordered that the camp be expanded,[51] although Peter Hayes notes that, on 10 January 1941, the Polish underground told the Polish government-in-exile in London: "the Auschwitz concentration camp ...can accommodate approximately 7,000 prisoners at present, and is to be rebuilt to hold approximately 30,000."[52] Construction of Auschwitz II-Birkenau—called a Kriegsgefangenenlager (prisoner-of-war camp) on blueprints—began in October 1941 in Brzezinka, about three kilometers from Auschwitz I.[53] The initial plan was that Auschwitz II would consist of four sectors (Bauabschnitte I–IV), each consisting of six subcamps (BIIa–BIIf) with their own gates and fences. The first two sectors were completed (sector BI was initially a quarantine camp), but the construction of BIII began in 1943 and stopped in April 1944, and the plan for BIV was abandoned.[54] SS-Sturmbannführer Karl Bischoff, an architect, was the chief of construction.[51] Based on an initial budget of RM 8.9 million, his plans called for each barracks to hold 550 prisoners, but he later changed this to 744 per barracks, which meant the camp could hold 125,000, rather than 97,000.[55] There were 174 barracks, each measuring 35.4 by 11.0 m (116 by 36 ft), divided into 62 bays of 4 m2 (43 sq ft). The bays were divided into "roosts", initially for three inmates and later for four. With personal space of 1 m2 (11 sq ft) to sleep and place whatever belongings they had, inmates were deprived, Robert-Jan van Pelt wrote, "of the minimum space needed to exist".[56] The prisoners were forced to live in the barracks as they were building them; in addition to working, they faced long roll calls at night. As a result, most prisoners in BIb (the men's camp) in the early months died of hypothermia, starvation or exhaustion within a few weeks.[57] Some 10,000 Soviet prisoners of war arrived at Auschwitz I between 7 and 25 October 1941,[58] but by 1 March 1942 only 945 were still registered; they were transferred to Auschwitz II,[39] where most of them had died by May.[59] Crematoria II–V Further information: § Gas chambers The first gas chamber at Auschwitz II was operational by March 1942. On or around 20 March, a transport of Polish Jews sent by the Gestapo from Silesia and Zagłębie Dąbrowskie was taken straight from the Oświęcim freight station to the Auschwitz II gas chamber, then buried in a nearby meadow.[45] The gas chamber was located in what prisoners called the "little red house" (known as bunker 1 by the SS), a brick cottage that had been turned into a gassing facility; the windows had been bricked up and its four rooms converted into two insulated rooms, the doors of which said "Zur Desinfektion" ("to disinfection"). A second brick cottage, the "little white house" or bunker 2, was converted and operational by June 1942.[60] When Himmler visited the camp on 17 and 18 July 1942, he was given a demonstration of a selection of Dutch Jews, a mass-murder in a gas chamber in bunker 2, and a tour of the building site of Auschwitz III, the new IG Farben plant being constructed at Monowitz.[61] Use of bunkers I and 2 stopped in spring 1943 when the new crematoria were built, although bunker 2 became operational again in May 1944 for the murder of the Hungarian Jews. Bunker I was demolished in 1943 and bunker 2 in November 1944.[62] Plans for crematoria II and III show that both had an oven room 30 by 11.24 m (98.4 by 36.9 ft) on the ground floor, and an underground dressing room 49.43 by 7.93 m (162.2 by 26.0 ft) and gas chamber 30 by 7 m (98 by 23 ft). The dressing rooms had wooden benches along the walls and numbered pegs for clothing. Victims would be led from these rooms to a five-yard-long narrow corridor, which in turn led to a space from which the gas chamber door opened. The chambers were white inside, and nozzles were fixed to the ceiling to resemble showerheads.[63] The daily capacity of the crematoria (how many bodies could be burned in a 24-hour period) was 340 corpses in crematorium I; 1,440 each in crematoria II and III; and 768 each in IV and V.[64] By June 1943 all four crematoria were operational, but crematorium I was not used after July 1943. This made the total daily capacity 4,416, although by loading three to five corpses at a time, the Sonderkommando were able to burn some 8,000 bodies a day. This maximum capacity was rarely needed; the average between 1942 and 1944 was 1,000 bodies burned every day.[65] Auschwitz III–Monowitz Main article: Monowitz concentration camp  Detailed map of Buna Werke, Monowitz, and nearby subcamps After examining several sites for a new plant to manufacture Buna-N, a type of synthetic rubber essential to the war effort, the German chemical conglomerate IG Farben chose a site near the towns of Dwory and Monowice (Monowitz in German), about 7 km (4.3 mi) east of Auschwitz I.[66] Tax exemptions were available to corporations prepared to develop industries in the frontier regions under the Eastern Fiscal Assistance Law, passed in December 1940. In addition to its proximity to the concentration camp, a source of cheap labour, the site had good railway connections and access to raw materials.[67] In February 1941, Himmler ordered that the Jewish population of Oświęcim be expelled to make way for skilled laborers; that all Poles able to work remain in the town and work on building the factory; and that Auschwitz prisoners be used in the construction work.[68] Auschwitz inmates began working at the plant, known as Buna Werke and IG-Auschwitz, in April 1941, demolishing houses in Monowitz to make way for it.[69] By May, because of a shortage of trucks, several hundred of them were rising at 3 am to walk there twice a day from Auschwitz I.[70] Because a long line of exhausted inmates walking through the town of Oświęcim might harm German-Polish relations, the inmates were told to shave daily, make sure they were clean, and sing as they walked. From late July they were taken to the factory by train on freight wagons.[71] Given the difficulty of moving them, including during the winter, IG Farben decided to build a camp at the plant. The first inmates moved there on 30 October 1942.[72] Known as KL Auschwitz III–Aussenlager (Auschwitz III subcamp), and later as the Monowitz concentration camp,[73] it was the first concentration camp to be financed and built by private industry.[74]  Heinrich Himmler (second left) visits the IG Farben plant in Auschwitz III, July 1942. Measuring 270 m × 490 m (890 ft × 1,610 ft), the camp was larger than Auschwitz I. By the end of 1944, it housed 60 barracks measuring 17.5 m × 8 m (57 ft × 26 ft), each with a day room and a sleeping room containing 56 three-tiered wooden bunks.[75] IG Farben paid the SS three or four Reichsmark for nine- to eleven-hour shifts from each worker.[76] In 1943–1944, about 35,000 inmates worked at the plant; 23,000 (32 a day on average) were killed through malnutrition, disease, and the workload. Within three to four months at the camp, Peter Hayes writes, the inmates were "reduced to walking skeletons".[77] Deaths and transfers to the gas chambers at Auschwitz II reduced the population by nearly a fifth each month.[78] Site managers constantly threatened inmates with the gas chambers, and the smell from the crematoria at Auschwitz I and II hung heavy over the camp.[79] Although the factory had been expected to begin production in 1943, shortages of labour and raw materials meant start-up was postponed repeatedly.[80] The Allies bombed the plant in 1944 on 20 August, 13 September, 18 December, and 26 December. On 19 January 1945, the SS ordered that the site be evacuated, sending 9,000 inmates, most of them Jews, on a death march to another Auschwitz subcamp at Gliwice.[81] From Gliwice, prisoners were taken by rail in open freight wagons to the Buchenwald and Mauthausen concentration camps. The 800 inmates who had been left behind in the Monowitz hospital were liberated along with the rest of the camp on 27 January 1945 by the 1st Ukrainian Front of the Red Army.[82] Subcamps Further information: List of subcamps of Auschwitz Several other German industrial enterprises, such as Krupp and Siemens-Schuckert, built factories with their own subcamps.[83] There were around 28 camps near industrial plants, each camp holding hundreds or thousands of prisoners.[84] Designated as Aussenlager (external camp), Nebenlager (extension camp), Arbeitslager (labor camp), or Aussenkommando (external work detail),[85] camps were built at Blechhammer, Jawiszowice, Jaworzno, Lagisze, Mysłowice, Trzebinia, and as far afield as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in Czechoslovakia.[86] Industries with satellite camps included coal mines, foundries and other metal works, and chemical plants. Prisoners were also made to work in forestry and farming.[87] For example, Wirtschaftshof Budy, in the Polish village of Budy near Brzeszcze, was a farming subcamp where prisoners worked 12-hour days in the fields, tending animals, and making compost by mixing human ashes from the crematoria with sod and manure.[88] Incidents of sabotage to decrease production took place in several subcamps, including Charlottengrube, Gleiwitz II, and Rajsko.[89] Living conditions in some of the camps were so poor that they were regarded as punishment subcamps.[90] |

収容所 アウシュビッツI 発展  アウシュヴィッツⅠ、2013年(北緯50.0275度、東経19.2050度)  アウシュヴィッツI、2009年。アウシュヴィッツIの囚人収容所は、アウシュヴィッツ・ビルケナウ州立博物館のビジター・レセプション・センターとなった[22]。  かつての囚人収容所。左端の煙突の連なった建物は収容所の厨房だった。  1944年4月4日、アウシュヴィッツ強制収容所の航空偵察写真。 かつての第一次世界大戦中の一時的労働者収容所であり、のちにポーランド軍の兵舎となったアウシュヴィッツI収容所は、収容所複合体の主要収容所 (Stammlager)であり、管理本部であった。クラクフの南西50kmにあるこの場所は、1940年2月、シレジアの高等SS・警察指導者エーリ ヒ・フォン・デム・バッハ=ツェレフスキの副官であった保安警察(Sicherheitspolizei)監察官アルパド・ヴィガンドによって、ポーラン ド人囚人の隔離収容所として最初に提案された。強制収容所監察局長のリヒャルト・グリュクスは、ドイツのオラニエンブルクにあるザクセンハウゼン強制収容 所の元指揮官ヴァルター・アイスフェルドを視察に派遣した[23]。長さ約1000m、幅400mのアウシュヴィッツは、当時22棟の煉瓦造りの建物から 成っており[24]、そのうちの8棟は2階建てであった。1943年に他の建物に2階建てが追加され、8つの新しいブロックが建設された[25]。 親衛隊長ハインリヒ・ヒムラーは、収容所監察局のルドルフ・ヘス親衛隊親衛隊長の推薦によって、1940年4月にこの場所を承認した。ヘスは収容所の開発 を監督し、最初の司令官を務めた。最初の30名の囚人は1940年5月20日にザクセンハウゼン収容所から到着した。ドイツの "職業犯罪人"(Berufsverbrecher)である彼らは、囚人服の緑の三角形にちなんで "グリーン"(Grünen)と呼ばれた。このグループは、政治犯がその役割を引き継ぐまで、特にポーランド人収容者に向けられた初期の収容所生活のサ ディズムを確立するために大いに貢献した[26]。最初の囚人(通し番号1を与えられた)ブルーノ・ブロドニェヴィッチは、ラーゲレルトシュテ(収容所の 長老)となった。他の囚人たちはカポやブロック監督といった役職を与えられた[27]。 最初の大量移送 さらなる情報 アウシュヴィッツ強制収容所への最初の大量移送 カトリック司祭とユダヤ人を含む728名のポーランド人男性政治犯の最初の集団移送は、1940年6月14日にポーランドのタルフから到着した。彼らには 通し番号31から758までが与えられた[b]。1940年7月12日の手紙の中で、ヘスはグリュックスに、地元の住民は「狂信的なポーランド人であり、 憎むべきSS隊員に対するあらゆる種類の作戦を実行する用意がある」と述べている[29]。 [29]1940年末までに、SSは収容所周辺の土地を没収し、SS、ゲシュタポ、地元警察が巡回する40平方キロメートルの「関心地帯」 (Interessengebiet)を作った[30]。1941年3月までに10,900人が収容所に収監され、そのほとんどがポーランド人であった [24]。 収容者とアウシュヴィッツとの最初の出会いは、登録され、ガス室に直行させられなかった場合、Arbeit macht freiの看板のある門の近くにある囚人レセプションセンターであった。1942年から1944年にかけて建設されたこのセンターには、浴場、洗濯場、衣 類を脱色するための19のガス室があった。アウシュヴィッツIの囚人収容所は、アウシュヴィッツ・ビルケナウ州立博物館の見学者収容所となった[22]。 火葬場I、最初のガス処刑 さらなる情報 § ガス室  2016年に撮影された火葬場I、戦後に再建された[31]。 火葬場Ⅰの建設は1940年6月末か7月初めにアウシュヴィッツⅠで開始された[32]。当初は大量殺戮のためではなく、処刑された囚人や収容所で死亡し た囚人のためのものであったが、火葬場は1940年8月から1943年7月まで稼働し、そのころにはアウシュヴィッツⅡの火葬場が引き継いでいた [33]。1942年5月までに火葬場Ⅰには3つの炉が設置され、合わせて24時間で340体を焼却することができた[34]。 最初の実験的ガス処刑は、1941年8月頃、ルドルフ・ヘスの指示を受けたカール・フリッツシュ親衛隊長が、アウシュヴィッツIのブロック11の地下独房 にツィクロンBの結晶を投げ込んで、ソ連軍捕虜の一団を殺害したときに行われた。9月3-5日、600名のソ連軍捕虜と約250名の病気のポーランド人捕 虜の第二のグループがガス処刑された[35]。死体安置室は、のちに、少なくとも700-800名を収容できるガス室に改造された[34][c]。ツィク ロンBは天井のスリットから室内に投下された[34]。 ユダヤ人の最初の大量移送 さらなる情報 ビトムシナゴーグとベウテンユダヤ人共同体 ユダヤ人だけの移送がアウシュヴィッツに到着し始めた日付については、歴史家の間でも意見が分かれている。フランシシェク・ピペルによると、アウシュ ヴィッツの司令官ルドルフ・ヘスは、戦後、絶滅が1941年12月、1942年1月、あるいは1942年3月の女性収容所設立以前に始まったとする一貫性 のない説明をした。 [37]『アウシュヴィッツの司令官』の中で、彼は、「1942年春、最初のユダヤ人の移送が、すべて絶滅の対象として上シレジアから到着した。 「38] ダヌータ・チェコによると、1942年2月15日、上シレジアのボイテン(ポーランドのビトム)からのユダヤ人の移送がアウシュヴィッツIに到着し、その ままガス室に送られた[d][40]。 1998年、目撃者は、その列車には「ボイテンの女性たち」が乗っていたと述べている。 [e] Saul Friedländerは、ボイヘンのユダヤ人は組織シュメルト労働収容所の出身であり、労働に適さないとみなされていたと書いている[42]。 Christopher Browningによると、労働に適さないユダヤ人の移送は、1941年秋からアウシュヴィッツのガス室に送られていた[43]。 これと1942年2月の移送の証拠については、2015年にNikolaus Wachsmannが異議を唱えている[44]。 ダヌータ・チェコによると、1942年3月20日頃、シレジアとザグウェビー・ドブロウスキーからのポーランド系ユダヤ人の移送は、駅から稼動し始めたば かりのアウシュヴィッツUガス室に直行させられた。 [45]3月26日と28日には、スロヴァキア系ユダヤ人の2つの移送が、女性収容所の囚人として登録され、奴隷労働のために収容された。これらは、アド ルフ・アイヒマンの帝国保安本部(RSHA)のIV部B4(ユダヤ人事務所)が組織した最初の移送であった[f]。ピペルは、これはドイツの労働力の必要 性の高まりを反映したものであったと記している。労働に適さないと選別された人々は、囚人として登録されることなくガス処刑された[47]。 アウシュヴィッツIでは何名がガス処刑されたのかについても意見の相違がある。SSウンターシャルフューラーであったペリー・ブロードは、「アウシュ ヴィッツ[I]の火葬場では、輸送車が次々と消えていった」と書いている[48]。アウシュヴィッツIゾンダーコマンドの一人であったフィリップ・ミュ ラーの見解では、フランス、オランダ、スロヴァキア、上シレジア、ユーゴスラヴィア、およびテレジエンスタット、チエチャノフ、グロドノのゲットーから数 万のユダヤ人が殺害された。 [これに対して、ジャン=クロード・プレサックは、アウシュヴィッツIでは最大10,000名が殺害されたと見積もっている[48]。1942年12月、 そこでガス処刑された最後の収容者は、アウシュヴィッツIIゾンダーコマンドの約400名のメンバーであった。彼らは、10万以上の死体を収容していると 考えられている収容所の集団墓地の残骸を掘り起こして焼却することを強制されていた[50]。 アウシュヴィッツ II -ビルケナウ "Birkenau "はここにリダイレクトされる。他の用法については、ビルケナウ (曖昧さ回避)を参照のこと。 建設  収容所内部からのアウシュヴィッツ2世ビルケナウ門、2007年  同じ光景、1944年5月/6月、ゲートを背景に。ハンガリー系ユダヤ人の労働用またはガス室用の「選別」。収容所のErkennungsdienstが撮影した『アウシュヴィッツ・アルバム』から。  収容所跡を背景にしたゲート、2009年 1941年3月にアウシュヴィッツIを訪問した後、ヒムラーは収容所の拡張を命じたようであるが[51]、ピーター・ヘイズは、1941年1月10日に、 ポーランドの地下組織がロンドンのポーランド亡命政府に次のように伝えている:「アウシュヴィッツ強制収容所は...現在およそ7000名の囚人を収容す ることができ、およそ30,000名を収容するために再建されることになっている。 「アウシュヴィッツU-ビルケナウの建設は、設計図ではKriegsgefangenlager(捕虜収容所)と呼ばれていたが、1941年10月、アウ シュヴィッツIから3キロメートルほど離れたブレジンカで始まった[53]。当初の計画では、アウシュヴィッツUは4つのセクター (Bauabschnitte I-IV)から構成され、それぞれが独自のゲートとフェンスを持つ6つの小収容所(BIIa-BIIf)からなっていた。最初の2つのセクターは完成した が(セクターBIは当初は検疫収容所であった)、BIIIの建設は1943年に開始され、1944年4月に中止され、BIVの計画は放棄された[54]。 建築家であったカール・ビショフ親衛隊上級大将が建設主任であった[51]。890万ルミアの当初予算に基づく彼の計画では、各兵舎は550名の囚人を収 容することになっていたが、後に彼はこれを各兵舎あたり744名に変更した。ベイは「ねぐら」に分けられ、当初は3人用、後に4人用になった。寝たり、持 ち物を置いたりするための個人的なスペースは1㎡(11平方フィート)であったため、受刑者は「存在するために必要な最小限のスペース」を奪われていたと ロベルト=ヤン・ヴァン・ペルトは記している[56]。 囚人たちは、バラックを建設しながら、バラックでの生活を余儀なくされ、労働に加えて、夜間の長い点呼に直面した。その結果、初期の数カ月にBIb(男子 収容所)にいた囚人の大半は、数週間以内に低体温症、飢餓、疲労のために死亡した[57]。1941年10月7日から25日のあいだに、約10,000名 のソ連軍捕虜がアウシュヴィッツIに到着したが[58]、1942年3月1日までにまだ登録されていたのは945名だけであった。 火葬場II-V さらに詳しい情報 § ガス室 アウシュヴィッツUの最初のガス室は1942年3月までに稼動していた。3月20日頃、ゲシュタポがシレジアとザグウェビー・ドブロウスキーから送り込ん だポーランド系ユダヤ人の移送車は、オシヴィエンチム貨物駅からアウシュヴィッツUガス室に直行し、その後、近くの草地に埋葬された。 [45] ガス室は、囚人たちが「小さな赤い家」(SSは第1地下壕と呼んでいた)と呼んでいた、ガス処刑施設と化したレンガ造りのコテージにあった。窓はふさが れ、4つの部屋は2つの断熱された部屋に改造され、そのドアには「Zur Desinfektion」(「消毒へ」と書かれていた)と書かれていた。1942年7月17日と18日にヒムラーが収容所を訪れたとき、彼は、オランダ 系ユダヤ人の選別の実演、壕2のガス室での大量殺戮、モノヴィッツに建設中のIGファルベンの新しい工場であるアウシュヴィッツIIIの建設現場の見学を 受けた[60]。 [61] 壕Iと2の使用は、新しい火葬場が建設された1943年春に停止したが、壕2はハンガリー系ユダヤ人の殺戮のために1944年5月に再び稼働した。壕Iは 1943年に、壕2は1944年11月に取り壊された[62]。 火葬場ⅡとⅢの図面によると、どちらも一階に30×11.24m(98.4×36.9フィート)の炉室があり、地下に49.43×7.93m(162.2 ×26.0フィート)の脱衣室と30×7m(98×23フィート)のガス室があった。脱衣室には、壁に沿って木製のベンチがあり、衣服用の番号のついたペ グがあった。犠牲者はこれらの部屋から、5ヤードの長さの狭い廊下に案内され、そこからガス室のドアが開くスペースにつながっていた。室内は白く、ノズル はシャワーヘッドのように天井に固定されていた[63]。火葬場の1日の収容能力(24時間に焼却できる死体の数)は、I号火葬場では340体、II号火 葬場とIII号火葬場ではそれぞれ1,440体、IV号火葬場とV号火葬場ではそれぞれ768体であった[64]。1943年6月までに、4つの火葬場す べてが稼動していたが、I号火葬場は1943年7月以降使われなかった。このため、1日の総火葬能力は4,416体であったが、一度に3体から5体の死体 を積み込むことによって、ゾンダーコマンドは1日に約8,000体を焼却することができた。1942年から1944年までの平均は、毎日1,000体の焼 却であった[65]。 アウシュヴィッツIII-モノヴィッツ 主な記事 モノヴィッツ強制収容所  ブナ・ヴェルケ、モノヴィッツ、および近隣の小収容所の詳細地図 ドイツの化学複合企業IGファルベンは、戦争に不可欠な合成ゴムの一種であるブナNを製造する新工場の建設地をいくつか検討した後、アウシュヴィッツIの 東約7kmにあるドヴォリーとモノヴィツェ(ドイツ語ではモノヴィッツ)の町の近くに建設地を選んだ[66]。1941年2月、ヒムラーは、熟練労働者を 確保するためにオシヴィエチムのユダヤ人人口を追放すること、就労可能なすべてのポーランド人を町に残して工場建設に従事させること、アウシュヴィッツの 囚人を建設作業に使用することを命じた[68]。 アウシュヴィッツの囚人たちは、1941年4月から、ブナ・ヴェルケ(Buna Werke)およびIG-アウシュヴィッツ(IG-Auschwitz)として知られる工場で働き始め、そのためにモノヴィッツの家々を取り壊した [69]。5月までに、トラック不足のために、数百人の囚人が午前3時に起床し、アウシュヴィッツIから1日2回歩いてそこに向かった。 [70] 疲弊した収容者の長い列がオシヴィエンチムの町を歩くことはドイツとポーランドの関係を害するかもしれないので、収容者は毎日ひげを剃り、清潔にし、歩き ながら歌うように言われた。7月下旬から、彼らは貨車で列車で工場に運ばれた[71]。冬期も含めて移動が困難であることから、IGファルベンは工場に収 容所を建設することを決定した。最初の収容者は1942年10月30日にそこに移動した[72]。KLアウシュヴィッツIII-アウセンラーガー(アウ シュヴィッツIII小収容所)として知られ[73]、後にモノヴィッツ強制収容所として知られるようになったが、民間企業によって資金が提供され建設され た最初の強制収容所であった[74]。  1942年7月、アウシュヴィッツIIIのIGファルベン工場を視察するハインリヒ・ヒムラー(左から2番目)。 1944年末までに、17.5m×8m(57ft×26ft)の60のバラックが収容され、それぞれのバラックには、昼間の部屋と56の3段の木製の寝台 を含む寝室があった。 [1943-1944 年、約 35,000 人の収容者が工場で働いていたが、23,000 人(1 日平均 32 人)が栄養失調、病気、労働負荷によって死亡した。ピーター・ヘイズは、収容所では3-4ヶ月のうちに、収容者は「歩く骸骨になった」と記している [77]。 アウシュヴィッツUのガス室での死亡と移送によって、収容者は毎月5分の1近く減少した[78]。敷地管理者は収容者をガス室で常に脅し、アウシュヴィッ ツIとIIの火葬場からの臭気が収容所に重くのしかかった[79]。 工場は1943年に生産を開始する予定であったが、労働力と原材料の不足のために、稼働は何度も延期された[80]。連合国は1944年、8月20日、9 月13日、12月18日、12月26日に工場を爆撃した。1945年1月19日、SSは工場からの退去を命じ、9,000人の収容者(そのほとんどがユダ ヤ人)をグリヴィツェの別のアウシュヴィッツ収容所に死の行進に送った[81]。モノヴィッツの病院に取り残されていた800人の収容者は、1945年1 月27日に赤軍の第1ウクライナ戦線によって収容所の他の部分とともに解放された[82]。 サブキャンプ さらなる情報 アウシュヴィッツの小収容所のリスト クルップやシーメンス・シュッケルトのようなドイツの他のいくつかの工業企業は、独自の小収容所を持つ工場を建設した[83]。工業工場の近くには約28 の収容所があり、それぞれの収容所は数百人から数千人の囚人を収容していた。 [84]アウセンラーガー(外部収容所)、ネーベンラーガー(拡張収容所)、アルベッツラーガー(労働収容所)、アウセンコマンド(外部作業細部)として 指定され[85]、収容所はブレヒハンマー、ヤヴィショヴィツェ、ヤヴォルツノ、ラギシェ、ミスウォヴィツェ、トルツェビニア、遠くはチェコスロバキアの ボヘミアおよびモラヴィア保護領に建設された。囚人は林業や農業にも従事させられた[87]。例えば、ブルツェシュチェの近くのポーランドのブディ村にあ るヴィルトシャフトホフ・ブディは農業の分屯地で、囚人は畑で12時間労働し、家畜の世話をし、火葬場から出る人灰を草地や糞尿と混ぜて堆肥を作った。 [88]シャルロッテングルーベ、グライヴィッツⅡ、ラジスコを含むいくつかの小収容所では、生産量を減少させるためのサボタージュ事件が起こった [89]。いくつかの収容所の生活環境は非常に劣悪であったので、懲罰小収容所とみなされていた[90]。 |

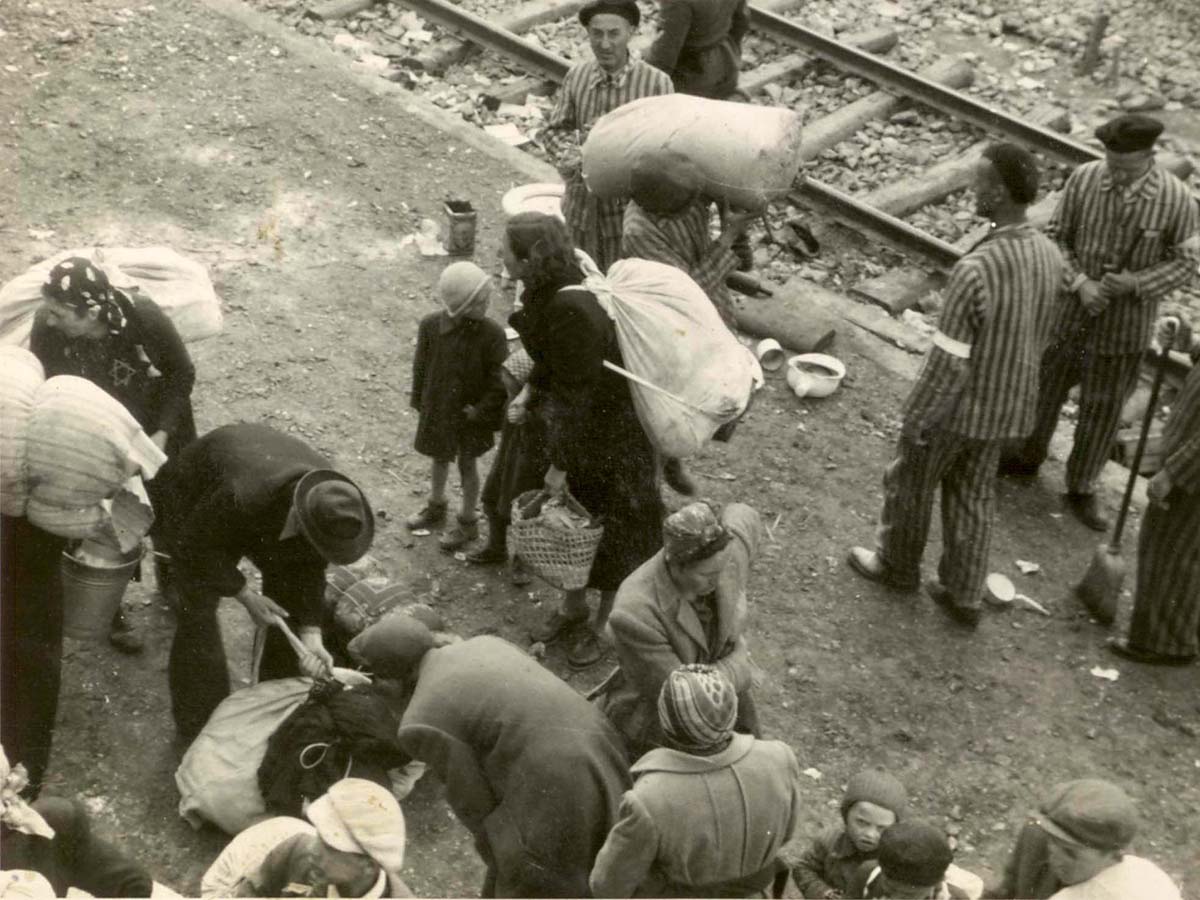

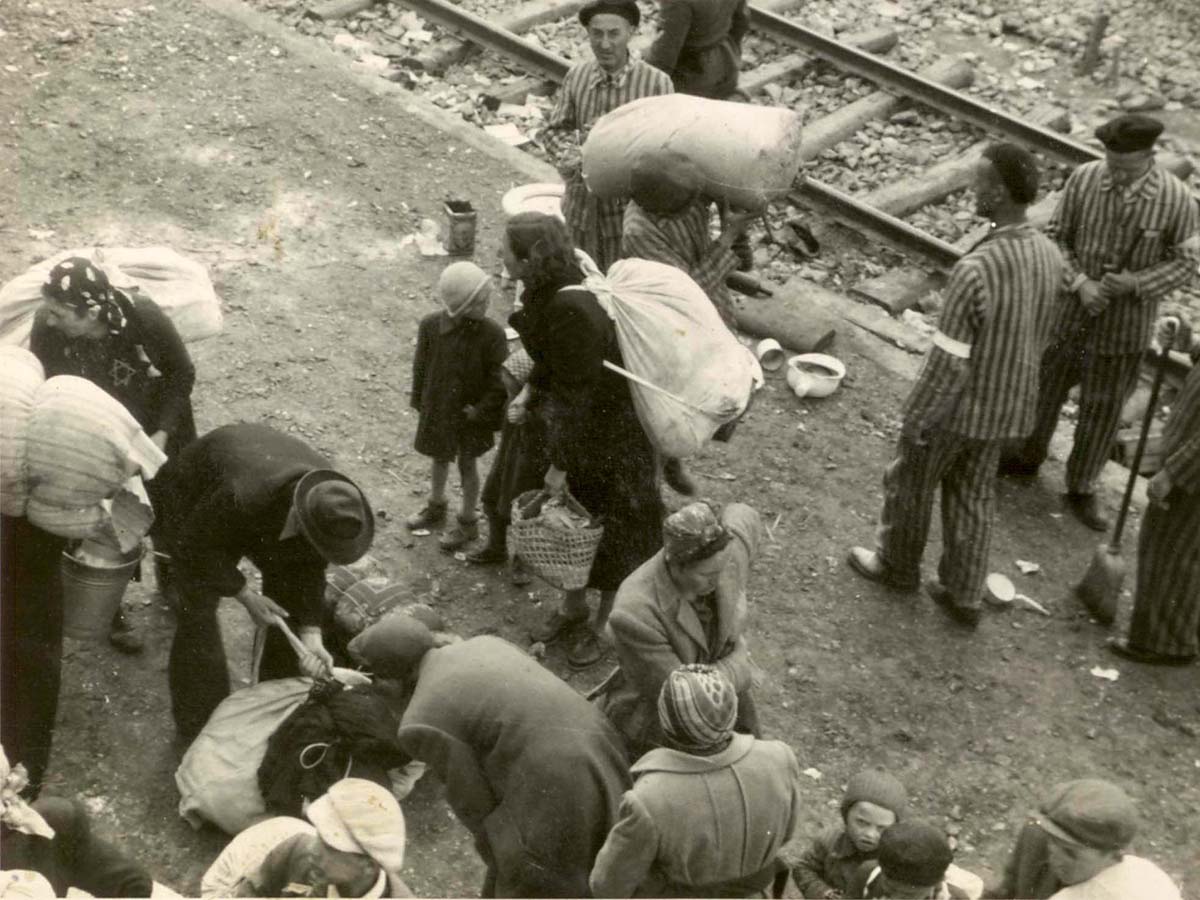

| Life in the camps SS garrison Main articles: SS command of Auschwitz concentration camp and SS-Totenkopfverbände  From the Höcker Album (left to right): Richard Baer (Auschwitz commandant from May 1944), Josef Mengele (camp physician), and Rudolf Höss (first commandant) in Solahütte, an SS resort near Auschwitz, summer 1944.[91]  The commandant's and administration building, Auschwitz I Rudolf Höss, born in Baden-Baden in 1900,[92] was named the first commandant of Auschwitz when Heinrich Himmler ordered on 27 April 1940 that the camp be established.[93] Living with his wife and children in a two-story stucco house near the commandant's and administration building,[94] he served as commandant until 11 November 1943,[93] with Josef Kramer as his deputy.[24] Succeeded as commandant by Arthur Liebehenschel,[93] Höss joined the SS Business and Administration Head Office in Oranienburg as director of Amt DI,[93] a post that made him deputy of the camps inspectorate.[95] Richard Baer became commandant of Auschwitz I on 11 May 1944 and Fritz Hartjenstein of Auschwitz II from 22 November 1943, followed by Josef Kramer from 15 May 1944 until the camp's liquidation in January 1945. Heinrich Schwarz was commandant of Auschwitz III from the point at which it became an autonomous camp in November 1943 until its liquidation.[96] Höss returned to Auschwitz between 8 May and 29 July 1944 as the local SS garrison commander (Standortältester) to oversee the arrival of Hungary's Jews, which made him the superior officer of all the commandants of the Auschwitz camps.[93] According to Aleksander Lasik, about 6,335 people (6,161 of them men) worked for the SS at Auschwitz over the course of the camp's existence;[97] 4.2 percent were officers, 26.1 percent non-commissioned officers, and 69.7 percent rank and file.[98] In March 1941, there were 700 SS guards; in June 1942, 2,000; and in August 1944, 3,342. At its peak in January 1945, 4,480 SS men and 71 SS women worked in Auschwitz; the higher number is probably attributable to the logistics of evacuating the camp.[99] Female guards were known as SS supervisors (SS-Aufseherinnen).[100] Most of the staff were from Germany or Austria, but as the war progressed, increasing numbers of Volksdeutsche from other countries, including Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia, and the Baltic states, joined the SS at Auschwitz. Not all were ethnically German. Guards were also recruited from Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia.[101] Camp guards, around three quarters of the SS personnel, were members of the SS-Totenkopfverbände (death's head units).[102] Other SS staff worked in the medical or political departments, or in the economic administration, which was responsible for clothing and other supplies, including the property of dead prisoners.[103] The SS viewed Auschwitz as a comfortable posting; being there meant they had avoided the front and had access to the victims' property.[104] Functionaries and Sonderkommando  Auschwitz I, 2009 Certain prisoners, at first non-Jewish Germans but later Jews and non-Jewish Poles,[105] were assigned positions of authority as Funktionshäftlinge (functionaries), which gave them access to better housing and food. The Lagerprominenz (camp elite) included Blockschreiber (barracks clerk), Kapo (overseer), Stubendienst (barracks orderly), and Kommandierte (trusties).[106] Wielding tremendous power over other prisoners, the functionaries developed a reputation as sadists.[105] Very few were prosecuted after the war, because of the difficulty of determining which atrocities had been performed by order of the SS.[107] Although the SS oversaw the murders at each gas chamber, the forced labor portion of the work was done by prisoners known from 1942 as the Sonderkommando (special squad).[108] These were mostly Jews but they included groups such as Soviet POWs. In 1940–1941 when there was one gas chamber, there were 20 such prisoners, in late 1943 there were 400, and by 1944 during the Holocaust in Hungary the number had risen to 874.[109] The Sonderkommando removed goods and corpses from the incoming trains, guided victims to the dressing rooms and gas chambers, removed their bodies afterwards, and took their jewelry, hair, dental work, and any precious metals from their teeth, all of which was sent to Germany. Once the bodies were stripped of anything valuable, the Sonderkommando burned them in the crematoria.[110] Because they were witnesses to the mass murder, the Sonderkommando lived separately from the other prisoners, although this rule was not applied to the non-Jews among them.[111] Their quality of life was further improved by their access to the property of new arrivals, which they traded within the camp, including with the SS.[112] Nevertheless, their life expectancy was short; they were regularly murdered and replaced.[113] About 100 survived to the camp's liquidation. They were forced on a death march and by train to the camp at Mauthausen, where three days later they were asked to step forward during roll call. No one did, and because the SS did not have their records, several of them survived.[114] Tattoos and triangles Further information: Nazi concentration camp badge  Auschwitz clothing Uniquely at Auschwitz, prisoners were tattooed with a serial number, on their left breast for Soviet prisoners of war[115] and on the left arm for civilians.[116][117] Categories of prisoner were distinguishable by triangular pieces of cloth (German: Winkel) sewn onto on their jackets below their prisoner number. Political prisoners (Schutzhäftlinge or Sch), mostly Poles, had a red triangle, while criminals (Berufsverbrecher or BV) were mostly German and wore green. Asocial prisoners (Asoziale or Aso), which included vagrants, prostitutes and the Roma, wore black. Purple was for Jehovah's Witnesses (Internationale Bibelforscher-Vereinigung or IBV)'s and pink for gay men, who were mostly German.[118] An estimated 5,000–15,000 gay men prosecuted under German Penal Code Section 175 (proscribing sexual acts between men) were detained in concentration camps, of whom an unknown number were sent to Auschwitz.[119] Jews wore a yellow badge, the shape of the Star of David, overlaid by a second triangle if they also belonged to a second category. The nationality of the inmate was indicated by a letter stitched onto the cloth. A racial hierarchy existed, with German prisoners at the top. Next were non-Jewish prisoners from other countries. Jewish prisoners were at the bottom.[120] Transports  Freight car inside Auschwitz II-Birkenau, near the gatehouse, used to transport deportees, 2014[121] Deportees were brought to Auschwitz crammed in wretched conditions into goods or cattle wagons, arriving near a railway station or at one of several dedicated trackside ramps, including one next to Auschwitz I. The Altejudenrampe (old Jewish ramp), part of the Oświęcim freight railway station, was used from 1942 to 1944 for Jewish transports.[121][122] Located between Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II, arriving at this ramp meant a 2.5 km journey to Auschwitz II and the gas chambers. Most deportees were forced to walk, accompanied by SS men and a car with a Red Cross symbol that carried the Zyklon B, as well as an SS doctor in case officers were poisoned by mistake. Inmates arriving at night, or who were too weak to walk, were taken by truck.[123] Work on a new railway line and ramp (right) between sectors BI and BII in Auschwitz II, was completed in May 1944 for the arrival of Hungarian Jews[122] between May and early July 1944.[124] The rails led directly to the area around the gas chambers.[121] |

収容所での生活 SS駐屯地 主な記事 アウシュヴィッツ強制収容所のSS司令部、SS-Totenkopfverbände  ヘッカー・アルバムから(左から右): リヒャルト・ベール(1944年5月からのアウシュヴィッツ司令官)、ヨーゼフ・メンゲレ(収容所医師)、ルドルフ・ヘス(初代司令官)、1944年夏、アウシュヴィッツ近くのSS保養地ソラヒュッテにて[91]。  アウシュヴィッツIの司令官室と管理棟 1900年バーデンバーデン生まれのルドルフ・ヘス[92]は、ハインリヒ・ヒムラーが1940年4月27日に収容所の設立を命じたとき、アウシュヴィッ ツの初代所長に任命された[93]。所長・管理棟の近くの2階建ての漆喰の家に妻と子供たちと住み[94]、ヨーゼフ・クラマーを副所長として、1943 年11月11日まで所長として勤務した[93]。 [24]アルトゥール・リーベヘンシェルに指揮官を引き継がれ[93]、ヘスはオラニエンブルクのSS事業管理本部にDI部長として参加し[93]、収容 所監察官代理となった[95]。 リヒャルト・ベールは1944年5月11日にアウシュヴィッツIの所長に、フリッツ・ハートイェンシュタインは1943年11月22日からアウシュヴィッ ツIIの所長に、ヨーゼフ・クラマーは1944年5月15日から1945年1月に収容所が清算されるまで所長になった。ハインリヒ・シュヴァルツは、アウ シュヴィッツIIIが1943年11月に独立収容所となった時点からその清算まで、アウシュヴィッツの指揮官であった[96]。ヘスは1944年5月8日 から7月29日にかけて、ハンガリーのユダヤ人の到着を監督するために、地元のSS駐屯地司令官(Standortältester)としてアウシュ ヴィッツに戻った。 アレクサンダー・ラシックによると、アウシュヴィッツ収容所の存続期間中、約6,335名(うち男性6,161名)がSSのために働いた[97]。 1941年3月には700名のSS看守がおり、1942年6月には2,000名、1944年8月には3,342名であった。1945年1月のピーク時に は、4,480名のSS男性と71名のSS女性がアウシュヴィッツで働いていたが、この数が多かったのは、おそらく収容所からの避難のための兵站に起因し ている[99]。 職員のほとんどはドイツかオーストリア出身であったが、戦争が進むにつれて、チェコスロバキア、ポーランド、ユーゴスラビア、バルト諸国など、他の国々か らアウシュヴィッツのSSに加わるヴォルクス・ドイッチェの数が増えていった。すべてが民族的にドイツ人であったわけではない。看守はハンガリー、ルーマ ニア、スロヴァキアからもリクルートされた[101]。収容所の看守は、SS隊員のおよそ4分の3であり、SS-Totenkopfverbände(死 者の頭目部隊)のメンバーであった[102]。 その他のSS隊員は、医療部門や政治部門、あるいは、死んだ囚人の財産を含む衣服やその他の物資を管理する経済管理部門で働いた[103]。 要員とゾンダーコマンド  アウシュヴィッツI、2009年 最初は非ユダヤ系ドイツ人であったが、後にユダヤ人と非ユダヤ系ポーランド人となった特定の囚人[105]は、より良い住居と食料を手に入れることができ るFunktionshäftlinge(ファンクショナリー)として権威ある地位を割り当てられた。Lagerprominenz(収容所のエリート) には、Blockschreiber(兵舎事務員)、Kapo(監督者)、Stubendienst(兵舎命令係)、Kommandierte(信頼係) が含まれていた[106]。他の囚人に対して絶大な権力を振るう機能係は、サディストとしての評判を高めていった[105]。どの残虐行為がSSの命令に よって行われたかを決定することが困難であったため、戦後に訴追された者はほとんどいなかった[107]。 SSは各ガス室での殺人を監督していたが、強制労働の部分は、1942年からゾンダーコマンド(特別部隊)として知られていた囚人たちによって行なわれて いた[108]。ガス室が1つであった1940-1941年には、このような囚人は20名であったが、1943年後半には400名、ハンガリーでのホロ コーストの最中の1944年には874名に増えていた[109]。ゾンダーコマンドは、入線してくる列車から荷物や死体を運び出し、犠牲者を脱衣室やガス 室に案内し、その後死体を運び出し、宝石、髪の毛、歯の細工物、歯についた貴金属を持ち去り、そのすべてをドイツに送った。遺体から貴重なものが取り除か れると、ゾンダーコマンドは火葬場で焼却した[110]。 彼らは大量殺人の目撃者であったため、ゾンダーコマンドは他の囚人とは別に生活していたが、このルールは彼らの中の非ユダヤ人には適用されなかった [111]。彼らは死の行進と列車でマウトハウゼンの収容所に強制連行され、3日後、点呼の際に前に出るよう求められた。誰も名乗り出なかったが、SSは 彼らの記録を持っていなかったので、何人かは生き残った[114]。 タトゥーと三角形 さらなる情報 ナチ強制収容所バッジ  アウシュヴィッツの服装 アウシュヴィッツではユニークなことに、囚人には通し番号の刺青が入れられ、ソ連軍捕虜の場合は左胸に[115]、民間人の場合は左腕に入れられた [116][117]。 囚人番号の下の上着に縫い付けられた三角形の布片(ドイツ語でヴィンケル)によって、囚人のカテゴリーが区別された。政治犯 (Schutzhäftlinge、Sch)はほとんどがポーランド人であり、赤い三角形をしていたが、犯罪者(Berufsverbrecher、 BV)はほとんどがドイツ人であり、緑色をしていた。浮浪者、売春婦、ロマ人を含む非社会的囚人(AsozialeまたはAso)は黒を着ていた。紫色は エホバの証人(Internationale Bibelforscher-Vereinigung、IBV)のものであり、ピンク色はほとんどがドイツ人であった同性愛者のものであった[118]。 ドイツ刑法175条(男性間の性行為の禁止)のもとで起訴された推定5,000~15,000人の同性愛者が強制収容所に収容され、そのうちアウシュ ヴィッツに送られた者の数は不明であった[119]。ユダヤ人はダビデの星の形をした黄色のバッジをつけており、第二のカテゴリーにも属している場合に は、第二の三角形が重なっていた。収容者の国籍は、布に縫い付けられた文字によって示された。ドイツ人囚人を頂点とする人種階層が存在した。次に他の国の 非ユダヤ人囚人。ユダヤ人囚人は最下位であった[120]。 移送  アウシュヴィッツⅡ=ビルケナウ内部、ゲートハウス付近、移送者の移送に使われた貨物車(2014年)[121]。 アウシュヴィッツに移送された被収容者は、悲惨な状況の中で、貨車や牛車に詰め込まれ、鉄道駅の近くか、アウシュヴィッツIの隣にあるものを含むいくつか の専用線路脇のランプの一つに到着した。アウシュヴィッツIとアウシュヴィッツIIの間に位置し、このタラップに到着することは、アウシュヴィッツIIと ガス室への2.5kmの旅を意味した[121][122]。ほとんどの強制送還者は、SS隊員と、ツィクロンBを運ぶ赤十字のシンボルの車、さらに将校が 間違って毒殺された場合に備えてSS医師を伴って、歩くことを余儀なくされた。夜間に到着した収容者、あるいは歩くことができないほど弱っている収容者 は、トラックで運ばれた[123]。 アウシュヴィッツUのBIとBIIのセクターを結ぶ新しい鉄道線路とスロープ(右)の工事は、1944年5月に完成し、1944年5月から7月初頭にかけ て、ハンガリー系ユダヤ人[122]が到着した[124]。レールはガス室周辺に直接つながっていた[121]。 |

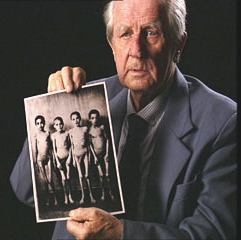

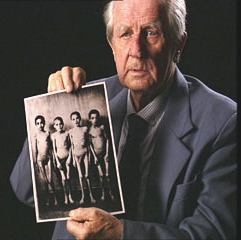

| Life for the inmates The day began at 4:30 am for the men (an hour later in winter), and earlier for the women, when the block supervisor sounded a gong and started beating inmates with sticks to make them wash and use the latrines quickly.[125] There were few latrines and there was a lack of clean water. Each washhouse had to service thousands of prisoners. In sectors BIa and BIb in Auschwitz II, two buildings containing latrines and washrooms were installed in 1943. These contained troughs for washing and 90 faucets; the toilet facilities were "sewage channels" covered by concrete with 58 holes for seating. There were three barracks with washing facilities or toilets to serve 16 residential barracks in BIIa, and six washrooms/latrines for 32 barracks in BIIb, BIIc, BIId, and BIIe.[126] Primo Levi described a 1944 Auschwitz III washroom:  Latrine in the men's quarantine camp, sector BIIa, Auschwitz II, 2003 It is badly lighted, full of draughts, with the brick floor covered by a layer of mud. The water is not drinkable; it has a revolting smell and often fails for many hours. The walls are covered by curious didactic frescoes: for example, there is the good Häftling [prisoner], portrayed stripped to the waist, about to diligently soap his sheared and rosy cranium, and the bad Häftling, with a strong Semitic nose and a greenish colour, bundled up in his ostentatiously stained clothes with a beret on his head, who cautiously dips a finger into the water of the washbasin. Under the first is written: "So bist du rein" (like this you are clean), and under the second, "So gehst du ein" (like this you come to a bad end); and lower down, in doubtful French but in Gothic script: "La propreté, c'est la santé" [cleanliness is health].[127] Prisoners received half a litre of coffee substitute or a herbal tea in the morning, but no food.[128] A second gong heralded roll call, when inmates lined up outside in rows of ten to be counted. No matter the weather, they had to wait for the SS to arrive for the count; how long they stood there depended on the officers' mood, and whether there had been escapes or other events attracting punishment.[129] Guards might force the prisoners to squat for an hour with their hands above their heads or hand out beatings or detention for infractions such as having a missing button or an improperly cleaned food bowl. The inmates were counted and re-counted.[130]  Auschwitz II brick barracks, sector BI, 2006; four prisoners slept in each partition, known as a buk.[131]  Auschwitz II wooden barracks, 2008 After roll call, to the sound of "Arbeitskommandos formieren" ("form work details"), prisoners walked to their place of work, five abreast, to begin a working day that was normally 11 hours long—longer in summer and shorter in winter.[132] A prison orchestra, such as the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz, was forced to play cheerful music as the workers left the camp. Kapos were responsible for the prisoners' behaviour while they worked, as was an SS escort. Much of the work took place outdoors at construction sites, gravel pits, and lumber yards. No rest periods were allowed. One prisoner was assigned to the latrines to measure the time the workers took to empty their bladders and bowels.[133] Lunch was three-quarters of a litre of watery soup at midday, reportedly foul-tasting, with meat in the soup four times a week and vegetables (mostly potatoes and rutabaga) three times. The evening meal was 300 grams of bread, often moldy, part of which the inmates were expected to keep for breakfast the next day, with a tablespoon of cheese or marmalade, or 25 grams of margarine or sausage. Prisoners engaged in hard labour were given extra rations.[134] A second roll call took place at seven in the evening, in the course of which prisoners might be hanged or flogged. If a prisoner was missing, the others had to remain standing until the absentee was found or the reason for the absence discovered, even if it took hours. On 6 July 1940, roll call lasted 19 hours because a Polish prisoner, Tadeusz Wiejowski, had escaped; following an escape in 1941, a group of prisoners was picked out from the escapee's barracks and sent to block 11 to be starved to death.[135] After roll call, prisoners retired to their blocks for the night and received their bread rations. Then they had some free time to use the washrooms and receive their mail, unless they were Jews: Jews were not allowed to receive mail. Curfew ("nighttime quiet") was marked by a gong at nine o'clock.[136] Inmates slept in long rows of brick or wooden bunks, or on the floor, lying in and on their clothes and shoes to prevent them from being stolen.[137] The wooden bunks had blankets and paper mattresses filled with wood shavings; in the brick barracks, inmates lay on straw.[138] According to Miklós Nyiszli: Eight hundred to a thousand people were crammed into the superimposed compartments of each barracks. Unable to stretch out completely, they slept there both lengthwise and crosswise, with one man's feet on another's head, neck, or chest. Stripped of all human dignity, they pushed and shoved and bit and kicked each other in an effort to get a few more inches' space on which to sleep a little more comfortably. For they did not have long to sleep.[139] Sunday was not a workday, but prisoners had to clean the barracks and take their weekly shower,[140] and were allowed to write (in German) to their families, although the SS censored the mail. Inmates who did not speak German would trade bread for help.[141] Observant Jews tried to keep track of the Hebrew calendar and Jewish holidays, including Shabbat, and the weekly Torah portion. No watches, calendars, or clocks were permitted in the camp. Only two Jewish calendars made in Auschwitz survived to the end of the war. Prisoners kept track of the days in other ways, such as obtaining information from newcomers.[142] Women's camp See also: Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz  Women in Auschwitz II, May 1944  Roll call in front of the kitchen building, Auschwitz II About 30 percent of the registered inmates were female.[143] The first mass transport of women, 999 non-Jewish German women from the Ravensbrück concentration camp, arrived on 26 March 1942. Classified as criminal, asocial and political, they were brought to Auschwitz as founder functionaries of the women's camp.[144] Rudolf Höss wrote of them: "It was easy to predict that these beasts would mistreat the women over whom they exercised power ... Spiritual suffering was completely alien to them."[145] They were given serial numbers 1–999.[46][g] The women's guard from Ravensbrück, Johanna Langefeld, became the first Auschwitz women's camp Lagerführerin.[144] A second mass transport of women, 999 Jews from Poprad, Slovakia, arrived on the same day. According to Danuta Czech, this was the first registered transport sent to Auschwitz by the Reich Security Head Office (RSHA) office IV B4, known as the Jewish Office, led by SS Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann.[46] (Office IV was the Gestapo.)[146] A third transport of 798 Jewish women from Bratislava, Slovakia, followed on 28 March.[46] Women were at first held in blocks 1–10 of Auschwitz I,[147] but from 6 August 1942,[148] 13,000 inmates were transferred to a new women's camp (Frauenkonzentrationslager or FKL) in Auschwitz II. This consisted at first of 15 brick and 15 wooden barracks in sector (Bauabschnitt) BIa; it was later extended into BIb,[149] and by October 1943 it held 32,066 women.[150] In 1943–1944, about 11,000 women were also housed in the Gypsy family camp, as were several thousand in the Theresienstadt family camp.[151] Conditions in the women's camp were so poor that when a group of male prisoners arrived to set up an infirmary in October 1942, their first task, according to researchers from the Auschwitz Museum, was to distinguish the corpses from the women who were still alive.[150] Gisella Perl, a Romanian-Jewish gynecologist and inmate of the women's camp, wrote in 1948: There was one latrine for thirty to thirty-two thousand women and we were permitted to use it only at certain hours of the day. We stood in line to get in to this tiny building, knee-deep in human excrement. As we all suffered from dysentry, we could barely wait until our turn came, and soiled our ragged clothes, which never came off our bodies, thus adding to the horror of our existence by the terrible smell that surrounded us like a cloud. The latrine consisted of a deep ditch with planks thrown across it at certain intervals. We squatted on those planks like birds perched on a telegraph wire, so close together that we could not help soiling one another.[152] Langefeld was succeeded as Lagerführerin in October 1942 by SS Oberaufseherin Maria Mandl, who developed a reputation for cruelty. Höss hired men to oversee the female supervisors, first SS Obersturmführer Paul Müller, then SS Hauptsturmführer Franz Hössler.[153] Mandl and Hössler were executed after the war. Sterilisation experiments were carried out in barracks 30 by a German gynecologist, Carl Clauberg, and another German doctor, Horst Schumann.[150] Medical experiments, block 10 Main articles: Block 10 and Nazi human experimentation  Block 10, Auschwitz I, where medical experiments were performed on women German doctors performed a variety of experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz. SS doctors tested the efficacy of X-rays as a sterilization device by administering large doses to female prisoners. Carl Clauberg injected chemicals into women's uteruses in an effort to glue them shut. Prisoners were infected with spotted fever for vaccination research and exposed to toxic substances to study the effects.[154] In one experiment, Bayer—then part of IG Farben—paid RM 150 each for 150 female inmates from Auschwitz (the camp had asked for RM 200 per woman), who were transferred to a Bayer facility to test an anesthetic. A Bayer employee wrote to Rudolf Höss: "The transport of 150 women arrived in good condition. However, we were unable to obtain conclusive results because they died during the experiments. We would kindly request that you send us another group of women to the same number and at the same price." The Bayer research was led at Auschwitz by Helmuth Vetter of Bayer/IG Farben, who was also an Auschwitz physician and SS captain, and by Auschwitz physicians Friedrich Entress and Eduard Wirths.[155]  Defendants during the Doctors' trial, Nuremberg, 1946–1947 The most infamous doctor at Auschwitz was Josef Mengele, the "Angel of Death", who worked in Auschwitz II from 30 May 1943, at first in the gypsy family camp.[156] Interested in performing research on identical twins, dwarfs, and those with hereditary disease, Mengele set up a kindergarten in barracks 29 and 31 for children he was experimenting on, and for all Romani children under six, where they were given better food rations.[157] From May 1944, he would select twins and dwarfs from among the new arrivals during "selection",[158] reportedly calling for twins with "Zwillinge heraus!" ("twins step forward!").[159] He and other doctors (the latter prisoners) would measure the twins' body parts, photograph them, and subject them to dental, sight and hearing tests, x-rays, blood tests, surgery, and blood transfusions between them.[160] Then he would have them killed and dissected.[158] Kurt Heissmeyer, another German doctor and SS officer, took 20 Polish Jewish children from Auschwitz to use in pseudoscientific experiments at the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg, where he injected them with the tuberculosis bacilli to test a cure for tuberculosis. In April 1945, the children were murdered by hanging to conceal the project.[161] A Jewish skeleton collection was obtained from among a pool of 115 Jewish inmates, chosen for their perceived stereotypical racial characteristics. Rudolf Brandt and Wolfram Sievers, general manager of the Ahnenerbe (a Nazi research institute), delivered the skeletons to the collection of the Anatomy Institute at the Reichsuniversität Straßburg in Alsace-Lorraine. The collection was sanctioned by Heinrich Himmler and under the direction of August Hirt. Ultimately 87 of the inmates were shipped to Natzweiler-Struthof and murdered in August 1943.[162] Brandt and Sievers were executed in 1948 after being convicted during the Doctors' trial, part of the Subsequent Nuremberg trials.[163] |

受刑者の生活 一日の始まりは、男性は午前4時30分(冬季は1時間遅くなる)、女性はそれよりも早く、ブロックの監督官がゴングを鳴らし、受刑者を棒で叩いて洗濯と便 所の使用を早くさせ始めた[125]。便所は少なく、清潔な水も不足していた。各洗面所は何千人もの囚人にサービスを提供しなければならなかった。アウ シュヴィッツⅡのセクターBIaとBIbでは、1943年に、便所と洗面所を含む2つの建物が設置された。これらには、洗浄用の桶と90の蛇口があった。 トイレ施設は、座席用の58の穴のあるコンクリートで覆われた「汚水溝」であった。BIIaには、16の居住用バラックに対応する洗浄施設やトイレを備え た3つのバラックがあり、BIIb、BIIc、BIId、BIIeには、32のバラックに対応する6つの洗面所・便所があった[126]。プリモ・レヴィ は、1944年のアウシュヴィッツIIIの洗面所について述べている:  2003年、アウシュヴィッツU、セクターBIIa、男子隔離収容所の便所。 レンガ造りの床は泥の層で覆われている。水は飲めず、ぞっとするような臭いがし、何時間も出ないこともしばしばである。例えば、腰まで丸裸にされた善良な ヘフトリング(囚人)が、刈り取られたバラ色の頭蓋を熱心に石鹸で洗おうとしているところや、セム系の強い鼻を持ち、緑がかった色をした悪質なヘフトリン グが、仰々しく汚れた服に身を包み、頭にはベレー帽をかぶり、洗面台の水に慎重に指を浸しているところなどが描かれている。その下にはこう書かれている: 「そしてその下には、怪しげなフランス語だがゴシック体でこう書かれている: 「La propreté, c'est la santé」(清潔は健康である)[127]。 囚人たちは朝、半リットルの代用コーヒーかハーブティーを受け取ったが、食事は与えられなかった[128]。どれくらいの時間そこに立っているかは、看守 の気分や、脱走や罰を受けるような出来事があったかどうかに左右された[129]。看守は、囚人たちに両手を頭の上に上げて1時間しゃがむことを強要した り、ボタンがなかったり、食器が掃除されていなかったりといった違反に対して、殴打や居残りを命じたりした。収容者は数えられ、数え直された[130]。  アウシュヴィッツUレンガ造りのバラック、セクターBI、2006年、ブクとして知られている各仕切りに4名の囚人が寝ていた[131]。  アウシュヴィッツU木造兵舎、2008年 点呼の後、「Arbeitskommandos formieren」(「作業の詳細を編成せよ」)の音とともに、囚人たちは5人並んで自分の仕事場まで歩き、通常夏場は11時間、冬場はそれより短い労 働時間が始まった[132]。アウシュヴィッツの女性オーケストラのような監獄オーケストラは、労働者たちが収容所を出るときに陽気な音楽を演奏すること を強制された。カポは、SSの護衛と同様に、作業中の囚人の行動に責任を負っていた。労働の多くは、建設現場、砂利採取場、材木置き場などの屋外で行われ た。休憩時間は与えられなかった。一人の囚人が便所に割り当てられ、労働者が膀胱と腸を空にするのにかかる時間を測定した[133]。 昼食は正午に4分の3リットルの水っぽいスープで、不味かったと伝えられており、スープの中に肉が週に4回、野菜(主にジャガイモとルタバガ)が3回入っ ていた。夕方の食事は300グラムのパンで、カビが生えていることも多く、その一部は翌日の朝食用に取っておくことになっており、チーズやマーマレードが 大さじ1杯、マーガリンやソーセージが25グラム入っていた。重労働に従事する囚人には、余分の配給が与えられた[134]。 夕方7時に2回目の点呼が行われ、その間に囚人は絞首刑や鞭打ち刑にされることがあった。囚人が行方不明になった場合、他の囚人は、何時間かかっても、欠 席者が見つかるまで、あるいは欠席の理由が判明するまで、立ったままでいなければならなかった。1941年の脱走事件では、脱走した囚人のバラックから囚 人グループが選ばれ、飢え死にさせるために11ブロックに送られた[135]。その後、ユダヤ人でない限り、洗面所を使ったり、郵便物を受け取ったりする 自由な時間があった: ユダヤ人は郵便物を受け取ることが許されなかった。夜間外出禁止令(「夜の静寂」)は9時のゴングで告げられた[136]。被収容者は、レンガや木製の寝 台の長い列、または床に横たわり、盗まれないように衣服や靴の中や上に寝た[137]。 木製の寝台には毛布と木屑を詰めた紙のマットレスがあり、レンガ造りのバラックでは、被収容者は藁の上に寝た[138]: ミクローシュ・ニシズリによると、各兵舎の重なり合った区画に800人から1000人が詰め込まれた。完全に体を伸ばすことができず、縦にも横にも、一人 の男の足が他の男の頭、首、胸にかかるようにして寝た。人間としての尊厳を奪われた彼らは、あと数センチでも快適に眠れるスペースを確保しようと、押し合 いへし合い、噛み合い、蹴り合った。彼らに眠る時間は長くはなかったからだ[139]。 日曜日は労働日ではなかったが、囚人たちはバラックを掃除し、週に一度のシャワーを浴びなければならなかった[140]。ドイツ語を話せない受刑者は、パ ンを交換し、助けを求めた[141]。観察熱心なユダヤ人は、安息日を含むヘブライ暦とユダヤ教の祝日、そして毎週の律法の部分を記録しようとした。収容 所では時計、カレンダー、時計は許可されなかった。アウシュヴィッツで作られた2つのユダヤ暦だけが、終戦まで生き残った。囚人たちは、新参者から情報を 得るなど、他の方法で日々を把握していた[142]。 女性収容所 以下も参照: アウシュヴィッツ女性管弦楽団  アウシュヴィッツUの女性たち、1944年5月  アウシュヴィッツU、厨房棟前での点呼 登録収容者の約30%は女性であった[143]。最初の女性の大量移送は、ラーヴェンスブリュック強制収容所からの999名の非ユダヤ系ドイツ人女性で、 1942年3月26日に到着した。犯罪者、非社会的、政治的と分類された彼女たちは、女性収容所の創設者機能としてアウシュヴィッツに連れてこられた [144]。ルドルフ・ヘスは彼女たちについてこう記している: 「これらの野獣が権力を行使する女性たちを虐待することは容易に予想できた。精神的苦痛は彼女たちにとってまったく異質なものであった」[145]。彼女 たちには1-999の通し番号が与えられた[46][g]。ラーヴェンスブリュックからの女性看守ヨハンナ・ランゲフェルドは、アウシュヴィッツ女性収容 所の最初の所長となった[144]。ダヌータ・チェコによると、これは、SS親衛隊親衛隊長アドルフ・アイヒマンが率いるユダヤ人事務所として知られてい た帝国保安本部(RSHA)IV B4事務所がアウシュヴィッツに送った最初の登録輸送であった[46](IV事務所はゲシュタポであった)[146]。3月28日には、スロヴァキアのブ ラチスラヴァから798名のユダヤ人女性の第三の輸送が続いた[46]。 女性は最初アウシュヴィッツIの1-10区画に収容されたが[147]、1942年8月6日から[148]、13,000名の収容者がアウシュヴィッツ IIの新しい女性収容所(Frauenkonzentrationslager、FKL)に移送された。この収容所は当初、セクター (Bauabschnitt)BIaの15棟のレンガ造りのバラックと15棟の木造のバラックで構成されていたが、後にBIbに拡張され[149]、 1943年10月までに32,066名の女性が収容された[150]。1943年から1944年にかけて、約11,000名の女性がジプシー家族収容所に も収容され、テレジエンシュタット家族収容所にも数千名が収容された[151]。 アウシュヴィッツ博物館の研究者によると、女性収容所の状況は非常に劣悪で、1942年10月に医務室を設置するために男性囚人のグループが到着したと き、彼らの最初の仕事は、まだ生きている女性たちと死体を区別することであった[150]。 ルーマニア系ユダヤ人の婦人科医で女性収容所の収容者であったジゼラ・ペールは、1948年にこう書いている: 3万から3万2千人の女性たちのために便所が一つあり、私たちは一日のうち特定の時間帯にだけその便所を使うことが許されていました。私たちはこの小さな 建物に入るために列を作り、膝まで人糞に浸かった。私たちは皆、赤痢を患っていたので、順番が来るまで待つのがやっとで、ボロボロの服を汚した。便所は深 い溝で、一定の間隔で板が投げられていた。私たちは、電信線にとまった鳥のように、その板の上にしゃがみこみ、互いに汚さずにはいられないほど接近してい た[152]。 ランゲフェルドは、1942年10月に、残酷なことで評判になったSS親衛隊長マリア・マンドルに親衛隊長の座を譲った。ヘスは女性監督官を監督するため に男性を雇い、最初はSS親衛隊長のパウル・ミュラー(Paul Müller)、次にSS親衛隊長のフランツ・ヘスラー(Franz Hössler)となった[153]。不妊化実験は、ドイツ人婦人科医カール・クラウベルクともう一人のドイツ人医師ホルスト・シューマンによって30兵 舎で行われた[150]。 医学実験、第10ブロック 主な記事 ブロック10とナチスの人体実験  女性に対する医学実験が行われたアウシュヴィッツIの10ブロック ドイツの医師たちは、アウシュヴィッツで囚人に対してさまざまな実験を行った。SSの医師たちは、女性囚人に大量のX線を投与して、殺菌装置としてのX線 の有効性をテストした。カール・クラウベルクは、女性の子宮に化学薬品を注入し、子宮を接着剤で閉じさせようとした。ある実験では、バイエル(当時はIG ファルベンの一部)がアウシュヴィッツの女性収容者150名に150リンギットをそれぞれ支払い(収容所は女性一人当たり200リンギットを要求してい た)、彼女たちは麻酔薬のテストのためにバイエルの施設に移送された[154]。バイエルの従業員がルドルフ・ヘスに手紙を書いた: 「150名の女性の移送は良好な状態で到着しました。しかし、実験中に死亡したため、決定的な結果を得ることができませんでした。同じ人数、同じ値段で、 別の女性グループを送ってくれるようお願いします」。バイエルの研究は、アウシュヴィッツでは、アウシュヴィッツの医師でありSS隊長でもあったバイエル /IGファルベンのヘルムート・ヴェッターと、アウシュヴィッツの医師フリードリヒ・エントレスとエドゥアルド・ヴィルトスによって主導されていた [155]。  医師裁判の被告(ニュルンベルク、1946-1947年) アウシュヴィッツでもっとも悪名高い医師は、「死の天使」ヨーゼフ・メンゲレであり、1943年5月30日からアウシュヴィッツUで、最初はジプシー家族 収容所で働いていた[156]。メンゲレは、一卵性双生児、小人、遺伝性疾患をもつ人々の研究を行うことに関心をもち、29号棟と31号棟に、自分が実験 している子供たちのための幼稚園を設立し、6歳未満のロマニ族の子供たち全員のために、よりよい食糧配給を与えた。 [157] 1944年5月から、メンゲレは「選別」の際に新入者の中から双子や小人を選び出し、"Zwillinge heraus! (彼と他の医師たち(後者の囚人たち)は、双子の身体の部位を測定し、写真を撮り、歯科検査、視力検査、聴力検査、X線検査、血液検査、手術、そして双子 の間の輸血を行った[160]。 [もう一人のドイツ人医師でありSS将校であったクルト・ハイスマイヤーは、20人のポーランド系ユダヤ人の子どもたちをアウシュヴィッツから連れて行 き、ハンブルク近郊のノイエンガンメ強制収容所での疑似科学実験に使用した。1945年4月、子供たちはこの計画を隠すために絞首刑で殺害された [161]。 ユダヤ人の骨格標本は、115人のユダヤ人収容者の中から、ステレオタイプ的な人種的特徴から選ばれたものであった。ルドルフ・ブラントとアーネンナーベ (ナチスの研究機関)の総支配人ヴォルフラム・シーヴァースは、アルザス・ロレーヌ地方のシュトラーセブルク帝国大学の解剖学研究所のコレクションに骨格 標本を提供した。この収集はハインリヒ・ヒムラーによって認可され、アウグスト・ヒルトの指揮の下で行われた。最終的に87名の収容者がナッツヴァイラー =シュトルートホーフに移送され、1943年8月に殺害された[162]。ブラントとシーヴァースは、ニュルンベルク裁判の一部である医師裁判で有罪判決 を受けた後、1948年に処刑された[163]。 |

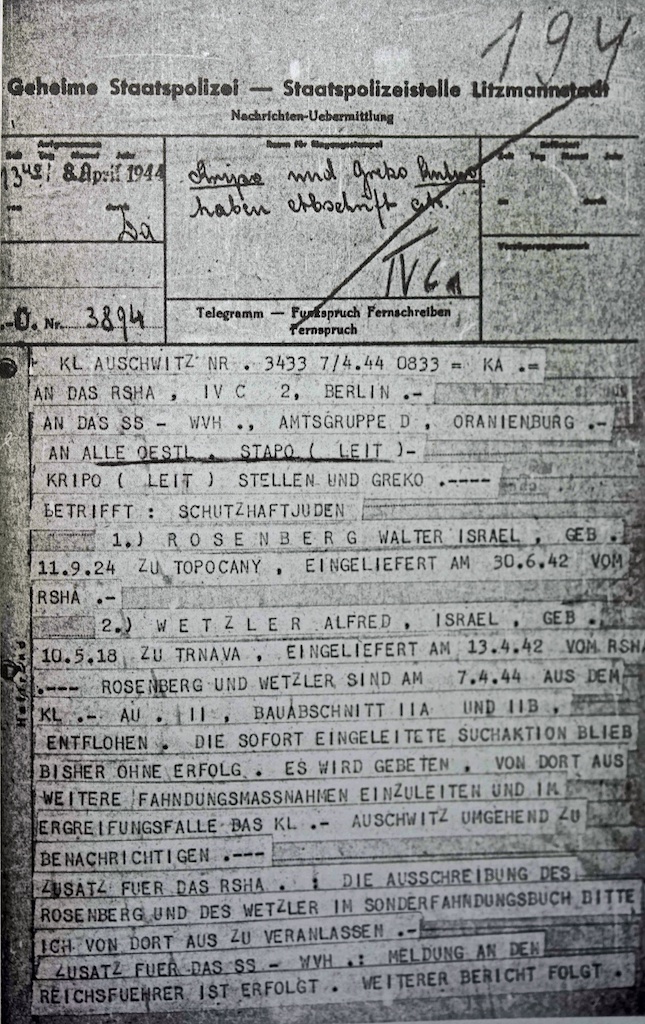

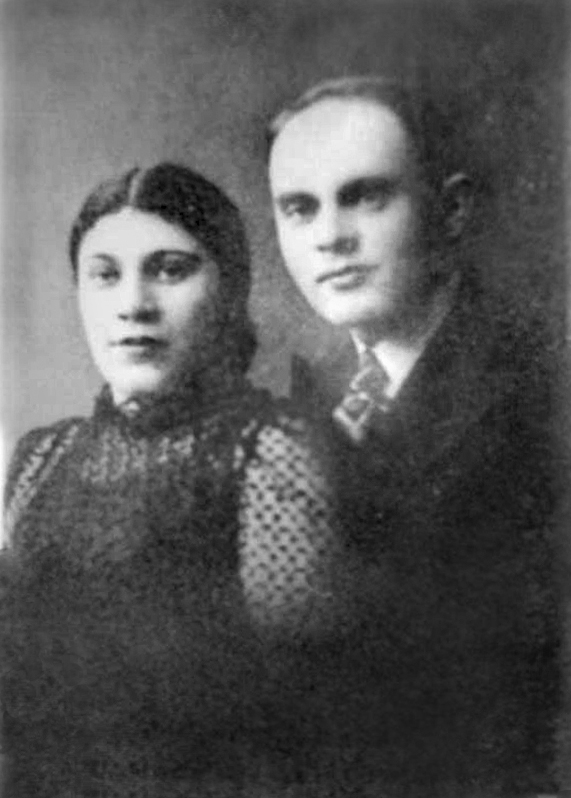

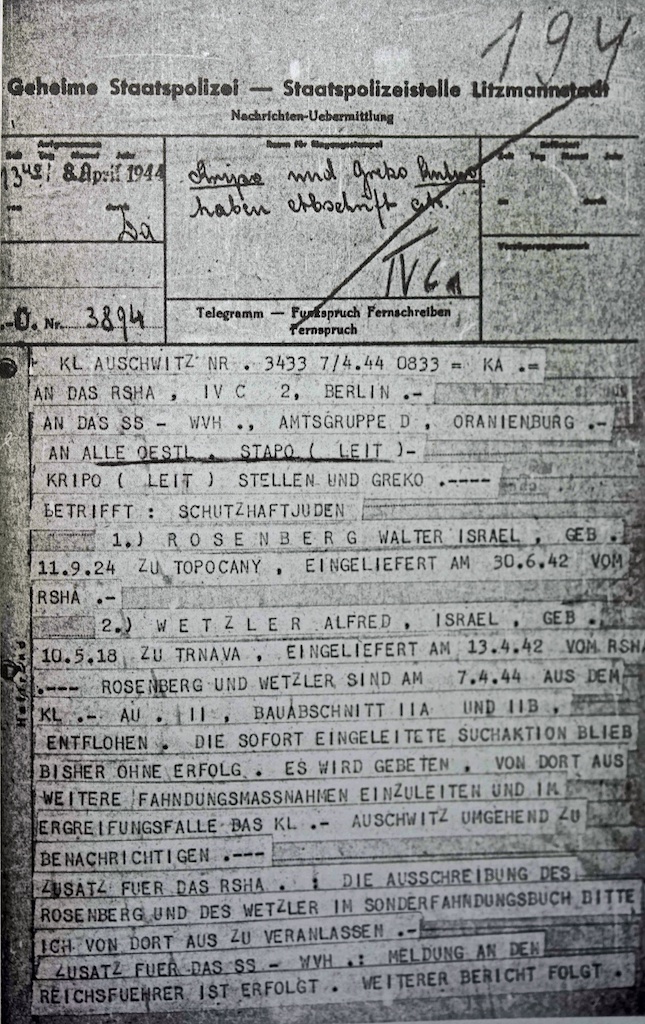

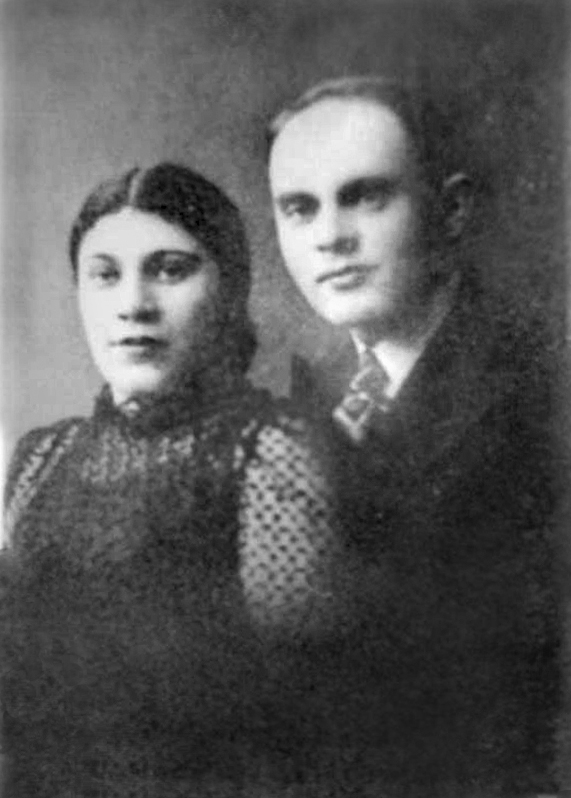

| Punishment, block 11 Main article: Block 11  Block 11 and (left) the "death wall", Auschwitz I, 2000 Prisoners could be beaten and killed by guards and kapos for the slightest infraction of the rules. Polish historian Irena Strzelecka writes that kapos were given nicknames that reflected their sadism: "Bloody", "Iron", "The Strangler", "The Boxer".[164] Based on the 275 extant reports of punishment in the Auschwitz archives, Strzelecka lists common infractions: returning a second time for food at mealtimes, removing one’s gold teeth to buy bread, breaking into the pigsty to steal the pigs' food, putting one’s hands into one’s pockets.[165] Flogging during rollcall was common. A flogging table called "the goat" immobilised prisoners' feet in a box, while they stretched themselves across the table. Prisoners had to count out the lashes—"25 mit besten Dank habe ich erhalten" ("25 received with many thanks")— and if they got the figure wrong, the flogging resumed from the beginning.[165] Punishment by "the post" involved tying prisoners' hands behind their backs with chains attached to hooks, then raising the chains so the prisoners were left dangling by the wrists. If their shoulders were too damaged afterwards to work, they might be sent to the gas chamber. Prisoners were subjected to the post for helping a prisoner who had been beaten, and for picking up a cigarette butt.[166] To extract information from inmates, guards would force their heads onto the stove, and hold them there, burning their faces and eyes.[167] Known as block 13 until 1941, block 11 of Auschwitz I was the prison within the prison, reserved for inmates suspected of resistance activities.[168] Cell 22 in block 11 was a windowless standing cell (Stehbunker). Split into four sections, each section measured less than 1.0 m2 (11 sq ft) and held four prisoners, who entered it through a hatch near the floor. There was a 5 cm × 5 cm (2 in × 2 in) vent for air, covered by a perforated sheet. Strzelecka writes that prisoners might have to spend several nights in cell 22; Wiesław Kielar spent four weeks in it for breaking a pipe.[169] Several rooms in block 11 were deemed the Polizei-Ersatz-Gefängnis Myslowitz in Auschwitz (Auschwitz branch of the police station at Mysłowice).[170] There were also Sonderbehandlung cases ("special treatment") for Poles and others regarded as dangerous to Nazi Germany.[171] Death wall  The "death wall" showing the death-camp flag, the blue-and-white stripes with a red triangle signifying the Auschwitz uniform of political prisoners. The courtyard between blocks 10 and 11, known as the "death wall", served as an execution area, including for Poles in the General Government area who had been sentenced to death by a criminal court.[171] The first executions, by shooting inmates in the back of the head, took place at the death wall on 11 November 1941, Poland's National Independence Day. The 151 accused were led to the wall one at a time, stripped naked and with their hands tied behind their backs. Danuta Czech noted that a "clandestine Catholic mass" was said the following Sunday on the second floor of Block 4 in Auschwitz I, in a narrow space between bunks.[172] An estimated 4,500 Polish political prisoners were executed at the death wall, including members of the camp resistance. An additional 10,000 Poles were brought to the camp to be executed without being registered. About 1,000 Soviet prisoners of war died by execution, although this is a rough estimate. A Polish government-in-exile report stated that 11,274 prisoners and 6,314 prisoners of war had been executed.[173] Rudolf Höss wrote that "execution orders arrived in an unbroken stream".[170] According to SS officer Perry Broad, "[s]ome of these walking skeletons had spent months in the stinking cells, where not even animals would be kept, and they could barely manage to stand straight. And yet, at that last moment, many of them shouted 'Long live Poland', or 'Long live freedom'."[174] The dead included Colonel Jan Karcz and Major Edward Gött-Getyński, executed on 25 January 1943 with 51 others suspected of resistance activities. Józef Noji, the Polish long-distance runner, was executed on 15 February that year.[175] In October 1944, 200 Sonderkommando were executed for their part in the Sonderkommando revolt.[176] Family camps Gypsy family camp Main articles: Gypsy family camp (Auschwitz) and Romani genocide  Romani children, Mulfingen, Germany, 1943; the children were studied by Eva Justin and later sent to Auschwitz.[177] A separate camp for the Roma, the Zigeunerfamilienlager ("Gypsy family camp"), was set up in the BIIe sector of Auschwitz II-Birkenau in February 1943. For unknown reasons, they were not subject to selection and families were allowed to stay together. The first transport of German Roma arrived on 26 February that year. There had been a small number of Romani inmates before that; two Czech Romani prisoners, Ignatz and Frank Denhel, tried to escape in December 1942, the latter successfully, and a Polish Romani woman, Stefania Ciuron, arrived on 12 February 1943 and escaped in April.[178] Josef Mengele, the Holocaust's most infamous physician, worked in the gypsy family camp from 30 May 1943 when he began his work in Auschwitz.[156] The Auschwitz registry (Hauptbücher) shows that 20,946 Roma were registered prisoners,[179] and another 3,000 are thought to have entered unregistered.[180] On 22 March 1943, one transport of 1,700 Polish Sinti and Roma was gassed on arrival because of illness, as was a second group of 1,035 on 25 May 1943.[179] The SS tried to liquidate the camp on 16 May 1944, but the Roma fought them, armed with knives and iron pipes, and the SS retreated. Shortly after this, the SS removed nearly 2,908 from the family camp to work, and on 2 August 1944 gassed the other 2,897. Ten thousand remain unaccounted for.[181] Theresienstadt family camp Main article: Theresienstadt family camp The SS deported around 18,000 Jews to Auschwitz from the Theresienstadt ghetto in Terezin, Czechoslovakia,[182] beginning on 8 September 1943 with a transport of 2,293 male and 2,713 female prisoners.[183] Placed in sector BIIb as a "family camp", they were allowed to keep their belongings, wear their own clothes, and write letters to family; they did not have their hair shaved and were not subjected to selection.[182] Correspondence between Adolf Eichmann's office and the International Red Cross suggests that the Germans set up the camp to cast doubt on reports, in time for a planned Red Cross visit to Auschwitz, that mass murder was taking place there.[184] The women and girls were placed in odd-numbered barracks and the men and boys in even-numbered. An infirmary was set up in barracks 30 and 32, and barracks 31 became a school and kindergarten.[182] The somewhat better living conditions were nevertheless inadequate; 1,000 members of the family camp were dead within six months.[185] Two other groups of 2,491 and 2,473 Jews arrived from Theresienstadt in the family camp on 16 and 20 December 1943.[186] On 8 March 1944, 3,791 of the prisoners (men, women and children) were sent to the gas chambers; the men were taken to crematorium III and the women later to crematorium II.[187] Some of the groups were reported to have sung Hatikvah and the Czech national anthem on the way.[188] Before they were murdered, they had been asked to write postcards to relatives, postdated to 25–27 March. Several twins were held back for medical experiments.[189] The Czechoslovak government-in-exile initiated diplomatic manoeuvers to save the remaining Czech Jews after its representative in Bern received the Vrba-Wetzler report, written by two escaped prisoners, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, which warned that the remaining family-camp inmates would be gassed soon.[190] The BBC also became aware of the report; its German service broadcast news of the family-camp murders during its women's programme on 16 June 1944, warning: "All those responsible for such massacres from top downwards will be called to account."[191] The Red Cross visited Theresienstadt in June 1944 and were persuaded by the SS that no one was being deported from there.[184] The following month, about 2,000 women from the family camp were selected to be moved to other camps and 80 boys were moved to the men's camp; the remaining 7,000 were gassed between 10 and 12 July.[192] |

処罰, ブロック11 主な記事 ブロック11  ブロック11と「死の壁」(左)、アウシュヴィッツI、2000年 囚人は、わずかな規則違反でも看守やカポに殴られ、殺されることがあった。ポーランドの歴史家イレーナ・シュトレレッカは、カポにはサディズムを反映した あだ名がつけられていたと書いている: 「血まみれ」、「鉄」、「絞殺者」、「ボクサー」[164]。アウシュヴィッツの公文書館に現存する275の処罰報告書にもとづいて、ストレゼレッカは、 よくある違反行為を列挙している:食事時に食べ物を求めて二度目に戻ってくること、パンを買うために金歯をはずすこと、豚の餌を盗むために豚小屋に侵入す ること、ポケットに手を入れること[165]。 点呼の際の鞭打ちは一般的であった。ヤギ」と呼ばれる鞭打ち台は、囚人の足を箱の中に固定し、囚人はテーブルの上で体を伸ばした。囚人は鞭打ちの数を数え なければならず、「25 mit besten Dank habe ich erhalten」(「多くの感謝をもって25を受け取った」)と言い、その数を間違えると、鞭打ちは最初から再開された[165]。「ポスト」による処 罰は、フックに取り付けられた鎖で囚人の手を背中の後ろで縛り、その後、囚人が手首をぶら下げたままになるように鎖を上げるというものであった。その後、 肩が損傷して働けなくなれば、ガス室に送られることもあった。囚人は、殴られた囚人を助けたり、タバコの吸い殻を拾ったりしただけでポストに入れられた [166]。 囚人から情報を引き出すために、看守は囚人の頭をストーブの上に無理やり押し付け、そこに押さえつけ、顔と目を焼いた[167]。 1941年までブロック13として知られていたアウシュヴィッツIのブロック11は、レジスタンス活動の疑いのある収容者のために用意された監獄内の監獄 であった[168]。4つの区画に分割され、各区画の面積は1.0㎡(11平方フィート)未満で、4名の囚人が収容され、床近くのハッチから入った。 5cm×5cmの通気口があり、穴のあいたシートで覆われていた。Strzeleckaは、囚人は22号房で数夜を過ごさなければならないかもしれないと 記している。ヴィエスワフ・キエラルはパイプを壊したために4週間を過ごした[169]。11号棟のいくつかの部屋は、アウシュヴィッツのPolizei -Ersatz-Gefängnis Myslowitz(Mysłowiceの警察署のアウシュヴィッツ支所)とみなされていた[170]。また、ナチス・ドイツにとって危険とみなされた ポーランド人やその他の人々のためのSonderbehandlungケース(「特別待遇」)もあった[171]。 死の壁  「死の壁」は、政治犯のアウシュヴィッツの制服を示す青と白のストライプと赤い三角形の収容所旗を示している。 死の壁」として知られる10ブロックと11ブロックの間の中庭は、刑事裁判で死刑を宣告された一般政府区域のポーランド人を含む処刑場として使われた [171]。後頭部を銃殺する最初の処刑は、ポーランドの国家独立記念日である1941年11月11日に死の壁で行われた。151人の被告人は一人ずつ壁 に導かれ、裸にされ、手を後ろに縛られた。ダヌータ・チェコは、次の日曜日、アウシュヴィッツIのブロック4の2階、寝台と寝台の間の狭いスペースで、 「秘密のカトリック・ミサ」が行われたと記している[172]。 収容所のレジスタンスのメンバーを含めて、推定4,500名のポーランドの政治犯が死の壁で処刑された。さらに10,000名のポーランド人が、登録され ることなく処刑されるために収容所に連行された。これは概算だが、約1,000人のソ連軍捕虜が処刑によって死亡した。ルドルフ・ヘス(Rudolf Höss)は、「処刑命令は絶え間なく届いていた」と書いている[173]。 SS将校ペリー・ブロード(Perry Broad)によると、「これらの歩く骸骨の中には、動物さえも飼われないような悪臭のする独房で何ヶ月も過ごし、まっすぐ立っているのがやっとの者もい た。それでも、最後の瞬間、彼らの多くが『ポーランド万歳』、『自由万歳』と叫んだ」[174]。死者の中には、ヤン・カルツ大佐とエドワード・ゲトゲチ ンスキ少佐も含まれており、1943年1月25日、レジスタンス活動の疑いのある他の51人とともに処刑された。1944年10月には、200人のゾン ダーコマンドがゾンダーコマンドの反乱に参加した罪で処刑された[176]。 家族収容所 ジプシー家族収容所 主な記事 ジプシー家族収容所(アウシュヴィッツ)、ロマニ虐殺  ロマニ族の子どもたち、1943年、ドイツ、ミュルフィンゲン、子どもたちはエヴァ・ユスティンによって研究され、後にアウシュヴィッツに送られた[177]。 1943年2月、アウシュヴィッツⅡ-ビルケナウのBⅡe地区に、ロマのための別個の収容所、ツィゲウナーファミリエンラーガー(「ジプシー家族収容 所」)が設置された。理由は不明だが、彼らは選別の対象とはされず、家族が一緒に滞在することが許された。同年2月26日、ドイツ系ロマの最初の移送が到 着した。それ以前にも、少数のロマ人収容者がいた。2人のチェコ人ロマ人囚人イグナーツとフランク・デンヘルは1942年12月に脱走を試み、後者は成功 し、ポーランド人ロマ人女性ステファニア・シウロンは1943年2月12日に到着し、4月に脱走した[178]。ホロコーストで最も悪名高い医師ヨーゼ フ・メンゲレは、アウシュヴィッツでの仕事を開始した1943年5月30日から、ジプシー家族収容所で働いていた[156]。 アウシュヴィッツの登録簿(Hauptbücher)によると、20,946人のロマが登録囚であり[179]、さらに3,000人が未登録のまま入所し たと考えられている[180]。 1943年3月22日、1,700人のポーランド人シンティとロマからなる1つの移送団は到着時に病気のためにガス処刑され、1943年5月25日の 1,035人からなる第2陣も同様であった[179]。SSは1944年5月16日に収容所を清算しようとしたが、ロマたちはナイフと鉄パイプで武装して 彼らと戦い、SSは退却した。この直後、SSは家族収容所から2,908人近くを労働に駆り出し、1944年8月2日に残りの2,897人をガス処刑し た。1万人が行方不明のままである[181]。 テレジエンシュタット家族収容所 主な記事 テレジエンシュタット家族収容所 SSは、1943年9月8日、男性2,293人、女性2,713人の移送を皮切りに、チェコスロバキアのテレジンのテレジエンシュタットのゲットーから約 18,000人のユダヤ人をアウシュヴィッツに移送した[182]。 [182]アドルフ・アイヒマンの事務所と国際赤十字との間の書簡は、赤十字のアウシュヴィッツ訪問の計画に合わせて、大量殺戮がアウシュヴィッツで行わ れているという報告に疑念を抱かせるために、ドイツ軍が収容所を設置したことを示唆している[184]。女性と女児は奇数番号のバラックに、男性と男児は 偶数番号のバラックに入れられた。診療所がバラック30と32に設置され、バラック31は学校と幼稚園になった[182]。それでも、いくらか良くなった 生活条件は不十分であり、家族収容所の1,000名のメンバーは6ヵ月以内に死亡した[185]。 1944年3月8日、3,791名の囚人(男性、女性、子ども)がガス室に送られ、男性はIII号火葬場に、女性はその後II号火葬場に運ばれた [187]。殺害される前に、彼らは親族に3月25-27日付の葉書を書くように求められていた[188]。チェコスロバキア亡命政府は、ベルンの代表 が、脱獄囚ルドルフ・ヴルバとアルフレッド・ヴェッツラーという二人の囚人によって書かれたヴルバ・ヴェッツラー報告書を受け取った後、残されたチェコ系 ユダヤ人を救うための外交工作を開始した。BBCもこの報告書を知っており、そのドイツ語放送は1944年6月16日の女性向け番組で家族収容所殺人事件 のニュースを放送し、警告を発した: 「赤十字は1944年6月にテレジエンシュタットを訪問し、そこからは誰も強制送還されていないとSSに説得された[184]。 翌月、家族収容所から約2,000名の女性が他の収容所に移されることが決定され、80名の少年が男子収容所に移された。 |