ゾンダーコマンド

Sonderkommando

☆

ゾンダーコマンドス(ドイツ語: [ˈzɔndɐkɔ↪Lm_2], special

unit)は、ドイツのナチスの死のキャンプの囚人から構成された作業部隊である。死刑収容所のゾンダーコマンドは、常に収容者であり、1938年から

1945年の間に様々なSS事務所のメンバーからアドホックに結成されたSSゾンダーコマンドとは無関係であった。

このドイツ語用語は、ナチスが最終解決の側面を指すのに使った曖昧で婉曲的な言葉の一部であった(例:Einsatzkommando、「配備部隊」)。

ゾンダーコマンドの隊員は殺人に直接参加することはなかった。その責任はSSに与えられており、ゾンダーコマンドの主な任務[3]は死体の処理であった

[4]。ほとんどの場合、彼らは収容所に到着するとすぐに入隊させられ、死の脅しのもとで強制的にその地位に就かされた。彼らは、どのような仕事をしなけ

ればならないのか、事前に知らされることはなかった。ゾンダーコマンドは、場所や環境によっては、Arbeitsjuden(仕事のためのユダヤ人)と婉

曲的に呼ばれることもあった。ビルケナウでは、ゾンダーコマンドは1943年までに400人にまで増え、1944年にハンガリー系ユダヤ人が強制送還され

たときには、殺人と絶滅の回数の増加に対応するために、その数は900人以上にまで膨れ上がった。

彼らは自分たちのバラックで眠り、ガス室に送られた人々が収容所に持ち込んだ食料、医薬品、タバコなどのさまざまな物品を保管し、使用することが許可され

ていた。普通の収容者とは違って、彼らは通常、看守による恣意的な殺戮の対象にはならなかった。その結果、ゾンダーコマンドのメンバーは他の囚人よりも長

く死の収容所で生き延びたが、戦争を生き延びた者はほとんどいなかった。

ゾンダーコマンドは、ナチスの大量殺人のやり方について詳しい知識を持っていたため、ゲヘイムニストレーガー(秘密の伝達者)とみなされた。そのため、彼

らは奴隷労働に使われる囚人たちから隔離されていた。SSの方針に従って、3ヶ月ごとに、死のキャンプの殺戮エリアで働くほとんどすべてのゾンダーコマン

ドは自らガス処刑され、秘密保持のために新入りと入れ替わった。通常、新しいゾンダーコマンド部隊の仕事は、前任者の死体を処理することであった。調査に

よると、死の収容所の最初のゾンダーコマンドが創設されてから収容所が清算されるまで、ゾンダーコマンドはおよそ 14世代にわたった。History

of the Auschwitz Sonderkommando

(2022)』(アウシュヴィッツ博物館刊)によれば、アウシュヴィッツ・ビルケナウのゾンダーコマンドによる再度の絶滅は神話であり、そのような絶滅は

一度しか行われていない。

Los Sonderkommandos

(en español "comandos especiales") fueron unidades de trabajo formadas

por prisioneros de los nazis. Estos, normalmente judíos, fueron

obligados1 a colaborar en diversas actividades en los campos de

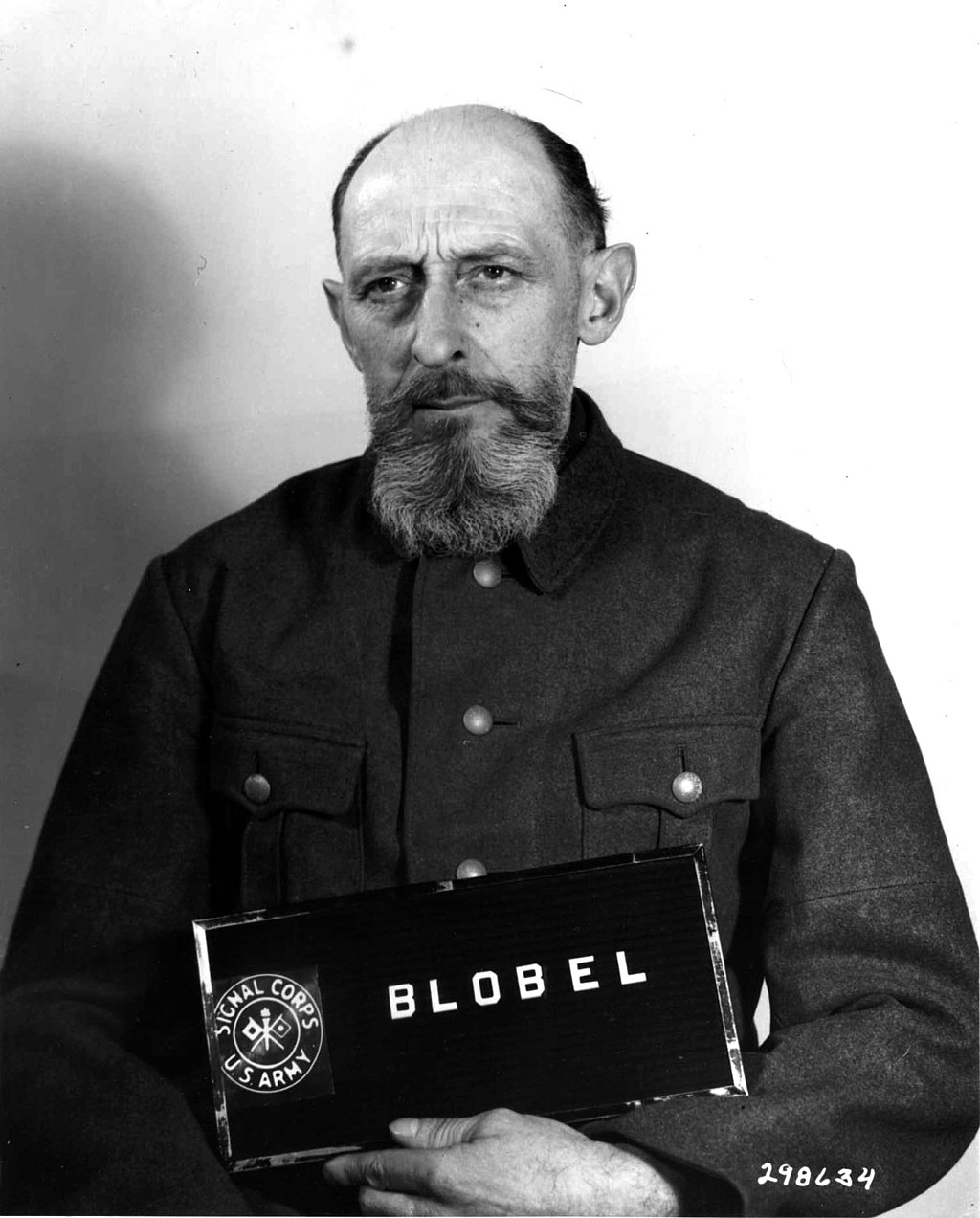

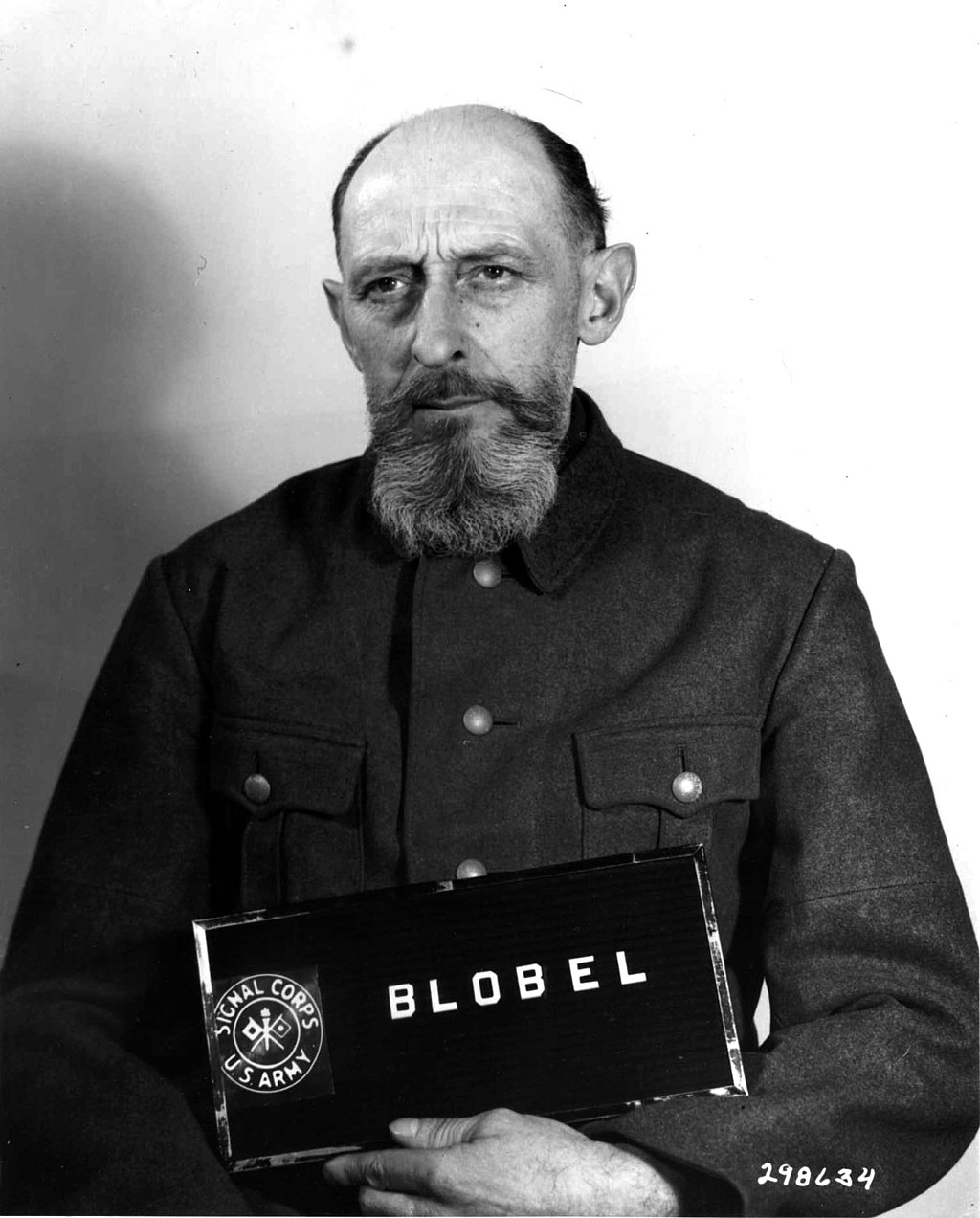

exterminio durante el Holocausto.23 El Sonderkommando 1005 fue el encargado de cumplir la Aktion 1005, una orden llevada a cabo entre junio de 1942 y finales de 1944 por el coronel de las SS Paul Blobel, para incinerar y deshacerse de los cadáveres que habían sido enterrados en fosas comunes.45 |

ゾンダーコマンドス(英語では

"特殊コマンドス")は、ナチスの囚人で構成された労働部隊であった。彼らはたいていユダヤ人であり、ホロコーストの間、絶滅収容所でのさまざまな活動を

強制的に手伝わされた23。 ゾンダーコマンド1005は、パウル・ブロベルSS大佐が1942年6月から1944年末にかけて実行した、集団墓地に埋められた死体を焼却処分するとい う命令、アクティオン1005の実行を担当していた45。 |

| Trabajadores de los

campos[editar] Los miembros del Sonderkommando no participaban directamente en el asesinato. Esa era una responsabilidad reservada a las SS. El principal deber de los sonderkommandos6 era hacerse cargo de los cadáveres.7 En la mayoría de los casos, eran reclutados inmediatamente después de llegar al campo y eran obligados a ocupar el puesto bajo amenaza de muerte. No se les avisaba previamente de las tareas que iban a realizar. Para su horror, a veces los incluidos en un "sonderkommando" descubrían miembros de su propia familia en medio de los cadáveres.8 No tenían forma de negarse o renunciar. Para evitar la labor solo podían suicidarse.9 En algunos lugares y ambientes, los sonderkommandos podían ser llamados eufemísticamente como Arbeitsjuden ("judíos para trabajar").10 Otras veces, los Sonderkommandos eran llamados Hilflinge ("ayudadores").11 En Auschwitz-Birkenau el Sonderkommando estuvo formado por 400 personas en 1943, y cuando los judíos húngaros fueron deportados allí en 1944, su número aumentó a más de 900 para el aumento de las rondas de asesinatos del exterminio.12 Como los alemanes necesitaban a los Sonderkommandos, se les concedió condiciones de vida mucho menos miserables que a otros reclusos: dormían en sus propios barracones y se les permitía mantener y usar diversos productos como alimentos, medicinas y cigarrillos traídos al campamento por aquellos que fueron enviados a las cámaras de gas. A diferencia de los reclusos comunes, normalmente no estaban sujetos a asesinatos arbitrarios y aleatorios por parte de los guardias. Su sustento y utilidad estaban determinados por la eficiencia con la que podían mantener funcionando la fábrica de muerte nazi.13 Como tenían un profundo conocimiento de la política de asesinatos en masa de los nazis, los Sonderkommando fueron considerados Geheimnisträger, portadores de secretos, y como tales, fueron mantenidos en aislamiento, lejos de los prisioneros utilizados como esclavos.14 Cada tres meses, de acuerdo con la política de las SS, casi todos los Sonderkommandos que trabajan en las áreas de exterminio de los campos de exterminio eran gaseados y reemplazados por recién llegados para garantizar el secreto. Sin embargo, algunos reclusos sobrevivieron hasta por un año o más porque poseían habilidades especializadas.151 Por lo general, la tarea de una nueva unidad Sonderkommando sería deshacerse de los cadáveres de sus predecesores. Una investigación ha calculado que desde la creación del primer Sonderkommando del campo de exterminio de Auschwitz hasta la liquidación del campo, hubo aproximadamente 14 generaciones de Sonderkommandos.16 |

収容所労働者[編集] ゾンダーコマンドのメンバーは殺戮に直接関与しなかった。それはSSに与えられた責任であった。ゾンダーコマンド6の主な任務は、死体の世話であった7。 ほとんどの場合、彼らは収容所に到着するとすぐにリクルートされ、死の脅しのもとでその職に就くことを余儀なくされた。ほとんどの場合、彼らは収容所に到 着するとすぐに採用され、死の脅しのもとで強制的にその職に就かされた。彼らは、自分が行うべき仕事について事前に何も知らされていなかった。恐ろしいこ とに、「ゾンダーコマンド」に入れられた者が、死体の中に自分の家族のメンバーを発見することもあった8。仕事を避けるためには、自殺するしかなかった 9。 アウシュヴィッツ・ビルケナウでは、ゾンダーコマンドは1943年には400人であったが、1944年にハンガリー系ユダヤ人が強制送還されると、その数 は900人以上に増加した。 ドイツ軍がゾンダーコマンドを必要としていたため、彼らは他の収容者よりもはるかに悲惨な生活条件を与えられていなかった。彼らは自分たちのバラックで眠 り、ガス室に送られた人々が収容所に持ち込んだ食糧、医薬品、タバコなどのさまざまな製品を保管し、使用することが許されていた。一般の収容者とは異な り、彼らは通常、看守による恣意的で無作為な殺戮の対象にはならなかった。彼らの生計と有用性は、ナチスの死の工場をいかに効率よく稼動させるかによって 決定されたのである13。 ナチスの大量殺戮政策を熟知していたため、ゾンダーコマンドは ゲヘイムニストレーガー(秘密の伝達者)とみなされ、奴隷として使われる囚人たちから隔離された14。親衛隊の方針に従って、3ヶ月ごとに、死のキャンプ の絶滅地区で働くゾンダーコマンドのほぼ全員がガス処刑され、秘密保持のために新入りと入れ替わった。151通常、新しいゾンダーコマンド部隊の任務は、 前任者の死体を処理することであった。調査によると、アウシュヴィッツ死の収容所の最初のゾンダーコマンドが創設されてから、収容所が清算されるまで、お よそ14世代のゾンダーコマンドが存在したと計算されている16。 |

| Testimonio de testigos

presenciales Entre 1943 y 1944, algunos miembros de los "Sonderkommando" pudieron obtener equipo para la escritura y registrar algunas de sus experiencias y lo que habían presenciado en Birkenau. Estos documentos fueron enterrados en los terrenos de los crematorios y recuperados después de la guerra. Se ha identificado a cinco hombres como los autores de estos manuscritos: Zalman Gradowski, Zalman Lewental, Leib Langfus, Chaim Herman y Marcel Nadjary. Los tres primeros escribieron en yiddish, Herman en francés y Nadjary en griego. La mayoría de estos manuscritos están guardados en el archivo del Museo Estatal de Auschwitz-Birkenau, aparte están la carta de Herman (guardada en los archivos del Amicale des déportés d’Auschwitz-Birkenau) y los textos de Gradowski, uno de los cuales está en el Museo Médico Militar de San Petersburgo y otro en Yad Vashem.1718 Algunos de los manuscritos fueron publicados en la obra «Los Rollos de Auschwitz» («The Scrolls of Auschwitz»), editada por Ber Mark.19 El Museo de Auschwitz publicó algunos otros en la obra «En medio de una pesadilla del crimen» («Amidst a Nightmare of Crime»).20 «Los Rollos de Auschwitz» han sido reconocidos como algunos de los testimonios más importantes que se han escrito sobre el Holocausto, ya que incluyen relatos de testigos oculares contemporáneos del funcionamiento de las cámaras de gas en Birkenau.18 La siguiente nota, que fue encontrada enterrada en un crematorio de Auschwitz, fue escrita por Zalman Gradowski, un miembro del Sonderkommando que murió en la revuelta del Crematorio IV el 7 de octubre de 1944: Querido buscador de estas notas, tengo una petición suya, que es, de hecho, el objetivo práctico de mi escritura ... que mis días del Infierno, que mi mañana desesperado encuentre un propósito en el futuro. Estoy transmitiendo solo una parte de lo que sucedió en el Infierno de Birkenau-Auschwitz. Te darás cuenta de cómo era la realidad ... De todo esto tendrás una imagen de cómo pereció nuestra gente.21 Cerca de 110 miembros del Sonderkommando sobrevivieron en Auschwitz-Birkenau, la mayoría de los cuales eran judíos polacos.22 |

目撃証言[編集] 1943年から1944年にかけて、「ゾンダーコマンド」の一部のメンバーは筆記用具を手に入れることができ、ビルケナウでの体験や目撃したことのいくつ かを記録することができた。これらの文書は火葬場の敷地に埋葬され、戦後に回収された。これらの原稿の著者として、5人の男性が特定されている: ザルマン・グラドフスキ、ザルマン・レヴェンタル、ライプ・ラングフス、チャイム・ハーマン、マルセル・ナジャリーである。最初の3人はイディッシュ語 で、ハーマンはフランス語で、ナジャリーはギリシャ語で書いた。これらの手稿のほとんどはアウシュヴィッツ・ビルケナウ州立博物館の書庫に保管されている が、ハーマンの手紙(Amicale des déportés d'Auschwitz-Birkenauの書庫に保管)とグラドフスキの文章は別である。 18写本の一部は、ベル・マークが編集した『アウシュヴィッツの写本』に掲載された19。他の一部は、アウシュヴィッツ博物館が『犯罪の悪夢の中で』とい う本に掲載した20。 「アウシュヴィッツ写本は、ホロコーストについて書かれたもっとも重要な証言のいくつかとして認められている。 アウシュヴィッツの火葬場で埋葬されているのが発見された次のメモは、1944年10月7日の第四火葬場の暴動で死亡したゾンダーコマンドのメンバー、ザ ルマン・グラドフスキが書いたものである: 親愛なるこのノートの求道者たちよ、私にはあなたからのお願いがある、それは事実、私の執筆の実際的な目的である......私の地獄の日々が、絶望的な 明日が、未来に目的を見出すことができますように。私はビルケナウ・アウシュビッツの地獄で起こったことのほんの一部しか伝えていない。あなたは現実がど のようなものであったかを理解するだろう.これらのことから、私たちの仲間がどのように死んでいったのかがわかるだろう21。 ゾンダーコマンドのメンバー約110人はアウシュヴィッツ・ビルケナウで生き残り、そのほとんどがポーランド系ユダヤ人であった22。 |

| Revueltas Operación Reinhard Hubo dos levantamientos conocidos de Sonderkommandos en los campos de exterminio construidos durante la Operación Reinhard. Treblinka La primera revuelta ocurrió en Treblinka el 2 de agosto de 1943 cuando 100 prisioneros lograron escapar del campo.23 Robaron entre 20 y 25 fusiles, 20 granadas de mano y varias pistolas del arsenal del campo con una llave duplicada. A las 3:45 p. m., 700 judíos lanzaron un ataque contra los guardias y trawnikis de las SS del campo que duró 30 minutos.24 Los edificios se incendiaron y se incendió un camión cisterna de combustible. Judíos armados atacaron la puerta principal, mientras que otros intentaron escalar la cerca. Sin embargo, los guardias bien armados concentraron su fuego en los prisioneros creando una matanza casi total. Aunque unos 200 judíos2524 escaparon del campo, la mitad de ellos fueron asesinados después de una persecución en automóviles y caballos porque no cortaron los cables del teléfono.26 Esto permitió a las SS solicitar refuerzos de cuatro ciudades diferentes y establecer bloqueos de carreteras.24 Partisanos de la Armia Krajowa (en polaco: Ejército Nacional) transportaron a algunos de los prisioneros escapados supervivientes a través del río27 mientras que otros fueron ayudados y alimentados por los aldeanos polacos.26 De los 700 Sonderkommando que participaron en la revuelta, 100 lograron salir del campo, y se sabe que alrededor de 70 sobrevivieron a la guerra.28 Entre ellos estuvieron Richard Glazar, Chil Rajchman, Jankiel Wiernik y Samuel Willenberg que fueron coautores de la obra «Memorias de Treblinka» («Treblinka memoirs»).29 Sobibor Dos meses después de Treblinka, se produjo un levantamiento similar en el campo de Sobibor I la noche del 14 de octubre de 1943.30 El Sonderkommando que formaba parte del Arbeitshäftlinge, el trabajo esclavo general requerido para operar el campo de exterminio (por ejemplo, trabajar en el centro de llegadas, procesar las posesiones de las víctimas, grupos de trabajo, etc.),31 liderado por el prisionero de guerra soviético y judío Alexander Pechersky de Minsk,32 mató a escondidas a 11 oficiales alemanes SS, venció a los guardias del campo y se apoderó del arsenal. 33 Escaparon 300 personas durante el levantamiento. En junio de 2019 se reportó que el último supervivente de los que habían escapado de Sobibor había muerto en Tel Aviv, Israel, a los 96 años.34 Auschwitz En octubre de 1944, un Sonderkommando se rebeló en el Crematorio IV en Auschwitz II. Durante meses, las jóvenes judías habían estado sacando pequeños paquetes de pólvora de Weichsel-Union-Metallwerke, una fábrica de municiones en una zona industrial entre el campo principal de Auschwitz I y Auschwitz II. Finalmente, la pólvora pasó por una cadena de contrabando a un Sonderkommando del Crematorio IV. El plan era destruir las cámaras de gas y los crematorios antes de lanzar un levantamiento.35 En la mañana del 7 de octubre de 1944, la resistencia del campo dio un aviso anticipado al Sonderkommando del Crematorio IV de que ellos serían asesinados. Los miembros del Sonderkommando atacaron a las SS y a los Kapos con dos ametralladoras, hachas, cuchillos y granadas. Los guardias sufrieron 15 bajas, de las cuales 12 eran heridos y 3 muertos.36 Algunos de los miembros de Sonderkommando escaparon del campo pero la mayoría fueron capturados de nuevo el mismo día.16 251 miembros del Sonderkommando murieron durante la lucha y, después del alzamiento, 200 se vieron obligados a desnudarse y tumbarse boca abajo antes de recibir un disparo en la parte posterior de la cabeza. Un total de 451 miembros del Sonderkommando fueron asesinados ese día.373839 Días después, cinco mujeres, cuatro de ellas judías, fueron acusadas de proporcionar explosivos al Sonderkommando y fueron asesinadas.40 Holocausto Shlomo Venezia Sonderkommando 1005 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonderkommando |

反乱[編集] ラインハルト作戦[編集] ラインハルト作戦中に建設された絶滅収容所では、ゾンダーコマンドの蜂起が2回知られている。 トレブリンカ[編集] 最初の反乱は1943年8月2日、トレブリンカで発生し、100名の囚人が収容所からの脱走に成功した23。彼らは合鍵を使って、収容所の武器庫から 20~25丁のライフル、20個の手りゅう弾、数丁のピストルを盗んだ。午後3時45分、700人のユダヤ人が収容所のSS看守とトラウニキに攻撃を開始 し、30分間続いた24。建物が放火され、燃料タンカーが放火された。武装したユダヤ人は正門を攻撃し、他のユダヤ人はフェンスを乗り越えようとした。し かし、武装した警備兵は囚人たちに集中砲火を浴びせ、ほぼ総崩れとなった。約200人のユダヤ人2524が収容所を脱出したが、その半数は、電話線を切断 しなかったために、車や馬での追跡の末に殺された26。このため、SSは4つの異なる都市から援軍を呼び寄せ、道路を封鎖することができた24。 アルミア・クラジョワ(ポーランド語:内地軍)のパルチザンは、生き残った脱走囚の何人かを川を渡って輸送し27、他の囚人たちはポーランドの村人に助け られ、食事を与えられた26。 反乱に参加した700人のゾンダーコマンドのうち、100人が収容所を出ることができ、約70人が戦争を生き延びたことが知られている28。その中には、 『トレブリンカ回想録』を共著したリヒャルト・グラザール、チル・ラジュマン、ヤンキエル・ヴィエルニク、サミュエル・ヴィレンベルクがいた29。 ソビボル[編集] トレブリンカから2ヵ月後の1943年10月14日夜、ソビボル第一収容所でも同様の蜂起が起こった30。ゾンダーコマンドは Arbeitshäftlingeの一部であり、死の収容所の運営に必要な一般奴隷労働者(到着センターでの労働、犠牲者の所持品の処理、労働グループな ど)であった31。 ミンスク出身のソ連人・ユダヤ人捕虜アレクサンドル・ペチェルスキーに率いられた31。33 この蜂起で300人が逃亡した。2019年6月、ソビボルから脱出した最後の生存者がイスラエルのテルアビブで96歳で死亡したと報告された34。 アウシュヴィッツ[編集] 1944年10月、アウシュヴィッツIIの第4火葬場でゾンダーコマンドが反乱を起こした。数ヶ月前から、若いユダヤ人女性たちが、アウシュヴィッツI収 容所とアウシュヴィッツII収容所の間の工業地帯にある軍需工場ヴァイヒゼル・ユニオン・メタルヴェルケから火薬の小包を持ち出していた。最終的に、火薬 は密輸チェーンを通じて、火葬場IVのゾンダーコマンドに密輸された。その計画は、蜂起を開始する前にガス室と火葬場を破壊することであった35。 1944年10月7日の朝、収容所のレジスタンスは、クレマトリウムIVのゾンダーコマンドに、彼らが殺されるであろうという事前警告を与えた。ゾンダー コマンドのメンバーは、2丁の機関銃、斧、ナイフ、手榴弾でSSとカポを攻撃した。251名のゾンダーコマンド隊員が戦闘中に殺され、蜂起後、200名 が、後頭部を撃たれる前に、裸にされ、うつ伏せにさせられた。その日、合計451人のゾンダーコマンドのメンバーが殺された373839。その数日後、5 人の女性(うち4人はユダヤ人)が、ゾンダーコマンドに爆発物を提供したとして告発され、殺された40。 ホロコースト シュロモ・ヴェネツィア ゾンダーコマンド10 https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonderkommando |

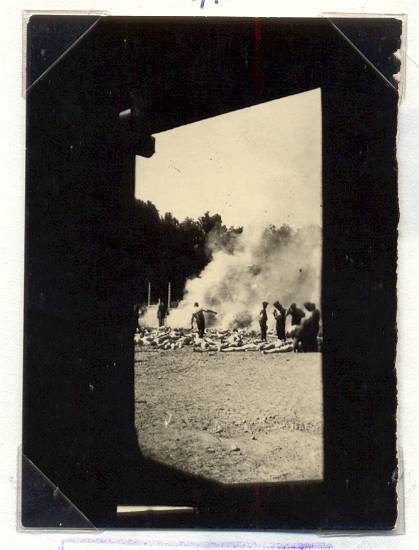

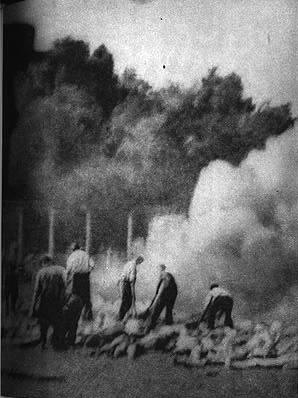

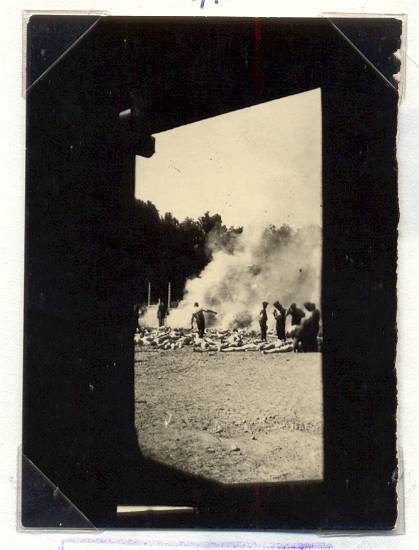

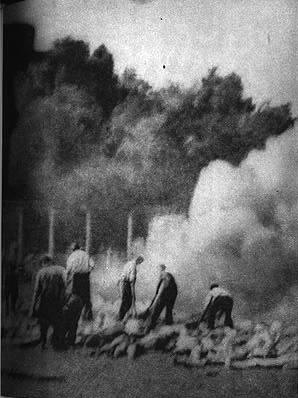

Fotografías del Sonderkommando en agosto de 1944 en Auschwitz-Birkenau por “Alex” (Alberto Errera)    Recortes de las fotografías de la parte superior https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonderkommando |

Fotografías del Sonderkommando en agosto de 1944 en Auschwitz-Birkenau por “Alex” (Alberto Errera)    ページ上部の写真の切り抜き https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonderkommando |

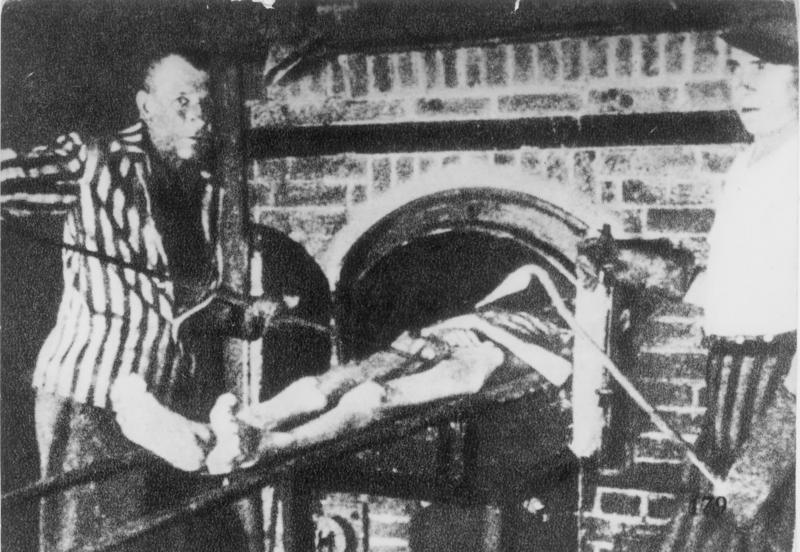

Crematorium at Dachau, May 1945 (photo taken after liberation) |

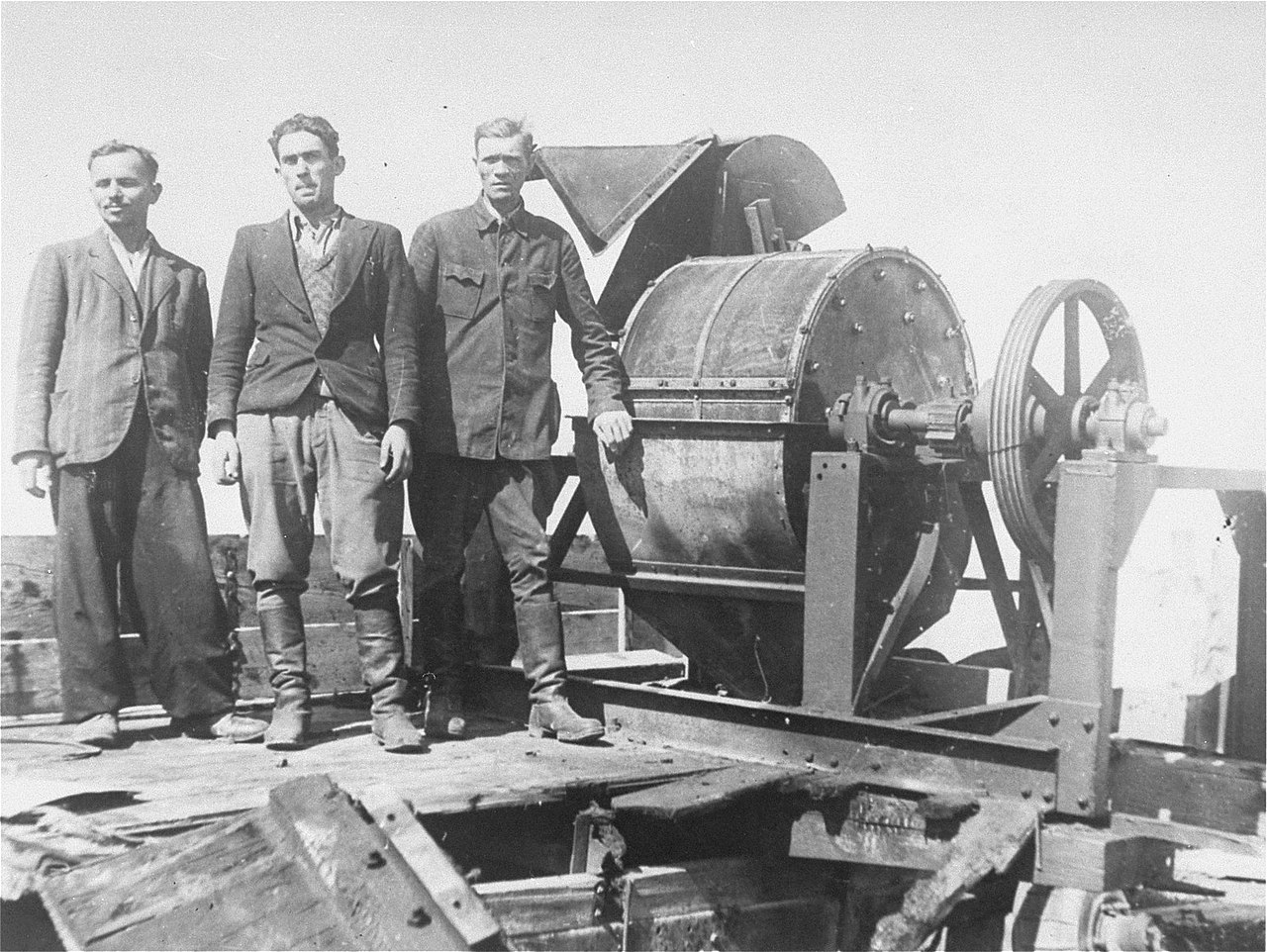

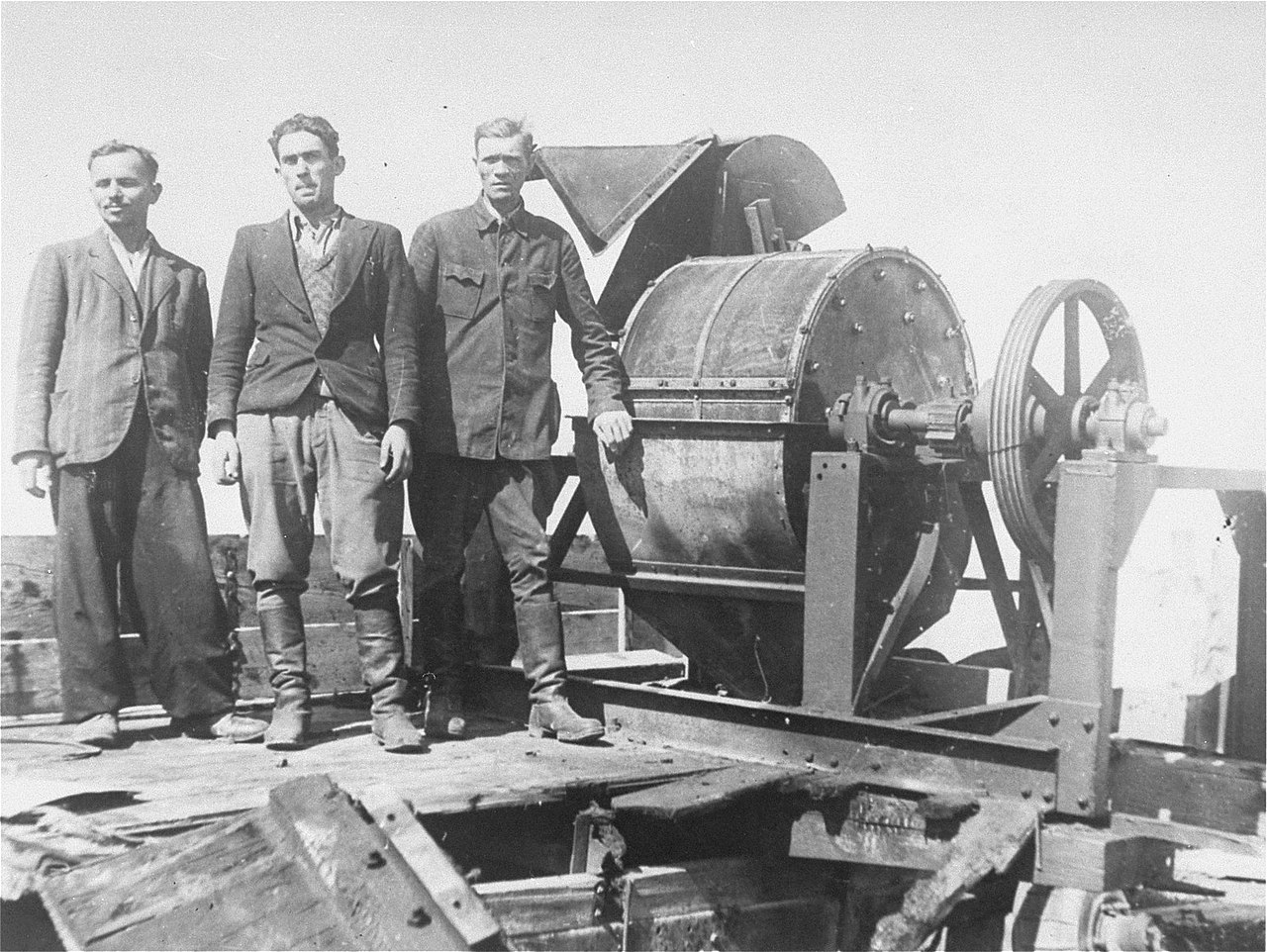

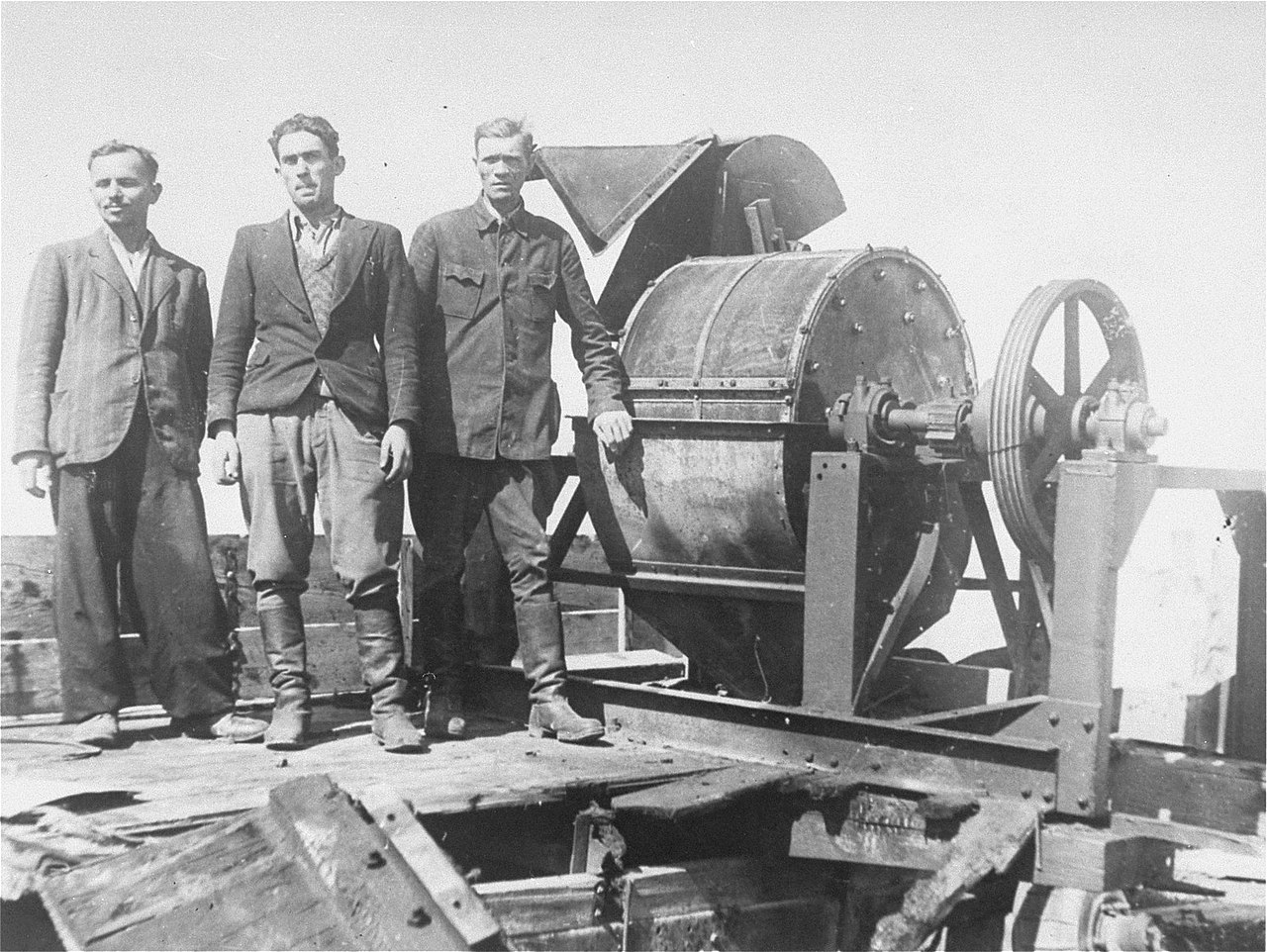

Jewish

prisoners forced to work for a Sonderkommando 1005 unit pose next to a

bone crushing machine in the Janowska concentration camp in a photo

taken by the Soviet war crimes investigation team called officially the

"Extraordinary State Commission for ascertaining and investigating

crimes perpetrated by the German–Fascist invaders and their

accomplices", August 1944. Pictured from left to right are: unknown,

David Manusevitz, and Moses Korn. This photograph was taken soon after

liberation for the Extraordinary Commission or the Red Army. Jewish

prisoners forced to work for a Sonderkommando 1005 unit pose next to a

bone crushing machine in the Janowska concentration camp in a photo

taken by the Soviet war crimes investigation team called officially the

"Extraordinary State Commission for ascertaining and investigating

crimes perpetrated by the German–Fascist invaders and their

accomplices", August 1944. Pictured from left to right are: unknown,

David Manusevitz, and Moses Korn. This photograph was taken soon after

liberation for the Extraordinary Commission or the Red Army. |

| Sonderkommandos Sonderkommandos (German: [ˈzɔndɐkɔˌmando], special unit) were work units made up of German Nazi death camp prisoners. They were composed of prisoners, usually Jews, who were forced, on threat of their own deaths, to aid with the disposal of gas chamber victims during the Holocaust.[1][2] The death-camp Sonderkommandos, who were always inmates, were unrelated to the SS-Sonderkommandos, which were ad hoc units formed from members of various SS offices between 1938 and 1945. The German term was part of the vague and euphemistic language which the Nazis used to refer to aspects of the Final Solution (e.g., Einsatzkommando, "deployment units"). |

ゾ

ンダーコマンドス ゾ ンダーコマンドス(ドイツ語: [ˈzɔndɐkɔ↪Lm_2], special unit)は、ドイツのナチスの死のキャンプの囚人から構成された作業部隊である。死刑収容所のゾンダーコマンドは、常に収容者であり、1938年から 1945年の間に様々なSS事務所のメンバーからアドホックに結成されたSSゾンダーコマンドとは無関係であった。 このドイツ語用語は、ナチスが最終解決の側面を指すのに使った曖昧で婉曲的な言葉の一部であった(例:Einsatzkommando、「配備部隊」)。 |

| Sonderkommando

members did not participate directly in killing; that responsibility

was reserved for the SS, while the Sonderkommandos' primary duty[3] was

disposing of the corpses.[4] In most cases, they were inducted

immediately upon arrival at the camp and forced into the position under

threat of death. They were not given any advance notice of the tasks

they would have to perform. To their horror, sometimes the

Sonderkommando inductees would discover members of their own family

amid the bodies.[5] They had no way to refuse or resign other than by

committing suicide.[6] In some places and environments, the

Sonderkommandos might be euphemistically called Arbeitsjuden (Jews for

work).[7] Other times, Sonderkommandos were called Hilflinge

(helpers).[8] At Birkenau the Sonderkommandos numbered up to 400 people

by 1943 and, when Hungarian Jews were deported there in 1944, their

numbers swelled to more than 900 persons, in order to keep up with the

increased rounds of murder and extermination.[9] Because the Germans needed the Sonderkommandos to remain physically able, they were granted much less squalid living conditions than other inmates: they slept in their own barracks and were allowed to keep and use various goods such as food, medicines and cigarettes brought into camp by those who were sent to the gas chambers. Unlike ordinary inmates, they were not normally subject to arbitrary killing by guards. Their livelihood and utility were determined by how efficiently they could keep the Nazi death factory running.[10] As a result, Sonderkommando members survived longer in the death camps than other prisoners – but few survived the war. As they had detailed knowledge of the Nazis' practice of mass murder, the Sonderkommando were considered Geheimnisträger – bearers of secrets. As such, they were held in isolation away from prisoners being used as slave labor (see SS Main Economic and Administrative Office).[11] Every three months, according to SS policy, almost all the Sonderkommandos working in the death camps' killing areas would be gassed themselves and replaced with new arrivals to ensure secrecy. However, some inmates survived for up to a year or more because they possessed specialist skills.[12] Usually, the task of a new Sonderkommando unit would be to dispose of the bodies of their predecessors. Research has calculated that from the creation of a death camp's first Sonderkommando to the liquidation of the camp, there were approximately 14 generations of Sonderkommando.[13][page needed] However, according to historian Igor Bartosik, author of Witnesses from the Pit of Hell. History of the Auschwitz Sonderkommando (2022) published by the Auschwitz Museum, the renewed exterminations of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Sonderkommandos are a myth, since such an extermination only took place there once.[14] |

ゾ

ンダーコマンドの隊員は殺人に直接参加することはなかった。その責任はSSに与えられており、ゾンダーコマンドの主な任務[3]は死体の処理であった

[4]。ほとんどの場合、彼らは収容所に到着するとすぐに入隊させられ、死の脅しのもとで強制的にその地位に就かされた。彼らは、どのような仕事をしなけ

ればならないのか、事前に知らされることはなかった。ゾンダーコマンドは、場所や環境によっては、Arbeitsjuden(仕事のためのユダヤ人)と婉

曲的に呼ばれることもあった[6]。

[8]ビルケナウでは、ゾンダーコマンドは1943年までに400人にまで増え、1944年にハンガリー系ユダヤ人が強制送還されたときには、殺人と絶滅

の回数の増加に対応するために、その数は900人以上にまで膨れ上がった。 彼らは自分たちのバラックで眠り、ガス室に送られた人々が収容所に持ち込んだ食料、医薬品、タバコなどのさまざまな物品を保管し、使用することが許可され ていた。普通の収容者とは違って、彼らは通常、看守による恣意的な殺戮の対象にはならなかった。その結果、ゾンダーコマンドのメンバーは他の囚人よりも長 く死の収容所で生き延びたが、戦争を生き延びた者はほとんどいなかった。 ゾンダーコマンドは、ナチスの大量殺人のやり方について詳しい知識を持っていたため、ゲヘイムニストレーガー(秘密の伝達者)とみなされた。そのため、彼 らは奴隷労働に使われる囚人たちから隔離されていた(SS主要経済管理局を参照)[11]。SSの方針に従って、3ヶ月ごとに、死のキャンプの殺戮エリア で働くほとんどすべてのゾンダーコマンドは自らガス処刑され、秘密保持のために新入りと入れ替わった。通常、新しいゾンダーコマンド部隊の仕事は、前任者 の死体を処理することであった。調査によると、死の収容所の最初のゾンダーコマンドが創設されてから収容所が清算されるまで、ゾンダーコマンドはおよそ 14世代にわたった[13][要出典]。History of the Auschwitz Sonderkommando (2022)』(アウシュヴィッツ博物館刊)によれば、アウシュヴィッツ・ビルケナウのゾンダーコマンドによる再度の絶滅は神話であり、そのような絶滅は 一度しか行われていない[14]。 |

| Eyewitness testimony Fewer than 20 of several thousand members of the Sonderkommandos are documented to have survived until liberation and to have testified about the events (although some sources claim more[15]). Among them were Henryk (Tauber) Fuchsbrunner, Filip Müller, Daniel Behnnamias, Dario Gabbai, Morris Venezia, Shlomo Venezia, Antonio Boldrin,[16] Alter Fajnzylberg, Samuel Willenberg, Abram Dragon, David Olère, Henryk Mandelbaum and Martin Gray. Another six or seven are confirmed to have survived, but they have not given witness (or at least, such testimony is not documented). Buried and hidden accounts by members of the Sonderkommando were later found at some camps.[17] Between 1943 and 1944, some members of the Birkenau Sonderkommando were able to obtain writing materials and record some of their experiences and what they had witnessed. These documents were buried in the grounds of the crematoria and recovered after the war. Five men have been identified as the authors of these manuscripts: Zalman Gradowski, Zalman Lewental, and Leib Langfus, who wrote in Yiddish; Chaim Herman, who wrote in French; and Marcel Nadjary, who wrote in Greek. Of the five, only Nadjary survived until liberation; Gradowski was killed in the revolt at Crematorium IV on 7 October 1944 (see below), or in retaliation for it; Lewental, Langfus, and Herman are believed to have been killed in November 1944.[18] Gradowski wrote the following note, found buried at an Auschwitz crematorium site: Dear finder of these notes, I have one request of you, which is, in fact, the practical objective for my writing ... that my days of Hell, that my hopeless tomorrow will find a purpose in the future. I am transmitting only a part of what happened in the Birkenau-Auschwitz Hell. You will realize what reality looked like ... From all this you will have a picture of how our people perished.[19] The manuscripts are kept primarily in the archive of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Memorial Museum. Exceptions are Herman's letter (kept in the archives of the Amicale des déportés d'Auschwitz-Birkenau) and Gradowski's texts, one of which is held in the Russian Museum of Military Medicine in St. Petersburg, and another in Yad Vashem, Israel.[20][21] Some of the manuscripts were published as The Scrolls of Auschwitz, edited by Ber Mark.[22] The Auschwitz Museum published some others as Amidst a Nightmare of Crime.[23] The Scrolls of Auschwitz have been recognised as some of the most important testimony to be written about the Holocaust, as they include contemporaneous eyewitness accounts of the workings of the gas chambers in Birkenau.[21] |

目撃証言 数千人のゾンダーコマンドスのメンバーのうち、解放まで生き残り、その出来事について証言しているのは20人以下であると記録されている(もっと多いとす る資料もあるが[15])。その中には、ヘンリク(タウバー)・フクスブルナー、フィリップ・ミュラー、ダニエル・ベーンナミアス、ダリオ・ガバイ、モリ ス・ヴェネツィア、シュロモ・ヴェネツィア、アントニオ・ボルドリン、[16]アルター・ファインツィルベルク、サミュエル・ウィレンベルク、アブラム・ ドラゴン、ダヴィッド・オレール、ヘンリク・マンデルバウム、マーティン・グレイがいた。さらに6、7人が生存していることが確認されているが、証言はし ていない(少なくともそのような証言は文書化されていない)。ゾンダーコマンドのメンバーによる埋もれた、隠された証言が後にいくつかの収容所で発見され た[17]。 1943年から1944年にかけて、ビルケナウのゾンダーコマンドの何人かのメンバーは、筆記用具を手に入れることができ、自分たちの経験の一部と目撃し たことを記録することができた。これらの文書は火葬場の敷地に埋葬され、戦後に回収された。これらの原稿の著者として、5人の男性が特定されている: イディッシュ語で書いたザルマン・グラドフスキ、ザルマン・レヴェンタル、ライプ・ラングフス、フランス語で書いたチャイム・ハーマン、ギリシャ語で書い たマルセル・ナジャリーである。グラドフスキは、1944年10月7日の第四火葬場での反乱(後述)かその報復で殺され、レヴェンタル、ラングフス、ハー マンは1944年11月に殺されたと考えられている[18]。グラドフスキは、アウシュヴィッツの火葬場で埋葬されているのを発見された次のメモを書いて いる: 私の地獄の日々、絶望的な明日が、未来に目的を見出すことができるように。私はビルケナウ・アウシュビッツの地獄で起こったことのほんの一部しか伝えてい ない。あなたは現実がどのようなものであったかを理解するでしょう.これらすべてから、私たちの人々がどのように滅んでいったのかがわかるでしょう」 [19]。 原稿は主にアウシュヴィッツ・ビルケナウ州立記念博物館のアーカイブに保管されている。例外は、ハーマンの手紙(Amicale des déportés d'Auschwitz-Birkenauのアーカイブに保管)とグラドフスキの文章で、そのうちの一つはサンクトペテルブルクのロシア軍事医学博物館 に、もう一つはイスラエルのヤド・ヴァシェムに保管されている[20][21]。原稿の一部は、ベル・マーク編集の『アウシュヴィッツの巻物』として出版 された[22]。 『アウシュヴィッツの写本』には、ビルケナウのガス室の仕組みについての同時代の目撃証言が含まれているため、ホロコーストについて書かれた最も重要な証 言の一部と認識されている[21]。 |

| Revolts Sonderkommando prisoners participated in uprisings on two occasions. Treblinka The first revolt occurred at Treblinka on 2 August 1943.[24] Prisoners used a duplicate key to open the camp arsenal and steal 20 to 25 rifles, 20 hand grenades, and several pistols. At 3:45 p.m., 700 Jews launched an attack on the camp's SS guards and trawnikis that lasted for 30 minutes.[25] They set buildings and a fuel tanker ablaze. Armed Jews attacked the main gate, while others attempted to climb the fence. About 200 Jews escaped from the camp,[a][26][25] but the well-armed guards slaughtered hundreds of others.[27] They phoned for SS reinforcements from four towns, and these set up roadblocks[25] and pursued escapees in cars and on horses. Only about 100 prisoners ultimately escaped. Partisans of the Armia Krajowa (Polish: Home Army) transported some of the surviving escaped prisoners across the Bug River,[28] while others were helped and fed by Polish villagers.[27] Of the 700 Sonderkommando who took part in the revolt, 100 managed to survive and escape from the camp, and around 70 of these are known to have survived the war.[29] These include Richard Glazar, Chil Rajchman, Jankiel Wiernik, and Samuel Willenberg, who co-wrote the Treblinka Memoirs.[30] Auschwitz In October 1944, the Sonderkommando rebelled at Crematorium IV in Auschwitz II. For months, young Jewish women workers had been smuggling small packets of gunpowder out of the Weichsel-Union-Metallwerke, a munitions factory in an industrial area between the main camp of Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II. The gunpowder was passed along a smuggling chain to Sonderkommando in Crematorium IV. The plan was to destroy the gas chambers and crematoria and launch an uprising.[31] However, on the morning of 7 October 1944, the camp resistance warned the Sonderkommando in Crematorium IV that they were to be killed, and the Sonderkommando attacked the SS and Kapos with two machine guns, axes, knives, and grenades, killing three and injuring about a dozen more.[32] Some of the Sonderkommando escaped from the camp, but most were recaptured later the same day.[13] Of those who did not die during the uprising itself, 200 were later forced to strip and lie face down before being shot in the back of the head. A total of 451 Sonderkommandos were killed that day.[33][34][35] |

反乱 ゾンダーコマンドの囚人たちは2度、反乱に参加した。 トレブリンカ 最初の反乱は1943年8月2日にトレブリンカで起こった[24]。囚人たちは合鍵を使って収容所の武器庫を開け、20~25丁のライフル、20個の手榴 弾、数丁のピストルを盗んだ。午後3時45分、700人のユダヤ人が収容所のSS看守とトラウニキに対する攻撃を開始し、30分間続いた[25]。武装し たユダヤ人は正門を攻撃し、他のユダヤ人はフェンスをよじ登ろうとした。約200人のユダヤ人が収容所から脱出したが[a][26][25]、よく武装し た看守は他の数百人を虐殺した[27]。 彼らは4つの町からSSの増援を要請し、これらの増援は道路封鎖[25]を設置し、脱走者を車や馬で追跡した。最終的に脱走したのは約100人の囚人だけ であった。 アルミア・クラジョワ(ポーランド語:内地軍)のパルチザンは、生き残った脱走囚の何人かをブグ川を渡って輸送し[28]、他の囚人はポーランドの村人に 助けられ、食事を与えられた。 [27] 反乱に参加した700名のゾンダーコマンドのうち、100名が収容所から脱走して生き延びることに成功し、そのうち約70名が戦争を生き延びたことが知ら れている[29]。 その中には、リヒャルト・グラザール、チル・ラージマン、ヤンキエル・ヴィエルニク、そして『トレブリンカ回想録』を共同執筆したサミュエル・ヴィレンベ ルクが含まれている[30]。 アウシュヴィッツ 1944年10月、アウシュヴィッツIIの第4火葬場で、ゾンダーコマンドが反乱を起こした。アウシュヴィッツI収容所とアウシュヴィッツII収容所の間 にある工業地帯にある軍需工場Weichsel-Union-Metallwerkeから、若いユダヤ人女性労働者たちが数ヶ月にわたって火薬の小包を密 輸していたのである。火薬は密輸の連鎖によって、火葬場IVのゾンダーコマンドに渡された。その計画は、ガス室と火葬場を破壊し、蜂起を開始することで あった[31]。 しかし、1944年10月7日の朝、収容所の抵抗勢力は火葬場IVのゾンダーコマンドに、自分たちは殺されると警告し、ゾンダーコマンドは2丁の機関銃、 斧、ナイフ、手榴弾でSSとカポを攻撃し、3名を殺害し、さらに約12名を負傷させた。 [蜂起自体で死ななかった者のうち、200名は後に、後頭部を撃たれる前に服を脱がされ、うつ伏せにさせられた[13]。その日、合計451人のゾンダー コマンドスが殺害された[33][34][35]。 |

| Media portrayals The earliest portrayals of the Sonderkommando were generally unflattering. Miklos Nyiszli, in Auschwitz: A Doctor's Eyewitness Account, described the Sonderkommando as enjoying a virtual feast, complete with chandeliers and candlelight, as other prisoners died of starvation. Nyiszli, an admitted collaborator who assisted Josef Mengele in his medical experiments on Auschwitz prisoners, would appear to have been in a good position to observe the Sonderkommando in action, as he had an office in Krematorium II. But some of his inaccurate physical descriptions of the crematoria diminishes his credibility in this regard. Historian Gideon Greif characterized Nyiszli's writings as among the "myths and other wrong and defamatory accounts" of the Sonderkommando, which flourished in the absence of first-hand testimony by surviving Sonderkommando members.[36] Primo Levi, in The Drowned and the Saved, characterizes the Sonderkommando as being "akin to collaborators." He said that their testimonies should not be given much credence, since they had much to atone for and would naturally attempt to rehabilitate themselves at the expense of the truth.[37] But, he asked his readers to refrain from condemnation: "Therefore I ask that we meditate upon the story of 'the crematorium ravens' with pity and rigor, but that judgment of them be suspended."[38] Filip Müller was one of the few Sonderkommando members who survived the war and was also unusual in that he served on the Sonderkommando far longer than most. He wrote of his experiences in his book Eyewitness Auschwitz: Three Years in the Gas Chambers (1979).[39] Among other incidents he related, Müller recounted how he tried to enter the gas chamber to die with a group of his countrymen but was dissuaded from suicide by a girl who asked him to remain alive and bear witness.[40] Since the late 20th century, several other more sympathetic accounts of the Sonderkommando have been published, beginning with Gideon Greif's own book We Wept Without Tears (1999 in Hebrew, 2005 in English), which consists of interviews with former Sonderkommando members. Greif includes as his prologue Gunther Anders' poem "And What Would You Have Done?", which says that one who has not been in that situation has little right to judge the Sonderkommando: "Not you, not me! We were not put to that ordeal!"[41] The first depiction of the Sonderkommando revolt was titled Ikh leb (I live), a play written by Jewish author Moshe Pinchevski. It was also the first post-World War 2, Yiddish-language performance at the Idisher Kultur Farband Teater in Bucharest, Romania, in 1945.[42] A theatre play that explores the moral dilemmas of the Sonderkommando was The Grey Zone, directed by Doug Hughes and produced in New York at MCC Theater in 1996.[43] The play was later adapted as a film of the same title by producer Tim Blake Nelson.[44] The film took its mood, as well as much of its plot, from Nyiszli, portraying members of the Sonderkommando as crossing the line from victim to perpetrator. Sonderkommando Hoffman (played by David Arquette) beats a man to death in the undressing room under the eyes of a smiling SS member. Nelson emphasizes that the subject of the film is that very moral ambiguity. "We can see each one of ourselves in that situation, perhaps acting in that way, because we are human. But we're not sanctified victims."[45] A "novelized" memoir, A Damaged Mirror (2014), by Yael Shahar and Ovadya ben Malka, explores the lengths to which a former Sonderkommando will go to obtain forgiveness and closure: "The fact that good people can be forced to do wrong doesn't make them less good," the survivor says of himself, "but it also doesn't make the wrong less wrong."[46] Son of Saul, a 2015 Hungarian film directed by László Nemes, and winner of the 2015 Cannes Film Festival Grand Prix, details the story of one Sonderkommando attempting to bury a dead child he takes for his son. Géza Röhrig, who starred in the film, reacted with anger to the suggestion, made by a journalist, that members of the Sonderkommando were "half-victim, half-hangman". There has to be a clarification," he said. "They are 100% victims. They have not spilled blood or been involved in any sort of killing. They were inducted on arrival under the threat of death. They had no control of their destinies. They were as victimised as any other prisoners in Auschwitz.[47] |

メディアによる描写 ゾンダーコマンドに関する初期の描写は、概して好ましくないものだった。ミクローシュ・ナイシュリは『アウシュヴィッツ』(Auschwitz: A Doctor's Eyewitness Account』の中で、ゾンダーコマンドは、他の囚人たちが餓死していく中で、シャンデリアとろうそくの明かりで、事実上の宴会を楽しんでいたと描写し ている。アウシュヴィッツの囚人に対する医学実験でヨーゼフ・メンゲレを援助した協力者であることを自認しているナイシュリは、クレマトリウムUに執務室 を持っていたので、ゾンダーコマンドの行動を観察するのに適した立場にあったように思われる。しかし、火葬場に関する彼の不正確な物理的記述は、この点で の彼の信憑性を低下させている。歴史家ギデオン・グライフは、ニーシュリの著作を、生存しているゾンダーコマンドのメンバーによる直接の証言がないときに 盛んになったゾンダーコマンドに関する「神話やその他の間違った中傷的な記述」の一つであると特徴づけている[36]。 プリモ・レーヴィは、『溺れさせられた者、救われた者』の中で、ゾンダーコマンドを「協力者に似ている」と評している。彼らは償うべきことが多く、真実を 犠牲にして自らを更生させようとするのは当然だからである[37]。しかし、彼は読者に非難を控えるよう求めた「 それゆえ、私は『火葬場のカラス』の話を憐れみと厳しさをもって黙想することを求めるが、彼らに対する判断は一時停止することを求める」[38]。 フィリップ・ミュラーは戦争を生き延びた数少ないゾンダーコマンド隊員の一人であり、他の隊員よりもはるかに長くゾンダーコマンド隊に在籍していたという 点でも異例であった。彼はその体験を著書『アウシュビッツの目撃者』(1919年)に書いている: 彼が語った他の出来事の中で、ミュラーは、同胞のグループと一緒に死ぬためにガス室に入ろうとしたが、生きて証人になるように頼んだ少女によって自殺を思 いとどまらせられたことを語っている[40]。 20世紀後半以降、ゾンダーコマンドについてのより同情的な証言がいくつか出版されており、ギデオン・グライフ自身の著書『We Wept Without Tears』(ヘブライ語では1999年、英語では2005年)はその筆頭である。グライフ氏のプロローグには、グンター・アンダースの詩 "And What Would You Have Done? "が含まれている: 「君でも私でもない!私たちはそんな試練を与えられていない!」[41]。 ゾンダーコマンドの反乱を初めて描いたのは、ユダヤ人作家モシェ・ピンチェフスキが書いた戯曲『Ikh leb(私は生きている)』であった。1945年、ルーマニアのブカレストにあるイディッシャー・クルトゥール・ファルバンド劇場で上演された、第二次世 界大戦後初のイディッシュ語による公演でもあった[42]。 ゾンダーコマンドの道徳的ジレンマを探求した演劇は、1996年にニューヨークのMCCシアターで上演されたダグ・ヒューズ演出の『The Grey Zone』である。デヴィッド・アークェット演じるゾンダーコマンドのホフマンは、脱衣室でSS隊員の微笑む目の前で男を殴り殺す。ネルソンは、この映画 の主題がまさにその道徳的曖昧さであることを強調する。「私たちは人間だから、そのような状況に置かれ、そのような行動をとるかもしれない。しかし、私た ちは神聖化された犠牲者ではない」[45]。 Yael ShaharとOvadya ben Malkaによる "小説化された "回顧録『A Damaged Mirror』(2014年)は、元ゾンダーコマンドが赦しと終結を得るためにどこまでやるかを探求している。「善良な人々が間違ったことを強いられると いう事実は、彼らを善良でなくするものではない」と生存者は自身について語り、「しかしそれはまた、間違ったことを間違ったことでなくするものでもない」 [46]。 ラースロー・ネメス監督による2015年のハンガリー映画で、2015年カンヌ国際映画祭グランプリを受賞した『サウルの息子』は、息子のように思ってい る死んだ子どもを埋葬しようとする一人のゾンダーコマンドの物語を詳細に描いている。この映画で主演を務めたゲザ・レーリヒは、ゾンダーコマンドのメン バーが「半分被害者、半分手下」であったというジャーナリストの指摘に怒りを露わにした。 はっきりさせる必要がある。「彼らは100%被害者です。彼らは血を流したわけでも、殺人に関与したわけでもない。彼らは死の恐怖の下に入隊させられた。 自分たちの運命をコントロールすることはできなかった。彼らはアウシュヴィッツの他の囚人と同じように犠牲になっていたのです」[47]。 |

kapo or

prisoner functionary kapo or

prisoner functionary A kapo or prisoner functionary (German: Funktionshäftling) was a prisoner in a Nazi camp who was assigned by the Schutzstaffel (SS) guards to supervise forced labor or carry out administrative tasks. Also called "prisoner self-administration", the prisoner functionary system minimized costs by allowing camps to function with fewer SS personnel. The system was designed to turn victim against victim, as the prisoner functionaries were pitted against their fellow prisoners in order to maintain the favor of their SS overseers. If they neglected their duties, they would be demoted to ordinary prisoners and be subject to other kapos. Many prisoner functionaries were recruited from the ranks of violent criminal gangs rather than from the more numerous political, religious, and racial prisoners; such criminal convicts were known for their brutality toward other prisoners. This brutality was tolerated by the SS and was an integral part of the camp system. Prisoner functionaries were spared physical abuse and hard labor, provided they performed their duties to the satisfaction of the SS functionaries. They also had access to certain privileges, such as civilian clothes and a private room.[1] While the Germans commonly called them kapos, the official government term for prisoner functionaries was Funktionshäftling. After World War II, the term was reused as an insult; according to The Jewish Chronicle, it is "the worst insult a Jew can give another Jew".[2] |

囚人官吏 囚人官吏囚人官吏(ドイツ語: Funktionshäftling)とは、ナチス収容所の囚人で、強制労働の監督や管理業務を行うために、親衛隊(SS)の看守によって任命された者の ことである。 囚人の自己管理」とも呼ばれ、囚人機能員制度は、より少ないSS要員で収容所を機能させることを可能にし、コストを最小限に抑えた。囚人機能員は、SSの 監督者の好意を維持するために、仲間の囚人と対立させられたからである。もし彼らが任務を怠れば、普通の囚人に降格され、他のカポスの支配下に置かれるこ とになった。このような犯罪囚は、他の囚人に対して残忍であることで知られていた。このような残虐性はSSによって容認され、収容所システムの不可欠な一 部であった。 囚人の役人たちは、SSの役人たちが満足するような職務を果たせば、肉体的虐待や重労働を免れた。彼らはまた、私服や個室などの特定の特権を利用すること ができた[1]。ドイツ人は一般に彼らをカポと呼んでいたが、囚人機能員の公式な政府用語はファンクションシャフトリング (Funktionshäftling)であった。 第二次世界大戦後、この用語は侮辱として再使用された。『ユダヤ人クロニクル』によれば、これは「ユダヤ人が他のユダヤ人に与えることのできる最悪の侮 辱」である[2]。 |

| Etymology The word "kapo" could have come from the Italian word for "head" and "boss", capo. According to the Duden, it is derived from the French word for "Corporal" (caporal).[3][4][5] Journalist Robert D. McFadden believes that the word "kapo" is derived from the German word Lagercapo, meaning camp captain.[6] |

語源 「カポ」の語源は、イタリア語で「頭」と「ボス」を意味するカポ(capo)である可能性がある。ドゥーデンによれば、フランス語の「伍長」 (caporal)に由来する[3][4][5]。 ジャーナリストのロバート・D・マクファーデンは、「カポ」の語源はドイツ語で収容所の隊長を意味するLagercapoであると考えている[6]。 |

| System of thrift and manipulation Camps were controlled by the SS, but day-to-day organization was supplemented by the system of functionary prisoners, a second hierarchy that made it easier for the Nazis to control the camps. These prisoners made it possible for the camps to function with fewer SS personnel. The prisoner functionaries sometimes numbered as high as 10% of the inmates.[7][8] The Nazis were able to keep the number of paid staff who had direct contact with the prisoners very low in comparison to normal prisons today. Without the functionary prisoners, the SS camp administrations would not have been able to keep the day-to-day operations of the camps running smoothly.[9][10] The kapos often did this work for extra food, cigarettes, alcohol or other privileges.[11] At Buchenwald, these tasks were originally assigned to criminal prisoners, but after 1939, political prisoners began to displace the criminal prisoners,[12] though criminals were preferred by the SS. At Mauthausen, on the other hand, functionary positions remained dominated by criminal prisoners until just before liberation.[13] The system and hierarchy also inhibited solidarity among the prisoners.[13] There were tensions between the various nationalities and prisoner groups, who were distinguished by different Nazi concentration camp badges. Jews wore yellow stars; other prisoners wore colored triangles pointed downward.[14] Prisoner functionaries were often hated by other prisoners and spat upon as Nazi henchmen.[15] While some barrack leaders (Blockälteste) tried to assist the prisoners under their command by secretly helping them get extra food or easier jobs, others were more concerned with their own survival and, to that end, did more to assist the SS.[16][17] Identified by green triangles, the Berufsverbrecher or "BV" ("career criminals") kapos,[18] were called "professional criminals" by other prisoners and were known for their brutality and lack of scruples. Indeed, they were selected by the SS because of those qualities.[1][13][19] According to former prisoners, criminal functionaries were more apt to be helpful to the SS than political functionaries, who were more apt to be helpful to other prisoners.[16] From Oliver Lustig's Dictionary of the Camp: Vincenzo and Luigi Pappalettera wrote in their book The Brutes Have the Floor[20] that, every time a new transport of detainees arrived at Mauthausen, Kapo August Adam picked out the professors, lawyers, priests and magistrates and cynically asked them: "Are you a lawyer? A professor? Good! Do you see this green triangle? This means I am a killer. I have five convictions on my record: one for manslaughter and four for robbery. Well, here I am in command. The world has turned upside down, did you get that? Do you need a Dolmetscher, an interpreter? Here it is!" And he was pointing to his bat, after which he struck. When he was satisfied, he formed a Scheisskompanie with those selected and sent them to clean the latrines.[21] |

倹約と操作のシステム 収容所はSSによって管理されていたが、日々の組織は、ナチスが収容所 を管理しやすくするための第二の階層である機能囚人制度によって補完されていた。この囚人たちのおかげで、収容所は少ないSS隊員で機能することができた。 機能囚の数は収容者の10%にも達することもあった[7][8]。ナチスは、今日の通常の刑務所と比較して、囚人と直接接触する有給職員の数を非常に少な く抑えることができた。機能的な囚人がいなければ、SS収容所管理局は収容所の日々の運営を円滑に行うことができなかったであろう[9][10] 。 ブッヘンヴァルトでは、これらの仕事はもともと犯罪囚に割り当てられていたが、1939年以降、政治犯が犯罪囚に取って代わるようになった[12]。一 方、マウトハウゼンでは、解放直前まで、機能的な地位は犯罪人囚人によって支配されたままであった[13]。 システムとヒエラルキーは、囚人間の連帯も阻害した[13]。ユダヤ人は黄色の星をつけ、他の囚人は下を向いた色のついた三角形をつけた[14]。 囚人たちはしばしば他の囚人たちから嫌われ、ナチスの子分として唾を吐かれた[15]。 緑色の三角形で識別されるBerufsverbrecherまたは「BV」(「職業犯罪者」)カポス[18]は、他の囚人たちから「職業犯罪者」と呼ば れ、その残忍さと良心の欠如で知られていた。実際、彼らはそのような資質ゆえにSSによって選ばれたのである[1][13][19]。 元囚人によれば、犯罪者の機能員は、他の囚人に役立つ傾向が強い政治的機能員よりもSSに役立つ傾向が強かった[16]。 オリバー・ルスティグの『収容所の辞典』より: ヴィンチェンツォとルイジ・パッパレッテラは、その著書『The Brutes Have the Floor』[20]の中で、マウトハウゼンに新しい収容者の移送が到着するたびに、カポ・アウグスト・アダムは、教授、弁護士、司祭、判事を選び出し、 皮肉たっぷりに尋ねたと書いている: 「あなたは弁護士ですか?君は弁護士か?よろしい!この緑の三角形が見えるか?これは私が殺人者であることを意味する。前科は5犯ある。傷害致死が1犯、 強盗が4犯だ。さて、私はここで指揮を執る。世界はひっくり返った、わかったか?通訳のドルメッチャーが必要ですか?これだ!" そして彼はバットを指差した。彼は満足すると、選ばれた者たちでシャイスコンパニーを結成し、便所掃除に行かせた[21]。 |

| Domination and terror The SS used domination and terror to control the camps' large populations with just a few SS functionaries. The system of prisoner guards was a "key instrument of domination",[1] and was commonly called "prisoner self-government" (Häftlings-Selbstverwaltung) in SS parlance.[22] The camp's draconian rules, constant threat of beatings, humiliation, punishment, and the practice of punishing entire groups for the actions of one prisoner were psychological and physical torments added to the starvation and physical exhaustion from back-breaking labor. Prisoner guards were used to push other inmates to work harder, saving the need for paid SS supervision. Many kapos felt caught in the middle, being both victims and perpetrators. Though kapos generally had a bad reputation, many suffered guilt about their actions, both at the time and after the war, as revealed in a book about Jewish kapos.[7] Many prisoner functionaries, primarily from the ranks of the "greens" or criminal prisoners, could be quite ruthless in order to justify their privileges, especially when an SS man was around.[18][23] They also played an active role in the beatings, even killing fellow prisoners. One non-criminal functionary was Josef Heiden [de], a notorious Austrian political prisoner. Feared and hated, he was known as a sadist and was responsible for several deaths. He was released from Dachau in 1942 and became a member of the Waffen-SS.[24] Some guards were personally involved in the mass murder of other prisoners.[25] Beginning in October 1944, criminal functionaries from among the German Reichsdeutsche were sought out for transfer to the Dirlewanger Brigade.[1] |

支配と恐怖 親衛隊は、収容所の大人数を少数の親衛隊幹部だけで統制するために、支配と恐怖を利用した。囚人看守のシステムは「支配の重要な手段」[1]であり、SS の用語では一般に「囚人自治」(Häftlings-Selbstverwaltung)と呼ばれていた[22]。 収容所の厳格な規則、殴打の絶え間ない脅威、屈辱、懲罰、一人の囚人の行動のためにグループ全体を罰する習慣は、背負い労働による飢餓と肉体的疲労に加え て、心理的・肉体的な苦痛であった。囚人看守は、他の受刑者にもっと働けと押し付けるために使われ、SSの監督を雇う必要をなくした。多くのカポは、被害 者であると同時に加害者でもあり、中間に挟まれていると感じていた。カポは一般的に評判が悪かったが、ユダヤ人カポに関する本で明らかにされているよう に、当時も戦後も、自分たちの行為について罪悪感に苦しんでいた者が多かった[7]。 囚人機能員の多くは、主に「グリーン」または犯罪囚人の階級に属しており、特にSS隊員が近くにいるときには、自分たちの特権を正当化するために、かなり 冷酷になることがあった[18][23]。彼らはまた、仲間の囚人を殺すことさえあり、殴打において積極的な役割を果たした。非犯罪者の一人に、悪名高い オーストリアの政治犯ヨーゼフ・ハイデン[デ]がいた。恐れられ、嫌われ、サディストとして知られ、数人の死者を出した。彼は1942年にダッハウを釈放 され、ヴァッフェンSSの一員となった[24]。1944年10月から、ドイツ帝国軍人の中からディルレヴァンガー旅団に移送される犯罪者が探し出された [25]。 |

| Ranks of functionary The important functionary positions inside the camp were Lagerältester (camp leader or camp senior), Blockältester (block or barracks leader or senior), and Stubenältester (room leader).[note 1] The highest position that a prisoner could reach was Lagerältester,[16][26][27] who was placed directly under the camp commandant and expected to implement his orders to ensure that the camp's daily routines ran smoothly and that regulations were followed. The Lagerälteste had a key role in the selection of other prisoners as functionaries, making recommendations to the SS. Though dependent on the goodwill of the SS, through them, he had access to special privileges, such as access to civilian clothes or a private room. The Blockältester (block or barracks leader) had to ensure that rules were followed in the individual barracks. He or she was also responsible for the prisoners in the barracks.[13][16] The Stubenälteste (room leader) was responsible for the hygiene, such as delousing, and order of each room in a barracks. The Blockschreiber (registrar or barrack clerk) was a record-keeping job that included tasks such as keeping track at roll calls. Work crews outside the camp were supervised by a Vorarbeiter (foreman), a Kapo, or Oberkapo (chief kapo). These functionaries pushed their fellow prisoners to work harder, hitting, beating, and even killing them.[23] Prisoner functionaries could often help other prisoners by getting them into better barracks or assigned to lighter work.[16] On occasion, the functionaries could effect other prisoners' removal from transport lists or even secure new identities in order to protect them from persecution.[12] This assistance was generally limited to the prisoners in the functionary's own group (fellow citizens or political comrades). The prisoner functionaries were in a precarious hierarchy between their fellow inmates and the SS. This situation was intentionally created, as revealed in a speech by Heinrich Himmler. The moment he becomes a Kapo, he no longer sleeps with them. He is held accountable for the performance of the work, that they are clean, that the beds are well-built. [...] So, he must drive his men. The moment we become dissatisfied with him, he is no longer Kapo, he's back to sleeping with his men. And he knows that he will be beaten to death by them the first night. — Heinrich Himmler, 21 June 1944[1] In National Socialism's racial ideology, some races were "superior" and others "inferior". Similarly, the SS sometimes had racial criteria for the prisoner functionaries; one sometimes had to be racially "superior" to be a functionary. The group category was also sometimes a factor. A knowledge of foreign languages was also advantageous, particularly as the international population of the camps increased, and because the SS preferred a certain level of education.[13] An eager prisoner functionary could have a camp "career" as an SS favorite and be promoted from Kapo to Oberkapo and eventually to Lagerältester, but could also just as easily run afoul of the SS and be sent to the gas chambers.[28] |

役職者の階級 収容所内の重要な官職はラーゲレルトシュテスター(収容所リーダーまたは収容所上級職)、ブロックヘルテスター(ブロックまたはバラックリーダーまたは上 級職)、シュトゥーベンヘルテスター(部屋長)であった[注釈 1]。 囚人が到達できる最高の地位はラーゲレルトシュテスターであり[16][26][27]、収容所司令官の直下に置かれ、収容所の日常生活が円滑に運営さ れ、規則が遵守されるように、司令官の命令を実行することが期待されていた。ラーゲレルトシュテは、他の囚人を官吏として選抜する際、SSに推薦するとい う重要な役割を担っていた。SSの好意に依存していたが、SSを通じて、私服や個室の利用などの特別な特権を得ることができた。 ブロック長(Blockältester)は、個々の兵営で規則が守られるようにしなければならなかった。Stubenälteste(部屋長)は、バ ラック内の各部屋の消毒などの衛生や秩序に責任を負っていた[13][16]。ブロックシュライバー(登録係または兵舎書記)は、点呼時に記録をつけるな どの仕事を含む記録係であった。 収容所外の作業班は、フォアラバイター(監督)、カポ、またはオーバーカポ(チーフカポ)が監督した。これらの機能員は、仲間の囚人たちにもっと働くよう に迫り、殴ったり、叩いたり、殺したりもした[23]。 囚人機能員は、他の囚人たちをより良い兵舎に入れたり、より軽い仕事を割り当てたりすることによって、しばしば他の囚人たちを助けることができた [16]。 時には、機能員は他の囚人たちを迫害から守るために、他の囚人たちを移送リストから除外したり、新しい身分を確保したりすることさえできた[12]。 この援助は一般的に、機能員自身のグループの囚人(仲間や政治的同志)に限られていた。囚人機能員は、仲間の囚人とSSとの間の不安定なヒエラルキーの中 にいた。この状況は、ハインリヒ・ヒムラーの演説で明らかになったように、意図的に作り出されたものだった。 カポになった瞬間、彼はもはや彼らとは寝ない。彼は、仕事をこなし、清潔にし、ベッドをきちんと作る責任を負わされる。[だから、彼は部下を駆り立てなけ ればならない。私たちが彼に不満を抱いた瞬間、彼はカポではなくなり、部下と寝るようになる。そして、彼は、最初の夜に、自分が部下に殴り殺されることを 知っているのだ。- ハインリヒ・ヒムラー、1944年6月21日[1]。 国家社会主義の人種イデオロギーでは、ある種族は「優れ」、ある種族は「劣って」いた。同様に、親衛隊は囚人機能要員に人種的基準を設けることがあった。 機能要員になるためには人種的に「優れて」いなければならないこともあった。また、集団のカテゴリーが要因になることもあった。外国語の知識も有利であっ た。特に収容所の国際人口が増加し、SSが一定の教育レベルを好んだからである[13]。 熱心な囚人機能員は、SSのお気に入りとして収容所の「キャリア」を積み、カポからオーバーカポ、そして最終的にはラーゲレルトスターに昇進することもで きたが、SSの逆鱗に触れてガス室に送られることもあった[28]。 |

| Prosecution of kapos During the 1946-47 Stutthof trials in Gdańsk, Poland, in which Stutthof concentration camp personnel were prosecuted, five kapos were found to have used extreme brutality and were sentenced to death. Four of them were executed on 4 July 1946, and one on 10 October 1947. Another was sentenced to three years' imprisonment and one acquitted and released on 29 November 1947.[29][30] The Israeli Nazis and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law of 1950, most famously used to prosecute Adolf Eichmann in 1961 and Ivan Demjanjuk in 1986, was originally introduced with the principal aim of prosecuting Jewish people who collaborated with the Nazis.[31][32] Between 1951 and 1964, approximately 40 trials were held, mostly of people alleged to have been kapos.[32] Fifteen trials are known to have resulted in convictions, but scant details are available since the records were sealed in 1995 for a period of 70 years from the trial date.[32] One person – Yehezkel Jungster – was convicted of crimes against humanity, which carried a mandatory death penalty, but the sentence was commuted[33][32] to two years in prison. Jungster was pardoned in 1952, but died a few days after his release.[34][35] According to teacher and researcher Dan Porat,[36] the way in which former kapos were officially viewed – and tried – by the state of Israel went through four distinct phases. Initially viewed as co-perpetrators of Nazi atrocities, they eventually came to be perceived as victims themselves. During the first stage described by Porat (August 1950 – January 1952), those alleged to have served or to have collaborated with the Nazis were placed on an equal footing with their captors, with some measure of leniency appearing only in the sentencing phase for some cases. It was during this phase that Jungster was sentenced to death; six other former kapos were each sentenced to an average of almost five years in prison. Jungster’s death sentence had not been anticipated by either the legislators nor the prosecutors, according to Porat, and triggered a number of amendments to pre-trial charges in order to remove any indictment that would potentially carry a death penalty. During this second phase (February 1952 – 1957), the Israeli Supreme Court overturned Jungster’s sentence and essentially ruled that while Nazis could be charged with crimes against humanity and war crimes, their former collaborators could not. While prosecutions of kapos continued, doubts emerged amongst some of those in the public sphere as to whether the trials should continue at all. The official view remained that kapos had been Jewish collaborators, not Nazis themselves. By 1958, when the third phase began (lasting until 1962), the legal system had begun to view kapos as having committed wrongs but with good intentions. Thus, only those whom prosecutors believed had aligned themselves with the Nazis' aims were brought to trial. There were calls from some survivors that the trials should end, though other survivors still demanded that justice be served. The fourth phase (1963 – 1972) was marked by the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the principal architects of the Final Solution, and of Hirsch Barenblat two years later. Kapos and collaborators were now seen by the courts as ordinary victims, a complete reversal from the initial official perspective. Eichmann’s prosecutor was very clear in drawing a line between the Jewish collaborators and camp functionaries, and the evil Nazis. Barenblat’s trial in 1963 drove this point home. Barenblat, conductor of the Israel National Opera, was tried for having turned Jews over to the Nazis as head of the Jewish police in the Bendzin ghetto in Poland.[37] Having arrived in Israel in 1958–9, Barenblat was arrested after a ghetto survivor recognised him while he was conducting an opera. Found guilty of helping the Nazis by ensuring that Jews selected for the death camps did not escape, Barenblat was sentenced to five years in prison. On 1 May 1964, after having served three months, Barenblat was freed and Israel’s Supreme Court quashed his conviction.[38] The acquittal may have been due to the court’s aim of putting an end to the trials against kapos and other alleged Nazi collaborators.[39] A small number of kapos were prosecuted in East and West Germany. In a well-publicised 1968 case, two Auschwitz kapos were put on trial in Frankfurt.[11] They were indicted for 189 murders and multiple assaults, found guilty of several murders, and sentenced to life imprisonment.[11] |

カポの起訴 ポーランドのグダニスクで1946-47年に開かれたストゥットホフ強制収容所職員が訴追されたストゥットホフ裁判では、5名のカポが極端な残虐行為を行 なったと認定され、死刑判決を受けた。そのうち4人は1946年7月4日に、1人は1947年10月10日に処刑された。別の1人は禁固3年の判決を受 け、1人は無罪となり、1947年11月29日に釈放された[29][30]。 1961年にアドルフ・アイヒマン、1986年にイヴァン・デムヤンユクを起訴したことで最も有名な1950年のイスラエルのナチスおよびナチス協力者 (処罰)法は、元々はナチスに協力したユダヤ人を起訴することを主目的として導入された[31][32]。 [32] 15の裁判が有罪判決を受けたことが知られているが、1995年に記録が裁判日から70年間封印されたため、詳細はほとんどわかっていない[32]。イェ ヘズケル・ユングスターという1人の人間が、死刑が義務付けられている人道に対する罪で有罪判決を受けたが、判決は減刑され[33][32]、2年の懲役 刑となった。ユングスターは1952年に赦免されたが、釈放の数日後に死亡した[34][35]。 教師であり研究者でもあるダン・ポラトによれば[36]、元カポがイスラエル国家によって公式に見なされ、裁判にかけられる方法は、4つの異なる段階を経 た。当初はナチスの残虐行為の共同加害者と見なされていた彼らは、やがて被害者そのものとして認識されるようになった。ポラットによって説明された最初の 段階(1950年8月~1952年1月)では、ナチスに仕えた、あるいはナチスに協力したとされる人々は、捕虜と同等の立場に置かれ、いくつかのケースに ついては、判決の段階でのみ多少の寛大さが示された。ユングスターが死刑を宣告されたのはこの段階であり、他の6人の元カポにはそれぞれ平均5年近い懲役 刑が言い渡された。ポラットによれば、ユングスターの死刑判決は、立法府も検察も予想していなかったことであり、死刑の可能性がある起訴内容を削除するた めに、公判前の起訴内容を何度も修正するきっかけとなった。この第二段階(1952年2月~1957年)において、イスラエル最高裁判所はユングスターの 判決を覆し、ナチスは人道に対する罪や戦争犯罪で起訴される可能性があるが、彼らの元協力者は起訴されないという本質的な判決を下した。カポスの起訴は続 けられたが、裁判を続けるべきかどうかについては、世論の一部から疑問の声が上がった。カポーはユダヤ人の協力者であって、ナチスそのものではなかったと いうのが公式見解であった。第3段階が始まった1958年(1962年まで続く)までに、法制度は、カポーは悪事を働いたが善意であったとみなすように なった。そのため、ナチスの目的に賛同したと検察が考える者だけが裁判にかけられた。一部の生存者からは裁判を終わらせるべきだという声が上がったが、他 の生存者はそれでも正義を貫くことを求めた。第4段階(1963年-1972年)は、最終的解決の主要な立役者の一人であるアドルフ・アイヒマンと、その 2年後のヒルシュ・バレンブラットの裁判によって特徴づけられた。カポスや協力者は、裁判所から普通の被害者とみなされるようになり、当初の公式見解とは 完全に逆転した。アイヒマンの検事は、ユダヤ人協力者や収容所の役人と、邪悪なナチスとの間に一線を引くことを非常に明確にしていた。1963年のバレン ブラットの裁判は、この点を明確にした。イスラエル国立歌劇場の指揮者であったバレンブラットは、ポーランドのベンジン・ゲットーでユダヤ人警察の責任者 としてユダヤ人をナチスに引き渡したとして裁判にかけられた[37]。1958年から9年にかけてイスラエルに到着したバレンブラットは、オペラを指揮し ているときにゲットーの生存者に気づかれ、逮捕された。死の収容所に選ばれたユダヤ人が逃亡しないようにしてナチスを助けた罪で有罪となり、バレンブラッ トは5年の禁固刑を言い渡された。1964年5月1日、3ヶ月間服役した後、バレンブラットは釈放され、イスラエルの最高裁判所は彼の有罪判決を破棄した [38]。この無罪判決は、カポやその他のナチス協力者とされる者に対する裁判に終止符を打つという裁判所の目的によるものだったのかもしれない [39]。 少数のカポーが東西ドイツで起訴された。よく知られた1968年の事件では、2人のアウシュヴィッツ・カポがフランクフルトで裁判にかけられた[11]。 彼らは189件の殺人と複数の暴行で起訴され、数件の殺人で有罪となり、終身刑を宣告された[11]。 |

| Significance German historian Karin Orth wrote that there was hardly a measure so perfidious as the SS attempt to delegate the implementation of terror and violence to the victims themselves.[1] Eugen Kogon, an avowed opponent of Nazism from prewar Germany and a Buchenwald concentration camp survivor, wrote after the war that the concentration camp system owed its stability in no small way to the cadre of kapos, who took over the daily operations of the camp and relieved SS personnel. The absolute power was ubiquitous. The system of discipline and supervision would have promptly disintegrated, according to Kogon, without the delegation of power. The rivalry over supervisory and warehouse functionary jobs was, for the SS, an opportunity to pit prisoners against each other. Regular prisoners were at the mercy of a dual authority: the SS, who often hardly seemed to be at the camp, and the prisoner kapos, who were always there.[17] The term kapo has been used as a slur in the twenty-first century, particularly for Jews deemed insufficiently supportive of Israel or Zionism. In 2017, David Friedman, soon to become US ambassador to Israel, apologized for referring to supporters of the J Street advocacy group as "far worse than kapos".[40][2] |

意義 ドイツの歴史家カリン・オルトは、恐怖と暴力の実行を犠牲者自身に委ねようとするSSほど卑劣な手段はなかったと書いている[1]。戦前のドイツでナチズ ム反対を公言し、ブッヘンヴァルト強制収容所の生存者であったオイゲン・コーゴンは戦後、強制収容所システムが安定したのは、収容所の日常業務を引き継 ぎ、SS隊員を解放した幹部カポスのおかげであると書いている。絶対的な権力はどこにでもあった。権力の委譲がなければ、規律と監督のシステムはたちまち 崩壊していただろうと小言は言う。監督や倉庫係の仕事をめぐる対立は、SSにとって、囚人同士を対立させる好機であった。普通の囚人は、しばしば収容所に ほとんどいないように見えるSSと、常にそこにいる囚人カポという二重の権威に翻弄されていた[17]。 カポという用語は、21世紀には、特にイスラエルやシオニズムを十分に支持していないとみなされたユダヤ人に対する中傷として使われてきた。2017年、 まもなく米国の駐イスラエル大使に就任するデイヴィッド・フリードマンは、Jストリートの支持者を「カポーよりはるかに悪い」と呼んだことを謝罪した [40][2]。 |

| Belsen Trial, the Trial of

Joseph Kramer and 44 others (former kapos, convicted in late 1945 for

war crimes). Bitch Wars in the Soviet Gulag system. Divide and rule Eliezer Gruenbaum, notable kapo[41] Jewish Ghetto Police Judenrat - Jewish councils under Nazi administration for self-government in Ghettos and other Jewish communities in occupied territories. Line management Plantations in the American South#Overseer Triangulation (psychology) Trusty system (prison) Kapo, a 1960 film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo. Escape from Sobibor, a 1987 television movie which features a kapo helping prisoners escape from Sobibór extermination camp. The Counterfeiters, a film which features several kapos, in various camps. |

ベルゼン裁判、ヨゼフ・クラマー他44名の裁判(元カポ、戦争犯罪で

1945年末に有罪判決)。 ソ連の収容所システムにおける愚痴合戦。 分割統治 エリエゼル・グリューンバウム、注目すべきカポー[41]。 ユダヤ人ゲットー警察 ユダヤ人ゲットー警察 - ゲットーや占領地のユダヤ人社会における自治のためのナチス政権下のユダヤ人評議会。 ライン管理 アメリカ南部のプランテーション#Overseer 三角測量(心理学) トラスティシステム(刑務所) ジロ・ポンテコルヴォ監督の1960年の映画『カポ』。 『ソビボルからの脱出』1987年のテレビ映画で、カポがソビボル絶滅収容所からの囚人の脱出を助ける。 『偽造者たち』(The Counterfeiters)は、さまざまな収容所の複数のカポが登場する映画である。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kapo |

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099