CONAIE

Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador

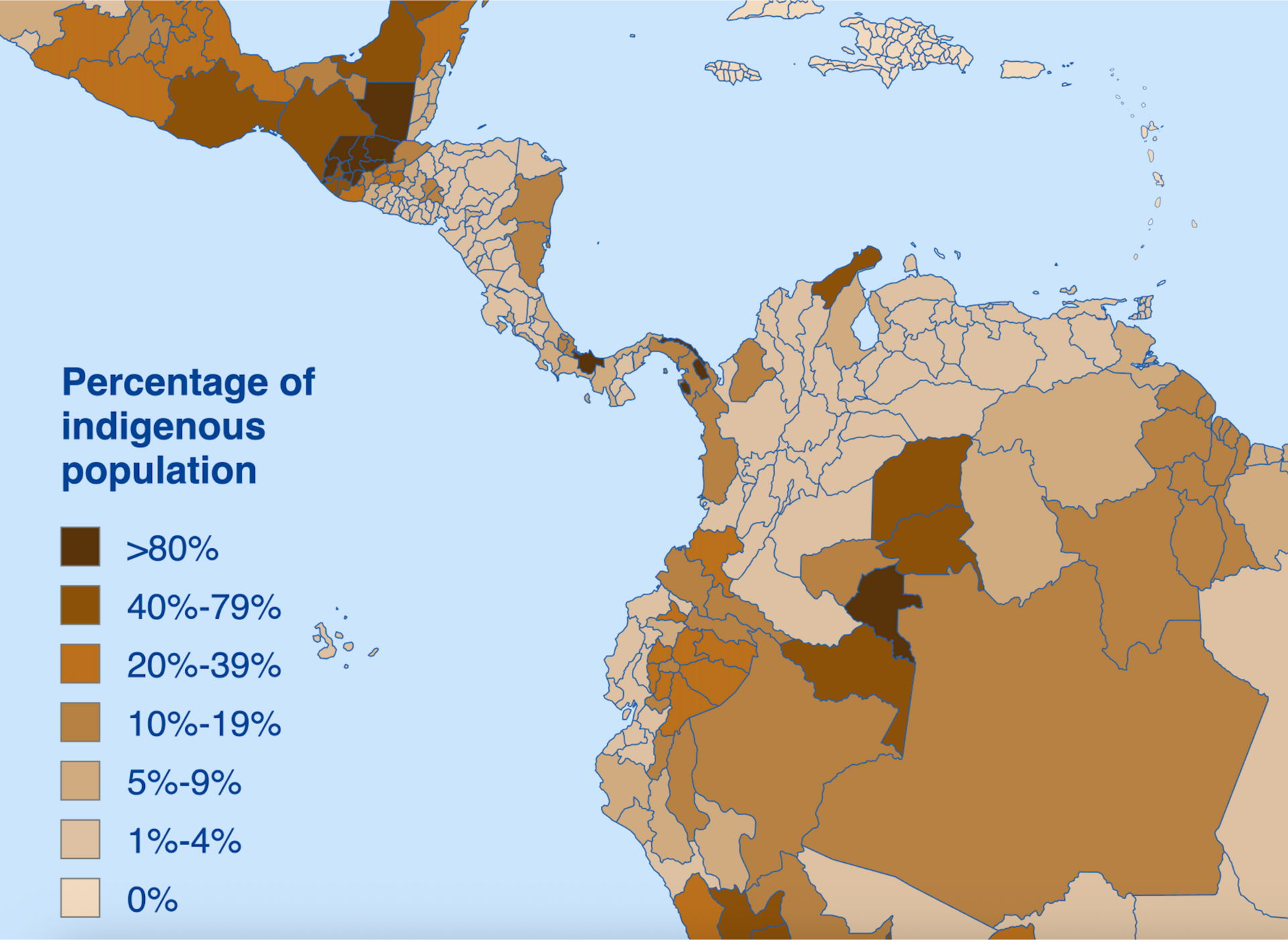

Percentage of indigenous population of the Northern South America/ Bartolo Ushigua, Zapara delegate at the 2nd CONAIE congress

☆ エクアドルの先住民、またはエクアドル先住民(Indigenous peoples in Ecuador or Native Ecuadorians; スペイン語: Ecuatorianos Nativos)は、スペインによるアメリカ大陸植民地化以前にエクアドルに存在した人々のグループである。この言葉には、スペインによる征服時代から現 在に至るまでの子孫も含まれる。エクアドルの人口の7パーセントが先住民族であり、残りの70パーセントは先住民族とヨーロッパ人の混血であるメスティー ソである[3]。

★

コナイエ(CONAIE, Confederación

de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador )

★Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador = Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (CONAIE)

☆ エクアドル先住民族連合(スペイン語: Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador)、 通称コナイエは、エクアドル最大の先住民族権利団体である。コナイエ主導のエクアドル先住民族運動は、ラテンアメリカで最も組織化され影響力のある先住民 族運動としてしばしば言及される。[1][2]1986年に結成されたCONAIEは、1990年5月から6月にかけて全国規模の農村蜂起を組織する役割 を果たし、強力な国民的勢力としての地位を確固 たるものにした。数千の人民が道路を封鎖し、交通網を麻痺させ、一週間にわたり国を機能停止に追い込みながら、二言語教育、農地改革、エクアドルの多民族 国家としての承認を要求した。これはエクアドル史上最大の反乱であり、後に続く一連の反乱の青写真となる新たな対抗形態を確立した。CONAIE主導の反 乱は、アブダラ・ブカラム大統領の失脚と、それに続く1998年の新憲法制定に関与した。CONAIE指導者たちはまた、ジャミ ル・マウアド大統領を追放した2000年のクーデターにも参加・貢献した。

| The

Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador

(Spanish: Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador) or,

more commonly, CONAIE, is Ecuador's largest indigenous rights

organization. The Ecuadorian Indian movement under the leadership of

CONAIE is often cited as the best-organized and most influential

Indigenous movement in Latin America.[1][2] Formed in 1986, CONAIE firmly established itself as a powerful national force in May and June 1990 when it played a role in organising a rural uprising on a national scale. Thousands of people blocked roads, paralyzed the transport system, and shut down the country for a week while making demands for bilingual education, agrarian reform, and recognition of the plurinational state of Ecuador. This was the largest uprising in Ecuador's history and established a new form of contention that would serve as a blueprint for a string of later uprisings.[2][3] CONAIE-led uprisings had a role in the fall of president Abdalá Bucaram and subsequent drafting of a new constitution in 1998. CONAIE leaders also participated in the 2000 coup d'état that deposed president Jamil Mahuad. |

エクアドル先住民族連合(スペイン語: Confederación

de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador)、通称コナイエは、エクアドル最大の先住民族権利団体であ

る。コナイエ主導のエクアドル先住民族運動は、ラテンアメリカで最も組織化され影響力のある先住民族運動としてしばしば言及される。[1][2] 1986年に結成されたCONAIEは、1990年5月から6月にかけて全国規模の農村蜂起を組織する役割を果たし、強力な国民的勢力としての地位を確固 たるものにした。数千の人民が道路を封鎖し、交通網を麻痺させ、一週間にわたり国を機能停止に追い込みながら、二言語教育、農地改革、エクアドルの多民族 国家としての承認を要求した。これはエクアドル史上最大の反乱であり、後に続く一連の反乱の青写真となる新たな対抗形態を確立した。[2] [3] CONAIE主導の反乱は、アブダラ・ブカラム大統領の失脚と、それに続く1998年の新憲法制定に関与した。CONAIE指導者たちはまた、ジャミル・ マウアド大統領を追放した2000年のクーデターにも参加・貢献した。 |

Bartolo Ushigua, Zapara delegate at the 2nd CONAIE congress |

バルトロ・ウシグア、ザパラ代表(Sápara)、 第2回コナイエ大会 |

| Overview CONAIE's political agenda includes the strengthening of a positive Indigenous identity, recuperation of land rights, environmental sustainability, opposition to neoliberalism and rejection of U.S. military involvement in South America (for example Plan Colombia).[4][5] The Indigenous movement in Ecuador was consolidated during the 1990 uprising when CONAIE leaders issued 16 demands, the first of which was the declaration of Ecuador as a plurinational state. The return of lands to Indigenous people and control over territory have been consistent central demands for the Indigenous movement in Ecuador.[5] In addition to these central concerns, CONAIE's 16-point platform broadly addressed cultural issues such as bilingual education and control of archaeological sites; economic concerns such as development programs; and political demands such as local autonomy.[6] The CONAIE position on the plurinational state was integrated into the 2008 constitution of Ecuador.[5] |

概要 CONAIEの政治的アジェンダには、先住民族としての積極的なアイデンティティの強化、土地権利の回復、環境の持続可能性、新自由主義への反対、そして 南米における米国軍の関与(例えばコロ ンビア計画)の拒否が含まれる。[4] [5] エクアドルの先住民運動は1990年の蜂起時に固まった。CONAIE指導部が16項目の要求を提示し、その第一が「エクアドルを多元ナショナリズムと宣 言すること」だった。先住民への土地返還と領土支配権の確立は、エクアドル先住民運動における一貫した核心的要求である。[5] これらの核心的な問題に加え、CONAIEの16項目の綱領は、二言語教育や考古学遺跡の管理といった文化問題、開発計画といった経済問題、地方自治と いった政治的要求など、幅広い課題を扱っていた。[6] 多元ナショナリズムに関するCONAIEの立場は、2008年のエクアドル憲法に組み込まれ た。[5] |

| Organization CONAIE represents the following indigenous peoples: Shuar, Achuar, Siona, Secoya, Cofán, Huaorani, Záparo, Chachi, Tsáchila, Awá, Epera, Manta, Wancavilca and Quichua.[7] CONAIE was founded in 1986 from the union of two confederations of Indigenous nations: the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE) in the eastern Amazon region, and The Confederation of Peoples of Quichua Nationality (ECUARUNARI) in the central mountain region.[8][4] |

組織 CONAIEは以下の先住民を代表する:シュアル族、アチュアル族、シオナ族、セコヤ族、コファン族、ワオラニ族、ザパロ族、チャチ族、ツァチラ族、アワ 族、エペラ族、マンタ族、ワンカビルカ族、キチュア族。[7] CONAIEは1986年、二つの先住民族連合の統合により設立された。東部アマゾン地域の「エクアドル・アマゾン先住民族連合(CONFENIAE)」 と、中央山岳地域の「ケチュア民族連合 (ECUARUNARI)」である。[8][4] |

| History CONAIE was founded at a convention of some 500 indigenous representatives on November 13–16, 1986.[7] Initially forbidding its leaders from holding political office, CONAIE opposed alliances with political parties and presidential candidates. Instead, it promoted local campaigns. By 1996, however, grassroots pressure had pushed the organisation to rethink their position on electoral politics, with the president of CONAIE, Luis Macas running for national congress and the launching of the Pachakutik Plurinational Unity Movement - a political party based on the Indigenous movement.[2][9] Through the 1990s and early 2000s, CONAIE organised at least five national Indigenous uprisings, mobilising thousands of campesinos to shut down Quito. During these uprisings CONAIE made demands for land rights and plurinationalism while protesting corruption, deregulation, privatisation, and dollarisation of the Ecuadorian economy.[4] Beginning in 1993, CONAIE supported lawsuits against Chevron saying that the corporation deliberately dumped billions of gallons of toxic oil waste onto Indigenous lands as a cost-saving measure at the Lago Agrio oil fields.[10][11] |

歴史 コナイエは1986年11月13日から16日にかけて、約500人の先住民代表が集まった大会で設立された。[7] 当初、CONAIEは指導者が公職に就くことを禁じ、政党や大統領候補との提携に反対した。代わりに地域レベルの運動を推進した。しかし1996年まで に、草の根の圧力により組織は選挙政治への姿勢を見直すこととなり、CONAIE会長ルイス・マカスが国民議会選挙に出馬。先住民運動を基盤とする政党 「パチャクティック多元ナショナリズム統一運動」が結成された[2]。[9] 1990年代から2000年代初頭にかけて、CONAIEは少なくとも5回の全国的な先住民蜂起を組織し、数千人の農民を動員してキトを封鎖した。これら の蜂起においてCONAIEは、土地権利と多元ナショナリズムを要求すると同時に、汚職、規制緩和、民営化、エクアドル経済のドル化に抗議した。[4] 1993年から、CONAIEはシェブロン社に対する訴訟を支援した。同社はアグリオ湖油田でコスト削減策として、意図的に数十億ガロンの有毒な石油廃棄 物を先住民の土地に投棄したと主張している。[10][11] |

| 1990 uprising In May/June 1990, CONAIE organised the largest uprising in Ecuador's history, using trees and boulders to block roads, paralyze the transport system, and shutting down the country for a week. The 1990 uprising is generally regarded as marking the emergence of Indigenous peoples as new political actors on the national level, as CONAIE forced negotiation on their demands for bilingual education, agrarian reform, and recognition of the plurinational state of Ecuador.[3] The 1990 uprising marked the 500th anniversary since Columbus' first trip to the Americas. In Quito, protestors occupied the Santa Domingo Church and, protesting the failure of the legal system to process land claims.[12] The protesters intended to occupy the church until CONAIE was able to meet with a government representative to discuss changes in policy regarding their land claim issues. Police surrounded the church. The occupiers in the Santa Domingo church were about to begin a hunger strike when "hundreds of thousands of Indians, in some areas with the support of mestizo peasants, blocked local highways and took over urban plazas. Their demands were focused mostly on land, but also included such issues as state services, cultural rights, and the farm prices of agricultural products.[13] This movement caused so much disruption that the government relented and met with the leaders of CONAIE; the government made some concessions to people in rural areas and settled some land disputes, but the status of ancestral lands in the lowlands remained an unresolved issue.[2] |

1990年の反乱 1990年5月から6月にかけて、CONAIEはエクアドル史上最大の反乱を組織した。彼らは木や岩で道路を封鎖し、交通網を麻痺させ、一週間もの間国を 機能停止に追い込んだ。1990年の反乱は、先住民が国家レベルで新たな政治的主体として台頭した契機と広く認識されている。CONAIEは二言語教育、 農地改革、エクアドルの多元ナショナリズムとしての承認を求める要求について、政府に交渉を強いたのである。[3] 1990年の蜂起は、コロンブスが初めてアメリカ大陸に到達してから500周年を迎えた年であった。キトでは、抗議者たちがサンタ・ドミンゴ教会を占拠 し、土地権利請求を処理しない司法制度の失敗に抗議した。[12] 抗議者たちは、CONAIEが政府代表者と土地権利問題に関する政策変更を協議できるまで教会を占拠し続けるつもりだった。警察が教会を包囲した。サン タ・ドミンゴ教会の占拠者たちがハンガーストライキを始めようとした時、「数十万のインディアンが、一部地域ではメスティソ農民の支援を得て、地方の幹線 道路を封鎖し、都市の広場を占拠した。彼らの要求は主に土地問題に集中していたが、公共サービス、文化的権利、農産物の農産物価格なども含まれていた。 [13] この運動は甚大な混乱を引き起こしたため、政府は折れてコナイェの指導者と会談した。政府は農村地域の人民に対して一定の譲歩を行い、いくつかの土地紛争 を解決したが、低地における先祖伝来の土地の地位は未解決の問題として残った。[2] |

| 1992-1994 uprisings advocating

for land and water rights In April 1992, two thousand Kichwa, Shuar, and Achuar people marched 240 miles (385 kilometers) from the Amazon to Quito to demand legalization of land holdings. Protestors refused to leave the capital until President Rodrigo Borja agreed to demarcate and title their lands.[2] In June 1994, Indigenous organizations protested a neoliberal economic reforms and privatisation of water resources.[3] A coalition of Indigenous groups called for an uprising that shut down the country for several days in opposition to an Agrarian Reform Law that provided state support for capitalist agriculture, eliminated communal property, and privatized irrigation water.[2] President Sixto Durán was forced to negotiate, and the final version of the law supported peasant agriculture, recognised water as a public resource, and reaffirmed communal land ownership.[2] |

1992年から1994年にかけて、土地と水資源の権利を求める蜂起が

起こった。 1992年4月、キチュワ族、シュアル族、アチュアル族の2000の人民がアマゾンからキトまで385キロを徒歩で進み、土地所有権の法的承認を要求し た。抗議者たちはロドリゴ・ボルハ大統領が彼らの土地の境界設定と権利証発行に同意するまで首都を離れることを拒否した。[2] 1994年6月、先住民組織は新自由主義的経済改革と水資源の民営化に抗議した。[3] 先住民族団体連合は、資本主義農業への国家支援を規定し、共同所有制を廃止し、灌漑用水の民営化を定めた農地改革法に反対し、数日間にわたり国を麻痺させ る蜂起を呼びかけた。[2] シクスト・デュラン大統領は交渉を余儀なくされ、最終的な法律案は小作農業を支援し、水を公共資源と認め、共同土地所有権を再確認する内容となった。 [2] |

| Pachakutik Main article: Pachakutik Plurinational Unity Movement – New Country CONAIE initially forbid its members from holding political office,[9] but in its December 1995 assembly it played a major role in the formation of the Pachakutik Plurinational Unity Movement,[2] an electoral coalition of Indigenous and non-Indigenous social movements including CONFEUNASSC-CNC, Ecuador's largest campesino federation. Pachakutik won 10% of the congressional seats in the 1996 elections, though the presidential candidate Freddy Ehlers failed to qualify for the second presidential round of votes.[2] |

パチャクティック 主な記事: パチャクティック多元ナショナリズム統一運動 – 新たな国 CONAIEは当初、そのメンバーが公職に就くことを禁じていた[9]。しかし1995年12月の総会において、CONFEUNASSC-CNC(エクア ドル最大の農民連合)を含む先住民および非先住民の社会運動による選挙連合であるパチャクティック多元ナショナリズム統一運動の結成に主要な役割を果たし た[2]。 1996年の選挙でパチャクティックは議席の10%を獲得したが、大統領候補のフレディ・エーラーズは大統領選挙の決選投票に進む資格を得られなかった [2]。 |

| 1997 uprising and constitutional

assembly In August 1997 CONAIE led two straight days of protest demanding constitutional reform. CONAIE's leadership had a role in the fall of president Abdali Bucaram and the convening of a constitutional assembly.[2][1] The resulting 1998 constitution defined Ecuador as a multiethnic and multicultural state. Many new rights were explicitly granted to indigenous groups in the new document, including "the right to maintain, develop, and fortify their spiritual, cultural, linguistic, social, political and economic identity and traditions." Through the constitution the state was given many new responsibilities and standards to follow in terms of environmental conservation, the elimination of contamination, and sustainable management. It also included the right of free, prior, informed consent for development projects on Indigenous lands. Finally, the document provides protection of self-determination among indigenous lands, preserving traditional political structures, and follows International Labour Organization, Convention 169 that outlines generally accepted international law on indigenous rights. All of these points had been sought after for so many years and were finally guaranteed in this rewrite of the most important document in the country. Despite CONAIE and Pachakutik's triumph in this endeavor, government implementation of the policy has not exactly been consistent with the outline in that new constitution and the indigenous organizations have struggled since 1998. In cases such as ARCO’s deal to exploit oil resources in the Amazon, the government has totally ignored these new indigenous rights and sold communal land to be developed without another thought. Such violations have become commonplace and the reformation of the constitution seems in many ways to have just been a populist tactic used by the government to appease the indigenous groups while continuing to persistently pursue its neoliberal agenda. Because of this there has been an increasing amount of tension and differences of opinion within the indigenous movement, both between Pachakutik and CONAIE and within CONAIE itself. There even exists frustration among local tribes and the efforts of CONAIE because of the inability to stop the aggression of the government despite all that had been achieved. |

1997年の蜂起と憲法制定議会 1997年8月、CONAIEは憲法改正を要求する抗議行動を2日連続で主導した。CONAIEの指導部はアブダリ・ブカラム大統領の失脚と憲法制定議会 の招集に関与した。[2][1] その結果生まれた1998年憲法は、エクアドルを多民族・多文化国家と定義した。新憲法では先住民族グループに対し、「精神的・文化的・言語的・社会的・ 政治的・経済的アイデンティティと伝統を維持・発展・強化する権利」を含む多くの新たな権利が明示的に認められた。憲法により国家は環境保全、汚染除去、 持続可能な管理に関して多くの新たな責任と遵守すべき基準を課された。また先住民族の土地における開発プロジェクトには自由で事前かつ十分な情報に基づく 同意の権利が盛り込まれた。最後に、この文書は先住民地域における自己決定権の保護、伝統的政治構造の維持を規定し、先住民権利に関する国際的に認められ た法原則を定めた国際労働機関(ILO)第169号条約に準拠している。これら全ての点は長年求められてきたものであり、ついにこの国で最も重要な文書の 改訂によって保障されたのである。 CONAIEとパチャクティクのこの取り組みにおける勝利にもかかわらず、政府による政策の実施は新憲法の骨子と必ずしも一致しておらず、先住民族組織は 1998年以降苦闘を続けている。アマゾン地域における石油資源開発をめぐるARCOとの契約のような事例では、政府はこれらの新たな先住民族の権利を完 全に無視し、共同所有地を開発のために何の躊躇もなく売却した。こうした権利侵害は日常茶飯事となり、憲法改正は多くの点で、政府が先住民グループをなだ めつつ新自由主義政策を執拗に推進するためのポピュリスト的戦術に過ぎなかったように見える。このため先住民運動内部では、パチャクティクとコナイエの 間、そしてコナイエ内部においても、緊張と異なる意見が増大している。これまでに達成された成果にもかかわらず、政府の攻撃を止められないことに、現地の 部族やコナイエの取り組みに対する不満さえ存在している。 |

| 1998-99 uprisings and 2000 coup

d'état See also: 2000 Ecuadorian coup d'état and 1998–1999 Ecuador economic crisis Because of falling oil prices and agricultural failures, Ecuador experienced an economic collapse in 1998–99. President Jamil Mahuad sought a stabilisation loan from the IMF, but popular resistance to IMF reforms led to three large uprisings in 1998 and 1999 led by CONAIE. At the end of 1999, Mahuad announced plance to implement the IMF measures and dollarise the Ecuadorian economy.[2] On January 21, 2000, in response to Mahuad's plans, CONAIE, in coordination with organizations like CONFEUNASSC-CNC, blocked roads and cut off agricultural supplies to Ecuador's major cities. At the same time, rural indigenous protesters marched on Quito. In response, government officials ordered transit lines not to service Indians and individuals with indigenous characteristics were forcibly removed from interprovincial buses in an effort to prevent protesters from reaching the capitol. Nevertheless, 20,000 arrived in Quito where they were joined by students, local residents, 500 military personnel, and a group of rogue colonels. Angry demonstrators led by Colonel Lucio Gutiérrez and CONAIE president Antonio Vargas stormed the Congress of Ecuador and declared a new "National Salvation Government".[2] Five hours later, the armed forces called for the resignation of President Mahuad. For a period of less than 24 hours, Ecuador was ruled by a three-man junta – CONAIE's president Antonio Vargas, army colonel Lucio Gutiérrez, and retired Supreme Court justice Carlos Solórzano. Only a few hours after taking the presidential palace, Col. Gutiérrez other collaborators handed over power to the armed forces' chief of staff, General Carlos Mendoza.[2] That night Mendoza was contacted by the Organization of American States as well as the U.S. State Department, which hinted at the imposition of a Cuban-style isolation on Ecuador if power was not returned to the neoliberal Mahuad administration.[14] Additionally, Mendoza was contacted by senior White House policy makers who threatened to end all bilateral aid[clarification needed] and World Bank[clarification needed] lending to Ecuador. The next morning, General Mendoza dissolved the new government and ceded power to Vice President Gustavo Noboa. |

1998-99年の反乱と2000年のクーデター 関連項目: 2000年エクアドルクーデター、1998-1999年エクアドル経済危機 原油価格の下落と農業不振により、エクアドルは1998年から1999年にかけて経済崩壊を経験した。ジャミル・マウアド大統領はIMFに安定化融資を要 請したが、IMF改革への民衆の抵抗により、1998年から1999年にかけてCONAIE主導の3回の大規模な反乱が発生した。1999年末、マウアド はIMF措置の実施とエクアドル経済のドル化計画を発表した。[2] 2000年1月21日、マワドの計画に対抗するため、CONAIEはCONFEUNASSC-CNCなどの組織と連携し、道路を封鎖して主要都市への農産 物供給を遮断した。同時に、農村部の先住民抗議者たちがキトへ進軍した。これに対し政府当局は、抗議者が首都へ到達するのを阻止するため、交通機関にイン ディアンへのサービス提供を停止するよう命令し、インディアンおよび先住民の特徴を持つ個人を州間バスから強制的に降ろした。にもかかわらず、2万人がキ トに到着し、学生、地元住民、500人の軍人、そして一派の反乱将校グループが合流した。 ルシオ・グティエレス大佐とCONAIEのアントニオ・バルガス会長が率いる怒れるデモ隊はエクアドル議会を襲撃し、新たな「国民救済政府」の樹立を宣言 した。[2] 5時間後、軍部はマウアド大統領の辞任を要求した。24時間にも満たない期間、エクアドルは3人による軍事政権――コナイエ会長アントニオ・バルガス、陸 軍大佐ルシオ・グティエレス、退役最高裁判事カルロス・ソロルサノ――によって統治された。 大統領宮殿を占拠してからわずか数時間後、グティエレス大佐らは権力を軍参謀総長カルロス・メンドーサ将軍に委譲した[2]。その夜、メンドーサ将軍は米 州機構(OAS)と米国務省から接触を受けた。彼らは、新自由主義のマウアド政権に権力を返還しなければ、キューバ式にエクアドルを孤立させる可能性を示 唆した。さらにメンドーサはホワイトハウスの上級政策担当者からも連絡を受け、二国間援助[注釈が必要]と世界銀行[注釈が必要]によるエクアドルへの融 資を全て停止すると脅された。翌朝、メンドーサ将軍は新政府を解散させ、グスタボ・ノボア副大統領に権力を移譲した。 |

2002 elections and the FTAA Members of CONAIE marched against the FTAA summit in Quito (October 31, 2002) In 2002, CONAIE split its resources between political campaigning and a mobilization against the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) 7th Summit, which was being held in Quito. In the presidential elections CONAIE backed populist Lucio Gutiérrez, a military man who had supported the 2000 coup. Gutiérrez was not widely trusted, but he was seen as the only alternative to rival candidate Álvaro Noboa, the richest man in Ecuador who embodied popular fears of crony capitalism. Lucio Gutiérrez won the presidential race with 55% of the final vote, owing much of his victory to support from Pachakutik. |

2002年の選挙とFTAA CONAIEのメンバーがキトで開催されたFTAAサミットに抗議して行進した(2002年10月31日) 2002年、CONAIEは政治運動と、キトで開催された米州自由貿易地域(FTAA)第7回サミットへの抗議活動に資源を割いた。 大統領選挙では、CONAIEは2000年のクーデターを支持した軍人出身のポピュリスト、ルシオ・グティエレスを支持した。グティエレスは広く信頼され ていなかったが、エクアドルで最も裕福な人物であり、縁故資本主義への民衆の懸念を体現する対立候補アルヴァロ・ノボアに対する唯一の選択肢と見なされて いた。 ルシオ・グティエレスは最終投票で55%を獲得し大統領選に勝利したが、その勝利の多くはパチャクティックの支持によるものだった。 |

| 2005 uprising Six months after the election of Gutiérrez, CONAIE proclaimed its official break with the government in response to what CONAIE termed a betrayal of "the mandate given to it by the Ecuadorian people in the last elections." Among other things, Gutiérrez's signing of a Letter of Intent with the International Monetary Fund sparked outrage. (see Indigenous Movement Breaks with President Lucio Guiterrez) In 2005, CONAIE participated in an uprising which ousted president Lucio Gutiérrez. In an April 2005 Assembly of Peoples, and in their own contentious assembly in May, CONAIE made public calls for the ouster of both Gutiérrez and the entire mainstream political class under the slogan "Que se vayan todos" (They all must go), a phrase popularized by the December 2001 Argentine uprising. In August 2005 CONAIE called for action among indigenous peoples in the Sucumbios and Orellana provinces to protest political repression, Petrobras' attempt to expand their petroleum extracting activities to the Yasuní National Park, and the general activities of Occidental Petroleum in the Amazon. Hundreds of protestors from the Amazon region took control of airports and oil installations in the two provinces for five days, which has prompted a strong response from Alfredo Palacio's government in Quito. The government called for a state of emergency in the two provinces and the army was sent in to disperse the protestors with tear gas, but in response to the growing crisis the state oil company has temporarily suspended exports of petroleum. Protestors have gone on record as saying that they want oil revenues to be redirected toward society, making way for more jobs and greater expenditures in infrastructure. |

2005年の反乱 グティエレス大統領の当選から6か月後、CONAIEは「前回の選挙でエクアドル人民から与えられた使命」に対する裏切り行為として、政府との公式な決別 を宣言した。特に、グティエレスが国際通貨基金(IMF)と覚書に署名したことが激しい怒りを招いた。(先住民族運動、ルシオ・グティエレス大統領との決 別を参照) 2005年、CONAIEはルシオ・グティエレス大統領を追放する蜂起に参加した。2005年4月の「人民の集会」及び5月の自派集会において、 CONAIEは「全員退陣せよ(Que se vayan todos)」のスローガンを掲げ、グティエレス大統領と主流政治家全体の退陣を公に要求した。このスローガンは2001年12月のアルゼンチン蜂起で広 まったものである。 2005年8月、CONAIEはスクンビオス州とオレリャーナ州の先住民に対し、政治的弾圧、ペトロブラスのヤスニ国立公園への石油採掘活動拡大計画、お よびアマゾン地域におけるオクシデンタル石油の活動全般への抗議行動を呼びかけた。アマゾン地域から数百人の抗議者が両州の空港と石油施設を5日間占拠し た。これに対しキトのアルフレド・パラシオ政権は強硬な対応に出た。政府は両州に非常事態宣言を発令し、軍隊を派遣して催涙ガスで抗議者を排除しようとし た。しかし危機が深刻化する中、国営石油会社は石油輸出を一時停止した。抗議者らは石油収入を社会還元し、雇用創出とインフラ投資拡大に充てるよう要求し ていると公言している。 |

| 2010 and 2014 protests against

water privatisation A water bill proposed by the government of Rafael Correa was opposed by Indigenous organisations who charged that the legislation would allow transnational mining corporations to appropriate water (and privatisation of water in general), and that the bill would violate protection of water provided by the 2008 constitution. In April and May 2010 massive nationwide protests condemned Correa's legislation; protestors viewed the water bill as a neoliberal, extractivist policy that violated the tenets of sumak kawsay. CONAIE coordinated a National Mobilization in Defense of Water, Life, and Food Sovereignty, and protests blockaded the congressional building and roads across the country. Police responded with violent repression, but the campaign did result in the delay of the water law pending a referendum in Indigenous communities.[6] In 2014, the government fast-tracked a new water law that allowed the privatisation of water and permitted extractive activities near freshwater sources. Indigenous organisations responded with a Walk for Water, Life and People's Freedom beginning in June 2014 from the Zamora-Chinchipe province to Quito.[15] |

2010年と2014年の水民営化反対抗議運動 ラファエル・コレア政権が提案した水法案に対し、先住民族組織が反対した。彼らはこの法案が国際鉱業企業による水の収奪(および水一般の民営化)を許容 し、2008年憲法が定める水の保護を侵害すると主張した。2010年4月から5月にかけて、全国規模の大規模抗議活動がコレアの法案を糾弾した。抗議者 らはこの法案を、スマック・カウサイの理念に反する新自由主義的・搾取主義的政策と見なした。CONAIE(全国先住民組織連合)は「水・生命・食糧主権 を守る全国動員」を組織し、抗議活動により国会議事堂や全国の道路が封鎖された。警察は暴力的な弾圧で応じたが、この運動の結果、先住民族コミュニティで の住民投票を待つ形で水法案の施行は延期された。[6] 2014年、政府は新たな水法案を急ぎ成立させた。この法案は水の民営化を認め、淡水源付近での採掘活動を許可する内容だった。これに対し先住民組織は 2014年6月、サモラ・チンチペ県からキトまで「水と生命と人民の自由のための行進」を開始した。[15] |

| 2012 protests In 2012, the Ecuadorian government under Rafael Correa made agreements with China to enable investment of $1.4 billion to develop copper-gold mines in the Amazon rainforest in the Zamora Chinchipe province. Following these agreements, CONAIE organized several weeks of marching and demonstration in 2012 demanding consultation with affected Indigenous people and protection of water.[16] Chinese companies eventually developed the Mirador mine, which exported its first copper in 2019, although Indigenous opposition stopped development of the San Carlos Panantza mine in 2020.[17] |

2012年の抗議活動 2012年、ラファエル・コレア政権下のエクアドル政府は中国と合意し、ザモラ・チンチペ州のアマゾン熱帯雨林における銅・金鉱山開発のため14億ドルの 投資を可能にした。これを受け、コナイエ(CONAIE)は2012年に数週間にわたる行進とデモを組織し、影響を受ける先住民との協議と水の保護を要求 した[16]。中国企業は最終的にミラドール鉱山を開発し、2019年に初の銅を輸出した。しかし先住民の反対により、サン・カルロス・パナンツァ鉱山の 開発は2020年に中止された[17]。 |

| 2013 The largest involvement CONAIE has had in recent politics is with large national oil companies who wish to drill and build on indigenous land. On "November 28th, 2013, plain-clothes officers in Quito, Ecuador summarily closed the offices of Fundación Pachamama, a nonprofit that for 16 years has worked in defense of the rights of Amazonian indigenous peoples and the rights of nature. The dissolution, which the government blamed on their “interference in public policy,” was a retaliatory act that sought to repress Fundación Pachamama's legitimate right to disagree with the government's policies, such as the decision to turn over Amazonian indigenous people's land to oil companies."[18] |

2013 CONAIEが近年の政治で最も深く関わったのは、先住民の土地で掘削や建設を望む大手国営石油会社との問題だ。2013年11月28日、エクアドルのキ トで私服警官がパチャママ財団の事務所を突然閉鎖した。この非営利団体は16年間、アマゾンの先住民の権利と自然の権利を守る活動を行ってきた。政府は解 散理由を「公共政策への干渉」と説明したが、これはパチャママ財団が政府の政策に異議を唱える正当な権利を抑圧しようとする報復行為であった。例えばアマ ゾンの先住民の土地を石油会社に譲渡する決定などに対する異議である。」[18] |

| 2015 These paragraphs are an excerpt from 2015 Ecuadorian protests.[edit] The 2015 Ecuadorian protests were a series of protests against the government of President Rafael Correa. Protests began in the first week of June, triggered by legislation increasing inheritance and capital gains taxes.[19] By August, an alliance of rural farmworkers, Indigenous federations such as CONAIE, student groups, and labor unions had organised protests involving hundreds of thousands of people with a wide range of grievances, including the controversial tax laws; constitutional amendments removing presidential term limits; expanding oil and mining projects; water, education, and labour policies; a proposed free trade agreement with the European Union; and increasing repression of freedom of speech.[20][21][22] On August 15, the government declared a state of exception that allowed the military to crackdown on protests. Protestors blocked roads and declared a general strike in August. Violence and human rights violations were reported in clashes between militarised police and protestors.[22][23][24] Protestors stated that Correa wanted to follow "the same path as Venezuela's government," creating a "criminal war of classes," while President Correa stated that the protests were aimed at destabilizing the government, and the proposed measures were for combatting inequality.[25] |

2015年 これらの段落は2015年のエクアドル抗議運動からの抜粋である。[編集] 2015年のエクアドル抗議運動は、ラファエル・コレア大統領の政府に対する一連の抗議活動であった。抗議は6月の第1週に始まり、相続税とキャピタルゲ イン税を引き上げる法案が引き金となった。[19] 8月までに、農村労働者、CONAIEなどの先住民連合、学生団体、労働組合の連合が組織した抗議活動には数十万人が参加し、物議を醸した税制改正、大統 領の任期制限を撤廃する憲法改正、石油・鉱業プロジェクトの拡大、水資源・教育・労働政策、欧州連合との自由貿易協定案、言論の自由に対する弾圧の強化な ど、幅広い不満が表明された。[20][21][22] 8月15日、政府は軍による抗議活動弾圧を可能とする非常事態宣言を発令した。 抗議者らは8月に道路封鎖とゼネストを実施。武装警察と抗議者との衝突で暴力行為や人権侵害が報告された。[22][23] [24] 抗議者らは、コレア大統領が「ベネズエラ政府と同じ道を歩もうとしている」と主張し、「犯罪的な階級戦争」を引き起こしていると述べた。一方、コレア大統 領は、抗議活動は政府を不安定化させることを目的としており、提案された措置は不平等と戦うためのものだと述べた。[25] |

| 2019 protests over austerity

measures These paragraphs are an excerpt from 2019 Ecuadorian protests.[edit] The 2019 Ecuadorian protests were a series of protests and riots against austerity measures including the cancellation of fuel subsidies, adopted by President of Ecuador Lenín Moreno and his administration.[26][27] Organized protests ceased after indigenous groups and the Ecuadorian government reached a deal to reverse the austerity measures, beginning a collaboration on how to combat overspending and public debt.[28] |

2019年の緊縮政策に対する抗議活動 これらの段落は2019年エクアドル抗議活動からの抜粋である。[編集] 2019年のエクアドル抗議活動は、燃料補助金廃止を含む緊縮財政措置に反対する一連の抗議活動と暴動であった。これらの措置はエクアドル大統領レニン・ モレノとその政権によって採択された。[26][27] 先住民グループとエクアドル政府が緊縮財政措置を撤回する合意に達した後、組織的な抗議活動は終息した。これにより、過剰支出と公的債務対策に関する協力 が始まった。[28] |

| 2022 uprising This section is an excerpt from 2022 Ecuadorian protests.[edit]  Protests seen on 25 June 2022 A series of protests against the economic policies of Ecuadorian president Guillermo Lasso, triggered by increasing fuel and food prices, began on 13 June 2022. Initiated by and primarily attended by Indigenous activists, in particular the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), the protests have since been joined by students and workers who have also been affected by the price increases. Lasso condemned the protests and labelled them as an attempted "coup d'état" against his government.[29] As a result of the protests, Lasso has declared a state of emergency.[30] As the protests have blocked exits, entries and ports in Quito and Guayaquil, there have been food and fuel shortages across the country as a result.[31][32][33] Lasso has been criticized for allowing violent and deadly responses towards protestors. The President narrowly escaped impeachment in a vote in National Assembly on 29 June: 81 MPs voted in favour of impeachment, 42 voted against and 14 abstained; 92 votes were needed to achieve impeachment. |

2022年の反乱 この節は2022年エクアドル抗議運動からの抜粋である。[編集]  2022年6月25日に確認された抗議活動 エクアドルのギジェルモ・ラッソ大統領の経済政策に対する一連の抗議活動が、燃料と食料価格の高騰をきっかけに2022年6月13日に始まった。先住民族 活動家、特にエクアドル先住民族連合(CONAIE)によって開始され、主に彼らによって参加された抗議活動は、その後、価格上昇の影響を受けた学生や労 働者も加わった。ラッソは抗議活動を非難し、これを政府に対する「クーデター未遂」と断じた。[29] 抗議活動の結果、ラッソは非常事態宣言を発令した。[30] キトとグアヤキルの出入り口や港湾が抗議活動によって封鎖されたため、国内では食料と燃料の不足が生じている。[31][32][33] ラッソは抗議者に対する暴力的かつ致命的な対応を許容したことで批判されている。大統領は6月29日の国民議会における弾劾投票で辛うじて弾劾を免れた。 弾劾賛成81票、反対42票、棄権14票という結果で、弾劾成立には92票が必要だった。 |

| Leadership CONAIE’s past presidents include:[34] Miguel Tankamash (Shuar) Luis Macas (Kichwa Saraguro) Antonio Vargas (Kichwa Amazónico) Leonidas Iza (Kichwa Panzaleo) Marlon Santi (Kichwa Sarayaku) Humberto Cholango (Kichwa Kayambi) Jorge Herrera (Kichwa Panzaleo) September 2017 – May 2021: Jaime Vargas Vargas (Ashuar) Manuel Castillo June 2021 – present: Leonidas Iza |

指導者 コナイエの歴代会長には以下の人物が含まれる:[34] ミゲル・タンカマシュ(シュアル族) ルイス・マカス(キチュワ・サラグロ族) アントニオ・バルガス(キチュワ・アマゾニコ族) レオニダス・イサ(キチュワ・パンザレオ族) マーロン・サンティ(キチュワ・サラヤク族) ウンベルト・チョランゴ(キチュワ・カヤンビ族) ホルヘ・エレラ(キチュワ・パンザレオ族) 2017年9月~2021年5月:ハイメ・バルガス・バルガス(アシュアル族) マヌエル・カスティーヨ 2021年6月~現在:レオニダス・イサ |

| American Indian Movement Anti-globalization Indigenous Movements in the Americas Indigenous peoples in Ecuador |

アメリカインディアン運動 反グローバリゼーション アメリカ大陸の先住民運動 エクアドルの先住民 |

| References 1. "Ecuador: Latin America's Strongest Indigenous Movement", Contesting Citizenship in Latin America, Cambridge University Press, pp. 85–151, 2005-03-07, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511790966.004, ISBN 9780521827461, retrieved 2022-07-10 2. Zamosc, Leon (2007). "The Indian Movement and Political Democracy in Ecuador". Latin American Politics and Society. 49 (3): 1–34. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2007.tb00381.x. ISSN 1531-426X. JSTOR 30130809. S2CID 143533815. 3. Becker, Marc (2008). Stearns, Peter N. (ed.). Ecuador, Indigenous uprisings in. Oxford University Press. {{cite book}}: |work= ignored (help) 4. Chiriboga, Manuel (2004). "Desigualdad, exclusión étnica y participación política: el caso de Conaie y Pachacutik en Ecuador" (PDF). Alteridades. 14 (28): 51–64. 5. Jameson, Kenneth P. (2011). "The Indigenous Movement in Ecuador: The Struggle for a Plurinational State". Latin American Perspectives. 38 (1): 63–73. doi:10.1177/0094582X10384210. ISSN 0094-582X. S2CID 147335114. 6. Becker, Marc (2010). "The Children of 1990". Alternatives: Global, Local, Political. 35 (3): 291–316. doi:10.1177/030437541003500307. ISSN 0304-3754. JSTOR 41319262. S2CID 144712843. 7. Becker, Marc (2011). Pachakutik : indigenous movements and electoral politics in Ecuador. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-0755-4. OCLC 700438480. 8. Lucero, Jose Antonio (2003). "Locating the "Indian Problem" Community, Nationality, and Contradiction in Ecuadorian Indigenous Politics" (PDF). Latin American Perspectives. 30 (128): 23–48. doi:10.1177/0094582X02239143. S2CID 144551714. 9. Becker, Marc (1996-05-01). "President of CONAIE runs for Congress". NACLA Report on the Americas. 29 (6): 45. ISSN 1071-4839. 10. Nations, Assembly of First. "Assembly of First Nations Lends Support to CONAIE and FDA Efforts to Hold Chevron Accountable for Environmental Damage in Ecuador". www.newswire.ca. Retrieved 2022-07-09. 11. "Chevron Faces More Scrutiny in Ecuador over Pollution | Amazon Watch". 2007-03-15. Retrieved 2022-07-09. 12. Colloredo-Mansfeld, Rudi. Fighting like a community Andean civil society in an era of Indian uprisings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009. 13. Korovkin, Tanya. "Indians, peasants, and the state: The growth of a community movement in the ecuadorian andes." CERLAC Occasional Paper Series 1 (1992): 1–47. 14. Rohter, Larry (2000-01-23). "Ecuador Coup Shifts Control To No. 2 Man". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-11-26. 15. Picq, Manuela. "Conflict over water rights in Ecuador". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2022-07-09. 16. "Ecuador indigenous protesters march against mining". BBC News. 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2022-07-02. 17. "Strife with indigenous groups could derail Ecuador's drive to be a mining power". Reuters. 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2022-07-03. 18. Zuckerman, Adam. "Ecuador Cracks Down on Indigenous Leaders Opposed to Oil". Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014. 19. Marty, Belén (11 June 2015). "Ecuadorians Protest Ballooning Price of Socialist Revolution". PanAm Post. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2015. 20. Glickhouse, Rachel (25 August 2015). "Explainer: What's Behind Ecuador's 2015 Protests?". Americas Society/Council of the Americas. 21. Morla, Rebeca (26 June 2015). "Correa Feels the Wrath of Massive Protests in Ecuador". PanAm Post. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015. 22. "Protests by 1,000s of Ecuadorians meet with brutal repression". the Guardian. 2015-08-19. Retrieved 2022-07-10. 23. "Ecuador: Crackdown on Protesters". Human Rights Watch. 2015-11-10. Retrieved 2022-07-17. 24. "After crackdown, protesters to march again against Ecuador's 'extractivism'". Mongabay Environmental News. 2015-09-14. Retrieved 2022-07-17. 25. Alvaro, Mercedes (25 June 2015). "Protesters in Ecuador Demonstrate Against Correa's Policies". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2015. 26. Lucas, Dave (2019-10-11). "Protests rage over Ecuador austerity measures Pictures". Reuters. Retrieved 2019-10-11. 27. "'We're going to fight until he leaves': Ecuador protests call for Moreno to quit – video". The Guardian. Reuters. 2019-10-10. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-10-13. 28. "Ecuador deal cancels austerity plan, ends indigenous protest". The Washington Post. 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019. 29. "Lasso denuncia un intento de golpe de Estado detrás de protestas en Ecuador" (in Spanish). Swiss Info. 24 June 2022. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022. 30. "Ecuador Indigenous protesters arrive in Quito as president extends state of emergency". France 24. 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-06-22. Retrieved 2022-06-22. 31. "Ecuador facing food and fuel shortages as country rocked by violent protests". The Guardian. 22 June 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-06-23. Retrieved 2022-06-23. 32. "In Protest-hit Ecuador, Shortages Of Key Goods Start To Bite". Barrons. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022. 33. "Ecuador protests take increasingly violent turn in capital". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022. 34. Picq, manuela L. (1 January 2018). Vernacular Sovereignties: Indigenous Women Challening World Politics. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Retrieved 22 June 2025. |

参考文献 1. 「エクアドル:ラテンアメリカ最強の先住民族運動」、『ラテンアメリカにおける市民権の争い』、ケンブリッジ大学出版局、pp. 85–151、2005年3月7日、doi:10.1017/cbo9780511790966.004、 ISBN 9780521827461, 2022-07-10 参照 2. Zamosc, Leon (2007). 「エクアドルにおけるインディアン運動と政治的民主主義」. 『ラテンアメリカ政治と社会』. 49 (3): 1–34. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2007.tb00381.x. ISSN 1531-426X. JSTOR 30130809. S2CID 143533815. 3. ベッカー、マーク(2008年)。スターンズ、ピーター・N.(編)。『エクアドルにおける先住民蜂起』オックスフォード大学出版局。{{cite book}}: |work=が無視された (ヘルプ) 4. チリボガ、マヌエル(2004)。「不平等、民族的排除、政治参加:エクアドルにおけるコナイエとパチャクティックの事例」 (PDF)。『アルテリダデス』 14 (28): 51–64. 5. ジェイムソン、ケネス・P. (2011). 「エクアドルにおける先住民運動:多元ナショナリズム国家をめぐる闘争」. 『ラテンアメリカ・パースペクティブス』. 38 (1): 63–73. doi:10.1177/0094582X10384210. ISSN 0094-582X. S2CID 147335114. 6. ベッカー、マーク (2010). 「1990年の子供たち」. 『オルタナティヴズ:グローバル、ローカル、ポリティカル』. 35 (3): 291–316. doi:10.1177/030437541003500307. ISSN 0304-3754. JSTOR 41319262. S2CID 144712843. 7. ベッカー, マーク (2011). 『パチャクティック:エクアドルにおける先住民族運動と選挙政治』. ランハム、メリーランド州:ローマン&リトルフィールド出版社。ISBN 978-1-4422-0755-4。OCLC 700438480。 8. ルセロ、ホセ・アントニオ(2003)。「『インディアン問題』の位置づけ:エクアドル先住民政治における共同体、国民性、そして矛盾」 (PDF)。ラテンアメリカ展望。30 (128): 23–48. doi:10.1177/0094582X02239143. S2CID 144551714. 9. ベッカー、マーク (1996-05-01). 「CONAIE 会長が議会選挙に出馬」. NACLA Report on the Americas. 29 (6): 45. ISSN 1071-4839. 10. ファースト・ネーションズ議会.「ファースト・ネーションズ議会、エクアドルにおける環境被害に対するシェブロンの責任追及に向けたCONAIEおよび FDAの取り組みを支援」. www.newswire.ca. 2022年7月9日閲覧。 11. 「エクアドルで汚染問題をめぐりシェブロン社への監視強化 | Amazon Watch」. 2007年3月15日. 2022年7月9日閲覧. 12. コロレド=マンスフェルト, ルディ. 『共同体として戦う:インディアン蜂起の時代におけるアンデス市民社会』. シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局, 2009. 13. コロフキン、ターニャ。「インディアン、農民、そして国家:エクアドル・アンデスにおける共同体運動の成長」『CERLAC Occasional Paper Series』1号(1992年):1–47頁。 14. ローター、ラリー(2000年1月23日)。「エクアドルクーデター、権力をナンバー2に移す」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ。ISSN 0362-4331。2021-11-26 取得。 15. ピック、マヌエラ。「エクアドルにおける水権をめぐる紛争」。www.aljazeera.com。2022-07-09 取得。 16. 「エクアドル先住民、鉱業反対で抗議行進」BBCニュース. 2012年3月9日. 2022年7月2日閲覧. 17. 「先住民グループとの対立がエクアドルの鉱業大国化計画を阻害する恐れ」ロイター. 2020年12月10日. 2022年7月3日閲覧. 18. ザッカーマン、アダム。「エクアドル、石油開発に反対する先住民指導者を弾圧」。2014年3月18日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2014年3月2日に 取得。 19. マーティ、ベレン(2015年6月11日)。「エクアドル人、社会主義革命の膨張する代償に抗議」。PanAm Post。2016年3月4日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。2015年6月28日に取得。 20. グリックハウス、レイチェル(2015年8月25日)。「解説:エクアドルの2015年抗議行動の背景とは?」。アメリカズ協会/アメリカ大陸評議会。 21. モルラ、レベカ(2015年6月26日)。「エクアドルで大規模抗議の怒り、コレア大統領が直面」。パナム・ポスト。2015年6月28日にオリジナルか らアーカイブ。2015年6月28日に取得。 22. 「数千人のエクアドル人による抗議、残忍な弾圧に直面」。ガーディアン。2015年8月19日。2022年7月10日に閲覧。 23. 「エクアドル:抗議者への弾圧」。ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチ。2015年11月10日。2022年7月17日に閲覧。 24. 「弾圧後、抗議者たちがエクアドルの『資源搾取主義』に再び抗議行進」。モンガベイ環境ニュース。2015年9月14日。2022年7月17日閲覧。 25. アルヴァロ、メルセデス(2015年6月25日)。「エクアドルの抗議者、コレア政策に反対デモ」。ウォール・ストリート・ジャーナル。2019年10月 11日オリジナルからアーカイブ。2015年6月28日閲覧。 26. ルカーチ、デイブ(2019年10月11日)。「エクアドルの緊縮政策に抗議活動が激化 写真付き」。ロイター。2019年10月11日閲覧。 27. 「『彼が去るまで戦う』:エクアドル抗議活動、モレノ大統領の辞任を求める-動画付き」。ガーディアン。ロイター。2019年10月10日. ISSN 0261-3077. 2019年10月13日閲覧. 28. 「エクアドル合意で緊縮計画撤回、先住民抗議終結」. ワシントン・ポスト. 2019年10月14日. 2019年10月14日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2019年10月14日閲覧. 29. 「ラッソ大統領、エクアドル抗議の背景にクーデター企図を告発」(スペイン語)。スイス・インフォ。2022年6月24日。2022年6月25日にオリジ ナルからアーカイブ。2022年6月29日に閲覧。 30. 「エクアドル先住民抗議者、大統領が非常事態宣言延長する中キトに到着」. France 24. 2022年6月21日. 2022年6月22日にオリジナルからアーカイブ. 2022年6月22日に閲覧. 31. 「エクアドル、暴力抗議で揺れる中食糧・燃料不足に直面」. ガーディアン。2022年6月22日。2022年6月23日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年6月23日に取得。 32. 「抗議活動に見舞われたエクアドルで、主要物資の不足が深刻化」。バロンズ。2022年6月30日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年6月30日に取 得。 33. 「エクアドル抗議活動、首都で激化の一途」。ワシントン・ポスト。2022年6月30日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2022年6月30日閲覧。 34. ピック、マヌエラ・L.(2018年1月1日)。『土着の主権:世界政治に挑む先住民族女性たち』。ツーソン:アリゾナ大学出版局。2025年6月22日 閲覧。 |

| External links CONAIE official website "Mainstreaming the Indigenous Movement in Ecuador: The Electoral Strategy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-01-23. (58.0 KiB), by Kenneth Mijeski and Scott Beck Ecuadorian Protests, by Duroyan Fertl, ZNet Protests halt Ecuador oil exports, BBC article in August 2005 protests |

外部リンク CONAIE公式ウェブサイト 「エクアドルにおける先住民運動の主流化:選挙戦略」(PDF)。2005年1月23日時点のオリジナル(PDF)からアーカイブされたもの。(58.0 KiB)、ケネス・ミジェスキとスコット・ベックによる エクアドルの抗議活動、デュロヤン・ファートル著、ZNet 抗議活動がエクアドルの石油輸出を停止、2005年8月の抗議活動に関するBBC記事 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confederation_of_Indigenous_Nationalities_of_Ecuador |

★CONAIE (スペイン語ウィキペディア)

| La Confederación de

Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (Conaie) es una organización

indígena ecuatoriana, la más grande a nivel nacional. Precedida por el

Consejo Nacional de Coordinación de Nacionalidades Indígenas, fue

fundada el 16 de noviembre de 1986 en Quito. Está conformada por tres

organizaciones filiales, las mismas que pertenecen a las tres regiones

del país (excluyendo las islas Galápagos, donde no existen pueblos o

territorios ancestrales), las mismas que aglutinan a todos los pueblos

y nacionalidades indígenas de Ecuador. La Conaie funge como el principal representante social de la población indígena ecuatoriana, siendo una de las organizaciones sociales más destacadas en la política nacional. Además ejerce una gran influencia sobre el Movimiento de Unidad Plurinacional Pachakutik, el cual es su representante político en los procesos electorales. Actualmente, el presidente de la Conaie es Marlon Vargas Santi. |

エクアドル先住民民族連合(Conaie)は、エクアドル最大の先住民

組織である。先住民民族調整全国評議会を前身とし、1986年11月16日にキトで設立された。3つの関連組織で構成され、それらは国内の3つの地域(先

住民や先祖伝来の領土が存在しないガラパゴス諸島を除く)に属し、エクアドルのすべての先住民および民族を統合している。 コナイエは、エクアドルの先住民を社会的に代表する主要組織であり、国内政治において最も影響力のある社会組織の一つだ。また、選挙においてコナイエの政 治的代表である多民族統一運動パチャクティックにも大きな影響力を持っている。現在、コナイエの会長はマーロン・バルガス・サンティが務めている。 |

| Orígenes La población indígena fue históricamente marginada de la política ecuatoriana, es así que a inicios del siglo xx, se empiezan a organizar en pequeñas agrupaciones, asesorados por el Partido Socialista Ecuatoriano y el Partido Comunista del Ecuador.[1] En agosto de 1944 se realiza el Primer Congreso Ecuatoriano de Indígenas, en la Casa del Obrero, en Quito. En aquella reunión, líderes indígenas como Jesús Gualavisí, Dolores Cacuango, Tránsito Amaguaña, Agustín Vega, Ambrosio Lasso fundaron la Federación Ecuatoriana de Indios (FEI).[2] Posteriormente, el 9 de marzo de 1965 surgió la Federación de Trabajadores Agropecuarios (FETAP), como organización filial a la Confederación Ecuatoriana de Obreros Católicos (CEDOC); la misma que era adherente al Partido Conservador Ecuatoriano (PCE). En noviembre de 1968, la FETAP se transformó en la Federación Nacional de Organizaciones Campesinas (FENOC), con una pequeña, pero cada vez mayor participación indígena en sus filas. En junio de 1972, nació la Ecuador Runakunapak Rikcharimuy (Ecuarunari), con la asistencia de más de 200 delegados de organizaciones indígenas de Imbabura, Pichincha, Cotopaxi, Bolívar, Chimborazo y Cañar. Dicha organización se fundó en base en las nuevas corrientes ideológicas dentro de la Iglesia Católica, surgidas de la II Conferencia General del Episcopado Latinoamericano y el Concilio Vaticano II. El carácter clerical se evidenció en la presencia de sacerdotes como asesores en las organizaciones provinciales.[1] En la Amazonía, el proceso es más lento, el 24 de agosto de 1980 se realiza el Primer Congreso Regional de las Nacionalidades Indígenas de la Amazonía ecuatoriana, al que asistieron la Federación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Napo (FOIN), la Federación de Centros Shuar, Organización de Pueblos Indígenas de Pastaza (OPIP), Asociación Independiente del Pueblo Shuar Ecuatoriano (AIPSE), y Jatun Comuna Aguarico (JCA), los mismos que tras el evento, fundan la Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas de la Amazonía Ecuatoriana (Confeniae).[3] Para aquel entonces, la estructura de las organizaciones indígenas era claramente descentralizada; coexistiendo a través de hegemonías regionales y cooperaciones puntuales, pero ninguna organización tenía una representatividad a nivel nacional. La creciente colaboración entre Ecuarunari y Confeniae llevó a planes de fundar una coordinadora nacional de organizaciones indígenas. Posteriormente, el 25 de octubre de 1980, se realizó en Sucúa, el Primer Encuentro de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador, en el que surgió el Consejo Nacional de Coordinación de las Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (CONACNIE). Dicho organismo tuvo un segundo congreso en abril de 1984, en Quito, en el mismo que se declaró independiente de todo partido político. Finalmente, en el tercer encuentro de la CONACNIE, se llevó a cabo la creación de la Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (Conaie), el 16 de noviembre de 1986, en Quito.[1] |

起源 先住民は歴史的にエクアドルの政治から疎外されてきたため、20世紀初頭、エクアドル社会党とエクアドル共産党の助言を受けて、小さな集団で組織化を始め ました。[1] 1944年8月、キトの労働者会館で第1回エクアドル先住民会議が開催されました。この会議で、ヘスス・グアラヴィシ、ドロレス・カクアンゴ、トランシ ト・アマグアナ、アグスティン・ベガ、アンブロシオ・ラッソといった先住民指導者たちが、エクアドル先住民連盟(FEI)を設立した。その後、1965年 3月9日、農業労働者連盟(FETAP)が、エクアドルカトリック労働者連盟(CEDOC)の関連組織として誕生した。CEDOCはエクアドル保守党 (PCE)の支持組織であった。1968年11月、FETAPは全国農民組織連盟(FENOC)へと変貌し、その組織には少数ながら、インディオの参加が 徐々に増えていった。 1972年6月、インバブラ、ピチンチャ、コトパクシ、ボリバル、チンボラソ、カニャールの先住民組織から200人以上の代表者が参加し、エクアドル・ル ナクナパック・リクチャリムイ(Ecuarunari)が誕生した。この組織は、第2回ラテンアメリカ司教協議会および第2バチカン公会議から生まれた、 カトリック教会内の新しい思想的潮流に基づいて設立された。その聖職者的な性格は、地方組織に顧問として司祭たちが参加していることから明らかだ。アマゾ ン地域では、このプロセスはより遅れており、1980年8月24日に、エクアドル・アマゾン先住民地域第1回地域会議が開催された。この会議には、ナポ先 住民連盟(FOIN)、シュアルセンター連盟、パスタサ先住民組織(OPIP)、 エクアドル・シュアル民族独立協会(AIPSE)、ハトゥン・コムナ・アグアリコ(JCA)が参加した。これらの団体は、この会議の後、エクアドル・アマ ゾン先住民民族連合(Confeniae)を設立した。[3] 当時、先住民組織の構造は明らかに分散化しており、地域的な覇権や特定の協力関係によって共存していたが、全国的な代表権を持つ組織は存在しなかった。エ クアルナリとコンフェニアの協力関係が高まったことで、先住民組織の全国的な調整機関を設立する計画が進んだ。その後、1980年10月25日にスクアで 第1回エクアドル先住民族会議が開催され、エクアドル先住民族全国調整協議会(CONACNIE)が誕生した。同協議会は1984年4月にキトで第2回大 会を開催し、あらゆる政党からの独立を宣言した。そして、1986年11月16日にキトで開催された第3回CONACNIE会議において、エクアドル先住 民ナショナリズム連合(Conaie)が創設された。 |

Crecimiento y consolidación Luis Macas lideró la Conaie durante el Levantamiento Indígena de 1990. Sus primeras apariciones en la coyuntura política nacional, se dieron con la participación en las huelgas nacionales de 1987 y 1988, contra los gobiernos de León Febres-Cordero Ribadeneyra y Rodrigo Borja Cevallos.[4] En 1990, la Conaie protagonizó el primer levantamiento indígena nacional, iniciado el 28 de mayo con la toma de la iglesia de Santo Domingo, en el centro histórico de Quito. La madrugada del 4 de junio, los indígenas realizaron bloqueos viales en Imbabura, Pichincha, Cotopaxi, Tungurahua, Bolívar, Chimborazo y Cañar; además paralizaron la capital por varios días. Esto tomó por sorpresa al gobierno y a toda la población, principalmente en las ciudades donde se realizaron las manifestaciones, ya que fue la primera ocasión en que la población indígena realizaba una paralización de magnitud nacional. En días posteriores se incrementaron los cortes de carreteras, extendiéndose a las provincias de Azuay, Loja y toda la región Amazónica, además de la toma de haciendas y algunos edificios públicos en las capitales provinciales. Tras la mediación de la Iglesia Católica, el gobierno de Borja y la Conaie comenzaron una serie de diálogos, el levantamiento concluyó el 8 de junio.[5] Aquel levantamiento catapultó a la Conaie como protagonista en la política nacional, además de convertirla en la vocera más poderosa de la población indígena ecuatoriana.[6] Posteriormente, se realizó la marcha indígena encabezada por la Organización de Pueblos Indios de Pastaza (OPIP) en mayo de 1992, con la cual se logró el reconocimiento de miles de hectáreas a favor de los indígenas amazónicos, además la Conaie consiguió la personería jurídica.[7] Para las elecciones presidenciales de 1992 las organizaciones indígenas llamaron a sus seguidores a la abstención electoral y promovieron un discurso anti-institucional, al no sentirse identificados con ninguna candidatura.[8] En el gobierno de Sixto Durán-Ballén, la Conaie protagonizó un nuevo levantamiento indígena en junio de 1994, en contra de la aprobación de la Ley de Desarrollo Agrario, que suprimía la reforma agraria y paralizaba el reparto de la tierra. La movilización fue similar a la de 1990, pero de menor intensidad, los indígenas bloquearon carreteras y provocaron desabastecimiento de víveres en las principales ciudades, logrando que el gobierno desistiera de dicha ley.[4] |

成長と統合 ルイス・マカスは、1990年の先住民蜂起の際にコナイエを率いた。 彼が国内政治の舞台に初めて登場したのは、1987年と1988年にレオン・フェブレス・コルデロ・リバデネイラ政権とロドリゴ・ボルハ・セバロス政権に 対して行われた全国ストライキへの参加だった。[4] 1990年、コナイは5月28日にキトの歴史的中心部にあるサント・ドミンゴ教会を占拠したことを発端とする、初の全国的な先住民蜂起の主導者となった。 6月4日の未明、先住民たちはインバブラ、ピチンチャ、コトパクシ、トゥングラワ、ボリバル、チンボラソ、カニャールで道路封鎖を行い、さらに首都を数日 間麻痺させた。これは政府と国民、特にデモが行われた都市の住民を驚かせた。先住民が全国規模のストライキを行ったのはこれが初めてだったからだ。その後 数日間、道路封鎖は拡大し、アズアイ、ロハ、アマゾン地域全体に広がった。さらに、州都ではアシエンダや公共施設が占拠された。カトリック教会の仲介によ り、ボルハ政権とコナイエは一連の対話を開始し、反乱は6月8日に終結した。この反乱により、コナイエは国内政治の主役として台頭し、エクアドルの先住民 にとって最も強力な代弁者となった。 その後、1992年5月には、パスタサ先住民組織(OPIP)が先頭に立った先住民行進が行われ、アマゾン先住民に数千ヘクタールの土地の所有権が認めら れたほか、コナイエは法人格を取得した。1992年の大統領選挙では、先住民組織は、どの候補者にも共感を持てなかったため、支持者に投票の棄権を呼びか け、反体制的な言説を推進した。[8] シスト・デュラン・バジェン政権下、1994年6月、Conaieは、農地改革を廃止し、土地分配を停滞させる農地開発法の成立に反対し、新たな先住民蜂 起を起こした。この動員は1990年と同様のものだったが、その激しさはより穏やかだった。先住民たちは道路を封鎖し、主要都市で食糧不足を引き起こし、 政府に同法の撤回を勝ち取った。[4] |

| Participación en las urnas y golpes de estado La consulta popular de 1994 convocada por Durán-Ballén comenzó a dar una idea a las organizaciones indígenas para realizar una participación electoral, algo que sería más tarde aceptado por la Conaie. Fue así como el 5 de junio de 1995,[9] nace el Movimiento de Unidad Plurinacional Pachakutik - Nuevo País[8] En este proyecto se integrarían, además de la Conaie: la Coordinadora de Movimientos Sociales (CMS), los trabajadores petroleros, el Movimiento de Ciudadanos por un Nuevo País, y además pequeños grupos de izquierda ecuatoriana. Se auspiciaría la candidatura presidencial del entonces periodista Freddy Ehlers en las elecciones de 1996, consiguiendo con este binomio el tercer lugar en la elección. En las legislativas, Pachakutik alcanzó 8 escaños en el Congreso Nacional con una lista liderada por el dirigente de la Conaie, Luis Macas, quedando como primera fuerza de izquierda en la cámara.[8] La Conaie fue parte de la oposición al efímero gobierno de Abdalá Bucaram, siendo una de las principales organizaciones que protagonizaron las movilizaciones sociales,[10] formando el "Frente Patriótico de Defensa del Pueblo". Una vez más, realizaron el cierre de carreteras y luego marchas sobre la ciudad de Quito, en las que participaron múltiples organizaciones políticas, que desembocaron en el derrocamiento de Bucaram, el 6 de febrero de 1997. Tras las elecciones presidenciales de 1998, formaron parte de la oposición al gobierno de Jamil Mahuad, en cuyo periodo se dio la crisis financiera de 1999. Fueron activos participantes de manifestaciones y paralizaciones, siendo la Conaie uno de los principales protagonistas de la caída del gobierno de Mahuad,[10] el 21 de enero de 2000, después de haber marchado desde la Amazonía y el norte del país, exigiendo la interrupción del proceso de dolarización, el retorno al sucre, y la renuncia de Mahuad, marcha a la cual se adhirió el coronel Lucio Gutiérrez junto a otros militares. Para el mediodía, la marcha ocupó el Congreso y el Tribunal Supremo al retirarse la policía. Lucio Gutiérrez, Carlos Solórzano, expresidente de la Corte Suprema de Justicia y cercano al Partido Roldosista Ecuatoriano de Abdalá Bucaram, y el presidente de la Conaie, Antonio Vargas, formaron un triunvirato simbólico llamado "Junta de Salvación Nacional", posesionándose dentro del ocupado Congreso, pero sin más poder que dentro de las instalaciones del edificio tomado.[11] Las Fuerzas Armadas del Ecuador aprovecharon la conmoción causada para retirar el apoyo militar a Mahuad, controlar a la agrupación Junta de Salvación Nacional, intentar establecer un gobierno militar; no obstante, luego de no obtener apoyo internacional, organizaron el traspaso de poder al entonces vicepresidente, Gustavo Noboa el 22 de enero.[12] |

投票への参加とクーデター 1994年にデュラン・バジェンが呼びかけた国民投票は、先住民組織に選挙参加の考えを与え始めた。これは後にコナイエによって受け入れられることにな る。こうして1995年6月5日、多民族統一運動パチャクティック・ヌエボ・パイス(Movimiento de Unidad Plurinacional Pachakutik - Nuevo País)が誕生した。このプロジェクトには、コナイエに加え、社会運動調整委員会(CMS)、石油労働者、新国のための市民運動、そしてエクアドルの小 さな左翼グループも参加した。1996年の選挙では、当時ジャーナリストだったフレディ・エーラーズの大統領候補を擁立し、このコンビで選挙3位を獲得し た。議会選挙では、パチャクティックはコナイエの指導者ルイス・マカスをトップに掲げたリストで、国民議会に8議席を獲得し、議会における左派の第一勢力 となった。 コナイは、アブダラ・ブカラムの一時的な政権に対する反対勢力の一部であり、社会運動の主導的な役割を果たした主要組織の一つであった。そして、「人民防 衛愛国戦線」を結成した。再び、彼らは道路を封鎖し、その後、複数の政治組織が参加したキト市への行進を行い、1997年2月6日にブカラムを転覆させ た。 1998年の大統領選挙後、彼らはジャミル・マウアド政権に対する反対勢力の一翼を担い、その任期中に1999年の金融危機が発生した。彼らはデモやスト ライキに積極的に参加し、コナイエはマウアド政権の崩壊の主役の一つとなった[10]。。2000年1月21日、アマゾン地域や北部から行進してドル化政 策の中止、スクレ通貨への復帰、マウアドの辞任を要求した。この行進にはルシオ・グティエレス大佐や他の軍関係者も参加した。正午までに、警察が撤退する と、行進隊は議会と最高裁判所を占拠した。ルシオ・グティエレス、カルロス・ソロルサノ(元最高裁判所長官、アブダラ・ブカラムのエクアドル・ロルドス党 と親しい)、アントニオ・バルガス(コナイエ会長)は、「国民救済会議(フンタ)」と呼ばれる象徴的な三頭政治体制を築き、占拠した議会内に居を構えた が、その権力は占拠した建物内に限られていた。[11] エクアドル軍は、この騒動に乗じてマウアドへの軍事支援を撤回し、国民救済会議(フンタ)を掌握して軍事政権の樹立を試みた。しかし、国際的な支持を得ら れなかったため、1月22日に当時の副大統領グスタボ・ノボアへの政権移譲を行った。[12] |

Llegada al poder y primeras fricciones Marcha de la Conaie contra el Área de Libre Comercio de las Américas (ALCA), en 2002. Tras la toma simbólica del poder en el golpe de Estado del 2000, empezarían las primeras pugnas dentro de la Conaie y Pachakutik, en vísperas de las elecciones de 2002. Es así que dirigentes indígenas, como Antonio Vargas, se pasarían hacia el Movimiento Indígena Amauta Jatari, el cual lanzó a Vargas como candidato presidencial.[13] Por su parte, Pachakutik y la Conaie apoyarían la candidatura de Lucio Gutiérrez; su apoyo fue fundamental para que Gutiérrez alcanzara la presidencia. Tras la posesión de Gutiérrez, la Conaie, a través de Pachakutik, formó parte de la coalición de gobierno. No obstante, Gutiérrez estructuró un gabinete diverso pero contradictorio: el frente económico y político se encontraba en manos de los sectores tradicionales de la derecha. Por otro lado, entregó 4 ministerios a Pachakutik, entre los que destacaban los de Relaciones Exteriores y Agricultura, cuyos ministros eran Nina Pacari y Luis Macas, históricos dirigentes de la Conaie.[14] Pronto las discrepancias políticas con quienes lo habían ayudado a acceder al poder también se hicieron latentes y los movimientos indígenas, empezaron a presionar al mandatario hasta que el acuerdo se rompió a los seis meses, después de los cuales, se sumaron a la oposición culpando a Gutiérrez de romper con el mandato popular expresado en su elección al dar un viraje en su política, dejando de lado las propuestas de corte izquierdista originales, teniendo acercamientos con el Partido Social Cristiano y Estados Unidos.[15] Sin embargo, ciertos dirigentes indígenas, como Antonio Vargas, prefirieron quedarse en el gobierno de Gutiérrez, a pesar de su evidente viraje hacia la derecha. Es así que surgen las primeras fisuras dentro de la Conaie y Pachakutik, principalmente en la amazonía, bastión político de Gutiérrez. Es así que, como parte de la oposición a Lucio Gutiérrez, participaron y organizaron varias manifestaciones, destacándose la de enero del 2005, en la que mostraron su rechazo al Tratado de Libre Comercio con Estados Unidos, que Gutiérrez pretendía firmar.[1] Fueron partícipes de la caída del gobierno de Gutiérrez, en la Rebelión de los forajidos del abril de 2005, no obstante, en aquella ocasión los protagonistas del golpe de Estado serían los quiteños, mientras la Conaie tuvo una participación minoritaria. El sucesor de Gutiérrez, Alfredo Palacio, continuó con las negociaciones de Tratados de Libre Comercio, teniendo avances en las negociaciones con Estados Unidos, siendo considerado esto como una traición de su promesa de retomar el modelo de gobierno progresista por el que fue elegido como vicepresidente, además de bajar estándares de soberanía económica,[16] por lo que la Conaie nuevamente organizó movilizaciones en las que expresaban su rechazo al TLC y al Área de Libre Comercio de las Américas (ALCA).[17] Para las elecciones de 2006, Pachakutik candidateó a Luis Macas, con el apoyo de la Conaie. Macas quedó en sexto lugar, con apenas el 2,19 % de los votos. En el balotaje, mostraron su apoyo a Rafael Correa, quien venció en las elecciones.[18] |

政権掌握と最初の摩擦 2002年、米州自由貿易地域(ALCA)に反対するコナイのデモ行進。 2000年のクーデターによる象徴的な政権掌握後、2002年の選挙を前に、コナイエとパチャクティック内で最初の争いが始まった。こうして、アントニ オ・バルガスなどの先住民指導者は、バルガスを大統領候補として擁立した先住民運動アマウタ・ジャタリに移籍した。[13] 一方、パチャクティックとコナイエはルシオ・グティエレスの立候補を支持し、その支持はグティエレスが大統領に当選する上で決定的なものとなった。グティ エレスの就任後、コナイエはパチャクティックを通じて連立政権の一翼を担った。しかし、グティエレスは多様でありながら矛盾した内閣を構成した。経済・政 治面は伝統的な右派勢力の手に委ねられた。一方、パチャクティックには4つの省庁が割り当てられ、その中には外務省と農業省が含まれ、その大臣にはコナイ エの歴史的な指導者であるニーナ・パカリとルイス・マカスが就任した。[14] しかし、彼を政権に就かせる手助けをした者たちとの政治的な意見の相違もすぐに表面化し、先住民運動は大統領に圧力をかけ始め、6か月後に合意は破棄され た。その後、彼らは野党に加わり、グティエレスが選挙で表明された民衆の意思に背き、政策を転換して、当初の左派的な提案を放棄し、社会キリスト教党や米 国に接近したことを非難した。しかし、アントニオ・バルガスなどの一部の先住民指導者は、グティエレスの明らかな右傾化にもかかわらず、彼の政権に残留す ることを選んだ。こうして、グティエレスの政治的拠点であるアマゾン地域を中心に、コナイエとパチャクティック内に最初の亀裂が生じた。こうして、ルシ オ・グティエレスに対する反対勢力の一員として、彼らはいくつかのデモに参加・組織した。特に2005年1月のデモでは、グティエレスが締結しようとして いた米国との自由貿易協定への反対を表明した。[1] 彼らは、2005年4月の「無法者たちの反乱」でグティエレス政権の崩壊に関わったが、その時はクーデターの主役はキトの人々で、コナイエの参加は少数 だった。 グティエレスの後継者であるアルフレド・パラシオは、自由貿易協定の交渉を継続し、米国との交渉で進展を見せた。これは、副大統領に選出された進歩的な統 治モデルを復活させるという公約の背信行為とみなされ、さらに経済的主権の基準を低下させるものだったため、 そのため、コナイは再び、FTAおよび米州自由貿易地域(ALCA)への反対を表明するデモを組織した[17]。2006年の選挙では、パチャクティック はコナイの支援を受けてルイス・マカスを候補者として擁立した。マカスはわずか2.19%の得票率で6位に留まった。決選投票では、ラファエル・コレアを 支持し、彼は選挙で勝利した。[18] |

| Pérdida de influencia La ulterior participación en el gobierno de Gutiérrez conllevó una pérdida de cohesión interna; así la integración de dirigentes indígenas en el gobierno, en una confusión entre la organización social con la política, al que se sumó el ejercicio de prácticas que se atribuían a los partidos políticos tradicionales, tal el nepotismo o el clientelismo, acabaron por fraccionar a la organización y a la población indígena. El decepcionante resultado de Macas en las elecciones de 2006, evidenciaron la pérdida de influencia de la Conaie en los territorios indígenas.[19] Luego del triunfo de Rafael Correa, la Conaie y Pachakutik apoyaron al oficialismo, haciendo campaña a favor de la aprobación de la Constitución de 2008 en el referéndum constitucional y en la reelección de Correa en las elecciones de 2009. No obstante, al poco tiempo del segundo período presidencial de Correa, Pachakutik y la Conaie rompieron con el gobierno de Rafael Correa por estar en desacuerdo con la Ley de Recursos Hídricos y por la creación de nuevas instituciones civiles indígenas y del magisterio pro gobierno. La ruptura con Correa, evidenció el quiebre interno que se venía arrastrando en la Conaie y Pachakutik desde años anteriores, es así que en la primera movilización contra Correa, en septiembre de 2009, apenas unos 2000 indígenas arribaron a la capital.[20] Fueron varios los dirigentes y organizaciones de base que se apartaron de la línea política que representaban Pachakutik y la Conaie tras la ruptura con Correa, entre ellos Virgilio Hernández Enríquez, Humberto Cholango, Mario Conejo, Gilberto Guamangate, entre otros.[19] Algunos se integraron a Alianza PAIS, o pasaron a ser aliados indirectos del oficialismo. En medio del levantamiento policial del 30-S, el movimiento indígena hizo un llamado «a constituir un solo frente nacional para exigir la salida del Presidente Correa»,[21] por lo que posteriormente Correa los señalaría como parte de un complot planificado por la oposición para derrocar al presidente, por lo que la catalogó como un intento de golpe de Estado.[22][23][24]  Carlos Pérez Guartambel, en ese entonces presidente de la Ecuarunari, encabezó la movilización del 13 de agosto de 2015, junto con Salvador Quishpe, Jorge Herrera, entre otros.[25] Durante el periodo de oposición a Correa, el principal aliado de la Conaie y Pachakutik fue el Movimiento Popular Democrático, y las organizaciones sociales que la conformaban: el Frente Unitario de Trabajadores (FUT), la Unión Nacional de Educadores (UNE), entre otros. Es así que el 8 de marzo de 2012, organizan una nueva movilización desde El Pangui, en la región amazónica, rumbo a Quito.[26] La movilización llegó a la capital el 22 de marzo, día que marcharon en conjunto con el MPD, el FUT, la UNE, organizaciones ambientalistas, y demás opositores al gobierno de Correa. El gobierno desestimó la magnitud de la movilización, la misma que terminó en incidentes frente a la Asamblea Nacional y sin mayores resultados.[27] Para las elecciones presidenciales de 2013, la Conaie apoyaría a la Unidad Plurinacional de las Izquierdas, conformada por el MPD y Pachakutik, quienes lanzaron la candidatura presidencial de Alberto Acosta. Obtuvieron apenas el 3,26 % de votos, quedando Acosta en el sexto lugar de ocho participantes, lo que evidenció la pérdida de influencia en el país de Pachakutik y la Conaie. Es así que el entonces presidente de la Conaie, Jorge Herrera, admitió en diciembre de 2014 que «el 60% de quienes forman la organización está consolidado, mientras que el 40% ha decidido en estos últimos años marcharse por decisión propia o por unirse al Gobierno».[28] Participaron en las manifestaciones en Ecuador de 2015, en rechazo a los proyectos de ley que el gobierno de Rafael Correa envió a la Asamblea Nacional, sobre la oficialización de un impuesto a las grandes herencias[29] y a la plusvalía,[30] la aplicación de salvaguardias arancelarias a ciertas importaciones[31] para remediar la caída internacional del precio del petróleo, entre otros reclamos, en los que participaron todos los partidos y organizaciones opositoras a Correa, tanto de derecha como izquierda. La Conaie organizó una movilización desde Tundayme, parroquia del cantón El Pangui, en Zamora Chinchipe, con rumbo a la capital; salieron el 2 de agosto con decenas de personas.[32] La movilización recorrió en 10 días gran parte de la región interandina, adhiriéndose a la movilización varios cientos de manifestantes en el camino y llegaron a Quito el 12 de agosto. Varias organizaciones sociales, encabezadas por Unidad Popular, la Conaie y el FUT, hicieron un llamado a la ciudadanía para apoyar el paro nacional indefinido que estaban planificando para el 13 de agosto. Se registraron manifestaciones violentas en varias ciudades del país, principalmente en Quito, Puyo y Macas y el cierre de algunas carreteras,[33] mas la ciudadanía laboró con normalidad, fracasando el llamado al paro nacional.[34] En las elecciones presidenciales de 2017, la organización indígena integró la coalición denominada, Acuerdo Nacional por el Cambio, la cual respaldaba la candidatura de Paco Moncayo.[35] En la primera vuelta, Mocayo obtuvo el 6,71% de votos, quedando en cuarto lugar; es así que en el balotaje, la Conaie dio su respaldo a la candidatura de Guillermo Lasso, aunque al ser Lasso representante de la derecha política, muchos miembros de la Conaie criticaron dicho respaldo, e inclusive varias organizaciones filiales y dirigentes, como el Movimiento Indígena y Campesino de Cotopaxi (MICC), negaron dar su apoyo a Lasso.[36] Lenín Moreno venció a Lasso en el balotaje y asumió la presidencia el 24 de mayo de 2017, el cual, al iniciar su periodo, tuvo un acercamiento con todos los sectores políticos del país. Fue así como el 4 de julio del 2017, tuvo una reunión con los dirigentes de la Conaie, en la cual le devolvió a la organización su sede tradicional.[37] |

影響力の喪失 グティエレス政権へのさらなる参加は、内部結束の喪失をもたらした。つまり、社会組織と政治の混同の中で、先住民指導者が政府に参加し、さらに、縁故主義 や顧客主義といった伝統的な政党に由来する慣行が行われた結果、組織と先住民社会は分裂してしまったのだ。2006年の選挙におけるマカスの期待外れの結 果は、先住民地域におけるコナイエの影響力の低下を明らかにした。[19] ラファエル・コレアの勝利後、コナイエとパチャクティックは与党を支持し、憲法国民投票では2008年憲法の承認、2009年の選挙ではコレアの再選を支 持するキャンペーンを行った。しかし、コレア大統領の2期目が始まって間もなく、パチャクティックとコナイエは、水資源法や、親政府的な新しい先住民市民 団体や教師団体の創設に反対して、ラファエル・コレア政権との関係を断ち切った。 コレアとの決別は、コナイエとパチャクティックで数年前から続いていた内部の不和を明らかにした。そのため、2009年9月にコレアに対する最初の抗議行 動が行われた際には、首都に集まった先住民はわずか2000人ほどだった。[20] コレアとの決別後、パチャクティックやコナイエの政治方針から離脱した指導者や草の根組織は数多く、その中にはヴィルヒリオ・エルナンデス・エンリケス、 ウンベルト・チョランゴ、マリオ・コネホ、ジルベルト・グアマンガテなどがいた。[19] 彼らの中には、アリアンサ・パイスに加わった者や、間接的に与党の同盟者となった者もいた。9月30日の警察の反乱の中で、先住民運動は「コレア大統領の 退陣を求める単一の国民戦線を構築しよう」と訴えた[21]。そのため、コレアは彼らを、大統領を転覆させるために野党が計画した陰謀の一部であると指摘 し、クーデター未遂と断じた[22][23][24]。  当時エクアドル先住民連合(Ecuarunari)の会長だったカルロス・ペレス・グアルタンベルは、サルバドール・キシュペ、ホルヘ・エレーラらとともに、2015年8月13日のデモを主導した[25]。 コレア大統領に対する反対運動の間、コナイエとパチャクティックの主な同盟者は、人民民主運動(Movimiento Popular Democrático)と、それを構成する社会組織、すなわち労働者統一戦線(FUT)、全国教育者組合(UNE)などであった。こうして2012年3 月8日、彼らはアマゾン地域のエル・パンギからキトに向けて新たなデモを組織した。[26] デモは3月22日に首都に到着し、その日、MPD、FUT、UNE、環境保護団体、その他コレア政権の反対派と共同でデモ行進を行った。政府はデモの規模 を過小評価したが、デモは国民議会前で事件に発展し、大きな成果は得られなかった。2013年の大統領選挙では、コナイエはMPDとパチャクティックで構 成される多民族左派連合を支持し、アルベルト・アコスタを大統領候補として擁立した。しかし、得票率はわずか3.26%に留まり、アコスタは8人の候補者 の中で6位に終わった。これは、パチャクティックとコナイの国内での影響力の低下を明らかにする結果であった。そのため、当時のコナイ会長であるホルヘ・ エレーラは、2014年12月に「組織を構成するメンバーの60%は組織に定着しているが、40%はここ数年、自らの意思で脱退するか、政府に合流するこ とを決めた」と認めた[28]。 彼らは、ラファエル・コレア政権が国民議会に提出した、大相続税[29]およびキャピタルゲイン税の導入、 [30]、国際的な石油価格の下落を補うための特定の輸入品に対する関税保護措置の適用[31]など、コレア政権に反対する右派、左派を問わず、すべ ての政党や組織が参加した抗議活動に参加した。Conaieは、サモラ・チンチペ州エル・パンギ郡のトゥンダイメから首都に向けてデモ行進を組織した。8 月2日、数十人が出発した。[32] このデモ行進は10日間でアンデス山脈の地域の大部分を巡り、道中で数百人のデモ参加者が加わり、8月12日にキトに到着した。Unidad Popular、Conaie、FUT を筆頭とする複数の社会団体は、8月13日に予定していた無期限の全国ストライキへの支持を市民に呼びかけた。国内のいくつかの都市、主にキト、プヨ、マ カスで暴力的なデモが発生し、一部の道路が閉鎖されたが[33]、市民は通常通り仕事を続け、全国ストライキの呼びかけは失敗に終わった[34]。 2017年の大統領選挙では、この先住民組織は、パコ・モンカヨの立候補を支持する「変化のための国民合意」という連合に参加した[35]。第一回投票で は、モンカヨは6.71%の得票率で4位となった。そのため、決選投票では、コナイエはギジェルモ・ラッソの立候補を支持したが、ラッソは右派の政治家で あるため、コナイエの多くのメンバーがこの支持を批判し、コトパクシ先住民農民運動(MICC)などのいくつかの関連組織や指導者たちは、ラッソへの支持 を拒否した。[36] レニン・モレノは決選投票でラッソを破り、2017年5月24日に大統領に就任した。モレノは任期開始当初、国内のあらゆる政治勢力に接近した。こうして 2017年7月4日、彼はコナイエの指導者たちと会談し、同組織に伝統的な本部を返還した。[37] |

Resurgimiento Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana durante el Paro Nacional de 2019. Si bien al principio del Gobierno de Lenín Moreno, la Conaie tuvo una relación cordial con el gobierno, conforme se evidenciaba más el viraje de Moreno hacia la derecha,[38][39] se fueron distanciando del gobierno. Mientras tanto, debido a la caída de popularidad del presidente Moreno y el partido oficialista Alianza PAIS, las organizaciones indígenas que se habían distanciado de la línea política de la Conaie durante el gobierno de Correa, fueron reintegrándose, dando a la Conaie una recuperación en la coyuntura política ecuatoriana. Dicha unificación fue liderada por Jaime Vargas Vargas, quien fue electo presidente de la Conaie el 16 de septiembre de 2017, por unanimidad durante el XI Congreso celebrado en Zamora, con la premisa de reunificar la organización indígena.[40][41] Tras esta reunificación, la Conaie lideró el Paro Nacional de 2019, realizado del 2 al 13 de octubre de 2019, en contra de las medidas económicas del gobierno de Moreno. El Paro Nacional fue realizado con el bloqueo de carreteras, masivas protestas a las cuales se sumó un numeroso sector de la población y la movilización de miles de manifestantes indígenas hacia Quito, donde permanecieron durante días, intentando llegar al Palacio de Carondelet, sin éxito, debido a la cruenta represión policial. La situación se tornó más crítica con el pasar de los días, por lo que el gobierno decretó el estado de excepción, e incluso llegando a ordenar el 8 de octubre un toque de queda y el traslado de la sede de gobierno a Guayaquil. Los principales enfrentamientos se dieron entre los manifestantes indígenas y la policía, la cual llegó a cometer crímenes de lesa humanidad[42][43][44][45][46] lo que ocasionó al menos 11 fallecidos, 1340 heridos[47] y 1192 detenidos,[48] ocasionando una grave conmoción social; no obstante, el 13 de octubre se llevó a cabo un foro mediado por el representante de la ONU en Ecuador y la Iglesia Católica, donde los dirigentes de la Conaie y el gobierno llegaron a un acuerdo que finalizó con el conflicto.[49] Para las elecciones presidenciales de 2021, los nombres de Jaime Vargas y Leonidas Iza sonaban como precandidatos por Pachakutik, no obstante, la dirigencia del partido candidateó a Yaku Pérez a la presidencia, mientras Salvador Quishpe lideró la lista en las elecciones legislativas de 2021, dejando de lado a los dirigentes de la Conaie, por lo cual se dio una evidente una ruptura entre la organización indígena y Pachakutik, aunque al final de la campaña electoral, la Conaie brindó su respaldo a Pérez, quien obtuvo el tercer lugar.[50] En el balotaje, la Conaie respaldó a Pachakutik, que hizo campaña por el voto nulo; no obstante, Vargas brindó su respaldo a Andrés Arauz a nombre de la organización, por lo que la misma lo desconoció de su calidad de presidente por “irrespetar las decisiones colectivas”. Manuel Castillo, vicepresidente de la organización, asumió la representación temporalmente mientras se designaba al nuevo presidente.[51] Las diferentes direcciones políticas a las que apuntaban la Conaie y Pachakutik, se hicieron evidentes tras el triunfo de Guillermo Lasso en las elecciones presidenciales y su llegada al poder, ya que Pachakutik realizó un pacto legislativo con el Movimiento CREO (perteneciente a Lasso), la Izquierda Democrática y partidos políticos con menor representación, en el que Pachakutik obtenía la presidencia legislativa en la figura de Guadalupe Llori.[52] Esto mientras, la Conaie ha mantenido una postura crítica al Gobierno de Guillermo Lasso,[53] liderada por Leonidas Iza, tras su elección como presidente de la organización en el VII Congreso Nacional, el 27 de junio de 2021.[54]  Jornada de movilizaciones en Quito, durante el Paro Nacional de 2022. Tras reunirse varias veces con el gobierno, sin recibir respuesta a sus propuestas,[55] la Conaie, junto con la Feine y la Fenocin convocaron a un nuevo Paro Nacional, realizado entre el 13 y el 30 de junio de 2022, en oposición a las políticas del gobierno de Lasso.[56] Al Paro Nacional de 2022 se adhirieron varias organizaciones sociales y un considerable sector de la población, quienes en conjunto con las organizaciones indígenas, durante 18 días realizaron un sinnúmero de manifestaciones, bloqueos viales, toma de gobernaciones y una paralización laboral que provocó desabastecimiento de combustibles, gas y abastos en gran parte del país.[2][57] El 24 de junio, tras 11 días de manifestaciones, la Asamblea Nacional invocó el artículo 130.2 de la Constitución, solicitando la destitución de Lasso y el adelanto de elecciones, con el fin de solucionar el conflicto.[58] La Conaie mostró su respaldo a dicho proceso e hizo un llamado a los asambleístas de Pachakutik a votar por la destitución del presidente, sin embargo, en la votación realizada el 28 de junio, la propuesta no obtuvo los votos necesarios, ya que la bancada oficialista, el PSC, la ID e incluso algunos legisladores de Pachakutik (como Llori), votaron en contra de la destitución de Lasso.[59] Finalmente, tras 18 días del Paro Nacional, las organizaciones indígenas y el gobierno lograron un acuerdo gracias a la mediación de la Conferencia Episcopal Ecuatoriana.[60] |

復活 2019年の全国ストライキ中のエクアドル文化会館。 レニン・モレノ政権発足当初、コナイエは政府と友好的な関係にあったが、モレノの右傾化が進むにつれて[38]、[39]、政府との距離が広がっていっ た。一方、モレノ大統領と与党アリアンサ・パイス党の人気低下に伴い、コレア政権時代にコナイエの政治方針から距離を置いていた先住民組織が再び合流し、 コナイエはエクアドルの政治情勢において復活を遂げた。この統合は、2017年9月16日にサモラで開催された第11回大会で、先住民組織の再統合を前提 として満場一致でコナイエの会長に選出されたハイメ・バルガス・バルガスが主導した[40]、[41]。 この再統合後、コナイエは2019年10月2日から13日まで、モレノ政権の経済政策に反対する全国ストライキを主導した。全国ストライキは、道路封鎖、 多くの国民が参加した大規模な抗議行動、そして何千人もの先住民デモ参加者がキトに向かって移動し、数日間滞在してカロンドレット宮殿に到達しようとした が、警察の厳しい弾圧により失敗に終わった。状況は日を追うごとに深刻化し、政府は非常事態を宣言、10月8日には夜間外出禁止令を発令し、政府の本拠地 をグアヤキルに移転することさえ命じた。主な衝突は先住民デモ隊と警察の間で発生し、警察は人道に対する罪[42][43][44][45][46]を犯 し、少なくとも11人が死亡、1340人が負傷[47]、1192人が拘束[48]され、深刻な社会的混乱を引き起こした。しかし、10月13日、国連エ クアドル代表とカトリック教会が仲介するフォーラムが開催され、コナイエの指導者と政府が合意に達し、紛争は終結した[49]。 2021年の大統領選挙では、ハイメ・バルガスとレオニダス・イサがパチャクティック党の予備候補として名乗りを上げていたが、 しかし、党指導部はヤク・ペレスを大統領候補に指名し、サルバドール・キシュペが2021年議会選挙のトップ候補となったため、コナイエの指導者たちは排 除された。これにより、先住民組織とパチャクティックの間に明らかな亀裂が生じたが、選挙戦終盤には、コナイエは3位となったペレスを支持した。[50] 決選投票では、コナイは白票を投じるよう呼びかけたパチャクティックを支持したが、バルガスは組織を代表してアンドレス・アラウスを支持したため、組織 は「集団の決定を尊重しなかった」として彼の会長としての地位を否認した。同組織の副代表であるマヌエル・カスティーヨが、新代表が任命されるまで暫定的 に代表を務めた。[51] コナイエとパチャクティックの政治方針の違いは、ギジェルモ・ラッソが大統領選挙で勝利し政権を握った後、パチャクティックが(ラッソが所属する) CREO運動、 民主左翼、および小規模政党との立法協定を締結し、パチャクティックはグアダルーペ・ロリを立法府議長に送り込んだ。[52] 一方、コナイは、2021年6月27日に開催された第7回全国大会でレオニダス・イサが組織会長に選出された後、ギジェルモ・ラッソ政権に対して批判的な 姿勢を維持している。[53]  2022年の全国ストライキ中のキトでのデモ活動。 政府と何度か会談したが、その提案に対する返答は得られなかったため[55]、コナイはフェインおよびフェノシンとともに、ラッソ政権の政策に反対して、 2022年6月13日から30日まで新たな全国ストライキを呼びかけた。[56] 2022年の全国ストライキには、複数の社会団体やかなりの数の国民が参加し、先住民団体と協力し、18日間にわたって無数のデモ、道路封鎖、州政府庁舎 の占拠、労働争議を行い、その結果、国の大部分で燃料、ガス、食糧の供給不足が発生した。[2][57] 6月24日、11日間にわたるデモの後、国民議会は憲法第130条2項を引用し、紛争解決のためにラッソ大統領の解任と選挙の前倒しを要求した。[58] コナイエはこの動きを支持し、パチャクティック党の議員たちに大統領解任の投票を呼びかけた。しかし、6月28日に行われた投票では、与党、PSC、 ID、さらにはパチャクティックの議員(ロリなど)もラッソ大統領の解任に反対票を投じたため、この提案は必要な票数を獲得できなかった。[59] 結局、18日間にわたる全国ストライキの後、エクアドル司教会議の仲介により、先住民組織と政府は合意に達した。[60] |

| Gobierno y organización La Conaie está conformada por tres organizaciones filiales, que representan a los pueblos y nacionalidades indígenas de las tres regiones del Ecuador (excluyendo las islas Galápagos, donde no existen pueblos o territorios ancestrales): la Confederación Nacionalidades y Pueblos Indígenas de la Costa Ecuatoriana (Conaice), la Confederación de Pueblos de la Nacionalidad Kichwa del Ecuador (Ecuarunari) y la Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas de la Amazonía Ecuatoriana (Confeniae). En cuanto a su dirección, la organización tiene un Consejo de Gobierno, el cual está encabezado por el presidente, seguido por el vicepresidente. Tras ellos, existen varias comisiones, tales como: educación, comunicación, salud, entre otras; cada una de ellas está liderada por un Coordinador. Aquella directiva es elegida en elecciones internas, mediante un Congreso, en el que participan todos los delegados de los pueblos y nacionalidades que conforman las tres organizaciones filiales de la Conaie. El Congreso de la Conaie, es la instancia máxima que adopta resoluciones y posturas. Tras el Congreso, se encuentra el Consejo Ampliado de la Conaie, conformado por el Consejo de Gobierno y los dirigentes de las organizaciones filiales.[61]  |

政府と組織 Conaieは、エクアドルの3つの地域(先住民や先祖伝来の領土が存在しないガラパゴス諸島を除く)の先住民や民族を代表する3つの関連組織で構成され ている。すなわち、エクアドル沿岸部先住民民族連合(Conaice)、 エクアドルキチュワ民族連合(Ecuarunari)、エクアドルアマゾン先住民連合(Confeniae)である。運営面では、組織には統治評議会があ り、議長がトップ、副議長が次席を務める。その下には、教育、コミュニケーション、健康などの各委員会があり、それぞれコーディネーターが率いている。こ の指導部は、Conaie の 3 つの関連組織を構成する民族および民族グループの代表全員が参加する議会による内部選挙で選出される。Conaie 議会は、決議や立場を採択する最高機関である。議会の下には、政府評議会と関連組織の指導者で構成されるコナイエ拡大評議会がある。[61]  |

| Agenda política La agenda política de la Conaie incluye cuatro pilares básicos: el reforzamiento de una identidad indígena positiva, la recuperación del derecho de las tierras, la sostenibilidad medioambiental y el rechazo de la presencia militar estadounidense en Sudamérica (caso Plan Colombia). El eje conductor de la política del Movimiento Indígena del Ecuador es el proyecto político que fue consolidado en 1994 en el que se detalle los principios políticos e ideológica, así como los planes de acción.[63] En 2013, el movimiento se vio más involucrado con otras organizaciones indígenas sobre el derecho a la tierra y la sostenibilidad, para luchar contra los acuerdos realizados por el gobierno con una gran cantidad de multinacionales petrolíferas. En 1990 la Conaie movilizó miles de indígenas y campesinos para varias expresiones artísticas en la capital de Quito como formas de protesta contra el gobierno. El programa de la confederación recogía 16 demandas:[64] 1. Declaración pública de que Ecuador como país plurinacional (que fue recogida en la constitución) 2. El gobierno debe otorgar las tierras y los títulos de tierras a sus nacionalidades 3. Solucionar los problemas de las necesidades del agua y el riego. 4. Absolución de las deudas de indígenas de Foderuma y el Banco de Desarrollo Nacional 5. Congelar los precios de los productos de consumo 6. Concluir con especial prioridad los proyectos de las comunidades indígenas 7. No pago de las tasas de las tierras rurales 8. Expulsión del Instituto Lingüístico de Verano 9. Venta de artesanías comerciales exenta de tasas 10. Protección de yacimientos arqueológicos 11. Legalización de medicina indígena 12. Cancelación del decreto gubernamental que creó la reforma de la tierra que las concedía a organismos 13. Concesión gubernamental de fondos para las nacionalidades 14. Concesión gubernamental de fondos para la educación bilingüe 15. Respeto de los derechos del niño 16. Fijación de precios justos para los productos |

政治課題 コナイの政治課題は、4つの基本方針から成っている。すなわち、先住民としてのアイデンティティの強化、土地の権利の回復、環境の持続可能性、そして南米における米国軍の駐留(コロンビア計画など)の拒否である。 エクアドル先住民運動の政策の指針は、1994年に確立された政治プロジェクトであり、そこでは政治的・イデオロギー的原則と行動計画が詳述されている。[63] 2013年、この運動は、政府と多くの多国籍石油企業との間で締結された協定に対抗するため、土地の権利と持続可能性について、他の先住民組織とより深く関わることになった。 1990年、コナイエは、政府に対する抗議の手段として、首都キトで数千人の先住民や農民を動員し、さまざまな芸術的表現を行った。 同連合のプログラムには、16の要求事項が盛り込まれていた。[64] 1. エクアドルが plurinacional 国家であることを公に宣言すること(憲法に盛り込まれた) 2. 政府は、各民族に土地と土地の所有権を与えること 3. 水と灌漑のニーズに関する問題を解決すること 4. フォデルマおよび国立開発銀行に対する先住民の債務免除 5. 消費財の価格凍結 6. 先住民コミュニティのプロジェクトを優先的に完了させること 7. 農村部の土地税を免除すること 8. 夏期言語研究所の追放 9. 商業用手工芸品の免税販売 10. 遺跡の保護 11. 先住民の医療の合法化 12. 土地を機関に譲渡する土地改革を制定した政府令の廃止 13. 政府による民族への資金援助 14. 政府による二言語教育への資金援助 15. 子どもの権利の尊重 16. 製品の公正な価格設定 |

| Referencias | |

☆ECUARUNARI(エクアルナリ)

| ECUARUNARI (in

Kichwa: Ecuador Runakunapak Rikcharimuy, "Movement of the indigenous

people of Ecuador"), also known as Confederation of Peoples of Kichwa

Nationality (Ecuador Kichwa Llaktakunapak Jatun Tantanakuy, in Spanish

Confederación de Pueblos de la Nacionalidad Kichwa del Ecuador) is the

organization of indigenous peoples of Kichwa nationality in the

Ecuadorian central mountain region, founded in 1972. |

エクアルナリ(キチュワ語で:エクアドル・ルナクナパク・リクチャリム イ、 「エクアドル先住民の運動」)、別名キチュワ民族連合(スペイン語でConfederación de Pueblos de la Nacionalidad Kichwa del Ecuador)は、1972年に設立されたエクアドル中央山岳地帯のキチュワ先住民組織である。 |

| Twelve ethnic groups of the

region—Natabuela, Otavalos, Karanki (Caranqui), Kayampi (Cayambi), Kitu

Kara (Quitu), Panzaleo, Salasaca, Chibuleo, Puruhá, Guranga, Kañari and

Saraguros—are represented politically by the Confederation. ECUARUNARI

is one of three major regional groupings that constitute the

Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE). It is

also member of the Andean indigenous organization, Coordination of

Indigenous Organizations of the Andes (Coordinadora Andina de

Organizaciones Indígenas, CAOI). |

この地域の十二の民族集団―ナタブエラ、オタバロス、カランキ(カラ

ニ)、カヤンピ(カヤンビ)、キトゥ・カラ(キトゥ)、パンサレオ、サラサカ、チブレオ、プルハ、グランガ、カニャリ、サラグロス―は、連合によって政治

的に代表されている。エクアルナリは、エクアドル先住民族連合(CONAIE)を構成する三つの主要地域連合の一つである。また、アンデス先住民族組織連

合(CAOI)の加盟団体でもある。 |

| The current president of ECUARUNARI is Alberto Ainawano from Kichwa-chibuleo. A notable member is Carmen Tiupul who is a member of Ecuador's National Assembly.[1] |

ECUARUNARIの現会長はキチュワ・チブレオ出身のアルベルト・アイナワノである。著名なメンバーには、エクアドルの国立議会議員であるカルメン・ティウプルがいる。[1] |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099