チャールズ・ライト・ミルズ

C. Wright Mills, 1916-1962

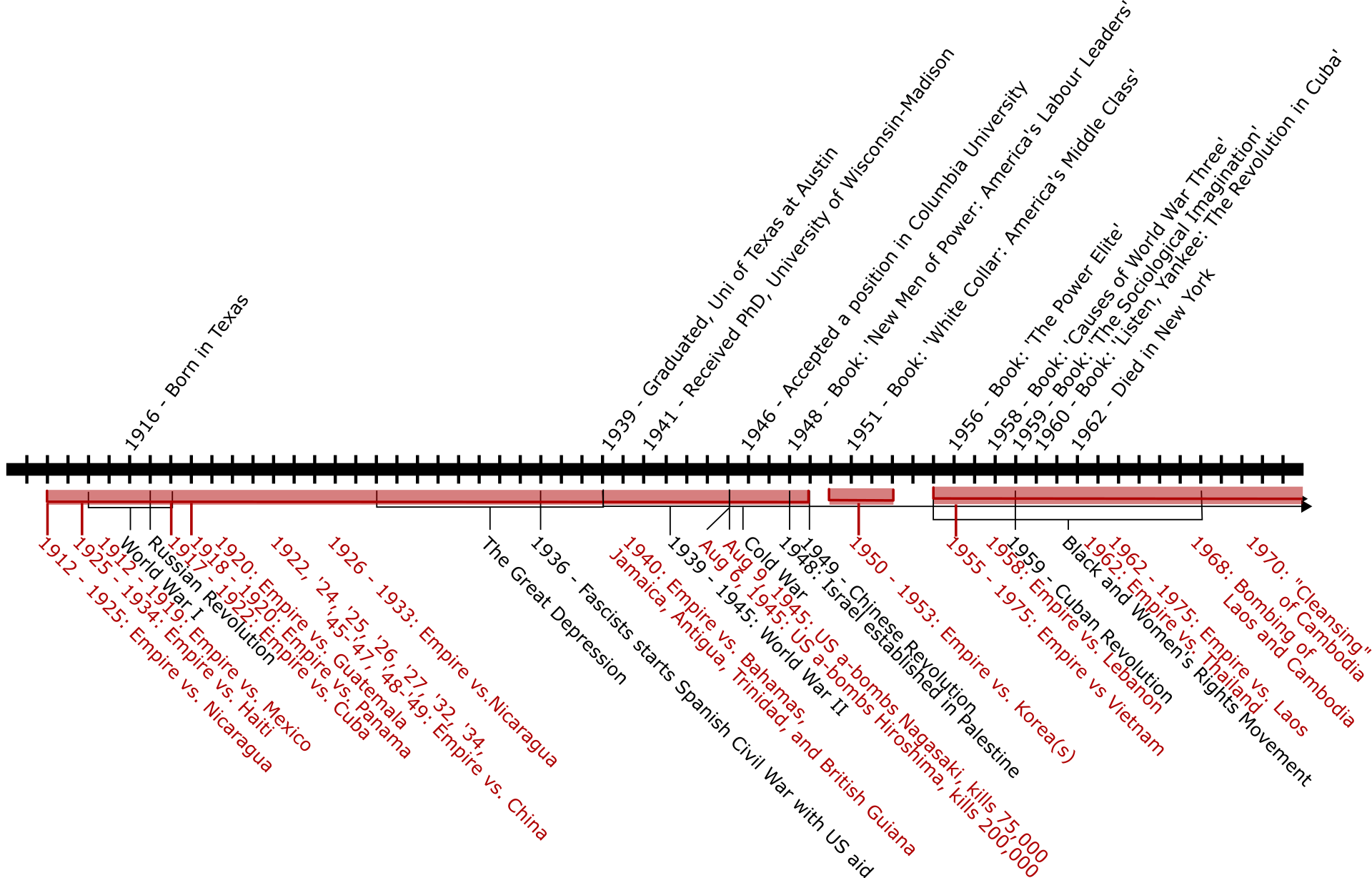

☆ チャールズ・ライト・ミルズ(Charles Wright Mills;1916 年8月28日-1962年3月20日)はアメリカの社会学者で、1946年から1962年に亡くなるまでコロンビア大学の社会学教授を務めた。ミルズがポ ピュラーな雑誌と知的な雑誌の両方で広く発表し、『パワー・エリート』、『ホワイトカラー』、『アメリカの中流階級』などの著書で知られている: ミルズは第二次世界大戦後の社会における知識人の責任に関心を持ち、無関心な観察よりも公共的・政治的関与を提唱した。ミルズの伝記作家の一人であるダニ エル・ギアリーは、ミルズの著作は「1960年代の新左翼社会運動に特に大きな影響を与えた」と書いている。1960年の公開書簡「新左翼への手紙」にお いて、アメリカで新左翼という言葉を広めたのはミルズであった(→「チャールズ・ライト・ミルズ年譜」)。

| Charles Wright Mills

(August 28, 1916 – March 20, 1962) was an American sociologist, and a

professor of sociology at Columbia University from 1946 until his death

in 1962. Mills published widely in both popular and intellectual

journals, and is remembered for several books, such as The Power Elite,

White Collar: The American Middle Classes, and The Sociological

Imagination.[13] Mills was concerned with the responsibilities of

intellectuals in post–World War II society, and he advocated public and

political engagement over disinterested observation. One of Mills's

biographers, Daniel Geary, writes that Mills's writings had a

"particularly significant impact on New Left social movements of the

1960s era."[13] It was Mills who popularized the term New Left in the

U.S. in a 1960 open letter, "Letter to the New Left".[14] |

チャー

ルズ・ライト・ミルズ(1916年8月28日-1962年3月20日)はアメリカの社会学者で、1946年から1962年に亡くなるまでコロンビア大学の

社会学教授を務めた。ミルズがポピュラーな雑誌と知的な雑誌の両方で広く発表し、『パワー・エリート』、『ホワイトカラー』、『アメリカの中流階級』など

の著書で知られている:

ミルズは第二次世界大戦後の社会における知識人の責任に関心を持ち、無関心な観察よりも公共的・政治的関与を提唱した。ミルズの伝記作家の一人であるダニ

エル・ギアリーは、ミルズの著作は「1960年代の新左翼社会運動に特に大きな影響を与えた」と書いている[13]。1960年の公開書簡「新左翼への手

紙」において、アメリカで新左翼という言葉を広めたのはミルズであった[14]。 |

| Biography Early life C. Wright Mills was born in Waco, Texas, on August 28, 1916. His father, Charles Grover Mills (1889-1973), worked as an insurance broker, leaving his family to constantly move around; his mother, Frances Ursula (Wright) Mills (1893-1989), was a homemaker.[15] His parents were pious and middle class, with an Irish-English background. Mills was a choirboy in the Catholic Church of Waco, and he developed a lifelong aversion to Christianity. Although being brought up in an Anglo-Irish Catholic family, Mills strayed away from the church, defining himself as an atheist.[16] Mills attended Dallas Technical High School, with an interest in engineering, and his parents were preparing him for a practical career in a rapidly industrializing world of Texas. His focuses of study besides engineering were algebra, physics, and mechanical drawing.[17] Education In 1934, Mills graduated from Dallas Technical High School, and his father pressed him to attend Texas A&M University. To fulfill his father’s wishes, Mills attended the university, but he found the atmosphere "suffocating" and left after his first year.[18] He transferred to the University of Texas at Austin where he studied anthropology, social psychology, sociology, and philosophy.[19] At this time, the university was developing a strong department of graduate instruction in both the social and physical sciences.[17] Mills' benefited from this unique development, and he impressed professors with his powerful intellect.[15] In 1939, he graduated with a bachelor's degree in sociology, as well as a master's in philosophy. By the time he graduated, he had already been published in the two leading sociology journals, the American Sociological Review and The American Journal of Sociology.[20] While studying at Texas, Mills met his first wife, Dorothy Helen Smith,[21] a fellow student seeking a master's degree in sociology. She had previously attended Oklahoma College for Women, where she graduated with a bachelor's degree in commerce.[22] After their marriage, in 1937, Dorothy Helen, or "Freya", worked as a staff member of the director of the Women's Residence Hall at the University of Texas. She supported the couple while Mills completed his graduate work; she also typed, copied and edited much of his work, including his Ph.D. dissertation.[23] There, he met Hans Gerth, a German political refugee and a professor in the Department of Sociology. Although Mills did not take any courses with him, Gerth became a mentor and close friend. Together, Mills and Gerth translated and edited a few of Max Weber's works. Both collaborated on Character and Social Structure, a social psychology text.[19] This work combined Mills's understanding of socialization from his work in American Pragmatisim and Gerth's understanding of past and present societies.[19] Mills received his Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1942. His dissertation was entitled A Sociological Account of Pragmatism: An Essay on the Sociology of Knowledge.[24] Mills refused to revise his dissertation while it was reviewed by his committee. It was later accepted without approval from the review committee.[25][verification needed] Mills left Wisconsin in early 1942, after he had been appointed Professor of Sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park. Early career Before Mills furthered his career, he avoided the draft by failing his physical due to high blood pressure and received a deferment. He was divorced from Freya in August 1940, but after a year he convinced Freya to change her mind. The couple remarried in March 1941. A few years later, their daughter, Pamela Mills, was born on January 15, 1943.[26] During this time, his work as an Associate Professor of Sociology from 1941 until 1945 at the University of Maryland, College Park, Mills's awareness and involvement in American politics grew. During World War II, Mills befriended the historians Richard Hofstadter, Frank Freidel, and Ken Stampp. The four academics collaborated on many topics, and each wrote about contemporary issues of the war and how it affected American society.[27] While still at the University of Maryland, Mills began contributing "journalistic sociology" and opinion pieces to intellectual journals such as The New Republic, The New Leader, as well as Politics, a journal established by his friend Dwight Macdonald in 1944.[28][29] During his time at the University of Maryland, William Form befriended Mills and quickly recognized that "work overwhelmingly dominated" Mills's life.[19] Mills continued his work with Gerth while trying to publish Weber's "Class, Status, and Parties".[19] Form explains that Mills was determined to improve his writing after receiving criticism on one of his works; "Setting his portable Corona on the large coffee table in the living room, he would type triple-spaced on coarse yellow paper, revising the manuscript by writing between the lines with a sharp pencil. Unscrambling the additions and changes could present a formidable challenge. Each day before leaving for campus, he left a manuscript for Freya to retype."[19] In 1945, Mills moved to New York after earning a research associate position at Columbia University's Bureau of Applied Social Research. He separated from Freya with this move, and the couple later divorced a second time in 1947.[30] Mills was appointed assistant professor in the university's sociology department in 1946.[30] Mills received a grant of $2,500 from the Guggenheim Foundation in April 1945 to fund his research in 1946. During that time, he wrote White Collar, which was later published in 1951.[31] In 1946, Mills published From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, a translation of Weber's essays co-authored with Hans Gerth.[27] In 1953, the two published a second work, Character and Social Structure: The Psychology of Social Institutions.[32] In 1947, Mills married his second wife, Ruth Harper, a statistician at the Bureau of Applied Social Research. She worked with Mills on New Men of Power (1948), White Collar (1951), and The Power Elite (1956). In 1949, Mills and Harper moved to Chicago so that Mills could serve as a visiting professor at the University of Chicago. Mills returned to teaching at Columbia University after a quarter at the University of Chicago, and was promoted to Associate Professor of Sociology on July 1, 1950. In only six years, Mills was promoted to Professor of Sociology at Columbia on July 1, 1956. In 1955, Harper gave birth to their daughter Kathryn. From 1956 to 1957, the family moved to Copenhagen, where Mills acted as a Fulbright lecturer at the University of Copenhagen. Mills and Harper separated in December 1957 and officially divorced in 1959.[33][page needed] Later career Mills married his third wife, Yaroslava Surmach, an American artist of Ukrainian descent, and settled in Rockland County, New York, in 1959. Their son, Nikolas Charles, was born on June 19, 1960.[34][page needed] In August 1960, Mills spent time in Cuba, where he worked on developing his text Listen, Yankee. He spent 16 days there, interviewing Cuban government officials and Cuban civilians. Mills asked them questions about whether the guerrilla organization that made the revolution was the same as a political party.[35] Additionally, Mills interviewed President Fidel Castro, who claimed to have read and studied Mills's The Power Elite.[36] Although Mills only spent a short amount of his time in Cuba with Castro, they got along well and Castro sent flowers when Mills passed a few years later. Mills was described as a man in a hurry. Aside from his hurried nature, he was largely known for his combativeness. Both his private life – four marriages to three women, a child from each, and several affairs – and his professional life, which involved challenging and criticizing many of his professors and coworkers, have been characterized as "tumultuous.” He wrote a fairly obvious, though slightly veiled, essay in which he criticized the former chairman[who?] of the Wisconsin department, and called the senior theorist there, Howard P. Becker, a "real fool.” [37] During a visit to the Soviet Union, Mills was honored as a major critic of American society. While there he criticized censorship in the Soviet Union through his toast to an early Soviet leader who was "purged and murdered by the Stalinists." He toasted "To the day when the complete works of Leon Trotsky are published in the Soviet Union!"[37] Health C. Wright Mills struggled with poor health due to his heart. After receiving his doctorate in 1942, Mills had failed his Army physical exam due to having high blood pressure. Because of this he was excused from serving in the United States military during World War II.[38] Death In a biography of Mills by Irving Louis Horowitz, the author writes about Mills's acute awareness of his heart condition. He speculates that it affected the way he lived his adult life. Mills was described as someone who worked quickly, yet efficiently. Horowitz suggests that Mills worked at a fast pace because he felt that he would not live long, describing him as "a man in search of his destiny".[39] In 1942, Mills' wife Freya had characterized him as being in excellent health and having no heart issue. His cardiac problem was not identified until 1956, and he did not have a major heart attack until December 1960, despite his excessive blood pressure. In 1962, Mills suffered his fourth and final heart attack at the age of 45, and died on March 20 in West Nyack, New York.[40][41] Roughly fifteen months prior, Mills’s doctors had warned him that his next heart attack would be his last one. His service was held at Columbia University, where Hans Gerth and Daniel Bell both travelled to speak on his behalf. A service for friends and family was held at the interfaith pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation in Nyack.[41] |

略歴 生い立ち C. ライト・ミルズは1916年8月28日、テキサス州ウェイコに生まれた。父チャールズ・グローバー・ミルズ(1889-1973)は保険ブローカーとして 働き、家族は常に転居を余儀なくされた。ミルズが聖歌隊員だったウェーコのカトリック教会では、生涯キリスト教に嫌悪感を抱くようになる。アングロ・アイ リッシュ系のカトリックの家庭に育ちながら、ミルズ自身は教会から離れ、無神論者と定義していた[16]。ミルズがダラス工業高校に通ったのは、工学に興 味があったからで、両親は急速に工業化が進むテキサスで実用的な職業に就く準備をしていた。工学の他に彼が勉強したのは代数学、物理学、機械製図だった [17]。 教育 1934年、ミルズがダラス工業高校を卒業すると、父親は彼にテキサスA&M大学への進学を勧めた。テキサス大学オースティン校に編入し、人類 学、社会心理学、社会学、哲学を学んだ[18]。 [ミルズ はこのユニークな発展の恩恵を受け、その強力な知性で教授たちを感心 させた[15]。卒業するまでに、彼はすでに2つの主要な社会学雑誌、American Sociological ReviewとThe American Journal of Sociologyに掲載されていた[20]。 テキサス大学在学中に、ミルズ は最初の妻であるドロシー・ヘレン・スミス[21]と出会う。彼女はそれまでオクラホマ女子大学に在籍し、商学部を卒業していた[22]。 結婚後の1937年、ドロシー・ヘレン(通称「フレイヤ」)は、テキサス大学の女子学生寮の館長のスタッフとして働いた。彼女は、ミルズが大学院での研究 を終えている間、夫妻を支えた。彼女はまた、博士論文を含む彼の仕事の多くをタイプし、コピーし、編集した[23]。ミルズがゲルトの講義を受講したわけ ではなかったが、ゲルトはミルズを指導し、親しい友人となった。ミルズとゲルトは一緒にマックス・ウェーバーの著作のいくつかを翻訳し、編集した。この著 作は、ミルズが『アメリカン・プラグマティズム』の研究から得た社会化についての理解と、ガースの過去と現在の社会についての理解を組み合わせたもので あった[19]。 ミルズは1942年にウィスコンシン大学マディソン校で社会学の博士号を取得した。学位論文のタイトルは『プラグマティズムの社会学的説明(A Sociological Account of Pragmatism)』であった: ミルズが学位論文を修正することを拒否したのは、学位論文が委員会によって審査される間だけであった[24]。ミルズがメリーランド大学カレッジパーク校 の社会学教授に任命された後、1942年初めにウィスコンシン大学を去った。 初期のキャリア ミルズがさらにキャリアを積む前に、彼は高血圧のため身体検査で不合格となり、徴兵猶予を受けることで徴兵を免れた。1940年8月にフレイアと離婚した が、1年後にフレイアの考えを変えるよう説得。夫妻は1941年3月に再婚した。その数年後、1943年1月15日に娘のパメラ・ミルズが生まれた [26]。この間、1941年から1945年までメリーランド大学カレッジパーク校で社会学の助教授として働き、ミルズがアメリカ政治への意識と関与を深 めていった。第二次世界大戦中、ミルズは歴史家のリチャード・ホフスタッター、フランク・フライデル、ケン・スタンプと親しくなった。この4人の学者は多 くのテーマで共同研究を行い、それぞれが戦争の現代的な問題と、それがアメリカ社会にどのような影響を与えたかについて執筆した[27]。 メリーランド大学在学中、ミルズ は「ジャーナリスティックな社会学」とオピニオン・ピースを、『ニュー・リパブリック』、『ニュー・リーダー』、そして1944年に友人のドワイト・マク ドナルドによって創刊された『ポリティックス』などの知的雑誌に寄稿し始めた[28][29]。 メリーランド大学在学中、ウィリアム・フォルムはミルズと親しくなり、ミルズが「圧倒的に仕事が人生を支配している」ことをすぐに認識した[19]。ミル ズはウェーバーの『階級、地位、政党』を出版しようとしながら、ガースとの仕事を続けていた。 [携帯用のコロナを居間の大きなコーヒーテーブルの上に置き、粗い黄色の紙にトリプル・スペースでタイプし、シャープペンシルで行間を書いて原稿を修正し た。追加や変更のスクランブルを解除するのは大変な作業だった。毎日キャンパスに行く前に、彼はフレイアに原稿を残してタイプし直させた」[19]。 1945年、コロンビア大学応用社会調査局で研究助手の職を得た後、ミルズはニューヨークに移った。この引っ越しを機にフレイアとは別居し、夫妻はその後1947年に2度目の離婚をした[30]。 ミルズは1946年に同大学の社会学部の助教授に任命された[30]。ミルズは1945年4月にグッゲンハイム財団から2,500ドルの助成金を受け取り、1946年の研究資金とした。その間、後に1951年に出版される『ホワイトカラー』を執筆した[31]。 1946年、ミルズは『マックス・ウェーバーより』を出版した: 1953年、二人は第二の著作『性格と社会構造』を出版した: 社会制度の心理学』である[32]。 1947年、ミルズは2番目の妻であり、応用社会調査局の統計学者であったルース・ハーパーと結婚した。彼女はミルズとともに『権力の新人たち』 (1948年)、『ホワイトカラー』(1951年)、『パワー・エリート』(1956年)を執筆した。1949年、ミルズとハーパーはシカゴに移り、ミル ズがシカゴ大学の客員教授を務めることになった。ミルズがシカゴ大学での四半期を終えてコロンビア大学で教鞭をとるようになり、1950年7月1日に社会 学の助教授に昇進した。1956年7月1日には、わずか6年でコロンビア大学の社会学教授に昇進した。 1955年、ハーパーは娘のキャサリンを出産した。1956年から1957年にかけて、一家はコペンハーゲンに移り住み、ミルズがコペンハーゲン大学でフ ルブライト講師を務めた。ミルズとハーパーは1957年12月に別居し、1959年に正式に離婚した[33][要ページ]。 その後のキャリア ミルズとハーパーは1957年12月に別居し、1959年に正式に離婚した[33][要出典]。ミルズは3番目の妻であるウクライナ系のアメリカ人アー ティスト、ヤロスラーヴァ・スルマックと結婚し、1959年にニューヨーク州ロックランド郡に定住した。1960年6月19日に息子のニコラス・チャール ズが生まれた[34][要ページ]。 1960年8月、ミルズ監督はキューバに滞在し、『Listen, Yankee』というテキストを作成した。彼はそこで16日間を過ごし、キューバ政府高官やキューバの市民にインタビューを行った。ミルズが彼らに質問し たのは、革命を起こしたゲリラ組織は政党と同じなのかということだった[35]。さらにミルズがインタビューしたのはフィデル・カストロ大統領で、カスト ロはミルズの『パワー・エリート』を読んで勉強したと主張した[36]。ミルズがカストロとキューバで過ごした時間は短かったが、2人は仲良くなり、数年 後にミルズが亡くなったときにはカストロが花を贈ってくれた。 ミルズは急ぐ男と評された。そのせっかちな性格もさることながら、彼は戦闘的なことで大きく知られていた。人の女性と4度の結婚をし、それぞれから子供を もうけ、何度か不倫をした-という私生活も、多くの教授や同僚に異議を唱え、批判した職業生活も、「波乱万丈 」と特徴づけられてきた。彼は、ウィスコンシン大学の前理事長[誰?]を批判し、そこの上級理論家であるハワード・P・ベッカーを 「本物の愚か者 」と呼んだ、少しベールに包まれてはいるが、かなり明白なエッセイを書いている。[37] ソビエト連邦を訪問した際、ミルズはアメリカ社会の主要な批評家として表彰された。ソ連訪問中、彼は「スターリニストによって粛清され、殺害された」初期 のソ連の指導者に乾杯し、ソ連の検閲を批判した。彼は「レオン・トロツキーの全著作がソビエト連邦で出版される日に乾杯!」[37]と乾杯した。 健康 C. ライト・ミルズは、心臓のために不健康と闘った。1942年に博士号を取得した後、ミルズが高血圧であったために陸軍の身体検査で不合格となった。このため、彼は第二次世界大戦中のアメリカ軍への従軍を免除された[38]。 死 アーヴィング・ルイス・ホロヴィッツによるミルズ伝の中で、著者はミルズが心臓の状態を強く自覚していたことについて書いている。彼は、それが彼の成人後 の生き方に影響を与えたと推測している。ミルズ氏は、てきぱきと、しかも効率的に仕事をこなす人物として描かれている。ホロヴィッツは、ミルズが速いペー スで仕事をしたのは、自分が長くは生きられないと感じていたからだと示唆し、彼を「運命を求める男」と表現している[39]。1942年、ミルズ夫人のフ レイヤは、ミルズが健康で心臓に問題はないと評していた。彼の心臓の問題は1956年まで特定されず、過度の血圧にもかかわらず、1960年12月まで大 きな心臓発作を起こさなかった。1962年、ミルズが45歳のときに4回目の、そして最後の心臓発作を起こし、3月20日にニューヨークのウェストナイ アックで亡くなった。彼の葬儀はコロンビア大学で行われ、ハンス・ゲルトとダニエル・ベルが彼のために講演した。友人と家族のための礼拝は、ナイアックに ある宗教間の平和主義者であるFellowship of Reconciliationで行われた[41]。 |

| Relationships to other theorists Mills was an intense student of philosophy before he became a sociologist. His vision of radical, egalitarian democracy was a direct result of the influence of ideas from Thorstein Veblen, John Dewey, and Mead.[42] During his time at the University of Wisconsin, Mills was deeply influenced by Hans Gerth, a sociology professor from Germany. Mills gained an insight into European learning and sociological theory from Gerth.[43] Mills and Gerth began their thirteen year collaboration in 1940. Almost immediately, Gerth expressed his doubts about working collaboratively with Mills. He ended up being right, as they had critical tensions in their collaboration in relation to intellectual ethics. They both recruited advocates to support their sides, and they used ethical positions as a weapon. They still worked together though, and each had their own jobs within the collaboration. Mills worked out a division of labor, edited, organized and rewrote Gerth's drafts. Gerth interpreted and translated the German material. Their first publication together was "A Marx for the Managers", which was a critique of The Managerial Revolution: What is Happening in the World by James Burnham. Mills and Gerth took most of their position from German sources. They had their disagreements, yet they grew a partnership and became fruitful collaborators who worked together for a long time to create influential viewpoints for the field of sociology.[44] C. Wright Mills was strongly influenced by pragmatism, specifically the works of George Herbert Mead, John Dewey, Charles Sanders Peirce, and William James.[45] Although it is commonly recognized that Mills was influenced by Karl Marx and Thorstein Veblen, the social structure aspects of Mills's works are shaped largely by Max Weber and the writing of Karl Mannheim, who followed Weber's work closely.[46] Max Weber's works contributed greatly to Mills's view of the world overall.[46] Being one of Weber's students, Mills's work focuses a great deal on rationalism.[46] Mills also acknowledged a general influence of Marxism; he noted that Marxism had become an essential tool for sociologists, and therefore all must naturally be educated on the subject; any Marxist influence was then a result of sufficient education. Neo-Freudianism also helped shape Mills's work.[47] Influenced by Mills This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Stanley Cohen: was a sociologist and criminologist, Professor of Sociology at the London School of Economics, known for breaking academic ground on "emotional management", including the mismanagement of emotions in the form of sentimentality, overreaction, and emotional denial.[48] G. William Domhoff: is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus and research professor of psychology and sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a founding faculty member of UCSC's Cowell College.[49] Tom Hayden: was an American social and political activist, author, and politician.[50] Rosabeth Moss Kanter: is the Ernest L. Arbuckle professor of business at Harvard Business School; Her book Men and Women of the Corporation won the 1977 C. Wright Mills Award for the year's outstanding book on social issues.[51] Arnold Kaufman: was a French engineer, professor of Applied Mechanics and Operations Research at the Mines ParisTech in Paris, at the Grenoble Institute of Technology and the Université catholique de Louvain, and scientific advisor at Bull Group .[52] Ralph Miliband: was a British sociologist and has been described as "one of the best known academic Marxists of his generation",[53] Teodor Shanin: was a British sociologist who was for many years Professor of Sociology at the University of Manchester.[54] William Appleman Williams: was one of the 20th century's most prominent revisionist historians of American diplomacy.[55] Jock Young: was a British sociologist and an influential criminologis.t[56] Jock holds the titles of Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Criminal Justice at The Graduate Center in New York City and Professor of Sociology at the University of Kent in the United Kingdom.[57] |

他の理論家との関係 ミルズは社会学者になる前から哲学を熱心に学んでいた。彼の急進的で平等主義的な民主主義というビジョンは、ソーシュタイン・ヴェブレン、ジョン・デュー イ、ミードからのアイデアの影響を直接受けた結果であった[42]。ウィスコンシン大学時代、ミルズが深く影響を受けたのは、ドイツ出身の社会学教授ハン ス・ゲルトであった。ミルズがゲルトから得たのは、ヨーロッパの学問と社会学理論に対する洞察であった[43]。 ミルズとゲルトは1940年から13年間の共同研究を開始した。ミルズとゲルトは1940年から13年にわたる共同研究を開始した。彼らは知的倫理に関連 して、共同作業において決定的な緊張を抱えたからである。二人はそれぞれの立場を支持する擁護者を募り、倫理的立場を武器にした。しかし、それでも二人は 協力し合い、共同作業の中でそれぞれが自分の仕事を持っていた。ミルズが分業体制をとり、ゲルトの草稿を編集し、整理し、書き直した。ゲルトはドイツ語の 資料を解釈し翻訳した。彼らの最初の共同出版物は『経営者のためのマルクス』で、『経営者革命』の批評であった: ジェームズ・バーナムの『経営者革命:世界で起きていること』を批判したものである。ミルズとガースは、自分たちの立場のほとんどをドイツの資料から得 た。彼らは意見の相違を抱えながらも、パートナーシップを育み、社会学の分野に影響力のある視点を生み出すために長い間協力し合う実りある共同研究者と なった[44]。 C. ミルズがカール・マルクスとソーシュタイン・ヴェブレンから影響を受けていたことは一般的に認識されているが、ミルズ作品の社会構造的側面はマックス・ ウェーバーとウェーバーの研究に忠実に従ったカール・マンハイムによって形成されている。 [46]マックス・ウェーバーの著作は、ミルズが全体的に世界観を持っていることに大きく寄与している[46]。ネオ・フロイト主義もまたミルズの仕事を 形成するのに役立った[47]。 ミルズからの影響 このセクションでは出典を引用していない。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。出典のないものは、異議を唱えられ、削除される可能性がある。(2022年11月) (このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) スタンレー・コーエン:社会学者、犯罪学者であり、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスの社会学教授であり、感傷、過剰反応、感情的否定といった形の感情の誤った管理を含む「感情管理」に関する学問的境地を切り開いたことで知られている[48]。 G・ウィリアム・ドムホフ:カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校の特別名誉教授であり、心理学と社会学の研究教授である。 トム・ヘイデン:アメリカの社会・政治活動家、作家、政治家である[50]。 ロザベス・モス・カンター:ハーバード・ビジネス・スクールのアーネスト・L・アーバックル教授。彼女の著書『Men and Women of the Corporation』は、社会問題に関するその年の優れた書籍に贈られる1977年C・ライト・ミルズ賞を受賞した[51]。 アーノルド・カウフマン:フランスのエンジニアで、パリのミネ・パリ工科大学、グルノーブル工科大学、ルーバン大学の応用力学とオペレーションズ・リサーチの教授であり、ブル・グループの科学顧問であった[52]。 ラルフ・ミリバンド:イギリスの社会学者であり、「彼の世代で最も有名なアカデミック・マルクス主義者の一人」と評されている[53]。 テオドール・シャニン:イギリスの社会学者で、長年マンチェスター大学の社会学教授を務めていた[54]。 ウィリアム・アップルマン・ウィリアムズ:20世紀で最も著名なアメリカ外交の修正主義的歴史家の一人である[55]。 ジョック・ヤング:イギリスの社会学者であり、影響力のある犯罪学者である[56]。ジョックはニューヨークの大学院センターの社会学・刑事司法特別教授、イギリスのケント大学の社会学教授の肩書きを持つ[57]。 |

| Outlook "I do not believe that social science will 'save the world', although I see nothing at all wrong with 'trying to save the world' ... If there are any ways out of the crises of our period by means of intellect, is it not up to the social scientist to state them? ... It is on the level of human awareness that virtually all solutions to great problems must now lie" – Mills 1959:193[58] There has long been debate over Mills's intellectual outlook. Mills is often seen as a "closet Marxist" because of his emphasis on social classes and their roles in historical progress, as well as his attempt to keep Marxist traditions alive in social theory. Just as often, however, others argue Mills more closely identified with the work of Max Weber, whom many sociologists interpret as an exemplar of sophisticated (and intellectually adequate) anti-Marxism and modern liberalism. However, Mills clearly gives precedence to social structure described by the political, economic and military institutions, and not culture, which is presented in its massified form as a means to the ends sought by the power elite. Therefore placing him firmly in the Marxist and not Weberian camp, so much so that in his collection of classical essays, Weber's Protestant Ethic is not included. Although Mills embraced Weber's idea of bureaucracy as internalized social control, as was the historicity of his[whose?] method, he[who?] was far from liberalism (being its critic). Mills was a radical who was culturally forced[how?] to distance himself from Marx while being "near" him[citation needed]. While Mills never embraced the "Marxist" label, he told his closest associates that he felt much closer to what he saw as the best currents of a flexible humanist Marxism than to alternatives. He considered himself a "plain Marxist", working in the spirit of young Marx as he claims in his collected essays: "Power, Politics and People" (Oxford University Press, 1963). In a November 1956 letter to his friends Bette and Harvey Swados, Mills declared "[i]n the meantime, let's not forget that there's more [that's] still useful in even the Sweezy[a] kind of Marxism than in all the routineers of J. S. Mill[b] put together." There is an important quotation from Letters to Tovarich (an autobiographical essay) dated Fall 1957 titled "On Who I Might Be and How I Got That Way": You've asked me, 'What might you be?' Now I answer you: 'I am a Wobbly.' I mean this spiritually and politically. In saying this I refer less to political orientation than to political ethos, and I take Wobbly to mean one thing: the opposite of bureaucrat. ... I am a Wobbly, personally, down deep, and for good. I am outside the whale, and I got that way through social isolation and self-help. But do you know what a Wobbly is? It's a kind of spiritual condition. Don't be afraid of the word, Tovarich. A Wobbly is not only a man who takes orders from himself. He's also a man who's often in the situation where there are no regulations to fall back upon that he hasn't made up himself. He doesn't like bosses—capitalistic or communistic—they are all the same to him. He wants to be, and he wants everyone else to be, his own boss at all times under all conditions and for any purposes they may want to follow up. This kind of spiritual condition, and only this, is Wobbly freedom.[59][c] These two[clarification needed] quotations are the ones chosen by Kathryn Mills for the better acknowledgement of his nuanced thinking.[citation needed] It appears that Mills understood his position as being much closer to Marx than to Weber but influenced by both, as Stanley Aronowitz argued in "A Mills Revival?".[60] Mills argues that micro and macro levels of analysis can be linked together by the sociological imagination, which enables its possessor to understand the large historical sense in terms of its meaning for the inner life and the external career of a variety of individuals. Individuals can only understand their own experiences fully if they locate themselves within their period of history. The key factor is the combination of private problems with public issues: the combination of troubles that occur within the individual's immediate milieu and relations with other people with matters that have to do with institutions of an historical society as a whole. Mills shares with Marxist sociology and other "conflict theorists" the view that American society is sharply divided and systematically shaped by the relationship between the powerful and powerless. He also shares their concerns for alienation, the effects of social structure on the personality, and the manipulation of people by elites and the mass media. Mills combined such conventional Marxian concerns with careful attention to the dynamics of personal meaning and small-group motivations, topics for which Weberian scholars are more noted. Mills had a very combative outlook regarding and towards many parts of his life, the people in it, and his works. In that way, he was a self-proclaimed outsider: "I am an outlander, not only regionally, but deep down and for good."[61][page needed] Above all, Mills understood sociology, when properly approached, as an inherently political endeavor and a servant of the democratic process. In The Sociological Imagination, Mills wrote: It is the political task of the social scientist – as of any liberal educator – continually to translate personal troubles into public issues, and public issues into the terms of their human meaning for a variety of individuals. It is his task to display in his work – and, as an educator, in his life as well – this kind of sociological imagination. And it is his purpose to cultivate such habits of mind among the men and women who are publicly exposed to him. To secure these ends is to secure reason and individuality, and to make these the predominant values of a democratic society.[62][page needed] — C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination, page 187 Contemporary American scholar Cornel West argued in his text American Evasion of Philosophy that Mills follows the tradition of pragmatism. Mills shared Dewey's goal of a "creative democracy" and emphasis on the importance of political practice but criticized Dewey for his inattention to the rigidity of power structure in the U.S. Mills's dissertation was titled Sociology and Pragmatism: The Higher Learning in America, and West categorized him along with pragmatists in his time Sidney Hook and Reinhold Niebuhr as thinkers during pragmatism's "mid-century crisis." |

展望 私は社会科学が 「世界を救う 」とは思っていないが、「世界を救おうとする 」こと自体は悪いことだとは思わない。知性によってこの時代の危機を打開する方法があるとすれば、それを示すのは社会科学者ではないだろうか?... 大問題に対する事実上すべての解決策は、今や人間の意識のレベルにあるに違いない」-ミルズ1959:193[58]。 ミルズの知的展望をめぐっては長い間議論があった。ミルズがしばしば「クローゼット・マルクス主義者」とみなされるのは、社会階級と歴史的進歩におけるそ の役割を重視し、マルクス主義の伝統を社会理論に生かそうとしたからである。しかし、それと同様に、多くの社会学者が洗練された(そして知的に適切な)反 マルクス主義と近代自由主義の模範として解釈しているマックス・ウェーバーの仕事とミルズをより密接に同一視していると主張する者もいる。しかし、ミルズ が政治的、経済的、軍事的制度によって説明される社会構造を優先していることは明らかであり、パワーエリートが求める目的のための手段として大衆化された 形で提示される文化は優先していない。そのため、ミルズをウェーバー派ではなくマルクス主義派にしっかりと位置づけ、彼の古典的エッセイ集にはウェーバー の『プロテスタント倫理』が含まれていないほどである。ミルズがウェーバーの官僚制を内面化された社会的統制とする考え方を受け入れたのは、彼[誰?]の 方法の歴史性と同様であったが、彼[誰?]は(その批判者である)リベラリズムからはかけ離れていた。ミルズが急進主義者であったのは、文化的にマルクス から距離を置くことを余儀なくされた[方法?]一方で、マルクスに「近い」存在であった[要出典]。 ミルズが「マルクス主義者」というレッテルを受け入れることはなかったが、親しい仲間には、代替案よりも、柔軟な人文主義的マルクス主義の最良の潮流と思 われるものにずっと近いものを感じていると語っていた。彼は自らを「平凡なマルクス主義者」だと考えており、エッセイ集『権力・政治・人間』(オックス フォード大学出版局、1963年)で主張しているように、若きマルクスの精神に則って活動していた。1956年11月、友人のベットとハーヴェイ・スワド ス夫妻に宛てた手紙の中で、ミルズはこう宣言している。「とりあえず、スウィージー[a]のようなマルクス主義にも、J.S.ミル[b]のルーチナーたち を合わせたものよりも、まだ役に立つものがあることを忘れてはならない」。 1957年秋の『トヴァーリッチへの手紙』(自伝的エッセイ)には、「私が誰であるかもしれないか、そしてどのようにしてそのようになったかについて」と題された重要な引用がある: あなたは私に『あなたは何であるかもしれないか』と尋ねた。と聞かれた: 私はウォブリーだ。これは精神的な意味でも政治的な意味でもだ。私は、政治的志向というよりも政治的エートスを指しているのであり、Wobblyとは、官 僚の反対を意味するものだと考えている。... 私は個人的に、心の底から、そして善意から、ウォブリーなのだ。私はクジラの外にいて、社会的孤立と自助努力によってそうなった。しかし、「ウォブリー 」とは何かご存知だろうか?一種の精神状態だ。その言葉を恐れるな、トバリッチ。「ふらふら 」とは、自分から命令する人間だけではない。彼はまた、自分自身で作り上げたものでない規則がない状況に置かれることが多い人間でもある。資本主義的であ ろうと共産主義的であろうと、上司は嫌いだ。資本主義的であろうと共産主義的であろうと、彼にとってはどれも同じなのだ。彼は、どんな状況でも、どんな目 的でも、常に自分自身のボスになりたいと願っているし、他のみんなにもそうなってほしいと願っている。このような精神的な状態、そしてこれだけがグラグラ の自由なのである[59][c]。 この2つの[clarification needed]引用は、キャサリン・ミルズが彼のニュアンスに富んだ考え方をよりよく認めるために選んだものである[citation needed]。 スタンリー・アロノヴィッツが「ミルズ・リヴァイヴァル? ミルズが主張するのは、ミクロとマクロの分析レベルは社会学的想像力によって結びつけられるということであり、その想像力は、様々な個人の内的生活と外的 キャリアにとっての意味という観点から、大きな歴史的意味を理解することを可能にする。個人が自分自身の経験を完全に理解できるのは、自分自身を歴史の時 代の中に位置づける場合だけである。重要な要素は、私的な問題と公的な問題との組み合わせである。個人の身近な環境や他の人々との関係の中で起こる問題 と、歴史的社会全体の制度に関係する問題との組み合わせである。 ミルズはマルクス主義社会学や他の「コンフリクト理論家」たちと、アメリカ社会は権力者と無権力者の関係によって鋭く分断され、組織的に形成されていると いう見解を共有している。彼はまた、疎外、社会構造が人格に及ぼす影響、エリートやマスメディアによる人々の操作に対する懸念も共有している。ミルズは、 このような従来のマルクス主義的な懸念と、ウェーバー派の学者がより得意とする個人的な意味や小集団の動機の力学への注意深い注意を組み合わせた。 ミルズには、自分の人生、そこに登場する人々、そして自分の作品の多くの部分に関して、またそれに対して、非常に闘争的な見通しがあった。その意味で、彼 は自称アウトサイダーであった: 「私は地域的にだけでなく、心の底から、そして善良な意味において、よそ者である」[61][要ページ]。 とりわけミルズ は、社会学が適切にアプローチされた場 合、本質的に政治的な試みであり、民主的プ ロセスの奉仕者であると理解していた。社会学的想像力』の中で、ミルズ はこう書いている: 個人的な問題を公共的な問題に変換し、公共的な問題をさまざまな個人にとっての人間的な意味の用語に変換しつづけることは、社会科学者の政治的な仕事であ り、あらゆるリベラルな教育者の仕事である。このような社会学的想像力を仕事において、そして教育者として人生においても発揮することが彼の仕事である。 そして、公に彼の目に触れる男女の間に、そのような心の習慣を培うことが彼の目的である。これらの目的を確保することは、理性と個性を確保することであ り、これらを民主主義社会の優勢な価値観とすることである[62][要ページ]。 - C・ライト・ミルズ『社会学的想像力』187ページ 現代のアメリカ人学者コーネル・ウェストは、その著書『アメリカ人の哲学回避』の中で、ミルズがプラグマティズムの伝統に従っていると論じている。ミルズ はデューイの「創造的民主主義」という目標と政治的実践の重要性を共有していたが、デューイがアメリカにおける権力構造の硬直性に無頓着であったことを批 判した: ウェストは彼を、同時代のプラグマティストであるシドニー・フックやラインホルド・ニーバーとともに、プラグマティズムの 「世紀半ばの危機 」における思想家に分類した。 |

| Mills's critique of sociology at the time Since he was a sociologist himself, some[who?] may be surprised to learn that Mills was quite critical of the sociological approach during his time. In fact, scholars saw The Sociological Imagination as "Mills' final break with academic sociology."[63] In this work, Mills was critical of specific people, such as Parsons and Paul Lazarsfeld, a member of his department at Columbia. While Mills did have frustrations with Parsons's theories and the Columbia department, his arguments in The Sociological Imagination are based in more than retaliatory remarks.[63] While The Sociological Imagination was and is still sometimes read as "an attack on empirical research" when it is really "a critique of a certain research style."[63] Mills was worried about sociology falling into the traps of normative thinking and ceasing to be a critic of social life. Throughout his academic career, Mills fought with mainstream sociology about different conflicting sociological styles.[63] Mills was primarily worried about social sciences being susceptible to the "power and prestige of normative culture" and veering away from its original objective.[63] It is difficult to say whether or not sociology moved in the direction that Mills feared. However, scholars do know that until his death, Mills fought to maintain what he thought was the integrity of sociology.[editorializing] |

当時のミルズによる社会学批判 ミルズ自身が社会学者であったため、ミルズが同時代の社会学的アプローチに対してかなり批判的であったことに驚く人もいるかもしれない。事実、学者たちは 『社会学的想像力』を「ミルズがアカデミックな社会学と最後に決別した作品」[63]とみなしている。この作品の中でミルズが批判しているのは、パーソン ズやコロンビア大学で教鞭をとっていたポール・ラザースフェルドといった特定の人物たちである。ミルズにはパーソンズの理論やコロンビア大学学部に対する 不満があったとはいえ、『社会学的想像力』における彼の主張は報復的な発言以上のものである[63]。『社会学的想像力』は、本当は「ある研究スタイルに 対する批判」であるにもかかわらず、「経験的研究に対する攻撃」として読まれることがあったし、今でもそう読まれている。ミルズが主に心配していたのは、 社会科学が「規範文化の権力と威信」の影響を受けやすくなり、本来の目的から遠ざかってしまうことであった。しかし学者たちは、ミルズが死ぬまで、社会学 の完全性だと考えるものを維持するために戦っていたことを知っている[論説]。 |

| Published work This section relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this section by adding secondary or tertiary sources. (November 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology (1946) was edited and translated in collaboration with Gerth.[64][page needed] Mills and Gerth had begun collaborating in 1940, selected a few of Weber's original German text, and translated them into English.[65] The preface of the book begins by explaining the disputable difference of meaning that English words give to German writing. The authors attempt to explain their devotion to being as accurate as possible in translating Weber's writing. The New Men of Power: America's Labor Leaders (1948) studies the "Labor Metaphysic" and the dynamic of labor leaders cooperating with business officials. The book concludes that the labor movement had effectively renounced its traditional oppositional role and become reconciled to life within a capitalist system. The Puerto Rican Journey (1950), published in New York, was written in collaboration with Clarence Senior and Rose Kohn Goldsen. Clarence Senior was a Socialist Political activist who specialized in Puerto Rican affairs. Rose Kohn Goldsen was a sociology professor at Cornell University who studied the social effects of television and popular culture. The book documents a methodological study and does not address a theoretical sociological framework. White Collar: The American Middle Classes (1951) offers a rich historical account of the middle classes in the United States and contends that bureaucracies have overwhelmed middle-class workers, robbing them of all independent thought and turning them into near-automatons, oppressed but cheerful. Mills states there are three types of power within the workplace: coercion or physical force; authority; and manipulation.[66] Through this piece, the thoughts of Mills and Weber seem to coincide in their belief that Western Society is trapped within the iron cage of bureaucratic rationality, which would lead society to focus more on rationality and less on reason.[66] Mills's fear was that the middle class was becoming "politically emasculated and culturally stultified," which would allow a shift in power from the middle class to the strong social elite.[67][page needed] Middle-class workers receive an adequate salary but have become alienated from the world because of their inability to affect or change it. Frank W. Elwell describes this work as "an elaboration and update on Weber's bureaucratization process, detailing the effects of the increasing division of labor on the tone and character of American social life."[46] Character and Social Structure (1953) was co-authored with Gerth. This was considered his most theoretically sophisticated work. Mills later came into conflict with Gerth, though Gerth positively referred to him as, "an excellent operator, a whippersnapper, promising young man on the make, and Texas cowboy à la ride and shoot."[37] Generally speaking, Character and Social Structure combines the social behaviorism and personality structure of pragmatism with the social structure of Weberian sociology. It is centered on roles, how they are interpersonal, and how they are related to institutions.[68][page needed] The Power Elite (1956) describes the relationships among the political, military, and economic elites, noting that they share a common world view; that power rests in the centralization of authority within the elites of American society.[69][page needed] The centralization of authority is made up of the following components: a "military metaphysic", in other words a military definition of reality; "class identity", recognizing themselves as separate from and superior to the rest of society; "interchangeability" (they move within and between the three institutional structures and hold interlocking positions of power therein); cooperation/socialization, in other words, socialization of prospective new members is done based on how well they "clone" themselves socially after already established elites. Mills's view on the power elite is that they represent their own interest, which include maintaining a "permanent war economy" to control the ebbs and flow of American Capitalism and the masking of "a manipulative social and political order through the mass media."[67][page needed] Additionally, this work can be described as "an exploration of rational-legal bureaucratic authority and its effects on the wielders and subjects of this power."[46] President Dwight D. Eisenhower referenced Mills and this book in his farewell address of 1961. He warned about the dangers of a "military-industrial complex" as he had slowed the push for increased military defense in his time as president for two terms. This idea of a "military-industrial complex" is a reference to Mills' writing in The Power Elite, showing what influence this book had on certain powerful figures.[70] The Causes of World War Three (1958) and Listen, Yankee (1960) were important works that followed. In both, Mills attempts to create a moral voice for society and make the power elite responsible to the "public".[71][page needed] Although Listen, Yankee was considered highly controversial, it was an exploration of the Cuban Revolution written from the viewpoint of a Cuban revolutionary and was a very innovative style of writing for that period in American history.[72][page needed] In his paper on Mills's work, Elwell describes The Causes of World War Three as a jeremiad on Weber's ideas. More specifically on his view of "crackpot realism" (" the disjunction between institutional rationality and human reason").[46] The Sociological Imagination (1959), which is considered Mills's most influential book,[d] describes a mindset for studying sociology, the sociological imagination, that stresses being able to connect individual experiences and societal relationships. The three components that form the sociological imagination are history, biography, and social structure. Mills asserts that a critical task for social scientists is to "translate personal troubles into public issues".[74][page needed] The distinction between troubles and issues is that troubles relate to how a single person feels about something while issues refer to how a society affects groups of people. For instance, a man who cannot find employment is experiencing a trouble, while a city with a massive unemployment rate makes it not just a personal trouble but a public issue.[75] This book helped the "penetration of a field by a new generation of social scientists dedicated to problems of social change rather than system maintenance".[76] Mills bridged the gap between truth and purpose in sociology[citation needed]. Another important part of this book is the interpersonal relations Mills talks about, specifically marriage and divorce. Mills rejects all external class attempts at change because he sees them as a contradiction to the sociological imagination. Mills had[dubious – discuss] a lot of sociologists talk about his book, and the feedback was varied. Mills' writing can be seen as a critique of some of his colleagues, which resulted in the book generating a large debate. His critique of the sociological profession is one that was monumental in the field of sociology and that got lots of attention as his most famous work. One can interpret Mills's claim in The Sociological Imagination as the difficulty humans have in balancing biography and history, personal challenges and societal issues. Sociologists, then, rightly connect their autobiographical, personal challenges to social institutions. Social scientists should then connect those institutions to social structures and locate them within a historical narrative. The version of Images of Man: The Classic Tradition in Sociological Thinking (1960) worked on by C. Wright Mills is simply an edited copy with the addition of an introduction written himself.[77][page needed] Through this work, Mills explains that he believes the use of models is the characteristic of classical sociologists, and that these models are the reason classical sociologists maintain relevance.[68][page needed] The Marxists (1962) takes Mills's explanation of sociological models from Images of Man and uses it to criticize modern liberalism and Marxism. He believes that the liberalist model does not work and cannot create an overarching view of society, but rather it is more of an ideology for the entrepreneurial middle class. Marxism, however, may be incorrect in its overall view, but it has a working model for societal structure, the mechanics of the history of society, and the roles of individuals. One of Mills's problems with the Marxist model is that it uses units that are small and autonomous, which he finds too simple to explain capitalism. Mills then provides discussion on Marx as a determinist.[68][page needed] |

出版物 このセクションは、一次資料への言及に過度に依存している。二次または三次ソースを追加することで、このセクションを改善していただきたい。(2021年11月) (このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) マックス・ウェーバーより ミルズとゲルトは1940年に共同研究を始めており、ウェーバーのドイツ語の原文から数編を選び、英語に翻訳した[65]。本書の序文は、英語の単語がド イツ語の文章に与える意味の違いについて説明することから始まる。著者は、ウェーバーの文章をできるだけ正確に翻訳することに専念していることを説明しよ うとしている。 新しい権力者たち アメリカの労働指導者たち』(1948年)は、「労働形而上学」と労働指導者が企業幹部と協力するダイナミズムについて研究している。本書は、労働運動が伝統的な反対運動の役割を事実上放棄し、資本主義体制内での生活に和解したと結論付けている。 ニューヨークで出版された『プエルトリコの旅』(1950年)は、クラレンス・シニアとローズ・コーン・ゴールドセンとの共著である。クラレンス・シニア はプエルトリコ問題を専門とする社会主義政治活動家であった。ローズ・コーン・ゴールドセンはコーネル大学の社会学教授で、テレビと大衆文化の社会的影響 を研究していた。本書は方法論的研究の記録であり、理論的な社会学の枠組みには触れていない。 ホワイトカラー アメリカの中流階級』(1951年)は、アメリカの中流階級について豊かな歴史的説明を提供し、官僚機構が中流階級の労働者を圧倒し、自主的な思考を奪 い、抑圧されているが陽気なオートマトンに近い存在に変えてしまったと論じている。ミルズとウェーバーの考えは、この作品を通して、西洋社会が官僚的合理 性という鉄の檻の中に閉じ込められ、社会が合理性を重視するようになり、理性を重視しなくなるという信念において一致しているように見える。 [ミルズが恐れていたのは、中産階級が「政治的に男性化し、文化的に文化化」していくことであり、それによって中産階級から強力な社会的エリートへと権力 がシフトしていくことであった[67][要出典]。中産階級の労働者は十分な給与を受け取っているが、世界に影響を与えたり変えたりすることができないた めに、世界から疎外されるようになっている。フランク・W・エルウェルはこの著作を「ウェーバーの官僚化プロセスの精緻化と更新であり、分業の増大がアメ リカの社会生活の基調と性格に及ぼす影響を詳述している」と評している[46]。 性格と社会構造』(1953年)はガースとの共著である。これは彼の最も理論的に洗練された著作と考えられていた。ミルズは後にガースと対立するようにな るが、ガースは彼のことを「優秀な工作員であり、気の早い、将来有望な若者であり、テキサスのカウボーイ・ア・ラ・ライド・アンド・シュートである」と肯 定的に評している[37]。一般的に言えば、『性格と社会構造』はプラグマティズムの社会的行動主義や性格構造とウェーバー社会学の社会構造を組み合わせ たものである。それは役割、それらがどのように対人関係にあるのか、そしてそれらがどのように制度と関連しているのかを中心にしている[68][要ペー ジ]。 パワー・エリート』(1956年)は政治的、軍事的、経済的エリート間の関係を記述しており、彼らが共通の世界観を共有していること、アメリカ社会のエ リート内の権威の集中に権力があることを指摘している。 [軍事的形而上学」、言い換えれば現実の軍事的定義、「階級的アイデンティティ」、自らを社会の他の部分から切り離された優れた存在として認識すること、 「交換可能性」(彼らは3つの制度構造内を移動し、その間を行き来し、そこで権力の連動した地位を保持する)、「協力/社会化」、言い換えれば、新メン バー候補の社会化は、すでに確立されたエリートの後に社会的にどれだけうまく「クローン化」されるかに基づいて行われる。ミルズによる権力エリートについ ての見解は、彼らが自らの利益を代表しているというものであり、その中には、アメリカ資本主義の浮沈をコントロールするための「恒久的な戦争経済」の維持 や、「マスメディアを通じて操作的な社会的・政治的秩序」を覆い隠すことなどが含まれる[67][要ページ] さらに、この著作は「合理的・合法的な官僚的権威と、この権力の行使者と臣民に対するその影響についての探求」[46]と言える。アイゼンハワー大統領 は、2期にわたる大統領在任中、軍備増強の推進を遅らせたため、「軍産複合体」の危険性について警告した。この「軍産複合体」という考え方は、ミルズが 『パワー・エリート』で書いた文章に言及したもので、この本が特定の権力者にどのような影響を与えたかを示している[70]。 第三次世界大戦の原因』(1958年)と『リッスン、ヤンキー』(1960年)は、その後に続く重要な著作である。どちらも、ミルズが社会に道徳的な声を 生み出し、権力エリートに「大衆」に対する責任を負わせようとしたものである[71][page needed]。『リッスン、ヤンキー』は非常に物議を醸すと考えられていたが、キューバ革命の探求をキューバの革命家の視点から書いたものであり、アメ リカ史のその時期としては非常に革新的な文体であった[72][page needed]。 エルウェルはミルズに関する論文の中で、『第三次世界大戦の原因』をウェーバーの思想に対する嫉妬であると述べている。より具体的には、彼の見解である 「クラクポット・リアリズム」(「制度的合理性と人間の理性との断絶」)についてである[46]。 ミルズの最も影響力のある著書とされる『社会学的想像力』(1959年)[d]は、社会学を研究するための考え方、すなわち社会学的想像力について述べて おり、個人の経験と社会の関係を結びつけることができることを強調している。社会学的想像力を形成する3つの要素は、歴史、伝記、社会構造である。ミルズ は、社会科学者にとって重要な仕事は「個人的な悩みを公共的な問題に変換する」ことであると主張している[74][要出典]。悩みと問題の区別は、悩みが 一人の人間が何かについてどう感じるかに関係するのに対し、問題は社会が人々の集団にどのような影響を与えるかに関係するということである。例えば、就職 できない人がトラブルを経験しているのに対して、大量の失業率を抱える都市では、それは単なる個人的なトラブルではなく、公共的な問題なのである。本書の もう一つの重要な部分は、ミルズが語る対人関係、特に結婚と離婚である。ミルズが外部階級による変革の試みをすべて拒絶するのは、それが社会学的想像力に 対する矛盾であるとみなすからである。ミルズには多くの社会学者が彼の本について語り、その感想はさまざまであった。ミルズの文章は、一部の同僚に対する 批評として見ることができ、その結果、この本は大きな議論を巻き起こすことになった。社会学の専門職に対する彼の批判は、社会学の分野において記念碑的な ものであり、彼の最も有名な著作として多くの注目を集めた。社会学的想像力』におけるミルズの主張は、伝記と歴史、個人的課題と社会的課題を両立させるこ との難しさとして解釈することができる。そして社会学者は、自伝的で個人的な 課題を社会制度と結びつけるのが正しい。そして社会科学者は、それらの制度を社会構造と結びつけ、歴史的な物語の中に位置づけるべきである。 イメージ・オブ・マン』の版である: 77][ページが必要]この著作を通して、ミルズ はモデルの使用が古典的社会学者の特徴であり、こ れらのモデルが古典的社会学者が妥当性を 維持する理由であると信じていると説明している[68][ページが必要]。 The Marxists』(1962年)は、『Images of Man』からの社会学的モデルに関するミルズの説明を、現代の自由主義とマルクス主義を批判するために用いている。彼は、リベラリズムのモデルは機能せ ず、社会の包括的な見方を作り出すことはできず、むしろ企業家的な中産階級のためのイデオロギーであると信じている。しかし、マルクス主義は、その全体的 な見方は間違っているかもしれないが、社会の構造、社会の歴史の仕組み、個人の役割については、機能するモデルを持っている。ミルズのマルクス主義モデル の問題点の一つは、それが小規模で自律的な単位を用いていることであり、資本主義を説明するには単純すぎると彼は考えている。その後、ミルズが決定論者と してのマルクスについて議論を提供している[68][要ページ]。 |

| Legacy This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) According to Stephen Scanlan and Liz Grauerholz, writing in 2009, Mills's thinking on the intersection of biography and history continued to influence scholars and their work, and also impacted the way they interacted with and taught their students.[78] The "International Sociological Association recognized The Sociological Imagination as second on its list of the 'Books of the Century'".[78] At his memorial service, Hans Gerth (Mills's coauthor and coeditor) referred to Mills as his "alter ego", despite the many disagreements they had.[19] Interestingly, many of Mills's close friends "reminisced about their earlier friendship and later estrangement when Mills mocked them for supporting the status quo and their conservative universities."[19] In addition to the impact Mills left on those in his life, his legacy can also be seen through the prominence of his work after his passing. William Form describes a 2005 survey of the eleven best selling texts and in these Mills was referenced 69 times, far more than any other prominent author.[19] Frank W. Elwell, in his paper "The Sociology of C. Wright Mills" further explains the legacy Mills left as he "writes about issues and problems that matter to people, not just to other sociologists, and he writes about them in a way to further our understanding."[46] His work is not just useful to students of sociology, but the general population as well. Mills tackled relevant topics such as the growth of white collar jobs, the role of bureaucratic power, as well as the Cold War and the spread of communism.[46] In 1964, the Society for the Study of Social Problems established the C. Wright Mills Award for the book that "best exemplifies outstanding social science research and a great mutual understanding of the individual and society in the tradition of the distinguished sociologist, C. Wright Mills."[79] |

レガシー このセクションの検証には追加の引用が必要である。このセクションに信 頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは異議申し立てされ、削除される可能性がある。 (2021年11月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 2009年に書かれたスティーヴン・スカンランとリズ・グラウアホルツによれば、伝記と歴史の交差点に関するミルズの考え方は、学者や彼らの仕事に影響を 与え続け、また学生との関わり方や教え方にも影響を与えた[78]。 国際社会学会は、『社会学的想像力』を「今世紀の書籍」リストの第2位に認定した」[78]。 彼の追悼式において、ハンス・ガース(ミルズの共著者であり共同編集者)は、多くの意見の相違があったにもかかわらず、ミルズのことを彼の「分身」と呼ん だ[19]。興味深いことに、ミルズの親しい友人の多くは、「ミルズが現状維持と保守的な大学を支持する彼らを嘲笑したとき、彼らの以前の友情と後の疎遠 について回想していた」[19]。ウィリアム・フォルムは、2005年に行われたベストセラーのテキスト11冊の調査について述べているが、その中でミル ズが言及された回数は69回であり、他の著名な著者よりもはるかに多かった[19]。フランク・W・エルウェルは、その論文「C・ライト・ミルズの社会 学」の中で、ミルズが残した遺産について、「他の社会学者だけでなく、人々にとって重要な問題や課題について書き、我々の理解を深めるように書いている」 とさらに説明している[46]。ミルズが取り組んだのは、ホワイトカラーの仕事の増加、官僚権力の役割、さらには冷戦と共産主義の広がりといった関連する トピックであった[46]。 1964年、社会問題研究学会は「卓越した社会科学研究と、著名な社会学者であるC.ライト・ミルズの伝統における個人と社会の偉大な相互理解を最もよく例証する」本に対してC.ライト・ミルズ賞を設立した[79]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C._Wright_Mills |

|

| Bibliography Aronowitz, Stanley (2003). "A Mills Revival?". Logos. 2 (3). Retrieved May 5, 2019. Elliott, Gregory C. (2001). "The Self as Social Product and Social Force: Morris Rosenberg and the Elaboration of a Deceptively Simple Effect". In Owens, Timothy J.; Stryker, Sheldon; Goodman, Norman (eds.). Extending Self-Esteem Theory and Research: Sociological and Psychological Currents. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press (published 2006). pp. 10–28. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511527739.002. ISBN 978-0-521-02842-4. Feeley, Malcolm M.; Simon, Jonathan (2011) [2007]. "Folk Devils and Moral Panics: An Appreciation from North America". In Downes, David; Rock, Paul; Chinkin, Christine; Gearty, Conor (eds.). Crime, Social Control and Human Rights: From Moral Panics to States of Denial. Abingdon, England: Routledge. pp. 39–52. doi:10.4324/9781843925583. ISBN 978-1-134-00595-6. Geary, Daniel (2009). "C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought". Radical Ambition: C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-94344-5. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppzdg. Horowitz, Irving Louis (1983). C. Wright Mills: An American Utopian. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-914970-6. Mann, Doug (2008). Understanding Society: A Survey of Modern Social Theory. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-542184-2. Mattson, Kevin (2001). "Responding to a Problem: A W.P.A. for PhDs?" (PDF). Thought & Action. 17 (2): 17–24. ISSN 0748-8475. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2019. Mills, C. Wright (1960). "Letter to the New Left". New Left Review. 1 (5). Retrieved May 5, 2019 – via Marxists Internet Archive. ——— (2000a). Mills, Kathryn; Mills, Pamela (eds.). C. Wright Mills: Letters and Autobiographical Writings. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21106-3. ——— (2000b). The Sociological Imagination (40th anniversary ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513373-8. ——— (2012). "From The Sociological Imagination". In Massey, Gareth (ed.). Readings for Sociology (7th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-91270-8. Mills, Thomas (2015). The End of Social Democracy and the Rise of Neoliberalism at the BBC (PhD thesis). Bath, England: University of Bath. Retrieved June 18, 2020. Oakes, Guy; Vidich, Arthur J. (1999). Collaboration, Reputation, and Ethics in American Academic Life: Hans H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06807-2. Philips, Bernard (2005). "Mills, Charles Wright (1916–62)". In Shook, John R. (ed.). The Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers. Vol. 3. Bristol, England: Thoemmes Continuum. pp. 1705–1709. ISBN 978-1-84371-037-0. Ritzer, George (2011). Sociological Theory. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-811167-9. Ross, Robert J. S. (2015). "Democracy, Labor, and Globalization: Reflections on Port Huron". In Brick, Howard; Parker, Gregory (eds.). A New Insurgency: The Port Huron Statement and Its Times. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Michigan Publishing. doi:10.3998/maize.13545967.0001.001. ISBN 978-1-60785-350-3. Scimecca, Joseph A. (1977). The Sociological Theory of C. Wright Mills. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0-8046-9155-0. Sica, Alan, ed. (2005). Social Thought: From the Enlightenment to the Present. Boston, Massachusetts: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-39437-1. Sim, Stuart; Parker, Noel, eds. (1997). The A–Z Guide to Modern Social and Political Theorists. London: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-524885-0. Tilman, Rick (1979). "The Intellectual Pedigree of C. Wright Mills: A Reappraisal". The Western Political Quarterly. 32 (4): 479–496. doi:10.1177/106591297903200410. ISSN 0043-4078. JSTOR 447909. S2CID 143494357. ——— (1984). C. Wright Mills: A Native Radical and His American Intellectual Roots. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00360-3. Wallerstein, Immanuel (2008). "Mills, C. Wright". International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Detroit, Michigan: Thomson Gale. Retrieved May 5, 2019. Young, Jock (2014). "In Memoriam: Jock Young". Punishment & Society. 16 (3). Interviewed by van Swaaningen, René: 353–359. doi:10.1177/1462474514539440. ISSN 1741-3095. S2CID 220635491. |

参考文献 Aronowitz, Stanley (2003). 「A Mills Revival?」. Logos. 2 (3). Retrieved May 5, 2019. Elliott, Gregory C. (2001). 「The Self as Social Product and Social Force: Morris Rosenberg and the Elaboration of a Deceptively Simple Effect」. In Owens, Timothy J.; Stryker, Sheldon; Goodman, Norman (eds.). 自尊感情理論と研究の拡張:社会学と心理学の潮流。ケンブリッジ、イングランド:ケンブリッジ大学出版局(2006年発行)。10-28ページ。doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511527739.002。ISBN 978-0-521-02842-4。 Feeley, Malcolm M.; Simon, Jonathan (2011) [2007]. 「Folk Devils and Moral Panics: An Appreciation from North America」. In Downes, David; Rock, Paul; Chinkin, Christine; Gearty, Conor (eds.). Crime, Social Control and Human Rights: From Moral Panics to States of Denial. アビンドン、イングランド: ルートレッジ。 pp. 39–52. doi:10.4324/9781843925583. ISBN 978-1-134-00595-6. ギアリー、ダニエル(2009年)。「C.ライト・ミルズ、左派、そしてアメリカの社会思想」。『ラディカルな野望:C.ライト・ミルズ、左派、そしてア メリカの社会思想』カリフォルニア大学出版、バークレー、カリフォルニア。ISBN 978-0-520-94344-5。 JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppzdg. ホロウィッツ、アーヴィング・ルイス(1983年)。C.ライト・ミルズ:アメリカのユートピアン。ニューヨーク:フリープレス。ISBN 978-0-02-914970-6。 マン、ダグ(2008年)。社会を理解する:現代社会理論の概観。オンタリオ州ドンミルズ:オックスフォード大学出版。ISBN 978-0-19-542184-2。 マッツソン、ケビン(2001年)。「問題への対応:博士号取得者向けWPA?」(PDF)。『思想と行動』第17巻第2号、17-24ページ。ISSN 0748-8475。オリジナル(PDF)のアーカイブ(2018年4月11日)。2019年5月5日取得。 ミルズ、C・ライト (1960年). 「ニューレフトへの手紙」. New Left Review. 1 (5). 2019年5月5日閲覧 – マルキシスト・インターネット・アーカイブ経由. ——— (2000a). ミルズ、キャサリン、ミルズ、パメラ(編). C. Wright Mills: Letters and Autobiographical Writings. カリフォルニア州バークレー: カリフォルニア大学出版. ISBN 978-0-520-21106-3. ——— (2000b). 『社会学的想像力』(40周年記念版). オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-513373-8. ——— (2012). 「『社会学的想像力』より」. Massey, Gareth (編). 社会学のための読本(第7版)』ニューヨーク:W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-91270-8. ミルズ、トーマス(2015年)。『社会民主主義の終焉とBBCにおける新自由主義の台頭』(博士論文)。イングランド、バース:バース大学。2020年6月18日取得。 Oakes, Guy; Vidich, Arthur J. (1999). Collaboration, Reputation, and Ethics in American Academic Life: Hans H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06807-2. フィリップス、バーナード(2005年)。「ミルズ、チャールズ・ライト(1916年~1962年)」。ショック、ジョン・R.(編)『現代アメリカ哲学 者辞典』第3巻。ブリストル、イングランド:Thoemmes Continuum。1705~1709ページ。ISBN 978-1-84371-037-0。 リッツァー、ジョージ(2011年)。『社会学理論』。ニューヨーク:McGraw Hill。ISBN 978-0-07-811167-9。 ロス、ロバート・J・S(2015年)。「民主主義、労働、そしてグローバリゼーション:ポートヒューロンについての考察」。ブリック、ハワード、および パーカー、グレゴリー(編)『新たな蜂起:ポートヒューロン声明とその時代』。ミシガン州アナーバー: ミシガン出版. doi:10.3998/maize.13545967.0001.001. ISBN 978-1-60785-350-3. Scimecca, Joseph A. (1977). C. Wright Millsの社会学理論. ニューヨーク州ポートワシントン:Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0-8046-9155-0. Sica, Alan, ed. (2005). Social Thought: From the Enlightenment to the Present. マサチューセッツ州ボストン:Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-39437-1. シム、スチュアート、ノエル・パーカー編 (1997年). 『現代の社会・政治理論家ガイド』. ロンドン: プレンティスホール. ISBN 978-0-13-524885-0. ティルマン、リック (1979年). 「C.ライト・ミルの知的系譜:再評価」. The Western Political Quarterly. 32 (4): 479–496. doi:10.1177/106591297903200410. ISSN 0043-4078. JSTOR 447909. S2CID 143494357. ——— (1984). C. Wright Mills: ネイティブ・ラディカルと彼のアメリカ的知性のルーツ』。ペンシルベニア州ユニバーシティ・パーク:ペンシルベニア州立大学出版。ISBN 978-0-271-00360-3。 ウォーラーステイン、イマニュエル(2008年)。「ミルズ、C・ライト」。『国際社会科学百科事典』。ミシガン州デトロイト:トムソン・ゲイル。2019年5月5日取得。 ヤング、ジョック(2014年)。「追悼:ジョック・ヤング」『Punishment & Society』16 (3)。インタビュー:ヴァン・スワーニンゲン、ルネ:353-359。doi:10.1177/1462474514539440。ISSN 1741-3095。S2CID 220635491。 |

| Further reading Aptheker, Herbert (1960). The World of C. Wright Mills. New York: Marzani and Munsell. OCLC 244597. Aronowitz, Stanley (2012). Taking It Big: C. Wright Mills and the Making of Political Intellectuals. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13540-5. Domhoff, G. William (2006). "Review: Mills's The Power Elite 50 Years Later". Contemporary Sociology. 35 (6): 547–550. doi:10.1177/009430610603500602. ISSN 1939-8638. JSTOR 30045989. S2CID 152155235. Retrieved May 5, 2019. Dowd, Douglas F. (1964). "On Veblen, Mills... and the Decline of Criticism". Dissent. Vol. 11, no. 1. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 29–38. ISSN 0012-3846. Eldridge, John E. T. (1983). C. Wright Mills. Key Sociologists Series. Chichester, England: E. Horwood Tavistock Publications. ISBN 978-0-85312-534-1. Frauley, Jon, ed. (2021). The Routledge International Handbook of C. Wright Mills Studies. New York: Routledge. Geary, Daniel (2008). "'Becoming International Again': C. Wright Mills and the Emergence of a Global New Left". Journal of American History. 95 (3): 710–736. doi:10.2307/27694377. ISSN 1945-2314. JSTOR 27694377. Hayden, Tom (2006). Radical Nomad: C. Wright Mills and His Times. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59451-202-5. Kerr, Keith (2009). Postmodern Cowboy: C. Wright Mills and a New 21st Century Sociology. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59451-579-8. Landau, Saul (1963). "C. Wright Mills: The Last Six Months". Root and Branch. 2. Root and Branch Press: 3–16. Mattson, Kevin (2002). Intellectuals in Action: The Origins of the New Left and Radical Liberalism, 1945–1970. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02206-2. Miliband, Ralph. "C. Wright Mills," New Left Review, whole no. 15 (May–June 1962), pp. 15–20. Muste, A. J.; Howe, Irving (1959). "C. Wright Mills' Program: Two Views". Dissent. Vol. 6, no. 2. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 189–196. ISSN 0012-3846. Swados, Harvey (1963). "C. Wright Mills: A Personal Memoir". Dissent. 10 (1). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press: 35–42. ISSN 0012-3846. Thompson, E. P. (1979). "C. Wright Mills: The Responsible Craftsman" (PDF). Radical America. Vol. 13, no. 4. Somerville, Massachusetts: Alternative Education Project. pp. 60–73. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2019. Treviño, A. Javier (2012). The Social Thought of C. Wright Mills. Thousand Oaks, California: Pine Forge Press. ISBN 978-1-4129-9393-7. |

さらに読む Aptheker, Herbert (1960). The World of C. Wright Mills. New York: Marzani and Munsell. OCLC 244597. Aronowitz, Stanley (2012). Taking It Big: C. Wright Mills and the Making of Political Intellectuals. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13540-5. ドムホフ、G. ウィリアム(2006年)。「書評:ミルズ著『権力エリート 50年後』」『現代社会学』35(6):547-550。doi:10.1177/009430610603500602。ISSN 1939-8638。 JSTOR 30045989。S2CID 152155235. 2019年5月5日取得。 ダウド、ダグラス・F. (1964年). 「ヴェブレン、ミル...そして批評の衰退について」. ディセンダント. 第11巻、第1号. ペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィア: ペンシルベニア大学出版. pp. 29–38. ISSN 0012-3846. エルドリッジ、ジョン・E・T. (1983年). C.ライト・ミルズ. キー・ソシオロジスト・シリーズ. イギリス、チチェスター: E. ホーウッド・タビストック・パブリケーションズ. ISBN 978-0-85312-534-1. フラウリー、ジョン、編 (2021年). ザ・ルートレッジ・インターナショナル・ハンドブック・オブ・C.ライト・ミルズ・スタディーズ. ニューヨーク: ルートレッジ. ギアリー、ダニエル(2008年)。「再び国際化へ」:C.ライト・ミルズとグローバル・ニューレフトの台頭。『アメリカ史ジャーナル』95(3): 710-736。doi:10.2307/27694377。ISSN 1945-2314。 JSTOR 27694377。 ヘイデン、トム(2006年)。『ラディカル・ノマド:C. ライト・ミルズとその時代』。コロラド州ボールダー:パラダイム・パブリッシャーズ。ISBN 978-1-59451-202-5。 キース・カー(2009年)。ポストモダン・カウボーイ:C. ライト・ミルズと21世紀の新しい社会学。コロラド州ボールダー:パラダイム・パブリッシャーズ。ISBN 978-1-59451-579-8。 ソール・ランドー(1963年)。「C. ライト・ミルズ:この半年間」。ルート・アンド・ブランチ。2。ルート・アンド・ブランチ・プレス:3-16。 マッツソン、ケビン(2002年)。『行動する知識人:ニューレフトとラディカル・リベラリズムの起源、1945年~1970年』。ペンシルベニア州ユニバーシティ・パーク:ペンシルベニア州立大学出版。ISBN 978-0-271-02206-2。 ミリバンド、ラルフ。「C. ライト・ミルズ」『ニューレフト・レビュー』通号 15 (1962年5月-6月), pp. 15–20. マステ, A. J.; ハウ, アーヴィング (1959). 「C. ライト・ミルズのプログラム:2つの視点」. ディセンスト. 第6巻、第2号. フィラデルフィア、ペンシルベニア州: ペンシルベニア大学出版局. pp. 189–196. ISSN 0012-3846. スワドス、ハーヴェイ(1963年)。「C. ライト・ミルズ:個人的な回想録」。『Dissent』10(1)。ペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィア:ペンシルベニア大学出版:35-42。ISSN 0012-3846。 トンプソン、E. P.(1979年)。「C. ライト・ミルズ:責任ある職人」(PDF)。『Radical America』第13巻第4号。マサチューセッツ州サマービル:オルタナティブ・エデュケーション・プロジェクト。60-73ページ。2021年3月8 日アーカイブ(PDF)オリジナルより。2019年5月5日取得。 トレヴィーニョ、A.ハビエル(2012年)。C.ライト・ミルの社会思想。カリフォルニア州サウザンドオークス:パインフォージプレス。ISBN 978-1-4129-9393-7。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆