児童労働

Child labour

Child

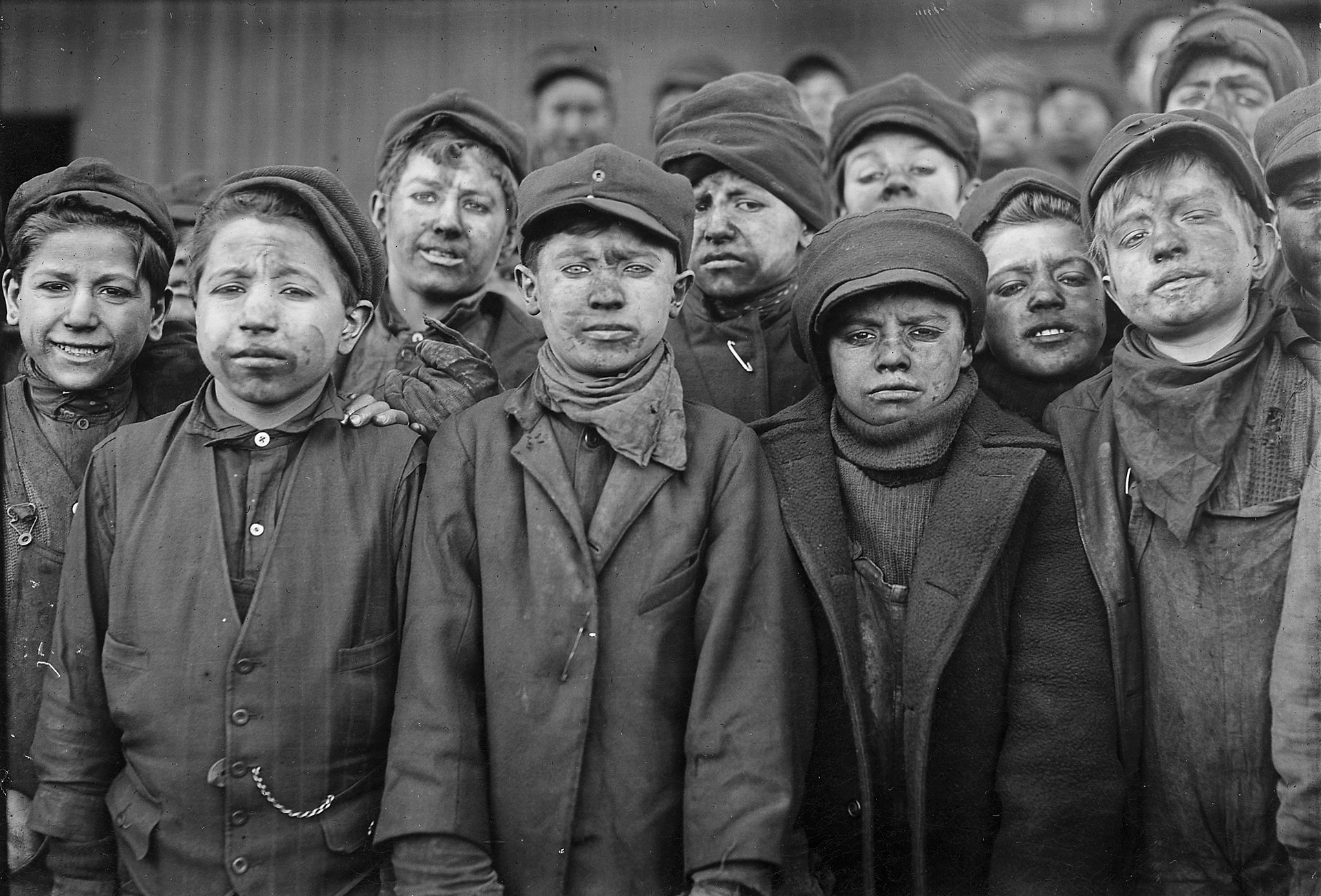

labour in a coal mine, United States, c. 1912. Photograph by Lewis Hine.

☆ 児童労働とは、通常の学校に通う能力を妨げたり、精神的、身体的、社会的、道徳的に有害なあらゆる形態の労働を通じて、子どもを搾取することである。この ような搾取は、世界中の法律によって禁止されているが、これらの法律は、子どもによるすべての労働を児童労働とみなしているわけではない。例外として、子 ども芸術家による労働、家族の義務、監督された訓練、アーミッシュの子どもやアメリカ大陸の先住民の子どもが請け負ういくつかの形態の労働などがある。児 童労働は、主に貧困が原因で発生する。 児童労働は、歴史を通じて様々な程度で存在してきた。19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、欧米諸国やその植民地では、貧しい家庭の5~14歳の多くの子ど もたちが働いていた。これらの子どもたちは主に、農業、家庭での組立作業、工場、鉱業、ニュースボーイなどのサービス業で働き、中には12時間に及ぶ夜勤 をする者もいた。世帯収入の増加、学校の利用可能性、児童労働法の成立により、児童労働の発生率は低下した。 2023年現在、世界の最貧国では、およそ5人に1人の子どもが児童労働に従事しており、その中で最も多いのはサハラ以南のアフリカで、4人に1人以上の 子どもが児童労働に従事している。 これは、過去半年の間に児童労働が減少したことを表している。 2017年には、アフリカの4カ国(マリ、ベナン、チャド、ギニアビサウ)で、5~14歳の子どもの50%以上が働いていた。世界の農業は、児童労働の最 大の雇用主である。 [貧困と学校の不足が、児童労働の主な原因であると考えられている。ユニセフは、「少年少女が児童労働に関与する可能性は同じ」であるが、役割は異なり、 少女は無報酬の家事労働を行う可能性がかなり高いと指摘している[12]。 世界銀行によれば、世界的に児童労働の発生率は1960年から2003年の間に25%から10%に減少した。それにもかかわらず、児童労働者の総数は依然 として多く、ユニセフとILOは、2013年には世界中で推定1億6,800万人の5歳から17歳の子どもが児童労働に関与していると認めている。

| Child labour is

the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes

with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally,

physically, socially and morally harmful.[3] Such exploitation is

prohibited by legislation worldwide,[4][5] although these laws do not

consider all work by children as child labour; exceptions include work

by child artists, family duties, supervised training, and some forms of

work undertaken by Amish children, as well as by Indigenous children in

the Americas.[6][7][8] Child labour mainly occurs due to poverty. Child labour has existed to varying extents throughout history. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, many children aged 5–14 from poorer families worked in Western nations and their colonies alike. These children mainly worked in agriculture, home-based assembly operations, factories, mining, and services such as news boys – some worked night shifts lasting 12 hours. With the rise of household income, availability of schools and passage of child labour laws, the incidence rates of child labour fell.[9][10][11] As of 2023, in the world's poorest countries, around one in five children are engaged in child labour, the highest number of whom live in sub-saharan Africa, where more than one in four children are so engaged.[12] This represents a decline in child labour over the preceding half decade.[13] In 2017, four African nations (Mali, Benin, Chad and Guinea-Bissau) witnessed over 50 per cent of children aged 5–14 working.[13] Worldwide agriculture is the largest employer of child labour.[14] The vast majority of child labour is found in rural settings and informal urban economies; children are predominantly employed by their parents, rather than factories.[15] Poverty and lack of schools are considered the primary cause of child labour.[16] UNICEF notes that "boys and girls are equally likely to be involved in child labour", but in different roles, girls being substantially more likely to perform unpaid household labour.[12] Globally the incidence of child labour decreased from 25% to 10% between 1960 and 2003, according to the World Bank.[17] Nevertheless, the total number of child labourers remains high, with UNICEF and ILO acknowledging an estimated 168 million children aged 5–17 worldwide were involved in child labour in 2013.[18] |

児童労働とは、通常の学校に通う能力を妨げたり、精神的、身体的、社会

的、道徳的に有害なあらゆる形態の労働を通じて、子どもを搾取することである[3]。このような搾取は、世界中の法律によって禁止されている[4][5]

が、これらの法律は、子どもによるすべての労働を児童労働とみなしているわけではない。例外として、子ども芸術家による労働、家族の義務、監督された訓

練、アーミッシュの子どもやアメリカ大陸の先住民の子どもが請け負ういくつかの形態の労働などがある[6][7][8]。児童労働は、主に貧困が原因で発

生する。 児童労働は、歴史を通じて様々な程度で存在してきた。19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、欧米諸国やその植民地では、貧しい家庭の5~14歳の多くの子ど もたちが働いていた。これらの子どもたちは主に、農業、家庭での組立作業、工場、鉱業、ニュースボーイなどのサービス業で働き、中には12時間に及ぶ夜勤 をする者もいた。世帯収入の増加、学校の利用可能性、児童労働法の成立により、児童労働の発生率は低下した[9][10][11]。 2023年現在、世界の最貧国では、およそ5人に1人の子どもが児童労働に従事しており、その中で最も多いのはサハラ以南のアフリカで、4人に1人以上の 子どもが児童労働に従事している[12]。 これは、過去半年の間に児童労働が減少したことを表している[13]。 2017年には、アフリカの4カ国(マリ、ベナン、チャド、ギニアビサウ)で、5~14歳の子どもの50%以上が働いていた[13]。世界の農業は、児童 労働の最大の雇用主である。 [貧困と学校の不足が、児童労働の主な原因であると考えられている[16]。ユニセフは、「少年少女が児童労働に関与する可能性は同じ」であるが、役割は 異なり、少女は無報酬の家事労働を行う可能性がかなり高いと指摘している[12]。 世界銀行によれば、世界的に児童労働の発生率は1960年から2003年の間に25%から10%に減少した[17]。それにもかかわらず、児童労働者の総 数は依然として多く、ユニセフとILOは、2013年には世界中で推定1億6,800万人の5歳から17歳の子どもが児童労働に関与していると認めている [18]。 |

| History Preindustrial societies Child labour forms an intrinsic part of pre-industrial economies.[19][20] In pre-industrial societies, there is rarely a concept of childhood in the modern sense. Children often begin to actively participate in activities such as child rearing, hunting and farming as soon as they are competent. In many societies, children as young as 13 are seen as adults and engage in the same activities as adults.[19] The work of children was important in pre-industrial societies, as children needed to provide their labour for their survival and that of their group.[21] Pre-industrial societies were characterised by low productivity and short life expectancy; preventing children from participating in productive work would be more harmful to their welfare and that of their group in the long run. In pre-industrial societies, there was little need for children to attend school. This is especially the case in non-literate societies. Most pre-industrial skill and knowledge were amenable to being passed down through direct mentoring or apprenticing by competent adults.[19] |

歴史 産業革命以前の社会 産業革命以前の経済では、児童労働は本質的な部分を形成している[19][20]。 産業革命以前の社会では、現代的な意味での子ども時代という概念はほとんどない。多くの場合、子どもたちは、能力を発揮するとすぐに、育児、狩猟、農耕な どの活動に積極的に参加し始める。多くの社会では、13歳の子どもは大人とみなされ、大人と同じ活動に従事する[19]。 産業革命以前の社会では、子どもの労働は重要であり、子どもは自分たちと集団の生存のために労働力を提供する必要があった。産業革命以前の社会では、子ど もたちが学校に通う必要性はほとんどなかった。特に文字を持たない社会ではそうである。産業革命以前の技術や知識のほとんどは、有能な大人による直接的な 指導や徒弟制度を通じて受け継ぐことが可能であった[19]。 |

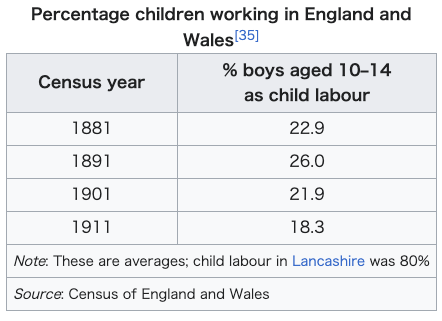

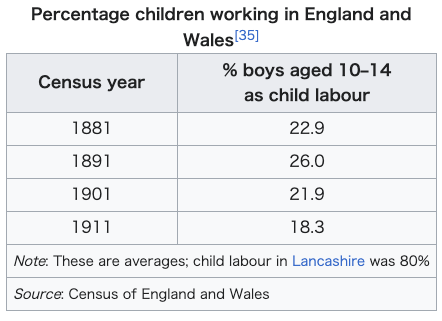

Industrial Revolution Children going to a 12-hour night shift in the United States (1908)  The early 20th century witnessed many home-based enterprises involving child labour. An example is shown above from New York in 1912. Wikisource has original text related to this article: "The Factory", a poem by L. E. L. With the onset of the Industrial Revolution in Britain in the late 18th century, there was a rapid increase in the industrial exploitation of labour, including child labour. Industrial cities such as Birmingham, Manchester, and Liverpool rapidly grew from small villages into large cities and improving child mortality rates. These cities drew in the population that was rapidly growing due to increased agricultural output. This process was replicated in other industrialising countries.[22] The Victorian era in particular became notorious for the conditions under which children were employed.[23] Children as young as four were employed in production factories and mines working long hours in dangerous, often fatal, working conditions.[24] In coal mines, children would crawl through tunnels too narrow and low for adults.[25] Children also worked as errand boys, crossing sweepers, shoe blacks, or selling matches, flowers and other cheap goods.[26] Some children undertook work as apprentices to respectable trades, such as building or as domestic servants (there were over 120,000 domestic servants in London in the mid-18th century). Working hours were long: builders worked 64 hours a week in the summer and 52 hours in winter, while servants worked 80-hour weeks.[27] Child labour played an important role in the Industrial Revolution from its outset, often brought about by economic hardship. The children of the poor were expected to contribute to their family income.[26] In 19th-century Great Britain, one-third of poor families were without a breadwinner, as a result of death or abandonment, obliging many children to work from a young age. In England and Scotland in 1788, two-thirds of the workers in 143 water-powered cotton mills were described as children.[28] A high number of children also worked as prostitutes.[29] The author Charles Dickens worked at the age of 12 in a blacking factory, with his family in a debtor's prison.[30] Child wages were often low, the wages were as little as 10–20% of an adult male's wage.[31][better source needed] Karl Marx was an outspoken opponent of child labour,[32] saying British industries "could but live by sucking blood, and children's blood too", and that U.S. capital was financed by the "capitalized blood of children".[33][34] Letitia Elizabeth Landon castigated child labour in her 1835 poem "The Factory", portions of which she pointedly included in her 18th Birthday Tribute to Princess Victoria in 1837. Throughout the second half of the 19th century, child labour began to decline in industrialised societies due to regulation and economic factors because of the Growth of trade unions. The regulation of child labour began from the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution. The first act to regulate child labour in Britain was passed in 1803. As early as 1802 and 1819 Factory Acts were passed to regulate the working hours of workhouse children in factories and cotton mills to 12 hours per day. These acts were largely ineffective and after radical agitation, by for example the "Short Time Committees" in 1831, a Royal Commission recommended in 1833 that children aged 11–18 should work a maximum of 12 hours per day, children aged 9–11 a maximum of eight hours, and children under the age of nine were no longer permitted to work. This act however only applied to the textile industry, and further agitation led to another act in 1847 limiting both adults and children to 10-hour working days. Lord Shaftesbury was an outspoken advocate of regulating child labour.[citation needed] As technology improved and proliferated, there was a greater need for educated employees. This saw an increase in schooling, with the eventual introduction of compulsory schooling. Improved technology, automation and further legislation significantly reduced child labour particularly in western Europe and the U.S.[citation needed] |

産業革命 アメリカで12時間夜勤をする子どもたち(1908年)  20世紀初頭には、児童労働を伴う家庭内企業が数多く見られた。上の写真は1912年のニューヨークの例である。 ウィキソースには、この記事に関連する原文がある: L.E.L. の詩「工場」。 18世紀後半にイギリスで産業革命が始まると、児童労働を含む労働力の産業的搾取が急増した。バーミンガム、マンチェスター、リバプールなどの工業都市 は、小さな村から大都市へと急速に発展し、子どもの死亡率が改善した。これらの都市は、農業生産高の増加によって急増した人口を引き込んだ。このプロセス は、他の工業化国でも再現された[22]。 特にヴィクトリア朝は、子どもたちが雇用される条件について悪名高いものとなった[23]。4歳の子どもたちが生産工場や鉱山で、危険な、しばしば致命的 な労働条件のもとで長時間労働に従事した[24]。 [25]子どもたちはまた、使い走り、踏切掃除人、靴の黒子、マッチや花などの安物の販売員としても働いていた[26]。一部の子どもたちは、建築業や家 事使用人(18世紀半ばのロンドンには12万人以上の家事使用人がいた)などの立派な職業の見習いとして仕事を請け負った。労働時間は長く、建築業者は夏 は週64時間、冬は52時間働き、使用人は週80時間働いた[27]。 児童労働は産業革命の初期から重要な役割を果たし、しばしば経済的苦境によってもたらされた。19世紀のイギリスでは、貧困家庭の3分の1が、死亡や育児 放棄のために生計維持者を失っていた。1788年のイングランドとスコットランドでは、143の水力綿工場で働く労働者の3分の2が子どもであった [28]。 また、多くの子どもが売春婦として働いていた[29]。 児童の賃金はしばしば低く、成人男性の賃金の10~20%程度であった[31][要出典]。カール・マルクスは児童労働に率直な反対者であり[32]、イ ギリスの産業は「血を吸うことでしか生きられない。 レティシア・エリザベス・ランドンは1835年に発表した詩「工場」の中で児童労働を非難しており、その一部は1837年にヴィクトリア王女に贈った18 歳の誕生日の賛辞の中で指摘されている。 19世紀後半を通じて、労働組合の成長による規制と経済的要因により、児童労働は工業化社会で減少し始めた。児童労働の規制は産業革命の初期から始まっ た。英国で児童労働を規制する最初の法律は1803年に成立した。早くも1802年と1819年に工場法が制定され、工場や綿工場で働く児童労働者の労働 時間を1日12時間に規制した。これらの法律はほとんど効果がなく、1831年の「短時間委員会」などによる急進的な扇動の後、1833年に王立委員会 が、11~18歳の子どもの労働時間を1日最大12時間、9~11歳の子どもの労働時間を最大8時間、9歳未満の子どもの労働を禁止するよう勧告した。し かし、この法律は繊維産業のみに適用され、さらなる煽動によって1847年には大人も子供も1日10時間労働に制限する別の法律が制定された。シャフツベ リー卿は、児童労働の規制を率先して提唱した[要出典]。 技術の向上と普及に伴い、教育を受けた従業員の必要性が高まった。そのため学校教育が増加し、最終的には義務教育が導入された。技術の向上、自動化、そし てさらなる法整備によって、特に西ヨーロッパとアメリカでは児童労働が大幅に減少した[要出典]。 |

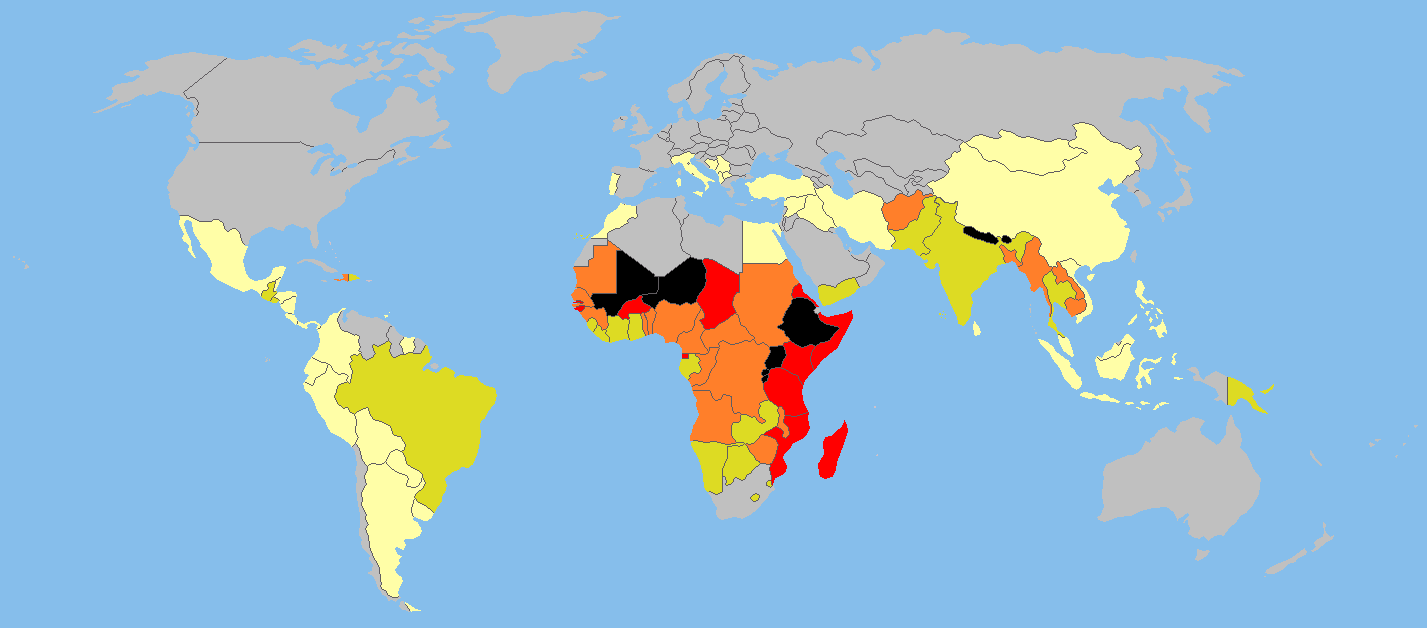

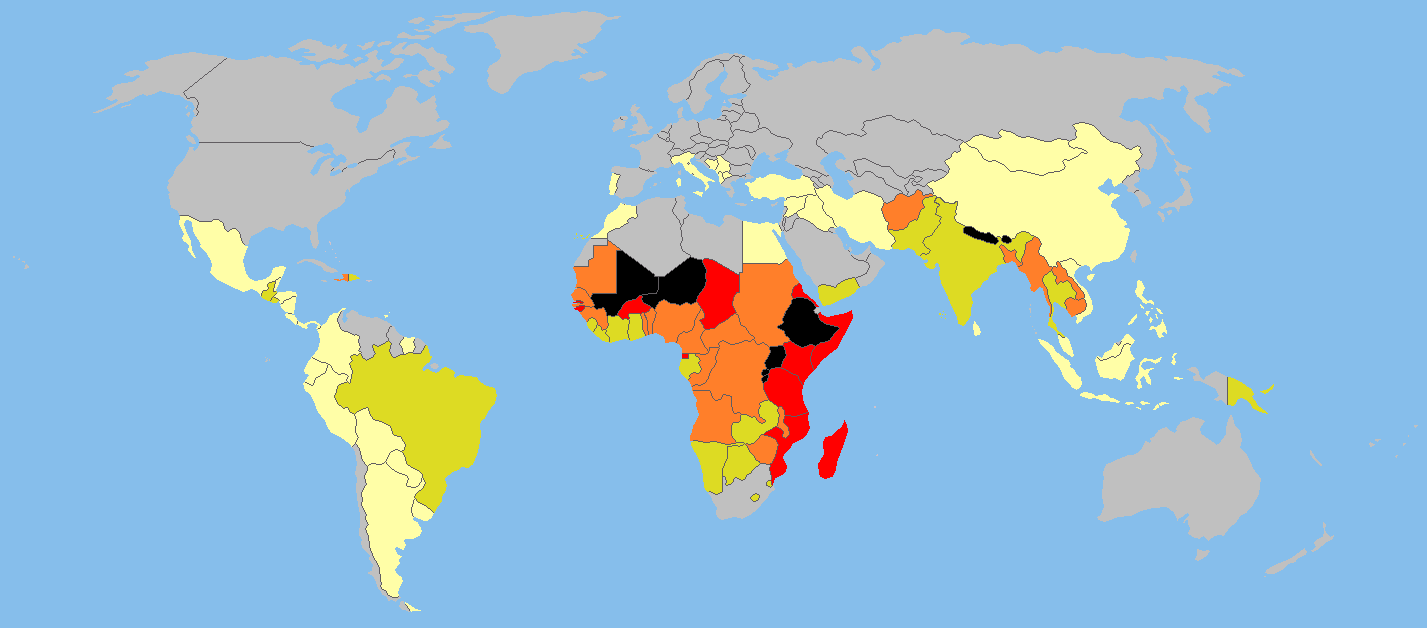

Early 20th century In the early 20th century, thousands of boys were employed in glass making industries. Glass making was a dangerous and tough job especially without the current technologies. The process of making glass includes intense heat to melt glass (3,133 °F (1,723 °C)). When the boys are at work, they are exposed to this heat. This could cause eye trouble, lung ailments, heat exhaustion, cuts, and burns. Since workers were paid by the piece, they had to work productively for hours without a break. Since furnaces had to be constantly burning, there were night shifts from 5:00 pm to 3:00 am. Many factory owners preferred boys under 16 years of age.[36] An estimated 1.7 million children under the age of fifteen were employed in American industry by 1900.[37] In 1910, over 2 million children in the same age group were employed in the United States.[38] This included children who rolled cigarettes,[39] engaged in factory work, worked as bobbin doffers in textile mills, worked in coal mines and were employed in canneries.[40] Lewis Hine's photographs of child labourers in the 1910s powerfully evoked the plight of working children in the American south. Hine took these photographs between 1908 and 1917 as the staff photographer for the National Child Labor Committee.[41] Household enterprises Factories and mines were not the only places where child labour was prevalent in the early 20th century. Home-based manufacturing across the United States and Europe employed children as well.[9] Governments and reformers argued that labour in factories must be regulated and the state had an obligation to provide welfare for poor. Legislation that followed had the effect of moving work out of factories into urban homes. Families and women, in particular, preferred it because it allowed them to generate income while taking care of household duties.[citation needed] Home-based manufacturing operations were active year-round. Families willingly deployed their children in these income generating home enterprises.[42] In many cases, men worked from home. In France, over 58% of garment workers operated out of their homes; in Germany, the number of full-time home operations nearly doubled between 1882 and 1907; and in the United States, millions of families operated out of home seven days a week, year round to produce garments, shoes, artificial flowers, feathers, match boxes, toys, umbrellas and other products. Children aged 5–14 worked alongside the parents. Home-based operations and child labour in Australia, Britain, Austria and other parts of the world was common. Rural areas similarly saw families deploying their children in agriculture. In 1946, Frieda S. Miller – then Director of the United States Department of Labor – told the International Labour Organization (ILO) that these home-based operations offered "low wages, long hours, child labour, unhealthy and insanitary working conditions".[9][43][44][45] 21st century See also: Children's rights  Map for child labour worldwide in the 10–14 age group, in 2003, per World Bank data.[46] The data is incomplete, as many countries do not collect or report child labour data (coloured gray). The colour code is as follows: yellow (<10% of children working), green (10–20%), orange (20–30%), red (30–40%) and black (>40%). Some nations such as Guinea-Bissau, Mali and Ethiopia have more than half of all children aged 5–14 at work to help provide for their families.[47] Child labour is still common in many parts of the world. Estimates for child labour vary. It ranges between 250 and 304 million, if children aged 5–17 involved in any economic activity are counted. If light occasional work is excluded, ILO estimates there were 153 million child labourers aged 5–14 worldwide in 2008. This is about 20 million less than ILO estimate for child labourers in 2004. Some 60 per cent of the child labour was involved in agricultural activities such as farming, dairy, fisheries and forestry. Another 25% of child labourers were in service activities such as retail, hawking goods, restaurants, load and transfer of goods, storage, picking and recycling trash, polishing shoes, domestic help, and other services. The remaining 15% laboured in assembly and manufacturing in informal economy, home-based enterprises, factories, mines, packaging salt, operating machinery, and such operations.[48][49][50] Two out of three child workers work alongside their parents, in unpaid family work situations. Some children work as guides for tourists, sometimes combined with bringing in business for shops and restaurants. Child labour predominantly occurs in the rural areas (70%) and informal urban sector (26%). Contrary to popular belief, most child labourers are employed by their parents rather than in manufacturing or formal economy. Children who work for pay or in-kind compensation are usually found in rural settings as opposed to urban centres. Less than 3% of child labour aged 5–14 across the world work outside their household, or away from their parents.[15] Child labour accounts for 22% of the workforce in Asia, 32% in Africa, 17% in Latin America, 1% in the US, Canada, Europe and other wealthy nations.[51] The proportion of child labourers varies greatly among countries and even regions inside those countries. Africa has the highest percentage of children aged 5–17 employed as child labour, and a total of over 65 million. Asia, with its larger population, has the largest number of children employed as child labour at about 114 million. Latin America and the Caribbean region have lower overall population density, but at 14 million child labourers has high incidence rates too.[52]  A boy repairing a tire in Gambia Accurate present day child labour information is difficult to obtain because of disagreements between data sources as to what constitutes child labour. In some countries, government policy contributes to this difficulty. For example, the overall extent of child labour in China is unclear due to the government categorising child labour data as "highly secret".[53] China has enacted regulations to prevent child labour; still, the practice of child labour is reported to be a persistent problem within China, generally in agriculture and low-skill service sectors as well as small workshops and manufacturing enterprises.[54][55] In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor issued a List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, where China was attributed 12 goods, the majority of which were produced by both underage children and indentured labourers.[56] The report listed electronics, garments, toys, and coal, among other goods. The Maplecroft Child Labour Index 2012 survey[57] reports that 76 countries pose extreme child labour complicity risks for companies operating worldwide. The ten highest risk countries in 2012, ranked in decreasing order, were: Myanmar, North Korea, Somalia, Sudan, DR Congo, Zimbabwe, Afghanistan, Burundi, Pakistan and Ethiopia. Of the major growth economies, Maplecroft ranked Philippines 25th riskiest, India 27th, China 36th, Vietnam 37th, Indonesia 46th, and Brazil 54th, all of them rated to involve extreme risks of child labour uncertainties, to corporations seeking to invest in developing world and import products from emerging markets. |

20世紀初期 20世紀初頭、何千人もの少年がガラス製造業に従事していた。現在のような技術がなかった時代には、ガラス製造は危険で過酷な仕事だった。ガラスを作る過 程では、ガラスを溶かすために強い熱(3,133 °F (1,723 °C))が加えられる。少年たちは仕事中、この熱にさらされる。少年たちはこの熱にさらされ、目の病気、肺の病気、熱中症、切り傷、火傷などを引き起こす 可能性がある。労働者は出来高払いだったため、休憩なしで何時間も生産的に働かなければならなかった。炉は常に燃えていなければならないため、午後5時か ら午前3時までの夜勤があった。どの工場主も16歳未満の少年を好んだ[36]。 1900年までに推定170万人の15歳未満の子供がアメリカの産業界で雇用されていた[37]。 これには、タバコを巻く子ども、工場労働に従事する子ども[39]、織物工場でボビン・ドッファーとして働く子ども、炭鉱で働く子ども、缶詰工場で働く子 どもが含まれていた[40]。彼は1908年から1917年にかけて、全国児童労働委員会のスタッフ写真家としてこれらの写真を撮影した[41]。 家庭内企業 20世紀初頭に児童労働が蔓延していたのは、工場や鉱山だけではなかった。政府や改革者たちは、工場での労働は規制されるべきであり、国家は貧しい人々に 福祉を提供する義務があると主張した。その後に制定された法律は、労働を工場から都市の家庭に移すという効果をもたらした。特に家族や女性は、家事をしな がら収入を得ることができるため、それを好んだ[要出典]。 オメガベースの製造業は一年中活動していた。多くの場合、男性は自宅で働いた。フランスでは、縫製労働者の58%以上が自宅で働いていた。ドイツでは、フ ルタイムの家庭内事業の数が1882年から1907年の間にほぼ倍増した。アメリカでは、何百万もの家族が、衣服、靴、造花、羽毛、マッチ箱、玩具、傘、 その他の製品を生産するために、週7日、一年中、自宅で働いていた。5歳から14歳の子どもたちが親と一緒に働いていた。オーストラリア、イギリス、オー ストリアなどでは、オメガ労働と児童労働が一般的だった。農村部でも同様に、家族が子供を農業に従事させていた。1946年、フリーダ・S・ミラー(当時 アメリカ合衆国労働省長官)は、国際労働機関(ILO)に対し、こうした家庭的経営は「低賃金、長時間労働、児童労働、不健康で不衛生な労働条件」を提供 していると述べた[9][43][44][45]。 21世紀 以下も参照: 子どもの権利  世界銀行のデータによる、2003年の10~14歳における世界の児童労働のap。[46]多くの国が児童労働のデータを収集または報告していないため、 データは不完全である(色は灰色)。カラーコードは、黄色(働いている子どもの割合が10%未満)、緑色(10~20%)、オレンジ色(20~30%)、 赤色(30~40%)、黒色(40%以上)である。ギニアビサウ、マリ、エチオピアなどの一部の国では、5~14歳の子どもの半数以上が、家族を養うため に働いている[47]。 児童労働は、世界の多くの地域で依然として一般的である。児童労働の推定はさまざまである。あらゆる経済活動に従事している5~17歳の子どもを数えた場 合、その数は2億5,000万人から3億400万人の間である。軽い臨時労働を除いた場合、ILOの推計によると、2008年の世界の5~14歳の児童労 働者は1億5,300万人である。これは、2004年のILO推計の児童労働者数より約2,000万人少ない。児童労働の約60%は、農業、酪農、漁業、 林業などの農業活動に従事していた。さらに25%の児童労働者は、小売、行商、レストラン、荷物の積み下ろし、保管、ゴミ拾い、リサイクル、靴磨き、家事 手伝いなどのサービス業に従事していた。残りの15%は、インフォーマル経済、家庭内企業、工場、鉱山、塩の包装、機械の操作、およびそのような業務にお ける組立および製造に従事していた[48][49][50]。児童労働者の3人に2人は、無給の家族労働の状況で、親とともに働いている。子どもたちの中 には、観光客のガイドとして働いている者もおり、商店やレストランの営業と兼任している場合もある。児童労働は、主に農村部(70%)と都市のイン フォーマル部門(26%)で発生している。 一般に考えられているのとは逆に、児童労働者の ほとんどは、製造業や正規経済ではなく、親に雇われて いる。有給または現物支給で働く子どもたちは、通常、 都市部とは対照的に農村部で見られる。世界の5~14歳の児童労働者の3%未満が、家庭外で、ある いは親元を離れて働いている[15]。 児童労働は、アジアで労働力の22%、アフリカで32%、ラテンアメリカで17%、米国、カナダ、ヨーロッパ、その他の裕福な国々で1%を占めている [51]。 児童労働者の割合は、国によって、また国内の地域によっても大きく異なる。児童労働に従事する5~17歳の子どもの割合が最も高いのはリ カで、その総数は6,500万人を超える。人口の多いアジアは、児童労働として雇用されている子どもの数が最も多く、約1億1,400万人である。錫アメ リカとカリブ海地域は、全体的な人口密度は低いが、児童労働者数は1,400万人で、発生率も高い[52]。  ガンビアでタイヤを修理する少年 何をもって児童労働とするかについて、データソース間で見解の相違があるため、現在の児童労働情報を入手することは困難である。国によっては、政府の政策 がこの困難を助長している。例えば、中国では、政府が児童労働のデータを「極秘」に分類しているため、児童労働の全体的な程度は不明確である[53]。中 国は児童労働を防止するための規制を制定しているが、それでもなお、児童労働の慣行は中国国内で根強い問題であると報告されており、一般に農業や低技能の サービス業、小規模な作業場や製造企業で行われている[54][55]。 2014年、米国労働省は「児童労働または強制労働によって生産された商品リスト」を発表し、中国は12の商品に該当し、その大半は未成年の児童と年季奉 公労働者の両方によって生産されたものであった[56]。この報告書には、電子機器、衣料品、玩具、石炭などが挙げられている。 Maplecroft Child Labour Index 2012の調査[57]によれば、76カ国が、世界中で事業を展開する企業にとって、極度の児童労働加担リスクをもたらしている。2012年に最もリスク の高かった10カ国を、低い順に並べると、以下の通りである。アンマール、北朝鮮、ソマリア、スーダン、コンゴ民主共和国、ジンバブエ、アフガニスタン、 ブルンジ、パキスタン、エチオピアである。メープルクロフトは、発展途上国への投資や新興市場からの製品輸入を目指す企業にとって、児童労働の不確実性と いう極度のリスクを伴うと評価されたフィリピンを25位、インドを27位、中国を36位、ベトナムを37位、インドネシアを46位、ブラジルを54位とし た。 |

Causes Young girl working on a loom in Aït Benhaddou, Morocco, in May 2008  Agriculture deploys 70% of the world's child labour.[14] Above, child worker on a rice farm in Vietnam. The ILO suggests that poverty is the greatest single cause behind child labour.[16] For impoverished households, income from a child's work is usually crucial for his or her own survival or for that of the household. Income from working children, even if small, may be between 25 and 40% of the household income. Other scholars such as Harsch on African child labour, and Edmonds and Pavcnik on global child labour have reached the same conclusion.[15][58][59] Lack of meaningful alternatives, such as affordable schools and quality education, according to the ILO,[16] is another major factor driving children to harmful labour. Children work because they have nothing better to do. Many communities, particularly rural areas where between 60 and 70% of child labour is prevalent, do not possess adequate school facilities. Even when schools are sometimes available, they are too far away, difficult to reach, unaffordable or the quality of education is so poor that parents wonder if going to school is really worth it.[15][60] Cultural factors In European history when child labour was common, as well as in contemporary child labour of modern world, certain cultural beliefs have grounded it. Some view that work is good for the character-building and skill development of children. In many cultures, particular where the informal economy and small household businesses thrive, the cultural tradition is that children follow in their parents' footsteps; child labour then is a means to learn and practice that trade from a very early age. Similarly, in many cultures the education of girls is less valued or girls are simply not expected to need formal schooling, and these girls pushed into child labour such as providing domestic services.[16][61][62][63] Macroeconomics Biggeri and Mehrotra have studied the macroeconomic factors that encourage child labour. They focus their study on five Asian nations including India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Thailand and Philippines. They suggest[64] that child labour is a serious problem in all five, but it is not a new problem. Macroeconomic causes encouraged widespread child labour across the world, over most of human history. They suggest that the causes for child labour include both the demand and the supply side. While poverty and unavailability of good schools explain the child labour supply side, they suggest that the growth of low-paying informal economy rather than higher paying formal economy is amongst the causes of the demand side. Other scholars too suggest that inflexible labour market, size of informal economy, inability of industries to scale up and lack of modern manufacturing technologies are major macroeconomic factors affecting demand and acceptability of child labour.[65][66][67] |

原因 2008年5月、モロッコのアイト・ベン・ハッドゥで織機で働く少女。  上の写真は、ベトナムの稲作農場で働く児童労働者である。 ILOは、貧困が児童労働の背後にある単一の最大の原因であることを示唆している[16]。 貧困にあえぐ世帯にとって、子どもの労働からの収入は、通常、子ども自身または世帯の生存にとって極めて重要である。働いている子どもからの収入は、たと え少額であっても、世帯収入の25~40%を占めることもある。アフリカの児童労働に関するHarschや、世界の児童労働に関するEdmondsと Pavcnikなど、他の学者も同じ結論に達している[15][58][59]。 ILO[16]によれば、手頃な価格の学校や質の高い教育など、有意義な代替手段の欠如も、子どもたちを有害な労働に駆り立てる大きな要因である。子ども たちが働くのは、他にすることがないからである。多くの地域社会、特に児童労働の60~70%が蔓延し ている農村部には、十分な学校施設がない。学校がある場合でも、遠すぎたり、通学が困難であったり、学費が払えなかったり、教育の質があまりに低かったり するため、親は学校に行く価値が本当にあるのか疑問に思っている[15][60]。 文化的要因 児童労働が一般的であったヨーロッパの歴史においても、現代世界の児童労働においても、ある種の文化的信念が児童労働を根拠づけている。労働は子どもの人 格形成や能力開発に良いという見方もある。多くの文化、特にインフォーマル経済や小規模な家庭事業が盛んな地域では、子どもは親の跡を継ぐという文化的伝 統がある。同様に、多くの文化では、女児の教育はあまり重視されないか、あるいは女児が正規の学校教育を受ける必要がないと思われているだけであり、その ような女児は家事サービスの提供などの児童労働に押し込められている[16][61][62][63]。 マクロ経済学 BiggeriとMehrotraは、児童労働を助長するマクロ経済的要因を研究している。彼らは、インド、パキスタン、インドネシア、タイ、フィリピン のアジア5カ国に焦点を当てて研究している。彼らは、児童労働は5カ国すべてにおいて深刻な問題であるが、新しい問題ではないことを示唆している [64]。マクロ経済的な原因が、人類の歴史の大半にわたって、世界中で児童労働の蔓延を促してきたのである。彼らは、児童労働の原因には需要側と供給側 の両方が含まれることを示唆している。児童労働の供給側については、貧困と良い学校がないことが説明できるが、需要側については、高賃金の正規経済ではな く、低賃金の非正規経済が成長したことが原因のひとつであると指摘している。他の学者も、融通の利かない労働市場、インフォーマル経済の規模、産業のス ケールアップができないこと、近代的な製造技術の欠如が、児童労働の需要と受容性に影響を与える主要なマクロ経済的要因であると指摘している[65] [66][67]。 |

| By country See also: List of countries by child labour rate Working children out of school vs hours worked by children[68] Colonial empires Systematic use of child labour was commonplace in the colonies of European powers between 1650 and 1950. In Africa, colonial administrators encouraged traditional kin-ordered modes of production, that is hiring a household for work not just the adults. Millions of children worked in colonial agricultural plantations, mines and domestic service industries.[69][70] Sophisticated schemes were promulgated where children in these colonies between the ages of 5 and 14 were hired as an apprentice without pay in exchange for learning a craft. A system of Pauper Apprenticeship came into practice in the 19th century where the colonial master neither needed the native parents' nor child's approval to assign a child to labour, away from parents, at a distant farm owned by a different colonial master.[71] Other schemes included 'earn-and-learn' programs where children would work and thereby learn. Britain for example passed a law, the so-called Masters and Servants Act of 1899, followed by Tax and Pass Law, to encourage child labour in colonies particularly in Africa. These laws offered the native people the legal ownership to some of the native land in exchange for making labour of wife and children available to colonial government's needs such as in farms and as picannins.[citation needed] Beyond laws, new taxes were imposed on colonies. One of these taxes was the Head Tax in the British and French colonial empires. The tax was imposed on everyone older than 8 years, in some colonies. To pay these taxes and cover living expenses, children in colonial households had to work.[72][73][74] In southeast Asian colonies, such as Hong Kong, child labour such as the Mui tsai (妹仔), was rationalised as a cultural tradition and ignored by British authorities.[75][76] The Dutch East India Company officials rationalised their child labour abuses with, "it is a way to save these children from a worse fate." Christian mission schools in regions stretching from Zambia to Nigeria too required work from children, and in exchange provided religious education, not secular education.[69] Elsewhere, the Canadian Dominion Statutes in form of so-called Breaches of Contract Act, stipulated jail terms for uncooperative child workers.[77] Proposals to regulate child labour began as early as 1786.[78] Africa Main article: Child labour in Africa Child labour in the former German colony of Kamerun, 1919 Children working at a young age has been a consistent theme throughout Africa. Many children began first working in the home to help their parents run the family farm.[79] Children in Africa today are often forced into exploitative labour due to family debt and other financial factors, leading to ongoing poverty.[79] Other types of domestic child labour include working in commercial plantations, begging, and other sales such as boot shining.[80] In total, there is an estimated five million children who are currently working in the field of agriculture which steadily increases during the time of harvest. Along with 30% of children who are picking coffee, there are an estimated 25,000 school age children who work year round.[81] Little girl carrying heavy items. Katanga region, DRC; Congo, Africa. What industries children work in depends on whether they grew up in a rural area or an urban area. Children who were born in urban areas often found themselves working for street vendors, washing cars, helping in construction sites, weaving clothing, and sometimes even working as exotic dancers.[80] While children who grew up in rural areas would work on farms doing physical labour, working with animals, and selling crops.[80] Many children can also be found working in hazardous environments, with some using bare hands, stones and hammers to take apart CRT-based televisions and computer monitors.[82] Of all the child workers, the most serious cases involved street children and trafficked children due to the physical and emotional abuse they endured by their employers.[80] To address the issue of child labour, the United Nations Conventions on the Rights of the Child Act was implemented in 1959.[83] Yet due to poverty, lack of education and ignorance, the legal actions were not/are not wholly enforced or accepted in Africa.[84] Young street vendors in Benin Other legal factors that have been implemented to end and reduce child labour includes the global response that came into force in 1979 by the declaration of the International Year of the Child.[84] Along with the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations, these two declarations worked on many levels to eliminate child labour.[84] Although many actions have been taken to end this epidemic, child labour in Africa is still an issue today due to the unclear definition of adolescence and how much time is needed for children to engage in activities that are crucial for their development. Another issue that often comes into play is the link between what constitutes as child labour within the household due to the cultural acceptance of children helping run the family business.[85] In the end, there is a consistent challenge for the national government to strengthen its grip politically on child labour, and to increase education and awareness on the issue of children working below the legal age limit. With children playing an important role in the African economy, child labour still plays an important role for many in the 20th century.[citation needed] Australia From European settlement in 1788, child convicts were occasionally sent to Australia where they were made to work. Child labour was not as excessive in Australia as in Britain. With a low population, agricultural productivity was higher and families did not face starvation as in established industrialised countries. Australia also did not have significant industry until the later part of the 20th century, when child labour laws and compulsory schooling had developed under the influence of Britain. From the 1870s, child labour was restricted by compulsory schooling.[citation needed] Child labour laws in Australia differ from state to state. Generally, children are allowed to work at any age, but restrictions exist for children under 15 years of age. These restrictions apply to work hours and the type of work that children can perform. In all states, children are obliged to attend school until a minimum leaving age, 15 years of age in all states except Tasmania and Queensland where the leaving age is 17.[86] Brazil Main article: Child labour in Brazil Child labour in Brazil, leaving after collecting recyclables from a landfill Child labour has been a consistent struggle for children in Brazil ever since Portuguese colonisation in the region began in 1500.[87] Work that many children took part in was not always visible, legal, or paid. Free or slave labour was a common occurrence for many youths and was a part of their everyday lives as they grew into adulthood.[88] Yet due to there being no clear definition of how to classify what a child or youth is, there has been little historical documentation of child labour during the colonial period. Due to this lack of documentation, it is hard to determine just how many children were used for what kinds of work before the nineteenth century.[87] The first documentation of child labour in Brazil occurred during the time of indigenous societies and slave labour where it was found that children were forcibly working on tasks that exceeded their emotional and physical limits.[89] Armando Dias, for example, died in November 1913 whilst still very young, a victim of an electric shock when entering the textile industry where he worked. Boys and girls were victims of industrial accidents on a daily basis.[90] In Brazil, the minimum working age has been identified as fourteen due to constitutional amendments that passed in 1934, 1937, and 1946.[91] Yet due to a change in the dictatorship by the military in the 1980s, the minimum age restriction was reduced to twelve but was reviewed due to reports of dangerous and hazardous working conditions in 1988. This led to the minimum age being raised once again to 14. Another set of restrictions was passed in 1998 that restricted the kinds of work youth could partake in, such as work that was considered hazardous like running construction equipment, or certain kinds of factory work.[91] Although many steps were taken to reduce the risk and occurrence of child labour, there is still a high number of children and adolescents working under the age of fourteen in Brazil. It was not until recently in the 1980s that it was discovered that almost nine million children in Brazil were working illegally and not partaking in traditional childhood activities that help to develop important life experiences.[92] Brazilian census data (PNAD, 1999) indicate that 2.55 million 10- to 14-year-olds were illegally holding jobs. They were joined by 3.7 million 15- to 17-year-olds and about 375,000 5- to 9-year-olds.[citation needed] Due to the raised age restriction of 14, at least half of the recorded young workers had been employed illegally, which led to many not being protected by important labour laws.[citation needed] Although substantial time has passed since the time of regulated child labour, there are still many children working illegally in Brazil. Many children are used by drug cartels to sell and carry drugs, guns, and other illegal substances because of their perception of innocence. This type of work that youth are taking part in is very dangerous due to the physical and psychological implications that come with these jobs. Yet despite the hazards that come with working with drug dealers, there has been an increase in this area of employment throughout the country.[93] Britain Many factors played a role in Britain's long-term economic growth, such as the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s and the prominent presence of child labour during the industrial age.[94] Children who worked at an early age were often not forced; but did so because they needed to help their family survive financially. Due to poor employment opportunities for many parents, sending their children to work on farms and in factories was a way to help feed and support the family.[94] Child labour first started to occur in England when household businesses were turned into local labour markets that mass-produced the once homemade goods. Because children often helped produce the goods out of their homes, working in a factory to make those same goods was a simple change for many of these youths.[94] Although there are many counts of children under the age of ten working for factories, the majority of children workers were between the ages of ten and fourteen. Another factor that influenced child labour was the demographic changes that occurred in the eighteenth century.[95] By the end of the eighteenth century, 20 per cent of the population was made up of children between the ages of 5 and 14. Due to this substantial shift in available workers, and the development of the industrial revolution, children began to work earlier in life in companies outside of the home.[96] Yet, even though there was an increase of child labour in factories such as cotton textiles, there were large numbers of children working in the field of agriculture and domestic production.[96] With such a high percentage of children working, the rising of illiteracy, and the lack of a formal education became a widespread issue for many children who worked to provide for their families.[97] Due to this problematic trend, many parents developed a change of opinion when deciding whether or not to send their children to work. Other factors that lead to the decline of child labour included financial changes in the economy, changes in the development of technology, raised wages, and continuous regulations on factory legislation.[98] In 1933 Britain adopted legislation restricting the use of children under 14 in employment. The Children and Young Persons Act 1933, defined the term child as anyone of compulsory school age (age sixteen). In general no child may be employed under the age of fifteen years, or fourteen years for light work.[99] Cambodia Main article: Child labour in Cambodia A little girl making money for her family by posing with a snake in a water village of Tonle Sap Lake Significant levels of child labour appear to be found in Cambodia.[100] In 1998, ILO estimated that 24.1% of children in Cambodia aged between 10 and 14 were economically active.[100] Many of these children work long hours and Cambodia Human Development Report 2000 reported that approximately 65,000 children between the ages of 5 and 13 worked 25 hours a week and did not attend school.[101] There are also many initiative and policies put in place to decrease the prevalence of child labour such as the United States generalised system of preferences, the U.S.-Cambodia textile agreement, ILO Garment Sector Working Conditions Improvement Project, and ChildWise Tourism.[102][103] Ecuador Child labour in a quarry, Ecuador An Ecuadorean study published in 2006 found child labour to be one of the main environmental problems affecting children's health. It reported that over 800,000 children are working in Ecuador, where they are exposed to heavy metals and toxic chemicals and are subject to mental and physical stress and the insecurity caused by being at risk of work-related accidents. Minors performing agricultural work along with their parents help apply pesticides without wearing protective equipment.[104] India Main article: Child labour in India Working girl in India In 2015, the country of India is home to the largest number of children who are working illegally in various industrial industries. Agriculture in India is the largest sector where many children work at early ages to help support their family.[91] Many of these children are forced to work at young ages due to many family factors such as unemployment, large families, poverty, and lack of parental education. This is often the major cause of the high rate of child labour in India.[90] On 23 June 1757, the English East India Company defeated Siraj-ud-Daula, the Nawab of Bengal, in the Battle of Plassey. The British thus became masters of east India (Bengal, Bihar, Orissa) – a prosperous region with a flourishing agriculture, industry and trade.[93] This led to many children being forced into labour due to the increasing need of cheap labour to produce large numbers of goods. Many multinationals often employed children because that they can be recruited for less pay, and have more endurance to utilise in factory environments.[105] Another reason many Indian children were hired was because they lack knowledge of their basic rights, they did not cause trouble or complain, and they were often more trustworthy. The innocence that comes with childhood was utilised to make a profit by many and was encouraged by the need for family income.[105] A sign at a construction site in Bangalore: "Child labour prohibited" A variety of Indian social scientists as well as the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have done extensive research on the numeric figures of child labour found in India and determined that India contributes to one-third of Asia's child labour and one-fourth of the world's child labour.[93] Due to many children being illegally employed, the Indian government began to take extensive actions to reduce the number of children working, and to focus on the importance of facilitating the proper growth and development of children.[93] International influences help to encourage legal actions to be taken in India, such as the Geneva Declaration of the Right of Children Act was passed in 1924. This act was followed by The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 to which incorporated the basic human rights and needs of children for proper progression and growth in their younger years.[106] These international acts encouraged major changes to the workforce in India which occurred in 1986 when the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act was put into place. This act prohibited hiring children younger than the age of 14, and from working in hazardous conditions.[93] Due to the increase of regulations and legal restrictions on child labour, there has been a 64 per cent decline in child labour from 1993 to 2005.[107] Although this is a great decrease in the country of India, there is still high numbers of children working in the rural areas of India. With 85 per cent of the child labour occurring in rural areas, and 15 per cent occurring in urban areas, there are still substantial areas of concern in the country of India.[107] India has legislation since 1986 which allows work by children in non-hazardous industry. In 2013, the Punjab and Haryana High Court gave a landmark order that directed that there shall be a total ban on the employment of children up to the age of 14 years, be it hazardous or non-hazardous industries. However, the Court ruled that a child can work with his or her family in family based trades/occupations, for the purpose of learning a new trade/craftsmanship or vocation.[citation needed] Iran Main article: Child labour in Iran The phenomenon of children labour is one of the social issues of Iranian society, which has taken on serious and diverse dimensions over time. Researches and official and unofficial data show that this social damage is more common in big cities. Also, research data shows that most of the working children in Tehran province are related to Afghan children who have immigrated to Iran legally or illegally.[108][109][110][111][112] Kameel Ahmady, a social researcher and winner of the Literature and Humanities award from the World Peace Foundation, while emphasizing the fact that most of the children labour in Tehran province are Afghan children, along with his colleagues believes that with the continuation of Iran's economic crisis, the lack of proper mechanisms to manage and control the phenomenon and absence of legal working visa scheme for Afghan immigrants have caused this social harm to spread.[113][114][115][116][117] Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, the Minister of Interior at the time in August 2019, while analysing and describing the situation of working children in Tehran, said: "Reports show that street children live in poor conditions and are exploited." One thing that should be noted is that up to 80% of these children are non-Iranian. Considering that some of these children were Afghan nationals, we have raised the issue with the embassy of this country. If other institutions cooperate, we can take appropriate measures to organise street children, but if they do not cooperate. It has also been decided to issue arrest warrants for gangs exploiting children with the cooperation of the police force and the judicial system.[118][119][120] In Isfahan province, the Iranian Department of State Welfare (behzisti) keeps a database of the scanned retina irises of a number of working street kids, and have put "child friendly" measures in place to support them, reduce the social harm from their presence, and improve their quality of life.[121] Only Tehran as of June 2023 has seventy thousand working children they also collect recycles.[122][123] As of July 2023 %15 of children are child labour, 8% do not have a residence. 10 per cent of children are not in school.[124] Ireland In post-colonial Ireland, the rate of child exploitation was extremely high as children were used as farm labourers once they were able to walk, these children were never paid for the labour that they carried out on the family farm. Children were wanted and desired in Ireland for the use of their labour on the family farm. Irish parents felt that it was the children's duty to carry out chores on the family farm.[125] Japan Though banned in modern Japan, shonenko (child labourers) were a feature of the Imperial era until its end in 1945. During World War II labour recruiting efforts targeted youths from Taiwan (Formosa), then a Japanese territory, with promises of educational opportunity. Though the target of 25,000 recruits was never reached, over 8,400 Taiwanese youths aged 12 to 14 relocated to Japan to help manufacture the Mitsubishi J2M Raiden aircraft.[126][127][128] Pakistan Main article: Child labour in Pakistan The Netherlands Main article: Child labour in the Netherlands Child labour existed in the Netherlands up to and through the Industrial Revolution. Laws governing child labour in factories were first passed in 1874, but child labour on farms continued to be the norm up until the 20th century.[129] Soviet Union and successor states Although formally banned since 1922, child labour was widespread in the Soviet Union, mostly in the form of mandatory, unpaid work by schoolchildren on Saturdays and holidays. The students were used as a cheap, unqualified workforce on kolhoz (collective farms) as well as in industry and forestry. The practice was formally called "work education".[130] From the 1950s on, the students were also used for unpaid work at schools, where they cleaned and performed repairs.[131] This practice has continued in the Russian Federation, where up to 21 days of the summer holidays is sometimes set aside for school works. By law, this is only allowed as part of specialised occupational training and with the students' and parents' permission, but those provisions are widely ignored.[132][better source needed] In 2012 there was an accident near the city of Nalchik where a car killed several pupils cleaning up a highway shoulder during their "holiday work", as well as their teacher, who was supervising them.[133] Out of former Soviet Union republics Uzbekistan continued and expanded the program of child labour on industrial scale to increase profits on the main source of Islam Karimov's income, cotton harvesting. In September, when school normally starts, the classes are suspended and children are sent to cotton fields for work, where they are assigned daily quotas of 20 to 60 kg of raw cotton they have to collect. This process is repeated in spring, when collected cotton needs to be hoed and weeded. In 2006 it is estimated that 2.7 million children were forced to work this way.[134] Switzerland Main article: Child labour in Switzerland As in many other countries, child labour in Switzerland affected among the so-called Kaminfegerkinder ("chimney sweep children") and children working p.e. in spinning mills, factories and in agriculture in 19th-century Switzerland,[135] but also to the 1960s so-called Verdingkinder (literally: "contract children" or "indentured child laborers") were children who were taken from their parents, often due to poverty or moral reasons – usually mothers being unmarried, very poor citizens, of Gypsy–Yeniche origin, so-called Kinder der Landstrasse,[136] etc. – and sent to live with new families, often poor farmers who needed cheap labour.[137] There were even Verdingkinder auctions where children were handed over to the farmer asking the least money from the authorities, thus securing cheap labour for his farm and relieving the authority from the financial burden of looking after the children. In the 1930s 20% of all agricultural labourers in the Canton of Bern were children below the age of 15. Swiss municipality guardianship authorities acted so, commonly tolerated by federal authorities, to the 1960s, not all of them of course, but usually communities affected of low taxes in some Swiss cantons[138] Swiss historian Marco Leuenberger investigated, that in 1930 there were some 35,000 indentured children, and between 1920 and 1970 more than 100,000 are believed to have been placed with families or homes. 10,000 Verdingkinder are still alive.[138][139] Therefore, the so-called Wiedergutmachungsinitiative was started in April 2014. In April 2014 the collection of targeted at least authenticated 100,000 signatures of Swiss citizens has started, and still have to be collected to October 2015.[citation needed] United States Main article: Child labor in the United States Missouri Governor Joseph W. Folk inspecting child labourers in 1906 in an image drawn by journalist Marguerite Martyn Child labour laws in the United States are found at the federal and state levels. The most sweeping federal law that restricts the employment and abuse of child workers is the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). Child labour provisions under FLSA are designed to protect the educational opportunities of youth and prohibit their employment in jobs that are detrimental to their health and safety. FLSA restricts the hours that youth under 16 years of age can work and lists hazardous occupations too dangerous for young workers to perform. Under the FLSA, for non-agricultural jobs, children under 14 may not be employed, children between 14 and 16 may be employed in allowed occupations during limited hours, and children between 16 and 17 may be employed for unlimited hours in non-hazardous occupations.[140] A number of exceptions to these rules exist, such as for employment by parents, newspaper delivery, and child actors.[140] The regulations for agricultural employment are generally less strict. States have varying laws covering youth employment. Each state has minimum requirements such as, earliest age a child may begin working, number of hours a child is allowed to be working during the day, number of hours a child is allowed to be worked during the week. The United States Department of Labor lists the minimum requirements for agricultural work in each state.[141] Where state law differs from federal law on child labour, the law with the more rigorous standard applies.[140] Individual states have a wide range of restrictions on labour by minors, often requiring work permits for minors who are still enrolled in high school, limiting the times and hours that minors can work by age and imposing additional safety regulations. |

国別 関連項目:児童労働率の高い国の一覧 学校に通っていない労働児童と児童労働時間[68] 植民地帝国 1650年から1950年にかけて、ヨーロッパ列強の植民地では、組織的な児童労働が日常的に行われていた。アフリカでは、植民地行政官が伝統的な親族に よる生産形態を奨励し、成人だけでなく、労働力として家庭を雇うことを推奨していた。何百万人もの子どもたちが、植民地時代の農業プランテーション、鉱 山、家事サービス業で働いていた[69][70]。これらの植民地で、5歳から14歳の子どもたちが、技術を習得する代わりに無報酬で徒弟として雇われる という巧妙な計画が広まっていた。19世紀には、貧しい見習い制度が実践されるようになった。この制度では、植民地の主人は、別の植民地の主人が所有する 遠く離れた農場で、子供たちを労働に従事させるにあたり、先住民の親や子供の承認を必要としなかった[71]。その他の制度には、子供たちが働きながら学 ぶ「働きながら学ぶ」プログラムが含まれていた。例えば、イギリスは1899年にいわゆる「主人と使用人の法」を制定し、その後「税金と通行法」を制定し て、特にアフリカの植民地で児童労働を奨励した。これらの法律により、先住民は、農場やピカンニン(雑役夫)として、妻や子供の労働力を植民地政府のニー ズに提供することを条件に、一部の先住民の土地の法的所有権が与えられた。 法律以外にも、植民地には新たな税金が課せられた。その一つが、イギリスとフランスの植民地帝国における人頭税である。この税金は、植民地によっては8歳 以上のすべての人々に課せられた。これらの税金を支払い、生活費をまかなうために、植民地家庭の子供たちは働かざるを得なかった[72][73] [74]。 香港などの東南アジアの植民地では、ムイ・ツァイ(妹仔)と呼ばれる児童労働が文化的な伝統として正当化され、イギリス当局もそれを黙認していた[75] [76]。オランダ東インド会社の役人たちは、児童労働の虐待を「子供たちをより悲惨な運命から救う方法だ」と正当化していた。ザンビアからナイジェリア にまたがる地域のキリスト教のミッションスクールでも、子供たちに労働を課し、その見返りとして世俗的な教育ではなく宗教教育を提供していた[69]。一 方、カナダのドミニオン法では、いわゆる契約違反法として、非協力的な児童労働者に懲役刑を規定していた[77]。 児童労働を規制する提案は、早くも1786年に始まった[78]。 アフリカ メイン記事:アフリカにおける児童労働 1919年、旧ドイツ植民地カメルーンにおける児童労働 幼い子どもたちが労働に従事することは、アフリカ全土で一貫して問題視されてきた。多くの子どもたちは、まず家庭で働き始め、両親が家族経営の農場を経営 するのを手伝っていた[79]。今日のアフリカの子どもたちは、しばしば家族の借金やその他の経済的な要因により搾取的な労働を強いられ、それが継続的な 貧困につながっている[79]。商業用プランテーションでの労働、物乞い、靴磨きなどの販売業務などである[80]。収穫期には農業分野での労働者が急増 し、現在農業に従事している児童は推定500万人に上るとされている。コーヒー豆を摘む児童の 30% に加え、年間を通じて働く学齢児童は推定 25,000 人いる[81]。 重い荷物を運ぶ少女。コンゴ民主共和国、カタンガ地方。 子どもたちがどのような産業で働くかは、彼らが農村地域で育ったか都市部で育ったかによって異なる。都市部で生まれた子どもたちは、路上販売、洗車、建設 現場での手伝い、衣類の織り、時にはエキゾチックダンサーとして働くことになることが多い[80]。一方、農村部で育った子どもたちは、農場で肉体労働や 家畜の世話、農作物の販売に従事する[80]。また、多くの子どもたちが危険な環境で働いている。中には、CRT ベースのテレビやコンピュータのモニターを素手や石、ハンマーを使って分解する子どももいる[ [82] 児童労働者のうち、最も深刻なケースは、ストリートチルドレンや人身売買された児童が雇用主から受けた身体的・精神的虐待によるものである[80]。児童 労働の問題に対処するため、1959年に国連児童の権利に関する条約が施行された[83]。しかし、貧困、教育不足、無知などの理由により、アフリカでは 法的措置が完全に施行・受け入れられていない[84]。 ベニンの若い路上販売員 児童労働を廃止し、削減するために実施されたその他の法的要因には、1979年に国際児童年宣言によって発効した世界的な対応がある[84]。国連人権委 員会とともに、これら2つの宣言は 児童労働の撲滅に向けて、さまざまなレベルで取り組んできた[84]。この蔓延を終わらせるために多くの対策がとられてきたが、思春期の定義が曖昧で、子 どもの成長に不可欠な活動に従事する期間も明確でないため、アフリカにおける児童労働は今日でも問題となっている。また、家庭内で子どもが家業を手伝うこ とが文化的に容認されていることから、家庭内で子ども労働と見なされるものとの関連性も、しばしば問題となる。アフリカ経済において子どもたちが重要な役 割を果たしていることから、20世紀においても多くの人々にとって児童労働は依然として重要な役割を果たしている[出典が必要]。 オーストラリア 1788年のヨーロッパ人入植以来、オーストラリアには時折、労働を強いられるために送られた少年犯罪者がいた。オーストラリアでは、イギリスほど児童労 働が横行することはなかった。人口が少なく、農業生産性が高かったため、先進工業国のように家族が飢餓に苦しむことはなかった。オーストラリアは20世紀 後半まで産業が発達しておらず、児童労働法や義務教育はイギリスの影響下で発展した。1870年代以降、児童労働は義務教育によって制限された[要出 典]。 オーストラリアの児童労働法は州によって異なる。一般的に、児童は年齢に関係なく労働することが認められているが、15歳未満の児童には制限が設けられて いる。これらの制限は、労働時間と児童が従事できる仕事の種類に適用される。すべての州において、児童は最低就業年齢に達するまで学校に通う義務がある。 最低就業年齢は、タスマニア州とクイーンズランド州が17歳であるのに対し、その他の州では15歳である[86]。 ブラジル 主な記事:ブラジルの児童労働 ブラジルにおける児童労働。埋立地からリサイクル可能な資源を回収した後、立ち去る 1500年にポルトガルによる植民地化が始まって以来、ブラジルの子供たちにとって児童労働は常に問題となってきた[87]。多くの子供たちが従事してい た労働は、必ずしも目に見えるものでも、合法的なものでも、報酬が支払われるものでもなかった。多くの若者にとって、無償労働や奴隷労働は日常茶飯事で、 彼らが大人になるまでの間、彼らの生活の一部であった[88]。しかし、子どもや若者をどのように分類するかについて明確な定義がないため、植民地時代に おける児童労働に関する歴史的記録はほとんど残されていない。このような記録の欠如により、19世紀以前にどのような種類の労働に何人の子どもたちが従事 していたかを特定することは困難である[87]。ブラジルにおける児童労働の最初の記録は、先住民社会と奴隷労働の時代に行われた。子供たちが感情的・肉 体的な限界を超える仕事を強制的にさせられていたことが判明した。例えば、アルマンド・ディアスは、1913年11月にまだ若くして亡くなったが、その死 因は、彼が働いていた繊維産業に入った際に感電したことだった。少年少女たちは日常的に労働災害の犠牲になっていた[90]。 ブラジルでは、1934年、1937年、1946年に可決された憲法改正により、最低就業年齢は14歳と定められた[91]。しかし、1980年代に軍部 による独裁体制が変化したことにより、最低年齢制限は12歳に引き下げられたが、1988年に危険な労働環境や危険な労働条件に関する報告が出されたた め、見直された。これにより、最低年齢は再び 14 歳に引き上げられた。1998年には、建設機械の運転や特定の工場作業など、危険と見なされる作業に従事することを禁止するなど、若者が従事できる仕事の 種類を制限する別の規制が制定された[91]。児童労働のリスクと発生を減らすために多くの措置が取られたが、ブラジルでは 14 歳未満の児童や青少年の就労者が依然として多い。ブラジルでおよそ900万人の子どもたちが違法に就労し、人生で重要な経験となるはずの伝統的な子ども時 代の活動に参加していないことが明らかになったのは、つい最近、1980年代になってからのことである[92]。 ブラジルの国勢調査データ(1999年PNAD)によると、10歳から14歳の児童のうち255万人が違法に就労していた。さらに、15歳から17歳まで の370万人と、5歳から9歳までの約37万5千人もこれに続いた[出典が必要]。14歳という年齢制限引き上げにより、 4歳に引き上げられた年齢制限により、記録された若年労働者の少なくとも半数は違法に雇用されており、その結果、多くの労働者が重要な労働法によって保護 されていないという事態を招いた[要出典]。児童労働が規制された当時からかなりの時間が経過しているが、ブラジルではいまだに多くの児童が違法に働いて いる。多くの子どもたちが麻薬カルテルに雇われ、麻薬や銃、その他の違法な物品の販売や運搬に従事している。これは、子どもたちが無邪気であるとカルテル 側が考えているためである。若者が従事するこの種の仕事は、肉体面や精神面に悪影響を及ぼすため非常に危険である。しかし、麻薬ディーラーとの仕事に伴う 危険性にもかかわらず、この種の雇用は国内全体で増加している[93]。 イギリス 1700年代後半の産業革命や産業革命期における児童労働の顕著な存在など、英国の長期的な経済成長には多くの要因が関係している[94]。幼い頃から働 いていた子供たちは、強制されていたわけではなく、家計を支えるために働かざるを得なかった場合が多かった。多くの親にとって雇用機会が乏しかったため、 子どもを農場や工場で働かせることは、家族の食糧確保と生計を支えるための手段であった[94]。家庭内労働が地域の労働市場へと変わり、かつては自家製 だった商品を大量生産するようになると、イングランドで児童労働が最初に発生し始めた。子どもたちはしばしば家庭で商品の生産を手伝っていたため、工場で 同じ商品を製造することは、多くの若者にとって簡単な変化だった[94]。10歳未満の子どもたちが工場で働いている例は数多くあるが、児童労働者の大半 は10歳から14歳であった。 児童労働に影響を与えたもう一つの要因は、18世紀に起こった人口動態の変化である[95]。18世紀末には、人口の20%が5歳から14歳の子供たちで 占められていた。労働力人口の大幅な変化と産業革命の発展により、家庭以外の企業で子どもたちがより早い年齢から働くようになった[96]。しかし、綿織 物などの工場での児童労働が増加したにもかかわらず、農業や家庭内生産の分野では多くの子どもたちが働いていた[96]。 このように多くの子どもたちが働いている状況では、非識字率の上昇や正規の教育を受けられないことが、家族のために働く多くの子どもにとって大きな問題と なった[97]。このような問題のある傾向により、子どもを労働に就かせるかどうかを決める際に、多くの親は考え方を変えるようになった。児童労働の減少 につながったその他の要因としては、経済における金融の変化、技術開発の変化、賃金の引き上げ、工場法に関する継続的な規制などが挙げられる[98]。 1933年、英国は14歳未満の児童の就労を制限する法律を制定した。1933年児童・年少者法は、児童を義務教育年齢(16歳)に達した者と定義した。 一般的に、児童は15歳未満、軽作業の場合は14歳未満で就労することはできない[99]。 カンボジア カンボジアにおける児童労働」を参照 トンレサップ湖の水上村で、蛇とポーズを取って家族のために小遣い稼ぎをする少女 カンボジアでは、児童労働が深刻な問題となっている[100]。1998年の国際労働機関(ILO)の推計によると、カンボジアでは10歳から14歳の児 童の24.1%が経済活動に従事している[100]。これらの児童の多くは長時間労働を強いられており、2000年のカンボジア人間開発報告書によると、 5歳から13歳の児童の約6万5000人が 5歳から13歳の約6万5千人の子どもたちが週25時間働き、学校に通っていないことが報告されている[101]。また、児童労働の蔓延を減らすために、 米国の一般特恵関税制度、米カンボジア繊維協定、ILOの衣料品部門労働条件改善プロジェクト、ChildWise Tourismなど、多くのイニシアティブや政策が導入されている[102][103]。 エクアドル エクアドルの採石場における児童労働 2006年に発表されたエクアドルの研究では、児童労働が子どもたちの健康に影響を及ぼす主な環境問題の1つであることが明らかになった。この研究による と、エクアドルでは80万人以上の子どもたちが労働に従事しており、重金属や有毒化学物質にさらされ、精神的・肉体的なストレスや労働災害のリスクによる 不安にさらされているという。両親と一緒に農業作業に従事する未成年者は、防護服を着用せずに農薬散布を手伝っている[104]。 インド インドにおける児童労働」を参照。 インドで働く少女 2015年、インドはさまざまな産業で違法に働いている子どもの数が最も多い国である。インドの農業は、多くの子どもたちが家族の生計を支えるために幼い 頃から働いている最大の分野である[91]。これらの子どもたちの多くは、失業、大家族、貧困、親の教育不足など、多くの家庭要因により幼い頃から働かざ るを得ない状況にある。これは、インドにおける児童労働率が高い主な原因となっていることが多い[90]。 1757年6月23日、イギリス東インド会社はプラッシーの戦いでベンガル藩王シラジュ・ウッダウラを破った。これによりイギリスは東インド(ベンガル、 ビハール、オリッサ)の支配者となり、農業、工業、貿易が盛んなこの地域を支配した[93]。これにより、大量の商品を生産するために安価な労働力がます ます必要となり、多くの子どもたちが労働を強いられるようになった。多くの多国籍企業は、低賃金で雇用でき、工場環境での労働に耐える体力があることか ら、しばしば児童を雇用していた[105]。インドの多くの児童が雇用されたもう一つの理由は、児童が基本的な権利について知識がなく、問題を起こしたり 不満を言ったりせず、また信頼性が高い場合が多かったためである。幼少期の無邪気さは、多くの人々によって利益を生み出すために利用され、家計収入の必要 からも奨励されていた[105]。 バンガロールの建設現場に掲げられた看板: 「児童労働禁止」 インドの社会学者や非政府組織(NGO)は、インドにおける児童労働の数字について広範な調査を行い、インドはアジアの児童労働の3分の1、世界の児童労 働の4分の1を占めていると結論付けた[93]。多くの児童が違法に雇用されていることから、 インド政府は、児童労働の数を減らすための広範な対策を開始し、児童の適切な成長と発達を促進することの重要性に焦点を当てるようになった[93]。国際 的な影響により、インドで法的措置が取られるよう促すことにも役立った。例えば、1924年にジュネーブ児童権利宣言法が制定された。この法律は、 1948年の世界人権宣言に続いて制定された。世界人権宣言には、幼い子供たちが適切に成長し発達していくために必要な、基本的な人権とニーズが盛り込ま れている[106]。これらの国際的な法律は、インドの労働力に大きな変化をもたらした。1986年に児童労働(禁止および規制)法が制定されたのだ。こ の法律は、14歳未満の児童を雇用すること、および危険な環境での労働を禁止した[93]。 児童労働に対する規制や法的制限の強化により、1993年から2005年にかけて児童労働は64%減少した[107]。これはインド国内において大幅な減 少といえるが、インドの農村地域では依然として多くの子どもたちが働いている。児童労働の 85% は農村部で、15% は都市部で発生しており、インド国内には依然として懸念すべき地域が数多く存在する[107]。 インドでは、1986年以来、危険性のない産業における児童労働を認める法律が施行されている。2013年、パンジャブ州とハリヤナ州の高等裁判所は、危 険性がある産業、ない産業を問わず、14歳未満の児童の雇用を全面的に禁止するという画期的な命令を下した。しかし、裁判所は、新しい技術や技能、職業を 習得することを目的として、児童が家族とともに家族経営の職業に従事することは可能であると裁定した。 イラン メイン記事:イランにおける児童労働 児童労働という現象は、イラン社会における社会問題の一つであり、深刻かつ多様な側面を帯びている。調査や公式・非公式のデータによると、この社会的な弊 害は大都市でより一般的である。また、調査データによると、テヘラン州で働く児童のほとんどは、合法または非合法にイランに移住したアフガニスタンの児童 と関係がある[108][109][110][111][112]。 テヘラン州で働く児童のほとんどがアフガニスタンの子どもであるという事実を強調する一方で、社会研究家で世界平和財団の文学・人文科学賞を受賞したカ メール・アーマディは、同僚たちとともに、イランの 経済危機が続き、この現象を管理・統制する適切な仕組みがなく、アフガニスタン移民向けの合法的な就労ビザ制度がないことが、このような社会的な害悪の拡 大につながっていると考えている[113][114][115][116][117]。 2019年8月当時、内務大臣であったアブドルレザ・ラフマニ・ファズリは、テヘランで働く子供たちの状況を分析し、次のように述べた。「報告によると、 ストリートチルドレンは劣悪な環境で搾取されている。注目すべき点として、これらの子供たちの最大80%はイラン人ではない。これらの子供たちの一部がア フガニスタン国籍であったことを考慮し、私たちは同国の大使館にこの問題を提起した。他の機関が協力すれば、ストリートチルドレンを組織化する適切な措置 を講じることができるが、協力が得られない場合は、警察と司法制度の協力のもと、子どもを搾取するギャングの逮捕状を発行することも決定した。 イランのイスファハン州では、イランの社会福祉省(behzisti)が、多くのストリートチルドレンの虹彩をスキャンしたデータベースを管理しており、 彼らを支援し、彼らの存在による社会的害悪を軽減し、彼らの生活の質を改善するための「子どもに優しい」対策を実施している[121]。 2023年6月時点で、テヘランには7万人の働く子供たちがおり、彼らはリサイクル品も回収している[122][123]。 2023年7月現在、子どもの15%が児童労働に従事しており、8%は住居を持たない。10%の子どもが学校に通っていない。 アイルランド 植民地支配から独立したアイルランドでは、歩けるようになった子どもたちが農場の労働力として使役されていたため、子どもの搾取率が非常に高かった。子ど もたちは、家族の農場で働く対価として報酬を支払われることはなかった。アイルランドでは、家族の農場で働くために子どもたちが求められ、望まれていた。 アイルランドの親たちは、家族の農場で家事をこなすのが子どもたちの義務だと感じていた[125]。 日本 現代の日本では禁止されているが、少年工は1945年の終戦まで、帝国時代の特徴であった。第二次世界大戦中、労働力募集は、教育機会を約束することで、 当時日本の領土であった台湾(Formosa)の若者を対象としていた。2万5千人の募集目標は達成されなかったが、12歳から14歳の台湾人青年 8,400人以上が、三菱 J2M 雷電の製造を手伝うために日本に移住した[126][127][128]。 パキスタン 主な記事:パキスタンの児童労働 オランダ 「オランダにおける児童労働」を参照 オランダでは産業革命まで、そしてその後も児童労働が存在していた。工場における児童労働を規制する法律は1874年に初めて制定されたが、農場における 児童労働は20世紀まで一般的であった[129]。 ソビエト連邦とその後継国家 1922年に正式に禁止されたものの、ソビエト連邦では児童労働が広く行われており、そのほとんどは、児童が土曜日や休日に行う義務的な無報酬労働という 形であった。児童は、農業や林業だけでなく、コルホーズ(集団農場)でも安価で資格を持たない労働力として使われていた。この慣行は「労働教育」と呼ばれ ていた[130]。 1950年代以降、生徒たちは学校での無報酬労働にも従事させられ、掃除や修繕作業を行っていた[131]。この慣習はロシア連邦でも続いており、夏休み のうち最大21日間が学校の作業に充てられることもある。法律では、これは職業訓練の一環として、生徒と保護者の許可を得た場合にのみ認められているが、 これらの規定は広く無視されている[132][より確かな情報が必要]。2012年にはナルチク近郊で、生徒数人が「休暇中の仕事」として道路脇の清掃作 業中に乗用車にはねられ、生徒たちを監督していた教師も巻き添えになって死亡する事故が発生した[133]。 旧ソビエト連邦の共和国の中で、ウズベキスタンは、イスラム・カリモフの主な収入源である綿花の収穫による利益を増やすために、産業規模での児童労働プロ グラムを継続し拡大した。通常学校が始まる9月になると、授業は中断され、子どもたちは綿花畑に労働者として送られ、そこで1日20~60kgの生綿を集 めるノルマが課せられる。この作業は春にも繰り返され、収穫した綿花を鋤で掘り起こし、雑草を取り除く必要がある。2006年には、270万人の子どもた ちがこのような労働を強いられていたと推定されている[134]。 スイス 主な記事:スイスにおける児童労働 他の多くの国々と同様、スイスの児童労働は、19世紀のスイスでいわゆるKaminfegerkinder(煙突掃除の子供たち)や紡績工場、工場、農業 でP.E.で働く子供たちに影響を与えたが、1960年代にはいわゆるVerd (文字通りには「契約児童」または「年季奉公児童労働者」)とは、貧困や道徳的理由から親元から引き離された子供たちのことである。通常、母親が未婚で非 常に貧しい市民、ジプシー・イェニチェの出身、いわゆる「Kinder der Landstrasse(ランドシュトラーセの子供たち)」などである。そして、安い労働力を必要としていた貧しい農家の家庭に預けられた。 ヴェルディンキンダーのオークションさえ存在し、そこで子どもたちは農民に引き渡され、農民は当局に最も安い金額を要求することで、自分の農場に安い労働 力を確保し、当局は子どもを養育する経済的負担から解放されていた。1930年代、ベルン州の農業労働者の20%は15歳未満の子どもだった。スイスの市 町村後見人当局は、連邦当局に一般的に容認されながら、1960年代までそうしていた。もちろん、すべての市町村がそうしていたわけではないが、通常、ス イスのいくつかの州で税金が安い影響を受けた地域社会であった[138]。スイスの歴史家マルコ・ロイエンベルガーの調査によると、 1930年には約3万5千人の児童労働者がおり、1920年から1970年の間に10万人以上が家庭や施設に引き取られたと考えられている。1万人のヴェ ルディンクインダーが今も存命している[138][139]。そのため、いわゆる「償い」イニシアチブが2014年4月に開始された。2014年4月、少 なくともスイス国民の10万人の認証済み署名を集めることが開始され、2015年10月まで集め続けなければならない[要出典]。 アメリカ合衆国 主な記事:アメリカ合衆国の児童労働 1906年、ジャーナリストのマーガレット・マーティンが描いた絵に描かれた、児童労働者を視察するミズーリ州知事ジョセフ・W・フォーク 米国の児童労働法は、連邦政府と州政府の両レベルで定められている。児童労働者の雇用と虐待を制限する最も広範な連邦法は、公正労働基準法(FLSA)で ある。FLSA の児童労働条項は、青少年の教育機会を保護し、彼らの健康と安全を損なうような仕事への雇用を禁止することを目的としている。FLSA は、16 歳未満の青少年の労働時間を制限し、若年労働者が行うには危険すぎる危険な職業を列挙している。 FLSA によると、農業以外の仕事では、14歳未満の児童は雇用できず、14歳から16歳までの児童は許可された職業に制限時間内で雇用でき、16歳から17歳ま での児童は 危険性のない職業であれば、無制限に雇用することができる[140]。これらの規則には、両親による雇用、新聞配達、子役など、多くの例外が存在する [140]。農業雇用に関する規制は、一般的にそれほど厳格ではない。 各州は、若年者の雇用に関するさまざまな法律を定めている。各州には、子どもが労働を開始できる最低年齢、1日に子どもが労働できる時間数、1週間に子ど もが労働できる時間数など、最低要件が定められている。米国労働省は、各州の農業労働に関する最低要件をリスト化している[141]。児童労働に関する州 法が連邦法と異なる場合、より厳しい基準が適用される[140]。 各州は未成年者の労働に対して幅広い制限を設けている。多くの場合、高校に在籍中の未成年者には就労許可証が必要であり、年齢に応じて未成年者が働ける時 間や時間帯が制限され、さらに安全規制が課せられる。 |

| Laws and initiatives Main article: Child labour law See also: Legal working age Almost every country in the world has laws relating to and aimed at preventing child labour. International Labour Organization has helped set international law, which most countries have signed on and ratified. According to ILO minimum age convention (C138) of 1973, child labour refers to any work performed by children under the age of 12, non-light work done by children aged 12–14, and hazardous work done by children aged 15–17. Light work was defined, under this convention, as any work that does not harm a child's health and development, and that does not interfere with his or her attendance at school. This convention has been ratified by 171 countries.[142] The United Nations adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990, which was subsequently ratified by 193 countries.[143] Article 32 of the convention addressed child labour, as follows: ...Parties recognise the right of the child to be protected from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child's education, or to be harmful to the child's health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.[4] Under Article 1 of the 1990 Convention, a child is defined as "every human being below the age of eighteen years unless, under the law applicable to the child, a majority is attained earlier." Article 28 of this Convention requires States to, "make primary education compulsory and available free to all."[4] As of 2024, 196 countries are party to the convention; the only nation that has not ratified the treaty is the United States.[144] In 1999, ILO helped lead the Worst Forms Convention 182 (C182),[145] which has so far been signed upon and domestically ratified by 151 countries including the United States. This international law prohibits worst forms of child labour, defined as all forms of slavery and slavery-like practices, such as child trafficking, debt bondage, and forced labour, including forced recruitment of children into armed conflict. The law also prohibits the use of a child for prostitution or the production of pornography, child labour in illicit activities such as drug production and trafficking; and in hazardous work. Both the Worst Forms Convention (C182) and the Minimum Age Convention (C138) are examples of international labour standards implemented through the ILO that deal with child labour. In addition to setting the international law, the United Nations initiated International Program on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) in 1992.[146] This initiative aims to progressively eliminate child labour through strengthening national capacities to address some of the causes of child labour. Amongst the key initiative is the so-called time-bounded programme countries, where child labour is most prevalent and schooling opportunities lacking. The initiative seeks to achieve amongst other things, universal primary school availability. The IPEC has expanded to at least the following target countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, El Salvador, Nepal, Tanzania, Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, Philippines, Senegal, South Africa and Turkey. Targeted child labour campaigns were initiated by the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) in order to advocate for prevention and elimination of all forms of child labour. The global Music against Child Labour Initiative was launched in 2013 in order to involve socially excluded children in structured musical activity and education in efforts to help protect them from child labour.[147] Exceptions granted The United States has passed a law that allows Amish children older than 14 to work in traditional wood enterprises with proper supervision. In 2004, the United States passed an amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. The amendment allows certain children aged 14–18 to work in or outside a business where machinery is used to process wood.[148] The law aims to respect the religious and cultural needs of the Amish community of the United States. The Amish believe that one effective way to educate children is on the job.[6] The new law allows Amish children the ability to work with their families, once they are past eighth grade in school. Similarly, in 1996, member countries of the European Union, per Directive 94/33/EC,[8] agreed to a number of exceptions for young people in its child labour laws. Under these rules, children of various ages may work in cultural, artistic, sporting or advertising activities if authorised by the competent authority. Children above the age of 13 may perform light work for a limited number of hours per week in other economic activities as defined at the discretion of each country. Additionally, the European law exception allows children aged 14 years or over to work as part of a work/training scheme. The EU Directive clarified that these exceptions do not allow child labour where the children may experience harmful exposure to dangerous substances.[149] Nonetheless, many children under the age of 13 do work, even in the most developed countries of the EU. For instance, a recent study showed over a third of Dutch twelve-year-old kids had a job, the most common being babysitting.[150] More laws vs. more freedom Very often, however, these state laws were not enforced... Federal legislation was passed in 1916 and again in 1919, but both laws were declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. Although the number of child workers declined dramatically during the 1920s and 1930s, it was not until the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938 that federal regulation of child labor finally became a reality. — Smithsonian, on child labour in early 20th century United States[151] Scholars disagree on the best legal course forward to address child labour. Some suggest the need for laws that place a blanket ban on any work by children less than 18 years old. Others suggest the current international laws are enough, and the need for more engaging approach to achieve the ultimate goals.[152] Some scholars[who?] suggest any labour by children aged 18 years or less is wrong since this encourages illiteracy, inhumane work and lower investment in human capital. These activists claim that child labour also leads to poor labour standards for adults, depresses the wages of adults in developing countries as well as the developed countries, and dooms the third world economies to low-skill jobs only capable of producing poor quality cheap exports. More children that work in poor countries, the fewer and worse-paid are the jobs for adults in these countries. In other words, there are moral and economic reasons that justify a blanket ban on labour from children aged 18 years or less, everywhere in the world.[153][154] Child labour in Bangladesh Other scholars[who?] suggest that these arguments are flawed and ignore history, and that more laws will do more harm than good. According to them, child labour is merely the symptom of poverty. If laws ban all lawful work that enables the poor to survive, informal economy, illicit operations and underground businesses will thrive. These will increase abuse of the children. In poor countries with very high incidence rates of child labour – such as Ethiopia, Chad, Niger and Nepal – schools are not available, and the few schools that exist offer poor quality education or are unaffordable. The alternatives for children who currently work, claim these studies, are worse: grinding subsistence farming, militia or prostitution. Child labour is not a choice, it is a necessity, the only option for survival. It is currently the least undesirable of a set of very bad choices.[155][156] Traidcraft Exchange and Homeworkers Worldwide argue that attempts to eliminate child labour without addressing the level of adult earnings may lead to children being engaged in labour in "less visible and more hazardous occupations".[157] Nepali girls working in brick factory These scholars suggest, from their studies of economic and social data, that early 20th-century child labour in Europe and the United States ended in large part as a result of the economic development of the formal regulated economy, technology development and general prosperity. Child labour laws and ILO conventions came later. Edmonds suggests, even in contemporary times, the incidence of child labour in Vietnam has rapidly reduced following economic reforms and GDP growth. These scholars suggest economic engagement, emphasis on opening quality schools rather than more laws and expanding economically relevant skill development opportunities in the third world. International legal actions, such as trade sanctions increase child labour.[152][158][159][160] The Incredible Bread Machine, a book published by "World Research, Inc." in 1974, stated: Child labour was a particular target of early reformers. William Cooke Tatlor wrote at the time about these reformers who, witnessing children at work in the factories, thought to themselves: 'How much more delightful would have been the gambol of the free limbs on the hillside; the sight of the green mead with its spangles of buttercups and daisies; the song of the bird and the humming bee...' But for many of these children the factory system meant quite literally the only chance for survival. Today we overlook the fact that death from starvation and exposure was a common fate before the Industrial Revolution, for the pre-capitalist economy was barely able to support the population. Yes, children were working. Formerly they would have starved. It was only as goods were produced in greater abundance at a lower cost that men could support their families without sending their children to work. It was not the reformer or the politician that ended the grim necessity for child labour; it was capitalism. |

法律と取り組み メイン記事:児童労働法 関連項目:法定労働年齢 世界のほぼすべての国が、児童労働の防止を目的とした関連法を有している。国際労働機関は国際法の制定に貢献しており、ほとんどの国がこれに署名し、批准 している。1973年のILO最低年齢条約(C138)によると、児童労働とは、12歳未満の児童による労働、12歳から14歳の児童による非軽易労働、 15歳から17歳の児童による有害労働を指す。この条約では、軽労働とは、子どもの健康や発育を損なわず、学校への出席を妨げることのない労働と定義され ている。この条約は171カ国で批准されている[142]。 国連は 1990 年に「児童の権利条約」を採択し、その後 193 カ国が批准した[143]。同条約の第 32 条では児童労働について次のように規定されている。 ...締約国は、児童が経済的搾取から保護され、危険を伴うおそれのある労働や児童の教育に支障をきたすおそれのある労働、児童の健康または身体的、精神 的、道徳的、社会的な発達に有害な労働を強制されない権利を認める。 1990年の条約の第1条では、子どもとは「18歳未満のすべての人間をいい、ただし、当該子どもに適用される法律により、それより早く成年に達するもの とされている場合はこの限りではない」と定義されている。この条約の第28条では、各国に対し「初等教育を義務化し、すべての人に無料で提供すること」を 求めている[4]。 2024年現在、196カ国が条約に加盟しており、批准していないのは米国だけである[144]。 1999年、ILOは最悪の形態の児童労働条約(C182)の策定を主導した[145]。この国際法は、児童売買、債務による束縛、強制労働など、あらゆ る形態の奴隷制度や奴隷制度に類似した慣行を最悪の形態の児童労働と定義し、これを禁止している。また、児童の売春やポルノグラフィーの制作への利用、麻 薬の製造や密売などの違法行為における児童労働、危険な労働も禁止されている。最悪の形態の児童労働条約(C182)と最低年齢条約(C138)は、児童 労働に対処するILOを通じて実施される国際労働基準の例である。 国際法制定に加え、国連は1992年に児童労働撤廃国際計画(IPEC)を開始した[146]。この取り組みは、児童労働の原因に対処する各国の能力を強 化することで、児童労働を段階的に撤廃することを目的としている。主な取り組みの一つに、児童労働が最も蔓延し、就学機会が不足している国々を対象とし た、いわゆる時間制限プログラムがある。この取り組みは、特に初等教育の普遍的な普及を目指している。IPECは、少なくとも以下の対象国にまで拡大して いる。バングラデシュ、ブラジル、中国、エジプト、インド、インドネシア、メキシコ、ナイジェリア、パキスタン、コンゴ民主共和国、エルサルバドル、ネ パール、タンザニア、ドミニカ共和国、コスタリカ、フィリピン、セネガル、南アフリカ、トルコ。 児童労働撲滅キャンペーンは、あらゆる形態の児童労働の防止と撲滅を訴えるために、児童労働撤廃国際計画(IPEC)によって開始された。2013年に は、社会から排除された子どもたちが体系的な音楽活動や教育に参加し、児童労働から保護されるよう支援することを目的とした「児童労働反対の音楽」という 世界的なイニシアチブが開始された[147]。 例外規定 米国では、14歳以上のアーミッシュの子供たちが適切な監督のもとで伝統的な木材関連企業で働くことを認める法律が制定された。 2004年、米国は1938年の公正労働基準法の改正案を可決した。この改正案により、14歳から18歳までの特定の児童は、木材加工用の機械を使用する 事業所内または事業所外で就労することが認められる[148]。この法律は、米国のアーミッシュ共同体の宗教的・文化的ニーズを尊重することを目的として いる。アーミッシュは、子どもを教育する効果的な方法のひとつは仕事を通じてであると信じている[6]。この新しい法律により、アーミッシュの子どもたち は、中学校2年生を過ぎれば家族と一緒に働くことができるようになった。 同様に、1996年には欧州連合(EU)加盟国が指令94/33/EC[8]に基づき、児童労働法における若年層に対するいくつかの例外を承認した。この 規則の下では、管轄当局の許可があれば、さまざまな年齢の子どもたちが文化、芸術、スポーツ、広告活動に従事することができる。13歳以上の児童は、各国 が独自に定義するその他の経済活動において、週当たりの労働時間が制限された軽作業に従事することができる。さらに、欧州法の例外規定により、14歳以上 の児童は、就労・訓練制度の一環として働くことができる。EU 指令では、これらの例外規定は、子どもたちが危険な物質に有害にさらされる可能性がある場合、児童労働を認めるものではないと明確化された[149]。そ れにもかかわらず、EU の最も先進的な国々でさえ、13 歳未満の多くの子どもたちが働いている。例えば、最近の調査では、オランダの 12 歳の子どもたちの 3 分の 1 以上が仕事を持っており、最も一般的な仕事はベビーシッターであることが示された[150]。 より多くの法律 vs. より多くの自由 しかし、これらの州法はほとんど施行されなかった。連邦法は1916年と1919年に制定されたが、両法とも最高裁により違憲とされた。1920年代から 1930年代にかけて児童労働者の数は劇的に減少したが、児童労働の連邦規制が現実のものとなったのは、1938年の公正労働基準法(Fair Labor Standards Act)が制定されてからのことである。 — スミソニアン、20世紀初頭の米国における児童労働について[151] 児童労働に対処するための最善の法的措置については、学者の間でも意見が分かれている。18歳未満の児童による労働を全面的に禁止する法律が必要だという 意見がある一方で、現在の国際法でも十分であり、最終的な目標を達成するためには、より効果的なアプローチが必要だという意見もある[152]。 一部の学者[?]は、18歳以下の児童による労働は、非識字、非人道的な労働、人的資本への投資の低下を助長するため、すべて間違っていると主張してい る。これらの活動家たちは、児童労働は大人にとっても劣悪な労働条件につながり、先進国だけでなく発展途上国でも大人の賃金を低下させ、第三世界の経済を 低技能労働、つまり粗悪な安価な輸出品しか生産できない労働に追い込むと主張している。貧困国では、働く子どもの数が増えれば増えるほど、その国の大人向 けの仕事の数は減り、賃金が低くなる。言い換えれば、18歳以下の子どもの労働を世界中で一律に禁止することは、道徳的および経済的理由から正当化でき る。 バングラデシュにおける児童労働 他の学者[は?]は、これらの議論は欠陥があり、歴史を無視しており、法律を増やすことは良いことよりも害になるだけだと指摘している。彼らによると、児 童労働は単に貧困の兆候にすぎない。法律によって貧困層が生活できる合法的な労働がすべて禁止されれば、非公式経済、違法な事業、地下ビジネスが盛んにな る。その結果、児童虐待が増加する。児童労働の発生率が非常に高い貧困国(エチオピア、チャド、ニジェール、ネパールなど)では、学校が利用できないか、 わずかな学校でも教育の質が悪かったり、学費が高額だったりする。現在働いている子供たちにとって、これらの研究が主張するように、他の選択肢はさらに悪 い。自給自足の農業、民兵、売春を強いられるのだ。児童労働は選択ではなく、生き残るための唯一の選択肢である。現在、それは非常に悪い選択肢の中で最も 望ましくないものである。[155][156] トラッドクラフト・エクスチェンジとホームワーカーズ・ワールドワイドは、大人の収入水準に対処せずに児童労働を排除しようとする試みは、子どもたちが 「目立ちにくく、より危険な職業」に従事する結果につながる可能性がある、と主張している。[157] レンガ工場で働くネパールの少女たち これらの学者は、経済および社会データの研究から、20世紀初頭のヨーロッパとアメリカにおける児童労働は、公式に規制された経済の経済発展、技術開発、 および全般的な繁栄の結果として、大部分が終焉を迎えたと示唆している。児童労働法およびILO条約はその後になって制定された。エドモンズは、現代にお いても、ベトナムにおける児童労働の発生率は、経済改革とGDP成長に続いて急速に減少したと示唆している。これらの学者は、経済的な取り組み、より多く の法律よりも質の高い学校の開設の重視、第三世界の経済関連スキルの開発機会の拡大を提言している。貿易制裁などの国際的な法的措置は児童労働を増やす [152][158][159][160]。 1974年に「ワールドリサーチ社」から出版された『The Incredible Bread Machine』には、次のように書かれている。 児童労働は初期の改革者たちの特別な標的であった。ウィリアム・クック・タトルは当時、工場で働く子供たちを目撃し、こう考えた改革者たちについて書いて いる。「丘陵地帯で自由に動く手足はどれほど楽しいだろう。キンポウゲやヒナギクが散りばめられた緑色の花蜜。小鳥のさえずりとミツバチの羽音…。しか し、これらの子供たちにとって、工場での労働は文字通り生き残るための唯一のチャンスだった。今日では、産業革命以前には飢えと寒さによる死が日常的だっ たという事実を見過ごしがちだが、それは資本主義経済以前の経済では人口を養うのがやっとだったためである。そう、子供たちは働いていた。以前は、子供た ちは飢えていただろう。商品がより豊富に、より低コストで生産されるようになって初めて、人々は子供を働かせずに家族を養うことができたのだ。児童労働の 悲惨な必要性を終わらせたのは、改革者でも政治家でもなく、資本主義だった。 |