Conspiracy Theory

陰謀理論

Conspiracy Theory

かいせつ 池田光穂

陰謀(conspiracy)とは、さまざまな 社会現象の背景に、それを仕組ん だ個人や集団の「陰謀」があると、根拠もなく思いこむ思考方法のこと(→「陰謀理論の歴史」)。

陰謀は、社会集団を営む人間がしばしば、自分たちの利 益を守ったり進展しようとしたりするときに、秘密裏にかつ非合法的にそれをやりとげようとする現象で、それ自体はとりたて珍しいものではない。しかし陰謀 集団の存在は、社会的不正義を蔓延させ社会 の崩壊につながるために、しばしばそのようなことがおこらないように近代社会では、その行為そのものを非難したり、また生起しないような道徳的規準もうけ ている。

すなわち、ここでいう陰謀理論とは、社会の中の異質分 子を非難する際に、その個人ないしは集団を〈陰謀をもった悪意ある存在〉と根拠なく位置づける便法のことを指している。陰謀理論は、人間のもつステレオタ イプや偏見の一例とみる ことができる。カール・ポパー(Karl Popper, 1902-1994)は陰謀理論による説明が、迷信の世俗化したものであり、結果として起こったことと陰謀集団の意図という説明 の不整合から、この理 論を論破できると主張する。しかし、非合理的なこと、あるいは事前には想像もできな かったことなどに、陰謀理論がしばしば登場することから、ポパー流の論駁が、実際の歴史的社会的現実にどれほどの判断力を行使できるのかは不明確である。

魔 女裁判、妖術、流言飛語と、それにもとづく社会の変動 は、事後的にはさまざまな理由をつけて解釈することができるが、解釈しにくい奇妙な出来事も、我々の現実には数多く存在する。武漢(Wuhan)を起源地 といわれる COVID-19(2020年新型コロナウィルス)の世界的蔓延の流行に際し、米国大統領ドナルド・トランプ(Donald John Trump, 1946- )ならびに当時の国務長官マイク・ポンペオ(Michael Richard Pompeo, 1963- )が、武漢ウイルスと呼ぶことを提唱したり、中国の武漢の医学研究所で開発された生物兵器であると主 張するのも、限りなく陰謀理論に近い。

陰謀理論は、ポスト・ホック(事後的; post hoc) には容易に論破でき るが——なぜならその多くは誇大妄想的で根拠がないから、事後的に証拠が不在ということで判断することができる——その渦中において抑止させることがきわ めて難しいからである。もちろん陰謀理論の再燃を防ぐためには、ポパー流の論理的 判断を鍛える教育と、過去の陰謀理論の無根拠性についての歴史的検討の継続が不可欠である。

陰謀理論は、社会の情報化がある程度促進されなけば「普 及」しない。その意味で、近代社会最大の陰謀理論の例は、帝政ロシア時代の警察が捏造した「シオンの議定書(The Protocols of the Elders of Zion)」であり、ヘンリー・フォードやアドルフ・ヒトラーは、 それを真に 受けて未曾有の社会的差別と虐殺を引き起こした。

"In law, a conspiracy theory is a theory of a case that presents a conspiracy to be considered by a trier of fact." - Conspiracy theory (legal term).

「法律において陰謀論とは、事実審理者が考慮すべき陰謀を提示する事件の理論であ

る。」 - 陰謀論(法律用語)。

A conspiracy

theory

is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence

of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political

in motivation),[3][4][5] when other explanations are more

probable.[3][6][7] The term generally has a negative connotation,

implying that the appeal of a conspiracy theory is based in prejudice,

emotional conviction, or insufficient evidence.[8] A conspiracy theory

is distinct from a conspiracy; it refers to a hypothesized conspiracy

with specific characteristics, including but not limited to opposition

to the mainstream consensus among those who are qualified to evaluate

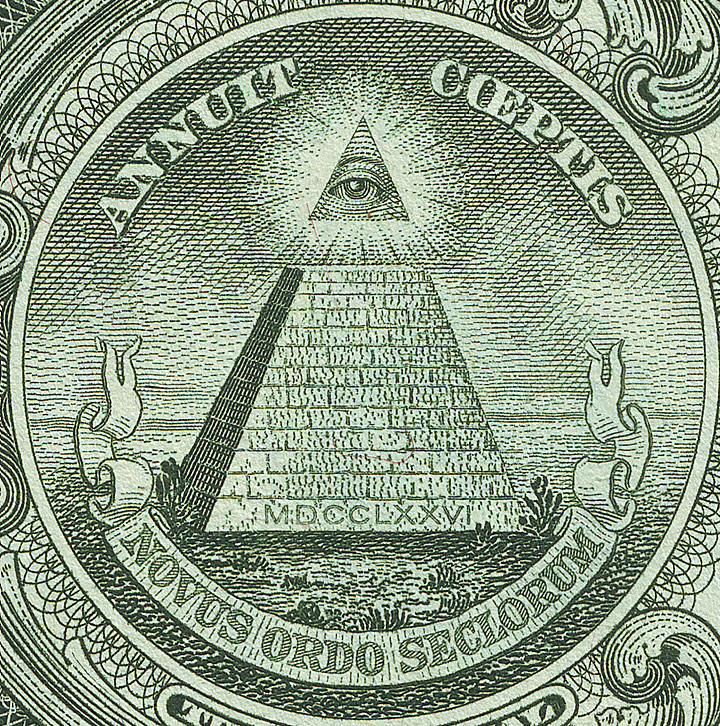

its accuracy, such as scientists or historians.[9][10][11] The Eye of Providence, as seen on the US$1 bill, has been perceived by some to be evidence of a conspiracy linking the Founding Fathers of the United States to the Illuminati.[1]: 58 [2]: 47–49 Conspiracy theories tend to be internally consistent and correlate with each other;[12] they are generally designed to resist falsification either by evidence against them or a lack of evidence for them.[13] They are reinforced by circular reasoning: both evidence against the conspiracy and absence of evidence for it are misinterpreted as evidence of its truth.[8][14] Stephan Lewandowsky observes "This interpretation relies on the notion that, the stronger the evidence against a conspiracy, the more the conspirators must want people to believe their version of events."[15] As a consequence, the conspiracy becomes a matter of faith rather than something that can be proven or disproven.[1][16] Studies have linked belief in conspiracy theories to distrust of authority and political cynicism.[17][18][19] Some researchers suggest that conspiracist ideation—belief in conspiracy theories—may be psychologically harmful or pathological.[20][21] Such belief is correlated with psychological projection, paranoia, and Machiavellianism.[22][23] Psychologists usually attribute belief in conspiracy theories to a number of psychopathological conditions such as paranoia, schizotypy, narcissism, and insecure attachment,[9] or to a form of cognitive bias called "illusory pattern perception".[24][25] It has also been linked with the so-called Dark triad personality types, whose common feature is lack of empathy.[26] However, a 2020 review article found that most cognitive scientists view conspiracy theorizing as typically nonpathological, given that unfounded belief in conspiracy is common across both historical and contemporary cultures, and may arise from innate human tendencies towards gossip, group cohesion, and religion.[9] One historical review of conspiracy theories concluded that "Evidence suggests that the aversive feelings that people experience when in crisis—fear, uncertainty, and the feeling of being out of control—stimulate a motivation to make sense of the situation, increasing the likelihood of perceiving conspiracies in social situations."[27] Historically, conspiracy theories have been closely linked to prejudice, propaganda, witch hunts, wars, and genocides.[12][28][29][30][31] They are often strongly believed by the perpetrators of terrorist attacks, and were used as justification by Timothy McVeigh and Anders Breivik, as well as by governments such as Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union,[28] and Turkey.[32] AIDS denialism by the government of South Africa, motivated by conspiracy theories, caused an estimated 330,000 deaths from AIDS.[33][34][35] QAnon and denialism about the 2020 United States presidential election results led to the January 6 United States Capitol attack,[36][37][38] and belief in conspiracy theories about genetically modified foods led the government of Zambia to reject food aid during a famine,[29] at a time when three million people in the country were suffering from hunger.[39] Conspiracy theories are a significant obstacle to improvements in public health,[29][40] encouraging opposition to such public health measures as vaccination and water fluoridation. They have been linked to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.[29][33][40][41] Other effects of conspiracy theories include reduced trust in scientific evidence,[12][29][42] radicalization and ideological reinforcement of extremist groups,[28][43] and negative consequences for the economy.[28] Conspiracy theories once limited to fringe audiences have become commonplace in mass media, the Internet, and social media,[9][12] emerging as a cultural phenomenon of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[44][45][46][47] They are widespread around the world and are often commonly believed, some even held by the majority of the population.[48][49][50] Interventions to reduce the occurrence of conspiracy beliefs include maintaining an open society, encouraging people to use analytical thinking, and reducing feelings of uncertainty, anxiety, or powerlessness.[42][48][49][51] |

陰謀論とは、ある出来事や状況について、他の説明の方がより可能性が高

いにもかかわらず、陰謀(一般的には強力な不吉なグループによるもので、動機としては政治的なものが多い)の存在を主張する説明のことである[3][4]

[5]。この用語は一般的に否定的な意味合いを持ち、陰謀論の魅力が偏見や感情的な確信、不十分な証拠に基づいていることを意味する。

[8]陰謀論は陰謀とは区別され、科学者や歴史家などその正確性を評価する資格のある人々の間で主流のコンセンサスに反対することを含むがそれに限定され

ない、特定の特徴を持つ仮説上の陰謀を指す[9][10][11]。 1米ドル紙幣に描かれている「プロビデンスの目」は、アメリカ建国の父とイルミナティを結びつける陰謀の証拠であるとの見方もある[1]: 58 [2]: 47-49 陰謀論は内部的に一貫性があり、互いに相関する傾向がある[12]。陰謀論は一般的に、陰謀論に反対する証拠や陰謀論に賛成する証拠の欠如によって改竄さ れないように設計されている[13]。 [8][14]ステファン・ルヴァンドフスキーは、「この解釈は、陰謀に反対する証拠が強ければ強いほど、陰謀家たちは人々に自分たちの言い分を信じても らいたいに違いないという考え方に依拠している」と観察している。 「その結果、陰謀論は証明されたり反証されたりするものではなく、むしろ信仰の問題になる。 [17][18][19]一部の研究者は、陰謀論的イデア、すなわち陰謀論への信念は心理的に有害であるか病的である可能性を示唆している[20] [21]。 心理学者は通常、陰謀論に対する信念を、パラノイア、統合失調症、自己愛、不安定な愛着といった多くの精神病理学的状態[9]、あるいは「錯覚的パターン 知覚」と呼ばれる認知バイアスの一種であるとしている[24][25]。 また、陰謀論は、共感性の欠如を共通の特徴とする、いわゆるダークトライアドのパーソナリティタイプとも関連している。 [しかし、2020年に発表された総説によると、ほとんどの認知科学者は、陰謀論は一般的に非病理学的であるとみなしており、陰謀に対する根拠のない信念 は歴史的にも現代文化においても一般的であり、ゴシップ、集団結束、宗教に対する人間の生得的傾向から生じている可能性があるとしている。 [9] 陰謀論に関するある歴史的なレビューでは、「人が危機的状況に陥ったときに経験する嫌悪的感情-恐怖、不確実性、コントロール不能感-が、状況を理解しよ うとする動機を刺激し、社会的状況において陰謀を知覚する可能性を高めることを示唆する証拠がある」と結論付けている[27]。 歴史的に、陰謀論は偏見、プロパガンダ、魔女狩り、戦争、大量虐殺と密接に結びついてきた[12][28][29][30][31]。テロ攻撃の実行犯に よって強く信じられていることが多く、ティモシー・マクベイやアンデシュ・ブレイビク、またナチス・ドイツ、ソビエト連邦、トルコ[28]などの政府に よって正当化として用いられた。 [32] 陰謀論に突き動かされた南アフリカ政府によるエイズ否定主義は、エイズによる推定33万人の死亡を引き起こした。 [33][34][35]QAnonと2020年のアメリカ合衆国大統領選挙結果に関する否定論は、1月6日のアメリカ合衆国国会議事堂襲撃事件を引き起 こし[36][37][38]、遺伝子組み換え食品に関する陰謀論への信仰は、ザンビア政府が飢饉の際に食糧援助を拒否することにつながった。 [陰謀論は公衆衛生の改善にとって大きな障害であり[29][40]、ワクチン接種や水道水フロリデーションなどの公衆衛生対策への反対を促している。陰 謀論はワクチンで予防可能な病気の発生に関連している[29][33][40][41]。陰謀論の他の影響としては、科学的証拠に対する信頼の低下、 [12][29][42]過激化、過激派グループのイデオロギー的強化、[28][43]経済への悪影響などがある[28]。 かつてはフリンジに限られていた陰謀論は、マスメディア、インターネット、ソーシャルメディアにおいてありふれたものとなり[9][12]、20世紀後半 から21世紀初頭の文化現象として台頭した[44][45][46][47]。 [48][49][50]陰謀論の発生を抑えるための介入策としては、開かれた社会を維持すること、人々に分析的思考を用いることを奨励すること、不確実 性、不安、無力感などの感情を軽減することなどが挙げられる[42][48][49][51]。 |

| Origin and usage The Oxford English Dictionary defines conspiracy theory as "the theory that an event or phenomenon occurs as a result of a conspiracy between interested parties; spec. a belief that some covert but influential agency (typically political in motivation and oppressive in intent) is responsible for an unexplained event". It cites a 1909 article in The American Historical Review as the earliest usage example,[52][53] although it also appeared in print for several decades before.[54] The earliest known usage was by the American author Charles Astor Bristed, in a letter to the editor published in The New York Times on January 11, 1863.[55] He used it to refer to claims that British aristocrats were intentionally weakening the United States during the American Civil War in order to advance their financial interests. England has had quite enough to do in Europe and Asia, without going out of her way to meddle with America. It was a physical and moral impossibility that she could be carrying on a gigantic conspiracy against us. But our masses, having only a rough general knowledge of foreign affairs, and not unnaturally somewhat exaggerating the space which we occupy in the world's eye, do not appreciate the complications which rendered such a conspiracy impossible. They only look at the sudden right-about-face movement of the English Press and public, which is most readily accounted for on the conspiracy theory.[55] The term is also used as a way to discredit dissenting analyses.[56] Robert Blaskiewicz comments that examples of the term were used as early as the nineteenth century and states that its usage has always been derogatory.[57] According to a study by Andrew McKenzie-McHarg, in contrast, in the nineteenth century the term conspiracy theory simply "suggests a plausible postulate of a conspiracy" and "did not, at this stage, carry any connotations, either negative or positive", though sometimes a postulate so-labeled was criticized.[58] The author and activist George Monbiot argued that the terms "conspiracy theory" and "conspiracy theorist" are misleading, as conspiracies truly exist and theories are "rational explanations subject to disproof". Instead, he proposed the terms "conspiracy fiction" and "conspiracy fantasist".[59] |

由来と用法 オックスフォード英語辞典は陰謀論を「ある出来事や現象が利害関係者間の陰謀の結果として起こるという説。アメリカン・ヒストリカル・レビュー』誌に掲載 された1909年の論文が最も古い用例として引用されているが[52][53]、その数十年前から印刷物にも掲載されていた[54]。 最も古い用例として知られているのは、1863年1月11日に『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙に掲載されたアメリカ人作家チャールズ・アスター・ブリステッ ドによる編集者への手紙である[55]。 彼はこの言葉を、アメリカ南北戦争中にイギリス貴族が自分たちの経済的利益を高めるために意図的にアメリカを弱体化させていたという主張について言及する ために使用した。 わざわざアメリカに干渉しなくても、イギリスはヨーロッパとアジアで十分なことをしてきた。イギリスが我々に対して巨大な陰謀を企てることは、物理的にも 道徳的にも不可能だった。しかし、われわれの大衆は、外交問題についての大まかな一般知識しか持たず、世界の目から見てわれわれが占めている空間を不自然 でない程度に誇張しているため、そのような陰謀を不可能にしている複雑さを理解していない。彼らは、陰謀説で最も容易に説明できる、イギリスのマスコミと 大衆の突然の右往左往する動きにしか目を向けない[55]。 ロバート・ブラスキーヴィッチは、この用語の例は19世紀にはすでに使われていたとコメントし、その用法は常に侮蔑的であったと述べている[56]。 [57] アンドリュー・マッケンジー=マクハーグの研究によると、対照的に19世紀には陰謀論という用語は単に「陰謀のもっともらしい仮定を示唆する」ものであ り、「この段階では否定的な意味合いも肯定的な意味合いも持っていなかった」が、そのようにレッテルを貼られた仮定が批判されることもあった。 [58]作家で活動家のジョージ・モンビオは、陰謀は本当に存在し、理論は「反証の対象となる合理的な説明」であるため、「陰謀論」や「陰謀論者」という 用語は誤解を招くと主張した。その代わりに、彼は「陰謀フィクション」や「陰謀ファンタジスト」という言葉を提唱した[59]。 |

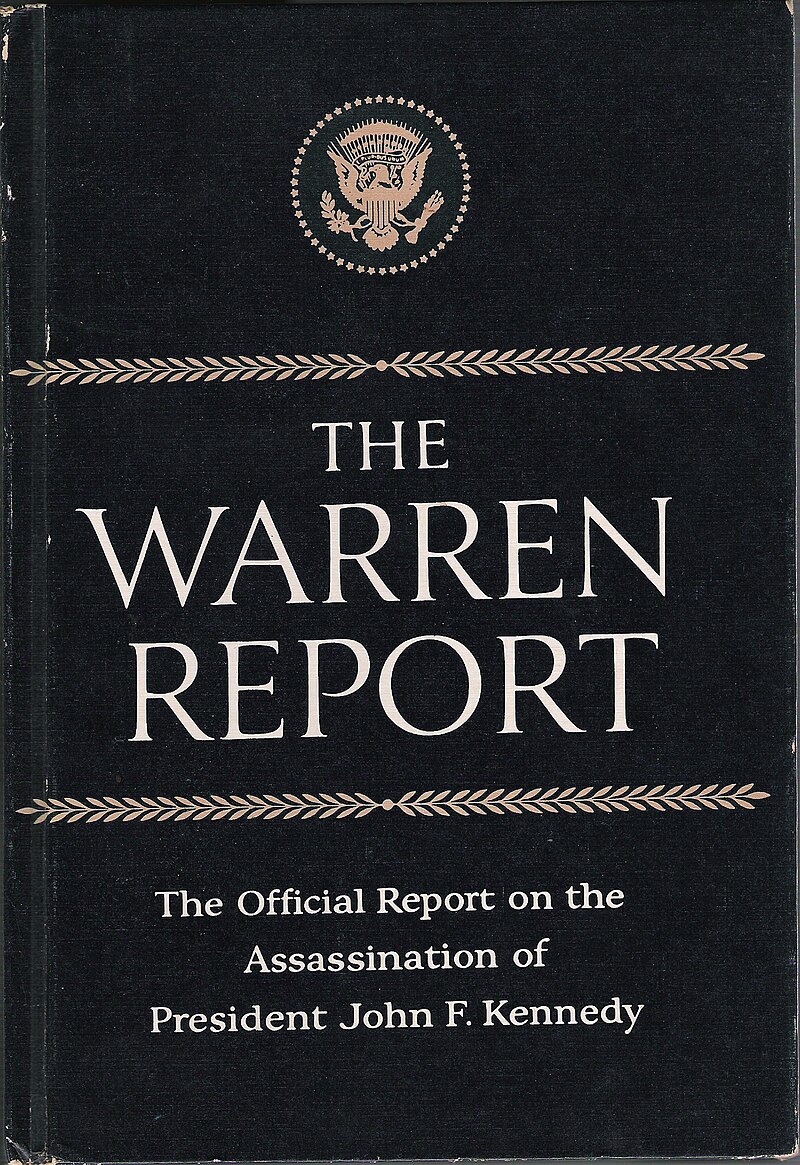

Alleged CIA origins The Warren Report The term "conspiracy theory" is itself the subject of a conspiracy theory, which posits that the term was popularized by the CIA in order to discredit conspiratorial believers, particularly critics of the Warren Commission, by making them a target of ridicule.[60] In his 2013 book Conspiracy Theory in America, the political scientist Lance deHaven-Smith wrote that the term entered everyday language in the United States after 1964, the year in which the Warren Commission published its findings on the assassination of John F. Kennedy, with The New York Times running five stories that year using the term.[61] Whether the CIA was responsible for popularising the term "conspiracy theory" was analyzed by Michael Butter, a Professor of American Literary and Cultural History at the University of Tübingen. Butter wrote in 2020 that the CIA document Concerning Criticism of the Warren Report, which proponents of the theory use as evidence of CIA motive and intention, does not contain the phrase "conspiracy theory" in the singular, and only uses the term "conspiracy theories" once, in the sentence: "Conspiracy theories have frequently thrown suspicion on our organisation [sic], for example, by falsely alleging that Lee Harvey Oswald worked for us."[62] |

CIAの出自疑惑 ウォーレン報告書 「陰謀論」という言葉自体が陰謀論の主題であり、陰謀論的な信者、特にウォーレン委員会の批判者を嘲笑の的にすることで信用を落とすために、CIAによって この言葉が広められたという仮説がある。 [60]政治学者のランス・デヘイブン・スミスは、2013年の著書『Conspiracy Theory in America(アメリカにおける陰謀論)』の中で、この言葉はウォーレン委員会がジョン・F・ケネディ暗殺に関する調査結果を発表した1964年以降に アメリカで日常的に使われるようになり、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙はその年にこの言葉を使った5つの記事を掲載したと書いている[61]。 CIAが「陰謀論」という言葉を広めた責任があるかどうかは、チュービンゲン大学のアメリカ文学・文化史教授であるマイケル・バターによって分析された。 バターは2020年に、この理論の支持者がCIAの動機と意図の証拠として使用しているCIAの文書『ウォーレン報告書批判について』には、単数形で「陰 謀論」という表現はなく、「陰謀論」という用語は一度だけ使われている、と書いている: 「陰謀論は、たとえば、リー・ハーヴェイ・オズワルドがわれわれのために働いていたという誤った主張によって、われわれの組織[中略]にたびたび疑念を投 げかけてきた」[62]。 |

| Difference from conspiracy A conspiracy theory is not simply a conspiracy, which refers to any covert plan involving two or more people.[10] In contrast, the term "conspiracy theory" refers to hypothesized conspiracies that have specific characteristics. For example, conspiracist beliefs invariably oppose the mainstream consensus among those people who are qualified to evaluate their accuracy, such as scientists or historians.[11] Conspiracy theorists see themselves as having privileged access to socially persecuted knowledge or a stigmatized mode of thought that separates them from the masses who believe the official account.[10] Michael Barkun describes a conspiracy theory as a "template imposed upon the world to give the appearance of order to events".[10] Real conspiracies, even very simple ones, are difficult to conceal and routinely experience unexpected problems.[63] In contrast, conspiracy theories suggest that conspiracies are unrealistically successful and that groups of conspirators, such as bureaucracies, can act with near-perfect competence and secrecy. The causes of events or situations are simplified to exclude complex or interacting factors, as well as the role of chance and unintended consequences. Nearly all observations are explained as having been deliberately planned by the alleged conspirators.[63] In conspiracy theories, the conspirators are usually claimed to be acting with extreme malice.[63] As described by Robert Brotherton: The malevolent intent assumed by most conspiracy theories goes far beyond everyday plots borne out of self-interest, corruption, cruelty, and criminality. The postulated conspirators are not merely people with selfish agendas or differing values. Rather, conspiracy theories postulate a black-and-white world in which good is struggling against evil. The general public is cast as the victim of organised persecution, and the motives of the alleged conspirators often verge on pure maniacal evil. At the very least, the conspirators are said to have an almost inhuman disregard for the basic liberty and well-being of the general population. More grandiose conspiracy theories portray the conspirators as being Evil Incarnate: of having caused all the ills from which we suffer, committing abominable acts of unthinkable cruelty on a routine basis, and striving ultimately to subvert or destroy everything we hold dear.[63] |

陰謀との違い 陰謀論は単なる陰謀ではなく、2人以上の人間が関与するあらゆる秘密の計画を指す[10]。対照的に、「陰謀論」という用語は、特定の特徴を持つ陰謀の仮 説を指す。例えば、陰謀論者の信念は、科学者や歴史家など、その正確さを評価する資格を持つ人々の間で主流となっているコンセンサスに必ず反対する [11]。陰謀論者は、自分たちが社会的に迫害された知識への特権的なアクセスや、公式の説明を信じる大衆とは異なる汚名を着せられた思考様式を持ってい ると考えている[10]。マイケル・バーカンは陰謀論を「出来事に秩序を与えるために世界に押し付けられたテンプレート」と表現している[10]。 これに対して陰謀論は、陰謀は非現実的に成功し、官僚組織のような陰謀を企てる集団は完璧に近い能力と秘密性をもって行動できるとする。出来事や状況の原 因は単純化され、複雑な要因や相互作用する要因、偶然や意図しない結果の役割が排除される。ほぼすべての観測は、共謀者とされる人物によって意図的に計画 されたものとして説明される[63]。 陰謀論では、共謀者は通常、極度の悪意を持って行動していると主張される[63]: ほとんどの陰謀論が想定する悪意は、私利私欲、腐敗、残酷さ、犯罪性から生まれる日常的な陰謀をはるかに超えている。陰謀論者が想定するのは、単に利己的 な意図や価値観の違いを持つ人々ではない。むしろ陰謀論は、善が悪と闘う白黒の世界を想定している。一般市民は組織的な迫害の犠牲者とされ、陰謀家とされ る人物の動機はしばしば純粋な狂気の悪に近い。少なくとも、共謀者たちは一般市民の基本的な自由と幸福をほとんど非人間的に無視していると言われている。 より壮大な陰謀論では、共謀者は悪の化身であり、われわれが苦しんでいるあらゆる悪を引き起こし、日常的に想像を絶する残酷な忌まわしい行為を行い、最終 的にはわれわれが大切にしているものすべてを転覆させ、破壊しようと努力していると描かれる[63]。 |

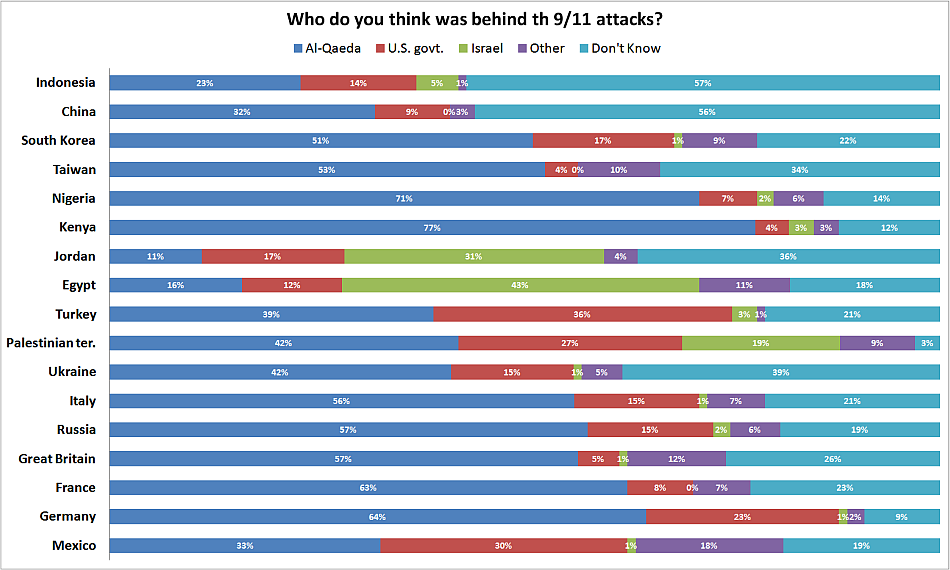

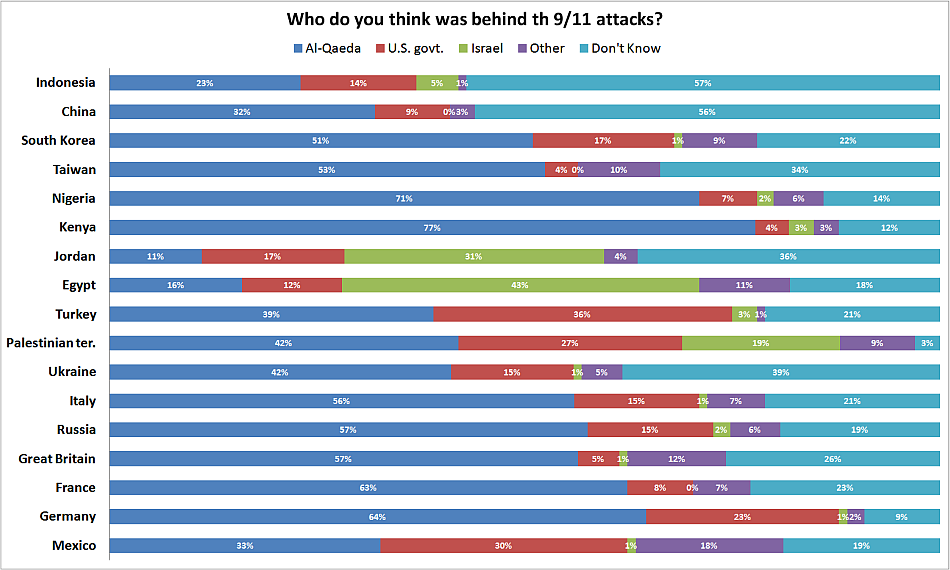

| Examples Further information: List of conspiracy theories A conspiracy theory may take any matter as its subject, but certain subjects attract greater interest than others. Favored subjects include famous deaths and assassinations, morally dubious government activities, suppressed technologies, and "false flag" terrorism. Among the longest-standing and most widely recognized conspiracy theories are notions concerning the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the 1969 Apollo Moon landings, and the 9/11 terrorist attacks, as well as numerous theories pertaining to alleged plots for world domination by various groups, both real and imaginary.[64] |

事例 さらに詳しい情報 陰謀論の一覧 陰謀論はどのようなものでも題材にすることができるが、特定の題材は他のものよりも大きな関心を集める。好んで取り上げられるのは、有名な死や暗殺、道徳 的に疑わしい政府の活動、抑制された技術、「偽旗」テロなどである。最も古くから存在し、最も広く認知されている陰謀論の中には、ジョン・F・ケネディ暗 殺、1969年のアポロ月面着陸、9.11テロ事件に関する仮説や、現実と空想の両方における様々なグループによる世界征服の陰謀疑惑に関する数多くの仮 説がある[64]。 |

| Popularity Conspiracy beliefs are widespread around the world.[48] In rural Africa, common targets of conspiracy theorizing include societal elites, enemy tribes, and the Western world, with conspirators often alleged to enact their plans via sorcery or witchcraft; one common belief identifies modern technology as itself being a form of sorcery, created with the goal of harming or controlling the people.[48] In China, one widely published conspiracy theory claims that a number of events including the rise of Hitler, the 1997 Asian financial crisis, and climate change were planned by the Rothschild family, which may have led to effects on discussions about China's currency policy.[49][65] Conspiracy theories once limited to fringe audiences have become commonplace in mass media, contributing to conspiracism emerging as a cultural phenomenon in the United States of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[44][45][46][47] The general predisposition to believe conspiracy theories cuts across partisan and ideological lines. Conspiratorial thinking is correlated with antigovernmental orientations and a low sense of political efficacy, with conspiracy believers perceiving a governmental threat to individual rights and displaying a deep skepticism that who one votes for really matters.[66] Conspiracy theories are often commonly believed, some even being held by the majority of the population.[48][49][50] A broad cross-section of Americans today gives credence to at least some conspiracy theories.[67] For instance, a study conducted in 2016 found that 10% of Americans think the chemtrail conspiracy theory is "completely true" and 20–30% think it is "somewhat true".[68] This puts "the equivalent of 120 million Americans in the 'chemtrails are real' camp".[68] Belief in conspiracy theories has therefore become a topic of interest for sociologists, psychologists and experts in folklore. Conspiracy theories are widely present on the Web in the form of blogs and YouTube videos, as well as on social media. Whether the Web has increased the prevalence of conspiracy theories or not is an open research question.[69] The presence and representation of conspiracy theories in search engine results has been monitored and studied, showing significant variation across different topics, and a general absence of reputable, high-quality links in the results.[70] One conspiracy theory that propagated through former US President Barack Obama's time in office[71] claimed that he was born in Kenya, instead of Hawaii where he was actually born.[72] Former governor of Arkansas and political opponent of Obama Mike Huckabee made headlines in 2011[73] when he, among other members of Republican leadership, continued to question Obama's citizenship status. |

人気 アフリカの農村部では、陰謀説の一般的な対象は社会のエリート、敵対する部族、西洋世界であり、陰謀者はしばしば魔術や呪術によって計画を実行するとされ ている。 [中国では、ヒトラーの台頭、1997年のアジア金融危機、気候変動など多くの出来事がロスチャイルド家によって計画されたとする陰謀論が広く発表されて おり、中国の通貨政策に関する議論に影響を与えた可能性がある[49][65]。 陰謀論は、かつてはフリンジのオーディエンスに限られていたが、マスメディアではありふれたものとなり、20世紀後半から21世紀初頭のアメリカにおいて 陰謀論が文化現象として台頭する一因となった[44][45][46][47]。陰謀論を信じる一般的な素因は、党派やイデオロギーの違いを超えている。 陰謀論的思考は反政府的志向や政治的効力感の低さと相関しており、陰謀論信者は個人の権利に対する政府の脅威を感じ、誰に投票するかが本当に重要であるか ということに深い懐疑を示している[66]。 陰謀論はしばしば一般的に信じられており、なかには人口の大多数に信じられているものさえある[48][49][50]。 今日のアメリカ人の幅広い層は、少なくともいくつかの陰謀論を信用している[67]。例えば、2016年に実施された調査では、アメリカ人の10%がケム トレイル陰謀論を「完全に真実」だと考えており、20~30%が「ある程度真実」だと考えていることがわかった[68]。 [68]これは「1億2千万人のアメリカ人が『ケムトレイルは本当だ』派に相当する」ということになる[68]。それゆえ陰謀論への信奉は、社会学者、心 理学者、民間伝承の専門家の関心の的となっている。 陰謀論はソーシャルメディアだけでなく、ブログやYouTubeの動画という形でウェブ上に広く存在している。検索エンジンの検索結果における陰謀論の存 在と表現がモニターされ研究されているが、異なるトピック間で大きなばらつきがあり、評判が高く質の高いリンクが検索結果に含まれないことが一般的である [70]。 バラク・オバマ前アメリカ大統領の在任中[71]に広まった陰謀論のひとつは、オバマが実際に生まれたハワイではなくケニアで生まれたと主張した [72]。マイク・ハッカビー元アーカンソー州知事とオバマの政敵は、2011年[73]、共和党指導部の他のメンバーに混じって、オバマの市民権ステー タスに疑問を呈し続けたことで話題となった。 |

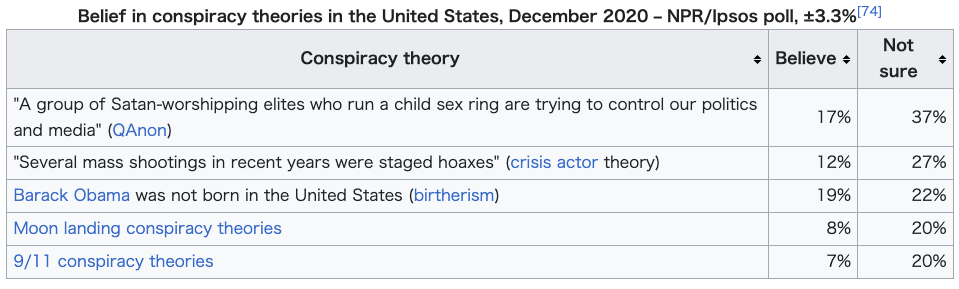

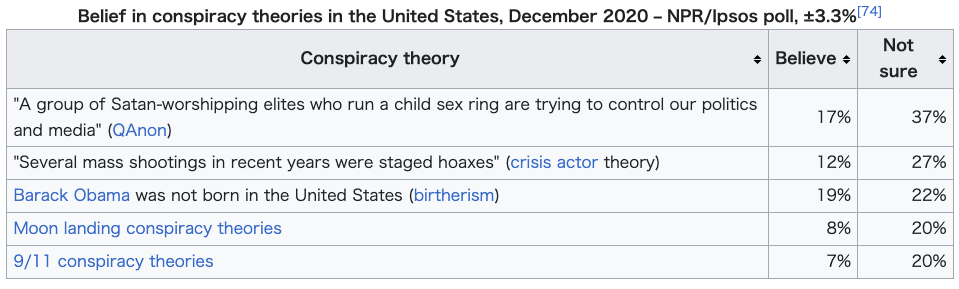

| Belief in conspiracy theories in

the United States, December 2020 – NPR/Ipsos poll, ±3.3%[74] Conspiracy theory Believe Not sure "A group of Satan-worshipping elites who run a child sex ring are trying to control our politics and media" (QAnon) 17% 37% "Several mass shootings in recent years were staged hoaxes" (crisis actor theory) 12% 27% Barack Obama was not born in the United States (birtherism) 19% 22% Moon landing conspiracy theories 8% 20% 9/11 conspiracy theories 7%  |

米国における陰謀説の信憑性、2020年12月 -

NPR/イプソス世論調査、±3.3%[74]。 陰謀説 信じる わからない 「児童性愛団体を運営する悪魔崇拝のエリート集団が、政治とメディアを支配しようとしている」(QAnon) 17% 37 「近年起きた複数の銃乱射事件は、演出されたデマである」(危機アクター説) 12% 27 バラク・オバマは米国生まれではない(アメリカ国外出生説[birtherism]) 19% 22 月面着陸陰謀説 8% 20% 9.11陰謀説 7  |

| Types A conspiracy theory can be local or international, focused on single events or covering multiple incidents and entire countries, regions and periods of history.[10] According to Russell Muirhead and Nancy Rosenblum, historically, traditional conspiracism has entailed a "theory", but over time, "conspiracy" and "theory" have become decoupled, as modern conspiracism is often without any kind of theory behind it.[75][76] Walker's five kinds Jesse Walker (2013) has identified five kinds of conspiracy theories:[77] The "Enemy Outside" refers to theories based on figures alleged to be scheming against a community from without. The "Enemy Within" finds the conspirators lurking inside the nation, indistinguishable from ordinary citizens. The "Enemy Above" involves powerful people manipulating events for their own gain. The "Enemy Below" features the lower classes working to overturn the social order. The "Benevolent Conspiracies" are angelic forces that work behind the scenes to improve the world and help people. Barkun's three types Michael Barkun has identified three classifications of conspiracy theory:[78] Event conspiracy theories. This refers to limited and well-defined events. Examples may include such conspiracies theories as those concerning the Kennedy assassination, 9/11, and the spread of AIDS. Systemic conspiracy theories. The conspiracy is believed to have broad goals, usually conceived as securing control of a country, a region, or even the entire world. The goals are sweeping, whilst the conspiratorial machinery is generally simple: a single, evil organization implements a plan to infiltrate and subvert existing institutions. This is a common scenario in conspiracy theories that focus on the alleged machinations of Jews, Freemasons, Communism, or the Catholic Church. Superconspiracy theories. For Barkun, such theories link multiple alleged conspiracies together hierarchically. At the summit is a distant but all-powerful evil force. His cited examples are the ideas of David Icke and Milton William Cooper. Rothbard: shallow vs. deep Murray Rothbard argues in favor of a model that contrasts "deep" conspiracy theories to "shallow" ones. According to Rothbard, a "shallow" theorist observes an event and asks Cui bono? ("Who benefits?"), jumping to the conclusion that a posited beneficiary is responsible for covertly influencing events. On the other hand, the "deep" conspiracy theorist begins with a hunch and then seeks out evidence. Rothbard describes this latter activity as a matter of confirming with certain facts one's initial paranoia.[79] |

種類 陰謀論は地域的なものであったり国際的なものであったりし、単一の出来事に焦点を当てたものであったり、複数の事件や国、地域、歴史の時代全体をカバーす るものであったりする[10]。 ラッセル・ミュアヘッドとナンシー・ローゼンブラムによれば、歴史的に伝統的な陰謀論は「理論」を伴うものであったが、時代とともに「陰謀」と「理論」は 切り離されるようになり、現代の陰謀論は背後に何らかの理論を持たないことが多くなっている[75][76]。 ウォーカーの5つの種類 ジェシー・ウォーカー(2013年)は陰謀論の5つの種類を特定している[77]。 「外なる敵」とは、外部からコミュニティに対して陰謀を企てているとされる人物に基づく理論を指す。 「内なる敵」は、陰謀を企てる人物が国民内部に潜んでおり、一般市民と見分けがつかないというものである。 「上の敵」は、権力者が自らの利益のために事件を操作する。 「下の敵」には、社会秩序を覆そうとする下層階級が登場する。 慈悲深い陰謀」は、世界を改善し、人々を助けるために舞台裏で働く天使のような力である。 バークンの3つのタイプ マイケル・バークンは陰謀論を次の3つに分類している[78]。 イベント陰謀論。これは限定的で明確な出来事を指す。例えば、ケネディ暗殺、9.11、エイズの蔓延などに関する陰謀論が挙げられる。 組織的陰謀論。陰謀には広範な目標があると考えられており、通常、国、地域、あるいは世界全体の支配権を確保することが考えられている。目標は広範である 一方、陰謀の仕組みは概して単純である。単一の邪悪な組織が、既存の制度に潜入し、それを破壊する計画を実行に移すのである。これは、ユダヤ人、フリー メーソン、共産主義、カトリック教会の陰謀に焦点を当てた陰謀論によく見られるシナリオである。 超陰謀論だ。バークンにとってこのような理論は、複数の陰謀疑惑を階層的に結びつけるものである。その頂点に立つのは、遠いが万能の悪の力である。その例 として、デビッド・アイクやミルトン・ウィリアム・クーパーの考えを挙げている。 ロスバード:浅い対深い マレー・ロスバードは、「深い」陰謀論と「浅い」陰謀論を対比するモデルを支持している。ロスバードによれば、「浅い」理論家はある出来事を観察し、 Cui bono? (誰が得をするのか」と問いかけ、ある受益者が密かに出来事に影響を及ぼしているという結論に飛びつく。一方、「深い」陰謀論者は、直感から始まり、証拠 を探し求める。ロスバードはこの後者の活動を、自分の最初のパラノイアを確かな事実で確認することだと説明している[79]。 |

| Lack of evidence Belief in conspiracy theories is generally based not on evidence, but in the faith of the believer.[80] Noam Chomsky contrasts conspiracy theory to institutional analysis which focuses mostly on the public, long-term behavior of publicly known institutions, as recorded in, for example, scholarly documents or mainstream media reports.[81] Conspiracy theory conversely posits the existence of secretive coalitions of individuals and speculates on their alleged activities.[82][83] Belief in conspiracy theories is associated with biases in reasoning, such as the conjunction fallacy.[84] Clare Birchall at King's College London describes conspiracy theory as a "form of popular knowledge or interpretation".[a] The use of the word 'knowledge' here suggests ways in which conspiracy theory may be considered in relation to legitimate modes of knowing.[b] The relationship between legitimate and illegitimate knowledge, Birchall claims, is closer than common dismissals of conspiracy theory contend.[86] Theories involving multiple conspirators that are proven to be correct, such as the Watergate scandal, are usually referred to as investigative journalism or historical analysis rather than conspiracy theory.[87] Bjerg (2016) writes: "the way we normally use the term conspiracy theory excludes instances where the theory has been generally accepted as true. The Watergate scandal serves as the standard reference."[88] By contrast, the term "Watergate conspiracy theory" is used to refer to a variety of hypotheses in which those convicted in the conspiracy were in fact the victims of a deeper conspiracy.[89] There are also attempts to analyze the theory of conspiracy theories (conspiracy theory theory) to ensure that the term "conspiracy theory" is used to refer to narratives that have been debunked by experts, rather than as a generalized dismissal.[90] |

証拠の欠如 ノーム・チョムスキーは、陰謀論を、例えば学術文書や主流メディアの報道に記録されているような、公に知られた機関の公的で長期的な行動に主に焦点を当て る制度分析と対比している[80]。 [81]陰謀論は逆に、個人の秘密連合体の存在を仮定し、彼らの主張する活動について推測している[82][83]。 陰謀論を信じることは、接続詞の誤謬のような推論におけるバイアスと関連している[84]。 キングス・カレッジ・ロンドンのクレア・バーチャルは陰謀論を「一般的な知識や解釈の一形態」[a]と表現している。ここで「知識」という言葉を使用して いることは、陰謀論が正当な知識様式との関係において考慮される可能性があることを示唆している[b]。 ウォーターゲート事件のように、複数の共謀者が関与し、その正しさが証明された理論は、通常、陰謀論というよりもむしろ調査報道または歴史分析と呼ばれる [87]。ウォーターゲート事件はその標準的な参照例として機能している」[88]。対照的に、「ウォーターゲート陰謀論」という用語は、陰謀で有罪判決 を受けた人々が実際にはより深い陰謀の犠牲者であったという様々な仮説を指すために使用されている。 [89]また、「陰謀論」という用語が一般化された否定としてではなく、専門家によって論破された物語を指すために使われるように、陰謀論の理論(陰謀論 理論)を分析する試みもある[90]。 |

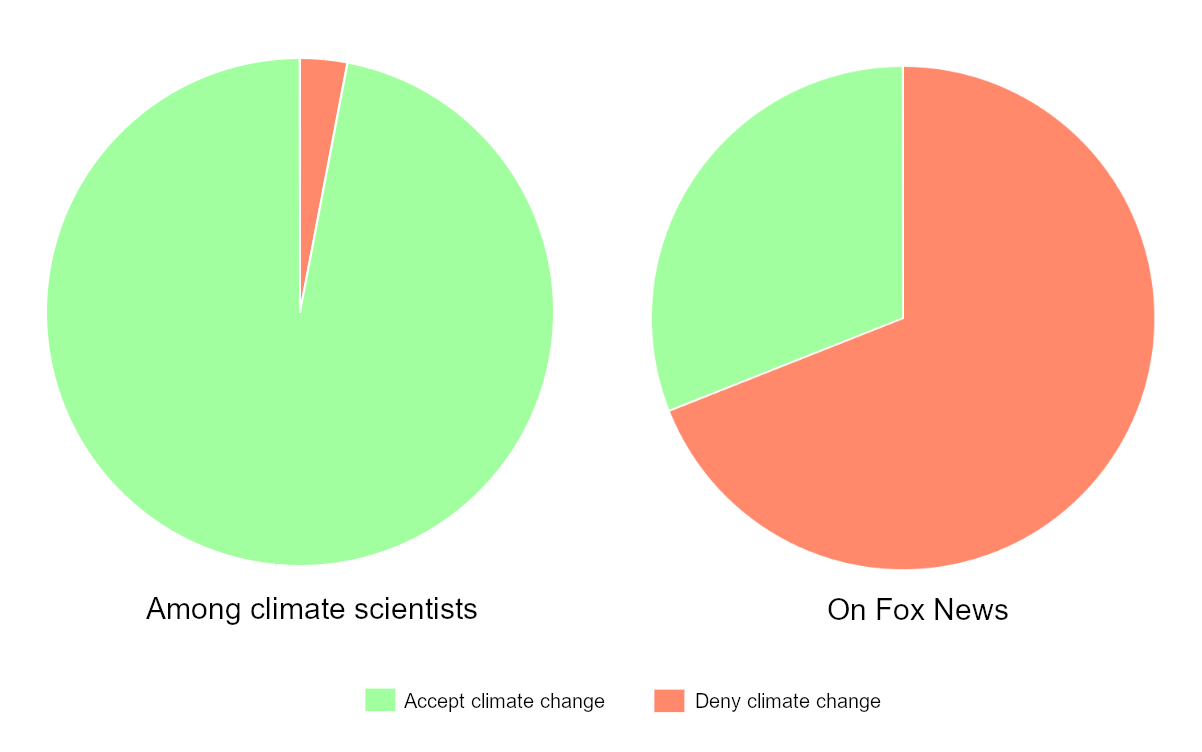

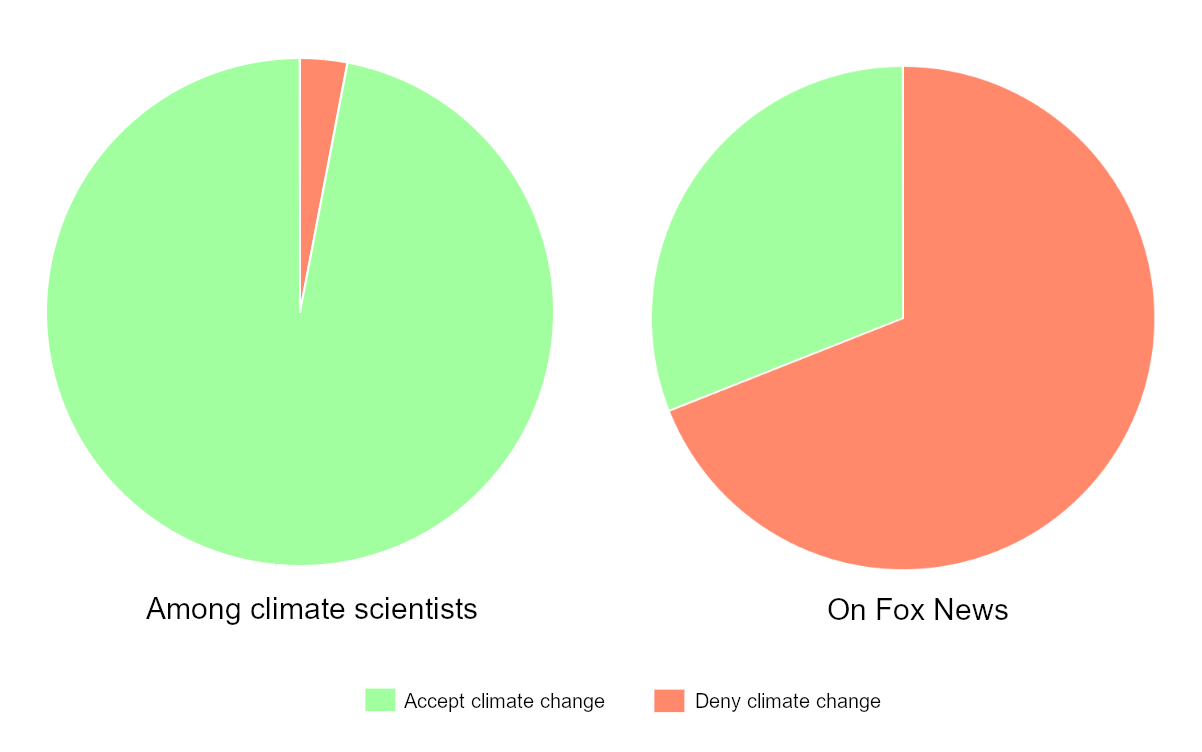

| Rhetoric Conspiracy theory rhetoric exploits several important cognitive biases, including proportionality bias, attribution bias, and confirmation bias.[33] Their arguments often take the form of asking reasonable questions, but without providing an answer based on strong evidence.[91] Conspiracy theories are most successful when proponents can gather followers from the general public, such as in politics, religion and journalism. These proponents may not necessarily believe the conspiracy theory; instead, they may just use it in an attempt to gain public approval. Conspiratorial claims can act as a successful rhetorical strategy to convince a portion of the public via appeal to emotion.[29] Conspiracy theories typically justify themselves by focusing on gaps or ambiguities in knowledge, and then arguing that the true explanation for this must be a conspiracy.[63] In contrast, any evidence that directly supports their claims is generally of low quality. For example, conspiracy theories are often dependent on eyewitness testimony, despite its unreliability, while disregarding objective analyses of the evidence.[63] Conspiracy theories are not able to be falsified and are reinforced by fallacious arguments. In particular, the logical fallacy circular reasoning is used by conspiracy theorists: both evidence against the conspiracy and an absence of evidence for it are re-interpreted as evidence of its truth,[8][14] whereby the conspiracy becomes a matter of faith rather than something that can be proved or disproved.[1][16] The epistemic strategy of conspiracy theories has been called "cascade logic": each time new evidence becomes available, a conspiracy theory is able to dismiss it by claiming that even more people must be part of the cover-up.[29][63] Any information that contradicts the conspiracy theory is suggested to be disinformation by the alleged conspiracy.[42] Similarly, the continued lack of evidence directly supporting conspiracist claims is portrayed as confirming the existence of a conspiracy of silence; the fact that other people have not found or exposed any conspiracy is taken as evidence that those people are part of the plot, rather than considering that it may be because no conspiracy exists.[33][63] This strategy lets conspiracy theories insulate themselves from neutral analyses of the evidence, and makes them resistant to questioning or correction, which is called "epistemic self-insulation".[33][63]  In 2013, 97% of peer-reviewed climate science papers that took a position on the cause of global warming said that humans are responsible, 3% said they were not. Among Fox News guests the same year, this was presented as a false balance between the two viewpoints, with 31% of invited guests believing it was happening and 69% not.[92] Conspiracy theorists often take advantage of false balance in the media. They may claim to be presenting a legitimate alternative viewpoint that deserves equal time to argue its case; for example, this strategy has been used by the Teach the Controversy campaign to promote intelligent design, which often claims that there is a conspiracy of scientists suppressing their views. If they successfully find a platform to present their views in a debate format, they focus on using rhetorical ad hominems and attacking perceived flaws in the mainstream account, while avoiding any discussion of the shortcomings in their own position.[29] The typical approach of conspiracy theories is to challenge any action or statement from authorities, using even the most tenuous justifications. Responses are then assessed using a double standard, where failing to provide an immediate response to the satisfaction of the conspiracy theorist will be claimed to prove a conspiracy. Any minor errors in the response are heavily emphasized, while deficiencies in the arguments of other proponents are generally excused.[29] In science, conspiracists may suggest that a scientific theory can be disproven by a single perceived deficiency, even though such events are extremely rare. In addition, both disregarding the claims and attempting to address them will be interpreted as proof of a conspiracy.[29] Other conspiracist arguments may not be scientific; for example, in response to the IPCC Second Assessment Report in 1996, much of the opposition centered on promoting a procedural objection to the report's creation. Specifically, it was claimed that part of the procedure reflected a conspiracy to silence dissenters, which served as motivation for opponents of the report and successfully redirected a significant amount of the public discussion away from the science.[29] |

レトリック 陰謀論のレトリックは、比例性バイアス、帰属バイアス、確証バイアスなど、いくつかの重要な認知バイアスを悪用している[33]。彼らの主張はしばしば、 合理的な質問を投げかける形をとるが、強力な証拠に基づく答えを提供することはない[91]。陰謀論が最も成功するのは、政治、宗教、ジャーナリズムな ど、一般大衆から支持者を集めることができる場合である。これらの支持者は必ずしも陰謀説を信じているわけではなく、世間の承認を得ようとして陰謀説を利 用しているだけかもしれない。陰謀論的主張は、感情に訴えることによって大衆の一部を納得させる修辞戦略として成功することがある[29]。 陰謀論は一般的に、知識のギャップや曖昧さに焦点を当て、その真の説明が陰謀に違いないと主張することで自らを正当化する[63]。対照的に、彼らの主張 を直接裏付ける証拠は一般的に質が低い。例えば、陰謀論は、証拠の客観的分析を無視する一方で、その信頼性の低さにもかかわらず、目撃証言に依存すること が多い[63]。 陰謀論は改ざんすることができず、誤った議論によって補強される。特に、論理的誤謬である循環推論は陰謀論者によって使用される。陰謀に反対する証拠も、 それを証明する証拠がないことも、陰謀が真実であることの証拠として再解釈され[8][14]、それによって陰謀は証明されたり反証されたりするものでは なく、信仰の問題となる。 [陰謀論の認識論的戦略は「カスケード論理」と呼ばれている。新たな証拠が入手可能になるたびに、陰謀論はさらに多くの人々が隠蔽工作に加担しているに違 いないと主張することでそれを退けることができる[29][63]。陰謀論と矛盾する情報はすべて、疑惑の陰謀による偽情報であると示唆される。 [同様に、陰謀論者の主張を直接裏付ける証拠が欠如し続けることは、沈黙の陰謀の存在を裏付けるものとして描かれる。他の人々が陰謀を発見したり暴露した りしなかったという事実は、陰謀が存在しないからかもしれないということを考慮するのではなく、それらの人々が陰謀の一部であるという証拠とされる。 [33][63]この戦略によって陰謀論は中立的な証拠分析から隔離され、疑問や訂正に対して抵抗力を持つようになる。  2013年、地球温暖化の原因について見解を示した査読済みの気候科学論文の97%は、人類に責任があると述べ、3%は責任がないと述べた。同年のフォッ クス・ニュースのゲストの間では、これは2つの視点の間の誤ったバランスとして提示され、招待されたゲストの31%がそれが起こっていると信じ、69%が そうではないと信じていた[92]。 陰謀論者はしばしばメディアにおける誤ったバランスを利用する。例えば、この戦略は、インテリジェント・デザインを推進するための「論争を教える」キャン ペーンによって使用されており、彼らはしばしば、自分たちの意見を抑圧する科学者の陰謀があると主張している。ディベート形式で自分たちの見解を発表する 場をうまく見つけることができた場合、彼らは修辞的な名誉棄損を使い、主流派の説明の欠点と思われる部分を攻撃することに集中するが、一方で自分たちの立 場の欠点についての議論は避ける[29]。 陰謀論の典型的なアプローチは、当局のいかなる行動や声明に対しても、最も根拠の乏しい正当化でさえ用いて異議を唱えることである。そして、その回答はダ ブルスタンダードで評価され、陰謀論者が満足するような回答を即座に出せなかった場合、陰謀を証明したと主張される。回答におけるどんな些細な誤りでも重 く強調される一方で、他の提案者の議論の欠陥は一般的に免責される[29]。 科学においては、陰謀論者は、そのような事象は極めてまれであるにもかかわらず、科学的理論がたった一つの認識された欠陥によって反証される可能性がある ことを示唆することがある。さらに、主張を無視することも、それに対処しようとすることも、陰謀の証拠と解釈される[29]。1996年のIPCC第2次 評価報告書に対する反対運動の多くは、報告書の作成に対する手続き的な反対を推進することに集中していた。具体的には、手続きの一部が反対論者を黙らせる ための陰謀を反映していると主張され、これが報告書反対派の動機付けとなり、世論の議論のかなりの部分を科学から遠ざけることに成功した[29]。 |

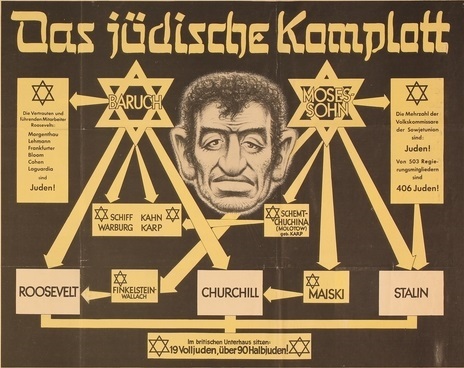

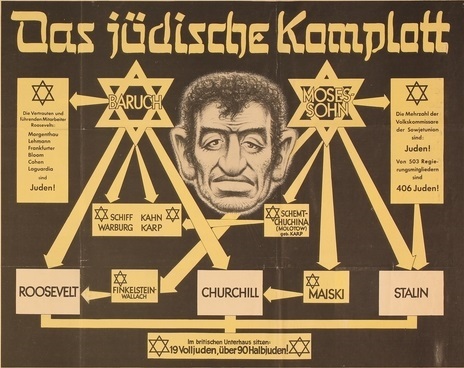

Consequences Third Reich Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda poster entitled Das jüdische Komplott ("The Jewish Conspiracy") Historically, conspiracy theories have been closely linked to prejudice, witch hunts, wars, and genocides.[28][29] They are often strongly believed by the perpetrators of terrorist attacks, and were used as justification by Timothy McVeigh, Anders Breivik and Brenton Tarrant, as well as by governments such as Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.[28] AIDS denialism by the government of South Africa, motivated by conspiracy theories, caused an estimated 330,000 deaths from AIDS,[33][34][35] while belief in conspiracy theories about genetically modified foods led the government of Zambia to reject food aid during a famine,[29] at a time when 3 million people in the country were suffering from hunger.[39] Conspiracy theories are a significant obstacle to improvements in public health.[29][40] People who believe in health-related conspiracy theories are less likely to follow medical advice, and more likely to use alternative medicine instead.[28] Conspiratorial anti-vaccination beliefs, such as conspiracy theories about pharmaceutical companies, can result in reduced vaccination rates and have been linked to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.[33][29][41][40] Health-related conspiracy theories often inspire resistance to water fluoridation, and contributed to the impact of the Lancet MMR autism fraud.[29][40] Conspiracy theories are a fundamental component of a wide range of radicalized and extremist groups, where they may play an important role in reinforcing the ideology and psychology of their members as well as further radicalizing their beliefs.[28][43] These conspiracy theories often share common themes, even among groups that would otherwise be fundamentally opposed, such as the antisemitic conspiracy theories found among political extremists on both the far right and far left.[28] More generally, belief in conspiracy theories is associated with holding extreme and uncompromising viewpoints, and may help people in maintaining those viewpoints.[42] While conspiracy theories are not always present in extremist groups, and do not always lead to violence when they are, they can make the group more extreme, provide an enemy to direct hatred towards, and isolate members from the rest of society. Conspiracy theories are most likely to inspire violence when they call for urgent action, appeal to prejudices, or demonize and scapegoat enemies.[43] Conspiracy theorizing in the workplace can also have economic consequences. For example, it leads to lower job satisfaction and lower commitment, resulting in workers being more likely to leave their jobs.[28] Comparisons have also been made with the effects of workplace rumors, which share some characteristics with conspiracy theories and result in both decreased productivity and increased stress. Subsequent effects on managers include reduced profits, reduced trust from employees, and damage to the company's image.[28][93] Conspiracy theories can divert attention from important social, political, and scientific issues.[94][95] In addition, they have been used to discredit scientific evidence to the general public or in a legal context. Conspiratorial strategies also share characteristics with those used by lawyers who are attempting to discredit expert testimony, such as claiming that the experts have ulterior motives in testifying, or attempting to find someone who will provide statements to imply that expert opinion is more divided than it actually is.[29] It is possible that conspiracy theories may also produce some compensatory benefits to society in certain situations. For example, they may help people identify governmental deceptions, particularly in repressive societies, and encourage government transparency.[49][94] However, real conspiracies are normally revealed by people working within the system, such as whistleblowers and journalists, and most of the effort spent by conspiracy theorists is inherently misdirected.[43] The most dangerous conspiracy theories are likely to be those that incite violence, scapegoat disadvantaged groups, or spread misinformation about important societal issues.[96] |

結果 第三帝国ナチスの反ユダヤ宣伝ポスター「ユダヤ人の陰謀」(Das jüdische Komplott) 歴史的に、陰謀論は偏見、魔女狩り、戦争、大量虐殺と密接に結びついてきた。[28][29] 陰謀論はしばしばテロ攻撃の実行犯によって強く信じられており、ティモシー・マクベイ、アンダース・ブレイヴィク、ブレントン・タラント、またナチス・ド イツやソビエト連邦などの政府によって正当化の理由として使われた。 [28]。南アフリカ政府によるエイズ否定論は、陰謀論に動機づけられ、エイズによる推定33万人の死亡を引き起こした[33][34][35]。一方、 遺伝子組み換え食品に関する陰謀論を信じることによって、ザンビア政府は飢饉の際に食糧援助を拒否した[29]。 陰謀論は公衆衛生の改善にとって重大な障害である[29][40]。健康に関連する陰謀論を信じる人々は、医学的アドバイスに従う可能性が低く、代わりに 代替医療を利用する可能性が高い。 [28] 製薬会社に関する陰謀論など、陰謀論的な反ワクチン信仰は、ワクチン接種率の低下を招き、ワクチンで予防可能な疾病の発生に関連している[33][29] [41][40] 健康関連の陰謀論は、しばしば水道水フロリデーションへの抵抗を鼓舞し、ランセットMMR自閉症詐欺の影響に寄与した[29][40]。 陰謀論は広範な過激化した過激派グループの基本的な構成要素であり、メンバーのイデオロギーや心理を強化し、彼らの信念をさらに過激化させる上で重要な役 割を果たしている可能性がある[28][43]。これらの陰謀論は、極右と極左の両方の政治的過激派の間で見られる反ユダヤ主義的陰謀論のように、そうで なければ根本的に対立しているグループの間でさえ、しばしば共通のテーマを共有している。 [28] より一般的には、陰謀論への信奉は極端で妥協のない視点を持つことと関連しており、そうした視点を維持するのに役立っている可能性がある[42]。陰謀論 は過激派集団に常に存在するわけではなく、存在しても暴力につながるとは限らないが、集団をより過激にし、憎悪の矛先を向ける敵を提供し、社会の他の部分 からメンバーを孤立させる可能性がある。陰謀論が暴力を触発する可能性が最も高いのは、緊急行動を呼びかけたり、偏見に訴えたり、敵を悪者にしてスケープ ゴートにしたりするときである[43]。 職場における陰謀論はまた、経済的な結果をもたらすこともある。例えば、仕事の満足度の低下やコミットメントの低下を招き、その結果、労働者は離職しやす くなる[28]。職場の噂の影響との比較も行われており、陰謀論といくつかの特徴を共有し、生産性の低下やストレスの増加をもたらす。その後の経営者への 影響としては、利益の減少、従業員からの信頼の低下、企業イメージの低下などがある[28][93]。 陰謀論は、重要な社会的、政治的、科学的問題から注意をそらす可能性がある[94][95]。さらに、一般大衆に対する科学的証拠の信用を失墜させるた め、または法的文脈で使用されてきた。陰謀論的戦略は、専門家の証言に下心があると主張したり、専門家の意見が実際よりも分かれていることをほのめかす発 言をする人物を見つけようとしたりするなど、専門家の証言を信用させまいとする弁護士が用いるものと特徴も共通している[29]。 陰謀論が特定の状況において社会に何らかの代償的利益をもたらす可能性もある。例えば、陰謀論は、特に抑圧的な社会における政府の欺瞞を特定するのに役立 ち、政府の透明性を促進するかもしれない[49][94]。しかし、実際の陰謀は通常、内部告発者やジャーナリストなど、システム内で働く人々によって明 らかにされ、陰謀論者が費やす努力のほとんどは本質的に誤った方向に向けられたものである[43]。 最も危険な陰謀論は、暴力を扇動したり、不利な立場にある集団をスケープゴートにしたり、重要な社会問題について誤った情報を広めたりするものである可能 性が高い[96]。 |

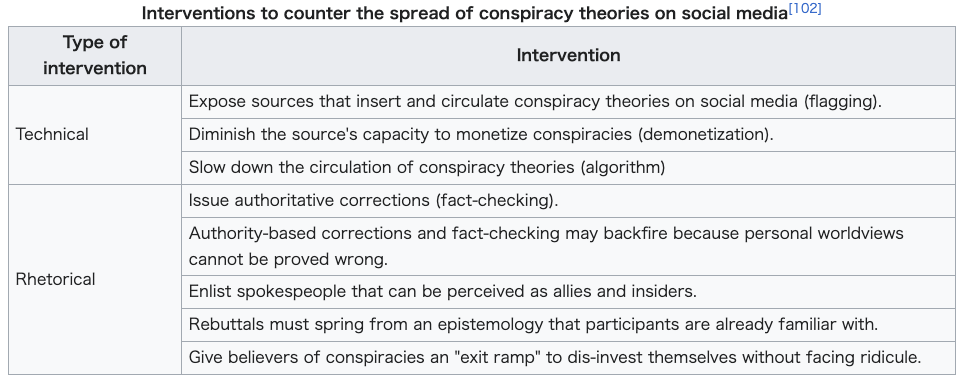

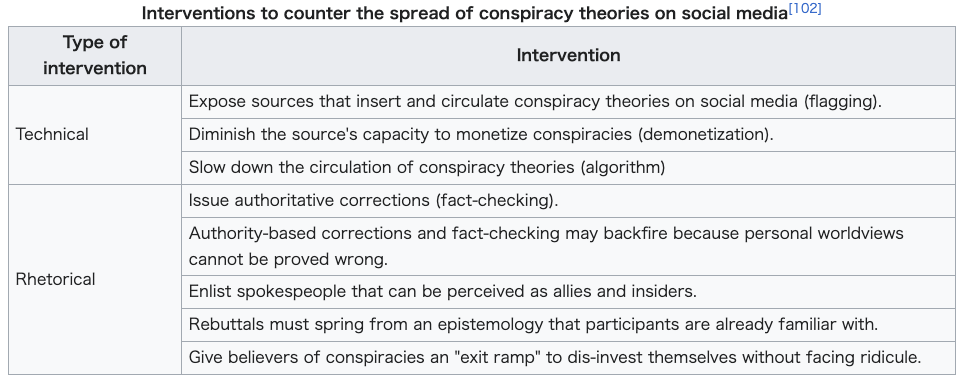

| Interventions See also: Misinformation § Countering misinformation Target audience Strategies to address conspiracy theories have been divided into two categories based on whether the target audience is the conspiracy theorists or the general public.[51][49] These strategies have been described as reducing either the supply or the demand for conspiracy theories.[49] Both approaches can be used at the same time, although there may be issues of limited resources, or if arguments are used which may appeal to one audience at the expense of the other.[49] Brief scientific literacy interventions, particularly those focusing on critical thinking skills, can effectively undermine conspiracy beliefs and related behaviors. Research led by Penn State scholars, published in the Journal of Consumer Research, found that enhancing scientific knowledge and reasoning through short interventions, such as videos explaining concepts like correlation and causation, reduces the endorsement of conspiracy theories. These interventions were most effective against conspiracy theories based on faulty reasoning and were successful even among groups prone to conspiracy beliefs. The studies, involving over 2,700 participants, highlight the importance of educational interventions in mitigating conspiracy beliefs, especially when timed to influence critical decision-making.[97][98] General public People who feel empowered are more resistant to conspiracy theories. Methods to promote empowerment include encouraging people to use analytical thinking, priming people to think of situations where they are in control, and ensuring that decisions by society and government are seen to follow procedural fairness (the use of fair decision-making procedures).[51] Methods of refutation which have shown effectiveness in various circumstances include: providing facts that demonstrate the conspiracy theory is false, attempting to discredit the source, explaining how the logic is invalid or misleading, and providing links to fact-checking websites.[51] It can also be effective to use these strategies in advance, informing people that they could encounter misleading information in the future, and why the information should be rejected (also called inoculation or prebunking).[51][99][100] While it has been suggested that discussing conspiracy theories can raise their profile and make them seem more legitimate to the public, the discussion can put people on guard instead as long as it is sufficiently persuasive.[9] Other approaches to reduce the appeal of conspiracy theories in general among the public may be based in the emotional and social nature of conspiratorial beliefs. For example, interventions that promote analytical thinking in the general public are likely to be effective. Another approach is to intervene in ways that decrease negative emotions, and specifically to improve feelings of personal hope and empowerment.[48] Conspiracy theorists It is much more difficult to convince people who already believe in conspiracy theories.[49][51] Conspiracist belief systems are not based on external evidence, but instead use circular logic where every belief is supported by other conspiracist beliefs.[51] In addition, conspiracy theories have a "self-sealing" nature, in which the types of arguments used to support them make them resistant to questioning from others.[49] Characteristics of successful strategies for reaching conspiracy theorists have been divided into several broad categories: 1) Arguments can be presented by "trusted messengers", such as people who were formerly members of an extremist group. 2) Since conspiracy theorists think of themselves as people who value critical thinking, this can be affirmed and then redirected to encourage being more critical when analyzing the conspiracy theory. 3) Approaches demonstrate empathy, and are based on building understanding together, which is supported by modeling open-mindedness in order to encourage the conspiracy theorists to do likewise. 4) The conspiracy theories are not attacked with ridicule or aggressive deconstruction, and interactions are not treated like an argument to be won; this approach can work with the general public, but among conspiracy theorists it may simply be rejected.[51] Interventions that reduce feelings of uncertainty, anxiety, or powerlessness result in a reduction in conspiracy beliefs.[42] Other possible strategies to mitigate the effect of conspiracy theories include education, media literacy, and increasing governmental openness and transparency.[99] Due to the relationship between conspiracy theories and political extremism, the academic literature on deradicalization is also important.[51] One approach describes conspiracy theories as resulting from a "crippled epistemology", in which a person encounters or accepts very few relevant sources of information.[49][101] A conspiracy theory is more likely to appear justified to people with a limited "informational environment" who only encounter misleading information. These people may be "epistemologically isolated" in self-enclosed networks. From the perspective of people within these networks, disconnected from the information available to the rest of society, believing in conspiracy theories may appear to be justified.[49][101] In these cases, the solution would be to break the group's informational isolation.[49] Reducing transmission Public exposure to conspiracy theories can be reduced by interventions that reduce their ability to spread, such as by encouraging people to reflect before sharing a news story.[51] Researchers Carlos Diaz Ruiz and Tomas Nilsson have proposed technical and rhetorical interventions to counter the spread of conspiracy theories on social media.[102] |

インターベンション こちらも参照のこと: 誤報 § 誤報への対抗 対象読者 陰謀論に対処するための戦略は、対象読者が陰謀論者であるか一般市民であるかに基づいて、2つのカテゴリーに分けられている[51][49]。これらの戦 略は、陰謀論の供給と需要のどちらかを減らすものとして説明されている[49]。両方のアプローチを同時に用いることができるが、資源が限られているとい う問題や、一方の読者を犠牲にして他方の読者に訴えるような議論が用いられる場合がある[49]。 短時間の科学リテラシー介入、特に批判的思考スキルに焦点を当てた介入は、陰謀論的信念と関連する行動を効果的に弱めることができる。Journal of Consumer Research』誌に掲載されたペンシルベニア州立大学の学者が主導した研究によると、相関関係や因果関係といった概念を説明するビデオなど、短い介入 によって科学的知識や推論力を高めると、陰謀論の支持を減らすことがわかった。このような介入は、誤った推論に基づく陰謀論に対して最も効果的であり、陰 謀説を信じやすいグループにおいても成功した。2,700人以上の参加者を対象としたこの研究は、特に重要な意思決定に影響を与えるタイミングであれば、 陰謀説を緩和する教育的介入の重要性を強調している[97][98]。 一般大衆 エンパワーメントを感じている人は、陰謀論に対してより抵抗力がある。エンパワーメントを促進する方法には、人々に分析的思考を用いるよう奨励すること、 人々がコントロールできる状況を考えるよう呼びかけること、社会や政府による決定が手続き上の公正さ(公正な意思決定手続きの使用)に従っていると見られ るようにすることなどが含まれる[51]。 様々な状況において有効であることが示されている反論の方法には、陰謀論が誤りであることを証明する事実を提供すること、情報源の信用を失墜させようとす ること、論理がいかに無効であるかまたは誤解を招くかを説明すること、事実確認ウェブサイトへのリンクを提供することなどがある。 [51]また、これらの戦略を事前に使用し、将来誤解を招くような情報に遭遇する可能性があること、そしてなぜその情報が否定されるべきなのかを人々に知 らせる(予防接種またはプレバンキングとも呼ばれる)ことも効果的である[51][99][100]。陰謀論について議論することで、陰謀論の知名度が上 がり、一般大衆にとって陰謀論がより正当なものに見えるようになることが示唆されているが、十分に説得力がある限り、議論はかえって人々を警戒させること ができる[9]。 一般大衆の間で陰謀論全般の魅力を減少させるための他のアプローチは、陰謀論的信念の感情的・社会的性質に基づいているかもしれない。例えば、一般大衆の 分析的思考を促進するような介入は効果的であろう。もう一つのアプローチは、否定的な感情を減少させるような方法で介入することであり、特に個人的な希望 やエンパワーメントの感情を向上させることである[48]。 陰謀論者 陰謀論者の信念体系は外的証拠に基づくものではなく、あらゆる信 念が他の陰謀論者の信念によって支えられているという循環論理を用い ている[51]。 加えて、陰謀論には「自己封印」的な性質があり、陰謀論を支えるために用い られる論証の種類が、他者からの問いかけに対して抵抗力を持たせてい る[49]。 陰謀論者に働きかけるための成功戦略の特徴は、いくつかの大まかなカテゴリーに分けられている: 1) かつて過激派グループのメンバーだった人など、「信頼できるメッセンジャー」によって論証を提示することができる。2) 陰謀論者は自分たちを批判的思考を重視する人間だと考えているため、これを肯定した上で、陰謀論を分析する際にはより批判的になるよう方向転換することが できる。3) アプローチは共感を示し、共に理解を深めることに基づいている。これは、陰謀論者にも同じようにするよう促すために、オープンマインドを模範とすることで 支えられる。4) 陰謀論は嘲笑や攻撃的な脱構築で攻撃されず、交流は勝利すべき議論のように扱われない。このアプローチは一般大衆には有効だが、陰謀論者の間では単に拒否 されるかもしれない[51]。 不確実性、不安、無力感を軽減する介入は、結果として陰謀論的信念を減少させる[42]。陰謀論の影響を軽減するために考えられる他の戦略には、教育、メ ディアリテラシー、政府の開放性と透明性を高めることなどが含まれる[99]。陰謀論と政治的過激主義との関係から、脱過激化に関する学術文献も重要であ る[51]。 あるアプローチでは、陰謀論は、人が関連する情報源にほとんど出会わなかったり、受け入れたりしない「不自由な認識論」から生じるものであると説明してい る[49][101]。このような人々は、自己閉鎖的なネットワークの中で「認識論的に孤立」している可能性がある。このようなネットワークの中で、社会 の他の人々が利用できる情報から切り離された人々から見れば、陰謀論を信じることは正当化されるように見えるかもしれない[49][101]。このような 場合、解決策は集団の情報的孤立を解消することであろう[49]。 伝達を減らす 陰謀論への一般大衆の暴露は、ニュース記事を共有する前に人々に反省を促すなど、陰謀論の拡散能力を低下させる介入によって減少させることができる [51]。研究者カルロス・ディアス・ルイスとトマス・ニルソンは、ソーシャルメディア上の陰謀論の拡散に対抗するための技術的・修辞的介入を提案してい る[102]。 |

| Interventions to counter the

spread of conspiracy theories on social media[102] Type of intervention Intervention Technical Expose sources that insert and circulate conspiracy theories on social media (flagging). Diminish the source's capacity to monetize conspiracies (demonetization). Slow down the circulation of conspiracy theories (algorithm) Rhetorical Issue authoritative corrections (fact-checking). Authority-based corrections and fact-checking may backfire because personal worldviews cannot be proved wrong. Enlist spokespeople that can be perceived as allies and insiders. Rebuttals must spring from an epistemology that participants are already familiar with. Give believers of conspiracies an "exit ramp" to dis-invest themselves without facing ridicule.  |

ソーシャルメディアにおける陰謀論の拡散に対抗するための介入

[102]。 介入の種類 介入 技術的 ソーシャルメディア上で陰謀論を挿入し流布する情報源を暴露する(フラグを立てる)。 陰謀論を収益化するソースの能力を低下させる(デマネタイゼーション)。 陰謀論の流通を遅らせる(アルゴリズム) 修辞的な問題 権威に基づく訂正(ファクトチェック)。 権威に基づく訂正やファクトチェックは、個人の世界観が間違っていることを証明できないため、裏目に出る可能性がある。 味方やインサイダーと思われるスポークスマンを起用する。 反論は、参加者がすでによく知っている認識論から生まれなければならない。 陰謀の信奉者には、嘲笑に直面することなく、自分自身を投資から外すための「出口ランプ」を与える。  |

| Government policies The primary defense against conspiracy theories is to maintain an open society, in which many sources of reliable information are available, and government sources are known to be credible rather than propaganda. Additionally, independent nongovernmental organizations are able to correct misinformation without requiring people to trust the government.[49] The absence of civil rights and civil liberties reduces the number of information sources available to the population, which may lead people to support conspiracy theories.[49] Since the credibility of conspiracy theories can be increased if governments act dishonestly or otherwise engage in objectionable actions, avoiding such actions is also a relevant strategy.[99] Joseph Pierre has said that mistrust in authoritative institutions is the core component underlying many conspiracy theories and that this mistrust creates an epistemic vacuum and makes individuals searching for answers vulnerable to misinformation. Therefore, one possible solution is offering consumers a seat at the table to mend their mistrust in institutions.[103] Regarding the challenges of this approach, Pierre has said, "The challenge with acknowledging areas of uncertainty within a public sphere is that doing so can be weaponized to reinforce a post-truth view of the world in which everything is debatable, and any counter-position is just as valid. Although I like to think of myself as a middle of the road kind of individual, it is important to keep in mind that the truth does not always lie in the middle of a debate, whether we are talking about climate change, vaccines, or antipsychotic medications."[104] Researchers have recommended that public policies should take into account the possibility of conspiracy theories relating to any policy or policy area, and prepare to combat them in advance.[99][9] Conspiracy theories have suddenly arisen in the context of policy issues as disparate as land-use laws and bicycle-sharing programs.[99] In the case of public communications by government officials, factors that improve the effectiveness of communication include using clear and simple messages, and using messengers which are trusted by the target population. Government information about conspiracy theories is more likely to be believed if the messenger is perceived as being part of someone's in-group. Official representatives may be more effective if they share characteristics with the target groups, such as ethnicity.[99] In addition, when the government communicates with citizens to combat conspiracy theories, online methods are more efficient compared to other methods such as print publications. This also promotes transparency, can improve a message's perceived trustworthiness, and is more effective at reaching underrepresented demographics. However, as of 2019, many governmental websites do not take full advantage of the available information-sharing opportunities. Similarly, social media accounts need to be used effectively in order to achieve meaningful communication with the public, such as by responding to requests that citizens send to those accounts. Other steps include adapting messages to the communication styles used on the social media platform in question, and promoting a culture of openness. Since mixed messaging can support conspiracy theories, it is also important to avoid conflicting accounts, such as by ensuring the accuracy of messages on the social media accounts of individual members of the organization.[99] |

政府の方針 陰謀論に対する第一の防御策は、信頼できる情報源が数多くあり、政府の情報源がプロパガンダではなく信頼できることが知られている、開かれた社会を維持す ることである。さらに、独立した非政府組織は、人々が政府を信頼することを要求することなく、誤った情報を修正することができる[49]。市民権や市民的 自由がないと、人々が利用できる情報源の数が減少するため、人々が陰謀論を支持するようになる可能性がある[49]。政府が不誠実な行動をとったり、その 他の好ましくない行動をとったりすると、陰謀論の信憑性が高まる可能性があるため、そのような行動を避けることも関連する戦略である[99]。 ジョセフ・ピエールは、権威ある機関に対する不信が多くの陰謀論の根底にある中核的な要素であり、この不信が認識論的空白を生み出し、答えを探す個人を 誤った情報に脆弱にすると述べている。このアプローチの課題に関して、ピエールは次のように述べている[103]。「公共圏の中で不確実な領域を認めるこ との課題は、そうすることが、あらゆることが議論可能であり、どのような反論も同様に有効であるというポスト真実の世界観を強化する武器になりうるという ことだ。私は自分のことを中道的な人間だと思いたいが、気候変動、ワクチン、抗精神病薬など、真実が常に議論の中間にあるとは限らないことを心に留めてお くことが重要だ」[104]。 研究者たちは、公共政策があらゆる政策や政策領域に関連する陰謀説の可能性を考慮に入れ、事前にそれに対抗する準備をすべきであると提言している[99] [9]。陰謀説は、土地利用法や自転車シェアリング・プログラムなど、異質な政策問題の文脈で突如として生じている[99]。政府関係者による公共コミュ ニケーションの場合、コミュニケーションの効果を高める要因として、明確でシンプルなメッセージを使用すること、対象住民に信頼されるメッセンジャーを使 用することなどが挙げられる。陰謀論に関する政府の情報は、メッセンジャーが誰かの内集団の一員であると認識されれば、信じられる可能性が高くなる。公的 な代表者は、民族性などターゲットとする集団と特徴を共有していれば、より効果的かもしれない[99]。 加えて、政府が陰謀論に対抗するために市民とコミュニケーションをとる場合、印刷出版物などの他の方法と比較して、オンラインの方法が効率的である。これ はまた、透明性を促進し、メッセージの知覚される信頼性を向上させることができ、代表的でない層にリーチする上でより効果的である。しかし、2019年現 在、多くの政府のウェブサイトは、利用可能な情報共有の機会を十分に活用していない。同様に、ソーシャルメディアのアカウントも、市民からのリクエストに 応えるなど、市民との有意義なコミュニケーションを実現するために効果的に活用する必要がある。その他のステップとしては、問題のソーシャルメディア・プ ラットフォームで使用されているコミュニケーション・スタイルにメッセージを適合させることや、オープンな文化を促進することなどがある。混在したメッ セージは陰謀説を支持する可能性があるため、組織の個々のメンバーのソーシャルメディアアカウントのメッセージの正確性を確保するなど、矛盾したアカウン トを避けることも重要である[99]。 |

| Public health campaigns Successful methods for dispelling conspiracy theories have been studied in the context of public health campaigns. A key characteristic of communication strategies to address medical conspiracy theories is the use of techniques that rely less on emotional appeals. It is more effective to use methods that encourage people to process information rationally. The use of visual aids is also an essential part of these strategies. Since conspiracy theories are based on intuitive thinking, and visual information processing relies on intuition, visual aids are able to compete directly for the public's attention.[9] In public health campaigns, information retention by the public is highest for loss-framed messages that include more extreme outcomes. However, excessively appealing to catastrophic scenarios (e.g. low vaccination rates causing an epidemic) may provoke anxiety, which is associated with conspiracism and could increase belief in conspiracy theories instead. Scare tactics have sometimes had mixed results, but are generally considered ineffective. An example of this is the use of images that showcase disturbing health outcomes, such as the impact of smoking on dental health. One possible explanation is that information processed via the fear response is typically not evaluated rationally, which may prevent the message from being linked to the desired behaviors.[9] A particularly important technique is the use of focus groups to understand exactly what people believe, and the reasons they give for those beliefs. This allows messaging to focus on the specific concerns that people identify, and on topics that are easily misinterpreted by the public, since these are factors which conspiracy theories can take advantage of. In addition, discussions with focus groups and observations of the group dynamics can indicate which anti-conspiracist ideas are most likely to spread.[9] Interventions that address medical conspiracy theories by reducing powerlessness include emphasizing the principle of informed consent, giving patients all the relevant information without imposing decisions on them, to ensure that they have a sense of control. Improving access to healthcare also reduces medical conspiracism. However, doing so by political efforts can also fuel additional conspiracy theories, which occurred with the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) in the United States. Another successful strategy is to require people to watch a short video when they fulfil requirements such as registration for school or a drivers' license, which has been demonstrated to improve vaccination rates and signups for organ donation.[9] Another approach is based on viewing conspiracy theories as narratives which express personal and cultural values, making them less susceptible to straightforward factual corrections, and more effectively addressed by counter-narratives.[100][105] Counter-narratives can be more engaging and memorable than simple corrections, and can be adapted to the specific values held by individuals and cultures. These narratives may depict personal experiences, or alternatively they can be cultural narratives. In the context of vaccination, examples of cultural narratives include stories about scientific breakthroughs, about the world before vaccinations, or about heroic and altruistic researchers. The themes to be addressed would be those that could be exploited by conspiracy theories to increase vaccine hesitancy, such as perceptions of vaccine risk, lack of patient empowerment, and lack of trust in medical authorities.[100] |

公衆衛生キャンペーン 陰謀説を払拭するための成功法は、公衆衛生キャンペーンの文脈で研究されてきた。医療陰謀論に対処するコミュニケーション戦略の重要な特徴は、感情的な訴 えにあまり頼らない手法を用いることである。人々が情報を理性的に処理するよう促す手法を用いる方が効果的である。視覚教材の使用も、こうした戦略には欠 かせない。陰謀論は直感的な思考に基づいており、視覚的な情報処理は直感に依存しているため、視覚的な補助手段は大衆の注意を直接奪い合うことができる [9]。 公衆衛生キャンペーンでは、より極端な結末を含む損失フレーミングのメッセージが、一般市民の情報保持率を最も高める。しかし、破滅的なシナリオ(例:ワ クチン接種率が低いと伝染病が流行する)を過度にアピールすることは、陰謀論と関連する不安を誘発し、かえって陰謀論への信仰を高める可能性がある。恐怖 を煽る戦術は時にさまざまな結果をもたらすが、一般的には効果がないと考えられている。その例として、喫煙が歯の健康に与える影響など、健康に悪影響を及 ぼす結果を紹介する画像の使用が挙げられる。考えられる説明のひとつは、恐怖反応を介して処理される情報は一般的に合理的に評価されないため、メッセージ が望ましい行動に結びつくのを妨げる可能性があるということである[9]。 特に重要な技法は、フォーカスグループを利用して、人々が何を信じているのか、またその理由を正確に理解することである。これによって、人々が認識してい る具体的な懸念事項や、一般大衆に誤解されやすいトピックに焦点を当てたメッセージングが可能になる。加えて、フォーカス・グループとの議論やグループ・ ダイナミクスの観察によって、どのような反陰謀主義的な考えが最も広まりやすいかを示すことができる[9]。 無力感を軽減することで医療陰謀論に対処する介入策としては、インフォームド・コンセントの原則を強調し、患者に決定を押し付けることなく関連するすべて の情報を与え、患者がコントロールできるという感覚を持てるようにすることが挙げられる。医療へのアクセスを改善することも、医療陰謀論を減らすことにな る。しかし、政治的な努力によってそうすることは、米国の医療費負担適正化法(オバマケア)で起こったように、さらなる陰謀論を煽ることにもなりかねな い。もう一つの成功した戦略は、就学登録や運転免許取得などの要件を満たす際に、人々に短いビデオの視聴を義務付けることで、予防接種率や臓器提供の申し 込み率が向上することが実証されている[9]。 もう一つのアプローチは、陰謀論を個人的・文化的価値観を表現する物語とみなすことに基づくものであり、そのため単純な事実訂正の影響を受けにくく、対と なる物語によってより効果的に対処することができる[100][105]。対となる物語は、単純な訂正よりも魅力的で記憶に残りやすく、個人や文化が持つ 特定の価値観に適応させることができる。こうした語りは、個人的な経験を描くこともあれば、文化的な語りであることもある。ワクチン接種の文脈では、文化 的ナラティブの例として、科学的ブレークスルーの話、ワクチン接種以前の世界の話、英雄的で利他的な研究者の話などがある。取り上げるべきテーマは、ワク チンリスクに対する認識、患者のエンパワーメントの欠如、医療当局に対する信頼の欠如など、ワクチン接種へのためらいを増大させる陰謀論に利用されうるも のである[100]。 |

| Backfire effects It has been suggested that directly countering misinformation can be counterproductive. For example, since conspiracy theories can reinterpret disconfirming information as part of their narrative, refuting a claim can result in accidentally reinforcing it,[63][106] which is referred to as a "backfire effect".[107] In addition, publishing criticism of conspiracy theories can result in legitimizing them.[94] In this context, possible interventions include carefully selecting which conspiracy theories to refute, requesting additional analyses from independent observers, and introducing cognitive diversity into conspiratorial communities by undermining their poor epistemology.[94] Any legitimization effect might also be reduced by responding to more conspiracy theories rather than fewer.[49] There are psychological mechanisms by which backfire effects could potentially occur, but the evidence on this topic is mixed, and backfire effects are very rare in practice.[100][107][108] A 2020 review of the scientific literature on backfire effects found that there have been widespread failures to replicate their existence, even under conditions that would be theoretically favorable to observing them.[107] Due to the lack of reproducibility, as of 2020 most researchers believe that backfire effects are either unlikely to occur on the broader population level, or they only occur in very specific circumstances, or they do not exist.[107] Brendan Nyhan, one of the researchers who initially proposed the occurrence of backfire effects, wrote in 2021 that the persistence of misinformation is most likely due to other factors.[108] In general, people do reject conspiracy theories when they learn about their contradictions and lack of evidence.[9] For most people, corrections and fact-checking are very unlikely to have a negative impact, and there is no specific group of people in which backfire effects have been consistently observed.[107] Presenting people with factual corrections, or highlighting the logical contradictions in conspiracy theories, has been demonstrated to have a positive effect in many circumstances.[48][106] For example, this has been studied in the case of informing believers in 9/11 conspiracy theories about statements by actual experts and witnesses.[48] One possibility is that criticism is most likely to backfire if it challenges someone's worldview or identity. This suggests that an effective approach may be to provide criticism while avoiding such challenges.[106] |

逆効果 誤った情報に直接反論することは逆効果になる可能性が示唆されている。例えば、陰謀論は確証のない情報を自分たちの物語の一部として再解釈する可能性があ るため、主張に反論することで誤ってその主張を補強してしまう可能性があり[63][106]、これは「逆効果」と呼ばれている[107]。さらに、陰謀 論に対する批判を発表することで、陰謀論を正当化する結果にもなりかねない。 [94]この文脈では、どの陰謀論に反論すべきかを慎重に選択すること、独立した観察者に追加的な分析を依頼すること、陰謀論者の貧弱な認識論を弱体化さ せることによって陰謀論者のコミュニティに認知的多様性を導入することなどが可能な介入である[94]。 バックファイア効果が発生する可能性のある心理学的メカニズムが存在するが、このトピックに関する証拠はまちまちであり、バックファイア効果は実際には非 常にまれである[100][107][108]。2020年のバックファイア効果に関する科学文献のレビューでは、理論的にはバックファイア効果を観察す るのに有利な条件下であっても、その存在を再現することに広く失敗していることが判明した。 [107]再現性の欠如のため、2020年の時点でほとんどの研究者は、バックファイア効果はより広い集団レベルでは起こりにくいか、非常に特殊な状況で のみ起こるか、存在しないと考えている[107]。 一般的に、人々は陰謀説の矛盾や証拠の欠如を知ると、陰謀説を否定する[9]。ほとんどの人々にとって、訂正や事実確認が悪影響を及ぼす可能性は非常に低 く、バックファイア効果が一貫して観察されている特定の集団は存在しない。 [107] 事実の訂正を人々に提示したり、陰謀論の論理的矛盾を強調 したりすることは、多くの状況で肯定的な効果をもたらすことが実証 されている[48][106]。例えば、これは9.11陰謀論の信者に実際の専門 家や目撃者の発言を知らせるケースで研究されている[48]。このことは、そのような挑戦を避けながら批判を提供することが効果的なアプローチである可能 性を示唆している[106]。 |

| Psychology The widespread belief in conspiracy theories has become a topic of interest for sociologists, psychologists, and experts in folklore since at least the 1960s, when a number of conspiracy theories arose regarding the assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy. Sociologist Türkay Salim Nefes underlines the political nature of conspiracy theories. He suggests that one of the most important characteristics of these accounts is their attempt to unveil the "real but hidden" power relations in social groups.[109][110] The term "conspiracism" was popularized by academic Frank P. Mintz in the 1980s. According to Mintz, conspiracism denotes "belief in the primacy of conspiracies in the unfolding of history":[111]: 4 Conspiracism serves the needs of diverse political and social groups in America and elsewhere. It identifies elites, blames them for economic and social catastrophes, and assumes that things will be better once popular action can remove them from positions of power. As such, conspiracy theories do not typify a particular epoch or ideology.[111]: 199 Research suggests, on a psychological level, conspiracist ideation—belief in conspiracy theories—can be harmful or pathological,[20][21] and is highly correlated with psychological projection, as well as with paranoia, which is predicted by the degree of a person's Machiavellianism.[112] The propensity to believe in conspiracy theories is strongly associated with the mental health disorder of schizotypy.[113][114][115][116][117] Conspiracy theories once limited to fringe audiences have become commonplace in mass media, emerging as a cultural phenomenon of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[44][45][46][47] Exposure to conspiracy theories in news media and popular entertainment increases receptiveness to conspiratorial ideas, and has also increased the social acceptability of fringe beliefs.[28][118] Conspiracy theories often make use of complicated and detailed arguments, including ones which appear to be analytical or scientific. However, belief in conspiracy theories is primarily driven by emotion.[48] One of the most widely confirmed facts about conspiracy theories is that belief in a single conspiracy theory tends be correlated with belief in other conspiracy theories.[33][119] This even applies when the conspiracy theories directly contradict each other, e.g. believing that Osama bin Laden was already dead before his compound in Pakistan was attacked makes the same person more likely to believe that he is still alive. One conclusion from this finding is that the content of a conspiracist belief is less important than the idea of a coverup by the authorities.[33][95][120] Analytical thinking aids in reducing belief in conspiracy theories, in part because it emphasizes rational and critical cognition.[42] Some psychological scientists assert that explanations related to conspiracy theories can be, and often are "internally consistent" with strong beliefs that had previously been held prior to the event that sparked the conspiracy.[42] People who believe in conspiracy theories tend to believe in other unsubstantiated claims – including pseudoscience and paranormal phenomena.[121] |

心理学 陰謀論が社会学者、心理学者、民間伝承の専門家の間で広く信じられているのは、少なくとも1960年代、ジョン・F・ケネディ米大統領暗殺事件に関して多 くの陰謀論が生まれたときからである。社会学者のテュルケイ・サリム・ネフェスは、陰謀論の政治的性質を強調している。彼は、陰謀論の最も重要な特徴のひ とつは、社会集団における「現実的だが隠されている」権力関係を明らかにしようとする点にあると指摘している[109][110]。陰謀論」という用語 は、1980年代に学者のフランク・P・ミンツによって広められた。ミンツによれば、陰謀主義とは「歴史の展開における陰謀の優位性を信じること」である [111]: 4 陰謀論は、アメリカやその他の地域の多様な政治的・社会的集団のニーズに応えるものである。エリートを特定し、経済的・社会的大災害の原因を彼らになすり つけ、民衆の行動によって彼らを権力の座から追い出すことができれば、事態は好転すると仮定している。そのため、陰謀論は特定の時代やイデオロギーを代表 するものではない: 199 心理学的なレベルでは、陰謀論的なイデア-陰謀論を信じること-は有害であったり病的であったりすることが研究で示唆されており[20][21]、心理的 投影や、人のマキャベリズムの度合いによって予測されるパラノイアと高い相関がある[112]。 陰謀論を信じる傾向は統合失調症という精神衛生上の障害と強く関連している[113][114]。 [113][114][115][116][117]かつてはフリンジのオーディエンスに限られていた陰謀論は、マスメディアではありふれたものとなり、 20世紀後半から21世紀初頭の文化現象として出現した[44][45][46][47]。ニュースメディアや大衆娯楽において陰謀論に触れることは、陰 謀論的な考えに対する受容性を高め、フリンジ信仰の社会的受容性をも高めている[28][118]。 陰謀論はしばしば、分析的または科学的に見えるものも含め、複雑で詳細な議論を用いる。陰謀論について最も広く確認されている事実の一つは、一つの 陰謀論を信じることは、他の陰謀論を信じることと相関する傾向が あるということである[33][119]。これは、陰謀論が互いに直接矛盾してい る場合にも当てはまる。例えば、パキスタンにあるオサマ・ビンラディ ンのアジトが攻撃される前にオサマ・ビンラディンは既に死んでいたと信 じることで、同じ人が彼はまだ生きていると信じる可能性が高くなる。この発見から得られる一つの結論は、陰謀論者の信念の内容は、当局による隠蔽という考 えよりも重要ではないということである[33][95][120]。分析的思考は、合理的で批判的な認知を重視することもあり、陰謀論への信念を減らすの に役立つ[42]。 一部の心理科学者は、陰謀論に関連する説明は、陰謀の火付け役となった出来 事の前に抱いていた強い信念と「内的に一致」しうるし、しばしばそうであ ると主張している[42]。陰謀論を信じる人は、疑似科学や超常現象を含む、他の根拠のない 主張を信じる傾向がある[121]。 |

| Attractions Psychological motives for believing in conspiracy theories can be categorized as epistemic, existential, or social. These motives are particularly acute in vulnerable and disadvantaged populations. However, it does not appear that the beliefs help to address these motives; in fact, they may be self-defeating, acting to make the situation worse instead.[42][106] For example, while conspiratorial beliefs can result from a perceived sense of powerlessness, exposure to conspiracy theories immediately suppresses personal feelings of autonomy and control. Furthermore, they also make people less likely to take actions that could improve their circumstances.[42][106] This is additionally supported by the fact that conspiracy theories have a number of disadvantageous attributes.[42] For example, they promote a negative and distrustful view of other people and groups, who are allegedly acting based on antisocial and cynical motivations. This is expected to lead to increased alienation and anomie, and reduced social capital. Similarly, they depict the public as ignorant and powerless against the alleged conspirators, with important aspects of society determined by malevolent forces, a viewpoint which is likely to be disempowering.[42] Each person may endorse conspiracy theories for one of many different reasons.[122] The most consistently demonstrated characteristics of people who find conspiracy theories appealing are a feeling of alienation, unhappiness or dissatisfaction with their situation, an unconventional worldview, and a feeling of disempowerment.[122] While various aspects of personality affect susceptibility to conspiracy theories, none of the Big Five personality traits are associated with conspiracy beliefs.[122] The political scientist Michael Barkun, discussing the usage of "conspiracy theory" in contemporary American culture, holds that this term is used for a belief that explains an event as the result of a secret plot by exceptionally powerful and cunning conspirators to achieve a malevolent end.[123][124] According to Barkun, the appeal of conspiracism is threefold: First, conspiracy theories claim to explain what institutional analysis cannot. They appear to make sense out of a world that is otherwise confusing. Second, they do so in an appealingly simple way, by dividing the world sharply between the forces of light, and the forces of darkness. They trace all evil back to a single source, the conspirators and their agents. Third, conspiracy theories are often presented as special, secret knowledge unknown or unappreciated by others. For conspiracy theorists, the masses are a brainwashed herd, while the conspiracy theorists in the know can congratulate themselves on penetrating the plotters' deceptions.[124] This third point is supported by research of Roland Imhoff, professor of social psychology at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. The research suggests that the smaller the minority believing in a specific theory, the more attractive it is to conspiracy theorists.[125] Humanistic psychologists argue that even if a posited cabal behind an alleged conspiracy is almost always perceived as hostile, there often remains an element of reassurance for theorists. This is because it is a consolation to imagine that difficulties in human affairs are created by humans, and remain within human control. If a cabal can be implicated, there may be a hope of breaking its power or of joining it. Belief in the power of a cabal is an implicit assertion of human dignity—an unconscious affirmation that man is responsible for his own destiny.[126] People formulate conspiracy theories to explain, for example, power relations in social groups and the perceived existence of evil forces.[c][124][109][110] Proposed psychological origins of conspiracy theorising include projection; the personal need to explain "a significant event [with] a significant cause;" and the product of various kinds and stages of thought disorder, such as paranoid disposition, ranging in severity to diagnosable mental illnesses. Some people prefer socio-political explanations over the insecurity of encountering random, unpredictable, or otherwise inexplicable events.[127][128][129][130][131][132] According to Berlet and Lyons, "Conspiracism is a particular narrative form of scapegoating that frames demonized enemies as part of a vast insidious plot against the common good, while it valorizes the scapegoater as a hero for sounding the alarm".[133] |

魅力 陰謀論を信じる心理的動機は、認識論的動機、実存的動機、社会的動機に分類できる。これらの動機は、社会的弱者や不利な立場に置かれた人々において特に顕 著である。しかし、その信念がこれらの動機に対処するのに役立つとは 思われず、むしろ状況を悪化させるように作用し、自滅的であ る可能性がある[42][106]。例えば、陰謀論的信念は無力感から生じる可能性があ るが、陰謀論に触れることは、自律性や制御に対する個人的な感情を即 座に抑制する。さらに、陰謀論は人々が自分の状況を改善できるような行動を取る可能性を低くする[42][106]。 このことはさらに、陰謀論が多くの不利な属性を持っているという事実によっても裏付けられている[42]。例えば、陰謀論は、反社会的で皮肉な動機に基づ いて行動しているとされる他者や集団に対する否定的で不信感を助長する。これは疎外感やアノミーの増大、ソーシャル・キャピタルの減少につながると予想さ れる。同様に、陰謀論は、社会の重要な側面が悪意ある力によって決定され、陰謀を企てたとされる人々に対して一般大衆が無知で無力であると描いており、こ の視点は力を奪う可能性が高い[42]。 陰謀論に魅力を感じる人の特徴として最も一貫して示されているのは、疎外感、自分の置かれた状況に対する不幸や不満、型破りな世界観、脱力感である [122]。陰謀論に対する感受性には性格の様々な側面が影響するが、ビッグファイブの性格特性のどれもが陰謀論的信念とは関連していない[122]。 政治学者のマイケル・バーカンは、現代のアメリカ文化における「陰謀論」の用法について論じており、この用語は、ある出来事を、悪意ある目的を達成するた めの、特別に強力で狡猾な陰謀家たちによる秘密の陰謀の結果であると説明する信念に用いられるとしている[123][124]。 バーカンによれば、陰謀論の魅力は3つある: 第一に、陰謀論は制度分析では説明できないことを説明すると主張する。第一に、陰謀論は制度分析では説明できないことを説明しようとする。 第二に、陰謀論は世界を光の勢力と闇の勢力に峻別することによって、魅力的なほど単純な方法でそれを実現する。陰謀論は、すべての悪を、陰謀を企てる者と その手先という単一の源に遡らせる。 第三に、陰謀論はしばしば、他者には知られていない、あるいは認められていない特別な秘密の知識として提示される。陰謀論者にとって、大衆は洗脳された群 れであり、その一方で、陰謀を知る陰謀論者は、陰謀を企てる者の欺瞞を突き止めたことを自画自賛することができる[124]。 この第三の点は、ヨハネス・グーテンベルク大学マインツ校の社会心理学教授ローランド・イムホフの研究によって支持されている。この研究は、特定の理論を 信じる少数派が少なければ少ないほど、陰謀論者にとって魅力的であることを示唆している[125]。人間性心理学者は、陰謀疑惑の背後にある陰謀団がほと んど常に敵対的であると認識されているとしても、しばしば理論家にとって安心できる要素が残っていると主張する。というのも、人間関係の困難は人間が作り 出したものであり、人間がコントロールできる範囲にとどまっていると想像することが慰めになるからである。陰謀団が関与していることが分かれば、その力を 断ち切るか、その陰謀団に加わることができるかもしれない。陰謀団の力を信じることは、人間の尊厳を暗黙のうちに主張することであり、人間は自らの運命に 責任があるという無意識の肯定である[126]。 陰謀説の心理学的起源として提案されているものには、投影、「重要な原因による重要な出来事」を説明する個人的な必要性、診断可能な精神疾患に至る重症度 の偏執狂的気質など様々な種類や段階の思考障害の産物などがある。ベレットとライオンズによれば、「陰謀論はスケープゴーティングの特殊な物語形式であ り、悪魔化された敵を共通善に対する巨大で陰湿な陰謀の一部であるかのように仕立て上げる一方で、スケープゴートとなった人物を警鐘を鳴らした英雄として 評価する」[133]。 |

| Causes Some psychologists believe that a search for meaning is common in conspiracism. Once cognized, confirmation bias and avoidance of cognitive dissonance may reinforce the belief. In a context where a conspiracy theory has become embedded within a social group, communal reinforcement may also play a part.[134] Inquiry into possible motives behind the accepting of irrational conspiracy theories has linked[135] these beliefs to distress resulting from an event that occurred, such as the events of 9/11. Additional research suggests that "delusional ideation" is the trait most likely to indicate a stronger belief in conspiracy theories.[136] Research also shows an increased attachment to these irrational beliefs leads to a decreased desire for civic engagement.[84] Belief in conspiracy theories is correlated with low intelligence, lower analytical thinking, anxiety disorders, paranoia, and authoritarian beliefs.[137][138][139] Professor Quassim Cassam argues that conspiracy theorists hold their beliefs due to flaws in their thinking and more precisely, their intellectual character. He cites philosopher Linda Trinkaus Zagzebski and her book Virtues of the Mind in outlining intellectual virtues (such as humility, caution and carefulness) and intellectual vices (such as gullibility, carelessness and closed-mindedness). Whereas intellectual virtues help in reaching sound examination, intellectual vices "impede effective and responsible inquiry", meaning that those who are prone to believing in conspiracy theories possess certain vices while lacking necessary virtues.[140] Some researchers have suggested that conspiracy theories could be partially caused by psychological mechanisms the human brain possesses for detecting dangerous coalitions. Such a mechanism could have been useful in the small-scale environment humanity evolved in but are mismatched in a modern, complex society and thus "misfire", perceiving conspiracies where none exist.[141] |

原因 一部の心理学者は、陰謀論には意味の探求が一般的だと考えている。いったん認知されると、確証バイアスと認知的不協和の回避が信念を強化する可能性があ る。陰謀論が社会集団の中に埋め込まれている状況では、共同体的な強化も一役買っている可能性がある[134]。 非合理的な陰謀論を受け入れる背後にある可能性のある動機につい ての調査では、こうした信念が、9.11の出来事のような、発生した出来事に起因 する苦痛と関連している[135]。さらなる研究によると、「妄想的な考え」は陰謀論への信 念が強いことを示す可能性が最も高い特性である[136]。 研究はまた、こうした非合理的な信念への執着が高まると、市民参加への欲求が低下することも示している[84]。 陰謀論への信念は、低い知能、低い分析的思考、不安障害、パラノイア、権威主義的信念と相関している[137][138][139]。 クアッシム・カッサム教授は、陰謀論者は思考の欠陥、より正確には知的性格の欠陥のために信念を持っていると主張している。彼は哲学者リンダ・トリンカウ ス・ザグゼブスキーと彼女の著書『心の美徳』を引き合いに出し、知的美徳(謙虚さ、注意深さ、慎重さなど)と知的悪徳(だまされやすさ、不注意、閉鎖的な 考え方など)を概説している。知的美徳が健全な検証に到達するのに役立つのに対して、知的悪徳は「効果的で責任ある探究を妨げる」ものであり、陰謀論を信 じやすい人々は、必要な美徳を欠いている一方で、ある種の悪徳を持っていることを意味している[140]。 陰謀論は、人間の脳が危険な連合を察知するための心理的メカニズムによって部分的に引き起こされている可能性を示唆する研究者もいる。このようなメカニズ ムは、人類が進化してきた小規模な環境では有用であったかもしれないが、現代の複雑な社会ではミスマッチであるため、「誤作動」を起こし、何も存在しない ところで陰謀を察知してしまうのである[141]。 |

| Projection Some historians have argued that psychological projection is prevalent amongst conspiracy theorists. This projection, according to the argument, is manifested in the form of attribution of undesirable characteristics of the self to the conspirators. Historian Richard Hofstadter stated that: This enemy seems on many counts a projection of the self; both the ideal and the unacceptable aspects of the self are attributed to him. A fundamental paradox of the paranoid style is the imitation of the enemy. The enemy, for example, may be the cosmopolitan intellectual, but the paranoid will outdo him in the apparatus of scholarship, even of pedantry. ... The Ku Klux Klan imitated Catholicism to the point of donning priestly vestments, developing an elaborate ritual and an equally elaborate hierarchy. The John Birch Society emulates Communist cells and quasi-secret operation through "front" groups, and preaches a ruthless prosecution of the ideological war along lines very similar to those it finds in the Communist enemy. Spokesmen of the various fundamentalist anti-Communist "crusades" openly express their admiration for the dedication, discipline, and strategic ingenuity the Communist cause calls forth.[130] Hofstadter also noted that "sexual freedom" is a vice frequently attributed to the conspiracist's target group, noting that "very often the fantasies of true believers reveal strong sadomasochistic outlets, vividly expressed, for example, in the delight of anti-Masons with the cruelty of Masonic punishments".[130] |

投影 陰謀論者には心理的投影が蔓延していると主張する歴史家もいる。その主張によれば、この投影は、自己の好ましくない特徴を陰謀論者に帰属させるという形で 現れる。歴史家のリチャード・ホフスタッターは次のように述べている: この敵は、多くの点で、自己の投影であると思われる。自己の理想的な側面と受け入れがたい側面の両方が、敵に帰属しているのである。被害妄想的なスタイル の基本的な逆説は、敵を模倣することである。例えば、敵はコスモポリタンな知識人かもしれないが、偏執狂は学問の装置や衒学においてさえ、彼を凌駕す る。... クー・クラックス・クランは、司祭の法衣を着るところまでカトリシズムを模倣し、精巧な儀式と同様に精巧なヒエラルキーを発展させた。ジョン・バーチ協会 は、共産主義者の細胞や「フロント」グループによる準秘密活動を模倣し、共産主義者の敵に見られるものと非常によく似た路線で、イデオロギー戦争を冷酷に 遂行することを説いている。さまざまな原理主義的な反共「十字軍」のスポークスマンは、共産主義の大義が呼び起こす献身、規律、戦略的な工夫に対する賞賛 を公然と表明している[130]。 ホーフスタッターはまた、「性的自由」が陰謀論者のターゲットとする集団に頻繁に起因する悪癖であることを指摘し、「真の信者の空想は、強いサドマゾヒズ ムの出口を明らかにすることが非常に多く、例えば、メーソンの残酷な処罰に対する反メーソンの喜びの中に鮮明に表現されている」と述べている[130]。 |