Culture(s) of Poverty

Oscar Lewis,

1914-1970, picture from University

of Illinois Archives

貧困の文化

Culture(s) of Poverty

Oscar Lewis,

1914-1970, picture from University

of Illinois Archives

解説:池田光穂

☆「貧民に文化はないと考える人には、「貧困

の文化」という概念は名辞矛盾のように思えるかもしれない。また貧しさに風格と地位を与えるものに思えるかもしれない。私の意図はそういうことではないの

だ。人類学上の用法では、文化という語は本質的には、世代から世代へ伝えられる生活の構想を含意するものである」(オスカー・ルイス1969a:xix)

★貧困の文化とは、貧困を経験した人々の価値観が、貧困状態を永続させ、世代を超えて貧困の連鎖を持続させる上で 重要な役割を果たすと主張する社会理論の概念で ある。オスカー・ルイスが最初に提唱した。1970年代に政策的な注目を集め、学術的な批判を受け(Goode & Eames 1996; Bourgois 2001; Small, Harding & Lamont 2010)、21世紀の初めに復活した[1]。

★反貧困プログラムにもかかわらず貧困が存在する理由を説明する一つの方法を提供している。初期の形成は、貧 困層が資源に乏しく、貧困を永続させる価値観を身につけていることを示唆している。初期の貧困の文化論の批評家たちは、貧困の説明には、構造的要因がどの ように個々人の特質と相互作用し、条件付けしているかを分析する必要があると主張している(Goode & Eames 1996; Bourgois 2001; Small, Harding & Lamont 2010)。Small, Harding & Lamont (2010) が言うように、「人間の行動は、人々が自分の行動に与える意味によって制約され、また可能にされるのであるから、こうした力学は、貧困と社会的不平等の生 産と再生産を理解する上で中心となるべきである」。さらなる言説は、オスカー・ルイスの 仕事が誤解されていたことを示唆している[2]。

| The culture of

poverty

is a concept in social theory that asserts that the values of people

experiencing poverty play a significant role in perpetuating their

impoverished condition, sustaining a cycle of poverty across

generations. It attracted policy attention in the 1970s, and received

academic criticism (Goode & Eames 1996; Bourgois 2001; Small,

Harding & Lamont 2010), and made a comeback at the beginning of the

21st century.[1] It offers one way to explain why poverty exists

despite anti-poverty programs. Early formations suggest that poor

people lack resources and acquire a poverty-perpetuating value system.

Critics of the early culture of poverty arguments insist that

explanations of poverty must analyze how structural factors interact

with and condition individual characteristics (Goode & Eames 1996;

Bourgois 2001; Small, Harding & Lamont 2010). As put by Small,

Harding & Lamont (2010), "since human action is both constrained

and enabled by the meaning people give to their actions, these dynamics

should become central to our understanding of the production and

reproduction of poverty and social inequality." Further discourse

suggests thats Oscar Lewis’s work was misunderstood.[2] |

貧困の文化とは、貧困を経験した人々の価値観が、貧困状態を永続させ、世代を超えて貧困の連鎖を持続させる上で

重要な役割を果たすと主張する社会理論の概念で

ある。1970年代に政策的な注目を集め、学術的な批判を受け(Goode & Eames 1996; Bourgois 2001;

Small, Harding & Lamont

2010)、21世紀の初めに復活した[1]。反貧困プログラムにもかかわらず貧困が存在する理由を説明する一つの方法を提供している。初期の形成は、貧

困層が資源に乏しく、貧困を永続させる価値観を身につけていることを示唆している。初期の貧困の文化論の批評家たちは、貧困の説明には、構造的要因がどの

ように個々人の特質と相互作用し、条件付けしているかを分析する必要があると主張している(Goode & Eames 1996;

Bourgois 2001; Small, Harding & Lamont 2010)。Small, Harding &

Lamont (2010)

が言うように、「人間の行動は、人々が自分の行動に与える意味によって制約され、また可能にされるのであるから、こうした力学は、貧困と社会的不平等の生

産と再生産を理解する上で中心となるべきである」。さらなる言説は、オスカー・ルイスの

仕事が誤解されていたことを示唆している[2]。 |

| Overview De Antuñano, E. (2019) states the theory of the culture of poverty was popularized in 1958 by anthropologist Oscar Lewis, following his research in Mexico City. The culture of poverty frames low-income earners as existing within a culture that perpetuates poverty in a generational cycle. The theory suggests that the economic climate does not play a significant role in poverty. Those existing within a culture of poverty largely bring poverty upon themselves through acquired habits and behaviours. Oscar Lewis’s work sparked debates in the following decades. Many people disagree with his theory and believe it has little to no merit, De Antuñano, E. (2019) quotes that the culture of poverty was “denounced as methodologically vague and politically misguided.” [3] |

概要 De Antuñano, E. (2019)によれば、貧の困文化の理論は、1958年に人類学者オスカー・ルイスがメキシコシティでの調査後に広めたものである。貧困の文化は、低所得者が 世代的なサイクルで貧困を永続させる文化の中に存在するという枠組みである。この理 論は、貧困において経済情勢は重要な役割を果たさないことを示唆している。貧困文化の中に存在する人々は、後天的な習慣や行動を通じて、貧困を自ら招いて いるのである。オスカー・ルイスの研究は、その後数十年にわたって議論を巻き起こした。De Antuñano, E. (2019)は、貧困の文化は「方法論的に曖昧で政治的に見当違いであると非難された」と引用している。[3] |

| Early formulations The term "culture of poverty" (previously "subculture of poverty") made its first appearance in Lewis's ethnography Five Families: Mexican Case Studies in the Culture of Poverty.[4] Lewis struggled to render "the poor" as legitimate subjects whose lives were transformed by poverty. He argued that although the burdens of poverty were systemic and imposed upon these members of society, they led to the formation of an autonomous subculture as children were socialized into behaviors and attitudes that perpetuated their inability to escape the underclass. Early proponents of the theory argued that the poor are not only lacking resources but also acquire a poverty-perpetuating value system. According to anthropologist Oscar Lewis, "The subculture [of the poor] develops mechanisms that tend to perpetuate it, especially because of what happens to the worldview, aspirations, and character of the children who grow up in it". (Lewis 1969, p. 199) Lewis gave 70 characteristics (Lewis (1996), Lewis (1998)) that indicated the presence of the culture of poverty, which he argued was not shared among all of the lower classes. Oscar Lewis's interest in poverty inspired other cultural anthropologists to study poverty. Their interest was based on his idea of a culture of poverty.[5] The people in the culture of poverty have a strong feeling of marginality, of helplessness, of dependency, of not belonging. They are like aliens in their own country, convinced that the existing institutions do not serve their interests and needs. Along with this feeling of powerlessness is a widespread feeling of inferiority, of personal unworthiness. This is true of the slum dwellers of Mexico City, who do not constitute a distinct ethnic or racial group and do not suffer from racial discrimination. In the United States the culture of poverty of African Americans has the additional disadvantage of racial discrimination. People with a culture of poverty have very little sense of history. They are a marginal people who know only their own troubles, their own local conditions, their own neighborhood, their own way of life. Usually, they have neither the knowledge, the vision nor the ideology to see the similarities between their problems and those of others like themselves elsewhere in the world. In other words, they are not class conscious, although they are very sensitive indeed to status distinctions. Although Lewis (1998) was concerned with poverty in the developing world, the culture of poverty concept proved attractive to US public policy makers and politicians. It strongly informed documents such as the Moynihan Report (1965) as well as the War on Poverty. The culture of poverty emerges as a key concept in Michael Harrington's discussion of American poverty in The Other America.[6] For Harrington, the culture of poverty is a structural concept defined by social institutions of exclusion that create and perpetuate the cycle of poverty in America. Some later scholars[who?] contend that the poor do not have different values.[citation needed]  Chicago ghetto on the South Side, May 1974 |

初期の定式化 貧困の文化」(以前は「貧困のサブカルチャー」)という用語が初めて登場したのは、ルイスの民族誌『5つの家族』である[4]: ルイスは、「貧困層」を、貧困によって生活が変容する正当な主体として位置づけようと苦闘した。彼は、貧困の重荷は制度的なものであり、社会のこれらの構 成員に課されたものではあるが、子どもたちが下層階級から逃れられないことを永続させる行動や態度に社会化されるにつれて、自律的なサブカルチャーの形成 につながると主張した。 この理論の初期の支持者たちは、貧困層は資源が不足しているだけでなく、貧困を永続させる価値観を身につけていると主張した。人類学者のオスカー・ルイス によれば、「(貧困層の)サブカルチャーは、特にその中で育つ子どもたちの世界観、願望、性格に何が起こるかという理由から、それを永続させる傾向のある メカニズムを発達させる」(Lewis 1969, p. 1969)。(ルイス1969、p.199)。 ルイスは、貧困の文化の存在を示す70の特徴(Lewis (1996), Lewis (1998))を挙げ、それはすべての下層階級に共有されているわけではないと主張した。オスカー・ルイスの貧困に対する関心は、他の文化人類学者たちに 貧困を研究するよう促した。彼らの関心は彼の貧困文化という考えに基づいていた[5]。 貧困の文化の中にいる人々は、疎外感、無力感、依存心、居場所のなさを強く感じている。彼らは自国の外国人のようであり、既存の制度が自分たちの利益や ニーズに役立たないと確信している。この無力感とともに、劣等感、個人的な無価値感が蔓延している。これはメキシコシティのスラムに住む人々にも言えるこ とだが、彼らは明確な民族や人種集団を構成しているわけではなく、人種差別に苦しんでいるわけでもない。アメリカでは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の貧困文化に は、人種差別という欠点もある。 貧困の文化を持つ人々は、歴史に対する感覚が希薄である。自分たちの問題、自分たちの地域の状況、自分たちの地域、自分たちの生き方しか知らない、周縁的 な人々である。通常、彼らは自分たちの問題と、世界の他の場所で自分たちと同じような人々が抱える問題の共通点を見出す知識も、視野も、イデオロギーも持 ち合わせていない。つまり、身分の区別には敏感だが、階級意識はないのだ。 Lewis(1998)は開発途上国の貧困に関心を寄せていたが、貧困の文化という概念は、米国の公共政策立案者や政治家にとって魅力的なものであった。 貧困文化は、モイニハン報告書『ニグロの家族』(1965)や貧困 戦争といった文書に強い影響を与えた。 貧困の文化は、マイケル・ハリントンの『もうひとつのアメリカ』(The Other America)におけるアメリカの貧困の議論において、重要な概念として登場する[6]。ハリントンにとって貧困の文化とは、アメリカにおける貧困の連 鎖を生み出し、永続させる排除の社会制度によって定義される構造的概念である。 後の学者[誰?]の中には、貧困層は異なる価値観を持っていないと主張する者もいる[要出典]。  Chicago ghetto on the South Side, May 1974 |

| Reactions Since the 1960s, critics of the culture of poverty explanations for the persistence of the underclasses have attempted to show that real world data does not fit Lewis's model (Goode & Eames 1996). In 1974, anthropologist Carol Stack issued a critique of it, calling it "fatalistic" and noticed that believing in the idea of a culture of poverty does not describe the poor so much as it serves the interests of the rich. She writes, citing Hylan Lewis another critic of Oscar Lewis' Culture of Poverty The culture of poverty, as Hylan Lewis points out, has a fundamental political nature. The ideas matter most to political and scientific groups attempting to rationalize why some Americans have failed to make it in American society. It is, Lewis (1971) argues, “an idea that people believe, want to believe, and perhaps need to believe.” They want to believe that raising the income of the poor would not change their life styles or values, but merely funnel greater sums of money into bottomless, self-destructing pits. This fatalistic view has wide acceptance among scholars, welfare planners, and voters. At the most prestigious university, the country's theories alleging racial inferiority have become increasingly prevalent. [7] She demonstrates the way that political interests to keep the wages of the poor low create a climate in which it is politically convenient to buy into the idea of culture of poverty (Stack 1974). In sociology and anthropology, the concept created a backlash, pushing scholars to look to structures rather than "blaming-the-victim" (Bourgois 2001). Since the late 1990s, the culture of poverty has witnessed a resurgence in social sciences, but most scholars now reject the notion of a monolithic and unchanging culture of poverty. Newer research typically rejects the idea that whether people are poor can be explained by their values. It is often reluctant to divide explanations into "structural" and "cultural," because of the increasingly questionable utility of this old distinction.[8] An example of this is discussed by critical race theorist Gloria Ladson-Billings (2017). She observed the culture of poverty theory used to explain why some urban schools are unsuccessful. She says that parents of children in low-income families care immensely for their children, and encourage their education and success. Ladson-Billings (2017) quotes that, “ I find the culture of poverty discourse so disturbing because it distorts the concept of culture and absolves social structures—government and institutional— of responsibility for the vulnerabilities that poor children regularity face.” [9] |

反応 1960年代以降、貧困層の存続を説明する「貧困の文化」に対する批判者たちは、現実世界のデータがルイスのモデルに当てはまらないことを示そうとしてき た(Goode & Eames 1996)。1974年、人類学者のキャロル・スタックは、これを「宿命論的」と呼び、貧困文化という考え方を信じることは、貧困層を説明するものではな く、富裕層の利益に資するものであると指摘し、批判を発表した。 彼女は、オスカー・ルイスの『貧困の文化』のもう一人の批判者であるハイラン・ルイスを引き合いに出して、次のように書いている。 ハイラン・ルイスが指摘するように、貧困の文化には根本的な政治性がある。その考え方は、なぜ一部のアメリカ人がアメリカ社会で成功できなかったのかを合 理化しようとする政治的・科学的グループにとって最も重要である。ルイス(1971)は、「人々が信じ、信じたいと思い、そしておそらく信じる必要がある 考え」だと論じている。貧困層の所得を引き上げても、彼らの生活様式や価値観が変わるわけではなく、底なしの自滅の淵に大金が流れ込むだけだと信じたいの だ。この宿命論的見解は、学者、福祉プランナー、有権者の間で広く受け入れられている。最も権威ある大学では、人種的劣等を主張する国の理論がますます広 まっている。 [7] 彼女は、貧困層の賃金を低く抑えようとする政治的利害が、貧困の文化という考え方を受け入れることが政治的に都合がよいという風潮を作り出していることを 実証している(Stack 1974)。社会学や人類学では、この概念は反発を生み、学者たちは「被害者を責める」のではなく、むしろ構造に目を向けるようになった (Bourgois 2001)。 1990年代後半以降、貧困文化は社会科学において復活を遂げたが、現在ではほとんどの学者が、一枚岩で不変の貧困文化という概念を否定している。新しい 研究では、人々が貧しいかどうかは彼らの価値観によって説明できるという考え方を否定するのが一般的である。構造的」と「文化的」に説明を分けることには 消極的であることが多いが、それはこの古い区別の有用性がますます疑問視されているからである[8]。 この例については、批判的人種理論家のグロリア・ラドソン=ビリングス(2017年)が論じている。彼女は、一部の都市部の学校が成功しない理由を説明す るために使用される貧困の文化理論を観察した。彼女によれば、低所得家庭の子どもたちの親は子どもたちのことを非常に気にかけており、彼らの教育と成功を 奨励している。ラドソン=ビリングス(2017)は、「貧困の文化という言説は、文化の概念を歪め、貧困層の子どもたちが常日頃直面している脆弱性に対す る社会構造(政府や組織)の責任を免除するものであるため、とても不穏なものだと感じる」と引用している。[9] |

| Further discourse Hill, R. (2002) states that some recent scholars believe the work of Oscar Lewis on the culture of poverty was misinterpreted. They believe his theory was not intended to suggest that low-income earners choose to live in poverty. They believe the culture of poverty is a result of coping mechanisms developed by low-income earners. It helps them accept their circumstances, which takes a great deal of personal strength. Recent scholars also suggest that Oscar Lewis acknowledged institutional shortcomings.[10] According to Kurtz, D. (2014), Oscar Lewis studied and acknowledged how traumatic poverty is. During his research in Mexico in the 1950s, he discovered ways people cope and manage their impoverished state. Oscars Lewis's work inspired cultural anthropologists to study the culture of poverty. Kurtz, D. (2014) states the research concludes that “ Poverty has always been more than a social and economic issue. The politics of poverty always exists dialectically among competing interests that use power either to allocate or withhold aid to the impoverished depending upon whether those who possess power think that the poor either deserve or do not deserve relief from their impoverishment.” [11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_poverty |

さらなる言説 Hill, R. (2002)は、最近の学者の中には、貧困文化に関するオスカー・ルイスの研究は誤解されていると考える者もいると述べている。彼らは、彼の理論は、低所 得者が貧困の中で生きることを選択することを示唆するものではなかったと考えている。彼らは、貧困文化は低所得者が発達させた対処メカニズムの結果である と考えている。それは、彼らが自分の置かれた状況を受け入れるのを助けるものであり、個人的に大きな力を必要とする。最近の学者たちは、オスカー・ルイス が制度上の欠点を認めていたことも示唆している。 Kurtz, D. (2014)によれば、オスカー・ルイスは貧困がいかにトラウマ的であるかを研究し、認めていた。1950年代にメキシコで調査した際、彼は人々が貧困状 態に対処し、管理する方法を発見した。オスカー・ルイスの研究は、文化人類学者が貧困の文化を研究するきっかけとなった。Kurtz, D. (2014)は、研究の結論として「貧困は常に社会的、経済的な問題以上のものであった。貧困の政治は常に、権力を持つ者が貧困者を貧困からの救済に値す ると考えるか、そうでないと考えるかによって、権力を使って貧困者への援助を配分したり差し控えたりする、競合する利害関係者の間に弁証法的に存在する。 " |

| Attributions for poverty Cycle of poverty In-group favoritism In-group and out-group Involuntary unemployment Causes of income inequality in the United States Wealth inequality in the United States Welfare's effect on poverty When Work Disappears Economic inequality Pound Cake speech Desert (philosophy) Social inequality Unemployment Social mobility Social stigma Racism |

貧困の原因 貧困の連鎖(貧困のサイクル) 集団内贔屓 内集団と外集団 非自発的失業 米国における所得格差の原因 米国における富の不平等 生活保護が貧困に及ぼす影響 仕事がなくなるとき 経済的不平等 パウンドケーキのスピーチ 砂漠(哲学) 社会的不平等 失業 社会的流動性 社会的汚名 人種差別 |

| 1.

Small, Mario Luis; Harding, David J.; Lamont, Michèle (2010-05-01).

"Reconsidering Culture and Poverty". The Annals of the American Academy

of Political and Social Science. 629 (1): 6–27.

doi:10.1177/0002716210362077. ISSN 0002-7162. 2. Cohen, Patricia (2010-10-18). "'Culture of Poverty' Makes a Comeback". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2025-01-30. 3. Hill, Ronald Paul (September 2002). "Consumer Culture and the Culture of poverty: Implications for Marketingtheory and Practice". Marketing Theory. 2 (3): 273–293. doi:10.1177/1470593102002003279. ISSN 1470-5931. S2CID 145326406. 4. de Antuñano, Emilio (2018-04-12). "Mexico City as an Urban Laboratory: Oscar Lewis, the "Culture of Poverty" and the Transnational History of the Slum". Journal of Urban History. 45 (4): 813–830. doi:10.1177/0096144218768501. ISSN 0096-1442. S2CID 220163153. 5. Lewis, Oscar (1959). Five Families: Mexican case studies in the culture of poverty. Basic Books. 6. Lewis, Oscar (1966). The Culture of Poverty. Scientific American . 7. Lewis, Oscar (1998-01-01). "The culture of poverty". Society. 35 (2): 7–9. doi:10.1007/BF02838122. ISSN 1936-4725. 8. Kurtz, Donald V (2014-08-21). "Culture, poverty, politics: Cultural sociologists, Oscar Lewis, Antonio Gramsci". Critique of Anthropology. 34 (3): 327–345. doi:10.1177/0308275x14530577. ISSN 0308-275X. S2CID 145787075. 9. Harrington, Michael (1962). The Other America: Poverty in the United States. Macmillan. ISBN 9781451688764. 10. Stack, Carol (1975). All our kin: strategies for survival in a Black community. New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0061319821. 11. Ladson-Billings, Gloria (September 2017). ""Makes Me Wanna Holler": Refuting the "Culture of Poverty" Discourse in Urban Schooling". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 673 (1): 80–90. doi:10.1177/0002716217718793. ISSN 0002-7162. S2CID 149226410. 12. Kurtz, Donald V (2014-08-21). "Culture, poverty, politics: Cultural sociologists, Oscar Lewis, Antonio Gramsci". Critique of Anthropology. 34 (3): 327–345. doi:10.1177/0308275x14530577. ISSN 0308-275X. S2CID 145787075. |

1.

スモール、マリオ・ルイス;ハーディング、デイヴィッド・J.;ラモント、ミシェル(2010年5月1日)。「文化と貧困の再考」。『アメリカ政治社会科

学アカデミー紀要』。629巻(1号):6–27頁。doi:10.1177/0002716210362077。ISSN 0002-7162. 2. コーエン、パトリシア (2010-10-18). 「『貧困の文化』が復活する」. ニューヨーク・タイムズ. ISSN 0362-4331. 2025-01-30 取得. 3. ヒル、ロナルド・ポール (2002年9月). 「消費文化と貧困文化:マーケティング理論と実践への示唆」. マーケティング理論. 2 (3): 273–293. doi:10.1177/1470593102002003279. ISSN 1470-5931. S2CID 145326406. 4. de Antuñano, Emilio (2018-04-12). 「都市実験場としてのメキシコシティ:オスカー・ルイス、『貧困の文化』、そしてスラムの越境的歴史」. 都市史ジャーナル. 45 (4): 813–830. doi:10.1177/0096144218768501. ISSN 0096-1442. S2CID 220163153. 5. ルイス, オスカー (1959). 『五つの家族:貧困文化に関するメキシコ事例研究』. ベーシック・ブックス. 6. ルイス, オスカー (1966). 『貧困の文化』. サイエンティフィック・アメリカン. 7. ルイス, オスカー (1998-01-01). 「貧困の文化」. ソーサエティ. 35 (2): 7–9. doi:10.1007/BF02838122. ISSN 1936-4725. 8. カート、ドナルド・V(2014-08-21)。「文化、貧困、政治:文化社会学者、オスカー・ルイス、アントニオ・グラムシ」。『人類学批評』。34巻 3号:327–345頁。doi:10.1177/0308275x14530577。ISSN 0308-275X. S2CID 145787075. 9. Harrington, Michael (1962). The Other America: Poverty in the United States. Macmillan. ISBN 9781451688764. 10. Stack, Carol (1975). 我らの同胞たち:黒人コミュニティにおける生存戦略。ニューヨーク:ハーパー・アンド・ロウ。ISBN 0061319821。 11. ラドソン=ビリングス、グロリア(2017年9月)。「叫びたくなる:都市部教育における『貧困文化』言説への反論」。アメリカ政治社会科学アカデミー紀 要。673 (1): 80–90. doi:10.1177/0002716217718793. ISSN 0002-7162. S2CID 149226410. 12. カーツ、ドナルド・V(2014-08-21)。「文化、貧困、政治:文化社会学者、オスカー・ルイス、アントニオ・グラムシ」『人類学批評』34巻3 号、327–345頁。doi:10.1177/0308275x14530577。ISSN 0308-275X。S2CID 145787075。 |

| Bourgois, Phillippe (2015)

[2001]. "Poverty, Culture of". International Encyclopedia of the Social

& Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition). pp. 719–721.

doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.12048-3. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5. Cohen, Patricia (18 October 2010). "Scholars Return to 'Culture of Poverty'". The New York Times. Duvoux, Nicolas (6 October 2010). "The culture of poverty reconsidered". Books and Ideas. ISSN 2105-3030. Goode, Judith; Eames, Edwin (1996). "An Anthropological Critique of the Culture of Poverty". In G. Gmelch; W. Zenner (eds.). Urban Life. Waveland Press. Harrington, Michael (1962). The Other America: Poverty in the United States. Macmillan. ISBN 9781451688764. Lewis, Oscar (1959). Five families; Mexican case studies in the culture of poverty. Basic Books. Lewis, Oscar (1969). "Culture of Poverty". In Moynihan, Daniel P. (ed.). On Understanding Poverty: Perspectives from the Social Sciences. New York: Basic Books. pp. 187–220. Lewis, Oscar (1996) [1966]. "The Culture of Poverty". In G. Gmelch; W. Zenner (eds.). Urban Life. Waveland Press. Lewis, Oscar (1998). "The culture of poverty". Society. 35 (2): 7–9. doi:10.1007/BF02838122. PMID 5916451. S2CID 144250495. Mayer, Susan E. (1997). What money can't buy: Family income and children's life chances. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-58733-5. LCCN 96034429. Small, Mario Luis; Harding, David J.; Lamont, Michèle (2010). "Reconsidering Culture and Poverty" (PDF). Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 629 (1): 6–27. doi:10.1177/0002716210362077. ISSN 0002-7162. S2CID 53443130. Stack, Carol B. (1974). All Our Kin: Strategies For Survival In A Black Community. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-013974-2. |

ブルゴワ、フィリップ(2015年)[2001年]。「貧困、文化とし

ての」。『社会・行動科学国際百科事典』(第2版)。719–721頁。doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.12048-

3。ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5。 コーエン、パトリシア(2010年10月18日)。「学者たちが『貧困の文化』に回帰する」。ニューヨーク・タイムズ。 デュヴー、ニコラ(2010年10月6日)。「貧困の文化の再考」。Books and Ideas. ISSN 2105-3030. グッド、ジュディス; イームズ、エドウィン (1996). 「貧困文化に対する人類学的批判」. G. グメルチ; W. ゼナー (編). 『都市生活』. ウェイブランド・プレス. ハリントン、マイケル(1962年)。『もうひとつのアメリカ:アメリカ合衆国の貧困』。マクミラン。ISBN 9781451688764。 ルイス、オスカー(1959年)。『五つの家族:貧困文化におけるメキシコ人ケーススタディ』。ベーシック・ブックス。 ルイス、オスカー(1969年)。「貧困文化」。ダニエル・P・モイニハン編『貧困を理解する:社会科学からの視点』ベーシック・ブックス刊、187-220頁。 ルイス、オスカー(1996年)[1966年]。「貧困の文化」。G. グメルチ、W. ゼナー編『都市生活』ウェーブランド・プレス刊。 ルイス、オスカー(1998)。「貧困の文化」。『Society』35巻2号:7–9頁。doi:10.1007/BF02838122。PMID 5916451。S2CID 144250495。 メイヤー、スーザン・E.(1997)。『お金で買えないもの:家族の収入と子どもの人生の機会』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-674-58733-5。LCCN 96034429。 スモール、マリオ・ルイス;ハーディング、デイヴィッド・J.;ラモント、ミシェル(2010)。「文化と貧困の再考」(PDF)。『アメリカ政治社会科 学アカデミー紀要』。629巻(1号):6–27頁。doi:10.1177/0002716210362077。ISSN 0002-7162. S2CID 53443130. スタック、キャロル・B. (1974). 『我らの親族:黒人コミュニティにおける生存戦略』. ハーパー&ロウ. ISBN 978-0-06-013974-2. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_poverty |

| Attributions for poverty

are the beliefs people hold about the causes of poverty. These beliefs

are defined in terms of attribution theory, which is a social

psychological perspective on how people make causal explanations about

events in the world.[1] In forming attributions, people rely on the

information that is available to them in the moment, and their

heuristics, or mental shortcuts.[2] When considering the causes of

poverty, people form attributions using the same tools: the information

they have and mental shortcuts that are based on their experiences.

Consistent with the literature on heuristics, people often rely on

shortcuts to make sense of the causes of their own behavior and that of

others, which often results in biased attributions.[3] This information

leads to perceptions about the causes of poverty, and in turn, ideas

about how to eradicate poverty. |

貧困の帰属(原因)とは、人民が貧困の原因について抱く信念である。これらの信念は帰属理論(attribution theory)

によって定義される。帰属理論とは、人民が世の中の出来事について因果関係を説明する方法を考察する社会心理学の視点である[1]。帰属を形成する際、人

民はその瞬間に利用可能な情報と、ヒューリスティック(精神的近道)に依存する。貧困の原因を考える際、人々は同じ手段で帰属を形成する。つまり、自身が

持つ情報と、経験に基づく思考の近道だ。ヒューリスティクスに関する文献と一致して、人々は自身の行動や他者の行動の原因を理解するために近道に頼ること

が多く、これがしばしば偏った帰属をもたらす。この情報は貧困の原因に関する認識を生み、ひいては貧困を根絶する方法についての考えへとつながる。 |

| Context/history of concept Key themes from attribution theory One finding in attribution theory is the actor-observer bias, where actors (someone taking an action) tend to attribute their own actions to situational cues, while observers (those observing the actor take action) may attribute the same action to stable, dispositional factors.[4] Due to the actor-observer bias, an observer may understand the intentions and drivers to a person's behavior to be very different from the intentions or drivers perceived by the actor. There is an asymmetry in information that is available and salient between the actor and the observer.[5] This bias has been cited in social psychology as the Fundamental Attribution Error.[3] An observer's impression of the dispositional causes of behavior is linked to the uniqueness of the behavior in the situation.[4] If an action seems unique to the person in a specific situation, where others act differently in the same situation, an observer is more likely to attribute the action to the person's individual characteristics. Another relevant tendency in forming attributions of behaviors is the augmentation principle: when external factors suppresses the likelihood of an action, the presence of these external factors heighten the perceived individual internal drivers of behavior.[5] In this situation, high risks or costs of taking an action introduced by external factors translates to greater dispositional attributions of the action to the actor. One example is the quintessential view of the American Dream: a person who successfully immigrated to the United States and created a prosperous life for herself and her family. This person's actions in creating success were made in a high-risk environment, in which an observer might attribute this person's actions to heightened levels internal resolve, determination, and ability. Related attribution tendencies are depicted by the covariation and configuration concepts. The covariation concept posits that when an observer has information about an effect at two points in time, the observer will draw covariation attributions, in which one factor is associated in a certain direction with the other factor.[1] The potential causes of the effect involve the person, the entity, and the time of the event. The phenomenology of attribution validity is born from this idea, in which responses to a particular stimulus are categorized by the distinctiveness of the effect in relation to the way other people and entities interact over time.[1] The configuration concept builds on this phenomenon, where an observer uses a single observation to depict a causal inference between two factors, if there are no other plausible causes for the effect salient to the observer.[1] The correspondence bias shows that people tend to assume that behavior is attributed to internal characteristics in the absence of other information.[6] In sum, people tend to believe that behavior reveals internal dispositions. |

概念の背景/歴史 帰属理論の主要テーマ 帰属理論における一つの知見は、行為者-観察者バイアスである。行為者(行動を起こす者)は自身の行動を状況的要因に帰属させる傾向がある一方、観察者 (行為者の行動を観察する者)は同じ行動を安定した性格的要因に帰属させることがある。[4] 行為者-観察者バイアスにより、観察者は人格の意図や動機を、行為者自身が認識する意図や動機とは大きく異なるものとして理解する可能性がある。行為者と 観察者の間で、入手可能な情報や注目される情報に非対称性が生じるのである。[5] このバイアスは社会心理学において「基本的帰属誤り」として引用されてきた。[3] 行動の気質的要因に対する観察者の印象は、その行動が状況において如何に独特であるかに関連している。[4] 特定の状況下で、他者が異なる行動を取る中で、ある行動がその人格に特有に見える場合、観察者はその行動をその人格の個人的特性に帰属させやすい。 行動帰属形成における別の関連傾向が「増幅原理」である。外部要因が行動発生確率を抑制する場合、その外部要因の存在は行動の内的要因としての個人特性の 認知度を高める。[5] この状況下では、外部要因による行動のリスクやコストの高さが、行為者への特性帰属を強める。典型的な例がアメリカン・ドリームの典型像だ。米国への移民 に成功し、自身と家族のために豊かな生活を作り上げた人格である。この人格の成功をもたらした行動は、高リスク環境下でなされたものであり、観察者はその 行動を、高まった内発的決意、決断力、能力に帰属させるかもしれない。 関連する帰属傾向は共変関係と構成概念によって説明される。共変関係概念は、観察者が二時点における効果の情報を持つ場合、一方の要因が他方と特定の方向 で関連する共変帰属を行うと主張する[1]。効果の潜在的原因には人格、実体、出来事の時間が関わる。帰属妥当性の現象学はこの考えから生まれた。特定の 刺激に対する反応は、他の人々や実体が時間をかけて相互作用する様子との関連性において、その効果の独自性によって分類されるのだ[1]。構成概念はこの 現象を発展させたもので、観察者が単一の観察から二つの要因間の因果推論を描く場合を指す。ただし、観察者にとって顕著な効果の他の妥当な原因が存在しな い場合に限られる。[1] 対応バイアスは、他の情報が欠如している場合、人々が行動を内的特性に帰属させがちであることを示す。[6] 要するに、人々は行動が内的傾向性を明らかにすると信じやすいのだ。 |

| Theory and/or experimental evidence Individual differences in attributions for poverty In the 1970s and 1980s, researchers found consistent preference among Americans for an individualistic view to explain poverty, which focuses the personal ability and effort-related factors.[7][8][9] This individualistic view aligns with tendencies to blame the poor for their condition, since the causes of poverty are perceived to be from personal deficiencies. This stems from the American societal influence of meritocratic values.[9] However, a study in 1996 in southern California found that structuralist views were more popular in explaining the causes of poverty, which displays more recently the influence of systemic and external drivers of poverty.[10] Identity and attributions for poverty The "underdog perspective" indicates that society's most disadvantaged groups, or underdogs, will support views that challenge the merit of the dominant group's privileged status.[11] Studies in England and the United States found support for this perspective by demonstrating that participants who favored egalitarian policy views were more likely to be in minority racial groups (nonwhite), have occupations with relatively lower prestige, be part of families with lower income, and identify as lower and working class. This perspective was reinforced in a study in southern California that assessed beliefs about the causes of poverty as being either individualistic - driven by ability and effort - or situational - caused by external and systemic forces.[10] Black and Latino participants, who are the minority in both southern California and in the U.S. at large, were more likely to favor the external determinants for poverty than white participants.[10] Consistent with the underdog perspective, women were more likely to favor the structural determinants of poverty than men.[10] Having lower income increased the likelihood of favoring the structural perspective on causes to poverty than individualistic determinants as well.[10] In a study of Australian adults in 1989, attributions for poverty were associated with respondents' own explanations about their personal background.[12] Individuals who felt that their experiences in life were driven by internal factors, such as their own disposition, efforts, and abilities, were more likely to attribute causes of poverty to internal factors. Individuals who felt that their life experiences were driven by chance or by other external factors outside one's control were associated with the sense that poverty was the result of societal or structural causes.[12] Political ideology and attributions for poverty There is evidence for associations between political ideology and attributions for poverty. Support for welfare policies, which is associated with more progressive political ideology, was positively associated with situational attributions for poverty and negatively associated with individualistic views.[9] On the other hand, conservative ideology was linked to less favorable opinions, less empathy, and more dislike of the welfare client than people with more liberal views.[13] Individuals with more societal determinations of poverty were less favorable towards politically conservative approaches to addressing poverty.[14] In sociological studies, researchers have identified strong relationships between assigning blame on individuals who are poor for their disadvantage and the belief that welfare programs are overfunded.[15][16][17] Participants' self reported ratings of conservatism were associated with support for an individualistic perspective on the causes of poverty, as well as the controllability of poverty, the amount of blame associated towards those who were in conditions of poverty, and anger felt towards individuals in poverty.[18] The same investigation revealed that conservatism was negatively correlated with a sense of pity towards people in poverty and a lower tendency to have prosocial intentions to help those in poverty.[18] Motivations in attributions for poverty People are motivated to form attributions that are consistent with perceptions of the world.[19] One consistency is based in the just world fallacy, in which people have a need to believe that the world is an orderly place, where people always get what they deserve eventually.[20] This belief affects a person's reaction to the suffering of others, where people tend to devalue those that appear to be suffering, primarily to fulfill this belief that people ultimately get the outcome in life that they deserve.[21] Additional research contributes to these motivated attributions for poverty, identifying that just world beliefs are associated with negative attitudes towards people in poverty.[22] American societal values, and the belief in the American Dream, are based in meritocracy, or the belief that people are rewarded for their merit.[9] Evidence from this area of work highlights attributions for poverty among individuals who face poverty or are otherwise marginalized in society. In controlled studies, individuals from disadvantaged groups that considered meritocratic values justified the disadvantage that they faced both in their personal lives and for their groups by noting a decreased perception of discrimination and increase in self and own-group stereotyping.[23] Experimental evidence There is evidence that attributions for poverty are malleable. There have been experimental manipulations aimed at shifting attributions from dispositional to situational when considering the drivers of poverty. Some successful manipulations include writing exercises where individuals listed reasons why someone may be in poverty but does not deserve to be.[24] Another experimental manipulation that shifted attributions from individual to situational involved simulations of poverty using the online game called SPENT, where participants must make a series of decisions on a very tight budget.[24] In these experiments, participants with greater situational attributions for poverty were more likely to support egalitarian policy and wealth redistribution policy in the United States than participants with more dispositional attributions for poverty.[24] |

理論および/または実験的証拠 貧困の帰属に関する個人差(異なる) 1970年代から1980年代にかけて、研究者らはアメリカ人が貧困を説明する際に個人主義的見解を一貫して好むことを発見した。この見解は個人の能力や 努力に関連する要因に焦点を当てるものである。[7][8][9] この個人主義的見解は、貧困の原因が個人の欠陥に起因すると認識されるため、貧困状態を貧困者の責任とする傾向と一致する。これはアメリカ社会における能 力主義的価値観の影響に起因する。[9] しかし1996年に南カリフォルニアで行われた研究では、貧困の原因説明において構造主義的見解がより支持されていることが判明した。これは近年、貧困の システム的・外的要因の影響が顕在化していることを示している。[10] 貧困のアイデンティティと帰属 「弱者視点」とは、社会で最も不利な立場にある集団、すなわち弱者が、支配的集団の特権的地位の正当性に異議を唱える見解を支持することを指す。[11] 英国と米国での研究は、平等主義的政策観を支持する参加者が、少数人種グループ(非白人)に属し、比較的社会的地位の低い職業に就き、低所得世帯の一員で あり、自身を下層階級・労働者階級と認識する傾向が強いことを実証し、この視点を裏付けた。この視点は、貧困の原因を「個人の能力や努力によるもの(個人 主義的)」か「外的・制度的要因によるもの(状況主義的)」かの認識を評価した南カリフォルニアの研究でも裏付けられた[10]。南カリフォルニアおよび 全米で少数派である黒人・ラテン系参加者は、白人参加者より貧困の外的決定要因を支持する傾向が強かった。[10] 弱者視点と一致して、女性は男性より貧困の構造的要因を支持する傾向が強かった。[10] 低所得層であることも、個人要因より貧困の構造的要因を支持する可能性を高めた。[10] 1989年のオーストラリア成人調査では、貧困の帰属要因は回答者自身の人格説明と関連していた。[12] 人生の経験が自身の気質・努力・能力といった内的要因によって駆動されると感じる個人は、貧困の原因を内的要因に帰属させる傾向が強かった。一方、人生経 験が偶然や制御不能な外的要因によって駆動されると感じる個人は、貧困が社会的・構造的要因の結果であるという認識と関連していた。[12] 政治的イデオロギーと貧困帰属 政治的イデオロギーと貧困帰属の関連性を示す証拠がある。より進歩的な政治的イデオロギーと関連する福祉政策への支持は、状況帰属の貧困観と正の相関を示 し、個人主義的見解とは負の相関を示した。[9] 一方で保守的なイデオロギーは、リベラルな見解を持つ人々と比較して、福祉受給者に対する好意的な意見の欠如、共感の不足、嫌悪感の増大と結びついてい た。[13] 貧困の社会的決定要因を強く認める個人は、貧困対策における政治的保守主義的アプローチに対して好意的ではなかった。[14] 社会学的研究では、貧困層の不利な状況を個人の責任と帰属させることと、福祉プログラムの過剰資金提供という信念との間に強い関連性が確認されている。 [15][16][17] 参加者が自己申告した保守性評価は、貧困の原因に対する個人主義的視点への支持、貧困の制御可能性、貧困状態にある者への帰属される責任の度合い、貧困層 への怒りと関連していた。[18] 同じ調査では、保守性は貧困層への憐憫の感情と負の相関を示し、貧困層を助けるための利他的意図を持つ傾向が低いことも明らかになった。[18] 貧困帰属における動機 人は世界観と整合する帰属を形成しようとする動機を持つ。[19] その一つが「公正世界誤謬」に基づく整合性である。これは世界が秩序ある場所であり、人は最終的に相応の報いを受けるという信念を必要とする現象だ。 [20] この信念は他者の苦悩への反応に影響し、人々は主に「人は最終的に相応の結果を得る」という信念を満たすため、苦悩しているように見える者を軽視する傾向 がある。[21] 貧困に対するこうした動機付けられた帰属を裏付ける追加研究では、公正世界信念が貧困層への否定的態度と関連していることが明らかになっている。[22] アメリカ社会の価値観やアメリカン・ドリームへの信仰は、実力主義、すなわち人の功績に応じて報われるという信念に基づいている。[9] この分野の研究証拠は、貧困に直面する個人や社会的に境界化された集団における貧困帰属を浮き彫りにしている。統制された研究では、不利な立場にある集団 の個人が、能力主義的価値観を正当化することで、個人生活や集団が直面する不利な状況を説明していた。具体的には、差別認識の低下と、自己及び自集団への ステレオタイプ化の増加が指摘されている。[23] 実験的証拠 貧困の原因帰属は可塑的であるという証拠が存在する。貧困の要因を考察する際、帰属を「個人の性質」から「状況」へ移行させる実験的操作が行われてきた。 成功した操作例には、貧困状態にあるが「貧困に値しない」理由を列挙する作文課題が含まれる。[24] 貧困の帰属を個人から状況へ移行させた別の実験操作では、オンラインゲーム「SPENT」を用いた貧困シミュレーションが用いられた。参加者は非常に厳し い予算内で一連の決断を下さねばならない。[24] これらの実験では、貧困に対する状況帰属が強い参加者は、性格帰属が強い参加者よりも、米国における平等主義政策や富の再分配政策を支持する傾向が強かっ た。[24] |

| Implications Attributions for poverty are associated with tendencies to help those in poverty and to support policies related to addressing poverty.[18][14] The perception that the cause of a person's need is due to controllable factors leads to neglect, while the perception of uncontrollable causes of need leads to feelings of pity and an increased tendency to offer help.[25] Relatedly, people who were randomly assigned to a condition that induced situational attributions for poverty were more supportive of egalitarian policy positions and of wealth redistribution in the U.S. when compared with people who were assigned to a condition that induced individual attributions for poverty.[24] There are individual, societal, and situational factors that inform perceptions about poverty, and these perceptions affect behaviors. |

示唆 人格の貧困の原因帰属は、貧困層への支援傾向や貧困対策政策への支持と関連している。[18][14] 人格の困窮が制御可能な要因によるという認識は無視を招く一方、制御不能な要因によるという認識は同情を呼び起こし、支援を提供する傾向を高める。 [25] 関連して、貧困を状況的帰属と認識させる条件に無作為に割り当てられた人々はその傾向が認められ、貧困を個人的帰属と認識させる条件に割り当てられた人々 よりも、米国における平等主義的政策立場や富の再分配をより支持する傾向があった。[24] 貧困に関する認識を形成する個人的・社会的・状況的要因が存在し、これらの認識は行動に影響を与える。 |

| Theories of poverty |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attributions_for_poverty |

| Theories on the causes of poverty are the foundation upon which poverty reduction strategies are based. While in developed nations poverty is often seen as either a personal or a structural defect, in developing nations the issue of poverty is more profound due to the lack of governmental funds. Some theories on poverty in the developing world focus on cultural characteristics as a retardant of further development. Other theories focus on social and political aspects that perpetuate poverty; perceptions of the poor have a significant impact on the design and execution of programs to alleviate poverty. |

貧困の原因に関する理論は、貧困削減戦略の基盤となるものである。 先進国では貧困は人格の欠陥か構造的な欠陥と見なされることが多いが、発展途上国民では政府資金の不足により貧困問題はより深刻だ。発展途上国民の貧困に 関する理論の中には、さらなる発展を阻害する要因として文化的特性に焦点を当てるものもある。他の理論は貧困を永続させる社会的・政治的側面に着目する。 貧困層に対する認識は、貧困緩和プログラムの設計と実施に重大な影響を及ぼす。 |

| Causes of poverty in the United States Poverty as a personal failing See also: individualism and Infrahumanisation When it comes to poverty in the United States, there are two main lines of thought. The most common line of thought within the U.S. is that a person is poor because of personal traits.[1] These traits in turn have caused the person to fail. Supposed traits range from personality characteristics, such as laziness, to educational levels. Despite this range, it is always viewed as the individual's personal failure not to climb out of poverty. This thought pattern stems from the idea of meritocracy and its entrenchment within U.S. thought. Meritocracy, according to Katherine S. Newman is "the view that those who are worthy are rewarded and those who fail to reap rewards must also lack self-worth."[2] This does not mean that all followers of meritocracy believe that a person in poverty deserves their low standard of living. Rather the underlying ideas of personal failure show in the resistance to social and economic programs such as welfare; a poor individual's lack of prosperity shows a personal failure and should not be compensated (or justified) by the state. |

アメリカにおける貧困の原因 貧困は個人の人格の失敗である 関連項目:個人主義と非人間化 アメリカにおける貧困については、主に二つの考え方がある。アメリカ国内で最も一般的な考え方は、貧困は個人の人格の特性によるものだということだ [1]。これらの特性が、その人格の失敗を引き起こしたのである。想定される特性は、怠惰といった性格的特徴から教育水準まで多岐にわたる。この幅広さに もかかわらず、貧困から抜け出せないのは常に個人の失敗と見なされる。この思考パターンは能力主義の思想と、それが米国思想に根付いていることに由来す る。キャサリン・S・ニューマンによれば、能力主義とは「価値ある者は報われ、報いを得られない者は自己価値も欠いているという見解」である。[2] これは能力主義の支持者全員が、貧困層が低水準の生活を当然受けると信じているわけではない。むしろ、個人の失敗という根底にある考え方は、福祉などの社 会経済プログラムへの抵抗に現れている。貧困層の繁栄の欠如は個人の失敗を示しており、国家によって補償(または正当化)されるべきではないというのだ。 |

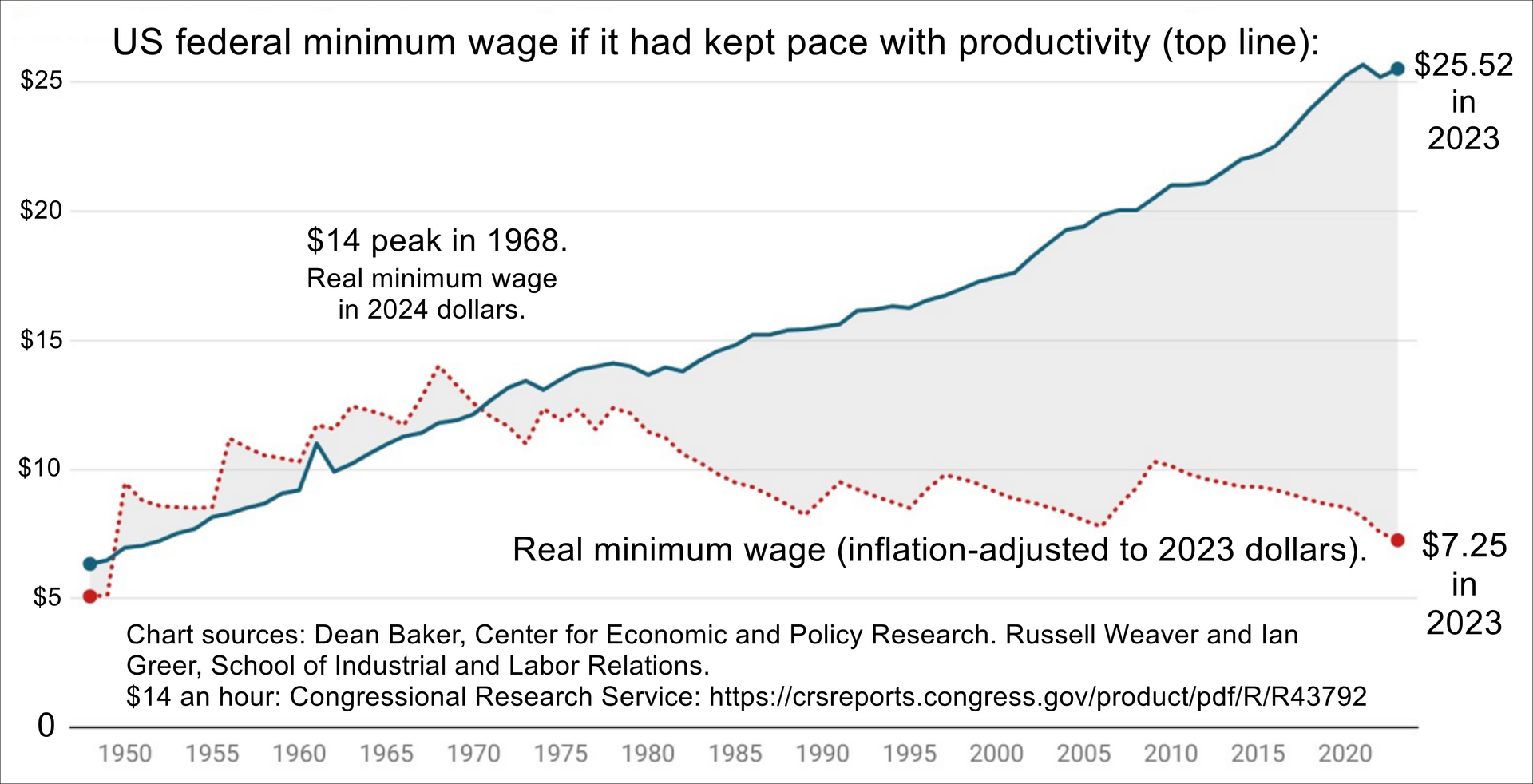

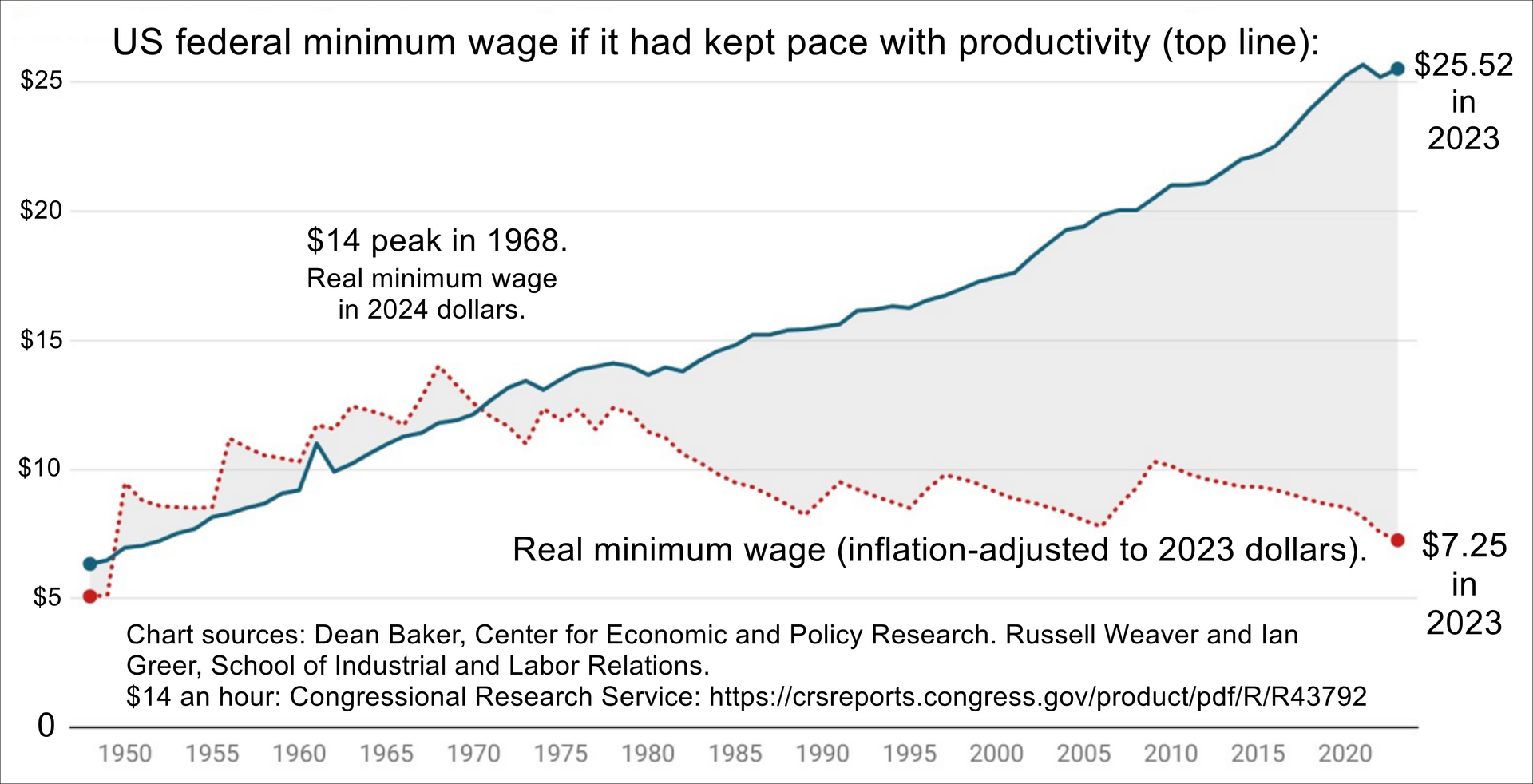

Poverty as a structural failing US federal minimum wage if it had kept pace with productivity. Also, the real minimum wage. Rank, Yoon, and Hirschl (2003) present a contrary argument to the idea that personal failings are the cause of poverty. The argument presented is that poverty in the United States is the result of "failings at the structural level."[3] Key social and economic structural failings which contribute heavily to poverty within the U.S. are identified in the article. The first is a failure of the job market to provide a proper number of jobs which pay enough to keep families out of poverty. Even if unemployment is low, the labor market may be saturated with low-paying, part-time work that lacks benefits (thus limiting the number of full-time, good paying jobs). Rank, Yoon and Hirschl examined the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), a longitudinal study on employment and income. Using the 1999 official poverty line of $17,029 for a family of four, it was found that 9.4% of persons working full-time and 14.9% of persons working at least part-time did not earn enough annually to keep them above the poverty line.[4] The investor, billionaire, and philanthropist Warren Buffett, one of the wealthiest people in the world,[5] voiced in 2005 and once more in 2006 his view that his class, the "rich class", is waging class warfare on the rest of society. In 2005 Buffet said to CNN: "It's class warfare, my class is winning, but they shouldn't be."[6] In a November 2006 interview in The New York Times, Buffett stated that "[t]here’s class warfare all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning."[7] One study[when?] showed that 29% of families in The United States could go six months or longer during a hardship with no income. Over 50% of respondents said around two months with no income and another 20% said they could not go longer than two weeks.[8] Low minimum wage, combined with part-time jobs which offer no benefits, have contributed to the labor market's inability to produce enough jobs which can keep a family out of poverty is an example of an economic structural failure.[1] Rank, Yoon and Hirschl point to the minimal amount of social safety nets found within the U.S. as a social structural failure and a major contributor to poverty in the U.S. Other industrialized nations devote more resources to assisting the poor than the U.S.[9] As a result of this difference poverty is reduced in nations which devote more to poverty reduction measure and programs. Rank et al. use a table to drive this point home. The table shows that in 1994, the actual rate of poverty (what the rate would be without government interventions) in the U.S. was 29%. When compared to actual rates in Canada (29%), Finland (33%), France (39%), Germany (29%), the Netherlands (30%), Norway (27%), Sweden (36%) and the United Kingdom (38%), the United States rate is low. But when government measures and programs are included, the rate of reduction in poverty in the United States is low (38%). Canada and the United Kingdom had the lowest reduction rates outside of the U.S. at 66%, while Sweden, Finland and Norway had reduction rates greater than 80%.[10] Redlining intentionally excluded black Americans from accumulating intergenerational wealth. The effects of this exclusion on black Americans' health continue to play out daily, generations later, in the same communities. This is evident currently in the disproportionate effects that COVID-19 has had on the same communities which the HOLC redlined in the 1930s. Research published in September 2020 overlaid maps of the highly affected COVID-19 areas with the HOLC maps, showing that those areas marked "risky" to lenders because they contained minority residents were the same neighborhoods most affected by COVID-19. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) looks at inequities in the social determinants of health like concentrated poverty and healthcare access that are interrelated and influence health outcomes with regard to COVID-19 as well as quality of life in general for minority groups. The CDC points to discrimination within health care, education, criminal justice, housing, and finance, direct results of systematically subversive tactics like redlining which led to chronic and toxic stress that shaped social and economic factors for minority groups, increasing their risk for COVID-19. Healthcare access is similarly limited by factors like a lack of public transportation, child care, and communication and language barriers which result from the spatial and economic isolation of minority communities from redlining. Educational, income, and wealth gaps that result from this isolation mean that minority groups' limited access to the job market may force them to remain in fields that have a higher risk of exposure to the virus, without options to take time off. Finally, a direct result of redlining is the overcrowding of minority groups into neighborhoods that do not boast adequate housing to sustain burgeoning populations, leading to crowded conditions that make prevention strategies for COVID-19 nearly impossible to implement.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17] Additionally, filial responsibility laws are usually not enforced, resulting in parents of adult children remaining more impoverished than otherwise. |

貧困は構造的な欠陥である 米国連邦最低賃金が生産性の上昇に追随していた場合の金額。また実質最低賃金。 ランク、ユン、ハーシュル(2003)は、貧困の原因が個人の人格にあるという考えに反論している。彼らの主張は、米国の貧困は「構造レベルでの欠陥」の 結果であるというものだ。[3] 本論文では、米国内の貧困に大きく寄与する主要な社会経済的構造的欠陥を特定している。第一に、家族を貧困から救うのに十分な賃金を支払う適切な数の雇用 を労働市場が提供できていないことだ。失業率が低くても、福利厚生のない低賃金のパートタイム労働で労働市場が飽和状態にある可能性がある(その結果、高 賃金のフルタイム職の数が制限される)。ランク、ユン、ハーシュルは雇用と所得に関する縦断調査「所得・プログラム参加調査(SIPP)」を分析した。 1999年の公式貧困ライン(4人家族で17,029ドル)を用いると、フルタイム労働者の9.4%、少なくともパートタイム労働者の14.9%の労働者 が、貧困ラインを上回る十分な年収を得られていないことが判明した。[4] 投資家、億万長者、慈善家であるウォーレン・バフェットは、世界で最も裕福な人々の一人[5]として、2005年と2006年に自身の階級である「富裕 層」が社会全体に対して階級闘争を仕掛けているとの見解を表明した。2005年、バフェットはCNNに対し「これは階級戦争だ。私の階級が勝っているが、 勝つべきではない」と述べた[6]。2006年11月のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のインタビューでは「確かに階級戦争は起きている。だが戦争を仕掛けてい るのは私の階級、富裕階級だ。そして我々が勝っている」と発言した[7]。 ある調査[時期不明]によれば、米国の世帯の29%は、収入が途絶えた困難な状況でも6か月以上耐えられるという。回答者の50%以上が収入なしで約2か 月間、さらに20%が2週間以上は耐えられないと答えた[8]。低賃金の最低賃金と福利厚生のないパートタイム労働が組み合わさり、家族を貧困から救える 十分な雇用を生み出せない労働市場の構造的失敗の一例だ[1]。 ランク、ユン、ハーシュルらは、米国における社会的安全網の不足を社会的構造的失敗と位置付け、貧困の主要因と指摘している。他の先進国の多くは、米国よ り貧困層支援に多くの資源を投入している[9]。この差の結果、貧困対策に注力する国民では貧困率が低下する。ランクらはこの点を強調するため表を用いて いる。この表は、1994年時点で米国の実際の貧困率(政府介入がなかった場合の率)が29%であったことを示している。カナダ(29%)、フィンランド (33%)、フランス(39%)、ドイツ(29%)、オランダ(30%)、ノルウェー(27%)、スウェーデン(36%)、英国(38%)の実際の貧困率 と比較すると、米国の数値は低い。しかし政府の対策やプログラムを含めると、米国の貧困率低下率は低い(38%)。米国以外ではカナダと英国が66%で最 も低く、スウェーデン、フィンランド、ノルウェーは80%を超える低下率を示した。[10] レッドライニングは意図的に黒人アメリカ人を世代を超えた富の蓄積から排除した。この排除が黒人アメリカ人の健康に与えた影響は、何世代も経った今も、同 じ地域社会で日々続いている。これは現在、1930年代にHOLCがレッドラインを引いた同じ地域社会がCOVID-19による不均衡な影響を受けている ことから明らかだ。2020年9月に発表された研究では、COVID-19の感染が深刻な地域の地図とHOLCの地図を重ね合わせ、少数民族住民が居住す る地域として貸し手にとって「リスクが高い」とされた地域が、COVID-19の影響を最も受けた地域と一致していることを示した。疾病対策センター (CDC)は、COVID-19に関する健康結果や少数派グループの一般的な生活の質に影響を与える、相互に関連し合う健康の社会的決定要因における不平 等、例えば貧困の集中や医療アクセスを検討している。CDCは、健康・教育・刑事司法・住宅・金融分野における差別を指摘する。レッドライニング(地域差 別的融資)のような体系的な破壊的戦術の直接的結果として生じた慢性的な有害ストレスが、少数派グループの健康・社会経済的要因を形成し、COVID- 19リスクを高めたのである。同様に、公共交通機関の不足、保育サービスの欠如、通信・言語障壁といった要因も健康アクセスを制限している。これらはレッ ドライニングによる少数派コミュニティの空間的・経済的孤立から生じている。この隔離から生じる教育・所得・資産格差は、少数派集団の雇用市場へのアクセ ス制限を意味し、ウイルス曝露リスクの高い職種に留まることを余儀なくされ、休暇を取る選択肢すら奪われる。最後に、レッドライニングの直接的な結果とし て、少数派集団が急増する人口を支える十分な住宅を備えていない地域に過密状態に押し込められ、COVID-19予防戦略の実施がほぼ不可能となる混雑状 態が生じている。[11][12][13][14][15][16][17] 加えて、親孝行義務法は通常施行されないため、成人した子供の親は本来よりも貧困状態に置かれたままとなる。 |

| Causes of poverty in developing nations Shiva Kumar - The importance of MDGs in redefining what are the poverty drivers Poverty as cultural characteristics Development plays a central role to poverty reduction in third world countries. Some authors feel that the national mindset itself plays a role in the ability of a country to develop and to thus reduce poverty. Mariano Grondona (2000) outlines twenty "cultural factors" which, depending on the culture's view of each, can be indicators as to whether the cultural environment is favorable or resistant to development. In turn Lawrence E. Harrison (2000) identifies ten "values" which, like Grondona's factors, can be indicative of the nation's developmental environment. Finally, Stace Lindsay (2000) claims the differences between development-prone and development-resistant nations is attributed to mental models (which, like values, influence the decisions humans make). Mental models are also cultural creations. Grondona, Harrison and Lindsay all feel that without development-orientated values and mindsets, nations will find it difficult if not impossible to develop efficiently, and that some sort of cultural change will be needed in these nations in order to reduce poverty. In "A Cultural Typology of Economic Development", from the book Culture Matters, Mariano Grondona claims development is a matter of decisions. These decisions, whether they are favorable to economic development or not, are made within the context of culture. All cultural values considered together create "value systems". These systems heavily influence the way decisions are made as well as the reactions and outcomes of said decisions. In the same book, Stace Lindsay's chapter claims the decisions individuals make are a result of mental models. These mental models influence all aspects of human action. Like Grondona's value systems, these mental models which dictate a nations stance toward development and hence its ability to deal with poverty. Grondona presents two ideal value systems (mental models), one of which has values only favoring development, the other only with value which resist development.[18] Real value systems fluctuate and fall somewhere between the two poles, but developed countries tend to bunch near one end, while undeveloped countries bunch near the other. Grondona goes on to identify twenty cultural factors on which the two value systems stand in opposition. These factors include such things as the dominant religion; the role of the individual in society; the value placed on work; concepts of wealth, competition, justice and time; and the role of education. In "Promoting Progressive Cultural Change", also from Culture Matters, Lawrence E. Harrison identifies values, like Grondona's factors, which differ between "progressive" cultures and "static" cultures. Religion, value of work, overall justice and time orientation are included in his list, but Harrison also adds frugality and community as important factors. Stace Lindsay also presents "patterns of thought" which differ between nations that stand at opposite poles of the developmental scale. Lindsay focuses more on economic aspects such as the form of capital focused upon and market characteristics. Key themes which emerge from these lists as characteristic of developmental cultures are: trust in the individual with a fostering of individual strengths; the ability for free thinking in an open, safe environment; importance of questioning/innovation; law is supreme and holds the power; future orientated time frame with an emphasis on achievable, practical goals; meritocracy; an autonomous mindset within the larger world; strong work ethic is highly valued and rewarded; a microeconomic focus; and a value that is non-economic, but not anti-economic, which is always wanting. Characteristics of the ideal non-developmental value system are: suppression of the individual through control of information and censorship; present/past time orientation with emphasis on grandiose, often unachievable, goals; macroeconomic focus; access to leaders allowing for easier and greater corruption; unstable distribution of law and justice (family and its connections matter most); and a passive mindset within the larger world. Grondona, Harrison, and Lindsay all feel that at least some aspects of development-resistant cultures need to change in order to allow under-developed nations (and cultural minorities within developed nations) to develop effectively. According to their argument, poverty is fueled by cultural characteristics within under-developed nations, and in order for poverty to be brought under control, said nations must move down the development path. |

発展途上国の貧困の原因 シヴァ・クマール - 貧困要因の再定義におけるMDGsの重要性 貧困を文化的特性として捉える 開発は第三世界諸国における貧困削減の中核的役割を担う。一部の研究者は、ナショナリズムそのものが、その国の発展能力、ひいては貧困削減能力に影響を与 えると指摘する。マリアーノ・グロンダナ(2000年)は、文化が各要素をどう捉えるかによって、その文化的環境が開発に有利か抵抗的かを示す指標となり 得る20の「文化的要因」を概説している。一方、ローレンス・E・ハリソン(2000年)は、グロンダナの要因と同様に、国民の開発環境を示す可能性のあ る10の「価値観」を特定している。最後に、ステイス・リンジー(2000)は、発展しやすい国民と発展しにくい国民の異なる点は、メンタルモデル(価値 観と同様に人間の意思決定に影響を与える)に起因すると主張している。メンタルモデルもまた文化的産物である。グロンドーナ、ハリソン、リンジーはいずれ も、発展志向の価値観やマインドセットがなければ、国民が効率的に発展することは困難か不可能であり、貧困削減のためには何らかの文化的変革が必要だと考 えている。 『文化が重要である』収録の「経済発展の文化的類型論」において、マリアーノ・グロンダナは、発展は意思決定の問題だと主張する。これらの意思決定は、経 済発展に有利か否かを問わず、文化の文脈の中で行われる。全ての文化的価値観が総合されて「価値観体系」を形成する。この体系は意思決定の方法、そしてそ の意思決定に対する反応や結果に大きく影響する。同書において、ステイス・リンゼイの章は、個人が下す決定はメンタルモデルの結果であると主張する。これ らのメンタルモデルは人間の行動のあらゆる側面に影響を与える。グロンドナの価値体系と同様に、これらのメンタルモデルは国民の発展に対する姿勢、ひいて は貧困に対処する能力を決定づける。 グロンドナは二つの理想的な価値体系(メンタルモデル)を提示する。一つは発展を促進する価値のみを持ち、もう一つは発展を阻害する価値のみを持つ。 [18] 実際の価値観体系は変動し、両極の間のどこかに位置するが、先進国は一方の端に、未開発国は他方の端に集まる傾向がある。グロンドナはさらに、両価値観体 系が対立する二十の文化的要因を特定する。これには支配的な宗教、社会における個人の役割、労働への評価、富・競争・正義・時間に関する概念、教育の役割 などが含まれる。同じく『文化が重要である』所収の「進歩的な文化的変化の促進」において、ローレンス・E・ハリソンは、グロンドナの要因と同様に、「進 歩的」文化と「静的」文化の間で異なる価値観を特定している。宗教、労働の価値、総合的な正義、時間観が彼のリストに含まれるが、ハリソンは倹約と共同体 も重要な要素として追加している。 ステイス・リンゼイもまた、発展段階の対極に位置する国民間で異なる「思考パターン」を提示している。リンゼイは資本の形態や市場特性といった経済的側面 に重点を置く。これらのリストから発展的文化的特質として浮かび上がる主要テーマは次の通りだ:個人の能力を育む個人への信頼、開放的で安全な環境下での 自由な思考能力、疑問視/革新の重要性、 法が至高の権威を持つこと;達成可能な現実的な目標を重視する未来志向の時間軸;実力主義;世界の中での自律的思考;強い労働倫理が高く評価され報われる こと;ミクロ経済への焦点;そして非経済的だが反経済的ではない、常に不足している価値。非発展的価値体系の理想的な特徴は以下の通りである:情報統制と 検閲による個人の抑圧;壮大で往々にして達成不可能な目標を重視する現在・過去志向;マクロ経済的焦点;指導者への接近が容易で腐敗を助長する構造;法と 正義の不安定な分配(家族とその繋がりが最も重要);そして広い世界における受動的な思考様式。 グロンドーナ、ハリソン、リンジーは、少なくとも開発抵抗文化のいくつかの側面は、未開発国民(および先進国内の文化的少数派)が効果的に発展するために 変革が必要だと考えている。彼らの主張によれば、貧困は未開発国内の文化的特性によって助長されており、貧困を制御するためには、それらの国民が開発の道 を歩まねばならない。 |

| Poverty as a label Various theorists believe the way poverty is approached, defined, and thus thought about, plays a role in its perpetuation. Maia Green (2006) explains that modern development literature tends to view poverty as agency filled. When poverty is prescribed agency, poverty becomes something that happens to people. Poverty absorbs people into itself and the people, in turn, become a part of poverty, devoid of their human characteristics. In the same way, poverty, according to Green, is viewed as an object in which all social relations (and persons involved) are obscured. Issues such as structural failings (see earlier section), institutionalized inequalities, or corruption may lie at the heart of a region's poverty, but these are obscured by broad statements about poverty. Arjun Appadurai writes of the "terms of recognition" (drawn from Charles Taylor's 'points of recognition'), which are given the poor and are what allows poverty to take on this generalized autonomous form.[19] The terms are "given" to the poor because the poor lack social and economic capital, and thus have little to no influence on how they are represented and/or perceived in the larger community. Furthermore, the term "poverty" is often used in a generalized matter. This further removes the poor from defining their situation as the broadness of the term covers differences in histories and causes of local inequalities. Solutions or plans for reduction of poverty often fail precisely because the context of a region's poverty is removed and local conditions are not considered. The specific ways in which the poor and poverty are recognized frame them in a negative light. In development literature, poverty becomes something to be eradicated, or, attacked.[20] It is always portrayed as a singular problem to be fixed. When a negative view of poverty (as an animate object) is fostered, it can often lead to an extension of negativity to those who are experiencing it. This in turn can lead to justification of inequalities through the idea of the deserving poor. Even if thought patterns do not go as far as justification, the negative light poverty is viewed in, according to Appadurai, does much to ensure little change in the policies of redistribution.[21] |

貧困というレッテル 様々な理論家は、貧困への取り組み方や定義の仕方、そしてそれによる認識の仕方が、貧困の永続化に関与していると考えている。マイア・グリーン (2006)は、現代の開発文献は貧困を主体性を持つものとして捉える傾向があると説明する。貧困に主体性が与えられると、貧困は人々に降りかかるものと なる。貧困は人々をその中に吸収し、人々は逆に貧困の一部となり、人間的な特徴を失ってしまうのだ。同様にグリーンによれば、貧困はあらゆる社会的関係 (及び関与する人格)が隠蔽された対象として捉えられる。構造的欠陥(前節参照)、制度化された不平等、腐敗といった問題が地域の貧困の核心にあるかもし れないが、こうした事実は貧困に関する大雑把な主張によって覆い隠されるのだ。アルジュン・アッパドゥライは「認識の条件」(チャールズ・テイラーの「認 識のポイント」に由来)について論じている。これは貧困者に与えられるものであり、貧困がこうした一般化された自律的な形態をとることを可能にするものだ [19]。貧困者が社会的・経済的資本を欠いているため、より大きな共同体における自らの表現や認識にほとんど影響力を持たないことから、これらの条件は 貧困者に「与えられる」のである。さらに「貧困」という用語は概括的に用いられることが多い。この広範な用語は地域的不平等の歴史的差異や原因を覆い隠す ため、貧困層が自らの状況を定義する機会をさらに奪う。貧困削減策や計画が失敗するのは、まさに地域の貧困の文脈が排除され、現地の条件が考慮されないか らだ。 貧困層や貧困が認識される具体的な方法は、彼らを否定的な光で捉える。開発文献では、貧困は根絶すべきもの、あるいは攻撃すべき対象となる[20]。常に 単一の解決すべき問題として描かれるのだ。貧困を否定的に捉える見方(生命を持つ対象として)が育まれると、その否定性が貧困を経験する人々へも拡大され がちだ。これが「自業自得の貧者」という概念を通じて不平等を正当化する結果を招く。たとえ思考パターンが正当化まで至らなくとも、アッパドゥライによれ ば、貧困が否定的に見られることは再分配政策にほとんど変化をもたらさない要因となっている。 |

| Poverty as restriction of opportunities The environment of poverty is one marked with unstable conditions and a lack of capital (both social and economical) which together create the vulnerability characteristic of poverty.[22] Because a person's daily life is lived within the person's environment, a person's environment determines daily decisions and actions based on what is present and what is not. Dipkanar Chakravarti argues that the poor's daily practice of navigating the world of poverty generates a fluency in the poverty environment but a near illiteracy in the environment of the larger society. Thus, when a poor person enters into transactions and interactions with the social norm, that person's understanding of it is limited, and thus decisions revert to decisions most effective in the poverty environment. Through this a sort of cycle is born in which the "dimensions of poverty are not merely additive, but are interacting and reinforcing in nature."[23] According to Appadurai, the key to the environment of poverty, which causes the poor to enter into this cycle, is the poor's lack of capacities. Appardurai's idea of capacity relates to Albert Hirschman's ideas of "voice" and "exit" which are ways in which people can decline aspects of their environment; to voice displeasure and aim for change or to leave said aspect of environment.[24] Thus, a person in poverty lacks adequate voice and exit (capacities) with which they can change their position. Appadurai specifically deals with the capacity to aspire and its role in the continuation of poverty and its environment. Aspirations are formed through social life and its interactions. Thus, it can be said, that one's aspirations are influenced by one's environment. Appadurai claims that the better off one is, the more chances one has to not only reach aspirations but to also see the pathways which lead to the fulfillment of aspirations. By actively practicing the use of their capacity of aspiration the elite not only expand their aspiration horizon but also solidify their ability to reach aspirations by learning the easiest and most efficient paths through said practice. On the other hand, the poor's horizon of aspiration is much closer and less steady than that of the elite. Thus, the capacity to aspire requires practice, and, as Chakravarti argues, when a capacity (or decision making process) is not refined through practice it falters and often fails. The unstable life of poverty often limits the poor's aspiration levels to those of necessity (such as having food to feed ones family) and in turn reinforces the lowered aspiration levels (someone who is busy studying, instead of looking for ways to get enough food, will not survive long in the poverty environment). Because the capacity to aspire (or lack thereof) reinforces and perpetuates the cycle of poverty, Appadurai claims that expanding the poor's aspiration horizon will help the poor to find both voice and exit. Ways of doing this include changing the terms of recognition (see previous section) and/or creating programs which provide the poor with an arena in which to practice capacities. An example of one such arena may be a housing development built for the poor, by the poor. Through this, the poor are able to not only show their abilities but to also gain practice dealing with governmental agencies and society at large. Through collaborative projects, the poor are able to expand their aspiration level above and beyond tomorrow's meal to the cultivation of skills and the entrance into the larger market.[25] |

貧困とは機会の制限である 貧困環境とは、不安定な状況と(社会的・経済的双方の)資本の欠如が特徴であり、これらが相まって貧困特有の脆弱性を生み出す。[22] 個人の人格の日常生活はその環境の中で営まれるため、環境は「存在するもの」と「存在しないもの」に基づいて日々の決断と行動を決定づける。ディプカナー ル・チャクラヴァルティは、貧困層が貧困の世界を生き抜く日々の実践が、貧困環境においては流暢さを生む一方で、より広い社会環境においてはほぼ文盲状態 に陥らせると論じる。したがって貧困層が社会規範との取引や交流に臨む際、その人格の理解は限定的であり、結果として意思決定は貧困環境で最も効果的な選 択へと回帰する。これにより「貧困の諸次元は単に加算されるだけでなく、相互に作用し合い、増幅し合う性質を持つ」という循環が生まれる[23]。 アッパドゥライによれば、貧困者がこの循環に陥る原因となる貧困環境の鍵は、貧困者の能力の欠如にある。アッパドゥライの能力概念は、アルバート・ハー シュマンの「発言権」と「退出権」の思想と関連する。これらは人々が環境の特定側面を拒否する手段であり、不満を表明して変化を目指すか、あるいはその環 境要素から離脱する道である。[24] したがって貧困層の人格は、自らの立場を変えるための十分な「声」と「退出」(能力)を欠いている。アッパドゥライは特に「志向する能力」と、それが貧困 とその環境の継続に果たす役割を論じている。志向は社会生活とその相互作用を通じて形成される。つまり個人の志向は環境の影響を受けると言える。アッパ ドゥライは、より恵まれた立場にある者ほど、願望を達成する機会が多いだけでなく、願望実現への道筋を見出す機会も多いと主張する。エリート層は願望能力 を積極的に実践することで、願望の地平を拡大するだけでなく、その実践を通じて最も容易で効率的な道筋を学び、願望達成能力を確固たるものにする。一方、 貧困層の願望の地平はエリート層に比べてはるかに狭く、不安定である。 したがって、願望を持つ能力は実践を必要とする。チャクラヴァルティが論じるように、能力(あるいは意思決定プロセス)が実践を通じて洗練されない場合、 それは機能不全に陥り、しばしば失敗する。貧困という不安定な生活は、貧しい人々の志向レベルを必要性(家族を養うための食糧確保など)に限定しがちであ り、結果として志向レベルの低下を強化する(食糧確保の方法を模索する代わりに勉強に忙しい者は、貧困環境では長く生き残れない)。志向する能力(あるい はその欠如)が貧困の循環を強化し永続させるため、アッパドゥライは貧困層の志向の視野を広げることが、彼らに「発言権」と「脱出」の両方を見出す助けに なると主張する。その方法には、承認の条件を変えること(前節参照)や、貧困層が能力を実践できる場を提供するプログラムの創設などが含まれる。その一例 として、貧困層のために貧困層によって建設される住宅開発が挙げられる。これを通じて貧困層は自らの能力を示すだけでなく、政府機関や社会全体との関わり 方を実践的に学ぶことができる。共同プロジェクトを通じて、貧困層は明日の食事以上の目標、すなわち技能の習得やより大きな市場への参入へと、自らの志向 水準を拡大できるのである。[25] |

| Attributions for poverty Basic income Citizen's dividend Criticism of credit scoring systems in the United States Distributive justice Economic inequality Extreme poverty Foreign aid Georgism Guaranteed minimum income Homelessness Land monopoly Negative income tax Political corruption Poverty reduction Progress and Poverty Regressive tax Rent-seeking Social safety net Unemployment Urban renewal Wage slavery The Wealth of Nations |

貧困の原因 ベーシックインカム 市民配当 米国における信用スコアリング制度への批判 分配的正義 経済的不平等 極度の貧困 対外援助 ジョージズム 最低所得保障 ホームレス 土地独占 負の所得税 政治腐敗 貧困削減 進歩と貧困 逆進的課税 レントシーキング 社会的安全網 失業 都市再開発 賃金奴隷制 国富論 |

| Alkire, Sabina (2005). "Why the

capabilities approach?". Journal of Human Development. 6 (1): 115–133.

doi:10.1080/146498805200034275. S2CID 15074994. Lewis, Oscar (January–February 1998). "The culture of poverty". Society. 35 (2): 7–9. doi:10.1007/BF02838122. S2CID 144250495. Sen, Amartya (2004), "How Does Culture Matter?", in Rao, Vijayendra; Walton, Michael (eds.), Culture and Public Action, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 37–58, ISBN 9780804747875. Sen, Amartya (2005). "Human rights and capabilities". Journal of Human Development. 6 (2): 151–166. doi:10.1080/14649880500120491. S2CID 15868216. |

アルカイア、サビーナ(2005)。「能力アプローチの意義とは?」。『人間開発ジャーナル』。6巻1号:115–133頁。doi:10.1080/146498805200034275。S2CID 15074994。 ルイス、オスカー(1998年1月–2月)。「貧困の文化」。『社会』35巻2号:7–9頁。doi:10.1007/BF02838122。S2CID 144250495。 セン、アマルティア(2004)、「文化はどのように重要か?」、ラオ、ヴィジャイェンドラ;ウォルトン、マイケル(編)、『文化と公共行動』、スタンフォード、CA:スタンフォード大学出版局、pp. 37–58、ISBN 9780804747875。 セン、アマルティア(2005)。「人権と能力」。『人間開発ジャーナル』。6巻2号:151–166頁。doi:10.1080/14649880500120491。S2CID 15868216。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theories_of_poverty |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆