Oscar Lewis, 1914-1970, picture from University of Illinois Archives

オスカー・ルイス

Oscar Lewis, 1914-1970, picture from University of Illinois Archives

解説:池田光穂

★オ スカー・ルイス(Oscar Lewis, 姓はLefkowitzとして生まれた、1914年12月25日 - 1970年12月16日)は、アメリカの人類学者。スラムの住人の生活を生き生きと描き、貧困という世代を超えた文化は国境を越えるという主張で知られる (→「貧困の文化(culture of poverty)」)。ルイスは、文化的類似性は「共通の問題に対する共通 の適応」であったために生じたと主張し、「貧困の文化は、階級的に階層化され、高度に個人主義的で、資本主義的な社会における周縁的な立場に対する貧困層 の適応であると同時に反動でもある」と主張した。ル イスは(ユダヤ教の)ラビの息子であり、1914年にニューヨークで生まれ、ニューヨーク州北部の小さな農場で育った[4]。1936年にニューヨーク・ シティ・カレッジで歴史学の学士号を取得し、そこで後に妻となる研究仲間のルース・マズローと出会った[5]。義兄のアブラハム・マズローの勧めで、人類 学部のルース・ベネディクトと話をした[4]。 その後、学部を変え、1940年にコロンビア大学で人類学の博士号を取得した[6]。ブラックフィート・インディアンにおける白人との接触の影響に関する 博士論文は1942年に出版された[2]。ブ ルックリン・カレッジ、セントルイスのワシントン大学で教鞭をとり、イリノイ大学アーバナ・シャンペーン校では人類学部の創設に貢献した。 [2][7]最も物議を醸した著書は、6番目の夫と暮らすプエルトリコ人売春婦の生活を綴った『La Vida』で、多くの中流階級のアメリカ人読者には想像もつかないような状況で子供たちを育てていた[8]。 1970年に55歳で心不全のためニューヨークで死去し[1]、ニューヨーク州サフォーク郡ウェスト・バビロンのニュー・モンテフィオーレ墓地に埋葬され た[9]。https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oscar_Lewis より翻訳。

| Lewis,

Oscar 1914-1970 The anthropologist Oscar Lewis is best known for devising the “culture of poverty” theory and applying the life history and family studies approach to studies of urban poverty. The concept of the culture of poverty is cited often, especially in the popular press, and at times it is misapplied as an argument that supports the idea of “blaming the victim.” Not surprisingly, given the continuing salience of debates about the causes of poverty, Oscar Lewis’s legacy within anthropology and the social sciences is still very much debated. Indeed, the notion of a “culture of poverty” has since reemerged in discussions of the “urban underclass.” While most researchers view the causes of poverty in terms of economic and political factors, there is still a strain of thinking that blames poverty on the behavior of the poor. |

ルイス,オスカー 1914-1970 人類学者オスカー・ルイスは、「貧困の文化」理論を考案し、ライフヒストリーや家族研究のアプローチを都市の貧困研究に応用したことで知られている。貧困 の文化」という概念は、特に一般紙で頻繁に引用され、時には「被害者を責める(犠牲者非難)」 という考えを支持する議論として誤用されることもある。貧困の原因に関する議論が依然として盛んであることを考えれば、人類学や社会科学におけるオス カー・ルイスの遺産は、驚くにはあたらない。実際、「貧困の文化」とい う概念は、それ以来、「都市のアンダークラ ス(下層階級)」をめぐる議論に再び登場し ている。ほとんどの研究者が貧困の原因を経済的・政治的要因の観点から捉えている一方で、貧困の原因を貧困層の行動に求める考え方もまだ残っている。 |

| Oscar Lewis was born on December 25, 1914, in New York City, and he was raised in upstate New York. He received a BA in history from the City College of New York While in college he met his future wife, the former Ruth Maslow, who would also become his co-collaborator in many of his research projects. He enrolled in graduate school in history at Columbia University, but under Ruth Benedict’s guidance he switched to anthropology. Partially due to a lack of funding, his PhD dissertation on the impact of white contact on Blackfoot culture was library based. After graduating he took on several jobs, including United States representative to the Inter-American Indian Institute in Mexico, which led him to begin conducting research on the peasant community of Tepoztlán. Lewis’s critique of Robert Redfield’s 1930 study of the same village is considered a classic in Mexican anthropology. Lewis’s research shows, in contrast to Redfield’s, that peasant culture in Tepoztlán is not based on “folk” solidarity but is rather highly conflictual, driven by struggles over land and power. In 1948 Lewis joined the faculty at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he was one of the founders of the anthropology department. | オスカー・ルイスは1914年12月25日にニューヨークで生まれ、 ニューヨーク北部で育った。シティ・カレッジ・オブ・ニューヨークで歴史学の学士号を 取得。大学在学中に、後に妻となるルース・マズローと出会う。コロンビア大学大学院の歴史学科に入学したが、ルース・ベネディクトの 指導の下、人類学に転向した。資金不足もあり、白人の接触がブラックフット族の文化に与えた影響に関する博士論文は図書館をベースにしたものだった。卒業 後は、メキシコの米州インディアン研究所の米国代表など、いくつかの仕事を引き受け、テポズトランの農民コミュニティの調査を始めた。1930年にロバー ト・レッドフィールドが行った同村の調査に対するルイスの批評は、メキシコ人類学の古典とされている。ルイスの研究は、レッドフィールドの研究とは対照的 に、テポスランの農民文化は「民俗的」な連帯に基づくものではなく、むしろ土地と権力をめぐる闘争を原動力とする非常に対立的なものであることを示してい る。1948年、ルイスはイリノイ大学アーバナ・シャンペーン校の教員となり、人類学部の創設者の一人となった。 |

| During his tenure at Illinois, Lewis produced his best-known works including Five Families (1959), The Children of Sánchez (1961), and Anthropological Essays (1970). In both Five Families and The Children of Sánchez, Lewis describes the culture of poverty theory and provides rich insights on urban poverty in Mexico through the narratives of his informants. In Anthropological Essays, Lewis reiterates the culture of poverty theory, which at its most basic level is an adaptation to economic circumstances: “The culture of poverty is … a reaction of the poor to their marginal position in a class-stratified, highly individuated, capitalistic society” (Lewis 1970, p. 69). Included in Lewis’s trait list of the culture of poverty are feelings of inferiority and aggressiveness, fatalism, sexism, and a low level of aspiration. Lewis saw the culture of poverty as resulting from class divisions, and therefore present not only in Mexico but throughout the world. | イリノイ大学在職中に、ルイスは『5つの家族』(1959年)、『サン チェスの子供たち』(1961年)、『人類学エッセイ』(1970年)などの代表作 を生み出した。Five Families』と『The Children of Sánchez』の両作品において、ルイスは貧困文化論を述べ、情報提供者の語りを通してメキシコの都市貧困に関する豊かな洞察を提供している。ルイスは 『人類学論考』の中で、最も基本的なレベルでは経済状況への適応である貧困文化論を繰り返し述べている: 「貧困の文化とは......階層化され、高度に個人化された資本主義社会における周縁的な立場に対する貧困層の反応である」(Lewis 1970, p.69)。ルイスの貧困文化の特徴リストに含まれているのは、劣等感と攻撃性、宿命論、性差別、志の低さである。ルイスは、貧困の文化は階級間の分裂か ら生じるものであり、したがってメキシコだけでなく世界中に存在すると考えた。 |

| Because Lewis’s description of the poor went against the clean-cut image presented by the Mexican media, there was, within Mexico, harsh criticism of the notion of a culture of poverty. This response, as Miguel Díaz-Barriga (1997) points out, obfuscates the overlap between Lewis’s representations of the urban poor and Mexican social thinkers such as Samuel Ramos and Octavio Paz. Díaz-Barriga shows that in their interviews, many of Lewis’s informants ironically played off of well-known stereotypes of the urban poor, and that Lewis took their statements literally. | ルイスの言う貧困層は、メキシコのメディアが提示する清廉潔白なイメー ジに反するものであったため、メキシコ国内では、貧困文化という概念に対する厳しい 批判が巻き起こった。この反応は、Miguel Díaz-Barriga(1997)が指摘するように、ルイスが表現した都市の貧困層と、サミュエル・ラモスやオクタビオ・パスのようなメキシコの社会 思想家との重なりを難解にしている。ディアス=バリガは、ルイスの情報提供者の多くが、インタビューにおいて、都市貧困層に関するよく知られたステレオタ イプを皮肉り、ルイスが彼らの発言を文字通り受け止めていたことを示す。 |

| In the United States, the

culture of poverty theory became well known through its application in

Daniel Moynihan’s 1965 report for the Department of Labor, The Negro

Family: The Case for National Action, which informed national

policymaking, including Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty. By focusing

on the “pathologies” that emerged from slavery, discrimination, and the

breakdown of the nuclear family, Moynihan saw the emergence of a

culture of poverty among the African American poor. This emphasis on

the pathologies of poverty has since been reframed in terms of theories

of the urban underclass that seek to understand the urban poor as being

both economically and culturally isolated from the middle-class. While

sociologists such as William Julius Wilson (1980) have devised

sophisticated understandings of the urban underclass, this concept,

especially in the popular press, has become a stand-in for arguments

that see the causes of poverty in terms of cultural pathologies. |

米国では、ダニエル・モイニハンが1965年に労働省に提出した報告書 『The Negro Family(ニグロの家族)』で貧困文化 論が応用されたことでよく知られるようになった: この報告書は、リンドン・B・ジョンソンの「貧困との戦い」など、国の政策立案に影響を与えた。奴隷制度、差別、核家族の崩壊から生まれた「病理」に焦点 を当てることで、モイニハンはアフリカ系アメリカ人の貧困層の間に貧困文化が出現していることを見抜いた。貧困の病理を強調するこの考え方は、それ以来、 都市の貧困層を経済的にも文化的にも中流階級から 隔離された存在として理解しようとする、都市下層階級 の理論という観点から見直されてきた。ウィリアム・ジュリアス・ウィ ルソン(William Julius Wilson)(1980)のような社会学者は、アーバン・ア ンダークラスの洗練された理解を考案してきたが、特 に大衆紙では、この概念は、貧困の原因を文化的病理 の観点から捉える議論の代用品となっている。 |

| In their well-known 1973 refutation of the application of the culture of poverty theory, Edwin Eames and Judith Goode argued that many of the characteristics associated with poverty, including matrifocal families and mutual aid, are rational adaptations. The continuing prevalence of poverty, they stated, must be understood in terms of restricted access to and attainment of job skills. Studies that pathologize the poor have received justified criticism for privileging middle-class values, being vague about the overall characteristics of poverty and their interrelations, and viewing matrifocal households as being a cause rather than a result of poverty. The historian Michael Katz argues that, when given educational and employment opportunities (instead of dead-end service sector jobs), the urban poor aspire to succeed as much as their middle-class counterparts. Katz convincingly calls for a historical understanding of the educational, housing, and economic policies that have generated urban poverty. | エドウィン・イームズ(Edwin Eames)とジュディス・グッド(Judith Goode)は、よく知られた1973年の「貧困文化論」の適用に対する反論の中で、母子家庭や相互扶助など、貧困に関連する特徴の多くは合理的な適応で あると主張した。貧困の継続的な蔓延は、職業技能へのアクセスや達成の制限という観点から理解されなければならない、と彼らは述べている。貧困層を病理化 する研究は、中流階級の価値観を特権化し、貧困の全体的な特徴やそれらの相互関係について曖昧であり、母子家庭を貧困の結果というよりもむしろ原因である かのように見ているとして、正当な批判を受けてきた。歴史学者マイケル・カッツは、(行き止まりのサービス業ではなく)教育や雇用の機会が与えられれば、 都市の貧困層は中流階級の人々と同じように成功を目指すと主張している。カッツは説得力を持って、都市の貧困を生み出した教育、住宅、経済政策の歴史的理 解を求めている。 |

| As evidenced by essays marking the fortieth anniversary of the Moynihan Report in the popular press, many continue to believe that the culture of the poor must be understood as a cycle of broken households and disruptive behavior. This renewed cycle of applying the culture of poverty theory represents the pathological ways that American society has sought to overcome class-based and racial inequalities. Indeed, it is easier to blame the poor for their poverty than to do the hard work of understanding the historical and economic factors that have generated poverty and the policy options that can transform cities. | 一般紙におけるモイニハン報告40周年を記念したエッセイからも明らか なように、貧困層の文化は、壊れた家庭と破壊的行動の連鎖として理解されなければならないと、多くの人々が信じ続けている。貧困の文化理論を適用するこの 新たなサイクルは、アメリカ社会が階級に基づく不平等や人種的不平等を克服しようとする病的な方法を表している。実際、貧困を生み出してきた歴史的・経済 的要因を理解し、都市を変革できる政策オプションを考えるという大変な作業をするよりも、貧困層を非難する方が簡単なのだ。 |

| When Oscar Lewis died, on

December 16, 1970, social scientists were

beginning to forcefully criticize his work for blaming the victim.

Lewis’s death at fifty-five years old was particularly untimely because

he was not able to respond to these critiques. Indeed, the social

sciences lost an opportunity to engage Lewis’s responses and, perhaps,

reach agreement on more fruitful ways to explore urban poverty. SEE ALSO Culture of Poverty; Moynihan Report; Moynihan, Daniel Patrick; Poor, The; Poverty |

1970年12月16日にオスカー・ルイスが亡くなったとき、社会科学

者たちは、被

害者を非難する彼

の研究を力強く批判し始めていた。ルイスが55歳という若さで亡くなったのは、こうした批判に応えることができなかったため、とりわけ早すぎる死であっ

た。実際、社会科学はルイスの反応に関与する機会を失い、おそらくは都市の貧困を探求するための、より実りある方法について合意に達する機会を失ったので

ある。 貧困の文化; モイニハン報告書; モイニハン、ダニエル・パトリック; 貧困; 貧困層 |

| https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/social-sciences-and-law/anthropology-biographies/oscar-lewis |

★ウィキペディア(英語)のエントリー

| Oscar Lewis, born

Lefkowitz (December 25, 1914 – December 16, 1970)[1] was an American

anthropologist. He is best known for his vivid depictions of the lives

of slum dwellers and his argument that a cross-generational culture of

poverty transcends national boundaries. Lewis contended that the

cultural similarities occurred because they were "common adaptations to

common problems" and that "the culture of poverty is both an adaptation

and a reaction of the poor classes to their marginal position in a

class-stratified, highly individualistic, capitalistic society."[2] He

won the 1967 U.S. National Book Award in Science, Philosophy and

Religion for La vida: a Puerto Rican family in the culture of

poverty--San Juan and New York.[3] |

オスカー・ルイス(Oscar Lewis、1914年12月25日

-

1970年12月16日)[1]はアメリカの人類学者である。スラムの住人の生活を生き生きと描き、貧困という世代を超えた文化はナショナリズムを超越し

たものであると主張したことで知られる。ルイスは、文化的類似性は「共通の問題に対する共通の適応」であったために生じたと主張し、「貧困の文化は、階級

的に階層化され、高度に個人主義的で資本主義的な社会における境界的な立場に対する貧困層の適応であると同時に反動でもある」と述べた[2]。 |

| Early life and education Lewis was Jewish, the son of a Rabbi, born 1914 in New York City and raised on a small farm in upstate New York.[4] He received a bachelor's degree in history in 1936 from City College of New York, where he met his future wife and research associate, Ruth Maslow.[5] As a graduate student at Columbia University, he became dissatisfied with the History Department at Columbia. At the suggestion of his brother-in-law, Abraham Maslow, Lewis had a conversation with Ruth Benedict of the Anthropology Department.[4] He switched departments and then received a Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia in 1940.[6] His Ph.D. dissertation on the effects of contact with white people on the Blackfeet Indians was published in 1942.[2] |

生い立ちと教育 ルイスはユダヤ教徒で、ラビの息子として1914年にニューヨークで生まれ、ニューヨーク州北部の小さな農場で育った[4]。1936年にニューヨーク・ シティ・カレッジで歴史学の学士号を取得し、そこで後に妻となる研究仲間のルース・マズローに出会った[5]。義兄のアブラハム・マズローの勧めで、人類 学部のルース・ベネディクトと話をした[4]。 その後、学部を変え、1940年にコロンビア大学で人類学の博士号を取得した[6]。ブラックフィート・インディアンにおける白人との接触の影響に関する 博士論文は1942年に出版された[2]。 |

| Career Lewis taught at Brooklyn College, and Washington University in St. Louis, and helped to found the anthropology department at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.[2][7] His most controversial book was ‘La Vida’ that chronicled the life of Puerto Rican prostitute, living with her sixth husband, who was raising her children in conditions unimaginable to many middle-class American readers.[8] Another well-known book was "The children of Sanchez" about an impoverished Mexico City family. Lewis died in New York City of heart failure, at age 55 in 1970,[1] and was buried in New Montefiore Cemetery in West Babylon, Suffolk County, New York.[9] Lewis is best known for his "Culture of Poverty" social theory: The theory states that being subjected to conditions of poverty, will lead to a culture adapted thereto, characterized by pervasive feelings of helplessness, dependency, and powerlessness. Furthermore, Lewis describes individuals living within a culture of poverty, as lacking or having limited means or knowledge to alleviate their inferior social status, focusing instead on their current needs. Nevertheless, the theory acknowledges factors leading to initial poverty, such as lack of available fair employment opportunities, proper free schooling, with decent social services and available standard housing. Thus, for Lewis, the mere imposition of poverty on a needy disadvantaged population, is the structural cause of specific cultural nature. Autonomous in its behaviors and attitudes, this culture passes down to the subsequent generation. The theory further concludes that once a needy population is exposed to poverty, no charity or low- income allowances will alleviate its allied image of social inferiority. A poverty trap, for which blame, should be shifted from the poor themselves, to those who may profit from a faulty economy.[citation needed] |

経歴 ルイスはブルックリン・カレッジとセントルイスのワシントン大学で教鞭をとり、イリノイ大学アーバナ・シャンペーン校の人類学部の設立に貢献した[2] [7]。最も物議を醸したのは、6番目の夫と暮らすプエルトリコ人娼婦の生活を綴った『La Vida』で、アメリカの中流階級の読者には想像もつかないような状況で子供たちを育てていた。ルイスは1970年に55歳で心不全のためニューヨークで 死去し[1]、ニューヨーク州サフォーク郡ウェスト・バビロンのニュー・モンテフィオーレ墓地に埋葬された[9]。 ルイスは「貧困の文化」という社会理論で最もよく知られている: この理論では、貧困の状況に置かれることで、無力感、依存心、無力感が蔓延することを特徴とする、貧困に適応した文化が形成されると述べている。さらにル イスは、貧困文化の中で生活する個人は、劣った社会的地位を軽減する手段や知識が不足しているか、あるいは限られており、代わりに現在のニーズに焦点を当 てていると述べている。 とはいえ、この理論は、利用可能な公正な雇用機会、適切な無料学校教育、まともな社会サービス、利用可能な標準的住宅の欠如など、初期の貧困につながる要 因を認めている。このように、ルイスにとって、困窮した不利な立場にある人々に貧困を押し付けることは、特定の文化的性質を持つ構造的原因なのである。 その行動や態度は自律的であり、この文化は次の世代へと受け継がれていく。この理論はさらに、いったん困窮した集団が貧困にさらされると、いかなる慈善事 業や低所得者手当も、それに付随する社会的劣等感のイメージを緩和することはできないと結論づけている。貧困の罠は、その責任を貧困層自身から、欠陥のあ る経済から利益を得る可能性のある人々に転嫁されるべきである[要出典]。 |

| High Sierra Country, 1955 Village Life in Northern India; Studies in a Delhi village, 1958 Five Families; Mexican Case Studies in the Culture of Poverty, 1959 Life in a Mexican Village; Tepoztlán restudied, 1960 [first edition 1951] The Children of Sanchez, Autobiography of a Mexican Family, 1961 Pedro Martinez - A Mexican Peasant and His Family, 1964 La Vida; A Puerto Rican Family in the Culture of Poverty—San Juan and New York, 1966 A Death in the Sánchez Family, 1969 |

ハイシエラ・カントリー、1955年 北インドの村落生活;デリーの村落研究(1958年 5つの家族;貧困文化におけるメキシコの事例研究』1959年 メキシコの村の生活;テポスラン再研究、1960年[初版1951年] サンチェスの子供たち-あるメキシコ人家族の自伝』1961年 ペドロ・マルティネス-メキシコ農民とその家族』1964年 La Vida; A Puerto Rican Family in the Culture of Poverty-サンフアンとニューヨーク、1966年 サンチェス家の死, 1969 |

| 1. "Oscar Lewis". NNDB. Soylent

Communications. Retrieved 22 May 2013. 2. Whitman, Alden. "Oscar Lewis, Author and Anthropologist, Dead; U. of Illinois Professor, 55, Wrote of Slum Dwellers", The New York Times, December 18, 1970. Retrieved 2009-08-04. 3. "National Book Awards – 1967". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-05. 4. "Oscar Lewis". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Encyclopedia.com. 2004. Retrieved 22 May 2013. 5. "Oscar and Ruth Lewis Papers, 1944-76". University of Illinois Archives. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 22 May 2013. 6. Lewis, Oscar (1961). The Children of Sanchez (Vintage Edition 1963 ed.). New York: Random House. p. 501 (Appendix). 7. Gardner, David (2007). "A short biography". Mankato: EMuseum at Minnesota State University. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-28. 8. Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. pp. 430. ISBN 9780415252256. 9. Whitman, Alden (December 18, 1970). "Oscar Lewis, Author and Anthropologist, Dead". New York Times. p. 42. Retrieved 23 September 2016. |

1. 「オスカー・ルイス". NNDB.

ソイレント・コミュニケーションズ. 2013年5月22日取得。 2. Whitman, Alden. 「Oscar Lewis, Author and Anthropologist, Dead; U. of Illinois professor, 55, Wrote of Slum Dwellers", The New York Times, December 18, 1970. Retrieved 2009-08-04. 3. 「National Book Awards - 1967」. 国民図書財団。2012-03-05を参照。 4. 「オスカー・ルイス". 世界伝記百科事典. 百科事典.com. 2004. 2013年5月22日取得。 5. 「Oscar and Ruth Lewis Papers, 1944-76」. University of Illinois Archives. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. 2013年5月22日取得。 6. Lewis, Oscar (1961). The Children of Sanchez (Vintage Edition 1963 ed.). ニューヨーク: 501 ページ(付録)。 7. Gardner, David (2007). 「A short biography". Mankato: EMuseum at Minnesota State University. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-28. 8. Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. 430. ISBN 9780415252256。 9. Whitman, Alden (December 18, 1970). 「Oscar Lewis, Author and Anthropologist, Dead". New York Times. Retrieved 23 September 2016. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oscar_Lewis |

・︎被害者を責める(犠牲者非難)▶ダニエ

ル・モイニハン︎▶︎︎『The Negro Family(ニグロの家族)』▶︎貧困の文化▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

著作:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oscar_Lewis より.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

年譜

| 1914 |

1914年12月25日 ニューヨーク市にて、ラビの男児として出生(ウクライナ系ユダヤ人) |

| 1915 |

|

| 1916 |

|

| 1917 |

|

| 1918 |

|

| 1919 |

|

| 1920 |

|

| 1921 |

|

| 1923 |

|

| 1924 |

|

| 1926 |

|

| 1927 |

|

| 1928 |

|

| 1929 |

|

| 1930 |

|

| 1931 |

|

| 1932 |

|

| 1933 |

|

| 1934 |

|

| 1935 |

|

| 1936 |

ニューヨーク市立大学卒業(歴史学)City College of New York, CCNY。同年コロンビア大学の歴史学の大学院に進学する。 |

| 1937 |

Ruth

Maslowと結婚(CCNYでの同級生)。Ruthの兄はAbraham Harold

Maslow,1908-1970.(マズロー一家は、キエフからの移民ユダヤ人)。同大学で教えていたルース・ベネディクト(Ruth Fulton

Benedict, 1887-1948)と出会い、歴史学から人類学に転向する。 |

| 1938 |

|

| 1939 |

カナダ・アルバータ州の Brocton 居留地にて最初のフィールドワーク。ブラックフット(Blackfoot, Niitsitapi or Siksikaitsitapi)の白人との接触に関する(主に文献)研究で学位をとる。 |

| 1940 |

|

| 1941 |

|

| 1942 |

The effects of white contact

upon Blackfoot culture : with special reference to the rôle of the fur

trade, University of Washington Press 1942 Monographs / American

Ethnological Society 6 |

| 1943 |

メキシコにあった、インターアメリカン先住民協会(Inter-American Indian Institute)[pdf]の米国代表としてメキシコに赴任。Tepoztlán研究をはじめる。 |

| 1944 |

|

| 1945 |

|

| 1946 |

|

| 1947 |

|

| 1948 |

Urbana- Champaignのイリノイ大学人類学部に赴任 |

| 1949 |

|

| 1950 |

|

| 1951 |

Life in a Mexican Village; Tepoztlán restudied, 1960 [first edition 1951] Life in a Mexican village : Tepoztlán restudied, by Oscar Lewis ; with drawings by Alberto Beltrán, University of Illinois Press 1951 |

| 1952 |

イリノイ大学にジュリアン・スチュワード(1902-1972)が赴任。 |

| 1953 1954 |

Group dynamics in a north-Indian village : a study of factions, Oscar Lewis, Manager of Publications 1954 |

| 1955 |

High Sierra Country, 1955 |

| 1956 |

|

| 1957 |

|

| 1958 |

|

| 1959 |

Five families : Mexican case

studies in the culture of poverty, Oscar Lewis ; with a foreword by

Oliver La Farge, Basic Books c1959 |

| 1960 |

Tepoztlán, Village In México, 1960, Holt, Rinehart and Winston 1960 Case studies in cultural anthropology |

| 1961 |

The Children of Sanchez, Autobiography of a Mexican Family, 1961, Random House c1961 Antropología de la pobreza : cinco familias / Oscar Lewis : prólogo de Oliver La Farge ; [traducción de Emma Sánchez Ramírez], Fondo de Cultura Económica , 1961 . - (Sección de obras de antropología) |

| 1962 |

|

| 1963 |

Life in a Mexican village:

Tepoztlán restudied, by Oscar Lewis ; with drawings by Alberto Beltrán,

University of Illinois Press 1963 Illini books IB-9 |

| 1964 |

Pedro Martínez; a Mexican peasant and his family, Oscar Lewis ; drawings by Alberto Beltrán, Random House c1964 |

| 1965 |

Village life in northern India :

studies in a Delhi village, by Oscar Lewis ; with the assistance of

Victor Barnouw, Vintage Books 1965 A Vintage giant V284(再版) |

| 1966 |

La Vida; A Puerto Rican Family

in the Culture of Poverty—San Juan and New York, 1966/ ラ・ビーダ :

プエルト・リコの一家族の物語 / オスカー・ルイス [著] ; 行方昭夫, 上島建吉訳, みすず書房 , 1970 . -

(みすず叢書, 31-33) |

| 1967 |

Die Kinder von Sánchez :

Selbstporträt einer mexikanischen Familie, Oscar Lewis ; [aus dem

Amerikanischen übertragen von Margarete Bormann], Fischer Bücherei

1967, c1961 Fischer Bücherei . Bücher des Wissens ; 804 |

| 1968 |

A study of slum culture : backgrounds for La vida, Oscar Lewis ; with the assistance of Douglas Butterworth, Random House c1968 |

| 1969 |

A Death in the Sánchez Family, 1969 Los hijos de Sánchez : autobiografía de una familia Mexicana, Oscar Lewis. Joaquín Mortiz 1969, c1965 9a ed サンチェスの子供たち, オスカー・ルイス [著] ; 柴田稔彦, 行方昭夫訳, みすず書房 1969.3-1969.6 みすず叢書 28-29, 1,2. |

| 1970 |

1970年12月16日心筋梗塞で 55歳で死去(ニューヨークにて) Life in a Mexican village: Tepoztlán restudied, Oscar Lewis ; with drawings by Alberto Beltrán, University of Illinois Press 1970 Anthropological essays, Oscar Lewis, Random House [1970] [1st ed.] A death in the Sánchez family, Oscar Lewis, Vintage Books 1970 A Vintage book V-634 貧困の文化 : 五つの家族, オスカー・ルイス著 ; 高山智博訳, 新潮社 1970.3 新潮選書 ラ・ビーダ : プエルト・リコの一家族の物語, オスカー・ルイス [著] ; 行方昭夫, 上島建吉訳, みすず書房 1970.10-1971.3 みすず叢書 31-33, 1,2,3. |

| 1971 |

Tepoztlán : un pueblo de México, por Oscar Lewis ; [traducción directa de, Lauro J. Zavala], Joaquín Mortiz 1971 2a ed |

| 1972 |

|

| 1973 |

|

| 1974 |

Los hijos de Sánchez : autobiografía de una familia Mexicana, Oscar Lewis. Joaquín Mortiz 1974, c1965 13. ed |

| 1975 |

Five families : Mexican case

studies in the culture of poverty, Oscar Lewis ; with a new

introduction by Margaret Mead ; foreword by Oliver La Farge. Basic

Books c1975 |

| 1976 |

Una muerte en la familia Sánchez, Oscar Lewis. J. Mortiz 1976 2a ed Tepoztlán : un pueblo de México, por Oscar Lewis ; [traducción directa de, Lauro J. Zavala], Editorial J. Mortiz 1976 3. ed Five families : Mexican case studies in the culture of poverty, Oscar Lewis ; foreword by Oliver La Farge, Souvenir Press 1976 [1st ed. reprinted] / with a new introduction by Margaret Mead A condor book |

| 1977 |

Living the revolution : an oral

history of contemporary Cuba, Oscar Lewis, Ruth M. Lewis, Susan M.

Rigdon, University of Illinois Press c1977-1978, v. 1. Four men , v. 2.

Four women , v. 3. Neighbors Viviendo la revolucion : una historia oral de cuba contemporanea, Oscar Lewis, Ruth M. Lewis, Susan M. Rigdon, J. Mortiz 1977, v. 1. Cuatro hombres , v. 2. Cuatro mujeres , v. 3. Vecinos |

| 1978 |

Les enfants de Sánchez,

autobiographie d'une famille mexicaine, Oscar Lewis ; traduit de

l'anglais par Céline Zins, Gallimard [1978], c1963 Collection Tel 31 The children of Sanchez, directed and produced by Hall Bartlett ; adapted from thebook by Oscar Lewis ; screenplay by Cesare Zavattini, International Video Entertaiment c1978 Monterey home video, ビデオレコード (ビデオ (カセット)) |

| 1979 |

|

| 1980 |

|

| 1981 |

カストロの家族, Oscar Lewis[著] ; 上野政夫編[注], 芸林書房 1981.2(スペイン語の教材?) |

| 1982 |

Los hijos de Sánchez, Oscar Lewis ; [traducción de la introducción Carlos Villegas]. Editorial Grijalbo c1982 Una muerte en la familia Sanchéz, Oscar Lewis, Grijalbo c1982 3a ed |

| 1983 |

The children of Sańchez :

autobiography of a Mexican family, Oscar Lewis, Penguin in association

with Secker & Warburg 1983 A Peregrine book |

| 1984 |

|

| 1985 |

貧困の文化 : メキシコの<五つの家族>, オスカー・ルイス著 ; 高山智博訳, 思索社 1985.11 |

| 1986 |

サンチェスの子供たち : メキシコの一家族の自伝, オスカー・ルイス [著] ; 柴田稔彦, 行方昭夫共訳, みすず書房 1986.4, : 新装版 |

| 1987 |

|

| 1988 |

The culture facade : art, science, and politics in the work of Oscar Lewis, Susan M. Rigdon. University of Illinois Press c1988 Kisah lima keluarga : telaah-telaah kasus orang Meksiko dalam kebudayaan kemiskinan, Oscar Lewis ; penerjemah, Rochmulyati Hamzah. Yayasan Obor Indonesia 1988 Buku Obo |

| 2003 |

貧困の文化, オスカー・ルイス著 ; 高山智博, 染谷臣道, 宮本勝訳, 筑摩書房 2003.6 ちくま学芸文庫 [ル2-1] |

| 2007 |

キューバ 革命の時代を生きた四人の男 : スラムと貧困現代キューバの口述史, オスカー・ルイス, ルース・M.ルイス, スーザン・M.リグダン著 ; 江口信清訳, 明石書店 2007.4 |

”In Anthropological Essays,

Lewis reiterates the culture of poverty theory, which at its most basic

level is an adaptation to economic circumstances: “The culture of

poverty is … a reaction of the poor to their marginal position in a

class-stratified, highly individuated, capitalistic society” (Lewis

1970, p. 69). ” Oscar

Lewis.

| The Children of

Sanchez is a 1961 book by American anthropologist Oscar Lewis about a

Mexican family living in the Mexico City slum of Tepito, which he

studied as part of his program to develop his concept of culture of

poverty.[1] The book is subtitled "Autobiography of a Mexican

family".[2] According to the dedication by the author in the opening

pages of the book, the actual last name of the family is not "Sanchez",

in order to maintain the privacy of the family members.[3] |

『サンチェスの子供たち』は、アメリカの人類学者オスカー・ルイスが、

貧困文化の概念を確立するための研究の一環として、メキシコシティのスラム街テピトに住むメキシコ人家族を調査して1961年に発表した著作です。[1]

この本の副題は「メキシコの一家族の自伝」だ。[2]

著者が本書の冒頭で記した献辞によると、家族メンバーのプライバシーを守るため、実際の姓は「サンチェス」ではない。[3] |

| Due to criticisms expressed by

members of the family regarding the Partido Revolucionario

Institucional (PRI) government and Mexican presidents such as Adolfo

Ruiz Cortines and Adolfo López Mateos, and its being written by a

foreigner, the book was banned in Mexico for a few years before

pressure from literary figures resulted in its publication. |

家族から、革命制度党(PRI)政府やアドルフォ・ルイス・コルティネ

ス、アドルフォ・ロペス・マテオスなどのメキシコ大統領に対する批判が寄せられたこと、また、この本が外国人によって執筆されたことを理由に、この本はメ

キシコで数年間禁止されたが、文学者たちの圧力を受けて出版された。 |

| The particular ethnographic

reality that Lewis is focussing on in his book was the plight of the

urban poor in a developing country. The political implications of this

approach caused some concern when The Children of Sánchez was published

in Mexico in Spanish in 1964. Formal charges were made against Lewis

and the publisher by the Mexican Geographical and Statistical Society,

accusing them of writing and publishing an obscene and denigrating

book. The hearing of the case, the text of which was appended to the

second Mexican edition by Joaquin Mortiz, resulted in the dismissal of

the charges against Lewis and the publisher as unfounded.[4] |

ルイスが本書で焦点を当てている特定の民族誌的現実は、発展途上国の都

市部の貧困層の苦境だった。このアプローチの政治的意味合いにより、1964年に『サンチェスの子供たち』がスペイン語でメキシコで出版されたとき、いく

つかの懸念が生じた。メキシコ地理統計協会は、ルイスと出版社を、卑猥で中傷的な本を書いた、出版したとして正式に告発した。この裁判の審理は、ホアキ

ン・モルティスによって第 2 版に付記され、ルイスと出版社に対する告発は根拠がないとして却下された[4]。 |

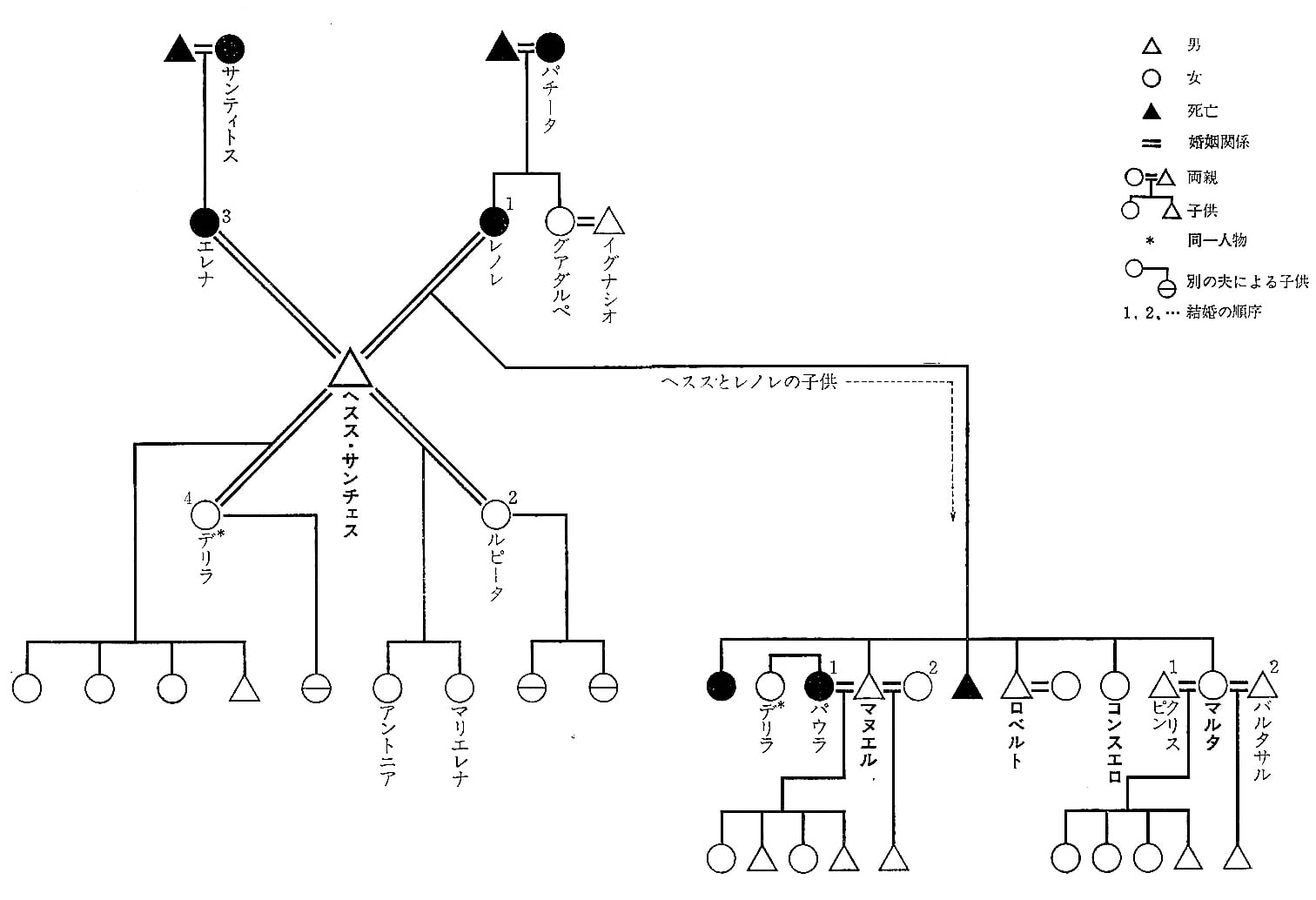

| Jesús Sánchez, age fifty, is the

father, and his four children are Manuel, age thirty-two; Roberto,

twenty-nine; Consuelo, twenty-seven; and Marta, twenty-five. The

content of the book itself consists of the life stories and accounts of

these five people, as recorded in their own words by the author. Most

of the interviews and the recorded events center around the Casa Grande

Vecindad, a large one-story slum settlement, in the center of Mexico

City. Elizabeth Hardwick described the result as "a moving, strange

tragedy, not an interview, a questionnaire or a sociological

study."[5][6] |

50歳の父親、ヘスス・サンチェス、32歳の息子マヌエル、29歳の息

子ロベルト、27歳の娘コンスエロ、25歳の娘マルタの4人の子供たち。この本の内容は、著者によって彼らの言葉で記録された、5人の人生物語と証言で構

成されています。インタビューや記録された出来事のほとんどは、メキシコシティの中心部にある 1

階建ての貧民街、カサ・グランデ・ベシナッドを中心に展開している。エリザベス・ハードウィックは、この作品を「インタビューやアンケート、社会学的研究

ではなく、感動的で奇妙な悲劇」と表現している[5][6]。 |

| Film A film based on the book and with the same title was directed by Hall Bartlett and was released in 1979. It stars Anthony Quinn as Jesús Sánchez. |

映画 この本をもとに、ホール・バートレット監督、1979年に同名の映画が製作された。主演は、アンソニー・クインがヘスス・サンチェス役を演じている。 |

| 1. Lewis, Oscar (1961). The Children of Sanchez (Vintage Edition 1963 ed.). New York: Random House. 2. Lewis, coverpage 3. Lewis, opening page 4. Grossman, Lois (1978). ""The Children of Sánchez" on stage". Latin American Theatre Review (Spring 1978): 34-35. Retrieved 16 April 2022. 5. Hardwick, Elizabeth. "The Children of Sanchez". The New York Times Book Review: back cover of Oscar Lewis "The Children of Sanchez". 6. Hardwick, Elizabeth (29 November 2011). The New York Times Book Review. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Children_of_Sanchez_(book) |

★その他(邦訳)

■『5つの家族』(→リンク)

1.マルティネスの家族

2.ゴメスの家族

3.グティエレスの家族

4.サンチェスの家族

5.カストロの家族

■『サンチェスの子供たち』

ヘスス:本人

マヌエル:長男

ロベルト:次男

コンスエルロ:長女(第三子)

マルタ:次女(末子)

★■その他

■スーザン・リグドンによる伝記: The culture facade : art, science, and politics in the work of Oscar Lewis / Susan M. Rigdon: alk. paper. - Urbana : University of Illinois Press , c1988(邦訳・未公開版 2.3MB:with password)

■著作

■論文、共著論文、報告書等——元の 資料がOCR読み取りをもとにしているので誤記あるいは変換ミスがあります

(includes only those book reviews cited in the text)

■インターネット・アーカイブ

■文献(文献集「貧困の文化」も参照してください)

■サイト内リンク

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆