女たらしドン・ファンは罰せられるべきか?

Should the Lady killer Don Juan be

punished?

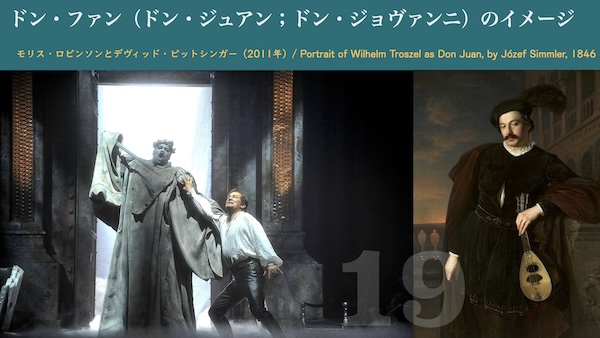

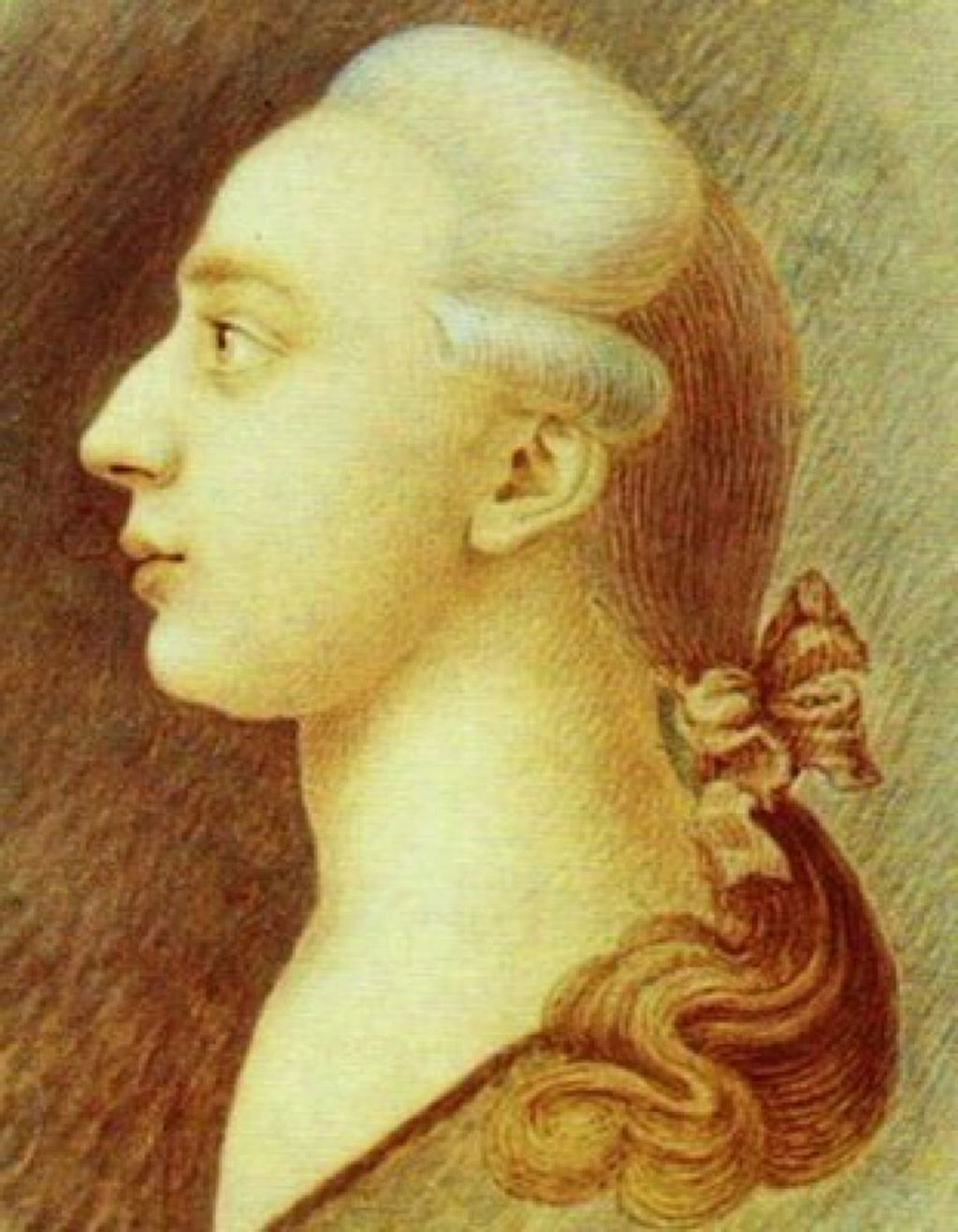

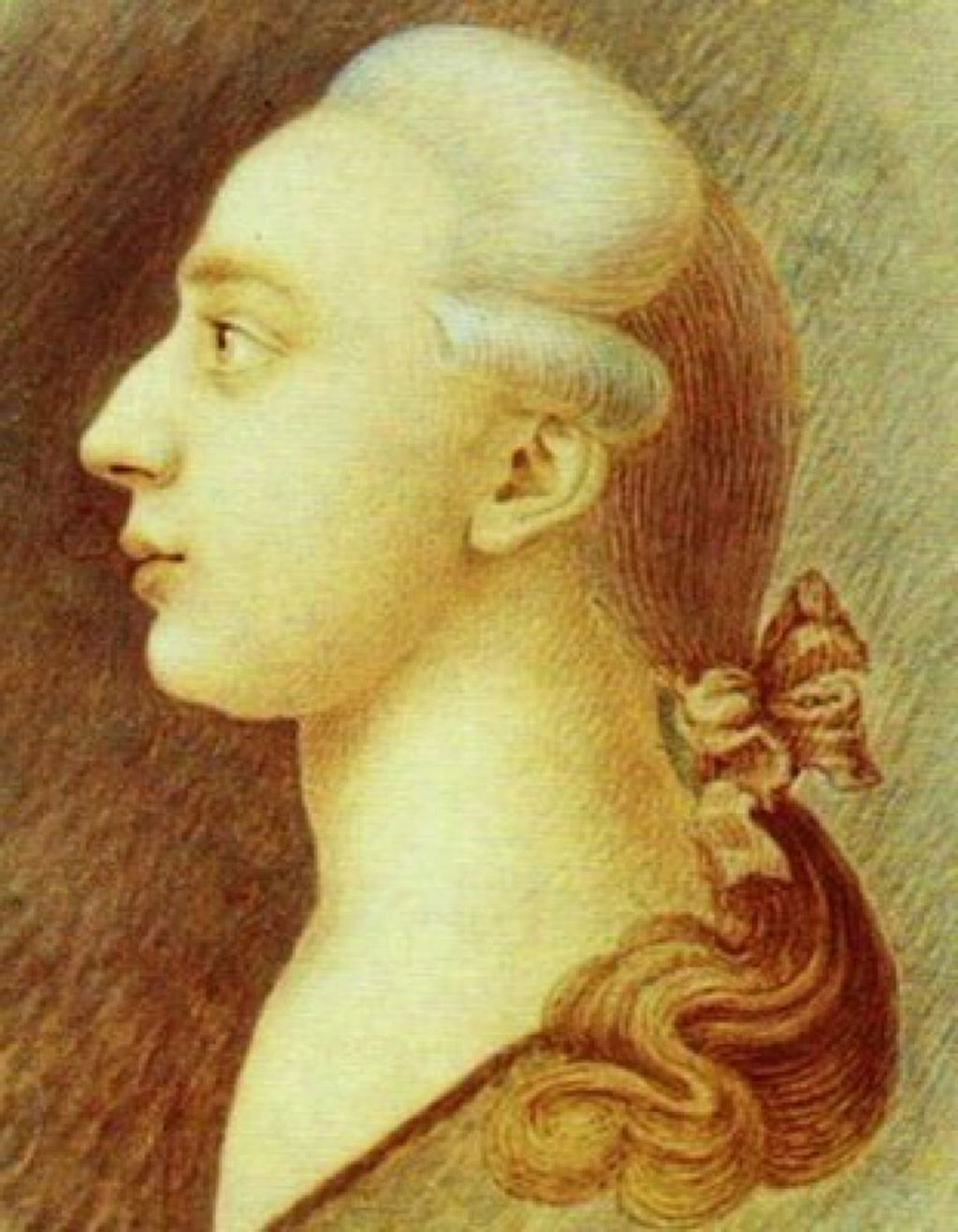

左:

モリス・ロビンソンとデヴィッド・ピットシンガー(2011年)/ Portrait of Wilhelm Troszel as Don

Juan, by Józef Simmler, 1846

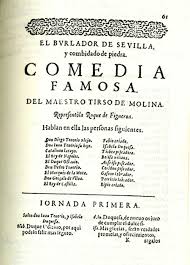

★ドン・ファン(Don Juan)は、17世紀スペインのフィクションあるいは説教物語における架空の人物像である。ティルソ・デ・モリーナによる戯曲「セビリアの色事師 (El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra)」が原型。好色放蕩な美男として多くの文学作品に描写されている。プレイボーイ、女たらしの代名詞としても使われている。

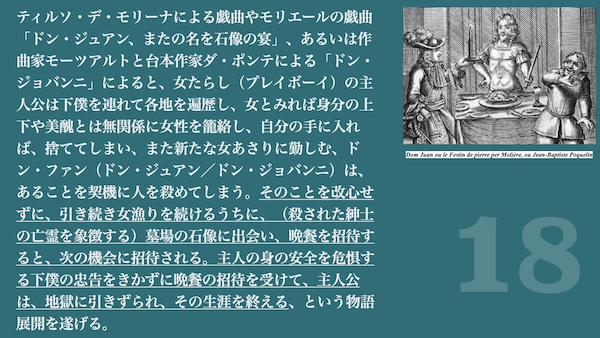

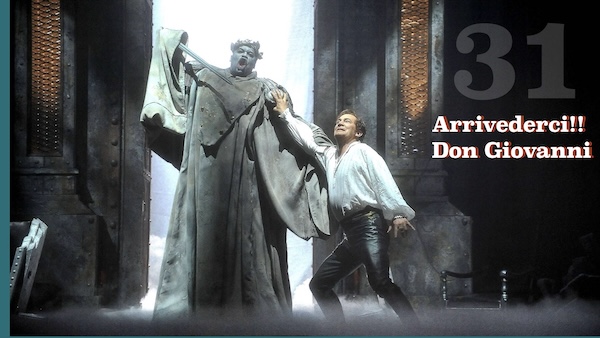

★ティルソ・デ・モリーナによる戯曲やモリエールの戯曲「ドン・ジュアン、またの名を石像の宴」、あるいは作曲家モーツアルトと台本作家ダ・ポンテによる「ドン・ジョバンニ」によると、女たらし(プレイボーイ)の 主人公は下僕を連れて各地を遍歴し、女とみれば身分の上下や美醜とは無関係に女性を籠絡し、自分の手に入れば、捨ててしまい、また新たな女あさりに勤し む、ドン・ファン(ドン・ジュアン/ドン・ジョバンニ)は、あることを契機に人を殺めてしまう。そのことを改心せずに、ひきつづき女漁りを続けるうちに、 (殺された紳士の亡霊を象徴する)墓場の石像に出会い、晩餐を招待すると、次の機会に招待される。主人の身の安全を危惧する下僕の忠告をきかずに晩餐の招 待を受けて、主人公は、地獄に引きずられ、その生涯を終える、という物語展開を遂げる。

★ 主人公は墓場の石像と晩餐を共にしても恐る様子がなく、あるいは女漁りへの反省もないために、地獄に連れていかれて罰せられる、という勧善懲悪の物語展開 をとげる(→悪に関するショートレクチャー)勧善懲悪の技法は「詩的正義(Poetic justice)」と 呼ばれる。詩的正義は詩的皮肉とも呼ばれ、最終的に美徳が報われ、悪行が罰せられる文学的装置である。

★

審問(このページの末尾で再度掲示します):

(1)

「女たらしドン・ファンは、その悪業のゆえに罰せられるべきか?」

・

全面的イエス:どうしてか、その理由

・

部分的イエス/部分的ノー:どうしてか、その理由

・

全面的ノー:どうしてか、その理由

(2) 女たらしドン・ファンの歴史は、もはや過去のものか?

・イエス:だったら、現在の男女のセクシュアリティと「騙しや籠絡」とはどのようなものか?

・

ノー:だったら、現在の男女のセクシュアリティと「騙しや籠絡」は変わっていないことに同意するか?

(3)

ドン・ファン的気分にある男性を、逆にカモにする美人局(つつもたせ)を知っているか?

・

イエス:つつもたせとはなにか?

・

ノー:美人局の英語は、Beauty Bureauや Badger gameといいます。

| 「悪ないしは邪悪に関するポータルサイト」より まとめ 1. 悪とは、道徳的に正しくないこと、不必要な心身の痛みや苦しみを引き起こすこと、と定義できる。 2. 善よりも悪のほうが我々の生活のなかで衝撃的である。悪の存在は、我々の倫理的生活を(反面教師の形で)形づくることに形成している。 3. 悪への考察を通して、人類は悪の本質を解明しようと努力してきており、この探求は今後も続くだろう。 4. 悪は無くならないという古来から続く悲観的な見解と、悪は厄介ではあるが、反省と分析を通して、以前よりも軽減するための努力は必要であり、実際にそうな りつつあるという現代的な楽観的な見解の2つがある。 |

|

|

12 悪が定義できれば、道徳的なこと、倫理的なこと、つまり善の考察が次に求められる!!がそれは来年にやろう!! |

|

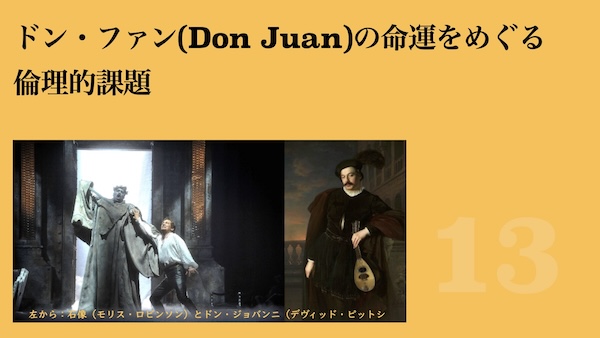

13 ドン・ファン(Don Juan)の命運をめぐる 倫理的課題 |

|

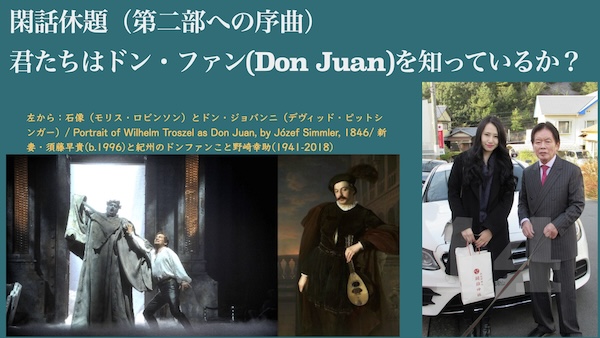

14 閑話休題(第二部への序曲) 君たちはドン・ファン(Don Juan)を知っているか? 左から:石像(モリス・ロビンソン)とドン・ジョバンニ(デヴィッド・ピットシンガー)/ Portrait of Wilhelm Troszel as Don Juan, by Józef Simmler, 1846/ 新妻・須藤早貴(b.1996)と紀州のドンファンこと野崎幸助(1941-2018) |

|

15 本日(24.07.10)の審問は、 「女たらしドン・ファンは罰せられるべきか?」について考えよう!! 審問(しんもん)=問いかけ |

|

16 本日(24.07.10)の課題は ・異性間あるいは同性間の親密なセクシュアリティにおける倫理的課題を考えてみる ・親密なセクシュアリティには行為責任が生じるのか? ・親密なセクシュアリティにおける「騙しや籠絡」は何を帰結するのか? |

|

17 ・ドン・ファン(Don Juan)は、17世紀スペインのフィクションあるいは説教物語における架空の人物像である。ティルソ・デ・モリーナによる戯曲「セビリアの色事師と石の 招待客 (El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra)」が原型。好色放蕩な美男として多くの文学作品に描写されている。プレイボーイ、女たらしの代名詞としても使われている。 |

|

18 ティルソ・デ・モリーナによる戯曲やモリエールの戯曲「ドン・ジュアン、またの名を石像の宴」、あるいは作曲家モーツアルトと台本作家ダ・ポンテによる 「ドン・ジョバンニ」によると、女たらし(プレイボーイ)の主人公は下僕を連れて各地を遍歴し、女とみれば身分の上下や美醜とは無関係に女性を籠絡し、自 分の手に入れば、捨ててしまい、また新たな女あさりに勤しむ、ドン・ファン(ドン・ジュアン/ドン・ジョバンニ)は、あることを契機に人を殺めてしまう。 そのことを改心せずに、引き続き女漁りを続けるうちに、(殺された紳士の亡霊を象徴する)墓場の石像に出会い、晩餐を招待すると、次の機会に招待される。 主人の身の安全を危惧する下僕の忠告をきかずに晩餐の招待を受けて、主人公は、地獄に引きずられ、その生涯を終える、という物語展開を遂げる。 |

|

19 ドン・ファン(ドン・ジュアン;ドン・ジョヴァンニ)のイメージ モリス・ロビンソンとデヴィッド・ピットシンガー(2011年)/ Portrait of Wilhelm Troszel as Don Juan, by Józef Simmler, 1846 |

|

20 主人公は墓場の石像と晩餐を共にしても恐る様子がなく、あるいは女漁りへの反省もないために、地獄に連れていかれて罰せられる、という勧善懲悪の物語展開 をとげる(前半の「悪に関するショートレクチャー」を思い起こそう)勧善懲悪の技法は「詩的正義(Poetic justice)」と呼ばれる。詩的正義は詩的皮肉とも呼ばれ、最終的に美徳が報われ、悪行が罰せられる文学的=芸術的装置である。 |

|

21 (1)「女たらしドン・ファンは、その悪業のゆえに罰せられるべきか?」 🔶全面的イエス:どうしてか、その理由 🔶部分的イエス/部分的ノー:どうしてか、その理由 🔶全面的ノー:どうしてか、その理由 (2)女たらしドン・ファンの歴史は、もはや過去のものか? 🔷イエス:だったら、現在の男女のセクシュアリティと「騙しや籠絡」とはどのようなものか? 🔷ノー:だったら、現在の男女のセクシュアリティと「騙しや籠絡」は変わっていないことに同意するか? |

|

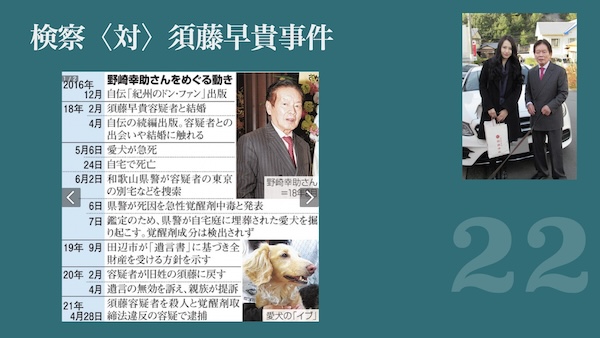

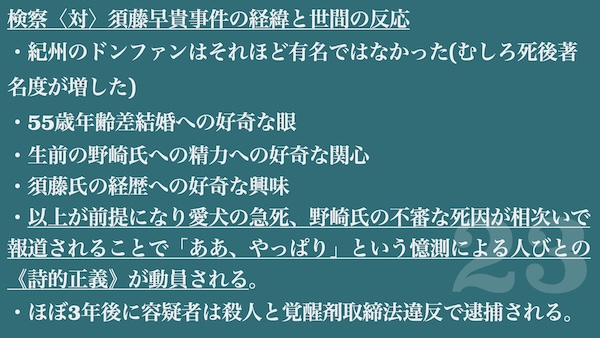

22 検察〈対〉須藤早貴事件 |

|

23 検察〈対〉須藤早貴事件の経緯と世間の反応 ・紀州のドンファンはそれほど有名ではなかった(むしろ死後著名度が増した) ・55歳年齢差結婚への好奇な眼 ・生前の野崎氏への精力への好奇な関心 ・須藤氏の経歴への好奇な興味 ・以上が前提になり愛犬の急死、野崎氏の不審な死因が相次いで報道されることで「ああ、やっぱり」という憶測による人びとの《詩的正義》が動員される。 ・ほぼ3年後に容疑者は殺人と覚醒剤取締法違反で逮捕される。 |

|

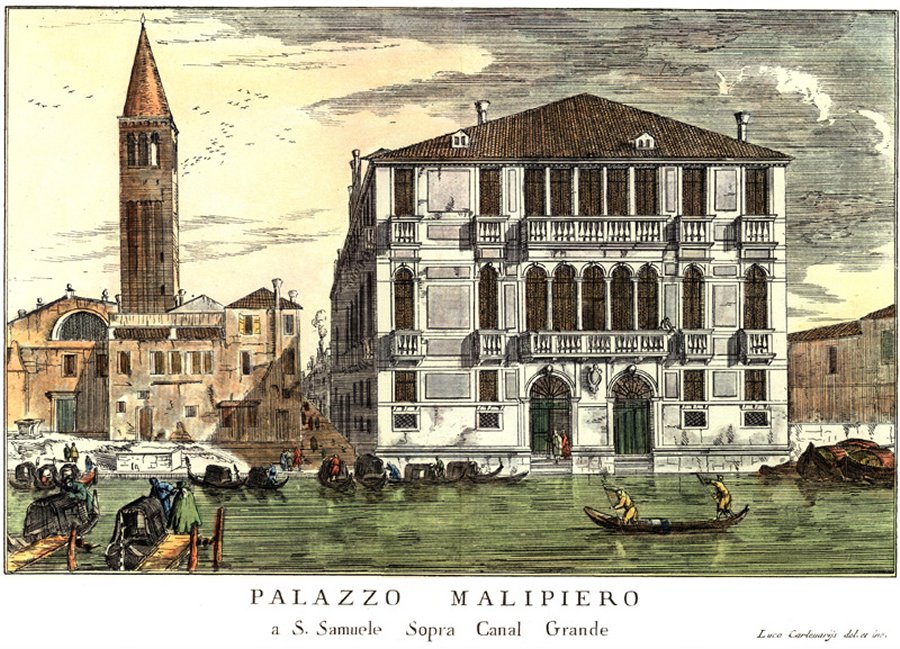

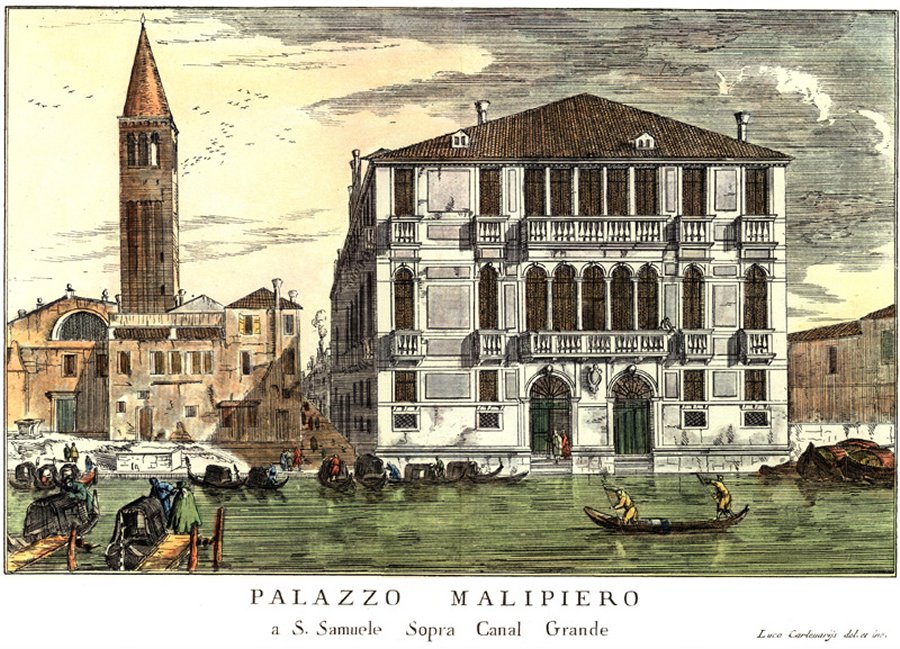

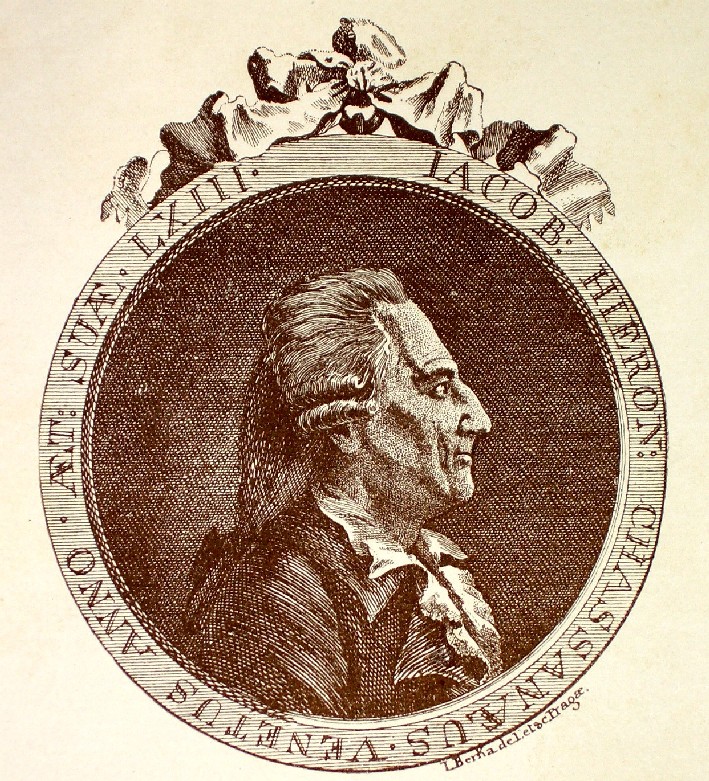

24 ドン・ファンではなくカサノヴァ?! ジャコモ・ジロラモ・カサノヴァ (Giacomo Casanova, 1725-1798)はヴェネツィア共和国出身のイタリアの冒険家、作家である。彼の自伝であるHistoire de ma vie(Story of My Life)は、18世紀のヨーロッパ社会生活の習慣や規範に関する最も信憑性が高く挑発的な情報源のひとつとみなされている。カサノヴァは、ファルシ男爵 や伯爵、シュヴァリエ・ド・セインガルトなどの偽名を使うことで知られていた。ヴェネツィアからの2度目の亡命後、フランス語で執筆を始めた後、彼はしば しば作品に「ジャック・カサノヴァ・ド・セインガルト」と署名した。彼はヨーロッパの王族、教皇、枢機卿、芸術家であるヴォルテール、ゲーテ、モーツァル ト※らと交わったと主張している。女性との複雑で手の込んだ情事をしばしば行ったことで有名になり、その名はリベルタンの代名詞と言える。晩年はワルト シュタイン伯爵家の司書とし デュックス・シャトー(ボヘミア)で過ごし、そこで自伝も執筆した。 ※カサノヴァは1787年10月29日プラハでのノスティッツ国立劇場での「ドン・ジョバンニ」のモーツアルト指揮の初演を鑑賞している可能性が高い |

|

25 カサノヴァ?!と言えばフェデリコ・フェリーニ Fellini's Casanova (Italian: Il Casanova di Federico Fellini, lit. 'The Casanova by Federico Fellini') is a 1976 Italian film directed by Federico Fellini from a screenplay he co-wrote with Bernardino Zapponi, adapted from the autobiography of 18th-century Venetian adventurer and writer Giacomo Casanova, played by Donald Sutherland. |

|

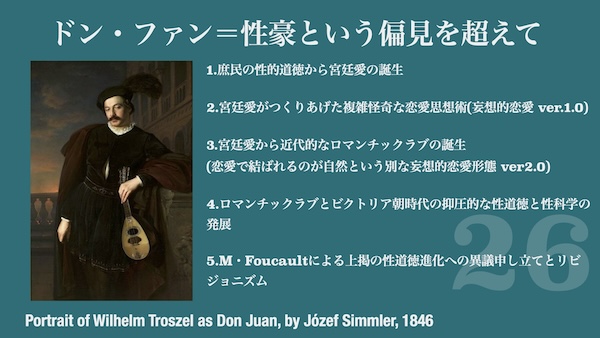

26 ドン・ファン=性豪という偏見を超えて 1.庶民の性的道徳から宮廷愛の誕生 2.宮廷愛がつくりあげた複雑怪奇な恋愛思想術(妄想的恋愛 ver.1.0) 3.宮廷愛から近代的なロマンチックラブの誕生 (恋愛で結ばれるのが自然という別な妄想的恋愛形態 ver2.0) 4.ロマンチックラブとビクトリア朝時代の抑圧的な性道徳と性科学の発展 5.M・Foucaultによる上掲の性道徳進化への異議申し立てとリビジョニズム |

|

27 社会学者ミラ・コマロフスキーのエスノグラフィー On Gender Battle, or our Modus Operandi for ture love 「私はデートのときにときどき〈少し足りないふりをするの〉、でも後味がよくないわ。複雑な気持ね。私のなかには、疑うことを知らない男を〈だましおおす ことに〉喜びを感ずる部分があるのよ。でも彼に対するこの優越感は、私の偽善に対する罪悪感と混り合ってるんです。〈デートの相手〉に対しては、彼が私の 手管に〈欺かれている〉ということで軽べつを感じたり、もしその人が好きなら一種の母性的ないたわりを感じたりするんです。ときには彼を恨めしく思うこと もあるわ!なぜ男性が優れていて当然とされていることで、彼は私よりも優れてはいないのか、彼が私より優れていれば私は自然のままの私でいられるのに?な んで彼とこんなところにいるのかしら、一体?安売り?」(Komarovsky 1946:188). |

|

28 恋愛関係における主と奴の弁証法 Poor is the man Whose pleasures depend On the permission of another Love me, that's right, love me I wanna be your baby (Lenny Kravitz, Ingrid Chavez and Madonna, Justify My Love,1990) 男子(おのこ)は哀れなものよ きゃつの悦びは…… 女子(おなご)の承認を必要とす 男子(おのこ)よ我を愛せ、それでよい、我を愛せ お前の愛人になってやろう [原義:愛人になりたい] |

|

29 私の回答とみなさんの回答は??? (1)女たらしドン・ファンは、その悪業のゆえに罰せられるべきか? (2)女たらしドン・ファンの歴史は、もはや過去のものか? (3)自分より学歴の低い男の子とデートする時に「同じレベルの教養」を偽装する女の子の行為は倫理的に正当化されるか? |

|

30 偽装の非倫理的なことが証明できれば、反対に道徳的なこと、倫理的なことの考察が可能になる!!だが、それはまた次の機会に!! |

|

Arrivederci!! Don Giovanni |

☆ 「セ ビリアの色事師 (El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra)」と詩的正義とコントラバッソについて

| El burlador de

Sevilla y convidado de piedra es una obra de teatro que recoge el mito

de don Juan, sin duda el personaje más universal del teatro español. De

autoría discutida, se atribuye tradicionalmente a Tirso de Molina y se

conserva en una publicación de 1630, aunque tiene como precedente la

versión conocida como Tan largo me lo fiais representada en Córdoba en

1617 por la compañía de Jerónimo Sánchez.2 Alfredo Rodríguez

López-Vázquez señala al dramaturgo Andrés de Claramonte como autor de

la obra en función de pruebas de carácter métrico, estilístico e

histórico.34 Sin embargo, tanto Luis Vázquez como José María Ruano de

la Haza la dan sin dudar como obra de Tirso y otros críticos concluyen

que tanto El burlador como el Tan largo me lo fiais descienden de un

arquetipo común del Burlador de Sevilla escrito por Tirso entre 1612 y

1625.5 |

El burlador de Sevilla y

convidado de

piedra』は、スペイン演劇界で最も普遍的なキャラクターであるドン・ファンの神話を取り上げた戯曲である。作者については議論があり、伝統的には

ティルソ・デ・モリーナの作とされ、1630年の出版物に残されているが、その前例は、1617年にコルドバで上演されたジェロニモ・サンチェスの劇団に

よる「Tan largo me lo fiais」として知られるバージョンである2。

4しかし、ルイス・バスケスもホセ・マリア・ルアノ・デ・ラ・ハサも、迷うことなくティルソの作品とし、他の批評家も、『エル・ブルラドール』と『タン・

ラルゴ・メ・ロ・フィアイス』の両方が、1612年から1625年の間にティルソによって書かれた『セビリアのブルラドール』という共通の原型に由来する

と結論付けている5。 |

| Contexto Don Juan personifica una leyenda sevillana que inspiró a Molière, Antonio de Zamora, Carlo Goldoni, Lorenzo da Ponte (autor del libreto de Don Giovanni de Mozart), lord Byron, Espronceda, Pushkin, Zorrilla, Azorín, Marañón y a muchos otros autores. Es un libertino que cree en la justicia divina («no hay plazo que no se cumpla ni deuda que no se pague») pero que confía en que podrá arrepentirse y ser perdonado antes de comparecer ante Dios («¡Cuán largo me lo fiais!»). Si además recordamos que El burlador de Sevilla se publicó en 1630, podemos concluir que se trata de una obra cuya vocación es moralizante, y que podría haber sido concebida como respuesta a la teoría de la predestinación de Don Juan, según la cual la salvación y la entrada en el reino de los cielos ya ha sido determinada por Dios desde el nacimiento de uno, dado por gracia a través de Cristo y recibido solamente por fe, por lo que los actos no son determinantes para la salvación de las almas. Se ha especulado mucho sobre la posible inspiración en un personaje real, y se ha señalado a Miguel Mañara como principal candidato. Sin embargo, si aceptamos la opinión mayoritaria respecto a la autoría y la fecha, no podrá considerarse el personaje de don Juan inspirado en la vida de Mañara, ya que este nació en 1627 y la obra se editó solo tres años después. Más aún, una versión precedente del Burlador, el Cuán largo me lo fiais, con el mismo argumento, podría datar de 1617.  |

文脈[編集] ドン・ファンは、モリエール、アントニオ・デ・ザモラ、カルロ・ゴルドーニ、ロレンツォ・ダ・ポンテ(モーツァルトの『ドン・ジョヴァンニ』のリブレット の作者)、バイロン卿、エスプロンセダ、プーシキン、ゾリージャ、アゾリン、マラニョン、その他多くの作家に影響を与えたセビリアの伝説を擬人化したもの である。彼は、神の正義を信じ(「守られない期限はなく、払われない負債もない」)、神の前に現れる前に悔い改めて赦されることを信じる自由人である (「いつまで私を信じてくれるの!」)。この作品は、救いと天の御国への参入は、生まれたときから神によってすでに決定されており、キリストによる恵みに よって与えられ、信仰のみによって受け取られる。 実在の人物からインスピレーションを受けた可能性について多くの憶測が飛び交い、ミゲル・マニャラがその有力候補に挙げられている。しかし、作者や年代に 関する多数説を受け入れるなら、ドン・ファンのキャラクターはマニャラの生涯から着想を得たとは考えられない。彼は1627年に生まれ、この作品が出版さ れたのはそのわずか3年後だからだ。さらに、同じ筋書きの『ブルラドール』の初期版『Cuán largo me lo fiais』は、1617年の作品かもしれない。  |

| Argumento Un joven noble español llamado don Juan, el gran seductor y libertino, seduce en Nápoles a la duquesa Isabela haciéndose pasar por su prometido, el duque Octavio, lo que ella descubre al querer alumbrarlo con el farol. Tras esto, en la huida mientras gritaba fue de pato va a parar a la habitación del rey, quien encarga a la guardia y a don Pedro Tenorio (pariente del protagonista y embajador de España) que atrape al hombre que ha deshonrado a la joven. Al entrar don Pedro en la habitación y descubrir que el burlador es su sobrino, decide escucharlo y ayudarle a escapar, para alegar más tarde que no pudo alcanzarlo debido a su agilidad al saltar desde la habitación a los jardines. Tras esto, don Juan viaja a España y naufraga en la costa de Tarragona; Catalinón (su criado) consigue llevarlo hasta la orilla, donde los aguarda la pescadora Tisbea, que ha oído su grito de socorro. Tisbea manda a Catalinón a buscar a los pescadores a un lugar no muy lejano y en el tiempo que están ellos solos don Juan la seduce y esa misma noche la goza en su cabaña, de la que más tarde huirá con las dos yeguas que Tisbea había criado. Cuando don Juan y Catalinón regresan a Sevilla, el escándalo de Nápoles llega a oídos del rey Alfonso XI, quien busca solucionarlo comprometiéndolo con Isabela (el padre de don Juan trabaja para el rey). Mientras, don Juan se encuentra con su conocido, el marqués de la Mota, el cual le habla sobre su amada, doña Ana de Ulloa, tras hablar de burlas, “ranas” y mujeres en todos los aspectos; y como el marqués de la Mota dice de Ana que es la más bella sevillana llegada desde Lisboa, don Juan tiene la imperiosa necesidad de gozarla y, afortunadamente para él, recibe la carta destinada al Marqués, al que luego informará de la cita pero con un retraso de una hora para así él gozar a Ana. Por la noticia de la carta de Ana de Ulloa, Mota le ofrece una burla a don Juan, para lo cual este ha de llevar la capa del marqués, que se la presta sin saber que la burla no iba a ser la estipulada, sino la deshonra de Ana al estilo de la de Isabela. Don Juan consigue engañar a la dama, pero es descubierto por el padre de esta, don Gonzalo de Ulloa, con quien se enfrenta en un combate en el que don Gonzalo muere. Entonces don Juan huye en dirección a Dos Hermanas. Mientras se encuentra lejos de Sevilla, lleva a cabo otra burla, interponiéndose en el matrimonio de dos plebeyos, Arminta y Batricio, a los que engaña hábilmente: en la noche de bodas, don Juan llega a parecer interesado en un casamiento con Arminta, Batricio le cree y se deja llevar por el engaño. Arminta una vez en el cuarto, don Juan se presenta con ella, y la seduce diciéndole sobre su amor y prometido matrimonio con ella misma, para poder gozarla. Don Juan vuelve a Sevilla, donde se topa con la tumba de don Gonzalo y se burla del difunto, invitándolo a cenar. Sin embargo, la estatua de este llega a la cita (el convidado de piedra) cuando realmente nadie esperaba que un muerto fuera a hacer cosa semejante. Luego, el mismo don Gonzalo convida a don Juan y a su lacayo Catalinón a cenar a su capilla, y don Juan acepta la invitación acudiendo al día siguiente. Allí, la estatua de don Gonzalo de Ulloa se venga arrastrándolo a los infiernos sin darle tiempo para el perdón de los pecados de su «Tan largo me lo fiais», famosa frase del Burlador que significa que la muerte y el castigo de Dios están muy lejanos y que por el momento no le preocupa la salvación de su alma. Tras esto se recupera la honra de todas aquellas mujeres que habían sido deshonradas, y puesto que no hay causa de deshonra, todas ellas pueden casarse con sus pretendientes. El mito de don Juan Artículo principal: Don Juan Protagonista de la obra, El burlador de Sevilla, y personaje en torno al cual gira la obra entera, que durante toda la obra se dedica a burlar a todas aquellas damas que encuentra en estado de gracia para así él poseerlas, haciendo uso de trucos, engaños y burlas y deshonrando de esta forma a la mujer y perdiendo el honor del hombre con el que ella realmente deseaba gozar. Orígenes Los orígenes de don Juan son difíciles de determinar. Según Youssef Saad, el don Juan de España es una figura auténticamente española, pero tiene muchas semejanzas con una figura árabe, Imru al-Qays, quien vivió en Arabia durante el quinto siglo: como don Juan, era un burlador y un seductor famoso de mujeres; como el don Juan de Zorrilla, fue rechazado por su padre por sus burlas y también desafió abiertamente a la ira divina. Según Víctor Said Armesto, las raíces literarias de don Juan se pueden encontrar en los romances gallegos y leoneses medievales. Su precursor típicamente llevaba el nombre de “Don Galán” y este hombre también trata de engañar y seducir a las mujeres, pero tiene una actitud más piadosa hacia Dios. Evolución Tras esta acuñación del personaje de don Juan Tenorio, El Burlador de Sevilla como llega él a llamarse, se dan varias reinterpretaciones del mito, como el Don Juan de Molière, cuyo Don Juan no solo roza los límites de la más cínica arrogancia, sino que también nos muestra un personaje con un gran escepticismo religioso, lo que es una gran distinción con el del dramaturgo español. A la mentalidad del siglo xviii corresponden tres obras sobre don Juan: la española de Antonio de Zamora, No hay plazo que no se cumpla, la italo-austriaca, Don Giovanni con libreto de Lorenzo da Ponte y música de Mozart y la italiana de Carlo Goldoni, titulada Don Juan o el castigo del libertino. En el romanticismo se dio un nuevo rumbo al mito; unas veces se une al tipo primitivo y otras a la expresión de la vivencia personal de creadores cuya vida tuvo que ver con la del seductor. Como el Don Juan de Byron, y el protagonista de El estudiante de Salamanca, de Espronceda. Y en relación con los primitivos están la versión de Zorrilla, Don Juan Tenorio, y las francesas de Merimée y Alejandro Dumas. Aunque el don Juan romántico pierde con respecto al primitivo ya que a veces llega a mostrarse como un simple juguete del destino y hasta se enamora sinceramente, dejando de ser el mito eterno del cínico seductor que fácilmente olvidaba para volver a seducir. |

プロット[編集]。 スペイン貴族のドン・ファンという青年が、ナポリのイサベラ公爵夫人の婚約者オクタビオ公爵になりすまし、ナポリのイサベラ公爵夫人を誘惑する。その後、 "フエ・デ・パト "と叫びながら逃走した彼は国王の部屋に辿り着き、国王は衛兵とドン・ペドロ・テノリオ(主人公の親戚でスペイン大使)に若い女性の名誉を傷つけた男を捕 まえるよう指示する。部屋に入ったドン・ペドロは、あざ笑う男が自分の甥であることを知ると、彼の話を聞くことにして逃走を助けるが、後に、部屋から庭園 に飛び移る彼の機敏さのために捕まえることができなかったと主張する。 この後、ドン・ファンはスペインに渡り、タラゴナの海岸で難破する。カタリノン(彼の召使い)は何とか彼を岸に上げることに成功し、助けを求める彼の叫び を聞いた漁師のティスベアが二人を待っていた。ティスベアはカタリノンに漁師を探しに行かせ、二人きりになったその夜、ドン・ファンはカタリノンを誘惑 し、自分の小屋で彼女を楽しませる。 ドン・ファンとカタリノンがセビーリャに戻ると、ナポリのスキャンダルがアルフォンソ11世の耳に入り、アルフォンソ11世はドン・ファンとイサベラ(ド ン・ファンの父は王に仕えている)を婚約させることで解決しようとする。一方、ドン・ファンは知り合いのラ・モタ侯爵に会い、嘲笑、「蛙」、女性のあらゆ る面について話した後、彼の最愛の女性ドニャ・アナ・デ・ウジョアについて話す。ラ・モタ侯爵が、アナはリスボンから来たセビリアの女性の中で最も美しい と言うので、ドン・ファンは彼女を楽しませなければならないという衝動に駆られ、幸運にも侯爵宛ての手紙を受け取る。アナ・デ・ウジョアの手紙を聞いたモ タは、ドン・ファンに嘲笑を申し入れる。そのために侯爵の外套を持ってこなければならなかったが、侯爵は、嘲笑が定められたものではなく、イサベラ風にア ナの名誉を傷つけるものだと知らずに貸してくれた。 ドン・フアンは、何とか女性を欺くことに成功するが、彼女の父、ドン・ゴンサロ・デ・ウジョアに見つかってしまい、ドン・ゴンサロと一騎打ちとなり、ド ン・ゴンサロは死んでしまう。その後、ドン・フアンはドス・エルマナス方面へ逃げる。 セビーリャから遠く離れている間に、彼はもう一つの策略を実行する。二人の平民、アルミンタとバトリシオの結婚を邪魔し、巧みに騙すのだ。結婚初夜、ド ン・ファンはアルミンタとの結婚に興味があるように見せかけ、バトリシオは彼を信じ、騙される。アルミンタが部屋に入ると、ドン・ファンは彼女に自己紹介 し、彼女を楽しませるために、自分への愛と結婚の約束を告げて誘惑する。 セビーリャに戻ったドン・ファンは、偶然ドン・ゴンザロの墓を見つけ、故人をあざ笑って夕食に誘う。しかし、誰も死人がそんなことをするとは思っていな かったのに、故人の像が待ち合わせの場所(石の客)にやってくる。その後、ドン・ゴンサロ自身がドン・フアンとその下僕カタリノンを礼拝堂での食事に招待 し、ドン・フアンはその招待を受け、翌日出席する。そこで、ドン・ゴンサロ・デ・ウジョア像は、彼の罪を許す暇も与えず、彼を地獄に引きずり込んで復讐を 果たす。"Tan largo me lo fiais "とは、死と神の罰は遥か彼方にあり、当分の間は魂の救済には関心がないことを意味するブルラドールの有名な言葉である。 この後、不名誉な扱いを受けていた女性たちの名誉は回復し、不名誉な扱いを受ける理由がなくなったため、彼女たちは皆求婚者と結婚できるようになる。 ドン・ファン神話[編集] 主な記事:ドン・ファン 戯曲の主人公で、劇全体がこの人物を中心に展開される。劇中では、優美な状態にある女性たちをすべてあざ笑い、自分がその女性を所有できるようにすること に専心し、策略、欺瞞、嘲笑を駆使し、その結果、女性の名誉を傷つけ、女性が本当に楽しみたいと願った男性の名誉を失う。 起源[編集] ドン・ファンの起源を特定するのは難しい。ユセフ・サードによれば、スペインのドン・ファンは正真正銘のスペイン人だが、5世紀にアラビアに住んでいたイ ムル・アル・カイーズというアラブの人物と多くの類似点があるという。ドン・ファンのように、彼はあざ笑う男であり、有名な女性の誘惑者であった。ビクト ル・シド・アルメストによれば、ドン・ファンの文学的ルーツは中世ガリシアとレオンのロマンスにあるという。彼の前身は一般的に「ドン・ガラン」という名 前で、この男もまた女性を欺き誘惑しようとするが、神に対してはより敬虔な態度をとる。 進化[編集] ドン・フアン・テノリオ、エル・ブルラドール・デ・セビージャと呼ばれるようになったこの人物の造語の後、モリエールの『ドン・フアン』のように、この神 話を再解釈したものがいくつかある。 アントニオ・デ・サモーラのスペイン語劇『No hay plazo que no se cumpla』、ロレンツォ・ダ・ポンテの台本とモーツァルトの音楽によるイタリア・オーストリアの『ドン・ジョヴァンニ』、カルロ・ゴルドーニのイタリ ア語劇『ドン・ファン o el castigo del libertino』である。 ロマン主義では、神話は新たな方向性を与えられた。ある時は原始的なタイプに結びつき、またある時は、誘惑者の人生と関係していた創作者たちの個人的な経 験の表現に結びつく。バイロンの『ドン・ファン』やエスプロンセダの『サラマンカの学生』の主人公がそうである。また、原始人たちとの関係では、ゾリー リャ版『ドン・ファン・テノリオ』、メリメや アレクサンドル・デュマのフランス版などがある。ロマンチックなドン・ファンは原始的なドン・ファンには負けるが、彼は時に運命に翻弄され、心から恋に落 ちることもある。 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_burlador_de_Sevilla_y_convidado_de_piedra |

|

| Poetic justice,

also called poetic irony, is a literary device with which ultimately

virtue is rewarded and misdeeds are punished. In modern literature,[1]

it is often accompanied by an ironic twist of fate related to the

character's own action, hence the name poetic irony.[2] |

詩的正義は

詩的皮肉とも呼ばれ、最終的に美徳が報われ、悪行が罰せられる文学的装置である。現代文学では[1]、登場人物自身の行動に関連した運命の皮肉な展開を伴

うことが多く、それゆえ詩的皮肉と呼ばれる[2]。 |

| Etymology English drama critic Thomas Rymer coined the phrase in The Tragedies of the Last Age Consider'd (1678) to describe how a work should inspire proper moral behaviour in its audience by illustrating the triumph of good over evil. The demand for poetic justice is consistent in Classical authorities and shows up in Horace, Plutarch, and Quintillian, so Rymer's phrasing is a reflection of a commonplace. Philip Sidney, in The Defence of Poesy (1595) argued that poetic justice was, in fact, the reason that fiction should be allowed in a civilized nation. |

語源[編集] イギリスの戯曲批評家トーマス・ライマーは、『The Tragedies of the Last Age Consider'd』(1678年)の中で、作品が悪に対する善の勝利を描くことによって、観客に適切な道徳的行動を促すべきことを説明するために、こ の言葉を作った。詩的正義の要求は古典的権威に一貫しており、ホレス、プルターク、キンティリアヌスにも見られるので、ライマーの言い回しはありふれたも のの反映である。フィリップ・シドニーは 『ポエジーの弁明』(1595年)の中で、詩的正義こそが、文明国家においてフィクションが許されるべき理由であると主張した。 |

| History Notably, poetic justice does not merely require that vice be punished and virtue rewarded, but also that logic triumph. If, for example, a character is dominated by greed for most of a romance or drama, they cannot become generous. The action of a play, poem, or fiction must obey the rules of logic as well as morality. During the late 17th century, critics pursuing a neo-classical standard criticized William Shakespeare in favor of Ben Jonson precisely on the grounds that Shakespeare's characters change during the course of the play.[3] When Restoration comedy, in particular, flouted poetic justice by rewarding libertines and punishing dull-witted moralists, there was a backlash in favor of drama, in particular, of more strict moral correspondence. |

歴史[編集] 特筆すべきは、詩的正義は単に悪を罰し、徳に報いることを要求するだけでなく、論理が勝利することも要求するということだ。例えば、ロマンスやドラマの大 半で登場人物が欲に支配されている場合、彼らは寛大になることはできない。戯曲、詩、小説の行動は、道徳だけでなく論理のルールにも従わなければならな い。17世紀後半、新古典主義の基準を追求する批評家たちは、ウィリアム・シェイクスピアを批判し、ベン・ジョンソンを支持したが、それはまさに、シェイ クスピアの登場人物が戯曲の途中で変化するという理由によるものであった[3]。特に王政復古期の喜劇が、詩的正義に背き、自由主義者に報酬を与え、頭の 鈍い道徳主義者を罰するものであったため、戯曲、特により厳格な道徳的対応を支持する反発が起こった。 |

| Contrapasso Karma Unintended consequences Irony |

コントラパッソ カルマ 意図しない結果 皮肉 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poetic_justice |

|

| In Dante's Inferno, contrapasso

(or, in modern Italian,[1] contrappasso, from Latin contra and patior,

meaning "suffer the opposite") is the punishment of souls "by a process

either resembling or contrasting with the sin itself."[2] A similar

process occurs in the Purgatorio.[2] One of the examples of contrapasso occurs in the fourth Bolgia of the eighth circle of Hell, where the sorcerers, astrologers, and false prophets have their heads turned back on their bodies such that it is "necessary to walk backward because they could not see ahead of them."[3] This alludes to the consequences of predicting the future by evil means and displays the twisted nature of magic in general.[4] This example of contrapasso "functions not merely as a form of divine revenge, but rather as the fulfillment of a destiny freely chosen by each soul during his or her life."[5] The word contrapasso can be found in Inferno, in which the decapitated Bertran de Born declares: Così s'osserva in me lo Contrapasso (XXVIII.142),[6] which was translated by Longfellow as "thus is observed in me the counterpoise",[7] and by Singleton as "thus is the retribution observed in me."[8] Dante believes that De Born is in the ninth Bolgia of schismatics for causing Henry the Young King's rebellion against his father, Henry II of England.[9] De Born is decapitated as a contrapasso for his supposed act of political decapitation in undermining a rightful head of the state.[9] Dante inherited the idea of "contrapasso" from various theological and literary sources. These include Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica as well as medieval ‘visions’ such as Visio Pauli, Visio Alberici, and Visio Tnugdali.[1]  The Contrapasso of the sorcerers, astrologers, and false prophets, illustrated by Stradanus |

ダンテの『地獄篇』において、コントラパッソ(現代イタリア語では

[1] コントラッパッソ、ラテン語の contraと

patiorに由来し、「正反対の苦しみを受ける」を意味する)とは、「罪そのものに似ているか対照的な過程」[2]によって魂を罰することである。同様

の過程が『プルガトリオ』にもある[2]。 魔術師、占星術師、偽預言者たちは、「前が見えないので、後ろ向きに歩かなければならない」ように、頭を後ろに向けられる。 「このコントラパッソの例は、「単に神の復讐としてではなく、むしろ、それぞれの魂が生前に自由に選んだ運命の成就として機能している」[5]。 コントラパッソという言葉は、『インフェルノ』の中で、首を切られたベルトラン・ド・ボルンがこう宣言している: と宣言している(XXVIII.142)[6]。 ダンテは、デ・ボルンが幼王ヘンリーの父であるイングランド王ヘンリー2世に対する反乱を引き起こしたことで、分裂主義者の9番目のボルジアにいると考え ている[9]。デ・ボルンは、正当な国家元首を貶めるという政治的な断末魔の行為のために、コントラパッソとして断頭される[9]。 ダンテは様々な神学的・文学的資料から「コントラパッソ」の思想を受け継いだ。その中には、トマス・アクィナスの『スンマ・テオロジカ』や、『ヴィジオ・ パウリ』、『ヴィジオ・アルベリチ』、『ヴィジオ・トゥヌグダリ』といった中世の「ヴィジョン」が含まれる[1]。  魔術師、占星術師、偽預言者たちのコントラパッソ』(ストラダヌス画 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contrapasso |

★ ドン・ファン伝説が受容される社会的条件

・ セクシュアリティの「欲望」を秘匿したり、節制したりすることがノーマルとみなされる、性道徳と性道徳秩序の存在

・ セックスや恋愛は、男性がイニシアチブをとるべきだという伝統。ドン・ファンはそれが「過剰」な状態にある

・ ドン・ファン的ふるまいを可能にする、経済的あるいは身分的特権階級であること

・ モーツアルト「ドン・ジョヴァンニ」のレポレッロの「カタログのアリア」のように、モノにした女性の数の地域や数を綿密に数え上げる、記録フェチあるいは 記号化される獲物の存在

・仮に不誠実でも魅力ある男性により籠絡されるという「女性の天性(Women's

nature)」の容認

☆ ドン・ファン伝説

| Don Juan (Spanish:

[doŋ ˈxwan]), also known as Don Giovanni (Italian), is a legendary,

fictional Spanish libertine who devotes his life to seducing women. The original version of the story of Don Juan appears in the 1630 play El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra (The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest) by Tirso de Molina. The play includes most of the elements found and later adapted in subsequent works, including the setting (Seville), the characters (Don Juan, his servant, his love interest, and her father, whom he kills), moralistic themes (honor, violence and seduction, vice and retribution), and the dramatic ending in which Don Juan dines with and is then dragged down to hell by the stone statue of the father he had previously slain. Tirso de Molina's play was subsequently adapted into numerous plays and poems, of which the most famous include a 1665 play, Dom Juan, by Molière, a 1787 opera, Don Giovanni, with music by Mozart and a libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte largely adapting Tirso de Molina's play, a satirical and epic poem, Don Juan, by Lord Byron, and Don Juan Tenorio, a romantic play by José Zorrilla. By linguistic extension, from the name of the character, "Don Juan" has become a generic expression for a womanizer, and stemming from this, Don Juanism is a non-clinical psychiatric descriptor. |

ドン・ファン(スペイン語:[doŋ

ˈwan])は、ドン・ジョヴァンニ(イタリア語)としても知られる、伝説上の架空のスペインの 自由人で、女性を誘惑することに生涯を捧げる。 ドン・ファンの物語の原作は、ティルソ・デ・モリーナによる1630年の戯曲『セビリアのトリックスターと石の客』に登場する。この戯曲には、舞台設定 (セビリア)、登場人物(ドン・ファン、使用人、恋敵、彼が殺した彼女の父親)、道徳的テーマ(名誉、暴力と誘惑、悪徳と報復)、ドン・ファンが以前に殺 した父親の石像と一緒に食事をし、その後地獄に引きずり込まれるという劇的な結末など、その後の作品で発見され、脚色された要素のほとんどが含まれてい る。ティルソ・デ・モリーナの戯曲はその後、数多くの戯曲や詩に翻案されたが、最も有名なものには、モリエールによる1665年の戯曲『ドン・ジュア ン』、ティルソ・デ・モリーナの戯曲を大きく脚色したロレンツォ・ダ・ポンテの 台本と モーツァルトの音楽による1787年のオペラ『ドン・ジョヴァンニ』、バイロン卿による風刺的で叙事詩的な詩『ドン・ジュアン』、ホセ・ゾリーリャによる ロマンチックな戯曲『ドン・ジュアン・テノリオ』などがある。 ドン・ファン」は、その登場人物の名前から言語学的に拡張され、女たらしの総称となり、これに由来するドン・ジュアニズムは、非臨床的な精神医学的記述語 である。 |

| Pronunciation In Spanish, it is pronounced [doŋˈxwan]. The usual English pronunciation is /ˌdɒnˈwɑːn/, with two syllables and a silent "J", but today, as more English-speakers are becoming influenced by Spanish, the pronunciation /ˌdɒnˈhwɑːn/ is becoming more common. However, in Lord Byron's verse version the name rhymes with ruin and true one, and traditionally the name was pronounced with three syllables, possibly /ˌdɒnˈʒuːən/ or /ˌdɒnˈdʒuːən/, in England at the time and by later critics. This would have been characteristic of English literary precedent, where English pronunciations were often imposed on Spanish names, such as Don Quixote /ˌdɒnˈkwɪksət/. |

発音 スペイン語では[doŋˈxwan] と発音する。 しかし、バイロン卿の詩編では、この名前は破滅と 真の1つと韻を踏んでおり、伝統的にこの名前は3音節で発音されていた。これは、ドン・キホーテ /ˌdɪksət/のようなスペイン語の名前に英語の発音がしばしば押し付けられる、イギリス文学の先例の特徴であったろう。 |

| Synopsis There have been many versions of the Don Juan story, but the basic outline remains the same: Don Juan is a wealthy Andalusian libertine who devotes his life to seducing women. He takes great pride in his ability to seduce women of all ages and stations in life, and he often disguises himself and assumes other identities in order to seduce women. The aphorism that Don Juan lives by is: "Tan largo me lo fiáis" (translated as "What a long term you are giving me!"[1]). This is his way of indicating that he is young and that death is still distant—he thinks he has plenty of time to repent later for his sins.[2] His life is also punctuated with violence and gambling, and in most versions he kills a man: Don Gonzalo (the Commendatore), the father of Doña Ana, a girl he has seduced. This murder leads to the famous "last supper" scene, where Don Juan invites a statue of Don Gonzalo to dinner. There are different versions of the outcome: in some versions Don Juan dies, having been denied salvation by God; in other versions he willingly goes to Hell, having refused to repent; in some versions Don Juan asks for and receives a divine pardon. |

あらすじ[編集]。 ドン・ファンはアンダルシアの裕福な自由人で、女性を誘惑することに人生を捧げている。彼は、あらゆる年齢や身分の女性を誘惑する能力に誇りを持ってお り、女性を誘惑するためにしばしば変装したり、別の身分になりすましたりする。ドン・ファンの口癖はこうだ: "Tan largo me lo fiáis"(直訳すると、「なんて長い期間、私に尽くしてくれるんだ!」[1])である。これは彼がまだ若く、死はまだ遠いことを示すもので、自分の罪 を後で悔い改める時間は十分にあると考えている[2]。 また、彼の人生は暴力とギャンブルに彩られており、ほとんどの版で彼は人を殺している: ドン・ゴンサロ(コメンダトーレ)は、彼が誘惑した少女ドニャ・アナの父親である。この殺人は、ドン・ファンがドン・ゴンザロの像を夕食に招待する有名な 「最後の晩餐」のシーンにつながる。あるバージョンではドン・ファンは神に救いを拒否されて死ぬが、別のバージョンでは悔い改めることを拒否した彼は自ら 進んで地獄に落ちる。 |

| Earliest written version The first written version of the Don Juan story was a play, El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra (The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest), published in Spain around 1630 by Tirso de Molina (pen name of Gabriel Téllez).[3] In Tirso de Molina's version Don Juan is portrayed as an evil man who seduces women thanks to his ability to manipulate language and disguise his appearance. This is a demonic attribute, since the devil is known for shape-shifting or taking other peoples' forms.[2] In fact Tirso's play has a clear moralizing intention. Tirso felt that young people were throwing their lives away, because they believed that as long as they made an Act of Contrition before they died, they would automatically receive God's forgiveness for all the wrongs they had done, and enter into heaven. Tirso's play argues in contrast that there is a penalty for sin, and there are even unforgivable sins. The devil himself, who is identified with Don Juan as a shape-shifter and a "man without a name", cannot escape eternal punishment for his unforgivable sins. As in a medieval Danse Macabre, death makes us all equal in that we all must face eternal judgment.[2] Tirso de Molina's theological perspective is quite apparent through the dreadful ending of his play.[2] Another aspect of Tirso's play is the cultural importance of honor in Spain of the golden age. This was particularly focused on women's sexual behavior, in that if a woman did not remain chaste until marriage, her whole family's honor would be devalued.[4][2] |

最古の文書版[編集] ドン・ファンの物語が最初に書かれたのは、ティルソ・デ・モリーナ(ガブリエル・テレスのペンネーム)によって1630年頃にスペインで出版された戯曲 『セビリアの詐欺師と石の客』(El burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra)である[3]。 ティルソ・デ・モリーナの版では、ドン・ファンは、言葉を操り、姿を偽る能力のおかげで女性を誘惑する悪人として描かれている。悪魔は変身したり他人の姿 になったりすることで知られているため、これは悪魔的な性質である[2]。ティルソは、若者が自分の人生を投げ出していると感じていた。というのも、死ぬ 前に「悔悛の儀式」を行いさえすれば、自分が行ったすべての過ちを自動的に神から赦され、天国に行けると信じていたからである。ティルソの戯曲はこれとは 対照的に、罪には罰があり、許されざる罪さえ存在することを主張している。ドン・ジュアンと同一視される悪魔自身は、変幻自在の「名前のない男」であり、 許されざる罪のために永遠の罰を免れることはできない。中世のダンス・マカブルのように、死は私たちすべてを平等にし、私たちはみな永遠の裁きを受けなけ ればならないのだ[2]。ティルソ・デ・モリーナの神学的な視点は、彼の戯曲の恐ろしい結末を通してきわめて明白である[2]。 ティルソの戯曲のもう一つの側面は、黄金時代のスペインにおける名誉の文化的重要性である。これは特に女性の性行為に焦点を当てたもので、女性が結婚まで 貞節を守らなければ、一族全体の名誉が傷つけられるというものであった[4][2]。 |

| Later versions The original play was written in the Spanish Golden Age according to its beliefs and ideals. But as time passed, the story was translated into other languages, and it was adapted to accommodate cultural changes.[3] Other well-known versions of Don Juan are Molière's play Dom Juan ou le Festin de pierre (1665), Antonio de Zamora's play No hay plazo que no se cumpla, ni deuda que no se pague, y Convidado de piedra (1722), Goldoni's play Don Giovanni Tenorio (1735), José de Espronceda's poem El estudiante de Salamanca (1840), and José Zorrilla's romantic play Don Juan Tenorio (1844). Don Juan Tenorio is still performed throughout the Spanish-speaking world on 2 November ("All Souls Day", the Day of the Dead). Mozart's opera Don Giovanni has been called "the opera of all operas".[5] First performed in Prague in 1787, it inspired works by E. T. A. Hoffmann, Alexander Pushkin, Søren Kierkegaard, George Bernard Shaw, and Albert Camus. The critic Charles Rosen analyzes the appeal of Mozart's opera in terms of "the seductive physical power" of a music linked with libertinism, political fervor, and incipient Romanticism.[6] After seeing a performance of Mozart's opera, Pushkin wrote a story in the form of a play, not intended for the stage, "The Stone Guest" (Каменный гость) in a series "The Little Tragedies" (1830). Alexander Dargomyzhsky composed an opera using the exact text of Pushkin for the libretto (unfinished at the composer's death 1869, completed by César Cui, 1872). The first English version of Don Juan was The Libertine (1676) by Thomas Shadwell. A revival of this play in 1692 included songs and dramatic scenes with music by Henry Purcell. Another well-known English version is Lord Byron's epic poem Don Juan (1821). Don Juans Ende, a play derived from an unfinished 1844 retelling of the tale by poet Nikolaus Lenau, inspired Richard Strauss's orchestral tone poem Don Juan.[7] This piece premiered on 11 November 1889, in Weimar, Germany, where Strauss served as Court Kapellmeister and conducted the orchestra of the Weimar Opera. In Lenau's version of the story, Don Juan's promiscuity springs from his determination to find the ideal woman. Despairing of ever finding her, he ultimately surrenders to melancholy and wills his own death.[8] In the film Adventures of Don Juan starring Errol Flynn (1948), Don Juan is a swashbuckling lover of women who also fights against the forces of evil. Don Juan in Tallinn (1971) is an Estonian film version based on a play by Samuil Aljošin. In this version, Don Juan is a woman dressed in men's clothes. She is accompanied by her servant Florestino on her adventure in Tallinn, the capital of Estonia.[9] In Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman (1973), a French-Italian co-production, Brigitte Bardot plays a female version of the character.[10] Don Juan DeMarco (1995), starring Johnny Depp and Marlon Brando, is a film in which a mental patient is convinced he is Don Juan, and retells his life story to a psychiatrist. Don Jon (2013), a film set in New Jersey of the 21st century, features an attractive young man whose addiction to online pornography is compared to his girlfriend's consumerism. Donna Giovanna, l'ingannatrice di Salerno (2015), written by Menotti Lerro, is an innovative[11][12] female and bisexual version of the historical seducer published both as a play (first performed on 25 November 2017 at the Biblioteca Marucelliana)[13][14] and libretto. |

後のバージョン[編集]。 原作はスペイン黄金時代に、その信仰と理想に従って書かれた。しかし、時が経つにつれ、物語は他の言語に翻訳され、文化の変化に合わせて脚色された [3]。 ドン・ジュアンの他の有名なバージョンは、モリエールの戯曲『Dom Juan ou le Festin de pierre』(1665年)、アントニオ・デ・サモラの戯曲『No hay plazo que no se cumpla, ni deuda que no se pague、 y Convidado de piedra(1722)、ゴルドーニの戯曲Don Giovanni Tenorio(1735)、ホセ・デ・エスプロンセダの詩El estudiante de Salamanca(1840)、ホセ・ソリージャのロマンチックな戯曲Don Juan Tenorio(1844)などがある。ドン・ファン・テノリオは、今でもスペイン語圏で11月2日(「万霊節」、死者の日)に上演されている。 1787年にプラハで初演されたモーツァルトのオペラ『ドン・ジョヴァンニ』は、E・T・A・ホフマン、アレクサンドル・プーシキン、セーレン・キェルケ ゴール、ジョージ・バーナード・ショー、アルベール・カミュらの作品に影響を与えた。批評家のシャルル・ローゼンは、モーツァルトのオペラの魅力を、自由 主義、政治的熱狂、初期のロマン主義に結びついた音楽の「魅惑的な肉体的力」という観点から分析している[6]。モーツァルトのオペラの上演を観たプーシ キンは、『小悲劇』シリーズ(1830年)の中で、舞台用ではない戯曲の形の物語『石の客』(Каменный гость)を書いた。アレクサンドル・ダーゴミジスキーは、プーシキンのテクストをそのまま台本に使ったオペラを作曲した(作曲者の死後1869年に未 完成、1872年にセザール・キュイによって完成)。 ドン・ファン』の最初の英語版は、トマス・シャドウェルによる 『放蕩者』(1676年)である。この戯曲は1692年に再演され、ヘンリー・パーセルが音楽を担当し、歌と劇のシーンが盛り込まれた。もうひとつの有名 な英語版は、バイロン卿の叙事詩『ドン・ファン』(1821年)である。 ドン・ジュアン・エンデ』は、詩人ニコラウス・レナウが1844年に書いた未完の再話から生まれた戯曲で、リヒャルト・シュトラウスの管弦楽曲『ドン・ ファン』にインスピレーションを与えた[7]。レナウ版の物語では、ドン・ファンの乱交は、理想の女性を見つけようとする彼の決意から生まれている。彼女 を見つけることに絶望した彼は、最終的に憂鬱に身を任せ、自ら死を選ぶ[8]。 エロール・フリン主演の映画『ドン・ファンの冒険』(1948年)では、ドン・ファンは、悪の力とも戦う剣呑な女性の恋人である。 タリンのドン・ファン』(1971年)は、サムイル・アルジョシンの戯曲に基づくエストニア映画版である。このバージョンでは、ドン・ファンは男装した女 性である。彼女は召使いのフロレスティーノに連れられて、エストニアの首都タリンを冒険する[9]。 フランスとイタリアの合作映画『ドン・ファン、あるいはドン・ファンが女だったら』(1973年)では、ブリジット・バルドーが女性版のキャラクターを演 じている[10]。 ジョニー・デップと マーロン・ブランド主演の『ドン・ファン・デマルコ』(1995年)は、精神病患者が自分がドン・ファンであると確信し、自分の人生を精神科医に語り聞か せる映画である。 21世紀のニュージャージーを舞台にした映画『ドン・ジョン』(2013年)は、ネットポルノに溺れる魅力的な青年を主人公に、ガールフレンドの消費主義 になぞらえている。 メノッティ・レッロ原作の『Donna Giovanna, l'ingannatrice di Salerno』(2015)は、歴史上の誘惑者の革新的な[11][12]女性・バイセクシュアル版で、戯曲(2017年11月25日にマルセリアーナ 図書館で初演)[13][14]とリブレットの両方が出版されている。 |

Cultural influence Monument to Don Juan Tenorio in Dos Hermanas, Seville Don Juan fascinated the 19th-century English novelist Jane Austen: "I have seen nobody on the stage who has been a more interesting Character than that compound of Cruelty and Lust".[15] The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard discussed Mozart's version of the Don Juan story at length in his 1843 treatise Either/Or.[16] In 1901, Finnish composer Jean Sibelius wrote the second movement of his second symphony based on the climax of Don Juan. The piece begins with a representation of Death walking up the road to Don Juan's house, where Don Juan pleads with Death to let him live. Also, the 1905 novel The Song of the Blood-Red Flower by the Finnish author Johannes Linnankoski has been influenced by Don Juan along the protagonist of the story. The protagonist of Shaw's 1903 Man and Superman is a modern-day Don Juan named not Juan Tenorio but John Tanner. The actor playing Tanner morphs into his model in the mammoth third act, usually called Don Juan in Hell and often produced as a separate play due to its length. In it, Don Juan (played by Charles Boyer in a noted 1950s recording) exchanges philosophical barbs with the devil (Charles Laughton). In 1911, Ukrainian writer Lesya Ukrainka wrote poetic drama The Stone Host about Don Juan. As the author herself determined[citation needed], it's about the victory of the conservative principle[clarification needed] over the split soul of Donna Anna, and through her – over Don Juan. The traditional seducer of women became a victim of the woman who had broken his will. In Spain, the first three decades of the twentieth century saw more cultural fervor surrounding the Don Juan figure than perhaps any other period. In one of the most provocative pieces to be published, the endocrinologist Gregorio Marañón argued that, far from the paragon of masculinity he was often assumed to be, Don Juan actually suffered from an arrested psychosexual development.[17] During the 1918 influenza epidemic in Spain, the figure of Don Juan served as a metaphor for the flu microbe.[18] The mid-20th-century French author Albert Camus referred to Don Juan in his 1942 essay The Myth of Sisyphus. Camus describes Don Juan as an example of an "absurd hero", as he maintains a reckless abandon in his approach to love. His seductive lifestyle "brings with it all the faces in the world, and its tremor comes from the fact that it knows itself to be mortal". He "multiplies what he cannot unify ... It is his way of giving and vivifying".[19] In the 1956 Buddy Holly single "Modern Don Juan", the singer gains a reputation for being like the libertine in his pursuit of a romantic relationship. Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman wrote and directed a comic sequel in 1960 titled The Devil's Eye in which Don Juan, accompanied by his servant, is sent from Hell to contemporary Sweden to seduce a young woman before her marriage. Anthony Powell in his 1960 novel Casanova's Chinese Restaurant contrasts Don Juan, who "merely liked power" and "obviously did not know what sensuality was", with Casanova, who "undoubtedly had his sensuous moments".[20] Stefan Zweig observes the same difference between both characters in his biography of "Casanova".[21] in 1970 Faroese author William heinesen released his short story "Don Juan fra Tranhuset", in which a character embodying Don Juan is washed up on the Faroe Islands in Torshavn and begins to seduce the women of that town. In the 1910 French novel The Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux, the titular character (also known as Erik) had spent much of his life writing an opera, Don Juan Triumphant, refusing to play it for Christine Daaé and telling her that it was unlike any music she ever heard and that when it was complete, he would die with it, never sharing it with mankind. Following the unmasking scene, Erik refers to himself as Don Juan as he confronts Christine, verbally and physically abusing her as he uses her hands to gouge his face, exclaiming "When a woman has seen me – as you have – she becomes mine ... I'm a real Don Juan ... Look at me! I'm Don Juan Triumphant!" Don Juan is also a plot point in Susan Kay's novel Phantom, which expands on Gaston Leroux's novel The Phantom of the Opera. The titular character was referred to as "Don Juan" in his childhood, a nickname given to him by Javert, a man who exploited Erik as a child. Later in life, he began writing Don Juan Triumphant, spending decades on the piece, which Christine Daaé heard after hiding in her room after removing Erik's mask. In the 1986 Broadway musical adaptation of Gaston Leroux's 1910 The Phantom of the Opera, the character of the Phantom writes an opera based on the legend of Don Juan called Don Juan Triumphant. Don Juan is mentioned in the 1980 Broadway musical adaptation of Victor Hugo's 1862 novel Les Misérables, in which the character Grantaire states that Marius Pontmercy is acting like Don Juan. The former Thai Queen Sirikit once told reporters that her son Crown Prince Vajiralongkorn, now King Rama X, was "a bit of a Don Juan". Don Juan is referenced in Star Trek the Original Series, season one episode 16 "Shore Leave". "Don Juan" is Cockney rhyming slang for a 2:1 degree classification.[22] |

文化的影響[編集] セビリアの ドス・エルマナスにあるドン・フアン・テノリオの記念碑 ドン・ファンは、19世紀のイギリスの小説家ジェーン・オースティンを魅了した: 「あの残酷さと欲望の化合物ほど興味深い人物を舞台で見たことがない」[15]。 デンマークの哲学者セーレン・キルケゴールは、1843年の論文『Either/Or』の中で、モーツァルト版のドン・ファンについて詳しく論じている [16]。 1901年、フィンランドの作曲家ジャン・シベリウスは、『ドン・ファン』のクライマックスに基づいて交響曲第2番の第2楽章を作曲した。この曲は、死が ドン・フアンの家までの道を歩き、そこでドン・フアンが生かすよう死に懇願する描写で始まる。また、フィンランドの作家ヨハネス・リンナコスキの1905 年の小説『血染めの花の歌』は、物語の主人公に沿ってドン・ファンから影響を受けている。 ショウの1903年の『人間とスーパーマン』の主人公は、フアン・テノリオではなくジョン・タナーという現代のドン・ファンである。タナー役の俳優は、通 常「地獄のドン・ファン」と呼ばれ、その長さからしばしば別の劇として上演される、巨大な第3幕で彼のモデルに変身する。その中で、ドン・ファン (1950年代の名録音でシャルル・ボワイエが演じた)は悪魔(チャールズ・ロートン)と哲学的な辛辣な言葉を交わす。 1911年、ウクライナの作家レシャ・ウクラインカが、ドン・ファンを題材にした詩劇『石の宿主』を書いた。作者自身が断定しているように[要出典]、こ の作品は、ドンナ・アンナの分裂した魂に対する保守主義[要出典]の勝利、そして彼女を通してのドン・ファンに対する勝利を描いている。伝統的な女性の誘 惑者は、自分の意志を打ち砕いた女性の犠牲者となった。 スペインでは、20世紀の最初の30年間、おそらく他のどの時代よりもドン・ファンという人物を取り巻く文化的熱狂が見られた。内分泌学者のグレゴリオ・ マラニョンは、最も挑発的な作品のひとつを発表し、ドン・ファンはしばしば想定される男らしさの模範とはほど遠く、実際には精神発達の停止に苦しんでいる と主張した[17]。 1918年にスペインでインフルエンザが流行した際、ドン・ファンの姿はインフルエンザ微生物のメタファーとして機能した[18]。 20世紀半ばのフランスの作家アルベール・カミュは、1942年のエッセイ『シジフォスの神話』の中でドン・ファンについて言及している。カミュはドン・ ファンを「不条理な英雄」の一例としており、彼は愛へのアプローチにおいて無謀なまでの奔放さを保っている。彼の魅惑的な生き方は、「この世のあらゆる顔 を持ち、その震えは自分が死すべき存在であることを知っていることから来る」。統一できないものを増殖させる。それが彼の与える方法であり、生かす方法な のだ」[19]。 1956年のバディ・ホリーのシングル「現代のドン・ファン」では、この歌手は恋愛関係を追い求める自由主義者のようだという評判を得ている。 スウェーデンの映画監督イングマール・ベルイマンは、1960年に『悪魔の目』というタイトルのコミカルな続編を脚本・監督しており、そこではドン・ファ ンが召使いを伴って地獄から現代のスウェーデンに送られ、結婚前の若い女性を誘惑する。 アンソニー・パウエルは1960年の小説『Casanova's Chinese Restaurant』の中で、「単に権力が好きだった」だけで、「明らかに官能が何であるかを知らなかった」ドン・ファンと、「間違いなく官能的な瞬間 を持っていた」カサノヴァを対比している[20]。ステファン・ツヴァイクは『カサノヴァ』の伝記の中で、両人物の同じ違いを観察している[21]。 1970年にフェロー諸島の作家ウィリアム・ハイネセンが発表した短編小説『Don Juan fra Tranhuset』では、ドン・ファンを体現した人物がフェロー諸島のトースハウンに流れ着き、その町の女性たちを誘惑し始める。 ガストン・ルルーによる1910年のフランスの小説『オペラ座の怪人』では、主人公(エリックとも呼ばれる)が人生の大半を費やして書いたオペラ『ドン・ ファン凱旋』が、クリスティーヌ・デーエのために演奏されることを拒み、彼女が聴いたことのない音楽であること、そして完成した暁には、決して人類と分か ち合うことなく、それとともに死ぬことを告げた。仮面を剥ぐシーンに続いて、エリックはクリスティーヌと対峙しながら、自分のことをドン・ファンだと言 い、彼女の手を使って自分の顔をえぐりながら、言葉でも身体でも彼女を罵倒し、こう叫ぶ。俺は本物のドン・ファンだ.俺を見ろ!俺はドン・ファンの凱旋 だ!"と叫ぶ。 ドン・ファンは、ガストン・ルルーの小説『オペラ座の怪人』を発展させたスーザン・ケイの小説『ファントム』にも登場する。主人公は幼少期、エリックを搾 取した男ジャヴェールからつけられたあだ名で「ドン・ファン」と呼ばれていた。その後、彼は『ドン・ファンの凱旋』を書き始め、何十年もかけてこの曲を完 成させた。クリスティーヌ・ダエは、エリックの仮面を外した後、部屋に隠れてこの曲を聴いた。 ガストン・ルルーが1910年に発表した『オペラ座の怪人』を1986年にブロードウェイでミュージカル化した作品では、ファントムの役がドン・ファン伝 説に基づくオペラ『ドン・ファン凱旋』を書いている。 ドン・ファンは、ヴィクトル・ユーゴーの1862年の小説『レ・ミゼラブル』を1980年にブロードウェイでミュージカル化した作品でも言及されており、 登場人物のグランテールが、マリウス・ポンメルシーはドン・ファンのように振る舞っていると述べている。 タイのシリキット前王妃は、息子のヴァジラロンコーン皇太子(現ラーマ10世)を「ドン・ファンみたいな人」と記者団に語ったことがある。 ドン・ファンは『スタートレック』オリジナル・シリーズのシーズン1エピソード16 "Shore Leave "で言及されている。 「ドン・ファン」はコックニーの韻を踏んだスラングで、2:1の学位分類を意味する[22]。 |

| Folkloristics In folkloristics, the theme of a human living recklessly inviting a dead person or skull for dinner is classified in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as ATU 470A, "The Offended Skull".[23][24] |

民俗学[編集] 民俗学では、生きている人間が無謀にも死者や頭蓋骨を夕食に招くというテーマは、アーネ・トンプソン・ウザー・インデックスではATU 470A「The Offended Skull」として分類されている[23][24]。 |

| Casanova Don Juanism |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_Juan |

|

| Don Juanism or Don

Juan syndrome Don Juanism or Don Juan syndrome is a non-clinical term for the desire, in a man, to have sex with many different female partners. The name derives from the Don Juan of opera and fiction. The term satyriasis is sometimes used as a synonym for Don Juanism. The term has also been referred to as the male equivalent of nymphomania in women.[1] These terms no longer apply with any accuracy as psychological or legal categories of psychological disorder.[1] |

ドン・ファニズム(Don

Juanism)またはドン・ファン・シンドローム(Don Juan syndrome) ドン・ジュアニズム(Don Juanism)またはドン・ジュアンシンドローム(Don Juan syndrome)とは、多くの異なる女性パートナーとセックスしたいという男性の願望を指す非臨床用語である。この名前は、オペラや小説のドン・ファン に由来する。ドン・ジュアニズムの同義語としてサチリア症という用語が使われることもある。また、この用語は、女性におけるニンフォマニアの男性版とも呼 ばれている[1]。これらの用語は、心理学的あるいは法的な精神障害のカテゴリーとしては、もはや正確には当てはまらない[1]。 |

| Analytical psychology Psychiatrist Carl Jung believed that Don Juanism was an unconscious desire of a man to seek his mother in every woman he encountered. However, he did not see the trait as entirely negative; Jung felt that positive aspects of Don Juanism included heroism, perseverance and strength of will.[2] Jung argues that related to the mother-complex "are homosexuality and Don Juanism, and sometimes also impotence. In homosexuality, the son's entire heterosexuality is tied to the mother in an unconscious form; in Don Juanism, he unconsciously seeks his mother in every woman he meets....Because of the difference in sex, a son's mother-complex does not appear in pure form. This is the reason why in every masculine mother-complex, side by side with the mother archetype, a significant role is played by the image of the man's sexual counterpart, the anima."[3] One of Theodore Millon's five narcissist variations is the amorous narcissist which includes histrionic features. According to Millon, the Don Juan or Casanova of our times is erotic and exhibitionistic.[4] |

分析心理学[編集] 精神科医のカール・ユングは、ドン・ファン主義とは、出会うすべての女性に母親を求める男性の無意識の欲求であると考えた。しかし、ユングはドンファニズ ムの肯定的な側面として、英雄主義、忍耐強さ、意志の強さなどを挙げている[2]。ユングは、マザー・コンプレックスに関連して、「同性愛とドンファニズ ム、そして時にはインポテンツがある」と主張している。同性愛では、息子の異性愛全体が無意識のうちに母親と結びついている。ドン・ファン主義では、息子 は出会うすべての女性に無意識のうちに母親を求める......性の違いのために、息子の母親コンプレックスは純粋な形では現れない。これが、あらゆる男 性的な母コンプレックスにおいて、母の原型と並んで、男性の性的な相手であるアニマのイメージが重要な役割を果たす理由である」[3]。 セオドア・ミロンの5つのナルシシストのバリエーションの1つは、ヒストリオ的特徴を含む情愛的ナルシシストである。ミロンによれば、現代のドン・ファン やカサノバはエロティックで露出狂である[4]。 |

| Psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud explored the connections between mother-fixation and a long series of love-attachments in the first of his articles on the 'Psychology of Love';[5] while Otto Rank published an article on the Don Juan gestalt in 1922.[6] Otto Fenichel saw Don Juanism as linked to the quest for narcissistic supply, and for proof of achievement (as seen in the number of conquests).[7] He also described what he called the 'Don Juans of Achievement' – people compelled to flee from one achievement to another in an unconscious but never ending quest to overcome an unconscious sense of guilt[8] Sándor Ferenczi stressed the fear of punishment (Hell) in the syndrome, linking it to the Oedipus complex.[9] Contemporary psychoanalysis stresses the denial of psychic reality and the avoidance of change implicit in Don Juan's (identificatory) pursuit of multiple females.[10] |

精神分析[編集] ジークムント・フロイトは、「愛の心理学」に関する論文の最初のもので、母親への執着と一連の長い愛の執着とのつながりを探求した[5]。オットー・ラン クは1922年にドン・ファン・ゲシュタルトに関する論文を発表した[6] 。 [7]彼はまた、「達成のドン・ファン」と呼ばれる人々-無意識的な罪悪感を克服するために、無意識的だが終わることのない探求の中で、ある達成から別の 達成へと逃避することを余儀なくされる人々-について述べた[8] 。 現代の精神分析は、ドン・ファンが複数の女性を(同一視して)追い求めることに暗黙のうちにある心的現実の否定と変化の回避を強調している[10]。 |

| Cultural references Aspects of the character are examined by Mozart and his librettist Da Ponte in their opera Don Giovanni, perhaps the best-known artistic work on this subject. To write their opera, Mozart and Da Ponte are known to have consulted with the famous libertine, Giacomo Casanova, the usual historic example of Don Juanism. Although not conclusively established, it is probable that Casanova attended the premiere of this opera, which was likely understood by the audience to be about himself.[11] Charles Rosen saw what he called "the seductive physical power" of Mozart's music as linked to 18th-century libertinism, political fervor and incipient Romanticism,[12] while in a famous passage the philosopher Kierkegaard discusses Mozart's version of the Don Juan story.[13] Albert Camus has also written on the subject;[14] while Jane Austen was fascinated by the character of Don Juan: "I have seen nobody on the stage who has been a more interesting Character than that compound of Cruelty and Lust".[15] Anthony Powell in his novel Casanova's Chinese Restaurant distinguishes Don Juan from Casanova: "Don Juan merely liked power. He obviously did not know what sensuality was....Casanova, on the other hand, undoubtedly had his sensuous moments".[16] In the 4th season Cheers episode "Don Juan is Hell", Diane Chambers writes a sexual history study that suggests Sam Malone as a perfect model for Don Juanism. |

文化的言及[編集] モーツァルトとその脚本家ダ・ポンテは、オペラ『ドン・ジョヴァンニ』の中で、ドン・ジョヴァンニの性格について考察している。オペラを書くために、モー ツァルトとダ・ポンテは有名な自由人ジャコモ・カサノヴァに相談したことが知られている。決定的な証拠はないが、カサノヴァがこのオペラの初演に出席した 可能性は高く、観客はこのオペラがカサノヴァ自身のことを歌っていると理解していた可能性が高い[11]。チャールズ・ローゼンは、モーツァルトの音楽の 「魅惑的な肉体的力」と呼ばれるものを、18世紀の自由主義、政治的熱狂、初期のロマン主義と結びついていると見ており[12]、哲学者キルケゴールは有 名な一節でモーツァルトのドン・ファン物語版について論じている[13]。 アルベール・カミュもこのテーマについて書いている[14]。一方、ジェーン・オースティンはドン・ファンのキャラクターに魅了された。「残酷さと欲望の 化合物ほど興味深いキャラクターを舞台上で見たことがない」[15]。アンソニー・パウエルは小説『カサノヴァの中華料理店』の中で、ドン・ファンとカサ ノヴァを区別している。一方、カサノヴァには間違いなく官能的な瞬間があった」[16]。 第4シーズンの『チアーズ』のエピソード「ドン・ファンは地獄」で、ダイアン・チェンバースは、ドン・ファン主義の完璧なモデルとしてサム・マローンを示 唆する性史研究を書いている。 |

| Acting out Free love Giacomo Casanova Hypersexuality Narcissistic personality disorder (Millon's variations) Repetition compulsion Sex addict |

行動する(アクティング・アウト) 自由な愛 ジャコモ・カサノバ 性欲過剰 自己愛性人格障害(ミロンのバリエーション) 反復強迫 セックス依存症 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_Juanism |

|

| Lothario is an Italian name used

as shorthand for an unscrupulous seducer of women, based upon a

character in The Fair Penitent, a 1703 tragedy by Nicholas Rowe.[1][2]

In Rowe's play, Lothario is a libertine who seduces and betrays

Calista; and his success is the source for the proverbial nature of the

name in the subsequent English culture.[3] The Fair Penitent itself was

an adaptation of The Fatal Dowry (1632), a play by Philip Massinger and

Nathan Field.[4] The name Lothario was previously used for a somewhat

similar character in The Cruel Brother (1630) by William Davenant.[5] A

character with the same name also appears in The Ill-Advised Curiosity,

a story within a story in Miguel de Cervantes' 1605 novel, Don Quixote,

Part One, however the "Lothario" there is most unwilling to seduce his

friend's wife and only does so upon the urging of the former, who

recklessly wants to test her fidelity. It was first mentioned in the modern sense in 1756 in The World, the 18th century London weekly newspaper, No. 202 ("The gay [meaning joyful, merry] Lothario dresses for the fight").[5] Samuel Richardson used "haughty, gallant, gay Lothario" as the model for the self-indulgent Robert Lovelace in his novel Clarissa (1748), and Calista suggested the character of Clarissa Harlowe.[4] Edward Bulwer-Lytton used the name allusively in his 1849 novel The Caxtons ("And no woman could have been more flattered and courted by Lotharios and lady-killers than Lady Castleton has been").[6] Anthony Trollope in Barchester Towers (1857) wrote of "the elegant fluency of a practised Lothario".[7] Because of the allusive use the name sometimes is not capitalised.[1]  Camilla threatens Lothario with a dagger. Illustration by Apeles Mestres [ca], engraving by Francisco Fusté. |

ロタリオは、1703年にニコラス・ロウによって書かれた悲劇『公正な

懺悔者』の登場人物に基づく、女性を誘惑する不謹慎な人物の略称として使われるイタリア語の名前である[1][2]。

[ロウの戯曲では、ロサリオはカリスタを誘惑して裏切る自由主義者であり、彼の成功が、その後のイギリス文化におけるこの名前のことわざ的性質の源となっ

ている。 [ミゲル・デ・セルバンテスの1605年の小説『ドン・キホーテ』第一部に登場する物語の中の物語である

『不謹慎な好奇心』にも同名の人物が登場するが、そこでの「ロサリオ」は友人の妻を誘惑することを最も嫌がり、彼女の貞節を無謀にも試したがる前者の勧め

で誘惑するのみである。 現代的な意味で初めて言及されたのは1756年、18世紀のロンドンの週刊新聞『ザ・ワールド』の202号(「The gay [陽気な、愉快な]Lothario dresses for the fight」)である[5]。サミュエル・リチャードソンは小説『クラリッサ』(1748年)の中で、「高慢で、胆振りが強く、ゲイなLothario」 をわがままなロバート・ラブレスのモデルとして使い、カリスタはクラリッサ・ハーロウのキャラクターを提案した。 [4] エドワード・ブルワー=リットンは1849年の小説『The Caxtons』でこの名前を暗示的に使っている(「キャッスルトン夫人ほどロサリオやレディキラーに媚びへつらわれ、求愛された女性はいない」) [6]。アンソニー・トロロープは『Barchester Towers』(1857年)の中で「実践的なロサリオの優雅な流暢さ」について書いている[7]。 冗長な用法のため、名前は大文字で表記されないこともある[1]。  短剣でロタリオを脅すカミラ。挿絵:アペレス・メストレス[ca]、版画:フランシスコ・フステ。 |

★ モリエールのドン・ジュアン

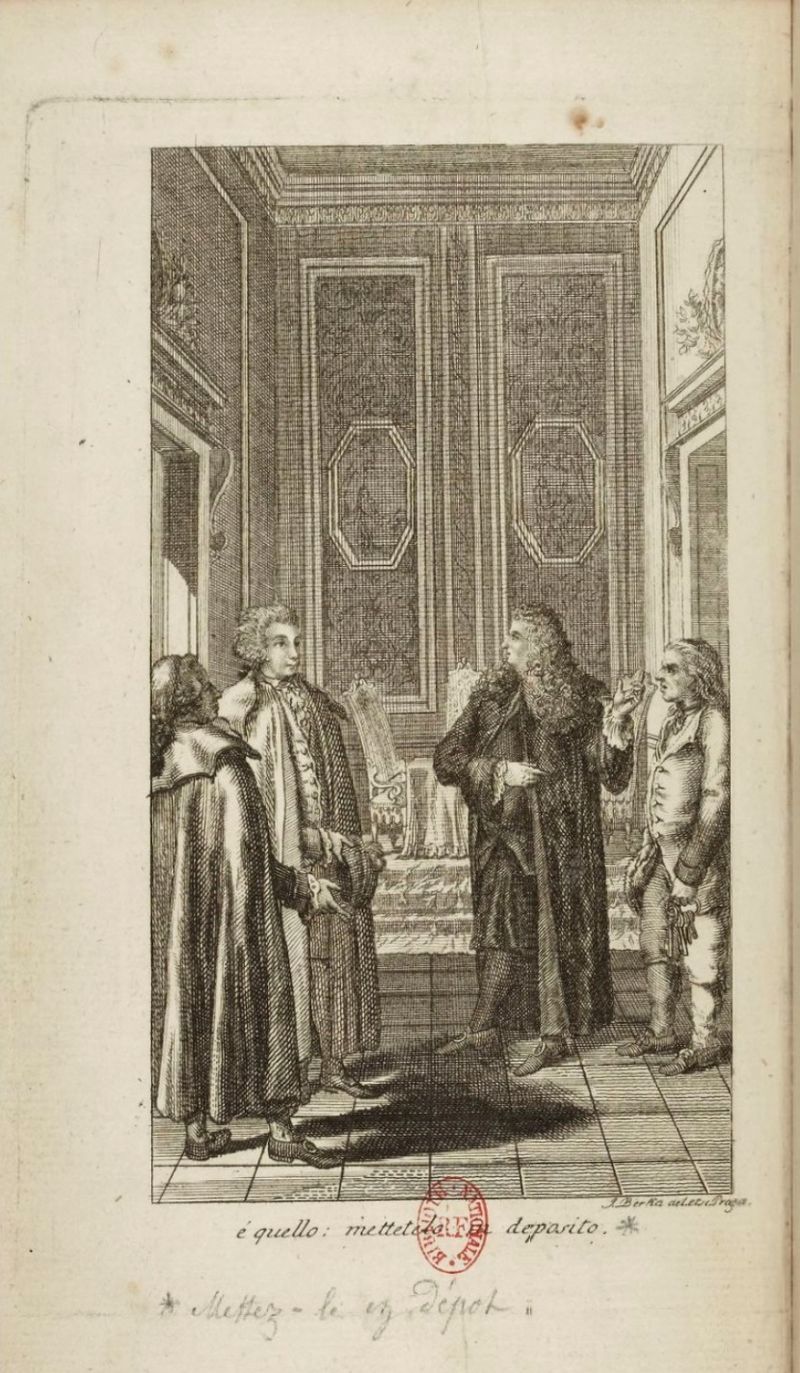

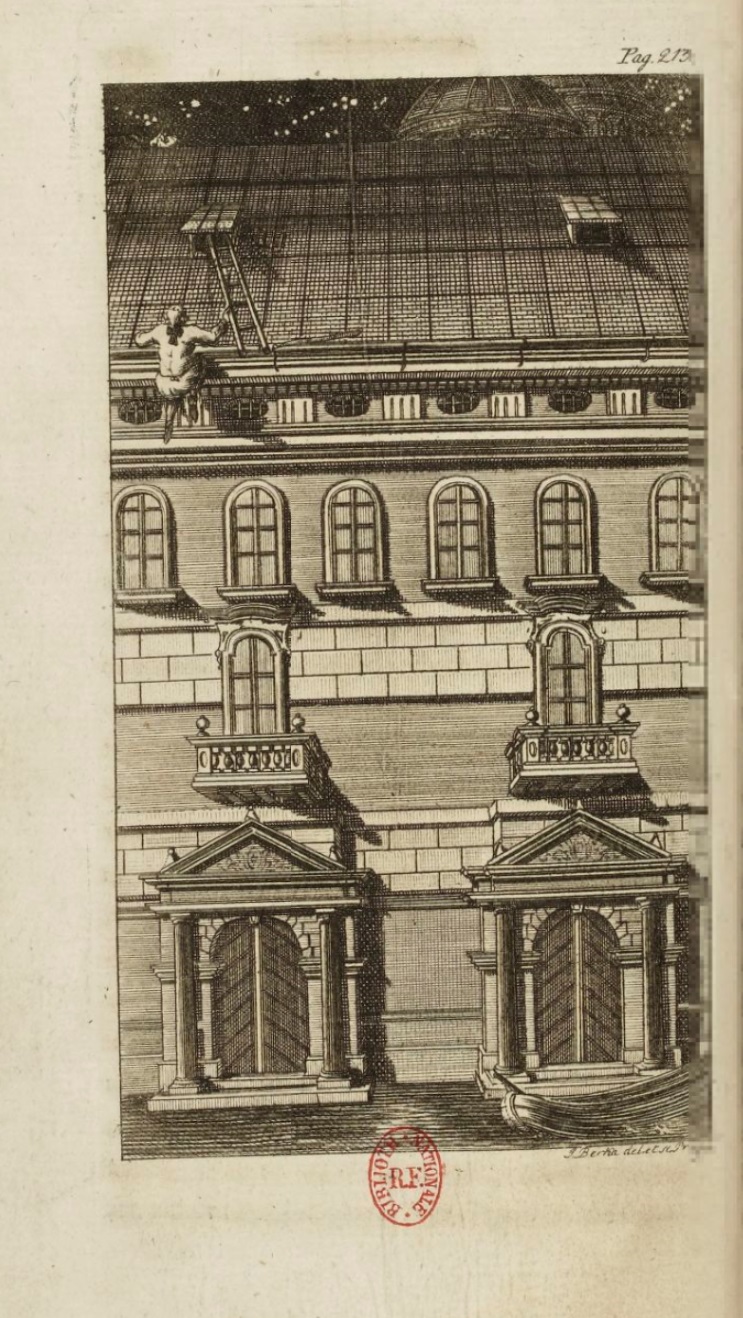

【背 景】「「モ リエールはこのころ、私生活においては極めて波乱に満ちた生活を送っていた。1662年に結婚した妻・アルマンド・ベジャールとの夫婦関係はうまくいか ず、数年前から抱えていた胸部の疾患が悪化しており、健康状態も良くなかった。そこへ来て『タルチュフ』は上演を禁止され、その解禁を取り付けるための画 策に労力を費やさなければならない。そのうえ6月の公演で無料入場者を拒否したために、パレ・ロワイヤル入り口では流血騒ぎが起こり、多額の見舞金を支払 わされる羽目になった。9月には親友が、10月には南フランス修業時代から苦楽を共にしてきた団員のデュ・パルク(マルキーズの夫)が、11月10日には 息子のルイが1歳にもならずにこの世を去った。[77]。/ こうして肉体的にも精神的にも激しいダメージを負ったモリエールは、積極的に劇場で上演を行うよりも、王弟殿下や貴族の私邸で『タルチュフ』を含む自らの これまでの作品を上演にかけることが多くなった。劇場では11月に『エリード姫』の市民向け公演がパレ・ロワイヤルで始まり、ある程度は成功をおさめた が、その成功もいつまでも続くとは思えなかった[77]。/ だがモリエールは、こうして足踏みしているわけにもいかなかった。ライバルたちとの競争に敗けるわけにはいかないし、すでに彼は多くの座員を抱える劇団の 座長であり、その生活を保証しなければならない重い責任を抱えていたからである。こうして追い詰められたモリエールは、手っ取り早く成功を収めるためにド ン・ジュアン伝説に目を付けた。ちょうどパリで流行していたし、おあつらえ向きなことに喜劇的な題材でもある。そして何より、自分を苦しめるキリスト教狂 信者たちへの恨みを晴らし、奴らへの激烈な批判をも容易く盛り込める話の筋ではないか。これ以上ない題材を見つけたモリエールは、一気呵成に作品を書き上 げた。こうして完成したのが『ドン・ジュアン』である。短期間のうちに書き上げられ たために、当時戯曲を書く際に守るべき規則(アレクサンドラン、三一致の法則)などを悉く踏みにじっており、形式的な完成度は決して高くない[78]。/ 「ドン・ジュアン (戯曲)」 も参照/ 『ドン・ジュアン』は1665年2月15日に上演が開始された。モリエールの目論み通りに滑り出しから興行成績は絶好調であったが、やはり狂信者たちは 黙っていなかった。彼らの批判が早速始まったので、モリエールもこの批判内容の一部を汲んで、作品の場面を一部削除するなどして再び上演にかけたが、批判 は止むどころかますます強くなっていった。そのため、観客の反応が良いにも関わらず、わずか15回で上演を取りやめなければならなかった。一時的な上演自 粛であればまだよかったものの、この作品はこれ以後、モリエールの生存中には2度と上演・出版されなかった。その内容があまりに過激であったため、 1682年に初めてモリエール全集が世に出た時もこの作品は大幅な削除が加えられた形で収録された。徹底して忌避され続けたため、誰の手も加えられていな い、モリエールが書いたままの『ドン・ジュアン』は散逸しかけたが、再び1841年に舞台にかけられた。実に200年近くの眠りから覚めての舞台復帰で あった[79][80]」」

【シ ノプシス】

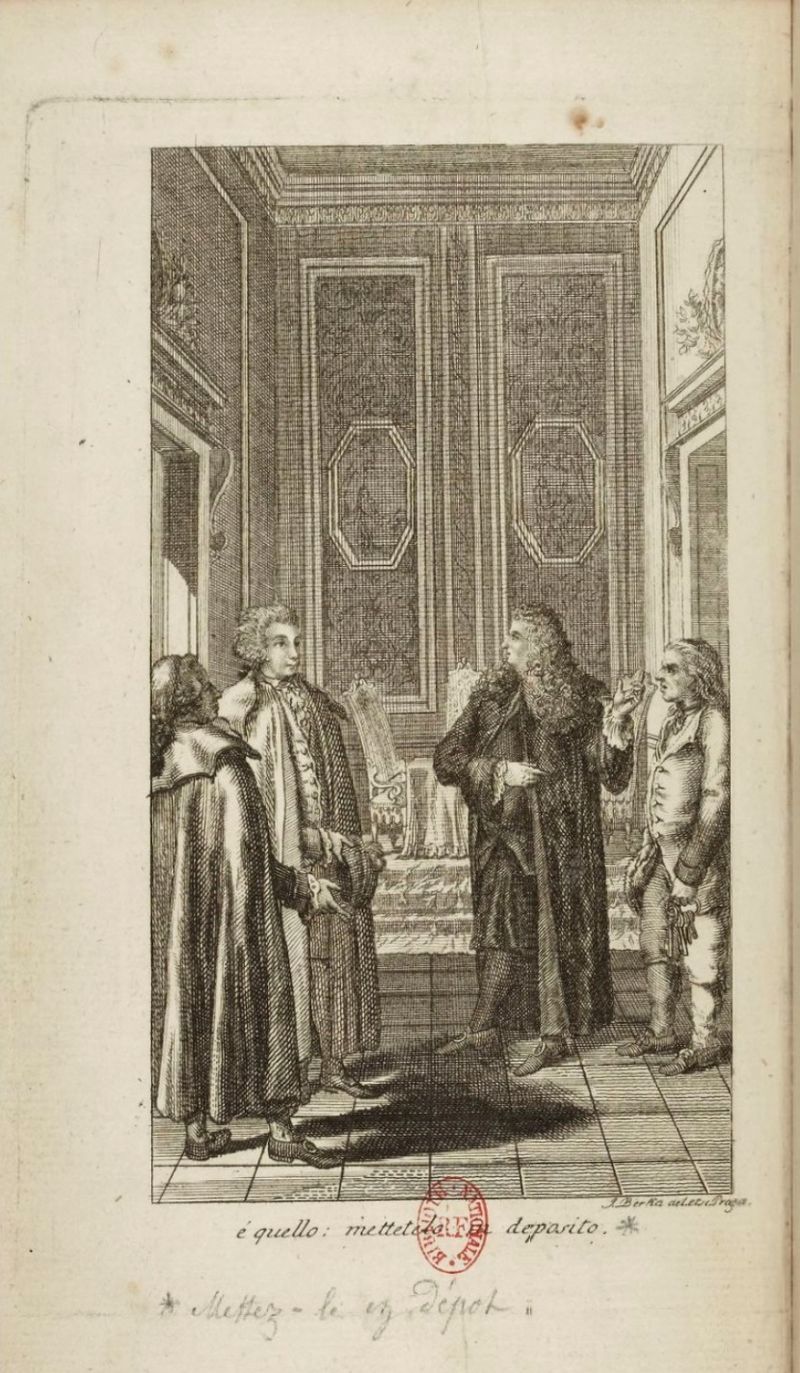

「■ 第1幕

舞

台はシチリア島。スペインの青年貴族ドン・ジュアンは、スガナレルを連れて旅に出ている。妻のドンヌ・エルヴィールに飽きたので、浮気をするためである。

スガナレルにそのことを諫められるが、ドン・ジュアンには最初にできた女とずっと一緒にいることなどは束縛でしかなく、とても耐えられないことなのであっ

た。エルヴィールが彼を追って来たが、ドン・ジュアンは彼女の嘆きを軽くいなしてしまう。ドン・ジュアンは、スガナレルさえも呆れかえるほどの放蕩者なの

であった。

■ 第2幕

舞

台は海岸に近い田舎。百姓・ピエロが婚姻関係にある恋人のシャルロットに手柄話をしている。海で溺れている男性2人を救助したのだという。身なりから察す

るに2人とも相当に立派な階級のもので、まさしくその2人はドン・ジュアンとスガナレルなのであった。新たに目を付けていた女性を追って船を出したが、強

風に呷られ転覆し、危うく死にかけたのである。ドン・ジュアンは早速シャルロットを口説きはじめ、成功しかかるが、ピエロは当然怒りを見せる。シャルロッ

トの不貞行為を言いつけようと、マチュリーヌを呼びよせるが、そのマチュリーヌまで口説きおとされ、まさに「ミイラ取りがミイラになった」のであった。ド

ン・ジュアンの言葉を信用していては、どのみち不幸になるのがわかっているので、彼のいない間に2人の女を優しく説得しようとするスガナレル。しかしそう

こうしているうちに、12名の騎士がドン・ジュアンを追ってきていることが判明する。

■ 第3幕

ド

ン・ジュアンは田舎者に、スガナレルは医者に変装しての幕開け。医術を信じるかどうかで、ドン・ジュアンはスガナレルを言い負かすが、議論に白熱して道に

迷ってしまう。そこで森の貧者に声をかけ、街への道を教えてもらうが、その見返りに施しを求められた。この貧者は信心深く、神への祈りに毎日明け暮れてい

るが赤貧に喘いでおり、ドン・ジュアンは「神様を呪ってみろ、そうすればルイ金貨を1枚恵んでやるぞ」と言い放つ[1]。結局金貨を恵んでやったドン・

ジュアンだが、今度は3人の賊を相手に孤軍奮闘する貴族を見かけ、助太刀に飛び入る。首尾よく救出に成功するのだが、なんとその男はエルヴィールの兄であ

るドン・カルロスであり、まさにドン・ジュアンを追ってやってきたのであった。そうと知って立場を「ドン・ジュアンの友人」と偽り、「彼に償いをつけさせ

る」と約束してしまう。が、その直後にドン・カルロスの弟ドン・アロンスが来てしまい、正体が露見してしまう。ドン・カルロスは騎士として命を救われた恩

を忘れず、その返礼として仇を討とうといきり立つ弟を宥めて、ドンヌ・エルヴィールとの約束を守るようにドン・ジュアンに告げて立ち去った。恐怖で隠れて

いたスガナレルをドン・ジュアンが叱りつけていると、今度は立派な建物が見えてきた。この建物は以前ドン・ジュアンが決闘で殺した騎士の墓なのであった。

大理石のその騎士の像を見てスガナレルが恐がるので、ふざけて晩餐に招かせたところ、なんと像がうなずき、それを承諾したのであった。

■

第4幕

晩

餐に現れた騎士の像(中央)、ドン・ジュアン(左)、スガナレル(右)

ドン・ジュアンの部屋から幕開け。像が頷いたのは、単なる錯覚だと気にも留めないドン・ジュアン。そこへ様々な人間が現れる。借金の返済を求めてディマン

シュが現れ、厳格な父ドン・ルイは息子の放蕩ぶりを説教しにやってきた。修道女になる覚悟も決め、ドン・ジュアンのためを思って心から身持ちを改めるよう

エルヴィールも勧めに来たが、何れもドン・ジュアンには何の効果もなく、ただ聞き流してしまう。ようやく晩餐をはじめるが、やたらと戸を叩く者がいる。戸

を叩いていたのは騎士の像で、晩餐に招いてもらったお礼に、ドン・ジュアンを晩餐に誘いに来たのであった。それを承諾して、第4幕終了。

■ 第5幕

舞

台は郊外。ドン・ジュアンは父に改宗を誓い、スガナレルは大変な喜びを見せるが、これは偽りだった。ドン・ジュアンは偽善者になることにしたのである。そ

こへドン・カルロスが現れる。妹のエルヴィールと共に暮らすことを要求しに来たのであるが、ドン・ジュアンは「エルヴィールは世を捨てる覚悟を決めたし、

神にお伺いを立てたところ、『エルヴィールのことは気にかけるな、一緒に暮らしてはお前の魂は救われぬ』とのことであったのでそれはできない」と返答し、

ドン・カルロスの怒りを買ってしまう。それどころか、決闘の約束までしたのだった。以前よりも性質が悪くなった主人の姿にあきれ返るスガナレルであった

が、そこへ亡霊がやってきた。亡霊は悔悛を進めるが、これを無下に断るドン・ジュアン。そこへ騎士の像が現れ、手を握った瞬間に、ドン・ジュアンの体の上

に雷が落ち、大きな炎が噴き出した。ドン・ジュアンが死んで誰もが満足し、丸く事は収まったが、長年仕えてきたスガナレルだけが報われない。「おれの給

料!おれの給料!」とスガナレルが連呼しているところで、幕切れ。」

★ ドン・ジョバンニ自身は反省していないというスラヴォイ・ジジェク師匠の御説

「モー ツァルトの『ドン・ジョヴァンニ』のことを思い起こそう。コメンダトーレ (騎士 長)の石像との最後の対面の場面で、ドン・ジョヴァンニは、彼の罪深い過去を悔い改め、 否認することを拒むとき、根源的な倫理的な立場としか呼ぶ以外にはない何かを完成させ るのである。そのときの彼の頑強さは、カント自身が『実践理性批判』で挙げた、代償が 絞首台であると知るや否やすぐさま自分の情熱の満足を断念する覚悟を決めるリベルタン という例を、嘲笑いながら転倒させるかのようなのだ。ドン・ジョヴァンニは、彼を待ち 受けているものが、ただ絞首台のみであって、いかなる満足でもないということをはっき りと知っているまさにそのときに、自らのリベルタン的態度に執着する。つまり、病理的 な利害の立場からするなら、なすべきことは改悛の身振りをかたちばかりしてみせるとい うことであったはずだ。ドン・ジョヴァンニは死が近いことを知っている、したがって 自 らの行いを悔い改めたところで失うものは何もなく、ただ得るばかりである(つまり、死 後に責め苛まれることを避けることができる)。しかし、彼は「原理にしたがって」リベ ルタンの反抗的なスタンスを一貫させることを選ぶ。石像に対する、この生ける死者に対 する、彼の不屈の「ノー」を、その内容が「悪」であるにもかかわらず、非妥協的な倫理 的態度のモデルとして経験しないことなど、どのようにしてできようか。pp.186-」否定的なもののもとへの滞留 : カント、ヘーゲル、イデオロギー批判 / スラヴォイ・ジジェク著 ; 酒井隆史, 田崎英明訳, 筑摩書房 , 2006.1. - (ちくま学芸文庫)

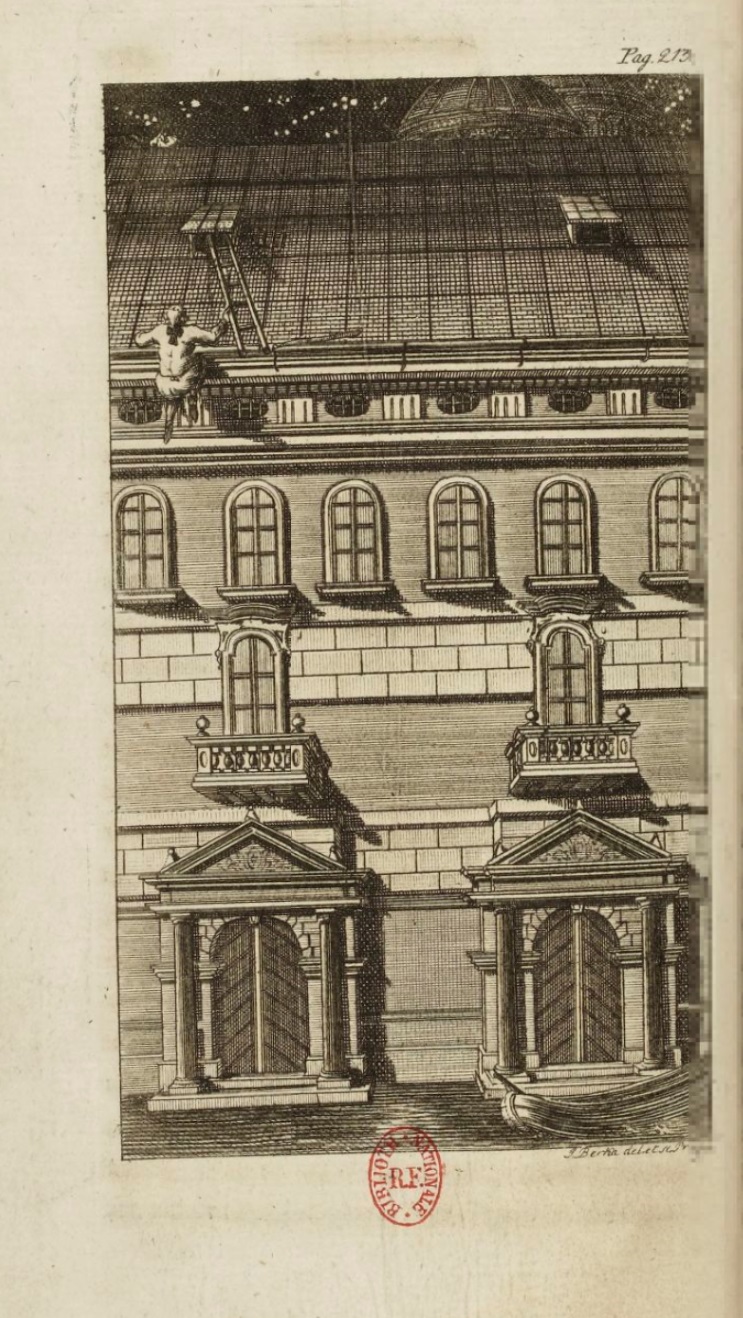

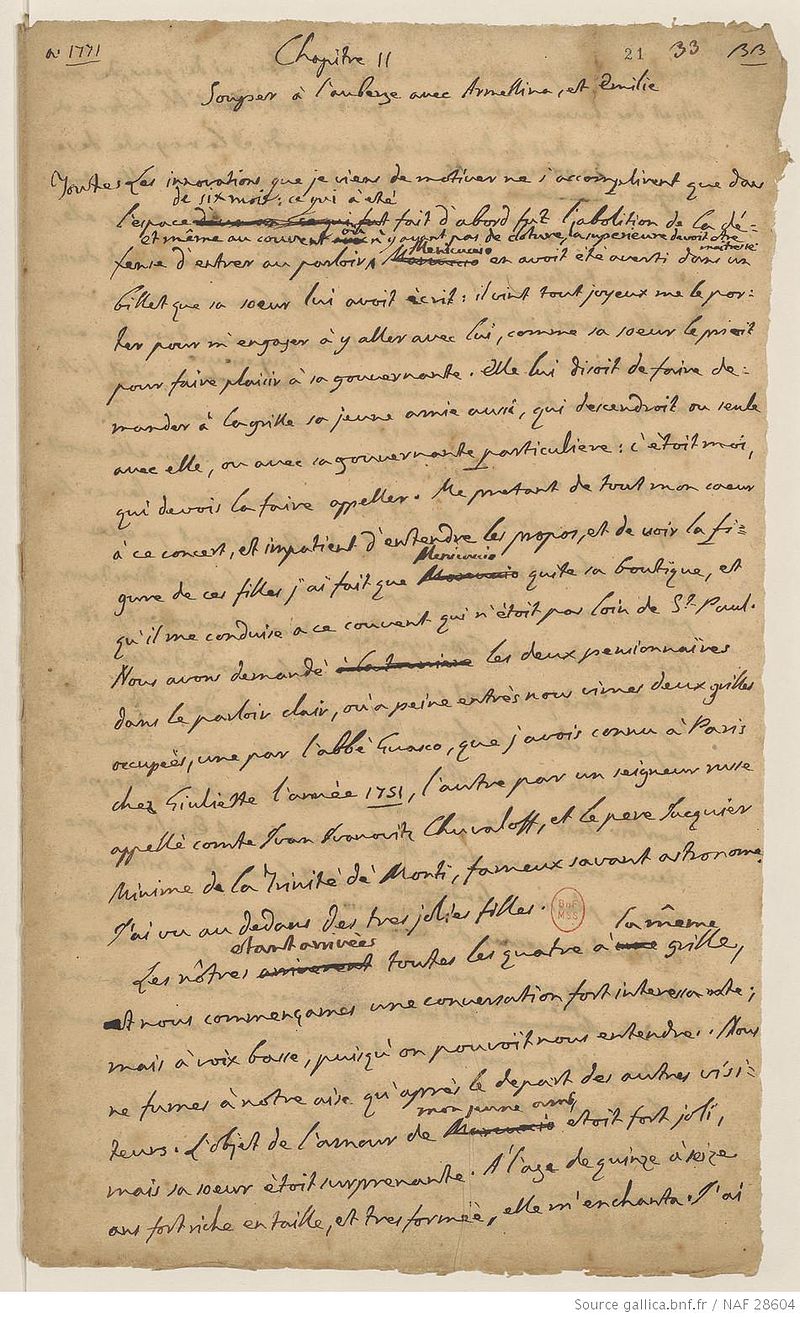

★ ジアコーモ・カサノーヴァ(Giacomo Casanova, 1725-1798)——リアルな人物像としての女たらしあるいは現実に存在した「性豪」

| Giacomo Girolamo

Casanova (/ˌkæsəˈnoʊvə, ˌkæzə-/,[1][2][3] Italian: [ˈdʒaːkomo

dʒiˈrɔːlamo kazaˈnɔːva, kasa-]; 2 April 1725 – 4 June 1798) was an

Italian adventurer and author from the Republic of Venice.[4][5] His

autobiography, Histoire de ma vie (Story of My Life), is regarded as

one of the most authentic and provocative sources of information about

the customs and norms of European social life during the 18th

century.[6] Casanova was known to use pseudonyms, such as baron or count of Farussi (the maiden name of his mother) or Chevalier de Seingalt (French pronunciation: [sɛ̃ɡɑl]).[7] After he began writing in French, following his second exile from Venice, he often signed his works as "Jacques Casanova de Seingalt".[a] He claims to have mingled with European royalty, popes, and cardinals, along with the artistic figures Voltaire, Goethe, and Mozart. He has become so famous for his often complicated and elaborate affairs with women, that his name "might be said to be synonymous with libertine".[8] His final years were spent in Dux Chateau (Bohemia) as a librarian in Count Waldstein's household, where he also wrote his autobiography. |

ジャコモ・ジロラモ・カサノヴァ

(/ˌkæsəˈnoʊə/,[1][2][3]イタリア語: [ˈdʒaːkomo dˈdʒ kazaˈnɔːva, kasa-];

1725年4月2日 - 1798年6月4日)はヴェネツィア共和国出身のイタリアの冒険家、作家である。

[4][5]彼の自伝であるHistoire de ma vie(Story of My

Life)は、18世紀のヨーロッパ社会生活の習慣や規範に関する最も信憑性が高く挑発的な情報源のひとつとみなされている[6]。 カサノヴァは、ファルシ男爵や伯爵(母親の旧姓)、シュヴァリエ・ド・セインガルト(フランス語発音:[sɛ̃ɑ])などの偽名を使うことで知られてい た。 [7]ヴェネツィアからの2度目の亡命後、フランス語で執筆を始めた後、彼はしばしば作品に「ジャック・カサノヴァ・ド・セインガルト」と署名した [a]。彼はヨーロッパの王族、教皇、枢機卿、芸術家であるヴォルテール、ゲーテ、モーツァルトらと交わったと主張している。 女性との複雑で手の込んだ情事をしばしば行ったことで有名になり、その名は「自由主義者(リベルタン) の代名詞と言えるかもしれない」[8]。晩年はワルトシュタイン伯爵家の司書として デュックス・シャトー(ボヘミア)で過ごし、そこで自伝も執筆した。 |