Migrants pass through Ixtepec, Mexico, atop a train known as “la bestia.” (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images.)

*

**

***

****

*****

****

***

**

*

|

"The Maya peoples (/ˈmaɪə/) are an ethnolinguistic group of indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. The ancient Maya civilization was formed by members of this group, and today's Maya are generally descended from people who lived within that historical civilization. Today they inhabit southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras. "Maya" is a modern collective term for the peoples of the region, however, the term was not historically used by the indigenous populations themselves. There was no common sense of identity or political unity among the distinct populations, societies and ethnic groups because they each had their own particular traditions, cultures and historical identity.[7] It is estimated that six million Maya were living in this area at the start of the 21st century.[1][2] Guatemala, southern Mexico and the Yucatán Peninsula, Belize, El Salvador and western Honduras have managed to maintain numerous remnants of their ancient cultural heritage. Some are quite integrated into the majority hispanicized mestizo cultures of the nations in which they reside, while others continue a more traditional, culturally distinct life, often speaking one of the Mayan languages as a primary language. The largest populations of contemporary Maya inhabit Guatemala, Belize, and the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador, as well as large segments of population within the Mexican states of Yucatán, Campeche, Quintana Roo, Tabasco and Chiapas." - Maya peoples. | 「マヤ民族は、メソアメリカの先住民族の民族言語グループである。古代マヤ文明はこのグルー プのメンバーによって形成され、今日のマヤ族は一般的にその歴史的文明の中で生きた人々の子孫である。現在、彼らはメキシコ南部、グアテマラ、ベリーズ、 エルサルバドル、ホンジュラスに居住している。「マヤ 」は、この地域の人々のための現代的な総称であるが、この言葉は歴史的に先住民族自身によって使用されていなかった。それぞれの集団、社会、民族が独自の 伝統、文化、歴史的アイデンティティを持っていたため、異なる集団、社会、民族の間に共通のアイデンティティや政治的統一感はなかった。21世紀初頭、こ の地域には600万人のマヤ族が住んでいたと推定されている。グアテマラ、メキシコ南部、ユカタン半島、ベリーズ、エルサルバドル、ホンジュラス西部は、 古代の文化遺産の名残を数多く維持することに成功している。あるものは、彼らが居住する国の大多数のヒスパニック化されたメスティーソ文化に完全に統合さ れ、他のものは、より伝統的な、文化的に独特の生活を続け、多くの場合、主要言語としてマヤ語のいずれかを話している。現代マヤの最大人口は、グアテマ ラ、ベリーズ、ホンジュラスとエルサルバドルの西部、メキシコのユカタン、カンペチェ、キンタナ・ロー、タバスコ、チアパスの各州に居住している。」 |

|

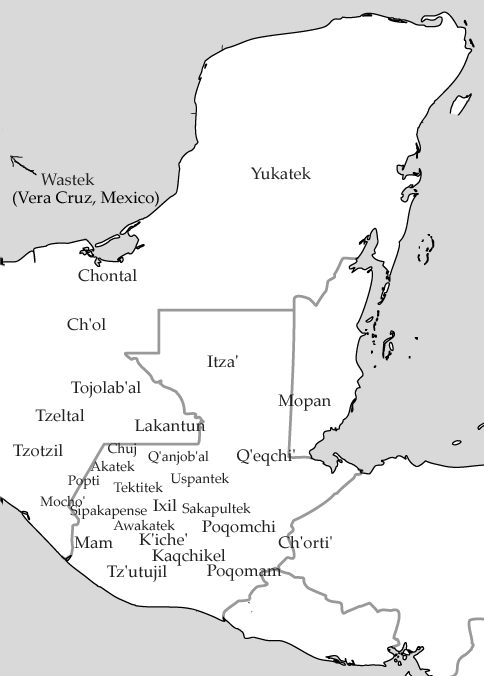

Map showing the

extent of the Maya civilization (red), compared to all other

Mesoamerica cultures (black). Within Central America and southern North

America (Mexico). This map also shows the cities and cultural

mainsteads of the Maya, who did not have an empire but rather a group

of loosely associated city-states. Map of Maya linguistic distribution ここでは、グアテマラのマヤ民族を中心に説明する "In Guatemala, indigenous people of Maya descent comprise around 42% of the population.[3][20] The largest and most traditional Maya populations are in the western highlands in the departments of Baja Verapaz, Quiché, Totonicapán, Huehuetenango, Quetzaltenango, and San Marcos; their inhabitants are mostly Maya.[21] The Maya people of the Guatemala highlands include the Achi, Akatek, Chuj, Ixil, Jakaltek, Kaqchikel, Kʼicheʼ, Mam, Poqomam, Poqomchiʼ, Qʼanjobʼal, Qʼeqchiʼ, Tzʼutujil and Uspantek. The Qʼeqchiʼ live in lowland areas of Alta Vera Paz, Peten, and Western Belize. Over the course of the succeeding centuries a series of land displacements, re-settlements, persecutions and migrations resulted in a wider dispersal of Qʼeqchiʼ communities, into other regions of Guatemala (Izabal, Petén, El Quiché). They are the 2nd largest ethnic Maya group in Guatemala (after the Kʼicheʼ) and one of the largest and most widespread throughout Central America. In Guatemala, the Spanish colonial pattern of keeping the native population legally separate and subservient continued well into the 20th century.[citation needed] This resulted in many traditional customs being retained, as the only other option than traditional Maya life open to most Maya was entering the Hispanic culture at the very bottom rung. Because of this many Guatemalan Maya, especially women, continue to wear traditional clothing, that varies according to their specific local identity. The southeastern region of Guatemala (bordering with Honduras) includes groups such as the Chʼortiʼ. The northern lowland Petén region includes the Itza, whose language is near extinction but whose agroforestry practices, including use of dietary and medicinal plants may still tell us much about pre-colonial management of the Maya lowlands.[22]" →"Mayan languages" |

マヤ文明(赤)の範囲を他のメソアメリカ文化(黒)と比較した地図。中

央アメリカと北アメリカ南部(メキシコ)の範囲。この地図はまた、帝国を持たず、緩やかに関連した都市国家のグループであったマヤの都市と文化的な主要拠

点を示している。 グ アテマラでは、マヤ系の先住民が人口の約42%を占める。最大かつ最も伝統的なマヤの人口は、バハ・ベラパス県、キチェ県、トトニカパン県、フエウエテナ ンゴ県、ケツァルテナンゴ県、サンマルコス県の西部高地に存在する。 グアテマラ高地のマヤ族には、Achi、Akatek、Chuj、Ixil、Jakaltek、Kaqchikel、Kʼicheʼ、Mam、 Poqomam、Poqomchiʼ、Qʼanjobʼal、Qʼeqchiʼ、Tzʼutujil、Uspantekが含まれる。Qʼeqchiʼは Alta Vera Paz、Peten、西ベリーズの低地に住む。その後何世紀にもわたって、土地の移動、再定住、迫害、移住が繰り返され、Qʼeqchiʼのコミュニティ はグアテマラの他の地域(Izabal、Petén、El Quiché)へと広く分散した。彼らはグアテマラでKʼicheʼ族に次いで2番目に大きなマヤ民族グループであり、中央アメリカ全体で最も大きく、最 も広く分布しているグループのひとつである。グアテマラでは、先住民を法的に分離し従属させるというスペインの植民地支配のパターンが20世紀まで続いた [要出典]。その結果、多くの伝統的な習慣が保持されることになり、ほとんどのマヤにとって伝統的なマヤの生活以外の選択肢は、最底辺のヒスパニック文化 に入ることしかなかった。このため、グアテマラ・マヤの多く、特に女性は、それぞれの地域のアイデンティティによって異なる伝統的な衣服を着続けている。 グアテマラ南東部(ホンジュラスとの国境)にはChʼortiʼのようなグループがある。ペテン北部の低地にはイツァ族がおり、彼らの言語は絶滅寸前だ が、食用植物や薬用植物の利用を含む農林業の実践は、植民地時代以前のマヤ低地の管理について、まだ多くのことを物語っているかもしれない。」 |

|

"The

Guatemalan genocide, also referred to as the Maya genocide,[2] or

the Silent Holocaust[3] (Spanish: Genocidio guatemalteco, Genocidio

maya, o Holocausto silencioso), was the massacre of Maya civilians

during the Guatemalan military government's counterinsurgency

operations. Massacres, forced disappearances, torture and summary

executions of guerrillas and especially civilian collaborators at the

hands of US-backed security forces had been widespread since 1965 and

was a longstanding policy of the military regime, which US officials

were aware of.[4][5][6] A report from 1984 discussed "the murder of

thousands by a military government that maintains its authority by

terror".[7] Human Rights Watch has described "extraordinarily cruel"

actions by the armed forces, mostly against unarmed civilians.[8]

The repression reached genocidal levels in the predominantly indigenous

northern provinces where the EGP guerrillas operated. There, the

Guatemalan military viewed the Maya – traditionally seen as subhumans –

as siding with the insurgency and began a campaign of wholesale

killings and disappearances of Mayan peasants. While massacres of

indigenous peasants had occurred earlier in the war, the systematic use

of terror against the indigenous population began around 1975 and

peaked during the first half of the 1980s.[9] The military had carried

out 626 massacres against the Maya during the conflict.[10] The

Guatemalan army itself acknowledged destroying 440 Mayan villages

between 1981 and 1983, during the most intense phase of the repression.

In some municipalities such as Rabinal and Nebaj, at least one-third of

the villages were evacuated or destroyed. A study by the Juvenile

Division of the Supreme Court sanctioned in March 1985 revealed that

over 200,000 children had lost at least one parent in the killings, of

whom 25% had lost both since 1980, meaning that between 45,000 and

60,000 adult Guatemalans were killed during the period from 1980 and

1985.[11] This does not account for the fact that children often became

targets of mass killings by the army in events such as the Río Negro

massacres.[12] Former military dictator General Efrain Ríos Montt

(1982–1983) was indicted for his role in the most intense stage of the

genocide.

An estimated 200,000 Guatemalans were killed during the Guatemalan

Civil War including at least 40,000 persons who "disappeared". 93% of

civilian executions were carried out by government forces. Of the

42,275 individual cases of killing and "disappearances" documented by

the Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH), 83% of the victims

were Maya and 17% Ladino.[1] A UN-sponsored Commission for Historical

Clarification in 1999 concluded that a genocide had taken place at the

hands of the US-backed Armed Forces of Guatemala, and that US training

of the officer corps in counterinsurgency techniques "had a significant

bearing on human rights violations during the armed

confrontation".[9][13][5][14]" Guatemalan

Genocide. |

グ

アテマラ大虐殺(グアテマラだいぎゃくさつ、スペイン語: Genocidio guatemalteco, Genocidio maya, o

Holocausto

silencioso)は、グアテマラ軍政の対反乱作戦におけるマヤ系市民の虐殺である。アメリカの支援を受けた治安部隊の手によるゲリラや特に民間人協

力者の虐殺、強制失踪、拷問、即決処刑は1965年以来広まっており、アメリカ政府高官も認識していた軍事政権の長年の政策であった。1984年の報告書

では、「恐怖によって権威を維持する軍事政権による数千人の殺害」について論じている。ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは、武装勢力による「非常に残酷な」

行為について、そのほとんどが非武装の市民に対するものであったと述べている。EGPゲリラが活動していた先住民族が多い北部州では、弾圧は虐殺レベルに

達した。そこでグアテマラ軍は、伝統的に亜人種とみなされてきたマヤ族を反乱軍に味方するとみなし、マヤ族の農民の大規模な殺害と失踪のキャンペーンを開

始した。先住民農民の虐殺は戦争の初期にもあったが、先住民に対する組織的な恐怖の行使は1975年頃から始まり、1980年代前半にピークを迎えた。グ

アテマラ軍自身も、弾圧が最も激しかった1981年から1983年の間に、440のマヤ族の村を破壊したことを認めている。ラビナルやネバジのようないく

つかの自治体では、少なくとも村の3分の1が避難または破壊された。1985年3月に認可された最高裁判所少年部の調査によると、20万人以上の子どもが

殺害によって少なくとも片親を失い、そのうち25%は1980年以降に両親を失っており、1980年から1985年の間に45,000人から60,000

人の成人グアテマラ人が殺害されたことになる。これは、リオ・ネグロの大虐殺のような事件で、子どもたちがしばしば軍隊による大量殺戮の標的になったとい

う事実を考慮に入れていない。元軍人独裁者エフレイン・リオス・モント将軍(1982年~1983年)は、ジェノサイドの最も激しい段階での役割で起訴さ

れた。グアテマラ内戦中、少なくとも4万人の「失踪者」を含め、推定20万人のグアテマラ人が殺害された。民間人処刑の93%は政府軍によって行われた。

歴史解明委員会(CEH)が記録した42,275件の殺害と「失踪」のうち、犠牲者の83%がマヤ人、17%がラディーノ人であった。1999年に国連が

主催した歴史解明委員会は、米国が支援したグアテマラ軍によってジェノサイドが行われ、米国が将校隊に対反乱戦技術を訓練したことが「武力衝突中の人権侵

害に重大な影響を及ぼした」と結論づけた。 |

|

"The

Maya people

are known for their brightly colored, yarn-based, textiles that are

woven into capes, shirts, blouses, huipiles and dresses. Each village

has its own distinctive pattern, making it possible to distinguish a

person's home town. Women's clothing consists of a shirt and a long

skirt.

The Maya religion is Roman Catholicism combined with the indigenous

Maya religion to form the unique syncretic religion which prevailed

throughout the country and still does in the rural regions prior to

2010s of "orthodoxing" the western rural areas by Christian Orthodox

missionaries. Beginning from negligible roots prior to 1960s, however,

Protestant Pentecostalism has grown to become the predominant religion

of Guatemala City and other urban centers, later to 2010s that almost

of all Maya of several rural areas of West Guatemala, living rural

areas were mostly mass converted from Catholicism or possibly Maya

religion due of various reasons to either Eastern or Oriental Orthodoxy

by late Fr. Andres Giron and some other Orthodox missionaries, and also

smaller to mid-sized towns also slowly converted as well since

2013.[35] The unique religion is reflected in the local saint, Maximón,

who is associated with the subterranean force of masculine fertility

and prostitution. Always depicted in black, he wears a black hat and

sits on a chair, often with a cigar placed in his mouth and a gun in

his hand, with offerings of tobacco, alcohol, and Coca-Cola at his

feet. The locals know him as San Simon of Guatemala.

Maximón, a Maya deity

The Popol Vuh is the most significant work of Guatemalan literature in

the Kʼicheʼ language, and one of the most important works of

Pre-Columbian American literature. It is a compendium of Maya stories

and legends, aimed to preserve Maya traditions. The first known version

of this text dates from the 16th century and is written in Quiché

transcribed in Latin characters. It was translated into Spanish by the

Dominican priest Francisco Ximénez in the beginning of the 18th

century. Due to its combination of historical, mythical, and religious

elements, it has been called the Maya Bible. It is a vital document for

understanding the culture of Pre-Columbian America. The Rabinal Achí is

a dramatic work consisting of dance and text that is preserved as it

was originally represented. It is thought to date from the 15th century

and narrates the mythical and dynastic origins of the Toj Kʼicheʼ

rulers of Rabinal, and their relationships with neighboring Kʼicheʼ of

Qʼumarkaj.[36] The Rabinal Achí is performed during the Rabinal

festival of January 25, the day of Saint Paul. It was declared a

masterpiece of oral tradition of humanity by UNESCO in 2005. The 16th

century saw the first native-born Guatemalan writers that wrote in

Spanish."- Maya

heritage. |

マ

ヤの人々は、色鮮やかな糸を使った織物で知られ、ケープ、シャツ、ブラウス、ホイピレ、ドレスなどに織られている。村ごとに独特の模様があり、出身地を見

分けることができる。女性の服装はシャツとロングスカート。マヤの宗教はローマ・カトリックとマヤの土着宗教が融合したもので、2010年代にキリスト教

正教会の宣教師が西部の農村部を「正教化」する以前は、マヤ全土に広がり、現在も農村部で信仰されている独特のシンクレティック宗教である。しかし、

1960年代以前のごくわずかなルーツから始まり、プロテスタントのペンテコステ派がグアテマラ・シティやその他の都市部で優勢な宗教に成長し、その後

2010年代には、西グアテマラのいくつかの農村部のほとんどすべてのマヤ人が、故アンドレス・ギロン神父や他の正教宣教師たちによって、様々な理由から

カトリックやおそらくはマヤの宗教から東方正教会や東洋正教会に集団改宗し、さらに2013年以降、中小の町も徐々に改宗した。このユニークな宗教は、地

元の聖人マクシモンに反映されている。マクシモンは、男性的な豊穣と売春の地下的な力に関連している。常に黒い姿で描かれ、黒い帽子をかぶり、椅子に座

り、しばしば葉巻を口にくわえ、手には銃を持ち、足元にはタバコ、アルコール、コカ・コーラなどの供物を置いている。地元ではグアテマラのサン・シモンと

呼ばれている。マヤの神、マキシモン

ポポル・ヴフは、グアテマラ文学の中で最も重要なKʼicheʼ言語の作品であり、先コロンブス期のアメリカ文学の中でも最も重要な作品のひとつである。

マヤの伝統の保存を目的とした、マヤの物語と伝説の大要である。最初に知られたのは16世紀のもので、ラテン文字に転写されたキチェ語で書かれている。

18世紀初頭にドミニコ会司祭フランシスコ・ヒメネスによってスペイン語に翻訳された。歴史的、神話的、宗教的要素の組み合わせから、マヤの聖書と呼ばれ

ている。先コロンビア・アメリカの文化を理解する上で欠かせない文献である。ラビナル・アチは、舞踊とテキストからなる劇作品で、当初の表現そのままに保

存されている。15世紀に作られたと考えられており、ラビナルのToj

Kʼicheʼ支配者の神話と王朝の起源、そして近隣のQʼmarkajのKʼicheʼとの関係が語られている[36]。Rabinal

Achíは、1月25日の聖パウロの日に行われるラビナルの祭りで上演される。2005年にユネスコによって人類の口承伝統の傑作とされた。16世紀に

は、スペイン語で書かれたグアテマラ初の生粋の作家が誕生した。 |

|

Migrants

pass through Ixtepec, Mexico, atop a train known as “la bestia.”

(Photo by John Moore/Getty Images.) "First wave of migration:Due to the war in Guatemala, many Maya people were killed. The two parties in the war were both hurting the basic living circumstances of Maya people by destroying infrastructure, such as railroads, farmlands, factories, they also burned most of the Mayan books. The destruction of these basic tools created a very difficult environment for Maya people to make a living. Without a way to sustain themselves, many Maya people decided to move somewhere that they were able to live. Many people moved to Mexico and some moved to the United States, which was also their first encounter with the US. Many Mayans who moved to the US mainly moved to areas like Florida, Houston, and Los Angeles:Second wave of migration: After the peace agreement among both parties in Guatemala after a 36-year war, the two parties built a new government. But the new government is also not protecting the benefit of people, especially the native people like Maya people. The new government was trying to unite all the culture together which in another word, is trying to assimilate all the culture within Maya people. In addition, the new government was not only trying to eliminate the culture but also was keeping the lands to itself rather than gave them back to the Maya people. Without a way to grow crops and food, Maya people were in extreme poverty. They have to find a way to make a living which they started the second migration movement to the United States" |

移

住の第一波:グアテマラでの戦争により、多くのマヤの人々が殺された。戦争の両当事者は、鉄道、農地、工場などのインフラを破壊することによって、マヤの

人々の基本的な生活環境を傷つけた。こうした基本的な道具の破壊は、マヤの人々が生計を立てるのに非常に困難な環境を作り出した。自活する術を失ったマヤ

の人々の多くは、自分たちが暮らせる場所に移住することを決めた。多くの人々はメキシコに移り住み、ある人々はアメリカに移り住んだ。アメリカに移住した

多くのマヤ人は、主にフロリダ、ヒューストン、ロサンゼルスといった地域に移り住んだ:

グアテマラでは36年にわたる戦争の後、両当事者間の和平合意後、両当事者は新政府を建設した。しかし、新政府もまた人々の利益、特にマヤの人々のような

先住民の利益を守っていない。新政府は、すべての文化をひとつにまとめようとしており、別の言葉で言えば、マヤ民族の中のすべての文化を同化させようとし

ている。さらに、新政府は文化を排除しようとしただけでなく、土地をマヤの人々に返すのではなく、自分たちのものにしようとしていた。農作物や食料を栽培

する方法がないため、マヤの人々は極度の貧困に陥っていた。彼らは生計を立てる方法を見つけなければならず、それがアメリカへの第二次移住運動の始まり

だった。 |

|

八杉佳穂編『マヤ学を学ぶ人のために』

世界思想社、2004年 第1章 古代マヤ人の社会と文化―マヤ文明概観 第2章 生活を復元する―土器 第3章 権力と経済のかたち―石器 第4章 ジャングルのなかの神殿ピラミッド―古代マヤ建築 第5章 マヤ人は何をしるしたか―マヤ文字 第6章 究極の新石器時代の都市文明―マヤの技術と科学 第7章 スペインのくびきのもとに―マヤ人の植民地時代 第8章 文化を受け継ぐ―マヤ民族学への誘い 第9章 未来の宇宙につながる身体―マヤ医学の文化人類学(→「マヤ医学とその倫理 について考える」) 第10章 ことばの研究―マヤ諸語の特徴 第11章 世界の始まりと双子の英雄―マヤの神話・伝承(→「ポポル・ヴフ神話 (Popol Vuj)」) |

Links

- ︎Maya

civilization▶︎︎Maya

peoples▶︎先住民言語文化論▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎︎

リンク

- 新しい「先住民学」の提唱▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

文献

その他の情報