エルサレムのアイヒマン

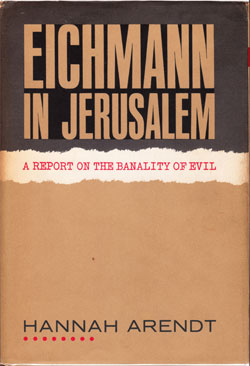

Eichmann in Jerusalem, 1963

☆

『エルサレムのアイヒマン A Report on the Banality of

Evil』は、政治思想家ハンナ・アーレントによる1963年の著書。アドルフ・ヒトラーの台頭期にドイツを逃れたユダヤ人であるアーレントは、『ニュー

ヨーカー』誌のためにホロコーストの主要な組織者の一人であるアドルフ・アイヒマンの裁判について報告した。1964年に改訂増補版が出版された(→「アイヒマン裁判」)。

| Eichmann

in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil is a 1963 book by

political thinker Hannah Arendt. Arendt, a Jew who fled Germany during

Adolf Hitler's rise to power, reported on the trial of Adolf Eichmann,

one of the major organizers of the Holocaust, for The New Yorker. A

revised and enlarged edition was published in 1964. |

『エ

ルサレムのアイヒマン A Report on the Banality of

Evil』は、政治思想家ハンナ・アーレントによる1963年の著書。アドルフ・ヒトラーの台頭期にドイツを逃れたユダヤ人であるアーレントは、『ニュー

ヨーカー』誌のためにホロコーストの主要な組織者の一人であるアドルフ・アイヒマンの裁判について報告した。1964年に改訂増補版が出版された。 |

Theme Arendt during the trial Arendt's subtitle famously introduced the phrase "the banality of evil". In part the phrase refers to Eichmann's deportment at the trial as the man displayed neither guilt for his actions nor hatred for those trying him, claiming he bore no responsibility because he was simply "doing his job". ("He did his 'duty'...; he not only obeyed 'orders', he also obeyed the 'law'.")[1] |

テーマ 裁判取材中のアーレント アーレントの副題に「悪の凡庸さ」という言葉があるのは有名である。このフ レーズは、アイヒマンが自分の行為に対する罪の意識も、彼を裁く人々に対する憎しみも示さず、単に「自分の仕事をした」だけなので責任はないと主張した、 裁判でのアイヒマンの態度を指している。(彼は自分の "義務 "を果たした...。"命令 "に従っただけでなく、"法律 "にも従ったのだ」[1]。 |

| Eichmann Arendt takes Eichmann's court testimony and the historical evidence available, and she makes several observations about Eichmann: Eichmann stated in court that he had always tried to abide by Immanuel Kant's categorical imperative.[2] She argues that Eichmann had essentially taken the wrong lesson from Kant: Eichmann had not recognized the "golden rule" and principle of reciprocity implicit in the categorical imperative, but had understood only the concept of one man's actions coinciding with general law. Eichmann attempted to follow the spirit of the laws he carried out, as if the legislator himself would approve. In Kant's formulation of the categorical imperative, the legislator is the moral self, and all people are legislators; in Eichmann's formulation, the legislator was Hitler. Eichmann claimed this changed when he was charged with carrying out the Final Solution, at which point Arendt claims "he had ceased to live according to Kantian principles, that he had known it, and that he had consoled himself with the thoughts that he no longer 'was master of his own deeds,' that he was unable 'to change anything'". [3] Eichmann's inability to think for himself was exemplified by his consistent use of "stock phrases and self-invented clichés". The man demonstrated his unrealistic worldview and crippling lack of communication skills through reliance on "officialese" (Amtssprache) and the euphemistic Sprachregelung (convention of speech) that made implementation of Hitler's policies "somehow palatable." While Eichmann might have had antisemitic leanings, Arendt argued that he showed "no case of insane hatred of Jews, of fanatical antisemitism or indoctrination of any kind. He personally never had anything whatever against Jews". [4] Eichmann was a "joiner" his entire life, in that he constantly joined organizations in order to define himself, and had difficulties thinking for himself without doing so. As a youth, he belonged to the YMCA, the Wandervogel, and the Jungfrontkämpferverband. In 1933, he failed in his attempt to join the Schlaraffia (a men's organization similar to Freemasonry), at which point a family friend (and future war criminal) Ernst Kaltenbrunner encouraged him to join the SS. At the end of World War II, Eichmann found himself depressed because "it then dawned on him that thenceforward he would have to live without being a member of something or other".[5] Arendt pointed out that his actions were not driven by malice, but rather blind dedication to the regime and his need to belong, to be a joiner. In his own words: "I sensed I would have to live a leaderless and difficult individual life, I would receive no directives from anybody, no orders and commands would any longer be issued to me, no pertinent ordinances would be there to consult—in brief, a life never known before lay ahead of me."[6] Despite his claims, Eichmann was not, in fact, very intelligent. As Arendt details in the book's second chapter, he was unable to complete either high school or vocational training, and only found his first significant job (traveling salesman for the Vacuum Oil Company) through family connections. Arendt noted that, during both his SS career and Jerusalem trial, Eichmann tried to cover up his lack of skills and education, and even "blushed" when these facts came to light. Arendt confirms Eichmann and the heads of the Einsatzgruppen were part of an "intellectual elite."[7] Unlike the Einsatzgruppen leaders, however, Eichmann would suffer from a “lack of imagination” and an "inability to think."[7] Arendt confirms several points where Eichmann actually claimed he was responsible for certain atrocities, even though he lacked the power or expertise to take these actions. Moreover, Eichmann made these claims even though they hurt his defense, hence Arendt's remark that "Bragging was the vice that was Eichmann's undoing".[8] Arendt also suggests that Eichmann may have preferred to be executed as a war criminal than live as a nobody. This parallels his overestimation of his own intelligence and his past value in the organizations in which he had served, as stated above. Arendt argues that Eichmann, in his peripheral role at the Wannsee Conference, witnessed the rank-and-file of the German civil service heartily endorse Reinhard Heydrich's program for the Final Solution of the Jewish question in Europe (German: die Endlösung der Judenfrage). Upon seeing members of "respectable society" endorsing mass murder, and enthusiastically participating in the planning of the solution, Eichmann felt that his moral responsibility was relaxed, as if he were "Pontius Pilate". During his imprisonment before his trial, the Israeli government sent no fewer than six psychologists to examine Eichmann. These psychologists found no trace of mental illness, including personality disorder. One doctor remarked that his overall attitude towards other people, especially his family and friends, was "highly desirable", while another remarked that the only unusual trait Eichmann displayed was being more "normal" in his habits and speech than the average person. [9] Arendt suggests that this most strikingly discredits the idea that the Nazi criminals were manifestly psychopathic and different from "normal" people. From this document, many concluded that situations such as the Holocaust can make even the most ordinary of people commit horrendous crimes with the proper incentives, but Arendt adamantly disagreed with this interpretation, as Eichmann was voluntarily following the Führerprinzip. Arendt insists that moral choice remains even under totalitarianism, and that this choice has political consequences even when the chooser is politically powerless: [U]nder conditions of terror most people will comply but some people will not, just as the lesson of the countries to which the Final Solution was proposed is that "it could happen" in most places but it did not happen everywhere. Humanly speaking, no more is required, and no more can reasonably be asked, for this planet to remain a place fit for human habitation. Arendt mentions, as a case in point, Denmark: One is tempted to recommend the story as required reading in political science for all students who wish to learn something about the enormous power potential inherent in non-violent action and in resistance to an opponent possessing vastly superior means of violence. It was not just that the people of Denmark refused to assist in implementing the Final Solution, as the peoples of so many other conquered nations had been persuaded to do (or had been eager to do) — but also, that when the Reich cracked down and decided to do the job itself it found that its own personnel in Denmark had been infected by this and were unable to overcome their human aversion with the appropriate ruthlessness, as their peers in more cooperative areas had. On Eichmann's personality, Arendt concludes: Despite all the efforts of the prosecution, everybody could see that this man was not a "monster," but it was difficult indeed not to suspect that he was a clown. And since this suspicion would have been fatal to the entire enterprise [his trial], and was also rather hard to sustain in view of the sufferings he and his like had caused to millions of people, his worst clowneries were hardly noticed and almost never reported. [10] Arendt ended the book by writing: And just as you [Eichmann] supported and carried out a policy of not wanting to share the earth with the Jewish people and the people of a number of other nations—as though you and your superiors had any right to determine who should and who should not inhabit the world—we find that no one, that is, no member of the human race, can be expected to want to share the earth with you. This is the reason, and the only reason, you must hang. |

アイヒマン アーレントはアイヒマンの法廷証言と入手可能な歴史的証拠をもとに、アイヒマンについていくつかの見解を述べている: アイヒマンは法廷で、イマヌエル・カントの定言命法を常に守ろうとしてきたと述べた: アイヒマンは定言命法に暗黙のうちに含まれている「黄金律(=普遍的な立法の原理)」と互恵性(=互酬性)の原則を認識しておらず、一人の人間の行為が一般法と一致するという概念しか理解していなかった。アイヒマンは、あたかも立法者自身が承認するかのように、自分が実行した法律の精神に従おうとした。カントの定言命法の 定式化では、立法者は道徳的自己であり、すべての人が立法者であるが、アイヒマンの定式化では、立法者はヒトラーであった。アイヒマンは、最終的解決策を 実行する責任を負わされたときに、このことが変わったと主張したが、その時点でアーレントは、「彼はカントの原則に従って生きることをやめ、それを知り、 もはや自分は『自分の行いの主人ではない』、『何も変えることはできない』という考えで自分を慰めていた」と主張している[3]。[3] アイヒマンが自分の頭で考えることができなかったことは、彼が一貫して「常套句や自作自演の決まり文句」を使っていたことに象徴されている。アイヒマン は、ヒトラーの政策を "どうにか受け入れられる "ようにするための「公式語」(Amtssprache)と婉曲的な「言論慣例」(Sprachregelung)に依存することで、非現実的な世界観と コミュニケーション能力の不自由さを示した。 アイヒマンには反ユダヤ主義的な傾向があったかもしれないが、アーレントは「ユダヤ人に対する狂気的な憎悪、狂信的な反ユダヤ主義、いかなる種類の教化もなかった。彼は個人的にユダヤ人に恨みを持つことはなかった」。[4] アイヒマンは生涯を通じて "加入者 "であり、自分を定義するために常に組織に加入し、そうしなければ自分の頭で考えることができなかった。青年時代にはYMCA、ヴァンデルフォーゲル、ユ ングフロントケンプファーバンドに所属した。1933年、シュラーラフィア(フリーメーソンに似た男性組織)に入ろうとして失敗し、その時、家族の友人 (後の戦犯)エルンスト・カルテンブルンナーから親衛隊に入るよう勧められた。第二次世界大戦が終わったとき、アイヒマンは自分自身が落ち込んでいること に気づいた。アーレントは、アイヒマンの行動は悪意によるものではなく、体制への盲目的な献身であり、所属すること、仲間になることの必要性によるものだ と指摘した。彼自身の言葉を借りれば 「私は、リーダー不在の困難な個人生活を送らなければならないことを感じた。 彼の主張とは裏腹に、アイヒマンは実際にはあまり知的ではなかった。アーレントが本書の第2章で詳述しているように、彼は高校も職業訓練も修了できず、家 族のコネで初めて重要な仕事(真空油脂会社の巡回セールスマン)に就いただけであった。アーレントは、アイヒマンが親衛隊でのキャリアとエルサレム裁判の 両方で、技術や教育の欠如を隠蔽しようとし、これらの事実が明るみに出たときには「赤面」さえしたと指摘している。 アーレントは、アイヒマンとアインザッツグルッペンの首脳たちが「知的エリート」の一員であったことを確認している[7]。しかし、アインザッツグルッペンの首脳たちとは異なり、アイヒマンは「想像力の欠如」と「思考力の欠如」に苦しむことになる[7]。 アーレントは、アイヒマンが、これらの行動をとるための権力や専門知識を欠いていたにもかかわらず、ある種の残虐行為については自分に責任があると実際に 主張していた点をいくつか確認している。アーレントはまた、アイヒマンは無名の人間として生きるよりも、戦犯として処刑されることを望んだかもしれないと 示唆している。このことは、アイヒマンが自らの知性と、彼が仕えた組織における過去の価値を過大評価していたことと類似している。 アーレントは、アイヒマンがヴァンゼー会議で周辺的な役割を担っていたとき、ラインハルト・ハイドリヒのヨーロッパにおけるユダヤ人問題の最終的解決(ド イツ語:die Endlösung der Judenfrage)プログラムを、ドイツの公務員たちが心から支持しているのを目撃したと論じている。立派な社会」のメンバーが大量殺人を支持し、解 決策の計画に熱心に参加しているのを見て、アイヒマンは、まるで自分が「ポンテオ・ピラト」であるかのように、道徳的責任が緩和されたと感じた。 裁判前の投獄中、イスラエル政府は6人以上の心理学者をアイヒマンの診察に派遣した。これらの心理学者たちは、人格障害を含む精神病の痕跡を発見しなかっ た。ある医師は、他の人々、特に彼の家族や友人に対する彼の全体的な態度は「非常に好ましい」ものであったと述べ、別の医師は、アイヒマンが示した唯一の 異常な特徴は、彼の習慣や話し方が平均的な人よりも「普通」であったことであると述べた[9]。[9] アーレントは、このことが、ナチスの犯罪者が明らかに精神病質であり、「普通の」人々とは異なっていたという考えを最も顕著に否定していると指摘してい る。この文書から、ホロコーストのような状況は、適切な動機付けがあれば、ごく普通の人でも恐ろしい犯罪を犯すことができると多くの人が結論づけたが、 アーレントは、アイヒマンは自発的に総統のプリンツィップに従っていたとして、この解釈に断固反対した。アーレントは、全体主義の下でも道徳的な選択は残 るのであり、選択者が政治的に無力であっても、この選択は政治的な結果をもたらすと主張している: [恐怖の条件下では、ほとんどの人が従うが、そうでない人もいる。最終的解決策が提案された国々の教訓が、ほとんどの場所で「起こりうる」ことではある が、どこでも起こったわけではないのと同じである。人間的に言えば、この惑星が人間の居住に適した場所であり続けるためには、これ以上のことは必要ではな いし、これ以上のことを合理的に求めることもできない。 アーレントはその一例としてデンマークを挙げている: 非暴力行動や、はるかに優れた暴力手段を持つ相手に対する抵抗に内在する巨大な力の可能性について何かを学びたいと願うすべての学生たちに、この物語を政 治学の必読書として推薦したくなる。デンマークの人々が、他の多くの被征服国の人々がそうするように説得されていた(あるいはそうすることを熱望してい た)ように、最終的解決策の実施に協力することを拒否したというだけではない。 アイヒマンの性格について、アーレントは次のように結んでいる: 検察側のあらゆる努力にもかかわらず、この男が "怪物 "でないことは誰にでもわかった。そして、この疑惑は(彼の裁判という)事業全体にとって致命的であっただろうし、また、彼や彼のような人物が何百万人も の人々に与えた苦しみを考えれば、それを維持することはむしろ困難であったので、彼の最悪の道化はほとんど注目されず、ほとんど報道されなかった。 [10] アーレントはこの本の最後にこう書いている: あなた(=アイヒマン)が、ユダヤ人や他の多くの国の人々と地球を共有したくないという政策を支持し、実行したように、まるであなたやあなたの上司が、誰 が世界に住むべきで、誰が住むべきでないかを決定する権利があるかのように。これが、あなたが首を吊らなければならない理由であり、唯一の理由なのだ。 |

| Legality of the trial Beyond her discussion of Eichmann himself, Arendt discusses several additional aspects of the trial, its context, and the Holocaust. She points out that Eichmann was kidnapped by Israeli agents in Argentina and transported to Israel, an illegal act, and that he was tried in Israel even though he was not accused of committing any crimes there. "If he had not been found guilty before he appeared in Jerusalem, guilty beyond any reasonable doubt, the Israelis would never have dared, or wanted, to kidnap him in formal violation of Argentine law." She describes his trial as a show trial arranged and managed by Prime Minister Ben-Gurion, and says that Ben-Gurion wanted, for several political reasons, to emphasize not primarily what Eichmann had done, but what the Jews had suffered during the Holocaust.[11] She points out that the war criminals tried at Nuremberg were "indicted for crimes against the members of various nations," without special reference to the Nazi genocide against the Jews. She questions Israel's right to try Eichmann. Israel was a signatory to the 1950 UN Genocide Convention, which rejected universal jurisdiction and required that defendants be tried 'in the territory of which the act was committed' or by an international tribunal. The court in Jerusalem did not pursue either option.[12] Eichmann's deeds were not crimes under German law, as, at that time, in the eyes of the Third Reich, he was a law-abiding citizen. He was tried for 'crimes in retrospect'.[13] The prosecutor, Gideon Hausner, followed the tone set by Prime Minister Ben-Gurion, who stated, 'It is not an individual nor the Nazi regime on trial, but Antisemitism throughout history.' Hausner's corresponding opening statements, which heavily referenced biblical passages, was 'bad history and cheap rhetoric,' according to Arendt. Furthermore, it suggested that Eichmann was no criminal, but the 'innocent executor of some foreordained destiny.'[14] |

裁判の合法性 アーレントは、アイヒマン自身についての議論だけでなく、裁判、その背景、ホロコーストのいくつかの側面についても論じている。 彼女は、アイヒマンがアルゼンチンでイスラエルの諜報員に拉致され、イスラエルに移送されたのは違法行為であり、イスラエルでの犯罪を告発されていないに もかかわらず、イスラエルで裁判にかけられたことを指摘している。「もし彼がエルサレムに出頭する前に、合理的な疑いを差し挟む余地なく有罪とされていな ければ、イスラエル人はアルゼンチンの法律に正式に違反して彼を誘拐する勇気がなかっただろうし、そうすることを望まなかっただろう」。 彼女は、彼の裁判はベン=グリオン首相が手配し、管理したショー・トライアルであったと述べ、ベン=グリオンはいくつかの政治的理由から、アイヒマンが 行ったことを第一に強調するのではなく、ユダヤ人がホロコーストの間に受けた苦しみを強調したかったのだと言う[11]。彼女は、ニュルンベルクで裁かれ た戦犯たちは、ユダヤ人に対するナチスの大量虐殺に特別な言及をすることなく、「さまざまな国の構成員に対する罪に対して起訴された」と指摘する。 彼女は、アイヒマンを裁くイスラエルの権利に疑問を呈している。イスラエルは1950年の国連ジェノサイド条約に加盟しており、同条約は普遍的管轄権を否 定し、被告は『その行為が行われた領土内』もしくは国際法廷によって裁かれることを要求している。エルサレムの裁判所はどちらの選択肢も追求しなかった [12]。 アイヒマンの行為は、当時、第三帝国の目から見れば、法を遵守する市民であったため、ドイツ法上の犯罪ではなかった。彼は「回顧の罪」で裁かれた[13]。 検察官のギデオン・ハウスナーは、ベン=グリオン首相が示した論調に従った。彼は、「裁判にかけられるのは個人でもナチス政権でもなく、歴史全体にわたる 反ユダヤ主義である」と述べた。それに対応するハウスナーの冒頭陳述は、聖書の一節を多用したもので、アーレントによれば『悪い歴史と安っぽいレトリッ ク』であった。さらに、アイヒマンは犯罪者ではなく、「定められた運命の無実の実行者」であることを示唆した[14]。 |

| Banality of evil Arendt's book introduced the expression and concept of the banality of evil.[15] Her thesis is that Eichmann was actually not a fanatic or a sociopath, but instead an average and mundane person who relied on clichéd defenses rather than thinking for himself,[16] was motivated by professional promotion rather than ideology, and believed in success which he considered the chief standard of "good society".[17] Banality, in this sense, does not mean that Eichmann's actions were in any way ordinary, but that his actions were motivated by a sort of complacency which was wholly unexceptional.[18] Many mid-20th century pundits were favorable to the concept,[19][20] which has been called "one of the most memorable phrases of 20th-century intellectual life,"[21] and it features in many contemporary debates about morality and justice,[22][16] as well as in the workings of truth and reconciliation commissions.[23] Others see the popularization of the concept as a valuable warrant against walking negligently into horror, as the evil of banality, in which failure to interrogate received wisdom results in individual and systemic weakness and decline.[24] |

悪の凡庸さ(陳腐さ) アーレントの著書は、「悪の凡庸性」という表現と概念を紹介した。 彼女のテーゼは、アイヒマンは実際には狂信者でも社会病質者でもなく、その代わりに、自分で考えるよりも決まりきった弁明に頼り、イデオロギーよりもむし ろ職業上の昇進に突き動かされ、「良い社会」の主要な基準であると考えた成功を信じた、平凡でありふれた人間であったというものである[16]。 [17] この意味での凡庸さとは、アイヒマンの行動が平凡であったという意味ではなく、彼の行動がまったく例外的でない一種の自己満足に突き動かされていたという 意味である[18]。 20世紀半ばの識者の多くはこの概念に好意的であり[19][20]、「20世紀の知的生活の中で最も記憶に残るフレーズの一つ」[21]と呼ばれてお り、道徳と正義に関する多くの現代的な議論[22][16]や、真実と和解の委員会の活動の中で取り上げられている。 [23]また、この概念の普及を、恐怖の中に怠慢に足を踏み入れることを防ぐための貴重な保証とみなす者もおり、それは陳腐さの弊害であり、既成の常識を 疑うことを怠れば、個人やシステムの弱体化や衰退を招くというものである[24]。 |

| Alleged Jewish cooperation Another one of the most controversial points raised by Arendt in her book is her criticism concerning the alleged role of Jewish authorities in the Holocaust.[25][26] In her writings, Arendt expressed her objections to the prosecution's refusal to address the cooperation of the leaders of the Judenräte (the Jewish councils) with the Nazis. In the book, Arendt asserts that Jewish organizations and leaderships in Europe collaborated with the Nazis and were directly responsible for the numbers of Jewish victims reaching the dimensions they did:[21] Wherever Jews lived, there were recognized Jewish leaders, and this leadership, almost without exception, cooperated in one way or another, for one reason or another, with the Nazis. The whole truth was that if the Jewish people had really been unorganized and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between four and a half and six million people. According to Freudiger's calculations about half of them could have saved themselves if they had not followed the instructions of the Jewish Councils. [27] The aforementioned Pinchas Freudiger was a witness in the trial, and during his deposition there were many objections from the public. To the accusation of not having advised the Jews to flee rather than passively surrender to the Germans, Freudiger replied that about half of the fugitives would have been captured and killed. Arendt says in her book that Freudiger should have remembered that as many as ninety-nine percent of those who did not flee were killed. Furthermore, she claims that Freudiger, like many other leaders of the Jewish Councils, had managed to survive the genocide because they were wealthy and able to buy the favors of the Nazi authorities.[28] |

ユダヤ人の協力の疑い アーレントがその著書の中で提起したもう一つの最も議論の的となった点は、ホロコーストにおけるユダヤ人当局の役割に関する彼女の批判である[25] [26]。アーレントはその著作の中で、ユダヤ人評議会の指導者たちのナチスとの協力について検察が言及しないことに異議を表明している。この本の中で アーレントは、ヨーロッパのユダヤ人組織や指導者たちがナチスに協力し、ユダヤ人の犠牲者の数がそのような規模に達した直接的な責任があると主張している [21]。 ユダヤ人が住んでいるところにはどこでも、公認のユダヤ人指導者がいて、この指導者は、ほとんど例外なく、何らかの形で、何らかの理由で、ナチスに協力し ていた。もしユダヤ人が本当に組織化されておらず、指導者もいなかったとしたら、混乱と多くの悲惨はあっただろうが、犠牲者の総数は450万人から600 万人の間には到底収まらなかっただろう。フロイディガーの計算によれば、ユダヤ人評議会の指示に従わなければ、そのうちの約半数は助かることができたとい う。[27] 前述のピンチャス・フロイディガーは裁判の証人であったが、彼の宣誓証言の際には一般市民から多くの反論があった。受動的にドイツ軍に降伏するのではな く、逃亡するようユダヤ人に勧めなかったという非難に対して、フロイディガーは、逃亡者の約半数は捕らえられて殺されただろうと答えた。アーレントは著書 の中で、フロイディガーは、逃げなかった人の99%もが殺されたことを思い出すべきだったと述べている。さらに彼女は、フロイディガーはユダヤ人評議会の 他の多くの指導者たちと同様に、裕福でナチス当局の便宜を買うことができたために、大量虐殺を生き延びることができたと主張している[28]。 |

| Reception Eichmann in Jerusalem upon publication and in the years following was controversial.[29][30] Arendt has long been accused of "blaming the victim" in the book.[31][32] She responded to the initial criticism in a postscript to the book: The controversy began by calling attention to the conduct of the Jewish people during the years of the Final Solution, thus following up the question, first raised by the Israeli prosecutor, of whether the Jews could or should have defended themselves. I had dismissed that question as silly and cruel, since it testified to a fatal ignorance of the conditions at the time. It has now been discussed to exhaustion, and the most amazing conclusions have been drawn. The well-known historico-sociological construct of "ghetto mentality"… has been repeatedly dragged in to explain behavior which was not at all confined to the Jewish people and which therefore cannot be explained by specifically Jewish factors… This was the unexpected conclusion certain reviewers chose to draw from the "image" of a book, created by certain interest groups, in which I allegedly had claimed that the Jews had murdered themselves.[33] Stanley Milgram, who would conduct controversial experiments on obedience, maintains that "Arendt became the object of considerable scorn, even calumny" because she highlighted Eichmann's "banality" and "normalcy", and accepted Eichmann's claim that he did not have evil intents or motives to commit such horrors; nor did he have a thought to the immorality and evil of his actions, or indeed, display, as the prosecution depicted, that he was a sadistic "monster".[34] Jacob Robinson published And the Crooked Shall be Made Straight, the first full-length rebuttal of her book.[19] Robinson presented himself as an expert in international law, not saying that he was an assistant to the prosecutor in the case.[20] In his 2006 book, Becoming Eichmann: Rethinking the Life, Crimes and Trial of a "Desk Murderer", Holocaust researcher David Cesarani questioned Arendt's portrait of Eichmann on several grounds. According to his findings, Arendt attended only part of the trial, witnessing Eichmann's testimony for "at most four days" and basing her writings mostly on recordings and the trial transcript. Cesarani feels that this may have skewed her opinion of him, since it was in the parts of the trial that she missed that the more forceful aspects of his character appeared.[35] Cesarani also suggested that Eichmann was in fact highly anti-Semitic and that these feelings were important motivators of his actions. Thus, he alleges that Arendt's claims that his motives were "banal" and non-ideological and that he had abdicated his autonomy of choice by obeying Hitler's orders without question may stand on weak foundations.[36] This is a recurrent[37] criticism of Arendt, though nowhere in her work does Arendt deny that Eichmann was an anti-Semite, and she also did not claim that Eichmann was "simply" following orders, but rather had internalized the rationalities of the Nazi regime.[37] Cesarani suggests that Arendt's own prejudices influenced the opinions she expressed during the trial. He argues that like many Jews of German origin, she held Ostjuden (Jews from Eastern Europe) in great disdain. This, according to Cesarani, led her to attack the conduct and efficacy of the chief prosecutor, Gideon Hausner, who was of Galician-Jewish origin. According to Cesarani, in a letter to the noted German philosopher Karl Jaspers she stated that Hausner was "a typical Galician Jew... constantly making mistakes. Probably one of those people who doesn't know any language."[38] Cesarani claims that some of her opinions of Jews of Middle Eastern origin verged on racism as she described the Israeli crowds in her letter to Karl Jaspers: "My first impression: On top, the judges, the best of German Jewry. Below them, the prosecuting attorneys, Galicians, but still Europeans. Everything is organized by a police force that gives me the creeps, speaks only Hebrew, and looks Arabic. Some downright brutal types among them. They would obey any order. And outside the doors, the Oriental mob, as if one were in Istanbul or some other half-Asiatic country. In addition, and very visible in Jerusalem, the peies [sidelocks] and caftan Jews, who make life impossible for all reasonable people here."[39] Cesarani's book was itself criticized. In a review that appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Barry Gewen argued that Cesarani's hostility stemmed from his book standing "in the shadow of one of the great books of the last half-century", and that Cesarani's suggestion that both Arendt and Eichmann had much in common in their backgrounds, making it easier for her to look down on the proceedings, "reveals a writer in control neither of his material nor of himself."[40] Eichmann in Jerusalem, according to Hugh Trevor-Roper, is deeply indebted to Raul Hilberg's The Destruction of the European Jews, so much so that Hilberg himself spoke of plagiarism.[41][42][43] Arendt also made use of H.G. Adler's book Theresienstadt 1941-1945. The Face of a Coerced Community (Cambridge University Press. 2017), which she had read in manuscript. Adler took her to task on her view of Eichmann in his keynote essay "What does Hannah Arendt know about Eichmann and the Final Solution?" (Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland. 20 November 1964).[44] Arendt also received criticism in the form of responses to her article, also published in the New Yorker. One instance of this came mere weeks after the publication of her articles in the form of an article entitled "Man With an Unspotted Conscience".[45] This work was written by witness for the defense, Michael A. Musmanno. He argued that Arendt fell prey to her own preconceived notions that rendered her work ahistorical. He also directly criticized her for ignoring the facts offered at the trial in stating that "the disparity between what Miss Arendt states, and what the ascertained facts are, occurs with such a disturbing frequency in her book that it can hardly be accepted as an authoritative historical work."[45] He further condemned Arendt and her work for her prejudices against Hauser and Ben-Gurion depicted in Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Musmanno argued that Arendt revealed "so frequently her own prejudices" that it could not stand as an accurate work.[45] In more recent years, Arendt has received further criticism from authors Bettina Stangneth and Deborah Lipstadt. Stangneth argues in her work, Eichmann Before Jerusalem, that Eichmann was, in fact, an insidious antisemite.[46] She utilized the Sassen Papers and accounts of Eichmann while in Argentina to prove that he was proud of his position as a powerful Nazi and the murders that this allowed him to commit. While she acknowledges that the Sassen Papers were not disclosed in the lifetime of Arendt, she argues that the evidence was there at the trial to prove that Eichmann was an antisemitic murderer and that Arendt simply ignored this.[46] Deborah Lipstadt contends in her work, The Eichmann Trial, that Arendt was too distracted by her own views of totalitarianism to objectively judge Eichmann.[42] She refers to Arendt's own work on totalitarianism, The Origins of Totalitarianism, as a basis for Arendt's seeking to validate her own work by using Eichmann as an example.[42] Lipstadt further contends that Arendt "wanted the trial to explicate how these societies succeeded in getting others to do their atrocious biddings" and so framed her analysis in a way which would agree with this pursuit.[42] However, Arendt has also been praised for being among the first to point out that intellectuals, such as Eichmann and other leaders of the Einsatzgruppen, were in fact more accepted in the Third Reich despite Nazi Germany's persistent use of anti-intellectual propaganda.[7] During a 2013 review of historian Christian Ingrao's book Believe and Destroy, which pointed out that Hitler was more accepting of intellectuals with German ancestry and that at least 80 German intellectuals assisted his "SS War Machine,"[7][47] Los Angeles Review of Books journalist Jan Mieszkowski praised Arendt for being "well aware that there was a place for the thinking man in the Third Reich."[7] |

レセプション アーレントは、本書の中で「被害者を非難している」と長い間非難されてきた[31][32]が、本書のあとがきで最初の批判に反論している: 論争が始まったのは、最終解決期のユダヤ人の行為に注意を喚起すること で、イスラエルの検事によって最初に提起された、ユダヤ人は自らを守ることができたのか、あるいはすべきだったのかという疑問を追及したためである。私は その疑問を、愚かで残酷なものだと一蹴した。なぜなら、その疑問は当時の状況に対する致命的な無知を物語っているからである。その疑問は今、徹底的に議論 され、驚くべき結論が導き出されている。「ゲットー精神」というよく知られた歴史社会学的な構成が......ユダヤ人にまったく限定されず、したがって ユダヤ人特有の要因では説明できない行動を説明するために、繰り返し引きずり込まれた......これは、私がユダヤ人が自分たちを殺したと主張したとさ れる、ある利益団体によって創作された本の「イメージ」から、ある評者が導き出すことを選んだ予想外の結論であった[33]。 スタンレー・ミルグラムは、アイヒマンの「平凡さ」と「正常さ」を強調し、アイヒマンにはそのような恐怖を犯す邪悪な意図や動機はなかったというアイヒマ ンの主張を受け入れ、自分の行為の不道徳さや悪について考えたこともなかったし、実際、検察側が描いたように、アイヒマンがサディスティックな「怪物」で あることを示したので、「アーレントは相当な軽蔑の対象となり、中傷の対象にさえなった」と主張している[34]。 ジェイコブ・ロビンソンは『And the Crooked Shall be Made Straight』を出版し、彼女の著書に対する初の全面的な反論を行った[19]。ロビンソンは自らを国際法の専門家として紹介し、この事件の検察官の アシスタントであったとは言わなかった[20]。 2006年の著書『Becoming Eichmann: Rethinking the Life, Crimes and Trial of a "Desk Murderer", ホロコースト研究者デイヴィッド・チェザラーニは、いくつかの理由からアーレントのアイヒマン像に疑問を呈している。彼の発見によれば、アーレントは裁判 の一部に出席しただけで、アイヒマンの証言に立ち会ったのは「せいぜい4日間」であり、彼女の著作のほとんどは録音と裁判記録に基づいている。チェザラー ニは、アイヒマンが実際には非常に反ユダヤ的であり、その感情が彼の行動の重要な動機であったことを示唆している[35]。したがって、彼の動機は「平 凡」で非理念的なものであり、ヒトラーの命令に疑問を抱くことなく従うことによって選択の自律性を放棄したというアーレントの主張は脆弱な基盤の上に立っ ている可能性があると彼は主張している[36]。 チェサラニは、アーレント自身の偏見が裁判中に彼女が表明した意見に影響を与えたことを示唆している。彼は、多くのドイツ系ユダヤ人と同様に、彼女はオス トジュデン(東欧出身のユダヤ人)を非常に軽蔑していたと論じている。このことが、ガリシア系ユダヤ人である主任検事ギデオン・ハウスナーの行動と効力を 攻撃することにつながった、とチェサラニは言う。チェサラニによれば、彼女はドイツの著名な哲学者カール・ヤスパースに宛てた手紙の中で、ハウズナーは 「典型的なガリシア系ユダヤ人...常に間違いを犯す。おそらく、どの言語も知らない人々の一人でしょう」[38]。チェザラーニは、カール・ヤスパース への手紙の中でイスラエルの群衆について述べているように、中東出身のユダヤ人に対する彼女の意見の一部は人種差別に近いものであったと主張している: 「私の第一印象: 私の第一印象は、裁判官たちはドイツ系ユダヤ人の中でも最高の人たち。その下にいるのは、ガリシア人だが、やはりヨーロッパ人である検事たち。ヘブライ語 しか話せず、アラビア人に見える。中には残忍なタイプもいる。彼らはどんな命令にも従う。そしてドアの外には、まるでイスタンブールか他の半分アジアの国 にいるかのような東洋人の群衆がいる。加えて、エルサレムでは非常に目立ちますが、ペイ(鬢付け油)とカフタンのユダヤ人が、ここでのすべての理性的な人 々の生活を不可能にしているのです」[39]。ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のブックレビューに掲載された書評の中で、バリー・ゲーウェンは、セサラニの敵意 は彼の本が「過去半世紀の偉大な書物の陰に隠れている」ことに起因しており、アーレントとアイヒマンにはその経歴において共通点が多く、アーレントがアイ ヒマンを見下すことを容易にしているというセサラニの示唆は、「この作家が自分の材料も自分自身もコントロールできていないことを露呈している」と論じた [40]。 ヒュー・トレヴァー=ローパーによれば、『エルサレムのアイヒマン』はラウル・ヒルバーグの『ヨーロッパ・ユダヤ人の破壊』に深く依存しており、ヒルバーグ自身が盗作だと語ったほどである[41][42][43]。 アーレントはまた、H.G.アドラーの著書『テレジエンシュタット1941-1945』も利用している。The Face of a Coerced Community』(Cambridge University Press. アドラーは、基調エッセイ "What does Hannah Arendt Know about Eichmann and the Final Solution? "の中で、彼女のアイヒマンに対する見方を問題にした。(Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland. 1964年11月20日)[44]。 アーレントはまた、『ニューヨーカー』誌に掲載された彼女の論文に対する反応という形で批判を受けた。その一例として、彼女の論文が発表されたわずか数週 間後に、「汚れのない良心を持つ人間」と題された論文が発表された[45]。彼はアーレントが彼女自身の先入観に陥っており、それが彼女の著作を非歴史的 なものにしていると主張した。彼はまた、「アーレント女史が述べていることと、確認された事実との間の不一致は、彼女の著書において、そのような不穏な頻 度で生じており、それが権威ある歴史的著作として受け入れられるとは到底思えない」と述べ、彼女が裁判で提示された事実を無視していることを直接的に批判 した[45]。彼はさらに、『エルサレムのアイヒマン』に描かれているハウザーとベン=グリオンに対する彼女の偏見について、アーレントと彼女の著作を非 難した: A Report on the Banality of Evil. ムスマンノは、アーレントが「彼女自身の偏見をあまりにも頻繁に」露呈しているため、正確な著作として成り立たないと主張した[45]。 近年、アーレントは作家のベッティナ・スタングネットとデボラ・リップシュタットからさらなる批判を受けている。スタングネットはその著作『アイヒマン・ ビフォア・エルサレム』の中で、アイヒマンが実際には陰湿な反ユダヤ主義者であったと主張している[46]。彼女はサッセン文書とアルゼンチン滞在中のア イヒマンの証言を利用し、アイヒマンが強大なナチスとしての地位とそれによって犯すことができた殺人に誇りを持っていたことを証明している。デボラ・リッ プシュタットはその著作『アイヒマン裁判』の中で、アーレントは全体主義に対する自身の見解に気を取られていて、アイヒマンを客観的に裁くことができな かったと主張している。 [さらにリップシュタットは、アーレントが「これらの社会がいかにして他者に自分たちの残虐な命令を実行させることに成功したかを説明するために裁判を望 んだ」ので、この追求に同意するような方法で自分の分析を組み立てたのだと主張する[42]。 [42] しかしながら、アーレントはまた、ナチス・ドイツが反知性主義的なプロパガンダを執拗に用いていたにもかかわらず、アイヒマンやアインザッツグルッペンの 他の指導者たちのような知識人たちが、第三帝国では実際に受け入れられていたことを最初に指摘したことでも称賛されている。 [7] 歴史家クリスチャン・イングラオの著書『Believe and Destroy』の2013年の書評の中で、ヒトラーはドイツ人の血筋を持つ知識人をより受け入れており、少なくとも80人のドイツ人知識人が彼の「SS ウォーマシーン」を支援していたと指摘している[7][47]。ロサンゼルス・レビュー・オブ・ブックスのジャーナリストであるヤン・ミエシュコフスキ は、アーレントが「第三帝国には考える人間の居場所があったことをよく認識していた」と称賛している[7]。 |

| Little Eichmanns Moral disengagement Milgram experiment (obedience to authority, 1961) Stanford prison experiment (Zimbardo, 1972) Superior orders https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eichmann_in_Jerusalem |

小さなアイヒマンたち 道徳的離脱 ミルグラム実験(権威への服従、1961年) スタンフォード監獄実験(ジンバルド、1972年) 上官の命令 |

| "Little

Eichmanns" is a term used to describe people whose actions, while on an

individual scale may seem relatively harmless even to themselves, taken

collectively create destructive and immoral systems in which they are

actually complicit. The name comes from Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi

bureaucrat who helped to orchestrate the Holocaust, but claimed that he

did so without feeling anything about his actions, merely following the

orders given to him. The use of "Eichmann" as an archetype stems from Hannah Arendt's notion of the "banality of evil".[1] According to Arendt in her 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem, Eichmann relied on propaganda rather than thinking for himself, and carried out Nazi goals mostly to advance his career, appearing at his trial to have an ordinary and common personality while displaying neither guilt nor hatred. She suggested that this most strikingly discredits the idea that the Nazi war criminals were manifestly psychopathic and fundamentally different from ordinary people.[1][2][3] The idea that Eichmann – or, indeed, the majority of Nazis or of those working in such regimes – actually fit this concept has been criticized by those who contend that Eichmann and the majority of Nazis were in fact deeply ideological and extremely anti-Semitic, with Eichmann in particular having been fixated on and obsessed with the Jews from a young age.[4] German political scientist Clemens Heni goes so far as to say the phrase "belittles the Holocaust".[5] Barbara Mann wrote that the term was perhaps best known for its use by anarcho-primitivist writer John Zerzan in his essay Whose Unabomber? written in 1995, although it was already common in the 1960s,[6][7] as various prior examples are known.[8][9][10] It gained prominence in American political culture several years after the September 11, 2001 attacks, when a controversy ensued[11][12] over the 2003 book On the Justice of Roosting Chickens,[13] republishing a similarly titled essay Ward Churchill wrote shortly after the attacks.[14][15] In the essay, Churchill used the phrase to describe technocrats working at the World Trade Center:[16] If there was a better, more effective, or in fact any other way of visiting some penalty befitting their participation upon the little Eichmanns inhabiting the sterile sanctuary of the twin towers, I'd really be interested in hearing about it. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Eichmanns |

「リ

トル・アイヒマンズ」とは、個人としては比較的無害に見えるが、集団としては破壊的で不道徳なシステムを作り上げ、それに加担している人々を指す言葉であ

る。この呼称は、ホロコーストの指揮を助けたナチスの官僚アドルフ・アイヒマンに由来するが、彼は自分の行為について何も感じず、ただ与えられた命令に

従っただけだと主張した。 「アイヒマン」の原型としての使用は、ハンナ・アーレントの「悪の凡庸性」という概念に由来する[1]。 アーレントは1963年に出版した著書『エルサレムのアイヒマン』の中で、アイヒマンは自分で考えるよりもプロパガンダに頼り、ナチスの目標を遂行したの は主に出世のためであり、裁判では罪悪感も憎悪も示さず、平凡でありふれた人格であるように見えたと述べている。彼女はこのことが、ナチスの戦争犯罪人が 明らかに精神病質であり、普通の人々とは根本的に異なるという考えを最も顕著に否定していると示唆した[1][2][3]。 アイヒマン、あるいは実際、ナチスの大多数やそのような体制で働く人々が実際にこの概念に当てはまるとする考え方は、アイヒマンやナチスの大多数が実際に は深いイデオロギーと極度の反ユダヤ主義者であり、特にアイヒマンは若い頃からユダヤ人に固執し、執着していたと主張する人々によって批判されている [4]。 ドイツの政治学者クレメンス・ヘニは、この言葉は「ホロコーストを軽んじている」とまで述べている[5]。 バーバラ・マンは、この言葉はおそらく1995年に書かれたアナーコ原理主義者の作家ジョン・ツェルザンのエッセイ『ユナボマーは誰のものか』で使われた ことで最もよく知られているが、1960年代にはすでに一般的であったと書いている[6][7]。 [8][9][10]2001年9月11日の同時多発テロの数年後、2003年に出版された書籍『On the Justice of Roosting Chickens』[13]をめぐって論争が起こり[11][12]、ウォード・チャーチルが同時多発テロの直後に書いた同様のタイトルのエッセイが再出 版された[14][15]。 そのエッセイの中でチャーチルは、世界貿易センタービルで働く技術者を表現するためにこのフレーズを使っている[16]。 ツインタワーという無菌の聖域に生息する小さなアイヒマンたちに、彼らの参加にふさわしい、より良い、より効果的な、あるいは実際に他の何らかのペナルティを科す方法があるのなら、ぜひとも教えてもらいたいものだ。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆