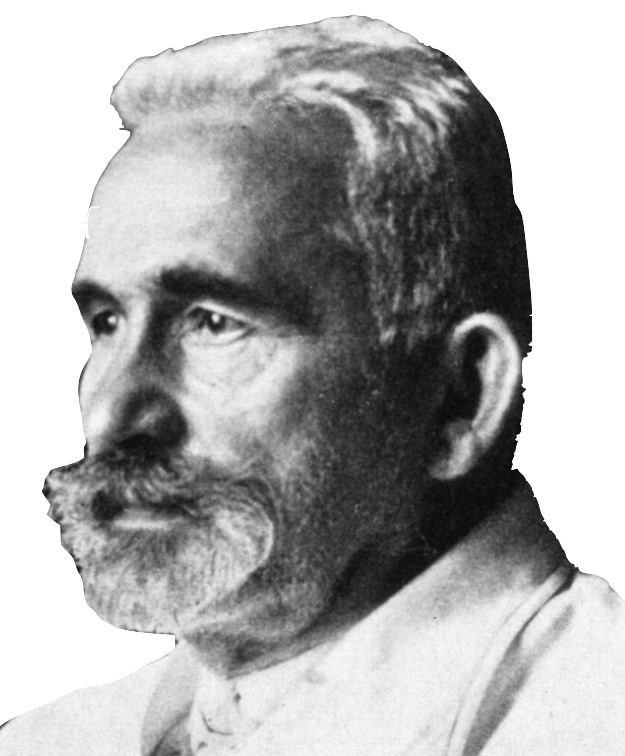

エミール・クレペリン

Emil Wilhelm Georg Magnus Kraepelin, 1856-1926

エミール・クレペリン

Emil Wilhelm Georg Magnus Kraepelin, 1856-1926

エミール・ヴィルヘルム・ゲオルグ・マグヌス・クレーペリン(1856-1926)は、ドイツの精神科医である。

| Emil

Wilhelm Georg Magnus Kraepelin (/ˈkrɛpəlɪn/; German: [ˈeːmiːl

'kʁɛːpəliːn]; 15 February 1856 – 7 October 1926) was a German

psychiatrist. H. J. Eysenck's Encyclopedia of Psychology identifies him as the founder of modern scientific psychiatry, psychopharmacology and psychiatric genetics. Kraepelin believed the chief origin of psychiatric disease to be biological and genetic malfunction. His theories dominated psychiatry at the start of the 20th century and, despite the later psychodynamic influence of Sigmund Freud and his disciples, enjoyed a revival at century's end. While he proclaimed his own high clinical standards of gathering information "by means of expert analysis of individual cases", he also drew on reported observations of officials not trained in psychiatry. His textbooks do not contain detailed case histories of individuals but mosaic-like compilations of typical statements and behaviors from patients with a specific diagnosis. He has been described as "a scientific manager" and "a political operator", who developed "a large-scale, clinically oriented, epidemiological research programme".[2][3] |

エミール・ヴィルヘルム・ゲオルグ・マグヌス・クレーペリン(1856-1926)は、ドイツの精神科医である。 H. H. J. EysenckのEncyclopedia of Psychologyでは、近代科学的精神医学、精神薬理学、精神医学的遺伝学の創始者とされている。 クレペリンは、精神疾患の主な原因は、生物学的および遺伝学的な機能不全にあると考えた。20世紀初頭、彼の理論は精神医学を支配し、その後ジークムン ト・フロイトとその弟子たちによる精神力動的な影響にもかかわらず、世紀末に復活を遂げた。彼は、「個々の症例の専門的な分析によって」情報を収集すると いう独自の高い臨床基準を宣言する一方で、精神医学の訓練を受けていない関係者の報告による観察も参考にしていた。 彼の教科書には、個人の詳細な症例記録はなく、特定の診断を受けた患者の典型的な発言や行動をモザイク状にまとめたものが掲載されている。彼は「科学的管理者」「政治的運営者」と評され、「大規模で臨床志向の疫学的研究プログラム」を開発した[2][3]。 |

| Family and early life Kraepelin, whose father, Karl Wilhelm, was a former opera singer, music teacher, and later successful story teller,[4] was born in 1856 in Neustrelitz, in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz in Germany. He was first introduced to biology by his brother Karl, 10 years older and, later, the director of the Zoological Museum of Hamburg.[5] |

家族・生い立ち 1856年、ドイツのメクレンブルク=シュトレリッツ公国のノイシュトレリッツに生まれる。10歳年上で後にハンブルク動物博物館の館長となる兄のカールから生物学を教わったのが最初であった[5]。 |

| Education and career Kraepelin began his medical studies in 1874 at the University of Leipzig and completed them at the University of Würzburg (1877–78).[1] At Leipzig, he studied neuropathology under Paul Flechsig and experimental psychology with Wilhelm Wundt. Kraepelin would be a disciple of Wundt and had a lifelong interest in experimental psychology based on his theories. While there, Kraepelin wrote a prize-winning essay, "The Influence of Acute Illness in the Causation of Mental Disorders".[6] At Würzburg he completed his Rigorosum (roughly equivalent to an MBBS viva-voce examination) in March 1878, his Staatsexamen (licensing examination) in July 1878, and his Approbation (his license to practice medicine; roughly equivalent to an MBBS) on 9 August 1878.[1] From August 1878 to 1882,[1] he worked with Bernhard von Gudden at the University of Munich. Returning to the University of Leipzig in February 1882,[1] he worked in Wilhelm Heinrich Erb's neurology clinic and in Wundt's psychopharmacology laboratory.[6] He completed his habilitation thesis at Leipzig;[1] it was entitled "The Place of Psychology in Psychiatry".[6] On 3 December 1883 he completed his umhabilitation ("rehabilitation" = habilitation recognition procedure) at Munich.[1] Kraepelin's major work, Compendium der Psychiatrie: Zum Gebrauche für Studirende und Aerzte (Compendium of Psychiatry: For the Use of Students and Physicians), was first published in 1883 and was expanded in subsequent multivolume editions to Ein Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie (A Textbook: Foundations of Psychiatry and Neuroscience). In it, he argued that psychiatry was a branch of medical science and should be investigated by observation and experimentation like the other natural sciences. He called for research into the physical causes of mental illness, and started to establish the foundations of the modern classification system for mental disorders. Kraepelin proposed that by studying case histories and identifying specific disorders, the progression of mental illness could be predicted, after taking into account individual differences in personality and patient age at the onset of disease.[6] In 1884, he became senior physician in the Prussian provincial town of Leubus, Silesia Province, and the following year he was appointed director of the Treatment and Nursing Institute in Dresden. On 1 July 1886,[1] at the age of 30, Kraepelin was named Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Dorpat (today the University of Tartu) in what is today Estonia (see Burgmair et al., vol. IV). Four years later, on 5 December 1890,[1] he became department head at the University of Heidelberg, where he remained until 1904.[6] While at Dorpat he became the director of the 80-bed University Clinic. There he began to study and record many clinical histories in detail and "was led to consider the importance of the course of the illness with regard to the classification of mental disorders". In 1903, Kraepelin moved to Munich to become Professor of Clinical Psychiatry at the University of Munich.[7] In 1908, he was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.[citation needed] In 1912, at the request of the DVP (Deutscher Verein für Psychiatrie; German Association for Psychiatry),[8] of which he was the head from 1906 to 1920, he began plans to establish a centre for research. Following a large donation from the Jewish German-American banker James Loeb, who had at one time been a patient, and promises of support from "patrons of science", the German Institute for Psychiatric Research was founded in 1917 in Munich.[9][10] Initially housed in existing hospital buildings, it was maintained by further donations from Loeb and his relatives. In 1924 it came under the auspices of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science. The German-American Rockefeller family's Rockefeller Foundation made a large donation enabling the development of a new dedicated building for the institute along Kraepelin's guidelines, which was officially opened in 1928.[6] Kraepelin spoke out against the barbarous treatment that was prevalent in the psychiatric asylums of the time, and crusaded against alcohol, capital punishment and the imprisonment rather than treatment of the insane. For the sedation of agitated patients Kraepelin recommended potassium bromide.[11] He rejected psychoanalytical theories that posited innate or early sexuality as the cause of mental illness, and he rejected philosophical speculation as unscientific. He focused on collecting clinical data and was particularly interested in neuropathology (e.g., diseased tissue).[6] In the later period of his career, as a convinced champion of social Darwinism, he actively promoted a policy and research agenda in racial hygiene and eugenics.[12] Kraepelin retired from teaching at the age of 66, spending his remaining years establishing the institute. The ninth and final edition of his Textbook was published in 1927, shortly after his death. It comprised four volumes and was ten times larger than the first edition of 1883.[6] In the last years of his life, Kraepelin was preoccupied with Buddhist teachings and was planning to visit Buddhist shrines at the time of his death, according to his daughter, Antonie Schmidt-Kraepelin.[13] |

教育・経歴 1874年にライプツィヒ大学で医学を学び始め、1877-78年にヴュルツブルク大学で修了した[1]。ライプツィヒでは、パウル・フレヒシクに神経病理学を、ヴィルヘルム・ヴントに実験心理学を学んだ。その後、ヴントの弟子となり、ヴントの理論に基づく実験心理学に生涯関心を持ち続けることになる。その間、クレペリンは「精神障害の原因における急性疾患の影響」という賞を受賞するようなエッセイを書いた[6]。 ヴュルツブルクでは、1878年3月にRigorosum(MBBSにほぼ相当する実地試験)、1878年7月にStaatsexamen(免許試験)、 1878年8月9日にApprobation(医師免許、MBBSにほぼ相当)を取得した[1]。1878年8月から1882年にかけて、ベルンハルト・ フォングデンとミュンヘン大学で仕事をする[1]。 1882年2月にライプチヒ大学に戻り[1]、ヴィルヘルム・ハインリッヒ・エルブの神経学クリニックとヴントの精神薬理学研究室で働く。[6] ライプチヒで「精神医学における心理学の位置」と題するハビリタチオン(大学資格)論文を完成させる。[6] 1883年12月3日にミュンヘンでウムハビリテーション(「リハビリ」=ハビリタチオン認知手続き)[1]を完了する。 クレペリンの主著『精神医学大系』(Compendium der Psychiatrie: 精神医学の大要:学生と医師のために』は1883年に初版が出版され、その後の多巻にわたる版で『精神医学の教科書:精神医学と神経科学の基礎』にまで拡 大されました。その中で彼は、精神医学は医学の一分野であり、他の自然科学と同様に観察と実験によって研究されるべきであると主張しました。彼は、精神疾 患の物理的な原因を研究することを求め、現代の精神疾患の分類体系の基礎を確立し始めた。クレペリンは、症例を研究して特定の疾患を特定することで、性格 の個人差や患者の発症年齢を考慮した上で、精神疾患の進行が予測できると提唱した[6]。 1884年にはプロイセンの地方都市シレジア州ロイバスの上級医となり、翌年にはドレスデンの治療・看護研究所の所長に任命された。1886年7月1日、 30歳のクレペリンは、現在のエストニアにあるドルパト大学(現在のタルトゥ大学)の精神医学教授に就任した(Burgmair et al, vol.IV参照)。4年後の1890年12月5日にハイデルベルク大学の学科長となり[1]、1904年まで在籍した[6]。ドルパトでは、80床の大 学診療所の所長になった。そこで彼は多くの臨床歴を詳細に研究し記録するようになり、「精神疾患の分類に関して病気の経過が重要であると考えるようになっ た」のである。 1903年、クレペリンはミュンヘンに移り、ミュンヘン大学の臨床精神医学の教授となった[7](47歳)。 1908年、スウェーデン王立科学アカデミーの会員に選出された[citation needed]。 1912年、1906年から1920年まで代表を務めていたDVP (Deutscher Verein für Psychiatrie; ドイツ精神医学協会)[8]の要請により、研究センターを設立する計画を開始した。かつて患者であったユダヤ系ドイツ系アメリカ人の銀行家ジェームズ・ ローブからの多額の寄付と「科学の後援者」からの支援の約束を受けて、1917年にドイツ精神医学研究所がミュンヘンに設立された[9][10]。当初は 既存の病院の建物を使っていたが、ローブと彼の親族からのさらなる寄付によって維持されていた。1924年には、カイザー・ヴィルヘルム科学振興協会の後 援を受けるようになった。ドイツ系アメリカ人のロックフェラー家のロックフェラー財団は多額の寄付を行い、クレペリンの指針に沿った研究所のための新しい 専用建物の開発を可能にし、1928年に正式に開所した[6]。 クレペリンは、当時の精神科病院に蔓延していた野蛮な扱いに反対し、アルコール、死刑、精神障害者の治療ではなく監禁に反対する運動を展開した。興奮した 患者の鎮静のために臭化カリウムを推奨した[11]。精神疾患の原因として生得的あるいは初期の性癖を仮定する精神分析的理論を否定し、哲学的な推測を非 科学的なものとして否定した。彼は臨床データの収集に焦点を当て、特に神経病理学(例えば、病的な組織)に興味を持っていた[6]。 彼のキャリアの後期には、社会ダーウィニズムの確信的な擁護者として、彼は人種衛生学と優生学の政策と研究課題を積極的に推進した[12]。 66歳の時に教職を退き、残りの年月を研究所の設立に費やした。彼の死後間もない1927年に『教科書』の最終版となる第9版が出版された。4巻からなり、1883年の初版の10倍の大きさであった[6]。 晩年、クレペリンは仏教の教えに傾倒しており、娘のアントニー・シュミット=クレペリンによると、死の間際に仏教の寺院を訪れる予定であったという[13]。 |

| Theories and classification schemes Kraepelin announced that he had found a new way of looking at mental illness, referring to the traditional view as "symptomatic" and to his view as "clinical". This turned out to be his paradigm-setting synthesis of the hundreds of mental disorders classified by the 19th century, grouping diseases together based on classification of syndrome—common patterns of symptoms over time—rather than by simple similarity of major symptoms in the manner of his predecessors. Kraepelin described his work in the 5th edition of his textbook as a "decisive step from a symptomatic to a clinical view of insanity. . . . The importance of external clinical signs has . . . been subordinated to consideration of the conditions of origin, the course, and the terminus which result from individual disorders. Thus, all purely symptomatic categories have disappeared from the nosology".[14] |

理論と分類法 クレペリンは、精神疾患の新しい見方を発見したと発表し、従来の考え方を「症候学的」と呼び、自分の考え方を「臨床的」と呼んだ。これは、19世紀までに 分類された何百もの精神疾患を統合し、先人のように主要症状の単純な類似性ではなく、時間の経過とともに生じる共通の症状パターンである症候群の分類に基 づいて病気をグループ化するという、彼のパラダイムを設定するものであったことが判明した。 クレペリンは、教科書の第5版で自分の仕事を「精神病の対症療法的な見方から臨床的な見方への決定的な一歩」と表現している。. . . 外見的な臨床症状の重要性は、......個々の障害に起因する発生条件、経過、終点を考察することに従属させられた。こうして、純粋に症状的なカテゴ リーはすべて、病名論から姿を消した」[14]。 |

| Psychosis and mood Kraepelin is specifically credited with the classification of what was previously considered to be a unitary concept of psychosis, into two distinct forms (known as the Kraepelinian dichotomy): manic depression (now seen as comprising a range of mood disorders such as recurrent major depression and bipolar disorder), and dementia praecox. Drawing on his long-term research, and using the criteria of course, outcome and prognosis, he developed the concept of dementia praecox, which he defined as the "sub-acute development of a peculiar simple condition of mental weakness occurring at a youthful age". When he first introduced this concept as a diagnostic entity in the fourth German edition of his Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie in 1893, it was placed among the degenerative disorders alongside, but separate from, catatonia and dementia paranoides. At that time, the concept corresponded by and large with Ewald Hecker's hebephrenia. In the sixth edition of the Lehrbuch in 1899 all three of these clinical types are treated as different expressions of one disease, dementia praecox.[15] One of the cardinal principles of his method was the recognition that any given symptom may appear in virtually any one of these disorders; e.g., there is almost no single symptom occurring in dementia praecox which cannot sometimes be found in manic depression. What distinguishes each disease symptomatically (as opposed to the underlying pathology) is not any particular (pathognomonic) symptom or symptoms, but a specific pattern of symptoms. In the absence of a direct physiological or genetic test or marker for each disease, it is only possible to distinguish them by their specific pattern of symptoms. Thus, Kraepelin's system is a method for pattern recognition, not grouping by common symptoms. It has been claimed that Kraepelin also demonstrated specific patterns in the genetics of these disorders and patterns in their course and outcome,[16] but no specific biomarkers have yet been identified. Generally speaking, there tend to be more people with schizophrenia among the relatives of schizophrenic patients than in the general population, while manic depression is more frequent in the relatives of manic depressives. Though, of course, this does not demonstrate genetic linkage, as this might be a socio-environmental factor as well. He also reported a pattern to the course and outcome of these conditions. Kraepelin believed that schizophrenia had a deteriorating course in which mental function continuously (although perhaps erratically) declines, while manic-depressive patients experienced a course of illness which was intermittent, where patients were relatively symptom-free during the intervals which separate acute episodes. This led Kraepelin to name what we now know as schizophrenia, dementia praecox (the dementia part signifying the irreversible mental decline). It later became clear that dementia praecox did not necessarily lead to mental decline and was thus renamed schizophrenia by Eugen Bleuler to correct Kraepelin's misnomer. In addition, as Kraepelin accepted in 1920, "It is becoming increasingly obvious that we cannot satisfactorily distinguish these two diseases"; however, he maintained that "On the one hand we find those patients with irreversible dementia and severe cortical lesions. On the other are those patients whose personality remains intact".[17] Nevertheless, overlap between the diagnoses and neurological abnormalities (when found) have continued, and in fact a diagnostic category of schizoaffective disorder would be brought in to cover the intermediate cases. Kraepelin devoted very few pages to his speculations about the etiology of his two major insanities, dementia praecox and manic-depressive insanity. However, from 1896 to his death in 1926 he held to the speculation that these insanities (particularly dementia praecox) would one day probably be found to be caused by a gradual systemic or "whole body" disease process, probably metabolic, which affected many of the organs and nerves in the body but affected the brain in a final, decisive cascade.[18] |

精神病と気分 クレペリンは、それまで精神病という単一の概念と考えられていたものを、2つの異なる形態に分類したことで知られている(クレペリン的二分法として知られる)。 ・躁うつ病(現在では、再発性大うつ病や双極性障害など、さまざまな気分障害を含むと考えられている)、および ・前駆症状 彼は長期にわたる研究をもとに、経過、転帰、予後を基準にして、「若年期に発生する精神的弱さの特異な単純状態の亜急性発症」と定義する前駆痴呆の概念を 作り上げた。1893年、ドイツ語版『Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie』の第4版でこの概念を診断名として初めて紹介したとき、この疾患は緊張病や妄想病とは別に、変性疾患の中に位置づけられた。当 時、この概念はエワルド・ヘッカーのヘベフレニアとほぼ一致していた。1899年のLehrbuch第6版では、これら3つの臨床タイプはすべて、1つの 疾患である認知症praecoxの異なる表現として扱われている[15]。 例えば、躁うつ病に見られない症状が、前駆病変に見られることはほとんどないのである。各疾患を症状的に区別するのは(基礎となる病態とは対照的に)、特 定の(予兆となる)症状ではなく、特定の症状のパターンである。各疾患に対する直接的な生理学的、遺伝学的検査やマーカーがない場合、症状の特異的パター ンによってのみ疾患を区別することが可能である。このように、クレペリンのシステムはパターン認識のための方法であって、共通の症状によるグループ分けで はない。 また、クレペリンはこれらの疾患の遺伝学上の特異的パターンや経過・転帰のパターンを示したと主張されているが[16]、特異的バイオマーカーはまだ同定 されていない。一般に、精神分裂病患者の親族には一般集団よりも精神分裂病患者が多く、躁うつ病患者の親族には躁うつ病患者が多い傾向があると言われてい る。もちろん、これは社会環境的な要因もあるかもしれないので、遺伝的な関連を示すものではない。 彼はまた、これらの疾患の経過と結果にはパターンがあると報告している。精神分裂病は精神機能が継続的に(不規則かもしれないが)低下していく経過をたど るが、躁うつ病は急性期のエピソードをはさんで比較的症状のない間欠的な経過をたどるとクレペリンは考えていた。このことからクレペリンは、現在私たちが 精神分裂病と呼んでいるものを「前駆性痴呆」と名づけた(痴呆の部分は不可逆的な精神衰退を意味する)。その後、前駆性痴呆は必ずしも精神の衰えをもたら さないことが明らかになり、オイゲン・ブルーレーがクレペリンの誤った呼称を訂正するために精神分裂病と改名した。 また、1920年にクレペリンが「この2つの疾患を満足に区別できないことはますます明白になってきている」と認めたように、彼は「一方では、不可逆的な 痴呆と重度の皮質病変を持つ患者がいる。しかし、「一方では、不可逆的な痴呆と重度の皮質病変を持つ患者がおり、他方では、人格が損なわれていない患者が いる」[17]とし、「それでも、診断の重複と神経学的異常(見つかった場合)は続いており、実際、中間例をカバーするために分裂感情障害という診断カテ ゴリーが持ち込まれた。 クレペリンは、2大発狂症である「前駆性痴呆」と「躁うつ病」の病因に関する思索にほとんどページを割いていない。しかし、1896年から1926年に亡 くなるまで、これらの精神異常(特に前駆性痴呆)は、おそらく代謝性であり、体内の多くの器官や神経に影響を与え、最終的に決定的なカスケードで脳に影響 を与える緩やかな全身または「全身」の疾患プロセスによって引き起こされることがいつか判明するだろうという推測を持ち続けた[18]。 |

| Psychopathic personalities In the first through sixth edition of Kraepelin's influential psychiatry textbook, there was a section on moral insanity, which meant then a disorder of the emotions or moral sense without apparent delusions or hallucinations, and which Kraepelin defined as "lack or weakness of those sentiments which counter the ruthless satisfaction of egotism". He attributed this mainly to degeneration. This has been described as a psychiatric redefinition of Cesare Lombroso's theories of the "born criminal", conceptualised as a "moral defect", though Kraepelin stressed it was not yet possible to recognise them by physical characteristics.[19] In fact from 1904 Kraepelin changed the section heading to "The born criminal", moving it from under "Congenital feeble-mindedness" to a new chapter on "Psychopathic personalities". They were treated under a theory of degeneration. Four types were distinguished: born criminals (inborn delinquents), pathological liars, querulous persons, and Triebmenschen (persons driven by a basic compulsion, including vagabonds, spendthrifts, and dipsomaniacs). The concept of "psychopathic inferiorities" had been recently popularised in Germany by Julius Ludwig August Koch, who proposed congenital and acquired types. Kraepelin had no evidence or explanation suggesting a congenital cause, and his assumption therefore appears to have been simple "biologism". Others, such as Gustav Aschaffenburg, argued for a varying combination of causes. Kraepelin's assumption of a moral defect rather than a positive drive towards crime has also been questioned, as it implies that the moral sense is somehow inborn and unvarying, yet it was known to vary by time and place, and Kraepelin never considered that the moral sense might just be different. Kurt Schneider criticized Kraepelin's nosology on topics such as Haltlose for appearing to be a list of behaviors that he considered undesirable, rather than medical conditions, though Schneider's alternative version has also been criticised on the same basis. Nevertheless, many essentials of these diagnostic systems were introduced into the diagnostic systems, and remarkable similarities remain in the DSM-V and ICD-10.[19] The issues would today mainly be considered under the category of personality disorders, or in terms of Kraepelin's focus on psychopathy. Kraepelin had referred to psychopathic conditions (or "states") in his 1896 edition, including compulsive insanity, impulsive insanity, homosexuality, and mood disturbances. From 1904, however, he instead termed those "original disease conditions, and introduced the new alternative category of psychopathic personalities. In the eighth edition from 1909 that category would include, in addition to a separate "dissocial" type, the excitable, the unstable, the Triebmenschen driven persons, eccentrics, the liars and swindlers, and the quarrelsome. It has been described as remarkable that Kraepelin now considered mood disturbances to be not part of the same category, but only attenuated (more mild) phases of manic depressive illness; this corresponds to current classification schemes.[20] |

サイコパス・パーソナリティ これは、明らかな妄想や幻覚を伴わない感情や道徳感覚の障害を意味し、クレペリンはこれを「エゴイズムの冷酷な満足に対抗する情緒の欠如または弱さ」と定 義している。彼はこれを主に変性によるものとした。これはチェーザレ・ロンブローゾの「生まれながらの犯罪者」の理論の精神医学的再定義として説明され、 「道徳的欠陥」として概念化されたが、クレペリンは身体的特徴によってそれらを認識することはまだ不可能であると強調した[19]。 実際、1904年からクレペリンは「生まれながらの犯罪者」というセクションの見出しを変更し、「先天性精神薄弱」の下から「精神病質人格」の新しい章に 移動させたのである。彼らは、変性論に基づいて扱われました。生まれながらの犯罪者(先天的な非行者)、病的な嘘つき、屁理屈屋、 Triebmenschen(浮浪者、浪費家、偏執狂など基本的な衝動に駆られた者)の4種類が区別された。 サイコパス的劣等感」という概念は、最近ドイツでユリウス・ルートヴィヒ・アウグスト・コッホによって広まり、先天性と後天性のタイプを提唱していた。ク レペリンには先天性の原因を示唆する証拠も説明もなく、したがって彼の仮定は単純な「生物学主義」であったようである。また、グスタフ・アシャッフェンブ ルク(Gustav Aschaffenburg)のように、様々な原因が絡み合っていると主張する人もいた。また、クレペリンが犯罪への積極的な衝動ではなく、道徳的な欠陥 を仮定したことについても疑問が呈されている。それは、道徳的感覚が何らかの形で先天的かつ不変的であることを意味するが、道徳的感覚は時代と場所によっ て異なることが知られており、クレペリンは、ただその感覚が異なるかもしれないと考えたことはない。 クルト・シュナイダーは、ハルトローゼなどのトピックについて、クレペリンのノゾロジーが医学的条件ではなく、彼が望ましくないと考える行動のリストに見 えると批判したが、シュナイダーの代替版も同じ理由で批判されている。とはいえ、これらの診断システムの多くのエッセンスが導入され、DSM-VやICD -10には顕著な類似性が残っている[19]。 今日では主に人格障害のカテゴリーで、あるいはクレペリンが注目した精神病質という観点から問題視されることになろう。 クレペリンは1896年の版で強迫性狂気、衝動性狂気、同性愛、気分障害などの精神病質状態(または「状態」)に言及していた。しかし、1904年から は、それらを「原病状態」と呼び、サイコパスパーソナリティという新たなカテゴリーを導入したのです。1909年の第8版では、このカテゴリーには、別の 「非社会的」タイプに加えて、興奮しやすい人、不安定な人、トライプメンシェン駆動者、奇人、嘘つき、詐欺師、喧嘩っ早い人などが含まれることになった。 クレペリンが気分障害を同じカテゴリーではなく、躁鬱病の減衰した(より軽度の)相に過ぎないと考えたことは注目に値するとされており、これは現在の分類 体系に対応している[20]。 |

| Alzheimer's disease Kraepelin postulated that there is a specific brain or other biological pathology underlying each of the major psychiatric disorders.[citation needed] As a colleague of Alois Alzheimer, he was a co-discoverer of Alzheimer's disease, and his laboratory discovered its pathological basis. Kraepelin was confident that it would someday be possible to identify the pathological basis of each of the major psychiatric disorders.[citation needed] |

アルツハイマー病 アロイス・アルツハイマー(Alzheimer)の同僚として、アルツハイマー病の共同発見者となり、彼の研究室でその病理学的基盤が発見された [citation needed]。クレペリンは、いつの日か主要な精神疾患のそれぞれの病理学的基盤を特定することが可能になると確信していた[citation needed]。 |

| Eugenics Upon moving to become Professor of Clinical Psychiatry at the University of Munich in 1903, Kraepelin increasingly wrote on social policy issues. He was a strong and influential proponent of eugenics and racial hygiene. His publications included a focus on alcoholism, crime, degeneration and hysteria.[2] Kraepelin was convinced that such institutions as the education system and the welfare state, because of their trend to break the processes of natural selection, undermined the Germans' biological "struggle for survival".[12] He was concerned to preserve and enhance the German people, the Volk, in the sense of nation or race. He appears to have held Lamarckian concepts of evolution, such that cultural deterioration could be inherited. He was a strong ally and promoter of the work of fellow psychiatrist (and pupil and later successor as director of the clinic) Ernst Rüdin to clarify the mechanisms of genetic inheritance as to make a so-called "empirical genetic prognosis".[2] Martin Brune has pointed out that Kraepelin and Rüdin also appear to have been ardent advocates of a self-domestication theory, a version of social Darwinism which held that modern culture was not allowing people to be weeded out, resulting in more mental disorder and deterioration of the gene pool. Kraepelin saw a number of "symptoms" of this, such as "weakening of viability and resistance, decreasing fertility, proletarianisation, and moral damage due to "penning up people" [Zusammenpferchung]. He also wrote that "the number of idiots, epileptics, psychopaths, criminals, prostitutes, and tramps who descend from alcoholic and syphilitic parents, and who transfer their inferiority to their offspring, is incalculable". He felt that "the well-known example of the Jews, with their strong disposition towards nervous and mental disorders, teaches us that their extraordinarily advanced domestication may eventually imprint clear marks on the race". Brune states that Kraepelin's nosological system "was, to a great deal, built on the degeneration paradigm".[21] |

優生学 1903年にミュンヘン大学の臨床精神医学の教授に転任したクレペリンは、社会政策の問題について執筆することが多くなった。彼は、優生学と人種衛生学の強 力かつ影響力のある提唱者であった。彼の出版物は、アルコール中毒、犯罪、退化、ヒステリーなどに焦点を当てたものであった[2]。 クレペリンは、教育制度や福祉国家などの制度が自然淘汰のプロセスを壊す傾向にあるため、ドイツ人の生物学的な「生存のための闘い」を損なっていると確信 していた[12]。 彼は、国家や人種という意味でのドイツ人の民族性(フォルク)を維持し強化しようと考えていた。彼はラマルク的な進化の概念を持っていたようで、文化的な 劣化は継承されることができると考えていた。同じ精神科医のエルンスト・ルーディン(弟子であり、後に院長を継ぐ)が遺伝のメカニズムを解明し、いわゆる 「経験的遺伝予後」を作ろうとする研究の強力な味方であり推進者であった[2]。 マーティン・ブルーンは、クレペリンとルーディンが、現代文化が人々を淘汰することを許さず、結果として精神障害を増やし、遺伝子プールを劣化させるとい う社会ダーウィニズムの版である自己淘汰説を熱心に唱えていたようにも見えると指摘している[3]。クレペリンは、その「症状」として、「生存力と抵抗力 の弱体化、出生率の低下、プロレタリア化、『人を囲い込む』ことによる道徳的損害」[Zusammenpferchung]などを挙げていたのである。ま た、「アルコール依存症や梅毒の親の子孫で、自分の劣等感を子孫に移す白痴、癲癇患者、精神病質者、犯罪者、売春婦、浮浪者の数は計り知れない」とも書い ている。また、「神経症や精神障害に強い気質を持つユダヤ人のよく知られた例は、彼らの非常に進んだ家畜化が、やがて人種にはっきりとした痕跡を刻み込む かもしれないことを教えてくれる」とも感じている。ブルーンは、クレペリンの病名論的システムは「かなりの部分、退化のパラダイムに基づいて構築されてい た」と述べている[21]。 |

| Influence Kraepelin's great contribution in classifying schizophrenia and manic depression remains relatively unknown to the general public, and his work, which had neither the literary quality nor paradigmatic power of Freud's, is little read outside scholarly circles. Kraepelin's contributions were also to a large extent marginalized throughout a good part of the 20th century during the success of Freudian etiological theories. However, his views now dominate many quarters of psychiatric research and academic psychiatry. His fundamental theories on the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders form the basis of the major diagnostic systems in use today, especially the American Psychiatric Association's DSM-IV and the World Health Organization's ICD system, based on the Research Diagnostic Criteria and earlier Feighner Criteria developed by espoused "neo-Kraepelinians", though Robert Spitzer and others in the DSM committees were keen not to include assumptions about causation as Kraepelin had.[14][22] Kraepelin has been described as a "scientific manager"[23][24] and political operator, who developed a large-scale, clinically oriented, epidemiological research programme. In this role he took in clinical information from a wide range of sources and networks. Despite proclaiming high clinical standards for himself to gather information "by means of expert analysis of individual cases", he would also draw on the reported observations of officials not trained in psychiatry. The various editions of his textbooks do not contain detailed case histories of individuals, however, but mosaiclike compilations of typical statements and behaviors from patients with a specific diagnosis. In broader terms, he has been described as a bourgeois or reactionary citizen.[2][3] Kraepelin wrote in a knapp und klar (concise and clear) style that made his books useful tools for physicians. Abridged and clumsy English translations of the sixth and seventh editions of his textbook in 1902 and 1907 (respectively) by Allan Ross Diefendorf (1871–1943), an assistant physician at the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane at Middletown, inadequately conveyed the literary quality of his writings that made them so valuable to practitioners.[25] Among the doctors trained by Alois Alzheimer and Emil Kraepelin at Munich at the beginning of the 20th century were the Spanish neuropathologists and neuropsychiatres Nicolás Achúcarro and Gonzalo Rodríguez Lafora, two distinguished disciples of Santiago Ramón y Cajal and members of the Spanish Neurological School. |

影響力 精神分裂病と躁うつ病の分類におけるクレペリンの偉大な貢献は、一般にはまだあまり知られておらず、彼の研究はフロイトのような文学性も範例的な力もな かったため、学者以外の人々にはほとんど読まれていない。また、フロイトの病因論が隆盛を極めた20世紀の大半の時期には、クレペリンの貢献は周辺に追い やられていた。しかし、現在では、精神医学の研究と学術的な精神医学の多くの分野で、彼の見解が主流となっている。精神疾患の診断に関する彼の基本的な理 論は、今日使用されている主要な診断システム、特にアメリカ精神医学会のDSM-IVと世界保健機関のICDシステムの基礎を形成しており、「新クレペリ ン派」の信奉する研究診断基準と初期のファイナー基準に基づくが、DSM委員会のロバート・スピッツァーとその他の人々はクレペリンのように因果関係に関 する仮定を含まないことに熱心だった [14][22] 。 クレペリンは「科学的管理者」[23][24]であり、大規模で臨床志向の疫学研究プログラムを開発した政治家であると評されることがある。この役割にお いて、彼は幅広い情報源とネットワークから臨床情報を取り込んでいた。個々の症例の専門的な分析によって」情報を収集するために、自らに高い臨床基準を宣 言したにもかかわらず、精神医学の訓練を受けていない関係者の報告された観察結果も利用することになった。しかし、彼の教科書の様々な版には、個人の詳細 なケースヒストリーはなく、特定の診断を受けた患者の典型的な発言や行動をモザイク状にまとめたものが掲載されている。広い意味では、ブルジョワあるいは 反動的な市民と評されている[2][3]。 クレペリンは、「ナップ・ウント・クラー(簡潔明瞭)」なスタイルで執筆し、その著書は医師にとって有用な道具となった。1902年と1907年にミドル タウンのコネティカット精神病院助手のアラン・ロス・ディーフェンドルフ(1871-1943)が彼の教科書の第6版と第7版を要約して不器用な英語に翻 訳したが、彼の著作が開業医にとって非常に貴重である文学性を十分に伝えることができなかった[25]。 20世紀初頭、ミュンヘンでアロイス・アルツハイマーとエミール・クレペリンから訓練を受けた医師の中には、スペインの神経病理学者で神経精神科医のニコ ラス・アチュカロとゴンサロ・ロドリゲス・ラフォラ、サンティアゴ・ラモン・イ・カハルの優れた弟子でスペイン神経学会のメンバーである2人の医師が含ま れていた。 |

| Dreaming for psychiatry's sake In the Heidelberg and early Munich years he edited Psychologische Arbeiten, a journal on experimental psychology. One of his own famous contributions to this journal also appeared in the form of a monograph (105 pp.) entitled Über Sprachstörungen im Traume (On Language Disturbances in Dreams).[26] Kraepelin, on the basis of the dream-psychosis analogy, studied for more than 20 years language disorder in dreams in order to study indirectly schizophasia. The dreams Kraepelin collected are mainly his own. They lack extensive comment by the dreamer. In order to study them the full range of biographical knowledge available today on Kraepelin is necessary (see, e.g., Burgmair et al., I-IX). |

精神医学のための夢 ハイデルベルクやミュンヘン時代初期には、実験心理学に関する雑誌『Psychologische Arbeiten』を編集していた。この雑誌への彼自身の有名な寄稿のひとつは、『夢における言語障害について』と題されたモノグラフ(105ページ)の 形で掲載された[26]。クレペリンは、夢と精神病のアナロジーに基づいて、統合失調症を間接的に研究するために、20年以上も夢の中の言語障害を研究し ていた。クレペリンが収集した夢は、主に彼自身のものである。夢想家による広範なコメントはない。これらを研究するためには、今日クレペリンに関して利用 可能なあらゆる伝記的知識が必要である(例えば、Burgmair et al, I-IX参照)。 |

| Bibliography Kraepelin, E. (1906). Über Sprachstörungen im Traume. Leipzig: Engelmann. ([1] Online.) Kraepelin, E. (1987). Memoirs. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-642-71926-4. |

|

| Collected works Burgmair, Wolfgang & Eric J. Engstrom & Matthias Weber et al., eds. Emil Kraepelin. 9 vols. Munich: belleville, 2000–2019. Vol. I: Persönliches, Selbstzeugnisse (2000), ISBN 3-933510-90-2 Vol. II: Kriminologische und forensische Schriften: Werke und Briefe (2001), ISBN 3-933510-91-0 Vol. III: Briefe I, 1868–1886 (2002), ISBN 3-933510-92-9 Vol. IV: Kraepelin in Dorpat, 1886–1891 (2003), ISBN 3-933510-93-7 Vol. V: Kraepelin in Heidelberg, 1891–1903 (2005), ISBN 3-933510-94-5 Vol. VI: Kraepelin in München I: 1903–1914 (2006), ISBN 3-933510-95-3 Vol. VII: Kraepelin in München II: 1914–1920 (2009), ISBN 978-3-933510-96-9 Vol. VIII: Kraepelin in München III: 1921–1926 (2013), ISBN 978-3-943157-22-2 Vol. IX: Briefe und Dokumente II: 1876-1926 (2019), ISBN 978-3-946875-28-4 |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emil_Kraepelin |

|

| Emil Wilhelm Georg Magnus Kraepelin

(* 15. Februar 1856 in Neustrelitz; † 7. Oktober 1926 in München) war

ein deutscher Psychiater, auf den bedeutende Entwicklungen in der

wissenschaftlichen Psychiatrie zurückgehen und sich auch mit

psychologischen Fragestellungen befasste. Er war Hochschullehrer an der

Universität Dorpat, der Universität Heidelberg und der Universität

München. |

Emil Wilhelm Georg Magnus

Kraepelin, * 1856年2月15日 in Neustrelitz, † 1926年10月7日 in Munich)

は、ドイツの精神科医で、科学的精神医学の重要な発展が見られ、また心理的問題を扱った人物。ドルパット大学、ハイデルベルク大学、ミュンヘン大学で大学

講師を務めた。 |

| Bedeutung Von Emil Kraepelin stammen die Grundlagen des heutigen Systems der Klassifizierung psychischer Störungen. Er führte experimentalpsychologische Methoden in die Psychiatrie ein und gilt als Begründer der modernen empirisch orientierten Psychopathologie, mit der in ersten Ansätzen ein psychologisches Denken in der Psychiatrie üblich wurde. Auch die Entwicklung der modernen Psychopharmakologie geht auf Kraepelin zurück. Ihn jedoch als deren Begründer zu bezeichnen, ist weder durch Kraepelins Forschungsarbeiten noch seine Publikationen gerechtfertigt. Denn diese Zuschreibung beruht vor allem auf dem schmalen Werk Über die Beeinflussung einfacher psychischer Vorgänge durch einige Arzneimittel von 1892. |

意義 エミール・クレペリンは、今日の精神疾患の分類システムの基礎を築いた。精神医学に実験心理学的手法を導入し、精神医学の最初のアプローチである心理学的 思考が一般化した、現代の経験主義的精神病理学の創始者とみなされている。現代の精神薬理学の発展も、クレペリンにさかのぼる。しかし、彼を創始者と呼ぶ ことは、クレペリンの研究からも、彼の出版物からも正当化されることはない。この帰属は、主に1892年の細著『On the Influence of Some Drugs on Simple Mental Processes』に基づくものである。 |

| Emil Kraepelin wurde als

jüngstes von drei Kindern des Musiklehrers und Schauspielers Karl

Kraepelin geboren. Sein Abitur legte er 1874 am Gymnasium Carolinum in

Neustrelitz ab. Seit 1871 war er mit der um sieben Jahre älteren Ina

Schwabe verlobt, die er 1884 heiratete. Mit ihr hatte er acht Kinder,

von denen vier bereits im Kleinkindalter starben. 1885 wurde seine

erste Tochter geboren. Die vielleicht engste Beziehung hatte er zu

seinem neun Jahre älteren Bruder Karl. Von ihm angeregt, studierte er

nach dem in Leipzig abgeleisteten Militärdienst ab 1874 Medizin an der

Universität Leipzig und der Universität Würzburg. In Würzburg konnte er schon 1875 bei Franz von Rinecker an der psychiatrischen Universitätsklinik tätig werden, der ihn nach einem nochmaligen kurzen Aufenthalt in Leipzig, bei dem er Wilhelm Wundt kennenlernte, Ende 1877 als Assistenten einstellte. 1878 schloss Kraepelin sein Studium mit der Promotion ab, wechselte für vier Jahre zu Bernhard von Gudden an die Kreis-Irrenanstalt in München und ging 1882 nach Leipzig zu Paul Flechsig, wo er den Unmut Flechsigs auf sich zog und „in hohem Grade“ dessen „Unzufriedenheit“ erregte, weil Kraepelin seinen ärztlichen Aufgaben in der Klinik nicht nachkam und schließlich gekündigt wurde (Kündigungsschreiben: „… behandelt … den Dienst für die Klinik thatsächlich als … Nebensache“). Mit Unterstützung seines Mentors Wilhelm Wundt gelang es ihm dennoch, mit einigen, gerade eben ausreichenden Publikationen – ohne eine eigene Habilitationsschrift zu verfassen – seine Habilitation zu erlangen. Nachdem er im Herbst 1883 nochmals zu Bernhard von Gudden nach München zurückgekehrt war, dort aber seine Forschungsmethoden nicht durchsetzen konnte, gab Kraepelin – mitbeeinflusst auch durch die geplante Hochzeit mit Ina Schwabe – seine akademische Karriere zunächst auf und arbeitete von August 1884 bis April 1885 als Oberarzt an der preußischen Provinzial-Irrenanstalt von Leubus, die im ehemaligen Kloster untergebracht war.[1] Am 1. Juli 1886 erhielt er die Berufung auf seine erste Professur an der Universität Dorpat, verließ diese aber mit den einsetzenden Russifizierungsbestrebungen 1889. 1890 begann er in Heidelberg mit Laboratoriumsversuchen zur Hygiene der Arbeit, wie er es nannte, verfasste ab 1896 psychologische Arbeiten[2] und erforschte arbeitspsychologische Zusammenhänge von Ermüdung und Übung bei der Arbeit[3] mit Hilfe einer Arbeitskurve. 1891 übernahm er für zwölf Jahre die Leitung der Großherzoglich Badischen Universitäts-Irrenklinik in Heidelberg, an der er entscheidende Neuerungen einführte. Aus Unzufriedenheit mit den geringen Möglichkeiten des Ausbaus der Klinik nahm er 1903 einen Ruf nach München an. Am 21. Dezember 1903 unternahm Kraepelin zusammen mit seinem Bruder Karl von Heidelberg aus eine Reise, die ihn über Genua nach Südostasien führte. In Buitenzorg auf Java führte Kraepelin Studien an der einheimischen Bevölkerung durch. Diese veröffentlichte Kraepelin u. a. unter dem Titel Psychiatrisches aus Java, 1904. Das machte ihn wiederum zum Begründer der vergleichenden oder auch transkulturellen Psychiatrie. In München beschäftigte er sich bereits vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg mit dem Gedanken, eine Forschungsstätte für Psychiatrie zu gründen. Mithilfe einer großzügigen Finanzierung durch James Loeb[4] gelang ihm 1917 die Gründung der Deutschen Forschungsanstalt für Psychiatrie (Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut) in München, aus der das heute Max-Planck-Institut für Psychiatrie (Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Psychiatrie) hervorging. Die Forschungsanstalt hatte folgende Abteilungen: klinische Abteilung (Johannes Lange), hirnpathologische Abteilung (Brodmann, Nissl, Spielmeyer), serologische Abteilung (Plaut, Jahnel) und die genealogische Abteilung (Rüdin, ein Anhänger der Degenerationslehre).[5] Während des Ersten Weltkriegs beteiligte sich Kraepelin an der Gründung der bayerischen Sektion der Deutschen Vaterlandspartei. 1920 erhielt er ehrenhalber den Doktortitel der philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Königsberg. Kraepelin legte seine persönliche Einstellung zur Degenerationslehre z. B. 1908 in dem Werk Zur Entartungsfrage oder 1918 in dem Werk Geschlechtliche Verirrungen und Volksvermehrung dar. Der Psychiater Kurt Kolle bezeichnete in einem seiner Werke (Große Nervenärzte, 1956/1970) diese Kraepelinsche Einstellung als „betont völkisch“. Kraepelin war mit dem brasilianischen Psychiater Juliano Moreira (1872–1933) bekannt und stand mit ihm in Briefwechsel.[6] Emil Kraepelin wurde auf dem Bergfriedhof Heidelberg beigesetzt. Seine letzte Ruhestätte liegt in der Abteilung V. |

エミール・クレーペリンは、音楽教師で俳優のカール・クレーペリンの3

人兄弟の末っ子として生まれた。1874年、ノイシュトレリッツのギムナジウム・カロリヌムを卒業した。1871年から7歳年上のイナ・シュワーベと婚約

し、1884年に結婚した。彼女との間には8人の子供がいたが、そのうち4人は幼少時に死亡した。1885年、長女が誕生した。最も親しかったのは、9歳

年上の兄のカールであろう。彼の影響を受け、ライプツィヒで兵役を終えた後、1874年からライプツィヒ大学およびヴュルツブルク大学で医学を学んだ。 1875年、ヴュルツブルクではすでにフランツ・フォン・リネッカーのもとで精神科の大学病院として働くことができ、さらにライプツィヒに短期滞在し、そ こでヴィルヘルム・ヴントと出会った後、1877年末に助手として雇用された。1878年に博士号を取得したクレペリンは、ミュンヘンの精神病院のベルン ハルト・フォン・グッデンのもとで4年間過ごし、1882年にライプツィヒのパウル・フレヒスヒのもとで働くことになったが、クレペリンが診療所での医療 義務を果たさなかったためフレヒスヒの不興を買い「高度に不満」、ついに解雇された(解雇通知:「・・・は、・・・は診療所のために働くことを軽々と扱っ ています」)。しかし、師であるヴィルヘルム・ヴントの支援を受け、ハビリテーション論文を書くことなく、数少ない十分な出版物でハビリテーションを取得 することに成功した。 1883年秋に再びミュンヘンのベルンハルト・フォン・グッデンのもとに戻ったが、そこでは研究方法が受け入れられなかったため、イナ・シュワーベとの結 婚を予定していた影響もあり、クレペリンは学究生活を一旦あきらめ、1884年8月から1885年4月まで旧修道院の中にあるプロイセン州立精神病院ロイ バスで上級医として勤務していた[1]。 1886年7月1日、ドルパト大学で最初の教授職に任命されたが、1889年のロシア化努力の開始とともに退職した。 1890年、ハイデルベルクで彼が言うところの労働衛生に関する実験室実験を始め、1896年から心理学論文を書き、作業曲線を用いて職場での疲労と運動 の職業心理相関を研究[3]した。1891年、ハイデルベルクにあるバーデン大公国の精神病院の経営を12年間引き継ぎ、決定的な改革を行った。しかし、 診療所拡大の可能性が限られていることに不満を抱き、1903年にミュンヘンに呼び出された。 1903年12月21日、クレペリンと弟のカールはハイデルベルクを出発し、ジェノバ経由で東南アジアへ向かう旅に出た。クレペリンは、ジャワ島のブイテ ンゾルグで、現地の人々の調査を行った。クレペリンは、これらの研究を『ジャワの精神医学』(Psychiatrisches aus Java, 1904)というタイトルで発表し、比較精神医学あるいはトランスカルチャー精神医学の創始者となったのである。 第一次世界大戦前のミュンヘンでは、すでに精神医学の研究所の設立を考えていた。ジェームズ・ローブ[4]からの多額の資金援助を受けて、1917年に ミュンヘンにドイツ精神医学研究所(カイザー・ヴィルヘルム研究所)を設立することに成功し、そこから現在のマックス・プランク精神医学研究所(ドイツ精 神医学研究所)が誕生した。研究所には、臨床部門(ヨハネス・ラング)、脳病理部門(ブロドマン、ニッスル、シュピールマイヤー)、血清部門(プラウト、 ジャーネル)、家系部門(リューディン、変性説の支持者)があった[5]。 第一次世界大戦中、クレペリンはドイツ祖国党バイエルン支部の設立に参加した。1920年、ケーニヒスベルク大学哲学科から名誉博士号を授与された。 クレペリンは、1908年に『Zur Entartungsfrage』、1918年に『Geschlechtliche Verirrungen und Volksvermehrung』で、変性論に対する個人的な見解を示している。精神科医のクルト・コレは、その著作(Große Nervenärzte, 1956/1970)の中で、このクレペリンの姿勢を「emphatically völkisch」と表現している。 クレペリンは、ブラジルの精神科医ジュリアーノ・モレイラ(1872-1933)と知り合い、手紙のやり取りをした[6]。 エミール・クレーペリンは、ハイデルベルクのベルクフリードホーフ墓地に埋葬された。彼の永眠の地はセクションVにある。 |

| Werk Auf Kraepelin gehen der Begriff und Konzept der Dementia praecox (vorzeitige Demenz) zurück. Diese Bezeichnung übernahm er vom französischen Psychiater Bénédict Augustin Morel, der damit die Erkrankung eines Jugendlichen beschrieb, der – zuvor vollkommen unauffällig – sich zunehmend zurückzog und in einen demenzartigen Zustand verfiel. Kraepelin erweiterte den Begriff jedoch um die von Kahlbaum und Hecker beschriebenen Krankheiten Hebephrenie und Katatonie, zu denen er Parallelen sah. Nun bezog sich die Bezeichnung also nicht mehr nur auf eine einzelne Unterform, sondern auf eine ganze Krankheitsgruppe. Als gemeinsames Kennzeichen von allen Krankheitsbildern innerhalb dieser Gruppe beobachtete Kraepelin „eine eigenartige Zerstörung des inneren Zusammenhangs der psychischen Persönlichkeit mit vorwiegender Schädigung des Gemütslebens und des Willens“.[7] Dieser Ansatz erwies sich allerdings als zu eingeschränkt und wurde von Eugen Bleuler durch den weitergefassten Begriff Schizophrenie ersetzt.[8] Bedeutsam ist jedoch Kraepelins Vorgehensweise, die heute selbstverständlich erscheint: Statt wie zuvor üblich psychische Störungen allein nach der von außen feststellbaren Symptomähnlichkeiten einzuteilen, berücksichtigte er bei seinen Forschungen auch die Veränderung der Symptome im Laufe der Zeit und damit den Verlauf eines Krankheitsbildes. Damit gewann er ein weiteres Kriterium zur Unterscheidung, Einschätzung und Beurteilung krankheitswertiger Symptome und Symptomkomplexe (Syndrome) bei psychischen Auffälligkeiten, das zudem in der Lage war, nicht nur zeitliche, sondern auch kausale Zusammenhänge näherungsweise einzugrenzen. In der 5. Auflage seines psychiatrischen Lehrbuches von 1896 beschäftigte er sich ausführlich mit den Wahnideen.[9] 1899 entwickelte er in der 6. Auflage seines psychiatrischen Lehrbuches[10] die noch heute geltende Zweiteilung der Psychosen, indem er die Dementia praecox dem manisch-depressiven Irresein gegenüberstellte. Kriterium für diese Dichotomie war der unterschiedliche Verlauf: Im Gegensatz zur Dementia praecox (heute die Gruppe der Schizophrenien) bilden sich die Symptome des manisch-depressiven Irreseins (heute Affektive Störung) wieder zurück. Dass diese Regel nicht in jedem Fall zutrifft, weiß die psychiatrische Wissenschaft inzwischen. Die grundsätzliche Tendenz galt aber lange Zeit als unbestritten. Aufgrund von Befunden der neueren genetischen Forschung wird diese Dichotomie aber wissenschaftlich jetzt wohl nicht mehr länger aufrechterhalten werden können.[11] Einen guten Überblick über die Kontroverse um Kraepelin gibt eine 2007 erschienene Publikation der World Psychiatric Association.[12] In der Behandlung psychischer Störungen setzte Kraepelin auf die zu seiner Zeit bekannten Therapien. Besonders Opium, Hyoscin und Brom wurden von ihm empfohlen.[13] Die Goldene Kraepelin-Medaille ist ebenso nach ihm benannt wie der Kraepelinweg im Hamburger Stadtteil Barmbek-Süd und im Berliner Stadtteil Spandau sowie die Kraepelinstraße im Münchner Stadtteil Schwabing. |

仕事内容 早発性痴呆という言葉や概念は、クレペリンにさかのぼる。この言葉は、フランスの精神科医ベネディクト・モレルが、それまで全く目立たなかった青年が次第 に引きこもり、認知症に似た状態に陥っていく様子を表現するために使った言葉から採用した。しかし、クレペリンは、この言葉を、カールバウムやヘッカーが 述べたヘベフレニアやカタトニアという病気にも拡張し、これらに類似性を見いだした。そして、この言葉はもはや一つのサブタイプだけを指すのではなく、病 気のグループ全体を指すようになったのである。このグループのすべての臨床像に共通する特徴として、クレペリンは「精神と意志の生命に対する優勢な損傷を 伴う、精神的人格の内的な一貫性の特異な破壊」[7]を観察した。しかし、このアプローチはあまりにも単純すぎることが判明した。 しかし、クレペリンは、それまでのように症状の外見的な類似性だけで精神疾患を分類するのではなく、症状の時間的な変化、つまり臨床像の経過を考慮して研 究を行ったことが、今日では自明のこととされている[8]。そして、精神異常の症状や症状複合体(症候群)を鑑別、評価し、時間的関係だけでなく因果関係 も絞り込めるような、さらなる判断基準を得たのである。 1896年の『精神医学の教科書』第5版では、妄想について詳述し[9]、1899年の『精神医学の教科書』第6版では、前駆病変と躁鬱病を対比させ、現 在も有効な精神病の二分法を開発した[10]。その二分化の基準となったのが、コースの違いである。前駆症状(現在の統合失調症群)とは対照的に、躁鬱病 (現在の感情障害)の症状が退行するのである。精神医学の科学は、このルールがすべてのケースに適用されるわけではないことを知っています。しかし、その 基本的な傾向は、長い間、議論の余地のないものとされていた。しかし、近年の遺伝子研究の成果により、この二分法はもはや科学的に維持できないだろう [11]。クレペリンをめぐる論争の概要は、2007年に出版された世界精神医学会の刊行物に詳しい[12]。 精神疾患の治療において、クレペリンは「精神分析」の原理に基づいて仕事をしている。 クレペリンは、精神疾患の治療において、当時知られていた治療法に頼っていた。特に、アヘン、ヒヨスキン、臭素を推奨していた[13]。 ハンブルクのバルベック・スード地区とベルリンのシュパンダウ地区にあるクレーペリン通り、ミュンヘンのシュヴァービング地区にあるクレーペリン通りは、彼の名にちなんで名づけられた。 |

| Kritische Würdigung Aufgrund seiner Forschungen konnte Kraepelin postulieren, dass psychotische Erkrankungen – noch 1991 bis zur Klassifikation nach ICD-10 endogene Psychosen genannt – eigengesetzlich entstehen. Gestörten Gehirnfunktionen wurde dabei vornehmliche Beachtung geschenkt und Kraepelin förderte die Hirnforschung auf jede Weise. Soziokulturellen Aspekten schenkte er Aufmerksamkeit durch die Begründung der transkulturellen Psychiatrie im Jahr 1904. Dagegen scheint er an den Weiterentwicklungen psychopathologischen Denkens über seinen klinisch-deskriptiven Ansatz hinaus durch die mit dem Namen Jaspers verbundene methodisch genaue phänomenologische Erfassung der seelischen Zustände, die Kranke wirklich erleben, kaum interessiert gewesen zu sein (obwohl Franz Nissl, Kraepelins jahrelanger Mitarbeiter, Jaspers’ Lehrbuch höher einschätzte als das Kraepelins). Das gilt noch mehr für die Erforschung der Psychodynamik seelischen Geschehens, um die sich zur gleichen Zeit Forscher wie Freud, Adler, Jung und andere bemühten. Von der Freudschen Traumdeutung hielt er nichts. Kraepelin veröffentlichte jedoch 1906 eine längere Monografie über Sprachstörungen in seinen Träumen (286 Vorbilder insgesamt), die er auf eigene Weise analysierte. Er setzte die Aufzeichnung seiner Träume nach 1906 fort bis zu seinem Tode 1926. Dieses zweite Traumkorpus – ebenfalls mit Sprachstörungen (391 Vorbilder) – befindet sich noch heute im Historischen Archiv des Max-Planck-Instituts für Psychiatrie. Kritiker wie Dorothea Buck machen Kraepelin für die inhumanen Methoden in der deutschen Psychiatrie des 20. Jahrhunderts mit verantwortlich.[14] Seine Begegnung mit Kraepelin während seines Aufenthalts in der psychiatrischen Klinik schildert der Schriftsteller Ernst Toller in seiner Autobiographie „Eine Jugend in Deutschland“.[15] |

批判的評価 クレペリンはその研究に基づいて、精神病(1991年にICD-10に基づく分類がなされるまでは内因性精神病と呼ばれていた)はそれ自身の法則によって 発症すると仮定することができたのだ。脳機能の障害は特に注目され、クレペリンはあらゆる手段で脳研究を推進した。その一方で、ヤスパースの名で知られ る、病人が実際に体験する精神状態を現象学的に正確に記録することによる臨床記述的アプローチ以上の精神病理学的思考の発展にはほとんど関心がなかったよ うだ(ただし、クレペリンの長年の協力者であるフランツ・ニスルは、クレペリンよりもヤスパースの教科書を高く評価している)。これは、フロイト、アド ラー、ユングなどの研究者が同時期に目指していた、心の出来事のサイコダイナミクスに関する研究にも、より一層当てはまる。 彼は、フロイトの夢の解釈をあまりよく思っていなかった。しかし、1906年にクレペリンは、夢の中の言語障害について、自分なりに分析した長大なモノグ ラフ(全部で286例)を発表している。1906年以降、1926年に亡くなるまで夢を記録し続け、言語障害(391モデル)を含むこの第二の夢コーパス は、現在もマックス・プランク精神医学研究所の歴史資料室に所蔵されている。 ドロシア・バックのような批評家は、20世紀にドイツの精神医学で用いられた非人道的な方法の一端をクレペリンが担ったと考えている[14]。 作家エルンスト・トラーは自伝『あるドイツの青年』で、精神病院に入院中のクレペリンとの出会いについて述べている[15]。 |

| Schriften (Auswahl) Einzelne Schriften Compendium der Psychiatrie. Zum Gebrauche für Studirende und Aerzte. Abel, Leipzig 1883 (Digitalisat). Psychiatrie. Ein Lehrbuch für Studierende und Ärzte (ältere Auflagen des späteren Lehrbuchs unter abweichenden Titeln). (1. Auflage) Compendium der Psychiatrie zum Gebrauche für Studirende und Aerzte. Abel, Leipzig 1883. 2., gänzlich umgearbeitete Auflage. Psychiatrie. Ein kurzes Lehrbuch für Studirende und Aerzte. Abel, Leipzig 1887 (Digitalisat). 3., vielfach umgearbeitete Auflage. Psychiatrie. Ein kurzes Lehrbuch für Studirende und Aerzte. Abel, Leipzig 1889 (Abel’s medizinische Lehrbücher; Digitalisat). 4., vollständig umgearbeitete Auflage. Abel, Leipzig 1893. 5., vollständig umgearbeitete Auflage 1896. Barth, Leipzig (Digitalisat). 6., vollständig umgearbeitete Auflage 1899, 2 Bände. (Digitalisate: I, II). 7., vielfach umgearbeitete Auflage. Psychiatrie. Ein Lehrbuch für Studierende und Ärzte. 2 Bände. 1903/04. 8., vollständig umgearbeitete Auflage Bd. I-IV. Ein Lehrbuch für Studierende und Ärzte. Barth, Leipzig 1909–1915 (Digitalisate: Bd. I, II, III, IV). (mit Johannes Lange) 9., vollständig umgearbeitete Auflage. Psychiatrie. Bd. I, Allgemeine Psychiatrie, von Johannes Lange. Bd. II, Klinische Psychiatrie, Erster Teil, von Emil Kraepelin. Barth, Leipzig 1927. Einführung in die psychiatrische Klinik. (1. Auflage) Leipzig 1901 (Digitalisat). 3., völlig umgearbeitete Aufl., Leipzig 1916 (Digitalisat). 4., völlig umgearbeitete Aufl., 3 Bände. Barth, Leipzig 1921. Zur Psychologie des Komischen. In: Philosophische Studien. Band 2, 1885, S. 128–160, 327–361 (Digitalisat). Ueber die Beeinflussung einfacher psychischer Vorgänge durch einige Arzneimittel. Fischer, Jena 1892 (Digitalisat und Volltext im Deutschen Textarchiv). Zur Hygiene der Arbeit. Fischer, Jena 1896 Über Sprachstörungen im Traume. Engelmann, Leipzig 1906 (archive.org). Ein Jahrhundert Psychiatrie. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte menschlicher Gesittung. Berlin 1918. Korrespondenz und Werkausgabe Edition Emil Kraepelin. Hrsg. von Wolfgang Burgmair, Eric J. Engstrom und Matthias Weber. Belleville, München; bisher erschienen: Band I* Persönliches, Selbstzeugnisse. 2000, ISBN 3-933510-90-2. Band II* Kriminologische und forensische Schriften. Werke und Briefe. 2001, ISBN 3-933510-91-0. Band III* Briefe I, 1868–1886. 2002, ISBN 3-933510-92-9. Band IV* Kraepelin in Dorpat, 1886–1891. 2003, ISBN 3-933510-93-7. Band V* Kraepelin in Heidelberg, 1891–1903. 2005, ISBN 3-933510-94-5. Band VI* Kraepelin in München I, 1903–1914. 2006, ISBN 3-933510-95-3. Band VII* Kraepelin in München II, 1914–1921. 2009, ISBN 978-3-933510-96-9. Band VIII* Kraepelin in München III, 1921–1926. 2013, ISBN 978-3-943157-22-2. Band IX* Briefe und Dokumente II, 1876–1926. 2019, ISBN 978-3-946875-28-4. |

|

| Literatur Huub Engels: Emil Kraepelins Traumsprache: erklären und verstehen. In: Dietrich von Engelhardt, Horst-Jürgen Gerigk (Hrsg.): Karl Jaspers im Schnittpunkt von Zeitgeschichte, Psychopathologie, Literatur und Film. Mattes, Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-86809-018-5, S. 331–343. Birk Engmann, Holger Steinberg: Die Dorpater Zeit von Emil Kraepelin – Hinterließ dieser Aufenthalt Spuren in der russischen und sowjetischen Psychiatrie? Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2017; 85(11): 675–682. DOI: 10.1055/s-0043-106049. Eric J. Engstrom: Emil Kraepelin: Leben und Werk des Psychiaters im Spannungsfeld zwischen positivistischer Wissenschaft und Irrationalität. Magisterarbeit, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, 1990. Eric J. Engstrom and Kenneth Kendler: Emil Kraepelin: Icon and Reality. American Journal of Psychiatry 172.12 (2015), S. 1190–1196. Eric J. Engstrom, Matthias M. Weber (Hrsg.): Making Kraepelin History: A Great Instauration? Special Issue of History of Psychiatry 18.3 (2007). Eric J. Engstrom, Wolfgang Burgmair, Matthias M. Weber: Emil Kraepelin’s Self-Assessment: Clinical Autography in Historical Context. History of Psychiatry 13 (2002), S. 89–119. Ernst Klee: Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945. Frankfurt am Main 2005, 333. Helmut Siefert: Kraepelin, Emil. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-428-00193-1, S. 639 f. (Digitalisat). Holger Steinberg: Kraepelin in Leipzig. Eine Begegnung von Psychiatrie und Psychologie. Psychiatrie-Verlag, Bonn 2001 (Edition Das Narrenschiff), ISBN 978-3-88414-300-1. Holger Steinberg (Hrsg.): Der Briefwechsel zwischen Wilhelm Wundt und Emil Kraepelin. Zeugnis einer jahrzehntelangen Freundschaft. Hans Huber, Bern 2002, ISBN 3-456-83805-0. Holger Steinberg, Matthias Claus Angermeyer: Emil Kraepelin’s years at Dorpat as professor of psychiatry in nineteenth-century Russia. History of Psychiatry 2001; 12: S. 297–327. Holger Steinberg: Die schlesische Provinzial-Irrenanstalt Leubus im 19. Jahrhundert unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Wirkens von Emil Kraepelin. Würzburger medizinhistorische Mitteilungen 21, 2002, S. 533–553; hier S. 538–547. Holger Steinberg: Emil Kraepelin in Leipzig: Wie einer Entlassung eine Habilitation folgen kann – Eine Quellenstudie. In: Holger Steinberg (Hrsg.): Leipziger Psychiatriegeschichtliche Vorlesungen. [Beiträge zur Leipziger Universitäts- und Wissenschaftsgeschichte B 7]. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2005, S. 75–102, ISBN 3-374-02326-6. Matthias M Weber: Kraepelin, Emil. In: Werner E. Gerabek, Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil, Wolfgang Wegner (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin und New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4, S. 785 f. Matthias M. Weber, Wolfgang Burgmair, Eric J. Engstrom: Zwischen klinischen Krankheitsbildern und psychischer Volkshygiene: Emil Kraepelin 1856–1926. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 13. Oktober 2006, 103.41, 2006: A2685–2690. Benedikt Weyerer: Der Mäzen James Loeb. In: ausgegrenzt-entrechtet-deportiert Hrsg. Ilse Macek, München 2008, 457. Dagmar Drüll: Heidelberger Gelehrtenlexikon 1803–1932. (Hrsg.): Rektorat der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität-Heidelberg. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg / Tokio 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-70761-2. |

|

| Weblinks Commons: Emil Kraepelin – Sammlung von Bildern, Videos und Audiodateien Wikisource: Emil Kraepelin – Quellen und Volltexte Wikiversity: Zusammenfassung der hebephrenen, katatonen und paranoiden Psychosen als Dementia praecox durch E. Kraepelin 1899 – Kursmaterialien Literatur von und über Emil Kraepelin im Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Zeitungsartikel über Emil Kraepelin in der Pressemappe 20. Jahrhundert der ZBW – Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft Abhandlung zu Leben und Werk von Emil Kraepelin von Eric J. Engstrom (PDF; 595 kB) Kurzbiografie und Verweise auf digitale Quellen im Virtual Laboratory des Max-Planck-Instituts für Wissenschaftsgeschichte (englisch) Übersicht der Lehrveranstaltungen von Emil Kraepelin an der Universität Leipzig (Sommersemester 1883 bis Wintersemester 1883) Kraepelins erste Beiträge zur Etablierung psychologischer Forschung in der Psychiatrie Internationale Kraepelin-Gesellschaft Burkhart Brückner, Julian Schwarz (2015): Biographie von Emil Wilhelm Georg Magnus Kraepelin In: Biographisches Archiv der Psychiatrie (BIAPSY). |

|

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emil_Kraepelin |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報