道徳形而上学から純粋実践理性批判への移行

『人倫の形而上学的基礎づけ』の第3章

Grundlegung

zur Metaphysik der Sitten

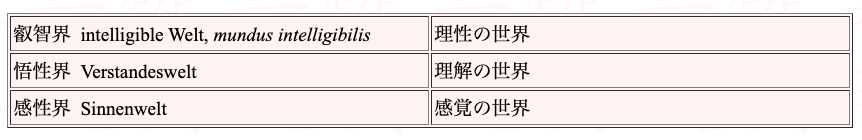

☆ 第3章は、定言命法を可能にする、諸前提、つまり、自由、自律、理性的存在者、そして、実践哲学の限界について論じられる。第二章にくらべて、議論の展開が散漫なような気がするのは、私だけだろうか?た だし、定言命法を可能にするための論証をカントが真摯に取り組んでいるとすれば、やはり、手を抜いて読めない章になっている。一言でいうと、我々は理性的 存在者になることを目指すことがまず最初にある。理性的存在者は意志をもつが、それを可能にする条件は、自由であること。人間が自由であるということは、 自律した存在として、自己も他者も扱い扱われるべきであり、それを人間がもつ、それ自体の「目的」だと言われる。目的の非対称的な概念が「手段」であっ て、人間を目的としないことは、人間を手段として扱うことだ。だからカントはつねに、人間を目的として考えよと繰り返し主張する。人間が手段でなくて目的 であるという主張は、なかなか、すんなりとは理解できないために、解釈が必要なるが、比喩を使って理解することは、形而上学的ではない。そしてわ我々は もっと先に進まないとならない。それゆえ第3章は道徳形而上学から純粋実践理性批判となっている。人間という理性的存在者、あるいは理性的存在者は、どこ にいるのかというトポロジーは、感性界、悟性界、叡智界という区分から考えるということなのだろう。また、実践の問題は、純粋理性批判からさらに、人間世 界の現実原則に投げ出される経験的世界のなかで、アクションすることに関与するので、そのような現実世界のなかで、理性はどのような姿をとるのかという課 題にまで到達しなければならない。それがカントのいう「純粋実践理性批判」ということなのだろう。この「純粋実践理性批判」という用語は、この後に出版される『実践理性批判』のなかで再度登場する。それゆえに、2章から展開して、実践理性とはどのようなもので、どのような性質をもつのかについての議論が展開されていると言っても過言ではない。

☆ 第3章拾い読み

道 徳形而上学から純粋実践理性批判への移り行き(カント)

★ 用語集

| 自由 |

(191) |

| 原因性 |

|

| 演繹 |

|

| 関心 |

|

| 交換概念 |

|

| 感性界 |

|

| 悟性界 |

|

| 知性界 |

☆ノート

| 1 |

131 |

446 |

・「自由の概念は意志の自律を解明するための鍵である」(131) ・意志(131)——生きている存在者が理性的であるかぎりもつ一種の原因性 ・自由(131)——自分を外部から規定してくる原因から独立(=自由になり)してできる、その原因性が自由である(131) ・これは、消極的な自由 |

| 2 |

131 |

・積極的な自由——生産的自由 ・定言命法は(完全に)自由だという(132) |

|

| 3 |

|||

| 4 |

134 |

・「自由はあらゆる理性的存在者の意志の特性として前提されなければならない」(134) |

|

| 5 |

136 |

・「道徳性の諸理念に付帯している関心について」(136) |

|

| 6 |

|||

| 7 |

|||

| 8 |

|||

| 9 |

140 |

・循環論法(140) |

|

| 10 |

|||

| 11 |

141-143 |

・感性界と悟性界 |

|

| 12 |

|||

| 13 |

144 |

・理性の定義=自分の内外に対して、自分自身と対象を切り分ける能力を理性と呼ぶ(144) ・理性は悟性よりもすぐれている(144)——感性、悟性、叡智の階層性に注意  |

|

| 14 |

|||

| 15 |

|||

| 16 |

|||

| 17 |

147 |

・定言命法はどのようにして可能なのか?(147) ・理性的存在者は、自分を叡智性としては悟性界に数え入れて、もっぱらこの悟性界に属する作用原因としての自分の原因性を意志となづける(147)。 |

|

| 18 |

148 |

・定言命法が可能になる知のエピステモロジーにおける位相(148) |

|

| 19 |

|||

| 20 |

151 |

・実践哲学の限界(151) ・「あらゆる実践哲学の究極の限界について」(151) ・人間はみな、自分は意志に関しては自由であると考えている(I・カント)(151)——だからこそ、為されなかったことについても、為されるべきだったと考えるのである(151)——このこと(自己の判断)は経験論でも決定論でも説明できない。 |

|

| 21 |

152 |

・理性のひとつの弁証論(152) |

|

| 22 |

|||

| 23 |

153 |

・自分が自由だと思っている主体のジレンマ?(153) |

|

| 24 |

154 |

・実践哲学上の課題(154-155) |

|

| 25 |

|||

| 26 |

|||

| 27 |

157 |

・実践理性の脆弱性?(→理性の綱渡り) ・悟性界という概念は理性が自分自身を実践的であると考えるために、諸現象の外部に取らざるをえないとみなされる一つの立場でしかない(157) |

|

| 28 |

|||

| 29 |

|||

| 30 |

161 |

460 |

・意志の自由を解明することは主観的には不可能(161) |

| 31 |

|||

| 32 |

|||

| 33 |

|||

| 34 |

|||

| 35 |

***

★ 人倫の形而上学的基礎づけの第3章(本文)

| SEC 3 THIRD SECTION TRANSITION FROM THE METAPHYSIC OF MORALS TO THE CRITIQUE OF PURE PRACTICAL REASON |

SEC 3 第3部(第3章) 道徳の形而上学から純粋実践理性批判への移行 |

| The Concept of Freedom is the

Key that explains the Autonomy of the Will |

自由の概念は意志の自律性を説明する鍵である |

| The

will is a kind of causality belonging to living beings in so far as

they are rational, and freedom would be this property of such causality

that it can be efficient, independently of foreign causes determining

it; just as physical necessity is the property that the causality of

all irrational beings has of being determined to activity by the

influence of foreign causes. |

意志とは、理性を持つ存在に属する因果関係の一種であり、自由とは、外

的要因に左右されることなく、効率的に作用することができる因果関係の特性である。物理的な必然性とは、非理性的な存在の因果関係が、外的要因の影響を受

けて活動へと決定されるという特性である。 |

| The

preceding definition of freedom is negative and therefore unfruitful

for the discovery of its essence, but it leads to a positive conception

which is so much the more full and fruitful. |

先の自由の定義は消極的なものであり、その本質を発見するには不十分で

あるが、より完全で有益な積極的な概念へと導く。 |

| Since

the conception of causality involves that of laws, according to which,

by something that we call cause, something else, namely the effect,

must be produced; hence, although freedom is not a property of the will

depending on physical laws, yet it is not for that reason lawless; on

the contrary it must be a causality acting according to immutable laws,

but of a peculiar kind; otherwise a free will would be an absurdity.

Physical necessity is a heteronomy of the efficient causes, for every

effect is possible only according to this law, that something else

determines the efficient cause to exert its causality. What else then

can freedom of the will be but autonomy, that is, the property of the

will to be a law to itself? But the proposition: "The will is in every

action a law to itself," only expresses the principle: "To act on no

other maxim than that which can also have as an object itself as a

universal law." Now this is precisely the formula of the categorical

imperative and is the principle of morality, so that a free will and a

will subject to moral laws are one and the same. |

因

果律の概念には法則が関わっているため、原因と呼ばれる何らかの作用によって、別の作用、すなわち結果が生じなければならない。したがって、自由は物理法

則に依存する意志の性質ではないが、それゆえに無法であるわけではない。それどころか、不変の法則に従って作用する因果律でなければならない。そうでなけ

れば、自由意志は不合理である。物理的な必然性は、効果的な原因の他律である。あらゆる効果は、この法則に従ってのみ可能であり、つまり、何か他のものが

効果的な原因に因果関係を発揮させることを決定する。それでは、意志の自由とは、自律性、つまり、意志がそれ自体の法となる性質以外の何であろうか?しか

し、

「意志はあらゆる行動において、それ自体が法である」という命題は、単に「普遍的な法則としてそれ自体を目的とすることもできるような格律以外の格律に

従って行動しないこと」という原則を表現しているにすぎない。今、これはまさに定言命法の定式であり、道徳の原則である。したがって、自由意志と道徳法に

従う意志は同一のものである。 |

| On

the hypothesis, then, of freedom of the will, morality together with

its principle follows from it by mere analysis of the conception. |

意志の自由という仮説を前提とすれば、道徳とその原則は、概念の分析に

よって導かれる。 |

| However,

the latter is a synthetic proposition; viz., an absolutely good will is

that whose maxim can always include itself regarded as a universal law;

for this property of its maxim can never be discovered by analysing the

conception of an absolutely good will. Now such synthetic propositions

are only possible in this way: that the two cognitions are connected

together by their union with a third in which they are both to be

found. The positive concept of freedom furnishes this third cognition,

which cannot, as with physical causes, be the nature of the sensible

world (in the concept of which we find conjoined the concept of

something in relation as cause to something else as effect). We cannot

now at once show what this third is to which freedom points us and of

which we have an idea a priori, nor can we make intelligible how the

concept of freedom is shown to be legitimate from principles of pure

practical reason and with it the possibility of a categorical

imperative; but some further preparation is required. |

し

かし、後者は総合命題である。すなわち、絶対的に善なる意志とは、その格律が常に普遍法則としてそれ自身を含みうるようなものである。なぜなら、絶対的に

善なる意志の格律のこの性質は、その概念を分析しても決して発見されることはないからだ。さて、このような総合命題は、次の方法によってのみ可能である。

すなわち、2つの認識が、両者がともに見出される第3のものとの結合によって結びつけられるという方法である。自由の肯定的概念は、この第3の認識を提供

する。この認識は、物理的な原因のように、感覚世界の本質であることはできない(感覚世界の概念においては、何かが、何か他のものに対する関係において、

効果として原因となる何かの概念と結合されている)。自由が私たちを導くこの第三の概念が何であるか、また、私たちがア・プリオリに考えを持っていること

を、今すぐに示すことはできない。また、自由の概念が純粋実践理性の原理から正当であることが示され、それによって定言命法の可能性が示されることを理解

させることもできない。しかし、さらなる準備が必要である。 |

| Freedom must be presupposed as a

Property of the Will of all Rational Beings |

自由は、すべての理性的存在の意志の特性として前提されなければならな

い。 |

| It

is not enough to predicate freedom of our own will, from Whatever

reason, if we have not sufficient grounds for predicating the same of

all rational beings. For as morality serves as a law for us only

because we are rational beings, it must also hold for all rational

beings; and as it must be deduced simply from the property of freedom,

it must be shown that freedom also is a property of all rational

beings. It is not enough, then, to prove it from certain supposed

experiences of human nature (which indeed is quite impossible, and it

can only be shown a priori), but we must show that it belongs to the

activity of all rational beings endowed with a will. Now I say every

being that cannot act except under the idea of freedom is just for that

reason in a practical point of view really free, that is to say, all

laws which are inseparably connected with freedom have the same force

for him as if his will had been shown to be free in itself by a proof

theoretically conclusive. * Now I affirm that we must attribute to

every rational being which has a will that it has also the idea of

freedom and acts entirely under this idea. For in such a being we

conceive a reason that is practical, that is, has causality in

reference to its objects. Now we cannot possibly conceive a reason

consciously receiving a bias from any other quarter with respect to its

judgements, for then the subject would ascribe the determination of its

judgement not to its own reason, but to an impulse. It must regard

itself as the author of its principles independent of foreign

influences. Consequently as practical reason or as the will of a

rational being it must regard itself as free, that is to say, the will

of such a being cannot be a will of its own except under the idea of

freedom. This idea must therefore in a practical point of view be

ascribed to every rational being. |

我

々の自由意志を述べるには、それがどのような理由からであれ、すべての理性的存在についても同じことが言えるだけの十分な根拠がなければ十分ではない。な

ぜなら、道徳が我々にとって法則となるのは、我々が理性的存在であるからに他ならないから、それはまた、すべての理性的存在にも当てはまるはずである。そ

して、それは自由という性質から単純に導かれるはずであるから、自由もまた、すべての理性的存在の性質であることを示す必要がある。したがって、人間の本

性に関する特定の想定された経験からそれを証明するだけでは不十分である(実際、それはまったく不可能であり、ア・プリオリに示されるにすぎない)。しか

し、意志を備えたすべての理性的存在の活動に属することを示さなければならない。今、私は、自由という観念のもとでしか行動できないあらゆる存在は、まさ

にその理由から、実際的な観点において本当に自由であると言う。つまり、自由と不可分の関係にあるあらゆる法は、理論的に決定的な証明によってその意志が

それ自体自由であることが示された場合と同様に、その存在にとって同じ力をもつ。*

私は、意志をもつあらゆる理性的存在には自由の観念があり、その観念のもとで完全に活動していると主張する。なぜなら、そのような存在においては、実践的

な理性、すなわち、対象との因果関係を持つ理性を想定することができるからだ。今、私たちは、判断に関して他のいかなる方面からも偏見を受け入れる意識的

な理性を想定することはできない。なぜなら、そうすると、その主体は、判断の決定を自身の理性ではなく衝動に帰するからだ。その主体は、外的影響とは無関

係に、自身の原則の作者であるとみなさなければならない。したがって、実践理性または理性的存在の意志として、自由であるとみなさなければならない。つま

り、自由という概念なしには、そのような存在の意志は、その存在自身の意志であるとは言えない。したがって、この概念は、実践的な観点から、すべての理性

的存在に帰属する。 |

| *

I adopt this method of assuming freedom merely as an idea which

rational beings suppose in their actions, in order to avoid the

necessity of proving it in its theoretical aspect also. The former is

sufficient for my purpose; for even though the speculative proof should

not be made out, yet a being that cannot act except with the idea of

freedom is bound by the same laws that would oblige a being who was

actually free. Thus we can escape here from the onus which presses on

the theory. |

*

私は、自由を仮定するというこの方法を、理性的な存在がその行動において仮定する考えとしてのみ採用する。理論的な側面でもそれを証明する必要性を回避す

るためである。私の目的には、前者の考え方で十分である。たとえ思弁的な証明が成り立たないとしても、自由という考えなしには行動できない存在は、実際に

自由であった存在を拘束するのと同じ法則に縛られる。したがって、ここでは理論上の重荷から逃れることができる。 |

| Of the Interest attaching to the

Ideas of Morality |

道徳の観念に付随する関心事 |

| We

have finally reduced the definite conception of morality to the idea of

freedom. This latter, however, we could not prove to be actually a

property of ourselves or of human nature; only we saw that it must be

presupposed if we would conceive a being as rational and conscious of

its causality in respect of its actions, i.e., as endowed with a will;

and so we find that on just the same grounds we must ascribe to every

being endowed with reason and will this attribute of determining itself

to action under the idea of its freedom. |

私たちはついに、道徳の明確な概念

を自由という概念に還元した。しかし、この後者は、私たち自身や人間の本質が実際に持つ性質であると証明することはできなかった。ただ、行為に関して因果

関係を認識する理性的な存在、すなわち意志を備えた存在として考えるのであれば、この概念が前提されなければならないことは明らかであった。そして、同じ

理由から、理性と意志を備えたあらゆる存在には、自由という概念のもとで、自らを行動へと駆り立てるこの属性が備わっていると考える必要があることが分

かった。 |

| Now

it resulted also from the presupposition of these ideas that we became

aware of a law that the subjective principles of action, i.e., maxims,

must always be so assumed that they can also hold as objective, that

is, universal principles, and so serve as universal laws of our own

dictation. But why then should I subject myself to this principle and

that simply as a rational being, thus also subjecting to it all other

being endowed with reason? I will allow that no interest urges me to

this, for that would not give a categorical imperative, but I must take

an interest in it and discern how this comes to pass; for this properly

an "I ought" is properly an "I would," valid for every rational being,

provided only that reason determined his actions without any hindrance.

But for beings that are in addition affected as we are by springs of a

different kind, namely, sensibility, and in whose case that is not

always done which reason alone would do, for these that necessity is

expressed only as an "ought," and the subjective necessity is different

from the objective. |

ま

た、行動の主観的原則、すなわち格律は、客観的原則、すなわち普遍的原則としても成り立つように常に想定されなければならないという法則に気づいたのも、

これらの考えを前提としていたからである。しかし、なぜ私は理性を持つ存在として、この原理に従わなければならないのか。そして、理性を持つ他の存在もそ

れに従うべきなのか。私は、何の利害関係も私をそうさせないことを認める。なぜなら、それは定言命法ではないからだ。しかし、私はそれに興味を持ち、それ

がどのようにして起こるのかを見極めなければならない。なぜなら、これは正しく「私はそうすべきだ」であり、正しく「私はそうしたい」であり、理性が何の

妨げもなく行動を決定する限り、あらゆる理性を持つ存在にとって妥当である。しかし、私たちと同じように、異なる種類の源泉、すなわち感性によっても影響

を受ける存在の場合、理性のみによって行われるとは限らない。このような存在にとっては、その必要性は「〜すべきである」という表現のみで表され、主観的

な必要性は客観的なものとは異なる。 |

| It

seems then as if the moral law, that is, the principle of autonomy of

the will, were properly speaking only presupposed in the idea of

freedom, and as if we could not prove its reality and objective

necessity independently. In that case we should still have gained

something considerable by at least determining the true principle more

exactly than had previously been done; but as regards its validity and

the practical necessity of subjecting oneself to it, we should not have

advanced a step. For if we were asked why the universal validity of our

maxim as a law must be the condition restricting our actions, and on

what we ground the worth which we assign to this manner of acting- a

worth so great that there cannot be any higher interest; and if we were

asked further how it happens that it is by this alone a man believes he

feels his own personal worth, in comparison with which that of an

agreeable or disagreeable condition is to be regarded as nothing, to

these questions we could give no satisfactory answer. |

そ

れでは、道徳律、すなわち、意志の自律性の原則は、自由という概念にのみ前提されているにすぎず、その現実性と客観的必然性を独立して証明することはでき

ないように思われる。その場合でも、少なくとも、真の原則を以前よりも正確に決定することによって、相当な成果は得られたはずである。しかし、その妥当性

と、それに従うことの実践的な必要性に関しては、一歩も前進していない。なぜなら、もし私たちが、私たちの格律としての普遍的な妥当性が、私たちの行動を

制限する条件でなければならない理由、そして、私たちがこの行動様式に与える価値をどのような根拠に基づいて決定しているのか、その価値はこれ以上ないほ

どに高く、これ以上の利益はありえないのか、と問われた場合、

さらに、このことだけによって、人は自分の個人的な価値を感じていると考えるのはなぜなのか、快い状態や不快な状態は、それと比較すると何でもないように

思えるのはなぜなのか、という質問をされた場合、私たちは満足のいく答えを出すことはできなかった。 |

| We

find indeed sometimes that we can take an interest in a personal

quality which does not involve any interest of external condition,

provided this quality makes us capable of participating in the

condition in case reason were to effect the allotment; that is to say,

the mere being worthy of happiness can interest of itself even without

the motive of participating in this happiness. This judgement, however,

is in fact only the effect of the importance of the moral law which we

before presupposed (when by the idea of freedom we detach ourselves

from every empirical interest); but that we ought to detach ourselves

from these interests, i.e., to consider ourselves as free in action and

yet as subject to certain laws, so as to find a worth simply in our own

person which can compensate us for the loss of everything that gives

worth to our condition; this we are not yet able to discern in this

way, nor do we see how it is possible so to act- in other words, whence

the moral law derives its obligation. |

私

たちは、外的条件に関わる利害が一切ない個人的な性質であっても、その性質が理由によって配分が行われる場合にその条件に参加できる能力を与えてくれるの

であれば、その性質に関心を持つことができると確かに時々気づく。つまり、幸福になるだけの価値があるという事実自体が、この幸福に参加するという動機が

なくても関心を持たせるのである。しかし、この判断は、実際には、私たちが(自由という概念によって経験的なあらゆる利害から自らを切り離す際に)先に前

提した道徳法則の重要性の効果にすぎない。しかし、私たちはこれらの利害から自らを切り離すべきであり、すなわち、行動の自由を享受しながらも、特定の法

則に従属しているとみなすべきである。そうすることで、私たちの状態に価値を与えるあらゆるものを失ったとしても、私たち自身に価値を見出すことができ

る。しかし、私たちはまだこの方法でそれを理解することができず、また、そう行動することが可能である理由も理解していない。つまり、道徳律がその義務を

どこから引き出しているのかを理解していないのだ。 |

| It

must be freely admitted that there is a sort of circle here from which

it seems impossible to escape. In the order of efficient causes we

assume ourselves free, in order that in the order of ends we may

conceive ourselves as subject to moral laws: and we afterwards conceive

ourselves as subject to these laws, because we have attributed to

ourselves freedom of will: for freedom and self-legislation of will are

both autonomy and, therefore, are reciprocal conceptions, and for this

very reason one must not be used to explain the other or give the

reason of it, but at most only logical purposes to reduce apparently

different notions of the same object to one single concept (as we

reduce different fractions of the same value to the lowest terms). |

こ

こには、そこから逃れることが不可能であるように思われる一種の循環があることを認めざるを得ない。

効果的な原因の順序において、私たちは自らを自由であると想定し、目的の順序において、私たちは自らを道徳律に従属するものとして考える。そして、私たち

はその後、自らに意志の自由を帰属させたため、自らをこれらの法に従属するものとして考える。自由と意志の自己立法は、いずれも自律であり、

、したがって、相互に概念であり、この理由から、一方を他方の説明や理由付けに用いてはならず、せいぜい、同じ対象の異なる概念を単一の概念に還元する論

理的目的にのみ用いるべきである(同じ値の異なる分数を最小公倍数に還元するように)。 |

| One

resource remains to us, namely, to inquire whether we do not occupy

different points of view when by means of freedom we think ourselves as

causes efficient a priori, and when we form our conception of ourselves

from our actions as effects which we see before our eyes. |

私たちに残された唯一の手段は、すなわち、自由によって自らを原因と見

なし、ア・プリオリに効率的であると考える場合と、目の前にある結果としての行動から自らを捉える場合とで、異なる視点に立っていないかどうかを問うこと

である。 |

| It

is a remark which needs no subtle reflection to make, but which we may

assume that even the commonest understanding can make, although it be

after its fashion by an obscure discernment of judgement which it calls

feeling, that all the "ideas" that come to us involuntarily (as those

of the senses) do not enable us to know objects otherwise than as they

affect us; so that what they may be in themselves remains unknown to

us, and consequently that as regards "ideas" of this kind even with the

closest attention and clearness that the understanding can apply to

them, we can by them only attain to the knowledge of appearances, never

to that of things in themselves. As soon as this distinction has once

been made (perhaps merely in consequence of the difference observed

between the ideas given us from without, and in which we are passive,

and those that we produce simply from ourselves, and in which we show

our own activity), then it follows of itself that we must admit and

assume behind the appearance something else that is not an appearance,

namely, the things in themselves; although we must admit that as they

can never be known to us except as they affect us, we can come no

nearer to them, nor can we ever know what they are in themselves. This

must furnish a distinction, however crude, between a world of sense and

the world of understanding, of which the former may be different

according to the difference of the sensuous impressions in various

observers, while the second which is its basis always remains the same,

Even as to himself, a man cannot pretend to know what he is in himself

from the knowledge he has by internal sensation. For as he does not as

it were create himself, and does not come by the conception of himself

a priori but empirically, it naturally follows that he can obtain his

knowledge even of himself only by the inner sense and, consequently,

only through the appearances of his nature and the way in which his

consciousness is affected. At the same time beyond these

characteristics of his own subject, made up of mere appearances, he

must necessarily suppose something else as their basis, namely, his

ego, whatever its characteristics in itself may be. Thus in respect to

mere perception and receptivity of sensations he must reckon himself as

belonging to the world of sense; but in respect of whatever there may

be of pure activity in him (that which reaches consciousness

immediately and not through affecting the senses), he must reckon

himself as belonging to the intellectual world, of which, however, he

has no further knowledge. To such a conclusion the reflecting man must

come with respect to all the things which can be presented to him: it

is probably to be met with even in persons of the commonest

understanding, who, as is well known, are very much inclined to suppose

behind the objects of the senses something else invisible and acting of

itself. They spoil it, however, by presently sensualizing this

invisible again; that is to say, wanting to make it an object of

intuition, so that they do not become a whit the wiser. |

こ

れは、考えるまでもなく、ごく当たり前の理解でもできるはずだと想定できるような発言である。しかし、それは、感覚のように無意識に浮かんでくる「観念」

は、

それらが私たちに影響を与えるものとしてしか、対象を知ることができない。そのため、それ自体が何であるかについては依然として私たちには未知のままであ

り、その結果、この種の「観念」に関しては、理解がそれらに適用できる最も注意深く明晰なものであっても、私たちはそれによって外見の知識に到達すること

はできても、それ自体の知識に到達することは決してできない。この区別が一度なされれば(おそらく、外から与えられ、私たちが受動的である観念と、私たち

が自分自身から単に作り出す観念、そして私たちが自身の能動性を示す観念との間に観察される差延の結果として)、

外見の背後に、外見ではない何か、すなわち物自体を認める必要がある。ただし、物自体は、それが私たちに影響を与える場合を除いて、私たちに知られること

は決してないため、私たちはそれに近づくことはできず、それが物自体として何であるかを決して知ることはできないことを認めなければならない。これは感覚

の世界と理解の世界の間の、粗野ではあるが、区別を明らかにするものでなければならない。感覚の世界は、さまざまな観察者における感覚的印象の差異に応じ

て異なるかもしれないが、その基礎となる理解の世界は常に同じである。人間は、内省によって自分が何者であるかを知っていると主張することはできない。な

ぜなら、人は自分自身を創造するわけではなく、また、ア・プリオリに自己概念を獲得するわけでもなく、経験的に獲得するからだ。したがって、当然ながら、

人は自分の知識を内面的感覚によってのみ、つまり、自分の本質と意識が影響を受ける方法の表象を通じてのみ獲得できることになる。同時に、単なる外見で構

成される自己の主題のこうした特徴を超えて、彼は必然的に、その基盤として何か他のものを想定しなければならない。すなわち、それがそれ自体どのような特

徴を持つものであっても、自己のエゴである。したがって、感覚の知覚と感受性に関しては、彼は感覚の世界に属するとみなさなければならない。しかし、彼の

中に純粋な活動(感覚に影響を与えることなく、直接的に意識に到達するもの)があるならば、彼はそれを知的な世界に属するとみなさなければならない。ただ

し、彼にはそれ以上の知識はない。思慮深い人間は、自分に提示されるすべてのものについて、このような結論に達さなければならない。これは、よく知られて

いるように、感覚の対象の背後に目に見えない何かが作用していると考える傾向が強い、最も平凡な理解力を持つ人々にも当てはまるだろう。しかし、彼らはす

ぐにこの不可視のものを再び感覚化することで台無しにしてしまう。つまり、直観の対象にしようとするが、それによって彼らは少しも賢くはならないのだ。 |

| Now

man really finds in himself a faculty by which he distinguishes himself

from everything else, even from himself as affected by objects, and

that is reason. This being pure spontaneity is even elevated above the

understanding. For although the latter is a spontaneity and does not,

like sense, merely contain intuitions that arise when we are affected

by things (and are therefore passive), yet it cannot produce from its

activity any other conceptions than those which merely serve to bring

the intuitions of sense under rules and, thereby, to unite them in one

consciousness, and without this use of the sensibility it could not

think at all; whereas, on the contrary, reason shows so pure a

spontaneity in the case of what I call ideas [ideal conceptions] that

it thereby far transcends everything that the sensibility can give it,

and exhibits its most important function in distinguishing the world of

sense from that of understanding, and thereby prescribing the limits of

the understanding itself. |

今、

人間は、自分自身を他のあらゆるものから、さらには対象物によって影響を受けた自分自身からも区別する能力を本当に自分自身の中に発見する。それが理性で

ある。これは純粋な自発性であり、理解力よりもさらに高いものである。なぜなら、後者は自発性であり、感覚のように、物事に影響を受ける(したがって受動

的である)ときに生じる直観だけを含むわけではないが、その活動から感覚の直観を規則の下に置き、それによって一つの意識にそれらを統合するのに役立つも

の以外の概念を生み出すことはできない。そして、感受性のこの使用がなければ、

それなしにはまったく思考することができない。一方、私が観念と呼ぶもの[観念的観念]の場合、理性は純粋な自発性を示し、それによって感性から与えられ

るものをはるかに超え、感覚の世界と理解の世界を区別し、それによって理解自体の限界を規定するという、最も重要な機能を果たす。 |

| For

this reason a rational being must regard himself qua intelligence (not

from the side of his lower faculties) as belonging not to the world of

sense, but to that of understanding; hence he has two points of view

from which he can regard himself, and recognise laws of the exercise of

his faculties, and consequently of all his actions: first, so far as he

belongs to the world of sense, he finds himself subject to laws of

nature (heteronomy); secondly, as belonging to the intelligible world,

under laws which being independent of nature have their foundation not

in experience but in reason alone. |

こ

のため、理性的な存在は、知性(低次の能力の側面ではなく)によって、感覚の世界ではなく理解の世界に属しているとみなさなければならない。したがって、

人は自分自身を認識し、能力の行使の法則、

第一に、感覚の世界に属する限りにおいて、彼は自然法則に従属する(他律)存在である。第二に、感覚の世界に属する限りにおいて、自然とは独立した法則に

従属する存在であり、その法則の基礎は経験ではなく理性のみにある。 |

| As

a rational being, and consequently belonging to the intelligible world,

man can never conceive the causality of his own will otherwise than on

condition of the idea of freedom, for independence of the determinate

causes of the sensible world (an independence which reason must always

ascribe to itself) is freedom. |

理性的存在であり、したがって理解可能な世界に属する人間は、自由とい

う概念を前提とせずに、自身の意志の因果関係を理解することは決してできない。なぜなら、感覚世界における決定要因からの独立(理性が常に自らに帰属させ

なければならない独立)は自由であるからだ。 |

| Now

the idea of freedom is inseparably connected with the conception of

autonomy, and this again with the universal principle of morality which

is ideally the foundation of all actions of rational beings, just as

the law of nature is of all phenomena. |

今や、自由という概念は自律という概念と不可分の関係にある。そして、

この自律という概念は、自然法則がすべての現象の基礎であるように、理想的に言えば、理性的な存在のすべての行動の基礎となる普遍的な道徳的原則と再び結

びついている。 |

| Now

the suspicion is removed which we raised above, that there was a latent

circle involved in our reasoning from freedom to autonomy, and from

this to the moral law, viz.: that we laid down the idea of freedom

because of the moral law only that we might afterwards in turn infer

the latter from freedom, and that consequently we could assign no

reason at all for this law, but could only [present] it as a petitio

principii which well disposed minds would gladly concede to us, but

which we could never put forward as a provable proposition. |

今、私たちが最初に抱いた疑念は取

り除かれた。すなわち、自由から自律へ、そしてそこから道徳法へと至る私たちの推論には、潜在的な循環が関わっているのではないかという疑念である。つま

り、私たちが自由という概念を打ち立てたのは、道徳法があるからこそ、その後で順番に

後者は自由から推論できるという理由から、この法則にはまったく理由を割り当てることができず、良心的な人々が喜んで認める帰結論としてのみ提示できる

が、証明可能な命題として提示することは決してできない。 |

| For

now we see that, when we conceive ourselves as free, we transfer

ourselves into the world of understanding as members of it and

recognise the autonomy of the will with its consequence, morality;

whereas, if we conceive ourselves as under obligation, we consider

ourselves as belonging to the world of sense and at the same time to

the world of understanding. |

今のところ、私たちは、自由であると考えるとき、理解の世界にその一員

として自分自身を移し、その結果としての道徳とともに意志の自律性を認識していることが分かる。一方、義務を負っていると考える場合、感覚の世界と理解の

世界の両方に属するものとして自分自身を考える。 |

| How is a Categorical Imperative

Possible? |

定言命法はいかにして可能なのか?(文庫版 pp.147-) |

| Every

rational being reckons himself qua intelligence as belonging to the

world of understanding, and it is simply as an efficient cause

belonging to that world that he calls his causality a will. On the

other side he is also conscious of himself as a part of the world of

sense in which his actions, which are mere appearances [phenomena] of

that causality, are displayed; we cannot, however, discern how they are

possible from this causality which we do not know; but instead of that,

these actions as belonging to the sensible world must be viewed as

determined by other phenomena, namely, desires and inclinations. If

therefore I were only a member of the world of understanding, then all

my actions would perfectly conform to the principle of autonomy of the

pure will; if I were only a part of the world of sense, they would

necessarily be assumed to conform wholly to the natural law of desires

and inclinations, in other words, to the heteronomy of nature. (The

former would rest on morality as the supreme principle, the latter on

happiness.) Since, however, the world of understanding contains the

foundation of the world of sense, and consequently of its laws also,

and accordingly gives the law to my will (which belongs wholly to the

world of understanding) directly, and must be conceived as doing so, it

follows that, although on the one side I must regard myself as a being

belonging to the world of sense, yet on the other side I must recognize

myself as subject as an intelligence to the law of the world of

understanding, i.e., to reason, which contains this law in the idea of

freedom, and therefore as subject to the autonomy of the will:

consequently I must regard the laws of the world of understanding as

imperatives for me and the actions which conform to them as duties. |

理

性ある存在は、知性という観点から、自らを理解の世界に属するものとみなす。そして、その世界に属する能動的な原因として、自らの因果律を意志と呼ぶので

ある。一方で、彼はまた、自分の行動が示される感覚の世界の一部としての自分自身を意識している。しかし、この因果関係から、その行動がどのように可能な

のかを我々は見分けることはできない。その代わりに、感覚の世界に属するこれらの行動は、他の現象、すなわち、欲望や傾向によって決定されていると見なさ

なければならない。したがって、私が理解の世界の構成員であるだけなら、私の行動はすべて純粋な意志の自律性の原則に完全に適合するだろう。私が感覚の世

界の一部であるだけなら、それらは必然的に、欲望と傾向の自然法則に完全に適合すると想定されるだろう。つまり、自然の他律に適合すると想定されるだろ

う。(前者は道徳を最高原理とし、後者は幸福を最高原理とする。)しかし、理解の世界は感覚の世界の基礎を含み、その結果、その法則も含み、それゆえに私

の意志(これは完全に理解の世界に属する)に直接法則を与え、そうしているとみなされなければならない。したがって、一方では感覚の世界に属する存在とし

て自らをみなさなければならないが、

他方では、私は自分自身を理解の世界の法則に従う知性、すなわち自由の概念にこの法則を含んでいる理性、したがって意志の自律に従う主体として認識しなけ

ればならない。したがって、私は理解の世界の法則を自分にとっての命令として、またそれらに従う行動を義務としてみなさなければならない。 |

| And

thus what makes categorical imperatives possible is this, that the idea

of freedom makes me a member of an intelligible world, in consequence

of which, if I were nothing else, all my actions would always conform

to the autonomy of the will; but as I at the same time intuite myself

as a member of the world of sense, they ought so to conform, and this

categorical "ought" implies a synthetic a priori proposition, inasmuch

as besides my will as affected by sensible desires there is added

further the idea of the same will but as belonging to the world of the

understanding, pure and practical of itself, which contains the supreme

condition according to reason of the former will; precisely as to the

intuitions of sense there are added concepts of the understanding which

of themselves signify nothing but regular form in general and in this

way synthetic a priori propositions become possible, on which all

knowledge of physical nature rests. |

そ

して、定言命法を可能にするのは、自由という観念が私を理解可能な世界の構成員とするということである。その結果、私が他の何者でもなかったとしても、私

の行動はすべてつねに意志の自律性に適合することになる。しかし、同時に私は感覚の世界の構成員であると直観するので、それらの行動はそう適合すべきであ

り、この定言的「〜すべき」は、感覚的な欲望によって影響を受ける私の意志に加えて、

感覚的な欲望によって影響を受ける私の意志に加えて、理解力の世界に属する同じ意志の概念がさらに追加される。この理解力の世界は、それ自体が純粋かつ実

際的なものであり、前者の意志の理性に基づく最高の条件を含んでいる。感覚の直観には、それ自体は規則的な形式一般を意味する理解力の概念が追加される。

このようにして、総合的ア・プリオリ命題が可能になり、自然界のすべての知識がこの命題に依拠している。 |

| The practical use of common

human reason confirms this reasoning. |

一般的な人間の理性を実際に活用すれば、この推論が正しいことが確認で

きる。 |

| There is no one, not even the most consummate villain, provided only that he is otherwise accustomed to the use of reason, who, when we set before him examples of honesty of purpose, of steadfastness in following good maxims, of sympathy and general benevolence (even combined with great sacrifices of advantages and comfort), does not wish that he might also possess these qualities. Only on account of his inclinations and impulses he cannot attain this in himself, but at the same time he wishes to be free from such inclinations which are burdensome to himself. He proves by this that he transfers himself in thought with a will free from the impulses of the sensibility into an order of things wholly different from that of his desires in the field of the sensibility; since he cannot expect to obtain by that wish any gratification of his desires, nor any position which would satisfy any of his actual or supposable inclinations (for this would destroy the pre-eminence of the very idea which wrests that wish from him): he can only expect a greater intrinsic worth of his own person. This better person, however, he imagines himself to be when be transfers himself to the point of view of a member of the world of the understanding, to which he is involuntarily forced by the idea of freedom, i.e., of independence on determining causes of the world of sense; and from this point of view he is conscious of a good will, which by his own confession constitutes the law for the bad will that he possesses as a member of the world of sense- a law whose authority he recognizes while transgressing it. What he morally "ought" is then what he necessarily "would," as a member of the world of the understanding, and is conceived by him as an "ought" only inasmuch as he likewise considers himself as a member of the world of sense. | 最

も悪辣な悪人であっても、理性の使用に慣れてさえいれば、目的が正直であること、善き格律に従うことの堅固さ、同情心、そして一般的な博愛主義(たとえ、

利点や快適さの大きな犠牲を伴うとしても)の例を目の前に示されれば、自分もこれらの資質を備えたいと望まない者はいない。ただ、彼の傾向や衝動のせい

で、彼自身ではそれを達成できない。しかし同時に、彼自身にとって負担となるような傾向から自由になりたいとも思っている。彼は、このことによって、感覚

の衝動から自由な意志によって、思考を感覚の領域における彼の欲望とは全く異なる事物の秩序へと移すことを証明している。なぜなら、その願いによって欲望

が満たされることも、

また、現実の、あるいは想定されるいかなる傾向をも満足させるような立場も期待できない(なぜなら、それはまさにその願いを彼から奪い去る考えの卓越性を

破壊してしまうからだ)。彼が期待できるのは、彼自身のより本質的な価値だけである。しかし、このより優れた人間は、自由、すなわち感覚界の原因を決定す

るものからの独立という考えによって、否応なく理解の世界の住人へと移行させられる。。そして、この観点から、彼は善意を自覚する。これは、彼自身の告白

によると、感覚界の一員として彼が持つ悪意に対する法則であり、彼はその権威を認めながらも、それを犯している。彼が道徳的に「すべき」ことは、理解の世

界の構成員として、彼が必然的に「望む」ことであり、彼が感覚の世界の構成員として自らを考える限りにおいてのみ、「すべき」こととして彼に考えられる。 |

| Of the Extreme Limits of all

Practical Philosophy. |

実践哲学の極限について。 |

| All

men attribute to themselves freedom of will. Hence come all judgements

upon actions as being such as ought to have been done, although they

have not been done. However, this freedom is not a conception of

experience, nor can it be so, since it still remains, even though

experience shows the contrary of what on supposition of freedom are

conceived as its necessary consequences. On the other side it is

equally necessary that everything that takes place should be fixedly

determined according to laws of nature. This necessity of nature is

likewise not an empirical conception, just for this reason, that it

involves the motion of necessity and consequently of a priori

cognition. But this conception of a system of nature is confirmed by

experience; and it must even be inevitably presupposed if experience

itself is to be possible, that is, a connected knowledge of the objects

of sense resting on general laws. Therefore freedom is only an idea of

reason, and its objective reality in itself is doubtful; while nature

is a concept of the understanding which proves, and must necessarily

prove, its reality in examples of experience. |

すべての人間は、自由意志を自分自

身に帰属させる。それゆえ、行動に関するすべての判断は、実際には行われなかったとしても、そうすべきであった行動として下される。しかし、この自由は経

験の概念ではなく、また、そうであるはずもない。なぜなら、自由が必然的な帰結として想定されることの反対が経験によって示されるとしても、自由は依然と

して残るからだ。一方で、起こることはすべて、自然法則に従って固定的に決定される必要がある。この自然の必然性もまた経験的な概念ではなく、必然的な運

動、ひいてはア・プリオリな認識を伴うという理由からである。しかし、この自然の体系の概念は経験によって確認されており、経験そのものが可能であるため

には、すなわち、一般的な法則に基づく感覚対象の関連知識であるためには、必然的に前提されなければならない。したがって、自由とは理性の観念にすぎず、

その客観的な現実性は疑わしい。一方、自然とは理解の概念であり、経験の例によってその現実性を証明し、必然的に証明しなければならない。 |

| There

arises from this a dialectic of reason, since the freedom attributed to

the will appears to contradict the necessity of nature, and placed

between these two ways reason for speculative purposes finds the road

of physical necessity much more beaten and more appropriate than that

of freedom; yet for practical purposes the narrow footpath of freedom

is the only one on which it is possible to make use of reason in our

conduct; hence it is just as impossible for the subtlest philosophy as

for the commonest reason of men to argue away freedom. Philosophy must

then assume that no real contradiction will be found between freedom

and physical necessity of the same human actions, for it cannot give up

the conception of nature any more than that of freedom. |

意

志に帰属する自由は自然の必然性と矛盾するように見えるため、このことから理性の弁証法が生じる。思弁的な目的のために理性を働かせる場合、物理的な必然

性の道は、自由の道よりもはるかに踏み固められ、より適切であるように見える。しかし実際的な目的のためには、自由という狭い小道こそが、行動において理

性を利用できる唯一の道である。それゆえ、最も洗練された哲学であろうと、最もありふれた人間の理性であろうと、自由を論破することは不可能である。哲学

は、自由と同一の人間の行動における物理的必然性との間に真の矛盾は見出されないと仮定しなければならない。なぜなら、哲学は自然の概念を放棄することは

できないからだ。 |

| Nevertheless,

even though we should never be able to comprehend how freedom is

possible, we must at least remove this apparent contradiction in a

convincing manner. For if the thought of freedom contradicts either

itself or nature, which is equally necessary, it must in competition

with physical necessity be entirely given up. |

とはいえ、自由がどのようにして可

能なのかを理解することは決してできないとしても、少なくともこの明白な矛盾を説得力のある方法で取り除く必要がある。なぜなら、自由という考えが、それ

自体または同様に必要な自然のいずれかと矛盾するならば、物理的な必要性との競争において、自由という考えは完全に放棄されなければならないからだ。 |

| It

would, however, be impossible to escape this contradiction if the

thinking subject, which seems to itself free, conceived itself in the

same sense or in the very same relation when it calls itself free as

when in respect of the same action it assumes itself to be subject to

the law of nature. Hence it is an indispensable problem of speculative

philosophy to show that its illusion respecting the contradiction rests

on this, that we think of man in a different sense and relation when we

call him free and when we regard him as subject to the laws of nature

as being part and parcel of nature. It must therefore show that not

only can both these very well co-exist, but that both must be thought

as necessarily united in the same subject, since otherwise no reason

could be given why we should burden reason with an idea which, though

it may possibly without contradiction be reconciled with another that

is sufficiently established, yet entangles us in a perplexity which

sorely embarrasses reason in its theoretic employment. This duty,

however, belongs only to speculative philosophy. The philosopher then

has no option whether he will remove the apparent contradiction or

leave it untouched; for in the latter case the theory respecting this

would be bonum vacans, into the possession of which the fatalist would

have a right to enter and chase all morality out of its supposed domain

as occupying it without title. |

し

かし、もし自由であると思われる思考主体が、自らを自由と呼ぶ場合と、同じ行為に関して自らを自然法則に従属する主体であるとみなす場合とで、同じ意味ま

たはまったく同じ関係において自らを捉えているのであれば、この矛盾から逃れることは不可能である。したがって、自由と呼ぶときと、自然の一部であり自然

法則に従属する存在として見る場合とで、人間を異なる意味と関係において考えているという点に、その矛盾に関する幻想の根拠があることを示すことは、思弁

哲学にとって不可欠な問題である。したがって、両者は共存できるだけでなく、同じ対象において必然的に結びついていると考えなければならないことを示さな

ければならない。そうでなければ、矛盾なく十分に確立された別の考えと調和する可能性があるにもかかわらず、理論的な使用において理性をひどく困惑させる

困惑に私たちを巻き込む考えを理性に負担させる理由が与えられないからだ。しかし、この義務は思索哲学のみに属する。したがって、哲学者には、見かけ上の

矛盾を解消するか、そのままにしておくかという選択肢はない。なぜなら、後者の場合、この理論は「空席の善」となり、宿命論者はそこに権利を持って入り込

み、その領域から道徳性をすべて追い出す権利を持つことになるからだ。 |

| We

cannot however as yet say that we are touching the bounds of practical

philosophy. For the settlement of that controversy does not belong to

it; it only demands from speculative reason that it should put an end

to the discord in which it entangles itself in theoretical questions,

so that practical reason may have rest and security from external

attacks which might make the ground debatable on which it desires to

build. |

しかし、我々はまだ、

実用的な哲学の限界に触れているとは言えない。その論争の解決は、実用的な哲学の領域ではない。それは、理論的な問題で自らを混乱させる不和に終止符を打

つことを思弁的な理性に要求するだけである。そうすれば、実用的な理性は、その構築を望む基盤を議論の余地のあるものにする外部からの攻撃から、休息と安

全を得ることができる。 |

| The claims to freedom of will

made even by common reason are founded on the consciousness and the

admitted supposition that reason is independent of merely subjectively

determined causes which together constitute what belongs to sensation

only and which consequently come under the general designation of

sensibility. Man considering himself in this way as an intelligence

places himself thereby in a different order of things and in a relation

to determining grounds of a wholly different kind when on the one hand

he thinks of himself as an intelligence endowed with a will, and

consequently with causality, and when on the other he perceives himself

as a phenomenon in the world of sense (as he really is also), and

affirms that his causality is subject to external determination

according to laws of nature. Now he soon becomes aware that both can

hold good, nay, must hold good at the same time. For there is not the

smallest contradiction in saying that a thing in appearance (belonging

to the world of sense) is subject to certain laws, of which the very

same as a thing or being in itself is independent, and that he must

conceive and think of himself in this twofold way, rests as to the

first on the consciousness of himself as an object affected through the

senses, and as to the second on the consciousness of himself as an

intelligence, i.e., as independent on sensible impressions in the

employment of his reason (in other words as belonging to the world of

understanding). |

一般的な理性によってさえ主張される自由意志の主張は、意識と、理性は

感覚のみに属するものを構成する、単に主観的に決定された原因から独立しているという認められた仮定に基づいている。このように自らを理性として考える人

間は、一方では自らを意志、ひいては因果性を持つ理性として考え、他方では自らを感覚界における現象(実際にもそうである)として考え、自らの因果性が自

然法則に従って外的決定に従属していると主張する。そして、やがて彼は、両者が同時に成り立つ可能性がある、いや、同時に成り立たなければならないことに

気づく。感覚の世界に属する)外見上の事物が、それ自体の事物や存在が従属する特定の法則に従うという主張には、いささかの矛盾もない。また、彼は自分自

身をこの二重の方法で考え、理解しなければならない。最初のものは感覚を通して影響を受ける対象としての自己の意識に、2番目のものは理性の使用において

感覚的印象から独立した知性としての自己の意識に、すなわち、理解の世界に属するものとして(言い換えれば、)基づいている。 |

| Hence it comes to pass that man

claims the possession of a will which takes no account of anything that

comes under the head of desires and inclinations and, on the contrary,

conceives actions as possible to him, nay, even as necessary which can

only be done by disregarding all desires and sensible inclinations. The

causality of such actions lies in him as an intelligence and in the

laws of effects and actions [which depend] on the principles of an

intelligible world, of which indeed he knows nothing more than that in

it pure reason alone independent of sensibility gives the law; moreover

since it is only in that world, as an intelligence, that he is his

proper self (being as man only the appearance of himself), those laws

apply to him directly and categorically, so that the incitements of

inclinations and appetites (in other words the whole nature of the

world of sense) cannot impair the laws of his volition as an

intelligence. Nay, he does not even hold himself responsible for the

former or ascribe them to his proper self, i.e., his will: he only

ascribes to his will any indulgence which he might yield them if he

allowed them to influence his maxims to the prejudice of the rational

laws of the will. |

それゆえ、人は、欲望や傾向の範疇に入るものを一切考慮に入れない意志 の所有を主張し、それどころか、行動を自分にとって可能であると、いや、むしろ、すべての欲望や感覚的な傾向を無視することによってのみ可能となる必要で あるとさえ考える。そのような行動の因果関係は、知性としての彼と、知性ある世界における原理に依存する効果と行動の法則に存在する。彼は、知性ある世界 において、純粋理性だけが感性から独立して法則を与えることを知っているが、それ以上のことは何も知らない。さらに、知性として、彼が彼自身であるのは、 その世界においてのみであるため(人間として、彼は自分の外見だけである)、 理性としてのみ、彼は本来の自己である(人間として存在しているのは、その外見にすぎない)。それゆえ、それらの法則は彼に直接かつ明確に適用される。そ のため、傾向や欲望の誘因(言い換えれば、感覚世界の性質のすべて)は、理性としての彼の意志の法則を損なうことはできない。いや、彼はそれらを自分の責 任だと考えたり、自分の本質である自己、すなわち自分の意志に帰するとも考えない。彼は、自分の意志が理性の意志の法則に反して自分の格律に影響を与える ことを許した場合に、それらに甘んじることを自分の意志に帰するだけである。 |

| When practical reason thinks

itself into a world of understanding, it does not thereby transcend its

own limits, as it would if it tried to enter it by intuition or

sensation. The former is only a negative thought in respect of the

world of sense, which does not give any laws to reason in determining

the will and is positive only in this single point that this freedom as

a negative characteristic is at the same time conjoined with a

(positive) faculty and even with a causality of reason, which we

designate a will, namely a faculty of so acting that the principle of

the actions shall conform to the essential character of a rational

motive, i.e., the condition that the maxim have universal validity as a

law. But were it to borrow an object of will, that is, a motive, from

the world of understanding, then it would overstep its bounds and

pretend to be acquainted with something of which it knows nothing. The

conception of a world of the understanding is then only a point of view

which reason finds itself compelled to take outside the appearances in

order to conceive itself as practical, which would not be possible if

the influences of the sensibility had a determining power on man, but

which is necessary unless he is to be denied the consciousness of

himself as an intelligence and, consequently, as a rational cause,

energizing by reason, that is, operating freely. This thought certainly

involves the idea of an order and a system of laws different from that

of the mechanism of nature which belongs to the sensible world; and it

makes the conception of an intelligible world necessary (that is to

say, the whole system of rational beings as things in themselves). But

it does not in the least authorize us to think of it further than as to

its formal condition only, that is, the universality of the maxims of

the will as laws, and consequently the autonomy of the latter, which

alone is consistent with its freedom; whereas, on the contrary, all

laws that refer to a definite object give heteronomy, which only

belongs to laws of nature and can only apply to the sensible world. |

実践理性が理解の世界に自らを思考するとき、直観や感覚によってそれを

試みる場合のように、それによって自身の限界を超越することはない。感覚の世界に関して、前者は単に否定的な思考にすぎず、意志を決定する際に理性にいか

なる法則も与えることはなく、この否定的な特性としての自由が同時に(肯定的な)能力と結びついているという点においてのみ肯定的である。すなわち、行為

の原理が理性的な動機の本質的特性に適合するような行動をとる能力、すなわち、格律が普遍的な法則として妥当する条件を意味する。しかし、意志の対象、す

なわち動機を理解の世界から借りるのであれば、それは限界を超え、何も知らないのに何かに精通しているかのようにふるまうことになる。理解の世界という概

念は、理性が実践的であると考えるために、外見とは別に捉えざるを得ない視点に過ぎない。しかし、感性による影響が人間に決定権を与えるのであれば、それ

は不可能である。理性によって動機づけられ、つまり自由に活動する知性として、また理性的な原因として、自己の意識を否定しない限り、それは必要である。

この考えには、感覚的世界に属する自然のメカニズムとは異なる、秩序と法則の体系という考えが確かに含まれている。そして、理解可能な世界(すなわち、そ

れ自体として存在する理性的な存在の全体的な体系)という概念が必要となる。しかし、それは、形式的な条件、すなわち、法則としての意志の格律の普遍性、

そしてその結果として、自由と矛盾しない唯一の自律性としてのみ、それを考えることを私たちに許可するものではない。それとは逆に、明確な対象を参照する

すべての法は、自然法則のみに属し、感覚世界にのみ適用できる他律を与える。 |

| But reason would overstep all

its bounds if it undertook to explain how pure reason can be practical,

which would be exactly the same problem as to explain how freedom is

possible. |

しかし、純粋理性が実践的であることを説明しようとするなら、理性は限

界を超えてしまうだろう。それは、自由がどのようにして可能であるかを説明することとまったく同じ問題である。 |

| For we can explain nothing but

that which we can reduce to laws, the object of which can be given in

some possible experience. But freedom is a mere idea, the objective

reality of which can in no wise be shown according to laws of nature,

and consequently not in any possible experience; and for this reason it

can never be comprehended or understood, because we cannot support it

by any sort of example or analogy. It holds good only as a necessary

hypothesis of reason in a being that believes itself conscious of a

will, that is, of a faculty distinct from mere desire (namely, a

faculty of determining itself to action as an intelligence, in other

words, by laws of reason independently on natural instincts). Now where

determination according to laws of nature ceases, there all explanation

ceases also, and nothing remains but defence, i.e., the removal of the

objections of those who pretend to have seen deeper into the nature of

things, and thereupon boldly declare freedom impossible. We can only

point out to them that the supposed contradiction that they have

discovered in it arises only from this, that in order to be able to

apply the law of nature to human actions, they must necessarily

consider man as an appearance: then when we demand of them that they

should also think of him qua intelligence as a thing in itself, they

still persist in considering him in this respect also as an appearance.

In this view it would no doubt be a contradiction to suppose the

causality of the same subject (that is, his will) to be withdrawn from

all the natural laws of the sensible world. But this contradiction

disappears, if they would only bethink themselves and admit, as is

reasonable, that behind the appearances there must also lie at their

root (although hidden) the things in themselves, and that we cannot

expect the laws of these to be the same as those that govern their

appearances. |

なぜなら、我々は法則に還元できるものしか説明できないからだ。その対

象は、何らかの経験によって与えられる可能性がある。しかし、自由とは単なる観念であり、その客観的な実在性は、自然法則によって示すことはできないし、

したがって、いかなる経験によって示すこともできない。このため、自由は決して理解されることはない。なぜなら、我々はそれをいかなる種類の例や類推に

よっても裏付けることができないからだ。それは、意志を意識していると信じる存在、つまり、単なる欲求とは異なる能力(すなわち、知性として行動すること

を自ら決定する能力、言い換えれば、自然的な本能とは無関係に理性の法則によって)の、理性の必要仮説としてのみ妥当する。さて、自然法則に従った決定が

停止する場所では、あらゆる説明も停止し、防御、すなわち、物事の本質をより深く見通したかのように装い、自由は不可能だと大胆に宣言する人々の反対意見

を退けること以外には何も残らない。彼らが発見したとされる矛盾は、自然法則を人間の行動に適用できるようにするためには、人間を必然的に現象として捉え

なければならないという事実から生じるだけである。そして、人間をそれ自体として存在する知性として考えるよう彼らに要求しても、彼らは依然として、この

点でも人間を現象として捉えようとする。この見解では、同じ主体(すなわち、彼の意志)の因果関係が感覚世界のすべての自然法則から取り除かれると考える

のは、確かに矛盾しているだろう。しかし、この矛盾は、彼らが自らを顧みて、道理にかなったように、外見の背後には(隠されているとはいえ)物自体も存在

しなければならないことを認めさえすれば、消える。そして、これらの法則が外見を支配する法則と同じであると期待することはできない。 |

| The subjective impossibility of

explaining the freedom of the will is identical with the impossibility

of discovering and explaining an interest * which man can take in the

moral law. Nevertheless he does actually take an interest in it, the

basis of which in us we call the moral feeling, which some have falsely

assigned as the standard of our moral judgement, whereas it must rather

be viewed as the subjective effect that the law exercises on the will,

the objective principle of which is furnished by reason alone. |

意志の自由を説明することの主観的な不可能は、人間が道徳法則に抱く関

心を発見し説明することの不可能と同一である。それにもかかわらず、人間は実際にその関心を持っている。その関心の基礎を、私たちは道徳感情と呼んでい

る。一部の人々はこれを誤って私たちの道徳的判断の基準として位置づけているが、むしろこれは、道徳法則が意志に及ぼす主観的な効果であり、その客観的原

則は理性のみによって与えられると見るべきである。 |

| * Interest is that by which

reason becomes practical, i.e., a cause determining the will. Hence we

say of rational beings only that they take an interest in a thing;

irrational beings only feel sensual appetites. Reason takes a direct

interest in action then only when the universal validity of its maxims

is alone sufficient to determine the will. Such an interest alone is

pure. But if it can determine the will only by means of another object

of desire or on the suggestion of a particular feeling of the subject,

then reason takes only an indirect interest in the action, and, as

reason by itself without experience cannot discover either objects of

the will or a special feeling actuating it, this latter interest would

only be empirical and not a pure rational interest. The logical

interest of reason (namely, to extend its insight) is never direct, but

presupposes purposes for which reason is employed. |

*

関心とは、理由が現実的になること、すなわち、意志を決定する原因である。したがって、理性的な存在は、ある事柄に関心を持つとだけ言える。非理性的な存

在は、感覚的な欲求を感じるだけである。理性が直接的に行動に関心を持つのは、その格律の普遍的な妥当性のみが意志を決定するのに十分な場合のみである。

そのような関心のみが純粋である。しかし、それが別の欲望の対象によって、あるいは主体の特定の感情の示唆によってのみ意志を決定できるのであれば、理性

は行動に対して間接的な関心しか持たない。そして、経験のない理性だけでは、意志の対象やそれを動かす特別な感情を発見することはできないため、この後者

の関心は経験に基づくものであり、純粋な理性的関心ではない。理性の論理的な関心(すなわち、洞察を深めること)は決して直接的ではなく、理性が用いられ

る目的を前提としている。 |

| In order indeed that a rational

being who is also affected through the senses should will what reason

alone directs such beings that they ought to will, it is no doubt

requisite that reason should have a power to infuse a feeling of

pleasure or satisfaction in the fulfilment of duty, that is to say,

that it should have a causality by which it determines the sensibility

according to its own principles. |

感覚によっても影響を受ける理性的存在者が、理性のみが指示するような 意志を持つためには、理性が義務の遂行における喜びや満足感という感情を吹き込む力を持つことが必要であることは疑いない。つまり、理性が自身の原則に 従って感覚を決定する因果関係を持つことが必要である。 |

| But it is quite impossible to

discern, i.e., to make it intelligible a priori, how a mere thought,

which itself contains nothing sensible, can itself produce a sensation

of pleasure or pain; for this is a particular kind of causality of

which as of every other causality we can determine nothing whatever a

priori; we must only consult experience about it. But as this cannot

supply us with any relation of cause and effect except between two

objects of experience, whereas in this case, although indeed the effect

produced lies within experience, yet the cause is supposed to be pure

reason acting through mere ideas which offer no object to experience,

it follows that for us men it is quite impossible to explain how and

why the universality of the maxim as a law, that is, morality,

interests. This only is certain, that it is not because it interests us

that it has validity for us (for that would be heteronomy and

dependence of practical reason on sensibility, namely, on a feeling as

its principle, in which case it could never give moral laws), but that

it interests us because it is valid for us as men, inasmuch as it had

its source in our will as intelligences, in other words, in our proper

self, and what belongs to mere appearance is necessarily subordinated

by reason to the nature of the thing in itself. |

しかし、感覚的なものを何も含まない単なる思考が、それ自体で快楽や苦

痛の感覚を生み出すことができるのか、つまり、それをア・プリオリに理解可能にするのは、まったく不可能である。なぜなら、これは特定の因果関係であり、

他のあらゆる因果関係と同様に、ア・プリオリに決定できるものは何もないからだ。これについては、経験に頼るしかない。しかし、これは経験の対象である2

つの事物間の因果関係を除いては、私たちに因果関係を一切与えることができない。この場合、確かに生じる効果は経験の範囲内にあるが、原因は経験に何の対

象も提供しない純粋理性が単なる観念を通じて作用すると想定されている。したがって、私たち人間にとって、格律としての格律の普遍性、つまり道徳がなぜ、

どのようにして関心を持つのかを説明することはまったく不可能である。ただ確かなのは、それが私たちにとって有益だから妥当性を持つわけではないというこ

とだ(そうであれば、それは実践理性が感性、すなわち感情をその原理として従属する他律であり、その場合、道徳法則を与えることは決してできない)。そう

ではなく、

それは、それが人間としての私たちにとって妥当であるからこそ、私たちにとって興味深いのである。なぜなら、それは私たちの意志、すなわち私たちの本質的

な自己にその源泉があるからであり、単なる外見に属するものは、必然的に本質的なものに従属するからである。 |

| The question then, "How a

categorical imperative is possible," can be answered to this extent,

that we can assign the only hypothesis on which it is possible, namely,

the idea of freedom; and we can also discern the necessity of this

hypothesis, and this is sufficient for the practical exercise of

reason, that is, for the conviction of the validity of this imperative,

and hence of the moral law; but how this hypothesis itself is possible

can never be discerned by any human reason. On the hypothesis, however,

that the will of an intelligence is free, its autonomy, as the

essential formal condition of its determination, is a necessary

consequence. |

それでは、「定言命法はどのようにして可能なのか」という問いに対して

は、この命題が可能な唯一の仮説、すなわち自由という考えを仮定できるという点まで答えられる。また、この仮説の必然性も見極めることができる。これは、

理性を実践的に行使する上で十分であり、すなわち、この命題の妥当性、ひいては道徳法則の妥当性を確信するのに十分である。しかし、この仮説自体がどのよ

うにして可能なのかは、いかなる人間の理性によっても見極めることは決してできない。しかし、知性の意志が自由であるという仮説を前提とすれば、その決定

の本質的な形式的条件としての自律性は、必然的な帰結である。 |

| Moreover, this freedom of will

is not merely quite possible as a hypothesis (not involving any

contradiction to the principle of physical necessity in the connexion

of the phenomena of the sensible world) as speculative philosophy can

show: but further, a rational being who is conscious of causality

through reason, that is to say, of a will (distinct from desires), must

of necessity make it practically, that is, in idea, the condition of

all his voluntary actions. But to explain how pure reason can be of

itself practical without the aid of any spring of action that could be

derived from any other source, i.e., how the mere principle of the

universal validity of all its maxims as laws (which would certainly be

the form of a pure practical reason) can of itself supply a spring,

without any matter (object) of the will in which one could antecedently

take any interest; and how it can produce an interest which would be

called purely moral; or in other words, how pure reason can be

practicalto explain this is beyond the power of human reason, and all

the labour and pains of seeking an explanation of it are lost. |

さらに、この自由意志は、観念哲学が示すように、単に可能性があるとい

うだけでなく(感覚世界の現象の関連性における物理的必然性の原則に矛盾しない)、さらに、理性によって因果関係を意識する理性的存在、すなわち、意志

(欲望とは異なる)を意識する存在は、必然的にそれを実践的に、つまり、考えの中で、自発的な行動の条件とする必要がある。しかし、いかなる他の源泉から

も導き出される行動の源泉の助けを借りることなく、純粋理性がそれ自体で実践的であることができる理由、すなわち、純粋実践理性の形であるに違いない、あ

らゆる格律の普遍妥当性の原理がそれ自体で源泉を供給できる理由、

すなわち、意志の対象(対象)が先行して関心を持つことができるものではなく、いかにして純粋に道徳的と呼ばれる関心を生み出すことができるのか、あるい

は言い換えれば、いかにして純粋理性が実践的であるのかを説明することは、人間の理性の力の範囲を超えており、それを説明しようとする労力や苦心はすべて

無駄である。 |

| It is just the same as if I

sought to find out how freedom itself is possible as the causality of a

will. For then I quit the ground of philosophical explanation, and I

have no other to go upon. I might indeed revel in the world of

intelligences which still remains to me, but although I have an idea of

it which is well founded, yet I have not the least knowledge of it, nor

an I ever attain to such knowledge with all the efforts of my natural

faculty of reason. It signifies only a something that remains over when

I have eliminated everything belonging to the world of sense from the

actuating principles of my will, serving merely to keep in bounds the

principle of motives taken from the field of sensibility; fixing its

limits and showing that it does not contain all in all within itself,

but that there is more beyond it; but this something more I know no

further. Of pure reason which frames this ideal, there remains after

the abstraction of all matter, i.e., knowledge of objects, nothing but

the form, namely, the practical law of the universality of the maxims,

and in conformity with this conception of reason in reference to a pure

world of understanding as a possible efficient cause, that is a cause

determining the will. There must here be a total absence of springs;

unless this idea of an intelligible world is itself the spring, or that

in which reason primarily takes an interest; but to make this

intelligible is precisely the problem that we cannot solve. |

それは、意志の因果関係として自由そのものがどのように可能なのかを解

明しようとするのとまったく同じことである。なぜなら、そうすれば私は哲学的な説明の土台を離れることになり、他に頼るものがないからだ。確かに、私には

まだ知性の世界が残っているので、その世界に浸ることはできるかもしれない。しかし、私はその世界について確かな考えを持っているが、その世界について

まったく知識がない。また、生まれ持った理性の能力を最大限に駆使しても、そのような知識を得ることは決してないだろう。それは、私の意志の作用原理から

感覚界に属するものをすべて排除した後に残るものであり、単に感性界から得られた動機の原理を一定の範囲内に留める役割を果たすだけである。その限界を定

め、それ自体がすべてを内包しているわけではなく、その先にもっと何かがあることを示す。しかし、この「もっと何か」については、私はそれ以上何も知らな

い。この理想を形作る純粋理性には、すべての物質、すなわち対象の知識が抽象された後、形式、すなわち格律の普遍性の実践的法則のみが残る。そして、理解

の純粋世界におけるこの理性の概念に準拠し、可能な有効原因として、すなわち意志を決定する原因として、

この理解可能な世界という考え自体が「ばね」であるか、あるいは理性が最初に興味を抱く対象であるばねでなければ、ばねは存在しないはずである。しかし、

この理解を可能にするということは、まさに私たちが解決できない問題なのである。 |

| Here now is the extreme limit of

all moral inquiry, and it is of great importance to determine it even

on this account, in order that reason may not on the one band, to the

prejudice of morals, seek about in the world of sense for the supreme

motive and an interest comprehensible but empirical; and on the other

hand, that it may not impotently flap its wings without being able to

move in the (for it) empty space of transcendent concepts which we call

the intelligible world, and so lose itself amidst chimeras. For the

rest, the idea of a pure world of understanding as a system of all

intelligences, and to which we ourselves as rational beings belong

(although we are likewise on the other side members of the sensible

world), this remains always a useful and legitimate idea for the

purposes of rational belief, although all knowledge stops at its

threshold, useful, namely, to produce in us a lively interest in the

moral law by means of the noble ideal of a universal kingdom of ends in

themselves (rational beings), to which we can belong as members then

only when we carefully conduct ourselves according to the maxims of

freedom as if they were laws of nature. |

ここに、あらゆる道徳的探究の極限がある。この理由から、道徳を損なう

ことなく、理性が感覚の世界で究極の動機や

理解はできるが経験的な究極の動機と利益を感覚の世界に求めたり、他方で、我々が「理解可能な世界」と呼ぶ超越的概念の空虚な空間で動くことができずに無

力に羽ばたき、キメラの中で自分を見失ったりすることがないようにするためである。それ以外に、すべての知性の体系としての純粋な理解の世界という考え方

があり、そこに我々自身も理性的存在として属している(ただし、我々は感覚的世界の他の側面にも属している)。この考え方は、理性的信念の目的のためには

常に有用かつ正当な考え方であり続けるが、すべての知識はその入り口で止まってしまう。その敷居で、つまり、道徳律に対する生き生きとした関心を私たちの

中に生み出すのに役立つ。すなわち、私たち自身が(理性的存在としての)目的の普遍的な王国という高貴な理想によって、その一員として所属できるのは、私

たちが自然法則であるかのように自由の格律に従って慎重に行動するときだけである。 |

| Concluding Remark The speculative employment of reason with respect to nature leads to the absolute necessity of some supreme cause of the world: the practical employment of reason with a view to freedom leads also to absolute necessity, but only of the laws of the actions of a rational being as such. Now it is an essential principle of reason, however employed, to push its knowledge to a consciousness of its necessity (without which it would not be rational knowledge). It is, however, an equally essential restriction of the same reason that it can neither discern the necessity of what is or what happens, nor of what ought to happen, unless a condition is supposed on which it is or happens or ought to happen. In this way, however, by the constant inquiry for the condition, the satisfaction of reason is only further and further postponed. Hence it unceasingly seeks the unconditionally necessary and finds itself forced to assume it, although without any means of making it comprehensible to itself, happy enough if only it can discover a conception which agrees with this assumption. It is therefore no fault in our deduction of the supreme principle of morality, but an objection that should be made to human reason in general, that it cannot enable us to conceive the absolute necessity of an unconditional practical law (such as the categorical imperative must be). It cannot be blamed for refusing to explain this necessity by a condition, that is to say, by means of some interest assumed as a basis, since the law would then cease to be a supreme law of reason. And thus while we do not comprehend the practical unconditional necessity of the moral imperative, we yet comprehend its incomprehensibility, and this is all that can be fairly demanded of a philosophy which strives to carry its principles up to the very limit of human reason. |

結びの言葉 自然に対する理性の思弁的な使用は、世界の何らかの至高の原因の絶対的必然性を導き出す。自由に対する理性の実践的な使用もまた、絶対的必然性を導き出す が、それは理性的存在の行為の法則についてのみである。さて、理性の本質的な原理は、どのように理性を働かせるにせよ、その知識を必然性の意識に押し上げ ることである(これがなければ理性的な知識とはいえない)。しかし、理性が、あること、起こること、起こるべきことの必然性を見分けることができないの は、同じ理性の同様に本質的な制約である。しかし、このように、条件をたえず探求することによって、理性の満足はますます先延ばしにされるだけである。そ れゆえ、理性は絶えず無条件に必要なものを探し求め、それを自らに理解させる手段がないにもかかわらず、それを仮定せざるを得ないことに気づく。したがっ て、われわれが道徳の至高の原理を推論することに誤りがあるのではなく、(定言命法がそうでなければならないような)無条件の実践法則の絶対的必然性を考 えることができないという、人間の理性一般に対してなされるべき反論なのである。この必然性を条件によって、つまり根拠として想定される何らかの利害に よって説明することを拒否することを非難することはできない。こうしてわれわれは、道徳的命令の実際的な無条件の必然性を理解することはできないが、その 不可解さは理解することができるのであり、このことは、その原理を人間の理性の限界にまで引き上げようと努力する哲学に正当に要求されうるすべてなのであ る。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆