道徳の形而上学的基礎づけ

(ポータル:全文へのリンク集)

Grundlegung

zur Metaphysik der Sitten

Immanuel Kant 1785 - Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals full

audiobook

☆ カントの定言命法とは『人倫の形而上学の 基礎づけ(あるいは、道徳形而上学の基礎づけ)』 (Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten, 1785) において示され、1781年『純粋理性批判』Kant, Immanuel: Kritik der reinen Vernunft. Riga: J. F. Hartknoch 1781, 856 Seiten, Erstdruck.に、理論的に修正されたもの。『人倫の形而上学の基礎づけ』(じんりんのけいじじょうがくのきそづけ、独: Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten)は、1785年に出版されたイマヌエル・カントの倫理学・形而上学に関する著作。3年後の1788年に出版される『実践理性批判』と共に実 践哲 学を扱っている。実践理性批判、人倫の形而上学と並びカント倫理学の主要著書の一つである。『道徳形而上学の基礎づけ』や『道徳形而上学原論』とも訳され てきた。

☆ 「失敗するのはわかっている、でも求めつづけなきゃいけないんだ」——(スラヴォイ・ジジェク 2019:121)

☆「よくよく見てみれば、道徳律とは純然たる欲望にすぎない」——ジャック・ラカン(冨樫 2003:320)

★人倫の形而上学的基礎づけ(解説)

★00:序文「人倫の形而上学的基礎づけ」

★01:第1章:道徳についての普通の合理的知識から哲学的なも のへの移行

☆

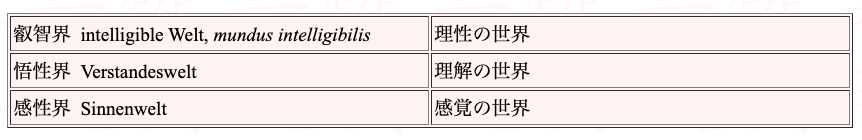

世界の領域区分(→「カントの宗教概念」より)

★ 読解のポイント

1) ここでの道徳性は、あらゆる人間のそれではなく、理性的存在者であるかぎりの人間の能力のこと

2) ここでの理性は、理論理性のことではなく、実践理性のこと である。

3)

ここでの「形而上学」「基礎づけ」「道徳」についてのカントの用語法には注意せよ。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆