グアテマラ内戦

Guatemalan Civil War

Queqchí

people carrying their loved one's remains after an exhumation in

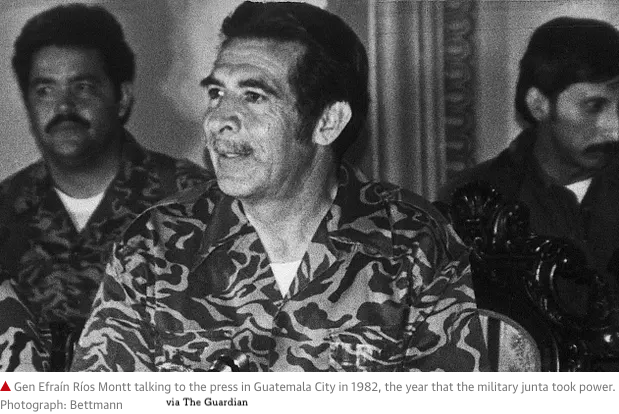

Cambayal in Alta Verapaz/ José Efraín Ríos Montt, 1926-2018

☆ グアテマラ内戦(Guatemalan Civil War)は、1960年から1996年までグアテマラ政府と様々な左派反乱軍との間で戦われたグアテマラの内戦である。政府 軍は内戦中、グアテマラのマヤ系住民に対してジェノサイドを行い、市民に対する広範な人権侵害を行ったとして非難されている[15]。この闘争の背景に は、不公平な土地分配という長年の問題があった。主にヨーロッパ系の裕福なグアテマラ人と、アメリカのユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーなどの外国企業 が土地の大部分を支配し、その見返りとしてほとんど税金を払っていなかった。1944年と1951年に行われたグアテマラ革命の民主的選挙で、労働条件の改善と土地分配の実施を目指した民衆左派政権が誕生した。1954年、アメリ カの支援を受けたクーデターにより、改革を阻止するためカルロス・カスティージョ・アルマスの軍事政権が樹立され、その後、一連の右派軍事独裁者が続い た。内戦は1960年11月13日に始まった。左翼の下級将校のグループがイディゴラス・フエンテス将軍の政府に対する反乱を起こし、失敗した。生き残った将 校たちはMR-13として知られる反乱運動を起こした。1970年、カルロス・マヌエル・アラナ・オソリオ大佐が、制度的民主党(PID)を代表する一連 の軍事独裁者の第一号となった。PIDは、カルロス・アラナ大佐の2人の子分(1974年のキェル・エウジェニオ・ラウゲルド・ガルシア将軍と1978年 のロメオ・ルーカス・ガルシア将軍)を支持する不正選挙によって、12年間グアテマラの政治を支配した。PIDは、1982年3月23日の軍事クーデター でエフライン・リオス・モント将軍が下級陸軍将校のグループとともに権力を掌握すると、グアテマラ政治への支配力を失った。1970年代には、先住民や農 民の大規模な集団の間で社会的不満が続いた。多くの人々が反政府グループを組織し、政府軍に抵抗し始めた[16]。紛争中、14万人から20万人が殺害され、あるいは強制的に「失踪」させられたと推定されており、その中には4万人から5万人の失踪者も含まれている。戦 闘は政府軍と反政府グループとの間で行われたが、暴力の多くは、1960年代半ば以降、グアテマラ国家による民間人に対する一方的な暴力の大規模な調整 キャンペーンであった。軍の情報機関は、国家に反対する人々の殺害と「失踪」を調整した。1996年和平合意締結。2009年、グアテマラの裁判所は、強制失踪を命じた罪で初めて有罪判決を受けた元軍事総監フェリペ・クサネロに判決を下した。2013年、政府は 1982年から83年の統治時代に1,700人以上の先住民イクシルマヤを殺害・失踪させたジェノサイドの罪で、エフライン・リオス・モント元大統領の裁 判を実施した。ジェノサイドの容疑は、国連が任命した歴史解明委員会が作成した「沈黙の記憶」報告書に基づいていた。グアテマラの裁判所がマヤの女性が受 けたレイプと虐待を認めたのも、これが初めてだった。報告された1465件のレイプのうち、兵士が94.3パーセントの責任を負っていた[20]。委員会 は、政府が1981年から1983年の間にキチェでジェノサイドを犯した可能性があると結論づけた[8]。リオス・モントは、自国の司法制度によってジェ ノサイドの罪で裁かれた最初の元首であり、有罪が確定し、懲役80年の判決を受けた[21]。彼らは、司法の異常が疑われるとして、裁判のやり直しを求め た。裁判は2015年7月23日に再び始まったが、2018年4月1日にモントが拘留中に死亡するまで、陪審は評決に至らなかった[22](→「グアテマラ内戦・年表」)。

| The Guatemalan Civil War

was a civil war in Guatemala fought from 1960 to 1996 between the

government of Guatemala and various leftist rebel groups. The

government forces have been condemned for committing genocide against

the Maya population of Guatemala during the civil war and for

widespread human rights violations against civilians.[15] The context

of the struggle was based on longstanding issues of unfair land

distribution. Wealthy Guatemalans, mainly European-descended, and

foreign companies such as the American United Fruit Company had

dominated control over much of the land, and paid almost zero taxes in

return – leading to conflicts with the rural indigenous poor who worked

the land under miserable terms. Democratic elections during the Guatemalan Revolution in 1944 and 1951 had brought popular leftist governments to power, who sought to ameliorate working conditions and implement land distribution. A United States-backed coup d'état in 1954 installed the military regime of Carlos Castillo Armas to prevent reform, who was followed by a series of right-wing military dictators. The Civil War started on 13 November 1960, when a group of left-wing junior military officers led a failed revolt against the government of General Ydigoras Fuentes. The surviving officers created a rebel movement known as MR-13. In 1970, Colonel Carlos Manuel Arana Osorio became the first of a series of military dictators representing the Institutional Democratic Party or PID. The PID dominated Guatemalan politics for twelve years through electoral frauds favoring two of Colonel Carlos Arana's protégés (General Kjell Eugenio Laugerud García in 1974 and General Romeo Lucas García in 1978). The PID lost its grip on Guatemalan politics when General Efraín Ríos Montt, together with a group of junior army officers, seized power in a military coup on 23 March 1982. In the 1970s social discontent continued among the large populations of indigenous people and peasants. Many organized into insurgent groups and began to resist the government forces.[16] During the 1980s, the Guatemalan military assured almost absolute government power for five years; it had successfully infiltrated and eliminated enemies in every socio-political institution of the nation, including the political, social, and intellectual classes.[17] In the final stage of the civil war, the military developed a parallel, semi-visible, low profile but high-effect, control of Guatemala's national life.[18] It is estimated that 140,000 to 200,000 people were killed or forcefully "disappeared" during the conflict, including 40,000 to 50,000 disappearances. While fighting took place between government forces and rebel groups, much of the violence was a large coordinated campaign of one-sided violence by the Guatemalan state against the civilian population from the mid-1960s onward. The military intelligence services coordinated killings and "disappearances" of opponents of the state. In rural areas, where the insurgency maintained its strongholds, the government repression led to large massacres of the peasantry, including entire villages. These took place first in the departments of Izabal and Zacapa (1966–68), and in the predominantly Mayan western highlands from 1978 onward. In the early 1980s, the widespread killing of the Mayan people was considered a genocide. Other victims of the repression included activists, suspected government opponents, returning refugees, critical academics, students, left-leaning politicians, trade unionists, religious workers, journalists, and street children.[16] The "Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico" has estimated that government forces committed 93% of human right abuses in the conflict, with 3% committed by the guerrillas.[19] In 2009, Guatemalan courts sentenced former military commissioner Felipe Cusanero, the first person to be convicted of the crime of ordering forced disappearances. In 2013, the government conducted a trial of former president Efraín Ríos Montt on charges of genocide for the killing and disappearances of more than 1,700 indigenous Ixil Maya during his 1982–83 rule. The charges of genocide were based on the "Memoria del Silencio" report – prepared by the UN-appointed Commission for Historical Clarification. This was also the first time that the Guatemalan Court recognized the rape and abuse that Mayan women suffered. Out of the 1465 cases of rape that were reported, soldiers were responsible for 94.3 percent.[20] The Commission concluded that the government could have committed genocide in Quiché between 1981 and 1983.[8] Ríos Montt was the first former head of state to be tried for genocide by his own country's judicial system; he was found guilty and sentenced to 80 years in prison.[21] A few days later, however, the sentence was reversed by the country's high court. They called for a renewed trial because of alleged judicial anomalies. The trial began again on 23 July 2015, but the jury had not reached a verdict before Montt died in custody on 1 April 2018.[22] |

グアテマラ内戦(Guatemalan Civil War)

は、1960年から1996年までグアテマラ政府と様々な左派反乱軍との間で戦われたグアテマラの内戦である。政府軍は内戦中、グアテマラのマヤ系住民に

対してジェノサイドを行い、市民に対する広範な人権侵害を行ったとして非難されている[15]。この闘争の背景には、不公平な土地分配という長年の問題が

あった。主にヨーロッパ系の裕福なグアテマラ人と、アメリカのユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーなどの外国企業が土地の大部分を支配し、その見返りとし

てほとんど税金を払っていなかった。 1944年と1951年に行われたグアテマラ革命の民主的選挙で、労働条件の改善と土地分配の実施を目指した民衆左派政権が誕生した。1954年、アメリ カの支援を受けたクーデターにより、改革を阻止するためカルロス・カスティージョ・アルマスの軍事政権が樹立され、その後、一連の右派軍事独裁者が続い た。 内戦は1960年11月13日に始まった。左翼の下級将校のグループがイディゴラス・フエンテス将軍の政府に対する反乱を起こし、失敗した。生き残った将 校たちはMR-13として知られる反乱運動を起こした。1970年、カルロス・マヌエル・アラナ・オソリオ大佐が、制度的民主党(PID)を代表する一連 の軍事独裁者の第一号となった。PIDは、カルロス・アラナ大佐の2人の子分(1974年のキェル・エウジェニオ・ラウゲルド・ガルシア将軍と1978年 のロメオ・ルーカス・ガルシア将軍)を支持する不正選挙によって、12年間グアテマラの政治を支配した。PIDは、1982年3月23日の軍事クーデター でエフライン・リオス・モント将軍が下級陸軍将校のグループとともに権力を掌握すると、グアテマラ政治への支配力を失った。1970年代には、先住民や農 民の大規模な集団の間で社会的不満が続いた。多くの人々が反政府グループを組織し、政府軍に抵抗し始めた[16]。 1980年代、グアテマラ軍は5年間にわたりほぼ絶対的な政府権力を保証し、政治、社会、知識階級を含む国家のあらゆる社会政治機構に潜入し、敵を排除す ることに成功した[17]。 内戦の最終段階において、軍はグアテマラの国民生活において、並行して、半可視的で、目立たないが効果の高い支配を展開した[18]。 紛争中、14万人から20万人が殺害され、あるいは強制的に「失踪」させられたと推定されており、その中には4万人から5万人の失踪者も含まれている。戦 闘は政府軍と反政府グループとの間で行われたが、暴力の多くは、1960年代半ば以降、グアテマラ国家による民間人に対する一方的な暴力の大規模な調整 キャンペーンであった。軍の情報機関は、国家に反対する人々の殺害と「失踪」を調整した。 反政府勢力が拠点を維持していた農村部では、政府の弾圧によって、村全体を含む農民の大規模な虐殺が行われた。こうした虐殺は、まずイザバル県とサカパ県 で(1966~68年)、1978年以降はマヤ族が多い西部高地で起こった。1980年代初頭、マヤの人々の広範な殺害はジェノサイドとみなされた。その 他の弾圧の犠牲者は、活動家、政府反対派の容疑者、帰還難民、批判的な学者、学生、左派政治家、労働組合員、宗教活動家、ジャーナリスト、ストリートチル ドレンなどであった[16]。「Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico 」は、この紛争における人権侵害の93%は政府軍によるもので、ゲリラによるものは3%であったと推定している[19]。 2009年、グアテマラの裁判所は、強制失踪を命じた罪で初めて有罪判決を受けた元軍事総監フェリペ・クサネロに判決を下した。2013年、政府は 1982年から83年の統治時代に1,700人以上の先住民イクシルマヤを殺害・失踪させたジェノサイドの罪で、エフライン・リオス・モント元大統領の裁 判を実施した。ジェノサイドの容疑は、国連が任命した歴史解明委員会が作成した「沈黙の記憶」報告書に基づいていた。グアテマラの裁判所がマヤの女性が受 けたレイプと虐待を認めたのも、これが初めてだった。報告された1465件のレイプのうち、兵士が94.3パーセントの責任を負っていた[20]。委員会 は、政府が1981年から1983年の間にキチェでジェノサイドを犯した可能性があると結論づけた[8]。リオス・モントは、自国の司法制度によってジェ ノサイドの罪で裁かれた最初の元首であり、有罪が確定し、懲役80年の判決を受けた[21]。彼らは、司法の異常が疑われるとして、裁判のやり直しを求め た。裁判は2015年7月23日に再び始まったが、2018年4月1日にモントが拘留中に死亡するまで、陪審は評決に至らなかった[22]。 |

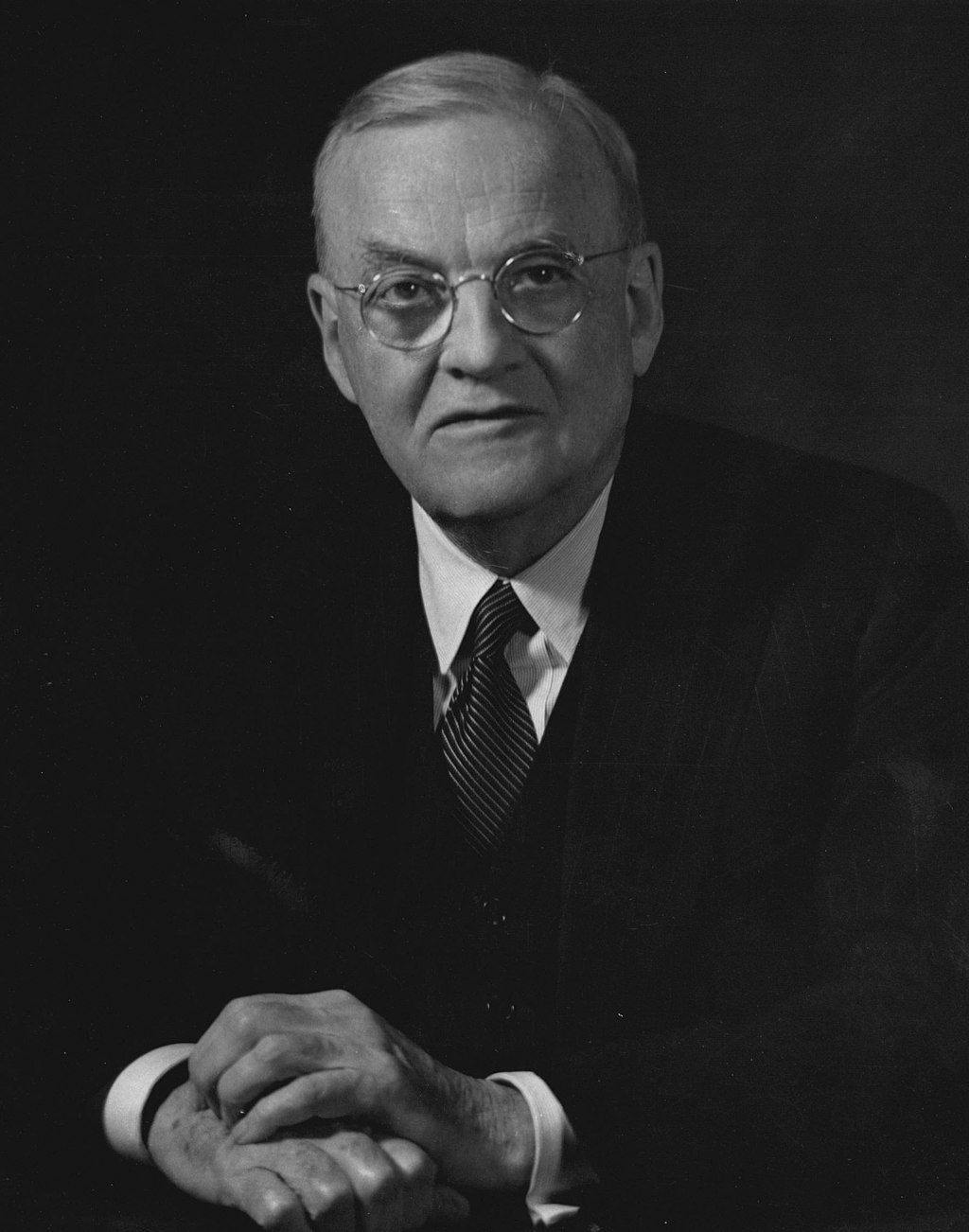

| Background See also: Rafael Carrera, Manuel Estrada Cabrera, José María Orellana, Jorge Ubico, Juan José Arévalo, and United Fruit Company After the 1871 revolution, the Liberal government of Justo Rufino Barrios escalated coffee production in Guatemala, which required much land and many workers. Barrios established the Settler Rule Book, which forced the native population to work for low wages for the landowners, who were Criollos and later German settlers.[23] Barrios also confiscated the common native land, which had been protected during the Spanish Colony and during the Conservative government of Rafael Carrera.[24] He distributed it to his Liberal friends, who became major landowners.[23] In the 1890s, the United States began to implement the Monroe Doctrine, pushing out European colonial powers in Latin America. Its commercial interests established U.S. hegemony over resources and labor in the region. The dictators that ruled Guatemala during the late 19th and early 20th centuries were very accommodating to U.S. business and political interests, because they personally benefitted. Unlike in such nations as Haiti, Nicaragua, and Cuba, the U.S. did not have to use overt military force to maintain dominance in Guatemala. The Guatemalan military/police worked closely with the U.S. military and State Department to secure U.S. interests. The Guatemalan government exempted several U.S. corporations from paying taxes, especially the United Fruit Company. It also privatized and sold off publicly owned utilities, and gave away huge swaths of public land.[25]  President Manuel Estrada Cabrera's official portrait from his last presidential term. During his government, the American United Fruit Company became a major economic and political force in Guatemala. Societal structure Main article: Manuel Estrada Cabrera In 1920, the prince Wilhelm of Sweden visited Guatemala and described Guatemalan society and Estrada Cabrera government in his book Between Two Continents, notes from a journey in Central America, 1920.[26] He analyzed Guatemalan society at the time, pointing out that even though it called itself a "Republic", Guatemala had three sharply defined classes:[27] Criollos: a minority made up of descendants of the Spaniards who conquered Central America; by 1920, the Criollos made up much of the members of both political parties and the elite in the country. For centuries they had intermarried with indigenous peoples and other people of European ancestry. The great majority had some indigenous ancestry but largely identified with European culture.[28] They led the country both politically and intellectually, partly because their education was far superior to that of most of the rest of the residents. Only criollos were admitted to the main political parties,[27] and their families largely controlled and, for the most part, owned the cultivated parts of the country.[28] Ladinos: middle class. Descendants of peoples of indigenous, African, and criollo ancestry, they held almost no political power in 1920. They made up the bulk of artisans, storekeepers, tradesmen, and minor officials.[29] In the eastern part of the country, they worked as agricultural laborers.[29] Indigenous Peoples: The majority of the population was composed of native or indigenous Guatemalans, most of whom were Mayan peoples. Many had little to no formal education. Indigenous people served as soldiers for the Army, and they were often raised to positions of considerable trust.[29] They made up most of the agricultural workers. The prince classified them into three categories: "Mozos colonos": settled on the plantations. Were given a small piece of land to cultivate on their own account, in return for work in the plantations a certain number of months a year, similar to sharecroppers or tenant farmers in the US.[29] "Mozos jornaleros": day-laborers who were contracted to work for certain periods of time.[29] They were paid a daily wage. In theory, each "mozo" was free to dispose of his labor as he or she pleased, but they were bound to the property by economic ties. They could not leave until they had paid off their debt to the owner. They were often victimized by owners, who encouraged them to get into debt by granting credit or lending cash. The owners recorded the accounts and the mozos were usually illiterate and at a disadvantage. [30] If the mozos ran away, the owner could have them pursued and imprisoned by the authorities. Associated costs would be added to the ever-increasing debt of the mozo. If one of them refused to work, he or she was put in prison on the spot.[30] The wages were also extremely low. The work was done by contract, but since every "mozo" starts with a large debt, the usual advance on engagement, they effectively became servants indentured to the landowner.[31] "Independent tillers": Living in the most remote provinces, some people, often Mayan, survived by growing crops of maize, wheat or beans. They tried to cultivate some excess to sell in the market places of the towns. They often carried their goods on their back for up to 40 kilometres (25 mi) a day to reach such markets.[31] Jorge Ubico regime Main article: Jorge Ubico In 1931, the dictator General Jorge Ubico came to power, backed by the United States. While an efficient administrator,[32] he initiated one of the most brutally repressive military regimes in Central American history. Just as Estrada Cabrera had done during his government, Ubico created a widespread network of spies and informants and had political opponents tortured and put to death. A wealthy aristocrat (with an estimated income of $215,000 per year in 1930s dollars) and a staunch anti-communist, he consistently sided with the United Fruit Company, Guatemalan landowners and urban elites in disputes with peasants. After the crash of the New York Stock Exchange in 1929, the peasant system established by Barrios in 1875 to jump start coffee production in the country[33] faltered, and Ubico was forced to implement a system of debt slavery and forced labor to make sure that there was enough labor available for the coffee plantations and that the UFCO workers were readily available.[23] Allegedly, he passed laws allowing landowners to execute workers as a "disciplinary" measure.[34][35][36][37][38] He also identified as a fascist; he admired Mussolini, Franco, and Hitler, saying at one point: "I am like Hitler. I execute first and ask questions later."[39][40][41][42][43] Ubico was disdainful of the indigenous population, calling them "animal-like", and stated that to become "civilized" they needed mandatory military training, comparing it to "domesticating donkeys". He gave away hundreds of thousands of hectares to the United Fruit Company, exempted them from taxes in Tiquisate, and allowed the U.S. military to establish bases in Guatemala.[34][35][36][37][38] Ubico considered himself to be "another Napoleon". He dressed ostentatiously and surrounded himself with statues and paintings of the emperor, regularly commenting on the similarities between their appearances. He militarized numerous political and social institutions—including the post office, schools, and even symphony orchestras—and placed military officers in charge of many government posts. He frequently travelled around the country performing "inspections" in dress uniform, followed by a military escort, a mobile radio station, an official biographer, and cabinet members.[34][44][45][46][47] After 14 years, Ubico's repressive policies and arrogant demeanor finally led to pacific disobedience by urban middle-class intellectuals, professionals, and junior army officers in 1944. On 1 July 1944, Ubico resigned from office amidst a general strike and nationwide protests. He had planned to hand over power to the former director of policy, General Roderico Anzueto, whom he felt he could control. But his advisors noted that Anzueto's pro-Nazi sympathies had made him unpopular and that he would not be able to control the military. So Ubico instead chose to select a triumvirate of Major General Buenaventura Piñeda, Major General Eduardo Villagrán Ariza, and General Federico Ponce Vaides. The three generals promised to convene the national assembly to hold an election for a provisional president, but when the congress met on 3 July, soldiers held everyone at gunpoint and forced them to vote for General Ponce rather than the popular civilian candidate, Dr. Ramón Calderón. Ponce, who had previously retired from military service due to alcoholism, took orders from Ubico and kept many of the officials who had worked in the Ubico administration. The repressive policies of the Ubico administration were continued.[34][48][49]  John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State of the Eisenhower administration and board member of the United Fruit Company. Opposition groups began organizing again, this time joined by many prominent political and military leaders, who deemed the Ponce regime unconstitutional. Among the military officers in the opposition were Jacobo Árbenz and Major Francisco Javier Arana. Ubico had fired Árbenz from his teaching post at the Escuela Politécnica, and since then Árbenz had been living in El Salvador, organizing a band of revolutionary exiles. On 19 October 1944, a small group of soldiers and students led by Árbenz and Arana attacked the National Palace in what later became known as the "October Revolution".[50] Ponce was defeated and driven into exile; Árbenz, Arana, and a lawyer named Jorge Toriello established a junta. They declared that democratic elections would be held before the end of the year.[51] The winner of the 1944 elections was a teaching major named Juan José Arévalo, Ph.D., who had earned a scholarship in Argentina during the government of general Lázaro Chacón due to his superb professor skills. Arévalo remained in South America for a few years, working as a university professor in several countries. Back in Guatemala during the early years of the Jorge Ubico regime, his colleagues asked him to present a project to the president to create the Faculty of Humanism at the National University, to which Ubico was strongly opposed. Realizing the dictatorial nature of Ubico, Arévalo left Guatemala and went back to Argentina. He went back to Guatemala after the 1944 Revolution and ran under a coalition of leftist parties known as the Partido Acción Revolucionaria ("Revolutionary Action Party", PAR), and won 85 percent of the vote in elections that are widely considered to have been fair and open.[52] Arévalo implemented social reforms, including minimum wage laws, increased educational funding, near-universal suffrage (excluding illiterate women), and labor reforms. But many of these changes only benefited the upper-middle classes and did little for the peasant agricultural laborers who made up the majority of the population. Although his reforms were relatively moderate, he was widely disliked by the United States government, portions of the Catholic Church, large landowners, employers such as the United Fruit Company, and Guatemalan military officers, who viewed his government as inefficient, corrupt, and heavily influenced by communists. At least 25 coup attempts took place during his presidency, mostly led by wealthy liberal military officers.[53][54] In 1944, the "October Revolutionaries" took control of the government. They instituted liberal economic reform, benefiting and politically strengthening the civil and labor rights of the urban working class and the peasants. Elsewhere, a group of leftist students, professionals, and liberal-democratic government coalitions developed, led by Juan José Arévalo and Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. Decree 900, passed in 1952, ordered the redistribution of fallow land on large estates, threatening the interests of the landowning elite and, mainly, the United Fruit Company. Given the strong ties of the UFCO with high Eisenhower administration officers such as the brothers John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles, who were Secretary of State and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) director, respectively, and were both in the company board,[55] the U.S. government ordered the CIA to launch Operation PBFortune (1952–1954) and halt Guatemala's "communist revolt", as perceived by the United Fruit Company and the U.S. State Department.[55] The CIA chose right-wing Guatemalan Army Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas to lead an "insurrection" in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état. Upon deposing the Árbenz Guzmán government, Castillo Armas began to dissolve a decade of social and economic reform and legislative progress, and banned labor unions and left-wing political parties, a disfranchisement of left-wing Guatemalans.[56] He also returned all the confiscated land to the United Fruit and the elite landlords.[55] A series of military coups d'état followed, featuring fraudulent elections in which only military personnel were the winner candidates. Aggravating the general poverty and political repression motivating the civil war was the widespread socioeconomic discrimination and racism practiced against Guatemalan indigenous peoples, such as the Maya; many later fought in the civil war. Although the indigenous Guatemalans constitute more than half of the national populace, they were landless, having been dispossessed of their lands since the Justo Rufino Barrios times. The landlord upper classes of the oligarchy, generally descendants of Spanish and other Europe immigrants to Guatemala, although often with some mestizo ancestry as well, controlled most of the land after the Liberal Reform of 1871.[57] |

背景 以下も参照のこと: ラファエル・カレラ、マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラ、ホセ・マリア・オレリャーナ、ホルヘ・ウビコ、フアン・ホセ・アレバロ、ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニー 1871年の革命後、フスト・ルフィノ・バリオス自由党政権はグアテマラでのコーヒー生産を拡大した。バリオスはまた、スペイン植民地時代やラファエル・ カレーラの保守党政権時代に保護されていた先住民の共有地を没収した[24]。バリオスはそれを自由党の友人たちに分配し、彼らは大地主となった [23]。 1890年代、アメリカはモンロー・ドクトリンを実行に移し、ラテンアメリカにおけるヨーロッパの植民地大国を追い出した。その商業的利益は、この地域の 資源と労働力に対するアメリカの覇権を確立した。19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけてグアテマラを支配した独裁者たちは、個人的に利益を得ていたため、ア メリカのビジネスや政治的利益に非常に好意的だった。ハイチ、ニカラグア、キューバなどとは異なり、アメリカはグアテマラでの支配を維持するためにあから さまな軍事力を行使する必要はなかった。グアテマラ軍/警察は米軍や国務省と緊密に連携し、米国の利益を確保した。グアテマラ政府はいくつかのアメリカ企 業、特にユナイテッド・フルーツ社の納税を免除した。また、公営の公益事業を民営化して売却し、広大な公有地を手放した[25]。  マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラ大統領の最後の大統領任期中の公式肖像。彼の政権下、アメリカのユナイテッド・フルーツ社はグアテマラの主要な経済・政治勢力となった。 社会構造 主な記事 マヌエル・エストラーダ・カブレラ 1920年、スウェーデンのウィルヘルム王子はグアテマラを訪問し、著書『Between Two Continents, notes from a journey in Central America, 1920』の中でグアテマラ社会とエストラーダ・カブレラ政権について記述した[26]。彼は当時のグアテマラ社会を分析し、グアテマラは自らを「共和 国」と称していたにもかかわらず、次の3つの階級が明確に定義されていたと指摘した[27]。 クリオージョ:中央アメリカを征服したスペイン人の子孫からなる少数派。1920年までには、クリオージョは国内の両政党の党員とエリートの多くを占めて いた。何世紀にもわたり、クリオージョは先住民やヨーロッパ系の人々と交配してきた。彼らは政治的にも知的にも国をリードしていたが、その理由のひとつ は、彼らの教育が他の住民のそれよりもはるかに優れていたからである。クリオージョのみが主要政党に名を連ね[27]、彼らの一族が国内の耕作地をほぼ支 配し、ほとんどの部分を所有していた[28]。 ラディーノ:中産階級。先住民、アフリカ人、クリオージョの血を引く人々の子孫であり、1920年当時はほとんど政治的権力を持たなかった。彼らは職人、店主、商人、小役人の大部分を占めていた[29]。国土の東部では農業労働者として働いていた[29]。 先住民: 人口の大半は先住民またはグアテマラ人で構成され、そのほとんどはマヤ族であった。多くは正規の教育をほとんど受けていなかった。先住民は陸軍の兵士とし て仕え、しばしば相当な信頼のおける地位に引き上げられた[29]。彼らは農業労働者のほとんどを占めていた。 農事労働者は3つのカテゴリーに分類される: 「モソス・コロノス」:プランテーションに定住した。農園に定住し、農園で1年に一定期間働く代わりに、自分の勘定で耕作するための小さな土地を与えられた。 「モソス・ジョルナレロス」:一定期間労働を請け負う日雇い労働者[29]。彼らには日給が支払われた。理論的には、各「モゾ」は自分の労働力を好きなよう に自由に処分することができたが、経済的な結びつきによってその土地に拘束されていた。彼らは所有者への借金を返済するまで、その場を離れることはできな かった。彼らはしばしば所有者の犠牲となり、所有者は彼らに信用を与えたり現金を貸したりして借金をするよう勧めた。所有者は帳簿をつけるが、モゾたちは たいてい読み書きができず、不利な立場にあった。[30] モゾが逃げ出せば、オーナーは彼らを当局に追わせ、投獄することができた。それに関連する費用は、モゾの借金が増え続けることになる。モゾの一人が労働を 拒否すれば、その場で牢屋に入れられた[30]。仕事は契約によって行われたが、どの「モゾ」も多額の借金、つまり通常の婚約の前借金から始まるので、彼 らは事実上、地主に年季奉公する使用人となった[31]。 「独立耕作者」: 最も人里離れた地方に住む一部の人々は、多くの場合マヤ人であったが、トウモロコシ、小麦、豆などの作物を栽培することで生き延びていた。彼らは町の市場 で売るために余剰分を栽培しようとした。彼らはしばしば、そのような市場に到達するために、1日に40キロ(25マイル)もの距離を背負って商品を運んだ [31]。 ホルヘ・ウビコ政権 主な記事 ホルヘ・ウビコ 1931年、アメリカの支援を受けた独裁者ホルヘ・ウビコ将軍が政権を握った。彼は有能な行政官であったが[32]、中米史上最も残虐な軍事政権を発足さ せた。エストラーダ・カブレラが政権時代に行ったように、ウビコは広くスパイや情報提供者のネットワークを構築し、政敵を拷問や死刑に処した。裕福な貴族 (1930年代のドル換算で推定年収21万5,000ドル)であり、強固な反共主義者であった彼は、農民との紛争において、一貫してユナイテッド・フルー ツ社、グアテマラの地主、都市エリート側についた。1929年のニューヨーク証券取引所の暴落の後、1875年にコーヒー生産を飛躍させるためにバリオス によって確立された農民制度[33]は頓挫し、ウビコはコーヒー農園に十分な労働力を確保し、UFCOの労働者を容易に利用できるようにするために、債務 奴隷制度と強制労働制度を実施せざるを得なくなった。 [23] 伝えられるところによると、彼は「懲戒」措置として地主が労働者を処刑することを認める法律を可決した[34][35][36][37][38]。彼はま たファシストであることを認め、ムッソリーニ、フランコ、ヒトラーを賞賛し、ある時こう言った。私はヒトラーのようだ」[39][40][41][42] [43] ウビコは先住民を「動物のようだ」と呼んで軽蔑し、「文明化」するためには強制的な軍事訓練が必要だと述べ、それを「ロバの家畜化」に例えた。彼は何十万 ヘクタールもの土地をユナイテッド・フルーツ社に譲渡し、ティキサーテの税金を免除し、米軍がグアテマラに基地を設置することを許可した[34][35] [36][37][38]。ウビコは自らを「もう一人のナポレオン」だと考えていた。彼は仰々しい服装をし、皇帝の像や絵画に囲まれ、定期的にその外見の 類似性についてコメントした。郵便局、学校、交響楽団など、多くの政治的・社会的制度を軍国主義化し、多くの政府ポストを軍人が担当するようにした。彼は 頻繁に、軍服、移動ラジオ局、公式伝記作成者、閣僚を従えて、国内を「視察」して回った[34][44][45][46][47]。 14年後、ウビコの抑圧的な政策と傲慢な態度は、1944年についに都市の中産階級の知識人、専門家、下級陸軍将校による平和的不服従につながった。 1944年7月1日、ウビコはゼネストと全国的な抗議の中で退陣した。ウビコは、前政策局長のロデリコ・アンズエト将軍に権力を譲るつもりだった。しか し、彼のアドバイザーは、アンズエトが親ナチス派であったために不人気であり、軍をコントロールできないだろうと指摘した。そこでウビコは代わりに、ブエ ナベントゥーラ・ピニェダ少将、エドゥアルド・ビジャグラン・アリザ少将、フェデリコ・ポンセ・バイデス大将の三人組を選んだ。3将軍は国民議会を招集 し、臨時大統領選挙を実施すると約束したが、7月3日に議会が開かれると、兵士たちは全員に銃を突きつけ、民間の人気候補ラモン・カルデロン医師ではな く、ポンセ将軍に投票するよう強要した。ポンセ将軍は、アルコール中毒のため退役していたが、ウビコの命令を受け、ウビコ政権で働いたことのある官僚を多 く残した。ウビコ政権の抑圧的な政策は継続された[34][48][49]。  ジョン・フォスター・ダレスはアイゼンハワー政権の国務長官であり、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の取締役であった。 ポンセ政権を違憲と見なした多くの著名な政治家、軍人が加わり、反対派が再び組織され始めた。反対派の軍人の中には、ハコボ・アルベンスとフランシスコ・ ハビエル・アラナ少佐がいた。ウビコはアルベンスを政治学院の教職から解雇し、それ以来、アルベンスはエルサルバドルに住み、革命亡命者の一団を組織して いた。1944年10月19日、アルベンスとアラナに率いられた兵士と学生の小集団が、後に「十月革命」として知られることになる国家宮殿を襲撃した [50]。ポンセは敗北し亡命に追い込まれ、アルベンス、アラナ、ホルヘ・トリエロという弁護士の3人は政権を樹立した。彼らは年内に民主的な選挙を実施 すると宣言した[51]。 1944年の選挙で当選したのは、フアン・ホセ・アレバロ博士という名の教育学専攻の学生であった。彼は、その優れた教授能力を買われ、ラサロ・チャコン 将軍の政権時代にアルゼンチンで奨学金を得ていた。アレバロは数年間南米に留まり、いくつかの国で大学教授として働いた。ホルヘ・ウビコ政権初期のグアテ マラに戻ったとき、同僚から国立大学に人文主義学部を創設するプロジェクトを大統領に提出するよう依頼されたが、ウビコは強く反対した。ウビコの独裁的な 性格を知ったアレバロはグアテマラを離れ、アルゼンチンに戻った。彼は1944年の革命後にグアテマラに戻り、パルティド・アクシオン・レボルシオナリア (「革命行動党」、PAR)として知られる左派政党の連合の下で出馬し、公正で開かれた選挙であったと広く考えられている選挙で85%の得票率を獲得した [52]。しかし、これらの改革の多くは上流中産階級に恩恵を与えただけで、人口の大半を占める農民の農業労働者にはほとんど恩恵を与えなかった。彼の改 革は比較的穏健であったが、アメリカ政府、カトリック教会の一部、大地主、ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーなどの雇用主、グアテマラ軍将校からは広く 嫌われ、政府は非効率的で腐敗し、共産主義者の影響を強く受けているとみなされた。彼の大統領在任中に少なくとも25回のクーデター未遂が起こり、そのほ とんどは裕福なリベラル派軍将校が主導していた[53][54]。 1944年、「十月革命派」が政府を掌握した。彼らは自由主義的な経済改革を実施し、都市労働者階級と農民の市民権と労働権に恩恵を与え、政治的に強化し た。その他の地域では、フアン・ホセ・アレバロとハコボ・アルベンス・グスマンに率いられた左派の学生、専門家、自由民主主義の政府連合が発展した。 1952年に可決された法令900号は、大規模農地の休耕地の再分配を命じ、地主エリートや主にユナイテッド・フルーツ社の利益を脅かした。 UFCOとアイゼンハワー政権の高官であるジョン・フォスター・ダレスやアレン・ダレス兄弟(それぞれ国務長官と中央情報局(CIA)長官であり、ともに UFCOの役員であった)が強い絆で結ばれていたことから[55]、アメリカ政府はCIAにP. 政府はCIAにPBフォーチュン作戦(1952-1954)を開始し、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社とアメリカ国務省が認識していたグアテマラの「共産主義者 の反乱」を阻止するよう命じた[55]。CIAは1954年のグアテマラ・クーデターで「反乱」を指揮する人物として、右派のグアテマラ陸軍大佐カルロ ス・カスティージョ・アルマスを選んだ。アルベンス・グスマン政権を退陣させると、カスティーリョ・アルマスは10年にわたる社会・経済改革と立法府の進 歩を解消し始め、労働組合と左派政党を禁止し、左派グアテマラ人の権利を剥奪した[56]。 一連の軍事クーデターが続き、軍関係者だけが勝者候補となる不正選挙が行われた。内戦の動機となった一般的な貧困と政治的抑圧をさらに悪化させたのは、マ ヤ族などのグアテマラ先住民に対して行われた広範な社会経済的差別と人種差別であった。グアテマラ先住民は国民の半数以上を占めるが、フスト・ルフィノ・ バリオス時代から土地を奪われ、土地を持たなかった。1871年の自由主義改革以降、寡頭制の地主上流階級は、一般的にスペインやその他のヨーロッパから グアテマラに移住した人々の子孫であったが、メスティーソの先祖を持つことも多かった[57]。 |

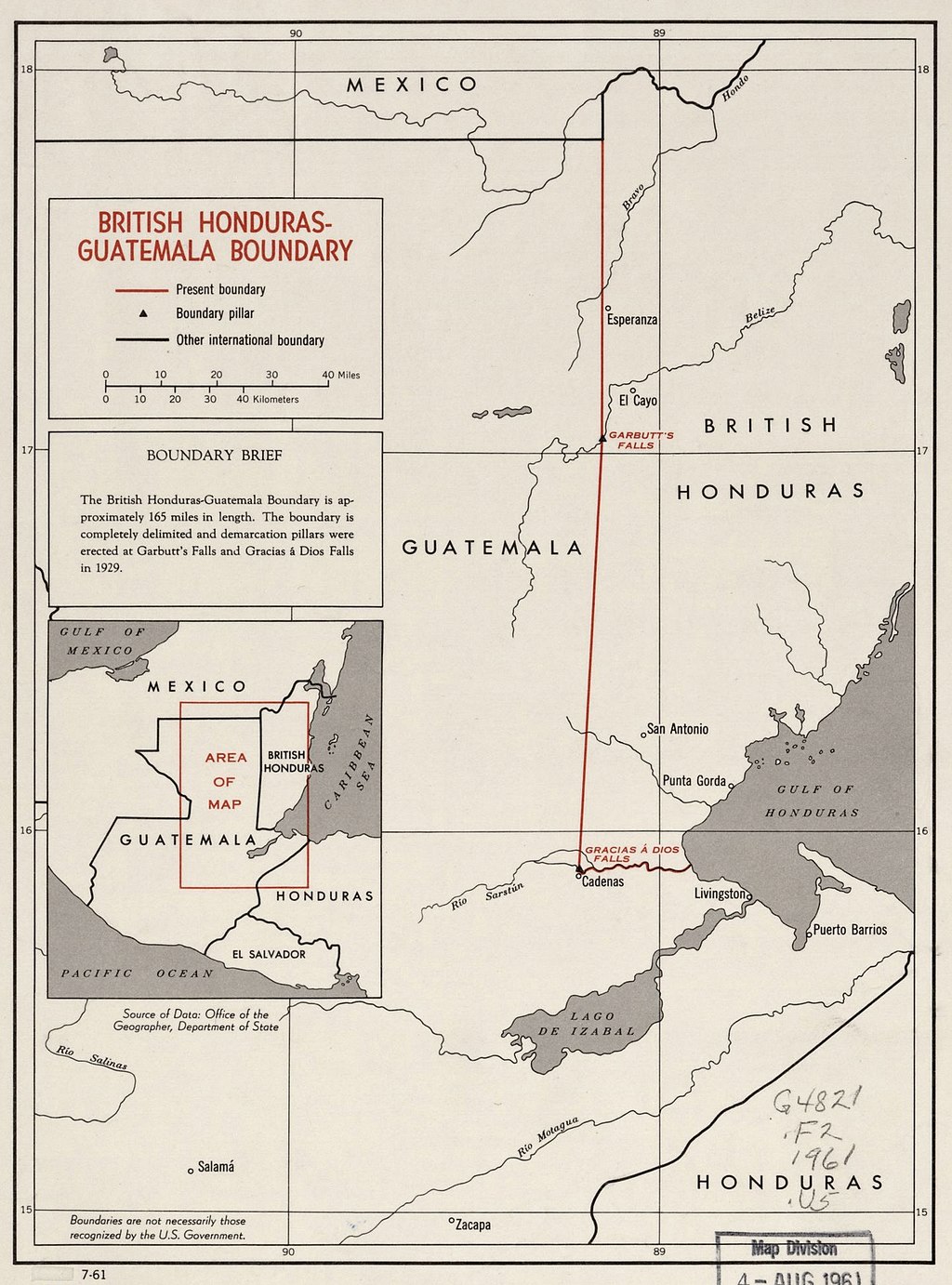

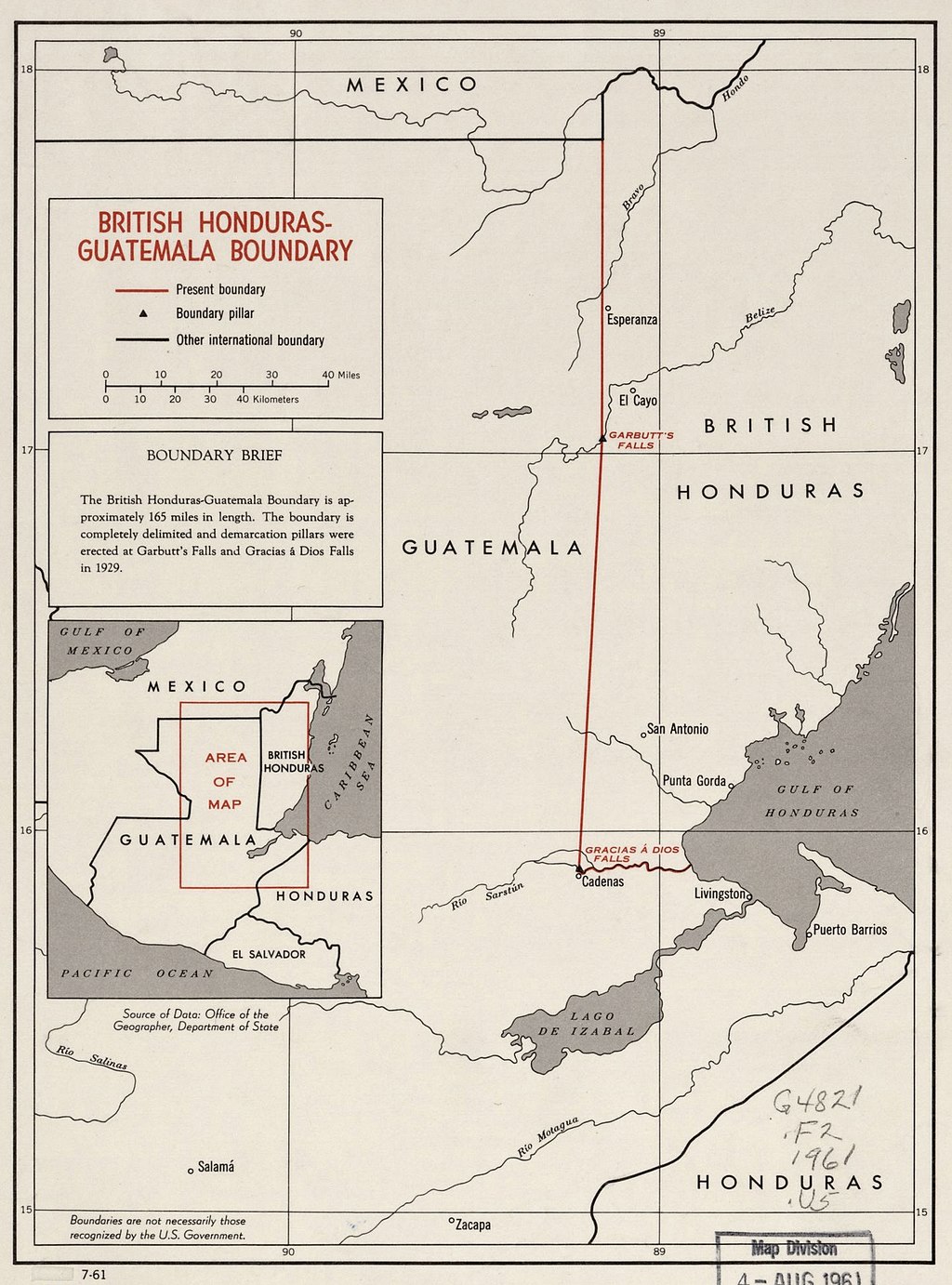

| Initial phase of the civil war: 1960's and early 1970's On 13 November 1960, a group of left-wing junior military officers of the Escuela Politécnica national military academy led a failed revolt against the autocratic government (1958–63) of General Ydígoras Fuentes, who had usurped power in 1958, after the assassination of the incumbent Colonel Castillo Armas. The young officers' were outraged by the staggering corruption of the Ydígoras regime, the government's showing of favoritism in giving military promotions and other rewards to officers who supported Ydígoras, and what they perceived as incompetence in running the country. The immediate trigger for their revolt, however, was Ydígoras' decision to allow the U.S. to train an invasion force in Guatemala to prepare for the planned Bay of Pigs Invasion of Cuba without consulting the Guatemalan military and without sharing with the military the payoff he received in exchange from the U.S. government. The military was concerned about the infringement on the sovereignty of their country as unmarked U.S. warplanes piloted by US-based Cuban exiles flew in large numbers over their country and the U.S. established a secret airstrip and training camp at Retalhuleu to prepare for its invasion of Cuba. The rebellion was not ideological in its origins.[58] The CIA flew B-26 bombers disguised as Guatemalan military jets to bomb the rebel bases because the coup threatened U.S. plans for the invasion of Cuba as well as the Guatemalan regime it supported. The rebels fled to the hills of eastern Guatemala and neighboring Honduras and formed the kernel of what became known as MR-13 (Movimiento Revolucionario 13 Noviembre).[59] The surviving officers fled into the hills of eastern Guatemala, and later established communication with the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. By 1962, those surviving officers had established an insurgent movement known as the MR-13, named after the date of the officers' revolt. MR-13 attacks United Fruit Company office They returned in early 1962, and on 6 February 1962 in Bananera they attacked the offices of the United Fruit Company (present-day Chiquita Brands), an American corporation that controlled vast territories in Guatemala as well as in other Central American countries. The attack sparked sympathetic strikes and university student walkouts throughout the country, to which the Ydígoras regime responded with a violent crackdown. This violent crackdown sparked the civil war.[59] Through the early phase of the conflict, the MR-13 was a principal component of the insurgent movement in Guatemala.[60] The MR-13 later initiated contact with the outlawed PGT (Guatemalan Labour Party, composed and led by middle-class intellectuals and students) and a student organization called the Movimiento 12 de Abril (12 April Movement) and merged into a coalition guerilla organization called the Rebel Armed Forces (FAR) in December 1962. Also affiliated with the FAR was the FGEI (Edgar Ibarra Guerrilla Front). The MR-13, PGT and the FGEI each operated in different parts of the country as three separate "frentes" (fronts); the MR-13 established itself in the mostly Ladino departments of Izabal and Zacapa, the FGEI established itself in Sierra de las Minas and the PGT operated as an urban guerrilla front. Each of these three "frentes" (comprising no more than 500 combatants) were led by former members of the 1960 army revolt, who had previously been trained in counterinsurgency warfare by the United States.[61][62][63][64][65] U.S. intelligence and counterinsurgency assistance to government  1961 CIA map of British Honduras-Guatemala border In 1964 and 1965, the Guatemalan Armed Forces began engaging in counterinsurgency operations against the MR-13 in eastern Guatemala. In February and March 1964, the Guatemalan Air Force began a selective bombing campaign against MR-13 bases in Izabal, which was followed by a counterinsurgency sweep in the neighboring province of Zacapa under the code-name "Operation Falcon" in September and October of the following year.[66] It was at this phase in the conflict that the U.S. government sent Green Berets and CIA advisers to instruct the Guatemalan military in counterinsurgency (anti-guerrilla warfare). In addition, U.S. police and "Public Safety" advisers were sent to reorganize the Guatemalan police forces.[67] In response to increased insurgent activity in the capital, a specialty squad of the National Police was organized in June 1965 called Comando Seis ('Commando Six') to deal with urban guerilla assaults. 'Commando Six' received special training from the U.S. Public Safety Program and money and weapons from U.S. Public Safety Advisors.[68] In November 1965, U.S. Public Safety Advisor John Longan arrived in Guatemala on temporary loan from his post in Venezuela to assist senior military and police officials in establishing an urban counterinsurgency program.[69] With the assistance of Longan, the Guatemalan Military launched "Operation Limpieza" (Operation Cleanup) an urban counterinsurgency program under the command of Colonel Rafael Arriaga Bosque. This program coordinated the activities of all of the country's main security agencies (including the Army, the Judicial Police and the National Police) in both covert and overt anti-guerrilla operations. Under Arriaga's direction, the security forces began to abduct, torture and kill the PGT's key constituents.[70] With money and support from U.S. advisors, President Enrique Peralta Azurdia established a Presidential Intelligence Agency in the National Palace, under which a telecommunications database is known as the Regional Telecommunications Center or La Regional existed, linking the National Police, the Treasury Guard, the Judicial Police, the Presidential House and the Military Communications Center via a VHF-FM intracity frequency. La Regional also served as a depository for the names of suspected "subversives" and had its own intelligence and operational unit attached to it known as the Policía Regional.[71] This network was built on the "Committees against Communism" created by the CIA after the coup in 1954.[72] Escalation of state terror On 3 and 5 March 1966, the G-2 (military intelligence) and the Judicial Police raided three houses in Guatemala City, capturing twenty-eight trade unionists and members of the PGT. Those captured included most of the PGT's central committee and peasant federation leader Leonardo Castillo Flores. All subsequently "disappeared" while in the custody of the security force and became known in subsequent months by the Guatemalan press as "the 28". This incident was followed by a wave of unexplained "disappearances" and killings in Guatemala City and in the countryside which were reported by the Guatemala City press. When press censorship was lifted for a period, relatives of "the 28" and of others who had "disappeared" in the Zacapa-Izabal military zone went to the press or to the Association of University Students (AEU). Using its legal department, the AEU subsequently pressed for habeas corpus on behalf of the "disappeared" persons. The government denied any involvement in the killings and disappearances. On 16 July 1966, the AEU published a detailed report on abuses in the last months of the Peralta regime in which it named thirty-five individuals as involved in killings and disappearances, including military commissioners and members of the Ambulant Military Police (PMA) in coordination with the G-2.[73] After the publication of this report, "death-squad" attacks on the AEU and on the University of San Carlos began to intensify. Many law students and members of the AEU were assassinated.[74] The use of such tactics increased dramatically after the inauguration of President Julio César Méndez Montenegro, who – in a bid to placate and secure the support of the military establishment – gave it carte blanche to engage in "any means necessary" to pacify the country. The military subsequently ran the counterinsurgency program autonomously from the Presidential House and appointed Vice-Defense Minister, Col. Manuel Francisco Sosa Avila as the main "counterinsurgency coordinator". In addition, the Army General Staff and the Ministry of Defense took control of the Presidential Intelligence Agency – which controlled the La Regional annex – and renamed it the Guatemalan National Security Service (Servicio de Seguridad Nacional de Guatemala – SSNG).[75] In the city and in the countryside, persons suspected of leftist sympathies began to disappear or turn up dead at an unprecedented rate. In the countryside most "disappearances" and killings were carried out by uniformed army patrols and by locally known PMA or military commissioners, while in the cities the abductions and "disappearances" were usually carried out by heavily armed men in plainclothes, operating out of the army and police installations.[76] The army and police denied responsibility, pointing the finger at right-wing paramilitary death squads autonomous from the government. One of the most notorious death squads operating during this period was the MANO, also known as the Mano Blanca ("White Hand"); initially formed by the MLN as a paramilitary front in June 1966 to prevent President Méndez Montenegro from taking office, the MANO was quickly taken over by the military and incorporated into the state's counter-terror apparatus.[77] The MANO – while being the only death squad formed autonomously from the government – had a largely military membership, and received substantial funding from wealthy landowners.[78] The MANO also received information from military intelligence through La Regional, with which it was linked to the Army General Staff and all of the main security forces.[79] The first leaflets by the MANO appeared on 3 June 1966 in Guatemala City, announcing the impending creation of the "White Hand" or "the hand that will eradicate National Renegades and traitors to the fatherland."[80] In August 1966, MANO leaflets were distributed over Guatemala City by way of light aircraft openly landing in the Air Force section of La Aurora airbase. Their main message was that all patriotic citizen must fully support the army's counterinsurgency initiative and that the army was "the institution of the greatest importance at any latitude, representative of Authority, of Order, and of Respect" and that to "attack it, divide it, or to wish its destruction is indisputedly treason to the fatherland."[81] Counterinsurgency in Zacapa With increased military aid from the United States, the 5,000-man Guatemalan Army mounted a larger pacification effort in the departments of Zacapa and Izabal in October 1966 dubbed "Operation Guatemala." Colonel Arana Osorio was appointed commander of the Zacapa-Izabal Military Zone and took charge of the counter-terror program with guidance and training from 1,000 U.S. Green Berets.[82] Under Colonel Arana's jurisdiction, military strategists armed and fielded various paramilitary death squads to supplement regular army and police units in clandestine terror operations against the FAR's civilian support base. Personnel, weapons, funds and operational instructions were supplied to these organizations by the armed forces.[83] The death squads operated with impunity – permitted by the government to kill any civilians deemed to be either insurgents or insurgent collaborators.[77] The civilian membership of the army's paramilitary units consisted largely of right-wing fanatics with ties to the MLN, founded and led by Mario Sandoval Alarcón, a former participant in the 1954 coup. By 1967, the Guatemalan army claimed to have 1,800 civilian paramilitaries under its direct control. [84] Blacklists were compiled of suspected guerilla's collaborators and those with communist leanings,[85] as troops and paramilitaries moved through Zacapa systematically arresting suspected insurgents and collaborators; prisoners were either killed on the spot or "disappeared" after being taken to clandestine detention camps for interrogation. [76] In villages which the Army suspected were pro-guerrilla, the Army rounded up all of the peasant leaders and publicly executed them, threatening to kill additional civilians if the villagers did not cooperate with the authorities. In a 1976 report, Amnesty International cited estimates that between 3,000 and 8,000 peasants were killed by the army and paramilitary organizations in Zacapa and Izabal between October 1966 and March 1968.[61][86] [87] Other estimates put the death toll at 15,000 in Zacapa during the Mendez period.[88] As a result, Colonel Arana Osorio subsequently earned the nickname "The Butcher of Zacapa" for his brutality. State of Siege On 2 November 1966 a nationwide 'state of siege' was declared in Guatemala in which civil rights – including the right to habeas corpus – were suspended. The entire security apparatus – including local police and private security guards – was subsequently placed under then Minister of Defense, Col. Rafael Arriaga Bosque. Press censorship was imposed alongside these security measures, including measures designed to keep the Zacapa campaign entirely shrouded in secrecy. These controls ensured that the only reports made public on the counter-terror program in Zacapa were those handed out by the army's public relations office. Also on the day of the 'state of siege,' a directive was published banning publication of reports on arrests until authorization by military authorities.[80] At the time of the Zacapa campaign, the government launched a parallel counter-terror program in the cities. Part of this new initiative was the increased militarization of the police forces and the activation of several new counter-terror units of the army and the National Police for performing urban counter-terror functions, particularly extralegal activities against opponents of the state. The National Police were subsequently transformed into an adjunct of the military and became a frontline force in the government's urban pacification program against the left.[89] In January 1967, the Guatemalan Army formed the 'Special Commando Unit of the Guatemalan Army' – SCUGA – a thirty-five man commando unit composed of anti-communist army officers and right-wing civilians, which was placed under the command of Colonel Máximo Zepeda. The SCUGA – which the CIA referred to as a "government-sponsored terrorist organization...used primarily for assassinations and political abductions"[90] – carried out abductions, bombings, street assassinations, torture, "disappearances" and summary executions of both real and suspected communists. The SCUGA also worked with the Mano Blanca for a period before inter-agency rivalry took over.[91] In March 1967, after Vice-Defense Minister and counterinsurgency coordinator Col. Francisco Sosa Avila was named director-general of the National Police, a special counterinsurgency unit of the National Police known as the Fourth Corps was created to carry out extralegal operations alongside the SCUGA.[92] The Fourth Corps was an illegal fifty-man assassination squad which operated in secrecy from other members of the National Police, taking orders from Col. Sosa and Col. Arriaga.[93] Operations carried out under by the SCUGA and the Fourth Corps were usually carried out under the guise of paramilitary fronts, such as RAYO, NOA, CADEG and others.[91] By 1967, at least twenty such death squads operated in Guatemala City which posted blacklists of suspected "communists" who were then targeted for murder. These lists were often published with police mugshots and passport photographs which were only accessible to the Ministry of the Interior.[94] In January 1968, a booklet containing 85 names was distributed throughout the country entitled People of Guatemala, Know the Traitors, the Guerillas of the FAR. Many of those named in the booklet were killed or forced to flee. Death threats and warnings were sent to both individuals and organizations; for example, a CADEG leaflet addressed to the leadership of the labor federation FECETRAG read: "Your hour has come. Communists at the service of Fidel Castro, Russia, and Communist China. You have until the last day of March to leave the country."[94] Victims of government repression in the capital included guerrilla sympathizers, labor union leaders, intellectuals, students, and other vaguely defined "enemies of the government." Some observers referred to the policy of the Guatemalan government as "White Terror" -a term previously used to describe similar periods of anti-communist mass killings in countries such as Taiwan and Spain.[95] By the end of 1967, the counterinsurgency program had resulted in the virtual defeat of the FAR insurgency in Zacapa and Izabal and the retreat of many of its members to Guatemala City. President Mendez Montenegro suggested in his annual message to congress in 1967 that the insurgents had been defeated. Despite the defeat of the insurgency, the government's killings continued. In December 1967, 26-year-old Rogelia Cruz Martinez, former "Miss Guatemala" of 1959, who was known for her left-wing sympathies, was picked up and found dead. Her body showed signs of torture, rape and mutilation. Amidst the outcry over the murder, the FAR opened fire on a carload of American military advisors on 16 January 1968. Colonel John D. Webber (chief of the U.S. military mission in Guatemala) and Naval Attache Lieutenant Commander Ernest A. Munro were killed instantly; two others were wounded. The FAR subsequently issued a statement claiming that the killings were a reprisal against the Americans for creating "genocidal forces" which had "resulted in the death of nearly 4,000 Guatemalans" during the previous two years.[citation needed] The kidnapping of Archbishop Casariego On 16 March 1968, kidnappers apprehended Roman Catholic Archbishop Mario Casariego y Acevedo within 100 yards of the National Palace in the presence of heavily armed troops and police. The kidnappers (possible members of the security forces on orders from the army high command) intended to stage a false flag incident by implicating guerilla forces in the kidnapping; the Archbishop was well known for his extremely conservative views and it was considered that he might have organized a "self-kidnapping" to harm the reputation of the guerillas. However, he refused to go along with the scheme and his kidnappers plan to "create a national crisis by appealing to the anti-communism of the Catholic population."[96] The Archbishop was released unharmed after four days in captivity. In the aftermath of the incident, two civilians involved in the operation – Raul Estuardo Lorenzana and Ines Mufio Padilla – were arrested and taken away in a police patrol car. In transit, the car stopped and the police officers exited the vehicle as gunmen sprayed it with submachine gunfire. One press report said Lorenzana's body had 27 bullet wounds and Padilla's 22. The police escorts were unharmed in the assassination. Raul Lorenzana was a known "front man" for the MANO death squad and had operated out of the headquarters of the Guatemalan Army's Cuartel de Matamoros and a government safe house at La Aurora airbase.[97] The army was not left unscathed by the scandal and its three primary leaders of the counterinsurgency program were replaced and sent abroad. Defense Minister Rafael Arriaga Bosque was sent to Miami, Florida to become Consul General; Vice-Defense Minister and Director-General of the National Police, Col. Francisco Sosa Avila was dispatched as a military attache to Spain and Col. Arana Osorio was sent as Ambassador to Nicaragua, which was under the rule of Anastasio Somoza Debayle at the time. Political murders by "death squads" declined in subsequent months and the "state of siege" was reduced to a "state of alarm" on 24 June 1968.[98] The assassinations of Ambassador John Gordon Mein and Count Karl Von Sprite The lull in political violence in the aftermath of the "kidnapping" of Archbishop Casariego ended after several months. On 28 August 1968, U.S. Ambassador John Gordon Mein was assassinated by FAR rebels one block from the U.S. consulate on Avenida Reforma in Guatemala City. U.S. officials believed that FAR intended to kidnap him in order to negotiate an exchange, but instead, they shot him when he attempted to escape.[99] Some sources suggested that the high command of the Guatemalan Army was involved in the assassination of Ambassador Mein. This was alleged years later to U.S. investigators by a reputed former bodyguard of Col. Arana Osorio named Jorge Zimeri Saffie, who had fled to the U.S. in 1976 and had been arrested on firearms charges in 1977.[100][101] The Guatemalan police claimed to have "solved" the crime almost immediately, announcing that they had located a suspect on the same day. The suspect "Michele Firk, a French socialist who had rented the car used to kidnap Mein" shot herself as police came to interrogate her.[96] In her notebook Michele had written: It is hard to find the words to express the state of putrefaction that exists in Guatemala, and the permanent terror in which the inhabitants live. Everyday bodies are pulled out of the Motagua River, riddled with bullets and partially eaten by fish. Every day men are kidnapped right in the street by unidentified people in cars, armed to the teeth, with no intervention by the police patrols.[102] The assassination of Ambassador Mein led to public calls for tougher counterinsurgency measures by the military and an increase in U.S. security assistance. This was followed by a renewed wave of "death squad" killings of members of the opposition, under the guise of new Defense Minister Col. Rolando Chinchilla Aguilar and Army chief of staff Col. Doroteo Reyes, who were both subsequently promoted to the rank of "General" in September 1968. [103] On 31 March 1970 West German Ambassador Count Karl Von Sprite was kidnapped when his car was intercepted by armed men belonging to the FAR. The FAR subsequently put out a ransom note in which they demanded $700,000 ransom and the release of 17 political prisoners (which was eventually brought up to 25). The Mendez government refused to cooperate with the FAR, causing outrage among the diplomatic community and the German government. Ten days later on 9 April 1970, Von Sprite was found dead after an anonymous phone call was made disclosing the whereabouts of his remains. Domination by military rulers Main article: Carlos Arana Osorio In July 1970, Colonel Carlos Arana Osorio assumed the presidency. Arana, backed by the army, represented an alliance of the MLN – the originators of the MANO death squad – and the Institutional Democratic Party (MLN-PID). Arana was the first of a string of military rulers allied with the Institutional Democratic Party who dominated Guatemalan politics in the 1970s and 1980s (his predecessor, Julio César Méndez, while dominated by the army, was a civilian). Colonel Arana, who had been in charge of the terror campaign in Zacapa, was an anti-communist hardliner who once stated, "If it is necessary to turn the country into a cemetery in order to pacify it, I will not hesitate to do so."[104][105] Despite minimal armed insurgent activity at the time, Arana announced another "state of siege" on 13 November 1970 and imposed a curfew from 9:00 PM to 5:00 AM, during which time all vehicle and pedestrian traffic — including ambulances, fire engines, nurses, and physicians—were forbidden throughout the national territory. The siege was accompanied by a series of house to house searches by the police, which reportedly led to 1,600 detentions in the capital in the first fifteen days of the "State of Siege." Arana also imposed dress codes, banning miniskirts for women and long hair for men.[106] High government sources were cited at the time by foreign journalists as acknowledging 700 executions by security forces or paramilitary death squads in the first two months of the "State of Siege".[107] This is corroborated by a January 1971 secret bulletin of the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency detailing the elimination of hundreds of suspected "terrorists and bandits" in the Guatemalan countryside by the security forces.[108] While government repression continued in the countryside, the majority of victims of government repression under Arana were residents of the capital. "Special commandos" of the military and the Fourth Corps of the National Police acting "under government control but outside the judicial processes",[109] abducted, tortured and killed thousands of leftists, students, labor union leaders and common criminals in Guatemala City. In November 1970, the 'Judicial Police' were formally disbanded and a new semi-autonomous intelligence agency of the National Police was activated known as the 'Detectives Corps' – with members operating in plainclothes – which eventually became notorious for repression.[110] One method of torture commonly used by the National Police at the time consisted of placing a rubber "hood" filled with insecticide over the victim's head to the point of suffocation.[61] Some of the first victims of Arana's state of the siege were his critics in the press and in the university. In Guatemala City on 26 November 1970, security forces captured and disappeared journalists Enrique Salazar Solorzano and Luis Perez Diaz in an apparent reprisal for newspaper stories condemning the repression. On 27 November, National University law professor and government critic Julio Camey Herrera was found murdered. On the following day, radio station owner Humberto Gonzalez Juarez, his business associate Armando Bran Valle and a secretary disappeared, their bodies were subsequently found in a ravine. Later in 1975, a former member of the Detective Corps of the National Police – jailed for a non-political murder – took credit for the killing.[111] In October 1971, over 12,000 students at the University of San Carlos of Guatemala went on a general strike to protest the killing of students by the security forces; they called for an end to the "state of siege." On 27 November 1971, the Guatemalan military responded with an extensive raid on the main campus of the university, seeking cached weapons. It mobilized 800 army personnel, as well as tanks, helicopters and armored cars, for the raid. They conducted a room-to-room search of the entire campus but found no evidence or supplies.[112] A number of death squads – run by the police and intelligence services – emerged in the capital during this period. In one incident on 13 October 1972, ten people were knifed to death in the name of a death squad known as the "Avenging Vulture." Guatemalan government sources confirmed to the U.S. Department of State that the "Avenging Vulture" and other similar death squads operating during the time period were a "smokescreen" for extralegal tactics being employed by the National Police against non-political delinquents.[113] Another infamous death squad active during this time was the 'Ojo por Ojo' (Eye for an Eye), described in a U.S. State Department intelligence cable as "a largely military membership with some civilian cooperation".[114] The 'Ojo por Ojo' tortured, killed and mutilated scores of civilians linked to the PGT or suspected of collaborating with the FAR in the first half of the 1970s.[8] According to Amnesty International and domestic human rights organizations such as 'Committee of Relatives of Disappeared Persons', over 7,000 civilian opponents of the security forces were 'disappeared' or found dead in 1970 and 1971, followed by an additional 8,000 in 1972 and 1973.[115] In the period between January and September 1973, the Guatemalan Human Rights Commission documented the deaths and forced disappearances of 1,314 individuals by death squads.[116] The Guatemalan Human Rights Commission estimated 20,000 people killed or "disappeared" between 1970 and 1974.[117] Amnesty International mentioned Guatemala as one of several countries under a human rights state of emergency, while citing "the high incidence of disappearances of Guatemalan citizens" as a major and continuing problem in its 1972–1973 annual report.[118][119] Overall, as many as 42,000 Guatemalan civilians were killed or "disappeared" between 1966 and 1973.[120] |

内戦の初期段階:1960年代と1970年代初頭 1958年、現職のカスティーリョ・アルマス大佐が暗殺され、権力を簒奪したイディゴラス・フエンテス将軍の独裁政権(1958~63年)に対し、 1960年11月13日、国立士官学校の左翼下級将校のグループが反乱を起こし、失敗に終わった。若い将校たちは、イディゴラス政権の驚くべき腐敗、イ ディゴラスを支持する将校に軍人の昇進やその他の褒賞を与えるという政府の優遇ぶり、そして国の運営における彼らの無能さに憤慨した。しかし、彼らの反乱 の直接的な引き金となったのは、イディゴラスがグアテマラ軍に相談することなく、またアメリカ政府から受け取った報酬を軍と共有することなく、キューバへ のピッグス湾侵攻計画に備えてアメリカがグアテマラで侵攻部隊を訓練することを許可したことであった。軍部は、米国在住のキューバ亡命者が操縦する無名の 米軍機が自国上空を大量に飛行し、米国がキューバ侵攻の準備のためにレタルフレウに秘密の滑走路と訓練キャンプを設置したことから、自国の主権が侵害され ることを懸念した。反乱の起源はイデオロギー的なものではなかった[58]。 CIAはグアテマラ軍のジェット機に偽装したB-26爆撃機を飛ばして反乱軍の基地を爆撃したが、それはクーデターがキューバ侵攻のためのアメリカの計画 だけでなく、それが支援していたグアテマラ政権をも脅かしたからであった。反乱軍はグアテマラ東部と隣接するホンジュラスの丘陵地帯に逃げ込み、MR- 13(Movimiento Revolucionario 13 Noviembre)として知られるようになる核を形成した[59]。生き残った将校たちはグアテマラ東部の丘陵地帯に逃げ込み、後にフィデル・カストロ のキューバ政府と連絡を取るようになった。1962年までに、生き残った将校たちは、将校たちの反乱の日にちなんで名付けられたMR-13として知られる 反政府運動を立ち上げた。 MR-13がユナイテッド・フルーツ社の事務所を襲撃 彼らは1962年初めに帰還し、1962年2月6日にバナネラで、グアテマラだけでなく他の中米諸国に広大な領土を支配するアメリカ企業、ユナイテッド・ フルーツ・カンパニー(現在のチキータ・ブランズ)の事務所を襲撃した。この襲撃事件は、グアテマラ全土で同調ストライキや大学生のウォークアウトを引き 起こし、イディゴラス政権は暴力的な弾圧でこれに対抗した。この暴力的な弾圧が内戦の火種となった[59]。 紛争の初期段階を通じて、MR-13はグアテマラの反乱運動の主要な構成要素であった[60]。MR-13は後に非合法のPGT(グアテマラ労働党、中流 階級の知識人と学生によって構成され、指導された)とMovimiento 12 de Abril(4月12日運動)と呼ばれる学生組織と接触を開始し、1962年12月に反乱軍(FAR)と呼ばれる連合ゲリラ組織に統合された。FARには FGEI(エドガー・イバラ・ゲリラ戦線)も加盟していた。MR-13、PGT、FGEIはそれぞれ3つの「フレンテ」(戦線)として国内の異なる地域で 活動した。MR-13はラディーノが多いイザバル県とサカパ県に、FGEIはシエラ・デ・ラス・ミナス県に、PGTは都市ゲリラ戦線として活動した。これ ら3つの「フレンテ」(500人以下の戦闘員で構成)はそれぞれ、1960年の陸軍反乱の元メンバーによって率いられ、彼らは以前にアメリカによって対反 乱戦の訓練を受けていた[61][62][63][64][65]。 政府に対する米国の諜報活動と対反乱援助  1961年CIAによる英領ホンジュラス・グアテマラ国境の地図 1964年と1965年、グアテマラ軍はグアテマラ東部でMR-13に対する反乱作戦に従事し始めた。1964年2月と3月、グアテマラ空軍はイザバルの MR-13基地に対する選択的爆撃作戦を開始し、翌年の9月と10月には「ファルコン作戦」というコードネームの下、隣接するサカパ県で反乱軍の掃討作戦 が行われた[66]。 米国政府がグリーンベレーとCIAの顧問を派遣してグアテマラ軍に対ゲリラ戦を指導したのは、紛争のこの段階であった。さらに、グアテマラ警察部隊を再編 成するために、米国の警察と「公安」顧問が派遣された[67]。首都における反政府勢力の活動の活発化に対応して、1965年6月、国家警察の専門部隊が 都市ゲリラの襲撃に対処するために「コマンド・シックス」(Comando Seis)と呼ばれる特殊部隊を組織した。コマンドー・シックス」は米国公安プログラムから特別訓練を受け、米国公安アドバイザーから資金と武器を受け 取った[68]。 1965年11月、ジョン・ロンガン米国公安顧問は、ベネズエラの赴任先からグアテマラに一時的に出向して到着し、軍と警察の高官を支援して都市反乱プロ グラムを確立した[69]。ロンガンの支援を受けて、グアテマラ軍はラファエル・アリアガ・ボスケ大佐の指揮の下、都市反乱プログラム「リンピエサ作戦」 (クリーンアップ作戦)を開始した。この作戦は、グアテマラの主要治安機関(陸軍、司法警察、国家警察を含む)の活動を調整し、秘密裡に、また公然と対ゲ リラ作戦を展開した。アリアガの指揮の下、治安部隊はPGTの主要構成員を拉致、拷問、殺害し始めた[70]。 エンリケ・ペラルタ・アズールディア大統領は、米国のアドバイザーからの資金と支援を受けて、大統領情報機関を国立宮殿に設立し、その下に、国家警察、財 務省警備隊、司法警察、大統領官邸、軍事通信センターをVHF-FMの都市内周波数で結ぶ、地域通信センター(La Regional)として知られる通信データベースが存在した。このネットワークは、1954年のクーデター後にCIAによって作られた「共産主義に反対 する委員会」に基づいて構築された[72]。 国家的恐怖の拡大 1966年3月3日と5日、G-2(軍事情報部)と司法警察はグアテマラ・シティの3つの家屋を急襲し、28人の労働組合員とPGTのメンバーを捕らえ た。捕らえられた者の中には、PGT中央委員会の大部分と農民連盟指導者のレオナルド・カスティージョ・フローレスも含まれていた。その後、全員が治安部 隊に拘束されたまま「失踪」し、その後数カ月間、グアテマラのマスコミによって「28人」として知られるようになった。この事件の後、グアテマラ・シティ と地方で原因不明の「失踪」と殺害が相次ぎ、グアテマラ・シティのマスコミによって報道された。報道検閲が一時的に解除されると、「28人」やサカパ・イ サバル軍事地帯で「失踪」した人々の親族が、報道機関や大学生協会(AEU)に相談に行った。AEUはその法務部門を使って、「失踪」した人々のために人 身保護令状を請求した。政府は殺害と失踪への関与を否定した。1966年7月16日、AEUはペラルタ政権末期の虐待に関する詳細な報告書を発表し、その 中で殺害と失踪に関与したとして、軍事委員やG-2と連携した機動軍事警察(PMA)のメンバーなど35人の名前を挙げた[73]。この報告書の発表後、 AEUとサンカルロス大学に対する「死の部隊」による攻撃が激化し始めた。多くの法学部の学生やAEUのメンバーが暗殺された[74]。 このような戦術の使用は、フリオ・セザール・メンデス・モンテネグロ大統領の就任後、劇的に増加した。彼は、軍部をなだめ、軍部の支持を確保するために、 軍部に、国を平和にするために「必要なあらゆる手段」に従事する全権を与えた。その後、軍は大統領府から独立して対反乱プログラムを運営し、国防副大臣の マヌエル・フランシスコ・ソサ・アビラ大佐を主要な「対反乱コーディネーター」に任命した。さらに陸軍参謀本部と国防省は、ラ・リージョナル分室を管理し ていた大統領情報局を掌握し、グアテマラ国家安全保障局(Servicio de Seguridad Nacional de Guatemala - SSNG)と改称した[75]。 都市部でも地方でも、左翼シンパと疑われた人物が失踪したり、死体で発見されたりすることがかつてない勢いで起こり始めた。田舎では、ほとんどの「失踪」 と殺害は、軍服を着た軍隊のパトロール隊や地元で知られるPMAや軍事委員によって行われたが、都市では、拉致と「失踪」は通常、私服の重武装した男たち によって行われ、軍隊や警察の施設から出て活動した[76]。軍隊と警察は責任を否定し、政府から独立した右翼の準軍事的決死隊に矛先を向けた。 この時期に活動していた最も悪名高い決死隊のひとつが、マノ・ブランカ(「白い手」)としても知られるMANOであった。当初、MANOは、メネデス・モ ンテネグロ大統領の就任を阻止するため、1966年6月にMLNによって準軍事戦線として結成されたが、すぐに軍に引き継がれ、国家の対テロ組織に組み込 まれた。 [77]。MANOは、政府から独立して結成された唯一の決死隊でありながら、メンバーの大部分は軍人で構成され、裕福な地主から多額の資金援助を受けて いた[78]。MANOはまた、ラ・リージョナルを通じて軍の諜報機関から情報を得ており、ラ・リージョナルは陸軍参謀本部や主要な治安部隊のすべてと連 携していた[79]。 MANOによる最初のビラは1966年6月3日にグアテマラ・シティに現れ、「白い手」あるいは「祖国への反逆者と反逆者を撲滅する手」の差し迫った創設 を告知した[80]。1966年8月、MANOのビラはラ・アウロラ空軍基地の空軍セクションに公然と着陸する軽飛行機によってグアテマラ・シティ上空で 配布された。その主なメッセージは、すべての愛国的市民は軍の反乱イニシアチブを全面的に支持しなければならず、軍は「いかなる緯度においても最も重要な 機関であり、権威、秩序、尊敬の代表」であり、「それを攻撃し、それを分裂させ、その破壊を望むことは、紛れもなく祖国に対する反逆である」というもの だった[81]。 サカパにおける反乱 アメリカからの軍事援助が強化され、5,000人規模のグアテマラ軍は1966年10月、サカパ県とイザバル県で「グアテマラ作戦」と名付けられた大規模 な平和化活動を行った。アラナ・オソリオ大佐がサカパ・イザバル軍事地帯の司令官に任命され、1,000人の米国グリーンベレーの指導と訓練を受けて、対 テロプログラムを指揮した[82]。アラナ大佐の管轄下で、軍事戦略家たちは、正規軍と警察部隊を補完するために、さまざまな準軍事的決死隊を武装させ、 実戦投入し、FARの民間人支援基盤に対する秘密テロ作戦を行った。これらの組織には、軍から人員、武器、資金、作戦指示が提供された[83]。決死隊 は、政府によって反乱分子または反乱分子協力者とみなされた民間人を殺害することが許可されており、無罰で活動した[77]。軍の準軍事組織の民間人メン バーは、1954年のクーデターの元参加者であるマリオ・サンドバル・アラルコンが創設し率いたMLNとつながりのある右翼狂信者が大部分を占めていた。 1967年までにグアテマラ軍は1,800人の民間の準軍事組織を直接支配下に置いていると主張した。[84] 軍と準軍事組織がサカパを組織的に移動し、反乱軍と協力者と疑われる者を逮捕したため、ゲリラの協力者と共産主義に傾倒していると疑われる者のブラックリ ストが作成された[85]。[陸軍が親ゲリラだと疑った村では、陸軍は農民指導者を全員検挙して公開処刑し、村民が当局に協力しなければ、さらに民間人を 殺すと脅した。1976年の報告書で、アムネスティ・インターナショナルは、1966年10月から1968年3月の間にサカパとイザバルで3,000人か ら8,000人の農民が軍と準軍事組織によって殺害されたという推定を引用した[61][86][87]。他の推定では、メンデス時代のサカパでの死者数 は15,000人とされている[88]。その結果、アラナ・オソリオ大佐はその後、その残虐性から「サカパの虐殺者」というニックネームを得た。 包囲状態 1966年11月2日、グアテマラでは全国的な「包囲状態」が宣言され、人身保護権を含む市民権が停止された。その後、地方警察や民間の警備員を含む治安 組織全体が、当時の国防大臣ラファエル・アリアガ・ボスケ大佐の下に置かれた。サカパ作戦を完全に秘密にするための措置も含め、こうした治安対策と並行し て報道検閲が行われた。こうした統制によって、サカパでのテロ対策プログラムについて公表されるのは、軍の広報室が配る報告書だけとなった。また「包囲状 態」の当日には、軍当局の承認があるまで逮捕に関する報告の公表を禁止する指令が発表された[80]。 サカパ・キャンペーンのとき、政府は都市部における並行テロ対策プログラムを開始した。この新たなイニシアチブの一環として、警察部隊の軍事化が強化さ れ、都市部での対テロ機能、特に国家の敵対者に対する非合法的な活動を行うために、陸軍と国家警察のいくつかの新しい対テロ部隊が活性化された。国家警察 はその後、軍の付属部隊へと変貌し、左翼に対する政府の都市平定計画の最前線部隊となった[89]。 1967年1月、グアテマラ陸軍は「グアテマラ陸軍特別コマンド部隊」-SCUGA-を結成した。SCUGAは反共軍将校と右翼市民から構成された35人 のコマンド部隊で、マキシモ・ゼペダ大佐の指揮下に置かれた。SCUGAは、CIAが「政府が支援するテロ組織...主に暗殺と政治的拉致のために使われ る」[90]と呼んだ組織で、本物の共産主義者と疑われる共産主義者の拉致、爆弾テロ、路上暗殺、拷問、「失踪」、略式処刑を行った。1967年3月、国 防副大臣で対反乱コーディネーターのフランシスコ・ソサ・アビラ大佐が国家警察長官に任命されると、国家警察の対反乱特別部隊として知られる第4部隊が創 設され、SCUGAとともに非合法活動を行った[92]。 [92] 第4部隊は50人の非合法暗殺部隊で、ソサ大佐とアリアガ大佐の命令を受け、国家警察の他のメンバーから秘密裏に活動していた[93]。 SCUGAと第4部隊の下で実行された作戦は、通常、RAYO、NOA、CADEGなどの準軍事戦線を装って実行された[91]。1967年までに、少な くとも20のこのような暗殺部隊がグアテマラ・シティで活動し、殺人の標的とされた「共産主義者」と疑われる人物のブラックリストを掲載していた。 1968年1月、『グアテマラの人々よ、裏切り者であるFARのゲリラを知れ』と題された85人の名前を含む小冊子がグアテマラ全土に配布された。小冊子 に名前が記された者の多くは殺されるか、逃亡を余儀なくされた。殺害予告や警告が個人と組織の両方に送られた。例えば、CADEGのリーフレットには、労 働総同盟FECETRAGの指導部に宛ててこう書かれていた: 「あなたの時代が来た。フィデル・カストロ、ロシア、共産中国に仕える共産主義者たちよ。3月末日までに出国せよ」[94]。首都で政府の弾圧の犠牲に なったのは、ゲリラのシンパ、労働組合の指導者、知識人、学生、その他漠然と定義された「政府の敵」であった。一部の観察者は、グアテマラ政府の政策を 「白い恐怖」と呼んでいた。この用語は、台湾やスペインなどの国々における同様の反共産主義者による大量殺戮の時期を表すために以前使われていたものであ る[95]。 1967年末までに、対反乱プログラムはサカパとイザバルにおけるFAR反乱軍の事実上の敗北をもたらし、そのメンバーの多くがグアテマラ・シティに撤退 した。メンデス・モンテネグロ大統領は1967年、議会への年次メッセージで、反乱軍は敗北したと示唆した。反乱軍の敗北にもかかわらず、政府による殺害 は続いた。1967年12月、1959年の元「ミス・グアテマラ」で、左翼シンパとして知られていた26歳のロジェリア・クルス・マルティネスが逮捕さ れ、遺体で発見された。彼女の遺体には拷問、レイプ、切断の跡があった。1968年1月16日、この殺人事件への反発の中、連邦保安庁がアメリカ軍の顧問 団を乗せた車に発砲した。ジョン・D・ウェバー大佐(在グアテマラ米軍公館長)とアーネスト・A・マンロー海軍中佐が即死、他2人が負傷した。その後、 FARは、この殺害は、それまでの2年間に「4000人近いグアテマラ人を死に至らしめた」「大量虐殺勢力」を作り出したアメリカ人に対する報復であると 主張する声明を発表した[要出典]。 カサリエゴ大司教誘拐事件 1968年3月16日、誘拐犯は、重武装した軍隊と警察の面前で、ローマ・カトリックのマリオ・カサリエゴ・イ・アセベド大司教を国立宮殿から100ヤー ド以内で逮捕した。誘拐犯(陸軍上層部の命令を受けた治安部隊のメンバーの可能性もある)は、ゲリラ部隊を誘拐に関与させることで偽旗事件を演出するつも りだった。大司教は極めて保守的な見解で知られており、ゲリラの評判を落とすために「自己誘拐」を組織したのではないかと考えられた。しかし、大司教はこ の計画に乗ることを拒否し、誘拐犯は「カトリック信者の反共主義に訴えることで国家的危機を作り出す」ことを計画した[96]。大司教は4日間の拘束の 後、無傷で解放された。事件の余波で、作戦に関わった2人の民間人、ラウル・エストゥアルド・ロレンサナとイネス・ムフィオ・パディージャが逮捕され、警 察のパトカーで連行された。移動中、車は停止し、警察官たちは、武装集団がサブマシンガンを浴びせる中、車を降りた。ある報道によれば、ロレンサナの遺体 には27カ所、パディラの遺体には22カ所の銃創があったという。この暗殺事件で護衛の警察官は無傷だった。ラウル・ロレンサナはMANO決死隊の「フロ ントマン」として知られ、グアテマラ陸軍のクアルテル・デ・マタモロス本部とラ・アウロラ空軍基地にある政府の隠れ家を拠点に活動していた[97]。ラ ファエル・アリアガ・ボスケ国防相はフロリダ州マイアミに派遣され総領事となり、フランシスコ・ソサ・アビラ国防副大臣兼国家警察長官はスペイン駐在武官 として派遣され、アラナ・オソリオ大佐は当時アナスタシオ・ソモサ・デバイレの支配下にあったニカラグア駐在大使として派遣された。死の部隊」による政治 的殺人はその後数カ月で減少し、「包囲状態」は1968年6月24日に「警戒状態」にまで緩和された[98]。 ジョン・ゴードン・マイン大使とカール・フォン・スプライト伯爵の暗殺 カサリエゴ大司教の「誘拐」の余波による政治的暴力の小康状態は、数カ月後に終わった。1968年8月28日、ジョン・ゴードン・マイン米国大使が、グア テマラ・シティのレフォルマ通りにある米国領事館から1ブロックのところで、FARの反乱軍によって暗殺された。米国政府関係者は、FARが交換交渉のた めに彼を誘拐するつもりだったと考えたが、その代わりに、彼が逃げようとしたときに射殺された[99]。いくつかの情報源は、グアテマラ軍の最高司令部が マイン大使の暗殺に関与していたことを示唆した。これは、1976年に米国に逃亡し、1977年に銃器使用容疑で逮捕されたホルヘ・ジメリ・サフィという アラナ・オソリオ大佐の元ボディガードとされる人物によって、数年後に米国の捜査当局に主張されたことであった[100][101]。 グアテマラ警察は、ほぼ即座に犯罪を「解決」したと主張し、その日のうちに容疑者を突き止めたと発表した。その容疑者「ミシェール・ファーク(マイン誘拐 に使われた車を借りていたフランス人社会主義者)」は、警察が取り調べに来たときに拳銃自殺した[96]。ミシェールは手帳にこう書いていた: グアテマラに存在する腐敗の状態、そして住民たちが生きている永続的な恐怖を表現する言葉を見つけるのは難しい。毎日、モタグア川から死体が引き上げら れ、銃弾が撃ち込まれ、一部が魚に食べられている。警察のパトロールが介入することもなく、毎日、路上で、武装した車に乗った正体不明の人々によって男性 が誘拐されている[102]。 マイン大使が暗殺されたことで、軍によるより厳しい対反乱対策と米国の安全保障援助の増額を求める世論が高まった。これに続いて、新国防相ロランド・チン チラ・アギラール大佐と陸軍参謀長ドロテオ・レイエス大佐が、1968年9月に「大将」に昇進したという名目で、反対派メンバーの「決死隊」による殺害が 再開された。[103] 1970年3月31日、西ドイツ大使カール・フォン・スプライト伯爵は、FARの武装した男たちに車を妨害され、誘拐された。その後、FARは身代金70 万ドルと17人の政治犯(最終的には25人にまで引き上げられた)の釈放を要求する身代金要求書を出した。メンデス政府はFARとの協力を拒否し、外交界 とドイツ政府の怒りを買った。10日後の1970年4月9日、フォン・スプライトは匿名の電話で遺体の所在を知らされた後、遺体で発見された。 軍事政権による支配 主な記事 カルロス・アラナ・オソリオ 1970年7月、カルロス・アラナ・オソリオ大佐が大統領に就任した。軍の支援を受けたアラナは、MANO決死隊の発案者であるMLNと制度的民主党 (MLN-PID)の同盟を代表した。アラナは、1970年代から1980年代にかけてグアテマラの政治を支配した、制度民主党と手を組んだ一連の軍人支 配者の最初の人物であった(彼の前任者フリオ・セザール・メンデスは、軍に支配されていたとはいえ、文民であった)。サカパでのテロ作戦を担当していたア ラナ大佐は反共強硬派で、「国を平和にするために墓地にする必要があるなら、私は躊躇なくそうする」と述べたこともある[104][105]。 当時、武装反乱軍の活動は最小限であったにもかかわらず、アラナは1970年11月13日に再び「包囲状態」を宣言し、午後9時から午前5時まで夜間外出 禁止令を出し、その間、救急車、消防車、看護師、医師を含むすべての車両と歩行者の通行は国土全域で禁止された。包囲は警察による家宅捜索を伴い、「包囲 状態 」の最初の15日間で首都で1,600人が拘束されたと報告されている。アラナはまた服装規定を課し、女性のミニスカートと男性の長髪を禁止した [106]。当時、外国人ジャーナリストによって引用された政府高官筋は、「包囲状態」の最初の2ヶ月間に治安部隊または準軍事的な決死隊によって700 人の処刑が行われたことを認めている[107]。 このことは、治安部隊によってグアテマラの田舎で「テロリストと盗賊」と疑われる数百人が排除されたことを詳述した、1971年1月のアメリカ国防情報局 の秘密情報によって裏付けられた[108]。 地方では政府による弾圧が続いたが、アラナのもとでの政府による弾圧の犠牲者の大半は首都の住民であった。「政府の統制下でありながら司法手続きの外で」 行動する軍と国家警察第4部隊の「特殊コマンド」[109]は、グアテマラ・シティで数千人の左翼、学生、労働組合の指導者、常習犯を拉致し、拷問し、殺 害した。1970年11月、「司法警察」は正式に解散させられ、国家警察の新しい半自律的な情報機関として、私服で活動するメンバーで構成される「刑事 団」が発足し、最終的には弾圧で悪名高いものとなった[110]。 当時国家警察が一般的に用いていた拷問方法のひとつは、殺虫剤を入れたゴム製の「フード」を被害者の頭からかぶせて窒息させるというものだった[61]。 アラナによる包囲状態の最初の犠牲者の一部は、マスコミや大学における彼の批判者であった。1970年11月26日、グアテマラシティで、治安部隊は、弾 圧を非難する新聞記事に対する明らかな報復として、ジャーナリストのエンリケ・サラサール・ソロルサノとルイス・ペレス・ディアスを捕らえ、消息を絶っ た。11月27日、国立大学法学部教授で政府批判者のフリオ・カメイ・エレーラが殺害されているのが発見された。翌日、ラジオ局経営者のウンベルト・ゴン ザレス・フアレス、仕事仲間のアルマンド・ブラン・バジェ、秘書が失踪し、その後、谷間で遺体が発見された。その後、1975年に、国家警察の刑事部隊の 元メンバー(非政治的な殺人罪で投獄された)が、この殺害の手柄を立てた[111]。 1971年10月、グアテマラ・サンカルロス大学の12,000人以上の学生が、治安部隊による学生殺害に抗議するゼネストを行った。1971年11月 27日、グアテマラ軍は武器庫を求めて大学のメインキャンパスを大々的に襲撃した。800人の軍人と戦車、ヘリコプター、装甲車を動員した。彼らはキャン パス全体を部屋ごとに捜索したが、証拠も物資も発見できなかった[112]。 この時期、首都では警察と諜報機関によって運営される多くの決死隊が出現した。1972年10月13日のある事件では、「復讐するハゲタカ 」として知られる決死隊の名の下に、10人がナイフで刺殺された。グアテマラ政府筋は米国務省に対し、この時期に活動していた「復讐のハゲタカ」やその他 の類似の決死隊は、国家警察が非政治的な非行少年に対して採用していた非合法戦術の「煙幕」であったことを確認した[113]。 [113] この時期に活動していたもうひとつの悪名高い決死隊は「オホ・ポル・オホ」(目には目を)で、米国務省の情報公電では「民間人の協力もあるが、大部分が軍 人のメンバー」と記述されていた[114]。「オホ・ポル・オホ」は1970年代前半に、PGTに関係する、あるいはFARに協力した疑いのある民間人を 拷問し、殺害し、切断した。 アムネスティ・インターナショナルや「失踪者親族委員会」のような国内の人権団体によれば、1970年と1971年には7,000人以上の治安部隊に反対 する民間人が「失踪」または死体で発見され、1972年と1973年にはさらに8,000人が失踪した[115]。 1973年1月から9月の間に、グアテマラ人権委員会は、決死隊による1,314人の死亡と強制失踪を記録した[116]。 アムネスティ・インターナショナルは、1972年から1973年の年次報告書において、「グアテマラ市民の失踪の多発」を主要かつ継続的な問題として挙げ ながら、人権非常事態下にあるいくつかの国の一つとしてグアテマラを挙げた[118][119]。 全体として、1966年から1973年の間に42,000人ものグアテマラ市民が殺害されるか「失踪」した[120]。 |

| Franja Transversal del Norte Main article: Franja Transversal del Norte  Location of Franja Transversal del Norte -Northern Transversal Strip- in Guatemala. The first settler project in the FTN was in Sebol-Chinajá in Alta Verapaz. Sebol, then regarded as a strategic point and route through Cancuén river, which communicated with Petén through the Usumacinta River on the border with Mexico and the only road that existed was a dirt one built by President Lázaro Chacón in 1928. In 1958, during the government of General Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) financed infrastructure projects in Sebol.[b] In 1960, then Army captain Fernando Romeo Lucas García inherited Saquixquib and Punta de Boloncó farms in northeastern Sebol. In 1963 he bought the farm "San Fernando" El Palmar de Sejux and finally bought the "Sepur" farm near San Fernando. During those years, Lucas was in the Guatemalan legislature and lobbied in Congress to boost investment in that area of the country.[121] In those years, the importance of the region was in livestock, exploitation of precious export wood, and archaeological wealth. Timber contracts were granted to multinational companies such as Murphy Pacific Corporation from California, which invested US$30 million for the colonization of southern Petén and Alta Verapaz, and formed the North Impulsadora Company. Colonization of the area was made through a process by which inhospitable areas of the FTN were granted to native peasants.[122] In 1962, the DGAA became the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INTA), by Decree 1551 which created the law of Agrarian Transformation. In 1964, INTA defined the geography of the FTN as the northern part of the departments of Huehuetenango, Quiché, Alta Verapaz and Izabal and that same year priests of the Maryknoll order and the Order of the Sacred Heart began the first process of colonization, along with INTA, carrying settlers from Huehuetenango to the Ixcán sector in Quiché.[123] It is of public interest and national emergency, the establishment of Agrarian Development Zones in the area included within the municipalities: San Ana Huista, San Antonio Huista, Nentón, Jacaltenango, San Mateo Ixtatán, and Santa Cruz Barillas in Huehuetenango; Chajul and San Miguel Uspantán in Quiché; Cobán, Chisec, San Pedro Carchá, Lanquín, Senahú, Cahabón and Chahal, in Alta Verapaz and the entire department of Izabal. -- Decreto 60–70, artítulo 1o.[124] The Northern Transversal Strip was officially created during the government of General Carlos Arana Osorio in 1970, by Legislative Decree 60–70, for agricultural development.[125] Guerrilla Army of the Poor Main article: Guerrilla Army of the Poor On 19 January 1972, members of a new Guatemalan guerrilla movement (made up of surviving former leaders of the FAR) entered Ixcán, from Mexico, and were accepted by many farmers; in 1973, after an exploratory foray into the municipal seat of Cotzal, the insurgent group decided to set up camp underground in the mountains of Xolchiché, municipality of Chajul.[126] In 1974 the insurgent guerrilla group held its first conference, where it defined its strategy of action for the coming months and called itself Guerrilla Army of the Poor (-Ejército Guerrillero de Los Pobres -EGP-). In 1975 the organization had spread around the area of the mountains of northern municipalities of Nebaj and Chajul. As part of its strategy, EGP decided to perpetrate notorious acts which also symbolized the establishment of a "social justice" against the inefficiency and ineffectiveness of the judicial and administrative State institutions. They also wanted that with these actions the indigenous rural population of the region identified with the insurgency, thus motivating them to join their ranks. As part of this plan it was agreed to do the so-called "executions"; in order to determine who would be subject to "execution", the EGP gathered complaints received from local communities. For example, they selected two victims: Guillermo Monzón, who was a military Commissioner in Ixcán and José Luis Arenas, the largest landowner in the area, and who had been reported to the EGP for allegedly having land conflicts with neighboring settlements and abusing their workers.[126][c] |

ノルテ横断地帯 主な記事 フランハ・トランスヴェルサル・デル・ノルテ  グアテマラのフランハ・トランスヴェルサル・デル・ノルテ(北部横断帯)の位置。 FTNにおける最初の入植者プロジェクトは、アルタ・ベラパスのセボル-シナハであった。セボルは当時、メキシコとの国境にあるウスマシンタ川を通じてペ テンと連絡していたカンクエン川を通るルートであり、戦略上の要衝と見なされていたため、1928年にラサロ・チャコン大統領が建設した未舗装の道路しか 存在しなかった。1958年、ミゲル・イディゴラス・フエンテス将軍の政権時代に、米州開発銀行(IDB)はセボルのインフラ・プロジェクトに融資した [b] 1960年、当時の陸軍大尉フェルナンド・ロメオ・ルーカス・ガルシアは、セボル北東部のサキスキブとプンタ・デ・ボロンコ農場を相続した。1963年に は「サン・フェルナンド」エル・パルマル・デ・セジュクス農場を購入し、最終的にはサン・フェルナンド近郊の「セプール」農場を購入した。その間、ルーカ スはグアテマラ議会議員を務め、同国への投資を促進するよう議会に働きかけた[121]。 当時、この地域の重要性は畜産、貴重な輸出木材の搾取、考古学的な富にあった。木材契約は、ペテン南部とアルタ・ベラパスの植民地化のために3,000万 米ドルを投資し、ノース・インプルサドーラ社を設立したカリフォルニアのマーフィー・パシフィック社などの多国籍企業に付与された。この地域の植民地化 は、FTNの人を寄せ付けない地域が先住民の農民に与えられるというプロセスを通じて行われた[122]。 1962年、農地改革法を制定した政令1551号によって、DGAAは国立農地改革研究所(INTA)となった。1964年、INTAはFTNの地理をフ エヘテナンゴ県、キチェ県、アルタ・ベラパス県、イザバル県の北部と定義し、同年、メリノール会と聖心会の司祭たちはINTAとともに、フエヘテナンゴか らキチェのイクスカン地区への入植者を運ぶ最初の植民地化プロセスを開始した[123]。 公共的な関心と国家的な緊急事態であり、市町村に含まれる地域に農業開発地帯を設立することである: フエウエテナンゴのサン・アナ・ウイスタ、サン・アントニオ・ウイスタ、ネントン、ハカルテナンゴ、サン・マテオ・イスタタン、サンタ・クルス・バリジャ ス、キチェのチャジュルとサン・ミゲル・ウスパンタン、アルタ・ベラパスのコバン、チセック、サン・ペドロ・カルチャ、ランキン、セナフー、カハボン、 チャハル、およびイザバル県全域である。 -- デクレト60-70、第1条[124]。 北部横断帯は、1970年のカルロス・アラナ・オソリオ将軍の政権時代に、農業開発のために政令60-70号によって正式に作られた[125]。 貧民ゲリラ軍団 主な記事 貧民ゲリラ軍 1972年1月19日、新しいグアテマラ・ゲリラ運動(FARの元指導者たちの生き残りで構成)のメンバーがメキシコからイクスカンに入り、多くの農民た ちに受け入れられた。1973年、コツァルの市庁所在地に探検的に侵入した後、反乱グループはチャジュルの自治体であるソルチチェの山中に地下キャンプを 張ることを決定した[126]。 1974年、反乱ゲリラ・グループは最初の会議を開き、そこで今後数ヶ月の行動戦略を定義し、自らを貧民ゲリラ軍(Ejército Guerrillero de Los Pobres -EGP)と名乗った。1975年、この組織はネバジとチャジュルの北部自治体の山間部一帯に広がっていた。その戦略の一環として、EGPは、司法・行政 国家機関の非効率・無能に対する「社会正義」の確立を象徴する悪名高い行為を行うことを決定した。彼らはまた、こうした行為によって、この地域の土着の農 村住民が反乱軍に同調し、彼らの仲間入りをする動機付けになることを望んでいた。この計画の一環として、いわゆる「処刑」を行うことが合意された。「処 刑」の対象となる人物を決定するために、EGPは地元コミュニティから寄せられた苦情を集めた。例えば、彼らは2人の犠牲者を選んだ: 例えば、イクスカンの軍事委員であったギジェルモ・モンソンと、この地域で最大の地主であり、近隣の集落との土地紛争や労働者の虐待の疑いでEGPに報告 されていたホセ・ルイス・アレナスである[126][c]。 |